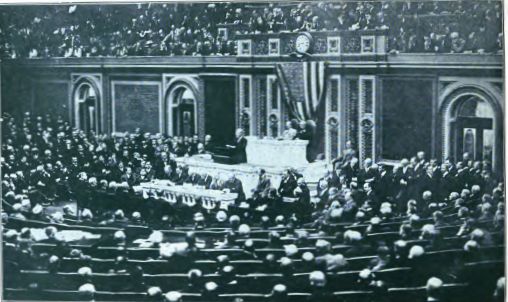

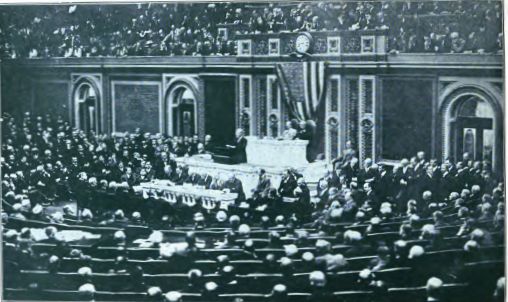

PRESIDENT WILSON READING HIS WAR MESSAGE TO CONGRESS, APRIL 2, 1917

PRESIDENT WILSON READING HIS WAR MESSAGE TO CONGRESS, APRIL 2, 1917

Title: World's War Events, Vol. II

Editor: Francis J. Reynolds

Allen L. Churchill

Release date: July 4, 2008 [eBook #25963]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

PRESIDENT WILSON READING HIS WAR MESSAGE TO CONGRESS, APRIL 2, 1917

PRESIDENT WILSON READING HIS WAR MESSAGE TO CONGRESS, APRIL 2, 1917

| ARTICLE | PAGE | |

| I. | The Battle of Verdun | 7 |

| Raoul Blanchard | ||

| II. | The Battle of Jutland Bank | 30 |

| Admiral Sir John Jellicoe's Official Despatch | ||

| III. | Taking the Col di Lana | 55 |

| Lewis R. Freeman | ||

| IV. | The Battle of the Somme | 67 |

| Sir Douglas Haig | ||

| V. | Russia's Refugees | 114 |

| Gregory Mason | ||

| VI. | The Tragedy of Rumania | 124 |

| Stanley Washburn | ||

| VII. | Sixteen Months a War Prisoner | 142 |

| Private "Jack" Evans | ||

| VIII. | Under German Rule in France and Belgium | 159 |

| J. P. Whitaker | ||

| IX. | The Anglo-Russian Campaign in Turkey | 174 |

| James B. MacDonald | ||

| X. | Kitchener | 188 |

| Lady St. Helier | ||

| XI. | Why America Broke with Germany | 194 |

| President Woodrow Wilson | ||

| XII. | How the War Came to America | 205 |

| Official Account | ||

| XIII. | The War Message | 226 |

| President Woodrow Wilson | ||

| XIV. | British Operations at Saloniki | 244 |

| Official Report of General Milne | ||

| XV. | In Petrograd During the Seven Days | 253 |

| Arno Dosch-Fleurot[6] | ||

| XVI. | America's First Shot | 271 |

| J.R. Keen | ||

| XVII. | German Activities in the United States | 278 |

| House Committee on Foreign Affairs | ||

| XVIII. | Preparing for War | 298 |

| Newton D. Baker, Secretary of War | ||

| XIX. | The Capture of Jerusalem | 344 |

| General E. H. H. Allenby | ||

| XX. | American Ships and German Submarines | 369 |

| From Official Reports | ||

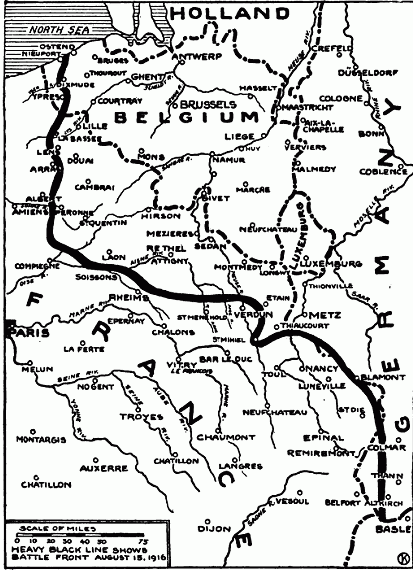

The Battle of Verdun, which continued through from February 21, 1916, to the 16th of December, ranks next to the Battle of the Marne as the greatest drama of the world war. Like the Marne, it represents the checkmate of a supreme effort on the part of the Germans to end the war swiftly by a thunderstroke. It surpasses the Battle of the Marne by the length of the struggle, the fury with which it was carried on, the huge scale of the operations. No complete analysis of it, however, has yet been published—only fragmentary accounts, dealing with the beginning or with mere episodes. Neither in France nor in Germany, up to the present moment, has the whole story of the battle been told, describing its vicissitudes, and following step by step the development of the stirring drama. That is the task I have set myself here.

The year 1915 was rich in successes for the Germans. In the West, thanks to an energetic defensive, they had held firm against the Allies' onslaughts in Artois and in Champagne. Their offensive in the East was most fruitful. Galicia had been almost completely recovered, the kingdom of Poland occupied, Courland, Lithuania, and Volhynia invaded. To the South they had crushed Serbia's opposition, saved Turkey, and won over Bulgaria. These triumphs, however, had not brought them peace, for the heart and soul of the Allies lay, after all, in the West—in England and France.[8] The submarine campaign was counted on to keep England's hands tied; it remained, therefore, to attack and annihilate the French army. And so, in the autumn of 1915, preparations were begun on a huge scale for delivering a terrible blow in the West and dealing France the coup de grâce.

The determination with which the Germans followed out this plan and the reckless way in which they drew on their resources leave no doubt as to the importance the operation held for them. They staked everything on putting their adversaries out of the running by breaking through their lines, marching on Paris, and shattering the confidence of the French people. This much they themselves admitted. The German press, at the beginning of the battle, treated it as a matter of secondary import, whose object was to open up free communications between Metz and the troops in the Argonne; but the proportions of the combat soon gave the lie to such modest estimates, and in the excitement of the first days official utterances betrayed how great were the expectations.

On March 4 the Crown Prince urged his already over-taxed troops to make one supreme effort to "capture Verdun, the heart of France"; and General von Deimling announced to the 15th Army Corps that this would be the last battle of the war. At Berlin, travelers from neutral countries leaving for Paris by way of Switzerland were told that the Germans would get there first. The Kaiser himself, replying toward the end of February to the good wishes of his faithful province of Brandenburg, congratulated himself publicly on seeing his warriors of the 3d Army Corps about to carry "the most important stronghold of our principal enemy." It is plain, then, that the object was to take Verdun, win a decisive victory, and[9] start a tremendous onslaught which would bring the war to a triumphant close.

We should next examine the reasons prompting the Germans to select Verdun as the vital point, the nature of the scene of operations, and the manner in which the preparation was made.

Why did the Germans make their drive at Verdun, a powerful fortress defended by a complete system of detached outworks? Several reasons may be found for this. First of all, there were the strategic advantages of the operation. Ever since the Battle of the Marne and the German offensive against St. Mihiel, Verdun had formed a salient in the French front which was surrounded by the Germans on three sides,—northwest, east, and south,—and was consequently in greater peril than the rest of the French lines. Besides, Verdun was not far distant from Metz, the great German arsenal, the fountain-head for arms, food, and munitions. For the same reasons, the French defense of Verdun was made much harder because access to the city was commanded by the enemy. Of the two main railroads linking Verdun with France, the Lérouville line was cut off by the enemy at St. Mihiel; the second (leading through Châlons) was under ceaseless fire from the German artillery. There remained only a narrow-gauge road connecting Verdun and Bar-le-Duc. The fortress, then, was almost isolated.

For another reason, Verdun was too near, for the comfort of the Germans, to those immense deposits of iron ore in Lorraine which they have every intention of retaining after the war. The moral factor involved in the fall of Verdun was also immense. If the stronghold were captured, the French, who look on it as their chief bulwark in the East, would be greatly disheartened, whereas it would delight the[10] souls of the Germans, who had been counting on its seizure since the beginning of the war. They have not forgotten that the ancient Lotharingia, created by a treaty signed eleven centuries ago at Verdun, extended as far as the Meuse. Finally, it is probable that the German General Staff intended to profit by a certain slackness on the part of the French, who, placing too much confidence in the strength of the position and the favorable nature of the surrounding countryside, had made little effort to augment their defensive value.

This value, as a matter of fact, was great. The theatre of operations at Verdun offers far fewer inducements to an offensive than the plains of Artois, Picardy, or Champagne. The rolling ground, the vegetation, the distribution of the population, all present serious obstacles.

The relief-map of the region about Verdun shows the sharply marked division of two plateaus situated on either side of the river Meuse. The plateau which rises on the left bank, toward the Argonne, falls away on the side toward the Meuse in a deeply indented line of high but gently sloping bluffs, which include the Butte de Montfaucon, Hill 304, and the heights of Esnes and Montzéville. Fragments of this plateau, separated from the main mass by the action of watercourses, are scattered in long ridges over the space included between the line of bluffs and the Meuse: the two hills of Le Mont Homme (295 metres), the Côte de l'Oie, and, farther to the South, the ridge of Bois Bourrus and Marre. To the east of the river, the country is still more rugged. The plateau on this bank rises abruptly, and terminates at the plain of the Woëvre in the cliffs of the Côtes-de-Meuse, which tower 100 metres over the plain. The brooks which flow[11] down to the Woëvre or to the Meuse have worn the cliffs and the plateau into a great number of hillocks called côtes: the Côte du Talon, Côte du Poivre, Côte de Froideterre, and the rest. The ravines separating these côtes are deep and long: those of Vaux, Haudromont, and Fleury cut into the very heart of the plateau, leaving between them merely narrow ridges of land, easily to be defended.

These natural defenses of the country are strengthened by the nature of the vegetation. On the rather sterile calcareous soil of the two plateaus the woods are thick and numerous. To the west, the approaches of Hill 304 are covered by the forest of Avocourt. On the east, long wooded stretches—the woods of Haumont, Caures, Wavrille, Herbebois, la Vauche, Haudromont, Hardaumont, la Caillette, and others—cover the narrow ridges of land and dominate the upper slopes of the ravines. The villages, often perched on the highest points of land, as their names ending in mont indicate, are easily transformed into small fortresses; such are Haumont, Beaumont, Louvemont, Douaumont. Others follow the watercourses, making it easier to defend them—Malancourt, Béthincourt and Cumières, to the west of the Meuse; Vaux to the east.

These hills, then, as well as the ravines, the woods, and the favorably placed villages, all facilitated the defense of the countryside. On the other hand, the assailants had one great advantage: the French positions were cut in two by the valley of the Meuse, one kilometre wide and quite deep, which, owing to swampy bottom-lands, could not be crossed except by the bridges of Verdun. The French troops on the right bank had therefore to fight with a river at their backs, thus imperiling their retreat. A grave danger, this, in the face of an enemy determined to take full advantage of[12] the circumstance by attacking with undreamed-of violence.

The German preparation was, from the start, formidable and painstaking. It was probably under way by the end of October, 1915, for at that time the troops selected to deliver the first crushing attack were withdrawn from the front and sent into training. Four months were thus set aside for this purpose. To make the decisive attack, the Germans made selection from four of their crack army corps, the 18th active, the 7th reserve, the 15th active (the Mühlhausen corps), and the 3d active, composed of Brandenburgers.

These troops were sent to the interior to undergo special preparation. In addition to these 80,000 or 100,000 men, who were appointed to bear the brunt of the assault, the operation was to be supported by the Crown Prince's army on the right and by that of General von Strautz on the left—300,000 men more. Immense masses of artillery were gathered together to blast open the way; fourteen lines of railroad brought together from every direction the streams of arms and munitions. Heavy artillery was transported from the Russian and Serbian fronts. No light pieces were used in this operation—in the beginning, at any rate; only guns of large calibre, exceeding 200 millimetres, many of 370 and 420 millimetres.

The battle plans were based on the offensive power of the heavy artillery. The new formula was to run, "The artillery attacks, the infantry takes possession." In other words, a terrible bombardment was to play over every square yard of the terrain to be captured; when it was decided that the pulverization had been sufficient, a scouting-party of infantry would be sent out to look the situation over; behind them would come the pioneers, and then the first wave of the assault. In case the enemy[13] still resisted, the infantry would retire and leave the field once more to the artillery.

The point chosen for the attack was the plateau on the right bank of the Meuse. The Germans would thus avoid the obstacle of the cliffs of Côtes de Meuse, and, by seizing the ridges and passing around the ravines, they could drive down on Douaumont, which dominates the entire region, and from there fall on Verdun and capture the bridges. At the same time, the German right wing would assault the French positions on the left bank of the Meuse; the left wing would complete the encircling movement, and the entire French army of Verdun, driven back to the river and attacked from the rear, would be captured or destroyed.

The Battle of Verdun lasted no less than ten months—from February 21 to December 16. First of all, came the formidable German attack, with its harvest of success during the first few days of the frontal drive, which was soon checked and forced to wear itself out in fruitless flank attacks, kept up until April 9. After this date the German programme became more modest: they merely wished to hold at Verdun sufficient French troops to forestall an offensive at some other point. This was the period of German "fixation," lasting from April to the middle of July. It then became the object of the French to hold the German forces and prevent transfer to the Somme. French "fixation," ended in the successes of October and December.

The first German onslaught was the most intense and critical moment of the battle. The violent frontal attack on the plateau east of the Meuse, magnificently executed, at first carried all before it. The commanders at Verdun had shown a lack of foresight. There were too few trenches, too few cannon, too few troops. The soldiers had had too little experience[14] in the field, and it was their task to face the most terrific attack ever known.

On the morning of February 21 the German artillery opened up a fire of infernal intensity. This artillery had been brought up in undreamed-of quantities. French aviators who flew over the enemy positions located so many batteries that they gave up marking them on their maps; the number was too great. The forest of Grémilly, northeast of the point of attack, was just a great cloud shot through with lightning-flashes. A deluge of shells fell on the French positions, annihilating the first line, attacking the batteries and finding their mark as far back as the city of Verdun. At five o'clock in the afternoon the first waves of infantry assaulted and carried the advanced French positions in the woods of Haumont and Caures. On the 22d the French left was driven back about four kilometres.

The following day a terrible engagement took place along the entire line of attack, resulting toward evening in the retreat of both French wings; on the left Samognieux was taken by the Germans; on the right they occupied the strong position of Herbebois.

The situation developed rapidly on the 24th. The Germans enveloped the French centre, which formed a salient; at two in the afternoon they captured the important central position of Beaumont, and by nightfall had reached Louvemont and La Vauche forest, gathering in many prisoners. On the morning of the 25th the enemy stormed Bezonvaux, and entered the fort of Douaumont, already evacuated.

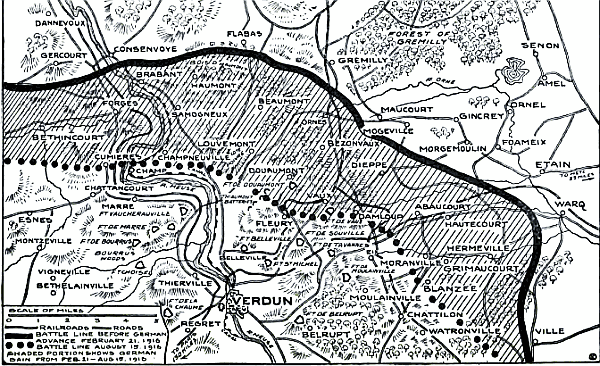

FIRST ATTACK ON VERDUN

FIRST ATTACK ON VERDUN

In less than five days the assaulting troops sent forward over the plateau had penetrated the French positions to a depth of eight kilometres, and were masters of the most important elements of the defense of the fortress. Verdun and its bridges were only seven kilometres[16] distant. The commander of the fortified region himself proposed to evacuate the whole right bank of the Meuse; the troops established in the Woëvre were already falling back toward the bluffs of Côtes de Meuse. Most luckily, on this same day there arrived at Verdun some men of resource, together with substantial reinforcements. General de Castelnau, Chief of the General Staff, ordered the troops on the right bank to hold out at all costs. And on the evening of the 25th General Pétain took over the command of the entire sector. The Zouaves, on the left bank, were standing firm as rocks on the Côtes du Poivre, which cuts off access from the valley to Verdun. During this time the Germans, pouring forward from Douaumont, had already reached the Côte de Froideterre, and the French artillerymen, out-flanked, poured their fire into the gray masses as though with rifles. It was at this moment that the 39th division of the famous 20th French Army Corps of Nancy met the enemy in the open, and, after furious hand-to-hand fighting, broke the backbone of the attack.

That was the end of it. The German tidal wave could go no farther. There were fierce struggles for several days longer, but all in vain. Starting on the 26th, five French counter-attacks drove back the enemy to a point just north of the fort of Douaumont, and recaptured the village of the same name. For three days the German attacking forces tried unsuccessfully to force these positions; their losses were terrible, and already they had to call in a division of reinforcements. After two days of quiet the contest began again at Douaumont, which was attacked by an entire army corps; the 4th of March found the village again in German hands. The impetus of the great blow had been broken, however, after five days of success, the attack had fallen flat.[17]

Were the Germans then to renounce Verdun? After such vast preparations, after such great losses, after having roused such high hopes, this seemed impossible to the leaders of the German army. The frontal drive was to have been followed up by the attack of the wings, and it was now planned to carrying this out with the assistance of the Crown Prince's army, which was still intact. In this way the scheme so judiciously arranged would be accomplished in the appointed manner. Instead of adding the finishing touch to the victory, however, these wings now had the task of winning it completely—and the difference is no small one.

These flank attacks were delivered for over a month (March 6-April 9) on both sides of the river simultaneously, with an intensity and power which recalled the first days of the battle. But the French were now on their guard. They had received great reinforcements of artillery, and the nimble "75's," thanks to their speed and accuracy, barred off the positions under attack by a terrible curtain of fire. Moreover, their infantry contrived to pass through the enemy's barrage-fire, wait calmly until the assaulting infantry were within 30 metres of them, and then let loose the rapid-fire guns. They were also commanded by energetic and brilliant chiefs: General Pétain, who offset the insufficient railroad communications with the rear by putting in motion a great stream of more than 40,000 motor trucks, all traveling on strict schedule time; and General Nivelle, who directed operations on the right bank of the river, before taking command of the Army of Verdun. The German successes of the first days were not duplicated.

These new attacks began on the left of the Meuse. The Germans tried to turn the first line of the French defense by working down along the river, and then capture the second[18] line. On March 6 two divisions stormed the villages of Forges and Regnéville, and attacked the woods of Corbeaux on the Côte de l'Oie, which they captured on the 10th. After several days of preparation, they fell suddenly upon one of the important elements of the second line, the hill of Le Mort Homme, but failed to carry it (March 14-16). Repulsed on the right, they tried the left. On March 20 a body of picked troops just back from the Russian front—the 11th Bavarian Division—stormed the French positions in the wood of Avocourt and moved on to Hill 304, where they obtained foothold for a short time before being driven back with losses of from 50 to 60 per cent of their effectives.

At the same time the Germans were furiously assaulting the positions of the French right wing east of the Meuse. From the 8th to the 10th of March the Crown Prince brought forward again the troops which had survived the ordeal of the first days, and added to them the fresh forces of the 5th Reserve Corps. The action developed along the Côte du Poivre, especially east of Douaumont, where it was directed against the village and fort of Vaux. The results were negative, except for a slight gain in the woods of Hardaumont. The 3d Corps had lost 22,000 men since the 21st of February—that is, almost its entire original strength. The 5th Corps was simply massacred on the slopes of Vaux, without being able to reach the fort. New attempts against this position, on March 16 and 18, were no more fruitful. The battle of the right wing, then, was also lost.

The Germans hung on grimly. One last effort remained to be made. After a lull of six days (March 22-28) savage fighting started again on both sides of the river. On the right bank, from March 31 to April 2, the Germans[19] got a foothold in the ravine of Vaux and along its slopes; but the French dislodged them the next day, inflicting great damage, and drove them back to Douaumont.

Their greatest effort was made on the left bank. Here the French took back the woods of Avocourt; from March 30 to the 8th of April, however, the Germans succeeded in breaking into their adversaries' first line, and on April 9, a sunny Sabbath-day, they delivered an attack against the entire second line, along a front of 11 kilometres, from Avocourt to the Meuse. There was terrific fighting, the heaviest that had taken place since February 26, and a worthy sequel to the original frontal attack. The artillery preparation was long and searching. The hill of Le Mort Homme, said an eye-witness, smoked like a volcano with innumerable craters. The assault was launched at noon, with five divisions, and in two hours it had been shattered. New attacks followed, but less orderly, less numerous, and more listless, until sundown. The checkmate was complete. "The 9th of April," said General Pétain to his troops, "is a day full of glory for your arms. The fierce assaults of the Crown Prince's soldiers have everywhere been thrown back. Infantry, artillery, sappers, and aviators of the Second Army have vied with one another in heroism. Courage, men: on les aura!"

And, indeed, this great attack of April 9, was the last general effort made by the German troops to carry out the programme of February—to capture Verdun and wipe out the French army which defended it. They had to give in. The French were on their guard now; they had artillery, munitions, and men. The defenders began to act as vigorously as the attackers; they took the offensive, recaptured the woods of La Caillette, and occupied the trenches before Le Mort Homme. The German plans were[20] ruined. Some other scheme had to be thought out.

Instead of employing only eight divisions of excellent troops, as originally planned, the Germans had little by little cast into the fiery furnace thirty divisions. This enormous sacrifice could not be allowed to count for nothing. The German High Command therefore decided to assign a less pretentious object to the abortive enterprise. The Crown Prince's offensive had fallen flat; but, at all events, it might succeed in preventing a French offensive. For this reason it was necessary that Verdun should remain a sore spot, a continually menaced sector, where the French would be obliged to send a steady stream of men, material, and munitions. It was hinted then in all the German papers that the struggle at Verdun was a battle of attrition, which would wear down the strength of the French by slow degrees. There was no talk now of thunderstrokes; it was all "the siege of Verdun." This time they expressed the true purpose of the German General Staff; the struggle which followed the fight of April 9, now took the character of a battle of fixation, in which the Germans tried to hold their adversaries' strongest units at Verdun and prevent their being transferred elsewhere. This state of affairs lasted from mid-April to well into July, when the progress of the Somme offensive showed the Germans that their efforts had been unavailing.

It is true that during this new phase of the battle the offensive vigor of the Germans and their procedure in attacking were still formidable.

Their artillery continued to perform prodigies. The medium-calibre pieces had now come into action, particularly the 150 mm. guns, with their amazing mobility of fire,[21] which shelled the French first line, as well as their communications and batteries, with lightning speed. This storm of artillery continued night and day; it was the relentless, crushing continuity of the fire which exhausted the adversary and made the Battle of Verdun a hell on earth. There was one important difference, however: the infantry attacks now took place over restricted areas, which were rarely more than two kilometres in extent. The struggle was continual, but disconnected. Besides, it was rarely in progress on both sides of the river at once. Until the end of May the Germans did their worst on the left; then the French activities brought them back to the right side, and there they attacked with fury until mid-July.

The end of April was a period of recuperation for the Germans. They were still suffering from the confusion caused by their set-backs of March, and especially of April 9. Only two attempts at an offensive were made—one on the Côte du Poivre (April 18) and one on the front south of Douaumont. Both were repulsed with great losses. The French, in turn, attacked on the 15th of April near Douaumont, on the 28th north of Le Mort Homme. It was not until May that the new German tactics were revealed: vigorous, but partial, attacks, directed now against one point, now against another.

On May 4 there began a terrible artillery preparation, directed against Hill 304. This was followed by attacks of infantry, which surged up the shell-blasted slopes, first to the northwest, then north, and finally northeast. The attack of the 7th was made by three divisions of fresh troops which had not previously been in action before Verdun. No gains were secured. Every foot of ground taken in the first rush was recaptured by French counter-attacks.[22] During the night of the 18th a savage onslaught was made against the woods of Avocourt, without the least success. On the 20th and 21st, three divisions were hurled against Le Mort Homme, which they finally took; but they could go no farther. The 23d and 24th were terrible days. The Germans stormed the village of Cumières; their advance guard penetrated as far as Chattancourt. On the 26th, however, the French were again in possession of Cumières and the slopes of Le Mort Homme; and if the Germans, by means of violent counter-attacks, were able to get a fresh foothold in the ruins of Cumières, they made no attempt to progress farther. The battles of the left river-bank were now over; on this side of the Meuse there were to be only unimportant local engagements and the usual artillery fire.

This shift of the German offensive activity from the left side of the Meuse to the right is explained by the activity shown at the same time in this sector by the French. The French command was not deceived by the German tactics; they intended to husband their strength for the future Somme offensive. For them Verdun was a sacrificial sector to which they sent, from now on, few men, scant munitions, and only artillery of the older type. Their object was only to hold firm, at all costs. However, the generals in charge of this thankless task, Pétain and Nivelle, decided that the best defensive plan consisted in attacking the enemy. To carry this out, they selected a soldier bronzed on the battlefields of Central Africa, the Soudan, and Morocco, General Mangin, who commanded the 5th Division and had already played a distinguished part in the struggle for Vaux, in March. On May 21 Mangin's division attacked on the right bank of the Meuse and occupied the quarries of Haudromont; on the 22d it stormed the German lines for a length[23] of two kilometres, and took the fort of Douaumont with the exception of one salient.

The Germans replied to this with the greatest energy; for two days and nights the battle raged round the ruins of the fort. Finally, on the night of the 24th, two new Bavarian divisions succeeded in getting a footing in this position, to which the immediate approaches were held by the French. This vigorous effort alarmed the enemy, and from now on, until the middle of July, all their strength was focused on the right bank of the river.

This contest of the right bank began on May 31. It is, perhaps the bloodiest, the most terrible, chapter of all the operations before Verdun; for the Germans had determined to capture methodically, one by one, all the French positions, and get to the city. The first stake of this game was the possession of the fort of Vaux. Access to it was cut off from the French by a barrage-fire of unprecedented intensity; at the same time an assault was made against the trenches flanking the fort, and also against the defenses of the Fumin woods. On June 4 the enemy reached the superstructure of the fort and took possession, showering down hand-grenades and asphyxiating gas on the garrison, which was shut up in the casemates. After a heroic resistance the defenders succumbed to thirst and surrendered on June 7.

Now that Vaux was captured, the German activity was directed against the ruins of the small fort of Thiaumont, which blocks the way to the Côte de Froideterre, and against the village of Fleury, dominating the mouth of a ravine leading to the Meuse. From June 8 to 20, terrible fighting won for the Germans the possession of Thiaumont; on the 23d, six divisions, representing a total of at least 70,000 men, were hurled against Fleury, which they held from the 23d to the 26th. The French,[24] undaunted, returned to the charge. On August 30 they reoccupied Thiaumont, lost it at half-past three of the same day, recaptured it at half-past four, and were again driven out two days later. However, they remained close to the redoubt and the village.

The Germans then turned south, against the fortifications which dominated the ridges and ravines. There, on a hillock, stands the fort of Souville, at approximately the same elevation as Douaumont. On July 3, they captured the battery of Damloup, to the east; on the 12th, after insignificant fighting, they sent forward a huge mass of troops which got as far as the fort and battery of L'Hôpital. A counterattack drove them away again, but they dug themselves in about 800 metres away.

After all, what had they accomplished? For twelve days they had been confronted with the uselessness of these bloody sacrifices. Verdun was out of reach; the offensive of the Somme was under way, and the French stood before the gates of Péronne. Decidedly, the Battle of Verdun was lost. Neither the onslaught of the first period nor the battles of fixation had brought about the desired end. It now became impossible to squander on this field of death the munitions and troops which the German army needed desperately at Péronne and Bapaume. The leaders of the German General Staff accepted the situation. Verdun held no further interest for them.

Verdun, however, continued to be of great interest to the French. In the first place, they could not endure seeing the enemy intrenched five kilometres away from the coveted city. Moreover, it was most important for them to prevent the Germans from weakening the Verdun front and transferring their men and guns to the Somme. The French troops, therefore, were to take the initiative out of the hands of[25] the Germans and inaugurate, in their turn, a battle of fixation. This new situation presented two phases: in July and August the French were satisfied to worry the enemy with small forces and to oblige them to fight; in October and December General Nivelle, well supplied with troops and material, was able to strike two vigorous blows which took back from the Germans the larger part of all the territory they had won since February 21.

From July 15 to September 15, furious fighting was in progress on the slopes of the plateau stretching from Thiaumont to Damloup. This time, however, it was the French who attacked savagely, who captured ground, and who took prisoners. So impetuous were they that their adversaries, who asked for nothing but quiet, were obliged to be constantly on their guard and deliver costly counter-attacks.

The contest raged most bitterly over the ruins of Thiaumont and Fleury. On the 15th of July the Zouaves broke into the southern part of the village, only to be driven out again. However, on the 19th and 20th the French freed Souville, and drew near to Fleury; from the 20th to the 26th they forged ahead step by step, taking 800 prisoners. A general attack, delivered on August 3, carried the fort of Thiaumont and the village of Fleury, with 1500 prisoners. The Germans reacted violently; the 4th of August they reoccupied Fleury, a part of which was taken back by the French that same evening. From the 5th to the 9th the struggle went on ceaselessly, night and day, in the ruins of the village. During this time the adversaries took and retook Thiaumont, which the Germans held after the 8th. But on the 10th the Colonial regiment from Morocco reached Fleury, carefully prepared the assault, delivered it on the 17th, and captured the northern and southern portions of the village,[26] encircling the central part, which they occupied on the 18th. From this day Fleury remained in French hands. The German counter-assaults of the 18th, 19th, and 20th of August were fruitless; the Moroccan Colonials held their conquest firmly.

On the 24th the French began to advance east of Fleury, in spite of incessant attacks which grew more intense on the 28th. Three hundred prisoners were taken between Fleury and Thiaumont on September 3, and 300 more fell into their hands in the woods of Vaux-Chapître. On the 9th they took 300 more before Fleury.

It may be seen that the French troops had thoroughly carried out the programme assigned to them of attacking the enemy relentlessly, obliging him to counter-attack, and holding him at Verdun. But the High Command was to surpass itself. By means of sharp attacks, it proposed to carry the strong positions which the Germans had dearly bought, from February to July, at the price of five months of terrible effort. This new plan was destined to be accomplished on October 24 and December 15.

Verdun was no longer looked on by the French as a "sacrificial sector." To this attack of October 24, destined to establish once for all the superiority of the soldier of France, it was determined to consecrate all the time and all the energy that were found necessary. A force of artillery which General Nivelle himself declared to be of exceptional strength was brought into position—no old-fashioned ordnance this time, but magnificent new pieces, among them long-range guns of 400 millimetres calibre. The Germans had fifteen divisions on the Verdun front, but the French command judged it sufficient to make the attack with three divisions, which advanced along a front of seven kilometres. These, however, were[27] made up of excellent troops, withdrawn from service in the first lines and trained for several weeks, who knew every inch of the ground. General Mangin was their commander.

The French artillery opened fire on October 21, by hammering away at the enemy's positions. A feint attack forced the Germans to reveal the location of their batteries, more than 130 of which were discovered and silenced. At 11.40 a.m., October 24, the assault started in the fog. The troops advanced on the run, preceded by a barrage-fire. On the left, the objective points were reached at 2.45 p.m., and the village of Douaumont captured. The fort was stormed at 3 o'clock by the Moroccan Colonials, and the few Germans who held out there surrendered when night came on. On the right, the woods surrounding Vaux were rushed with lightning speed. The battery of Damloup was taken by assault. Vaux alone resisted. In order to reduce it, the artillery preparation was renewed from October 28 to November 2, and the Germans evacuated the fort without fighting on the morning of the 2d. As they retreated, the French occupied the villages of Vaux and Damloup, at the foot of the côtes.

Thus the attack on Douaumont and Vaux resulted in a real victory, attested to by the reoccupation of all the ground lost since the 25th of February, the capture of 15 cannon and more than 6000 prisoners. This, too, despite the orders found on German prisoners bidding them to "hold out at all cost" (25th Division), and to "make a desperate defense" (von Lochow). The French command, encouraged by this success, decided to do still better and to push on farther to the northeast.

The operations of December 15 were more difficult. They were directed against a zone occupied by the enemy for more than nine[28] months, during which time he had constructed a great network of communication trenches, field-railways, dug-outs built into the hillsides, forts, and redoubts. Moreover, the French attacks had to start from unfavorable ground, where ceaseless fighting had been in progress since the end of February, where the soil, pounded by millions of projectiles, had been reduced to a sort of volcanic ash, transformed by the rain into a mass of sticky mud in which men had been swallowed up bodily. Two whole divisions were needed to construct twenty-five kilometres of roads and ten kilometres of railway, make dug-outs and trenches, and bring the artillery up into position. All was ready in five weeks; but the Germans, finding out what was in preparation, had provided formidable means of defense.

The front to be attacked was held by five German divisions. Four others were held in reserve at the rear. On the French side, General Mangin had four divisions, three of which were composed of picked men, veterans of Verdun. The artillery preparation, made chiefly by pieces of 220, 274, and 370 mm., lasted for three full days. The assault was let loose on December 15, at 10 a.m.; on the left the French objectives were reached by noon; the whole spur of Hardaumont on the right was swiftly captured, and only a part of the German centre still resisted, east of Bezonvaux. This was reduced the next day. The Côte du Poivre was taken entire; Vacherauville, Louvemont, Bezonvaux as well. The front was now three kilometres from the fort of Douaumont. Over 11,000 prisoners were taken by the French, and 115 cannon. For a whole day their reconnoitring parties were able to advance in front of the new lines, destroying batteries and bringing in prisoners, without encountering any serious resistance.[29]

The success was undeniable. As a reply to the German peace proposals of December 12, the Battle of Verdun ended as a real victory; and this magnificent operation, in which the French had shown such superiority in infantry and artillery, seemed to be a pledge of future triumphs.

The conclusion is easily reached. In February and March Germany wished to end the war by crushing the French army at Verdun. She failed utterly. Then, from April to July, she wished to exhaust French military resources by a battle of fixation. Again she failed. The Somme offensive was the offspring of Verdun. Later on, from July to December, she was not able to elude the grasp of the French, and the last engagements, together with the vain struggles of the Germans for six months, showed to what extent General Nivelle's men had won the upper hand.

The Battle of Verdun, beginning as a brilliant German offensive, ended as an offensive victory for the French. And so this terrible drama is an epitome of the whole great war: a brief term of success for the Germans at the start, due to a tremendous preparation which took careless adversaries by surprise—terrible and agonizing first moments, soon offset by energy, heroism, and the spirit of sacrifice; and finally, victory for the Soldiers of Right.

On May 31st, 1916, there was fought in the North Sea off Jutland, the most important naval battle of the Great War. While the battle was undecisive in some of the results attained, it was an English victory, in that the Germans suffered greater losses and were forced to flee. The narrative of this battle which follows is by the Admiral of the British Fleet.

The German High Sea Fleet was brought to action on 31st May, 1916, to the westward of the Jutland Bank, off the coast of Denmark.

The ships of the Grand Fleet, in pursuance of the general policy of periodical sweeps through the North Sea, had left its bases on the previous day, in accordance with instructions issued by me.

In the early afternoon of Wednesday, 31st May, the 1st and 2nd Battle-cruiser Squadrons, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Light-cruiser Squadrons, and destroyers from the 1st, 9th, 10th, and 13th Flotillas, supported by the 5th Battle Squadron, were, in accordance with my directions, scouting to the southward of the Battle Fleet, which was accompanied by the 3rd Battle-cruiser Squadron, 1st and 2nd Cruiser Squadrons, 4th Light-cruiser Squadron, 4th, 11th, and 12th Flotillas.

The junction of the Battle Fleet with the scouting force after the enemy had been sighted was delayed owing to the southerly course steered by our advanced force during the first hour after commencing their action with the enemy battle-cruisers. This was, of course, unavoidable, as had our battle-cruisers not followed the enemy to the southward the main fleets would never have been in contact.

The Battle-cruiser Fleet, gallantly led by[31] Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty, K.C.B., M.V.O., D.S.O., and admirably supported by the ships of the Fifth Battle Squadron under Rear-Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas, M.V.O., fought an action under, at times, disadvantageous conditions, especially in regard to light, in a manner that was in keeping with the best traditions of the service.

The following extracts from the report of Sir David Beatty give the course of events before the Battle Fleet came upon the scene:

"At 2.20 p.m. reports were received from Galatea (Commodore Edwyn S. Alexander-Sinclair, M.V.O., A.D.C.), indicating the presence of enemy vessels. The direction of advance was immediately altered to SSE., the course for Horn Reef, so as to place my force between the enemy and his base.

"At 2.35 p.m. a considerable amount of smoke was sighted to the eastward. This made it clear that the enemy was to the northward and eastward, and that it would be impossible for him to round the Horn Reef without being brought to action. Course was accordingly altered to the eastward and subsequently to north-eastward, the enemy being sighted at 3.31 p.m. Their force consisted of five battle-cruisers.

"After the first report of the enemy, the 1st and 3rd Light-cruiser Squadrons changed their direction, and, without waiting for orders, spread to the east, thereby forming a screen in advance of the Battle-cruiser Squadrons and 5th Battle Squadron by the time we had hauled up to the course of approach. They engaged enemy light-cruisers at long range. In the meantime the 2nd Light-cruiser Squadron had come in at high speed, and was able to take station ahead of the battle-cruisers by the time we turned to ESE., the course on which we first engaged the enemy. In this respect the[32] work of the Light-cruiser Squadrons was excellent, and of great value.

"From a report from Galatea at 2.25 p.m. it was evident that the enemy force was considerable, and not merely an isolated unit of light-cruisers, so at 2.45 p.m. I ordered Engadine to send up a seaplane and scout to NNE. This order was carried out very quickly, and by 3.8 p.m. a seaplane was well under way; her first reports of the enemy were received in Engadine about 3.30 p.m. Owing to clouds it was necessary to fly very low, and in order to identify four enemy light-cruisers the seaplane had to fly at a height of 900 feet within 3,000 yards of them, the light-cruisers opening fire on her with every gun that would bear.

"At 3.30 p.m. I increased speed to 25 knots, and formed line of battle, the 2nd Battle-cruiser Squadron forming astern of the 1st Battle-cruiser Squadron, with destroyers of the 13th and 9th Flotillas taking station ahead. I turned to ESE., slightly converging on the enemy, who were now at a range of 23,000 yards, and formed the ships on a line of bearing to clear the smoke. The 5th Battle Squadron, who had conformed to our movements, were now bearing NNW., 10,000 yards. The visibility at this time was good, the sun behind us and the wind SE. Being between the enemy and his base, our situation was both tactically and strategically good.

"At 3.48 p.m. the action commenced at a range of 18,500 yards, both forces opening fire practically simultaneously. Course was altered to the southward, and subsequently the mean direction was SSE., the enemy steering a parallel course distant about 18,000 to 14,500 yards.

"At 4.8 p.m. the 5th Battle Squadron came into action and opened fire at a range of 20,000 yards. The enemy's fire now seemed to slacken. The destroyer Landrail, of 9th Flotilla, who[33] was on our port beam, trying to take station ahead, sighted the periscope of a submarine on her port quarter. Though causing considerable inconvenience from smoke, the presence of Lydiard and Landrail undoubtedly preserved the battle-cruisers from closer submarine attack. Nottingham also reported a submarine on the starboard beam.

"Eight destroyers of the 13th Flotilla, Nestor, Nomad, Nicator, Narborough, Pelican, Petard, Obdurate, Nerissa, with Moorsom and Morris, of 10th Flotilla, Turbulent and Termagant, of the 9th Flotilla, having been ordered to attack the enemy with torpedoes when opportunity offered, moved out at 4.15 p.m., simultaneously with a similar movement on the part of the enemy Destroyers. The attack was carried out in the most gallant manner, and with great determination. Before arriving at a favorable position to fire torpedoes, they intercepted an enemy force consisting of a light-cruiser and fifteen destroyers. A fierce engagement ensued at close quarters, with the result that the enemy were forced to retire on their battle-cruisers, having lost two destroyers sunk, and having their torpedo attack frustrated. Our destroyers sustained no loss in this engagement, but their attack on the enemy battle-cruisers was rendered less effective, owing to some of the destroyers having dropped astern during the fight. Their position was therefore unfavorable for torpedo attack.

"Nestor, Nomad, and Nicator pressed home their attack on the battle-cruisers and fired two torpedoes at them, being subjected to a heavy fire from the enemy's secondary armament. Nomad was badly hit, and apparently remained stopped between the lines. Subsequently Nestor and Nicator altered course to the SE., and in a short time, the opposing battle-cruisers having turned 16 points, found themselves within[34] close range of a number of enemy battleships. Nothing daunted, though under a terrific fire, they stood on, and their position being favorable for torpedo attack fired a torpedo at the second ship of the enemy line at a range of 3,000 yards. Before they could fire their fourth torpedo, Nestor was badly hit and swung to starboard, Nicator altering course inside her to avoid collision, and thereby being prevented from firing the last torpedo. Nicator made good her escape. Nestor remained stopped, but was afloat when last seen. Moorsom also carried out an attack on the enemy's battle fleet.

"Petard, Nerissa, Turbulent, and Termagant also pressed home their attack on the enemy battle cruisers, firing torpedoes after the engagement with enemy destroyers. Petard reports that all her torpedoes must have crossed the enemy's line, while Nerissa states that one torpedo appeared to strike the rear ship. These destroyer attacks were indicative of the spirit pervading His Majesty's Navy, and were worthy of its highest traditions. I propose to bring to your notice a recommendation of Commander Bingham and other Officers for some recognition of their conspicuous gallantry.

"From 4.15 to 4.43 p.m. the conflict between the opposing battle-cruisers was of a very fierce and resolute character. The 5th Battle Squadron was engaging the enemy's rear ships, unfortunately at very long range. Our fire began to tell, the accuracy and rapidity of that of the enemy depreciating considerably. At 4.18 p.m. the third enemy ship was seen to be on fire. The visibility to the north-eastward had become considerably reduced, and the outline of the ships very indistinct.

"At 4.38 p.m. Southampton reported the enemy's Battle Fleet ahead. The destroyers were recalled, and at 4.42 p.m. the enemy's[35] Battle Fleet was sighted SE. Course was altered 16 points in succession to starboard, and I proceeded on a northerly course to lead them towards the Battle Fleet. The enemy battle-cruisers altered course shortly afterwards, and the action continued. Southampton, with the 2nd Light-cruiser Squadron, held on to the southward to observe. They closed to within 13,000 yards of the enemy Battle Fleet, and came under a very heavy but ineffective fire. Southampton's reports were most valuable. The 5th Battle Squadron were now closing on an opposite course and engaging the enemy battle-cruisers with all guns. The position of the enemy Battle Fleet was communicated to them, and I ordered them to alter course 16 points. Led by Rear-Admiral Evan-Thomas, in Barham, this squadron supported us brilliantly and effectively.

"At 4.57 p.m. the 5th Battle Squadron turned up astern of me and came under the fire of the leading ships of the enemy Battle Fleet. Fearless, with the destroyers of 1st Flotilla, joined the battle-cruisers, and, when speed admitted, took station ahead. Champion, with 13th Flotilla, took station on the 5th Battle Squadron. At 5 p.m. the 1st and 3rd Light-cruiser Squadrons, which had been following me on the southerly course, took station on my starboard bow; the 2nd Light-cruiser Squadron took station on my port quarter.

"The weather conditions now became unfavorable, our ships being silhouetted against a clear horizon to the westward, while the enemy were for the most part obscured by mist, only showing up clearly at intervals. These conditions prevailed until we had turned their van at about 6 p.m. Between 5 and 6 p.m. the action continued on a northerly course, the range being about 14,000 yards. During this time the enemy received very severe punishment,[36] and one of their battle-cruisers quitted the line in a considerably damaged condition. This came under my personal observation, and was corroborated by Princess Royal and Tiger. Other enemy ships also showed signs of increasing injury. At 5.5 p.m. Onslow and Moresby, who had been detached to assist Engadine with the seaplane, rejoined the battle-cruiser squadrons and took station on the starboard (engaged) bow of Lion. At 5.10 p.m. Moresby, being 2 points before the beam of the leading enemy ship, fired a torpedo at a ship in their line. Eight minutes later she observed a hit with a torpedo on what was judged to be the sixth ship in the line. Moresby then passed between the lines to clear the range of smoke, and rejoined Champion. In corroboration of this, Fearless reports having seen an enemy heavy ship heavily on fire at about 5.10 p.m., and shortly afterwards a huge cloud of smoke and steam.

"At 5.35 p.m. our course was NNE., and the estimated position of the Battle Fleet was N. 16 W., so we gradually hauled to the north-eastward, keeping the range of the enemy at 14,000 yards. He was gradually hauling to the eastward, receiving severe punishment at the head of his line, and probably acting on information received from his light-cruisers which had sighted and were engaged with the Third Battle-cruiser Squadron. Possibly Zeppelins were present also.

"At 5.50 p.m. British cruisers were sighted on the port bow, and at 5.56 p.m. the leading battleships of the Battle Fleet, bearing north 5 miles. I thereupon altered course to east, and proceeded at utmost speed. This brought the range of the enemy down to 12,000 yards. I made a report to you that the enemy battle-cruisers bore south-east. At this time only three of the enemy battle-cruisers were visible,[37] closely followed by battleships of the Koenig class.

"At about 6.5 p.m. Onslow, being on the engaged bow of Lion, sighted an enemy light-cruiser at a distance of 6,000 yards from us, apparently endeavoring to attack with torpedoes. Onslow at once closed and engaged her, firing 58 rounds at a range of from 4,000 to 2,000 yards, scoring a number of hits. Onslow then closed the enemy battle-cruisers, and orders were given for all torpedoes to be fired. At this moment she was struck amidships by a heavy shell, with the result that only one torpedo was fired. Thinking that all his torpedoes had gone, the Commanding Officer proceeded to retire at slow speed. Being informed that he still had three torpedoes, he closed with the light-cruiser previously engaged and torpedoed her. The enemy's Battle Fleet was then sighted, and the remaining torpedoes were fired at them and must have crossed the enemy's track. Damage then caused Onslow to stop.

"At 7.15 p.m. Defender, whose speed had been reduced to 10 knots, while on the disengaged side of the battle-cruisers, by a shell which damaged her foremost boiler, closed Onslow and took her in tow. Shells were falling all round them during this operation, which, however, was successfully accomplished. During the heavy weather of the ensuing night the tow parted twice, but was re-secured. The two struggled on together until 1 p.m., 1st June, when Onslow was transferred to tugs."

On receipt of the information that the enemy had been sighted, the British Battle Fleet, with its accompanying cruiser and destroyer force, proceeded at full speed on a SE. by S. course to close the Battle-cruiser Fleet. During the two hours that elapsed before the arrival of the Battle Fleet on the scene the steaming qualities of the older battleships were severely[38] tested. Great credit is due to the engine-room departments for the manner in which they, as always, responded to the call, the whole Fleet maintaining a speed in excess of the trial speeds of some of the older vessels.

The Third Battle-cruiser Squadron, commanded by Rear-Admiral the Hon. Horace L.A. Hood, C.B., M.V.O., D.S.O., which was in advance of the Battle Fleet, was ordered to reinforce Sir David Beatty. At 5.30 p.m. this squadron observed flashes of gunfire and heard the sound of guns to the south-westward. Rear-Admiral Hood sent the Chester to investigate, and this ship engaged three or four enemy light-cruisers at about 5.45 p.m. The engagement lasted for about twenty minutes, during which period Captain Lawson handled his vessel with great skill against heavy odds, and, although the ship suffered considerably in casualties, her fighting and steaming qualities were unimpaired, and at about 6.5 p.m. she rejoined the Third Battle-cruiser Squadron.

The Third Battle-cruiser Squadron had turned to the north-westward, and at 6.10 p.m. sighted our battle-cruisers, the squadron taking station ahead of the Lion at 6.21 p.m. in accordance with the orders of the Vice-Admiral Commanding Battle-cruiser Fleet. He reports as follows:

"I ordered them to take station ahead, which was carried out magnificently, Rear-Admiral Hood bringing his squadron into action ahead in a most inspiring manner, worthy of his great naval ancestors. At 6.25 p.m. I altered course to the ESE. in support of the Third Battle-cruiser Squadron, who were at this time only 8,000 yards from the enemy's leading ship. They were pouring a hot fire into her and caused her to turn to the westward of south. At the same time I made a report to you of the bearing and distance of the enemy battle-fleet.[39]

"By 6.50 p.m. the battle-cruisers were clear of our leading battle squadron then bearing about NNW. 3 miles, and I ordered the Third Battle-cruiser Squadron to prolong the line astern and reduced to 18 knots. The visibility at this time was very indifferent, not more than 4 miles, and the enemy ships were temporarily lost sight of. It is interesting to note that after 6 p.m., although the visibility became reduced, it was undoubtedly more favorable to us than to the enemy. At intervals their ships showed up clearly, enabling us to punish them very severely and establish a definite superiority over them. From the report of other ships and my own observation it was clear that the enemy suffered considerable damage, battle-cruisers and battleships alike. The head of their line was crumpled up, leaving battleships as targets for the majority of our battle-cruisers. Before leaving us the Fifth Battle Squadron was also engaging battleships. The report of Rear-Admiral Evan-Thomas shows that excellent results were obtained, and it can be safely said that his magnificent squadron wrought great execution.

"From the report of Rear-Admiral T. D. W. Napier, M.V.O., the Third Light-cruiser Squadron, which had maintained its station on our starboard bow well ahead of the enemy, at 6.25 p.m. attacked with the torpedo. Falmouth and Yarmouth both fired torpedoes at the leading enemy battle-cruiser, and it is believed that one torpedo hit, as a heavy underwater explosion was observed. The Third Light-cruiser Squadron then gallantly attacked the heavy ships with gunfire, with impunity to themselves, thereby demonstrating that the fighting efficiency of the enemy had been seriously impaired. Rear-Admiral Napier deserves great credit for his determined and effective attack. Indomitable reports that about this time one of[40] the Derfflinger class fell out of the enemy's line."

Meanwhile, at 5.45 p.m., the report of guns had become audible to me, and at 5.55 p.m. flashes were visible from ahead round to the starboard beam, although in the mist no ships could be distinguished, and the position of the enemy's battle fleet could not be determined. The difference in estimated position by "reckoning" between Iron Duke and Lion, which was inevitable under the circumstances, added to the uncertainty of the general situation.

Shortly after 5.55 p.m. some of the cruisers ahead, under Rear-Admirals Herbert L. Heath, M.V.O., and Sir Robert Arbuthnot, Bt., M.V.O., were seen to be in action, and reports received show that Defence, flagship, and Warrior, of the First Cruiser Squadron, engaged an enemy light-cruiser at this time. She was subsequently observed to sink.

At 6 p.m. Canterbury, which ship was in company with the Third Battle-cruiser Squadron, had engaged enemy light-cruisers which were firing heavily on the torpedo-boat destroyer Shark, Acasta, and Christopher; as a result of this engagement the Shark was sunk.

At 6 p.m. vessels, afterwards seen to be our battle-cruisers, were sighted by Marlborough bearing before the starboard beam of the battle fleet.

At the same time the Vice-Admiral Commanding, Battle-cruiser Fleet, reported to me the position of the enemy battle-cruisers, and at 6.14 p.m. reported the position of the enemy battle fleet.

At this period, when the battle fleet was meeting the battle-cruisers and the Fifth Battle Squadron, great care was necessary to ensure that our own ships were not mistaken for enemy vessels.

I formed the battle fleet in line of battle on[41] receipt of Sir David Beatty's report, and during deployment the fleets became engaged. Sir David Beatty had meanwhile formed the battle-cruisers ahead of the battle-fleet.

The divisions of the battle fleet were led by:

| The Commander-in-Chief. |

| Vice-Admiral Sir Cecil Burney, K.C.B., K.C.M.G. |

| Vice-Admiral Sir Thomas Jerram, K.C.B. |

| Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee, Bt., K.C.B., C.V.O., C.M.G. |

| Rear-Admiral Alexander L. Duff, C.B. |

| Rear-Admiral Arthur C. Leveson, C.B. |

| Rear-Admiral Ernest F. A. Gaunt, C.M.G. |

At 6.16 p.m. Defence and Warrior were observed passing down between the British and German Battle Fleets under a very heavy fire. Defence disappeared, and Warrior passed to rear disabled.

It is probable that Sir Robert Arbuthnot, during his engagement with the enemy's light-cruisers and in his desire to complete their destruction, was not aware of the approach of the enemy's heavy ships, owing to the mist, until he found himself in close proximity to the main fleet, and before he could withdraw his ships they were caught under a heavy fire and disabled. It is not known when Black Prince of the same squadron, was sunk, but a wireless signal was received from her between 8 and 9 p.m.

The First Battle Squadron became engaged during deployment, the Vice-Admiral opening fire at 6.17 p.m. on a battleship of the Kaiser class. The other Battle Squadrons, which had previously been firing at an enemy light cruiser, opened fire at 6.30 p.m. on battleships of the Koenig class.

At 6.6 p.m. the Rear-Admiral Commanding Fifth Battle Squadron, then in company with the battle-cruisers, had sighted the starboard[42] wing-division of the battle-fleet on the port bow of Barham, and the first intention of Rear-Admiral Evan-Thomas was to form ahead of the remainder of the battle-fleet, but on realizing the direction of deployment he was compelled to form astern, a manœuvre which was well executed by the squadron under a heavy fire from the enemy battle-fleet. An accident to Warspite's steering gear caused her helm to become jammed temporarily and took the ship in the direction of the enemy's line, during which time she was hit several times. Clever handling enabled Captain Edward M. Phillpotts to extricate his ship from a somewhat awkward situation.

Owing principally to the mist, but partly to the smoke, it was possible to see only a few ships at a time in the enemy's battle line. Towards the van only some four or five ships were ever visible at once. More could be seen from the rear squadron, but never more than eight to twelve.

The action between the battle-fleets lasted intermittently from 6.17 p.m. to 8.20 p.m. at ranges between 9,000 and 12,000 yards, during which time the British Fleet made alterations of course from SE. by E. by W. in the endeavour to close. The enemy constantly turned away and opened the range under cover of destroyer attacks and smoke screens as the effect of the British fire was felt, and the alterations of course had the effect of bringing the British Fleet (which commenced the action in a position of advantage on the bow of the enemy) to a quarterly bearing from the enemy battle line, but at the same time placed us between the enemy and his bases.

At 6.55 p.m. Iron Duke passed the wreck of Invincible, with Badger standing by.

During the somewhat brief periods that the ships of the High Sea Fleet were visible[43] through the mist, the heavy and effective fire kept up by the battleships and battle-cruisers of the Grand Fleet caused me much satisfaction, and the enemy vessels were seen to be constantly hit, some being observed to haul out of the line and at least one to sink. The enemy's return fire at this period was not effective, and the damage caused to our ships was insignificant.

Regarding the battle-cruisers, Sir David Beatty reports:—

"At 7.6 p.m. I received a signal from you that the course of the Fleet was south. Subsequently signals were received up to 8.46 p.m. showing that the course of the Battle Fleet was to the southwestward.

"Between 7 and 7.12 p.m. we hauled round gradually to SW. by S. to regain touch with the enemy, and at 7.14 p.m. again sighted them at a range of about 15,000 yards. The ships sighted at this time were two battle-cruisers and two battleships, apparently of the Koenig class. No doubt more continued the line to the northward, but that was all that could be seen. The visibility having improved considerably as the sun descended below the clouds, we re-engaged at 7.17 p.m. and increased speed to 22 knots. At 7.32 p.m. my course was SW., speed 18 knots, the leading enemy battleship bearing NW. by W. Again, after a very short time, the enemy showed signs of punishment, one ship being on fire, while another appeared to drop right astern. The destroyers at the head of the enemy's line emitted volumes of grey smoke, covering their capital ships as with a pall, under cover of which they turned away, and at 7.45 p.m. we lost sight of them.

"At 7.58 p.m. I ordered the First and Third Light-cruiser Squadrons to sweep to the westward and locate the head of the enemy's line,[44] and at 8.20 p.m. we altered course to west in support. We soon located two battle-cruisers and battleships, and were heavily engaged at a short range of about 10,000 yards. The leading ship was hit repeatedly by Lion, and turned away eight points, emitting very high flames and with a heavy list to port. Princess Royal set fire to a three-funnelled battleship. New Zealand and Indomitable report that the third ship, which they both engaged, hauled out of the line, heeling over and on fire. The mist which now came down enveloped them, and Falmouth reported they were last seen at 8.38 p.m. steaming to the westward.

"At 8.40 p.m. all our battle-cruisers felt a heavy shock as if struck by a mine or torpedo, or possibly sunken wreckage. As however, examination of the bottoms reveals no sign of such an occurrence, it is assumed that it indicated the blowing up of a great vessel.

"I continued on a south-westerly course with my light cruisers spread until 9.24 p.m. Nothing further being sighted, I assumed that the enemy were to the north-westward, and that we had established ourselves well between him and his base. Minotaur (Captain Arthur C. S. H. D'Aeth) was at this time bearing north 5 miles, and I asked her the position of the leading battle squadron of the Battle Fleet. Her reply was that it was in sight, but was last seen bearing NNE. I kept you informed of my position, course, and speed, also of the bearing of the enemy.

"In view of the gathering darkness, and the fact that our strategical position was such as to make it appear certain that we should locate the enemy at daylight under most favorable circumstances, I did not consider it desirable or proper to close the enemy Battle Fleet during the dark hours. I therefore concluded that I should be carrying out your wishes by[45] turning to the course of the Fleet, reporting to you that I had done so."

As was anticipated, the German Fleet appeared to rely very much on torpedo attacks, which were favored by the low visibility and by the fact that we had arrived in the position of a "following" or "chasing" fleet. A large number of torpedoes were apparently fired, but only one took effect (on Marlborough), and even in this case the ship was able to remain in the line and to continue the action. The enemy's efforts to keep out of effective gun range were aided by the weather conditions, which were ideal for the purpose. Two separate destroyer attacks were made by the enemy.

The First Battle Squadron, under Vice-Admiral Sir Cecil Burney, came into action at 6.17 p.m. with the enemy's Third Battle Squadron, at a range of about 11,000 yards, and administered severe punishment, both to the battleships and to the battle-cruisers and light-cruisers, which were also engaged. The fire of Marlborough was particularly rapid and effective. This ship commenced at 6.17 p.m. by firing seven salvoes at a ship of the Kaiser class, then engaged a cruiser, and again a battleship, and at 6.54 she was hit by a torpedo and took up a considerable list to starboard, but we opened at 7.3 p.m. at a cruiser and at 7.12 p.m. fired fourteen rapid salvoes at a ship of the Koenig class, hitting her frequently until she turned out of the line. The manner in which this effective fire was kept up in spite of the disadvantages due to the injury caused by the torpedo was most creditable to the ship and a very fine example to the squadron.

The range decreased during the course of the action to 9,000 yards. The First Battle Squadron received more of the enemy's return fire than the remainder of the battle-fleet, with the[46] exception of the Fifth Battle Squadron. Colossus was hit, but was not seriously damaged, and other ships were straddled with fair frequency.

In the Fourth Battle Squadron—in which squadron my flagship Iron Duke was placed—Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee leading one of the divisions—the enemy engaged was the squadron consisting of the Koenig and Kaiser class and some of the battle-cruisers, as well as disabled cruisers and light-cruisers. The mist rendered range-taking a difficult matter, but the fire of the squadron was effective. Iron Duke, having previously fired at a light-cruiser between the lines, opened fire at 6.30 p.m. on a battleship of the Koenig class at a range of 12,000 yards. The latter was very quickly straddled, and hitting commenced at the second salvo and only ceased when the target ship turned away.

The fire of other ships of the squadron was principally directed at enemy battle-cruisers and cruisers as they appeared out of the mist. Hits were observed to take effect on several ships.

The ships of the Second Battle Squadron, under Vice-Admiral Sir Thomas Jerram, were in action with vessels of the Kaiser or Koenig classes between 6.30 and 7.20 p.m., and fired also at an enemy battle-cruiser which had dropped back apparently severely damaged.

During the action between the battle fleets the Second Cruiser Squadron, ably commanded by Rear-Admiral Herbert L. Heath, M.V.O., with the addition of Duke of Edinburgh of the First Cruiser Squadron, occupied a position at the van, and acted as a connecting link between the battle fleet and the battle-cruiser fleet. This squadron, although it carried out useful work, did not have an opportunity of coming into action.[47]

The attached cruisers Boadicea, Active, Blanche and Bellona carried out their duties as repeating-ships with remarkable rapidity and accuracy under difficult conditions.

The Fourth Light-cruiser Squadron, under Commodore Charles E. Le Mesurier, occupied a position in the van until ordered to attack enemy destroyers at 7.20 p.m., and again at 8.18 p.m., when they supported the Eleventh Flotilla, which had moved out under Commodore James R. P. Hawksley, M.V.O., to attack. On each occasion the Fourth Light-cruiser Squadron was very well handled by Commodore Le Mesurier, his captains giving him excellent support, and their object was attained, although with some loss in the second attack, when the ships came under the heavy fire of the enemy battle fleet at between 6,500 and 8,000 yards. The Calliope was hit several times, but did not sustain serious damage, although I regret to say she had several casualties. The light-cruisers attacked the enemy's battleships with torpedoes at this time, and an explosion on board a ship of the Kaiser class was seen at 8.40 p.m.

During these destroyer attacks four enemy torpedo-boat destroyers were sunk by the gunfire of battleships, light-cruisers, and destroyers.

After the arrival of the British Battle Fleet the enemy's tactics were of a nature generally to avoid further action, in which they were favored by the conditions of visibility.

At 9 p.m. the enemy was entirely out of sight, and the threat of torpedo-boat-destroyer attacks during the rapidly approaching darkness made it necessary for me to dispose the fleet for the night, with a view to its safety from such attacks, whilst providing for a renewal of action at daylight. I accordingly manœuvred to remain between the enemy and his[48] bases, placing our flotillas in a position in which they would afford protection to the fleet from destroyer attack, and at the same time be favorably situated for attacking the enemy's heavy ships.

During the night the British heavy ships were not attacked, but the Fourth, Eleventh, and Twelfth Flotillas, under Commodore Hawksley and Captains Charles J. Wintour and Anselan J. B. Stirling, delivered a series of very gallant and successful attacks on the enemy, causing him heavy losses.

It was during these attacks that severe losses in the Fourth Flotilla occurred, including that of Tipperary, with the gallant leader of the Flotilla, Captain Wintour. He had brought his flotilla to a high pitch of perfection, and although suffering severely from the fire of the enemy, a heavy toll of enemy vessels was taken, and many gallant actions were performed by the flotilla.

Two torpedoes were seen to take effect on enemy vessels as the result of the attacks of the Fourth Flotilla, one being from Spitfire, and the other from either Ardent, Ambuscade, or Garland.

The attack carried out by the Twelfth Flotilla was admirably executed. The squadron attacked, which consisted of six large vessels, besides light-cruisers, and comprised vessels of the Kaiser class, was taken by surprise. A large number of torpedoes was fired, including some at the second and third ships in the line; those fired at the third ship took effect, and she was observed to blow up. A second attack, made twenty minutes later by Mænad on the five vessels still remaining, resulted in the fourth ship in the line being also hit.

The destroyers were under a heavy fire from the light-cruisers on reaching the rear of the line, but the Onslaught was the only vessel[49] which received any material injuries. In the Onslaught Sub-Lieutenant Harry W. A. Kemmis, assisted by Midshipman Reginald G. Arnot, R.N.R., the only executive officers not disabled, brought the ship successfully out of action and reached her home port.

During the attack carried out by the Eleventh Flotilla, Castor leading the flotilla, engaged and sank an enemy torpedo-boat-destroyer at point-blank range.

Sir David Beatty reports:—

"The Thirteenth Flotilla, under the command of Captain James U. Farie, in Champion, took station astern of the battle fleet for the night. At 0.30 a.m. on Thursday, 1st June, a large vessel crossed the rear of the flotilla at high speed. She passed close to Petard and Turbulent, switched on searchlights and opened a heavy fire, which disabled Turbulent. At 3.30 a.m. Champion was engaged for a few minutes with four enemy destroyers. Moresby reports four ships of Deutschland class sighted at 2.35 a.m., at whom she fired one torpedo. Two minutes later an explosion was felt by Moresby and Obdurate.

"Fearless and the 1st Flotilla were very usefully employed as a submarine screen during the earlier part of the 31st May. At 6.10 p.m., when joining the Battle Fleet, Fearless was unable to follow the battle cruisers without fouling the battleships, and therefore took station at the rear of the line. She sighted during the night a battleship of the Kaiser class steaming fast and entirely alone. She was not able to engage her, but believes she was attacked by destroyers further astern. A heavy explosion was observed astern not long after."

There were many gallant deeds performed by the destroyer flotillas; they surpassed the very highest expectations that I had formed of them.[50]

Apart from the proceedings of the flotillas, the Second Light-cruiser Squadron in the rear of the battle fleet was in close action for about 15 minutes at 10.20 p.m. with a squadron comprising one enemy cruiser and four light-cruisers, during which period Southampton and Dublin suffered rather heavy casualties, although their steaming and fighting qualities were not impaired. The return fire of the squadron appeared to be very effective.

Abdiel, ably commanded by Commander Berwick Curtis, carried out her duties with the success which has always characterized her work.

At daylight, 1st June, the battle fleet, being then to the southward and westward of the Horn Reef, turned to the northward in search of enemy vessels and for the purpose of collecting our own cruisers and torpedo-boat destroyers. At 2.30 a.m. Vice-Admiral Sir Cecil Burney transferred his flag from Marlborough to Revenge, as the former ship had some difficulty in keeping up the speed of the squadron. Marlborough was detached by my direction to a base, successfully driving off an enemy submarine attack en route. The visibility early on 1st June (three to four miles) was less than on 31st May, and the torpedo-boat destroyers, being out of visual touch, did not rejoin until 9 a.m. The British Fleet remained in the proximity of the battle-field and near the line of approach to German ports until 11 a.m. on 1st June, in spite of the disadvantage of long distances from fleet bases and the danger incurred in waters adjacent to enemy coasts from submarines and torpedo craft. The enemy, however, made no sign, and I was reluctantly compelled to the conclusion that the High Sea Fleet had returned into port. Subsequent events proved this assumption to have been correct. Our position must have[51] been known to the enemy, as at 4 a.m. the Fleet engaged a Zeppelin for about five minutes, during which time she had ample opportunity to note and subsequently report the position and course of the British Fleet.

The waters from the latitude of the Horn Reef to the scene of the action were thoroughly searched, and some survivors from the destroyers Ardent, Fortune, and Tipperary were picked up, and the Sparrowhawk, which had been in collision and was no longer seaworthy, was sunk after her crew had been taken off. A large amount of wreckage was seen, but no enemy ships, and at 1.15 p.m., it being evident that the German Fleet had succeeded in returning to port, course was shaped for our bases, which were reached without further incident on Friday, 2nd June. A cruiser squadron was detached to search for Warrior, which vessel had been abandoned whilst in tow of Engadine on her way to the base owing to bad weather setting in and the vessel becoming unseaworthy, but no trace of her was discovered, and a further subsequent search by a light-cruiser squadron having failed to locate her, it is evident that she foundered.