Amy Walton

"Thistle and Rose"

Chapter One.

The Picture.

A countenance in which did meet

Sweet records, promises as sweet.

Wordsworth.

“And so, my dear Anna, you really leave London to-morrow!”

“By the ten o’clock train,” added an eager voice, “and I shan’t get to Dornton until nearly five. Father will go with me to Paddington, and then I shall be alone all the way. My very first journey by myself—and such a long one!”

“You don’t seem to mind the idea,” said the governess, with a glance at her pupil’s bright, smiling face. “You don’t mind leaving all the people and things you have been used to all your life?”

Anna tried to look grave. “I see so little of father, you know,” she said, “and I’m sure I shall like the country better than London. I shall miss you, of course, dear Miss Milverton,” she added quickly, bending forward to kiss her governess.

Miss Milverton gave a little shake of the head, as she returned the kiss; perhaps she did not believe in being very much missed.

“You are going to new scenes and new people,” she said, “and at your age, Anna, it is easier to forget than to remember. I should like to think, though, that some of our talks and lessons during the last seven years might stay in your mind.”

She spoke wistfully, and her face looked rather sad. As she saw it, Anna felt ungrateful to be so glad to go away, and was ready to promise anything. “Oh, of course they will,” she exclaimed. “Indeed, I will never forget what you have told me. I couldn’t.”

“You have lived so very quietly hitherto,” continued Miss Milverton, “that it will be a new thing for you to be thrown with other people. They will be nearly all strangers to you at Waverley, I think?”

“There will be Aunt Sarah and Uncle John at the Rectory,” said Anna. “Aunt Sarah, of course, I know; but I’ve never seen Uncle John. He’s father’s brother, you know. Then there’s Dornton; that’s just a little town near. I don’t know any one there, but I suppose Aunt Sarah does. Waverley’s quite in the country, with a lovely garden—oh, I do so long to see it!”

“You will make friends, too, of your own age, I daresay,” said Miss Milverton.

“Oh, I hope so,” said Anna earnestly. “It has been so dull here sometimes! After you go away in the afternoon there’s nothing to do, and when father dines out there’s no one to talk to all the evening. You can’t think how tired I get of reading.”

“Well, it will be more cheerful and amusing for you at Waverley, no doubt,” said Miss Milverton, “and I hope you will be very happy there; but what I want to say to you is this: Try, whether you are at Waverley or wherever you are, to value the best things in yourself and others.”

Anna’s bright eyes were gazing over the blind into the street, where a man with a basket of flowers on his head was crying, “All a-blowing and a-growing.” In the country she would be able to pick flowers instead of buying them. She smiled at the thought, and said absently, “Yes, Miss Milverton.” Miss Milverton’s voice, which always had a regretful sound in it, went steadily on, while Anna’s bright fancies danced about gaily.

“It is so easy to value the wrong things most. They often look so attractive, and the best things lie so deeply hidden from us. And yet, to find them out and treasure them, and be true to them, makes the difference between a worthy and an unworthy life. If you look for them, my dear Anna, you will find them. My last wish before we part is, that you may be quick to see, and ready to do them honour, and to prize them as they should be prized. Bless you, my dear!”

Miss Milverton had felt what she said so deeply, that the tears stood in her eyes, as she finished her speech and kissed her pupil for the last time.

Anna returned the kiss affectionately, and as she followed her governess out into the hall and opened the door for her, she was quite sorry to think that she had so often been tiresome at her lessons. Perhaps she had helped to make Miss Milverton’s face so grave and her voice so sad. Now she should not see her any more, and there was no chance of doing better.

For full five minutes after she had waved a last good-bye, Anna remained in a sober mood, looking thoughtfully at all the familiar, dingy objects in the schoolroom, where she and Miss Milverton had passed so many hours. It was not a cheerful room. Carpet, curtains, paper, everything in it had become of one brownish-yellow hue, as though the London fog had been shut up in it, and never escaped again. Even the large globes, which stood one on each side of the fireplace, had the prevailing tinge over their polished, cracked surfaces; but as Anna’s eye fell on these, her heart gave a sudden bound of joy. She would never have to do problems again! She would never have to pass any more dull hours in this room, with Miss Milverton’s grave face opposite to her, and the merest glimpses of sunshine peering in now and then over the brown blinds. No more sober walks in Kensington Gardens, where she had so often envied the ragged children, who could play about, and laugh, and run, and do as they liked. There would be freedom now, green fields, flowers, companions perhaps of her own age. Everything new, everything gay and bright, no more dullness, no more tedious days—after all, she was glad, very glad!

It was so pleasant to think of, that she could not help dancing round and round the big table all alone, snapping her fingers at the globes as she passed them. When she was tired, she flung herself into Miss Milverton’s brown leather chair, and looked up at the clock, which had gone soberly on its way as though nothing were to be changed in Anna’s life. She felt provoked with its placid face. “To-morrow at this time,” she said to it, half aloud, “I shan’t be here, and Miss Milverton won’t be here, and I shall be seeing new places and new people, and—oh, I do wonder what it will all be like!”

The clock ticked steadily on, regardless of anything but its own business. Half-past six! Miss Milverton had stayed longer than usual. Anna began to wonder what time her father would be home. They were to dine together on this, their last evening, but Mr Forrest was so absorbed in his preparations for leaving England that he was likely to be very late. Perhaps he would not be in till eight o’clock, and even then would have his mind too full of business to talk much at dinner, and would spend the evening in writing letters. Anna sighed. There were some questions she very much wanted to ask him, and this would be her only chance. To-morrow she was to go to Waverley, and the next day Mr Forrest started for America, and she would not see him again for two whole years.

It was strange to think of, but not altogether sad from Anna’s point of view, for her father was almost a stranger to her. He lived a life apart, into which she had never entered: his friends, his business, his frequent journeys abroad, occupied him fully, and he was quite content that Anna’s welfare should be left in the hands of Miss Milverton, her daily governess. It was Aunt Sarah who recommended Miss Milverton to the post, which she had now filled, with ceaseless kindness and devotion, for seven years. “You will find her invaluable,” Mrs Forrest had said to her brother-in-law, and so she was. When Anna was ill, she nursed her; when she wanted change of air, she took her to the sea-side; she looked after her both in body and mind, with the utmost conscientiousness. But there was one thing she could not do: she could not be an amusing companion for a girl of fifteen, and Anna had often been lonely and dull.

Now that was all over. A sudden change had come into her life. The London house was to be given up, her father was going away, and she was to be committed to Aunt Sarah’s instruction and care for two whole years. Waverley and Aunt Sarah, instead of London and Miss Milverton! It was a change indeed, in more than one way, for although Anna was nearly fifteen, she had never yet stayed in the country; her ideas of it were gathered from books, and from what she could see from a railway carriage, as Miss Milverton and she were carried swiftly on their way to the sea-side for their annual change of air. She thought of it all now, as she sat musing in the old brown chair.

It had often seemed strange that Aunt Sarah, who arranged everything, and to whom appeal was always made in matters which concerned Anna, should never have asked her to stay at Waverley before. Certainly there were no children at the Rectory, but still it would have been natural, she thought, for was not Uncle John her father’s own brother, and she had never even seen him!

Aunt Sarah came to London occasionally and stayed the night, and had long talks with Mr Forrest and Miss Milverton, but she had never hinted at a visit from Anna.

When, a little later, her father came bustling in, with a preoccupied pucker on his brow, and his most absent manner, she almost gave up all idea of asking questions. Dinner passed in perfect silence, and she was startled when Mr Forrest suddenly mentioned the very place that was in her mind.

“Well, Anna,” he said, “I’ve been to Waverley to-day.”

“Oh, father, have you?” she answered eagerly.

Mr Forrest sipped his wine reflectively.

“How old are you?” he asked.

“Fifteen next August,” replied Anna.

“Then,” he continued, half to himself, “it must be over sixteen years since I saw Waverley and Dornton.”

“Are they just the same?” asked his daughter; “are they pretty places?”

“Waverley’s pretty enough. Your Uncle John has built another room, and spoilt the look of the old house, but that’s the only change I can see.”

“And Dornton,” said Anna, “what is that like?”

“Dornton,” said Mr Forrest absently—“Dornton is the same dull little hole of a town I remember it then.”

“Oh,” said Anna in a disappointed voice.

“There’s a fine old church, though, and the river’s nice enough. I used to know every turn in that river.—Well,” rising abruptly and leaning his arm against the mantel-piece, “it’s a long while ago—a long while ago—it’s like another life.”

“Used you to stay often at Waverley?” Anna ventured to ask presently.

Mr Forrest had fallen into a day-dream, with his eyes fixed on the ground. He looked up when Anna spoke as though he had forgotten her presence.

“It was there I first met your mother,” he said, “or rather, at Dornton. We were married in Dornton church.”

“Oh,” said Anna, very much interested, “did mother live at Dornton? I never knew that.”

“And that reminds me,” said Mr Forrest, taking a leather case out of his pocket, and speaking with an effort, “I’ve something I want to give you before you go  away. You may as well have it now. To-morrow we shall be both in a hurry. Come here.”

away. You may as well have it now. To-morrow we shall be both in a hurry. Come here.”

He opened the case and showed her a small round portrait painted on ivory. It was the head of a girl of eighteen, exquisitely fair, with sweet, modest-looking eyes. “Your mother,” he said briefly.

Anna almost held her breath. She had never seen a picture of her mother before, and had very seldom heard her mentioned.

“How lovely!” she exclaimed. “May I really have it to keep?”

“I had it copied for you from the original,” said Mr Forrest.

“Oh, father, thank you so much,” said Anna earnestly. “I do so love to have it.”

Mr Forrest turned away suddenly, and walked to the window. He was silent for some minutes, and Anna stood with the case in her hand, not daring to speak to him. She had an instinct that it was a painful subject.

“Well,” he said at last, “I need not tell you to take care of it. When I come back you’ll be nearly as old as she was when that was painted. I can’t hope more than that you may be half as good and beautiful.”

Anna gazed earnestly at the portrait. There were some words in tiny letters beneath it: “Priscilla Goodwin,” she read, “aged eighteen.”

Priscilla! A soft, gentle sort of name, which seemed to suit the face.

If father wanted me to look like this, she thought to herself, he shouldn’t have called me “Anna.” How could any one named Anna grow so pretty!

“Why was I named Anna?” she asked.

“It was your mother’s wish,” replied Mr Forrest. “I believe it was her mother’s name.”

“Is my grandmother alive?” said Anna.

“No; she died years before I ever saw your mother. Your grandfather, old Mr Goodwin, is living still—at Dornton.”

“At Dornton!” exclaimed Anna in extreme surprise. “Then why don’t I go to stay with him while you’re away, instead of at Waverley?”

“Because,” said Mr Forrest, turning from the window to face his daughter, “it has been otherwise arranged.”

Anna knew that tone of her father’s well; it meant that she had asked an undesirable question. She was silent, but her eager face showed that she longed to hear more.

“Your grandfather and I have not been very good friends,” said Mr Forrest at length, “and have not met for a good many years—but you’re too young to understand all that. He lives in a very quiet sort of way. Once, if he had chosen, he might have risen to a different position. But he didn’t choose, and he remains what he has been for the last twenty years—organist of Dornton church. He has great musical talent, I’ve always been told, but I’m no judge of that.”

These new things were quite confusing to Anna; it was difficult to realise them all at once. The beautiful, fair-haired mother, whose picture she held in her hand, was not so strange. But her grandfather! She had never even heard of his existence, and now she would very soon see him and talk to him. Her thoughts, hitherto occupied with Waverley and the Rectory, began to busy themselves with the town of Dornton, the church where her mother had been married, and the house where she had lived.

“Aunt Sarah knows my grandfather, of course,” she said aloud. “He will come to Waverley, and I shall go sometimes to see him at Dornton?”

“Oh, no doubt, no doubt, your aunt will arrange all that,” said Mr Forrest wearily. “And now you must leave me, Anna; I’ve no time to answer any more questions. Tell Mary to take a lamp into the study, and bring me coffee. I have heaps of letters to write, and people to see this evening.”

“Your aunt will arrange all that!” What a familiar sentence that was. Anna had heard it so often that she had come to look upon Aunt Sarah as a person whose whole office in life was to arrange and settle the affairs of other people, and who was sure to do it in the best possible way.

When she opened her eyes the next morning, her first movement was to feel under her pillow for the case which held the picture of her mother. She had a half fear that she might have dreamt all that her father had told her. No. It was real. The picture was there. The gentle face seemed to smile at her as she opened the case. How nice to have such a beautiful mother! As she dressed, she made up her mind that she would go to see her grandfather directly she got to Waverley. What would he be like? Her father had spoken of his musical talent in a half-pitying sort of way. Anna was not fond of music, and she very much hoped that her grandfather would not be too much wrapped up in it to answer all her questions. Well, she would soon find out everything about him. Her reflections were hurried away by the bustle of departure, for Mr Forrest, though he travelled so much, could never start on a journey without agitation and fuss, and fears as to losing his train. So, for the next hour, until Anna was safely settled in a through carriage for Dornton, with her ticket in her purse, a benevolent old lady opposite to her, and the guard prepared to give her every attention, there was no time to realise anything, except that she must make haste.

“Well, I think you’re all right now,” said Mr Forrest, with a sigh of relief, as he rested from his exertions. “Look out for your aunt on the platform at Dornton; she said she would meet you herself.—Why,” looking at his watch, “you don’t start for six minutes. We needn’t have hurried after all. Well, there’s no object in waiting, as I’m so busy; so I’ll say good-bye now. Remember to write when you get down. Take care of yourself.”

He kissed his daughter, and was soon out of sight in the crowded station. Anna had now really begun her first journey out into the world.

Chapter Two.

Dornton.

A bird of the air shall carry the matter.

On the same afternoon as that on which Anna was travelling towards Waverley, Mrs Hunt, the doctor’s wife in Dornton, held one of her working parties. This was not at all an unusual event, for the ladies of Dornton and the neighbourhood had undertaken to embroider some curtains for their beautiful old church, and this necessitated a weekly meeting of two hours, followed by the refreshment of tea, and conversation. The people of Dornton were fond of meeting in each other’s houses, and very sociably inclined. They met to work, they met to read Shakespeare, they met to sing and to play the piano, they met to discuss interesting questions, and they met to talk. It was not, perhaps, so much what they met to do that was the important thing, as the fact of meeting.

“So pleasant to meet, isn’t it?” one lady would say to the other. “I’m not very musical, you know, but I’ve joined the glee society, because it’s an excuse for meeting.”

And, certainly, of all the houses in Dornton where these meetings were held, Dr Hunt’s was the favourite. Mrs Hunt was so amiable and pleasant, the tea was so excellent, and the conversation of a most superior flavour. There was always the chance, too, that the doctor might look in for a moment at tea-time, and though he was discretion itself, and never gossiped about his patients, it was interesting to gather from his face whether he was anxious, or the reverse, as to any special case.

This afternoon, therefore, Mrs Hunt’s drawing-room presented a busy and animated scene. It was a long, low room, with French windows, through which a pleasant old garden, with a wide lawn and shady trees, glimpses of red roofs beyond, and a church tower, could be seen. Little tables were placed at convenient intervals, holding silk, scissors, cushions full of needles and pins, and all that could be wanted for the work in hand, which was to be embroidered in separate strips; over these many ladies were already deeply engaged, though it was quite early, and there were still some empty seats.

“Shall we see Mrs Forrest this afternoon?” asked one of those who sat near the hostess at the end of the room.

“I think not,” replied Mrs Hunt, as she greeted a new-comer; “she told me she had to drive out to Losenick about the character of a maid-servant.”

“Oh, well,” returned the other with a little shake of the head, “even Mrs Forrest can’t manage to be in two places at once, can she?”

Mrs Hunt smiled, and looked pleasantly round on her assembled guests, but did not make any other answer.

“Although I was only saying this morning, there’s very little Mrs Forrest can’t do if she makes up her mind to it,” resumed Miss Gibbins, the lady who had first spoken. “Look at all her arrangements at Waverley! It’s well known that she manages the schools almost entirely—and then her house—so elegant, so orderly—and such a way with her maids! Some people consider her a little stiff in her manner, but I don’t know that I should call her that.”

She glanced inquiringly at Mrs Hunt, who still smiled and said nothing.

“It’s not such a very difficult thing,” said Mrs Hurst, the wife of the curate of Dornton, “to be a good manager, or to have good servants, if you have plenty of money.” She pressed her lips together rather bitterly, as she bent over her work.

“There was one thing, though,” pursued Miss Gibbins, dropping her voice a little, “that Mrs Forrest was not able to prevent, and that was her brother-in-law’s marriage. I happen to know that she felt that very much. And it was a sad mistake altogether, wasn’t it?”

She addressed herself pointedly to Mrs Hunt, who was gazing serenely out into the garden, and that lady murmured in a soft tone:

“Poor Prissy Goodwin! How pretty and nice she was!”

“Oh, as to that, dear Mrs Hunt,” broke in a stout lady with round eyes and a very deep voice, who had newly arrived, “that’s not quite the question. Poor Prissy was very pretty, and very nice and refined, and as good as gold. We all know that. But was it the right marriage for Mr Bernard Forrest? An organist’s daughter! or you might even say, a music-master’s daughter!”

“Old Mr Goodwin has aged very much lately,” remarked Mrs Hunt. “I met him this morning, looking so tired, that I made him come in and rest a little. He had been giving a lesson to Mrs Palmer’s children out at Pynes.”

“How kind and thoughtful of you, dear Mrs Hunt,” said Miss Gibbins. “That’s very far for him to walk. I wonder he doesn’t give it up. I suppose, though, he can’t afford to do that.”

“I don’t think he has ever been the same man since Prissy’s marriage,” said Mrs Hunt, “though he plays the organ more beautifully than ever.”

With her spectacles perched upon her nose, her hands crossed comfortably on her lap, and a most beaming smile on her face, Mrs Hunt looked the picture of contented idleness, while her guests stitched away busily, with flying fingers, and heads bent over their work. She had done about half an inch of the pattern on her strip, and now, her needle being unthreaded, made no attempt to continue it.

“Delia’s coming in presently,” she remarked placidly, meeting Miss Gibbins’ sharp glance as it rested on her idle hands; “she will take my work a little while—ah, here she is,” as the door opened.

A girl of about sixteen came towards them, stopping to speak to the ladies as she passed them on her way up the room. She was short for her age, and rather squarely built, holding herself very upright, and walking with calmness and decision.

Everything about Delia Hunt seemed to express determination, from her firm chin to her dark curly hair, which would always look rough, although it was brushed back from her forehead and fastened up securely in a knot at the back of her head. Nothing could make it lie flat and smooth, however, and in spite of all Delia’s efforts, it curled and twisted itself defiantly wherever it had a chance. Perhaps, by doing so, it helped to soften a face which would have been a little hard without the good-tempered expression which generally filled the bright brown eyes.

“That sort of marriage never answers,” said Mrs Winn, as Delia reached her mother’s side. “Just see what unhappiness it caused. It was a bitter blow to Mr and Mrs Forrest; it made poor old Mr Goodwin miserable, and separated him from his only child; and as to Prissy herself—well, the poor thing didn’t live to find out her mistake, and left her little daughter to feel the consequences of it.”

“Poor little motherless darling,” murmured Mrs Hunt.—“Del, my love, go on with my work a little, while I say a few words to old Mrs Crow.”

Delia took her mother’s place, threaded her needle, raised her eyebrows with an amused air, as she examined the work accomplished, and bent her head industriously over it.

“Doesn’t it seem quite impossible,” said Miss Gibbins, “to realise that Prissy’s daughter is really coming to Waverley to-morrow! Why, it seems the other day that I saw Prissy married in Dornton church!”

“It must be fifteen years ago at the least,” said Mrs Winn, in such deep tones that they seemed to roll round the room. “The child must be fourteen years old.”

“She wore grey cashmere,” said Miss Gibbins, reflectively, “and a little white bonnet. And the sun streamed in upon her through the painted window. I remember thinking she looked like a dove. I wonder if the child is like her.”

“The Forrests have never taken much notice of Mr Goodwin, since the marriage,” said Mrs Hurst, “but I suppose, now his grandchild is to live there, all that will be altered.”

Delia looked quickly up at the speaker, but checked the words on her lips, and said nothing.

“You can’t do away with the ties of blood,” said Mrs Winn; “the child’s his grandchild. You can’t ignore that.”

“Why should you want to ignore it?” asked Delia, suddenly raising her eyes and looking straight at her.

The attack was so unexpected that Mrs Winn had no answer ready. She remained speechless, with her large grey eyes wider open than usual, for quite a minute before she said, “These are matters, Delia, which you are too young to understand.”

“Perhaps I am,” answered Delia; “but I can understand one thing very well, and that is, that Mr Goodwin is a grandfather that any one ought to be proud of, and that, if his relations are not proud of him, it is because they’re not worthy of him.”

“Oh, well,” said Miss Gibbins, shaking her head rather nervously as she looked at Delia, “we all know what a champion Mr Goodwin has in you, Delia. ‘Music with its silver sound’ draws you together, as Shakespeare says. And, of course, we’re all proud of our organist in Dornton, and, of course, he has great talent. Still, you know, when all’s said and done, he is a music-master, and in quite a different position from the Forrests.”

“Socially,” said Mrs Winn, placing her large, white hand flat on the table beside her, to emphasise her words, “Mr Goodwin is not on the same footing. When Delia is older she will know what that means.”

“I know it now,” replied Delia. “I never consider them on the same footing at all. There are plenty of clergymen everywhere, but where could you find any one who can play the violin like Mr Goodwin?”

She fixed her eyes with innocent inquiry on Mrs Winn. Mrs Hurst bridled a little.

“I do think,” she said, “that clergymen occupy a position quite apart. I like Mr Goodwin very much. I’ve always thought him a nice old gentleman, and Herbert admires his playing, but—”

“Of course, of course,” said Mrs Winn, “we must be all agreed as to that.—You’re too fond, my dear Delia, of giving your opinion on subjects where ignorance should keep you silent. A girl of your age should try to behave herself, lowly and reverently, to all her betters.”

“So I do,” said Delia, with a smile; “in fact, I feel so lowly and reverent sometimes, that I could almost worship Mr Goodwin. I am ready to humble myself to the dust, when I hear him playing the violin.”

Mrs Winn was preparing to make a severe answer to this, when Miss Gibbins, who was tired of being silent, broke adroitly in, and changed the subject.

“You missed a treat last Thursday, Mrs Winn, by losing the Shakespeare reading. It was rather far to get out to Pynes, to be sure, but it was worth the trouble, to hear Mrs Hurst read ‘Arthur.’”

The curate’s wife gave a little smile, which quickly faded as Miss Gibbins continued: “I had no idea there was anything so touching in Shakespeare. Positively melting! And then Mrs Palmer looked so well! She wore that rich plum-coloured silk, you know, with handsome lace, and a row of most beautiful lockets. I thought to myself, as she stood up to read in that sumptuous drawing-room, that the effect was regal. ‘Regal,’ I said afterwards, is the only word to express Mrs Palmer’s appearance this afternoon.”

“What part did Mrs Palmer read?” asked Delia, as Miss Gibbins looked round for sympathy.

“Let me see. Dear me, it’s quite escaped my memory. Ah, I have it. It was the mother of the poor little boy, but I forget her name.—You will know, Mrs Hurst; you have such a memory!”

“It was Constance,” said the curate’s wife. “Mrs Palmer didn’t do justice to the part. It was rather too much for her. Indeed, I don’t consider that they arranged the parts well last time. They gave my husband nothing but ‘messengers,’ and the Vicar had ‘King John.’ Now, I don’t want to be partial, but I think most people would agree that Herbert reads Shakespeare rather better than the Vicar.”

“I wonder,” said Miss Gibbins, turning to Delia, as the murmur of assent to this speech died away, “that you haven’t joined us yet, but I suppose your studies occupy you at present.”

“But I couldn’t read aloud, in any case, before a lot of people,” said Delia, “and Shakespeare must be so very difficult.”

“You’d get used to it,” said Miss Gibbins. “I remember,” with a little laugh, “how nervous I felt the first time I stood up to read. My heart beat so fast I thought it would choke me. The first sentence I had to say was, ‘Cut him in pieces!’ and the words came out quite in a whisper. But now I can read long speeches without losing my breath or feeling at all uncomfortable.”

“I like the readings,” said Mrs Hurst, “because they keep up one’s knowledge of Shakespeare, and that must be refining and elevating, as Herbert says.”

“So pleasant, too, that the clergy can join,” added Miss Gibbins.

“Mrs Crow objects to that,” said Mrs Hurst. “She told me once she considered it wrong, because they might be called straight away from reading plays to attend a deathbed. Herbert, of course, doesn’t agree with her, or he wouldn’t have helped to get them up. He has a great opinion of Shakespeare as an elevating influence, and though he did write plays, they’re hardly ever acted. He doesn’t seem, somehow, to have much to do with the theatre.”

“Between ourselves,” said Miss Gibbins, sinking her voice and glancing to the other end of the room, where Mrs Crow’s black bonnet was nodding confidentially at Mrs Hunt, “dear old Mrs Crow is rather narrow-minded. I should think the presence of the Vicar at the readings might satisfy her that all was right.”

“The presence of any clergyman,” began Mrs Hurst, “ought to be sufficient warrant that—”

But her sentence was not finished, for at this moment a little general rustle at the further end of the room, the sudden ceasing of conversation, and the door set wide open, showed that it was time to adjourn for tea. Work was rolled up, thimbles and scissors put away in work-bags, and very soon the whole assembly had floated across the hall into the dining-room, and was pleasantly engaged upon Mrs Hunt’s hospitable preparations for refreshment. Brisk little remarks filled the air as they stood about with their teacups in their hands.

“I never can resist your delicious scones, Mrs Hunt.—Home-made? You don’t say so. I wish my cook could make them.”—“Thank you, Delia; I will take another cup of coffee: yours is always so good.”—“Such a pleasant afternoon! Dear me, nearly five o’clock? How time flies.”—“Dr Hunt very busy? Fever in Back Row? So sorry. But decreasing? So glad.”—“Good-bye, dear Mrs Hunt. We meet next Thursday, I hope?”—and so on, until the last lady had said farewell and smiled affectionately at her hostess, and a sudden silence fell on the room, left in the possession of Delia and her mother.

“Del, my love,” said the latter caressingly, “go and put the drawing-room straight, and see that all those things are cleared away. I will try to get a little nap. Dear old Mrs Crow had so much to tell me that my head quite aches.”

Delia went into the deserted drawing-room, where the chairs and tables, standing about in the little groups left by their late occupiers, still seemed to have a confidential air, as though they were telling each other interesting bits of news. She moved about with a preoccupied frown on her brow, picking up morsels of silk from the floor, rolling up strips of serge, and pushing back chairs and tables, until the room had regained its ordinary look. Then she stretched her arms above her head, gave a sigh of relief, and strolled out of the open French windows into the garden. The air was very calm and still, so that various mingled noises from the town could be plainly heard, though not loudly enough to produce more than a subdued hum, which was rather soothing than otherwise. Amongst them the deep recurring tones of the church bell, ringing for evening prayers, fell upon Delia’s ear as she wandered slowly up the gravel path, her head full of busy thoughts.

They were not wholly pleasant thoughts, and they had to do chiefly with two people, one very well known to her, and the other quite a stranger—Mr Goodwin, and his grandchild, Anna Forrest. Delia could hardly make up her mind whether she were pleased or annoyed at the idea of Anna’s arrival. Of course she was glad, she told herself, of anything that would please the “Professor,” as she always called Mr Goodwin; and she was curious and anxious to see what the new-comer would be like, for perhaps they might be companions and friends, though Anna was two years younger than herself. She could not, however, prevent a sort of suspicion that made her feel uneasy. Anna might be proud. She might even speak of the Professor in the condescending tone which so many people used in Dornton. Mrs Forrest at Waverley always looked proud, Delia thought. Perhaps Anna would be like her.

“If she is,” said Delia to herself, suddenly stopping to snap off the head of a snapdragon which grew in an angle of the old red wall—“if she is—if she dares—if she doesn’t see that the Professor is worth more than all the people in Dornton—I will despise her—I will—”

She stopped and shook her head.

“And if it’s the other way, and she loves and honours him as she ought, and is everything to him, and, and, takes my place, what shall I do then? Why, then, I will try not to detest her.”

She laughed a little as she stooped to gather some white pinks which bordered the path, and fastened them in her dress.

“Pretty she is sure to be,” she continued to herself, “like her mother, whom they never mention without praise—and she is almost certain to love music. Dear old Professor, how pleased he will be! I will try not to mind, but I do hope she can’t play the violin as well as I do. After all, it would be rather unfair if she had a beautiful face and a musical soul as well.”

The bell stopped, and the succeeding silence was harshly broken by the shrill whistle of a train.

“There’s the five o’clock train,” said Delia to herself; “to-morrow by this time she will be here.”

Mrs Winn and Miss Gibbins meanwhile had pursued their way home together, for they lived close to each other.

“It’s a pity Delia Hunt has such blunt manners, isn’t it?” said the latter regretfully, “and such very decided opinions for a young girl? It’s not at all becoming. I felt quite uncomfortable just now.”

“She’ll know better by-and-by,” said Mrs Winn. “There’s a great deal of good in Delia, but she is conceited and self-willed, like all young people.”

Miss Gibbins sighed. “She’ll never be so amiable as her dear mother,” she said.—“Why!” suddenly changing her tone to one of surprise, “isn’t that Mr Oswald?”

“Yes, I think so,” said Mrs Winn, gazing after the spring-cart which had passed them rapidly. “What then?”

“He had a child with him,” said Miss Gibbins impressively. “A child with fair hair, like Prissy Goodwin’s, and they came from the station. Something tells me it was Prissy’s daughter.”

“Nonsense, Julia,” replied Mrs Winn; “she’s not expected till to-morrow. Mrs Forrest told Mrs Hunt so herself. Besides, how should Mr Oswald have anything to do with meeting her? That was his own little girl with him, I daresay.”

“Daisy Oswald has close-cropped, black hair,” replied Miss Gibbins, quite unshaken in her opinion. “This child was older, and her hair shone like gold. I feel sure it was Prissy’s daughter.”

Chapter Three.

Waverley.

Meadows trim with daisies pied,

Shallow brooks and rivers wide.

Milton.

While this went on at Dornton, Anna was getting nearer and nearer to her new home. At first she was pleased and excited at setting forth on a journey all by herself, and found plenty to occupy her with all she saw from the carriage windows, and with wondering which of the villages and towns she passed so rapidly were like Dornton and Waverley. It was surprising that the old lady sitting opposite to her could look so placid and calm. Perhaps, however, she was not going to a strange place amongst new people, and most likely had taken a great many journeys already in her life. Anna was glad this was not her own ease: it must be very dull, she thought, to be old, and to have got used to everything, and to have almost nothing to look forward to.

As the day wore on, and the hot afternoon sun streamed in at the windows, the old lady, who was her only companion, fell fast asleep, and Anna began to grow rather weary. She took the case with her mother’s picture in it out of her pocket and studied it again attentively. The gentle, sweet face seemed to smile back kindly at her. “If you are half as beautiful and a quarter as good,” her father had said. Was she at all like the picture now? Anna wondered. Surely her hair was rather the same colour. She pulled a piece of it round to the front - it was certainly yellow, but hardly so bright. Well, her grandfather would tell her—she would ask him on the very first opportunity. Her grandfather! It was wonderful to think she should really see him soon, and ask him all sorts of questions about her mother. He lived at Dornton, but that was only two miles from Waverley, and, no doubt, she should often be able to go there. He was an organist.

Her father’s tone, half-pitying, half-disapproving, came back to her with the word. She tried to think of what she knew about organists. It was not much. There was an organist in the church in London to which she had gone every Sunday with Miss Milverton, but he was always concealed behind red curtains, so that she did not even know what he looked like. The organist must certainly be an important person in a church. Anna did not see how the service could get on without him. What a pity that her grandfather did not play the organ in her Uncle John’s church, instead of at Dornton!

She made a great many resolves as she sat there, with her mother’s portrait in her hand: she would be very fond of her grandfather, and, of course, he would be very fond of her; and as he lived all alone, there would be a great many things she could do to make him happier. She pictured herself becoming very soon his chief comforter and companion, and began to wonder how he had done without her so long.

Lost in these thoughts, she hardly noticed that the train had begun to slacken its pace; presently, it stopped at a large station. The old lady roused herself, tied her bonnet strings, and evidently prepared for a move.

“You’re going farther, my dear,” she said kindly. “Dornton is the next station but one. You won’t mind being alone a little while?”

She nodded and smiled from the platform. Anna handed out her numerous parcels and baskets: the train moved on, and she was now quite alone. She might really begin to look out for Dornton, which must be quite near. It seemed a long time coming, however, and she had made a good many false starts, grasping her rugs and umbrella, before there was an unmistakable shout of “Dornton!” She got out and looked up and down the platform, but it was easy to see that Mrs Forrest was not there. Two porters, a newspaper boy, and one or two farmers, were moving about in the small station, but no one in the least like Aunt Sarah. Anna stood irresolute. She had been so certain that Aunt Sarah would be there, that she had not even wondered what she should do in any other case. Mrs Forrest had promised to come herself, and Anna could not remember that she had ever failed to carry out her arrangements at exactly the time named.

“If it had been father, now,” she said to herself in her perplexity, “he would perhaps have forgotten, but Aunt Sarah—”

“Any luggage, miss?” asked the red-faced young porter.

“Oh yes, please,” said Anna; “and I expected some one to meet me—a lady.”

She looked anxiously at him.

“Do ’ee want to go into the town?” he asked, as Anna pointed out her trunks. “There’s a omnibus outside.”

“No; I want to go to Waverley Vicarage,” said Anna, feeling very deserted. “How can I get there?”

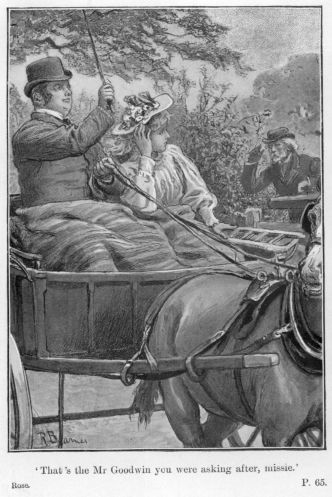

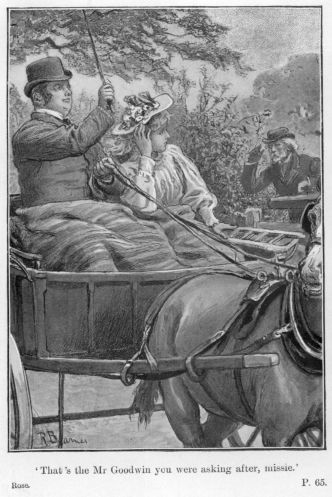

She followed the porter as he wheeled the boxes outside the station, where a small omnibus was waiting, and also a high spring-cart, in which sat a well-to-do-looking farmer.

“You ain’t seen no one from Waverley, Mr Oswald?” said the porter. “This ’ere young lady expects some one to meet her.”

The farmer looked thoughtfully at Anna.

“Waverley, eh,” he repeated, “Vicarage?”

“Ah,” said the porter, nodding.

Another long gaze.

“Well, I’m going by the gate myself,” he said at last. “I reckon Molly wouldn’t make much odds of the lot,” glancing at the luggage, “if the young lady would like a lift.”

“Perhaps,” said Anna, hesitatingly, “I’d better have a cab, as Mrs Forrest is not here.”

“I could order you a fly at the Blue Boar,” said the porter. “’Twouldn’t be ready, not for a half-hour or so. Mr Oswald ’d get yer over a deal quicker.”

No cabs! What a strange place, and how unlike London! Anna glanced uncertainly at the high cart, the tall strawberry horse stamping impatiently, and the good-natured, brown face of the farmer. It would be an odd way of arriving at Waverley, and she was not at all sure that Aunt Sarah would approve of it; but what was she to do? It was very kind of the farmer; would he expect to be paid?

“Better come along, missie,” said Mr Oswald, as these thoughts passed rapidly through her mind. “You’ll be over in a brace of shakes.—Hoist them things in at the back, Jim.”

Almost before she knew it, Anna had taken the broad hand held out to help her, had mounted the high step, and was seated by the farmer’s side.

“Any port in a storm, eh?” he said, good-naturedly, as he put the rug over her knees.—“All right at the back, Jim?”

A shake of the reins, and Molly dashed forward with a bound that almost threw Anna off her seat, and whirled the cart out of the station-yard at what seemed to her a fearful pace.

“She’ll quiet down directly,” said Mr Oswald; “she’s fretted a bit standing at the station. Don’t ye be nervous, missie; there’s not a morsel of harm in her.”

Nevertheless, Anna felt obliged to grasp the side of the cart tightly as Molly turned into the principal street of Dornton, which was wide, and, fortunately, nearly empty. What a quiet, dull-looking street it was, after the noisy rattle of London, and how low and small the shops and houses looked! If only Molly would go a little slower!

“Yonder’s the church,” said Mr Oswald, pointing up a steep side-street with his whip; “and yonder’s the river,” waving it in the opposite direction.

Anna turned her head quickly, and caught a hurried glimpse of a grey tower on one side, and a thin white streak in the distant, low-lying meadows on the other.

“And here’s the new bank,” continued Mr Oswald, with some pride, as they passed a tall, red brick building which seemed to stare the other houses out of countenance; “and the house inside the double white gates is Dr Hunt’s.”

“I suppose you know Dornton very well?” Anna said as he paused.

“Been here, man and boy, a matter of forty years—leastways, in the neighbourhood,” replied the farmer.

“Then you know where Mr Goodwin lives, I suppose?” said Anna.

“Which of ’em?” said the farmer. “There’s Mr Goodwin, the baker; and Mr Goodwin, the organist at Saint Mary’s.”

“Oh, the organist,” said Anna.

“To be sure I do. He lives in Number 4 Back Row. You can’t see it from here; it’s an ancient part of Dornton, in between High Street and Market Street. He’s been here a sight of years—every one knows Mr Goodwin—he’s as well known as the parish church is.”

Anna felt pleased to hear that. It convinced her that her grandfather must be an important person, although Back Row did not sound a very important place.

“How fast your horse goes,” she said, by way of continuing the conversation, for, after her long silence in the train, it was quite pleasant to talk to somebody.

“Ah, steps out, doesn’t she?” said the farmer, with a gratified chuckle. “You won’t beat her for pace this side of the county. She was bred at Leas Farm, and she’s a credit to it.”

They were now clear of the town, and had turned off the dusty high-road into a lane, with high hedges on either side.

“Oh, how pretty!” cried Anna.

She could see over these hedges, across the straggling wreaths of dog-roses and clematis, to the meadows on either hand, where the tall grass, sprinkled with silvery ox-eyed daisies, stood ready for hay. Beyond these again came the deep brown of some ploughed land, and now and then bits of upland pasture, with cows and sheep feeding. The river Dorn, which Mr Oswald had pointed out from the town, wound its zigzag course along the valley, which they were now leaving behind them. As they mounted a steep hill, Molly had considerably slackened her speed, so that Anna could look about at her ease and observe all this.

“What a beautiful place this is!” she exclaimed with delight.

“Well enough,” said the farmer; “nice open country. Yonder pasture, where the cows are, belongs to me; if you’re stopping at Waverley, missie, I can show you a goodish lot of cows at Leas Farm.”

“Oh, I should love to see them!” said Anna.

“My little daughter ’ll be proud to show ’em yer; she’s just twelve years old, Daisy is. Now, you wouldn’t guess what I gave her as a birthday present?”

“No,” said Anna; “I can’t guess at all.”

“’Twas as pretty a calf as you ever saw, with a white star on its forehead. Nothing would do after that but I must buy her a collar for it. ‘Puppa,’ she says, ‘when you go into Dornton, you must get me a collar and a bell, like there is in my picture-book.’ My word!” said the farmer, slapping his knee, “how all the beasts carried on when they first heard that bell in the farmyard! You never saw such antics! It was like as if they were clean mad!”

He threw back his head and gave a jolly laugh at the bare recollection; it was so hearty and full of enjoyment, that Anna felt obliged to laugh a little too.

“Here you are, my lass,” he said, touching Molly lightly with the whip as they reached the top of the hill. “All level ground now between here and Waverley.—Now, what are you shying at?” as Molly swerved away from a stile in the hedge.

It was at an old man who was climbing slowly over it into the steep lane. He wore shabby, black clothes: his shoulders were bent, and his grey hair rather long; in his hand he carried a violin-case.

“That’s the Mr Goodwin you were asking after, missie,” said the farmer, touching his hat with his whip, as they passed quickly by. “Looks tired, poor old gentleman; hot day for a long walk.”

Anna started and looked eagerly back, but Molly’s long stride had already placed a good distance between herself and the figure which was descending the hill. That her grandfather! Was it possible? He looked so poor, so dusty, so old, such a contrast to the merry June evening, as he tramped wearily down the flowery lane, a  little bent to one side by the weight of his violin-case. Not an important or remarkable person, such as she had pictured to herself, but a tired old man, of whom the farmer spoke in a tone of pity. Her father had done so too, she remembered. Did every one pity her grandfather? There was all the more need, certainly, that she should help and cheer him, yet Anna felt vaguely disappointed, she hardly knew why.

little bent to one side by the weight of his violin-case. Not an important or remarkable person, such as she had pictured to herself, but a tired old man, of whom the farmer spoke in a tone of pity. Her father had done so too, she remembered. Did every one pity her grandfather? There was all the more need, certainly, that she should help and cheer him, yet Anna felt vaguely disappointed, she hardly knew why.

These thoughts chased away her smiles completely, and such a grave expression took their place that the farmer noticed the change.

“Tired, missie, eh?” he inquired. “Well, we’re there now, so to speak. Yonder’s the spire of Waverley church, and the Vicarage is close against it—steady then, lass,” as Molly objected to turning in at a white gate.

“It’s a terrible business is travelling by rail,” he continued, “to take the spirit out of you; I’d sooner myself ride on horseback for a whole day, than sit in a train half a one.”

A long, narrow road, with iron railings on either side, dividing it from broad meadows, brought them to another gate, which the farmer got down to open, and then led Molly up to the porch of the Vicarage.

A boy running out from the stable-yard close by stood at the horse’s head while Mr Oswald carefully helped Anna down from her high seat, took out her trunks from the back of the cart, and rang the bell. Again the question of payment troubled her, but he did not leave her long to consider it.

“Well, you’re landed now, missie,” he said with his good-natured smile, as he took the reins and turned the impatient Molly towards the gate; “so I’ll say good-day to you, and my respects to Mr and Mrs Forrest.”

Molly seemed to Anna to make but one bound from the door to the gate, and to carry the cart and the farmer out of sight, while she was still murmuring her thanks.

She turned to the maid-servant, who had opened the door and was gazing at her and her boxes with some surprise.

“Yes, miss,” she said, in answer to Anna’s inquiry; “Mrs Forrest is at home; she’s in the garden, if you’ll please to come this way; we didn’t expect you till to-morrow.”

Through the door opposite, Anna could see a lawn, a tea-table under a large tree, a gentleman in a wicker chair, and a lady, in a broad-brimmed hat, sauntering about with a watering-pot in her hand. When she saw Anna following the maid, the lady dropped her watering-pot, and stood rooted to the ground in an attitude of intense surprise.

“Why, Anna!” she exclaimed.

“Didn’t you expect me, Aunt Sarah?” said Anna. “Father said you would meet me to-day.”

“Now,” said Mrs Forrest, turning round to her husband in the wicker chair, “isn’t that exactly like your brother Bernard?”

“Well, in the meantime, here is Anna, safe and sound,” he replied; “so there’s no harm done.—Come and sit down in the shade, my dear; you’ve had a hot journey.”

“Where’s your luggage?” continued Mrs Forrest, as she kissed her niece. “Did you walk up from the station, and leave it there?”

“Oh no, aunt; I didn’t know the way,” said Anna.

She began to feel afraid she had done quite the wrong thing in coming with Mr Oswald.

“Oh, you had to take a fly,” said Mrs Forrest. “It’s a most provoking thing altogether.”

“It doesn’t really matter much, my dear, does it?” said Mr Forrest, as he placed a chair for his niece. “She’s managed to get here without any accident, although you did not meet her.—Suppose you give us some tea.”

“I took the trouble to make a note of the train and day,” continued Mrs Forrest, “and I repeated them twice to Bernard, so that there should be no mistake.”

“Well, you couldn’t have done more,” said Mr Forrest, soothingly. “Bernard always was a forgetful fellow, you know.”

“Such a very unsuitable thing for the child to arrive quite alone at the station, and no one to meet her there! And I had made all my arrangements for to-morrow so carefully.”

As Anna drank her tea, she listened to all this, and intended every moment to mention that Mr Oswald had driven her from the station, but she was held back by a mixture of shyness and fear of what her aunt would say; perhaps she had done something very silly, and what Mrs Forrest would call unsuitable! At any rate, it was easier just now to leave her under the impression that she had taken a fly; but, of course, directly she got a chance, she would tell her all about it. For some time, however, Mrs Forrest continued to lament that her arrangements had not been properly carried out, and when the conversation did change, Anna had a great many questions to answer about her father and his intended journey. Then a message was brought out to her uncle, over which he and Mrs Forrest bent in grave consultation. She had now leisure to look about her. How pretty it all was! The long, low front of the Vicarage stood facing her, with the smooth green lawn between them, and up the supports of the veranda there were masses of climbing plants in full bloom. The old part of the house had a very deep, red-tiled roof, with little windows poking out of it here and there, and the wing which the present Vicar had built stood at right angles to it. Anna thought her father was right in not admiring the new bit as much as the old, but, nevertheless, with the evening light resting on it, it all looked very pretty and peaceful just now.

“And how do you like the look of Waverley, Anna?” asked Mrs Forrest.

Anna could answer with great sincerity that she thought it was a lovely place, and she said it so heartily that her aunt was evidently pleased. She kissed her.

“I hope you will be happy whilst you are with us, my dear,” she said, “and that Waverley may always be full of pleasant recollections to you.”

Anna was wakened next morning from a very sound sleep by a little tapping noise at her window, which she heard for some time in a sort of half-dream, without being quite roused by it; it was so persistent, however, that at last she felt she must open her eyes to find out what it was. Where was she? For the first few minutes she looked round the room in puzzled surprise, and could not make out at all. It was so quiet, and clear, and bright, with sunbeams dancing about on the walls, so different altogether from the dingy, grey colour of a morning in London. Soon, however, she remembered she was in the country at Waverley; and her mother’s picture on the toilet-table brought back to her mind all that had passed yesterday—her journey, her drive with the farmer, her grandfather in the lane.

There were two things she must certainly do to-day, she told herself, as she watched the quivering shadows on the wall. First, she must ask her aunt to let her go at once and see her grandfather; and then she must tell her all about her arrival at the station yesterday, and how kindly Farmer Oswald had come to her help. It was strange that, now she had actually got to Waverley, and was only two miles away from her grandfather, that she did not feel nearly so eager to talk to him as she had while she was on her journey. However, she need not think about that now. Here she was at Waverley, where it was all sunny and delightful; she should not see smoky London, or have any more walks in the Park with her governess, for a long while, perhaps never again. She meant to enjoy herself, and be very happy, and nothing disagreeable or tiresome could happen in this beautiful place.

There was the little tapping noise again! What could it be? Anna jumped out of bed, went softly to the window, and drew up the blind. Her bedroom was over the veranda, up which some cluster-roses had climbed, flung themselves in masses on the roof, and reached out some of their branches as far as the window-sill. One bold little bunch had pressed itself close up against the pane, and the tight pink buds clattered against it whenever they were stirred by the breeze. The tapping noise was fully accounted for, but Anna could not turn away, it was all so beautiful and so new to her.

She pushed up the window, and leaned out. What a lovely smell! There was a long bed of mignonette and heliotrope just below, but, besides the fragrance from this, the air was full of all the sweet scents which belong to an early summer morning in the country. What nice, curious noises, too, all mixed up together! The bees buzzing in the flowers beneath, the little winds rustling in the leaves, the cheerful chirps and scraps of song from the birds, the crow of a distant cock, the deep, low cooing of the pigeons in the stable-yard near. Anna longed to be out-of-doors, among these pleasant sights and sounds; she suddenly turned away, and began to dress herself quickly. The stable clock struck seven just as she was ready, and she ran down-stairs into the garden with a delightful sense of freedom. The sunshine was splendid; this was indeed different from walking in a London park; how happy she should be in this beautiful place! On exploring a little, she found that the garden was not nearly so large as it looked, for the end of it was hidden by a great walnut tree which stood on the lawn. Behind this came a square piece of kitchen garden, divided from the fields by a sunk fence, with a little wooden foot-bridge across it.

Anna danced along by the side of the border, where the flowers stood in blooming luxuriance and the most perfect order. Aunt Sarah was justly proud of her garden, and at present it was in brilliant perfection. Anna knew hardly any of their names, and indeed, except the roses, they were strange to her; she had not thought there could be so many kinds, and all so beautiful. Reaching the kitchen garden, however, she found some old friends—a long row of sweet-peas, fluttering on their stems, like many-coloured butterflies poised for flight; these were familiar, for she had seen them in greengrocers’ shops in London, tied up in tight, close bunches. How different they looked at Waverley! The colours were twice as bright.

“I like these best of all,” she said aloud, and as she spoke, a step sounded on the gravel, and there was Aunt Sarah, in her garden hat, with a basket, and scissors in her hand.

“You admire my sweet-peas, Anna,” she said, kissing her. “I came out to gather some. I find it is so much better to get my flowers before the sun is too hot. Now, you can help me.”

They walked slowly along the hedge of sweet-peas together, picking them as they went.

“What a beautiful garden yours is, Aunt Sarah,” cried Anna.

Mrs Forrest looked pleased.

“There are many larger ones about here,” she said, “but I certainly think my flowers do me credit. I attend to them a great deal myself, but, of course, I cannot give them as much time as I should like. Now you are come, we shall be busier than ever, because we must give some time every day to your studies.”

“Miss Milverton said she would write to you about the lessons I have been doing, aunt,” said Anna.

“I have arranged,” continued Aunt Sarah, “to read with you for an hour every morning; it is difficult to squeeze it in, but I have managed it. And then I am hoping that you will join in some lessons with the Palmers—girls of your own age, who live near. If their governess will allow you to learn French and German with them, it would be a good plan, and would give you companions besides.—By the way, Anna, Miss Milverton says in her letter that you don’t make any progress in your music. How is that?”

“I don’t care very much for music,” said Anna. “I would much rather not go on with it, unless you want me to.”

She thought that her aunt looked rather relieved, as she remarked that it was useless for people who were not musical to waste their time in learning to play, and that she should not make a point of music-lessons at present.

“Now I must cut some roses,” added Mrs Forrest, as she put the glowing bunches of sweet-peas into her basket. “Come this way.”

Anna followed to a little nursery of standard rose-trees near the foot-bridge.

“What are those chimneys I can just see straight over the fields?” she asked her aunt.

“Leas Farm,” she replied. “It belongs to Mr Oswald, a very respectable farmer, who owns a good deal of land round here. We have our milk and butter from him. Your uncle used to keep his own cows, but he found them a trouble, and Mrs Oswald is an excellent dairy woman.”

Here was an opportunity for Anna’s explanation. The words were on her lips, when they were interrupted by the loud sound of a bell from the house.

“The breakfast bell!” said Mrs Forrest, abruptly turning away from her roses, and beginning to hasten towards the house, without pausing a moment. “I hope you will always be particular in one point, my dear Anna, and that is punctuality. More hangs upon it than most people recognise: the comfort of a household certainly does. If you are late for one thing, you are late for the next, and so on, until the whole day is thrown into disorder. I am obliged to map my day carefully out to get through my business, and I expect others to do the same. I speak seriously, because your father is one of the most unpunctual men I ever knew; and if you have inherited his failing, you cannot begin to struggle against it too soon.”

Anna had not been many days at the Vicarage before she found that punctuality was Aunt Sarah’s idol, and that nothing offended her more than want of respect to it from others. Certainly everything went like clockwork at Waverley, and though Anna fancied that Mr Forrest inwardly rebelled a little, he was outwardly quite submissive. All Aunt Sarah’s arrangements and plans were so neatly fitted into each other that the least transgression in one upset the next, and the effect of this was that she had no odds and ends of leisure to spare. Anna even found it difficult to put all the questions she had in her mind.

“Not now, my dear, I am engaged,” was the frequent reply. She managed to learn, however, that a visit to her grandfather had already been planned for that week, and that Mrs Forrest intended to leave her at his house at Dornton and fetch her again after driving farther on to make a call.

With this she was obliged to be satisfied, and it was quite strange how, after a few days, the new surroundings and rules and pleasures of Waverley seemed to make much that had filled her mind on her arrival fade and grow less important. She still wished to see her grandfather again; but the idea of being his chief comforter and support now seemed impossible, and rather foolish, and she would not have hinted it to Aunt Sarah on any account. Neither did it seem necessary, as the days went on, to mention her drive with Mr Oswald and the accident of passing her grandfather in the lane.

Chapter Four.

The Professor.

...I have heard a grave divine say that God has two dwellings—one in heaven, and the other in a meek and thankful heart.—Izaak Walton.

“Del, my love,” said Mrs Hunt, “I feel one of my worst headaches coming on. Will you go this afternoon to see Mrs Winn, instead of me?” Delia stood under the medlar tree on the lawn, ready to go out, with a bunch of roses in her hand, and her violin-case. She looked at her mother inquiringly, for Mrs Hunt had not just then any appearance of discomfort. She was sitting in an easy canvas chair, a broad-brimmed hat upon her head, and a newspaper in her hands; her slippered feet rested on a little wooden stool, and on a table by her side were a cup of tea, a nicely buttered roll, and a few very ripe strawberries.

“Hadn’t you better wait,” said Delia, after a moment’s pause, “until you can go yourself? Mrs Winn would much rather see you. Besides—it is my music afternoon.”

Mrs Hunt was looking up and down the columns of the paper while her daughter spoke: she did not answer at once, and when she did, it was scarcely an answer so much as a continuation of her own train of thoughts.

“She has had a tickling cough for so many nights. She can hardly sleep for it, and I promised her a pot of my own black currant jelly.”

“It’s a great deal out of my way,” said Delia.

“If you go,” continued Mrs Hunt, without raising her eyes, “you will find the row of little pots on the top shelf of the storeroom cupboard.”

Delia bit her lip.

“If I go,” she said, “I must shorten my music-lesson.”

Mrs Hunt said nothing, but looked as amiable as ever. A frown gathered on Delia’s forehead: she stood irresolute for a minute, and then, with a sudden effort, turned and went quickly into the house. Mrs Hunt stirred her tea, tasted a strawberry, and leant back in her chair with a gentle sigh of comfort. In a few minutes Delia reappeared hurriedly.

“There is no black currant jelly in the storeroom,” she said, with an air of exasperation.

Mrs Hunt looked up in mild surprise.

“How strange!” she said. “Could I have moved those pots? Ah, now I remember! I had a dream that all the jam was mouldy, and so I moved it into that cupboard in the kitchen. That was why cook left. She didn’t like me to use that cupboard for the jam.”

“And, meanwhile, where is it?” said Delia.

“Such a wicked mother to give you so much trouble!” murmured Mrs Hunt, with a sweet smile. “But, Del, my love, you must try not to look so morose for trifles—it gives such an ugly turn to the features. You’ll find the jelly in that nice corner cupboard in the kitchen. Here’s the key”—feeling in her pocket—“no; it is not here—where did I leave my keys? Oh, you’ll find them in the pocket of my black serge dress—and if they’re not there, they are sure to be in the pocket of my gardening apron. My kind love to Mrs Winn. Tell her to take it constantly in the night. And don’t hurry, love, it’s so warm; you look heated already.”

In spite of this last advice, it was almost at a run that Delia, having at last found the keys and the jam, set forth on her errand. Perhaps, if she were very quick, she need not lose much time with the Professor, after all, but she felt ruffled and rather cross at the delay. It was not an unusual frame of mind, for she was not naturally of a patient temper, and did not bear very well the little daily frets and jars of her life. She chafed inwardly as she went quickly on her way, that her music, which seemed to her the most important thing in the world, should be sacrificed to anything so uninteresting and dull as Mrs Winn’s black currant jam. It was all the more trying this afternoon, because, since Anna Forrest’s arrival, she had purposely kept away from the Professor, and had not seen him for a whole fortnight. A mixed feeling of jealousy and pride had made her determined that Anna should have every opportunity of making Mr Goodwin’s acquaintance without any interference from herself. It was only just and right that his grandchild should have the first place in his affections, the place which hitherto had been her own. Well, now she must take the second place, and if Anna made the Professor happier, it would not matter. At any rate, no one should know, however keenly she felt it.

Mrs Winn, who was a widow, lived in an old-fashioned, red brick house facing the High Street; it had a respectable, dignified appearance, suggesting solid comfort, like the person of its owner. Mrs Winn, however, was a lady not anxious for her own well-being only, but most charitably disposed towards others who were not so prosperous as herself. She was the Vicar’s right hand in all the various methods for helping the poor of his parish: clothing clubs, Dorcas meetings, coal clubs, lending library, were all indebted to Mrs Winn for substantial aid, both in the form of money and personal help.

She was looked up to as a power in Dornton, and her house was much frequented by all those interested in parish matters, so that she was seldom to be found alone. Perhaps, also, the fact that the delightful bow-window of her usual up-stairs sitting-room looked straight across to Appleby’s, the post-office and stationer, increased its attractions. “It makes it so lively,” Mrs Winn was wont to observe. “I seldom pass a day, even if I don’t go out, without seeing Mr Field, or Mr Hurst, or some of the country clergy, going in and out of Appleby’s. I never feel dull.”

To-day, to her great relief, Delia found Mrs Winn quite alone. She was sitting at a table drawn up into the bow-window, busily engaged in covering books with whitey-brown paper. On her right was a pile of gaily bound volumes, blue, red, and purple, which were quickly reduced to a pale brown, unattractive appearance in her practised hands, and placed in a pile on her left. Delia thought Mrs Winn looked whitey-brown as well as the books, for there was no decided colour about her: her eyes were pale, as well as the narrow line of hair which showed beneath the border of her white cap; and her dresses were always of a doubtful shade, between brown and grey.

She welcomed Delia kindly, but with the repressed air of severity which she always reserved for her.

“How like your dear mother!” she exclaimed, on receiving the pot of jelly.—“Yes; my cough is a little better, tell her, but I thought I would keep indoors to-day—and, you see, I’ve all these books to get through, so it’s just as well. Mr Field got them in London for the library the other day.”

“What a pity they must be covered,” said Delia, glancing from one pile to the other; “the children would like the bright colours so much better.”

“A nice state they would be in, in a week,” said Mrs Winn, stolidly, as she folded, and snipped, and turned a book about in her large, capable hands. “Besides, it’s better to teach the children not to care for pretty things.”

“Is it?” said Delia. “I should have thought that was just what they ought to learn.”

“The love of pretty things,” said Mrs Winn, sternly, “is like the love of money, the root of all evil; and has led quite as many people astray.—All these books have to be labelled and numbered,” she added, after a pause. “You might do some, Delia, if you’re not in a hurry.”

“Oh, but I am,” said Delia, glancing at the clock. “I am going to Mr Goodwin for a lesson, and I am late already.”

Mrs Winn had, however, some information to give about Mr Goodwin. Julia Gibbins, who had just looked in, had met him on the way to give a lesson at Pynes.

“So,” she added, “he can’t possibly be home for another half-hour at least, you know; and you may just as well spend the time in doing something useful.”

With a little sigh of disappointment, Delia took off her gloves and seated herself opposite to Mrs Winn. Everything seemed against her to-day.

“And how,” said that lady, having supplied her with scissors and paper, “do you get on with Anna Forrest? You’re with Mr Goodwin so much, I suppose you know her quite well by this time.”

“Indeed, I don’t,” said Delia. “I haven’t even seen her yet; have you?”

“I’ve seen her twice,” said Mrs Winn. “She’s pretty enough, though not to be compared to her mother; more like the Forrests, and has her father’s pleasant manners. If looks were the only things to consider, she would do very well.”

“What’s the matter with her?” asked Delia, bluntly, for Mrs Winn spoke as though she knew much more than she expressed.

“Why, I’ve every reason to suppose,” she began deliberately—then breaking off—“Take care, Delia,” she exclaimed; “you’re cutting that cover too narrow. Let me show you. You must leave a good bit to tuck under, don’t you see, or it will be off again directly.”

Delia had never in her life been so anxious for Mrs Winn to finish a sentence, but she tried to control her impatience, and bent her attention to the brown paper cover.

“It only shows,” continued Mrs Winn, when her instructions were ended, “that I was right in what I said the other day about Mr Bernard Forrest’s marriage. That sort of thing never answers. That child has evidently been brought up without a strict regard for truth.”

“What has she done?” asked Delia.

“Not, of course,” said Mrs Winn, “that poor Prissy could have had anything to do with that.”

The book Delia held slipped from her impatient fingers, and fell to the ground flat on its face.

“My dear Delia,” said Mrs Winn, picking it up, and smoothing the leaves, with a shocked look, “the books get worn out quite soon enough, without being tossed about like that.”

“I’m very sorry,” said Delia, humbly.—“But do tell me what it is you mean about Anna Forrest.”

“It’s nothing at all pleasant,” said Mrs Winn, “but as you’re likely to see something of her, you ought to know that I’ve every reason to believe that she’s not quite straightforward. Now, with all your faults, Delia—and you’ve plenty of them—I never found you untruthful.”

She fixed her large, round eyes on her companion for a moment, but as Delia made no remark, resumed—

“On the evening of your last working party but one, Julia Gibbins and I saw Mr Oswald of Leas Farm driving Anna Forrest from the station. Of course, we didn’t know her then. But Julia felt sure it was Anna, and it turned out she was right. Curiously enough, we met Mrs Forrest and the child in Appleby’s shortly after, and Mrs Forrest said how unlucky it had been that there was a confusion about the day of her niece’s arrival, and no one to meet her at the station; but, fortunately, she said, Anna was sensible enough to take a fly, so that was all right. Now, you see, my dear Delia, she didn’t take a fly,” added Mrs Winn, solemnly, “so she must have deceived her aunt.”

Mrs Winn’s most important stories had so often turned out to be founded on mistakes, that Delia was not much impressed by this one, nor disposed to think worse of Anna because of it.

“Oh, I daresay there’s a mistake somewhere,” she said, lightly, rising and picking up her flowers and her violin-case. “I must go now, Mrs Winn; the Professor will be back by the time I get there—good-bye.”

She hurried out of the room before Mrs Winn could begin another sentence; for long experience had taught her that the subject would not be exhausted for a long while, and that a sudden departure was the only way of escape.

A quarter of an hour’s quick walk brought her to Number 4 Back Row, and looking in at the sitting-room window, as her custom was, she saw that the Professor had indeed arrived before her.

His dwelling was a contrast in every way to that of Mrs Winn. For one thing, instead of standing boldly out before the world of Dornton High Street, it was smuggled away, with a row of little houses like itself, in a narrow sort of passage, enclosed between two wide streets. This passage ended in a blank wall, and was, besides, too narrow for any but foot-passengers to pass up it, so that it would have been hard to find a quieter or more retired spot. The little, old houses in it were only one storey high, and very solidly built, with thick walls, and the windows in deep recesses; before each a strip of garden, and a gravel walk stretched down to a small gate. Back Row was the very oldest part of Dornton, and though the houses were small, they had always been lived in by respectable people, and preserved a certain air of gentility.

Without waiting to knock, Delia hurried in at the door of Number 4, which led straight into the sitting-room. The Professor was leaning back in his easy-chair, his boots white with dust, and an expression of fatigue and dejection over his whole person.

“Oh, Professor,” was her first remark, as she threw down her violin-case, “you do look tired! Have you had your tea?”

“I believe, my dear,” he replied, rather faintly, “Mrs Cooper has not come in yet.”

Mrs Cooper was a charwoman, who came in at uncertain intervals to cook the Professor’s meals and clean his rooms: as he was not exacting, the claims of her other employers were always satisfied first, and if she were at all busier than usual, he often got scanty attention.

Without waiting to hear more, Delia made her way to the little kitchen, and set about her preparations in a very business-like manner. She was evidently well acquainted with the resources of the household, for she bustled about, opening cupboards, and setting tea-things on a tray, as though she were quite at home. In a wonderfully short time she had prepared a tempting meal, and carried it into the sitting-room, so that, when the Professor came back from changing his boots, he found everything quite ready. His little round table, cleared of the litter of manuscripts and music-books, was drawn up to the open window, and covered with a white cloth. On it there was some steaming coffee, eggs, and bread and butter, a bunch of roses in the middle, and his arm-chair placed before it invitingly.

He sank into it with a sigh of comfort and relief.

“How very good your coffee smells, Delia!” he said; “quite different from Mrs Cooper’s.”

“I daresay, if the truth were known,” said Delia, carefully pouring it out, “that you had no dinner to speak of before you walked up to Pynes and back again.”

“I had a sandwich,” answered Mr Goodwin, meekly, for Delia was bending a searching and severe look upon him.

“Then Mrs Cooper didn’t come!” she exclaimed. “Really we ought to look out for some one else: I believe she does it on purpose.”

“Now I beg of you, Delia,” said the Professor, leaning forward earnestly, “not to send Mrs Cooper away. She’s a very poor woman, and would miss the money. She told me only the last time she was here that the doctor had ordered cod-liver oil for the twins, and she couldn’t afford to give it them.”

“Oh, the twins!” said Delia, with a little scorn.

“Well, my dear, she has twins; she brought them here once in a perambulator.”

“But that’s no reason at all she should not attend properly to you,” said Delia.

Mr Goodwin put down his cup of coffee, which he had begun to drink with great relish, and looked thoroughly cast down.

Delia laughed a little.

“Well, I won’t, then,” she said. “Mrs Cooper shall stay, and neglect her duties, and spoil your food as long as you like.”

“Thank you, my dear,” said the Professor, brightening up again, “she really does extremely well, though, of course, she doesn’t”—glancing at the table—“make things look so nice as you do.”

Delia blamed herself for staying away so long, when she saw with what contented relish her old friend applied himself to the simple fare she had prepared; it made her thoroughly ashamed to think that he should have suffered neglect through her small feelings of jealousy and pride. He should not be left for a whole fortnight again to Mrs Cooper’s tender mercies.

“We are to have a lesson to-night, I hope,” said Mr Goodwin presently; “it must be a long time since we had one, Delia, isn’t it?”

“A whole fortnight,” she answered, “but”—glancing wistfully at her violin-case—“you’ve had such hard work to-day, I know, if you’ve been to Pynes; perhaps it would be better to put it off.”

But Mr Goodwin would not hear of this: it would refresh him; it would put the other lessons out of his head; they would try over the last sonata he had given Delia to practise.

“Did you make anything of it?” he asked. “It is rather difficult.”

Delia’s face, which until now had been full of smiles and happiness, clouded over mournfully.