Title: The Renaissance of the Vocal Art

Author: Edmund J. Myer

Release date: July 8, 2004 [eBook #12856]

Most recently updated: December 15, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Newman and PG Distributed Proofreaders

"When you see something new to you in art, or hear a proposition in philosophy you never heard before, do not make haste to ridicule, deny or refute. Possibly the trouble is with yourself—who knows?"

To my readers once again through this little work, greetings. For the many kind things said of my former works by my friends, my pupils, the critic and the profession, thanks! To those who have understood and appreciated the principles laid down in my last book, "Position and Action in Singing," I will say that this little work will be an additional help. To my readers in general, who may not have fully understood or appreciated the principles of vitality, of vitalized energy, aroused and developed through the movements set forth in my last book, to such I will say that I hope this little work will make clearer those principles. I hope that it may lead them to a better understanding of the fundamental principles of the system, principles which are founded upon natural laws and common sense. In this work I have endeavored to logically formulate my system.

As it is not possible to fully study and develop any one fundamental principle of singing without some understanding or mastery of all others, so it is not possible to write a work like this without more or less repetition. Certain subjects are so closely related, are so interdependent, that repetition cannot be avoided. I am not offering an apology for this; I am simply stating that a certain amount of repetition is necessary.

PREFACE. EXORDIUM.

PART FIRST.

EVOLUTION.

ARTICLE 1. THE OLD ITALIAN SCHOOL OF SINGING " 2. THE DARK AGES OF THE VOCAL ART " 3. THE TWO PREVAILING SYSTEMS " 4. THE RENAISSANCE OF THE VOCAL ART " 5. THE COMING SCHOOL OR SYSTEM " 6. CONDITIONS " 7. THE INFLUENCE OF RIGHT BODILY ACTION

RAISON D'ÊTRE

PART SECOND.

VITALITY.

ARTICLE 1. THE FIRST PRINCIPLE OF ARTISTIC TONE-PRODUCTION " 2. THE SECOND PRINCIPLE OF ARTISTIC TONE-PRODUCTION " 3. THE THIRD PRINCIPLE OF ARTISTIC TONE-PRODUCTION

PART THIRD.

AESTHETICS.

ARTICLE 1. THE FOURTH PRINCIPLE OF ARTISTIC SINGING " 2. THE FIFTH PRINCIPLE OF ARTISTIC SINGING " 3. THE SIXTH PRINCIPLE OF ARTISTIC SINGING " 4. THE SEVENTH PRINCIPLE OF ARTISTIC SINGING

Man, to see far and clearly, must rise above his surroundings. To win great possessions, to master great truths, we must climb all the hills, all the mountains, which confront us. Unfortunately the vocal profession dwells too much upon the lowlands of tradition, or is buried too deep in the valleys of prejudice. Better things, however, will come. They must come. The current of the advanced thought, the higher thought, of this, the opening year of the twentieth century, will slowly but surely increase in power and influence, will slowly but surely broaden and deepen, until the light of reason breaks upon the vocal world. We may confidently look, in the near future, for the Renaissance of the Vocal Art.

The Shibboleth, or trade cry, of the average modern vocal teacher is "The Old Italian School of Singing." How much of value there is in this may be surmised when we stop to consider that of the many who claim to teach the true Old Italian method no two of them teach at all alike, unless they happen to be pupils of the same master.

A system, a method, or a theory is not true simply because it is old. It may be old and true; it may be old and false. It may be new and false; or, what is more important, it may be new and yet true; age alone cannot stamp it with the mark of truthfulness.

The truth is, we know but little of the Old Italian School of Singing. We do know, however, that the old Italians were an emotional and impulsive people. Their style of singing was the flexible, florid, coloratura style. This demanded freedom of action and emotional expression, which more largely than anything else accounts for their success.

The old Italians knew little or nothing of the science of voice as we know it to-day. They did know, however, the great fundamental principles of singing, which are freedom of form and action, spontaneity and naturalness. They studied Nature, and learned of her. Their style of singing, it is true, would be considered superficial at the present day, but it is generally conceded that they did make a few great singers. If the principles of the old school had not been changed or lost, if they had been retained and developed up to the present day, what a wonderful legacy the vocal profession might have inherited in this age, the beginning of the twentieth century. Adversity, however, develops art as well as individuality; hence the vocal art has much to expect in the future.

Even in the palmiest days of the Old Italian School, there were forces at work which were destined to influence the entire vocal world. The subtle influence of these forces was felt so gradually, and yet so surely and powerfully, that while the profession, as one might say, peacefully slept, art was changed to artificiality. Thus arose that which may be called the dark ages of the vocal art,—an age when error overshadowed truth and reason; for while real scientists, after great study and research, discovered much of the true science of voice, many who styled themselves scientists discovered much that they imagined was the true science of voice.

Upon the theories advanced by self-styled scientists, many systems of singing were based, without definite proof as to their being true or false. These systems were exploited for the benefit of those who formulated them. This condition of things prevailed, not only through the latter part of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth, but still manifests itself at the present day, and no doubt will continue to do so for many years to come.

The vocal world undoubtedly owes much to the study and research of the true scientist. All true art is based upon science, and none more than the art of voice and of singing.

Science is knowledge of facts co-ordinated, arranged, and systematized; hence science is truth. The object of science is knowledge; the object of art is works. In art, truth is the means to an end; in science, truth is the end.

The science of voice is a knowledge of certain phenomena or movements which are found under certain conditions to occur regularly. The object of the true art of voice is to study the conditions which allow these phenomena to occur.

The greatest mistake of the many systems of singing, formulated upon the theories of the scientists, and of the so-called scientists, was not so much in their being based upon theories which oftentimes were wrong, as in the misunderstanding and misapplication of true theories. The general mistake of these systems was and is that they attempt by direct local effort, by direct manipulation of muscle, to compel the phenomena of voice, instead of studying the conditions which allow them to occur. In this way they attempt to do by direct control, that which Nature alone can do correctly.

While it is true that the vocal world owes much to science and the scientists, yet "the highest science can never fully explain the true phenomena of the voice, which are truly the phenomena of Nature." The phenomena of the voice no doubt interest the scientists from an anatomical standpoint, but these things are of little practical value to the singer. As someone has said, "To examine into the anatomical construction of the larynx, to watch it physiologically, and learn to understand the motions of the vocal cords in their relation to vocal sounds, is not much more than looking at the dial of a clock; the movements of the hands will give you no idea of the construction of the intricate works hidden behind the face of the clock."

We should never lose sight of the fact that there is a true science of voice, and that the art of song is based upon this science. The true art of song, however, is not so much a direct study of the physical or mechanical action of the parts, as it is a study of the spirituelle side; a study of the forces which move the parts automatically, in accordance with the laws of nature. In other words, voice, true voice, is more psychological than physiological; is more an expression of mind and soul than a physical expression or a physical force. It is true, the body is the medium through which the soul, the real man, gives expression to thought and feeling; and yet voice that is simply mechanical or physical is always common and meaningless and as a rule unmusical. The normal condition of true artistic voice is emotional and soulful.

The misunderstanding or the misapplication of any principle, theory or device, always leads to error. This was eminently true of the misunderstanding and misapplication on the part of many writers and teachers who based their systems upon the theories of the scientists and the self-styled scientists. The result is evident; it is that which is known as the local-effort, muscular school of the nineteenth century; the school which to this day so largely prevails; the school which makes of man a mere vocal machine, instead of a living, emotional, thinking soul.

The local-effort school attempts, by direct control and manipulation of muscle and of the vocal parts, to compel the phenomena of voice. In this respect it is unique; in this respect it stands alone. The truth of this statement becomes evident when we stop to consider that in nothing known which requires muscular development, as does the art of singing, is this development or training secured by direct manipulation and control of muscle. There is nothing in the arts or sciences, nothing in the broad field of athletics or physical culture, nothing in the wide world that requires physical development, in which the attempt is made to develop by direct effort as does the local-effort school. Hence we say the mistake they make is in attempting to compel the phenomena of voice, instead of studying the conditions which allow them to occur. It might be interesting, it certainly would be very amusing, to enumerate and illustrate the many things done under the name of science, to compel the phenomena of voice; but space will not permit. Many of them are well known; many more are too ridiculous to consider except that they should be exposed for the good of the profession.

The result of all this direct manipulation of muscle is ugliness—everywhere hard, unmusical, unsympathetic voices. The public is so used to hearing hard, muscular voices that the demand for beautiful tone is not what it should be. In fact, it is not generally known that it is possible to make almost any voice more or less beautiful that is at all worth training. The hard, unmusical voice of the day is a hybrid, unnatural and altogether unnecessary voice. Physical effort in singing develops physical tone and physical effect. Common tone makes common singing. A great artist must be great in tone as well as in interpretation.

The disciples of the local-effort school lose sight of the fact that when a muscle is set and rigid, either in attempting to hold the breath or to force the tone, it is virtually out of action; that instead of actually helping the voice it is really preventing a free, natural production, and that other parts are then compelled to do its work; this accounts for many ruined voices. "To make a part rigid is equal to the extirpation of such part. While it is in a state of rigidity it ceases to take part in any action whatsoever: it is inert and the same as if it had ceased to exist."

The local-effort school is accountable for many errors of the day. The incubus of this school is fastened upon the vocal profession with octopus-like tentacles which reach out in every direction, and which strive to strangle the truth in every possible way; but, while "life is short, art is long;" the truth must prevail.

As an outgrowth of the local-effort school, and as an attempt to counteract its evil tendencies, there is to-day in existence another school or system known as the limp or relaxed school, or the system of complete relaxation. The object of this relaxation is to overcome muscular tension and rigidity. This is the other extreme. The followers of this school forget that there can be no tonicity without tension. Flexible firmness without rigidity, the result of flexible, vitalized position and action, is the only true condition. The tone of the school of relaxation is nearly always depressed and breathy; it always lacks vitality.

We are in the habit of measuring time by days, weeks, months, years, decades and centuries. The world at large measures time by epochs and eras. While this is true in the physical world, it is equally true of the arts and sciences, and it is especially true of the art of song. Thus we have had the period known as "The Old Italian School of Singing." This was followed by the modern school, or "The Local-Effort School" of the nineteenth century, the period which may be called The Dark Ages of the Vocal Art.

There is a constant evolution in all things progressive, and this evolution is felt very perceptibly to-day in the vocal world. Great principles, great truths, are of slow growth, slow development. Times change, however, and we change with them. While the changes may be slow and almost imperceptible to the observer, they are sure, and finally become evident by the accumulation of event after event.

The prevailing systems of the nineteenth century tried to develop voice by direct local muscular effort. These systems have proved themselves failures. The vocal world is looking for and demanding something better. We may say that we are now on the eve of great events in the vocal art. When the morn comes, and the light breaks, we may confidently expect that awakening or reawakening which may properly be called The Renaissance of the Vocal Art.

This is the age of physical culture in all its forms. There is a tendency from the artificial habits of life, back, or rather one should say forward, to Nature and Nature's laws. "Athletes appreciate the value of physical training: brain-workers appreciate the value of mental training, of thinking before acting, and if you would become either you must follow the methods of both."

Many of our foremost educators in all branches of development, physical, mental and musical, are now making a bold stand for natural methods of education. However, all vocal training and development in the past, we are glad to say, has not been on the wrong side of the question.

There have been, at all ages and under all circumstances and conditions, men who have been at the root or the bottom of things,—men who have preserved the truth in spite of their surroundings. So in the vocal art, there have been at every decade a few men who have known the truth, and who have handed it down through the dark ages of the vocal art. The work of these men has not been lost. Its influence has been felt, and is today more powerful than ever. Hence the trend of the best thought of the profession is away from the ideas of the local-effort school, away from rigidity and artificiality, and more in the direction of naturalness and common sense. I believe we are now, as a profession, slowly but surely awakening to truths which will grow, and which will in time bring to pass that which must come sooner or later, the new school of the twentieth century.

There is to-day that which is known as "The New Movement in the Vocal Art"—a movement based upon natural laws and common sense and opposed to the ideas of the local-effort school;—movement in the direction of freedom of action, spontaneity and flexible strength as opposed to rigidity and direct effort;—a movement which advocates vitalized energy instead of muscular effort;—a movement which had its origin in the belief that no man ever learned to sing because he locally fixed or puckered his lips; because he held down his tongue with a spatulum or a spoon; because he locally lowered or raised his soft palate; because he consciously moved or locally fixed his larynx; because he consciously, rigidly set or firmly pulled in one direction or another, his breathing muscles; because he carried an unnaturally high chest at the sacrifice of form, position and strength in every other way; because he sang with a stick or a pencil or a cork in his mouth; or because he did a hundred other unnatural things too foolish to mention. No man ever learned or ever will learn to sing because of these things. It is true he may have learned to sing in spite of them, which shows that Nature is kind; but as compared to the whole, he is one in a thousand.

"The New Movement" has come to stay. It will, of course, meet with bitter opposition. Why not? The custom of many has been, and is, to condemn without investigation; to condemn because it does not happen to be in the line of their teaching and study. Someone has said, "He who condemns without knowledge or investigation is dishonest."

"The New Movement" is simply a study of the conditions which allow the phenomena of voice to occur naturally and automatically. The day will come, when a right training of the voice will be recognized as a flexible, artistic, physical training of the human body, and a consequent right use of the voice, as a soulful expression of the emotional nature. Matter or muscle will be taught to obey mind or will spontaneously. The thought before the effort, or rather before the action, will be the controlling influence, and vitalized emotional energy will be the true motor power of the voice. The elocutionists and the physical culturists understand this far better, as a rule, than the vocalists.

Abuse brings reform in art as well as in all other things. So the abuse of Nature's laws and the lack of common sense in the training of the singing voice has led, through a gradual evolution, to "The New Movement." This movement is the outgrowth of the best or advanced thought of the profession rebelling against unnatural methods.

In the fundamental principles of "The New Movement," there is nothing new claimed by its advocates. All is founded upon the science of voice, as are all true systems of teaching. The claims are made with regard to the devices used to study natural laws, to develop the God-given powers of the singer. Remember that Nature incarnates or reflects God's thoughts and desires and not man's ideas or inventions. Someone has said that there was nothing new, nor could there be anything new, in the art of singing. There are many, alas! who talk and write as did this man. Is not this simply proof of the fact that ignorance cheapens and belittles that which wisdom views with awe and admiration? And this is true of nothing so much as it is of the arts and sciences.

Is, then, ours in all the world, the only profession based upon science and art that must stand still, that must accept blindly the traditions handed down to us, without investigation? Are we to feel and believe that with us progress is impossible, that we may not and cannot keep up with the spirit of the age? God forbid. Is it not true that "each age refutes much which a previous age believed, and all things human wax old and vanish away to make room for new developments, new ideals, new possibilities"? Is it possible this is true of all professions but ours? The signs of the times indicate differently. Hence we may confidently expect the Renaissance of the Vocal Art in this, the first half of the new century.

This is an age of progress; and, as we have said, many educators are making a bold stand for natural, common-sense methods. The trend of the higher thought of the vocal profession is away from artificiality, and in the direction of naturalness.

The coming school, or system, of the twentieth century will undoubtedly find its form, its power, its expressional and artistic force and value, its home, its life, in America. The old country is too much in the toils, too much in the ruts of tradition; hence natural forces are suppressed, and artificiality reigns supreme in the training of the voice. While this is not true in regard to the strictly aesthetic side of the question, it is painfully true as far as the fundamental principles of voice development are concerned. Of course we are glad to say there are bright and shining exceptions to this rule in all lands, but to the new country we must undoubtedly look for the new school.

So far the world has produced but two great teachers. The first of these is Nature; the second is Common Sense. Nature lays down the fundamental principles of voice; Common Sense formulates the devices for development according to these principles. Therefore we say, Go to Nature and learn of her, and use Common Sense in studying and developing her principles. The nearer the approach to Nature, the higher the art; hence the new school must be founded upon artistic laws which are Nature's laws, and not upon artificiality.

The coming school must teach the idealized tone. The ideal in its completeness means the truth,—all the truth,—and not, as many suppose, an exaggerated form of expression. The truth in tone, or the idealized tone, is beautiful and soulful, and demands for its production and use all the forces that Nature has given to the singer,—physical, mental, and emotional or spirituelle. Unmusical, muscular tone is not the true tone. It contains much that it should not have on the physical side, and lacks much that it should have on the spirituelle. As a rule, it means nothing; in fact, it is often simply a noise. The idealized tone always represents a thought, an idea, an emotion; it is the expression of the inner—the higher—man; it is, in reality, self-expression.

"The human voice is the most delicately attuned musical instrument that God has created. It is capable of a cultivation beyond the dreams of those who have given it no thought. It maybe made to express every emotion in the gamut of human sensation, from abject misery to boundless ecstasy. It marks the man without his consent; it makes the man if he will but cultivate it."

The coming school must be founded upon freedom of form and action, upon flexible bodily movements, the result of vitalized energy instead of muscular effort. There must be no set, rigid, static condition of the muscles. Artistic singing is a form of self-expression; and self-expression, to be natural and beautiful, must be the result of correct position and action.

The first principle of artistic singing is the removal of all restraint. This is a fundamental law of Nature and cannot be changed. Under the influence of direct local muscular effort, the removal of all restraint is impossible. Hence the coming school must be based upon free flexible action. In this respect it will be much like the old Italian school, except that it will be as far in advance of the old school in the science of voice as the twentieth century is in advance of the eighteenth. It must also be far in advance of the old school in the devices used to develop the fundamental principles of voice.

In this age of progress and knowledge of laws and facts, the new school, under the influence of Nature's laws and common sense, with the aid of flexible movements and vitalized energy, must do as much for the development of the singing voice in three or four years as the old school was able to do in eight or ten. This is necessary, both because the singing world demands it, and Nature and common sense teach us that it does not take years and years of hard study and practice simply to develop the voice. From a strictly musical standpoint, however, it does take years to ripen a great singer, to make a great artist. Many voices are ruined musically by years of hard, muscular practice. Hence we say the new school must give the voice freedom, and remove all muscular restraint by or through natural, common-sense, vitalized movements.

Nature's laws are God's laws. All nature, the universe itself, is an expression of God's thoughts or desires in accordance with His laws. This one controlling force, this principle of law, is at the bottom of everything in nature and art. Everything which man says or does under normal, free conditions, is self-expression, an expression of his inner nature; but this expression must be under the law. If not, the expression is unnatural and therefore artificial. This principle, which holds true in all of man's expression, in all art, is in nothing more evident than in the use of the singing voice.

"Nature does nothing for man except what she enables him to do for himself." Nature gives him much, but never compels him to use what she gives. Man is a free agent. He can obey or violate the laws of Nature at will; but he cannot violate Nature's laws, and not pay the penalty. This thought or principle constantly stands out as a warning to the vocal world. The student of the voice who violates Nature's laws must not expect to escape the penalty, which is hard, harsh, unmusical tone or ruined voice. Nature demands certain conditions in order to produce beautiful, artistic tone. If the student of the voice desires to develop beautiful, artistic tone he is compelled to study the conditions, the fundamental principles under the law; and this can be done only by the use of common-sense methods.

All artistic tone is the result of certain conditions, conditions demanded by Nature and not man's ideas or fancies. These conditions are dependent upon form and adjustment, or we might better say adjustment and form, as form is the result of the adjustment of the parts. So far all writers on the voice, and all teachers, agree; but here comes the parting of the ways. One man attempts form and adjustment by locally influencing the parts,—the tongue, the lips, the soft palate, the larynx, etc. This results in muscular singing and artificiality. We have found that form and adjustment, to be right, must be automatic. This condition cannot be secured by any system of direct local effort, but must be the result of flexible, vitalized bodily movements—movements which arouse and develop all the true conditions of tone; movements which allow the voice to sing spontaneously.

The fundamental conditions of singing demanded by Nature we find are as follows:

It is not my intention here to enlarge upon these conditions to any extent. I have already done so in my last book, "Position and Action in Singing." I know many writers on the voice, and many teachers, do not agree with me on this subject of conditions; but facts are stubborn things, and "A physical fact is as sacred as a moral principle." "The sources of all phenomena, the sources of all life, intelligence and love, are to be sought in the internal—the spiritual realm; not in the external or material." "A man is considerably out of date who says he does not believe a thing, simply because he cannot do that thing or does not understand how the thing is done. There are three classes of people—the 'wills,' the 'won'ts,' and the 'can'ts': the first accomplish everything, the second oppose everything, and the third fail in everything." These things [these conditions] can be understood and fully appreciated by investigation only. There is no absolute definite knowledge in this world except that gained from experience.

The voice in correct use is always tuned like an instrument. This must be in order to have resonance and freedom, and this is done only through natural or automatic adjustment of all the parts. In singing there are always two forces in action, pressure and resistance, or motor power and control. In order to have automatic adjustment these two forces must prevail. When the organ of sound is automatically adjusted, the breath bands approximate: This gives the true resisting or controlling force. When the breath bands approximate we have inflation of the ventricles of the larynx, the most important of all the resonance cavities, for when this condition prevails we have freedom of tone, and the inflation of all other cavities. And not only this; it also enables us to remove all restraint or interference from the parts above the larynx, and especially from the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the throat. This automatic adjustment, approximation of the breath bands and inflation of the ventricles, gives us a yet more important condition, namely, automatic breath control; this is beyond question the most important of all problems solved for the singer through this system of flexible vitalized movements.

The removal of all interference or direct local control of the parts above the larynx, gives absolute freedom of form and action; and when the form and action are free, articulation becomes automatic and spontaneous. When all restraint is thus removed, the air current comes to the front, and we secure the important condition of high placing. Furthermore, under these conditions, when the air current strikes the roof of the mouth freely, it is reflected into the inflated cavities, and there is heard and felt, through sympathetic vibration of the air in the cavities, added resonance or the wonderful reinforcing power of inflation: in this way is secured not only the added resonance of all other cavities, but especially the resonance of the chest, the greatest of all resonance or reinforcing powers.

When the voice is thus freed under true conditions, it is possible to arouse easily and quickly the mental and emotional power and vitality of the singer. In this way is aroused that which I have called the singer's sensation, or, for want of a better name, the third power of the voice. This power is not a mere fancy. It is not imagination; for it is absolutely necessary to the complete mental and emotional expression of the singer, to the development of all his powers. This life or vital force is to the singer a definite, controllable power. "Various terms have been applied to this mysterious force. Plato called it 'the soul of the world.' Others called it the 'plastic spirit of the world,' while Descartes gave it the afterward popular name of 'animal spirits.' The Stoics called it simply 'nature,' which is now generally changed to 'nervous principle.'" "The far-reaching results of so quiet and yet so tremendous a force may be seen in the lives of the men and women who have the mental acumen to understand what is meant by it." The singer who has developed and controlled "the third power" through the true conditions of voice, never doubts its reality; and he, and he only, is able to fully appreciate it.

The development of all the above conditions depends upon one important thing, the education of the body; upon a free, flexible, vitalized body.

In art, as in all things else, man must be under the law until he becomes a law unto himself. In other words, he must study his technique, his method, his art, until all becomes a part of himself, becomes, as it were, second nature. There is a wide difference between art and artificiality. True art is based upon Nature's laws. Artificiality, in almost every instance, is a violation of Nature's laws, and at best is but a poor imitation.

The impression prevails that art is something far off, something that is within the grasp of the favored few only. We say of a man, he is a genius, and we bow down to him accordingly. The genius is an artist by the grace of God and his own efforts. Nature has given some men the power to easily and quickly grasp and understand things which pertain to art, but if such men do not apply their understanding they never become great or useful artists. Talent is the ability to study and apply, and is of a little lower order than genius; but the genius of application, and the talent to apply that which is learned, have made the great and useful men, the great artists of the world. As someone has said, "Art is not a thing separate and apart; art is only the best way of doing things;" and while this is true of all the arts, it is eminently so of the art of voice and of song.

Artistic tone, as we have found, is the result of certain conditions demanded by Nature. These conditions are dependent upon form and adjustment; and form and adjustment, to be right, must be automatic. All writers and teachers agree that correct tone is the result of form and adjustment; but here, as we have said, comes the parting of the ways. One man attempts, by directly controlling and adjusting the parts, to do that which nature alone can do correctly; result—hard, muscular tone. Another attempts, by relaxation, to secure the conditions of tone; result—vocal depression, or depressed, relaxed tone.

If artistic tone be the result of conditions due to form and adjustment, and if form and adjustment, to be right, must be automatic, if these things are true, and they are as true as the fact that the world moves, then there is only one way under heaven by which it is possible to secure these conditions; that way is through a flexible, vitalized body, through flexible bodily position and action.

The rigid, muscular school cannot secure these conditions, for they make flexible freedom impossible. The limp, relaxed school cannot secure them, for there is no tone without tonicity and vitality of muscle. Vitalized energy can secure these true conditions, but through flexible bodily position and action only.

The rigid school is muscle-bound, and lacks life and vitality. The limp school, of course, is depressed and lacks energy. The world is full of dead singers,—dead so far as vitality and emotional energy are concerned. Singing is a form of emotional or self-expression, and requires life and vitality. Life is action. Life is vital force aroused. Life in singing is emotional energy. Life is a God-given, eternal condition, and is a fundamental principle of the true art of song.

It is wonderfully strange that this idea or principle of flexible, vitalized bodily position and action is not better understood by the vocal profession. That a right use or training of the body, automatically influences form and adjustment, and secures right conditions of tone, has been and is being demonstrated day by day. This is a revelation to many who have tried to sing by the rigid or limp methods. There is really nothing new claimed for it, for it is as old as the hills. Truth is eternal, and yet a great truth may be lost to the world for a time. The only things new which we claim, are the movements and the simple and effective devices used to study and apply them. These movements have a wonderful influence on the voice, for the simple reason that they are based upon Nature's laws and common sense. These truths are destined to influence, sooner or later, the entire vocal world.

A great truth cannot always be suppressed, and some day someone will present these truths in a way that will compel their recognition. They are never doubted now by those who understand them, and they are appreciated by such to a degree of enthusiasm. I am well aware that when these movements are spoken of in the presence of the followers of the prevailing rigid or limp schools, they exclaim, "Why, we do the same thing. We use the body too." Of course they use the body, but it is by no means the same. Their use of the body is often abuse, and not only of the body, but of the voice as well.

The influence on the singing voice of a rightly used or rightly trained body is almost beyond the ability of man to put in words.

All singing should be rhythmical. These flexible bodily movements develop rhythm.

All singing should be the result of vitalized energy and never of muscular effort. These movements arouse energy and make direct effort unnecessary.

Singing should be restful, should be the result of power in repose or under control. These movements, and these movements alone, make such conditions possible.

All singing should be idealized, should be the result of self-expression, of an expression of the emotions. This is impossible except through correct bodily action. "By nature the expression of man is his voice, and the whole body through the agency of that invisible force, sound, expresses the nobility, dignity, and intellectual emotions, from the foot to the head, when properly produced and balanced. Nothing short of the whole body can express this force perfectly in man or woman."

These movements develop in a common-sense way the power of natural forces, of all the forces which Nature has given to man for the production and use of the voice. Rigid, set muscles, or relaxed, limp muscles dwarf and limit in every way the powers of the singer, physical, mental, and emotional; the physical action is wrong, the thought is wrong, and the expression is wrong. A trained, developed muscle responds to thought, to right thought, in a free, natural manner. A rigid or limp muscle is, in a certain sense, for the time being, actually out of use.

An important point to consider in this connection is the fact that there is no strength properly applied without movement; but when right movements are not used, the voice is pushed and forced by local effort and by contraction of the lung cells and of the throat. This of course means physical restraint, and physical restraint prevents self-expression. Singing is more psychological than physiological; hence the importance of free self-expression. Direct physical effort produces physical effect; relaxation produces depression.

All artistic tone is reinforced sound. There are two ways of reinforcing tone. First, by direct muscular effort, the wrong way; second, by expansion and inflation, the added resonance of air in the cavities, the right way. This condition of expansion and inflation is the distinguishing feature of many great voices, and is possible only through right bodily position and action. These movements are used by many great artists, who develop them as they themselves develop, through giving expression to thought, feeling, and emotion, through using the impressive, persuasive tone, the fervent voice. This brings into action the entire vocal mechanism, in fact all the powers of the singer; hence these movements become a part of the great artist. He may not be able to give a reason for them, but he knows their value. The persuasive, fervent voice demands spontaneity and automatic form and adjustment; these conditions are impossible without flexible, vitalized movements. The great artist finds by experience that the throat was made to sing and not to sing with; that he must sing from the body through the throat. He finds that the tone must be allowed and not made to sing. Hence in the most natural way he develops vitalized bodily energy.

Next in importance to absolute freedom of voice, which these movements give, is the fact that through them absolute, automatic, perfect breath-control is developed and mastered. These movements give the breath without a thought of breathing, for they are all breathing movements. The singer cannot lift and expand without filling the lungs naturally and automatically, unless he purposely resists the breath. The conscious breath unseats the voice, that is, disturbs or prevents correct adjustment, and thus compels him to consciously hold it; but this very act makes it impossible to give the voice freedom. Through these movements, through correct position, we secure automatic adjustment, which means approximation of the breath bands, the principle of the double valve in the throat, which secures automatic breath-control. In other words, the singer whose position and action are correct need never give his breathing a thought. This is considered by many as the greatest problem—for the singer—solved in the nineteenth century.

To study and master these movements and apply them practically, the singer needs to know absolutely nothing of the mechanism of his vocal organs. He need not consider at all the physiological side of the question. Of course the study of these movements must at first be more or less mechanical, until they respond automatically to thought or will. Then they are controlled mentally, the thought before the action, as should be the case in all singing; and finally the whole mechanism, or all movements, respond naturally and freely to emotional or self-expression.

These flexible, vitalized movements are not generally understood or used, because they have not been in the line of thought or study of the rigid muscular school or the limp relaxed school; and yet they are destined to influence sooner or later all systems of singing. They have been used more or less in all ages by great artists. It is strange that they are not better understood by the profession.

In this connection it might be well to speak of the importance of physical culture for the singer. A series of simple but effective exercises should be used, exercises that will develop and vitalize every muscle of the body. There are also nerve calisthenics, nervo-muscular movements, which strengthen and control the nervous system. These nerve calisthenics generate electrical vitality and give life and confidence. "The body by certain exercises and regime may be educated to draw a constantly increasing amount of vitality from growing nature."

A singer to be successful must be healthy and strong. He should take plenty of out-door exercise. Exercise, fresh air, and sunlight are the three great physicians of the world. But beside this, all singers need physical training and development, which tense and harden the muscles, and increase the lung capacity; that training which expands all the resonance cavities, especially the chest, and which directly develops and strengthens the vocal muscles themselves, particularly the extrinsic and intrinsic muscles of the throat. As we have learned, a trained muscle responds more spontaneously to thought or will than an uneducated one; flexible spontaneity the singer always needs. Beyond a doubt, the singer who takes a simple but effective course of physical training in connection with vocal training will accomplish twice as much in a given time, in regard to tone, power and control, as he could possibly do with the vocal training alone. This is the day of physical training, of physical culture in all things; and the average vocal teacher will have to awake to the fact that his pupils need it as much as, or more than, they need the constant practice of tone.

Of course it is not possible to give a system of physical training in a small work like this. The student of the voice can get physical training and physical culture from many teachers and many books. It may not be training that will so directly and definitely develop and strengthen the vocal muscles and the organ of sound itself, or training that will so directly influence the voice as does our system, which is especially arranged for the singer; but any good system of physical development, any system that gives the student health and strength, is good for the singing voice. "Activity is the source of growth, both physical and mental." "Strength to be developed, must be used. Strength to be retained, must be used."

Since writing my last book, "Position and Action in Singing," and after four or five years more of experience, I have been doubly impressed and more than convinced of the power and influence of certain things necessary to a right training and use of the voice. Herbert Spencer says, "Experience is the sole origin of knowledge;" and my experience has convinced me, not only that certain things are necessary in the training of the voice, but that certain of the most important principles or conditions demanded by Nature, are entirely wanting in most systems of singing.

Singers, as a rule, are artificial and unnatural. They do not use all the powers with which Nature has endowed them. This has been most forcibly impressed upon my mind by the general lack of vitality, or vital energy, among singers; by a general lack of physical vitality, and, I venture to say, largely of mental vitality, and undoubtedly of emotional vitality, often, but mistakenly, called temperament. These things have been forced upon me by the general condition of depression which prevails. Vitality, however, or vitalized energy, is in fact the true means or device whereby the singer is enabled to arouse his temperament, be it great or otherwise; to arouse it, to use it, and to make it felt easily and naturally.

Out of every hundred voices tried I am safe in saying that at least ninety are physically depressed, are physically below the standard of artistic singing. Singing, it is true, is more mental than physical, and more emotional than mental; but a right physical condition is absolutely necessary, and the development of it depends upon the way the pupil is taught to think. Singing is a form of self-expression, of an expression of the emotions. This is impossible when there is physical depression. The singer must put himself and keep himself upon a level with the tone and upon a level with his song, the atmosphere of his song; upon a level with the sentiment to be expressed, physically, mentally and emotionally. This cannot be done, or these conditions cannot prevail, when there is depression.

There is, to my mind, but one way to account for this condition of depression among singers. That is, the way they think, or are taught to think, in regard to the use of their bodies in singing. The way in which they breathe and control the breath, the way in which they drive and control the tone. It is the result of rigid muscular effort or relaxation, and both depress not only the voice but the singer as well. The tonal result is indisputable evidence of this.

Knowledge comes through experience; and my experience in studying both sides of this question has convinced me that there is but one way to develop physical, mental and emotional vitality in the singer, and that is through some system of flexible, vitalized bodily movements. There must be flexible firmness, firmness without rigidity. The movements as given in my book, "Position and Action in Singing," and as here given, develop these conditions. They give the singer physical vitality, freedom of voice, spontaneity, absolute automatic breath control, and make self-expression, emotional expression, and tone-color, not only possible but comparatively easy. Singing is self-expression, an expression of thought and feeling. There must be a medium, however, for the expression of feeling aroused through thought; that medium is the body and the body alone. Therefore it is easy to see the importance of so training the body that it will respond automatically to the thought and will of the singer.

The opposite of depression, which local effort develops, is vitalized energy, the singer's sensation, that which I have called the third power, and which is a revelation to those who have studied both sides of the question. These things, as I have said, have been given to the vocal world in my book, "Position and Action in Singing." Many have understood them, have used them, and are enthusiastic advocates of the idea. Others have not fully understood them, as was and is to be expected. For that reason I have written this little book in the hope that it might make things plainer to all. I have endeavored to embody these practical, natural, necessary movements in the formula of study given in this book.

The formula which follows is systematically and logically arranged for the study and development of fundamental principles through or by the means of these flexible vitalized movements. In this way I hope to make these ideas plainer and more definite to pupil and teacher.

Every correct system of voice-training is based upon principle, theory, and the devices used to develop the principles. There are certain fundamental principles of voice, which are Nature's laws laid down to man, and which cannot be violated. Upon these principles we formulate theories. The theories may be right or wrong, as they are but the works of man. If they are right, the devices used are more apt to be right. If they are wrong, wrong effort is sure to follow, and the result is disastrous.

After all, the most important question for consideration is that of the devices used to develop and train the voice. All depends upon whether the writer, the teacher, and the pupil study Nature's laws through common-sense methods or resort to artificiality. If the devices used are right, if they develop vitality, emotional energy, if they avoid rigidity and depression, then the singer need not know so much about principle and theory. But with the teacher it is different. He must know what to think and how to think it before he can intelligently impart the ideas to his pupils. Hence a system based upon correct principle, theory, and device is absolutely necessary for the teacher who hopes to succeed.

The following system, as formulated, is largely the outgrowth of my summer work at Point Chautauqua, on Lake Chautauqua. There we have a school every summer, not only for the professional singer and teacher, but for those who desire to become such. Beside the private lessons we give a practical normal course in class lessons. There the principles, the theory, and the devices used are studied and worked out in a practical way by lecture, by illustration, and by the study of all kinds of voices. Many who have taught for years have there obtained for the first time an idea, the true idea, of flexible vitalized movements, the devices demanded by nature for giving the voice vitality, freedom, ease, etc. These teachers who are thus aroused become the most enthusiastic supporters of, and believers in, our system of flexible vitalized movements.

It is, therefore, through the Chautauqua work that I have been impressed with the importance of placing this system in a plainer and more definite way, if possible, before the vocal world.

The first principle of artistic tone-production is

The Removal of All Restraint.

The theory founded upon this principle is as follows: Correct tone is the result of certain conditions demanded by Nature, not man's ideas. These conditions are dependent upon form and adjustment; and form and adjustment, to be right, must be automatic, and not the result of direct or local effort.

The devices used for developing the above conditions are simple vocal exercises which are favorable to correct form and adjustment, and are studied and made to influence the voice through correct position and action.

A correct system for training and developing the voice must be based upon principle, theory, and device; upon the principles of voice which are Nature's laws, upon the theories based upon these principles, and upon the devices for the study and development of such principles.

My purpose in this little work is to give just enough musical figures or exercises to enable us to study and apply the movements, the practical part of our system.

The first principle of artistic tone-production is the removal of all restraint. This no one can deny without stultifying himself. The removal of all restraint means absolute freedom, not only of form and action, but of tone. It is evident, then, that any local hardening or contracting of muscle, any tension or contraction which would prevent elasticity, would make the removal of all restraint impossible. Hence we find that this first principle is an impossibility with the rigid local-effort school. On the other hand, relaxation, while it may remove restraint, makes artistic control and tonicity impossible. Hence artistic tone, based upon this first principle, is an impossible condition with the limp or relaxed school.

That tone is the result of certain conditions demanded by Nature, and that these conditions are dependent upon form and adjustment, cannot be denied; but unless form and adjustment give freedom to the voice, unless they result in the removal of all restraint, then the manner or method in which they are secured must surely be wrong. Local effort or contraction cannot do this. Relaxation cannot secure the true conditions. There is and can be but one principle which makes true form and adjustment possible: All form and adjustment must be automatic, and not the result of direct or local effort.

This brings us to a study of devices; and devices, to influence correctly not only the voice but the individual, must be in accordance with natural and not artificial conditions. The singer must put himself and keep himself upon a level with the tone—upon a level with the tone physically, mentally and emotionally. The device which we use, or the formula, is, lift, expand, and let go.

With the singer who contracts the throat muscles during the act of singing, that which may be called the center of gravity or of effort is at the throat. With the singer who carries a consciously high chest and a drawn-in or contracted diaphragm, the center of gravity is at the chest. With the singer who takes a conscious full breath, and hardens and sets the diaphragm to hold it, the center of gravity is at the diaphragm. In none of these cases is it possible to remove all restraint; for they all result in contraction, especially of the throat muscles, and make flexible expansion—a condition necessary to absolute freedom—impossible.

Place the center of gravity, by thought and action, at the hips. Everything above the hips must be free, flexible, elastic and vitalized when singing. We say, lift, expand, and let go, which must be in the following proportion: Lift a little, expand more than you lift, and let go entirely. The lift is from the hips up, and must be done in a free, flexible manner, with a constant study to make the body lighter and lighter, and the movement more elastic and flexible. Do not lift as though lifting a weight, but lift lightly as though in response to thought or suggestion.

Expand the entire body in a flexible, elastic manner. This will bring into action every muscle of the body, and apply strength and support to the voice; for, as we have found, there is no strength correctly applied except through right movement. When we lift and expand properly, we expand the body as a whole, and not the chest alone, nor the diaphragm, nor the sides. These all come into action and expand with proper movement; but there must be no conscious thought of, nor conscious local effort of, any particular part of the body. When we lift and expand properly the chest becomes active, the diaphragm goes into a singing position, and every muscle of the body is on the alert and ready to respond to the thought or desire of the singer. Not only this; when we lift and expand properly, we influence directly the form and adjustment of all the vocal muscles, and especially the organ of sound itself. In this way the voice is actually and artistically tuned for the production of correct tone, as is the violin in the hands of the master before playing.

Lift, expand, and let go. This brings us to a consideration of the third part of this expression, let go. This is in some respects the most important of the three; for unless the singer knows how to let go properly, absolute freedom or the removal of all restraint is impossible, and the true conditions of tone are lacking. The let go does not mean relaxation, for there must be flexible firmness without rigidity. With the beginner the tendency is to lift, expand, and harden or contract all the muscles. This, of course, means restraint. The correct idea of let go may be studied and better understood by the following experiment or illustration.

Stand with the right arm hanging limp by the side. Lift it to a horizontal position, the back of the hand upward. While lifting, grip and contract every muscle of the arm and hand out to the finger-tips. This is much like the contraction placed upon the muscles of the body and of the throat by the conscious-breathing, local-effort school. Lift the arm again from the side, and in lifting have the thought or sensation of letting go all contraction of the muscles. Make the arm light and flexible, and use just enough strength to lift it, and hold it in a horizontal position. This should be the condition of all the muscles of the body under the influence of correct, lift, expand, and let go. Lift the arm the third time without contraction or with the sensation of letting go, hold it in a horizontal position, the back of the hand upward. Now will to devitalize the entire hand from the wrist to the finger-tips. Let the hand drop or droop, the arm remaining in a horizontal position. This condition of the hand is the let go, or the condition of devitalization, which should be upon the muscles of the face, the mouth, the tongue, the jaw, and the extrinsic muscles of the throat during the act of singing.

Thus, when we say, lift, expand, and let go, we mean lift from the hips, the center of gravity, in an easy, flexible manner; expand the body with a free movement without conscious thought of any part of it; have the sensation of letting go all contraction or rigidity, and absolutely release the muscles of the throat and face. The let go is in reality more a negative than a positive condition, and virtually means, when you lift and expand, do not locally grip, harden, or set any muscle of the body, throat, or face.

The lift, expand, and let go must be in proportion to the pitch and power of the tone. This, if done properly, will result in automatic form and adjustment, the removal of all restraint, and open, free throat and voice. This is the only way in which it is possible to truly vitalize, to arouse the physical, mental and emotional powers of the singer. This is the only way in which it is possible to put yourself and keep yourself upon a level with the tone—upon a level, physically, mentally and emotionally. This is in truth and in fact the singer's true position and true condition; this is in truth and in fact self-assertion; and this, and this only, makes it possible to easily and naturally arouse "the singer's sensation," the true sensation of artistic singing.

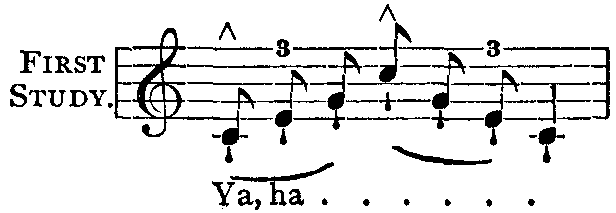

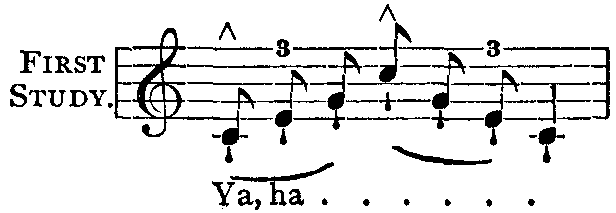

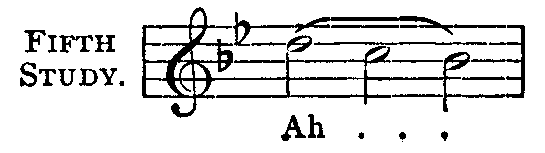

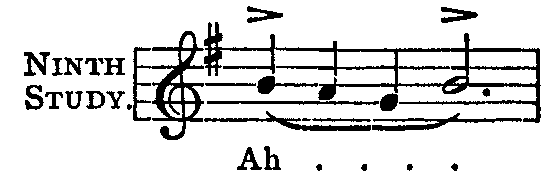

We will take for our first study a simple arpeggio, using the syllables Ya ha, thus:

We use Ya on the first tone, because when sung freely it helps to place the tone well forward. Ya is pronounced as the German Ja. We use ha on all other tones of this study for the reason that it is the natural staccato of the voice. Think it and sing it "in glossic" or phonetically, thus: hA, very little h but full, inflated, expanded A. A full explanation for the use of Ya and ha may be found in "Position and Action in Singing," page 117. All the studies given in this little work for the illustration and study of the movements of our system should be sung on all keys as high and as low as they can be used without effort and without strain.

It has been said that "the production of the human voice is the effect of a muscular effort born of a mental cause." Therefore it is important to know what to think and how to think it.

We say, put yourself and keep yourself constantly upon a level with the tone, mentally, physically and emotionally. For the present we have to do with the mental and physical only.

Stand in an easy, natural manner, the hands and arms hanging loosely by the sides. You desire to sing the above exercise. Turn the palms of the hands up in a free, flexible manner, and lift the hands up and out a little, not high, not above the waist line. When moving the hands up and out, move the body from the hips up and out in exactly the same manner and proportion. The hands and arms must not move faster than the body; the body must move rhythmically with the arms. This rhythmical movement of body and arms is highly important. In moving, the sensation is as though the body were lifted lightly and freely upon the palms of the hands. The hands say to the body, "Follow us." In this way, lift, expand, and let go. Do not raise the shoulders locally. The movement is from the hips up. The entire body expands easily and freely by letting go all contraction of muscle. Do not first lift, and after lifting expand, and then finally try to let go, as is the habit of many; but lift, and when lifting expand, and when lifting and expanding let go as directed. Three thoughts in one movement—three movements in one—lifting, expanding, and letting go simultaneously as one movement, which in fact it must finally become. This is the only way in which it is possible to secure all true conditions of tone.

With this thought in mind, and having tried the movement without singing, sing the above exercise. Start from repose, as described, and by using the hands and body in a free, flexible manner, move to what you might think should be the level of the first tone. Just when you reach the level of the first tone let the voice sing. Move up with the arpeggio to the highest note, using hands, body, and voice with free, flexible action; then move body and hands with the voice down to the lowest note of the arpeggio; when the last tone is sung go into a position of repose.

The movement from repose to the level of the first tone is highly important, for the reason that it arouses the energies of the singer, and secures all true conditions through automatic form and adjustment. Do not hesitate, do not hurry. All movement must be rhythmical and spontaneous, and never the result of effort. In singing the arpeggio the tones of the voice must be strictly staccato; but the movement of the hands and body must be very smooth, even, and continuous—no short, jerky movements.

The movement of the body is very slight, and at no time, in studying these first exercises, should the hands be raised above the level of the hips or of the waist line. Of course with beginners these movements may be more or less exaggerated. When singing songs, however, they do not show, at least not nearly as much as wrong breathing and wrong effort. They simply give the singer the appearance of proper dignity, position, and self-assertion. By all means use the hands in training the movements of the body. You can train the body by the use of the hands in one-fourth of the time that it is possible to do it without using them. Be careful, however, not to raise the hands too high, as is the tendency; when lifted too high the energy is often put into the hands and arms instead of the body; in this way the body is not properly aroused and influenced, and of course true conditions are not secured.

"Practical rules must rest upon theory, and theory upon nature, and nature is ascertained by observation and experience." Now, if you will practice this arpeggio with a free, flexible movement of hands and body, getting under the tone, as it were, and moving to a level of every tone, you will soon find by practice and experience that these movements are perfectly natural, that they arouse all the forces which nature gave us for the production of tone, that they vitalize the singer and give freedom to the voice. By moving properly to a level of the first tone you secure all true conditions of tone; and if you have placed yourself properly upon a level with the high tone, when that is reached you will have maintained those true conditions—you will have freedom, inflation and vitality instead of contraction and strain.

By moving with the voice in this flexible manner we bring every part of the body into action, and apply strength as nature demands it, without effort or strain. Remember, there is no strength properly applied in singing without movement. In this way the voice is an outward manifestation of an inward feeling or emotion. "The voice is your inner or higher self, expressed not at or by but through the vocal organs, aided by the whole body as a sound-board."

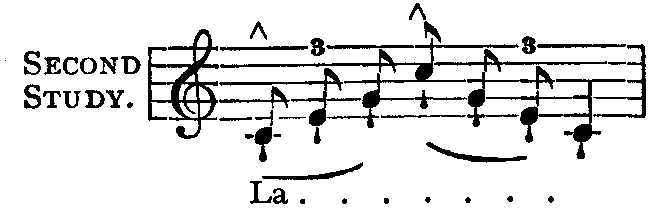

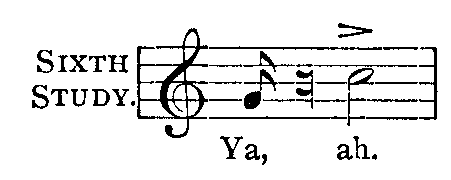

Our next study will be a simple arpeggio sung with the la sound, thus:

This movement, of course, must be sung with the same action of hands and body, starting from repose to the level of the first tone, and keeping constantly upon a level with the voice by ascending and descending. Sing this exercise first semi staccato, afterwards legato.

The special object of this exercise is to relax the jaw, the face, and the throat muscles. A stiff, set jaw always means throat contraction. In this exercise, if sung in every other respect according to directions, a stiff jaw would defeat the whole thing, and make impossible a correct production of every high tone.

In singing the la sound, the tip of the tongue touches the roof of the mouth, just back of the upper front teeth. Think the tone forward at this point, and let the jaw rise and fall with the tongue. Devitalize the jaw and the muscles of the face, move up in a free, flexible manner to the level of every tone, and you will be surprised at the freedom and ease with which the high tones come. The moving up in the proper way applies strength, and secures automatic form and adjustment; develops or strengthens the resisting or controlling muscles of the voice; in fact, gives the voice expansion, inflation, and tonicity.

Remember that one can act in singing; and by acting I mean the movements as here described, lifting, expanding, etc., without influencing the voice or the tone, without applying the movements to the voice; of course such action is simply an imitation of the real thing. Herein, however, lies the importance of correct thinking. The thought must precede the action. The singer must have some idea of what he wants to sing and how he wants to sing it. A simple chance, a simple hit or miss idea, will not do. Make your tone mean something. Arouse the singer's sensation, and you can soon tell whether the movement is influencing the tone or not. Of course these movements are all more easily applied on the middle and low tones than on the higher tones, but these are the great successful movements for the study and development of the high tones.

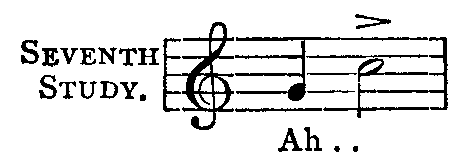

As we have learned in our former publications, there are but three movements in singing,—ascending, descending, and level movements. We have so far studied ascending and descending movements or arpeggios. We will now study level movements on a single tone, thus:

Place yourself in a free, flexible manner upon a level with the tone by the use of the movements as before described; lift, expand, and let go without hurrying or without hesitation, and just when you reach that which you feel to be the level of the tone let the voice sing. All must be done in a moment, rhythmically and without local effort. Sing spontaneously, sing with abandon, trust the movements. They will always serve you if you trust them. If you doubt them, they are doubtful; for your very doubt brings hesitation, and hesitation brings contraction. Sing from center to circumference, with the thought of expansion and inflation, and not from outside to center. The first gives freedom and fullness of form, the latter results in local effort and contraction. The first sends the voice out full and free, the latter restrains it. Expansion through flexible movement is the important point to consider. When the tone is thus sung, it should result in the removal of all restraint, especially from the face, jaw, and throat. In this way the tone will come freely to the front, and will flow or float as long as the level of the tone is maintained without effort.

Remember the most important point is the movement from repose to the level of the tone. If this is done according to directions, all restraint will be removed and all true conditions will prevail. Never influence form. Let form and adjustment be automatic, the result of right thought, position, and action. Study to constantly make these movements of the body easier and more natural. Take off all effort. Do not work hard. It is not hard work. It is play. It is a delight when properly done. Make no conscious, direct effort of any part of the body. Never exaggerate the movement or action of one part of the body at the sacrifice of the true position of another. The tendency is to locally raise the chest so high that the abdomen is unnaturally drawn in. This, of course, is the result of local effort, and is not the intention of the movements. The center of gravity must be at the hips; and all movement above that must be free, flexible, and uniform.1

Do not give a thought to any wrong thing you may be in the habit of doing in singing, but place your mind upon freeing the voice, upon the removal of all restraint through these flexible vitalized movements: think the ideal tone and sing. When the right begins to come through these movements the wrong must go. Over and against every wrong there is a right. We remove the wrong by developing the right. Sing in a free, flexible manner, the natural power of the voice. Make no effort to suppress the tone or increase its power. After the movements are understood and all restraint is removed, then study the tone on all degrees of power, but remember when singing soft and loud, and especially loud, that the first principle of artistic singing is the removal of all restraint.

The second principle of artistic tone-production is

Automatic Breathing and Automatic Breath-Control.

Theory.—The singing breath should be as unconscious,—or, rather, as sub-conscious,—as involuntary, as the vital or living breath. It should be the result of flexible action, and never of local muscular effort. The muscular breath compels muscular control; hence throat contraction. The nervous breath, nervous control; hence relaxation and loss of breath.

Devices.—Expand to breathe. Do not breathe to expand. Expand by flexible, vitalized movements; control by position the level of the tone, and thus balance the two forces, "pressure and resistance." In this way is secured automatic adjustment and absolute automatic breath-control.

More has probably been written and said upon this important question of breathing in singing than upon any other question in the broad field of the vocal art; and yet the fact remains that it is less understood than any of the really great principles of correct singing. This is due to the fact that most writers, teachers, and singers believe that they must do something—something out of the ordinary—to develop the breathing powers. The result is, that most systems of breathing are artificial; therefore unnatural. Most systems of breathing attempt to do by direct effort that which Nature alone can do correctly. Most breathing in singing is the result of direct conscious effort.

The conscious or artificial breath is a muscular breath, and compels muscular control. The conscious breath—the breath that is taken locally and deliberately (one might almost say maliciously) before singing—expands the body unnaturally, and thus creates a desire to at once expel it. In order to avoid this, the singer is compelled to harden and tighten every muscle of the body; and not only of the body, but of the throat as well. Under these conditions the first principle of artistic tone-production—the removal of all restraint—is impossible.

As the breath is taken, so must it be used. Nature demands—aye, compels—this. If we take (as we are so often told to do) "a good breath, and get ready," it means entirely too much breath for comfort, to say nothing of artistic singing. It means a hard, set diaphragm, an undue tension of the abdominal muscles, and an unnatural position and condition of the chest. This of course compels the hardening and contraction of the throat muscles. This virtually means the unseating of the voice; for under these conditions free, natural singing is impossible. The conscious, full, muscular breath compels conscious, local muscular effort to hold it and control it. Result: a stiff, set, condition of the face muscles, the jaw, the tongue and the larynx. This makes automatic vowel form, placing, and even freedom of expression, impossible. The conscious, artificial breath is a handicap in every way. It compels the singer to directly and locally control the parts. In this way it is not possible to easily and freely use all the forces which Nature has given to man for the production of beautiful tone.

Now note the contrast. The artistic breath must be as unconscious or as involuntary as the vital or living breath. It must be the result of free, flexible action, and never of conscious effort. The artistic, automatic breath is the result of doing the thing which gives the breath and controls the breath without thought of breath. The automatic breath is got through the movements suggested when we say, Lift, expand, and let go.

When the singer lifts and expands in a free, flexible manner the body fills with breath. One would have to consciously resist this to prevent the filling of the lungs. The breath taken in this way means expansion, inflation, ease, freedom. There is no desire to expel the breath got in this way; it is controlled easily and naturally from position—the level of the tone. When the breath is thus got through right position and action, we secure automatic form and adjustment; and correct adjustment means approximation of the breath bands, inflation of the cavities—in fact, all true conditions of tone. Nature has placed within the organ of sound the principle of a double valve,—one of the strongest forces known in mechanics,—for the control of the breath during the act of singing. This is what we mean by automatic breath-control—using the forces which Nature has given us for that purpose, using them in the proper manner.

If the reader is familiar with my last two works, "Vocal Reinforcement" and "Position and Action in Singing," he will have learned through them that we have not direct, correct control of the form and adjustment of the parts which secure the true conditions of tone and automatic breath-control. These conditions, as we have learned, are secured through the flexible movements which are the ground-work of our system. Therefore we say, Trust the movements. If you have confidence in them, they will always serve you. If you doubt them, they are doubtful; for the least doubt on the part of the singer means more or less contraction and restraint; hence they fail to produce the true conditions.

This automatic breathing, the result of the movements described, does not show effort or action half so much as the old-fashioned, conscious muscular breath. Breathing in this way means the use of all the forces which Nature has given us. Breathing in this way is Nature's demand, and the reward is Nature's help.

The devices we use to develop automatic breathing and automatic breath-control are the simplest possible exercises, studied and developed through the movements, as before described. In this way through right action we expand to breathe, or rather we breathe through flexible expansion, and we control by position, by the true level of the tone. In this way, as we have found, all true conditions are secured and maintained.

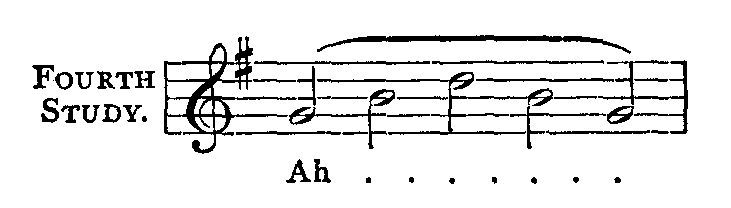

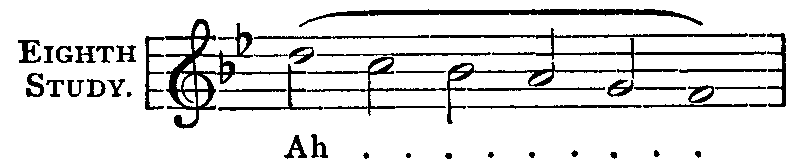

We will take for our first study a single tone about the middle of the voice. Exercise three in Article One of this second part of the book will suggest the idea.

Sing a tone about the middle of the voice with the syllable ah. Lift, expand, and let go, by the use of the hands and the body, as before suggested. The lifting and expanding in a free, flexible manner will give you all the breath that is needed; and the position, the level of the tone, will hold or control the breath if you have confidence. Remember that automatic breathing depends upon first action, the movement from repose to the level of the tone. If the action is as described, sufficient breath will be the result. If the position, the level of the tone, is maintained without contraction, absolute automatic breath-control will be the result so sure as the sun shines.

The tendency with beginners and with those who have formed wrong habits of breathing, is to take a voluntary breath before coming into action. This of course defeats the whole thing. Again, the tendency of beginners or of those who have formed wrong habits, is to sing before finding the level of the tone through the movements, or to start the tone before the action. This of course compels local effort and contraction, and makes success impossible. The singer must have breath; and if he does not get it automatically through the flexible movements herein described, or some such movements, he is compelled to take it consciously and locally. The conscious local breath in singing is always an artificial breath, and compels local control. Under these conditions ease and perfect freedom are impossible.

As we have said, the important thing to consider in this study is the movement from repose to the level of the first tone. Move in a free, flexible manner as before described, and give no thought to breath-taking. When you have found the level of the tone, all of which is done rhythmically and in a moment, let the voice sing,—sing spontaneously. Make no effort to hold or control the breath. Maintain correct position the level of the tone, in a free, flexible manner, and sing with perfect freedom, with abandon. As the movement or action gave you the breath, so will the position hold it. The more you let go all contraction of body and throat muscles, the more freedom you give the voice, the more will the breath be controlled,—controlled through automatic form and adjustment. This is a wonderful revelation to many who have tried it and mastered it. Those who have constantly thought in the old way, and attempted to breathe and control in the old way, cannot of course understand it. The tendency of such is to condemn it,—to condemn it, we are sorry to say, without investigation.

Knowledge is gained through experience. The singer or pupil who tries this system of breathing and succeeds, needs no argument to convince him that it is true, natural and correct. The greatest drawback to the mastering of it on the part of many singers and teachers, is the artificial habits acquired by years of wrong thinking and wrong effort. With the beginner it is the simplest, the easiest, and the most quickly acquired of all systems of breathing; for automatic breathing is a fundamental, natural law of artistic singing.

For further illustration of this principle of breathing we will use the following exercise: