Title: My Studio Neighbors

Author: W. Hamilton Gibson

Release date: July 28, 2007 [eBook #22165]

Most recently updated: January 2, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Janet Blenkinship and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

1898

Copyright, 1897, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

Transcriber note: Page 132 has wide margins to accommodate the illustration.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

| Page | |

| A Familiar Guest | 3 |

| The Cuckoos and the Outwitted Cow-bird | 23 |

| Door-step Neighbors | 57 |

| A Queer Little Family on the Bittersweet | 87 |

| The Welcomes of the Flowers | 105 |

| A Honey-dew Picnic | 151 |

| A Few Native Orchids and Their Insect Sponsors | 171 |

| The Milkweed | 227 |

| Index | 239 |

LIST OF DESIGNS

LIST OF DESIGNS

| Page | |

| William Hamilton Gibson | Frontispiece |

| Initial. The Studio Door | 3 |

| The Rose-bush Episode | 9 |

| A Corner of My Table | 12 |

| An Animated Brush | 14 |

| A Specimen in Three Stages | 16 |

| The Studio Table | 18 |

| Initial | 23 |

| The European Cuckoo | 24 |

| The Yellow-billed Cuckoo | 26 |

| Browsing Kine | 29 |

| A Greedy Foster-child | 34 |

| The Yellow Warbler | 44 |

| A Blighted Home | 46 |

| The Normal Nest of the Yellow Warbler | 47 |

| The Yellow Warbler at Home | 49 |

| A Suspicious Nest of the Yellow Warbler | 50 |

| The Nest Separated | 52 |

| Initial | 57 |

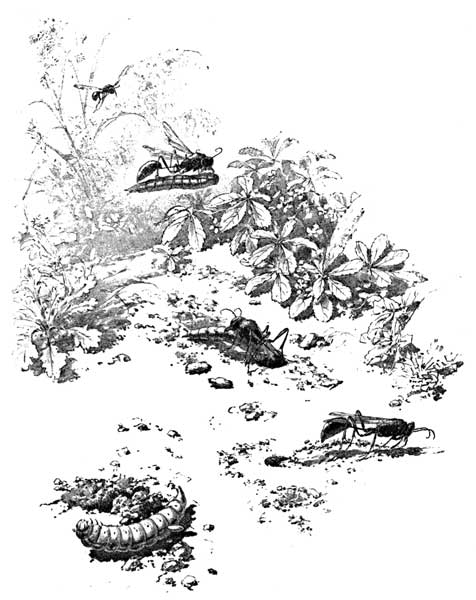

| The Door-step Arena, with its Pitfalls | 60 |

| Fishing for Tigers | 65 |

| Tiger-beetle | 68 |

| The Spider Victim | 70 |

| Filling the Spider's Grave | 71 |

| Black Digger-wasp | 73 |

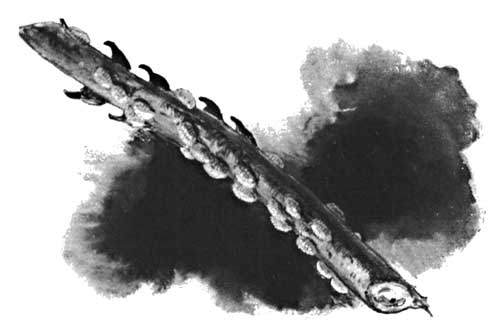

| Black Digger-wasp and His Victim, Showing the Egg of the Wasp Attached | 75 |

| Protecting the Burrow while Searching for Prey | 79 |

| The "Cow-spit" Mystery Disclosed | 81 |

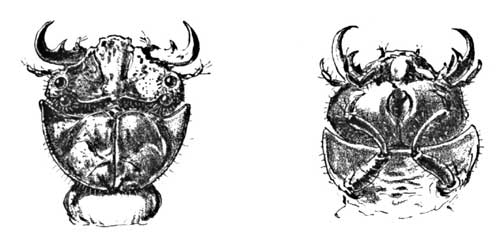

| The Tiger's Head, from the Victim's Stand-point | 84 |

| Initial. Branch of the Bittersweet | 87 |

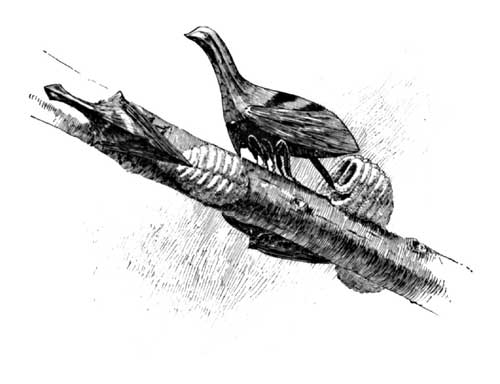

| A Bittersweet Covey | 90 |

| Flushing the Game | 92 |

| Specimen Twig | 94 |

| Building Froth-tent | 100 |

| Butterflies and Flowers | 105 |

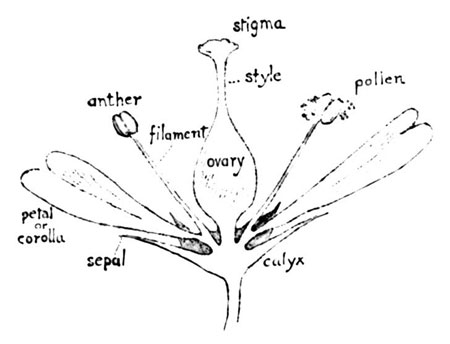

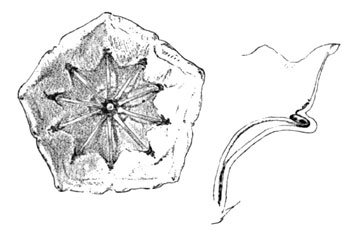

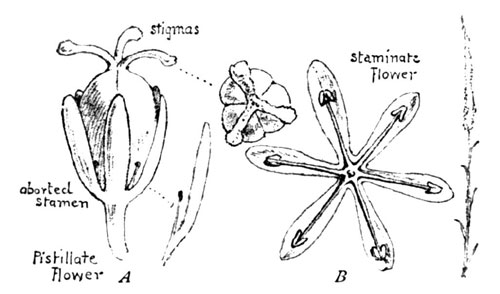

| A Row of Stamens | 106 |

| The Parts of a Flower | 109 |

| Historical Series, Showing the Progress of Discovery of Flower Fertilization | 110 |

| The Garden Sage | 120 |

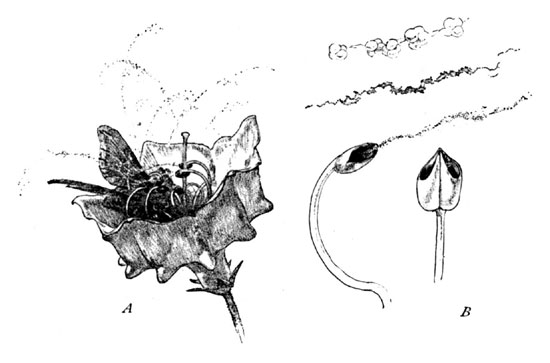

| Cross-fertilization of the Sage | 121 |

| Elastic Stamens. Anthers Inserted in their Pockets | 124 |

| Elastic Stamens of Mountain-laurel | 125 |

| Andromeda Ligustrina | 127 |

| Fertilisation of Andromeda | 128 |

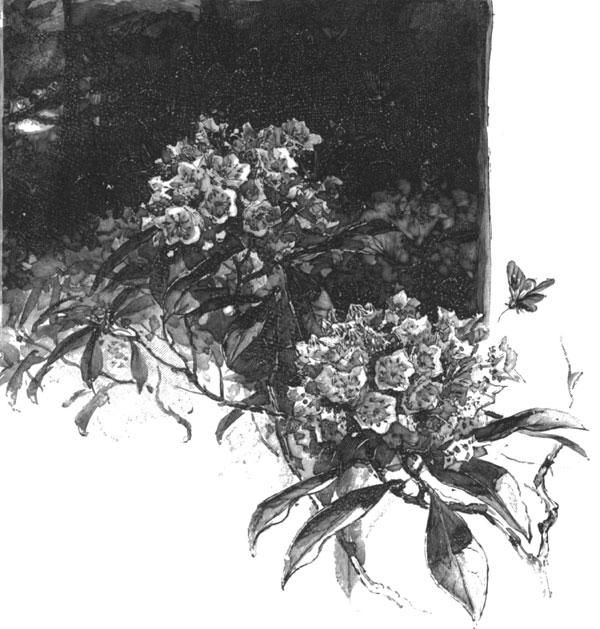

| The Laurel | 130 |

| Cross-fertilization of the Blue-flag | 131 |

| Blue-flag | 132 |

| Pogonia and Devil's-bit | 133 |

| Devil's-bit | 134 |

| Horse-balm. Collinsonia | 135 |

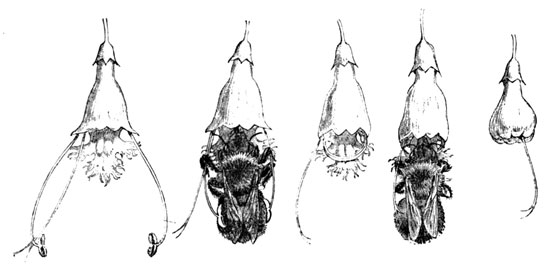

| Cross-fertilization of the Horse-balm—Flowers in Various Stages, and in the Order of their Visitation by the Bee | 136 |

| The Cone-flower | 137 |

| Cone-flower, Showing Numerous Florets, Some in Pollen, Others in Stigmatic Stage | 139 |

| Cross-fertilization of Cone-flower | 140 |

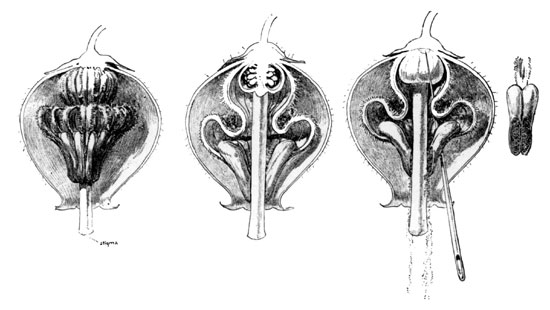

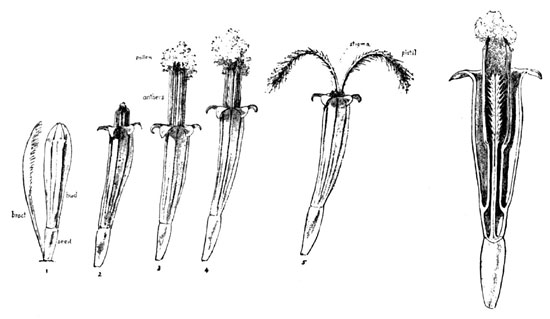

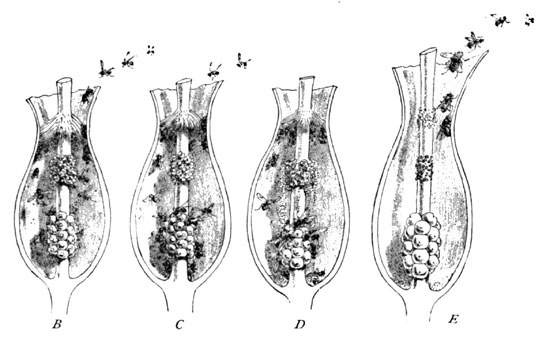

| The Fertilization of the English Arum, 1st Stage | 141 |

| The Fertilization of the English Arum. 2d, 3d, 4th, and 5th Stages | 142 |

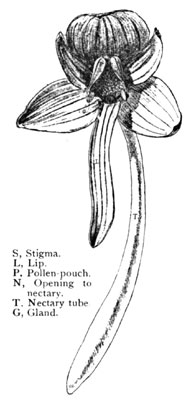

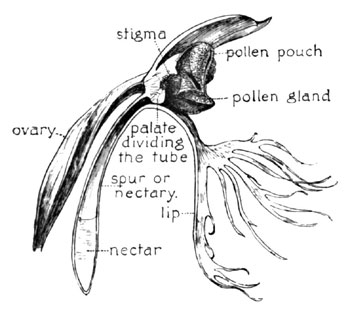

| Pogonia | 145 |

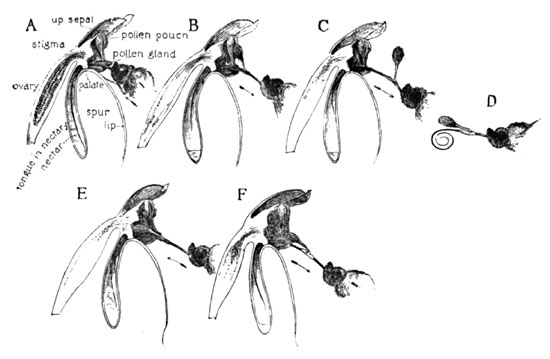

| Cross-fertilization | 146 |

| A Pine Branch | 151 |

| Initial | 151 |

| The Picnic | 159 |

| Tail-piece | 167 |

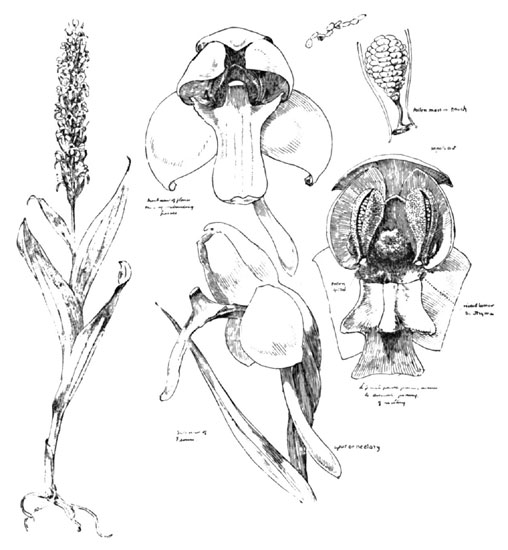

| Habenaria Orbiculata | 171 |

| Arethusa Bulbosa | 177 |

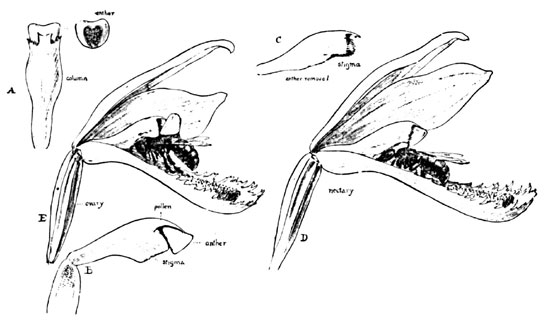

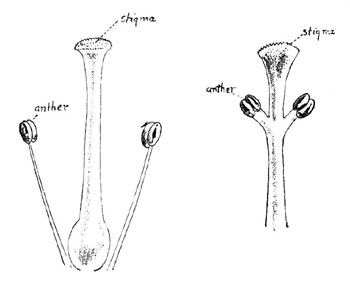

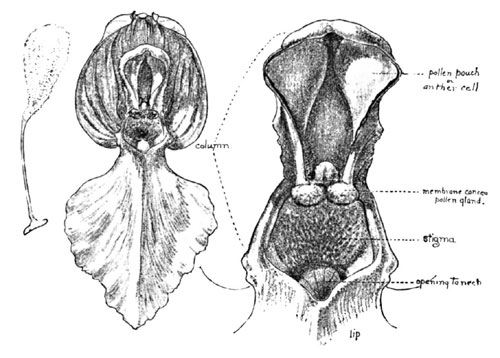

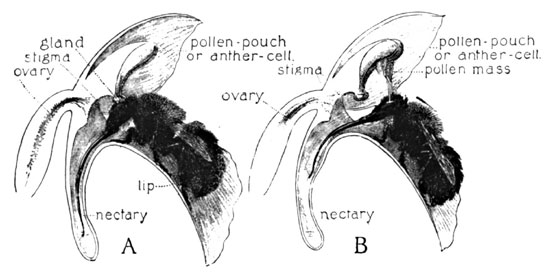

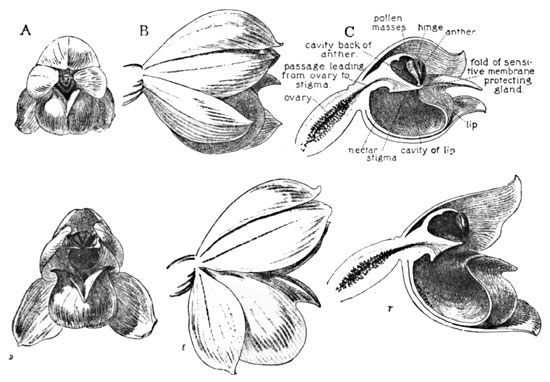

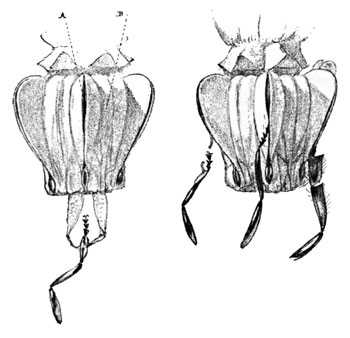

| The Botanical Distribution of an Ordinary Flower and of the Orchid | 182 |

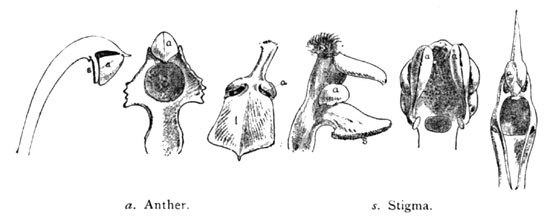

| The "Column" in Various Orchids | 183 |

| The Result of the Bee's Visit | 184 |

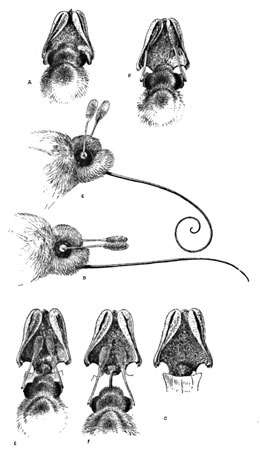

| Cross-fertilization of Arethusa | 188 |

| Habenaria Orbiculata. A Single Flower Enlarged | 190 |

| Orchis Spectabilis | 191 |

| Cross-fertilization of H. Orbiculata (Sphinx-moth) | 193 |

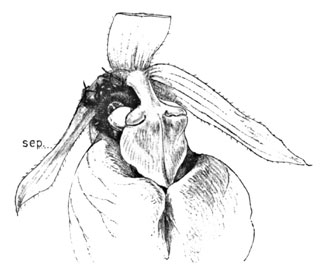

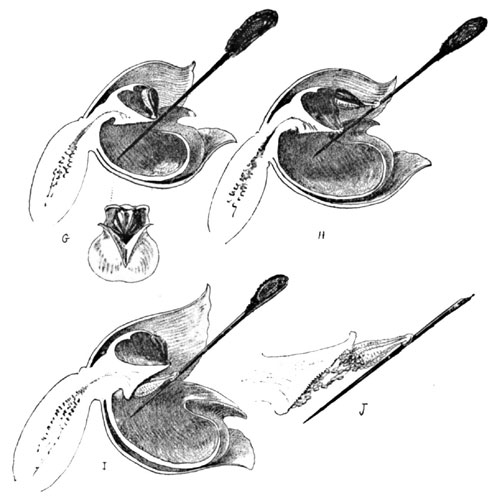

| The Flower and Column of Orchis Spectabilis, Enlarged | 195 |

| Orchis Spectabilis | 195 |

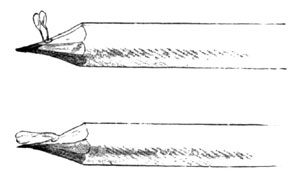

| Position of Pollen of Orchis Spectabilis Withdrawn on Pencil | 197 |

| The Cross-fertilization of Orchis Spectabilis | 197 |

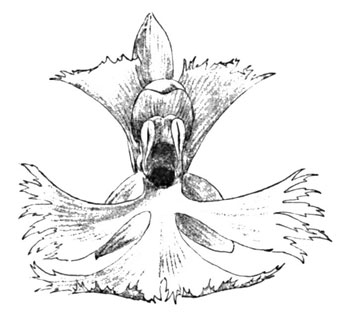

| The Purple-fringed Orchid | 199 |

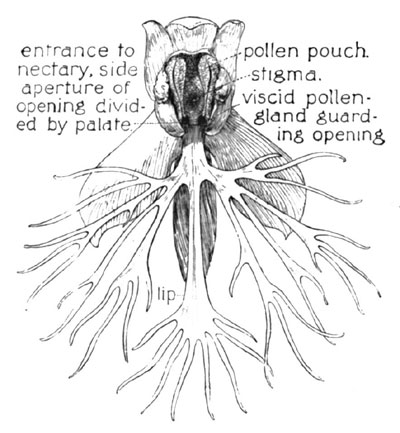

| The Ragged Orchid (Front Section) | 200 |

| The Ragged Orchid (Profile Section) | 202 |

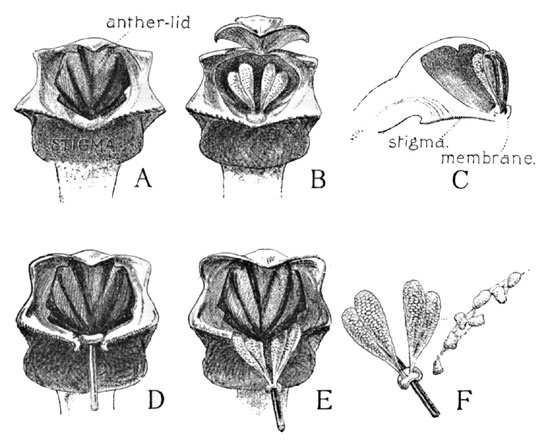

| The Ragged Orchid (H. Lacera) and the Butterfly's Tongue. Cross-fertilization | 203 |

| The Yellow Orchid (H. Flava) | 204 |

| The Ragged Orchid (H. Lacera) | 205 |

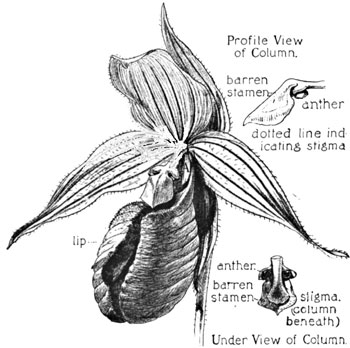

| Cypripedium Acaule | 207 |

| Moccasin-flower (C. Acaule) | 208 |

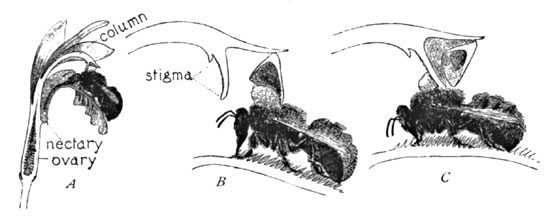

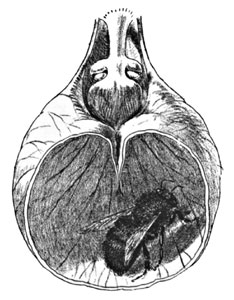

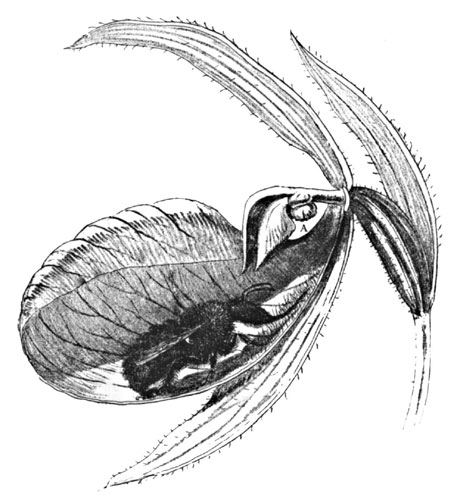

| The Bee Imprisoned in the Lips of Cypripedium | 210 |

| Moccasin-flower. Bee Sipping Nectar | 211 |

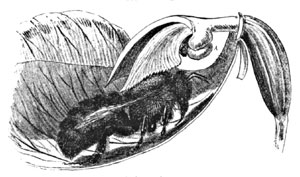

| The Bee Passing Beneath the Stigma | 213 |

| A Bee Receiving Pollen-plaster on His Thorax | 214 |

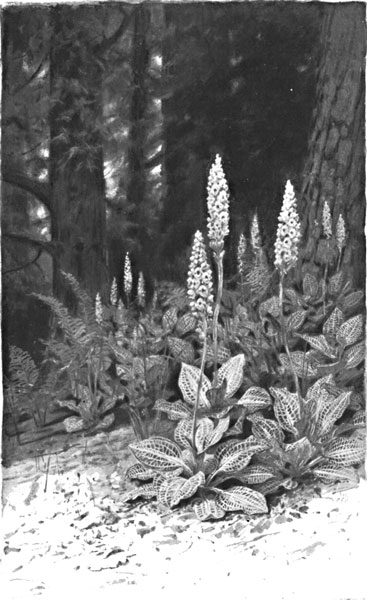

| Rattlesnake-Plantain—the Young and the Old | 215 |

| Cross-fertilization of the Rattlesnake-Plantain. Side Sections | 216 |

| Cross-fertilisation of the Rattlesnake-Plantain. Front View | 217 |

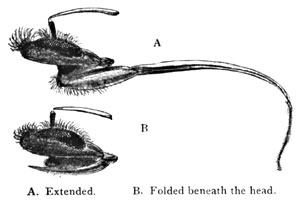

| The Tongue of a Bumblebee | 218 |

| Goodyera, or Periamium Pubescens | 221 |

| Milkweed Captives | 231 |

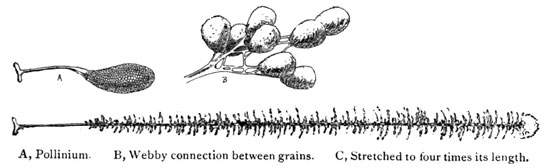

| The Pollen Masses and the Fissure | 232 |

| The Tragedy of the Bees | 235 |

| A Moth Caught by the Tongue in Dogbane | 237 |

olitude! Where under trees and sky shall you find it? The more solitary the recluse and the more confirmed and grounded his seclusion, the wider and more familiar becomes the circle of his social environment, until at length, like a very dryad of old,[Pg 4] the birds build and sing in his branches and the "wee wild beasties" nest in his pockets. If he fails to be aware of the fact, more's the pity. His desolation is within, not without, in spite of, not because of, his surroundings.

Here in my country studio—not a hermitage, 'tis true, but secluded among trees, some distance isolated from my own home and out of sight of any other—what company! What occasional "tumultuous privacy" is mine! I have frequently been obliged to step out upon the porch and request a modulation of hilarity and a more courteous respect for my hospitality. But this is evidently entirely a matter of point of view, and, judging from the effects of my protests at such times, my assumed superior air of condescension is apparently construed as a huge joke. If the resultant rejoinder of wild volapük and expressive pantomime has any significance, it is plain that I am desired to understand that my exact status is that of a squatter on contested territory.

There are those snickering squirrels, for instance! At this moment two of them are having a rollicking game of tag on the shingled roof—a pandemonium of scrambling, scratching, squealing, and growling—ever and anon clambering[Pg 5] down at the eaves to the top of a blind and peeping in at the window to see how I like it.

A woodchuck is perambulating my porch—he was a moment ago—presumably in renewed quest of that favorite pabulum more delectable than rowen clover, the splintered cribbings from the legs of a certain pine bench, which, up to date, he has lowered about three inches—a process in which he has considered average rather than symmetry, or the comfort of the too trusting visitor who happens to be unaware of his carpentry.

The drone of bees and the carol of birds are naturally an incessant accompaniment to my toil—at least, in these spring and summer months. The tall, straight flue of the chimney, like the deep diapason of an organ, is softly murmurous with the flurry of the swifts in their afternoon or vesper flight. There is a robin's nest close by one window, a vireo's nest on a forked dogwood within touch of the porch, and continual reminders of similar snuggeries of indigo-bird, chat, and oriole within close limits, to say nothing of an ants' nest not far off, whose proximity is soon manifest as you sit in the grass—and immediately get up again.

Fancy a wild fox for a daily entertainment! For several days in succession last year I spent a[Pg 6] half-hour observing his frisky gambols on the hillside across the dingle below my porch, as he jumped apparently for mice in the sloping rowen-field. How quickly he responded to my slightest interruption of voice or footfall, running to the cover of the alders!

The little red-headed chippy, the most familiar and sociable of our birds, of course pays me his frequent visit, hopping in at the door and picking up I don't know what upon the floor. A barn-swallow occasionally darts in through the open window and out again at the door, as though for very sport, only a few days since skimming beneath my nose, while its wings fairly tipped the pen with which I was writing. The chipmonk has long made himself at home, and his scratching footsteps on my door-sill, or even in my closet, is a not uncommon episode. Now and then through the day I hear a soft pat-pat on the hard-wood floor, at intervals of a few seconds, and realize that my pet toad, which has voluntarily taken up its abode in an old bowl on the closet floor, is taking his afternoon outing, and with his always seemingly inconsistent lightning tongue is picking up his casual flies at three inches sight around the base-board.

A mouse, I see, has heaped a neat little pile of[Pg 7] seeds upon the top of the wainscot near by—cherry pits, polygonum, and ragweed seeds, and others, including some small oak-galls, which I find have been abstracted from a box of specimens which I had stored in the closet for safe-keeping. I wonder if it is the same little fellow that built its nest in an old shoe in the same closet last year, and, among other mischief, removed the white grub in a similar lot of specimen galls which I also missed, and subsequently found in the shoe and scattered on the closet floor?

I have mentioned the murmur of the bees, but the incessant buzzing of flies and wasps is an equally prominent sound. Then there is the occasional sortie of the dragon-fly, making his gauzy, skimming circuit about the room, or suggestively bobbing around against wall or ceiling; and that occasional audible episode of the stifled, expiring buzz of a fly, which is too plainly in the toils of Arachne up yonder! For in one corner of my room I boast of a prize dusty "cobweb," as yet spared from the household broom, a gossamer arena of two years' standing, which makes a dense span of a length of about two feet from a clump of dried hydrangea blossoms to the sill of a transom-window, and which, of course, some[Pg 8]where in its dusty spread, tapers off into a dark tunnel, where lurks the eight-eyed schemer, "o'erlooking all his waving snares around."

Sooner or later, it would seem, every too constant buzzing visitor encroaches on its domain, and is drawn to its silken vortex, and is eventually shed below as a clean dried specimen; for this is an agalena spider, which dispenses with the winding-sheet of the field species—epeira and argiope. Last week a big bumble-bee-like fly paid me a visit and suddenly disappeared. To-day I find him dried and ready for the insect-pin and the cabinet on the window-sill beneath the web, which affords at all times its liberal entomological assortment—Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Diptera, and Lepidoptera. Many are the rare specimens which I have picked from these charnel remnants of my spider net.

Ah, hark! The talking "robber-fly" (Asilus), with his nasal, twangy buzz! "Waiow! Wha-a-ar are ye?" he seems to say, and with a suggestive onslaught against the window-pane, which betokens his satisfied quest, is out again at the window with a bluebottle-fly in the clutch of his powerful legs, or perhaps impaled on his horny beak.

Solitude! Not here. Amid such continual distraction and entertainment concentration on[Pg 9] the immediate task in hand is not always of easy accomplishment.

The Rose-bush Episode

The Rose-bush Episode

Last week, after a somewhat distracted morning with some queer beguiling little harlequins on the bittersweet-vine about my porch, of which I have previously written, I had finally settled down to my work, and was engaged in putting the finishing touches upon a long-delayed drawing, when a new visitor claimed my attention—a small hornet, which alights upon the window-sill within half a yard from my face. To be sure, she was no stranger here at my studio—even now there are two of her yonder beneath the spider-nest—and was, moreover, an old friend, whose ways were perfectly familiar to me; but this time the insect engaged my particular attention be[Pg 10]cause it was not alone, being accompanied by a green caterpillar bigger than herself, which she held beneath her body as she travelled along on the window-sill so near my face. "So, so! my little wren-wasp, you have found a satisfactory cranny at last, and have made yourself at home. I have seen you prying about here for a week and wondered where you would take up your abode."

The insect now reaches the edge of the sill, and, taking a fresh grip on her burden, starts off in a bee-line across my drawing-board and towards the open door, and disappears. Wondering what her whimsical destination might be, my eye involuntarily began to wander about the room in quest of nail-holes or other available similar crannies, but without reward, and I had fairly settled back to my work and forgotten the incident, when the same visitor, or another just like her, again appeared, this time clearing the window-sill in her flight, and landing directly upon my drawing-board, across which she sped, half creeping, half in flight, and tugging her green caterpillar as before—longer than herself—which she held beneath her body.

"This time I shall learn your secret," I thought. "Two such challenges as this are not to be ig[Pg 11]nored." So I concluded this time to observe her progress carefully. In a moment she had reached the right-hand edge of my easel-board, from which she made a short flight, and settled upon a large table in the centre of the room, littered with its characteristic chaos of professional paraphernalia—brushes, paints, dishes, bottles, color-boxes, and cloths—among which she disappeared. It was a hopeless task to disclose her, so I waited patiently to observe the spot from which she would emerge, assuming that this, like the window-sill and my easel, was a mere way-station on her homeward travels. But she failed to appear, while I busied my wits in trying to recall which particular item in the collection had a hole in it. Yes, there was a spool among other odds and ends in a Japanese boat-basket. That must be it! But on examination the paper still covered both ends, and I was again at a loss. What, then, can be the attraction on my table? My wondering curiosity was immediately satisfied, for as I turned back to the board and resumed my work I soon discovered another wasp, with its caterpillar freight, on the drawing-board. After a moment's pause she made a quiet short flight towards the table, and what was my astonishment to observe her alight directly upon the tip of the[Pg 12] very brush which I held in my hand, which, I now noted for the first time, had a hole in its end! In another moment she disappeared within the cavity, tugging the caterpillar after her!

A Corner of My Table

A Corner of My Table

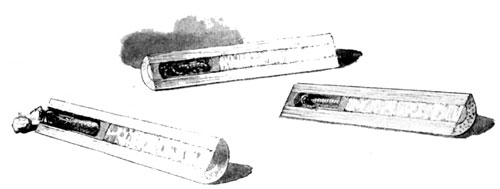

My bamboo brushes! I had not thought of[Pg 13] them! By mere chance a few years since I happened upon some of these bamboo brushes in a Japanese shop—large, long-handled brushes, with pure white hair nicely stiffened to a tapering point, which was neatly protected with a sheathing cover of bamboo. A number of them were at my elbow, a few inches distant, in a glass of water, and on the table by the vase beyond were a dozen or so in a scattered bundle.

Normally each of these brushes is closed at the end by the natural pith of the bamboo. I now find them all either open or otherwise tampered with, and the surrounding surface of the table littered with tiny balls, apparently of sawdust. I picked up one of the nearest brushes, and upon inverting it and giving it a slight tap, a tiny green worm fell out of the opening. From the next one I managed to shake out seven of the caterpillars, while the third had passed beyond this stage, the aperture having been carefully plugged with a mud cork, which was even now moist. Two or three others were in the same plugged condition, and investigation showed that no single brush had escaped similar tampering to a greater or less extent. One brush had apparently not given entire satisfaction, for the plug had been removed, and the caterpillars, eight or ten in number, were[Pg 14] scattered about the opening. But the dissatisfaction probably lay with one of these caterpillars rather than with the maternal wasp, who had apparently failed in the full dose of anæsthetic, for one of her victims which I observed was quite lively, and had probably forced out the soft plug, and in his squirming had ousted his luckless companions.

An Animated Brush

An Animated Brush

The caterpillars were all of the same kind, though varying in size, their length being from one-half to three-quarters of an inch. To all appearances they were dead, but more careful observation revealed signs of slight vitality. Recognizing the species as one which I had long known, from its larva to its moth, it was not difficult to understand how my brushes might thus have been expeditiously packed with them. Not far from my studio door is a small thicket of[Pg 15] wild rose, which should alone be sufficient to account for all those victimized caterpillars. This species is a regular dependent on the rose, dwelling within its cocoon-like canopy of leaves, which are drawn together with a few silken webs, and in which it is commonly concealed by day. A little persuasion upon either end of its leafy case, however, soon brings the little tenant to view as he wriggles out, backward or forward, as the case may be, and in a twinkling, spider-like, hangs suspended by a web, which never fails him even in the most sudden emergency.

I can readily fancy the tiny hornet making a commotion at one end of this leafy domicile and the next instant catching the evicted caterpillar "on a fly" at the other. Grasping her prey with her legs and jaws, in another moment the wriggling body is passive in her grasp, subdued by the potent anæsthetic of her sting—a hypodermic injection which instantly produces the semblance of death in its insect victim, reducing all the vital functions to the point of dissolution, and then holds them suspended—literally prolongs life, it would sometimes seem, even beyond its normal duration—by a process which I might call ductile equation. This chemical resource is common to all the hornets, whether their victims be grass[Pg 16]hoppers, spiders, cicadæ, or caterpillars. In a condition of helpless stupor they are lugged off to the respective dens provided for them, and then, hermetically sealed on storage, are preserved as fresh living food for the young hornet larva, which is left in charge of them, and has a place waiting for them all. The developments within my brush-handles may serve as a commentary on the ways and transformations of the average hornet.

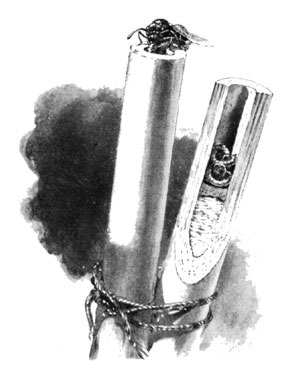

A Specimen in Three Stages

A Specimen in Three Stages

One after another of the little green caterpillars is packed into the bamboo cell, which is about an inch deep, and plugged with mud at the base. From seven to ten of the victims are thus stored, after which the little wasp deposits an egg among them, and seals the doorway with a pellet of mud. The young larva, which soon hatches from this egg, finds itself in a land of plenty, surrounded[Pg 17] with living food, and, being born hungry, he loses no time in making a meal from the nearest victim. One after another of the caterpillars is devoured, until his larder, nicely calculated to carry him to his full growth, is exhausted. Thus the first stage is passed. The second stage is entered into within a few hours, and is passed within a silken cocoon, with which the white grub now surrounds itself, and with which, transformed to a pupa, it bides its time for about three weeks, as I now recall, when—third stage—out pops the mud cork, and the perfect wasp appears at the opening of the cell. I have shown sections of one of my brushes in the three stages.

This interesting little hornet is a common summer species, known as the solitary hornet—one of them—Odynerus flavipes. The insect is about a half-inch in length, and to the careless observer might suggest a yellow-jacket, though the yellow is here confined to two triangular spots on the front of the thorax and three bands upon the abdomen.

Like the wren among birds, it is fond of building in holes, and will generally obtain them ready-made if possible. Burroughs has said of the wren that it "will build in anything that has a hole in it, from an old boot to a bombshell." In[Pg 18] similar whim our little solitary hornet has been known to favor nail-holes, hollow reeds, straws, the barrels of a pistol, holes in kegs, worm-holes in wood, and spools, to which we may now add bamboo brushes.

The Studio Table

The Studio Table

Ovid declared and the ancient Greeks believed that hornets were the direct progeny of the snorting war-horse. The phrase "mad as a hornet"[Pg 19] has become a proverb. Think, then, of a brush loaded and tipped with this martial spirit of Vespa, this cavorting afflatus, this testy animus! There is more than one pessimistic "goose-quill," of course, "mightier than the sword," which, it occurs to me in my now charitable mood, might have been thus surreptitiously voudooed by the war-like hornet, and the plug never removed.[Pg 20]

how has that "blessed bird" and "sweet messenger of spring," the "cuckoo," imposed upon the poetic sensibilities of its native land!

And what is this cuckoo which has thus bewitched all the poets? What is the personality behind that "wandering voice?" What the distinguishing trait which has made this wily attendant on the spring notorious from the times of Aristotle and Pliny? Think of "following the cuckoo," as Logan longed to do, in its "annual visit around the globe," a voluntary witness and accessory to the blighting curse of its vagrant, almost unnatural life! No, my indiscriminate bards; on this occasion we must part company. I cannot "follow" your cuckoo—except with a[Pg 24] gun, forsooth—nor welcome your "darling of the spring," even though he were never so captivating as a songster.

The European Cuckoo

The European Cuckoo

The song and the singer are here identical and inseparable, to my prosaic and rational senses; for does not that "blithe new-comer," as Tennyson says, "tell his name to all the hills"—"Cuckoo! Cuckoo!"

The poet of romance is prompted to draw on his imagination for his facts, but the poet of nature must first of all be true, and incidentally as beautiful and good as may be; and a half-truth or a truth with a reservation may be as dangerous[Pg 25] as falsehood. The poet who should so paint the velvety beauty of a rattlesnake as to make you long to coddle it would hardly be considered a safe character to be at large. Likewise an ode to the nettle, or to the autumn splendor of the poison-sumac, which ignored its venom would scarcely be a wise botanical guide for indiscriminate circulation among the innocents. Think, then, of a poetic eulogium on a bird of which the observant Gilbert could have written:

"This proceeding of the cuckoo, of dropping its eggs as it were by chance, is such a monstrous outrage on maternal affection, one of the first great dictates of nature, and such a violence on instinct, that had it only been related of a bird in the Brazils or Peru, it would never have merited our belief.... She is hardened against her young ones as though they were not hers.... 'Because God hath deprived her of wisdom, neither hath He imparted to her understanding.'"

America is spared the infliction of this notorious "cuckoo." Its nearest congeners, our yellow-billed and black-billed cuckoos, while suggesting their foreign ally in shape and somewhat in song, have mended their ways, and though it is true they make a bad mess of it, they at least try to build their own nest, and rear their own young[Pg 26] with tender solicitude. The nest is usually so sparse and flimsy an affair that you can see through its coarse mesh of sticks from below, the fledglings lying as on a grid-iron or toaster; and it is, moreover, occasionally so much higher in the centre than at the sides that the chicks tumble out of bed and perish. Still, it is a beginning in the right direction.

The Yellow-billed Cuckoo

The Yellow-billed Cuckoo

Yes, it would appear that our American cuckoo is endeavoring to make amends for the sins of its ancestors; but,[Pg 27] what is less to its credit, it has apparently found a scapegoat, to which it would ever appear anxious to call our attention, as it stammers forth, in accents of warning, "c, c, cow, cow, cow! cowow, cowow!" It never gets any further than this; but doubtless in due process of vocal evolution we shall yet hear the "bunting," or "black-bird," which is evidently what he is trying to say.

Owing to the onomatopoetic quality of the "kow, kow, kow!" of the bird, it is known in some sections as the "kow-bird," and is thus confounded with the real cow-bird, and gets the credit of her mischief, even as in other parts of the country, under the correct name of "cuckoo," it bears the odium of its foreign relative.

For though we have no disreputable cuckoo, ornithologically speaking, let us not congratulate ourselves too hastily. We have his counterpart in a black sheep of featherdom which vies with his European rival in deeds of cunning and cruelty, and which has not even a song to recommend him—no vocal accomplishment which by the greatest of license could prompt a poet to exclaim,

"I hear thee and rejoice,"

without having his sanity called in question.

The cow-blackbird, it is true, executes a certain[Pg 28] guttural performance with its throat—though apparently emanating from a gastric source—which some ornithologists dignify by the name of "song." But it is safe to affirm that with this vocal resource alone to recommend him he or his kind would scarcely have been known to fame. The bird has yet another lay, however, which has made it notorious. Where is the nest of song-sparrow, or Maryland yellow-throat, or yellow warbler, or chippy, that is safe from the curse of the cow-bird's blighting visit?

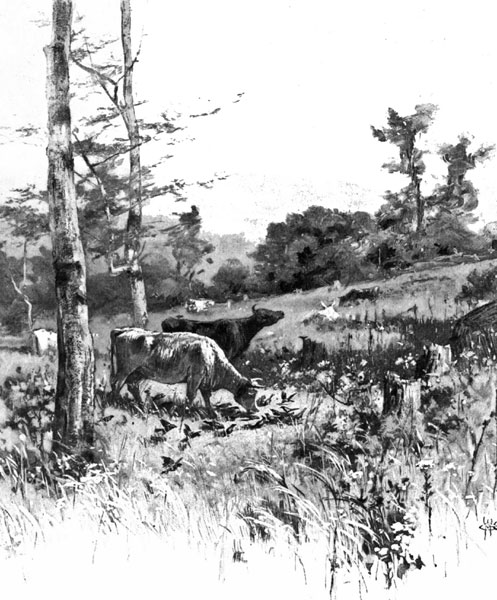

And yet how few of us have ever seen the bird to recognize it, unless perchance in the occasional flock clustering about the noses and feet of browsing kine and sheep, or perhaps perched upon their backs, the glossy black plumage of the males glistening with iridescent sheen in the sunshine.

"Haow them blackbirds doos love the smell o' thet caow's breath!" said an old dame to me once in my boyhood. "I don't blame um: I like it myself." Whether it was this same authority who was responsible for my own similar early impression I do not know, but I do recall the surprise at my ultimate discovery that it was alone the quest of insects that attracted the birds.[Pg 29]

Browsing Kine

Browsing Kine

Upon the first arrival of the bird in the spring an attentive ear might detect its discordant voice, or the chuckling note of his mischievous spouse and accomplice, in the great bird medley; but later her crafty instinct would seem to warn her that silence is more to her interest in the pursuit of her wily mission. In June, when so many an ecstatic love-song among the birds has modulated from accents of ardent love to those of glad fruition, when the sonnet to his "mistress's eyebrow" is shortly to give place to the lullaby, then, like the "worm i' the bud," the cow-bird begins her parasitical career. How many thousands are the bird homes which are blasted in her "annual visit?"

Stealthily and silently she pries among the thickets, following up the trail of warbler, sparrow, or thrush like a sleuth-hound. Yonder a tiny yellow-bird with a jet-black cheek flits hither with a wisp of dry grass in her beak, and disappears in the branches of a small tree close to my studio door. Like the shadow of fate the cow-bird suddenly appears, and has doubtless soon ferreted out her cradle.

In a certain grassy bank not far from where I am writing, at the foot of an unsuspecting fern, a song-sparrow has built her nest. It lies in a hol[Pg 31]low among the dried leaves and grass, and is so artfully merged with its immediate surroundings that even though you know its precise location it still eludes you. Only yesterday the last finishing-touches were made upon the nest, and this morning, as I might have anticipated from the excess of lisp and twitter of the mother bird, I find the first pretty brown-spotted egg.

Surely our cow-bird has missed this secret haunt on her rounds. Be not deceived! Within a half-hour after this egg was laid the sparrow and its mate, returning from a brief absence to view their prize, discover two eggs where they had been responsible for but one. The prowling foe had already discovered their secret; for she, too, is "an attendant on the spring," and had been simply biding her time. The parent birds once out of sight, she had stolen slyly upon the nest, and after a very brief interval as slyly retreated, leaving her questionable compliments, presumably with a self-satisfied chuckle. The intruded egg is so like its fellow as to be hardly distinguishable except in its slightly larger size. It is doubtful whether the sparrow, in particular, owing to this similarity, ever realizes the deception. Indeed, the event is possibly considered a cause for self-congratulation rather than otherwise—at least,[Pg 32] until her eyes are opened by the fateful dénouement of a few weeks later. And thus the American cow-bird outcuckoos the cuckoo as an "attendant on the spring," taking her pick among the nurseries of featherdom, now victimizing the oriole by a brief sojourn in the swinging hammock in the elm, here stopping a moment to leave her charge to the care of an indigo-bird, to-morrow creeping through the grass to the secreted nest of the Maryland yellow-throat, or Wilson's thrush, or chewink. And, unaccountable as it would appear, here we find the same deadly token safely lodged in the dainty cobweb nest of the vireo, a fragile pendent fabric hung in the fork of a slender branch which in itself would barely appear sufficiently strong to sustain the weight of a cow-bird without emptying the nest.

Indeed, the presence of this intruded egg, like that of the European cuckoo in similar fragile nests, has given rise to the popular belief that the bird must resort to exceptional means in these instances. Sir William Jardine, for instance, in an editorial foot-note in one of Gilbert White's pages, remarks:

"It is a curious fact, and one, I believe, not hitherto noticed by naturalists, that the cuckoo[Pg 33] deposits its egg in the nests of the titlark, robin, and wagtail by means of its foot. If the bird sat on the nest while the egg was laid, the weight of its body would crush the nest and cause it to be forsaken, and thus one of the ends of Providence would be defeated. I have found the eggs of the cuckoo in the nest of a white-throat, built in so small a hole in a garden wall that it was absolutely impossible for the cuckoo to have got into it."

In the absence of substantiation, this, at best, presumptive evidence is discounted by the well-attested fact that the cuckoo has frequently been shot in the act of carrying a cuckoo's egg in its mouth, and there is on record an authentic account of a cuckoo which was observed through a telescope to lay her egg on a bank, and then take it in her bill and deposit it in the nest of a wagtail.

There is no evidence to warrant a similar resource in our cow-bird, though the inference would often appear irresistible, did we not know that Wilson actually saw the cow-bird in the act of laying in the diminutive nest of a red-eyed vireo, and also in that of the bluebird.

And what is the almost certain doom of the bird-home thus contaminated by the cow-bird?[Pg 34]

A Greedy Foster-child

A Greedy Foster-child

The egg is always laid betimes, and is usually the first to hatch, the period of incubation being a day or two less than that of the eggs of the foster-parent. And woe be to the fledglings whom fate has associated with a young cow-bird! He is the "early bird that gets the worm." His is the clamoring red mouth which takes the provender of the entire family. It is all "grist into his mill," and everything he eats seems to go to appetite—his bedfellows, if not thus starved to death, being at length crushed by his comparatively ponderous bulk, or ejected[Pg 35] from the nest to die. It is a pretty well established fact that the cuckoo of Europe deliberately ousts its companion fledglings—a fact first noted by the famous Dr. Jenner. And Darwin has even asserted that the process of anatomical evolution has especially equipped the young cuckoo for such an accomplishment—a practice in which some accommodating philosophic minds detect the act of "divine beneficence," in that "the young cuckoo is thus insured sufficient food, and that its foster-brothers thus perish before they have acquired much feeling."

The following account, written by an eye-witness, bears the stamp of authenticity, and is furthermore re-enforced by a careful and most graphic drawing made on the spot, which I here reproduce, and fully substantiates the previous statement by Dr. Jenner. The scene of the tragedy was the nest of a pipit, or titlark, on the ground beneath a heather-bush. When first discovered it contained two pipit's eggs and the egg of a cuckoo.

"At the next visit, after an interval of forty-eight hours," writes Mrs. Blackburn, "we found the young cuckoo alone in the nest, and both the young pipits lying down the bank, about ten[Pg 36] inches from the margin of the nest, but quite lively after being warmed in the hand. They were replaced in the nest beside the cuckoo, which struggled about till it got its back under one of them, when it climbed backward directly up the open side of the nest and pitched the pipit from its back on to the edge. It then stood quite upright on its legs, which were straddled wide apart, with the claws firmly fixed half-way down the inside of the nest, and, stretching its wings apart and backward, it elbowed the pipit fairly over the margin so far that its struggles took it down the bank instead of back into the nest. After this the cuckoo stood a minute or two feeling back with its wings, as if to make sure that the pipit was fairly overboard, and then subsided into the bottom of the nest.

"I replaced the ejected one and went home. On returning the next day, both nestlings were found dead and cold out of the nest.... But what struck me most was this: the cuckoo was perfectly naked, without a vestige of a feather, or even a hint of future feathers; its eyes were not yet opened, and its neck seemed too weak to support the weight of the head. The pipit had well-developed quills on the wings and back, and had bright eyes, partially open, yet they seemed quite[Pg 37] helpless under the manipulations of the cuckoo, which looked a much less developed creature. The cuckoo's legs, however, seemed very muscular; and it appeared to feel about with its wings, which were absolutely featherless, as with hands, the spurious wing (unusually large in proportion) looking like a spread-out thumb."

Considering how rarely we see the cow-bird in our walks, her merciless ubiquity is astonishing. It occasionally happens that almost every nest I meet in a day's walk will show the ominous speckled egg. In a single stroll in the country I have removed eight of these foreboding tokens of misery. Only last summer I discovered the nest of a wood-sparrow in a hazel-bush, my attention being attracted thither by the parent bird bearing food in her beak. I found the nest occupied, appropriated, monopolized, by a cow-bird fledgling—a great, fat, clamoring lubber, completely filling the cavity of the nest, the one diminutive, puny remnant of the sparrow's offspring being jammed against the side of the nest, and a skeleton of a previous victim hanging among the branches below, with doubtless others lost in the grass somewhere in the near neighborhood, where they had been removed by the bereaved mother. The ravenous young parasite, though not half grown,[Pg 38] was yet bigger by nearly double than the foster-mother. What a monster this! The "Black Douglass" of the bird home; a blot on Nature's page!

As in previous instances, observing that the interloper had a voice fully capable of making his wants known, I gave the comfortable little beast ample room to spread himself on the ground, and let the lone little starveling survivor of the rightful brood have his cot all to himself.

And yet, as I left the spot, I confess to a certain misgiving, as the pleading chirrup of the ousted fledgling followed me faintly and more faintly up the hill, recalling, too, the many previous similar acts of mine—and one in particular, when I had slaughtered in cold blood two of these irresponsibles found in a single nest. But sober second thought evoked a more philosophic and conscientious mood, the outcome of which leading, as always, to a semi-conviction that the complex question of reconciliation of duty and humanity in the premises was not thus easily disposed of, considering, as I was bound to do, the equal innocence of the chicks, both of which had been placed in the nest in obedience to a natural law, which in the case of the cow-bird was none the less a divine institution because I failed to un[Pg 39]derstand it. Such is the inevitable, somewhat penitent conclusion which I always arrive at on the cow-bird question; and yet my next cow-bird fledgling will doubtless follow the fate of all its predecessors, the reminiscent qualms of conscience finding a ready philosophy equal to the emergency; for if, indeed, this parasite of the bird home be a factor in the divine plan of Nature's equilibrium, looking towards the survival of the fittest and the regulation of the sparrow and small-bird population, which we must admit, how am I to know but that this righteous impulse of the human animal is not equally a divine, as it is certainly a natural institution looking to the limitations of the cow-bird? One June morning, a year or two ago, I heard a loud squeaking, as of a young bird in the grass near my door, and, on approaching, discovered the spectacle of a cow-bird, almost full-fledged, being fed by its foster-mother, a chippy not more than half its size, and which was obliged to stand on tiptoe to cram the gullet of the parasite.

The victims of the cow-bird are usually, as in this instance, birds of much smaller size, the fly-catchers, the sparrows, warblers, and vireos, though she occasionally imposes on larger species, such as the orioles and the thrushes. The following[Pg 40] are among its most frequent dupes, given somewhat in the order of the bird's apparent choice: song-sparrow, field-sparrow, yellow warbler, chipping-sparrow, other sparrows, Maryland yellow-throat, yellow-breasted chat, vireos, worm-eating warbler, indigo-bird, least-flycatcher, bluebird, Acadian flycatcher, Canada flycatcher, oven-bird, king-bird, cat-bird, phœbe, Wilson's thrush, chewink, and wood-thrush.

But one egg is usually deposited in a single nest; the presence of two eggs probably indicates, as in the case of the European cuckoo, the visits of two cow-birds rather than a second visit from the same individual—the presence of two cow-bird chicks of equal size being rather a proof of this than otherwise, in that kind Nature would seem to have accommodated the bird with an exceptional physiological resource, which matures its eggs at intervals of three or more days, as against the daily oviposition of its dupes, thus giving it plenty of time to make its search and take its pick among the bird-homes. Whether the process of evolution has similarly equipped our cow-bird I am not aware; but the vicious habits of the two birds are so identical that the same accommodating functional conditions might reasonably be expected. It is, indeed, an interesting[Pg 41] fact well known to ornithologists that our own American cuckoos, both the yellow-billed and black-billed, although rudimentary nest-builders, still retain the same exceptional interval in their egg-laying as do their foreign namesake. The eggs are laid from four days to a week apart, instead of daily, as with most birds, their period of perilous nidification on that haphazard apology of a nest being thus possibly prolonged to six weeks. Thus we find, in consequence, the anomalous spectacle of the egg and full-grown chick, and perhaps one or two fledglings of intermediate stages of growth, scattered about at once, helter-skelter, in the same nest. Only two years ago I discovered such a nest not a hundred feet from my house, containing one chick about two days old, another almost full-fledged, while a fresh-broken egg lay upon the ground beneath. Such a household condition would seem rather demoralizing to the cares of incubation, and doubtless the addled or ousted egg is a frequent episode in our cuckoo's experience.

It is an interesting question which the contrast of the American and European cuckoo thus presents. Is the American species a degenerate or a progressive nest-builder? Has she advanced in process of evolution from a parasitical progenitor[Pg 42] building no nest, or is the bird gradually retrograding to the evil ways of her notorious namesake?

The evidence of this generic physiological peculiarity in the intervals of oviposition, taken in consideration with the fact of the rudimentary nest, would seem to indicate the retention of a now useless physiological function, and that the bird is thus a reformer who has repudiated the example of her ancestors, and has henceforth determined to look after her own babes.

With the original presumed object of this remarkable prolonged interval in egg-laying now removed, the period will doubtless be reduced through gradual evolution to accommodate itself to the newly adopted conditions. The week's interval, taken in connection with the makeshift nest or platform of sticks, is now a disastrous element in the life of the bird. Such of the cuckoos, therefore, as build the more perfect nests, or lay at shortest intervals, will have a distinct advantage over their less provident fellows, and the law of heredity will thus insure the continual survival of the fittest.

The cuckoo is not alone among British birds in its intrusion on other nests. Many other species are occasionally addicted to the same prac[Pg 43]tice, though such acts are apparently accidental rather than deliberate, so far as parasitical intent is concerned. The lapse is especially noticeable among such birds as build in hollow trees and boxes, as the woodpeckers and wagtails. Thus the English starling will occasionally impose upon and dispossess the green woodpecker. In the process of nature in such cases the stronger of the two birds would retain the nest, and thus assume the duties of foster-parent. Starting from this reasonable premise concerning the prehistoric cuckoo, it is not difficult to see how natural selection, working through ages of evolution by heredity, might have developed the habitual resignation of the evicted bird, perhaps to the ultimate entire abandonment of the function of incubation. Inasmuch as "we have no experience in the creation of worlds," we can only presume.

Indeed, the similarities and contrasts afforded by a comparison of the habits of all these birds—European cuckoo, American cuckoo, and cow-bird—afford an interesting theme for the student of evolution. What is to be the ultimate outcome of it all? for the murderous cuckoo must be considered merely as an innocent factor in the great scheme of Nature's equilibrium, in which the devourer and the parasite would seem to play the[Pg 44] all-important parts, the present example being especially emphasized because of its conspicuousness and its violence to purely human sentiment. The parasite would often seem to hold the balance of power.

The Yellow Warbler

The Yellow Warbler

Jonathan Swift's epitome of the subject, if not specifically true, is at least correct in its general application:

"A flea

Has smaller fleas that on him prey;

And these have smaller still to bite 'em;

And so proceed ad infinitum."

[Pg 45]

Even the tiny egg of a butterfly has its ichneumon parasite, a microscopic wasp, which lays its own egg within the larger one, which ultimately hatches a wasp instead of the baby caterpillar.

But who ever heard of anything but good luck falling to the lot of cow-bird or cuckoo, except as its blighting course is occasionally arrested by the outraged human? They always find a feathered nest.

In this connection it is interesting to note certain developments in bird life upon the lines of which evolution might work with revolutionary effect. Most of our birds are helpless and generally resigned victims to the cow-bird, but there are indications of occasional effective protest among them. Thus the little Maryland yellow-throat, according to various authorities, often ousts the intruded egg, and its broken remains are also occasionally seen on the ground beneath the nests of the cat-bird and the oriole. The red-eyed vireo, on the other hand, though having apparently an easier task than the latter, in the lesser depth of her pensile nest, commonly abandons it altogether to the unwelcome speckled ovum—always, I believe, if the cow-bird has anticipated her own first egg.[Pg 46]

A Blighted Home

A Blighted Home

But we have a more remarkable example of opposition in the resource of the little yellow warbler, which I have noted as one of the favorite dupes of the cow-bird—a deliberate, intelligent, courageous defiance and frequent victory which are unique in bird history, and which, if through evolutionary process they became the fashion in featherdom, would put the cow-bird's mischief greatly at a discount. The[Pg 47] identity of this pretty little warbler is certainly familiar to most observant country dwellers, even if unknown by name, though its golden-yellow plumage faintly streaked with dusky brown upon the breast would naturally suggest its popular title of "summer yellow-bird." It is one of the commonest of the mnio-tiltidæ, or wood-warblers, though more properly a bird of the copse and shrubbery than of the woods.

The Normal Nest of

The Normal Nest ofThis nest is a beautiful piece of bird architecture. In a walk in search of one only a day or two ago I procured one, which is now before me. It was built in the fork of an elder-bush, to which it was moored by strips of fine bark and cobweb, its downy bulk being composed by a fitted mass of fine grass, willow cotton, fern wood, and other similar ingredients. It is about three inches in depth, outside measurement. But this depth greatly varies in different specimens. Our next specimen may afford quite a contrast, for the yellow[Pg 48] warbler occasionally finds it to her interest to extend the elevation of her dwelling to a remarkable height. On page 50 is shown one of these nests, snugly moored in the fork of a scrub apple-tree. Its depth from the rim to the base, viewed from the outside, is about five inches, at least two inches longer than necessity would seem to require, and apparently with a great waste of material in the lower portion, as the hollow with the pretty spotted eggs is of only the ordinary depth of about two inches, thus hardly reaching half-way to[Pg 49] the base. Let us examine it closely. There certainly is a suspicious line or division across its upper portion, about an inch below the rim, and extending more or less distinctly completely around the nest. By a very little persuasion with our finger-tip the division readily yields, and we discover the summit of the nest to be a mere rim—a top story, as it were—with a full-sized nest beneath it as a foundation. Has our warbler, then, come back to his last year's home and fitted it up anew for this summer's brood? Such would be a natural supposition, did we not see that the foundation is as fresh in material as the summit. Perhaps, then, the bird has already raised her first spring brood, and has simply extended her May domicile, and provided a new[Pg 50] nursery for a second family. But either supposition is quickly dispelled as we further examine the nest; for in separating the upper compartment we have just caught a glimpse of what was, perhaps only yesterday, the hollow of a perfect nest; and, what is more to the point of my story, the hollow contains an egg—perhaps two, in which case they will be very dissimilar, one of delicate white with faint spots of brown on its larger end, the putting of the warbler, the other much larger, with its greenish surface entirely speckled with brown, and which, if we have had any experience in bird-nesting, we immediately recognize as the mischievous token of the cow-bird. We have discovered a most interesting curiosity for our natural-history cabinet—the embodiment of a presumably new form of intelligence in the divine plan looking to the survival of the fittest. It is not known how many years or centuries it has taken the little warbler to develop this clever resource to outwit the cow-bird. It is certain, however, that the little mother has got tired of being thus imposed upon, and is the first of her kind on record which has taken these peculiar measures for rising above her besetting[Pg 51] trouble.

The Yellow Warbler at Home

The Yellow Warbler at Home

A Suspicious Nest of

A Suspicious Nest ofWho can tell what the future may develop in the nests of other birds whose homes are similarly invaded? I doubt not that this crying cow-bird and cuckoo evil comes up as a matter of consideration in bird councils. The two-storied nest may yet become the fashion in featherdom, in which case the cow-bird and European cuckoo would be forced to build nests of their own or perish.

But have we fully examined this nest of our yellow warbler? Even now the lower section seems more bulky than the normal nest should be. Can we not trace still another faint outline of a transverse division in the fabric, about an inch below the one already separated? Yes; it parts easily with a little disentangling of the fibres, and another spotted egg is seen within. A three-storied nest! A nest full of stories—certainly. I recently read of a specimen containing four stories, upon the top of which downy pile the little warbler sat like Patience on a monument,[Pg 52] presumably smiling at the discomfiture of the outwitted cow-bird parasite, who had thus exhausted her powers of mischief for the season, and doubtless convinced herself of the folly of "putting all her eggs in one basket."

The Nest Separated

The Nest Separated

When we consider the life of the cow-bird, how suggestive is this spectacle which we may see every year in September in the chuckling flocks massing for their migration, occasionally fairly blackening the trees as with a mildew, each one the visible witness of a double or quadruple cold-blooded murder, each the grim substitute for a whole annihilated singing family of song-sparrow, warbler, or thrush! What a blessing, at least humanly speaking, could the epicurean population en route in the annual Southern passage of this dark throng only learn what a surpassing substi[Pg 53]tute they would prove—on toast—for the bobolinks which as "reed-birds" are sacrificed by the thousands to the delectable satisfaction of those "fine-mouthed and daintie wantons who set such store by their tooth"!

And what the cow-bird is, so is the Continental "cuckoo." Shall we not discriminate in our employment of the superlative? What of the throstle and the lark? Shall we still sing—all together:

"O cuckoo! I hear thee and rejoice!

Thrice welcome darling of the spring."

ow little do we appreciate our opportunities for natural observation![Pg 57] Even under the most apparently discouraging and commonplace environment, what a neglected harvest! A back-yard city grass-plot, forsooth, what an invitation! Yet there is one interrogation to which the local naturalist is continually called to respond. If perchance he dwells in Connecticut, how repeatedly is he asked, "Don't you find your particular locality in Connecticut a specially rich field for natural observation?" The botanist of New Jersey or the ornithologist of Esopus-on-Hudson is expected to give an affirmative reply to similar questions concerning his chosen hunting-grounds, if, indeed, he does not[Pg 58] avail himself of that happy aphorism with which Gilbert White was wont to instruct his questioners concerning the natural-history harvest of his beloved Selborne: "That locality is always richest which is most observed."

The arena of the events which I am about to describe and picture comprised a spot of almost bare earth less than one yard square, which lay at the base of the stone step to my studio door in the country.

The path leading to the studio lay through a tangle of tall grass and weeds, with occasional worn patches showing the bare earth. As it approached the door-step the surface of the ground was quite clean and baked in the sun, and barely supported a few scattered, struggling survivors of the sheep's-sorrel, silvery cinquefoil, ragweed, various grasses, and tiny rushes which rimmed the border. Sitting upon this threshold stone one morning in early summer, I permitted my eyes to scan the tiny patch of bare ground at my feet, and what I observed during a very few moments suggested the present article as a good piece of missionary work in the cause of nature, and a suggestive tribute to the glory of the commonplace. The episodes which I shall describe represent the chronicle of a single day—in truth, of but a[Pg 59] few hours in that day—though the same events were seen in frequent repetition at intervals for months. Perhaps the most conspicuous objects—if, indeed, a hole can be considered an "object"—were those two ever-present features of every trodden path and bare spot of earth anywhere, ant-tunnels and that other circular burrow, about the size of a quill, usually associated, and which is also commonly attributed to the ants.

As I sat upon my stone step that morning, I counted seven of these smooth clean holes within close range, three of them hardly more than an inch apart. They penetrated beyond the vision, and were evidently very deep. Knowing from past experience the wary tenant which dwelt within them, I adjusted myself to a comfortable attitude, and remaining perfectly motionless, awaited developments. After a lapse of possibly five minutes, I suddenly discovered that I could count but five holes; and while recounting to make sure, moving my eyes as slowly as possible, my numeration was cut short at four. In another moment two more had disappeared, and the remaining two immediately followed in obscurity, until no vestige of a hole of any kind was to be seen. The ground appeared absolutely level and unbroken. Were it not for the circular depression, or "door-[Pg 60]yard," around each hole, their location would, indeed, have been almost impossible. A slight motion of one of my feet at this juncture, however, and, presto! what a change! Seven[Pg 61] black holes in an instant! And now another wait of five minutes, followed by the same hocus-pocus, and the black spots, one by one, vanishing from sight even as I looked upon them. But let us keep perfectly quiet this time and examine the suspected spots more carefully. Locating the position of the hole by the little circular "door-yard," we can now certainly distinguish a new feature, not before noted, at the centre of each—two sharp curved prongs, rising an eighth of an inch or more above the surface and widely extended.

The Door-step Arena, with its Pitfalls

The Door-step Arena, with its Pitfalls

What a danger signal to the creeping insect innocent in its neighborhood! How many a tragedy in the bug world has been enacted in these inviting, clean-swept little door-yards—these pitfalls, so artfully closed in order that their design may be the more surely effective. As I have said, these tunnels are commonly called "ant-holes," perhaps with some show of reason. It is true that ants occasionally are seen to go into them, but not by their own choice, while the most careful observer will wait in vain to see the ant come out again. Here at the edge of the grass we see one approaching now—a big red ant from yonder ant-hill. He creeps this way and that, and anon is seen trespassing in the precincts of the unhealthy court. He crosses its centre,[Pg 62] when, click! and in an instant his place knows him no more, and a black hole marks the spot where he met his fate, which is now being duly celebrated in a supplementary fête several inches belowground.

A poor unfortunate green caterpillar, which, with a very little forcible persuasion in the interest of science, was induced to take a short-cut across this nice clean space of earth to the clover beyond, was the next martyr to my passion for original observation. He might have pursued his even course across the arena unharmed, but he too persisted in trespassing, and suddenly was seen to transform from a slow creeping laggard into the liveliest acrobat, as he stood on his head and apparently dived precipitately into the hole which suddenly appeared beneath him. A certain busy fly made itself promiscuous in the neighborhood, more than once to the demoralization of my necessary composure, as it crept persistently upon my nose. What was my delight when I observed the fickle insect in curious contemplation of a pair of calipers at the centre of one of the little courts! But, whether from past experience or innate philosophy in the insect I know not, the pronged hooks, though coming together with a click once or twice at the near[Pg 63] proximity of the tempter, failed in their opportunity, and the trap was soon seen carefully set again, flush with the ground at the mouth of the burrow.

The contrast of these clean-swept door-yards with the mound of débris of the ants suggested an investigation of the comparative methods of burrowing and the disposal of the excavated material. Here is a hole evidently some inches in depth; what, then, has become of the earth removed? Suiting action to the thought, I swept into the openings of two or three of the holes quite a quantity of loose earth scraped from the close vicinity, and thus completely obliterated the opening of burrow, door-yard and all.

I awaited in vain any sign of returning activity at the surface, and, my patience being somewhat taxed, I entered my studio, where I remained for a quarter of an hour, perhaps. Upon stealing cautiously to the doorway, I observed all the obliterated holes had reappeared, and upon taking once more my original position I was soon rewarded with a demonstration of the method of excavation. After a moment or two a pellet of earth seemed suddenly to rise from within the cavity, and when arrived at the level of the ground was suddenly shot forth a distance of five[Pg 64] or six inches, as though thrown from a tiny round flat shovel, which suddenly flashed from the opening, and as quickly retired to its depths, though not without a momentary display of two curved prongs and a formidable show of spider-like legs.

After a short lapse of time the act was repeated, this time a tiny stone being brought to the surface, and, after a brief pause at the doorway, was jerked to a distance as from a catapult. I now concluded to try the power of this propelling force, and taking a small stone, about three-quarters of an inch in length and a quarter-inch in thickness, laid it over the mouth of the tunnel. A few minutes passed, when I noticed a slight motion in the stone, immediately followed by a forcible ejectment, which threw it nearly an inch, the propelling instrument retiring so quickly into the burrow beneath as to scarce afford a glimpse. The stone appeared almost to have jumped voluntarily.

For an hour or more the bombardment of pellets and small stones continued from the mouth of the pit, until a small pile of the spent ammunition had accumulated at several inches distance, and at length the hole entirely disappeared, the earth in its vicinity presenting an apparently level surface—an armed peace, in truth, with the[Pg 65] two touchy curved calipers on duty, as already described.

Fishing for Tigers

Fishing for Tigers

Following the hint of past experience, I concluded to explore the depths of one of these tunnels, especially as I desired a specimen of the wily tenant for portraiture; and it is, indeed, an odd fish that one may land on the surface if he be sufficiently alert in his angling. No hook or bait is required in this sort of fishing. Taking a long culm of timothy-grass, I inserted the tip into the burrow. It progressed without impediment two, three, six, eight inches, and when at the depth of about ten inches appeared to touch bottom, which in this kind of angling is the signal for a "strike" and the landing of the game. Instantly withdrawing the grass culm, I[Pg 66] found my fish at its tip, from which he quickly dropped to the ground. His singular identity is shown in my illustration—an uncouth nondescript among grubs. His body is whitish and soft, with a huge hump on the lower back armed with two small hooks. His enormous head is now seen to be apparently circular in outline, and we readily see how perfectly it would fill the opening of the burrow like an operculum. But a close examination shows us that this operculum is really composed of two halves, on two separate segments of the body, the segment at the extremity only being the true head, armed with its powerful, sharp, curved jaws. As he lies there sprawling on his six spider-like legs, we may now easily test the skill of his trap, and gain some idea of his voracious personality.

If with the point of our knife-blade, holding it in the direction of the insect's body, we now touch its tail, what a display of vehement acrobatics! Instantly the agile body is bent backward in a loop, while the teeth fasten to the knife-blade with an audible click. If our finger-tip is substituted for the steel, the force of the stroke and the prick and grip of the jaws are unpleasantly perceptible.

In order to fully comprehend the make-up of this curious cave-dweller we must turn biologists for the moment. He must be considered from[Pg 67] the evolutionary stand-point, or at least from the stand-point of comparative anatomy.

The first discovery that we make is that as we now see him he is crawling on his back—a fact which seems to have escaped his biographers heretofore. It is, in truth, the underside of his head which is uppermost at the mouth of the burrow, and his six zigzag legs are distorted backward to enable him to keep this contrary position. And what a hideous monster is this, whose flat, metallic, dirt-begrimed face stares skyward from this circular burrow! Well might it strike terror to the heart of the helpless insect which should suddenly find himself confronted by the motionless stare of these four cruel, glistening black eyes! But he is now a "fish out of water," and is about as helpless, nature never having intended him to be seen outside of his burrow—at least, in this present form. There he dwells, setting his circular trap at the mouth of his pitfall, and waiting for the voluntary sacrifice of his insect neighbors to fill his maw.

Tiger-beetle

Tiger-beetle

But this uncouth shape, which so courts obscurity, is not always thus so reasonably retiring. A few glass tumblers inverted above as many of these larger holes during the summer will intercept the winged sprite into which he is shortly to[Pg 68] be transfigured—a brilliant metallic-hued beetle, perhaps flashing with bronzy gold or glittering like an emerald—the beautiful cicindela, or tiger-beetle, known to the entomologist as the most agile winged among the coleopterous tribe; known to the populace, perhaps, simply as a bright glittering fly that revels in the hot summer sands of the sea-shore or dusty country road, making its short spans of glittering flight from the very feet of the observer.

If we capture one of them with our butterfly-net he will be found to bear a general resemblance to the portrait here indicated—a slender-legged, proportionably large-headed beetle, with formidable jaws capable of wide extension, and re-enforced by an insatiate carnivorous hunger inherited from his former estate.

It will thus be seen that all the holes which we observe in the ground are not ant-holes; nor, indeed, are they monopolized by the tiger-beetles. There were other tunnels which I saw dug in my square yard of earth on that morning, which, while not of quite such depth, represented equally deep-laid plans.

While observing my cicindelas on that morn[Pg 69]ing, my attention was at length diverted by an old friend of mine, who gave promise of much entertainment—a tiny black wasp, whose restless, rapid, zigzag, apparently aimless wanderings over the ground brought him into continual danger of contact with the snatching jaws of the cave-dwelling tiger, from which, however, he somehow escaped, though I distinctly heard the occasional clicking of the eager jaws.

The Spider Victim

The Spider Victim

With short abrupt flights or agile runs of a few inches, accompanied by nervous periodic flirts of the folded wings, the insect had covered pretty much of the ground in a short time, until she at length appeared to have discovered the object of her search, as she withdrew from beneath a sorrel leaf a big fat spider several times as large as herself. Its legs were folded beneath its body, and it was perfectly plain that this was not the first time that it had been in the toils of the wasp, which had evidently stung it into submission and stupor some minutes previous. Tugging bravely at her charge, the little black Amazon dragged her burden nimbly over the ground, pulling it after her in entire disregard of obstacles, now this way, now that, with the same exasperating disregard of eternity which she at first displayed, and at length deposited it on the top of a little flat weed, where it[Pg 70] was left, while for five minutes more she pursued the same zigzag, apparently senseless meandering over the entire field of earth. Now she seems again to stumble upon her neglected prey, and taking it once more in her formidable jaws, she lugs it again for a long helter-skelter jaunt, this time depositing it in the neighborhood of a hole, which at first sight might have been considered an "ant-hole," from the débris which lay scattered about in its vicinity. After considerable needless delay, she is seen for once motionless, so far as her legs are concerned, but with her head over the tunnel, while, with flipping wings and rapidly waving antennæ, she investigates its depths. Satisfied that all is well, she again reaches her drowsy spider, by a tangled circuit of about a quarter of a mile—wasp measurement—and taking the victim in her teeth for the third time, finally succeeds in reaching the burrow, into which, without a parti[Pg 71]cle of ceremony, she instantly retreats, dragging her helpless burden after her. Both wasp and spider are soon out of sight, and so remain perhaps for a space of two minutes, when the tips of the nervous antennæ appear at the doorway and the wasp emerges. What now follows is most curious and interesting. With an energy and directness in striking contrast to her previous proceedings, she proceeds to fill the cavity, biting the earth with her mandibles, and with her spiked legs kicking and shoving in the loose soil thus collected, ever and anon backing up to the hole and inserting the tip of her tail to force down the mass. As the filling is nearly completed, with the fore feet and jaws the surrounding earth is scraped for material, which she immediately proceeds to pack by a rhythmic tamping motion of the tail, until, at the end of five minutes, perhaps, the ground-level is finally reached, the surface smoothed, and no sign remains to mark the grave of the stupefied spider victim.

Filling the Spider's Grave

Filling the Spider's Grave

Not an hour after this episode I was treated to[Pg 72] another of even more interest. As I took my seat upon the door-step I started into flight a big black wasp, upon whose doings I had evidently been intruding.

This wasp was much larger than the one just described, being about an inch in length. Its wings were pale brown and its body jet-black, with sundry small yellowish spots about the thorax. But its most conspicuous feature, and one which would ever fix the identity of the creature, was the long, slender, wire-like waist, occupying a quarter of the length of its entire body.

In a moment or two the wasp had returned, and stood at the mouth of the shallow pit. Eying me intently for a space, and satisfied that there was nothing to fear, she dived into the hollow and began to excavate, turning round and round as she gnawed the earth at the bottom, and shovelling it out with her spiked legs. Now and then she would back out of the burrow to reconnoitre, and her alert attitude at such times was very amusing—her antennæ drooping towards the burrow and in incessant motion; the abdomen on its long wire stem bobbing up and down at regular intervals, accompanied by a flipping motion of the wings; the short fore legs, one or both, upraised with comical effect.[Pg 73]

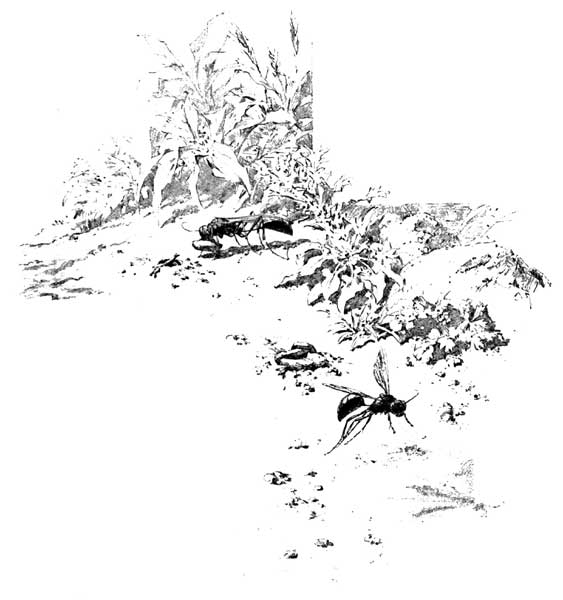

Black Digger-wasp

Black Digger-wasp

As the tunnel was deepened a new method of excavation was employed. It has now reached a depth of an[Pg 74] inch, only the extremity of the insect's body appearing, and the two hindermost legs clinging to surrounding earth for purchase. The deep digging is now accompanied by a continual buzzing noise, resembling that produced by a bluebottle fly held captive between one's fingers. At intervals of about ten or fifteen seconds the wasp would quickly back out of the burrow, bringing a load of sand, which it held between the back of the jaws and its thorax, sustained at the sides by the two upraised fore legs. After a moment's pause with this burden, the insect would make a sudden short darting flight of a foot or more in a quick circuit, hurling the sand a yard or more distant from the burrow. At the end of about fifteen minutes the burrow was sunk to the depth of an inch and a half, the wasp entirely disappearing, and indicated only by the continuous buzzing.

At this time, the luncheon hour having arrived, I was obliged to pause in my investigations, and in order to be able to locate the burrow in the event of its obliteration by the wasp before my return, I scratched a circle in the hard dirt, the hole being at its exact centre.[Pg 75]

Black Digger-wasp and His Victim, Showing the Egg of the Wasp Attached

Black Digger-wasp and His Victim, Showing the Egg of the Wasp Attached

Upon my return, an hour later, I was met with a surprise. The ways of the digger-wasps of various species were familiar, but I now noted a feature of wasp-engineering which indeed seems to await its chron[Pg 76]icler, as I find no mention of it by the wasp-historians.

At the exact centre of my circle, in place of a cavity, I now found a tiny pile of stones, supported upon a small stick and fragment of leaf, which had been first drawn across the opening.

This was evidently a mere temporary protection of the burrow, I reasoned, while the digger had departed in search of prey, and my surmise was soon proved to be correct, as I observed the wasp, with bobbing abdomen and flipping wings, zigzagging about the vicinity. Presently disappearing beneath a small plantain leaf, she quickly emerged, drawing behind her not a spider, as in the case of her smaller predecessor, but a big green caterpillar, nearly double her own length, and as large around as a slate-pencil—a peculiar, pungent, waspy-scented species of "puss-moth" larva, which is found on the elm, and with which I chanced to be familiar.

The victim being now ready for burial, the wasp sexton proceeded to open the tomb. Seizing one stone after another in her widely opened jaws, they were scattered right and left, when, with apparent ease and prompt despatch, the listless larva was drawn towards the burrow, into whose depths he soon disappeared. Then, after a short[Pg 77] and suggestive interval, followed the emergence of the wasp, and the prompt filling in of the requisite earth to level the cavity, much as already described, after which the wasp took wing and disappeared, presumably bent upon a repetition of the performance elsewhere. But she had not simply buried this caterpillar victim, nor was the caterpillar dead, for these wasp cemeteries are, in truth, living tombs, whose apparently dead inmates are simply sleeping, narcotized by the venom of the wasp sting, and thus designed to afford fresh living food for the young wasp grub, into whose voracious care they are committed.

By inserting my knife-blade deep into the soil in the neighborhood of this burrow I readily unearthed the buried caterpillar, and disclosed the ominous egg of the wasp firmly imbedded in its body. The hungry larva which hatches from this egg soon reaches maturity upon the all-sufficient food thus stored, and before many weeks is transformed to the full-fledged, long-waisted wasp like its parent.

The disproportion in the sizes of the predatory wasps and their insect prey is indeed astonishing. The great sand-hornet selects for its most frequent victim the buzzing cicada, or harvest-fly, an insect much larger than itself, and which it carries[Pg 78] off to its long sand tunnels by short flights from successive elevated points, such as the limbs of trees and summits of rocks, to which it repeatedly lugs its clumsy prey. In the present instance the contrast between the slight body of the wasp and the plump dimensions of the caterpillar was even more marked, and I determined to ascertain the proportionate weight of victor and victim. Constructing a tiny pair of balances with a dead grass stalk, thread, and two disks of paper, I weighed the wasp, using small square pieces of paper of equal size as my weights. I found that the wasp exactly balanced four of the pieces. Removing the wasp and substituting the caterpillar, I proceeded to add piece after piece of the paper squares until I had reached a total of twenty-eight, or seven times the number required by the wasp, before the scales balanced. Similar experiments with the tiny black wasp and its spider victim showed precisely the same proportion, and the ratio was once increased eight to one in the instance of another species of slender orange-and-black-bodied digger which I subsequently found tugging its caterpillar prey upon my door-step patch.[Pg 79]

Protecting the Burrow while Searching for Prey

Protecting the Burrow while Searching for Prey

The peculiar feature of the piling of stones above the completed burrow was not a mere individual accomplishment of my wire-waisted wasp. On several occasions since I have observed the same manœuvre, which is doubtless the regular procedure with this and other species. The smaller orange-spotted wasp just alluded to indicated to me the location of her den by pausing suggestively in front of a tiny cairn. In this instance a small flat stone, considerably larger than the tunnel, had been laid over the opening, and the others piled upon it. On two[Pg 80] occasions I have surprised this same species of wasp industriously engaged in the selection of a suitable flat foundation-stone with which to cover her burrow: her widely extended slender jaws enable her to grasp a pebble nearly a third of an inch in width.

In my opening vignette I have indicated two other door-step neighbors which bore my industrious wasps company in their arena of one square yard. To the left, surrounding a grass stem, will be seen an object which is unpleasantly familiar to most country folks—that salivary mass variously known by the libellous names of "snake-spit," "cow-spit," "cuckoo-spit," "toad-spit," and "sheep-spit," or the inelegant though expressive substitute of "gobs." The foam-bath pavilion of the "spume-bearer," with his glittering, bubbly domicile of suds, is certainly familiar to most of my readers; but comparatively few, I find, have cared to investigate the mysterious mass, or to learn the identity of the proprietor of the foamy lavatory.

The common name of "cow-spit," with the implied indignity to our "rural divinity," becomes singularly ludicrous when we observe not only the frequent generous display of the suds samples, thousands upon thousands in a single small[Pg 81] meadow, but the further fact that each mass is so exactly landed upon the central stalk of grass or other plant—"spitted" through its centre, as it were. The true expectorator is within, laved in his own home-made suds. If we care to blow or scrape off the bubbles, we readily disclose him—- a green speckled bug, about a third of an inch in length in larger specimens, with prominent black eyes, and blunt, wedge-shaped body.

The "Cow-spit" Mystery Disclosed

The "Cow-spit" Mystery Disclosed

In the appended sketch I have indicated two views of him, back and profile, creeping upon a grass stalk. A glance at the insect tells the entomologist just where to place him, as he is plainly allied to the cicadæ, and thus belongs to the order Hemiptera, or family of "bugs," which implies, among other things, that the insect possesses a "beak for sucking." To what extent this tiny soaker is possessed of such a beak may be inferred from the amount of moisture with which[Pg 82] he manages to inundate himself, which has all been withdrawn from the stem upon which he has fastened himself, and finally exuded from the pores of his body.

This is the spume-bearer, Aprophora, in his first or larval estate, which continues for a few weeks only. Erelong he will graduate from these ignominious surroundings, and we shall see quite another sort of creature—an agile, pretty atom, one of which I have indicated in flight, its upper wings being often brilliantly colored, and re-enforced by a pair of hind feet which emulate those of the flea in their powers of jumping, which agility has won the insect the popular name of "froghopper." They abound in the late summer meadow, and hundreds of them may be captured by a few sweeps of a butterfly-net among the grass.