Mrs George de Horne Vaizey

"Big Game"

Chapter One.

Plans.

It was the old story of woman comforting man in his affliction; the trouble in this instance appearing in the shape of a long blue envelope addressed to himself in his own handwriting. Poor young poet! He had no more appetite for eggs and bacon that morning; he pushed aside even his coffee, and buried his head in his hands.

“Back again!” he groaned. “Always back, and back, and back, and these are my last verses: the best I have written. I felt sure that these would have been taken!”

“So they will be, some day,” comforted the woman. “You have only to be patient and go on trying. I’ll re-type the first and last pages, and iron out the dog’s ears, and we will send it off on a fresh journey. Why don’t you try the Pinnacle Magazine? There ought to be a chance there. They published some awful bosh last month.”

The poet was roused to a passing indignation.

“As feeble as mine, I suppose! Oh, well, if even you turn against me, it is time I gave up the struggle.”

“Even you” was not in this instance a wife, but “only a sister,” so instead of falling on her accuser’s neck with explanations and caresses, she helped herself to a second cup of coffee, and replied coolly—

“Silly thing! You know quite well that I do nothing of the sort, so don’t be high-falutin. I should not encourage you to waste time if I did not know that you were going to succeed in the end. I don’t think; I know!”

“How?” queried the poet. “How?” He had heard the reason a dozen times before, but he longed to hear it again. He lifted his face from his hands—an ideal face for a poet; clean-cut, sensitive, with deep-set eyes, curved lips, and a finely-modelled chin. “How do you know?”

“I feel!” replied the critic simply. “Of course, I am prejudiced in favour of your work; but that would not make it haunt me as if it were my own. I can see your faults; you are horribly uneven. There are lines here and there which make me cold; lines which are put in for the sake of the rhyme, and nothing more; but there are other bits,”—the girl’s eyes turned towards the window, and gazed dreamily into space—“which sing in my heart! When it is fine, when it is dark, when I am glad, when I am in trouble, why do your lines come unconsciously into my mind, as if they expressed my own feelings better than I can do it myself? That’s not rhyme—that’s poetry! It is the real thing; not pretence.”

A glad smile passed over the boy’s face; he stretched out his hand towards the neglected cup, and quaffed coffee and hope in one reviving draught. “But no one seems to want poetry nowadays!”

“True! I think you may have to wait until you have made a name in the other direction. Why not try fiction? Your prose is excellent, almost as good as your verse.”

“Can’t think of a plot!”

“Bah! you are behind the times, my dear! You don’t need a plot. Begin in the middle, meander back to the beginning, and end in the thick of the strife. Then every one wonders and raves, and the public—‘mostly fools!’—think it must be clever, because they don’t understand what it’s about.”

“Like the lady and the tiger,—which came out first?”

“Ah! if you could think of anything as baffling as that, your future would be made. Write a novel, Ron, and take me for the heroine. You might have a poet, too, and introduce some of your own love-songs. I’d coach you in the feminine parts, and you could give me a royalty on the sales.”

But Ronald shook his head.

“I might try short stories, perhaps—I’ve thought of that—but not a novel. It’s too big a venture; and we can’t spare the time. There are only four months left, and unless I make some money soon, father will insist upon that hateful partnership.”

The girl left her seat and strolled over to the window. She was strikingly like her brother in appearance, but a saucy imp of humour lurked in the corners of her curving lips, and danced in her big brown eyes.

Margot Vane at twenty-two made a delightful picture of youth and happiness, and radiant, unbroken health. Her slight figure was upright as a dart; her cheeks were smooth and fresh as a petal of a rose; her hair was thick and luxuriant, and she bore herself with the jaunty, self-confident gait of one whose lines have been cast in pleasant places, and who is well satisfied of her own ability to keep them pleasant to the end.

“Anything may happen in four months—and everything!” she cried cheerily. “I don’t say that you will have made your name by September, but if you have drawn a reasonable amount of blood-money, father will have to be satisfied. It is in the bond! Work away, and don’t worry. You are improving all the time, and spring is coming, when even ordinary people like myself feel inspired. We will stick to the ordinary methods yet awhile, but if matters get desperate, we will resort to strategy. I’ve several lovely plans simmering in my brain!”

The boy looked up eagerly.

“Strategy! Plans! What plans? What can we possibly do out of the ordinary course?”

But Margot only laughed mischievously, and refused to be drawn.

The cruel parent in the case of Ronald Vane was exemplified by an exceedingly worthy and kind-hearted gentleman, who followed the profession of underwriter at Lloyd’s. His family had consisted of three daughters before Ronald appeared to gratify a long ambition. Now, Mr Vane was a widower, and his son engrossed a large share in his affections, being at once his pride, his hope, and his despair. The lad was a good lad; upright, honourable, and clean-living; everything, in fact, that a father could wish, if only,—but that “if” was the mischief! It was hard lines on a steady-going City man, who was famed for his level-headed sobriety, to possess a son who eschewed fact in favour of fancy, and preferred rather to roam the countryside composing rhymes and couplets, than to step into a junior partnership in an established and prosperous firm.

It is part of an Englishman’s creed to appreciate the great singers of his race,—Shakespeare, Milton, Tennyson, not to mention a dozen lesser fry; but, strange to say, though he feels a due pride in the row of poets on his library shelves, he yet regards a poet by his own fireside as a humiliation and an offence. A budding painter, a sculptor, a musician, may be the boast of a proud family circle, but to give a youth the reputation of writing verses is at once to call down upon his head a storm of ridicule and patronising disdain! He is credited with being effeminate, sentimental, and feeble-minded; his failure is taken as a preordained fact; he becomes a butt and a jest.

Mr Vane profoundly hoped that none of the underwriters at Lloyd’s would hear of Ronald’s scribbling. It would handicap the boy in his future work, and make it harder for him to get rid of his “slips”! No one could guess from the lad’s appearances that there was anything wrong,—that was one comfort! He kept his hair well cropped, and wore as high and glossy collars as any fellow in his right mind.

“You don’t know when you are well off!” cried the irate father. “How many thousands would be thankful to be in your shoes, with a place kept warm to step into, and an income assured from the start! I am not asking you to sit mewed up at a desk all day. If you want to use your gift of words, you couldn’t have a better chance than as a writer at Lloyd’s. There’s scope for imagination too,—judiciously applied! And you would have your evenings free for scribbling, if you haven’t had enough of it in the daytime.”

Ronald’s reply dealt at length with the subject of environment, and his father was given to understand that the conditions in which his life was spent were mean, sordid, demoralising; fatal to all that was true and beautiful. The lad also gave it as his opinion that, so far from regarding money as a worthy object for a life’s ambition, the true lover of Nature would be cumbered by the possession of more than was absolutely necessary for food and clothing. And as for neglecting a God-given gift—

“What authority have you for asking me to believe that the gift exists at all, except in your own imagination? Tell me that, if you please!” cried the father. “You spend a small income in stamps and paper, but so far as I know no human creature can be induced to publish your God-given rhymes!”

At this point matters became decidedly strained, and a serious quarrel might have developed, had it not been for the diplomatic intervention of Margot, the youngest and fairest of Mr Vane’s three daughters.

Margot pinched her father’s ears and kissed him on the end of his nose, a form of caress which he seemed to find extremely soothing.

“He is only twenty-one, darling,” she said, referring to the turbulent heir. “You ought to be thankful that he has such good tastes, instead of drinking and gambling, like some other young men. Really and truly I believe he is a genius, but even if he is not, there is nothing to be gained by using force. Ron has a very strong will—you have yourself, you know, dear, only of course in your case it is guided by judgment and common sense—and you will never drive him into doing a thing against his will. Now just suppose you let him go his own way for a time! Six months or a year can’t matter so very much out of a lifetime, and you will never regret erring on the side of kindness.”

“Since when, may I ask, have you set yourself up as your father’s mentor?” cried that gentleman with a growl; but he was softening obviously, and Margot knew as much, and pinched his nose for a change.

“You must try to remember how you felt yourself when you were young. If you wanted a thing, how badly you wanted it, and how soon, and how terribly cruel every one seemed who interfered! Give Ron a chance, like the dear old sportsman as you are, before you tie him down for life! It’s a pity I’m not a boy—I should have loved to be at Lloyd’s. Even now—if I went round with the slips, and coaxed the underwriters, don’t you think it might be a striking and lucrative innovation?”

Mr Vane laughed at that, and reflected with pride that not a man in the room could boast such a taking little witch for his daughter. Then he grew grave, and returned to the subject in hand.

“In what way do you propose that I shall give the boy a chance?”

“Continue his allowance for a year, and let him give himself up to his work! If at the end of the year he has made no headway, it should be an understanding that he joins you in business without any more fuss; but if he has received real encouragement,—if even one or two editors have accepted his verses, and think well of them—”

“Yes? What then?”

“Then you must consider that Ron has proved his point! It is really a stiff test, for it takes mediocre people far longer than a year to make a footing on the literary ladder. You would then have to continue his allowance, and try to be thankful that you are the father of a poet, instead of a clerk!”

Mr Vane growled again, and, what was worse, sighed into the bargain, a sigh of real heartache and disappointment.

“I have looked forward for twenty years to the time when my son should be old enough to help me! I have slaved all my life to keep a place for him, and now he despises me for my pains! And you will want to be off with him, I suppose, rambling about the country while he writes his rhymes. I shall have to say good-bye to the pair of you! It doesn’t matter how dull or lonely the poor old father may be.”

Margot looked at him with a reproving eye.

“That’s not true, and you know it isn’t! I love you best of any one on earth, and I am only talking to you for your own good. I’d like to stay in the country with Ronald in summer, for he does so hate the town, but I’ll strike a bargain with you, too! Last year I spent three months in visiting friends. This year I’ll refuse all invitations, so that you shan’t be deprived of any more of my valuable society.”

“And why should you give up your pleasures, pray? Why are you so precious anxious to be with the boy? Are you going to aid and abet him in his efforts?”

“Yes, I am!” answered Margot bravely. “He has his life to live, and I want him to spend it in his own way. If he becomes a great writer, I’ll be prouder of him than if he were the greatest millionaire on earth. I’ll move heaven and earth to help him, and if he fails I’ll move them again to make him a good underwriter! So now you know!”

Mr Vane chewed his moustache, disconsolately resigned.

“Ah well! the partnership will have to go to a stranger, I suppose. I can’t get on much longer without help. I hoped it might be one of my own kith and kin, but—”

“Don’t be in a hurry, dear. I may fall in love with a pauper, and then you can have a son-in-law to help you, instead of a son.”

Mr Vane pushed her away with an impatient hand.

“No more son-in-laws, thank you! One is about as many as I can tackle at a time. Edith has been at me again with a sheaf of bills—”

His eldest daughter’s husband had recently failed in business, in consequence of which he himself was at present supporting a second establishment. He sighed, and reflected that it was a thankless task to rear a family. The infantine troubles of teething, whooping-cough, and scarlatina were trifles as compared with the later annoyance and difficulties of dealing with striplings who had the audacity to imagine themselves grown-up, and competent to have a say in their own lives!

If things turned out well, they took the credit to themselves! If ill, then papa had to pay the bills! Mr Vane was convinced that he was an ill-used and much-to-be-pitied martyr.

Chapter Two.

The Sisters.

Mr Vane’s house overlooked Regent’s Park, and formed the corner house of a white terrace boasting Grecian pillars and a railed-in stretch of grass in front of the windows. The rooms were large and handsome, and of that severe, box-like outline which are the despair of the modern upholsterer. The drawing-room boasted half a dozen windows, four in front, and two at the side, and as regards furnishings was a curious graft of modern art upon an Early Victoria stock. Logically the combination was an anachronism; in effect it was charming and harmonious, for the changes had been made with the utmost caution, in consideration of the feelings of the head of the household.

Mr Vane’s argument was that he preferred solid old-fashioned furniture to modern gimcracks, and had no wish to conform to artistic fads, and his daughters dutifully agreed, and—disobeyed! Their mode of procedure was to withdraw one article at a time, and to wait until the parental eye had become accustomed to the gap before venturing on a second confiscation. On the rare occasions when the abduction was discovered, it was easy to fall back upon the well-worn domestic justification, “Oh, that’s been gone a long time!” when, in justice to one’s own power of observation, the matter must be allowed to drop.

The eldest daughter of the household had married five years before the date at which this narrative opens, and during that period had enjoyed the happiness of a true and enduring devotion, and the troubles inseparable from a constant financial struggle, ending with bankruptcy, and a retreat from a tastefully furnished villa at Surbiton to a dreary lodging in Oxford Terrace. Poor Edith had lost much of her beauty and light-hearted gaiety as a result of anxiety and the constant care of two delicate children; but never in the blackest moment of her trouble had she wished herself unwed, or been willing to change places with any woman who had not the felicity of being John Martin’s wife.

Trouble had drawn Jack and herself more closely together; she was in arms in a passion of indignation against that world which judged a man by the standpoint of success or failure, and lay in readiness to heave another stone at the fallen. At nightfall she watched for his coming to judge of the day’s doings by the expression of his face, before it lit up with the dear welcoming smile. At sight of the weary lines, strength came to her, as though she could move mountains on his behalf. As they sat together on the horsehair sofa, his tired head resting on her shoulder, the strain and the burden fell from them both, and they knew themselves millionaires of blessings.

The second daughter of the Vane household was a very different character from her sensitive and highly-strung sister. The fairies who had attended her christening, and bequeathed upon the infant the gifts of industry, common sense, and propriety, forgot to bestow at the same time that most valuable of all qualities,—the power to awaken love! Her relatives loved Agnes—“Of course,” they would have said; but when “of course” is added in this connection, it is sadly eloquent! The poor whom she visited were basely ungrateful for her doles, and when she approached empty-handed, took the occasion to pay a visit to a neighbour’s back yard, leaving her to flay her knuckles on an unresponsive door.

Agnes had many acquaintances, but no friends, and none of the young men who frequented the house had exhibited even a passing inclination to pay her attention.

Edith had been a belle in her day; while as for Margot, every masculine creature gravitated towards her as needles to a magnet. Among various proposals of marriage had been one from so solid and eligible a parti, that even the doting father had laid aside his grudge, and turned into special pleader. He had advanced one by one the different claims to consideration possessed by the said suitor, and to every argument Margot had meekly agreed, until the moment arrived at which she was naturally expected to say “Yes” to the concluding exhortation, when she said “No” with much fervour, and stuck to it to the end of the chapter. Pressed for reasons for her obstinacy, she could advance none more satisfying than that “she did not like the shape of his ears”! but the worthy man was rejected nevertheless, and took a voyage to the Cape to blow away his disappointment.

No man crossed as much as a road for the sake of Agnes Vane! It was a tragedy, because this incapacity of her nature by no means prohibited the usual feminine desire for appreciation. Agnes could not understand why she was invariably passed over in favour of her sisters, and why even her father was more influenced by the will-o’-the-wisp Margot than by her own staid maxims. Agnes could not understand many things. In this obtuseness, perhaps, and in a deadly lack of humour lay the secret of her limitations.

On the morning after the conversation between the brother and sister recorded in the last chapter the young poet paced his attic sitting-room, wrestling with lines that halted, and others which were palpably artificial. Margot’s accusations had gone home, and instead of indulging in fresh flights, he resolved to correct certain errors in the lines now on hand until the verses should be polished to a flawless whole. Any one who has any experience with the pen understands the difficulty of such a task, and the almost hopeless puzzle of changing a stone in the mosaic without disturbing the whole. The infinite capacity for taking pains is not by any means a satisfying definition of genius, but it is certainly one great secret of success.

Ronald’s awkward couplet gave him employment for the rest of the morning, and lunch-time found him still dissatisfied. An adjective avoided his quest—the right adjective; the one and only word which expressed the precise shade of meaning desired. From the recesses of his brain it peeped at him, now advancing so near that it was almost within grasp, anon retreating to a shadowy distance. There was no help for it but to wait for the moment when, tired of its game of hide-and-seek, it would choose the most unexpected and inappropriate moment to peer boldly forward, and make its curtsy.

Meantime Margot had dusted the china in the drawing-room, watered the plants, put in an hour’s practising, and done a few odds and ends of mending; in a word, had gone through the programme which comprises the duties of a well-to-do modern maiden, and by half-past eleven was stepping out of the door, arrayed in a pretty spring dress, and her third best hat. She crept quietly along the hall, treading with the cautious steps of one who wishes to escape observation; but her precautions were in vain, for just as she was passing the door of the morning-room it was thrown open from within, and Agnes appeared upon the threshold—Agnes neat and trim in her morning gown of serviceable fawn alpaca, her hands full of tradesmen’s books, on her face an expression of acute disapproval.

“Going out, Margot? So early? It’s not long past eleven o’clock!”

“I know?”

“Where are you going?”

“Don’t know!”

“If you are passing down Edgware Road—”

“I’m not!”

The front door closed with a bang, leaving Agnes discomfited on the mat. There was no denying that at times Margot was distinctly difficult in her dealings with her elder sister. She herself was aware of the fact, and repented ardently after each fresh offence, but alas! without reformation.

“We don’t fit. We never shall, if we live together a hundred years. Edgware Road, indeed, on a morning like this, when you can hear the spring a-calling, and it’s a sin and a shame to live in a city at all! If I had told her I was going into the Park, she would have offered stale bread for the ducks!” Margot laughed derisively as she crossed the road in the direction of the Park, and passing in through a narrow gateway, struck boldly across a wide avenue between stretches of grass where the wind and sun had full play, and she could be as much alone as possible, within the precincts of the great city.

In spite of her light and easy manner, the problem of her brother’s future weighed heavily upon the girl’s mind. The eleventh hour approached, and nothing more definite had been achieved in the way of encouragement than an occasional written line at the end of the printed rejections: “Pleased to see future verses,” “Unsuitable; but shall be glad to consider other poems.” Even the optimism of two-and-twenty recognised that such straws as these could not weigh against the hard-headed logic of a business man!

It was in the last degree unlikely that Ronald would make any striking success in literature in the time still remaining under the terms of the agreement, unless—as she herself had hinted—desperate measures were adopted to meet desperate needs. A scheme was hatching in Margot’s brain,—daring, uncertain; such a scheme as no one but a young and self-confident girl could have conceived, but holding nevertheless the possibilities of success. She wanted to think it out, and movement in the fresh air gave freedom to her thoughts.

Really it was simple enough,—requiring only a little trouble, a little engineering, a little harmless diplomacy. Ronald was a mere babe where such things were concerned, but he would be obedient and do as he was told, and for the rest, Margot was confident of her own powers.

The speculative frown gave way to a smile; she laughed, a gleeful, girlish laugh, and tossed her head, unconsciously acting a little duologue, with nods and frowns and upward languishing glance. All things seem easy to sweet and twenty, when the sun shines, and the scent of spring is in the air. The completed scheme stood out clear and distinct in Margot’s mind. Only one small clue was lacking, and that she was even now on the way to discover!

Chapter Three.

A Tonic.

Margot wandered about the Park so lost in her own thoughts that she was dismayed to find that it was already one o’clock, when warned by the departing stream of nursemaids that it must be approaching luncheon hour she at last consulted her watch.

Half an hour’s walk, cold cutlets and an irate Agnes, were prospects which did not smile upon her; it seemed infinitely more agreeable to turn in an opposite direction, and make as quickly as possible for Oxford Terrace, where she would be certain of a welcome from poor sad Edith, who was probably even now lunching on bread and cheese and anxiety, while her two sturdy infants tucked into nourishing beefsteak. Edith was one of those dear things who did not preach if you were late, but was content to give you what she had, without apologising.

Margot trotted briskly past Dorset Square, took a short cut behind the Great Central Hotel, and emerged into the dreary stretch of Marylebone Road.

Even in the spring sunshine it looked dull and depressing, with the gloomy hospital abutting at the corner, the flights of dull red flats on the right.

A block of flats—in appearance the most depressing—in reality the most interesting of buildings!

Inside those walls a hundred different households lived, and moved, and had their being. Every experience of life and death, of joy and grief, was acted on that stage, the innumerable curtains of which were so discreetly drawn. Margot scanned the several rows of windows with a curious interest. To-day new silk brise-bise appeared on the second floor, and a glimpse of a branching palm. Possibly some young bride had found her new home in this dull labyrinth, and it was still beautiful in her sight! Alas, poor bird, to be condemned to build in such a nest! Those curtains to the right were shockingly dirty, showing that some over-tired housewife had retired discomfited from the struggle against London grime. Up on the sixth floor there was a welcome splash of colour in the shape of Turkey red curtains, and a bank of scarlet geranium. Margot had decided long since that this flat must belong to an art student to whom colour was a necessity of life; who toiled up the weary length of stairs on her return from the day’s work, tasting in advance the welcome of the cosy room. She herself never forgot to look up at that window, or to send a mental message of sympathy and cheer to its unknown occupant.

Oxford Terrace looked quite cheerful in comparison with the surrounding roads,—and almost countrified into the bargain, now that the beech trees were bursting into leaf. Margot passed by two or three blocks, then mounting the steps at the corner of a new terrace, walked along within the railed-in strip of lawn until she reached a house in the middle of the row. A peep between draped Nottingham lace curtains showed a luncheon table placed against the wall, after the cheerful fashion of furnished apartments, when one room does duty for three, at which sat two little sailor-suited lads and a pale mother, smiling bravely at their sallies.

Margot felt the quick contraction of the heart which she experienced afresh at every sight of Edith’s changed face, but next moment she whistled softly in the familiar key, and saw the light flash back. Edith sprang to the door, and appeared flushed and smiling.

“Margot, how sweet of you! I am glad! Have you had lunch?”

“No. Give me anything you have. I’m awfully late. Bread and jam will do splendidly. Halloa, youngsters, how are you? We’ll defer kisses, I think, till you are past the sticky stage. I’ve been prowling about the Park for the last two hours enjoying the spring breezes, and working out problems, and suddenly discovered it was too late to go home.”

She sank down on a seat by the table, shaking her head in response to an anxious glance. “No, not my own affairs, dear; only Ron’s! Can’t the boys run away now, and let us have a chat? I know you have had enough of them by your face, and I’ve such a lot to say. Don’t grumble, boys! Be good, and you shall be happy, and your aunt will take you to the Zoo. Yes, I promise! The very first afternoon that the sun shines; but first I shall ask mother if you have deserved it by doing what you are told.”

“Run upstairs, dears, and wash, and put on your boots before Esther comes,” said Mrs Martin fondly; and the boys obeyed, with a lingering obedience which was plainly due rather to bribery than training.

The elder of the two was a sturdy, plain-featured lad, uninteresting except to the parental eye; the younger a beauty, a bewitching, plump, curly-headed cherub of four years, with widely-opened grey eyes and a Cupid’s bow of a mouth. Margot let Jim pass by with a nod, but her hand stretched out involuntarily to stroke Pat’s cheek, and ruffle his curly pow.

Edith smiled in sympathetic understanding, but even as she smiled she turned her head over her shoulder to speak a parting word to the older lad.

“Good-bye, darling! We’ll have a lovely game after tea!” Then the door shut, and she turned to her sister with a sigh.

“Poor Jim! everybody overlooks him to fuss over Pat, and it is hard lines. Children feel these things much more than grown-up people realise. I heard yells resounding from their bedroom one day last year, and flew upstairs to see what was wrong. There was Pat on the floor, with Jim kneeling on his chest, with his fingers twined in his hair, which he was literally dragging out by the roots. He was put to bed for being cruel to his little brother, but when I went to talk quietly to him afterwards, he sobbed so pitifully, and said, ‘I only wanted some of his curls to put on, to make people love me too!’ Poor wee man! You know what a silly way people have of saying, ‘Will you give me one of your curls?’ and poor Jim had grown tired of walking beside the pram, and having no notice taken of him. I vowed that from that day if I showed the least preference to either of the boys it should be to Jim. The world will be kind to Pat; he will never need friends.”

“No, Pat is all right. He has the ‘come-hither eye,’ as his mother had before him!”

“And his aunt!”

Margot chuckled complacently. “Well! it’s a valuable thing to possess. I find it most useful in my various plights. They are dear naughty boys, both of them, and I always love them, but rather less than usual when I see you looking so worn out. You have enough strain on you without turning nursemaid into the bargain.”

Mrs Martin sighed, and knitted her delicate brows.

“I do feel such a wicked wretch, but one of the hardest bits of life at the present is being shut up with the boys in one room all day long. They are very good, poor dears, but when one is racked with anxiety, it is a strain to play wild Indians and polar bears for hours at a stretch. We do some lessons now, and that’s a help—and Jack insisted that I should engage this girl to take them out in the afternoon. I must be a wretched mother, for I am thankful every day afresh to hear the door bang behind them, and to know that I am free until tea-time.”

“Nonsense! Don’t be artificial, Edie! You know that you are nothing of the sort, and that it’s perfectly natural to be glad of a quiet hour. You are a marvel of patience. I should snap their heads off if I had them all day, packed up in this little room. What have you had for lunch? No meat? And you look so white and spent. How wicked of you!”

“Oh, Margot,” sighed the other pathetically, “it’s not food that I need! What good can food do when one is racked with anxiety? It’s my mind that is ill, not my body. We can’t pay our way even with the rent of the house coming in, unless Jack gets something to do very soon, and I am such a stupid, useless thing that I can do nothing to help.”

“Except to give up your house, and your servants, and turn yourself into nurse, and seamstress, and tailor, and dressmaker, rolled into one; and live in an uproar all day long, and be a perfect angel of sympathy every night—that’s all!—and try to do it on bread and cheese into the bargain! There must be something inherently mean in women, to skimp themselves as they do. You’d never find a man who would grudge tenpence for a chop, however hard up he might be, but a woman spends twopence on lunch, and a sovereign on tonics! Darling, will it comfort you most if I sympathise, or encourage? I know there are moods when it’s pure aggravation to be cheerful!”

Edith sighed and smiled at one and the same moment.

“I don’t know! I’d like to hear a little of both, I think, just to see what sort of a case you could make out.”

“Very well, then, so you shall, but first I’ll make you comfy. Which is the least lumpy chair which this beautiful room possesses? Sit down then, and put up your feet while I enjoy my lunch. I do love damson jam! I shall finish the pot before I’m satisfied... Well, to take the worst things first, I do sympathise with you about the table linen! One clean cloth a week, I suppose? It must be quite a chronicle of the boys’ exploits! I should live on cold meat, so that they couldn’t spill he gravy. And the spoons. They feel gritty, don’t they? What is it exactly that they are made of? Poor old, dainty Edie! I know you hate it, and the idea that aliens are usurping your own treasures. Stupid people like Agnes would say that these are only pin-pricks, which we should not deign to notice, but sensible people like you and me know that constant little pricks take more out of one than the big stabs. If the wall-paper had not been so hideous, your anxieties would have seemed lighter, but it’s difficult to bear things cheerfully against a background of drab roses. Here’s an idea now! If all else fails, start a cheerful lodging-house. You’d make a fortune, and be a philanthropist to boot... This is good jam! I shall have to hide the stones, for the sake of decency.—I know you think fifty times more of Jack than of yourself. It’s hard luck to feel that all his hard work ends in this, and men hate failure. They have the responsibility, poor things, and it must be tragic to feel that through their mistakes, or rashness, or incapacity, as the case may be, they have brought hard times upon their wives. I expect Jack feels the table cloth even more than you do! You smart, but you don’t feel, ‘This is my fault!’”

“It isn’t Jack’s fault,” interrupted Jack’s wife quickly. “He never speculated, nor shirked work, nor did anything but his best. It was that hateful war, and the upset of the market, and—”

“Call it misfortune, then; in any case the fact remains that he is the bread-winner, and has failed to provide—cake! We are not satisfied with dry bread nowadays. You are always sure of that from father, if from no one else.”

“But I loathe taking it! And I would sooner live in one room than go home again, as some people do. When one marries one loses one’s place in the old home, and it is never given back. Father loves me, but he would feel it a humiliation to have me back on his hands. Agnes would resent my presence, and so would you. Yes, you would! Not consciously, perhaps, but in a hundred side-issues. We should take up your spare rooms, and prevent visitors, and upset the maids. If you ran into debt, father would pay your debts as a matter of course, but he grudges paying mine, because they are partly Jack’s.”

“Yes, I understand. It must be hateful for you, dear. I suppose no man wishes to pay out more money than he need, especially when he has worked hard to make it, as the pater has done; but if you take him the right way he is a marvel of goodness. - This year—next year—sometime—never;—I’m going to be married next year! Just what I had decided myself... I must begin to pick up bargains at the sales.”

Margot rose from her seat, flicking the crumbs off her lap with a fine disregard of the flower-wreathed carpet, and came over to a seat beside her sister.

“Now, shall I change briefs, and expatiate on the other side of the question? ... Why, Edie, every bit of this trouble depends on your attitude towards it, and on nothing else. You are all well; you are young; you adore each other; you have done nothing dishonourable; you have been able to pay your debts—what does the rest matter? Jack has had a big disappointment. Very well, but what’s the use of crying over spilt milk? Get a fresh jug, and try for cream next time! The children are too young to suffer, and think it’s fine fun to have no nursery, and live near Edgware Road. If you and Jack could just manage to think the same, you might turn it all into a picnic and a joke. Jack is strong and clever and industrious, and you have a rich father; humanly speaking, you will never want. Take it with a smile, dear! If you will smile, so will Jack. If you push things to the end, it rests with you, for he won’t fret if he sees you happy. He does love you, Edie! I’m not sentimental, but I think it must be just the most beautiful thing in the world to be loved like that. I should like some one to look at me as he does at you, with his eyes lighting up with that deep, bright glow. I’d live in an attic with my Jack, and ask for nothing more!”

The elder woman smiled—a smile eloquent of a sadder, maturer wisdom. She adored her husband, and gloried in the knowledge of his love of herself, but she knew that attics are not conducive to the continuance of devotion. Love is a delicate plant, which needs care and nourishment and discreet sheltering, if it is to remain perennially in bloom. The smile lingered on her lips, however; she rested her head against the cushions of her chair and cried gratefully—

“Oh, Margot, you do comfort me! You are so nice and human. Do you really, truly think I am taking things too seriously? Do you think I am depressing Jack? Wouldn’t he think me heartless if I seemed bright and happy?”

“Try it and see! You can decide according to the effect produced, but first you must have a tonic, to brace you for the effort. I’ve a new prescription, and we are going to Edgware Road to get it this very hour.”

“Quinine, I suppose. Esther and the boys can get it at the chemist’s, but really it will do roe no good.”

“I’m sure it wouldn’t. Mine is a hundred times more powerful.”

“Iron? I can’t take it. It gives me headaches.”

“It isn’t iron. Mine won’t give you a headache, unless the pins get twisted. It’s a finer specific for low spirits feminine, than any stupid drugs. A new hat!”

Edith stared, and laughed, and laughed again.

“You silly girl! What nonsense! I don’t need a hat.”

“That’s nonsense if you like! It depresses me to see you going about in that dowdy thing, and it must be a martyrdom for you to wear it every day. Come out and buy a straw shape for something and ‘eleven-three’,” (it’s always “eleven-three” in Edgware Road), “and I’ll trim it with some of your scraps. You have such nice scraps. Then we’ll have tea, and you shall walk part of the way home with me, and meet Jack, and smile at him and look pretty, and watch him perk up to match. What do you say?”

Edith lifted her eyes with a smile which brought back the youth and beauty to her face.

“I say, thank you!” she said simply. “You are a regular missionary, Margot. You spend your life making other people happy.”

“Goodness!” cried Margot, aghast. “Do I? How proper it sounds! You just repeat that to Agnes, and see what she says. You’ll hear a different story, I can tell you!”

Chapter Four.

Margot’s Scheme.

The sisters repaired to Edgware Road, and after much searching finally ran to earth a desirable hat for at least the odd farthing less than it would have cost round the corner in Oxford Street. This saving would have existed only in imagination to the ordinary customer, who is presented with a paper of nail-like pins, a rusty bodkin, or a highly-superfluous button-hook as a substitute for lawful change; but Margot took a mischievous delight in collecting farthings and paying down the exact sum in establishments devoted to eleven-threes, to the disgust of the young ladies who supplied her demands.

The hat was carried home in true Bohemian fashion, encased in a huge paper bag, and a happy hour ensued, when the contents of the scrap-box were scattered over the bed, and a dozen different effects studied in turn. Edith sat on a chair before the glass with the skeleton frame perched on her head at the accepted fashionable angle, criticising fresh draperies and arrangement of flowers, and from time to time uttering sharp exclamations of pain as Margot’s actions led to an injudicious use of the dagger-like pins. Her delicate finely-cut face and misty hair made her a delightful model, and she smiled back at the face in the mirror, reflecting that if you happened to be a pauper, it was at least satisfactory to be a pretty one, and that to possess long, curling eyelashes was a distinct compensation in life. Margot draped an old lace veil over the hard brim, caught it together at the back with a paste button, and pinned a cluster of brown roses beneath the brim, with just one pink one among the number, to give the cachet to the whole.

“There’s Bond Street for you!” she cried triumphantly; and Edith flushed with pleasure, and wriggled round and round to admire herself from different points of view.

“It is a tonic!” she declared gratefully. “You are a born milliner, Margot. It will be a pleasure to go out in this hat, and I shall feel quite nice and conceited again. It’s so long since I’ve felt conceited! I’m ever and ever so much obliged. Can you stay on a little longer, dear, or are you in a hurry to get back?”

“No! I shall get a scolding anyway, so I might as well have all the fling I can get. I’ll have tea with you and the boys, and a little private chat with Jack afterwards. You won’t mind leaving us alone for a few minutes? It’s something about Ron, but I won’t promise not to get in a little flirtation on my own account.”

Jack’s wife laughed happily.

“Flirt away—it will cheer him up! I’ll put the boys to bed, and give you a fine opportunity. Here they come, back from their walk. I must hurry, dear, and cut bread and butter. I’ll carry down the hat, and put it on when Jack comes in.”

Aunt Margot’s appearance at tea was hailed with a somewhat qualified approval.

“You must talk to us, mother,” Jim said sternly; “talk properly, not only, ‘Yes, dear,’ ‘No, dear,’ like you do sometimes, and then go on speaking to her about what we can’t understand. She’s had you all afternoon!”

“So I have, Jim. It’s your turn now. What do you want to say?”

Jim immediately lapsed into silence. Having gained his point, he had no remark to offer, but Pat lifted his curly head and asked eagerly—

“Muzzer, shall I ever grow up to be a king?”

“No, my son; little boys like you are never kings.”

“Not if I’m very good, and do what I’m told?”

“No, dear, not even then. No one can be a king unless his father is a king, too, or some very, very great man. What has put that in your head, I wonder? Why do you want to be a king?”

Pat widened his clear grey eyes; the afternoon sunshine shone on his ruffled head, turning his curls to gold, until he looked like some exquisite cherub, too good and beautiful for this wicked world.

“’Cause if I was a king I could take people prisoners and cut off their heads, and stick them upon posts,” he said sweetly; his mother and aunt exchanged horrified glances. Pat alternated between moods of angelic tenderness, when every tiger was a “good, good tiger,” and naughty children “never did it any more,” and a condition of frank cannibalism, when he literally wallowed in atrocities. His mother forbode to lecture, but judiciously turned the conversation.

“Kings can do much nicer things than that, Patsy boy. Our kind King Edward doesn’t like cutting off heads a bit. He is always trying to prevent men from fighting with each other.”

“Is he?”

“Yes, he is. People call him the Peace-maker, because he prevents so many wars.”

“Bother him!” cried Pat fervently.

Margot giggled helplessly. Mrs Martin stared fixedly out of the window, and Jim in his turn took up the ball of conversation.

“Mummie, will you die before me?”

“I can’t tell, dear; nobody knows.”

“Will daddy die before me?”

“Probably he will.”

“May I have his penknife when he’s dead?”

“I think it’s about time to cut up that lovely new cake!” cried Margot, saving the situation with admirable promptitude. “We bought it for you this afternoon, and it tastes of chocolate, and all sorts of good things.”

The bait was successful, and a silence followed, eloquent of intense enjoyment; then the table was cleared and various games were played, in the midst of which Jack’s whistle sounded from without, and his wife and sons rushed to meet him. They looked a typical family group as they re-entered the room, Edith happily hanging on to his arm, the boys prancing round his feet, and the onlooker felt a little pang of loneliness at the sight.

John Martin was a tall, well-made man, with a clean-shaven face and deep-set grey eyes. He was pale and lined, and a nervous twitching of the eyelids testified to the strain through which he had passed, but it was a strong face and a pleasant face, and, when he looked at his wife, a face of indescribable tenderness. At the moment he was smiling, for it was always a pleasure to see his pretty sister-in-law, and to-night Edith’s anxious looks had departed, and she skipped by his side as eager and excited as the boys themselves.

“Dad, dad, has there been any more ’splosions?”

“Hasn’t there been no fearful doings on in the world, daddy?”

“Jack! Jack! I’ve got a new tonic. It has done me such a lot of good!”

Jack turned from one to the other.

“No, boys, no,—no more accidents to-day! What is it, darling? You look radiant. What is the joke?”

“Look out of the window for a minute! Margot, you talk to him, and don’t let him look round.”

Edith pinned on the new hat before the mirror, carefully adjusting the angles, and pulling out her cloudy hair to fill in the necessary spaces. Her cheeks were flushed, her eyes sparkled; it was no longer the worn white wife, but a pretty, coquettish girl, who danced up to Jack’s side with saucy, uplifted head.

“There! What do you think of that?”

The answer of the glowing eyes was more eloquent than words. Jack whistled softly beneath his breath, walking slowly round and round to take in the whole effect.

“I say, that is fetching! That’s something like a hat you wore the summer we were engaged. You don’t look a day older. Where did you run that to earth, darling?”

“Can’t you see Bond Street in every curve? I should have thought it was self-evident. Margot said I was shabby, and that a new hat would do me good, so we went out and bought it. Do you think I am extravagant? It’s better to spend on this than on medicine, and three guineas isn’t expensive for real lace, is it?”

She peered in her husband’s face with simulated anxiety, but his smile breathed pleasure unqualified.

“I’m delighted that you have bought something at last! You have not spent a penny on yourself for goodness knows how long.”

“Goose!” cried Edith. “He has swallowed it at a gulp. Three guineas, indeed—as if I dare! Four and eleven-pence three-farthings in Edgware Road, and my old lace veil, and one of the paste buttons you gave me at Christmas, and some roses off last year’s hat, and Margot’s clever fingers, and my—pretty face! Do you think I am pretty still?”

“I should rather think I do!” Jack framed his wife’s face in his hands, stooping to kiss the soft flushed cheeks as fondly as he had done in the time of that other lace-wreathed hat six years before. Pat and Jim returned to their dominoes, bored by such foolish proceedings on the part of their parents, while Margot covered her face with her hands, with ostentatious propriety.

“This is no place for me! Consider my feelings, Jack. I’m like a story I once read in an old volume of Good Words, ‘Lovely yet Unloved!’ When you have quite finished love-making, I want a private chat with you, while Edie puts the boys to bed. They will hate me for suggesting such a thing, but it is already past their hour, and I must have ten minutes’ talk on a point of life and death!”

“Come away, boys; we are not wanted here. Daddy will come upstairs and see you again before you go to sleep.”

Mother and sons departed together, and Jack Martin sat down on the corner of the sofa and leant his head on his hand. With his wife’s departure the light went out of his face, but he smiled at his sister-in-law with an air of affectionate camaraderie.

“You are a little brick, Margot! You have done Edie a world of good. What can I do for you in return? I am at your service.”

Margot pulled forward the chair that her sister had chosen as the least lumpy which the room afforded, and seated herself before him, returning his glance with an odd mixture of mischief and embarrassment.

“It’s about Ron. The year of probation is nearly over.”

“I know it.”

“Two months more will decide whether he is to be a broker or a poet. It will mean death to Ronald to be sent into the City.”

“You are wrong there. If he is a poet, no amount of brokering will alter the fact, any more than it will change the colour of his eyes or hair. It is bound to come out sooner or later. You will probably think me a brute, if I suggest that a little discipline and knowledge of the world might improve the value of his writings.”

“Yes, I will! What does a poet want with a knowledge of the world, in the common, sordid sense? Let him keep his mind unsullied, and be an inspiration to others. When we were children, we used to keep birds in the nursery, in a very fine cage with golden bars, and we fed them with every bird delicacy we could find. They lived for a little time, and tried to sing, poor brave things! We threw away the cage in a fury, after finding one soft dead thing after another lying huddled up in a corner. No one shall cage Ronald, if I can prevent it! It’s no use pretending to be cold-blooded and middle-aged, Jack, for I know you are with us at heart. This means every bit as much to Ron as your business troubles do to you.”

Jack drew in his breath with a wince of pain.

“Well, what is it you wish me to do? I am afraid I have very little influence in the literary world, and I have always heard that introductions do more harm than good. An editor would soon ruin his paper if he accepted all the manuscripts pressed upon him by admiring relatives.”

“But you see I don’t ask you for an introduction. It’s just a piece of information I want, which I can’t get for myself. You know the Loadstar Magazine?”

“Certainly I do.”

“Well, the Loadstar is—the Loadstar! The summit of Ron’s ambition. It’s the magazine of all others which he likes and admires, and the editor is known to be a man of great power and discernment. It is said that if he has the will, he can do more than any man in London to help on young writers. It is useless sending manuscripts, for he refuses to consider unsolicited poetical contributions. He shuts himself up in a fastness in Fleet Street, and the door thereof is guarded with dragons with lying tongues. I know! I have made it my business to inquire, but I feel convinced that if he once gave Ron a fair reading, he would acknowledge his gifts. There is no hope of approaching him direct, but I intend to get hold of him all the same.”

Jack Martin looked up at that, his thin face twitching into a smile.

“You little baggage! and you expect me to help you. I must hear some more about this before I involve myself any further. What mischief are you up to now?”

“Dear Jack, what can I do; a little girl like me?” cried Miss Margot, mightily meek all of a sudden, as she realised that she had ventured a step too far. “I wouldn’t for the whole world get you into trouble. It’s just a little, simple thing that I want you to find out from some one in the office.”

“I don’t know any one in the office.”

“But you could find out some one who did? For instance, you know that Mr Oliver who illustrates? I’ve seen his things in the Loadstar. You could ask him in a casual, off-hand manner without ever mentioning our name.”

“What could I ask him?”

“Such a nice, simple little question! Just the name of the place where the editor proposes to spend this summer holiday, and the date on which he will start.”

Jack stared in amazement, but the meekest, most demure of maidens confronted him from the opposite chair, with eyes so translucently candid, lips so guilelessly sweet, that it seemed incredible that any hidden mischief could lurk behind the innocent question. Nevertheless seven years’ intimacy with Miss Margot made Jack Martin suspicious of mischief.

“What do you know about this editor man? Have you seen him anywhere? He is handsome, I suppose, and a bachelor?”

“You’re a wretch!” retorted Miss Margot. “I don’t know the man from Adam, and he may be a Methuselah for all I care; but if possible I want it to happen that Ron and I chance to be staying in the same place, in the same house, or hotel, or pension, whichever it may be, when he goes away for his yearly rest. We are going to the country in any case—why should we not be guided by the choice of those older and wiser than ourselves? Why should we not meet the one of all others we are most anxious to know?”

“Just so! and having done so, you will confide in the editor that Ronald is an embryo Poet Laureate, and try to enlist his kind sympathy and assistance!”

Margot smiled; a smile of lofty superiority.

“No, indeed! I know rather better than that! He will be out on a holiday, poor man, and won’t want to be troubled with literary aspirants. He has enough of them all the year round. We’ll never mention poetry, but we will try to get to know him, and to make him like us so much that he will want to see more of us when we return to town. No one can live in the same house with Ron, and have an opportunity of talking to him day by day, without feeling that he is different from other boys, and alone together in the country one can never tell what may happen. Opportunities may arise, too; opportunities for help and service. We would be on the look-out for them, and would try by every means in our power to forge the first link in the chain. Don’t look so solemn, old Jack, it’s all perfectly innocent! You can trust me to do nothing you would disapprove.”

“I believe I can. You are a madcap, Margot, but you are a good girl. I’m not afraid of you, but I imagine that the editor will be a match for a dozen youngsters like you and Ron, and will soon see through your little scheme. However, I’ll do what I can. In big offices holiday arrangements have to be made a good while ahead, so it ought not to be difficult to get the information you want. Now I must be off upstairs to see the boys before they get into bed. Shall I see you again when I come down?”

“No, indeed! I’ve played truant since half-past eleven, so I shall have to hang about the end of the terrace until father appears, and go in under his wing, to escape a scolding from Agnes. I had arranged to pay calls with her this afternoon. I wonder how it is that my memory is so dreadfully uncertain about things I don’t want to do! Good-bye then, Jack, and a hundred thanks. Posterity will thank you for your help.”

Jack Martin laughed and shrugged his shoulders. He had a man’s typical disbelief in the ability of his wife’s relatives.

Chapter Five.

An Explosion.

Relationships were somewhat strained in the Vane household during the next few weeks, the two elder members being banded together in an unusual partnership to bring about the confusion of the younger.

“I can’t understand what you are making such a fuss about. You’ll have to give in, in the end. You a poet, indeed! What next? If you would come down to breakfast in time, and give over burning the gas till one o’clock in the morning, it would be more to the point than writing silly verses. I’d be ashamed to waste my time scribbling nonsense all day long!” So cried Agnes, in Martha-like irritation, and Ronald turned his eyes upon her with that deep, dreamy gaze which only added fuel to the flame.

He was not angry with Agnes, who, as she herself truly said, “did not understand.” Out of the storm of her anger an inspiration had fluttered towards him, like a crystal out of the surf. “The Worker and the Dreamer”—he would make a poem out of that idea! Already the wonderful inner vision pictured the scene—the poet sitting idle on the hillside, the man of toil labouring in the heat and glare of the fields, casting glances of scorn and impatience at the inert form. The lines began to take shape in his brain.

”...And the worker worked from the misty dawn,

Till the east was golden and red;

But the dreamer’s dream which he thought to scorn,

Lived on when they both were dead...”

“I asked him three times over if he would have another cup of coffee, and he stared at me as if he were daft! I believe he is half daft at times, and he will grow worse and worse, if Margot encourages him like this!” Agnes announced to her father, on his weary return from City.

It was one of Agnes’s exemplary habits to refuse all invitations which could prevent her being at home to welcome her father every afternoon, and assist him to tea and scones, accompanied by a minute résumé of the bad news of the day. What the housemaid had broken; what the cat had spilt; the parlourmaid’s impertinences; the dressmaker’s delinquencies; Ronald’s vapourings; the new and unabashed transgressions of Margot—each in its turn was dropped into the tired man’s cup with the lumps of sugar, and stirred round with the cream. There was no escaping the ordeal. On the hottest day of summer there was the boiling tea, with the hot muffins, and the rich, indigestible cake, exactly as they had appeared amidst the ice and snows of January; and the accompanied recital hardly varied more. It was a positive relief to hear that the chimney had smoked, or the parrot had had a fit.

Once a year Agnes departed on a holiday, handing over the keys to Margot, who meekly promised to follow in her footsteps; and then, heigho! for a fortnight of Bohemia, with every arrangement upside down, and appearing vastly improved by the change of position. Instead of tea in the drawing-room, two easy-chairs on the balcony overlooking the Park; cool iced drinks sipped through straws, and luscious dishes of fruit. Instead of Agnes, stiff and starched and tailor-made, a radiant vision in muslin and laces, with a ruffled golden head, and distracting little feet peeping out from beneath the frills.

“Isn’t this fun?” cried the vision. “Don’t you feel quite frivolous and Continental? Let’s pretend we are a newly-married couple, and you adore me, and can’t deny a thing I ask! There was a blouse in Bond Street this morning... Sweetest darling, wouldn’t you like me to buy it to-morrow, and show me off in it to your friends? I told them to send it home on approval. I knew you couldn’t bear to see your little girl unhappy for the sake of four miserable guineas!”

This sort of treatment was very agreeable to a worn-out City man, and as a pure matter of bargaining, the blouse was a cheap price to pay for the refreshment of that cool, restful hour, and the pretty chatter which smoothed the tired lines out of his face, and made him laugh and feel young again.

Another night Mr Vane would be decoyed to a rendezvous at Earl’s Court, when Margot would wear the blouse, and insist upon turning round the pearl band on her third finger, so as to imitate a wedding-ring, looking at him in languishing fashion across the table the while, to the delight of fellow-diners and his own mingled horror and amusement. Then they would wander about beneath the glimmer of the fairy-lights, listening to the band, as veritable a pair of lovers as any among the throng.

As summer approached, Mr Vane’s thoughts turned to these happy occasions, and it strengthened his indignation against his son to realise that this year a cloud had arisen between himself and his dearest daughter. Margot had openly ranked herself against him, which was a bitter pill to swallow, and, so far from showing an inclination to repent as the prescribed time drew to a close, the conspirators appeared only to be the more determined. Long envelopes were continually being dispatched to the post, to appear with astonishing dispatch on the family breakfast-table. The pale, wrought look on Ronald’s face as he caught sight of them against the white cloth! No parent’s heart could fail to be wrung for the lad’s misery; but the futility of it added to the inward exasperation. Thousands of men walking the streets of London vainly seeking for work, while this misguided youth scorned a safe and secure position!

The pent-up irritation exploded one Sunday evening, when the presence of Edith and her husband recalled the consciousness of yet another disappointment. Mr Vane had made his own way, and, after the manner of successful men, had little sympathy with failure. The presence of the two pale, dejected-looking young men filled him with impatient wrath. At the supper-table he was morose and irritable, until a chance remark set the fuse ablaze.

“Yes, yes! You all imagine yourselves so clever nowadays that you can afford to despise the experience of men who knew the world before you were born! I can see you look at each other as I speak! I’m not blind! I’m an out-of-date old fogey who doesn’t know what he is talking about, and hasn’t even the culture to appreciate his own children. Because one has composed a bundle of rhymes that no one will publish, he must needs assume an attitude of forbearance with the man who supplies the bread and butter! I’ve never been accustomed to regard failure as an instance of superiority, but no doubt I am wrong—no doubt I am behind the times—no doubt you are all condemning me in your minds as a blundering old ignoramus! A father is nothing but a nuisance who must be tolerated for the sake of what can be got out of him.”

He looked round the table with his tired, angry eyes. Jack Martin sat with bent head and lips pressed tightly together, repressing himself for his wife’s sake. Edith struggled against tears. Agnes served the salad dressing and grunted approval. Margot, usually so pert and ready of retort, stared at the cloth with a frown of strained distress. Only Ronald faced him with steady eyes.

“That is not true, father, and you know it yourself!”

“I know nothing, it appears! That’s just what I say. Why don’t you undertake my education? You never show me your work; you take the advice of a child like Margot, and leave me out in the cold, and then expect me to have faith enough to believe you a genius without a word of proof. You want to become known to the public? Very well, bring down some of that precious poetry and read it aloud to us now! You can’t say then that I haven’t given you a chance!”

It was a frightful prospect! The criticism of the family is always an ordeal to the budding author, and the moment was painfully unpropitious. It would have been as easy for a bird to sing in the presence of the fowler. Ronald turned white to the lips, but his reply came as unwavering as the last.

“Do you think you would care to hear even the finest poetry in the world read aloud to-night? Mine is very far from the best. I will read it to you if you wish, but you must give me a happier opportunity.”

Agnes laughed shortly.

“Shilly-shally! I can’t understand what opportunity you want. If it’s good, it can’t be spoilt by being read one day instead of another; if it’s bad, it won’t be improved by waiting. This is cherry-pie, and there is some tipsy cake. Edith, which will you have?”

Edith would have neither. She was still trembling with wounded indignation against her father for that cruel hit at her husband. She sat pale and silent, vowing never to enter the house again until Jack’s fortunes were restored; never to accept another penny from her father’s hands. She was comparatively little interested in the discussion about poetry. Ron was a dear boy; she would be sorry if he were disappointed, but Jack was her life, and Jack was working for bread!

If she had followed the moment’s impulse, she would have risen and left the room, and though better counsel prevailed, she could not control the spice of temper which made the cherry-pie abhorrent.

Jack, as a man, saw no reason why he should deny himself the mitigations of the situation; he helped himself to cream and sifted sugar with leisurely satisfaction, and sensibly softened in spirit. After all, there was a measure of truth in what the old man said, and his bark was worse than his bite. If his own boy, Pat, took it into his head to go off on some scatter-brain prank when he came of age, it would be a big trouble, or if later on he came a cropper in business— Jack waited for a convenient pause, and then deftly turned the conversation to politics, and by the time that cheese was on the table, he and his father-in-law were discussing the mysteries of the last Education Bill with the satisfaction of men who hold similar views on the inanities of the opposite party. Later on they bade each other a friendly good-night; but Edith went straight from the bedroom to the street, and clung tightly to her husband’s arm as they walked along the pavement opposite the Park, enjoying the quiet before entering the busy streets.

“We’ll never come again!” she cried tremulously. “We’ll stay at home, and have a supper of bread and cheese and love with it! You shan’t be taunted and sneered at by any man on earth, if he were twenty times my father! What an angel you were, Jack, to keep quiet, and then talk as if nothing had happened! I was choking with rage!”

“Poor darling!” said Jack Martin tenderly. “You  take things too much to heart. It’s rough on you, but you must remember that it’s rough on the old man too. You are his eldest child, and the beauty of the family. He hoped great things for you, and it is wormwood and gall to his proud spirit to see you struggling along in cheap lodgings. We can’t wonder if he explodes occasionally. It’s wonderful that he is as civil to me as he is; he has put me down as a hopeless blunderer!”

take things too much to heart. It’s rough on you, but you must remember that it’s rough on the old man too. You are his eldest child, and the beauty of the family. He hoped great things for you, and it is wormwood and gall to his proud spirit to see you struggling along in cheap lodgings. We can’t wonder if he explodes occasionally. It’s wonderful that he is as civil to me as he is; he has put me down as a hopeless blunderer!”

There was a touch of bitterness in the speaker’s voice, for all his brave assumption of composure, and his wife winced at the sound. She clung more tightly to his arm, and raised her face to his with eager comfort.

“Don’t mind what he says! Don’t mind what any one says. I believe in you. I trust you! The good times will come back again, dear, and we will be happier than ever, because we shall know how to appreciate them. Even if we were always poor, I’d rather have you for my husband than the greatest millionaire in the world!”

“Thank God for my wife!” said Jack Martin solemnly.

Chapter Six.

A Managing Woman.

Meanwhile Ronald and Margot were holding a conclave on the third floor. “I must get away from home at once!” cried the lad feverishly. “I can’t write in this atmosphere of antagonism. I breathe it in the air. It poisons everything I do. If I am to have only three more months of liberty, I must spend them in my own way, in the country with you, Margot, away from all this fret and turmoil. It’s my last chance. I might as well throw up the sponge at once, if we are to stay here.”

“Yes, we must go away; for father’s sake as well as our own,” replied Margot slowly. She leant her head against the back of her chair, and pushed the hair from her brow. Without the smile and the sparkle she was astonishingly like her brother,—both had oval faces, well-marked eyebrows, flexible scarlet lips, and hazel eyes, but the girl’s chin was made in a firmer mould, and the expression of dreamy abstraction which characterised the boy’s face was on hers replaced by animation and alertness.

“Father will be miserable to-night because he flared out at supper; but he’ll flare again unless we put him out of temptation. He likes his own way as much as we like ours, and it’s so difficult for parents to realise that their children are grown-up. We seem silly babies in his eyes, and he longs to be able to shut us up in the nursery until we are sorry, as he used to do in the old days. As for our own plans, Ron, they are all settled. I was just waiting for a quiet opportunity to tell you. I have been busy planning and scheming for some time back, but it was only to-night that my clue arrived. Jack, my emissary, slipped it into my hand after supper. Read that!”

She held out a half sheet of paper with an air of triumph, on which were scribbled the following lines:—

“Name, Elgood. Great walker, climber, etcetera. Goes every June with brother to small lonely inn (Nag’s Head)—Glenaire—six miles’ drive from S—, Perthshire. Scenery fine, but wild; accommodation limited; landlady refuses lady visitors, which fact is supposed to be one of the chief attractions; Elgood reported to be tough nut to crack; chief object of holiday, quiet and seclusion; probably dates two or three weeks from June 15.”

Ronald read, and lifted a bewildered face.

“What does it all mean? How do this man’s plans affect ours? I don’t understand what you are driving at, Margot, but I should love to go to Scotland! The mountains in the dawning, and the shadows at night, and the dark green of the firs against the blue of the heather—oh, wouldn’t it be life to see it all again, after this terrible brick city! How clever of you to think of Scotland!”

“My dear boy, if it had been Southend it would have been all the same. We are going where Mr Elgood goes, for Mr Elgood, you must know, is the editor of The Loadstar—the man of all others who could give you a helping hand. Now, Ron, I am quite prepared for you to be shocked, but I know that you will agree in the end, so please give in as quickly as possible, and don’t make a fuss. You have been sending unknown poems to unknown editors for the last two years, with practically no result. It’s not the fault of your poems—of that I am convinced. In ten years’ time every one will rave about them, but you can’t afford to wait ten years, or even ten months. Our only hope is to interest some big literary light, whose verdict can’t be ignored, and persuade him to plead your cause, or at least to give you such encouragement as will satisfy father that you are not deluded by your own conceit. I’ve thought and thought, and lain awake thinking, till I feel quite tired out, and then at last I hit on this plan,—to find out where Mr Elgood is going for his holidays, and go to the same place, so that he can’t help getting to know us, whatever he may wish. Ordinary methods are useless at this stage of affairs. We must try a desperate remedy for a desperate situation!”

“I’m sure I am willing. I would try any crazy plan that had a possibility of success for the next three months. But yours isn’t possible. The landlady won’t take ladies. That’s an unsurmountable objection at the start.”

But Margot only preened her head with a smile of undaunted self-confidence.

“She’ll take me!” she declared complacently. “She can’t refuse me shelter for a night at least, after such a long, tiring journey, and I’ll be such a perfect dear, that after twenty-four hours she wouldn’t be bribed to do without me! You can leave Mrs McNab to me, Ron. I’ll manage her. Very well then, there we shall be, away from the madding crowd, shut up in that lonely Highland glen, in the quaint little inn; two nice, amiable, attractive young people with nothing to do but make ourselves amiable and useful to our companions. Mr Elgood can’t be young; he is certainly middle-aged, perhaps quite old; he will be very tired after his year’s work, and perhaps even ill. Very well then, we will wait upon him and save him trouble! You shall bicycle to the village for his tobacco and papers, and I’ll read aloud and bring him cups of tea. We won’t worry him, but we’ll be there all the time, waiting and watching for an opportunity. One never knows what may happen in the country. He might slip into the river some day, and you could drag him out. Ronald, wouldn’t it be perfectly lovely if you could save his life!”

The two youthful faces confronted each other breathlessly for a moment, and then simultaneously boy and girl burst into a peal of laughter. They laughed and laughed again, till the tear-drops shone on Margot’s lashes, and Ronald’s pale face was flushed with colour.

“You silly girl! What nonsense you talk! I’m afraid Mr Elgood won’t give me a chance of rescuing him. He won’t want to be bothered with literary aspirants on his summer holiday, and he will guess that I want his help—”

“He mustn’t guess anything of the kind until the end of the time. You must even never mention the word poetry. It would neither be fair to him, nor wise for ourselves. What we have to do is to make ourselves so charming and interesting that at the end of the three weeks he will want to help us as much as we want to be helped. I understand how to manage old gentlemen I’ve had experience, you see, in rather a difficult school. Poor father! I must run down to comfort him before I go to bed. I feel sure he is sitting in the library, puffing away at his pipe, and feeling absolutely retched. He always does after he has been cross.”

Ronald’s face hardened with youthful disapproval. “Why should you pity him? It’s his own fault.”

“That makes it all the harder, for he has remorse to trouble him, as well as disappointment. You must not be hard on the pater, Ron. Remember he has looked forward to having you with him in business ever since you were born, and it is awfully hard on him to be disappointed just when he is beginning to feel old and tired, and would be glad of a son’s help. It is not easy to give up the dream of twenty years!”

Ronald felt conscience-stricken. He knew in his own heart that he would find it next to impossible to relinquish his own dawning ambitions, and the thought silenced his complaints. He looked at his sister and smiled his peculiarly sweet smile.

“You have a wide heart, Margot. It can sympathise with both plaintiff and defendant at the same time.”

“Why, of course!” asserted Margot easily. “I love them both, you see, and that makes things easy. Go to bed, dear boy, and dream of Glenaire! Your chance is coming at the eleventh hour.”

The light flashed in the lad’s eyes as he bent his head for the good-night kiss—a light of hope and expectation, which was his sister’s best reward.

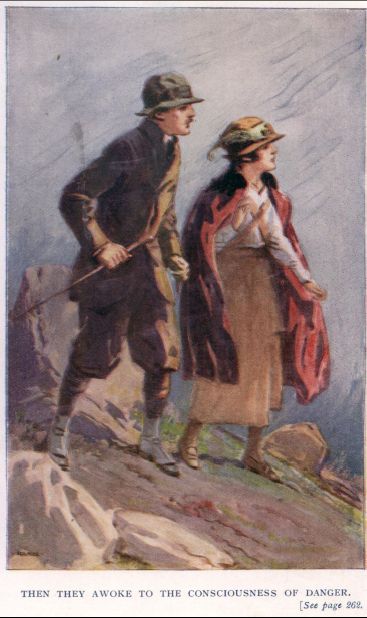

Ron had worked, fretted, and worried of late, and his health itself might break down under the strain, for his constitution was not strong. During one long, anxious year there had been fear of lung trouble, and mental agitation of any kind told quickly upon him. Margot’s thoughts flew longingly to the northern glen where the wind blew fresh and cool over the heather, with never a taint of smoke and grime to mar its God-given purity. All that would be medicine indeed, after the year’s confinement in the murky city! Ron would lift up his head again, like a plant refreshed with dew; body and mind alike would then expand in jubilant freedom.

Margot crept down the darkened staircase, treading with precaution as she passed her sister’s room. The hall beneath was in utter darkness, for it was against Agnes’s economical instincts to leave a light burning after eleven o’clock, even for the convenience of the master of the house. When Mr Vane demurred, she pointed out that it was the easiest thing in the world for him to put a match to the candle which was left waiting for his use, and that each electric light cost—she had worked it all out, and mentioned a definite and substantial sum which would be wasted by the end of the year if the light were allowed to burn in hall or staircase while he enjoyed his nightly read and smoke.

“Would you wish this money to be wasted?” she asked calmly; and thus questioned, there was no alternative but to reply in the negative. It would never do for the head of the house to pose as an advocate of extravagance; but all the same he was irritated by the necessity, and with Agnes for enforcing it.

Margot turned the handle of the door and stood upon the threshold looking across the room.

It was as she had imagined. On the big leather chair beside the tireless grate sat Mr Vane, one hand supporting the pipe at which he was drearily puffing from time to time, the other hanging limp and idle by his side. Close at hand stood his writing-table, the nearer corner piled high with books, papers, and reviews, but to-night they had remained undisturbed. The inner tragedy of the man’s own life had precluded interest in outside happenings. He wanted his wife! That was the incessant cry of his heart, which, diminished somewhat by the passage of the years, awoke to fresh intensity at each new crisis of life! The one love of his youth and his manhood; the dearest, wisest, truest friend that was ever sent by God to be the helpmeet of man—why had she been taken from him just when he needed her most, when the children were growing up, and her son, the longed-for Benjamin, was at his most susceptible age? It was a mystery which could never be solved this side of the grave. As a Christian Mr Vane hung fast to the belief that love and wisdom were behind the cloud; but, though his friends commented on his bravery and composure, no one but himself knew at what a cost his courage was sustained. Every now and then, when the longing was like an ache in his soul, and when he felt weary and dispirited, and irritated by the self-will of the children who were children no longer, then, alas! he was apt to forget himself, and to utter bitter, hasty words which would have grieved her ears, if she had been near to listen. After each of these outbreaks he suffered tortures of remorse and loneliness, realising that by his own deed he had alienated his children; grieving because they did not, could not understand!