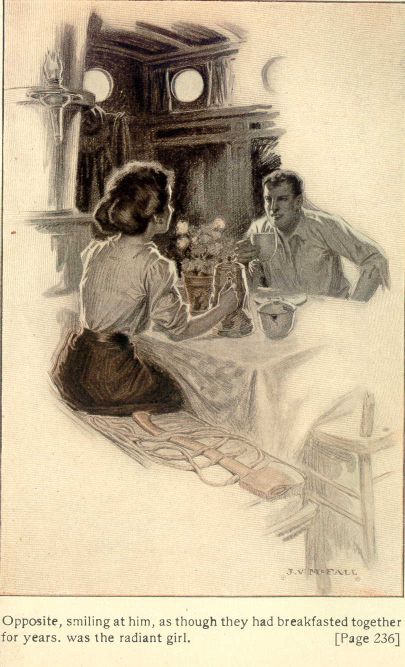

Title: Dan Merrithew

Author: Lawrence Perry

Illustrator: J. V. McFall

Release date: September 24, 2005 [eBook #16742]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

Author of "From the Depths of Things," "Two Tramps," "The Bounder," "The Sacrifice," etc.

Thanks are due Mr. Arthur W. Little, president of the Pearson Publishing Company, for permission to use in this novel several incidents in the life of Dan Merrithew which originally appeared in "Pearson's Magazine."

The big coastwise tug Hydrographer slid stern-ward into a slip cluttered with driftwood and bituminous dust, stopping within heaving distance of three coal-laden barges which in their day had reared "royal s'ls" to the wayward winds of the seven seas.

Near-by lay Horace Howland's ocean-going steam yacht, Veiled Ladye, which had put into Norfolk from Caribbean ports, to replenish her bunkers. There were a number of guests aboard, and most of them arose from their wicker chairs on the after-deck and went to the rail, as the great tug pounded alongside.

Grateful for any kind of a break in the monotony of the long morning, they observed with interest the movements of a tall young man, in a blue shirt open at the throat and green corduroy trousers, who caught the heaving line hurtling from the bow of the nearest barge, and hauled the attached towing-cable dripping and wriggling from the heavy waters.

He did it gracefully. There was a fine play of broad shoulders, a resilient disposition of the long, straight limbs, an impression of tiger-like strength and suppleness, not lost upon his observers, upon Virginia Howland least of all. She was not a girl to suppress a thought or emotion uppermost in her mind; and now she turned to her father with an exclamation of pleasure.

"Father," she cried, "look! Isn't he simply stunning! The Greek ideal—and on a tugboat!" Her dark eyes lightened with mischief. "Do you suppose he'd mind if I spoke to him?"

"He'd probably swear at you," said young Ralph Oddington, with a grin. Then, seized by a sudden impulse for which he afterwards kicked himself, being a decent sort of chap, he drew his cigarette case from his pocket and, as the tug came to a standstill, tossed a cigarette across the intervening space. It struck the man in the back, and as he turned, Oddington called,

"Have a cigarette, Bill?"

The tugman's lips parted, giving a flashing glimpse of big, straight, white teeth. Then they closed, and for an instant he regarded the speaker with a hard, curious expression in his quiet gray eyes, and the proffered cigarette, as though by accident, was shapeless under his heel.

It was distinctly embarrassing for the yachting party; and partly to relieve Oddington, partly out of curiosity, Virginia Howland leaned over the rail with a smile. "Please pardon us, Mr. Tugboatman. We didn't mean to offend you; we—"

The young man again swept the party with his eyes, and then meeting the girl's gaze full, he waited for her to complete the sentence.

"We," she continued, "of course meant no harm."

He did not reply for a moment, did not reply till her eyes fell.

"All right—thanks," he said simply and then hurried forward.

At sunset the Veiled Ladye was well on her way to New York, and the Hydrographer was plugging past Hog Island light with her cumbersome tows plunging astern.

It came to be a wild night. The tumbling blue-black clouds of late afternoon fulfilled their promise of evil things for the dark. There were fierce pounding hours when the wrath of the sea seemed centred upon the Hydrographer and her lumbering barges, when the towing-lines hummed like the harp strings of Aeolus.

It was man's work the crew of the Hydrographer performed that night; when the dawn came and the wind departed with a farewell shriek, and the seas began to fall, Dan Merrithew sat quiet for a while, gazing vacantly out over the gray waters, wrestling with the realization that through all the viewless turmoil the face of a girl he did not know—never would know, probably—had not been absent from his mind; that the sound of her voice had lingered in his ears rising out of the elemental confusion, as the notes of a violin, freeing themselves from orchestral harmony, suddenly rise clear, dominating the motif in piercing obligato.

When he arose it was with the conviction that this meant something which eventually would prove of interest to him. One evening some three months before, he had visited the little sailors' church which floats in the East River at the foot of Pike Street in New York, and listened to a preacher who was speaking in terms as simple as he could make them, with Fate as his text.

Fate, he said, works, in mysterious ways and does queer things with its instruments. It may sear a soul, or alter the course of a life in seeming jest; but the end proves no jest at all, and if we live long enough and grow wise with our years, we learn that at the bottom, ever and always, in everything, was a guiding hand, a sure intent, and a serious purpose.

It was a good, plain, simple talk such as longshoremen, dock-rats, tugmen, and seamen often hear in this place, but it impressed young Merrithew; for, although he had never accepted his misfortunes, nor reasoned away the things that tried his soul in this philosophical manner, yet he had always had a vague conviction that everything that happened was for his good and would work out in the end.

The words of the preacher seemed to give him clearer understanding in this regard, taught him to weigh carefully things which, as they appeared to him, were on the face insignificant. This had led him into strange trends of thought, had encouraged, in a way, superstitious fancies not altogether good for him. He knew that, and he had cursed his folly, and yet on this morning after the storm, on the after-deck of a throbbing tugboat he nodded his head sharply, outward acquiescence to an inward conviction that somehow, somewhere, he was going to see that face again and hear that voice. That was as certain as that he lived. And when this took place he would not be a tugboat mate. That was all.

Whatever he did thereafter he had this additional incentive, the future meeting with a tall, lithe girl with dark-brown hair and gray eyes—brave, deep eyes, and slightly swarthy cheeks, which were crimson as she spoke to him.

Daniel Merrithew was one of the Merrithews of a town near Boston, a prime old seafaring family. His father had a waning interest in three whaling-vessels; and when two of them opened like crocuses at their piers in New Bedford, being full of years, and the third foundered in the Antarctic, the old man died, chiefly because he could see no clear way of longer making a living.

Young Merrithew at the time was in a New England preparatory school, playing excellent football and passing examinations by the skin of his teeth. Thrown upon his own resources, his mother having died in early years, he had to decide whether he would work his way through the school and later through college, or trust to such education as he already had to carry him along in the world.

It was altogether adequate for practical purposes, he argued, and so he lost little time in proceeding to New York, where he began a business career as a clerk in the office of the marine superintendent of a great coal-carrying railroad. It was a beginning with a quick ending. The clerkly pen was not for him; he discovered this before he was told. The blood of the Merrithews was not to be denied; and turning to the salt water, his request for a berth on one of the company's big sea-going tugs was received with every manifestation of approval.

When he first presented himself to the Captain of the Hydrographer, the bluff skipper set the young man down as a college boy in search of sociological experience and therefore to be viewed with good-humored tolerance—good-humored, because Dan was six feet tall and had combative red-gold hair. His steel eyes were shaded by long straw-colored lashes; he had a fighting look about him. He had a magnificent temper, red, but not uncalculating, with a punch like a mule's kick back of it.

As week after week passed, and the new hand revealed no temperamental proclivities, no "kid-glove" inclinations, seemingly content with washing down decks, lassooing pier bitts with the bight of a hawser at a distance of ten feet, and hauling ash-buckets from the fireroom when the blower was out of order—both of which last were made possible by his mighty shoulders—the Captain began to take a different sort of interest in him.

He allowed Dan to spend all his spare moments with him in the pilot-house; and as the Captain could shoot the sun and figure latitude and longitude and talk with fair understanding upon many other elements of navigation, the young man's time was by no means wasted. Later, Dan arranged with the director of a South Street night school of navigation for the evenings when he was in port, and by the time they made him mate of the Hydrographer, he was almost qualified to undergo examination for his master's certificate.

Mental changes are not always attended by outward manifestations, but all the crew of the Hydrographer, after that mad night off the Virginia Capes, could see that something had hit the stalwart mate. The edge seemed to be missing from his occasional moods of abandon; sometimes he looked thoughtfully at a man without hearing what the man was saying to him. But it did not impair his usefulness, and his Captain could see indications of a better defined point in his ambitions.

So that was the way things were with him when, on a gray December afternoon, the day before Christmas, the Hydrographer, just arrived from Providence, slid against her pier in Jersey City, and the crew with jocular shouts made the hawsers fast to the bitts. Some months before, the Hydrographer had stumbled across a lumber-laden schooner, abandoned in good condition off Fire Island, and had towed her into port. The courts had awarded goodly salvage; and the tug's owners, filled with the spirit of the season, had sent a man to the pier to announce that at the office each of the crew would find his share of the bounty, and a little extra, in recognition of work in the company's interest.

"Dan," said the Captain, as the young man entered the pilot-house in his well-fitting shore clothes, "you ought to get a pot of money out of this; now don't go ashore and spend it all tonight. You bank most of it. Take it from me—if I'd started to bank my money at your age, I would be paying men to run tugboats for me now."

"Oh, I've money in the bank," laughed Dan. "I'll bank most of this; but first I'm going to lay out just fifty dollars, which ought to buy about all the Christmas joy I need. I was going to Boston to shock some sober relations of mine, but I've changed my mind. About seven o'clock this evening you'll find me in a restaurant not far from Broadway and Forty-second Street; an hour later you'll locate me in the front row of a Broadway theatre; and—better come with me, Captain Bunker."

"No, thanks, Dan," said the Captain. "If you come with me over to the house in Staten Island about two hours from now, you'll see just three little noses pressed against the window pane—waiting for daddy and Santa Claus." The Captain's big red face grew tender and his eyes softened. "When you get older, Dan," he added, "you'll know that Christmas ain't so much what you get out of it as what you put into it."

Dan thought of the Captain's words as he crossed the ferry to New York. All through the day he had been filled with the pleasurable conviction that the morrow was a pretty decent sort of day to be ashore, and he had intended to work up to the joys thereof to the utmost of his capacity.

Now, with his knowledge as to the sort of enjoyment which Captain Bunker was going to get out of the day, his well-laid plans seemed to turn to ashes. The trouble was, he could not exactly say why this should be. He finally decided that his prospective sojourn amid the gay life of the metropolis had not been at all responsible for the mental uplift which had colored his view of the day.

It had come, he now believed, solely from the attitude of the Captain and Jeff Morrill the engineer, and Sam Tonkin the deck-hand—soon to become a mate—and Bill Lawson, another deck-hand; all of whom had little children at home. Well, he had no little children at home. That settled the matter so far as he was concerned. Blithely he began to plan his dinner and select the theatre he should attend. But, no; the old problem returned insistently, and at length he was obliged to confess that he could devise no solution, and that he did not feel half as good as he had a few hours before.

At all events he would be as happy as he could. After leaving the company's office, where he received a hearty "Merry Christmas" and a fat yellow envelope, he went to the neat little brick house on Cherry Street where he had rooms, and learned that Mrs. O'Hare, his landlady, had gone to her daughter's house on Varick Street to set up a Christmas tree and help to start things for the children. Dan was sorry. He had rather looked forward to meeting this cheerful person with her spectacles and kindly old face, who mothered him so assiduously when he was ashore.

Why the devil had he not thought of finding out about those grandchildren and of buying them something for Christmas? But he had not, and now he did not know whether they were girls or boys or both, nor how many of them there were. So he had no way of knowing what to buy, or how much. Somehow he had here a feeling that he had been on the verge of an interesting discovery. But only on the verge.

He walked slowly out of the house and turned into South Street. In the life of this quaint thoroughfare he had cast his lot, and here he spent his leisure hours; not that he had ever found the place or the men he met there especially congenial. But they were the men he knew, the men he worked with or worked against; and any young fellow who is lonely in a big city and placed as Dan was is just as liable, until he has found himself and located his rut in life, to mingle with persons as strange, with natures as alien, and to frequent places which in later years fill him with repulsive memories.

At all events Dan did, and he was not worrying about it a bit, either, as he sauntered under the Brooklyn Bridge span at Dover Street and turned into South, where Christmas Eve is so joyous, in its way. The way on this particular evening was in no place more clearly interpreted than Red Murphy's resort, where the guild of Battery rowboatmen, who meet steamships in their Whitehall boats and carry their hawsers to longshoremen waiting to make them fast to the pier bitts, congregate and have their social being.

Here, on this day, the wealthy towboat-owners and captains are wont to distribute their largess to the boatmen as a mark of appreciation for favors rendered,—a suggestion that future favors are expected,—and here, also, punch of exalted brew is concocted and drunk.

An occasional flurry of snow swept down the street as Dan reached the entrance. Murphy was out on the sidewalk directing the adornment of his doorway with several faded evergreen wreaths, while inside, the boatmen gathered closer around the genial potstove and were not sorry that ice-bound rivers and harbor had brought their business to a temporary standstill. They were discussing the morrow, which logically led to a consideration of the ice-pack, among other things, and thence to Cap'n Barney Hodge's ill luck.

"Take a hard and early winter," old Bill Darragh, the dean of the boatmen, was saying, "then a thaw in the middle o' December, and then a friz-up, and ye git conditions that ain't propitious, as ye may say, fur towboatmen—nur fur us, neither."

"True fur ye," said "Honest Bill" Duffy. "Nigh half the tugs in the harbor is in the Erie Basin with screw blades twisted off by the ice-pack, or sheathin' ripped. And it's gittin' worse. They'll be little enough money for us this year—an' I was countin' on a hunder to pay a doctor's bill."

"Well, maybe you'll get more than you think," said Dan, whose words always carried weight because he was mate of a deep-sea tug. "Captain Barney Hodge's Three Sisters was laid up yesterday; a three-foot piece of piling bedded in an ice-cake got caught in her screw, and—zip! The other fellows are feeling so good about it that I think they'll be apt to be generous."

"We'll drink to Barney's bad health," said Darragh, raising his glass. "I saw him half an hour gone. He looked like a dead man. Cap'n Jim Skelly o' the John Quinn piloted Gypsum Prince inter her dock last night. No one ever handled her afore but Cap'n Barney. An' the Kentigern from Liverpool is due to-night. Skelly's layin' fur her too; an' he'll git her. That'll take two vessels from Barney's private monopoly."

Darragh was right. The towboatmen had Captain Barney where they wanted him, and they meant to gaff him hard. He had always been too sharp for the rest, too good at a bargain, too mean; and what was more, he was in every way the best towboatman that ever lived. No one liked him; but the steamship-captains engaged his services for towing and piloting, nevertheless, for the reason that they considered him a disagreeable necessity, believing that no other tugboatman could serve them so well.

As a matter of fact, there were several tugboat-captains hardly less skilful than Captain Barney, and in the time of his idleness they bade fair to secure not a few of his customers. It was an old saying that Captain Barney, touched in his pocket, was touched in his heart and brain also—they meant to touch him in just those places.

"I see him this morning," said Duffy, "when he heard that Cap'n Jim Skelly 'd come in on the bridge of the Gypsum Prince. He was a-weepin' and cursin' like a drunk. Hereafter he'll have to divide the Gypsum, and she arrives reg'lar, too."

"And he'll lose the Kentigern to-night," laughed Dan. "Well, I don't care. It'll do him good. I hope they put him out of business."

"Thankee, gents, for your Christmas wishes. I'm glad my friends are with me." The words, in low, mournful cadence, came from the doorway; and all eyes turning there saw the stout, melancholy figure of Captain Barney, his great hooked nose falling dejectedly toward his chin, his hawk eyes dull and sombre. He had been drinking; and as Duffy made as though to throw a bottle at him, the fallen great man turned and stumbled away.

A few minutes later Dan left the resort, faced the biting north wind, and walked slowly up South Street. Somehow he could not get Captain Barney out of his mind.

The year before, in violation of an explicit agreement, Captain Barney had worked in with an outside rowboatman from West Street, towing him to piers where vessels were about to dock. This, of course, got that boatman on the scene in advance of the Battery men, who had only their strong arms and their oars to depend upon. Thus the rival had the first chance at the job of carrying the lines from the docking steamships to men waiting on the pier to make them fast. Captain Barney received part of the money which this boatman made. It was little enough, to be sure, but no amount of money was too small for him. And so Dan, the Battery boatmen being his friends, was glad to see Hodge on his knees—yet he was the slickest tugboat-captain on earth.

Dan could not help admiring him for that; and now he could not dismiss from his mind the pitiable picture which Murphy's doorway had framed but a few minutes before. He tried to, for Dan was an impressionable young fellow and was worrying too much about this Christmas idea, endeavoring to solve his emotions, without bothering about the troubles of a towboat-skipper who deserved all he got and more.

All along the street were Christmas greens. The ship chandlers had them festooned about huge lengths of rusty chains and barnacled anchors and huge coils of hawser, and the tawdry windows of the dram shops were hidden by them. A frowsy woman, with a happy smile upon her face, hurried past with a new doll in her arms. Dan stopped a minute to watch her.

Something turned him into a little toyshop near Coenties Slip and he saw a tugboat deck-hand purchase a pitiful little train of cars, laying his quarter on the counter with the softest smile he had seen on a man's face in a twelvemonth.

"Something for the kid, eh?" said Dan rather gruffly.

"Sure," replied the deck-hand, and he took his bundle with a sort of defiant expression.

He saw a little mother, a girl not more than twelve years old, with a pinched face and a rag shawl about her shoulders, spend ten cents for a bit of a doll and a bag of Christmas candy.

"Going to have a good time, all by yourself?" growled Dan.

"Naw, this is fur me little sister," said the girl bravely, if a little contemptuously. A great lump came into Dan's throat, and feeling somewhat weak and ashamed, he left the shop. Elemental sensations which he could not define thrilled him, and the spirit of Christmas, now entirely unsatisfied, rested on his soul like an incubus. He began to feel outside of everything—as though the season had come for every one but him.

Near Pike Street a little group of the Salvation Army stood on the curb. One of them was a fat, uncomely woman, and she was singing, accompanying herself upon a guitar. The music was that of a popular ballad, and the verses were of rude manufacture.

There were perhaps half a dozen listeners scattered about the sidewalk at a distance sufficient to prevent possible scoffers from including them in the service. Two of them were rough workmen, and they stood in the middle of the sidewalk staring vacantly ahead, trying to look oblivious. Two longshoremen sat on the curb ten feet away, and a man and a woman leaned against the door of a near-by warehouse. When the song was finished the two workmen hurriedly approached and threw nickels on the face of the big bass drum lying flat on the street, retreating hastily, as though ashamed; the woman did likewise, and one of the longshoremen.

"Buying salvation," grinned Dan, as he walked on up the street. But the pleasantry made inadequate appeal. Every one was getting more out of the season than he was. Once he drew a dollar from his pocket and started back. But no. What was a dollar to him? He knew where there were more. That wasn't it. He put the money in his pocket and walked on.

Dan's mental processes leading to a determination to help Captain Barney were too clouded for clear interpretation, but he knew there was no more uncertainty in his mind after he had sought the Captain out and offered to put him on board the Kentigern.

Hodges fairly wept his gratitude. "Dan, Dan, you say you can put me aboard the Kentigern! You'll save my business if you do. I don't care about the towing part, because if I can get aboard and pilot her in, I can hand the towing over to those who'll take care of me. Dan, you're a good boy. How'll you do it?"

"No time to tell now," said Dan. "Meet me at Pier 3 in an hour."

"Say," cried Captain Barney, as Dan hurried away; "how much'll it be? Not too much—"

Dan stopped short.

"Nothing!" he roared. "It's—it's a Christmas present."

The short gray December twilight was creeping over the bay as Dan pulled out from the Battery basin in a boat which he kept there for recreative jaunts about the harbor. Hard pulling and cold it was, but the boatman bent his back and shot up the East River with the strength of the young giant he was. He could see Captain Barney, muffled to the ears, stamping impatiently about on the end of the designated pier. Without a word he swung his boat in such a position that the Captain could drop into it.

Barney was delighted, so far forgetting himself, indeed, as to attempt to establish cordial understanding.

"Hello, my boy," he said genially, "we're a-goin' to fix 'em!" Then noting a blank expression on Dan's face, his jaws closed with a click and he lowered himself from the pier and into the boat without further words, while Dan shoved out into the river and started for the pier above, where Captain Jim Skelly's tug, the John Quinn, was lying. She had steam up and was all ready for her journey to meet the Kentigern. That vessel had been reported east of Fire Island and would be well across the bar by eight o'clock. She would anchor on the bar for the night, and it was there that Captain Jim Skelly meant to board her in order to forestall any possible scheme that wily Captain Barney might devise to gain the bridge of the freighter.

As Dan paddled noiselessly around the other side of the pier, they could see the pipe lights of the Quinn's crew. Finally the rowboat turned straight under the pier, threading its way among the greasy green piles. Reaching under the seat, Dan drew out a stout inch line.

"When I back in on the Quinn," he whispered, "make that line fast to the rudder post. We'll let her tow us to the Kentigern."

"What!" hissed Captain Barney, and his face turned pale. But it was only for a second, after which he chuckled.

Slowly, gently, quietly, the rowboat slid among the green piles until the stern of the big tug loomed overhead. When it was within reach Captain Barney leaned out, made one end of the line fast to the tug's rudder post and then, paying out about twenty feet, he fastened the other end to the bitts in the bow of the rowboat.

It seemed an hour's waiting before the Quinn's crew cast off the lines, but in reality it was not more than ten minutes. As the screw began to thresh the water and the tug to move swiftly out into the river, it required rare skill on the part of the young boatman to manoeuvre the boat so she should not be upset at the start. But Dan had the skill required and more besides, as he knelt in the stern with one oar deep in the water to the port side.

In the course of a few minutes they were fairly on their way, and Captain Jim Skelly was losing no time. He had full speed before the tug was a hundred yards from the pier, and the spray and the splintered chips of ice flew back from the sharp bow, smiting the faces of the two men in the little boat dragging astern with three-quarters of her length out of water. Dan, kneeling aft, watched with eagle eye each quirk and turn of the tow-line.

It is the hardest thing a man has to do—to tow behind a tug or ferryboat, even under fair conditions. In this case, the conditions were far from fair, for there was the ice, lazily rolling and cracking in the heavy wake of the tug, grinding against the sides of the rowboat, until it seemed that they must be crushed. There was great danger that they would be. There was danger also that the tow-line might slue both men into the icy waters and upset the boat.

Captain Barney was tingling with fear. Dan knew it, and smiled. It was not often that any one had the privilege of seeing Captain Barney frightened.

As the tug veered to starboard to round Governor's Island the tow-line slued to port and thence quickly to starboard. The rowboat was snapped over on her gunwales and the water poured in like a mill-race. A roar of an oath escaped Captain Barney's lips, but before he had closed them the boat had righted.

"Shut up, will you?" hissed Dan. "Do you want them to discover and drown us? Ugh—she skated clean over that ice-cake!"

"You've got me out here to kill me, Dan," whimpered Captain Barney. "'A Christmas present!' I see—now."

"Will you keep still?" whispered Dan. "If they hear us, you'll find out who wants to kill you. The root she took that time was nothing. There'll be worse ones—this boat is not through rooting yet."

Neither was she. Ahead the tug loomed, a great dark shape; and the pulse of her engines was lost in the roiling water rising from the screw blades and the hiss of it as it raced by the row-boat. There was a dim blur of light from one of the after-cabin portholes and the shadow of figures passing to and fro inside could be seen. The decks were deserted. It was too cold to brave the night wind except under necessity—a night wind that cut through the pea-jackets and ear-caps and thick woollen gloves of the two men in the rowboat. Captain Barney felt a fierce resentment that the Quinn's men should be so warm and comfortable while he was shivering.

"Christmas Eve!" he exclaimed. "Fine, ain't it?" and he flailed his arms about to keep the blood in circulation.

"Christmas Eve," said Dan solemnly, as though to himself, "the finest I ever spent"; and he added apologetically, "even if I am making an eternal fool of myself."

On they sped. Frequently the tug would hit a large stretch of clear water, and at such times the jingle-bell would sound in the engine-room and the Quinn would shoot forward at a rate that fairly lifted the rowboat out of the water, while Dan, kneeling astern, oar in hand, muscles tense, and mind alert, was ready to do anything that lay in his skill to prevent an untoward accident.

Swish! Zip! and the rowboat would suddenly shoot to one side or the other, compelling Dan to dig his oar way down into the water, bending all his strength in efforts to keep the bow straight.

"She's rooting every second," he grumbled, opening and shutting his hand to drive away the stiffness and then casting a vindictive glance at Captain Barney, the source of all the trouble.

And as for the tugboat-skipper, he sat and watched his companion, and resolved that, after all, there were a few things he did not know about watermanship.

Between the shadowy banks of the Narrows shot the Quinn. Out of the harbor in a rowboat! Even professional Battery boatmen do this about once in a generation. The immense, shadowless darkness smote their eyes so that they turned to the cabin light for relief.

There was likely to be little ice out there, and the northwest wind had knocked the sea flat, as Dan knew would be the case when he figured his chances at the start. It was bad enough though, for there was certain to be something of a swell—and other things; and now that he was in the midst of it, he had grave doubts as to what would happen. But his strange exaltation rose supreme to all fears; no danger seemed too great, no possibility too ominous, to dampen the ardor of this, his first big act of self-sacrifice. The song the Salvation woman sang passed through his mind.

"Gawd is mighty and grateful;

No act of my brother's or mine

Escapes His understandin',

In the good old Christmas time."

"As soon as we get near the Kentigern," he said, "we'll cut loose from the Quinn, and while she is warping alongside we'll make a dash, and you can hail 'em and get 'em to lower a ladder. You can beat Skelly that way. That's what I'm banking on."

"You just put me alongside and I'll see to the rest," replied the Captain impatiently. He would have attempted to scale the steel sides of the vessel themselves, if only to escape from that little boat, tailing astern of the Quinn in the heart of the darkness, rooting, twisting, threatening to dive under the water.

"What are you goin' to do after I get aboard?" asked Captain Barney, rubbing his hands as though the victory were already won. "I declare, I never thought of you! You can't row back."

Dan raised his head angrily and started to utter a sneering reply, when the first good swell caught the boat—a great lazy, greasy fellow. The Quinn went up and then down, and after her shot the rowboat, like a young colt frisking at the end of her tether, then careening down the incline on her side as though to ram the stern of the tug ahead, which, fortunately, was climbing another hill.

What the rowboat had been through before was child's play to this, and Dan's face grew very stern. Reaching down with one hand, he seized the other oar and shoved it along to Captain Barney. "Put that down on the port side. Hang on for your life and keep her steady!" he cried.

Then he gave his attention to his side of the boat while Captain Barney struggled in the bow. It was a fight that would have thrilled the soul of whoever could have seen it. But that is always the way in the bravest, most hopeless fights—no one ever sees them. They are fought alone, in the dark, on the sea; and sometimes the lion-hearted live to make a modest tale of it around a winter's fire; but more often the sequel is, "Found drowned"—if even that.

Captain Barney, frightened into desperate courage, and Dan, in grim realization that the measure of his good deed this night was the measure of the soul he was getting to know, fought sternly. They were on the open sea with all its mystery and lurking fate, and the dark was all about. There was not even the impression of distance; the swells arose as though at their elbows, tossed them with great, slimy ease, let them down again, plucked them this way and that, while the humming tow-line ran out to the vague, phantom, reeling tug ahead.

There was a suspicion of snow in the veiled sky, and the wind stabbed like a knife. Twice the tug cut through a field of ice making out on an offshore current, and the thumping the little row-boat received seemed likely to rend her into drift-wood. But that was only one of the chances; and the two men went on into the icy blast with jaws so tightly clenched that their cheek muscles stood out in great knots.

The silence, the danger, the vagueness hung heavily. As Dan cast his eyes gloomily into the wake of the tug, he saw a dark object shoot out of the foam and dart down upon them like a torpedo; in fact a torpedo could not have worked more serious effect upon the boat than did that heavy, water-soaked log.

"Starboard your oar!" shouted Dan, at the same time digging his own oar deep down on the port side and pulling upon it with all the magnificent strength of his arms until it bent like a reed. There was just time to avert the direct impact, not to escape altogether.

It was a glancing blow just above the water line; it punched a great, jagged hole and gouged out the paint clear to the stern. Dan drew a long breath and murmured in a half-sick voice, "They might as well kill a man as scare him to death," while Captain Barney's face made a gray streak in the darkness.

The Quinn was now past the point of Sandy Hook and was skirting the shore. The muffled beat of the breakers could be heard through the gloom, which was riven every second by the great, swinging search-light in the Navesink. Not a mile ahead was the bar; and the masthead light of the Kentigern could be seen, twinkling like a planet.

In twenty minutes the dark hull of the Kentigern came looming out of the night. A hail shot from the Quinn, and a faint reply came back. Dark figures could now be seen, outlined by the cabin lights in the forward section of the tramp.

"Hello, what tug is that?" sounded from the bridge. "Is that you, Captain Barney?"

"No, it's the Quinn, Cap'n Jim Skelly. Hodge is laid up to-night; I'll take you into dock."

"All right; come aboard," and after a minute's scurrying of figures on the deck a flimsy companion-ladder rattled down over the side of the freighter.

Dan heard it and ground his teeth in disappointment.

"Gripes!" he exclaimed. "They've that ladder down an hour before I thought they would. Now we're up against it, sure."

With a growl Captain Barney whipped out his knife and made a pass at the tow-line. He missed it and dropped back in the stern as Dan struck at him with his oar.

"Wait!" hissed the young boatman. "We'd have no chance at all. We've got to get nearer. The tug 'd beat us a mile. Sit tight, you old fool!"

Captain Barney recognized the wisdom of the words with a groan. He was far past the arguing point. The tide was boiling past the side of the vessel, swashing like a mill-race. All they could do under present conditions was to cast off when the tug was very near the freighter, cut in across, and get under the ladder before the tug could properly warp alongside.

Nearer lumbered the Quinn. When within twenty feet of the Kentigern she swung broadside on, ceasing all headway and drifting into position on the tide.

"Now, then," cried Dan, suddenly leaping into the thwarts and manning the oars. "Haul on the line. Bring her right under the Quinn's stern and then cut, quick!"

Hand over hand hauled Captain Barney and the rowboat came under the stern with a jump. Then he cut the line. Dan dug his oars into the water and the slim boat shot for the ladder, while the great tug came down, more slowly, on the side. Ten, twenty strokes; and then, as Dan with a great sigh unshipped his oars, Captain Barney chuckled, seized the sides of the ladder, and hauling himself on the bottom rung, skipped up with the agility of a monkey.

With a swish and a splash up pounded the Quinn.

"Look out!" roared Dan, "there's a boat here!"

It saved him; for a bell clanged in the engine-room, and the tug began to make sternway. It saved him for but a minute, though.

Thoughtless, selfish, and for once an utter fool, the exultant skipper of the Three Sisters sought to gloat over his rival.

"On board the Quinn," yelled Barney. "Say, Jim Skelly, this is Barney Hodge talkin'. You didn't know he had friends in the rowboat business, did you?"

A curse rang from the Quinn's pilot-house, and Dan did not wait for anything else. Well he knew what would happen next, and he bent all his strength to his oars. He heard the jingle of a bell, and the tug started right for him.

"Look out!" yelled Dan, working the oars like a madman. But not a word came from the tug, moving silently, inexorably upon him like, some black, implacable monster.

Suddenly Dan cast aside his oars and dived over the side. The next instant the sharp, copper-bound nose of the tug struck the rowboat fairly amidships, grinding it against the steel side of the freighter, crushing it into matchwood.

A great numbness passed over the man. He was dazed; and as wave after wave splashed over his head, he struggled dumbly to reach the ladder. Then under the reaction from the icy shock, an electric thrill of energy and vitality passed through his body.

He saw that he had been carried to about amidships, and the ladder was well toward the bow. With lusty strokes he struck out along the steel sides, rising over the waves like a duck. Five minutes elapsed, and then with a sudden fear, Dan realized, in glancing at the bow, that he had not made ten feet in all that time and effort.

It was the current, which was ripping along the hull at the rate that would have affected the speed of a powerful steam launch. Dan had not noticed it before. He struggled desperately, but to no avail, and then he uttered his first cry for help. He could not see the deck, being so close to the hull; and for the same reason he could not have been seen had his cry been heard. Again he called for assistance, but there was no answer, no sound, save that of the water buffeting past the vessel.

He ceased to waste his strength in fruitless cries, devoting all that remained to his struggle to reach the ladder. But his strokes were weaker than before and he found he was being carried back upon the current instead of making headway against it. Fight as he would, he could feel that sliding, hopeless drag against which he was powerless to combat. His strength vanished ounce by ounce. His arms grew so numb with fatigue and cold that he could do nothing but move them up and down, dog fashion. On he went, down toward the stern of the vessel.

He was moving as swiftly as the current was, whirling, twisting like a piece of wood. His mind dulled. He longed for death now. Instinctively he wished to get out of all the worry and struggle against dissolution. His one dominant idea was to throw up his hands and go down, down the deep descent. With a great cry of relief he yielded to the alluring thought. Up flew his arms above his head—and he felt so warm and cheerful! Something struck his outstretched hand and the fingers closed upon it. For a minute they gripped the swinging piece of rope. Then he opened his eyes to find he was hanging to a flimsy Jacob's ladder, suspended from the stern. With a new strength born of hope he flung up his feet, shooting them through the hempen rungs; and there he stayed for a while—it seemed almost an eternity. Then laboriously climbing the ladder, he made the deck and there dropped as insensate as a log.

It was the happiest Christmas Day that Dan had ever known, and he told himself so as he walked slowly down South Street. Unschooled in the ethics of self-sacrifice as he was, he yet knew he had done something for a fellow man, for a man he despised; and something indefinable yet unmistakable told him it was very good. He felt bigger, broader, felt as though he had attained new stature in something that was not physical. And always, vaguely, he had been as anxious to feel this as he had been to get on in a material way. He had lost his rowboat in the act. And yet withal there was a certain fierce satisfaction in his loss—he had caught the spirit of Christmas. How much wiser, how much stronger he was to-day than on the previous afternoon.

So deep were his thoughts that he almost ran into Captain Barney.

"Hey, there!" snarled the tugboatman, most ungraciously, "I just left a new rowboat down in the Battery basin for you." And that was all he said.

And Dan, as he trembled with rage, knew that Captain Barney might have said the right word and made Christmas Day all the more glorious. But he had said the wrong thing, done the wrong thing, and he had by his words and in his act taken much from Dan's Christmas happiness. Dan knew it well; something told him so. He gazed at the tugboatman silently for a minute,—and then he knocked Captain Barney to the sidewalk.

Before the Winter passed, Dan had taken his master's examination with flying colors and was made Captain of the Fledgling, owned by the Phoenix Towboat Company. She was a new boat, rugged, powerful, one hundred and twenty-five feet water line, designed and built to go anywhere and do anything.

The Phoenix Company was known as a venturesome organization, as willing to send its fleet ramping out through the fog to the assistance of a distressed liner as to transport arms to West Indian or Central American revolutionists. Before Dan had commanded the Fledgling many months he had done both, and was beginning to be known up and down the coast as a captain to be called upon in emergencies verging upon the extraordinary, not to say extra-hazardous.

All of which he accepted joyously, as the portion of youth in search of experience that life has to offer. He was sufficiently introspective to rate the temper of his spirit at something approaching its real value, and he knew it was to be cherished, guarded, lest the fine edge be lost. As the world reckons things it was a humble calling upon which he had entered, a calling hardly qualified to enlist the pride of the family whose name he bore.

As a matter of fact, the pride of his few relations was not enlisted. He had been made to feel that. He did not complain. He appreciated their attitude. But that did not curb a high-hearted ambition to lift his vocation to the ideals he had formulated concerning it—and the future lay before him.

But he was not thinking of these things now. The face of the sea was gray in sullen fury. From a blue horizon, dulled and almost obliterated by long, jagged layers of steely clouds, came the ceaseless rush of deep-chested waves, as even, as fascinating as the vermiculations of a serpent. And the wind, tearing along the floor of the sea, whipped off the wave crests and sent them shivering, shimmering ahead, like the plumes of hard-riding cavalry.

The storm had passed. The effects remained, and Dan Merrithew shifted his wheel several spokes east of north and took the brunt bow on. She bore it well, did the stout Fledgling; she did that—she split the waves or crashed through them, or laughed over them, as a stout tug should when coaxed by hands of skill, guided by an iron will. The Long Island coast lay to port, a narrow band of ochre, and all about lay the heaving gray of mighty waters, in which the Fledgling was a black speck.

Dan's hat was off and his red-gold hair was flying wild; his teeth were bared. He was always thus in a fight. This was one; a dandy—a clinker! He gave the wheel another spoke and the Fledgling slued across a sea and smashed down hard. From below came a sliding rattle, a great crash of crockery, and then a series of imprecations. The next instant Arthur M'Gill, the steward, dashed up the companionway and burst into the pilot-house.

"Doggone it all, Cap'n!" yelled the angry man, "why in hell don't ye let me know when ye're goin' to sling 'er across seas? Here I had the table all set fur breakfast, an' ye put 'er inter a grayback afore I could hold on to anything; and smash goes the hull mess on the floor—plates, forks, vittles. Holee mackerel!" he exclaimed under increasing impulse of anger, "what am I?—a steward, or a—or a monkey?"

Dan, clutching grimly at the wheel, turned a genial smile upon his cook.

"Sorry, old man. Fact is, I forgot. But never mind. Pick up the best you can." He smiled again. "Just a little bit dusty out here, eh, Arthur?"

"That's what it is, Cap'n," replied Arthur, mollified by Dan's words of regret.

The steward looked at Dan admiringly. In a way he was the skipper's father confessor, not alone because he had a glib, advising tongue, but because he was possessed of a certain amount of raw, psychological instinct and knew his Shakespeare and could quote from Young's "Night Thoughts." Arthur had something of a fishy look and a slick way with him; but he was a good cook.

"It seems funny to call such a kid 'Cap'n,'" he said. And then he added apologetically, "It's 'cause I've sailed under so many grayheads, ye know."

"Oh, I'll be gray enough before long," laughed Dan, and his momentary inattention to his duties at the wheel was promptly seized upon by the wily sea, which smacked the rudder hard and nearly spun the wheel out of his grip. "Stop talking, will you!" roared Dan, wrestling at the spokes. "Do you want me to put you all into the trough?"

Mulhatton, the mate, stumbled into the pilot-house and glared at the cook.

"Artie," he cried, "you go below, or I'll just gently heft you down! I went in to git grub just now and 't was all on the floor. Go on now—git!" And Arthur went, grumbling and sighing that a man's stomach should govern his temper.

"Take the wheel a while, Cap'n?" said the mate; and as Dan nodded he stepped in close, braced his feet, and took the strain as Dan's hands left the spokes.

"We'll both be on the wheel together before long," remarked Dan, sitting heavily on the chart locker and opening and shutting his stiffened fingers.

"Where is she and what's ashore?" asked Mulhatton. "You jumped us out in such a hurry this morning, I ain't had time to ask you."

"It's an old lumber hooker, and she's ashore on Jones Inlet bar; stranded just before midnight last night. Lord knows how much there is left of her by this time. But I took it a good salvage job to go after. Cripes!" The Fledgling on her altered course had topped a wave forward, which wave, travelling swiftly aft, had withdrawn from the bow the support of its mighty shoulder. Down went the bow with a great slap and up went the stern, screw racing and racking the engines, sending Mulhatton crashing to the floor. But bruised as he was and dazed, he was on his feet with the quickness of a cat, and seizing the spokes, assisted Dan in bringing up the tug's head to where it ought to be.

"It's a-goin' to be lively work salvin' any hooker to-day," said the mate.

"It is," replied Dan, "but I'll tell you this, Mul; we'll land her if anybody can. For I've a tug under me built under my very eyes. I know every beam and bolt in her. And I've a crew of rustlers," he added, gazing proudly at Mulhatton's broad back—Mulhatton, with round, red, bristly, laughing face and eyes like raw onions.

The next minute Dan, in all the delight of the struggle, was making his way along the lower deck to the engine-room door. The water was racing past the rail like a wet blur and the deck sloshed ankle deep. High up a wave climbed the Fledgling, and as she paused on the top for a downward glide, Dan hastily opened the door and clambered down the iron ladder.

"Well, Sam, how are they working?" he shouted to Crampton, the chief, bending over a fizzing valve bonnet.

Sam rose, pushed back his oily peaked cap until the straight raven hair flowed out from under like a cataract, and gave his thin, waterfall moustache a twist, while his swarthy, parchment face cracked into a hundred smiles.

"Workin'," he said, "as sweet as a babe breathin'."

Up reared the stern, lifting the propeller clear of the water. The engines expending their force in air, raced free. The clatter was infernal; the pistons seemed trying to jump out of the cylinders, while the throws and eccentrics lost all semblance of good order.

"Oh, damn!" cried Sam, who, being hurled to the iron floor, swore as though he enjoyed it.

Whitey Welch, the fireman, burst into a huge guffaw, in which Sam finally joined.

"You're all right down here," laughed Dan, "as happy as a sewing circle! There may be some pulling to do later."

"You get something to pull; we'll tend to the rest," and Sam Crampton grinned.

Emerging on deck, Dan collided with Pete Noonan, the deck-hand, with shoulders as big as Dan's and a bigger chest. Pete smiled genially.

"This'll put hair on yer teeth, eh, Cap'n, this will," he said, while from the galley below floated Arthur's voice in a deep sea chanty:

"I'll go no more a-roaming,

No more a-ro-o-o-a-ming with you, fair maid."

"Go on back to harbor, you little lobster pot; we'll take care of the wreck."

The corpulent captain of the great wrecking tug Sovereign, lying outside the breakers off Jones Inlet, megaphoned this insult to the deck of the Fledgling, as she drew near the scene of the wreck, rising and falling on the waves like a piece of driftwood.

It was a deadly day. The promise of the sunlight had waned with the earlier hours, and heavy blue-black clouds palled the heavens. Not one hundred yards apart lay the two tugs, rolling and pitching in the seaway; the Fledgling trim and stanch, the Sovereign big and cumbersome, the funnel belching thunderclouds of sepia, her derrick booms creaking and rattling and slatting infernally.

Straight on ahead, where the line of swelling waves burst into breakers, where the spume sang like whip-lashes, and where the whine of the wind tore itself into a nasty snarl, lay the wreck of the schooner Zeitgeist. She lay half on her side and the waves licked up and over the faded gray hull, completing the work that time already had begun. One mast was very far forward, the other very far aft—Great Lake rig; and between the two was a deck-load of thousands of feet of Maine lumber. The topmasts had snapped off, leaving the stumps.

Lashed in the foremast were two men; and in the mainmast were Captain Ephraim Sayles and three more of his crew. At first glance they seemed lifeless; at first glance, indeed, they seemed nothing more than faded lengths of canvas. But an occasional lifting of a hand, a flash of a gray face, showed that they were men and that they still lived and hoped. Under them, over the deck raced the breakers, waist deep, each one a swift, excited trip-hammer. It was only the lumber that was holding the aged hull together. As it was, sections of the sides had ripped out and planks and pieces of deal issuing from the gashes littered the waters. Three times had the life-savers launched their boats, and three times they had been cast on the beach like logs, while thrice had the lines from their mortars fallen short.

"Go on back; we'll take care of her."

And Dan, his teeth bared and coated with blood from anger-bitten lips, gave the wheel to Mulhatton, ran from the pilot-house, and shook his fist at the big wrecking tug.

"Why don't you take care of her then, curse you! Why don't you take care of her? Don't you see there are lives to save? Oh, you cowardly beasts!"

"Nothin' doin' till the sea goes down," came the reply, and Dan sobbed aloud in his rage as he entered the pilot-house, where most of the crew were gathered, peering out of the windows at the tragedy across the waters.

The men in the rigging could be seen plainly now. There was no excitement. They kept very still, watching the futile efforts of the life-savers, waving their hands occasionally as though in token of their thanks and their knowledge of the utter futility of human efforts. No, there was no excitement; the uncertainty that breeds that was lacking. Fate was simply clamping its damp hand down over those men. Such things are always quiet—there is nothing to thrill the heart or stir the soul in them. It is just a mighty thing dealing death to weaklings, that is all. And we wonder whether the All-seeing Eye does not sometimes close in sheer pity, to shut out the inequality of it.

While they looked, a venomous wave got under the bow and lifted it high. Then down it went as a man would crash his palms together, bursting out the forepeak like a rotten apple. Thus weakened forward, the loss of the foremast was an imminent certainty. And there were two men in the fore rigging! Captain Ephraim leaned far out from the mainmast; the tug men could see him plainly as he pointed at the tottering mast and then at the deck.

"He wants them to leave the mast and go into the mainmast," cried Mulhatton.

"But they won't—see, they are shaking their heads 'no,'" shouted Dan. "They couldn't; the breakers would sweep them away in a minute."

"Look!"

For man is brave and man does fight, even in the face of injustice, in the face of odds. Thus did Martin Loughran, in the fore rigging of the Zeitgeist, as with set jaws he struggled upward toward the stump of the topmast. Between the trucks of the fore and maintopmasts ran a horizontal line of wire. It is called the "triatic stay," and Loughran was climbing to it. Dan—all the Fledgling's crew and the crew of the Sovereign—foresaw his intention, and stentorian shouts, "You can't do it!" bounded over the water. But the sailor did not pause, if, indeed, he heard their warnings.

Slowly, laboriously he climbed. He stretched up one hand and grasped the stay. Up went the other hand. Then out against the glooming sky was limned the swaying form, working its way along the triatic stay hand over hand, in an effort to reach the mainmast. A faint cheer came from the men in the main rigging, while two of the Fledgling's crew cheered, and two bowed their heads in agony, and Dan sobbed aloud.

"Look at him," cried Dan. "Oh, God!"

"A sandy man cashin' in," muttered Mulhatton solemnly.

Out, out worked the swaying form. But he had more than one hundred feet to go. Twenty-five feet—progress ceased. It hung there silent, that figure—it seemed almost an eternity. It hung as silent as a piece of sail and as fitfully swaying. Suddenly one hand relaxed and fell limp. It was as though something had sucked the breath from every onlooker. The hand was feebly raised in a futile clutch to regain the lost hold. It fell again. Still there was silence.

A dark form cleaved the gloom and lay in a black huddle upon the lumber amidships, until a boarding wave kindly removed it and spurned it upon the beach as it would a drowned dog. Ten minutes later the foremast went and the life-savers, dashing into the surf, took out of the rigging a dead sea-cook.

And still the tugs lay like vultures awaiting carrion. Both had come down to the wreck in the hope of getting a line over her and pulling her from the sands, for which there would have been ample reward. But it was too rough to approach her and she was too far gone to warrant salving, even were it possible. But there were men dying before their eyes and no one was lifting a hand. Dan was in a red-headed glare of emotion. He was too young to look upon such things calmly. He turned his eyes from the wreck to the Sovereign, just as her bow went up on a wave, showing the red underbody. And it reminded him of the yawning mouth of some sea monster hungry for prey.

"We're lying here like bloodsuckers!" he yelled. "Waiting for salvage while good men are dying! Dying—and we're doing nothing! Fellows," he roared, "I'm going to take the tug in to her. I'm not afraid of a risk to save the lives of brave men."

"All right, Cap'n," said Mulhatton, "you know we'll go with you. But there's no use in bein' fools. Take the tug in—yes. But how'll you take her out again?"

Dan glared across the heaving waters with bloodshot eyes. "No use; you couldn't, couldn't get her out again. No, you couldn't." He repeated this several times. "Is there anything that could?" he added finally.

He looked at his men for the answer, but their eyes were still fastened on the wreck with almost hypnotic fascination.

"Her deck-load's beginning to shift. It'll be clear off soon and that'll take the other mast," announced Noonan.

One of the men in the rigging, a giant, tow-headed fellow, suddenly went crazy,—at least so it seemed. For his lips writhed in a haunting scream as he whipped out his knife and cut his lashings. Then he turned a bloodless face toward the Fledgling, uttered a short, rasping shout, and jumped into the sea. A great wave seized him greedily and swirled him high. Dan caught a fleeting glimpse of that face, turned reproachfully, it seemed, toward him.

It set him crazy too. His mind was working like lightning.

"Mul," he screamed, "launch the lifeboat, with you fellows holding on to a line from her bow! We're to windward, and she'll drift right down to the wreck. Then you can haul us back again. It's been done before. God, why didn't I think of it sooner!"

Mulhatton looked at his Captain closely.

"One chance in a thousand that our boat would live to make the trip, Cap'n," he said.

Dan snarled his impatience.

"One chance in ten thousand, one chance in a million, I'll take it!" he cried in a sharp, metallic voice. "I never saw a man die until to-day—I'll see no more, God willing."

Without a word Mulhatton turned and rushed for the lifeboat.

"Remember, I go in that boat," yelled Dan as he followed his mate. But Mulhatton only turned back a defiant look. Together they wrenched the boat from its blocks and lowered it to Noonan, standing below on the main deck astern. Crampton, the engineer, was at the wheel, while Whitey Welch stood by the engines. As the lifeboat was straining on the top of a swell, Mulhatton attempted to leap in, but was viciously punched back by Dan, who then sprang out five feet and sprawled in the stern sheets.

"Damn!" cried the disappointed mate as he sprang to Noonan's side and seized the line, which was already paying out.

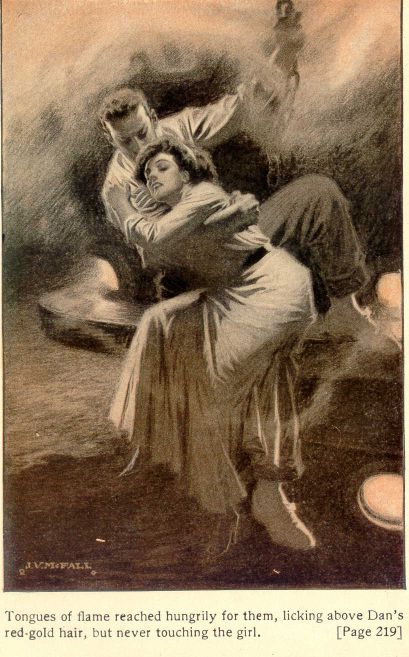

Into the riot went Dan. There was neither mercy nor tolerance in the waters,—the waves ripped all about in wanton fury; the spume cloaked the face of them in wet clouds and the sea hollows lay like black pits. But merciless and intolerant as were the waters, Dan asked no odds of them. Crouching in the stern with one oar dug deep, he was hurled on his errand of mercy. The Sovereign whistled its commendation, while ashore the spectators and life-savers stood breathless. A stealthy wave slashed the oar, almost pulling his shoulder from its socket, but he kept the oar. Aye, he kept it and cursed the wave that sought to take it away. On, on, as determined, as indomitable as the elements. A wave cut the boat full. It skidded on its side and righted. A comber rose green behind, hiding the Fledgling. It caught the lifeboat before it broke. It hoisted it high and then, passing on, expended its crushing force against the wreck ahead. And Dan laughed, and the spindrift flying like buckshot beat against his teeth. On, on, until the wreck, boiling in water, loomed ahead. On past the stern of the wreck shot the small boat, until it was just under the lee of it. There he signalled to his men to pay out the line no more.

"Jump!" he called to the three men in the rigging. First jumped Daniel James, and Dan caught him out of the waters and hauled him in. And he caught the next, the boat careening, shipping a rush of water. As Captain Ephraim crouched for the leap, the sough of the rotten hull, working and heaving like the carcass of a shark, was bursting out in a score of places and the lumber deck-load rose and fell and quivered and flailed huge planks into the waves. The end was near. Dan shouted the skipper to hurry. Ephraim obeyed, and had fought his way through the caldron to the boat and was dragged aboard, when suddenly, with a great straining sigh, the hull of the wreck parted amidships, both ends sinking in the waters. A comber rushed in between, swelling and hissing. The lumber deck-load rose in the air like a living thing. The remaining fastenings holding it to the deck parted, and there was a rending and grinding as it slued off into the sea, carrying with it the main-mast, which crashed down and impaled the bar on which the wreck rested.

The currents had carried the rowboat almost—quite, in fact—in front of this terrible heaving mass of wood, one hundred feet long and chained together to a height of ten feet—and only the mainmast, which seemed to be serving as a sort of anchor, held it. Dan saw the danger, and the shouts of those on the Fledgling told him that they had seen it too. The line leading from the boat to the tug was taut and singing, evidence that the men were hauling upon it. But the pull of the shoreward rushing waters was as great as their strength. The boat made no movement out of her dangerous position. Dan was sculling like mad, but his efforts, compared to the might of the sea, were puny. In deep silence the mass of lumber worried at its unforeseen anchor. It ripped free and, rolling and twisting in spineless abandon, bore down upon the lifeboat with crushing momentum. On it came. They began to pay out the line in order that the boat might keep ahead of it for a few extra minutes. But Dan knew there could be no salvation in that. He could see every foot of the advancing mass. He could see the hundreds of planks flailing out in the air like arms; he could see the thick water spurting through thousands of cracks and crevices; could hear the gnashing of plank on plank. Nearer it came, as powerful, as inexorable as the glacial drift. It rose before him in all its crushing might.

Then he felt the boat, as though suddenly endowed with life, start forward, and, glancing at the Fledgling, saw that she had made a tangent course to the wreck in order that the boat could be pulled outward from it and away. Dan knew in an instant that they had lashed the line to the stern bitts and had taken the desperate chance, the only chance, of making the tug pull her lifeboat from danger. Could the little line stand the strain? That was the question. It was so tight that it vibrated like thin wire, and it was humming musically, monotonously. It held—the boat was moving! But the lumber was moving too. On it came. Ten feet—a plank wrenched clear of the mass and shot on ahead, ramming out the lifeboat's stern-board, above the water line. Another plank, as though hurled by some sinister force, sailed clear over Dan's head. Ten feet—the line was fraying out at the ring bolts. Just a second now—five feet. With one bound the lumber swept down, and past the stern of the boat, and Captain Ephraim fell to his knees and thanked his God.

The fight off Jones Island Inlet came at a time when it meant much to Dan. It was the deep sea, and he had measured his might with it. And as a man is dignified by the prowess of his opponent, so was Dan dignified by the prowess of the sea. Perhaps that was why the sea had always called Dan—faintly, dimly; far away sometimes, but always unmistakably. It came in every wind that blew; a voice that involved not the sea alone, but the things it stood for—a broader, deeper life and bigger things; more to do, a final and definite place to make. He had never met or been influenced by the big men—the men who think and teach and sing and do the world's work. His environment in these, his early years of manhood, had been far from them. He could touch them only in books, which were not entirely satisfactory. And so he learned from the sea and it spoke to him of breadth, and power, and determination, and majesty of character. Dan was instinctively seeking all these things, and in the work he was now doing he felt that he was nearer to them than he had ever been before.

One Fall afternoon, six months after the rescue of the men of the Zeitgeist, the Fledgling, as though sentient with the instinct of self-preservation, was struggling through the riot of wind and waves, seeking the security of the Delaware Breakwater, while ten miles back, somewhere in the wild half gloom off Hog Island, three loaded coal barges which she had been towing from Norfolk were rolling, twisting, careening helplessly to destruction—if, indeed, the seas had not already taken deadly toll of them.

Dan and two of his men were at the wheel spokes, which had torn the palms of their hands until they were raw and bleeding, and the dull light flooding in through the windows revealed the indomitable will of these men, the death-fight spirit which actuated them.

Dan's face was bloodless and strained, and his hair fell across his eyes, while crouching beneath him, with hands on the under spokes, were the gigantic shoulders of his mate, the sweaty gray hair and the red, thick nape of the neck suggesting the very epitome of muscular effort; and on the other side, writhing and quivering, was the deck-hand, a study in steel and wire.

The afternoon was still young, but the heavens were darker than twilight, and the rocking sea was as black as slate, save where a comber, as though gnashing its teeth in fury, flashed a sudden white crest, which crumbled immediately into the heaving pall.

"Now, boys, together! Catch back that last spoke we lost!"

And while Dan's words were being shattered into shreds of sound by the shriek of the gale, the three men bent their backs in a fresh effort to put the Fledgling's nose a point better into the on-rushing waves.

They did it too. With a hiss and a crunch the bow swung in square to the watery thunderbolts and the stanch craft, survivor of a hundred perils, a ten-foot section of her port rail gone, a great dent in the steel deck-house forward, began to climb over the water hills with much of her usual precision—down on her side, clear to the bottom of a hollow, then settling on an even keel with a jerk, climbing the slaty incline, stiff as a church, then down, down, half on her side again, then up once more.

"She's making good weather of it," and Dan took his hands from the wheel, stood erect, and gazed through the after windows, searching a horizon which he could see only when the tug climbed to a wave top. He turned to his mate.

"There's no use hunting for those barges," he said tentatively. "When that tow-line broke back there, it seemed as though one of my heart strings went too. But there was nothing to do about it; nothing we could do. It was all we could do to work the Fledgling through."

"Most captains would 'a' cut them barges adrift long before the line broke," replied the mate; "no use thinkin' about them now; they've gone, long ago."

Dan worked his way along the pitching floor to the side windows. His face was tense and drawn. He had never lost a tow before—this was a part of his reputation. And now.₀ He turned slowly to resume his place at the wheel, when suddenly, as the tug was sidling down a wave, the tail of his eye caught a glimpse of a buff funnel protruding above the wave tops a good quarter of a mile away. His first impression was that the water had claimed all but the funnel. He was not sure. He waited. It seemed an age while the tug climbed to the top of the next comber. Slowly, slowly the buff funnel again came into view, and then as the tug still climbed he saw it all—a white, broad-waisted yacht cluttering in the grip of the waters, throwing her stern toward heaven, reeling over, taking water on one rail, letting it through the opposite scuppers, sticking her bow into the waves and rising, shaking off the water like a fat spaniel. Puffs of steam were escaping jerkily from the whistle valve, and, although Dan could not hear, he knew she was whistling for assistance.

It was all a quick, pulsating scene, as one views something in a kinetoscope, and then it was lost as the waters rose between them. Dan stumbled over to the wheel. He was not a man of many words.

"Boys, there's work for us to do. There's a yacht in distress about a quarter of a mile off on the port hand. We'll go over and see."

"It'll mean throwing her head off from seas that we've been bucking since morning," said the mate. And the inflection cast into the words suggested no protest, only a reminder that it would be no child's play.

"Yes," said Dan simply, leaning forward to take advantage of the uproll of the tug to locate the yacht more exactly. "There—there—throw her off three points—— That's it," he added, as the tug floundered on her new course,—a course no longer into, but across, the waves, which now began to come from everywhere, buffeting the tug, keel and bow, rail and pilot-house—crazy cross-seas, fighting among themselves, slashing, crashing, falling over one another.

But on the Fledgling went, climbing the waves insanely now, sometimes bow on, sometimes crab-wise—but ever on. Each wave that was topped gave a better view of the yacht, also enabling those on that wallowing craft to see the tug, as evidence of which the continuous blasts of the whistle were borne to the towmen's ears.

Nearer, until the yacht was never lost to view. Evidently she was not under control; but, even so, it was plain that no high degree of intelligence was being exerted in handling her. She was not steaming at all, merely drifting in the trough, and none of the means to bring her head into the seas which sailors utilize at a pinch had even been attempted. Whatever was the matter with the yacht, Dan and his men were sure that the officers and crew were nothing less than blockheads.

Making a wide detour, they brought the tug around under the lee of the craft and about fifty yards away, where Dan, leaving the wheel to his men, seized a megaphone and ran on deck.

"What's the matter with you?" he shouted angrily through his megaphone, aimed toward a group of men on the shattered bridge. "Are you trying to see how quickly you can sink? Why don't you put her head up?"

A young officer in a wet and bedraggled uniform crawled along the swaying platform to the megaphone rack and, seizing a cone, shouted from a kneeling posture:

"Help us, for God's sake! Our thrust shaft has cracked!" The words came faintly. "Our Captain was washed from the bridge.₀ Tried to put out sea anchor, but couldn't make it hold without steerage way.₀ It broke adrift.₀ This … the Veiled Ladye, with Mr. Horace Howland and a party aboard."

The Veiled Ladye! Absorbed as Dan was, he felt a momentary flash of surprise that the announcement of that name came to him almost as a matter of course. Through the long course of nearly two years the conviction that a time would come when he should once more meet the girl who had spoken to him from the Veiled Ladye's deck at Norfolk had strengthened inexplicably, until he had come to accept it as an assured fact. Was she aboard that yacht now? Aboard that laboring section of gingerbread, in the hands of incompetents and poltroons? Was she? It could not be otherwise. And this was the nature of the meeting which had colored his dreams and intensified the ambitions of his waking moments!

A strange thrill quivered through him, and he glanced dazedly at Mulhatton, as a stout man in yachting garb stumbled to the officer's side and snatched the megaphone from his hands.

"On board the tug!" he cried. "I'm Horace Howland of the Coastwise and West Indian Shipping Company. We're helpless; we can't last an hour unless you hold our head up. Engineer making a collar for cracked shaft … have it made and fitted in twelve hours. Twelve hours. Hold us up that long and we are safe! Do you hear me … twelve hours!"

Dan looked at the yacht, rolling to her beam ends almost every minute. It would be a bad business fooling with that craft; and with iron will he fought back his surging emotions. He had his tug and his men to consider, if not himself. His tug was weakened by her long struggle, and to the best of his judgment he knew it would be wiser for his own interests to go his way, leaving the yacht to her life fight, while the Fledgling fought hers. And yet he could not go away. Aside from the wild theory that the girl might be aboard, there were lives to save over there. That was it. There were lives to save over there. Duty called—a stern, clear call; at least, Dan so heard it, and he was willing to answer it with his life, if necessary. But he did not think of that part of it. It was the lives of those imperilled persons that concerned him. He and his tug were there that they might live. There were women aboard; he had seen their white faces gazing imploringly at him through the cabin portholes—bright, beautiful lives—and men in the glorious prime of their youth. His heart went out to them, and as Mr. Howland laid aside his megaphone the problem was clear. He waved his megaphone in assent and then, levelling it at the yacht, he cried:

"All right. Float a hawser down to us; you are pitching too wild-eyed to come within heaving-line distance." Passing the pilot-house on his way below, he nodded and smiled at the men inside. There had been no need to question them. They had been too long with Dan, and too faithful, not to catch his drift of mind in all emergencies long before he expressed it in words; too brave and hardened to danger, in fact, to care what Dan wanted, just so that he was willing to lead them—to share with them the work to be done.

In the course of a few minutes a small raft, bearing a heaving-line which the yachtsmen had streamed, drifted down upon the tug, clearing the bow by a few feet. Dan leaned out and caught it with his boat-hook, bringing the line aboard. Then he and his fireman tailed on to the end of it, bringing in the attached hawser hand over hand. This they hurried to the stern bitts, taking a pass also around the steam winch. Leaving the fireman to watch it, Dan dashed into the pilot-house and sounded the jingle-bell in the engine-room.

For a few minutes the churnings of the screw were discounted by the bulk of the yacht plus the elemental forces which sought to keep her head just where it was—in the trough of the sea. The tow-line vibrated itself into a blur, the tug strained and quivered and groaned.

"Why don't you help us in some way, you fools!" roared Dan, struggling at the wheel. "You can at least steer, or—"

Before he could proceed there was a report like the bark of a cannon and a torn and shredded end of hawser came writhing and twisting up out of the sea, sluing across the face of the pilot-house as though possessed of all the venom of the living thing it resembled—a python.

There was silence on both the tug and the yacht for a full minute. Dan watched the distressed craft as she tossed up her bow and glided sternward from his view behind a jet of black wave, while the Fledgling seemed to slide from under his feet in the opposite direction. As the yacht came up again he could see that this mishap had scattered all semblance of fortitude to the winds. Except for the young second officer, Mr. Howland, and a sailor, all holding their places pluckily on the bridge, terror reigned. Sailors, men in yachting costumes, and women with hair flying flashed along the decks or in and out of doorways, while forward a group of three young men lashed to a big anchor held out their hands toward the tug.

Dan turned to his deck-hand, his face hard and determined.

"Pete," he said, "go down and get out the double cables. Welch is astern and will help you. I'm going to swerve the tug in close and you heave the lines aboard when we re near enough. We won't trust any more to their rotten hemp."

As a knight, with reckless abandon, might have urged his steed into the very midst of his foes, so Dan urged the Fledgling up to the wildly pitching yacht. Nearer the tug advanced, so near that the tugmen could see the streaks through the red underbody. Nearer yet, head on, and then the wheel was swung broad, while Dan leaned out of the pilot-house, looking down at the two men forward, who were whirling weighted heaving-lines about their heads like lariats. "Now, now then!" yelled Dan, as the mate in response to a wave of his hand began to sheer off from the yacht. "Aye, aye," came the replies from below, and a second later two lines whistled clean over the forward decks of the white craft. Eager hands seized them and hauled in the great cables and made them fast.

Just for an instant Dan and the mate peered at the yacht to see if the lines had carried, an instant of which the wily sea took full advantage. An oily wave reared the bow of the yacht while the swell of its predecessor slued the Fledgling in and around and upward, so that the two craft reared, side by side, bows up and not more than five feet apart. A scream fluttered from the bridge; men's voices raised in curses at the clumsy yacht were borne from the pilot-house. Dan, however, had not time for words; he stood with hands on the wheel watching the red, reeking bow rearing almost in his face; watched it, cool, ready to take the first chance of escape, if the present danger offered such a chance. Slowly, easily, the wave passed, and down came the two bows with a crash. The bow of the Veiled Ladye just grazed the Fledgling's weather rail, tearing off a fender, while Dan signalled full speed astern. It was fortunate that he had his wits about him, for the erratic yacht, instead of falling back as she naturally should have done, suddenly moved forward under the impulse of a swell, butting the tug, almost gently, about ten feet from the bow. Then the tug backed clear, and, breasting the waves, began to take up the slack cables. A hundred yards she went and then stopped headway with a jerk as the men slipped the cables over the bitts.