Title: Dick Lionheart

Author: Mary Rowles Jarvis

Release date: October 16, 2006 [eBook #19554]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| CHAP. | |

| I. | SOMETHING TO LOVE |

| II. | FIGHTING FIRE |

| III. | A DASH FOR FREEDOM |

| IV. | IN A CARRIER'S WAGGON |

| V. | PAT LOST AND FOUND |

| VI. | A HOME IN IRONBORO' |

| VII. | PADDY'S RESOLVE |

| VIII. | LIONHEART'S BRAVE STAND |

| IX. | STOPPING A BURGLARY |

| X. | SUCCESS AT LAST |

"There, take that, and be off with you! And no dawdling, mind. It's ten minutes late, and you'll have to step it to be there by one. That's your dinner, and more than you deserve."

Dick Crosby took the one thick slice she offered, slipped the handle of the tin of tea on his arm, and with the big basin, tied up in a blue handkerchief, in his other hand, marched off in the direction of the tin works, while slatternly Mrs. Fowley went back into her cottage.

"Only bread and dripping again," he muttered, "while they've all got cooked dinner. How good it smells! She might have given me at least some taters and gravy. And I'm so thirsty. Perhaps if he is in a good mood I shall get a drink of tea. I s'pose nobody would know if I helped myself in Fell Lane, but I can't be Lionheart and do mean things, teacher said. Only if ever I grow up and have a little chap in my house what's only a 'cumbrance, he shall have the same dinner as all the rest!"

Taking frugal bites at the bread and dripping, to make it last as long as possible, Dick hurried on to the Works, whose tall chimney sent out clouds of black smoke.

The hooter sounded for the dinner hour as he reached the last turning, and a crowd of men and boys passed him, and one of the boys called out, "Hulloa, Slavey! How much a day for scrubbing floors and minding babbies?"

Dick's face flushed hotly, and the small hard hand that held the dinner trembled with a passionate desire to fight the tormentors, among whom Tim Fowley, his cousin, laughed loudest.

But his uncle was standing at the gate, and he had to hurry up with the dinner.

His reward for good speed was a surly word from the man and a box on the ear, that made his head reel.

"Take that for dawdling, and be off with you!"

"Oi don't think he deserved that, mate," said the cheery voice of Paddy the fireman, as he passed down the yard. "Shure, ye can see by the sweat of his brow he's been hurrying."

The man turned sulkily away, and Paddy whispered, "Come along of me, Dick, I've got somethin' to show you—somethin' you'll like almost as much as engines."

Dick followed eagerly, feeling that he had honestly earned ten minutes of dinner hour for his own.

It was hot in the great boiler house, where the stoke holes were glowing with fiery heat, and the throb of the machinery went on, like giant's music, all the time.

Paddy had worked there for years, and had found out Dick's intense love for engines and his secret ambition, some day, to be a stoker, too. And the Irishman's warm heart had often been made angry by the Fowleys' unkind treatment of the boy.

To-day he had a bacon sandwich and a drink of coffee to spare, and when Dick had gratefully disposed of these he took him to a warm corner behind the door, and showed him an old basket.

On the straw inside slept a tiny black and tan terrier, that as yet could hardly see. Dick was on his knees in a moment, fondling the little bundle, and crying, "Oh, Paddy, is he yours? What a dear little doggie."

Paddy's homely face was beaming as he said, "Shure, an' I'm glad ye like him, Dick, me boy. Can ye kape a secret if I tell ye? His mother's dead and I begged him, and when he's a bit bigger, if I can rare him, he shall be your very own."

Dick fairly gasped with delight, as the little warm bundle was put into his arms, for he had never had a pet, or anything living, of his own, to love since his father died.

"And his name's 'Pat,' unless there's something you'd like better, and I'll kape him till he's big enough to look after himself."

Suddenly Dick's face changed, and a sob came into his throat as he said, "Oh, Paddy, it's so good of you to offer him, but they'll never let me have him to keep. There is nowhere I could hide him, and Tim would hurt him every time he came near."

"Bad luck to him then, for a ondacent spalpeen as he is. It's a shame how they trate you. Oh, oi know, without telling. But shure, ye won't be there for ever. They've no claim on ye at all, at all. The bit of money your father left, and the insurance, have paid for your keep over and over, to say nothing of the work you're doing for that lazybones all the while. If you could only get to Ironboro' now, and find your Uncle Richard, he'd see you righted. And more by token he's a fitter, and would put you in the way of the same trade, and give you engines to your heart's content."

Dick's face was a study, as he held the puppy closely in his arms and looked up eagerly at Paddy.

"Do you mean that the Fowleys are not relations, and that I'm not beholden to stay there?"

"No relations in the world, me boy; and if I was you, I'd be off some fine morning and give 'em the slip. Your poor father was only a lodger there, after your mother died, and they took all he had and kept you, so to say, out of charity. Of course you was too young to know any different. I was well acquainted with your father and your uncle, years agone, but he had got work at Ironboro' long before your father died."

"And which is the way to Ironboro', and what is a fitter?"

"Ironboro'? Oh that's a hundred and fifty miles off, way up in the north, and you couldn't walk it yet, all alone. But some day—— And a fitter is a man who has learned his trade making engines, and can pull them to pieces, and put them together again as easy as I can fire these stoke holes."

Dick gently put the puppy back into the basket and straightened himself, like one taking a great resolve.

"Thank you, Paddy, ever so much for telling me, and if you'll only keep Pat till I can go, I'll save him a bit of my dinner every day."

"Indade and you won't, then, seein' as your dinner's none too hearty, judging by the leanness of your bones. No, I've no chick nor child of me own, and shure I can let the cratur alone enough to pay the milkman's bill for this little mite. You'll have to bring the dinner every day this week, and you'll see he'll get on fine in that time."

Dick gave his friend a hug of gratitude, and kissed Pat's silky head before he went away. And he hurried home and washed the dinner things, and cleared up the untidy kitchen like one in a dream. Sometimes it seemed to Dick that all his work went for nothing at all, for Mrs. Fowley always muddled things as soon as she came in.

She might have kept the house well on her husband's wages, but a large slice went to the "Blue Dragon," and out of the remainder she never had any left by the middle of the week. And she never did any work that could possibly be handed over to Dick, and the boy was in very truth the "slavey" they called him, and he rarely had enough to eat. Now she told him that he must stay away from school that afternoon and mind the baby, as she had business down the road at a neighbour's. And slipping a black bottle under her apron, she went out, and Susy, the youngest but one, followed her, leaving the baby fretting in the old wooden box that served as cradle.

As soon as Dick had finished he took her out into the dreary little garden and tried to pacify her. She was generally good with him, but the heat, and teething, had made her fretful, and he had to walk up and down the cinder path till his arms ached almost beyond bearing. She went to sleep at last, and Dick sat down and took a tattered book from his pocket and began to read once more the story of Richard the King.

It was the story that he loved best in the history lessons, for his own name was Richard Hart Crosby, and the fancy had come into his life like a sunbeam, that he might be Richard Lionheart too.

There were no books in the Fowleys' kitchen, and none of the children went to Sunday school regularly. Just for a week or two before the annual treat, or Christmas tree, they would go in great force, but Dick could not be spared.

But he had one other little book that was kept as a hidden treasure—his mother's Bible, that she had left to him. And in that he had learned how to be a true Lionheart and a good soldier of Jesus Christ. And every day he managed to read a few verses at least.

Now, as the sultry afternoon wore away, and the baby still slept, he thought again and again of the discovery he had made, that he did not really belong to the Fowleys.

"I have tried to please them and be brave and do my duty because they've given me a home," he reasoned to himself, "but perhaps if they had money when father died, I'm not beholden after all, as they always say I am. And oh, I would like to find a real relation! And isn't it good of Paddy to get that dear little Pat for me? I must wait till he is big enough to go too, and then I can have him for my very, very own."

Dick was thirteen, and small for his age, but his mental powers were keen, and he knew that if he stayed with the Fowleys he would have no chance to get on in life.

And looking up into the blue summer sky, he prayed to his heavenly Father to help him to get away.

A sudden scream of terror from the cottage roused Dick from his thinking, and laying the baby down he rushed in.

On the doorstep he met little Susy, with her lilac pinafore in flames. She had been trying to reach something from the mantelpiece, and had climbed up on the unsteady old fender. There was no guard in front of the open fire, and the draught had drawn her pinafore towards the bars and set it on fire, and the flames were mounting around her, and already her hair was singed.

But Lionheart knew what to do. With a spring and a cry he caught her just as she was rushing out-of-doors, and flinging her down he fell on her, and tore and clutched at the burning rags with his bare hands.

She screamed with fright rather than with pain, but Dick did not let go till the danger was past; and his clothes, being woollen, did not catch.

There was a scuffle of footsteps as Mrs. Fowley and two other women came in with a great outcry. And the sobbing child was wrapped in a big shawl, and the doctor sent for.

And her mother, to relieve her own fears, began as usual to upbraid Dick.

"It's all your fault, you good-for-nothing pauper! Why didn't you look after the child?"

"I thought you had her, she went out with you," he said, trembling with dread of more than a scolding, and scarcely able to bear the pain in his poor burned hands.

"Then you'd no business to think," she screamed. "What you've got to do is to mind the children, and anything else I've a mind to order you to do. Three years and better we've kep' you out of charity, and you don't earn shoe leather yet. Where's the baby?"

"Asleep in the garden, I put her down under the tree when I heard Susy cry out."

"Then go and fetch her this minute. And a fine hiding you'll get when Fowley comes home. Susy's his favourite out of 'em all."

Dick looked appealingly at the neighbours and muttered, "I—I can't carry her—my hands——"

"Bless me, there's work for the doctor here," said one of the women in consternation, as she looked at his poor scorched fingers.

"Depend upon 't, Mrs. Fowley, he's saved your Susy's life. Best not talk about hidings."

"What's the matter here?" cried a brisk voice at the door, as the old doctor entered. He had been visiting in the next street, and was fortunately met by the messenger.

"Burns. Ah! the old story—open fires and no guard. When will you women learn wisdom?"

Mrs. Fowley shrank from his stern look, and whined, "How can the likes of we afford guards, I should like to know?"

"Afford?" he echoed sharply, as he turned from his examination of Susy's hurts. "You women spend enough at the 'Blue Dragon' every week to put a guard at every fire-place, to say nothing of what the men spend. If you hadn't been drinking together, and neglecting home, this wouldn't have happened. I can smell the gin here and now!"

The old doctor was noted for his plain speaking, but with all his sternness to wrong doing, he was very tender-hearted, and nothing could have been more gentle than his touch on Susy's arm.

Fortunately her hurts were surface burns, and no vital part had been touched by the flame. But Dick's were more severe, and the doctor took infinite pains in bandaging the scarred hands and wrists.

"You're a brave lad," he said, when the pain was eased, and the last strip of lint put on. "How did you come to be burned like this?"

"I ran in from the garden when she screamed, and I got her down and scrambled out the flames somehow with my hands and jacket. You see, I had to be Lionheart," he added softly.

"Lionheart, is he your hero, the crusader king?"

Dick nodded, half scared at finding his cherished aspirations shared by another.

"But there is a living Leader to follow, my boy, who is better than all the knights of old. Do you know whom I mean?"

"Yes, sir, the Lord Jesus."

"Yes, He is the Lion of Judah, and the true Captain of all true crusaders to-day. Follow Him, and he will make you Lionheart indeed."

Then turning to Mrs. Fowley, he said in a different tone, "You owe your child's life to this brave little lad. Now take care of him in return. He'll not be able to work for a good while, and he wants feeding up as well. He has no business to be so thin and ill-nourished. See that his hands are kept covered, and Susy's arm too. I'll send liniment down to-night for both. And you will have to nurse the baby yourself, and do the work for many a day."

The old doctor's voice was stern as he finished, for he had known Dick's father and mother in their own tidy little home, and he hated Mrs. Fowley's drinking habits, and her neglect of the children, and unkindness to the orphan boy. For once she looked ashamed of herself, and the neighbours, feeling guilty themselves, slipped away. They knew the doctor was right, and that most of the accidents he had to attend, and the poverty that caused him to work for nothing, were alike due to the drink.

And life was certainly a little easier for Dick in the next few days.

His bandaged hands made house-work impossible, and so he was allowed to go to school in peace.

And the knowledge that Susy owed her life to him, made even the ill-tempered father a shade less surly.

He could not write or do sums, but the teacher saw that his time was well filled. Dick was a favourite of his because his work was so faithfully done, in spite of drawbacks.

Home lessons had small chance in Mrs. Fowley's presence, and the frequent excuses for keeping him at home had sadly interfered with his getting on, but in school no boy was happier than he.

In the playground there might be taunts about his shabby clothes, and rough usage from the Fowley boys, that were hard to bear patiently.

And he did not always succeed in keeping his temper down.

But when, once or twice, he had struck a blow for freedom, garbled tales were carried home and he had to suffer tenfold afterwards for his daring.

But the thought of Lionheart and his long waiting made him brave to suffer and endure. And more and more the thought of Jesus, as the Friend and Leader of those who follow Him, filled the darkest hours with joy.

The annual examination was drawing near, and Dick was very anxious to be able to use his hands by then, and "pass the standard" successfully.

Meanwhile, he worked doubly hard, and went far ahead of the other boys in lessons that had to be learned by heart.

And the teacher lent him books to read that helped him wonderfully, though he could only read them by snatches.

He saw how boys as poor and friendless as himself had had to bear hardship and unkindness, and how they had fought their way onward, through all difficulties, to success and freedom, and his own resolve grew stronger every day.

Now and then Mrs. Fowley would order him to be off out of her way, and when this happened in the evening he gladly went to Paddy's lodgings.

It was so quiet there, after the scolding and quarrelling at home, and Paddy always had a welcome for him, while bright-eyed Pat quickly learned to know his owner.

He grew very fast, and was so full of fun and frolic, that there were no dull times when he was awake.

And Paddy, who seemed to know all about dogs and their doings, suggested that he should be taught tricks "because of his knowingness."

And teaching him to beg and sing and shake hands, filled many a merry half-hour that autumn, and the Fowley's would scarcely have known Dick, if they had seen him there.

When the examination day came he managed to get through successfully, though his paperwork had to have allowances made for its deficiencies.

But at home all the effects of Susy's rescue had passed away, and Dick was more scolded and starved than ever before.

"Here, you young rascal, I'll teach you to meddle with my tools! What have you done with my knife?"

"I haven't had it," said Dick, looking up from the stocking he was awkwardly trying to darn by the firelight.

His hands were quite healed now, but still stiff and scarred from the burns, though the doctor had said the marks would get less as time went on.

"None of your tales, now. Tim said he saw you with it to-day. Give it me back this minute, or you shall have a dressing you won't forget in a hurry!"

"But I haven't seen it even," cried Dick earnestly. "Tim must have made a mistake."

"Oh, of course! Putting it on Tim, as usual," sneered Mrs. Fowley. "Your impudence is getting past bearing. Just go and get the knife this minute."

Dick stood up uncertainly, not knowing how to prove his innocence.

Everything that went wrong in that ill-managed household, was always in some mysterious way due to his shortcomings, but nothing had ever yet made him tell a lie, and in their hearts they knew it.

"I haven't seen it," he repeated, and there was absolute truth in the clear brown eyes, and Mrs. Fowley shifted her own uneasily as he looked at her.

But she said aloud, "He wants something to break down his spirit, Fowley, he ain't half so biddable as he used to be, and now he's passed the standard and can go to work, we shan't live for his pride and upstartness."

Now, Dick had not once refused to obey her commands, but since Paddy had told him about his uncle, and the possibility of going next year to find him and independence at the same time, the new hope had given him a bolder bearing.

There were times when he quite forgot to be afraid of blows and short rations, and when sharp words passed over him almost unheard. He was so sure the way would be made plain for him, and that his bondage would soon be at an end.

"Impudent, is he?" said Fowley, with an ugly scowl on his face, as he turned to the corner where the cruel strap was hung, to be the terror of all the children.

"I'll teach you manners, you young thief that we've kep' out of the workhouse and supported for nothing all these years."

"Not for nothing!" said Dick, with a sudden flash of passionate indignation. "You had all father's money and kept it, and I've worked just like a slave besides. It's not I that am a thief."

For a moment Fowley looked confounded, while his wife turned pale and shivered. Then, with a brutal laugh, he clutched the strap and reached forward.

But the table was between them, and Dick had never felt more like a Lionheart than at that moment.

"You shall never beat me again, or call me names, never!" he cried, as he opened the door and dashed out into the November night.

There was a dense fog outside that seemed to swallow him instantly, and by the time Fowley got to the door the boy had vanished.

"He's escaped me this time, but he shall have a double dose when I set eyes on him again," said the man grimly, as he hung up the strap; "I'll let him know about father's money!"

"But who could have told him?" asked his wife, in a frightened tone. "What if he goes with his tale to the police, or to that meddling doctor, that took such notice of him. He's never been the same boy since then."

"Police! not he, but if he should, 'mum's' the word, mind. We never had naught but just enough to pay for the buryin'. He'll be back again, meek enough, come bedtime, and then you can find out."

And flinging the tools back into the box, the man, who had already drunk too much on his way home, lurched off to the "Blue Dragon," where all his evenings now were spent. But his wife sat over the fire and looked at the grate Dick had laboriously black-leaded that morning, and her thoughts were busy with the past. And her long sleeping conscience was awake, and she heard again the feeble voice of a dying man, "Send this letter to brother Richard at once. We quarrelled before he went off to Ironboro', but he'll come and see to things and take charge of little Dick. And there'll be enough to pay for his upbringing, when all's said and done." But the letter was conveniently forgotten, and presently thrust into the flames, and the leathern pouch with its store of gold greedily taken possession of, as soon as the lodger was dead. And like all ill-gotten gains, the gold rapidly melted away.

"Who could have knowed about it, and told the boy?" she muttered with growing anxiety, as she went to the door to look out for the runaway.

But there was nothing but the murky gloom, with a faint reflection of light from the lamps far down the road, and a noise of rough play in the distance. The children of the row—her own among them—were having their usual street games in spite of the fog and chill, but Dick would not be there, she knew. For he was different from the rest, and hated the rough horse-play and bad language with all his might.

"I must have a sup to make me forget it," she muttered again. "He looked for all the world like his father. I told Fowley at the time it would come home to us, and it will."

Noisily the children came in, clamoured for supper, and took it in their dirty hands, and then went to bed.

Their father was helped home at closing time, too far gone to remember what had happened, but no Dick came in.

Bareheaded he had run away through the fog, his thin jacket and broken boots a poor protection from the biting cold, but in his excitement he scarcely felt it.

In a hiding place in the lining of his old jacket he had the little pocket Bible that had been his mother's gift, with his name, Richard Hart Crosby, on the fly leaf.

Folded small within it were the torn remains of a once handsome crimson and blue silk handkerchief, the only memento of his father he possessed. Somehow it had escaped the utter destruction that visited all good things in Mrs. Fowley's keeping, and Dick treasured it more than words could tell.

Feeling with his hand to be sure his treasures were safe, he ran breathlessly on to Paddy's lodgings, in a back street not far from the tin works.

Paddy had good work and fair wages, and might have been comfortably off, but, alas, the "Blue Dragon" was not the only evil beast in Venley, and much of Paddy's money went to the till of the "Brown Bear" at the corner. Not that he drank deeply himself, but he loved the warmth and company, and was too generous to others in the matter of treating. There was always a chorus of welcome for Paddy when he entered the bar.

But to-night he was at home, busily engaged in putting a clumsy patch on his blue "slop" jacket, and he answered Dick's timid knock with a boisterous welcome.

"And have ye railly left the wretches entirely and going off to Ironboro' to seek your fortin? Shure, and its could weather for the job. And of course ye want Pat. But ye can't have him to-night. Come and have a bite and a sup and share me cot, and ye can be off in the mornin' before anybody's astir, if ye like. Down then, me beauty; shure and ye needn't' be so glad at the prospect of leaving Paddy!"

For Pat was wagging his short tail and barking and jumping in a storm of delight, while Dick hugged him with the blissful thought that now he would have him for always.

"You're so good to me," he cried gratefully, "but I'm afraid they'll find me if I wait till morning."

"Not they. Let me look at your boots."

Dick held up a shabby foot, and Paddy sniffed in disdain. Two of the Fowley's had worn the boots in turn, and they were now falling apart from stress of wear and weather.

"They're no good for the road, me boy. We'll see." And soon a supper of herrings and bread and butter and tea smoked invitingly on the table, and when this had been disposed of Paddy went out, locking the door.

In a surprisingly short time he came back with a stout pair of boots and some warm stockings, and a half-worn cloth overcoat and cap. "Shure, and ye won't mind their coming from the second-hand shop with the three yallow balls put up for ornyment. Me uncle lives there and he's very obligin'."

Dick flushed with a mixture of gratitude and shrinking. All his experiences at the Fowley's had not made him like to wear other people's clothes. But the boots were such a good fit. And the jacket would keep him so warm and be such a grand bed quilt if he and Pat had to sleep out.

But how could he take so much from Paddy? The Irishman's quick eyes saw and understood, and he said easily, "You can pay me back when you're Lord Mayor of Ironboro', with a gold chain round your neck and Pat with a leather collar and a brass plate to tell his name and nation."

"I'll pay long before that, if I live," cried Dick earnestly. "I don't mean to beg my way, either, if I can only get work going along."

"That's right, lad, work your passage out; but anyways this half-crown won't come amiss—we'll put it down in the ledger with the rest of the good debt accounts. You'll look out for your uncle—a foine dark man with brown eyes like your own, only maybe not so shiny. Give my best respecks to him, and tell him I persuaded you to get clear away from the villains."

Dick took out his pocket Bible to read his chapter with a glad feeling of security. He would never need to hide it from the Fowley's again. "Read it out, me boy, read it. There's good words in it, whatever the praste may say." And Dick read the first chapter of Joshua, and his voice rang out triumphantly in the words, "Be strong and of a good courage, be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed, for the Lord thy God is with thee, whithersoever thou goest."

"Shure, them's good marching orders," said Paddy thoughtfully. "A body could even get past the 'Brown Bear' o' nights if he thought of them."

"It's easy to be Lionheart when the Lord God is along," said Dick wistfully. "I wish you wouldn't go in any more, Paddy, because I love you so, and God wouldn't maybe care to go into such places, and you'd have to leave Him outside."

"Just hark to the boy," said Paddy lightly, jumping up and making ready for bed.

But long after Dick's gentle breathing told of peaceful sleep Paddy lay wide awake, thinking of wasted money and worse than wasted health and time, and he almost resolved to leave the drink alone for ever.

There was a good breakfast ready by candle light next morning, and then Dick and Paddy parted, with an affectionate good-bye. When the hooters summoned the hands to the tin works at seven o'clock Pat and his little master were out on the dark north road, with houses and lamplight left far behind.

At first they went quickly, for fear of pursuit, but, as the short day wore on, Dick lost his fears and enjoyed Pat's runs and gambols by the roadside. Apparently he quite realised the new position, and had no regrets at leaving Paddy for his lawful owner.

Their noonday lunch, provided by their kind Friend, tasted wonderfully good, but both the travellers were feeling very tired before any prospect of the next meal came in sight. The brief daylight was already fading when they saw a neat thatched cottage, standing back from the roadside.

Close to the rustic gate was a heap of firewood, logs and blocks and smaller chips together, and an old woman was stooping painfully, trying to carry them in.

"Let me help you," cried Dick, hurrying forward, "I'd be so glad of a job!"

The worker looked sharply at him, and at once said, with a sigh of relief, "I don't mind if you do. Carry them into the woodshed there and stack them tidy, and I'll give you three-pence. You look honest, and that's a nice little dog you've got."

"Yes, isn't he? Sit up, Pat!"

The old woman laughed, as Pat stood up obediently on his tired little legs and begged, and Dick went on, "I don't beg myself, though I am tramping, but Pat learned to do it before we came."

And encouraged by this friendly notice Pat wagged his tail and immediately followed the old woman into her bright kitchen and stretched himself on the gay rag carpet before the fire.

Like her, he kept one eye on the little toiler outside, but Dick had set to work with a will. He plodded on, making a threefold stack in the woodshed, with the logs at one end and the blocks at the other, and all the chips in the middle.

"Must be Lionheart when there's threepence to be earned, even if you are tired all over," he murmured, as he trudged to and fro. Presently a cheerful sound of teacups and a delightful smell of toast came from the cottage, and then the old woman brought out a broom to sweep up the mess.

"That's right, my lad. Why, bless me, you have been quick! And you've stacked them a sight better than I could myself. You shall wash your hands and come in and have some tea before you go on. As to the little dog I should like to keep him, he's so pretty and peart. I s'pose you don't want to part with him?"

"Oh, no, thank you, ma'am," said Dick quickly, "but I should like some tea, I am so thirsty." And in five minutes Dick was sitting at the round table and telling Mrs. Grey a little bit of his story, while Pat finished a saucerful of sop and then looked up knowingly at his master, as if to say, "These are famous quarters—don't tramp any further to-night."

"Poor boy," said Mrs. Grey, as she wiped her spectacles, "it's a long way for you to go, and coming on dead of winter too. I don't see how you're going to manage it. But you shall have a shakedown on the old sofa here, for to-night. I am sure I can trust you, or rather trust Him who said 'Inasmuch.'"

"I knew He would help me," said Dick gratefully, "but I didn't expect anything so good as this."

"But He always gives more than our expectings or deservings," said the old woman kindly, as she put another log on the fire. "See what a splendid load of wood He's sent me for the winter, and then He sent you along, just in time to stow it away. As I get older my prayers always seem turned to praise before I've done, there's so much to be glad for."

Dick slept soundly on the old sofa, with Pat curled up at his feet, but he woke next morning in time to light the fire and put the kettle on, before Mrs. Grey came down. And, looking at his bright face and seeing his handy ways, she felt almost inclined to keep Pat and his master.

But after breakfast they started at once, Dick's jacket pockets stuffed full of provisions and the threepenny bit jingling merrily against Paddy's half-crown. But there was no chance of earning more that day, and they had to sleep in the loose hay at the foot of a hay rick, belonging to a distant farm.

Fortunately the wind had changed and the weather was warmer, and they were none the worse for the camping out.

Dick was trudging manfully on a day or two afterwards, hoping to reach the town of Weyn before nightfall, when a lumbering carrier's waggon with a black canvas roof came jolting along, at a great rate, behind. "Steady, there! Whoa, I say. What ails thee now? Steady!"

The big brown horse was pulling and straining at the bit and looking very wild, while the driver tugged at the reins in a frantic attempt to pull up, and two women passengers inside the van began to scream.

Without a thought of danger Lionheart sprang from the side of the road and dashed towards the horse's head, clutching at the reins, and a farm labourer, coming in the opposite direction, threw up his arms in front.

Startled by this double onslaught the horse swerved and then stood still, trembling with fright.

"It's the strap!" cried Dick, breathlessly. "See, that strap has broken and the end was flicking his side, and that frightened him."

"Sure enough, and I couldn't think what ailed him," cried the driver, wiping the perspiration from his brow. "Seven years I've had Boxer, and he never played me that trick afore. I'm very much obliged to ye, my brave lad, and you too, friend, and I'll stand a shilling apiece and thankful. The canal bridge is just a half mile further on, and if he hadn't been stopped and the bridge had chanced to be open——"

The labourer took the shilling with a grin, and held the horse while the carrier mended the broken strap with string, but Dick said hesitatingly, "I don't want a whole shilling just for trying to hold him, it's too much. But would you mind giving me a lift instead. We're going to Weyn, and we've walked such a long way."

"With all the pleasure in life," said carrier Brown, good-naturedly. "You want to get to fair, I suppose? Ah well, a fair's no good without money to spend. So take this and jump up. Boxer will be all right when he's had a bite from his nose-bag."

The inside of the van was like a cave, and the narrow seat that ran round the inside was packed with country folks and their baskets and parcels, going to the fair. Clean straw carpeted the floor, and a tiny glass window at the back, six inches square, let in a few murky rays of daylight. Two schoolboys shared the front seat with the driver, but he made a few inches of room for Dick, and Pat snuggled down contentedly at his feet.

The women inside talked loudly of their feelings when Boxer bolted, but the driver still looked pale and anxious, and Dick, feeling shaken now the strain was over, was very glad to lean back against the side and rest. Mile after mile they rumbled on, leaving the canal with its barges behind, and the low lying meadows with their fringes of elm and willow.

Sometimes the way lay through narrow lanes, where the branches almost met overhead, and the tangled hedgerows swept the canvas roof; and sometimes the road wound upwards, and Boxer plodded from side to side taking a zigzag course to ease the climbing, while Dick rested luxuriously and dreamed of Ironboro'. Gradually the way became less lonely, carts and waggons and droves of sheep were passed and houses were more frequently seen by the wayside, and from these groups of children came, talking joyously about the fair and counting their pennies as they went along.

Half-a-mile from the little town they had to wait. A gaily painted group of show waggons filled the roadway, for one of these had broken down, and for a time nothing could pass by.

There was a great noise of talking and shouting orders, and one big man, with tiny corkscrew curls of very black hair and silver rings in his ears and a coat of faded velveteen, stood close by the carrier's waggon and ordered others to do his bidding.

Pat was broad awake now, and when the carrier, seeing they would have to wait awhile, took out a lunch of bread and meat and began to cut it with a pocket knife, the dog stood on his hind legs and begged in his most insinuating way.

"He's as smart as his master," said the carrier, laughing, while the gipsy-like man turned and glanced keenly at the van.

"Does he know any more tricks?" asked one of the boys eagerly.

Dick bent down and whispered something to Pat, and he threw back his head, half shut his eyes, and gave vent to a succession of shrill howls that were the best music his voice was capable of, while his master whistled the air of "Killarney" as an accompaniment.

Everybody laughed, and then Pat made a funny little bow and held up his paw to shake hands.

"How much do you want for him?" said the showman in the velveteen coat. "I'm looking out for a smart little terrier to guard my show. I wouldn't mind a couple of shillings."

"He's not for sale, thank you," answered Dick politely.

"Nonsense! Every dog has a price, and most likely you've picked him up somewhere underhanded. So come along."

Dick flushed scarlet at the insult and again said "No!" decidedly.

The man turned and whispered something to a girl in an orange scarf and black and green frock, who had come out of the show waggon, and she tossed her head and laughed merrily. But now the broken caravan was pulled aside and the road was partly clear again, and the carrier drove on, and soon with a mighty flourish of the reins he stopped in front of the "George Inn" at Weyn, and everyone got down.

For two days in the year at the annual fair, the quiet little town of Weyn gave itself up to merrymaking. Shows and caravans choked the narrow streets; huge roundabouts as "patronised by all the crowned heads of Europe," swung giddily round in the market-place, and the shouts of the stall-keepers, and the din of the orchestra, and the ceaseless crack of the rifle ranges, where boys were shooting for cocoa-nuts, made a noise that was almost deafening.

The piles of gingerbread and coloured rock on the stalls looked very tempting, and Dick, with Pat in his arms, and three-and-ninepence in his pocket, felt rich as he walked by. But though he liked sweet things, all the more because he had had so few to enjoy, he would not be tempted to buy.

"Don't believe Lionheart had cakes and candy—not when he was on the crusades, anyhow. It must be bread and cheese, and maybe a whole ha'poth of milk for us, Pat, to-day. When I'm a fitter you shall have a good meaty bone every day of your life!"

Pat looked up, as if he quite understood, and on some old stone steps in one of the quieter streets they were soon sharing rations, with appetites that a duke might have envied.

"Here, boy, hold my horse for a couple of minutes, will you? Don't let go; he doesn't like this pandemonium any better than I do."

In a moment Dick was on his feet and ready for business, and for the second time that day he gripped a bit of strap, with the resolve to hold on at all costs.

Only this horse was a beautiful chestnut, with a coat like satin, and harness that must have cost more than carrier Brown's whole turn-out.

The gentleman went into the post-office opposite, but the noise of the fair evidently upset the spirited horse, and he was very restless and impatiently pawed the ground and tossed his head.

"What a lot of stamps he must be getting!" thought Dick, when five minutes had gone by and there was still no sign of the rider's return. A party of children, blowing penny trumpets, clattered past and the horse gave a spring that taxed Dick's wrists to the utmost.

He was too busy and anxious to think about Pat, so he did not see or hear the girl in the orange scarf steal up to him and offer a dainty piece of meat, as he sat patiently waiting behind. Alas! for dogs' nature, the temptation was too great! He followed the decoy for a few yards and was then allowed to seize the bait. In a moment a black shawl was flung over the silky head, and the dog was snatched up and carried round the corner and across the Market Place.

Pat struggled and snapped and barked in vain, and the girl hurried through the town to a back lane where a number of caravans were drawn up out of the way. At one of these the showman in the velveteen coat was standing, and he instantly opened an inner compartment and, giving Pat a sharp blow, thrust him inside and turned the key.

"Good for you, Meg!" he cried with a chuckle. "That dog 'll be worth money to the show, by the time I've trained him. 'The Wonderful Black and Tan Performer,' &c. We'll keep him shut up till we're far from here, and if any questions is asked it's our dog, and that boy's a thief that have stole him from our 'appy 'ome."

"All right, dad, that's a good idea. We'll go back to the Square now. They won't be likely to come and look here."

The Post Office was very full that morning, and the girl behind the counter looked worried, as she tried to meet all the demands of hurried customers.

But at last the owner of the chestnut horse got his business of money orders and telegrams finished and came out.

"That's right, my lad; here's sixpence for your trouble," he said as he took the reins from Dick and mounted and rode off.

"Sixpence." Another good payment for a small piece of hard work!

Dick looked down triumphantly at the coin, but his face changed in a moment. This was no sixpence, such as he had often been entrusted with on Mrs. Fowley's errands, but a coin of shining yellow gold.

"It's half a sovereign," he cried breathlessly, and just for one moment the thought came, "Now I can take the train and ride to Ironboro'. Surely ten shillings would buy a ticket for all the way."

But like a flash the temptation came and went. "Lionhearts don't steal," he cried as he dashed down the street after the horseman crying, "Stop! Stop!"

But the fleet and spirited horse was already far on the way, and though Dick ran as fast as his feet could go the distance increased every moment.

He would have had no chance of success but for a carriage coming in the opposite direction. It carried several ladies and the rider reined in his horse for a chat.

Dick ran on and reached the group just as the rider was preparing to go on again.

"You are followed," said one of the ladies softly. "I am sure this boy wants to speak to you."

The rider looked round, and recognising Dick said, "Well, my boy, what is it?"

"The money sir, please, you said you gave me sixpence and it was half a sovereign. I've brought it back."

"Well done. There's one honest boy in the fair, at any rate. Take this for your trouble, but don't spend it all on ginger bread."

"Oh, thank you, sir, I shan't spend any. I'm going to Ironboro'."

"But that is a hundred miles off, at least. Why are you going so far?" asked the lady.

"To find my uncle and learn to be an engineer."

"H'm, a large order for a small man," said the gentleman kindly. "Here, I'll give you a character that may help you more than money." And tearing a leaf out of his pocket book, he wrote on it, "I have proved the bearer to be a quick and honest boy. Dale Melville."

"There, laddie, that name is known in Ironboro', and it may do you a good turn."

"Are you going alone?" asked the lady with white hair, who had been listening to all that passed, and seemed amused at Dick's gratitude.

"Oh, yes, ma'am—at least only Pat and me. He is my little dog, you know."

Then with sudden recollection he turned hurriedly and looked for his faithful follower. But there was no Pat in sight, and flushing painfully, he cried, "Oh, he's left behind. I must run back at once, or he'll be lost in the fair."

And scarcely waiting to lift his old cap to the ladies, he darted back towards the town. Thrusting the new half-crown deep into his pocket, he sped on, calling Pat and whistling for him in vain.

"Maybe he dropped asleep from tiredness, and I'll find him by the steps again."

But there was no trace of the little dog there, and Dick felt very unlike Lionheart as he searched for his lost companion, and asked all the passers by if they had seen him. But all the people seemed intent on their own pleasure, and for an hour Dick walked up and down without any tidings of Pat.

Then a mischievous looking urchin playing marbles looked up as Dick passed and said mysteriously, "I know about your dog, but I shan't tell for nothing. Give me a penny, for a ride on the gallopin' horses." Dick put a penny into the grimy hand, and the boy said in a loud whisper, "A girl had him while you was holding the horse—'ticed him off with a piece of meat. I see her."

"What was she like?" cried Dick eagerly, "and which way did she go?"

"Down the Market Place, and she was belonging to one of the shows. She was bigger'n you, and she had a yellow scarf on and eardrops."

The girl on the caravan whose master had wanted Pat! Dick had the clue now, but how could he recover his treasure?

Shutting his eyes for a moment he prayed to his Heavenly Father for help, and then began another tour of the shows.

There were dogs in plenty, ugly and lean-looking curs lying on the straw under the waggons or loafing around the shops in search of plunder, but none at all like Pat.

Again and again as he passed he called and whistled, but there was no answering bark. Suddenly he saw the girl just inside a gaily painted show while her father stood on the steps and called out, "Walk up, ladies and gentlemen! Walk up and see the smallest dwarf in the world with his performing happy family, dogs and cats and birds, all living together. Only 2d., for the greatest wonder of the age."

Without a moment's hesitation, Dick ran forward and said to the girl, "What have you done with my dog? Please let me have him back at once!"

"Your dog," she said with a toss of her head that set the earrings dancing. "I like your impudence. Haven't seen or heard of your dog."

"But you had him and took him away; a boy told me so!"

"Haven't seen him, I tell you."

"Now, you young rascal, be off at once, or I'll give you in charge!" said the man threateningly. "Coming here with such cock-and-bull tales."

"What's it all about?" said a tall policeman, stepping forward.

"Why, this young varmint has lost his dog and comes here after it, as cheeky as can be. We ain't got no dog except the happy family one in here as we've had for years, and that's a white one, as you can see for yourself."

"Was yours white?" said the officer to Dick.

"No, sir, black and tan. A boy told me he saw that girl pick him up and run off."

"Best go and find the boy," said the policeman not unkindly, "then we'll see."

"I'll make it hot for you, if you show your impudent face here again!" shouted the man, who was red with passion. He grew redder still as the officer asked quickly, "How did you know this dog was not white?"

"They've got him, I know they have," Dick muttered as he turned away with a sob in his throat. "James Cross—that's the name on the show, and I'll follow them everywhere, till I get Pat back."

But he went through all the Fair again, without finding any trace of the boy who had told him. Presently he saw the empty waggons drawn up in the side alley, and with fresh hope in his heart he hurried along.

And in the last in the row "James Cross" was painted and, from somewhere within, there came a low, unhappy whine.

Instantly Dick was at the door calling "Pat!" and whistling the familiar call, and this was answered by a storm of eager muffled barking. The locked door was shaken in vain, and there was no possible way of rescue there.

But Dick rushed back to the middle of the Fair, and going at once to the friendly policeman cried, "I've found him! I've found him! He's locked up in their waggon down that side street. Oh, please make them come and let him out."

"Is this true?" said the officer sternly to the showman, who had heard every word. "Have you got his dog?"

"'Tisn't his, it's mine. The young rascal stole him from me and now wants to make out it's his own."

"But you said just now you hadn't got another dog. When did he steal it?"

"This morning, and I got him back, of course."

"I didn't steal it, sir," cried Dick indignantly. "It's my very own. Come and hear how he barks when I call him."

"Come and let him out at once," said the officer, "and we'll soon settle the ownership."

"Can't leave the show," muttered the man angrily.

"Oh, yes, you can. It isn't far, and this girl can manage without you!"

The man sullenly got down and marched along most unwillingly with the officer and Dick, followed by an interested crowd.

"Now open the door; there's a dog in there, undoubtedly. We shall know directly who's telling the truth."

Two doors were unlocked, and then like a small whirlwind Pat scrambled out, rushed to Dick's feet and grovelled there in an ecstasy of joy. "Hum, considering you say this boy only stole him this morning, they've got uncommon fond of one another! Call him and see if he'll come to you." But the showman's wiles were in vain. Pat would not go near him.

"Have you any witnesses to prove he's yours, my lad?"

Dick thought a moment and said, "I couldn't find the boy who saw him stolen from me. But Mr. Brown the carrier knows. He heard this man offer to buy Pat this morning."

"Run round to the George Yard and ask Brown to step here a minute, if he's still there."

Two or three messengers at once darted away.

"Anything else in proof?"

"He'll do tricks for me, sir."

And Dick stooped and whispered in Pat's ear, and the dog, not at all abashed by the cheers and laughter of the crowd, begged and danced and sang in his very best manner, till Mr. Brown appeared, driving his carrier's van, for he was just starting again for the homeward journey. His emphatic testimony settled what nobody doubted, and the officer prepared to take the showman to the lock-up.

But Dick's only desire was to get away as soon as possible on his delayed journey, and he begged that nothing more might be said about prosecution.

So the showman was allowed to go, scowling and muttering, and the crowd jeered as he went, though more than one present would have been willing to risk stealing and its penalties for the possession of Pat.

"Best get away at once, and don't let him out of your sight again," said the man in blue, kindly. "That dog's too fetching to be on the road with such a small owner."

"Better both jump up into the van and go back with me to Turningham," said carrier Brown. "I want a boy to help with the horse and do odd jobs about the shop, and I know the missus would take to you and the dog. You've been a brave boy and a smart one to-day. Eighteen-pence a week and your keep to begin. Come, now!"

But Dick shook his head.

"I'm ever so much obliged, sir, but I must go on to Ironboro', whatever happens."

"Well, then, take my advice and train it as far as your money will go. A ticket for thirty or forty miles will get you beyond the beat of these fair folks, and be cheaper than tramping in the end. Jump up, and I'll drive round by the station and see about a train. Nonsense about trouble. You've saved me more than that to-day."

Dick made a rapid calculation, and felt that he could not spend more wisely the rider's half-crown, and, indeed, all the wonderful takings of the day, and in a few minutes he found himself in the corner of a third class carriage, bound northwards, with a ticket good for forty miles of travel in his hand, and Pat's fare "seen to" by his kind-hearted friend.

Dick could only dimly remember one railway journey before and he curled up in the corner of the carriage with a sense of luxurious ease and held Pat close, rejoicing in his rescue. An old woman sat on the same seat, dressed in a black gown and lilac print apron, with a curtain bonnet of the same print on her head. She held tightly the handle of a huge marketing basket that seemed full to overflowing, while on the top a bunch of late chrysanthemums made a spot of gay colour.

Opposite, a tired-looking mother sat with two fractious children, going home from the fair. They were very naughty at first, but the sight of Pat's black head arrested their crying, and Dick and his dog kept them amused till they got out at the next station. "A pity to bring children up like that," said the country-woman, confidentially. "Sweets enough to make 'em bad for a week, to say nothing of the giddy-go-rounds and ginger-bread. Ah, well, 'twasn't like it in my young days. Not that I'm against a good wholesome cake or two, especially for young folks. I'll give you one if you'll read this letter to me?" she added, looking inquiringly at Dick. "You see, I'm going to see my son at Manchester, and they've sent to tell me all about the changing at Crow Junction, and I can't read writing very well."

Dick had been enjoying the sight of fields and hedges rushing past and trying to count the telegraph wires, but he turned at once and said, "I'll read it with pleasure, if I can. And I'm getting out at Crow Junction, and I can help you change, if I can find out what it means."

"It's getting out of one train into another, and you might carry my basket, maybe. You see, I've got a band-box, and my umbrella and pattens besides. I had to bring them, not knowing how the roads might be up there, and with damp feet I get rheumaticy directly."

Dick managed to get through the ill-spelled letter, and learned its instructions by heart, and then was rewarded with a home-made flakey cake, out of the big basket, that was better than all the fairings they had left behind.

It was splendid to feel that the swift engine was bearing him on towards his destination so easily, and that every mile made one less to be tramped on foot.

Both Pat and his master would have been willing to travel on all night by rail, but the forty miles were soon passed, and they got out at the busy junction.

The old woman was helped in her changing, and then Dick earned twopence by carrying a heavy portmanteau for another passenger. And then the two pilgrims took to the road again.

The days that followed were very much alike, and in after years Dick remembered little about this part of the journey.

Sometimes he earned enough to buy a meal or pay for a humble night's lodging, but they would often have been very hungry but for Paddy's half-crown. This was spent carefully, a penny at a time, and chiefly for dry bread.

The last sixpence had been changed when a sign-post with the words "Ironboro' two miles" was passed. Dick took off his cap and looked up to the wintry sky with joy and gratitude, and there and then thanked God.

No Lionheart crusader could have felt more fervent gladness at the first sight of the Holy City!

Bub Dick's goal did not look very promising, as he drew near. A pall of smoke hung low over the narrow streets, tall chimneys sent black clouds into the biting air, and there was the clang and whirl of machinery, and the throb of huge hammers going on all the time.

He was entering the town by the least inviting road. On one side were rows of miserable houses with broken windows and grimy walls and doors, that looked as if all their brightness had gone into the smart public-houses on each corner.

On the other side stretched a piece of waste land, where iron clinkers and slag lay in great heaps, and rubbish of all kinds was deposited. Not a blade of grass or tree could be seen, and the children playing and quarrelling together were as dingy as the dirt they played with.

Two big lads were standing by the edge of a dark pool, not far from the roadside, laughing at something that wriggled in their hands.

Suddenly a little girl darted across and snatched at this, crying, "It's my kitty! It's mine, I tell you. Give her to me, she's mine!"

But the cruel tormenter only held the kitten higher, and showed the string and the stone his companion was tying to her neck.

The little girl screamed aloud, and flung herself upon him in a vain attempt to reach the kitten, which was mewing pitifully. In her excitement she was in great danger of falling into the black water.

"Now then, one, two, three, and——" Before he could finish and throw the captive in, Dick had sprung to the rescue.

"For shame! How can you be such a coward?" he cried, seizing the outstretched arm of the bully so fiercely that he released his hold.

"And who are you, I should like to know? Take that for interfering!" And he flung out his clenched fist for a terrific blow.

But Lionheart was too quick for him, darting aside he dodged the blow and at the same moment snatched the kitten and pushed her into the child's outstretched arms. The other coward had drawn back at Pat's threatening growl. The dog looked fierce enough for anything, and when he saw the blow aimed at his master he seized the bully by the leg and held him fast.

What might have happened next cannot be told, for at that moment the little girl raised a joyous shout. "Daddy, oh, daddy, come quick! Here, daddy!"

At her eager cry a man hurrying down the road stopped and then ran to the pool.

"Nellie, where have you been, and what's all this?"

"It's my kitty, daddy, they were going to drown her, and this boy and his doggie saved her life."

And with tears and smiles together the child clung to her father and hugged the almost suffocated kitten in her pinafore.

"Jem Whatman, at your cowardly pranks again! How dare you touch the kitten?"

At this moment, as if conscious that able reinforcements had come, Pat let go the mouthful of cloth, and without stopping to reply Jem darted away after his companion, muttering threats as he went.

"You are a brave boy to tackle two bullies at once in that fashion," said the father kindly as he swung the little girl up in his strong arms. "And there's breeding about that terrier of yours, and no mistake!"

Pat was still breathing quickly and wagging his tail excitedly, as if expecting another battle. "You are a stranger to me, and yet I seem to know your face. What is your name?"

Dick almost answered "Lionheart," but stopped just in time. "Richard Hart Crosby."

"Of course! And you're his living image; but he had neither wife nor child."

"Do you mean my uncle, sir. Do you know him."

"Know Dick Crosby? Almost as well as I know Nellie here. And I've heard him speak of his brother many times."

"Then, sir, if you know him, won't you tell me where he lives, that I may go to him at once? I only heard about him just lately, and I've come all the way from Venley to find him."

"I'll tell you all I can, but you can't go to him to-day, for he went off to Klondyke more than a year ago, and I've only heard from him once since he went."

Poor Dick! The disappointment following so quickly on success was almost too much. A big lump came in his throat and tears blurred his sight, so that he could scarcely see the ugly rubbish heap and the cinders that lay around.

But he had made resolve that he would not cry, whatever happened, and so he resolutely ordered tears away and again faced his new friend.

"How did you get here, laddie?"

"Walked from Venley—all but forty miles I came by train."

"Well, then, you must walk a bit further and come home with me. Dick Crosby was my good friend, and you have saved the kitten and maybe Nellie herself from ill-usage. It's dinner time, so you are just right. Run, Nellie, there is mother watching at the door."

They were walking now in a wider thoroughfare with better houses on either side. At the door of one a motherly woman stood looking out anxiously, and to her Nellie ran with a joyous shout. "Oh, mother, I've got kitty, and daddy's got a boy out there with such a nice dog, only kitty doesn't like him. She makes her tail like a sweeping brush."

"But where have you been, Nellie? We lost you, and father had to come after you."

"It's all right now, wife. I found her—or rather this little man found her, and helped her too, so I've brought him home to dinner." And in a few words he told the tale, while Pat sent Nellie into shrieks of delight by standing up and begging in his best manner. Doubtless he smelled the savoury Irish stew that was just ready.

And Mrs. Dainton hurried them all in to enjoy it.

Over the pleasant little dinner table Dick's heart was quite won. The room was so clean and pretty, and the hot meal so good after the meagre fare of the last fortnight. And the new friends were so kind and sympathising, it was easy to tell them about the long march from Venley, and all his hopes about the future. Only there was no uncle Dick to help him in his heart's desire to become an engineer, and he would have to fight his own way.

But Mr. Dainton was quite disposed to be a true friend.

"I like your pluck, my boy, and I'll see what I can do, for my old friend's sake, and for your kindness to a little kitten. I may be able to get you into our yard, though you'll have to be content with rough work and very small wages at first. I suppose you haven't a reference or testimonial of any sort?"

Dick suddenly remembered the slip of paper given him by the gentleman on horseback, and he gave it silently into Mr. Dainton's hand.

"Why, this is first-rate, my boy! Couldn't be better. Sir Dale Melville is one of the directors of the line we do so much work for, and it was luck, or something better, that brought you in his way."

"Something better, I should say," Mrs. Dainton remarked softly, and Dick answered her smile with one as bright.

"You're right, wife, it strikes me God has been guiding Dick here right to our door, and I can see he thinks so, too."

"He could stop here, couldn't he mother, till Teddy comes back from grandma's, and have his little room?" said Nellie, eagerly. "Then Pat and Kitty could quite make friends, and have such fun together."

"That's not a bad notion, pet, if mother is willing."

And Mrs. Dainton at once said "Yes," and so Dick found himself with home and food and friends, before he had been an hour in Ironboro'.

How wonderfully God had answered his prayers!

"Hulloa, you young hopeful, what do you mean by sleeping all through dinner, and then waking just as we've cleared the dishes?" And Mr. Dainton stooped to the cradle by the hearth, where a bonny six-month's old baby had wakened with a cry.

"What, fretty, little man? Those teeth do bother you, don't they? And I can't stop to take you now."

"Let me have him!" cried Dick, quickly, holding out his arms. "I've had a lot to do with babies."

And to their great surprise, baby Jack went to him at once with a contented chuckle, and settled down as if he had known him always.

"I like that, now," said the father as he took his cap to go. "He's mostly so shy with strangers."

Mrs. Dainton nodded her head as if to say "He'll do." And before the day was over she was inclined to think they had indeed entertained an angel unawares.

"He's as handy in the house as a woman," she told her husband that night, "and a master-hand with baby. I think we had better keep him, instead of the nurse-girl you've been wanting me to have."

"Too late, wifie. I'm hoping to get him into the starting shed to-morrow or Monday. Anyhow, the loco. manager will see him. We'll keep him here this week and rig him out with clothes, if only for Richard's sake."

"And for Christ's sake," said the mother softly. "It will be a case for 'Inasmuch' I know. He says his teacher used to call him 'Lionheart' and he means to earn the name."

"I rather think he's done that already, judging by the way he stood up to those bullies on the Waste. We'll see if old Mrs. Garth can give him a lodging. He'll be comfortable there, and we can have him round often, and I hope he and Teddy will be chums. I believe he's going to do well."

The next day it was settled, and Dick was seen by the manager and engaged as handy-boy for the cleaning shed. The small wages he would have at first seemed wealth indeed to Dick, though anybody else might have wondered how lodging and food and clothing could be managed on such an income. But Mr. Dainton had a private understanding with the tidy old woman where Dick's uncle had lodged, and she agreed to find board and lodging for what he could afford to pay, if he would carry coal and chop sticks and do errands for her, for a little while every day, now that she was growing old.

It was a good bargain for both, and Dick faithfully kept his share of the compact, spending half-an-hour morning and evening in helping her, while Pat fitted into the little household as if he had belonged there always. It was the proudest moment of Dick's life when he entered the great gates of the engine works on Monday morning.

The crowd of men going in at the summons of the hooter was not so large as on other days. So many of the workmen were keeping Saint Monday after drinking hard on Saturday and Sunday, and of those who came some looked sleepy and muddled as if, they, too, had been having too much.

But Dick was not in a critical mood. Everything looked strange and delightful to the eager boy, and even the dirty work he was ordered to do seemed pleasant because there were engines everywhere, and mysteries of cogs and wheels that he would be able to find out, as the days went by.

The all-pervading smell of oil and grease reminded him of Paddy's boiler-house, and he resolved to spend his first evening in writing to him.

There were three other boys in the shed, all older than himself, and half-a-dozen men, and Dick was fairly bewildered by the orders they gave him.

As a new hand and the youngest it was quite evident he would be expected to fag for all, and long before night his back and legs were very tired.

But Mrs. Garth had a good tea all ready, and Pat, who had been disconsolate all day, nearly wagged off his short tail for joy when he got home.

And then he wrote a letter.

"DEAR PADDY,

"We got to Ironboro' quite safely, after a lot of ups and downs on the road. Pat was nearly lost, so many people wanted to steal, or beg, or buy him, and no wonder.

"My uncle Richard is gone to Klondyke, and I am going to write him a letter.

"His friend, Mr. Dainton, found me, or I found his little girl, and they have been so kind. He is a foreman at Lisle & Co.'s, and he knew uncle ever so well. He has got me a place in their sheds, and I began work to-day.

"Our firm is splendid, I should think six times as big as the tin works, and I am going to try so hard there.

"Ironboro' is very dirty, and there are publics everywhere. The men drink a great deal here, and it is such a pity. Mr. Dainton says they could do well if they liked, because the pay is so good.

"One of the men offered me a drink of beer to-day, but of course I said 'No.' When I told him I never meant to touch it the others laughed, and said they'd soon make me know better. But I mean to be Lionheart still.

"Pat sends his love to you. He has a box for a kennel in Mrs. Garth's wood shed where I lodge.

"Dear Paddy, I know God does hear when we pray, because he brought me

here, and made people so kind to me coming along, and gave me friends

and work directly. I wish you would come here, too, that Pat and I

could see you again. He is so knowing. Everybody likes him. Do come.

"Your loving friend,

DICK."

"I've got slops and overalls just like the other men, to work in, and I'm going to a night school and a technical class, and Mr. Dainton has lent me a big book about engines, with pictures all through.

"I should like to know how baby Lily is at Mrs. Fowley's, if you could

find out, and whether they were vexed at my running away. But please

don't tell them I am here.

"DICK."

This letter gave Paddy so much pleasure when it reached him that his first impulse was to take it to the "Brown Bear" and read it to some of his cronies there, just for the joy of sharing it.

But better thoughts came.

"And shure if I hearkened to the good book he was reading that night and what he says here about the drink I should never touch the beer again at all, at all. He said we could all be Lionhearts, and that God wouldn't like to go into them places with me. And he says again here that God does answer when we pray. Maybe if I went round to Dick's teacher and signed the pledge the Almighty would help me to keep it, and then I could save a bit of money and go to Ironboro' too."

Paddy had been sitting by his little fire after tea when the letter came, and he sat on for a long while, staring into the bright coals and seeing in fancy Dick's pleading face again. Suddenly he got down awkwardly upon his knees, and with the letter in his hand prayed his first real prayer.

And that night he signed the pledge and hung up the card over his mantelpiece where all might see it, and the sight of his own name, put to such a promise, was a continual help to him in the fight that lay before him.

Paddy's courage and determination were soon put to the test. He had been a bar favourite so long that his absence was soon noticed, and the men he had so often entertained and treated were loud in their complaints and jeers. The ridicule was hard enough to bear, but the sneers at his stingy ways hurt him most.

For Paddy's warm Irish heart loved to give, and to make pleasure for others, and many a time he had spent his last coin in treating a comrade.

The publicans, too, missed his songs and merry stories, that always led to rounds of applause and renewed treating. The landlord of the "Brown Bear" stood at his door to watch for Paddy, and offers of free drinks and boisterous welcome met him almost every night.

But he had learned to distrust his own strength, and to lean upon the promised help of God. Night and morning he knelt by his chair and prayed for the victory, and with the thought of Lionheart to help him he went out to the battle girded with the strength that never fails.

On the first wage night after signing the pledge he went straight to the Post Office and put a good portion of his money into the Savings Bank, and then went home by a roundabout way to avoid the public-houses. "It's no use to pray 'Lead us not into temptation' and then go right by the Bear's Den when you aren't obloiged to," he said to himself.

He bought a large print New Testament and spelled out a chapter before he went to bed—the chapter which told of the Prodigal going home to the Father's house, and the sweet sense of God's forgiveness for all his wasted years, made him feel so happy that he could not sleep for a long while.

"I'll save me money and go after that boy to Ironboro', for shure; it's to him I owe it all. And maybe we could help one another there, for something tells me he'll still need a friend."

And truly Dick had not been long in the cleaning shed before his trials began. The man who had offered him beer on his first day was Jem Whatman's father, and Dick's quiet refusal had angered him greatly, and his threat to make him know better had not been an idle one.

"We'll have no Band-of-Hopers amongst us jokers, eh mates?" he said with rough wit, a few days afterwards.

"So look here, young 'un, the boss is out of the way, and you take this shilling and nip across to the 'Jolly Founders' and fetch half-a-gallon of fivepenny in this jar. We'll soon see where your teetotalling will be." The other workers in the shed applauded loudly at the prospect of a drink and some fun into the bargain.

But Dick had spent a very serious quarter of an hour on his first day in reading the Rules posted up conspicuously in every workshop, and one of them said, "No intoxicating drinks must be fetched during working hours."

So he looked up bravely and said, "I can't do that, for it would be breaking the rules to fetch beer. Besides, I can't go inside a public-house, at any time.

"Rules be hanged!" said Whatman fiercely. "You are here to do as you're told and not to cheek your betters. Quick! Off with the jar, or it'll be the worse for you."

But Dick stood still, while the thought of Lionheart gave him courage.

"I'll do anything for you that's right, but I can't do that," he said bravely. "I'll never go into a public-house, and the rules are up there as plain as can be." And he pointed to the glazed and somewhat dingy copy of rules and regulations on the wall.

"You young impudence, I'll teach you!" said Whatman in ungovernable rage. "If you don't go this minute I'll give you such a hiding as you'll never forget. I owe you one for interfering with Jem the other day."

But Dick did not move, and his brown eyes met Whatman's angry scowl without shrinking.

Suddenly, Hal Smith, one of the other lads, said, "Here, Whatman, I'll fetch it this time, same as I have before, and we'll make him have a drink, and that will put a stop to his teetotal whining."

Seizing the jar and looking out cautiously to see that the coast was clear, he hurried off, while Whatman, muttering angrily, turned away.

Dick went on with his cleaning of some brass fittings, polishing and rubbing till they shone like gold.

But while his hands worked vigorously his thoughts were away beyond the grimy shed and the troubles of the hour, seeking One who said, "I will never leave thee nor forsake thee."

He needed all his faith a few minutes afterwards, when Hal came back with the foaming jar.

"Now, young sir," said Whatman, with mock politeness, "you'll drink best respects to us in this here cup of beer. Every drop, mind! What, you won't have it? Here, Smith and Perkins, hold his head while I pour it down. He's got to learn manners!"

Dick struggled violently in his captors' hands and almost got free. But the men were too strong for him, and he was held fast.

Clenching his teeth and resolved to choke rather than swallow it he waited till the cup was at his lips, and then, with a sudden jerk of his head, knocked it aside and caused the stream of brown liquid to fall on the dirty floor.

Whatman's answer to this was a violent blow that made blue and green stars dance before the boy's eyes and almost stunned him.

"What is going on here?" said a stern voice in the doorway. Instantly the men closed round the jar, hoping to hide it, but Macleod, the Scotch foreman, was not easily hoodwinked.

"Drinking and fighting too. What do you mean by it?"

"It's this young rascal here," said Whatman. "Cheeking us and drinking our beer."

Dick was too dazed to answer, but there was no need. Macleod had seen the cowardly blow. "Your beer? And how did that jar get here at this time of day? I shall report you, Whatman and Smith; you've had warnings enough, I should say, but one of these times will be the last. And if you put upon this boy again you'll have to reckon with Dainton and me. He's under Dainton's care, anyhow, and you haven't heard the last of this, I can tell you."

For the time Whatman and the other men were silenced, but Dick had a black eye, as the result of the blow, and the reason had to be told when he went to Mr. Dainton's that evening to tea.

For Teddy had come home from his visit to the country, and Dick was eager to see the brother of whom little Nellie talked so much.

He was a fun-loving urchin who never spent a minute more over his lessons than he could possibly help, and was only clever in getting into mischief and, at Dick's age, was far behind him in learning.

In his frequent visits to his grandmother's farm he had been allowed too much of his own way, and his father grumbled and threatened to stop this spoiling, by keeping him at home.

To ride, bare backed, the farm colts and to go fishing and birds' nesting at all hours was far more pleasant than sitting at a school desk and bothering one's head with fractions, and over the tea table he spoke his mind.

"You won't catch me going into the sheds, father, when I leave school. I'm going to be a farmer and ride on horseback all day long."

"You'll be a poor farmer at that rate, Ted," his mother said quietly. "What about feeding stock and ploughing and sowing and reaping?"

"Oh, but I should keep men to do all that," was the lofty reply.

"Yes, but you must at least know how it is all done, if you are to make farming pay. That's why Dick here has to begin at the very bottom and do all sorts of black work before he can be a great engineer and come out at the top of the tree."

"And must he have black eyes as well?" asked Nellie pointedly; "and have his face spoiled?"

"No, little one, that is another matter. Whatman ought to be sent about his business and should be, if I had the management. But a black eye is no disgrace when you get it for resisting evil."

"There's a verse that's just meant for you, Dick," said Mrs. Dainton kindly, "and you ought to learn it by heart. 'Consider Him who endured such contradiction of sinners against Himself, lest ye be weary and faint in your minds.' I'll show it to you after tea."

"And then, as it is a wet night, you can all have a game with Pat in the kitchen before Dick goes to school."

"School at night," asked Teddy in amazement. "And after working all day. Haven't you learned enough?"

"Not half," said Dick, laughing at the comical tone of dismay.

"There's a world-full of things I don't know anything about, especially drawing and hard sums. I want them because they'll help me to be a fitter by and by."

But Teddy whistled in a very unbelieving way, and presently went off to the kitchen, as he explained, to give the poor dog a bone.

And when the others moved a few minutes afterwards, they were startled by a cry from Nellie, who had gone after Teddy.

All her family of five cherished dolls were hanging by their back hair from the hooks on the kitchen dresser, while Pat marched about with her Sunday doll's best velvet hat set rakishly on his head, and a Red Riding Hood cloak on his back!

It was Saturday afternoon and the great machine shops at Lisle & Co.'s were closing for the weekly half holiday. There was to be an important football match at the Marshes outside the town, and the boys and men had talked of little else all the week.

"Art coming, Dick, to see the match?" asked one of the lads, who had seemed inclined to be friendly during the last week or two. "Yon's a grand team ours are going to play."

"To the match? Not he," sneered Hal Smith, who stood near. "He couldn't spare a tanner for gate money, and he's going to stop at home and say his prayers, little dear, because football's wicked, and he's got to get ready for the Sabbath day."

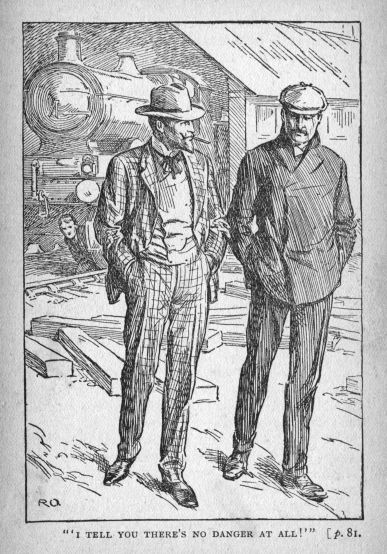

"Nonsense! There's no harm in football. Own up now, Dick, wouldn't you like to see the match?"