Title: The Nursery, March 1873, Vol. XIII.

Author: Various

Release date: January 31, 2008 [eBook #24476]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| IN PROSE. | |

| PAGE. | |

| The Pigeons and their Friend | 65 |

| The Obedient Chickens | 69 |

| John Ray's Performing Dogs | 71 |

| Ellen's Cure for Sadness | 75 |

| Kitty and the Bee | 78 |

| Little Mischief | 82 |

| How the Wind fills the Sails | 85 |

| Ida's Mouse | 88 |

| Almost Lost | 91 |

| Little May | 93 |

| An Important Disclosure | 95 |

IN VERSE. | |

| PAGE. | |

| Rowdy-Dowdy | 67 |

| The Sliders | 74 |

| Mr. Prim | 77 |

| Minding Baby | 80 |

| Deeds, not Words | 84 |

| Molly to her Dolly | 87 |

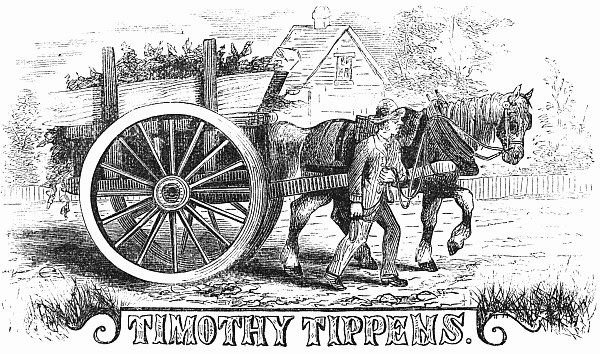

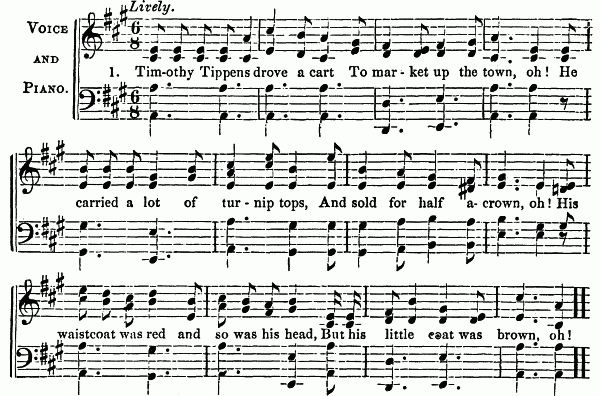

| Timothy Tippens (with music) | 96 |

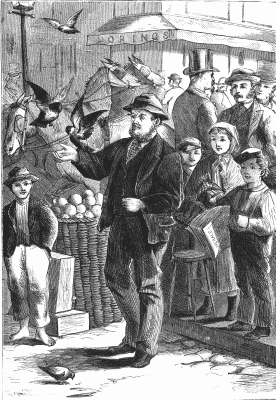

THE PIGEONS AND THEIR FRIEND.

THE PIGEONS AND THEIR FRIEND.

Here, just as you turn into Franklin Street, on the right, a poor peddler used to stand with a few baskets of oranges or apples or peanuts, which he offered for sale to the passers-by.

The street-pigeons had found in him a good friend; for he used to feed them with bits of peanuts, crumbs of bread, and seed: and every day, at a certain hour, they would fly down to get their food.

On the day when I stopped to see them, the sun shone, and the street was crowded; and many people stopped, like myself, to see the pretty sight.

The pigeons did not seem to be at all disturbed or frightened by the noise of carriages or the press of people; but would fly down, and light on the peddler's wrist, and peck the food from the palm of his hand.

He had made them so tame, that they would often light on his shoulders or on his head; and, if he put food in his mouth, they would try to get it even from between his teeth.

The children would flock round to see him; and even the busy newsboy would pause, and forget the newspapers under his arm, while he watched these interviews between the birds and their good friend.

A year afterwards I was in Boston again; but the poor peddler and his birds were not to be seen. All Franklin Street, and much of the eastern side of Washington Street,[67] were in ruins. There had been a great fire in Boston,—the largest that was ever known there; and more than fifty acres, crowded with buildings, had been made desolate, so that nothing but smoking ruins was left. This was in November, 1872.

I do not know where the poor peddler has gone; but I hope that his little friends, the pigeons, have found him out, and that they still fly down to bid him good-day, and take their dinner from his open hand.

The picture is an actual drawing from life, made on the spot, and not from memory. The likeness of the peddler is a faithful one; and I thank the artist for reproducing the scene so well to my mind. Folks do say that he has hit off my likeness also in the man standing behind the taller of the two little girls.

When I was a little girl, I had a nice great Shanghai hen given to me. She soon laid a nest full of eggs; and then I let her sit on them, till, to my great joy, she brought out a beautiful brood of chickens.

They were big fellows even at first, and had longer legs and fewer feathers than the other little yellow roly-poly broods that lived in our barn-yard. But, although I could see that they were not quite so pretty as the others, I made great pets of them.[70]

They were a lively, stirring family, and used to go roving all over the farm; but never was there a better behaved, or more thoroughly trained set of children. If a hawk, or even a big robin, went sailing over head, how quickly they scampered, and hid themselves at their mother's note of warning! and how meekly they all trotted roost-ward at the first sound of her brooding-call! I wish all little folks were as ready to go to bed at the right time.

One day when the chickens were five or six weeks' old, I saw them all following their mother into an old shed near the house. She led them up into one corner, and then, after talking to them for a few minutes in the hen language, went out and left them all huddled together.

She was gone for nearly an hour; and never once did they stir away from the place where she left them. Then she came back, and said just as plain as your mother could say it, only in another way, "Cluck, cluck, cluck! You've all been good chickens while I was away; have you? Well, now, we'll see what a good dinner we can pick up."

Out they rushed, pell-mell, as glad to be let out of their prison, and as pleased to see their mother again, as so many boys and girls would have been.

Well, day after day, this same thing happened. It came to be a regular morning performance; and we hardly knew what to make of it, until one day we followed old Mother Shanghai, and discovered her secret.

She had begun to lay eggs again, and was afraid some harm would come to her young family if she left them out in the field while she was in the barn on her nest. So she took this way of keeping them out of danger.

Of course, what she said to her brood when she left them must have been, "My dears, my duties now call me away from you for a little while; and you must stay right here,[71] where no harm can come to you, till I come back. Good-by!" And then off she would march as dignified and earnest as you please.

She did this for a number of weeks, until she thought her young folks were old and wise enough to be trusted out alone. Then she let them take care of themselves.

This is a true story.

There was once a little boy whose name was John Ray, and who lived near a large manufacturing town in England. When only seven years old, he fell from a tree, and was made a cripple for life.

His father, who was a sailor, was lost at sea soon afterwards;[72] and then, John's mother dying, the little boy was left an orphan. He was nine years of age when he went to live with Mrs. Lamson, his aunt,—a poor woman with a large family of young children.

It was a sad thought to John that he could not work so as to help his good aunt. It was his frequent prayer that he might do something so as not to be a burden to her; but for a long time he could not think of any thing to do.

One day a stray dog came to the house; and John gave him a part of his dinner. The dog liked the attention so well, that he staid near the house, and would not be driven off. Every day John gave him what he could spare.

One day, John said to him, "Doggie, what is your name? Is it Fido? Is it Frisk? Is it Nero? Is it Nap? Is it Tiger? Is it Toby? Is it Plato? Is it Pomp?"

When John uttered the word "Pomp," the dog began to bark; and John said, "Well, sir, then your name shall be Pomp." Then John began to play with him, and found that Pomp was not only acquainted with a good many tricks, but was quick to learn new ones.

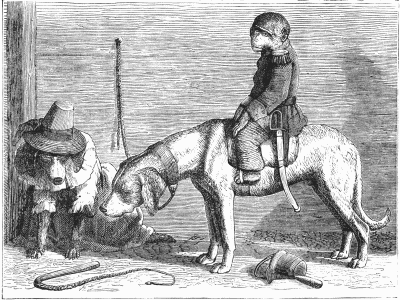

Pomp would walk on his hind-legs better than any dog that John ever saw. Pomp would let John dress him up in an old coat and a hat; and would sit on a chair, and hold the reins that were put in his paws, just as if he were a coachman.

Pomp learned so well, and afforded such amusement to those who saw his tricks, that the thought occurred to John, "What if I try to earn some money by exhibiting Pomp?"

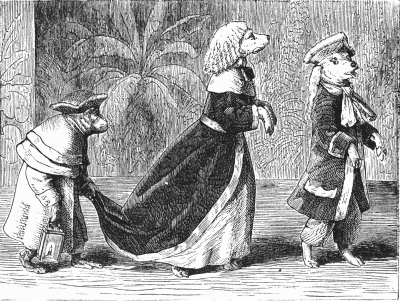

So John exhibited him in a small way, to some of the neighbors, and with so much success, that he bought another dog and a monkey, and began to teach all three to play tricks together.

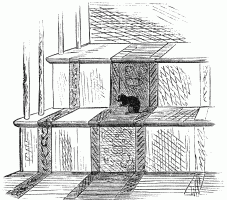

A kind lady, who had been informed of his efforts to do something for his aunt, made some nice dresses for the dogs[73] and the monkey. The pictures will show you how the animals looked when dressed up for an exhibition.

The kind lady did still more: she hired a hall in which John could show off his dogs; and then she sold five hundred tickets for a grand entertainment. It was so successful, that John was called upon to repeat it many times.

Oh! was he not a proud and happy little boy when he found himself so rich that he could put a twenty-pound note in the hands of his aunt as a token that he was grateful for all her care of him?

It was more money than the poor woman had had at any one time in her whole life before; and she kissed her little nephew, and called him the best boy in the world.

John and his dogs grew to be so famous, that he had to go to other cities to show them; and soon he earned money enough to keep him till he could learn to be a watchmaker.[74]

As he was a diligent, faithful workman, he at last became the owner of a nice house, and then took his aunt and some of her children to live with him.

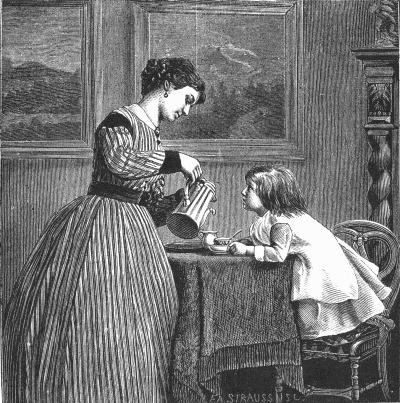

Our little Ellen is never in a good temper when she comes down late to breakfast, and finds the things cleared away. First she complains that her bowl of bread and milk is too hot; and then, when Aunt Alice pours in some water to cool it, Ellen says, "It is now too cold."

I think the fault is in herself. She is five years old,—quite old enough to know that she ought to get up when the first bell rings, and come down to breakfast. She knows she is in fault. She has missed papa's kiss, for he had to leave home early on business; and this adds to her grief.

But, after she had eaten her bread and milk on the day I am speaking of, she asked Aunt Alice what she should do to cure herself of her "sadness." "I think that the best plan, in such cases, is to try to do some good to somebody,"[76] said Aunt Alice. "The best way to cheer yourself is to cheer another."

This made Ellen thoughtful; and she stood at the window, looking out on the street, long after Aunt Alice had left the room. It was a cold, cloudy day, and there were flakes of snow in the air. Ellen stood watching a poor woman at the corner, who was trying to sell shoe-strings; but nobody stopped to buy of her.

"That poor woman looks sad and discouraged," said Ellen[77] to herself: "she must be almost as sad as I am. How can I comfort her? Why, by buying some of her shoestrings, of course."

Ellen had some money of her own put away in a box. She ran and got it, then, putting on her bonnet, went out and bought a whole bunch of shoestrings. Then, with her aunt's consent, she asked the poor woman to come in and get some luncheon.

The poor woman gladly accepted the invitation; and Ellen soon had her seated by a nice fire in the kitchen, chatting and laughing with the maids as merrily as if she had no care in the world.

"Have I made you happy?" asked Ellen. "That you have, you darling," said the poor woman, with a tear in her eye. "And so you have made me happy," replied Ellen. Yes, she had found that Aunt Alice was in the right. "The best way to cheer yourself is to cheer another."

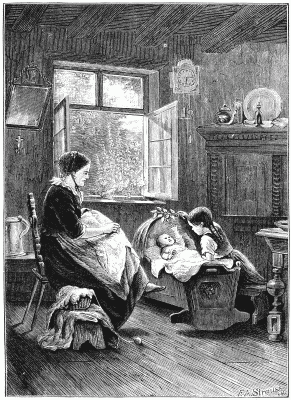

MINDING BABY.

MINDING BABY.

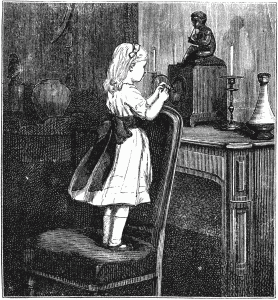

Bessie went into the parlor one day, and noticed that the clock did not tick. "I must wind it up," thought she. "It must be very easy, for you only have to turn the key round and round."

So Bessie began to turn the key. At first it would not move; but then she tried it the other way, and it went round and round quite easily. She was determined to do it thoroughly while she was about it: so she went on winding and winding, and was charmed to hear it begin to tick.

But all at once it made a noise,—burr-r-r-r,—and then it stopped ticking.[83]

The hands, too, that had been going so fast, stood still. What could be the reason of it? Had it really stopped? Bessie put her ear quite near, and listened. Yes, there was not a sound.

She began to feel frightened, and to think that perhaps, after all, she had better have left it alone. Her mother came into the room and said, "What are you doing, Bessie? You must have broken the mainspring of the clock."

"I saw it was not going, mamma, and so I wound it up," sobbed out Bessie: "I did not mean to break it." That was all she could say.

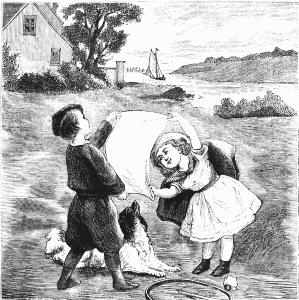

"What makes the vessel move on the river?" asked little Anna one day of her brother Harry.

"Why," said Harry, "it's the wind, of course, that fills the sails, and that pushes the vessel on. Come out on the bank, and I will show you how it is done."

So Anna, Harry, and Bravo, all ran out on the lawn. Bravo was a dog; but he was always curious to see what was going on.

When they were on the lawn, Harry took out his handkerchief, and told Anna to hold it by two of the corners while he held the other two.

As soon as they had done this, the wind made it swell out, and look just like a sail.

"Now you see how the wind fills the sails," said Harry.[86]

"Yes; but how does it make the ship go?" asked Anna.

"Well, now let go of the handkerchief, and see what becomes of it," said Harry.

So they both let go of it; and off the wind bore it up among the bushes by the side of the house.

In order to explain the matter still further to his sister, Harry made a little flat boat out of a shingle, and put in it a mast, and on the mast a paper sail.

Then they went down to the river and launched it; and, much to Anna's delight, the wind bore it far out towards the middle of the stream.

Bravo swam out, took it in his mouth, and brought it back; and Anna was at last quite satisfied that she knew how it is that the wind makes the vessel go on the river.

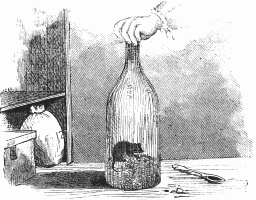

One morning when Ida went to the closet for the birdseed to feed her canary, she found a wee brown mouse in the bottom of the bottle where the seed was kept. Instead of screaming and running away, Ida clapped her fat little hand over the mouth of the bottle, and mousie was a prisoner.

Mamma said mousie should be drowned; but Ida begged so hard to keep him, that mamma got a glass jar, put mousie into it, with a bit of bread and cheese to keep him company,[89] tied a piece of tin, all pricked with little holes, over the mouth of the jar, and set it on the shelf.

Ida spent half the day in watching the mouse.

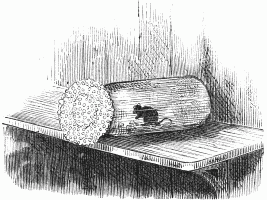

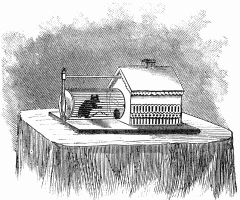

When papa came home at night, he brought a funny little tin house for mousie's cage. Mousie was put into it; and he soon began to make the wire-wheel go round. He turned the wheel so fast and so long, that he soon made his nose sore. Ida thought he was very tame; but I think he only wanted to get out and run away.

One day mousie managed to get his door open and scamper off. Then Ida cried and cried, and was afraid her dear mousie would starve. But after a day or two, as grandma was going up stairs, she saw little mousie hopping up ahead of her.

He ran into Ida's closet. Ida brought the cage; and mamma and grandma made mousie run into it.

"Perhaps it is not the same mouse," said grandma.

"Oh, yes, it is!" said Ida. "I know him by his sore nose."

Ida took good care of mousie till warm weather came, and it was time to go into the country for the summer. Then she took the cage outside the back-gate, and opened mousie's door. Mousie was very quiet at first; but soon he peeped out, and, seeing nothing to hinder, he ran away as fast as his little legs could carry him.

I am glad that he was set free; for I do not think he was happy in the cage. I hope he will keep away from traps and cats, and live to a good old age.

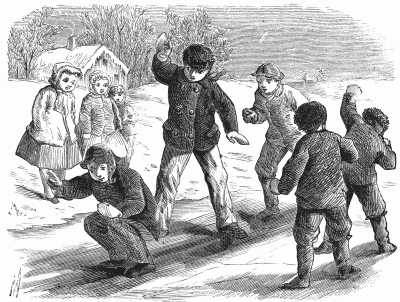

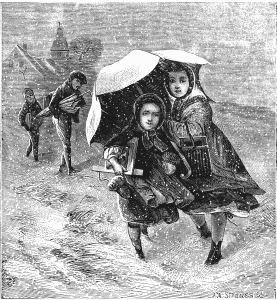

Soon after school had commenced, it began snowing so, that the mistress dismissed all the scholars, and they started for their homes.

Among the girls were two little sisters, Julia and Emily Burns, who lived a mile and a half from the schoolhouse, and had to cross a wide field, and pass through a wood, before they could reach the well-known road that led up to their own house.[92]

They had an umbrella with them; and Julia, the elder sister, had a leather bag on her arm, containing their luncheon. Soon the snow began to fall with blinding force: the wind blew, and they could not see their way.

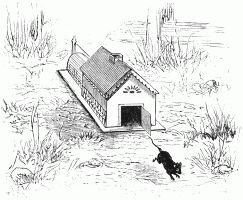

They were by this time near the entrance to the wood. Emily began to cry with alarm; but Julia said, "Do not be afraid. See! there is the little old shanty where the wood-choppers used to go in winter to eat their dinners. We will go in there, and stop till somebody comes for us."

So they went in; and, as good luck would have it, Julia found some matches in an old box on the shelf. There were plenty of pine-chips, too, lying in the corner of the one room, which was all that the shanty afforded.

Soon Julia had a merry fire blazing on the hearth; then Emily began to laugh. They sat down on a log, and warmed themselves; and Julia drew forth their luncheon from the leather bag, and they ate a hearty meal.

What do you suppose the sisters did after that? Why, they began to sing songs, and tell stories, and repeat riddles; and they were in the midst of this, when they heard the sound of voices.

"Oh, dear! what's that?" cried Emily.

"It sounds very much like papa's voice," said Julia; "and that bow-wow sounds like the voice of old Tiger. Yes, here they come."

And the next moment the children's father, with two big boys, sons of one of their neighbors, burst into the room; and papa exclaimed, "Why, you little rogues, how I have worried about you! And here you are as comfortable as a mouse in a meal-bag!"

Then old Tiger began to frisk round them, and to jump up as if to kiss them. "Down, old fellow!" said Mr. Burns: "you told us where they were; didn't you, old Tiger?"[93]

Tiger barked loudly, as much as to say, "Yes, I told you where they were; and I think I am the smartest dog that ever lived. Bow-wow! Of all the dogs ever told about in 'The Nursery,' I am the wisest, the bravest, the handsomest, and the best. Bow-wow!"

There were pigs and chickens and cows and a good old gray pony on the farm where little May lived.

May loved them all; and they all seemed to love her.

The cows, as they lay chewing their cud, would let the little girl pat them as much as she pleased. They never[94] shrank from the touch of her soft little hands. Sometimes papa would let May stand beside him when he milked. Then she would be sure to get a good saucer of milk to feed the kittens with. She was a great friend of all the cats.

She took great delight in feeding the chickens; and she even liked to throw bits to the pigs. It made her laugh to see piggy, with one foot in the trough, champing his food with such a relish.

Once she saw her papa scratch piggy's back with an old broom. So, a few days after, she thought she would try it; but, instead of getting an old broom, she took a nice new one, and, reaching over the side of the pen, managed to touch the pig's back with it.

Now, what do you think that ungrateful animal did? He caught the broom in his mouth, and began to chew it.

Off went May to her mother as fast as her little feet could carry her. "Mamma, mamma!" said she, "come quick. Oh, dear, dear! piggy is eating the broom."

To be sure, there was mamma's best carpet-broom all chewed down to a stub; and the pig was still eating away.

May cried then; but it was so very funny, that mamma only laughed, and by and by May laughed too. When papa got home, he was told the story, and it made him laugh.

May was almost ready to cry again; for she felt sorry, and she did not like to be laughed at. "There's nothing to cry about, darling," said her papa; "but don't try to scratch the pig's back again until I show you how to do it."

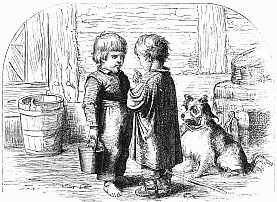

"I want to tell you something, Tommy."

"What is it?"

"The country is going to ruin."

"You don't say so! What's the matter?"

"Rag currency is the matter."

"What's that?"

"I'll explain. You paid for that kettle of milk ten cents. You paid in rag currency. Did you ever see a silver dime?"

"No, Billy; but my big brother has seen one."

"Well, that is specie. Now, what we want is specie payment."

"How do you know?"

"My father says so."

Carlo the dog listens attentively, and seems to be absorbed in a profound reflection upon the currency question.

2

| 3

|

Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

The last line of the second verse of the song on page 96 was not indented in the original.

This issue was part of an omnibus. The original text for this issue did not include a title page or table of contents. This was taken from the January issue with the "No." added. The original table of contents covered the entire year of 1873. The remaining text of the table of contents can be found in the rest of the year's issues.