Title: A booke called the Foundacion of Rhetorike

Author: Richard Rainolde

Release date: July 14, 2008 [eBook #26056]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Lindahl, Linda Cantoni, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Notes

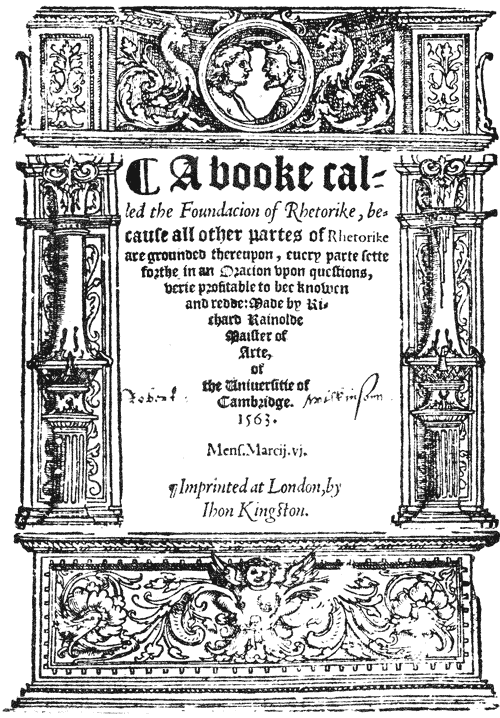

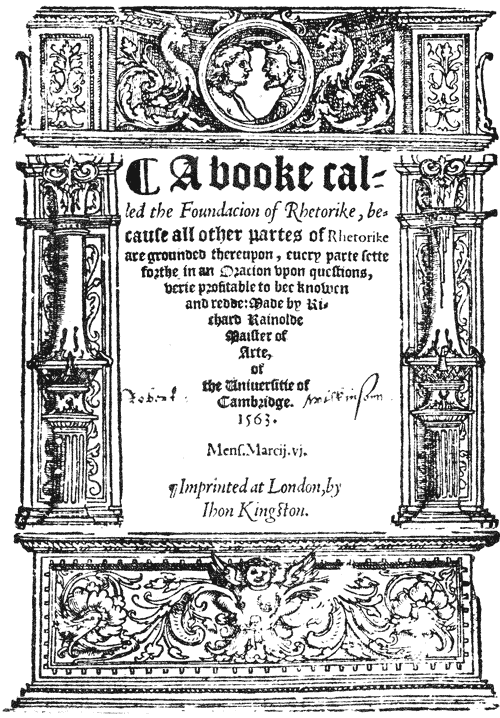

About this book: A booke called the Foundacion of Rhetorike was published in 1563. Only five copies of the original are known to exist. This e-book was transcribed from microfiche scans of the original in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. The scans can be viewed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France website at http://gallica.bnf.fr.

Typography: The original line and paragraph breaks, hyphenation, spelling, capitalization, punctuation, inconsistent use of an acute accent over ee, the use of u for v and vice versa, and the use of i for j and vice versa, have been preserved. All apparent printer errors have also been preserved, and are listed at the end of this document.

The following alterations have been made:

1. Long-s (ſ) is regularized as s.

2. The paragraph symbol, resembling a C in the original, is rendered as ¶.

3. Missing punctuation, hyphens, and paragraph symbols have been added in brackets, e.g. [-].

4. Except for the dedication, which is in modern italics, the majority of the original book is in blackletter font, with some words in a modern non-italic font. All modern-font passages are rendered in italics.

5. Incorrect page numbers are corrected, but are included in the list of printer errors at the end of this e-book.

6. Abbreviations and contractions represented as special characters in the original have been expanded as noted in the table below. “Supralinear” means directly over a letter; “sublinear” means directly under a letter. The y referred to below is an Early Modern English form of the Anglo-Saxon thorn character, representing th, but identical in appearance to the letter y.

| Original | Expansion |

| y with supralinear e | ye (i.e., the) |

| accented q with semicolon | q[ue] |

| w with supralinear curve | w[ith] |

| e with sublinear hook | [ae] |

A macron over a vowel represents m or n, and is rendered as it appears in the original, e.g., cōprehēded = comprehended.

Pagination: This book was paginated using folio numbers in a recto-verso scheme. The front of each folio is the recto page (the right-hand page); the back of each folio is the verso page (the left-hand page in a book). In the original, folio numbers (beginning after the table of contents) are printed only on the recto side of each leaf. For the reader’s convenience, all folio pages in this e-book, including the verso pages, have been numbered in brackets according to the original format, with the addition of r for recto and v for verso, e.g., Fol. x.r is Folio 10 recto, Fol. x.v is Folio 10 verso.

Sources consulted: The uneven quality of the microfiche scans, as well as the blackletter font and some ink bleed-through and blemishes in the original, made the scans difficult to read in some places. To ensure accuracy, the transcriber has consulted the facsimile reprint edited by Francis R. Johnson (Scholars’ Facsimiles and Reprints, New York, 1945). The 1945 reprint was prepared primarily from the Bodleian copy, with several pages reproduced from the copy in the Chapin Library at Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, where the Bodleian copy was unclear.

¶ A booke cal-

led the Foundacion of Rhetorike, be-

cause all other partes of Rhetorike

are grounded thereupon, euery parte sette

forthe in an Oracion vpon questions,

verie profitable to bee knowen

and redde: Made by Ri-

chard Rainolde

Maister of

Arte,

of

the Uniuersitie of

Cambridge.

1563.

Mens. Marcij. vj.

¶ Imprinted at London, by

Ihon Kingston.

THE EPISTLE DEDICATORIE

¶ To the right honorable and my singuler good Lorde,

my Lorde Robert Dudley, Maister of the

Queenes Maiesties horse, one of her highes pri-

uie Counsaile, and knight of the moste honou-

rable order of the Garter: Richard Rai-

nolde wisheth longe life, with

increase of honour.

RISTOTLE the famous Phi-

RISTOTLE the famous Phi-

losopher, writing a boke to king

Alexāder, the great and migh-

tie conquerour, began the Epi-

stle of his Booke in these woor-

des. Twoo thynges moued me

chieflie, O King, to betake to thy Maiesties handes,

this worke of my trauile and labour, thy nobilitie and

vertue, of the whiche thy nobilitie encouraged me, thy

greate and singuler vertue, indued with all humanitie,

forced and draue me thereto. The same twoo in your

good Lordshippe, Nobilitie and Vertue, as twoo migh-

tie Pillers staied me, in this bolde enterprise, to make

your good Lordshippe, beyng a Pere of honour, indued

with all nobilitie and vertue: a patrone and possessoure

of this my booke. In the whiche although copious and

aboundaunte eloquence wanteth, to adorne and beau-

tifie thesame, yet I doubte not for the profite, that is in

this my trauaile conteined, your honour indued with

all singuler humanitie, will vouchsaufe to accepte my

willyng harte, my profitable purpose herein. Many fa-

mous menne and greate learned, haue in the Greke

tongue and otherwise trauailed, to profite all tymes

their countrie and common wealthe. This also was my

ende and purpose, to plante a worke profitable to all ty-

mes, my countrie and common wealthe.

And because your Lordshippe studieth all singula-

ritie to vertue, and wholie is incensed thereto: I haue

compiled this woorke, and dedicated it to your Lorde-

shippe, as vnto whō moste noble and vertuous. Wher-

in are set forthe soche Oracions, as are right profitable

to bee redde, for knowledge also necessarie. The duetie

of a subiecte, the worthie state of nobilitie, the prehe-

minent dignitie and Maiestie of a Prince, the office of

counsailours, worthie chiefe veneracion, the office of a

Iudge or Magestrate are here set foorthe. In moste for-

tunate state is the kyngdome and Common wealthe,

where the Nobles and Peres, not onelie daiely doe stu-

die to vertue, for that is the wisedome, that all the

graue and wise Philophers searched to attaine to. For

the ende of all artes and sciences, and of all noble actes

and enterprises is vertue, but also to fauour and vphold

the studentes of learnyng, whiche also is a greate ver-

tue. Whoso is adorned with nobilitie and vertue, of

necessitie nobilitie and vertue, will moue and allure thē

to fauour and support vertue in any other, yea, as Tul-

lie the moste famous Oratour dooeth saie, euen to loue

those whō we neuer sawe, but by good fame and brute

beutified to vs. For the encrease of vertue, God

dooeth nobilitate with honour worthie

menne, to be aboue other in dignitie

and state, thereupon vertue

doeth encrease your

Lordshipps

honor,

beyng a louer of vertue

and worthie no-

bilitie.

Your lordshippes humble ser-

uaunt Richard Rainolde.

To the Reader.

PHTHONIVS a famous man, wrote

PHTHONIVS a famous man, wrote

in Greke of soche declamacions, to en-

structe the studentes thereof, with all fa-

cilitée to grounde in them, a moste plenti-

ous and riche vein of eloquence. No man

is able to inuente a more profitable waie

and order, to instructe any one in the ex-

quisite and absolute perfeccion, of wisedome and eloquence,

then Aphthonius Quintilianus and Hermogenes. Tullie al-

so as a moste excellente Orator, in the like sorte trauailed,

whose Eloquence and vertue all tymes extolled, and the of-

spryng of all ages worthilie aduaunceth. And because as yet

the verie grounde of Rhetorike, is not heretofore intreated

of, as concernyng these exercises, though in fewe yeres past,

a learned woorke of Rhetorike is compiled and made in the

Englishe toungue, of one, who floweth in all excellencie of

arte, who in iudgement is profounde, in wisedome and elo-

quence moste famous. In these therefore my diligence is em-

ploied, to profite many, although not with like Eloquence,

beutified and adorned, as the matter requireth. I haue cho-

sen out in these Oracions soche questions, as are right ne-

cessarie to be knowen and redde of all those, whose cogitaciō

pondereth vertue and Godlines. I doubte not, but seyng my

trauaile toucheth vertuous preceptes, and vttereth to light,

many famous Histories, the order of arte obserued also, but

that herein the matter it self, shall defende my purpose aga-

inste the enuious, whiche seketh to depraue any good enter-

prise, begon of any one persone. The enuious manne

though learned, readeth to depraue that, which he

readeth, the ignoraunt is no worthie Iudge,

the learned and godlie pondereth vp-

rightly & sincerely, that which

he iudgeth, the order of

these Oracions

followeth afterward, and

the names of thē.

¶ The contentes of

this Booke.

N Oracion made, vpon the Fable of the Shepher-

N Oracion made, vpon the Fable of the Shepher-

des and the Wolues, the Wolues requestyng the

Bandogges: wherein is set forthe the state of eue-

ry subiecte, the dignitie of a Prince, the honoura-

ble office of counsailours.

An Oracion vpon the Fable of the Ante and the Gres-

hopper, teachyng prouidence.

An Oracion Historicall, howe Semiramis came to bee

Quéene of Babilon.

An Oracion Historicall, vpon Kyng Richard the thirde

sometyme Duke of Glocester.

An Oracion Historicall, of the commyng of Iulius Ce-

ser into Englande.

An Oracion Ciuill or Iudiciall, vpon Themistocles, of

the walle buildyng at Athenes.

An Oracion Poeticall vpon a redde Rose.

A profitable Oracion, shewyng the decaie of kingdomes

and nobilitie.

An Oracion vpon a Sentence, preferryng a Monarchie,

conteinyng all other states of common wealthe.

The confutacion of the battaile of Troie.

A confirmacion of the noble facte of Zopyrus.

An Oracion called a Common place against Theues.

The praise of Epaminundas Duke of Thebes, wherein

the grounde of nobilitée is placed.

The dispraise of Domicius Nero Emperour of Roome.

A comparison betwene Demosthenes and Tullie.

A lamentable Oracion of Hecuba Queene of Troie.

A descripcion vpon Xerxes kyng of Persia.

An Oracion called Thesis, as concerning the goodly state

of Mariage.

An Oracion confutyng a certaine lawe of Solon.

The foundacion of

Rhetorike.

Ature hath indued euery man, with

Ature hath indued euery man, with

a certain eloquence, and also subtili-

Rhetorike

and Logike

giuen of na-

ture.

tée to reason and discusse, of any que-

stion or proposicion propounded, as

Aristotle the Philosopher, in his

Booke of Rhetorike dooeth shewe.

These giftes of nature, singuler doe

flowe and abounde in vs, accordyng

to the greate and ample indumente

and plentuousnes of witte and wisedome, lodged in vs, there-

fore Nature it self beyng well framed, and afterward by arte

Arte furthe-

reth nature.

and order of science, instructed and adorned, must be singular-

lie furthered, helped, and aided to all excellencie, to exquisite

Logike.

inuencion, and profounde knowledge, bothe in Logike and

Rhetorike.

Rhetorike. In the one, as a Oratour to pleate with all facili-

tee, and copiouslie to dilate any matter or sentence: in the other

to grounde profunde and subtill argument, to fortifie & make

stronge our assercion or sentence, to proue and defende, by the

Logike.

force and power of arte, thinges passyng the compasse & reach

of our capacitée and witte. Nothyng can bee more excellently

Eloquence.

giuen of nature then Eloquence, by the which the florishyng

state of commonweales doe consiste: kyngdomes vniuersally

are gouerned, the state of euery one priuatelie is maintained.

The commonwealth also should be maimed, and debilitated,

Zeno.

except the other parte be associate to it. Zeno the Philosopher

comparing Rhetorike and Logike, doeth assimilate and liken

Logike.

them to the hand of man. Logike is like faith he to the fiste, for

euen as the fiste closeth and shutteth into one, the iointes and

partes of the hande, & with mightie force and strength, wrap-

Similitude[.]

Logike.

peth and closeth in thynges apprehended: So Logike for the

deepe and profounde knowlege, that is reposed and buried in

it, in soche sort of municion and strength fortified, in few wor-

des taketh soche force and might by argumente, that excepte

[Fol. j.v]like equalitée in like art and knowledge doe mate it, in vain

the disputacion shalbe, and the repulse of thaduersarie readie.

Rhetorike

like to the

hande.

Rhetorike is like to the hand set at large, wherein euery part

and ioint is manifeste, and euery vaine as braunches of trées

Rhetorike.

sette at scope and libertee. So of like sorte, Rhetorike in moste

ample and large maner, dilateth and setteth out small thyn-

ges or woordes, in soche sorte, with soche aboundaunce and

plentuousnes, bothe of woordes and wittie inuencion, with

soche goodlie disposicion, in soche a infinite sorte, with soche

pleasauntnes of Oracion, that the moste stonie and hard har-

tes, can not but bee incensed, inflamed, and moued thereto.

Logike and

Rhetorike

absolute in

fewe.

These twoo singuler giftes of nature, are absolute and perfect

in fewe: for many therebe, whiche are exquisite and profound

in argument, by art to reason and discusse, of any question or

proposicion propounded, who by nature are disabled, & smal-

lie adorned to speake eloquently, in whom neuertheles more

aboundaunt knowlege doeth somtymes remaine then in the

other, if the cause shalbe in controuersie ioined, and examined

to trie a manifeste truthe. But to whom nature hath giuen

soche abilitée, and absolute excellencie, as that thei can bothe

The vertue

of eloquence.

copiouslie dilate any matter or sentence, by pleasauntnes and

swetenes of their wittie and ingenious oracion, to drawe vn-

to theim the hartes of a multitude, to plucke doune and extir-

pate affecciōs and perturbacions of people, to moue pitee and

compassion, to speake before Princes and rulers, and to per-

swade theim in good causes and enterprises, to animate and

incense them, to godlie affaires and busines, to alter the coū-

saill of kynges, by their wisedome and eloquence, to a better

state, and also to be exquisite in thother, is a thing of all most

Demosthe-

nes.

Tisias.

Gorgias.

Eschines[.]

Tullie.

Cato.

noble and excellent. The eloquence of Demosthenes, Isocra-

tes, Tisias, Gorgias, Eschines, were a great bulwarke and

staie to Athens and all Grece, Rome also by the like vertue

of Eloquence, in famous and wise orators vpholded: the wise

and eloquente Oracions of Tullie againste Catiline. The

graue and sentencious oracions of Cato in the Senate, haue

[Fol. ij.r]

The Empe-

rors of Rome

famous in

Eloquence.

been onelie the meane to vpholde the mightie state of Rome,

in his strength and auncient fame and glorie. Also the Chro-

nicles of auncient time doe shewe vnto vs, the state of Rome

could by no meanes haue growen so meruailous mightie,

but that God had indued the whole line of Cesars, with sin-

guler vertues, with aboundaunt knowlege & singuler Elo-

quence. Thusidides the famous Historiographer sheweth,

Thusidides.

how moche Eloquence auailed the citees of Grece, fallyng to

Corcurians.

dissenciō. How did the Corcurians saue them selues from the

Pelopone-

sians.

inuasiō and might, of the Poloponesians, their cause pleated

before the Athenians, so moche their eloquence in a truthe

Corinthians[.]

preuailed. The Ambassadours of Corinth, wanted not their

copious, wittie, and ingenious Oracions, but thei pleated

before mightie, wise, and graue Senators, whose cause, ac-

cordyng to iudgemēt, truthe, and integritée was ended. The

Lacedemo-

nians.

Vituleniās.

Athenians.

eloquēt Embassages of the Corinthiās, the Lacedemoniās,

& the Vituleneans, the Athenians, who so readeth, shall sone

sée that of necessitee, a common wealth or kyngdome must be

fortefied, with famous, graue, and wise counsailours. How

Demosthe-

nes.

often did Demosthenes saue the cōmon wealthes of Athens,

how moche also did that large dominion prospere and florish

Socrates.

Cato.

Crassus.

Antonius.

Catulus.

Cesar.

by Isocrates. Tullie also by his Eloquēt please, Cato, Cras-

sus, Antonius, Catulus Cesar, with many other, did support

and vphold the state of that mightie kyngdō. No doubte, but

that Demosthenes made a wittie, copious, and ingenious o-

racions, when the Athenians were minded to giue and be-

Philippe the

kyng of the

Macidoniās[.]

take to the handes of Philip kyng of the Macedonians, their

pestiferous enemie moste vile and subtell, the Orators of A-

thens. This Philip forseyng the discorde of Grece, as he by

subtill meanes compassed his enterprices, promised by the

faithe of a Prince, to be at league with the Athenians, if so be

thei would betake to his handes, the eloquente Oratours of

The saiyng

of Philippe.

Athens, for as long saith he, as your Oratours are with you

declaryng, so longe your heddes and counsaill are moued to

variaunce and dissencion, this voice ones seased emong you,

[Fol. ij.v]

Demosthe-

nes.

in tranquilitée you shalbee gouerned. Demosthenes beyng

eloquente and wise, foresawe the daungers and the mischie-

uous intent of him, wherevpon he framed a goodly Oracion

vpon a Fable, whereby he altered their counsaile, and repul-

sed the enemie. This fable is afterward set forth in an Ora-

cion, after the order of these exercises, profitable to Rhetorike.

¶ A Fable.

The ground

of al learning[.]

Irste it is good that the learner doe vnderstand

Irste it is good that the learner doe vnderstand

what is a fable, for in all matters of learnyng,

it is the firste grounde, as Tullie doeth saie, to

knowe what the thing is, that we may the bet-

What is a

fable.

ter perceiue whervpō we doe intreate. A fable

is a forged tale, cōtaining in it by the colour of a lie, a matter

Morall.

of truthe. The moralle is called that, out of the whiche some

godlie precepte, or admonicion to vertue is giuen, to frame

and instruct our maners. Now that we knowe what a fable

is, it is good to learne also, how manifolde or diuers thei be,

Three sortes

of fables.

i. A fable of

reason.

I doe finde three maner of fables to be. The first of theim is,

wherein a man being a creature of God indued with reason,

is onely intreated of, as the Fable of the father and his chil-

dren, he willing thē to concorde, and this is called Rationalis

fabula, whiche is asmoche to saie, as a Fable of men indued

ii. Morall.

with reason, or women. The second is called a morall fable,

but I sée no cause whie it is so called, but rather as the other

is called a fable of reasonable creatures, so this is contrarilie

named a fable of beastes, or of other thinges wanting reason

or life, wanting reason as of the Ante and the Greshopper, or

of this the beame caste doun, and the Frogges chosyng their

iii. Mixt.

king. The thirde is a mixt Fable so called, bicause in it bothe

man hauyng reason, and a beaste wantyng reason, or any o-

ther thing wanting life, is ioyned with it, as for the example,

of the fable of the woodes and the housebandman, of whom

Poetes in-

uentours of

fables.

Oratours

vse fables.

he desired a helue for his hatchet. Aucthours doe write, that

Poetes firste inuented fables, the whiche Oratours also doe

[Fol. iij.r]vse in their perswasions, and not without greate cause, both

Poetes and Oratours doe applie theim to their vse. For, fa-

Good doctrin

in fables.

Hesiodus.

bles dooe conteine goodlie admonicion, vertuous preceptes

of life. Hesiodus the Poete, intreatyng of the iniurious dea-

lyng of Princes and gouernours, against their subiectes, ad-

monished them by the fable of the Goshauke, and the Nigh-

Ouide.

tyngale in his clause. Ouid also the Poete intreated of di-

uers fables, wherein he giueth admonicion, and godly coun-

Demosthe-

nes vsed fa-

bles.

saile. Demosthenes the famous Oratour of Athens, vsed

the fable of the Shepeherdes, and Wolues: how the Wol-

ues on a tyme, instauntlie required of the Shepeherdes their

bande dogges, and then thei would haue peace and concorde

with theim, the Shepeherdes gaue ouer their Dogges, their

Dogges deliuered and murdered, the shepe were immediat-

ly deuoured: So saieth he, if ye shall ones deliuer to Philip,

the king of the Macedonians your Oratours, by whose lear-

nyng, knowlege and wisedome, the whole bodie of your do-

minions is saued, for thei as Bandogges, doe repell all mis-

cheuous enterprises and chaunses, no doubte, but that raue-

nyng Wolfe Philip, will eate and consume your people, by

this Fable he made an Oracion, he altered their counsailes

and heddes of the Athenians, from so foolishe an enterprise.

Also thesame Demosthenes, seyng the people careles, sloth-

full, and lothsome to heare the Oratours, and all for the flo-

rishing state of the kingdome: he ascended to the place or pul-

pet, where the Oracions were made, and began with this fa-

The fable of

Demosthe-

nes, of the

Asse and the

shadowe.

ble. Ye men of Athens, saied he, it happened on a tyme, that

a certaine man hired an Asse, and did take his iourney from

Athens to Megara, as we would saie, frō London to Yorke,

the owner also of the Asse, did associate hymself in his iour-

ney, to brynge backe the Asse againe, in the voyage the

weather was extreame burning hotte, and the waie tedious

the place also for barenes and sterilitée of trees, wanted sha-

dowe in this long broyle of heate: he that satte one the Asse,

lighted and tooke shadowe vnder the bellie of the Asse, and

[Fol. iij.v]because the shadowe would not suffice bothe, the Asse beyng

small, the owner saied, he muste haue the shadowe, because

the Asse was his, I deny that saieth the other, the shadowe is

myne, because I hired the Asse, thus thei were at greate con-

tencion, the fable beyng recited, Demosthenes descended frō

his place, the whole multitude were inquisitiue, to knowe

The conten-

cion vpon the

shadowe and

the Asse.

the ende about the shadowe, Demosthenes notyng their fol-

lie, ascended to his place, and saied, O ye foolishe Athenians,

whiles I and other, gaue to you counsaill and admoniciō, of

graue and profitable matters, your eares wer deafe, and your

mindes slombred, but now I tell of a small trifeling matter,

you throng to heare the reste of me. By this Fable he nipped

their follie, and trapped them manifestlie, in their owne dol-

tishenes. Herevpon I doe somwhat long, make copie of wor-

Fables well

applied bee

singuler.

des, to shewe the singularitee of fables well applied. In the

tyme of Kyng Richard the thirde, Doctour Mourton, beyng

Bishop of Elie, and prisoner in the Duke of Buckynghams

house in Wales, was often tymes moued of the Duke, to

speake his minde frelie, if king Richard wer lawfully king,

and said to him of his fidelitée, to kepe close and secret his sen-

tence: but the Bishop beyng a godlie man, and no lesse wise,

waied the greate frendship, whiche was sometyme betwene

the Duke & King Richard, aunswered in effect nothyng, but

beyng daily troubled with his mocions & instigacions, spake

a fable of Esope: My lorde saied he, I will aunswere you, by

The fable of

the Bisshop

of Elie, to the

duke of Buc-

kyngham.

a Fable of Esope. The Lion on a tyme gaue a commaunde-

ment, that all horned beastes should flie from the woode, and

none to remain there but vnhorned beastes. The Hare hea-

ring of this commaundement, departed with the horned bea-

stes from the woodde: The wilie Foxe metyng the Hare, de-

maunded the cause of his haste, forthwith the Hare aunswe-

red, a commaundemente is come from the Lion, that all hor-

ned beastes should bee exiled, vpon paine of death, from the

woode: why saied the Foxe, this commaundement toucheth

not any sorte of beast as ye are, for thou haste no hornes but

[Fol. iiij.r]knubbes: yea, but said the Hare, what, if thei saie I haue hor-

nes, that is an other matter, my lorde I saie no more: what he

ment, is euident to all men.

In the time of king Hēry theight (a prince of famous me-

morie) at what time as the small houses of religiō, wer giuen

ouer to the kinges hand, by the Parliament house: the bishop

of Rochester, Doctour Fisher by name stepped forthe, beyng

greued with the graunt, recited before them, a fable of Esope

to shewe what discommoditee would followe in the Clergie.

The fable of

the Bisshop

of Rochester,

againste the

graunt of the

Chauntries.

My lordes and maisters saieth he, Esope recited a fable: how

that on a tyme, a housebande manne desired of the woodes, a

small helue for his hatchet, all the woodes consented thereto

waiyng the graunt to be small, and the thyng lesse, therevpō

the woodes consented, in fine the housbande man cut doune

a small peece of woodde to make a helue, he framyng a helue

to the hatchette, without leaue and graunt, he cut doune the

mightie Okes and Cedars, and destroyed the whole woodd,

then the woodes repented them to late. So saith he, the gift of

these small houses, ar but a small graunt into the kinges hā-

des: but this small graunt, will bee a waie and meane to pull

doune the greate mightie fatte Abbees, & so it happened. But

there is repentaūce to late: & no profite ensued of the graunte.

¶ An Oracion made by a fable, to the first exer-

cise to declame by, the other, bee these,

| { | A Fable, a Narracion. Chria, | } | |

| { | Sentence. Confutacion, | } | |

| An Oracion made by a | { | Confirmacion. Common place. | } |

| { | The praise. The dispraise. | } | |

| { | The Comparison, Ethopeia. | } | |

| { | A Discripcion. Thesis, Legislatio | } |

F euery one of these, a goodlie Oraciō maie be made

F euery one of these, a goodlie Oraciō maie be made

these excercises are called of the Grekes Progimnas-

mata, of the Latines, profitable introduccions, or fore

exercises, to attain greater arte and knowlege in Rhetorike,

[Fol. iiij.v]and bicause, for the easie capacitée and facilitée of the learner,

to attain greater knowledge in Rhetorike, thei are right pro-

fitable and necessarie: Therefore I title this booke, to bee the

foundaciō of Rhetorike, the exercises being Progimnasmata.

I haue chosen out the fable of the Shepeherdes, and the

Wolues, vpon the whiche fable, Demosthenes made an elo-

quente, copious, and wittie Oracion before the Athenians,

whiche fable was so well applied, that the citée and common

wealth of Athens was saued.

The firste

exercise.

¶ A fable.

These notes must be obserued, to make an Oracion by a

Fable.

¶ Praise.

1.Firste, ye shall recite the fable, as the aucthour telleth it.

2.There in the seconde place, you shall praise the aucthoure

who made the fable, whiche praise maie sone bee gotte of any

studious scholer, if he reade the aucthours life and actes ther-

in, or the Godlie preceptes in his fables, shall giue abundant

praise.

3.Then thirdlie place the morall, whiche is the interpreta-

cion annexed to the Fable, for the fable was inuented for the

moralles sake.

4.Then orderlie in the fowerth place, declare the nature of

thynges, conteined in the Fable, either of man, fishe, foule,

beaste, plante, trées, stones, or whatsoeuer it be. There is no

man of witte so dulle, or of so grosse capacitée, but either by

his naturall witte, or by reading, or sences, he is hable to saie

somwhat in the nature of any thyng.

5.In the fifte place, sette forthe the thynges, reasonyng one

with an other, as the Ant with the Greshopper, or the Cocke

with the precious stone.

6.Thē in the vj. place, make a similitude of the like matter.

7.Then in the seuenth place, induce an exāple for thesame

matter to bée proued by.

8.Laste of all make the Epilogus, whiche is called the con-

clusion, and herein marke the notes folowyng, how to make

[Fol. v.r]an Oracion thereby.

¶ An Oracion made vpon the fable of the

Shepeherdes and the wolues.

¶ The fable.

He Wolues on a tyme perswaded the Shepeher-

He Wolues on a tyme perswaded the Shepeher-

des, that thei would ioyne amitée, and make a

league of concord and vnitee: the demaunde plea-

sed the Shepeherdes, foorthwith the Wolues re-

quested to haue custodie of the bande Dogges, because els

thei would be as thei are alwaies, an occasion to breake their

league and peace, the Dogges beyng giuen ouer, thei were

one by one murthered, and then the Shepe were wearied.

¶ The praise of the aucthour.

He posteritee of tymes and ages, muste needes praise

He posteritee of tymes and ages, muste needes praise

the wisedome and industrie, of all soche as haue lefte

in monumentes of writyng, thynges worthie fame,

Inuentours

of al excellent

artes and sci-

ences, com-

mended to the

posteritee.

what can bee more excellently set foorthe: or what deserueth

chiefer fame and glorie, then the knowledge of artes and sci-

ences, inuented by our learned, wise, and graue aūcestours:

and so moche the more thei deserue honour, and perpetuall

commendacions, because thei haue been the firste aucthours,

and beginners to soche excellencies. The posteritée praiseth

Apelles.

Parthesius.

Polucletus.

and setteth forth the wittie and ingenious workes of Apelles,

Parthesius, and Polucletus, and all soche as haue artificial-

ly set forth their excellent giftes of nature. But if their praise

for fame florishe perpetuallie, and increaseth for the wor-

thines of theim, yet these thynges though moste excellent, are

The ende of

all artes, is to

godlie life.

inferiour to vertue: for the ende of artes and sciences, is ver-

tue and godlines. Neither yet these thynges dissonaunt from

vertue, and not associate, are commendable onely for vertues

sake: and to the ende of vertue, the wittes of our auncestours

were incensed to inuent these thynges. But herein Polucle-

tus, Apelles, and Perthesius maie giue place, when greater

Esope wor-

thie moche

commendaciō[.]

vertues come in place, then this my aucthour Esope, for his

godly preceptes, wise counsaill and admonicion, is chiefly to

[Fol. v.v]bée praised: For, our life maie learne all goodnes, all vertue,

Philophie in

fables.

of his preceptes. The Philosophers did neuer so liuely sette

forthe and teache in their scholes and audience, what vertue

Realmes

maie learne

concorde out

of Esopes

fables.

and godlie life were, as Esope did in his Fables, Citees, and

common wealthes, maie learne out of his fables, godlie con-

corde and vnitee, by the whiche meanes, common wealthes

florisheth, and kingdoms are saued. Herein ample matter ri-

seth to Princes, and gouernours, to rule their subiectes in all

Preceptes to

Kynges and

Subiectes.

Preceptes to

parentes and

children.

godlie lawes, in faithfull obedience: the subiectes also to loue

and serue their prince, in al his affaires and busines. The fa-

ther maie learne to bring vp, and instructe his childe thereby.

The child also to loue and obeie his parentes. The huge and

monsterous vices, are by his vertuous doctrine defaced and

extirpated: his Fables in effect contain the mightie volumes

and bookes of all Philosophers, in morall preceptes, & the in-

The content

of al Lawes.

finite monumētes of lawes stablished. If I should not speake

of his commendacion, the fruictes of his vertue would shewe

his commendacions: but that praise surmounteth all fame of

A true praise

commēded by

fame it self.

glory, that commendeth by fame itself, the fruictes of fame

in this one Fable, riseth to my aucthour, whiche he wrote of

the Shepeherd, and the Wolues.

¶ The Morall.

Herein Esope wittely admonisheth all menne to be-

Herein Esope wittely admonisheth all menne to be-

ware and take heede, of cloked and fained frendship,

of the wicked and vngodlie, whiche vnder a pretence

and offer of frendship or of benefite, seeke the ruin, dammage,

miserie or destruccion of man, toune, citée, region, or countree.

¶ The nature of the thyng.

F all beastes to the quantitée of his bodie, the

F all beastes to the quantitée of his bodie, the

The Wolue

moste raue-

ning & cruell.

Wolue passeth in crueltee and desire of bloode,

alwaies vnsaciable of deuouryng, neuer conten-

ted with his pray. The Wolfe deuoureth and ea-

teth of his praie all in feare, and therefore oftentymes he ca-

steth his looke, to be safe from perill and daunger. And herein

[Fol. vj.r]his nature is straunge frō all beastes: the iyes of the Wolfe,

tourned from his praie immediatlie, the praie prostrate vnder

The Wolues

of all beastes,

moste obliui-

ous.

his foote is forgotten, and forthwith he seeketh a newe praie,

so greate obliuion and debilitée of memorie, is giuen to that

beaste, who chieflie seketh to deuoure his praie by night. The

The Wolue

inferiour to

the bandogge[.]

Wolues are moche inferior to the banddogges in strength, bi-

cause nature hath framed thē in the hinder parts, moche more

weaker, and as it were maimed, and therefore the bandogge

dooeth ouermatche theim, and ouercome them in fight. The

Wolues are not all so mightie of bodie as the Bandogges,

of diuers colours, of fight more sharpe, of lesse heddes: but in

The Dogge

passeth all

creatures in

smellyng.

smellyng, the nature of a Dogge passeth all beastes and

creatures, whiche the historie of Plinie dooe shewe, and Ari-

stotle in his booke of the historie of beastes, therein you shall

knowe their excellente nature. The housholde wanteth not

faithfull and trustie watche nor resistaunce, in the cause of the

Plinie.

maister, the Bandogge not wantyng. Plinie sheweth out of

his historie, how Bandogges haue saued their Maister, by

their resistaunce. The Dogge of all beastes sheweth moste

loue, and neuer leaueth his maister: the worthines of the bā-

dogge is soche, that by the lawe in a certaine case, he is coun-

ted accessarie of Felonie, who stealeth a Bandogge from his

maister, a robberie immediatly folowing in thesame family.

The worthi-

nes of Shepe[.]

As concernyng the Shepe, for their profite and wealthe,

that riseth of theim, are for worthines, waiyng their smalle

quantitie of bodie, aboue all beastes. Their fleshe nourisheth

purely, beyng swete and pleasaunt: their skinne also serueth

The wolle of

Shepe, riche

and commo-

dious.

to diuers vses, their Wolles in so large and ample maner,

commmodious, seruyng all partes of common wealthes. No

state or degrée of persone is, but that thei maie goe cladde and

adorned with their wolles. So GOD in his creatures, hath

Man a chief

creature.

created and made man, beyng a chief creatour, and moste ex-

cellent of all other, all thinges to serue him: and therefore the

Stoike Phi-

losophers.

Stoicke Philosophers doe herein shewe thexcellencie of man

to be greate, when all thinges vpon the yearth, and from the

[Fol. vj.v]yearth, doe serue the vse of man, yet emong men there is a di-

uersitee of states, and a difference of persones, in office and cō-

The office of

the shepeher-

des, are pro-

fitable and

necessarie.

dicion of life. As concernyng the Shepherde, he is in his state

and condicion of life, thoughe meane, he is a righte profi-

table and necessarie member, to serue all states in the commō

wealthe, not onely to his maister whom he serueth: for by his

diligence, and warie keping of thē, not onely from rauenyng

beastes, but otherwise he is a right profitable member, to all

Wealth, pro-

fit, and riches

riseth of the

Wolles of

Shepe.

partes of the common wealth. For, dailie wée féele the cōmo-

ditie, wealth and riches, that riseth of theim, but the losse wée

féele not, except flockes perishe. In the body of man God hath

created & made diuerse partes, to make vp a whole and abso-

lute man, whiche partes in office, qualitée and worthinesse,

are moche differing. The bodie of man it self, for the excellent

workemanship of God therein, & meruailous giftes of nature

Man called

of the Philo-

sophers, a lit-

tle worlde.

and vertues, lodged and bestowed in thesame bodie, is called

of the Philosophers Microcosmos, a little worlde. The body

of man in all partes at cōcord, euery part executing his func-

cion & office, florisheth, and in strength prospereth, otherwise

The bodie of

man without

concord of the

partes, peri-

sheth.

The common

wealthe like

to the bodie

of manne.

Menenius.

thesame bodie in partes disseuered, is feeble and weake, and

thereby falleth to ruin, and perisheth. The singuler Fable of

Esope, of the belie and handes, manifestlie sheweth thesame

and herein a florishing kingdom or common wealth, is com-

pared to the body, euery part vsing his pure vertue, strēgth &

operacion. Menenius Agrippa, at what time as the Romai-

were at diuision against the Senate, he vsed the Fable of E-

sope, wherewith thei were perswaded to a concorde, and vni-

The baseste

parte of the

bodie moste

necessarie.

tée. The vilest parte of the bodie, and baseste is so necessarie,

that the whole bodie faileth and perisheth, thesame wantyng

although nature remoueth them from our sight, and shame

fastnes also hideth theim: take awaie the moste vilest parte of

the bodie, either in substaunce, in operacion or function, and

forthwith the principall faileth. So likewise in a kyngdome,

or common wealth, the moste meane and basest state of man

taken awaie, the more principall thereby ceaseth: So God to

[Fol. vij.r]

The amiable

parte of the

body doe con-

siste, by the

baseste and

moste defor-

meste.

a mutuall concorde, frendship, and perpetuall societie of life,

hath framed his creatures, that the moste principall faileth,

it not vnited with partes more base and inferiour, so moche

the might and force of thynges excellente, doe consiste by the

moste inferiour, other partes of the bodie more amiable and

pleasaunt to sight, doe remain by the force, vse and integritée

of the simpliest. The Prince and chief peres doe decaie, and al

the whole multitude dooe perishe: the baseste kinde of menne

The Shepe-

herdes state

necessarie.

wantyng. Remoue the Shepeherdes state, what good follo-

weth, yea, what lacke and famine increaseth not: to all states

The state of

the husbande

manne, moste

necessarie.

the belie ill fedde, our backes worse clad. The toilyng house-

bandman is so necessarie, that his office ceasyng vniuersallie

the whole bodie perisheth, where eche laboureth to further

and aide one an other, this a common wealth, there is pro-

sperous state of life. The wisest Prince, the richest, the migh-

tiest and moste valianntes, had nede alwaies of the foolishe,

the weake, the base and simplest, to vpholde his kingdomes,

not onely in the affaires of his kyngdomes, but in his dome-

sticall thinges, for prouisiō of victuall, as bread, drinke, meat[,]

clothyng, and in all soche other thynges. Therefore, no office

or state of life, be it neuer so méete, seruyng in any part of the

No meane

state, to be

contempned.

common wealthe, muste bée contemned, mocked, or skorned

at, for thei are so necessarie, that the whole frame of the com-

mon wealth faileth without theim: some are for their wicked

behauiour so detestable, that a common wealthe muste séeke

Rotten mem[-]

bers of the cō[-]

mon wealth.

meanes to deface and extirpate theim as wéedes, and rotten

members of the bodie. These are thefes, murtherers, and ad-

ulterers, and many other mischiuous persones. These godly

Lawes, vpright and sincere Magistrates, will extirpate and

cutte of, soche the commo wealth lacketh not, but rather ab-

horreth as an infectiue plague and Pestilence, who in thende

through their owne wickednesse, are brought to mischief.

Plato.

Read Plato in his booke, intiteled of the common wealth

who sheweth the state of the Prince, and whole Realme, to

stande and consiste by the vnitee of partes, all states of the cō-

[Fol. vij.v]

A common

wealth doe

consiste by

vnitie of all

states.

mon wealth, in office diuers, for dignitée and worthines, bea-

ring not equalitée in one consociatée and knit, doe raise a per-

fite frame, and bodie of kingdome or common wealthe.

Aristotle.

What is a cō-

mon wealth.

Aristotle the Philosopher doeth saie, that a cōmon welth

is a multitude gathered together in one Citée, or Region, in

state and condicion of life differing, poore and riche, high and

low, wise and foolishe, in inequalitee of minde and bodies dif-

feryng, for els it can not bée a common wealthe. There must

be nobles and peres, kyng and subiect: a multitude inferiour

and more populous, in office, maners, worthines alteryng.

A liuely exā-

ple of commō

wealthe.

Manne needeth no better example, or paterne of a common

wealthe, to frame hymself, to serue in his state and callyng,

then to ponder his owne bodie. There is but one hedde, and

many partes, handes, feete, fingers, toes, ioyntes, veines, si-

newes, belie, and so forthe: and so likewise in a cōmon welth

there muste be a diuersitee of states.

¶ The reasonyng of the thynges

conteined in this Fable.

Hus might the Wolues reason with them sel-

Hus might the Wolues reason with them sel-

ues, of their Embassage: The Wolues dailie

molested and wearied, with the fearce ragyng

Masties, and ouercome in fight, of their power

and might: one emong the reste, more politike

and wise then the other, called an assemble and counsaill of

The counsail

of Wolues.

Wolues, and thus he beganne his oracion. My felowes and

compaignions, sithe nature hath from the beginnyng, made

vs vnsaciable, cruell, liuyng alwaies by praies murthered,

and bloodie spoiles, yet enemies wée haue, that séeke to kepe

vnder, and tame our Woluishe natures, by greate mightie

Bandogges, and Shepeherdes Curres. But nature at the

firste, did so depely frame and set this his peruerse, cruell, and

bloodie moulde in vs, that will thei, nill thei, our nature wil

bruste out, and run to his owne course. I muse moche, wai-

yng the line of our firste progenitour, from whence we came

[Fol. viij.r]firste: for of a man wee came, yet men as a pestiferous poison

doe exile vs, and abandon vs, and by Dogges and other sub-

Lycaon.

till meanes doe dailie destroie vs. Lycaon, as the Poetes doe

faine, excedyng in all crueltées and murthers horrible, by the

murther of straungers, that had accesse to his land: for he was

king and gouernor ouer the Molossians, and in this we maie

worthilie glorie of our firste blood and long auncientrée, that

The firste

progenie of

Wolues.

he was not onelie a man, but a kyng, a chief pere and gouer-

nour: by his chaunge and transubstanciacion of bodie, wée

loste by him the honour and dignitee due to him, but his ver-

tues wée kepe, and daily practise to followe them. The fame

The inuen-

cion of the

Poet Ouide

to compare a

wicked man,

to a Wolue.

of Lycaons horrible life, ascended before Iupiter, Iupiter the

mightie God, moued with so horrible a facte, left his heauen-

lie palace, came doune like an other mortall man, and passed

doune by the high mountaine Minalus, by twilighte, and

so to Licaons house, our firste auncestoure, to proue, if this

Lycaon.

thing was true. Lycaon receiued this straunger, as it semed

doubtyng whether he were a God, or a manne, forthwith he

feasted him with mannes fleshe baked, Iupiter as he can doe

Lycaon chaū-

ged into a

Wolue.

what he will, brought a ruine on his house, and transubstan-

ciated hym, into this our shape & figure, wherein we are, and

so sens that time, Wolues were firste generated, and that of

manne, by the chaunge of Lycaon, although our shape is

chaunged from the figure of other men, and men knoweth

Wolue.

Manne.

vs not well, yet thesame maners that made Wolues, remai-

neth vntill this daie, and perpetuallie in men: for thei robbe,

thei steale, and liue by iniurious catching, we also robbe, al-

so wée steale, and catche to our praie, what wee maie with

murther come to. Thei murther, and wee also murther, and

so in all poinctes like vnto wicked menne, doe we imitate the

like fashion of life, and rather thei in shape of men, are Wol-

ues, and wee in the shape of Wolues menne: Of all these

thynges hauyng consideracion, I haue inuented a pollicie,

whereby we maie woorke a slauter, and perpetuall ruine on

the Shepe, by the murther of the Bandogges. And so wée

[Fol. viij.v]shall haue free accesse to our bloodie praie, thus we will doe,

wee will sende a Embassage to the Shepeherdes for peace,

The counsail

of Wolues.

saiyng, that wee minde to ceasse of all bloodie spoile, so that

thei will giue ouer to vs, the custodie of the Bandogges, for

otherwise the Embassage sent, is in vaine: for their Dogges

being in our handes, and murthered one by one, the daunger

and enemie taken awaie, we maie the better obtain and en-

ioye our bloodie life. This counsaill pleased well the assem-

ble of the Wolues, and the pollicie moche liked theim, and

with one voice thei houled thus, thus. Immediatlie cōmuni-

cacion was had with the Shepeherdes of peace, and of the gi-

uyng ouer of their Bandogges, this offer pleased theim, thei

cōcluded the peace, and gaue ouer their Bandogges, as pled-

ges of thesame. The dogges one by one murthered, thei dis-

solued the peace, and wearied the Shepe, then the Shepeher-

des repented them of their rashe graunt, and foly committed:

The counsail

of wicked mē

to mischief.

So of like sorte it alwaies chaunceth, tyrauntes and bloodie

menne, dooe seke alwaies a meane, and practise pollicies to

destroye all soche as are godlie affected, and by wisedome and

godlie life, doe seke to subuerte and destroie, the mischeuous

The cogita-

cions of wic-

ked men, and

their kyngdō

bloodie.

enterprise of the wicked. For, by crueltie their Woluishe na-

tures are knowen, their glorie, strength, kyngdome and re-

nowne, cometh of blood, of murthers, and beastlie dealynges

and by might so violent, it continueth not: for by violence and

blooddie dealyng, their kyngdome at the last falleth by blood

and bloodilie perisheth. The noble, wise, graue, and goodlie

counsailes, are with all fidelitée, humblenes and sincere har-

The state of

counsailours

worthie chief

honour and

veneracion.

tes to be obeied, in worthines of their state and wisedome, to

be embraced in chief honour and veneracion to bee taken, by

whose industrie, knowledge and experience, the whole bodie

of the common wealth and kyngdome, is supported and sa-

ued. The state of euery one vniuersallie would come to par-

dicion, if the inuasion of foraine Princes, by the wisedom and

pollicie of counsailers, were not repelled. The horrible actes

of wicked men would burste out, and a confusion ensue in al

[Fol. ix.r]states, if the wisedom of politike gouernors, if good lawes if

the power and sword of the magistrate, could uot take place.

The peres and nobles, with the chief gouernour, standeth as

Plato.

Shepherds ouer the people: for so Plato alledgeth that name

well and properlie giuen, to Princes and Gouernours, the

Homere.

which Homere the Poete attributeth, to Agamemnon king

of Grece: to Menelaus, Ulisses, Nestor, Achillas, Diomedes,

The Shepe-

herdes name

giuē to the of-

fice of kyngs.

Aiax, and al other. For, bothe the name and care of that state

of office, can be titeled by no better name in all pointes, for di-

ligent kepyng, for aide, succoryng, and with all equitie tem-

peryng the multitude: thei are as Shepeherdes els the selie

poore multitude, would by an oppression of pestiferous men.

The commonaltee or base multitude, liueth more quietlie

The state or

good counsai-

lers, trou-

blous.

then the state of soche as daily seke, to vpholde and maintaine

the common wealthe, by counsaill and politike deliberacion,

how troublous hath their state alwaies been: how vnquiete

from time to time, whose heddes in verie deede, doeth seke for

a publike wealth. Therefore, though their honor bée greater,

and state aboue the reste, yet what care, what pensiuenesse of

minde are thei driuen vnto, on whose heddes aucthoritée and

regiment, the sauegard of innumerable people doeth depend.

A comparison

from a lesse,

to a greater.

If in our domesticall businesse, of matters pertainyng to our

housholde, euery man by nature, for hym and his, is pensiue,

moche more in so vaste, and infinite a bodie of cōmon wealth,

greater must the care be, and more daungerous deliberacion.

We desire peace, we reioyce of a tranquilitée, and quietnesse

to ensue, we wishe, to consist in a hauen of securitée: our hou-

ses not to be spoiled, our wiues and children, not to bee mur-

The worthie

state of Prin-

ces and coun-

sailours.

thered. This the Prince and counsailours, by wisedome fore-

sée, to kéepe of, all these calamitées, daungers, miseries, the

whole multitude, and bodie of the Common wealthe, is

without them maimed, weake and feable, a readie confusion

to the enemie. Therefore, the state of peeres and nobles, is

with all humilitée to be obaied, serued and honored, not with-

out greate cause, the Athenians were drawen backe, by the

[Fol. ix.v]wisedome of Demosthenes, when thei sawe thē selues a slau-

ter and praie, to the enemie.

¶ A comparson of thynges.

Hat can bée more rashly and foolishly doen, then the

Hat can bée more rashly and foolishly doen, then the

Shepeherdes, to giue ouer their Dogges, by whose

might and strength, the Shepe were saued: on the o-

ther side, what can be more subtlie doen and craftely, then the

Wolues, vnder a colour of frendship and amitee, to séeke the

The amitie

of wicked

menne.

blood of the shepe, as all pestiferous men, vnder a fained pro-

fer of amitée, profered to seeke their owne profite, commoditee

and wealthe, though it be with ruine, calamitie, miserie, de-

struccion of one, or many, toune, or citée, region and countree,

whiche sort of men, are moste detestable and execrable.

¶ The contrarie.

S to moche simplicitie & lacke of discrecion, is a fur-

S to moche simplicitie & lacke of discrecion, is a fur-

theraunce to perill and daunger: so oftētimes, he ta-

To beleue

lightly, afur-

theraunce to

perill.

steth of smarte and woe, who lightly beleueth: so con-

trariwise, disimulaciō in mischeuous practises begon w[ith] frēd-

ly wordes, in the conclusion doeth frame & ende pernisiouslie.

¶ The Epilogus.

Herefore fained offers of frendship, are to bee taken

Herefore fained offers of frendship, are to bee taken

heede of, and the acte of euery man to bee examined,

proued, and tried, for true frendship is a rare thyng,

when as Tullie doth saie: in many ages there are fewe cou-

ples of friendes to be found, Aristotle also cōcludeth thesame.

¶ The Fable of the Ante, and Greshopper.

¶ The praise of the aucthour.

The praise of

Esope.

Sope who wrote these Fables, hath chief fame of all

Sope who wrote these Fables, hath chief fame of all

learned aucthours, for his Philosophie, and giuyng

wisedome in preceptes: his Fables dooe shewe vnto

all states moste wholsome doctrine of vertuous life. He who-

ly extolleth vertue, and depresseth vice: he correcteth all states

and setteth out preceptes to amende them. Although he was

deformed and ill shaped, yet Nature wrought in hym soche

[Fol. x.r]vertue, that he was in minde moste beautifull: and seing that

the giftes of the body, are not equall in dignitie, with the ver-

tue of the mynde, then in that Esope chiefly excelled, ha-

uyng the moste excellente vertue of the minde. The wisedom

Cresus.

and witte of Esope semed singuler: for at what tyme as Cre-

sus, the kyng of the Lidians, made warre against the Sami-

ans, he with his wisedome and pollicie, so pacified the minde

of Cresus, that all warre ceased, and the daunger of the coun-

Samians.

tree was taken awaie, the Samiās deliuered of this destruc-

cion and warre, receiued Esope at his retourne with many

honours. After that Esope departyng from the Isle Samus,

wandered to straunge regions, at the laste his wisedome be-

Licerus.

yng knowen: Licerus the kyng of that countrée, had hym in

soche reuerence and honor, that he caused an Image of gold

to be set vp in the honour of Esope. After that, he wanderyng

Delphos.

ouer Grece, to the citée of Delphos, of whom he beyng mur-

thered, a greate plague and Pestilence fell vpon the citee, that

reuenged his death: As in all his Fables, he is moche to bee

commended, so in this Fable he is moche to be praised, which

he wrote of the Ante and the Greshopper.

¶ The Fable.

N a hotte Sommer, the Grashoppers gaue them sel-

N a hotte Sommer, the Grashoppers gaue them sel-

ues to pleasaunt melodie, whose Musicke and melo-

die, was harde from the pleasaunt Busshes: but the

Ante in all this pleasaunt tyme, laboured with pain and tra-

uaile, she scraped her liuyng, and with fore witte and wise-

Winter.

dome, preuented the barande and scarce tyme of Winter: for

when Winter time aprocheth, the ground ceasseth frō fruict,

The Ante.

then the Ante by his labour, doeth take the fruicte & enioyeth

it: but hunger and miserie fell vpon the Greshoppers, who in

the pleasaunt tyme of Sommer, when fruictes were aboun-

dauute, ceassed by labour to put of necessitée, with the whiche

the long colde and stormie tyme, killed them vp, wantyng al

sustinaunce.

¶ The Morall.

Ere in example, all menne maie take to frame their

Ere in example, all menne maie take to frame their

owne life, and also to bryng vp in godlie educacion

their children: that while age is tender and young,

thei maie learne by example of the Ante, to prouide in their

grene and lustie youth, some meane of art and science, wher-

by thei maie staie their age and necessitée of life, al soche as do

flie labour, and paine in youth, and seeke no waie of Arte and

science, in age thei shall fall in extreme miserie and pouertée.

¶ The nature of the thyng.

Ot without a cause, the Philosophers searchyng the

Ot without a cause, the Philosophers searchyng the

nature and qualitee of euery beaste, dooe moche com-

The Ante.

mende the Ante, for prouidence and diligence, in that

not oneie by nature thei excell in forewisedome to thē selues,

Manne.

but also thei be a example, and mirrour to all menne, in that

thei iustlie followe the instincte of Nature: and moche more,

where as men indued with reason, and all singulare vertues

and excellent qualitées of the minde and body. Yet thei doe so

moche leaue reason, vertue, & integritée of minde, as that thei

had been framed without reason, indued with no vertue, nor

adorned with any excellent qualitée. All creatures as nature

hath wrought in them, doe applie them selues to followe na-

ture their guide: the Ante is alwaies diligent in his busines,

and prouident, and also fore séeth in Sommer, the sharpe sea-

son of Winter: thei keepe order, and haue a kyng and a com-

mon wealthe as it were, as nature hath taught them. And so

haue all other creatures, as nature hath wrought in thē their

giftes, man onelie leaueth reason, and neclecteth the chief or-

namentes of the minde: and beyng as a God aboue all crea-

tures, dooeth leese the excellent giftes. A beaste will not take

excesse in feedyng, but man often tymes is without reason,

and hauyng a pure mynde and soule giuen of God, and a face

to beholde the heauens, yet he doeth abase hymself to yearth-

Greshopper.

lie thynges, as concernyng the Greshopper: as the Philoso-

phers doe saie, is made altogether of dewe, and sone perisheth[.]

[Fol. xj.r]The Greshopper maie well resemble, slothfull and sluggishe

persones, who seke onely after a present pleasure, hauyng no

fore witte and wisedom, to foresée tymes and ceasons: for it is

A poincte of

wisedome.

the poinct of wisedō, to iudge thinges present, by thinges past

and to take a cōiecture of thinges to come, by thinges present.

¶ The reasonyng of the twoo thynges.

Hus might the Ante reason with her self, althoughe

Hus might the Ante reason with her self, althoughe

the seasons of the yere doe seme now very hotte, plea-

A wise cogi-

tacion.

saunt and fruictfull: yet so I do not trust time, as that

like pleasure should alwaies remaine, or that fruictes should

alwaies of like sorte abounde. Nature moueth me to worke,

and wisedome herein sheweth me to prouide: for what hur-

teth plentie, or aboundaunce of store, though greate plentie

commeth thereon, for better it is to bee oppressed with plen-

tie, and aboundaunce, then to bee vexed with lacke. For, to

whom wealthe and plentie riseth, at their handes many bee

releued, and helped, all soche as bee oppressed with necessi-

tie and miserie, beyng caste from all helpe, reason and proui-

dence maimed in theim: All arte and Science, and meane of

life cutte of, to enlarge and maintain better state of life, their

Pouertie.

miserie, necessitie, and pouertie, shall continuallie encrease,

who hopeth at other mennes handes, to craue relief, is decei-

ued. Pouertie is so odious a thing, in al places & states reiected

for where lacke is, there fanour, frendship, and acquaintance

Wisedome.

decreaseth, as in all states it is wisedome: so with my self I

waie discritlie, to take tyme while tyme is, for this tyme as a

Housebande

menne.

floure will sone fade awaie. The housebande manne, hath he

not times diuers, to encrease his wealth, and to fill his barne,

at one tyme and ceason: the housebande man doeth not bothe

plante, plowe, and gather the fruicte of his labour, but in one

tyme and season he ploweth, an other tyme serueth to sowe,

and the laste to gather the fruictes of his labour. So then, I

must forsee time and seasons, wherin I maie be able to beare

of necessitie: for foolishly he hopeth, who of no wealth and no

abundaunt store, trusteth to maintain his own state. For, no-

[Fol. xj.v]

Frendship.

thyng soner faileth, then frendship, and the soner it faileth, as

Homere.

fortune is impouerished. Seyng that, as Homere doeth saie,

a slothfull man, giuen to no arte or science, to helpe hymself,

or an other, is an vnprofitable burdein to the yearth, and God

dooeth sore plague, punishe, and ouerthrowe Citees, kyng-

domes, and common wealthes, grounded in soche vices: that

the wisedome of man maie well iudge, hym to be vnworthie

of all helpe, and sustinaunce. He is worse then a beast, that is

not able to liue to hymself & other: no man is of witte so vn-

Nature.

descrite, or of nature so dulle, but that in hym, nature alwa-

yes coueteth some enterprise, or worke to frame relife, or help

The cause of

our bearth.

to hymself, for all wée are not borne, onelie to our selues, but

many waies to be profitable, as to our owne countrie, and all

partes thereof. Especiallie to soche as by sickenes, or infirmi-

tie of bodie are oppressed, that arte and Science can not take

place to help thē. Soche as do folowe the life of the Greshop-

per, are worthie of their miserie, who haue no witte to foresée

seasons and tymes, but doe suffer tyme vndescretly to passe,

Ianus.

whiche fadeth as a floure, thold Romaines do picture Ianus

with two faces, a face behind, & an other before, which resem-

ble a wiseman, who alwaies ought to knowe thinges paste,

thynges presente, and also to be experte, by the experience of

many ages and tymes, and knowledge of thynges to come.

¶ The comparison betwene

the twoo thynges.

Hat can be more descritlie doen, then the Ante to be

Hat can be more descritlie doen, then the Ante to be

so prouident and politike: as that all daunger of life,

& necessitie is excluded, the stormie times of Winter

ceaseth of might, & honger battereth not his walles, hauyng

Prouidence.

soche plentie of foode, for vnlooked bitter stormes and seasons,

happeneth in life, whiche when thei happen, neither wisedō

nor pollicie, is not able to kepe backe. Wisedome therefore,

it is so to stande, that these thynges hurte not, the miserable

ende of the Greshopper sheweth vnto vs, whiche maie be an

example to all menne, of what degree, so euer thei bee, to flie

[Fol. xij.r]slothe and idelnesse, to be wise and discrite.

¶ Of contraries.

Diligence.

S diligence, prouidence, and discrete life is a singu-

S diligence, prouidence, and discrete life is a singu-

lare gift, whiche increaseth all vertues, a pillar, staie

and a foundacion of all artes and science, of common

wealthes, and kyngdomes. So contrarily sloth and sluggish-

nesse, in all states and causes, defaseth, destroyeth, and pul-

leth doune all vertue, all science and godlines. For, by it, the

mightie kyngdome of the Lidiās, was destroied, as it semeth

Idelnes.

no small vice, when the Lawes of Draco, dooe punishe with

death idelnesse.

¶ The ende.

The Ante.

Herefore, the diligence of the Ante in this Fable,

Herefore, the diligence of the Ante in this Fable,

not onelie is moche to be commended, but also her

example is to bee followed in life. Therefore, the

wiseman doeth admonishe vs, to go vnto the Ant

and learne prouidence: and also by the Greshopper, lette vs

learne to auoide idelnes, leste the like miserie and calamitie

fall vpon vs.

¶ Narratio.

His place followyng, is placed of Tullie, after the

His place followyng, is placed of Tullie, after the

exordium or beginnyng of Oracion, as the seconde

parte: whiche parte of Rhetorike, is as it were the

light of all the Oracion folowing: conteining the cause, mat-

ter, persone, tyme, with all breuitie, bothe of wordes, and in-

uencion of matter.

¶ A Narracion.

Narracion

is an exposicion, or declaracion of any

Narracion

is an exposicion, or declaracion of any

thyng dooen in deede, or els a settyng forthe, for-

ged of any thyng, but so declaimed and declared,

as though it were doen.

A narracion is of three sortes, either it is a narracion hi-

storicall, of any thyng contained, in any aunciente storie, or

true Chronicle.

[Fol. xij.v]

Or Poeticall, whiche is a exposicion fained, set forthe by

inuencion of Poetes, or other.

Or ciuill, otherwise called Iudiciall, whiche is a matter

of controuersie in iudgement, to be dooen, or not dooen well

or euill.

In euery Narracion, ye must obserue sixe notes.

1. Firste, the persone, or doer of the thing, whereof you intreate.

2. The facte doen.

3. The place wherein it was doen.

4. The tyme in the whiche it was doen.

5. The maner must be shewed, how it was doen.

6. The cause wherevpon it was doen.

There be in this Narracion, iiij. other properties belōging[.]

1. First, it must be plain and euident to the hearer, not obscure,

2. short and in as fewe wordes as it maie be, for soche amatter.

3. Probable, as not vnlike to be true.

4. In wordes fine and elegante.

¶ A narracion historicall, vpon Semiramis Queene of Babilon

how and after what sort she obtained the gouernment thereof.

Tyme.

Persone.

Fter the death of Ninus, somtime kyng of Ba-

Fter the death of Ninus, somtime kyng of Ba-

bilon, his soonne Ninus also by name, was left

to succede hym, in all the Assirian Monarchie,

Semiramis wife to Ninus the firste, feared the

tender age of her sonne, wherupon she thought

The cause.

The facte.

that those mightie nacions and kyngdomes, would not obaie

so young and weake a Prince. Wherfore, she kept her sonne

from the gouernmente: and moste of all she feared, that thei

The waie

how.

would not obaie a woman, forthwith she fained her self, to be

the soonne of Ninus, and bicause she would not be knowen

to bee a woman, this Quene inuented a newe kinde of tire,

the whiche all the Babilonians that were men, vsed by her

commaundement. By this straunge disguised tire and appa-

rell, she not knowen to bee a woman, ruled as a man, for the

The facte.

The place.

space of twoo and fourtie yeres: she did marueilous actes, for

she enlarged the mightie kyngdome of Babilon, and builded

[Fol. xiij.r]thesame citée. Many other regions subdued, and valiauntlie

ouerthrowen, she entered India, to the whiche neuer Prince

came, sauing Alexander the greate: she passed not onely men

in vertue, counsaill, and valiaunt stomacke, but also the fa-

mous counsailours of Assiria, might not contende with her

in Maiestie, pollicie, and roialnes. For, at what tyme as thei

knewe her a woman, thei enuied not her state, but maruei-

led at her wisedome, pollicie, and moderacion of life, at the

laste she desiryng the vnnaturall lust, and loue of her soonne

Ninus, was murthered of hym.

¶ A narracion historicall vpon kyng Ri-

chard the third, the cruell tiraunt[.]

The persone[.]

Ichard duke of Glocester, after the death of Ed-

Ichard duke of Glocester, after the death of Ed-

ward the fowerth his brother king of England,

vsurped the croune, moste traiterouslie and wic-

kedlie: this kyng Richard was small of stature,

deformed, and ill shaped, his shoulders beared

not equalitee, a pulyng face, yet of countenaunce and looke

cruell, malicious, deceiptfull, bityng and chawing his nether

lippe: of minde vnquiet, pregnaunt of witte, quicke and liue-

ly, a worde and a blowe, wilie, deceiptfull, proude, arrogant

The tyme.

The place.

in life and cogitacion bloodie. The fowerth daie of Iulie, he

entered the tower of London, with Anne his wife, doughter

to Richard Erle of Warwick: and there in created Edward

his onely soonne, a child of ten yeres of age, Prince of Wa-

les. At thesame tyme, in thesame place, he created many no-

ble peres, to high prefermente of honour and estate, and im-

mediatly with feare and faint harte, bothe in himself, and his

The horrible

murther of

king Richard[.]

nobles and commons, was created king, alwaies a vnfortu-

nate and vnluckie creacion, the harts of the nobles and com-

mons thereto lackyng or faintyng, and no maruaile, he was

a cruell murtherer, a wretched caitiffe, a moste tragicall ty-

raunt, and blood succour, bothe of his nephewes, and brother

George Duke of Clarence, whom he caused to bee drouned

in a Butte of Malmsie, the staires sodainlie remoued, wher-

[Fol. xiij.v]

The facte.

on he stepped, the death of the lorde Riuers, with many other

nobles, compassed and wrought at the young Princes com-

myng out of Wales, the .xix. daie of Iuly, in the yere of our

lorde .1483. openly he toke vpon him to be king, who sekyng

hastely to clime, fell according to his desart, sodainly and in-

gloriously, whose Embassage for peace, Lewes the Frenche

king, for his mischeuous & bloodie slaughter, so moche abhor-

red, that he would neither sée the Embassador, nor heare the

Embassage: for he murthered his .ij. nephues, by the handes

The tyme.

The maner

how.

of one Iames Tirrell, & .ij. vilaines more associate with him

the Lieutenaunt refusyng so horrible a fact. This was doen

he takyng his waie & progresse to Glocester, whereof he was

before tymes Duke: the murther perpetrated, he doubed the

good squire knight. Yet to kepe close this horrible murther,

he caused a fame and rumour to be spread abrode, in all par-

tes of the realme, that these twoo childrē died sodainly, there-

The cause.

by thinkyng the hartes of all people, to bee quietlie setteled,

no heire male lefte a liue of kyng Edwardes children. His

mischief was soche, that God shortened his vsurped raigne:

he was al together in feare and dread, for he being feared and

dreaded of other, did also feare & dread, neuer quiete of minde

faint harted, his bloodie conscience by outward signes, condē-

pned hym: his iyes in euery place whirlyng and caste about,

The state of

a wicked mā.

his hand moche on his Dagger, the infernall furies tormen-

ted him by night, visions and horrible dreames, drawed him

from his bedde, his vnquiet life shewed the state of his consci-

ence, his close murther was vttered, frō the hartes of the sub-

iectes: thei called hym openlie, with horrible titles and na-

mes, a horrible murtherer, and excecrable tiraunt. The peo-

A dolefull

state of a

quene.

ple sorowed the death of these twoo babes, the Queene, kyng

Edwardes wife, beeyng in Sanctuarie, was bestraught of

witte and sences, sounyng and falling doune to the grounde

as dedde, the Quéene after reuiued, knéeled doune, and cal-

led on God, to take vengaunce on this murtherer. The con-

science of the people was so wounded, of the tolleracion of the

[Fol. xiiij.r]

The wicked

facte of kyng

Richard, a

horror and

dread to the

commons.

facte, that when any blustryng winde, or perilous thonder, or

dreadfull tempest happened: with one voice thei cried out and

quaked, least God would take vengauce of them, for it is al-

waies séen the horrible life of wicked gouernors, bringeth to

ruin their kyngdom and people, & also wicked people, the like

daungers to the kyngdome and Prince: well he and his sup-

porters with the Duke of Buckyngham, died shamefullie.

God permit

meanes, to

pull doune

tyrauntes.

The knotte of mariage promised, betwene Henrie Erle of

Richemonde, and Elizabeth doughter to kyng Edward the

fowerth: caused diuerse nobles to aide and associate this erle,

fledde out of this lande with all power, to the attainmente of

the kyngdome by his wife. At Nottyngham newes came to

kyng Richard, that the Erle of Richmonde, with a small cō-

paignie of nobles and other, was arriued in Wales, forthe-

with exploratours and spies were sent, who shewed the Erle

Lichefelde.

Leicester.

to be encamped, at the toune of Litchfield, forthwith all pre-

paracion of warre, was set forthe to Leicester on euery side,

the Nobles and commons shranke from kyng Richarde, his

Bosworthe[.]

power more and more weakened. By a village called Bos-

worthe, in a greate plaine, méete for twoo battailes: by Lei-

cester this field was pitched, wherin king Richard manfully

fightyng hande to hande, with the Erle of Richmonde, was

Kyng Ri-

chard killed

in Bosworth

fielde.

slaine, his bodie caried shamefullie, to the toune of Leicester

naked, without honor, as he deserued, trussed on a horse, be-

hinde a Purseuaunte of Armes, like a hogge or a Calfe, his

hedde and his armes hangyng on the one side, and his legges

on the other side: caried through mire and durte, to the graie

Friers churche, to all men a spectacle, and oprobrie of tiran-

nie this was the cruell tirauntes ende.

¶ A narracion historicall, of the commyng

of Iulius Cesar into Britaine.

The tyme.

The persone.

Hen Iulius Cesar had ended his mightie and huge

Hen Iulius Cesar had ended his mightie and huge

battailes, about the flood Rhene, he marched into the

regiō of Fraunce: at thesame time repairing with a

freshe multitude, his Legiōs, but the chief cause of his warre

[Fol. xiiij.v]in Fraunce was, that of long time, he was moued in minde,

The cause.

The fame

and glorie of

Britaine.

to see this noble Islande of Britain, whose fame for nobilitée

was knowen and bruted, not onelie in Rome, but also in the

vttermoste lādes. Iulius Cesar was wroth with thē, because

in his warre sturred in Fraunce, the fearce Britaines aided

the Fenche men, and did mightilie encounter battaill with

the Romaines: whose prowes and valiaunt fight, slaked the

proude and loftie stomackes of the Romaines, and droue thē

The prowes

of Iulius

Cesar.

to diuerse hasardes of battaill. But Cesar as a noble warrier

preferryng nobilitee, and worthinesse of fame, before money

or cowardly quietnes: ceased not to enter on ye fearce Britai-

nes, and thereto prepared his Shippes, the Winter tyme fo-

lowyng, that assone as oportunitee of the yere serued, to passe

The maner

how.

Cesars com-

municacion

with the mar[-]

chauntes, as

concernyng

the lande of

Britaine.

with all power against them. In the meane tyme, Cesar in-

quired of the Marchauntes, who with marchaundise had ac-