Title: Lines in Pleasant Places: Being the Aftermath of an Old Angler

Author: William Senior

Release date: November 5, 2007 [eBook #23343]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Al Haines

E-text prepared by Al Haines

The half a dozen or so of Angling books which stand to my name were headed by Waterside Sketches, and this is really and truly a continuation, if not the end, of the series. They were inspired by my old friend Richard Gowing, at the Whitefriars Club, of which he was for many years the well-remembered honorary secretary, and of which I still have the grateful pride of being entitled to the name of father.

Gowing had become editor of the Gentleman's Magazine in 1874, and in his sturdy efforts to give it new life he looked round amongst the youngsters who seemed likely to serve him. The result was that he invited me to try my hand at something. He had read my Notable Shipwrecks, which the house of Cassells was at that time bringing out, and said that its author, known to the public as "Uncle Hardy" only, ought to be able to offer a suggestion.

The Stoke Newington reservoirs had about that time given me some good sport with pike, large perch, chub, and tench, and I had long been an angling enthusiast. Out of the fullness of my heart I spoke. I told him that fishing was my best subject; that if he would accept a series of contributions the direct object of which was to make Angling articles as interesting to non-anglers as to anglers themselves, I would be his man.

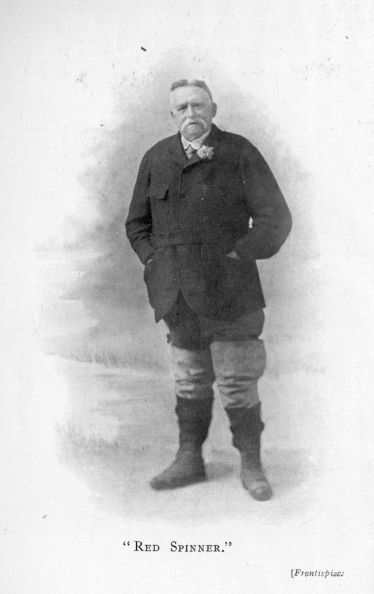

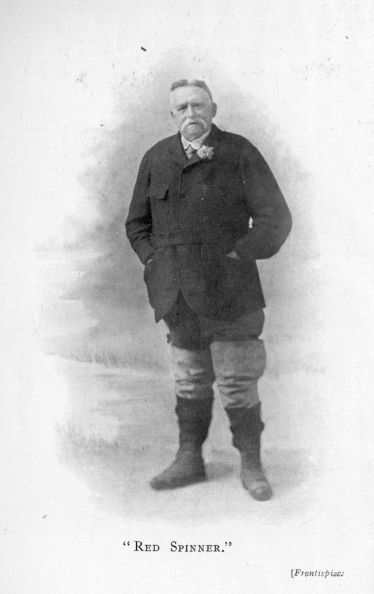

Verily I would not wonder if, in showing how botany, agriculture, out-of-door life generally might be woven into the warp and woof of the fabric, I became eloquent; for, as I have said, out of the heart the mouth spoke. So it was agreed, and for a while "Red Spinner's" articles graced the pages of the magazine, and they were by and by republished in Waterside Sketches. They afterwards gave me entrance to Bell's Life and to the Field, and a name at any rate amongst the brethren of the Angle, as to which I must not gush, but which is very dear to the musings of an old man's eventide. How much I owe to "Red Spinner" I shall never know. The name has followed me, and my brothers of the Highbury Anglers have adopted it, but last year, in honour of their always loyal, but I feel sure no longer useful President. I was much amused to find how it had also followed me to Queensland. During one of the Parliamentary recesses I went up country, the guest of a squatter who was afterwards in the Ministry, and he introduced me to a fellow squatter member in my surname as an officer of Parliament. Neither the name nor office meant anything to him. But when we were smoking in the veranda, and my friend mentioned, as an aside, that I was "Red Spinner," the visitor leaped to his feet, came at me with a double grip, and shouted a Scotch salmon-fisher's welcome, turning to my host and furiously demanding, "Why the dickens didn't you tell me so at first?"

On another Bush visit an officer in the Mounted Police showed me amongst his curiosities a copy of Waterside Sketches half devoured by dingoes, and found with the scraps scattered around the skeleton of a poor wayfarer left at the foot of a gum-tree. To fly-fishers the name had an intelligible story of course, and it puzzled those non-anglers for whom I tried always to write. The scores of times I was asked "What does 'Red Spinner' mean?" by ladies as well as gentlemen, told me how well I had kept the promise to the good Richard Gowing when those articles were arranged.

Journalism proper, now and henceforth for the rest of my life claimed me. It became my profession in fact; but it was always fishing that kept the longing eye turned towards the waterside. Somehow for a time the water was all round me, but I had not the means of learning the art at that time, nor of practising it. Somehow I was always being reminded that the fishing rod was to obtain the mastery by and by, but I had to wait a long while for the opportunity. At first I was in what may be called a good fishing country, but I seemed to have no say in it. I had no rod; no fisheries were open. Indeed, it was journalism that gripped me, and in those early days I followed the mastership of it very closely, for there was so much to learn, as I shall be able, I hope, to explain when any reminiscences that I am able to write call for it. That longing must meanwhile be kept open for some years to come.

Now, however, came the time when, as I have always considered, my real life began. It was my fate to be appointed representative of the Lymington Chronicle in 1858, when I was duly installed in its office in that town, engaged to look after the local news, the advertisements, the circulation; and especially it was my business to see that not a single paragraph was ever missing from the budget which I duly sent to the head office in Poole at the end of every week. But still there was no fishing, save in the river, where bass came occasionally to my hook in the tidal portions; and one of six pounds I remember as the best that came to me on the hand line. There was some talk once of a visit that I was to pay to a trout river at Brockenhurst; but practically nothing came of it, nor did a casual chance which Lord Palmerston gave me at Broadlands, which was too far from my beat and altogether above me in its salmon runs. As for perch, which I had fished for as a boy, there were none to be heard of in the district.

In due time I was transferred from Lymington to Southampton, where I remember catching smelts, and nice little baskets of them, from the pier at the bottom of High Street. Next I went to Manchester, where there was less of such fishing as I required than before; and on a daily paper like the Guardian, journalism soon proved to be real business to engage my attention, and left me without the slight opportunities I found even with the Lymington Chronicle or Hants Independent. In due time fortune, as I thought, beamed upon me when I got an appointment on the London Daily News, which was then in its prime. Here I began to find what fishing meant, for very early, thanks to the kindness of Moy Thomas and his friend Miles, the publisher, who was one of the directors, I got a ticket for the famous New River reservoirs. I was here introduced to many members of the fishing club—men of the place—and became a member of the Stanley Anglers, where I won some prizes, and of the somewhat famous and somewhat high-class True Waltonian Society, which met at Stoke Newington. The general result of this was that wherever there was fishing to be secured I got it, and was seldom without opportunity of turning that longing eye of which I aforetime spoke to the waterside. I made pretty rapid progress too, for I became a well-known pike fisher at Stoke Newington, got large chub and much perch, and generally took various degrees in the piscatorial art.

Best of all, by means of my membership of the True Waltonians, I had the run of the Rickmansworth water. It was here that I learnt fly-fishing, even to the extent of catching my first trout, and here that I went through a course of practice at some large dace which then existed in the Colne; and they very freely, to the extent of half a pound or so weight, took the dry fly, which in later years they did not. As a very active travelling member of the special correspondence staff of the Daily News I went here and there on various errands, and was soon known never to travel without my rod and creel. Then the introduction to my old friend Gowing of the Gentleman's Magazine, as I have already described, made me as eager to write as I was to fish; and, in a word, this was how "Red Spinner" was manufactured.

Now I have explained how I became a practical angling writer, and the half-dozen or so of books which I inflicted upon my brethren of the Angle gradually came into existence. It is necessary to mention this to account for the fact that the majority of what I write has appeared before the public from year to year. Indeed, I did not allow the grass to grow under my feet. My voyage to Queensland gave me a book, and a series of the Gentleman's Magazine chapters gave me another; and so it went on from time to time, as I had the opportunity, in magazines and papers, finding what I may call even a ready market for all I chose to publish. The reader will understand, therefore, that after these half-dozen books, if any of them are to be found registered against me, there was not a great deal left for gathering together; and that is the excuse for this volume which I have ventured to call the Aftermath of Red Spinner. Indeed, just before the war broke out I had agreed to supply a book to my old friend Mr. Shaylor, to be published by Simpkin, Marshall & Co. It was to contain just what had been left over by Bell's Life, the Field, and various magazines, and this I have described as the "Aftermath." I therefore publish it, and I do so, if I may be permitted, just as an old man's indulgence. Will the reader be so good as to let it stand at that, and will my old friends accept a humble plea for that indulgence? I make it very sincerely, and with a grateful heart for long years of brotherhood and kindly comradeship.

There are obligations which must, however, be clearly and promptly acknowledged with thanks most cordial: to the proprietors of the Field, (now the Field Press, Limited), to Baily's Magazine, the Windsor Magazine, and many others who kindly gave permission to select what was required for my purpose. I hereby thank them one and all, with apologies to others not mentioned through inadvertence.

MY DEAR RED SPINNER,

Only the other day I found in a bookseller's catalogue your Waterside Sketches with the word "scarce" against it. I already possess three copies, one the gift of the author, but I very nearly wrote off for a fourth because one cannot have too much of so good a thing. What restrained me really was honest altruism. "Hold," I said to myself, "there must be some worthy man who has no copy at all. Let him have a chance." For it is a melancholy fact that Red Spinner's books have been out of print an unconscionable while, only to be obtained in the second-hand market, and even there with difficulty.

I am not surprised at this (failing new editions at rather frequent intervals), but as a friend of man, and especially of man the angler, I am sorry. I believe I have read almost everything that has been written on the subject of fishing which comes within ordinary scope, and a certain amount which is outside that scope, and I have amassed fishing books to the number of several hundred. There is, however, comparatively little of all this considerable literature that I keep on a special shelf for reading and re-reading, a couple of dozen volumes maybe—and a quarter of those Red Spinner's. Realising what a pleasure and refreshment these books are to me and how often one or other of them companions the evening tobacco, I can the better appreciate the loss occasioned to other anglers by their gradual removal from the lists of the obtainable.

But not very long ago I heard the good news that you had another volume on the stocks, and I felt that the situation was improving. And now I have had the privilege of actually reading that volume in the proof sheets and can report the glad tidings for the benefit of my brethren of the angle. At last they will be able to procure one of your books by the simple process of entering a bookseller's and asking for it. I do not propose here to say much about the new volume except that it will certainly stand beside Waterside Sketches on that special shelf and that it will take its turn with the others in the regular sequence of re-reading. It is the real article, what I may call "genuine Red Spinner," hallmark and all. I must express my satisfaction that you have given in it some further record of the angling in other lands which you have enjoyed in your much-travelled experience. The Antipodes, Canada, the United States, Norway, Belgium before the tragedy—you make it all just as vivid to us as those cold spring days on the rolling Tay, the glowing time of lilac and Mayfly, or the serene evenings when the roach float dips sweetly at every swim. Whatever one's mood, salmon or gudgeon, spinning bait or black gnat, Middlesex or Mississippi, your pages have something to suit it.

Ever since I first met you, on a September evening at Newbury now

nearly twenty years ago, you have consistently given me ever-increasing

cause for gratitude. Whether as accomplished journalist and Editor of

the Field, as writer and author of books, as a man with a genius for

friendship, if I may quote the phrase, or as an expert with rod and

line—in whatever guise you appeared I had cause to thank you for

allowing me "to call you Master." That I am able to do so now thus

publicly means that one at least of my ambitions has been realised.

And I will take leave to subscribe myself with all affection, "Your

scholar,"

H. T. SHERINGHAM.

One of the commonest misconceptions about angling is that it is just the pastime for an idle man. "The lazy young vagabond cares for nothing but fishing!" exclaims the despairing mother to her sympathetic neighbour of the next cottage listening to the family troubles. Even those who ought to know better lightly esteem the sport, as if, forsooth, there were something in the nature of effeminacy in its pursuit.

Not many summers ago a couple of trout-fishers were enjoined by the open-handed country gentleman who had invited them to try his stream to be sure and come in to lunch. They sought to be excused on the plea that they could not afford to leave the water upon any such trifling pretence, but they compounded by promising to work down the water-meads in time for afternoon tea under the dark cedar on the bright emerald lawn. As they sauntered up through the shrubberies, hot and weary, the ladies mocked their empty baskets, and that was all fair and square; but a town-bred member of the house-party shot at a venture a shaft which they considered cruel:

"You ought to have joined us at luncheon, Captain Vandeleur," said she. "I can't imagine what amusement you can find in sitting all day watching a float."

To men whose shoulders and arms were aching after five hours' greenheart drill at long distances, and who prided themselves upon being above every form of fishing lower than spinning, the truly knock-down nature of this blow can only be imagined by those who understand the subject. The captain, who is reckoned one of the worst men in the regiment to venture with in the way of repartee, was so amazed at the damsel's ignorance that he answered never a word, leaving some of her friends in muslin on the garden chairs around to explain the difference between fishing with and without a float—a duty which they appeared to perform with true womanly relish as a set-off against the previous scoring of the pert maid from Mayfair, who had borne rather heavily upon them from a London season elevation.

Allow me to recommend angling as a manly exercise, as physically hard in some of its aspects as any other field sport. During the lifetime of those of us who will no more see middle age this recreation has become actually popular, and it is generally supposed that the multiplication a hundredfold of rod-and-line fishermen in a generation is explained by the cheaper and easier modes of locomotion, the increase of cheap literature pertaining to the sport, and the establishment of a periodical press devoted to it amongst other forms of national recreation. These reasons are undoubtedly admissible. Yet I venture to add another, namely, the great and beneficial movement which has opened the eyes of men and women to the importance of physical exercise.

When the young men who had in their boyhood been taught to regard almost every form of recreation as a sin to be guarded against and repented of, were taught another doctrine, a new impulse was given to cricket, football, and all manner of athletics, and angling was quickly discovered by many to offer exercise in variety, and to carry with it charms of its own. To-day it is therefore so popular that anglers have to protect themselves against one another if they would prevent the depletion of lakes and rivers, and salmon and trout streams are quoted as highly remunerative investments.

Let us see, however, where exercise worthy of the name is found—the inquiry will at the same time indicate the nature of the fascinations which to not a few good people are wholly incomprehensible, if, indeed, they are not a mild form of lunacy. We may take for granted the antiquity of the sport, though probably the first anglers had an eye to nothing nobler than the pot. Angling has never been worth following as an industry, for one of the first lessons learned by the rod fisherman is that there are superior devices for filling a basket if that alone is the object. "Because I like it," is the least troublesome reply to one who asks you why you will go a-fishing. Happy he who can go a little further and aver, "Because I find it the most entrancing of sports." And with equally sound sense may it be urged by old and young alike, "Because it is splendid exercise."

Angling in truth is often made much severer than it need be. The American fishing-men, in their instinctive search for notions, discovered long ago that the rods which they had copied from us were too long and heavy, and the necessary tackle altogether too cumbersome. They seldom use a longer salmon-rod than 15 feet, and frequently kill the heavy trout of their lakes and rivers with delicate weapons of 8 and 9 feet.

In Scotland and Ireland, where the best of our salmon fishing is, you may still meet with anglers who will have no rod under 18 or 20 feet. Only big strong men accustomed to it can wield an implement of this calibre through a hard day's casting without extreme fatigue. They have a sound justification for their choice on such streams as Tweed, Dee, and Spey, where the pools are of the major size and the getting out of a long line is a necessity. They are not on such sure ground when they urge that a heavy salmon can only be landed by a rod of maximum dimensions. I saw a friend last autumn produce a 15-foot greenheart rod on Tweedside. The gillies shook their heads incredulously at the innovation, but honestly unlearned what they had always believed to be infallible dogma when he killed his twenty-three pound fish as quickly and safely as if the cause had been the 18-foot rod which they had implored him to substitute for his most unorthodox concern. It is true that there are "catches" which can only be covered by long rods, with their undoubted advantages in sending out the fly, picking the line off the water, and settling a fish with the promptest dispatch.

The young salmon-fisher should learn to handle a rod that is sufficient for his height and strength and no more. For ordinary purposes 17 feet of greenheart or split-cane are ample, and the modern salmon angler has come to look upon even this—which our forefathers would have pooh-poohed as a mere grilse-rod—as excessive. The secret of comfortable and successful angling, as an exercise no less than as a sport, is in the choice of a rod. Some men seem to be unable to make the right selection; they seem to lack the correct sense of touch and balance. Others suffer from love of change; disloyal to the old friend which fitted their hand to a nicety, they discard it for the passing attractions of some newly-advertised pattern.

It is distressing to watch the efforts of the right man with the wrong rod, or vice versa. With man and rod in harmony the latter does the real work; unfitted to each other, the power of man and rod is alike at its worst. Unfortunately this matter is one upon which the angler must be his own teacher; but the angler's troubles, in the majority of instances, arise from the fatal predilection for a rod heavier than the owner can legitimately bear, or from the use of a line too fine or too coarse for the rod. Exercise is then over-exercise, injurious, and not good for body or temper.

Salmon fishing from a boat is imagined by some to be objectionable because it demands no exertion by the angler. This is an erroneous conclusion, though doubtless the method brings certain muscles into play to an unequal degree. At the same time, fishing from the bank, as it is called for convenience, though the angler never stands upon one, is the most enjoyable of all methods. There is a rapture in the stream as in the pathless woods.

In the foregoing remarks upon heavy rods I had possibly in my mind the angler whose life is not entirely devoted to the open air. The increase to which reference has been made has been chiefly from the class of professional men, merchants, and others who have duties which allow of only occasional relaxation devoted to the river. To such the donning of wading gear for the first time in the season, the entrance into the clear running water, the cautious advance upon the amber gravel or solid rock, the swirl of the rushing stream around the knees, the sensation of cold through the waterproofing, the arrival at length at the point where the head of the pool is within range—these are a keen delight. The pulses fly again when the hooked salmon is felt, and the tightening line curves the rod from point to hand. Exercise, indeed! Half an hour's battle with a fighting salmon, including a race in brogues of a hundred yards or more over shingle or boulders will, when the fish is gaffed and laid on the strand, find the best of men well breathed and not sorry to sit him down till his excitement has cooled and his nerves are once more steady.

Next in order, as a form of healthy exercise, comes pike fishing, as practised by the spinner with small dead fish, the artificial imitations of them, or the endless variations of the spoon, invented, it is claimed, by an angler in the United States. Live baiting in a river with float requires sufficient energy to walk at the same speed as the current flows; by still water or in a boat the angler comes, of course, fairly into the comprehension of the lady who was introduced on another page. He watches and waits, and the more closely he imitates the heron in his motionless patience the better for his chances. The troller of olden times was at any rate always moving, and finer exercise for a winter day than trolling four or five miles of river could not be prescribed. But the gorge hook has gone out of fashion and is discountenanced.

Spinning is for pike what the artificial fly is for salmon, the most scientific method, and followed perseveringly it is downright hard work, bringing, as the use of the salmon rod does, all the muscles of the body into play. The degree of exercise depends upon the style adopted. Casting direct from the Nottingham winch is less trying than the ordinary and more familiar custom of working the incoming line dropped upon the grass or floor of the boat, or gathered in the left hand in coils after the manner of Thames fishermen. Few anglers are masters of the Nottingham style, which has many distinct recommendations, such as freedom from the entanglements of undergrowth and rough ground.

The recovery of the spinning bait by regular revolutions of the winch is not always a gain, since, with all his shark-like voracity, the pike has his little caprices, and sometimes suspects the lure which is moving evenly on a straight course through the water. The bait spun home by the left hand manipulating the line while the right gives the proper motion to the rod top is considered best for pike if not for salmon. One of the good points about spinning for pike is that it is a recreative exercise to be followed after the fly-rod is laid by after autumn. November, December, and January are indeed the months to be preferred before all the rest, and when pike fall out of season the salmon and trout rivers are open again.

Trout fishing is the sport of the many amongst fly-fishermen, and the exercise required in the methods which are recognised as quite orthodox is probably the happy medium, yielding pleasure with the least penalty of toil. The members of the most recent school of trout fishers are believers in the floating fly, but it is wrong to assume that there is any burning question in the matter. The best angler is the man who is master of all the legitimate devices for beguiling fish into his landing net, and I am not now concerned with any controversial aspects of the dry-fly question. The spectacle of an angler upon a chalk stream, where this style is to all intents and purposes Hobson's choice, is not at all suggestive of bodily activity should he happen to be "waiting for a rise." The trout will only heed an artificial fly that is dropped in front of them with upstanding wings, and in form of body and appendages, as in the manner of its progress on the surface of the stream, this counterfeit presentment must strictly imitate the small ephemeridae which are hatching in the bed and floating down the surface of the stream. As the trout do not rise until the natural fly appears, and as the hatches of fly are capricious, there are often weary hours of waiting when the angler must be perforce inactive. His exercise comes in full measure when the hour of action does arrive, and he will find some motion even in the eventless intervals by walking up the river on the look-out for olive dun or black gnat.

The whipper of the mountain streams, or the wet-fly practitioner who fishes a river where the trout are not particular in their tastes, is in the way of exercise the most fortunate of all. He is ever passing from pool to pool, lightly equipped, changing his scenery every hour, now whipping in the shadow of overhanging branches, now crouching behind a mossy crag, and now brushing the sedges of an open section of the stream. The broad tranquil flow is exchanged for merry ripples and sparkling shallows, and these are succeeded by strong and concentrated streams foaming and eddying down a rocky gorge. Trout here and there are dropped into the pannier from time to time, and it is a wholesomely tired angler, with a grand appetite and capacities for sound sleep, who at night will welcome his slippers at the inn.

Sea-trout angling is to me the choicest sport offered by rod and line. One degree more exacting to arms and legs than the more universal employment of the pretty 10-foot trout rod with the purely fresh-water species of the salmonidae, it still falls short of the heavier demands of the salmon or pike rod. The double-handed rod, the moderately strong line and collar, and the flies that are a compromise between the March brown or alder and the Jock Scott or Wilkinson, offer you salmon fishing in miniature. The sea trout are regular visitors to the rivers which are honoured by their periodical visits, but they never linger as long as salmon in the pools, and must be taken on their passage without shilly-shallying.

A good sea trout on a 14-foot rod, and in a bold run of water fretted by opposition from hidden rocks and obstinate outstanding boulders, is game for a king. The exquisitely shaped silver model is a dashing and gallant foe, worthy of the finest steel tempered at Kendal or Redditch. No other fish leaps so desperately out of the water in its efforts to escape, or puts so many artful dodges into execution, forcing the angler with his arched rod and sensitive winch to meet wile with wile, and determination with a firmness of which gentleness is the warp and woof. While it lasts, and when the fish are in a sporting humour, there is nothing more exciting than sea-trout angling. Perhaps for briskness of sport one ought to bracket with it the Mayfly carnival of the non-tidal trout streams in the generally hot days of early June, when the English meadows are in all their glory, and the fish for a few days cast shyness to the green and grey drakes and run a fatal riot in their annual gormandising.

The greatest happiness for the greatest number in angling, I suppose, must be credited to the patient disciples of Izaak Walton who take their sport at their ease by the margins, or afloat on the bosom, of the slow-running rivers which come under the regulations of what is known as the Mundella Act. They are mostly the home of the coarse fish of the British waters—pike, perch, roach, dace, chub, barbel, and the rest. Some of them also hold trout and one or two salmon in their season. They yield little of the kind of sport that gives the exercise which I have made my theme as an excuse for, and recommendation of, angling. But the humbler practices of angling with modest tackle and homely baits take thousands of working people into the country, and if sitting on a box or basket, or in the Windsor chair of a punt on Thames or Lea does not involve physical exertion of a positive kind, it means fresh air, rural sights and sounds, and the tranquil rest which after all is the best holiday for the day-by-day toiler.

It would be interesting to know who invented the phrase "Cockney Sportsman"; we may fairly conclude, at any rate, that The Pickwick Papers, backed persistently by Punch, gave it a firm riveting. It applied perhaps more to the man with the gun than the rod, though the most telling illustration was the immortal Briggs and his barking pike. The term of contempt has long lost its sting, though it still holds lightly. The angler of that ilk fifty years ago, as I can well remember, for all his cockneyism, worked hard for his sport, and enjoyed a fair amount of it. When, for example, I used to fish at Rickmansworth in the middle 'sixties, you would see anglers walking away with their rods and creels from Watford station to various waters four or five miles distant. There are more railways now, but less available fishing, and the anglers have multiplied a thousandfold, making a wonderful change of conditions.

There were plenty of little-known, out-of-the-way places where common fishing could be had for the asking, and excellent bags made by the competent. Manford and Serton were two young men who, I suppose, would have been in the category of Cockney Sportsmen, being workers in City warehouses, members of neither club nor society, free and independent lovers of all manner of out-of-door pursuits and country life. They were both devoted to all-round angling, and Manford, in a modest degree, fancied himself with the gun. These young men are here introduced to the reader because a passing sketch of one of their sporting excursions to the country will indicate a type, and show that they might be cockney, but were also not undeserving the name of sportsmen.

The young fellows made their plans in the billiard-room of the Bottle's Head, just out of Eastcheap, chatting leisurely on the cushions while waiting for a couple of bank mashers to finish their apparently never-ending game. Thirty or forty years ago young fellows in the City did not think so much about holidays as they now do. We have reached a stage of civilisation when it seems absolutely necessary for our bodily and spiritual welfare, however comfortably we may be situated in life, to rush away for a change as regularly as the months of August and September come round. Manford declared that exhausted nature would hold out no longer unless he could take a holiday. Serton suggested that he should try and rub along somehow until nearer October, when he might go down with him to a quiet little place, where he gushingly assured him there was splendid fishing, where they might live for next to nothing, meet with nice people, and be in the midst of one of the most beautiful parts of the country. The one condition was that probably they would have to rough it a little. All these were genuine attractions to S., who agreed to go, M. adding, as they rose to secure the cues, that besides fishing there would be chances with the rabbits.

A spring-cart and a horsey-looking person were awaiting the travellers outside the small roadside railway station at the end of their journey, and they were already joyous and alert. They and their belongings were bundled into the "trap" (how many misfits are covered by the word!) and driven through a tree-arched lane. M. could extract something even from the autumnal seediness of the hedgerows, affirming that they were for all the world like a theatre when the holland coverings are on. S. exclaimed with surprise as a squirrel ran across the track, telling M. that this proved how really they were in the country, squirrels being seldom seen, as weasels are, crossing a road. The driver, who was in fact the keeper, found his opportunity in the uprising from a field of two magpies chattering a welcome. "I think you'll have luck, genl'men," he said. "'Tis allus a good sign to see two mags at once. See one 'tis bad luck; see two it be fun or good luck; see three 'tis a wedding; see four and cuss me if it bain't death."

A rustic cottage, approached between solid hedges of yew, was the bespoken lodging, and M. and S. were quickly out of the cart, and roaming the garden among fruit trees, autumn flowers, and beehives. Thence they were summoned to the little front room, the oaken window-sill bright with fuchsias and geraniums, the walls adorned with an old eight-day clock, a copper warming-pan and antique trays, while over the mantel-piece was a small fowling piece, years ago reduced from flint to percussion. Upon the rafters there were half a side of bacon, bunches of dried sweet herbs, and the traditional strings of onions. The pictures consisted of four highly coloured prints of celebrated race-horses, long ago buried and forgotten. It was in this cottage that the young men remained, and very comfortable they were, for the bedrooms were fitted up with the queerest of four-posters, made in the last century, while the walls were covered with prints from sundry illustrated papers, and illuminated texts. Serton had sojourned in this humble dwelling-place before, and expatiated upon its manifold merits to his friend, who prided himself upon being practical, and said 'twould do, but a five-pound note, he supposed, would buy the lot. "No doubt," replied S., "but to me 'tis a cosy nest for anglers."

The fishing, however, was the first consideration, and with a sense of satisfaction induced by good quarters out went the anglers, across meadows, by the banks of a river. It was fine fun to help the lock-keeper with his cast-net and store the bait-can with gudgeons and minnows, and to crack jokes before the tumbling and rumbling weir, with its deep, wide pool, high banks around, and overhanging bushes. Serton, electing for a little Waltonian luxury, sat him down in comfort, plumbed a hard bottom in six feet of water, caught a dace at the first swim, and, with his cockney-bred maggots, took five others in succession—three roach, and a bleak which he reported in town, at the Bottle's Head, as the largest ever seen.

Meanwhile M., who was paternostering with worm and minnow, came down to inform S. that he had already landed four perch, and that the shoal was still unfrightened. With a recommendation to his friend to do likewise, he returned to his station, and his basketed perch might soon have recited, "Master, we are seven." Thereabouts a shout from S. made the welkin ring; he cried aloud for help, and M. sprinted along in time to save the fine tackle by netting a big chub. From the merry style of the beginning, the captor had felt assured of more roach, and now confessed that they and dace had ceased biting, though he had used paste and maggot alternately. Then he took to small red worm and angled forth a dish of fat gudgeon, that would have put a Seine fisher in raptures. Next he lost a fish by breakage, and while repairing damages was arrested by a distant summons from his companion, whom he discovered wrestling with something—no perch, however—that had gained the further side of the pool, and was now heading remorselessly for the apron of the weir, under which it fouled and freed. The witnesses of the defeat were probably right in their conclusion that this was the aged black trout that had become a legend, and was believed to be the only trout left in those parts.

During the afternoon M. and S., in peaceful brotherhood, sat over the pool, plied paternoster and roach pole, and fished till the float could be no more identified in the dusk. They carried to the cottage each ten or twelve pounds' weight extra in fish caught, but in his memories of the homeward walk S. must have been mistaken in his eloquent reference to the crake of the landrail, though he might have been correct as to the weak, piping cry of the circling bats, and the ghostly passage of flitting owl mousing low over the meadow. These alone, he said, broke the silence; in this M. took him to task, having himself heard the tinkling of sheep bells and the barking of the shepherd's dog.

Next morning the anglers were somewhat put out at first at the necessity of fulfilling an engagement with the keeper, being reminded of the promise by the appearance of a shock-headed youth in the cottage garden, staggering under two sacks. M. was better versed in these things than the other, and able to inform him that this meant rabbiting; here were the nets and the ferrets, and he had undertaken to stand by with the single-barrel and see fair play. Ferreting is a business generally transacted without hustle, and the keeper was a noted slowcoach. With this knowledge, and the presence under his eye of a basket containing ground-bait kneaded in the woodhouse while the breakfast rashers were frying, S. opined that he might snatch an hour or so of honest reaching in the backwater while the rabbit people were getting ready.

The roach master eventually came to the rendezvous, indeed, with a dozen and five of those beautifully graded roach which are between three-quarters and half pound, and which, when they are "on the feed," run marvellously even in size and quality. M. did not now concern himself about the roach. He was no longer a Waltonian; his mind had taken the tone of the keeper's. Yesterday his soul was of the fish, fishy; to-day it was full of muzzle-loaders, nets, and ferrets. But he, too, had his reward, and S. noticed that as they plodded athwart a fallow he looked out keenly and knowingly for feathered or four-footed game as if he were Colonel Hawker in person, and not the patient paternosterer with downcast eye. After S. had witnessed his bright eye and upstanding boldness when he brought the single-barrel to shoulder and dropped a gloriously burnished woodpigeon at long shot, he conceived an enhanced respect for him evermore, and was endued with a spirit of toleration to watch the coming operations, in which he took no part.

Nets were pegged down; there was much talk of bolt holes between the keeper and the rustic shockhead working on different sides of the bank, and M. and the dog Spider had vision and thought for nothing but the open holes they guarded. It transpired that the keeper wanted rabbits for commerce. The couples that speedily met fate in the nets were insufficient. He required fifteen couple. M. rolled over a white scut with obvious neatness and dispatch, and in shifting over to another hedgerow he shot a jay and gloried in its splendour. The keeper, however, moderated any secret intentions there might have been as to the plumage by one sentence: "That's another for the vermin book. I gets a bob for that."

The keeper's cottage gave lunch and rest to the party, and the talk was either of ferrets, hares, and rabbits, or of the two rudely carpentered cases which contained well-set-up specimens of teal, cuckoo, wryneck, abnormally marked swallow, pied rat, landrail, and polecat, each being a chapter in the life history of the keeper.

The tale of rabbits being incomplete, M. returned to his former occupation, but S. fished again, continually finding sport of the miscellaneous kind, such as a chub with cheese paste, perch with dew worm out of the milk-prepared moss, roach rod with running tackle, and leger tackle on a spinning rod. With this and a great worm on strong hook he had the surprise of a fight that gave him not a little concern. The fish at first appeared to be going to ground, even boring bodily into it. Then it gave way to panic, and shot about the pool as if pursued by a water fiend. Winched in slowly, it plunged into the bank, thought better of it, and ran up stream. At this crisis M. arrived, commandeered the net, and stood around offering advice. It was a monster eel, he said. Give him more butt; be careful; be more energetic; certainly, all right. The last remark was simply a receipt in form of a little speech from S., who had briefly bidden him to mind his own business. The unseen fish abruptly had given in. Was it collapse? Slowly, slowly it followed the revolution of the reel, both men peering intent for first sight and grounds for identification of species. The first sight, however, must have been on the part of the fish, which went off in a fright deep down with renewed strength, and then it did surrender, a barbel of 6 lb., a somewhat rare fish for the river, and only taken when, as in this case, it had wandered up into the weir pool.

Having told M. to mind his own business with a minimum of ceremony, it was not surprising that S. was left alone, not exactly to his sport, since, as it happened, the barbel closed his account, unless one or two losses may be included in that definition, and, to give him his due, he was so thorough a fisherman that he did regard losses, shortcomings, and mishaps as legitimate assets in the general game. He had forgotten in his barbeline absorption to inquire, according to usage, how his comrade had been faring, and did not meet him again till they were in the throat of the lane cottage-wards bound. "Well, old 'un; what luck with the paternoster?" he asked, cheerily. M., with a sly twinkle in the eye, said, yes, he had done somewhat; three pike. It may be premised that the young men had both been trying at intervals for a certain marauding pike reported to them as a ferocious duck destroyer by a gentleman farmer who came down to gossip. He indicated the field and a gravel pit as a guide to the place where his cowman had seen a duckling seized by a pike, and the man embellished his account by swearing that the fish had ploughed his way down the river half out of water, with the ball of feathers bewhiskering his jaws. Manford, it seems, had revenged the raided ducks. A large pike lay at the bottom of his rush basket underneath three jack and a covering of rushes, and it was produced as a crowning show, a golden fish of 17 lb. lured to execution by a live bait. There was talk of nothing else that night but this prize at keeper's cottage, village tap-room, at the lockheads, and by five-barred gates; and the exultant keeper, who took credit for all, was heard to say that it was the best bloomin' jack he had seen "for seven year come last plum blight," whenever and whatever that might be.

[SCENE: straw-roofed fishing-hut, door and windows wide open. Table covered with remnants of luncheon, floor ditto with mineral water and other bottles, very empty. In the shade outside, fishermen lying on the grass gazing at the river, upon which the sun strikes fiercely. Keeper and keeper's boys standing sentinel up and down the meadow, under orders to report the first appearance of mayfly. Heat intense. Swallows hawking over the water. Fields a sheet of yellow buttercups, with faint lilac lines formed by cuckoo-flowers on the margins of carriers and ditches. Much yawning and silence amongst the lazy sportsmen sprawling in a variety of attitudes; caps thrown off their sun-scorched faces, waders peeled down to the ankles.]

R. O. (the Riparian Owner, and host of the party): Well, it's about time, I fancy, something stirred. The fly was up an hour before this yesterday, and it would be naturally a little later to-day.

SUFFIELD (a barrister of repute, tall and thin, sarcastic, and a first-rate angler): I don't believe we shall see a fly till three o'clock, and then we shall have the old game over again—short rises and bad language all along the line. Terlan's rod is enough to drive flies and fish out of the county.

TERLAN (a merry little squire, who takes business and pleasure alike with imperturbable placidity of temper, and who always uses a double-handed rod for mayfly fishing): The same to you, old blue-bag. I'll back my 14-footer against your miserable little split cane.

The GENERAL (a retired Indian officer, given to ancient recollections and gloomy views of life): Yes, and very little to brag about either. A brace and half of trout on this river in the mayfly week is a very pitiable sight. When I was a boy nobody had a basket of less than eight brace. Even the trout seem under the curse of this so-called new age.

SUFFIELD: Ay, you not only could, but did, get them easily in the good old times. Why, I have seen the old fogies up at Lord Tummer's water fish from chairs and camp-stools. (Laughter.) Fact, 'pon my word. Each man took his place with his footman behind him, and every man jack of 'em fished in kid gloves.

The GENERAL: But they got their trout, and plenty of 'em, and if they did take it easy, they filled their baskets.

The PARSON (the least parson-like member of the party, and beloved, as the right sort of parson always is, by everybody): This is stale matter. We went over all that ground yesterday, and agreed to take the modern trout as he is, and make the best of him. Call it education or what you like, trout-fishing is not what it was.

The GENERAL (grunting): And never will be. I say it all comes from your overstocking and returning hooked fish to the water. You are all too particular by half, and are eaten up with new-fangled notions.

R. O.: If we fail, it is not, at any rate, for want of preparations, precautions, and theories. Here, Georgy, get up, and arm yourself in regular order.

GEORGY (a stout, elderly stockbroker, supposed to be like the lamented George IV, rising with a laugh, and leisurely filling his pipe): Begad! what am I the worse for my paraphernalia? The General there and all of you, i' faith, are very glad to make use of my little odds and ends.

The GENERAL (contemptuously): When I was a young man we never bothered ourselves very often with so much as a landing-net. Now you are laden with stuff like a pack mule. Look at Georgy's priest dangling from one button, his oil-bottle from another, his weighing machine from another.

R. O.: Ay, and there's the damping box for the gut points, and the pin to clear the eyeholes of the hooks, and the linen cloth to wrap the trout in, and the clearing-ring, and the knee-pads, and whole magazines of flies.

The PARSON: Good! I know Georgy has at least twenty patterns, and by the time he has found out which is the killer the rise is over.

SUFFIELD: Hello! See that?

ALL: What? Where?

SUFFIELD: I beg your pardon: it was only a swallow, or a rat.

R. O.: No; Harvey is signalling up at the bridge. Let us be moving. The fly is coming. Tight lines to you all. [Piscatorum Personae collect their rods, pull up their waders, and stroll away in various directions.]

GEORGY (an hour later, seated amongst the sedges by a broad part of the river, mopping his forehead, rod laid aside on the grass behind: to him approaches the Parson from the shallow above): That was a warm bout while it lasted, parson. How did you get on?

PARSON: Get on? Not at all. For a time the fish rose in all directions, but they did not seem to take the natural even. Flopped at 'em and let 'em pass on.

GEORGY: I didn't like to say it before the R. O., but I'm sure we begin this mayfly fishing too soon. There ought not to be a rod out till the fly has been on at least a couple of days, and not a line should be cast till the fish are taking them freely.

PARSON: What have you done?

GEORGY (motioning to his creel, and creeping softly up the bank, with rod lowered): Only a couple, and handsome fellows, too. Why one of them is full to the muzzle with drakes; there's one crawling from between its jaws at this moment.

PARSON: Heigho! he's into another.

GEORGY (having stalked his fish and hooked him, retires from the bank and brings a two-pounder down to the net, which the parson handles): Well, I've got my brace and half, anyhow.

PARSON (laughing): To tell you the truth, I came down to beg a touch of the paraffin this time.

GEORGY: I thought so. Here you are. (Parson returns to his wooden bridge.) They laugh at my fads, but somehow take toll of 'em. (General approaches from below.) Any luck, General?

GENERAL (disgusted): Yes, infernal bad luck! Two fish broke away one after another. They won't fasten a bit. Never saw anything like it. But I want you to give me one of those gut points out of your damping box. I must get one of those boxes for myself.

GEORGY (supplying the requisitioned goods): You'll find it a very useful thing. Your gut will always be ready to use. Ha! my friend (to trout rising madly twenty yards out), I rather think you'll make number four. (Done accordingly. Spring balance produced; trout weighed at 2 lb. 1 oz. in sight of General.)

GENERAL (moving off to the next meadow, and commanding a deep bend, the haunt of heavy trout); I suppose I have lost the trick; but catch them I can't. I have risen six fish, and lost the only ones that took me. Here's the keeper. What are they doing at the ford, Harvey?

HARVEY: The master's got four, General, and he wants you to come down. The shallow's all alive, and they are taking well. There's a trout, sir, at the tail of that weed.

GENERAL (casting a loose line): Missed it again, by Jove! Why was that, Harvey?

HARVEY (coughing slightly): Well, General, if you ask me, I fancy you had too much slack on the water. You'll have a better chance on the sharp stream below. Let me carry your rod, sir. (Hitches fly in small ring.) No wonder, General, the fish got off: the barb's gone from the hook.

GENERAL (pacing downwards): That's it, is it? Nobody knows better than I that after a fish balks at the hook, one should examine the point. Yet I preach without practice. Ah, me! I'm not in it.

R. O. (genially greeting, and wading out of the shallow): Come along, General; they are rising well, fly and fish both; and this is a bit of water where they generally mean business. Good luck to you! There's a grand trout a little higher up, look. He takes every fly that sails over to him. Pitch your Champion just four inches before his nose, and he's a gone coon.

GENERAL (encouraged and inspired, casting with confidence; and, believing that he is going to be successful, succeeding): You are all right, my spotted enemy (playing the fish down stream firmly). Come along, Harvey, no quarter; get below those flags, and I'll run him in before he knows where he is. That's it: two pounds and a half for a ducat!

R. O.: Capital! We can't send for Georgy's scales, but I bet you he is two and three-quarters (as the General bangs the head of fish on the edge of his brogue sole). Georgy's priest would come in convenient here, too.

SUFFIELD (at upper end of water, kneeling patiently at the edge of an older coppice, smoking the pipe of perfect peace, and soliloquising): They don't rise yet. But a time will come. Hang it! but this is sweet. Yea, it is good to be here. Now, if that little Waterside Sketches chap was here, let me see, how would he tick it off? Forget-me-nots—and deuced pretty they are; sedge warblers, three; kingfishers, one; rooks melodious; picturesque cottages on the downs nestling—they always put it that way—nestling under the beech wood; balmy air—'tis a trifle nice; cuckoo mentioning his name to all the hills—Tennyson, I know, said so; drowsy bees and gaudy dragon flies—yes, they are actually in the bond; and all the rest of it, here it is. And I've chaffed my friend at the club time out of mind for his gush, and swore by the gods that all the angler cares about is gross weight of fish killed. Yet, somehow, I must have taken all this in many a time, without, I suppose, knowing it. Softly now. (Casts deftly with a short line, lightly and straightly delivered, to a corner up-stream where the current swerves round a chestnut tree leaning into the river. Leaps to feet with a split-cane rod arched like a bow. Retires down stream, smiling.) No you don't! I know you. If you get back to that first floor front of yours, I'm done. Out of your familiar ground you're done. Steady, steady! Keep your head up, and on you come. What? More line? Well, well; one more run for the last. Thanks; here you are. (Turns a short, thick two-pounder out of the net into a bed of wild hyacinths in the copse.)

TERLAN (in possession of a side stream which he had won at the friendly toss after breakfast): Fortune has smiled upon me to-day. They laugh at my big rod, but I make it work for me. A fish has no chance with it. I saw the Parson weeded four times yesterday with his little ten-foot greenheart. My fish don't weed me; they can't. Ha, ha! Now look at that trout close under the farther bank, sucking in the fat Mayflies with a gusto worthy of an alderman. Here I am yards away in the meadow; I am out of sight. The rod seems to know that I rely upon it. I don't cast, so to speak; simply give the rod its head, as it were, and there you are. (Fly alights on opposite bank, drops gently, with upstanding wings; is seized with a flourish; trout is brought firmly and rapidly over a bed of weeds, never permitted to twist or turn, and attendant boy nets him out with a grin on his chubby face.) Dip the net a little more, Tommy; you don't want to assault a fish, only to lift him out. How many is that? Eight do you say? Then I want no more.

[SCENE: Straw-roofed fishing hut, as before. Fishing men returning in straggling order. Bottles opened without loss of time. Black drakes dancing in the air. Surface of river marked by never a sign of fish. Flotsam and jetsam of shucks drifting down, and forming in mass at the eddies. Swifts and swallows exceedingly busy everywhere. Sun hastening to western hill-tops. Beautiful evening effects on field and wood, especially on hawthorn grove, in the light of the hour, snow-white, touched with golden gleam.]

R. O. (handing rod to keeper, and taking creel from boy): It's all over now. Short rise to-day. We shall be having a morning and evening rise to-morrow very likely. Now for the spoil. Where's Georgy? We want his steelyard.

GEORGY: Here I am. Here's my basket, and here's my game-book on my shirt cuff—1 1/2, 1 3/4, 2, 2 1/4, 1 1/4, 1 1/4, a d——d big dace, and a black grayling.

R. O.: Oh, a grayling on the 3rd June!

GEORGY: Couldn't help it; fly right down his gullet. Besides, you said you wanted them all out of the water.

The PARSON (weighing his fish): Mine is a back seat. I had twenty misses to one hit. Still, I'm content—3 lb., 2 1/4 lb., and a pound roach.

The GENERAL (smoking a cheroot on a chair brought out of the hut): My muster roll is soon read—three fish, total 4 lb.

R. O.: Harvey has reckoned me up. There are five fish, weighing 10 lb.

SUFFIELD (sauntering up and humming "Now the labourer's task is o'er," and surveying the groups of trout, disposed on the grass in their tribes and households apart): What a sight for the tired angler. Ah! after you with the shandy-gaff. How many? I really haven't counted; but I've had a lovely time at the wood. (Harvey turns out basket, and weighs fish.) Only seven—well, I must do better next time. 13 lb., too; that's not high average; but I report myself satisfied. Here comes Terlan with the mainmast of his brother's yacht.

TERLAN (smiling): Yes, the spar is all right. Sport? Pretty fair, but I haven't been working like galley slaves as some of you have. Lay the lot out decently, Tommy, and don't smother them in grass next time.

R. O.: This is the bag of bags, gentlemen. Four brace of trout, and at the head of the row a fish of 3 3/4 lb. Have him set up, Terlan; it's the most shapely fellow I ever saw taken out of the river. But I see the wagonette coming down to the mill. Where's the doctor?

SUFFIELD: Oh! we shall find him presently. He has been away at the mill-heads and carriers; what the General would call outpost duty.

[SCENE: Road in front of mill. Music of droning and dripping wheel. Bats wheeling overhead. Mother in cottage singing child to sleep. Dogs barking in distance. Sack-laden wagon rumbling over bridge. Doctor seated on a cask smoking, and pulling the ears of a setter. Gleam of fading light on quiet, mirror-like water. Corncrake heard near. Nightingales in concert in adjacent park. Scent of May-bloom heavy in the air.]

R. O. (on box of wagonette with tired fishermen behind): Well, Doctor, what have you done?

DOCTOR (youthful and of goodly countenance): Six brace.

PARSON: You mean fish—not brace.

DOCTOR (shrugging his shoulders): What time did the Mayfly come up? Three or thereabouts, did it? That is just about the time I came in to have a nap, and I have not fished since. I told you not to idle about waiting for Mayfly. Here are my trout, and I got every one of them with the small fly—Welshman's button—before one o'clock.

The GENERAL: They run small.

DOCTOR: H'm, perhaps they do. Two of them seem to have rather bad teeth, too. Still, I don't grumble. Ah, well; good-night. (Wagonette rumbles off down the dusty road.)

R. O.: Good chap, that. He always sleeps at the mill; says the wheel grinds him to sleep. (Later, at the porch of the Black Bull.) We shall have the great rise very likely to-morrow; but I really do think there's something in that small-fly business.

TERLAN: Not forgetting my mainmast.

GEORGY: And, while you are about it, my fads and fanglements.

It may, I trust, be forgiven me if, when thinking of all the salmon I have taken in half a century of attempts and hopes for that 70-pounder which is ever lying expectant in the angler's imagination, I catch my first Tweed salmon over again. A good deal of water must have run through Kelso Bridge since, for I had better confess it was in the month of October, 1889. In that year the autumn fishing in all Scotland on the rivers that remained open during the month was decidedly capricious. This was one of those expeditions when it is wise to make the most of the tiniest opportunities of amusement, and I began very fairly with a fellow-passenger in the train, one of the class which, seeing your fishing things amongst the baggage, arrogates to itself the right to open a volley of questions and remarks upon you about fishing. This example at once showed the extent of his knowledge upon the subject by the declaration: "I never have the patience to fish; it's so long waiting for a bite." He also hinted agreement with the saying attributed to Johnson. There is not so much ignorance in these days on the subject, and the majority of people I fancy now know the difference between sitting down before a painted float and the downright hard work and incessant activity of a day with salmon or trout rod.

Next morning, in clean, quiet Kelso, I mused over the intruded opinions of the gentleman in the train (whom I had ticked off as a good-natured bagman), and having been warned beforehand by a laconic postscript, "Prospects not rosy," remembered that in angling there is something needed besides endurance and energy, and that when you are waiting day by day for the water to fall into condition there is a substantial demand upon patience. However, the thought must not spoil breakfast, nor did it. Then I read my letters, glanced down the columns of the Scotsman, lighted the first tobacco (the best of the day verily!), and issued forth from the yard of the Cross Keys, hallowed by the periodical residence of eminent salmon fishers, such as Alfred Denison, who, with so many of the familiar sportsmen of his day, has gone hence, leaving pleasant memories behind.

The stony square of the town is in front of you; Forrest's shop is next door as you stand in the gateway of the old inn, and after a glance at the sky and at the weathercock on the top of the market house you look in there. A local fisherman was coming out, and in reply to the inevitable question as to the state of the river, he said, "Weel, she's awa' again." Pithy and characteristic, and full of information was this. It was a verdict—You may fish, but shall fish in vain this day. The Tweed is away again.

Gloomily now you walk ahead, leaving your call at the tackle shop for a more convenient season; at present, at any rate, time is of no account. Past the interesting ruins of Kelso Abbey you proceed, and soon, leaning over the parapet of Rennie's Bridge, on the right-hand side, your eye straightaway seeks the Tweedometer fixed against the wall of Mr. Drummond's Ednam House garden. The bold black figures on the whitened post mark 2 1/2 ft. above orthodox level. Two days ago the 3 ft. point had been reached; then Tweed sank to 2 ft.; now "she" is up again 6 in.

One does not care how high a river may rise, provided it gets over the business once for all, and recedes steadily, to have done with change for a reasonable time. The worst phase of all is that which is represented by intermittent ups and downs on a small scale; for the fish follow the example of the river most religiously in one respect—when it is unsettled they are unsettled too. Such experience as this, morning after morning, for many days, may be handsome exercise in the finishing-off touches of your lessons in patience, and are probably entertaining enough to your friends who are not anglers. There is no amusement for you; only resignation. Make up your mind to that, my brother.

There must have been a quantity of downpour away to the west up amongst the hills; the skies are leaden with rain clouds even now; the air is saturated with moisture. Up beyond the picturesque little island at the junction of the two rivers the water thunders over the rocky ledge which forms the dub at the bottom of Floors Castle lower water, and if you observe closely you will soon conclude that Teviot is bringing down an undue amount of Scottish soil. Cross the bridge and look over to the heavy pool under the wooded slope, and note, where the light strikes the eddy, the yellow hue; 18 in. above ordinary level is the outside limit which the initiated on Tweed give you as a bare chance for a fish, and it is evident that, even if those dark clouds do not fulfil their threats, this chance will scarcely come to-morrow, or perchance next day. Wherefore, once more, let patience have her perfect work.

The bait fishers are busy, to be sure. Your extremity is their opportunity. With the worm they make fair baskets of trout in this dirty water. The public on Tweedside are indeed a privileged race. Nearly the whole of the river is free to trout anglers, and there is an abundance of trout in it. The inhabitants of Kelso ought to be full of gratitude to the Duke of Roxburghe, for he gave them, as a generous supplement to their free trouting, miles of the Teviot for salmon fishing. They had only to enrol themselves members of a local association and pay a nominal fee to obtain salmon fishing on the Teviot for a certain number of days in every week. Mr. James Tait, the clerk to the Tweed Commissioners (whom hundreds of anglers had to thank for much kindness to strangers), informed me that when the water was right plenty of salmon were taken in Teviot, especially at the back end. I think, though some people of course are never satisfied, that this great boon was duly appreciated by the inhabitants. You talk to people by the riverside about the Duke, whose fine mansion crowns the high ground ending the pretty landscape above bridge, and they curiously harp upon one string. They say nothing about his Grace's rank, or wealth, or good looks, or the historical associations of his ancient house. They simply remark, "Eh! but the Duke's a kind mon."

The Duke walked down to the opposite side once and hailed me in my boat, said he was glad to give "Red Spinner" a day on his beat, and chatted for a quarter of an hour, the embodiment of man and sportsman. The late Duke of Abercorn was just such another nature's nobleman, and while upon the subject of dukes I may include the Duke of Teck as one with whom I had many a friendly chat about fishing.

That, with the terrible worming the Tweed gets in these autumnal floods, the trout fishing should be so good is marvellous. The plentiful supply of suitable food is one reason why the Tweed has not long been ruined for this summer sport. The hatch of March Browns in the early portion of the season is a sight not to be imagined unless seen. All the summer through insect life abounds, and I have seen in the middle of October hatches of olive duns that would satisfy even a Hampshire chalk streamer, while the trout were rising at them beautifully on every hand. On one of the flood days I strolled up and down Tweedside, and of the dozen or so of anglers I encountered pottering about with the worm, the majority had something like a dozen trout in their baskets. On a day when Teviot was cleared down to porter colour I met a young gentleman who had been fishing down with flies (the blue dun and Greenwell were on the cast), and had filled his basket. There were some fish of three-quarters and half a pound, but the bulk were smaller. These trout were not in good condition, for they spawn early in these parts, but they were not so bad as one might have supposed.

But let us return to our salmon. While you are trying to play your game of patience like a philosopher, you will naturally make a superficial acquaintance with such portions of the river as are accessible to a wayfarer, and if you have not seen it before you will speedily understand why "she" (on Tweedside you always hear the river referred to in the feminine gender) has so many admirers, who pledge her in a life-long devotion. It is indeed a winsome river, and the scenery, never tame, is in many parts lovely. Where can there be a more beautiful place than Sir Richard Waldie-Griffith's park at Hendersyde, as it shows from the other bank of the river? The autumnal tints are in advance of those farther south, and the beeches glow ruddy from afar. This borderland is admirably wooded, and the Tweed valley is pre-eminent in that respect. The historical associations are so numerous and so interesting that the mind, if you allow it to run riot, will become overburdened with them. For myself, to assist in the development of the ripe fruit of patience, I kept mostly to musings that had Abbotsford for its centre, and re-read Lockhart on the spot with which that ponderous volume is so closely concerned. Thanks to Mr. David Tait, I secured one of the early editions, where are to be found all the references to fishing and other sports which are not included in other editions.

The Wizard of the North lived awhile at Rosebank, a short distance below Kelso, and the old tree, I believe, was still flourishing in which he used to sit and take pot shots at herons as they flew over the Tweed, which rolled beneath his leafy perch. Driving down to Carham, "Tweedside," who was my companion, showed me Rosebank across the broad stream, and, while I was reminding him of Walter Scott's gunnery, we saw in an adjacent ploughed field three herons standing close together, apparently in doleful contemplation. On this drive also we crossed a burn which divides English from Scottish soil, and it was tumbling down in angry mood. Scores of other rivulets on either side were pouring their off-scourings into the vexed river, each precisely as gracefully described in the lines:

Now murmuring hoarse, and frequent seen,

Through bush and briar no longer green,

An angry brook, it sweeps the glade,

Brawls over rock and wild cascade.

And, foaming brown with double speed,

Hurries its waters to the Tweed.

The morning, however, comes at last when John, who has been to the station with the early train, meets you as you descend to the coffee-room with "She'll fush the day." But you will not forget that Tweed has been out of order for twelve days, rising and falling, never settled. Still, though the chance is very much an off one, it has to be taken. A day on any water, from Galashiels down to the last pool below Coldstream, is exceeding precious at this time of the year. Every boat is apportioned for the riparian owners and their friends to the very end of the season. If, therefore, you have had kindly leave to fish any of these celebrated waters, and have been unable through bad weather to live up to the opportunities, I could almost weep with or for you; or, if you think strong language more manly, I would make an effort for once to meet you on that ground. I speak, alas, from the book. The wounds inflicted by jade Fortune in these regards are yet unhealed. Take, then, your very off-chance and be thankful.

The truth is that you never quite know what will happen in salmon fishing. On that drenching Saturday, when you were working like a galley slave without raising or seeing a fish on the Lower Floors water (where Lord Randolph Churchill subsequently slew his four fish), did not Mr. Gilbey take five at Carham and Mr. Arkwright four at Birgham? On the Monday, when the water was a little better, did you not find that the salmon had moved right away from the beat for which you were that day booked? It was surely so; and the only sport obtained was by a young gentleman who had handled a rod for the first time on the previous Friday, and who now happened upon a 25-lb. fish, the only one killed that day, with the exception of a pound yellow trout, which took your own fly—a Silver Doctor 1 1/2 in. long. This, and a couple of false rises from salmon, constituted your only luck. Yet there were salmon and grilse in all the streams, splashing in the slow oily sweep that crept under the wood yonder.

It was consolation that night to discover that not much had been done anywhere. A gossip in Mr. Forrest's shop had heard that the Duke of Roxburghe had killed a couple, and the Duchess, who fishes fair with a good salmon rod and casts the fly in a masterly style, also a brace. Mr. Drummond, up at the meeting point of Teviot and Tweed, had done something also. That night, too, the gallant General arrived from Tayside, to make your mouth water as he, being cross-examined as to sport, elaborated the record which had appeared in Saturday's Field. If there is any wrinkle in salmon fishing that the General does not know, you would like to hear of it, would you not? Mark his artful little plan of using the common safety-pin of commerce for stringing his flies upon, threading them upon the pin by the loop before the affair is closed up.

If you are wise, upon a river like the Tweed, where all the fishermen are men of experience and skill, you will not only ask their advice, but take it in the main—say, when it suits you. You were pretty hopeful at the beginning of this final day, though Jamie and his colleague were cautious in expressing an opinion. No doubt Scotchmen are nothing if not cautious, and the trifle of doubt they adventured when they surveyed the sky and studied the water might be merely national caution asserting itself in the very nature of things. Time passed, and when at noon or thereabouts you sat down upon that very comfortable platform near the stern of the boat, and wondered whether your back were as broken as it felt to be, a cold shiver went through you as the horrible thought flashed into your mind. "Good heavens! surely this is not going to be another blank?" The sun, at any rate, after shining brightly for a couple of hours, retired behind the clouds now rolling up from south-west; wind, in meagre catspaws, skirmished across the dub below, reserved for the afternoon, and you prayed that it would strengthen to half a gale.

That grand water above—all streams of a model character—was fished fairly, perseveringly; Wilkinson, Jock Scott, Silver Grey, Greenwell, and Stephenson were tried in succession, large and medium. The afternoon wore on apace without a sign. Down under the high rocks, wooded to the water's edge, you repeated the work of the forenoon, trying, in addition to the flies already named, a harlequin-looking pattern which you had seen amongst Forrest's tempting collection, a novelty named Tommy Adkins. It did no effective service, however. With a levity pardonable at that time you hummed, "Tommy, make room for your uncle," and put up a large Wilkinson, one of the Kelso-tied double hooks, than which you cannot get better. Down to the weir and back again to the same old tune—nothing. An angler from below came up for a chat and told you that he had taken a grilse, and you envied him the possession of that measly little kipper.

By and by there was a pluck beneath the water, and you struck. Whatever else it was, it was no fish; but you carefully winched up and brought in a black kitten not long drowned. Fortune was not content with smiting you, it derided. As you blushingly remarked to the laughing but unappreciative Jamie, this was nothing short of catastrophe. Jamie beguiled the next drift by reminiscences of Sir George Griffith (the angling father of an angling son), Alfred Denison, Liddell, John Bright, George Rooper, and other anglers whom he had piloted to victory—a charming method of rubbing the salt into your smarts.

The dogcart was to be at the head of the dub at five, and the rumble of its wheels had been heard while we were yet about fifty yards from the landing place on the upward course, fishing deep, and letting the long line work slowly round to its farthest limit in the wake. There were no more puns now; I freely admit that I was silent—ay, depressed. Jamie, too, was disappointed; a couple of spectators on the bank were also practising the silence of sympathy. The game was up, and nothing need be said.

Ah! what a magnificent swirl. Deep down went the fish, as up went the rod, and, backache and despondency vanishing, I held him hard. The first dash of the fish told me an unexpected and alarming bit of news. The confounded winch would not run out with the salmon, and I had to ease out line with the left hand and keep the big rod raised with the right. Luckily the winch worked after a fashion when reeled in, and if the single gut at the end of the twisted cast would hold all might be well. And behold it did hold. The fish was heavy, as everyone saw from the first, and it behaved fairly well. One ugly rush, which was the critical point of the battle, passed without accident, and the salmon was revealed—a silvery beauty that was more than ever your heart's desire. Easy and firm was the motto now. The fish was at last safe in Jamie's net, and if it was beaten so was I, thanks to the treacherous reel. The prize was a baggit of 22 lb., as bright as a spring fish, and perfectly shaped.

Here I am riding along the sandy track all alone in the Australian bush, flicking off a wattle blossom singled out from the yellow mass with my hunting crop, fancying it is a fly rod, and rehearsing the old trick of sending a fly into a particular leaf. Ah! little mare Brownie, what are you doing? Did you never before see a charred stump that you should shy so? Do you fancy that you are a thoroughbred that you should bolt at such a gentle touch of the spur? So you espy the half-way house, do you, and fancy that fifteen miles, up and down, in a trifle under two hours, has earned you a spell, a bit of a feed, and something of a washing? And you are right. Take charge, Mr. Blackfellow-ostler, and while you do your duty let me amuse myself with my notebook. After all, memory is even-handed. It keeps us in remembrance of many things we would fain never think of more; but it performs similar service for others that are pleasant to ponder over. Out of the saddle bag I have taken a copy of the Gentleman's Magazine, newly arrived by this morning's mail, and while the mare took her own time up the hills I have been glancing through a "Red Spinner" article on "Angling in Queensland," with an author's pardonable desire to see how it comes out in print. That was why I took to making casts at the leaves with the riding whip. That is why, halting here for an hour on the crest of a hill, overlooking scrub of glossy green, bright patches of young maize, and a river shimmering in the valley, I am noting a few of the best-day memories which the easy paces of Brownie have allowed me in the saddle.

What a day was that amongst the trout on the Chess! I wrote for permission to spend one afternoon only upon certain private waters, and the noble owner by return of post sent me an order for two days. It was June. The meadows, hedgerows—ay! and even the prosaic railway embankments—were decked with floral colouring, and at Rickmansworth I had to linger on the platform to take another look at the foliage heavily shading the old churchyard, and at the distant woods to the left. When I came back to quarters, after dark, having fished the river for a few hours, I began to think I might as well have stopped in London. The fish would not rise that afternoon, and there was but a beggarly brace in the basket. Some wretch above had been mowing his lawn and casting the contents of the machine into the stream at regular intervals. He got rid of his grass, certainly; but this was no gain to me, whose hooks perseveringly caught the fragments floating by. At last the grass pest ceased. The mowing man had left his task at six o'clock, no doubt, and the soft twilight would soon come on—time dear to anglers. But the cattle had an innings then. During the most precious hour they waded into the river—higher up, of course—and a pretty state of discolour they made of it. In this way the first essay left me abundance of room to hope for the morrow.