Title: The Emigrant Trail

Author: Geraldine Bonner

Release date: August 24, 2006 [eBook #19113]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER I | CHAPTER II | CHAPTER III | CHAPTER IV |

| CHAPTER V | CHAPTER VI | CHAPTER VII | CHAPTER VIII |

| CHAPTER I | CHAPTER II | CHAPTER III | CHAPTER IV |

| CHAPTER V | CHAPTER VI | CHAPTER VII | CHAPTER VIII |

| CHAPTER I | CHAPTER II | CHAPTER III | CHAPTER IV |

| CHAPTER V | CHAPTER VI | CHAPTER VII | CHAPTER VIII |

| CHAPTER I | CHAPTER II | CHAPTER III | CHAPTER IV |

| CHAPTER V | CHAPTER VI |

| CHAPTER I | CHAPTER II | CHAPTER III | CHAPTER IV |

It had rained steadily for three days, the straight, relentless rain of early May on the Missouri frontier. The emigrants, whose hooded wagons had been rolling into Independence for the past month and whose tents gleamed through the spring foliage, lounged about in one another's camps cursing the weather and swapping bits of useful information.

The year was 1848 and the great California emigration was still twelve months distant. The flakes of gold had already been found in the race of Sutter's mill, and the thin scattering of men, which made the population of California, had left their plows in the furrow and their ships in the cove and gone to the yellow rivers that drain the Sierra's mighty flanks. But the rest of the world knew nothing of this yet. They were not to hear till November when a ship brought the news to New York, and from city and town, from village and cottage, a march of men would turn their faces to the setting sun and start for the land of gold.

Those now bound for California knew it only as the recently acquired strip of territory that lay along the continent's Western rim, a place of perpetual sunshine, where everybody had a chance and there was no malaria. That was what they told each other as they lay under the wagons or sat on saddles in the wet tents. The story of old Roubadoux, the French fur trader from St. Joseph, circulated cheeringly from mouth to mouth—a man in Monterey had had chills and people came from miles around to see him shake, so novel was the spectacle. That was the country for the men and women of the Mississippi Valley, who shook half the year and spent the other half getting over it.

The call of the West was a siren song in the ears of these waiting companies. The blood of pioneers urged them forward. Their forefathers had moved from the old countries across the seas, from the elm-shaded towns of New England, from the unkempt villages that advanced into the virgin lands by the Great Lakes, from the peace and plenty of the splendid South. Year by year they had pushed the frontier westward, pricked onward by a ceaseless unrest, "the old land hunger" that never was appeased. The forests rang to the stroke of their ax, the slow, untroubled rivers of the wilderness parted to the plowing wheels of their unwieldy wagons, their voices went before them into places where Nature had kept unbroken her vast and pondering silence. The distant country by the Pacific was still to explore and they yoked their oxen, and with a woman and a child on the seat started out again, responsive to the cry of "Westward, Ho!"

As many were bound for Oregon as for California. Marcus Whitman and the missionaries had brought alluring stories of that great domain once held so cheaply the country almost lost it. It was said to be of a wonderful fertility and league-long stretches of idle land awaited the settler. The roads ran together more than half the way, parting at Green River, where the Oregon trail turned to Fort Hall and the California dipped southward and wound, a white and spindling thread, across what men then called "The Great American Desert." Two days' journey from Independence this road branched from the Santa Fé Trail and bent northward across the prairie. A signboard on a stake pointed the way and bore the legend, "Road to Oregon." It was the starting point of one of the historic highways of the world. The Indians called it "The Great Medicine Way of the Pale-face."

Checked in the act of what they called "jumping off" the emigrants wore away the days in telling stories of the rival countries, and in separating from old companies and joining new ones. It was an important matter, this of traveling partnerships. A trip of two thousand miles on unknown roads beset with dangers was not to be lightly undertaken. Small parties, frightened on the edge of the enterprise, joined themselves to stronger ones. The mountain men and trappers delighted to augment the tremors of the fearful, and round the camp fires listening groups hung on the words of long-haired men clad in dirty buckskins, whose moccasined feet had trod the trails of the fur trader and his red brother.

This year was one of special peril for, to the accustomed dangers from heat, hunger, and Indians, was added a new one—the Mormons. They were still moving westward in their emigration from Nauvoo to the new Zion beside the Great Salt Lake. It was a time and a place to hear the black side of Mormonism. A Missourian hated a Latter Day Saint as a Puritan hated a Papist. Hawn's mill was fresh in the minds of the frontiersmen, and the murder of Joseph Smith was accounted a righteous act. The emigrant had many warnings to lay to heart—against Indian surprises in the mountains, against mosquitoes on the plains, against quicksands in the Platte, against stampedes among the cattle, against alkaline springs and the desert's parching heats. And quite as important as any of these was that against the Latter Day Saint with the Book of Mormon in his saddlebag and his long-barreled rifle across the pommel.

So they waited, full of ill words and impatience, while the rain fell. Independence, the focusing point of the frontier life, housing unexpected hundreds, dripped from all its gables and swam in mud. And in the camps that spread through the fresh, wet woods and the oozy uplands, still other hundreds cowered under soaked tent walls and in damp wagon boxes, listening to the rush of the continuous showers.

On the afternoon of the fourth day the clouds lifted. A band of yellow light broke out along the horizon, and at the crossings of the town and in the rutted country roads men and women stood staring at it with its light and their own hope brightening their faces.

David Crystal, as he walked through the woods, saw it behind a veining of black branches. Though a camper and impatient to be off like the rest, he did not feel the elation that shone on their watching faces. His was held in a somber abstraction. Just behind him, in an opening under the straight, white blossoming of dogwood trees, was a new-made grave. The raw earth about it showed the prints of his feet, for he had been standing by it thinking of the man who lay beneath.

Four days before his friend, Joe Linley, had died of cholera. Three of them—Joe, himself, and George Leffingwell, Joe's cousin—had been in camp less than a week when it had happened. Until then their life had been like a picnic there in the clearing by the roadside, with the thrill of the great journey stirring in their blood. And then Joe had been smitten with such suddenness, such awful suddenness! He had been talking to them when David had seen a suspension of something, a stoppage of a vital inner spring, and with it a whiteness had passed across his face like a running tide. The awe of that moment, the hush when it seemed to David the liberated spirit had paused beside him in its outward flight, was with him now as he walked through the rustling freshness of the wood.

The rain had begun to lessen, its downfall thinning into a soft patter among the leaves. The young man took off his hat and let the damp air play over his hair. It was thick hair, black and straight, already longer than city fashions dictated, and a first stubble of black beard was hiding the lines of a chin perhaps a trifle too sensitive and pointed. Romantic good looks and an almost poetic refinement were the characteristics of the face, an unusual type for the frontier. With thoughtful gray eyes set deep under a jut of brows and a nose as finely cut as a woman's, it was of a type that, in more sophisticated localities, men would have said had risen to meet the Byronic ideal of which the world was just then enamored. But there was nothing Byronic or self-conscious about David Crystal. He had been born and bred in what was then the Far West, and that he should read poetry and regard life as an undertaking that a man must face with all honor and resoluteness was not so surprising for the time and place. The West, with its loneliness, its questioning silences, its solemn sweep of prairie and roll of slow, majestic rivers, held spiritual communion with those of its young men who had eyes to see and ears to hear.

The trees grew thinner and he saw the sky pure as amber beneath the storm pall. The light from it twinkled over wet twigs and glazed the water in the crumplings of new leaves. Across the glow the last raindrops fell in slanting dashes. David's spirits rose. The weather was clearing and they could start—start on the trail, the long trail, the Emigrant Trail, two thousand miles to California!

He was close to the camp. Through the branches he saw the filmy, diffused blueness of smoke and smelled the sharp odor of burning wood. He quickened his pace and was about to give forth a cheerful hail when he heard a sound that made him stop, listen with fixed eye, and then advance cautiously, sending a questing glance through the screen of leaves. The sound was a woman's voice detached in clear sweetness from the deeper tones of men.

There was no especial novelty in this. Their camp was just off the road and the emigrant women were wont to pause there and pass the time of day. Most of them were the lean and leathern-skinned mates of the frontiersmen, shapeless and haggard as if toil had drawn from their bodies all the softness of feminine beauty, as malaria had sucked from their skins freshness and color. But there were young, pretty ones, too, who often strolled by, looking sideways from the shelter of jealous sunbonnets.

This voice was not like theirs. It had a quality David had only heard a few times in his life—cultivation. Experience would have characterized it as "a lady voice." David, with none, thought it an angel's. Very shy, very curious, he came out from the trees ready at once and forever to worship anyone who could set their words to such dulcet cadences.

The clearing, green as an emerald and shining with rain, showed the hood of the wagon and the new, clean tent, white as sails on a summer sea, against the trees' young bloom. In the middle the fire burned and beside it stood Leff, a skillet in his hand. He was a curly-headed, powerful country lad, twenty-four years old, who, two months before, had come from an Illinois farm to join the expedition. The frontier was to him a place of varied diversion, Independence a stimulating center. So diffident that the bashful David seemed by contrast a man of cultured ease, he was now blushing till the back of his neck was red.

On the other side of the fire a lady and gentleman stood arm in arm under an umbrella. The two faces, bent upon Leff with grave attention, were alike, not in feature, but in the subtly similar play of expression that speaks the blood tie. A father and daughter, David thought. Against the rough background of the camp, with its litter at their feet, they had an air of being applied upon an alien surface, of not belonging to the picture, but standing out from it in sharp and incongruous contrast.

The gentleman was thin and tall, fifty or thereabouts, very pale, especially to one accustomed to the tanned skins of the farm and the country town. His face held so frank a kindliness, especially the eyes which looked tired and a little sad, that David felt its expression like a friendly greeting or a strong handclasp.

The lady did not have this, perhaps because she was a great deal younger. She was yet in the bud, far from the tempering touch of experience, still in the state of looking forward and anticipating things. She was dark, of medium height, and inclined to be plump. Many delightful curves went to her making, and her waist tapered elegantly, as was the fashion of the time. Thinking it over afterwards, the young man decided that she did not belong in the picture with a prairie schooner and camp kettles, because she looked so like an illustration in a book of beauty. And David knew something of these matters, for had he not been twice to St. Louis and there seen the glories of the earth and the kingdoms thereof?

But life in camp outside Independence had evidently blunted his perceptions. The small waist, a round, bare throat rising from a narrow band of lace, and a flat, yellow straw hat were the young woman's only points of resemblance to the beauty-book heroines. She was not in the least beautiful, only fresh and healthy, the flat straw hat shading a girlish face, smooth and firmly modeled as a ripe fruit. Her skin was a glossy brown, softened with a peach's bloom, warming through deepening shades of rose to lips that were so deeply colored no one noticed how firmly they could come together, how their curving, crimson edges could shut tight, straighten out, and become a line of forceful suggestions, of doggedness, maybe—who knows?—perhaps of obstinacy. It was her physical exuberance, her downy glow, that made David think her good looking; her serene, brunette richness, with its high lights of coral and scarlet, that made her radiate an aura of warmth, startling in that woodland clearing, as the luster of a firefly in a garden's glooming dusk.

She stopped speaking as he emerged from the trees, and Leff's stammering answer held her in a riveted stare of attention. Then she looked up and saw David.

"Oh," she said, and transferred the stare to him. "Is this he?"

Leff was obviously relieved:

"Oh, David, I ain't known what to say to this lady and her father. They think some of joining us. They've been waiting for quite a spell to see you. They're goin' to California, too."

The gentleman lifted his hat. Now that he smiled his face was even kindlier, and he, too, had a pleasant, mellowed utterance that linked him with the world of superior quality of which David had had those two glimpses.

"I am Dr. Gillespie," he said, "and this is my daughter Susan."

David bowed awkwardly, a bow that was supposed to include father and daughter. He did not know whether this was a regular introduction, and even if it had been he would not have known what to do. The young woman made no attempt to return the salutation, not that she was rude, but she had the air of regarding it as a frivolous interruption to weighty matters. She fixed David with eyes, small, black, and bright as a squirrel's, so devoid of any recognition that he was a member of the rival sex—or, in fact, of the human family—that his self-consciousness sunk down abashed as if before reproof.

"My father and I are going to California and the train we were going with has gone on. We've come from Rochester, New York, and everywhere we've been delayed and kept back. Even that boat up from St. Louis was five days behind time. It's been nothing but disappointments and delays since we left home. And when we got here the people we were going with—a big train from Northern New York—had gone on and left us."

She said all this rapidly, poured it out as if she were so full of the injury and annoyance of it, that she had to ease her indignation by letting it run over into the first pair of sympathetic ears. David's were a very good pair. Any woman with a tale of trouble would have found him a champion. How much more a fresh-faced young creature with a melodious voice and anxious eyes.

"A good many trains have gone on," he said. And then, by way of consolation for her manner demanded, that, "But they'll be stalled at the fords with this rain. They'll have to wait till the rivers fall. All the men who know say that."

"So we've heard," said the father, "but we hoped that we'd catch them up. Our outfit is very light, only one wagon, and our driver is a thoroughly capable and experienced man. What we want are some companions with whom we can travel till we overhaul the others. I'd start alone, but with my daughter——"

She cut in at once, giving his arm a little, irritated shake:

"Of course you couldn't do that." Then to the young men: "My father's been sick for quite a long time, all last winter. It's for his health we're going to California, and, of course, he couldn't start without some other men in the party. Indians might attack us, and at the hotel they said the Mormons were scattered all along the road and thought nothing of shooting a Gentile."

Her father gave the fingers crooked on his arm a little squeeze with his elbow. It was evident the pair were very good friends.

"You'll make these young men think I'm a helpless invalid, who'll lie in the wagon all day. They won't want us to go with them."

This made her again uneasy and let loose another flow of authoritative words.

"No, my father isn't really an invalid. He doesn't have to lie in the wagon. He's going to ride most of the time. He and I expect to ride all the way, and the old man who goes with us will drive the mules. What's been really bad for my father was living in that dreadful hotel at Independence with everything damp and uncomfortable. We want to get off just as soon as we can, and this gentleman," indicating Leff, "says you want to go, too."

"We'll start to-morrow morning, if it's clear."

"Now, father," giving the arm she held a renewed clutch and sharper shake, "there's our chance. We must go with them."

The father's smile would have shown something of deprecation, or even apology, if it had not been all pride and tenderness.

"These young men will be very kind if they permit us to join them," was what his lips said. His eyes added: "This is a spoiled child, but even so, there is no other like her in the world."

The young men sprang at the suggestion. The spring was internal, of the spirit, for they were too overwhelmed by the imminent presence of beauty to show a spark of spontaneity on the outside. They muttered their agreement, kicked the ground, and avoided the eyes of Miss Gillespie.

"The people at the hotel," the doctor went on, "advised us to join one of the ox trains. But it seemed such a slow mode of progress. They don't make much more than fifteen to twenty miles a day."

"And then," said the girl, "there might be people we didn't like in the train and we'd be with them all the time."

It is not probable that she intended to suggest to her listeners that she could stand them as traveling companions. Whether she did or not they scented the compliment, looked stupid, and hung their heads, silent in the intoxication of this first subtle whiff of incense. Even Leff, uncouth and unlettered, extracted all that was possible from the words, and felt a delicate elation at the thought that so fine a creature could endure his society.

"We expect to go a great deal faster than the long trains," she continued. "We have no oxen, only six mules and two extra horses and a cow."

Her father laughed outright.

"Don't let my daughter frighten you. We've really got a very small amount of baggage. Our little caravan has been made up on the advice of Dr. Marcus Whitman, an old friend of mine. Five years ago when he was in Washington he gave me a list of what was needed for the journey across the plains. I suppose he's the best authority on that subject. We all know how successfully the Oregon emigration was carried through."

David was glad to show he knew something of that. A boy friend of his had gone to Oregon with this, the first large body of emigrants that had ventured on the great enterprise. Whitman was to him a national hero, his ride in the dead of winter from the far Northwest to Washington, as patriotically inspiring as Paul Revere's.

There was more talk, standing round the fire, while the agreements for the start were being made. No one thought the arrangement hasty, for it was a place and time of quick decisions. Men starting on the emigrant trail were not for wasting time on preliminaries. Friendships sprang up like the grass and were mown down like it. Standing on the edge of the unknown was not the propitious moment for caution and hesitation. Only the bold dared it and the bold took each other without question, reading what was on the surface, not bothering about what might be hidden.

It was agreed, the weather being fair, that they would start at seven the next morning, Dr. Gillespie's party joining David's at the camp. With their mules and horses they should make good time and within a month overhaul the train that had left the Gillespies behind.

As the doctor and his daughter walked away the shyness of the young men returned upon them in a heavy backwash. They were so whelmed by it that they did not even speak to one another. But both glanced with cautious stealth at the receding backs, the doctor in front, his daughter walking daintily on the edge of grass by the roadside, holding her skirts away from the wet weeds.

When she was out of sight Leff said with an embarrassed laugh:

"Well, we got some one to go along with us now."

David did not laugh. He pondered frowningly. He was the elder by two years and he felt his responsibilities.

"They'll do all right. With two more men we'll make a strong enough train."

Leff was cook that night, and he set the coffee on and began cutting the bacon. Occupied in this congenial work, the joints of his tongue were loosened, and as the skillet gave forth grease and odors, he gave forth bits of information gleaned from the earlier part of the interview:

"I guess they got a first rate outfit. The old gentleman said they'd been getting it together since last autumn. They must be pretty well fixed."

David nodded. Being "well fixed" or being poor did not count on the edge of the prairie. They were frivolous outside matters that had weight in cities. Leff went on,

"He's consumpted. That's why he's going. He says he expects to be cured before he gets to California."

A sudden zephyr irritated the tree tops, which bent away from its touch and scattered moisture on the fire and the frying pan. There was a sputter and sizzle and Leff muttered profanely before he took up the dropped thread:

"The man that drives the mules, he's a hired man that the old gentleman's had for twenty years. He was out on the frontier once and knows all about it, and there ain't nothing he can't drive"—turning of the bacon here, Leff absorbed beyond explanatory speech—"They got four horses, two to ride and two extra ones, and a cow. I don't see how they're goin' to keep up the pace with the cow along. The old gentleman says they can do twenty to twenty-five miles a day when the road's good. But I don't seem to see how the cow can keep up such a lick."

"A hired man, a cow, and an outfit that it took all winter to get together," said David thoughtfully. "It sounds more like a pleasure trip than going across the plains."

He sat as if uneasily debating the possible drawbacks of so elaborate an escort, but he was really ruminating upon the princess, who moved upon the wilderness with such pomp and circumstance.

As they set out their tin cups and plates they continued to discuss the doctor, his caravan, his mules, his servant, and his cow, in fact, everything but his daughter. It was noticeable that no mention of her was made till supper was over and the night fell. Then their comments on her were brief. Leff seemed afraid of her even a mile away in the damp hotel at Independence, seemed to fear that she might in some way know he'd had her name upon his tongue, and would come to-morrow with angry, accusing looks like an offended goddess. David did not want to talk about her, he did not quite know why. Before the thought of traveling a month in her society his mind fell back reeling, baffled by the sudden entrance of such a dazzling intruder. A month beside this glowing figure, a month under the impersonal interrogation of those cool, demanding eyes! It was as if the President or General Zachary Taylor had suddenly joined them.

But of course she figured larger in their thoughts than any other part or all the combined parts of Dr. Gillespie's outfit. In their imaginations—the hungry imaginations of lonely young men—she represented all the grace, beauty, and mystery of the Eternal Feminine. They did not reason about her, they only felt, and what they felt—unconsciously to themselves—was that she had introduced the last, wildest, and most disturbing thrill into the adventure of the great journey.

The next day broke still and clear. The dawn was yet a pale promise in the East when from Independence, out through the dripping woods and clearings, rose the tumult of breaking camps. The rattle of the yoke chains and the raucous cry of "Catch up! Catch up!" sounded under the trees and out and away over valley and upland as the lumbering wagons, freighted deep for the long trail, swung into the road.

David's camp was astir long before the sun was up. The great hour had come. They were going! They sung and shouted as they harnessed Bess and Ben, a pair of sturdy roans bought from an emigrant discouraged before the start, while the saddle horses nosed about the tree roots for a last cropping of the sweet, thick grass. Inside the wagon the provisions were packed in sacks and the rifles hung on hooks on the canvas walls. At the back, on a supporting step, the mess chest was strapped. It was a businesslike wagon. Its contents included only one deviation from the practical and necessary—three books of David's. Joe had laughed at him about them. What did a man want with Byron's poems and Milton and Bacon's "Essays" crossing the plains? Neither Joe nor Leff could understand such devotion to the printed page. Their kits were of the compactest, not a useless article or an unnecessary pound, unless you counted the box of flower seeds that belonged to Joe, who had heard that California, though a dry country, could be coaxed into productiveness along the rivers.

Dr. Gillespie and his daughter were punctual. David's silver watch, large as the circle of a cup and possessed of a tick so loud it interrupted conversation, registered five minutes before seven, when the doctor and his daughter appeared at the head of their caravan. Two handsome figures, well mounted and clad with taste as well as suitability, they looked as gallantly unfitted for the road as armored knights in a modern battlefield. Good looks, physical delicacy, and becoming clothes had as yet no recognized place on the trail. The Gillespies were boldly and blithely bringing them, and unlike most innovators, romance came with them. Nobody had gone out of Independence with so confident and debonair an air. Now advancing through a spattering of leaf shadows and sunspots, they seemed to the young men to be issuing from the first pages of a story, and the watchers secretly hoped that they would go riding on into the heart of it with the white arch of the prairie schooner and the pricked ears of the six mules as a movable background.

There was no umbrella this morning to obscure Miss Gillespie's vivid tints, and in the same flat, straw hat, with her cheeks framed in little black curls, she looked a freshly wholesome young girl, who might be dangerous to the peace of mind of men even less lonely and susceptible than the two who bid her a flushed and bashful good morning. She had the appearance, however, of being entirely oblivious to any embarrassment they might show. There was not a suggestion of coquetry in her manner as she returned their greetings. Instead, it was marked by a businesslike gravity. Her eyes touched their faces with the slightest welcoming light and then left them to rove, sharply inspecting, over their wagon and animals. When she had scrutinized these, she turned in her saddle, and said abruptly to the driver of the six mules:

"Daddy John, do you see—horses?"

The person thus addressed nodded and said in a thin, old voice,

"I do, and if they want them they're welcome to them."

He was a small, shriveled man, who might have been anywhere from sixty to seventy-five. A battered felt hat, gray-green with wind and sun, was pulled well down to his ears, pressing against his forehead and neck thin locks of gray hair. A grizzle of beard edged his chin, a poor and scanty growth that showed the withered skin through its sparseness. His face, small and wedge-shaped, was full of ruddy color, the cheeks above the ragged hair smooth and red as apples. Though his mouth was deficient in teeth, his neck, rising bare from the band of his shirt, corrugated with the starting sinews of old age, he had a shrewd vivacity of glance, an alertness of poise, that suggested an unimpaired spiritual vitality. He seemed at home behind the mules, and here, for the first time, David felt was some one who did not look outside the picture. In fact, he had an air of tranquil acceptance of the occasion, of adjustment without effort, that made him fit into the frame better than anyone else of the party.

It was a glorious morning, and as they fared forward through the checkered shade their spirits ran high. The sun, curious and determined, pried and slid through every crack in the leafage, turned the flaked lichen to gold, lay in clotted light on the pools around the fern roots. They were delicate spring woods, streaked with the white dashes of the dogwood, and hung with the tassels of the maple. The foliage was still unfolding, patterned with fresh creases, the prey of a continuous, frail unrest. Little streams chuckled through the underbrush, and from the fusion of woodland whisperings bird notes detached themselves, soft flutings and liquid runs, that gave another expression to the morning's blithe mood.

Between the woods there were stretches of open country, velvet smooth, with the trees slipped down to where the rivers ran. The grass was as green as sprouting grain, and a sweet smell of wet earth and seedling growths came from it. Cloud shadows trailed across it, blue blotches moving languidly. It was the young earth in its blushing promise, fragrant, rain-washed, budding, with the sound of running water in the grass and bird voices dropping from the sky.

With their lighter wagons they passed the ox trains plowing stolidly through the mud, barefoot children running at the wheel, and women knitting on the front seat. The driver's whip lash curled in the air, and his nasal "Gee haw" swung the yoked beasts slowly to one side. Then came detachments of Santa Fé traders, dark men in striped serapes with silver trimmings round their high-peaked hats. Behind them stretched the long line of wagons, the ponderous freighters of the Santa Fé Trail, rolling into Independence from the Spanish towns that lay beyond the burning deserts of the Cimarron. They filed by in slow procession, a vision of faded colors and swarthy faces, jingle of spur and mule bell mingling with salutations in sonorous Spanish.

As the day grew warmer, the doctor complained of the heat and went back to the wagon. David and the young girl rode on together through the green thickness of the wood. They had talked a little while the doctor was there, and now, left to themselves, they suddenly began to talk a good deal. In fact, Miss Gillespie revealed herself as a somewhat garrulous and quite friendly person. David felt his awed admiration settling into a much more comfortable feeling, still wholly admiring but relieved of the cramping consciousness that he had entertained an angel unawares. She was so natural and girlish that he began to cherish hopes of addressing her as "Miss Susan," even let vaulting ambition carry him to the point where he could think of some day calling himself her friend.

She was communicative, and he was still too dazzled by her to realize that she was not above asking questions. In the course of a half hour she knew all about him, and he, without the courage to be thus flatteringly curious, knew the main points of her own history. Her father had been a practicing physician in Rochester for the past fifteen years. Before that he had lived in New York, where she had been born twenty years ago. Her mother had been a Canadian, a French woman from the Province of Quebec, whom her father had met there one summer when he had gone to fish in Lake St. John. Her mother had been very beautiful—David nodded at that, he had already decided it—and had always spoken English with an accent. She, the daughter, when she was little, spoke French before she did English; in fact, did not Mr. Crystal notice there was still something a little queer about her r's?

Mr. Crystal had noticed it, noticed it to the extent of thinking it very pretty. The young lady dismissed the compliment as one who does not hear, and went on with her narrative:

"After my mother's death my father left New York. He couldn't bear to live there any more. He'd been so happy. So he moved away, though he had a fine practice."

The listener gave forth a murmur of sympathetic understanding. Devotion to a beautiful woman was matter of immediate appeal to him. His respect for the doctor rose in proportion, especially when the devotion was weighed in the balance against a fine practice. Looking at the girl's profile with prim black curls against the cheek, he saw the French-Canadian mother, and said not gallantly, but rather timidly:

"And you're like your mother, I suppose? You're dark like a French woman."

She answered this with a brusque denial. Extracting compliments from the talk of a shy young Westerner was evidently not her strong point.

"Oh, no! not at all. My mother was pale and tall, with very large black eyes. I am short and dark and my eyes are only just big enough to see out of. She was delicate and I am very strong. My father says I've never been sick since I got my first teeth."

She looked at him and laughed, and he realized it was the first time he had seen her do it. It brightened her face delightfully, making the eyes she had spoken of so disparagingly narrow into dancing slits. When she laughed men who had not lost the nicety of their standards by a sojourn on the frontier would have called her a pretty girl.

"My mother was of the French noblesse," she said, a dark eye upon him to see how he would take this dignified piece of information. "She was a descendant of the Baron de Poutrincourt, who founded Port Royal."

David was as impressed as anyone could have desired. He did not know what the French noblesse was, but by its sound he judged it to be some high and honorable estate. He was equally ignorant of the identity of the Baron de Poutrincourt, but the name alone was impressive, especially as Miss Gillespie pronounced it.

"That's fine, isn't it?" he said, as being the only comment he could think of which at once showed admiration and concealed ignorance.

The young woman seemed to find it adequate and went on with her family history. Five years ago in Washington her father had seen his old friend, Marcus Whitman, and since then had been restless with the longing to move West. His health demanded the change. His labors as a physician had exhausted him. His daughter spoke feelingly of the impossibility of restraining his charitable zeal. He attended the poor for nothing. He rose at any hour and went forth in any weather in response to the call of suffering.

"That's what he says a doctor's duties are," she said. "It isn't a profession to make money with, it's a profession for helping people and curing them. You yourself don't count, it's only what you do that does. Why, my father had a very large practice, but he made only just enough to keep us."

Of all she had said this seemed to the listener the best worth hearing. The doctor now mounted to the top of the highest pedestal David's admiration could supply. Here was one of the compensations with which life keeps the balances even. Joe had died and left him friendless, and while the ache was still sharp, this stranger and his daughter had come to soothe his pain, perhaps, in the course of time, to conjure it quite away.

Early in the preceding winter the doctor had been forced to decide on the step he had been long contemplating. An attack of congestion of the lungs developed consumption in his weakened constitution. A warm climate and an open-air life were prescribed. And how better combine them than by emigrating to California?

"And so," said the doctor's daughter, "father made up his mind to go and sold out his practice. People thought he was crazy to start on such a trip when he was sick, but he knows more than they do. Besides, it's not going to be such hard work for him. Daddy John, the old man who drives the mules, knows all about this Western country. He was here a long time ago when Indiana and Illinois were wild and full of Indians. He got wounded out here fighting and thought he was going to die, and came back to New York. My father found him there, poor and lonely and sick, and took care of him and cured him. He's been with us ever since, more than twenty years, and he manages everything and takes care of everything. He and father'll tell you I rule them, but that's just teasing. It's really Daddy John who rules."

The mules were just behind them, and she looked back at the old man and called in her clear voice:

"I'm talking about you, Daddy John. I'm telling all about your wickedness."

Daddy John's answer came back, slow and amused:

"Wait till I get the young feller alone and I'll do some talking."

Laughing, she settled herself in her saddle and dropped her voice for David's ear:

"I think Daddy John was quite pleased we missed the New York train. It was a big company, and he couldn't have managed everything the way he can now. But we'll soon catch it up and then"—she lifted her eyebrows and smiled with charming malice at the thought of Daddy John's coming subjugation. "We ought to overtake it in three or four weeks they said in Independence."

Her companion made no answer. The cheerful conversation had suddenly taken a depressing turn. Under the spell of Miss Gillespie's loquacity and black eyes he had quite forgotten that he was only a temporary escort, to be superseded by an entire ox train, of which even now they were in pursuit. David was a dreamer, and while the young woman talked, he had seen them both in diminishing perspective, passing sociably across the plains, over the mountains, into the desert, to where California edged with a prismatic gleam the verge of the world. They were to go riding, and talking on, their acquaintance ripening gradually and delightfully, while the enormous panorama of the continent unrolled behind them. And it might end in three or four weeks! The Emigrant Trail looked overwhelmingly long when he could only see himself and Leff riding over it, and California lost its color and grew as gray as a line of sea fog.

That evening's camp was pitched in a clearing near the road. The woods pressed about them, whispering and curious, thrown out and then blotted as the fires leaped or died. It was the first night's bivouac, and much noise and bustle went to its accomplishment. The young men covertly watched the Gillespie Camp. How would this ornamental party cope with such unfamiliar labors? With its combination of a feminine element which must be helpless by virtue of a rare and dainty fineness and a masculine element which could hardly be otherwise because of ill health, it would seem that all the work must devolve upon the old man.

Nothing, however, was further from the fact. The Gillespies rose to the occasion with the same dauntless buoyancy that they had shown in ever attempting the undertaking, and then blithely defying public opinion with a servant and a cow. The sense of their unfitness which had made the young men uneasy now gave way to secret wonder as the doctor pitched the tent like a backwoodsman, and his daughter showed a skilled acquaintance with campers' biscuit making.

She did it so well, so without hurry and with knowledge, that it was worth while watching her, if David's own cooking could have spared him. He did find time once to offer her assistance and that she refused, politely but curtly. With sleeves rolled to the elbow, her hat off, showing a roll of hair on the crown of her head separated by a neat parting from the curls that hung against her cheeks, she was absorbed in the business in hand. Evidently she was one of those persons to whom the matter of the moment is the only matter. When her biscuits were done, puffy and brown, she volunteered a preoccupied explanation:

"I've been learning to do this all winter, and I'm going to do it right."

And even then it was less an excuse for her abruptness than the announcement of a compact with herself, steadfast, almost grim.

After supper they sat by the fire, silent with fatigue, the scent of the men's tobacco on the air, the girl, with her hands clasping her knees, looking into the flames. In the shadows behind the old servant moved about. They could hear him crooning to the mules, and then catch a glimpse of his gnomelike figure bearing blankets from the wagon to the tent. There came a point where his labors seemed ended, but his activity had merely changed its direction. He came forward and said to the girl,

"Missy, your bed's ready. You'd better be going."

She gave a groan and a movement of protest under which was the hopeless acquiescence of the conquered:

"Not yet, Daddy John. I'm so comfortable sitting here."

"There's two thousand miles before you. Mustn't get tired this early. Come now, get up."

His manner held less of urgence than of quiet command. He was not dictatorial, but he was determined. The girl looked at him, sighed, rose to her knees, and then made a last appeal to her father:

"Father, do take my part. Daddy John's too interfering for words!"

But her father would only laugh at her discomfiture.

"All right," she said as she bent down to kiss him. "It'll be your turn in just about five minutes."

It was an accurate prophecy. The tent flaps had hardly closed on her when Daddy John attacked his employer.

"Goin' now?" he said, sternly.

The doctor knew his fate, and like his daughter offered a spiritless and intimidated resistance.

"Just let me finish this pipe," he pleaded.

Daddy John was inexorable:

"It's no way to get cured settin' round the fire puffin' on a pipe."

"Ten minutes longer?"

"We'll roll out to-morrer at seven."

"Daddy John, go to bed!"

"I got to see you both tucked in for the night before I do. Can't trust either of you."

The doctor, beaten, knocked the ashes out of his pipe and rose with resignation.

"This is the family skeleton," he said to the young men who watched the performance with curiosity. "We're ground under the heel of Daddy John."

Then he thrust his hand through the old servant's arm and they walked toward the wagon, their heads together, laughing like a pair of boys.

A few minutes later the camp had sunk to silence. The doctor was stowed away in the wagon and Miss Gillespie had drawn the tent flaps round the mystery of her retirement. David and Leff, too tired to pitch theirs, were dropping to sleep by the fire, when the girl's voice, low, but penetrating, roused them.

"Daddy John," it hissed in the tone children employ in their games of hide-and-seek, "Daddy John, are you awake?"

The old man, who had been stretched before the fire, rose to a sitting posture, wakeful and alert.

"Yes, Missy, what's the matter? Can't you sleep?"

"It's not that, but it's so hard to fix anything. There's no light."

Here it became evident to the watchers that Miss Gillespie's head was thrust out through the tent opening, the canvas held together below her chin. Against the pale background, it was like the vision of a decapitated head hung on a white wall.

"What is it you want to fix?" queried the old man.

"My hair," she hissed back. "I want to put it up in papers, and I can't see."

Then the secret of Daddy John's power was revealed. He who had so remorselessly driven her to bed now showed no surprise or disapprobation at her frivolity. It was as if her wish to beautify herself received his recognition as an accepted vagary of human nature.

"Just wait a minute," he said, scrambling out of his blanket, "and I'll get you a light."

The young men could not but look on all agape with curiosity to see what the resourceful old man intended getting. Could the elaborately complete Gillespie outfit include candles? Daddy John soon ended their uncertainty. He drew from the fire a thick brand, brilliantly aflame, and carried it to the tent. Miss Gillespie's immovable head eyed it with some uneasiness.

"I've nothing to put it in," she objected, "and I can't hold it while I'm doing up my hair."

"I will," said the old man. "Get in the tent now and get your papers ready."

The head withdrew, its retirement to be immediately followed by her voice slightly muffled by the intervening canvas:

"Now I'm ready."

Daddy John cautiously parted the opening, inserted the torch, and stood outside, the canvas flaps carefully closed round his hand. With the intrusion of the flaming brand the tent suddenly became a rosy transparency. The young' girl's figure moved in the midst of the glow, a shape of nebulous darkness, its outlines lost in the mist of enfolding draperies.

Leff, softly lifting himself on his elbows, gazed fascinated upon this discreet vision. Then looking at David he saw that he had turned over and was lying with his face on his arms. Leff leaned from the blankets and kicked him, a gentle but meaning kick on the leg.

To his surprise David lifted a wakeful face, the brow furrowed with an angry frown.

"Can't you go to sleep," he muttered crossly. "Let that girl curl her hair, and go to sleep like a man."

He dropped his face once more on his arms. Leff felt unjustly snubbed, but that did not prevent him from watching the faintly defined aura of shadow which he knew to be the dark young woman he was too shy to look at when he met her face to face. He continued watching till the brand died down to a spark and Daddy John withdrew it and went back to his fire.

In their division of labor David and Leff had decided that one was to drive the wagon in the morning, the other in the afternoon. This morning it was David's turn, and as he "rolled out" at the head of the column he wondered if Leff would now ride beside Miss Gillespie and lend attentive ear to her family chronicles. But Leff was evidently not for dallying by the side of beauty. He galloped off alone, vanishing through the thin mists that hung like a fairy's draperies among the trees. The Gillespies rode at the end of the train. Even if he could not see them David felt their nearness, and it added to the contentment that always came upon him from a fair prospect lying under a smiling sky. At harmony with the moment and the larger life outside it, he leaned back against the canvas hood and let a dreamy gaze roam over the serene and opulent landscape.

Nature had always soothed and uplifted him, been like an opiate to anger or pain. As a boy his troubles had lost their sting in the consoling largeness of the open, under the shade of trees, within sight of the bowing wheat fields with the wind making patterns on the seeded grain. Now his thoughts, drifting aimless as thistle fluff, went back to those childish days of country freedom, when he had spent his vacations at his uncle's farm. He used to go with his widowed mother, a forlorn, soured woman who rarely smiled. He remembered his irritated wonder as she sat complaining in the ox cart, while he sent his eager glance ahead over the sprouting acres to where the log farmhouse—the haven of fulfilled dreams—stretched in its squat ugliness. He could feel again the inward lift, the flying out of his spirit in a rush of welcoming ecstasy, as he saw the woods hanging misty on the horizon and the clay bluffs, below which the slow, quiet river uncoiled its yellow length.

The days at the farm had been the happiest of his life—wonderful days of fishing and swimming, of sitting in gnarled tree boughs so still the nesting birds lost their fear and came back to their eggs. For hours he had lain in patches of shade watching the cloud shadows on the fields, and the great up-pilings when storms were coming, rising black-bosomed against the blue. There had been some dark moments to throw out these brighter ones—when chickens were killed and he had tried to stand by and look swaggeringly unconcerned as a boy should, while he sickened internally and shut his lips over pleadings for mercy. And there was an awful day when pigs were slaughtered, and no one knew that he stole away to the elder thickets by the river, burrowed deep into them, and stopped his ears against the shrill, agonized cries. He knew such weakness was shameful and hid it with a child's subtlety. At supper he told skillful lies to account for his pale cheeks and lost appetite.

His uncle, a kindly generous man, without children of his own, had been fond of him and sympathized with his wish for an education. It was he who had made it possible for the boy to go to a good school at Springfield and afterwards to study law. How hard he had worked in those school years, and what realms of wonder had been opened to him through books, the first books he had known, reverently handled, passionately read, that led him into unknown worlds, pointed the way to ideals that could be realized! With the law books he was not in so good an accord. But it was his chosen profession, and he approached it with zeal and high enthusiasm, a young apostle who would sell his services only for the right.

Now he smiled, looking back at his disillusion. The young apostle was jostled out of sight in the bustle of the growing town. There was no room in it for idealists who were diffident and sensitive and stood on the outside of its self-absorbed activity bewildered by the noises of life. The stream of events was very different from the pages of books. David saw men and women struggling toward strange goals, fighting for soiled and sordid prizes, and felt as he had done on the farm when the pigs were killed. And as he had fled from that ugly scene to the solacing quiet of Nature, he turned from the tumult of the little town to the West, upon whose edge he stood.

It called him like a voice in the night. The spell of its borderless solitudes, its vast horizons, its benign silences, grew stronger as he felt himself powerless and baffled among the fighting energies of men. He dreamed of a life there, moving in unobstructed harmony. A man could begin in a fresh, clean world, and be what he wanted, be a young apostle in his own way. His boy friend who had gone to Oregon fired his imagination with stories of Marcus Whitman and his brother missionaries. David did not want to be a missionary, but he wanted, with a young man's solemn seriousness, to make his life of profit to mankind, to do the great thing without self-interest. So he had yearned and chafed while he read law and waited for clients and been as a man should to his mother, until in the summer of 1847 both his mother and his uncle had died, the latter leaving him a little fortune of four thousand dollars. Then the Emigrant Trail lay straight before him, stretching to California.

The reins lay loose on the backs of Bess and Ben and the driver's gaze was fixed on the line of trees that marked the course of an unseen river. The dream was realized, he was on the trail. He lifted his eyes to the sky where massed clouds slowly sailed and birds flew, shaking notes of song down upon him. Joe was dead, but the world was still beautiful, with the sun on the leaves and the wind on the grass, with the kindliness of honest men and the gracious presence of women.

Dr. Gillespie was the first dweller in that unknown world east of the Alleghenies whom David had met. For this reason alone it would be a privilege to travel with him. How great the privilege was, the young man did not know till he rode by the doctor's side that afternoon and they talked together on the burning questions of the day; or the doctor talked and David hungrily listened to the voice of education and experience.

The war with Mexico was one of the first subjects. The doctor regarded it as a discreditable performance, unworthy a great and generous nation. The Mormon question followed, and on this he had much curious information. Living in the interior of New York State, he had heard Joseph Smith's history from its beginning, when he posed as "a money digger" and a seer who could read the future through "a peek stone." The recent polygamous teachings of the prophet were a matter to mention with lowered voice. Miss Gillespie, riding on the other side, was not supposed to hear, and certainly appeared to take no interest in Mexico, or Texas, or Joseph Smith and his unholy doctrines.

She made no attempt to enter into the conversation, and it seemed to David, who now and then stole a shy look at her to see if she was impressed by his intelligent comments, that she did not listen. Once or twice, when the talk was at its acutest point of interest, she struck her horse and left them, dashing on ahead at a gallop. At another time she dropped behind, and his ear, trained in her direction, heard her voice in alternation with Daddy John's. When she joined them after this withdrawal she was bright eyed and excited.

"Father," she called as she came up at a sharp trot, "Daddy John says the prairie's not far beyond. He says we'll see it soon—the prairie that I've been thinking of all winter!"

Her enthusiasm leaped to David and he forgot the Mexican boundaries and the polygamous Mormons, and felt like a discoverer on the prow of a ship whose keel cuts unknown seas. For the prairie was still a word of wonder. It called up visions of huge unpeopled spaces, of the flare of far flung sunsets, of the plain blackening with the buffalo, of the smoke wreath rising from the painted tepee, and the Indian, bronzed and splendid, beneath his feathered crest.

"It's there," she cried, pointing with her whip. "I can't wait. I'm going on."

David longed to go with her, but the doctor was deep in the extension of slavery and of all the subjects this burned deepest. The prairie was interesting but not when the repeal of the Missouri Compromise was on the carpet. Watching the girl's receding shape, David listened respectfully and heard of the dangers and difficulties that were sure to follow on the acquisition of the great strip of Mexican territory.

All afternoon they had been passing through woods, the remnant of that mighty forest which had once stretched from the Missouri to the Alleghenies. Now its compact growth had become scattered and the sky, flaming toward sunset, shone between the tree trunks. The road ascended a slight hill and at the top of this Miss Gillespie appeared and beckoned to them. As they drew near she turned and made a sweeping gesture toward the prospect. The open prairie lay before them.

No one spoke. In mute wonderment they gazed at a country that was like a map unrolled at their feet. Still as a vision it stretched to where sky and earth fused in a golden haze. No sound or motion broke its dreaming quiet, vast, brooding, self-absorbed, a land of abundance and accomplishment, its serenity flowing to the faint horizon blur. Lines of trees, showing like veins, followed the wandering of streams, or gathered in clusters to suck the moisture of springs. Nearby a pool gleamed, a skin of gold linked by the thread of a rivulet to other pools. They shone, a line of glistening disks, imbedded in the green. Space that seemed to stretch to the edges of the world, the verdure of Eden, the silence of the unpolluted, unconquered earth were here.

So must it have looked when the beaked Viking ships nosed along the fretted shores of Rhode Island, when Columbus took the sea in his high-pooped caravals, when the Pilgrims saw the rocks and naked boughs of the New England coast. So it had been for centuries, roamed by wild men who had perished from its face and left no trace, their habitation as a shadow in the sun, their work as dew upon the grass, their lives as the lives of the mayfly against its immemorial antiquity.

The young man felt his spirit mount in a rush of exaltation like a prayer. Some fine and exquisite thing in himself leaped out in wild response. The vision and the dream were for a moment his. And in that moment life, all possible, all perfect, stretched before him, to end in a triumphant glory like the sunset.

The doctor took off his hat.

"The heavens declare the glory of God. All the earth doth magnify his name," he said in a low voice.

A broken line of moving dots, the little company trailed a slow way across this ocean of green. Nothing on its face was more insignificant than they. The birds in the trees and the bees in the flowers had a more important place in its economy. One afternoon David riding in the rear crested a ridge and saw them a mile in advance, the road stretching before and behind them in a curving thread. The tops of the wagons were like the backs of creeping insects, the mounted figures, specks of life that raised a slight tarnish of dust on the golden clearness. He wondered at their lack of consequence, unregarded particles of matter toiling across the face of the world.

This was what they suggested viewed largely from the distance. Close at hand—one of them—and it was a very different matter. They enjoyed it. If they were losing their significance as man in the aggregate, the tamer, and master, they were gaining a new importance as distinct and separate units. Convention no longer pressed on them. What law there was they carried with them, bore it before them into the wilderness like the Ark of the Covenant. But nobody wanted to be unlawful. There was no temptation to be so. Envy, hatred and malice and all uncharitableness had been left behind in the cities. They were a very cheerful company, suffering a little from fatigue, and with now and then a faint brush of bad temper to put leaven into the dough.

There was a Biblical simplicity in their life. They had gone back to the era when man was a nomad, at night pitching his tent by the water hole, and sleeping on skins beside the fire. When the sun rose over the rim of the prairie the camp was astir. When the stars came out in the deep blue night they sat by the cone of embers, not saying much, for in the open, spoken words lose their force and the human creature becomes a silent animal.

Each day's march was a slow, dogged, progression, broken by fierce work at the fords. The dawn was the beautiful time when the dew was caught in frosted webs on the grass. The wings of the morning were theirs as they rode over the long green swells where the dog roses grew and the leaves of the sage palpitated to silver like a woman's body quivering to the brushing of a beloved hand. Sometimes they walked, dipped into hollows where the wattled huts of the Indians edged a creek, noted the passage of earlier trains in the cropped grass at the spring mouth and the circles of dead fires.

In the afternoons it grew hot. The train, deliberate and determined as a tortoise, moved through a shimmer of light. The drone of insect voices rose in a sleepy chorus and the men drowsed in the wagons. Even the buoyant life of the young girl seemed to feel the stupefying weight of the prairie's deep repose. She rode at a foot pace, her hat hanging by its strings to the pommel, her hair pushed back from her beaded forehead, not bothering about her curls now.

Then came the wild blaze of the sunset and the pitching of the camp, and after supper the rest by the fire with pipe smoke in the air, and overhead the blossoming of the stars.

They were wonderful stars, troops and troops of them, dust of myriad, unnumbered worlds, and the white lights of great, bold planets staring at ours. David wondered what it looked like from up there. Was it as large, or were we just a tiny, twinkling point too? From city streets the stars had always chilled him by their awful suggestion of worlds beyond worlds circling through gulfs of space. But here in the primordial solitudes, under the solemn cope of the sky, the thought lost its terror. He seemed in harmony with the universe, part of it as was each speck of star dust. Without question or understanding he felt secure, convinced of his oneness with the great design, cradled in its infinite care.

One evening while thus dreaming he caught Susan's eye full of curious interest like a watching child's.

"What are you thinking of?" she asked.

"The stars," he answered. "They used to frighten me."

She looked from him to the firmament as if to read a reason for his fear:

"Frighten you? Why?"

"There were so many of them, thousands and millions, wandering about up there. It was so awful to think of them, how they'd been swinging round forever and would keep on forever. And maybe there were people on some of them, and what it all was for."

She continued to look up and then said indifferently:

"It doesn't seem to me to matter much."

"It used to make me feel that nothing was any use. As if I was just a grain of dust."

Her eyes came slowly down and rested on him in a musing gaze.

"A grain of dust. I never felt that way. I shouldn't think you'd like it, but I don't see why you were afraid."

David felt uncomfortable. She was so exceedingly practical and direct that he had an unpleasant feeling she would set him down as a coward, who went about under the fear that a meteor might fall on him and strike him dead. He tried to explain:

"Not afraid actually, just sort of frozen by the idea of it all. It's so—immense, so—so crushing and terrible."

Her gaze continued, a questioning quality entering it. This gained in force by a slight tilting of her head to one side. David began to fear her next question. It might show that she regarded him not only as a coward but also as a fool.

"Perhaps you don't understand," he hazarded timidly.

"I don't think I do," she answered, then dropped her eyes and added after a moment of pondering, "I can't remember ever being really afraid of anything."

Had it been daylight she would have noticed that the young man colored. He thought guiltily of certain haunting fears of his childhood, ghosts in the attic, a banshee of which he had once heard a fearsome story, a cow that had chased him on the farm. She unconsciously assisted him from this slough of shame by saying suddenly:

"Oh, yes, I can. I remember now. I'm afraid of mad dogs."

It was not very comforting for, after all, everybody was afraid of mad dogs.

"And there was a reason for that," she went on. "I was frightened by a mad dog when I was a little girl eight years old. I was going out to spend some of my allowance. I got twenty cents a month and I had it all in pennies. And suddenly there was a great commotion in the street, everybody running and screaming and rushing into doorways. I didn't know what was the matter but I was startled and dropped my pennies. And just as I stooped to pick them up I saw the dog coming toward me, tearing, with its tongue hanging out. And, would you believe it, I gathered up all those pennies before I ran and just had time to scramble over a fence."

It was impossible not to laugh, especially with her laughter leading, her eyes narrowed to cracks through which light and humor sparkled at him.

He was beginning to know Miss Gillespie—"Miss Susan" he called her—very well. It was just like his dream, riding beside her every day, and growing more friendly, the spell of her youth, and her dark bloom, and her attentive eyes—for she was an admirable listener if her answers sometimes lacked point—drawing from him secret thoughts and hopes and aspirations he had never dared to tell before. If she did not understand him she did not laugh at him, which was enough for David with the sleepy whisperings of the prairie around him, and new, strange matter stirring in his heart and making him bold.

There was only one thing about her that was disappointing. He did not admit it to himself but it kept falling on their interviews with a depressive effect. To the call of beauty she remained unmoved. If he drew up his horse to gaze on the wonders of the sunset the waiting made her impatient. He had noticed that heat and mosquitoes would distract her attention from the hazy distances drowsing in the clear yellow of noon. The sky could flush and deepen in majestic splendors, but if she was busy over the fire and her skillets she never raised her head to look. And so it was with poetry. She did not know and did not care anything about the fine frenzies of the masters. Byron?—wrinkling up her forehead—yes, she thought she'd read something in school. Shelley?—"The Ode to the West Wind?" No, she'd never read that. What was an ode anyway? Once he recited the "Lines to an Indian Air," his voice trembling a little, for the words were almost sacred.

She pondered for a space and then said:

"What are champak odors?"

David didn't know. He had never thought of inquiring.

"Isn't that odd," she murmured. "That would have been the first thing I would have wanted to know. Champak? I suppose it's some kind of a flower—something like a magnolia. It has a sound like a magnolia."

A lively imagination was evidently not one of Miss Gillespie's possessions.

Late one afternoon, riding some distance in front of the train, she and David had seen an Indian loping by on his pony. It was not an unusual sight. Many Indians had visited their camp and at the crossing of the Kaw they had come upon an entire village in transit to the summer hunting grounds. But there was something in this lone figure, moving solitary through the evening glow, that put him in accord with the landscape's solemn beauty, retouched him with his lost magnificence. In buckskins black with filth, his blanket a tattered rag, an ancient rifle across his saddle, the undying picturesqueness of the red man was his.

"Look," said David, his imagination fired. "Look at that Indian."

The savage saw them and turned a face of melancholy dignity upon them, giving forth a deep "How, How."

"He's a very dirty Indian," said Susan, sweeping him with a glance of disfavor.

David did not hear her. He looked back to watch the lonely figure as it rode away over the swells. It seemed to him to be riding into the past, the lordly past, when the red man owned the land and the fruits thereof.

"Look at him as he rides away," he said. "Can't you seem to see him coming home from a battle with his face streaked with vermilion and his war bonnet on? He'd be solemn and grand with the wet scalps dripping at his belt. When they saw him coming his squaws would come out in front of the lodges and begin to sing the war chant."

"Squaws!" in a tone of disgust. "That's as bad as the Mormons."

The muse had possession of David and a regard for monogamy was not sufficient to stay his noble rage.

"And think how he felt! All this was his, the pale face hadn't come. He'd fought his enemies for it and driven them back. In the cool of the evening when he was riding home he could look out for miles and miles, clear to the horizon, and know he was the King of it all. Just think what it was to feel like that! And far away he could see the smoke of his village and know that they were waiting for the return of the chief."

"Chief!" with even greater emphasis, "that poor dirty creature a chief!"

The muse relinquished her hold. The young man explained, not with impatience, but as one mortified by a betrayal into foolish enthusiasm:

"I didn't mean that he was a chief. I was just imagining."

"Oh," with the falling inflexion of comprehension. "You often imagine, don't you? Let's ride on to where the road goes down into that hollow."

They rode on in silence, both slightly chagrined, for if David found it trying to have his fine flights checked, Susan was annoyed when she said things that made him wear a look of forbearing patience. She may not have had much imagination, but she had a very observing eye, and could have startled not only David, but her father by the shrewdness with which she read faces.

The road sloped to a hollow where the mottled trunks of cotton woods stood in a group round the dimpling face of a spring. With well-moistened roots the grass grew long and rich. Here was the place for the night's camp. They would wait till the train came up. And even as they rested on this comfortable thought they saw between the leaves the canvas top of a wagon.

The meeting of trains was one of the excitements of life on the Emigrant Trail. Sometimes they were acquaintances made in the wet days at Independence, sometimes strangers who had come by way of St. Joseph. Then the encountering parties eyed one another with candid curiosity and from each came the greeting of the plains, "Be you for Oregon or California?"

The present party was for Oregon from Missouri, six weeks on the road. They were a family, traveling alone, having dropped out of the company with which they had started. The man, a gaunt and grizzled creature, with long hair and ragged beard, was unyoking his oxen, while the woman bent over the fire which crackled beneath her hands. She was as lean as he, shapeless, saffron-skinned and wrinkled, but evidently younger than she looked. The brood of tow-headed children round her ran from a girl of fourteen to a baby, just toddling, a fat, solemn-eyed cherub, almost naked, with a golden fluff of hair.

At sight of him Susan drew up, the unthinking serenity of her face suddenly concentrated into a hunger of admiration, a look which changed her, focused her careless happiness into a pointed delight.

"Look at the baby," she said quickly, "a lovely fat baby with curls," then slid off her horse and went toward them.

The woman drew back staring. The children ran to her, frightened as young rabbits, and hid behind her skirts. Only the baby, grave and unalarmed, stood his ground and Susan snatched him up. Then the mother smiled, gratified and reassured. She had no upper front teeth, and the wide toothless grin gave her a look of old age that had in it a curious suggestion of debasement.

David stood by his horse, making no move to come forward. The party repelled him. They were not only uncouth and uncomely, but they were dirty. Dirt on an Indian was, so to speak, dirt in its place—but unwashed women and children—! His gorge rose at it. And Susan, always dainty as a pink, seemed entirely indifferent to it. The children, with unkempt hair and legs caked in mud, crowded about her, and as she held the baby against her chest, her glance dwelt on the woman's face, with no more consciousness of its ugliness than when she looked over the prairie there was consciousness of Nature's supreme perfection.

On the way back to camp he asked her about it. Why, if she objected to the Indian's dirt, had she been oblivious to that of the women and the children? He put it judicially, with impersonal clearness as became a lawyer. She looked puzzled, then laughed, her fresh, unusual laugh:

"I'm sure I don't know. I don't know why I do everything or why I like this thing and don't like that. I don't always have a reason, or if I do I don't stop to think what it is. I just do things because I want to and feel them because I can't help it. I like children and so I wanted to talk to them and hear about them from their mother."

"But would your liking for them make you blind to such a thing as dirt?"

"I don't know. Maybe it would. When you're interested in anything or anybody small things don't matter."

"Small things! Those children were a sight!"

"Yes, poor little brats! No one had washed the baby for weeks. The woman said she was too tired to bother and it wouldn't bathe in the creeks with the other children, so they let it go. If we kept near them I could wash it for her. I could borrow it and wash it every morning. But there's no use thinking about it as we'll pass them to-morrow. Wasn't it a darling with little golden rings of hair and eyes like pieces of blue glass?"

She sighed, relinquishing the thought of the baby's morning bath with pensive regret. David could not understand it, but decided as Susan felt that way it must be the right way for a woman to feel. He was falling in love, but he was certainly not falling in love—as students of a later date have put it—with "a projection of his own personality."

They had passed the Kaw River and were now bearing on toward the Vermilion. Beyond that would be the Big and then the Little Blue and soon after the Platte where "The Great Medicine way of the Pale Face" bent straight to the westward. The country continued the same and over its suave undulations the long trail wound, sinking to the hollows, threading clumps of cotton-wood and alder, lying white along the spine of bolder ridges.

Each day they grew more accustomed to their gypsy life. The prairie had begun to absorb them, cut them off from the influences of the old setting, break them to its will. They were going back over the footsteps of the race, returning to aboriginal conditions, with their backs to the social life of communities and their faces to the wild. Independence seemed a long way behind, California so remote that it was like thinking of Heaven when one was on earth, well fed and well faring. Their immediate surroundings began to make their world, they subsided into the encompassing immensity, unconsciously eliminating thoughts, words, habits, that did not harmonize with its uncomplicated design.

On Sundays they halted and "lay off" all day. This was Dr. Gillespie's wish. He had told the young men at the start and they had agreed. It would be a good thing to have a day off for washing and general "redding up." But the doctor had other intentions. In his own words, he "kept the Sabbath," and each Sunday morning read the service of the Episcopal Church. Early in their acquaintance David had discovered that his new friend was religious; "a God-fearing man" was the term the doctor had used to describe himself. David, who had only seen the hysterical, fanaticism of frontier revivals now for the first time encountered the sincere, unquestioning piety of a spiritual nature. The doctor's God was an all-pervading presence, who went before him as pillar of fire or cloud. Once speaking to the young man of the security of his belief in the Divine protection, he had quoted a line which recurred to David over and over—in the freshness of the morning, in the hot hush of midday, and in the night when the stars were out: "Behold, He that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep."

Overcome by shyness the young men had stayed away from the first Sunday's service. David had gone hunting, feeling that to sit near by and not attend would offer a slight to the doctor. No such scruples restrained Leff, who squatted on his heels at the edge of the creek, washing his linen and listening over his shoulder. By the second Sunday they had mastered their bashfulness and both came shuffling their hats in awkward hands and sitting side by side on a log. Leff, who had never been to church in his life, was inclined to treat the occasion as one for furtive amusement, at intervals casting a sidelong look at his companion, which, on encouragement, would have developed into a wink. David had no desire to exchange glances of derisive comment. He was profoundly moved. The sonorous words, the solemn appeal for strength under temptation, the pleading for mercy with that stern, avenging presence who had said, "I, the Lord thy God am a jealous God," awed him, touched the same chord that Nature touched and caused an exaltation less exquisite but more inspiring.

The light fell flickering through the leaves of the cotton-woods on the doctor's gray head. He looked up from his book, for he knew the words by heart, and his quiet eyes dwelt on the distance swimming in morning light. His friend, the old servant, stood behind him, a picturesque figure in fringed buckskin shirt and moccasined feet. He held his battered hat in his hand, and his head with its spare locks of grizzled hair was reverently bowed. He neither spoke nor moved. It was Susan's voice who repeated the creed and breathed out a low "We beseech thee to hear us, Good Lord."

The tents and the wagons were behind her and back of them the long green splendors of the prairie. Flecks of sun danced over her figure, shot back and forth from her skirt to her hair as whiffs of wind caught the upper branches of the cotton woods. She had been sitting on the mess chest, but when the reading of the Litany began she slipped to her knees, and with head inclined answered the responses, her hands lightly clasped resting against her breast.

David, who had been looking at her, dropped his eyes as from a sight no man should see. To admire her at this moment, shut away in the sanctuary of holy thoughts, was a sacrilege. Men and their passions should stand outside in that sacred hour when a woman is at prayer. Leff had no such high fancies. He only knew the sight of Susan made him dumb and drove away all the wits he had. Now she looked so aloof, so far removed from all accustomed things, that the sense of her remoteness added gloom to his embarrassment. He twisted a blade of grass in his freckled hands and wished that the service would soon end.

The cotton-wood leaves made a light, dry pattering as if rain drops were falling. From the picketed animals, looping their trail ropes over the grass, came a sound of low, continuous cropping. The hum of insects swelled and sank, full of sudden life, then drowsily dying away as though the spurt of energy had faded in the hour's discouraging languor. The doctor's voice detached itself from this pastoral chorus intoning the laws that God gave Moses when he was conducting a stiff-necked and rebellious people through a wilderness:

"Thou shalt do no murder.

"Thou shalt not commit adultery.

"Thou shalt not steal."

And to each command Susan's was the only voice that answered, falling sweet and delicately clear on the silence:

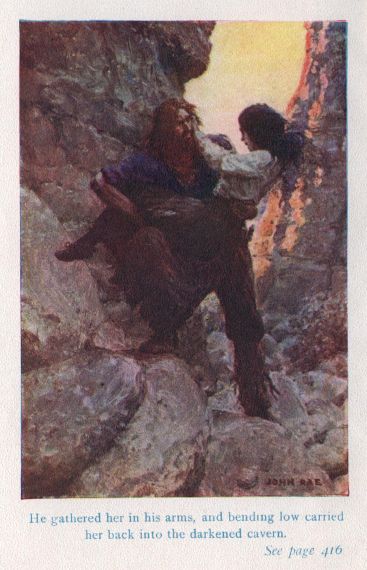

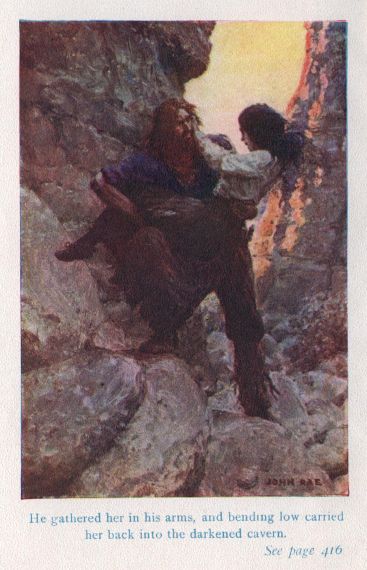

"Lord have mercy upon us and incline our hearts to keep this law."