Title: History of the United States

Author: Charles A. Beard

Mary Ritter Beard

Release date: October 28, 2005 [eBook #16960]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Curtis Weyant, M and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

As things now stand, the course of instruction in American history in our public schools embraces three distinct treatments of the subject. Three separate books are used. First, there is the primary book, which is usually a very condensed narrative with emphasis on biographies and anecdotes. Second, there is the advanced text for the seventh or eighth grade, generally speaking, an expansion of the elementary book by the addition of forty or fifty thousand words. Finally, there is the high school manual. This, too, ordinarily follows the beaten path, giving fuller accounts of the same events and characters. To put it bluntly, we do not assume that our children obtain permanent possessions from their study of history in the lower grades. If mathematicians followed the same method, high school texts on algebra and geometry would include the multiplication table and fractions.

There is, of course, a ready answer to the criticism advanced above. It is that teachers have learned from bitter experience how little history their pupils retain as they pass along the regular route. No teacher of history will deny this. Still it is a standing challenge to existing methods of historical instruction. If the study of history cannot be made truly progressive like the study of mathematics, science, and languages, then the historians assume a grave responsibility in adding their subject to the already overloaded curriculum. If the successive historical texts are only enlarged editions of the first text—more facts, more dates, more words—then history deserves most of the sharp criticism which it is receiving from teachers of science, civics, and economics.

In this condition of affairs we find our justification for offering a new high school text in American history. Our first contribution is one of omission. The time-honored stories of exploration and the biographies of heroes are left out. We frankly hold that, if pupils know little or nothing about Columbus, Cortes, Magellan, or Captain John Smith by the time they reach the high school, it is useless to tell the same stories for perhaps the fourth time. It is worse than useless. It is an offense against the teachers of those subjects that are demonstrated to be progressive in character.

In the next place we have omitted all descriptions of battles. Our reasons for this are simple. The strategy of a campaign or of a single battle is a highly technical, and usually a highly controversial, matter about which experts differ widely. In the field of military and naval operations most writers and teachers of history are mere novices. To dispose of Gettysburg or the Wilderness in ten lines or ten pages is equally absurd to the serious student of military affairs. Any one who compares the ordinary textbook account of a single Civil War campaign with the account given by Ropes, for instance, will ask for no further comment. No youth called upon to serve our country in arms would think of turning to a high school manual for information about the art of warfare. The dramatic scene or episode, so useful in arousing the interest of the immature pupil, seems out of place in a book that deliberately appeals to boys and girls on the very threshold of life's serious responsibilities.

It is not upon negative features, however, that we rest our case. It is rather upon constructive features.

First. We have written a topical, not a narrative, history. We have tried to set forth the important aspects, problems, and movements of each period, bringing in the narrative rather by way of illustration.

Second. We have emphasized those historical topics which help to explain how our nation has come to be what it is to-day.

Third. We have dwelt fully upon the social and economic aspects of our history, especially in relation to the politics of each period.

Fourth. We have treated the causes and results of wars, the problems of financing and sustaining armed forces, rather than military strategy. These are the subjects which belong to a history for civilians. These are matters which civilians can understand—matters which they must understand, if they are to play well their part in war and peace.

Fifth. By omitting the period of exploration, we have been able to enlarge the treatment of our own time. We have given special attention to the history of those current questions which must form the subject matter of sound instruction in citizenship.

Sixth. We have borne in mind that America, with all her unique characteristics, is a part of a general civilization. Accordingly we have given diplomacy, foreign affairs, world relations, and the reciprocal influences of nations their appropriate place.

Seventh. We have deliberately aimed at standards of maturity. The study of a mere narrative calls mainly for the use of the memory. We have aimed to stimulate habits of analysis, comparison, association, reflection, and generalization—habits calculated to enlarge as well as inform the mind. We have been at great pains to make our text clear, simple, and direct; but we have earnestly sought to stretch the intellects of our readers—to put them upon their mettle. Most of them will receive the last of their formal instruction in the high school. The world will soon expect maturity from them. Their achievements will depend upon the possession of other powers than memory alone. The effectiveness of their citizenship in our republic will be measured by the excellence of their judgment as well as the fullness of their information.

| PART I. THE COLONIAL PERIOD | ||

| chapter | page | |

| I. | The Great Migration to America | 1 |

| The Agencies of American Colonization | 2 | |

| The Colonial Peoples | 6 | |

| The Process of Colonization | 12 | |

| II. | Colonial Agriculture, Industry, and Commerce | 20 |

| The Land and the Westward Movement | 20 | |

| Industrial and Commercial Development | 28 | |

| III. | Social and Political Progress | 38 |

| The Leadership of the Churches | 39 | |

| Schools and Colleges | 43 | |

| The Colonial Press | 46 | |

| The Evolution in Political Institutions | 48 | |

| IV. | The Development of Colonial Nationalism | 56 |

| Relations with the Indians and the French | 57 | |

| The Effects of Warfare on the Colonies | 61 | |

| Colonial Relations with the British Government | 64 | |

| Summary of Colonial Period | 73 | |

PART II. CONFLICT AND INDEPENDENCE | ||

| V. | The New Course in British Imperial Policy | 77 |

| George III and His System | 77 | |

| George III's Ministers and Their Colonial Policies | 79 | |

| Colonial Resistance Forces Repeal | 83 | |

| Resumption of British Revenue and Commercial Policies | 87 | |

| Renewed Resistance in America | 90 | |

| Retaliation by the British Government | 93 | |

| From Reform to Revolution in America | 95 | |

| VI. | The American Revolution | 99 |

| Resistance and Retaliation | 99 | |

| American Independence | 101 | |

| The Establishment of Government and the New Allegiance | 108 | |

| Military Affairs | 116 | |

| The Finances of the Revolution | 125 | |

| The Diplomacy of the Revolution | 127 | |

| Peace at Last | 132 | |

| Summary of the Revolutionary Period | 135 | |

PART III. FOUNDATIONS OF THE UNION AND NATIONAL POLITICS | ||

| VII. | The Formation of the Constitution | 139 |

| The Promise and the Difficulties of America | 139 | |

| The Calling of a Constitutional Convention | 143 | |

| The Framing of the Constitution | 146 | |

| The Struggle over Ratification | 157 | |

| VIII. | The Clash of Political Parties | 162 |

| The Men and Measures of the New Government | 162 | |

| The Rise of Political Parties | 168 | |

| Foreign Influences and Domestic Politics | 171 | |

| IX. | The Jeffersonian Republicans in Power | 186 |

| Republican Principles and Policies | 186 | |

| The Republicans and the Great West | 188 | |

| The Republican War for Commercial Independence | 193 | |

| The Republicans Nationalized | 201 | |

| The National Decisions of Chief Justice Marshall | 208 | |

| Summary of Union and National Politics | 212 | |

PART IV. THE WEST AND JACKSONIAN DEMOCRACY | ||

| X. | The Farmers beyond the Appalachians | 217 |

| Preparation for Western Settlement | 217 | |

| The Western Migration and New States | 221 | |

| The Spirit of the Frontier | 228 | |

| The West and the East Meet | 230 | |

| XI. | Jacksonian Democracy | 238 |

| The Democratic Movement in the East | 238 | |

| The New Democracy Enters the Arena | 244 | |

| The New Democracy at Washington | 250 | |

| The Rise of the Whigs | 260 | |

| The Interaction of American and European Opinion | 265 | |

| XII. | The Middle Border and the Great West | 271 |

| The Advance of the Middle Border | 271 | |

| On to the Pacific—Texas and the Mexican War | 276 | |

| The Pacific Coast and Utah | 284 | |

| Summary of Western Development and National Politics | 292 | |

PART V. SECTIONAL CONFLICT AND RECONSTRUCTION | ||

| XIII. | The Rise of the Industrial System | 295 |

| The Industrial Revolution | 296 | |

| The Industrial Revolution and National Politics | 307 | |

| XIV. | The Planting System and National Politics | 316 |

| Slavery—North and South | 316 | |

| Slavery in National Politics | 324 | |

| The Drift of Events toward the Irrepressible Conflict | 332 | |

| XV. | The Civil War and Reconstruction | 344 |

| The Southern Confederacy | 344 | |

| The War Measures of the Federal Government | 350 | |

| The Results of the Civil War | 365 | |

| Reconstruction in the South | 370 | |

| Summary of the Sectional Conflict | 375 | |

PART VI. NATIONAL GROWTH AND WORLD POLITICS | ||

| XVI. | The Political and Economic Evolution of the South | 379 |

| The South at the Close of the War | 379 | |

| The Restoration of White Supremacy | 382 | |

| The Economic Advance of the South | 389 | |

| XVII. | Business Enterprise and the Republican Party | 401 |

| Railways and Industry | 401 | |

| The Supremacy of the Republican Party (1861-1885) | 412 | |

| The Growth of Opposition to Republican Rule | 417 | |

| XVIII. | The Development of the Great West | 425 |

| The Railways as Trail Blazers | 425 | |

| The Evolution of Grazing and Agriculture | 431 | |

| Mining and Manufacturing in the West | 436 | |

| The Admission of New States | 440 | |

| The Influence of the Far West on National Life | 443 | |

| XIX. | Domestic Issues before the Country(1865-1897) | 451 |

| The Currency Question | 452 | |

| The Protective Tariff and Taxation | 459 | |

| The Railways and Trusts | 460 | |

| The Minor Parties and Unrest | 462 | |

| The Sound Money Battle of 1896 | 466 | |

| Republican Measures and Results | 472 | |

| XX. | America a World Power(1865-1900) | 477 |

| American Foreign Relations (1865-1898) | 478 | |

| Cuba and the Spanish War | 485 | |

| American Policies in the Philippines and the Orient | 497 | |

| Summary of National Growth and World Politics | 504 | |

PART VII. PROGRESSIVE DEMOCRACY AND THE WORLD WAR | ||

| XXI. | The Evolution of Republican Policies(1901-1913) | 507 |

| Foreign Affairs | 508 | |

| Colonial Administration | 515 | |

| The Roosevelt Domestic Policies | 519 | |

| Legislative and Executive Activities | 523 | |

| The Administration of President Taft | 527 | |

| Progressive Insurgency and the Election of 1912 | 530 | |

| XXII. | The Spirit of Reform in America | 536 |

| An Age of Criticism | 536 | |

| Political Reforms | 538 | |

| Measures of Economic Reform | 546 | |

| XXIII. | The New Political Democracy | 554 |

| The Rise of the Woman Movement | 555 | |

| The National Struggle for Woman Suffrage | 562 | |

| XXIV. | Industrial Democracy | 570 |

| Coöperation between Employers and Employees | 571 | |

| The Rise and Growth of Organized Labor | 575 | |

| The Wider Relations of Organized Labor | 577 | |

| Immigration and Americanization | 582 | |

| XXV. | President Wilson and the World War | 588 |

| Domestic Legislation | 588 | |

| Colonial and Foreign Policies | 592 | |

| The United States and the European War | 596 | |

| The United States at War | 604 | |

| The Settlement at Paris | 612 | |

| Summary of Democracy and the World War | 620 | |

| Appendix | 627 | |

| A Topical Syllabus | 645 | |

| Index | 655 |

| page | ||

| The Original Grants (color map) | Facing | 4 |

| German and Scotch-Irish Settlements | 8 | |

| Distribution of Population in 1790 | 27 | |

| English, French, and Spanish Possessions in America, 1750 (color map) | Facing | 59 |

| The Colonies at the Time of the Declaration of Independence (color map) | Facing | 108 |

| North America according to the Treaty of 1783 (color map) | Facing | 134 |

| The United States in 1805 (color map) | Facing | 193 |

| Roads and Trails into Western Territory (color map) | Facing | 224 |

| The Cumberland Road | 233 | |

| Distribution of Population in 1830 | 235 | |

| Texas and the Territory in Dispute | 282 | |

| The Oregon Country and the Disputed Boundary | 285 | |

| The Overland Trails | 287 | |

| Distribution of Slaves in Southern States | 323 | |

| The Missouri Compromise | 326 | |

| Slave and Free Soil on the Eve of the Civil War | 335 | |

| The United States in 1861 (color map) | Facing | 345 |

| Railroads of the United States in 1918 | 405 | |

| The United States in 1870 (color map) | Facing | 427 |

| The United States in 1912 (color map) | Facing | 443 |

| American Dominions in the Pacific (color map) | Facing | 500 |

| The Caribbean Region (color map) | Facing | 592 |

| Battle Lines of the Various Years of the World War | 613 | |

| Europe in 1919 (color map) | Between | 618-619 |

The tide of migration that set in toward the shores of North America during the early years of the seventeenth century was but one phase in the restless and eternal movement of mankind upon the surface of the earth. The ancient Greeks flung out their colonies in every direction, westward as far as Gaul, across the Mediterranean, and eastward into Asia Minor, perhaps to the very confines of India. The Romans, supported by their armies and their government, spread their dominion beyond the narrow lands of Italy until it stretched from the heather of Scotland to the sands of Arabia. The Teutonic tribes, from their home beyond the Danube and the Rhine, poured into the empire of the Cæsars and made the beginnings of modern Europe. Of this great sweep of races and empires the settlement of America was merely a part. And it was, moreover, only one aspect of the expansion which finally carried the peoples, the institutions, and the trade of Europe to the very ends of the earth.

In one vital point, it must be noted, American colonization differed from that of the ancients. The Greeks usually carried with them affection for the government they left behind and sacred fire from the altar of the parent city; but thousands of the immigrants who came to America disliked the state and disowned the church of the mother country. They established compacts of government for themselves and set up altars of their own. They sought not only new soil to till but also political and religious liberty for themselves and their children.

It was no light matter for the English to cross three thousand miles of water and found homes in the American wilderness at the opening of the seventeenth century. Ships, tools, and supplies called for huge outlays of money. Stores had to be furnished in quantities sufficient to sustain the life of the settlers until they could gather harvests of their own. Artisans and laborers of skill and industry had to be induced to risk the hazards of the new world. Soldiers were required for defense and mariners for the exploration of inland waters. Leaders of good judgment, adept in managing men, had to be discovered. Altogether such an enterprise demanded capital larger than the ordinary merchant or gentleman could amass and involved risks more imminent than he dared to assume. Though in later days, after initial tests had been made, wealthy proprietors were able to establish colonies on their own account, it was the corporation that furnished the capital and leadership in the beginning.

The Trading Company.—English pioneers in exploration found an instrument for colonization in companies of merchant adventurers, which had long been employed in carrying on commerce with foreign countries. Such a corporation was composed of many persons of different ranks of society—noblemen, merchants, and gentlemen—who banded together for a particular undertaking, each contributing a sum of money and sharing in the profits of the venture. It was organized under royal authority; it received its charter, its grant of land, and its trading privileges from the king and carried on its operations under his supervision and control. The charter named all the persons originally included in the corporation and gave them certain powers in the management of its affairs, including the right to admit new members. The company was in fact a little government set up by the king. When the members of the corporation remained in England, as in the case of the Virginia Company, they operated through agents sent to the colony. When they came over the seas themselves and settled in America, as in the case of Massachusetts, they became the direct government of the country they possessed. The stockholders in that instance became the voters and the governor, the chief magistrate.

Four of the thirteen colonies in America owed their origins to the trading corporation. It was the London Company, created by King James I, in 1606, that laid during the following year the foundations of Virginia at Jamestown. It was under the auspices of their West India Company, chartered in 1621, that the Dutch planted the settlements of the New Netherland in the valley of the Hudson. The founders of Massachusetts were Puritan leaders and men of affairs whom King Charles I incorporated in 1629 under the title: "The governor and company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England." In this case the law did but incorporate a group drawn together by religious ties. "We must be knit together as one man," wrote John Winthrop, the first Puritan governor in America. Far to the south, on the banks of the Delaware River, a Swedish commercial company in 1638 made the beginnings of a settlement, christened New Sweden; it was destined to pass under the rule of the Dutch, and finally under the rule of William Penn as the proprietary colony of Delaware.

In a certain sense, Georgia may be included among the "company colonies." It was, however, originally conceived by the moving spirit, James Oglethorpe, as an asylum for poor men, especially those imprisoned for debt. To realize this humane purpose, he secured from King George II, in 1732, a royal charter uniting several gentlemen, including himself, into "one body politic and corporate," known as the "Trustees for establishing the colony of Georgia in America." In the structure of their organization and their methods of government, the trustees did not differ materially from the regular companies created for trade and colonization. Though their purposes were benevolent, their transactions had to be under the forms of law and according to the rules of business.

The Religious Congregation.—A second agency which figured largely in the settlement of America was the religious brotherhood, or congregation, of men and women brought together in the bonds of a common religious faith. By one of the strange fortunes of history, this institution, founded in the early days of Christianity, proved to be a potent force in the origin and growth of self-government in a land far away from Galilee. "And the multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul," we are told in the Acts describing the Church at Jerusalem. "We are knit together as a body in a most sacred covenant of the Lord ... by virtue of which we hold ourselves strictly tied to all care of each other's good and of the whole," wrote John Robinson, a leader among the Pilgrims who founded their tiny colony of Plymouth in 1620. The Mayflower Compact, so famous in American history, was but a written and signed agreement, incorporating the spirit of obedience to the common good, which served as a guide to self-government until Plymouth was annexed to Massachusetts in 1691.

Three other colonies, all of which retained their identity until the eve of the American Revolution, likewise sprang directly from the congregations of the faithful: Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire, mainly offshoots from Massachusetts. They were founded by small bodies of men and women, "united in solemn covenants with the Lord," who planted their settlements in the wilderness. Not until many a year after Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson conducted their followers to the Narragansett country was Rhode Island granted a charter of incorporation (1663) by the crown. Not until long after the congregation of Thomas Hooker from Newtown blazed the way into the Connecticut River Valley did the king of England give Connecticut a charter of its own (1662) and a place among the colonies. Half a century elapsed before the towns laid out beyond the Merrimac River by emigrants from Massachusetts were formed into the royal province of New Hampshire in 1679.

Even when Connecticut was chartered, the parchment and sealing wax of the royal lawyers did but confirm rights and habits of self-government and obedience to law previously established by the congregations. The towns of Hartford, Windsor, and Wethersfield had long lived happily under their "Fundamental Orders" drawn up by themselves in 1639; so had the settlers dwelt peacefully at New Haven under their "Fundamental Articles" drafted in the same year. The pioneers on the Connecticut shore had no difficulty in agreeing that "the Scriptures do hold forth a perfect rule for the direction and government of all men."

The Proprietor.—A third and very important colonial agency was the proprietor, or proprietary. As the name, associated with the word "property," implies, the proprietor was a person to whom the king granted property in lands in North America to have, hold, use, and enjoy for his own benefit and profit, with the right to hand the estate down to his heirs in perpetual succession. The proprietor was a rich and powerful person, prepared to furnish or secure the capital, collect the ships, supply the stores, and assemble the settlers necessary to found and sustain a plantation beyond the seas. Sometimes the proprietor worked alone. Sometimes two or more were associated like partners in the common undertaking.

Five colonies, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the Carolinas, owe their formal origins, though not always their first settlements, nor in most cases their prosperity, to the proprietary system. Maryland, established in 1634 under a Catholic nobleman, Lord Baltimore, and blessed with religious toleration by the act of 1649, flourished under the mild rule of proprietors until it became a state in the American union. New Jersey, beginning its career under two proprietors, Berkeley and Carteret, in 1664, passed under the direct government of the crown in 1702. Pennsylvania was, in a very large measure, the product of the generous spirit and tireless labors of its first proprietor, the leader of the Friends, William Penn, to whom it was granted in 1681 and in whose family it remained until 1776. The two Carolinas were first organized as one colony in 1663 under the government and patronage of eight proprietors, including Lord Clarendon; but after more than half a century both became royal provinces governed by the king.

The English.—In leadership and origin the thirteen colonies, except New York and Delaware, were English. During the early days of all, save these two, the main, if not the sole, current of immigration was from England. The colonists came from every walk of life. They were men, women, and children of "all sorts and conditions." The major portion were yeomen, or small land owners, farm laborers, and artisans. With them were merchants and gentlemen who brought their stocks of goods or their fortunes to the New World. Scholars came from Oxford and Cambridge to preach the gospel or to teach. Now and then the son of an English nobleman left his baronial hall behind and cast his lot with America. The people represented every religious faith—members of the Established Church of England; Puritans who had labored to reform that church; Separatists, Baptists, and Friends, who had left it altogether; and Catholics, who clung to the religion of their fathers.

New England was almost purely English. During the years between 1629 and 1640, the period of arbitrary Stuart government, about twenty thousand Puritans emigrated to America, settling in the colonies of the far North. Although minor additions were made from time to time, the greater portion of the New England people sprang from this original stock. Virginia, too, for a long time drew nearly all her immigrants from England alone. Not until the eve of the Revolution did other nationalities, mainly the Scotch-Irish and Germans, rival the English in numbers.

The populations of later English colonies—the Carolinas, New York, Pennsylvania, and Georgia—while receiving a steady stream of immigration from England, were constantly augmented by wanderers from the older settlements. New York was invaded by Puritans from New England in such numbers as to cause the Anglican clergymen there to lament that "free thinking spreads almost as fast as the Church." North Carolina was first settled toward the northern border by immigrants from Virginia. Some of the North Carolinians, particularly the Quakers, came all the way from New England, tarrying in Virginia only long enough to learn how little they were wanted in that Anglican colony.

The Scotch-Irish.—Next to the English in numbers and influence were the Scotch-Irish, Presbyterians in belief, English in tongue. Both religious and economic reasons sent them across the sea. Their Scotch ancestors, in the days of Cromwell, had settled in the north of Ireland whence the native Irish had been driven by the conqueror's sword. There the Scotch nourished for many years enjoying in peace their own form of religion and growing prosperous in the manufacture of fine linen and woolen cloth. Then the blow fell. Toward the end of the seventeenth century their religious worship was put under the ban and the export of their cloth was forbidden by the English Parliament. Within two decades twenty thousand Scotch-Irish left Ulster alone, for America; and all during the eighteenth century the migration continued to be heavy. Although no exact record was kept, it is reckoned that the Scotch-Irish and the Scotch who came directly from Scotland, composed one-sixth of the entire American population on the eve of the Revolution.

These newcomers in America made their homes chiefly in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. Coming late upon the scene, they found much of the land immediately upon the seaboard already taken up. For this reason most of them became frontier people settling the interior and upland regions. There they cleared the land, laid out their small farms, and worked as "sturdy yeomen on the soil," hardy, industrious, and independent in spirit, sharing neither the luxuries of the rich planters nor the easy life of the leisurely merchants. To their agriculture they added woolen and linen manufactures, which, flourishing in the supple fingers of their tireless women, made heavy inroads upon the trade of the English merchants in the colonies. Of their labors a poet has sung:

"O, willing hands to toil; Strong natures tuned to the harvest-song and bound to the kindly soil; Bold pioneers for the wilderness, defenders in the field." |

The Germans.—Third among the colonists in order of numerical importance were the Germans. From the very beginning, they appeared in colonial records. A number of the artisans and carpenters in the first Jamestown colony were of German descent. Peter Minuit, the famous governor of New Motherland, was a German from Wesel on the Rhine, and Jacob Leisler, leader of a popular uprising against the provincial administration of New York, was a German from Frankfort-on-Main. The wholesale migration of Germans began with the founding of Pennsylvania. Penn was diligent in searching for thrifty farmers to cultivate his lands and he made a special effort to attract peasants from the Rhine country. A great association, known as the Frankfort Company, bought more than twenty thousand acres from him and in 1684 established a center at Germantown for the distribution of German immigrants. In old New York, Rhinebeck-on-the-Hudson became a similar center for distribution. All the way from Maine to Georgia inducements were offered to the German farmers and in nearly every colony were to be found, in time, German settlements. In fact the migration became so large that German princes were frightened at the loss of so many subjects and England was alarmed by the influx of foreigners into her overseas dominions. Yet nothing could stop the movement. By the end of the colonial period, the number of Germans had risen to more than two hundred thousand.

The majority of them were Protestants from the Rhine region, and South Germany. Wars, religious controversies, oppression, and poverty drove them forth to America. Though most of them were farmers, there were also among them skilled artisans who contributed to the rapid growth of industries in Pennsylvania. Their iron, glass, paper, and woolen mills, dotted here and there among the thickly settled regions, added to the wealth and independence of the province.

Unlike the Scotch-Irish, the Germans did not speak the language of the original colonists or mingle freely with them. They kept to themselves, built their own schools, founded their own newspapers, and published their own books. Their clannish habits often irritated their neighbors and led to occasional agitations against "foreigners." However, no serious collisions seem to have occurred; and in the days of the Revolution, German soldiers from Pennsylvania fought in the patriot armies side by side with soldiers from the English and Scotch-Irish sections.

Other Nationalities.—Though the English, the Scotch-Irish, and the Germans made up the bulk of the colonial population, there were other racial strains as well, varying in numerical importance but contributing their share to colonial life.

From France came the Huguenots fleeing from the decree of the king which inflicted terrible penalties upon Protestants.

From "Old Ireland" came thousands of native Irish, Celtic in race and Catholic in religion. Like their Scotch-Irish neighbors to the north, they revered neither the government nor the church of England imposed upon them by the sword. How many came we do not know, but shipping records of the colonial period show that boatload after boatload left the southern and eastern shores of Ireland for the New World. Undoubtedly thousands of their passengers were Irish of the native stock. This surmise is well sustained by the constant appearance of Celtic names in the records of various colonies.

The Jews, then as ever engaged in their age-long battle for religious and economic toleration, found in the American colonies, not complete liberty, but certainly more freedom than they enjoyed in England, France, Spain, or Portugal. The English law did not actually recognize their right to live in any of the dominions, but owing to the easy-going habits of the Americans they were allowed to filter into the seaboard towns. The treatment they received there varied. On one occasion the mayor and council of New York forbade them to sell by retail and on another prohibited the exercise of their religious worship. Newport, Philadelphia, and Charleston were more hospitable, and there large Jewish colonies, consisting principally of merchants and their families, flourished in spite of nominal prohibitions of the law.

Though the small Swedish colony in Delaware was quickly submerged beneath the tide of English migration, the Dutch in New York continued to hold their own for more than a hundred years after the English conquest in 1664. At the end of the colonial period over one-half of the 170,000 inhabitants of the province were descendants of the original Dutch—still distinct enough to give a decided cast to the life and manners of New York. Many of them clung as tenaciously to their mother tongue as they did to their capacious farmhouses or their Dutch ovens; but they were slowly losing their identity as the English pressed in beside them to farm and trade.

The melting pot had begun its historic mission.

Considered from one side, colonization, whatever the motives of the emigrants, was an economic matter. It involved the use of capital to pay for their passage, to sustain them on the voyage, and to start them on the way of production. Under this stern economic necessity, Puritans, Scotch-Irish, Germans, and all were alike laid.

Immigrants Who Paid Their Own Way.—Many of the immigrants to America in colonial days were capitalists themselves, in a small or a large way, and paid their own passage. What proportion of the colonists were able to finance their voyage across the sea is a matter of pure conjecture. Undoubtedly a very considerable number could do so, for we can trace the family fortunes of many early settlers. Henry Cabot Lodge is authority for the statement that "the settlers of New England were drawn from the country gentlemen, small farmers, and yeomanry of the mother country.... Many of the emigrants were men of wealth, as the old lists show, and all of them, with few exceptions, were men of property and good standing. They did not belong to the classes from which emigration is usually supplied, for they all had a stake in the country they left behind." Though it would be interesting to know how accurate this statement is or how applicable to the other colonies, no study has as yet been made to gratify that interest. For the present it is an unsolved problem just how many of the colonists were able to bear the cost of their own transfer to the New World.

Indentured Servants.—That at least tens of thousands of immigrants were unable to pay for their passage is established beyond the shadow of a doubt by the shipping records that have come down to us. The great barrier in the way of the poor who wanted to go to America was the cost of the sea voyage. To overcome this difficulty a plan was worked out whereby shipowners and other persons of means furnished the passage money to immigrants in return for their promise, or bond, to work for a term of years to repay the sum advanced. This system was called indentured servitude.

It is probable that the number of bond servants exceeded the original twenty thousand Puritans, the yeomen, the Virginia gentlemen, and the Huguenots combined. All the way down the coast from Massachusetts to Georgia were to be found in the fields, kitchens, and workshops, men, women, and children serving out terms of bondage generally ranging from five to seven years. In the proprietary colonies the proportion of bond servants was very high. The Baltimores, Penns, Carterets, and other promoters anxiously sought for workers of every nationality to till their fields, for land without labor was worth no more than land in the moon. Hence the gates of the proprietary colonies were flung wide open. Every inducement was offered to immigrants in the form of cheap land, and special efforts were made to increase the population by importing servants. In Pennsylvania, it was not uncommon to find a master with fifty bond servants on his estate. It has been estimated that two-thirds of all the immigrants into Pennsylvania between the opening of the eighteenth century and the outbreak of the Revolution were in bondage. In the other Middle colonies the number was doubtless not so large; but it formed a considerable part of the population.

The story of this traffic in white servants is one of the most striking things in the history of labor. Bondmen differed from the serfs of the feudal age in that they were not bound to the soil but to the master. They likewise differed from the negro slaves in that their servitude had a time limit. Still they were subject to many special disabilities. It was, for instance, a common practice to impose on them penalties far heavier than were imposed upon freemen for the same offense. A free citizen of Pennsylvania who indulged in horse racing and gambling was let off with a fine; a white servant guilty of the same unlawful conduct was whipped at the post and fined as well.

The ordinary life of the white servant was also severely restricted. A bondman could not marry without his master's consent; nor engage in trade; nor refuse work assigned to him. For an attempt to escape or indeed for any infraction of the law, the term of service was extended. The condition of white bondmen in Virginia, according to Lodge, "was little better than that of slaves. Loose indentures and harsh laws put them at the mercy of their masters." It would not be unfair to add that such was their lot in all other colonies. Their fate depended upon the temper of their masters.

Cruel as was the system in many ways, it gave thousands of people in the Old World a chance to reach the New—an opportunity to wrestle with fate for freedom and a home of their own. When their weary years of servitude were over, if they survived, they might obtain land of their own or settle as free mechanics in the towns. For many a bondman the gamble proved to be a losing venture because he found himself unable to rise out of the state of poverty and dependence into which his servitude carried him. For thousands, on the contrary, bondage proved to be a real avenue to freedom and prosperity. Some of the best citizens of America have the blood of indentured servants in their veins.

The Transported—Involuntary Servitude.—In their anxiety to secure settlers, the companies and proprietors having colonies in America either resorted to or connived at the practice of kidnapping men, women, and children from the streets of English cities. In 1680 it was officially estimated that "ten thousand persons were spirited away" to America. Many of the victims of the practice were young children, for the traffic in them was highly profitable. Orphans and dependents were sometimes disposed of in America by relatives unwilling to support them. In a single year, 1627, about fifteen hundred children were shipped to Virginia.

In this gruesome business there lurked many tragedies, and very few romances. Parents were separated from their children and husbands from their wives. Hundreds of skilled artisans—carpenters, smiths, and weavers—utterly disappeared as if swallowed up by death. A few thus dragged off to the New World to be sold into servitude for a term of five or seven years later became prosperous and returned home with fortunes. In one case a young man who was forcibly carried over the sea lived to make his way back to England and establish his claim to a peerage.

Akin to the kidnapped, at least in economic position, were convicts deported to the colonies for life in lieu of fines and imprisonment. The Americans protested vigorously but ineffectually against this practice. Indeed, they exaggerated its evils, for many of the "criminals" were only mild offenders against unduly harsh and cruel laws. A peasant caught shooting a rabbit on a lord's estate or a luckless servant girl who purloined a pocket handkerchief was branded as a criminal along with sturdy thieves and incorrigible rascals. Other transported offenders were "political criminals"; that is, persons who criticized or opposed the government. This class included now Irish who revolted against British rule in Ireland; now Cavaliers who championed the king against the Puritan revolutionists; Puritans, in turn, dispatched after the monarchy was restored; and Scotch and English subjects in general who joined in political uprisings against the king.

The African Slaves.—Rivaling in numbers, in the course of time, the indentured servants and whites carried to America against their will were the African negroes brought to America and sold into slavery. When this form of bondage was first introduced into Virginia in 1619, it was looked upon as a temporary necessity to be discarded with the increase of the white population. Moreover it does not appear that those planters who first bought negroes at the auction block intended to establish a system of permanent bondage. Only by a slow process did chattel slavery take firm root and become recognized as the leading source of the labor supply. In 1650, thirty years after the introduction of slavery, there were only three hundred Africans in Virginia.

The great increase in later years was due in no small measure to the inordinate zeal for profits that seized slave traders both in Old and in New England. Finding it relatively easy to secure negroes in Africa, they crowded the Southern ports with their vessels. The English Royal African Company sent to America annually between 1713 and 1743 from five to ten thousand slaves. The ship owners of New England were not far behind their English brethren in pushing this extraordinary traffic.

As the proportion of the negroes to the free white population steadily rose, and as whole sections were overrun with slaves and slave traders, the Southern colonies grew alarmed. In 1710, Virginia sought to curtail the importation by placing a duty of £5 on each slave. This effort was futile, for the royal governor promptly vetoed it. From time to time similar bills were passed, only to meet with royal disapproval. South Carolina, in 1760, absolutely prohibited importation; but the measure was killed by the British crown. As late as 1772, Virginia, not daunted by a century of rebuffs, sent to George III a petition in this vein: "The importation of slaves into the colonies from the coast of Africa hath long been considered as a trade of great inhumanity and under its present encouragement, we have too much reason to fear, will endanger the very existence of Your Majesty's American dominions.... Deeply impressed with these sentiments, we most humbly beseech Your Majesty to remove all those restraints on Your Majesty's governors of this colony which inhibit their assenting to such laws as might check so very pernicious a commerce."

All such protests were without avail. The negro population grew by leaps and bounds, until on the eve of the Revolution it amounted to more than half a million. In five states—Maryland, Virginia, the two Carolinas, and Georgia—the slaves nearly equalled or actually exceeded the whites in number. In South Carolina they formed almost two-thirds of the population. Even in the Middle colonies of Delaware and Pennsylvania about one-fifth of the inhabitants were from Africa. To the North, the proportion of slaves steadily diminished although chattel servitude was on the same legal footing as in the South. In New York approximately one in six and in New England one in fifty were negroes, including a few freedmen.

The climate, the soil, the commerce, and the industry of the North were all unfavorable to the growth of a servile population. Still, slavery, though sectional, was a part of the national system of economy. Northern ships carried slaves to the Southern colonies and the produce of the plantations to Europe. "If the Northern states will consult their interest, they will not oppose the increase in slaves which will increase the commodities of which they will become the carriers," said John Rutledge, of South Carolina, in the convention which framed the Constitution of the United States. "What enriches a part enriches the whole and the states are the best judges of their particular interest," responded Oliver Ellsworth, the distinguished spokesman of Connecticut.

1. America has been called a nation of immigrants. Explain why.

2. Why were individuals unable to go alone to America in the beginning? What agencies made colonization possible? Discuss each of them.

3. Make a table of the colonies, showing the methods employed in their settlement.

4. Why were capital and leadership so very important in early colonization?

5. What is meant by the "melting pot"? What nationalities were represented among the early colonists?

6. Compare the way immigrants come to-day with the way they came in colonial times.

7. Contrast indentured servitude with slavery and serfdom.

8. Account for the anxiety of companies and proprietors to secure colonists.

9. What forces favored the heavy importation of slaves?

10. In what way did the North derive advantages from slavery?

The Chartered Company.—Compare the first and third charters of Virginia in Macdonald, Documentary Source Book of American History, 1606-1898, pp. 1-14. Analyze the first and second Massachusetts charters in Macdonald, pp. 22-84. Special reference: W.A.S. Hewins, English Trading Companies.

Congregations and Compacts for Self-government.—A study of the Mayflower Compact, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut and the Fundamental Articles of New Haven in Macdonald, pp. 19, 36, 39. Reference: Charles Borgeaud, Rise of Modern Democracy, and C.S. Lobingier, The People's Law, Chaps. I-VII.

The Proprietary System.—Analysis of Penn's charter of 1681, in Macdonald, p. 80. Reference: Lodge, Short History of the English Colonies in America, p. 211.

Studies of Individual Colonies.—Review of outstanding events in history of each colony, using Elson, History of the United States, pp. 55-159, as the basis.

Biographical Studies.—John Smith, John Winthrop, William Penn, Lord Baltimore, William Bradford, Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, Thomas Hooker, and Peter Stuyvesant, using any good encyclopedia.

Indentured Servitude.—In Virginia, Lodge, Short History, pp. 69-72; in Pennsylvania, pp. 242-244. Contemporary account in Callender, Economic History of the United States, pp. 44-51. Special reference: Karl Geiser, Redemptioners and Indentured Servants (Yale Review, X, No. 2 Supplement).

Slavery.—In Virginia, Lodge, Short History, pp. 67-69; in the Northern colonies, pp. 241, 275, 322, 408, 442.

The People of the Colonies.—Virginia, Lodge, Short History, pp. 67-73; New England, pp. 406-409, 441-450; Pennsylvania, pp. 227-229, 240-250; New York, pp. 312-313, 322-335.

The Significance of Land Tenure.—The way in which land may be acquired, held, divided among heirs, and bought and sold exercises a deep influence on the life and culture of a people. The feudal and aristocratic societies of Europe were founded on a system of landlordism which was characterized by two distinct features. In the first place, the land was nearly all held in great estates, each owned by a single proprietor. In the second place, every estate was kept intact under the law of primogeniture, which at the death of a lord transferred all his landed property to his eldest son. This prevented the subdivision of estates and the growth of a large body of small farmers or freeholders owning their own land. It made a form of tenantry or servitude inevitable for the mass of those who labored on the land. It also enabled the landlords to maintain themselves in power as a governing class and kept the tenants and laborers subject to their economic and political control. If land tenure was so significant in Europe, it was equally important in the development of America, where practically all the first immigrants were forced by circumstances to derive their livelihood from the soil.

Experiments in Common Tillage.—In the New World, with its broad extent of land awaiting the white man's plow, it was impossible to introduce in its entirety and over the whole area the system of lords and tenants that existed across the sea. So it happened that almost every kind of experiment in land tenure, from communism to feudalism, was tried. In the early days of the Jamestown colony, the land, though owned by the London Company, was tilled in common by the settlers. No man had a separate plot of his own. The motto of the community was: "Labor and share alike." All were supposed to work in the fields and receive an equal share of the produce. At Plymouth, the Pilgrims attempted a similar experiment, laying out the fields in common and distributing the joint produce of their labor with rough equality among the workers.

In both colonies the communistic experiments were failures. Angry at the lazy men in Jamestown who idled their time away and yet expected regular meals, Captain John Smith issued a manifesto: "Everyone that gathereth not every day as much as I do, the next day shall be set beyond the river and forever banished from the fort and live there or starve." Even this terrible threat did not bring a change in production. Not until each man was given a plot of his own to till, not until each gathered the fruits of his own labor, did the colony prosper. In Plymouth, where the communal experiment lasted for five years, the results were similar to those in Virginia, and the system was given up for one of separate fields in which every person could "set corn for his own particular." Some other New England towns, refusing to profit by the experience of their Plymouth neighbor, also made excursions into common ownership and labor, only to abandon the idea and go in for individual ownership of the land. "By degrees it was seen that even the Lord's people could not carry the complicated communist legislation into perfect and wholesome practice."

Feudal Elements in the Colonies—Quit Rents, Manors, and Plantations.—At the other end of the scale were the feudal elements of land tenure found in the proprietary colonies, in the seaboard regions of the South, and to some extent in New York. The proprietor was in fact a powerful feudal lord, owning land granted to him by royal charter. He could retain any part of it for his personal use or dispose of it all in large or small lots. While he generally kept for himself an estate of baronial proportions, it was impossible for him to manage directly any considerable part of the land in his dominion. Consequently he either sold it in parcels for lump sums or granted it to individuals on condition that they make to him an annual payment in money, known as "quit rent." In Maryland, the proprietor sometimes collected as high as £9000 (equal to about $500,000 to-day) in a single year from this source. In Pennsylvania, the quit rents brought a handsome annual tribute into the exchequer of the Penn family. In the royal provinces, the king of England claimed all revenues collected in this form from the land, a sum amounting to £19,000 at the time of the Revolution. The quit rent,—"really a feudal payment from freeholders,"—was thus a material source of income for the crown as well as for the proprietors. Wherever it was laid, however, it proved to be a burden, a source of constant irritation; and it became a formidable item in the long list of grievances which led to the American Revolution.

Something still more like the feudal system of the Old World appeared in the numerous manors or the huge landed estates granted by the crown, the companies, or the proprietors. In the colony of Maryland alone there were sixty manors of three thousand acres each, owned by wealthy men and tilled by tenants holding small plots under certain restrictions of tenure. In New York also there were many manors of wide extent, most of which originated in the days of the Dutch West India Company, when extensive concessions were made to patroons to induce them to bring over settlers. The Van Rensselaer, the Van Cortlandt, and the Livingston manors were so large and populous that each was entitled to send a representative to the provincial legislature. The tenants on the New York manors were in somewhat the same position as serfs on old European estates. They were bound to pay the owner a rent in money and kind; they ground their grain at his mill; and they were subject to his judicial power because he held court and meted out justice, in some instances extending to capital punishment.

The manors of New York or Maryland were, however, of slight consequence as compared with the vast plantations of the Southern seaboard—huge estates, far wider in expanse than many a European barony and tilled by slaves more servile than any feudal tenants. It must not be forgotten that this system of land tenure became the dominant feature of a large section and gave a decided bent to the economic and political life of America.

The Small Freehold.—In the upland regions of the South, however, and throughout most of the North, the drift was against all forms of servitude and tenantry and in the direction of the freehold; that is, the small farm owned outright and tilled by the possessor and his family. This was favored by natural circumstances and the spirit of the immigrants. For one thing, the abundance of land and the scarcity of labor made it impossible for the companies, the proprietors, or the crown to develop over the whole continent a network of vast estates. In many sections, particularly in New England, the climate, the stony soil, the hills, and the narrow valleys conspired to keep the farms within a moderate compass. For another thing, the English, Scotch-Irish, and German peasants, even if they had been tenants in the Old World, did not propose to accept permanent dependency of any kind in the New. If they could not get freeholds, they would not settle at all; thus they forced proprietors and companies to bid for their enterprise by selling land in small lots. So it happened that the freehold of modest proportions became the cherished unit of American farmers. The people who tilled the farms were drawn from every quarter of western Europe; but the freehold system gave a uniform cast to their economic and social life in America.

Social Effects of Land Tenure.—Land tenure and the process of western settlement thus developed two distinct types of people engaged in the same pursuit—agriculture. They had a common tie in that they both cultivated the soil and possessed the local interest and independence which arise from that occupation. Their methods and their culture, however, differed widely.

The Southern planter, on his broad acres tilled by slaves, resembled the English landlord on his estates more than he did the colonial farmer who labored with his own hands in the fields and forests. He sold his rice and tobacco in large amounts directly to English factors, who took his entire crop in exchange for goods and cash. His fine clothes, silverware, china, and cutlery he bought in English markets. Loving the ripe old culture of the mother country, he often sent his sons to Oxford or Cambridge for their education. In short, he depended very largely for his prosperity and his enjoyment of life upon close relations with the Old World. He did not even need market towns in which to buy native goods, for they were made on his own plantation by his own artisans who were usually gifted slaves.

The economic condition of the small farmer was totally different. His crops were not big enough to warrant direct connection with English factors or the personal maintenance of a corps of artisans. He needed local markets, and they sprang up to meet the need. Smiths, hatters, weavers, wagon-makers, and potters at neighboring towns supplied him with the rough products of their native skill. The finer goods, bought by the rich planter in England, the small farmer ordinarily could not buy. His wants were restricted to staples like tea and sugar, and between him and the European market stood the merchant. His community was therefore more self-sufficient than the seaboard line of great plantations. It was more isolated, more provincial, more independent, more American. The planter faced the Old East. The farmer faced the New West.

The Westward Movement.—Yeoman and planter nevertheless were alike in one respect. Their land hunger was never appeased. Each had the eye of an expert for new and fertile soil; and so, north and south, as soon as a foothold was secured on the Atlantic coast, the current of migration set in westward, creeping through forests, across rivers, and over mountains. Many of the later immigrants, in their search for cheap lands, were compelled to go to the border; but in a large part the path breakers to the West were native Americans of the second and third generations. Explorers, fired by curiosity and the lure of the mysterious unknown, and hunters, fur traders, and squatters, following their own sweet wills, blazed the trail, opening paths and sending back stories of the new regions they traversed. Then came the regular settlers with lawful titles to the lands they had purchased, sometimes singly and sometimes in companies.

In Massachusetts, the westward movement is recorded in the founding of Springfield in 1636 and Great Barrington in 1725. By the opening of the eighteenth century the pioneers of Connecticut had pushed north and west until their outpost towns adjoined the Hudson Valley settlements. In New York, the inland movement was directed by the Hudson River to Albany, and from that old Dutch center it radiated in every direction, particularly westward through the Mohawk Valley. New Jersey was early filled to its borders, the beginnings of the present city of New Brunswick being made in 1681 and those of Trenton in 1685. In Pennsylvania, as in New York, the waterways determined the main lines of advance. Pioneers, pushing up through the valley of the Schuylkill, spread over the fertile lands of Berks and Lancaster counties, laying out Reading in 1748. Another current of migration was directed by the Susquehanna, and, in 1726, the first farmhouse was built on the bank where Harrisburg was later founded. Along the southern tier of counties a thin line of settlements stretched westward to Pittsburgh, reaching the upper waters of the Ohio while the colony was still under the Penn family.

In the South the westward march was equally swift. The seaboard was quickly occupied by large planters and their slaves engaged in the cultivation of tobacco and rice. The Piedmont Plateau, lying back from the coast all the way from Maryland to Georgia, was fed by two streams of migration, one westward from the sea and the other southward from the other colonies—Germans from Pennsylvania and Scotch-Irish furnishing the main supply. "By 1770, tide-water Virginia was full to overflowing and the 'back country' of the Blue Ridge and the Shenandoah was fully occupied. Even the mountain valleys ... were claimed by sturdy pioneers. Before the Declaration of Independence, the oncoming tide of home-seekers had reached the crest of the Alleghanies."

Beyond the mountains pioneers had already ventured, harbingers of an invasion that was about to break in upon Kentucky and Tennessee. As early as 1769 that mighty Nimrod, Daniel Boone, curious to hunt buffaloes, of which he had heard weird reports, passed through the Cumberland Gap and brought back news of a wonderful country awaiting the plow. A hint was sufficient. Singly, in pairs, and in groups, settlers followed the trail he had blazed. A great land corporation, the Transylvania Company, emulating the merchant adventurers of earlier times, secured a huge grant of territory and sought profits in quit rents from lands sold to farmers. By the outbreak of the Revolution there were several hundred people in the Kentucky region. Like the older colonists, they did not relish quit rents, and their opposition wrecked the Transylvania Company. They even carried their protests into the Continental Congress in 1776, for by that time they were our "embryo fourteenth colony."

Though the labor of the colonists was mainly spent in farming, there was a steady growth in industrial and commercial pursuits. Most of the staple industries of to-day, not omitting iron and textiles, have their beginnings in colonial times. Manufacturing and trade soon gave rise to towns which enjoyed an importance all out of proportion to their numbers. The great centers of commerce and finance on the seaboard originated in the days when the king of England was "lord of these dominions."

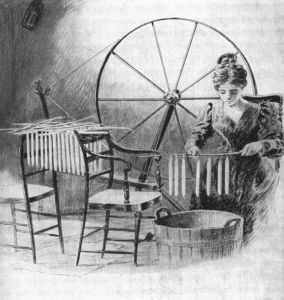

Textile Manufacture as a Domestic Industry.—Colonial women, in addition to sharing every hardship of pioneering, often the heavy labor of the open field, developed in the course of time a national industry which was almost exclusively their own. Wool and flax were raised in abundance in the North and South. "Every farm house," says Coman, the economic historian, "was a workshop where the women spun and wove the serges, kerseys, and linsey-woolseys which served for the common wear." By the close of the seventeenth century, New England manufactured cloth in sufficient quantities to export it to the Southern colonies and to the West Indies. As the industry developed, mills were erected for the more difficult process of dyeing, weaving, and fulling, but carding and spinning continued to be done in the home. The Dutch of New Netherland, the Swedes of Delaware, and the Scotch-Irish of the interior "were not one whit behind their Yankee neighbors."

The importance of this enterprise to British economic life can hardly be overestimated. For many a century the English had employed their fine woolen cloth as the chief staple in a lucrative foreign trade, and the government had come to look upon it as an object of special interest and protection. When the colonies were established, both merchants and statesmen naturally expected to maintain a monopoly of increasing value; but before long the Americans, instead of buying cloth, especially of the coarser varieties, were making it to sell. In the place of customers, here were rivals. In the place of helpless reliance upon English markets, here was the germ of economic independence.

If British merchants had not discovered it in the ordinary course of trade, observant officers in the provinces would have conveyed the news to them. Even in the early years of the eighteenth century the royal governor of New York wrote of the industrious Americans to his home government: "The consequence will be that if they can clothe themselves once, not only comfortably, but handsomely too, without the help of England, they who already are not very fond of submitting to government will soon think of putting in execution designs they have long harboured in their breasts. This will not seem strange when you consider what sort of people this country is inhabited by."

The Iron Industry.—Almost equally widespread was the art of iron working—one of the earliest and most picturesque of colonial industries. Lynn, Massachusetts, had a forge and skilled artisans within fifteen years after the founding of Boston. The smelting of iron began at New London and New Haven about 1658; in Litchfield county, Connecticut, a few years later; at Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in 1731; and near by at Lenox some thirty years after that. New Jersey had iron works at Shrewsbury within ten years after the founding of the colony in 1665. Iron forges appeared in the valleys of the Delaware and the Susquehanna early in the following century, and iron masters then laid the foundations of fortunes in a region destined to become one of the great iron centers of the world. Virginia began iron working in the year that saw the introduction of slavery. Although the industry soon lapsed, it was renewed and flourished in the eighteenth century. Governor Spotswood was called the "Tubal Cain" of the Old Dominion because he placed the industry on a firm foundation. Indeed it seems that every colony, except Georgia, had its iron foundry. Nails, wire, metallic ware, chains, anchors, bar and pig iron were made in large quantities; and Great Britain, by an act in 1750, encouraged the colonists to export rough iron to the British Islands.

Shipbuilding.—Of all the specialized industries in the colonies, shipbuilding was the most important. The abundance of fir for masts, oak for timbers and boards, pitch for tar and turpentine, and hemp for rope made the way of the shipbuilder easy. Early in the seventeenth century a ship was built at New Amsterdam, and by the middle of that century shipyards were scattered along the New England coast at Newburyport, Salem, New Bedford, Newport, Providence, New London, and New Haven. Yards at Albany and Poughkeepsie in New York built ships for the trade of that colony with England and the Indies. Wilmington and Philadelphia soon entered the race and outdistanced New York, though unable to equal the pace set by New England. While Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina also built ships, Southern interest was mainly confined to the lucrative business of producing ship materials: fir, cedar, hemp, and tar.

Fishing.—The greatest single economic resource of New England outside of agriculture was the fisheries. This industry, started by hardy sailors from Europe, long before the landing of the Pilgrims, flourished under the indomitable seamanship of the Puritans, who labored with the net and the harpoon in almost every quarter of the Atlantic. "Look," exclaimed Edmund Burke, in the House of Commons, "at the manner in which the people of New England have of late carried on the whale fishery. Whilst we follow them among the tumbling mountains of ice and behold them penetrating into the deepest frozen recesses of Hudson's Bay and Davis's Straits, while we are looking for them beneath the arctic circle, we hear that they have pierced into the opposite region of polar cold, that they are at the antipodes and engaged under the frozen serpent of the south.... Nor is the equinoctial heat more discouraging to them than the accumulated winter of both poles. We know that, whilst some of them draw the line and strike the harpoon on the coast of Africa, others run the longitude and pursue their gigantic game along the coast of Brazil. No sea but what is vexed by their fisheries. No climate that is not witness to their toils. Neither the perseverance of Holland nor the activity of France nor the dexterous and firm sagacity of English enterprise ever carried this most perilous mode of hard industry to the extent to which it has been pushed by this recent people."

The influence of the business was widespread. A large and lucrative European trade was built upon it. The better quality of the fish caught for food was sold in the markets of Spain, Portugal, and Italy, or exchanged for salt, lemons, and raisins for the American market. The lower grades of fish were carried to the West Indies for slave consumption, and in part traded for sugar and molasses, which furnished the raw materials for the thriving rum industry of New England. These activities, in turn, stimulated shipbuilding, steadily enlarging the demand for fishing and merchant craft of every kind and thus keeping the shipwrights, calkers, rope makers, and other artisans of the seaport towns rushed with work. They also increased trade with the mother country for, out of the cash collected in the fish markets of Europe and the West Indies, the colonists paid for English manufactures. So an ever-widening circle of American enterprise centered around this single industry, the nursery of seamanship and the maritime spirit.

Oceanic Commerce and American Merchants.—All through the eighteenth century, the commerce of the American colonies spread in every direction until it rivaled in the number of people employed, the capital engaged, and the profits gleaned, the commerce of European nations. A modern historian has said: "The enterprising merchants of New England developed a network of trade routes that covered well-nigh half the world." This commerce, destined to be of such significance in the conflict with the mother country, presented, broadly speaking, two aspects.

On the one side, it involved the export of raw materials and agricultural produce. The Southern colonies produced for shipping, tobacco, rice, tar, pitch, and pine; the Middle colonies, grain, flour, furs, lumber, and salt pork; New England, fish, flour, rum, furs, shoes, and small articles of manufacture. The variety of products was in fact astounding. A sarcastic writer, while sneering at the idea of an American union, once remarked of colonial trade: "What sort of dish will you make? New England will throw in fish and onions. The middle states, flax-seed and flour. Maryland and Virginia will add tobacco. North Carolina, pitch, tar, and turpentine. South Carolina, rice and indigo, and Georgia will sprinkle the whole composition with sawdust. Such an absurd jumble will you make if you attempt to form a union among such discordant materials as the thirteen British provinces."

On the other side, American commerce involved the import trade, consisting principally of English and continental manufactures, tea, and "India goods." Sugar and molasses, brought from the West Indies, supplied the flourishing distilleries of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. The carriage of slaves from Africa to the Southern colonies engaged hundreds of New England's sailors and thousands of pounds of her capital.

The disposition of imported goods in the colonies, though in part controlled by English factors located in America, employed also a large and important body of American merchants like the Willings and Morrises of Philadelphia; the Amorys, Hancocks, and Faneuils of Boston; and the Livingstons and Lows of New York. In their zeal and enterprise, they were worthy rivals of their English competitors, so celebrated for world-wide commercial operations. Though fully aware of the advantages they enjoyed in British markets and under the protection of the British navy, the American merchants were high-spirited and mettlesome, ready to contend with royal officers in order to shield American interests against outside interference.

Measured against the immense business of modern times, colonial commerce seems perhaps trivial. That, however, is not the test of its significance. It must be considered in relation to the growth of English colonial trade in its entirety—a relation which can be shown by a few startling figures. The whole export trade of England, including that to the colonies, was, in 1704, £6,509,000. On the eve of the American Revolution, namely, in 1772, English exports to the American colonies alone amounted to £6,024,000; in other words, almost as much as the whole foreign business of England two generations before. At the first date, colonial trade was but one-twelfth of the English export business; at the second date, it was considerably more than one-third. In 1704, Pennsylvania bought in English markets goods to the value of £11,459; in 1772 the purchases of the same colony amounted to £507,909. In short, Pennsylvania imports increased fifty times within sixty-eight years, amounting in 1772 to almost the entire export trade of England to the colonies at the opening of the century. The American colonies were indeed a great source of wealth to English merchants.

Intercolonial Commerce.—Although the bad roads of colonial times made overland transportation difficult and costly, the many rivers and harbors along the coast favored a lively water-borne trade among the colonies. The Connecticut, Hudson, Delaware, and Susquehanna rivers in the North and the many smaller rivers in the South made it possible for goods to be brought from, and carried to, the interior regions in little sailing vessels with comparative ease. Sloops laden with manufactures, domestic and foreign, collected at some city like Providence, New York, or Philadelphia, skirted the coasts, visited small ports, and sailed up the navigable rivers to trade with local merchants who had for exchange the raw materials which they had gathered in from neighboring farms. Larger ships carried the grain, live stock, cloth, and hardware of New England to the Southern colonies, where they were traded for tobacco, leather, tar, and ship timber. From the harbors along the Connecticut shores there were frequent sailings down through Long Island Sound to Maryland, Virginia, and the distant Carolinas.

Growth of Towns.—In connection with this thriving trade and industry there grew up along the coast a number of prosperous commercial centers which were soon reckoned among the first commercial towns of the whole British empire, comparing favorably in numbers and wealth with such ports as Liverpool and Bristol. The statistical records of that time are mainly guesses; but we know that Philadelphia stood first in size among these towns. Serving as the port of entry for Pennsylvania, Delaware, and western Jersey, it had drawn within its borders, just before the Revolution, about 25,000 inhabitants. Boston was second in rank, with somewhat more than 20,000 people. New York, the "commercial capital of Connecticut and old East Jersey," was slightly smaller than Boston, but growing at a steady rate. The fourth town in size was Charleston, South Carolina, with about 10,000 inhabitants. Newport in Rhode Island, a center of rum manufacture and shipping, stood fifth, with a population of about 7000. Baltimore and Norfolk were counted as "considerable towns." In the interior, Hartford in Connecticut, Lancaster and York in Pennsylvania, and Albany in New York, with growing populations and increasing trade, gave prophecy of an urban America away from the seaboard. The other towns were straggling villages. Williamsburg, Virginia, for example, had about two hundred houses, in which dwelt a dozen families of the gentry and a few score of tradesmen. Inland county seats often consisted of nothing more than a log courthouse, a prison, and one wretched inn to house judges, lawyers, and litigants during the sessions of the court.

The leading towns exercised an influence on colonial opinion all out of proportion to their population. They were the centers of wealth, for one thing; of the press and political activity, for another. Merchants and artisans could readily take concerted action on public questions arising from their commercial operations. The towns were also centers for news, gossip, religious controversy, and political discussion. In the market places the farmers from the countryside learned of British policies and laws, and so, mingling with the townsmen, were drawn into the main currents of opinion which set in toward colonial nationalism and independence.

J. Bishop, History of American Manufactures (2 vols.).

E.L. Bogart, Economic History of the United States.

P.A. Bruce, Economic History of Virginia (2 vols.).

E. Semple, American History and Its Geographical Conditions.

W. Weeden, Economic and Social History of New England. (2 vols.).

1. Is land in your community parceled out into small farms? Contrast the system in your community with the feudal system of land tenure.

2. Are any things owned and used in common in your community? Why did common tillage fail in colonial times?

3. Describe the elements akin to feudalism which were introduced in the colonies.

4. Explain the success of freehold tillage.

5. Compare the life of the planter with that of the farmer.

6. How far had the western frontier advanced by 1776?

7. What colonial industry was mainly developed by women? Why was it very important both to the Americans and to the English?

8. What were the centers for iron working? Ship building?

9. Explain how the fisheries affected many branches of trade and industry.

10. Show how American trade formed a vital part of English business.

11. How was interstate commerce mainly carried on?

12. What were the leading towns? Did they compare in importance with British towns of the same period?

Land Tenure.—Coman, Industrial History (rev. ed.), pp. 32-38. Special reference: Bruce, Economic History of Virginia, Vol. I, Chap. VIII.

Tobacco Planting in Virginia.—Callender, Economic History of the United States, pp. 22-28.

Colonial Agriculture.—Coman, pp. 48-63. Callender, pp. 69-74. Reference: J.R.H. Moore, Industrial History of the American People, pp. 131-162.

Colonial Manufactures.—Coman, pp. 63-73. Callender, pp. 29-44. Special reference: Weeden, Economic and Social History of New England.

Colonial Commerce.—Coman, pp. 73-85. Callender, pp. 51-63, 78-84. Moore, pp. 163-208. Lodge, Short History of the English Colonies, pp. 409-412, 229-231, 312-314.