Title: The Substance of a Journal During a Residence at the Red River Colony, British North America

Author: John West

Release date: August 6, 2007 [eBook #22254]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by A www.PGDP.net Volunteer, Riikka Talonpoika

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by the Canadian Institute for

Historical Microreproductions (www.canadiana.org))

A JOURNAL.

PRINTED BY L. B. SEELEY,

WESTON GREEN, THAMES DITTON.

THE

SUBSTANCE OF A JOURNAL

DURING A RESIDENCE

AT THE RED RIVER COLONY,

British North America;

AND FREQUENT EXCURSIONS

AMONG THE NORTH-WEST AMERICAN INDIANS,

IN THE YEARS 1820, 1821, 1822, 1823.

By

JOHN WEST, M. A.

LATE CHAPLAIN TO THE HON. THE HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY.

PRINTED FOR L. B. SEELEY AND SON,

FLEET STREET, LONDON.

MDCCCXXIV.

TO THE

REV. HENRY BUDD, M. A.

CHAPLAIN TO BRIDEWELL HOSPITAL, MINISTER OF BRIDEWELL PRECINCT,

AND RECTOR OF WHITE ROOTHING, ESSEX,

AS A TESTIMONY

OF GRATITUDE FOR HIS KINDNESS AND FRIENDSHIP,

AND OF HIGH ESTEEM FOR HIS UNWEARIED EXERTIONS IN EVERY

CAUSE OF BENEVOLENCE AND ENLIGHTENED ENDEAVOUR

TO PROMOTE THE BEST INTERESTS OF MAN,

THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED

BY THE AUTHOR.

| Transcriber's Notes: |

| Variant spellings have been retained. |

| The Errata have been moved to the beginning of the text. |

| To improve readability, dashes between entries in the Table of Contents and in chapter subheadings have been converted to periods. |

ERRATA.

| Page 1, | line 7, for Salteaux, read Saulteaux. |

| 21, | line 6, for 1820, read 1817. |

| 36, | line 2 from bottom, for spiritous, read spirituous. |

| 57, | line 24, for forty, read sixty. |

| 70, | bottom of the page, for Heritics, read Heretics. |

| 131, | line 24, for Loom, read Loon. |

| 156, | line 3, for a, read no. |

| 180, | line 3, for intrepedity, read intrepidity. |

| 204, | line 19, for intention it, read intention of it. |

PREFACE.

We live in a day when the most distant parts of the earth are opening as the sphere of Missionary labours. The state of the heathen world is becoming better known, and the sympathy of British Christians has been awakened, in zealous endeavours to evangelize and soothe its sorrows. In these encouraging signs of the times, the Author is induced to give the following pages to the public, from having traversed some of the dreary wilds of North America, and felt deeply interested in the religious instruction and amelioration of the condition of the natives. They are wandering, in unnumbered tribes, through vast wildernesses, where generation after generation have passed away, in gross ignorance and almost brutal degradation.

Should any information he is enabled to give excite a further Christian sympathy, and more active benevolence in their behalf, it will truly rejoice his heart: and his prayer to God, is, that the Aborigines of a British Territory, may not remain as outcasts from British Missionary exertions; but may be raised through their instrumentality, to what they are capable of enjoying, the advantages of civilized and social life, with the blessings of Christianity.

September, 1824.

CONTENTS.

PAGE.

Chapter I.—Departure from England. Arrival at the Orkney Isles. Enter Hudson's Straits. Icebergs. Esquimaux. Killing a Polar Bear. York Factory. Embarked for the Red River Colony. Difficulties of the Navigation. Lake Winipeg. Muskeggowuck, or Swamp Indians. Pigewis, a chief of the Chipewyans, or Saulteaux Tribe. Arrival at the Red River. Colonists. School established. Wolf dogs. Indians visit Fort Douglas. Design of a Building for Divine Worship1

Chapter II.—Visit the School. Leave the Forks for Qu'appelle. Arrival at Brandon House. Indian Corpse staged. Marriages at Company's Posts. Distribution of the Scriptures. Departure from Brandon House. Encampment. Arrival at Qu'appelle. Character and Customs of Stone Indians. Stop at some Hunter's Tents on return to the Colony. Visit Pembina. Hunting Buffaloes. Indian address. Canadian Voyageurs. Indian Marriages. Burial Ground. Pemican. Indian Hunter sends his son to be educated. Mosquitoes. Locusts28

Chapter III.—Norway House. Baptisms. Arrival at York Factory. Swiss Emigrants. Auxiliary Bible Society formed. Boat wrecked. Catholic Priests. Sioux Indians killed at the Colony. Circulation of the Scriptures among the Colonists. Scarcity of Provisions. Fishing under the Ice. Wild Fowl. Meet the Sioux Indians at Pembina. They scalp an Assiniboine. War dance. Cruelly put to death a Captive Boy. Indian expression of gratitude for the Education of his Child. Sturgeon64

Chapter IV.—Arrival of Canoe from Montreal. Liberal Provision for Missionary Establishment. Manitobah Lake. Indian Gardens. Meet Captain Franklin and Officers of the Arctic Expedition at York Factory. First Anniversary of the Auxiliary Bible Society. Half-Caste Children. Aurora Borealis. Conversation with Pigewis. Good Harvest at the Settlement, and arrival of Cattle from United States. Massacre of Hunters. Produce of Grain at Colony94

Chapter V.—Climate of Red River. Thermometer. Pigewis's Nephew. Wolves. Remarks of General Washington. Indian Woman shot by her son. Sufferings of Indians. Their notions of the Deluge. No visible object of adoration. Acknowledge a Future Life. Left the Colony for Bas la Rivière. Lost on Winipeg Lake. Recover the Track, and meet an intoxicated Indian. Apparent facilities for establishing Schools West of Rocky Mountains. Russians affording Religious instruction on the North West Coast of North America. Rumours of War among the surrounding Tribes with the Sioux Indians110

Chapter VI.—Progress of Indian Children in reading. Building for Divine Worship. Left the Colony. Arrival at York Fort. Departure for Churchill Factory. Bears. Indian Hieroglyphics. Arrival at Churchill. Interview with Esquimaux. Return to York Factory. Embark for England. Moravian Missionaries. Greenland. Arrival in the Thames150

DIRECTIONS TO THE BINDER.

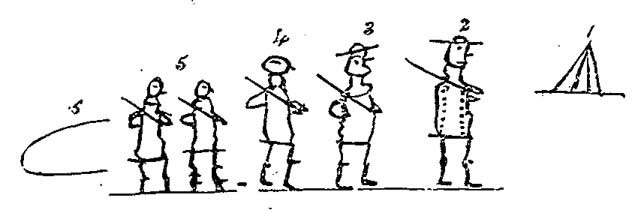

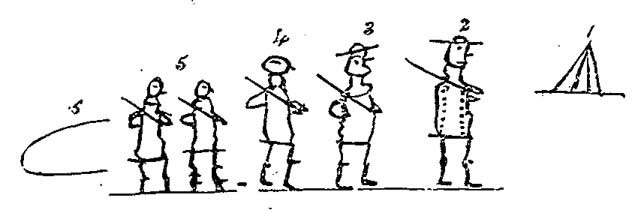

1. The engraving of meeting the Indians, to face the title page.

2. Scalping the Indians to face page 85.

3. The Protestant Church, to face page 155.

CHAPTER I.

DEPARTURE FROM ENGLAND. ARRIVAL AT THE ORKNEY ISLES. ENTER HUDSON'S STRAITS. ICEBERGS. ESQUIMAUX. KILLING A POLAR BEAR. YORK FACTORY. EMBARKED FOR THE RED RIVER COLONY. DIFFICULTIES OF THE NAVIGATION. LAKE WINIPEG. MUSKEGGOWUCK, OR SWAMP INDIANS. PIGEWIS, A CHIEF OF THE CHIPPEWAYS OR SALTEAUX TRIBE. ARRIVAL AT THE RED RIVER. COLONISTS. SCHOOL ESTABLISHED. WOLF-DOGS. INDIANS VISIT FORT DOUGLAS. DESIGN OF A BUILDING FOR DIVINE WORSHIP.

On the 27th of May, 1820, I embarked at Gravesend, on board the Honourable Hudson's Bay Company's ship, the Eddystone; accompanied by the ship, Prince of Wales, and the Luna brig, for Hudson's Bay. In my appointment as Chaplain to the Company, my instructions were, to reside at the Red River Settlement, and under the encouragement and aid of the Church Missionary Society, I was to seek the instruction, and endeavour to meliorate the condition of the native Indians.

The anchor was weighed early on the following morning, and sailing with a fine breeze, the sea soon opened to our view. The thought that I was now leaving all that was dear to me upon earth, to encounter the perils of the ocean, and the wilderness, sensibly affected me at times; but my feelings were relieved in the sanguine hope that I was borne on my way under the guidance of a kind protecting Providence, and that the circumstances of the country whither I was bound, would soon admit of my being surrounded with my family. With these sentiments, I saw point after point sink in the horizon, as we passed the shores of England and Scotland for the Orkneys.

We bore up for these Isles on the 10th of June, after experiencing faint and variable winds for several days: and a more dreary scene can scarcely be imagined than they present to the eye, in general. No tree or shrub is visible; and all is barren except a few spots of cultivated ground in the vales, which form a striking contrast with the barren heath-covered hills that surround them. These cultivated spots mark the residence of the hardy Orkneyman in a wretched looking habitation with scarcely any other light, (as I found upon landing on one of the islands) than from a smoke hole, or from an aperture in the wall, closed at night with a tuft of grass. The calf and pig were seen as inmates, while the little furniture that appeared, was either festooned with strings of dried fish, or crossed with a perch for the fowls to roost on.

A different scene, however, presented itself, as we anchored the next day in the commodious harbour of Stromness. The view of the town, with the surrounding cultivated parts of the country, and the Hoy Hill, is striking and romantic, and as our stay here was for a few days, I accepted an invitation to the Manse, from the kind and worthy minister of Hoy, and ascended with him the hill, of about 1620 feet high.

The sabbath we spent at sea was a delight to me, from the arrangement made by the captain for the attendance of the passengers and part of the crew on divine worship, both morning and afternoon. Another sabbath had now returned, and the weather being fair, all were summoned to attend on the quarter deck. We commenced the service by singing the Old Hundredth Psalm, and our voices being heard by the crews of several ships, lying near to us at anchor, they were seen hurrying on deck from below, so as to present to us a most interesting and gratifying sight—

""We stood, and under open sky adored

The God, that made both 'seas,' air, earth, and heaven.""

There appeared to be a solemn impression; and I trust that religion was felt among us as a divine reality.

June 22.—The ships got under weigh to proceed on our voyage; and as we passed the rugged and broken rocks of Hoy Head, we were reminded of the fury of a tempestuous ocean, in forming some of them into detached pillars, and vast caverns; while they left an impression upon the mind, of desolation and danger. We had not sailed more than one hundred miles on the Atlantic before it blew a strong head wind, and several on board with myself were greatly affected by the motion of the ship. It threw me into such a state of languor, that I felt as though I could have willingly yielded to have been cast overboard, and it was nearly a week before I was relieved from this painful sensation and nausea, peculiar to sea sickness.

Without any occurrence worthy of notice we arrived in Davis's Straits on the 19th of July, where Greenland ships are sometimes met with, returning from the whale fishery, but we saw not a single whaler in this solitary part of the ocean. The Mallemuk, found in great numbers off Greenland, and the ""Larus crepidatus,"" or black toed gull, frequently visited us; and for nearly a whole day, a large shoal of the ""Delphinus deductor,"" or leading whale, was observed following the ship. The captain ordered the harpoons and lances to be in readiness in case we fell in with the great Greenland whale, but nothing was seen of this monster of the deep.

In approaching Hudson's straits, we first saw one of those beautiful features in the scenery of the North, an Iceberg, which being driven with vast masses of ice off Cape Farewell, South Greenland, are soon destroyed by means of the solar heat, and tempestuous force of the sea. The thermometer was at 27°#176; on the night of the 22nd, with ice in the boat; and in the afternoon we saw an iceblink, a beautiful effulgence or reflection of light over the floating ice, to the extent of forty or fifty miles. The next day we passed Resolution Island, Lat. 61°#176; 25', Long. 65°#176; 2' and all was desolate and inhospitable in the view over black barren rocks, and in the aspect of the shore. This being Sunday, I preached in the morning, catechized the young people in the afternoon, and had divine service again in the evening, as was our custom every sabbath in crossing the Atlantic, when the weather would permit: and it afforded me much pleasure to witness the sailors at times in groups reading the life of Newton, or some religious tracts which I put into their hands. The Scotch I found generally well and scripturally informed, and several of them joined the young people in reading to me the New Testatament, and answering the catechetical questions. In our passage through the Straits, our progress was impeded by vast fields of ice, and icebergs floating past us in every form of desolate magnificence. The scene was truly grand and impressive, and mocks imagination to describe. There is a solemn and an overwhelming sensation produced in the mind, by these enormous masses of snow and ice, not to be conveyed in words. They floated by us from one to two hundred feet above the water, and sometimes of great length, resembling huge mountains, with deep vallies between, lofty cliffs, and all the imposing objects in nature, passing in silent grandeur, except at intervals, when the fall of one was heard, or the crashing of the ice struck the ear like the noise of distant thunder.

When nearly off Saddle Back, with a light favourable breeze, and about ten miles from the shore, the Esquimaux who, visit the Straits during summer, were observed with their one man skin canoes, followed by women in some of a larger size, paddling towards the ship. No sooner was the sail shortened than we were surrounded by nearly two hundred of them: the men raising their paddles as they approached us, shouting with much exultation, 'chimo! chimo! pillattaa! pillattaa!' expressions probably of friendship, or trade. They were particularly eager to exchange all that they apparently possessed, and hastily bartered with the Eddystone, blubber, whalebone, and seahorse teeth, for axes, saws, knives, tin kettles, and bits of old iron hoop. The women presented image toys, made from the bones and teeth of animals, models of canoes, and various articles of dress, made of seal skins, and the membranes of the abdomen of the whale, all of which displayed considerable ingenuity and neatness, and for which they received in exchange, needles, knives, and beads. It was very clear that European deception had reached them, from the manner in which they tenaciously held their articles till they grasped what was offered in barter for them; and immediately they got the merchandise in possession, they licked it with their tongues, in satisfaction that it was their own. The tribe appeared to be well-conditioned in their savage state, and remarkably healthy. Some of the children, I observed, were eating raw flesh, from the bones of animals that had been killed, and given them by their mothers, who appeared to have a strong natural affection for their offspring. I threw one of them a halfpenny, which she caught; and pointing to the child she immediately gave it to him with much apparent fondness. It has been supposed that in holding up their children, as is sometimes the case, it is for barter, but I should rather conclude that it is for the purpose of exciting commiseration, and to obtain some European article for them. A few of the men were permitted to come on board, and the good humour of the captain invited one to dance with him: he took the step with much agility and quickness, and imitated every gesture of his lively partner. The breeze freshening, we soon parted with this barbarous people, and when at a short distance from the ship, they assembled in their canoes, each taking hold of the adjoining one, in apparent consultation, as to what bargains they had made, and what articles they possessed, till a canoe was observed to break off from the group, which they all followed for their haunts along the shores of Terra Neiva, and the Savage Islands. Having a copy of the Esquimaux Gospels from the British and Foreign Bible Society, it was my wish to have read part of a chapter to them, with a view to ascertain, if possible, whether they knew of the Moravian Missionary establishment at Nain, on the Labrador coast; but such was the haste, bustle, and noise of their intercourse with us, that I lost the opportunity. Though they have exchanged articles in barter for many years, it is not known whether they are from the Labrador shore on a summer excursion for killing seals, and the whale fishery, or from the East main coast, where they return and winter.

The highest point of latitude we reached in our course, was 62°#176; 44'—longitude 74°#176; 16', and when off Cape Digges we parted company with the Prince of Wales, as bound to James's Bay. We stood on direct for York Factory, and when about fifty miles from Cary Swan's Nest, the chief mate pointed out to me a polar bear, with her two cubs swimming towards the ship. He immediately ordered the jolly-boat to be lowered, and asked me to accompany him in the attempt to kill her. Some axes were put into the boat, in case the ferocious animal should approach us in the attack; and the sailors pulled away in the direction she was swimming. At the first shot, when within about one hundred yards, she growled tremendously, and immediately made for the boat; but having the advantage in rowing faster than she could swim, our guns were reloaded till she was killed, and one of the cubs also accidentally, from swimming close to the mother; the other got upon the floating carcase, and was towed to the side of the ship, when a noose was put around its neck, and it was hauled on board for the captain to take with him alive, on his return to England.

August 3.—We fell in with a great deal of floating ice, the weather was very foggy, and the thermometer at freezing point. The ship occasionally received some heavy blows, and with difficulty made way along a vein of water. On the 5th we were completely blocked in with ice, and nothing was to be seen in every part of the horizon, but one vast mass, as a barrier to our proceeding. It was a terrific, and sublime spectacle; and the human mind cannot conceive any thing more awful, than the destruction of a ship, by the meeting of two enormous fields of ice, advancing against each other at the rate of several miles an hour. ""It may easily be imagined,"" says Captain Scoresby, ""that the strongest ship can no more withstand the shock of the contact of two fields, than a sheet of paper can stop a musket-ball. Numbers of vessels since the establishment of the Whale Fishery have been thus destroyed. Some have been thrown upon the ice. Some have had their hulls completely thrown open, and others have been buried beneath the heaped fragments of the ice.""—

Sunday, the 6th.—Text in the morning 1st book Samuel, 30th chapter, latter part of the 6th verse. The weather was very variable, with much thunder and lightening; which was awful and impressive. On the 12th the thermometer was below freezing point, and the rigging of the ship was covered with large icicles. Intense fogs often prevailed, but of very inconsiderable height. They would sometimes obscure the hull of the ship, when the mast head was seen, and the sun was visible and effulgent.

In the evening of the 13th, the sailors gave three cheers, as we got under weigh on the opening of the ice by a strong northerly wind, and left the vast mass which had jammed us in for many days. The next day we saw the land, and came to the anchorage at York Flatts the following morning, with sentiments of gratitude to God for his protecting Providence through the perils of the ice and of the sea, and for the little interruption in the duties of my profession from the state of the weather, during the voyage.

I was kindly received by the Governor at the Factory, the principal depôt of the Hudson's Bay Company, and on the sabbath, every arrangement was made for the attendance of the Company's servants on divine worship, both parts of the day. Observing a number of half-breed children running about, growing up in ignorance and idleness; and being informed that they were a numerous offspring of Europeans by Indian women, and found at all the Company's Posts; I drew up a plan, which I submitted to the Governor, for collecting a certain number of them, to be maintained, clothed, and educated upon a regularly organized system. It was transmitted by him to the Committee of the Hudson's Bay Company, whose benevolent feelings towards this neglected race, had induced them to send several schoolmasters to the country, fifteen or sixteen years ago; but who were unhappily diverted from their original purpose, and became engaged as fur traders.

During my stay at this post, I visited several Indian families, and no sooner saw them crowded together in their miserable-looking tents, than I felt a lively interest (as I anticipated) in their behalf. Unlike the Esquimaux I had seen in Hudson's Straits, with their flat, fat, greasy faces, these 'Swampy Crees' presented a way-worn countenance, which depicted ""Suffering without comfort, while they sunk without hope."" The contrast was striking, and forcibly impressed my mind with the idea, that Indians who knew not the corrupt influence and barter of spirituous liquors at a Trading Post, were far happier, than the wretched-looking group around me. The duty devolved upon me, to seek to meliorate their sad condition, as degraded and emaciated, wandering in ignorance, and wearing away a short existence in one continued succession of hardships in procuring food. I was told of difficulties, and some spoke of impossibilities in the way of teaching them Christianity or the first rudiments of settled and civilized life; but with a combination of opposing circumstances, I determined not to be intimidated, nor to ""confer with flesh and blood,"" but to put my hand immediately to the plough, in the attempt to break in upon this heathen wilderness. If little hope could be cherished of the adult Indian in his wandering and unsettled habits of life, it appeared to me, that a wide and most extensive field, presented itself for cultivation in the instruction of the native children. With the aid of an interpreter, I spoke to an Indian, called Withaweecapo, about taking two of his boys to the Red River Colony with me to educate and maintain. He yielded to my request; and I shall never forget the affectionate manner in which he brought the eldest boy in his arms, and placed him in the canoe on the morning of my departure from York Factory. His two wives, sisters, accompanied him to the water's edge, and while they stood gazing on us, as the canoe was paddled from the shore, I considered that I bore a pledge from the Indian that many more children might be found, if an establishment were formed in British Christian sympathy, and British liberality for their education and support.

I had to establish the principle, that the North-American Indian of these regions would part with his children, to be educated in white man's knowledge and religion. The above circumstance therefore afforded us no small encouragement, in embarking for the colony. We overtook the boats going thither on the 7th of September, slowly proceeding through a most difficult and laborious navigation. The men were harnessed to a line, as they walked along the steep declivity of a high bank, dragging them against a strong current. In many places, as we proceeded, the water was very shoal, and opposed us with so much force in the rapids, that the men were frequently obliged to get out, and lift the boats over the stones; at other times to unload, and launch them over the rocks, and carry the goods upon their backs, or rather suspended in slings from their heads, a considerable distance, over some of the portages. The weather was frequently very cold, with snow and rain; and our progress was so slow and mortifying, particularly up Hill River, that the boats' crews were heard to execrate the man who first found out such a way into the interior.

The blasphemy of the men, in the difficulties they had to encounter, was truly painful to me. I had hoped better things of the Scotch, from their known moral and enlightened education; but their horrid imprecations proved a degeneracy of character in an Indian country. This I lamented to find was too generally the case with Europeans, particularly so in their barbarous treatment of women. They do not admit them as their companions, nor do they allow them to eat at their tables, but degrade them merely as slaves to their arbitrary inclinations; while the children grow up wild and uncultivated as the heathen.

The scenery throughout the passage is dull and monotonous (excepting a few points in some of the small lakes, which are picturesque), till you reach the Company's post, Norway House; when a fine body of water bursts upon your view in Lake Winipeg. We found the voyage, from the Factory to this point, so sombre and dreary, that the sight of a horse grazing on the bank greatly exhilarated us, in the association of the idea that we were approaching some human habitation. Our provisions being short, we recruited our stock at this post; and I obtained another boy for education, reported to me as the orphan son of a deceased Indian and a half-caste woman; and taught him the prayer which the other used morning and evening, and which he soon learned:—""Great Father, bless me, through Jesus Christ."" May a gracious God hear their cry, and raise them up as heralds of his salvation in this truly benighted and barbarous part of the world.

It often grieved me, in our hurried passage, to see the men employed in taking the goods over the carrying places, or in rowing, during the Sabbath. I contemplated the delight with which thousands in England enjoyed the privileges of this sacred day, and welcomed divine ordinances. In reading, meditation, and prayer, however, my soul was not forsaken of God, and I gladly embraced an opportunity of calling those more immediately around me to join in reading the scriptures, and in prayer in my tent.

October the 6th. The ground was covered with snow, and the weather most winterly, when we embarked in our open boats to cross the lake for the Red River. Its length, from north to south, is about three hundred miles; and it abounds with sunken rocks, which are very dangerous to boats sailing in a fresh breeze. It is usual to run along shore, for the sake of an encampment at night, and of getting into a creek for shelter, in ease of storms and tempestuous weather. We had run about half the lake, when the boat, under a press of sail, struck upon one of these rocks, with so much violence as to threaten our immediate destruction. The idea of never more seeing my family upon earth, rushed upon my mind; but the pang of thought was alleviated by the recollection that life at best was short, and that they would soon meet me in 'brighter worlds,' whither I expected to be hurried, through the supposed hasty death of drowning. Providentially however we escaped being wrecked; and I could not but bless the God of my salvation, for the anchor of hope afforded me amidst all dangers and difficulties and possible privations of life.

As I sat at the door of my tent near a fire one evening, an Indian joined me, and gave me to understand that he knew a little English. He told me that he was taken prisoner when very young, and subsequently fell into the hands of an American gentleman, who took him to England, where he was very much frightened lest the houses should fall upon him. He further added that he knew a little of Jesus Christ, and hoped that I would teach him to read, when he came to the Red River, which he intended to do after he had been on a visit to his relations. He has a most interesting intelligent countenance, and expressed much delight at my coming over to his country to teach the Indians. We saw but few of them in our route along the courses of the river, and on the banks of the Winipeg. These are called Muskeggouck, or Swamp Indians, and are considered a distinct tribe, between the Nahathaway or Cree and Saulteaux. They subsist on fish, and occasionally the moose deer or elk, with the rein deer or caribou, vast numbers of which, as they swim the river in spring and in the fall of the year, the Indians spear in their canoes. In times of extremity they gather moss from the rocks, that is called by the Canadians 'tripe de roche,' which boils into a clammy substance, and has something of a nutritious quality. The general appearance of these Indians is that of wretchedness and want, and excited in my mind much sympathy towards them. I shook hands with them, in the hope that ere the rising generation at least had passed away, the light of Christianity, like the aurora borealis relieving the gloom of their winter night, would shed around them its heavenly lustre, and cheer their suffering existence with a scriptural hope of immortality.

In crossing the Winipeg, we saw almost daily large flocks of wild fowl, geese, ducks, and swans, flying to the south; which was a sure indication to us that winter was setting in with severity to the north. In fact it had already visited us, and inflicted much suffering from cold; and it was with no small delight that we entered the mouth of Red River, soon after the sun rose in majestic splendour over the lake, on the morning of the 13th of October. We proceeded to Netley Creek to breakfast, where we met Pigewis the chief of a tribe of Saulteaux Indians, who live principally along the banks of the river. This chief breakfasted with the party, and shaking hands with me most cordially, expressed a wish that ""more of the stumps and brushwood were cleared away for my feet, in coming to see his country."" On our apprising him of the Earl of Selkirk's death, he expressed much sorrow, and appeared to feel deeply the loss which he and the colony had sustained in his Lordship's decease. He shewed me the following high testimony of his character, given him by the late Earl when at Red River.

""The bearer, Pigewis, one of the principal chiefs of the Chipewyans, or Saulteaux of Red River, has been a steady friend of the settlement ever since its first establishment, and has never deserted its cause in its greatest reverses. He has often exerted his influence to restore peace; and having rendered most essential services to the settlers in their distress, deserves to be treated with favour and distinction by the officers of the Hudson's Bay Company, and by all the friends of peace and good order.""

(Signed.)SELKIRK.

Fort Douglas, July 17, 1820.

As we proceeded, the banks were covered with oak, elm, ash, poplar, and maple, and rose gradually higher as we approached the Colony, when the praries, or open grassy plains, presented to the eye an agreeable contrast with the almost continued forest of pine we were accustomed to in the route from York Factory. On the 14th of October we reached the settlement, consisting of a number of huts widely scattered along the margin of the river; in vain did I look for a cluster of cottages, where the hum of a small population at least might be heard as in a village. I saw but few marks of human industry in the cultivation of the soil. Almost every inhabitant we passed bore a gun upon his shoulder and all appeared in a wild and hunter-like state. The colonists were a compound of individuals of various countries. They were principally Canadians, and Germans of the Meuron regiment; who were discharged in Canada at the conclusion of the American war, and were mostly Catholics. There was a large population of Scotch emigrants also, who with some retired servants of the Hudson's Bay Company were chiefly Protestants, and by far the most industrious in agricultural pursuits. There was an unfinished building as a Catholic church, and a small house adjoining, the residence of the Priest; but no Protestant manse, church, or school house, which obliged me to take up my abode at the Colony Fort, (Fort Douglas,) where the 'Chargè d'Affaires' of the settlement resided; and who kindly afforded the accommodation of a room for divine worship on the sabbath. My ministry was generally well attended by the settlers; and soon after my arrival I got a log-house repaired about three miles below the Fort, among the Scotch population, where the schoolmaster took up his abode, and began teaching from twenty to twenty-five of the children.

Nov. the 8th.—The river was frozen over, and the winter set in with severity. Many were harnessing and trying their dogs in sledges, with a view to trip to Pembina, a distance of about seventy miles, or to the Hunters' tents, on the plains, for buffaloe meat. The journey generally takes them a fortnight, or sometimes more, before they return to the settlement with provisions; and this rambling and uncertain mode of obtaining subsistence in their necessity, (the locusts having then destroyed their crops,) has given the settlers a fondness for tripping, to the neglect of improving their dwellings and their farms. The dogs used on these occasions, and for travelling in carioles over the snow, strongly resemble the wolf in size, and frequently in colour. They have pointed noses, small sharp ears, long bushy tails, and a savage aspect. They never bark, but set up a fierce growl, and when numerous about a Fort, their howling is truly melancholy. A doubt can no longer exist, that the dogs brought to the interior of these wilds by Europeans, engendered with the wolf, and produced these dogs in common use. They have no attachment, and destroy all domestic animals. They are lashed to a sledge, and are often brutally driven to travel thirty or forty miles a day, dragging after them a load of three and four hundred pounds weight. When fat, they are eaten by the Canadians as a great delicacy; and are generally presented by the Indians at their feasts.

Many Indian families came frequently to the Fort, and as is common, I believe, to all the aborigines were of a copper colour complexion, with black coarse hair. Whenever they dressed for any particular occasion, they anointed themselves all over with charcoal and grease, and painted their eyebrows, lips and forehead, or cheeks, with vermillion. Some had their noses perforated through the cartilage, in which was fixed part of a goose quill, or a piece of tin, worn as an ornament, while others strutted with the skin of a raven ingeniously folded as a head dress, to present the beak over the forehead, and the tail spreading over the back of the neck. Their clothing consisted principally of a blanket, a buffaloe skin, and leggings, with a cap, which hung down their back, and was fastened to a belt round the waist. Scoutaywaubo, or fire water, (rum) was their principal request; to obtain which they appeared ready to barter any thing, or every thing they possessed. The children ran about almost naked, and were treated by their parents with all the instinctive fondness of animals. They know of no restraint, and as they grow up into life, they are left at full liberty to be absolute masters of their own actions. They were very lively, and several of them had pleasing countenances which indicated a capacity for much intellectual improvement. Most of their ears were cut in large holes, to which were suspended various ornaments, but principally those of beads. Their mothers were in the practice of some disgusting habits towards them particularly that of devouring the vermin which were engendered from their dirty heads. They put into their mouths all that they happen to find, and will sometimes reserve a quantity, and present the choice collection as a bonne bouche to their husbands.

After a short stay at the settlement, they left us to roam through the forests, like animals, without any fixed residence, in search of provisions, till the rivers open in the following spring, when they return to the Company's Post, and trade with the skins and furs which they have taken in hunting.

December the 6th. My residence was now removed to the farm belonging to the late Earl of Selkirk, about three miles from Fort Douglas, and six from the school. Though more comfortable in my quarters, than at the Fort, the distance put me to much inconvenience in my professional duties. We continued, however, to have divine service regularly on the Sabbath; and having frequently enforced the moral, and social obligation of marriage upon those who were living with, and had families by Indian, or half caste women, I had the happiness to perform the ceremony for several of the most respectable of the settlers, under the conviction, that the institution of marriage, and the security of property, were the fundamental laws of society. I had also many baptisms; and with infants, some adult half-breeds were brought to be baptized. I endeavoured to explain to them simply and faithfully the nature and object of that Divine ordinance; but found great difficulty in conveying to their minds any just and true ideas of the Saviour, who gave the commission, on his ascension into heaven ""To go and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost."" This difficulty produced in me a strong desire to extend the blessing of education to them: and from this period it became a leading object with me, to erect in a central situation, a substantial building, which should contain apartments for the school-master, afford accommodation for Indian children, be a day-school for the children of the settlers, enable us to establish a Sunday school for the half-caste adult population who would attend, and fully answer the purpose of a church for the present, till a brighter prospect arose in the colony, and its inhabitants were more congregated. I became anxious to see such a building arise as a Protestant land-mark of Christianity in a vast field of heathenism and general depravity of manners, and cheerfully gave my hand and my heart to perfect the work. I expected a willing co-operation from the Scotch settlers; but was disappointed in my sanguine hopes of their cheerful and persevering assistance, through their prejudices against the English Liturgy, and the simple rites of our communion. I visited them however in their affliction, and performed all ministerial duties as their Pastor; while my motto, was—Perseverance.

CHAPTER II.

VISIT THE SCHOOL. LEAVE THE FORKS FOR QU'APPELLE. ARRIVAL AT BRANDON HOUSE. INDIAN CORPSE STAGED. MARRIAGES AT COMPANY'S POST. BAPTISMS. DISTRIBUTION OF THE SCRIPTURES. DEPARTURE FROM BRANDON HOUSE. ENCAMPMENT. ARRIVAL AT QU'APPELLE. CHARACTER AND CUSTOMS OF STONE INDIANS. STOP AT SOME HUNTERS' TENTS ON RETURN TO THE COLONY. VISIT PEMBINA. HUNTING BUFFALOES. INDIAN ADDRESS. CANADIAN VOYAGEURS. INDIAN MARRIAGES. BURIAL GROUND. PEMICAN. INDIAN HUNTER SENDS HIS SON TO BE EDUCATED. MOSQUITOES. LOCUSTS.

January 1, 1821.—I went to the school this morning, a distance of about six miles from my residence, to examine the children, and was much pleased at the progress which they had already made in reading. Having addressed them, and prayed for a divine blessing on their instruction: I distributed to those who could read a little book, as a reward for their general good conduct in the school. In returning to the farm, my mind was filled with sentiments of gratitude and love to a divine Saviour for his providential protection, and gracious favour towards me during the past year. He has shielded me in the shadow of his hand through the perils of the sea and of the wilderness from whence I may derive motives of devotion and activity in my profession. Thousands are involved in worse than Egyptian darkness around me, wandering in ignorance and perishing through lack of knowledge. When will this wide waste howling wilderness blossom as the rose, and the desert become as a fruitful field! Generations may first pass away; and the seed of instruction that is now sown, may lie buried, waiting for the early and the latter rain, yet, the sure word of Prophecy, will ever animate Christian liberality and exertion, in the bright prospect of that glorious period, when Christianity shall burst upon the gloomy scene of heathenism, and dispel every cloud of ignorance and superstition, till the very ends of the earth shall see the salvation of the Lord.

As I returned from divine service at the Fort, to the farm, on the 7th, it rained hard for nearly two hours, which is a very unusual thing during winter in this northern latitude. We have seldom any rain for nearly six months, but a continued hard frost the greater part of this period. The sky is generally clear, and the snow lies about fifteen, or at the utmost eighteen inches deep. As the climate of a country is not known by merely measuring its distance from the equator, but is affected differently in the same parallel of latitude by its locality, and a variety of circumstances, we find that of Red River, though situated in the same parallel, far different from, and intensely more cold than, that of England. The thermometer is frequently at 30°#176; and 40°#176; below zero, when it is only about freezing point in the latter place. This difference is probably occasioned by the prevailing north-westerly wind, that blows with piercing keenness over the rocky mountains, or Andes, which run from north to south through the whole Continent, and over a country which is buried in ice and snow.

As my instructions were to afford religious instruction and consolation to the servants in the active employment of the Hudson's Bay Company, as well as to the Company's retired servants, and other inhabitants of the settlement, upon such occasions as the nature of the country and other circumstances would permit; I left the Forks[1] in a cariole drawn by three dogs, accompanied by a sledge with two dogs, to carry the luggage and provisions, and two men as drivers, on the 15th of January, for Brandon House, and Qu'appelle, on the Assiniboine River. After we had travelled about fifteen miles, we stopped on the edge of a wood, and bivouacked on the snow for the night. A large fire was soon kindled, and a supply of wood cut to keep it up; when supper being prepared and finished, I wrapped myself in my blankets and buffaloe robe, and laid down with a few twigs under me in place of a bed, with my feet towards the fire, and slept soundly under the open canopy of heaven. The next morning we left our encampment before sunrise; and the country as we passed presented some beautiful points and bluffs of wood. We started again early the following morning, which was intensely cold; and I had much difficulty in keeping my face from freezing, on my way to the encampment rather late in the evening, at the 'Portage de Prairè.' In crossing the plain the next morning, with a sharp head wind, my nose and part of my face were frozen quite hard and white. I was not conscious of it, till it was perceived by the driver, who immediately rubbed the parts affected well with snow, and restored the circulation, so that I suffered no inconvenience from the circumstance, but was obliged to keep my face covered with a blanket as I lay in the cariole the remaining part of the day.

On the 19th we were on the march as early as half past four, and had a sharp piercing wind in our faces, which drifted the snow, and made the track very bad for the dogs. This greatly impeded our progress; and our provisions being short, I shot some ptarmigans, which were frequently seen on our route. We perceived some traces of the buffaloe, and the wolf was frequently seen following our track, or crossing in the line we were travelling. Jan. 20. We started at sunrise, with a very cold head wind; and my favourite English watch dog, Neptune, left the encampment, to follow us, with great reluctance. I was apprehensive that he might turn back, on account of the severity of the morning; and being obliged to put my head under the blanket in the cariole, I requested the driver to encourage him along. We had not pursued our journey however more than an hour, before I was grieved to find that the piercing keenness of the wind had forced him to return; and the poor animal was probably soon after devoured by the wolves.

We arrived at Brandon House, the Company's provision post, about three o'clock; and the next day, being Sunday, the servants were all assembled for divine worship at eleven o'clock: and we met again in the evening at six, when I married the officer of the post, and baptized his two children. On the following morning, I saw an Indian corpse staged, or put upon a few cross sticks, about ten feet from the ground, at a short distance from the fort. The property of the dead, which may consist of a kettle, axe, and a few additional articles, is generally put into the case, or wrapped in the buffaloe skin with the body, under the idea that the deceased will want them, or that the spirit of these articles will accompany the departed spirit in travelling to another world. And whenever they visit the stage or burying-place, which they frequently do for years afterwards, they will encircle it, smoke their pipes, weep bitterly, and, in their sorrow, cut themselves with knives, or pierce themselves with the points of sharp instruments. I could not but reflect that theirs is a sorrow without hope: all is gross darkness with them as to futurity; and they wander through life without the consolatory and cheering influence of that gospel which has brought life and immortality to light.

Before I left this post, I married two of the Company's servants, and baptized ten or twelve children. As their parents could read, I distributed some Bibles and Testaments, with some Religious Tracts among them. On the 24th, we set off for Qu'appelle, but not without the kind attention of the officer, in adding two armed servants to our party, from the expectation that we might fall in with a tribe of Stone Indians, who had been threatening him, and had acted in a turbulent manner at the post a few days before. In the course of the afternoon, we saw a band of buffaloes, which fled from us with considerable rapidity. Though an animal apparently of a very unwieldy make, and as large as a Devonshire ox, they were soon out of our sight in a laboured canter. In the evening our encampment was surrounded by wolves, which serenaded us with their melancholy howling throughout the night: and when I first put my head from under the buffaloe robe in the morning, our encampment presented a truly wild and striking scene;—the guns were resting against a tree, and pistols with powder horns were hanging on its branches; one of the men had just recruited the fire, and was cooking a small piece of buffaloe meat on the point of a stick, while the others were lying around it in every direction. Intermingled with the party were the dogs, lying in holes which they had scratched in the snow for shelter, but from which they were soon dragged, and harnessed that we might recommence our journey. We had not proceeded far before we met one of the Company's servants going to the fort which we had left, who told us that the Indians we were apprehensive of meeting had gone from their track considerably to the north of our direction. In consequence of this information we sent back the two armed servants who had accompanied us. In the course of the day we saw vast numbers of buffaloes; some rambling through the plains, while others in sheltered spots were scraping the snow away with their feet to graze. In the evening we encamped among some dwarf willows; and some time after we had kindled the fire, we were considerably alarmed by hearing the Indians drumming, shouting, and dancing, at a short distance from us in the woods. We immediately almost extinguished the fire, and lay down with our guns under our heads, fully expecting that they had seen our fire, and would visit us in the course of the night. We dreaded this from the known character of the Stone Indians, they being great thieves; and it having been represented to us, that they murdered individuals, or small parties of white people, for plunder; or stripped them, leaving them to travel to the posts without clothing, in the most severe weather. We had little sleep, and started before break of day, without having been observed by them. We stopped to breakfast at the Standing Stone, where the Indians had deposited bits of tobacco, small pieces of cloth, &c. as a sacrifice, in superstitious expectation that it would influence their manitou to give them buffaloes and a good hunt. Jan. 27th. soon after midnight, we were disturbed by the buffaloes passing close to our encampment: we rose early, and arrived at Qu'appelle about three o'clock. Nearly about the same time, a large band of Indians came to the fort from the plains with provisions. Many of them rode good horses, caparisoned with a saddle or pad of dressed skin, stuffed with buffaloe wool, from which were suspended wooden stirrups; and a leathern thong, tied at both ends to the under jaw of the animal, formed the bridle. When they had delivered their loads, they paraded the fort with an air of independence. It was not long however before they became clamorous for spiritous liquors; and the evening presented such a bacchanalia, including the women and the children, as I never before witnessed. Drinking made them quarrelsome, and one of the men became so infuriated, that he would have killed another with his bow, had not the master of the post immediately rushed in and taken it from him. The following day, being Sunday, the servants were all assembled for divine worship, and again in the evening. Before I left the fort, I married several of the Company's servants, who had been living with, and had families by, Indian or half-caste women, and baptized their children. I explained to them the nature and obligations of marriage and baptism; and distributed among them some Bibles and Testaments, and Religious Tracts.

With the Indians who were at the Fort, there was one of the Company's servants who had been with the tribe nearly a year and a half, to learn their language as an interpreter. They were very partial to him, and treated him with great kindness and hospitality. He usually lived with their chief, and upon informing him who I was, and the object for which I came to the country, he welcomed me by a hearty shake of the hand; while others came round me, and stroked me on the head, as a fond father would his favourite boy. On one occasion, when I particularly noticed one of their children, the boy's father was so affected with the attention, that with tears he exclaimed, ""See! the God takes notice of my child."" Many of these Indians were strong, athletic men, and generally well-proportioned; their countenances were pleasing, with aquiline noses, and beautifully white and regular teeth. The buffaloe supplies them with food, and also with clothing. The skin was the principal, and almost the only article of dress they wore, and was wrapped round them, or worn tastefully over the shoulder like the Highland plaid. The leggins of some of them were fringed with human hair, taken from the scalps of their enemies; and their moccassins, or shoes, were neatly ornamented with porcupine quills. They are notorious horse-stealers, and often make predatory excursions to the Mandan villages on the banks of the Missouri, to steal them. They sometimes visit the Red River for this purpose, and have swept off, at times, nearly the whole of our horses from the settlement. Such indeed is their propensity for this species of theft, that they have fired upon, and killed the Company's servants, close to the forts for these useful animals. They run the buffaloe with them in the summer, and fasten them to sledges which they drag over the snow when they travel in the winter; while the dogs carry burdens upon their backs, like packs upon the pack-horse. It does not appear that chastity is much regarded among them. They take as many wives as they please, and part with them for a season, or permit others to cohabit with them in their own lodges for a time, for a gun, a horse, or some article they may wish to possess. They are known, however, to kill the woman, or cut off her ears or nose, if she be unfaithful without their knowledge or permission. All the lowest and most laborious drudgery is imposed upon her, and she is not permitted to eat till after her lord has finished his meal, who amidst the burdensome toil of life, and a desultory and precarious existence, will only condescend to carry his gun, take care of his horse, and hunt as want may compel him. During the time the interpreter was with these Indians the measles prevailed, and carried off great numbers of them, in different tribes. They often expressed to him a very low opinion of the white people who introduced this disease amongst them, and threatened to kill them all, at the same time observing, that they would not hurt him, but send him home down the Missouri. When their relations, or children of whom they are passionately fond, were sick, they were almost constantly addressing their manitou drumming, and making a great noise; and at the same time they sprinkled them with water where they complained of pain. And when the interpreter was sick, they were perpetually wanting to drum and conjure him well. He spoke to them of that God and Saviour whom white people adore; but they called him a fool, saying that he never came to their country, or did any thing for them, ""So vain were they in their imaginations, and their foolish heart was darkened.""

Jan. 30.—We left Qu'appelle to return to the colony, and stopped for the night at an encampment of Indians, some of whom were engaged as hunters for the company. They welcomed me with much cordiality to their wigwams. We smoked the calumet as a token of friendship; and a plentiful supply of buffaloe tongues was prepared for supper. I slept in one of their tents, wrapt in a buffaloe robe, before a small fire in the centre, but the wind drawing under it, I suffered more from cold than when I slept in an open encampment. As we were starting the next morning I observed a fine looking little boy standing by the side of the cariole, and told his father that if he would send him to me at the Settlement by the first opportunity, I would be as a parent to him, clothe him, and feed him, and teach him what I knew would be for his happiness, with the Indian boys I had already under my care. We proceeded, and after we had travelled about three hours, the whole scene around us was animated with buffaloes; so numerous, that there could not be less, I apprehend, than ten thousand, in different bands, at one time in our view. It took us nearly the whole day to cross the plain, before we came to any wood for the night. We resumed our journey at the dawn of the following morning, and after travelling about three hours we stopped at a small creek to breakfast: as soon as we had kindled the fire, two Indians made their appearance, and pointing to the willows, shewed me a buffaloe that they had just shot. They were very expert in cutting up the animal, and ate some of the fat, I observed, with a few choice pieces, in a raw state. Soon afterwards I saw another Indian peeping over an eminence, whose head-dress at first gave him the appearance of a wolf: and, fearing some treachery, we hurried our breakfast and started.

Feb. 2.—The night was so intensely cold that I had but little sleep, and we hurried from our encampment at break of day. The air was filled with small icy particles; and some snow having fallen the evening before, one of the men was obliged to walk in snow shoes, to make a track for the dogs to follow. Our progress was slow, but we persevered, and arrived at Brandon house about four o'clock. We saw some persons at this post, who had just come from the Mandan villages: they informed us of the custom that prevails among these Indians, as with many others, of presenting females to strangers; the husband his wife or daughter, and the brother his sister, as a mark of hospitality: and parents are known to lend their daughters of tender age for a few beads or a little tobacco! During our stay, a Sunday intervened, when all met for divine worship in the morning and evening, and I had an opportunity of baptizing several more children, whose parents had come in from the hunting grounds, since my arrival at the Post, in my way to Qu'appelle. On the 5th we left the fort, and returning by the same track that we came, I searched for traces of my favourite lost dog, but found none. The next morning I got into the cariole very early, and the rising sun gradually opened to my view a beautiful and striking scenery. All nature appeared silently and impressively to proclaim the goodness and wisdom of God. Day unto day, in the revolutions of that glorious orb, which shed a flood of light over the impenetrable forests and wild wastes that surrounded me, uttereth speech. Yet His voice is not heard among the heathen, nor His name known throughout these vast territories by Europeans in general, but to swear by.——Oh! for wisdom, truly Christian faith, integrity and zeal in my labours as a minister, in this heathen and moral desert.

Feb. 9.—The wind drifted the snow this morning like a thick fog, that at times we could scarcely see twenty yards from the cariole. It did not stop us however in our way, and I reached the farm about five o'clock, with grateful thanks to God, for protecting me through a perilous journey, drawn by dogs over the snow a distance of between five and six hundred miles among some of the most treacherous tribes of Indians in this northern wilderness.

March 4.—The weather continues very cold, so as to prevent the women and the children from attending regularly divine service on the Sabbath. The sun however is seldom obscured with clouds, but shines with a sickly face; without softening at all at present, the piercing north-westerly wind that prevails throughout the winter.

A wish having been expressed to me, that I would attend a general meeting of the principal settlers at Pembina, I set off in a cariole for this point of the Settlement, a distance of nearly eighty miles, on the 12th. We stopped a few hours at the Salt Springs, and then proceeded on our journey so as to reach Fort Daer the next morning to breakfast; so expeditiously will the dogs drag the cariole in a good track, and with a good driver. We met for the purpose of considering the best means of protection, and of resisting any attack that might be made by the Sioux Indians, who were reported to have hostile intentions against this part of the colony, in the Spring. They had frequently killed the hunters upon the plains; and a war party from the Mississippi, scalped a boy last summer within a short distance of the fort where we were assembled; leaving a painted stick upon the mangled body, as a supposed indication that they would return for slaughter.

The 18th being the Sabbath, I preached to a considerable number of persons assembled at the Fort. They heard me with great attention; but I was often depressed in mind, on the general view of character, and at the spectacle of human depravity and barbarism I was called to witness. During my stay, I went to some hunter's tents on the plains, and saw them kill the buffaloe, by crawling on the snow, and pushing their guns before them, and this for a considerable distance till they got very near the band. Their approach to the animals was like the appearance of wolves, which generally hover round them to devour the leg-wearied and the wounded; and they killed three before the herd fled. But in hunting the buffaloes for provisions it affords great diversion to pursue them on horseback. I once accompanied two expert hunters to witness this mode of killing them. It was in the spring: at this season the bulls follow the bands of cows in the rear on their return to the south, whereas in the beginning of the winter, in their migration to the north, they preceded them and led the way. We fell in with a herd of about forty, on an extensive prarie. They were covering the retreat of the cows. As soon as our horses espied them they shewed great spirit, and became as eager to chase them as I have understood the old English hunter is to follow the fox-hounds in breaking cover. The buffaloes were grazing, and did not start till we approached within about half a mile of them, when they all cantered off in nearly a compact body. We immediately threw the reins upon the horses' necks, and in a short time were intermingled with several of them. Pulling up my horse I then witnessed the interesting sight of the hunters continuing the chase, till they had separated one of the bulls from the rest, and after driving it some distance, they gallopped alongside and fired upon the animal, with the gun resting upon the front of the saddle. Immediately it was wounded, it gave chase in the most furious manner, and the horses aware of their danger, turned and cantered away at the same pace as the buffaloe. While the bull was pursuing them, the men reloaded their guns, which they do in a most expeditious manner, by pouring the charge of powder into the palm of their hand half closed, from a horn hung over the shoulder, and taking a ball from the pouch that is fastened to their side, and then suddenly breaking out of the line, they shot the animal through the heart as it came opposite to them. It was of a very large size, with long shaggy hair on the head and shoulders, and the head when separated from the carcase was nearly as much as I could lift from the ground.

The Indians have another mode of pursuing the buffaloes for subsistence, by driving them into a pound. They make the inclosure of a circular form with trees felled on the spot, to the extent of one or two hundred yards in diameter, and raise the entrance with snow, so as to prevent the retreat of the animals when they have once entered. As soon as a herd is seen in the horizon coming in the direction of the pound, a party of Indians arrange themselves singly in two opposite lines, branching out gradually on each side to a considerable distance, that the buffaloes may advance between them. In taking their station at the distance of twenty or thirty yards from each other, they lie down, while another party manœuvre on horseback, to get in rear of the band. Immediately they have succeeded they give chace, and the party in ambush rising up as the buffaloes come opposite to them, they all halloo, and shout, and fire their guns, so as to drive them, trampling upon each other, into the snare, where they are soon slaughtered by the arrow or the gun.

The buffaloe tongue, when well cured, is of excellent flavour, and is much esteemed, together with the bos, or hump of the animal, that is formed on the point of the shoulders. The meat is much easier of digestion than English beef; and many pounds of it are often taken by the hungry traveller just before he wraps himself in his buffaloe robe for the night without the least inconvenience.

On my return to the Fort, I had an opportunity of hearing from a chief of a small tribe of Chipewyans, surrounded by a party of his young men, a most pathetic account, and a powerful declaration of revenge against the Sioux Indians, who had tomahawked and scalped his son. Laying his hand upon his heart as he related the tragical circumstance, he emphatically exclaimed, 'It is here I am affected, and feel my loss;' then raising his hand above his head, he said, 'the spirit of my son cries for vengeance. It must be appeased. His bones lie on the ground uncovered. We want ammunition: give us powder and ball, and we will go and revenge his death upon our enemies.' Their public speeches are full of bold metaphor, energy and pathos. ""No Greek or Roman orator ever spoke perhaps with more strength and sublimity than one of their chiefs when asked to remove with his tribe to a distance from their native soil."" 'We were born,' said he, 'on this ground, our fathers lie buried in it, shall we say to the bones of our fathers, arise, and come with us into a foreign land?'

One of the Indians left his wampum, or belt, at the Fort as a pledge that he would return and pay the value of an article which was given to him at his request. They consider this deposit sacred and inviolable, and as giving a sanction to their words, their promises and their treaties. They are seldom known to fail in redeeming the pledge; and they ratify their agreements with each other by a mutual exchange of the wampum, regarding it with the smoking of tobacco, as the great test of sincerity.

In conducting their war excursions, they act upon the same principle as in hunting. They are vigilant in espying out the track of those whom they pursue, and will follow them over the praries, and through the forests, till they have discovered where they halt; when they wait with the greatest patience, under every privation, either lurking in the grass, or concealing themselves in the bushes, till an opportunity offers to rush upon their prey, at a time when they are least able to resist them. These tribes are strangers to open warfare, and laugh at Europeans as fools for standing out, as they say, in the plains, to be shot at.

On the 22nd I reached the Farm, and from the expeditious mode of travelling over the snow, I began to think, as is common among the Indians, that one hundred miles was little more than a step, or in fact but a short distance. It often astonished me to see with what an unwearied pace, the drivers hurry along their dogs in a cariole, or sledge, day after day in a journey of two and three hundred miles. I have seen some of the English half-breeds greatly excel in this respect. Many of the Canadians however are very expert drivers, as they are excellent voyageurs in the canoe. There is a native gaiety, and vivacity of character, which impel them forward, and particularly so, under the individual and encouraging appellation of 'bon homme.' When tripping, they are commonly all life, using the whip, or more commonly a thick stick, barbarously upon their dogs, vociferating as they go ""Sacres Crapeaux,"" ""Sacrée Marne,"" ""Saintes Diables,"" and uttering expressions of the most appalling blasphemy. In the rivers, their canoe songs, as sung to a lively air and chorus with the paddle, are very cheerful and pleasing. They smoke immediately and almost incessantly, when the paddle is from their hands; and none exceed them in skill, in running the rapids, passing the portages with pieces of eighty and ninety pounds weight upon their backs, and expeditiously performing a journey of one thousand miles.

April 1.—Last Friday I married several couples, at the Company's Post; nearly all the English half-breeds were assembled on the occasion, and so passionately fond are they of dancing, that they continued to dance almost incessantly from two o'clock on Friday afternoon, till late on Saturday night. This morning the Colony Fort was nearly thronged with them to attend divine service; and it was my endeavour to address them, with plainness, simplicity, and fidelity. There was much attention; but, I fear, from their talking, principally, their mother tongue, the Indian language, that they did not comprehend a great deal of my discourse. This is the case also, with a few of the Scotch Highland settlers, who speak generally the Gaelic language.

Marriage, I would enforce upon all, who are living with, and have children by half-caste, or Indian women. The apostolic injunction is clear and decisive against the too common practice of the country, in putting them away, after enjoying the morning of their days; or deserting them to be taken by the Indians with their children, when the parties, who have cohabited with them, leave the Hudson's Bay Company's territories.[2] And if a colony is to be organized, and established in the wilderness, the moral obligation of marriage must be felt. It is ""the parent,"" said Sir William Scott, ""not the child of civil society."" Some form, or religious rite in marriage is also requisite, and has generally been observed by enlightened and civilized nations. It is a civil contract in civil society, but the sanction of religion should be superadded. The ancients considered it as a religious ceremony. They consulted their imaginary gods, before the marriage was solemnized, and implored their assistance by prayers, and sacrifices; the gall was taken out of the victim, as the seat of anger and malice, and thrown behind the altar, as hateful to the deities who presided over the nuptial ceremonies. Marriage, by its original institution[3] is the nearest of all earthly relations, and as involving each other's happiness through life, it surely ought to be entered upon by professing Christians, with religious rites, invoking heaven as a party to it, while the consent of the individuals is pledged to each other, ratified and confirmed by a vow.

Incestuous cohabitation is common with the Indians, and in some instances, they will espouse several sisters at the same time; but so far from adopting the custom of others in presenting their wives, or daughters as a mark of hospitality due to a stranger, the Chipewyans or Saulteaux tribe of Red River, appear very jealous of them towards Europeans. There is something patriarchal in their manner of first choosing their wives. When a young man wishes to take a young woman to live with him; he may perhaps mention his wishes to her, but generally, he speaks to the father, or those who have authority over her. If his proposal be accepted, he is admitted into the tent, and lives with the family, generally a year, bringing in the produce of his hunting for the general mess. He then separates to a tent of his own, and adds to the number of wives, according to his success and character as a hunter. The Indians have been greatly corrupted in their simple and barbarous manners, by their intercourse with Europeans, many of whom have borne scarcely any other mark of the Christian character than the name; and who have not only fallen into the habits of an Indian life, but have frequently exceeded the savage in their savage customs. When a female is taken by them, it does not appear that her wishes are at all consulted, but she is obtained from the lodge as an inmate at the Fort, for the prime of her days generally, through that irresistible bribe to Indians, rum. Childbirth, is considered by them, as an event of a trifling nature; and it is not an uncommon case for a woman to be taken in labour, step aside from the party she is travelling with, and overtake them in the evening at their encampment, with a new-born infant on her back. It has been confidently stated that Indian women suffer more from parturition with half-breed children than when the father is an Indian. If this account be true, it can only be in consequence of their approach to the habits of civilized life, exerting an injurious influence over their general constitution. When taken to live with white men, they have larger families, and at the same time are liable to more disease consequent upon it, than in their wild and wandering state. They have customs, such as separation for forty days at the birth of a child, setting apart the female in a separate lodge at peculiar seasons, and forbidding her to touch any articles in common use, which bear a strong resemblance to the laws of uncleanness, and separation commanded to be observed towards Jewish females. These strongly corroborate the idea, that they are of Asiatic origin; descended from some of the scattered tribes of the children of Israel: and through some ancient transmigration, came over by Kamtchatka into these wild and extensive territories. When they name their children, it is common for them to make a feast, smoke the calumet, and address the Master of life, asking him to protect the child, whom they call after some animal, place, or object in nature, and make him a good hunter. The Stone Indians add to the request, a good horse-stealer. The women suckle their children generally, till the one supplants the other, and it is not an uncommon circumstance to see them of three or four years old running to take the breast. They have a burial ground at the Settlement, and usually put the property of the deceased into the grave with the corpse. If any remains, it is given away from an aversion they have to use any thing that belonged to their relations who have died. Some of the graves are very neatly covered over with short sticks and bark as a kind of canopy, and a few scalps are affixed to poles that are stuck in the ground at the head of several of them. You see also occasionally at the grave, a piece of wood on which is either carved or painted the symbols of the tribe the deceased belonged to, and which are taken from the different animals of the country.

April 6.—One of the principal settlers informed me this morning, that an Indian had stabbed one of his wives in a fit of intoxication at an encampment near his house. I immediately went to the Lodge to inquire into the circumstance, and found that the poor woman had been stabbed in wanton cruelty, through the shoulder and the arm, but not mortally. The Indians were still drunk, and some of them having knives in their hands, I thought it most prudent to withdraw from their tents, without offering any assistance. The Indians appear to me to be generally of an inoffensive and hospitable disposition; but spirituous liquors, like war, infuriate them with the most revengeful and barbarous feelings. They are so conscious of this effect of drinking, that they generally deliver up their guns, bows and arrows, and knives, to the officers, before they begin to drink at the Company's Post; and when at their tents, it is the first care of the women to conceal them, during the season of riot and intoxication.

A considerable quantity of snow fell on the night of the 12th, and the weather continuing very cold, it is not practicable yet to begin any operations in farming. Though I see not as yet any striking effects of my ministry among the settlers, yet, I trust, some little outward reformation has taken place, in the better observance of the Sabbath.

May 2.—The rivers have broken up this spring unusually late, and the ice is now floating down in large masses. The settlers, who went to Pembina and the plains, for buffaloe meat in the Fall, are returning upon rafts, or in canoes formed by hollowing the large trunks of trees: many of them are as improvident of to-morrow as the Indians, and have brought with them no dried provisions for the summer. This is not the case however with the Scotch, who have been provident enough to bring with them a supply of dried meat and pemican for a future day. The dried meat is prepared by cutting the flesh of the buffaloe thin, and hanging it on stages of wood to dry by the fire; and is generally tied in bundles of fifty or forty pounds weight. It is very rough, and tasteless, except a strong flavour of the smoke. Pemican is made by pounding the dried meat, and mixing it with boiled fat, and is then put into bags made of buffaloe skin, which weigh about eighty and a hundred pounds each. It is a species of food well adapted to travelling in the country; but so strongly cemented in the bag, that when it is used, it is necessary to apply the axe; and very much resembles in appearance tallow-chandler's grease.

The 10th.—The plains have been on fire to a considerable extent for several days past, and the awful spectacle is seen this evening, through the whole of the northern, and western horizon. Idle rumours prevail that the Sioux Indians will attack the Settlement; which unhappily unsettle the minds, and interrupt the industry of the colonists. But none of these things move me, in carrying on my plans, and making arrangements to erect a substantial building, sixty feet by twenty. The Red River appears to me, a most desirable spot for a Missionary establishment, and the formation of schools; from whence Christianity may arise, and be propagated among the numerous tribes of the north. The settlers are now actively employed in preparing to sow the small lots of land which they have cleared: but this season is short from the great length of the winter.—The 20th being Sunday more than one hundred of them assembled at the Fort for divine service; and their children from the school were present for public examination. They gave general satisfaction in their answers to questions from the ""Chief Truths of the Christian Religion, and Lewis's Catechism.""—Text Proverbs iii. 17.

By the arrival of the boats from Qu'appelle, on the 25th, I received the little Indian boy, I noticed, when leaving the Hunter's Tents, during my excursion to that quarter in January last. Soon after my departure, the father of the boy observed, that ""as I had asked for his son, and stood between the Great Spirit and the Indians, he would send him to me;"" and just before the boats left the Post for the Red River, he brought the boy, and requested that he might be delivered to my care. Thus was I encouraged in the idea, that native Indian children might be collected from the wandering tribes of the north, and educated in ""the knowledge of the true God, and Jesus Christ whom he hath sent.""

Every additional Indian child I obtained for this purpose, together with the great inconvenience of having no place appropriated for public worship, gave a fresh stimulus to exertion in erecting the proposed building. There was but little willing assistance however, towards this desirable object; as few possessed any active spirit of public improvement; and the general habits of the people being those of lounging and smoking, were but little favourable to voluntary exertions.

Sturgeon are caught at this period, from sixty to one hundred pounds weight and more, in great abundance at the Settlement; and also for about a month in the fall of the year, a little below the rapids towards the mouth of the river. The oil of this fish is sometimes used as lamp oil by the settlers; and the sound, when carefully and quickly dried in the shade, by hanging it upon a line in a good breeze, forms isinglass, the simple solution of which in water makes a good jelly, and may be seasoned by the addition of syrup and wine, or of the expressed juices of any ripe fruit. The roe is often cooked immediately it is taken from the fish; but, when salted and placed under a considerable pressure until dry, it forms the very nutritious article of food named caviare. They generally afford us an abundant supply of provisions for about a month or five weeks; and when they leave the river, we have usually a good supply of cat fish, weighing about seven or eight pounds each, and which are taken in greater or less quantities for the most part of the summer months.