Mrs. G. de Horne Vaizey

"About Peggy Saville"

Chapter One.

A New Inmate.

The afternoon post had come in, and the Vicar of Renton stood in the bay window of his library reading his budget of letters. He was a tall, thin man, with a close-shaven face, which had no beauty of feature, but which was wonderfully attractive all the same. It was not an old face, but it was deeply lined, and those who knew and loved him best could tell the meaning of each of those eloquent tracings. The deep vertical mark running up the forehead meant sorrow. It had been stamped there for ever on the night when Hubert, his first-born, had been brought back, cold and lifeless, from the river to which he had hurried forth but an hour before, a picture of happy boyhood. The vicar’s brow had been smooth enough before that day. The furrow was graven to the memory of Teddy, the golden-haired lad who had first taught him the joys of fatherhood. The network of lines about the eyes were caused by the hundred and one little worries of everyday life, and the strain of working a delicate body to its fullest pitch; and the two long, deep streaks down the cheeks bore testimony to that happy sense of humour which showed the bright side of a question, and helped him out of many a slough of despair. This afternoon, as he stood reading his letters one by one, the different lines deepened, or smoothed out, according to the nature of the missive. Now he smiled, now he sighed, anon he crumpled up his face in puzzled thought, until the last letter of all was reached, when he did all three in succession, ending up with a low whistle of surprise—

“Edith! This is from Mrs Saville. Just look at this!”

Instantly there came a sound of hurried rising from the other end of the room; a work-basket swayed to and fro on a rickety gipsy-table, and the vicar’s wife walked towards him, rolling half a dozen reels of thread in her wake with an air of fine indifference.

“Mrs Saville!” she exclaimed eagerly. “How is my boy?” and without waiting for an answer she seized the letter, and began to devour its contents, while her husband went stooping about over the floor picking up the contents of the scattered basket and putting them carefully back in their places. He smiled to himself as he did so, and kept turning amused, tender glances at his wife as she stood in the uncarpeted space in the window, with the sunshine pouring in on her eager face. Mrs Asplin had been married for twenty years, and was the mother of three big children; but such was the buoyancy of her Irish nature and the irrepressible cheeriness of her heart, that she was in good truth the youngest person in the house, so that her own daughters were sometimes quite shocked at her levity of behaviour, and treated her with gentle, motherly restraint. She was tall and thin, like her husband, and he, at least, considered her every whit as beautiful as she had been a score of years before. Her hair was dark and curly; she had deep-set grey eyes, and a pretty fresh complexion. When she was well, and rushing about in her usual breathless fashion, she looked like the sister of her own tall girls; and when she was ill, and the dark lines showed under her eyes, she looked like a tired, wearied girl, but never for a moment as if she deserved such a title as an old, or elderly, woman. Now, as she read, her eyes glowed, and she uttered ecstatic little exclamations of triumph from time to time; for Arthur Saville, the son of the lady who was the writer of the letter, had been the first pupil whom her husband had taken into his house to coach, and as such had a special claim on her affection. For the first dozen years of their marriage all had gone smoothly with Mr and Mrs Asplin, and the vicar had had more work than he could manage in his busy city parish; then, alas, lung trouble had threatened; he had been obliged to take a year’s rest, and to exchange his living for a sleepy little parish, where he could breathe fresh air, and take life at a slower pace. Illness, the doctor’s bills, the year’s holiday, ran away with a large sum of money; the stipend of the country church was by no means generous, and the vicar was lamenting the fact that he was shortest of money just when his children were growing up and he needed it most, when an old college friend requested, as a favour, that he would undertake the education of his only son, for a year at least, so that the boy might be well grounded in his studies before going on to the military tutor who was to prepare him for Sandhurst. Handsome terms were quoted, the vicar looked upon the offer as a leading of Providence, and Arthur Saville’s stay at the vicarage proved a success in every sense of the word. He was a clever boy who was not afraid of work, and the vicar discovered in himself an unsuspected genius for teaching. Arthur’s progress not only filled him with delight, but brought the offer of other pupils, so that he was but the forerunner of a succession of bright, handsome boys, who came from far and wide to be prepared for college, and to make their home at the vicarage. They were honest, healthy-minded lads, and Mrs Asplin loved them all, but no one had ever taken Arthur Saville’s place. During the year which he had spent under her roof he had broken his collar-bone, sprained his ankle, nearly chopped off the top of one of his fingers, scalded his foot, and fallen crash through a plate-glass window. There had never been one moment’s peace or quietness; she had gone about from morning to night in chronic fear of a disaster; and, as a matter of course, it followed that Arthur was her darling, ensconced in a little niche of his own, from which subsequent pupils tried in vain to oust him.

Mrs Saville dwelt upon the latest successes of her clever son with a mother’s pride, and his second mother beamed, and smiled, and cried, “I told you so!”

“Dear boy!”

“Of course he did!” in delighted echo. But when she came to the second half of the letter her face changed, and she grew grave and anxious. “And now, dear Mr Asplin,” Mrs Saville wrote, “I come to the real burden of my letter. I return to India in autumn, and am most anxious to see Peggy happily settled before I leave. She has been at this Brighton school for four years, and has done well with her lessons, but the poor child seems so unhappy at the thought of returning, that I am sorely troubled about her. Like most Indian children, she has had very little home life, and after being with me for the last six months she dreads the prospect of school, and I cannot bear the thought of sending her back against her will. I was puzzling over the question yesterday, when it suddenly occurred to me that perhaps you, dear Mr Asplin, could help me out of my difficulty. Could you—would you, take her in hand for the next three years, letting her share the lessons of your own two girls? I cannot tell you what a relief and joy it would be to feel that she was under your care. Arthur always looks back on the year spent with you as one of the brightest of his life; and I am sure Peggy would be equally happy. I write to you from force of habit, but really I think this letter should have been addressed to Mrs Asplin, for it is she who would be most concerned. I know her heart is large enough to mother my dear girl during my absence; and if strength and time will allow her to undertake this fresh charge, I think she will be glad to help another mother by doing so. Peggy is bright and clever, like her brother, and strong on the whole, though her throat needs care. She is nearly fifteen—the age, I think, of your youngest girl—and we should be pleased to pay the same terms as we did for Arthur. Now, please, dear Mr Asplin, talk the matter over with your wife, and let me know your decision as soon as possible.”

Mrs Asplin dropped the letter on the floor, and turned to confront her husband.

“Well!”

“Well?”

“It is your affair, dear, not mine. You would have the trouble. Could you do with an extra child in the house?”

“Yes, yes, so far as that goes. The more the merrier. I should like to help Arthur’s mother, but,”—Mrs Asplin leant her head on one side, and put on what her children described as her “Ways and Means” expression. She was saying to herself,—“Clear out the box-room over the study. Spare chest-of-drawers from dressing-room—cover a box with one of the old chintz curtains for an ottoman—enamel the old blue furniture—new carpet and bedstead, say five or six pounds outlay—yes! I think I could make it pretty for five pounds!...” The calculations lasted for about two minutes, at the end of which time her brow cleared, she nodded brightly, and said in a crisp, decisive tone, “Yes, we will take her! Arthur’s throat was delicate too. She must use my gargle.”

The vicar laughed softly.

“Ah! I thought that would decide it. I knew your soft heart would not be able to resist the thought of the delicate throat! Well, dear, if you are willing, so am I. I am glad to make hay while the sun shines, and lay by a little provision for the children. How will they take it, do you think? They are accustomed to strange boys, but a girl will be a new experience. She will come at once, I suppose, and settle down to work for the autumn. Dear me! dear me! It is the unexpected that happens. I hope she is a nice child.”

“Of course she is. She is Arthur’s sister. Come! the young folks are in the study. Let us go and tell them the news. I have always said it was my ambition to have half a dozen children, and now, at last, it is going to be gratified.”

Mrs Asplin thrust her hand through her husband’s arm, and led him down the wide, flagged hall, towards the room whence the sound of merry young voices fell pleasantly upon the ear.

Chapter Two.

Mellicent’s Prophecy.

The schoolroom was a long, bare apartment running along one side of the house, and boasting three tall windows, through which the sun poured in on a shabby carpet and ink-stained tables. Everything looked well worn and, to a certain extent, dilapidated, yet there was an air of cheerful comfort about the whole which is not often found in rooms of the kind. Mrs Asplin revelled in beautiful colours, and would tolerate no drab and saffron papers in her house; so the walls were covered with a rich soft blue; the cushions on the wicker chairs rang the changes from rose to yellow; a brilliant Japanese screen stood in one corner, and a wire stand before the open grate held a number of flowering plants. A young fellow of seventeen or eighteen was seated at one end of the table employed in arranging a selection of foreign stamps. This was Maxwell, the vicar’s eldest surviving son, who was to go up to Oxford at the beginning of the year, and was at present reading under his father’s supervision. His sister Mellicent was perched on the table itself, watching his movements, and vouchsafing scraps of advice. Her suggestions were received with sniffs of scornful superiority, but Mellicent prattled on unperturbed, being a plump, placid person, with flaxen hair, blue eyes, and somewhat obtuse sensibilities. The elder girl was sitting reading by the window, leaning her head on her hand, and showing a long, thin face, comically like her father’s, with the same deep lines running down her cheeks. She was neither so pretty nor so even-tempered as her sister, but she had twice the character, and was a young person who made her individuality felt in the house; while Maxwell was the beauty of the family, with his mother’s crisp, dark locks, grey eyes, and brunette colouring.

These three young people were the vicar’s only surviving children; but there were two more occupants of the room—the two lads who were being coached to enter the University at the same time as his own son. Number one was a fair, dandified-looking youth, who sat astride a deck-chair, with his trousers hitched up so as to display long, narrow feet, shod in scarlet silk socks and patent-leather slippers. He had fair hair, curling over his forehead; bold blue eyes, an aquiline nose, and an air of being very well satisfied with the world in general and himself in particular. This was Oswald Elliston, the son of a country squire, who had heard of the successes of Mr Asplin’s pupils, and was storing up disappointment for himself in expecting similar exploits from his own handsome, but by no means over-brilliant, son. The second pupil had a small microscope in his hand, and was poring over a collection of “specimens,” with his shoulders hitched up to his ears, in a position the reverse of elegant. Every now and then he would bend his head to write down a few notes on the paper beside him, showing a square-chinned face, with heavy eyebrows and strong roughly-marked features. His clothes were worn, his cuffs invisible, and his hair ruffled into wild confusion by the unconscious rubbings of his hands; and this was the Honourable Robert Darcy, third son of Lord Darcy, a member of the Cabinet, and a politician of world-wide reputation.

The servants at the vicarage were fond of remarking, apropos of the Honourable Robert, that he “didn’t look it”; which remark would have been a subject of sincere gratification to the lad himself, had it been overheard; for there was no surer way of annoying him than by referring to his position, or giving him the prefix to which he was entitled.

The young folks looked up inquiringly as Mr and Mrs Asplin entered the room, for the hour after tea was set apart for recreation, and the elders were usually only too glad to remain in their own quiet little sanctum. Oswald, the gallant, sprang to his feet and brought forward a chair for Mrs Asplin, but she waved him aside, and broke impetuously into words.

“Children! we have news for you. You are going to have a new companion. Father has had a letter this afternoon about another pupil—”

Mellicent yawned, and Esther looked calmly uninterested, but the three lads were full of interest. Their faces turned towards the vicar with expressions of eager curiosity.

“A new fellow! This term! From what school, sir?”

“A ladies’ boarding-school at Brighton!” Mrs Asplin spoke rapidly, so as to be beforehand with her husband, and her eyes danced with mischievous enjoyment, as she saw the dismay depicted on the three watching faces. A ladies’ school! Maxwell, Oswald, and Robert, had a vision of a pampered pet in curls, and round jacket, and their backs stiffened in horrified indignation at the idea that grown men of seventeen and eighteen should be expected to associate with a “kid” from a ladies’ school!

The vicar could not restrain a smile, but he hastened to correct the mistake. “It’s not a ‘fellow’ at all, this time. It’s a girl! We have had a letter from Arthur Saville’s mother, asking us to look after her daughter while she is in India. She will come to us very soon, and stay, I suppose, for three or four years, sharing your lessons, my dears, and studying with you—”

“A girl! Good gracious! Where will she sleep?” cried Mellicent, with characteristic matter-of-fact curiosity, while Esther chimed in with further inquiries.

“What is her name? How old is she? What is she like? When will she come? Why is she leaving school?”

“Not very happy. Peggy. In the little box-room over the study. About fifteen, I believe. Haven’t the least idea. In a few weeks from now,” said Mrs Asplin, answering all the questions at once in her impulsive fashion, the while she walked round the table, stroked Maxwell’s curls, bent an interested glance at Robert’s collection, and laid a hand on Esther’s back, to straighten bowed shoulders. “She is Arthur’s sister, so she is sure to be nice, and both her parents will be in India, so you must all be kind to the poor little soul, and give her a hearty welcome.”

Silence! Nobody had a word to say in response to this remark; but the eyes of the young people met furtively across the table, and Mr Asplin felt that they were only waiting until their seniors should withdraw before bursting into eager conversation.

“Better leave them to have it out by themselves,” he whispered significantly to his wife; then added aloud, “Well, we won’t interrupt you any longer. Don’t turn the play-hour into work, Rob! You will study all the better for a little relaxation. You have proved the truth of that axiom, Oswald—eh?” and he went laughing out of the room, while Oswald held the door open for his wife, smiling assent in lazy fashion.

“Another girl!” he exclaimed, as he reseated himself on his chair, and looked with satisfaction at his well-shod feet. “This is an unexpected blow! A sister of the redoubtable Saville! From all I have heard of him, I should imagine a female edition would be rather a terror in a quiet household. I never saw Saville,—what sort of a fellow was he to look at, don’t you know?”

Mellicent reflected.

“He had a nose!” she said solemnly. Then, as the others burst into hilarious laughter, “Oh, it’s no use shrieking at me; I mean what I say,” she insisted. “A big nose—like Wellington’s! When people are very clever, they always have big noses. I imagine Peggy small, with a little thin face, because she was born in India, and lived there until she was six years old, and a great big nose in the middle—”

“Sounds appetising,” said Maxwell shortly. “I don’t! I imagine Peggy like her mother, with blue eyes and brown hair. Mrs Saville is awfully pretty. I have seen her often, and if her daughter is like her—”

“I don’t care in the least how she looks,” said Esther severely. “It’s her character that matters. Indian children are generally spoiled, and if she has been to a boarding-school she may give herself airs. Then we shall quarrel. I am not going to be patronised by a girl of fourteen. I expect she will be Mellicent’s friend, not mine.”

“I wonder what sums she is in!” said Mellicent dreamily. “Rob! what do you think about it? Are you glad or sorry? You haven’t said anything yet.”

Robert raised his eyes from his microscope, and looked her up and down, very much as a big Newfoundland dog looks at the terrier which disturbs its slumber.

“It’s nothing to me,” he said loftily. “She may come if she likes.” Then, with sudden recollection, “Does she learn the violin? Because we have already one girl in this house who is learning the violin, and life won’t be worth living if there is a second.”

He tucked his big notebook under his chin as he spoke, and began sawing across it with a pencil, wagging his head and rolling his eyes, in imitation of Mellicent’s own manner of practising, producing at the same time such long-drawn, catlike wails from between his closed lips as made the listeners shriek with laughter. Mellicent, however, felt bound to expostulate.

“It’s not the tune at all,” she cried loudly. “Not like any of my pieces; and if I do roll my eyes, I don’t rumple up my hair and pull faces at the ceiling, as some people do, and I know who they are, but I am too polite to say so! I hope Peggy will be my friend, because then there will be two of us, and you won’t dare to tease me any more. When Arthur was here, a boy pulled my hair, and he carried him upstairs and held his head underneath the shower-bath.”

“I’ll pull it again, and see if Peggy will do the same,” said Rob pleasantly; and poor Mellicent stared from one smiling face to another, conscious that she was being laughed at, but unable to see the point of the joke.

“When Peggy comes,” she said, in an injured tone, “I hope she will be sympathetic. I’m the youngest, and I think you ought all to do what I want; instead of which you make fun, and laugh among yourselves, and send me messages. For instance, when Max wanted his stamps brought down—”

Maxwell passed his big hand over her hair and face, then, reversing the direction, rubbed up the point of the little snub nose.

“Never mind, chubby, your day is over! We will make Peggy the message-boy now. Peggy will be a nice, meek little girl, who will like to run messages for her betters! She shall be my fag, and attend to me. I’ll give her my stamps to sort.”

“I rather thought of having her for fag myself; we can’t admit a girl to our study unless she makes herself useful,” said Oswald languidly; whereupon Rob banged the notebook on the table with clanging decision.

“Peggy belongs to me,” he announced firmly. “It’s no use you two fellows quarrelling. That matter is settled once for all. Peggy will be my fag; I’ve barleyed her for myself, and you have nothing to say in the matter.”

But Esther tossed her head with an air of superior wisdom.

“Wait till she comes,” she said sagely. “If Peggy is anything like her brother, you may spare yourself the trouble of planning as to what she must or must not do. It is waste of time. Peggy will be mistress over us all!”

Chapter Three.

Enter Miss Saville!

A fortnight later Peggy Saville arrived at the vicarage. Her mother brought her, stayed for a couple of hours, and then left for the time being; but as she was to pay some visits in the neighbourhood it was understood that this was not the final parting, and that she would spend several afternoons with her daughter before sailing for India. On this occasion, however, none of the young people saw her, for they were out during the afternoon, and were just settling down to tea in the schoolroom when the wheels of the departing carriage crunched down the drive.

“Now for it!” cried Maxwell, and they looked at one another in silence, knowing full well what would happen. Mrs Asplin would think an introduction to her young friends the best distraction for the strange girl after her mother’s departure, and the next item in the programme would be the appearance of Miss Peggy herself. Esther rearranged the scattered tea-things; Oswald felt to see if his necktie was in position, and Robert hunched his shoulders and rolled his eyes at Mellicent in distracting fashion. Each one sat with head cocked on one side, in an attitude of eager attention. The front door banged, footsteps approached, and Mrs Asplin’s high, cheerful tones were heard drawing nearer and nearer.

“This way, dear,” she was saying. “They are longing to see you!”

The listeners gave a simultaneous gulp of excitement, the door opened, and—Peggy entered!

She was not in the least what they had expected! This was neither the blonde beauty of Maxwell’s foretelling, nor the black-haired elf described by Mellicent. The first glance was unmitigated disappointment.

“She is not a bit pretty,” was the mental comment of the two girls. “What a funny little soul!” that of the three big boys, who had risen on Mrs Asplin’s entrance, and now stood staring at the new-comer with curious eyes.

Peggy was slight and pale, and at the first sight her face gave a comical impression of being made up of a succession of peaks. Her hair hung in a pigtail down her back, and grew in a deep point on her forehead; her finely-marked eyebrows were shaped like eaves, and her chin was for all the world like that of a playful kitten. Even the velvet trimming on her dress accentuated this peculiarity, as it zigzagged round the sleeves and neck. The hazel eyes were light and bright, and flitted from one figure to another with a suspicious twinkling; but nothing could have been more composed, more demure, or patronisingly grown-up than the manner in which this strange girl bore the scrutiny which was bent upon her.

“Here are your new friends, Peggy,” cried Mrs Asplin cheerily. “They always have tea by themselves in the schoolroom, and do what they please from four to five o’clock. Now just sit down, dear, and take your place among them at once. Esther will make room for you by her side, and introduce you to the others. I will leave you to make friends. I know young people get on better when they are left alone.”

She whisked out of the room in her impetuous fashion, and Peggy Saville seated herself in the midst of a ghastly silence. The young people had been prepared to cheer and encourage a bashful stranger, but the self-possession of this thin, pale-faced girl took them by surprise, so that they sat round the table playing uncomfortably with teaspoons and knives, and irritably conscious that they, and not the new-comer, were the ones to be overcome with confusion. The silence lasted for a good two minutes, and was broken at last by Miss Peggy herself.

“Cream and sugar!” she said, in a tone of sweet insinuation. “Two lumps, if you please. Not very strong, and as hot as possible. Thank you! So sorry to be a trouble.”

Esther fairly jumped with surprise, and seizing the teapot, filled the empty cup in haste. Then she remembered the dreaded airs of the boarding-school miss, and her own vows of independence, and made a gallant effort to regain composure.

“No trouble at all. I hope that will be right. Please help yourself. Bread—and—butter—scones—cake! I must introduce you to the rest, and then you will feel more at home! I am Esther, the eldest, a year older than you, I think. This is Mellicent, my younger sister, fourteen last February. I think you are about the same age.” She paused a moment, and Peggy looked across the table and said, “How do you do, dear?” in an affable, grandmotherly fashion, which left poor Mellicent speechless, and filled the others with delighted amusement. But their own turn was coming. Esther pulled herself together, and went on steadily with her introductions. “This is Maxwell, my brother, and these are father’s two pupils—Oswald Elliston, and Robert—the Honourable Robert Darcy.” She was not without hope that the imposing sound of the latter name would shake the self-possession of the stranger, but Peggy inclined her head with the air of a queen, drawled out a languid, “Pleased to see you!” and dropped her eyes with an air of indifference, which seemed to imply that an “Honourable” was an object of no interest whatever, and that she was really bored by the number of her titled acquaintances. The boys looked at each other with furtive glances of astonishment. Mellicent spread jam all over her plate, and Esther unconsciously turned on the handle of the urn and deluged the tray with water, but no one ventured a second remark, and once again it was Peggy’s voice that opened the conversation.

“And is this the room in which you pursue your avocations? It has a warm and cheerful exposure.”

“Er—yes! This is the schoolroom. Mellicent and I have lessons here in the morning from our German governess, while the boys are in the study with father. In the afternoon, from two to four, they use it for preparation, and we go out to classes. We have music lessons on Monday, painting on Tuesday, calisthenics and wood-carving on Thursday and Friday. Wednesday and Saturday are half-holidays. Then from four to six the room is common property, and we have tea together and amuse ourselves as we choose.”

“A most desirable arrangement. Thank you! Yes,—I will take a scone, as you are so kind!” said Peggy blandly; a remark which covered the five young people with confusion, since none of them had noticed that her plate was empty. Each one made a grab in the direction of the plate of scones; the girls failed to reach it, while Oswald, twitching it from Robert’s hands, jerked half the contents on the table, and had to pick them up, while Miss Saville looked on with a smile of indulgent superiority.

“Accidents will happen, will they not?” she said sweetly, as she lifted a scone from the plate, with her little finger cocked well in the air, and nibbled it daintily between her small white teeth. “A most delicious cake! Home-made, I presume? Perhaps of your own concoction?”

Esther muttered an inarticulate assent, and once more the conversation languished. She looked appealingly at Maxwell. As the son of the house, the eldest of the boys, it was his place to take the lead, but Maxwell looked the picture of embarrassment. He did not suffer from bashfulness as a rule, but since Peggy Saville had come into the room he had been seized with an appalling self-consciousness. His feet felt in the way, his arms seemed too long for practical purposes, his elbows had a way of invading other people’s precincts, and his hands looked red and clammy. It occurred to him dimly that he was not a man after all, but only a big overgrown schoolboy, and that little Miss Saville knew as much, and was mildly pitiful of his shortcomings. He was not at all anxious to attract the attention of the sharp little tongue, so he passed on the signal to Mellicent, kicking her foot under the table, and frowning vigorously in the direction of the stranger.

“Er,”—began Mellicent, anxious to respond to the signal, but lamentably short of ideas,—“Er,—Peggy! Are you fond of sums? I’m in decimals. Do you like fractions? I think they are hateful. I could do vulgars pretty well, but decimals are fearful. They never come right. So awfully difficult.”

“Patience and perseverance overcome difficulties. Keep up your courage. I’ll help you with them, dear,” said Peggy encouragingly, closing her eyes the while, and coughing in a faint and ladylike manner.

She could not really be only fourteen, Mellicent reflected. She talked as if she were quite grown-up,—older than Esther, seventeen or eighteen at the very least. What a little white face she had! what a great thick plait of hair! How erect she held herself! Fräulein would never have to rebuke her new pupil for stooping shoulders. It was kind of her to promise help with those troublesome decimals! Quite too good an offer to refuse.

“Thank you very much,” she said heartily, “I’ll show you some after tea. Perhaps you may be able to make me understand better than Fräulein. It’s very good of you, P—” A quick change of expression warned her that something was wrong, and she checked herself to add hastily, “You want to be called ‘Peggy,’ don’t you? No? Then what must we call you? What is your real name?”

“Mariquita!” sighed the damsel pensively, “after my grandmother—Spanish. A beautiful and unscrupulous woman at the court of Philip the Second.” She said “unscrupulous” with an air of pride, as though it had been “virtuous,” or some other word of a similar meaning, and pronounced the name of the king with a confidence that made Robert gasp.

“Philip the Second? Surely not? He was the husband of our Mary in 1572. That would make it just a trifle too far back for your grandmother, wouldn’t it?” he inquired sceptically; but Mariquita remained absolutely unperturbed.

“It must have been someone else, then, I suppose. How clever of you to remember! I see you know something about history,” she said suavely; a remark which caused an amused glance to pass between the young people, for Robert had a craze for history of all description, and had serious thought of becoming a second Carlyle so soon as his college course was over.

Maxwell put his handkerchief to his mouth to stifle a laugh, and kicked out vigorously beneath the table, with the intention of sharing his amusement with his friend Oswald. It seemed, however, that he had aimed amiss, for Mariquita fell back in her chair, and laid her hand on her heart.

“I think there must be some slight misunderstanding. That’s my foot that you are kicking! I cut it very badly on the ice last winter, and the least touch causes acute suffering. Please don’t apologise; it doesn’t matter in the least,” and she rolled her eyes to the ceiling, like one in mortal agony.

It was the last straw. Maxwell’s embarrassment had reached such a pitch that he could bear no more. He murmured some unintelligible words, and bolted from the room, and the other two boys lost no time in following his example.

In subsequent conversations, Mellicent always referred to this occasion as “the night when Robert had one cup,” it being, in truth, the only occasion since this young gentleman entered the vicarage when he had neglected to patronise the teapot three or four times in succession.

Chapter Four.

Good-Bye, Mariquita!

For four long days had Mariquita Saville dwelt beneath Mr Asplin’s roof, and her companions still gazed upon her with fear and trembling, as a mysterious and extraordinary creature whom they altogether failed to understand. She talked like a book; she behaved like a well-conducted old lady of seventy, and she sat with folded hands gazing around, with a curious, dancing light in her hazel eyes, which seemed to imply that there was some tremendous joke on hand, the secret of which was known only to herself. Esther and Mellicent had confided their impressions to their mother; but in Mrs Asplin’s presence Peggy was just a quiet, modest girl, a trifle shy, as was natural under the circumstances, but with no marked peculiarity of any kind. She answered to the name of “Peggy,” to which address she was at other times persistently deaf, and sat with neat little feet crossed before her, the picture of a demure, well-behaved young schoolgirl. The sisters assured their mother that Mariquita was a very different person in the schoolroom, but when she inquired as to the nature of the difference, it was not easy to explain.

She talked so grandly, and used such great big words!—“A good thing, too,” Mrs Asplin averred. She wished the rest would follow her example, and not use so much foolish, meaningless slang.—Her eyes looked so bright and mocking, as if she were laughing at something all the time.—Poor, dear child! could she not talk as she liked? It was a great blessing she could be bright, poor lamb, with such a parting before her!—She was so grown-up, and patronising, and superior!—Tut! tut! Nonsense! Peggy had come from a boarding-school, and her ways were different from theirs—that was all. They must not take stupid notions, but be kind and friendly, and make the poor girl feel at home.

Fräulein on her side reported that her new pupil was docile and obedient, and anxious to get on with her studies, though not so far advanced as might have been expected. Esther was far ahead of her in most subjects, and Mellicent learned with pained surprise that she knew nothing whatever about decimal fractions.

“Circumstances, dear,” she explained, “circumstances over which I had no control prevented an acquaintance, but no doubt I shall soon know all about them, and then I shall be pleased to give you the promised help;” and Mellicent found herself saying, “Thank you,” in a meek and submissive manner, instead of indulging in a well-merited rebuke.

No amount of ignorance seemed to daunt Mariquita, or to shake her belief in herself. When Maxwell came to grief in a Latin essay, she looked up and said, “Can I assist you?” and when Robert read aloud a passage from Carlyle, she laid her head on one side and said, “Now, do you know, I am not altogether sure that I am with him on that point!” with an assurance which paralysed the hearers.

Esther and Mellicent discussed seriously together as to whether they liked, or disliked, this extraordinary creature, and had great difficulty in coming to a conclusion. She teased, puzzled, aggravated, and provoked them; therefore, if they had any claim to be logical, they should dislike her cordially, yet somehow or other they could not bring themselves to say that they disliked Mariquita. There were moments when they came perilously near loving the aggravating creature. Already it gave them quite a shock to look back upon the time when there was no Peggy Saville to occupy their thoughts, and life without the interest of her presence would have seemed unspeakably flat and uninteresting. She was a bundle of mystery. Even her looks seemed to exercise an uncanny fascination. On the evening of her arrival the unanimous opinion had been that she was decidedly plain, but there was something about the pale little face which always seemed to invite a second glance, and the more closely you gazed, the more complete was the feeling of satisfaction.

“Her face is so neat,” Mellicent said to herself; and the adjective was not inappropriate, for Peggy’s small features looked as though they had been modelled by the hand of a fastidious artist, and the air of dainty finish extended to her hands and feet and slight, graceful figure.

The subject came up for discussion on the third evening after Peggy’s arrival, when she had been called out of the room to speak to Mrs Asplin for a few minutes. Esther gazed after her as she walked across the floor with her dignified tread, and when the door was closed she said slowly—

“I don’t think Mariquita is as plain now as I did at first; do you, Oswald?”

“N–no! I don’t think I do. I should not call her exactly plain. She is a funny little thing, but there’s something nice about her face.”

“Very nice!”

“Last night in the pink dress she looked almost pretty.”

“Y–es!”

“Quite pretty!”

“Y–es! really quite pretty.”

“We shall think her lovely in another week,” said Mellicent tragically. “Those awful Savilles! They are all alike—there is something Indian about them. Indian people have a lot of secrets that we know nothing about; they use spells, and poisons, and incantations that no English person can understand, and they can charm snakes. I’ve read about it in books. Arthur and Peggy were born in India, and it’s my opinion that they are bewitched. Perhaps the ayahs did it when they were in their cradles. I don’t say it is their own fault, but they are not like other people, and they use their charms on us, as there are no snakes in England. Look at Arthur! He was the naughtiest boy—always hurting himself, and spilling things, and getting into trouble, and yet everyone in the house bowed down before him, and did what he wanted.—Now mark my words, Peggy will be the same!”

Mellicent’s companions were not in the habit of “marking her words,” but on this occasion they looked thoughtful, for there was no denying that they were already more or less under the spell of the remorseless stranger.

On the afternoon of the fourth day Miss Peggy came down to tea with her pigtail smoother and more glossy than ever, and the light of war shining in her eyes. She drew her chair to the table, and looked blandly at each of her companions in turn.

“I have been thinking,” she said sweetly, and the listeners quaked at the thought of what was coming. “The thought has been weighing on my mind that we neglect many valuable and precious opportunities. This hour, which is given to us for our own use, might be turned to profit and advantage, instead of being idly frittered away—

“‘In work, in work, in work alway,

Let my young days be spent.’

“It was the estimable Dr Watts, I think, who wrote those immortal lines! I think it would be a desirable thing to carry on all conversation at this table in the French language for the future. Passez-moi le beurre, s’il vous plait, Mellicent, ma très chère. J’aime beaucoup le beurre, quand il est frais. Est-ce que vous aimez le beurre plus de la,—I forget at the moment how you translate jam, il fait très beau, ce après-midi, n’est pas?”

She was so absolutely, imperturbably grave that no one dared to laugh. Mellicent, who took everything in deadly earnest, summoned up courage to give a mild little squeak of a reply. “Wee—mais hier soir, il pleut;” and in the silence that followed Robert was visited with a mischievous inspiration. He had had French nursery governesses in his childhood, and had, moreover, spent two years abroad, so that French came as naturally to him as his own mother-tongue. The temptation to discompose Miss Peggy was too strong to be resisted. He raised his dark, square-chinned face, looked straight into her eyes, and rattled off a breathless sentence to the effect that there was nothing so necessary as conversation, if one wished to master a foreign language; that he had talked French in the nursery; and that the same Marie who had nursed him as a baby was still in his father’s service, acting as maid to his sister. She was getting old now, but was a most faithful creature, devoted to the family, though she had never overcome her prejudices against England and English ways. He rattled on until he was fairly out of breath, and Peggy leant her little chin on her hand, and stared at him with an expression of absorbing attention. Esther felt convinced that she did not understand a word of what was being said, but the moment that Robert stopped, she threw back her head, clasped her hands together, and exclaimed—

“Mais certainement, avec pleasure!” with such vivacity and Frenchiness of manner that she was forced into unwilling admiration.

“Has no one else a remark to make?” continued this terrible girl, collapsing suddenly into English, and looking inquiringly round the table. “Perhaps there is some other language which you would prefer to French. It is all the same to me. We ought to strive to become proficient in foreign tongues. At the school where I was at Brighton there was a little girl in the fourth form who could write, and even speak, Greek with admirable fluency. It impressed me very much, for I myself knew so little of the language. And she was only six—”

“Six!” The boys straightened themselves at that, roused into eager protest. “Six years old! And spoke Greek! And wrote Greek! Impossible!”

“I have heard her talking for half an hour at a time. I have known the girls in the first form ask her to help them with their exercises. She knew more than anyone in the school.”

“Then she is a human prodigy. She ought to be exhibited. Six years old! Oh, I say—that child ought to turn out something great when she grows up. What did you say her name was, by the bye?”

Peggy lowered her eyelids, and pursed up her lips. “Andromeda Michaelides,” she said slowly. “She was six last Christmas. Her father is Greek Consul in Manchester.”

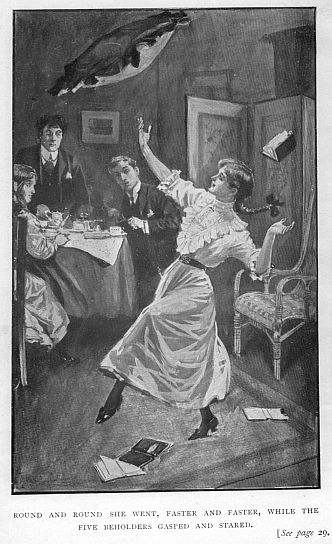

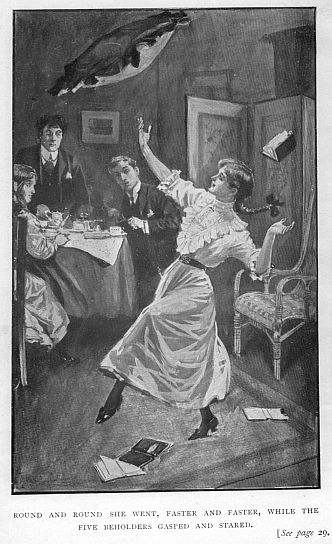

There was a pause of stunned surprise; and then, suddenly, an extraordinary thing happened. Mariquita bounded from her seat, and began flying wildly round and round the table. Her pigtail flew out behind her; her arms waved like the sails of a windmill, and as she raced along she seized upon every loose article which she could reach, and tossed it upon the floor. Cushions from chairs and sofa went flying into the window; books were knocked off the table with one rapid sweep of the hand; magazines went tossing up in the air, and were kicked about like so many footballs. Round and round she went, faster and faster, while the five beholders gasped and stared, with visions of madhouses, strait-jackets, and padded rooms, rushing through their bewildered brains. Her pale cheeks glowed with colour; her eyes shone; she gave a wild shriek of laughter, and threw herself, panting, into a chair by the fireside.

“Three cheers for Mariquita! Ho! ho! he! Didn’t I do it well? If you could have seen your faces!”

“P–P–P–eggy! Do you mean to say you have been pretending all this time? What do you mean? Have you been putting on all those airs and graces for a joke?” asked Esther severely; and Peggy gave a feeble splutter of laughter.

“W–wanted to see what you were like! Oh, my heart! Ho! ho! ho! wasn’t it lovely? Can’t keep it up any longer! Good-bye, Mariquita! I’m Peggy now, my dears.—Give me some more tea!”

Chapter Five.

Explanations.

In the explanations that followed, no one showed a livelier interest than Peggy herself. She was in her element answering the questions which were showered upon her, and took an artistic pleasure in the success of her plot.

“You see,” she explained, “I knew you would all be talking about me, and wondering what I was like, just as I was thinking about you. As I was Arthur’s sister, I knew you would be sure to imagine me a mischievous tom-boy, so I came to the conclusion that the best way to shock you would be to be quite too awfully proper and well-behaved. I never enjoyed anything so much in my life as that first tea-time, when you all looked dumb with astonishment. I had made up my mind to go on for a week, but mother is coming to-morrow, and I couldn’t keep it up before her, so I was obliged to explode to-night. Besides, I’m really quite fatigued with being good—”

“And are you—are you—really not proper, after all?” gasped Mellicent blankly; whereat Peggy clasped her hands in emphatic protest.

“Proper! Oh, my dear, I am the most awful person. I am always getting into trouble. You know what Arthur was? Well, I tell you truly, he is nothing to me. It’s an extraordinary thing. I have excellent intentions, but I seem bound to get into scrapes. There was a teacher at Brighton, Miss Baker,—a dear old thing. I called her ‘Buns.’—She vowed and declared that I shortened her life by bringing on palpitation of the heart. I set the dressing-table on fire by spilling matches and crunching them beneath my heels. It was not a proper dressing-table, you know—just a wooden thing frilled round with muslin. We had two blazes in the last term. And a dreadful thing occurred! Would you believe that I was actually careless enough to sit down on the top of her best Sunday hat, and squash it as flat as a pancake!”

Despite her protestations of remorse, Peggy’s voice had an exultant ring as she detailed the history of her escapades, and Esther shrewdly suspected that she was by no means so penitent as she declared. She put on her most severe expression, and said sternly—

“You must be dreadfully careless. It is to be hoped you will be more careful here, for your room is far-away from ours, and you might be burned to death before anyone discovered you. Mother never allows anyone to read in bed in this house, and she is most particular about matches. You wouldn’t like to be burned to a cinder all by yourself some fine night, I should say?”

“No, I shouldn’t—or on a wet one either. It would be so lonely,” said Peggy calmly. “No; I am a reformed character about matches. I support home industries, and go in for safeties, which ‘strike only on the box.’ But the boys would rescue me.” She turned with a smile, and beamed upon the three tall lads. “Wouldn’t you, boys? If you hear me squealing any night, don’t stop to think. Just catch up your ewers of water, and rush to my bedroom. We might get up an amateur fire-brigade, to be in readiness. You three would be the brigade, and I would be the captain and train you. It would be capital fun. At any moment I could give the signal, and then, whatever you were doing—playing,—working,—eating,—or on cold frosty nights, just when you were going to bed, off you would have to rush, and get out your fire-buckets. Sometimes you might have to break the ice, but there’s nothing like being prepared. We might have the first rehearsal to-night—”

“It’s rather funny to hear you talking of being captain over the boys, because the day we heard that you were coming, they all said that if they were to be bothered with a third girl in the house, you would have to make yourself useful, and that you should be their fag. Max said so, and so did Oswald, and then Robert said they shouldn’t have you. He had lots of little odd things he wanted done, and he could make you very useful. He said the other boys shouldn’t have you; you were his property.”

“Tut, tut!” said Peggy pleasantly. She looked at the three scowling, embarrassed faces, and the mocking light danced back into her eyes. “So they were all anxious to have me, were they? How nice! I’m gratified to hear it. Is there any little thing I can do for your honourable self now, Mr Darcy, before I dress for dinner?”

Robert looked across the room at Mellicent with an expression which made that young person tremble in her shoes.

“All right, young lady, I’ll remember you!” he said quietly. “I’ve warned you before about repeating conversations. Now you’ll see what happens. I’ll cure you of that little habit, my dear, as sure as my name is Robert Darcy—”

“The Honourable Robert Darcy!” murmured a silvery voice from the other side of the fireplace. Robert turned his head sharply, but Peggy was gazing into the coals with an air of lamb-like innocence, and he subsided into himself with a grunt of displeasure.

The next day Mrs Saville came to lunch, and spent the afternoon at the vicarage. As Maxwell had said, she was a beautiful woman; tall, fair, and elegant, and looking a very fashionable lady when contrasted with Mrs Asplin in her well-worn serge, but her face was sad and anxious in expression. Esther noticed that her eyes filled with tears more than once as she looked round the table at the husband and wife and the three tall, well-grown children; and when the two ladies were alone in the drawing-room she broke into helpless sobbings.

“Oh, how happy you are! How I envy you! Husband, children,—all beside you. Oh, never, never let one of your girls marry a man who lives abroad. My heart is torn in two; I have no rest. I am always longing for the one who is not there. I must go back,—the major needs me; but my Peggy,—my own little girl! It is like death to leave her behind!”

Mrs Asplin put her arms round the tall figure, and rocked her gently to and fro.

“I know! I know!” she said brokenly. “I ache for you, dear; but I understand! I have parted with a child of my own—not for a few years, but for ever, till we meet again in God’s heaven. I’ll help you every way I can. I’ll watch her night and day; I’ll coddle her when she’s ill; I’ll try to make her a good woman. I’ll love her, dear, and she shall be my own special charge. I’ll be a second mother to her.”

“You dear, good woman! God bless your kind heart!” said Mrs Saville brokenly. “I can’t help breaking down, but indeed I have much to be thankful for. I can’t tell you what a relief it is to feel that she is in this house. The principals of that school at Brighton were all that is good and excellent, but they did not understand my Peggy.” The tears were still in her eyes, but she broke into a flickering smile at the last word. “My children have such spirits! I am afraid they really do give more trouble than other boys and girls, but they are not really naughty. They are truthful and generous, and wonderfully warm-hearted. I never needed to punish Peg when she was a little girl; it was enough to show that she had grieved me. She never did the same thing again after that; but—oh, dear me!—the ingenuity of that child in finding fresh fields for mischief! Dear Mrs Asplin, I am afraid she will try your patience. You must be sure to keep a list of all the breakages and accidents, and charge them to our account. Peggy is an expensive little person. You know what Arthur was.”

“Bless him—yes! I had hardly a tumbler left in the house,” said Mrs Asplin, with gusto. “But I don’t grieve myself about a few breakages. I have had too much to do with schoolboys for that!—And now give me all the directions you can about this precious little maid, while we have the room to ourselves.”

For the next hour there the two ladies sat in conclave about Miss Peggy’s mental, moral, and physical welfare. Mrs Asplin had a book in her hand, in which from time to time she jotted down notes of a curious and inconsequent character. “Pay attention to private reading. Gas-fire in her bedroom for chilly weather. See dentist in Christmas holidays. Query: gold plate over eye-tooth? Boots to order, Beavan and Company, Oxford Street. Cod-liver oil in winter. Careless about changing shoes. Damp brings on throat. Aconite and belladonna.” So on, and so on. There seemed no end to the warnings and instructions of this anxious mother; but when all was settled as far as possible, the ladies adjourned into the schoolroom to join the young people at their tea, so that Mrs Saville might be able to picture her daughter’s surroundings when separated from her by those weary thousands of miles.

“What a bright, cheery room!” she said smilingly, as she took her seat at the table, and her eyes wandered round as if striving to print the scene in her memory. How many times, as she lay panting beneath the swing of the punkah, she would recall that cool English room, with its vista of garden through the windows, the long table in the centre, the little figure with the pale face and plaited hair, seated midway between the top and bottom! Oh! the moments of longing—of wild, unbearable longing—when she would feel that she must break loose from her prison-house and fly away,—that not the length of the earth itself could keep her back, that she would be willing to give up life itself just to hold Peggy in her arms for five minutes, to kiss the sweet lips, to meet the glance of the loving eyes—

But this would never do! Had she not vowed to be cheerful? The young folks were looking at her with troubled glances. She roused herself, and said briskly—

“I see you make this a playroom as well as a study. Somebody has been wood-carving over there, and you have one of those dwarf billiard-tables. I want to give a present to this room—something that will be a pleasure and occupation to you all; but I can’t make up my mind what would be best. Can you give me a few suggestions? Is there anything that you need, or that you have fancied you might like?”

“It’s very kind of you,” said Esther warmly; and echoes of “Very kind!” came from every side of the table, while boys and girls stared at each other in puzzled consideration. Maxwell longed to suggest a joiner’s bench, but refrained out of consideration for the girls’ feelings. Mellicent’s eager face, however, was too eloquent to escape attention, and Mrs Saville smiled at her in an encouraging manner.

“Well, dear, what is it? Don’t be afraid. I mean something really nice and handsome; not just a little thing. Tell me what you thought?”

“A—a new violin!” cried Mellicent eagerly. “Mine is so old and squeaky, and my teacher said I needed a new one badly. A new violin would be nicest of all.”

Mrs Saville looked round the table, caught an expressive grimace going the round of three boyish faces, and raised her eyebrows inquiringly.

“Yes? Whatever you like best, of course. It is all the same to me. But would the violin be a pleasure to all? What about the boys?”

“They would hear me play! The pieces would sound nicer. They would like to hear them.”

“Ahem!” coughed Maxwell loudly; and at that there was a universal shriek of merriment. Peggy’s clear “Ho! ho!” rang out above the rest, and her mother looked at her with sparkling eyes. Yes, yes, yes; the child was happy! She had settled down already into the cheery, wholesome life of the vicarage, and was in her element among these merry boys and girls! She hugged the thought to her heart, finding in it her truest comfort. The laughter lasted several minutes, and broke out intermittently from time to time as that eloquent cough recurred to memory, but after all it was Mellicent who was the one to give the best suggestion.

“Well then, a—a what-do-you-call-it!” she cried. “A thing-um-me-bob! One of those three-legged things for taking photographs! The boys look so silly sometimes, rolling about together in the garden, and we have often and often said, ‘Don’t you wish we could take their photographs? They would look such frights!’ We could have ever so much fun with a what-do-you-call-it?”

“Ah, that’s something like!” “Good business.” “Oh, wouldn’t it be sweet!” came the quick exclamations; and Mrs Saville looked most pleased and excited of all.

“A camera!” she cried. “What a charming idea! Then you would be able to take photographs of Peggy and the whole household, and send them out for me to see. How delightful! That is a happy thought, Mellicent. I am so grateful to you for thinking of it, dear. I’ll buy a really good large one, and all the necessary materials, and send them down at once. Do any of you know how to set to work?”

“I do, Mrs Saville,” Oswald said. “I had a small camera of my own, but it got smashed some years ago. I can show them how to begin, and we will take lots of photographs of Peggy for you, in groups and by herself. They mayn’t be very good at first, but you will be interested to see her in different positions. We will take her walking, and bicycling, and sitting in the garden, and every way we can think of—”

“And whenever she has a new dress or hat, so that you may know what they are like,” added Mellicent anxiously. “Are her hats going to be the same as ours, or is she to choose them for herself?”

“She may choose them for herself, subject, of course, to your mother’s refraining influence. If she were to develop a fondness for scarlet feathers, for instance, I think Mrs Asplin should interfere; but Peggy has good taste. I don’t think she will go far wrong,” said the girl’s mother, looking at her fondly; and the little white face quivered before it broke into its sunny, answering smile.

Three times that evening, after Mrs Saville had left, did her companions surprise the glitter of tears in Peggy’s eyes; but there was a dignified reserve about her manner which forbade outspoken sympathy. Even when she was discovered to be quietly crying behind her book, when Maxwell flipped it mischievously out of her hands,—even then did Peggy preserve her wonderful self-possession. The tears were trickling down her cheeks, and her poor little nose was red and swollen, but she looked up at Maxwell without a quiver, and it was he who stood gaping before her, aghast and miserable.

“Oh, I say! I’m fearfully sorry!”

“So am I,” said Peggy severely. “It was rude, and not at all funny. And it injures the book. I have always been taught to reverence books, and treat them as dear and valued companions. Pick it up, please. Thank you. Don’t do it again.” She hitched herself round in her chair, and settled down once more to her reading, while Maxwell slunk back to his seat. When Peggy was offended she invariably fell back upon Mariquita’s grandiose manner, and the sting of her sharp little tongue left her victims dumb and smarting.

Chapter Six.

A New Friendship.

A week after this, Mrs Saville came to pay her farewell visit before sailing for India. Mother and daughter went out for a walk in the morning, and retired to the drawing-room together for the afternoon. There was much that they wanted to say to each other, yet for the most part they were silent, Peggy sitting with her head on her mother’s shoulder, and Mrs Saville’s arms clasped tightly round her. Every now and then she stroked the smooth brown head, and sometimes Peggy raised her lips and kissed the cheek which leant against her own, but the sentences came at long intervals.

“If I were ill, mother—a long illness—would you come?”

“On wings, darling! As fast as boat and train could bring me.”

“And if you were ill?”

“I should send for you, if it were within the bounds of possibility—I promise that! You must write often, Peggy—long, long letters. Tell me all you do, and feel, and think. You will be almost a woman when we meet again. Don’t grow up a stranger to me, darling.”

“Every week, mother! I’ll write something each day, and then it will be like a diary. I’ll tell you every bit of my life...”

“Be a good girl, Peggy. Do all you can for Mrs Asplin, who is so kind to you. She will give you what money you need, and if at any time you should want more than your ordinary allowance, for presents or any special purpose, just tell her about it, and she will understand. You can have anything in reason; I want you to be happy. Don’t fret, dearie. I shall be with father, and the time will pass. In three years I shall be back again, and then, Peg, then, how happy we shall be! Only three years.”

Peggy shivered, and was silent. Three years seem an endless space when one is young. She shut her eyes, and pondered drearily upon all that would happen before the time of separation was passed. She would be seventeen, nearly eighteen—a young lady who wore dresses down at her ankles, and did up her hair. This was the last time, the very, very last time when she would be a child in her mother’s arms. The new relationship might be nearer, sweeter, but it could never be the same, and the very sound of the words “the last time” sends a pang to the heart.

Half an hour later the carriage drove up to the door. Mr and Mrs Asplin came into the room to say a few words of farewell, and then left Peggy to see her mother off. There were no words spoken on the way, and so quietly did they move that Robert had no suspicion that anyone was near, as he took off his shoes in the cloak-room opening off the hall. He tossed his cap on to a nail, picked up his book, and was just about to sally forth, when the sound of a woman’s voice sent a chill through his veins. The tone of the voice was low, almost a whisper, yet he had never in his life heard anything so thrilling as its intense and yearning tenderness. “Oh, my Peggy!” it said. “My little Peggy!” And then, as in reply, came a low moaning sound, a feeble bleat like that of a little lamb torn from its mother’s side. Robert charged back into the cloak-room, and kicked savagely at the boots and shoes which were scattered about the floor, his lips pressed together, and his brows meeting in a straight black line across his forehead. Another minute, and the carriage rolled away. He peeped out of the door in time to see a little figure fly out into the rain, and walking slowly towards the schoolroom came face to face with Mrs Asplin.

“Gone?” she inquired sadly. “Well, I’m thankful it is over. Poor little dear, where is she? Flown up to her room, I suppose. We’ll leave her alone until tea-time. It will be the truest kindness.”

“Yes,” said Robert vaguely. He was afraid that the good lady would not be so willing to leave Peggy undisturbed if she knew her real whereabouts, and was determined to say nothing to undeceive her. He felt sure that the girl had hidden herself in the summer-house at the bottom of the garden, and a nice, damp, mouldy retreat it would be this afternoon, with the rain driving in through the open window, and the creepers dripping on the walls. Just the place in which to sit and break your heart, and catch rheumatic fever with the greatest possible ease. And yet Robert said no word of warning to Mrs Asplin. He had an inward conviction that if anyone were to go to the rescue, that person should be himself, and that he, more than anyone else, would be able to comfort Peggy in her affliction. He sauntered up and down the hall until the coast was clear, then dashed once more into the cloak-room, took an Inverness coat from a nail, a pair of goloshes from the floor, and sped rapidly down the garden-path. In less than two minutes he had reached the summer-house, and was peeping cautiously in at the door. Yes; he was right. There sat Peggy, with her arms stretched out before her on the rickety table, her shoulders heaving with long, gasping sobs. Her fingers clenched and unclenched themselves spasmodically, and the smooth little head rolled to and fro in an abandonment of grief. Robert stood looking on in silent misery. He had a boy’s natural hatred of tears, and his first impulse was to turn tail, go back to the house, and send someone to take his place; but even as he hesitated he shivered in the chilly damp, and remembered the principal reason of his coming. He stepped forward and dropped the cloak over the bent shoulders, whereupon Peggy started up and turned a scared white face upon him.

“Who, who—Oh! it is you! What do you want?”

“Nothing. I saw you come out, and thought you would be cold. I brought you out my coat.”

“I don’t want it; I am quite warm. I came here to be alone.”

“I know; I’m not going to bother. Mrs Asplin thinks you are in your room, and I didn’t tell her that I’d seen you go out. But it’s damp. If you catch cold, your mother will be sorry.”

Peggy looked at him thoughtfully, and there was a glimmer of gratitude in her poor tear-stained eyes.

“Yes; I p–p–romised to be careful. You are very kind, but I can’t think of anything to-night. I am too miserably wretched.”

“I know; I’ve been through it. I was sent away to a boarding-school when I was a little kid of eight, and I howled myself to sleep every night for weeks. It is worse for you, because you are older, but you will be happy enough in this place when you get settled. Mrs Asplin is a brick, and we have no end of fun. It is ever so much better than being at school; and, I say, you mustn’t mind what Mellicent said the other night. She’s a little muff, always saying the wrong thing. We were only chaffing when we said you were to be our fag. We never really meant to bully you.”

“You c–couldn’t if you t–tried,” stammered Peggy brokenly, but with a flash of her old spirit which delighted her hearer.

“No; of course not. You can stand up for yourself; I know that very well. But look here: I’ll make a compact, if you will. Let us be friends. I’ll stick to you and help you when you need it, and you stick to me. The other girls have their brother to look after them, but if you want anything done, if anyone is cheeky to you, and you want him kicked, for instance, just come to me, and I’ll do it for you. It’s all nonsense about being a fag, but there are lots of things you could do for me if you would, and I’d be awfully grateful. We might be partners, and help one another—”

Robert stopped in some embarrassment, and Peggy stared fixedly at him, her pale face peeping out from the folds of the Inverness coat. She had stopped crying, though the tears still trembled on her eyelashes, and her chin quivered in uncertain fashion. Her eyes dwelt on the broad forehead, the overhanging brows, the square, massive chin, and brightened with a flash of approval.

“You are a nice boy,” she said slowly. “I like you! You don’t really need my help, but you thought it would cheer me to feel that I was wanted. Yes; I’ll be your partner, and I’ll be of real use to you yet. You’ll find that out, Robert Darcy, before you have done with me.”

“All right, so much the better. I hope you will; but you know you can’t expect to have your own way all the time. I’m the senior partner, and you will have to do what I tell you. Now I say it’s damp in this hole, and you ought to come back to the house at once. It’s enough to kill you to sit in this draught.”

“I’d rather like to be killed. I’m tired of life. I shouldn’t mind dying a bit.”

“Humph!” said Robert shortly. “Jolly cheerful news that would be for your poor mother when she arrived at the end of her journey! Don’t be so selfish. Now then, up you get! Come along to the house.”

“I wo—” Peggy began, then suddenly softened, and glanced apologetically into his face. “Yes, I will, because you ask me. Smuggle me up to my room, Robert, and don’t, don’t, if you love me, let Mellicent come near me! I couldn’t stand her chatter to-night!”

“She will have to fight her way over my dead body,” said Robert firmly; and Peggy’s sweet little laugh quavered out on the air.

“Nice boy!” she repeated heartily. “Nice boy; I do like you!”

Chapter Seven.

Amateur Photographers.

Peggy looked very sad and wan after her mother’s departure, but her companions soon discovered that anything like outspoken sympathy was unwelcome. The redder her eyes, the more erect and dignified was her demeanour; if her lips trembled when she spoke, the more grandiose and formidable became her conversation, for Peggy’s love of long words and high-sounding expressions was fully recognised by this time, and caused much amusement in the family.

A few days after Mrs Saville sailed, a welcome diversion arrived in the shape of the promised camera. The Parcels Delivery van drove up to the door, and two large cases were delivered, one of which was found to contain the camera itself, the tripod and a portable dark room, while the other held such a collection of plates, printing-frames, and chemicals as delighted the eyes of the beholders. It was the gift of one who possessed not only a deep purse, but a most true and thoughtful kindness, for, when young people are concerned, two-thirds of the enjoyment of any present is derived from the possibility of being able to put it to immediate use. As it was a holiday afternoon, it was unanimously agreed to take two groups and develop them straightway.

“Professional photographers are so dilatory,” said Peggy severely; “and indeed I have noticed that amateurs are even worse. I have twice been photographed by friends, and they have solemnly promised to send me a copy within a few days. I have waited, consumed by curiosity, and, my dears, it has been months before it has arrived! Now we will make a rule to finish off our groups at once, and not keep people waiting until all the interest has died away. There’s no excuse for such dilatory behaviour!”

“There is some work to do, remember, Peggy. You can’t get a photograph by simply taking off and putting on the cap; you must have a certain amount of time and fine weather. I haven’t had much experience, but I remember thinking that photographs were jolly cheap, considering all the trouble they cost, and wondering how the fellows could do them at the price. There’s the developing, and washing, and printing, and toning,—half a dozen processes before you are finished.”

Peggy smiled in a patient, forbearing manner.

“They don’t get any less, do they, by putting them off? Procrastination will never lighten labour. Come, put the camera up for us, like a good boy, and we’ll show you how to do it.” She waved her hand towards the brown canvas bag, and the six young people immediately seized different portions of the tripod and camera, and set to work to put them together. The girls tugged and pulled at the sliding legs, which were too new and stiff to work with ease; Maxwell turned the screws which moved the bellows, and tried in vain to understand their working; Robert peered through the lenses, and Oswald alternately raved, chided, and jeered at their efforts. With so many cooks at work, it took an unconscionable time to get ready, and even when the camera was perched securely on its spidery legs, it still remained to choose the site of the picture, and to pose the victims. After much wandering about the garden, it was finally decided that the schoolroom window would be an appropriate background for a first effort; but a heated argument followed before the second question could be decided.

“I vote that we stand in couples, arm-on-arm,—like this!” said Mellicent, sidling up to her beloved brother, and gazing into his face in a sentimental manner, which had the effect of making him stride away as fast as he could walk, muttering indignant protests beneath his breath.

Then Esther came forward with her suggestion.

“I’ll hold a book as if I were reading aloud, and you can all sit round in easy, natural positions, and look as if you were listening. I think that would make a charming picture.”

“Idiotic, I call it! ‘Scene from the Goodchild family; mamma reading aloud to the little ones.’ Couldn’t possibly look easy and natural under the circumstances; should feel too miserable. Try again, my dear. You must think of something better than that.”

It was impossible to please those three fastidious boys. One suggestion after another was made, only to be waved aside with lordly contempt, until at last the girls gave up any say in the matter, and left Oswald to arrange the group in a manner highly satisfactory to himself and his two friends, however displeasing to the more artistic members of the party. Three girls in front, two boys behind, all standing stiff as pokers; with solemn faces, and hair ruffled by constant peepings beneath the black cloth. Peggy in the middle, with her eyebrows more peaked than ever, and an expression of resigned martyrdom on her small, pale face; Mellicent, large and placid, on the left; Esther on the right, scowling at nothing, and, over their shoulders, the two boys’ heads, handsome Max and frowning Robert.

“There,” cried Oswald, “that’s what I call a sensible arrangement! If you take a photograph, take a photograph, and don’t try to do a pastoral play at the same time. Keep still a moment, and I will see if it is focused all right. I can see you pulling faces, Peggy! It’s not at all becoming. Now then, I’ll put in the plate—that’s the way!—one—two—three—and I shall take you. Stea–dy?”

Instantly Mellicent burst into giggles of laughter, and threw up her hands to her face, to be roughly seized from behind and shaken into order.

“Be quiet, you silly thing! Didn’t you hear him say steady? What are you trying to do?”

“She has spoiled this plate, anyhow,” said Oswald icily. “I’ll try the other, and if she can’t keep still this time she had better run away and laugh by herself at the other end of the garden. Baby!”

“Not a ba—” began Mellicent indignantly; but she was immediately punched into order, and stood with her mouth wide open, waiting to finish her protest so soon as the ordeal was over.

Peggy forestalled her, however, with an eager plea to be allowed to take the third picture herself.

“I want to have one of Oswald to send to mother, for we are not complete without him, and I know it would please her to think I had taken it myself,” she urged; and permission was readily granted, as everyone felt that she had a special claim in the matter. Oswald therefore put in new plates, gave instructions as to how the shutters were to be worked, and retired to take up an elegant position in the centre of the group.

“Are you read-ee?” cried Peggy, in professional sing-song; then she put her head on one side and stared at the group with twinkling eyes. “Hee, hee! How silly you look! Everyone has a new expression for the occasion! Your own mothers would not recognise you! That’s better. Keep that smile going for another moment, and—how long must I keep off the cap, did you say?”

Oswald hesitated.

“Well, it varies. You have to use your own judgment. It depends upon—lots of things! You might try one second for the first, and two for the next, then one of them is bound to be right.”

“And one a failure! If I were going to depend on my judgment, I’d have a better one than that!” cried Peggy scornfully. “Ready! A little more cheerful, if you please—Christmas is coming! That’s one. Be so good as to remain in your positions, ladies and gentlemen, and I’ll try another.” The second shutter was pulled out, the cap removed, and the group broke up with sighs of relief, exhausted with the strain of cultivating company smiles for a whole two minutes on end. Max stayed to help the girls to fold up the camera, while Oswald darted into the house to prepare the dark room for the development of the plates.

When he came out, ten minutes later on, it was a pleasant surprise to discover Miss Mellicent holding a plate in her hand and taking sly peeps inside the shutter, just “to see how it looked.” He stormed and raved, while Mellicent looked like a martyr, wished to know how a teeny little light like that could possibly hurt anything, and seemed incapable of understanding that if one flash of sunlight could make a picture, it could also destroy it with equal swiftness. Oswald was forced to comfort himself with the reflection that there were still three plates uninjured; and, when all was ready, the six operators squeezed themselves in the dark room, to watch the process of development, indulging the while in the most flowery expectations.

“If it is very good, let me send it to an illustrated paper. Oh, do!” said Mellicent, with a gush. “I have often seen groups of people in them. ‘The thing-a-me-bob touring company,’ and stupid old cricketers, and things like that. We should be far more interesting.”

“It will make a nice present for mother, enlarged and mounted,” said Peggy thoughtfully. “I shall keep an album of my own, and mount every single picture we take. If there are any failures, I shall put them in too, for they will make it all the more amusing. Photograph albums are horribly uninteresting as a rule, but mine shall be quite different. There shall be nothing stiff and prim about it; the photographs shall be dotted about in all sorts of positions, and underneath each I shall put in—ah—conversational annotations.” Her tongue lingered over the words with triumphant enjoyment. “Conversational annotations, describing the circumstances under which it was taken, and anything about it which is worth remembering... What are you going to do with those bottles?”

Oswald ruffled his hair in embarrassment. To pose as an instructor in an art, when one is in doubt about its very rudiments, is a position which has its drawbacks.

“I don’t—quite—know. The stupid fellow has written instructions on all the other labels, and none on these except simply ‘Developer Number 1’ and ‘Developer Number 2’; I think the only difference is that one is rather stronger than the other. I’ll put some of the Number 2 in a dish, and see what happens; I believe that’s the right way—in fact, I’m sure it is. You pour it over the plate and jog it about, and in two or three minutes the picture ought to begin to appear. Like this!”

Five eager faces peered over his shoulders, rosy red in the light of the lamp; five pairs of lips uttered a simultaneous “Oh!” of surprise; five cries of dismay followed in instant echo. It was the tragedy of a second. Even as Oswald poured the fluid over the plate, a picture flashed before their eyes, each one saw and recognised some fleeting feature; and, in the very moment of triumph, lo, darkness, as of night, a sheet of useless, blackened glass!

“What about the conversational annotations?” asked Robert slily; but he was interrupted by a storm of indignant queries, levied at the head of the poor operator, who tried in vain to carry off his mistake with a jaunty air. Now that he came to think of it, he believed you did mix the two developers together! Just at the moment he had forgotten the proportions, but he would go outside and look it up in the book; and he beat a hasty retreat, glad to escape from the scene of his failure. It was rather a disconcerting beginning; but hope revived once more when Oswald returned, primed with information from the Photographic Manual, and Peggy’s plates were taken from their case and put into the bath. This time the result was slow in coming. Five minutes went by, and no signs of a picture—ten minutes, a quarter of an hour.

“It’s a good thing to develop slowly; you get the details better,” said Oswald, in so professional a manner that he was instantly reinstated in public confidence; but when twenty minutes had passed, he looked perturbed, and thought he would use a little more of the hastener. The bath was strengthened and strengthened, but still no signs of a picture. The plate was put away in disgust, and the second one tried with a like result. So far as it was possible to judge, there was nothing to be developed on the plate.

“A nice photographer you are, I must say! What are you playing at now?” asked Max, in scornful impatience; and Oswald turned severely to Peggy—