Title: Lady John Russell: A Memoir with Selections from Her Diaries and Correspondence

Editor: Desmond MacCarthy

Contributor: Frederic Harrison

Justin McCarthy

Editor: lady Agatha Russell

Release date: February 1, 2004 [eBook #10980]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Charles Aldarondo, Keren Vergon, Susan Skinner, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Lady John Russell, Edited by Desmond MacCarthy and Agatha Russell

The manuscripts which have supplied the material for a memoir of my mother deal much more fully with the life of my father than with her own life. Mr. Desmond MacCarthy has therefore linked into the narrative several important incidents in my father's career.

The greater part of the memoir is written by Mr. Desmond MacCarthy; the political and historical commentary is almost entirely his work. The impartial and independent opinion of one outside the family, both in writing the memoir and in selecting passages from the manuscripts for publication, has been of great value.

My grateful thanks are due to His Majesty the King for giving permission to publish letters from Queen Victoria.

I am also grateful to friends and relations who have placed letters at my disposal; especially to my brother, whose helpful encouragement throughout the work has been most valuable.

Mr. Justin McCarthy, who many years ago recorded his impressions of my mother in his Reminiscences, has now most kindly contributed to this book a chapter of Recollections.

My cordial thanks are also due to Mr. George Trevelyan for reading the proof sheets, and to Mr. Frederic Harrison for giving permission to publish his Memorial Address at the end of this volume.

AGATHA RUSSELL

ROZELDENE, HINDHEAD, SURREY

October, 1910

Early years--Paris--Lord Minto appointed Minister at Berlin-- Germany--Return to Minto

Lord Minto First Lord of the Admiralty--Life in London--Bowood--Mrs. Drummond's recollections--Friendship with Lord John Russell--Putney House--Minto--Admiralty--Her engagement

Marriage--Sketch of Lord John's career before marriage--His conversation with Napoleon--Moore's "Remonstrance"

Wilton Crescent--Endsleigh--Chesham Place--Birth of her eldest son--Anti-Corn Law agitation--Her illness--Lord John's letter from Edinburgh--He is summoned to Osborne--Attempts to form a Ministry

Illness in Edinburgh--Letters between Lord and Lady John--Repeal of the Corn Laws--Ireland and coercion--Lord John Prime Minister

Pembroke Lodge--Difficulties of the Ministry--Revolution in France --Chartism--Petersham School founded by Lord and Lady John--The Papal Bull--Durham Letter--The Queen and Lord Palmerston--The Coup d'État--Breach with Palmerston--Defeat of the Russell Government--Literary friends

Lord Aberdeen Prime Minister--Lord John joins Coalition Ministry--Lady John's misgivings--Gladstone's Budget--Death of Lady Minto--Samuel Rogers--The Reform Bill--The Crimean War--Withdrawal of Reform--Roebuck's motion--Lord John's resignation

Defeat of Aberdeen Ministry--Lord John's Mission to Vienna--He accepts Colonial Office in Palmerston Government--Vienna Conference--His resignation--Lady John's diary and letters

Retirement and foreign travel--Palmerston and China--City election --Reception at Sheffield--Orsini's attempt upon Napoleon III--Italy and Austria--Lord John's share in the liberation of Italy--Lady John's enthusiasm--Garibaldi at Pembroke Lodge

Death of Lord Minto--Lord John accepts peerage--American Civil War--Death of Lord Palmerston--Lord Russell Prime Minister--Reform Bill of 1866--Mr. Lowe and the "Adullamites"--Defeat and resignation of the Russell Government

Travel in Italy--Entry of Victor Emmanuel into Venice--Disraeli's Reform Bill--Irish Church question--Gladstone Prime Minister--Winter at San Remo--Paris--Dinner at the Tuileries--Return to England

Franco-German War--Renens-sur-Roche--Education question--Cannes--Herbert Spencer--Letters from Queen Victoria--Herzegovina--Death of Lord Amberley--Nonconformist deputation at Pembroke Lodge--Death of Lord Russell

Lady Russell--Her love of children--Literary tastes--Friendships-- Correspondence--Haslemere--Death of Tennyson--England and Ireland--Last meeting of Petersham Scholars--Illness and death

Letters from friends--Funeral at Chenies--Poem on Death

RECOLLECTIONS OF LADY RUSSELL. By JUSTIN MCCARTHY

MEMORIAL ADDRESS BY FREDERIC HARRISON

LADY JOHN RUSSELL AND HER ELDEST SON

From a miniature by Thorburn. 1844

Frontispiece

From a photograph

THE COUNTESS OF MINTO, MOTHER OF LADY JOHN RUSSELL

From a miniature by Sir William Ross. 1851

From a portrait by G. F. Watts. 1852

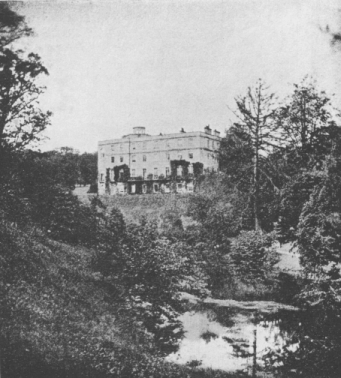

PEMBROKE LODGE, EAST SIDE. FROM THE PARK

From a water-colour drawing by W. C. Rainbow. 1883

PEMBROKE LODGE. FROM THE SOUTH LAWN

From a photograph by Frida Jones. 1902

LADY JOHN RUSSELL AND HER DAUGHTER

From a water-colour drawing by Mary Severn. 1854

WILD HYACINTHS, PEMBROKE LODGE.

From a water-colour drawing by Fred Dixey. 1899

VIEW FROM THE WEST WALK, PEMBROKE LODGE

From an oil painting by Samuel Helstead. 1896

From a photograph. 1884

On November 15, 1815, at Minto in Roxburghshire, the home of the Elliots, a second daughter was born to the Earl and Countess of Minto.

Frances Anna Maria Elliot, who afterwards became the first Countess Russell, was destined to a long, eventful life. As a girl she lived among those directing the changes of those times; as the wife of a Prime Minister of England unusually reticent in superficial relations but open in intimacy, in whom the qualities of administrator and politician overlay the detachment of sensitive reflection, she came to judge men and events by principles drawn from deep feelings and wide surveys; and in the long years of her widowhood, possessing still great natural vitality and vivacity of feeling, she continued open to the influences of an altered time, delighting and astonishing many who might have expected to find between her and them the ghostly barrier of a generation.

She died in January, 1898. The span of her life covers, then, many important political events, and we shall catch glimpses of these as they affect her. Though the intention of the following pages is biographical, the story of Lady Russell's life, after marriage, coincides so closely with her husband's public career that the thread connecting her letters together must be the political events in which he took part. Some of her letters, by throwing light on the sentiments and considerations which weighed with him at doubtful junctures, are not without value to the historian. It is not, however, the historian who has been chiefly considered in putting them together, but rather the general reader, who may find his notions of past politics vivified and refreshed by following history in the contemporary comments of one so passionately and so personally interested at every turn of events.

Another motive has also had a part in determining the possessors of Lady Russell's letters to publish them. Memory is the most sacred, but also the most perishable of shrines; hence it sometimes seems well worth while to break through reticence to give greater permanence to precious recollections. With this end also the following pages have been put together, and many small details included to help the subject of this memoir to live again in the imagination of the reader. For from brief and even superficial contact with the living we may gain much; but the dead, if they are to be known at all, must be known more intimately.

Minto House, where Lady Fanny was born, is beautifully situated above a steep and wooded glen, and is only a short distance from the river Teviot. The hills around are not like the wild rugged mountains of the Highlands, but have a soft and tender beauty of their own. Her childhood was far more secluded than the life that would have fallen to her lot had she been born in the next generation, for her home in Roxburghshire, in coach and turnpike days, was more remote from the central stir and business of life than any spot in the United Kingdom at the present time. Lady Fanny used to relate what a great event it was for the household at Minto when on very rare occasions her father brought from London a parcel of new books, which were eagerly opened by the family and read with delight. Those were not the days of circulating libraries, and both the old standard books on the Minto library shelves and the few new ones occasionally added were read and re-read with a thoroughness rare among modern readers, surrounded by a multiplicity of books old and new.

They were a large, young family, five boys and five girls, ranging from the ages of three years old to eighteen in 1830, when her diaries begin, all eager, high-spirited children, and exceptionally strong and healthy. In her early diaries, describing day-long journeys in coaches, early starts and late arrivals, she hardly ever mentions feeling tired, and she enjoyed the old methods of travelling infinitely more than the railway journeys of later days, about which she felt like the Frenchman who said: "On ne voyage plus; on arrive." Long wild country walks in Scotland and mountain-climbing in Switzerland were particularly delightful to her.

This stock of sound vitality stood her in good stead all her life; only during those years which followed the birth of her eldest son does it seem to have failed her. Her life was an exceptionally busy one, and her strong feelings and sense of responsibility made even small domestic affairs matters for close attention; yet in the diaries and letters of her later life there are no entries which betray either the lassitude or the restlessness of fatigue. She was not one of those busy women who only keep pace with their interests by deputing home management to others. This power of endurance in a deeply feeling nature is one of the first facts which any one attempting to tell the story of her life must bring before the reader's notice.

There was much reading aloud in the fireside circle at Minto, and for the boys much riding and sport. Many hours were spent upon the heather or in fishing the Teviot. Lady Fanny herself cared little for sport, or only for its picturesque side. Near the house are the rocks known as Minto Crags, mentioned by Sir Walter Scott in the "Lay of the Last Minstrel," where many and many a time Lady Fanny raced about on hunting days, watching the redcoats with childish eagerness--intensely interested in the joyousness and beauty of the sight, but in her heart always secretly thankful if the fox escaped. Fox-hunting on Minto Crags must indeed have been a picturesque sight, and there was a special rock overhanging a precipice upon which she loved to sit and watch the wild chase, men and horses appearing and disappearing with flashing rapidity among the woods and ravines beneath. The pleasures of an open-air life meant so much to her that, in so far as it was possible for one with her temperament to pine at all, she was often homesick in the town, longing for the peace and freedom of the country.

There were expeditions of other kinds too.

"Gibby 1 and I," she writes towards the end of one October, "up a little after five this morning and up the big hill to see the sun rise. It was moonlight when we went out, and all so still and indistinct--for it was a cloudy moon--that our steps and voices sounded quite odd. It was mild enough, but so wet with dew that our feet grew very cold. We waited some time on the top before he rose and had a long talk with the Kaims shepherd. It was well worth having gone; though there was nothing fine in the sky or clouds compared to what I have constantly seen at sunrise. But what I thought beautiful was the entire change that his rising made in everything. All we were looking at suddenly became so bright and cheerful, and a hum of people and noises of animals were heard from the village." "I wish people," she adds impetuously, "would shake off sleep as soon as the blushing morn does peep in at their windows."

The entries in these early diaries show a quality of clear authentic vision, which was afterwards so characteristic of her conversation. For those who remember their own youthful feelings, even the stiff occasional scraps of poetry she wrote at this time glow with a life not always discernible in the deft writing of more experienced verse-makers.

The household was a brisk, cheerful, active one, and ruled by the spirit of order necessary in a home where many different kinds of things are being done each day by its different inmates. The children were treated with no particular indulgence, and the elder ones were taught to be responsible not only for their own actions, but for the good behaviour, and, in a certain measure, for the education of the younger ones. As a girl she writes down in her diary many hopes and fears about her younger brothers and sisters, which resemble those afterwards awakened in her by the care of her own children. A big family in a great house, with all the different relations and contacts such a life implies, is in itself an education, and Lady Fanny seems to have profited by all that such experiences can give. If she came from such a home anticipating from everybody more loyalty and consistency of feeling than is common in human nature, and crediting everybody with it, that is in itself a kind of generous severity of expectation which, though it may be sometimes the cause of mistakes, helps also to create in others the qualities it looks to find.

The children had plenty of outlets for their high spirits. There are some slight records left of the opening of a "Theatre Royal, Minto," and of a glorious evening ending in an "excellent country bumpkin," with bed at two in the morning; of reels and dances, too, and many hours laconically summed up as "famous fun" in the diary. Then there were such September days as this:

"Bob'm 2 and I went in the phaeton to meet the boys. They were very successful--about twelve brace. The heather was in full blow, and in wet parts the ground white with parnassia. I never felt such an air--it made me feel quite wild. The sunset behind the far hills and reflected in the lonely little shaw loch most beautiful. When we began our walk there was a fine soft wind that felt as if it would lift one up to the clouds, but before we got back to the little house it had quite fallen, and all was as still as in a desert, except now and then the wild cry of the grouse and black-cock. Bob'm mad with spirits, and talked nonsense all the way home. Not too dark to see the beautiful outline of the country all the way."

Such tired, happy home-comings stay in the memory; drives back at the end of long days, when scraps of talk and laughter and the pleasure of being together mingle so kindly with the solemnity of the darkening country; drives which end in a sudden blaze of welcome, in fire-light and candles, tea and a hubbub of talk, when everything, though familiar, seems to confess to a new happiness.

Here is another entry a few days later:

"Beautiful day, but a very high, warm real Minto wind. We wandered out very late and sat under the lime, playing at being at sea, feeling the stem rock above us as we lent against it and hearing the roaring of the waves in the trees. No summer's day can be better than such a day and evening as this--there was a cloudy moon, too, above the branches. I wish I could express, but I never can, the sort of feeling I have at times--now more than I ever had before--which would sound like affectation if one talked of it. A fine day, or beautiful country, or very often nothing but the sky or earth or the singing of a bird gives it. One feels too much love and gratitude and admiration, and something swells my heart so that I do not know how to look or listen enough."

There was another kind of romance, too, in her young life, destined in future to be at times a source of pain and anxiety, though also of keen gratification and permanent pride. What can equal the romance of politics when we are quite young, when "politics" mean nothing but "serving one's country" and have no other associations but that one, when politicians seem necessarily great men? The love-dreams of adolescence have often been celebrated; but among young creatures whose lives give plenty of play to their affections in a spontaneous way, such dreams seldom vie in intensity with the mysterious call of religion or with the emotion of patriotism. It stands for an emotion which seems as large as the love of mankind, and its service calls for enthusiasm and self-devotion. The Mintos were in the thick of politics and the times were stirring times. "Throughout the last two centuries of our history," says Sir George Trevelyan in his Life of Macaulay, "there never was a period when a man, conscious of power, impatient of public wrongs, and still young enough to love a fight for its own sake, could have entered Parliament with a fairer prospect of leading a life worth living and doing work that would requite the pains, than at the commencement of the year 1830." Her father was not only the most genial and kindest of fathers, but he was to her something of a hero too. His political career had not begun during these days at Minto; still he was in the counsel of the leaders of the day--Lord Grey, Lord John Russell, Lords Melbourne and Althorp--great names indeed to her. And the new Cabinet was soon to appoint him Minister at Berlin.

The country was under the personal rule of the Duke of Wellington, who had sorted out from his Cabinet any who were tainted with sympathy for reform; but, as the election of July which resulted in his resignation showed, the country, however one-sided its representation might have been in the House of Commons, had been long in a state of political ferment. This state of affairs, the gradual breaking up of the Tory party dating from the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Bill, the brewing social troubles, and the prospect of power crossing to the party which was determined on meeting them with reform, made politics everywhere the most absorbing of themes.

In a country house like Minto, which was in close communication with the statesmen of the time, discussions were of course frequent and keen. The guests were often important politicians; and long before Lady Fanny saw her future husband, she frequently heard his name as one whom those she admired looked up to as a leader. In a girl by nature very susceptible to the appeal of great causes, whose active brain made her delight in the arguments of her elders, these surroundings were likely to foster a passionate interest in public affairs; while other influences round her were tending to increase in her a natural sense of the delicacy and preciousness of personal relations. In the course of telling her story occasions may come for remarking again on what was one of the chief graces of her character; but in a book of this kind the sooner the reader becomes acquainted with the subject of it, the more he is likely to see in what follows. So let it be said of her at once that in all relations in which affection was complicated on one side by gratitude, or on her side by superiority in education or social position, she was perfect. She could be employer and benefactress without letting such circumstances deflect in the slightest degree the stream of confidence and affection between her and another. She had the faculty of removing a sense of obligation and of forgetting it herself. Such a faculty is only found in its perfection where the mind is sensitive in perceiving the delicacy of the relations between people; and it must be added that like most people who possess that sensitiveness, she missed it acutely in those who markedly did not.

The life at Minto, with its many contacts, was a life in which such a faculty could grow to perfection. The daughters, while sharing much of the boys' lives at Minto, saw a great deal of the people upon the estate.

The intercourse between the family at the House and the people of Minto village was of an intimate and affectionate nature. Joys and sorrows were shared in unvarying friendliness and sympathy, and to the end of her life "Lady Fanny" remembered with warm affection the old village friends of her youth. Kindly, true-hearted folk they were, with a sturdy and independent spirit which she valued and respected.

She only remembered seeing Sir Walter Scott on one occasion--when he came to visit her parents. She was quite a child, and it was the day on which her old nurse left Minto. She had wept bitterly, and when Sir Walter Scott came she hardly dared even look at him with her tearful countenance. She always remembered regretfully her indifference about the great man, whose visit was ever after connected in her mind with one of the first sorrows of her childhood. She regretted still more that in those days political differences unhappily prevented the close and friendly intercourse which would otherwise have undoubtedly existed between the Minto family and Sir Walter Scott.

A word or two must be said upon the religion in which she was brought up, for from her childhood she was deeply religious. Like her love for those nearest to her, it entered into everything that interested or delighted her profoundly; into her interest in politics and social questions and into her enjoyment of nature.

The Mintos belonged to the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. The doctrines of this Church are not of significance here, but an indication of the attitude towards dogma, history, and conduct which harmonizes with these tenets is necessary to the understanding of her life. For this purpose it is only necessary to say that this Church belongs to that half of Protestantism which does not lay peculiar stress upon an inner conviction of salvation. It differs from the evangelical persuasions in this respect, and again from the Church of England in finding less significance in ecclesiastical symbols, in setting less store by traditional usages, and in a more constant and uncompromising disapproval of any doctrine which regards the clergy as having spiritual functions or privileges different from those of other men. In the latter half of her life she came gradually to a Unitarian faith, which she held with earnestness to the last; and the name "Free Church" became more significant to her through the suggestion it carried of a religion detached from creeds and articles. Many entries occur in her diaries protesting against what she felt as mischievous narrowness in the books she read and in the sermons she heard. She sympathized heartily with Lord John Russell's dislike of the Oxford movement. There are many prayers in her diaries and many religious reflections in her letters, and in all two emotions predominate; a trust in God and an earnest conviction that a life of love--love to God and man--is the heart of religion. Her religion was contemplative as well as practical; but it was a religion of the conscience rather than one of mystical emotions.

Of personal influences, her mother's, until marriage, was the strongest. There are only two long breaks in the diary she kept, when she had no heart to write down her thoughts; one occurs during the year of Lady Minto's long and serious illness at Berlin, which began in 1832, and the other after Lord John Russell's death in 1878.

Lady Minto was not strong; bringing many sons and daughters into the world had tried her; and her delicacy seems to have drawn her children closer round her. Lady Fanny's references to her mother are full of an anxious, protective devotion, as though she were always watching to see if any shadow of physical or mental trouble were threatening her. So in imagining the merry, active life of this large family, the presence of a mother most tenderly loved, from whom praise seemed something almost too good to be true, must not be forgotten.

In November, 1830 (the year Lady Fanny's diaries begin), the Duke of Wellington resigned, having emphatically declared that the system of representation ought to possess, and did possess, the entire confidence of the country. He had gone so far as to say that the wit of man could not have devised a better representative system than that which Lord John Russell, in the previous session, had attempted to alter by proposing to enfranchise Manchester, Leeds, and Birmingham. But the election which followed the death of George IV on June 26th had not borne out the Duke's assertion; it had gone heavily against him. Lord Grey, forming his Ministry out of the old Whigs and the followers of Canning and Grenville, at once made Reform a Cabinet measure. During the stormy elections of July the news came from Paris that Charles X had been deposed, and unlike the news of the French Revolution, it acted as a stimulus, not as a check, to the reforming party in England.

The next entry quoted from Lady Fanny's diary, begun at the age of fourteen, is dated November 22, 1830; the family were travelling towards Paris, matters having almost quieted down there. Louis Philippe had been recognized by England as King of the French the month before, and the only side of the revolution which came under her young eyes was the somewhat vamped up enthusiasm for the Citizen King which followed his acceptance of the crown and tricolor. It is said that any small boy in those days could exhibit the King to curious sightseers by raising a cheer outside the Tuileries windows, when His Majesty, to whom any manifestation of enthusiasm was extremely precious, would appear automatically upon the balcony and bow. But there were traces of agitation still to be felt up and down the country, and over Paris hung that deceptive, stolid air of indifference which is so puzzling a characteristic of crises in France.

The Mintos travelled in several carriages with a considerable retinue, with a doctor and servants, but not with a train which, in those days, would have been thought remarkable for an English peer.

MELUN, November 22, 1830 3

We left Sens at half past eight and did not stop to dine, but ate in the carriage. We passed through Fossard, Monteran, and got here about four. The doctor is quite grave about his tricolor and has worn it all day. We have had immense laughing at him. He was very much frightened at Sens, because Papa told him the people of the tricolor. A great many post-boys have it on their hats and all the fleurs-de-lis on the mile-posts are rubbed out.

By this date Charles X, surrounded by his gloomy, ceremonial little court of faithful followers, was playing his nightly game of whist in the melancholy shelter of Holyrood, where he was to remain for the next two years, an insipid, sorrowful figure, distinguished by such dignity as unquerulous passivity can lend to the foolish and unfortunate. Meanwhile, Paris was attempting to vamp up some interest in her new King, who walked the streets with an umbrella under his arm.

PARIS, December 23, 1830

We were in the Place Vendôme to-day, which was full of national guards waiting for the King. We stopped to see him. It looked very gay and pretty: the National Guard held hands in a long row and danced for ever so long round and round the pillar, with the people shouting as hard as they could. It looked very funny, but the King did not come whilst we were there. We heard them singing the Parisienne. The trial is over and the ministers are at Vincennes, going to be put in prison. There have been several mobs about the Luxembourg and the Palais Royal, but they think nothing more will happen now.

Who can hum now the tune of the "Parisienne"? It has not stayed in men's memories like the "Marseillaise"; no doubt it expressed the prosaic, middle-class spirit of the National Guard, which kept a King upon the throne, in his own way just as determined as his predecessors to rule in the interests of his family.

PARIS, February 5, 1831

Mama, Papa, Mary, Lizzy,4 Charlie, Doddy5 and I have been to a children's ball at the Palais Royal. It was the most beautiful thing I ever saw, and we danced all night long, but no big people at all danced. We saw famously all the royal people; and Lizzy danced with two of the little princes. The Duke of Orleans and M. Duc de Nemours were in uniform and so were all the other gentlemen. The King and Queen are nice-looking old bodies.6 It was capital fun and very merry indeed, the supper was beautiful. There was famous galloping.

PARIS, February 15, 1831

This is Mardi gras, the last day of the Carnival. We were out in the carriage this morning to see the masks on the boulevards; there were a great many masks and crowds of people, whilst there were mobs and rows going on in another part of the town. The people have quite destroyed the poor Archbishop's house, because on Sunday night the Duc de Bordeaux's bust was brought, and Mass was said for the Duc de Berry. They have taken all his books, furniture, and everything, and they wanted to throw some priests in the Seine, and they are breaking the things in the churches and taking down the crosses. All the National Guard is out.

These disturbances were the last struggles of the party who had not been satisfied by the spectacle of the son of Philippe Egalité, with the tricolor flag in one hand, embracing the ancient Lafayette on the balcony above the Place de Grève. Their animosity against the Church was the ground-swell of the storm which had washed away Charles X himself. The Sacrilege Law introduced in 1825 had revived the barbarous mediaeval penalty of amputating the hand of the offender. Charles's attempt to reintroduce primogeniture by declaring the French principle of the equal division of property to be inconsistent with the principle of monarchy had irritated the people less than the encouragement he had given to monastic corporations which were contrary to law. The controversy which followed between the ecclesiastics and their opponents was the cause of the repeal of the freedom of the Press; and when he had stifled controversy his next step was the suspension of Parliament. Whence followed the events which so abruptly disturbed his evening rubber at St. Cloud on July 25th.

These outbreaks of the republican anti-clerical party to which Lady Fanny refers were soon calmed; a few weeks later the soldiers had no more work to do, and a grand review was held in the Champ de Mars.

PARIS, March 27, 1831

We all went in the carriage to the heights of the Trocadéro and there got out. It was very pretty to look down at the Champ de Mars, which was quite full of soldiers, who sometimes ranged themselves in lines and sometimes in nice little bundles and squares. In front of the Ecole Militaire was a fine tent for the Queen and Princesses. The King and the Duc de Nemours rode about, and there were some loud cries of "Vive le Roi." Less than a year ago in the same place we saw old Charles X reviewing his soldiers and heard "Vive le Roi" shouted for him and saw white flags waving about the Champs de Mars instead of tricolor. It seems so odd that it should all be changed in so short a time, and spoils the "Vive le Roi" very much, because it makes one think they do not care really for him.

PARIS, April 2, 1831

We had a long walk with Mama to the places where the people that were killed in July were buried. There are tricolor flags over them all, and the flowers and crowns of everlastings were all nicely arranged about the tombs. Amongst them was the kennel of a poor dog whose master was one of the killed, which has come every day since and lain on his grave. The dog itself was not in. The poor Swiss are buried there, too, but without flowers or crowns or railings, or even stones, to show the place.

She had been "wishing horridly for fields and trees and grass" for some time past; on June 16, 1831, they were all back again in England.

DOVER, June 16, 1831

Everything seems odd here; pokers and leather harness, all the women and girls with bonnets and long petticoats and shawls and flounces and comfortable poky straw bonnets, and boys so nicely dressed, and urns and small panes (no glasses and no clocks), trays, good bread, and everybody with clean and fresh and pretty faces. We have been walking this evening by the sea, and all the English look very odd; they all look hangy and loose, so different from the Paris ladies, laced so tight they can hardly walk, and the men and boys look ten times better.

ROCHESTER, June 17, 1831

We did not leave Dover till near twelve--the country has really been beautiful to-day; all the beautiful gentlemen's places with large trees, and the pretty hedges all along the road full of honeysuckle and roses; clean cows and white fat sheep feeding in most beautiful rich green grass; the nicest little cottages with lattice windows and thatched roofs and neat gardens, and roses, ivy, and honeysuckle creeping to the tops of the chimneys; everybody and everything clean and tidy.... The cart-horses are beautiful, and even the beggars look as if they washed their faces.

October 9, 1831, BOGNOR

We heard this morning of the loss of the Reform Bill, and we were at first all very sorry, but in a little while rather glad because it gives us a chance of Minto. When the people of Bognor heard it was lost, they took the flowers and ribands off that they had dressed up the coaches with, thinking it had passed, and put them in mourning.

Lord John Russell had introduced the first Reform Bill on March 1, 1831; this was carried by a majority of one; but in a later division the Government was defeated by a majority of eight, and Parliament was dissolved. The elections resulted in an emphatic verdict in favour of Reform, and on June 24th Lord John introduced the second Reform Bill, which was carried by a large majority in the House of Commons. He had proposed to disfranchise partially or completely 110 boroughs; a proposition which had seemed so revolutionary that it was at first received with laughter by the Opposition, who were confident no such measure could ever pass. Lord Minto had returned from France to support this Bill in the Lords, which on his arrival he found had been rejected by them in a division on the 8th of October. The rejection of the Bill was followed by disturbances throughout the country. Several members of the House of Lords were mobbed, Nottingham Castle was burnt down, and there was fighting and bloodshed in the streets of Bristol. Before the third Reform Bill was brought forward and carried by a huge majority in the Commons, the whole Minto family were on their way North.

Lady Fanny announces the fact of her arrival at her beloved home with many ecstatic exclamation marks.

November 2, 1831, MINTO !!!!

Between Longtown and Langham we passed the toll that divides England and Scotland. Harry and the coachman waved their hats and all heads were poked out at window.

The moment we got into Scotland it felt much finer, the sun shone brighter and the country really became far prettier. We went along above the Esk, which is a little rattling, rumbling, clear, rocky river, prettier than any we ever saw in England....

As we drove into Langham we were much surprised by a loud cheer from some men and boys at the roadside, who all threw off their caps as we passed. While we were changing, a man offered to Papa that they would drag him through the town; Papa thanked him very much but said he would rather not; so the man said perhaps he would prefer three cheers, which they gave as we drove off.... The whole town crowded round the carriages. Just as we were setting off, however, we were very much surprised to see numbers of people take the pole of the little carriage and run off with Papa and Mama with all their might. They spun all through the town at a fine rate, and did not stop for ever so long. There was immense cheering as we drove off, and the people ran after us ever so far.... The house all looked beautiful, and this evening we feel as if we had never left Minto.

But she was not to stay there long, for early in 1832 they went to Roehampton House, near London, and the same year Lord Minto was appointed Minister at Berlin.

At this time Berlin was not a capital of sufficient dignity to entitle it to an embassy; but considering the state of European politics, the appointment was one of some diplomatic importance.

Germany was at the beginning of her task of consolidation. The revolution of July had not been without its effect on her. In the southern States the cause of representative government was not wholly powerless; but it had been weakened by the reaction after 1815. Since the government was no longer an undisguised tyranny and since the people themselves were growing richer, a strong sentiment of personal loyalty to the sovereign began to spread among them. Constitutional changes were therefore indefinitely postponed. The great work of the next few years for Prussian statesmen was the removal of commercial barriers between the various German States, and the establishment of a Zollverein between them. In this way the sway of Austria was weakened, and though political union as an aim was carefully kept in the background, the foundation for the subsequent consolidation of the German Empire was securely laid. During the two central years of this process, 1832-4, Lord Minto was at Berlin. The manners of the time were far simpler and the life at the court far more informal than they were soon to become. Law and custom still preserved some lingering barbarities: during their stay at Wittenberg they heard of a man being broken on the wheel.

They stopped at Brussels on the way. There is a characteristic entry in Lady Fanny's diary describing a visit to the battle-field.

NAMUR, September 6, 1832

We coach-people left Brussels much earlier than the others that we might have time to walk about Waterloo....

They showed us the house where the Duke of Wellington slept the night before and the night after the battle and wrote home his dispatches; then after a long and fierce dispute between a man and woman which was to guide us, the man took us to the Church, where we saw the monuments of immense numbers of poor common soldiers and officers--then to the place where four hundred are buried all together and one sees their graves just raised above the rest of the ground. Then we drove to the field of battle, and the man showed us everything; it was very nice and very sad to hear all about, but as I shall always remember it, I need say nothing about it. We are quite in a rage about a great mound that the Dutch have put up with a great yellow lion on the top, only because the Prince of Orange was wounded there, quite altering the ground from what it was at the time of the battle. The monument to Lord Anglesea's leg too, which we did not of course go to see, makes one very angry, as if he was the only one who was wounded there--and only wounded too when such thousands of poor men were killed and have nothing at all to mark the place where they are buried; and I think they are the people one feels most for, for though they do all they can, after they are dead one never hears any more about them.

Soon after their arrival at Berlin, Lady Minto fell dangerously ill. From September, 1832, there is a long gap in Lady Fanny's diary, for she had no heart to set anything down. This long stretch of anxiety coming when she was sixteen years old, if it did not change her nature, brought to light new qualities which were to mark her character henceforward. There is a little entry written down eight years afterwards on the birthday of her sister Charlotte which shows that she, as well as others, looked back on this time as a turning-point in her life.

Bob'm sixteen to-day, just the age I began to be unhappy, because I began to think. Heaven spare her from the doubts and fears that tormented me.

During the months of her mother's gradual recovery she seems each day to have been happier than on the one before.

June 6, 1833, POTSDAM

At a little before eleven this morning, Mary, Ginkie, Henry,7 Mr. Lettsom8 and I set off from Berlin in a very curious rickety machine of a carriage, to leave Mama for a whole day and night, which feels very impossible, and is the best sign of her (health) that one could have. We were very happy and we thought everything looking very nice. We were sorry to see no friends as we left Berlin, for we looked so beautiful in our jolting little conveyance with four horses and a post-boy blowing the old tune on his horn.

To escape the heat of Berlin they moved out to Freienwalde.

June 14, 1833, FREIENWALDE

A beautiful morning, and at about 10 they all set off from Berlin, leaving Mama, Papa, Bob'm and I to follow after in the coach. After they went, there were two long hours of going backwards and forwards through the empty rooms, then having said a sad good-bye to Senden,9 Hymen,9 Mr. Lettsom and Fitz, though we know we shall see them again soon, we got into the coach with the squirrel in a bag and drove off. I could not help feeling very sorry to leave it all, though it will be so very nice to be out of it, but I knew we should never be all there again as we have been, and all the misery we have had in that house makes one feel still more all the happiness of the last month there.

There is nothing to say of the country, for it is the same as on all the other sides of Berlin; the soil more horrid than anything I ever saw, and of course all as flat as water, but just now and then some rather nice villages.... After about two hours there we came on, first through nice, small Scotch fir woods, then quite ugly again till near here, when we got into really pretty banks of oak, beech, and fir, down a real steep road and along a nice narrow lane till we got here, where they were all standing on the steps of our mansion ready to receive us. Mama was carried to the drawing-room ... before the house is a wee sort of border all full of weeds, but nothing like a garden or place belonging to the house, but there seem very few people; then there is a terrace, which is very nice though it is public. Mama is not the least tired and quite pleased with it all. It is very, very nice to be here, able to go out without our things and expecting no company, and what at first one feels more nice than everything, not having any carriages or noises out of doors; for eight months and a half we have never been without that horrid, constant rumbling in the streets. It is very odd to feel ourselves here; unlike any place I ever lived in. The bath house is close by, but that is the only house near us.

There they lived all the summer the life that they liked best. They lost themselves in the forest, they read aloud, and they enjoyed the rustic theatre. The autumn brought visits to Teplitz and Dresden.

They were back in Berlin for the winter and early spring, when she began to take more part in society.

April 1, 1834, BERLIN

Stupid dinner of old gentlemen. Mary still being rather silly10 did not dine at table.... It was very awful to be alone, but at dinner I was happy enough as Löven sat on one side of me. Humboldt was on the other. Afterwards came Fitz for a moment and Deken and Bismarck.

April 5, 1834, BERLIN

I sat the second quadrille by my stupidity in refusing Bismarck.

Early in May came "the hateful morning of good-byes" to friends in Berlin, and at Marienbad. Lord Minto heard the news that Lord Grey had resigned owing to Lord Althorp's refusal to agree to the Irish Coercion Bill. Lord Melbourne succeeded him as Prime Minister. Lord Minto had not long returned to England when the King summarily dismissed Lord Melbourne and a provisional Government under the Duke of Wellington was patched together until Sir Robert Peel should return from abroad. The governorship of Canada had been offered meanwhile to Lord Minto, and the family started on their home journey fearing they would have to leave England immediately for Quebec. But this did not happen, and December found them at last once more on the road to Minto. The girls wrote poems celebrating their return on the journey, and tried every cure for impatience as the carriage rolled along.

MINTO, Thursday, December 25, 1834

We left Carlisle about eight, and for the three first stages were so slowly driven that our patience was nearly gone. To make it last a little longer Mary read some "Hamlet" aloud between Longtown and Langholme, and I had a nap.... As soon as we entered Hawick we were surrounded by an immense crowd.... The bells rang, there were flags hung all along the street, and fine shouting as we set off. Papa, which we did not know at the time, had to make a little speech, and contradict a shameful report of his having taken office. A few minutes on this side of Hawick we met the two boys and Robert riding to meet us, looking lovely. Our own country looked really beautiful; rocks, hills, and Rubers Law all seemed to have grown higher. We passed the awful ford in safety across our own lovely Teviot, and soon found ourselves at Nelly's Lodge, where old Nelly opened the gate to us.... The trees looked large and fine--in short, everything perfect. Catherine, Mrs. Fraser, and Wales received us at the door, and in a few minutes we were scattered all over the house. We spent a most happy evening.... This has really been a happy Christmas. It is wonderful to be here.

At this point Lady Fanny's early girlhood may be said to end. Her life in London society and the events which led to her marriage will be told in the next chapter.

While the Minto family were still on their way home from Germany a startling incident occurred in English politics. One morning a paragraph appeared in the Times announcing the fact that the King had dismissed Lord Melbourne.

We have no authority (it ran) for the important statement which follows, but we have every reason to believe that it is perfectly true. We give it without any comment or amplification, in the very words of the communication, which reached us at a late hour last night. "The King has taken the opportunity of Lord Spencer's death to turn out the Ministry, and there is every reason to believe the Duke of Wellington has been sent for. The Queen has done it all."

(The authority upon which the Times was relying was that of the Lord Chancellor.)

So on coming down to breakfast that morning the Ministers, having received no private communication whatever, read to their amazement that they had been already dismissed. Brougham had surreptitiously conveyed the information in order to embarrass the Court. The general trend of political gossip at the time was expressed by Palmerston, who wrote:

It is impossible to doubt that this has been a preconcerted measure and that the Duke of Wellington is prepared at once to form a Government. Peel is abroad; but it is not likely he would have gone away without a previous understanding one way or the other with the Duke, as to what he would do if a crisis were to arise.

As a matter of fact there had been no concerted plan. It was the first and last independent step William IV ever took, and a most unconstitutional instance of royal interference. The Duke, summoned by the King, expressed his willingness to occupy any position His Majesty thought fit, but considering the Liberal majority in the House of Commons was two to one, and it was but two years since the Reform Bill passed, he did his best to dissuade the King from dismissing all his Ministers. During the interview the King's secretary entered and called the attention of the King to the paragraph in the Times that morning, which concluded with the statement that the Queen had done it all. "There, Duke, you see how I am insulted and betrayed; nobody in London but Melbourne knew last night what had taken place here, nor of my sending for you: will your Grace compel me to take back people who have treated me in this way?"

Thereupon the Duke consented to undertake a provisional Government, while Mr. Hudson was sent off to Italy in search of Sir Robert Peel. He reached Rome in nine days; at that time very quick travelling. "I think you might have made the journey in a day less by taking another route," is said to have been Peel's only comment upon receiving the Duke's letter. He returned at once to England to relieve the temporary Cabinet, and formed a Ministry in December. The same month Parliament was dissolved, and the Conservative party went to the country on the policy of "Moderate Reform" enunciated in Peel's Tamworth manifesto. "The shameful report" referred to by Lady Fanny in the last chapter, and immediately contradicted by Lord Minto on his return to Scotland, was that he had joined the Peel Ministry.

Thus Lady Fanny came home to find the country-side preparing for a mid-winter election. Her uncle, George Elliot, was standing for the home constituency against Lord John Scott, whom he just succeeded in defeating. In most constituencies, however, the Liberals triumphed more easily, and when the new Parliament met they were in a majority of more than a hundred. In April Lord John Russell carried his motion for the appropriation of the surplus revenues of the Irish Church to general moral and religious purposes, so Peel resigned. Melbourne again became Prime Minister, and in the autumn of the same year, 1835, Lord Minto was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty.

This meant a great change in Lady Fanny's life; henceforward for the next eight years more than half of every year was spent by her in London. There is a change, too, in the spirit of her diaries. Her nature was the reverse of introspective and melancholy, but at this time she was often unhappy and dissatisfied for no definite reason; her diaries show it. It is not likely that others were aware of this private distress. She was leading at the time a busy life both at home and in society, and there were many things in which she was keenly interested. The troubles confided to these private pages were not due to compunction for anything she had done, nor were they caused by any particular event; they expressed simply a general discontent with herself and a kind of Weltschmerz not uncommon in a young and thoughtful mind. For the first time she seems glad of outside interests because they distract her.

The months in London were broken by occasional residence at Roehampton House and by visits to Bowood. At Bowood with the Lansdowne family she was always happy. There she heard with delight Tom Moore sing his Irish melodies for the first time. There was much, too, in London to distract and amuse her: breakfasts with Rogers, luncheons at Holland House, and dinner-parties at which all the leading Whig politicians were present. But society did not satisfy her; she wanted more natural and more intimate relations than social gatherings usually afford.

LONDON, May 9, 1835

We went to Miss Berry's in the evening. I thought it very tiresome, but was glad to see Lord John Russell and his wife.

BOWOOD, December 26, 1835

The evening was very quiet, there was not much to alarm one, and the prettiest music possible to listen to. Mr. Moore singing his own melodies--it was really delightful, and a kind of singing I never heard before. He has very little voice, but what he has is perfectly sweet, and his real Irish face looks quite inspired. The airs were most of them simply beautiful, and many of the words equally so.

January 31, 1836, ADMIRALTY

I am reading "Ivanhoe" for the first time, and delighted with it, but things cannot be as they should be, when I feel that I require to forget myself in order to be happy, and that unless I am taken up with an interesting book there never, or scarcely ever, is a moment of real peace and quiet for my poor weary mind. What is it I wish for? O God, Thou alone canst clearly know--and in Thy hands alone is the remedy. Oh let this longing cease! Turn it, O Father, to a worthy object! Unworthy it must now be, for were it after virtue, pure holy virtue, could I not still it? Dispel the mist that dims my eyes, that I may first plainly read the secrets of my wretched heart, and then give me, O Almighty God, the sincere will to root out all therein that beareth not good fruit....

February 4, 1836, ADMIRALTY

The great day of the opening of Parliament. Soon after breakfast we prepared to go to the House of Lords--that is to say, we made ourselves great figures with feathers and finery. The day has been, unfortunately, rainy and cold, and made our dress look still more absurd. The King did not come till two, so that we had plenty of time to see all the old lords assembling. Their robes looked very handsome, and I think His Majesty was the least dignified-looking person in the house. I cannot describe exactly all that went on. There was nothing impressive, but it was very amusing. The poor old man could not see to read his speech, and after he had stammered half through it Lord Melbourne was obliged to hold a candle to him, and he read it over again. Lord Melbourne looked very like a Prime Minister, but the more I see him and so many good and clever men obliged to do, at least in part, the bidding of anyone who happens to be born to Royalty, the more I wish that things were otherwise--however, as long as it is only in forms that one sees them give him the superiority one does not much mind. After the debate, several of Papa's friends came to dine here. Lord Melbourne, Lord Lansdowne, Lord Glenelg, and the Duke of Richmond, who has won my heart--they talked very pleasantly.

March 9, 1836, ADMIRALTY

I wonder what it is that makes one sometimes like and sometimes dislike balls, etc. It does not always depend on whom one meets. I am sure it is not, as most books and people seem to think, from love of admiration that one is fond of them or else how should I ever be so, when it is so impossible for anybody ever to admire my looks or think me agreeable? I sometimes wish I was pretty. And I do not think it is a very foolish wish: it would give me courage to be agreeable.

All through this year there are many troubled entries:

March 28, 1836, ADMIRALTY

Youth may and ought to have--yes, I see by others that it has--pleasures which surpass those of unthinking though lovely childhood: but have I experienced them? ... What makes the same sun seem one day to make all nature bright, and the next only to show more plainly the dreariness of the landscape? Oh wicked, sinful must be those feelings that make me miserable--selfish and sinful--and I cannot reason them away, for I do not understand them. Prayer has helped me before now, and I trust it will still do so. O Lord, forsake me not--take me into Thy own keeping.... Mama fifty to-day [March 30, 1836]. Oh the feelings that crowd into my heart as if they must burst it when I look to this day three years ago. I cannot write or think clearly of it yet. I can only feel--but what, I do not myself know--at one moment agony, doubts, and fears, as if it was still that fearful day; then joy almost too great to bear. When I think of her as she now is, then everything vanishes in one overpowering feeling of intense thankfulness. I have several times to-day seen her eyes fill with tears--every birthday of those one loves gives one a melancholy feeling, and the more rejoicings there are the stronger that feeling is.

June 27, 1836, ADMIRALTY

It was decided that we should go to the Duchess of Buccleuch's breakfast. My horror of breakfasts is only increased by having been to this one, though I believe it was particularly pleasant. Certainly the day was perfect, and the sight and the music pretty; but I scarcely ever disliked people more or felt more beaten down by shyness. My only thoughts from the moment we went in were: How I wish it was over, and how I wish nobody would speak to me.

September 6, 1836, ROEHAMPTON

Mama and I went to dine at Holland House.... The rooms are just what one would expect from the outside of the handsome old house, with a number of good pictures in the library, where we sat, all portraits. Lord Holland is perfectly agreeable, and not at all a man to be afraid of, in the common way of speaking, but for that very reason I always am afraid of him--much more than of her, who does not seem to me agreeable. I was very sorry Lord Melbourne did not come, as he would have made the conversation more general and agreeable.

The impression she made on others in her girlhood will be seen by this passage in the "Reminiscences of an Idler," by Chevalier Wyhoff: "I had the honour of dancing a quadrille with Lady Fanny Elliot, the charming daughter of the Earl of Minto. Her engaging manners and sweetness of disposition were even more winning than her admitted beauty."

In July it was decided that her brother Henry should go out to Australia with Sir John Franklin. The idea of parting troubled her extremely, and, moreover, the project dashed all the castles in the air she had built for him. August 21st was the day fixed for his sailing. The 20th came--"dismal, dismal day, making things look as if they understood it was his last." Long afterwards, whenever she saw the front of Roehampton House, where she said good-bye to him, the scene would come back to her mind--the waiting carriage and the last farewells. The autumn winds had a new significance to her now her brother was on the sea. She was troubled too about religious problems, but she found it difficult, almost impossible, to talk about the thoughts which were occupying her. Writing of her cousin Gilbert Elliot, afterwards Dean of Bristol, for whom she felt both affection and respect, she says: "In the evening Cousin Gilbert talked a great deal, and not only usefully but delightfully, about different religious sects and against the most illiberal Church to which he belongs--but how could I be happy? The more he talked of what I wished to hear, the more idiotically shy I felt and the more impossible it became to me to ask one of the many questions or make one of the many remarks (foolish very likely, but what would that have signified?) which were filling my mind."

December 24, 1836, BOWOOD

Mr. Moore sang a great deal, and one song quite overcame Lady Lansdowne. At dinner I sat between Henry11 and Miss Fazakerlie, who told me that last year she thought me impenetrable. How sad it is to appear to every one different from what one is.

I like both her and Henry better than ever, but oh, I dislike myself more than ever--and so does everybody else--almost. Is it vain to wish it otherwise?--no, surely it is not. If my manner is so bad must there not be some real fault in me that makes it so, and ought I not to pray that it may be corrected?

She read a great deal at this time; Jeremy Taylor, Milton, and Wesley, Heber, Isaac Walton, Burnet; Burns was her favourite on her happiest days. She thought that work among the poor of London might help her; but her time was so taken up both with looking after the younger children and by society that she seems to have got no further than wondering how to set about it.

On June 20th, 1837, William IV died, and in July Parliament was dissolved. On the 4th they were back again at Minto.

Her uncle John Elliot was successful in his candidature of Hawick. "Hawick," she writes, "has done her duty well indeed--in all ways; for the sheriff's terrible riots have been nothing at all. Some men ducked and the clothes of some torn off. We all felt so confused with joy that we did not know what to do all the evening." These rejoicings ended suddenly: Lady Minto was called to the death-bed of her mother, Mrs. Brydone.

August 19, 1837, MINTO

I feel this time as I always do after a great misfortune, that the shock at first is nothing to the quiet grief afterwards, when one really begins to understand what has happened.

I cannot help constantly repeating over and over to myself that she is gone, and sometimes I do not know how to bear it and however to be comforted for not having seen her once more.

When the new Queen's Parliament met after the General Election the strength of the Conservatives was 315 and of the Liberals 342. The Melbourne Ministry was in a weaker position; they could only hold a majority through the support of the Radical and Irish groups, and troubles were brewing in the country. On the other hand, Peel's position was not an easy one; the split among the Conservatives on Catholic Emancipation had left bitterness behind, and in addition to this complication, his followers in the Commons included both men like Stanley, who had voted for Parliamentary reform, and its implacable opponents. But in spite of this flaw in the solidarity of the Opposition, the Ministers were far from secure. There were the troubles in Canada, which Lord Durham had been sent out to deal with (the Canadian patriots had a great deal of Lady Fanny's sympathy), and in England the grievances of the poor were in the process of being formulated into the famous People's Charter. During the parliamentary sessions the Mintos remained in London, with only occasional very short absences.

ADMIRALTY, December 26, 1837

People all seem pleased with the news from Canada because we are beating the poor patriots--let people say what they will I must wish them success and pity them with all my heart.

EASTBOURNE, April 14, 1838

It is not only the out of doors pleasures, the sea, the air, etc., that we find here, but the way of living takes a weight from one's mind, of which one does not know the burden till one leaves London and is freed from it. "I love not man the less" from feeling as I do the great faults, to us at least, of our London society. It is because I love man, because I daily see people whose thoughts I long to share and profit by, that I am so disappointed in being unable to do so. Oh, why, why do people not all live in the country--or if towns must be, why must they bring stiffness and coldness on everybody?

ADMIRALTY, May 10, 1838

Court Ball.... Beautiful ball of beautiful people dancing to beautiful music. Queen dancing a great deal, looking very happy.

ADMIRALTY, June 22, 1838

Evening at a Concert at the Palace--all the good singers.... All the foreigners there, Soult and the Duke of Wellington shaking hands more heartily than any other two people there.

ADMIRALTY, June 28, 1838

Day ever memorable in the annals of Great Britain! Day of the coronation of Queen Victoria! ... We were up at six, and Lizzy, Bob'm, and I, being the Abbey party, dressed in all our grandeur. The ceremony was much what I expected, but less solemn and impressive from the mixture of religion with worldly vanities and distinctions. The sight was far more brilliant and beautiful than I had supposed it would be. Walked home in our fine gowns through the crowd; found the stand here well filled, and were quite in time to see the procession pass back. Nothing could be more beautiful, the streets either way being lined with the common people, as close as they could stand, and the windows, house-tops, balconies, and stands crowded with the better dressed. Great cheering when Soult's carriage passed, but really magnificent for the Duchess of Kent and the Queen. The carriages splendid. Did not feel in the Abbey one quarter of what I felt on the stand.

MINTO, November 4, 1838

This morning brought us the sad, sad news of the death of Lady John Russell. God give strength to her poor unhappy husband, and watch over his dear little motherless children.

The only event of importance which occurred in the family during 1838 was the marriage of the eldest daughter, Mary, to Ralph Abercromby, son of the Speaker and afterwards Lord Dunfermline. It was a very happy marriage, but Lady Fanny missed her sister very much, and her accounts of the wedding and the last days before it are mixed with regrets. She speaks of it as "an awful day," though it seems to have ended merrily enough in dancing and rejoicings.

In May, 1839, the Government resigned in consequence of the opposition to the Jamaica Bill. The object of the Bill was to suspend the constitution of Jamaica for five years, since difficulties had been made by the Jamaica Assembly in connection with the emancipation of slaves. The Radicals voted with the Conservatives against the Government and the Bill was lost.

ADMIRALTY, May 7, 1839

We are all out!!!!

Papa was summoned to a Cabinet at twelve this morning. Mama and I in the meantime drove to some shops, and when we came home found him anxiously expecting us with this overpowering news. We bore, and are still bearing it with tolerable fortitude; but we are all very, very sorry, and every moment find something new to regret. Mama, notwithstanding all she has said, is not better pleased than the rest of us. Papa looks very grave, or else tries to joke it off.

FRIDAY, May 10, 1839, ADMIRALTY

Agitating morning--one report following another every hour. Sir Robert Peel refused to form a Ministry unless the Queen would part with some of her household. To this she would not consent. To-day she sent for Lord Melbourne.... We went to the first Queen's ball, very anxious to see how she and other people looked, and to try to foresee coming events by the expression of faces.... I spoke to scarcely one Tory, but our Whig friends were in excellent spirits--the Queen also seemed to be so.

TUESDAY, May 14, 1839, ADMIRALTY

Papa and Bill12 came from the House of Lords quite delighted with Lord Melbourne's speech in explanation of what has passed--manner, matter, everything perfect.

Thus, within the week, the Whig Ministry had resigned and accepted office again: this is what had happened.

On his return from Italy to take office Sir Robert Peel requested the Queen to change the ladies of her household, and on her refusal to do so, the Melbourne Ministry had come in again. Their return to power has been generally considered a blunder, from the party point of view; but their action in this case was not the result of tactical calculations. The young Queen was strange as yet to the throne, and she could not bear to be deprived of her personal friends. When Peel made a change in her household the condition of accepting office, she turned to the Whigs, who felt they could not desert her. "My dear Melbourne," wrote Lord John, "I have seen Spencer, who says that we could not have done otherwise than we have done as gentlemen, but that bur difficulties with the Radicals are not diminished...."

They were, indeed, hard put to it to carry on the Government at all, and they only succeeded in passing their Education Bill by a majority of two.

On August 12th the Mintos were still kept in London. "Oh for the boys and guns and dogs, a heathery moor, and a blue Scotch heaven above me!" she writes. When they did get away home, they remained there until the beginning of the new year. At home she seems to have been much happier. She taught her young brothers and sisters, she visited her village friends, and rambled and read a great deal. In short, it was Minto!--all she found so hard to part from when marriage took her away.

Many of the extracts from the diaries quoted in this chapter must be read in the light of the reader's own recollections of the process of getting used to life. They show that if Lady Russell afterwards attained a happy confidence in action, she was not in youth without experience of bewilderment and doubts about herself. Following one another quickly, these extracts may seem to imply that she was gloomy and self-centred during these years; but that was never the impression she made on others. Like many at her age, when she wrote in a diary she dwelt most on the feelings about which she found it hardest to talk. Her diary was not so much the mirror of the days as they passed as the repository of her unspoken confidences. "Looked over my journals, with reflections," she writes later; "inclined to burn them all. It seems I have only written [on days] when I was not happy, which is very wrong--as if I had forgotten to be grateful for happy ones."

Mrs. Drummond, Lord John Russell's stepdaughter (who was then Miss Adelaide Lister), has recorded, in a letter to Lady Agatha Russell, her recollections of the Minto family at that time.

I think (she writes) my first visit to the Admiralty, where I was invited to children's parties, must have been in the winter before my mother's death. I have no distinct first impressions of the grown-up part of the family, except perhaps of your grandmother, Lady Minto. Although children exaggerate the age of their elders, and seldom appreciate beauty except that of people near their own age, I did realize her great good looks. She had very regular features and a beautiful skin, with a soft rose-colour in her cheeks. Her hair was brown, worn in loops standing out a little from the face, and she always wore a cap or headdress of some kind. Her manner was most kind and winning, and she had a pleasant voice. I am sure she must have been very even-tempered; and as I recall her image now, and the peace and serenity expressed in her beautiful face, I think she must have had a happy life. I never saw her otherwise than perfectly kind and gentle and quite unruffled by the little contretemps, which must have befallen her as they do others. With this gentleness there was something that made one feel she was capable and reliable, that there was a latent strength on which those she loved could lean and be at rest. But in speaking of these things I am going far beyond the impressions of the small child skipping about the large rooms of the Admiralty.

There came a time when I not only went to parties and theatricals at the Admiralty, but went in the afternoons to play with the children. One great game was the ghost game. To the delightful shudders produced by this was added some fear of the butler's interference, for it took place on the large dining-room table. The company was divided into two parties--the ghosts and the owners of the haunted house. At four o'clock in the afternoon (so as to give plenty of time to pile up the horror) the inmates of the house got into bed--that is, on to the table. The ghosts then walked solemnly round and round, while at intervals one of them imitated the striking of the clock; as the hours advanced the ghosts became more demonstrative and the company in bed more terror-stricken, and as the clock struck twelve the ghosts jumped on to the table! Then ensued a frightful scrimmage with ear-splitting squeals, and the game ended. I imagine it was this climax which used to bring the butler. We also had the game of giant all over the house. The yells in this case sometimes brought Lady Minto on the scene, who was always most good-natured. We were quieter when we got into mischief; as when we made a raid on Lord Minto's dressing-room, and each ate two or three of his compressed luncheon tablets and also helped ourselves to some of his pills. This last exploit did rather disturb Lady Minto; but, as it happens, neither luncheons nor pills took any effect on the raiders.

There were often delightful theatricals at the Admiralty. The best of the plays was a little operetta written by your mother, called "William and Susan," in which Lotty and Harriet13 sang delightfully in parts; but this must have been later on than the game period.

I come now to my first distinct impression of your mother. It is as clear as a miniature in my mind's eye, and it belongs to a very interesting time. I think her engagement to Papa14 must just have been declared. She came with Lord and Lady Minto to dine with him at 30, Wilton Crescent, the house he owned since his marriage to my mother. As she passed out of the room to go down to dinner, "Lady Fanny's" face and figure were suddenly photographed on my brain. Her dark and beautiful smooth hair was most becomingly dressed in two broad plaited loops, hanging low on the back of the neck; the front hair in bands according to the prevailing fashion. Her eyes were dark and very lustrous. Her face was freckled, but this was not disfiguring, as a rich colour in her cheeks showed itself through them. Her neck, shoulders, and arms were most beautifully white, and her slim upright figure showed to great advantage in the neat and simple dress then worn. Hers was of blue and silver gauze, the bodice prettily trimmed with folds of the stuff, and the sleeves short and rather full. I think she wore an enamelled necklet of green and gold. Mama15 long afterwards told me that at this dinner she went through a very embarrassing moment; Papa asked her what wine she would have, and she, just saying the first thing that came into her head, replied, "Oh, champagne." There was none. Papa was sadly disconcerted, and replied humbly, "Will hock do?" I used to take much interest at all times in Papa's dinner-parties, and sometimes suggested what I considered suitable guests. I was much disappointed when I found my selection of Madame Vestris and O'Connell did not altogether commend itself to Papa.

Mrs. Drummond, in another letter to Lady Agatha Russell, alluding to a visit to Minto before Lord John Russell's second marriage, writes:

Mama [then Lady Fanny Elliot] was very kind to me even then, and I took to her very much. I used to admire her bright eyes and her beautiful and very abundant dark hair, which was always exceedingly glossy, and her lovely throat, which was the whitest possible--also her sprightly ways, for she was very lively and engaging.

The winter of 1840 was spent between the Admiralty and Putney House, which the Mintos had taken. Lady Fanny's description of Putney sounds to us now improbably idyllic:

Out almost till bedtime--the river at night so lovely, so calm, still, undisturbed by anything except now and then a slow, sleepy-looking barge, gliding so smoothly along as hardly to make a ripple. The last few nights we have had a little crescent moon to add to the beauty. Then the air is so delightfully perfumed with azalea, hawthorn, and lilac, and the nightingales sing so beautifully on the opposite banks, that it is difficult to come in at all.

PUTNEY HOUSE, April 30, 1840

Finished my beloved "Sir Samuel Romilly." It is a book that everybody, especially men, should immediately read and meditate upon.

It was during the summer of this year, 1840, that she began to see more of Lord John Russell. She had met him a good many times at "rather solemn dinner-parties," and he had stayed at Minto. She had known him well enough to feel distress and the greatest sympathy for him when his wife died, leaving him with two young families to look after--six children in all, varying in age from the eldest Lister girl, who was fourteen, to Victoria, his own little daughter, whose birth in 1838 was followed in little more than a week by the death of her mother. Lord John was nearly forty-eight. Hitherto he had been a political hero in her eyes rather than a friend of her own; but, as the following entries in her diary show, she began now to realize him from another side.

June 3, 1840, PUTNEY HOUSE

Lord John Russell and Miss Lister16 came to spend the afternoon and dine. All the little Listers came. All very merry. Lord John played with us and the children at trap-ball, shooting, etc.

The next time they met was at the Admiralty: "Little unexpected Cabinet meeting after dinner. Lords John Russell and Palmerston, who talked War with France till bedtime. I hope papa tells the truth as to its improbability." Two days later she writes: "Lord John Russell again surprised us by coming in to tea. How much I like him." The next evening she dined at his house: "Sat between Lord John and Mr. E. Villiers. Utterly and for ever disgraced myself. Lord John begged me to drink a glass of wine, and I asked for champagne when there was none!"

On August 13th they left London for Minto:

We had two places to spare in the carriage, which were taken by Lord John Russell and little Tom [his stepson, Lord Ribblesdale]. We had wished it might be so, though I had some fears of his being tired of us, and of our being stupefied with shyness. This went off more than I expected, and our day's journey was very pleasant.

MINTO, August 14, 1840

Actually here on the second day! From Hawick we had the most lovely moonlight, making the river like silver and the fields like snow. Oh Scotland, bonny, bonny Scotland, dearest and loveliest of lands! if ever I love thee less than I do now, may I be punished by living far from thee.

MINTO, August 30, 1840

A great party to Church. Many eyes turned on Lord John as we walked from it. He was much amused by the remark of one man: "Lord John's a silly17 looking man, but he's smart, too!"--which he, of course, would have understood as an Englishman. In the evening he gave me a poem he had composed on the subject of my letter from Lancaster to Mrs. Law 18 announcing ourselves for the next day.... In the morning [September 1] Lord John begged to sit in our sitting-room with us.... I told him the library would be more comfortable, and we were established there (he very kindly reading the "Lay" aloud), when two Hawick Bailiffs arrived to present him with the freedom of the town.... After dinner, Miss Lister asked me so many questions chiefly relating to marrying, that I began to believe that Lord John's great kindness to us all, but especially to me, meant something more than I wished. I lay awake, wondering, feeling sure, and doubting again.

MINTO, September 2, 1840

Lord John, Miss Lister, Addy and I went to Melrose Abbey and Abbotsford.... It was his last evening, and in wishing me good-bye he said quite enough to make me tell Mama all I thought.... I could see that she was very glad I did not like him in that way. I am sure I do in every other.

MINTO, September 3, 1840

Lord John set off before seven this morning. I dreamed about him and waked about him all night.... Mama gave me a note from Lord John to me which he had left.... I wrote my answer immediately, begging him not to come back; but also telling him how grateful I feel. Had a long talk and walk with Miss Lister, whose great kindness makes it all more painful to me.

Lady Fanny wrote to her sister, Lady Mary Abercromby:

A proposal from Lord John Russell is at this moment lying before me. I see it lying, and I write to you that it is there, but yet I do not believe it, nor shall I ever.... Good, kind Miss Lister positively worships him.

MINTO, September 4, 1840

Went to the village with Mama and my darling Addy [Lord John's stepdaughter], to whom I may show how I love her now that he is away.

MINTO, September 7, 1840