Title: The Writings of James Russell Lowell in Prose and Poetry, Volume V

Author: James Russell Lowell

Release date: September 15, 2007 [eBook #22609]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Thierry Alberto and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Thierry Alberto

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

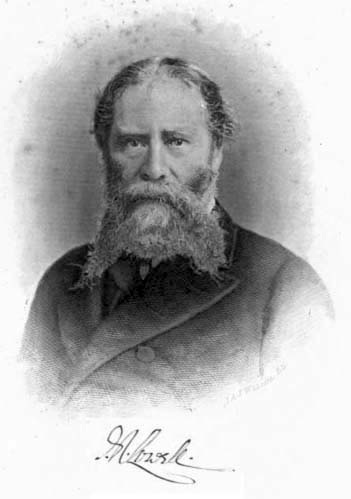

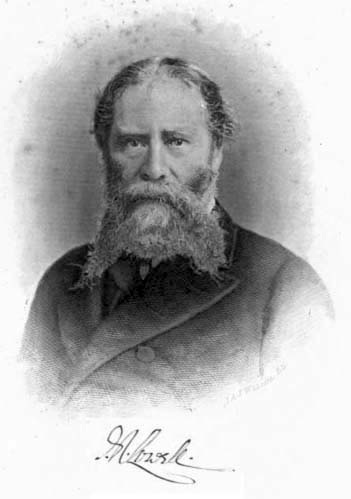

Mr. Lowell in 1881

RIVERSIDE EDITION

THE WRITINGS OF JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL

IN PROSE AND POETRY

VOLUME V

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

THE AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY

1858

There was no apologue more popular in the Middle Ages than that of the hermit, who, musing on the wickedness and tyranny of those whom the inscrutable wisdom of Providence had intrusted with the government of the world, fell asleep, and awoke to find himself the very monarch whose abject life and capricious violence had furnished the subject of his moralizing. Endowed with irresponsible power, tempted by passions whose existence in himself he had never suspected, and betrayed by the political necessities of his position, he became gradually guilty of all the crimes and the luxury which had seemed so hideous to him in his hermitage over a dish of water-cresses.

The American Tract Society from small beginnings has risen to be the dispenser of a yearly revenue of nearly half a million. It has become a great establishment, with a traditional policy, with the distrust of change and the dislike of disturbing questions (especially of such as would lessen its revenues) natural to great establishments. It had been poor and weak; it has become rich and powerful. The hermit has become king.

If the pious men who founded the American Tract Society had been told that within forty years they would be watchful of their publications, lest, by inadvertence, anything disrespectful might be spoken of the African Slave-trade,—that they would consider it an ample equivalent for compulsory dumbness on the vices of Slavery, that their colporteurs could awaken the minds of Southern brethren to the horrors of St. Bartholomew,—that they would hold their peace about the body of Cuffee dancing to the music of the cart-whip, provided only they could save the soul of Sambo alive by presenting him a pamphlet, which he could not read, on the depravity of the double shuffle,—that they would consent to be fellow members in the Tract Society with him who sold their fellow members in Christ on the auction block, if he agreed with them in condemning Transubstantiation (and it would not be difficult for a gentleman who ignored the real presence of God in his brother man to deny it in the sacramental wafer),—if those excellent men had been told this, they would have shrunk in horror, and exclaimed, "Are thy servants dogs, that they should do these things?"

Yet this is precisely the present position of the Society.

There are two ways of evading the responsibility of such inconsistency. The first is by an appeal to the Society's Constitution, and by claiming to interpret it strictly in accordance with the rules of law as applied to contracts, whether between individuals or States. The second is by denying that Slavery is opposed to the genius of Christianity, and that any moral wrongs are the necessary results of it. We will not be so unjust to the Society as to suppose that any of its members would rely on this latter plea, and shall therefore confine ourselves to a brief consideration of the other.

In order that the same rules of interpretation should be considered applicable to the Constitution of the Society and to that of the United States, we must attribute to the former a solemnity and importance which involve a palpable absurdity. To claim for it the verbal accuracy and the legal wariness of a mere contract is equally at war with common sense and the facts of the case; and even were it not so, the party to a bond who should attempt to escape its ethical obligation by a legal quibble of construction would be put in coventry by all honest men. In point of fact, the Constitution was simply the minutes of an agreement among certain gentlemen, to define the limits within which they would accept trust funds, and the objects for which they should expend them.

But if we accept the alternative offered by the advocates of strict construction, we shall not find that their case is strengthened. Claiming that where the meaning of an instrument is doubtful, it should be interpreted according to the contemporary understanding of its framers, they argue that it would be absurd to suppose that gentlemen from the Southern States would have united to form a society that included in its objects any discussion of the moral duties arising from the institution of Slavery. Admitting the first part of their proposition, we deny the conclusion they seek to draw from it. They are guilty of a glaring anachronism in assuming the same opinions and prejudices to have existed in 1825 which are undoubtedly influential in 1858. The Anti-slavery agitation did not begin until 1831, and the debates in the Virginia Convention prove conclusively that six years after the foundation of the Tract Society, the leading men in that State, men whose minds had been trained and whose characters had been tempered in that school of action and experience which was open to all during the heroic period of our history, had not yet suffered such distortion of the intellect through passion and such deadening of the conscience through interest, as would have prevented their discussing either the moral or the political aspects of Slavery, and precluded them from uniting in any effort to make the relation between master and slave less demoralizing to the one and less imbruting to the other.

Again, it is claimed that the words of the Constitution are conclusive, and that the declaration that the publications of the Society shall be such as are "satisfactory to all Evangelical Christians" forbids by implication the issuing of any tract which could possibly offend the brethren in Slave States. The Society, it is argued, can publish only on topics about which all Evangelical Christians are agreed, and must, therefore, avoid everything in which the question of politics is involved. But what are the facts about matters other than Slavery? Tracts have been issued and circulated in which Dancing is condemned as sinful; are all Evangelical Christians agreed about this? On the Temperance question, against Catholicism,—have these topics never entered into our politics? The simple truth is that Slavery is the only subject about which the Publishing Committee have felt Constitutional scruples. Till this question arose, they were like men in perfect health, never suspecting that they had any constitution at all; but now, like hypochondriacs, they feel it in every pore, at the least breath from the eastward.

If a strict construction of the words "all Evangelical Christians" be insisted on, we are at a loss to see where the committee could draw the dividing line between what might be offensive and what allowable. The Society publish tracts in which the study of the Scriptures is enforced and their denial to the laity by Romanists assailed. But throughout the South it is criminal to teach a slave to read; throughout the South no book could be distributed among the servile population more incendiary than the Bible, if they could only read it. Will not our Southern brethren take alarm? The Society is reduced to the dilemma of either denying that the African has a soul to be saved, or of consenting to the terrible mockery of assuring him that the way of life is to be found only by searching a book which he is forbidden to open.

If we carry out this doctrine of strict construction to its legitimate results, we shall find that it involves a logical absurdity. What is the number of men whose outraged sensibilities may claim the suppression of a tract? Is the taboo of a thousand valid? Of a hundred? Of ten? Or are tracts to be distributed only to those who will find their doctrine agreeable, and are the Society's colporteurs to be instructed that a Temperance essay is the proper thing for a total-abstinent infidel, and a sermon on the Atonement for a distilling deacon? If the aim of the Society be only to convert men from sins they have no mind to, and to convince them of errors to which they have no temptation, they might as well be spending their money to persuade schoolmasters that two and two make four, or geometricians that there cannot be two obtuse angles in a triangle. If this be their notion of the way in which the gospel is to be preached, we do not wonder that they have found it necessary to print a tract upon the impropriety of sleeping in church.

But the Society are concluded by their own action; for in 1857 they unanimously adopted the following resolution: "That those moral duties which grow out of the existence of Slavery, as well as those moral evils and vices which it is known to promote and which are condemned in Scripture, and so much deplored by Evangelical Christians, undoubtedly do fall within the province of this Society, and can and ought to be discussed in a fraternal and Christian spirit." The Society saw clearly that it was impossible to draw a Mason and Dixon's line in the world of ethics, to divide Duty by a parallel of latitude. The only line which Christ drew is that which parts the sheep from the goats, that great horizon-line of the moral nature of man, which is the boundary between light and darkness. The Society, by yielding (as they have done in 1858) to what are pleasantly called the "objections" of the South (objections of so forcible a nature that we are told the colporteurs were "forced to flee") virtually exclude the black man, if born to the southward of a certain arbitrary line, from the operation of God's providence, and thereby do as great a wrong to the Creator as the Episcopal Church did to the artist when without public protest they allowed Ary Scheffer's Christus Consolator, with the figure of the slave left out, to be published in a Prayer-Book.

The Society is not asked to disseminate Anti-slavery doctrines, but simply to be even-handed between master and slave, and, since they have recommended Sambo and Toney to be obedient to Mr. Legree, to remind him in turn that he also has duties toward the bodies and souls of his bondmen. But we are told that the time has not yet arrived, that at present the ears of our Southern brethren are closed against all appeals, that God in his good time will turn their hearts, and that then, and not till then, will be the fitting occasion to do something in the premises. But if the Society is to await this golden opportunity with such exemplary patience in one case, why not in all? If it is to decline any attempt at converting the sinner till after God has converted him, will there be any special necessity for a tract society at all? Will it not be a little presumptuous, as well as superfluous, to undertake the doing over again of what He has already done? We fear that the studies of Blackstone, upon which the gentlemen who argue thus have entered in order to fit themselves for the legal and constitutional argument of the question, have confused their minds, and that they are misled by some fancied analogy between a tract and an action of trover, and conceive that the one, like the other, cannot be employed till after an actual conversion has taken place.

The resolutions reported by the Special Committee at the annual meeting of 1857, drawn up with great caution and with a sincere desire to make whole the breach in the Society, have had the usual fate of all attempts to reconcile incompatibilities by compromise. They express confidence in the Publishing Committee, and at the same time impliedly condemn them by recommending them to do precisely what they had all along scrupulously avoided doing. The result was just what might have been expected. Both parties among the Northern members of the Society, those who approved the former action of the Publishing Committee and those who approved the new policy recommended in the resolutions, those who favored silence and those who favored speech on the subject of Slavery, claimed the victory, while the Southern brethren, as usual, refused to be satisfied with anything short of unconditional submission. The word Compromise, as far as Slavery is concerned, has always been of fatal augury. The concessions of the South have been like the "With all my worldly goods I thee endow" of a bankrupt bridegroom, who thereby generously bestows all his debts upon his wife, and as a small return for his magnanimity consents to accept all her personal and a life estate in all her real property. The South is willing that the Tract Society should expend its money to convince the slave that he has a soul to be saved so far as he is obedient to his master, but not to persuade the master that he has a soul to undergo a very different process so far as he is unmerciful to his slave.

We Americans are very fond of this glue of compromise. Like so many quack cements, it is advertised to make the mended parts of the vessel stronger than those which have never been broken, but, like them, it will not stand hot water,—and as the question of slavery is sure to plunge all who approach it, even with the best intentions, into that fatal element, the patched-up brotherhood, which but yesterday was warranted to be better than new, falls once more into a heap of incoherent fragments. The last trial of the virtues of the Patent Redintegrator by the Special Committee of the Tract Society has ended like all the rest, and as all attempts to buy peace at too dear a rate must end. Peace is an excellent thing, but principle and pluck are better; and the man who sacrifices them to gain it finds at last that he has crouched under the Caudine yoke to purchase only a contemptuous toleration, that leaves him at war with his own self-respect and the invincible forces of his higher nature.

But the peace which Christ promised to his followers was not of this world; the good gift he brought them was not peace, but a sword. It was no sword of territorial conquest, but that flaming blade of conscience and self-conviction which lightened between our first parents and their lost Eden,—that sword of the Spirit that searcheth all things,—which severs one by one the ties of passion, of interest, of self-pride, that bind the soul to earth,—whose implacable edge may divide a man from family, from friends, from whatever is nearest and dearest,—and which hovers before him like the air-drawn dagger of Macbeth, beckoning him, not to crime, but to the legitimate royalties of self-denial and self-sacrifice, to the freedom which is won only by surrender of the will. Christianity has never been concession, never peace; it is continual aggression; one province of wrong conquered, its pioneers are already in the heart of another. The mile-stones of its onward march down the ages have not been monuments of material power, but the blackened stakes of martyrs, trophies of individual fidelity to conviction. For it is the only religion which is superior to all endowment, to all authority,—which has a bishopric and a cathedral wherever a single human soul has surrendered itself to God. That very spirit of doubt, inquiry, and fanaticism for private judgment, with which Romanists reproach Protestantism, is its stamp and token of authenticity,—the seal of Christ, and not of the Fisherman.

We do not wonder at the division which has taken place in the Tract Society, nor do we regret it. The ideal life of a Christian is possible to very few, but we naturally look for a nearer approach to it in those who associate together to disseminate the doctrines which they believe to be its formative essentials, and there is nothing which the enemies of religion seize on so gladly as any inconsistency between the conduct and the professions of such persons. Though utterly indifferent to the wrongs of the slave, the scoffer would not fail to remark upon the hollowness of a Christianity which was horror-stricken at a dance or a Sunday drive, while it was blandly silent about the separation of families, the putting asunder whom God had joined, the selling Christian girls for Christian harems, and the thousand horrors of a system which can lessen the agonies it inflicts only by debasing the minds and souls of the race on which it inflicts them. Is your Christianity, then, he would say, a respecter of persons, and does it condone the sin because the sinner can contribute to your coffers? Was there ever a simony like this,—that does not sell, but withholds, the gift of God for a price?

The world naturally holds the Society to a stricter accountability than it would insist upon in ordinary cases. Were they only a club of gentlemen associated for their own amusement, it would be very natural and proper that they should exclude all questions which would introduce controversy, and that, however individually interested in certain reforms, they should not force them upon others who would consider them a bore. But a society of professing Christians, united for the express purpose of carrying both the theory and the practice of the New Testament into every household in the land, has voluntarily subjected itself to a graver responsibility, and renounced all title to fall back upon any reserved right of personal comfort or convenience.

We say, then, that we are glad to see this division in the Tract Society; not glad because of the division, but because it has sprung from an earnest effort to relieve the Society of a reproach which was not only impairing its usefulness, but doing an injury to the cause of truth and sincerity everywhere. We have no desire to impugn the motives of those who consider themselves conservative members of the Society; we believe them to be honest in their convictions, or their want of them; but we think they have mistaken notions as to what conservatism is, and that they are wrong in supposing it to consist in refusing to wipe away the film on their spectacle-glasses which prevents their seeing the handwriting on the wall, or in conserving reverently the barnacles on their ship's bottom and the dry-rot in its knees. We yield to none of them in reverence for the Past; it is there only that the imagination can find repose and seclusion; there dwells that silent majority whose experience guides our action and whose wisdom shapes our thought in spite of ourselves;—but it is not length of days that can make evil reverend, nor persistence in inconsistency that can give it the power or the claim of orderly precedent. Wrong, though its title-deeds go back to the days of Sodom, is by nature a thing of yesterday,—while the right, of which we became conscious but an hour ago, is more ancient than the stars, and of the essence of Heaven. If it were proposed to establish Slavery to-morrow, should we have more patience with its patriarchal argument than with the parallel claim of Mormonism? That Slavery is old is but its greater condemnation; that we have tolerated it so long, the strongest plea for our doing so no longer. There is one institution to which we owe our first allegiance, one that is more sacred and venerable than any other,—the soul and conscience of Man.

What claim has Slavery to immunity from discussion? We are told that discussion is dangerous. Dangerous to what? Truth invites it, courts the point of the Ithuriel-spear, whose touch can but reveal more clearly the grace and grandeur of her angelic proportions. The advocates of Slavery have taken refuge in the last covert of desperate sophism, and affirm that their institution is of Divine ordination, that its bases are laid in the nature of man. Is anything, then, of God's contriving endangered by inquiry? Was it the system of the universe, or the monks, that trembled at the telescope of Galileo? Did the circulation of the firmament stop in terror because Newton laid his daring finger on its pulse? But it is idle to discuss a proposition so monstrous. There is no right of sanctuary for a crime against humanity, and they who drag an unclean thing to the horns of the altar bring it to vengeance, and not to safety.

Even granting that Slavery were all that its apologists assume it to be, and that the relation of master and slave were of God's appointing, would not its abuses be just the thing which it was the duty of Christian men to protest against, and, as far as might be, to root out? Would our courts feel themselves debarred from interfering to rescue a daughter from a parent who wished to make merchandise of her purity, or a wife from a husband who was brutal to her, by the plea that parental authority and marriage were of Divine ordinance? Would a police-justice discharge a drunkard who pleaded the patriarchal precedent of Noah? or would he not rather give him another month in the House of Correction for his impudence?

The Anti-slavery question is not one which the Tract Society can exclude by triumphant majorities, nor put to shame by a comparison of respectabilities. Mixed though it has been with politics, it is in no sense political, and springing naturally from the principles of that religion which traces its human pedigree to a manger, and whose first apostles were twelve poor men against the whole world, it can dispense with numbers and earthly respect. The clergyman may ignore it in the pulpit, but it confronts him in his study; the church-member, who has suppressed it in parish-meeting, opens it with the pages of his Testament; the merchant, who has shut it out of his house and his heart, finds it lying in wait for him, a gaunt fugitive, in the hold of his ship; the lawyer, who has declared that it is no concern of his, finds it thrust upon him in the brief of the slave-hunter; the historian, who had cautiously evaded it, stumbles over it at Bunker Hill. And why? Because it is not political, but moral,—because it is not local, but national,—because it is not a test of party, but of individual honesty and honor. The wrong which we allow our nation to perpetrate we cannot localize, if we would; we cannot hem it within the limits of Washington or Kansas; sooner or later, it will force itself into the conscience and sit by the hearthstone of every citizen.

It is not partisanship, it is not fanaticism, that has forced this matter of Anti-slavery upon the American people; it is the spirit of Christianity, which appeals from prejudices and predilections to the moral consciousness of the individual man; that spirit elastic as air, penetrative as heat, invulnerable as sunshine, against which creed after creed and institution after institution have measured their strength and been confounded; that restless spirit which refuses to crystallize in any sect or form, but persists, a Divinely commissioned radical and reconstructor, in trying every generation with a new dilemma between ease and interest on the one hand, and duty on the other. Shall it be said that its kingdom is not of this world? In one sense, and that the highest, it certainly is not; but just as certainly Christ never intended those words to be used as a subterfuge by which to escape our responsibilities in the life of business and politics. Let the cross, the sword, and the arena answer, whether the world, that then was, so understood its first preachers and apostles. Cæsar and Flamen both instinctively dreaded it, not because it aimed at riches or power, but because it strove to conquer that other world in the moral nature of mankind, where it could establish a throne against which wealth and force would be weak and contemptible. No human device has ever prevailed against it, no array of majorities or respectabilities; but neither Cæsar nor Flamen ever conceived a scheme so cunningly adapted to neutralize its power as that graceful compromise which accepts it with the lip and denies it in the life, which marries it at the altar and divorces it at the church-door.

CHAPTERE ELECTION IN NOVEMBER

1860

While all of us have been watching, with that admiring sympathy which never fails to wait on courage and magnanimity, the career of the new Timoleon in Sicily; while we have been reckoning, with an interest scarcely less than in some affair of personal concern, the chances and changes that bear with furtherance or hindrance upon the fortune of united Italy, we are approaching, with a quietness and composure which more than anything else mark the essential difference between our own form of democracy and any other yet known in history, a crisis in our domestic policy more momentous than any that has arisen since we became a nation. Indeed, considering the vital consequences for good or evil that will follow from the popular decision in November, we might be tempted to regard the remarkable moderation which has thus far characterized the Presidential canvass as a guilty indifference to the duty implied in the privilege of suffrage, or a stolid unconsciousness of the result which may depend upon its exercise in this particular election, did we not believe that it arose chiefly from the general persuasion that the success of the Republican party was a foregone conclusion.

In a society like ours, where every man may transmute his private thought into history and destiny by dropping it into the ballot-box, a peculiar responsibility rests upon the individual. Nothing can absolve us from doing our best to look at all public questions as citizens, and therefore in some sort as administrators and rulers. For though during its term of office the government be practically as independent of the popular will as that of Russia, yet every fourth year the people are called upon to pronounce upon the conduct of their affairs. Theoretically, at least, to give democracy any standing-ground for an argument with despotism or oligarchy, a majority of the men composing it should be statesmen and thinkers. It is a proverb, that to turn a radical into a conservative there needs only to put him into office, because then the license of speculation or sentiment is limited by a sense of responsibility; then for the first time he becomes capable of that comparative view which sees principles and measures, not in the narrow abstract, but in the full breadth of their relations to each other and to political consequences. The theory of democracy presupposes something of these results of official position in the individual voter, since in exercising his right he becomes for the moment an integral part of the governing power.

How very far practice is from any likeness to theory, a week's experience of our politics suffices to convince us. The very government itself seems an organized scramble, and Congress a boy's debating-club, with the disadvantage of being reported. As our party-creeds are commonly represented less by ideas than by persons (who are assumed, without too close a scrutiny, to be the exponents of certain ideas) our politics become personal and narrow to a degree never paralleled, unless in ancient Athens or mediæval Florence. Our Congress debates and our newspapers discuss, sometimes for day after day, not questions of national interest, not what is wise and right, but what the Honorable Lafayette Skreemer said on the stump, or bad whiskey said for him, half a dozen years ago. If that personage, outraged in all the finer sensibilities of our common nature, by failing to get the contract for supplying the District Court-House at Skreemeropolisville City with revolvers, was led to disparage the union of these States, it is seized on as proof conclusive that the party to which he belongs are so many Catalines,—for Congress is unanimous only in misspelling the name of that oft-invoked conspirator. The next Presidential Election looms always in advance, so that we seem never to have an actual Chief Magistrate, but a prospective one, looking to the chances of reelection, and mingling in all the dirty intrigues of provincial politics with an unhappy talent for making them dirtier. The cheating mirage of the White House lures our public men away from present duties and obligations; and if matters go on as they have gone, we shall need a Committee of Congress to count the spoons in the public plate-closet, whenever a President goes out of office,—with a policeman to watch every member of the Committee. We are kept normally in that most unprofitable of predicaments, a state of transition, and politicians measure their words and deeds by a standard of immediate and temporary expediency,—an expediency not as concerning the nation, but which, if more than merely personal, is no wider than the interests of party.

Is all this a result of the failure of democratic institutions? Rather of the fact that those institutions have never yet had a fair trial, and that for the last thirty years an abnormal element has been acting adversely with continually increasing strength. Whatever be the effect of slavery upon the States where it exists, there can be no doubt that its moral influence upon the North has been most disastrous. It has compelled our politicians into that first fatal compromise with their moral instincts and hereditary principles which makes all consequent ones easy; it has accustomed us to makeshifts instead of statesmanship, to subterfuge instead of policy, to party-platforms for opinions, and to a defiance of the public sentiment of the civilized world for patriotism. We have been asked to admit, first, that it was a necessary evil; then that it was a good both to master and slave; then that it was the corner-stone of free institutions; then that it was a system divinely instituted under the Old Law and sanctioned under the New. With a representation, three fifths of it based on the assumption that negroes are men, the South turns upon us and insists on our acknowledging that they are things. After compelling her Northern allies to pronounce the "free and equal" clause of the preamble to the Declaration of Independence (because it stood in the way of enslaving men) a manifest absurdity, she has declared, through the Supreme Court of the United States, that negroes are not men in the ordinary meaning of the word. To eat dirt is bad enough, but to find that we have eaten more than was necessary may chance to give us an indigestion. The slaveholding interest has gone on step by step, forcing concession after concession, till it needs but little to secure it forever in the political supremacy of the country. Yield to its latest demand,—let it mould the evil destiny of the Territories,—and the thing is done past recall. The next Presidential Election is to say Yes or No.

But we should not regard the mere question of political preponderancy as of vital consequence, did it not involve a continually increasing moral degradation on the part of the Non-slaveholding States,—for Free States they could not be called much longer. Sordid and materialistic views of the true value and objects of society and government are professed more and more openly by the leaders of popular outcry,—for it cannot be called public opinion. That side of human nature which it has been the object of all lawgivers and moralists to repress and subjugate is flattered and caressed; whatever is profitable is right; and already the slave-trade, as yielding a greater return on the capital invested than any other traffic, is lauded as the highest achievement of human reason and justice. Mr. Hammond has proclaimed the accession of King Cotton, but he seems to have forgotten that history is not without examples of kings who have lost their crowns through the folly and false security of their ministers. It is quite true that there is a large class of reasoners who would weigh all questions of right and wrong in the balance of trade; but we cannot bring ourselves to believe that it is a wise political economy which makes cotton by unmaking men, or a far-seeing statesmanship which looks on an immediate money-profit as a safe equivalent for a beggared public sentiment. We think Mr. Hammond even a little premature in proclaiming the new Pretender. The election of November may prove a Culloden. Whatever its result, it is to settle, for many years to come, the question whether the American idea is to govern this continent, whether the Occidental or the Oriental theory of society is to mould our future, whether we are to recede from principles which eighteen Christian centuries have been slowly establishing at the cost of so many saintly lives at the stake and so many heroic ones on the scaffold and the battle-field, in favor of some fancied assimilation to the household arrangements of Abraham, of which all that can be said with certainty is that they did not add to his domestic happiness.

We believe that this election is a turning-point in our history; for, although there are four candidates, there are really, as everybody knows, but two parties, and a single question that divides them. The supporters of Messrs. Bell and Everett have adopted as their platform the Constitution, the Union, and the enforcement of the Laws. This may be very convenient, but it is surely not very explicit. The cardinal question on which the whole policy of the country is to turn—a question, too, which this very election must decide in one way or the other—is the interpretation to be put upon certain clauses of the Constitution. All the other parties equally assert their loyalty to that instrument. Indeed, it is quite the fashion. The removers of all the ancient landmarks of our policy, the violators of thrice-pledged faith, the planners of new treachery to established compromise, all take refuge in the Constitution,—

"Like thieves that in a hemp-plot lie,

Secure against the hue and cry."

In the same way the first Bonaparte renewed his profession of faith in the Revolution at every convenient opportunity; and the second follows the precedent of his uncle, though the uninitiated fail to see any logical sequence from 1789 to 1815 or 1860. If Mr. Bell loves the Constitution, Mr. Breckinridge is equally fond; that Egeria of our statesmen could be "happy with either, were t' other dear charmer away." Mr. Douglas confides the secret of his passion to the unloquacious clams of Rhode Island, and the chief complaint made against Mr. Lincoln by his opponents is that he is too Constitutional.

Meanwhile, the only point in which voters are interested is, What do they mean by the Constitution? Mr. Breckinridge means the superiority of a certain exceptional species of property over all others; nay, over man himself. Mr. Douglas, with a different formula for expressing it, means practically the same thing. Both of them mean that Labor has no rights which Capital is bound to respect,—that there is no higher law than human interest and cupidity. Both of them represent not merely the narrow principles of a section, but the still narrower and more selfish ones of a caste. Both of them, to be sure, have convenient phrases to be juggled with before election, and which mean one thing or another, or neither one thing nor another, as a particular exigency may seem to require; but since both claim the regular Democratic nomination, we have little difficulty in divining what their course would be after the fourth of March, if they should chance to be elected. We know too well what regular Democracy is, to like either of the two faces which each shows by turns under the same hood. Everybody remembers Baron Grimm's story of the Parisian showman, who in 1789 exhibited the royal Bengal tiger under the new character of national, as more in harmony with the changed order of things. Could the animal have lived till 1848, he would probably have found himself offered to the discriminating public as the democratic and social ornament of the jungle. The Pro-slavery party of this country seeks the popular favor under even more frequent and incongruous aliases: it is now national, now conservative, now constitutional; here it represents Squatter-Sovereignty, and there the power of Congress over the Territories; but, under whatever name, its nature remains unchanged, and its instincts are none the less predatory and destructive.

Mr. Lincoln's position is set forth with sufficient precision in the platform adopted by the Chicago Convention; but what are we to make of Messrs. Bell and Everett? Heirs of the stock in trade of two defunct parties, the Whig and Know-Nothing, do they hope to resuscitate them? or are they only like the inconsolable widows of Père la Chaise, who, with an eye to former customers, make use of the late Andsoforth's gravestone to advertise that they still carry on business at the old stand? Mr. Everett, in his letter accepting the nomination, gave us only a string of reasons why he should not have accepted it at all; and Mr. Bell preserves a silence singularly at variance with his patronymic. The only public demonstration of principle that we have seen is an emblematic bell drawn upon a wagon by a single horse, with a man to lead him, and a boy to make a nuisance of the tinkling symbol as it moves along. Are all the figures in this melancholy procession equally emblematic? If so, which of the two candidates is typified in the unfortunate who leads the horse?—for we believe the only hope of the party is to get one of them elected by some hocus-pocus in the House of Representatives. The little boy, we suppose, is intended to represent the party, which promises to be so conveniently small that there will be an office for every member of it, if its candidate should win. Did not the bell convey a plain allusion to the leading name on the ticket, we should conceive it an excellent type of the hollowness of those fears for the safety of the Union, in case of Mr. Lincoln's election, whose changes are so loudly rung,—its noise having once or twice given rise to false alarms of fire, till people found out what it really was. Whatever profound moral it be intended to convey, we find in it a similitude that is not without significance as regards the professed creed of the party. The industrious youth who operates upon it has evidently some notion of the measured and regular motion that befits the tongues of well-disciplined and conservative bells. He does his best to make theory and practice coincide; but with every jolt on the road an involuntary variation is produced, and the sonorous pulsation becomes rapid or slow accordingly. We have observed that the Constitution was liable to similar derangements, and we very much doubt whether Mr. Bell himself (since, after all, the Constitution would practically be nothing else than his interpretation of it) would keep the same measured tones that are so easy on the smooth path of candidacy, when it came to conducting the car of State over some of the rough places in the highway of Manifest Destiny, and some of those passages in our politics which, after the fashion of new countries, are rather corduroy in character.

But, fortunately, we are not left wholly in the dark as to the aims of the self-styled Constitutional party. One of its most distinguished members, Governor Hunt of New York, has given us to understand that its prime object is the defeat at all hazards of the Republican candidate. To achieve so desirable an end, its leaders are ready to coalesce, here with the Douglas, and there with the Breckinridge faction of that very Democratic party of whose violations of the Constitution, corruption, and dangerous limberness of principle they have been the lifelong denouncers. In point of fact, then, it is perfectly plain that we have only two parties in the field: those who favor the extension of slavery, and those who oppose it,—in other words, a Destructive and a Conservative party.

We know very well that the partisans of Mr. Bell, Mr. Douglas, and Mr. Breckinridge all equally claim the title of conservative: and the fact is a very curious one, well worthy the consideration of those foreign critics who argue that the inevitable tendency of democracy is to compel larger and larger concessions to a certain assumed communistic propensity and hostility to the rights of property on the part of the working classes. But the truth is, that revolutionary ideas are promoted, not by any unthinking hostility to the rights of property, but by a well-founded jealousy of its usurpations; and it is Privilege, and not Property, that is perplexed with fear of change. The conservative effect of ownership operates with as much force on the man with a hundred dollars in an old stocking as on his neighbor with a million in the funds. During the Roman Revolution of '48, the beggars who had funded their gains were among the stanchest reactionaries, and left Rome with the nobility. No question of the abstract right of property has ever entered directly into our politics, or ever will,—the point at issue being, whether a certain exceptional kind of property, already privileged beyond all others, shall be entitled to still further privileges at the expense of every other kind. The extension of slavery over new territory means just this,—that this one kind of property, not recognized as such by the Constitution, or it would never have been allowed to enter into the basis of representation, shall control the foreign and domestic policy of the Republic.

A great deal is said, to be sure, about the rights of the South; but has any such right been infringed? When a man invests money in any species of property, he assumes the risks to which it is liable. If he buy a house, it may be burned; if a ship, it may be wrecked; if a horse or an ox, it may die. Now the disadvantage of the Southern kind of property is—how shall we say it so as not to violate our Constitutional obligations?—that it is exceptional. When it leaves Virginia, it is a thing; when it arrives in Boston, it becomes a man, speaks human language, appeals to the justice of the same God whom we all acknowledge, weeps at the memory of wife and children left behind,—in short, hath the same organs and dimensions that a Christian hath, and is not distinguishable from ordinary Christians, except, perhaps, by a simpler and more earnest faith. There are people at the North who believe that, beside meum and tuum, there is also such a thing as suum,—who are old-fashioned enough, or weak enough, to have their feelings touched by these things, to think that human nature is older and more sacred than any claim of property whatever, and that it has rights at least as much to be respected as any hypothetical one of our Southern brethren. This, no doubt, makes it harder to recover a fugitive chattel; but the existence of human nature in a man here and there is surely one of those accidents to be counted on at least as often as fire, shipwreck, or the cattle-disease; and the man who chooses to put his money into these images of his Maker cut in ebony should be content to take the incident risks along with the advantages. We should be very sorry to deem this risk capable of diminution; for we think that the claims of a common manhood upon us should be at least as strong as those of Freemasonry, and that those whom the law of man turns away should find in the larger charity of the law of God and Nature a readier welcome and surer sanctuary. We shall continue to think the negro a man, and on Southern evidence, too, so long as he is counted in the population represented on the floor of Congress,—for three fifths of perfect manhood would be a high average even among white men; so long as he is hanged or worse, as an example and terror to others,—for we do not punish one animal for the moral improvement of the rest; so long as he is considered capable of religious instruction,—for we fancy the gorillas would make short work with a missionary; so long as there are fears of insurrection,—for we never heard of a combined effort at revolt in a menagerie. Accordingly, we do not see how the particular right of whose infringement we hear so much is to be made safer by the election of Mr. Bell, Mr. Breckinridge, or Mr. Douglas,—there being quite as little chance that any of them would abolish human nature as that Mr. Lincoln would abolish slavery. The same generous instinct that leads some among us to sympathize with the sorrows of the bereaved master will always, we fear, influence others to take part with the rescued man.

But if our Constitutional Obligations, as we like to call our constitutional timidity or indifference, teach us that a particular divinity hedges the Domestic Institution, they do not require us to forget that we have institutions of our own, worth maintaining and extending, and not without a certain sacredness, whether we regard the traditions of the fathers or the faith of the children. It is high time that we should hear something of the rights of the Free States, and of the duties consequent upon them. We also have our prejudices to be respected, our theory of civilization, of what constitutes the safety of a state and insures its prosperity, to be applied wherever there is soil enough for a human being to stand on and thank God for making him a man. Is conservatism applicable only to property, and not to justice, freedom, and public honor? Does it mean merely drifting with the current of evil times and pernicious counsels, and carefully nursing the ills we have, that they may, as their nature it is, grow worse?

To be told that we ought not to agitate the question of Slavery, when it is that which is forever agitating us, is like telling a man with the fever and ague on him to stop shaking, and he will be cured. The discussion of Slavery is said to be dangerous, but dangerous to what? The manufacturers of the Free States constitute a more numerous class than the slaveholders of the South: suppose they should claim an equal sanctity for the Protective System. Discussion is the very life of free institutions, the fruitful mother of all political and moral enlightenment, and yet the question of all questions must be tabooed. The Swiss guide enjoins silence in the region of avalanches, lest the mere vibration of the voice should dislodge the ruin clinging by frail roots of snow. But where is our avalanche to fall? It is to overwhelm the Union, we are told. The real danger to the Union will come when the encroachments of the Slave-Power and the concessions of the Trade-Power shall have made it a burden instead of a blessing. The real avalanche to be dreaded,—are we to expect it from the ever-gathering mass of ignorant brute force, with the irresponsibility of animals and the passions of men, which is one of the fatal necessities of slavery, or from the gradually increasing consciousness of the non-slaveholding population of the Slave States of the true cause of their material impoverishment and political inferiority? From one or the other source its ruinous forces will be fed, but in either event it is not the Union that will be imperilled, but the privileged Order who on every occasion of a thwarted whim have menaced its disruption, and who will then find in it their only safety.

We believe that the "irrepressible conflict"—for we accept Mr. Seward's much-denounced phrase in all the breadth of meaning he ever meant to give it—is to take place in the South itself; because the Slave System is one of those fearful blunders in political economy which are sure, sooner or later, to work their own retribution. The inevitable tendency of slavery is to concentrate in a few hands the soil, the capital, and the power of the countries where it exists, to reduce the non-slaveholding class to a continually lower and lower level of property, intelligence, and enterprise,—their increase in numbers adding much to the economical hardship of their position and nothing to their political weight in the community. There is no home-encouragement of varied agriculture,—for the wants of a slave population are few in number and limited in kind; none of inland trade, for that is developed only by communities where education induces refinement, where facility of communication stimulates invention and variety of enterprise, where newspapers make every man's improvement in tools, machinery, or culture of the soil an incitement to all, and bring all the thinkers of the world to teach in the cheap university of the people. We do not, of course, mean to say that slaveholding States may not and do not produce fine men; but they fail, by the inherent vice of their constitution and its attendant consequences, to create enlightened, powerful, and advancing communities of men, which is the true object of all political organizations, and is essential to the prolonged existence of all those whose life and spirit are derived directly from the people. Every man who has dispassionately endeavored to enlighten himself in the matter cannot but see, that, for the many, the course of things in slaveholding States is substantially what we have described, a downward one, more or less rapid, in civilization and in all those results of material prosperity which in a free country show themselves in the general advancement for the good of all, and give a real meaning to the word Commonwealth. No matter how enormous the wealth centred in the hands of a few, it has no longer the conservative force or the beneficent influence which it exerts when equably distributed,—even loses more of both where a system of absenteeism prevails so largely as in the South. In such communities the seeds of an "irrepressible conflict" are surely if slowly ripening, and signs are daily multiplying that the true peril to their social organization is looked for, less in a revolt of the owned labor than in an insurrection of intelligence in the labor that owns itself and finds itself none the richer for it. To multiply such communities is to multiply weakness.

The election in November turns on the single and simple question, Whether we shall consent to the indefinite multiplication of them; and the only party which stands plainly and unequivocally pledged against such a policy, nay, which is not either openly or impliedly in favor of it,—is the Republican party. We are of those who at first regretted that another candidate was not nominated at Chicago; but we confess that we have ceased to regret it, for the magnanimity of Mr. Seward since the result of the Convention was known has been a greater ornament to him and a greater honor to his party than his election to the Presidency would have been. We should have been pleased with Mr. Seward's nomination, for the very reason we have seen assigned for passing him by,—that he represented the most advanced doctrines of his party. He, more than any other man, combined in himself the moralist's oppugnancy to Slavery as a fact, the thinker's resentment of it as a theory, and the statist's distrust of it as a policy,—thus summing up the three efficient causes that have chiefly aroused and concentrated the antagonism of the Free States. Not a brilliant man, he has that best gift of Nature, which brilliant men commonly lack, of being always able to do his best; and the very misrepresentation of his opinions which was resorted to in order to neutralize the effect of his speeches in the Senate and elsewhere was the best testimony to their power. Safe from the prevailing epidemic of Congressional eloquence as if he had been inoculated for it early in his career, he addresses himself to the reason, and what he says sticks. It was assumed that his nomination would have embittered the contest and tainted the Republican creed with radicalism; but we doubt it. We cannot think that a party gains by not hitting its hardest, or by sugaring its opinions. Republicanism is not a conspiracy to obtain office under false pretences. It has a definite aim, an earnest purpose, and the unflinching tenacity of profound conviction. It was not called into being by a desire to reform the pecuniary corruptions of the party now in power. Mr. Bell or Mr. Breckinridge would do that, for no one doubts their honor or their honesty. It is not unanimous about the Tariff, about State-Rights, about many other questions of policy. What unites the Republicans is a common faith in the early principles and practice of the Republic, a common persuasion that slavery, as it cannot but be the natural foe of the one, has been the chief debaser of the other, and a common resolve to resist its encroachments everywhen and everywhere. They see no reason to fear that the Constitution, which has shown such pliant tenacity under the warps and twistings of a forty-years' pro-slavery pressure, should be in danger of breaking, if bent backward again gently to its original rectitude of fibre. "All forms of human government," says Machiavelli, "have, like men, their natural term, and those only are long-lived which possess in themselves the power of returning to the principles on which they were originally founded."

It is in a moral aversion to slavery as a great wrong that the chief strength of the Republican party lies. They believe as everybody believed sixty years ago; and we are sorry to see what appears to be an inclination in some quarters to blink this aspect of the case, lest the party be charged with want of conservatism, or, what is worse, with abolitionism. It is and will be charged with all kinds of dreadful things, whatever it does, and it has nothing to fear from an upright and downright declaration of its faith. One part of the grateful work it has to do is to deliver us from the curse of perpetual concession for the sake of a peace that never comes, and which, if it came, would not be peace, but submission,—from that torpor and imbecility of faith in God and man which have stolen the respectable name of Conservatism. A question which cuts so deep as that which now divides the country cannot be debated, much less settled, without excitement. Such excitement is healthy, and is a sign that the ill humors of the body politic are coming to the surface, where they are comparatively harmless. It is the tendency of all creeds, opinions, and political dogmas that have once defined themselves in institutions to become inoperative. The vital and formative principle, which was active during the process of crystallization into sects, or schools of thought, or governments, ceases to act; and what was once a living emanation of the Eternal Mind, organically operative in history, becomes the dead formula on men's lips and the dry topic of the annalist. It has been our good fortune that a question has been thrust upon us which has forced us to reconsider the primal principles of government, which has appealed to conscience as well as reason, and, by bringing the theories of the Declaration of Independence to the test of experience in our thought and life and action, has realized a tradition of the memory into a conviction of the understanding and the soul. It will not do for the Republicans to confine themselves to the mere political argument, for the matter then becomes one of expediency, with two defensible sides to it; they must go deeper, to the radical question of right and wrong, or they surrender the chief advantage of their position. What Spinoza says of laws is equally true of party platforms,—that those are strong which appeal to reason, but those are impregnable which compel the assent both of reason and the common affections of mankind.

No man pretends that under the Constitution there is any possibility of interference with the domestic relations of the individual States; no party has ever remotely hinted at any such interference; but what the Republicans affirm is, that in every contingency where the Constitution can be construed in favor of freedom, it ought to be and shall be so construed. It is idle to talk of sectionalism, abolitionism, and hostility to the laws. The principles of liberty and humanity cannot, by virtue of their very nature, be sectional, any more than light and heat. Prevention is not abolition, and unjust laws are the only serious enemies that Law ever had. With history before us, it is no treason to question the infallibility of a court; for courts are never wiser or more venerable than the men composing them, and a decision that reverses precedent cannot arrogate to itself any immunity from reversal. Truth is the only unrepealable thing.

We are gravely requested to have no opinion, or, having one, to suppress it, on the one topic that has occupied caucuses, newspapers, Presidents' messages, and Congress for the last dozen years, lest we endanger the safety of the Union. The true danger to popular forms of government begins when public opinion ceases because the people are incompetent or unwilling to think. In a democracy it is the duty of every citizen to think; but unless the thinking result in a definite opinion, and the opinion lead to considerate action, they are nothing. If the people are assumed to be incapable of forming a judgment for themselves, the men whose position enables them to guide the public mind ought certainly to make good their want of intelligence. But on this great question, the wise solution of which, we are every day assured, is essential to the permanence of the Union, Mr. Bell has no opinion at all, Mr. Douglas says it is of no consequence which opinion prevails, and Mr. Breckinridge tells us vaguely that "all sections have an equal right in the common Territories." The parties which support these candidates, however, all agree in affirming that the election of its special favorite is the one thing that can give back peace to the distracted country. The distracted country will continue to take care of itself, as it has done hitherto, and the only question that needs an answer is, What policy will secure the most prosperous future to the helpless Territories, which our decision is to make or mar for all coming time? What will save the country from a Senate and Supreme Court where freedom shall be forever at a disadvantage?

There is always a fallacy in the argument of the opponents of the Republican party. They affirm that all the States and all the citizens of the States ought to have equal rights in the Territories. Undoubtedly. But the difficulty is that they cannot. The slaveholder moves into a new Territory with his institution, and from that moment the free white settler is virtually excluded. His institutions he cannot take with him; they refuse to root themselves in soil that is cultivated by slave-labor. Speech is no longer free; the post-office is Austrianized; the mere fact of Northern birth may be enough to hang him. Even now in Texas, settlers from the Free States are being driven out and murdered for pretended complicity in a plot the evidence for the existence of which has been obtained by means without a parallel since the trial of the Salem witches, and the stories about which are as absurd and contradictory as the confessions of Goodwife Corey. Kansas was saved, it is true; but it was the experience of Kansas that disgusted the South with Mr. Douglas's panacea of "Squatter Sovereignty."

The claim of equal rights in the Territories is a specious fallacy. Concede the demand of the slavery-extensionists, and you give up every inch of territory to slavery, to the absolute exclusion of freedom. For what they ask (however they may disguise it) is simply this,—that their local law be made the law of the land, and coextensive with the limits of the General Government. The Constitution acknowledges no unqualified or interminable right of property in the labor of another; and the plausible assertion, that "that is property which the law makes property" (confounding a law existing anywhere with the law which is binding everywhere), can deceive only those who have either never read the Constitution, or are ignorant of the opinions and intentions of those who framed it. It is true only of the States where slavery already exists; and it is because the propagandists of slavery are well aware of this, that they are so anxious to establish by positive enactment the seemingly moderate title to a right of existence for their institution in the Territories,—a title which they do not possess, and the possession of which would give them the oyster and the Free States the shells. Laws accordingly are asked for to protect Southern property in the Territories,—that is, to protect the inhabitants from deciding for themselves what their frame of government shall be. Such laws will be passed, and the fairest portion of our national domain irrevocably closed to free labor, if the Non-slaveholding States fail to do their duty in the present crisis.

But will the election of Mr. Lincoln endanger the Union? It is not a little remarkable that, as the prospect of his success increases, the menaces of secession grow fainter and less frequent. Mr. W. L. Yancey, to be sure, threatens to secede; but the country can get along without him, and we wish him a prosperous career in foreign parts. But Governor Wise no longer proposes to seize the Treasury at Washington,—perhaps because Mr. Buchanan has left so little in it. The old Mumbo-Jumbo is occasionally paraded at the North, but, however many old women may be frightened, the pulse of the stock-market remains provokingly calm. General Cushing, infringing the patent-right of the late Mr. James, the novelist, has seen a solitary horseman on the edge of the horizon. The exegesis of the vision has been various, some thinking that it means a Military Despot,—though in that case the force of cavalry would seem to be inadequate,—and others the Pony Express. If it had been one rider on two horses, the application would have been more general and less obscure. In fact, the old cry of Disunion has lost its terrors, if it ever had any, at the North. The South itself seems to have become alarmed at its own scarecrow, and speakers there are beginning to assure their hearers that the election of Mr. Lincoln will do them no harm. We entirely agree with them, for it will save them from themselves.

To believe any organized attempt by the Republican party to disturb the existing internal policy of the Southern States possible presupposes a manifest absurdity. Before anything of the kind could take place, the country must be in a state of forcible revolution. But there is no premonitory symptom of any such convulsion, unless we except Mr. Yancey, and that gentleman's throwing a solitary somerset will hardly turn the continent head over heels. The administration of Mr. Lincoln will be conservative, because no government is ever intentionally otherwise, and because power never knowingly undermines the foundation on which it rests. All that the Free States demand is that influence in the councils of the nation to which they are justly entitled by their population, wealth, and intelligence. That these elements of prosperity have increased more rapidly among them than in communities otherwise organized, with greater advantages of soil, climate, and mineral productions, is certainly no argument that they are incapable of the duties of efficient and prudent administration, however strong a one it may be for their endeavoring to secure for the Territories the single superiority that has made themselves what they are. The object of the Republican party is not the abolition of African slavery, but the utter extirpation of dogmas which are the logical sequence of attempts to establish its righteousness and wisdom, and which would serve equally well to justify the enslavement of every white man unable to protect himself. They believe that slavery is a wrong morally, a mistake politically, and a misfortune practically, wherever it exists; that it has nullified our influence abroad and forced us to compromise with our better instincts at home; that it has perverted our government from its legitimate objects, weakened the respect for the laws by making them the tools of its purposes, and sapped the faith of men in any higher political morality than interest or any better statesmanship than chicane. They mean in every lawful way to hem it within its present limits.

We are persuaded that the election of Mr. Lincoln will do more than anything else to appease the excitement of the country. He has proved both his ability and his integrity; he has had experience enough in public affairs to make him a statesman, and not enough to make him a politician. That he has not had more will be no objection to him in the eyes of those who have seen the administration of the experienced public functionary whose term of office is just drawing to a close. He represents a party who know that true policy is gradual in its advances, that it is conditional and not absolute, that it must deal with facts and not with sentiments, but who know also that it is wiser to stamp out evil in the spark than to wait till there is no help but in fighting fire with fire. They are the only conservative party, because they are the only one based on an enduring principle, the only one that is not willing to pawn to-morrow for the means to gamble with to-day. They have no hostility to the South, but a determined one to doctrines of whose ruinous tendency every day more and more convinces them.

The encroachments of Slavery upon our national policy have been like those of a glacier in a Swiss valley. Inch by inch, the huge dragon with its glittering scales and crests of ice coils itself onward, an anachronism of summer, the relic of a by-gone world where such monsters swarmed. But it has its limit, the kindlier forces of Nature work against it, and the silent arrows of the sun are still, as of old, fatal to the frosty Python. Geology tells us that such enormous devastators once covered the face of the earth, but the benignant sunlight of heaven touched them, and they faded silently, leaving no trace, but here and there the scratches of their talons, and the gnawed boulders scattered where they made their lair. We have entire faith in the benignant influence of Truth, the sunlight of the moral world, and believe that slavery, like other worn-out systems, will melt gradually before it. "All the earth cries out upon Truth, and the heaven blesseth it; ill works shake and tremble at it, and with it is no unrighteous thing."

E PLURIBUS UNUM

1861

We do not believe that any government—no, not the Rump Parliament on its last legs—ever showed such pitiful inadequacy as our own during the past two months. Helpless beyond measure in all the duties of practical statesmanship, its members or their dependants have given proof of remarkable energy in the single department of peculation; and there, not content with the slow methods of the old-fashioned defaulter, who helped himself only to what there was, they have contrived to steal what there was going to be, and have peculated in advance by a kind of official post-obit. So thoroughly has the credit of the most solvent nation in the world been shaken, that an administration which still talks of paying a hundred millions for Cuba is unable to raise a loan of five millions for the current expenses of government. Nor is this the worst: the moral bankruptcy at Washington is more complete and disastrous than the financial, and for the first time in our history the Executive is suspected of complicity in a treasonable plot against the very life of the nation.

Our material prosperity for nearly half a century has been so unparalleled that the minds of men have become gradually more and more absorbed in matters of personal concern; and our institutions have practically worked so well and so easily that we have learned to trust in our luck, and to take the permanence of our government for granted. The country has been divided on questions of temporary policy, and the people have been drilled to a wonderful discipline in the manœuvres of party tactics; but no crisis has arisen to force upon them a consideration of the fundamental principles of our system, or to arouse in them a sense of national unity, and make them feel that patriotism was anything more than a pleasant sentiment,—half Fourth of July and half Eighth of January,—a feeble reminiscence, rather than a living fact with a direct bearing on the national well-being. We have had long experience of that unmemorable felicity which consists in having no history, so far as history is made up of battles, revolutions, and changes of dynasty; but the present generation has never been called upon to learn that deepest lesson of polities which is taught by a common danger, throwing the people back on their national instincts, and superseding party-leaders, the peddlers of chicane, with men adequate to great occasions and dealers in destiny. Such a crisis is now upon us; and if the virtue of the people make up for the imbecility of the Executive, as we have little doubt that it will, if the public spirit of the whole country be awakened in time by the common peril, the present trial will leave the nation stronger than ever, and more alive to its privileges and the duties they imply. We shall have learned what is meant by a government of laws, and that allegiance to the sober will of the majority, concentrated in established forms and distributed by legitimate channels, is all that renders democracy possible, is its only conservative principle, the only thing that has made and can keep us a powerful nation instead of a brawling mob.

The theory that the best government is that which governs least seems to have been accepted literally by Mr. Buchanan, without considering the qualifications to which all general propositions are subject. His course of conduct has shown up its absurdity, in cases where prompt action is required, as effectually as Buckingham turned into ridicule the famous verse,—

"My wound is great, because it is so small,"

by instantly adding,—

"Then it were greater, were it none at all."

Mr. Buchanan seems to have thought, that, if to govern little was to govern well, then to do nothing was the perfection of policy. But there is a vast difference between letting well alone and allowing bad to become worse by a want of firmness at the outset. If Mr. Buchanan, instead of admitting the right of secession, had declared it to be, as it plainly is, rebellion, he would not only have received the unanimous support of the Free States, but would have given confidence to the loyal, reclaimed the wavering, and disconcerted the plotters of treason in the South.

Either we have no government at all, or else the very word implies the right, and therefore the duty, in the governing power, of protecting itself from destruction and its property from pillage. But for Mr. Buchanan's acquiescence, the doctrine of the right of secession would never for a moment have bewildered the popular mind. It is simply mob-law under a plausible name. Such a claim might have been fairly enough urged under the old Confederation; though even then it would have been summarily dealt with, in the case of a Tory colony, if the necessity had arisen. But the very fact that we have a National Constitution, and legal methods for testing, preventing, or punishing any infringement of its provisions, demonstrates the absurdity of any such assumption of right now. When the States surrendered their power to make war, did they make the single exception of the United States, and reserve the privilege of declaring war against them at any moment? If we are a congeries of mediæval Italian republics, why should the General Government have expended immense sums in fortifying points whose strategic position is of continental rather than local consequence? Florida, after having cost us nobody knows how many millions of dollars and thousands of lives to render the holding of slaves possible to her, coolly proposes to withdraw herself from the Union and take with her one of the keys of the Mexican Gulf, on the plea that her slave-property is rendered insecure by the Union. Louisiana, which we bought and paid for to secure the mouth of the Mississippi, claims the right to make her soil French or Spanish, and to cork up the river again, whenever the whim may take her. The United States are not a German Confederation, but a unitary and indivisible nation, with a national life to protect, a national power to maintain, and national rights to defend against any and every assailant, at all hazards. Our national existence is all that gives value to American citizenship. Without the respect which nothing but our consolidated character could inspire, we might as well be citizens of the toy-republic of San Marino, for all the protection it would afford us. If our claim to a national existence was worth a seven years' war to establish, it is worth maintaining at any cost; and it is daily becoming more apparent that the people, so soon as they find that secession means anything serious, will not allow themselves to be juggled out of their rights, as members of one of the great powers of the earth, by a mere quibble of Constitutional interpretation.

We have been so much accustomed to the Buncombe style of oratory, to hearing men offer the pledge of their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor on the most trivial occasions, that we are apt to allow a great latitude in such matters, and only smile to think how small an advance any intelligent pawnbroker would be likely to make on securities of this description. The sporadic eloquence that breaks out over the country on the eve of election, and becomes a chronic disease in the two houses of Congress, has so accustomed us to dissociate words and things, and to look upon strong language as an evidence of weak purpose, that we attach no meaning whatever to declamation. Our Southern brethren have been especially given to these orgies of loquacity, and have so often solemnly assured us of their own courage, and of the warlike propensities, power, wealth, and general superiority of that part of the universe which is so happy as to be represented by them, that, whatever other useful impression they have made, they insure our never forgetting the proverb about the woman who talks of her virtue. South Carolina, in particular, if she has hitherto failed in the application of her enterprise to manufacturing purposes of a more practical kind, has always been able to match every yard of printed cotton from the North with a yard of printed fustian, the product of her own domestic industry. We have thought no harm of this, so long as no Act of Congress required the reading of the "Congressional Globe." We submitted to the general dispensation of long-windedness and short-meaningness as to any other providental visitation, endeavoring only to hold fast our faith in the divine government of the world in the midst of so much that was past understanding. But we lost sight of the metaphysical truth, that, though men may fail to convince others by a never so incessant repetition of sonorous nonsense, they nevertheless gradually persuade themselves, and impregnate their own minds and characters with a belief in fallacies that have been uncontradicted only because not worth contradiction. Thus our Southern politicians, by dint of continued reiteration, have persuaded themselves to accept their own flimsy assumptions for valid statistics, and at last actually believe themselves to be the enlightened gentlemen, and the people of the Free States the peddlers and sneaks they have so long been in the habit of fancying. They have argued themselves into a kind of vague faith that the wealth and power of the Republic are south of Mason and Dixon's line; and the Northern people have been slow in arriving at the conclusion that treasonable talk would lead to treasonable action, because they could not conceive that anybody should be so foolish as to think of rearing an independent frame of government on so visionary a basis. Moreover, the so often recurring necessity, incident to our system, of obtaining a favorable verdict from the people has fostered in our public men the talents and habits of jury-lawyers at the expense of statesmanlike qualities; and the people have been so long wonted to look upon the utterances of popular leaders as intended for immediate effect and having no reference to principles, that there is scarcely a prominent man in the country so independent in position and so clear of any suspicion of personal or party motives that they can put entire faith in what he says, and accept him either as the leader or the exponent of their thoughts and wishes. They have hardly been able to judge with certainty from the debates in Congress whether secession were a real danger, or only one of those political feints of which they have had such frequent experience.

Events have been gradually convincing them that the peril was actual and near. They begin to see how unwise, if nothing worse, has been the weak policy of the Executive in allowing men to play at Revolution till they learn to think the coarse reality as easy and pretty as the vaudeville they have been acting. They are fast coming to the conclusion that the list of grievances put forward by the secessionists is a sham and a pretence, the veil of a long-matured plot against republican institutions. And it is time the traitors of the South should know that the Free States are becoming every day more united in sentiment and more earnest in resolve, and that, so soon as they are thoroughly satisfied that secession is something more than empty bluster, a public spirit will be aroused that will be content with no half-measures, and which no Executive, however unwilling, can resist.