Emily Sarah Holt

"Our Little Lady"

Chapter One.

Six Hundred Years ago—What things were like.

The afternoon service was over in Lincoln Cathedral, and the congregation were slowly filing out of the great west door. But that afternoon service was six hundred years ago, and both the Cathedral and the congregation would look very strange to us if we saw them now. Those days were well called the Dark Ages, and how dark they were we can scarcely realise in the present day. Let us fancy ourselves coming out of that west door, and try to picture what we should have seen there, six hundred years ago.

The Cathedral itself is hardly to be known. It is crowded with painted images and embroidered banners, and filled with the smoke and scent of burning incense. The clergy are habited, not in white surplices or in black gowns, but in large stiff cloaks—copes they are called—of scarlet silk, heavy with gold embroidery. The Bishop, who is in the pulpit, wears a cope of white, thick with masses of gold, and on his head is a white and gold mitre. How unlike that upper chamber, where the disciples gathered together after the crucifixion of their Master! Is it better or worse, do you ask? Well, I think if the Master were to come in, it would be easier to see Him in the quiet upper chamber, where there was nothing else to see, than in the perfumed and decorated Cathedral where there was so much else!

But now let us look at the congregation as they pass out. Are they all women? for all alike seem to wear long skirts and thick hoods: there are neither trousers, nor hats, nor bonnets. No, there is a fair sprinkling of men; but men and women dressed more alike then than they do now. You will see, if you look, that some of these long skirts are open in front, and you may catch a glimpse of a beard here and there under the hood. This is a poor woman who comes now: she wears a serge dress which has cost her about three-halfpence a yard, and a threadbare hood for which she may have given sixpence.

Are things so cheap, then? No, just the other way about; money is so dear. The wages of a mason or a bricklayer are about sixpence a week; haymakers have the same; reapers get from a shilling to half-a-crown, and mowers one and ninepence. The gentlemen who wait on the King himself only receive a shilling a day.

Here comes one of them, in a long green robe of shining silky stuff, which is called samite; round his neck is a curiously cut collar of dark red cloth, and in his hand he carries a white hood. Men do not confine themselves to the quiet, sober colours that we are accustomed to see; they are smarter than the ladies themselves. This knight, as he passes out, throws his gown back, before mounting his horse, and you see his yellow hose striped with black—trousers and stockings all in a piece, as it were—with low black shoes, and gilt spurs.

But who follows him?—this superbly dressed woman in rich blue glistening samite, with a black and gold hood, under which we see her hair bound with a golden fillet, and a necklace of costly pearls clasped round her throat—for it is a warm day, and she has not tied her hood. She must be somebody of consequence, for a smart gentleman leads her by the hand, and one with a long staff walks in front, to keep the people from pressing too close on her. She is indeed somebody of consequence—the Countess of Lincoln herself, by birth an Italian Princess; and she is so grand, and so rich, and so beautiful and stately—and I am sorry to add, so proud—that people call her the Queen of Lincoln. She has not far to go home—only through the archway, and past Saint Michael’s Church and the Bull Gate, and then the great portcullis of the grim old Castle lifts its head to receive its lady, and she disappears from our sight.

Do you notice that carpets are spread along the streets for her?—not carpets like ours, but the only sort they have, which are a kind of rough matting. And indeed she needs them, if those purple velvet shoes of hers are not to be quite ruined by the time she reaches home. For there are no pavements, and the streets are almost ankle-deep in mud, and worse than mud. Dead cats, rotten vegetables, animal refuse, and every kind of abominable thing that you could see or think of, all lie about in heaps, in these narrow, narrow streets, where the sun can hardly get down to the ground, and two people might sometimes shake hands from opposite windows in the upper stories, for they come farther out than the lower ones. Everybody throws all his rubbish into the street; all his slops, all his ashes, all his everything of which he wants to get rid. The smells are something dreadful, as soon as you come out of the perfumed churches. It is pleasanter to have the churches perfumed, undoubtedly; but it would be a good deal healthier if they kept the streets clean.

Quietly following the grand young Countess, at a respectful distance, come two women who are evidently mother and daughter. Their dress shows that they are not absolutely poor, but it tells at least as plainly that they are not at all rich. Just as they reach the west door, a little girl of ten comes quickly after them, dressed just like themselves, a woman in miniature.

“Why, Avice, where hast thou been?” says the elder of the two women.

“I was coming, Grandmother,” explains little Avice, “and Father Thomas called me, and bade me tell you that the holy Bishop would come to see you this afternoon, and sup his four-hours with you.”

Four-hours, taken as its name shows at four o’clock, was the meal which answered to our tea. Bishops do not often drink tea with women of this class, but this was a peculiar Bishop, and the woman to whom he sent this message was his own foster-sister.

“Truly, and I shall be glad to see him,” says the Grandmother; and on they go out of the west door.

The carpets which were spread for the Countess have been rolled away, and our three humble friends pick their steps as best they may among the dirt-heaps, occasionally slipping into a puddle—I am afraid Avice now and then walks into it deliberately for the fun of the splash!—and following the road taken by the Countess as far as the Bull Gate, they then turn to the left, leaving the frowning Castle on their right, and begin to descend the steep slope well named Steephill.

They have not gone many yards when two people overtake them—a man and a woman. The man stops to speak: the woman marches on with her arms folded and her head in the air, as if they were invisible.

“Good morrow, Dan,” says the old lady.

“Good morrow, Mother,” answers Dan.

“What’s the matter with Filomena?”

“A touch of the old complaint, that’s all,” answers Dan drily. “We’d a few words o’ th’ road a-coming—leastwise she had, for she got it pretty much to herself—and for th’ next twelve hours or so she’ll not be able to see anybody under a squire.”

“Is she often like that, Dan?”

“Well, it doesn’t come more days than seven i’ th’ week.”

“Why, you don’t mean to say it’s so every day?” said Agnes, the younger woman of our trio.

Dan shook his head. “Happen there’s an odd un now and then as gets let off,” said he. “But I must after her, or there’ll be more hot water. And it comes to table boilin’, I can tell you. Good morrow!”

Dan runs rather heavily after his incensed spouse, and our friends continue to pick their way down Steephill. For rather more than half the way they go, and when just past the Church of Saint Lawrence, they turn into a narrow street on the left, and in a few yards more they are at home.

Home is one of the smallest houses you ever saw. It has only two rooms, one above the other; but they are a fair size, being about twenty-five feet by sixteen. The upper, of course, is the bedroom; the lower one is kitchen and parlour; and a ladder leads from one to the other. The upper chamber holds a bed, which is like a box out of which the bottom has been taken, filled with straw, and on that is a hard straw mattress, two excessively coarse blankets, and a thick, shaggy, woollen rug for a counterpane. There are not any sheets or pillow-cases; but a thick, hard bolster, stuffed like the mattress with straw, serves for a pillow.

At the foot of the oak bedstead is a large oak chest, big enough to hold a man, in which the owners keep all their small property of any value. There are no chairs, but the deep windows have wooden seats, and two wooden stools are in the corners. As to wardrobes, chests of drawers, dressing-tables, and washstands, nobody knows of such things at that day. The chest serves the purpose of all except the washstand, and they find that (as much as they have of it) at the draw-well in the little back yard. The window is just a square hole in the wall, closed with a wooden shutter, so that light and air—if not wind and rain—come in together. A looking-glass they have, but a poor makeshift it is, being of metal and rounded; and those who know what a comical aspect your face takes when you see it in a metal teapot, can guess how far anybody could see himself rightly in it. It is nailed up, too, so high on the wall that it is not easy to see anything. This is all the furniture of the bedroom.

Downstairs there is more though there are no chairs and tables, unless a leaf-table in the wall, which lets down, can go by that name. There are two or three long settles stretching across the wall—the settle was called a bench when it had a back to it, and a form if it had not. There is a large bake-stone in one corner; the bread is put on the top to bake, with the fire underneath, and when there is no fire, the top can be used as a table, a moulding board, or in many other ways. But it must not be supposed that such bread is in large square or cottage loaves like ours. It is made in flat cakes, large or small, thick or thin. By the side of the bake-stone is the sink, or rather that which answers to one, being a rough brick basin, with a plug in the bottom, and just beneath it is a little channel in the brick floor, by which, when the plug is pulled up, the dirty water finds its way out into the street under the house door. People who live in this way need—and wear—short gowns and stout shoes.

The opposite corner holds the pine-torches and chips; they burn nothing but wood, for though coal is known, it is very little used. This is partly because it is expensive; but also because it is considered shockingly unhealthy. The smoke from wood or turf is thought very wholesome; but that from coal is just the reverse. Opposite the bake-stone is the window; a very little one, much wider than it is high, and rilled with exceedingly small diamond-shaped panes of very poor greenish glass set in lead, there being so much lead and so little glass that the room is but dark in the brightest sunshine. Indeed, it is decidedly a sign of gentility that the house has any window at all, beyond the square hole with the wooden shutter.

Up and down the room there are several stools, high and low; the high ones serve when wanted as little movable tables. In the third corner is a bread-rack, filled with hard oat-cake above, and the soft flat cakes of wheat flour below; in the fourth stand several large barrels containing salt fish, salt meat, flour, meal, and ale. From the top of the room hang hams, herbs in canvas bags, strings of smoked fish, a few empty baskets and pails, and anything else which can be hung up. The rafters are so low that when the inmates move about they have every now and then to courtesy to a ham or a pail, which would otherwise hit them on the head. A door by the window leads into the street, and another beyond the barrels gives access to the back yard.

How would you like to go back, gentle reader, to this style of life? This was the way in which your forefathers lived, six hundred years ago—unless they were very grand people indeed. Then they lived in a big castle with walls two or three feet thick, and ate from gold or silver plates, and had the luxury of a chimney in their dining-rooms. But even then, there were a good many little matters in respect of which I do not fancy you would quite like to change with them! Would you like to eat with your fingers, and to find creeping creatures everywhere, and to have no books and newspapers, and no letters, and no shops except in great towns, and no way of getting about except on foot or horseback, and no lamps, candles, clocks or watches, china, spectacles, nor carpets on the floor? Yet this was the way in which kings and queens lived, six hundred years ago.

In respect of clothes, people were much better off. They dressed far more warmly than we do, and used a great deal of fur, not only for trimming or out-door wear, but to line their clothes in winter. But their furs comprised much commoner and cheaper skins than we use; ordinary people wore lambskins, with the fur of cats, hares, and squirrels. Such furs as ermine and miniver were kept for the great people; for there were curious rules and laws about dress in those days. It was not, as it is now, a question of what you could afford to buy, but of what rank you were. You could not wear ermine or samite unless you were an earl at the lowest; nor must you sleep on a feather bed unless you were a knight; nor might you eat your dinner from a metal plate, if you were not a gentleman. Such notions may sound ridiculous to us; but they were serious earnest, six hundred years ago. We should not like to find that we had to go before a magistrate and pay a fine, if our shoes were a trifle too long, or our trimmings an inch too wide. But in the time of which I am writing, this was an every-day affair.

In the house, women wore an odd sort of head-dress called a wimple, which came down to the eyebrows, and was fastened by pins above the ears. When they went out of doors, they tied on a fur or woollen hood above it. The gown was very loose, and had no particular waist; the sleeves were excessively wide and long. But when women were at work, they had a way of tucking up their dresses at the bottom, so as to keep them out of the perpetual slop of the stone or brick floor. Rich people put rushes on their floors except in winter, and as these were only moved once a year, all manner of unspeakable abominations were harboured underneath. In this respect the poor were the best off, since they could have their brick floors as clean as they chose: as, even yet, there are points in which they have the advantage of richer people—if they only knew it!

But our picture is not quite finished yet. Look out of the little window, and notice what you see. Can this be Sunday afternoon in a good street? for every shop is open, and in the doorways stand young men calling out to the passers-by to come in and look at their goods. “What lack you? what lack you?”

“Cherry ripe!”

“Buy my fine kerchiefs!”

“Any thimbles would you, maids?” Such cries as these ring on every side.

Yes, it is Sunday afternoon—“the rest of the holy Sabbath unto the Lord.” But look where you will, you can see no rest. Everywhere the rich are at play, and the poor are at work. What does this mean?

Think seriously of it, friends; for it will be no light matter if England return to such ways as these again, and there are plenty of people who are trying to bring them back. What it means is that if holiness be lost from the Sabbath, rest will never stay behind. Play for the few means work for the many. And let play get its head in, and work will soon follow.

If you want to walk the road of happiness, and to arrive at the home of heaven, you must follow after God, for any other guide will lead in the opposite direction. The people who tell you that religion is a gloomy thing are always the people who have not any themselves. And things are very different, according to whether you look at them from inside or outside. How can you tell what there may be inside a house, so long as all you know of it is walking past a shut door?

Ever since Adam hid himself from the presence of the Lord God among the trees of the garden, men and women have been prone to fancy that God likes best to see them unhappy. The old heathen always used to suppose that their gods were jealous of them, and they were afraid to be too happy, lest the gods should be vexed! But the real God “takes pleasure in the prosperity of His people,” and “godliness hath the promise of the life that now is, as well as of that which is to come.”

What language are our three friends talking? It sounds very odd. It is English, and yet it is not. Yes, it is what learned men call “Middle English”—because it stands midway between the very oldest English, or Anglo-saxon, and the modern English which we speak now. It is about as much like our English as broad Scotch is. A few words and expressions through the story will give an idea how different it is; but if I were to write exactly as they would have spoken, nobody would understand it now.

And how do they live inside this tiny house? Well, in some respects, in a poorer and meaner way than the very poorest would live now. Look up, and you will see that there is no chimney, but the smoke finds its way out through a hole above the fire, and when it is wet the rain comes in and puts the fire out. They know nothing about candles, but burn long shafts of pine-wood instead. There are such things as wax candles, indeed, but they are only used in church; nobody dreams of burning them in houses. And there are lamps, but they are made of gold and silver, and are never seen except in the big castles. There is no crockery; and metal plates, as I said, are only for the grand people. The middle classes use wooden trenchers—our friends have two—hollowed out to keep the gravy in; and the poor have no plates at all beyond a cake of bread. Their drinking-glasses are just cows’ horns, with the tip cut off and a wooden bottom put in. They have also a few wooden bowls, and one precious brass pot; half a dozen knives, rough unwieldy things, and four wooden spoons; one horn spoon is kept for best. Forks? Oh dear, no; nobody knows anything about forks, except a pitchfork. Table-linen? No, nor body-linen; those luxuries are only in the big castles. Let us watch Avice’s mother as she sets the table for four-hours, remembering that they are going to have company, and therefore will try to make things a little more comfortable than usual.

In the first place, there will be a table to set. If they were alone, they would use one or two of the high stools. But Agnes goes out into the little yard, and brings back two boards and a couple of trestles, which she sets up in the middle of the room. This is the table—rather a rickety affair, you may say; and it will be quite as well that nobody should lean his elbow on it. Next, she puts on the boards four of the cows’ horns, and the two trenchers, with one bowl. She then serves out a knife and spoon for each of four people, putting the horn spoon for the Bishop. Her preparations are now complete, with the addition of one thing which is never forgotten—a very large wooden salt-cellar, which she puts almost at one end, for where that stands is a matter of importance. Great people—and the Bishop is a very great person—must sit above the salt, and small insignificant folks are put below. We may also notice that the Bishop is honoured with a horn and a trencher to himself. This is an unusual distinction. Husband and wife always share the same plate, and other relatives very frequently. As to Avice, we see that nothing is set for her. The child will share her mother’s spoon and horn; and if the Bishop brings his chaplain, he will have a spoon and horn for himself, but will eat off the Grandmother’s plate.

Our picture is finished, and now the story may begin.

Chapter Two.

How Things Changed.

“Open the door, Avice, quick!” said Agnes, as a rap came upon it. “Yonder, methinks, must be the holy Bishop.”

Avice ran to the door, and opened it, to find two priests standing on the threshold. They entered, the foremost with a smile to the child, after which he held up his hand, saying, “Christ save all here!” Then he held out his hand, which both Agnes and her mother kissed, and sat down on one of the forms by the table. Every priest was then looked upon as a most holy person. Some of them were a long way from holiness. But there were some who really deserved the title, and few deserved it so well as Robert Copley, Bishop of Lincoln, whom, according to the fashion of that day, people called Grosteste, or Great-head.

For surnames were then only just beginning to grow, and very few people had them—I mean, very few had received any from their fathers. They had, therefore, to bear some name given to them. Sometimes a man was named from his father—he was Robert John-son, or John Wil-son. Sometimes it was from his trade; he was Robert the Smith, or John the Carter. Sometimes it was from the place where he lived; he was Robert at the Mill, or John by the Brook. But sometimes it was from something about himself, either as concerned his person or his ways; he was Robert Red-nose, or John White-hood, or William Turn-again. This is the way in which all surnames have grown. Now, as Bishop Copley’s soul lodged well (as Queen Elizabeth said of Lord Bacon), in a large head and massive brow, people took to calling him Great-head or Grosteste; and it is as Bishop Grosteste, not as Bishop Copley, that he has been known down to the present day.

I have said that he was a peculiar man. He was much more peculiar, at the time when he lived, than he would have been if he had lived now. Saint Peter told bishops that they were not to be lords over God’s heritage, but to be ensamples to the flock; but when Bishop Grosteste lived, most bishops were very great lords, and very poor examples. Bishops, and clergymen too, were fond of going about in gay clothes of all colours, playing at games, and even drinking at ale-houses. Many of them were positively not respectable men. But Bishop Grosteste and his chaplain were dressed in plain black, and they were of the few who walk not according to the course of this world. To them, “I like” was of no moment, and “I ought” was of great importance. And what other people would say, or what other people might be going to do, was a matter of no consequence whatever.

Such men are scarce in this follow-my-leader world. If you are so fortunate as to be related to one of them, take care you make much of him, for you may go a long way before you see another. With most people “I like” comes up at the top; and “What will people say?” comes next, and often pretty near; but “What does God tell me to do?” is a long way off, and sometimes so far off that they never come to it at all!

Bishop Grosteste lived in one of the darkest days of Christianity. Thick, dense ignorance, of all kinds, overwhelmed the masses of the people. Books were worth their weight in gold, there were so few of them; and still worse, very few could read them. When we know that there was a law by which a man who had been sentenced to death could claim pardon if he were able to read one verse of a Psalm, it gives us an idea how very little people can have known, and what a precious thing learning was held to be. Even the clergy were not much wiser than the rest, and they were generally the best educated of any. Most of them could just get through the services, not so much by reading them as by knowing what they had to say; and they often made very queer blunders between words which were nearly alike. A few, here and there, were really learned men; and Bishop Grosteste was one of them. He had learned “all that Europe could furnish,” and he knew so much that the poor ignorant people about him fancied he must have obtained his knowledge by magic. But far better than all this, Bishop Grosteste was taught of God. His soul was like a plant which grew up towards the light, and Jesus Christ was his Sun.

In this day of full, brilliant Gospel light, we can hardly imagine the state of affairs then. Perhaps one fact will help us to do it as well as many. In every house there was an image set up before which all prayers were said. Sometimes it was a crucifix, sometimes an image of the Virgin Mary, sometimes of some other saint—for the saints, male and female, were a great crowd. But the crucifix or the Virgin Mary were generally preferred; and why? Because the poor worshippers fancied that the crucifix had more power than the image of a saint, and that the Virgin was able to look after her own candle! A torch, or in later times a candle, was always burning in front of the image; and of course if the image could keep it alight, it was much less trouble to the worshipper!

But had they no common sense in those days? Well, really, it looks sometimes as if they had not. When men once turn aside from God’s Word, it is impossible to say to what folly or wickedness they will not go. “The entrance of Thy words giveth light; yea, it giveth understanding unto the simple.”

Very few bishops then living would have taken any notice of the humble foster-sister who lived in that tiny house, and worked: for her living—she and her daughter being both widows, and the child dependent on them. It was hard work then, as now, for such people to get along. It is often really harder for them than for the very poor.

The guests being now come, Agnes dished up the four-hours—if that can be called dishing up when there were no dishes! She lifted a great pan off the hook where it hung over the fire—for it must be remembered there were no bars, and pans had to be hung over the fire by a handle like that of a kettle—and poured out into the bowl a quantity of soup. She then served out a cake of white bread to the Bishop—a rare dainty—black bread to the chaplain and her mother, and hard oat-cake for herself and Avice. They then began to eat, after the Bishop had made the sign of the crossover the bowl, which answered to saying grace; all the spoons going into the one bowl, the Bishop being respectfully allowed to help himself first.

“And how goes it now with thee, my sister Muriel?” asked the Bishop.

The Grandmother gave a little shake of her head, though she answered cheerfully enough.

“Things go pretty well, holy Father, I thank you. Work is off and on, as it may be; but we manage to keep a roof over our heads, as you see, and we can even find a bowl of broth and a wheat-cake for our friends. The Lord be praised for all His mercies!”

“Well said, my sister. And what do you intend to make of your little maid here?”

“Marry, I intend to make a good worker of her,” said Agnes in her turn, “and not an idle giggling good-for-nought, as most of the lasses be. She shall spin, and weave, and card, and sew, and scour, and wash, and bake, and brew, and churn, and cook, and not let the grass grow under her feet, or else I’ll see!”

“Truly a goodly list of duties for one maid,” replied the Bishop, with a smile. “And yet, good Agnes, I am about to ask if thou canst find room for another on the top of them.”

“Verily, holy Father, I am she that should work my fingers to the bone to pleasure you,” was the hearty answer.

“I thank thee, good my daughter. How shouldst thou like to go to London?”

“To London, Father!” And Agnes’s eyes grew as round as shillings.

To go to London was then looked on as a very serious matter. People made their wills before they started. And to ignorant Agnes, who had never in her life been ten miles from Lincoln, it sounded almost as tremendous an idea as being asked to go to the moon.

The Bishop smiled. He had been to Paris and Lyons.

“Ay, even to London town. I do indeed mean it, my daughter. There is, methinks, a career open to thee, which most should reckon rare preferment, and good success. Ah, what is success?” he added, as if to himself. “Howbeit, thou shalt hear. The Lady Queen lacketh nurses for her children, and reckoning thou shouldst well fill such a place, I made bold to speak for thee. And she thus far granted me, that thou shouldst go up to Windsor, where the King’s children are kept, and she herself is at this present, there to talk with her, and let her see if thou art fit for the post. If on further acquaintance she be pleased with thee, then shalt thou be made nurse to one of the children; and if not, then the Lady Queen will pay thy charges home. What sayest, my daughter?—and thou also, Muriel, my sister?”

Both Muriel and Agnes felt as if their breath were taken away. As to Avice, she was listening with those large ears for which little pitchers are proverbial. The Bishop had spoken quietly, as if it were an every-day occurrence, of this enormous change which would affect their whole lives.

“Verily, Father, you are too good to us,” said Muriel gratefully.

“And I will try to thank you, Father,” added Agnes, “when I get back my senses, and can find out whether I am on my head or my heels.”

The Bishop and his chaplain laughed; and Agnes, recalled to her duties by seeing the soup-bowl empty, jumped up and took down the spit on which a chicken was roasting at the fire. Chickens were dear just then, and this one had cost three farthings, having been provided in honour of company. People helped themselves in those days in a very rough and simple manner. Agnes held the chicken on the spit to the Bishop, who cut from it with his own knife the part he preferred; then she served the chaplain and Muriel in the same way, and lastly cut some off for herself and Avice. Finally, when little was left beside the carcase, she opened the back door, and bestowed the remains on Manikin the turnspit dog, a little wiry, shaggy cur, which, released from his labours, had sat on the hearth licking his lips while the process of helping went on, knowing that his reward would come at last. Manikin trotted off into the yard with his treasure, and Agnes came back to the table and the subject.

“Truly, holy Father, I know not how to thank you. But indeed I will do my best to deserve your good word, should it please God so to order the same.”

“I doubt not thou wilt do well, my daughter. Bear thou in mind that Christ our Lord is thy Master, and thy service must be good enough to be laid at His feet. Then shalt thou well serve the Queen.”

Agnes was a very ignorant woman. Bishop Grosteste, being himself a wise man, could not at all realise how ignorant she was. She knew very little how to serve God, but she did really wish to do it. And that, after all, is the great thing. Those who have the will can surely, sooner or later, find out how.

When the guests were gone, Agnes threw another log of wood upon the fire, and came and stood before it. “Well, Mother, what must we do touching this matter? Verily I am all of a tumblement. What think you?”

“I think, my daughter,” said old Muriel calmly from the chimney-corner, “that we are not going to set forth for London within this next half-hour.”

“Nay, truly; yet we must think well on it.”

“We shall do well to sleep on it, and yet better to ask counsel of the Lord.”

“But we must go, Mother! It would never do to offend the holy Bishop!”

“Bishop Robert my brother is not he that should be angered because we preferred God’s counsel to his. But it may be that we shall find, after prayer and thought, that his counsel is God’s.”

It was to that conclusion they came the next day.

After the Bishop’s departure, for a long time all was bustle and confusion. Agnes declared that she did not know where her head was, nor sometimes whether she had any. Avice was at the height of enjoyment. Old Muriel went quietly about her work, keeping at it, “doing the next thing,” and got through more work than either.

The Bishop did all he could to help them. He found them a tenant for the house, lent them money—all his money not spent on real necessaries was either lent or given to such as needed it more than he did; and at last he sent them southwards on his own horses, and in charge of three of his servants. From Lincoln to Windsor was a five days’ journey of rather long stages; and when at last they reached the royal borough, simple—minded Agnes had begun to feel as if no further power of astonishment were left in her mind.

“Dear, I never thought the world was so big!” she had said before they left Grantham; and when they arrived at Aylesbury, her cry was—“Eh, what a power of folks be in this world!”

Old Muriel took her journey, as she did everything, calmly. She, like Bishop Grosteste himself, lived too much with God to be easily startled or overawed by the grandeur of man. Avice was in a state of excitement and delight through the whole time.

They slept at a small inn; and the next morning, one of the Bishop’s servants, who had received his orders beforehand, took up to the Castle a letter from his master, and waited to hear when it would please the Queen to see them. He came back in an hour, with the news that the Queen would receive them that afternoon.

Agnes was in a condition of restless flutter till the time came. Then they dressed themselves in their very best, and Luke, the Bishop’s servant, took them up to the Castle.

If Agnes had felt confused at the mere idea of her interview, she found the reality still more overwhelming than she expected. The first thing she realised was that she stood in an immense hall, surrounded by what seemed to her a crowd of very smart gentlemen. Then they were led through passages and galleries, upstairs and downstairs, till Agnes felt as though she could never hope to find her way back; and at last, in a very handsome room, where the walls were covered with painting, and the furniture upholstered in silk, they came into the midst of a second crowd of very grand ladies. By this time poor Agnes had quite lost her head; and when one of the fine ladies asked her what she wanted, she could only drop a succession of courtesies and look totally bewildered. Old Muriel managed better.

“Under your leave, Madam, we have been sent for by my Lady the Queen.”

“Oh, are you the people who come about the nurses’ place?” said the young lady, who looked good-natured enough. “Follow me, and I will lead you to the Queen’s chamber.”

How many more chambers can there be? was the wonder uppermost in the mind of Agnes. But they walked through several more, each to her eyes grander than the last, painted, with stained glass windows, and silk-covered furniture. At length the young lady desired them to wait a moment where they were, while she took in their names to the Queen. She drew back a crimson silk curtain, and disappeared behind it; and the three—for they had never thought of leaving Avice behind—stood looking round them in admiring astonishment. They were not left to wonder long. The curtain was drawn back, and the voice of some unseen person bade them go forward.

They found themselves in a smaller room than the last, beautifully decorated. The walls were painted a very pale blue, and large frescoes ornamented each side of the chamber. Thick marble columns, highly polished, jutted out into the room, and in the recess between each pair was a marble bench, with cushions of crimson samite. Two walnut-wood chairs, furnished with crimson samite cushions, stood in the middle of the room. Small leaf-tables were fixed to the walls here and there. The floor was of waxed wood, very slippery to tread upon. At the farther side of the room two doors stood open, side by side, the one leading to a little oratory in the turret, the other to a balcony which ran round the tower. In one corner a young lady sat at an embroidery frame, and in another a little girl of seven years old, who deeply interested Avice, was feeding her pet peacock. In one of the chairs, with some fancy work in her hand, sat a lady whose age was about twenty-eight, and whose rich dress of gold-coloured samite, and the gold and pearl fillet which bound her hair, divided Avice’s attention with the child and the peacock. Agnes was dropping flurried courtesies to everybody at once. Muriel, who seemed to have a much better notion of what she ought to do, took a step forward, and knelt before the lady who sat in the chair.

“Lady,” she said, “we are the Queen’s servants.”

Queen Eleanor, for it was she, looked up on them with a smile. She was a beautiful brunette, lively and animated when she spoke, but with an easy-going, lazy expression when she did not. It struck Avice, who had eyes for everything, and was making good use of them, that her Majesty might have brushed her rich dark hair a little smoother, and have fastened her diamond brooch less unevenly than she had done.

It was the pleasanter side of Queen Eleanor which was being shown to them. She could be very pleasant when she was pleased, and very kind and affable when she liked people. But she could be very harsh and tyrannical to those whom she did not like; and she was one of those many people with whom out of sight is out of mind. Let her see a suffering child, and she would be sorry and anxious to help; but a thousand suffering people whom she did not see, even if something which she did had made them suffer, were nothing at all to her.

The Queen liked her visitors. She thought old Muriel looked reliable; she was amused with the bewildered reverence of Agnes; and as to Avice, a child more or less in Windsor Castle mattered very little. She would do to feed the peacock when Princess Margaret did not choose to attend to it. So the bargain was soon struck; and almost before she had discovered what was going to happen to her, Agnes found herself the day-nurse of the Lord Richard, the little Prince who was then in the cradle. Muriel was made mistress of the nurses; and even little Avice received a formal appointment as waiting-damsel on the Princess Margaret, the little girl who was feeding the peacock. They were then dismissed from the royal presence.

“Thou hadst better go with them, Margaret Bysset,” said the Queen, with a rather amused smile, to the young lady who had brought them in; “otherwise they may wander about all day.”

Guided by Margaret Bysset, they retraced their steps through the suite of rooms, down winding stairs, and across the hall, to the great door which led into the courtyard of the Castle.

“Can you find your way now?” asked the young lady.

“Nay, we can but try!” said Agnes. “Pray you, my mistress, how many chambers be there in this Castle?”

“Truly, I have not counted them,” was the laughing answer.

“Eh, dear, but I marvel if I can ever find mine own when we come to dwell here!”

“That will you soon enough. Look, here cometh your serving-man. Give you good morrow!”

A few days saw them safely housed in the Castle, where two of them were to dwell for ten years before they returned to their own home at Lincoln. But old Muriel was never to return. She lived through half that time, just long enough to hear of the death of Bishop Grosteste, who passed away on the ninth of October 1253. He literally died weeping for the sins of his age.

“Christ came into the world to save souls,” were the words uttered with his last breath. “He who takes pains to ruin them, shall he not be called Antichrist? God built the universe in six days; but it took Him thirty years to redeem fallen man. The Church can never be delivered but by the sword from the Egyptian bondage in which the Popes hold her.”

The good old Bishop could say no more. His voice broke down in tears; and with one great sob for England he yielded up his soul.

Chapter Three.

At Uncle Dan’s Smithy.

The royal baby for whose benefit Muriel and Agnes had been engaged did not live long; but he was succeeded by his brother Prince William, and before he was old enough to do without nurses, a little Princess came upon the scene. She was the last of the family, and she lived three years and a half. After her death, the services of the nurses were no longer needed. Queen Eleanor dismissed them with liberal wages and handsome presents, and the two who were left—Agnes and Avice—determined to go back to Lincoln. Avice was now a young woman of twenty.

But when they reached their old home, they found many changes. The good Bishop Grosteste was gone, but his chaplain, Father Thomas, had looked after their interests, and Agnes found no difficulty in recovering her little property. Happily for them, their tenants were anxious to leave the house, and before many days were over, they had slipped quietly back into the old place.

There were no banks in those days. A man’s savings bank was an old stocking or a tin mug. Agnes disposed of the money she had left from the Queen’s payment, partly in the purchase of a cow, and partly in a stocking, which was carefully locked up in the oak chest. They could live very comfortably on the produce of the cow and the garden, aided by what small sums they might earn in one way and another. And so the years went on, until Avice in her turn married and was left a widow; but she had no child, and when her mother died Avice was left alone.

“I can never do to live alone,” she said to herself; “I must have somebody to love and work for.”

And she began to think whom she could find to live with her. As she sat and span in the twilight, one name after another occurred to her mind, but only to be all declined with thanks.

There was her neighbour next door, Annora Goldhue: she had three daughters. No, none of them would do. Joan was idle, and Amy was conceited, and Frethesancia had a temper. Little Roese might have done, who lived with old Serena at the mill end; but old Serena could not spare her. At last, as Avice broke her thread for the fourth time, she pushed back the stool on which she was sitting, and rose with her determination taken, and spoke it out—

“I will go and see Aunt Filomena.”

Aunt Filomena lived about a mile from Lincoln, on the Newport road. Her husband was a greensmith: that is to say, he worked in copper, and hawked his goods in the town when made. Avice lost no time in going, but set out at once.

As she rounded the last turn in the lane, she heard the ring of Daniel Greensmith’s hammer on the anvil, and a few minutes’ more walking brought her in sight of the smith himself, who laid down his hammer and shaded his eyes to see who was coming.

“Why, Uncle Dan, don’t you know me?” said Avice.

“Nay, who is to know thee, when thou comes so seldom?” said old Dan, wiping his hot face with his apron. “Art thou come to see me or my dame?”

“I want to see Aunt Filomena. Is she in, Uncle Dan?”

“She’s in, unless she’s out,” said Dan unanswerably. “And her tongue’s in, too. It’s at home, that is. Was this morning, anyhow. What dost thou want of her?”

“Well,” said Avice, hesitating, “I want her advice—”

“Then thou wants what thou’lt get plenty of,” said Dan, with a comical twist of his mouth, as he turned over some long nails to find a suitable one. “I’ll be fain if thou’lt cart away a middling lot, for there’s more coming my way than I’ve occasion for at this present.”

Avice laughed. “I daresay Aunt is overworked a bit,” she said. “Perhaps I can help her, Uncle Dan. Folks are apt to lose their tempers when they are tired.”

“Some folks are apt to lose ’em whether they are tired or not,” said the smith, with a shake of his grizzled head. “I’ve got six lasses, and four on ’em takes after her. I could manage one, and maybe I might tackle two; but when five on ’em gets a-top of a chap, why, he’s down afore he knows it. I’m a peaceable man enough if they’d take me peaceable. But them five rattling tongues, that gallops faster than Sir Otho’s charger up to the Manor—eh, I tell thee what, Avice, they do wear a man out!”

“Poor Uncle Dan! I should think they do. But are all the girls at home? I thought Mildred and Emma were to be bound apprentices in Lincoln.”

“Fell through wi’ Mildred,” said the smith. “Didn’t offer good enough; and She”—by which pronoun he usually designated his vixenish wife—“wouldn’t hear on it. Emma’s bound, worse luck! I could ha’ done wi’ Emma. She and Bertha’s the only ones as can be peaceable, like me.”

“Mildred’s still at home, then?”

“Mildred’s at home yet. And so’s El’nor, and so’s Susanna, and so’s Ankaret; and every one on ’em’s tongue’s worse nor t’other. And”—a very heavy sigh—“so’s She!”

Avice knew that Uncle Dan was usually a man of fewer words than this. For him to be thus loquacious showed very strong emotion or irritation of some sort. She went round to the back door, and before she reached it, she heard enough to let her guess the sort of welcome she might expect to receive.

Just inside the open door stood Aunt Filomena, a thin, red-faced, voluble woman, with her arms akimbo, pouring out words as fast as they could come; and in the yard, just outside the door, opposite to her, stood her daughter Ankaret, in exactly the same attitude, also thin, red-faced, and voluble. The two were such precise counterparts of one another that Avice had hard work to keep her gravity. Inside the house, Susanna and Mildred, and outside Eleanor, were acting as interested spectators; the funniest part of the scene being that neither of them listened to a word said by the other, but each ran at express speed on her own rails. The youngest daughter, Bertha, was nowhere to be seen.

For a minute the whole appearance of things struck Avice as so excessively comical that she could scarcely help laughing. But then she realised how shocking it really was. What sort of mothers, in their turn, could such daughters be expected to make? She waited for a moment’s pause, and when it occurred, which was not for some minutes, she said—

“Aunt Filomena!”

“Oh, you’re there, are you?” demanded the amiable Filomena. “You just thank the stars you’ve got no children! If ever an honest woman were plagued with six good-for-nothing, sluttish, slatternly shrews of girls as me! Here’s that Ankaret—I’ve told her ten times o’er to wash the tubs out, and get ’em ready for the pickling, and I come to see if they are done, and they’ve never been touched, and my lady sitting upstairs a-making her gown fine for Sunday! I declare, I’ll—”

Her intentions were drowned in an equally shrill scream from Miss Ankaret. “You never told me a word—not once! And ’tain’t my place to scour them tubs out, neither. It’s Susanna as always—”

“Then I won’t!” broke in Susanna. “And you might be ashamed of yourself, I should think, to put such messy work on me when Eleanor—”

“You’d best let me alone!” fiercely chimed in Eleanor.

“Oh dear, dear!” cried Avice, putting her hands over her ears. “My dear cousins, are you going to drive each other deaf? Why, I would rather scour out twenty tubs than fight over them like this! Are you not Christian women? Come, now, who is going to scour the tubs? I will take one myself if you will do the others. Who will join me?”

And Avice began to turn up her sleeves in good earnest. “No, Avice, don’t you; you’ll spoil your gown,” said Eleanor, looking ashamed of her vehemence. “See, I’ll get them done. Mildred, won’t you help?”

“Well, I don’t mind if I do,” was the rather lazy answer.

But Ankaret and Susanna declined to touch the work, the latter cynically offering to lend her apron to Avice.

As Avice scrubbed away, she began to regret her errand. To be afflicted with such a lifelong companion as one of these lively young ladies would be far worse than solitude. But where was the youngest?—the quiet little Bertha, who took after her peaceable father, and whom Avice had rarely heard to speak? She asked Eleanor for her youngest sister.

“Oh, she’s somewhere,” said Eleanor carelessly.

“She took her work down to the brook,” added Mildred. “She’s been crying her eyes out over Emma’s going.”

“Ay, Emma and Bertha are the white chicks among the black,” said Eleanor, laughing; “they’ll miss each other finely, I’ve no doubt.”

Avice finished her work, returned Susanna’s apron, and instead of requesting advice from her Aunt, went down to the brook in search of Bertha. She found her sitting on a green bank, with very red eyes.

“Well, my dear heart?” said Avice kindly to Bertha.

The kind tone brought poor Bertha’s tears back. She could only sob out—“Emma’s gone!”

“And thou art all alone, my child,” said Avice, stroking her hair. She knew that loneliness in a crowd is the worst loneliness of all. “Well, so am I; and mine errand this very day was to see if I could prevail on thy mother to grant me one of her young maids to dwell with me. What sayest thou? shall I ask her for thee?”

“O Cousin! I would be so—” Bertha’s ecstatic tone went no farther. It was in quite a different voice that she said—“But then there’s Father! Oh no, Cousin. Thank you so much, but it won’t do.”

“That will we ask Father,” said Avice.

“Father couldn’t get on, with me and Emma both away,” said Bertha, in a tone which she tried to make cheerful. “He’d be quite lost—I know he would.”

“Well, but—” began Avice.

“Then he’d find his self again as fast as he could,” said a gruff voice, and they looked up in surprise to see old Dan standing behind them. “Thou’s done well, lass. Thou’s ta’en advice o’ thy own kind heart, and not o’ other folks. Thee take the little maid to thee, and I’ll see thee safe out on’t. She’ll be better off a deal wi’ thee, and she can see our Emma every day then. So dry thy eyes, little un; it’ll be all right, thou sees.”

“But, Father, you’ll not do without me!”

“Don’t thee be conceited, lass.” Old Dan was trying hard to swallow a lump in his throat. “I’ll see thee by nows and thens. Thou’ll be a deal better off. And there’s—there’s El’nor.”

“Eleanor’s not always in a good temper,” said Bertha doubtfully.

“She’s best o’ t’other lot,” said old Dan. “She’s none so bad, by nows and thens. I shall do rarely, thou’ll see. But, Avice—dost thou think thou could just creep off like at th’ lee-side o’ th’ house, wi’ the little maid, afore She sees thee? When thou’rt gone I’ll tell her, and then I’ll have a run for’t till it’s o’er. She’s better to take when first comings-off is done. She’ll smooth down i’ th’ even, as like as not, and then I’ll send El’nor o’er wi’ the little maid’s bits o’ gear. Or, if she willn’t go, I can bring ’em myself, when work’s done. Let’s get it o’er afore She finds aught out!”

Avice scarcely knew whether to laugh or to be sorry. Poor, weak, easy-tempered Dan! They took his advice, and crept round by the lee-side of the house, under cover of the hedge. When they were out of sight, with a belt of trees between, old Dan took leave of them.

“Thou’ll be good to the little maid, Avice,” said he. “I know thou will, or I’d never ha’ let her go. But she’ll be better off—ay, a deal better off, she’ll be. She gets put upon, she does. And being youngest, thou sees—I say, my lass, thou’d best call her aunt. She’s so much elder than thee; it’ll sound better nor cousin.”

“Very good, Father,” said Bertha. “But, O Father! who’ll stitch your buttons on, and comb your hair when you rest after work, and sing to you? O Father, let me go back!”

“Tut, tut, lass!” said old Dan, clearing his throat energetically. “If one wife and four daughters cannot keep a man’s buttons on, there’s somewhat wanting somewhere. I shall miss thy singing, I dare say; but I can come down, thou knows, of a holy-day even, to hear thee. And as to combin’—stars knows I shall get enough o’ that, and a bit o’er that I can spare for old Christopher next door. He’s got no wife, and only one lass, and she’s a peaceable un. He’s a deal to be thankful for. Now, God be wi’ ye both. Keep a good heart, and step out. I’ll let ye get a bit on afore I tell Her. And then I’ll run for’t!”

Avice and Bertha “stepped out” accordingly; and as nobody came after them, they concluded that things were tolerably smooth. They did not see anybody from the smithy until two days later; and then, rather late in the evening—namely, about six o’clock—Dan himself made his appearance, with one bundle slung on a stick over his shoulder, and another carried like a baby.

“Well!” said he, as he sat down on the settle, and wiped his hot face with his apron. “Well!”

“O Father, I’m so glad!” said Bertha. “Are those my things? How good of you to bring them!”

“Ay, they be,” said Dan emphatically. “Take ’em and make the best thou can of ’em; for thou’ll get no more where they came from, I can tell thee.”

“Was Aunt Filomena very much put out?” asked Avice, in a rather penitent tone.

“She wasn’t put out o’ nothing,” answered Dan, “except conduct becoming a Christian woman. She was turned into a wild dragon, all o’er claws and teeth, and there was three little dragons behind her, and they was all a-top o’ me together. If El’nor hadn’t thought better on’t, and come and stood by me, there wouldn’t have been much o’ me to bring these here.”

“Then you did not run, Uncle Dan?” replied Avice.

“She clutched me, lass!” responded Dan, with awful solemnity. “And t’others, they had me too. Thee try to run with a wild dragon holding on to thy hair, and three more to thy arms and legs—just do! I wonder I’m not tore to bits—I do. Howsome’er, here I be; and I just wish I could stop. Ay, I do so!”

And Dan’s apron took another journey round his face.

“Uncle Dan, would you like to take Bertha back?” was Avice’s self-sacrificing suggestion.

“Don’t name it!” cried Dan, dropping the apron. “Don’t name it! There wouldn’t be an inch on her left by morning light! I wonder there’s any o’ me. Eh, but this world is a queer un. Is she a good lass, Avice?”

“Yes, indeed she is,” said Avice.

“I’m fain to hear it; and I’m fain thou’s fallen on thy feet, my little un. And, Avice—if thou knows of any young man as wants to go soldiering, and loves a fray, just thee send him o’er to th’ smithy, and he shall ha’ the pick o’ th’ dragons. I hope he’ll choose Ankaret. He’ll get my blessing!”

Aunt Filomena seemed to have washed her hands of her youngest daughter. She never came near them; and Avice thought it the better part of valour to keep away from the smithy. When Emma had a holiday, which was a rare treat, she often spent it with her sister; and on still rarer occasions Eleanor paid a short visit. But the only frequent visitor was old Uncle Dan, and he came whenever he could, and always seemed sorry to go home.

Chapter Four.

Baby.

A very quiet life was led by Avice and Bertha. The house work was done by the two in the early morning—cleaning, washing, baking, churning, and brewing, as they were severally needed; and in the afternoon they sat down to their work, enlivened either by singing or conversation. Sometimes both were silent, and when that was the case, unknown to Avice, Bertha was generally watching her features, and trying to read their meaning. At length, one evening after a long silence, she suddenly broke the stillness with a blunt question.

“Aunt, I wish you would tell me what you are thinking of when you look so.”

“How do I look, Bertha?”

“As if you were looking at something which nobody could see but yourself. Sometimes it seems to be something pretty, and sometimes something shocking; but oftener than either, something just a little sad, and yet as if there were pleasantness about it. I don’t know exactly how to describe it.”

“That will do. When a woman comes to fifty years, little Bertha, there are plenty of things in the past of her life, which nobody can see who did not go through them with her. And often those who did so cannot see them. That will leave a scar upon one which makes not a scratch upon another.”

“But of what were you thinking, Aunt, if I may know?”

“That thou mayest. I fancy, when thou spakest, I was thinking—as I very often do—about my little Lady.”

“Now, if Aunt Avice is very good,” said Bertha insinuatingly, and with brightened eyes, “that means a story.”

Aunt Avice smiled. “Ay, thou shalt have thy story. Only let us be sure first that all is done which need be. Cast a few more chips on the fire, and light another pine-torch; that is burnt nigh out. And see thy bodkin on the floor—careless child!”

Bertha jumped up and obeyed. From one corner of the room, where lay a heap of neatly-cut faggots, she brought a handful, and threw it into the wide fire-place, which stretched across half one side of the room, and had no grate, the fire burning on the stone hearth: then from a pile of long pointed stakes of pitch pine, she brought one, lighted it, and set it in an iron frame by the fire-place made for that purpose; and lastly, she picked up from the brick floor an article of iron, about a foot in length, and nearly as thick as her little finger, which she called a bodkin, but which we should think very rude and clumsy indeed.

“Hast thou heard, Bertha,” said Avice, “that when I was young, I dwelt for a season in the Castle of Windsor, and my mother was nurse to some of the children of the Lord King that then was? Brothers and sister they were of our Lord King Edward that reigns now.”

Bertha’s eyes brightened. She liked, as all girls do, to hear a story which had to do with great people.

“No, Aunt Avice, I never knew that. Won’t you tell me all about it?”

So Avice began and told her what we know already—how the Bishop had recommended Agnes to the Queen, and all about the journey, and the Castle, and the Queen herself. Then she went on to tell the rest of the story.

“We lived nigh five years,” said Avice, “in the Castle of Windsor—until the Lord Richard was dead, and the Lord William was nearly four years old. Then the Lady Queen removed to the royal Palace of Westminster, for the Lord King was gone over seas, and she with Earl Richard his brother was left to keep England. It was in August, the year of our Lord 1253, at we took up our abode in Thorney Island, where the Palace of Westminster stands. It is a marshy place—not over healthy, some folks say; but I never was ill while we dwelt there. And it was there, on Saint Katherine’s Day”—which is the 25th of November—“that our little Lady was born. Her royal mother named her Katherine, after the blessed saint. She was the loveliest babe that eye could rest on, and she was christened with great pomp. And on Saint Edward’s Day, when the Lady Queen was purified”—namely, churched—“there was such a feast as I never saw again while I dwelt with her. The provisions brought in for that feast were fourteen wild boars, twenty-four swans, one hundred and thirty-five rabbits, two hundred and fifty partridges, sixteen hundred and fifty fowls, fifty hares, two hundred and fifty wild ducks, thirty-six geese, and sixty-one thousand eggs.”

“Only think!” cried Bertha. “Did you get some, Aunt?”

“Surely I did, child. The Lady Queen, I told thee, was then keeper of England, for the Lord King was away across the seas; and good provision she made. Truly, she was free-handed enough at spending. Would she had been as just in the way she came by her money!”

“Why, Aunt, what mean you?” asked Bertha, when Avice expressed her wish that Queen Eleanor had been as just in gaining money as she was liberal in spending it.

“Why, child, taxes came heavy in those days. When the Lord King needed money, he sent home to his treasurer, and it was had as he could get it—sometimes by selling up divers rich folks, or by levying a good sum from the Jews, or any way man could; not always by equal tenths or fifteenths, as now, which comes not nigh so heavy on one or two when it is equally meted out to all. But never was there king like our late Lord King Henry (whom God pardon) for squeezing money out of his poor subjects. Yet old folks did use to say his father King John was as ill or worse.”

Taxes, in those days, were a very different thing from what they are now, and were far more at the mere pleasure of the King, not only as to the collecting of them, but as to the spending. Ignorant people fancy that this is the case still; but it is not so. Queen Victoria has no money from the taxes for her private spending. When she became Queen, she gave up all the land belonging to her as Queen, on condition that her daughters should be portioned, and that she should receive a certain sum of money every year, of less value than the land she gave up; so that it would be fraud and breach of trust in the people if they did not keep their word to pay the sum agreed on to the Queen. There is so much misunderstanding on this point that it is worth while to mention it.

“Then were the King and Queen—” Bertha began.

Avice answered the half-asked question. “They were like other folks, child. They liked their own way, and tried to get it. And they liked fine clothes, and great feasts, and plenty of company, and so forth; so they spent their money that way. I’ll not say they were bad folks, though they did some bad things they were folks that only thought what they liked, and did it; and folks that do that are sure to bring sorrow to themselves and others too, whether they be kings and queens or cooks and haymakers. The kings and queens can do it on a larger scale; that is all the difference. There are few enough that think what God likes, as holy Bishop Robert did, and like to do His will better than their own; those that do scatter happiness around them, as the other sort scatter misery.

“Well, after a while, the Lady Queen left England, to join the Lord King across seas; but before she went, she took our little Lady down to the Castle of Windsor to the rest of the King’s children. There was first the Lady Beatrice, who was a maiden of twelve years; and the Lord Edmund, a very pretty little boy of nine; and the Lord William, who was but four; and there were also with them other children of different ages that were brought up with them; but only one was near our little Lady’s age, or had much to do with her. That was Alianora de Montfort, daughter of Earl Simon of Leicester, that bold baron that headed the lords against the King; and her mother was the King’s own sister, the Lady Alianora. She was fifteen months older than our little Lady, and being youngest of all, the two used to play together. A sweet child she was, too; but not like my own little Lady—there never was a child like her.”

“What was she like, Aunt?”

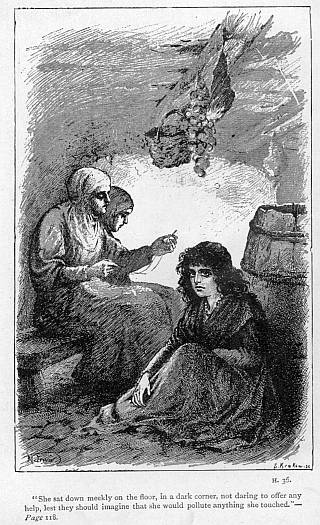

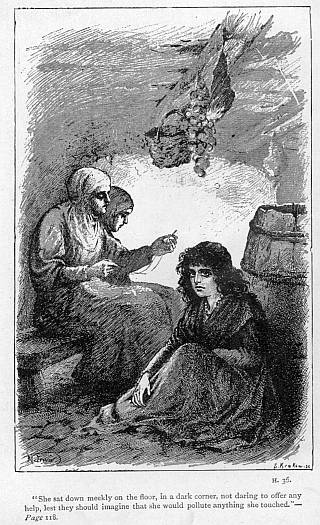

“Tell me what the angels are like in Heaven, and thou shalt hear then. She is an angel now—she hath been one these three-and-twenty years. But methinks there can have been little to change in her face when she blossomed into a cherub, and the wings would unfold themselves from her as by nature. Never a child like her!—no, there never was one. She had bright, dark eyes, wonderful eyes—eyes that her whole soul shone in, and that took in everything which passed. She spoke with her eyes; she had no other way. The souls of other children came out of their lips; but she had not spent many months in this lower world, before we saw with bitter apprehension and deep sorrow that God had sealed her sweet lips with eternal silence. She saw all; she heard nothing; she could never speak. My darling was deaf and dumb.”

“O Aunt Avice!”

“Ay, verily at times I wondered if she were indeed an angel that God had sent down to earth, for whose pure lips our English was too rough, and our French too rude, and who could only speak the tongue they speak in Heaven. She went back but whence she came; we were not fit company for her. Methinks she was sent to let our earthbound hearts have one glimpse of that upper world; and when her work was done, her Father sent for her back home.

“Though our little Lady could never speak, yet long before we discovered that, we found how lively, and earnest, and intelligent she was. As I told thee, she talked with her eyes. Nothing could be done in her presence but she must see and know all about it. A little pull at my gown would tell me she was there; and then I turned to see the bright eager eyes looking into mine, and asking me as plainly as eyes could ask to let her know all about it. She would never rest till she knew what she wanted. Ay me, those eager eyes look into angels’ faces now, and maybe into the face of God upon the throne.”

“But, Aunt, how could she understand, if she could not hear?”

“God told her somehow, child. He taught her, not we. We did our best, truly; but our best would have been a poor business, if He had not taken her in hand. Many a time, before I had finished trying to explain something to her, that quick little nod would come which meant, ‘I understand.’ Then she had certain signs for different things. She made those herself; we never taught them to her. She stroked what she liked, as man would stroke a dog; when she disliked anything, she made a feint of throwing her open hand out from her, as though she were pushing it away. She had odd little ways of indicating different persons, by something in them which struck her. Master Russell, the Queen’s clerk, and keeper of the royal children, used often to have a sprig of mint or thyme in his lips as he went about; her sign for him was a bit of stick or thread between her lips. For the priest, she tolled a bell. For the Lady Beatrice, her sister, who had a little airy way of putting her head on one side when anything vexed her, and my Lord Henry de Lacy, who pouted if he were cross (which he was pretty often)—my little Lady imitated them exactly. The Lady Alianora flourished her hands when she spoke; that was the sign for her. For the Lord King, her father, whose left eyelid drooped over his eye, she pulled her own down. She had some such sign for everybody. She noticed everything.”

“Could she not say one word, Aunt?”

“Yes, she could say three. Verily, sometimes I marvelled if she might not have been taught more; but we knew not how, and how she got hold of those three we could never tell.”

“What were they?”

“They were, ‘up,’ ‘who,’ and ‘poor.’”

“Well, she could not do much with those.”

“Could she not! ‘Who’ asked all her questions. It answered for who, what, where, when, how, and why. She went on saying it until we understood and replied to the sense in which she meant it. ‘Poor’ was the word of emotion; it signified ‘I pity you,’ ‘I love you,’ ‘I am sorry,’ and ‘Forgive me.’ And sometimes it meant, ‘Forgive him,’ or ‘Don’t you feel sorry for her?’ And I think ‘up’ served for everything else.”

“Aunt,” said Bertha softly, “how did you teach the little Lady to pray? She could tell her beads, I suppose; but would she know what they meant?”

For Bertha, like everybody else at that time, thought it necessary to keep count of her prayers. Prayer, in her eyes, was not so much communion with God, as it was a kind of charm which in some unaccountable way brought you good luck.

“Beads would have meant nothing to her but toys,” was Avice’s reply. “The Lady de la Mothe taught her the holy sign”—by which Avice meant the cross—“and led her to the image of blessed Mary, that she might do it before her. But I do not think she ever properly understood that She seemed only to have an idea that it was something she must do when she saw an image; and she did it to the statue of the Lady Queen in the great hall. We could not make her understand that one image was not the same thing as another image. But I fancy she had some idea—strange and dim it might be—of what we meant when we knelt and put our hands together and looked up. I know she did it very often, without telling—always at night, before she slept. But it was strange that she never went to the holy images at that time; she always seemed to go away from them, and kneel down in a corner. And in her last illness, several times, coming into the chamber, I found her lying with her hands folded in prayer, and her eyes lifted up to Heaven. Perhaps God Himself told her how to speak to Him. One of the strangest things of all was when the little Lord William died; she was nearly three years old then. She had been very fond of her little brother; he was nearest her age of all her brothers and sisters, though he was almost four years older than herself. She came to me sobbing bitterly, and with her little cry of ‘Who? who?’ I took it to mean ‘What has happened to him?’ and I was completely puzzled how to explain it to her. But all at once, while I was beating my brains to think what I could say that would make her comprehend it, she told me herself what I could not tell her. Making the sign for the little Lord who was dead, she laid her head  upon her hand, and closed her eyes; and then all at once, with a peculiar grace that I never saw in any child but herself, she lifted her arms, fluttering her fingers like a bird flaps its wings, and gazing up into the sky, while she said, ‘Up! up!’ in a kind of rapture. And I could only smile and bow my head to the truth which God had told her.” (See Note 1.)

upon her hand, and closed her eyes; and then all at once, with a peculiar grace that I never saw in any child but herself, she lifted her arms, fluttering her fingers like a bird flaps its wings, and gazing up into the sky, while she said, ‘Up! up!’ in a kind of rapture. And I could only smile and bow my head to the truth which God had told her.” (See Note 1.)

“But how could she know it?” asked astonished Bertha.

Avice shook her head. “I cannot explain it; I can only tell what happened. She was always very tender-hearted; she never could bear to see any quarrelling, or cruelty, or injustice. If two of the children strove together, our little Lady would run to them with a face of deep distress, and take a hand of each and draw them together, as though she were begging them to be friends; and if she could not get them to kiss each other, she would kiss first one and then the other. I missed her one day, and, after hunting a long while, I found her in the gallery before a fresco of our Lord upon the Cross. She was stroking it and kissing it, with tears in her eyes; and she turned to me saying, ‘Poor! poor!’ Her eyes always filled with tears when she saw the crucifix. The moon used to interest her exceedingly; she would sit and watch it, and kiss her hand to it. But, dear me! how the time must be getting on! Jump up, Bertha, and prepare supper.”

Bertha folded up her work and put it aside. She drew one of the high stools between her aunt and herself, and put out upon it the two wooden trenchers and two tin mugs. Going to a corner cupboard, Bertha brought out a few cakes of black bread, which she set on a smaller stool beside the other; and then, lifting a pan upon the fire, she threw into it some pieces of mutton fat. As soon as these were melted, Bertha broke four eggs into them, stirring this indigestible mixture with a wooden thible—an article of which my northern readers will not require a description, but the southern must be told that it is a long flat instrument with which porridge is stirred. For the eggs were not merely fried in the fat, but were beaten up with it, the dish when finished bearing the name of franche-mule. A sprig or two of dried herbs were then shred into the pan, and the whole poured out, half on each of the trenchers. It is more than possible that the extraordinarily rich, incongruous, indigestible dishes wherein our fathers delighted, may have something to do with the weaker digestions of their children. The tin mugs were filled with weak ale from a barrel which stood under the ladder. It was an oddity at that time to drink water.

When supper was finished, Bertha washed the mugs and scraped the trenchers clean (water never touched those), putting them back in their places. She had scarcely ended when a tap was heard at the door.

“Step in, Hildith,” said Bertha, as she opened it. “Christ give thee a good even!”

“The like to thee,” was the answer, as a rather worn-looking woman came in. “Mistress Avice, your servant. Pray you, would you lend me the loan of a tinder-box? I am but now come home from work, and am that weary I may scarce move; and yon careless Jaket hath let the fire out, and I must needs kindle the same again ere I may dress supper for the children.”

It was no wonder if Hildith looked worn out, or if she could not afford a tinder-box. That precious article cost a penny, and her wages were fifteen pence a year. If we do a sum to find out what that would be now, when money is much more plentiful, we shall find that Hildith’s wages come to twenty-two shillings and sixpence, and the tinder-box was worth eighteen-pence. We should fancy that nobody could live on such a sum. But we must remember two things: first, they then did a great deal for themselves which we pay for; they spun and wove their own linen and woollen, did their own washing, brewed their own ale and cider, made their own butter and cheese, and physicked themselves with herbs. Secondly, prices were very much lower as respected the necessaries of life; bread was four loaves, or cakes, for a penny, of the very best quality; a lamb or a goose cost fourpence, eight chickens were sold for fivepence, and twenty-four eggs for a penny. Clothing stuffs were dear, but then (as people sometimes say) they wore “for everlasting,” and ladies of rank would send half-worn gowns to one another as very handsome presents. Fourpence was a good price to give for a pair of shoes, and a halfpenny a day for food was a liberal allowance.

“Any news to-night, Hildith?” asked Avice, as she handed her neighbour the tinder-box.

“Well, nay; without you call it news that sheriffs man brought word this morrow that the Lord King had granted the half of her goods to old Barnaba o’ the Lichgate.”

“She that was a Jew, and was baptised at Whitsuntide? I am glad to hear that.”

“Ay, she. I am not o’er sorry; she is a good neighbour, Jew though she be.”

“Then I reckon she will tarry here, and not go to dwell in the House of Converts in London town?”

“Marry, she will so, if she have any wisdom teeth left. I would not like to be carried away from all I know, up to yon big town, though they do say the houses be made o’ gold and silver.”

Avice smiled, for she knew better.

“Nay, Hildith, London town is built of brick and stone like Lincoln.”

“Is it, now? I always heard it was made o’ gold. But aren’t there a vast sight o’ folk there? nigh upon ten thousand?”

“Ay, and more.”

“However do they get victuals for them all?”

“I got mine when I lived there,” said Avice, laughing.

“And don’t they burn sea-coal?”

“They did once; it is forbidden now.”

“Dirty, poisonous stuff! I wouldn’t touch it. Well, good-even. Shut the door quick, Bertha, and don’t watch me out o’ sight; ’tis the unluckiest thing man can do.”

And Bertha believed it, as she showed by shutting the door.

Old Barnaba, the Jewess, had been dealt with tenderly. In those days, if a Jew were baptised, he forfeited all he had to the King. Most unaccountable it is that any Christian country should have let such a law exist for an hour! These destitute Jews, however, were provided for in the House of Converts, in London, which stood at the bottom of Chancery Lane, between it and Saint Dunstan’s Church.

It was bed-time soon after. Avice put away her distaff, Bertha folded up her sewing, and they mounted the ladder. This was about seven o’clock, which was then as late an hour as it was thought that respectable people ought to be about. But by two o’clock the next morning, Bertha was sweeping the kitchen, and Avice carding flax in the corner. They did not trouble themselves about breakfast; it was an unknown luxury, except for people who were very old or very delicate. Two meals a day were the rule: dinner, at nine in the morning: supper, at three in the afternoon. In those days they lived in a far harder and less comfortable way than we do, and they had generally better health. But, it must be admitted, they did not live nearly so long, and the infant mortality among them was very great.

Morning was no time for story-telling. The rooms had to be swept, the bread to be baked, the clothes to be washed, the pigs and chickens to be fed. Moreover, to-day was the first day of the Michaelmas fair, and things must be bought in to last till Christmas. The active work was finished by about seven o’clock. Dinner was now got ready. It consisted of two bowls of broth, then boiled dumplings, and lastly some stewed giblets. Having made things tidy, our friends now tied on woollen hoods, and each taking down from the rafter-hooks a capacious basket, they went forth to do their shopping.

Note 1. The peculiar ways attributed to the little Princess, and especially this incident, are taken from an account of a real deaf and dumb child, published many years ago. There was certainly something about the Princess which her attendants considered wonderful and beautiful.

Chapter Five.

The Dumb Playmates.

Out into the Michaelmas fair our friends went.

In these days, when fairs have quite changed their character, we cannot easily form a notion of what they once were. The fair, held in every town four times a year, was a very important matter. There were much fewer shops than now; and not only in the town, but from all the surrounding villages people flocked to the fair, to lay in food and clothes and all sorts of necessaries, enough to last till the next fair-day. They had very little fresh butcher’s meat, and very few vegetables except what they grew themselves; so they ate numbers of things salted which we have fresh. Not only salt fish and salt neat, but salt cabbage formed a great part of their diet. The consequence of all this salt food was that they suffered dreadfully from scurvy. But they did not run to the doctor, for except in rare instances there was no doctor to run to! All doctors were clergymen then, and there were very few of them. In the large towns there were apothecaries, or chemists, who often prescribed for people; and there were “wise women” who knew a good deal about herbs, and sometimes gave good medicines, along with a great deal of foolish nonsense in the way of charms and all sorts of silly fancies. At that time, ladies were taught a good deal about medicine, and a benevolent lady was often the doctor for a large neighbourhood. But we are wandering away from the Michaelmas fair, and we must come back.

The fair was a very busy scene. In some places it was hard work to get along at all. The booths were set up, not in the streets but in the churchyards, the market place, and on any waste space available. And what with the noise of business, the hum of gossip, the shouts of competing sellers, and the sound of hundreds of clogs on the round paving-stones, it may be readily supposed that quiet was far away.