Outside

Outside

Title: A Short Account of King's College Chapel

Author: Walter Poole Littlechild

Release date: August 2, 2008 [eBook #26167]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet

Archive/American Libraries.)

Regret has been expressed by some, that I omitted to give a description of all the windows, and that there were no illustrations in the first edition. This I have endeavoured to remedy by giving the subjects of all the windows (with here and there a special note) and inserting some pictures of the Chapel both inside and out, also the arms and supporters (a dragon and greyhound) of Henry VII, crowned rose and portcullis, from the walls of the ante-chapel and the initials H.A. from the screen.

I am indebted to Messrs. Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Ltd., 1 Amen Corner, London, for the loan of the blocks of the former, which appeared in the late Sir William St. John Hope's book Heraldry for Craftsmen and Designers. The latter, together with three photographs of the[vi] Chapel, were specially taken for me by Mr. A. Broom. I wish also to thank the Provost of Eton, Dr. M. R. James, for permission to use some part of his description of the windows. I am also indebted to Mr. J. Palmer Clark for leave to reproduce the photograph of the ship in the window on the south side. I am also grateful to Mr. Benham and Dr. Mann for their assistance in compiling the lists of Provosts and Organists. I have again to thank Sir G. W. Prothero, Honorary Fellow of the College, for reading through the manuscript and proofs of both editions and for his valuable suggestions. In conclusion, I would ask for the kind indulgence of my readers for any errors that may be discovered in this little book, and shall be glad to have them pointed out to me.

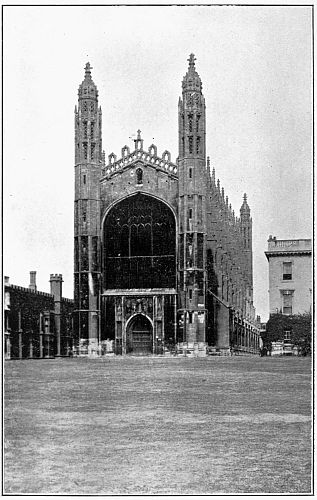

| Outside | Frontispiece | |

| PAGE | ||

| Looking East from Provost Stall | face | 4 |

| The Screen from West End | 8 | |

| Ship Window | 11 | |

| H.A. from the Screen | 27 | |

| Arms of Henry VII. | 35 | |

| Rose and Portcullis (Badges of Henry VII.) | 35 | |

On St. James' Day, July 25th, 1446, the King laid the foundation stone of the chapel, and so began a building which, as a distinguished member of the college (Lord Orford) said, would "alone be sufficient to ennoble any age." It has been classed with the chapel of Henry VII at Westminster and Saint George's collegiate church at Windsor, as one of "the three great royal chapels of the Tudor age"; but there is no edifice, except Eton College Chapel, which forms in any way a fair subject of comparison with that of King's College.

The style is rich perpendicular, marking the point where the last Gothic meets the early Renaissance. Nicholas Close has commonly been considered to be the architect. He was a man of Flemish family, and for a few years held the cure of the parish of St. John Zachary, which church stood on the west side of Milne Street, and probably so close to it that the high altar of the[3] church was on ground afterwards enclosed within the western bays of the Ante-Chapel. Close, in 1450, was appointed to the See of Carlisle, and in 1452 transferred to Lichfield. He certainly received from the King the grant of a coat of arms for his services, but it might fairly be said that John Langton, Master of Pembroke College, and Chancellor of the University, who also had the title of "Surveyor," a term generally admitted to be synonymous with architect, has an equally strong claim. But Mr. G. G. Scott, in his essay on English Church Architecture, says "the man who really should have had the credit of conceiving this great work was the master-mason, Reginald Ely, appointed by a patent of Henry VI to press masons, carpenters, and other workers." According to Mr. Scott's view, "Close and his successors did the work which in modern days would be done, though less efficiently, by a building committee. But they were ecclesiastics, not architects; it is the master-mason, not the more dignified 'surveyor,' to whom the honour of planning the building should be attributed."

It is stated that in the year 1506 sufficient progress had been made in the building to admit of the performance of divine service, at which Henry VII and his mother, Margaret Countess of Richmond, Foundress of St. John's and Christ's Colleges, who were on a visit to Cambridge, were present; and it is said that John Fisher, President of Queens' College, Bishop of Rochester, took part as chief celebrant. Professor Willis, in The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, takes exception to this statement. He is of opinion that, as the Screen and Stall work was not finished until 1536, and as the old Chapel[4] did not fall down until 1537 (in fact it was used on the eve of the day on which[6] it fell), it is unlikely that the new chapel was used for service until that time. He further quotes Dr. Caius to strengthen this view.

Henry VII, who has been credited with an excessive tendency to accumulate treasure, was, next to the Founder, much the largest contributor. A short time before his death in 1509[5], moved perhaps to emulate the liberal example of his pious mother, he gave £5,000 to the college, with instructions to his executors to finish the building. May we not also think that Richard Fox, Founder of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, Bishop of Winchester from 1500 to 1528, who was Henry VII's constant adviser, Privy Seal, and one of his executors, had something to do with this mark of Henry's generosity and favour? This sum of £5,000 was probably all spent by the beginning of 1512, when the King's executors[7] made over to the Provost and scholars, in 1511-12, a second sum of £5,000.

Thus in 1515, in the 7th year of King Henry VIII's reign, the stonework of the chapel was completed; it had cost, in the present value of money, about £160,000. The stone used in the construction is of different kinds. The white magnesian limestone from Huddlestone in Yorkshire is that which was chiefly used in the lifetime of the Founder. The lower part of the walls was built of this; the upper part was built with stone brought from Clipsham in Rutlandshire in 1477. A third kind, from Weldon in Northamptonshire, was used for the vaulting of the choir and ante-chapel, executed in 1512 and the following years. The north and south porches were vaulted with a magnesian limestone, more yellow in colour, from the Yorkshire quarry of Hampole.

The outside measurement of the chapel from turret to turret is 310 feet, the said turrets being 146 feet high. The four westernmost buttresses on the south and five on the north side are ornamented with heraldic devices, crowns, roses, and portcullises, while on the set-offs separating the stages are dragons, greyhounds, and antelopes bearing shields.

Inside, the chapel is 289 feet long, 40 feet wide[8] from pier to pier, and 80 feet high from the floor to the central point of the stone vault. The tracery of the roof is a fine specimen of the fan-vault which is rarely to be found in Continental architecture, but is the peculiar glory of the English style. It can truly be said that stone seems, by the cunning labour of the chisel, to have been robbed of its weight and density and suspended aloft as if by magic, while the fretted roof is achieved with the wonderful minuteness and airy security of a cobweb. Similar roofs appear in Bath Abbey (the architect of which was Dr. Oliver King, a member of King's), in St. George's Chapel, Windsor, in Henry VII's Chapel at Westminster, in Sherborne Minster, and in the ambulatory of the choir of Peterborough; but the earliest example of this kind of vaulting is the cloister of Gloucester (1381-1412), of which the late Dean Spence speaks in the following lines:

The same words can be applied to this chapel, for here we have the long fan-traceried arch, and beneath are stones and human dust, for many members of King's and others are buried within its walls.

Ample proof has been adduced that Henry VI was not only a Mason himself (having been admitted a member of the fraternity in 1450), but did a good deal for the craft; and Freemasonry has much to thank him for. In a history of Westminster Abbey, written by the late Dean Farrar, is to be found the following: "Even the geometrical designs which lie at the base of its ground plan are combinations of the triangle, the circle, and the oval." Masons' marks are to be found in various places on the walls in chapel.

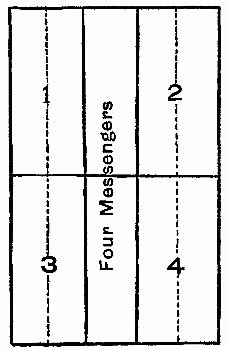

The windows of the Chapel contain the finest series in the world of pictures in glass on a large scale. The tracery is filled with heraldic devices. At the top of the centre light are the Royal Arms as borne by Henry VII, and the rest of the badges are Roses, Crowns, Portcullises, Hawthorn bushes and Fleur-de-lys, being all appropriate to Henry VII. There are also the initials H. E. (Henry VII and Elizabeth of York) and H. K. for Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon as Prince and Princess of Wales. These badges run all round the side windows. In each side window there are four subjects, two side lights above and two below the transom or crossbar, while in the centre light are four figures, men and angels alternately, "Messengers," as they are called, because they hold scrolls or tablets (in Latin) descriptive of the pictures at the sides. All the side windows, except the easternmost window on the south side, are carried out in a similar manner.[13]

In most cases the two lower pictures illustrate two scenes in the New Testament, and the two upper ones give types of these scenes drawn from the Old Testament or elsewhere. There are exceptions to this arrangement, as, for instance, the first two windows on the north side and in those illustrating the Acts of the Apostles.

The main subjects of the windows are the life of the Virgin Mary and the life of Christ. The scenes begin with the Birth of the Virgin, in the westernmost window on the north side, and proceed through the principal events of our Lord's life to the Crucifixion in the east window. This is followed on the south side by the following events as recorded in the Gospels, of which the last depicted is the Ascension in the one opposite the organ. Next comes the history of the Apostles as recorded in the Acts, while the legendary history of the Virgin occupies the last two windows.[6]

The following diagram may be of use in helping my readers to decipher the windows on the north and south sides.

| 1. The offering of Joachim and Anna rejected by the High Priest. | 2. Joachim is bidden by an Angel to return to Jerusalem, where he would meet his wife at the Golden Gate of the Temple. |

| 3. Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate of the Temple. | 4. Birth of the Virgin. |

| 1. Presentation of a Golden Table (found by fishermen entangled in their nets) in the Temple of the Sun. | 2. Marriage of Tobias and Sara. |

| 3. Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple. | 4. Marriage of Joseph and Mary. |

At the bottom of each picture in this window there is a small compartment containing a half-length figure of a man or angel bearing a legend.[16]

| 1. The Temptation of Eve. | 2. Moses and the Burning Bush. |

| 3. The Annunciation. | 4. The Nativity.[A] |

| 1. The Circumcision of Isaac by Abraham | 2. The visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon. |

| 3. The Circumcision of Christ. | 4. The Adoration of the Magi.[B] |

| 1. The Purification of Women under the Law. | 2. Jacob's Flight from Esau.[C] |

| 3. The Presentation of Christ in the Temple.[D] | 4. The Flight into Egypt. |

| 1. The Golden Calf on a Ruby Pillar. | 2. The Massacre of the Seed Royal by Athaliah. |

| 3. The Idols of Egypt falling.[E] | 4. The Massacre of the Innocents. |

| 1. Naaman Washing in Jordan. | 2. Jacob tempts Esau to sell his birthright. |

| 3. The Baptism of Christ. | 4. The Temptation of Christ.[F] |

| 1. Elisha raises the Shumanite's Son. | 2. The Triumph of David.[G] |

| 3. The raising of Lazarus. | 4. The entry into Jerusalem.[H] |

| 1. The Fall of Manna. | 2. The Fall of the Rebel Angels. |

| 3. The Last Supper.[I] | 4. The Agony in the Garden.[J] |

| 1. Cain killing Abel. | 2. Shemei cursing David. |

| 3. The Betrayal.[K] | 4. Christ mocked and blind-folded.[L] |

| 1. Jeremiah imprisoned. | 2. Noah mocked by Ham. |

| 3. Christ before Annas. | 4. Christ before Herod. |

| 1. Job tormented. | 2. Solomon crowned. |

| 3. The Scourging of Christ. | 4. Christ crowned with thorns. |

The East Window is quite different. For one thing it is much larger, and has nine vertical divisions instead of five. Here, in the tracery, in addition to other heraldic badges, is the "Dragon of the great Pendragonship," holding a banner with the arms of Henry VII. Also there is seen the ostrich feather of the Prince of Wales with the motto "Ich Dien."[7]

In this window there are no Messengers with inscriptions; only six scenes from the Passion beginning at the bottom left hand corner, and each occupying three lights instead of two. In the first three lights below the transom is the Ecce Homo; in the centre three, Pilate washing his hands, the final moment in the trial. Our Lord is represented in the centre light with his back to the spectator. In the three on the right is Christ bearing the Cross. Here is shown Saint Veronica kneeling and offering to our Lord a handkerchief to wipe his face. The legend goes on to say that, when he returned it to her, his face was impressed upon it; and it is now one of the four great relics preserved in the piers of the dome of St. Peter's at Rome.

Above the transom, the left three lights contain the Nailing to the Cross. In the centre three is Christ crucified between the thieves. At the base of the Cross may be seen our Lord's robe on the ground, and two figures kneeling upon it and pointing down to pieces of paper or dice, a scene depicting the fulfilment of the prophecy: "They parted my garments among them and upon my vesture they did cast lots." In the right three lights the body of Christ is taken down from the Cross.

The Brazen Serpent, after a picture by Rubens, now in the National Gallery.[M]

| 3. Naomi and her Daughters-in-Law. | 4. The Virgin and other Holy Women lamenting over the body of Christ. |

| 1. Joseph cast into the pit by his brethren. | 2. Israel going out of Egypt. |

| 3. Burial of Christ. | 4. The Harrowing of Hell. |

| 1. Jonah vomited up by the Whale.[N] | 2. Tobias returning to his Mother. |

| 3. The Resurrection of Christ. | 4. Christ appearing to his Mother at prayer. |

| 1. Reuben at the pit, he finds it empty, and Joseph gone. | 2. Darius visiting the lions' den finds Daniel alive. |

| 3. The three Marys at the Sepulchre, which they find empty. | 4. Christ, with a spade, appears to Mary Magdalene in the garden.[O] |

| 1. The Angel Raphael meets Tobias. | 2. Habakuk feeding Daniel in the lions' den. |

| 3. Christ meets the two Disciples on the way to Emmaus. | 4. The Supper at Emmaus. |

| 1. The Return of the Prodigal Son.[P] | 2. The meeting of Jacob and Joseph. |

| 3. The Incredulity of St. Thomas. | 4. Christ appearing to the Apostles without Thomas.[Q] |

| 1. Elijah carried up to Heaven.[R] | 2. Moses receives the Tables of Law. |

| 3. The Ascension of Christ. | 4. The Descent of the Holy Ghost. |

| 1. Peter and John heal the lame man at the gate of the Temple. | 2. The Apostles arrested.[S] |

| 3. Peter and the Apostles going to the Temple.[T] | 4. The Death of Annanias.[U] |

| 1. The Conversion of St. Paul. | 2. Paul conversing with Jews at Damascus.[V] |

| 3. Paul and Barnabas at Lystra. | 4. Paul stoned at Lystra. |

| 1. Paul and the Demoniac Woman. | 2. Paul before the Chief Captain Lysias at Jerusalem. |

| 3. Paul saying farewell at Philippi.[W] | 4. Paul before Nero. |

| 1. The Death of Tobit. | 2. The Burial of Jacob. |

| 3. The Death of the Virgin. | 4. The Funeral of the Virgin. |

| 1. The Translation of Enoch. | 2. Solomon receives his mother Bath-Sheba. |

| 3. Assumption of the Virgin. | 4. The Coronation of the Virgin.[X] |

The West Window was filled with stained glass depicting the Last Judgment, by Messrs. Clayton and Bell, of London, in 1879. There is no doubt that in the original scheme of the windows this was intended to be the subject of the west window.[8] Like the east window, it consists of nine lights, divided by a transom into two tiers. The general idea is to set forth the scene of the Judgment as within a vast hall of semi-circular plan. In the central light of the upper tier is seated the figure of our Lord on the throne of judgment. On each side of the principal figure are groups of angels jubilant with trumpets and bearing emblems of the Passion.

On the right and left, each in three divisions, are seated figures of Apostles and other Saints. In the three lights below the figure of our Lord are St. Michael and two other angels, the one on the dexter side (the left side as you look at it) bearing a Lily, the other on the sinister (right) holding a flaming sword. St. Michael in the centre is in full armour. He carries the scales of judgment, and rests one hand on a cruciferous shield.

The lower portions of the lights show, on the one side, the resurrection of the blessed, with angels receiving them. A special feature of the design is seen in the lowermost portion near the centre. Here appears the figure of the founder, King Henry VI. He rises from his grave gazing upward, and bearing in his hands a model of the chapel itself. On the other side the lost are shown, driven out by angels threatening them with flaming swords.

In the tracery are arranged various shields and heraldic devices, which comprise the arms of Queen Victoria, Henry VI, Henry VII, Henry VIII, the Provost (Dr. Okes), the Visitor (the Bishop of Lincoln, Chr. Wordsworth), F. E. Stacey, Esq. (the Donor), with those of King's College, Eton College, and the University.

The question has often been asked, How did the windows escape during the Civil War? There is one story that the west window was broken by Cromwell's soldiers (who certainly were quartered in the chapel), and that the rest of the glass was taken out and concealed inside the organ screen. Another, which appears in a small book called "The Chorister," is that all the glass was taken down and buried in pits in the college grounds in one night by a man and a boy. Both these stories are entirely fictitious. The best answer to the question may be found in the words of the Provost of Eton (Dr. M. R. James), who says, in one of his addresses on the windows: "It is most probable that Cromwell, anxious to have at least one of the universities on his side, gave some special order that no wilful damage should be wrought on this building, which, then as now, was the pride of Cambridge and of all the country round." The windows have been taken out and re-leaded at various times—first between 1657 and 1664; next in 1711-1712; thirdly in 1725-1730; fourthly in 1757-1765; fifthly in 1847-1850; and fourteen of them (one in each year) in a period extending from 1893 to 1906, by the late Mr. J. E. Kempe, when several mistakes which then existed were put right.

The organ was put up in 1688 by René Harris,[12] taking the place of one erected in 1606 by an organ-builder named Dalham; some portions of the case date back to the time of Henry VIII. On the outer towers of the organ facing west are two angels holding trumpets. These were put up in 1859, taking the place of two pinnacles, which in their turn were substituted for two figures about the size of David on this same side. In 1859 the organ was much enlarged by Messrs. Hill, of London.

The Coats of Arms at the back of the stalls on the north and south sides were put up at the expense of Thomas Weaver, a former Fellow of the College, in 1633. Amongst them are the arms of England as they were at the time; those of Henry V, VI, VII, VIII, Eton and King's College—for Henry VI (no doubt following out the scheme adopted by William of Wykeham, who founded Winchester School and New College, Oxford) founded Eton also—also the arms of Cambridge University, and, to show a friendly feeling to the sister University, those of Oxford placed on the opposite side. The canopies of the stalls and the panel work east of them were executed in 1675-1679.

The Altar Table, from a design by Mr. Garner, was first used on Advent Sunday, 1902; and the woodwork round the chancel was finished in 1911. The architects were Messrs. Blow and Billary, the work being executed by Messrs. Rattee and Kett, the celebrated ecclesiastical builders, of Cambridge.

The Candelabra which stand within the Chancel, were the gift of Messrs. Bryan, Wayte, and Witts, sometime Fellows; conjointly with the College, and are of the date 1872.

The Candlesticks on the Altar were given by Edward Balston, a former Fellow, in 1850; and[31] the Cross (by Mr. Bainbridge Reynolds) is in memory of the late Rev. Augustus Austen Leigh, Provost, 1889-1905.

The Picture on the north side, "The Deposition," by Daniel de Volterra, was presented to the College by the Earl of Carlisle in 1780. It previously occupied the central position in the woodwork placed there in 1774, and was removed in 1896 when the east window was re-leaded. The handsome Lectern was given to the College by Robert Hacomblen, who was Provost from 1509 to 1528. The candle branches were added in 1668. It was removed to the Library in 1774, where it remained until 1854.

Before I go on to speak of the side Chapels, I think it is worth recording that on Wednesday, May 4, 1763, nine Spanish Standards taken at Manilla by Brigadier General Draper, formerly Fellow, were carried in procession to the Chapel by the scholars of the College. A Te Deum was sung, and the Revd. William Barford, Fellow, and Public Orator, made a Latin oration. The colours were first placed on each side of the Altar rails, but afterwards were hung up on the Organ Screen; they eventually found a resting-place in one of the South Chapels. About 20 years ago they were sent to a needlework guild in London with a view to their being restored, but[32] it was found they were too far gone. Some of the remnants that were returned are preserved in a glass case in the vestry, where they may be seen.

The third chapel on the same side is Provost Brassie's Chapel, where he was buried in 1558. In the window is some fifteenth century glass, which, having been removed from the north[34] side chapels, was repaired in 1857 and placed here. The Provost of Eton, whose knowledge of old glass makes him a competent authority, is now of opinion that it was made for the side Chapels, and was probably the gift of John Rampaine, Vice-Provost in 1495.

Of the remaining chantries on the south side, the first contains the Music Library; the next three are to be utilized as a Library of Ancient Theological works; and the last two will be fitted up and dedicated, as a War Memorial to those members of the College who made the great sacrifice in the War 1914-1919. Some fine Flemish glass, given by Mrs. Laurence Humphrey, and two lights purchased of St. Catherine's College, and other fragments of the XVth and XVIth century of great interest and beauty have already been placed in the windows, and a reredos is in course of erection. In the window of the second chantry from the west on the north side are the arms of Roger Goad (Provost 1569-1610) impaling the arms of the College,[13] in a most beautiful floral border.

Two other Side Chapels deserve to be mentioned, viz. the two eastmost on the north side, which were the first roofed with lierne vaulting. The one furthest east has been lately restored to use for early celebrations of the Holy Communion and other devotional services. Visitors should pay special attention to the lovely doorway in stone through which you enter, and the one on the opposite side. In the apex of the arch are the arms of Edward the Confessor, on the left those of East Anglia, on the right those of England. On that of the opposite side is a figure of the Blessed Virgin Mary at the top, flanked on the right by one of St. Margaret, and on the left by St. Catherine. These figures have been defaced, probably by William Dowsing, who is said to have gone about the country like a lunatic, breaking windows, etc. He visited the College in 1644.

The Ante-chapel is profusely decorated with the arms of Henry VII, with a dragon and greyhound as supporters, "the dragon of the great Pendragonship" and the greyhound of Cecilia Neville, wife of Richard Duke of York in every severy, and with crowned roses and portcullis alternating with each other, intimating that, as the portcullis was the second defence of a fortress when the gate was broken down, so he[36] had a second claim to the crown through his mother, daughter of John de Beaufort. After the accession of the Tudor dynasty there arose a mania for heraldic devices; in some cases an unsatisfactory mode of decoration, but in this building one that possesses not only historical interest, but great decorative value.

During the time when these styles of Gothic architecture prevailed that are now called the Decorated and the Perpendicular, the roof,[14] the columns, the stained glass windows, the seats, altar, tombs, and even the flooring, were filled with emblasonment. Nor was heraldic ornament confined to architecture; it formed the grand embellishment of the interior of palaces and baronial castles.[15]

In the middle of one of the roses at the west end, toward the south, may be seen a small figure of the Virgin Mary, about which Malden says: "Foreigners make frequent enquiries, and never fail to pay it a religious reverence, crossing their breasts at the sight, and addressing it with a short prayer." I cannot say that, in my long experience, I have ever observed an instance of this.

One may notice two striking features contained in this epitaph: (1) He believes in the resurrection; (2) he does not care what man thinks of him, it is God who shall decide whether he was good or bad.

Money was not a dominant motive with those employed on our old buildings, but master and man worked together for a common object, with a common sympathy; and especially in our[38] cathedrals and minsters they kept uppermost in their minds that they were working for the glory of God. "They thought not of a perishable home Who thus could build."

Froude, in his History of England (I. 51), says of our ancestors: "They cannot come to us, and our imaginations can but feebly penetrate to them. Only among the aisles of the cathedrals, only as we gaze upon their silent figures sleeping on their tombs, some faint conceptions float before us of what these men were when they were alive."

There are four Sepulchral Brasses on the floor of the chantries. The earliest one is that of Dr. William Towne, who is buried in the second chantry from the east, to which I have already referred as being the first roofed in. He is represented in academical costume; and on his hands hangs a scroll with the following words: "Farewell to glory, to reputation in learning, to praise, to the arts, to all the vanity of this world. God is my only hope."[16] Under his feet is the inscription: "Pray for the soul of Master William Towne, Doctor of Divinity, once a Fellow of this College, who died on the eleventh day of March, 1494. Whose soul God pardon.[39] Amen." The words "Pray for the soul" and "Whose soul God pardon. Amen," have been partially effaced.[17]

The most ancient brass after Dr. Towne's is that of Dr. Argentine, who is buried in the vestry on the south side nearest to the east. His figure is placed, according to his last desire, on the tombstone in his doctoral robes, with his hands elevated towards the upper part of the stone, where there was formerly placed a Crucifix. From his mouth proceed these words: "O Christ, Son of God and the Virgin, crucified Lord, Redeemer of mankind, remember me." Below his feet are the words: "This stone buries the body of John Argentine, Master of Arts, Physician, Preacher of the Gospel; Passenger, remember, thou art mortal; pray in an humble posture, that my soul may live in Christ, in a state of immortality." On a fillet round the tombstone the following words are engraved: "Pray for the soul of John Argentine, Master of[40] Arts, Doctor of Physick and Divinity, and Provost of this College, who died February 2, 1507. May God have mercy on his soul. Amen."[18]

The next is that of Robert Hacumblen, in the second chantry from the west on the same side. He is represented in ecclesiastical costume in processional vestments. On a label proceeding from his mouth is inscribed the following line: "O Christ, be thy wounds my pleasing remedy." This applies to a shield in the sinister corner of the stone, which represents the five wounds of Christ. The shield in the dexter corner is missing. It probably contained his coat of arms, which were: vert, a cross saltire argent between four lilies of the second. On the fillet,[41] which on all sides surrounds the stone, are the words:

At the corners are the evangelistic emblems. The inscription that was under his feet has been taken away. It may be that it contained the words "Pray for the soul," etc.

The fourth brass is in the next chantry toward the east, and is that of Robert Brassie. He is also in ecclesiastical costume in processional vestments, without the cope exposing the almuce. The label that proceeded from his mouth is missing. At his feet are the following words: "Here lies Robert Brassie, Doctor of Divinity, formerly Provost of this College, who departed this life November 10, a.d. 1558."

On the walls of the Ante-chapel there are several Memorial Brasses. The oldest is a diamond-shaped one, on the left of the south porch, to the memory of John Stokys, Public Orator, who died 17th July, 1559. That of a similar shape on the right is a repoussé tablet in copper, and is to the memory of J. K. Stephen, Fellow, who died February, 1892. In the last bay is one to Richard Okes, Doctor in Theology,[42] who was Provost of the College from 1850 to 1888.

On the north wall there are seven tablets. Taking them in order of death, the first is to Roland Williams, S.T.P., Fellow, who died 15th February, 1870. Then Henry Bradshaw, M.A., Fellow, University Librarian, died 15th February, 1886; William Johnson (afterwards Cory), M.A., Fellow, and for many years a Master at Eton, died 1892; Charles Vickery Hawkins, Scholar, died 6th August, 1894; John Henry Middleton, M.A., Professorial Fellow, Slade Professor, died 1896; Arthur Thomas Reid, Scholar, who met his death in climbing a mountain near Bangor, North Wales, September, 1907; Frederick Whitting, M.A., Senior Fellow, who was for 24 years Bursar and 20 years Vice-Provost, died suddenly in London, 1st January, 1911. Other tablets in the chantries commemorate various members of the College.

I cannot end this brief sketch better than by quoting Wordsworth's two famous sonnets on King's College Chapel:—

| William Millington, D.D. | April 10, 1443 |

| John Chedworth, D.D. | Nov. 5, 1446[Y] |

| Robert Woodlarke, D.D. | May 17, 1452 |

| Walter Field, D.D. | Oct. 15, 1479 |

| John Dogget, D.C.L. (Oxon) | April 18, 1499 |

| John Argentine, D.D. and M.D. | May 4, 1501 |

| Richard Hatton, LL.D. | Mar. 21, 1507 |

| Robert Hacumblen, D.D. | June 28, 1509 |

| Edward Fox, D.D. | Sept. 27, 1528[Z] |

| George Day | June 5, 1538 |

| Sir John Cheke, M.A. | April 1, 1548 |

| Richard Atkinson, D.D. | Oct. 25, 1553 |

| Robert Brassie, D.D. | Oct. 3, 1556 |

| Philip Baker, D.D. | Dec. 12, 1558 |

| Roger Goad, D.D. | Mar. 19, 1569 |

| Fog Newton, D.D. | May 15, 1610 |

| William Smith, D.D. | Aug. 22, 1612 |

| Samuel Collins, D.D. | April 25, 1615 |

| Benjamin Whichcot, D.D. | Mar. 19, 1644 |

| James Fleetwood, D.D. | June 29, 1660 |

| [47]Sir Thomas Page, M.A. | Jan. 16, 1675[AA] |

| John Coplestone, D.D. | Aug. 24, 1681 |

| Charles Roderick, LL.D. and D.D. | Oct. 13, 1689 |

| John Adams, D.D. | May 2, 1712 |

| Andrew Snape, D.D. | Feb. 21, 1719 |

| William George, D.D. | Jan. 30, 1742 |

| John Sumner, D.D. | Oct. 18, 1756 |

| William Cooke, D.D. | Mar. 25, 1772 |

| Humphrey Sumner, D.D. | Nov. 3, 1797 |

| George Thackeray, D.D. | April 4, 1814 |

| Richard Okes, D.D. | Nov. 2, 1850 |

| Augustus A. Leigh, M.A. | Feb. 9, 1889 |

| Montague R. James, Litt.D. | May 13, 1905 |

| Sir Walter Durnford, LL.D. | Nov. 16, 1918 |

| Edward Gibbons, Mus.B. (Cantab. & Oxon) | 1592-1599 |

| John Tomkins, Mus.B. (Cantab.) | 1606-1622 |

| Matthew Barton | 1622-1625 |

| Giles Tomkins | 1625-1626 |

| —— Marshall | 1626-1627 |

| John Silver | 1627 |

| Henry Loosemore, Mus.B. (Cantab.) | 1627-1671 |

| Thomas Tudway, Mus.D. (Cantab.) | 1671-1728 |

| Robert Fuller, Mus.B. (Cantab.) | 1728-1743 |

| John Randall, Mus.D. (Cantab.) | 1743-1799 |

| John Pratt | 1799-1855 |

| William Amps, M.A. (Cantab.) | 1855-1876 |

| Arthur Henry Mann, F.R.C.O., Mus.D. (Oxon), 1882; M.A. (Cantab.), 1910 | 1876- |

[1] Henry was born at Windsor in the year 1421. When Henry V was informed that Catherine had borne him an heir he asked: Where was the boy born? At Windsor was the reply. Turning to his Chamberlain, he gave voice to the following prophetic utterance:

[2] The preamble to the charter granted by Henry in January 1441, and confirmed by Act of Parliament in February of the same year, as translated, reads as follows:—

"To the honour of Almighty God, in whose hand are the hearts of Kings; of the most blessed and immaculate Virgin Mary, mother of Christ; and also of the glorious Confessor and Bishop Nicholas, Patron of my intended College, on whose festival we first saw the light."

[3] In the College Library may be seen a small piece of silk in which his bones were wrapped, and which was taken from the coffin by the late Sir W. H. St. John Hope in the presence of Dr. M. R. James, when it was opened on the 4th November, 1910.

[4] The accounts show that a chapel existed from the beginning, and that it stood between the south side of the old court and the north side of the present Chapel. It consisted of a chancel, nave, and ante-chapel, and had a door at the west end, and east and west windows. It was richly fitted up; and numerous allusions to plate, hangings, relics, service books, vestments, choristers and large and small organs, show that the services were performed with full attention to the ritual of the day.

[5] He was buried in his chapel at Westminster beside that of his wife, Elizabeth of York. Lord Bacon says "He lieth at Westminster in one of the stateliest and daintiest monuments of Europe both for the chapel and the sepulchre. So that he dwelleth more richly dead in the monument of his tomb than he did alive in Richmond or in any of his palaces."

[6] The side windows are 49 feet in height from the base to the point of the arch, and 16 feet in width.

[A] Joseph, Mary, and a number of little angels adore the Child. Through an opening in the background are seen the Angels appearing to the Shepherds.

[B] The Virgin and Child on right: the Star above. Just above the Virgin in the picture the head of an Ox and an Ass may be seen.

[C] In the background on right Rebecca is seen bringing Jacob to Isaac to be blessed.

[D] Simeon is a conspicuous figure.

[E] At the bottom are the figures 15017, generally read as a date (1517).

[F] Below in front the devil (represented as an old man) tempts Christ to turn stones into bread. Above on left the two are seen on the high mountain: on right they stand on the pinnacle of the temple.

[G] David enters on left balancing the huge head of Goliath on the point of a sword. On right are the women with musical instruments.

[H] A man in a tree cuts down branches: others spread garments.

[I] Christ on left stands and gives the sop to Judas, who bends over the table from right. He is red-haired.

[J] A cup is shown at the left upper corner, and an angel is represented as coming down to comfort our Lord. The disciples are shown asleep at the bottom of the picture.

[K] Judas kisses Christ. Peter attacks Malchus.

[L] Annas and other Jews look on from above.

[7] This window from its base to the top of the arch is 53 feet and 25 feet wide.

[M] There was originally only half a window here. The lower half was intended to have a building (which was in part begun) abutting on it. This building was removed in 1827, and the lower part of the window opened up. The old glass was moved down to the lower lights in 1841, and in 1845 the glass which now occupies the upper main lights inserted by Hedgeland. The only thing that can be said in its favour is its vivid colours.

[N] This subject is often asked about. The whale is represented as a great green monster with a large black patch for the open mouth. Jonah is shown in a recumbent position on the ground. At the back is part of a ship, while in the extreme background may be seen Ninevah.

[O] Mary Magdalene is also seen alone in the background, looking into the Sepulchre.

[P] In the upper part of the left hand light is depicted the killing of the fatted calf.

[Q] This subject and its type ought to precede numbers 1 and 3.

[R] He casts his mantle, represented by a lovely piece of ruby glass, down to Elisha.

[S] In the background, Peter and John are seen bound to a pillar and scourged.

[T] In the background, Peter preaching inside the building.

[U] In the background is seen his body being carried out for burial.

[V] In the background he is seen being let down in a basket from a window. In this and the preceding window figures of St. Luke, habited as a doctor, with his ox by him, alternate with figures of angels in the central light.

[W] In this subject is a beautiful specimen of a late fifteenth century ship. The ship has her sails furled, and is anchored by her port anchor as her starboard anchor is fished (i.e. made fast with its shank horizontal) to the ship's side by her cable. An empty boat is alongside. At the top of the mainmast is a fighting top from which project two large spears.

An excellent article on this ship was contributed by Messrs. H. H. Brindley, M.A., and Alan H. Moore, B.A., and read to the members of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society in 1909.

[X] She kneels in the centre, full face. On right the Son, seated; on left the Father, crowning Mary. The dove between. Angels playing music in front.

[8] This window is 49 feet from its base to the top of the arch and 33 feet 6 inches in width.

[9] A rebus was invariably a badge or device forming a pun upon a man's surname. It probably originated in the canting heraldry of earlier days. A large number of rebuses ending in "ton" are based upon a tun or barrel; such are the lup on a ton of Robert Lupton, Provost of Eton 1504, which appears in the spandrils of the door in the screen leading into his chapel at Eton College, or the kirk and ton of Abbott Kirkton on the deanery gate at Peterborough. The eye and the slip of a tree, which form, together with a man falling from a tree (I slip!), the rebuses of Abbot Islip, are well known. The ox crossing a ford in the arms of Oxford, and the Cam and its great bridge in the arms of Cambridge are kindred examples.

[10] "The founder designed, by the colour of the field, to denote the perpetuity of his foundation; by the roses, his hope that the college might bring forth the choicest flowers, redolent of science of every kind, to the honour and most devout worship of Almighty God and the undefiled virgin and glorious mother; and by the chief, containing portions of the arms of France and England, he intended to impart something of royal nobility, which might declare the work to be truly regal and renowned."—Cooper's Memorials of Cambridge.

[11] At a meeting of old Etonian generals at Eton on May 20, 1919, the following reference was made to the arms of Eton:—

[12] Mr. T. F. Bumpas in his London Churches, Ancient and Modern, speaks of him as an organ builder of some note. Renatus Harris he is there styled. "In 1663 the Benchers of the Temple Church being anxious of obtaining the best possible organ, we find him in competition with one Bernard Schmidt, a German, who afterwards became Anglicized as 'Father Smith.' Each builder erected an organ which were played on alternate Sundays. Dr. Blow and Purcell played upon Smith's organ, while Draghi, organist to the Queen Consort, Catherine of Braganza, touched Harrises. The conflict was very severe and bitter. Smith was successful. Harrises organ having been removed, one portion of it was acquired by the parishioners of St. Andrew's, Holborn, while the other was shipped to Dublin, where it remained in Christ Church Cathedral until 1750, when it was purchased for the Collegiate Church of Wolverhampton. In 1684 he competed again with Father Smith for the contract for an organ for St. Laurance, Gresham Street, and was successful. In 1669 he built a fine large organ for St. Andrews, Undershaft." He was also engaged in 1693 to keep in order the organ in Jesus College Chapel, Cambridge, at a yearly salary of £3.

[13] Heads of Colleges have the right of impaling with their own arms the arms of the College of which they are the head in the same way as a Bishop impales the arms of the See over which he presides. Deans of secular churches and the Regius Professors of Divinity at Cambridge (since 1590) have the same privilege.

[14] Of Melrose it is written:

[16] In all cases I have refrained from using the Latin, and have contented myself with giving the English translation.

[17] The words "Pray for the soul," or "May whose soul God pardon," were sufficient excuse for fanatics such as Dowsing to destroy or deface the beautiful brasses in various parts of the kingdom. But the fanatics were not alone to blame; for it is well known that churchwardens and even incumbents of our churches have in many cases taken up and sold the brasses to satisfy some whim of their own in what they called "restoration" of the edifice over which they had charge.

[18] It may appear to my readers somewhat strange that in this case the words "Pray for the soul" and "May God have mercy, &c." are intact. Until 1898 this chantry had a boarded floor above the slab, the fillet round not being visible. The figure itself with label was affixed to a board and placed in the vestry for those who cared to inspect it. When the floor was removed the Brass was placed in its proper place on the slab and the whole inscription could then be seen. There are the matrixes of four coats of arms. Probably they were King's, Eton, the University, and Argentine's own coat, which was gules, three covered cups argent. At the upper corners of the fillet are the evangelistic emblems of St. Matthew and St. John, while those of St. Mark and St. Luke, which were evidently at the bottom, have been taken away.

[Y] The last Provost appointed by the Founder.

[Z] It is very strange, but there is no evidence of Provost Day having taken a degree of any kind. He was Master of St. John's College, Cambridge, 1537; Provost, 1538; Bishop of Chichester, 1543. On making enquiry at Chichester, the answer is "We have no reference whatever to his having taken a degree, odd as this is to us."

[AA] The last Provost nominated by the Crown.

Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

The remaining corrections made are indicated by dotted lines under the corrections. Scroll the mouse over the word and the original text will appear.