Title: The Tales of the Heptameron, Vol. 2 (of 5)

Author: King of Navarre consort of Henry II Queen Marguerite

Contributor: Le Roux de Lincy

Illustrator: Balthasar Anton Dunker

Sigmund Freudenberger

Translator: George Saintsbury

Release date: February 7, 2006 [eBook #17702]

Most recently updated: March 2, 2021

Language: English

Original publication: London: The Society of English Bibliophilists, 1894

Credits: Produced by David Widger

| Volume I. | Volume III. | Volume IV. | Volume V. |

Contents

List of Illustrations

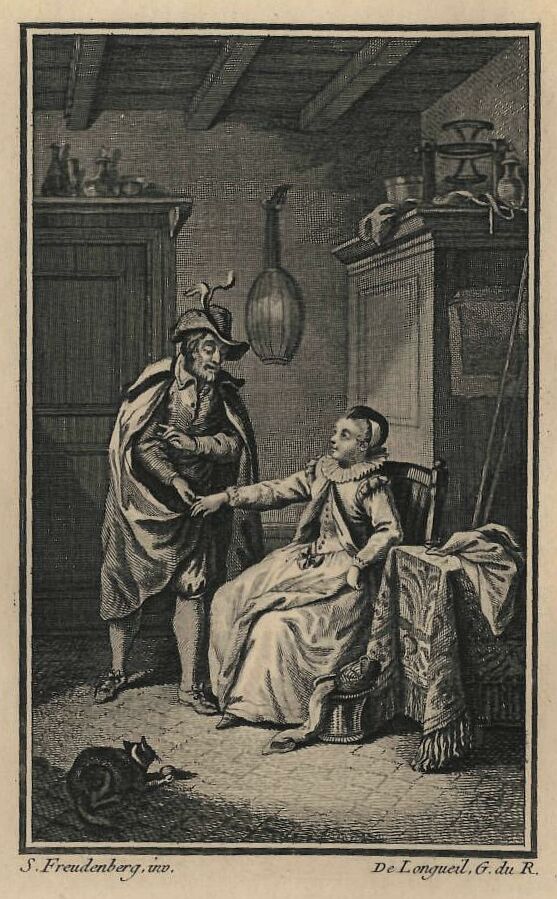

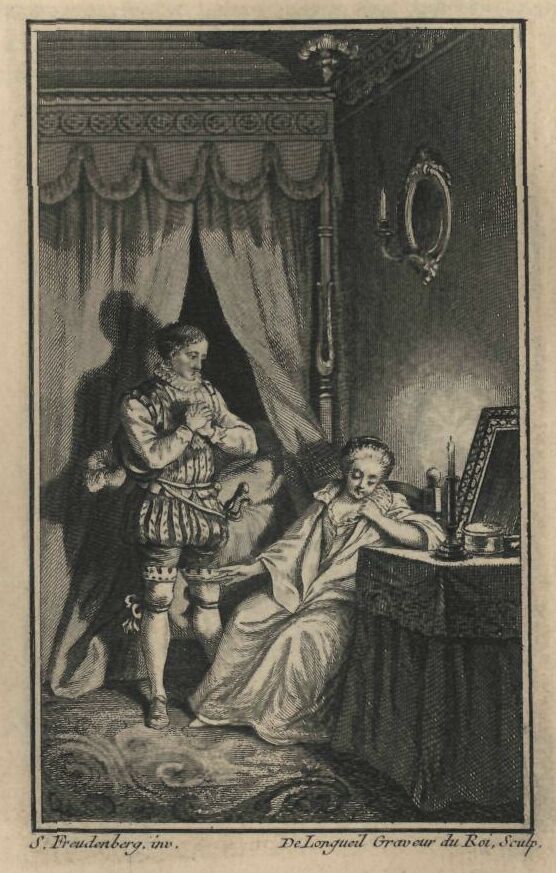

001a.jpg Bornet’s Concern on Discovering That his Wife Is Without Her Ring

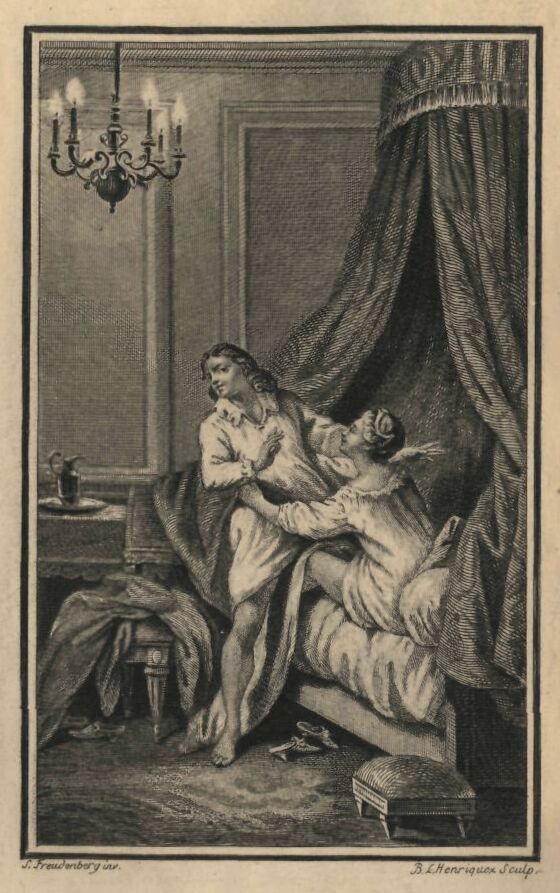

013a.jpg the Dying Gentleman Receiving The Embraces Of His Sweetheart

025a.jpg the Countess Asking an Explanation from Amadour

095a.jpg the Grey Friar Telling his Tales

101a.jpg the Gentleman Killing The Duke

119a.jpg the Sea-captain Talking to The Lady

141a.jpg Bonnivet and the Lady of Milan

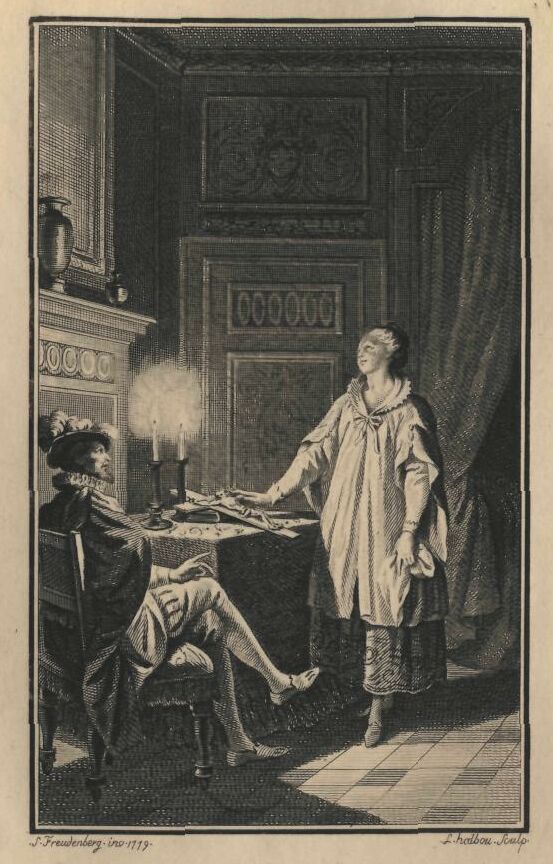

157a.jpg the Lady Taking Oath As to Her Conduct

183a.jpg the Gentleman Discovering The Trick

195a.jpg the King Showing his Sword

FIRST DAY—Continued.

Tale VIII. The misadventure of Bornet, who, planning with a friend of

his that both should lie with a serving-woman, discovers too late that

they have had to do with his own wife.

Tale IX. The evil fortune of a gentleman of Dauphiné, who dies of

despair because he cannot marry a damsel nobler and richer than himself.

Tale X. The Spanish story of Florida, who, after withstanding the love

of a gentleman named Amadour for many years, eventually becomes a nun.

SECOND DAY.

Prologue

Tale XI. (A). Mishap of the Lady de Roncex in the Grey Friars’ Convent

at Thouars.

Tale XI. (B). Facetious discourse of a Friar of Touraine.

Tale XII. Story of Alexander de’ Medici, Duke of Florence, whom his

cousin, Lorenzino de’ Medici, slew in order to save his sister’s honour.

Tale XIII. Praiseworthy artifice of a lady to whom a sea Captain sent

a letter and diamond ring, and who, by forwarding them to the Captain’s

wife as though they had been intended for her, united husband and wife

once more in all affection.

Tale XIV. The Lord of Bonnivet, after furthering the love entertained

by an Italian gentleman for a lady of Milan, finds means to take

the other’s place and so supplant him with the lady who had formerly

rejected himself.

Tale XV. The troubles and evil fortune of a virtuous lady who, after

being long neglected by her husband, becomes the object of his jealousy.

Tale XVI. Story of a Milanese Countess, who, after long rejecting the

love of a French gentleman, rewards him at last for his faithfulness,

but not until she has put his courage to the proof.

Tale XVII. The noble manner in which King Francis the First shows Count

William of Furstemberg that he knows of the plans laid by him against

his life, and so compels him to do justice upon himself and to leave

France.

Tale XVIII. A young gentleman scholar at last wins a lady’s love, after

enduring successfully two trials that she had made of him.

Appendix to Vol. II

A certain Bornet, less loyal to his wife than she to him,

desired to lie with his maidservant, and made his enterprise

known to a friend, who, hoping to share in the spoil, so

aided and abetted him, that whilst the husband thought to

lie with his servant he in truth lay with his wife. Unknown

to the latter, he then caused his friend to participate in

the pleasure which rightly belonged to himself alone, and

thus made himself a cuckold without there being any guilt on

the part of his wife. (1)

In the county of Alletz (2) there lived a man named Bornet, who being married to an upright and virtuous wife, had great regard for her honour and reputation, as I believe is the case with all the husbands here present in respect to their own wives. But although he desired that she should be true to him, he was not willing that the same law should apply to both, for he fell in love with his maid-servant, from whom he had nothing to gain save the pleasure afforded by a diversity of viands.

1 For a list of tales similar to this one, see post,

Appendix A.

2 Alletz, now Alais, a town of Lower Languedoc (department

of the Gard), lies on the Gardon, at the foot of the

Cevennes mountains. It was formerly a county, the title

having been held by Charles, Duke of Angoulême, natural son

of Charles IX.—M.

Now he had a neighbour of the same condition as his own, named Sandras, a tabourer (3) and tailor by trade, and there was such friendship between them that, excepting Bornet’s wife, they had all things in common. It thus happened that Bornet told his friend of the enterprise he had in hand against the maid-servant; and Sandras not only approved of it, but gave all the assistance he could to further its accomplishment, hoping that he himself might share in the spoil.

3 Tabourers are still to be found in some towns of Lower

Languedoc and in most of those of Provence, where they

perambulate the streets playing their instruments. They are

in great request at all the country weddings and other

festive gatherings, as their instruments supply the

necessary accompaniment to the ancient Provençal dance, the

farandole.—Ed.

The maid-servant, however, was loth to consent, and finding herself hard pressed, she went to her mistress, told her of the matter, and begged leave to go home to her kinsfolk, since she could no longer endure to live in such torment. Her mistress, who had great love for her husband and had often suspected him, was well pleased to have him thus at a disadvantage, and to be able to show that she had doubted him justly. Accordingly, she said to the servant—

“Remain, my girl, but lead my husband on by degrees, and at last make an appointment to lie with him in my closet. Do not fail to tell me on what night he is to come, and see that no one knows anything about it.”

The maid-servant did all that her mistress had commanded her, and her master in great content went to tell the good news to his friend. The latter then begged that, since he had been concerned in the business, he might have part in the result. This was promised him, and, when the appointed hour was come, the master went to lie, as he thought, with the maid-servant; but his wife, yielding up the authority of commanding for the pleasure of obeying, had put herself in the servant’s place, and she received him, not in the manner of a wife, but after the fashion of a frightened maid. This she did so well that her husband suspected nothing.

I cannot tell you which of the two was the better pleased, he at the thought that he was deceiving his wife, or she at really deceiving her husband. When he had remained with her, not as long as he wished, but according to his powers, which were those of a man who had long been married, he went out of doors, found his friend, who was much younger and lustier than himself, and told him gleefully that he had never met with better fortune. “You know what you promised me,” said his friend to him.

“Go quickly then,” replied the husband, “for she may get up, or my wife have need of her.”

The friend went off and found the supposed maid-servant, who, thinking her husband had returned, denied him nothing that he asked of her, or rather took, for he durst not speak. He remained with her much longer than her husband had done, whereat she was greatly astonished, for she had not been wont to pass such nights. Nevertheless, she endured it all with patience, comforting herself with the thought of what she would say to him on the morrow, and of the ridicule that she would cast upon him.

Towards daybreak the man rose from beside her, and toying with her as he was going away, snatched from her finger the ring with which her husband had espoused her, and which the women of that part of the country guard with great superstition. She who keeps it till her death is held in high honour, while she who chances to lose it, is thought lightly of as a person who has given her faith to some other than her husband.

The wife, however, was very glad to have it taken, thinking it would be a sure proof of how she had deceived her husband. When the friend returned, the husband asked him how he had fared. He replied that he was of the same opinion as himself, and that he would have remained longer had he not feared to be surprised by daybreak. Then they both went to the friend’s house to take as long a rest as they could. In the morning, while they were dressing, the husband perceived the ring that his friend had on his finger, and saw that it was exactly like the one he had given to his wife at their marriage. He thereupon asked his friend from whom he had received the ring, and when he heard he had snatched it from the servant’s finger, he was confounded and began to strike his head against the wall, saying—“Ah! good Lord! have I made myself a cuckold without my wife knowing anything about it?”

“Perhaps,” said his friend in order to comfort him, “your wife gives her ring into the maid’s keeping at night-time.”

The husband made no reply, but took himself home, where he found his wife fairer, more gaily dressed, and merrier than usual, like one who rejoiced at having saved her maid’s conscience, and tested her husband to the full, at no greater cost than a night’s sleep. Seeing her so cheerful, the husband said to himself—

“If she knew of my adventure she would not show me such a pleasant countenance.”

Then, whilst speaking to her of various matters, he took her by the hand, and on noticing that she no longer wore the ring, which she had never been accustomed to remove from her finger, he was quite overcome.

“What have you done with your ring?” he asked her in a trembling voice.

She, well pleased that he gave her an opportunity to say what she desired, replied—

“O wickedest of men! From whom do you imagine you took it? You thought it was from my maid-servant, for love of whom you expended more than twice as much of your substance as you ever did for me. The first time you came to bed I thought you as much in love as it was possible to be; but after you had gone out and were come back again, you seemed to be a very devil. Wretch! think how blind you must have been to bestow such praises on my person and lustiness, which you have long enjoyed without holding them in any great esteem. ‘Twas, therefore, not the maid-servant’s beauty that made the pleasure so delightful to you, but the grievous sin of lust which so consumes your heart and so clouds your reason that in the frenzy of your love for the servant you would, I believe, have taken a she-goat in a nightcap for a comely girl! Now, husband, it is time to amend your life, and, knowing me to be your wife, and an honest woman, to be as content with me as you were when you took me for a pitiful strumpet. What I did was to turn you from your evil ways, so that in your old age we might live together in true love and repose of conscience. If you purpose to continue your past life, I had rather be severed from you than daily see before my eyes the ruin of your soul, body, and estate. But if you will acknowledge the evil of your ways, and resolve to live in fear of God and obedience to His commandments, I will forget all your past sins, as I trust God will forget my ingratitude in not loving Him as I ought to do.”

If ever man was reduced to despair it was this unhappy husband. Not only had he abandoned this sensible, fair, and chaste wife for a woman who did not love him, but, worse than this, he had without her knowledge made her a strumpet by causing another man to participate in the leasure which should have been for himself alone; and thus he had made himself horns of everlasting derision. However, seeing his wife in such wrath by reason of the love he had borne his maid-servant, he took care not to tell her of the evil trick that he had played her; and entreating her forgiveness, with promises of full amendment of his former evil life, he gave her back the ring which he had recovered from his friend. He entreated the latter not to reveal his shame; but, as what is whispered in the ear is always proclaimed from the housetop, the truth, after a time, became known, and men called him cuckold without imputing any shame to his wife.

“It seems to me, ladies, that if all those who have committed like offences against their wives were to be punished in the same way, Hircan and Saffredent would have great cause for fear.”

“Why, Longarine,” said Saffredent, “are none in the company married save Hircan and I?”

“Yes, indeed there are others,” she replied, “but none who would play a similar trick.”

“Whence did you learn,” asked Saffredent, “that we ever solicited our wives’ maid-servants?”

“If the ladies who are in question,” said Longarine, “were willing to speak the truth, we should certainly hear of maid-servants dismissed without notice.”

“Truly,” said Geburon, “you are a most worthy lady! You promised to make the company laugh, and yet are angering these two poor gentlemen.”

“Tis all one,” said Longarine: “so long as they do not draw their swords, their anger will only serve to increase our laughter.”

“A pretty business indeed!” said Hircan. “Why, if our wives chose to believe this lady, she would embroil the seemliest household in the company.”

“I am well aware before whom I speak,” said Longarine. “Your wives are so sensible and bear you so much love, that if you were to give them horns as big as those of a deer, they would nevertheless try to persuade themselves and every one else that they were chaplets of roses.”

At this the company, and even those concerned, laughed so heartily that their talk came to an end. However, Dagoucin, who had not yet uttered a word, could not help saying—

“Men are very unreasonable when, having enough to content themselves with at home, they go in search of something else. I have often seen people who, not content with sufficiency, have aimed at bettering themselves, and have fallen into a worse position than they were in before. Such persons receive no pity, for fickleness is always blamed.”

“But what say you to those who have not found their other half?” asked Simontault. “Do you call it fickleness to seek it wherever it may be found?”

“Since it is impossible,” said Dagoucin, “for a man to know the whereabouts of that other half with whom there would be such perfect union that one would not differ from the other, he should remain steadfast wherever love has attached him. And whatsoever may happen, he should change neither in heart nor in desire. If she whom you love be the image of yourself, and there be but one will between you, it is yourself you love, and not her.”

“Dagoucin,” said Hircan, “you are falling into error. You speak as though we should love women without being loved in return.”

“Hircan,” replied Dagoucin, “I hold that if our love be based on the beauty, grace, love, and favour of a woman, and our purpose be pleasure, honour, or profit, such love cannot long endure; for when the foundation on which it rests is gone, the love itself departs from us. But I am firmly of opinion that he who loves with no other end or desire than to love well, will sooner yield up his soul in death than suffer his great love to leave his heart.”

“In faith,” said Simontault, “I do not believe that you have ever been in love. If you had felt the flame like other men, you would not now be picturing to us Plato’s Republic, which may be described in writing but not be put into practice.”

“Nay, I have been in love,” said Dagoucin, “and am so still, and shall continue so as long as I live. But I am in such fear lest the manifestation of this love should impair its perfection, that I shrink from declaring it even to her from whom I would fain have the like affection. I dare not even think of it lest my eyes should reveal it, for the more I keep my flame secret and hidden, the more does my pleasure increase at knowing that my love is perfect.”

“For all that,” said Geburon, “I believe that you would willingly have love in return.”

“I do not deny it,” said Dagoucin, “but even were I beloved as much as I love, my love would not be increased any more than it could be lessened, were it not returned with equal warmth.”

Upon this Parlamente, who suspected this fantasy of Dagoucin’s, said—

“Take care, Dagoucin; I have known others besides you who preferred to die rather than speak.”

“Such persons, madam;” said Dagoucin, “I deem very happy.”

“Doubtless,” said Saffredent, “and worthy of a place among the innocents of whom the Church sings:

‘Non loquendo sed moriendo confessi sunt.’ (4)

4 From the ritual for the Feast of the Holy Innocents.—M.

I have heard much of such timid lovers, but I have never yet seen one die. And since I myself have escaped death after all the troubles I have borne, I do not think that any one can die of love.”

“Ah, Saffredent!” said Dagoucin, “how do you expect to be loved since those who are of your opinion never die? Yet have I known a goodly number who have died of no other ailment than perfect love.”

“Since you know such stories,” said Longarine, “I give you my vote to tell us a pleasant one, which shall be the ninth of to-day.”

“To the end,” said Dagoucin, “that signs and miracles may lead you to put faith in what I have said, I will relate to you something which happened less than three years ago.”

The perfect love borne by a gentleman to a damsel, being too deeply concealed and disregarded, brought about his death, to the great regret of his sweetheart.

Between Dauphiné and Provence there lived a gentleman who was far richer in virtue, comeliness, and honour than in other possessions, and who was greatly in love with a certain damsel. I will not mention her name, out of consideration for her kinsfolk, who are of good and illustrious descent; but you may rest assured that my story is a true one. As he was not of such noble birth as herself, he durst not reveal his affection, for the love he bore her was so great and perfect that he would rather have died than have desired aught to her dishonour. Seeing that he was so greatly beneath her, he had no hope of marrying her; in his love, therefore, his only purpose was to love her with all his strength and as perfectly as he was able. This he did for so long a time that at last she had some knowledge of it; and, seeing that the love he bore her was so full of virtue and of good intent, she felt honoured by it, and showed him in turn so much favour that he, who sought nothing better than this, was well contented.

But malice, which is the enemy of all peace, could not suffer this honourable and happy life to last, and certain persons spoke to the maiden’s mother of their amazement at this gentleman being thought so much of in her house. They said that they suspected him of coming there more on account of her daughter than of aught else, adding that he had often been seen in converse with her. The mother, who doubted the gentleman’s honour as little as that of any of her own children, was much distressed on hearing that his presence was taken in bad part, and, dreading lest malicious tongues should cause a scandal, she entreated that he would not for some time frequent her house as he had been wont to do. He found this hard to bear, for he knew that his honourable conversation with her daughter did not deserve such estrangement. Nevertheless, in order to silence evil gossip, he withdrew until the rumours had ceased; then he returned as before, his absence having in no wise lessened his love.

One day, however, whilst he was in the house, he heard some talk of marrying the damsel to a gentleman who did not seem to him to be so very rich that he should be entitled to take his mistress from him. So he began to pluck up courage, and engaged his friends to speak for him, believing that, if the choice were left to the damsel, she would prefer him to his rival. Nevertheless, the mother and kinsfolk chose the other suitor, because he was much richer; whereupon the poor gentleman, knowing his sweetheart to be as little pleased as himself, gave way to such sorrow, that by degrees, and without any other distemper, he became greatly changed, seeming as though he had covered the comeliness of his face with the mask of that death, to which hour by hour he was joyously hastening.

Meanwhile, he could not refrain from going as often as was possible to converse with her whom he so greatly loved. But at last, when strength failed him, he was constrained to keep his bed; yet he would not have his sweetheart know of this, lest he should cast part of his grief on her. And giving himself up to despair and sadness, he was no longer able to eat, drink, sleep, or rest, so that it became impossible to recognise him by reason of his leanness and strangely altered features.

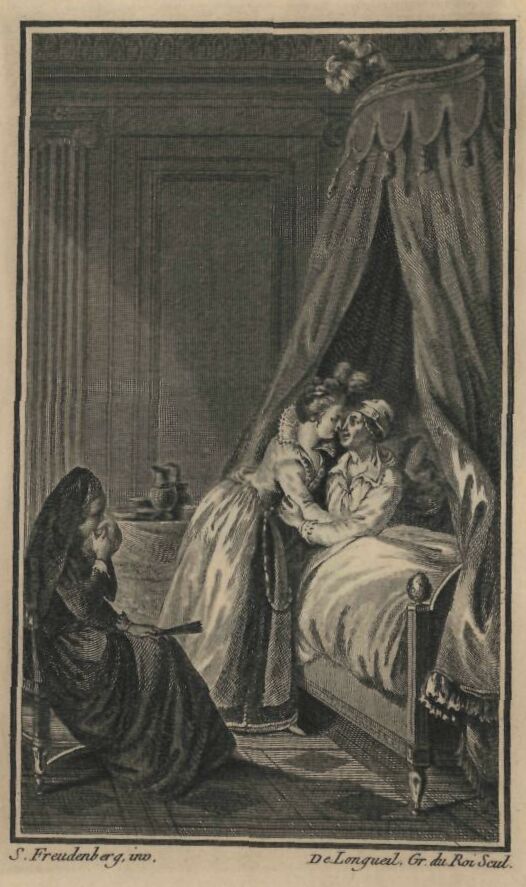

Some one brought the news of this to his sweetheart’s mother, who was a lady full of charity, and who had, moreover, such a liking for the gentleman, that if all the kinsfolk had been of the same opinion as herself and her daughter, his merits would have been preferred to the possessions of the other. But the kinsfolk on the father’s side would not hear of it. However, the lady went with her daughter to see the unhappy gentleman, and found him more dead than alive. Perceiving that the end of his life was at hand, he had that morning confessed and received the Holy Sacrament, thinking to die without seeing anybody more. But although he was at death’s door, when he saw her who for him was the resurrection and the life come in, he felt so strengthened that he started up in bed.

“What motive,” said he to the lady, “has inclined you to come and see one who already has a foot in the grave, and of whose death you are yourself the cause?”

“How is it possible,” said the lady, “that the death of one whom we like so well can be brought about by our fault? Tell me, I pray, why you speak in this manner?”

“Madam,” he replied, “I concealed my love for your daughter as long as I was able; and my kinsfolk, in speaking of a marriage between myself and her, made known more than I desired, since I have thereby had the misfortune to lose all hope; not, indeed, in regard to my own pleasure, but because I know that she will never have such fair treatment and so much love from any other as she would have had from me. Her loss of the best and most loving friend she has in the world causes me more affliction than the loss of my own life, which I desired to preserve for her sake only. But since it cannot in any wise be of service to her, the loss of it is to me great gain.”

Hearing these words, the lady and her daughter sought to comfort him.

“Take courage, my friend,” said the mother. “I pledge you my word that, if God gives you back your health, my daughter shall have no other husband but you. See, she is here present, and I charge her to promise you the same.”

The daughter, weeping, strove to assure him of what her mother promised. He well knew, however, that even if his health were restored he would still lose his sweetheart, and that these fair words were only uttered in order somewhat to revive him. Accordingly, he told them that had they spoken to him thus three months before, he would have been the lustiest and happiest gentleman in France; but that their aid came so late, it could bring him neither belief nor hope. Then, seeing that they strove to make him believe them, he said—

“Well, since, on account of my feeble state, you promise me a blessing which, even though you would yourselves have it so, can never be mine, I will entreat of you a much smaller one, for which, however, I was never yet bold enough to ask.”

They immediately vowed that they would grant it, and bade him ask boldly.

“I entreat you,” he said, “to place in my arms her whom you promise me for my wife, and to bid her embrace and kiss me.”

The daughter, who was unaccustomed to such familiarity, sought to make some difficulty, but her mother straightly commanded her, seeing that the gentleman no longer had the feelings or vigour of a living man. Being thus commanded, the girl went up to the poor sufferer’s bedside, saying—

“I pray you, sweetheart, be of good cheer.”

Then, as well as he could, the dying man stretched forth his arms, wherein flesh and blood alike were lacking, and with all the strength remaining in his bones embraced her who was the cause of his death. And kissing her with his pale cold lips, he held her thus as long as he was able. Then he said to her—

“The love I have borne you has been so great and honourable, that, excepting in marriage, I have never desired of you any other favour than the one you are granting me now, for lack of which and with which I shall cheerfully yield up my spirit to God. He is perfect love and charity. He knows the greatness of my love and the purity of my desire, and I beseech Him, while I hold my desire within my arms, to receive my spirit into His own.”

With these words he again took her in his arms, and with such exceeding ardour that his enfeebled heart, unable to endure the effort, was deprived of all its faculties and life; for joy caused it so to swell that the soul was severed from its abode and took flight to its Creator.

And even when the poor body had lain a long time without life, and was thus unable to retain its hold, the love which the damsel had always concealed was made manifest in such a fashion that her mother and the dead man’s servants had much ado to separate her from her lover. However, the girl, who, though living, was in a worse condition than if she had been dead, was by force removed at last out of the gentleman’s arms. To him they gave honourable burial; and the crowning point of the ceremony was the weeping and lamentation of the unhappy damsel, who having concealed her love during his lifetime, made it all the more manifest after his death, as though she wished to atone for the wrong that she had done him. And I have heard that although she was given a husband to comfort her, she has never since had joy in her heart. (1)

1 By an expression made use of by Dagoucin (see ante),

Queen Margaret gives us to understand that the incidents

here related occurred three years prior to the writing of

the story. It may be pointed out, however, that there is

considerable analogy between the conclusion of this tale and

the death of Geffroy Rudel de Blaye, one of the earliest

troubadours whose name has been handed down to us. Geffroy,

who lived at the close of the twelfth century, became so

madly enamoured of the charms of the Countess of Tripoli,

after merely hearing an account of her moral and physical

perfections, that, although in failing health, he embarked

for Africa to see her. On reaching the port of Tripoli, he

no longer had sufficient strength to leave the vessel,

whereupon the Countess, touched by his love, visited him on

board, taking his hand and giving him a kindly greeting.

Geffroy could scarcely say a few words of thanks; his

emotion was so acute that he died upon the spot. See J. de

Nostredame’s Vies des plus Célèbres et Anciens Poëtes

Provençaux(Lyons, 1575, p. 25); Raynouard’s Choix des

Poésies des Troubadours (vol. v. p. 165); and also

Raynouard’s Histoire Littéraire de la France (vol. xiv. p.

559).—L.

“What think you of that, gentlemen, you who would not believe what I said? Is not this example sufficient to make you confess that perfect love, when concealed and disregarded, may bring folks to the grave? There is not one among you but knows the kinsfolk on the one and the other side, (2) and so you cannot doubt the story, although nobody would be disposed to believe it unless he had some experience in the matter.”

2 This certainly points to the conclusion that the tale is

founded upon fact, and not, as M. Leroux de Lincy suggests,

borrowed from the story of Geffroy Rudel de Blaye. It will

have been observed (ante) that the Queen of Navarre

curiously enough lays the scene of her narrative between

Provence and Dauphiné. These two provinces bordered upon one

another, excepting upon one point where they were separated

by the so-called Comtat Venaissin or Papal state of Avignon.

Here, therefore, the incidents of the story, if authentic,

would probably have occurred. The story may be compared with

Tale L. (post).—Ed.

When the ladies heard this they all had tears in their eyes, but Hircan said to them—

“He was the greatest fool I ever heard of. By your faith, now, I ask you, is it reasonable that we should die for women who are made only for us, or that we should be afraid to ask them for what God has commanded them to give us? I do not speak for myself nor for any who are married. I myself have all that I want or more; but I say it for such men as are in need. To my thinking, they must be fools to fear those whom they should rather make afraid. Do you not perceive how greatly this poor damsel regretted her folly? Since she embraced the gentleman’s dead body—an action repugnant to human nature—she would not have refused him while he was alive had he then trusted as much to boldness as he trusted to pity when he lay upon his death-bed.”

“Nevertheless,” said Oisille, “the gentleman most plainly showed that he bore her an honourable love, and for this he will ever be worthy of all praise. Chastity in a lover’s heart is something divine rather than human.”

“Madam,” said Saffredent, “in support of Hircan’s opinion, which is also mine, I pray you believe that Fortune favours the bold, and that there is no man loved by a lady but may at last, in whole or in part, obtain from her what he desires, provided he seek it with wisdom and passion. But ignorance and foolish fear cause men to lose many a good chance; and then they impute their loss to their mistress’s virtue, which they have never verified with so much as the tip of the finger. A fortress was never well assailed but it was taken.”

“Nay,” said Parlamente, “I am amazed that you two should dare to talk in this way. Those whom you have loved owe you but little thanks, or else your courting has been carried on in such evil places that you deem all women to be alike.”

“For myself, madam,” said Saffredent, “I have been so unfortunate that I am unable to boast; but I impute my bad luck less to the virtue of the ladies than to my own fault, in not conducting my enterprises with sufficient prudence and sagacity. In support of my opinion I will cite no other authority than the old woman in the Romance of the Rose, who says—

‘Of all, fair sirs, it truly may be said,

Woman for man and man for woman’s made.’ (3)

3 From John de Mehun’s continuation of the poem.—M. 2

Accordingly I shall always believe that if love once enters a woman’s heart, her lover will have fair fortune, provided he be not a simpleton.”

“Well,” said Parlamente, “if I were to name to you a very loving woman who was greatly sought after, beset and importuned, and who, like a virtuous lady, proved victorious over her heart, flesh, love and lover, would you believe this true thing possible?”

“Yes,” said he, “I would.”

“Then,” said Parlamente, “you must all be hard of belief if you do not believe this story.”

“Madam,” said Dagoucin, “since I have given an example to show how the love of a virtuous gentleman lasted even until death, I pray you, if you know any such story to the honour of a lady, to tell it to us, and so end this day. And be not afraid to speak at length, for there is yet time to relate many a pleasant matter.”

“Then, since I am to wind up the day,” said Parlamente, “I will make no long preamble, for my story is so beautiful and true that I long to have you know it as well as I do myself. Although I was not an actual witness of the events, they were told to me by one of my best and dearest friends in praise of the man whom of all the world he had loved the most. But he charged me, should I ever chance to relate them, to change the names of the persons. Apart, therefore, from the names of persons and places the story is wholly true.”

Florida, after virtuously resisting Amadour, who had assailed her honour almost to the last extremity, repaired, upon her husbands death, to the convent of Jesus, and there took the veil. (1)

1 This tale appears to be a combination of fact and fiction.

Although Queen Margaret states that she has changed the

names of the persons, and also of the places where the

incidents happened, several historical events are certainly

brought into the narrative, the scene of which is laid in

Spain during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella. M. Le Roux

de Lincy is of opinion, however, that Margaret really refers

to some affair at the Court of Charles VIII. or Louis XII.,

and he remarks that there is great similarity between the

position of the Countess of Aranda, left a widow at an early

age with a son and a daughter, and that of Louise of Savoy

with her two children. M. Lacroix and M. Dillaye believe the

hero and heroine to be Admiral de Bonnivet and Margaret. It

has often been suspected that the latter regarded her

brother’s favourite with affection until after the attempt

related in Tale IV.—Ed.

In the county of Aranda, (2) in Aragon, there lived a lady who, while still very young, was left a widow, with a son and a daughter, by the Count of Aranda, the name of the daughter being Florida. This lady strove to bring up her children in all the virtues and qualities which beseem lords and gentlemen, so that her house was reputed to be one of the most honourable in all the Spains. She often went to Toledo, where the King of Spain dwelt, and when she came to Saragossa, which was not far from her house, she would remain a long while with the Queen and the Court, by whom she was held in as high esteem as any lady could be.

2 Aranda, in the valley of the Duero, between Burgos

and Madrid, is one of the most ancient towns in Spain, but of

miserable aspect, although a large trade is carried on there

in cheap red wines. (Ferdinand and Isabella resided for some

time at Aranda.—Ed.)

Going one day, according to her custom, to visit the King, then at his castle of La Jasserye, (3) at Saragossa, this lady passed through a village belonging to the Viceroy of Catalonia, (4) who, by reason of the great wars between the kings of France and Spain, had not been wont to stir from the frontier at Perpignan. But for the time being there was peace, so that the Viceroy and all his captains had come to do homage to the King. The Viceroy, learning that the Countess of Aranda was passing through his domain, went to meet her, not only for the sake of the ancient friendship he bore her, but in order to do her honour as a kinswoman of the King’s.

3 This castle is called La Jafferie in Boaistuau’s edition

of 1558, and several learned commentators have speculated as

to which is the correct spelling. Not one of them seems to

have been aware that in the immediate vicinity of Saragossa

there still stands an old castle called El Jaferia or

Aljaferia, which, after being the residence of the Moorish

sovereigns, became that of the Spanish kings of Aragon. It

has of modern times been transformed into barracks.—Ed.

4 Henry of Aragon, Duke of Segorbe and Count of Ribagorce,

was Viceroy of Catalonia at this period. He was called the

Infante of Fortune, on account of his father having died

before his birth in 1445.—B. J.

Now he had in his train many honourable gentlemen, who, in the long waging of war, had gained such great honour and renown that all who saw them and consorted with them deemed themselves fortunate. Among others there was one named Amadour, who, although but eighteen or nineteen years old, was possessed of such well-assured grace and of such excellent understanding that he would have been chosen from a thousand to hold a public office. It is true that this excellence of understanding was accompanied by such rare and winsome beauty that none could look at him without pleasure. And if his comeliness was of the choicest, it was so hard pressed by his speech that one knew not whether to give the greatest honour to his grace, his beauty, or the excellence of his conversation.

What caused him, however, to be still more highly esteemed was his great daring, which was no whit diminished by his youth. He had already shown in many places what he could do, so that not only the Spains, but France and Italy also made great account of his merits. For in all the wars in which he had taken part he had never spared himself, and when his country was at peace he would go in quest of wars in foreign lands, where he was loved and honoured by both friend and foe.

This gentleman, for the love he bore his commander, had come to the domain where the Countess of Aranda had arrived, and remarking the beauty and grace of her daughter Florida, who was then only twelve years old, he thought to himself that she was the fairest maiden he had ever seen, and that if he could win her favour it would give him greater satisfaction than all the wealth and pleasure he might obtain from another. After looking at her for a long time he resolved to love her, although his reason told him that what he desired was impossible by reason of her lineage as well as of her age, which was such that she could not yet understand any amorous discourse. In spite of this, he fortified himself with hope, and reflected that time and patience might bring his efforts to a happy issue. And from that moment the kindly love, which of itself alone had entered Amadour’s heart, assured him of all favour and the means of attaining his end.

To overcome the greatest difficulty before him, which consisted in the remoteness of his own home and the few opportunities he would have of seeing Florida again, he resolved to get married. This was contrary to what he had determined whilst with the ladies of Barcelona and Perpignan, in which places he was in such favour that little or nothing was refused him; and, indeed, by reason of the wars, he had dwelt so long on the frontiers that, although he was born near Toledo, he seemed rather a Catalan than a Castillan. He came of a rich and honourable house, but being a younger son, he was without patrimony; and thus it was that Love and Fortune, seeing him neglected by his kin, determined to make him their masterpiece, endowing him with such qualities as might obtain what the laws of the land had refused him. He was of much experience in the art of war, and was so beloved by all lords and princes that he refused their favours more frequently than he had occasion to seek them.

The Countess, of whom I have spoken, arrived then at Saragossa and was well received by the King and all his Court. The Governor of Catalonia often came to visit her, and Amadour failed not to accompany him that he might have the pleasure of merely seeing Florida, for he had no opportunity of speaking with her. In order to establish himself in this goodly company he paid his addresses to the daughter of an old knight, his neighbour. This maiden was named Avanturada, and was so intimate with Florida that she knew all the secrets of her heart. Amadour, as much for the worth which he found in Avanturada as for the three thousand ducats a year which formed her dowry, determined to address her as a suitor, and she willingly gave ear to him. But as he was poor and her father was rich, she feared that the latter would never consent to the marriage except at the instance of the Countess of Aranda. She therefore had recourse to the lady Florida and said to her—

“You have seen, madam, that Castilian gentleman who often talks to me. I believe that all his aim is to have me in marriage. You know, however, what kind of father I have; he will never consent to the match unless he be earnestly entreated by the Countess and you.”

Florida, who loved the damsel as herself, assured her that she would lay the matter to heart as though it were for her own benefit; and Avanturada then ventured so far as to present Amadour to her. He was like to swoon for joy on kissing Florida’s hand, and although he was accounted the readiest speaker in Spain, yet in her presence he became dumb. At this she was greatly surprised, for, although she was only twelve years old, she had already often heard it said that there was no man in Spain who could speak better or with more grace. So, finding that he said nothing to her, she herself spoke.

“Senor Amadour,” she began, “the renown you enjoy throughout all the Spains has made you known to everybody here, and all are desirous of affording you pleasure. If therefore I can in any way do this, you may dispose of me.”

Amadour was in such rapture at sight of the lady’s beauty that he could scarcely utter his thanks. However, although Florida was astonished to find that he made no further reply, she imputed it rather to some whim than to the power of love; and so she withdrew, without saying anything more.

Amadour, who perceived the qualities which even in earliest youth were beginning to show themselves in Florida, now said to her whom he desired to marry—

“Do not be surprised if I lost the power of utterance in presence of the lady Florida. I was so astonished at finding such qualities and such sensible speech in one so very young that I knew not what to say to her. But I pray you, Avanturada, you who know her secrets, tell me if she does not of necessity possess the hearts of all the gentlemen of the Court. Any who know her and do not love her must be stones or brutes.”

Avanturada, who already loved Amadour more than any other man in the world, could conceal nothing from him, but told him that Florida was loved by every one. However, by reason of the custom of the country, few spoke to her, and only two had as yet made any show of love towards her. These were two princes of Spain, and they desired to marry her, one being the son of the Infante of Fortune (5) and the other the young Duke of Cardona. (6)

5 M. Lacroix asserts that the Infante of Fortune left no son

by his wife, Guyomare de Castro y Norogna; whereas M. Le

Roux de Lincy contends that he had a son—Alfonso of Aragon—

who in 1506 was proposed as a husband for Crazy Jane.

Alfonso would therefore probably be the prince referred to

by Margaret.—Ed.

6 Cardona, a fortified town on the river Cardoner, at a few

miles from Barcelona, was a county in the time of Ferdinand

and Isabella, and was raised by them to the rank of a duchy

in favour of Ramon Folch I. To-day it has between two and

three thousand inhabitants, and is chiefly noted for its

strongly built castillo. The young Duke spoken of by Queen

Margaret would be Ramon Folch’s son, who was also named

Ramon.—B. J. and Ed.

“I pray you,” said Amadour, “tell me which of them you think she loves the most.”

“She is so discreet,” said Avanturada, “that on no account would she confess to having any wish but her mother’s. Nevertheless, as far as can be judged, she likes the son of the Infante of Fortune far more than she likes the young Duke of Cardona. But her mother would rather have her at Cardona, for then she would not be so far away. I hold you for a man of good understanding, and, if you are so minded, you may judge of her choice this very day, for the son of the Infante of Fortune, who is one of the handsomest and most accomplished princes in Christendom, is being brought up at this Court. If we damsels could decide the marriage by our opinions, he would be sure of having the Lady Florida, for they would make the comeliest couple in all Spain. You must know that, although they are both young, she being but twelve and he but fifteen, it is now three years since their love for each other first began; and if you would secure her favour, I advise you to become his friend and follower.”

Amadour was well pleased to find that Florida loved something, hoping that in time he might gain the place not of husband but of lover. He had no fear in regard to her virtue, but was rather afraid lest she should be insensible to love. After this conversation he began to consort with the son of the Infante of Fortune, and readily gained his favour, being well skilled in all the pastimes that the young Prince was fond of, especially in the handling of horses, in the practice of all kinds of weapons, and indeed in every diversion and pastime befitting a young man.

However, war broke out again in Languedoc, and it was necessary that Amadour should return thither with the Governor. This he did, but not without great regret, since he could in no wise contrive to return to where he might see Florida. Accordingly, when he was setting forth, he spoke to a brother of his, who was majordomo to the Queen of Spain, and told him of the good match he had found in the Countess of Aranda’s house, in the person of Avanturada; entreating him, in his absence, to do all that he could to bring about the marriage, by employing his credit with the King, the Queen, and all his friends. The majordomo, who was attached to his brother, not only by reason of their kinship, but on account of Amadour’s excellent qualities, promised to do his best. This he did in such wise that the avaricious old father forgot his own nature to ponder over the qualities of Amadour, as pictured to him by the Countess of Aranda, and especially by the fair Florida, as well as by the young Count of Aranda, who was now beginning to grow up, and to esteem people of merit. When the marriage had been agreed upon by the kinsfolk, the Queen’s majordomo sent for his brother, there being at that time a truce between the two kings. (7)

Meanwhile, the King of Spain withdrew to Madrid to avoid the bad air which prevailed in divers places, and, by the advice of his Council, as well as at the request of the Countess of Aranda, he consented to the marriage of the young Count with the heiress Duchess of Medina Celi. (8) He did this no less for their contentment and the union of the two houses than for the affection he bore the Countess of Aranda; and he caused the marriage to be celebrated at the castle of Madrid. (9)

7 There had been a truce in 1497, but Queen Margaret

probably alludes to that of four months’ duration towards

the close of 1503.—B.J.

8 Felix-Maria, widow of the Duke of Feria, and elder sister

of Luis Francisco de la Cerda, ninth of the name. She became

heiress to the titles and estates of the house of Medina-

Celi upon her brother’s death. If, however, Queen Margaret

is really describing some incident in her own life, she must

refer to Louis XII.‘s daughter, Claude, married in 1514 to

Francis I.—D.

9 The castle here referred to was the Moorish Alcazar,

destroyed by fire in 1734. The previous statement that King

Ferdinand withdrew to Madrid on account of the bad air

prevailing in other places is borne out by the fact that the

town enjoyed a most delightful climate prior to the

destruction of the forests which surrounded it.—Ed.

Amadour was present at this wedding, and succeeded so well in furthering his own union, that he married Avanturada, whose affection for him was far greater than his was for her. But this marriage furnished him with a very convenient cloak, and gave him an excuse for resorting to the place where his spirit ever dwelt. After he was married he became very bold and familiar in the Countess of Aranda’s household, so that he was no more distrusted than if he had been a woman. And although he was now only twenty-two years of age, he showed such good sense that the Countess of Aranda informed him of all her affairs, and bade her son consult with him and follow his counsel.

Having gained their esteem thus far, Amadour comported himself so prudently and calmly that even the lady he loved was not aware of his affection for her. By reason, however, of the love she bore his wife, to whom she was more attached than to any other woman, she concealed none of her thoughts from him, and was pleased to tell him of all her love for the son of the Infante of Fortune. Although Amadour’s sole aim was to win her entirely for himself, he continually spoke to her of the Prince; indeed, he cared not what might be the subject of their converse, provided only that he could talk to her for a long time. However, he had not remained a month in this society after his marriage when he was constrained to return to the war, and he was absent for more than two years without returning to see his wife, who continued to live in the place where she had been brought up.

Meanwhile Amadour often wrote to her, but his letters were for the most part messages to Florida, who on her side never failed to return them, and would with her own hand add some pleasant words to the letters which Avanturada wrote. It was on this account that the husband of the latter wrote to her very frequently; yet of all this Florida knew nothing except that she loved Amadour as if he had been her brother. Several times during the course of five years did Amadour return and go away again; yet so short was his stay that he did not see Florida for two months altogether. Nevertheless, in spite of distance and length of absence, his love continued to increase.

At last it happened that he made a journey to see his wife, and found the Countess far removed from the Court, for the King of Spain was gone into Andalusia, (10) taking with him the young Count of Aranda, who was already beginning to bear arms.

10 There had been a revolt at Granada in 1499, and in the

following year the Moors rose in the Alpujarras, whereupon

King Ferdinand marched against them in person.—L.

Thus the Countess had withdrawn to a country-house belonging to her on the frontiers of Aragon and Navarre. She was well pleased on seeing Amadour, who had now been away for nearly three years. He was made welcome by all, and the Countess commanded that he should be treated like her own son. Whilst he was with her she informed him of all the affairs of her household, leaving most of them to his judgment. And so much credit did he win in her house that wherever he visited all doors were opened to him, and, indeed, people held his prudence in such high esteem that he was trusted in all things as though he had been an angel or a saint.

Florida, by reason of the love she bore his wife and himself, sought him out wherever he went. She had no suspicion of his purpose, and was unrestrained in her manners, for her heart was free from love, save that she felt great contentment whenever she was near Amadour. To more than this she gave not a thought.

Amadour, however, had a hard task to escape the observation of those who knew by experience how to distinguish a lover’s looks from another man’s; for when Florida, thinking no evil, came and spoke familiarly to him, the fire that was hidden in his heart so consumed him that he could not keep the colour from rising to his face or sparks of flame from darting from his eyes. Thus, in order that none might be any the wiser, he began to pay court to a very beautiful lady named Paulina, a woman so famed for beauty in her day that few men who saw her escaped from her toils.

This Paulina had heard how Amadour had made love at Barcelona and Perpignan, insomuch that he had gained the affection of the highest and most beautiful ladies in the land, especially that of a certain Countess of Palamos, who was esteemed the first for beauty among all the ladies of Spain; and she told him that she greatly pitied him, since, after so much good fortune, he had married such an ugly wife. Amadour, who well understood by these words that she had a mind to supply his need, made her the fairest speeches he could devise, seeking to conceal the truth by persuading her of a falsehood. But she, being subtle and experienced in love, was not to be put off with mere words; and feeling sure that his heart was not to be satisfied with such love as she could give him, she suspected he wished to make her serve as a cloak, and so kept close watch upon his eyes. These, however, knew so well how to dissemble, that she had nothing to guide her but the barest suspicion.

Nevertheless, her observation sorely troubled Amadour; for Florida, who was ignorant of all these wiles, often spoke to him before Paulina in such a familiar fashion that he had to make wondrous efforts to compel his eyes to belie his heart. To avoid unpleasant consequences, he one day, while leaning against a window, spoke thus to Florida—

“I pray you, sweetheart, counsel me whether it is better for a man to speak or die?”

Florida forthwith replied—

“I shall always counsel my friends to speak and not to die. There are few words that cannot be mended, but life once lost can never be regained.”

“Will you promise me, then,” said Amadour, “that you will not be displeased by what I wish to tell you, nor yet alarmed at it, until you have heard me to the end?”

“Say what you will,” she replied; “if you alarm me, none can reassure me.”

“For two reasons,” he then began, “I have hitherto been unwilling to tell you of the great affection that I feel for you. First, I wished to prove it to you by long service, and secondly, I feared that you might deem it presumption in me, who am but a simple gentleman, to address myself to one upon whom it is not fitting that I should look. And even though I were of royal station like your own, your heart, in its loyalty, would suffer none save the son of the Infante of Fortune, who has won it, to speak to you of love. But just as in a great war necessity compels men to devastate their own possessions and to destroy their corn in the blade, that the enemy may derive no profit therefrom, so do I risk anticipating the fruit which I had hoped to gather in season, lest your enemies and mine profit by it to your detriment. Know, then, that from your earliest youth I have devoted myself to your service and have ever striven to win your favour. For this purpose alone I married her whom I thought you loved best, and, being acquainted with the love you bear to the son of the Infante of Fortune, I have striven to serve him and consort with him, as you yourself know. I have sought with all my power for everything that I thought could give you pleasure. You see that I have won the esteem of your mother, the Countess, and of your brother, the Count, and of all you love, so that I am regarded here, not as a dependant, but as one of the family. All my efforts for five years past have had no other end than that I might spend my whole life near you.

“Understand that I am not one of those who would by these means seek to obtain from you any favour or pleasure otherwise than virtuous. I know that I cannot marry you, and even if I could, I would not do so in face of the love you bear him whom I would fain see your husband. And as for loving you with a vicious love like those who hope that long service will bring them a reward to the dishonour of a lady, that is far from my purpose. I would rather see you dead than know that you were less worthy of being loved, or that your virtue had diminished for the sake of any pleasure to me. For the end and reward of my service I ask but one thing, namely, that you will be so faithful a mistress to me, as never to take your favour from me, and that you will suffer me to continue as I now am, trusting in me more than in any other, and accepting from me the assurance that if for your honour’s sake, or for aught concerning you, you ever have need of a gentleman’s life, I will gladly place mine at your disposal. You may be sure also that whatever I may do that is honourable and virtuous, will be done solely for love of you. If for the sake of ladies less worthy than you I have ever done anything that has been considered of account, be sure that, for a mistress like yourself, my enterprise will so increase, that things I heretofore found impossible will become very easy to me. If, however, you will not accept me as wholly yours, I am resolved to lay aside my arms and to renounce the valour which has failed to help me in my need. So I pray you grant me my just request, for your honour and conscience cannot refuse it.”

The maiden, hearing these unwonted words, began to change colour and to cast down her eyes like a woman in alarm. However, being sensible and discreet, she replied—

“Since you already have what you ask of me, Amadour, why make me such a long harangue? I fear me lest beneath your honourable words there be some hidden guile to deceive my ignorance and youth, and I am sorely perplexed what to reply. Were I to refuse the honourable love you offer, I should do contrary to what I have hitherto done, for I have always trusted you more than any other man in the world. Neither my conscience nor my honour oppose your request, nor yet the love I bear the son of the Infante of Fortune, for that is founded on marriage, to which you do not aspire. I know of nothing that should hinder me from answering you according to your desire, if it be not a fear arising from the small need you have for talking to me in this wise; for if what you ask is already yours, why speak of it so ardently?”

Amadour, who was at no loss for an answer, then said to her—

“Madam, you speak very discreetly, and you honour me so greatly by the trust which you say you have in me, that if I were not satisfied with such good fortune I should be quite unworthy of it. But consider, madam, that he who would build an edifice to last for ever must be careful to have a sure and stable foundation. In the same way I, wishing to continue for ever in your service, must not only take care to have the means of remaining near to you, but also to prevent any one from knowing of the great affection that I bear you. Although it is honourable enough to be everywhere proclaimed, yet those who know nothing of lovers’ hearts often judge contrary to the truth, and thence come reports as mischievous as though they were true. I have been prompted to say this, and led to declare my love to you, because Paulina, feeling in her heart that I cannot love her, holds me in suspicion and does nought but watch my face wherever I may be. Hence, when you come and speak to me so familiarly in her presence, I am in great fear lest I should make some sign on which she may ground her judgment, and should so fall into that which I am anxious to avoid. For this reason I am lead to entreat you not to come and speak to me so suddenly before her or before others whom you know to be equally malicious, for I would rather die than have any living creature know the truth. Were I not so regardful of your honour, I should not have sought this converse with you, for I hold myself sufficiently happy in the love and trust you bear me, and I ask nothing more save that they may continue.”

Florida, who could not have been better pleased, began to be sensible of an unwonted feeling in her heart. She saw how honourable were the reasons which he laid before her; and she told him that virtue and honour replied for her, and that she granted him his request. Amadour’s joy at this no true lover can doubt.

Florida, however, gave more heed to his counsel than he desired, for she became timid not only in presence of Paulina but elsewhere, and ceased to seek him out as she had been accustomed to do. While they were thus separated she took Amadour’s constant converse with Paulina in bad part, for, seeing that the latter was beautiful, she could not believe that Amadour did not love her. To beguile her sorrow she conversed continually with Avanturada, who was beginning to feel very jealous of her husband and Paulina, and often complained of them to Florida, who comforted her as well as she could, being herself smitten with the same disease. Amadour soon perceived the change in Florida’s demeanour, and forthwith thought that she was keeping aloof from him not merely by his own advice, but also on account of some bitter fancies of her own.

One day, when they were coming from vespers at a monastery, he spoke to her, and asked—

“What countenance is this you show me, madam?”

“That which I believe you desire,” replied Florida.

Thereupon, suspecting the truth, and desiring to know whether he was right, he said to her—

“I have used my time so well, madam, that Paulina no longer has any suspicion of you.”

“You could not do better,” she replied, “both for yourself and for me. While giving pleasure to yourself you bring me honour.”

Amadour gathered from this speech that she believed he took pleasure in conversing with Paulina, and so great was his despair that he could not refrain from saying angrily to her—

“In truth, madam, you begin betimes to torment your lover and pelt him with hard words. I do not think I ever had a more irksome task than to be obliged to hold converse with a lady I do not love. But since you take what I have done to serve you in bad part, I will never speak to her again, happen what may. And that I may hide my wrath as I have hidden my joy, I will betake me to some place in the neighbourhood, and there wait till your caprice has passed away. I hope, however, I shall there receive tidings from my captain and be called back to the war, where I will remain long enough to show you that nothing but yourself has kept me here.”

So saying, he forthwith departed without waiting for her reply.

Florida felt the greatest vexation and sorrow imaginable; and love, meeting with opposition, began to put forth its mighty strength. She perceived that she had been in the wrong, and wrote continually to Amadour entreating him to return, which he did after a few days, when his anger had abated.

I cannot undertake to tell you minutely all that they said to each other in order to destroy this jealousy. But at all events he won the victory, and she promised him that not only would she never believe he loved Paulina, but that she would ever be convinced he found it an intolerable martyrdom to speak either to Paulina or to any one else except to do herself a service.

When love had conquered this first suspicion, and while the two lovers were beginning to take fresh pleasure in conversing together, news came that the King of Spain was sending all his army to Salces. (11)

11 Salces, a village about fifteen miles north of Perpignan,

noted for its formidable fortress, still existing and

commanding a pass through the Corbière Mountains, which in

the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries separated France from

Roussillon, then belonging to Spain. The French burnt the

village and demolished the fort of Salces in 1496, but the

latter was rebuilt by the Spaniards in the most massive

style. The walls of the fort are 66 feet thick at the base

and 54 feet thick at the summit. When Queen Margaret

returned from Spain in 152,5 she reached France by the pass

of Salces. (See vol. i. p. xlvi.).—Ed.

Amadour, accustomed ever to be the first in battle, failed not to seize this opportunity of winning renown; but in truth he set forth with unwonted regret, both on account of the pleasure he was losing and because he feared that he might find a change on his return. He knew that Florida, who was now fifteen or sixteen years old, was sought in marriage by many great princes and lords, and he reflected that if she were married during his absence he might have no further opportunity of seeing her, unless, indeed, the Countess of Aranda gave her his wife, Avanturada, as a companion. However, by skilful management with his friends, he obtained a promise from both mother and daughter that wherever Florida might go after her marriage thither should his wife, Avanturada, accompany her. Although it was proposed to marry Florida in Portugal, it was nevertheless resolved that Avanturada should never leave her. With this assurance, yet not without unspeakable regret, Amadour went away and left his wife with the Countess.

When Florida found herself alone after his departure, she set about doing such good and virtuous works as she hoped might win her the reputation that belongs to the most perfect women, and might prove her to be worthy of such a lover as Amadour. He having arrived at Barcelona, was there welcomed by the ladies as of old; but they found a greater change in him than they believed it possible for marriage to effect in any man. He seemed to be vexed by the sight of things he had formerly desired; and even the Countess of Palamos, whom he had loved exceedingly, could not persuade him to visit her.

Amadour remained at Barcelona as short a time as possible, for he was impatient to reach Salces, where he alone was now awaited. When he arrived, there began between the two kings that great and cruel war which I do not purpose to describe. (12) Neither will I recount the noble deeds that were done by Amadour, for then my story would take up an entire day; but you must know that he won renown far above all his comrades. The Duke of Najera (13) having arrived at Perpignan in command of two thousand men, requested Amadour to be his lieutenant, and so well did Amadour fulfil his duty with this band, that in every skirmish the only cry was “Najera!” (14)

12 In 1503 the French, under Marshals de Rieux and de Gié,

again besieged Salces, which had a garrison of 1200 men. The

latter opposed a vigorous defence during two months, and

upon the arrival of the old Duke of Alba with an army of

succour the siege had to be raised.—B. J.

13 Pedro Manriquez de Lara, Count of Trevigno, created Duke

of Najera by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1501.—B. J.

14 The Duke’s war-cry, repeated by his followers as a

rallying signal in the mêlée. War-cries varied greatly.

“Montjoie St. Denis” was that of the kings of France, and

“Passavant le meilleur” (the best to the front) that of the

Counts of Champagne. In other instances the war-cry

consisted of a single word, “Bigorre” being that of the

kings of Navarre, and “Flanders” that of the Princess of

Beaujeu. When the war-cry was merely a name, as in the case

of the Duke of Najera, it belonged to the head of the

family.—D.

Now it came to pass that the King of Tunis, who for a long time had been at war with the Spaniards, heard that the kings of France and Spain were warring with each other on the frontiers of Perpignan and Narbonne, and bethought himself that he could have no better opportunity of vexing the King of Spain. Accordingly, he sent a great number of light galleys and other vessels to plunder and destroy all such badly-guarded places as they could find on the coasts of Spain. (15)The people of Barcelona seeing a great fleet passing in front of their town, sent word of the matter to the Viceroy, who was at Salces, and he forthwith despatched the Duke of Najera to Palamos. (16) When the Moors saw that place so well guarded, they made a feint of passing on; but returning at midnight, they landed a large number of men, and the Duke of Najera, being surprised by the enemy, was taken prisoner.

15 The above two sentences, deficient in the MS. followed by

M. Le Roux de Lincy, have been borrowed from MS. No. 1520

(Bib. Nat.). It was in 1503 that a Moorish flotilla ravaged

the coast of Catalonia.—Ed.

16 The village of Palamos, on the shores of the

Mediterranean, south of Cape Bagur, and within fifteen miles

from Gerona.—Ed.

Amadour, who was on the alert and heard the din, forthwith assembled as many of his men as possible, and defended himself so stoutly that the enemy, in spite of their numbers, were for a long time unable to prevail against him. But at last, hearing that the Duke of Najera was taken, and that the Turks had resolved to set fire to Palamos and burn him in the house which he was holding against them, he thought it better to yield than to cause the destruction of the brave men who were with him. He also hoped that by paying a ransom he might yet see Florida again. Accordingly, he gave himself up to a Turk named Dorlin, a governor of the King of Tunis, who brought him to his master. By the latter he was well received and still better guarded; for the King deemed that in him he held the Achilles of all the Spains.

Thus Amadour continued for two years in the service of the King of Tunis. The news of the captures having reached Spain, the kinsfolk of the Duke of Najera were in great sorrow; but those who held the country’s honour dear deemed Amadour the greater loss. The rumour came to the house of the Countess of Aranda, where the hapless Avanturada at that time lay grievously sick. The Countess, who had great misgivings as to the affection which Amadour bore to her daughter, though she suffered it and concealed it for the sake of the merits she perceived in him, took Florida apart and told her the mournful tidings. Florida, who was well able to dissemble, replied that it was a great loss to the entire household, and that above all she pitied his poor wife, who was herself so ill. Nevertheless, seeing that her mother wept exceedingly, she shed a few tears to bear her company; for she feared that if she dissembled too far the feint might be discovered. From that time the Countess often spoke to her of Amadour, but never could she surprise a look to guide her judgment.

I will pass over the pilgrimages, prayers, supplications, and fasts which Florida regularly performed to ensure the safety of Amadour. As soon as he had arrived at Tunis, he failed not to send tidings of himself to his friends, and by a trusty messenger he apprised Florida that he was in good health, and had hopes of seeing her again. This was the only consolation the poor lady had in her grief, and you may be sure that, since she was permitted to write, she did so with all diligence, so that Amadour had no lack of her letters to comfort him.

The Countess of Aranda was about this time commanded to repair to Saragossa, where the King had arrived; and here she found the young Duke of Cardona, who so pressed the King and Queen that they begged the Countess to give him their daughter in marriage. (17) The Countess consented, for she was unwilling to disobey them in anything, and moreover she considered that her daughter, being so young, could have no will of her own.

17 The Spanish historians state that in 1513 the King, to

put an end to a quarrel between the Count of Aranda and the

Count of Ribagorce, charged Father John of Estuniga,

Provincial of the Order of St. Francis, to negotiate a

reconciliation between them, based on the marriage of the

eldest daughter of the Count of Aranda with the eldest son

of the Count of Ribagorce. The latter refusing his consent,

was banished from the kingdom.—D.

When all was settled, she told Florida that she had chosen for her the match which seemed most suitable. Florida, knowing that when a thing is once done there is small room for counsel, replied that God was to be praised for all things; and, finding her mother look coldly upon her, she sought rather to obey her than to take pity on herself. It scarcely comforted her in her sorrows to learn that the son of the Infante of Fortune was sick even to death; but never, either in presence of her mother or of any one else, did she show any sign of grief. So strongly did she constrain herself, that her tears, driven perforce back into her heart, caused so great a loss of blood from the nose that her life was endangered; and, that she might be restored to health, she was given in marriage to one whom she would willingly have exchanged for death.

After the marriage Florida departed with her husband to the duchy of Cardona, taking with her Avanturada, whom she privately acquainted with her sorrow, both as regards her mother’s harshness and her own regret at having lost the son of the Infante of Fortune; but she never spoke of her regret for Amadour except to console his wife.

This young lady then resolved to keep God and honour before her eyes. So well did she conceal her grief, that none of her friends perceived that her husband was displeasing to her.

In this way she spent a long time, living a life that was worse than death, as she failed not to inform her lover Amadour, who, knowing the virtue and greatness of her heart, as well as the love that she had borne to the son of the Infante of Fortune, thought it impossible that she could live long, and mourned for her as for one that was more than dead. This sorrow was an increase to his former grief, and forgetting his own distress in that which he knew his sweetheart was enduring, he would willingly have continued all his life the slave he was if Florida could thereby have had a husband after her own heart. He learnt from a friend whom he had gained at the Court of Tunis that the King, wishing to keep him if only he could make a good Turk of him, intended to give him his choice between impalement and the renunciation of his faith. Thereupon he so addressed himself to his master, the governor who had taken him prisoner, that he persuaded him to release him on parole. His master named, however, a much higher ransom than he thought could be raised by a man of such little wealth, and then, without speaking to the King, he let him go.

When Amadour reached the Court of the King of Spain, he stayed there but a short time, and then, in order to seek his ransom among his friends, he repaired to Barcelona, whither the young Duke of Cardona, his mother, and Florida had gone on business. As soon as Avanturada heard that her husband was returned, she told the news to Florida, who rejoiced as though for love of her friend. Fearing, however, that her joy at seeing Amadour might make her change her countenance, and that those who did not know her might think wrongly of her, she remained at a window in order to see him coming from afar. As soon as she perceived him she went down by a dark staircase, so that none could see whether she changed colour, and embracing Amadour, led him to her room, and thence to her mother-in-law, who had never seen him. He had not been there for two days before he was loved as much as he had been in the household of the Countess of Aranda.

I leave you to imagine the conversation that he and Florida had together, and how she complained to him of the misfortunes that had come to her in his absence. After shedding many tears of sorrow, both for having been married against her will and also for having lost one she loved so dearly without any hope of seeing him again, she resolved to take consolation from the love and trust she had towards Amadour. Though she durst not declare the truth, he suspected it, and lost neither time nor opportunity to show her how much he loved her.

Just when Florida was all but persuaded to receive him, not as a lover, but as a true and perfect friend, a misfortune came to pass, for the King summoned Amadour to him concerning some important matter.

His wife was so grieved on hearing these tidings that she swooned, and falling down a staircase on which she was standing, was so hurt that she never rose again. Florida having by this death lost all her consolation, mourned like one who felt herself bereft of friends and kin. But Amadour grieved still more; for on the one part he lost one of the best wives that ever lived, and on the other the means of ever seeing Florida again. This caused him such sorrow that he was near coming by a sudden death. The old Duchess of Cardona visited him incessantly, reciting the arguments of philosophers why he should endure his loss with patience. But all was of no avail; for if on the one hand his wife’s death afflicted him, on the other his love increased his martyrdom. Having no longer any excuse to stay when his wife was buried, and his master again summoned him, his despair was such that he was like to lose his reason.

Florida, who thinking to comfort him, was herself the cause of his greatest grief, spent a whole afternoon in the most gracious converse with him in order to lessen his sorrow, and assured him that she would find means to see him oftener than he thought. Then, as he was to depart on the following morning, and was so weak that he could scarcely stir from his bed, he prayed her to come and see him in the evening after every one else had left him. This she promised to do, not knowing that love in extremity is void of reason.

Amadour altogether despaired of ever again seeing her whom he had loved so long, and from whom he had received no other treatment than I have described. Racked by secret passion and by despair at losing all means of consorting with her, he resolved to play at double or quits, and either lose her altogether or else wholly win her, and so pay himself in an hour the reward which he thought he had deserved. Accordingly he had his bed curtained in such a manner that those who came into the room could not see him; and he complained so much more than he had done previously that all the people of the house thought he had not twenty-four hours to live.

After every one else had visited him, Florida, at the request of her husband himself, came in the evening, hoping to comfort him by declaring her affection and by telling him that, so far as honour allowed, she was willing to love him. She sat down on a chair beside the head of his bed, and began her consolation by weeping with him. Amadour, seeing her filled with such sorrow, thought that in her distress he might the more readily achieve his purpose, and raised himself up in the bed. Florida, thinking that he was too weak to do this, sought to prevent him, but he threw himself on his knees before her saying, “Must I lose sight of you for ever?” Then he fell into her arms like one exhausted. The hapless Florida embraced him and supported him for a long time, doing all she could to comfort him. But what she offered him to cure his pain only increased it; and while feigning to be half dead, he, without saying a word, strove to obtain that which the honour of ladies forbids.