A BRAVE GIRL.

Title: St. Nicholas Magazine for Boys and Girls, Vol. 5, No. 08, June 1878

Author: Various

Editor: Mary Mapes Dodge

Release date: June 23, 2005 [eBook #16123]

Most recently updated: December 11, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Lesley Halamek and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

.

A BRAVE GIRL.

[Transcriber's Note: The Original had no Table of Contents;

I have added one for ease of navigation.

The main Title is the Link.]

A TRIUMPH. BY CELIA THAXTER. |

PAGE 513 |

|

ONE SATURDAY BY SARAH WINTER KELLOGG. |

514 |

|

MRS. PETER PIPER'S PICKLES. BY E. MÜLLER. |

519 |

|

UNDER THE LILACS. (Serial) CHAPTER XIV.-SOMEBODY GETS LOST. CHAPTER XV.-BEN'S RIDE. BY LOUISA M. ALCOTT. |

523 |

|

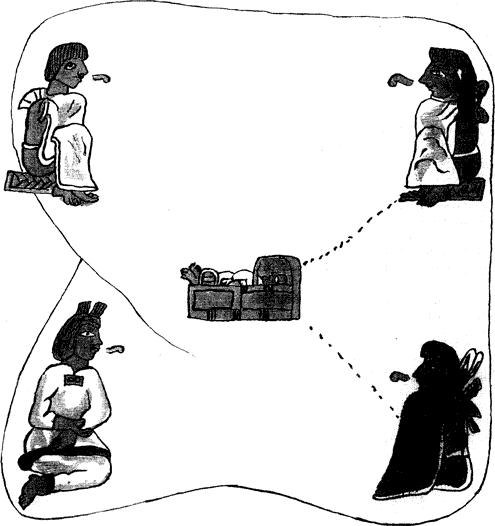

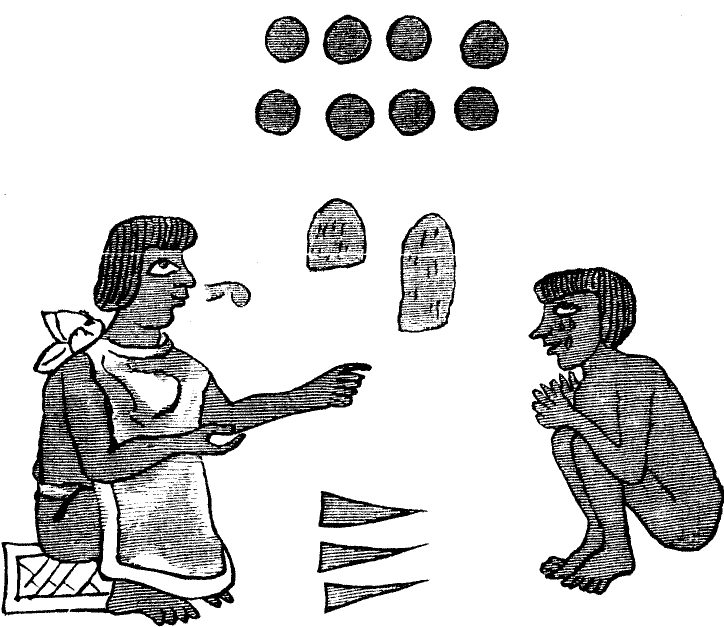

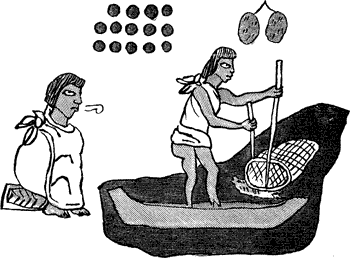

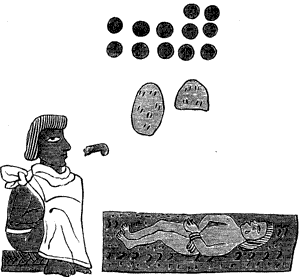

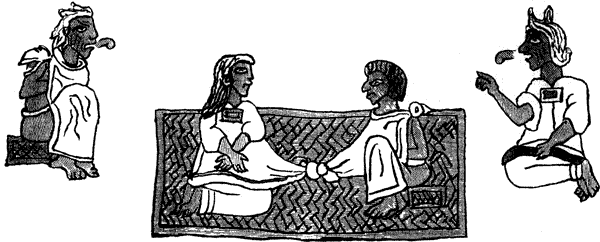

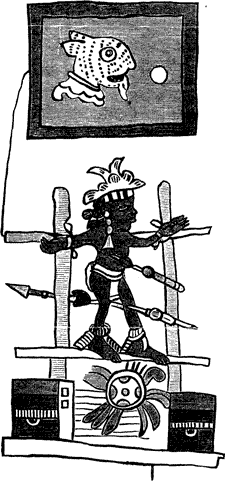

MASTER MONTEZUMA. (With Illustrations copied from Mexican Hieroglyphics.) By C.C. HASKINS. |

535 |

|

A LONG JOURNEY. BY JOSEPHINE POLLARD. |

540 |

|

THE LITTLE RED CANAL-BOAT. BY M.A. EDWARDS. |

541 |

|

THE BUTTERFLY CHASE. BY ELLIS GRAY. |

548 |

|

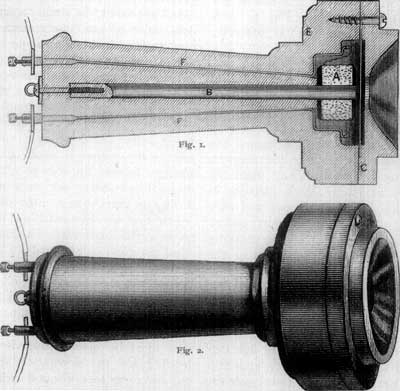

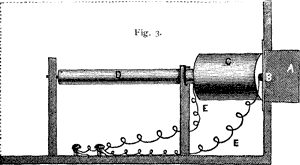

HOW TO MAKE A TELEPHONE. BY M.F. |

549 |

|

ONLY A DOLL! BY SARAH O. JEWETT. |

552 |

|

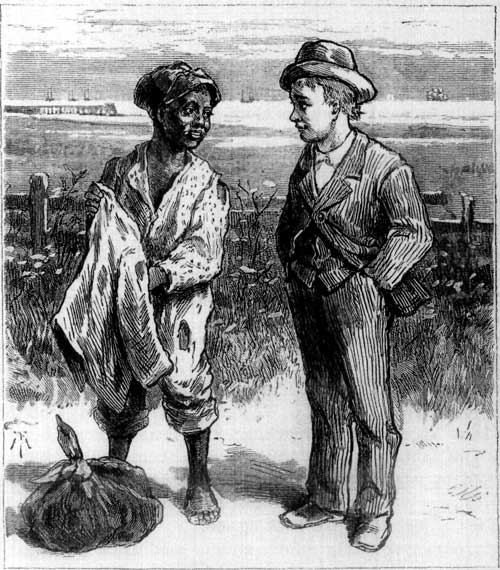

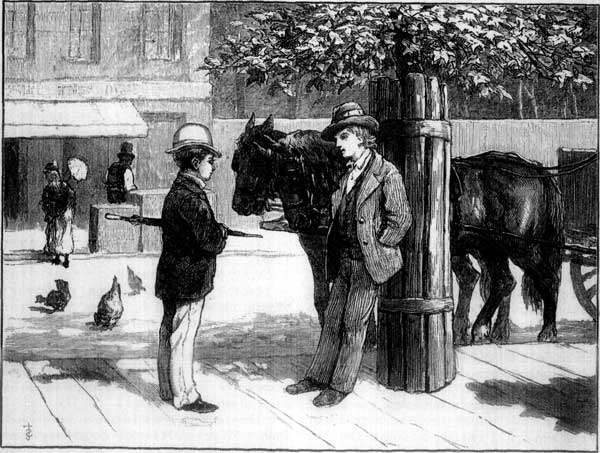

DAB KINZER: A STORY OF A GROWING BOY. (Serial) Chapters I, II, III, IV BY WILLIAM O. STODDARD. |

553 |

|

HOW WILLY WOLLY WENT A-FISHING. BY S.C. STONE. |

562 |

|

CRUMBS FROM OLDER READING. BY JULIA E. SARGENT. III.--THOMAS CARLYLE. |

565 |

|

JACK-IN-THE-PULPIT. (Letter-Box) A ROPE OF EGGS. CONVERSATION BY FISTICUFFS. A HORSE THAT LOVED TEA. TONGUES WHICH CARRY TEETH. DIZZY DISTANCES. LAND THAT INCREASES IN HEIGHT. THE ANGERED GOOSE. A CITY UNDER THE WATER. REFLECTION. |

566 |

| "FIDDLE-DIDDLE-DEE!" | 568 |

|

THE LETTER-BOX. (Dear St. Nicholas) A BRAVE GIRL. LETTERS... SOME THINGS WHICH WE EXPECT IN YEARS TO COME. THE TRUE STORY OF "MARY'S LITTLE LAMB". LETTERS... ACROSTIC. CITY CHILDREN'S COUNTRY REST. ANSWERS TO MR. CRANCH'S POETICAL CHARADES received from... ERRATUM.-- ANSWERS TO PUZZLES in the April number were received... CORRECT SOLUTIONS of all the puzzles were received from... |

572 |

|

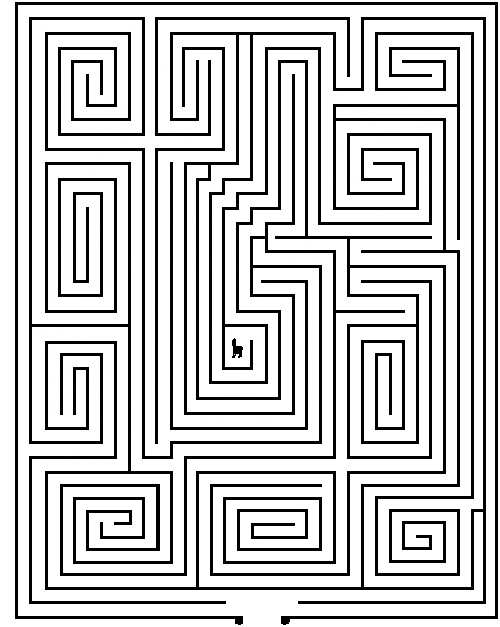

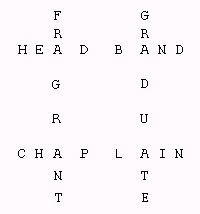

THE RIDDLE-BOX. EASY BEHEADINGS. ACCIDENTAL HIDINGS. METRICAL COMPOSITIONS. PORTIONS OF TIME. MELANGE. EASY CLASSICAL ACROSTIC. ENIGMA. ANAGRAMS. PICTORIAL PUZZLE. EASY DIAMOND PUZZLE. CHARADE. NUMERICAL PUZZLE. FOUR-LETTER SQUARE-WORD. EASY CROSS-WORD ENIGMA. METAGRAM. EASY ACROSTIC. BLANK WORD-SYNCOPATIONS. CHARADE. TRANSPOSITIONS OF PROPER NAMES. SQUARE-WORD. ADDITIONS. LABYRINTH. |

574 |

| ANSWERS TO PUZZLES IN MAY NUMBER. | 576 |

Little Roger up the long slope rushing

Through the rustling corn,

Showers of dewdrops from the broad leaves brushing

In the early morn,

At his sturdy little shoulder bearing

For a banner gay,

Stem of fir with one long shaving flaring

In the wind away!

Up he goes, the summer sunshine flushing

O'er him in his race,

Sweeter dawn of rosy childhood blushing

On his radiant face.

If he can but set his standard glorious

On the hill-top low,

Ere the sun climbs the clear sky victorious,

All the world aglow!

So he presses on with childish ardor,

Almost at the top!

Hasten, Roger! Does the way grow harder?

Wherefore do you stop?

From below the corn-stalks tall and slender

Comes a plaintive cry—

Turns he for an instant from the splendor

Of the crimson sky,

Wavers, then goes flying toward the hollow,

Calling loud and clear:

"Coming, Jenny! Oh, why did you follow?

Don't you cry, my dear!"

Small Janet sits weeping 'mid the daisies;[Page 514]

"Little sister sweet,

Must you follow Roger?" Then he raises

Baby on her feet,

Guides her tiny steps with kindness tender,

Cheerfully and gay,

All his courage and his strength would lend her

Up the uneven way,

Till they front the blazing East together;

But the sun has rolled

Up the sky in the still Summer weather,

Flooding them with gold.

All forgotten is the boy's ambition,

Low the standard lies,

Still they stand, and gaze—a sweeter vision

Ne'er met mortal eyes.

That was splendid; Roger, that was glorious,

Thus to help the weak;

Better than to plant your flag victorious

On earth's highest peak!

It was an autumn day in the Indian summer time,—that one Saturday. The Grammar Room class of Budville were going nutting; that is, eight of them were going,—"our set," as they styled themselves. Besides the eight of "our set," Bob Trotter was going along as driver, to take care of the horses and spring wagon on arrival at the woods, while the eight were taking care of the nutting and other fun. Bob was fourteen and three months, but he was well-grown. Beside, he was very handy at all kinds of work, as he ought to have been, considering that he had been kept at work since his earliest recollection, to the detriment of his schooling.

It had been agreed that the boys were to pay for the team, while the girls were to furnish the lunch. In order to economize space, it was arranged that all the contributions to the lunch should be sent on Friday to Mrs. Hooks, Clara of that surname undertaking to pack it all into one large basket.

It was a trifle past seven o'clock Saturday morning when Bob Trotter drove up to Mr. Hooks's to take in Clara, she being the picnicker nearest his starting point. He did not know that she was a put off-er. She was just trimming a hat for the ride when Bob's wagon was announced. She hadn't begun her breakfast, though all the rest of the family had finished the meal, while the lunch which should have been basketed the previous night was scattered over the house from the parlor center-table to the wood-shed.

Clara opened a window and called to Bob that she would be ready in a minute. Then she appealed to everybody to help her. There was a hurly-burly, to be sure. She asked mamma to braid her hair; little brother to bring her blue hair-ribbon from her bureau drawer; little Lucy to bring a basket for the prospective nuts; big brother to get the inevitable light shawl which mamma would be sure to make her take along. She begged papa to butter some bread for her, and cut her steak into mouthfuls to facilitate her breakfast, while the maid was put to collecting the widely scattered lunch. Mamma put baby, whom she was feeding, off her lap—he began to scream;[Page 515] little brother left his doughnut on a chair—the cat began to eat it; little Lucy left her doll on the floor—big brother stepped on its face, for he did not leave his book, but tried to read as he went to get the light shawl; papa laid down his cigar to prepare the put-offer's breakfast—it went out; the maid dropped the broom—the wind blew the trash from the dust-pan over the swept floor. Clara continued to trim the hat. As she was putting in the last pin, mamma reached the tip end of the hair, and called for the ribbon to tie the braid. "Here 'tis," said little brother. "Mercy!" cried Clara, "he's got my new blue sash, stringing it along through all the dust. Goose! do you think I could wear that great long wide thing on my hair?" Little brother said "Scat!" and rushed to the rescue of his doughnut, while Lucy came in dragging the clothes-basket, and big brother entered with mamma's black lace shawl.

"Well, you told me to get a light one," he replied to Clara's impatient remonstrance, while Lucy whimpered that they wouldn't have enough nuts if the clothes-basket wasn't taken along.

However, when Bob Trotter had secured Clara Hooks, the other girls were quickly picked up, and so were the four boys, for Bob was brisk and so were his horses. Dick Hart was the last called for. He had been ready since quarter past six, and with his forehandedness had worried his friends as effectually as the put-offer had hers. When the wagon at last appeared with its load of fun and laughter, he felt too ill-humored to return the merry greetings.

"A pretty time to be coming around!" he grumbled, climbing to his seat. "I've been waiting three hours."

"You houghtn't to 'ave begun to wait so hearly," said Bob, who had some peculiarities of pronunciation derived from his English parentage.

"It would be better for you to keep quiet," Dick retorted. "You ought to have your wages cut, coming around here after nine o'clock. We ought to be out to the woods this minute."

"'Taint no fault of mine that we haint," said Bob, touching up his horses.

"Whose fault is it, if it isn't yours?" Dick asked.

Clara Hooks was blushing.

"Let the sparrer tell who killed Cock Robin," was Bob's enigmatical reply.

"What's he talking about?" said Julius Zink.

"I dunno, and he don't either," replied Dick.

"He doesn't know that or anything else," said Sarah Ketchum.

It was not possible for Sarah to hear a dispute and not become an open partisan.

"I know a lady when I see 'er," said Bob.

"You don't," said Dick, warmly. "You can't parse horse. I heard you try at school once."

"I can curry him," said Bob.

"You said horse was an article."

"So he is, and a very useful harticle."

One of the girls nudged her neighbor, and in a loud whisper intimated her opinion that Bob was getting the better of Dick. At this Dick grew warmer and more boisterous, maintaining that the boys ought not to pay Bob the stipulated price since they were so late in starting.

"Hif folks haint ready I can't 'elp it," said Bob.

"Who wasn't ready?" demanded Constance Faber. "You didn't wait for me, I know."

"And you didn't wait for me or Mat Snead," added Sarah Ketchum, "because we walked down to meet the wagon."

Clara Hooks's face had grown redder and redder during the investigation; but if Clara was a put-offer, she was not a coward or a sneak.

"He waited for me," she now said, "but I think it's mean to tell it wherever he goes."

"I haint told it nowheres."

"You just the same as told; you hinted."

"Wouldn't 'ave 'inted ef they hadn't kept slappin' at me," was Bob's defense, which did not go far toward soothing the mortified Clara.

Not all of this party were pert talkers. Two were modest: Valentine Duke and Mat Snead. These sat together, forming what the others called the Quaker settlement, from the silence which prevailed in it. The silence was now broken by a remark from Valentine Duke irrelevant to any preceding.

"Nuts are plentier at Hawley's Grove than at Crow Roost," he jerked, out, and then locked up again.

"Say we go there, then," said Kit Pott.

"Let's take the vote on it. Those in favor of Hawley's say aye."

The ayes came storming out, as though each was bound to be the first and loudest.

"Contrary, no," continued the self-made president; and Bob Trotter voted solidly "No!"

"We didn't ask you to vote," said Dick, returning to his quarrel.

Dick was constitutionally and habitually pugnacious, but he had such a cordial way of forgiving everybody he injured that people couldn't stay mad with him. Indeed, he was quite a favorite.

"I'm the other side of the 'ouse," Bob answered Dick. "You can't carry this hidee through without my 'elp."

"We hired you to take us to the woods."

"You 'ired me and my wagin and them harticles—whoa!" (Bob's "harticles" stopped)—"to take you to Crow Roost. You didn't 'ire me for 'Awley's, and I haint goin' ther' without a new contract."

"What difference is it to you where we go?"[Page 516] Dick demanded. "You belong to us for the day."

"Four miles further and back,—height miles makes a difference to the harticles."

Murmurs of disapproval rendered Dick bold.

"Suppose we say you've got to take us to Hawley's," he said, warmly.

"Suppose you do," said Bob, coolly.

"I'd like to know what you'd say about it," said Dick, warmly.

"Say it and I'll let you know," said Bob, coolly,—so very coolly that Dick was cooled.

A timely prudence enforced a momentary silence. He forebore taking a position he might not be able to hold. "Say, boys, shall we make him take us to the grove?"

Bob smiled. Val Duke smiled, too, in his unobtrusive way, and suggested modestly, "We ought to pay extra for extra work."

"Pay him another quarter and be done with it," said Kit Pott.

Beside being good-natured, Kit didn't enjoy the stopping there in the middle of the road.

"It's mighty easy to pay out other people's money," sneered Dick, resenting it that Kit seemed going over to the enemy.

Kit's face was aflame. His father had refused him any money to contribute toward the picnic expenses, and here was Dick taunting him with it before all the girls.

"You boys teased me to come along because you didn't know where to find the nuts," said Kit.

The girls began to nudge each other, making whimpered explanations and commentaries, agreeing that is was mean in Dick to mind Kit, and Clara Hooks spoke up boldly;

"I wanted Kit to come along because he's pleasant and isn't forever quarreling."

"Oh!" Dick sneered more moderately, "we all know you like Kit Pott. You and he had better get hitched; then, you'd be pot-hooks."

This set everybody to laughing, even Dirk's adversary, Bob Trotter.

"Pretty bright!" said Julius Zink.

"Bright, but not pretty," said Mat Snead, blushing at the sound of her voice.

"Hurrah! Mat's waked up," said Julius.

"It's the first time she's spoken since we started," said Sarah Ketchum.

"This isn't the first time you've spoken," Mat quietly retorted, blushing over again.

Everybody laughed again, even Sarah Ketchum.

"Sarah always puts in her oar when there's any water," said Constance Faber.

"I want to know how long we're to sit here, standing in the middle of the road," said Julius.

Again everybody laughed. When grammar-school boys and girls are on a picnic, a thing needn't be very witty or very funny to make them laugh. From the ease with which this party exploded into laughter, it may be perceived that in spite of the high words and the pop-gun firing, there was no deep-seated ill-humor among them.

"To Crow Roost and be done with it!" said Dick.

"All right," assented several voices.

"Crow Roost, Bob, by the lightning express," said Dick, with enthusiasm.

"But, as you were so particular," said Sarah to Bob, "we're going to be, too. We aint going to give you any lunch unless you pay for it."

"Not a mouthful," said Clara.

"Not even a crumb," said Constance.

Nobody saw any dismay in Bob's face.

I don't intend to tell you about all the sayings and all the laughter of those boys and girls on their way to Crow Roost. They wouldn't like to have me, and you wouldn't. Bob Trotter ran over a good many grubs and way-side stumps, and at every jolt Constance screamed, and Dick scolded and then laughed. Mat Snead spoke three words. She and Valentine had been sitting as though in profound meditation for some forty minutes, when he said: "Quite a ride!"

"Very; no, quite," she answered, in confusion.

Sarah Ketchum said everything that Mat didn't say. She was Mat's counterpart.

All grew enthusiastic as they approached the woods, and when the wagon stopped they poured over the side in an excited way.

"What shall we do with the lunch-basket?"

"Leave it in the wagon," said Sarah Ketchum, whose counsel, Kit said, was as free as the waters of the school pump.

Clara objected to leaving it. Bob would eat everything up. "Let's take it along."

"Why, no," said Julius.

He was the largest of the boys, and, according to the knightly code, he remembered the carrying of the basket would devolve upon him.

"Yes, we must carry it along," Sarah Ketchum insisted. "Bob sha'n't have a chance at that basket if I have to carry it around on my back."

Constance, too, said, "Take it along."

"It's easy enough for you girls to insist on having the basket toted around," said Dick, "because girls can't carry anything when there are boys along; but suppose you were a poor little fellow like Jule."

"I wont have to climb the trees with it on my back, will I?" said Julius. "I'll tell you," he continued, lowering his tone—Bob had heard all the preceding remarks—"we'll hang our basket on a hickory limb. It will be safe from hogs, and the leaves will hide it from Bob."

This proposition was approved, and the basket[Page 517] was carried off a short distance and slyly swung into a sapling. Then the eight went scurrying through the woods, leaving Bob with the horses. Wherever they saw a lemon-tinted tree-top against the sky or crowded into one of those fine autumn bouquets a clump of trees can make, there rushed a squad of boys, each with his basket, followed by a squad of girls, each with her basket.

But in a very short time the girls were tired and the boys hungry. All agreed to go back to the lunch. So back they hurried, the nuts rolling about over the bottoms of the baskets. Julius had the most nuts; he had eleven. Mat had the smallest number; she had one.

"I hope you girls brought along lots of goodies," said Dick. "Seems to me I never was so hungry in my life."

"I believe boys are always hungry," said Sarah Ketchum.

Val Duke was leading the party. He got along faster than the others, because he wasn't turning around every minute to say something. He made an electrifying announcement:

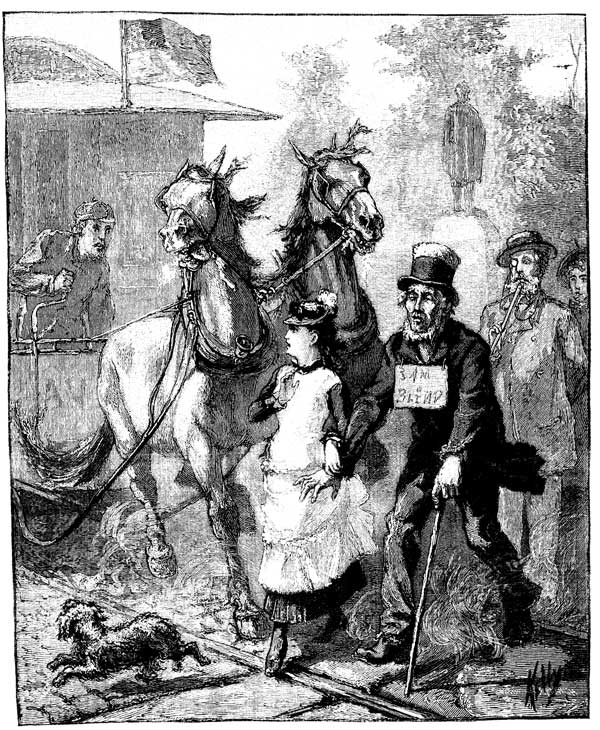

"A cow's in the basket!"

"Gee-whiz!" said Dick, rushing at the cow. "Thunder!" said Julius, and he gathered a handful of dried leaves and hurled them at the beast. Kit said "Ruination!" and threw his cap. Clara said "Begone!" and flapped her handkerchief in a scaring way. Sarah Ketchum said, "Shew! Scat!" and pitched a small tree-top. It hit Dick and Valentine. Constance said "Wretch!" and didn't throw anything. Mat didn't say anything and threw her hickory-nut. Val threw his basket, and hung it on the cow's horn. She shook it off walked away a few yards, then turned and stared at the party.

"Lunch is gone, every smitch of it!" said Kit.

"Hope it'll kill her dead!" said Sarah Ketchum.

"We'd better have left it in the wagon. Bob couldn't have eaten it all," said Clara.

"I wish Jule had taken it along," said Dick.

"I wish Dick had taken it along," said Julius.

"But what're we going to do?" said Constance.

"We might buy something if anybody lived about here."

"There isn't any money."

"Dick might give his note, with the rest of us as indorsers," said Julius.

"We might play tramps and beg something."[Page 518]

"But nobody lives around here."

"Hurrah!" said Dick, who had been prowling about among the slain. "Here's a biscuit, and here's a half loaf of bread."

"But they're all mussed and dirty," said Sarah.

"You might pare them," Mat suggested.

"Yes, peel them like potatoes," said Julius.

"But what are these among so many? The days of miracles are past."

"What shall we do?" said one and another.

"Milk the cow," said Mat.

Boys and girls clapped their hands with enthusiasm, and cried "Splendid!" "Capital!" etc.

"I'll milk her," said Dick. "Hand me that cup. I'm obliged to the cow for not eating it."

The cow happened to be a gentle animal, so she did not run away at Dick's approach, yet she seemed determined that he should not get into milking position. She kept her broad, white-starred face toward him, and her large, liquid eyes on his, turning, turning, turning, as he tried over and over to approach her flanks, while the others stood watching in mute expectancy.

"Give her some feed," said Mat.

"Feed! I shouldn't think she could bear the sight of anything more after all that lunch," said Dick. "Beside, there isn't any feed about here."

Somebody suggested that Bob Trotter had brought some hay and corn for his horses. Dick proposed that Julius should go for some. Julius proposed that Dick should go. Valentine offered to bring it, and brought it—some corn in a basket.

"Suke! Suke, Bossy! Suke, Bossy! Suke!" Dick yelled as though the cow had been two hundred feet off instead of ten. He held out the basket. She came forward, sniffed at the corn, threw up her lip and took a bite. Dick set the basket under her nose and hastened to put himself in milking position. But that was the end of it. He could not milk a drop.

"I can't get the hang of the thing," he said.

"Let me try," said Kit.

Dick gave way, and Kit pulled and squeezed and tugged and twisted, while the others shouted with laughter.

'I BELIEVE SHE'S GONE DRY,' SAID KIT.

'I BELIEVE SHE'S GONE DRY,' SAID KIT.

"I believe she's gone dry," said Kit, very red in the face. At this the laughers laughed anew.

"Some of you who are so good at laughing had better try."

Kit set the cup on a stump and retired.

Sarah Ketchum tried to persuade everybody else to try, but the other boys were afraid of failure and the girls were afraid of the cow. Sarah said if somebody would hold the animal's head so that it couldn't hook, she'd milk—she knew she could. But nobody offered to take the cow by the horns; so everything came to a stand-still except Sarah's talking and the cow's eating. Then Bob Trotter came in sight, all his pockets standing out with nuts. They called him. Sarah Ketchum explained the situation and asked him if he could milk.

"I do the milkin' at 'ome," Bob replied.

"Wont you please milk this cow for us? We don't know how, and we want the milk for dinner."

There came a comical look into Bob's face, but he said nothing. The eight knew what his thoughts must be.

"We oughtn't to have said that you couldn't have any of our lunch," said Sarah Ketchum.

"We didn't really mean it," said Clara. "When lunch-time came we would have given you lots of good things."

"That's so," said Dick. "Sarah told us an hour ago that she meant to give you her snow-ball cake because she felt compuncted."

By this time Bob had approached the cow. He spoke some kind words close to her broad ear, and gently stroked her back and flanks. Then he set to work in the proper way, forcing the milk in streams into the cup, the boys watching with admiration Bob's ease and expertness, Dick wondering why he couldn't do what seemed so easy. In a few seconds the cup was filled.

"Now, what're you going to do?" said Bob. "This wont be a taste around."

"You might milk into our hats," said Julius.

"I've got a thimble in my pocket," said Sarah Ketchum.

"Do stop your nonsense," said Constance; "it's a very serious question—a life and death matter. We're a company of Crusoes."

But the boys couldn't stop their nonsense immediately. Dick remarked that if the cow had not licked out the jelly-bowl and then kicked it to pieces it might have been utilized. Then some one remembered a tin water-pail at the wagon. This was brought, and Bob soon had it two-thirds filled with milk. Then the question arose as to how they were all to be served with just that quart-cup and two spoons. They were to take turns, two eating at a time.

"I don't want to eat with Jule," Dick said. "He eats too fast."

The young people paired off, leaving out Bob. Then they all looked at him in a shame-faced, apologetic way.

"You needn't mind me," said Bob, interpreting their glances. "I don't want to heat with none of you. I've got some wittals down to the wagon."

"Why, what have you got?" said Sarah Ketchum. She felt cheap, and so did the others.

"Some boiled heggs and some happles and some raw turnups," said Bob.

Eight mouths watered at this catalogue. Sarah [Page 519] Ketchum whispered:

"For a generous slice of turnip, I'd lay me down and die."

"I don't keer for nothing but a hegg and a happle, myself," said Bob. "May be you folks would heat the hother things. There's a good lot of happles."

The eight protested that they could do with the milk and bread, but urged the milk on Bob.

"No, I thank you," he said.

"He's mad at us yet," Mat whispered.

"Look here," said Sarah Ketchum to Bob, "if you don't eat some of this milk, none of us will. We'll give it to the cow."

"No, we won't do that," Julius said: "we'll hold you and make you drink it. If you have more apples than you wish, we'll be glad of some; but we aren't going to take them unless you'll take your share of the milk."

"And we'll get mad at you again," said Clara.

"I'll drink hall the milk necessary to a make-hup," said Bob.

When the lunch was eaten, Mat said she didn't think they ought to have milked the cow. The folks would be so disappointed when they came to milk her at night. May be a lot of poor children were depending on the milking for their supper. Val, too, showed that his conscience was disturbed.

"You needn't worry," said Dick. "They'll get this milk back from the lunch she stole."

"But they couldn't help her stealing."

"And I couldn't help milking her," said Dick.

At this there was a burst of laughter. Then Mat wrote on a scrap of paper: "This cow has been milked to save some boys and girls from starvation. The owner can get pay for the milk by calling at Mr. Snead's, Poplar street, Budville."

"Who'll tie it on her tail?" asked Mat.

"I will," said Val, promptly, glad to ease his conscience.

And this he did with a piece of blue ribbon from Mat Snead's hat.

HERE'S nothing in that

bush," said one old crow

to another old crow, as

they flew slowly along

the beach.

"No, nothing worth looking at," answered the other old crow, and then they alighted on a dead tree and complained that the egg season was over.

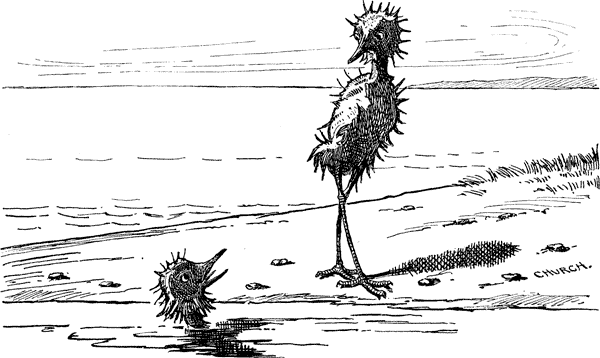

That was because they were fond of sandpipers' eggs, and there were none in that bush. No eggs were there, to be sure, but there sat Mrs. Peter Sandpiper, talking to two fine young sandpipers, just hatched.

"Nothing worth looking at!" said she, indignantly. "Well, anything but a crow would have more sense! Nothing in this bush, indeed! Pe-tweet, pe-tweet!"

And truly she might well be angry at any one snubbing those young ones of hers. Their eyes were so bright, their legs were so slim, and their beaks so sharp that it was delightful to see them. And they turned out their toes so gracefully that, the first time they went to the sea to bathe, everyone said Mrs. Peter Sandpiper had reason to be proud of her children. But just as soon as they could run they got into all sorts of troubles, and[Page 520] vexed Mrs. Sandpiper out of her wits.

"THEY TURNED OUT THEIR TOES SO GRACEFULLY."

"Such a pair of young pickles I never hatched before!" said she to Mrs. Kingfisher, who came to gossip one day.

"Well, well, my dear," said Mrs. Kingfisher, "boys will be boys; by the time they are grown up they will be all right. Now, my dear Pinlegs was just such—"

But Mrs. Sandpiper had to fly off, to see what Pipsy Sandpiper was doing, and keep Nipsy Sandpiper from swallowing a June beetle twice too big for him. They were great trials. They were always eating the wrong kind of bugs, and having indigestion and headaches. They were forever getting their legs tangled up in long wet grass, and screaming for Mrs. Peter Sandpiper to come help them out, and at night they chirped in their sleep and disturbed Mrs. Sandpiper dreadfully by kicking each other. At last she said she could stand it no longer; they must take care of themselves. So she cried "Pe-tweet, good-by," and then she flew away, leaving Pipsy and Nipsy alone by the sea to take care of themselves.

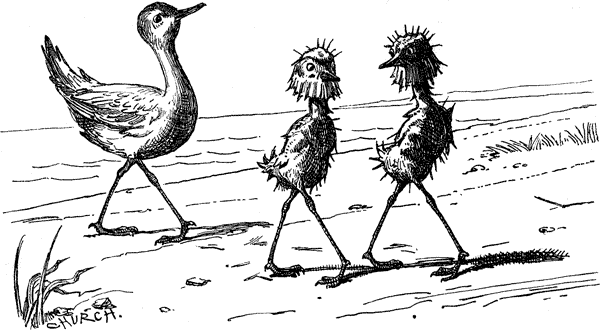

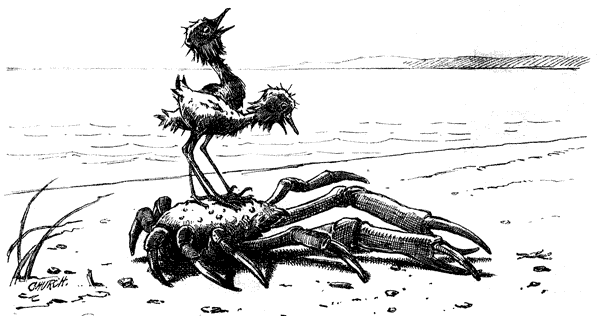

It was quite a trouble at first, for Mamma Sandpiper had always helped them to bugs and worms, one apiece, turn about, so all was fair. But now Pipsy always wanted the best of everything, and Nipsy, being good tempered, had to eat what his brother left. One day bugs were very scarce, and both little Sandpipers were so hungry that they could have eaten a whole starfish—if he had come out of his shelter. Suddenly Nipsy, who was a trifle near sighted, said he saw a large beetle coming along the beach. They ran quickly to meet it. But what in the world was it! It had legs; oh, such legs! They were larger than Pipsy's and Nipsy's put together. Its back was like a huge shell, and its eyes were dreadful. The little sandpipers looked at each other in terror.

But a mild little voice from the creature relieved [Page 522] them.

"I beg your pardon," said he. "Let me introduce myself. C. Crab, Esq., of Oyster Bay."

"Oh, ah! Indeed!" said Pipsy. "Glad to know you, I'm sure."

"I think I must have lost my way," said C. Crab, Esq. "Could you oblige me by telling me if you see any boys near?"

"Any boys?" said Pipsy and Nipsy, looking at each other. "Never saw one in my life. What do they look like? Have they many legs? Are they fat? Are they good to eat?" asked both the hungry little sandpipers.

"They are creatures," said the crab, with a groan,—"creatures a thousand times larger than we are. They have strings. They tie up legs and pull. They throw stones. If you ever see a boy, run for your life."

"Good gracious me!" cried both the little sandpipers. "How very dreadful!"

But there were no boys in sight; so C. Crab grew sociable, and offered to show them a place where bugs were plenty. "Just get on my back," said he, "and I'll have you there in no time."

"OH, MY! HE'S GOING BACKWARDS!"

So they got on his back. It was very wet and slippery, but they held on with their toes, while C. Crab gave himself a heave and started.

"Oh, my!" exclaimed Nipsy. "He's going backward!"

"He actually is!" cried Pipsy. "At this rate we'll get there day before yesterday, wont we?"

"Surely," said Nipsy. "How very horrid of him when we are so hungry! What a slow coach!"

"Let's jump off quick, or he'll take us clear into last week!" cried the silly sandpipers, and then they skipped off and ran down the beach in the opposite direction. C. Crab called to them, but it was no use, so he went on his way. But as for the sandpipers, they went on getting into trouble. The day was hot, and after they had run some distance, they stepped into the water to cool off. Nipsy stepped in first, but the water was up to his breast and it frightened him, so he stepped out again.

"Pooh!" said Pipsy. "You're afraid, YOU are! Look at me!"

Then he jumped in, and only his head stuck out.

"THIS IS TWICE AS DEEP AS YOU WERE IN."

"This is twice as deep as you were in!" he cried, turning up his bill, and rolling his eyes.

"You're sitting down, you are!" cried Nipsy, in scorn.

"I'm not," said Pipsy.

"You are. I can see your toes all doubled up, even if the water is muddy," said Nipsy, and rushed at him to punish him for bragging.

They both rolled under the water, and then out on the shore, dripping wet and very angry with each other.

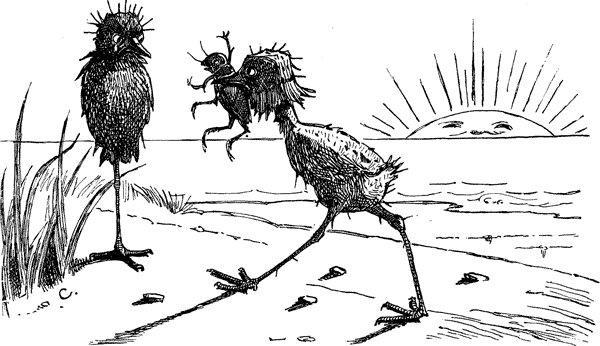

Pipsy went home to the old bush and was very miserable. He wanted something to eat, and did not know where to find anything. Nipsy went high up the beach, and found a lot of young hedge-crickets. But he did not half enjoy them. They were fat and smooth, and he was hungry, but crickets had no flavor without Pipsy to help eat them. But he was angry at him yet.

"He must come to me," he said, sternly, to the cricket he was eating.

"THERE, IN THE TWILIGHT, HE SAW A LONELY FIGURE STANDING ON ONE LEG."

The cricket said nothing, being half-way down his throat, and pretty soon Nipsy could stand his feelings no longer. Catching up the largest, smoothest, softest cricket, he ran down to the shore as fast as his legs could carry him. There, in the twilight, he saw a lonely figure standing on one leg.

"Pipsy!" he cried.

"Nipsy!" cried Pipsy.

And they flew to each other.

"Here's a glorious fat cricket for you."

"Forgive me, Nipsy," said his brother.

And then they were happy.

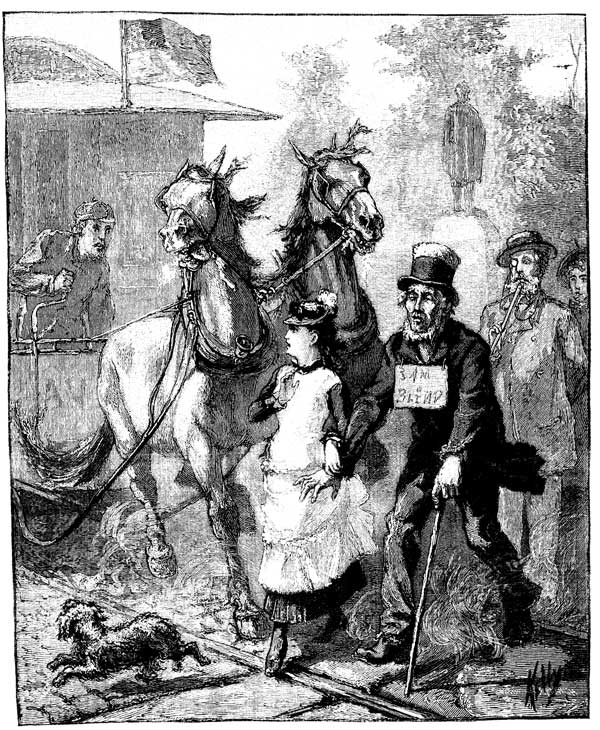

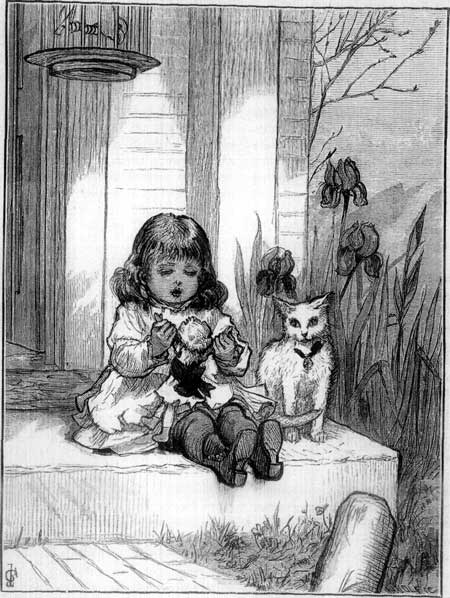

Putting all care behind them, the young folks ran down the hill, with a very lively dog gamboling beside them, and took a delightfully tantalizing survey of the external charms of the big tent. But people were beginning to go in, and it was impossible to delay when they came round to the entrance.

Ben felt that now "his foot was on his native heath," and the superb air of indifference with which he threw down his dollar at the ticket-office, carelessly swept up the change, and strolled into the tent with his hands in his pockets, was so impressive that even big Sam repressed his excitement and meekly followed their leader, as he led them from cage to cage, doing the honors as if he owned the whole concern. Bab held tight to the tail of his jacket, staring about her with round eyes, and listening with little gasps of astonishment or delight to the roaring of lions, the snarling of tigers, the chatter of the monkeys, the groaning of camels, and the music of the very brass band shut up in a red bin.

Five elephants were tossing their hay about in the middle of the menagerie, and Billy's legs shook under him as he looked up at the big beasts whose long noses and small, sagacious eyes filled him with awe. Sam was so tickled by the droll monkeys that they left him before the cage and went on to see the zebra, "striped just like Ma's muslin gown," Bab declared. But the next minute she forgot all about him in her raptures over the ponies and their tiny colts, especially one mite of a thing who lay asleep on the hay, such a miniature copy of its little mouse-colored mamma that one could hardly believe it was alive.

"Oh, Ben, I must feel of it!—the cunning baby horse!" and down went Bab inside the rope to pat and admire the pretty creature, while its mother smelt suspiciously at the brown hat, and baby lazily opened one eye to see what was going on.

"Come out of that, it isn't allowed!" commanded Ben, longing to do the same thing, but mindful of the proprieties and his own dignity.

Bab reluctantly tore herself away to find consolation in watching the young lions, who looked so like big puppies, and the tigers washing their faces just as puss did.

"If I stroked 'em, wouldn't they purr?" she asked, bent on enjoying herself, while Ben held her skirts lest she should try the experiment.

"You'd better not go to patting them, or you'll get your hands clawed up. Tigers do purr like fun when they are happy, but these fellers never are, and you'll only see 'em spit and snarl," said Ben, leading the way to the humpy camels, who were peacefully chewing their cud and longing for the desert, with a dreamy, far-away look in their mournful eyes.

Here, leaning on the rope, and scientifically chewing a straw while he talked, Ben played showman to his heart's content till the neigh of a horse from the circus tent beyond reminded him of the joys to come.

"We'd better hurry along and get good seats before folks begin to crowd. I want to sit near the curtain and see if any of Smithers's lot are 'round."

"I aint going way off there; you can't see half so well, and that big drum makes such a noise you can't hear yourself think," said Sam, who had rejoined them.

So they settled in good places where they could see and hear all that went on in the ring and still catch glimpses of white horses, bright colors, and the glitter of helmets beyond the dingy red curtains. Ben treated Bab to peanuts and pop-corn like an indulgent parent, and she murmured protestations of undying gratitude with her mouth full, as she sat blissfully between him and the congenial Billy.

Sancho, meantime, had been much excited by the familiar sights and sounds, and now was greatly exercised in his doggish mind at the unusual proceeding of his master; for he was sure that they ought to be within there, putting on their costumes, ready to take their turn. He looked anxiously at Ben, sniffed disdainfully at the strap as if to remind him that a scarlet ribbon ought to take its place, and poked peanut shells about with his paw as if searching for the letters with which to spell his famous name.

"I know, old boy, I know; but it can't be done. We've quit the business and must just look on. No larks for us this time, Sanch, so keep quiet and behave," whispered Ben, tucking the dog away under the seat with a sympathetic cuddle of the curly head that peeped out from between his feet.

"He wants to go and cut up, don't he?" said Billy, "and so do you, I guess. Wish you were going to. Wouldn't it be fun to see Ben showing off in there?"

"I'd be afraid to have him go up on a pile of[Page 524] elephants and jump through hoops like these folks," answered Bab, poring over her pictured play-bill with unabated relish.

"Done it a hundred times, and I'd just like to show you what I can do. They don't seem to have any boys in this lot; shouldn't wonder if they'd take me if I asked 'em," said Ben, moving uneasily on his seat and casting wistful glances toward the inner tent where he knew he would feel more at home than in his present place.

"AT THE CIRCUS"

"I heard some men say that it's against the law to have small boys now; it's so dangerous and not good for them, this kind of thing. If that's so, you're done for. Ben," observed Sam, with his most grown-up air, remembering Ben's remarks on "fat boys."

"Don't believe a word of it, and Sanch and I could go this minute and get taken on, I'll bet. We are a valuable couple, and I could prove it if I chose to," began Ben, getting excited and boastful.

"Oh, see, they're coming!—gold carriages and lovely horses, and flags and elephants, and everything!" cried Bab, giving a clutch at Ben's arm as the opening procession appeared headed by the band, tooting and banging till their faces were as red as their uniforms.

Round and round they went till every one had seen their fill, then the riders alone were left caracoling about the ring with feathers flying, horses prancing, and performers looking as tired and indifferent as if they would all like to go to sleep then and there.

"How splendid!" sighed Bab, as they went dashing out, to tumble off almost before the horses stopped.

"That's nothing! You wait till you see the bare-back riding and the 'acrobatic exercises,'" said Ben, quoting from the play-bill, with the air of one who knew all about the feats to come, and could never be surprised any more.

"What are 'crowbackic exercises?'" asked Billy, thirsting for information.

"Leaping and climbing and tumbling; you'll see—George! what a stunning horse!" and Ben forgot everything else to feast his eyes on the handsome creature who now came pacing in to dance, upset and replace chairs, kneel, bow, and perform many wonderful or graceful feats, ending with a swift gallop while the rider sat in a chair on its back fanning himself, with his legs crossed, as comfortably as you please.

"That, now, is something like," and Ben's eyes shone with admiration and envy as the pair vanished, and the pink and silver acrobats came leaping into the ring.

The boys were especially interested in this part, and well they might be; for strength and agility are manly attributes which lads appreciate, and these lively fellows flew about like India rubber balls, each trying to outdo the other, till the leader of the acrobats capped the climax by turning a double somersault over five elephants standing side by side.

"There, sir, how's that for a jump?" asked Ben, rubbing his hands with satisfaction as his friends clapped till their palms tingled.

"We'll rig up a spring-board and try it," said Billy, fired with emulation.

"Where'll you get your elephants?" asked Sam,[Page 525] scornfully, for gymnastics were not in his line.

"You'll do for one," retorted Ben, and Billy and Bab joined in his laugh so heartily that a rough-looking man who sat behind them, hearing all they said, pronounced them a "jolly set," and kept his eye on Sancho, who now showed signs of insubordination.

"Hullo, that wasn't on the bill!" cried Ben, as a parti-colored clown came in, followed by half a dozen dogs.

"I'm so glad; now Sancho will like it. There's a poodle that might be his ownty donty brother—the one with the blue ribbon," said Bab, beaming with delight as the dogs took their seats in the chairs arranged for them.

Sancho did like it only too well, for he scrambled out from under the seat in a great hurry to go and greet his friends, and, being sharply checked, set up and begged so piteously that Ben found it very hard to refuse and order him down. He subsided for a moment, but when the black spaniel, who acted the canine clown, did something funny and was applauded, Sancho made a dart as if bent on leaping into the ring to outdo his rival, and Ben was forced to box his ears and put his feet on the poor beast, fearing he would be ordered out if he made any disturbance.

Too well trained to rebel again, Sancho lay meditating on his wrongs till the dog act was over, carefully abstaining from any further sign of interest in their tricks, and only giving a sidelong glance at the two little poodles who came out of a basket to run up and down stairs on their fore paws, dance jigs on their hind legs, and play various pretty pranks to the great delight of all the children in the audience. If ever a dog expressed by look and attitude, "Pooh! I could do much better than that, and astonish you all, if I was only allowed to," that dog was Sancho, as he curled himself up and affected to turn his back on an unappreciative world.

"It's too bad, when he knows more than all those chaps put together. I'd give anything if I could show him off as I used to. Folks always liked it, and I was ever so proud of him. He's mad now because I had to cuff him, and wont take any notice of me till I make up," said Ben, regretfully eyeing his offended friend, but not daring to beg pardon yet.

More riding followed, and Bab was kept in a breathless state by the marvelous agility and skill of the gauzy lady who drove four horses at once, leaped through hoops, over banners and bars, sprang off and on at full speed, and seemed to enjoy it all so much it was impossible to believe that there could be any danger or exertion in it.

Then two girls flew about on the trapeze, and walked on a tight rope, causing Bab to feel that she had at last found her sphere, for, young as she was, her mother often said:

"I really don't know what this child is fit for, except mischief, like a monkey."

"I'll fix the clothes-line when I get home, and show Ma how nice it is. Then, may be, she'll let me wear red and gold trousers, and climb round like these girls," thought the busy little brain, much excited by all it saw on that memorable day.

Nothing short of a pyramid of elephants with a glittering gentleman in a turban and top boots on the summit would have made her forget this new and charming plan. But that astonishing spectacle and the prospect of a cage of Bengal tigers with a man among them, in imminent danger of being eaten before her eyes, entirely absorbed her thoughts till, just as the big animals went lumbering out, a peal of thunder caused considerable commotion in the audience. Men on the highest seats popped their heads through the openings in the tent-cover and reported that a heavy shower was coming up. Anxious mothers began to collect their flocks of children as hens do their chickens at sunset; timid people told cheerful stories of tents blown over in gales, cages upset and wild beasts let loose. Many left in haste, and the performers hurried to finish as soon as possible.

"I'm going now before the crowd comes, so I can get a lift home. I see two or three folks I know, so I'm off;" and, climbing hastily down, Sam vanished without further ceremony.

"Better wait till the shower is over. We can go and see the animals again, and get home all dry, just as well as not," observed Ben, encouragingly, as Billy looked anxiously at the billowing canvas over his head, the swaying posts before him, and heard the quick patter of drops outside, not to mention the melancholy roar of the lion which sounded rather awful through the sudden gloom which filled the strange place.

"I wouldn't miss the tigers for anything. See, they are pulling in the cart now, and the shiny man is all ready with his gun. Will he shoot any of them, Ben?" asked Bab, nestling nearer with a little shiver of apprehension, for the sharp crack of a rifle startled her more than the loudest thunder-clap she ever heard.

"Bless you, no, child; it's only powder to make a noise and scare 'em. I wouldn't like to be in his place, though; father says you can never trust tigers as you can lions, no matter how tame they are. Sly fellers, like cats, and when they scratch it's no joke, I tell you," answered Ben, with a knowing wag of the head, as the sides of the cage rattled down, and the poor, fierce creatures were seen leaping and snarling as if they resented this[Page 526] display of their captivity.

Bab curled up her feet and winked fast with excitement as she watched the "shiny man" fondle the great cats, lie down among them, pull open their red mouths, and make them leap over him or crouch at his feet as he snapped the long whip. When he fired the gun and they all fell as if dead, she with difficulty suppressed a small scream and clapped her hands over her ears; but poor Billy never minded it a bit, for he was pale and quaking with the fear of "heaven's artillery" thundering over head, and as a bright flash of lightning seemed to run down the tall tent-poles he hid his eyes and wished with all his heart that he was safe with mother.

"'Fraid of thunder, Bill?" asked Ben, trying to speak stoutly, while a sense of his own responsibilities began to worry him, for how was Bab to be got home in such a pouring rain.

"It makes me sick; always did. Wish I hadn't come," sighed Billy, feeling, all too late, that lemonade and "lozengers" were not the fittest food for man, or a stifling tent the best place to be in on a hot July day, especially in a thunder-storm.

"I didn't ask you to come; you asked me; so it isn't my fault," said Ben, rather gruffly, as people crowded by without pausing to hear the comic song the clown was singing in spite of the confusion.

"Oh, I'm so tired," groaned Bab, getting up with a long stretch of arms and legs.

"You'll be tireder before you get home, I guess. Nobody asked you to come, anyway;" and Ben gazed dolefully round him wishing he could see a familiar face or find a wiser head than his own to help him out of the scrape he was in.

"I said I wouldn't be a bother, and I wont. I'll walk right home this minute, I aint afraid of thunder, and the rain wont hurt these old clothes. Come along," cried Bab, bravely, bent on keeping her word, though it looked much harder after the fun was all over than before.

"My head aches like fury. Don't I wish old Jack was here to take me back," said Billy, following his companions in misfortune with sudden energy, as a louder peal than before rolled overhead.

"You might as well wish for Lita and the covered wagon while you are about it, then we could all ride," answered Ben, leading the way to the outer tent, where many people were lingering in hopes of fair weather.

"Why, Billy Barton, how in the world did you get here?" cried a surprised voice, as the crook of a cane caught the boy by the collar and jerked him face to face with a young farmer, who was pushing along followed by his wife and two or three children.

"Oh, Uncle Eben, I'm so glad you found me! I walked over, and it's raining, and I don't feel well. Let me go with you, can't I?" asked Billy, casting himself and all his woes upon the strong arm that had laid hold of him.

"Don't see what your mother was about to let you come so far alone, and you just over scarlet fever. We are as full as ever we can be, but we'll tuck you in somehow," said the pleasant-faced woman, bundling up her baby, and bidding the two little lads "keep close to father."

"I didn't come alone. Sam got a ride, and can't you tuck Ben and Bab in too? They aint very big, either of them," whispered Billy, anxious to serve his friends now that he was provided for himself.

"Can't do it, anyway. Got to pick up mother at the corner, and that will be all I can carry. It's lifting a little; hurry along, Lizzie, and let us get out of this as quick as possible," said Uncle Eben, impatiently; for going to a circus with a young family is not an easy task, as every one knows who has ever tried it.

"Ben, I'm real sorry there isn't room for you. I'll tell Bab's mother where she is, and may be some one will come for you," said Billy, hurriedly, as he tore himself away, feeling rather mean to desert the others, though he could be of no use.

"Cut away and don't mind us. I'm all right, and Bab must do the best she can," was all Ben had time to answer before his comrade was hustled away by the crowd pressing round the entrance with much clashing of umbrellas and scrambling of boys and men, who rather enjoyed the flurry.

"No use for us to get knocked about in that scrimmage. We'll wait a minute and then go out easy. It's a regular rouser, and you'll be as wet as a sop before we get home. Hope you'll like that?" added Ben, looking out at the heavy rain pouring down as if it never meant to stop.

"Don't care a bit," said Bab, swinging on one of the ropes with a happy-go-lucky air, for her spirits were not extinguished yet, and she was bound to enjoy this exciting holiday to the very end. "I like circuses so much! I wish I lived here all the time, and slept in a wagon, as you did, and had these dear little colties to play with."

"It wouldn't be fun if you didn't have any folks to take care of you," began Ben, thoughtfully looking about the familiar place where the men were now feeding the animals, setting their refreshment tables, or lounging on the hay to get such rest as they could before the evening entertainment. Suddenly he started, gave a long look, then turned to Bab, and thrusting Sancho's strap into her hand, said, hastily: "I see a fellow I used to know.[Page 527] May be he can tell me something about father. Don't you stir till I come back."

Then he was off like a shot, and Bab saw him run after a man with a bucket who had been watering the zebra. Sancho tried to follow, but was checked with an impatient:

"No, you can't go! What a plague you are, tagging around when people don't want you."

Sancho might have answered, "So are you," but, being a gentlemanly dog, he sat down with a resigned expression to watch the little colts, who were now awake and seemed ready for a game of bo-peep behind their mammas. Bab enjoyed their funny little frisks so much that she tied the wearisome strap to a post and crept under the rope to pet the tiny mouse-colored one who came and talked to her with baby whinneys and confiding glances of its soft, dark eyes.

Oh, luckless Bab! why did you turn your back? Oh, too accomplished Sancho! why did you neatly untie that knot and trot away to confer with the disreputable bull-dog who stood in the entrance beckoning with friendly wavings of an abbreviated tail? Oh, much afflicted Ben! why did you delay till it was too late to save your pet from the rough man who set his foot upon the trailing strap and led poor Sanch quickly out of sight among the crowd.

"It was Bascum, but he didn't know anything. Why, where's Sanch?" said Ben, returning.

A breathless voice made Bab turn to see Ben looking about him with as much alarm in his hot face as if the dog had been a two years' child.

"I tied him—he's here somewhere—with the ponies," stammered Bab, in sudden dismay, for no sign of a dog appeared as her eyes roved wildly to and fro.

Ben whistled, called and searched in vain, till one of the lounging men said, lazily:

"If you are looking after the big poodle you'd better go outside; I saw him trotting off with another dog."

Away rushed Ben, with Bab following, regardless of the rain, for both felt that a great misfortune had befallen them. But, long before this, Sancho had vanished, and no one minded his indignant howls as he was driven off in a covered cart.

"If he is lost I'll never forgive you; never, never, never!" and Ben found it impossible to resist giving Bab several hard shakes which made her yellow braids fly up and down like pump handles.

"I'm dreadful sorry. He'll come back—you said he always did," pleaded Bab, quite crushed by her own afflictions, and rather scared to see Ben look so fierce, for he seldom lost his temper or was rough with the little girls.

"If he doesn't come back, don't you speak to me for a year. Now, I'm going home." And, feeling that words were powerless to express his emotions, Ben walked away, looking as grim as a small boy could.

A more unhappy little lass is seldom to be found than Bab was, as she pattered after him, splashing recklessly through the puddles, and getting as wet and muddy as possible, as a sort of penance for her sins. For a mile or two she trudged stoutly along, while Ben marched before in solemn silence, which soon became both impressive and oppressive because so unusual, and such a proof of his deep displeasure. Penitent Bab longed for just one word, one sign of relenting; and when none came, she began to wonder how she could possibly bear it if he kept his dreadful threat and did not speak to her for a whole year.

But presently her own discomfort absorbed her, for her feet were wet and cold as well as very tired; pop-corn and peanuts were not particularly nourishing food, and hunger made her feel faint; excitement was a new thing, and now that it was over she longed to lie down and go to sleep; then the long walk with a circus at the end seemed a very different affair from the homeward trip with a distracted mother awaiting her. The shower had subsided into a dreary drizzle, a chilly east wind blew up, the hilly road seemed to lengthen before the weary feet, and the mute, blue flannel figure going on so fast with never a look or sound, added the last touch to Bab's remorseful anguish.

Wagons passed, but all were full, and no one offered a ride. Men and boys went by with rough jokes on the forlorn pair, for rain soon made them look like young tramps. But there was no brave Sancho to resent the impertinence, and this fact was sadly brought to both their minds by the appearance of a great Newfoundland dog who came trotting after a carriage. The good creature stopped to say a friendly word in his dumb fashion, looking up at Bab with benevolent eyes, and poking his nose into Ben's hand before he bounded away with his plumy tail curled over his back.

Ben started as the cold nose touched his fingers, gave the soft head a lingering pat, and watched the dog out of sight through a thicker mist than any the rain made. But Bab broke down; for the wistful look of the creature's eyes reminded her of lost Sancho, and she sobbed quietly as she glanced back longing to see the dear old fellow jogging along in the rear.

Ben heard the piteous sound and took a sly peep over his shoulder, seeing such a mournful spectacle that he felt appeased, saying to himself as if to excuse his late sternness:

"She is a naughty girl, but I guess she is about sorry enough now. When we get to that sign-post [Page 528] I'll speak to her, only I wont forgive her till Sanch comes back."

But he was better than his word; for, just before the post was reached, Bab, blinded by tears, tripped over the root of a tree, and, rolling down the bank, landed in a bed of wet nettles. Ben had her out in a jiffy, and vainly tried to comfort her; but she was past any consolation he could offer, and roared dismally as she wrung her tingling hands, with great drops running over her cheeks almost as fast as the muddy little rills ran down the road.

"Oh dear, oh dear! I'm all stinged up, and I want my supper; and my feet ache, and I'm cold, and everything is so horrid!" wailed the poor child lying on the grass, such a miserable little wet bunch that the sternest parent would have melted at the sight.

"Don't cry so, Babby; I was real cross, and I'm sorry. I'll forgive you right away now, and never shake you any more," cried Ben, so full of pity for her tribulations that he forgot his own, like a generous little man.

"Shake me again, if you want to; I know I was very bad to tag and lose Sanch. I never will any more, and I'm so sorry, I don't know what to do," answered Bab, completely bowed down by this magnanimity.

"Never mind; you just wipe up your face and come along, and we'll tell Ma all about it, and she'll fix us as nice as can be. I shouldn't wonder if Sanch got home now before we did," said Ben, cheering himself as well as her by the fond hope.

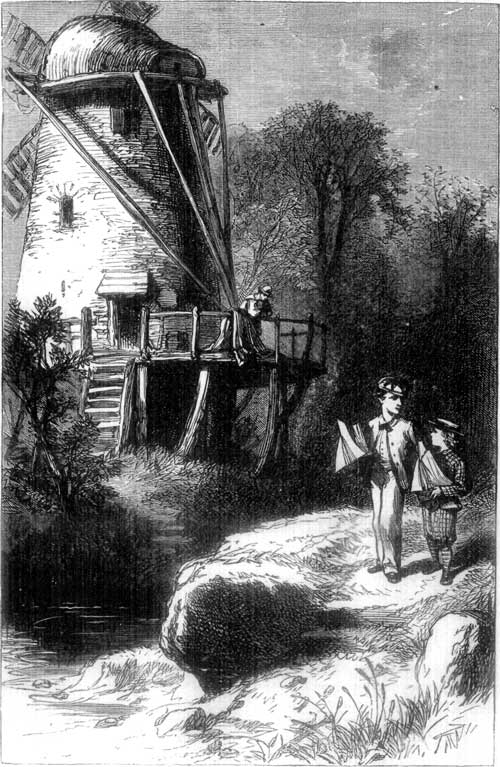

"I don't believe I ever shall, I'm so tired my legs wont go, and the water in my boots makes them feel dreadfully. I wish that boy would wheel me a piece. Don't you s'pose he would?" asked Bab, wearily picking herself up as a tall lad trundling a barrow came out of a yard near by.

"Hullo, Joslyn!" said Ben, recognizing the boy as one of the "hill fellows" who come to town Saturday nights for play or business.

"Hullo, Brown," responded the other, arresting his squeaking progress with signs of surprise at the moist tableau before him.

"Where goin'?" asked Ben with masculine brevity.

"Got to carry this home, hang the old thing!"

"Where to?"

"Batchelor's, down yonder," and the boy pointed to a farm-house at the foot of the next hill.

"Goin' that way, take it right along."

"What for?" questioned the prudent youth, distrusting such unusual neighborliness.

"She's tired, wants a ride; I'll leave it all right, true as I live and breathe," explained Ben, half ashamed yet anxious to get his little responsibility home as soon as possible, for mishaps seemed to thicken.

"Ho, you couldn't cart her all that way! she's most as heavy as a bag of meal," jeered the taller lad, amused at the proposition.

"I'm stronger than most fellers of my size. Try, if I aint," and Ben squared off in such scientific style that Joslyn responded with sudden amiability:

"All right, let's see you do it."

Bab huddled into her new equipage without the least fear, and Ben trundled her off at a good pace, while the boy retired to the shelter of the barn to watch their progress, glad to be rid of an irksome errand.

At first, all went well, for the way was down hill, and the wheel squeaked briskly round and round; Bab smiled gratefully upon her bearer, and Ben "went in on his muscle with a will," as he expressed it. But presently the road grew sandy, began to ascend, and the load seemed to grow heavier with every step.

"I'll get out now. It's real nice, but I guess I am too heavy," said Bab, as the face before her got redder and redder, and the breath began to come in puffs.

"Sit still. He said I couldn't. I'm not going to give in with him looking on," panted Ben, and pushed gallantly up the rise, over the grassy lawn to the side gate of the Batchelors' door-yard, with his head down, teeth set, and every muscle of his slender body braced to the task.

"Did ever ye see the like of that now? Ah, ha!

'The streets were so wide, and the lanes were so narry,

He brought his wife home on a little wheelbarry,'"

sung a voice with an accent which made Ben drop his load and push back his hat, to see Pat's red head looking over the fence.

To have his enemy behold him then and there was the last bitter drop in poor Ben's cup of humiliation. A shrill approving whistle from the hill was some comfort, however, and gave him spirit to help Bab out with composure, though his hands were blistered and he had hardly breath enough to issue the command:

"Go along home, and don't mind him."

"Nice childer, ye are, runnin' off this way, settin' the women disthracted, and me wastin' me time comin' after ye when I'd be milkin' airly so I'd get a bit of pleasure the day," grumbled Pat, coming up to untie the Duke, whose Roman nose Ben had already recognized, as well as the roomy chaise standing before the door.

"Did Billy tell you about us?" asked Bab, gladly following toward this welcome refuge.

"Faith he did, and the Squire sint me to fetch ye home quiet and aisy. When ye found me, I'd jist[Page 529] stopped here to borry a light for me pipe. Up wid ye, b'y, and not be wastin' me time stramashin' afther a spalpeen that I'd like to lay me whip over," said Pat, gruffly, as Ben came along, having left the barrow in the shed.

"Don't you wish you could? You needn't wait for me; I'll come when I'm ready," answered Ben, dodging round the chaise, bound not to mind Pat, if he spent the night by the road-side in consequence.

"Bedad, and I wont then. It's lively ye are; but four legs is better than two, as ye'll find this night, me young mon!"

With that he whipped up and was off before Bab could say a word to persuade Ben to humble himself for the sake of a ride. She lamented and Pat chuckled, both forgetting what an agile monkey the boy was, and as neither looked back, they were unaware that Master Ben was hanging on behind among the straps and springs, making derisive grimaces at his unconscious foe through the little glass in the leathern back.

At the lodge gate Ben jumped down to run before with whoops of naughty satisfaction, which brought the anxious waiters to the door in a flock; so Pat could only shake his fist at the exulting little rascal as he drove away, leaving the wanderers to be welcomed as warmly as if they were a pair of model children.

Mrs. Moss had not been very much troubled after all; for Cy had told her that Bab went after Ben, and Billy had lately reported her safe arrival among them, so, mother-like, she fed, dried, and warmed the runaways, before she scolded them.

Even then, the lecture was a mild one, for when they tried to tell the adventures which to them seemed so exciting, not to say tragical, the effect astonished them immensely, as their audience went into gales of laughter, especially at the wheelbarrow episode, which Bab insisted on telling, with grateful minuteness, to Ben's confusion. Thorny shouted, and even tender-hearted Betty forgot her tears over the lost dog to join in the familiar melody when Bab mimicked Pat's quotation from Mother Goose.

"We must not laugh any more, or these naughty children will think they have done something very clever in running away," said Miss Celia, when the fun subsided, adding soberly, "I am displeased, but I will say nothing, for I think Ben is already punished enough."

"Guess I am," muttered Ben, with a choke in his voice as he glanced toward the empty mat where a dear curly bunch used to lie with a bright eye twinkling out of the middle of it.

Great was the mourning for Sancho, because his talents and virtues made him universally admired and beloved. Miss Celia advertised, Thorny offered rewards, and even surly Pat kept a sharp look-out for poodle dogs when he went to market; but no Sancho or any trace of him appeared. Ben was inconsolable, and sternly said it served Bab right when the dog-wood poison affected both face and hands. Poor Bab thought so, too, and dared ask no sympathy from him, though Thorny eagerly prescribed plantain leaves, and Betty kept her supplied with an endless succession of them steeped in cream and pitying tears. This treatment was so successful that the patient soon took her place in society as well as ever, but for Ben's affliction there was no cure, and the boy really suffered in his spirits.

"I don't think it's fair that I should have so much trouble—first losing father and then Sanch. If it wasn't for Lita and Miss Celia, I don't believe I could stand it," he said, one day, in a fit of despair, about a week after the sad event.

"Oh, come now, don't give up so, old fellow. We'll find him if he's alive, and if he isn't I'll try and get you another as good," answered Thorny, with a friendly slap on the shoulder, as Ben sat disconsolately among the beans he had been[Page 530] hoeing.

"As if there ever could be another half as good!" cried Ben, indignant at the idea; "or as if I'd ever try to fill his place with the best and biggest dog that ever wagged a tail! No, sir, there's only one Sanch in all the world, and if I can't have him I'll never have a dog again."

"Try some other sort of a pet, then. You may have any of mine you like. Have the peacocks; do now," urged Thorny, full of boyish sympathy and good-will.

"They are dreadful pretty, but I don't seem to care about 'em, thank you," replied the mourner.

"Have the rabbits, all of them," which was a handsome offer on Thorny's part, for there were a dozen at least.

"They don't love a fellow as a dog does; all they care for is stuff to eat and dirt to burrow in. I'm sick of rabbits." And well he might be, for he had had the charge of them ever since they came, and any boy who has ever kept bunnies knows what a care they are.

"So am I! Guess we'll have an auction and sell out. Would Jack be a comfort to you? If he will, you may have him. I'm so well now, I can walk, or ride anything," added Thorny, in a burst of generosity.

"Jack couldn't be with me always, as Sanch was, and I couldn't keep him if I had him."

Ben tried to be grateful, but nothing short of Lita would have healed his wounded heart, and she was not Thorny's to give, or he would probably have offered her to his afflicted friend.

"Well, no, you couldn't take Jack to bed with you, or keep him up in your room, and I'm afraid he would never learn to do anything clever. I do wish I had something you wanted, I'd so love to give it to you."

He spoke so heartily and was so kind that Ben looked up, feeling that he had given him one of the sweetest things in the world—friendship; he wanted to tell him so, but did not know how to do it, so caught up his hoe and fell to work, saying, in a tone Thorny understood better than words:

"You are real good to me—never mind, I wont worry about it; only it seems extra hard coming so soon after the other——"

He stopped there, and a bright drop fell on the bean leaves, to shine like dew till Ben saw clearly enough to bury it out of sight in a great hurry.

"By Jove! I'll find that dog, if he is out of the ground. Keep your spirits up, my lad, and we'll have the dear old fellow back yet."

With which cheering prophecy Thorny went off to rack his brains as to what could be done about the matter.

Half an hour afterward, the sound of a hand-organ in the avenue roused him from the brown study into which he had fallen as he lay on the newly mown grass of the lawn. Peeping over the wall, Thorny reconnoitered, and, finding the organ a good one, the man a pleasant-faced Italian, and the monkey a lively animal, he ordered them all in, as a delicate attention to Ben, for music and monkey together might suggest soothing memories of the past, and so be a comfort.

In they came by way of the Lodge, escorted by Bab and Betty, full of glee, for hand-organs were rare in those parts, and the children delighted in them. Smiling till his white teeth shone and his black eyes sparkled, the man played away while the monkey made his pathetic little bows, and picked up the pennies Thorny threw him.

"It is warm, and you look tired. Sit down and I'll get you some dinner," said the young master, pointing to the seat which now stood near the great gate.

With thanks in broken English the man gladly obeyed, and Ben begged to be allowed to make Jacko equally comfortable, explaining that he knew all about monkeys and what they liked. So the poor thing was freed from his cocked hat and uniform, fed with bread and milk, and allowed to curl himself up in the cool grass for a nap, looking so like a tired little old man in a fur coat that the children were never weary of watching him.

Meantime, Miss Celia had come out, and was talking Italian to Giacomo in a way that delighted his homesick heart. She had been to Naples, and could understand his longing for the lovely city of his birth, so they had a little chat in the language which is all music, and the good fellow was so grateful that he played for the children to dance till they were glad to stop, lingering afterward as if he hated to set out again upon his lonely, dusty walk.

"I'd rather like to tramp round with him for a week or so. Could make enough to live on as easy as not, if I only had Sanch to show off," said Ben, as he was coaxing Jacko into the suit which he detested.

"You go wid me, yes?" asked the man, nodding and smiling, well pleased at the prospect of company, for his quick eye and what the boys let fall in their talk showed him that Ben was not one of them.

"If I had my dog I'd love to," and with sad eagerness Ben told the tale of his loss, for the thought of it was never long out of his mind.

"I tink I see droll dog like he, way off in New York. He do leetle trick wid letter, and dance, and go on he head, and many tings to make laugh," said the man, when he had listened to a list of Sanch's beauties and accomplishments.

"Who had him?" asked Thorny, full of interest[Page 531] at once.

"A man I not know. Cross fellow what beat him when he do letters bad.

"Did he spell his name?" cried Ben, breathlessly.

"No, that for why man beat him. He name Generale, and he go spell Sancho all times, and cry when whip fall on him. Ha! yes! that name true one, not Generale?" and the man nodded, waved his hands and showed his teeth, almost as much excited as the boys.

"It's Sanch! let's go and get him, now, right off!" cried Ben, in a fever to be gone.

"A hundred miles away, and no clue but this man's story? We must wait a little, Ben, and be sure before we set out," said Miss Celia, ready to do almost anything, but not so certain as the boys. "What sort of a dog was it? A large, curly, white poodle, with a queer tail?" she asked of Giacomo.

"No, Signorina mia, he no curly, no wite, he black, smooth dog, littel tail, small, so," and the man held up one brown finger with a gesture which suggested a short, wagging tail.

"There, you see how mistaken we were. Dogs are often named Sancho, especially Spanish poodles, for the original Sancho was a Spaniard, you know. This dog is not ours, and I'm so sorry."

The boys faces had fallen dismally as their hope was destroyed; but Ben would not give up, for him there was and could be only one Sancho in the world, and his quick wits suggested an explanation which no one else thought of.

"It may be my dog—they color 'em as we used to paint over trick horses. I told you he was a valuable chap, and those that stole him hide him that way, else he'd be no use, don't you see, because we'd know him."

"But the black dog had no tail," began Thorny, longing to be convinced, but still doubtful.

Ben shivered as if the mere thought hurt him, as he said, in a grim tone:

"They might have cut Sanch's off."

"Oh, no! no! they mustn't, they wouldn't!"

"How could any one be so wicked?" cried Bab and Betty, horrified at the suggestion.

"You don't know what such fellows would do to make all safe, so they could use a dog to earn their living for 'em," said Ben, with mysterious significance, quite forgetting in his wrath that he had just proposed to get his own living in that way himself.

"He no your dog? Sorry I not find him for you. Addio, signorina! Grazia, signor! Buon giorno, buon giorno," and, kissing his hand, the Italian shouldered organ and monkey, ready to go.

Miss Celia detained him long enough to give him her address, and beg him to let her know if he met poor Sanch in any of his wanderings, for such itinerant showmen often cross each other's paths. Ben and Thorny walked to the school-corner with him, getting more exact information about the black dog and his owner, for they had no intention of giving it up so soon.

That very evening, Thorny wrote to a boy cousin in New York giving all the particulars of the case, and begging him to hunt up the man, investigate the dog, and see that the police made sure that everything was right. Much relieved by this performance, the boys waited anxiously for a reply, and when it came found little comfort in it. Cousin Horace had done his duty like a man, but regretted that he could only report a failure. The owner of the black poodle was a suspicious character, but told a straight story, how he had bought the dog from a stranger, and exhibited him with success till he was stolen. Knew nothing of his history and was very sorry to lose him, for he was a remarkably clever beast.

"I told my dog man to look about for him, but he says he has probably been killed, with ever so many more, so there is an end of it, and I call it a mean shame."

"Good for Horace! I told you he'd do it up thoroughly and see the end of it," said Thorny, as he read that paragraph in the deeply interesting letter.

"May be the end of that dog, but not of mine. I'll bet he ran away, and if it was Sanch he'll come home. You see if he doesn't," cried Ben, refusing to believe that all was over.

"A hundred miles off? Oh, he couldn't find you without help, smart as he is," answered Thorny, incredulously.

Ben looked discouraged, but Miss Celia cheered him up again by saying:

"Yes, he could. My father had a friend who kept a little dog in Paris, and the creature found her in Milan and died of fatigue next day. That was very wonderful, but true, and I've no doubt that if Sanch is alive he will come home. Let us hope so, and be happy while we wait."

"We will!" said the boys, and day after day looked for the wanderer's return, kept a bone ready in the old place if he should arrive at night, and shook his mat to keep it soft for his weary bones when he came. But weeks passed, and still no Sanch.

Something else happened, however, so absorbing that he was almost forgotten for a time, and Ben found a way to repay a part of all he owed his best friend.

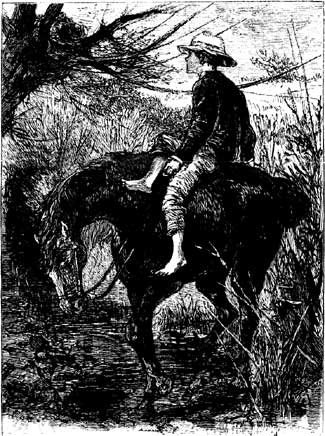

Miss Celia went off for a ride one afternoon, and an hour afterward, as Ben sat in the porch reading,[Page 532] Lita dashed into the yard with the reins dangling about her legs, the saddle turned round, and one side covered with black mud, showing that she had been down. For a minute, Ben's heart stood still, then he flung away his book, ran to the horse, and saw at once by her heaving flanks, dilated nostrils and wet coat, that she must have come a long way and at full speed.

"She has had a fall, but isn't hurt or frightened," thought the boy, as the pretty creature rubbed her nose against his shoulder, pawed the ground and champed her bit, as if she tried to tell him all about the disaster, whatever it was.

"Lita, where's Miss Celia?" he asked, looking straight into the intelligent eyes, which were troubled but not wild.

Lita threw up her head and neighed loud and clear as if she called her mistress, and turning, would have gone again if Ben had not caught the reins and held her.

"All right, we'll find her;" and, pulling off the broken saddle, kicking away his shoes, and ramming his hat firmly on, Ben was up like a flash, tingling all over with a sense of power as he felt the bare back between his knees, and caught the roll of Lita's eye as she looked round with an air of satisfaction.

"Hi, there! Mrs. Moss! Something has happened to Miss Celia, and I'm going to find her. Thorny is asleep; tell him easy, and I'll come back as soon as I can."

Then, giving Lita her head, he was off before the startled woman had time to do more than wring her hands and cry out:

"Go for the Squire! Oh, what shall we do?"

As if she knew exacty what was wanted of her, Lita went back the way she had come, as Ben could see by the fresh, irregular tracks that cut up the road where she had galloped for help. For a mile or more they went, then she paused at a pair of bars which were let down to allow the carts to pass into the wide hay-fields beyond. On she went again cantering across the new-mown turf toward a brook, across which she had evidently taken a leap before; for, on the further side, at a place where cattle went to drink, the mud showed signs of a fall.

"You were a fool to try there, but where is Miss Celia?" said Ben, who talked to animals as if they were people, and was understood much better than any one not used to their companionship would imagine.

Now Lita seemed at a loss, and put her head down as if she expected to find her mistress where she had left her, somewhere on the ground. Ben called, but there was no answer, and he rode slowly along the brook-side, looking far and wide with anxious eyes.

"May be she wasn't hurt, and has gone to that house to wait," thought the boy, pausing for a last survey of the great, sunny field, which had no place of shelter in it but one rock on the other side of the little stream. As his eye wandered over it, something dark seemed to blow out from behind it, as if the wind played in the folds of a skirt, or a human limb moved. Away went Lita, and in a moment Ben had found Miss Celia, lying in the shadow of the rock, so white and motionless he feared that she was dead. He leaped down, touched her, spoke to her, and receiving no answer, rushed away to bring a little water in his leaky hat to sprinkle in her face, as he had seen them do when any of the riders got a fall in the circus, or fainted from exhaustion after they left the ring, where "do or die" was the motto all adopted.

In a minute, the blue eyes opened, and she recognized the anxious face bending over her, saying faintly, as she touched it:

"My good little Ben, I knew you'd find me—I sent Lita for you—I'm so hurt I couldn't come."

"Oh, where? What shall I do? Had I better run up to the house?" asked Ben, overjoyed to hear her speak, but much dismayed by her seeming helplessness, for he had seen bad falls, and had them, too.

"I feel bruised all over, and my arm is broken, I'm afraid. Lita tried not to hurt me. She slipped, and we went down. I came here into the shade, and the pain made me faint, I suppose. Call somebody, and get me home."

Then, she shut her eyes, and looked so white that Ben hurried away and burst upon old Mrs. Paine, placidly knitting at the end door, so suddenly that, as she afterward said, "it sca't her like a clap o' thunder."