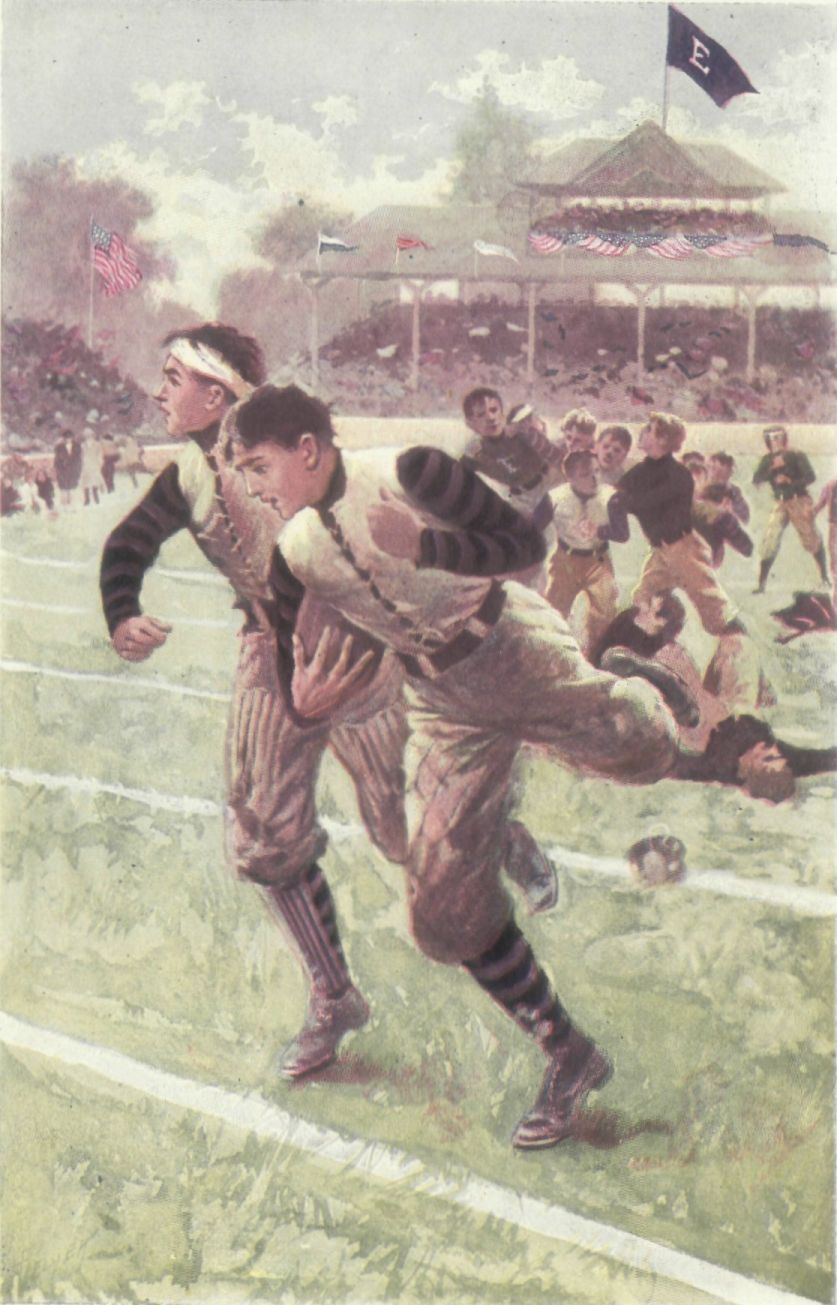

A critical moment.

Title: Behind the Line: A Story of College Life and Football

Author: Ralph Henry Barbour

Illustrator: C. M. Relyea

Release date: September 30, 2004 [eBook #13556]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Charlie Kirschner, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Behind the Line, by Ralph Henry Barbour, Illustrated by C. M. Relyea

| CHAPTER | ||

| I.-- | HEROES IN MOLESKIN | |

| II.-- | PAUL CHANGES HIS MIND | |

| III.-- | IN NEW QUARTERS | |

| IV.-- | NEIL MAKES ACQUAINTANCES | |

| V.-- | AND SHOWS HIS METTLE | |

| VI.-- | MILLS, HEAD COACH | |

| VII.-- | THE GENTLE ART OF HANDLING PUNTS | |

| VIII.-- | THE KIDNAPING | |

| IX.-- | THE BROKEN TRICYCLE | |

| X.-- | NEIL MAKES THE VARSITY | |

| XI.-- | THE RESULT OF A FUMBLE | |

| XII.-- | ON THE HOSPITAL LIST | |

| XIII.-- | SYDNEY STUDIES STRATEGY | |

| XIV.-- | MAKES A CALL | |

| XV.-- | AND TELLS OF A DREAM | |

| XVI.-- | ROBINSON SENDS A PROTEST | |

| XVII.-- | A PLAN AND A CONFESSION | |

| XVIII.-- | NEIL IS TAKEN OUT | |

| XIX.-- | ON THE EVE OF BATTLE | |

| XX.-- | COWAN BECOMES INDIGNANT | |

| XXI.-- | THE "ANTIDOTE" IS ADMINISTERED | |

| XXII.-- | BETWEEN THE HALVES | |

| XXIII.-- | NEIL GOES IN | |

| XXIV.-- | AFTER THE BATTLE |

| A critical moment | frontispiece |

| Getting settled | |

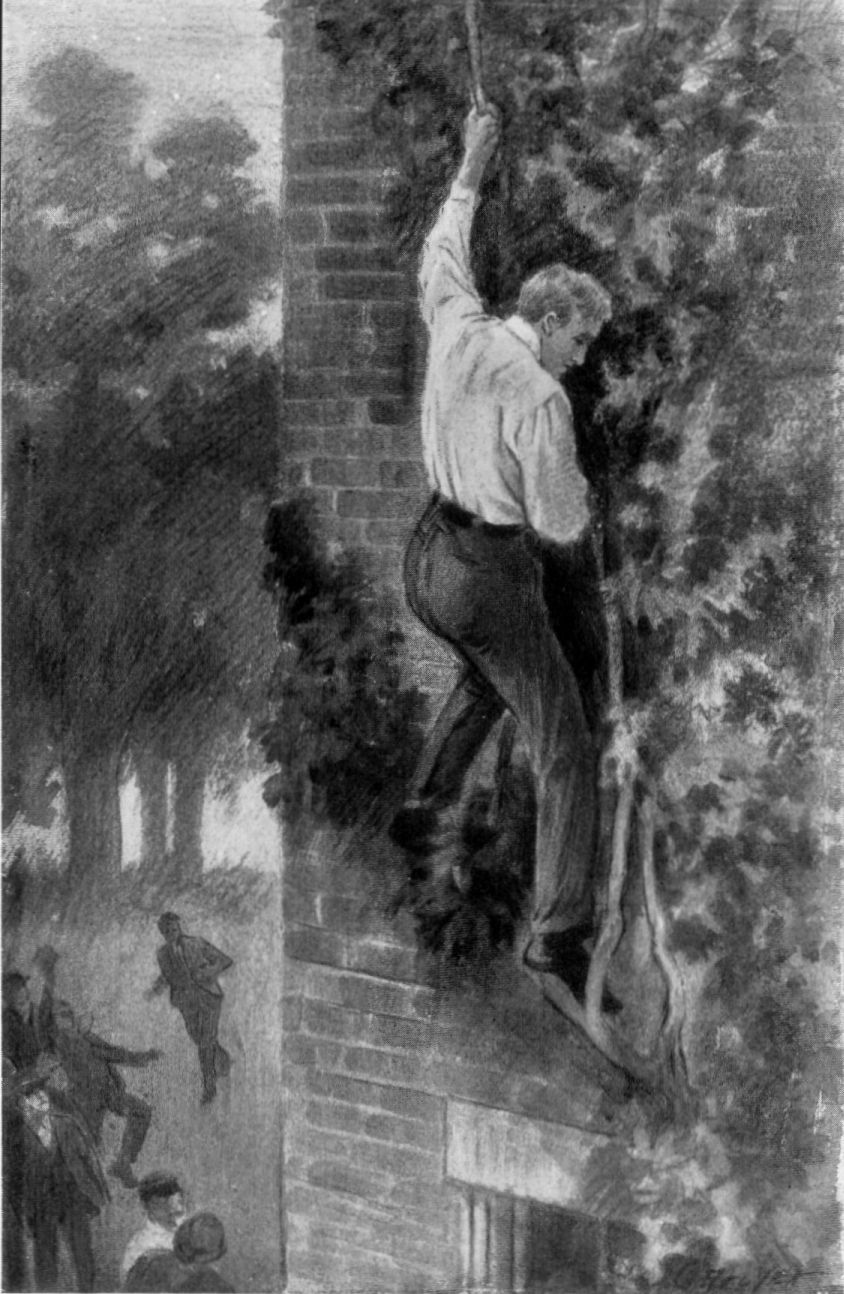

| The vine swayed at every strain | |

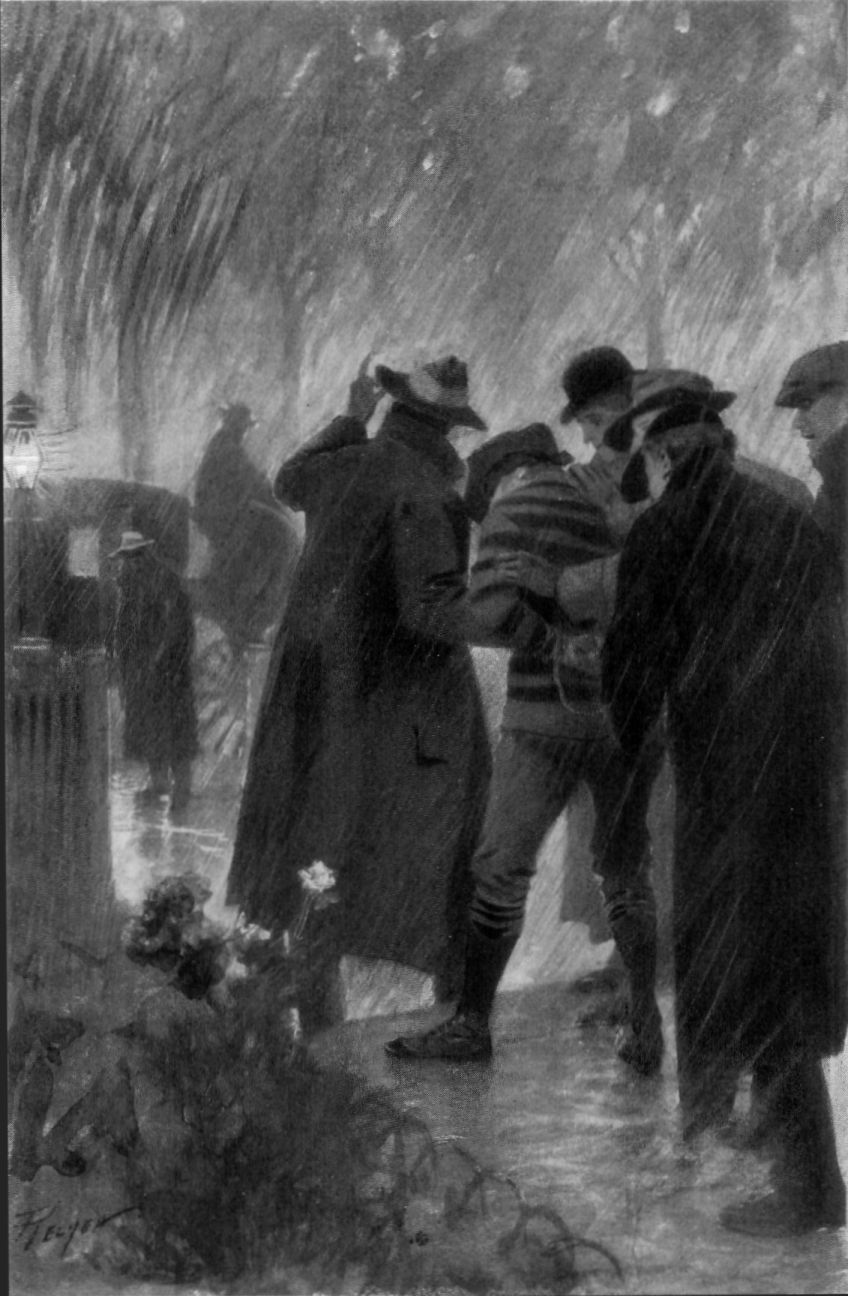

| Hiding his face, he cried for help | |

| "I guess you've broken down," said Neil | |

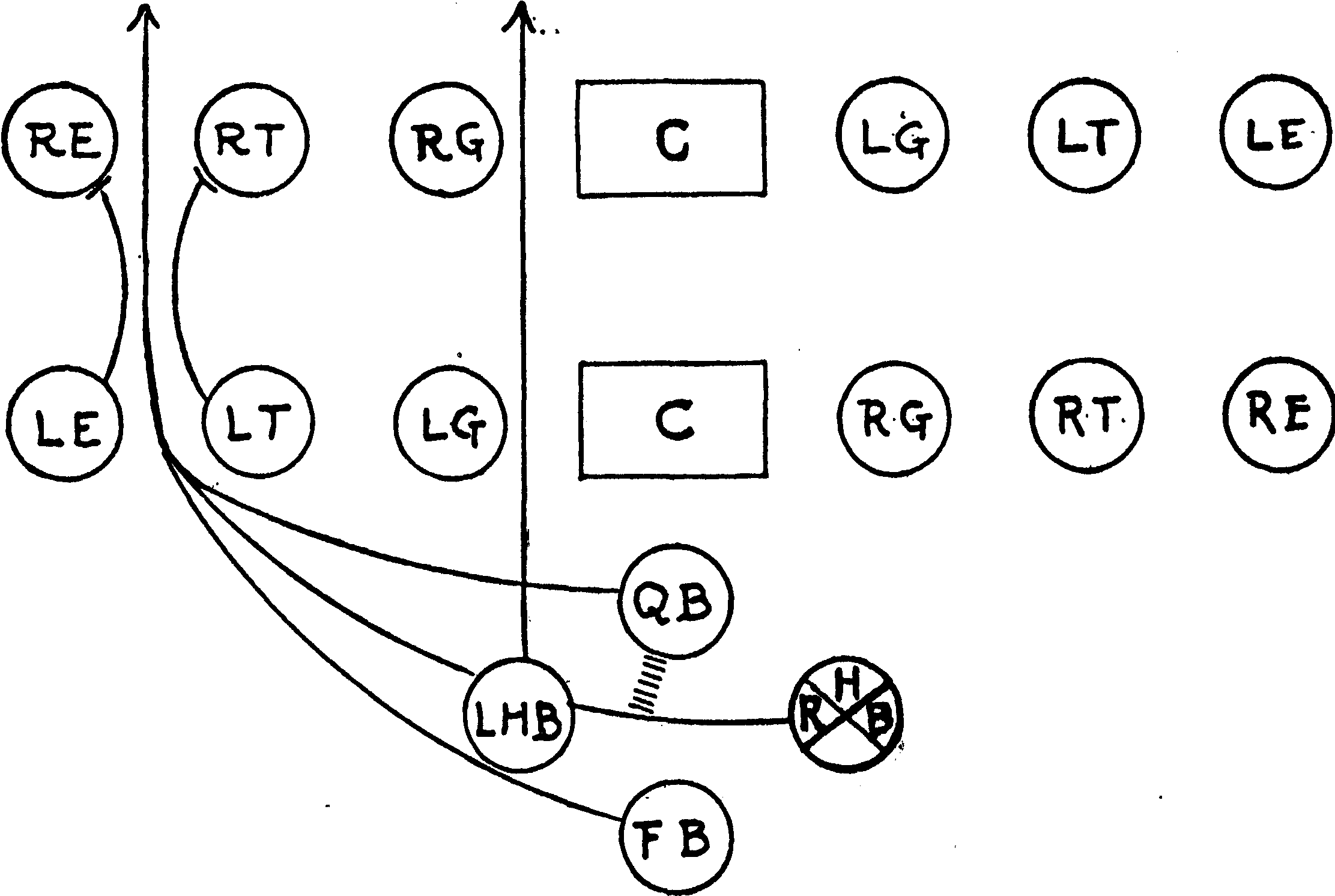

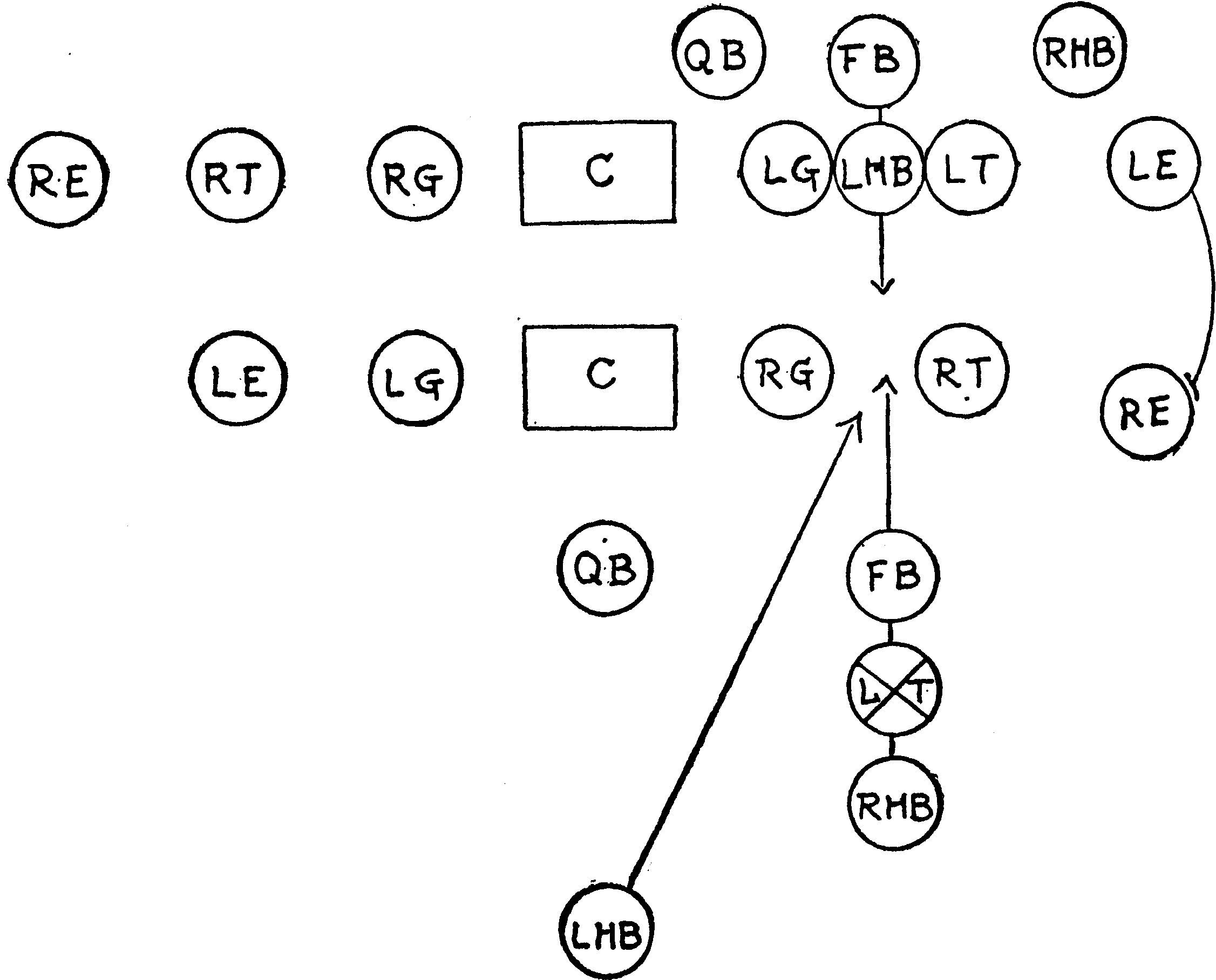

| Mills studied the diagram in silence |

"Third down, four yards to gain!"

The referee trotted out of the scrimmage line and blew his whistle; the Hillton quarter-back crouched again behind the big center; the other backs scurried to their places as though for a kick.

"9--6--12!" called quarter huskily.

"Get through!" shrieked the St. Eustace captain. "Block this kick!"

"4--8!"

The ball swept back to the full, the halves formed their interference, and the trio sped toward the right end of the line. For an instant the opposing ranks heaved and struggled; for an instant Hillton repelled the attack; then, like a shot, the St. Eustace left tackle hurtled through and, avoiding the interference, nailed the Hillton runner six yards back of the line. A square of the grand stand blossomed suddenly with blue, and St. Eustace's supporters, already hoarse with cheering and singing, once more broke into triumphant applause. The score-board announced fifteen minutes to play, and the ball went to the blue-clad warriors on Hillton's forty-yard line.

Hillton and St. Eustace were once more battling for supremacy on the gridiron in their annual Thanksgiving Day contest. And, in spite of the fact that Hillton was on her own grounds, St. Eustace's star was in the ascendant, and defeat hovered dark and ominous over the Crimson. With the score 5 to 0 in favor of the visitors, with her players battered and wearied, with the second half of the game already half over, Hillton, outweighted and outplayed, fought on with the doggedness born of despair in an almost hopeless struggle to avert impending defeat.

In the first few minutes of the first half St. Eustace had battered her way down the field, throwing her heavy backs through the crimson line again and again, until she had placed the pigskin on Hillton's three-yard line. There the Hillton players had held stubbornly against two attempts to advance, but on the third down had fallen victims to a delayed pass, and St. Eustace had scored her only touch-down. The punt-out had failed, however, and the cheering flaunters of blue banners had perforce to be content with five points.

Then it was that Hillton had surprised her opponents, for when the Blue's warriors had again sought to hammer and beat their way through the opposing line they found that Hillton had awakened from her daze, and their gains were small and infrequent. Four times ere the half was at an end St. Eustace was forced to kick, and thrice, having by the hardest work and almost inch by inch fought her way to within scoring distance of her opponent's goal, she met a defense that was impregnable to her most desperate assaults. Then it was that the Crimson had waved madly over the heads of Hillton's shrieking supporters and hope had again returned to their hearts.

In the second half Hillton had secured the ball on the kick-off, and, never losing possession of it, had struggled foot by foot to within fifteen yards of the Blue's goal. From there a kick from placement had been tried, but Gale, Hillton's captain and right half-back, had been thrown before his foot had touched the leather, and the St. Eustace right-guard had fallen on the ball. A few minutes later a fumble returned the pigskin to Hillton on the Blue's thirty-three yards, and once more the advance was taken up. Thrice the distance had been gained by plunges into the line and short runs about the ends, and once Fletcher, Hillton's left half, had got away safely for twenty yards. But on her eight-yard line, under the shadow of her goal, St. Eustace had held bravely, and, securing the ball on downs, punted it far down the field into her opponent's territory. Fletcher had run it back ten yards ere he was downed, and from there it had gone six yards further by one superb hurdle by the full-back. But St. Eustace had then held finely, and on the third down, as has been told, Hillton's fake-kick play had been demolished by the Blue's tackle, and the ball was once more in the hands of St. Eustace's big center rush.

On the side-line, his hands in his pockets and his short brier pipe clenched firmly between his teeth, Gardiner, Hillton's head coach, watched grimly the tide of battle. Things had gone worse than he had anticipated. He had not hoped for too much--a tie would have satisfied him; a victory for Hillton had been beyond his expectations. St. Eustace far outweighed his team; her center was almost invulnerable and her back field was fast and heavy. But, despite the modesty of his expectations, Gardiner was disappointed. The plays that he had believed would prove to be ground-gainers had failed almost invariably. Neil Fletcher, the left half, on whom the head coach had placed the greatest reliance, had, with a single exception, failed to circle the ends for any distance. To be sure, the St. Eustace end rushes had proved more knowing than he had given them credit for being, and so the fault was, after all, not with Fletcher; but it was disappointing nevertheless.

And, as is invariably the case, he saw where he had made mistakes in the handling of his team; realized, now that it was too late, that he had given too much attention to that thing, too little to this; that, as things had turned out, certain plays discarded a week before would have proved of more value than those substituted. He sighed, and moved down the line to keep abreast of the teams, now five yards nearer the Hillton goal.

"Crozier must come out in a moment," said a voice beside him. He turned to find Professor Beck, the trainer and physical director. "What a game he has put up, eh?"

Gardiner nodded.

"Best quarter in years," he answered. "It'll weaken us considerably, but I suppose it's necessary." There was a note of interrogation in the last, and the professor heard it.

"Yes, yes, quite," he replied. "The boy's on his last legs." Gardiner turned to the line of substitutes behind them.

"Decker!"

The call was taken up by those nearest at hand, and the next instant a short, stockily-built youth was peeling off his crimson sweater. The referee's whistle blew, and while the mound of squirming players found their feet again, Gardiner walked toward them, his hand on Decker's shoulder.

"Play slow and steady your team, Decker," he counseled. "Use Young and Fletcher for runs; try them outside of tackle, especially on the right. Give Gale a chance to hit the line now and then and diversify your plays well. And, my boy, if you get that ball again, and of course you will, don't let it go! Give up your twenty yards if necessary, only hang on to the leather!"

Then he thumped him encouragingly on the back and sped him forward. Crozier, the deposed quarter-back, was being led off by Professor Beck. The boy was pale of face and trembling with weariness, and one foot dragged itself after the other limply. But he was protesting with tears in his eyes against being laid off, and even the hearty cheers for him that thundered from the stand did not comfort him. Then the game went on, the tide of battle flowing slowly, steadily, toward the Crimson's goal.

"If only they don't score again!" said Gardiner.

"That's the best we can hope for," said Professor Beck.

"Yes; it's turned out worse than I expected."

"Well, you can comfort yourself with the knowledge that they've played as plucky a game against odds as I ever expect to see," answered the other. "And we won't say die yet; there's still"--he looked at his watch-- there's still eight minutes."

"That's good; I hope Decker will remember what I told him about runs outside right tackle," muttered Gardiner anxiously. Then he relighted his pipe and, with stolid face, watched events.

St. Eustace was still hammering Hillton's line at the wings. Time and again the Blue's big full-back plunged through between guard and tackle, now on this side, now on that, and Hillton's line ever gave back and back, slowly, stubbornly, but surely.

"First down," cried the referee. "Five yards to gain."

The pigskin now lay just midway between Hillton's ten-and fifteen-yard lines. Decker, the substitute quarter-back, danced about under the goal-posts.

"Now get through and break it up, fellows!" he shouted. "Get through! Get through!"

But the crimson-clad line men were powerless to withstand the terrific plunges of the foe, and back once more they went, and yet again, and the ball was on the six-yard line, placed there by two plunges at right tackle.

"First down!" cried the referee again.

Then Hillton's cup of sorrow seemed overflowing. For on the next play the umpire's whistle shrilled, and half the distance to the goal-line was paced off. Hillton was penalized for holding, and the ball was on her three yards!

From the section of the grand stand where the crimson flags waved came steady, entreating, the wailing slogan:

"Hold, Hillton! Hold, Hillton! Hold, Hillton!"

Near at hand, on the side-line, Gardiner ground his teeth on the stem of his pipe and watched with expressionless face. Professor Beck, at his side, frowned anxiously.

"Put it over, now!" cried the St. Eustace captain. "Tear them up, fellows!"

The quarter gave the signal, the two lines smashed together, and the whistle sounded. The ball had advanced less than a yard. The Hillton stand cheered hoarsely, madly.

"Line up! Line up!" cried the Blue's quarter. "Signal!"

Then it was that St. Eustace made her fatal mistake. With the memory of the delayed pass which had won St. Eustace her previous touch-down in mind, the Hillton quarter-back was on the watch.

The ball went back, was lost to view, the lines heaved and strained. Decker shot to the left, and as he reached the end of the line the St. Eustace left half-back came plunging out of the throng, the ball snuggled against his stomach. Decker, just how he never knew, squirmed past the single interferer, and tackled the runner firmly about the hips. The two went down together on the seven yards, the blue-stockinged youth vainly striving to squirm nearer to the line, Decker holding for all he was worth. Then the Hillton left end sat down suddenly on the runner's head and the whistle blew.

The grand stand was in an uproar, and cheers for Hillton filled the air. Gardiner turned away calmly and knocked the ashes from his pipe. Professor Beck beamed through his gold-rimmed glasses. Decker picked himself up and sped back to his position.

"Signal!" he cried. But a St. Eustace player called for time and the whistle piped again.

"If Decker tries a kick from there it'll be blocked, and they'll score again," said Gardiner. "Our line can't hold. There's just one thing to do, but I fear Decker won't think of it." He caught Gale's eye and signaled the captain to the side-line.

"What is it?" panted that youth, taking the nose-guard from his mouth and tenderly nursing a swollen lip. Gardiner hesitated. Then--

"Nothing. Only fight it out, Gale. You've got your chance now!" Gale nodded and trotted back. Gardiner smiled ruefully. "The rule against coaching from the side-lines may be a good one," he muttered, "but I guess it's lost this game for us."

The whistle sounded and the lines formed again.

"First down," cried the referee, jumping nimbly out of the way. Decker had been in conference with the full-back, and now he sprang back to his place.

"Signal!" he cried. "14--7--31!"

The Hillton full stood just inside the goal-line and stretched his hands out.

"16--8!"

The center passed the pigskin straight and true to the full-back, but the latter, instead of kicking it, stood as though bewildered while the St. Eustace forwards plunged through the Hillton line as though it had been of paper. The next moment he was thrown behind his goal-line with the ball safe in his arms, and Gardiner, on the side-line, was smiling contentedly.

"Touch-back," cried Decker. "Line up on the twenty yards, fellows!"

Hillton's ruse had won her a free kick, and in another moment the ball was arching toward the St. Eustace goal. The Blue's left half secured it, but was downed on his forty yards. The first attack netted four yards through Hillton's left-guard, and the crimson flags drooped on their staffs. On the next play St. Eustace's full-back hurdled the line for two yards, but lost the pigskin, and amid frantic cries of "Ball! Ball!" Fletcher, Hillton's left half, dropped upon it. The crimson banners waved again, and Hillton voices once more took up the refrain of Hilltonians, while hope surged back into loyal hearts.

"Five minutes to play," said Professor Beck. Gardiner nodded.

"Time enough to win in," he answered.

Decker crouched again, chanted his signal, and the Hillton full plunged at the blue-clad line. But only a yard resulted.

"Signal!" cried the quarter. "8--51--16--5!"

The ball came back into his waiting hands, was thrown at a short pass to the left half, and, with right half showing the way and full-back charging along beside, Fletcher cleared the line through a wide gap outside of St. Eustace's right tackle and sped down the field while the Hillton supporters leaped to their feet and shrieked wildly. The full-back met the St. Eustace right half, and the two were left behind on the turf. Beside Fletcher, a little in advance, ran the Hillton captain and right half-back, Paul Gale. Between them and the goal, now forty yards away, only the St. Eustace quarter remained, but behind them came pounding footsteps that sounded dangerous.

Gardiner, followed by the professor and a little army of privileged spectators, raced along the line.

"He'll make it," muttered the head coach. "They can't stop him!"

One line after another went under the feet of the two players. The pursuit was falling behind. Twenty yards remained to be covered. Then the waiting quarter-back, white-faced and desperate, was upon them. But Gale was equal to the emergency.

"To the left!" he panted.

Fletcher obeyed with weary limbs and leaden feet, and without looking knew that he was safe. Gale and the St. Eustace player went down together, and in another moment Fletcher was lying, faint but happy, over the line and back of the goal!

The stands emptied themselves on the instant of their triumphant burden of shouting, cheering, singing Hilltonians, and the crimson banners waved and fluttered on to the field. Hillton had escaped defeat!

But Fortune, now that she had turned her face toward the wearers of the Crimson, had further gifts to bestow. And presently, when the wearied and crestfallen opponents had lined themselves along the goal-line, Decker held the ball amid a breathless silence, and Hillton's right end sent it fair and true between the uprights: Hillton, 6; Opponents, 5.

The game, so far as scoring went, ended there. Four minutes later the whistle shrilled for the last time, and the horde of frantic Hilltonians flooded the field and, led by the band, bore their heroes in triumph back to the school. And, side by side, at the head of the procession, perched on the shoulders of cheering friends, swayed the two half-backs, Neil Fletcher and Paul Gale.

Two boys were sitting in the first-floor corner study in Haewood's. Those who know the town of Hillton, New York, will remember Haewood's as the large residence at the corner of Center and Village Streets, from the big bow-window of which the occupant of the cushioned seat may look to the four points of the compass or watch for occasional signs of life about the court-house diagonally across. To-night--the bell in the tower of the town hall had just struck half after seven--the occupants of the corner study were interested in things other than the view.

I have said that they were sitting. Lounging would be nearer the truth; for one, a boy of eighteen years, with merry blue eyes and cheeks flushed ruddily with health and the afterglow of the day's excitement, with hair just the color of raw silk that took on a glint of gold where the light fell upon it, was perched cross-legged amid the cushions at one end of the big couch, two strong, tanned, and much-scarred hands clasping his knees. His companion and his junior by but two months, a dark-complexioned youth with black hair and eyes and a careless, good-natured, but rather wilful face, on which at the present moment the most noticeable feature was a badly cut and much swollen lower lip, lay sprawled at the other end of the couch, his chin buried in one palm.

Both lads were well built, broad of chest, and long of limb, with bright, clear eyes, and a warmth of color that betokened the best of physical condition. They had been friends and room-mates for two years. This was their last year at Hillton, and next fall they were to begin their college life together. The dark-complexioned youth rolled lazily on to his back and stared at the ceiling. Then--

"I suppose Crozier will get the captaincy, Neil."

The boy with light hair nodded without removing his gaze from the little flames that danced in the fireplace. They had discussed the day's happenings thoroughly, had relived the game with St. Eustace from start to finish, and now the big Thanksgiving dinner which they had eaten was beginning to work upon them a spell of dormancy. It was awfully jolly, thought Neil Fletcher, to just lie there and watch the flames and--and--He sighed comfortably and closed his eyes. At eight o'clock he, with the rest of the victorious team, was to be drawn about the town in a barge and cheered at, but meanwhile there was time to just close his eyes--and forget--everything--

There was a knock at the study door.

"Go 'way!" grunted Neil.

"Oh, come in," called Paul Gale, without, however, removing his drowsy gaze from the ceiling or changing his position.

"I beg your pardon. I am looking for Mr. Gale, and--"

Paul dropped his legs over the side of the couch and sat up, blinking at the visitor. Neil followed his example. The caller was a carefully dressed man of about thirty-five, scarcely taller than Neil, but broader of shoulder. Paul recognized him, and, rising, shook hands.

"How do you do, Mr. Brill? Glad to see you. Sit down, won't you? I guess we were both pretty nigh asleep when you knocked."

"Small wonder," responded the visitor affably. "After the work you did this afternoon you deserve sleep, and anything else you want." He laid aside his coat and hat and sank into the chair which Paul proffered.

"By the way," continued the latter, "I don't think you've met my friend, Neil Fletcher. Neil, this is Mr. Brill, of Robinson; one of their coaches." The two shook hands.

"I'm delighted to meet the hero--I should say one of the heroes--of the day," said Mr. Brill. "That run was splendid; the way in which you two fellows got your speed up before you reached the line was worth coming over here to see, really it was."

"Yes, Paul set a pretty good pace," answered Neil.

The visitor discussed the day's contest for a few minutes, during which Neil glanced uneasily from time to time at the clock, wondered what the visitor wanted there, and heartily wished he'd take himself off. But presently Mr. Brill got down to business.

"You know we've had a little victory in football ourselves this fall," he was saying. "We won from Erskine by 17 to 6 last week, and we're feeling rather stuck up over it."

"Wait till next year," said Neil to himself, "and you'll get over it."

"And that," continued the coach, "brings me to the object of my call tonight. Frankly, we want you two fellows at Robinson College, and I'm here to see if we can't have you." He paused and smiled engagingly at the boys. Neil glanced surprisedly at Paul, who was thoughtfully examining the scars on his knuckles. "Don't decide until I've explained matters more clearly," went on the visitor. "Perhaps neither of you have been to Collegetown, but at least you know about where Robinson stands in the athletic world, and you know that as an institution of learning it is in the front rank of the smaller colleges; in fact, in certain lines it might dispute the place of honor with some of the big ones.

"To the fellow who wants a college where he can learn and where, at the same time, he can give some attention to athletics, Robinson's bound to recommend itself. I mention this because you know as well as I do that there are colleges--I mention no names--where a born football player, such as either of you, would simply be lost; where he would be tied down by such stringent rules that he could never amount to anything on the gridiron. I don't mean to say that at Robinson the faculty is lax regarding standing or attendance at lectures, but I do say that it holds common-sense views on the subject of college athletics, and does not hound a man to death simply because he happens to belong to the football eleven or the crew.

"Robinson is always on the lookout for first-class football, baseball, or rowing material, and she believes in offering encouragement to such material. She doesn't favor underhand methods, you understand; no hiring of players, no free scholarships--though there are plenty of them for those who will work for them--none of that sort of thing. But she is willing to meet you half-way. The proposition which I am authorized to make is briefly this"--the speaker leaned forward, smiling frankly, and tapped a forefinger on the palm of his other hand--"If you, Mr. Gale, and you, Mr. Fletcher, will enter Robinson next September, the--ah--the athletic authorities will guarantee you positions on the varsity eleven. Besides this, you will be given free tutoring for the entrance exams, and afterward, so long as you remain on the team, in any studies with which you may have difficulty. Now, there is a fair, honest proposition, and one which I sincerely trust you will accept. We want you both, and we're willing to do all that we can--in honesty, that is--to get you. Now, what do you say?"

During this recital Neil's dislike of the speaker had steadily increased, and now, under the other's smiling regard, he had difficulty in keeping from his face some show of his emotions. Paul looked up from his scarred knuckles and eyed Neil furtively before he turned to the coach.

"Of course," he said, "this is rather unexpected."

The coach's eyes flickered for an instant with amusement.

"For my part," Neil broke in almost angrily, "I'm due in September at Erskine, and unless Paul's changed his mind since yesterday so's he."

The Robinson coach raised his eyebrows in simulated surprise.

"Ah," he said slowly, "Erskine?"

"Yes, Erskine," answered Neil rather discourteously. A faint flush of displeasure crept into Mr. Brill's cheeks, but he smiled as pleasantly as ever.

"And your friend has contemplated ruining his football career in the same manner, has he?" he asked politely, turning his gaze as he spoke on Paul. The latter fidgeted in his chair and looked over a trifle defiantly at his room-mate.

"I had thought of going to Erskine," he answered. "In fact"--observing Neil's wide-eyed surprise at his choice of words--"in fact, I had arranged to do so. But--but, of course, nothing has been settled definitely."

"But, Paul--" exclaimed Neil.

"Well, I'm glad to hear that," interrupted Mr. Brill. "For in my opinion it would simply be a waste of your opportunities and--ah--abilities, Mr. Gale."

"Well, of course, if a fellow doesn't have to bother too much about studies," said Paul haltingly, "he can do better work on the team; there can't be any question about that, I guess."

"None at all," responded the coach.

Neil stared at his chum indignantly.

"You're talking rot," he growled. Paul flushed and returned his look angrily.

"I suppose I have the right to manage my own affairs?" he demanded. Neil realized his mistake and, with an effort, held his peace. Mr. Brill turned to him.

"I fear there's no use in attempting to persuade you to come to us also?" he said. Neil shook his head silently. Then, realizing that Paul was quite capable, in his present fit of stubbornness, of promising to enter Robinson if only to spite his room-mate, Neil used guile.

"Anyhow, September's a long way off," he said, "and I don't see that it's necessary to decide to-night. Perhaps we had both better take a day or two to think it over. I guess Mr. Brill won't insist on a final answer to-night."

The Robinson coach hesitated, but then answered readily enough:

"Certainly not. Think it over; only, if possible, let me hear your decision to-morrow, as I am leaving town then."

"Well, as far as I'm concerned," said Paul, "I don't see any use in putting it off. I'm willing--"

Neil jumped to his feet. A burst of martial music swept up to them as the school band, followed by a host of their fellows, turned the corner of the building.

"Come on, Paul," he cried; "get your coat on. Mr. Brill will excuse us if we leave him; we mustn't keep the fellows waiting. And we can think the matter over, eh, Paul? And we'll let him know in the morning. Here's your coat. Good-night, sir, good-night." He was holding the door open and smiling politely. Paul, scowling, arose and shook hands with the Robinson emissary. Neil kept up a steady stream of talk, and his chum could only mutter vague words about his pleasure at Mr. Brill's call and about seeing him to-morrow. When the door had closed behind him the coach stood a moment in the hall and thoughtfully buttoned his coat.

"I think I've got Gale all right," he said to himself, "but"--with a slight smile--"the other chap was too smart for me. And, confound him, he's just the sort we need!"

When he reached the entrance he was obliged to elbow his way through a solid throng of shouting youths who with excited faces and waving caps and flags informed the starlight winter sky over and over that they wanted Gale and Fletcher, to which demand the band lent hearty if rather discordant emphasis.

A good deal happened in the next two hours, but nothing that is pertinent to this narrative. Victorious Hillton elevens have been hauled through the village and out to the field many times in past years, and bonfires have flared and speeches have been made by players and faculty, and all very much as happened on this occasion. Neil and Paul returned to their room at ten o'clock, tired, happy, with the cheers and the songs still echoing in their ears.

Paul had apparently forgotten his resentment toward Neil and the whole matter of Brill's proposition. But Neil hadn't, and presently, when they were preparing for bed, he returned doggedly to the charge.

"When did you meet that fellow Brill?" he asked.

"In Gardiner's room this morning; he introduced us." Paul began to look sulky again. "Seems a decent sort, I think," he added defiantly. Neil accepted the challenge.

"I dare say," he answered carelessly. "There's only one thing I've got against him."

"What's that?" questioned Paul suspiciously.

"His errand."

"What's wrong with his errand?"

"Everything, Paul. You know as well as I that his offer is--well, it's shady, to say the least. Who ever heard of a decent college offering free tutoring in order to get fellows for its football team?"

"Lots of them do," growled Paul.

"No, they don't; not decent ones. Some do, I know; but they're not colleges a fellow cares to go to. Every one knows what rotten shape Robinson athletics are in; the papers have been full of it for two years. Their center rush this fall, Harden, just went there to play on the team, and everybody says that he got his tuition free. You don't want to play on a team like that and have people say things like that about you. I'm sure I don't."

"Oh, you!" sneered Paul. "You're getting crankier and crankier every day. I'll bet you're just huffy because Brill didn't ask you first."

Neil flushed, but kept his temper.

"You don't think anything of the sort, Paul. Besides--"

"It looks that way," muttered Paul.

"Besides," continued Neil calmly, "what's the advantage in going to Robinson? We've arranged everything; we've got our rooms picked out at Erskine; there are lots of fellows there we know; the college is the best of its class and its athletics are honest. If you play on the Erskine team you'll be somebody, and folks won't hint that you're receiving money or free scholarships or something for doing it. And as for Brill's guarantee of a place on the team, why, there's only one decent way to get on a football team, and that's by good, hard work; and there's no reason for doubting that you'll make the Erskine varsity eleven."

"Yes, there is, too," answered Paul angrily. "They've got lots of good players at Erskine, and you and I won't stand any better show than a dozen others."

"I don't want to."

"Huh! Well, I do; that is, I want to make the team. Besides, as Brill said, if a fellow has the faculty after him all the time about studies he can't do decent work on the team. I don't see anything wrong in it, and--and I'm going. I'll tell Brill so to-morrow!"

Neil drew his bath-robe about him, and looked thoughtfully into the flames. So far he had lost, but he had one more card to play. He turned and faced Paul's angry countenance.

"Well, if I should go to Robinson and play on her team under the conditions offered by that--by Brill I'd feel disgraced."

"You'd better stay away, then," answered Paul hotly.

"I wouldn't want to show my face around Hillton afterward, and if I met Gardiner or 'Wheels' I'd take the other side of the street."

"Oh, you would?" cried his room-mate. "You're trying to make yourself out a little fluffy angel, aren't you? And I suppose I'm not good enough to associate with you, am I? Well, if that's it, all I've got to say--"

"But," continued Neil equably, "if you accept Brill's offer, so will I."

Paul paused open-mouthed and stared at his chum. Then his eyes dropped and he busied himself with a stubborn stocking. Finally, with a muttered "Humph!" he gathered up his clothing and disappeared into the bedroom. Neil turned and smiled at the flames and, finding his own apparel, followed. Nothing more was said. Paul splashed the water about even more than usual and tumbled silently into bed. Neil put out the study light and followed suit.

"Good-night," he said.

"Good-night," growled Paul.

It had been a hard day and an exciting one, and Neil went to sleep almost as soon as his head touched the pillow. It seemed hours later, though in reality but some twenty minutes, that he was awakened by hearing his name called. He sat up quickly.

"Hello! What?" he shouted.

"Shut up," answered Paul from across in the darkness. "I didn't know you were asleep. I only wanted to say--to tell you--that--that I've decided not to go to Robinson!"

Almost every one has heard of Erskine College. For the benefit of the few who have not, and lest they confound it with Williams or Dartmouth or Bowdoin or some other of its New England neighbors, it may be well to tell something about it. Erskine College is still in its infancy, as New England universities go, with its centennial yet eight years distant. But it has its own share of historic associations, and although the big elm in the center of the campus was not planted until 1812 it has shaded many youths who in later years have by good deeds and great accomplishments endeared themselves to country and alma mater.

In the middle of the last century, when Erskine was little more than an academy, it was often called "the little green school at Centerport." It is not so little now, but it's greener than ever. Wide-spreading elms grow everywhere; in serried ranks within the college grounds, in smaller detachments throughout the village, in picket lines along the river and out into the country. The grass grows lush wherever it can gain hold, and, not content with having its own way on green and campus, is forever attempting the conquest of path and road. The warm red bricks of the college buildings are well-nigh hidden by ivy, which, too, is an ardent expansionist. And where neither grass nor ivy can subjugate, soft, velvety moss reigns humbly.

In the year 1901, which is the period of this story, the enrolment in all departments at Erskine was close to six hundred students. The freshman class, as had been the case for many years past, was the largest in the history of the college. It numbered 180; but of this number we are at present chiefly interested in only two; and these two, at the moment when this chapter begins--which, to be exact, is eight o'clock of the evening of the twenty-fourth day of September in the year above mentioned--were busily at work in a first-floor study in the boarding-house of Mrs. Curtis on Elm Street.

It were perhaps more truthful to say that one was busily at work and the other was busily advising and directing. Neil Fletcher stood on a small table, which swayed perilously from side to side at his every movement, and drove nails into an already much mutilated wall. Paul Gale sat in a hospitable armchair upholstered in a good imitation of green leather and nodded approval.

"That'll do for 'Old Abe'; now hang The First Snow a bit to the left and underneath."

"The First Snow hasn't any wire on it," complained Neil. "See if you can't find some."

"Wire's all gone," answered Paul. "We'll have to get some more. Where's that list? Oh, here it is. 'Item, picture wire.' I say, what in thunder's this you've got down--'Ring for waistband'?"

"Rug for wash-stand, you idiot! I guess we'll have to quit until we get some more wire, eh? Or we might hang a few of them with boot-laces and neckties?"

"Oh, let's call it off. I'm tired," answered Paul with a grin. "The room begins to look rather decent, doesn't it? We must change that couch, though; put it the other way so the ravelings won't show. And that picture of--"

But just here Neil attempted to step from the table and landed in a heap on the floor, and Paul forgot criticism in joyful applause.

"Oh, noble work! Do it again, old man; I didn't see the take-off!"

But Neil refused, and plumping himself into a wicker rocking-chair that creaked complainingly, rubbed the dust from his hands to his trousers and looked about the study approvingly.

"We're going to be jolly comfy here, Paul," he said. "Mrs. Curtis is going to get a new globe for that fixture over there."

[Illustration: Getting settled.]

"Then we will be," said Paul. "And if she would only find us a towel-rack that didn't fall into twelve separate pieces like a Chinese puzzle every time a chap put a towel on it we'd be simply reveling in luxury."

"I think I can fix that thing with string," answered Neil. "Or we might buy one of those nickel-plated affairs that you screw into the wall."

"The sort that always dump the towels on to the floor, you mean? Yes, we might. Of course, they're of no practical value judged as towel-racks, but they're terribly ornamental. You know we had one in the bath-room at the beach. Remember? When you got through your bath and groped round for the towel it was always lying on the floor just out of reach."

"Yes, I remember," answered Neil, smiling. "We had rather a good time, didn't we, at Seabright? It was awfully nice of you to ask me down there, Paul; and your folks were mighty good to me. Next summer I want you to come up to New Hampshire and see us for a while. Of course, we can't give you sea bathing, and you won't look like a red Indian when you go home, but we could have a good time just the same."

"Red Indian yourself!" cried Paul. "You're nearly twice as tanned as I am. I don't see how you did it. I was there pretty near all summer and you stayed just three weeks; and look at us! I'm as white as a sheet of paper--"

"Yes, brown paper," interpolated Neil.

"And you have a complexion like a--a football after a hard game."

Neil grinned, then--

"By the way," he said, "did I tell you I'd heard from Crozier?"

"About Billy and the ducks? And Gordon's not going back to Hillton? Yes, you got that at the beach; remember?"

"So I did. 'Old Cro' will be up to his ears in trouble pretty soon, won't he? I'm glad they made him captain, awfully glad. I think he can turn out a team that'll rub it into St. Eustace again just as you did last year."

"Yes; and Gardiner's going to coach again." Paul smiled reminiscently. Then, "By Jove, it does seem funny not to be going back to old Hillton, doesn't it? I suppose after a while a fellow'll get to feeling at home here, but just at present--" He sighed and shook his head.

"Wait until college opens to-morrow and we get to work; we won't have much time to feel much of anything, I guess. Practise is called for four o'clock. I wonder--I wonder if we'll make the team?"

"Why not?" objected Paul. "If I thought I wouldn't I think I'd pitch it all up and--and go to Robinson!" He grinned across at his chum.

"You stay here and you'll get a chance to go at Robinson; that's a heap more satisfactory."

"Well, I'm going to make the varsity, Neil. I've set my heart on that, and what I make up my mind to do I sometimes most always generally do. I'm not troubling, my boy; I'll show them a few tricks about playing half-back that'll open their eyes. You wait and see!"

Neil looked as though he was not quite certain as to that, but said nothing, and Paul went on:

"I wonder what sort of a fellow this Devoe is?"

"Well, I've never seen him, but we know that he's about as good an end as there is in college to-day; and I guess he's bound to be the right sort or they wouldn't have made him captain."

"He's a senior, isn't he?"

"Yes; he's played only two years, and they say he's going into the Yale Law School next year. If he does, of course he'll get on the team there. Well, I hope he'll take pity on two ambitious but unprotected freshmen and--"

There was a knock at the study door and Paul jumped forward and threw it open. A tall youth of twenty-one or twenty-two years of age stood in the doorway.

"I'm looking for Mr. Gale and Mr. Fletcher. Have I hit it right?"

"I'm Gale," answered Paul, "and that's Fletcher. Won't you come in?" The visitor entered.

"My name's Devoe," he explained smilingly. "I'm captain of the football team this year, and as you two fellows are, of course, going to try for the team, I thought we'd better get acquainted." He accepted the squeaky rocking-chair and allowed Paul to take his straw hat. Neil thought he'd ought to shake hands, but as Devoe made no move in that direction he retired to another seat and grinned hospitably instead.

"I've heard of the good work you chaps did for Hillton last year, and I was mighty glad when I learned from Gardiner that you were coming up here."

"You know Gardiner?" asked Neil.

"No, I've never met him, but of course every football man knows who he is. He wrote to me in the spring that you were coming, and rather intimated that if I knew my business I'd keep an eye on you and see that you didn't get lost in the shuffle. So here I am."

"He didn't say anything about having written," pondered Neil.

"Oh, he wouldn't," answered Devoe. "Well, how do you like us as far as you've seen us?"

"We only got here yesterday," replied Paul. "I think it looks like rather a jolly sort of place; awfully pretty, you know, and--er--historic."

"Yes, it is pretty; historic too; and it's the finest young college in the country, bar none," answered Devoe. "You'll like it when you get used to it. I like it so well I wish I wasn't going to leave it in the spring. Very cozy quarters you have here." He looked about the study.

"They'll do," answered Neil modestly. "Of course we couldn't get rooms in the Yard, and we liked this as well as anything we saw outside. The view's rather good from the windows."

"Yes, I know; you have the common and pretty much the whole college in sight; it is good." Devoe brought his gaze back and fixed it on Neil. "You played left half, didn't you?"

"Yes."

"What's your weight?"

"I haven't weighed this summer," answered Neil. "In the spring I was a hundred and sixty-two."

"Good. We need some heavy backs. How about you, Gale?"

"About a hundred and sixty."

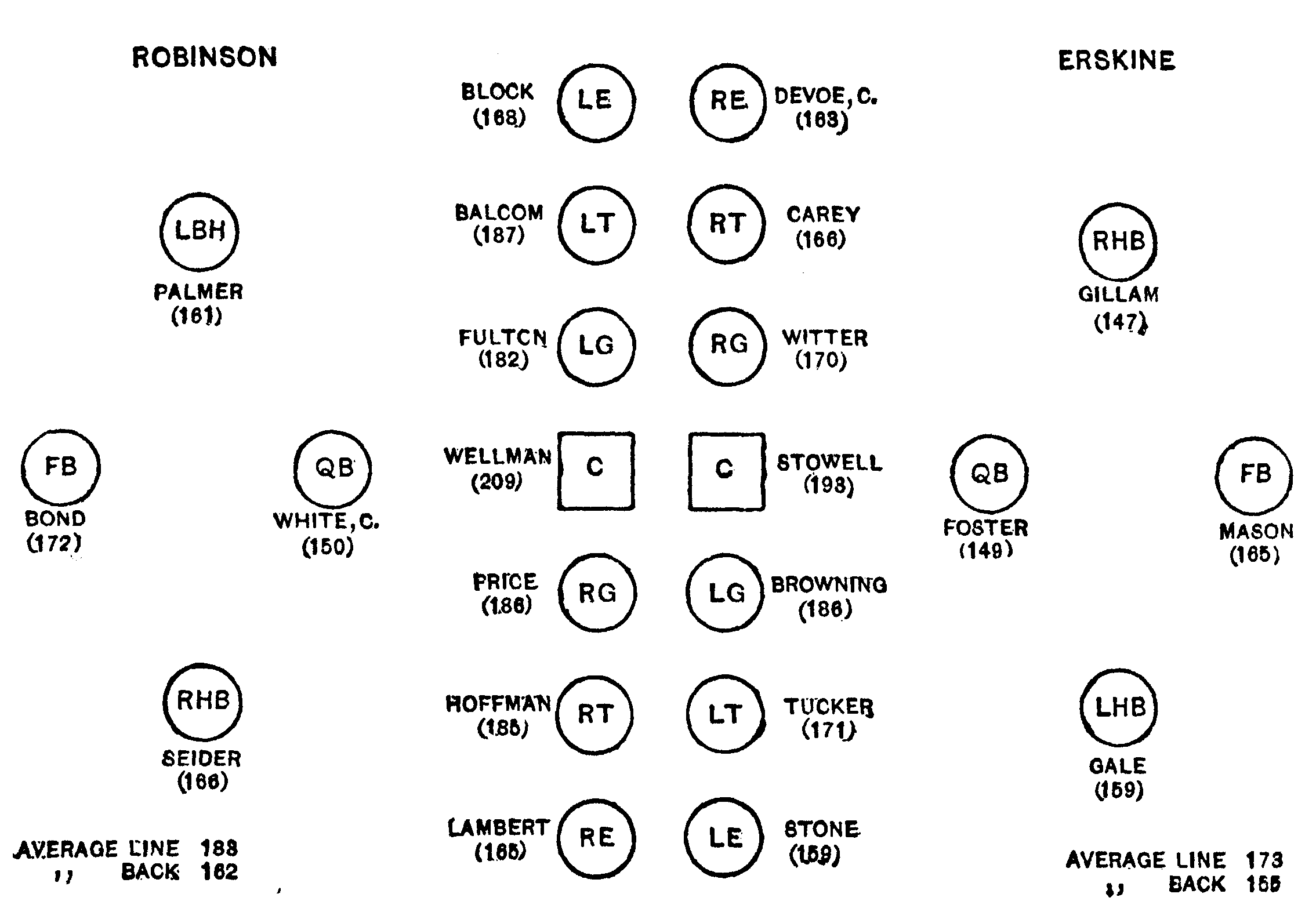

"Of course I haven't seen the new material yet," continued Devoe, "but the last year's men we have are a bit light, take them all around. That's what beat us, you see; Robinson had an unusually heavy line and rather heavy backs. They plowed through us without trouble."

Neil studied the football captain with some interest. He saw a tall and fairly heavy youth, with well-set head and broad shoulders. He looked quite as fast on his feet as rumor credited him with being, and his dark eyes, sharp and steady in their regard, suggested both courage and ability to lead. His other features were strong, the nose a trifle heavy, the mouth usually unsmiling, the chin determined, and the forehead, set off by carefully brushed dark-brown hair, high and broad. After the first few moments of conversation Devoe devoted his attention principally to Neil, questioning him regarding Gardiner's coaching methods, about Neil's experience on the gridiron, as to what studies he was taking up. Occasionally he included Paul in the conversation, but that youth discovered, with surprise and chagrin, that he was apparently of much less interest to Devoe than was Neil. After a while he dropped out of the talk altogether, save when directly appealed to, and sat silent with an expression of elaborate unconcern. At the end of half an hour Devoe arose.

"I must be getting on," he announced. "I'm glad we've had this talk, and I hope you'll both come over some evening and call on me; I'm in Morris, No. 8. We've got our work cut out this fall, and I hope we'll all pull together." He smiled across at Paul, evidently unaware of having neglected that young gentleman in his conversation. "Good-night. Four o'clock to-morrow is the hour."

"I never met any one that could ask more questions than he can," exclaimed Neil when Devoe was safely out of hearing. "But I suppose that's the way to learn, eh?"

Paul yawned loudly and shrugged his shoulders.

"Funny he should have come just when we were talking about him, wasn't it?" Neil pursued. "What do you think of him?"

"Well, if you ask me," Paul answered, "I think he's a conceited, stuck-up prig!"

Neil's and Paul's college life began early the next morning when, sitting side by side in the dim, hushed chapel, they heard white-haired Dr. Garrison ask for them divine aid and guidance. Splashes and flecks of purple and rose and golden light rested here and there on bowed head and shoulders or lay in shafts across the aisles. From where he sat Neil could look through an open window out into the morning world of greenery and sunlight. On the swaying branch of an elm that almost brushed the casement a thrush sang sweet and clear a matin of his own. Neil made several good resolutions that morning there in the chapel, some of which he profited by, all of which he sincerely meant. And even Paul, far less impressionable than his friend, looked uncommonly thoughtful all the way back to their room, a way that led through the elm-arched nave of College Place and across the common with its broad expanses of sun-flecked sward and its simple granite shaft commemorating the heroes of the civil war.

At nine o'clock, with the sound of the pealing bell again in their ears, with their books under their arms and their hearts beating a little faster than usual with pleasurable excitement, they retraced their path and mounted the well-worn granite steps of College Hall for their first recitation. What with the novelty of it all the day passed quickly enough, and four o'clock found the two lads dressed in football togs and awaiting the beginning of practise.

There were some sixty candidates in sight, boys--some of them men as far as years go--of all sizes and ages, several at the first glance revealing the hopelessness of their ambitions. The names were taken and fall practise at Erskine began.

The candidates were placed on opposite sides of the gridiron, and half a dozen footballs were produced. Punting and catching punts was the order of the day, and Neil was soon busily at work. The afternoon was warm, but not uncomfortably so, the turf was springy underfoot, the sky was blue from edge to edge, the new men supplied plenty of amusement in their efforts, the pigskins bumped into his arms in the manner of old friends, and Neil was happy as a lark. After one catch for which he had to run back several yards, he let himself out and booted the leather with every ounce of strength. The ball sailed high in a long arching flight, and sent several men across the field scampering back into the grand stand for it.

"I guess you've done that before," said a voice beside him. A short, stockily-built youth with a round, smiling face and blue eyes that twinkled with fun and good spirits was observing him shrewdly.

"Yes," answered Neil, "I have."

"I thought so," was the reply. "But you're a freshman, aren't you?"

"Yes," answered Neil, turning to let a low drive from across the gridiron settle into his arms. "And I guess you're not."

"No, this is my third year. I've been on the team two." He paused to send a ball back, and then wiped the perspiration from his forehead. "I was quarter last year."

"Oh," said Neil, observing his neighbor with interest, "then you're Foster?"

"That's me. What are you trying for?"

"Half-back. I played three years at Hillton."

"Of course; you're the fellow Bob Devoe was talking about--or one of them; I think he said there were two of you. Which one are you?"

"I'm the other one," laughed Neil. "I'm Fletcher. That's Gale over there, the fellow in the old red shirt; he was our captain at Hillton last year."

Foster looked across at Paul and then back at Neil. He was evidently comparing them. He shook his head.

"It's a good thing he's got dark hair and you've got light," he said. "Otherwise you wouldn't know yourselves apart; you're just of a height and build, and weight, too, I guess. Are you related?"

"No. But we are pretty much the same height and weight. He's half an inch taller, and I think I weigh two pounds more."

In the intervals of catching and returning punts the acquaintance ripened. When, at the end of three-quarters of an hour, Devoe gave the order to quit and the trainer sent them twice about the gridiron on a trot, Neil found Foster ambling along beside him.

"Phew!" exclaimed the latter. "I guess I lived too high last summer and put on weight. This is taking it out of me finely; I can feel whole pounds melting off. It doesn't seem to bother you any," he added.

"No, I haven't much flesh about me," panted Neil; "but I'm glad this is the last time around, just the same!"

After their baths in the little green-roofed locker-house the two walked back to the yard together, Paul, as Neil saw, being in close companionship with a big youth whose name, according to Foster, was Tom Cowan.

"He played right-guard last year," said Foster. "He's a soph; this is his third year."

"Third year!" exclaimed Neil. "But how--"

"Oh, Cowan was too busy to pass his exams last year," said Foster with a grin. "So they let him stay a soph. He doesn't care; a little thing like that never bothers Cowan." His tone was rather contemptuous.

"Is he liked?" Neil asked.

"Oh, yes; he's very popular among a small and select circle of friends--a very small circle." Then he dismissed Cowan with an airy wave of one hand. "By the way," he continued, "have you any candidate for the presidency of your class?"

"No," Neil replied. "I haven't heard anything about it yet."

"Good; then you can vote for 'Fan' Livingston. He's a protégé of mine, you see; used to know him at St. Mathias; you'll like him. He's an awfully good, manly, straightforward chap, just the fellow for the place. The election comes off next Thursday evening. How about your friend?"

"Gale? I don't think he has any one in view. I guess you can count on his vote, too."

"Thanks; just mention it to him, will you? I'm booming Livingston, and I want to see him win. Can't you come round some evening the first of the week? I'd like you to meet him. And meanwhile just talk him up a bit, will you?"

Neil promised and made an appointment to meet the candidate the following Saturday night at Foster's room in McLean Hall. The two parted at the gate, Foster going up to his room and Neil traversing the campus and the common to his own quarters. As he opened the study door he was surprised to hear voices within. Paul and his new acquaintance, Tom Cowan, were sitting side by side on the window-seat.

"Hello," greeted the former. "How'd it go? Like old times, wasn't it? Neil, I want you to meet Mr. Cowan. Cowan has quarters up-stairs here. He's an old player, and we've been telling each other how good we are."

Cowan looked for an instant as though he didn't quite appreciate the latter remark, but summoned a smile as he shook hands with Neil and complimented him on his playing in Hillton's last game with St. Eustace. Neil replied with extraordinary politeness. He was always extraordinarily polite to persons he didn't fancy, and his dislike of Cowan was instant and hearty. Cowan looked to be fully twenty-three years old, and owned to being twenty-one. He was fully six feet two, and apparently weighed about two hundred pounds. His face was rather handsome in a coarse, heavy-featured style, and his hands, as Neil observed, were not quite clean. Later, Neil discovered that they never were.

After listening politely for some moments to Cowan's tales of former football triumphs and defeats, in all of which the narrator played, according to his words, a prominent part, Neil broke into the stream of his eloquence and told Paul of his meeting with Foster, and of their talk regarding the freshman presidency.

"Well," answered Paul, smiling at Cowan, "you'll have to get out of that promise to Foster or whatever his name is, because we've got a plan better than that. The fact is, Neil, I'm going to try for the presidency myself!"

"I suppose you're fooling?" gasped Neil.

"Not a bit! Why shouldn't I have a fling at it? Cowan here has promised to help; in fact, it was he that suggested it. With his help and yours, and with the kind assistance of one or two fellows I know here, I dare say I can pull out on top. Anyhow, there's no harm in trying."

"I think you'll win," said Cowan. "This chump Livingston that Foster is booming is a regular milksop; does nothing but grind, so they say; came out of St. Mathias with all kinds of silly prizes and such. What the fellows always want is a good, popular chap that goes in for athletics and that will make a name for himself."

"Foster said Livingston was something of a dab at baseball," said Neil.

"Baseball!" cried Cowan. "What's baseball? Why not puss-in-the-corner? A chap with a football reputation like Gale here can walk all round your baseball man. We'll carry it with a rush! You'll see! Freshmen are like a lot of sheep--show 'em the way and they'll fall over themselves to get there."

"Well, we're freshmen ourselves, you know," said Neil sweetly. Cowan looked nonplussed for a moment. Then--

"Oh, but you fellows are different; you've got sense. I was speaking of the general run of freshmen," he explained.

"Thanks," murmured Neil. Paul scented danger.

"I'll put the campaign in your hands and Cowan's, Neil," he said. "You know several fellows here--there's Wallace and Knowles and Jones. They're not freshmen, but they can give you introductions. Knowles is a St. Agnes man and there are lots of St. Agnes fellows in our class."

"I think you're making a mistake," answered Neil soberly, "and I wish you'd give it up. Livingston's got lots of supporters, and he's had his campaign under way for a week. If you're defeated I think it'll hurt you; fellows don't like defeated candidates when--when they're self-appointed candidates."

"Oh, of course, if you don't want to help," cried Paul, with a trace of anger in his voice, "I guess we can get on without you."

"I'm sure you won't desert your chum, Fletcher," said Cowan. "And I think you're all wrong about defeated candidates. If a fellow makes a good fight and is worsted no fellow that isn't a cad does other than honor him."

"Well, if you've made up your mind, Paul," answered Neil reluctantly, "of course I'll do all I can if Foster will let me out of my promise to him."

"Oh, hang Foster!" cried Cowan. "He's a little fool!"

"Is he?" asked Neil innocently. "I hadn't noticed it. Well, as I say, I'll do all I can. And I'll begin now by going over to see him."

"That's the boy," said Paul. "Tell Foster there's a dark horse in the field."

"And tell him I say the dark horse will win," added Cowan.

Neil smiled back politely from the doorway.

"I don't think I'd better mention your name, Mr. Cowan." He closed the door behind him, leaving Cowan much puzzled as to the meaning of the last remark, and sought No. 12 McLean. He found the varsity quarter-back writing a letter by means of a small typewriter, his brow heavily creased with scowls and his feet kicking exasperatedly at the legs of his chair.

"Hello," was Foster's greeting. "Come in. And, I say, just look around on the floor there, will you, and see if you can find an L."

"Find what?" asked Neil, searching the carpet with his gaze.

"An L. There was one on this pesky machine a while ago, but I--can't--find--Ah, here it is! 'L-O-V-I-N-G-L-Y, T-E-D'! There, that's done. I bought this idiotic thing because some one said you could write letters on it in half the time it takes with a pen. Well, I began this letter last night, and I guess I've spent fully two hours on it altogether. For two cents I'd pitch it out the window!" He pushed back his chair and glared vindictively at the typewriter. "And look at the result!" He held up a sheet of paper half covered with strange characters and erasures. "Look how I've spelled 'allowance'--alliwzee! Do you think dad will know what I mean?"

Neil shook his head dubiously.

"Not unless he's looking for the word," he answered.

"Well, he will be," grinned Foster. "Don't suppose you want to buy a fine typewriter at half price, do you?"

Neil was sure he didn't and broached the subject of his call. Foster showed some amazement when he learned of Gale's candidacy, but at once absolved Neil from his promise.

"Frankly, Fletcher, I don't think your friend has the ghost of a show, you know, but, of course, if he wants to try it it's all right. And I'm just as much obliged to you."

During the next week Neil worked early and late for Paul's success. He made some converts, but not enough to give him much hope. Livingston was easily the popular candidate for the presidency, and Neil failed to understand where Cowan found ground for the encouraging reports that he made to Paul. Paul himself was hopeful all the way through, and lent ill attention to Neil's predictions of failure.

"You always were a raven, chum," he would exclaim. "Wait until Thursday night."

And Neil, without much hope, waited.

The freshman election took place in one of the lecture rooms of Grace Hall. There was a full attendance of the entering class, while the absence of sophomores was considered by those who had heard of former freshman elections at Erskine as something unnatural and of evil portent.

Paul, robbed of the support of Tom Cowan's presence, was noticeably ill at ease, and for the first time appeared to be in doubt as to his election. Fanwell Livingston was put in nomination by one of his St. Mathias friends in a speech that secured wide applause, and the nomination was duly seconded by a red-headed and very eloquent youth who, so Neil learned, was King, the captain of the St. Mathias baseball team of the preceding spring.

"Are there any more nominations?" asked the chairman, a member of the junior class.

South, a Hillton boy, arose and spoke at some length of the courage and ability for leadership of one of whom they had all heard; "of one who on the white-grilled field of battle had successfully led the hosts of Hillton Academy against the St. Eustace hosts." (Two St. Eustace graduates howled derisively.) South ended in a wild burst of flowery eloquence and placed in nomination "that triumphant football captain, that best of good fellows, Paul Dunlop Gale!"

The applause which followed was flattering, though, had Paul but known it, it was rather for the speech than the nominee. And the effect was somewhat marred by several inquiries from different parts of the hall as to who in thunder Gale was. Neil secured recognition ere the applause had subsided, and seconded the nomination. He avoided rhetoric, and told his classmates in few words and simple phrases that Paul Gale possessed pluck, generalship, and executive ability; that he had proved this at Hillton, and, given the chance, would prove it again at Erskine.

"Gale is a stranger to many of you fellows," he concluded, "but, whether you make him class president or whether you give that honor to another, he won't be a stranger long. A fellow that can pilot a Hillton football team to victory against almost overwhelming odds and through the greatest of difficulties as Gale did last year is not the sort to sit around in corners and watch the procession go by. No, sir; keep your eye on him. I'll wager that before the year's out you'll be prouder of him than of any man in your class. And, meanwhile, if you're looking for the right man for the presidency, a man that'll lead 1905 to a renown beside which the other classes will look like so many battered golf-balls, why, I've told you where to look."

Neil sat down amid a veritable roar of applause, and Paul, totally unembarrassed by the praise and acclaim, smiled with satisfaction. "That was all right, chum," he whispered. "I guess we've got them on the run, eh?"

But Neil shook his head doubtfully. Cries of "Vote! Vote!" arose, and in a moment or two the balloting began. While this was proceeding announcement was made that the annual Freshman Class Dinner would be held on the evening of the following Monday, October 7th. When the cheers occasioned by this information had subsided the chairman arose.

"The result of the balloting, gentlemen," he announced, "is as follows: Livingston, 97; Gale, 45. Mr. Livingston is elected by a majority of 52."

Shouts of "Livingston! Livingston! Speech! Speech!" filled the air, and were not stilled until some one arose and announced that the president-elect was not in the hall. Paul, after a glance of bewilderment at Neil, had sat silent in his chair with something between a sneer and a scowl on his face. Now he jumped up.

"Come on; let's get out of here," he muttered. "They act like a lot of idiots." Neil followed, and they found themselves in a pushing throng at the door. The chairman was vainly clamoring for some one to put a motion to adjourn, but none heeded him. The crowd pushed and shoved, but made no progress.

"Open that door," cried Paul.

"Try it yourself," answered a voice up front. "It's locked!"

A murmur arose that quickly gave place to cries of wrath and indignation. "The sophs did it!" "Where are they?" "Break the door down!" Those at the rear heaved and pushed.

"Stop shoving, back there!" yelled those in front. "You're squashing us flat."

"Everybody away from the door!" shouted Neil. "Let's see if we can't get it open." The fellows finally fell back to some extent, and Neil, Paul, and some of the others examined the lock. The key was still there, but, unfortunately, on the outside. Breaking the door down was utterly out of the question, since it was of solid oak and several inches thick. The self-appointed committee shook its several heads.

"We'll have to yell for the janitor," said Neil. "Where does he hang out?"

But none knew. Neil went to one of the three windows and raised it. Instantly a chorus of derision floated up from below. Gathered almost under the windows was a throng of sophomores, their upturned faces just visible in the darkness.

"O Fresh! O Fresh!" "Want to come down?" "Why don't you jump?" These gibes were followed by cheers for "'04" and loud groans. Neil turned and faced his angry classmates.

"Look here, fellows," he said, "we don't want to have to yell for the janitor with those sophs there; that's too babyish. The key's in the outside of the lock. I think I can get down all right by the ivy, and I'll unlock the door if those sophs will let me. If two or three of you will follow I guess we can do it all right."

"Bully for you!" "Plucky boy!" cried the audience. But for a moment none came forward to share the risk. Then Paul pushed his way to the window.

"Here, I'll go with you, chum," he said, with a suggestion of swagger. "We can manage those dubs down there alone. The rest of you can sit down and tell stories; we'll let you out in a minute," he added scathingly.

"That's Gale," whispered some one. "Fresh kid!", added another angrily. But the gibe had the desired effect. Four other freshmen signified their willingness to die for their class, and Neil climbed on to the broad window-sill. His reappearance was the signal for another outburst from the watching sophomores.

"Don't jump, sonny; you may hurt yourself." "He's going to fly, fellows! Good little Freshie's got wings!" "Say, we'll let you out in the morning! Good-night!"

But when Neil, divesting himself of coat and shoes, swung out and laid hold of the largest of the big ivy branches that clung there to the wall, the jeers died away. The hall where the meeting had been held was on the third floor, and when Neil stepped from the window-sill he hung fully twenty-five feet from the ground. The ivy branch, ages old, was almost as large as his wrist, and quite strong enough to bear his weight just as long as it did not tear from its fastenings. Whether it would hold in place remained to be seen. Neil judged that if he could lower himself fifteen feet by its aid he could easily drop the rest of the distance without injury. The window above was black with watchers as he began his journey, and many voices cheered him on. Paul, his feet hanging over the black void, sat on the narrow ledge and waited his turn.

"Go fast, chum," he counseled, "but don't lose your grip. I'll wait until you're down."

"All right," answered Neil. Then, with a great rustling of the thick-growing leaves, he lowered himself by arm's lengths. The vine swayed and gave at every strain, but held. From below came the sound of clapping. Hand under hand he went. The oblong of faint light above receded fast. His stockinged feet gripped the vine tightly. In the group of sophomores the clapping grew into cheers.

The vine swayed at every strain.

"Good work, Freshie!" "You're all right!"

Then, with the ground almost at his feet, Neil let go and dropped lightly into a bed of shrubbery. The fellows above applauded wildly. With a glance at the near-by group of sophomores, Neil ran. Several of the enemy started to intercept him, but were called back.

"Let him go! He's all right! We've had our fun!" And Neil sprang up the steps and into the building without molestation. Meanwhile Paul was making his descent and receiving his meed of applause from friend and foe. And as he dropped to earth there came a sound of cheering from the building, and the freshmen, released by the unlocking of the door, emerged on to the steps and path.

"Five this way!" was the cry. "Rush the sophs!"

But wiser counsels prevailed and, each cheering loudly, the representatives of the rival classes took themselves off.

Neil and Paul were the last to leave the building, since they had been obliged to return to the room for their shoes and coats. Paul had forgotten some of his disappointment during the later proceedings, and appeared very well satisfied with himself.

"We showed them what Hillton chaps can do, chum," he said. "And I'll bet they'll regret electing that fellow Livingston before I'm through with them! Much I care about their old presidency! They're a pack of silly little kids, any way. Let's go to bed."

"The class of 1904, an-i-mat-ed by the kind-li-est of sen-ti-ments, has, at an ex-pen-se of much time and thought, form-u-lat-ed the fol-low-ing RULES for the guid-ance of your todd-ling foot-steps at this the out-set of your col-lege car-eers. A strict ad-her-ence to these PRE-CEPTS will in-sure to you the ad-mi-ra-tion of your fond par-ents, the re-spect of your friends, and the love of the SOPH-O-MORE CLASS, which, in the ab-sence of rel-at-ives, will, with thought-ful, tender care, stand ever by to guard you from the world's hard knocks.

"ATTEND, INFANTS!

"1. R-spect for eld-ers and those in auth-or-ity is one of child-hood's most charm-ing traits. There-for take off your hat to all SOPH-O-MORES, and when in their pres-ence al-ways main-tain a def-er-en-tial sil-ence.

"2. Tall hats and canes as art-i-cles of child-ren's attire are ex-treme-ly un-be-com-ing, and are there-for strict-ly pro-hib-it-ed.

"3. Smok-ing, either of pipes, cig-ars, or cig-ar-ettes, stunts the growth and re-tards the dev-el-op-ment of in-tel-lect. Child-ren, be-ware!

"4. A suf-fic-ien-cy of sleep and plain, whole-some fare are strong-ly re-com-mend-ed.

"Early to bed and early to rise

Makes little Freshie healthy and wise.

"Avoid late hours and rich food, es-pec-ial-ly fudge.

"5. That you may not be tempt-ed to trans-gress the pre-ceed-ing rule, it has been thought best to pro-hib-it the Freshman Din-ner, which in pre-vi-ous years has ruin-ed so many young lives. The hab-it of hold-ing these din-ners is a per-nic-ious one and must be stamp-ed out. To this end the CLASS OF 1904 will ex-ert its strong-est ef-forts, and you are here-by warn-ed that any at-tempt to re-vive this lam-ent-able cust-om will bring down up-on you severe chast-ise-ment.

"We must be cruel only to be kind;

Pause and reflect, who would be dined.

"Heed and prof-it by these PRE-CEPTS, dear child-ren, that you may grow up to be great and noble men like those who sub-scribe them-selves,

"Pa-ter-nal-ly yours,

"THE CLASS OF 1904.

"You are ad-ver-tis-ed by your lov-ing friends."

This startling information, printed in sophomore red on big white placards, flamed from every available space in and about the campus the next morning. The nocturnal bill-posters had shown themselves no respecters of places, for the placards adorned not fences and walls alone, but were pasted on the granite steps of each recitation hall. All the forenoon groups of staid seniors, grinning juniors and sophomores, or vexed freshmen stood in front of the placards and read the inscriptions with varied emotions. But in the afternoon a cheering mob of the "infants" marched through the college and town and tore down or effaced every poster they could find. But they didn't get as far from the campus as the athletic field, and so it was not until Neil and Paul and one or two other freshmen reported for practise at four o'clock that it was discovered that the high board fence surrounding the field was a mass of the objectionable signs from end to end.

"Oh, let them stay," said Neil. "I think they're rather funny myself. And as for their stopping the freshman dinner, why we'll wait and see. If they try it we'll have our chance to get back at them."

"R-r-revenge!" muttered South, who, with a lacrosse stick over his shoulder and an attire consisting wholly of a pair of flapping white trunks, a faded green shirt, and a pair of canvas shoes, had come out to join the lacrosse candidates.

"King suggested our getting some small posters printed in blue with just the figures ''05' on them, and pasting one on every soph's window," said Paul, "but Livingston wouldn't hear of it. I think it would be a good game, eh?"

"Faculty'd kick up no end of a rumpus," said South.

"I haven't heard that they are doing much about these things," answered Paul. "If the sophs can stick things around why can't we?"

"You'd better ask the Dean," suggested Neil. "Hello, who's that chap?"

They had entered the grounds and were standing on the steps of the locker-house. The person to whom Neil referred was just coming through the gate. He was a medium-sized man of about thirty years, with a good-looking, albeit very freckled face, and a good deal of sandy hair. The afternoon was quite warm, and he carried his straw hat in one very brown hand, while over his arm lay a sweater of Erskine purple, a pair of canvas trousers, and two worn shoes.

"Blessed if I know who he is!" murmured South. They watched the newcomer as he traversed the path and reached the steps. As he passed them and entered the building he looked them over keenly with a pair of very sharp and very light blue eyes.

"Wow!" muttered Paul. "He looked as though he was trying to decide whether I would taste better fried or baked."

"I wonder--" began Neil. But at that moment Tom Cowan came up and Paul put the question to him.

"The fellow that just came in?" repeated Cowan. "That, my boy, is a gentleman who will have you standing on your head in just about twenty minutes. Some eight or ten years ago he was popularly known hereabouts as 'Whitey' Mills. To-day, if you know your business, you'll address him as Mister Mills."

"Oh," said Neil, "he's the head coach, is he?"

"He is, my young friend. And as he used to be one of the finest half-backs in the country, I guess you'll see something of him before you make the team. I dare say he can teach even you something about playing your position." Cowan grinned and passed on.

"Oh, go to thunder!" muttered Neil, following him into the building.

He found Mills being introduced by Devoe to such of the new candidates as were on hand.

"You remember Cowan, I guess," Devoe was saying. "He played right-guard last year." Mills and Cowan shook hands. "And this is Fletcher, a new man," continued the captain, "and Gale, too; they're both Hillton fellows and played at half. It was Fletcher that made that fine run in the St. Eustace game. Gale was the captain last year."

Mills shook hands with each, but beyond a short nod of his head and a brief "Glad to meet you," displayed no knowledge of their fame.

"Grouchy chap," commented Paul when, the coach out of hearing, they were changing their clothes.

"Well, he doesn't hurt himself talking," answered Neil. "But he looks as though he knew his business. His eyes are like little blue-steel gimlets."

"Doesn't look much for strength, though," said Paul.

But when, a few minutes later, Mills appeared on the gridiron in football togs, Paul was forced to alter his opinion. Chest, arms, and legs were a mass of muscle, and the head coach looked as though he could render a good account of himself against the stiffest line that could be put together.

The practise began with ten minutes of falling on the ball. The candidates were lined out in two strings across the field, the old men in one, the new material in another. Neil and Paul were among the latter, and Mills held their ball. Standing at the right end of the line, he rolled the pigskin in front of and slightly away from the line, and one after another the men leaped forward and flung themselves upon it, missing it at first as often as not, and rolling about on the turf as though suddenly seized with fits. Neil rather prided himself on his ability to fall on the ball, and went at it like an old stager, or so he thought. But if he expected commendation he found none. When the last man had rolled around after the elusive pigskin, Mills went to the other end of the line and did it all over again.

When it came Neil's turn he plunged out, found the ball nicely, and snuggled it against his breast. To his surprise when he arose Mills left his place and walked out to him.

"Let's try that again," he said. Neil tossed him the ball and went back to his place. Mills nodded to him and rolled the pigskin toward him. Neil dropped on his hip, securing the ball under his right arm. Like a flash Mills was over him, and with a quick blow of his hand had sent the leather bobbing across the turf yards away.

"When you get it, hold on to it," he said dryly. Neil arose with reddening cheeks and, amid the smiles of the others, went back to his place trying to decide whether, if he could have his way, the coach should perish by boiling oil or by merely being drawn and quartered. But after that it was a noticeable fact that the men clung to the ball when they got it as though it were a dearly loved friend.

Later, passing down the line in front from end to end, the head coach threw the ball swiftly at the feet of one after another of the candidates, and each was obliged to drop where he stood and have the ball in his arms when he landed. When Mills came to Neil the latter was still nursing his resentment, and his cheeks still proclaimed that fact. After the boy had dropped on the ball and had tossed it back to the coach their eyes met. In the coach's was just the merest twinkle, a very ghost of a smile; but Neil saw it, and it said to him as plainly as words could have said, "I know just how you feel, my boy, but you'll get over it after a while."

The coach passed on and the flush faded from Neil's cheeks; he even smiled a little. It was all right; Mills understood. It was almost as though they shared a secret between them. Alfred Mills, head football coach at Erskine College, had no more devoted admirer and partizan from that moment than Neil Fletcher, '05.

Next the men were spread out until there was a little space between each, and the coach passed behind the line and shot the ball through, and they had an opportunity to see what they could do with a pigskin that sped away ahead of them. By careful management it is possible in falling on a football to bring almost every portion of the anatomy in violent contact with the ground, and this fact was forcibly brought home to Neil, Paul, and all the others by the time the work was at an end.

"I've got bones I never knew the existence of before," mourned Neil.

"Me too," growled Paul. "And half a dozen of my front teeth are aching from trying to bite holes in the ground; I think they're all loose. If they come out I'll send the dentist's bill to the management."

A few minutes later Neil found himself at left half in one of the six squads of eleven men each that practised advancing the ball. They lined up in ordinary formation, and the ball was passed to one back after another for end runs. Mills went from squad to squad, criticizing briefly and succinctly.

"Don't wait for the quarter to pass," he told Paul, who was playing beside Neil. "On your toes and run hard. Have confidence in your quarter. If the ball isn't ready for you it's not your fault. Try that again."

And when Paul and Neil and the full-back had plowed round the left end once more--

"Quarter, don't hold that ball as though your hand was frozen; keep your hand limber and see that you get the belly of the ball in it, not one end; then it won't tilt itself out. When you get the ball from center rise quickly, put your back against guard, and throw your weight there. And it's just as necessary for you to have confidence in the runner as it is for him to have faith in you. Don't fear that you'll be too quick for him; don't doubt but that he'll be there at the right instant. Keep that in mind and you'll soon have things going like clock-work. Now once more; ball to left half for a run around right end."

When practise was over that day the new candidates were unanimous in the opinion that they had learned more that afternoon under Mills than they had learned during the whole previous week. Neil, Paul, and Cowan walked back to college together.

"Yes, he's a great little coach," said Cowan, "and a nice chap when you get to know him; no frills on him, you know. And he's plumb full of pluck. They say that once when he played here at half-back he got the ball on Robinson's forty yards and walked down the field and over the line for a touch-down with half the Robinson team hanging on to his legs, and said afterward that he thought he had felt some one tugging at him!" Neil laughed.

"But he doesn't look so awfully strong," he objected.

"Well, I guess he was in better trim then," answered Cowan. "Besides, he's built well, you see--most of his weight below his waist; when a chap's that way it's hard to pull him over. I remember last year in the game with Erstham I got through their tackle on a guard-back play, and--"