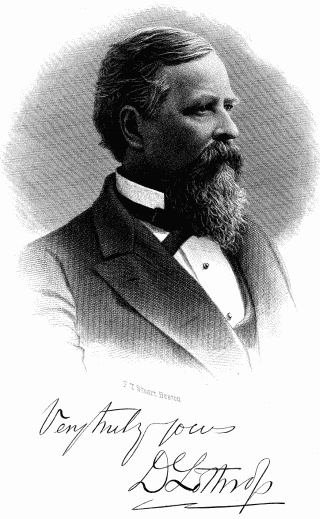

Daniel Lothrop

Title: The Bay State Monthly — Volume 2, No. 3, December, 1884

Author: Various

Release date: October 25, 2004 [eBook #13864]

Most recently updated: December 18, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Cornell University, Joshua Hutchinson, Josephine Paolucci

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

The fame, character and prosperity of a city have often depended upon its merchants,—burghers they were once called to distinguish them from haughty princes and nobles. Through the enterprise of the common citizens, Venice, Genoa, Antwerp, and London have become famous, and have controlled the destinies of nations. New England, originally settled by sturdy and liberty-loving yeomen and free citizens of free English cities, was never a congenial home for the patrician, with inherited feudal privileges, but has welcomed the thrifty Pilgrim, the Puritan, the Scotch Covenanter, the French Huguenot, the Ironsides soldiers of the great Cromwell. The men and women of this fusion have shaped our civilization. New England gave its distinctive character to the American colonies, and finally to the nation. New England influences still breathe from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and from the great lakes to Mexico; and Boston, still the focus of the New England idea, leads national movement and progress.

Perhaps one of the broadest of these influences—broadest inasmuch as it interpenetrates the life of our whole people—proceeds from the lifework of one of the merchants of Boston, known by his name and his work to the entire English speaking world: Daniel Lothrop, of the famous firm of D. Lothrop & Co., publishers—the people's publishing house. Mr. Lothrop is a good representative of this early New England fusion of race, temperament, fibre, conscience and brain. He is a direct descendant of John Lowthroppe, who, in the thirty-seventh year of Henry VIII. (1545), was a gentleman of quite extensive landed estates, both in Cherry Burton (four miles removed from Lowthorpe), and in various other parts of the country.

Lowthorpe is a small parish in the Wapentake of Dickering, in the East Riding of York, four and a half miles northeast from Great Driffield. It is a perpetual curacy in the archdeaconry of York. This parish gave name to the family of Lowthrop, Lothrop, or Lathrop. The Church, which was dedicated to St. Martin, and had for one of [pg 122] its chaplains, in the reign of Richard II., Robert de Louthorp, is now partly ruinated, the tower and chancel being almost entirely overgrown with ivy. It was a collegiate Church from 1333, and from the style of its architecture must have been built about the time of Edward III.

From this English John Lowthroppe the New England Lothrops have their origin:—

"It is one of the most ancient of all the famous New England families, whose blood in so many cases is better and purer than that of the so-called noble families in England. The family roll certainly shows a great deal of talent, and includes men who have proved widely influential and useful, both in the early and later periods. The pulpit has a strong representation. Educators are prominent. Soldiers prove that the family has never been wanting in courage. Lothrop missionaries have gone forth into foreign lands. The bankers are in the forefront. The publishers are represented. Art engraving has its exponent, and history has found at least one eminent student, while law and medicine are likewise indebted to this family, whose talent has been applied in every department of useful industry." 1

I. Mark Lothrop, the pioneer, the grandson of John Lowthroppe and a relative of Rev. John Lothrop, settled in Salem, Mass., where he was received as an inhabitant January 11, 1643-4. He was living there in 1652. In 1656 he was living in Bridgewater, Mass., of which town he was one of the proprietors, and in which he was prominent for about twenty-five years. He died October 25, 1685.

II. Samuel Lothrop, born before 1660, married Sarah Downer, and lived in Bridgewater. His will was dated April 11, 1724.

III. Mark Lothrop, born in Bridgewater September 9, 1689; married March 29, 1722, Hannah Alden [Born February 1, 1696; died 1777]. She was the daughter of Deacon Joseph Alden of Bridgewater, and great grand-daughter of Honorable John and Priscilla (Mullins) Alden of Duxbury, of Mayflower fame. He settled in Easton, of which town he was one of the original proprietors. He was prominent in Church and town affairs.

IV. Jonathan Lothrop, born March 11, 1722-3; married April 13, 1746, Susannah, daughter of Solomon and Susannah (Edson) Johnson of Bridgewater. She was born in 1723. He was a Deacon of the Church, and a prominent man in the town. He died in 1771.

V. Solomon Lothrop, born February 9, 1761; married Mehitable, daughter of Cornelius White of Taunlon; settled in Easton, and later in Norton, where he died October 19, 1843. She died September 14, 1832, aged 73.

VI. Daniel Lothrop, born in Easton, January 9, 1801; married October 16, 1825, Sophia, daughter of Deacon Jeremiah Horne of Rochester, N.H. She died September 23, 1848, and he married (2) Mary E. Chamberlain. He settled in Rochester, N.H., and was one of the public men of the town. Of the strictest integrity, and possessing sterling qualities of mind and heart Mr. Lothrop was chosen to fill important offices of public trust in his town and state. He repeatedly represented his town in the Legislature, where his sound practical sense and clear wisdom were of much service, particularly in the formation of the Free Soil party, in which he was a bold defender of the rights of liberty to all men. He died May 31, 1870.

VII. Daniel Lothrop, son of Daniel and Sophia (Horne) Lothrop, was born in Rochester, N.H., August 11, 1831.

"On the maternal side Mr. Lothrop is descended from William Horne, of Horne's Hill, in Dover, who held his exposed position in the Indian wars, and whose estate has been in the family name from 1662 until the present generation; but he was killed in the massacre of June 28, 1689. Through the Horne line, also, came descent from Rev. Joseph Hull, minister at Durham in 1662, a graduate at the University at Cambridge, England; from John Ham, of Dover; from the emigrant John Heard, and others of like vigorous stock. It was his ancestress, Elizabeth (Hull) Heard, whom the old historians call a "brave gentlewoman," who held her garrison house, the frontier fort in Dover in the Indian wars, and successfully defended it in the massacre of 1689. The father of the subject of this sketch was a man of sterling qualities, strong in mind and will, but commanding love as well as respect. The mother was a woman of outward beauty and beauty [pg 123] of soul alike; with high ideals and reverent conscientiousness. Her influence over her boys was life-long. The home was a centre of intelligent intercourse, a sample of the simplicity but earnestness of many of the best New Hampshire homesteads." 3

Descended, as is here evident, from men and women accustomed to govern, legislate, protect, guide and represent the people, it is not surprising to find the Lothrops of the present day of this branch standing in high places, shaping affairs, and devising fresh and far-reaching measures for the general good.

Daniel Lothrop was the youngest of the three sons of Daniel and Sophia Home Lothrop. The family residence was on Haven's Hill, in Rochester, and it was an ideal home in its laws, influences and pleasures. Under the guidance of the wise and gentle mother young Daniel developed in a sound body a mind intent on lofty aims, even in childhood, and a character early distinguished for sturdy uprightness. Here, too, on the farm was instilled into him the faith of his fathers, brought through many generations, and he openly acknowledged his allegiance to an Evangelical Church at the age of eleven.

As a boy Daniel is remembered as possessing a retentive and singularly accurate memory; as very studious, seeking eagerly for knowledge, and rapidly absorbing it. His intuitive mastery of the relations of numbers, his grasp of the values and mysteries of the higher mathematics, was early remarkable. It might be reasonably expected of the child of seven who was brought down from the primary benches and lifted up to the blackboard to demonstrate a difficult problem in cube root to the big boys and girls of the upper class that he should make rapid and masterful business combinations in later life.

At the age of fourteen he was sufficiently advanced in his studies to enter college, but judicious friends restrained him in order that his physique might be brought up to his intellectual growth, and presently circumstances diverted the boy from his immediate educational aspirations and thrust him into the arena of business:—the world may have lost a lawyer, a clergyman, a physician, or an engineer, but by this change in his youthful plans it certainly has gained a great publisher—a man whose influence in literature is extended, and who, by his powerful individuality, his executive force, and his originating brain has accomplished a literary revolution.

To understand the business career of Daniel Lothrop it will be necessary to trace the origin and progress of the firm of D. Lothrop and Company. On reaching his decision to remain out of college for a year he assumed charge of the drug store, then recently opened by his eldest brother, James E. Lothrop, who, desiring to attend medical lectures in Philadelphia, confidently invited his brother Daniel to carry on the business during his absence.

"He urged the young boy to take charge of the store, promising as an extra inducement an equal division as to profits, and that the firm should read 'D. Lothrop & Co.' This last was too much for our ambitious lad. When five years of age he had scratched on a piece of tin these magic words, opening to fame and honor, 'D. Lothrop & Co.,' nailing the embryo sign against the door of his play house. How then could he resist, now, at fourteen? And why not spend the vacation in this manner? And so the sign was made and put up, and thus began the house of 'D. Lothrop & Co.,' the name of which is spoken as a household word wherever the English language is used, and whose publications are loved in more than one of the royal families of Europe." 4

The drug store became very lucrative. The classical drill which had [pg 124] been received by the young druggist was of great advantage to him, his thorough knowledge of Latin was of immediate service, and his skill and care and knowledge was widely recognized and respected. The store became his college, where his affection for books soon led him to introduce them as an adjunct to his business.

Thus was he when a mere boy launched on a successful business career. His energy, since proved inexhaustible, soon began to open outward. When about seventeen his attention was attracted to the village of Newmarket as a desirable location for a drug store, and he seized an opportunity to hire a store and stock it. His executive and financial ability were strikingly honored in this venture. Having it in successful operation, he called the second brother, John C. Lothrop, who about this time was admitted to the firm, and left him in charge of the new establishment, while he started a similar store at Meredith Bridge, now called Laconia. The firm now consisted of the three brothers.

"These three brothers have presented a most remarkable spirit of family union. Remarkable in that there was none of the drifting away from each other into perilous friendships and moneyed ventures. They held firmly to each other with a trust beyond words. The simple word of each was as good as a bond. And as early as possible they entered into an agreement that all three should combine fortunes, and, though keeping distinct kinds of business, should share equal profits under the firm name of 'D. Lothrop & Co.' For thirty-six years, through all the stress and strain of business life in this rushing age, their loyalty has been preserved strong and pure. Without a question or a doubt, there has been an absolute unity of interests, although James E., President of the Cocheco Bank, and Mayor of the city of Dover, is in one city, John C. in another, and Daniel in still another, and each having the particular direction of the business which his enterprise and sagacity has made extensive and profitable." 5

In 1850 occurred a point of fresh and important departure. The stock of books held by Elijah Wadleigh, who had conducted a large and flourishing book store in Dover, N.H., was purchased. Mr. Lothrop enlarged the business, built up a good jobbing trade, and also quietly experimented in publishing. The bookstore under his management also became something more than a commercial success: it grew to be the centre for the bright and educated people of the town, a favorite meeting place of men and women alive to the questions of the day.

Now, arrived at the vigor of young manhood, Mr. Lothrop's aims and high reaches began their more open unfoldment. He rapidly extended the business into new and wide fields. He established branch stores at Berwick, Portsmouth, Amesbury, and other places. In each of these establishments books were prominently handled. While thus immediately busy, Mr. Lothrop began his "studies" for his ultimate work. He did not enter the publishing field without long surveys of investigation, comparison and reflection. In need of that kind of vacation we call "change of work and scene," Mr. Lothrop planned a western trip. The bookstores in the various large cities on the route were sedulously visited, and the tastes and the demands of the book trade were carefully studied from many standpoints.

The vast possibilities of the Great West caught his attention and he hastened to grasp his opportunities. At St. Peter, in Minnesota, he was welcomed and resolved to locate. They needed such men as Mr. Lothrop to help build the new town into a city. The opening of the St. Peter store was characteristic of its young proprietor.

The extreme cold of October and November, [pg 125] 1856, prevented, by the early freezing of the Upper Mississippi, the arrival of his goods. Having contracted with the St. Peter company to erect a building, and open his store on the first day of December, Mr. Lothrop, thinking that the goods might have come as far as some landing place below St. Paul, went down several hundred miles along the shore visiting the different landing places. Failing to find them he bought the entire closing-out stock of a drug store at St. Paul, and other goods necessary to a complete fitting of his store, had them loaded, and with several large teams started for St. Peter. The same day a blinding snow storm set in, making it extremely difficult to find the right road, or indeed any road at all, so that five days were spent in making a journey that in good weather could have been accomplished in two. When within a mile of St. Peter the Minnesota river was to be crossed, and it was feared the ice would not bear the heavy teams; all was unloaded and moved on small sledges across the river, and the drug store was opened on the day agreed upon. The papers of that section made special mention of this achievement, saying that it deserved honorable record, and that with such business enterprise the prosperity of Minnesota Valley was assured.

He afterwards opened a banking house in St. Peter, of which his uncle, Dr. Jeremiah Horne, was cashier; and in the book and drug store he placed one of his clerks from the East, Mr. B.F. Paul, who is now one of the wealthiest men of the Minnesota Valley. He also established two other stores in the same section of country.

Various elements of good generalship came into play during Mr. Lothrop's occupancy of this new field, not only in directing his extensive business combinations in prosperous times, but in guiding all his interests through the financial panic of 1857 and 1858. By the failure of other houses and the change of capital from St. Peter to St. Paul, Mr. Lothrop was a heavy loser, but by incessant labor and foresight he squarely met each complication, promptly paid each liability in full. But now he broke in health. The strain upon him had been intense, and when all was well the tension relaxed, and making his accustomed visit East to attend to his business interests in New England, without allowing himself the required rest, the change of climate, together with heavy colds taken on the journey, resulted in congestion of the lungs, and prostration. Dr. Bowditch, after examination, said that the young merchant had been doing the work of twenty years in ten. Under his treatment Mr. Lothrop so far recovered that he was able to take a trip to Florida, where the needed rest restored his health.

For the next five years our future publisher directed the lucrative business enterprises which he had inaugurated, from the quiet book store in Dover, N. H., while he carefully matured his plans for his life's campaign—the publication, in many lines, of wholesome books for the people. Soon after the close of the Civil war the time arrived for the accomplishment of his designs, and he began by closing up advantageously his various enterprises in order to concentrate his forces. His was no ordinary equipment. Together with well-laid plans and inspirations, for some of which the time is not yet due, and a rich birthright of sagacity, insight and leadership, he possessed also a practical experience of American book markets and the tastes of the people, trained financial ability, practiced judgment, literary [pg 126] taste, and literary conscience; and last, but not least, he had traversed and mapped out the special field he proposed to occupy,—a field from which he has never been diverted.

"The foundations were solid. On these points Mr. Lothrop has had but one mind from the first: 'Never to publish a work purely sensational, no matter what chances of money it has in it;' 'to publish books that will make true, steadfast growth in right living.' Not alone right thinking, but right living. These were his two determinations, rigidly adhered to, notwithstanding constant advice, appeals, and temptations. His thoughts had naturally turned to the young people, knowing from his own self-made fortunes, how young men and women need help, encouragement and stimulus. He had determined to throw all his time, strength and money into making good books for the young people, who, with keen imaginations and active minds, were searching in all directions for mental food. 'The best way to fight the evil in the world,' reasoned Mr. Lothrop, 'is to crowd it out with the good.' And therefore he bent the energies of his mind to maturing plans toward this object,—the putting good, helpful literature into their hands.

His first care was to determine the channels through which he could address the largest audiences. The Sunday School library was one. In it he hoped to turn a strong current of pure, healthful literature for those young people who, dieting on the existing library books, were rendered miserable on closing their covers, either to find them dry or obsolete, or so sentimentally religious as to have nothing in their own practical lives corresponding to the situations of the pictured heroes and heroines.

The family library was another channel. To make evident to the heads of households the paramount importance of creating a home library, Mr. Lothrop set himself to work with a will. In the spring of 1868 he invited to meet him a council of three gentlemen, eminent in scholarship, sound of judgment, and of large experience: the Reverend George T. Day, D. D., of Dover, N.H., Professor Heman Lincoln, D.D., of Newton Seminary, the Rev. J.E. Rankin, D.D., of Washington, D.C. Before them he laid his plans, matured and ready for their acceptance: to publish good, strong, attractive literature for the Sunday School, the home, the town, and school library, and that nothing should be published save of that character, asking their co-operation as readers of the several manuscripts to be presented for acceptance. The gentlemen, one and all, gave him their heartiest God-speed, but they frankly confessed it a most difficult undertaking, and that the step must be taken with the strong chance of failure. Mr. Lothrop had counted that chance and reaffirmed his purpose to become a publisher of just such literature, and imparted to them so much of his own courage that before they left the room, all stood engaged as salaried readers of the manuscripts to come in to the new publishing house of D. Lothrop & Co., and during all these years no manuscripts have been accepted without the sanction of one or more of these readers.

The store, Nos. 38 and 40 Cornhill, Boston, was taken, and a complete refitting and stocking made it one of the finest bookstores of the city. The first book published was 'Andy Luttrell.' How many recall that first book! 'Andy Luttrell' was a great success, the press saying that 'the series of which this is the initiatory volume, marks a new era in Sunday School literature.' Large editions were called for, and it is popular still. In beginning any new business there are many difficulties to face, old established houses to compete with, and new ones to contest every inch of success. But tides turn, and patience and pluck won the day, until from being steady, sure and reliable, Mr. Lothrop's publishing business was increasing with such rapidity as to soon make it one of the solid houses of Boston. Mr. Lothrop had a remarkable instinct as regarded the discovering of new talent, and many now famous writers owe their popularity with the public to his kindness and courage in standing by them. He had great enthusiasm and success in introducing this new element, encouraging young writers, and creating a fresh atmosphere very stimulating and enjoyable to their audience. To all who applied for work or brought manuscript for examination, he had a hopeful word, and in rapid, clear expression smoothed the difficulty out of their path if possible, or pointed to future success as the result of patient toil. He always brought out the best that was in a person, having the rare quality of the union of perfect honesty with kind consideration. This new blood in the old veins of literary life, soon wrought a marvelous change in this class of literature. Mr. Lothrop had been wise enough to see that such would be the case, and he kept [pg 127] constantly on the lookout for all means that might foster ambition and bring to the surface latent talent. For this purpose he offered prizes of $1,000 and $500 for the best manuscripts on certain subjects. Such a thing had scarcely been heard of before and manuscripts flowed in, showing this to have been a happy thought. It is interesting to look back and find many of those young authors to be identical with names that are now famous in art and literature, then presenting with much fear and trembling, their first efforts.

Mr. Lothrop considered no time, money, or strength ill-spent by which he could secure the wisest choice of manuscripts. As an evidence of his success, we name a few out of his large list: 'Miss Yonge's Histories;' 'Spare Minute Series,' most carefully edited from Gladstone, George MacDonald, Dean Stanley, Thomas Hughes, Charles Kingsley; 'Stories of American History;'' Lothrop's Library of Entertaining History,' edited by Arthur Gilman, containing Professor Harrison's 'Spain,' Mrs. Clement's 'Egypt,' 'Switzerland,' 'India,' etc.; 'Library of famous Americans, 1st and 2d series; George MacDonald's novels—Mr. Lothrop, while on a visit to Europe, having secured the latest novels by this author in manuscript, thus bringing them out in advance of any other publisher in this country or abroad, now issues his entire works in uniform style: 'Miss Yonge's Historical Stories;' 'Illustrated Wonders;' The Pansy Books,' of world-wide circulation;' 'Natural History Stories;' 'Poet's Homes Series;' S.G.W. Benjamin's 'American Artists;' 'The Reading Union Library,' 'Business Boy's Library,' library edition of 'The Odyssey,' done in prose by Butcher and Lang; 'Jowett's Thucydides;' 'Rosetti's Shakspeare,' on which nothing has been spared to make it the most complete for students and family use, and many others.

Mr. Lothrop is constantly broadening his field in many directions, gathering the rich thought of many men of letters, science and theology among his publications. Such writers as Professor James H. Harrison, Arthur Gilman, and Rev. E.E. Hale are allies of the house, constantly working with it to the development of pure literature; the list of the authors and contributors being so long as to include representatives of all the finest thinkers of the day. Elegant art gift books of poem, classic and romance, have been added with wise discrimination, until the list embraces sixteen hundred books, out of which last year were printed and sold 1,500,000 volumes.

The great fire of 1872 brought loss to Mr. Lothrop among the many who suffered. Much of the hard-won earnings of years of toil was swept away in that terrible night. About two weeks later, a large quantity of paper which had been destroyed during the great fire had been replaced, and the printing of the same was in process at the printing house of Rand, Avery & Co., when a fire broke out there, destroying this second lot of paper, intended for the first edition of sixteen volumes of the celebrated $1,000 prize books. A third lot of paper was purchased for these books and sent to the Riverside Press without delay. The books were at last printed, as many thousand readers can testify, an enterprise that called out from the Boston papers much commendation, adding, in one instance: 'Mr. Lothrop seems warmed up to his work.'

When the time was ripe, another form of Mr. Lothrop's plans for the creation of a great popular literature was inaugurated. We refer to the projection of his now famous 'Wide Awake,' a magazine into which he has thrown a large amount of money. Thrown it, expecting to wait for results. And they have begun to come. 'Wide Awake' now stands abreast with the finest periodicals in our country, or abroad. In speaking of 'Wide Awake' the Boston Herald says: 'No such marvel of excellence could be reached unless there were something beyond the strict calculations of money-making to push those engaged upon it to such magnificent results.' Nothing that money can do is spared for its improvement. Withal, it is the most carefully edited of all magazines; Mr. Lothrop's strict determination to that effect, having placed wise hands at the helm to co-operate with him. Our best people have found this out. The finest writers in this country and in Europe are giving of their best thought to filling its pages, the most celebrated artists are glad to work for it. Scientific men, professors, clergymen, and all heads of households give in their testimony of its merits as a family magazine, while the young folks are delighted with it. The fortune of 'Wide Awake' is sure. Next Mr. Lothrop proceeded to supply the babies with their own especial magazine. Hence came bright, winsome, sparkling 'Babyland.' The mothers caught at the idea. 'Babyland' jumped into success in an incredibly short space of time. The editors of 'Wide Awake,' Mr. and Mrs. Pratt, edit this also, which ensures it as safe, wholesome and sweet to put into baby's hands. The intervening spaces between 'Babyland' and 'Wide [pg 128] Awake' Mr. Lothrop soon filled with 'Our Little Men and Women,' and 'The Pansy.' Urgent solicitations from parents and teachers who need a magazine for those little folks, either at home or at school, who were beginning to read and spell, brought out the first, and Mrs. G.R. Alden (Pansy) taking charge of a weekly pictorial paper of that name, was the reason for the beginning and growth of the second. The 'Boston Book Bulletin,' a quarterly, is a medium for acquaintance with the best literature, its prices, and all news current pertaining to it.

[pg 129] [pg 130]'The Chatauqua Young Folk's Journal' is the latest addition to the sparkling list. This periodical was a natural growth of the modern liking for clubs, circles, societies, reading unions, home studies, and reading courses. It is the official voice of the Chatauqua Young Folks Reading Union, and furnishes each year a valuable and vivacious course of readings on topics of interest to youth. It is used largely in schools. Its contributors are among our leading clergymen, lawyers, university professors, critics, historians and scientists, but all its literature is of a popular character, suited to the family circle rather than the study. Mr. Lothrop now has the remarkable success of seeing six flourishing periodicals going forth from his house.

In 1875, Mr. Lothrop, finding his Cornhill quarters inaquate [sic], leased the elegant building corner Franklin and Hawley streets, belonging to Harvard College, for a term of years. The building is 120 feet long by 40 broad, making the salesroom, which is on the first floor, one of the most elegant in the country. On the second floor are Mr. Lothrop's offices, also the editorial offices of 'Wide Awake,' etc. On the third floor are the composing rooms and mailing rooms of the different periodicals, while the bindery fills the fourth floor.

This building also was found small; it could accommodate only one-fourth of the work done, and accordingly a warehouse on Purchase street was leased for storing and manufacturing purposes.

In 1879 Mr. Lothrop called to his assistance a younger brother, Mr. M.H. Lothrop, who had already made a brilliant business record in Dover, N.H., to whom he gives an interest in the business. All who care for the circulation of the best literature will be glad to know that everything indicates the work to be steadily increasing toward complete development of Mr. Lothrop's life-long purpose." 6

This man of large purposes and large measures has, of course, his sturdy friends, his foes as sturdy. He has, without doubt, an iron will. He is, without doubt, a good fighter—a wise counselor. Approached by fraud he presents a front of granite; he cuts through intrigue with sudden, forceful blows. It is true that the sharp bargainer, the overreaching buyer he worsts and puts to confusion and loss without mercy. But, no less, candor and honor meet with frankness and generous dealing. He is as loyal to a friend as to a purpose. His interest in one befriended and taken into trust is for life. It has been more than once said of this immovable business man that he has the simple heart of a boy.

Mr. Lothrop's summer home is in Concord, Mass. His house, known to literary pilgrims of both continents as "The Wayside," is a unique, many gabled old mansion, situated near the road at the base of a pine-covered hill, facing broad, level fields, and commanding a view of charming rural scenery. Its dozen green acres are laid out in rustic paths; but with the exception of the removal of unsightly underbrush, the landscape is left in a wild and picturesque state. Immediately in the rear of the house, however, A. Bronson Alcott, a former occupant, planned a series of terraces, and thereon is a system of trees. The house was commenced in the seventeenth century and has been added to at different periods, and withal is quaint enough to satisfy the most exacting antiquarian. At the back rise the more modern portions, and the tower, wherein was woven the most delightful of American romances, and about which cluster tender memories of the immortal Hawthorne. The boughs of the whispering pines almost touch the lofty windows.

The interior of the dwelling is seemly. [pg 131] It corresponds with the various eras of its construction. The ancient low-posted rooms with their large open fire-places, in which the genial hickory crackles and glows as in the olden time, have furnishings and appointments in harmony. The more modern apartments are charming, the whole combination making a most delightful country house.

Mr. Lothrop's enjoyment of art and his critical appreciation is illustrated here as throughout his publications, his house being adorned with many exquisite and valuable original paintings from the studios of modern artists; and there is, too, a certain literary fitness that his home should be in this most classic spot, and that the mistress of this home should be a lady of distinguished rank in literature, and that the fair baby daughter of the house should wear for her own the name her mother has made beloved in thousands of American and English households.

One of the most important questions now occupying the minds of the world's deepest and best thinkers, is the intellectual, physical, moral, and political position of woman.

Men are beginning to realize a fact that has been evident enough for ages: that the current of civilization can never rise higher than the springs of motherhood. Given the ignorant, debased mothers of the Turkish harem, and the inevitable result is a nation destitute of truth, honor or political position. All the power of the Roman legions, all the wealth of the imperial empire, could not save the throne of the Cæsars when the Roman matron was shorn of her honor, and womanhood became only the slave or the toy of its citizens. Men have been slow to grasp the fact that women are a "true constituent of the bone and sinew of society," and as such should be trained to bear the part of "bone and sinew." It has been finely said, "that as times have altered and conditions varied, the respect has varied [pg 133] in which woman has been held. At one time condemned to the field and counted with the cattle, at another time condemned to the drawing-room and inventoried with marbles, oils and water-colors; but only in instances comparatively rare, acknowledged and recognized in the fullness of her moral and intellectual possibilities, and in the beauteous completeness of her personal dignity, prowess and obligation."

Various and widely divergent as opinions are in regard to woman's place in the political sphere, there is fast coming to be unanimity of thought in regard to her intellectual development. Even in Turkey, fathers are beginning to see that their daughters are better, not worse, for being able to read and, write, and civilization is about ready to concede that the intellectual, physical and moral possibilities of woman are to [pg 134] be the only limits to her attainment. Vast strides in the direction of the higher and broader education of women have been made in the quarter of a century since John Vassar founded on the banks of the Hudson the noble college for women that bears his name; and others have been found who have lent willing hands to making broad the highway that leads to an ideal womanhood. Wellesley and Smith, as well as Vassar find their limits all too small for the throngs of eager girlhood that are pressing toward them. The Boston University, honored in being first to open professional courses to women, Michigan University, the New England Conservatory, the North Western University of Illinois, the Wesleyan Universities, both of Connecticut and Ohio, with others of the colleges of the country, have opened their doors and welcomed women to an equal share with men, in their advantages. And in the shadow of Oxford, on the Thames, and of Harvard, on the Charles, womanly [pg 135] minds are growing, womanly lives are shaping, and womanly patience is waiting until every barrier shall be removed, and all the green fields of learning shall be so free that whosoever will may enter.

Among the foremost of the great educational institutions of the day, the New England Conservatory of Music takes rank, and its remarkable development and wonderful growth tends to prove that the youth of the land desire the highest advantages that can be offered them. More than thirty years ago the germ of the idea that is now embodied in this great institution, found lodgment in the brain of the man who has devoted his life to its development. Believing that music had a positive influence [pg 136] upon the elevation of the world hardly dreamed of as yet even by its most devoted students, Eben Tourjee returned to America from years of musical study in the great Conservatories of Europe. Knowing from personal observation the difficulties that lie in the way of American students, especially of young and inexperienced girls who seek to obtain a musical education abroad, battling as they must, not only with foreign customs and a foreign language, but exposed to dangers, temptations and disappointments, he determined to found in America a music school that should be unsurpassed in the world. Accepting [pg 137] the judgment of the great masters, Mendelsshon, David, and Joachim, that the conservatory system was the best possible system of musical instruction, doing for music what a college of liberal arts does for education in general, Dr. Tourjee in 1853, with what seems to have been large and earnest faith, and most entire devotion, took the first public steps towards the accomplishment of his purpose. During the long years his plan developed step by step. In 1870 the institution was chartered under its present name in Boston. In 1881 its founder deeded to it his entire personal property, and by a deed of trust gave the institution into the hands of a Board of Trustees to be perpetuated forever as a Christian Music School.

In the carrying out of his plan to establish and equip an institution that should give the highest musical culture, Dr. Tourjee has been compelled, in order that musicians educated here [pg 138] should not be narrow, one-sided specialists only, but that they should be cultured men and women, to add department after department, until to-day under the same roof and management there are well equipped schools of Music, Art, Elocution, Literature, Languages, Tuning, Physical Culture, and a home with the safeguards of a Christian family life for young women students.

When, in 1882, the institution moved from Music Hall to its present quarters in Franklin Square, in what was the St. James Hotel, it became possessed of the largest and best equipped conservatory buildings in the world. It has upon its staff of seventy-five teachers, masters from the best schools of Europe. During the school year ending June 29, 1884, students coming from forty-one states and territories of the Union, from the British Provinces, from England and from the Sandwich Islands, have received instruction there. The growth [pg 139] of this institution, due in such large measure to the courage and faith of one man, has been remarkable, and it stands to-day self-supporting, without one dollar of endowment, carrying on alone its noble work, an institution of which Boston, Massachusetts and America may well be proud. From the first its invitation has been without limitation. It began with a firm belief that "what it is in the nature of a man or woman to become, is a Providential indication of what God wants it to become, by improvement and development," and it offered to men and women alike the same advantages, the same labor, and the same honor. It is working out for itself the problem of co-education, and it has never had occasion to take one backward step in the part it has chosen. Money by the millions has been poured out upon the schools and colleges of the land, and not one dollar too much has been given, for the money that educates is the money that saves the nation.

Among those who have been made stewards of great wealth some liberal benefactor should come forward in behalf of this great school, that, by eighteen years of faithful living, has proved its right to live. Its founder says of it: "The institution has not yet compassed my thought of it." Certainly it has not reached its possibilities of doing good. It needs a hall in which its concerts and lectures can be given, and in which the great organ of Music Hall, may be placed. It needs that its chapel, library, studios, gymnasium and recitation rooms should be greatly enlarged to meet the actual demands now made upon them. It needs what other institutions have needed and received, a liberal endowment, to enable it, with them, to meet and solve the great question of the day, the education of the people.

Saugus lies about eight miles northeast of Boston. It was incorporated as an independent town February 17, 1815, and was formerly a part of Lynn, which once bore the name of Saugus, being an Indian name, and signifies great or extended. It has a taxable area of 5,880 acres, and its present population may be estimated at about 2,800, living in 535 houses. The former boundary between Lynn and Suffolk County ran through the centre of the "Boardman House," in what is now Saugus, and standing near the line between Melrose and Saugus, and is one of the oldest houses in the town. It has forty miles of accepted streets and roads, which are proverbial as being kept in the very best condition. Its public buildings are a Town Hall, a wooden structure, of Gothic architecture, with granite steps and underpining, and has a seating capacity of seven hundred and eighty persons. It is considered to be the handsomest wooden building in Essex County, and cost $48,000. The High School is accommodated within its walls, and beside offices for the various boards of town officers; on the lower floor it has a room for a library. The upper flight has an auditorium with ante-rooms at the front and rear, a balcony at the front, seats one hundred and eighty persons, and a platform on the stage at the rear. It was built in 1874-5. The building committee were E.P. Robinson, Gilbert Waldron, J.W. Thomas, H.B. Newhall, Wilbur F. Newhall, Augustus B. Davis, George N. Miller, George H. Hull, Louis P. Hawkes, William F. Hitchings, E.E. Wilson, Warren P. Copp, David Knox, A. Brad. Edmunds and Henry Sprague. E.P. Robinson was chosen chairman and David Knox secretary. The architects were Lord & Fuller of Boston, and the work of building was put under contract to J.H. Kibby & Son of Chelsea.

The town also owns seven commodious schoolhouses, in which are maintained thirteen schools—one High, three Grammar, three Intermediate, three Primaries, one sub-Primary and two mixed schools, the town appropriating the sum of six thousand dollars therefor. There are five Churches—Congregational, Universalist, and three Methodist, besides two societies worshiping in halls (the St. John's Episcopal Mission and the Union at North Saugus). After the schism in the old Third Parish about 1809, the religious feud between the Trinitarians and the Unitarians became so intense that a lawsuit was had to obtain the fund, the Universalists retaining possession. The Trinitarians then built the old stone Church, under the direction of Squire Joseph Eames, which, as a piece of architecture, did not reflect much credit on builder or architect. It is now used as a grocery and post office; their present place of worship was built in 1852. The Church edifice of the old Third was erected in 1738, and was occupied without change until 1859, when it was sold and moved off the spot, and the site is now marked by a flag staff and band stand, known as Central Square. The old Church was moved a short distance and converted into tenements, with a store underneath. The Universalist society built their present Church [pg 141] in 1860. The town farm consists of some 280 acres, and has a fine wood lot of 240 acres, the remainder being valuable tillage, costing in 1823 $4,625.

The town is rich in local history and has either produced or been the residence of a number of notable men and women.

Judge William Tudor, the father of the ice business, now so colossal in its proportions, started the trade here, living on what is now the poor farm. The Saugus Female Seminary once held quite a place in literary circles, Cornelius C. Felton, afterward president of Harvard College, being its "chore boy" (the remains of his parents lie in the cemetery near by). Fanny Fern, the sister of N.P. Willis, the wife of James Parton, the celebrated biographer, as well as two sisters of Dr. Alexander Vinton, pursued their studies here, together with Miss Flint, who married Honorable Daniel P. King, member of Congress for the Essex District, and Miss Dustin, who became the wife of Eben Sutton, and who has been so devoted and interested in the library of the Peabody Institute. Mr. Emerson, the preceptor, was for a time the pastor of the Third Parish of Lynn (now Saugus Universalist society), where Parson Roby preached for a period of fifty-three years—more than half a century, with a devotion and fidelity that greatly endeared him to his people. In passing we give the items of his salary as voted him in 1747, taken from the records of the Parish, being kindly furnished by the Clerk, Mr. W.F. Hitchings: "A suitable house and barn, standing in a suitable place; pasturing and sufficient warter meet for two Cows and one horse—the winter meet put in his barn; the improvement of two acres of land suitable to plant and to be kept well fenced; sixty pounds in lawful silver money, at six shillings and eight pence per ounce; twenty cords of wood at his Dore, and the Loose Contributions; and also the following artikles, or so much money as will purchase them, viz: Sixty Bushels Indian Corn, forty-one Bushels of Rye, Six [pg 142] hundred pounds wait of Pork and Eight Hundred and Eighty Eight pounds wait of Beefe."

This would be considered a pretty liberal salary even now for a suburban people to pay. From the records of his parish it would seem he always enjoyed the love and confidence of his people, and was sincerely mourned by them at his death, which occurred January 31, 1803, at the advanced age of eighty years, and as stated above in the fifty-third year of his ministry. Among other good works and mementoes which he left behind him was the "Roby Elm," set out with his own hand, and which is now more than one hundred and twenty-five years old. It is in an excellent state of preservation, and with its perfectly conical shape at the top, attracts marked attention from all lovers and observers of trees. Among the names of worthy citizens who have impressed themselves upon the memory of their survivors, either as business men of rare executive ability, or as merchants of strict integrity, or scholars and men of literary genius, lawyers, artists, writers, poets, and men of inventive genius, we will first mention as eldest on the list "Landlord" Jacob Newhall, who used to keep a tavern in the east part of the town and gave "entertainment to man and beast" passing between Boston and Salem, notably so to General Washington on his journey from Boston to Salem in 1797, and later to the Marquis De Lafayette in 1824, when making a similar journey. We also mention Zaccheus Stocker, Jonathan Makepeace, Charles Sweetser, Dr. Abijah Cheever, Benjamin F. Newhall and Benjamin Hitchings. These last all held town office with great credit to themselves and their constituents.

Benjamin F. Newhall was a man of versatile parts. Beside writing rhymes he preached the Gospel, and was at one time County Commissioner for Essex County.

To these may be added Salmon Snow, who held the office of Selectman for several years, and also kept the poor of Saugus for many years with great acceptance. He was a man of good judgment, strong in his likes and dislikes, and bitter in his resentments. George Henry Sweetser was also a Selectman for years, and was elected to the Legislature for both branches, being Senator for two terms. Frederick Stocker, noted as a manufacturer of brick, was also a man of sterling qualities, and shared in the confidence and esteem of his fellow citizens. Joseph Stocker Newhall, a manufacturer of roundings in sole leather, was a just man, of positive views, and although interesting himself in the political issues of the day would not take office. Eminently social he was at times somewhat abrupt and laconic in denouncing what he conceived to be shams. As a manufacturer his motto was, "the laborer is worthy of his hire." He died in 1875, aged 67 years. George Pearson was Treasurer of the town and one of the Selectmen, and also Treasurer and Deacon of the Orthodox parish for twenty-five years, living to the advanced age of eighty-seven years. He died in 1883.

Later, about 1837, Edward Pranker, an Englishman, and Francis Scott, a Scotchman, became noted for their woollen factories, which they built in Saugus, and also became residents here for the rest of their lives. Enoch Train, too, a Boston ship merchant and founder of the famous line of packets between Boston and Liverpool for the transportation of emigrants, passed the last ten years of his life here, marrying Mrs. Almira Cheever. He was the father of Mrs. A.D.T. Whitney, the [pg 143] author of many works of fiction, which have been widely read; among them "Faith Gartney's Girlhood," "Odd or Even," "Sights and Insights," etc. In this connection we point to a living novelist of Saugus, Miss Ella Thayer, whose "Wired Lore" has been through several editions. George William Phillips, brother of Wendell, a lawyer of some note, also lived many years at Saugus and died in 1878. Joseph Ames, the artist, celebrated for his portraits, who was commissioned by the Catholics to visit Rome and paint Pope Pius IX., and who executed in a masterly manner other commissions, such as Rufus Choate, Daniel Webster, Abraham Lincoln, Madames Rachael and Ristori, learned the art in Saugus, though born in Roxbury, N.H. He died at New York while temporarily painting there, but was buried in Saugus in 1874. His brother Nathan was a patent solicitor, and considered an expert in such matters, and invented several useful machines. He was also a writer of both prose and poetry, writing among other books "Pirate's Glen," "Dungeon Rock" and "Childe Harold." He died in 1860.

Rev. Fales H. Newhall, D.D., who was Professor of Languages at Middletown College, and who, as a writer, speaker or preacher, won merited distinction, died in 1882, lamented that his light should go prematurely out at the early age of 56 years.

Henry Newhall, who went from Saugus to San Francisco, and there became a millionaire, may be spoken of as a succesful business man and merchant. The greatest instance of longevity since the incorporation of the town was that of Joseph Cheever, who was born February 22, 1772, and died June 19, 1872, aged 100 years, 4 months, 27 days. He was a farmer of great energy, industry and will power, and was given to much litigation. He, too, represented the town in 1817-18, 1820-21, 1831-32, and again in 1835.

Saugus, too, was the scene of the early labors of Rev. Edward T. Taylor, familiarly known as Father Taylor. Here he learned to read, and preached his first sermon at what was then known as the "Rock Schoolhouse," at East Saugus, though converted at North Saugus. Mrs. Sally Sweetser, a pious lady, taught him his letters, and Mrs. Jonathan Newhall used to read to him the chapter in the Bible from which he was to preach until he had committed it to memory.

North Saugus is a fine agricultural section with table land, pleasant and well watered, well adapted to farming purposes, and it was here that Adam Hawkes, the first of this name in this county, settled with his five sons in 1630, and took up a large tract of land. He built his house on a rocky knoll, the spot being at the intersection of the road leading from Saugus to Lynnfield with the Newburyport turnpike, known as Hawkes' Corner. This house being burned the bricks of the old chimney were put into another, and when again this chimney was taken down a few years ago there were found bricks with the date of 1601 upon them. This shows, evidently, that the bricks were brought from England. This property is now in the hands of one of his lineal descendants, Louis P. Hawkes, having been handed down from sire to son for more than 250 years. On the 28th and 29th of July, 1880, a family reunion of the descendents of Adam Hawkes was held to celebrate the 250th anniversary of his advent to the soil of Saugus. It was a notable meeting, and brought together the members of this respected and respectable [pg 144] family from Maine to California. Two large tents were spread and the trees and buildings were decorated with flags and mottoes in an appropriate and tasteful manner. Judges, Generals, artists, poets, clergymen, lawyers, farmers and mechanics were present to participate in the re-union. Addresses were made, poems suitable to the occasion rendered, and all passed off in a most creditable manner. Among the antique and curious documents in the possession of Samuel Hawkes was the "division of the estate of Adam Hawkes, made March 27, 1672."

Mrs. Dinsmore resided in this part of the town. A most amiable woman, a good nurse, kind in sickness, and it was in this way that she discovered a most valuable medicine. Her specific is claimed to be very efficacious in cases of croup and kindred diseases, and its use in such cases has become very general, as well as for headache. She is almost as widely known as Lydia Pinkham. She died in 1881.

Saugus nobly responded to the call for troops to put down the rebellion, furnishing a large contingent for Company K, Seventeenth Massachusetts Volunteers, which was recruited almost wholly from Malden and Saugus, under command of Captain Simonds of Malden. Thirty-six Saugus men also enlisted in Company A, Fortieth Massachusetts Volunteers, while quite a number joined the gallant Nineteenth Regiment, Col. E.W. Hinks, whose name Post 95, G.A.R., of Saugus bears, which is a large and flourishing organization. There were many others who enlisted in various other regiments, beside those who served in the navy.

NINETEENTH REGIMENT BADGE.

Charles A. Newhall of this town is secretary and treasurer of the Nineteenth Regiment association, whose survivors still number nearly one hundred members.

These justly celebrated works, the first of their kind in this country, were situated on the west bank of the Saugus river, about one-fourth of a mile north of the Town Hall, on the road leading to Lynnfield, and almost immediately opposite the mansion of A.A. Scott, Esq., the present proprietor of the woolen mills which are located just above, the site of the old works being still marked by a mound of scoria and [pg 145] debris, the locality being familiarly known as the "Cinder Banks." Iron ore was discovered in the vicinity of these works at an early period, but no attempt was made to work it until 1643. The Braintree iron works, for which some have claimed precedence, were not commenced until 1647, in that part of the town known as Quincy.

Among the artisans who found employment and scope for their mechanical skill at these works was Mr. Joseph Jenks who, when the colonial mint was started to coin the "Pine Tree Shilling," made the die for the first impressions at the Iron works at Saugus.

The old house, formerly belonging to the Thomas Hudson estate of sixty-nine acres first purchased by the Iron Works, is still standing, and is probably one of the oldest in Essex County, although it has undergone so many repairs that it is something like the boy's jack-knife, which belonged to his grandfather and had received three new blades and two new handles since he had known it. One of the fire-places, with all its modernizing, a few years ago measured about thirteen feet front, and its whole contour is yet unique. It is now owned by A.A. Scott and John B. Walton.

Near Pranker's Pond, on Appleton street, is a singular rock resembling a pulpit. This portion of the town is known as the Calemount.

There is a legend of the Colonial period that a man by the name of Appleton harangued or preached to the people of the vicinity, urging them to stand by the Republican cause, hence the name of "Pulpit Rock." The name "Calemount" also comes, according to tradition, from the fact that one of the people named Caleb Appleton, who had become obnoxious to the party, had agreed upon a signal with his wife and intimate friends, that, when in danger, they should notify him by this expressive warning, "Cale, mount!" upon which he would take refuge in the rocky mountain, which, being then densely wooded, afforded a secure hiding place. Several members of this family of Appletons have since, during successive generations, been distinguished and well known citizens of Boston, one of whom, William Appleton, was elected to Congress over Anson Burlingame, in 1860.

Recently, one of the descendants of this family has had a tablet of copper securely bolted to the rock with the following inscription:—

"APPLETOX'S PULPIT!

In September, 1687, from this rock tradition asserts that resisting the tyranny of Sir Edmond Andros, Major Samuel Appleton of Ipswich spake to the people in behalf of those principles which later were embodied in the declaration of Independence."

This tablet was formally presented to the town by letter from the late Thomas Appleton, at the annual March meeting in 1882, and its care assumed by the town of Saugus.

Among the present industries of Saugus are Pranker's Mills, a joint stock corporation, doing business under the style of Edward Pranker & Co., for the manufacture of woollen goods, employing about one hundred operatives, and producing about 1,800,000 yards of cloth annually—red, white and yellow flannel. The mill of A.A. Scott is just below on the same stream, making the same class of goods, with a much smaller production, both companies being noted for the standard quality of their fabrics. The spice and coffee mills of Herbert B. Newhall at East Saugus do a large business in their line, and his goods go all over New England and the West.

Charles S. Hitchings, at Saugus, turns [pg 146] out some 1,500 cases of hand-made slippers of fine quality for the New York and New England trade. Otis M. Burrill, in the same line, is making the same kind of work, some 150 cases, Hiram Grover runs a stitching factory with steam power, and employs a large number of employees, mostly females.

Win. E. Shaw also makes paper boxes and cartoons, and does quite a business for Lynn manufacturers.

Enoch T. Kent at Saugus and his brother, Edward S. Kent, at Cliftondale, are engaged in washing crude hair and preparing it for plastering and other purposes, such as curled hair, hair cloth, blankets, etc. They each give employment to quite a number of men. Albert H. Sweetser makes snuff, succeeding to the firm of Sweetser Bros., who did an extensive business until after the war. The demand for this kind of goods is more limited than formerly. Joseph. A. Raddin, manufactures the crude tobacco from the leaf into chewing and smoking tobacco. Edward O. Copp, Martha Fiske, William Parker and a few others still manufacture cigars.

Quite an, extensive ice business is done at Saugus by Solon V. Edmunds and Stephen Stackpole. A few years ago Eben Edmunds shipped by the Eastern Railroad some 1,200 tons to Gloucester, but the shrinkage and wastage of the ice by delays on the train did not render it a profitable operation.

The strawberry culture has recently become quite a feature in the producing industry of Saugus. In 1884 [pg 147] Elbridge S. Upham marketed 3,600 boxes, Charles S. Hitchings 1,200, Warren P. Copp 400, and others, Martin Carnes, Calvin Locke, Edward Saunders and Lorenzo Mansfield, more or less.

John W. Blodgett and the Hatch Bros. do a large business in early and late vegetables for Boston and Lynn markets, such as asparagus, spinach, etc., and employ quite a number of men.

Nor must we forget to mention the milk business. Louis P. Hawkes has a herd of some forty cows and has a milk route at Lynn. J.W. Blodgett keeps twenty-five cows, and takes his milk to market. Geo. N. Miller and T.O.W. Houghton also keep cows and have a route. Joshua Kingsbury, George H. Pearson and George Ames have a route, buying their milk. Byron Hone keeps fifty cows. Dudley Fiske has twenty-five, selling their milk. O.M. Hitchings, H. Burns, A.B. Davis, Lewis Austin, Richard Hawkes and others keep from seven to twelve cows for dairy purposes.

Having somewhat minutely noticed the industries we will speak briefly of some of the dwellings. The elegant mansion and gardens of Brainard and Henry George, Harmon Hall and Rufus A. Johnson of East Saugus, and Eli Barrett, A.A. Scott and E.E. Wilson of Saugus, C.A. Sweetser, C.H. Bond and Pliny Nickerson at Cliftondale, with their handsome lawns, rich and rare flowers and noble shade trees attract general attention. The last mentioned estate was formerly owned by a brother of Governor William Eustis, where his Excellency used to spend a portion of his time each year.

At the south-westerly part of the town, not far from the old Eustis estate, the boundaries of three counties and four towns intersect with each other, viz: Suffolk, Essex and Middlesex counties, and the towns of Revere, Saugus, Melrose and Maiden. Near by, too, is the old Boynton estate, and the Franklin Trotting park, where some [pg 148] famous trotting was had, when Dr. Smith managed it in 1866-7, Flora Temple, Fashion, Lady Patchen and other noted horses contending. After a few years of use it was abandoned, but it has recently been fitted up by Marshall Abbott of Lynn, and several trots have taken place the present summer.

The Boynton estate above referred to is divided by a small brook, known as "Bride's Brook," which is also the dividing line between Saugus and Revere, [pg 149] and the counties of Suffolk and Essex. Tradition asserts that many years ago a couple were married here, the groom standing on one side and the bride on the other; hence the name "Bride's Brook."

The existence of iron ore used for the manufacturing at the old Iron Works was well known, and there have been many who have believed that antimony also exists in large quantities in Saugus, but its precise location has as yet not become known to the public.

As early as the year 1848, a man by the name of Holden, who was given to field searching and prospecting, frequently brought specimens to the late Benjamin F. Newhall and solemnly affirmed that he obtained them from the earth and soil within the limits of Saugus. Every means was used to induce him to divulge the secret of its locality. But Holden was wary and stolidly refused to disclose or share the knowledge of the place of the lode with anyone. He averred that he was going to make his fortune by it. Detectives were put upon his trail in his roaming about the fields, but he managed to elude all efforts at discovery. Being an intemperate man, one cold night after indulging in his cups, he was found by the roadside stark and stiff. Many rude attempts and imperfect searches have been made upon the assurances of Holden to discover the existence of antimony, but thus far in vain, and the supposed suppressed secret of the existence of it in Saugus died with him.

"Pirate's Glen" is also within the territory of Saugus, while "Dungeon Rock," another romantic locality, described by Alonzo Lewis in his history of Lynn, is just over the line in that city. There is a popular tradition that the pirates buried their treasure at the foot of a certain hemlock tree in the glen, also the body of a beautiful female. The rotten stump of a tree may still be seen, and a hollow beside it, where people have dug in searching for human bones and treasure. This glen is highly romantic and is one of the places of interest to which all strangers visiting Saugus are conducted, and is invested with somewhat of the supernatural tales of Captain Kid and treasure trove.

There is a fine quarry or ledge of jasper located in the easterly part of the town, near Saugus River, just at the foot of the conical-shaped elevation known as "Round Hill." which Professor Hitchcock, in his last geological survey, pronounced to be the best specimen in the state. Mrs. Hitchcock, an artist, who accompanied her husband in his surveying tour, delineated from this eminence, looking toward Nahant and Egg Rock, which is full in view, and from which steamers may be seen with a glass plainly passing in and out of Boston harbor. The scenery and drives about Saugus are delightful, especially beautiful is the view and landscape looking from the "Cinder Banks," so-called, down Saugus river toward Lynn.

Saugus, (formerly the West Parish of Lynn), was formed in the year 1815, and the town was first represented by Mr. Robert Emes in 1816. Mr. Emes carried on morocco dressing, his business being located on Saugus river, on the spot now occupied by Scott's Flannel Mills.

In 1817-18 Mr. Joseph Cheever represented the town, and again in 1820-21; also, in 1831-32, and again, for the last time, in 1835. After having served the town seven times in the legislature, [pg 150] he seems to have quietly retired from political affairs.

In 1822 Dr. Abijah Cheever was the Representative, and again in 1829-30. The doctor held a commission as surgeon in the army at the time of our last war with Great Britain. He was a man very decided in his manners, had a will of his own, and liked to have people respect it.

In 1823 Mr. Jonathan Makepeace was elected. His business was the manufacture of snuff, at the old mills in the eastern part of the town, now owned by Sweetser Brothers, and known as the Sweetser Mills.

In 1826-28 Mr. John Shaw was the Representative.

In 1827 Mr. William Jackson was elected.

In 1833-34 Mr. Zaccheus N. Stocker represented the town. Mr. Stocker held various offices, and looked very closely after the interests of the town.

In 1837-38 Mr. William W. Boardman was the Representative. He has filled a great many offices in the town.

In 1839 Mr. Charles Sweetser was elected, and again in 1851. Mr. Sweetser was largely engaged in the manufacture of snuff and cigars. He was a gentleman very decided in his opinions, and enjoyed the confidence of the people to a large degree.

In 1840, the year of the great log cabin campaign, Mr. Francis Dizer was elected.

In 1841 Mr. Benjamin Hitchings, Jr., was elected, and in 1842 the town was represented by Mr. Stephen E. Hawkes.

In 1843-44 Benjamin F. Newhall, Esq., was the Representative, Mr. Newhall was a man of large and varied experience, and held various offices, always looking sharply after the real interests of the town. He also held the office of County Commissioner.

In 1845 Mr. Pickmore Jackson was the Representative. He has also held various offices in the town, and has since served on the school committee with good acceptance.

In 1846-47 Mr. Sewall Boardman represented the town.

In 1852 Mr. George H. Sweetser was the Representative. Mr. Sweetser has also held a seat in our State Senate two years, and filled various town offices. He was a prompt and energetic business man, engaged in connection with his brother, Mr. Charles A. Sweetser, in the manufacture of snuff and cigars.

In 1853 Mr. John B. Hitching was elected. He has held various offices in the town.

In 1854 the town was represented by Mr. Samuel Hawkes, who has also served in several other positions, proving himself a very straightforward and reliable man.

In 1855 Mr. Richard Mansfield was elected. He was for many years Tax Collector and Constable, and when he laid his hand on a man's shoulder, in the name of the law, the duty was performed in such a good-natured manner that it really did not seem so very bad, after all.

In 1856 Mr. William H. Newhall represented the town. He has held the offices of Town Clerk and Selectman longer than any other person in town, and is still in office.

In 1857 Mr. Jacob B. Calley was elected.

In 1858 the district system was adopted, and Mr. Jonathan Newhall was elected to represent the twenty-fourth Essex District, comprising the towns of Saugus, Lynnfield and Middleton.

In 1861 Mr. Harmon Hall represented the District. Mr. Hall is a very energetic business man, and has accumulated a very handsome property by [pg 152] the manufacture of boots and shoes. He has held various other important positions, and has been standing Moderator in all town meetings, always putting business through by daylight.

In 1863 Mr. John Hewlett was elected. He resides in that part of the town called North Saugus, and was for a long series of years a manufacturer of snuff and cigars.

In 1864 Mr. Charles W. Newhall was the Representative.

In 1867 Mr. Sebastian S. Dunn represented the District. Mr. Dunn was a dealer in snuff, cigars and spices, and is now engaged in farming in Dakota.

In 1870 Mr. John Armitage represented the District—the twentieth Essex—comprising the towns of Saugus, Lynnfield, Middleton and Topsfield. He has been engaged in the woollen business most of his life; formerly a partner with Pranker & Co. He has also held other town offices with great acceptance.

J.B. Calley succeeded Mr. Armitage, it being the second time he had been elected. Otis M. Hitchings was the next Representative, a shoe manufacturer, being elected over A.A. Scott, Esq., the republican candidate.

Joseph Whitehead was the next Representative from Saugus, a grocer in business. He was then and still is Town Treasurer, repeatedly having received every vote cast. J. Allston Newhall was elected in 1878 and for several years was selectman.

Albert H. Sweetser was our last Representative, elected in 1882-3, by one of the largest majorities ever given in the District. He is a snuff manufacturer, doing business at Cliftondale, under the firm of Sweetser Bros., whom he succeeds in business. Saugus is entitled to the next Representative in 1885-6. The womb of the future will alone reveal his name.

The future of Saugus would seem to be well assured, having frequent trains to and from Boston and Lynn, with enlarged facilities for building purposes, especially at Cliftondale, where a syndicate has recently been formed, composed of Charles H. Bond, Edward S. Kent, and Henry Waite, who have purchased thirty-four acres of land, formerly belonging to the Anthony Hatch estate, which, with other adjoining lands are to be laid out into streets and lots presenting such opportunities and facilities for building as cannot fail to attract all who are desirious of obtaining suburban residences, and thus largely add to the taxable property of Saugus and to the prosperity of this interesting locality.

The project of erecting a colossal statue of Liberty, which shall at once serve as a lighthouse and as a symbolic work of art, may be discussed from several different points of view. The abstract idea, as it occurred to the sculptor, Mr. Bartholdi, was noble. The colossus was to symbolize the historic friendship of the two great republics, the United States and France; it was to further symbolize the idea of freedom and fraternity which underlies the republican form of government. Lafayette and Jefferson would have been touched by the project. If we are not touched by it, it proves that we have forgotten much which it would become us to recall. Before our nation was, the democratic idea had been for many years existing and expanding among the French people; crushed again and again by tyrants, it ever rose, renewed and fresh for the irrepressible conflict. Through all their vicissitudes the people of France have upheld, unfaltering, their ideal—liberty, equality and fraternity. Our own republic exists to-day because France helped us when England sought to crush us. It is never amiss to freshen our memories as to these historic facts. The symbolism of the colossus would therefore be very fine; it would have a meaning which every one could understand. It would signify not only the amity of France and the United States, and the republican idea of brotherhood and freedom, as I have said; but it would also stand for American hospitality to the European emigrant, and Emma Lazarus has thus imagined the colossus endowed with speech:

Now, there can be no two ways of thinking among patriotic Americans as to this aspect of the Bartholdi colossus question. It must be agreed that the motive of the work is extremely grand, and that its significance would be glorious. The sculptor's project was a generous inspiration, for which he must be cordially remembered. To be sure, it may be said he is getting well advertised; that is very true, but it would be mean in us to begrudge him what personal fame he may derive from the work. To assume that the whole affair is a "job," or that it is entirely the outcome of one man's scheming egotism and desire for notoriety, is to take a deplorably low view of it; to draw unwarranted conclusions and to wrong ourselves. The money to pay for the statue—about $250,000—was raised by popular subscription in France, under the auspices of the Franco-American Union, an association of gentlemen whose membership includes such names as Laboulaye, de Lafayette, de Rochambeau, de Noailles, de Toqueville, de Witt, Martin, de Remusat. The identification of these excellent men with the project should be a sufficient guarantee of its disinterested character. The efforts made in this country to raise the money—$250,000—required to build a suitable pedestal for the statue, are a subject of every day comment, and the failure to obtain the whole amount is a matter for no small degree of chagrin.

Who and what is Mr. Bartholdi? He is a native of Colmar, in Alsace, and comes of a good stock; a pupil of the Lycee Louis-le-Grand, and of Ary Scheffer, he studied first painting then sculpture, and after a journey in the East with Gerome, established his atelier in Paris. He served in the irregular corps of Garibaldi during the war of 1870, and the following year visited the United States. It is admitted that he is a man of talent, but that he is not considered a great sculptor in his own country is equally beyond doubt. He would not be compared, for instance, with such men as Chapu, Dubois, Falguiere, Clesinger, Mercie, Fremiet, men who stand in the front rank of their profession. The list of his works is not long. It includes statues of General Rapp, Vercingetorix, Vauban, Champollion, Lafayette and Rouget de l'Isle; ideal groups entitled "Genius in the Grasp of Misery," and "the Malediction of Alsace;" busts of Messrs. Erckmann and Chatrain; single figures called "Le Vigneron," "Genie Funebre" and "Peace;" and a monument to Martin Schoengauer in the form of a fountain for the courtyard of the Colmar Museum. There may be a few others. Last, but by no means least, there is the great Lion of Belfort, his best work. This is about 91 by 52 feet in dimensions, and is carved from a block of reddish Vosges stone. It is intended to commemorate the defence of Belfort against the German army in 1870, an episode of heroic interest. The immense animal is represented as wounded but still capable of fighting, half lying, half standing, with an expression of rage and mighty defiance. It is not too much to say that Mr. Bartholdi in this case has shown a fine appreciation of the requirements of colossal sculpture. He has sacrificed all unnecessary details, and, taking a lesson from the old Egyptian stone-cutters, has presented an impressive arrangement of simple masses and unvexed surfaces which give to the composition a marvellous breadth of effect. The lion is placed in a sort of rude niche on the side of a rocky hill, which is the foundation of the fortress of Belfort. It is visible at a great distance, and is said to be strikingly noble from every point of view. The idea is not original, however well it may have been carried out, for the Lion of Lucerne by Thorwaldsen is its prototype on a smaller scale and commemorates an event of somewhat similar character. The bronze equestrian statue of Vercingetorix, the fiery Gallic chieftain, in the Clermont museum, is full of violent action. The horse is flying along with his legs in positions which set all the science of Mr. Muybridge at defiance; the man is brandishing his sword and half-turning in his saddle to shout encouragement to his followers. The whole is supported by a bit of artificial rock-work under the horse, and the body of a dead Gaul lies close beside it. In the statue of Rouget de l'Isle we see a young man striking an orator's attitude, with his right arm raised in a gesture which seems to say:

"Aux armes, citoyens / Formes vos bataillons!"

The Lafayette, in New York, is perhaps a mediocre statue, but even so, it is better than most of our statues. A Frenchman has said of it that the figure "resembles rather a young tenor hurling out his C sharp, than a hero offering his heart and sword to liberty." It represents our ancient ally extending his left hand in a gesture of greeting, while his right hand, which holds his sword, is pressed against his breast in a somewhat theatrical movement. It will be inferred that the general criticism to [pg 155] be made upon Mr. Bartholdi's statues is that they are violent and want repose. The Vercingetorix, the Rouget de l'Isle, the Lafayette, all have this exaggerated stress of action. They have counterbalancing features of merit, no doubt, but none of so transcendent weight that we can afford to overlook this grave defect.