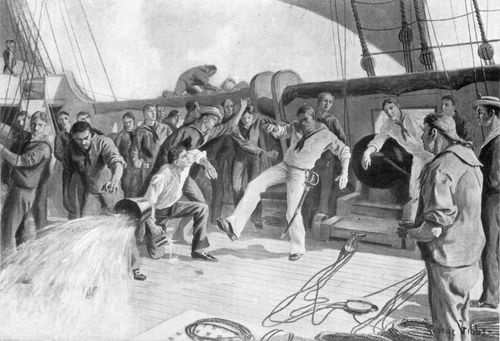

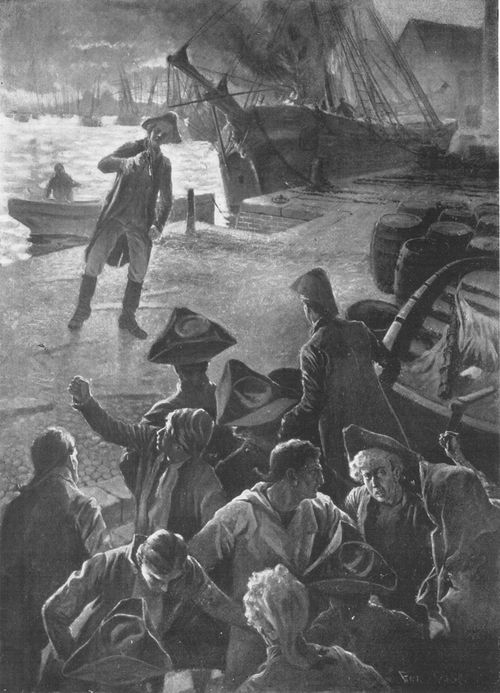

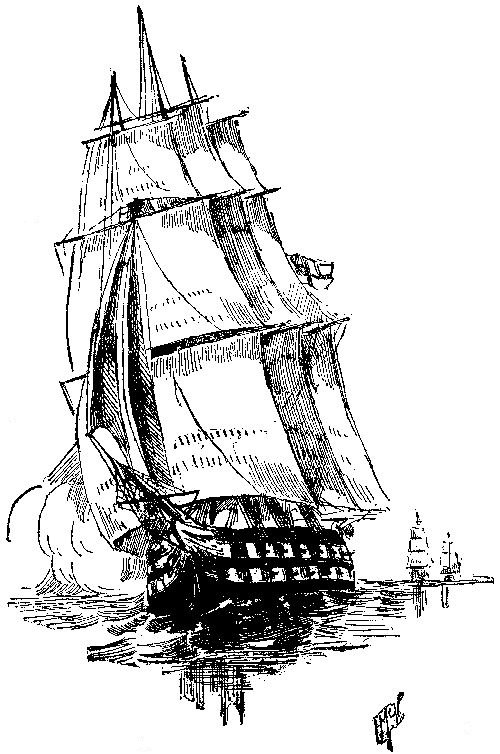

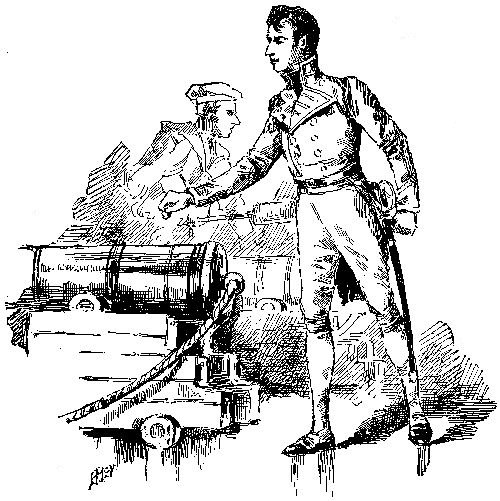

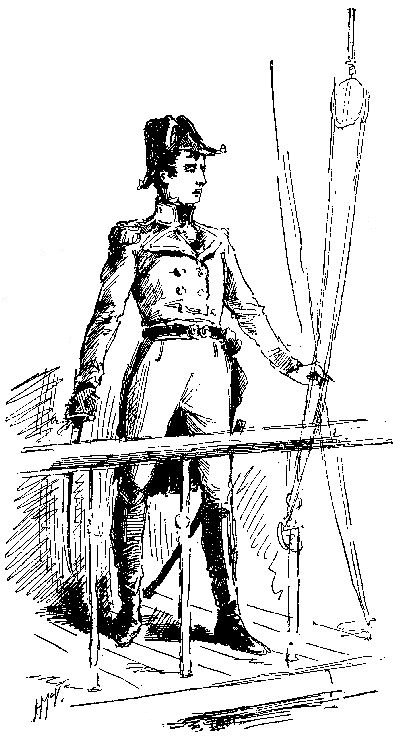

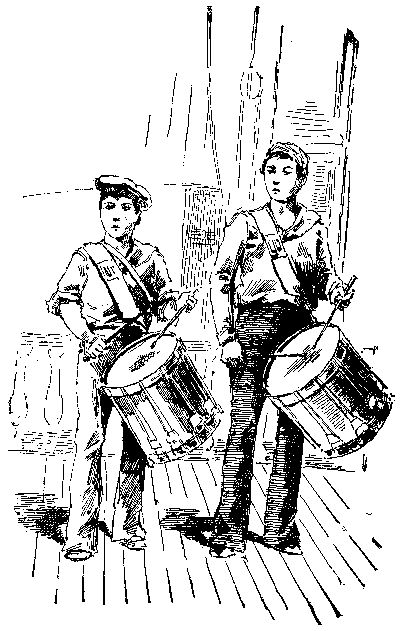

Spilling Grog on the "Constitution" before Going into Action

Title: The Naval History of the United States. Volume 1

Author: Willis J. Abbot

Release date: August 13, 2007 [eBook #22305]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Christine P. Travers and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all

other inconsistencies are as in the original. Author's spelling has

been maintained.

Accessibility: Expansions of abbreviations have been provided using the <abbr> tag, and changes in language are marked.

Speech rendering will be improved if voices for the following languages are available: Fr.

Spilling Grog on the "Constitution" before Going into Action

BY

With Many Illustrations

New York:

PETER FENELON COLLIER, PUBLISHER.

Copyright, 1886, 1887, 1888, 1890

BY

Dodd, Mead and Company

All rights reserved

Capture of the "Surveyor."—Work of the Gunboat Flotilla.—Operations on Chesapeake Bay.—Cockburn's Depredations.—Cruise of the "Argus."—Her Capture by the "Pelican."—Battle Between the "Enterprise" and "Boxer."—End of the Year 1813 on the Ocean.

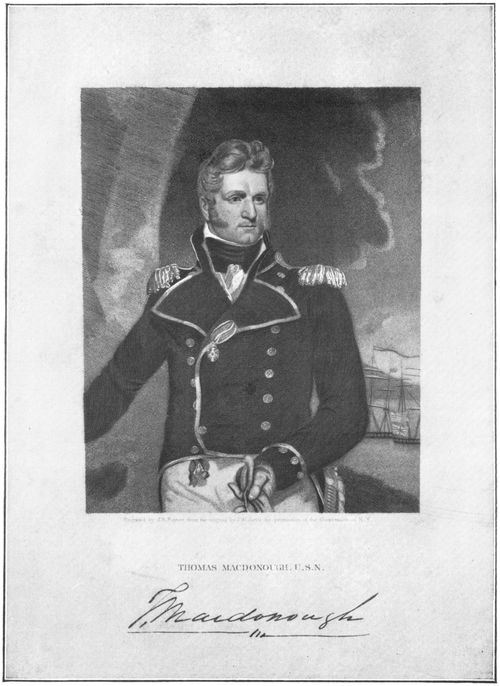

On the Lakes.—Close of Hostilities on Lakes Erie and Huron.—Desultory Warfare on Lake Ontario in 1813.—Hostilities on Lake Ontario in 1814.—The Battle of Lake Champlain.—End of the War upon the Lakes.

On the Ocean.—The Work of the Sloops-of-War.—Loss of the "Frolic."—Fruitless Cruise of the "Adams."—The "Peacock" Takes the "Épervier."—The Cruise of the "wasp."—She Captures the "Reindeer."—Sinks the "Avon."—Mysterious End of the "Wasp".

Operations on the New England Coast.—The Bombardment of Stonington.—Destruction Of the United States Corvette "Adams."—Operations on Chesapeake Bay.—Work of Barney's Barge Flotilla.—Advance of the British Upon Washington.—Destruction of the Capitol.—Operations Against Baltimore.—Bombardment of Fort McHenry.

Desultory Hostilities on the Ocean.—Attack Upon Fort Bowyer.—Lafitte the Pirate.—British Expedition Against New Orleans.—Battle of the Rigolets.—Attack On New Orleans, and Defeat of the British.—Work of the Blue-jackets.—Capture Of the Frigate "President."—The "Constitution" takes The "Cyane" and "Levant."—The "Hornet" Takes the "Penguin."—End of the War.

Privateers and Prisons of the War.—The "Rossie."—Salem Privateers.—The "Gen. Armstrong" Gives Battle To a British Squadron, and Saves New Orleans.—Narrative of a British Officer.—The "Prince de Neufchatel."—Experiences Of American Prisoners of War.—The End.

The Long Peace Broken by the War With Mexico.—Activity of the Navy.—Captain Stockton's Stratagem.—The Battle at San Jose.—The Blockade.—Instances of Personal Bravery.—The Loss of the "Truxton."—Yellow Fever in the Squadron.—The Navy at Vera Cruz.—Capture of Alvarado.

The Navy in Peace.—Surveying the Dead Sea.—Suppressing the Slave Trade.—The Franklin Relief Expedition.—Commodore Perry in Japan.—Signing of the Treaty.—Trouble in Chinese Waters.—The Koszta Case.—The Second Franklin Relief Expedition.—Foote at Canton.—"Blood is Thicker Than Water".

The Opening of the Conflict.—The Navies of the Contestants.—Dix's Famous Despatch.—The River-gunboats.

Fort Sumter Bombarded.—Attempt of the "Star of the West" to Re-enforce Anderson.—The Naval Expedition to Fort Sumter.—The Rescue of the Frigate "Constitution."—Burning the Norfolk Navy-Yard.

Difficulties of the Confederates in Getting a Navy.—Exploit of the "French Lady."—Naval Skirmishing on the Potomac.—The Cruise of the "Sumter"

The Potomac Flotilla.—Capture of Alexandria.—Actions at Matthias Point.—Bombardment of the Hatteras Forts.

The "Trent" Affair.—Operations in Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds.—Destruction of the Confederate Fleet.

Reduction of Newbern.—Exploits of Lieut. Cushing.—Destruction of the Ram "Albemarle".

The Blockade-runners.—Nassau and Wilmington.—Work of the Cruisers.

Du Pont's Expedition to Hilton Head and Port Royal.—The Fiery Circle.

The First Ironclad Vessels in History.—The "Merrimac" Sinks the "Cumberland," and Destroys the "Congress."—Duel between the "Monitor" and "Merrimac".

The Navy in the Inland Waters.—The Mississippi Squadron.—Sweeping the Tennessee River.

Famous Confederate Privateers,—The "Alabama," the "Shenandoah," the "Nashville".

Work of the Gulf Squadron.—The Fight at the Passes of the Mississippi.—Destruction of the Schooner "Judah."—The Blockade of Galveston, and Capture of the "Harriet Lane".

The Capture of New Orleans.—Farragut's Fleet passes Fort St. Philip and Fort Jackson.

Along the Mississippi.—Forts Jackson and St. Philip Surrender.—The Battle at St. Charles.—The Ram "Arkansas."—Bombardment and Capture of Port Hudson.

On To Vicksburg.—Bombardment of the Confederate Stronghold.—Porter's Cruise in the Forests.

Vicksburg Surrenders, and the Mississippi is opened.—Naval Events along the Gulf Coast.

Operations About Charleston.—The Bombardment, the Siege, and the Capture.

The Battle of Mobile Bay.

The Fall of Fort Fisher.—The Navy ends its Work.

Police Service on the High Seas.—War Service in Asiatic Ports.—Losses by the Perils of the Deep.—A Brush With the Pirates.—Admiral Rodgers at Corea.—Services in Arctic Waters.—The Disaster at Samoa.—The Attack on the "Baltimore's" Men at Valparaiso.—Loss of the "Kearsarge."—The Naval Review.

The Naval Militia.—A Volunteer Service which in Time of War will be Effective.—How Boys are Trained for the Life of a Sailor.—Conditions of Enlistment in the Volunteer Branch of the Service.—The Work of the Seagoing Militia in Summer.

How the Navy Has Grown.—The Cost and Character of Our New White Ships of War.—Our Period of Naval Weakness and our Advance to a Place among the Great Naval Powers.—The New Devices of Naval Warfare.—The Torpedo, the Dynamite Gun, and the Modern Rifle.—Armor and its Possibilities.

The State of Cuba.—Pertinacity of the Revolutionists.—Spain's Sacrifices and Failure.—Spanish Barbarities.—The Policy of Reconcentration.—American Sympathy Aroused.—The Struggle in Congress.—The Assassination of the "Maine."—Report of the Commission.—The Onward March to Battle.

The Opening Days of the War.—The First Blow Struck in the Pacific.—Dewey and his Fleet.—The Battle at Manila.—An Eye-witness' Story.—Delay and Doubt in the East.—Dull Times for the Blue-jackets.—The Discovery of Cervera.—Hobson's Exploit.—The Outlook.

The Spanish Fleet makes a Dash from the Harbor.—Its total Destruction.—Admiral Cervera a Prisoner.—Great Spanish Losses.—American Fleet Loses but one Man.

VOLUME ONE

VOLUME TWO

CHAPTER I.

EARLY EXPLOITS UPON THE WATER. — GALLOP'S BATTLE WITH THE INDIANS. — BUCCANEERS AND PIRATES. — MORGAN AND BLACKBEARD. — CAPT. KIDD TURNS PIRATE. — DOWNFALL OF THE BUCCANEERS' POWER.

n

May, 1636, a stanch little sloop of some twenty tons was standing

along Long Island Sound on a trading expedition. At her helm stood

John Gallop, a sturdy colonist, and a skilful seaman, who earned his

bread by trading with the Indians that at that time thronged the

shores of the Sound, and eagerly seized any opportunity to traffic

with the white men from the colonies of Plymouth or New Amsterdam. The

colonists sent out beads, knives, bright clothes, and sometimes,

unfortunately, rum and other strong drinks. The Indians in exchange

offered skins and peltries of all kinds; and, as their simple natures

had not been schooled to nice calculations of values, the traffic was

one of great profit to the more shrewd whites. But the trade was not

without its perils. Though the Indians were simple, and little likely

to drive hard bargains, yet they were savages, and little accustomed

to nice distinctions between their own property (p. b) and that of

others. Their desires once aroused for some gaudy bit of cloth or

shining glass, they were ready enough to steal it, often making their

booty secure by the murder of the luckless trader. It so happened,

that, just before John Gallop set out with his sloop on the spring

trading cruise, the people of the colony were excitedly discussing the

probable fate of one Oldham, who some weeks before had set out on a

like errand, in a pinnace, with a crew of two white boys and two

Indians, and had never returned. So when, on this May morning, Gallop,

being forced to hug the shore by stormy weather, saw a small vessel

lying at anchor in a cove, he immediately ran down nearer, to

investigate. The crew of the sloop numbered two men and two boys,

beside the skipper, Gallop. Some heavy duck-guns on board were no mean

ordnance; and the New Englander determined to probe the mystery of

Oldham's disappearance, though it might require some fighting. As the

sloop bore down upon the anchored pinnace, Gallop found no lack of

signs to arouse his suspicion. The rigging of the strange craft was

loose, and seemed to have been cut. No lookout was visible, and she

seemed to have been deserted; but a nearer view showed, lying on the

deck of the pinnace, fourteen stalwart Indians, one of whom, catching

sight of the approaching sloop, cut the anchor cable, and called to

his companions to awake.

n

May, 1636, a stanch little sloop of some twenty tons was standing

along Long Island Sound on a trading expedition. At her helm stood

John Gallop, a sturdy colonist, and a skilful seaman, who earned his

bread by trading with the Indians that at that time thronged the

shores of the Sound, and eagerly seized any opportunity to traffic

with the white men from the colonies of Plymouth or New Amsterdam. The

colonists sent out beads, knives, bright clothes, and sometimes,

unfortunately, rum and other strong drinks. The Indians in exchange

offered skins and peltries of all kinds; and, as their simple natures

had not been schooled to nice calculations of values, the traffic was

one of great profit to the more shrewd whites. But the trade was not

without its perils. Though the Indians were simple, and little likely

to drive hard bargains, yet they were savages, and little accustomed

to nice distinctions between their own property (p. b) and that of

others. Their desires once aroused for some gaudy bit of cloth or

shining glass, they were ready enough to steal it, often making their

booty secure by the murder of the luckless trader. It so happened,

that, just before John Gallop set out with his sloop on the spring

trading cruise, the people of the colony were excitedly discussing the

probable fate of one Oldham, who some weeks before had set out on a

like errand, in a pinnace, with a crew of two white boys and two

Indians, and had never returned. So when, on this May morning, Gallop,

being forced to hug the shore by stormy weather, saw a small vessel

lying at anchor in a cove, he immediately ran down nearer, to

investigate. The crew of the sloop numbered two men and two boys,

beside the skipper, Gallop. Some heavy duck-guns on board were no mean

ordnance; and the New Englander determined to probe the mystery of

Oldham's disappearance, though it might require some fighting. As the

sloop bore down upon the anchored pinnace, Gallop found no lack of

signs to arouse his suspicion. The rigging of the strange craft was

loose, and seemed to have been cut. No lookout was visible, and she

seemed to have been deserted; but a nearer view showed, lying on the

deck of the pinnace, fourteen stalwart Indians, one of whom, catching

sight of the approaching sloop, cut the anchor cable, and called to

his companions to awake.

This action on the part of the Indians left Gallop no doubt as to their character. Evidently they had captured the pinnace, and had either murdered Oldham, or even then had him a prisoner in their midst. The daring sailor wasted no time in debate as to the proper course to pursue, but clapping all sail on his craft, soon brought her alongside the pinnace. As the sloop came up, the Indians opened the fight with fire-arms and spears; but Gallop's crew responded with their duck-guns with such vigor that the Indians deserted the decks, and fled below for shelter. Gallop was then in a quandary. The odds against him were too great for him to dare to board, and the pinnace was rapidly drifting ashore. After some deliberation he put up his helm, and beat to windward of the pinnace; then, coming about, came scudding down upon her before the wind. The two vessels met with a tremendous shock. The bow of the sloop struck the pinnace fairly amidships, forcing her over on her beam-ends, until the water poured into the open hatchway. The affrighted (p. 001) Indians, unused to warfare on the water, rushed upon deck. Six leaped into the sea, and were drowned; the rest retreated again into the cabin. Gallop then prepared to repeat his ramming manœuvre. This time, to make the blow more effective, he lashed his anchor to the bow, so that the sharp flukes protruded; thus extemporizing an iron-clad ram more than two hundred years before naval men thought of using one. Thus provided, the second blow of the sloop was more terrible than the first. The sharp fluke of the anchor crashed through the side of the pinnace, and the two vessels hung tightly together. Gallop then began to double-load his duck-guns, and fire through the sides of the pinnace; but, finding that the enemy was not to be dislodged in this way, he broke his vessel loose, and again made for the windward, preparatory to a third blow. As the sloop drew off, four or five more Indians rushed from the cabin of the pinnace, and leaped overboard but shared the fate of their predecessors, being far from land. Gallop then came about, and for the third time bore down upon his adversary. As he drew near, an Indian appeared on the deck of the pinnace, and with humble gestures offered to submit. Gallop ran alongside, and taking the man on board, bound him hand and foot, and placed him in the hold. A second redskin then begged for quarter; but Gallop, fearing to allow the two wily savages to be together, cast the second into the sea, where he was drowned. Gallop then boarded the pinnace. Two Indians were left, who retreated into a small compartment of the hold, and were left unmolested. In the cabin was found the mangled body of Mr. Oldham. A tomahawk had been sunk deep into his skull, and his body was covered with wounds. The floor of the cabin was littered with portions of the cargo, which the murderous savages had plundered. Taking all that remained of value upon his own craft, Gallop cut loose the pinnace; and she drifted away, to go to pieces on a reef in Narragansett Bay.

This combat is the earliest action upon American waters of which we have any trustworthy records. The only naval event antedating this was the expedition from Virginia, under Capt. Samuel Argal, against the little French settlement of San Sauveur. Indeed, had it not been for the pirates and the neighboring French settlements, there would be little in the early history of the American Colonies to attract the lover of (p. 002) naval history. But about 1645 the buccaneers began to commit depredations on the high seas, and it became necessary for the Colonies to take steps for the protection of their commerce. In this year an eighteen-gun ship from Cambridge, Mass., fell in with a Barbary pirate of twenty guns, and was hard put to it to escape. And, as the seventeenth century drew near its close, these pests of the sea so increased, that evil was sure to befall the peaceful merchantman that put to sea without due preparation for a fight or two with the sea robbers.

It was in the low-lying islands of the Gulf of Mexico, that these predatory gentry—buccaneers, marooners, or pirates—made their headquarters, and lay in wait for the richly freighted merchantmen in the West India trade. Men of all nationalities sailed under the "Jolly Roger,"—as the dread black flag with skull and cross-bones was called,—but chiefly were they French and Spaniards. The continual wars that in that turbulent time racked Europe gave to the marauders of the sea a specious excuse for their occupation. Thus, many a Spanish schooner, manned by a swarthy crew bent on plunder, commenced her career on the Spanish Main, with the intention of taking only ships belonging to France and England; but let a richly laden Spanish galleon appear, after a long season of ill-fortune, and all scruples were thrown aside, the "Jolly Roger" sent merrily to the fore, and another pirate was added to the list of those that made the highways of the sea as dangerous to travel as the footpad infested common of Hounslow Heath. English ships went out to hunt down the treacherous Spaniards, and stayed to rob and pillage indiscriminately; and not a few of the names now honored as those of eminent English discoverers, were once dreaded as being borne by merciless pirates.

But the most powerful of the buccaneers on the Spanish Main were French, and between them and the Spaniards an unceasing warfare was waged. There were desperate men on either side, and mighty stories are told of their deeds of valor. There were Pierre François, who, with six and twenty desperadoes, dashed into the heart of a Spanish fleet, and captured the admiral's flag-ship; Bartholomew Portuguese, who, with thirty men, made repeated attacks upon a great Indiaman with a crew of seventy, and though beaten back time and again, persisted until the crew surrendered to the twenty buccaneers left alive; François l'Olonoise, who (p. 003) sacked the cities of Maracaibo and Gibraltar, and who, on hearing that a man-o'-war had been sent to drive him away, went boldly to meet her, captured her, and slaughtered all of the crew save one, whom he sent to bear the bloody tidings to the governor of Havana.

Such were the buccaneers,—desperate, merciless, and insatiate in their lust for plunder. So numerous did they finally become, that no merchant dared to send a ship to the West Indies; and the pirates, finding that they had fairly exterminated their game, were fain to turn landwards for further booty. It was an Englishman that showed the sea rovers this new plan of pillage; one Louis Scott, who descended upon the town of Campeche, and, after stripping the place to the bare walls, demanded that a heavy tribute be paid him, in default of which he would burn the town. Loaded with booty, he sailed back to the buccaneers' haunts in the Tortugas. This expedition was the example that the buccaneers followed for the next few years. City after city fell a prey to the demoniac attacks of the lawless rovers. Houses and churches were sacked, towns given to the flames, rich and poor plundered alike; murder was rampant; and men and women were subjected to the most horrid tortures, to extort information as to buried treasures.

Two great names stand out pre-eminent amid the host of outlaws that took part in this reign of rapine,—l'Olonoise and Sir Henry Morgan. The desperate exploits of these two worthies would, if recounted, fill volumes; and probably no more extraordinary narrative of cruelty, courage, suffering, and barbaric luxury could be fabricated. Morgan was a Welshman, an emigrant, who, having worked out as a slave the cost of his passage across the ocean, took immediate advantage of his freedom to take up the trade of piracy. For him was no pillaging of paltry merchant-ships. He demanded grander operations, and his bands of desperadoes assumed the proportions of armies. Many were the towns that suffered from the bloody visitations of Morgan and his men. Puerto del Principe yielded up to them three hundred thousand pieces of eight, five hundred head of cattle, and many prisoners. Porto Bello was bravely defended against the barbarians; and the stubbornness of the defence so enraged Morgan, that he swore that no quarter should be given the defenders. And so when some hours later the chief fortress surrendered, the merciless buccaneer locked its garrison in the guard-room, set a torch to (p. 004) the magazine, and sent castle and garrison flying into the air. Maracaibo and Gibraltar next fell into the clutches of the pirate. At the latter town, finding himself caught in a river with three men-of-war anchored at its mouth, he hastily built a fire-ship, put some desperate men at the helm, and sent her, a sheet of flame, into the midst of the squadron. The admiral's ship was destroyed; and the pirates sailed away, exulting over their adversaries' discomfiture. Rejoicing over their victories, the followers of Morgan then planned a venture that should eclipse all that had gone before. This was no less than a descent upon Panama, the most powerful of the West Indian cities. For this undertaking, Morgan gathered around him an army of over two thousand desperadoes of all nationalities. A little village on the island of Hispaniola was chosen as the recruiting station; and thither flocked pirates, thieves, and adventurers from all parts of the world. It was a motley crew thus gathered together,—Spaniards, swarthy skinned and black haired; wiry Frenchmen, quick to anger, and ever ready with cutlass or pistol; Malays and Lascars, half clad in gaudy colors, treacherous and sullen, with a hand ever on their glittering creeses; Englishmen, handy alike with fist, bludgeon, or cutlass, and mightily given to fearful oaths; negroes, Moors, and a few West Indians mixed with the lawless throng.

Having gathered his band, procured provisions (chiefly by plundering), and built a fleet of boats, Morgan put his forces in motion. The first obstacle in his path was the Castle of Chagres, which guarded the mouth of the Chagres River, up which the buccaneers must pass to reach the city of Panama. To capture this fortress, Morgan sent his vice-admiral Bradley, with four hundred men. The Spaniards were evidently warned of their approach; for hardly had the first ship flying the piratical ensign appeared at the mouth of the river, when the royal standard of Spain was hoisted above the castle, and the dull report of a shotted gun told the pirates that there was a stubborn resistance in store for them.

Landing some miles below the castle, and cutting their way with hatchet and sabre through the densely interwoven vegetation of a tropical jungle, the pirates at last reached a spot from which a clear view of the castle could be obtained. As they emerged from the forest to the open, the sight greatly disheartened them. They saw a powerful fort, with bastions, moat, drawbridge, and precipitous natural defences. Many (p. 005) of the pirates advised a retreat; but Bradley, dreading the anger of Morgan, ordered an assault. Time after time did the desperate buccaneers, with horrid yells, rush upon the fort, only to be beaten back by the well-directed volleys of the garrison. They charged up to the very walls, threw over fireballs, and hacked the timbers with axes, but to no avail. From behind their impregnable ramparts, the Spaniards fired murderous volleys, crying out.—

"Come on, you English devils, you heretics, the enemies of God and of the king! Let your comrades who are behind come also. We will serve them as we have served you. You shall not get to Panama this time."

As night fell, the pirates withdrew into the thickets to escape the fire of their enemies, and to discuss their discomfiture. As one group of buccaneers lay in the jungle, a chance arrow, shot by an Indian in the fort, struck one of them in the arm. Springing to his feet with a cry of rage and pain, the wounded man cried out as he tore the arrow from the bleeding wound,—

"Look here, my comrades. I will make this accursed arrow the means of the destruction of all the Spaniards."

So saying, he wrapped a quantity of cotton about the head of the arrow, charged his gun with powder, and, thrusting the arrow into the muzzle, fired. His comrades eagerly watched the flight of the missile, which was easily traced by the flaming cotton. Hurtling through the air, the fiery missile fell upon a thatched roof within the castle, and the dry straw and leaves were instantly in a blaze. With cries of savage joy, the buccaneers ran about picking up the arrows that lay scattered over the battle-field. Soon the air was full of the fire-brands, and the woodwork within the castle enclosure was a mass of flame. One arrow fell within the magazine; and a burst of smoke and flame, and the dull roar of an explosion, followed. The Spaniards worked valiantly to extinguish the flames, and to beat back their assailants; but the fire raged beyond their control, and the bright light made them easy targets for their foes. There could be but one issue to such a conflict. By morning the fort was in the hands of the buccaneers, and of the garrison of three hundred and fourteen only fourteen were unhurt. Over the ruins of the fort the English flag was hoisted, the shattered walls were repaired, and the place made a rendezvous for Morgan's forces.

(p. 006) On the scene of the battle Morgan drilled his forces, and prepared for the march and battles that were to come. After some days' preparation, the expedition set out. The road lay through tangled tropical forests, under a burning sun. Little food was taken, as the invaders expected to live on the country; but the inhabitants fled before the advancing column, destroying every thing eatable. Soon starvation stared the desperadoes in the face. They fed upon berries, roots, and leaves. As the days passed, and no food was to be found, they sliced up and devoured coarse leather bags. For a time, it seemed that they would never escape alive from the jungle; but at last, weak, weary, and emaciated, they came out upon a grassy plain before the city of Panama. Here, a few days later, a great battle was fought. The Spaniards outnumbered the invaders, and were better provided with munitions of war; yet the pirates, fighting with the bravery of desperate men, were victorious, and the city fell into their hands. Then followed days of murder, plunder, and debauchery. Morgan saw his followers, maddened by liquor, scoff at the idea of discipline and obedience. Fearing that while his men were helplessly drunk the Spaniards would rally and cut them to pieces, he set fire to the city, that the stores of rum might be destroyed. After sacking the town, the vandals packed their plunder on the backs of mules, and retraced their steps to the seaboard. Their booty amounted to over two millions of dollars. Over the division of this enormous sum great dissensions arose, and Morgan saw the mutinous spirit spreading rapidly among his men. With a few accomplices, therefore, he loaded a ship with the plunder, and secretly set sail; leaving over half of his band, without food or shelter, in a hostile country. Many of the abandoned buccaneers starved, some were shot or hanged by the enraged Spaniards; but the leader of the rapacious gang reached Jamaica with a huge fortune, and was appointed governor of the island, and made a baronet by the reigning king of England, Charles the Second.

Such were some of the exploits of some of the more notorious of the buccaneers. It may be readily imagined, that, with hordes of desperadoes such as these infesting the waters of the West Indies, there was little opportunity for the American Colonies to build up any maritime interests in that direction. And as the merchantmen became scarce on the Spanish Main, such of the buccaneers as did not turn landward in search (p. 007) of booty put out to sea, and ravaged the ocean pathways between the Colonies and England. It was against these pirates, that the earliest naval operations of the Colonies were directed. Several cruisers were fitted out to rid the seas of these pests, but we hear little of their success. But the name of one officer sent against the pirates has become notorious as that of the worst villain of them all.

It was in January, 1665, that William III., King of England, issued "to our true and well-beloved Capt. William Kidd, commander of the ship 'Adventure,'" a commission to proceed against "divers wicked persons who commit many and great piracies, robberies, and depredations on the seas." Kidd was a merchant of New York, and had commanded a privateer during the last war with France. He was a man of great courage, and, being provided with a stanch ship and brave crew, set out with high hopes of winning great reputation and much prize money. But fortune was against him. For months the "Adventure" ploughed the blue waves of the ocean, yet not a sail appeared on the horizon. Once, indeed, three ships were seen in the distance. The men of the "Adventure" were overjoyed at the prospect of a rich prize. The ship was prepared for action. The men, stripped to the waist, stood at their quarters, talking of the coming battle. Kidd stood in the rigging with a spy-glass, eagerly examining the distant vessels. But only disappointment was in store; for, as the ships drew nearer, Kidd shut his spy-glass with an oath, saying,—

"They are only three English men-o'-war."

Continued disappointment bred discontent and mutiny among the crew. They had been enlisted with lavish promises of prize money, but saw before them nothing but a profitless cruise. The spirit of discontent spread rapidly. Three or four ships that were sighted proved to be neither pirates nor French, and were therefore beyond the powers of capture granted Kidd by the king. Kidd fought against the growing piratical sentiment for a long time; but temptation at last overcame him, and he yielded. Near the Straits of Babelmandeb, at the entrance to the Red Sea, he landed a party, plundered the adjoining country for provisions, and, turning his ship's prow toward the straits, mustered his crew on deck, and thus addressed them:—

"We have been unsuccessful hitherto, my boys," he said, "but take (p. 008) courage. Fortune is now about to smile upon us. The fleet of the 'Great Mogul,' freighted with the richest treasures, is soon to come out of the Red Sea. From the capture of those heavily laden ships, we will all grow rich."

The crew, ready enough to become pirates, cheered lustily: and, turning his back upon all hopes of an honorable career, Kidd set out in search of the treasure fleet. After cruising for four days, the "Adventure" fell in with the squadron, which proved to be under convoy of an English and a Dutch man-of-war. The squadron was a large one, and the ships greatly scattered. By skilful seamanship, Kidd dashed down upon an outlying vessel, hoping to capture and plunder it before the convoying men-of-war could come to its rescue. But his first shot attracted the attention of the watchful guardians; and, though several miles away, they packed on all sail, and bore down to the rescue with such spirit that the disappointed pirate was forced to sheer off. Kidd was now desperate. He had failed as a reputable privateer, and his first attempt at piracy had failed. Thenceforward, he cast aside all scruples, and captured large ships and small, tortured their crews, and for a time seemed resolved to lead a piratical life. But there are evidences that at times this strange man relented, and strove to return to the path of duty and right. On one occasion, a Dutch ship crossed the path of the "Adventure," and the crew clamorously demanded her capture. Kidd firmly refused. A tumult arose. The captain drew his sabre and pistols, and gathering about him those still faithful, addressed the mutineers, saying,—

"You may take the boats and go. But those who thus leave this ship will never ascend its sides again."

The mutineers murmured loudly. One man, a gunner, named William Moore, stepped forward, saying,—

"You are ruining us all. You are keeping us in beggary and starvation. But for your whims, we might all be prosperous and rich."

At this outspoken mutiny, Kidd flew into a passion. Seizing a heavy bucket that stood near, he dealt Moore a terrible blow on the head. The unhappy man fell to the deck with a fractured skull, and the other mutineers sullenly yielded to the captain's will. Moore died the next day; and months after, when Kidd, after roving the seas, and robbing (p. 009) ships of every nationality, was brought to trial at London, it was for the murder of William Moore that he was condemned to die. For Kidd's career subsequent to the incident of the Dutch ship was that of a hardened pirate. He captured and robbed ships, and tortured their passengers. He went to Madagascar, the rendezvous of the pirates, and joined in their revelry and debauchery. On the island were five or six hundred pirates, and ships flying the black flag were continually arriving or departing. The streets resounded with shouts of revelry, with curses, and with the cries of rage. Strong drinks were freely used. Drunkenness was everywhere. It was no uncommon thing for a hogshead of wine to be opened, and left standing in the streets, that any might drink who chose. The pirates, flush with their ill-gotten gains, spent money on gambling and kindred vices lavishly. The women who accompanied them to this lawless place were decked out with barbaric splendor in silks and jewels. On the arrival of a ship, the debauchery was unbounded. Such noted pirates as Blackbeard, Steed Bonnet, and Avary made the place their rendezvous, and brought thither their rich prizes and wretched prisoners. Blackbeard was one of the most desperate pirates of the age. He, with part of his crew, once terrorized the officials of Charleston, S.C., exacting tribute of medicines and provisions. Finally he was killed in action, and sixteen of his desperate gang expiated their crimes on the gallows.

To Madagascar, too, often came the two female pirates, Mary Read and Anne Bonny. These women, masquerading in men's clothing, were as desperate and bloody as the men by whose side they fought. By a strange coincidence, these two women enlisted on the same ship. Each knowing her own sex, and being ignorant of that of the other, they fell in love; and the final discovery of their mutual deception increased their intimacy. After serving with the pirates, working at the guns, swinging a cutlass in the boarding parties, and fighting a duel in which she killed her opponent, Mary Read determined to escape. There is every evidence that she wearied of the evil life she was leading, and was determined to quit it; but, before she could carry her intentions into effect, the ship on which she served was captured, and taken to England, where the pirates expiated their crimes on the gallows, Mary Read dying in prison before the day set for her execution.

(p. 010) After some months spent in licentious revelry at Madagascar, Kidd set out on a further cruise. During this voyage he learned that he had been proscribed as a pirate, and a price set on his head. Strange as it may appear, this news was a surprise to him. He seems to have deceived himself into thinking that his acts of piracy were simply the legitimate work of a privateersman. For a time he knew not what to do; but as by this time the coarse pleasures of an outlaw's life were distasteful to him, he determined to proceed to New York, and endeavor to prove himself an honest man. This determination proved to be an unfortunate one for him; for hardly had he arrived, when he was taken into custody, and sent to England for trial. He made an able defence, but was found guilty, and sentenced to be hanged; a sentence which was executed some months later, in the presence of a vast multitude of people, who applauded in the death of Kidd the end of the reign of outlaws upon the ocean.[Back to Content]

CHAPTER II.

EXPEDITIONS AGAINST NEIGHBORING COLONIES. — ROMANTIC CAREER OF SIR WILLIAM PHIPPS. — QUELLING A MUTINY. — EXPEDITIONS AGAINST QUEBEC.

hile

it was chiefly in expeditions against the buccaneers, or in the

defence of merchantmen against these predatory gentry, that the

American colonists gained their experience in naval warfare, there

were, nevertheless, some few naval expeditions fitted out by the

colonists against the forces of a hostile government. Both to the

north and south lay the territory of France and Spain,—England's

traditional enemies; and so soon as the colonies began to give

evidence of their value to the mother country, so soon were they

dragged into the quarrels in which the haughty mistress of the seas

was ever plunged. Of the southern colonies, South Carolina was

continually embroiled with Spain, owing to the conviction of the

Spanish that the boundaries of Florida—at that time a Spanish

colony—included the greater part of the Carolinas. For the purpose of

enforcing this idea, the Spaniards, in 1706, fitted out an expedition

of four ships-of-war and a galley, which, under the command of a

celebrated French admiral, (p. 012) was despatched to take

Charleston. The people of Charleston were in no whit daunted, and on

the receipt of the news of the expedition began preparations for

resistance. They had no naval vessels; but several large merchantmen,

being in port, were hastily provided with batteries, and a large

galley was converted into a flag-ship. Having no trained naval

officers, the command of the improvised squadron was tendered to a

certain Lieut.-Col. Rhett, who possessed the confidence of the

colonists. Rhett accepted the command; and when the attacking party

cast anchor some miles below the city, and landed their shore forces,

he weighed anchor, and set out to attack them. But the Spaniards

avoided the conflict, and fled out to sea, leaving their land forces

to bear the brunt of battle. In this action, more than half of the

invaders were killed or taken prisoners. Some days later, one of the

Spanish vessels, having been separated from her consorts, was

discovered by Rhett, who attacked her, and after a sharp fight

captured her, bringing her with ninety prisoners to Charleston.

hile

it was chiefly in expeditions against the buccaneers, or in the

defence of merchantmen against these predatory gentry, that the

American colonists gained their experience in naval warfare, there

were, nevertheless, some few naval expeditions fitted out by the

colonists against the forces of a hostile government. Both to the

north and south lay the territory of France and Spain,—England's

traditional enemies; and so soon as the colonies began to give

evidence of their value to the mother country, so soon were they

dragged into the quarrels in which the haughty mistress of the seas

was ever plunged. Of the southern colonies, South Carolina was

continually embroiled with Spain, owing to the conviction of the

Spanish that the boundaries of Florida—at that time a Spanish

colony—included the greater part of the Carolinas. For the purpose of

enforcing this idea, the Spaniards, in 1706, fitted out an expedition

of four ships-of-war and a galley, which, under the command of a

celebrated French admiral, (p. 012) was despatched to take

Charleston. The people of Charleston were in no whit daunted, and on

the receipt of the news of the expedition began preparations for

resistance. They had no naval vessels; but several large merchantmen,

being in port, were hastily provided with batteries, and a large

galley was converted into a flag-ship. Having no trained naval

officers, the command of the improvised squadron was tendered to a

certain Lieut.-Col. Rhett, who possessed the confidence of the

colonists. Rhett accepted the command; and when the attacking party

cast anchor some miles below the city, and landed their shore forces,

he weighed anchor, and set out to attack them. But the Spaniards

avoided the conflict, and fled out to sea, leaving their land forces

to bear the brunt of battle. In this action, more than half of the

invaders were killed or taken prisoners. Some days later, one of the

Spanish vessels, having been separated from her consorts, was

discovered by Rhett, who attacked her, and after a sharp fight

captured her, bringing her with ninety prisoners to Charleston.

But it was chiefly in expeditions against the French colonies to the northward that the naval strength of the English colonies was exerted. Particularly were the colonies of Port Royal, in Acadia, and the French stronghold of Quebec coveted by the British, and they proved fertile sources of contention in the opening years of the eighteenth century. Although the movement for the capture of these colonies was incited by the ruling authorities of Great Britain, its execution was left largely to the colonists. One of the earliest of these expeditions was that which sailed from Nantasket, near Boston, in April, 1690, bound for the conquest of Port Royal.

This expedition was under the command of Sir William Phipps, a sturdy colonist, whose life was not devoid of romantic episodes. Though his ambitions were of the lowliest,—his dearest wish being "to command a king's ship, and own a fair brick house in the Green Lane of North Boston,"—he managed to win for himself no small amount of fame and respect in the colonies. His first achievement was characteristic of that time, when Spanish galleons, freighted with golden ingots, still sailed the seas, when pirates buried their booty, and when the treasures carried down in sunken ships were not brought up the next day by divers clad in patented submarine armor. From a weather-beaten (p. 013) old seaman, with whom he became acquainted while pursuing his trade of ship-carpentering Phipps learned of a sunken wreck lying on the sandy bottom many fathoms beneath the blue surface of the Gulf of Mexico. The vessel had gone down fifty years before, and had carried with her great store of gold and silver, which she was carrying from the rich mines of Central and South America to the Court of Spain. Phipps, laboriously toiling with adze and saw in his ship-yard, listened to the story of the sailor, his blood coursing quicker in his veins, and his ambition for wealth and position aroused to its fullest extent. Here, then, thought he, was the opportunity of a lifetime. Could he but recover the treasures carried down with the sunken ship, he would have wealth and position in the colony. With these two allies at his command, the task of securing a command in the king's navy would be an easy one. But to seek out the sunken treasure required a ship and seamen. Clearly his own slender means could never meet the demands of so great an undertaking. Therefore, gathering together all his small savings, William Phipps set sail for England, in the hopes of interesting capitalists there in his scheme. By dint of indomitable persistence, the unknown American ship-carpenter managed to secure the influence of certain officials of high station in England, and finally managed to get the assistance of the British admiralty. A frigate, fully manned, was given him, and he set sail for the West Indies.

Once arrived in the waters of the Spanish Main, he began his search. Cruising about the spot indicated by his seafaring informant as the location of the sunken vessel, sounding and dredging occupied the time of the treasure-seekers for months. The crew, wearying of the fruitless search, began to murmur, and signs of mutiny were rife. Phipps, filled with thoughts of the treasure for which he sought, saw not at all the lowering looks, nor heard the half-uttered threats, of the crew as he passed them. But finally the mutiny so developed that he could no longer ignore its existence.

It was then the era of the buccaneers. Doubtless some of the crew had visited the outlaws' rendezvous at New Providence, and had told their comrades of the revelry and ease in which the sea robbers spent their days. And so it happened that one day, as Phipps stood on the quarter-deck vainly trying to choke down the nameless fear that had begun to oppress him,—the fear that his life's venture had proved a failure,—his (p. 014) crew came crowding aft, armed to the teeth, and loudly demanded that the captain should abandon his foolish search, and lead them on a fearless buccaneering cruise along the Spanish Main. The mutiny was one which might well have dismayed the boldest sea captain. The men were desperate, and well armed. Phipps was almost without support; for his officers, by their irresolute and timid demeanor, gave him little assurance of aid.

Standing on the quarter-deck, Phipps listened impatiently to the complaints of the mutineers; but, when their spokesman called upon him to lead them upon a piratical cruise, he lost all control of himself, and, throwing all prudence to the winds, sprung into the midst of the malcontents, and laid about him right manfully with his bare fists. The mutineers were all well armed, but seemed loath to use their weapons; and the captain, a tall, powerful man, soon awed them all into submission.

Though he showed indomitable energy in overcoming obstacles, Phipps was not destined to discover the object of his search at this time; and, after several months' cruising, he was forced, by the leaky condition of his vessel, to abandon the search. But, before leaving the waters of the Spanish Main, he obtained enough information to convince him that his plan was a practicable one, and no mere visionary scheme. On reaching England, he went at once to some wealthy noblemen, and, laying before them all the facts in his possession, so interested them in the project that they readily agreed to supply him with a fresh outfit. After a few weeks spent in organizing his expedition, the treasure-seeker was again on the ocean, making his way toward the Mexican Gulf. This time his search was successful, and a few days' work with divers and dredges about the sunken ship brought to light bullion and specie to the amount of more than a million and a half dollars. As his ill success in the first expedition had embroiled him with his crew, so his good fortune this time aroused the cupidity of the sailors. Vague rumors of plotting against his life reached the ears of Phipps. Examining further into the matter, he learned that the crew was plotting to seize the vessel, divide the treasure, and set out upon a buccaneering cruise. Alarmed at this intelligence, Phipps strove to conciliate the seamen by offering them a share of the treasure. Each man should receive a portion, he promised, even if he himself had to pay it. The men agreed (p. 015) to this proposition; and so well did Phipps keep his word with them on returning to England, that, of the whole treasure, only about eighty thousand dollars remained to him as his share. This, however, was an ample fortune for those times; and with it Phipps returned to Boston, and began to devote himself to the task of securing a command in the royal navy.

His first opportunity to distinguish himself came in the expedition of 1690 against Port Royal. Throughout the wars between France and England, the French settlement of Port Royal had been a thorn in the flesh of Massachusetts. From Port Royal, the trim-built speedy French privateers put to sea, and seldom returned without bringing in their wake some captured coaster or luckless fisherman hailing from the colony of the Puritans. When the depredations of the privateers became unbearable, Massachusetts bestirred herself, and the doughty Phipps was sent with an expedition to reduce their unneighborly neighbor to subjection. Seven vessels and two hundred and eighty-eight men were put under the command of the lucky treasure-hunter. The expedition was devoid of exciting or novel features. Port Royal was reached without disaster, and the governor surrendered with a promptitude which should have won immunity for the people of the village. But the Massachusetts sailors had not undertaken the enterprise for glory alone, and they plundered the town before taking to their ships again.

This expedition, however, was but an unimportant incident in the naval annals of the colonies. It was followed quickly by an expedition of much graver importance.

When Phipps returned after capturing and plundering Port Royal, he found Boston vastly excited over the preparations for an expedition against Quebec. The colony was in no condition to undertake the work of conquest. Prolonged Indian wars had greatly depleted its treasury. Vainly it appealed to England for aid, but, receiving no encouragement, sturdily determined to undertake the expedition unaided. Sailors were pressed from the merchant-shipping. Trained bands, as the militia of that day was called, drilled in the streets, and on the common. Subscription papers were being circulated; and vessel owners were blandly given the choice between voluntarily loaning their vessels to the colony, or having them peremptorily seized. In this way a fleet of thirty-two vessels had been collected; the largest of which was a ship called the "Six (p. 016) Friends," built for the West India trade, and carrying forty-four guns. This armada was manned by seamen picked up by a press so vigorous, that Gloucester, the chief seafaring town of the colony, was robbed of two-thirds of its men. Hardly had Capt. Phipps, flushed with victory, returned from his Port Royal expedition, when he was given command of the armada destined for the capture of Quebec.

Early in August the flotilla set sail from Boston Harbor. The day was clear and warm, with a light breeze blowing. From his flag-ship Phipps gave the signal for weighing anchor, and soon the decks of the vessels thickly strewn about the harbor resounded to the tread of men about the capstan. Thirty-two vessels of the squadron floated lightly on the calm waters of the bay; and darting in and out among them were light craft carrying pleasure-seekers who had come down to witness the sailing of the fleet, friends and relatives of the sailors who were there to say farewell, and the civic dignitaries who came to wish the expedition success. One by one the vessels beat their way down the bay, and, rounding the dangerous reef at the mouth of the harbor, laid their course to the northward. It was a motley fleet of vessels. The "Six Brothers" led the way, followed by brigs, schooners, and many sloop-rigged fishing-smacks. With so ill-assorted a flotilla, it was impossible to keep any definite sailing order. The first night scattered the vessels far and wide, and thenceforward the squadron was not united until it again came to anchor just above the mouth of the St. Lawrence. It seemed as though the very elements had combined against the voyagers. Though looking for summer weather, they encountered the bitter gales of November. Only after they had all safely entered the St. Lawrence, and were beyond injury from the storms, did the gales cease. They had suffered all the injury that tempestuous weather could do them, and they then had to chafe under the enforced restraints of a calm.

Phipps had rallied his scattered fleet, and had proceeded up the great river of the North to within three days' sail of Quebec, when the calm overtook him. On the way up the river he had captured two French luggers, and learned from his prisoners that Quebec was poorly fortified, that the cannon on the redoubts were dismounted, and that hardly two hundred men could be rallied to its defence. Highly elated at this, the Massachusetts admiral pressed forward. He anticipated that Quebec, (p. 017) like Port Royal, would surrender without striking a blow. Visions of high honors, and perhaps even a commission in the royal navy, floated across his brain. And while thus hurrying forward his fleet, drilling his men, and building his air-castles, his further progress was stopped by a dead calm which lasted three weeks.

How fatal to his hopes that calm was, Phipps, perhaps, never knew. The information he had wrung from his French prisoners was absolutely correct. Quebec at that time was helpless, and virtually at his mercy. But, while the Massachusetts armada lay idly floating on the unruffled bosom of the river, a man was hastening towards Quebec whose timely arrival meant the salvation of the French citadel.

This man was Frontenac, then governor of the French colony, and one of the most picturesque figures in American history. A soldier of France; a polished courtier at the royal court; a hero on the battle-field, and a favorite in the ball-room; a man poor in pocket, but rich in influential connections,—Frontenac had come to the New World to seek that fortune and position which he had in vain sought in the Old. When the vague rumors of the hostile expedition of the Massachusetts colony reached his ears, Frontenac was far from Quebec, toiling in the western part of the colony. Wasting no time, he turned his steps toward the threatened city. His road lay through an almost trackless wilderness; his progress was impeded by the pelting rains of the autumnal storms. But through forest and through rain he rode fiercely; and at last as he burst from the forest, and saw towering before him the rocks of Cape Diamond, a cry of joy burst from his lips. On the broad, still bosom of the St Lawrence Bay floated not a single hostile sail. The soldier had come in time.

With the governor in the city, all took courage, and the work of preparation for the coming struggle went forward with a rush. Far and wide throughout the parishes was spread the news of war, and daily volunteers came flocking in to the defence. The ramparts were strengthened, and cannon mounted. Volunteers and regulars drilled side by side, until the four thousand men in the city were converted into a well-disciplined body of troops. And all the time the sentinels on the Saut au Matelot were eagerly watching the river for the first sign of the English invaders.

(p. 018) It was before dawn, on the morning of Oct. 16, that the people of the little city, and the soldiery in the tents, were awakened by the alarm raised by the sentries. All rushed to the brink of the heights, and peered eagerly out into the darkness. Far down the river could be seen the twinkling lights of vessels. As the eager watchers strove to count them, other lights appeared upon the scene, moving to and fro, but with a steady advance upon Quebec. The gray dawn, breaking in the east, showed the advancing fleet. Frontenac and his lieutenants watched the ships of the enemy round the jutting headland of the Point of Orleans; and, by the time the sun had risen, thirty-four hostile craft were at anchor in the basin of Quebec.

The progress of the fleet up the river, from the point at which it had been so long delayed, had been slow, and greatly impeded by the determined hostility of the settlers along the banks. The sailors at their work were apt to be startled by the whiz of a bullet; and an inquiry as to the cause would have probably discovered some crouching sharp-shooter, his long rifle in his hand, hidden in a clump of bushes along the shore. Bands of armed men followed the fleet up the stream, keeping pace with the vessels, and occasionally affording gentle reminders of their presence in the shape of volleys of rifle-balls that sung through the crowded decks of the transports, and gave the sailor lads a hearty disgust for this river fighting. Phipps tried repeatedly to land shore parties to clear the banks of skirmishers, and to move on the city by land. As often, however, as he made the effort, his troops were beaten back by the ambushed sharp-shooters, and his boats returned to the ships, bringing several dead and wounded.

While the soldiery on the highlands of Quebec were eagerly examining the hostile fleet, the invaders were looking with wonder and admiration at the scene of surpassing beauty spread out before them. Parkman, the historian and lover of the annals of the French in America, thus describes it:—

"When, after his protracted voyage, Phipps sailed into the basin of Quebec, one of the grandest scenes on the western continent opened upon his sight. The wide expanse of waters, the lofty promontory beyond, and the opposing Heights of Levi, the cataract of Montmorenci, the distant range of the Laurentian Mountains, the warlike rock with its diadem (p. 019) of walls and towers, the roofs of the Lower Town clustering on the strand beneath, the Chateau St. Louis perched at the brink of the cliff, and over it the white banner, spangled with fleurs de lis, flaunting defiance in the clear autumnal air."

Little time was spent, however, in admiration of the scene. When the click of the last chain-cable had ceased, and, with their anchors reposing at the bottom of the stream, the ships swung around with their bows to the current, a boat put off from the flag-ship bearing an officer intrusted with a note from Phipps to the commandant of the fort. The reception of this officer was highly theatrical. Half way to the shore he was taken into a French canoe, blindfolded, and taken ashore. The populace crowded about him as he landed, hooting and jeering him as he was led through winding, narrow ways, up stairways, and over obstructions, until at last the bandage was torn from his eyes, and he found himself in the presence of Frontenac. The French commander was clad in a brilliant uniform, and surrounded by his staff, gay in warlike finery. With courtly courtesy he asked the envoy for his letter, which, proving to be a curt summons to surrender, he answered forthwith in a stinging speech. The envoy, abashed, asked for a written answer.

"No," thundered Frontenac, "I will answer your master only by the mouths of my cannon, that he may learn that a man like me is not to be summoned after this fashion. Let him do his best, and I will do mine."

The envoy returned to his craft, and made his report. The next day hostilities opened. Wheeling his ships into line before the fortifications, Phipps opened a heavy fire upon the city. From the frowning ramparts on the heights, Frontenac's cannon answered in kind. Fiercely the contest raged until nightfall, and vast was the consumption of gunpowder; but damage done on either side was but little. All night the belligerents rested on their arms; but, at daybreak, the roar of the cannonade recommenced.

The gunners of the opposing forces were now upon their mettle, and the gunnery was much better than the day before. A shot from the shore cut the flagstaff of the admiral's ship, and the cross of St. George fell into the river. Straightway a canoe put out from the shore, and with swift, strong paddle-strokes was guided in chase of the floating trophy. The fire of the fleet was quickly concentrated upon the (p. 020) adventurous canoeists. Cannon-balls and rifle-bullets cut the water about them; but their frail craft survived the leaden tempest, and they captured the trophy, and bore it off in triumph.

Phipps felt that the incident was an unfavorable omen, and would discourage his men. He cast about in his mind for a means of retaliation. Far over the roofs of the city rose a tapering spire, that of the cathedral in the Upper Town. On this spire, the devout Catholics of the French city had hung a picture of the Holy Family as an invocation of Divine aid. Through his spy-glass, Phipps could see that some strange object hung from the steeple, and, suspecting its character, commanded the gunners to try to knock it down. For hours the Puritans wasted their ammunition in this vain target-practice, but to no avail. The picture still hung on high; and the devout Frenchmen ascribed its escape to a miracle, although its destruction would have been more miraculous still.

It did not take long to convince Phipps that in this contest his fleet was getting badly worsted, and he soon withdrew his vessels to a place of safety. The flag-ship had been fairly riddled with shot; and her rigging was so badly cut, that she could only get out of range of the enemy's guns by cutting her cables, and drifting away with the current. Her example was soon followed by the remaining vessels.

Sorely crestfallen, Phipps abandoned the fight, and prepared to return to Boston. His voyage thither was stormy; and three or four of his vessels never were heard of, having been dashed to pieces by the waves, or cast away upon the iron-bound coast of Nova Scotia or Maine. His expedition was the most costly in lives and in treasure ever undertaken by a single colony, and, despite its failure, forms the most notable incident in the naval annals of the colonies prior to the Revolution.

The French colonies continued to be a fruitful source of war and turmoil. Many were the joint military and naval expeditions fitted out against them by the British colonies. Quebec, Louisbourg, and Port Royal were all threatened; and the two latter were captured by colonial expeditions. From a naval point of view, these expeditions were but trifling. They are of some importance, however, in that they gave the colonists an opportunity to try their prowess on the ocean; and in this irregular service were bred some sailors who fought right valiantly for the rebellious colonies against the king, and others who did no less valiant service under the royal banner.[Back to Content]

OPENING OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION. — THE AFFAIR OF THE SCHOONER "ST. JOHN." — THE PRESS-GANG AND ITS WORK. — THE SLOOP "LIBERTY." — DESTRUCTION OF THE "GASPEE." — THE BOSTON TEA-PARTY.

t

is unnecessary to enter into an account of the causes that led up

to the revolt of the American Colonies against the oppression of King

George and his subservient Parliament. The story of the Stamp Act, the

indignation of the Colonies, their futile attempts to convince

Parliament of the injustice of the measure, the stern measures adopted

by the British to put down the rising insubordination, the Boston

Massacre, and the battles at Concord and Lexington are familiar to

every American boy. But not every young American knows that almost the

first act of open resistance to the authority of the king took place

on the water, and was to some extent a naval action.

t

is unnecessary to enter into an account of the causes that led up

to the revolt of the American Colonies against the oppression of King

George and his subservient Parliament. The story of the Stamp Act, the

indignation of the Colonies, their futile attempts to convince

Parliament of the injustice of the measure, the stern measures adopted

by the British to put down the rising insubordination, the Boston

Massacre, and the battles at Concord and Lexington are familiar to

every American boy. But not every young American knows that almost the

first act of open resistance to the authority of the king took place

on the water, and was to some extent a naval action.

The revenue laws, enacted by the English Parliament as a means of extorting money from the Colonies, were very obnoxious to the people of America. Particularly did the colonists of Rhode Island protest against them, and seldom lost an opportunity to evade the payment of the taxes.

Between Providence and Newport, illicit trade flourished; and the waters of Narragansett Bay were dotted with the sail of small craft carrying cargoes on which no duties had ever been paid. In order to stop this nefarious traffic, armed vessels were stationed in the Bay, with orders to chase and search all craft suspected of smuggling. The presence of these vessels gave great offence to the colonists, and the inflexible (p. 022) manner in which the naval officers discharged their duty caused more than one open defiance of the authority of King George.

The first serious trouble to grow out of the presence of the British cruisers in the bay was the affair of the schooner "St. John." This vessel was engaged in patrolling the waters of the bay in search of smugglers. While so engaged, her commander, Lieut. Hill, learned that a brig had discharged a suspicious cargo at night near Howland's Ferry. Running down to that point to investigate, the king's officers found the cargo to consist of smuggled goods; and, leaving a few men in charge, the cruiser hastily put out to sea in pursuit of the smuggler. The swift sailing schooner soon overtook the brig, and the latter was taken in to Newport as a prize. Although this affair occurred early in 1764, the sturdy colonists even then had little liking for the officers of the king. The sailors of the "St. John," careless of the evident dislike of the citizens of the town, swaggered about the streets, boasting of their capture, and making merry at the expense of the Yankees. Two or three fights between sailors and townspeople so stirred up the landsmen, that they determined to destroy the "St. John," and had actually fitted up an armed sloop for that purpose, when a second man-of-war appeared in the harbor and put a final stopper to the project. Though thus balked of their revenge, the townspeople showed their hatred for the king's navy by seizing a battery, and firing several shots at the two armed vessels, but without effect.

During the same year, the little town of Newport again gave evidence of the growth of the revolutionary spirit. This time the good old British custom of procuring sailors for the king's ships by a system of kidnapping, commonly known as impressment, was the cause of the outbreak. For some months the British man-of-war "Maidstone" lay in the harbor of Newport, idly tugging at her anchors. It was a period of peace, and her officers had nothing to occupy their attention. Therefore they devoted themselves to increasing the crew of the vessel by means of raids upon the taverns along the water-front of the city.

The seafaring men of Newport knew little peace while the "Maidstone" was in port. The king's service was the dread of every sailor; and, with the press-gang nightly walking the streets, no sailor could feel secure. All knew the life led by the sailors on the king's ships. Those were the days when the cat-o'-nine-tails flourished, and the command of a beardless bit of (p. 023) a midshipmen was enough to send a poor fellow to the gratings, to have his back cut to pieces by the merciless lash. The Yankee sailors had little liking for this phase of sea-life, and they gave the men-of-war a wide berth.

Often it happened, however, that a party of jolly mariners sitting over their pipes and grog in the snug parlor of some seashore tavern, spinning yarns of the service they had seen on the gun-decks of his Majesty's ships, or of shipwreck and adventure in the merchant service, would start up and listen in affright, as the measured tramp of a body of men came up the street. Then came the heavy blow on the door.

"Open in the king's name," shouts a gruff voice outside; and the entrapped sailors, overturning the lights, spring for doors and windows, in vain attempts to escape the fate in store for them. The press-gang seldom returned to the ship empty handed, and the luckless tar who once fell into their clutches was wise to accept his capture good-naturedly; for the bos'n's cat was the remedy commonly prescribed for sulkiness.

As long as the "Maidstone" lay in the harbor of Newport, raids such as this were of common occurrence. The people of the city grumbled a little; but it was the king's will, and none dared oppose it. The wives and sweethearts of the kidnapped sailors shed many a bitter tear over the disappearance of their husbands and lovers; but what were the tears of women to King George? And so the press-gang of the "Maidstone" might have continued to enjoy unopposed the stirring sport of hunting men like beasts, had the leaders not committed one atrocious act of inhumanity that roused the long-suffering people to resistance.

One breezy afternoon, a stanch brig, under full sail, came up the bay, and entered the harbor of Newport. Her sides were weather-beaten, and her dingy sails and patched cordage showed that she had just completed her long voyage. Her crew, a fine set of bronzed and hardy sailors, were gathered on her forecastle, eagerly regarding the cluster of cottages that made up the little town of Newport. In those cottages were many loved ones, wives, mothers, and sweethearts, whom the brave fellows had not seen for long and weary months; for the brig was just returning from a voyage to the western coast of Africa.

It is hard to describe the feelings aroused by the arrival of a ship in (p. 024) port after a long voyage. From the outmost end of the longest wharf the relatives and friends of the sailors eagerly watch the approaching vessel, striving to find in her appearance some token of the safety of the loved ones on board. If a flag hangs at half-mast in the rigging, bitter is the suspense, and fearful the dread, of each anxious waiter, lest her husband or lover or son be the unfortunate one whose death is mourned. And on the deck of the ship the excitement is no less great. Even the hardened breast of the sailor swells with emotion when he first catches sight of his native town, after long months of absence. With eyes sharpened by constant searching for objects upon the broad bosom of the ocean, he scans the waiting crowd, striving to distinguish in the distance some well-beloved face. His spirits are light with the happy anticipation of a season in port with his loved ones, and he discharges his last duties before leaving the ship with a blithe heart.

So it was with the crew of the home-coming brig. Right merrily they sung out their choruses as they pulled at the ropes, and brought the vessel to anchor. The rumble of the hawser through the hawseholes was sweet music to their ears; and so intent were they upon the crowd on the dock, that they did not notice two long-boats which had put off from the man-of-war, and were pulling for the brig. The captain of the merchantman, however, noticed the approach of the boats, and wondered what it meant. "Those fellows think I've smuggled goods aboard," said he. "However, they can spend their time searching if they want. I've nothing in the hold I'm afraid to have seen."

The boats were soon alongside; and two or three officers, with a handful of jackies, clambered aboard the brig.

"Muster your men aft, captain," said the leader, scorning any response to the captain's salutation. "The king has need of a few fine fellows for his service."

"Surely, sir, you are not about to press any of these men," protested the captain. "They are just returning after a long voyage, and have not yet seen their families."

"What's that to me, sir?" was the response. "Muster your crew without more words."

Sullenly the men came aft, and ranged themselves in line before the boarding-officers. Each feared lest he might be one of those chosen to (p. 025) fill the ship's roll of the "Maidstone;" yet each cherished the hope that he might be spared to go ashore, and see the loved ones whose greeting he had so fondly anticipated.

The boarding-officers looked the crew over, and, after consulting together, gruffly ordered the men to go below, and pack up their traps.

"Surely you don't propose to take my entire crew?" said the captain of the brig in wondering indignation.

"I know my business, sir," was the gruff reply, "and I do not propose to suffer any more interference."

The crew of the brig soon came on deck, carrying their bags of clothes, and were ordered into the man-o'-war's boats, which speedily conveyed them to their floating prison. Their fond visions of home had been rudely dispelled. They were now enrolled in his Majesty's service, and subject to the will of a blue-coated tyrant. This was all their welcome home.

When the news of this cruel outrage reached the shore, the indignation of the people knew no bounds. The thought of their fellow-townsmen thus cruelly deprived of their liberty, at the conclusion of a long and perilous voyage, set the whole village in a turmoil. Wild plots were concocted for the destruction of the man-of-war, that, sullen and unyielding, lay at her anchorage in the harbor. But the wrong done was beyond redress. The captured men were not to be liberated. There was no ordnance in the little town to compete with the guns of the "Maidstone," and the enraged citizens could only vent their anger by impotent threats and curses. Bands of angry men and boys paraded the streets, crying, "Down with the press-gang," and invoking the vengeance of Heaven upon the officers of the man-of-war. Finally, they found a boat belonging to the "Maidstone" lying at a wharf. Dragging this ashore, the crowd procured ropes, and, after pulling the captured trophy up and down the streets, took it to the common in front of the Court-House, where it was burned in the presence of a great crowd, which heaped execrations upon the heads of the officers of the "Maidstone," and King George's press-gang.

After this occurrence, there was a long truce between the people of Newport and the officers of the British navy. But the little town was intolerant of oppression, and the revolutionary spirit broke out again in 1769. Historians have eulogized Boston as the cradle of liberty, and (p. 026) by the British pamphleteers of that era the Massachusetts city was often called a hot-bed of rebellion. It would appear, however, that, while the people of Boston were resting contentedly under the king's rule, the citizens of Newport were chafing under the yoke, and were quick to resist any attempts at tyranny.

It is noticeable, that, in each outbreak of the people of Newport against the authority of the king's vessels, the vigor of the resistance increased, and their acts of retaliation became bolder. Thus in the affair of the "St. John" the king's vessel was fired on, while in the affair of the "Maidstone" the royal property was actually destroyed. In the later affairs with the sloop "Liberty" and the schooner "Gaspee," the revolt of the colonists was still more open, and the consequences more serious.

In 1769 the armed sloop "Liberty," Capt. Reid, was stationed in Narragansett Bay for the purpose of enforcing the revenue laws. Her errand made her obnoxious to the people on the coast, and the extraordinary zeal of her captain in discharging his duty made her doubly detested by seafaring people afloat or shore.

On the 17th of July the "Liberty," while cruising near the mouth of the bay, sighted a sloop and a brig under full sail, bound out. Promptly giving chase, the armed vessel soon overtook the merchantmen sufficiently to send a shot skipping along the crests of the waves, as a polite Invitation to stop. The two vessels hove to, and a boat was sent from the man-of-war to examine their papers, and see if all was right. Though no flaw was found in the papers of either vessel, Capt. Reid determined to take them back to Newport, which was done. In the harbor the two vessels were brought to anchor under the guns of the armed sloop, and without any reason or explanation were kept there several days. After submitting to this wanton detention for two days, Capt. Packwood of the brig went on board the "Liberty" to make a protest to Capt. Reid, and at the same time to get some wearing apparel taken from his cabin at the time his vessel had been captured. On reaching the deck of the armed vessel, he found Capt. Reid absent, and his request for his property was received with ridicule. Hot words soon led to violence; and as Capt. Packwood stepped in to his boat to return to his ship, he was fired at several times, none of the shots taking effect.

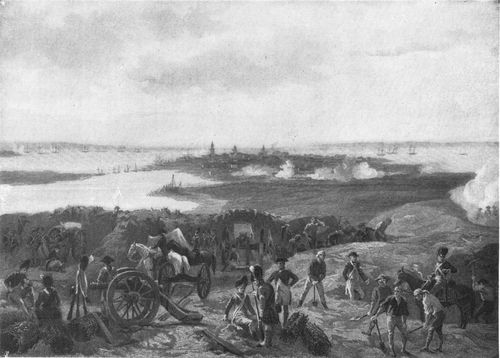

Siege Of Charleston, S.C., May, 1780.

Copyright, 1874, by Johnson, Wilson & Co.

The news of this assault spread like wildfire in the little town. The (p. 027) people congregated on the streets, demanding reparation. The authorities sent a message to Capt. Reid, demanding that the man who fired the shots be given up. Soon a boat came from the "Liberty," bringing a man who was handed over to the authorities as the culprit. A brief examination into the case showed that the man was not the guilty party, and that his surrender was a mere subterfuge. The people then determined to be trifled with no longer, and made preparations to take vengeance upon the insolent oppressors.

The work of preparation went on quietly; and by nightfall a large number of men had agreed to assemble at a given signal, and march upon the enemy. Neither the authorities of the town nor the officers on the threatened vessel were given any intimation of the impending outbreak. Yet the knots of men who stood talking earnestly on the street corners, or looked significantly at the trim navy vessel lying in the harbor, might have well given cause for suspicion.

That night, just as the dusk was deepening into dark, a crowd of men marched down the street to a spot where a number of boats lay hidden in the shadow of a wharf. Embarking in these silently, they bent to the oars at the whispered word of command; and the boats were soon gliding swiftly over the smooth, dark surface of the harbor, toward the sloop-of-war. As they drew near, the cry of the lookout rang out,—

"Boat ahoy!"

No answer. The boats, crowded with armed men, still advanced.

"Boat ahoy! Answer, or I'll fire."

And, receiving no response, the lookout gave the alarm, and the watch came tumbling up, just in time to be driven below or disarmed by the crowd of armed men that swarmed over the gunwale of the vessel. There was no bloodshed. The crew of the "Liberty" was fairly surprised, and made no resistance. The victorious citizens cut the sloop's cables, and allowed her to float on shore near Long Wharf. Then, feeling sure that their prey could not escape them, they cut away her masts, liberated their captives, and taking the sloop's boats, dragged them through the streets to the common, where they were burned on a triumphal bonfire, amid the cheers of the populace.

But the exploit was not to end here. With the high tide the next day, the hulk of the sloop floated away, and drifted ashore again on (p. 028) Goat Island. When night fell, some adventurous spirits stealthily went over, and, applying the torch to the stranded ship, burned it to the water's edge. Thus did the people of Newport resist tyranny.