|

The "Forward Pass" |

Title: Left End Edwards

Author: Ralph Henry Barbour

Illustrator: C. M. Relyea

Release date: February 24, 2007 [eBook #20650]

Most recently updated: January 1, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| chapter | page | |

| I | fathers and sons | 3 |

| II | off to school | 13 |

| III | stop thief! | 24 |

| IV | out for brimfield! | 40 |

| V | number 12 billings | 51 |

| VI | clues! | 62 |

| VII | the confidence-man | 73 |

| VIII | in the rubbing room | 86 |

| IX | back in togs | 98 |

| X | "cheap for cash" | 112 |

| XI | "hold 'em, third!" | 125 |

| XII | canterbury romps on—and off | 142 |

| XIII | sawyer vows vengeance | 157 |

| XIV | a lesson in tackling | 170 |

| XV | Steve winnows some chaff | 182 |

| XVI | mr. daley is out | 202 |

| XVII | the blue-book | 212 |

| XVIII | b plus and d minus | 225 |

| XIX | the second puts it over | 235 |

| XX | blows are struck | 251 |

| XXI | friends fall out | 267 |

| XXII | steve gets a surprise | 285 |

| XXIII | durkin sheds light | 297 |

| XXIV | the day before the battle | 309 |

| XXV | tom to the rescue | 323 |

| XXVI | at the end of the first half | 334 |

| XXVII | steve smiles | 346 |

| XXVIII | the chums read a telegram | 360 |

| The "Forward Pass" | Frontispiece |

| facing page | |

| Steve slipped on the tiling and fell sidewise into the water (page 166) | 80 |

| "Lift!" instructed the quarter-back. "Lift me up and yank my feet out from under me! Use your weight and throw me back!" | 178 |

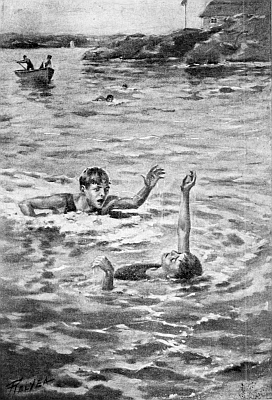

| It was Steve, Steve on his back, with only his head and shoulders above the water | 324 |

"Dad, what does 'Mens sana in corpore sano' mean?"

Mr. Edwards slightly lowered his Sunday paper and over the top of it frowned abstractedly at the boy on the window-seat. "Eh?" he asked. "What was that?"

"'Mens sana in corpore sano,' sir."

"Oh!" Mr. Edwards blinked through his reading glasses and rustled the paper. Finally, "For a boy who has studied as much Latin as you have," he said disapprovingly, "the question is extraordinary, to say the least. I'd advise you to—hm—find your dictionary, Steve." And Mr. Edwards again retired from sight.

Steve, cross-legged on the broad seat that filled the library bay, a seat which commanded an uninterrupted view up and down the street, smiled into the open pamphlet he held.

"He doesn't know," he said to himself with a chuckle. "It's something about your mind and your body, though. Never mind." He idly flut[4]tered the leaves of the pamphlet and glanced out into the street to see if any friends were in sight. But it was Sunday afternoon, and rainy, and the wide, maple-bordered street, its neat artificial stone sidewalks shimmering with moisture, was quite deserted. With a sigh Steve went back to the pamphlet. It bore the inscription on the outer cover: "Brimfield Academy," and, below, in parenthesis, "William Torrence Foundation."

"What does 'William Torrence Foundation' mean, dad?" asked the boy.

Again Mr. Edwards lowered his paper, with a sigh. "It means, as you will discover for yourself if you will take the trouble to read the catalogue, that a man named William Torrence gave the money to establish the school. Now, for goodness sake, Steve, let me read in peace for a minute!"

"Yes, sir. Thank you." Steve turned the pages, glanced again at the "View of Main Building from the Lawn" and began to read. "In 1878 William Torrence, Esq., of New York City, visited his native town of Brimfield and interested the citizens in a plan to establish a school on a large tract of land at the edge of the town which had been in the Torrence family for many generations. Two years later the school was built and,[5] under the title of Torrence Seminary, began a successful career which has lasted for thirty-two years. Under the principalship of Dr. Andrew Morey, the institution increased rapidly in usefulness, and in 1892 it was found necessary to add two wings to the original structure at a cost of $34,000, also the gift of the founder. Dr. Morey's connection with the school ended four years later, when the services of the present head, Mr. Joshua Fernald, A.M., were secured. The death of Mr. Torrence in 1897, after a long and honoured career, removed the school's greatest friend and benefactor, but, by the terms of his will, placed it beyond the reach of want for many years. With new buildings and improvements made possible by the generous provisions of the testament the school soon took its place amongst the foremost institutions of its kind. In 1908 the charter name was changed to Brimfield Academy—William Torrence Foundation, the course was lengthened from four years to six and the present era of well-deserved prosperity was entered on. Brimfield Academy now has accommodations for 260 boys, its faculty consists of 19 members and its buildings number 8. Situated as it is——"

Steve yawned frankly, viewed again the somnolent street and idly turned the pages. There[6] were several pictures, but he had seen them all many times and only the one labelled "'Varsity Athletic Field—Gymnasium Beyond" claimed his interest for a moment. At last,

"They've got a peach of an athletic field, dad," he observed approvingly. "I can see six goals, and that means three gridirons. And there's a baseball field besides. The catalogue says that 'provision is also made for tennis, boating and swimming,' but I don't see any tennis courts in the picture."

"All right," grunted his father from behind the paper.

"I wonder," continued Steve musingly, "where you get your boating and swimming. It says that Long Island Sound is two and a half miles distant. That's a long old ways to go for a swim, isn't it?"

Mr. Edwards laid the paper across his knees and regarded the boy severely. "Steve," he said, "about the only thing I've heard from you since that catalogue arrived is the athletic field and the gymnasium. I'd like to refresh your mind on one point, my son."

"Yes, sir?" said Steve without much eagerness.

"I'd like to remind you that you are not going to Brimfield Academy to play football or baseball,[7] or to swim. You're going there to study and learn! I don't propose to spend four hundred and fifty dollars a year, besides a whole lot for extras, to have you taught how to kick a football or make a home-hit. And——"

"A home-run, sir," corrected Steve humbly.

"Or whatever it is, then. I expect you to buckle down when you get there and learn. Remember that you've got just two years in which to prepare yourself for college. If you aren't ready then, you don't go. That's flat, my boy, and I want you to understand it. So, if you have any idea of football and tennis as your—er—principal courses you want to get it right out of your head. Now, for a change, suppose you have a look at the studies in front of you, and don't let me hear anything more about the gymnasium or the—the what-do-you-call-it field."

"All right, sir." Steve obediently turned the pages back. "Just the same," he said to himself, "he didn't know what 'mens sana in corpore sano' meant any better than I did! Bet you he didn't kill himself studying when he went to school!" With a sigh he found the "Courses of Study" and read: "Form IV. Classical. Latin: Vergil's Aeneid, IV—XII, Cicero and Ovid at sight, Composition (5). Greek: Xenophon's Hel[8]lenica, Selections, Iliad and Odyssey, Selections, Sight Reading, Reviews, Composition (5). German (optional) (4). French: Advanced Grammar and Composition, Le Siege de Paris, Le Barbier de Saville——"

At that moment a shrill whistle sounded outside the library window and Steve's eyes fled from the pamphlet to the grinning face of Tom Hall set between two of the fence pickets. The Catalogue of Brimfield Academy was tossed to the further end of the seat, and Steve, nodding vigorously through the window, jumped to his feet.

"I'm going for a walk with Tom, sir," he announced half-way to the hall door. Mr. Edwards, smothering a sigh of relief, glanced at the weather.

"Very well," he said. "Don't get your feet wet. And—er—be back before it's dark."

Steve disappeared into the dim hallway and Mr. Edwards gave honest expression to his sense of relief by elevating his feet to the seat of a neighbouring chair, dropping the newspaper and, with a luxurious sigh, composing himself for his Sunday afternoon nap. But peace was not yet his, for a minute or two later Steve came hurrying in again. Mr. Edwards opened his eyes with a frown.[9]

"Sorry, sir," said Steve, "but Tom wants to see the catalogue."

His father nodded drowsily and Steve, securing the pamphlet, stole out again with creaking Sunday shoes. Very quietly the front door went shut and peace at last pervaded the house. In the library, Mr. Edwards, dropping into slumber, was dimly conscious of a last disturbing thought. It was that he was going to miss that boy of his a whole lot after next week!

"It's all right," declared Tom Hall as he took the catalogue from Steve with eager fingers. "At least, I'm pretty sure it is. He said at dinner that he'd think it over, and when he says that it means—that it's all right. What do you say, eh?"

"Bully!" That was what Steve said. And he said it not only once but several times and with varying degrees of enthusiasm and volume. And, as though fearing his chum would doubt his satisfaction, he accompanied each "Bully!" with an emphatic thump on Tom's back. Tom, choking and coughing, squirmed out of the way.

"Here! Ho-ho-hold on, you silly chump! You don't have to kill a fellow!"

"Won't it be dandy!" exclaimed Steve, beaming. "We can room together! And—and——"[10]

"You bet! And we can have a bully time on the train, too. Gee, I never travelled as far as that alone!"

"I have! It's lots of fun! You eat your meals in a dining-car and there's a smoking-room where you can sit and chin as late as you want to and you get off at the stations and walk up and down the platform and you tip the negro porters and——"

"Wouldn't it be great if we both made the football team, Steve? Of course, you'll make it anyway, and I might if I had a little luck. Townsend said last year I didn't do so badly, you know, and if——"

"Of course you'll make it! We both will; next year anyway. I'll bet they've got lots of fellows on the team no better than you are, Tom. Wait till I show you the athletic field. It's a corker!" And Steve's fingers turned the pages of the school catalogue eagerly. "How's that?" he demanded at last in triumph.

They paused under a dripping tree while Tom viewed the picture, Steve looking over his shoulder.

"It's fine!" sighed Tom at last. "Gee, I hope—I hope he lets me!"

"Let's go over there now so you can show him[11] this," suggested Steve. But Tom shook his head wisely.

"Not now," he said. "He don't like to be disturbed Sunday afternoons. He—he sort of has a nap, you see."

"Just like dad," replied Steve. "Bet you when I get as old as that I won't stick around the house and go to sleep. Say, Tom, what does 'Mens sana in corpore sano' mean?"

"A sound mind in a sound body," replied Tom promptly. "Why?"

"It's in here and I asked dad and he didn't know." Steve chuckled. "He made believe he was peevish with me, so's he wouldn't have to fess up. Dad's foxy, all right!"

"Well, you ought to have known, Steve," said Tom severely.

"Sure," agreed Steve untroubledly. "That's what he said. Let's take that a minute. I want to show you the picture of the campus."

"Let's sit down somewhere and look it over," said Tom. "I told father that it was a school where they were terribly strict with the fellows and you had to study awfully hard all the time. I wonder if it is."

"I don't believe so," answered Steve. "They say so much about football and baseball and things[12] like that you can tell they aren't cranky about studying. And look at the pictures of the different teams in here. There's the baseball nine, see? Pretty husky looking bunch, aren't they? And—turn over—there you are—there's the football team. Some of those chaps aren't any bigger than I am, or you, either. Good looking uniforms, aren't they? Say, dad gave me a lecture on not thinking I was going there to just play football. Fathers are awfully funny sometimes!"

"You bet! I wonder—I wonder—would you mind if we tore out a couple of these pictures before he sees it? I'm afraid he might think there was too much in it about athletics."

"No, tear away! Here, I'll do it. We'll take the pictures of the teams out. How about the athletic field? Better tear that out too, do you think?"

"Well, maybe, just to be on the safe side, you know. Don't throw 'em away, though. We might want to look at them again. Let's go over to the library where we can talk, Steve."[13]

Possibly you are wondering why two boys, each of whom was possessed of a perfectly good home of his own, should select the Tannersville Public Library as a place in which to converse. The answer is that Steve's father and Tom's father were in the same line of trade, wholesale lumber, and had a few years before fallen out over some business matter. Since that time the two men had been at daggers drawn during office hours and only coldly civil at other times. Steve was forbidden to set foot in Tom's house and Tom was as strictly prohibited from entering Steve's. Had the fathers had their way at the beginning of the quarrel the boys would have ceased then and there to have anything to do with each other. But they had been close friends ever since primary school days and, while they reluctantly respected the dictum as to visiting at each other's residences, they had firmly refused to give up the friendship, and their fathers had finally been forced to sanction what they could not prevent.[14]

At the time this story opens, the quarrel between the two men, each a prominent and well-to-do member of the community, still continued, but its edge had been dulled by time. Both Mr. Edwards and Mr. Hall took active parts in municipal affairs and so were forced to meet often and to even serve together on various committees. They almost invariably took opposite sides on every question, but they did not allow their personal quarrel to interfere with their public duties.

The boys had at first found the condition of affairs very irksome, but had eventually got used to it. It was hard not to be able to run in and out of each other's houses as they had done when they had first known each other, but there were plenty of opportunities to be together away from home and they made the most of them and were well-nigh inseparable. Mr. Edwards had declared, when announcing the fact in the preceding spring, that Steve was to go to boarding school, that he was sending the boy away to remove him from the questionable association of Tom Hall. But Steve gave little credence to that statement, for he knew that secretly his father thought very well of Tom. The real reason was that Steve had not been making good progress at high school, owing principally to the fact that he gave too much time to[15] athletics and not enough to study. Mr. Edwards concluded that at a boarding school Steve would be under a stricter discipline and would profit by it. Steve's mother had died many years before, and his father, while perfectly able to command a large army of employees, was rather helpless when it came to exercising a proper authority over one sixteen-year-old boy!

Naturally enough, Tom, when he had learned of his chum's impending departure in the fall for boarding school, began a vigorous campaign to secure parental permission to accompany him. Mrs. Hall had soon yielded, but Mr. Hall had held out stubbornly until almost the last moment. "I guess," he had said more than once, "you see enough of that Edwards boy without going off to the same boarding school with him! If you want to go to some other school I'll consider it, Tom, but I'm blessed if I'll have you tagging after Steve Edwards the way you propose!" But in the end he, too, capitulated, though with ill-grace, and for a week there were not two busier persons in all Tannersville than Steve and Tom. Steve had taken time by the forelock and had accumulated most of the necessary outfit, but Tom had to attend to all his wants in six weekdays, and there was much scurrying around the shops by the two[16] lads, much hurry and worry and bustle in the Hall mansion. You had to take with you such a lot of silly truck, you see! Or, at least, that is the way Tom put it. The catalogue informed them that they must provide their own sheets, pillow-cases, spreads, towels, napkins and laundry bags, as well as take with them a knife, fork and spoon each. Steve sarcastically wondered if the school gave them beds to sleep in! The situation was further complicated by the eleventh-hour discovery on the part of Mrs. Hall that Tom's clothing, while quite good enough for Tannersville, would never do for Brimfield Academy, and poor Tom had to be fitted to new suits of clothes and shoes and hats and various other articles of apparel.

They were to leave early Monday morning, for in that way they could reach Brimfield before dark. Both boys, who had set their hearts on a night in a sleeping-car, with all its exciting possibilities, begged to be allowed to make their start Monday evening, which would allow them to arrive at school Tuesday forenoon in plenty of time. But neither Steve's father nor Tom's would listen to the suggestion.

"Then I'll get there a whole day before school opens," grumbled Tom, "and have to stay there all alone Monday night."[17]

"It won't hurt you a bit," replied Mr. Hall. "And the catalogue says that students will be received any time after Monday noon. I'm not going to have you two reckless youngsters travelling around the country together at night."

Tom, recognising the inevitable, said no more.

There was a somewhat awkward ten minutes at the station, for both Mr. Edwards and Mr. Hall, the latter accompanied by his wife, went down to see the boys off. The men nodded coldly to each other and then the odd situation of two boys who were to travel together side by side taking leave of their parents at opposite ends of the same car developed. Tannersville is not a large town and those who were on the platform that morning when the New York express pulled in understood the dilemma and smiled over it. Steve and Tom were both rather relieved when the good-byes were over and the train was pulling out of the station.

"Blamed foolishness," muttered Steve as he met Tom where their bags were piled on one of the seats.

"Yes, don't they make you tired?" agreed the other. "Say, how much did you get?"

Steve thrust his fingers into a waistcoat pocket[18] and drew out a carefully folded and very crisp ten-dollar bill, and Tom whistled.

"I only got seven," he said; "five from father and two from mother. I guess that will do, though. The only things we have to pay for are dinner and getting across New York. Got your ticket safe?"

Ensued then a breathless, panicky minute while Steve searched pocket after pocket for the envelope which contained his transportation to Brimfield, New York. The perspiration began to stand out on his forehead, his eyes grew large and round and his gaze set, Tom fidgetted mightily and persons in nearby seats, sensing the tragedy, grinned in heartless amusement. Then, at last, the precious envelope came to light from the depths of the very first pocket in which he had searched and, with sighs of vast relief, the two boys subsided into the seat. By that time Tannersville was left behind and the great adventure had begun!

There are lots of worse things in life than starting off to school for the first time when you have someone with you to share your pleasant anticipations and direful forebodings. It is an exciting experience, I can tell you! The feeling of being cast on your own resources is at once blissfully[19] uplifting and breathtakingly fearsome. Suppose they lost their way in New York? Suppose they were robbed of their tickets or their pocket money? You were always hearing about folks being robbed on trains, while, as for New York, why, every fellow knew that it was simply a den of iniquity! Or suppose the train was wrecked? It was Tom who supplied most of these direful contingencies and Steve who carelessly—or so it seemed—disposed of them.

"If we lost our way we'd ask a policeman," he said. "And if anyone pinched our money or our tickets we'd just telegraph home to the folks and wait until we heard from them."

"Where'd we wait?" asked Tom with great interest.

"Hotel."

"They wouldn't let us in unless we had money, would they?" Tom objected. "Maybe we could find the United States consul."

"That's only when you're abroad," corrected Steve scathingly. "There aren't any United States consuls in the United States, you silly chump!"

"I should think there ought to be," Tom replied uneasily. "What time do we get to New York?"[20]

"Two thirty-five, if we're on time. We ought to be. This is a peach of a train; one of the best on the road. Bet you she's making a mile a minute right now."

"Bet you she isn't!"

"Bet you she is! I'll ask the conductor."

That gentleman was approaching, and as they yielded their tickets to be punched Steve put the question. The conductor leaned down and took a glance at the flying landscape. "About forty-five miles an hour, I guess. That fast enough for you, boys?"

"Sure," replied Tom. "But he said we were going a mile a minute."

"No, we don't make better than fifty anywhere. You in a hurry, are you?"

"Only for dinner," laughed Steve. "Where do we get dinner, sir?"

"There's a dining-car on now," was the reply. "Or you can get out at Phillipsburg at twelve-twenty-three and get something at the lunch counter. We stop there five minutes."

"Me for the dining-car," declared Steve when the conductor had moved on. "What time is it now, I wonder."

It was only a very few minutes after eight, the discovery of which fact occasioned both surprise[21] and dismay. "Seems as though it ought to be pretty nearly noon, doesn't it?" asked Tom.

"Yes. What time did you have breakfast? I had mine at half-past six."

"Me too. Let's go through the train and see if we can find some apples or popcorn or something."

The trainboy was discovered in a corner of the smoking-car and they purchased apples, chocolate caramels and salted peanuts, as well as two humorous weeklies, and found a seat in the car and settled down to business. They were both frightfully hungry, since excitement had prevented full justice to breakfasts. It was horribly smoky in that car, but Steve declared that he liked it, and Tom, although his eyes were soon smarting painfully, pretended that he did too.

"I suppose we'll have to smoke at school," said Tom without enthusiasm.

Steve considered the question a moment. "I don't believe we will unless we want to," he replied at last. "We can say it's because we're in training, you know. They don't allow you to smoke when you're trying for the football team or anything like that."

Tom sighed his relief. "It makes me horribly squirmy," he said. "I thought, though, that if[22] all the fellows did it, you know, I'd better, too. In all the stories about boarding schools I've ever read, the fellows smoke on the sly and get found out. Don't see much fun in that, though, do you?"

"No." Steve devoured the last of his apple and started on the peanuts. "I don't believe those stories very well, anyway. There's always a goody-goody hero that gets suspected of something he didn't do and knows who really did it all the time and won't tell. And then he saves another fellow from drowning or something and it turns out that it was that fellow who did it, you know, and he goes and fesses up to the principal and the principal asks the hero's pardon in class and the captain of the football team comes to him and begs him to play quarter-back or something, which he does, and the school wins its big game because the hero gets the ball and runs the length of the field with it and scores a touchdown. I guess boarding school isn't really very much like that, Tom. I guess there's a heap more hard work to it than those fellows who write the stories tell you about. Anyway, we'll soon find out."

"Still, I guess some of those things do happen sometimes," said Tom a trifle wistfully, unwilling to relinquish the story-book romance. "Fel[23]lows do get wrongly accused of—of things, and they do rescue other fellows from drowning—sometimes, and fellows do win football games. I'd like to do that and be a hero!"

"Sure! So would I. Bet you, though, there won't be any of that kind of stuff at Brimfield. I dare say we'll wish ourselves out of it long before Christmas! If anyone wrongly accuses me of anything you can bet I'll make a kick. You won't see me getting punished for what some other fellow's done. That's all right in stories, but not for yours truly! Not a bit of it, Tom!"[24]

They descended on the dining-car at twelve o'clock promptly, being unable to remain away any longer, and gave an excellent imitation of a visitation of locusts performing their well-known devastating act. If any two travellers by land or sea ever received their money's worth in food it was Steve and Tom. They took the menu card and briskly demanded everything in order, and when, having finished their dessert, they made the discovery that a criminally careless waiter had deprived them of pineapple sherbert, they immediately and indignantly saw to it that the omission was corrected. Afterwards, groaning with happiness and repletion, they dragged themselves back to their own car and subsided on the seat in beatific silence.

An hour later they came out of their stupor to stare eagerly, excitedly out at the indications of the approaching metropolis. Meadows strung with enormous and glaring signboards gave place to towns and presently there came a pause at a[25] station where other trains whisked in and out with amazing frequency. Then on again, and they were suddenly dipping into a tunnel, conscious of an unpleasant pressure against their eardrums. Tom's expression of bewildered alarm moved a kind-hearted neighbour across the car aisle to lean over and explain smilingly that the train was now running under the river, a piece of information but little calculated to remove Tom's fears had he given the slightest credence to it, which he didn't.

"I guess," he muttered resentfully close to Steve's ear, "he thinks we're a couple of 'greenies' for fair! Going under a river!"

And then, almost before Tom's indignation had given way again to alarm, the tunnel was left behind and they were in New York at last, a dimly-lighted, subterranean New York filled with hurrying crowds, bustle, noise, confusion and importunate porters. Even though the two boys emerged to the platform in a somewhat dazed condition, they had no intention of wasting perfectly good pocket money having their bags carried for them, and so started out to find the office of the baggage transfer company quite bravely. For a minute they had only to follow the hurrying throng of fellow-passengers, but soon this throng divided and went separate ways and Steve and Tom, rest[26]ing their arms by depositing their hand luggage on the lower step of an apparently interminable flight of broad stairs, looked about for someone to question. But everyone seemed in a terrible hurry, and when, at last, Steve ventured to put a query to a benevolent-looking elderly gentleman who clutched a tightly-rolled umbrella in one hand and an afternoon paper in the other, he almost had his head bitten off! In the end, they proceeded up the stairway and at last came upon a returning porter who gave them their direction. By the time they had reached the transfer company's office they had walked so far that Tom wondered whether most of the city was not contained inside the station!

Presently, though, he saw that it wasn't. For they found themselves standing outside the terminal on a street that stretched, apparently, for millions of miles in each direction! They had received detailed advice from the man in the transfer company's office as to the best method of reaching the Grand Central Station, and the directions had sounded quite easy to follow. But now the feat didn't look so simple, for the man had told them to take a car going in a certain direction and there wasn't a car in sight! Moreover, when Tom came to look for car-tracks there weren't any![27] He pointed out the fact to Steve, and Steve, at first a bit dismayed, at last shrugged his shoulders and observed his chum pityingly.

"You don't suppose all the cars in this town run on tracks, do you?" he asked.

"What do they run on then?"

"Why—er—you wait and see!"

"That's all right, but it's almost three o'clock and our train goes from the other station at a quarter-past, and——"

"Well, we'll ask someone," said Steve. But, oddly enough, there was no one to ask. For a town as large as New York that block of street was strangely deserted. A team or two passed and an elderly woman crept by on the opposite sidewalk, but no one came near them. Finally Steve muttered:

"Looks to me as if we were on the wrong street. Maybe there are two doors to this old station, Tom."

"Of course there are! Let's walk down to that corner. There goes a car now!" And Tom, as though his future happiness depended on catching that particular car, seized his bag and started down the street at a run. Steve followed more leisurely, and when he reached the corner Tom was talking to a policeman. It was all very sim[28]ple. They had made the mistake of leaving the terminal by a wrong exit and had emerged on to a cross-town street. After that it was easy. A car lumbered up, the policeman stopped it for them, they climbed aboard, were hurled half the length of the aisle and fell into seats. A few minutes later they transferred to a cross-town line without misadventure.

"They certainly make you step lively in this town," panted Tom, clutching a strap and narrowly avoiding a seat in the lap of a very stout lady. "Glad I don't have to live here!"

Steve, however, whose eyes were darting hither and thither in a desperate effort to lose none of the sights, was more favourably disposed toward the city. Even when, owing to a blockade at one of the street intersections, it became evident that they could not possibly make the three-fifteen train to Brimfield, Steve refused to be troubled. "Maybe," he said, "we'll have time to walk around a bit and see something. Say we do it, anyway, Tom?"

"No, sir, this place is too blamed big! First thing we'd know we'd be lost for fair and never would get to Brimfield. When I get to that station I'm going to sit down and stay there!"

When they did reach it the three-fifteen train[29] had been gone nearly ten minutes, and inquiry at a window labelled "Information" elicited the announcement that the next train available for them would not leave until three-fifty-eight, since Brimfield, it seemed, was not a sufficiently important station to be served by all the trains.

"That gives us half an hour," said Steve eagerly. "Let's check our bags somewhere and go out and look around."

"Yes, and get lost! No, sir, not for mine!"

"Oh, don't be such a scarecrow! Come on!"

But Tom was obdurate. "You go if you want to," he said, "but I'm going to sit down right here and wait. You can leave your bag and I'll look after it. Only, if you don't get back by a quarter to four I'm going to the train, and I'll take your bag with me."

"All right. I just want to go out front awhile. I'll be back in ten minutes. You stay here. And keep your eye on the bags, Tom. I guess there's a lot of sneak-thieves around here." And Steve looked about him suspiciously, his glance finally falling on Tom's left-hand neighbour, a youth of perhaps nineteen years upon whose good-looking face rested an amused smile. Instantly, however, the paper he was holding was raised to hide his face, and Steve frowned. The fellow was, thought[30] Steve, altogether too well-dressed and slick-looking to be honest, and that smile disturbed him. He leaned down and whispered in Tom's ear:

"Look out for the fellow next to you! I think he's a crook!"

Tom turned an alarmed glance to his left and a disturbed one on Steve. "I—I guess," he said with elaborate carelessness, "I'll sit over there where it's lighter." Whereupon he gathered the bags up and literally fled across the waiting-room, Steve at his heels. In his new location, out of sight of the suspected youth, he said hoarsely: "I reckon he was a pickpocket, don't you?"

"You can't tell," responded Steve, shaking his head knowingly. "Anyway, you want to keep an eye on those bags every minute. I'll be right back, though. Want to see my paper?" And Steve handed an Evening Sun, purchased on the car, to his chum and wound his way through the throng toward the entrance.

Left to himself, Tom looked at the clock and saw that the hour was three-thirty-two, glanced apprehensively about him in search of possible malefactors, dragged the bags closer to his feet and unfolded the paper. But he couldn't find much to interest him in it. Besides, he had to look at the clock every few minutes, and whenever a man[31] in a uniform appeared with a megaphone and announced the impending departure of a train Tom had heart disease, seized both bags and crouched ready for instant flight until he was assured that the word "Brimfield" was not among the list of stations enunciated through the trumpet. It was after he had sunk back with a sigh of relief on finding that a train for "Pittsburgh, Chicago and the West" was not his that he discovered that an empty seat at his right had been occupied during his strained interest in the announcer. Glancing around he saw that the occupant was the well-dressed, good-looking youth who had been seated next to him before. The youth seemed very interested in the paper he was reading, his gaze being apparently fixed on a column headed "Tiger's Football Players Report," but Tom refused to be deceived. Only the fact that a grey-coated station policeman was standing within hail kept him from a second flight. Steve, he reflected nervously while he wound both feet around the bags, would return in a minute or two and then they could go to the train. Tom devoutly wished himself and the bags there now. Once he was conscious of the fact that the youth beside him was glancing his way, but he pretended not to be aware of it. Then his neighbour spoke.[32]

"Princeton ought to have a pretty good team this year," he observed genially. Tom, his heart in his mouth, nodded.

"Y-yes," he said.

"Interested in football?" went on the other. Tom dared a quick glance at the smiling face and shook his head.

"No, thank you. I mean—yes, a little." He didn't want to talk because he had read that confidence men always engaged their victims in conversation before selling them counterfeit money or leading them to gamble away their savings. Tom's eyes darted anxiously about in search of Steve and he wondered how soon the smooth-voiced stranger would call him by name or ask after the folks in Tannersville. He hadn't long to wait!

"It's a great game," pursued the other. Then, after a short pause: "Say, I've met you before, haven't I? Your face looks familiar."

"No," answered Tom shortly, digging his feet convulsively against the bulging sides of the bags on the floor.

"My mistake, then. I thought perhaps you were from Tannersville, Pennsylvania."

Tom almost jumped, although he had been expecting some such remark. It was, he reflected[33] agitatedly, absolutely marvellous the way these fellows learned things! In a moment the fellow would tell him his name!

The fellow didn't, though. He only said:

"Tannersville is a fine town. Ever been there?"

Tom shook his head energetically. "Never!" he fibbed.

"Oh!" The confidence-man—for Tom had fully decided that such he was—seemed disappointed. But he wasn't discouraged. "Which way are you travelling?" he asked.

Tom did a lot of thinking then in a fragment of a minute.

"Philadelphia," he blurted.

"Philadelphia! Why, say, you're in the wrong station. You ought to go to the Pennsylvania Terminal. I guess you're a stranger here, eh? Tell you what I'll do. You come with me and I'll put you on a car that'll take you right there."

"I—I've got to wait for a friend," muttered Tom desperately, sending an appealing glance toward the policeman who had now begun to saunter slowly away.

"That so? Well——" The other got up with a glance at the clock and reached down for his suit-case. Tom's gaze followed the direction of that hand closely. It was, he thought, odd that a[34] confidence-man should carry a suit-case, but that might be only an attempt to avert suspicion. The bag held the inscription "A. L. M., Orange, N. J." Probably the bag had been stolen. Tom fixed that inscription firmly in his mind. "I'll have to be going," said "A. L. M." "Sorry I can't be of assistance to you, kid. I thought that maybe if you were going my way, out to Brimfield, I could give you a hand with your bags."

Tom gasped! How did he know about Brimfield?

"Thanks," he muttered. "I—I'll get on all right." Standing there in front of him "A. L. M." looked very youthful to be such a deep-dyed villain and Tom felt a bit sorry for him. But the villain was smiling broadly and, as it seemed to Tom, a trifle mockingly.

"Better keep a sharp lookout for crooks," advised the other. "There are lots of 'em about here. See that old chap over there with the basket of fruit in his lap?" The stranger moderated his voice and leaned toward Tom. Tom, turning his head a trifle to follow the other's gaze, felt one of the bags between his feet move and made a grab toward it. But the stranger had not, apparently, touched it, unless with a foot. "That," he was saying, "is Four-Fingered Phillips, one of the[35] cleverest confidence-men in New York. Well, so long!"

The other moved away, walking nonchalantly past the station policeman who had now wandered back to his post. Tom held his breath. But the policeman, although he undoubtedly followed the youth with his gaze for a moment, failed to act, and Tom was not a little relieved. Even if the fellow was a crook he seemed an awfully decent sort and Tom was glad he hadn't been arrested.

It was getting perilously near a quarter to four now and still Steve had not returned. Tom watched the long hand crawl toward the figure IX, saw it reach it and pass. He would, he decided then, give Steve another five minutes. His gaze fell on "Four-Fingered Phillips" and he viewed that gentleman perplexedly. He didn't look in the least like a confidence-man. He appeared to be about sixty years of age, eminently respectable and slightly infirm. He clutched a basket of fruit and an ivory-headed cane and seemed quite oblivious to everything about him. New York, reflected Tom, with something like a shudder, must be a terribly wicked place! And then, while he was still striving to discern signs of depravity under the gentle and kindly exterior of the elderly confidence-man, a young woman, lead[36]ing a little boy of some three or four years of age and bearing many bundles, hurried up to "Four-Fingered Phillips," spoke, helped him to his feet and guided him away toward the train-shed. Tom sighed. It was too much for him! Of course he had read of female accomplices, but it didn't seem that a four-year-old child could be a part of the game! For the first time he wondered whether "A. L. M.," perhaps chagrined at his failure to decoy Tom to some secret lair, had deceived him about "Four-Fingered Phillips"!

Then it was ten minutes to four, good measure, and Tom, in a sudden panic, seized his bags, gazed about him despairingly and made for the train-shed. He had given Steve fair warning, he told himself, and now he could just fend for himself. But his steps got slower and slower as he approached the gate and when he reached it he set the bags down, got his ticket out and waited. After all, it would be a pretty mean trick to leave Steve. At least, he'd wait there until the last moment. The minutes passed and the hands on the clock further along the barrier crept nearer and nearer to the time set for the departure of the Brimfield accommodation. Tom wondered when the next train after this one would leave.

"Going on this train, son?" asked the gateman.[37]

"Yes," answered Tom, and took a step toward the gate. Then he stopped and shook his head. "No, I guess not," he muttered. "When does the next one go, sir?"

"Where to?" asked the gateman, punching the ticket of a late arrival.

"Brimfield."

"Four-twelve." The gate closed and the matter was irrevocably settled. Tom took his bags and hurried back to the waiting-room and found his place again. No Steve was in sight!

"I'll give him ten minutes," said Tom savagely. "Then I'll go. And—and I won't come back the next time!"

And then, just as the clock announced the hour Steve appeared, a little flushed and breathless, but smiling broadly.

"Gee, you ought to have been with me, Tom!" he said excitedly. "There was a peach of a fire just around in the next street! Seven engines and a hook-and-ladder and hundreds of hose-carts and one of those water-towers! And most of the engines were automobiles, Tom! It was corking!"

"Maybe it was," replied Tom coldly. "I'm going to Brimfield on the four-twelve. What you going to do? Find another fire?"

"Why, no. When I saw I'd lost that other[38] train I thought I might as well wait and see the fire out. There's lots of time, anyway. We'll have plenty of school before we get through with it, Tom."

"That's all right," responded Tom bitterly, "but you're way off if you think it's any fun for me sitting around here and waiting for you while you have a good time going to fires!"

"You said you didn't want to go——"

"Well, what if I did?" demanded Tom, working himself into a very respectable fit of anger. "I didn't want to go. But that's no reason why you should leave me alone for the rest of the day to—to stave off robbers and thieves and confidence-men and—and all!"

"Oh, well, come on," said Steve. "We haven't done anything but lose a train——"

"We've lost two trains!"

"And the man says there's another at twelve minutes after."

"And we'll lose that if you stand here talking much longer," declared Tom peevishly. "Take up your bag and come along. There's only six or seven minutes."

"Where is it? Haven't you got it?"

"Got what?"

"My bag," said Steve crossly.[39]

"Isn't it staring you in the face?" asked Tom disgustedly, indicating the suit-case against the seat. "Are you blind?"

"That? That isn't mine. Where——" Steve looked at the bag in Tom's hand and then around the floor. "Where's mine?"

"What!" Tom was gazing in stupefied amazement at the bag between them.

On the end appeared the legend: "A. L. M., Orange, N. J."[40]

Just as the conductor, snapping his watch shut, waved his hand to the engineer of the four-twelve two boys hurried down the platform and, with the assistance of a negro porter, climbed to the last platform of the moving train. From there, much out of breath, they entered the car, pushed aside a curtain and sank on to the seats of the smoking compartment. And as he did so each set a suit-case between his legs and the front of the seat in a way that suggested that only over his dead body could that bag be removed!

The first of the two, the one with his back to the engine, was a nice-looking youth of fifteen—almost sixteen, to be quite accurate—with a broad-shouldered, slim-hipped body that spoke of the best of physical condition. He had a pair of light-brown eyes, a short straight nose, a nice mouth and a rather sharp chin. His face was tanned, and slightly freckled as well, and he was tall for his age. His full name was Stephen Dana Edwards.

His companion was an inch shorter, a little heav[41]ier in build, although quite as well-conditioned physically, and was lighter in colouring. His hair was several shades less dark than his friend's, although it, too, was brown, his eyes were grey and under the sunburn his skin was quite fair. His full name was Thomas Perrin Hall.

Good, healthy, frank-looking youths both of them under normal conditions, but at this present moment very far from appearing at their best. Each face held an expression of gloom and resentment; on Mr. Stephen Edwards' countenance sat what might well be termed a scowl. And, after a minute, by which time the train had plunged into the tunnel and the travellers had somewhat recovered their breaths, the latter young gentleman gave voice to a remark which went well with his expression.

"I like the way you looked after it," he said with deep sarcasm. Mr. Thomas Hall, returning the other's scowl, drummed with his heels on the suit-case.

"Why didn't you stay and look after it yourself?" he asked angrily. "It isn't my fault that you went off chasing after fire-engines."

"I didn't chase after fire-engines. You said you'd watch my bag and——"

"I did watch it!"[42]

"Oh, yes, fine! Let someone pinch it right under your eyes! I notice you managed to keep your own bag all right!"

"Oh, dry up!" growled Tom.

Silence ensued until a conductor appeared and demanded tickets. Yielding their transportation, the boys were informed that they were in a parlour car and must pay twenty-five cents apiece to ride to Brimfield. Tom laid hold of his bag with a sigh, but Steve unemotionally produced a quarter and so Tom followed suit. When the conductor had disappeared again through the curtain Steve said:

"Why didn't they tell us this was a parlour car? How were we to know?"

"They just wanted our money, I suppose," replied Tom bitterly. "Everybody in this place is after your money. I wish I was home!"

"So do I," agreed Steve gloomily. More silence then, until,

"I don't see how he ever did it," remarked Tom. "I had both bags between my feet. He was certainly slick. I suppose when he told me to look at 'Four-Fingered Phillips' I sort of turned around and switched my legs away from the bags. But he must have been mighty quick."

"Of course he was quick," said Steve con[43]temptuously. "I warned you against that fellow."

"That's all right, but I'll bet he'd have played the same trick if it had been you instead of me," replied Tom warmly.

"I'll bet he wouldn't!"

"All right!" Tom shrugged his shoulders and looked out the window. They had the compartment to themselves, which, in view of the remarks which were passed, was fortunate.

"It isn't all right, though," pursued Steve. "That bag had all my things in it: pajamas, brushes and comb and collars and handkerchiefs and—and everything! I'd like to know what I'm going to sleep in!"

"I dare say we'll get our trunks to-night," said Tom soothingly. "If we don't you can have my pajamas."

"What'll you wear?" asked Steve more graciously.

"Anything. I don't mind. I say, Steve, let's see what's in the bag he left!"

"Would you?" asked Steve doubtfully.

"Why not? He's got yours, hasn't he?"

Steve lifted the suit-case to the seat beside him and tried the catch. It was not locked and opened readily. There wasn't a great deal in it: a pair[44] of lavender pajamas at which Steve sniffed sarcastically, a travelling case fitted with inexpensive brushes and things and marked "A. L. M.," a pair of slippers, a magazine, a soiled collar, one clean handkerchief and a grey flannel cap with a red B sewed on the front above the visor.

"Wonder whose they are," mused Tom, as Steve spread the trousers of the pajamas out and viewed them dubiously. They were several sizes two large for Steve, but they might do if his trunk didn't come in time. "I suppose that fellow swiped this bag, found there wasn't anything valuable in it and thought he'd swap it for another."

"Maybe there was something valuable in it when he got it," said Steve. He tossed the things back and closed it again. "It's a pretty good suit-case; better than mine. Do you suppose it would do any good to advertise?"

"I don't suppose so. Besides, that cop said that he'd have them search the pawnshops. If the police don't find it I guess an advertisement wouldn't do any good, Steve."

"Well, I suppose there's no use crying over spilled milk," replied the other, setting the suit-case back in its place. "After all I can buy new things for five dollars or so and I guess father will send me the money when I tell him about it."[45]

Tom frowned thoughtfully. Finally, "Say, Steve, if you won't tell him how it happened I'll pay for what you lost myself."

"What for?"

"I—I'd rather he didn't know, that's all."

"Oh! Well, I won't tell him you had anything to do with it, Tom. You didn't, either," he added after a moment. "It wasn't your fault, Tom. It—it would have happened to me just the same way, I'll bet."

"You could just say that the bag was stolen, couldn't you?" asked Tom more cheerfully. "I mean you needn't go into particulars, you know. It doesn't really matter how it happened as long as it did happen."

"No, of course not. I'll just say it was stolen while we were waiting for the train. I guess five dollars will be enough. Let's see. Pajamas cost two and a half, brushes——"

"You getting off at Brimfield, gentlemen?" asked the porter, putting his head through the curtains and waving a brush at them.

"Yes. Are we there?" asked Tom startledly.

"Pretty near, sir. Want me to brush you off, sir?"

"I guess so." By the time that ceremony had[46] been impressively performed and two dimes had changed places from the boys' pockets to the porter's, the train was slowing down for the station. A moment later they had alighted and were looking about them.

The station was small and attractive, being of stone and almost covered with vines, and beyond it, across the platform, several carriages were receiving passengers. A man in a long and shabby coat accosted them.

"Carriage, boys? Going up to the school?"

"Yes," replied Steve. "How much?"

"Twenty-five cents apiece. Any trunks?"

"Two. Can you take them up with us?"

"I'll have 'em up there in half an hour. Just you give me the checks."

"The checks," murmured Steve, a look of uneasiness coming to his face.

"Haven't you got them?" asked Tom anxiously.

Steve nodded. "I've got them all right," he said grimly, "but these are the transfer company's checks. We—we forgot to get new ones at the station!"

"Thunder!" said Tom disgustedly. "Now what'll we do?"

"I'll look after it, gentlemen," said the driver[47] comfortingly. "I'll have the agent telegraph the numbers back and they'll send 'em right along. It'll cost about half a dollar."

"Will we get them to-night?" asked Steve.

"You might. I wouldn't like to promise, though. Anyway, they'll be along first thing in the morning. Thank you, sir. Right this way to the carriage. I'll look after the bags."

"Not mine, you won't," replied Tom grimly, tightening his clasp on it. "I wouldn't trust the President of the United States with this bag. Anyway," he added as he followed Steve and the driver across the platform to a ricketty conveyance, "not if he lived in New York!"

By that time all the other carriages had rolled away, and while they waited for their driver to arrange with the station agent about the trunks they examined their surroundings. There wasn't much to see. The station was at the end of a well-shaded street, and beyond, across the right of way, the country seemed to begin. There were one or two houses within sight, set back amidst trees, and at the summit of a low hill the wheel of a windmill was clattering merrily. There were many hills in sight, all prettily wooded, and, on the whole, Brimfield looked attractive. They searched vainly for[48] a glimpse of the school buildings, and the driver, returning just then, explained in reply to their inquiry, that the school was nearly a mile away.

"You could have seen it from the train if you'd been looking," he added. "It's about a quarter of a mile from the track on the further side there. Get-ap, Abe Lincoln!"

Their way led down the straight and shaded street which presently began to show houses on either side, houses set in small gardens still aflame with autumn flowers and divided from the road by neat hedges or vine-clad fences. Then there were a few stores clustering about the intersection of the present street and one running at right angles with it, and a post-office and a fire-house and a diminutive town hall. The old horse turned to the right here and ambled westward.

"You boys are sort of late," observed the driver conversationally.

"Why, school doesn't begin until to-morrow, does it?" asked Tom.

"No. I meant you was late for to-day. About twenty boys came this afternoon, most of 'em on the train before this one. There was Prouty and Newhall and Miller and a lot of 'em. You're new boys, though, ain't you?"[49]

They acknowledged it and the driver nodded.

"Thought I didn't remember your faces. I got a good memory for faces, I have. Well, you're coming to a fine school, boys, a fine school! I guess there ain't another like it in the country. I been driving back and forth for nigh on twelve years and I know it pretty well now. Know lots o' the boys, too. Nice fellers, they be. Always have a good word for me. Generous, they be, too. Always handin' me a tip and thinkin' nothing of it."

Steve nudged Tom with his elbow. "That's fine," he said. "You must be pretty rich by now."

"Rich? Me rich?" The driver shook his head sorrowfully. "No, sir, there ain't much chance o' gettin' rich at this business, what with the high cost of feed and all. No, gentlemen, I'm a poor man and I don't never expect to be aught else. Get-ap, Abe Lincoln!"

The village, or what there was of it, had been left behind now and the road was winding slightly uphill through woodland. The sun was slanting into their faces, casting long shadows. Now and then a gate and the beginning of a well-kept driveway suggested houses set out of sight on the wooded knolls about them. The carriage crossed[50] the railroad track and the driver pointed ahead of him with his whip.

"There's the school," he said; and the boys craned forward to see.

"Gee, but ain't it big!" muttered Steve.[51]

The woods had given way to open fields, and they could follow with their eyes the course of the road ahead as it turned to the left and ran, almost parallel to the railroad, past where a pair of stone gate-posts guarded the entrance to the Academy. From the gate a drive went winding upward, hidden now and then by trees and shrubs, to where, at the crest of a hill, a half-dozen buildings looked down upon them with numberless windows.

"That's Main Hall," said Tom, "the big one in the centre. I remember it in the catalogue."

"And that's the gym at this end," added Steve. "It's a pretty good looking place, isn't it? What's the building where the tall chimney is, driver?"

"Torrence. There's rooms upstairs and a dining-room on the first floor. That chimney's from the kitchen at the back. Then the building in the middle's Main Hall, as they call it. That was the original building. I remember when there wasn't any others. The one to the left of it's Hensey[52] Hall. The fellows that lives there are called 'Chickens,'" chuckled the man. "Then there's Billings beyond Hensey, and The Cottage, where Mr. Fernald lives, is just around the corner, like. You can see the porch of it if you look."

But they couldn't, for at that moment the carriage turned to enter the gate and their view was cut off by a group of yellowing beeches.

Presently the carriage stopped in front of a broad flight of stone steps and the boys climbed out.

"Fifty cents, gentlemen," said the driver as he lifted the bags out. "Thank you, sir. Thank you, sir! I'll have your trunks up first thing in the morning. Just walk right in through the door and you'll find the office on your right. They'll look after you there. Much obliged, gentlemen. Any time you want a rig or anything you telephone to Jimmy Hoskins. That's me. Good-night, gentlemen, and good luck to you!"

Steve had contributed an extra quarter, which doubtless accounted for Mr. Hoskins' extreme affability. Bags in hand they climbed the well-worn granite steps and entered a dim, unlighted corridor. An open door on the right revealed a room divided by a railing, in front of which were a half-dozen wooden chairs and beyond which were two[53] desks, some filing cabinets, a book-case, a letter-press, some chairs and one small, middle-aged man with a shining bald head which was raised inquiringly as Steve led the way to the railing.

"How do you do, boys," greeted the sole occupant of the office in a thin, high voice. "What are the names, please?" As he spoke he took a card from a pile in front of him and dipped a pen in the ink-well.

"Stephen D. Edwards, sir."

"Full name, please."

"Stephen Dana."

"Very good. Place of residence?"

"Tannersville, Pennsylvania."

"A wonderful state, Pennsylvania. Parents' names, please."

"Charles L. Edwards. My mother isn't living."

"Tut, tut, tut!" said the school secretary regretfully and sympathetically. "A great misfortune, Edwards. Now, you are entering by certificate?"

"Yes, sir, from the Tannersville High School."

"And your age?"

"Fifteen; sixteen in——"

"Fifteen will do, thank you." He drew out a drawer in a small cabinet set at the left of the[54] broad-topped desk and ran his fingers over the indexed cards within it, finally extracting one and laying it very exactly above the one on which he had been setting down the information supplied by Steve. For a moment he silently compared the two. Then he nodded with much satisfaction. "Quite so, quite so," he said. "You will room in Billings Hall, Number 12, Edwards. You are provided with linen and other articles required?"

"Yes, sir, but my trunk hasn't got here yet."

"Quite so. One moment." He drew a telephone toward him, pressed a button on a little black board set at one end of the desk, glanced at the clock between the two broad windows and spoke into the transmitter: "Mrs. Calder? Edwards, 12 Billings, hasn't his trunk yet. Will you have his room made up, please? Eh? Quite so! Yes, 12 Billings. Just a moment." He turned to Steve. "May I ask whether the young gentleman with you is your room-mate, Hall?"

"Yes, sir."

"And his trunk, too, is missing?"

"Yes, sir."

"Quite so. Yes, Mrs. Calder, both beds, please. Thank you." He hung up the receiver and pushed the instrument aside. "That is all, Edwards. I trust you will like the school. Should[55] you want anything you may come to me here or you will find your Hall Master, Mr. Daley, in Number 8 Billings. Now, if you please, Hall."

Tom, in turn, answered the little man's interrogations and at last they were free to seek their room.

"Billings is the last dormitory to your right as you leave this building," said the secretary, "and you will find Number 12 on the second floor at the further end. Supper is served at six o'clock in the dining-room in Wendell, which is the last building in the other direction. As we have very few students with us yet, the supper hour is shortened and it will greatly assist if you will be prompt."

The boys thanked him and sought their room. A broad flagstone walk ran the length of the row of six buildings and along this they strode past the first building, which was Hensey, to the one beyond. The dormitories were uniform in material and style of architecture, each being three stories in height, the first story of stone and the others of red brick. The entrance was reached by a single stone step, above which hung an electric light just beginning to glow wanly in the early twilight. Inside, two slate steps led to the first floor[56] level and here a fireproof door divided the staircase well from the corridor. A flight of stone stairs took them to the second floor. "Rooms 11 to 20" was inscribed on the door and Steve pushed it open and led the way down to a very clean, well-lighted corridor to Number 12. There could be no mistake about it, for the figures were very plainly printed on the white door. Under the room number was a little metal frame which they afterwards discovered was for the purpose of holding a card bearing the names of the occupants. Steve pushed the door open and, followed by Tom, entered.

There was still enough light from the one broad window to see by, but Steve found a switch near the doorway and turned on the electricity. It was a pretty forlorn looking place at first glance, but doubtless the fact that the two beds were unmade, that the window-seat was empty of cushions and that the two slim chiffoniers and the desk-table were bare had a good deal to do with that first impression. The boys set their bags down and looked about them rather dejectedly. Finally,

"I suppose when we get our things around it'll look different," murmured Tom.

Steve grunted and tried a bed. "That feels pretty good," he said. "I hope Mrs. Thingama[57]bob won't forget to make it. Which side do you want?"

"I don't care," replied Tom. "There isn't any difference, I guess."

There didn't appear to be. The door was at the right as you entered, and beside it was a good-sized closet. The room was about fifteen feet long, from closet to window, by some twelve feet wide. A brown grass rug filled most of the floor space. The wainscoting, of clean white pine, ascended four feet and ended in a narrow ledge or shelf, devised, as they afterwards discovered, to hold photographs or small pictures which the rules prohibited them from placing on the walls. The walls were painted a light buff. The furniture consisted of two single-width beds, two chiffoniers, a study table and two straight-backed chairs. The beds were against the opposite walls, the table in the geometrical centre of the rug, the chiffoniers occupied a portion of the remaining wall space on each side and the two chairs were set between beds and bureaus. The window was in a slight bay and there was a six-foot seat below it. The room was lighted by a two-lamp electrolier above the table, but from one socket depended a green cord, suggesting that a previous occupant had used a drop light.[58]

"I wonder," said Steve, "where we are supposed to wash."

"Let's look for the bathroom," suggested Tom. So they returned to the silent corridor and presently discovered a commodious bath and wash-room at the farther end. There were six set bowls and four tubs there, and Tom thought it was pretty fine. Steve, however, was in a mood to find fault and he objected to the bathroom on several different counts. For one thing, it was too far away. Then, too, he didn't see how twenty fellows were going to wash at six bowls. Tom, however, promptly demonstrated how one fellow could do it by returning to Number 12 and bringing back his wash-cloth. In his absence Steve had been experimenting with the liquid soap apparatus with which each bowl was supplied, and by the time Tom got back was able to tell him why he didn't approve of them! By the time they had both cleaned up it was time to find the dining-hall, and so, leaving the light burning in brazen disregard of a notice under the switch, they clattered downstairs again and set off for the other end of the Row, as the line of buildings was called.

Two or three boys were standing on the steps of Wendell when they reached it and they were[59] aware of their frankly curious gaze as they passed them. The dining-hall wasn't hard to find, for its double doors faced them as they entered the building. They left their caps on one of the big racks outside and rather consciously stepped inside the doorway. It was a huge room, seemingly occupying the entire first floor of the building, and held what appeared to be hundreds of tables. Only four of them were occupied now, two across the hall from the door and two at one end. A boy of about seventeen or eighteen, wearing an apron and carrying a tray of dishes, saw them, and, setting down his burden, conducted them to one of the tables nearby. There were already five boys at the board and they each and all stared silently while Steve and Tom slid into their chairs. The newcomers surmised that they, too, were new boys, for, unlike the fellows at the next table beyond, who were laughing and chatting quite light-heartedly, they applied themselves grimly and silently to their food and seemed to view each other with deep distrust.

Steve and Tom, striving against the embarrassment that held them, conversed together in whispers. "It's a whaling big room," said Steve. "Just like a hotel, isn't it? Wonder what we get to eat."[60]

"Bet you I'll eat it, whatever it is," replied Tom. "I'm as hungry as a bear!"

They weren't left long in doubt, for a second waiter appeared very promptly and set their repast before them. There was cold roast beef, a baked potato apiece, toasted muffins, milk and cocoa, preserves and cookies. By the time they were half through their supper most of the others had finished and hurried away, removing much of the embarrassment of the situation. Steve ventured to stretch his legs comfortably under the table and turn his head to regard the occupants of the tables at the far end of the hall.

"I guess some of those are teachers," he said. "Gee, but I'd like some more meat. Would you ask for it?"

"I don't know. No one else did. These muffins are bully, only there aren't enough of them. I wonder if we'll sit here regularly."

"I don't suppose so. We'll probably be shoved to one of those tables over there by the wall. What time do you suppose they have breakfast? We'll have to ask someone, I guess. Didn't he say something about a Hall Master?"

"Yes, in Number 8. We'll stop and ask him when we go back." There was a scraping of chairs at the end of the room and several older[61] boys and two or three men came down the room toward the door. Steve and Tom turned to look and suddenly Tom seized his companion's arm.

"It's him!" he exclaimed.

"Who?" asked Steve.

"Or—anyway it looks lots like him," continued Tom breathlessly.

"Who looks like what?" demanded the other impatiently.

"Why, the tall fellow just going out now! See him? He—he looks just like the fellow in the station, the fellow who took your bag! The confidence-man!"[62]

"The confidence-man?" asked Steve incredulously. "Oh, you run away and play, Tom! What would he be doing here? Don't be a silly goat!"

"Well, I suppose it isn't he, but—but he certainly looked just like him."

"Pshaw, I saw him too, didn't I? Well, that chap doesn't look anything like him."

"Then you didn't look at the fellow I meant," returned Tom doggedly. "I—I believe it was he, Steve!"

"Oh, sure," said Steve sarcastically, "and the fellow behind him is a famous second-story burglar and the man with the flannel trousers on, who looks like a teacher, is a popular murderer. He escaped from Sing Sing this morning. And the little man with the grey moustache——"

"That's all right," replied Tom earnestly, "but you'll find I'm right. It—it was he, I tell you! There couldn't be two people as much alike!"[63]

"You'd better follow him then," laughed Steve, "and ask him for my suit-case. Tell him I want my pajamas, will you?"

But Tom refused to treat the matter so lightly. He was evidently quite convinced that he was really on the trail of the thief, and all Steve's ridicule failed to move him from that conviction. He was too anxious to begin the search for the "confidence-man" to do justice to the rest of his supper, and when, at last, they were once more outside the building he gazed up and down the Row eagerly and was disappointed to find that neither his quarry nor anyone else was visible in the half-darkness. As they passed Torrence Hall, however, an open window on the first floor sent a flood of light across the walk, and Tom, crossing the narrow strip of turf that divided building from pavement, raised himself on his tiptoes and looked into the room. The next instant a face appeared with disconcerting suddenness within a foot of his own and the occupant of the room, who had been reclining on the window-seat, enquiring abruptly:

"Well, fresh, what do you want?"

"N-Nothing, thanks," stammered Tom, withdrawing quickly.

"Keep your head out of my window then," was[64] the indignant response, "or I'll come out there and teach you manners!"

Tom hurried away into the friendly darkness and joined Steve, who was chuckling audibly.

"Did you find him, Tom?"

"No." And then, as Steve continued to be amused, Tom said with spirit; "I should think you'd be enough interested to help a fellow instead of giggling like a silly goat!"

"Oh, I'm not a Sherlock Holmes," replied Steve airily. "Detecting isn't in my line."

"I should think you'd want to get your bag back, though. I tell you that was really the fellow, Steve. Don't you believe me?"

"Oh, yes!"

"You don't, though," said Tom bitterly. "All right, then. You find your own bag. I'm through."

"Oh, don't say that!" begged Steve. "You were doing so nicely. Look, there's a lighted window up there, Tom. If you get a ladder now——"

"Aw, cut it!" growled Tom.

Mr. Daley was in when they rapped at the door of Number 8, on the first floor of Billings, and, accepting his invitation to enter, they found themselves in a very cosy, lamp-lighted, nicely fur[65]nished study, from which a smaller room, evidently a bedroom, opened. Mr. Horace Daley was a young man with an embarrassed manner and a desire to appear quite at ease. He shook hands heartily, stumbled through a few words of welcome and arranged chairs for them. He asked a good many questions, invariably remarking "Fine!" with deep enthusiasm after every answer and smiled jovially at all times. But the boys saw that he was much more embarrassed than they were and were secretly pleased and amused. When at last the instructor had finished the usual questions and was searching around in his mind for more, Steve began asking for information. Breakfast, responded Mr. Daley, was at seven-thirty and ran half an hour. Chapel was at eight-fifteen usually, although there would be none to-morrow, as school did not officially begin until noon. The first recitation hour was nine o'clock. Dinner ran from twelve-thirty to one-thirty. Recitations began again at two and lasted until half-past three. Supper was at six. Between seven and eight the students were required to remain in their rooms and study, although on permission of the House Master one could study in the library instead. All lights were supposed to be out at ten-thirty. And Mr. Daley hoped the[66] boys would get on swimmingly and become very fond of Brimfield.

"I—ah—I want you to feel that I am ready and anxious to help you at any time, fellows. I—ah—want you to look on me as—ah—as a big brother and come to me in your—ah—perplexities and troubles, should you have any, and of course there are bound to be—ah—little worries at first. One has to accustom oneself to any—ah—new environment. Don't hesitate to call on me for advice or assistance. Sometimes an older head—ah—you see what I mean?"

Steve replied that they did and thanked him and, with Tom crowding at his heels, withdrew.

"He's a funny dub," confided Steve, as they made their way up to the next floor. "Guess he must be new here. What does he teach, Tom?"

"Modern languages, I think the catalogue said. His first name is Horace."

"Horace!" Steve chuckled. "It ought to be Percy. Hello, they've fixed the beds up."

The room looked far more habitable when Steve had switched the light on. Tom sighed luxuriously as he stretched himself out on one of the beds. "Bet you I'm going to do a tall line of sleeping to-night, Steve," he said. "This bed isn't half bad, either."[67]

"Well, don't put your feet all over the spread," replied Steve. "Get up out of that and unpack your bag, you lazy duffer."

"I will in a minute. I'm tired. Say, what do you think of this place, anyway, Steve?"

"The school? Oh, I guess it'll do. You can't tell much about it yet, I suppose. I'm going to snoop around to-morrow after breakfast and see the sights. I suppose things will be a lot different when the crowd comes. I guess we're the only fellows in this dormitory to-night."

"Scared?" asked Tom, with a grin. "Remember Horace is downstairs to protect you."

"Huh! Bet you he'd crawl under the bed if he saw a burglar! I wonder if the rest of the faculty is like him."

"Oh, I dare say he's all right when you get to know him," said Tom, with a yawn. "Say, pull down that window, Steve. It's getting chilly in here."

"Get up and move around and you won't feel chilly," replied Steve unsympathetically. "Gee, I wish I had my pajamas and things."

"You might have had them by this time if you'd helped me look for that fellow," said Tom. "I'm just as certain as I am that I'm lying here[68] that the fellow we saw in the dining-hall was the fellow who swiped your suit-case!"

"Oh, forget that," said Steve disgustedly. "Common-sense ought to tell you that a sneak thief you saw in New York wouldn't be having his supper here at Brimfield!"

"He was, though," replied the other stubbornly.

"Oh, run away! Don't you suppose there are two people who look alike in this world?"

"Not as much alike as those two."

"Why, you didn't even get a good look at the fellow in the dining-hall. He had his back turned to you."

"Not when I saw him first, he didn't," answered Tom with a vigorous shake of his head. "I saw his face before he turned at the doorway and it was him!"

"You mean it was he, you ignoramus. All right, Tom, have your own way about it. Only someone ought to warn the principal about him. Why, he might run off with a couple of the buildings some night!"

"Enjoy yourself," murmured Tom. "But you'll find I was right some day, you old pig-headed chump!"[69]

"When I do I—I'll make you a present," answered Steve, with a grin.

"Any present you'd give me wouldn't cut much figure, I guess," said the boy on the bed contemptuously.

"Is that so? Say, what'll I do with this bag?" Steve laid the suit-case in question on his bed and threw open the lid. "The pajamas look clean, anyway," he continued as he viewed them. "I suppose I'll have to wear them." He drew the cap out and set it on his head. "Wonder what the B stands for, Tom."

"What bee?" asked Tom lazily.

"The B on this cap," replied the other, studying it.

Tom suddenly sat up on the bed. "Why, Brimfield, of course!" he exclaimed in triumph. "There now! Was I right or wasn't I?"

"Shucks! It might stand for anything: Brown, Brooklyn, beans, brownbread, basketball——"

"Yes, and Brimfield! And aren't the Brimfield colours maroon-and-grey, and isn't that cap grey, and isn't that B maroon?"

"It's red."

"So is maroon, a brownish-red." Tom had deserted his bed and was turning the cap about eagerly. "This belongs to some fellow here who has[70] won his letter, Steve," he said with deep conviction.

"Some fellow who has lost his letter, you mean," replied Steve with a laugh. "All right; it will save me from buying a cap when I make the football team. How does it look on me?"

"It's too big," said Tom. "It's about a seven, I guess. That's what that fellow would wear, I think." Tom frowned thoughtfully. "Are there any more clues?" he asked, dropping the cap and seizing the pajamas excitedly.

"Sure! There are brushes in the case and they mean that the fellow has hair on his head, Tom. So there's no use looking for a bald-headed man, eh? That's what they call 'the process of elimination,' isn't it? Say, what are you trying to do with those things? Ruin them? Please remember that I've got to wear them to-night."

"Looking for laundry marks," replied Tom. "But there aren't any. I guess they're new ones." He dropped the pajamas regretfully and turned his attention to the other objects in the bag. "A magazine," he muttered.

"'Fine'!—as Horace would say. The man can read. Therefore he is not blind. Elimination again! At this rate we'll know all about him in a minute, Tom. Gee, but you're a wise guy.[71] Have a look at the collar and tell me the fellow's name. Go on!"

"It begins with an M, anyway," muttered Tom, studying the object in question.

"Ha!" exclaimed Steve melodramatically. "The net is closing! He has hair on his head, is not blind, wears purple pajamas and spells his name with an M! The rest is easy, Tom. Put your hat on and we'll go out and get him."

"Oh, shut up, you silly goat!" Tom had the magazine in his hands again and was glancing through it. Suddenly, with an exclamation, he thrust it into Steve's hands. "There! Hold it up and let it fall open itself, Steve!"

"All right. What about it?"

"Look where it opened!"

"Page 64."

"Yes, but what's there?"

"'Men Who Have Made Football History, by——'"

"There you are! Don't you see! That's what he was reading. He's a football man and that B is his football letter!"

"Oh! But, say, Tom, you're forgetting that this suit-case is supposed to have been stolen from someone else. Then what?"

"We don't know that it was. We just thought[72] so. It looks now as if it really belonged to the fellow."

"And he went and swapped it for mine? What would he do that for?"

"Maybe he thought yours might have something valuable in it," faltered Tom. "Maybe—say, Steve, perhaps he got yours by mistake!"

"Sure!" replied the other sarcastically. "Reached down and dragged it from under your feet, thinking all the while it was his. Sounds very probable—I don't think!"

"Well, you can see for yourself——"

"What was that?" interrupted Steve.

"What was what?"

"I thought I heard a knock at the door." They listened. It sounded again. Steve hustled the things back into the bag and slammed the lid shut in a twinkling. Then, "Come in!" he called.

The door opened and a tall youth stepped inside. He carried a suit-case in one hand. Tom gasped. It was the "confidence-man"![73]