Title: Through the Wall

Author: Cleveland Moffett

Release date: February 1, 2004 [eBook #11373]

Most recently updated: December 25, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell and PG Distributed Proofreaders

It is worthy of note that the most remarkable criminal case in which the famous French detective, Paul Coquenil, was ever engaged, a case of more baffling mystery than the Palais Royal diamond robbery and of far greater peril to him than the Marseilles trunk drama—in short, a case that ranks with the most important ones of modern police history—would never have been undertaken by Coquenil (and in that event might never have been solved) but for the extraordinary faith this man had in certain strange intuitions or forms of half knowledge that came to him at critical moments of his life, bringing marvelous guidance. Who but one possessed of such faith would have given up fortune, high position, the reward of a whole career, simply because a girl whom he did not know spoke some chance words that neither he nor she understood. Yet that is exactly what Coquenil did.

It was late in the afternoon of a hot July day, the hottest day Paris had known that year (1907) and M. Coquenil, followed by a splendid white-and-brown shepherd dog, was walking down the Rue de la Cité, past the somber mass of the city hospital. Before reaching the Place Notre-Dame he stopped twice, once at a flower market that offered the grateful shade of its gnarled polenia trees just beyond the Conciergerie prison, and once under the heavy archway of the Prefecture de Police. At the flower market he bought a white carnation from a woman in green apron and wooden shoes, who looked in awe at his pale, grave face, and thrilled when he gave her a smile and friendly word. She wondered if it was true, as people said, that M. Coquenil always wore glasses with a slightly bluish tint so that no one could see his eyes.

The detective walked on, busy with pleasant thoughts. This was the hour of

his triumph and justification, this made up for the cruel blow that had

fallen two years before and resulted, no one understood why, in his leaving

the Paris detective force at the very moment of his glory, when the whole

city was praising him for the St. Germain investigation. Beau Cocono!

That was the name they had given him; he could hear the night crowds

shouting it in a silly couplet:

Il nous faut-o

Beau Cocono-o!

And then what a change within a week! What bitterness and humiliation! M. Paul Coquenil, after scores of brilliant successes, had withdrawn from the police force for personal reasons, said the newspapers. His health was affected, some declared; he had laid by a tidy fortune and wished to enjoy it, thought others; but many shook their heads mysteriously and whispered that there was something queer in all this. Coquenil himself said nothing.

But now facts would speak for him more eloquently than any words; now, within twenty-four hours, it would be announced that he had been chosen, on the recommendation of the Paris police department, to organize the detective service of a foreign capital, with a life position at the head of this service and a much larger salary than he had ever received, a larger salary, in fact, than Paris paid to its own chief of police.

M. Coquenil had reached this point in his musings when he caught sight of a red-faced man, with a large purplish nose and a suspiciously black mustache (for his hair was gray), coming forward from the prefecture to meet him.

"Ah, Papa Tignol!" he said briskly. "How goes it?"

The old man saluted deferentially, and then, half shutting his small gray eyes, replied with an ominous chuckle, as one who enjoys bad news: "Eh, well enough, M. Paul; but I don't like that." And, lifting an unshaven chin, he pointed over his shoulder with a long, grimy thumb to the western sky.

"Always croaking!" laughed the other. "Why, it's a fine sunset, man!"

Tignol answered slowly, with objecting nod: "It's too red. And it's barred with purple!"

"Like your nose. Ha, ha!" And Coquenil's face lighted gaily. "Forgive me, Papa Tignol."

"Have your joke, if you will, but," he turned with sudden directness, "don't you remember when we had a blood-red sky like that? Ah, you don't laugh now!"

It was true, Coquenil's look had deepened into one of somber reminiscence.

"You mean the murders in the Rue Montaigne?"

"Pre-cisely."

"Pooh! A foolish fancy! How many red sunsets have there been since we found those two poor women stretched out in their white-and-gold salon? Well, I must get on. Come to-night at nine. There will be news for you."

"News for me," echoed the old man. "Au revoir, M. Paul," and he watched the slender, well-knit figure as the detective moved across the Place Notre-Dame, snapping his fingers playfully at the splendid animal that bounded beside him and speaking to the dog in confidential friendliness.

"We'll show 'em, eh, Cæsar?" And the dog answered with eager barking and quick-wagging tail.

So these two companions advanced toward the great cathedral, directing their steps to the left-hand portal under the Northern tower. Here they paused before statues of various saints and angels that overhang the blackened doorway while Coquenil said something to a professional beggar, who straightway disappeared inside the church. Cæsar, meantime, with panting tongue, was eying the decapitated St. Denis, asking himself, one would say, how even a saint could carry his head in his hands.

And presently there appeared a white-bearded sacristan in a three-cornered hat of blue and gold and a gold-embroidered coat. For all his brave apparel he was a small, mild-mannered person, with kindly brown eyes and a way of smiling sadly as if he had forgotten how to laugh.

"Ah, Bonneton, my friend!" said Coquenil, and then, with a quizzical glance: "My decorative friend!"

"Good evening, M. Paul," answered the other, while he patted the dog affectionately. "Shall I take Cæsar?"

"One moment; I have news for you." Then, while the other listened anxiously, he told of his brilliant appointment in Rio Janeiro and of his imminent departure. He was sailing for Brazil in three days.

"Mon Dieu!" murmured Bonneton in dismay. "Sailing for Brazil! So our friends leave us. Of course I'm glad for you; it's a great chance, but—will you take Cæsar?"

"I couldn't leave my dog, could I?" smiled Coquenil.

"Of course not! Of course not! And such a dog! You've been kind to let him guard the church since old Max died. Come, Cæsar! Just a moment, M. Paul." And with real emotion the sacristan led the dog away, leaving the detective all unconscious that he had reached a critical moment in his destiny.

How the course of events would have been changed had Paul Coquenil remained outside Notre-Dame on this occasion it is impossible to know; the fact is he did not remain outside, but, growing impatient at Bonneton's delay, he pushed open the double swinging doors, with their coverings of leather and red velvet, and entered the sanctuary. And immediately he saw the girl.

She was in the shadows near a statue of the Virgin before which candles were burning. On the table were rosaries and talismans and candles of different lengths that it was evidently the girl's business to sell. In front of the Virgin's shrine was a prie dieu at which a woman was kneeling, but she presently rose and went out, and the girl sat there alone. She was looking down at a piece of embroidery, and Coquenil noticed her shapely white hands and the mass of red golden hair coiled above her neck. When she lifted her eyes he saw that they were dark and beautiful, though tinged with sadness. He was surprised to find this lovely young woman selling candles here in Notre-Dame Church.

And suddenly he was more surprised, for as the girl glanced up she met his gaze fixed on her, and immediately there came into her face a look so strange, so glad, and yet so frightened that Coquenil went to her quickly with reassuring smile. He was sure he had never seen her before, yet he realized that somehow she was equally sure that she knew him.

What followed was seen by only one person, that is, the sacristan's wife, a big, hard-faced woman with a faint mustache and a wart on her chin, who sat by the great column near the door dispensing holy water out of a cracked saucer and whining for pennies. Nothing escaped the hawklike eyes of Mother Bonneton, and now, with growing curiosity, she watched the scene between Coquenil and the candle seller. What interest could a great detective have in this girl, Alice, whom she and her husband had taken in as a half-charity boarder? Such airs as she gave herself! What was she saying now? Why should he look at her like that? The baggage!

"Holy saints, how she talks!" grumbled the sacristan's wife. "And see the eyes she makes! And how he listens! The man must be crazy to waste his time on her! Now he asks a question and she talks again with that queer, far-away look. He frowns and clinches his hands, and—upon my soul he seems afraid of her! He says something and starts to come away. Ah, now he turns and stares at her as if he had seen a ghost! Mon Dieu, quelle folie!"

This whole incident occupied scarcely five minutes, yet it wrought an extraordinary change in Coquenil. All his buoyancy was gone, and he looked worn, almost haggard, as he walked to the church door with hard-shut teeth and face set in an ominous frown.

"There's some devil's work in this," he muttered, and as his eyes caught the fires of the lurid sky he thought of Papa Tignol's words.

"What is it?" asked the sacristan, approaching timidly.

The detective faced him sharply. "Who is the girl in there? Where did she come from? How did she get here? Why does she—" He stopped abruptly, and, pressing the fingers of his two hands against his forehead, he stroked the brows over his closed eyes as if he were combing away error. "No, no!" he changed, "don't tell me yet. I must be alone; I must think. Come to me at nine to-night."

"I—I'll try to come," said Bonneton, with visions of an objecting wife.

"You must come," insisted the detective. "Remember, nine o'clock," and he started to go.

"Yes, yes, quite so," murmured the sacristan, following him. "But, M. Paul—er—which day do you sail?"

Coquenil turned and snapped out angrily: "I may not sail at all."

"But the—the position in Rio Janeiro?"

"A thousand thunders! Don't talk to me!" cried the other, and there was such black rage in his look that Bonneton cowered away, clasping and unclasping his hands and murmuring meekly: "Ah, yes, exactly."

So much for the humble influence that turned Paul Coquenil toward an unbelievable decision and led him ultimately into the most desperate struggle of his long and exciting career. A day of sinister portent this must have been, for scarcely had Coquenil left Notre-Dame when another scene was enacted there that should have been happy, but that, alas! showed only a rough and devious way stretching before two lovers. And again it was the girl who made trouble, this seller of candles, with her fine hands and her hair and her wistful dark eyes. A strange and pathetic figure she was, sitting there alone in the somber church. Quite alone now, for it was closing time, Mother Bonneton had shuffled off rheumatically after a cutting word—she knew better than to ask what had happened—and the old sacristan, lantern in hand and Cæsar before him, was making his round of the galleries, securing doors and windows.

With a shiver of apprehension Alice turned away from the whispering shadows and went to the Virgin's shrine, where she knelt and tried to pray. The candles sputtered before her, and she shut her eyes tight, which made colored patterns come and go behind the lids, fascinating geometrical figures that changed and faded and grew stronger. And suddenly, inside a widening green circle, she saw a face, the face of a young man with laughing gray eyes, and her heart beat with joy. She loved him, she loved him!--that was her secret and the cause of her unhappiness, for she must hide her love, especially from him; she must give him some cold word, some evasive reason, not the real one, when he should come presently for his answer. Ah, that was the great fact, he was coming for his answer—he, her hero man, her impetuous American with the name she liked so much, Lloyd Kittredge—how often she had murmured that name in her lonely hours!--he would be here shortly for his answer.

And alas! she must say "No" to him, she must give him pain; she could not hope to make him understand—how could anyone understand?—and then, perhaps, he would misjudge her, perhaps he would leave her in anger and not come back any more. Not come back any more! The thought cut with a sharp pang, and in her distress she moved her lips silently in the familiar prayer printed before her:

O Marie, souvenez vous du moment supreme où Jesus votre divin Fils, expirant sur la croix, nous confia à votre maternelle solicitude.

Her thoughts wandered from the page and flew back to her lover; Why was he so impatient? Why was he not willing to let their friendship go on as it had been all these months? Why must he ask this inconceivable question and insist on having an answer? His wife! Her cheeks flamed at the word and her heart throbbed wildly. His wife! How wonderful that he should have chosen her, so poor and obscure, for such an honor, the highest he could pay a woman! Whatever happened she would at least have this beautiful memory to comfort her loneliness and sorrow.

A descending step on the tower stairs broke in upon her meditations, and she rose quickly from her knees. The sacristan had finished his rounds and was coming to close the outer doors. It was time for her to go. And, with a glance at her hair in a little glass and a touch to her hat, she went out into the garden back of Notre-Dame, where she knew her lover would be waiting. There he was, strolling along the graveled walk near the fountain, switching his cane impatiently. He had not seen her yet, and she stood still, looking at him fondly, dreading what was to come, yet longing to hear the sound of his voice. How handsome he was! What a nice gray suit, and—then Kittredge turned.

"Ah, at last!" he exclaimed, springing toward her with a mirthful, boyish smile. His face was ruddy and clean shaven, the twinkling eyes and humorous lines about the mouth suggesting some joke or drollery always ready on his lips. Yet his was a frank, manly face, easily likable. He was a man of twenty-seven, slender of build, but carrying himself well. In dress he had the quiet good taste that some men are born with, besides a willingness to take pains about shirts, boots, and cravats—in short, he looked like a well-groomed Englishman. Unlike the average Englishman, however, he spoke almost perfect French, owing to the fact that his American father had married into one of the old Creole families of New Orleans.

"How is your royal American constitution?" She smiled, repeating in excellent English one of the nonsensical phrases he was fond of using. She tried to say it gayly, but he was not deceived, and answered seriously in French:

"Hold on. There's something wrong. We've been sad, eh?"

"Why—er—" she began, "I—er——"

"Been worrying, I know. Too much church. Too much of that old she dragon. Come over here and tell me about it." He led her to a bench shaded by a friendly sycamore tree. "Now, then."

She faced him with troubled eyes, searching vainly for words and finding nothing. The crisis had come, and she did not know how to meet it. Her red lips trembled, her eyes grew melting, and she sat there silent and delicious in her perplexity. Kittredge thrilled under the spell of her beauty; he longed to take her in his arms and comfort her.

"Suppose we go back a little," he said reassuringly. "About six months ago, I think it was in January, a young chap in a fur overcoat drifted into this old stone barn and took a turn around it. He saw the treasure and the fake relics and the white marble French gentleman trying to get out of his coffin. And he didn't care a hang about any of 'em until he saw you. Then he began to take notice. The next day he came back and you sold him a little red guidebook that told all about the twenty-five chapels and the seven hundred and ninety-two saints. No, seven hundred and ninety-three, for there was one saint with wonderful eyes and glorious hair and——"

"Please don't," she murmured.

"Why not? You don't know which saint I was talking about. It was My Lady of the Candles. She had the most beautiful hands in the world, and all day long she sat at a table making stitches on cloth of gold. Which was bad for her eyes, by the way."

"Ah, yes!" sighed Alice.

"There are all kinds of miracles in Notre-Dame," he went on playfully, "but the greatest miracle is how this saint with the eyes and the hands and the hair ever dropped down at that little table. Nobody could explain it, so the young fellow with the fur overcoat kept coming back and coming back to see if he could figure it out. Only soon he came without his overcoat."

"In bitter cold weather," she said reproachfully.

"He was pretty blue that day, wasn't he? Dead sore on the game. Money all blown in, overcoat up the spout, nothing ahead, and a whole year of—of damned foolishness behind. Excuse me, but that's what it was. Well, he blew in that day and—he walked over to where you were sitting, you darling little saint!"

"No, no," murmured Alice, "not a saint, only a poor girl who saw you were unhappy and—and was sorry."

Their eyes met tenderly, and for a moment neither spoke. Then Kittredge went on unsteadily: "Anyhow you were kind to me, and I opened up a little. I told you a few things, and—when I went away I felt more like a man. I said to myself: 'Lloyd Kittredge, if you're any good you'll cut out this thing that's been raising hell with you'—excuse me, but that's what it was—'and you'll make a new start, right now.' And I did it. There's a lot you don't know, but you can bet all your rosaries and relics that I've made a fair fight since then. I've worked and—been decent and—I did it all for you." His voice was vibrant now with passion; he caught her hand in his and repeated the words, leaning closer, so that she felt his warm breath on her cheek. "All for you. You know that, don't you, Alice?"

What a moment for a girl whose whole soul was quivering with fondness! What a proud, beautiful moment! He loved her, he loved her! Yet she drew her hand away and forced herself to say, as if reprovingly: "You mustn't do that!"

He looked at her in surprise, and then, with challenging directness: "Why not?"

"Because I cannot be what you—what you want me to be," she answered, looking down.

"I want you to be my wife."

"I know."

"And—and you refuse me?"

For a moment she did not speak. Then slowly she nodded, as if pronouncing her own doom.

"Alice," he cried, "look up here! You don't mean it. Say it isn't true."

She lifted her eyes bravely and faced him. "It is true, Lloyd; I can never be your wife."

"But why? Why?"

"I—I cannot tell you," she faltered.

He was about to speak impatiently, but before her evident distress he checked the words and asked gently: "Is it something against me?"

"Oh, no!" she answered quickly.

"Sure? Isn't it something you've heard that I've done or—or not done? Don't be afraid to hurt my feelings. I'll make a clean breast of it all, if you say so. God knows I was a fool, but I've kept straight since I knew you, I'll swear to that."

"I believe you, dear."

"You believe me, you call me 'dear,' you look at me out of those wonderful eyes as if you cared for me."

"I do, I do," she murmured.

"You care for me, and yet you turn me down," he said bitterly. "It reminds me of a verse I read," and drawing a small volume from his pocket he turned the pages quickly. "Ah, here it is," and he marked some lines with a pencil. "There!"

Alice took the volume and began to read in a low voice:

"Je n'aimais qu'elle au monde, et vivre un jour sans elle

Me semblait un destin plus affreux que la mort.

Je me souviens pourtant qu'en cette nuit cruelle

Pour briser mon lien je fis un long effort.

Je la nommai cent fois perfide et déloyale,

Je comptai tous les maux qu'elle m'avait causés."

She stopped suddenly, her eyes full of pain.

"You don't think that, you can't think that of me?" she pleaded.

"I'd rather think you a coquette than—" Again he checked himself at the sight of her trouble. He could not speak harshly to her.

"You dear child," he went on tenderly. "I'll never believe any ill of you, never. I won't even ask your reasons; but I want some encouragement, something to work for. I've got to have it. Just let me go on hoping; say that in six months or—or even a year you will be my own sweetheart—promise me that and I'll wait patiently. Can't you promise me that?"

But again she shook her head, while her eyes filled slowly with tears.

And now his face darkened. "Then you will never be my wife? Never? No matter what I do or how long I wait? Is that it?"

"That's it," she repeated with a little sob.

Kittredge rose, eying her sternly. "I understand," he said, "or rather I don't understand; but there's no use talking any more. I'll take my medicine and—good-by."

She looked at him in frightened supplication. "You won't leave me? Lloyd, you won't leave me?"

He laughed harshly. "What do you think I am? A jumping jack for you to pull a string and make me dance? Well, I guess not. Leave you? Of course I'll leave you. I wish I had never seen you; I'm sorry I ever came inside this blooming church!"

"Oh!" she gasped, in sudden pain.

"You don't play fair," he went on recklessly. "You haven't played fair at all. You knew I loved you, and—you led me on, and—this is the end of it."

"No," she cried, stung by his words, "it's not the end of it. I won't be judged like that. I have played fair with you. If I hadn't I would have accepted you, for I love you, Lloyd, I love you with all my heart!"

"I like the way you show it," he answered, unrelenting.

"Haven't I helped you all these months? Isn't my friendship something?"

He shook his head. "It isn't enough for me."

"Then how about me, if I want your friendship, if I'm hungry for it, if it's all I have in life? How about that, Lloyd?" Under their dark lashes her violet eyes were burning on him, but he hardened his heart to their pleading.

"It sounds well, but there's no sense in it. I can't stand for this let-me-be-a-sister-to-you game, and I won't."

He turned away impatiently and glanced at his watch.

"Lloyd," she said gently, "come to the house to-night."

He shook his head. "Got an appointment."

"An appointment?"

"Yes, a banquet."

She looked at him in surprise. "You didn't tell me!"

"No."

She was silent a moment. "Where is the banquet?"

"At the Ansonia. It's a new restaurant on the Champs Elysées, very swell. I didn't tell you because—well, because I didn't."

"Lloyd," she whispered, "don't go to the banquet."

"Don't go? Why, this is our national holiday. I'm down to tell some stories. I've got to go. Besides, I wouldn't come to you, anyway. What's the use? I've said all I can, and you've said 'No.' So it's all off—that's right, Alice, it's all off." His eyes were kinder now, but he spoke firmly.

"Lloyd," she begged, "come after the banquet."

"No!"

"I ask it for you. I—I feel that something is going to happen. Don't laugh. Look at the sky, there beyond the black towers. It's red, red like blood, and—Lloyd, I'm afraid."

Her eyes were fixed in the west with an enthralled expression, as if she saw something there besides the masses of red and purple that crowned the setting sun, something strange and terrifying. And in her agitation she took the book and pencil from the bench, and nervously, almost unconsciously wrote something on one of the fly leaves.

"Good-by, Alice," he said, holding out his hand.

"Good-by, Lloyd," she answered in a dull, tired voice, putting down the book and giving him her own little hand.

As he turned to go he picked up the volume and his eye fell on the fly leaf.

"Why," he started, "what is this?" He looked more closely at the words, then sharply at her.

"I—I'm so sorry," she stammered. "Have I spoiled your book?"

"Never mind the book, but—how did you come to write this?"

"I—I didn't notice what I wrote," she said, in confusion.

"Do you mean to say that you don't know what you wrote?"

"I don't know at all," she replied with evident sincerity.

"It's the damnedest thing I ever heard of," he muttered. And then, with a puzzled look: "See here, I guess I've been too previous. I'll cut out that banquet to-night—that is, I'll show up for soup and fish, and then I'll come to you. Do I get a smile now?"

"O Lloyd!" she murmured happily.

"I'll be there about nine."

"About nine," she repeated, and again her eyes turned anxiously to the blood-red western sky.

After leaving Notre-Dame, Paul Coquenil directed his steps toward the prefecture of police, but halfway across the square he glanced back at the church clock that shows its white face above the grinning gargoyles, and, pausing, he stood a moment in deep thought.

"A quarter to seven," he reflected; then, turning to the right, he walked quickly to a little wine shop with flowers in the windows, the Tavern of the Three Wise Men, an interesting fragment of old-time Paris that offers its cheery but battered hospitality under the very shadow of the great cathedral.

"Ah, I thought so!" he muttered, as he recognized Papa Tignol at one of the tables on the terrace. And approaching the old man, he said in a low tone: "I want you."

Tignol looked up quickly from his glass, and his face lighted. "Eh, M. Paul again!"

"I must see M. Pougeot," continued the detective. "It's important. Go to his office. If he isn't there, go to his house. Anyhow, find him and tell him to come to me at once. Hurry on; I'll pay for this."

"Shall I take an auto?"

"Take anything, only hurry."

"And you want me at nine o'clock?"

Coquenil shook his head. "Not until to-morrow."

"But the news you were going to tell me?"

"There'll be bigger news soon. Oh, run across to the church and tell Bonneton that he needn't come either."

"I knew it, I knew it," chuckled Papa Tignol, as he trotted off. "There's something doing!"

With this much arranged, Coquenil, after paying for his friend's absinthe, strolled over to a cab stand near the statue of Henri IV and selected a horse that could not possibly make more than four miles an hour. Behind this deliberate animal he seated himself, and giving the driver his address, he charged him gravely not to go too fast, and settled back against the cushions to comfortable meditations. "There is no better way to think out a tough problem," he used to insist, "than to take a very long drive in a very slow cab."

It may have been that this horse was not slow enough, for forty minutes later Coquenil's frown was still unrelaxed when they drew up at the Villa Montmorency, really a collection of villas, some dozens of them, in a private park near the Bois de Boulogne, each villa a garden within a garden, and the whole surrounded by a great stone wall that shuts out noises and intrusions. They entered by a massive iron gateway on the Rue Poussin and moved slowly up the ascending Avenue des Tilleuls, past lawns and trees and vine-covered walls, leaving behind the rush and glare of the city and entering a peaceful region of flowers and verdure where Coquenil lived.

The detective occupied a wing of the original Montmorency chateau, a habitation of ten spacious rooms, more than enough for himself and his mother and the faithful old servant, Melanie, who took care of them, especially during these summer months, when Madame Coquenil was away at a country place in the Vosges Mountains that her son had bought for her. Paul Coquenil had never married, and his friends declared that, besides his work, he loved only two things in the world—his mother and his dog.

It was a quarter to eight when M. Paul sat down in his spacious dining room to a meal that was waiting when he arrived and that Melanie served with solicitous care, remarking sadly that her master scarcely touched anything, his eyes roving here and there among painted mountain scenes that covered the four walls above the brown-and-gold wainscoting, or out into the garden through the long, open windows; he was searching, searching for something, she knew the signs, and with a sigh she took away her most tempting dishes untasted.

At eight o'clock the detective rose from the table and withdrew into his study, a large room opening off the dining room and furnished like no other study in the world. Around the walls were low bookcases with wide tops on which were spread, under glass, what Coquenil called his criminal museum. This included souvenirs of cases on which he had been engaged, wonderful sets of burglars' tools, weapons used by murderers—saws, picks, jointed jimmies of tempered steel, that could be taken apart and folded up in the space of a thick cigar and hidden about the person. Also a remarkable collection of handcuffs from many countries and periods in history. Also a collection of letters of criminals, some in cipher, with confessions of prisoners and last words of suicides. Also plaster casts of hands of famous criminals. And photographs of criminals, men and women, with faces often distorted to avoid recognition. And various grewsome objects, a card case of human skin, and the twisted scarf used by a strangler.

As for the shelves underneath, they contained an unequaled special library of subjects interesting to a detective, both science and fiction being freely drawn upon in French, English, and German, for, while Coquenil was a man of action in a big way, he was also a student and a reader of books, and he delighted in long, lonely evenings, when, as now, he sat in his comfortable study thinking, thinking.

Melanie entered presently with coffee and cigarettes, which she placed on a table near the green-shaded lamp, within easy reach of the great red-leather chair where M. Paul was seated. Then she stole out noiselessly. It was five minutes past eight, and for an hour Coquenil thought and smoked and drank coffee. Occasionally he frowned and moved impatiently, and several times he took off his glasses and stroked his brows over the eyes.

Finally he gave a long sigh of relief, and shutting his hands and throwing out his arms with a satisfied gesture, he rose and walked to the fireplace, over which hung a large portrait of his mother and several photographs, one of these taken in the exact attitude and costume of the painting of Whistler's mother in the Luxembourg gallery. M. Paul was proud of the striking resemblance between the two women. For some moments he stood before the fine, kindly face, and then he said aloud, as if speaking to her: "It looks like a hard fight, little mother, but I'm not afraid." And almost as he spoke, which seemed like a good omen, there came a clang at the iron gate in the garden and the sound of quick, crunching steps on the gravel walk. M. Pougeot had arrived.

M. Lucien Pougeot was one of the eighty police commissaries who, each in his own quarter, oversee the moral washing of Paris's dirty linen. A commissary of police is first of all a magistrate, but, unless he is a fool, he soon becomes a profound student of human nature, for he sees all sides of life in the great gay capital, especially the darker sides. He knows the sins of his fellow men and women, their follies and hypocrisies, he receives incredible confessions, he is constantly summoned to the scenes of revolting crime. Nothing, absolutely nothing, surprises him, and he has no illusions, yet he usually manages to keep a store of grim pity for erring humanity. M. Pougeot was one of the most distinguished and intelligent members of this interesting body. He was a devoted friend of Paul Coquenil.

The newcomer was a middle-aged man of strong build and florid face, with a brush of thick black hair. His quick-glancing eyes were at once cold and kind, but the kindness had something terrifying in it, like the politeness of an executioner. As the two men stood together they presented absolutely opposite types: Coquenil, taller, younger, deep-eyed, spare of build, with a certain serious reserve very different from the commissary's outspoken directness. M. Pougeot prided himself on reading men's thoughts, but he used to say that he could not even imagine what Coquenil was thinking or fathom the depths of a nature that blended the eagerness of a child with the austerity of a prophet.

"Well," remarked the commissary when they were settled in their chairs, "I suppose it's the Rio Janeiro thing? Some parting instructions, eh?" And he turned to light a cigar.

Coquenil shook his head.

"When do you sail?"

"I'm not sailing."

"Wha-at?"

For once in his life M. Pougeot was surprised. He knew all about this foreign offer, with its extraordinary money advantages; he had rejoiced in his friend's good fortune after two unhappy years, and now—now Coquenil informed him calmly that he was not sailing.

"I have just made a decision, the most important decision of my life," continued the detective, "and I want you to know about it. You are the only person in the world who will know—everything. So listen! This afternoon I went into Notre-Dame church and I saw a young girl there who sells candles. I didn't know her, but she looked up in a queer way, as if she wanted to speak to me, so I went to her and—well, she told me of a dream she had last night."

"A dream?" snorted the commissary.

"So she said. She may have been lying or she may have been put up to it; I know nothing about her, not even her name, but that's of no consequence; the point is that in this dream, as she called it, she brought together the two most important events in my life."

"Hm! What was the dream?"

"She says she saw me twice, once in a forest near a wooden bridge where a man with a beard was talking to a woman and a little girl. Then she saw me on a boat going to a place where there were black people."

"That was Brazil?"

"I suppose so. And there was a burning sun with a wicked face inside that kept looking down at me. She says she often dreams of this wicked face, she sees it first in a distant star that comes nearer and nearer, until it gets to be large and red and angry. As the face comes closer her fear grows, until she wakes with a start of terror; she says she would die of fright if the face ever reached her before she awoke. That's about all."

For some moments the commissary did not speak. "Did she try to interpret this dream?"

"No."

"Why did she tell you about it?"

"She acted on a sudden impulse, so she says. I'm inclined to believe her; but never mind that. Pougeot," he rose in agitation and stood leaning over his friend, "in that forest scene she brought up something that isn't known, something I've never even told you, my best friend."

"Tiens! What is that?"

"You think I resigned from the police force two years ago, don't you?"

"Of course."

"Everyone thinks so. Well, it isn't true. I didn't resign; I was discharged."

M. Pougeot stared in bewilderment, as if words failed him, and finally he repeated weakly: "Discharged! Paul Coquenil discharged!"

"Yes, sir, discharged from the Paris detective force for refusing to arrest a murderer—that's how the accusation read."

"But it wasn't true?"

"Judge for yourself. It was the case of a poacher who killed a guard. I don't suppose you remember it?"

M. Pougeot thought a moment—he prided himself on remembering everything. "Down near Saumur, wasn't it?"

"Exactly. And it was near Saumur I found him after searching all over France. We were clean off the track, and I made up my mind the only way to get him was through his wife and child. They lived in a little house in the woods not far from the place of the shooting. I went there as a peddler in hard luck, and I played my part so well that the woman consented to take me in as a boarder."

"Wonderful man!" exclaimed the commissary.

"For weeks it was a waiting game. I would go away on a peddling tour and then come back as boarder. Nothing developed, but I could not get rid of the feeling that my man was somewhere near in the woods."

"One of your intuitions. Well?"

"Well, at last the woman became convinced that they had nothing to fear from me, and she did things more openly. One day I saw her put some food in a basket and give it to the little girl. And the little girl went off with the basket into the forest. Then I knew I was right, and the next day I followed the little girl, and, sure enough, she led me to a rough cave where her father was hiding. I hung about there for an hour or two, and finally the man came out from the cave and I saw him talk to his wife and child near a bridge over a mountain torrent."

"The picture that girl saw in the dream!"

"Yes; I'll never forget it. I had my pistol ready and he was defenseless; and once I was just springing forward to take the fellow when he bent over and kissed his little girl. I don't know how you look at these things, Pougeot, but I couldn't break in there and take that man away from his wife and child. The woman had been kind to me and trusted me, and—well, it was a breach of duty and they punished me for it; but I couldn't do it, I couldn't do it, and I didn't do it."

"And you let the fellow go?"

"I let him go then, but I got him a week later in a fair fight, man to man. They gave him ten years."

"And discharged you from the force?"

"Yes. That is, in view of my past services, they allowed me to resign." Coquenil spoke bitterly.

"Outrageous! Unbelievable!" muttered Pougeot. "No doubt you were technically in the wrong, but it was a slight offense, and, after all, you got your man. A reprimand at the most, at the most, was called for, and not with you, not with Paul Coquenil."

The commissary spoke with deeper feeling than he had shown in years, and then, as if not satisfied with this, he clasped the detective's hand and added heartily: "I'm proud of you, old friend, I honor you."

Coquenil looked at Pougeot with an odd little smile. "You take it just as I thought you would, just as I took it myself—until to-day. It seems like a stupid blunder, doesn't it? Well, it wasn't a blunder; it was a necessary move in the game." His face lighted with intense eagerness as he waited for the effect of these words.

"The game? What game?" The commissary stared.

"A game involving a great crime."

"You are sure of that?"

"Perfectly sure."

"You have the facts of this crime?"

"No. It hasn't been committed yet."

"Not committed yet?" repeated the other, with a startled glance. "But you know the plan? You have evidence?"

"I have what is perfectly clear evidence to me, so clear that I wonder I never saw it before. Lucien, suppose you were a great criminal, I don't mean the ordinary clever scoundrel who succeeds for a time and is finally caught, but a really great criminal, the kind that appears once or twice, in a century, a man with immense power and intelligence."

"Like Vautrin in Napoleon's day?"

"Vautrin was a brilliant adventurer; he made millions with his swindling schemes, but he had no stability, no big purpose, and he finally came to grief. There have been greater criminals than Vautrin, men whose crimes have brought them everything—fortune, social position, political supremacy—and who have never been found out."

"Do you really think so?"

Coquenil nodded. "There have been a few like that with master minds, a very few; I have documents to prove it"—he pointed to his bookcases; "but we haven't time for that. Come back to my question: Suppose you were such a criminal, and suppose there was one person in this city who was thwarting your purposes, perhaps jeopardizing your safety. What would you naturally do?"

"I'd try to get rid of him."

"Exactly." Coquenil paused, and then, leaning closer to his friend, he said with extraordinary earnestness: "Lucien, for over two years some one has been trying to get rid of me!"

"The devil!" started Pougeot. "How long have you known this?"

"Only to-day," frowned the detective. "I ought to have known it long ago."

"Hm! Aren't you building a good deal on that dream?"

"The dream? Heavens, man," snapped Coquenil, "I'm building nothing on the dream and nothing on the girl. She simply brought together two facts that belong together. Why she did it doesn't matter; she did it, and my reason did the rest. There is a connection between this Rio Janeiro offer and my discharge from the force. I know it. I'll show you other links in the chain. Three times in the past two years I have received offers of business positions away from Paris, tempting offers. Notice that—business positions away from Paris! Some one has extraordinary reasons for wanting me out of this city and out of detective work."

"And you think this 'some one' was responsible for your discharge from the force?"

"I tell you I know it. M. Giroux, the chief at that time, was distressed at the order, he told me so himself; he said it came from higher up."

The commissary raised incredulous eyebrows. "You mean that Paris has a criminal able to overrule the wishes of a chief of police?"

"Is that harder than to influence the Brazilian Government? Do you think Rio Janeiro offered me a hundred thousand francs a year just for my beautiful eyes?"

"You're a great detective."

"A great detective repudiated by his own city. That's another point: why should the police department discharge me two years ago and recommend me now to a foreign city? Don't you see the same hand behind it all?"

M. Pougeot stroked his gray mustache in puzzled meditation. "It's queer," he muttered; "but——"

In spite of himself the commissary was impressed.

After all, he had seen strange things in his life, and, better than anyone, he had reason to respect the insight of this marvelous mind.

"Then the gist of it is," he resumed uneasily, "you think some great crime is preparing?"

"Don't you?" asked Coquenil abruptly.

"Why—er—" hesitated the Other.

"Look at the facts again. Some one wants me off the detective force, out of France. Why? There can be only one reason—because I have been successful in unraveling intricate crimes, more successful than other men on the force. Is that saying too much?"

The commissary replied impatiently: "It's conceded that you are the most skillful detective in France; but you're off the force already. So why should this person send you to Brazil?"

M. Paul thought a moment. "I've considered that. It is because this crime will be of so startling and unusual a character that it must attract my attention if I am here. And if it attracts my attention as a great criminal problem, it is certain that I will try to solve it, whether on the force or off it."

"Well answered!" approved the other; he was coming gradually under the spell of Coquenil's conviction. "And when—when do you think this crime may be committed?"

"Who can say? There must be great urgency to account for their insisting that I sail to-morrow. Ah, you didn't know that? Yes, even now, at this very moment, I am supposed to be on the steamer train, for the boat goes out early in the morning before the Paris papers can reach Cherbourg."

M. Pougeot started up, his eyes widening. "What!" he cried. "You mean that—that possibly—to-night?"

As he spoke a sudden flash of light came in through the garden window, followed by a resounding peal of thunder. The brilliant sunset had been followed by a violent storm.

Coquenil paid no heed to this, but answered quietly: "I mean that a great fight is ahead, and I shall be in it. Somebody is playing for enormous stakes, somebody who disposes of fortune and power and will stop at nothing, somebody who will certainly crush me unless I crush him. It will be a great case, Lucien, my greatest case, perhaps my last case." He stopped and looked intently at his mother's picture, while his lips moved inaudibly.

"Ugh!" exclaimed the commissary. "You've cast a spell over me. Come, come, Paul, it may be only a fancy!"

But Coquenil sat still, his eyes fixed on his mother's face. And then came one of the strange coincidences of this extraordinary case. On the silence of this room, with its tension of overwrought emotion, broke the sharp summons of the telephone.

"My God!" shivered the commissary. "What is that?" Both men sat motionless, their eyes fixed on the ominous instrument.

Again came the call, this time more strident and commanding. M. Pougeot aroused himself with an effort. "We're acting like children," he muttered. "It's nothing. I told them at the office to ring me up about nine." And he put the receiver to his ear. "Yes, this is M. Pougeot.... What?... The Ansonia?... You say he's shot?... In a private dining room?... Dead?... Quel malheur!"... Then he gave quick orders: "Send Papa Tignol over with a doctor and three or four agents. Close the restaurant. Don't let anyone go in or out. Don't let anyone leave the banquet room. I'll be there in twenty minutes. Good-by."

He put the receiver down, and turning, white-faced, said to his friend: "It has happened."

Coquenil glanced at his watch. "A quarter past nine. We must hurry." Then, flinging open a drawer in his desk: "I want this and—this. Come, the automobile is waiting."

The night was black and rain was falling in torrents as Paul Coquenil and the commissary rolled away in response to this startling summons of crime. Up the Rue Mozart they sped with sounding horn, feeling their way carefully on account of troublesome car tracks, then faster up the Avenue Victor Hugo, their advance being accompanied by vivid lightning flashes.

"He was in luck to have this storm," muttered Coquenil. Then, in reply to Pougeot's look: "I mean the thunder, it deadened the shot and gained time for him."

"Him? How do you know a man did it? A woman was in the room, and she's gone. They telephoned that."

The detective shook his head. "No, no, you'll find it's a man. Women are not original in crime. And this is—this is different. How many murders can you remember in Paris restaurants, I mean smart restaurants?"

M. Pougeot thought a moment. "There was one at the Silver Pheasant and one at the Pavillion and—and——"

"And one at the Café Rouge. But those were stupid shooting cases, not murders, not planned in advance."

"Why do you think this was planned in advance?"

"Because the man escaped."

"They didn't say so."

Coquenil smiled. "That's how I know he escaped. If they had caught him they would have told you, wouldn't they?"

"Why—er——"

"Of course they would. Well, think what it means to commit murder in a crowded restaurant and get away. It means brains, Lucien. Ah, we're nearly there!"

They had reached Napoleon's arch, and the automobile, swinging sharply to the right, started at full speed down the Champs Elysées.

"It's bad for Gritz," reflected the commissary; then both men fell silent in the thought of the emergency before them.

M. Gritz, it may be said, was the enterprising proprietor of the Ansonia, this being the last and most brilliant of his creations for cheering the rich and hungry wayfarer. He owned the famous Palace restaurant at Monte Carlo, the Queen's in Piccadilly, London, and the Café Royal in Brussels. Of all his ventures, however, this recently opened Ansonia (hotel and restaurant) was by far the most ambitious. The building occupied a full block on the Champs Elysées, just above the Rond Point, so that it was in the center of fashionable Paris. It was the exact copy of a well-known Venetian palace, and its exquisite white marble colonnade made it a real adornment to the gay capital. Furthermore, M. Gritz had spent a fortune on furnishings and decorations, the carvings, the mural paintings, the rugs, the chairs, everything, in short, being up to the best millionaire standard. He had the most high-priced chef in the world, with six chefs under him, two of whom made a specialty of American dishes. He had his own farm for vegetables and butter, his own vineyards, his own permanent orchestra, and his own brand of Turkish coffee made before your eyes by a salaaming Armenian in native costume. For all of which reasons the present somber happening had particular importance. A murder anywhere was bad enough, but a murder in the newest, the chic-est, and the costliest restaurant in Paris must cause more than a nine days' wonder. As M. Pougeot remarked, it was certainly bad for Gritz.

Drawing up before the imposing entrance, they saw two policemen on guard at the doors, one of whom, recognizing the commissary, came forward quickly to the automobile with word that M. Gibelin and two other men from headquarters had already arrived and were proceeding with the investigation.

"Is Papa Tignol here?" asked Coquenil.

"Yes, sir," replied the man, saluting respectfully.

"Before I go in, Lucien, you'd better speak to Gibelin," whispered M. Paul. "It's a little delicate. He's a good detective, but he likes the old-school methods, and—he and I never got on very well. He has been sent to take charge of the case, so—be tactful with him."

"He can't object," answered Pougeot. "After all, I'm the commissary of this quarter, and if I need your services——"

"I know, but I'd sooner you spoke to him."

"Good. I'll be back in a moment," and pushing his way through the crowd of sensation seekers that blocked the sidewalk, he disappeared inside the building.

M. Pougeot's moment was prolonged to five full minutes, and when he reappeared his face was black.

"Such stupidity!" he stormed.

"It's what I expected," answered Coquenil.

"Gibelin says you have no business here. He's an impudent devil! 'Tell Beau Cocono,' he sneered, 'to keep his hands off this case. Orders from headquarters.' I told him you had business here, business for me, and—come on, I'll show 'em."

He took Coquenil by the arm, but the latter drew back. "Not yet. I have a better idea. Go ahead with your report. Never mind me."

"But I want you on the case," insisted the commissary.

"I'll be on the case, all right."

"I'll telephone headquarters at once about this," insisted Pougeot. "When shall I see you again?"

Coquenil eyed his friend mysteriously. "I think you'll see me before the night is over. Now get to work, and," he smiled mockingly, "give M. Gibelin the assurance of my distinguished consideration."

Pougeot nodded crustily and went back into the restaurant, while Coquenil, with perfect equanimity, paid the automobile man and dismissed him.

Meantime in the large dining rooms on the street floor everything was going on as usual, the orchestra was playing in its best manner and few of the brilliant company suspected that anything was wrong. Those who started to go out were met by M. Gritz himself, and, with a brief hint of trouble upstairs, were assured that they would be allowed to leave shortly after some necessary formalities. This delay most of them took good-naturedly and went back to their tables.

As M. Pougeot mounted to the first floor he was met at the head of the stairs by a little yellow-bearded man, with luminous dark eyes, who came toward him, hand extended.

"Ah, Dr. Joubert!" said the commissary.

The doctor nodded nervously. "It's a singular case," he whispered, "a very singular case."

At the same moment a door opened and Gibelin appeared. He was rather fat, with small, piercing eyes and a reddish mustache. His voice was harsh, his manners brusque, but there was no denying his intelligence. In a spirit of conciliation he began to give M. Pougeot some details of the case, whereupon the latter said stiffly: "Excuse me, sir, I need no assistance from you in making this investigation. Come, doctor! In the field of his jurisdiction a commissary of police is supreme, taking precedence even over headquarters men." So Gibelin could only withdraw, muttering his resentment, while Pougeot proceeded with his duties.

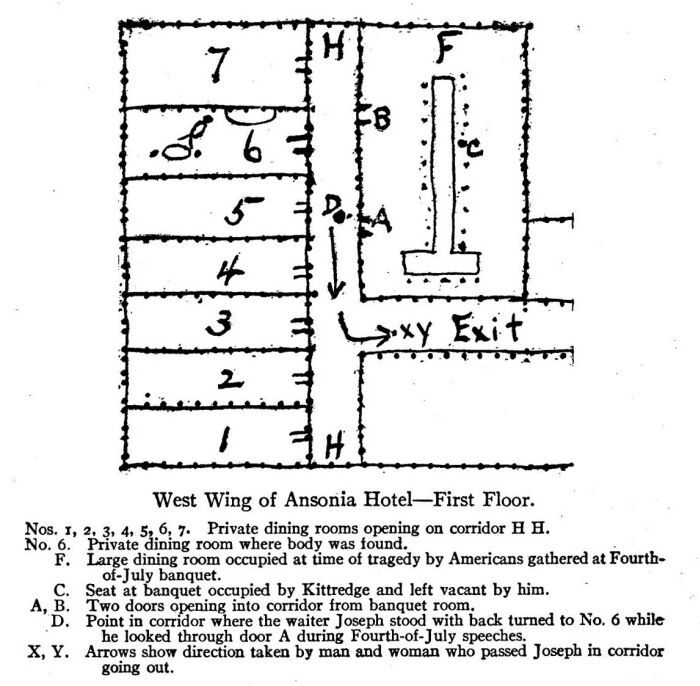

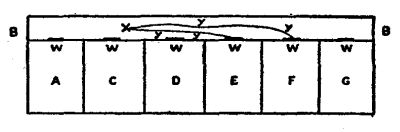

In general plan the Ansonia was in the form of a large E, the main part of the second floor, where the tragedy took place, being occupied by public dining rooms, but the two wings, in accordance with Parisian custom, containing a number of private rooms where delicious meals might be had with discreet attendance by those who wished to dine alone. In each of the wings were seven of these private rooms, all opening on a dark-red passageway lighted by soft electric lamps. It was in one of the west wing private rooms that the crime had been committed, and as the commissary reached the wing the waiters' awe-struck looks showed him plainly enough which was the room—there, on the right, the second from the end, where the patient policeman was standing guard.

M. Pougeot paused at the turn of the corridor to ask some question, but he was interrupted by a burst of singing on the left, a roaring chorus of hilarity.

"It's a banquet party," explained the doctor, "a lot of Americans. They don't know what has happened."

"Hah!" reflected the other. "Just across the corridor, too!"

Then, briefly, the commissary heard what the witnesses had to tell him about the crime. It had been discovered half an hour before, more precisely at ten minutes to nine, by a waiter Joseph, who was serving a couple in Number Six, a dark-complexioned man and a strikingly handsome woman. They had arrived at a quarter before eight and the meal had begun at once. Oddly enough, after the soup, the gentleman told the waiter not to bring the next course until he rang, at the same time slipping into his hand a ten-franc piece. Whereupon Joseph had nodded his understanding—he had seen impatient lovers before, although they usually restrained their ardor until after the fish; still, ma foi, this was a woman to make a man lose his head, and the night was to be a jolly one—how those young American devils were singing!... so vive l'amour and vive la jeunesse! With which simple philosophy and a twinkle of satisfaction Joseph had tucked away his gold piece—and waited.

Ten minutes! Fifteen minutes! An unconscionably long time when you have a delicious sole à la Regence getting cold on your hands. Joseph knocked discreetly, then again after a decent pause, and finally, weary of waiting, he opened the door with an official cough of warning and stepped inside the room. A moment later he started back, his eyes fixed with horror.

"Grand Dieu!" he cried.

"You saw the body, the man's body?" questioned the commissary.

"Yes, sir," answered the waiter, his face still pale at the memory.

"And the woman? Where was the woman?"

"Ah, I forgot," stammered Joseph. "She had come out of the room before this, while I was waiting. She asked where the telephone was, and I told her it was on the floor below. Then she went downstairs—at least I suppose she did, for she never came back."

"Did anyone see her leave the hotel?", demanded Pougeot sharply, looking at the others.

"It's extraordinary," answered the doctor, "but no one seems to have seen this woman go out. M. Gibelin made inquiries, but he could learn nothing except that she really went to the telephone booth. The girl there remembers her."

Again Pougeot turned to the waiter.

"What sort of a woman was she? A lady or—or not?"

Joseph clucked his tongue admiringly. "She was a lady, all right. And a stunner! Eyes and—shoulders and—um-m!" He described imaginary feminine curves with the unction of a male dressmaker. "Oh, there's one thing more!"

"You can tell me later. Now, doctor, we'll look at the room. I'll need you, Leroy, and you and you." He motioned to his secretary and to two of his men.

Dr. Joubert, bowing gravely, opened the door of Number Six, and the commissary entered, followed by his scribe, a very bald and pale young man, and by the two policemen. Last came the doctor, closing the door carefully behind him.

It was the commissary's custom on arriving at the scene of a crime to record his first impressions immediately, taking careful note of every fact and detail in the picture that seemed to have the slightest bearing on the case. These he would dictate rapidly to his secretary, walking back and forth, searching everywhere with keen eyes and trained intelligence, especially for signs of violence, a broken window, an overturned table, a weapon, and noting all suspicious stains—mud stains, blood stains, the print of a foot, the smear of a hand and, of course, describing carefully the appearance of a victim's body, the wounds, the position, the expression of the face, any tearing or disorder of the garments. Many times these quick, haphazard jottings, made in the precious moments immediately following a crime, had proved of incalculable value in the subsequent investigation.

In the present case, however, M. Pougeot was fairly taken aback by the lack of significant material. Everything in the room was as it should be, table spread with snowy linen, two places set faultlessly among flowers and flashing glasses, chairs in their places, pictures smiling down from the white-and-gold walls, shaded electric lights diffusing a pleasant glow—in short, no disorder, no sign of struggle, yet, there, stretched at full length on the floor near a pale-yellow sofa, lay a man in evening dress, his head resting, face downward, in a little red pool. He was evidently dead.

"Has anything been disturbed here? Has anyone touched this body?" demanded Pougeot sharply.

"No," said the doctor; "Gibelin came in with me, but neither of us touched anything. We waited for you."

"I see. Ready, Leroy," and he proceeded to dictate what there was to say, dwelling on two facts: that there was no sign of a weapon in the room and that the long double window opening on the Rue Marboeuf was standing open.

"Now, doctor," he concluded, "we will look at the body."

Dr. Joubert's examination established at once the direct cause of death. The man, a well-built young fellow of perhaps twenty-eight, had been shot in the right eye, a ball having penetrated the brain, killing him instantly. The face showed marks of flame and powder, proving that the weapon—undoubtedly a pistol—had been discharged from a very short distance.

This certainly looked like suicide, although the absence of the pistol pointed to murder. The man's face was perfectly calm, with no suggestion of fright or anger; his hands and body lay in a natural position and his clothes were in no way disordered. Either he had met death willingly, or it had come to him without warning, like a lightning stroke.

"Doctor," asked the commissary, glancing at the open window, "if this man shot himself, could he, in your opinion, with his last strength have thrown the pistol out there?"

"Certainly not," answered Joubert. "A man who received a wound like this would be dead before he could lift a hand, before he could wink."

"Ah!"

"Besides, a search has been made underneath that window and no pistol has been found."

"It must be murder," muttered Pougeot. "Was there any quarreling with the woman?"

"Joseph says not. On the contrary, they seemed on the friendliest terms."

"Hah! See what he has on his person. Note everything down. We must find out who this poor fellow was."

These instructions were carefully carried out, and it straightway became clear that robbery, at any rate, had no part in the crime. In the dead man's pockets was found a considerable sum of money, a bundle of five-pound notes of the Bank of England, besides a handful of French gold. On his fingers were several valuable rings, in his scarf was a large ruby set with diamonds, and attached to his waistcoat was a massive gold medal that at once established his identity. He was Enrico Martinez, a Spaniard widely known as a professional billiard player, and also the hero of the terrible Charity Bazaar fire, where, at the risk of his life, he had saved several women from the flames. For this bravery the city of Paris had awarded him a gold medal and people had praised him until his head was half turned.

So familiar a figure was Martinez that there was no difficulty in finding witnesses in the restaurant able to identify him positively as the dead man. Several had seen him within a few days at the Olympia billiard academy, where he had been practicing for a much-advertised match with an American rival. All agreed that Martinez was quite the last man in Paris to take his own life, for the simple reason that he enjoyed it altogether too much. He was scarcely thirty and in excellent health, he made plenty of money, he was fond of pleasure, and particularly fond of the ladies and had no reason to complain of bad treatment at their hands; in fact, if the truth must be told, he was ridiculously vain of his conquests among the fair sex, and was always saying to whoever would listen: "Ah, mon cher, I have met a woman! But such a woman!" Then his dark eyes would glow and he would snap his thumb nail under an upper tooth, with an expression of ravishing joy that only a Castilian billiard player could assume. And, of course, it was always a different woman!

"Aha!" muttered the commissary. "There may be a husband mixed up in this. Call that waiter again, and—er—we will continue the examination outside."

With this they removed to the adjoining private room, Number Five, leaving a policeman at the door of Number Six until proper disposal of the body should be made.

In the further questioning of Joseph the commissary brought out several important facts. The waiter testified that, after serving the soup to Martinez and the lady, he had not left the corridor outside the door of Number Six until the moment when he entered the room and discovered the crime. During this interval of perhaps a quarter of an hour he had moved down the corridor a short distance, but not farther than the door of Number Four. He was sure of this because one of the doors to the banquet room was just opposite the door of Number Four, and he had stood there listening to a Fourth-of-July speaker who was discussing the relations between France and America. Joseph, being something of a politician, was greatly interested in this.

"Then this banquet-room door was open?" questioned Pougeot.

"Yes, sir, it was open about a foot—some of the guests wanted air."

"How did you stand as you listened to the speaker? Show me." M. Pougeot led Joseph to the banquet-room door.

"Like this," answered the waiter, and he placed himself so that his back was turned to Number Six.

"So you would not have seen anyone who might have come out of Number Six at that time or gone into Number Six?"

"I suppose not."

"And if the door of Number Six had opened while your back was turned, would you have heard it?"

Joseph shook his head. "No, sir; there was a lot of applauding—like that," he paused as a roar of laughter came from across the hall.

The commissary turned quickly to one of his men. "See that they make less noise. And be careful no one leaves the banquet room on any excuse. I'll be there presently." Then to the waiter: "Did you hear any sound from Number Six? Anything like a shot?"

"No, sir."

"Hm! It must have been the thunder. Now tell me this, could anyone have passed you in the corridor while you stood at the banquet-room door without your knowing it?"

Joseph's round, red face spread into a grin. "The corridor is narrow, sir, and I"—he looked down complacently at his ample form—"I pretty well fill it up, don't I, sir?"

"You certainly do. Give me a sheet of paper." And with a few rapid pencil strokes the commissary drew a rough plan of the banquet room, the corridor, and the seven private dining rooms. He marked carefully the two doors leading from the banquet room into the corridor, the one where Joseph listened, opposite Number Four, and the one opposite Number Six.

"Here you are, blocking the corridor at Number Four"; he made a mark on the plan at that point. "By the way, are there any other exits from the banquet room except these two corridor doors?"

"No, sir."

"Good! Now pay attention. While you were listening at this door—I'll mark it A—with your back turned to Number Six, a person might have left the banquet room by the farther door—I'll mark it B—and stepped across the corridor into Number Six without your seeing him. Isn't that true?"

"Yes, sir, it's possible."

"Or a person might have gone into Number Six from either Number Five or Number Seven without your seeing him?"

"Excuse me, there was no one in Number Five during that fifteen minutes, and the party who had engaged Number Seven did not come."

"Ah! Then if any stranger went into Number Six during that fifteen minutes he must have come from the banquet room?"

"Yes, sir."

"By this door, B?"

"That's the only way he could have come without my seeing him."

"And if he went out from Number Six afterwards, I mean if he left the hotel, he must have passed you in the corridor?"

"Exactly." Joseph's face was brightening.

"Now, did anyone pass you in the corridor, anyone except the lady?"

"Yes, sir," answered the waiter eagerly, "a young man passed me."

"Going out?"

"Yes, sir."

"Did you know where he came from?"

"I supposed he came from the banquet room."

"Did this happen before the lady went out, or after?"

"Before."

"Can you describe this young man, Joseph?"

The waiter frowned and rubbed his red neck. "I think I should know him, he was slender and clean shaven—yes, I'm sure I should know him."

"Did anyone else pass you, either going out or coming in?"

"No, sir."

"Are you sure?"

"Absolutely sure."

"That will do."

Joseph heaved a sigh of relief and was just passing out when the commissary cried out with a startled expression: "A thousand thunders! Wait! That woman—what did she wear?"

The waiter turned eagerly. "Why, a beautiful evening gown, sir, cut low with a lot of lace and——"

"No, no. I mean, what did she wear outside? Her wraps? Weren't they in Number Six?"

"No, sir, they were downstairs in the cloakroom."

"In the cloakroom!" He bounded to his feet. "Bon sang de bon Dieu! Quick! Fool! Don't you understand?"

This outburst stirred Joseph to unexampled efforts; he fairly hurled his massive body down the stairs, and a few moments later returned, panting but happy, with news that the lady in Number Six had left a cloak and leather bag in the cloakroom. These articles were still there.

"Ah, that is something!" murmured the commissary, and he hurried down to see the things for himself.

The cloak was of yellow silk, embroidered in white, a costly garment from a fashionable maker; but there was nothing to indicate the wearer. The bag was a luxurious trifle in Brazilian lizard skin, with solid-gold mountings; but again there was no clew to the owner, no name, no cards, only some samples of dress goods, a little money, and an unmarked handkerchief.

"Don't move these things," directed M. Pougeot. "It's possible some one will call for them, and if anyone should call, why—that's Gibelin's affair. Now we'll see these Americans."

It was a quarter past ten, and the hilarity of proceedings at the Fourth-of-July banquet (no ladies present) had reached its height. A very French-looking student from Bridgeport, Connecticut, had just started an uproarious rendering of "My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean," with Latin-Quarter variations, when there came a sudden hush and a turning of heads toward the half-open door, through which a voice was heard in peremptory command. Something had happened, something serious, if one could judge by the face of François, the head waiter, who stood at the corridor entrance.

"Not so fast," he insisted, holding the young men back, and a moment later there entered a florid-faced man with authoritative mien, closely followed by two policemen.

"Horns of a purple cow!" muttered the Bridgeport art student, who loved eccentric oaths. "The house is pulled!"

"Gentlemen," began M. Pougeot, while the company listened in startled silence, "I am sorry to interrupt this pleasant gathering, especially as I understand that you are celebrating your national holiday; unfortunately, I have a duty to perform that admits of no delay. While you have been feasting and singing, as becomes your age and the occasion, an act of violence has taken place within the sound of your voices—I may say under cover of your voices."

He paused and swept his eyes in keen scrutiny over the faces before him, as if trying to read in one or the other of them the answer to some question not yet asked.

"My friends," he continued, and now his look became almost menacing, "I am here as an officer of the law because I have reason to believe that a guest at this banquet is connected with a crime committed in this restaurant within the last hour or two."

So extraordinary was this accusation and so utterly unexpected that for some moments no one spoke. Then, after the first dismay, came indignant protests; this man had a nerve to break in on a gathering of American citizens with a fairy tale like that!

"Silence!" rang out the commissary's voice sharply. "Who sat there?" He pointed to a vacant seat at the long central table.

All eyes turned to this empty chair, and heads came together in excited whispers.

"Bring me a plan of the tables," he continued, and when this was spread before him: "I will read off the names marked here, and each one of you will please answer."

In tense silence he called the names, and to each one came a quick "Here!" until he said "Kittredge!"

There was no answer.

"Lloyd Kittredge!" he repeated, and still no one spoke.

"Ah!" he muttered and went on calling names, but no one else was missing.

"All here but M. Kittredge. He was here, and—he went out. I must know why he went out, I must know when he went out—exactly when; I must know how he acted before he left, what he said—in short, I must know all you can tell me about him. Remember, the best service you can render your friend is to speak freely. If he is innocent, the truth will protect him"

Then began a wearisome questioning of witnesses, not very fruitful, either, for these Americans developed a surprising ignorance touching their fellow-countryman and all that concerned him. It must have been about nine o'clock when he went out, perhaps a few minutes earlier. No, there had been nothing peculiar in his actions or manner; in fact, most of the guests had not even noticed his absence.

As to Kittredge's life and personality the result was scarcely more satisfactory. He had appeared in Paris about a year before, just why was not known, and had passed as a good fellow, perhaps a little wild and hot-headed. Strangely enough, no one could say where Kittredge lived; he had left rather expensive rooms near the boulevards that he had occupied at first, and since then he had almost disappeared from his old haunts. Some said that his money had given out and he had gone to work, but this was only vague rumor.

These facts having been duly recorded, the banqueters were informed that they might depart, which they did in silence, the spirit of festivity having vanished.

Inquiries were now made in the hotel about Kittredge's movements, but nothing came to light except the statement of a big, liveried doorkeeper, who remembered distinctly the sudden appearance at about nine o'clock of a young man who was very anxious to get a cab. The storm was then at its height, and the doorkeeper had advised the young man to wait, feeling sure the tempest would cease as suddenly as it had begun; but the latter, apparently ill at ease, had insisted that he must go at once; he said he would find a cab himself, and turning up his collar so that his face was almost hidden, and drawing his thin overcoat tight about his evening dress, he had dashed into the black downpour, and a moment later the doorkeeper, surprised at this eccentric behavior, saw the young man hail a passing fiacre and drive away.

At this point in the investigation the unexpected happened. One of the policemen burst in to say that some one had called for the lady's cloak and bag. It was a young man with a check for the things; he was waiting for them now in the cloakroom and he seemed nervous.

"Well?" snapped the commissary.

"I was going to arrest him, sir," replied the other eagerly, "but——"

"Will you never learn your business?" stormed Pougeot. "Does Gibelin know this?"

"Yes, sir, we just told him."

"Send Joseph here—quick." And to the waiter when he appeared: "Tell the woman in the cloakroom to let this young man have the things. Don't let him see that you are suspicious, but take a good look at him."

"Yes, sir. And then?"

"And then nothing. Leave him to Gibelin."

A moment later Joseph returned to say that he had absolutely recognized the young man downstairs as the one who had passed him in the corridor, François was positive he was the missing banquet guest. In other words, they were facing this remarkable situation: that the cloak and leather bag left by the mysterious woman of Number Six had now been called for by the very man against whom suspicion was rapidly growing—Lloyd Kittredge himself.

When Kittredge, with cloak and bag, stepped into his waiting cab and, for the second time on this villainous night, started down the Champs Elysées he was under no illusion as to his personal safety. He knew that he would be followed and presently arrested, he knew this without even glancing behind him, he had understood the whispers and searching looks in the hotel; it was certain that his moments of liberty were numbered, so he must make a clean job of this thing that had to be done while still there was time. He had told the driver to cross the bridge and go down the Boulevard St. Germain, but now he changed the order and, half opening the door, he bade the man turn to the right and drive on to the Rue de Vaugirard. He knew that this was a long, ill-lighted street, one of the longest streets in Paris.

"There's no number," he called out. "Just keep going."

The driver grumbled and cracked his whip, and a moment later, peering back through the front window, he saw his eccentric fare absorbed in examining a white leather bag. He could see him distinctly by the yellow light of his two side lanterns. The young man had opened one of the inner pockets of the bag, drawing out a flap of leather under which a name was stamped quite visibly in gilt letters. Presently he took out a pocket knife and tried to scrape off the name, but the letters were deeply marked and could not be removed so easily. After a moment's hesitation the young man carefully drew his blade across the base of the flap, severing it from the bag, which he then threw back on the seat, holding the flap in apparent perplexity.

All this the driver observed with increasing interest until presently Kittredge looked up and caught his eye.

"You've got a nerve," the young man muttered. "I'll fix you." And, drawing the two black curtains, he shut off the driver's view.

As they neared the end of the Rue de Vaugirard, the American opened the door again and told the man to turn and drive back, he wanted to have a look at Notre-Dame, three full miles away. The driver swore softly, but obeyed, and back they went, passing another cab just behind them which also turned immediately and followed, as Kittredge noticed with a gloomy smile.

On the way to Notre-Dame, Kittredge changed their direction half a dozen times, acting on accountable impulses, going by zigzags through narrow, dark streets, instead of by the straight and natural way, so that it was after midnight when they entered the Rue du Cloitre Notre-Dame, which runs just beside the cathedral, and drew up at a house indicated by the American. The other cab drew up behind them.

"Tell your friend back there," remarked Kittredge to his driver as he got out, "that I have important business here. There'll be plenty of time for him to get a drink." Then, with a nervous tug at the bell, he disappeared in the house, leaving the cloak and bag in the cab.

And now two important things happened, one of them unexpected. The expected thing was that M. Gibelin came forward immediately from the second cab followed by Papa Tignol and a policeman. The shadowing detective was in a vile humor which was not improved when he got the message left by the flippant American.

"Time for a drink! Infernal impudence! We'll teach him manners at the depot! This farce is over," he flung out. "See where he went, ask the concierge," he said to Tignol. And to the policeman: "Watch the courtyard. If he isn't down in ten minutes we'll go up."

Then, as his men obeyed, Gibelin turned to Kittredge's driver. "Here's your fare. You can go. I'm from headquarters. I have a warrant for this man's arrest." And he showed his credentials. "I'll take the things he has left."

"Don't I get a pourboire?" grumbled the driver.

"No, sir. You're lucky to get anything."

"Am I?" retorted the Jehu, gathering up his reins (and now came the unexpected happening): "Well, I'll tell you one thing, my friend, this is the night they made a fool of M. Gibelin!"

The detective started. "You know my name? What do you mean?"

The cab was already moving, but the driver turned on his seat and, waving his hand in derision, he called back: "Ask Beau Cocono!" And then to his horse: "Hue, cocotte!"

Meantime Kittredge had climbed the four flights of stairs leading to the sacristan's modest apartment. And, in order to explain how he happened to be making so untimely a visit it is necessary to go back several hours to a previous visit here that the young American had already made on this momentous evening.