ATTIRED IN HIGH RUBBER THIGH BOOTS AND LEATHER-BOUND BLACK OILSKINS.

Title: A Master of Fortune: Being Further Adventures of Captain Kettle

Author: Charles John Cutcliffe Wright Hyne

Illustrator: Stanley L. Wood

Release date: June 1, 2004 [eBook #12556]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Charlie Kirschner and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, A Master of Fortune, by Cutcliffe Hyne, Illustrated by Stanley L. Wood

ATTIRED IN HIGH RUBBER THIGH BOOTS AND LEATHER-BOUND BLACK

OILSKINS.

My dear Kettle,--

With some considerable trepidation, I venture to offer you here the dedication of your unauthorized biography. You will read these memoirs, I know, and it is my pious hope that you do not fit the cap on yourself as their hero. Of course I have sent you along your cruises under the decent disguise of a purser's name, and I trust that if you do recognize yourself, you will appreciate this nice feeling on my part. Believe me, it was not entirely caused by personal fear of that practical form which I am sure your displeasure would take if you caught any one putting you into print. Even a working novelist has his humane moments; and besides if I made you more recognizable, there might be a more dangerous broth stirred up, with an ugly international flavor. Would it be indiscreet to bring one sweltering day in Bahia to your memory, where you made play with a German (or was he a Scandinavian?) and a hundredweight drum of good white lead? or might one hint at that little affair which made Odessa bad for your health, and indeed compelled you to keep away from Black Sea ports entirely for several years? I trust, then, that if you do detect my sin in making myself without leave or license your personal historian, you will be induced for the sake of your present respectability to give no sign of a ruffled temper, but recognize me as part of the cross you are appointed to bear, and incidentally remember my forbearance in keeping so much really splendid material (from my point of view) in snug retirement up my sleeve.

Finally, let me remind you that I made no promises not to publish, and that you did. Not only were you going to endow the world with a book of poems, but I was to have a free copy. This has not yet come; and if, for an excuse, you have published no secular verse, I am quite willing to commute for a copy of the Book of Hymns, provided it is suitably inscribed.

C.J.C.H.

OAK VALE, BRADFORD,

June 27, 1899.

"The pay is small enough," said Captain Kettle, staring at the blue paper. "It's a bit hard for a man of my age and experience to come down to a job like piloting, on eight pound a month and my grub."

"All right, Capt'n," replied the agent. "You needn't tell me what I know already. The pay's miserable, the climate's vile, and the bosses are beasts. And yet we have more applicants for these berths on the Congo than there are vacancies for. And f'why is it, Capt'n? Because there's no questions asked. The Congo people want men who can handle steamers. Their own bloomin' Belgians aren't worth a cent for that, and so they have to get Danes, Swedes, Norwegians, English, Eytalians, or any one else that's capable. They prefer to give small pay, and are willing to take the men that for various reasons can't get better jobs elsewhere. Guess you'll know the crowd I mean?"

"Thoroughly, sir," said Kettle, with a sigh. "There are a very large number of us. But we're not all unfortunate through our own fault."

"No, I know," said the agent. "Rascally owners, unsympathetic Board of Trade, master's certificate suspended quite unjustly, and all that--" The agent looked at his watch. "Well, Capt'n, now, about this berth? Are you going to take it?"

"I've no other choice."

"Right," said the agent, and pulled a printed form on to the desk before him, and made a couple of entries. "Let's see--er--is there a Mrs. Kettle?"

"Married," said the little sailor; "three children."

The agent filled these details on to the form. "Just as well to put it down," he commented as he wrote. "I'm told the Congo Free State has some fancy new pension scheme on foot for widdys and kids, though I expect it'll come to nothing, as usual. They're a pretty unsatisfactory lot all round out there. Still you may as well have your chance of what plums are going. Yer age, Capt'n?"

"Thirty-eight."

"And--er--previous employment? Well, I suppose we had better leave that blank as usual. They never really expect it to be filled in, or they wouldn't offer such wretchedly small pay and commission. You've got your master's ticket to show, and that's about all they want."

"There's my wife's address, sir. I'd like my half-pay sent to her."

"She shall have it direct from Brussels, skipper, so long as you are alive--I mean, so long as you remain in the Congo Service."

Captain Kettle sighed again. "Shall I have to wait long before this appointment is confirmed?"

"Why, no," said the agent. "There's a boat sailing for the Coast to-morrow, and I can give you an order for a passage by her. Of course my recommendation has to go to Brussels to be ratified, but that's only a matter of form. They never refuse anybody that offers. They call the Government 'Leopold and Co.' down there on the Congo. You'll understand more about it when you're on the spot.

"I'm sorry for ye, Capt'n, but after what you told me, I'm afraid it's the only berth I can shove you into. However, don't let me frighten ye. Take care of yourself, don't do too much work, and you may pull through all right. Here's the order for the passage down Coast by the Liverpool boat. And now I must ask you to excuse me. I've another client waiting."

In this manner, then, Captain Owen Kettle found himself, after many years of weary knocking about the seas, enlisted into a regular Government service; and although this Government, for various reasons, happened to be one of the most unsatisfactory in all the wide, wide world, he thrust this item resolutely behind him, and swore to himself that if diligence and crew-driving could bring it about, he would rise in that service till he became one of the most notable men in Africa.

"What I want is a competence for the missus and kids," he kept on repeating to himself, "and the way to finger that competence is to get power." He never owned to himself that this thirst for power was one of the greatest curses of his life; and it did not occur to him that his lust for authority, and his ruthless use of it when it came in his way, were the main things which accounted for his want of success in life.

Captain Kettle's voyage down to the Congo on the British and African S.S. M'poso gave time for the groundwork of Coast language and Coast thought (which are like unto nothing else on this planet) to soak into his system. The steamer progressed slowly. She went up rivers protected by dangerous bars; she anchored in roadsteads, off forts, and straggling towns; she lay-to off solitary whitewashed factories, which only see a steamer twice a year, and brought off little doles of cargo in her surf-boats and put on the beaches rubbishy Manchester and Brummagem trade goods for native consumption; and the talk in her was that queer jargon with the polyglot vocabulary in which commerce is transacted all the way along the sickly West African seaboard, from the Goree to St. Paul de Loanda.

Every white man of the M'poso's crew traded on his own private account, and Kettle was initiated into the mysteries of the unofficial retail store in the forecastle, of whose existence Captain Image, the commander, and Mr. Balgarnie, the purser, professed a blank and child-like ignorance.

Kettle had come across many types of sea-trader in his time, but Captain Image and Mr. Balgarnie were new to him. But then most of his surroundings were new. Especially was the Congo Free State an organization which was quite strange to him. When he landed at Banana, Captain Nilssen, pilot of the Lower Congo and Captain of the Port of Banana, gave him advice on the subject in language which was plain and unfettered.

"They are a lot of swine, these Belgians," said Captain Nilssen, from his seat in the Madeira chair under the veranda of the pilotage, "and there's mighty little to be got out of them. Here am I, with a wife in Kjobnhavn and another in Baltimore, and I haven't been able to get away to see either of them for five blessed years. And mark you, I'm a man with luck, as luck goes in this hole. I've been in the lower river pilot service all the time, and got the best pay, and the lightest jobs. There's not another captain in the Congo can say as much. Some day or other they put a steamboat on the ground, and then they're kicked out from the pilot service, and away they're off one-time to the upper river above the falls, to run a launch, and help at the rubber palaver, and get shot at, and collect niggers' ears, and forget what champagne and white man's chop taste like."

"You've been luckier?"

"Some. I've libbed for Lower Congo all my time; had a home in the pilotage here; and got a dash of a case of champagne, or an escribello, or at least a joint of fresh meat out of the refrigerator from every steamboat I took either up or down."

"But then you speak languages?" said Kettle.

"Seven," said Captain Nilssen; "and use just one, and that's English. Shows what a fat lot of influence this État du Congo has got. Why, you have to give orders even to your boat-boys in Coast English if you want to be understood. French has no sort of show with the niggers."

Now white men are expensive to import to the Congo Free State, and are apt to die with suddenness soon after their arrival, and so the State (which is in a chronic condition of hard-up) does not fritter their services unnecessarily. It sets them to work at once so as to get the utmost possible value out of them whilst they remain alive and in the country.

A steamer came in within a dozen hours of Kettle's first stepping ashore, and signalled for a pilot to Boma. Nilssen was next in rotation for duty, and went off in his boat to board her, and he took with him Captain Owen Kettle to impart to him the mysteries of the great river's navigation.

The boat-boys sang a song explanatory of their notion of the new pilot's personality as they caught at the paddles, but as the song was in Fiote, even Nilssen could only catch up a phrase here and there, just enough to gather the drift. He did not translate, however. He had taken his new comrade's measure pretty accurately, and judged that he was not a man who would accept criticism from a negro. So having an appetite for peace himself, he allowed the custom of the country to go on undisturbed.

The steamer was outside, leaking steam at an anchorage, and sending out dazzling heliograms every time she rolled her bleached awnings to the sun. The pilot's boat, with her crew of savages, paddled towards her, down channels between the mangrove-planted islands. The water spurned up by the paddle blades was the color of beer, and the smell of it was puzzlingly familiar.

"Good old smell," said Nilssen, "isn't it? I see you snuffling. Trying to guess where you met it before, eh? We all do that when we first come. What about crushed marigolds, eh?"

"Crushed marigolds it is."

"Guess you'll get to know it better before you're through with your service here. Well, here we are alongside."

The steamer was a Portuguese, officered by Portuguese, and manned by Krooboys, and the smell of her drowned even the marigold scent of the river. Her dusky skipper exuded perspiration and affability, but he was in a great hurry to get on with his voyage. The forecastle windlass clacked as the pilot boat drew into sight, heaving the anchor out of the river floor; the engines were restarted so soon as ever the boat hooked on at the foot of the Jacob's ladder; and the vessel was under a full head of steam again by the time the two white men had stepped on to her oily deck.

"When you catch a Portuguese in a hurry like this," said Nilssen to Kettle as they made their way to the awninged bridge, "it means there's something wrong. I don't suppose we shall be told, but keep your eyes open."

However, there was no reason for prying. Captain Rabeira was quite open about his desire for haste. "I got baccalhao and passenger boys for a cargo, an' dose don' keep," said he.

"We smelt the fish all the way from Banana," said Nilssen. "Guess you ought to call it stinking fish, not dried fish, Captain. And we can see your nigger passengers. They seem worried. Are you losing 'em much?"

"I done funeral palaver for eight between Loanda an' here, an' dem was a dead loss-a. I don' only get paid for dem dat lib for beach at Boma. Dere was a fire-bar made fast to the leg of each for sinker, an' dem was my dead loss-a too. I don' get paid for fire-bars given to gastados--" His English failed him. He shrugged his shoulders, and said "Sabbey?"

"Sabbey plenty," said Nilssen. "Just get me a leadsman to work, Captain. If you're in a hurry, I'll skim the banks as close as I dare."

Rabeira called away a hand to heave the lead, and sent a steward for a bottle of wine and glasses. He even offered camp stools, which, naturally, the pilots did not use. In fact, he brimmed with affableness and hospitality.

From the first moment of his stepping on to the bridge, Kettle began to learn the details of his new craft. As each sandbar showed up beneath the yellow ripples, as each new point of the forest-clad banks opened out, Nilssen gave him courses and cross bearings, dazing enough to the unprofessional ear, but easily stored in a trained seaman's brain. He discoursed in easy slang of the cut-offs, the currents, the sludge-shallows, the floods, and the other vagaries of the great river's course, and punctuated his discourse with draughts of Rabeira's wine, and comments on the tangled mass of black humanity under the forecastle-head awning.

"There's something wrong with those passenger boys," he kept on repeating. And another time: "Guess those niggers yonder are half mad with funk about something."

But Rabeira was always quick to reassure him. "Now dey lib for Congo, dey not like the idea of soldier-palaver. Dere was nothing more the matter with them but leetle sickness."

"Oh! it's recruits for the State Army you're bringing, is it?" asked Kettle.

"If you please," said Rabeira cheerfully. "Slaves is what you English would call dem. Laborers is what dey call demselves."

Nilssen looked anxiously at his new assistant. Would he have any foolish English sentiment against slavery, and make a fuss? Nilssen, being a man of peace, sincerely hoped not. But as it was, Captain Kettle preserved a grim silence. He had met the low-caste African negro before, and knew that it required a certain amount of coercion to extract work from him. But he did notice that all the Portuguese on board were armed like pirates, and were constantly on the qui vive, and judged that there was a species of coercion on this vessel which would stick at very little.

The reaches of the great beer-colored river opened out before them one after another in endless vistas, and at rare places the white roofs of a factory showed amongst the unwholesome tropical greenery of the banks. Nilssen gave names to these, spoke of their inhabitants as friends, and told of the amount of trade in palm-oil and kernels which each could be depended on to yield up as cargo to the ever-greedy steamers. But the attention of neither of the pilots was concentrated on piloting. The unrest on the forecastle-head was too obvious to be overlooked.

Once, when the cackle of negro voices seemed to point to an immediate outbreak, Rabeira gave an order, and presently a couple of cubical green boxes were taken forward by the ship's Krooboys, broken up, and the square bottles which they contained, distributed to greedy fingers.

"Dashing 'em gin," said Nilssen, looking serious. "Guess a Portugee's in a bad funk before he dashes gin at four francs a dozen to common passenger boys. I've a blame' good mind to put this vessel on the ground--by accident--and go off in the gig for assistance, and bring back a State launch."

"Better not risk your ticket," said Kettle. "If there's a row, I'm a bit useful in handling that sort of cattle myself."

Nilssen eyed wistfully a swirl of the yellow water which hid a sandbar, and, with a sigh, gave the quartermaster a course which cleared it. "Guess I don't like ructions myself," he said. "Hullo, what's up now? There are two of the passenger boys getting pushed off the forecastle-head by their own friends on to the main deck."

"They look a mighty sick couple," said Kettle, "and their friends seem very frightened. If this ship doesn't carry a doctor, it would be a good thing if the old man were to start in and deal out some drugs."

It seemed that Rabeira was of the same opinion. He went down to the main deck, and there, under the scorching tropical sunshine, interviewed the two sick negroes in person, and afterwards administered to each of them a draught from a blue glass bottle. Then he came up, smiling and hospitable and perspiring, on to the bridge, and invited the pilots to go below and dine. "Chop lib for cabin," said he; "palm-oil chop, plenty-too-much-good. You lib for below and chop. I take dem ship myself up dis next reach."

"Well, it is plain, deep water," said Nilssen, "and I guess you sabbey how to keep in the middle as well as I do. Come along, Kettle."

The pair of them went below to the baking cabin and dined off a savory orange-colored stew, and washed it down with fiery red wine, and dodged the swarming, crawling cockroaches. The noise of angry negro voices came to them between whiles through the hot air, like the distant chatter of apes.

The Dane was obviously ill at ease and frightened; the Englishman, though feeling a contempt for his companion, was very much on the alert himself, and prepared for emergencies. There was that mysterious something in the atmosphere which would have bidden the dullest of mortals prepare for danger.

Up they came on deck again, and on to the bridge. Rabeira himself was there in charge, dark, smiling, affable as ever.

Nilssen looked sharply down at the main deck below. "Hullo," said he, "those two niggers gone already? You haven't shifted them down below, I suppose?"

The Portuguese Captain shrugged his shoulders. "No," he said, "it was bad sickness, an' dey died an' gone over the side. I lose by their passage. I lose also the two fire-bar which I give for funeral palaver. Ver' disappointing."

"Sudden kind of sickness," said Nilssen.

"Dis sickness is. It make a man lib for die in one minute, clock time. But it don' matter to you pilot, does it? You lib for below--off duty--dis las' half hour. You see nothing, you sabby nothing. I don'-want no trouble at Boma with doctor palaver. I make it all right for you after. Sabby?"

"Oh, I tumble to what you're driving at, but I was just thinking out how it works. However, you're captain of this ship, and if you choose not to log down a couple of deaths, I suppose it's your palaver. Anyway, I don't want to cause no ill-will, and if you think it's worth a dash, I don't see why I shouldn't earn it. It's little enough we pick up else in this service, and I've got a wife at home in Liverpool who has to be thought about."

Kettle drew a deep breath. "It seems to me," he said, looking very hard at the Portuguese, "that those men died a bit too sudden. Are you sure they were pukka dead when you put them over the side?"

"Oh, yes," said Rabeira smilingly, "an' dey made no objection. It was best dey should go over quick. Bodies do not keep in this heat. An' pilot, I do you square-a, same as with Nilssen. You shall have your dash when doctor-palaver set."

"No," said Kettle, "you may keep it in your own trousers, Captain. Money that you've fingered, is a bit too dirty for me to touch."

"All right," said Rabeira with a genial shrug, "so much cheaper for me. But do not talk on the beach, dere's good boy, or you make trouble-palaver for me."

"I'll shut my head if you stop at this," said Kettle, "but if you murder any more of those poor devils, I'll see you sent to join them, if there's enough law in this State to rig a gallows."

The Portuguese did not get angry. On the contrary, he seemed rather pleased at getting what he wanted without having to bribe for it, and ordered up fresh glasses and another bottle of wine for the pilots' delectation. But this remained untouched. Kettle would not drink himself, and Nilssen (who wished to be at peace with both sides) did not wish to under the circumstances.

To tell the truth, the Dane was beginning to get rather scared of his grim-visaged little companion; and so, to prevent further recurrence to unpleasant topics, he plunged once more into the detail of professional matters. Here was a grassy swamp that was a deep water channel the year before last; there was a fair-way in the process of silting up; there was a mud-bar with twenty-four feet, but steamers drawing twenty-seven feet could scrape over, as the mud was soft. The current round that bend raced at a good eleven knots. That bank below the palm clump was where an Italian pilot stuck the M'poso for a month, and got sent to upper Congo (where he was eaten by some rebellious troops) as a recompense for his blunder.

Almost every curve of the river was remembered by its tragedy, and had they only known it, the steamer which carried them for their observation had hatching within her the germs of a very worthy addition to the series.

More trouble cackled out from the forecastle-head, and more of the green gin cases were handed up to quell it. The angry cries gradually changed to empty boisterous laughter, as the raw potato spirit soaked home; and the sullen, snarling faces melted into grotesque, laughing masks; but withal the carnival was somewhat grisly.

It was clear that more than one was writhing with the pangs of sickness. It was clear also that none of these (having in mind the physicking and fate of their predecessors) dared give way, but with a miserable gaiety danced, and drank, and guffawed with the best. Two, squatting on the deck, played tom-tom on upturned tin pans; another jingled two pieces of rusty iron as accompaniment; and all who in that crowded space could find foot room, danced shuff-shuff-shuffle with absurd and aimless gestures.

The fort at Chingka drew in sight, with a B. and A. boat landing concrete bags at the end of its wharf; and on beyond, the sparse roofs of the capital of the Free State blistered and buckled under the sun. The steamer, with hooting siren, ran up her gaudy ensign, and came to an anchor in the stream twenty fathoms off the State wharf. A yellow-faced Belgian, with white sun helmet and white umbrella, presently came off in the doctor's boat, and announced himself as the health officer of the port, and put the usual questions.

Rabeira lied pleasantly and glibly. Sickness he owned to, but when on the word the doctor hurriedly made his boat-boys pull clear, he laughed and assured him that the sickness was nothing more than a little fever, such as any one might suffer from in the morning, and be out, cured, and making merry again before nightfall.

That kind of fever is known in the Congo, and the doctor was reassured, and bade his boat-boys pull up again. Yet because of the evil liver within him, his temper was short, and his questioning acid. But Captain Rabeira was stiff and unruffled and wily as ever, and handed in his papers and answered questions, and swore to anything that was asked, as though care and he were divorced forever.

Kettle watched the scene with a drawn, moist face. He did not know what to do for the best. It seemed to him quite certain that this oily, smiling scoundrel, whom he had more than half suspected of a particularly callous and brutal double murder, would be given pratique for his ship, and be able to make his profits unrestrained. The shipmaster's esprit de corps prevented him from interfering personally, but he very much desired that the heavens would fall--somehow or other--so that justice might be done.

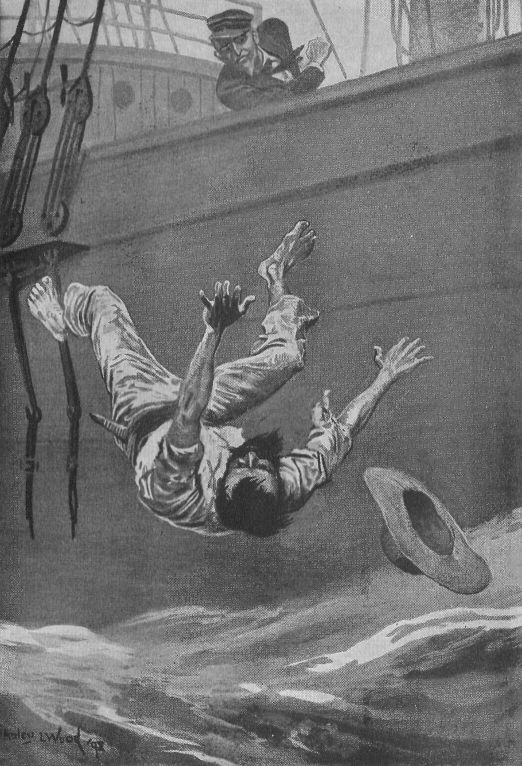

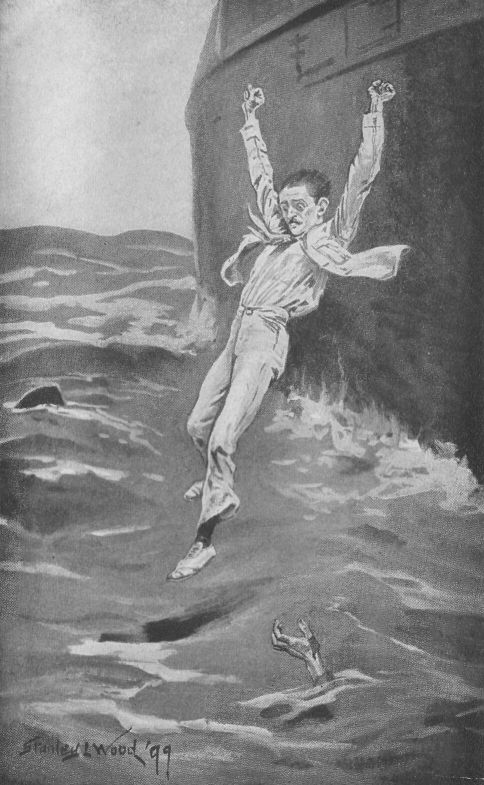

A dens ex machina came to fill his wishes. The barter of words and the conning of documents had gone on; the doctor's doubts were on the point of being lulled for good; and in a matter of another ten seconds pratique would have been given. But from the forecastle-head there came a yell, a chatter of barbaric voices, a scuffle and a scream; a gray-black figure mounted the rail, and poised there a moment, an offence to the sunlight, and then, falling convulsively downwards, hit the yellow water with a smack and a spatter of spray, and sank from sight.

A couple of seconds later the creature reappeared, swimming frenziedly, as a dog swims, and by a swirl of the current (before anybody quite knew what was happening) was swept down against the doctor's boat, and gripped ten bony fingers upon the gunwhale and lifted towards her people a face and shoulders eloquent of a horrible disorder.

Instantly there was an alarm, and a sudden panic. "Sacre nom d'un pipe," rapped out the Belgian doctor; "variole!"

"Small-pox lib," whimpered his boat-boys, and before their master could interfere, beat at the delirious wretch with their oars. He hung on tenaciously, enduring a perfect avalanche of blows. But mere flesh and bone had to wither under that onslaught, and at last, by sheer weight of battering, he was driven from his hold, and the beer-colored river covered him then and for always.

After that, there was no further doubt of the next move. The yellow-faced doctor sank back exhausted in the stern sheets of the gig, and gave out sentence in gasps. The ship was declared unclean until further notice; she was ordered to take up a berth a mile away against the opposite bank of the river till she was cleared of infection; she was commanded to proceed there at once, to anchor, and then to blow off all her steam.

The doctor's tortured liver prompted him, and he spoke with spite. He called Rabeira every vile name which came to his mind, and wound up his harangue by rowing off to Chingka to make sure that the guns of the fort should back up his commands.

The Portuguese captain was daunted then; there is no doubt about that. He had known of this outbreak of small-pox for two days, had stifled his qualms, and had taken his own peculiar methods of keeping the disease hidden, and securing money profit for his ship. He had even gone so far as to carry a smile on his dark, oily face, and a jest on his tongue. But this prospect of being shut up with the disorder till it had run its course inside the walls of the ship, and no more victims were to be claimed, was too much for his nerve. He fled like some frightened animal to his room, and deliberately set about guzzling a surfeit of neat spirit.

Nilssen, from the bridge, fearful for his credit with the State, his employer, roared out orders, but nobody attended to them. Mates, quartermasters, Krooboys, had all gone aft so as to be as far as possible from the smitten area; and in the end it was Kettle who went to the forecastle-head, and with his own hands let steam into the windlass and got the anchor. He stayed at his place. An engineer and fireman were still below, and when Nilssen telegraphed down, they put her under weigh again, and the older pilot with his own hands steered her across to the quarantine berth. Then Kettle let go the anchor again, paid out and stoppered the cable, and once more came aft; and from that moment the new regime of the steamer may be said to have commenced.

In primitive communities, from time immemorial, the strongest man has become chieftain through sheer natural selection. Societies which have been upheaved to their roots by anarchy, panic, or any of these more perfervid emotions, revert to the primitive state. On this Portuguese ship, authority was smashed into the smallest atoms, and every man became a savage and was in danger at the hands of his fellow savage.

Rabeira had drunk himself into a stupor before the boilers had roared themselves empty through the escapes. The two mates and the engineers cowered in their rooms as though the doors were a barrier against the small-pox germs. The Krooboys broached cargo and strewed the decks with their half-naked bodies, drunk on gin, amid a litter of smashed green cases.

Meals ceased. The Portuguese cook and steward dropped their collective duties from the first alarm; the Kroo cook left the rice steamer because "steam no more lib"; and any one who felt hunger or thirst on board, foraged for himself, or went without satisfying his wants. Nobody helped the sick, or chided the drunken. Each man lived for himself alone--or died, as the mood seized him.

Nilssen took up his quarters at one end of the bridge, frightened, but apathetic. With awnings he made himself a little canvas house, airy, but sufficient to keep off the dews of night. When he spoke, it was usually to picture the desolation of one or other of the Mrs. Nilssens on finding herself a widow. As he said himself, he was a man of very domesticated notions. He had no sympathy with Kettle's constantly repeated theory that discipline ought to be restored.

"Guess it's the captain's palaver," he would say. "If the old man likes his ship turned into a bear garden, 'tisn't our grub they're wasting, or our cargo they've started in to broach. Anyway, what can we do? You and I are only on board here as pilots. I wish the ship was in somewhere hotter than Africa, before I'd ever seen her."

"So do I," said Kettle. "But being here, it makes me ill to see the way she's allowed to rot, and those poor beasts of niggers are left to die just as they please. Four more of them have either jumped overboard, or been put there by their friends. The dirt of the place is awful. They're spreading small-pox poison all over the ship. Nothing is ever cleaned."

"There's dysentery started, too."

"Very well," said Kettle, "then that settles it. We shall have cholera next, if we let dirt breed any more. I'm going to start in and make things ship-shape again."

"For why?"

"We'll say I'm frightened of them as they are at present, if you like. Will you chip in and bear a hand? You're frightened, too."

"Oh, I'm that, and no error about it. But you don't catch me interfering. I'm content to sit here and take my risks as they come, because I can't help myself. But I go no further. If you start knocking about this ship's company they'll complain ashore, and then where'll you be? The Congo Free State don't like pilots who do more than they're paid for."

"Very well," said Kettle, "I'll start in and take my risks, and you can look on and umpire." He walked deliberately down off the bridge, went to where the mate was dozing against a skylight on the quarter deck, and stirred him into wakefulness with his foot.

"Well?" said the man.

"Turn the hands to, and clean ship."

"What!"

"You hear me."

The mate inquired, with abundant verbal garnishings, by what right Kettle gave the order.

"Because I'm a better man than you. Because I'm best man on board. Do you want proof?"

Apparently the mate did. He whipped out a knife, but found it suddenly knocked out of his hand, and sent skimming like a silver flying fish far over the gleaming river. He followed up the attack with an assault from both hands and feet, but soon discovered that he had to deal with an artist. He gathered himself up at the end of half a minute's interview, glared from two half-shut eyes, wiped the blood from his mouth, and inquired what Kettle wanted.

"You heard my order. Carry it out."

The man nodded, and went away sullenly muttering that his time would come.

"If you borrow another knife," said Kettle cheerfully, "and try any more of your games, I'll shoot you like a crow, and thank you for the chance. You'll go forrard and clean the forecastle-head and the fore main deck. Be gentle with those sick! Second Mate?"

"Si, Señor."

"Get a crew together and clean her up aft here. Do you want any rousing along?"

Apparently the second mate did not. He had seen enough of Captain Kettle's method already to quite appreciate its efficacy. The Krooboys, with the custom of servitude strong on them, soon fell-to when once they were started. The thump of holy-stones went up into the baking air, and grimy water began to dribble from the scuppers.

With the chief engineer Kettle had another scuffle. But he, too, was eased of the knife at the back of his belt, thumped into submissiveness, and sent with firemen and trimmers to wash paint in the stewy engine-room below, and clean up the rusted iron work. And then those of the passenger boys who were not sick, were turned-to also.

With Captain Rabeira, Kettle did not interfere. The man stayed in his own room for the present, undisturbed and undisturbing. But the rest of the ship's complement were kept steadily to their employment.

They did not like it, but they thought it best to submit. Away back from time unnumbered, the African peoples have known only fear as the governing power, and, from long acclimatization, the Portuguese might almost count as African. This man of a superior race came and set himself up in authority over them, in defiance of all precedent, law, everything; and they submitted with dull indifference. The sweets of freedom are not always appreciated by those who have known the easy luxury of being slaves.

The plague was visibly stayed from almost the very first day that Kettle took over charge. The sick recovered or died; the sound sickened no more; it seemed as though the disease microbes on board the ship were glutted.

A mile away, at the other side of the beer-colored river, the rare houses of Boma sprawled amongst the low burnt-up hills, and every day the doctor with his bad liver came across in his boat under the blinding sunshine to within shouting distance, and put a few weary questions. The formalities were slack enough. Nilssen usually made the necessary replies (as he liked to keep himself in the doctor's good books), and then the boat would row away.

Nilssen still remained gently non-interferent. He was paid to be a pilot by the État Indépendant du Congo--so he said--and he was not going to risk a chance of trouble, and no possibility of profit, by meddling with matters beyond his own sphere. Especially did he decline to be co-sharer in Kettle's scheme for dealing out justice to Captain Rabeira.

"It is not your palaver," he said, "or mine. If you want to stir up trouble, tell the State authorities when you get ashore. That won't do much good either. They don't value niggers at much out here."

"Nor do I," said Kettle. "There's nothing foolish with me about niggers. But there's a limit to everything, and this snuff-colored Dago goes too far. He's got to be squared with, and I'm going to do it."

"Guess it's your palaver. I've told you what the risks are."

"And I'm going to take them," said Kettle grimly. "You may watch me handle the risks now with your own eyes, if you wish."

He went down off the bridge, walked along the clean decks, and came to where a poor wretch lay in the last stage of small-pox collapse. He examined the man carefully. "My friend," he said at last, "you've not got long for this world, anyway, and I want to borrow your last moments. I suppose you won't like to shift, but it's in a good cause, and anyway you can't object."

He stooped and lifted the loathsome bundle in his arms, and then, in spite of a cry of expostulation from Nilssen, walked off with his burden to Rabeira's room.

The Portuguese captain was in his bunk, trying to sleep. He was sober for the first time for many days, and, in consequence, feeling not a little ill.

Kettle deposited his charge with carefulness on the littered settee, and Rabeira started up with a wild scream of fright and a babble of oaths. Kettle shut and locked the door.

"Now look here," he said, "you've earned more than you'll ever get paid in this life, and there's a tolerably heavy bill against you for the next. It looks to me as if it would be a good thing if you went off there to settle up the account right now. But I'm not going to take upon myself to be your hangman. I'm just going to give you a chance of pegging out, and I sincerely hope you'll take it. I've brought our friend here to be your room mate for the evening. It's just about nightfall now, and you've got to stay with him till daybreak."

"You coward!" hissed the man. "You coward! You coward!" he screamed.

"Think so?" said Kettle gravely. "Then if that's your idea, I'll stay here in the room, too, and take my risks. God's seen the game, and I'll guess He'll hand over the beans fairly."

Perspiration stood in beads on all their faces. The room, the one unclean room of the ship, was full of breathless heat, and stale with the lees of drink. Kettle, in his spruce-white drill clothes, stood out against the squalor and the disorder, as a mirror might upon a coal-heap.

The Portuguese captain, with nerves smashed by his spell of debauch, played a score of parts. First he was aggressive, asserting his rights as a man and the ship's master, and demanding the key of the door. Then he was warlike, till his frenzied attack earned him such a hiding that he was glad enough to crawl back on to the mattress of his bunk. Then he was beseeching. And then he began to be troubled with zoological hauntings, which occupied him till the baking air cooled with the approach of the dawn.

The smitten negro on the settee gave now and then a moan, but for the most part did his dying with quietness. Had Kettle deliberately worked for that purpose, he could not have done anything more calculated to make the poor wretch's last moments happy.

"Oh, Massa!" he kept on whispering, "too-much-fine room. You plenty-much good for let me lib for die heah." And then he would relapse into barbaric chatterings more native to his taste, and fitting to his condition.

Captain Kettle played his parts as nurse and warder with grave attention. He sat perspiring in his shirt sleeves, writing at the table whenever for a moment or two he had a spell of rest; and his screed grew rapidly. He was making verse, and it was under the stress of severe circumstances like these that his Muse served him best.

The fetid air of the room throbbed with heat; the glow from the candle lamp was a mere yellow flicker; and the Portuguese, who cowered with twitching fingers in the bunk, was quite ready to murder him at the slightest opening: it was not a combination of circumstances which would have inspired many men.

Morning came, with a shiver and a chill, and with the first flicker of dawn, the last spark of the negro's life went out. Kettle nodded to the ghastly face as though it had been an old friend. "You seemed to like being made use of," he said. "Well, daddy, I hope you have served your turn. If your skipper hasn't got the plague in his system now, I shall think God's forgotten this bit of Africa entirely."

He stood up, gathered his papers, slung the spruce white drill coat over his arm, and unlocked the door. "Captain Rabeira," he said, "you have my full permission to resume your occupation of going to the deuce your own way." With which parting salutation, he went below to the steamer's bathroom and took his morning tub.

Half an hour passed before he came to the deck again, and Nilssen met him at the head of the companion-way with a queer look on his face. "Well," he said, "you've done it."

"Done what?"

"Scared Rabeira over the side."

"How?"

"He came scampering on deck just now, yelling blue murder, and trying to catch crawly things that weren't there. Guess he'd got jim-jams bad. Then he took it into his head that a swim would be useful, and before any one could stop him, he was over the side."

"Well?"

"He's over the side still," said the Dane drily. "He didn't come to the surface. Guess a crocodile chopped him."

"There are plenty round."

"Naturally. We've been ground baiting pretty liberally these last few weeks. Well, I guess we are about through with the business now. Not nervous about yourself, eh?"

"No," said Kettle, and touched his cap. "God's been looking on at this gamble, as I told Rabeira last night, and He dealt over the beans the way they were earned."

"That's all right," said Nilssen cheerfully. "When a man keeps his courage he don't get small-pox, you bet."

"Well," said Kettle, "I suppose we'll be fumigated and get a clean bill in about ten days from now, and I'm sure I don't mind the bit of extra rest. I've got a lot of stuff I want to write up. It's come in my head lately, and I've had no time to get it down on paper. I shouldn't wonder but what it makes a real stir some day when it's printed; it's real good stuff. I wonder if that yellow-faced Belgian doctor will live to give us pratique?"

"I never saw a man with such a liver on him."

"D'you know," said Kettle, "I'd like that doctor to hang on just for another ten days and sign our bill. He's a surly brute, but I've got to have quite a liking for him. He seems to have grown to be part of the show, just like the crows, and the sun, and the marigold smell, and the crocodiles."

"Oh," said Nilssen, "you're a blooming poet. Come, have a cocktail before we chop."

The colored Mrs. Nilssen, of Banana, gave the pink gin cocktails a final brisk up with the swizzle-stick, poured them out with accurate division, and handed the tray to Captain Kettle and her husband. The men drank off the appetizer and put down the glasses. Kettle nodded a word of praise for the mixture and thanks to its concoctor, and Mrs. Nilssen gave a flash of white teeth, and then shuffled away off the veranda, and vanished within the bamboo walls of the pilotage.

Nilssen sank back into his long-sleeved Madeira chair, a perfect wreck of a man, and Kettle sat up and looked at him with a serious face. "Look here," he said, "you should go home, or at any rate run North for a spell in Grand Canary. If you fool with this health-palaver any longer, you'll peg out."

The Dane stared wistfully out across the blue South Atlantic waters, which twinkled beyond the littered garden and the sand beach. "Yes," he said, "I'd like well enough to go back to my old woman in Boston again, and eat pork and beans, and hear her talk of culture, and the use of missionaries, and all that good old homey rot; but I guess I can't do that yet. I've got to shake this sickness off me right here, first."

"And I tell you you'll never be a sound man again so long as you lib for Congo. Take a trip home, Captain, and let the salt air blow the diseases out of you."

"If I go to sea," said the pilot wearily, "I shall be stitched up within the week, and dropped over to make a hole in the water. I don't know whether I'm going to get well anywhere, but if I do, it's right here. Now just hear me. You're the only living soul in this blasted Congo Free State that I can trust worth a cent, and I believe you've got grit enough to get me cured if only you'll take the trouble to do it. I'm too weak to take on the job myself; and, even if I was sound, I reckon it would be beyond my weight. I tell you it's a mighty big contract. But then, as I've seen for myself, you're a man that likes a scuffle."

"You're speaking above my head. Pull yourself together, Captain, and then, perhaps, I'll understand what you want."

Nilssen drew the quinine bottle toward him, tapped out a little hill of feathery white powder into a cigarette paper, rolled it up, and swallowed the dose. "I'm not raving," he said, "or anywhere near it; but if you want the cold-drawn truth, listen here: I'm poisoned. I've got fever on me, too, I'll grant, but that's nothing more than a fellow has every week or so in the ordinary way of business. I guess with quinine, whiskey, and pills, I can smile at any fever in Africa, and have done this last eight years. But it's this poison that gets me."

"Bosh," said Kettle. "If it was me that talked about getting poisoned, there'd be some sense in it. I know I'm not popular here. But you're a man that's liked. You hit it off with these Belgian brutes, and you make the niggers laugh. Who wants to poison you?"

"All right," said Nilssen; "you've been piloting on the Congo some six months now, and so of course you know all about it. But let me know a bit better. I've watched the tricks of the niggers here-away for a good many years now, and I've got a big respect for their powers when they mean mischief."

"Have you been getting their backs up, then?"

"Yes. You've seen that big ju-ju in my room?"

"That foul-looking wooden god with the looking-glass eyes?"

"Just that. I don't know where the preciousness comes in, but it's a thing of great value."

"How did you get hold of it?"

"Well, I suppose if you want to be told flatly, I scoffed it. You see, it was in charge of a passenger boy, who brought it aboard the M'poso at Matadi. He landed across by canoe from Vivi, and wanted steamer passage down to Boma by the M'poso. I was piloting her, and I got my eye on that ju-ju[1] from the very first. Captain Image and that thief of a purser Balgarnie were after it, too, but as it was a bit of a race between us as to who should get it first, one couldn't wait to be too particular."

[1] A ju-ju in West African parlance may be a large carved idol, or merely a piece of rag, or skin, or anything else that the native is pleased to set up as a charm. Ju-ju also means witchcraft. If you poison a man, you put ju-ju on him. If you see anything you do not understand, you promptly set it down as ju-ju. Similarly chop is food, and also the act of feeding. "One-time" is immediately.

"What did you want it for? Did you know it was valuable then?"

"Oh, no! I thought it was merely a whitewashed carved wood god, and I wanted it just to dash to some steamer skipper who had dashed me a case of fizz or something. You know?"

"Yes, I see. Go on. How did you get hold of it?"

"Why, just went and tackled the passenger-boy and dashed him a case of gin; and when he sobered up again, where was the ju-ju? I got it ashore right enough to the pilotage here in Banana, and for the next two weeks thought it was my ju-ju without further palaver.

"Then up comes a nigger to explain. The passenger-boy who had guzzled the gin was no end of a big duke--witch-doctor, and all that, with a record of about three hundred murders to his tally--and he had the cheek to send a blooming ambassador to say things, and threaten, to try and get the ju-ju back. Of course, if the original sportsman had come himself to make his ugly remarks, I'd soon have stopped his fun. That's the best of the Congo Free State. If a nigger down here is awkward, you can always get him shipped off as a slave--soldier, that is--to the upper river, and take darned good care he never comes back again. And, as a point of fact, I did tip a word to the commandant here and get that particular ambassador packed off out of harm's way. But that did no special good. Before a week was through up came another chap to tackle me. He spoke flatly about pains and penalties if I didn't give the thing up; and he offered money--or rather ivory, two fine tusks of it, worth a matter of twenty pounds, as a ransom--and then I began to open my eyes."

"Twenty pounds for that ju-ju! Why, I've picked up many a one better carved for a shilling."

"Well, this bally thing has value; there's no doubt about that. But where the value comes in, I can't make out. I've overhauled it times and again, but can't see it's anything beyond the ordinary. However, if a nigger of his own free will offered two big tusks to get the thing back, it stands to reason it's worth a precious sight more than that. So when the second ambassador came, I put the price down at a quarter of a ton of ivory, and waited to get it."

Kettle whistled. "You know how to put on the value," he said. "That's getting on for £400 with ivory at its present rates."

"I was badly in want of money when I set the figure. My poor little wife in Bradford had sent me a letter by the last Antwerp mail saying how hard-up she was, and the way she wrote regularly touched me."

"I don't like it," Kettle snapped.

"What, my being keen about the money?"

"No; your having such a deuce of a lot of wives."

"But I am so very domesticated," said Nilssen. "You don't appreciate how domesticated I am. I can't live as a bachelor anywhere. I always like to have a dear little wife and a nice little home to go to in whatever town I may be quartered. But it's a great expense to keep them all provided for. And besides, the law of most countries is so narrow-minded. One has to be so careful."

Kettle wished to state his views on bigamy with clearness and point, but when he cast his eyes over the frail wreck of a man in the Madeira chair, he forebore. It would not take very much of a jar to send Captain Nilssen away from this world to the Place of Reckoning which lay beyond. And so with a gulp he said instead: "You're sure it's deliberate poisoning?"

"Quite. The nigger who came here last about the business promised to set ju-ju on me, and I told him to do it and be hanged to him. He was as good as his word. I began to be bad the very next day."

"How's it managed?"

"Don't know. They have ways of doing these things in Africa which we white men can't follow."

"Suspect any one?"

"No. And if you're hinting at Mrs. Nilssen in the pilotage there, she's as staunch as you are, bless her dusky skin. Besides, what little chop I've managed to swallow since I've been bad, I've always got out of fresh unopened tins myself."

"Ah," said Kettle; "I fancied some one had been mixing up finely powdered glass in your chop. It's an old trick, and you don't twig it till the doctors cut you up after you're dead."

"As if I wasn't up to a kid's game like that!" said the sick man with feeble contempt. "No, this is regular ju-ju work, and it's beyond the Belgian doctor here, and it's beyond all other white men. There's only one cure, and that's to be got at the place where the poisoning palaver was worked from."

"And where's that?"

Captain Nilssen nodded down the narrow slip of sand, and mangroves, and nut palms, on which the settlement of Banana is built, and gazed with his sunken eyes at the smooth, green slopes of Africa beyond. "Dem village he lib for bush," he said.

"Up country village, eh? They're a nice lot in at the back there, according to accounts. But can't you arrange it by your friend the ambassador?"

"He's not the kind of fool to come back. He's man enough to know he'd get pretty well dropped on if I could get him in my reach again."

"Then tell the authorities here, and get some troops sent up."

"What'd be the good of that? They might go, or they mightn't. If they did, they'd do a lot of shooting, collect a lot of niggers' ears, steal what there was to pick up, and then come back. But would they get what I want out of the witch-doctor? Not much. They'd never so much as see the beggar. He'd take far too big care of his mangy hide. He wouldn't stop for fighting-palaver. He'd be off for bush, one-time. No, Kettle, if I'm to get well, some white man will have to go up by his lonesome for me, and square that witch-doctor by some trick of the tongue."

"Which is another way of saying you want me to risk my skin to get you your prescription?"

"But, my lad, I won't ask you to go for nothing. I don't suppose you are out here on the Congo just for your health. You've said you've got a wife at home, and I make no doubt you're as fond of her and as eager to provide for her as I am for any of mine. Well and good. Here's an offer. Get me cured, and I'll dash you the ju-ju to make what you can out of it."

Kettle stretched out his fingers. "Right," he said. "We'll trade on that." And the pair of them shook hands over the bargain.

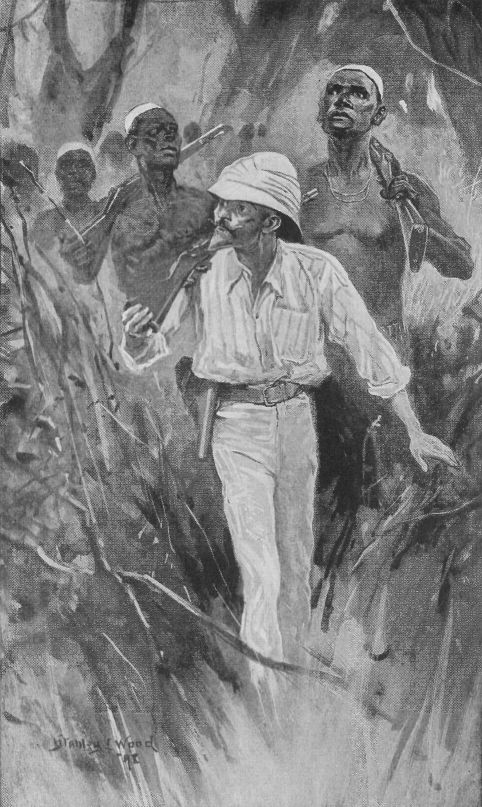

It was obvious, if the thing was to be done at all, it must be set about quickly. Nilssen was an utter wreck. Prolonged residence in this pestilential Congo had sapped his constitution; the poison was constantly eating at him; and he must either get relief in a very short time, or give up the fight and die. So that same afternoon saw Kettle journeying in a dug-out canoe over the beer-colored waters of the river, up stream, toward the witch-doctor's village.

Two savages (one of them suffering from a bad attack of yaws) propelled the craft from her forward part in erratic zig-zags; amidships sat Captain Kettle in a Madeira chair under a green-lined white umbrella; and behind him squatted his personal attendant, a Krooboy, bearing the fine old Coast name of Brass Pan. The crushed marigold smell from the river closed them in, and the banks crept by in slow procession.

The main channels of the Congo Kettle knew with a pilot's knowledge; but the canoe-men soon left these, and crept off into winding backwaters, with wire-rooted mangroves sprawling over the mud on their banks, and strange whispering beast-noises coming from behind the thickets of tropical greenery. The sun had slanted slow; ceibas and silk-cotton woods threw a shade dark almost as twilight; but the air was full of breathless heat, and Kettle's white drill clothes hung upon him clammy and damp. Behind him, in the stern of the canoe, Brass Pan scratched himself plaintively.

Dark fell and the dug-out was made fast to a mangrove root. The Africans covered their heads to ward off ghosts, and snored on the damp floor of the canoe. Kettle took quinine and dozed in the Madeira chair. Mists closed round them, white with damp, earthy-smelling with malaria. Then gleams of morning stole over the trees and made the mists visible, and Kettle woke with a seaman's promptitude. He roused Brass Pan, and Brass Pan roused the canoe-men, and the voyage proceeded.

Through more silent waterways the clumsy dug-out made her passage, where alligators basked on the mudbanks and sometimes swam up from below and nuzzled the sides of the boat, and where velvety black butterflies fluttered in dancing swarms across the shafts of sunlight; and at last her nose was driven on to a bed of slime, and Kettle was invited to "lib for beach."

Brass Pan stepped dutifully over the mud, and Captain Kettle mounted his back and rode to dry ground without as much as splashing the pipeclay on his dainty canvas shoes. A bush path opened out ahead of them, winding, narrow, uneven, and the man with the yaws went ahead and gave a lead.

As a result of exposure to the night mists of the river, Captain Kettle had an attack of fever on him which made him shake with cold and burn with heat alternately. His head was splitting, and his skin felt as though it had been made originally to suit a small boy, and had been stretched to near bursting-point to serve its present wearer.

In the forest, the path was a mere tunnel amongst solid blocks of wood and greenery; in the open beyond, it was a slim alley between grass-blades eight feet high; and the only air which nourished them as they marched was hot enough to scorch the lungs as it was inhaled. And if in addition to all this, it be remembered that the savages he was going to visit were practising cannibals, were notoriously treacherous, were violently hostile to all whites (on account of many cruelties bestowed by Belgians), and were especially exasperated against the stealer of their idol, it will be seen that from an ordinary point of view Captain Kettle's mission was far from appetizing.

The little sailor, however, carried himself as jauntily as though he were stepping out along a mere pleasure parade, and hummed an air as he marched. In ordinary moments I think his nature might be described as almost melancholy; it took times of stress like these to thoroughly brighten him.

The path wound, as all native paths do wind, like some erratic snake amongst the grasses, reaching its point with a vast disregard for distance expended on the way. It led, with a scramble, down the sides of ravines; it drew its followers up steep rock-faces that were baked almost to cooking heat by the sun; and finally, it broke up into fan-shape amongst decrepit banana groves, and presently ended amongst a squalid collection of grass and wattle huts which formed the village.

Dogs announced the arrival to the natives, and from out of the houses bolted men, women, and children, who dived out of sight in the surrounding patches of bush.

The man with the yaws explained: "Dem Belgians make war-palaver often. People plenty much frightened. People think we lib for here on war-palaver."

"Silly idiots!" said Captain Kettle. "Hullo, by James! here's a white man coming out of that chimbeque!"

"He God-man. Lib for here on gin-palaver."

"Trading missionary, is he? Bad breed that. And the worst of it is, if there's trouble, he'll hold up his cloth, and I can't hit him." He advanced toward the white man, and touched his helmet. "Bon jour, Monsieur."

"Howdy?" said the missionary. "I'm as English as yourself--or rather Amurrican. Know you quite well by sight, Captain. Seen you on the steamers when I was stationed at our headquarters in Boma. What might you be up here for?"

"I've a bit of a job on hand for Captain Nilssen of Banana."

"Old Cappie Nilssen? Know him quite well. Married him to that Bengala wife of his, the silly old fool. Well, captain, come right into my chimbeque, and chop."

"I'll have some quinine with you, and a cocktail. Chop doesn't tempt me just now. I've a dose of fever on hand."

"Got to expect that here, anyway," said the missionary. "I haven't had fever for three days now, but I'm due for another dose to-morrow afternoon. Fever's quite regular with me. It's a good thing that, because I can fit in my business accordingly."

"I suppose the people at home think you carry the Glad Tidings only?"

"The people at home are impracticable fools, and I guess when I was 'way back in Boston I was no small piece of a fool too. I was sent out here 'long with a lot more tenderfeet to plant beans for our own support, and to spread the gospel for the glory of America. Well, the other tenderfeet are planted, and I'm the only one that's got any kick left. The beans wouldn't grow, and there was no sort of living to be got out of spreading a gospel which nobody seemed to want. So I had to start in and hoe a new row for myself."

"Set up as a trader, that is?"

"You bet. It's mostly grist that comes to me: palm-oil, rubber, kernels, and ivory. Timber I haven't got the capital to tackle, and I must say the ivory's more to figure about than finger. But I've got the best connection of any trader in gin and guns and cloth in this section, and in another year I'll have made enough of a pile to go home, and I guess there are congregations in Boston that'll just jump at having a returned Congo missionary as their minister."

"I should draw the line at that, myself," said Kettle stiffly.

"Dare say. You're a Britisher, and therefore you're a bit narrow-minded. We're a vury adaptable nation, we Amurricans. Say, though, you haven't told me what you're up here for yet? I guess you haven't come just in search of health?"

Captain Kettle reflected. His gorge rose at this man, but the fellow seemed to have some sort of authority in the village, and probably he could settle the question of Nilssen's ailment with a dozen words. So he swallowed his personal resentment, and, as civilly as he could, told the complete tale as Nilssen had given it to him.

The trader missionary's face grew crafty as he listened. "Look here, you want that old sinner Nilssen cured?"

"That's what I came here for."

"Well, then, give me the ju-ju, and I'll fix it up for you."

"The ju-ju's to be my fee," said Kettle. "I suppose you know something about it? You're not the kind of man to go in for collecting valueless curiosities."

"Nop. I'm here on the make, and I guess you're about the same. But I wouldn't be in your shoes if the people in the village get to know that you've a finger in looting their idol."

"Why?"

"Oh, you'll die rather painfully, that's all. Better give the thing up, Captain, and let me take over the contract for you. It's a bit above your weight."

Kettle's face grew grim. "Is it?" he said. "Think I'm going to back down for a tribe of nasty, stinking, man-eating niggers? Not much."

"Well," said the missionary, "don't get ruffled. I've got no use for quarrelling. Go your way, and if things turn out ugly don't say I didn't give you the straight cinch, as one white man to another in a savage country. And now, it's about my usual time for siesta."

"Right," said Kettle. "I'll siesta too. My fever's gone now, and I'm feeling pretty rocky and mean. Sleep's a grand pick-me-up."

They took off their coats, and lay down then under filmy mosquito bars, and presently sleep came to them. Indeed, to Kettle came so dead an unconsciousness that he afterward had a suspicion (though it was beyond proof) that some drug had been mixed with his drink. He was a man who at all times was extraordinarily watchful and alert. Often and often during his professional life his bare existence had depended on the faculty for scenting danger from behind the curtain of sleep; and his senses in this direction were so abnormally developed as to verge at times on the uncanny. Cat-like is a poor-word to describe his powers of vigilance.

But there is no doubt that in this case his alertness was dulled. The fatigue of the march, his dose of fever, his previous night of wakefulness in the canoe, all combined to undermine his guard; and, moreover, the attack of the savages was stealthy in the extreme. Like ghosts, they must have crept back from the bush to reconnoitre their village; like daylight ghosts, they must have surrounded the trader missionary's hut and peered at the sleeping man between the bamboos of the wall, and then made their entrance; and it must have been with the quickness of wild beasts that they made their spring.

Kettle woke on the instant that he was touched, and started to struggle for his life, as indeed he had struggled many a time before. But the numbers of the blacks put effective resistance out of the question. Four of them pressed down each arm on to the bed, four each leg, three pressed on his head. Their animal faces champed and gibbered at him; the animal smell of them made him splutter and cough.

Captain Kettle was not a man who often sought help from others; he was used to playing a lone-handed fight against a mob; but the suddenness of the attack, the loneliness of his surroundings, and the dejection due to his recent dose of fever, for the first instant almost unnerved him, and on the first alarm he sang out lustily for the missionary's help. There was no answer. With a jerk he turned his head, and saw that the other bed was empty. The man had left the hut.

For a time the captive did not actively resist further. In a climate like that of the Congo one's store of physical strength is limited, and he did not wish to earn unnecessarily severe bonds by wasting it. As it was, he was tied up cruelly enough with grass rope, and then taken from the hut and flung down under the blazing sunshine outside.

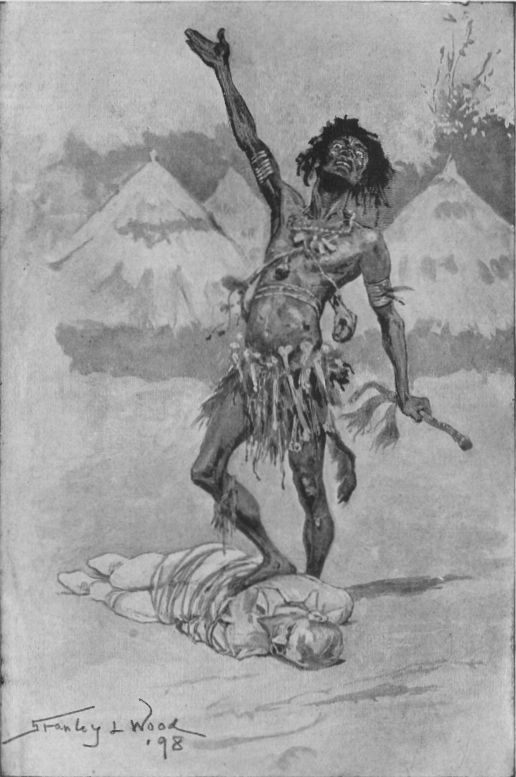

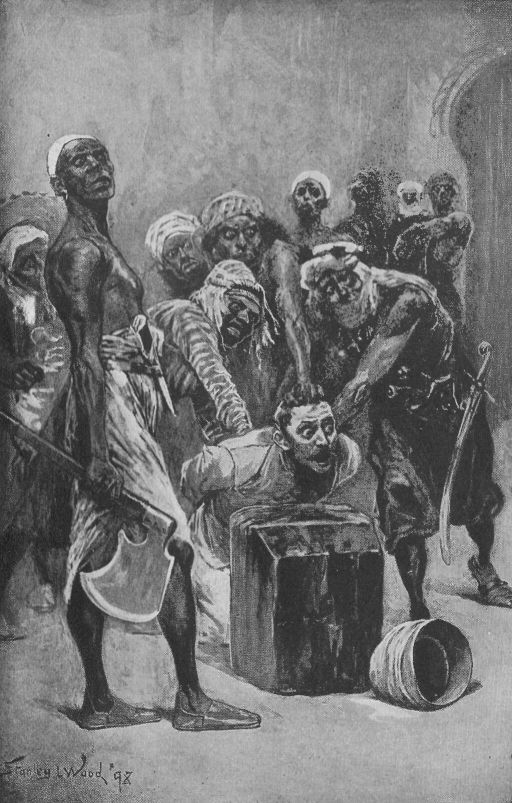

Presently a fantastic form danced up from behind one of the huts, daubed with colored clays, figged out with a thousand tawdry charms, and cinctured round the middle by a girdle of half-picked bones. He wafted an evil odor before him as he advanced, and he came up and stood with one foot on Kettle's breast in the attitude of a conqueror.

This was the witch-doctor, a creature who held power of life and death over all the village, whom the villagers suffered to test them with poison, to put them to unnamable tortures, to rob them as he pleased,--to be, in fact, a kind of insane autocrat working any whim that seized him freely in their midst. The witch-doctor's power of late had suffered. The white man Nilssen had "put bigger ju-ju" on him, and under its influence had despoiled him of valuable property. Now was his moment of counter triumph. The witch-doctor stated that he brought this other white man to the village by the power of his spells; and the villagers believed him. There was the white man lying on the ground before them to prove it.

Remained next to see what the witch-doctor would do with his captive.

The man himself was evidently at a loss, and talked, and danced, and screamed, and foamed, merely to gain time. He spoke nothing but Fiote, and of that tongue Kettle knew barely a single word. But presently the canoe-man with the yaws was dragged up, and, in his own phrase, was bidden to act as "linguister."

"He say," translated the man with the yaws, "if dem big ju-ju lib back for here, he let you go."

"And if not?"

He came and stood with one foot on Kettle's breast in the

attitude of a conqueror.

The interpreter put a question, and the witch-doctor screamed out a long reply, and then stooped and felt the captive over with his fingers, as men feel cattle at a fair.

"Well?" said Kettle impatiently; "if he doesn't get back the wooden god, let's hear what the game is next?"

"Me no sabbey. He say you too small and thin for chop."

Captain Kettle's pale cheeks flushed. Curiously enough it never occurred to him to be grateful for this escape from a cannibal dinner-table. But his smallness was a constant sore to him, and he bitterly resented any allusion to it.

"Tell that stinking scarecrow I'll wring his neck for him before I'm quit of this village."

"Me no fit," said the linguister candidly. "He kill me now if I say that, same's he kill you soon."

"Oh, he's going to kill me, is he?"

The interpreter nodded emphatically. "Or get dem big ju-ju," he added.

"Ask him how Cappie Nilssen can be cured."

The man with the yaws put the question timidly enough, and the witch-doctor burst into a great guffaw of laughter. Then after a preliminary dance, he took off a little packet of leopard skin, which hung amongst his other charms, and stuffed it deep inside Kettle's shirt.

The interpreter explained: "Him say he put ju-ju on Cappie Nilssen, and can take it off all-e-same easy. Him say you give Cappie Nilssen dis new ju-ju for chop, an' he live for well one-time."

"He doesn't make much trouble about giving it me, anyway," Kettle commented. "Looks as if he felt pretty sure he'd get that idol, or else take the change out of my skin." But, all the same, when the question was put to him again as to whether he would surrender the image, he flatly refused. There was a certain pride about Kettle which forbade him to make concessionary treaties with an inferior race.

So forthwith, having got this final refusal, the blacks took him up again, and under the witch-doctor's lead carried him well beyond the outskirts of the village. There was a cleared space here, and on the bare, baked earth they laid him down under the full glare of the tropical sunshine. For a minute or so they busied themselves with driving four stout stakes into the ground, and then again they took him up, and made him fast by wrists and ankles, spread-eagle fashion, to the stakes.

At first he was free to turn his head, and with a chill of horror he saw he was not the first to be stretched out in that clearing. There were three other sets of stakes, and framed in each was a human skeleton, picked clean. With a shiver he remembered travellers' tales on the steamers of how these things were done. But then the blacks put down other stakes so as to confine his head in one position, and were proceeding to prop open his mouth with a piece of wood, when suddenly there seemed to be a hitch in the proceedings.

The witch-doctor asked for honey--Kettle recognized the native word--and none was forthcoming. Without honey they could not go on, and the captive knew why. One man was going off to fetch it, but then news was brought that the Krooboy Brass Pan had been caught, and the whole gang of them went off helter-skelter toward the village--and again Kettle knew the reason for their haste.

So there he was left alone for the time being with his thoughts, lashed up beyond all chance of escape, scorched by an intolerable sun, bitten and gnawed by countless swarms of insects, without chance of sweeping them away. But this was ease compared with what was to follow. He knew the fate for which he was apportioned, a common fate amongst the Congo cannibals. His jaws would be propped open, a train of honey would be led from his mouth to a hill of driver ants close by, and the savage insects would come up and eat him piecemeal while he still lived.

He had seen driver ants attack a house before, swamp fires lit in their path by sheer weight of numbers, put the inhabitants to flight, and eat everything that remained. And here, in this clearing, if he wanted further proof of their power, were the three picked skeletons lying stretched out to their stakes.

There are not many men who could have preserved their reason under monstrous circumstances such as these, and I take it that there is no man living who dare up and say that he would not be abominably frightened were he to find himself in such a plight. In these papers I have endeavored to show Captain Owen Kettle as a brave man, indeed the bravest I ever knew; but I do not think even he would blame me if I said he was badly scared then.

He heard noises from the village which he could not see beyond the grass. He heard poor Brass Pan's death-shriek; he heard all the noises that followed, and knew their meaning, and knew that he was earning a respite thereby; he even heard from over the low hills the hoot of a steamer's siren as she did her business on the yellow waters of the Congo, in crow flight perhaps not a good rifle-shot from where he lay stretched.

It seemed like a fantastic dream to be assured in this way that there were white men, civilized white men, men who could read books and enjoy poetry, sitting about swearing and drinking cocktails under a decent steamer's awnings close by this barbaric scene of savagery. And yet it was no dream. The flies that crept into his nose and his mouth and his eye-sockets, and bit him through his clothing, and the hateful sounds from the village assured him of all its reality.

The blazing day burnt itself to a close, and night came hard upon its heels, still baking and breathless. The insects bit worse than ever, and once or twice Kettle fancied he felt the jaws of a driver ant in his flesh, and wondered if news would be carried to the horde in the ant-hill, which would bring them out to devour their prey without the train of honey being laid to lure them. Moreover, fever had come on him again, and with one thing and another it was only by a constant effort of will that he prevented himself from giving way and raving aloud in delirium.

It was under these circumstances, then, that the missionary came to him again, and once more put in a bid for the ju-ju which lay at the pilotage. Kettle roundly accused the man of having betrayed him, and the fellow did not deny it with any hope of being believed. He had got to get his pile somehow, so he said: the ju-ju had value, and if he could not get hold of it one way, he had to work it another. And finally, would Kettle surrender it then, or did he want any more discomfort.

Now I think it is not to the little sailor's discredit to confess that he surrendered without terms forthwith. "The thing's yours for when you like to fetch it," he snapped out ungraciously enough, and the missionary at once stooped and cut the grass ropes, and set to chafing his wrists and ankles. "And now," he said, "clear out for your canoe at the river-side for all you're worth, Captain. There's a big full moon, and you can't miss the way."

"Wait a bit," said Kettle. "I'm remembering that I had an errand here. Can you give me the right physic to pull Captain Nilssen round?"

"You have it in that leopard-skin parcel inside your shirt. I saw the witch-doctor give it you."

"Oh! you were looking on, were you?"

"Yes."

"By James! I've a big mind to leave my marks on you, you swine!"

The trader missionary whipped out a revolver. "Guess I'm heeled, sonny. You'd better go slow. You'd--"

There was a rush, a dodge, a scuffle, a bullet whistling harmlessly up into the purple night, and that revolver was Captain Kettle's.

"The cartridges you have in your pocket."

"I've only three. Here they are, confound you! Now, what are you going to do next? You've waked the village. You'll have them down on you in another moment. Run, you fool, or they'll have you yet."

"Will they?" said Kettle. "Well, if you want to know, I've got poor old Brass Pan to square up for yet. I liked that boy." And with that, he set off running down a path between the walls of grasses.

A negro met him in the narrow cut, yelled with surprise, and turned. He dropped a spear as he turned, and Kettle picked it up and drove the blade between his shoulder-blades as he ran. Then on through the village he raged like a man demented. With what weapons he fought he never afterward remembered. He slew with whatever came to his hand. The villagers, wakened up from their torpid sleep, rushed from the grass and wattle houses on every hand. Kettle in his Berserk rage charged them whenever they made a stand, till at last all fled from him as though he were more than human.

Bodies lay upon the ground staring up at the moon; but there were no living creatures left, though the little sailor, with bared teeth and panting breath, stood there waiting for them. No; he had cleared the place, and only one other piece of retribution lay in his power. The embers of a great fire smouldered in the middle of the clearing, and with a shudder (as he remembered its purpose) he shovelled up great handfuls of the glowing charcoal and sowed it broadcast on the dry grass roofs of the chimbeques. The little crackling flames leaped up at once; they spread with the quickness of a gunpowder train; and in less than a minute a great cataract of fire was roaring high into the night.

Then, and not till then, did Captain Kettle think of his own retreat. He put the three remaining cartridges into the empty chambers of his revolver, and set off at a jog-trot down the winding path by which he had come up from the river.

His head was throbbing then, and the stars and the grasses swam before his eyes. The excitement of the fight had died away--the ills of the place gripped every fibre of his body. Had the natives ambushed him along the path, I do not think he could possibly have avoided them. But those natives had had their lesson, and they did not care to tamper with Kettle's ju-ju again. And so he was allowed to go on undisturbed, and somehow or other he got down to the river-bank and the canoe.

He did not do the land journey at any astonishing pace. Indeed, it is a wonder he ever got over it at all. More than once he sank down half unconscious in the path, and up all the steeper slopes he had to crawl animal fashion on all-fours. But by daybreak he got to the canoe, and pushed her off, and by a marvellous streak of luck lost his way in the inner channels, and wandered out on to the broad Congo beyond.

I say this was a streak of luck, because by this time consciousness had entirely left him, and on the inner channels he would merely have died, and been eaten by alligators, whereas, as it was, he got picked up by a State launch, and taken down to the pilotage at Banana.

It was Mrs. Nilssen who tediously nursed him back to health. Kettle had always been courteous to Mrs. Nilssen, even though she was as black and polished as a patent leather boot; and Mrs. Nilssen appreciated Captain Owen Kettle accordingly.

With Captain Nilssen, pilot of the lower Congo, Kettle had one especially interesting talk during his convalescence. "You may as well take that troublesome wooden god for yourself now," said Nilssen. "But, if I were you, I'd ship it home out of harm's way by the next steamer."

"Hasn't that missionary brute sent for it yet?"

Captain Nilssen evaded the question. "I'll never forget what you've done for me, my lad. When you were brought in here after they picked you up, you looked fit to peg out one-time, but the only sane thing you could do was to waggle out a little leopard-skin parcel, and bid me swallow the stuff that was inside. You'd started out to get me that physic, and, by gum, you weren't happy till I got it down my neck."

"Well, you look fit enough now."

"Never better."

"But about the missionary brute?"

"Well, my lad, I suppose you're well enough to be told now. He's got his trading cut short for good. That nigger with the yaws who paddled you up brought down the news. The beggars up there chopped him, and I'm sure I hope he didn't give them indigestion."

"My holy James!"

"Solid. His missionary friends here have written home a letter to Boston which would have done you good to see. According to them, the man's a blessed martyr, nothing more or less. The gin and the guns are left clean out of the tale; and will Boston please send out some more subscriptions, one-time? You'll see they'll stick up a stained-glass window to that joker in Boston, and he'll stand up there with a halo round his head as big as a frying-pan. And, oh! won't his friends out here be resigned to his loss when the subscriptions begin to hop in from over the water."

"Well, there's been a lot of trouble over a trumpery wooden idol. I fancy we'd better burn it out of harm's way."

"Not much," said Nilssen with a sigh. "I've found out where the value comes in, and as you've earned them fairly and squarely, the dividends are yours to stick to. One of those looking-glass eyes was loose, and I picked it out. There was a bit of green glass behind. I picked out the other eye, and there was a bit of green glass at the back of that too."

"Oh, the niggers'll use anything for ju-ju."