Title: Disputed Handwriting

Author: Jerome Buell Lavay

Release date: November 10, 2004 [eBook #14003]

Most recently updated: December 18, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Ted Garvin and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Ted Garvin

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

"Handwriting is a gesture of the mind"

The first work of the kind ever published in the United States.

For the Protection of America's Banks and Business Houses.

1909

TO THE AMERICAN BANKERS' ASSOCIATION

THAT POWERFUL AGENCY WHICH HAS ELEVATED THE STANDARD OF BANKING IN THE UNITED STATES AND AN INSTITUTION THAT FOLLOWS ALL WRONGDOERS AGAINST MEMBERS OF THE FRATERNITY RELENTLESSLY AND SUCCESSFULLY THIS WORK IS MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED

| CHAPTER I | |

| HOW TO STUDY FORGED AND DISPUTED SIGNATURES |

All Titles Depend Upon the Genuineness of Signatures—Comparing Genuine with Disputed Signatures—A Word about Fac-simile Signatures—Process of Evolving a Signature—Evidence of Experience in Handling or Mishandling a Pen—Signature Most Difficult to Read—Simulation of Signature by Expert Penman—Hard to Imitate an Untrained Hand—A Well-Known Banker Presents Some Valuable Points—Perfectly Imitated Writings and Signatures—Bunglingly Executed Forgeries—The Application of Chemical Tests—Rules of Courts on Disputed Signatures—Forgers Giving Appearance of Age to Paper and Ink—Proving the Falsity of Testimony—Determining the Genuineness or Falsity by Anatomy or Skeleton—Making a Magnified Copy of a Signature—Effectiveness of the Photograph Process—Deception the Eye Will Not Detect—When Pen Strokes Cross Each Other—Experimenting With Crossed Lines—Signatures Written With Different Inks—Deciding Order of Sequence in Writing—An Important and Interesting Subject for Bankers—Determining the Genuineness of a Written Document—Ingenuity of Rogues Constantly Takes New Forms—A Systematic Analysis Will Detect Disputed Signatures

| CHAPTER II | |

| FORGERY BY TRACING |

Forgeries Perpetrated by the Aid of Tracing a Common and Dangerous Method—Using Transparent Tracing Paper—How the Movements are Directed—Formal, Broken and Nervous Lines—Retouched Lines and Shades—Tracing Usually Presents a Close Resemblance to the Genuine—Traced Forgeries Not Exact Duplicates of Their Originals—The Danger of an Exact Duplication—Forgers Usually Unable to Exactly Reproduce Tracing—Using Pencil or Carbon-Guided Lines—Retouching Revealed under the Microscope—Tracing with Pen and Ink Over a Transparency—Making a Practice and Study of Signatures—Forgeries and Tracings Made by Skillful Imitators Most Difficult of Detection—Free-Hand Forgery and Tracing—A Few Important Matters to Observe in Detecting Forgery by Tracing—Photographs a Great Aid in Detecting Tracing—How to Compare Imitated and Traced Writing—Furrows Traced by Pen Nibs—Tracing Made by an Untrained Hand—Tracing with Pen and Ink Over a Transparency—Internal Evidence of Forgery by Tracing—Forgeries Made by Skillful Imitators—How to Determine Evidences of Forgery by Tracing—Remains of Tracings—Examining Paper in Transmitted Light—Freely Written Tracings—A Dangerous Method of Forgery

| CHAPTER III | |

| HOW FORGERS REPRODUCE SIGNATURES |

Characteristics Appearing in Forged Signatures—Conclusions Reached by Careful Examinations—Signatures Written with Little Effort to Imitate—What a Clever Forger Can Do—Most Common Forgeries of Signatures—Reproducing a Signature over a Plate of Glass—A Window Frame Scheme for Reproducing Signatures—How the Paper is Held and the Ink Applied—How a Genuine Signature is Placed and Used—A Forger's Process of Tracing a Signature—How to Detect Earmarks of Fraud in a Reproduced Signature—Prominent Features of Signatures Reproduced—Method Resorted to by Novices in Forging Signatures—Conditions Appearing in All Traced Signatures—Reproduction of Signatures Adopted by Expert Forgers—Making a Lead-Pencil Copy of a Signature—Erasing Pencil Signatures Always Discoverable by the Aid of a Microscope—Appearances and Conditions in Traced Signatures—How to Tell a Traced Signature—All the Details Employed to Reproduce a Signature Given—Features in Which Forgers are Careless—Handling of the Pen Often Leads to Detection—A Noted Characteristic of Reproduced Signatures—Want of Proportion in Writing Names Should Be Studied—Rules to Be Followed in Examining Signatures—System Employed by Experts in Studying Proof of Reproduced Signatures—Bankers and Business Men Should Avoid Careless Signatures

| CHAPTER IV | |

| ERASURES, ALTERATIONS AND ADDITIONS |

What Erasure Means—The English Law—What a Fraudulent Alteration Means—Altered or Erased Parts Considered—Memoranda of Alterations Should Always Accompany Paper Changed—How Added Words Should be Treated—How to Erase Words and Lines Without Creating Suspicion—Writing Over an Erasure—How to Determine Whether or Not Erasures or Alterations Have Been Made—Additions and Interlineations—What to Apply to the Suspected Document—The Alcohol Test Absolute—How to Tell which of Crossing Ink Lines Were Made First—Ink and Pencil Alterations and Erasures—Treating Paper to Determine Erasures, Alterations and Additions—Appearance of Paper Treated as Directed—Paper That Does Not Reveal Tampering—How Removal of Characters From a Paper is Affected—Easy Means of Detecting Erasures—Washing with Chemical Reagents—Restoration of Original Marks—What Erasure on Paper Exhibits—Erasure in Parchments—Identifying Typewritten Matter—Immaterial Alterations—Altering Words in an Instrument—Alterations and Additions Are Immaterial When Interests of Parties Are Not Changed or Affected—Erasure of Words in an Instrument

| CHAPTER V | |

| HOW TO WRITE A CHECK TO PREVENT FORGING |

How a Paying Teller Determines the Amount of a Check—Written Amount and Amount in Figures Conflict—Depositor Protected by Paying Teller—Chief Concern of Drawer of a Check—Transposing Figures—Writing a Check That Cannot Be Raised—Writers who Are Easy Marks for Forgers—Safeguards for Those who Write Checks—An Example of Raised Checks—Payable "To Bearer" Is Always a Menace—Paying Teller and An Endorsement System Must Be Observed in Writing Checks—How a Check Must Be Written to Be Absolutely Safe—A Signature that Cannot Be Tampered with Without Detection—Paying Tellers Always Vigilant

| CHAPTER VI | |

| METHODS OF FORGERS, CHECK AND DRAFT RAISERS |

Professional Forgers and Their Methods—Using Engravers and Lithographers—Their Knowledge of Chemicals—Patching Perforated Paper—Difficult Matter to Detect Alterations and Forgeries—Selecting Men for the Work—The Middle Man, Presenter, and Shadow—Methods for Detecting Forgery—Detailed Explanation of How Forgers Work—Altering and Raising Checks and Drafts—A Favorite Trick of Forgers—Opening a Bank Account for a Blind—Private Marks on Checks no Safeguard—How a Genuine Signature Is Secured—Bankers Can Protect Themselves—A Forger the Most Dangerous Criminal—Bankers Should Scrutinize Signatures—Sending Photograph with Letter of Advice—How to Secure Protection Against Forgers—Manner in Which Many Banks Have Been Swindled—Points About Raising Checks and Drafts That Should Be Carefully Noted

| CHAPTER VII | |

| THE HANDWRITING EXPERT |

No Law Regulating Experience and Skill Necessary to Constitute an Expert—Expert Held Competent to Testify in Court—Bank Officials and Employees Favored—An Expert On Signatures—Methods Experts Employ to Identify the Work of the Pen—Where and When an Expert's Services Are Needed—Large Field and Growing Demand for Experts—Qualifications of a Handwriting Expert—How the Work is Done—A Good Expert Continously Employed—The Expert and the Charlatan—Qualifying as An Expert—A System Which Produces Results—Principal Tests Applied by Handwriting Experts to Determine Genuineness—Identification of Individual by His Handwriting—How to Tell Kind of Ink and Process Used to Forge a Writing—Rules Followed by Experts in Determining Cases—The Testimony of a Handwriting Expert—Explaining Methods Employed to Detect Forged Handwriting—The Courts and Experts—What an Expert May Testify to—Trapping a Witness—Proving Handwriting by Experts—General Laws Regulating Experts—The Basework of a Handwriting Expert—Important Facts an Expert Begins Examination With—A Few Words of Advice and Suggestion About "Pen Scope"—Detection of Forgery Easy—Rules Herewith Suggested Should Be Observed—Expert Witnesses, Courts, and Jurors

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| HOW TO DETECT FORGED HANDWRITING |

Frequency of Litigation Arising over Disputed Handwriting—Forged and Fictitious Claims Against the Estates of Deceased People—Forgery Certain to Be Detected When Subjected to Skilled Expert Examination—A Forger's Tracks Cannot Be Successfully Covered—With Modern Devices Fraudulent, Forged and Simulated Writing Can Be Determined Beyond the Possibility of a Mistake—Bank Officials and Disputed Handwriting—How to Test and Determine Genuine and Forged Signatures—Useful Information About Signature Writing—Guard Against an Illegible Signature—Avoid Gyrations, Whirls and Flourishes—Write Plain, Distinct and Legible—The Signature to Adopt—The People Forgers Pass By—How Many Imitate Successfully—How an Expert Detects Forged Handwriting—Examples of Signatures Forgers Desire to Imitate—Examining and Determining a Forgery—Comparisons of Disputed Handwriting—Microscopic Examinations a Great Help in Detecting Forged Handwriting—Comparison of Forged Handwriting

| CHAPTER IX | |

| GREATEST DANGER TO BANKS |

Check-Raising Always a Danger—A Scheme Almost Impossible to Prevent—The American Banker's Association the Greatest Foe to Forgers—It Follows Them Relentlessly and Successfully—Chemically Prepared Paper and Watermarks Not Always a Safeguard—Perforating Machines and Check Raisers—How Check Perforations Are Overcome—How an Ordinary Check Is Raised—How an Expert Alters Checks—How Perforations Are Filled—Hasty Examination by Paying Tellers Encourages Forgers—The Way Bogus Checks Creep Through a Bank Unnoticed—A Celebrated Forgery Case—Forgers Successful for a Time Always Caught—Where Forgers Usually Go That Have Made a Big Haul—A Professional Crook Is a Person of Large Acquaintance

| CHAPTER X | |

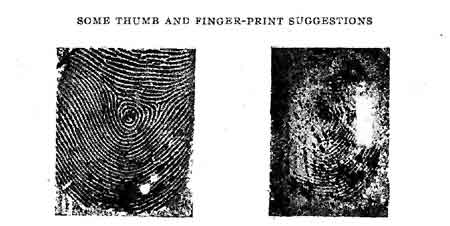

| THUMB PRINTS NEVER FORGED |

Thumb-Print Method of Identification Absolute—Now Brought to a High State of Perfection—Will Eventually Be Used in all Banks—Certified Checks and Also Drafts with Thumb-Print Signatures—Absolute Accuracy of a Thumb-Print Identification Assured—A Thumb-Print in Wax on Sealed Packages—Its Use an Advantage on Bankable Paper of All Kinds—How Strangers Are Easily Identified—Bankers, Merchants and Business Men Protected by This System—Full Particulars as to How Thumb-Prints Are Made—Can be Printed by Anyone in a Few Minutes—How and When to Place Your Thumb-Print on Bankable Paper—Finger-Prints as Reliable as Thumb-Prints—Use to Which This System Could Be Put—Thumb and Finger Tips Do Not Change From Birth to Death—Department of Justice at Washington Has Established a Bureau of Criminal Registry Using the Thumb-Print System—Thumb-Print System Said to Be a Chinese Invention—Its Use Spreading Rapidly—How to Secure Thumb-Print Impression Without Knowledge of Party—An Interesting and Valuable Study

| CHAPTER XI | |

| DETECTING FORGERY WITH THE MICROSCOPE |

Determining Questionable Signatures By the Aid of a Microscope—A Magnifying Glass Not Powerful Enough—Character of Ink Easily Told—The Microscope and a Knowledge of Its Use—Experience and Education of an Examiner of Great Assistance—An Expert's Opinion—The Use of the Microscope Recommended—Illustrating a Method of Forgery—What a Microscopic Examination Reveals—How to Examine Forged Handwriting with a Microscope—Experts and a Jury—What the Best Authorities Recommend

| CHAPTER XII | |

| SIGNATURE EXPERTS THE SAFETY OF THE MODERN BANK |

A New Departure in Banks—Examining All Signatures a Sure Preventive Against Forgery—The "Filling in" Process—How One Forger Operated—Marvelous Accuracy of a Paying Teller—How He Attained Perfection—How Signature Clerks Work—A Common Dodge of Forgers—Post Dated Checks—A System That Prevents Forged and Raised Checks—Not a Forged or Raised Check Paid in Years

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| HOW TO DETERMINE AGE OF ANY WRITING |

The Different Kinds of Ink Met With—Inks That Darken by Exposure to Sunlight and Air—Introduction of Aniline Colors to Determine the Age of Writings—An Almost Infallible Rule to Follow—Determining Age of Writing By Ink Used—The Ammonia System a Sure One—A Question of Great Interest to Bankers and Bank Employes—Thick and Thin Inks—So-Called Safety Inks That Are Not Safe—How to Restore Faded Inks—An Infallible Rule—Restoring Faded Writing—Restored By the Silk and Cotton System That Anyone Can Arrange—Danger of Exposing Restored Writing to the Sun

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| DETECTING FRAUD AND FORGERY IN PAPERS AND DOCUMENTS |

Infallible Rules for the Detection of Same—New Methods of Research—Changing Wills and Books of Accounts—Judgment of the Naked Eye—Using a Microscope or Magnifying Glass—Changeable Effects of Ink—How to Detect the Use of Different Inks—Sized Papers Not Easily Altered—Inks That Produce Chemical Effects—Inks That Destroy Fiber of Paper—How to Test Tampered or Altered Documents—Treating Papers Suspected of Forgery—Using Water to Detect Fraud—Discovering Scratched Paper—Means Forgers Use to Mask Fraudulent Operations—How to Prepare and Handle Test Papers—Detecting Paper That Has Been Washed—Various Other Valuable Tests to Determine Forgery—A Simple Operation That Anyone Can Apply—Iodine Used on Papers and Documents—An Alcohol Test That Is Certain—Bringing Out Telltale Spots—Double Advantage of Certain Tests—Reappearance of Former Letters or Figures—What Genuine Writing Reveals—When an Entire Paper or Document is Forged

| CHAPTER XV | |

| GUIDED HANDWRITING AND METHOD USED |

The Most Frequent and Dangerous Method of Forgery—How to Detect a Guided Signature—What Guided Handwriting Is and How It Is Done—Character of Such Writing—Writing by a Guided Hand—Difficulty in Writing—Force Exercised by Joint Hands—A Hand More or Less Passive—Work of the Controlling Hand—How Guided Writing Appears—Two Writers Acting in Opposition—Distorted Writing—How a Legitimate Guided Hand is Directed and Supported—Pen Motion Necessary to Produce Same—Influence in Guiding a Stronger Hand—Avoiding an Unnatural and Cramped Position—Effect of the Brain on Guided Hand—Separating Characteristics from Guided Joint Signature—Detecting Writing by a System of Measurement

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| TALES TOLD BY HANDWRITING |

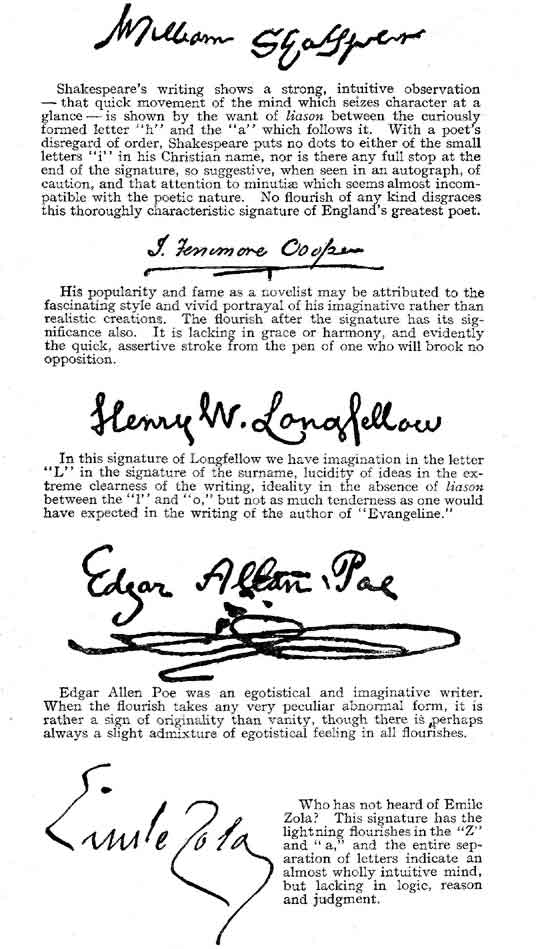

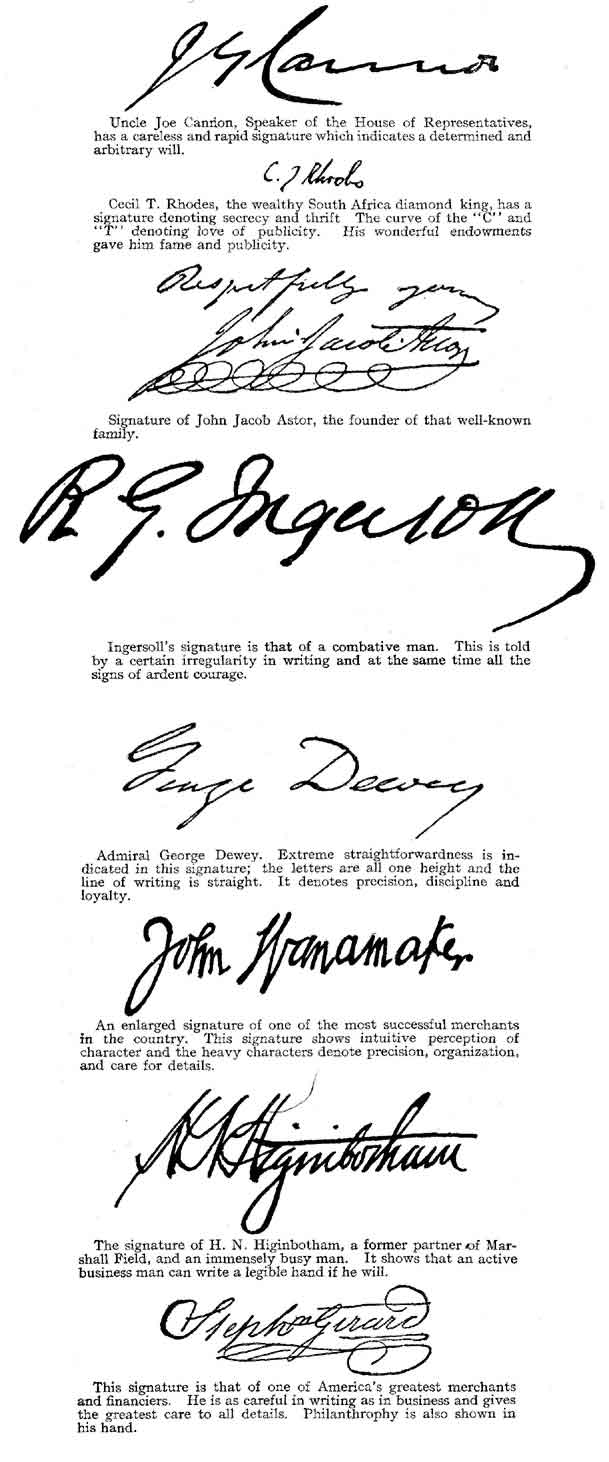

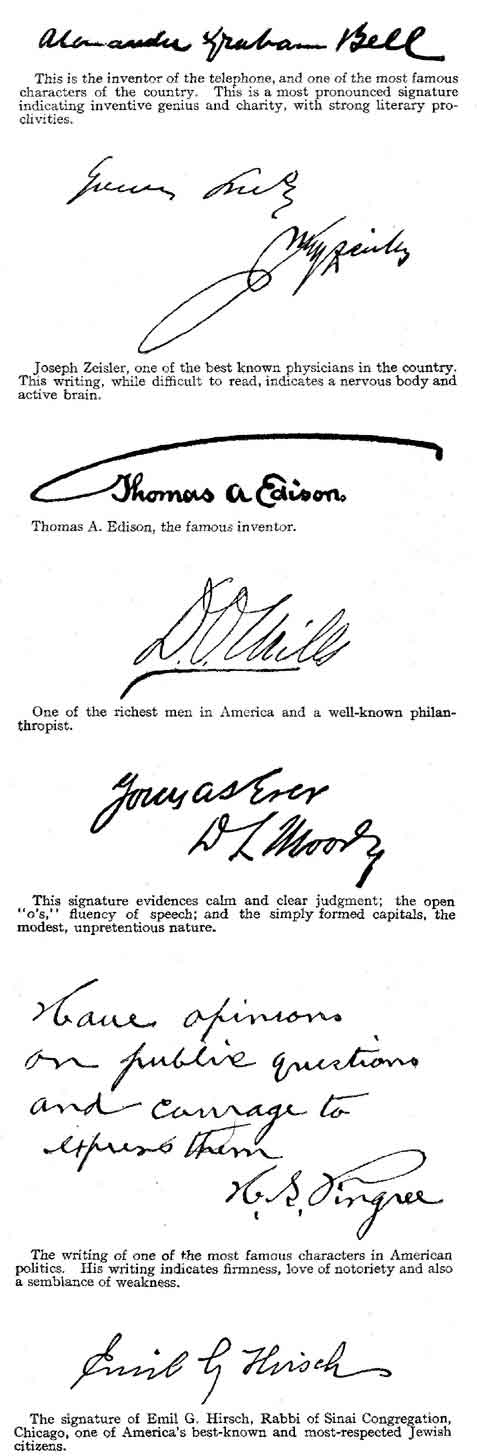

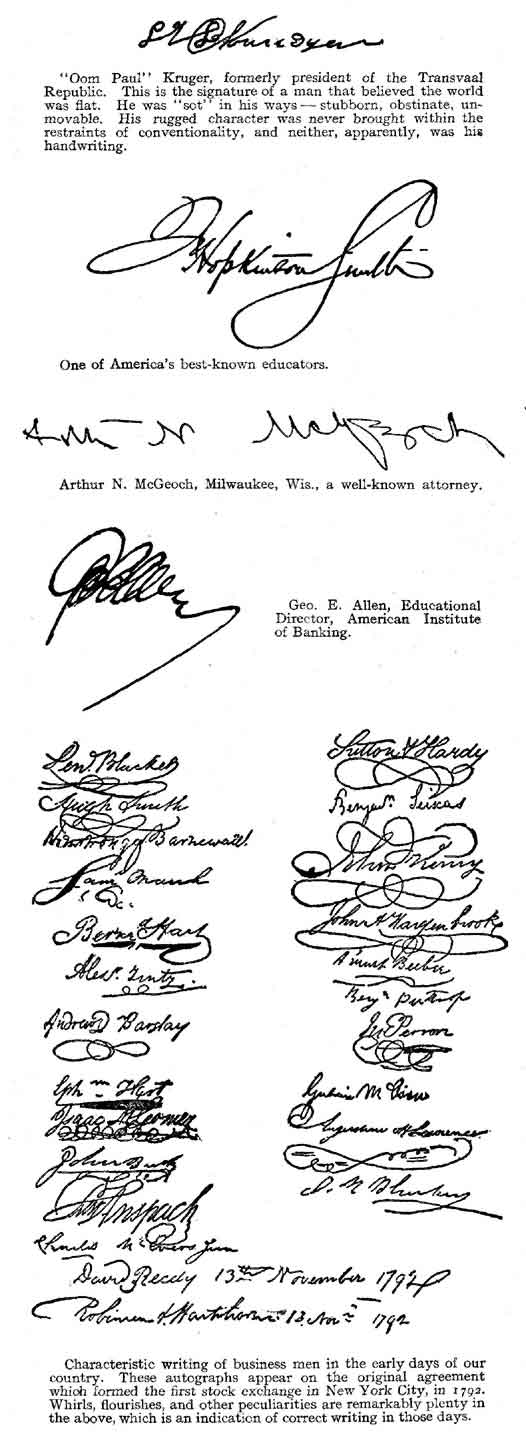

Telling the Nationality, Sex and Age of Anyone Who Executes Handwriting—Americans and Their Style of Writing—How English, German, and French Write—Gobert, the French Expert, and How He Saved Dreyfus—Miser Paine and His Millions Saved by an Expert—Writing with Invisible Ink—Professor Braylant's Secret Writing Without Ink—Professor Gross Discovers a Simple Secret Writing Method With a Piece of Pointed Hardwood—A System Extensively Used—Studying the Handwriting of Authors—How to Determine a Person's Character and Disposition by Handwriting

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| WORKINGS OF THE GOVERNMENT SECRET SERVICE |

Officials of This Department Talk About Their Work—How Criminals Are Traced, Caught and Punished—Its Work Extending to All Departments—Secret Service Districts—Reports Made to the Treasury Department—Good Money and Bad—How to Detect the False—System of Numbering United States Notes Explained—Counterfeiting on the Decrease—Counterfeiting Gold Certificates—Bank Tellers and Counterfeits—The Best Secret Service in the World

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| CHARACTER AND TEMPERAMENT INDICATED BY HANDWRITING | 191 |

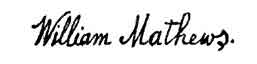

A Man's Handwriting a Part of Himself—Handwriting and Personality—Cheap Postage and Typewriters Playing Havoc with Writing by Hand—Old Time Correspondence Vanishing—Two Divisions of Handwriting—Fashion Has Changed Even Writing—Characteristic Writing of Different Professions—One's Handwriting a Sure Index to Character and Temperament—Personality of Handwriting—Handwriting a Voiceless Speaking—A Neglected Science—Interest in Disputed Handwriting Rapidly Coming to the Front—Set Writing Copies no Longer the Rule—Formal Handwriting—Education's Effect on Writing—Handwriting and Personality—The Character and Temperament of Writers Easily Told—Honest, Eccentric, and Weak People—How to Determine Character by Writing—The Marks of Truth and Straightforwardness—How Perseverance and Patience Are Indicated in Writing—Economy, Generosity and Liberality Easily Shown in Writing—The Character and Temperament of Any Writer Easily Shown—Studying Character from Handwriting a Fascinating Work—Rules for Its Study—Links in a Chain That Cannot be Hidden—A Person's Writing a Surer Index to Character Than His Face

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| HANDWRITING EXPERTS AS WITNESSES | 205 |

Who May Testify As An Expert—Bank Officials and Bank Employes Always Desired—Definition of Expert and Opinion Evidence—Both Witness and Advocate—Witness in Cross Examination—Men Who Have Made the Science of Disputed Handwriting a Study—Objections to Appear in Court—Experts Contradicting Each Other—The Truth or Falsity of Handwriting—Sometimes a Mass of Doubtful Speculations—Paid Experts and Veracity—Present Method of Dealing with Disputed Handwriting Experts—How the Bench and Bar Regard the System—Remedies Proposed—Should an Expert Be an Adviser of the Court?—Free from Cross-Examination—Opinions of Eminent Judges on Expert Testimony—Experts Who Testify Without Experience—What a Bank Cashier or Teller Bases His Opinions on—Actions and Deductions of the Trained Handwriting Expert—Admitting Evidence of Handwriting Experts—Occupation and Theories That Make an Expert—Difference Between an Expert and a Witness—Experts and Test Writing—What Constitutes An Expert in Handwriting—Present Practice Regarding Experts—Assuming to Be a Competent Expert—Testing a Witness with Prepared Forged Signatures—Care in Giving Answers—A Writing Teacher As an Expert—Familiarity with Signatures—What a Dash, Blot, or Distortion of a Letter Shows—What a Handwriting Expert Should Confine Himself to—Parts of Writing Which Demand the Closest Attention—American and English Laws on Experts in Handwriting—Examination of Disputed Handwriting

| CHAPTER XX | |

| TAMPERED, ERASED AND MANIPULATED PAPER | 219 |

Sure Rules for the Detection of Forged and Fraudulent Writing of Any Kind—European Professor Gives Rules for Detecting Fraud—How to Tell Alterations Made on Checks, Drafts, and Business Paper—An Infallible System Discovered—Results Always Satisfactory—Can Be Used by Anyone—Vapor of Iodine a Valuable Agent—Paper That Has Been Wet or Moistened—Colors That Tampered Paper Assumes—Tracing Written Characters with Water—Making Writing Legible—How to Tell Paper That Has Been Erased or Rubbed—What a Light Will Disclose—Erasing with Bread Crumbs—Hard to Detect—How to Discover Traces of Manipulation—Erased Surface Made Legible—Treating Partially Erased Paper—Detecting Nature of Substance Used for Erasing—Use of Bread Crumbs Colors Papers—Tracing Writing with a Glass Rod—Tracing Writing Under Paper—Writing With Glass Tubes Instead of Pens—What Physical Examination Reveals—Erasing Substance of Paper—Reproducing Pencil Writing in a Letter Press—Kind of Paper to Use in Making Experiments—Detecting Fraud in Old Papers—The Rubbing and Writing Method

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| FORGERY AS A PROFESSION | 227 |

How Professional Forgers Work—Valuable Points for Bankers and Business Men—Personnel of a Professional Forgery Gang—The Scratcher, Layer-down, Presenter and Middleman—How Banks Are Defrauded by Raised and Forged Paper—Detailed Method of the Work—Dividing the Spoils—Action in Case of Arrest—Employing Attorneys—What "Fall" Money Is—Fixing a Jury—Politicians with a Pull—Protecting Criminals—Full Description of How Checks and Drafts Are Altered—Alterations, Erasures and Chemicals—Raising Any Paper—Alert Cashiers and Tellers—Different Methods of Protection

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| A FAMOUS FORGERY | 243 |

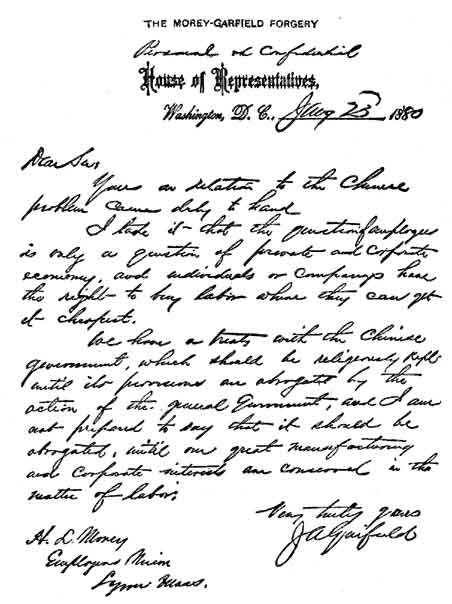

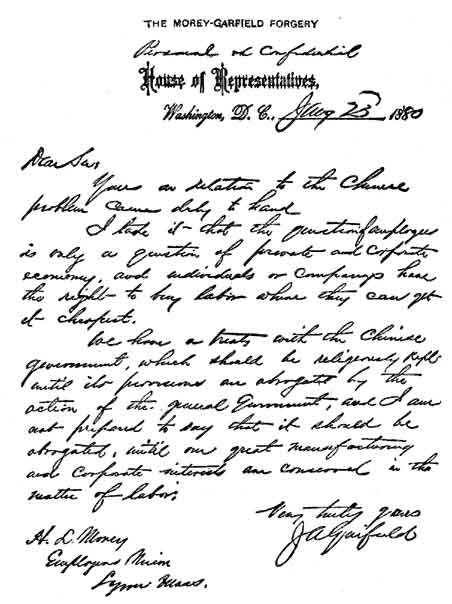

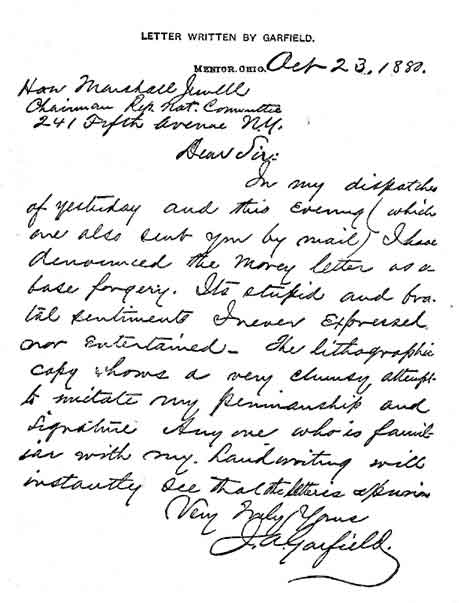

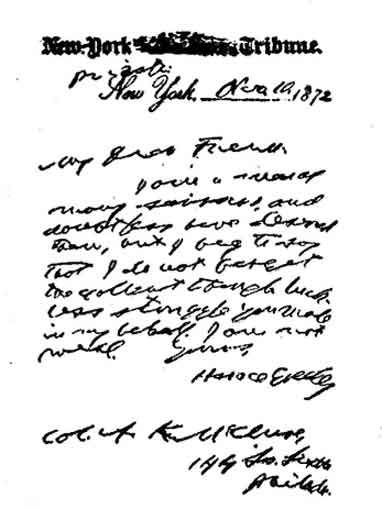

The Morey-Garfield Letter—Attempt to Defeat Mr. Garfield for the Presidency—A Clumsy Forgery—Both Letters Reproduced—Evidences of Forgery Pointed Out—The Work of an Illiterate Man—Crude Imitations Apparent—Undoubtedly the Greatest Forgery of the Age—General Garfield's Quick Disclaimer Kills Effect of the Forgery—The Letters Compared and Evidences of Forgery Made Complete

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| A WARNING TO BANKS AND BUSINESS HOUSES | 253 |

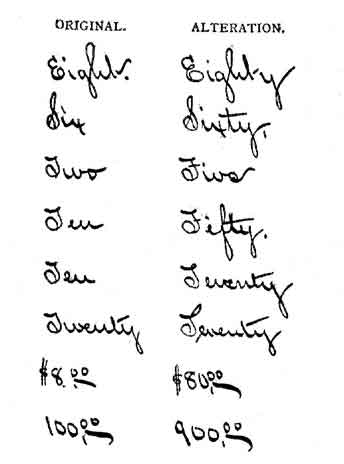

Information for Those Who Handle Commercial and Legal Documents—Peculiarity of Handwriting—Methods Employed in Forgery—Means Employed for Erasing Writing—Care to Be Used in Writing—Specimens of Originals and Alterations—Means of Discovering and Demonstrating Forgery—Disputed Signatures—Free Hand or Composite Signatures—Important Facts for the Banking and Business Public—How to Use the Microscope and Photography to Detect Forgery—Applying Chemical Tests—How to Handle Documents and Papers to Be Preserved—The Value of Expert Testimony—Using Chemical, Mechanical and Clerical Preventatives

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| HOW FORGERS ALTER BANK NOTES | 265 |

Bankers Easily Deceived—How Ten One Hundred Dollar Bills Are Made out of Nine—How to Detect Altered Bank Notes—Making a Ten-Dollar Bill out of a Five—A Ten Raised to Fifty—How Two-Dollar Bills are Raised to a Higher Denomination—Bogus Money in Commercial Colleges—Action of the United States Treasury Department—Engraving a Greenback—How They Are Printed—Making a Vignette—Beyond the Reach of Rascals—How Bank Notes Are Printed, Signed and Issued by the Government—Safeguards to Foil Forgers, Counterfeiters and Alterers of Bank Notes—Devices to Raise Genuine Bank Notes—Split Notes—Altering Silver Certificates

| APPENDIX | 273 |

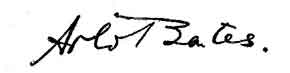

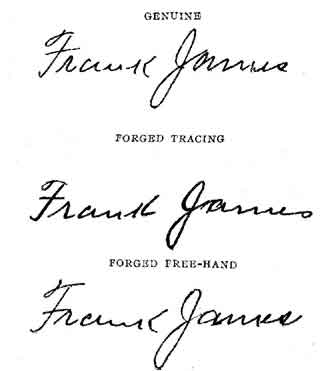

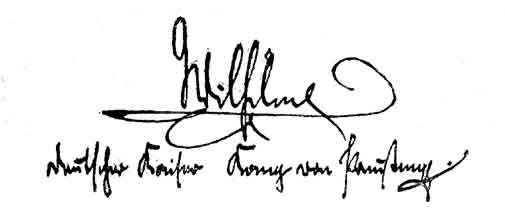

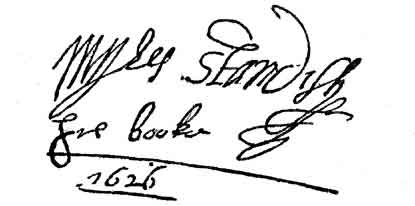

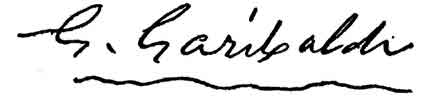

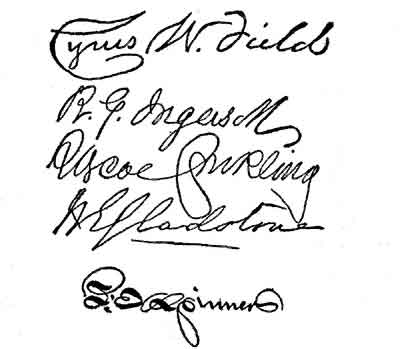

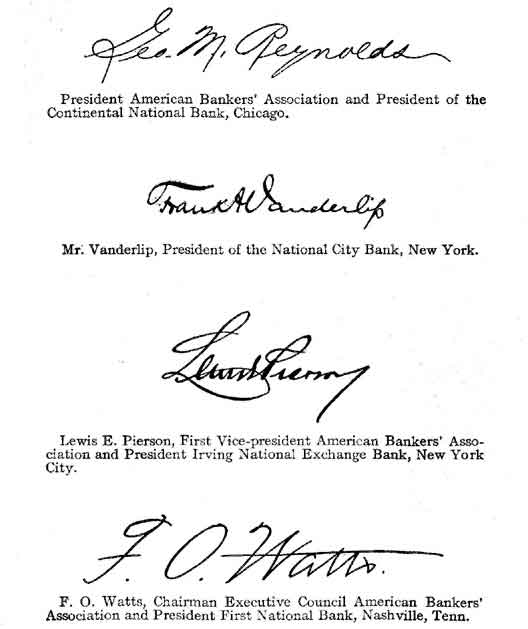

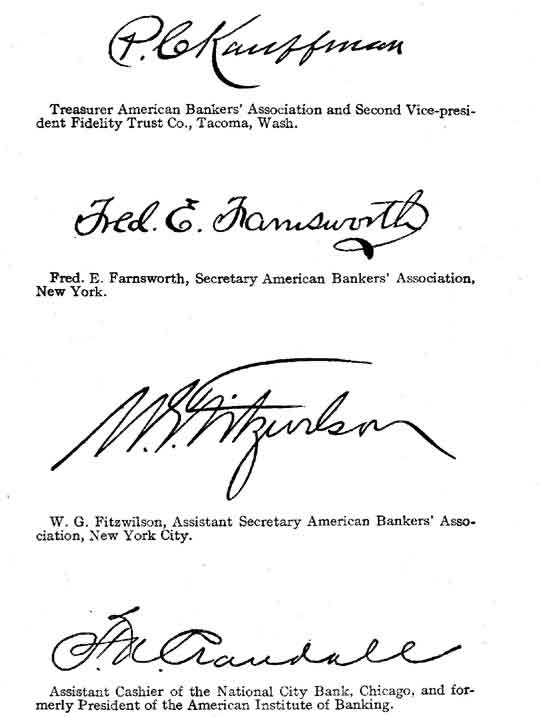

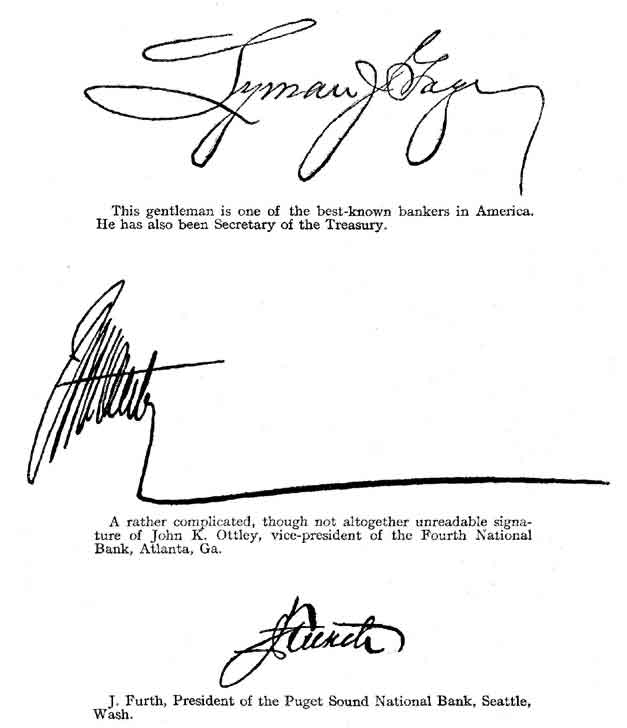

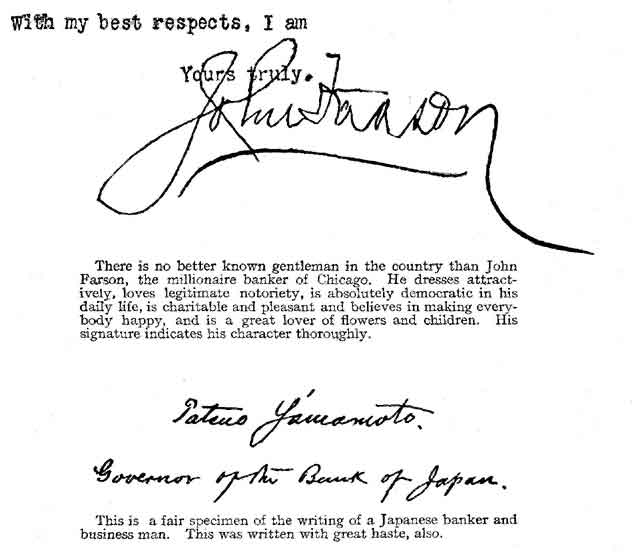

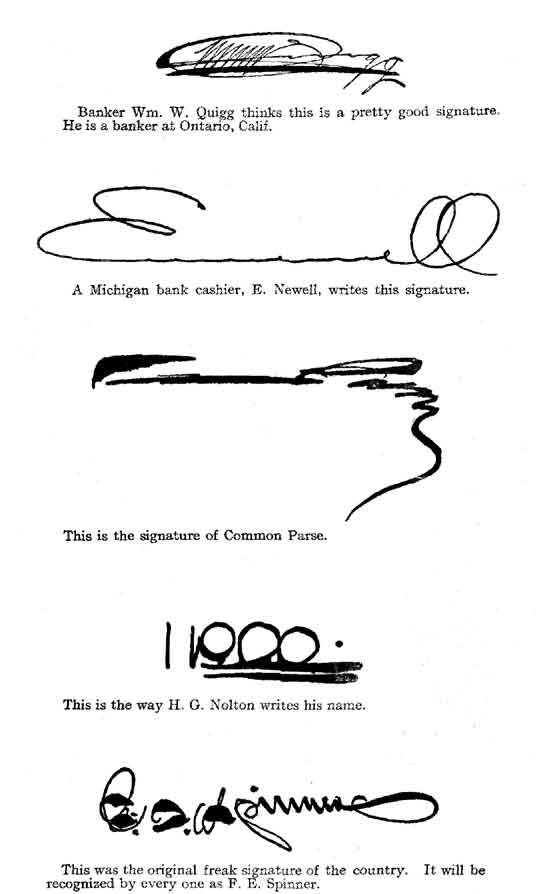

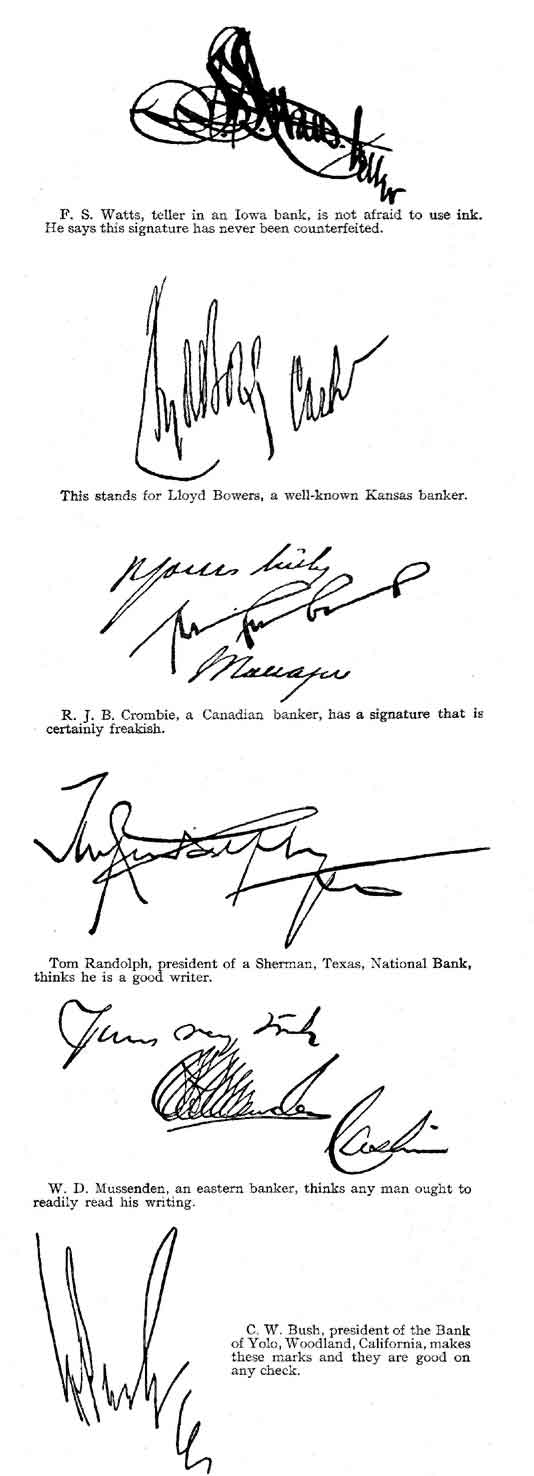

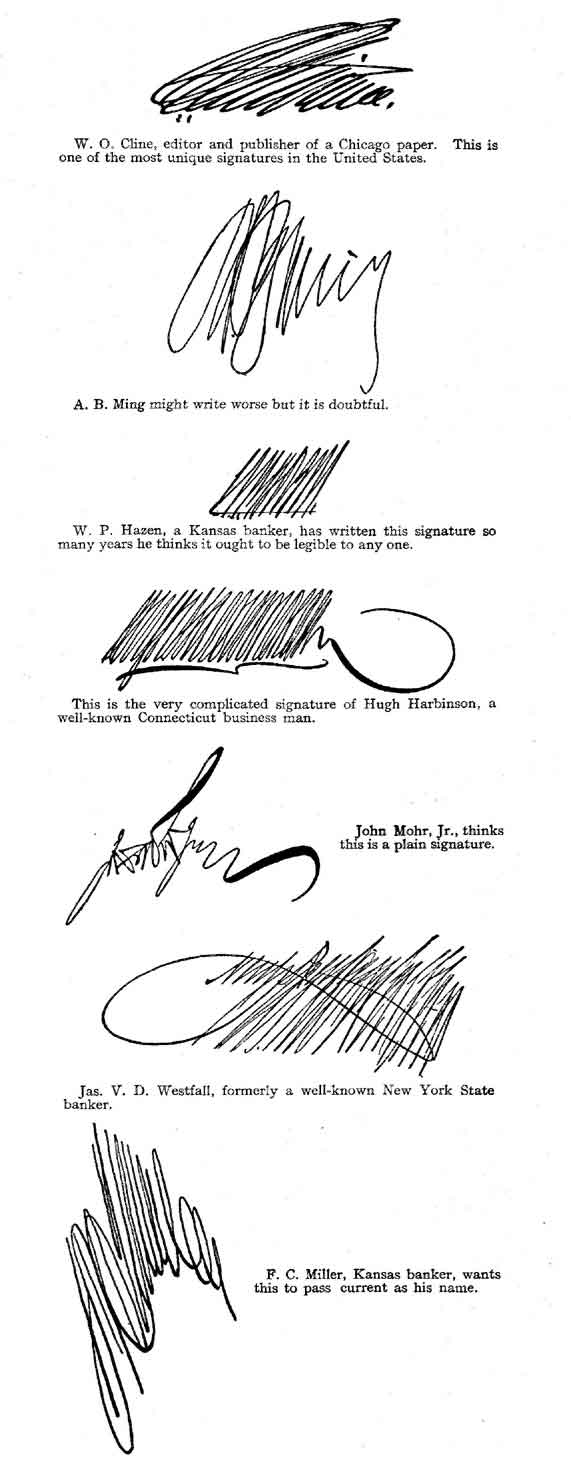

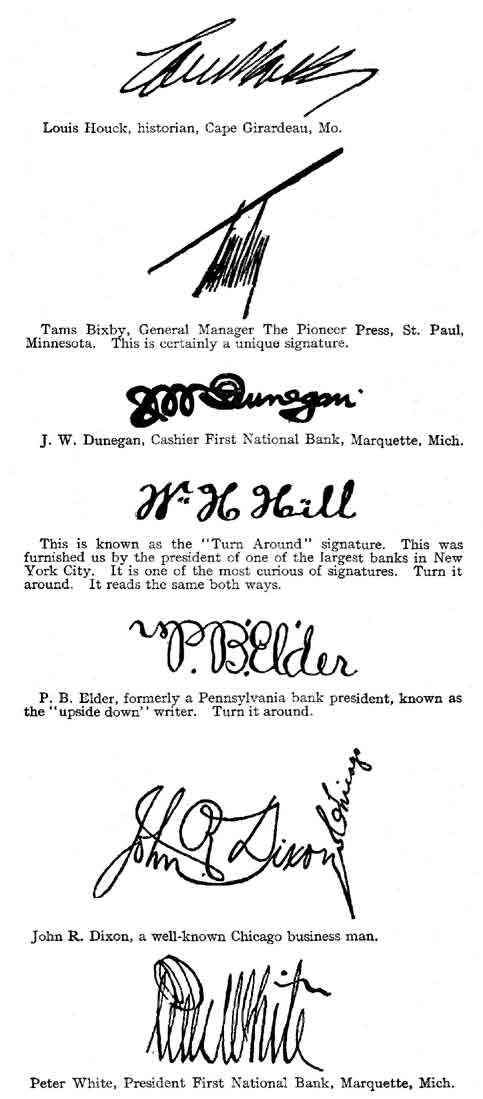

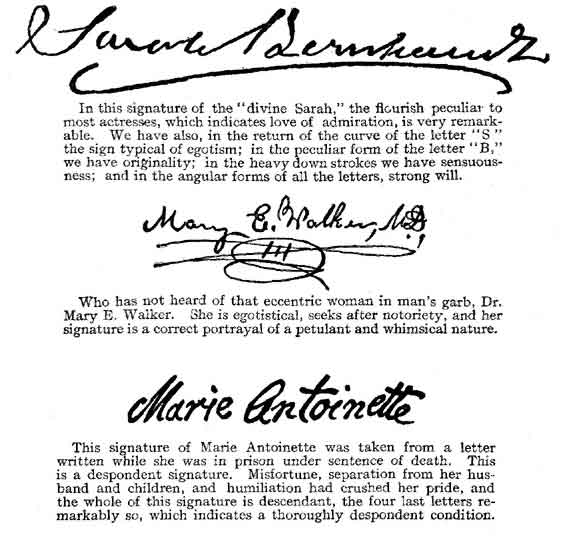

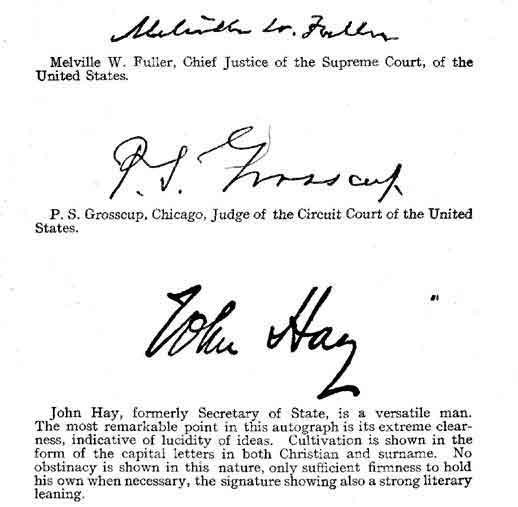

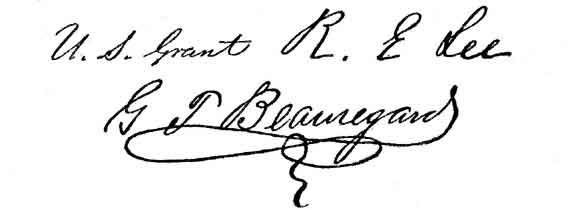

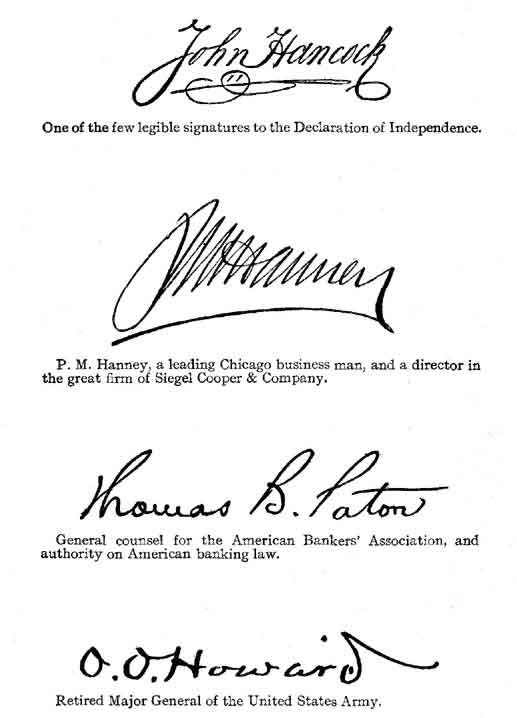

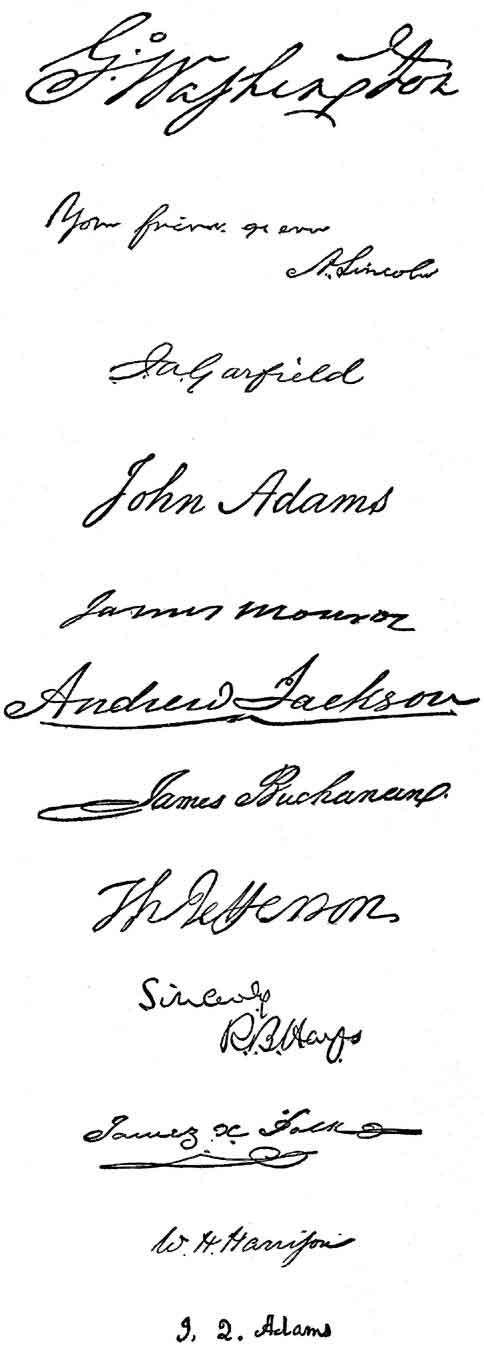

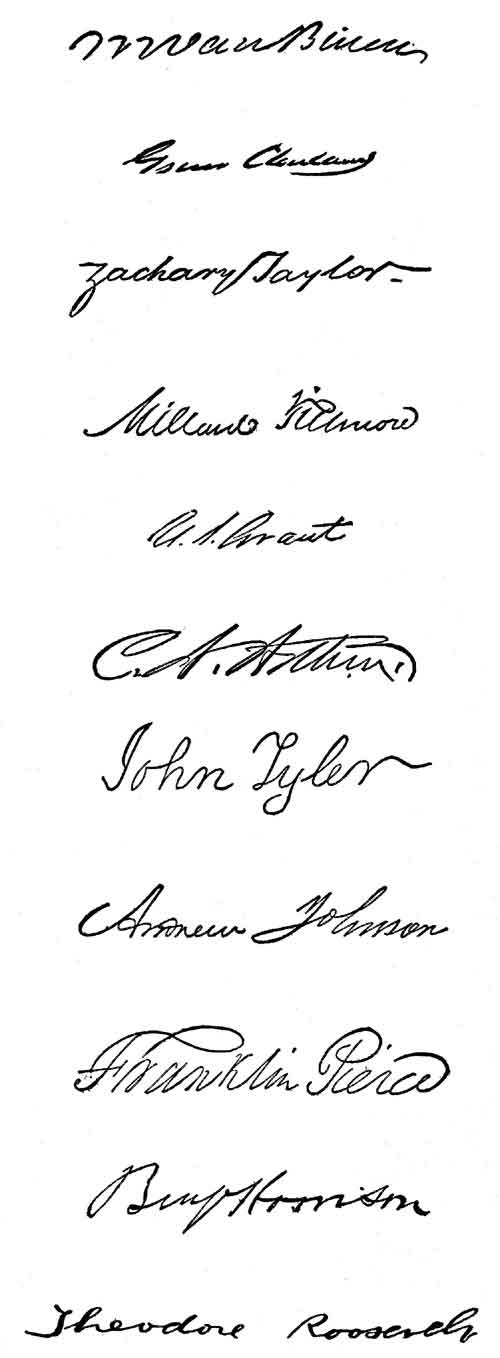

This follows with many pages of Illustrations and Descriptions of Various Kinds of Genuine, Traced, Forged and Simulated Writings and Autograph Signatures of Bankers, Statesmen, Jurists, Authors, Writers and the Leading Public Characters of the World; Individual Autographs of Every President of the United States; Freak Signatures and Curious and Complicated Writing; and Scores of Other Interesting and Instructive Autographs and Writings of Various Kinds That Will Prove of Great Worth and Value

But few writers in the United States have expended their genius in the field of disputed, forged, or fraudulent handwriting. In France and Germany the subject has been more studied, and in both languages several valuable books have appeared, while in this country it is only recently that disputed handwriting has been looked upon as one of the sciences.

Up to the time of the publication of this work nothing has appeared in the United States on the subject of disputed handwriting, short magazine and newspaper articles sufficing.

Interest in disputed handwriting and writing of all kinds is being rapidly developed, and is a study and research with which the banker and business man of the future must and will be perfectly familiar. A place will be made for the science among the permanent, necessary, and most helpful studies of the day.

No effort has been spared by the author of this work to make every feature of handwriting accurate. This work is the result of years of practical study in the field of disputed handwriting, and personal application has demonstrated that the facts and suggestions given will be found absolutely correct. The aim has been to make this the standard work on this subject.

In conclusion, the author wishes to acknowledge a debt to the leading handwriting experts of the United States and Europe for many suggestions that have materially assisted him in the preparation of this work. We trust it will prove a material aid to the bankers, business men and professional men of the United States.

THE AUTHOR.

Disputed Handwriting

HOW TO STUDY FORGED AND DISPUTED SIGNATURES

All Titles Depend Upon the Genuineness of Signatures—Comparing Genuine With Disputed Signatures—A Word About Fac-simile Signatures—Conditions Affecting Production of Signatures—Process of Evolving a Signature—Evidence of Experience in Handling or Mishandling a Pen—Signatures Most Difficult to Read—Simulation of Signature by Expert Penman—Hard to Imitate an Untrained Hand—A Well-known Banker Presents Some Valuable Points—Perfectly Imitated Writings and Signatures—Bunglingly Executed Forgeries—The Application of Chemical Tests—Rules of Courts on Disputed Signatures—Forgers Giving Appearance of Age to Paper and Ink—Proving the Falsity of Testimony—Determining the Genuineness or Falsity by Anatomy or Skeleton—Making a Magnified Copy of a Signature—Effectiveness of the Photograph Process—Deception the Eye Will Not Detect—When Pen Strokes Cross Each Other—Experimenting With Crossed Lines—Signatures Written With Different Inks—Deciding Order of Sequence in Writing—An Important and Interesting Subject for Bankers—Determining the Genuineness of a Written Document—Ingenuity of Rogues Constantly Takes New Forms—A Systematic Analysis Will Detect Disputed Signatures.[1]

The title to money and property of all kinds depends so lately upon the genuineness of signatures that no study or inquiry can be more interesting than one relating to the degree of certainty with which genuine writings can be distinguished from those which are counterfeited.

When comparing a disputed signature with a series of admittedly genuine signatures of the same person whose signature is being disputed, the general appearance and pictorial effect of the writing will suggest, as the measure of resemblances or differences predominates, an impression upon the mind of the examiner as to the genuine or forged character of the signature in question. When it is understood that to make a forgery available for the purposes of its production it must resemble in general appearance the writing of the person whose signature it purports to represent, it follows as a reasonable conclusion that resemblances in general appearances alone must be secondary factors in establishing the genuineness of a signature by comparison—and the fact that two signatures look alike is not always evidence that they were written by the same person.

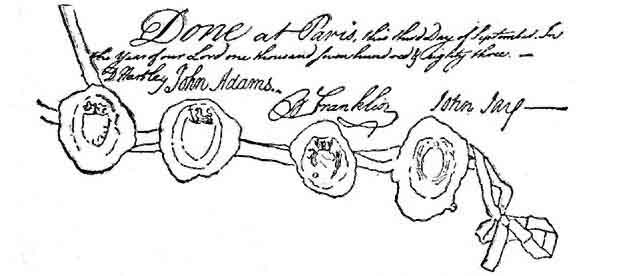

As an illustration of the uncertainty of an impression produced by the general appearances and close resemblance of signatures, even to an expert observer, is manifested when the fac-simile signatures of the signers of the Declaration of American Independence, as executed by different engravers, are examined. On comparing each individual fac-simile made by one engraver, with the fac-simile of the same signature made by another engraver, they will be found to exactly coincide in general appearance as to form and pictorial effect, and so much so, that the fac-similes of the same signature made by different engravers cannot be told one from the other. On examining them by the use of the microscope they may be easily determined as the work of different persons. While this is likewise true of the resemblances in general appearance which a disputed signature may have when compared with a genuine signature of the same person, it is also true that the measure of difference occurring in the general appearance of a disputed signature, when compared with genuine ones of the same person, are not always evidence of forgery.

There are many conditions affecting the production of signatures, habitually and uniformly apart from the causes which prevent a person from writing signatures twice precisely alike, under the influence of normal conditions of execution. The effect of fatigue, excitement, haste, or the use of a different pen from that with which the standards were written, are well known conditions operating to materially affect the general appearance of the writing, and may have been, in one form or another, an attendant cause when the questioned signature was produced, and thus have given to the latter some variation from the signatures of the same person, executed under the influence of normal surroundings.

In the process of evolving a signature, which must be again and again repeated from an early age till death, new ideas occur from time to time, are tried, modified, improved, and finally embodied in the design. The idea finally worked out may be merely a short method of writing the necessary sequence of characters, or it may present some novelty to the eye. Signatures consisting almost exclusively of straight up-and-down strokes, looking at a short distance like a row of needles with very light hair-lines to indicate the separate letters; signatures begun at the beginning or the end and written without removing the pen from the paper; signatures which are entirely illegible and whose component parts convey only the mutilated rudiments of letters, are not uncommon. All such signatures strike the eye and arrest the attention, and thus accomplish the object of their authors. The French signature frequently runs upward from left to right, ending with a strong down nourish in the opposite direction. All these, even the most illegible examples, give evidence of experience in handling or mishandling the pen. The signature most difficult to read is frequently the production of the hand which writes most frequently, and it is very much harder to decipher than the worst specimens of an untrained hand. The characteristics of the latter are usually an evident painstaking desire to imitate faulty ideals of the letters one after the other, without any attempt to attain a particular effect by the signature as a whole. In very extreme cases, the separate letters of the words constituting the signature are not even joined together.

A simulation of such a signature by an expert penman will usually leave enough traces of his ability in handling the pen to pierce his disguise. Even a short, straight stroke, into which he is likely to relapse against his will, gives evidence against the pretended difficulties of the act which he intends to convey. It is nearly as difficult for a master of the pen to imitate an untrained hand as for the untrained hand to write like an expert penman. The difference between an untrained signature and the trembling tracing of his signature by an experienced writer who is ill or feeble, is that in the former may be seen abundant instances of ill-directed strength, and in the latter equally abundant instances of well-conceived design, with a failure of the power to execute it.

Observations such as the preceding are frequently of great value in aiding the expert to understand the phenomena which he meets, and they belong to a class which does not require the application of standards of measure, but only experience and memory of other similar instances of which the history was known, and a sound judgment to discern the significance of what is seen.

No general rules other than those referred to above can be given to guide the student of handwriting in such cases, but the differences will become sufficiently apparent with sufficient practice.

A well-known banker, writing to the author of this work, makes some points on the subject which are rather disturbing. His fundamental proposition is that the judgment of experts is of no value when based as it ordinarily is, only upon an inspection of an alleged fraudulent signature, either with the naked eye or with the eye aided by magnifying glasses, and upon a comparison of its appearance with that of a writing or signature, admitted or known to the expert, to be genuine, of the same party.

He alleges, in fact, that writing and signatures can be so perfectly imitated that ocular inspection cannot determine which is true and which is false, and that the persons whose signatures are in controversy are quite as unable as anybody to decide that question. Nevertheless, the law permits experts to give their opinions to juries, who often have nothing except those opinions to control their decisions, and who naturally give them in favor of the side which is supported by the greatest number of experts, or by experts of the highest repute.

Decisions upon such testimony this banker regards as no better than, if quite as good as, the result of drawing lots. Of course he cannot mean to include under these observations, that class of forgeries which are so bunglingly executed as to be readily detected by the eye, even of persons not specially expert. He can only mean to say that imitations are possible and even common, which are so exact that their counterfeit character is not determinable by inspection, even when aided by glasses.

At first blush this contention of the banker is extremely a most unsatisfactory view of the case, and the more correct it looks likely to be, the more unsatisfactory. Courts may go beyond inspection and apply chemical on the tests, but such tests cannot be resorted to in the innumerable cases of checks and orders for money and property which are passed upon every day in the business world, and either accepted as genuine or rejected as counterfeit. But the real truth is, in fully ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, that no check or order is paid merely upon confidence in the genuineness of the signature, and without knowledge of the party to whom the payment is made, or some accompanying circumstance or circumstances tending to inspire confidence in the good faith of the transaction. In that aspect, the danger of deception as to the genuineness of signatures loses most of its terrors.

It is one of the recognized rules of court to admit as admissible testimony, the opinions of experts, whether the whole or any specified portion of an instrument was, or was not written by the same hand, with the same ink, and at the same time, which question arises when an addition to, or alteration of, an instrument is charged. It must be recollected that at this time It is a very easy matter for experienced forgers and rascals to so prepare ink that it may appear to the eye to be of the age required, and it is next to impossible for any expert to give any information in regard to the age of a certain writing. In many instances experts have easily detected the kind of ink employed, and have also successfully shown the falsity of testimony that the whole of a writing in controversy was executed at the same time, and with the same ink.

James D. Peacock, a London barrister, who has given considerable time and study to disputed handwritings, lays great stress upon the ability of determining the genuineness or falsity of a writing by what he calls its "anatomy" or "skeleton." He says that some persons in making successive strokes, make the turn from one to another sharply angular, while others make it rounded or looping. Writings produced in both ways appear the same to the eye, but under a magnifying glass the difference in the mode of executing is shown. As illustrating that point, he makes the following statement in respect to a case involving the genuineness of the alleged signature of an old man whose handwriting was fine and tremulous:

"On making a magnified copy of the signature, I found that the tremulous appearance of the letters was due to the fact that they were made up of a series of dashes, standing at varying angles with each other, and further, that these strokes, thus enlarged, were precisely like these constituting the letters in the body of the note, which were acknowledged to have been written by the alleged forger of the note. Upon the introduction of this testimony the criminal withdrew the plea of not guilty and implored the mercy of the court."

As one means of determining whether the whole of a writing was executed at the same time, and with the same ink, or at different times, and with different inks, Mr. Peacock further says that the photographic process is very effective because it not only copies the forms of letters but takes notice of differences in the color of two inks which are inappreciable by the eye. He states that:

"Where there is the least particle of yellow present in a color, the photograph will take notice of the fact by making the picture blacker, just in proportion as the yellow predominates, so that a very light yellow will take a deep black. So any shade of green, or blue, or red, where there is an imperceptible amount of yellow, will pink by the photographic process more or less black, while either a red or blue varying to a purple, will show more or less paint as the case may be."

As to deception which the eye will not detect, in regard to the age of paper, he says:

"I have repeatedly examined papers which have been made to appear old by various methods, such as washing with coffee, with tobacco, and by being carried in the pocket, near the person, by being smoked or partially burned, and in various other ways. I have in my possession a paper which has passed the ordeal of many examinations by experts and others, which purports to be two hundred years old, and to have been saved from the Boston fire. The handwriting is a perfect fac-simile of that of Thomas Addington, the town clerk of Boston, two hundred years ago, and yet the paper is not over two years old."

The most remarkable case of deception to the eye, even when aided by magnifying glasses, is in determining when two pen strokes cross each other, which stroke was made first. Mr. Peacock does not explain how the deception is possible, but that it occurs as matter of fact, he shows by an account of a very decisive experiment. Taking ten different kinds of ink, most commonly on sale, he drew lines on a piece of paper in such a way as to produce a hundred points of crossing and so that a line drawn with each of ink passed both over and under all the lines drawn with the other inks. He, of course, knew, in respect to each point of crossing, which ink was first applied, but the appearance to the eye corresponded with the fact in only forty-three cases. In thirty-seven cases the appearance was contrary to the fact, and in the remaining cases the eye was unable to come to any decision.

By wetting another piece of paper with a liquid compound acting as a solvent of ink, and pressing it upon the paper marked with lines, a thin layer of ink was transferred to the wet paper, and that shown correctly which was the superposed ink at every one of the one hundred points of crossing.

Many cases have occurred, in signatures written with different inks, where some letters in one cross, some letters in another, in which it becomes important to decide the order of sequence in writing. It is also frequently important to decide the order of sequence in writing. It is also frequently important when the genuineness of an addition, as of a date, is the thing in dispute.

No subject can be more important or interesting to the business public or especially to bankers than that of the reliability of the lists of the genuineness of written papers. While it is true that in most cases there is some ear-mark beside the appearance of a signature, whereby to determine the genuineness of a document, it is also true that in many cases, and frequently in cases of great magnitude, payments are made on no other basis than the appearance of a writing. The most common class of these last cases is where "A" has been long known to be an endorser for "B," and where the connection between the two, which leads to the endorsements, is well known. There is nothing in the appearance in the market of a note of "B" endorsed by "A," that is, in any degree calculated to excite suspicion or to put a prospective purchaser upon his inquiry. If the endorsement of "A" resembles his usual handwriting, it is almost always accepted as genuine and if losses result from its proving to be counterfeit, they are set down to the score, not of imprudence, but of unavoidable misfortune.

Thus, as the ingenuity of rogues constantly takes new forms, the ways and means by which they can be baffled in these enterprises are constantly being multiplied. The telegraph and telephone give facilities for promptly verifying a signature where one is in doubt.

It happens not infrequently that the desire to get a given number of words into a definite space leads to an entirely unusual and foreign style of writing, in which the accustomed characteristics are so obscured or changed that only a systematic analysis can detect them. If there be no apparent reason for this appearance in lack of space, the cause may be the physical state of the writer or an attempt at simulation. If a sufficient number of genuine signatures are available, it can generally be determined which of these two explanations is the right one.

Note illustrations of various kinds of handwriting in Appendix at end of this book. Particular attention is directed to the descriptions and analysis. They should be studied carefully.

FORGERY BY TRACING

Forgeries Perpetrated by the Aid of Tracing a Common and Dangerous Method—Using Transparent Tracing Paper—How the Movements are Directed—Formal, Broken and Nervous Lines—Retouched Lines and Shades—Tracing Usually Presents a Close Resemblance to the Genuine—Traced Forgeries Not Exact Duplicates of Their Originals—The Danger of an Exact Duplication—Forgers Usually Unable to Exactly Reproduce Tracing—Using Pencil or Carbon-Guided Lines—Retouching Revealed under the Microscope—Tracing with Pen and Ink Over a Transparency—Making a Practice and Study of Signatures—Forgeries and Tracings Made by Skilful Imitators Most Difficult of Detection—Free-Hand Forgery and Tracing—A Few Important Matters to Observe in Detecting Forgery by Tracing—Photographs a Great Aid in Detecting Tracing—How to Compare Imitated and Traced Writing—Furrows Traced by Pen Nibs—Tracing Made by an Untrained Hand—Tracing with Pen and Ink Over a Transparency—Internal Evidence of Forgery by Tracing—Forgeries Made by Skilful Imitators—How to Determine Evidences of Forgery by Tracing—Remains of Tracings—Examining Paper in Transmitted Light—Freely Written Tracings—A Dangerous Method of Forgery.

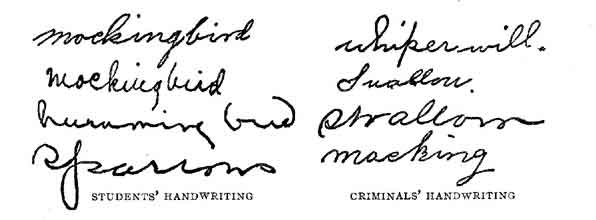

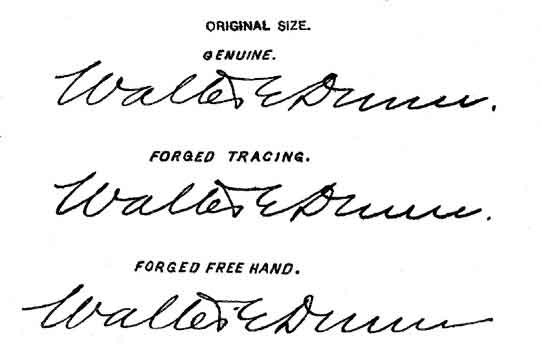

Forgery by tracing is one of the most common and most dangerous methods of forgery.

There are two general methods of perpetrating forgeries, one by the aid of tracing, the other by free-hand writing. These methods differ widely in details, according to the circumstances of each case.

Tracing can only be employed when a signature or writing is present in the exact or approximate form of the desired reproduction. It may then be done by placing the writing to be forged upon a transparency over a strong light, and then superimposing the paper upon which the forgery is to be made. The outline of the writing underneath will then appear sufficiently plain to enable it to be traced with pen or pencil, so as to produce a very accurate copy upon the superimposed paper. If the outline is with a pencil, it is afterward marked over with ink.

Again, tracings are made by placing transparent tracing-paper over the writing to be copied and then tracing the lines over with a pencil. This tracing is then penciled or blackened upon the obverse side. When it is placed upon the paper on which the forgery is made, the lines upon the tracing are retraced with a stylus or other smooth hard point, which impresses upon the paper underneath a faint outline, which serves as a guide to the forged imitation.

In forgeries perpetrated by the aid of tracing, the internal evidence is more or less conclusive according to the skill of the forger. In the perpetration of a forgery the mind, instead of being occupied in the usual function of supplying matter to be recorded, devotes its special attention to superintendence of the hand, directing its movements, so that the hand no longer glides naturally and automatically over the paper, but moves slowly with a halting, vacillating motion, as the eye passes to and from the copy to the pen, moving under the specific control of the will. Evidence of such a forgery is manifest in the formal, broken, nervous lines, the uneven flow of the ink, and the often retouched lines and shades. These evidences are unmistakable when studied with the aid of a microscope. Also, further evidence is adduced by a careful comparison of the disputed writing, noting the pen-pressure or absence of any of the delicate unconscious forms, relations, shades, etc., characteristic of the standard writing.

Forgeries by tracings usually present a close resemblance in general form to the genuine, and are therefore most sure to deceive the unfamiliar or casual observer. It sometimes happens that the original writing from which the tracings were made is discovered, in which case the closely duplicated forms will be positive evidence of forgery. The degree to which one signature of writing duplicates another may be readily seen by placing one over the other, and holding them to a window or other strong light, or by close comparative measurements.

Traced forgeries, however, are not, as is usually supposed, necessarily exact duplicates of their originals, since it is very easy to move the paper by accident or design while the tracing is being made, or while making the transfer copy from it; so that while it serves as a guide to the general features of the original, it will not, when tested, be an exact duplication. The danger of an exact duplication is quite generally understood by persons having any knowledge of forgery, and is therefore avoided. Another difficulty is that the very delicate features of the original writing are more or less obscured by the opaqueness of two sheets of paper, and are therefore changed or omitted from the forged simulation, and their absence is usually supplied, through force of habit, by equally delicate unconscious characteristics from the writing of the forger. Again, the forger rarely possesses the requisite skill to exactly reproduce his tracing. Much of the minutiae of the original writing is more or less microscopic, and from that reason passes unobserved by the forger. Outlines of writing to be forged are sometimes simply drawn with a pencil, and then worked up in ink. Such outlines will not usually furnish so good an imitation as to form, since they depend wholly upon the imitative skill of the forger.

Besides the forementioned evidences of forgery by tracing, where pencil or carbon guide-lines are used which must necessarily be removed by rubber, there are liable to remain some slight fragments of the tracing lines, while the mill finish of the paper will be impaired and its fiber more or less torn out, so as to lie loose upon the surface. Also the ink will be more or less ground off from the paper, thus giving the lines a gray and lifeless appearance. And as retouchings are usually made after the guide-lines have been removed, the ink, wherever they occur, will have a more black and fresh appearance than elsewhere. All these phenomena are plainly manifest under the microscope. Where the tracing is made directly with pen and ink over a transparency, as is often done, no rubbing is necessary, and of course, the phenomena from rubbering does not appear.

Where signatures or other writings have been forged by previously making a study and practice of the writing, to be copied until it has been to a greater or less degree idealized, the hand must be trained to its imitation so that it can be written with a more or less approximation as to form and natural freedom.

Forgeries and tracings made by skilful imitators are the most difficult of detection, as the internal evidence of forgery by tracing is mostly absent. The evidence of free-hand forgery and tracing is chiefly in the greater liability of the forger to inject into the writing his own unconscious habit and to fail to reproduce with sufficient accuracy that of the original writing, so that when subjected to rigid analysis and microscopic inspection, the spuriousness is made manifest and demonstrable. Specific attention should be given to any hesitancy in form or movement in tracing which is manifest in angularity or change of direction of lines, changed relations and proportions of letters, slant of the writing, its mechanical arrangement, disconnected lines, retouched shades, etc.

Photographs, greatly enlarged, of both the signatures in question and the exemplars placed side by side for comparison will greatly aid in making plain any evidence of forgery.

If practicable, use for comparison as standards both the imitated writing and that of the imitator's traced writing. These methods, employed by skilled and experienced examiners, will rarely fail of establishing the true relationship between any two disputed handwritings and more especially where the question of a forged or traced signature is under discussion.

Under the microscope tracing by the pen-nibs are usually easily visible, and they differ with every variety of pen employed. A stiff, fine-pointed pen makes two comparatively deep lines a short distance apart, which appear blacker in the writing than the space between them, because they fill with ink, which afterwards dries and produces a thicker layer of black sediment than those elsewhere. The variations of pressure upon the pen can be easily noticed by the alternate widening and narrowing of the band between these two furrows. The tracing appears knotty and uneven when made by an untrained hand, while it appears uniformly thin, and generally tremulous or in zigzags when made by a weak but trained hand.

Where the tracing is made directly with pen and ink over a transparency, as is often done, no rubbing is necessary, and of course the phenomena from rubbering do not appear.

Where signatures or other writings have been forged by previously making a study and practice of the writing to be copied until it has been to a greater or less degree idealized, the hand must be trained to its imitation so that it can be written with a more or less approximation as to form and with natural freedom.

Forgeries thus made by skilful imitators are the most difficult of detection, as the internal evidence of forgery by tracing is mostly absent. The evidence of free-hand forgery is chiefly in the greater liability of the forger to inject into the writing his own unconscious habit, and to fail to reproduce with sufficient accuracy that of the original writing, so that when subjected to rigid analysis and microscopic inspection, the spuriousness is made manifest and demonstrable. Specific attention should be given to any hesitancy in form or movement, manifest in angularity or change of direction of lines, changed relations and proportions of letters, slant of the writing, its mechanical arrangement, disconnected lines, retouched shades, etc.

Photographs, greatly enlarged, of both the signatures in question and the exemplars placed side by side for comparison will greatly aid in making plain any evidences of forgery by tracing.

It sometimes occurs that the forger, fearful that his attempt to imitate another's writing would be too easily detected if made with a free hand, sketches in pencil the characters he intends to make in ink on the document, or traces them by means of blackened paper at the appropriate place. The evidences of this are very likely to appear when the document is examined in transmitted light.

It is often asserted in trials that tracings of a genuine signature invariably show hesitation and painting. This is not always the fact. Tracings proven and subsequently admitted to have been such have shown an apparent absence of all constraint, and a careful examination of the result revealed no pause of the pen. But, on the other hand, these freely written tracings have invariably shown either a deviation from some habitual practice of the writer, or, if the model was followed with skill, two or three such tracings, when photographed on a transparent film and superposed, have shown such exact resemblances as to proclaim their character at once.

The natural tendency of man is to introduce some elements of symbolism in what he is attempting to trace and to seek some sort of geometrical symmetry in what he designs. Wherever he is not restricted by certain forms which he must introduce, and which may render a balance of parts about a median line unattainable, he tends to evolve symmetrical designs, as in the highest and simplest forms of ancient architecture. When the parts of the design are prescribed, as in the representation of objects in nature, he soon tires of mere mechanical repetition of the same things in a given sequence, and strives to convey some ulterior idea by the manner of joining these parts. This gives life and language to sculpture and painting, and gives character to handwriting. Tracing signatures is one of the most common and dangerous methods of forgery. Some specimens of traced signatures are illustrated and explained in an Appendix at the end of this book.

HOW FORGERS REPRODUCE SIGNATURES

Characteristics Appearing in Forged Signatures—Conclusions Reached by Careful Examinations—Signatures Written with Little Effort to Imitate—What a Clever Forger Can Do—Most Common Forgeries of Signatures—Reproducing a Signature over a Plate of Glass—A Window Frame Scheme for Reproducing Signatures—How the Paper is Held and the Ink Applied—How a Genuine Signature is Placed and Used—A Forger's Process of Tracing a Signature—How to Detect Ear Marks of Fraud in a Reproduced Signature—Prominent Features of Signatures Reproduced—Method Resorted to by Novices in Forging Signatures—Conditions Appearing in All Traced Signatures—Reproduction of Signatures Adopted by Expert Forgers—Making a Lead-Pencil Copy of a Signature—Erasing Pencil Signatures Always Discoverable by the Aid of a Microscope—Appearances and Conditions in Traced Signatures—How to Tell a Traced Signature—All the Details Employed to Reproduce a Signature Given—Features in Which Forgers are Careless—Handling of the Pen Often Leads to Detection—A Noted Characteristic of Reproduced Signatures—Want of Proportion in Writing Names Should Be Studied—Rules to Be Followed in Examining Signatures—System Employed by Experts in Studying Proof of Reproduced Signatures—Bankers and Business Men Should Avoid Careless Signatures.

In detailing matters which experience suggests as importantly connected with the examination of disputed signatures, there are none more essential to a proper consideration of the subject than an understanding of those characteristics often appearing in forged signatures, and by which they are distinguished as such. When the features occurring as a concomitant of most forgeries are understood, their appearance may suggest a short and easy route to reach a conclusion: yet the careful and conscientious examiner will, even with these indications present in a disputed signature, institute a very careful and detailed study of the latter by comparison with the standard writings; and with as much effort as if the indications of forgery were not present. To make these features positive evidence, each other developed detail must also tend to the same deduction, and each detail must be compatible with every other feature, and all point to the same conclusion.

As forgers differ in their capability as to accuracy in simulation, all grades of its proficiency come up in the experience of those who, as experts, are called upon to make such matters a study. At one extreme will be found to occur signatures written with but little effort to imitate the genuine signature they purport to represent; with all the intermediate grades of imitation extending to the other extreme, wherein a skilful forger will, by practice, so simulate the signature of a person and with such close resemblance that the very individual whose name is imitated cannot, independently of attending circumstances, tell the forgery from the signature which he knows he has written.

Among the most common forgeries of signatures are those which have been traced from genuine ones, and these are produced in various ways; the most common method being to place the genuine signature over a plate of glass horizontally arranged, with a strong light behind it, or against the window frame, and then to place over the signature so positioned the paper on which the forgery is to be made. When this has been done the papers are held in contact firmly, the pen is dipped-in ink and moved over the paper, guided by the lines of the genuine signature beneath, which show through the superimposed paper, and by means of which the form of the signature is transferred to the paper, which is exteriorly placed.

While the process of tracing produces very nearly the proper form of the matter thus copied, and if well done by the forger the copy will in general appearance and to a certain extent resemble in outline the signature thus traced, there are usually apparent in all reproduced signatures thus made, peculiarities and ear marks indicating the manner in which they were produced and by which they can be identified as such.

One of the most prominent features of reproduced signatures is the general sameness of the writing as appearing in the uniform width of the lines, and the omission of the usual shading emphasis. The cause of this appearance is the absence of habitual pen pressure, and the necessitated slow movement of the pen held closely in contact with the paper and by which a uniform and steady flow of ink is deposited thereon; thus making what should be the heavier and lighter lines of one width and density as to shading. This method of tracing and reproducing signatures is that usually resorted to by novices but is seldom employed by expert forgers.

Another condition appearing in all traced signatures is the absence of all evidence of pen pressure when examined as a transparency; this deficiency occurring as consequent upon the manner of moving the pen over the paper. While signatures thus made may resemble the one from which they are copied, the only likeness they have is that of pictorial resemblance and it will be found to be destitute of all the appearances and indications of habitual writing in other respects.

Another method of tracing signatures is frequently resorted to by persons adept in the art, and this consists in making a lead-pencil copy of the genuine signature holding the paper on which the forgery is to be produced; tracing the outline of the signature by means of a pencil, and then with ink to write over the pencil copy. But as the method necessitates the use of an india rubber to remove the surplus black lead where not covered by the ink, evidences of the use of the rubber will be found to occur, and traces of the black lead can be found by the microscope. While the appearances and conditions are common to traced signatures, there are in addition to their presence generally found evidences of pauses made in the writing, the effect of which will appear not as shading of the lines, but as irregularities or excrescences produced thereon by resting the hand in its movement, and by which at intervals more ink flowed from the pen than would occur when the latter was being moved habitually over the paper. Where the signatures of the same person exactly coincide when one is laid over the other in parallel arrangement with a strong light behind them, this condition of their appearance is very positive evidence that one of them was traced from the other and is a forgery, as it is a circumstance which cannot possibly occur in the writing of two signatures produced habitually.

In considering reproduced signatures and forged writing and in detailing some of the most common features which are found to occur in it, it must not be understood that all the phenomena attending the production of forged signatures can be given. Inasmuch as each person has a peculiar muscular co-ordination that is manifested in the production of habitually written signatures, so each forger from the same cause has an individual habit that must be used when simulating; hence there will be as many styles of writing manifested in production of forgeries as there are forgers to produce them. No positive rule can be laid down for the classification of their peculiarities excepting the manner of accuracy with which the simulation appearing in them is done. Each case of disputed writing must be examined by itself, and while there are certain process steps to be followed which experience suggests as facilitating the analysis, yet the examiner must wholly depend upon what is seen in the disputed signature that is, or is not, found in the admittedly genuine writing of the person whose signature is questioned, and the comparison of the one with the other.

Reproduced signatures often show a copying effort that is manifested in the details of their production. These evidences generally appear, in some instances, as pauses made in the lines connecting the letters of the signature, where the pen rested while the eye of the forger was directed from the writing being done to the copy, that the writer could fix in the mind the form of a succeeding letter. These pauses appear in different measure of prominence in different forgeries, and there is no rule as to their measure or appearance. With some forgers the pen rests with considerable emphasis and with others it is lifted from the paper and returned to the paper while the eye of the writer goes back to the copy. With others there will appear but little hesitancy. Some forgers, well skilled in the art, will, by practicing the simulation until they have the form of the genuine signature well fixed in the mind, become enabled to produce a forged copy of a genuine signature that will show no pauses—hence the absence of pauses is not proof of the genuine character of a signature. Another common characteristic of forged and reproduced signatures and particularly such of them as are not traced and are produced by persons not skilled in the art is found in the studied appearance which they have, as if written under restraint, and without the apparent freedom consequent upon habitual writing. Another characteristic of forged signatures that are not traced from a genuine signature is that they are written with greater length in proportion to the width and height of the letters, than occurs in the genuine signature from which they are copied in imitation. This want of proportion occurs generally from making the lines connecting the letters of the signature longer than those of the copy.

At the same time, while these characteristics are common to forged writing, to make them available in formulating an opinion from an analysis they must be substantiated by every other occurring in the writing. It must be clearly kept in view that general impressions derived from a cursory examination of a disputed or reproduced signature should have no weight in the mind of the examiner before proceeding with the analysis, as such an impression is apt to lead the investigation into a particular line of research and it should be understood that the work of the examiner must relate to the comparison of the details in each of the writings as to their correspondence or difference.

As before stated in this chapter, and a fact that should be remembered in studying fraudulent signatures, that one of the commonest and easiest means of reproducing a signature is to put the genuine signature on a piece of glass, lay another piece of glass on top of it and fasten the piece of paper that is to receive the forgery on top of that. Then by holding the glass strips to a bright light, the original signature casts a shadow through, which may be traced in pencil. From this tracing the ink forgery is completed.

But when a forgery done in this way is put under a strong magnifying lens it will not bear scrutiny. If the original has a strong down stroke on the capital letters the movement will be free and will leave the pen lines with smooth edges. The man who is tracing such letters cannot trust himself to the same free movement of the pen and the result under the glass shows hesitancy and uncertainty. Also if other lines in the signature be lighter than the forger naturally uses the same hesitancy will be shown. When the lines have passed scrutiny, too, there is another "line" test which will show that the impossibility of one's writing two signatures alike has been accomplished.

From dotted points made above the genuine signature straight lines are drawn radiating from it to certain portions of certain letters in the signature that is forged. When the forged signature is replaced in the glass and the other on top, as is done in the tracing, these radiating lines will fall one upon the other with the exactness of the lines in the signatures.

These radiating lines, too, may be used in the few cases where the forger is an expert penman depending upon an offhand duplication of a signature. This penman will have his inevitable natural slant to his letters. This characteristic slant never is the same in two individuals. In his free and easy forgery of a name written by another person this "Jim, the penman" exposes his acquired slant which disputes the original.

This slant of individual writing shows especially in any attempt to write a forged letter or document. When the pen scope of the original has been lined out, proving the characteristic common lengths between the lifting of the pen from the paper, the lines radiating from the points to individual letters in words or groups of words in authentic and bogus specimens, these radiations point at once to the fact that the same person did not write the matter.

These are some of the things upon which the handwriting expert works upon and brings to bear in proof of reproduced signatures and handwriting in general. How the more or less inexpert person discovers questionable showing in these duplications are many. His intuitions may suggest his doubts. Material evidences may have come to bear upon him. Likelihood of some one person's having self-interests in the matter may induce him to make sure.

In the case of a banker or business man, having large interests and required to affix his signature to many papers of moment, he ordinarily makes it certain that through adapted whorls and freehand sweeps of the pen, the signature will be least careless and inviting to the adventurous forger. In much of his personal correspondence with strangers, however, this adapted and unusual signature frequently becomes a source of loss to himself and irritation to his correspondents. In the case of hundreds of such individuals, the writing to a stranger in expectation of a reply becomes an absurdity for the reason that the person addressed is hopelessly barred from reading the name attached to the letter. A plain signature is always the best.

ERASURES, ALTERATIONS AND ADDITIONS

What Erasure Means—The English Law—What a Fraudulent Alteration Means—Altered or Erased Parts Considered—Memoranda of Alterations Should Always Accompany Paper Changed—How Added Words Should be Treated—How to Erase Words and Lines Without Creating Suspicion—Writing Over an Erasure—How to Determine Whether or Not Erasures or Alterations Have Been Made—Additions and Interlineations—What to Apply to the Suspected Document—The Alcohol Test Absolute—How to Tell which of Crossing Ink Lines were Made First—Ink and Pencil Alterations and Erasures—Treating Paper to Determine Erasures, Alterations and Additions—Appearance of Paper Treated as Directed—Paper That Does Not Reveal Tampering—How Removal of Characters From a Paper is Effected—Easy Means of Detecting Erasures—Washing With Chemical Reagents—Restoration of Original Marks—What Erasure on Paper Exhibits—Erasure in Parchments—Identifying Typewritten Matter—Immaterial Alterations—Altering Words in an Instrument—Alterations and Additions Are Immaterial When Interests of Parties Are Not Changed or Affected—Erasure of Words in an Instrument.

Erasure or erazuer, as it is more commonly called in England, from the Latin word "scrape or shave" is the scraping or shaving of a deed, note, signature, amount or of any formal writing. In England, except in the case of a will, the presumption, in the absence of rebutting testimony, is that the erasure was made at or before the execution thereof. If an alteration or erasure has been made in any instrument subsequent to its execution, that fact ought to be mentioned (in the abstract or epitome of the evidence of ownership) together with the circumstances under which it is done.

A fraudulent alteration, if made by the person himself, taking under it would vitiate his interest altogether. It was formerly considered that an alteration, erasure or interlineation would void the instrument entirely, even in those cases where it was made by a stranger; but the law is now otherwise, as it is clearly settled that no alterations made by a stranger will prevent the contents of an instrument from retaining its original effect and operation, where it can be plainly shown what that effect and operation actually was. To accomplish this the mutilated instrument may be given in evidence as far as its contents appear and evidence will be admitted to show what portions have been altered or erased, and also the words contained in such altered or erased parts; but if, for want of such evidence or any deficiency or uncertainty arising out of it the original contents of the instruments cannot be ascertained, then the old rule would become applicable or more correctly speaking, the mutilated instrument would become void for uncertainty. If a will contains any alterations or erasures, the attention of the witnesses ought to be directed to the particular parts in which such alterations occur, and they ought to place their initials in the margin opposite, before the will is executed, etc., notice this having been done by a memorandum added to the attestation clause at the end of the will.

In Scotland the rule as to erasure is somewhat stricter than in England and the United States, the legal inferences being that such alterations were made after execution. As to necessary or bona-fide alterations which may be desired by the parties, corrections or clerical errors and the like after a paper is written out but before signature, the rule usually followed is that the deed must show that they have been advisedly adopted by the party; and this will be effected by mentioning them in the body of the writing. Thus if some words are erased and others superinduced, you mention that the superinduced words were written over an erasure; if words are simply delite that fact is noticed, if words are added it ought to be on the margin and such additions signed by the party with his Christian name on one side and his surname on the other; and such marginal addition must be noticed in the body of the work so as to specify the page on which it occurs, the writer of it and that it is subscribed by the attesting witness.

The Roman rule was that the alterations should be made by the party himself and a formal clause was introduced with their deeds to that effect.

As a general rule alterations with the pen are in all cases to be preferred to erasure; and suspicion will be most effectually removed by not obliterating the words altered so completely as to conceal the nature of the correction.

The law of the United States follows that of England and Scotland in regard to alterations and erasures.

If any one will try the experiment of erasing an ink-mark on ordinary writing paper, and then writing over the erasure, he will notice a striking difference between the letters on the unaltered surface. The latter are broader, and in most cases, to the unaided eye, darker in color, while the erased spot, if not further treated to some substitute for sizing, may be noticed either when the paper is held between a light and the eye, or when viewed obliquely at a certain angle, or in both cases.

Very frequently it happens that so much of the size and the superficial layer of fibres must be removed that the mark of the ink can be distinctly seen on the reverse side of the paper, and the lines have a distinct border which makes them broader than in the same writing under normal conditions. If a sharp pen be used there is great likelihood that a hole will be made in the paper, or a sputter thrown over the parts adjacent to the erasure.

The latter effect is produced by the entanglement of the point of the pen among the disturbed fibres of the paper and its sudden release when sufficient force is used to carry it along in the direction of the writing.

It is often of importance to know, in case of a blot, whether the erasure it may partially mark was there before the blot, or whether it was made with the object of removing the latter.

Inasmuch as an attempt to correct such a disfigurement would in all probability not be made until the ink had dried, an inspection of the reverse side of the paper will usually furnish satisfactory evidence on the point. If the color of the ink be not more distinct on the under side of the paper than the color of other writing where there was no erasure, it is probable that the erasure was subsequent to the blot.

If the reverse be the case, the opposite conclusion may be drawn. Blots are sometimes used by ignorant persons to conceal the improper manipulation of the paper, but they are not adapted to aid this kind of fraud, and least of all to conceal erasures.

The decision as to whether they have been made legitimately and before a paper was executed, or subsequently to its execution, and with fraudulent intent, must be arrived at by a comparison of the handwriting in which the words appear, the ink with which they were written, and the local features of each special case which usually are not wanting.

To determine whether or not papers contain erasures the suspected document should be examined by reflected and transmitted light. Examine the surface for rough spots. Forgers after erasures frequently endeavor to hide the scratched and roughened surface by applying a sizing of alum, sandarach powder, etc., rubbing it to restore the finish to the paper.

Distilled water applied to the suspected document at the particular points under examination will dissolve the sizing applied by the forger. If held to the light the thinning will show. The water may be applied with a small brush or a medicine dropper. Water slightly warmed may be used with good results at times.

Alcohol, if applied as described for water, will act more promptly and show the scratched places. It may be well to use water first and then alcohol.

To discover whether or not acids were used to erase, if moistened litmus-paper be applied to the writing, the litmus-paper will become slightly red if there is any acid remaining on the suspected document. If the suspected spots be treated with distilled water, or alcohol, as already described, the doctored place will show, when examined in strong light.

Which of two inklines crossing each other was made first, is not always easy of demonstration. To the inexperienced observer the blackest line will always appear to be on top, and unless the examiner has given much intelligent observation to the phenomenon and the proper methods of observing it mistakes are very liable to be made. Owing to the well-known fact that an inked surface presents a stronger chemical affinity for ink than does a paper surface, when one ink-line crosses another, the ink will flow out from the crossing line upon the surface of the line crossed, slightly beyond where it flows upon the paper surface on each side, thus causing the crossing line to appear broadened upon the line crossed. Also an excess of ink will remain in the pen furrows of the crossing line, intensifying them and causing them to appear stronger and blacker than the furrows of the line crossed.

It is probable that ink and pencil alterations and erasures are more frequently made with a sharp steel scraper and ink-erasing sand rubber than otherwise. By these methods the evidence—first, the removal of the luster or mill-finish from the surface of the paper; second, the disturbance of the fibre of the paper, manifest under a microscope; third, if written over, the ink will run or spread more or less in the paper, presenting a heavier appearance, and the edges of the lines will be less sharply defined; fourth, if erasure is made on ruled paper, the base line will be broken or destroyed over the scraped or rubbed surface; fifth, the paper, since it has been more or less reduced in thickness where the erasure has been made, when held to the light will show more or less transparency. When erasures have been thus made the surface of the paper may be resized and polished, by applying white glue, and rubbing it over with a burnisher. When thus treated it may be again written over without difficulty. When erasures have been made with acids, there is a removal of the gloss, or mill-finish; and there is also more or less discoloration of the paper, which will vary according to the kind of paper, ink, and acid used, and the skill with which it has been applied. If the acid-treated surface is again written over, the writing will present a more or less ragged and heavy appearance, if the paper has not been first skillfully resized and burnished. It is very seldom that writing can be changed by erasure so as not to leave sufficient traces to lead to detection and demonstration through a skillful examination.

Upon hard uncalendered paper erasures by acid when skillfully made are not conspicuously manifest, nor when made upon any hard paper which has been "wet down" for printing, since the luster upon the paper would be thereby removed, and, so far as the surface of the paper is concerned, there would be no further change from the application of the acid. This applies to a wide range of printed blank business and professional forms.

A forgery consists either in erasing from a document certain marks which existed upon it, or in adding others not there originally, or in both operations, of which the first mentioned is necessarily antecedent to the last; as where one character or series of characters is substituted for another.

The removal of characters from a paper is effected either by erasure (seldom by pasting some opaque objects over the characters, painting over them, or affixing a seal, wafer, etc., to the spot where they existed) or by the use of chemical agents with the object of dissolving the writing fluid and affecting the underlying paper or parchment as little as possible.

If the erasure be effected by scratching or rubbing, this removes also the surface of the paper, which consists of some sort of "size" or paste with resin soap, which is pressed into the upper pores to give the paper a smooth appearance, and to prevent the writing fluid from "running," or entering the pores and blurring the edges of the lines.