Captain Mayne Reid

"The Land of Fire"

Preface.

This tale is the last from the pen of Captain Mayne Reid, whose stories have so long been the delight of English boys. Our readers may, perhaps, like to know something of the writer who has given them so much pleasure; especially as his own life was full of adventure and of brave deeds.

Mayne Reid was born in the north of Ireland in 1819; his father was a Presbyterian minister, and wished that his son should also be a clergyman; but the boy longed for adventure, and to see the world in its wildest places, and could not bring himself to settle down to a quiet life at home.

When he was twenty years old he set out on his travels, and, landing at New Orleans, began a life of adventure in the prairies and forests of America—good descriptions of which were given by him in his books.

In 1845 a war broke out between the United States and Mexico, and young Reid instantly volunteered his services to fight on the United States’ side.

He received the commission of lieutenant in a New York regiment, and fought all through the campaign with the most dauntless courage. He received several wounds, and gained a high reputation for generous good feeling.

The castle of Chapultepec commanded the high road to the city of Mexico, and as it was very strongly defended, and the Mexicans had thirty thousand soldiers to the American six thousand, to take it was a work requiring great courage.

Reid was guarding a battery which the Americans had thrown up on the south-east side of the castle, with a grenadier company of New York volunteers and a detachment of United States’ marines under his command. From thence he cannonaded the main gate for a whole day. The following morning a storming party was formed of five hundred volunteers, and at eleven o’clock the batteries ceased firing, and the attack began.

Reid and the artillery officers, standing by their guns, watched with great anxiety the advance of the line, and were alarmed when they saw that half-way up the hill there was a halt.

“I knew,” he said in his account, “that if Chapultepec was not taken, neither would the city be; and, failing that, not a man of us might ever leave the Valley of Mexico alive.” He instantly asked leave of the senior engineering officer to join the storming-party with his grenadiers and marines. The officer gave it, and Reid and his men at once started at a swift run, and came up with the storming-party under the brow of the hill, where it had halted to wait for scaling ladders.

The fire from the castle was constant, and very fatal. The men faltered, and several officers were wounded while urging them on. Suddenly Reid, conspicuous by his brilliant uniform, sprang to his feet, and shouted, “Men, if we don’t take Chapultepec, the American army is lost. Let us charge up the walls!”

The soldiers answered, “We are ready.”

At that moment the three guns on the parapet fired simultaneously. There would be a moment’s interval while they reloaded. Reid seized that interval, and crying “Come on,” leaped over the scarp, and rushed up to the very walls. Half-way up he saw that the parapet was crowded with Mexican gunners, just about to discharge their guns. He threw himself on his face, and thus received only a slight wound on his sword hand, while another shot cut his clothes.

Instantly on his feet again, he made for the wall, but in front of it he was struck down by a Mexican bullet tearing through his thigh.

There Lieutenant Cochrane, of the Voltigeurs, saw him as he advanced to the walls. Reid raised himself, and sang out, entreating the men to stand firm.

“Don’t leave the wall,” he cried, “or we shall be cut to pieces. Hold on, and the castle is ours.”

“There is no danger of our leaving it, captain,” said Cochrane; “never fear!”

Then the scaling ladders were brought, the rush was made, and the castle taken. But Reid had been the very first man under its walls.

When the war was over, Captain Reid resigned his commission in the American army, and organised a body of men in New York to go and fight for the Hungarians, but news reached him in Paris that the Hungarian insurrection was ended, so he returned to England.

Here he settled down to literary work, publishing “The Scalp Hunters,” and many wonderful stories of adventure and peril.

The great African explorer, the good Dr Livingstone, said in the last letter he ever wrote, “Captain Mayne Reid’s boys’ books are the stuff to make travellers.”

Captain Mayne Reid died on the twenty-first of October, 1883, and the “Land of Fire” is his unconscious last legacy to the boys of Great Britain, and to all others who speak the English language.

Chapter One.

“The Sea! The Sea! The Open Sea!”

One of the most interesting of English highways is the old coach road from London to Portsmouth. Its interest is in part due to the charming scenery through which it runs, but as much to memories of a bygone time. One travelling this road at the present day might well deem it lonely, as there will be met on it only the liveried equipage of some local magnate, the more unpretentious turn-out of country doctor or parson, with here and there a lumbering farm waggon, or the farmer himself in his smart two-wheeled “trap,” on the way to a neighbouring market.

How different it was half a century ago, when along this same highway fifty four-horse stages were “tooled” to and fro from England’s metropolis to her chief seaport town, top-heavy with fares—often a noisy crowd of jovial Jack tars, just off a cruise and making Londonward, or with faces set for Portsmouth, once more to breast the billows and brave the dangers of the deep! Many a naval officer of name and fame historic, such as the Rodneys, Cochranes, Collingwoods, and Codringtons,—even Nile’s hero himself,—has been whirled along this old highway.

All that is over now, and long has been. To-day the iron horse, with its rattling train, carries such travellers by a different route—the screech of its whistle being just audible to wayfarers on the old road, as in mockery of their crawling pace. Of its ancient glories there remain only the splendid causeway, still kept in repair, and the inns encountered at short distances apart, many of them once grand hostelries. They, however, are not in repair; instead, altogether out of it. Their walls are cracked and crumbling to ruins, the ample courtyards are grass-grown and the stables empty, or occupied only by half a dozen clumsy cart-horses; while of human kind moving around will be a lout or two in smock-frocks, where gaudily-dressed postillions, booted and spurred, with natty ostlers in sleeve-waistcoats, tight-fitting breeches, and gaiters, once ruled the roast.

Among other ancient landmarks on this now little-used highway is one of dark and tragic import. Beyond the town of Petersfield, going southward, the road winds up a long steep ridge of chalk formation—the “South Downs,” which have given their name to the celebrated breed of sheep. Near the summit is a crater-like depression, several hundred feet in depth, around whose rim the causeway is carried—a dark and dismal hole, so weird of aspect as to have earned for it the appellation of the “Devil’s Punch Bowl.” Human agency has further contributed to the appropriateness of the title. By the side of the road, just where it turns around the upper edge of the hollow, is a monolithic monument, recording the tragic fate of a sailor who was there murdered and his dead body flung into the “Bowl.” The inscription further states that justice overtook his murderers, who were hanged on the selfsame spot, the scene of their crime. The obelisk of stone, with its long record, occupying the place where stood the gallows-tree.

It is a morning in the month of June; the hour a little after daybreak. A white fog is over the land of South Hampshire—so white that it might be taken for snow. The resemblance is increased by the fact of its being but a layer, so low that the crests of the hills and tree-tops of copses appear as islets in the ocean, with shores well defined, though constantly shifting. For, in truth, it is the effect of a mirage, a phenomenon aught but rare in the region of the South Downs.

The youth who is wending his way up the slope leading to the Devil’s Punch Bowl takes no note of this illusion of nature. But he is not unobservant of the fog itself; indeed, he seems pleased at having it around him, as though it afforded concealment from pursuers. Some evidence of this might be gathered from his now and then casting suspicious glances rearward, and at intervals stopping to listen. Neither seeing nor hearing anything, however, he continues up the hill in a brisk walk, though apparently weary. That he is tired can be told by his sitting down on a bank by the roadside as soon as he reaches the summit, evidently to rest himself. What he carries could not be the cause of his fatigue—only a small bundle done up in a silk handkerchief. More likely it comes from his tramp along the hard road, the thick dust over his clothes showing that it had been a long one.

Now, high up the ridge, where the fog is but a thin film, the solitary wayfarer can be better observed, and a glance at his face forbids all thought of his being a runaway from justice. Its expression is open, frank, and manly; whatever of fear there is in it certainly cannot be due to any consciousness of crime. It is a handsome face, moreover, framed in a profusion of blonde hair, which falls curling down cheeks of ruddy hue. An air of rusticity in the cut of his clothes would bespeak him country bred, probably the son of a farmer. And just that he is, his father being a yeoman-farmer near Godalming, some thirty miles back along the road. Why the youth is so far from home at this early hour, and afoot—why those uneasy glances over the shoulder, as if he were an escaping convict—may be gathered from some words of soliloquy half-spoken aloud by him, while resting on the bank:

“I hope they won’t miss me before breakfast-time. By then I ought to be in Portsmouth, and if I’ve the luck to get apprenticed on board a ship, I’ll take precious good care not to show myself on shore till she’s off. But surely father won’t think of following this way—not a bit of it. The old bailiff will tell him what I said about going to London, and that’ll throw him off the scent completely.”

The smile that accompanied the last words is replaced by a graver look, with a touch of sadness in the tone of his voice as he continues:

“Poor dear mother, and sis Em’ly! It’ll go hard with them for a bit, grieving. But they’ll soon get over it. ’Tisn’t like I was leaving them never to come back. Besides, won’t I write mother a letter soon as I’m sure of getting safe off?”

A short interval of silent reflection, and then follow words of a self-justifying nature:

“How could I help it? Father would insist on my being a farmer, though he knows how I hate it. One clodhopper in the family’s quite enough; and brother Dick’s the man for that. As the song says, ‘Let me go a-ploughing the sea.’ Yes, though I should never rise above being a common sailor. Who’s happier than the jolly Jack tar? He sees the world, any way, which is better than to live all one’s life, with head down, delving ditches. But a common sailor—no! Maybe I’ll come home in three or four years with gold buttons on my jacket and a glittering band around the rim of my cap. Ay, and with pockets full of gold coin! Who knows? Then won’t mother be proud of me, and little Em too?”

By this time the uprisen sun has dispelled the last lingering threads of mist, and Henry Chester (such is the youth’s name) perceives, for the first time, that he has been sitting beside a tall column of stone. As the memorial tablet is right before his eyes, and he reads the inscription on it, again comes a shadow over his countenance. May not the fate of that unfortunate sailor be a forecast of his own? Why should it be revealed to him just then? Is it a warning of what is before him, with reproach for his treachery to those left behind? Probably, at that very moment, an angry father, a mother and sister in tears, all on his account!

For a time he stands hesitating; in his mind a conflict of emotions—a struggle between filial affection and selfish desire. Thus wavering, a word would decide him to turn back for Godalming and home. But there is no one to speak that word, while the next wave of thought surging upward brings vividly before him the sea with all its wonders—a vision too bright, too fascinating, to be resisted by a boy, especially one brought up on a farm. So he no longer hesitates, but, picking up his bundle, strides on toward Portsmouth.

A few hundred paces farther up, and he is on the summit of the ridge, there to behold the belt of low-lying Hampshire coastland, and beyond it the sea itself, like a sheet of blue glass, spreading out till met by the lighter blue of the sky. It is his first look upon the ocean, but not the last; it can surely now claim him for its own.

Soon after an incident occurs to strengthen him in the resolve he has taken. At the southern base of the “Downs,” lying alongside the road, is the park and mansion of Horndean. Passing its lodge-gate, he has the curiosity to ask who is the owner of such a grand place, and gets for answer, “Admiral Sir Charles Napier.” (See Note 1.)

“Might not I some day be an admiral?” self-interrogates Henry Chester, the thought sending lightness to his heart and quickening his steps in the direction of Portsmouth.

Note 1. The Sir Charles Napier known to history as the “hero of Saint Jean d’Acre,” but better known to sailors in the British navy as “Old Sharpen Your Cutlasses!” This quaint soubriquet he obtained from an order issued by him when he commanded a fleet in the Baltic, anticipating an engagement with the Russians.

Chapter Two.

The Star-Spangled Banner.

The clocks of Portsmouth are striking nine as the yeoman-farmer’s son enters the suburbs of the famous seaport. He lingers not there, but presses on to where he may find the ships—“by the Hard, Portsea,” as he learns on inquiry. Presently a long street opens before him, at whose farther end he descries a forest of masts, with their network of spars and rigging, like the web of a gigantic spider. Ship he has never seen before, save in pictures or miniature models; but either were enough for their identification, and the youth knows he is now looking with waking eyes at what has so often appeared to him in dreams.

Hastening on, he sees scores of vessels lying at anchor off the Hard, their boats coming and going. But they are men-of-war, he is told, and not the sort for him. Notwithstanding his ambitious hope of one day becoming a naval hero, he does not quite relish the idea of being a common sailor—at least on a man-of-war. It were too like enlisting in the army to serve as a private soldier—a thing not to be thought of by the son of a yeoman-farmer. Besides, he has heard of harsh discipline on war-vessels, and that the navy tar, when in a foreign port, is permitted to see little more of the country than may be viewed over the rail or from the rigging of his ship. A merchantman is the craft he inclines to—at least, to make a beginning with—especially one that trades from port to port, visiting many lands; for, in truth, his leaning toward a sea life has much to do with a desire to see the world and its wonders. Above all, would a whaler be to his fancy, as among the most interesting books of his reading have been some that described the “Chase of Leviathan,” and he longs to take a part in it.

But Portsmouth is not the place for whaling vessels, not one such being there.

For the merchantmen he is directed to their special harbour, and proceeding thither he finds several lying alongside the wharves, some taking in cargo, some discharging it, with two or three fully freighted and ready to set sail. These last claim his attention first, and, screwing up courage, he boards one, and asks if he may speak with her captain.

The captain being pointed out to him, he modestly and somewhat timidly makes known his wishes. But he meets only with an offhand denial, couched in words of scant courtesy.

Disconcerted, though not at all discouraged, he tries another ship; but with no better success. Then another, and another with like result, until he has boarded nearly every vessel in the harbour having a gangway-plank out. Some of the skippers receive him even rudely, and one almost brutally, saying, “We don’t want landlubbers on this craft. So cut ashore—quick!”

Henry Chester’s hopes, high-tide at noon, ere night are down to lowest ebb, and, greatly humiliated, he almost wishes himself back on the old farmstead by Godalming. He is even again considering whether it would not be better to give it up and go back, when his eyes chance to stray to a flag on whose corner is a cluster of stars on a blue ground, with a field of red and white bands alternating. It droops over the taffrail of a barque of some six hundred tons burden, and below it, on her stern, is lettered the Calypso. During his perambulations to and fro he has more than once passed this vessel, but the ensign not being English, he did not think of boarding her. Refused by so many skippers of his own country, what chance would there be for him with one of a foreign vessel? None whatever, reasoned he. But now, more intelligently reflecting, he bethinks him that the barque, after all, is not so much a foreigner, a passer-by having told him she is American—or “Yankee,” as it was put—and the flag she displays is the famed “Star-spangled Banner.”

“Well,” mutters the runaway to himself, “I’ll make one more try. If this one, too, refuses me, things will be no worse, and then—then—home, I suppose.”

Saying which, he walks resolutely up the sloping plank and steps on board the barque, to repeat there the question he has already asked that day for the twentieth time—“Can I speak with the captain?”

“I guess not,” answers he to whom it is addressed, a slim youth who stands leaning against the companion. “Leastways, not now, ’cause he’s not on board. What might you be wantin’, mister? Maybe I can fix it for you.”

Though the words are encouraging and the tone kindly, Henry Chester has little hopes that he can, the speaker being but a boy himself. Still, he speaks in a tone of authority, and though in sailor garb, it is not that of a common deck hand.

He is in his shirt-sleeves, the day being warm; but the shirt is of fine linen, ruffled at the breast, and gold-studded, while a costly Panama hat shades his somewhat sallow face from the sun. Besides, he is on the quarter-deck, seeming at home there.

Noting these details, the applicant takes heart to tell again his oft-told tale, and await the rejoinder.

“Well,” responds the young American, “I’m sorry I can’t give you an answer about that, the cap’n, as I told you, not being aboard. He’s gone ashore on some Custom House business. But, if you like, you can come again and see him.”

“I would like it much; when might I come?”

“Well, he might be back any minute. Still, it’s uncertain, and you’d better make it to-morrow morning; you’ll be sure to find him on board up till noon, anyhow.”

Though country born and bred, Henry Chester was too well-mannered to prolong the interview, especially after receiving such courteous treatment, the first shown him that day. So, bowing thanks as well as speaking them, he returns to the wharf. But, still under the influence of gratitude, he glances back over the barque’s counter, to see on her quarter-deck what intensifies his desire to become one of her crew. A fair vision it is—a slip of a girl, sweet-faced and of graceful form, who has just come out of the cabin and joined the youth, to all appearance asking some question about Chester himself, as her eyes are turned shoreward after him. At the same time a middle-aged ladylike woman shows herself at the head of the companion-ladder, and seems interested in him also.

“The woman must be the captain’s wife and the girl his daughter,” surmises the English youth, and correctly. “But I never knew that ladies lived on board ships, as they seem to be doing. An American fashion, I suppose. How different from all the other vessels I’ve visited! Come back to-morrow morning? No, not a bit of it. I’ll hang about here, and wait the captain’s return. That will I, if it be till midnight.”

So resolving, he looks around for a place where he may rest himself. After his thirty miles’ trudge along the king’s highway, with quite ten more back and forth on the wharves, to say nought of the many ships boarded, he needs rest badly. A pile of timber here, with some loose planks alongside it, offers the thing he is in search of; and on the latter he seats himself, leaning his back against the boards in such a position as to be screened from the sight of those on the barque, while he himself commands a view of the approaches to her gangway-plank.

For a time he keeps intently on the watch, wondering what sort of man the Calypso’s captain may be, and whether he will recognise him amidst the moving throng. Not likely, since most of those passing by are men of the sea, as their garb betokens. There are sailors in blue jackets and trousers that are tight at the hip and loose around the ankles, with straw-plaited or glazed hats, bright-ribboned, and set far back on the head; other seamen in heavy pilot-cloth coats and sou’-westers; still others wearing Guernsey frocks and worsted caps, with long points drooping down over their ears. Now, a staid naval officer passes along in gold-laced uniform, and sword slung in black leathern belt; now, a party of rollicking midshipmen, full of romp and mischief.

Not all who pass him are English: there are men loosely robed and wearing turbans, whom he takes to be Turks or Egyptians, which they are; others, also of Oriental aspect, in red caps with blue silk tassels—the fez. In short, he sees sailors of all nations and colours, from the blonde-complexioned Swede and Norwegian to the almost jet-black negro from Africa.

But while endeavouring to guess the different nationalities, a group at length presents itself which puzzles him. It is composed of three individuals—a man, boy, and girl, their respective ages being about twenty-five, fifteen, and ten. The oldest—the man—is not much above five feet in height, the other two short in proportion. All three, however, are stout-bodied, broad-shouldered, and with heads of goodly size, the short slender legs alone giving them a squat diminutive look. Their complexion is that of old mahogany; hair straight as needles, coarse as bristles, and crow-black; eyes of jet, obliqued to the line of the nose, this thin at the bridge, and depressed, while widely dilated at the nostrils; low foreheads and retreating chins—such are the features of this singular trio. The man’s face is somewhat forbidding, the boy’s less so, while the countenance of the girl has a pleasing expression—or, at least, a picturesqueness such as is commonly associated with gipsies. What chiefly attracts Henry Chester to them, however, while still further perplexing him as to their nationality, is that all three are attired in the ordinary way as other well-dressed people in the streets of Portsmouth. The man and boy wear broadcloth coats, tall “chimney-pot” hats, and polished boots; white linen shirts, too, with standing collars and silk neckties, the boy somewhat foppishly twirling a light cane he carries in his kid-gloved hand. The girl is dressed neatly and becomingly in a gown of cotton print, with a bright coloured scarf over her shoulders and a bonnet on her head, her only adornment being a necklace of imitation pearls and a ring or two on her fingers.

Henry Chester might not have taken such particular notice of them, but that, when opposite him, they came to a stand, though not on his account. What halts them is the sight of the starred and striped flag on the Calypso, which is evidently nothing new to them, however rare a visitor in the harbour of Portsmouth. A circumstance that further surprises Henry is to hear them converse about it in his own tongue.

“Look, Ocushlu!” exclaims the man, addressing the girl, “that the same flag we often see in our own country on sealing ships.”

“Indeed so—just same. You see, Orundelico?”

“Oh, yes!” responds the boy, with a careless toss of head and wave of the cane, as much as to say, “What matters it?”

“’Merican ship,” further observes the man. “They speak Inglis, same as people here.”

“Yes, Eleparu,” rejoins the boy, “that true; but they different from Inglismen—not always friends; sometimes they enemies and fight. Sailors tell me that when we were in the big war-ship.”

“Well, it no business of ours,” returns Eleparu. “Come ’long.” Saying which he leads off, the others following, all three at intervals uttering ejaculations of delighted wonder as objects novel and unknown come before their eyes.

Equally wonders the English youth as to who and what they may be. Such queer specimens of humanity! But not long does he ponder upon it. Up all the night preceding and through all that day, with his mind constantly on the rack, his tired frame at length succumbs, and he falls asleep.

Chapter Three.

Portsmouth Mud-Larks.

The Hampshire youth sleeps soundly, dreaming of a ship manned by women, with a pretty childlike girl among the crew. But he seems scarcely to have closed his eyes before he is awakened by a clamour of voices, scolding and laughing in jarring contrast. Rubbing his eyes and looking about him, he sees the cause of the strange disturbance, which proceeds from some ragged boys, of the class commonly termed “wharf-rats” or “mud-larks.” Nearly a dozen are gathered together, and it is they who laugh; the angry voices come from others, around whom they have formed a ring and whom they are “badgering.”

Springing upon his feet, he hurries toward the scene of contention, or whatever it may be, not from curiosity, but impelled by a more generous motive—a suspicion that there is foul play going on. For among the mud-larks he recognises one who, early in the day, offered insult to himself, calling him a “country yokel.” Having other fish to fry, he did not at the time resent it; but now he will see.

Arriving at the spot, he sees, what he has already dimly suspected, that the mud-larks’ victims are the three odd individuals who lately stopped in front of him. But it is not they who are most angry; instead, they are giving the “rats” change in kind, returning their “chaff,” and even getting the better of them, so much so that some of their would-be tormentors have quite lost their tempers. One is already furious—a big hulking fellow, their leader and instigator, and the same who had cried, “country yokel.” As it chances, he is afflicted with an impediment of speech, in fact, stutters badly, making all sorts of twitching grimaces in the endeavour to speak correctly. Taking advantage of this, the boy Orundelico—“blackamoor,” as he is being called—has so turned the tables on him by successful mimicry of his speech as to elicit loud laughter from a party of sailors loitering near. This brings on a climax, the incensed bully, finally losing all restraint of himself, making a dash at his diminutive mocker, and felling him to the pavement with a vindictive blow.

“Tit-it-it-take that, ye ugly mim-m–monkey!” is its accompaniment in speech as spiteful as defective.

The girl sends up a shriek, crying out:

“Oh, Eleparu! Orundelico killed! He dead!”

“No, not dead,” answers the boy, instantly on his feet again like a rebounding ball, and apparently but little injured. “He take me foul. Let him try once more. Come on, big brute!”

And the pigmy places himself in a defiant attitude, fronting an adversary nearly twice his own size.

“Stan’ side!” shouts Eleparu, interposing. “Let me go at him!”

“Neither of you!” puts in a new and resolute voice, that of Henry Chester, who, pushing both aside, stands face to face with the aggressor, fists hard shut, and eyes flashing anger. “Now, you ruffian,” he adds, “I’m your man.”

“Wh–wh–who are yi-yi-you? an’ wh–wh–what’s it your bi-bib-business?”

“No matter who I am; but it’s my business to make you repent that cowardly blow. Come on and get your punishment!”

And he advances towards the stammerer, who has shrunk back.

This unlooked-for interference puts an end to the fun-making of the mud-larks, all of whom are now highly incensed, for in their new adversary they recognise a lad of country raising—not a town boy—which of itself challenges their antagonistic instincts.

On these they are about to act, one crying out, “Let’s pitch into the yokel and gie him a good trouncin’!” a second adding, “Hang his imperence!” while a third counsels teaching him “Portsmouth manners.”

Such a lesson he seems likely to receive, and it would probably have fared hardly with our young hero but for the sudden appearance on the scene of another figure—a young fellow in shirt-sleeves and wearing a Panama hat—he of the Calypso.

“Thunder and lightning!” he exclaimed, coming on with a rush. “What’s the rumpus about? Ha! a fisticuff fight, with odds—five to one! Well, Ned Gancy ain’t going to stand by an’ look on at that; he pitches in with the minority.”

And so saying, the young American placed himself in a pugilistic attitude by the side of Henry Chester.

This accession of strength to the assailed party put a different face on the matter, the assailants evidently being cowed, despite their superiority of numbers. They know their newest adversary to be an American, and at sight of the two intrepid-looking youths standing side by side, with the angry faces of Eleparu and Orundelico in the background, they become sullenly silent, most of them evidently inclined to steal away from the ground.

The affair seemed likely thus to end, when, to the surprise of all, Eleparu, hitherto held back by the girl, suddenly released himself and bounded forward, with hands and arms wide open. In another instant he had grasped the big bully in a tiger-like embrace, lifted him off his feet, and dashed him down upon the flags with a violence that threatened the breaking of every bone in his body.

Nor did his implacable little adversary, who seemed possessed of a giant’s strength, appear satisfied with this, for he afterwards sprang on top of him, with a paving-stone in his uplifted hands.

The affair might have terminated tragically had not the uplifted hand been caught by Henry Chester. While he was still holding it, a man came up, who brought the conflict to an abrupt close by seizing Eleparu’s collar, and dragging him off his prostrate foe.

“Ho! what’s this?” demands the newcomer, in a loud authoritative voice. “Why, York! Jemmy! Fuegia! what are you all doing here? You should have stayed on board the steamship, as I told you to do. Go back to her at once.”

By this time the mud-larks have scuttled off, the big one, who had recovered his feet, making after them, and all speedily disappearing. The three gipsy-looking creatures go too, leaving their protectors, Henry Chester and Ned Gancy, to explain things to him who has caused the stampede. He is an officer in uniform, wearing insignia which proclaim him a captain in the Royal Navy; and as he already more than half comprehends the situation, a few words suffice to make it all clear to him, when, thanking the two youths for their generous and courageous interference in behalf of his protégés, as he styles the odd trio whose part they had taken, he bows a courteous farewell, and continues his interrupted walk along the Hard.

“Guess you didn’t get much sleep,” observes the young American, with a knowing smile, to Henry Chester.

“Who told you I was asleep?” replies the latter in some surprise.

“Who? Nobody.”

“How came you to know it, then?”

“How? Wasn’t I up in the maintop, and didn’t I see everything you did? And you behaved particularly well, I must say. But come! Let’s aboard. The captain has come back. He’s my father, and maybe we can find a berth for you on the Calypso. Come along!”

That night Henry Chester eats supper at the Calypso’s cabin table, by invitation of the captain’s son, sleeps on board, and, better still, has his name entered on her books as an apprentice.

And he finds her just the sort of craft he was desirous to go to sea in—a general trader, bound for the Oriental Archipelago and the isles of the Pacific Ocean. To crown all, she has completed her cargo and is ready to put to sea.

Sail she does, early the next day, barely leaving him time to keep that promise, made by the Devil’s Punch Bowl, of writing to his mother.

Chapter Four.

Off the “Furies.”

A ship tempest-tossed, labouring amid the surges of an angry sea; her crew on the alert, doing their utmost to keep her off a lee-shore. And such a shore! None more dangerous on all ocean’s edge; for it is the west coast of Tierra del Fuego, abreast the Fury Isles and that long belt of seething breakers known to mariners as the “Milky Way,” the same of which the great naturalist, Darwin, has said: “One sight of such a coast is enough to make a landsman dream for a week about shipwreck, peril, and death.”

There is no landsman in the ship now exposed to its dangers. All on board are familiar with the sea—have spent years upon it. Yet is there fear in their hearts and pallor on their cheeks, as their eyes turn to that belt of white frothy water between them and the land, trending north and south beyond the range of vision.

Technically speaking, the endangered vessel is not a ship, but a barque, as betokened by the fore-and-aft rig of her mizenmast. Nor is she of large dimensions; only some six or seven hundred tons. But the reader knows this already, or will, after learning her name. As her stern swings up on the billow, there can be read upon it the Calypso; and she is that Calypso in which Henry Chester sailed out of Portsmouth Harbour to make his first acquaintance with a sea life.

Though nearly four years have elapsed since then, he is still on board of her. There stands he by the binnacle. No more a boy, but a young man, and in a garb that bespeaks him of the quarter-deck—not before the mast, for he is now the Calypso’s third officer. And her second is not far-off; he is the generous youth who was the means of getting him the berth. Also grown to manhood, he, too, is aft, lending a hand at the helm, the strength of one man being insufficient to keep it steady in that heavily rolling sea. On the poop-deck is Captain Gancy himself, consulting a small chart, and filled with anxiety as at intervals looking towards the companion-ladder he there sees his wife and daughter, for he knows his vessel to be in danger and his dear ones as well.

A glance at the barque reveals that she has been on a long voyage. Her paint is faded, her sails patched, and there is rust along the chains and around the hawse-holes. She might be mistaken for a whaler coming off a four years’ cruise. And nearly that length of time has she been cruising, but not after whales. Her cargo, a full one, consists of sandal-wood, spices, tortoise-shell, mother-of-pearl, and real pearls also—in short, a miscellaneous assortment of the commodities obtained by traffic in the islands and around the coasts of the great South Sea.

Her last call has been at Honolulu Harbour in the Sandwich Isles, and she is now homeward-bound for New York around the Horn. A succession of westerly winds, or rather continuation of them, has forced her too far on to the Fuegian coast, too near the Furies; and now tossed about on a billowy sea, with the breakers of the Milky Way in sight to leeward, no wonder that her crew are apprehensive for their safety.

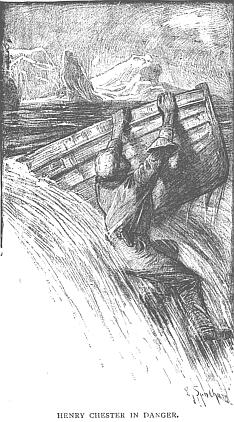

Still, perilous as their situation, they might not so much regard it were the Calypso sound and in sailing trim. Unfortunately she is far from this, having a damaged rudder, and with both courses torn to shreds. She is lying-to under storm fore-staysail and close-reefed try-sails, wearing at intervals, whenever it can be done with advantage, to keep her away from those “white horses” a-lee. But even under the diminished spread of canvas the barque is distressed beyond what she can bear, and Captain Gancy is about to order a further reduction of canvas, when, looking westward—in which direction he has been all along anxiously on the watch—he sees what sends a shiver through his frame: three huge rollers, whose height and steepness tell him the Calypso is about to be tried to the very utmost of her strength. Good sea-boat though he knows her to be, he knows also that a crisis is near. There is but time for him to utter a warning shout ere the first roller comes surging upon them. By a lucky chance the barque, having good steerage-way, meets and rises over it unharmed. But her way being now checked, the second roller deadens it completely, and she is thrown off the wind. The third then taking her right abeam, she careens over so far that the whole of her lee-bulwark, from cat-head to stern-davit, is ducked under water.

It is a moment of doubt, with fear appalling—almost despair. Struck by another sea, she would surely go under; but, luckily, the third is the last of the series, and she rights herself, rolling back again like an empty cask. Then, as a steed shaking his mane after a shower, she throws the briny water off, through hawse-holes and scuppers, till her decks are clear again.

A cry of relief ascends from the crew, instinctive and simultaneous. Nor does the loss of her lee-quarter boat, dipped under and torn from the davits, hinder them from adding a triumphant hurrah, the skipper himself waving his wet tarpaulin and crying aloud:

“Well done, old Calypso! Boys, we may thank our stars for being on board such a seaworthy craft!”

Alas! both the feeling of triumph and security are short-lived, ending almost on the instant. Scarce has the joyous hurrah ceased reverberating along her decks, when a voice is heard calling out, in a tone very different:

“The ship’s sprung a leak!—and a big one too! The water’s coming into her like a sluice!”

There is a rush for the fore hatchway, whence the words of alarm proceed, the main one being battened down and covered with tarpaulin. Then a hurried descent to the “’tween-decks” and an anxious peering into the hold below. True—too true! It is already half full of water, which seems mounting higher and by inches to the minute! So fancy the more frightened ones!

“Though bad enuf, ’tain’t altogether so bad’s that,” pronounced Seagriff the carpenter, after a brief inspection. “There’s a hole in the bottom for sartin’; but mebbe we kin beat it by pumpin’.”

Thus encouraged, the captain bounds back on deck, calling out, “All hands to the pumps!”

There is no need to say that. All take hold and work them with a will: it is as if every one were working for his own life.

A struggle succeeds, triangular and unequal, being as two to one. For the storm still rages, needing helm and sails to be looked after, while the inflow must be kept under in the hold. A terrible conflict it is, between man’s strength and the elements, but short, and alas! to end in the defeat of the former.

The Calypso is water-logged, will no longer obey her helm, and must surely sink.

At length, convinced of this, Captain Gancy calls out, “Boys, it’s no use trying to keep her afloat. Drop the pumps, and let us take to the boats.”

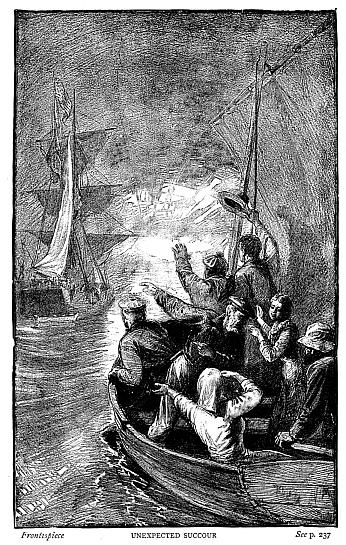

But taking to the boats is neither an easy nor hopeful alternative, seeming little better than that of a drowning man catching at straws. Still, though desperate, it is their only chance, and with not a moment to be wasted in irresolution. Luckily the Calypso’s crew is a well-disciplined one, every hand on board having served in her for years. The only two boats left them—the gig and pinnace—are therefore let down to the water, without damage to either, and, by like dexterous management, everybody got safely into them. It is a quick embarkation, however—so hurried, indeed, that few effects can be taken along, only those that chance to be readiest to hand. Another moment’s delay might have cost them their lives, for scarce have they taken their seats and pushed the boats clear of the ship’s side, when, another sea striking her, she goes down head foremost like a lump of lead, carrying masts, spars, torn sails, and rigging—everything—along with her.

Captain Gancy groans at the sight. “My fine barque gone to the bottom of the sea, cargo and all—the gatherings of years. Hard, cruel luck!”

Mingling with his words of sorrow are cries that seem cruel too: the screams of seabirds, gannets, gulls, and the wide-winged albatross, that have been long hovering above the Calypso, as if knowing her to be doomed, and hoping to find a feast among the floating remnants of the wreck.

Chapter Five.

The Castaways.

Not long does Captain Gancy lament the loss of his fine vessel and valuable cargo. In the face and fear of a far greater loss—his own life and the lives of his companions there is no time for vain regrets. The storm is still in full fury; the winds and the waves are as high as ever, and their boat is threatened with the fate of the barque.

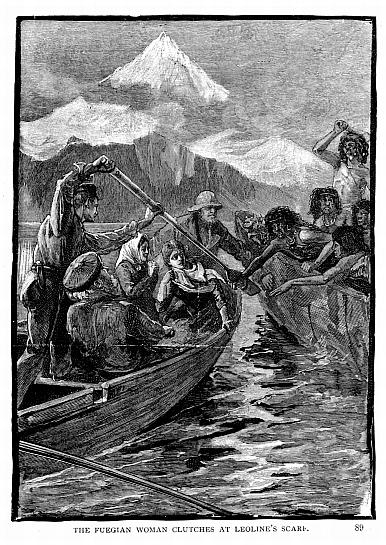

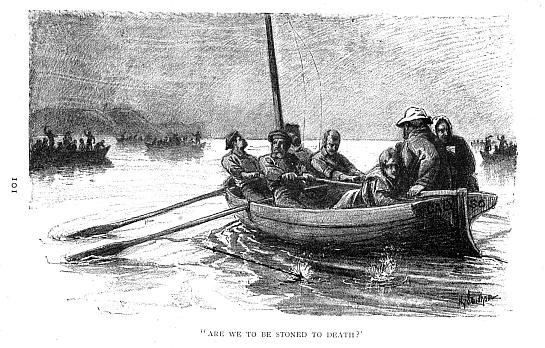

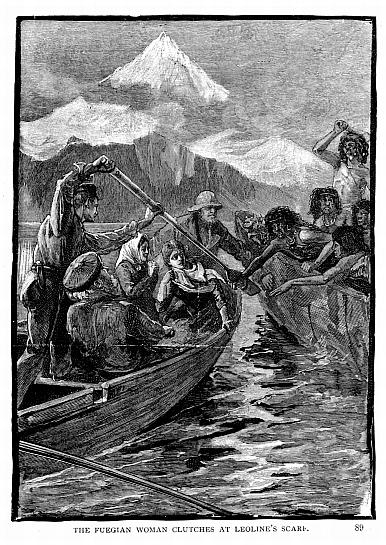

The bulk of the Calypso’s crew, with Lyons, the chief mate, have taken to the pinnace; and the skipper is in his own gig, with his wife, daughter, son, young Chester, and two others—Seagriff, the carpenter, and the cook, a negro. In all only seven persons, but enough to bring the gunwale of the little craft dangerously near the water’s edge. The captain himself is in the stern-sheets, tiller-lines in hand. Mrs Gancy and her daughter crouch beside him, while the others are at the oars, in which occupation Ned and Chester occasionally pause to bale out, as showers of spray keep breaking over the boat, threatening to swamp it.

What point shall they steer for? This is a question that no one asks, nor thinks of asking as yet. Course and direction are as nothing now; all their energies are bent on keeping the boat above water. However, they naturally endeavour to remain in the company of the pinnace. But those in the larger craft, like themselves, are engaged in a life-and-death conflict with the sea, and both must fight it out in their own way, neither being able to give aid to the other. So, despite their efforts to keep near each other, the winds and waves soon separate them, and they only can catch glimpses of each other when buoyed up on the crest of a billow. When the night comes on—a night of dungeon darkness—they see each other no more.

But, dark as it is, there is still visible that which they have been long regarding with dread—the breakers known as the “Milky Way.” Snow-white during the day, these terrible rock-tortured billows now gleam like a belt of liquid fire, the breakers at every crest seeming to break into veritable flames. Well for the castaways that this is the case; else how, in such obscurity, could the dangerous lee-shore be shunned? To keep off that is, for the time, the chief care of those in the gig; and all their energies are exerted in holding their craft well to windward.

By good fortune the approach of night has brought about a shifting of the wind, which has veered around to the west-north-west, making it possible for them to “scud,” without nearer approach to the dreaded fire-like line. In their cockleshell of a boat, they know that to run before the wind is their safest plan, and so they speed on south-eastward. An ocean current setting from the north-west also helps them in this course.

Thus doubly driven, they make rapid progress, and before midnight the Milky Way is behind them and out of sight. But, though they breathe more freely, they are by no means out of danger—alone in a frail skiff on the still turbulent ocean, and groping in thick darkness, with neither moon nor star to guide them. They have no compass, that having been forgotten in their scramble out of the sinking ship. But even if they had one it would be of little assistance to them at present, as, for the time being, they have enough to do in keeping the boat baled out and above water.

At break of day matters look a little better. The storm has somewhat abated, and there is land in sight to leeward, with no visible breakers between. Still, they have a heavy swell to contend with, and an ugly cross sea.

But land to a castaway! His first thought and most anxious desire is to set foot on it. So in the case of our shipwrecked party: risking all reefs and surfs, they at once set the gig’s head shoreward.

Closing in upon the land, they perceive a high promontory on the port bow, and another on the starboard, separated by a wide reach of open water; and about half-way between these promontories and somewhat farther out lies what appears to be an island. Taking it for one, Seagriff counsels putting in there instead of running on for the more distant mainland, though that is not his real reason.

“But why should we put in upon the island?” asks the skipper. “Wouldn’t it be much better to keep on to the main?”

“No, Captain; there’s a reason agin it, the which I’ll make known to you as soon as we get safe ashore.”

Captain Gancy is aware that the late Calypso’s carpenter was for a long time a sealer, and in this capacity had spent more than one season in the sounds and channels of Tierra del Fuego. He knows also that the old sailor can be trusted, and so, without pressing for further explanation, he steers straight for the island.

When about half a mile from its shore, they come upon a bed of kelp (Note 1), growing so close and thick as to bar their farther advance. Were they still on board the barque, the weed would be given a wide berth, as giving warning of rocks underneath; but in the light-draught gig they have no fear of these, and with the swell still tossing them about, they might be even glad to get in among the kelp—certainly there would be but that between it and the shore. They can descry waveless water, seemingly as tranquil as a pond.

Luckily the weed-bed is not continuous, but traversed by an irregular sort of break, through which it seems practicable to make way. Into this the gig is directed, and pulled through with vigorous strokes. Five minutes afterward her keel grates upon a beach, against which, despite the tumbling swell outside, there is scarce so much as a ripple. There is no better breakwater than a bed of kelp.

The island proves to be a small one—less than a mile in diameter—rising in the centre to a rounded summit, three hundred feet above sea-level.

It is treeless, though in part overgrown with a rank vegetation, chiefly tussac-grass (Note 2), with its grand bunches of leaves, six feet in height, surrounded by plume-like flower-spikes, almost as much higher.

Little regard, however, do the castaways pay to the isle or its productions. After being so long tossed about on rough seas, in momentary peril of their lives, and eating scarcely a mouthful of food the while, they are now suffering from the pangs of hunger. On the water this was the last thing to be thought of; on land it is the first; so as soon as the boat is brought to her moorings, and they have set foot on shore, the services of Caesar the cook are called into requisition.

As yet they scarcely know what provisions they have with them, so confusedly were things flung into the gig. An examination of their stock proves that it is scant indeed: a barrel of biscuits, a ham, some corned beef, a small bag of coffee in the berry, a canister of tea, and a loaf of lump sugar, were all they had brought with them. The condition of these articles, too, is most disheartening. Much of the biscuit seems a mass of briny pulp; the beef is pickled for the second time (on this occasion with sea-water); the sugar is more than half melted; and the tea spoiled outright, from the canister not having been water-tight. The ham and coffee have received least damage; yet both will require a cleansing operation to make them fit for food.

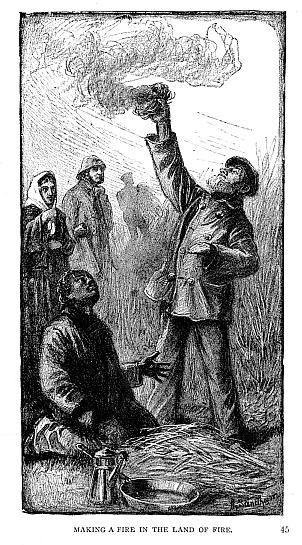

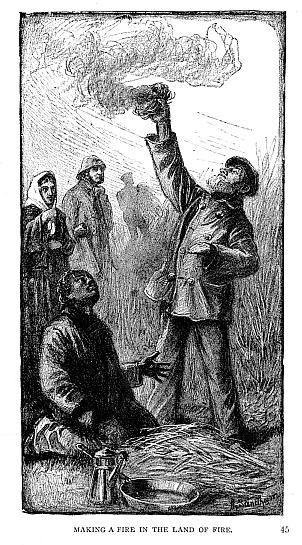

Fortunately, some culinary utensils are found in the boat the most useful of them being a frying-pan, kettle, and coffeepot. And now for a fire!—ah, the fire!

Up to this moment no one has thought of a fire; but now needing it, they are met with the difficulty, if not impossibility, of making one. The mere work of kindling it were an easy enough task, the late occupant of the Calypso’s caboose being provided with flint, steel, and tinder. So, too, is Seagriff, who, an inveterate smoker, is never without igniting apparatus, carried in a pocket of his pilot-coat. But where are they to find firewood? There is none on the islet—not a stick, as no trees grow there; while the tussac and other plants are soaking wet, the very ground being a sodden spongy peat.

A damper as well as a disappointment this, and Captain Gancy turns to Seagriff and remarks, with some vexation, “Chips, (All ship-carpenters are called ‘Chips.’) I think ’t would have been better if we’d kept on to the main. There’s timber enough there, on either side,” he adds, after a look through his binocular. “The hills appear to be thickly-wooded half-way up on the land both north and south of us.”

His words are manifestly intended as a reflection upon the judgment of the quondam seal-hunter, who rejoins shortly, “It would have been a deal worse, sir. Ay, worse nor if we should have to eat our vittels raw.”

“I don’t comprehend you,” said the skipper: “you spoke of a reason for our not making the mainland. What is it?”

“Wal, Captain, there is a reason, as I said, an’ a good one. I didn’t like to tell you, wi’ the others listenin’.” He nods toward the rest of the party, who are out of earshot, and then continues, “’Specially the women folks, as ’tain’t a thing they ought to be told about.”

“Do you fear some danger?” queries the skipper, in a tone of apprehension.

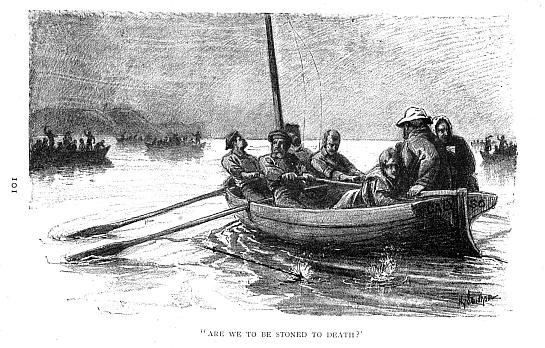

“Jest that; an’ bad kind o’ danger. As fur’s I kin see, we’ve drifted onto a part of the Feweegin coast where the Ailikoleeps live; the which air the worst and cruellest o’ savages—some of ’em rank cannyballs! It isn’t but five or six years since they murdered, and what’s more, eat sev’ral men of a  sealin’ vessel that was wrecked somewhere about here. For killin’ ’em, mebbe they might have had reason, seein’ as there had been blame on both sides, an’ some whites have behaved no better than the savages. But jest fur that, we, as are innocent, may hev to pay fur the misdeeds o’ the guilty! Now, Captain, you perceive the wharfor o’ my not wantin’ you to land over yonder. Ef we went now, like as not we’d have a crowd o’ the ugly critters yellin’ around us, hungering for our flesh.”

sealin’ vessel that was wrecked somewhere about here. For killin’ ’em, mebbe they might have had reason, seein’ as there had been blame on both sides, an’ some whites have behaved no better than the savages. But jest fur that, we, as are innocent, may hev to pay fur the misdeeds o’ the guilty! Now, Captain, you perceive the wharfor o’ my not wantin’ you to land over yonder. Ef we went now, like as not we’d have a crowd o’ the ugly critters yellin’ around us, hungering for our flesh.”

“But, if that’s so,” queried the captain, “shall we be any safer here?”

“Yes, we’re safe enough here—’s long as the wind’s blowin’ as ’tis now, an’ I guess it allers does blow that way, round this speck of an island. It must be all o’ five mile to that land either side, an’ in their rickety canoes the Feweegins never venture fur out in anythin’ o’ a rough sea. I calculate, Captain, we needn’t trouble ourselves much about ’em—leastways, not jest yet.”

“Ay—but afterward?” murmurs Captain Gancy, in a desponding tone, as his eyes turn upon those by the boat.

“Wal, sir,” says the old sealer, encouragingly, “the arterwards ’ll have to take care o’ itself. An’ now I guess I’d better determine ef thar ain’t some way o’ helpin’ Caesar to a spark o’ fire. Don’t look like it, but looks are sometimes deceivin’.”

And, so saying, he strolls off among the bunches of tussac-grass, and is soon out of sight.

But it is not long before he is again making himself heard, by an exclamation, telling of some discovery—a joyful one, as evinced by the tone of his voice. The two youths hasten to his side, and find him bending over a small heath-like bush, from which he has torn a handful of branches.

“What is it, Chips?” ask both in a breath.

“The gum plant, sure,” he replies.

“Well, what then? What’s the good of it?” they further interrogate. “You don’t suppose that green thing will burn—wet as a fish, too?”

“That’s jest what I do suppose,” replied the old sailor, deliberately. “You young ones wait, an’ you’ll see. Mebbe you’ll lend a hand, an’ help me to gather some of it. We want armfuls; an’ there’s plenty o’ the plants growin’ all about, you see.”

They do see, and at once begin tearing at them, breaking off the branches of some, and plucking up others by the roots, till Seagriff cries, “Enough!” Then, with arms full, they return to the beach in high spirits and with joyful faces.

Arrived there, Seagriff selects some of the finest twigs, which he rubs between his hands till they are reduced to a fine fibre and nearly dry. Rolling these into a rounded shape, resembling a bird’s nest, click! goes his flint and steel—a piece of “punk” is ignited and slipped into the heart of the ball. This, held on high, and kept whirling around his head, is soon ablaze, when it is thrust in among the gathered heap of green plants. Green and wet as these are, they at once catch fire and flame up like kindling-wood.

All are astonished and pleased, and not the least delighted is Caesar, who dances over the ground in high glee as he prepares to resume his vocation.

Note 1. The Fucus giganteus of Solander. The stem of this remarkable seaweed, though but the thickness of a man’s thumb, is often over one hundred and thirty yards in length, perhaps the longest of any known plant. It grows on every rock in Fuegian waters, from low-water mark to a depth of fifty or sixty fathoms, and among the most violent breakers. Often loose stones are raised up by it, and carried about, when the weed gets adrift. Some of these are so large and heavy that they can with difficulty be lifted into a boat. The reader will learn more of it further on.

Note 2. Dactylis caespitosa. The leaves of this singular grass are often eight feet in length, and an inch broad at the base, the flower-stalks being as long as the leaves. It bears much resemblance to the “pampas grass,” now well known as an ornamental shrub.

Chapter Six.

A Battle with Birds.

Through Caesar’s skilful manipulations the sea-water is extracted from the ham, and the coffee, which is in the berry and unroasted, after a course of judicious washing and scorching, is also rendered fit for use. The biscuits also turn out better than was anticipated. So their breakfast is not so bad, after all—indeed, to appetites keen as theirs, it seems a veritable feast.

While they are enjoying it, Seagriff tells them something more about the plant which has proved of such opportune service. They learn from him that it grows in the Falkland Islands, as well as in Tierra del Fuego, and is known as the “gum plant,” (Hydrocelice gummifera), because of a viscous substance it exudes in large quantities; this sap is called “balsam,” and is used by the natives of the countries where it is found as a cure for wounds. But its most important property, in their eyes, is the ease with which it can be set on fire, even when green and growing, as above described—a matter of no slight consequence in regions that are deluged with rain five days out of every six. In the Falkland Islands, where there are no trees, the natives often roast their beef over a fire of bones, the very bones of the animal from which, but the moment before, the meat itself was stripped, and they avail themselves of the gum plant to kindle this fire.

Just as Seagriff finishes his interesting dissertation, his listeners have their attention called to a spectacle quite new to them, and somewhat comical. Near the spot where they have landed, a naked sand-bar projects into the water, and along this a number of odd-looking creatures are seen standing side by side. There are quite two hundred of them, all facing the same way, mute images of propriety and good deportment, reminding one of a row of little charity children, all in white bibs and tuckers, ranged in a row for inspection.

But very different is the behaviour of the birds—for birds they are. One or another, every now and then, raises its head aloft, and so holds it, while giving utterance to a series of cries as hoarse and long-drawn as the braying of an ass, to which sound it bears a ludicrous resemblance.

“Jackass penguins,” (Note 1) Seagriff pronounces them, without waiting to be questioned; “yonder ’re more of ’em,” he explains, “out among the kelp, divin’ after shell-fish, the which are their proper food.”

The others, looking off toward the kelp, then see more of the birds. They had noticed them before, but supposed them to be fish leaping out of the water, for the penguin, on coming up after a dive, goes down again with so quick a plunge that an observer, even at short distance, may easily mistake it for a fish. Turning to those on the shore, it is now seen that numbers of them are constantly passing in among the tussac-grass and out again, their mode of progression being also very odd. Instead of a walk, hop, or run, as with other birds, it is a sort of rapid rush, in which the rudimentary wings of the birds are used as fore legs, so that, from even a slight distance, they might easily be mistaken for quadrupeds.

“It is likely they have their nests yonder,” observed Mrs Gancy, pointing to where the penguins kept going in and out of the tussac.

The remark makes a vivid impression on her son and the young Englishman, neither of whom is so old as to have quite outgrown a boyish propensity for nest-robbing.

“Sure to have, ma’am,” affirms Seagriff, respectfully raising his hand to his forelock; “an’ a pity we didn’t think of it sooner. We might ’a’ hed fresh eggs for breakfast.”

“Why can’t we have them for dinner, then?” demands the second mate; the third adding, “Yes; why not?”

“Sartin we kin, young masters. I knows of no reason agin it,” answers the old sealer.

“Then let’s go egg-gathering,” exclaimed Ned, eagerly.

The proposal is accepted by Seagriff, who is about to set out with the two youths, when, looking inquiringly round, he says, “As thar ain’t anything in the shape of a stick about, we had best take the boat-hook an’ a couple of oars.”

“What for?” ask the others, in some surprise.

“You’ll larn, by-an’-bye,” answers the old salt, who, like most of his kind, is somewhat given to mystification.

In accordance with this suggestion, each of the boys arms himself with an oar, leaving Seagriff the boat-hook.

They enter among the tussac, and after tramping through it a hundred yards or so, they come upon a “penguinnery,” sure enough. It is a grand one, extending over acres, with hundreds of nests—if a slight depression in the naked surface of the ground deserves to be so called. But no eggs are in any of them, fresh or otherwise; instead, in each sits a young, half-fledged bird, and one only, as this kind of penguin lays and hatches but a single egg. Many of the nests have old birds standing beside them, each occupied in feeding its solitary chick, duckling, gosling, or whatever the penguin offspring may be properly called. This being of itself a curious spectacle, the disappointed egg-hunters stop awhile to witness it, for they are still outside the bounds of the “penguinnery,” and the birds have as yet taken no notice of them. By each nest is a little mound, on which the mother stands perched, from time to time projecting her head outward and upward, at the same time giving forth a queer chattering noise, half quack, half bray, with the air of a stump orator haranguing an open-air audience. Meanwhile, the youngster stands patiently waiting below, evidently with a fore-knowledge of what is to come. Then, after a few seconds of the quacking and braying, the mother bird suddenly ducks her head, with the mandibles of her beak wide agape, between which the fledgling thrusts its head, almost out of sight, and so keeps it for more than a minute. Finally, withdrawing it, up again goes the head of the mother, with neck craned out, and oscillating from side to side in a second spell of speech-making. These curious actions are repeated several times, the entire performance lasting for a period of nearly a quarter of an hour. When it ends, possibly from the food supply having become exhausted, the mother bird leaves the little glutton to itself and scuttles off seaward to replenish her throat larder with a fresh stock of molluscs.

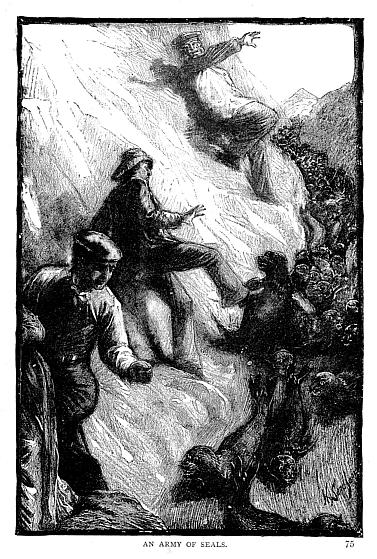

Although during their long four years’ cruise Edward Gancy and Henry Chester have seen many a strange sight, they think the one now before their eyes as strange as any, and unique in its quaint comicality. They would have continued their observations much longer but for Seagriff, to whom the sight is neither strange nor new. It has no interest for him, save economically, and in this sense he proceeds to utilise it, saying, after an interrogative glance sent all over the breeding-ground, “Sartin, there ain’t a single egg in any o’ the nests. It’s too late in the season for them now, an’ I might ’a’ known it. Wal, we won’t go back empty-handed, anyhow. The young penguins ain’t sech bad eatin’, though the old ’uns taste some’at fishy, b’sides bein’ tough as tan leather. So let’s heave ahead, an’ grab a few of the goslin’s. But look out, or you’ll get your legs nipped!”

At which all three advance upon the “penguinnery,” the two youths still incredulous as to there being any danger—in fact, rather under the belief that the old salt is endeavouring to impose on their credulity. But they are soon undeceived. Scarcely have they set foot within the breeding precinct, when fully half a score of old penguins rush fiercely at each of the intruders, with necks outstretched, mouths open, and mandibles snapping together with a clatter like that of castanets.

Then follows a laying about with oars and boat-hook, accompanied by shouts on the side of the attacking party, and hoarse, guttural screams on that of the attacked. The racket is kept up till the latter are at length beaten off, though but few of them are slain outright; for the jackass penguin, with its thick skull and dense coat of feathers, takes as much killing as a cat.

The young birds, too, make resistance against being captured, croaking and hissing like so many little ganders, and biting sharply. But all this does not prevent our determined party from finally securing some ten or twelve of the featherless creatures, and subsequently carrying them to the friends at the shore, where they are delivered into the eager hands of Caesar.

Note 1. Aptenodytes Patachonica. This singular bird has been christened “Jackass penguin” by sailors, on account of its curious note, which bears an odd resemblance to the bray of an ass. “King penguin” is another of its names, from its superior size, as it is the largest of the auk or penguin family.

Chapter Seven.

A World on a Weed.

A pair of penguin “squabs” makes an ample dinner for the entire party, nor is it without the accompaniment of vegetables; these being supplied by the tussac-grass, the stalks of which contain a white edible substance, in taste somewhat resembling a hazel-nut, while the young shoots boiled are almost equal to asparagus. (Note 1.)

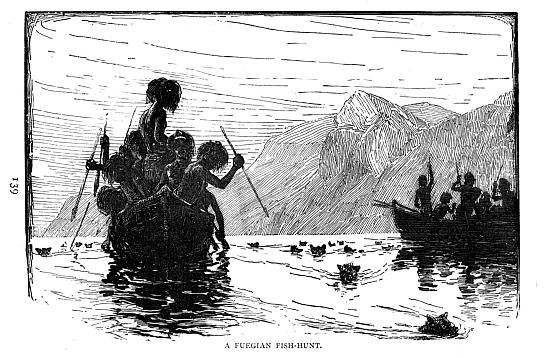

While seated at their midday meal, they have before their eyes a moving world of nature, such as may be found only in her wildest solitudes. All around the kelp-bed, porpoises are ploughing the water, now and then bounding up out of it; while seals and sea-otters show their human-like heads, swimming among the weeds. Birds hover above in such numbers as to darken the air, some at intervals darting down and going under with a plunge that sends the spray aloft in showers white as a snow-drift. Others do their fishing seated on the water; for there are many different kinds of water-fowl here represented—gulls, shags, cormorants, gannets, noddies, and petrels, with several species of Anativae, among them the beautiful black-necked swan. Nor are they all seabirds, or exclusively inhabitants of the water. Among those wheeling in the air above is an eagle and a small black vulture, with several sorts of hawks—the last, the Chilian jota (Note 2). Even the gigantic condor often extends its flight to the Land of Fire, whose mountains are but a continuation of the great Andean chain.

The ways and movements of this teeming ornithological world are so strange and varied that our castaways, despite all anxiety about their own future, cannot help being interested in observing them. They see a bird of one kind diving and bringing to the surface a fish, which another, of a different species, snatches from it and bears aloft, in its turn to be attacked by a third equally rapacious winged hunter, that, swooping at the robber, makes him forsake his ill-gotten prey, while the prey itself, reluctantly dropped, is dexterously re-caught in its whirling descent long ere it reaches its own element—the whole incident forming a very chain of tyranny and destruction! And yet a chain of but few links compared with that to be found in and under the water, among the leaves and stalks of the kelp itself. There the destroyers and the destroyed are legion, not only in numbers, but in kind. A vast world in itself, so densely populated and of so many varied organisms that, for a due delineation of it, I must again borrow from the inimitable pen of Darwin. Thus he describes it:—

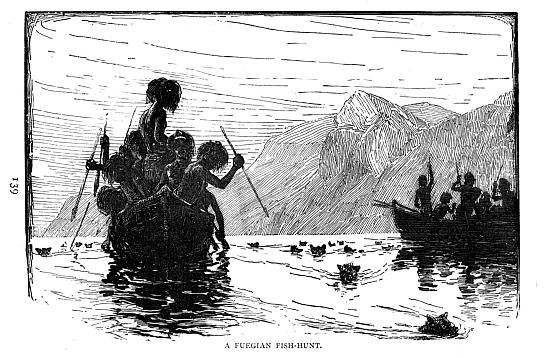

“The number of living creatures of all orders, whose existence entirely depends on the kelp, is wonderful. A great volume might be written describing the inhabitants of one of these beds of seaweed. Almost all the leaves, excepting those that float on the surface, are so thickly encrusted with corallines as to be of a white colour. We find exquisitely delicate structures, some inhabited by simple hydra-like polyps, others by more organised kinds. On the leaves, also, various shells, uncovered molluscs, and bivalves are attached. Innumerable Crustacea frequent every part of the plant. On shaking the great entangled roots, a pile of small fish-shells, cuttle-fish, crabs of all orders, sea-eggs, star-fish, sea-cucumbers, and crawling sea-centipedes of a multitude of forms, all fall out together. Often as I recurred to the kelp, I never failed to discover animals of new and curious structures... I can only compare these great aquatic forests of the Southern Hemisphere with the terrestrial ones of the inter-tropical regions. Yet, if in any country a forest were destroyed, I do not believe so many species of animals would perish as would here from the destruction of the kelp. Amidst the leaves of this plant numerous species of fish live, which nowhere else could find food or shelter; with their destruction, the many cormorants and other fishing-birds, the otters, seals, and porpoises, would perish also; and lastly, the Fuegian savage, the miserable lord of this miserable land, would redouble his cannibal feats, decrease in numbers, and perhaps cease to exist.”

While still watching the birds at their game of grab, the spectators observe that the kelp-bed has become darker in certain places, as though from the weeds being piled up in swathes.

“It’s lowering to ebb-tide,” remarks Captain Gancy, in reply to an interrogation from his wife, “and the rocks are awash. They’ll soon be above water, I take it.”

“Jest so, Captain,” assents Seagriff; “but tain’t the weeds that’s makin’ those black spots. They’re movin’ about—don’t you see?”

The skipper now observes, as do all the others, a number of odd-looking animals, large-headed, and with long slender bodies, to all appearance covered with a coat of dark brown wool, crawling and floundering about among the kelp, in constantly increasing numbers. Each new ledge of reef, as it rises to the surface, becomes crowded with them, while hundreds of others disport themselves in the pools between.

“Fur-seals they are,” (Note 3) pronounces Seagriff, his eyes fixed upon them as eagerly as were those of Tantalus on the forbidden water, “an’ every skin of ’em worth a mint o’ money. Bad luck!” he continues, in a tone of spiteful vexation. “A mine o’ wealth, an’ no chance to work it! Ef we only had the ship by us now, we could put a good thousan’ dollars’ worth o’ thar pelts into it. Jest see how they swarm out yonder! An’ tame as pet tabby cats! There’s enough of ’em to supply seal-skin jackets fur nigh all the women o’ New York!”

No one makes rejoinder to the old sealer’s regretful rhapsody. The situation is too grave for them to be thinking of gain by the capture of fur-seals, even though it should prove “a mine of wealth,” as Seagriff called it. Of what value is wealth to them while their very lives are in jeopardy? They were rejoiced when they first set foot on land; but time is passing; they have in part recovered from their fatigue, and the dark, doubtful future is once more uppermost in their minds. They cannot stay for ever on the isle—indeed, they may not be able to remain many days on it, owing to the exhaustion of their limited stock of provisions, if for no other reason. Even could they subsist on penguins’ flesh and tussac-stalks, the young birds, already well feathered, will ere long disappear, while the tender shoots of the grass, growing tougher as it ripens, will in time become altogether uneatable.

No; they cannot abide there, and must go elsewhere. But whither? That is the all-absorbing question. Ever since they landed the sky has been overcast, and the distant mainland is barely visible through a misty vapour spread over the sea between. All the better for that, Seagriff has been thinking hitherto, with the Fuegians in his mind.

“It’ll hinder ’em seein’ the smoke of our fire,” he said; “the which mout draw ’em on us.”

But he has now less fear of this, seeing that which tells him that the isle is never visited by the savages.

“They hain’t been on it fur years, anyhow,” he says, reassuring the Captain, who has again taken him aside to talk over the ticklish matter. “I’m sartin they hain’t.”

“What makes you certain?” questions the other.

“Them ’ere—both of ’em,” nodding first toward the fur-seals and then toward the penguins. “If the Feweegins dar’ fetch thar craft so fur out seaward, neither o’ them ud be so plentiful nor yit so tame. Both sort o’ critters air jest what they sets most store by—yieldin’ ’em not only thar vittels, but sech scant kiver as they’re ’customed to w’ar. No, Capting, the savagers hain’t been out hyar, an’ ain’t a-goin’ to be. An’ I weesh, now,” he continues, glancing up to the sky, “I weesh ’t wud brighten a bit. Wi’ thet fog hidin’ the hills over yonder, ’tain’t possybul to gie a guess az to whar we air. Ef it ud lift, I mout be able to make out some o’ the landmarks. Let’s hope we may hev a cl’ar sky the morrer, an’ a glimp’ o’ the sun to boot.”

“Ay, let us hope that,” rejoins the skipper, “and pray for it, as we shall.”

The promise is made in all seriousness, Captain Gancy being a religious man. So, on retiring to rest on their shake-down couches of tussac-grass, he summons the little party around him and offers up a prayer for their deliverance from their present danger, not forgetting those in the pinnace; no doubt the first Christian devotion ever heard ascending over that lone desert isle.

Note 1. It is the soft, crisp, inner part of the stem, just above the root, that is chiefly eaten. Horses and cattle are very fond of the tussac-grass, and in the Falkland Islands feed upon it. It is said, however, that there it is threatened with extirpation, on account of these animals browsing it too closely. It has been introduced with success into the Hebrides and Orkney Islands, where the conditions of its existence are favourable—a peaty soil, exposed to winds loaded with sea spray.

Note 2. Cathartes jota. Closely allied to the “turkey-buzzard” of the United States.

Note 3. Otaria Falklandica. There are several distinct species of “otary,” or “fur-seal”; those of the Falkland Islands and Tierra del Fuego being different from the fur-seals of northern latitudes.

Chapter Eight.

A Flurry with Fur-Seals.

As if Captain Gancy’s petition had been heard by the All-Merciful, and is about to have favourable response, the next morning breaks clear and calm; the fog all gone, and the sky blue, with a bright sun shining in it—rarest of sights in the cloudlands of Tierra del Fuego. All are cheered by it, and, with reviving hope, eat breakfast in better spirits, a fervent grace preceding.

They do not linger over the repast, as the skipper and Seagriff are impatient to ascend to the summit of the isle, the latter in hopes of making out some remembered landmark. The place where they have put in is on its west side, and the high ground interposed hinders their view to the eastward, while all seen north and south is unknown to the old carpenter.

They are about starting off, when Mrs Gancy says interrogatively, “Why shouldn’t we go too?”—meaning herself and Leoline, as the daughter is prettily named.

“Yes, papa,” urges the young girl; “you’ll take us with you, won’t you?”

With a glance up the hill, to see whether the climb be not too difficult, he answers, “Certainly, dear; I’ve no objection. Indeed, the exercise may do you both good, after being so long shut up on board ship.”

“It would do us all good,” thinks Henry Chester, for a certain reason wishing to be of the party, that reason, as a child might see, being Leoline. He does not speak his wish, however, backwardness forbidding, but is well pleased at hearing her brother, who is without bar of this kind, cry out, “Yes, father. And the other pair of us, Harry and myself, would like to go too. Neither of us have got our land legs yet, as we found yesterday while fighting the penguins. A little mountaineering will help to put the steady into them.”

“Oh, very well,” assents the good-natured skipper. “You may all come—except Caesar. He had better stay by the boat, and keep the fire burning.”

“Jess so, Massa Cap’n, an’ much obleeged to ye. Dis chile perfur stayin’. Golly! I doan’ want to tire myse’f to deff a-draggin’ up dat ar pressypus. ’Sides, I hab got ter look out for de dinner, ’gainst yer gettin’ back.”

“The doctor” (The popular sea-name for a ship’s cook) speaks the truth in saying he does not wish to accompany them, being one of the laziest mortals that ever sat roasting himself beside a galley fire. So, without further parley, they set forth, leaving him by the boat.

At first they find the uphill slope gentle and easy, their path leading through hummocks of tall tussac, whose tops rise above their heads, and the flower-scapes many feet higher. Their chief difficulty is the spongy nature of the soil, in which they sink at times ankle-deep. But farther up it is drier and firmer, the lofty tussac giving place to grass of humbler stature; in fact, a sward so short, that the ground appears as though freshly mown. Here the climbers catch sight of a number of moving creatures, which they might easily mistake for quadrupeds. Hundreds of them are running to and fro like rabbits in a warren, and quite as fast. Yet they are really birds, penguins of the same species which supplied so considerable a part of their yesterday’s dinner and to-day’s breakfast. The strangest thing of all is that these Protean creatures, which seem fitted only for an aquatic existence, should be so much at home on land, so ably using their queer wings as substitutes for legs that they can run up or down high and precipitous slopes with the swiftness of a hare.

From the experience of yesterday, Ned and Harry might anticipate attack by the penguins. But that experience has taught the birds a lesson, which they now profit by, scuttling off, frightened at the sight of the murderous invaders, who have made such havoc among them and their nestlings.

On the drier upland still another curious bird is encountered, singular in its mode of breeding and other habits. A petrel it is, about the size of a house pigeon, and of a slate-blue colour. This bird, instead of laying its eggs, like the penguin, on the surface of the ground, deposits them, like the sand-martin and burrowing owl, at the bottom of a burrow. Part of the ground over which the climbers have to pass is honeycombed with these holes, and they see the petrels passing in and out; Seagriff, meanwhile, imparting a curious item of information about them. It is that the Fuegians capture these birds by tying a string to the legs of certain small birds, and force them into the petrels’ nests, whereupon the rightful owners, attacking and following the intruders as they are jerked out by the cunning decoyers, are themselves captured.

Continuing upward, the slope is found to be steeper, and more difficult than was expected. What from below seemed a gentle acclivity turns out to be almost a precipice—a very common illusion with those unaccustomed to mountain climbing. But they are not daunted—every one of the men has stood on the main truck of a tempest-tossed ship. What to this were even the scaling of a cliff? The ladies, too, have little fear, and will not consent to stay below, but insist on being taken to the very summit.

The last stage proves the most difficult. The only practicable path is up a sort of gorge, rough-sided, but with the bottom smooth and slippery as ice. It is grass-grown all over, but the grass is beaten close to the surface, as if schoolboys had been “coasting” down it. All except Seagriff suppose it to be the work of the penguins—he knows better what has done it. Not birds, but beasts, or “fish,” as he would call them—the amphibia in the chasing, killing, and skinning of which he has spent many years of his life. Even with his eyes shut he could have told it was they, by a peculiar odour unpleasant to others, though not to him. To his olfactories it is the perfume of Araby.

“Them fur-seals hev been up hyar,” he says, glancing up the gorge. “They kin climb like cats, spite o’ thar lubberly look, and they delight in baskin’ on high ground. I’ve know’d ’em to go up a hill steeper an’ higher ’n this. They’ve made it as smooth as ice, and we’ll hev to hold on keerfully. I guess ye’d better all stay hyar till I give it a trial.”