Title: Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Author: W. W. Jacobs

Illustrator: Will Owen

Release date: January 1, 2004 [eBook #10573]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

Fine Feathers

Friends

in Need

Good Intentions

Fairy Gold

Watch-Dogs

The Bequest

The Guardian

Angel

Dual Control

Skilled Assistance

For

Better or Worse

The Old Man of The Sea

"Manners Makyth Man"

"Can I 'ave it took off while I eat my bloater,

mother?"

"Been paddlin'?” he inquired

"Cheer up,” said Mr George Brown

Mr Gibbs, with his back against the post, fought for

nearly half an hour

"Where is he?” she gasped

"Gone!” exclaimed both gentlemen “Where?"

"Why was wimmen made? Wot good are they?"

"As far as I'm concerned he can take this lady to a

music-'all every night"

Mr Chase, with his

friend in his powerful grasp, was doing his best

"What on earth's the matter?” she inquired

"As I was a-saying, kindness to animals is all very well"

"The quietest man o' the whole lot was Bob Pretty"

"Some of 'em went and told Mr Bunnett some more things

about Bob next day"

"Bob Pretty lifted 'is

foot and caught Joseph one behind"

"Me?” said

the other, with a gasp “Me?"

"Evening, Bob,”

he said, in stricken accents

"Just what I told

her,” said Mr Digson “What'll please you will be sure...

"She'll be riding in her carriage and pair in six months"

"The lodger was standing at the foot o' bed, going

through 'is pockets"

“'We thought you might

want it, Sam,' ses Peter"

A very faint squeeze

in return decided him

He felt the large and

clumsy hand of Mr Butler take him by the collar

"I

tell you, I am as innercent as a new-born babe"

"And

next moment I went over back'ards in twelve foot of water"

His friend complied

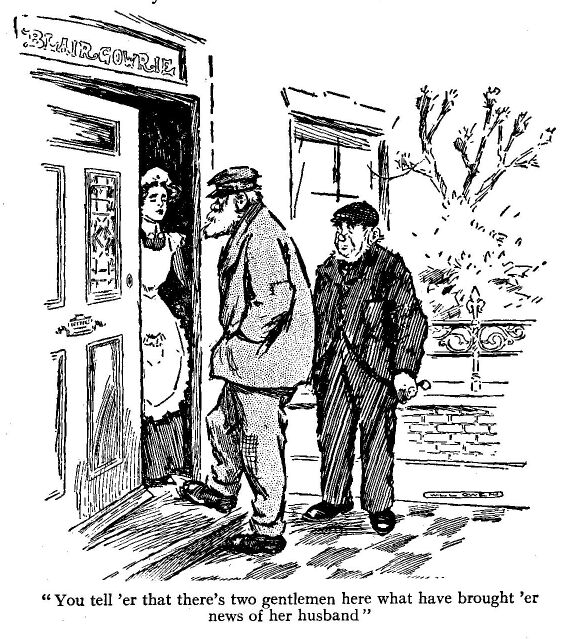

"You tell

'er that there's two gentlemen here what have brought her news"

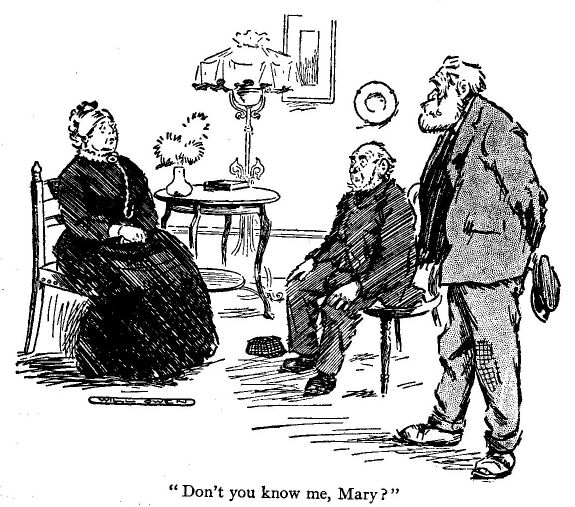

"Don't you know me, Mary?"

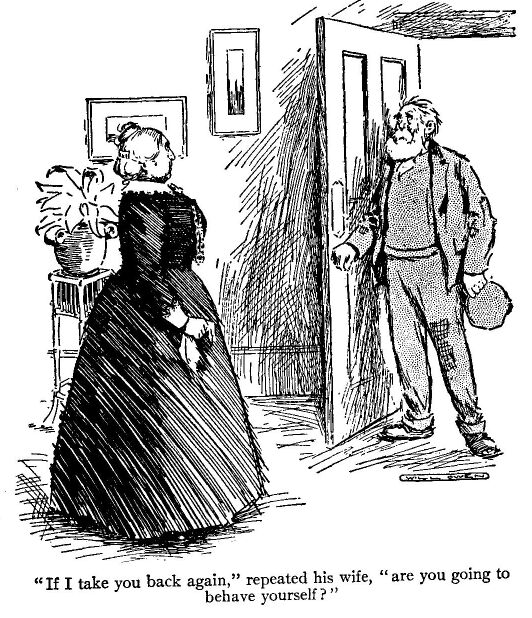

"If

I take you back again,” repeated his wife, “are you going to behave?"

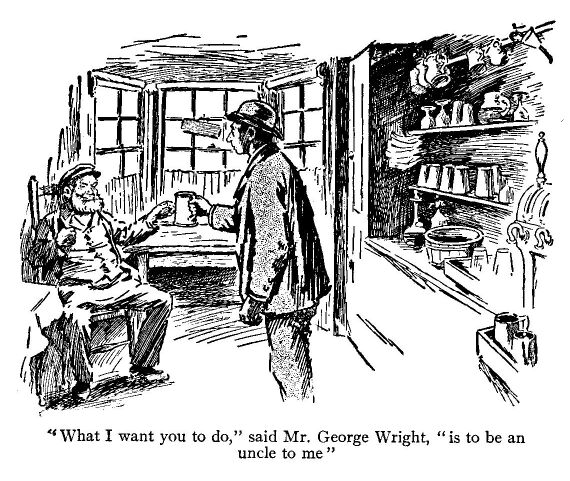

"What I want you to do,” said Mr George Wright, “is to

be an uncle to me"

"It'll do to go on with,”

he said

"'Ow much did you say you'd got in the

bank?"

"'Gal overboard!' I ses, shouting"

"Arter trying his 'ardest, he could only rock me a bit"

Mr. Jobson awoke with a Sundayish feeling, probably due to the fact that it was Bank Holiday. He had been aware, in a dim fashion, of the rising of Mrs. Jobson some time before, and in a semi-conscious condition had taken over a large slice of unoccupied territory. He stretched himself and yawned, and then, by an effort of will, threw off the clothes and springing out of bed reached for his trousers.

He was an orderly man, and had hung them every night for over twenty years on the brass knob on his side of the bed. He had hung them there the night before, and now they had absconded with a pair of red braces just entering their teens. Instead, on a chair at the foot of the bed was a collection of garments that made him shudder. With trembling fingers he turned over a black tailcoat, a white waistcoat, and a pair of light check trousers. A white shirt, a collar, and tie kept them company, and, greatest outrage of all, a tall silk hat stood on its own band-box beside the chair. Mr. Jobson, fingering his bristly chin, stood: regarding the collection with a wan smile.

“So that's their little game, is it?” he muttered. “Want to make a toff of me. Where's my clothes got to, I wonder?”

A hasty search satisfied him that they were not in the room, and, pausing only to drape himself in the counterpane, he made his way into the next. He passed on to the others, and then, with a growing sense of alarm, stole softly downstairs and making his way to the shop continued the search. With the shutters up the place was almost in darkness, and in spite of his utmost care apples and potatoes rolled on to the floor and travelled across it in a succession of bumps. Then a sudden turn brought the scales clattering down.

“Good gracious, Alf!” said a voice. “Whatever are you a-doing of?”

Mr. Jobson turned and eyed his wife, who was standing at the door.

“I'm looking for my clothes, mother,” he replied, briefly.

“Clothes!” said Mrs. Jobson, with an obvious attempt at unconcerned speech. “Clothes! Why, they're on the chair.”

“I mean clothes fit for a Christian to wear—fit for a greengrocer to wear,” said Mr. Jobson, raising his voice.

“It was a little surprise for you, dear,” said his wife. “Me and Bert and Gladys and Dorothy 'ave all been saving up for it for ever so long.”

“It's very kind of you all,” said Mr. Jobson, feebly—“very, but—”

“They've all been doing without things themselves to do it,” interjected his wife. “As for Gladys, I'm sure nobody knows what she's given up.”

“Well, if nobody knows, it don't matter,” said Mr. Jobson. “As I was saying, it's very kind of you all, but I can't wear 'em. Where's my others?”

Mrs. Jobson hesitated.

“Where's my others?” repeated her husband.

“They're being took care of,” replied his wife, with spirit. “Aunt Emma's minding 'em for you—and you know what she is. H'sh! Alf! Alf! I'm surprised at you!”

Mr. Jobson coughed. “It's the collar, mother,” he said at last. “I ain't wore a collar for over twenty years; not since we was walking out together. And then I didn't like it.”

“More shame for you,” said his wife. “I'm sure there's no other respectable tradesman goes about with a handkerchief knotted round his neck.”

“P'r'aps their skins ain't as tender as what mine is,” urged Mr. Jobson; “and besides, fancy me in a top-'at! Why, I shall be the laughing-stock of the place.”

“Nonsense!” said his wife. “It's only the lower classes what would laugh, and nobody minds what they think.”

Mr. Jobson sighed. “Well, I shall 'ave to go back to bed again, then,” he said, ruefully. “So long, mother. Hope you have a pleasant time at the Palace.”

He took a reef in the counterpane and with a fair amount of dignity, considering his appearance, stalked upstairs again and stood gloomily considering affairs in his bedroom. Ever since Gladys and Dorothy had been big enough to be objects of interest to the young men of the neighbourhood the clothes nuisance had been rampant. He peeped through the window-blind at the bright sunshine outside, and then looked back at the tumbled bed. A murmur of voices downstairs apprised him that the conspirators were awaiting the result.

He dressed at last and stood like a lamb—a redfaced, bull-necked lamb— while Mrs. Jobson fastened his collar for him.

“Bert wanted to get a taller one,” she remarked, “but I said this would do to begin with.”

“Wanted it to come over my mouth, I s'pose,” said the unfortunate Mr. Jobson. “Well, 'ave it your own way. Don't mind about me. What with the trousers and the collar, I couldn't pick up a sovereign if I saw one in front of me.”

“If you see one I'll pick it up for you,” said his wife, taking up the hat and moving towards the door. “Come along!”

Mr. Jobson, with his arms standing out stiffly from his sides and his head painfully erect, followed her downstairs, and a sudden hush as he entered the kitchen testified to the effect produced by his appearance. It was followed by a hum of admiration that sent the blood flying to his head.

“Why he couldn't have done it before I don't know,” said the dutiful Gladys. “Why, there ain't a man in the street looks a quarter as smart.”

“Fits him like a glove!” said Dorothy, walking round him.

“Just the right length,” said Bert, scrutinizing the coat.

“And he stands as straight as a soldier,” said Gladys, clasping her hands gleefully.

“Collar,” said Mr. Jobson, briefly. “Can I 'ave it took off while I eat my bloater, mother?”

“Don't be silly, Alf,” said his wife. “Gladys, pour your father out a nice, strong, Pot cup o' tea, and don't forget that the train starts at ha' past ten.”

“It'll start all right when it sees me,” observed Mr. Jobson, squinting down at his trousers.

Mother and children, delighted with the success of their scheme, laughed applause, and Mr. Jobson somewhat gratified at the success of his retort, sat down and attacked his breakfast. A short clay pipe, smoked as a digestive, was impounded by the watchful Mrs. Jobson the moment he had finished it.

“He'd smoke it along the street if I didn't,” she declared.

“And why not?” demanded her husband—“always do.”

“Not in a top-'at,” said Mrs. Jobson, shaking her head at him.

“Or a tail-coat,” said Dorothy.

“One would spoil the other,” said Gladys.

“I wish something would spoil the hat,” said Mr. Jobson, wistfully. “It's no good; I must smoke, mother.”

Mrs. Jobson smiled, and, going to the cupboard, produced, with a smile of triumph, an envelope containing seven dangerous-looking cigars. Mr. Jobson whistled, and taking one up examined it carefully.

“What do they call 'em, mother?” he inquired. “The 'Cut and Try Again Smokes'?”

Mrs. Jobson smiled vaguely. “Me and the girls are going upstairs to get ready now,” she said. “Keep your eye on him, Bert!”

Father and son grinned at each other, and, to pass the time, took a cigar apiece. They had just finished them when a swish and rustle of skirts sounded from the stairs, and Mrs. Jobson and the girls, beautifully attired, entered the room and stood buttoning their gloves. A strong smell of scent fought with the aroma of the cigars.

“You get round me like, so as to hide me a bit,” entreated Mr. Jobson, as they quitted the house. “I don't mind so much when we get out of our street.”

Mrs. Jobson laughed his fears to scorn.

“Well, cross the road, then,” said Mr. Jobson, urgently. “There's Bill Foley standing at his door.”

His wife sniffed. “Let him stand,” she said, haughtily.

Mr. Foley failed to avail himself of the permission. He regarded Mr. Jobson with dilated eyeballs, and, as the party approached, sank slowly into a sitting position on his doorstep, and as the door opened behind him rolled slowly over onto his back and presented an enormous pair of hobnailed soles to the gaze of an interested world.

“I told you 'ow it would be,” said the blushing Mr. Jobson. “You know what Bill's like as well as I do.”

His wife tossed her head and they all quickened their pace. The voice of the ingenious Mr. Foley calling piteously for his mother pursued them to the end of the road.

“I knew what it 'ud be,” said Mr. Jobson, wiping his hot face. “Bill will never let me 'ear the end of this.”

“Nonsense!” said his wife, bridling. “Do you mean to tell me you've got to ask Bill Foley 'ow you're to dress? He'll soon get tired of it; and, besides, it's just as well to let him see who you are. There's not many tradesmen as would lower themselves by mixing with a plasterer.”

Mr. Jobson scratched his ear, but wisely refrained from speech. Once clear of his own district mental agitation subsided, but bodily discomfort increased at every step. The hat and the collar bothered him most, but every article of attire contributed its share. His uneasiness was so manifest that Mrs. Jobson, after a little womanly sympathy, suggested that, besides Sundays, it might be as well to wear them occasionally of an evening in order to get used to them.

“What, 'ave I got to wear them every Sunday?” demanded the unfortunate, blankly; “why, I thought they was only for Bank Holidays.”

Mrs. Jobson told him not to be silly.

“Straight, I did,” said her husband, earnestly. “You've no idea 'ow I'm suffering; I've got a headache, I'm arf choked, and there's a feeling about my waist as though I'm being cuddled by somebody I don't like.”

Mrs. Jobson said it would soon wear off and, seated in the train that bore them to the Crystal Palace, put the hat on the rack. Her husband's attempt to leave it in the train was easily frustrated and his explanation that he had forgotten all about it received in silence. It was evident that he would require watching, and under the clear gaze of his children he seldom had a button undone for more than three minutes at a time.

The day was hot and he perspired profusely. His collar lost its starch— a thing to be grateful for—and for the greater part of the day he wore his tie under the left ear. By the time they had arrived home again he was in a state of open mutiny.

“Never again,” he said, loudly, as he tore the collar off and hung his coat on a chair.

There was a chorus of lamentation; but he remained firm. Dorothy began to sniff ominously, and Gladys spoke longingly of the fathers possessed by other girls. It was not until Mrs. Jobson sat eyeing her supper, instead of eating it, that he began to temporize. He gave way bit by bit, garment by garment. When he gave way at last on the great hat question, his wife took up her knife and fork.

His workaday clothes appeared in his bedroom next morning, but the others still remained in the clutches of Aunt Emma. The suit provided was of considerable antiquity, and at closing time, Mr. Jobson, after some hesitation, donned his new clothes and with a sheepish glance at his wife went out; Mrs. Jobson nodded delight at her daughters.

“He's coming round,” she whispered. “He liked that ticket-collector calling him 'sir' yesterday. I noticed it. He's put on everything but the topper. Don't say nothing about it; take it as a matter of course.”

It became evident as the days wore on that she was right... Bit by bit she obtained the other clothes—with some difficulty—from Aunt Emma, but her husband still wore his best on Sundays and sometimes of an evening; and twice, on going into the bedroom suddenly, she had caught him surveying himself at different angles in the glass.

And, moreover, he had spoken with some heat—for such a good-tempered man—on the shortcomings of Dorothy's laundry work.

“We'd better put your collars out,” said his wife.

“And the shirts,” said Mr. Jobson. “Nothing looks worse than a bad got-up cuff.”

“You're getting quite dressy,” said his wife, with a laugh.

Mr. Jobson eyed her seriously.

“No, mother, no,” he replied. “All I've done is to find out that you're right, as you always 'ave been. A man in my persition has got no right to dress as if he kept a stall on the kerb. It ain't fair to the gals, or to young Bert. I don't want 'em to be ashamed of their father.”

“They wouldn't be that,” said Mrs. Jobson.

“I'm trying to improve,” said her husband. “O' course, it's no use dressing up and behaving wrong, and yesterday I bought a book what tells you all about behaviour.”

“Well done!” said the delighted Mrs. Jobson.

Mr. Jobson was glad to find that her opinion on his purchase was shared by the rest of the family. Encouraged by their approval, he told them of the benefit he was deriving from it; and at tea-time that day, after a little hesitation, ventured to affirm that it was a book that might do them all good.

“Hear, hear!” said Gladys.

“For one thing,” said Mr. Jobson, slowly, “I didn't know before that it was wrong to blow your tea; and as for drinking it out of a saucer, the book says it's a thing that is only done by the lower orders.”

“If you're in a hurry?” demanded Mr. Bert Jobson, pausing with his saucer half way to his mouth.

“If you're in anything,” responded his father. “A gentleman would rather go without his tea than drink it out of a saucer. That's the sort o' thing Bill Foley would do.”

Mr. Bert Jobson drained his saucer thoughtfully.

“Picking your teeth with your finger is wrong, too,” said Mr. Jobson, taking a breath. “Food should be removed in a—a—un-undemonstrative fashion with the tip of the tongue.”

“I wasn't,” said Gladys.

“A knife,” pursued her father—“a knife should never in any circumstances be allowed near the mouth.”

“You've made mother cut herself,” said Gladys, sharply; “that's what you've done.”

“I thought it was my fork,” said Mrs. Jobson. “I was so busy listening I wasn't thinking what I was doing. Silly of me.”

“We shall all do better in time,” said Mr. Jobson. “But what I want to know is, what about the gravy? You can't eat it with a fork, and it don't say nothing about a spoon. Oh, and what about our cold tubs, mother?”

“Cold tubs?” repeated his wife, staring at him. “What cold tubs?”

“The cold tubs me and Bert ought to 'ave,” said Mr. Jobson. “It says in the book that an Englishman would just as soon think of going without his breakfus' as his cold tub; and you know how fond I am of my breakfus'.”

“And what about me and the gals?” said the amazed Mrs. Jobson.

“Don't you worry about me, ma,” said Gladys, hastily.

“The book don't say nothing about gals; it says Englishmen,” said Mr. Jobson.

“But we ain't got a bathroom,” said his son.

“It don't signify,” said Mr. Jobson. “A washtub'll do. Me and Bert'll 'ave a washtub each brought up overnight; and it'll be exercise for the gals bringing the water up of a morning to us.”

“Well, I don't know, I'm sure,” said the bewildered Mrs. Jobson. “Anyway, you and Bert'll 'ave to carry the tubs up and down. Messy, I call it.

“It's got to be done, mother,” said Mr. Jobson cheerfully. “It's only the lower orders what don't 'ave their cold tub reg'lar. The book says so.”

He trundled the tub upstairs the same night and, after his wife had gone downstairs next morning, opened the door and took in the can and pail that stood outside. He poured the contents into the tub, and, after eyeing it thoughtfully for some time, agitated the surface with his right foot. He dipped and dried that much enduring member some ten times, and after regarding the damp condition of the towels with great satisfaction, dressed himself and went downstairs.

“I'm all of a glow,” he said, seating himself at the table. “I believe I could eat a elephant. I feel as fresh as a daisy; don't you, Bert?”

Mr. Jobson, junior, who had just come in from the shop, remarked, shortly, that he felt more like a blooming snowdrop.

“And somebody slopped a lot of water over the stairs carrying it up,” said Mrs. Jobson. “I don't believe as everybody has cold baths of a morning. It don't seem wholesome to me.”

Mr. Jobson took a book from his pocket, and opening it at a certain page, handed it over to her.

“If I'm going to do the thing at all I must do it properly,” he said, gravely. “I don't suppose Bill Foley ever 'ad a cold tub in his life; he don't know no better. Gladys!”

“Halloa!” said that young lady, with a start.

“Are you—are you eating that kipper with your fingers?”

Gladys turned and eyed her mother appealingly.

“Page-page one hundred and something, I think it is,” said her father, with his mouth full. “'Manners at the Dinner Table.' It's near the end of the book, I know.”

“If I never do no worse than that I shan't come to no harm,” said his daughter.

Mr. Jobson shook his head at her, and after eating his breakfast with great care, wiped his mouth on his handkerchief and went into the shop.

“I suppose it's all right,” said Mrs. Jobson, looking after him, “but he's taking it very serious—very.”

“He washed his hands five times yesterday morning,” said Dorothy, who had just come in from the shop to her breakfast; “and kept customers waiting while he did it, too.”

“It's the cold-tub business I can't get over,” said her mother. “I'm sure it's more trouble to empty them than what it is to fill them. There's quite enough work in the 'ouse as it is.”

“Too much,” said Bert, with unwonted consideration.

“I wish he'd leave me alone,” said Gladys. “My food don't do me no good when he's watching every mouthful I eat.”

Of murmurings such as these Mr. Jobson heard nothing, and in view of the great improvement in his dress and manners, a strong resolution was passed to avoid the faintest appearance of discontent. Even when, satisfied with his own appearance, he set to work to improve that of Mrs. Jobson, that admirable woman made no complaint. Hitherto the brightness of her attire and the size of her hats had been held to atone for her lack of figure and the roomy comfort of her boots, but Mr. Jobson, infected with new ideas, refused to listen to such sophistry. He went shopping with Dorothy; and the Sunday after, when Mrs. Jobson went for an airing with him, she walked in boots with heels two inches high and toes that ended in a point. A waist that had disappeared some years before was recaptured and placed in durance vile; and a hat which called for a new style of hair-dressing completed the effect.

“You look splendid, ma!” said Gladys, as she watched their departure. “Splendid!”

“I don't feel splendid,” sighed Mrs. Jobson to her husband. “These 'ere boots feel red-'ot.”

“Your usual size,” said Mr. Jobson, looking across the road.

“And the clothes seem just a teeny-weeny bit tight, p'r'aps,” continued his wife.

Mr. Jobson regarded her critically. “P'r'aps they might have been let out a quarter of an inch,” he: said, thoughtfully. “They're the best fit you've 'ad for a long time, mother. I only 'ope the gals'll 'ave such good figgers.”

His wife smiled faintly, but, with little breath for conversation, walked on for some time in silence. A growing redness of face testified to her distress.

“I—I feel awful,” she said at last, pressing her hand to her side. “Awful.”

“You'll soon get used to it,” said Mr. Jobson, gently. “Look at me! I felt like you do at first, and now I wouldn't go back to old clothes—and comfort—for anything. You'll get to love them boots.

“If I could only take 'em off I should love 'em better,” said his wife, panting; “and I can't breathe properly—I can't breathe.”

“You look ripping, mother,” said her husband, simply.

His wife essayed another smile, but failed. She set her lips together and plodded on, Mr. Jobson chatting cheerily and taking no notice of the fact that she kept lurching against him. Two miles from home she stopped and eyed him fixedly.

“If I don't get these boots off, Alf, I shall be a 'elpless cripple for the rest of my days,” she murmured. “My ankle's gone over three times.”

“But you can't take 'em off here,” said Mr. Jobson, hastily. “Think 'ow it would look.”

“I must 'ave a cab or something,” said his wife, hysterically. “If I don't get 'em off soon I shall scream.”

She leaned against the iron palings of a house for support, while Mr. Jobson, standing on the kerb, looked up and down the road for a cab. A four-wheeler appeared just in time to prevent the scandal—of Mrs. Jobson removing her boots in the street.

“Thank goodness,” she gasped, as she climbed in. “Never mind about untying 'em, Alf; cut the laces and get 'em off quick.”

They drove home with the boots standing side by side on the seat in front of them. Mr. Jobson got out first and knocked at the door, and as soon as it opened Mrs. Jobson pattered across the intervening space with the boots dangling from her hand. She had nearly reached the door when Mr. Foley, who had a diabolical habit of always being on hand when he was least wanted, appeared suddenly from the offside of the cab.

“Been paddlin'?” he inquired.

Mrs. Jobson, safe in her doorway, drew herself up and, holding the boots behind her, surveyed him with a stare of high-bred disdain.

“Been paddlin'?” he inquired

“I see you going down the road in 'em,” said the unabashed Mr. Foley, “and I says to myself, I says, 'Pride'll bear a pinch, but she's going too far. If she thinks that she can squeedge those little tootsywootsies of 'ers into them boo—'”

The door slammed violently and left him exchanging grins with Mr. Jobson.

“How's the 'at?” he inquired.

Mr. Jobson winked. “Bet you a level 'arf-dollar I ain't wearing it next Sunday,” he said, in a hoarse whisper.

Mr. Foley edged away.

“Not good enough,” he said, shaking his head. “I've had a good many bets with you first and last, Alf, but I can't remember as I ever won one yet. So long.”

R. Joseph Gibbs finished his half-pint in the private bar of the Red Lion with the slowness of a man unable to see where the next was coming from, and, placing the mug on the counter, filled his pipe from a small paper of tobacco and shook his head slowly at his companions.

“First I've 'ad since ten o'clock this morning,” he said, in a hard voice.

“Cheer up,” said Mr. George Brown.

“It can't go on for ever,” said Bob Kidd, encouragingly.

“All I ask for—is work,” said Mr. Gibbs, impressively. “Not slavery, mind yer, but work.”

“It's rather difficult to distinguish,” said Mr. Brown.

“'Specially for some people,” added Mr. Kidd.

“Go on,” said Mr. Gibbs, gloomily. “Go on. Stand a man 'arf a pint, and then go and hurt 'is feelings. Twice yesterday I wondered to myself what it would feel like to make a hole in the water.”

“Lots o' chaps do do it,” said Mr. Brown, musingly.

“And leave their wives and families to starve,” said Mr. Gibbs, icily.

“Very often the wife is better off,” said his friend. “It's one mouth less for her to feed. Besides, she gen'rally gets something. When pore old Bill went they 'ad a Friendly Lead at the 'King's Head' and got his missis pretty nearly seventeen pounds.”

“And I believe we'd get more than that for your old woman,” said Mr. Kidd. “There's no kids, and she could keep 'erself easy. Not that I want to encourage you to make away with yourself.”

Mr. Gibbs scowled and, tilting his mug, peered gloomily into the interior.

“Joe won't make no 'ole in the water,” said Mr. Brown, wagging his head. “If it was beer, now—”

Mr. Gibbs turned and, drawing himself up to five feet three, surveyed the speaker with an offensive stare.

“I don't see why he need make a 'ole in anything,” said Mr. Kidd, slowly. “It 'ud do just as well if we said he 'ad. Then we could pass the hat round and share it.”

“Divide it into three halves and each 'ave one,” said Mr. Brown, nodding; “but 'ow is it to be done?”

“'Ave some more beer and think it over,” said Mr. Kidd, pale with excitement. “Three pints, please.”

He and Mr. Brown took up their pints, and nodded at each other. Mr. Gibbs, toying idly with the handle of his, eyed them carefully. “Mind, I'm not promising anything,” he said, slowly. “Understand, I ain't a-committing of myself by drinking this 'ere pint.”

“You leave it to me, Joe,” said Mr. Kidd.

Mr. Gibbs left it to him after a discussion in which pints played a persuasive part; with the result that Mr. Brown, sitting in the same bar the next evening with two or three friends, was rudely disturbed by the cyclonic entrance of Mr. Kidd, who, dripping with water, sank on a bench and breathed heavily.

“What's up? What's the matter?” demanded several voices.

“It's Joe—poor Joe Gibbs,” said Mr. Kidd. “I was on Smith's wharf shifting that lighter to the next berth, and, o' course Joe must come aboard to help. He was shoving her off with 'is foot when—”

He broke off and shuddered and, accepting a mug of beer, pending the arrival of some brandy that a sympathizer had ordered, drank it slowly.

“It all 'appened in a flash,” he said, looking round. “By the time I 'ad run round to his end he was just going down for the third time. I hung over the side and grabbed at 'im, and his collar and tie came off in my hand. Nearly went in, I did.”

He held out the collar and tie; and approving notice was taken of the fact that he was soaking wet from the top of his head to the middle button of his waistcoat.

“Pore chap!” said the landlord, leaning over the bar. “He was in 'ere only 'arf an hour ago, standing in this very bar.”

“Well, he's 'ad his last drop o' beer,” said a carman in a chastened voice.

“That's more than anybody can say,” said the landlord, sharply. “I never heard anything against the man; he's led a good life so far as I know, and 'ow can we tell that he won't 'ave beer?”

He made Mr. Kidd a present of another small glass of brandy.

“He didn't leave any family, did he?” he inquired, as he passed it over.

“Only a wife,” said Mr. Kidd; “and who's to tell that pore soul I don't know. She fair doated on 'im. 'Ow she's to live I don't know. I shall do what I can for 'er.”

“Same 'ere,” said Mr. Brown, in a deep voice.

“Something ought to be done for 'er,” said the carman, as he went out.

“First thing is to tell the police,” said the landlord. “They ought to know; then p'r'aps one of them'll tell her. It's what they're paid for.”

“It's so awfully sudden. I don't know where I am 'ardly,” said Mr. Kidd. “I don't believe she's got a penny-piece in the 'ouse. Pore Joe 'ad a lot o' pals. I wonder whether we could'nt get up something for her.”

“Go round and tell the police first,” said the landlord, pursing up his lips thoughtfully. “We can talk about that later on.”

Mr. Kidd thanked him warmly and withdrew, accompanied by Mr. Brown. Twenty minutes later they left the station, considerably relieved at the matter-of-fact way in which the police had received the tidings, and, hurrying across London Bridge, made their way towards a small figure supporting its back against a post in the Borough market.

“Well?” said Mr. Gibbs, snappishly, as he turned at the sound of their footsteps.

“It'll be all right, Joe,” said Mr. Kidd. “We've sowed the seed.”

“Sowed the wot?” demanded the other.

Mr. Kidd explained.

“Ho!” said Mr. Gibbs. “An' while your precious seed is a-coming up, wot am I to do? Wot about my comfortable 'ome? Wot about my bed and grub?”

His two friends looked at each other uneasily. In the excitement of the arrangements they had for gotten these things, and a long and sometimes painful experience of Mr. Gibbs showed them only too plainly where they were drifting.

“You'll 'ave to get a bed this side o' the river somewhere,” said Mr. Brown, slowly. “Coffee-shop or something; and a smart, active man wot keeps his eyes open can always pick up a little money.”

Mr. Gibbs laughed.

“And mind,” said Mr. Kidd, furiously, in reply to the laugh, “anything we lend you is to be paid back out of your half when you get it. And, wot's more, you don't get a ha'penny till you've come into a barber's shop and 'ad them whiskers off. We don't want no accidents.”

Mr. Gibbs, with his back against the post, fought for his whiskers for nearly half an hour, and at the end of that time was led into a barber's, and in a state of sullen indignation proffered his request for a “clean” shave. He gazed at the bare-faced creature that confronted him in the glass after the operation in open-eyed consternation, and Messrs. Kidd and Brown's politeness easily gave way before their astonishment.

“Well, I may as well have a 'air-cut while I'm here,” said Mr. Gibbs, after a lengthy survey.

“And a shampoo, sir?” said the assistant.

“Just as you like,” said Mr. Gibbs, turning a deaf ear to the frenzied expostulations of his financial backers. “Wot is it?”

He sat in amazed discomfort during the operation, and emerging with his friends remarked that he felt half a stone lighter. The information was received in stony silence, and, having spent some time in the selection, they found a quiet public-house, and in a retired corner formed themselves into a Committee of Ways and Means.

“That'll do for you to go on with,” said Mr. Kidd, after he and Mr. Brown had each made a contribution; “and, mind, it's coming off of your share.”

Mr. Gibbs nodded. “And any evening you want to see me you'll find me in here,” he remarked. “Beer's ripping. Now you'd better go and see my old woman.”

The two friends departed, and, to their great relief, found a little knot of people outside the abode of Mrs. Gibbs. It was clear that the news had been already broken, and, pushing their way upstairs, they found the widow with a damp handkerchief in her hand surrounded by attentive friends. In feeble accents she thanked Mr. Kidd for his noble attempts at rescue.

“He ain't dry yet,” said Mr. Brown.

“I done wot I could,” said Mr. Kidd, simply. “Pore Joe! Nobody could ha' had a better pal. Nobody!”

“Always ready to lend a helping 'and to them as was in trouble, he was,” said Mr. Brown, looking round.

“'Ear, 'ear!” said a voice.

“And we'll lend 'im a helping 'and,” said Mr. Kidd, energetically. “We can't do 'im no good, pore chap, but we can try and do something for 'er as is left behind.”

He moved slowly to the door, accompanied by Mr. Brown, and catching the eye of one or two of the men beckoned them to follow. Under his able guidance a small but gradually increasing crowd made its way to the “Red Lion.” For the next three or four days the friends worked unceasingly. Cards stating that a Friendly Lead would be held at the “Red Lion,” for the benefit of the widow of the late Mr. Joseph Gibbs, were distributed broadcast; and anecdotes portraying a singularly rare and beautiful character obtained an even wider circulation. Too late Wapping realized the benevolent disposition and the kindly but unobtrusive nature that had departed from it for ever.

Mr. Gibbs, from his retreat across the water, fully shared his friends' enthusiasm, but an insane desire—engendered by vanity—to be present at the function was a source of considerable trouble and annoyance to them. When he offered to black his face and take part in the entertainment as a nigger minstrel, Mr. Kidd had to be led outside and kept there until such time as he could converse in English pure and undefiled.

“Getting above 'imself, that's wot it is,” said Mr. Brown, as they wended their way home. “He's having too much money out of us to spend; but it won't be for long now.”

“He's having a lord's life of it, while we're slaving ourselves to death,” grumbled Mr. Kidd. “I never see'im looking so fat and well. By rights he oughtn't to 'ave the same share as wot we're going to 'ave; he ain't doing none of the work.”

His ill-humour lasted until the night of the “Lead,” which, largely owing to the presence of a sporting fishmonger who had done well at the races that day, and some of his friends, realized a sum far beyond the expectations of the hard-working promoters. The fishmonger led off by placing a five-pound note in the plate, and the packed audience breathed so hard that the plate-holder's responsibility began to weigh upon his spirits. In all, a financial tribute of thirty-seven pounds three and fourpence was paid to the memory of the late Mr. Gibbs.

“Over twelve quid apiece,” said the delighted Mr. Kidd as he bade his co-worker good night. “Sounds too good to be true.”

The next day passed all too slowly, but work was over at last, and Mr. Kidd led the way over London Bridge a yard or two ahead of the more phlegmatic Mr. Brown. Mr. Gibbs was in his old corner at the “Wheelwright's Arms,” and, instead of going into ecstasies over the sum realized, hinted darkly that it would have been larger if he had been allowed to have had a hand in it.

“It'll 'ardly pay me for my trouble,” he said, shaking his head. “It's very dull over 'ere all alone by myself. By the time you two have 'ad your share, besides taking wot I owe you, there'll be 'ardly anything left.”

“I'll talk to you another time,” said Mr. Kidd, regarding him fixedly. “Wot you've got to do now is to come acrost the river with us.”

“What for?” demanded Mr. Gibbs.

“We're going to break the joyful news to your old woman that you're alive afore she starts spending money wot isn't hers,” said Mr. Kidd. “And we want you to be close by in case she don't believe us.

“Well, do it gentle, mind,” said the fond husband. “We don't want 'er screaming, or anything o' that sort. I know 'er better than wot you do, and my advice to you is to go easy.”

He walked along by the side of them, and, after some demur, consented, as a further disguise, to put on a pair of spectacles, for which Mr. Kidd's wife's mother had been hunting high and low since eight o'clock that morning.

“You doddle about 'ere for ten minutes,” said Mr. Kidd, as they reached the Monument, “and then foller on. When you pass a lamp-post 'old your handkerchief up to your face. And wait for us at the corner of your road till we come for you.”

He went off at a brisk pace with Mr. Brown, a pace moderated to one of almost funeral solemnity as they approached the residence of Mrs. Gibbs. To their relief she was alone, and after the usual amenities thanked them warmly for all they had done for her.

“I'd do more than that for pore Joe,” said Mr. Brown.

“They—they 'aven't found 'im yet?” said the widow.

Mr. Kidd shook his head. “My idea is they won't find 'im,” he said, slowly.

“Went down on the ebb tide,” explained Mr. Brown; and spoilt Mr. Kidd's opening.

“Wherever he is 'e's better off,” said Mrs. Gibbs.

“No more trouble about being out o' work; no more worry; no more pain. We've all got to go some day.

“Yes,” began Mr. Kidd; “but—

“I'm sure I don't wish 'im back,” said Mrs. Gibbs; “that would be sinful.”

“But 'ow if he wanted to come back?” said Mr. Kidd, playing for an opening.

“And 'elp you spend that money,” said Mr. Brown, ignoring the scowls of his friend.

Mrs. Gibbs looked bewildered. “Spend the money?” she began.

“Suppose,” said Mr. Kidd, “suppose he wasn't drownded after all? Only last night I dreamt he was alive.”

“So did I,” said Mr. Brown.

“He was smiling at me,” said Mr. Kidd, in a tender voice. “'Bob,' he ses, 'go and tell my pore missis that I'm alive,' he ses; 'break it to 'er gentle.'”

“It's the very words he said to me in my dream,” said Mr. Brown. “Bit strange, ain't it?”

“Very,” said Mrs. Gibbs.

“I suppose,” said Mr. Kidd, after a pause, “I suppose you haven't been dreaming about 'im?”

“No; I'm a teetotaller,” said the widow.

The two gentlemen exchanged glances, and Mr. Kidd, ever of an impulsive nature, resolved to bring matters to a head.

“Wot would you do if Joe was to come in 'ere at this door?” he asked.

“Scream the house down,” said the widow, promptly.

“Scream—scream the 'ouse down?” said the distressed Mr. Kidd.

Mrs. Gibbs nodded. “I should go screaming, raving mad,” she said, with conviction.

“But—but not if 'e was alive!” said Mr. Kidd.

“I don't know what you're driving at,” said Mrs. Gibbs. “Why don't you speak out plain? Poor Joe is drownded, you know that; you saw it all, and yet you come talking to me about dreams and things.”

Mr. Kidd bent over her and put his hand affectionately on her shoulder. “He escaped,” he said, in a thrilling whisper. “He's alive and well.”

“WHAT?” said Mrs. Gibbs, starting back.

“True as I stand 'ere,” said Mr. Kidd; “ain't it, George?”

“Truer,” said Mr. Brown, loyally.

Mrs. Gibbs leaned back, gasping. “Alive!” she said. “But 'ow? 'Ow can he be?”

“Don't make such a noise,” said Mr. Kidd, earnestly. “Mind, if anybody else gets to 'ear of it you'll 'ave to give that money back.”

“I'd give more than that to get 'im back,” said Mrs. Gibbs, wildly. “I believe you're deceiving me.”

“True as I stand 'ere,” asseverated the other. “He's only a minute or two off, and if it wasn't for you screaming I'd go out and fetch 'im in.”

“I won't scream,” said Mrs. Gibbs, “not if I know it's flesh and blood. Oh, where is he? Why don't you bring 'im in? Let me go to 'im.”

“All right,” said Mr. Kidd, with a satisfied smile at Mr. Brown; “all in good time. I'll go and fetch 'im now; but, mind, if you scream you'll spoil everything.”

He bustled cheerfully out of the room and downstairs, and Mrs. Gibbs, motioning Mr. Brown to silence, stood by the door with parted lips, waiting. Three or four minutes elapsed.

“'Ere they come,” said Mr. Brown, as footsteps sounded on the stairs. “Now, no screaming, mind!”

Mrs. Gibbs drew back, and, to the gratification of all concerned, did not utter a sound as Mr. Kidd, followed by her husband, entered the room. She stood looking expectantly towards the doorway.

“Where is he?” she gasped.

“Eh?” said Mr. Kidd, in a startled voice. “Why here. Don't you know 'im?”

“It's me, Susan,” said Mr. Gibbs, in a low voice.

“Oh, I might 'ave known it was a joke,” cried Mrs. Gibbs, in a faint voice, as she tottered to a chair. “Oh, 'ow cruel of you to tell me my pore Joe was alive! Oh, 'ow could you?”

“Lor' lumme,” said the incensed Mr. Kidd, pushing Mr. Gibbs forward. “Here he is. Same as you saw 'im last, except for 'is whiskers. Don't make that sobbing noise; people'll be coming in.”

“Oh! Oh! Oh! Take 'im away,” cried Mrs. Gibbs. “Go and play your tricks with somebody else's broken 'art.”

“But it's your husband,” said Mr. Brown.

“Take 'im away,” wailed Mrs. Gibbs.

Mr. Kidd, grinding his teeth, tried to think. “'Ave you got any marks on your body, Joe?” he inquired.

“I ain't got a mark on me,” said Mr. Gibbs with a satisfied air, “or a blemish. My skin is as whi—”

“That's enough about your skin,” interrupted Mr. Kidd, rudely.

“If you ain't all of you gone before I count ten,” said Mrs. Gibbs, in a suppressed voice, “I'll scream. 'Ow dare you come into a respectable woman's place and talk about your skins? Are you going? One! Two! Three! Four! Five!”

Her voice rose with each numeral; and Mr. Gibbs himself led the way downstairs, and, followed by his friends, slipped nimbly round the corner.

“It's a wonder she didn't rouse the whole 'ouse,” he said, wiping his brow on his sleeve; “and where should we ha' been then? I thought at the time it was a mistake you making me 'ave my whiskers off, but I let you know best. She's never seen me without 'em. I 'ad a remarkable strong growth when I was quite a boy. While other boys was—”

“Shut-up!” vociferated Mr. Kidd.

“Sha'n't!” said Mr. Gibbs, defiantly. “I've 'ad enough of being away from my comfortable little 'ome and my wife; and I'm going to let 'em start growing agin this very night. She'll never reckernize me without 'em, that's certain.”

“He's right, Bob,” said Mr. Brown, with conviction.

“D'ye mean to tell me we've got to wait till 'is blasted whiskers grow?” cried Mr. Kidd, almost dancing with fury. “And go on keeping 'im in idleness till they do?”

“You'll get it all back out o' my share,” said Mr. Gibbs, with dignity. “But you can please yourself. If you like to call it quits now, I don't mind.”

Mr. Brown took his seething friend aside, and conferred with him in low but earnest tones. Mr. Gibbs, with an indifferent air, stood by whistling softly.

“'Ow long will they take to grow?” inquired Mr. Kidd, turning to him with a growl.

Mr. Gibbs shrugged his shoulders. “Can't say,” he replied; “but I should think two or three weeks would be enough for 'er to reckernize me by. If she don't, we must wait another week or so, that's all.”

“Well, there won't be much o' your share left, mind that,” said Mr. Kidd, glowering at him.

“I can't help it,” said Mr. Gibbs. “You needn't keep reminding me of it.”

They walked the rest of the way in silence; and for the next fortnight Mr. Gibbs's friends paid nightly visits to note the change in his appearance, and grumble at its slowness.

“We'll try and pull it off to-morrow night,” said Mr. Kidd, at the end of that period. “I'm fair sick o' lending you money.”

Mr. Gibbs shook his head and spoke sagely about not spoiling the ship for a ha'porth o' tar; but Mr. Kidd was obdurate.

“There's enough for 'er to reckernize you by,” he said, sternly, “and we don't want other people to. Meet us at the Monument at eight o'clock to-morrow night, and we'll get it over.”

“Give your orders,” said Mr. Gibbs, in a nasty voice.

“Keep your 'at well over your eyes,” commanded Mr. Kidd, sternly. “Put them spectacles on wot I lent you, and it wouldn't be a bad idea if you tied your face up in a piece o' red flannel.”

“I know wot I'm going to do without you telling me,” said Mr. Gibbs, nodding. “I'll bet you pots round that you don't either of you reckernize me tomorrow night.”

The bet was taken at once, and from eight o'clock until ten minutes to nine the following night Messrs. Kidd and Brown did their best to win it. Then did Mr. Kidd, turning to Mr. Brown in perplexity, inquire with many redundant words what it all meant.

“He must 'ave gone on by 'imself,” said Mr. Brown. “We'd better go and see.”

In a state of some disorder they hurried back to Wapping, and, mounting the stairs to Mrs. Gibbs's room, found the door fast. To their fervent and repeated knocking there was no answer.

“Ah, you won't make her 'ear,” said a woman, thrusting an untidy head over the balusters on the next landing. “She's gone.”

“Gone!” exclaimed both gentlemen. “Where?”

“Canada,” said the woman. “She went off this morning.”

Mr. Kidd leaned up against the wall for support; Mr. Brown stood open-mouthed and voiceless.

“It was a surprise to me,” said the woman, “but she told me this morning she's been getting ready on the quiet for the last fortnight. Good spirits she was in, too; laughing like anything.”

“Laughing!” repeated Mr. Kidd, in a terrible voice.

The woman nodded. “And when I spoke about it and reminded 'er that she 'ad only just lost 'er pore husband, I thought she would ha' burst,” she said, severely. “She sat down on that stair and laughed till the tears ran dowwn 'er face like water.”

Mr. Brown turned a bewildered face upon his partner. “Laughing!” he said, slowly. “Wot 'ad she got to laugh at?”

“Two born-fools,” replied Mr. Kidd.

“Jealousy; that's wot it is,” said the night-watchman, trying to sneer— “pure jealousy.” He had left his broom for a hurried half-pint at the “Bull's Head”—left it leaning in a negligent attitude against the warehouse-wall; now, lashed to the top of the crane at the jetty end, it pointed its soiled bristles towards the evening sky and defied capture.

“And I know who it is, and why 'e's done it,” he continued. “Fust and last, I don't suppose I was talking to the gal for more than ten minutes, and 'arf of that was about the weather.

“I don't suppose anybody 'as suffered more from jealousy than wot I 'ave: Other people's jealousy, I mean. Ever since I was married the missis has been setting traps for me, and asking people to keep an eye on me. I blacked one of the eyes once—like a fool—and the chap it belonged to made up a tale about me that I ain't lived down yet.

“Years ago, when I was out with the missis one evening, I saved a gal's life for her. She slipped as she was getting off a bus, and I caught 'er just in time. Fine strapping gal she was, and afore I could get my balance we 'ad danced round and round 'arfway acrost the road with our arms round each other's necks, and my missis watching us from the pavement. When we were safe, she said the gal 'adn't slipped at all; and, as soon as the gal 'ad got 'er breath, I'm blest if she didn't say so too.

“You can't argufy with jealous people, and you can't shame 'em. When I told my missis once that I should never dream of being jealous of her, instead of up and thanking me for it, she spoilt the best frying-pan we ever had. When the widder-woman next-door but two and me 'ad rheumatics at the same time, she went and asked the doctor whether it was catching.

“The worse trouble o' that kind I ever got into was all through trying to do somebody else a kindness. I went out o' my way to do it; I wasted the whole evening for the sake of other people, and got into such trouble over it that even now it gives me the cold shivers to think of.

“Cap'n Tarbell was the man I tried to do a good turn to; a man what used to be master of a ketch called the Lizzie and Annie, trading between 'ere and Shoremouth. 'Artful Jack' he used to be called, and if ever a man deserved the name, he did. A widder-man of about fifty, and as silly as a boy of fifteen. He 'ad been talking of getting married agin for over ten years, and, thinking it was only talk, I didn't give 'im any good advice. Then he told me one night that 'e was keeping company with a woman named Lamb, who lived at a place near Shoremouth. When I asked 'im what she looked like, he said that she had a good 'art, and, knowing wot that meant, I wasn't at all surprised when he told me some time arter that 'e had been a silly fool.

“'Well, if she's got a good 'art,' I ses, 'p'r'aps she'll let you go.'

“'Talk sense,' he ses. 'It ain't good enough for that. Why, she worships the ground I tread on. She thinks there is nobody like me in the whole wide world.'

“'Let's 'ope she'll think so arter you're married,' I ses, trying to cheer him up.

“'I'm not going to get married,' he ses. 'Leastways, not to 'er. But 'ow to get out of it without breaking her 'art and being had up for breach o' promise I can't think. And if the other one got to 'ear of it, I should lose her too.'

“'Other one?' I ses, 'wot other one?'

“Cap'n Tarbell shook his 'ead and smiled like a silly gal.

“'She fell in love with me on top of a bus in the Mile End Road,' he ses. 'Love at fust sight it was. She's a widder lady with a nice little 'ouse at Bow, and plenty to live on-her 'usband having been a builder. I don't know what to do. You see, if I married both of 'em it's sure to be found out sooner or later.'

“'You'll be found out as it is,' I ses, 'if you ain't careful. I'm surprised at you.'

“'Yes,' he ses, getting up and walking backwards and forwards; 'especially as Mrs. Plimmer is always talking about coming down to see the ship. One thing is, the crew won't give me away; they've been with me too long for that. P'r'aps you could give me a little advice, Bill.'

“I did. I talked to that man for an hour and a'arf, and when I 'ad finished he said he didn't want that kind of advice at all. Wot 'e wanted was for me to tell 'im 'ow to get rid of Miss Lamb and marry Mrs. Plimmer without anybody being offended or having their feelings hurt.

“Mrs. Plimmer came down to the ship the very next evening. Fine-looking woman she was, and, wot with 'er watch and chain and di'mond rings and brooches and such-like, I should think she must 'ave 'ad five or six pounds' worth of jewell'ry on 'er. She gave me a very pleasant smile, and I gave 'er one back, and we stood chatting there like old friends till at last she tore 'erself away and went on board the ship.

“She came off by and by hanging on Cap'n Tarbell's arm. The cap'n was dressed up in 'is Sunday clothes, with one of the cleanest collars on I 'ave ever seen in my life, and smoking a cigar that smelt like an escape of gas. He came back alone at ha'past eleven that night, and 'e told me that if it wasn't for the other one down Shoremouth way he should be the 'appiest man on earth.

“'Mrs. Plimmer's only got one fault,' he ses, shaking his 'cad, 'and that's jealousy. If she got to know of Laura Lamb, it would be all U.P. It makes me go cold all over when I think of it. The only thing is to get married as quick as I can; then she can't help 'erself.'

“'It wouldn't prevent the other one making a fuss, though,' I ses.

“'No,' he ses, very thoughtfully, 'it wouldn't. I shall 'ave to do something there, but wot, I don't know.'

“He climbed on board like a man with a load on his mind, and arter a look at the sky went below and forgot both 'is troubles in sleep.

“Mrs. Plimmer came down to the wharf every time the ship was up, arter that. Sometimes she'd spend the evening aboard, and sometimes they'd go off and spend it somewhere else. She 'ad a fancy for the cabin, I think, and the cap'n told me that she 'ad said when they were married she was going to sail with 'im sometimes.

“'But it ain't for six months yet,' he ses, 'and a lot o' things might 'appen to the other one in that time, with luck.'

“It was just about a month arter that that 'e came to me one evening trembling all over. I 'ad just come on dooty, and afore I could ask 'im wot was the matter he 'ad got me in the 'Bull's Head' and stood me three 'arf-pints, one arter the other.

“'I'm ruined,' he ses in a 'usky whisper; 'I'm done for. Why was wimmen made? Wot good are they? Fancy 'ow bright and 'appy we should all be without 'em.'

“'I started to p'int out one or two things to 'im that he seemed to 'ave forgot, but 'e wouldn't listen. He was so excited that he didn't seem to know wot 'e was doing, and arter he 'ad got three more 'arf-pints waiting for me, all in a row on the counter, I 'ad to ask 'im whether he thought I was there to do conjuring tricks, or wot?'

“'There was a letter waiting for me in the office,' he ses. 'From Miss Lamb—she's in London. She's coming to pay me a surprise visit this evening—I know who'll get the surprise. Mrs. Plimmer's coming too.'

“I gave 'im one of my 'arf-pints and made 'im drink it. He chucked the pot on the floor when he 'ad done, in a desprit sort o' way, and 'im and the landlord 'ad a little breeze then that did 'im more good than wot the beer 'ad. When we came outside 'e seemed more contented with 'imself, but he shook his 'ead and got miserable as soon as we got to the wharf agin.

“'S'pose they both come along at the same time,' he ses. 'Wot's to be done?'

“I shut the gate with a bang and fastened the wicket. Then I turned to 'im with a smile.

“'I'm watchman 'ere,' I ses, 'and I lets in who I thinks I will. This ain't a public 'ighway,' I ses; 'it's a wharf.'

“'Bill,' he ses, 'you're a genius.'

“'If Miss Lamb comes 'ere asking arter you,' I ses, 'I shall say you've gone out for the evening.'

“'Wot about her letter?' he ses.

“'You didn't 'ave it,' I ses, winking at 'im.

“'And suppose she waits about outside for me, and Mrs. Plimmer wants me to take 'er out?' he ses, shivering. 'She's a fearful obstinate woman; and she'd wait a week for me.'

“He kept peeping up the road while we talked it over, and then we both see Mrs. Plimmer coming along. He backed on to the wharf and pulled out 'is purse.

“'Bill,' he ses, gabbling as fast as 'e could gabble, 'here's five or six shillings. If the other one comes and won't go away tell 'er I've gone to the Pagoda Music-'all and you'll take 'er to me, keep 'er out all the evening some'ow, if you can, if she comes back too soon keep 'er in the office.'

“'And wot about leaving the wharf and my dooty?' I ses, staring.

“'I'll put Joe on to keep watch for you,' he ses, pressing the money in my 'and. 'I rely on you, Bill, and I'll never forget you. You won't lose by it, trust me.'

“He nipped off and tumbled aboard the ship afore I could say a word. I just stood there staring arter 'im and feeling the money, and afore I could make up my mind Mrs. Plimmer came up.

“I thought I should never ha' got rid of 'er. She stood there chatting and smiling, and seemed to forget all about the cap'n, and every moment I was afraid that the other one might come up. At last she went off, looking behind 'er, to the ship, and then I went outside and put my back up agin the gate and waited.

“I 'ad hardly been there ten minutes afore the other one came along. I saw 'er stop and speak to a policeman, and then she came straight over to me.

“'I want to see Cap'n Tarbell,' she ses.

“'Cap'n Tarbell?' I ses, very slow; 'Cap'n Tarbell 'as gone off for the evening.'

“'Gone off!' she ses, staring. 'But he can't 'ave. Are you sure?'

“'Sartain,' I ses. Then I 'ad a bright idea. 'And there's a letter come for 'im,' I ses.

“'Oh, dear!' she ses. 'And I thought it would be in plenty of time. Well, I must go on the ship and wait for 'im, I suppose.'

“If I 'ad only let 'er go I should ha' saved myself a lot o' trouble, and the man wot deserved it would ha' got it. Instead o' that I told 'er about the music-'all, and arter carrying on like a silly gal o' seventeen and saying she couldn't think of it, she gave way and said she'd go with me to find 'im. I was all right so far as clothes went as it happened. Mrs. Plimmer said once that I got more and more dressy every time she saw me, and my missis 'ad said the same thing only in a different way. I just took a peep through the wicket and saw that Joe 'ad taken up my dooty, and then we set off.

“I said I wasn't quite sure which one he'd gone to, but we'd try the Pagoda Music-'all fust, and we went there on a bus from Aldgate. It was the fust evening out I 'ad 'ad for years, and I should 'ave enjoyed it if it 'adn't been for Miss Lamb. Wotever Cap'n Tarbell could ha' seen in 'er, I can't think.

“She was quiet, and stupid, and bad-tempered. When the bus-conductor came round for the fares she 'adn't got any change; and when we got to the hall she did such eggsterrordinary things trying to find 'er pocket that I tried to look as if she didn't belong to me. When she left off she smiled and said she was farther off than ever, and arter three or four wot was standing there 'ad begged 'er to have another try, I 'ad to pay for the two.

“The 'ouse was pretty full when we got in, but she didn't take no notice of that. Her idea was that she could walk about all over the place looking for Cap'n Tarbell, and it took three men in buttons and a policeman to persuade 'er different. We were pushed into a couple o' seats at last, and then she started finding fault with me.

“'Where is Cap'n Tarbell?' she ses. 'Why don't you find him?'

“'I'll go and look for 'im in the bar presently,' I ses. 'He's sure to be there, arter a turn or two.'

“I managed to keep 'er quiet for 'arf an hour—with the 'elp of the people wot sat near us—and then I 'ad to go. I 'ad a glass o' beer to pass the time away, and, while I was drinking it, who should come up but the cook and one of the hands from the Lizzie and Annie.

“'We saw you,' ses the cook, winking; 'didn't we Bob?'

“'Yes,' ses Bob, shaking his silly 'ead; 'but it wasn't no surprise to me. I've 'ad my eye on 'im for a long time past.'

“'I thought 'e was married,' ses the cook.

“'So he is,' ses Bob, 'and to the best wife in London. I know where she lives. Mine's a bottle o' Bass,' he ses, turning to me.

“'So's mine,' ses the cook.

“I paid for two bottles for 'em, and arter that they said that they'd 'ave a whisky and soda apiece just to show as there was no ill-feeling.

“'It's very good,' ses Bob, sipping his, 'but it wants a sixpenny cigar to go with it. It's been the dream o' my life to smoke a sixpenny cigar.'

“'So it 'as mine,' ses the cook, 'but I don't suppose I ever shall.'

“They both coughed arter that, and like a goodnatured fool I stood 'em a sixpenny cigar apiece, and I 'ad just turned to go back to my seat when up come two more hands from the Lizzie and Annie.

“'Halloa, watchman!' ses one of 'em. 'Why, I thought you was a-taking care of the wharf.'

“'He's got something better than the wharf to take care of,' ses Bob, grinning.

“'I know; we see 'im,' ses the other chap. 'We've been watching 'is goings-on for the last 'arf-hour; better than a play it was.'

“I stopped their mouths with a glass o' bitter each, and went back to my seat while they was drinking it. I told Miss Lamb in whispers that 'e wasn't there, but I'd 'ave another look for him by and by. If she'd ha' whispered back it would ha' been all right, but she wouldn't, and, arter a most unpleasant scene, she walked out with her 'ead in the air follered by me with two men in buttons and a policeman.

“O' course, nothing would do but she must go back to the wharf and wait for Cap'n Tarbell, and all the way there I was wondering wot would 'appen if she went on board and found 'im there with Mrs. Plimmer. However, when we got there I persuaded 'er to go into the office while I went aboard to see if I could find out where he was, and three minutes arterwards he was standing with me behind the galley, trembling all over and patting me on the back.

“'Keep 'er in the office a little longer,' he ses, in a whisper. 'The other's going soon. Keep 'er there as long as you can.'

“'And suppose she sees you and Mrs. Plimmer passing the window?' I ses.

“'That'll be all right; I'm going to take 'er to the stairs in the ship's boat,' he ses. 'It's more romantic.'

“He gave me a little punch in the ribs, playfullike, and, arter telling me I was worth my weight in gold-dust, went back to the cabin agin.

“I told Miss Lamb that the cabin was locked up, but that Cap'n Tarbell was expected back in about 'arf-an-hour's time. Then I found 'er an old newspaper and a comfortable chair and sat down to wait. I couldn't go on the wharf for fear she'd want to come with me, and I sat there as patient as I could, till a little clicking noise made us both start up and look at each other.

“'Wot's that?' she ses, listening.

“'It sounded,' I ses 'it sounded like somebody locking the door.'

“I went to the door to try it just as somebody dashed past the window with their 'ead down. It was locked fast, and arter I had 'ad a try at it and Miss Lamb had 'ad a try at it, we stood and looked at each other in surprise.

“'Somebody's playing a joke on us,' I ses.

“'Joke!' ses Miss Lamb. 'Open that door at once. If you don't open it I'll call for the police.'

“She looked at the windows, but the iron bars wot was strong enough to keep the vans outside was strong enough to keep 'er in, and then she gave way to such a fit o' temper that I couldn't do nothing with 'er.

“'Cap'n Tarbell can't be long now,' I ses, as soon as I could get a word in. 'We shall get out as soon as e comes.'

“She flung 'erself down in the chair agin with 'er back to me, and for nearly three-quarters of an hour we sat there without a word. Then, to our joy, we 'eard footsteps turn in at the gate. Quick footsteps they was. Somebody turned the handle of the door, and then a face looked in at the window that made me nearly jump out of my boots in surprise. A face that was as white as chalk with temper, and a bonnet cocked over one eye with walking fast. She shook 'er fist at me, and then she shook it at Miss Lamb.

“'Who's that?' ses Miss Lamb.

“'My missis,' I ses, in a loud voice. 'Thank goodness she's come.'

“'Open the door!' ses my missis, with a screech.

“'OPEN THE DOOR!'

“'I can't,' I ses. 'Somebody's locked it. This is Cap'n Tarbell's young lady.'

“'I'll Cap'n Tarbell 'er when I get in!' ses my wife. 'You too. I'll music-'all you! I'll learn you to go gallivanting about! Open the door!'

“She walked up and down the alley-way in front of the window waiting for me just like a lion walking up and down its cage waiting for its dinner, and I made up my mind then and there that I should 'ave to make a clean breast of it and let Cap'n Tarbell get out of it the best way he could. I wasn't going to suffer for him.

“'Ow long my missis walked up and down there I don't know. It seemed ages to me; but at last I 'eard footsteps and voices, and Bob and the cook and the other two chaps wot we 'ad met at the music'all came along and stood grinning in at the window.

“'Somebody's locked us in,' I ses. 'Go and fetch Cap'n Tarbell.'

“'Cap'n Tarbell?' ses the cook. 'You don't want to see 'im. Why, he's the last man in the world you ought to want to see! You don't know 'ow jealous he is.'

“'You go and fetch 'im, I ses. ''Ow dare you talk like that afore my wife!'

“'I dursen't take the responserbility,' ses the cook. 'It might mean bloodshed.'

“'You go and fetch 'im,' ses my missis. 'Never mind about the bloodshed. I don't. Open the door!'

“She started banging on the door agin, and arter talking among themselves for a time they moved off to the ship. They came back in three or four minutes, and the cook 'eld up something in front of the window.

“'The boy 'ad got it,' he ses. 'Now shall I open the door and let your missis in, or would you rather stay where you are in peace and quietness?'

“I saw my missis jump at the key, and Bob and the others, laughing fit to split their sides, 'olding her back. Then I heard a shout, and the next moment Cap'n Tarbell came up and asked 'em wot the trouble was about.

“They all started talking at once, and then the cap'n, arter one look in at the window, threw up his 'ands and staggered back as if 'e couldn't believe his eyesight. He stood dazed-like for a second or two, and then 'e took the key out of the cook's 'and, opened the door, and walked in. The four men was close be'ind 'im, and, do all she could, my missis couldn't get in front of 'em.

“'Watchman!' he ses, in a stuck-up voice, 'wot does this mean? Laura Lamb! wot 'ave you got to say for yourself? Where 'ave you been all the evening?'

“'She's been to a music-'all with Bill,' ses the cook. 'We saw 'em.'

“'WOT?' ses the cap'n, falling back again. 'It can't be!'

“'It was them,' ses my wife. 'A little boy brought me a note telling me. You let me go; it's my husband, and I want to talk to 'im.'

“'It's all right,' I ses, waving my 'and at Miss Lamb, wot was going to speak, and smiling at my missis, wot was trying to get at me.

“'We went to look for you,' ses Miss Lamb, very quick. 'He said you were at the music-'all, and as you 'adn't got my letter I thought it was very likely.'

“'But I did get your letter,' ses the cap'n.

“'He said you didn't,' ses Miss Lamb.

“'Look 'ere,' I ses. 'Why don't you keep quiet and let me explain? I can explain everything.'

“'I'm glad o' that, for your sake, my man,' ses the cap'n, looking at me very hard. 'I 'ope you will be able to explain 'ow it was you came to leave the wharf for three hours.'

“I saw it all then. If I split about Mrs. Plimmer, he'd split to the guv'nor about my leaving my dooty, and I should get the sack. I thought I should ha' choked, and, judging by the way they banged me on the back, Bob and the cook thought so too. They 'elped me to a chair when I got better, and I sat there 'elpless while the cap'n went on talking.

“'I'm no mischief-maker,' he ses; 'and, besides, p'r'aps he's been punished enough. And as far as I'm concerned he can take this lady to a music-'all every night of the week if 'e likes. I've done with her.'

“There was an eggsterrordinary noise from where my missis was standing; like the gurgling water makes sometimes running down the kitchen sink at 'ome, only worse. Then they all started talking together, and 'arf-a-dozen times or more Miss Lamb called me to back 'er up in wot she was saying, but I only shook my 'ead, and at last, arter tossing her 'ead at Cap'n Tarbell and telling 'im she wouldn't 'ave 'im if he'd got fifty million a year, the five of 'em 'eld my missis while she went off.

“They gave 'er ten minutes' start, and then Cap'n Tarbell, arter looking at me and shaking his 'ead, said he was afraid they must be going.

“'And I 'ope this night'll be a lesson to you,' he ses. 'Don't neglect your dooty again. I shall keep my eye on you, and if you be'ave yourself I sha'n't say anything. Why, for all you know or could ha' done the wharf might ha' been burnt to the ground while you was away!'

“He nodded to his crew, and they all walked out laughing and left me alone—with the missis.”

“Come and have a pint and talk it over,” said Mr. Augustus Teak. “I've got reasons in my 'ead that you don't dream of, Alf.”

Mr. Chase grunted and stole a side-glance at the small figure of his companion. “All brains, you are, Gussie,” he remarked. “That's why it is you're so well off.”

“Come and have a pint,” repeated the other, and with surprising ease pushed his bulky friend into the bar of the “Ship and Anchor.” Mr. Chase, mellowed by a long draught, placed his mug on the counter and eyeing him kindly, said—

“I've been in my lodgings thirteen years.”

“I know,” said Mr. Teak; “but I've got a partikler reason for wanting you. Our lodger, Mr. Dunn, left last week, and I only thought of you yesterday. I mentioned you to my missis, and she was quite pleased. You see, she knows I've known you for over twenty years, and she wants to make sure of only 'aving honest people in the 'ouse. She has got a reason for it.”

He closed one eye and nodded with great significance at his friend.

“Oh!” said Mr. Chase, waiting.

“She's a rich woman,” said Mr. Teak, pulling the other's ear down to his mouth. “She—”

“When you've done tickling me with your whiskers,” said Mr. Chase, withdrawing his head and rubbing his ear vigorously, “I shall be glad.”

Mr. Teak apologized. “A rich woman,” he repeated. “She's been stinting me for twenty-nine years and saving the money—my money!—money that I 'ave earned with the sweat of my brow. She 'as got over three 'undred pounds!”

“'Ow much?” demanded Mr. Chase.

“Three 'undred pounds and more,” repeated the other; “and if she had 'ad the sense to put it in a bank it would ha' been over four 'undred by this time. Instead o' that she keeps it hid in the 'Ouse.”

“Where?” inquired the greatly interested Mr. Chase.

Mr. Teak shook his head. “That's just what I want to find out,” he answered. “She don't know I know it; and she mustn't know, either. That's important.”

“How did you find out about it, then?” inquired his friend.

“My wife's sister's husband, Bert Adams, told me. His wife told 'im in strict confidence; and I might 'ave gone to my grave without knowing about it, only she smacked his face for 'im the other night.”

“If it's in the house you ought to be able to find it easy enough,” said Mr. Chase.

“Yes, it's all very well to talk,” retorted Mr. Teak. “My missis never leaves the 'ouse unless I'm with her, except when I'm at work; and if she thought I knew of it she'd take and put it in some bank or somewhere unbeknown to me, and I should be farther off it than ever.”

“Haven't you got no idea?” said Mr. Chase.

“Not the leastest bit,” said the other. “I never thought for a moment she was saving money. She's always asking me for more, for one thing; but, then women alway do. And look 'ow bad it is for her—saving money like that on the sly. She might grow into a miser, pore thing. For 'er own sake I ought to get hold of it, if it's only to save her from 'erself.”

Mr. Chase's face reflected the gravity of his own.

“You're the only man I can trust,” continued Mr. Teak, “and I thought if you came as lodger you might be able to find out where it is hid, and get hold of it for me.”

“Me steal it, d'ye mean?” demanded the gaping Mr. Chase. “And suppose she got me locked up for it? I should look pretty, shouldn't I?”

“No; you find out where it is hid,” said the other; “that's all you need do. I'll find someway of getting hold of it then.”

“But if you can't find it, how should I be able to?” inquired Mr. Chase.

“'Cos you'll 'ave opportunities,” said the other. “I take her out some time when you're supposed to be out late; you come 'ome, let yourself in with your key, and spot the hiding-place. I get the cash, and give you ten-golden-sovereigns—all to your little self. It only occurred to me after Bert told me about it, that I ain't been in the house alone for years.”

He ordered some more beer, and, drawing Mr. Chase to a bench, sat down to a long and steady argument. It shook his faith in human nature to find that his friend estimated the affair as a twenty-pound job, but he was in no position to bargain. They came out smoking twopenny cigars whose strength was remarkable for their age, and before they parted Mr. Chase was pledged to the hilt to do all that he could to save Mrs. Teak from the vice of avarice.

It was a more difficult undertaking than he had supposed. The house, small and compact, seemed to offer few opportunities for the concealment of large sums of money, and after a fortnight's residence he came to the conclusion that the treasure must have been hidden in the garden. The unalloyed pleasure, however, with which Mrs. Teak regarded the efforts of her husband to put under cultivation land that had lain fallow for twenty years convinced both men that they were on a wrong scent. Mr. Teak, who did the digging, was the first to realize it, but his friend, pointing out the suspicions that might be engendered by a sudden cessation of labour, induced him to persevere.

“And try and look as if you liked it,” he said, severely. “Why, from the window even the back view of you looks disagreeable.”

“I'm fair sick of it,” declared Mr. Teak. “Anybody might ha' known she wouldn't have buried it in the garden. She must 'ave been saving for pretty near thirty years, week by week, and she couldn't keep coming out here to hide it. 'Tain't likely.”

Mr. Chase pondered. “Let her know, casual like, that I sha'n't be 'ome till late on Saturday,” he said, slowly. “Then you come 'ome in the afternoon and take her out. As soon as you're gone I'll pop in and have a thorough good hunt round. Is she fond of animals?”

“I b'lieve so,” said the other, staring. “Why?”

“Take 'er to the Zoo,” said Mr. Chase, impressively. “Take two-penn'orth o' nuts with you for the monkeys, and some stale buns for—for—for animals as likes 'em. Give 'er a ride on the elephant and a ride on the camel.”

“Anything else?” inquired Mr. Teak disagreeably. “Any more ways you can think of for me to spend my money?”

“You do as I tell you,” said his friend. “I've got an idea now where it is. If I'm able to show you where to put your finger on three 'undred pounds when you come 'ome it'll be the cheapest outing you have ever 'ad. Won't it?”

Mr. Teak made no reply, but, after spending the evening in deliberation, issued the invitation at the supper-table. His wife's eyes sparkled at first; then the light slowly faded from them and her face fell.

“I can't go,” she said, at last. “I've got nothing to go in.”

“Rubbish!” said her husband, starting uneasily.

“It's a fact,” said Mrs. Teak. “I should like to go, too—it's years since I was at the Zoo. I might make my jacket do; it's my hat I'm thinking about.”

Mr. Chase, meeting Mr. Teak's eye, winked an obvious suggestion.

“So, thanking you all the same,” continued Mrs. Teak, with amiable cheerfulness, “I'll stay at 'ome.”

“'Ow-'ow much are they?” growled her husband, scowling at Mr. Chase.

“All prices,” replied his wife.

“Yes, I know,” said Mr. Teak, in a grating voice. “You go in to buy a hat at one and eleven-pence; you get talked over and flattered by a man like a barber's block, and you come out with a four-and-six penny one. The only real difference in hats is the price, but women can never see it.”

Mrs. Teak smiled faintly, and again expressed her willingness to stay at home. They could spend the afternoon working in the garden, she said. Her husband, with another indignant glance at the right eye of Mr. Chase, which was still enacting the part of a camera-shutter, said that she could have a hat, but asked her to remember when buying it that nothing suited her so well as a plain one.

The remainder of the week passed away slowly; and Mr. Teak, despite his utmost efforts, was unable to glean any information from Mr. Chase as to that gentleman's ideas concerning the hiding-place. At every suggestion Mr. Chase's smile only got broader and more indulgent.

“You leave it to me,” he said. “You leave it to me, and when you come home from a happy outing I 'ope to be able to cross your little hand with three 'undred golden quids.”

“But why not tell me?” urged Mr. Teak.

“'Cos I want to surprise you,” was the reply. “But mind, whatever you do, don't let your wife run away with the idea that I've been mixed up in it at all. Now, if you worry me any more I shall ask you to make it thirty pounds for me instead of twenty.”

The two friends parted at the corner of the road on Saturday afternoon, and Mr. Teak, conscious of his friend's impatience, sought to hurry his wife by occasionally calling the wrong time up the stairs. She came down at last, smiling, in a plain hat with three roses, two bows, and a feather.

“I've had the feather for years,” she remarked. “This is the fourth hat it has been on—but, then, I've taken care of it.”

Mr. Teak grunted, and, opening the door, ushered her into the street. A sense of adventure, and the hope of a profitable afternoon made his spirits rise. He paid a compliment to the hat, and then, to the surprise of both, followed it up with another—a very little one—to his wife.

They took a tram at the end of the street, and for the sake of the air mounted to the top. Mrs. Teak leaned back in her seat with placid enjoyment, and for the first ten minutes amused herself with the life in the streets. Then she turned suddenly to her husband and declared that she had felt a spot of rain.

“'Magination,” he said, shortly.

Something cold touched him lightly on the eyelid, a tiny pattering sounded from the seats, and then swish, down came the rain. With an angry exclamation he sprang up and followed his wife below.

“Just our luck,” she said, mournfully. “Best thing we can do is to stay in the car and go back with it.”

“Nonsense!” said her husband, in a startled' voice; “it'll be over in a minute.”

Events proved the contrary. By the time the car reached the terminus it was coming down heavily. Mrs. Teak settled herself squarely in her seat, and patches of blue sky, visible only to the eye of faith and her husband, failed to move her. Even his reckless reference to a cab failed.

“It's no good,” she said, tartly. “We can't go about the grounds in a cab, and I'm not going to slop about in the wet to please anybody. We must go another time. It's hard luck, but there's worse things in life.”

Mr. Teak, wondering as to the operations of Mr. Chase, agreed dumbly. He stopped the car at the corner of their road, and, holding his head down against the rain, sprinted towards home. Mrs. Teak, anxious for her hat, passed him.

“What on earth's the matter?” she inquired, fumbling in her pocket for the key as her husband executed a clumsy but noisy breakdown on the front step.

“Chill,” replied Mr. Teak. “I've got wet.”

He resumed his lumberings and, the door being opened, gave vent to his relief at being home again in the dry, in a voice that made the windows rattle. Then with anxious eyes he watched his wife pass upstairs.

“Wonder what excuse old Alf'll make for being in?” he thought.