Title: The Nursery, No. 107, November, 1875, Vol. XVIII.

Author: Various

Release date: August 13, 2005 [eBook #16524]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Janet Blenkinship and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

BOSTON:

JOHN L. SHOREY, 36 BROMFIELD STREET.

American News Co., 119 Nassau St., New York.

New-England News Co., 41 Court St., Boston.

Central News Co., Philadelphia.

Western News Co., Chicago.

$1.60 a Year, in advance.

A single copy, 15 cents.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1875, by John L.

Shorey, in the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

... Now is the time for Canvassers to begin their operations for 1876. Now is the time for our friends to show their good will. We count all our subscribers as our friends; and all of them may do us a service by renewing their subscriptions immediately. A blank form for that purpose is furnished herewith, and there is plenty of room on it to add the names of a few new subscribers. We hope that every old subscriber will try to send us at least one new one.

... On the last page of our cover will be found the advertisement of "The Nursery Primer," the most charming book for children, considering its cheapness, that has yet been put upon the market. Look at it, see the beautiful and apt engravings, one or more on every page, and you will want at least a dozen copies to distribute among your little friends at Christmas.

... We call attention, also, to the advertisement of "The Easy Book" and "The Beautiful Book." No more useful or delightful books for beginners in reading have appeared. These, with "The Nursery Primer." form a cheap but elegant library for childhood.

... Progress, improvement, will be our motto in the future as they have been in the past. "The Nursery," we can assure our readers, is younger and more full of life than ever, notwithstanding its nine years.

... Unaccepted articles will be returned to the writers if stamps are sent with them to pay return postage. Manuscripts not so accompanied will not be preserved, and subsequent requests for their return cannot be complied with.

New Subscribers for 1876, whose names and money are sent us before December next, will receive the last two numbers of 1875 FREE.

We want a special agent in every town in the United States. Persons disposed to act in that capacity, are invited to communicate with the publisher.

The number of the Magazine with which your subscription expires is indicated by the number annexed to the address on the printed label. When no such number appears, it will be understood that the subscription ends with the current year. Please to look at the printed label. If the number upon it is 108, or if no number appears there, you will know that your subscription ends with this year (1875). In that case you are earnestly requested to send the renewal to us immediately, so that your address may remain on our printed list, and you may continue to receive the Magazine without any interruption. Remember that the amount to be remitted is $1.60, and that you will receive the Magazine postpaid. To save you the trouble of writing a letter, we annex a blank form that may be used in making the remittance.

JOHN L. SHOREY, 36 Bromfield St., Boston, Mass.

Enclosed please find $1.60 for renewal of subscription to "THE NURSERY," to begin with the number for...........,1876, to be sent to the following address:—

| NAME OF SUBSCRIBER | RESIDENCE |

FLORA'S LOOKING-GLASS.

N the edge of a thick wood dwelt a little girl whose name was Flora. She was an orphan, and lived with an old woman who got her living by gathering herbs.

Every morning, Flora had to go almost a quarter of a mile to a clear spring in the wood, and fill the kettles with fresh water. She had a sort of yoke, on which the kettles were hung as she carried them.

The pool formed by the spring was so smooth and clear, that Flora could see herself in it; and some one who found her looking in it, one bright morning, called the pool "Flora's Looking-Glass."

As Flora grew up, some of the neighbors tried to make her leave the old woman, and come and live with them; but Flora said, "No: she has been kind to me when there was no one to care for me, and I will not forsake her now."

So she kept on in her humble lot; and the old woman taught her the names of all the herbs and wild flowers that grew in the wood; and Flora became quite skilful in the art of selecting herbs, and extracting their essences.

There was one scarce herb that grew on the border of "Flora's Looking-Glass." It was used in a famous mixture prepared by the old woman; and, when the latter was about to die, she said to Flora, "Here is a recipe for a medicine which will, some day, have a great sale. Take it, and do with it as I have done."

Flora took the recipe, and the old woman died. But poor Flora was so kind and generous a girl, that she gave the medicine away freely to all the sick people; nor did she try to keep the recipe a secret.

So, though she was not made rich by it, she was made happy; and, as weeks passed on, a man who was a doctor, and had known her father, came to her, and said, "Come and live with me and my wife and daughters, and I will send you to school, and see that you are well taught."

"But how can I pay you for it all?" asked Flora.

"The recipe will more than pay me," said the good doctor. "You shall have a share in what I earn from it; and you shall help me make the extract."

Flora now goes to school in winter; but in midsummer she pays frequent visits to "Flora's Looking-Glass," and thinks of the kind old lady who taught her so much about herbs and flowers.

A SHOT AT AN EAGLE.

I have two little girls here in China, who are constant readers of "The Nursery." They think I can tell you little readers at home of some pretty sights they see here. They have asked me so often to do so, that, now they are tucked away for the night, I will try to please them.

In landing at Hong Kong, after a long voyage, it looks very odd to see the water covered with small boats, or sampans, as the Chinese call them. In each boat lives a family. It is their house and home; and they seldom go off of it.

They get their living by carrying people to the ships, and by fishing. They have a place in the bottom of the boat, where they sleep at night; and, in cold weather, they shut themselves up in it to keep from freezing. I went out in one of these boats a few days ago. The water was very rough; and I was quite astonished, after being out some time, to see a pair of bright eyes shining from below, through a small crack, nearly under my feet.

Coming back, it was not quite so rough; and the owner of the bright eyes—a little girl four years old, with a baby strapped on her back—came "up topside," as they call up above. When the baby was fussy, the girl would dance a little; and so the baby was put to sleep in this peculiar fashion.

It is a very common sight to see a boatwoman rowing the boat, with her baby strapped on her back. The child likes the motion, and is very quiet. It must be very hard for the mother; but the Chinese women have to endure more hardships than that, as I shall show you in future numbers of "The Nursery."

In cold weather, these people must suffer very much, they are so poorly clad. They put all the clothing they have on the upper part of their body; and their legs and feet are hardly covered at all. Fortunately for them, it is not very cold in this part of China.

In Canton, there are many more boats than here; for the floating population there is the largest in the world. I have seen as many as ten children in one boat. The small ones have ropes tied around them: so, if they fall into the water, they can be picked up easily.

A little fire in a small earthen vessel is all that these strange people have to cook their food by. The poorer ones have nothing but rice to eat, and consider themselves very fortunate if they get plenty of that. Those better off have a great variety of food; and some of it looks quite tempting; but the greater part is horrible to look at, and much worse to smell.

All the men and boys have their hair braided in long cues. The women have theirs done up in various styles; each province in China having its own fashion. Neither women nor men can dress their own hair. The poorest beggars in the street have their hair done up by a barber.

For the men there are street barbers, who shave heads on low seats by the roadside; but, for the higher classes and the women, a barber goes to their houses. The women's hair is made very stiff and shiny by a paste prepared from a wood which resembles the slippery-elm. It takes at least an hour to do up a Chinese woman's hair.

Hong Kong, China.

I read, the other day, an account, taken from an English paper, of a wonderful little dog, called Minos. He knows more arithmetic than many children. At an exhibition given of him by his mistress, he picked out from a set of numbered cards any figure which the company chose to call for. When six was called, for instance, he would bring it; and then, if some one said, "Tell him to add twelve to it."—"Add twelve, Minos," said his mistress. Minos looked at her, trotted over to the cards, and brought the one with eighteen on it.

Only once was he puzzled. A gentleman in the audience called out, "Tell him to give the half of twenty-seven." Poor Minos looked quite bewildered for a moment; but he was not to be baffled so. He ran off, and brought back the card with the figure on it. Was not that clever?

He has photographs of famous persons, all of which he knows by name, and will bring any one of them when told to. He can spell too; for when a French lady in the company wrote the word "esprit," and handed it to him, he first looked at it very hard, and then brought the letters, one by one, and placed them in the right order.

When Minos was born, he was very sickly and feeble; and his mother would not take care of him, and even tried to kill him. But little Marie Slager, daughter of the lady who has him now, took him and brought him up herself.

From that time he was her doll, her playfellow, her baby. She treated him so much like a child, that he really seemed to understand all that was said to him. She even taught him to play a little tune on the piano.

Almost all performing animals are treated so cruelly while they are being trained, and go through with their tricks in so much fear, that it is quite sad to see them. But the best thing about Minos's wonderful performances is, that they were all taught him by love and gentleness.

Remember this, boys, when you are trying to teach Dash or Carlo to fetch and carry, or draw your wagon: there is no teacher so good as love.

M.A.C.

"What relation is she to me?" said black-eyed Fred, as he heard his mother say that her Aunt Patience was coming to visit them.

"She is your great-aunt," said mamma; "and I want you and Bertie to be very polite to her."

The little boys had heard their mamma say that Aunt Patience was "a lady of the old school," and that she was afraid the children would trouble her, as they were not quite so still as the little boys and girls used to be forty or fifty years ago.

So Fred and Bertie stood somewhat in awe of this Great-Aunt Patience; and when the dear old lady arrived, and papa and mamma went to the cars to meet her, the two boys were watching rather timidly for the carriage, at the parlor-windows.

As she came up the steps, leaning on papa's arm, little Bertie exclaimed, "Oh, see, Freddie! she is not great at all: she is as little as a girl."

"Yes, and she laughs too," said Fred; "and her eyes are as blue as mamma's, and her hair as white as a snowdrift."

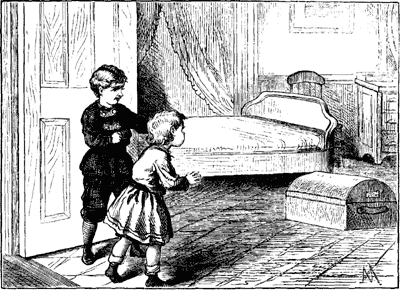

Just then, the driver took off a strange-looking thing from the carriage, and brought it up the steps. It was an old-fashioned trunk, covered with stiff, reddish-brown hair. The boys had never seen a hair trunk, and it seemed to them, at the first glance, more like some kind of an animal than a trunk.

Before they had a chance to examine it, their mamma called them to come and kiss their aunt, which they did very politely, as they had been directed. But her sweet face won their hearts at once; and Bertie exclaimed, "Oh, you are not a big Patience: you are a little good Patience, I know; and I am not a bit afraid of you!"

"Bless your little heart, dear! what has mamma been telling you to make you afraid of me?" said auntie with a merry laugh.

As soon as they could get away, the boys ran up stairs to see what the driver had carried to their aunt's room. Fred discovered what it was as soon as he opened the door; but Bertie, who was not yet four years old, was greatly puzzled. "What can it be?" said he, keeping a safe distance away from it.

Now, Fred liked to play tricks upon his little brother sometimes: so he said, with pretended alarm, "Why, perhaps it is a young lion."

After this startling suggestion, Bertie did not wait an instant. He ran as fast as his legs would carry him, screaming, "O mamma! there is a young lion up stairs. O papa! do get your pistol, and shoot him." The poor child was really in a great fright; and all the family ran at once to see what could be the matter.

They met naughty Fred, laughing, but looking rather guilty. "Why, it is only great Patience's trunk," said he. "Bertie thinks it is a lion." Papa told Fred he did very wrong to frighten the boy so; but they all had a good laugh at poor Bertie's mistake. Bertie was soon induced to take a nearer look at his frightful little lion; and, when Aunt Patience took out from it two or three quarts of chestnuts, it lost all its terrors. The boys were allowed to play in the room as much as they pleased; and the innocent hair trunk was made to do duty as a wolf, a bear, a tiger, and various other wild beasts.

"I wish you would stay here a hundred years!" said little Bertie to his aunt, one day. "I wish she would stay for ever and ever, and longer too!" said Fred. "What do you go back to your old school for?" said Bertie. "My school!" said Aunt Patience. "I have not any school, and never had any."—"Why," exclaimed the little boy, "my mamma said you were a lady of the old school!"

Then mamma and auntie had a merry laugh; and the boys were informed that mamma only meant that Aunt Patience was a very polite lady of the olden time.

The boys constantly forgot to call her "auntie," but remembered the title of "great," and the precious old lady was just as well pleased to have them call her "Great Patience."

When she bade them good-by, they both cried, though Fred was very private about his tears; and both boys declared that the best visitors they ever had were "Great Patience and her little red lion."

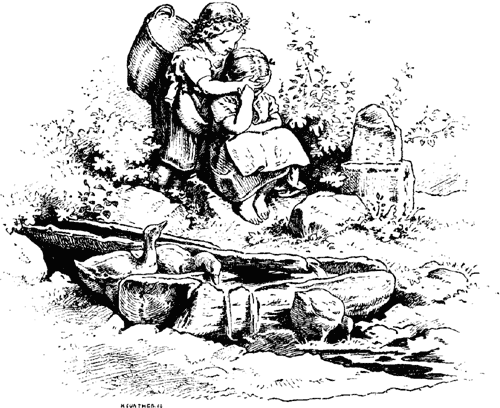

| Over the stepping-stones, one foot and then another; |

| And here we are safe on dry land, little brother. |

When Nellie was quite young, she lost her dear mother; and two sad years passed by for the little girl. She used to go and look at her mother's portrait, and wonder whether she could see Nellie, though Nellie could not see her.

But, at last, her father gave her a new mother, who was so kind and good, that Nellie loved her very much; though she never could forget her first dear mother. One happy day, Nellie learned that a little brother had been born. How glad she was then!

Some weeks passed by before Nellie was allowed to take the little fellow in her arms; but, when she was permitted to do this, it seemed to her that she had never felt such delight before. When he would put up his tiny hands, and feel of her face, she was ready to weep with joy.

But one night the nurse was ill; and there was nobody to take care of the baby. Nellie begged so hard to be allowed to sit up and attend to it, that she was at last permitted to do so. She passed two hours, watching baby as he slept, and thinking of the nice times she would have with him when he grew up.

At last he awoke; and then Nellie gave him some milk from the porringer, and tried to rock him to sleep again. But the little fellow wanted a frolic: so she had to take him in her arms, and walk about the room with him.

She walked and walked till it got to be twelve o'clock; and then she stood in the faint lamplight, before the portrait of her own mother, and it seemed as if the sweet face were trying to speak to her.

But Nellie was so very sleepy, that she hardly knew what she was about. She walked, like one in a dream,—from the bed to the cradle, and from the cradle to the bed,—and all at once baby seemed quiet, and she was walking no longer.

At last she started up, and found she had been lying on the bed. The faint light of the early dawn was coming through the eastern window-panes. Where was baby? Oh! what had Nellie done with him? She jumped from the bed, ran here and there, but could not find him.

At last she looked in the cradle, and there he was, lying snugly asleep. Without knowing what she had done, she had put him in the cradle, and had covered him up, and then, without undressing herself, had gone and lain down on the bed. "Oh, you darling, you darling!" cried Nellie; but the tears came to her eyes, and she could say no more.

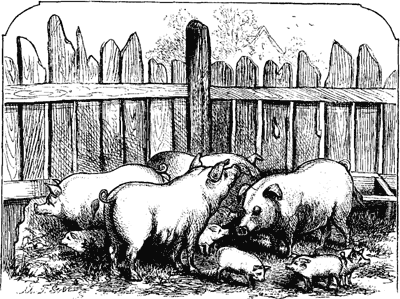

Outline drawing by Mr. Harrison Weir, as a drawing lesson.

Mamma says that I am only a little boy; but I think I am quite big. I shall be six years old next May.

Last summer, mamma took me to grandpa's, to stay a few weeks. When we got to the house, I asked grandpa if I might go with him every day to feed the pigs. He said, "Yes."

So the next morning I went. There were four large pigs, and six little ones; and, when the food was put into the trough, they were all so eager to get it, that they kept tumbling over one another.

One morning, there was not a pig in the pen. We hunted everywhere, but could not find them. At last, grandpa said, "They must be in the turnip-garden." Sure enough, there they were.

The moment they saw us, they scampered; but, after a while, we got them all back in the pen. Then grandpa said he wanted to know how they got out: so we hid in the barn.

By and by, an old pig peeped around, to see if anybody was watching. As he saw no one, he grunted, as much as to say, "All right," and started for a large hole beneath the fence. But, before he could get out, grandpa nailed a plank over the hole.

I wanted a pig to take home with me; but grandpa said it would not live in the city.

At the hotel near the seaside, where I staid last summer, there was a little fellow who was known to the guests as Captain Bob. He was from the West, where he had never seen a large sheet of water. But, at his first sight of old Ocean, he gave him his heart.

Old Ocean seemed to return the tender liking; for he was very kind to Captain Bob, who was nearly all day at the seaside, running some sort of risk. There was nobody to prevent his going in to swim as often as he chose.

Nobody had taught Captain Bob to swim. How he learned he could not explain. He was always ready to venture into a boat. He took to sculling and rowing quite as naturally as a duck takes to swimming.

One morning, we were all made sad by the report that Captain Bob was missing. He had not been seen since noon the previous day. Messengers were sent in every direction to make inquiries after the captain. Several persons said, that, the last they had seen of him, he was standing by the big post on the wharf, with a little boat in his hand that an old sailor had made for him.

Two days were at an end, and still there was no news of Captain Bob. His parents and friends were greatly distressed. But, on the morning of the third day, there was a shout from some of the gentlemen on the piazza; and, on hastening to find out what was the matter, whom should I see but Captain Bob, borne on the shoulders of two young men, and waving his cap over his head.

Bob's story was this: A mackerel-schooner was anchored off shore; and Bob had persuaded the sailor, who had given him the toy-boat, to take him on board. The sailor had done this, not suspecting what was to happen. A school of mackerel had been seen; and, as the breeze was fair, the skipper spread all sail, and was soon five miles off shore.

The mackerel were so plenty that the fishermen made the most of their luck, and did not return to the shore near the hotel till the third day.

"Did you have a good time, captain?" I asked.

"A good time!" exclaimed Captain Bob. "It was the jolliest time I ever had. You should have seen me pull in the fish."

After this adventure, Captain Bob was more of a hero than ever among the people of the hotel.

I have been reading in "The Nursery" the story about Mellie Hoyt and his dog Major. My papa often tells me about another good old dog, named Major. He was a soldier-dog, that papa knew when he went to the war.

Major was a kind dog to all his friends; but he would bark at strangers, and sometimes he would bite them. He once tried to bite a steam-engine as it came whistling by; but the engine knocked him off the track, and almost killed him. He had never seen a steam-engine before, and he knew better than to attack one after that. But he was not afraid of any thing else.

When the soldiers went out to battle, Major would go with them, and bark and growl all the time. Once, in a battle way down in Louisiana, Major began to bark and growl as usual, and to stand up on his hind-legs. Then he ran around, saying, "Ki-yi, ki-yi." By and by he saw a cowardly soldier, who was running away; and he seized that soldier by the leg, and would not let him go for a long time. He wanted him to go back and fight.

Soon after this, Major began to jump up in the air, trying to bite the bullets that whistled over his head. When a bullet struck the ground, he would run and try to dig it out with his paws. At last he placed himself right in front of an advancing line of soldiers, as much as to say, "Don't come any further!" He seemed to think that he could drive them back all alone.

By and by a bullet hit Major as he was jumping about; and he dropped down dead. The soldiers all felt sad, and some of them cried. They missed him like one of their comrades, and they had many to mourn for in that dreadful battle. I hope there never will be another war.

Portland, Me.

"Whose hands are over your eyes? Guess quick."

"Old Mother Hubbard's?"

"Wrong: guess again."

"The good fairy's, Teenty Tawnty?"

"There are no fairies in this part of the country, and you know it. Guess again."

"Well, I guess it is the old woman that lived in a shoe."

"She is not in these parts. I will give you one more chance. Who is it?"

"I think it must be little Miss Muffit,—the one who was frightened by a spider."

"Nonsense! One would think you had read nothing but 'Mother Goose's Melodies.'"

"Can it be Tom, Tom, the piper's son?"

"No, I never stole a pig in my life. Now give the right name this time, or prepare to have your ears pulled."

"Oh, that would never do! I think it must be my cousin, Jenny Mason, who is hiding the daylight from me."

"Right! Right at last! One kiss, and you may go."

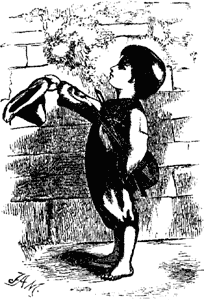

Pedro is a little Italian boy, who lives in Chicago. When I first knew him, he was roaming about from house to house, playing on the fiddle, and singing.

Sometimes kind persons gave him money, and then he always looked happy. But many times he got nothing for his music, and then he was very sad; for he lived with a cruel master, who always beat him when he came home at night without a good round sum.

One day last spring, he had worked very hard; but people were so busy moving, or cleaning house, that, when night came, he had very little money. He felt very tired: so he went home with what he had.

But his cruel master, without stopping to hear a word from the little fellow, gave him a whipping, and sent him out again. He came to my gate, long after I had gone to bed, and played and sang two or three songs; but he did not sing very well, for he was too tired and sleepy.

Just across the street, in an unfinished building, the carpenters had left a large pile of shavings. Pedro saw this by the moonlight, as he went along; and he thought he would step in and lie down to rest. His head had hardly touched the pillow of shavings before he was asleep.

He dreamed about his pleasant home far away in Italy. He thought he was with his little sisters, and he saw his dear mother smile as she gave him his supper; but, just as he was going to eat, some sudden noise awoke him.

He was frightened to find it was daylight, and that the sun was high in the sky. In the doorway stood a kind gentleman looking at him. Pedro sprang up, and took his fiddle; but the gentleman stopped him as he was going out, and asked if that pile of shavings was all the bed he had. He spoke so kindly, that Pedro told him his story.

The gentleman felt so sorry for him, and was so pleased with his sweet, sad face, that he took him to his own home, and gave him a nice warm breakfast; and, being in want of an errand-boy, he concluded to let Pedro have the place.

Pedro has lived happily in his new home ever since; and, though he still likes to play on his fiddle, he has no wish to return to his old wandering mode of life.

|

Swinging in a gilded cage, Petted like a baby's doll, Thus I spend my dull old age, And you call me "Poll." But in youth I roved at will Through the wild woods of Brazil.

When you ask me, "What's o'clock?" Or repeat some foolish rhyme, And I try your speech to mock, I recall the time When I raised my voice so shrill In the wild woods of Brazil.

Sporting with my comrades there, How I flew from bough to bough! Then I was as free as air: I'm a captive now. Oh that I were roaming still Through the wild woods of Brazil!

Jane Oliver. | |

Uncle Tom was walking slowly down the street, one sunny day, when he saw a boy put his hand into a paper bag, take out a lemon, and throw it at a plump gray pigeon that was trying to pick up some crumbs which had been thrown out.

Poor little pigeon! He had been fluttering, off and on, over the crumbs,—now scared away by a fast trotting-horse, now flying to a door-post to get rid of some rapid walker,—and had only just alighted to pick up his breakfast, when he was struck right in the back by the bullet-like lemon.

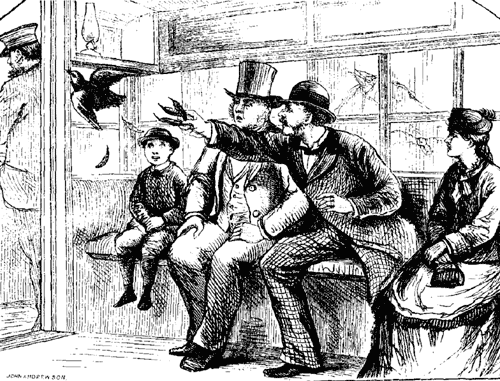

Uncle Tom ran as quickly as he could, and took the panting little thing up in his hand very gently. Just then the horse-car came along; and uncle jumped into it, saying to himself, "I'll take this pigeon out to little Emily. How she will dance and skip when she sees it!"

The car went on and on, ever so far away from Boston, and by and by was half-way across a bridge. The pigeon had lain nestled under Uncle Tom's coat; and the warmth seemed to make it feel better. First it put one round bright eye out, then the other, and took a peep at the people sitting near it.

Then, I think, its back must have ceased aching; for it grew lively, and stirred around. Uncle Tom felt it moving, and was afraid that it would presently try to get away: so he held it as close as he could without hurting it.

But just as he thought how safe he had it, and how tame it would be when it had lived with its little mistress a while, it popped its head out again.

It popped so far out this time, that there was nothing to take hold of but its tail-feathers. Uncle Tom clutched those firmly; but, to his great astonishment, the pigeon gave another spring, and pulled itself away, leaving all its beautiful tail-feathers behind it.

Away it flew, down the car, over the heads of the people, out of the door, past the head of the conductor (who did not know that he had such a strange passenger), and out over the water, back to Boston.

Uncle Tom was left with only a handful of dark-gray feathers to take home with him; and little Emily had no pet pigeon, after all.

Tantalus, as the old Greek fable tells us, was King of Lydia. Being invited by Jupiter to his table, he heard secrets which he afterwards divulged. To divulge a secret is to make it vulgar, or common, by telling it.

Poor Tantalus was punished rather severely for his offence; but he had sinned in betraying confidence. Sent to the lower world, he was placed in the middle of a lake, the waters of which rolled away from him as often as he tried to drink of them.

Over his head, moreover, hung branches of fruit, which drew away, in like manner, from his grasp, whenever he put forth his hand to reach them. And so, though all the time thirsty and hungry, he could not, in the midst of plenty, satisfy his desires.

Therefore we call it to tantalize a person to offer him a thing he longs for, and then to draw it away from him.

In the picture, a little chicken is looking up at a spider which sits over her in the midst of its web. She watches it, hoping that it will come so near to her little bill, that she can peck at it, and swallow it.

But the spider is on its guard. To and fro it swings, letting itself down a little bit, but never so far as to be in any danger; and then, just as the enemy prepares to snap at it, it climbs nimbly into its secure network.

The second Tantalus of our picture, the little dog, has, also, small prospects of reaching the object on which his heart is set. At some distance from him on the ground lies a bone, which he longs to get; but the chain which fastens him, prevents his going near enough to seize it. Both the dog and the chicken are tantalized, you see.

Let us keep down our desires, try to reach only what is fairly ours, be content with little, and never betray confidence. Then shall we avoid the fate of Tantalus.

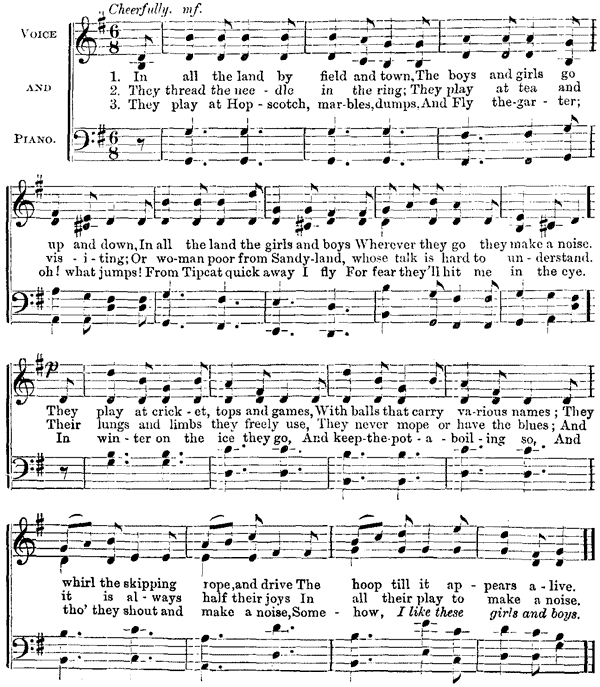

1. In all the land by field and town,

The boys and girls go up and down.

In all the land the girls and boys

Wherever they go they make a noise.

They play at cricket, tops and games,

With balls that carry various names;

They whirl the skipping rope, and drive

The hoop till it appears alive.

2. They thread the needle in the ring;

They play at tea and visiting;

Or woman poor from Sandyland,

whose talk is hard to understand.

Their lungs and limbs they freely use,

They never mope or have the blues;

And it is always half their joys

In all their play to make a noise.

3. They play at Hopscotch, marbles, dumps.

And Fly the garter; oh! what jumps!

From Tipcat quick away I fly

For fear they'll hit me in the eye.

In winter on the ice they go,

And keep the pot a-boiling so,

And tho' they shout and make a noise,

Somehow, I like these girls and boys.

VIOLET TOILET WATER.

CASHMERE BOUQUET EXTRACT.

CASHMERE BOUQUET Toilet Soap.

BOYS AND GIRLS. Send 10 cents and stamp, and receive 25 beautiful Decalcomania, the height of parlor amusement, with full instructions, new and novel, or send stamp for sample to E.W. HOWARD & CO. P.O. Box 143, Chicago.

HOW TO CANVASS. To make Frames, Easels, Passe, Picture Books, etc. Send two stamps for book and designs. J. JAY GOULD, Boston, Mass.

AGENTS WANTED. Men or women. $34 a week. Proof furnished. Business pleasant and honorable with no risks. A 16 page circular and Valuable Samples free. A postal-card on which to send your address costs but one cent. Write at once to F.M. REED, 8th st., new york

Any of the following articles will be sent by mail, postpaid on receipt of the price named:—

| PRICE | |

| Fret, or Jig-Saw, for fancy wood-carving. | |

| With 50 designs, 6 saw-blades, | |

| Impression-paper, &c. | $1.25 |

| Fuller's Jig-Saw Attachmentby the aid | |

| of which the use of the Saw is greatly | |

| facilitated. (See advertisement on another | |

| page) | 1.50 |

| Hollywood Designsfor Amateur Wood-Carvers, | |

| ready for cutting, twenty patterns | |

| in a box, for | .75 |

| New Spelling Blocks | 1.00 |

| Picture Cubes, For the Playroom | 1.50 |

| Initial Note-Paper and Envelopes | .50 |

| Initial Note-Paper and Envelopes | .75 |

| Initial Note-Paper and Envelopes | 1.00 |

| Initial Note-Paper and Envelopes | 1.50 |

| Boys and Girls Writing-Desk | 1.00 |

| The Kindergarten Alphabet and Building Blocks, Painted: | |

| Roman Alphabets, large and small letters, numerals, and animals | .75 |

| Roman Alphabets, large and small letters, numerals, and animals | 1.00 |

| Roman Alphabets, large and small letters, numerals, and animals | 1.50 |

| Crandall's Acrobat or Circus Blocks, with which hundreds of queer, | |

| fantastic figures may be formed by any child | 1.15 |

| Table-Croquet. This can be used on any table—making a Croquet-Board, | |

| at trifling expense | 1.50 |

| Game of Bible Characters and Events | .50 |

| Dissected Map of the United States | 1.00 |

Books will be sent at publishers' prices.

JOHN L. SHOREY,

Publisher of "The Nursery."

36 Bromfield Street, Boston, Mass.

PREMIUM-LIST FOR 1876.

For three new subscribers, at $1.60 each, we will give any one of the following articles: a heavily gold-plated pencil-case, a rubber pencil-case with gold tips, silver fruit-knife, a pen-knife, a beautiful wallet, any book worth $1.50. For five, at $1.60 each, any one of the following: globe microscope, silver fruit-knife, silver napkin-ring, book or books worth $2.50. For six, at $1.60 each, we will give any one of the following: a silver fruit-knife (marked), silver napkin-ring, pen-knives, scissors, backgammon board, note-paper and envelopes stamped with initials, books worth $3.00. For ten, at 1.60 each, select any one of the following: morocco travelling-bag, stereoscope with six views, silver napkin-ring, compound microscope, lady's work-box, sheet-music or books worth $5.00. For twenty, at $1.60 each, select any one of the following: a fine croquet-set, a powerful opera-glass, a toilet-case, Webster's Dictionary (unabridged), sheet-music or books worth $10.00.

Any other articles equally easy to transport may be selected as premiums, their value being in proportion to the number of subscribers sent. Thus, we will give for three new subscribers, at $1.60 each, a premium worth $1.50; for four, a premium worth $2.00; for five, a premium worth $2.50; and so on.

BOOKS for premiums may be selected from any publisher's catalogue: and we can always supply them at catalogue prices. Under this offer, subscriptions to any periodical or newspaper are included.

SPECIAL OFFERS.

BOOKS.—For two new subscribers, at $1.60 each, we will give any half-yearly volume of The Nursery; for three, any yearly volume: for two, Oxford's Junior Speaker; for two, The Easy Book; for two, The Beautiful Book; for three, Oxford's Senior Speaker; for three, Sargent's Original Dialogues; for three, an elegant edition of Shakspeare, complete in one volume, full cloth, extra gilt, and gilt-edge; or any one of the standard British Poets, in the same style. GLOBES.—For two new subscribers, we will give a beautiful Globe three inches in diameter; for three, a Globe four inches in diameter; for five, a Globe six inches in diameter, PRANG'S CHROMOS will be given as premiums at publisher's prices. Send stamp for a catalogue. GAMES, &c.—For two new subscribers, we will give any one of the following: The Checkered Game of Life, Alphabet and Building-Blocks, Dissected Maps, &c. &c. For three new subscribers, any one of the following: Japanese Backgammon or Kakeba, Alphabet and Building Blocks (extra). Croquet, Chivalrie, and any other of the popular games of the day may be obtained on the most favorable terms, by working for "The Nursery." Send stamp to us for descriptive circular.

MARSHALL'S ENGRAVED PORTRAITS OF LINCOLN AND GRANT.

Either of these large and superbly executed steel engravings will be sent, postpaid, as a premium for three new subscribers at $1.60 each.

*** Do not wait to make up the whole list before sending. Send the subscriptions as you get them, stating that they are to go to your credit for a premium; and, when your list is completed, select your premium, and it will be forthcoming.

*** Take notice that our offers of premiums apply only to subscriptions paid at the full price: viz., $1.60 a year. We do not offer premiums for subscriptions supplied at club-rates. We offer no premiums for one subscription only. We offer no premiums in money.

Address

JOHN L. SHOREY,

TERMS—1876.

SUBSCRIPTIONS,—$1.60 a year, in advance. Three copies for $4.30 year; four for $5.40; five for $6.50; six for $7.60; seven for $8.70; eight for $9.80; nine for $10.90, each additional copy for $1.20; twenty copies for $22.00, always in advance.

Postage is included in the above rates. All magazines are sent postpaid.

A Single Number will be mailed for 15 cents. One sample number will be mailed for 10 cents.

Volumes begin with January and July. Subscriptions may commence with any month, but, unless the time is specified, will date from the beginning of the current volume.

Back Numbers can always be supplied. The Magazine commenced January, 1867.

Bound Volumes, each containing the numbers for six months, will be sent by mail, postpaid, for $1.00 per volume; yearly volumes for $1.75.

Covers, for half-yearly volume, postpaid, 35 cents; covers for yearly volume, 40 cents.

Prices of Binding.—In the regular half-yearly volume, 40 cents; in one yearly volume (12 Nos. in one), 50 cents. If the volumes are to be returned by mail, add 14 cents for the half-yearly, and 22 cents for the yearly volume, to pay postage.

Remittances should be made, if possible, by Bank-check or by Postal money-order. Currency by mail is at the risk of the sender.

| Price | With Nursery | |

| Harper's Monthly | $4.00 | $4.75 |

| Harper's Weekly | 4.00 | 4.75 |

| Harper's Bazar | 4.00 | 4.75 |

| Atlantic Monthly | 4.00 | 4.75 |

| Scribner's Monthly | 4.00 | 4.75 |

| Galaxy | 4.00 | 4.75 |

| Lippincott's Magazine | 4.00 | 4.75 |

| Appleton's Journal | 4.00 | 4.75 |

| Leslie's Illustrated Weekly | 4.00 | 4.75 |

| Leslie's Lady's Journal | 4.00 | 4.75 |

| Demorest's Monthly | 3.10 | 4.25 |

| The Living Age | 8.00 | 9.00 |

| St. Nicholas | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| Arthur's Home Magazine | 2.50 | 3.60 |

| Wide-Awake | 2.00 | 3.20 |

| Godey's Lady's Book | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| Hearth and Home | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| The Horticulturist | 2.10 | 3.20 |

| American Agriculturist | 1.50 | 2.70 |

| Ladies Floral Cabinet | 1.30 | 2.60 |

| Mother's Journal | 2.00 | 3.25 |

| The Household | 1.00 | 2.20 |

| The Sanitarian | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| Phrenological Journal | 3.10 | 4.00 |

N.B.—To obtain the benefit of the above rates, it must be distinctly understood that a copy of "The Nursery" should be ordered with each magazine clubbed with it. Both Magazines must be subscribed for at the same time; but they need not be to the same address. We furnish our own Magazine, and agree to pay the subscription for the other. Beyond this we take no responsibility. The publisher of each Magazine is responsible for its prompt delivery; and complaints must be addressed accordingly.

The number of the Magazine with which your subscription expires is indicated by the number annexed to the address on the printed label. When no such number appears, it will be understood that the subscription ends with the current year. No notice of discontinuance need be given, as the Magazine is never sent after the term of subscription expires. Subscribers will oblige us by sending their renewals promptly. State always that your payment is for a renewal, when such is the fact. In changing the direction, the old as well as the new address should be given. The sending of "The Nursery" will be regarded as a sufficient receipt. Any one not receiving it will please notify us immediately, giving date of remittance. Address

JOHN L. SHOREY,

"Truly a Treasure of Delight for the Little Ones."

"Not only a Primer, but a Superb Present for a Child."

Ready Nov. 20, 1875,

Beautifully Bound, in Boards.

SIXTY-FOUR PAGES OF THE SIZE OF "THE NURSERY."

Every Page Richly Illustrated.

PRICE ONLY 30 CENTS!

"In cheapness and attractiveness, the greatest book ever put into the market as a Holiday-Gift for children."

"The Best Book yet for Teaching Children to Read."

"The Choicest and Cheapest of all books for children."

"With such tools as this, learning to read is no longer a task."

EXTRACT FROM THE PREFACE.

"We can confidently claim that no Primer or First Book for Children has yet appeared, either in Europe or America, which, in the variety, beauty, aptness, and interest of its illustrations, can be compared with this. As an aid in Object-Teaching it will be found invaluable."

Price 30 Cents. A single copy by mail for 30 Cents. Six Copies sent by mail for $1.50.

Dealers wanting a cheap, but truly elegant work for children, to place on their counters the coming holidays, should order at once.

Address

JOHN L. SHOREY,