Title: The Renewal of Life; How and When to Tell the Story to the Young

Author: Margaret Warner Morley

Release date: August 12, 2008 [eBook #26280]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, Annie McGuire and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note

Spelling, punctuation and inconsistencies in the original book have been retained.

| A Song of Life. 12mo | $1.25 |

| Life and Love. 12mo | 1.25 |

| The Bee People. 12mo | 1.25 |

| The Honey-Makers. 12mo | 1.25 |

| Little Mitchell. 12mo | 1.25 |

| The Renewal of Life. 12mo | 1.25 |

| I. | The Renewal of Life | 9 |

| II. | Who Is to Tell the Story, and When Is It to be Told? | 17 |

| III. | How to Tell the Story | 27 |

| IV. | Telling the Truth | 36 |

| V. | On Nature Study | 40 |

| VI. | The Development of the Seed | 52 |

| VII. | The Fertilization of the Flower | 87 |

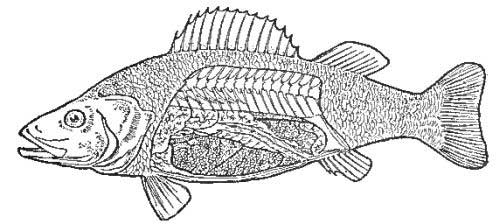

| VIII. | What Can be Learned from the Life of the Fish | 107 |

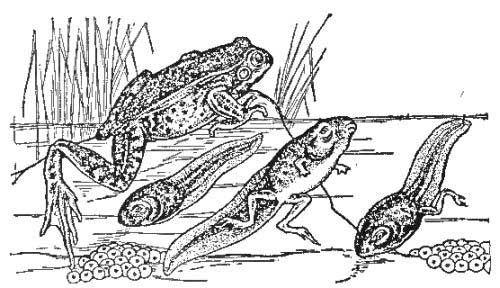

| IX. | Amphibious Life | 127 |

| X. | The Bird | 137 |

| XI. | The Mammal | 154 |

| XII. | Vigilance | 169 |

| XIII. | The Transformation | 178 |

| List of Books Helpful in Studying Plant and Animal Life | 193 |

Every human being must sooner or later know the facts concerning the origin of his life on the earth. One of the most puzzling questions is how and when such information should be given to the young.

There is nothing the parent more desires than that his child should have a high ideal in regard to the sex-life and that he should live in accordance with that ideal, yet nowhere is careful and systematic education so lacking as here.

What parent would allow his child to go untaught in the particulars concerning truth-telling, honesty, cleanliness, and behavior, trusting that in some way the[Pg 10] child would discover the facts necessary to the practice of these virtues and live accordingly? And yet with apparent inconsistency one of the prime virtues is neglected; one of the most vital needs of every human being—the understanding of his sex-nature—is too often left entirely to chance. Not only is the youth uninstructed, but no proper way of learning the truth is within his reach. It is as though he were set blindfold in the midst of dangerous pitfalls, with the admonition not to fall into any of them. Those who ought to tell the facts will not, consequently the facts must be gathered from chance sources which are too often bad, poisoning mind and heart. Even the physiologies, with the exception of those large, and to the average reader inaccessible, volumes used in medical schools, scarcely ever touch upon the subject. Of course these larger books give only the physiological facts couched in scientific terms. How and where, then, can the youth learn what he needs to know?

It is true there is a noble effort being made for young men, and to a less extent[Pg 11] for young women, by certain organizations that exist for the help of the young, to supply this curious defect in our educational system; but these efforts reach but comparatively few members in a community, and come too late in the life of the young to give them their first impressions on the subject. Perhaps the most encouraging sign for the future is the interest that thousands of mothers in all walks of life are to-day taking in the best methods of training their children to a right understanding and noble conception of sex-life. Innumerable mothers' clubs give the subject a place in the curriculum of the club work, at stated times discussing, reading, consulting all available authorities which may be of help. Some of these mothers live in poor homes in neighborhoods where their children are exposed to all sorts of evil communications and temptations. Others have sheltered homes, from which the children go out among refined associates from whom there may be little danger of learning that which is evil. Yet others live in moderate circumstances, where the home influences[Pg 12] may be good, but where the children are liable to mingle with a heterogeneous society in their school and perhaps in their social life.

Moreover, in all these homes there are children of different natures,—some with temperaments which make it easy for them to imbibe harmful information, while others as naturally resent such information.

Nor is the child of rich parents living in a costly home necessarily the child least likely to make mistakes. The facts quickly refute any such idea. It is the child most carefully trained at home, with the most inspiring counsel and the wisest guidance in all directions, who has the best chance for successful living, the child whose parents not only secure the best outside assistance where such is necessary, but who themselves take a vital and continuous interest in his education. Such parents, where the help of nurses and teachers is necessary in the home, see to it that these helpers are wholesome, high-minded companions for the growing minds put under their charge.[Pg 13]

The poorest child is the child of wealthy parents, who is turned over to hirelings, chosen more for their accent of a foreign tongue than for their knowledge of child life and of the laws which govern the growing mind and body. Such children not infrequently become as depraved as the most neglected and exposed child of the slums, later poisoning the minds or shocking the sensibilities of children in the schools they attend.

One of the difficulties every mother has to encounter is the presence of undesirable companions in the school. The argument that a child coming from a sheltered home will not be influenced by such companions is only in part true. He may not be influenced, or, again, he may. Among older children, if the wrongdoer be dazzling in manner, looks, social position, or even in power to lavish money, he will acquire a certain ascendency over many of his companions, who, if not safeguarded against his allurements by a clear knowledge of the facts of life, may fall into his snares.

How, then, can all these various[Pg 14] situations be dealt with? How, how much, when, and where shall the youth be safeguarded against influences, misconceptions, and mistakes which may mar his whole after-life? These are the questions which in part this book endeavors to answer.

The answers come from the writer's experience of many years' work with mothers interested in this subject, especially from the testimony and the questions of thousands of such mothers in all walks of life who possessed children of all temperaments.

The book is not meant to be either exhaustive or arbitrary. It is written with the single desire of helping the mother who may be groping her way in this matter, its aim being twofold,—to indicate methods of procedure among which the mother may find one adapted to her special needs and circumstances, or at least from which she may get hints which she can herself follow in her own way, and to indicate sources of information.

One trivial difficulty has presented itself in preparing the succeeding chapters,[Pg 15] and that is the lack in the English language of a pronoun including both genders. The English impersonal pronoun, being masculine in form, is liable to create the impression that "he" or "his" exclusive of "she" or "her" is the subject of discourse. This is not so. Generally the masculine pronoun is used impersonally in this discussion, and the discerning reader can easily decide from the context where this is not the case.

As a help to the busy mother in selecting books for herself and her children, a list is given at the end of the book. This list is by no means exhaustive. There are many other and doubtless equally good books. The books given are reliable, are prettily illustrated, are now in print, and are easily obtainable at any book-store. If they are not in stock the book-seller will be glad to send for them. Further, to aid in selecting and ordering, the retail price is added. A small circulating library of well chosen books adds greatly to the usefulness of a mother's club, and such a library can be collected at small cost.[Pg 16]

Where the club is composed of heterogeneous members it is advisable that the president, or some member chosen for the purpose, should lead the discussion, which should be on some one topic selected and made known beforehand. This leader should not only guide the discussion, but be ready to explain the books and make the subject clear to those tired and overworked mothers who have had fewer educational advantages but who are in need of such knowledge as will enable them to guide their children.

A mother unconnected with a club, and unable to afford all the books she wants, can find many of those here recommended in the village or city library; and where this is not the case the library is generally willing to make such purchases as its patrons request.[Pg 17]

Every thoughtful guardian of a child is sooner or later confronted with three questions in connection with this subject,—

Who is to tell the story to the child?

When should it be told?

How should it be told?

The best teachers in this subject are undoubtedly the child's parents.

Since the mother generally spends more time with him and is more accustomed to instruct him in manners and morals it naturally belongs to her to give him his first instruction here, and it is an opportunity which no mother understanding its value can afford to miss.

Nothing draws a child so close to his mother as the knowledge, rightly[Pg 18] conveyed, of how truly he is a part of her. Almost without exception the young boy learning the truth from the lips of his mother has a new feeling of reverence and love for her. Countless are the testimonies of mothers as to the result of telling this fact. One illustration will answer as an example of hundreds of similar ones. A certain little boy listened open-eyed to the story; then, the blood mounting to his cheeks, he threw himself into his mother's arms, exclaiming, "Oh, mamma, that is why I love you so!"

Moreover, if the right kind of confidence is established between mother and child, the child will come to his mother with his questions and difficulties instead of trying to satisfy his curiosity elsewhere.

The question is often asked, Will not close companionship and sympathy between mother and child in a general way produce the same result, causing the child to confide in the mother in case of needing information, without any previous talks on the subject?

Of course the closer the relationship between the two the more easily will the[Pg 19] child confide everything; yet with very many children, if this one subject is avoided (and particularly is this true as the child grows older), it will not be introduced by the child, no matter how much he may desire the knowledge, or how intimate in other ways may be his talks with his mother. The judicious mother can get a hold upon her son through this subject that nothing else gives; she can keep him closer to her, and oftentimes can guide him safely over difficult places. What is true of the son is of course true of the daughter. The little girl will respond as readily as her brother to confidences of this kind, and will find them as helpful. She very often escapes much that her brother in his freer life meets, yet undoubtedly in the great majority of cases the instruction is as vitally necessary to her as to him.

While the earliest teachings seem to fall most naturally to the mother, the father should also share the responsibility and the privilege, talking with frank confidence upon the subject whenever occasion offers.[Pg 20]

The question is often asked, Is it not better for the father to talk to the boys, the mother to the girls?

There no doubt are cases where this might be wise, but the mother, understanding the close relationship between her son and herself that may come through such talks,—a relationship continuing and increasing in value as the years go on,—would feel that she could not afford to lose anything so precious to both her boy and herself.

While the establishment of this relationship might be difficult or even impossible later, it is easily begun in childhood and as easily continued. Moreover, many boys are specially helped by talking with their mother. They often feel in her a quicker sympathy and a more perfect understanding of their needs; and as their instinctive desire is to understand life from her point of view as well, they often feel something in her which is lacking in the father. On the other hand, the boy who is talked to exclusively by the mother, particularly when he begins to develop into manhood may say, or think, "Oh,[Pg 21] you cannot understand; you never were a man." The father's voice here is needed, but if that is impossible there is abundant written testimony and advice from well-known men to youth on this subject which can be put into the boy's hands.

While the child's best teachers of these intimate truths are undoubtedly his parents, it may happen for various reasons that this is impossible. The child may have grown to an age where the timid parent, who has not hitherto realized the necessity, cannot approach him. Or there may be other reasons. In such cases the duty may devolve upon some one else capable of fulfilling it. Such a one may be, should be, the minister. It ought to be a part of the recognized duty of every minister of a congregation to see that such of his young men as desire it are instructed in the facts necessary to their well-being in this direction. It is not enough to tell them to live pure lives; they must be helped to understand their own organizations and everything pertaining to this side of life that they need or want to know. There should be similar help[Pg 22] obtainable by the young women of the congregation from some competent woman approved by the minister. Purity is an integral part of the religion of the new civilization, and purity and everything helping to it should be as conscientiously and thoroughly taught in the churches as are any other religious truths. In the church the young man, the young woman, should be able to find corroboration of the sex-truths taught him by his parents; and those young people not so fortunate as to receive instruction at home should be able to drink from their religious teachers deep draughts from this spring of salvation.

The family physician ought also to be a refuge of help for the young; and here the woman doctor, that blessing of these later days, can do a work of reformation and salvation. No one has more power to sow seeds of wisdom in the homes of the people, helping the mother to understand and desire the careful instruction of her children, and where the mother requests it, being ready to give the needed help to the young people themselves.

Again, the teacher or some friend[Pg 23] may be requested by the parent to come to the help of the needy child. But whoever gives this information, it is needless to say, should himself be pure in heart, of high moral principles, with a firm belief in the value and possibility of purity, and with sufficient knowledge of the subject in all its aspects to be a wise instructor, giving not only physiological information where that is desirable, but working specially for ethical and spiritual elevation. Physiological facts alone may not have the slightest effect upon the manner of living; there should be first and deeply implanted a spiritual desire for purity, when the knowledge of such facts may be a valuable help.

The question is very often asked, Should this subject be taught in schools?

To a certain extent it is taught. Every botany class teaches its rudiments; and in the higher grades, where biology is taught, the pupil comes to a clear understanding of the main facts. School botany, however, merely glimpses at the truth, and biological classes are few and far between. So, as far as the majority of children are concerned, the schools[Pg 24] can hardly be said to touch the subject. Whether it would be well for the schools to deal with it is a very difficult question, so much depending upon the way the work is done. It might be possible to introduce it helpfully in connection with a well graded system of nature-study, but since such does not exist in most schools, and since there is very great danger in speaking in public on this subject before children, no matter how well the speaking may be done, it is undoubtedly better not to approach it directly in the schools,—at least in grades below the high school. Like religious training, this belongs peculiarly to the home and the parent. Although she cannot give general instruction, the teacher of children can help by being watchful of her flock, alert to detect signs of wrong doing, ready to help by private counsel, and—when parents consent—to give information to any needy child. In dealing with this subject the teacher needs to be as wise as the serpent and as harmless as the dove, not only for her own sake but for the sake of those she wishes to help.[Pg 25]

It is an axiom of education that the foundations of knowledge should be laid in childhood. From all time it has been observed that what is learned in the earlier years remains most persistently through life. Hence we begin to inculcate moral truths at an early age. Ideas of truthfulness and honesty, for instance, are graven so deeply on the young mind that they can never afterwards be erased. "Just as the twig is bent the tree's inclined," said our forefathers, and it is true. "First impressions are the most lasting," is another true adage. This being so, we should see to it that the first impression the child gets on the subject in question is the one we wish him to keep. Many a life has been lamed and saddened because of the first terrible and ineradicable impressions it received upon this all-important subject. Many a high-minded man and woman have gone through life tormented by images of the first unworthy thoughts. No matter how good the after-knowledge may be, it is almost impossible to erase from the tablets of memory that old first impression.[Pg 26]

Of course it would be absurd to tell a young child most of the facts, just as it would be absurd to try to teach him the whole arithmetic in one school term. He could not understand, and, particularly in the case of the former subject, he would be harmed instead of helped. Just how and when to unfold the matter to his comprehension will be carefully considered as these pages progress. Here let it suffice to say that with the young child we may begin by building carefully block by block the foundation we want to use later; with the older one we must needs work faster, seeking to anticipate or counteract any unfortunate information from outside sources. Thus the age of the child and his surroundings will to an extent determine the time or times of telling the facts.[Pg 27]

This is the most difficult question to answer, and one that requires time. Indeed, one might say it cannot be answered excepting in a general way, and that any effort to tell the truth sacredly is better than not to tell it at all. Where the children are still young the task is comparatively simple when once begun. It develops naturally, with time for thought on the part of the teller; and the steps are easy and convincing.

One of the questions most frequently asked is this: Does not talking about these things fix the child's mind unduly upon them?

As a matter of experience it is just the other way. The child who has always known the facts is not curious. Why should he be? There is nothing to be curious about. It is all as much a[Pg 28] matter of course to him as the rising of the sun. And he is safeguarded against a certain pruriency that comes from wrongly stimulated and vilely fed curiosity. Instead of causing the child to think more about the subject, the tendency of good teaching is to prevent his thinking of it.

Another question frequently asked is, Does not talking on this subject arouse curiosity in children who otherwise would not be curious?

The answer is that it does not arouse harmful curiosity. The right kind of curiosity on any subject is of course good. Indeed without the desire to question and investigate everything about him man would be yet a savage living in a hole in the ground, and the starting-point of all the child's after-knowledge is curiosity. There are two kinds of curiosity, a good kind and a bad kind. The good kind is interested in finding out things for the sake of understanding them; the bad kind serves a bad end,—in connection with this subject it leads to investigations which produce wrong thoughts and feelings, and is gratified[Pg 29] for the sake of producing those thoughts and feelings. The same subject may give rise to either kind of curiosity, according as it is presented.

To-day we take every pains to stimulate the curiosity of our children. We teach them to observe carefully the flowers, the insects, the animals,—everything about them. We cannot expect them to exercise their stimulated minds on all other subjects and turn blind eyes upon this one which is obviously so important and so interesting. No, the more they learn to look and ask about other things the more they will look and wish to ask about this.

That children differ in curiosity is very true. Some children seem to have very little curiosity about anything. Yet such children are sent to school with as much care as are the children eager to know. A child might show no interest in books, might find the reading lesson irksome; but the mother would know he was learning to read for the use that reading would be to him later, not for the sake of the things in the reading-book. It is the same here, the child[Pg 30] learns the facts for the sake of his future. There are good reasons which will appear later why every child should have the right information on this subject whether he seeks it or not. If he is indifferent, one can be sure the proper kind of information will not hurt him; if he is eager, one can be sure he ought to be carefully and thoroughly instructed.

As a rule the most active and eager children and those with the quickest minds are the ones most curious to understand the origin of life, though there are exceptions. It is not legitimately gratified curiosity that harms, but suppressed curiosity, which in this subject is almost sure to result in the acquisition of wrong and often of perverting information. The surest way to arouse curiosity is to try to conceal something. The only thing, then, is to be ready to gratify honest curiosity by helpful information.

Nor is it safe to defer too long. What the mother wants her child to know in a certain way she should tell him herself, before he has a chance to hear it elsewhere. The moment he leaves her presence, the moment he starts alone to[Pg 31] school, he may receive information which she would give the world to prevent his receiving. Not that her telling will necessarily keep him from hearing what others say, but to have his mind preoccupied will tend to prevent the wrong ideas from taking firm root.

Another question very often asked is, Will teaching this subject not encourage children to talk about it with other children?

On the contrary, the tendency is to prevent talk. The children of a family equally instructed will not find it worth talking about. They know what they want to know, and understand that the only person who can really tell them anything more is their mother, or whoever takes her place in this. If they do talk of it in the spirit in which they have been taught, such talk can do no harm, excepting in the presence of children not equally well instructed.

To meet this danger the mother can take certain precautions. Having won the confidence of her child, she can generally trust him to keep these matters[Pg 32] confidential with her. She can explain that children do not always know the truth about these things, and sometimes do not know about them at all. That some mothers do not tell their children, but that she wants her child to understand everything just as it is, and to feel that she can trust him not to talk on these matters excepting when alone with her.

Of course there will be instances where this does not succeed, and the children eager and pure will speak in the presence of the neighbors' children and make trouble. Then the question is, Which is better, to run that risk and take the consequences, or to run the risk of allowing the child to remain ignorant? If the child could really remain ignorant, there might be room for argument against enlightening him, but there is great danger that he will be enlightened in a very unenlightened manner, and possibly by those same neighbors' children who are truly ignorant, though they may not be ignorant in just the way their fond parents believe them to be.

Many people still confound ignorance[Pg 33] with innocence, though these are by no means related. The most ignorant person in the world might be the least innocent, and the most innocent might very well be the most enlightened. It not infrequently happens that the very children whose mothers are most opposed to enlightenment on this subject are dangerous companions for good children.

To guard against unprofitable or otherwise harmful teaching, the mother should instruct the child not to listen to talk on this subject and not to join in it, and at the same time tell him that in case he does hear anything that troubles him he should come to her and she will talk it over and explain, so that he may know what is right and what wrong. She should promise to tell him the truth about whatever he may want to know.

Having made this promise she must keep it. There is nothing more dangerous than to put a child off with evasive answers. He immediately jumps to the conclusion that there is some reason why his mother is afraid or ashamed to explain things to him, and if he has heard evil rumors it is quite natural for[Pg 34] him to suspect that what he has heard is the truth and the whole truth, else why should his mother not help him? He soon feels ashamed to ask her questions which she refuses to answer, and he ceases to confide in her. There is nothing easier than to win and keep the confidence of a child, and often there is nothing more difficult than to regain it when once it is lost, particularly in this direction. It is a loss the mother can by no means afford to sustain.

Mothers sometimes object that their young sons bring them the most shocking or absurd stories which they have heard in school or elsewhere. The mother who gives one moment's serious thought to such a situation will be forced to the conclusion that for her to hear such tales is nothing compared to the child's hearing them, and that his coming to his mother is proof of his own innocence. It is surely her first duty, no matter how difficult or unsavory the task, to sift out the wrong from the right, to show the child wherein the story is absurd, wicked, and harmful. At such a crisis the mother should be[Pg 35] very careful not to show any offence because the child has brought her the story. She may condemn the story as severely as she likes, but she must be careful that the child does not feel himself included in the condemnation. She must also be careful in denying the story not to deny the germ of truth which it will contain, or the child may conclude that she is talking against the facts, and is either ignorant or trying to conceal the truth. Many a mother has said in despair, "My boy of nine knows more about these things than I know myself."

It would be a great mistake to let the boy hear such a confession, as his very best safeguard is his confidence in the knowledge of his mother, or whoever assumes the duty of instructing him in these matters.[Pg 36]

Should the mother tell pleasant but totally false stories as to the origin of the child,—or should she tell the truth?

It is generally safer to tell the truth. Excepting with very young children the fiction is not long believed, and a course of deception, having been entered upon, oftentimes proves a stumbling block in the way of later veracity. It is so much easier to go on telling fairy-tales. Moreover, the truth, properly conveyed, is far more beautiful than any fairy-tale.

The parent must not forget that the child's mind is a blank page upon which any picture may be drawn, and that the child sees only what is presented to him. The thousand problems, the thousand troubles and fears, and all the knowledge of evil that burden the mind of the adult are entirely absent from that of the child. He sees only the one shining[Pg 37] fact, that he was once a part of his dear mother, nourished and protected by her until he was ready to open his eyes on the big world. The child has very little interest in details as a rule; and how to meet the demand for them, should it arise, will be considered later.

If the mother tells the story of the stork bringing the newcomer to the home, or of the doctor carrying him in his pocket, or the apothecary selling him over the counter, the child very soon learns that this is not true. He gets an inkling of the truth, understands that he has been deceived, and according to his age, his nature, and what he has heard, he will draw his conclusions as to why his mother did not tell him the truth.

Mothers often ask whether there is any more reason for refraining from the stork fiction than from the Santa Claus one. When Santa Claus is found out, the whole thing is generally understood as a joke, a pleasant sort of fairy tale. There was nothing hidden behind the fiction. In the other case, if the child chances somewhere to hear the facts stated in a coarse manner, he will be[Pg 38] likely to feel instinctively that the new tale is the true one, and will naturally conclude that the pretty fable was told to conceal a most unsavory truth. His first impression of the real facts will in such a case be ugly and—in a deep sense—false. It will hurt his sensibilities, or arouse his lower nature, according to his temperament.

The mother can guide herself by a rule which has exceptions but which in the main holds good: The child able to ask a question is able to understand the answer.

This is by no means saying that all the facts should be stated at once. That would be absurd. The question asked should be answered as simply as possible, the parent remembering that children's questions are usually more profound to the hearer than to the asker. It is difficult for the adult not to read into the child's chance question all the profundity of his own years of experience, and the mother who approaches this subject with dread is almost invariably astonished and relieved to find how easily the child is satisfied.

Where the child asks by chance or[Pg 39] design (and it is a wise parent who can always decide which it is) a question beyond his comprehension, or one that the parent is not ready to answer, he can be put off temporarily with the promise to explain another time. The child may forget all about it. If not, then the promise must be kept; and the very fact that the child remembers shows that he is thinking, and therefore ought to be helped. If the child asks questions which the mother feels sure he is not ready to have answered, she can promise to tell him when he gets older, explaining that he could not understand now. In such cases, however, the mother should always manifest a willingness to tell him something; she should talk with him enough to make him feel sure she will keep her promise. He should never be allowed to forget that he can go to his mother as frankly as to his own heart, with the certainty of finding sympathy and aid. And she should not let him forget that he is not to seek information from outside sources, such information being unreliable.[Pg 40]

Since the most beautiful and ideal way of presenting the facts of the renewal of life is through nature-study, a few words as to the handling of this interesting topic may be helpful to some mothers.

In all nature-work with the child, the subjects treated should be made interesting and beautiful. This cannot be too strongly insisted upon. The child has a right to the pleasure, the elevation of sentiment, the play of imagination which the contemplation of nature is able to give in such a peculiar degree. He has a right to the romance of the flower, cloud, bird, fish, animal life, plant life, in all their ramifications. It is a part of his soul-development. Consequently, whatever is done for him should be done in such a way as not to hurt his sensibilities. His pleasure in nature should be[Pg 41] increased, not lessened, as a result of his study.

As his knowledge expands his interest should deepen. This will almost never be the case where the first instruction is purely technical. Nothing, for instance, has deadened the interest of children in plant life so much as the study of botany. This is because the school methods have been wrong, the work being almost always approached from the wrong end. It is because the learner's mind is dammed up by difficult and to him empty technical terms. As a consequence, the course of its flow in this direction is stopped, and instead of a clear stream leaping joyfully through the woods and meadows finally to reach the great goal of the boundless ocean, it resembles rather a motionless pond, the surface of which is covered with lifeless and unlovely debris. Naturally the child seeks to escape from this uninteresting and dead pool by turning his mental energies in other directions, and too often he loses interest forever, and with it the pleasure and the vast profit that might have come to him from a different conception of the subject.[Pg 42]

Facts about the life of the plant should be abundantly presented, and the facts as collected and told to-day are well-nigh inexhaustible as well as fascinating. True stories of plant life can be, and should be, as interesting as any other stories. Technical terms should be used at first with great restraint, and, as a rule, only where they are obviously convenient or of such universal application that they are a distinct help in developing a sense of the continuity of living things. Those that are used should be so skilfully introduced, and their meaning so thoroughly digested, that they do not seem like technical terms.

Perhaps an illustration will make this point clearer. A child who loves flowers goes to school; he is given one of his favorites and told to pull it to pieces, look at its different parts, and label them with such words as petals, sepals, pistil, stamens; to these are presently added calyx, corolla, monopetalous, polypetalous, innate, adnate, indehiscent, etc., until the child's mind resembles a lumber room of senseless rubbish, in which the flower is buried and lost. To a sensitive child[Pg 43] this process is exceedingly painful. He often feels as though he were murdering some helpless thing he had loved, and conceals his tears and his heartache for fear of being laughed at. Less sensitive children are soon wearied and disgusted, and the love for nature which might have been aroused in them, to the sweetening and steadying of their whole after-life, receives a fatal check.

While the child's love for flowers, and his sentiment concerning them, should not be harmed by his plant work, on the other hand a certain tendency to weak sentimentality wherever encountered should be restrained. He should not be a mere receptacle for dry ashes nor yet a mush of sentimentality. The wise leader will discover the broad middle course where love of the flower shall be deepened, and, as it were, broadened, by knowledge of its wonderful structure and functions. These can be well understood without so much as one technical term, though the skilful introduction of a few helpful words will not detract at all from the pleasure of the study, and will be most convenient.[Pg 44]

The Anemone or Wind-Flower

The Anemone or Wind-Flower

Even the botanical names of the flowers themselves are of questionable value. The main thing is to recognize the flower as we recognize any other friend, and of course some name is necessary, but that this name be technical is, in most cases, not even desirable. "Wind-flower" is quite as good as "anemone," better, indeed, as it expresses a certain feeling about the flower that "anemone" does not convey. So, too, "mayflower" is more suggestive than "trailing arbutus," and that than Epigæa repens. Thus at first let the children learn only the common names of the flowers, at the same time that they discover all that is interesting about them. Later, when their interest is sure, the pretty[Pg 45] name "anemone" will give an added charm. They can be told that it comes from the Greek word anemos, meaning wind, and that anemones grow in Greece, and all that part of the world, and are gathered by the little children there. If the children are of an age to be studying or reading the tales of mythology, or the fascinating beginnings of Greek and Roman history, they will be delighted to think that anemones were no doubt gathered by Ulysses and Hector and the other Trojan heroes when they were children in that far-away land, and that the grandson of Æneas saw them in the Campagna near the Rome he founded, as the Italian children see them to-day. Thus through his botany the child can get a more vivid sense of the life of the past, can have a link forged in that invaluable mental chain which links him, mind, body, and soul, to everything else in the universe, and the consciousness of which is one of our most precious and helpful endowments in this life.

The universality of life and mind and soul, the universality of the methods of their manifestations even, the unity of[Pg 46] life,—nothing by itself, everything going out into and permeating everything else,—this great truth, which ought to burst upon the young mind with controlling force at a critical period later, should have its way prepared in childhood.

So far as technical terms are concerned, the child will gladly take them—in small doses—when he understands the things they represent,—that is, when the knowledge comes before the label; and when he recognizes their convenience in grouping the different varieties and species so that their relations to themselves and to other plants can be kept in the mind with a minimum of exertion.

Wild Rose with Bees Gathering Honey

Wild Rose with Bees Gathering Honey

The time comes when the analysis of the flower can be as interesting as any part of the work, if it has been preceded by other information and if it is pursued intelligently and delightfully. To illustrate again. The wild rose looked at simply as a thing of beauty and perfume becomes yet more interesting to the child who watches the bee gather its golden pollen and its luscious nectar. There is a bond of union now between[Pg 47] the fragile flower and its winged guest that begets an altruism which later becomes normally the corner-stone of character. When the graceful tribute of the bee to the flower is presently understood, and the child learns that the seeds of the flower have to thank the bee for their life, the mind expands yet more, and glows at the thought of this relationship in which each of these charming creatures practically preserves the life of the other.

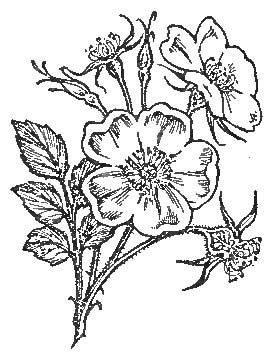

The Seed, the Child of the Plant, is at the Heart of

Every Flower

The Seed, the Child of the Plant, is at the Heart of

Every Flower

Now, too, the thought that the seed, the child of the plant, is at the heart of every flower, that it is for this nascent life, this new venture into the great world, that the blossom unfolds in beauty and sheds its perfume on the summer air, yet more expands the joyous[Pg 48] interest taken in the blossom. The mind, through a knowledge of these facts, can leap out into wider spaces of feeling and imagination. Thus every truth the child learns about the rose in those first tender years ought to add to his poetic conception of it. Thus he should learn his rose until the time comes when its relation to certain other plants will be full of meaning and full of interest. Perhaps the child has studied the apple blossom, the strawberry flower, the peach blossom in this same delightful way. With a very little help he will recognize the similarity of all three to the rose. He will be delighted to know that these are as truly related as they seem to be, that they are indeed cousins in one charming family. How they came to be so different will be a natural question, the answer to which[Pg 49] will involve the latest and most valuable scientific discoveries. Indeed, in studying nature we should begin with the latest discoveries of science, which are biological and vital, and end with man's earlier efforts toward knowledge,—that is, with classification and nomenclature. When the child knows his plants he may be interested in their relationships and willing to do the necessary drudgery toward establishing them. If not, it doesn't matter, he has the really vital part of the subject, the part that will best help him toward understanding all life, his own included.

It is to foster a high sentiment toward the life of the plant that the numerous so-called unscientific botanies which crowd the book-stores to-day are so valuable, and the numbers that are sold testify to the interest this side of the subject awakens. What technical botany has anything like the sale of these less technical books? So far as the real development of the world at large is concerned they are of inestimably more use than the technical works, though of course those were the stern Puritan parents who[Pg 50] have given rise to this flock of lovely non-puritanical children, and without which they of course could not have existed.

The technical botanies indeed have their use to-day, and it can be confidently expected that they will be more used than ever before, because of the large numbers who have had their interest quickened and a desire to know more awakened. Those who would have found botany interesting in spite of the old methods will pursue it yet more eagerly under the new. Many who would have turned away from it entirely will continue their study into the technical works, while great numbers who have no leaning toward technical study and would have had nothing to do with botany under the old methods, under the new will assimilate the best truths the study of this subject is able to give, and so far from finding a wild rose less fragrant or less beautiful because of their close scrutiny of it, they will find it infinitely more so,—infinitely more rich in affording poetical thoughts, comparisons, and images.[Pg 51]

What is true of plant life is equally true of animal life. The first attention should be directed toward the animal itself, its life and habits, technical information coming afterwards.[Pg 52]

In dealing with the special subject of this book too much stress cannot be laid upon the value of associating the phenomena of the renewal of life with all other vital phenomena, instead of divorcing it from them.

Two reasons why the subject of reproduction has such undue prominence in the minds of many people are, first, the manner in which it has been made conspicuous through concealment; and second, the fact that when spoken of at all, it has been treated as a unique phenomenon unrelated to anything else. These are not the only reasons, but they are strong ones, and their existence is quite unnecessary.

Education, therefore, should remove both of these stumbling-blocks. The first one is easily removed, though the value of its removal depends entirely[Pg 53] upon the manner in which that removal is accomplished. The second is also easily removed, the only difficulty being how to do it in the most helpful manner. The problem, then, for the instructor to solve is, how fully to acquaint the child with the phenomena of the reproductive life without making the subject unduly prominent.

This can well be done by interesting him in all the phenomena of living things, and allowing the reproductive function to take its place, not as something alone and different from everything else, but as one in a series of vital phenomena, all equally important and all interesting; not as something peculiar to human life or to the higher animals, but belonging equally to every living thing, whether animal or plant, and manifesting itself in the same way everywhere. Nor is this as difficult as at first glance it may seem. Indeed it is not difficult at all if one can begin with the young child, building little by little the foundation upon which later to erect a noble superstructure.

It is a beautiful fact that the plant[Pg 54] world offers illustrations of all the underlying phenomena of the reproductive life, and that through the flowers the little one can get his first introduction to the great subject. Not that he will at first understand the connection between the flower life and the human life, but the facts in the flower having been clearly perceived, there is nothing easier or more beautiful than to expand the idea when the time comes, until it embraces all life.

But what about those children who are no longer in their infancy? How are they to be taught?

In practically the same way, with some modification of method.

Since the aim here is to present the subject from the beginning, the first succeeding chapters will deal with it as applied to the young child. Following this, methods for use with older children will be discussed.

Objects to be accomplished with the younger children in the study of the plant.

(1) To make them feel that the plants[Pg 55] are living things with activities like other living things.

(2) To convey a clear idea of the true relation of seed to plant. This can be amplified later to cover the reproductive phenomena of human life.

(3) To give them a foundation for understanding the relation of father to child, when the time comes to explain that.

Some children naturally think of the plant as alive; they endow it with thought, feeling, and emotion; talk to it, consult it, caress it. Others do not. In both cases it is of value to the child to know the deeper truths concerning the life of the plant. In the one case it will steady sentimentality and guard against later loss of interest, in the other it will stimulate imagination and foster a high type of sentiment.

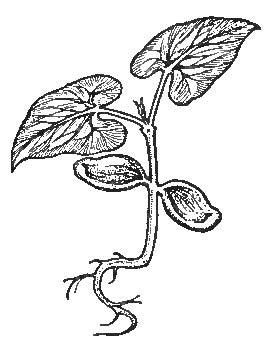

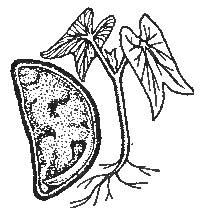

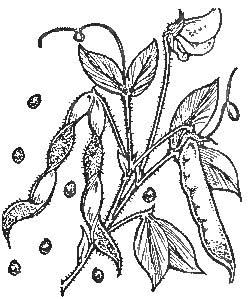

An easy and effective way to begin the study of the plant is to watch it as it sprouts from the seed. Since a large seed, easy to see and simple in structure, is best, an ordinary bean answers the purpose admirably, particularly as the[Pg 56] bean has the convenient habit of rising up above the ground when it sprouts, the development of the embryo proceeding in full view. Any of the common varieties will answer the purpose, though of course the larger the bean the more easily it can be observed.

A child of three or four will be interested in watching a seed grow. The first season he may get only one idea, the seed grows into a plant. The next season the experiment may be repeated with as much of the story of the plant added as the little one can understand. Thus Spring after Spring the child plants his seeds and watches them grow, constantly adding to his store of knowledge about them, until the story of the plant and its seed is as familiar to him as any fairy-tale, and has gone into his consciousness to stay there forever. Let us examine the bean, then, and see what can be learned from it, the information thus obtained to be shared with the child as fast as his age and his power of understanding permit.

The Bean, Sprouting, To Show the Two Seed-leaves And The

Embryo

The Bean, Sprouting, To Show the Two Seed-leaves And The

Embryo

First let us examine the dry bean. It is hard, so hard that we can scarcely[Pg 57] bite it. Put it to soak in tepid water, leaving it over night. Next day look at the changes that have taken place in it. The first thing we notice is that it has swollen until it is twice as large as it was, being now soaked full of water. It is also softer than it was. Its outer skin during the process of soaking has loosened, being no longer firmly attached to the body of the bean. This skin, being unable to stretch, soon splits open by the swelling of the bean inside. We can easily slip it entirely off.

The Bean—Embryo-Leaves, Seed-Leaves, and Root

The Bean—Embryo-Leaves, Seed-Leaves, and Root

Having done this let us take a good look at the bean that is now out of its[Pg 58] skin. We see that it is composed of two thick parts which are joined together at only one end. These two thick parts which make the bulk of the bean are called seed-leaves (cotyledons).

Just at the point where they seem to be joined together there is a tiny flat white object. Looking closely at this we discover it to be a plant consisting of two minute leaves and a little blunt tip. As a matter of fact, the two seed-leaves are not attached directly to each other, but each is attached to this tiny plant, or embryo, as it is called. The word "embryo" is a valuable one to use later, and its precise meaning can easily be fixed by always calling the young plant tucked away in the seed the embryo. The difficulty of learning new words does not lie in their length, but in not knowing what they mean. A child who has been to the circus has no trouble in remembering the word "elephant," and the child who frequently hears the word "embryo" spoken in connection with the plant concealed between the cotyledons quickly and unconsciously learns it.[Pg 59]

Place some of the soaked beans on damp cotton, and plant others in a pot of earth, or, if it is Summer, in the garden. Those sprouted in the house in the Winter must be kept warm. In a short time the little white embryo tucked away in the bean begins to grow. We say the bean sprouts. As the embryo develops, its little blunt tip grows down into the ground and gives off roots. At the same time its two tiny white leaves grow large and green, coming out from the seed-leaves (cotyledons) into the air and sunshine. As the stem lengthens the seed-leaves are lifted up above the ground along with the embryo. The bean thus seems to come out of the ground, and children are very apt to want to cover it up. But it has not really unplanted itself. The lower part of the stem and the roots hold it firmly in the earth.

The bean on the damp cotton grows as well at first as that planted in the earth, but it cannot get food enough to continue growth unless it can thrust its roots into the earth. What enables it to grow at all on the cotton, since that does[Pg 60] not supply food, but only holds the moisture, without which the bean could not sprout? There must be food somewhere, and it is found packed away in the thick seed-leaves, which contain a great deal of starch and a little of some other things.

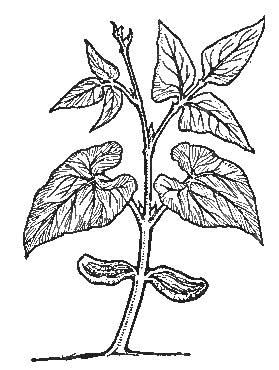

The Bean—Embryo-Leaves, Compound Leaves, and Beginning

of Stem

The Bean—Embryo-Leaves, Compound Leaves, and Beginning

of Stem

The young plant, under the influence of warmth and moisture, is able to draw out the nourishment from the seed-leaves. If we examine the seed-leaves after the seed has sprouted we shall find them less hard and firm; they have given part of their substance to the embryo. They have also turned greenish in color, while, as we know, the leaves of the embryo, which at first were so white and tiny, have also turned green and grown larger. Between the two embryo-leaves there is a little growing tip.

The young plant now no longer[Pg 61] depends upon the seed-leaves for its food. Down in the earth the roots are taking in nourishment, and up in the air the little green leaves are also busy supplying food to the growing plant. The little growing tip lengthens into a stem from which a leaf is seen unfolding. This new leaf is not shaped like the embryo-leaves nor like the seed-leaves. It has three leaflets. The stem continues to lengthen, and soon another compound leaf appears. Thus the stem lengthens and leaves keep coming, the little growing tip at the end of the stem always pushing upward.

Very soon the stem becomes too long and slender to stand upright. Then it does a strange thing. It circles about as though in search of something. It moves very slowly, but if you notice which way it is pointing in the morning, and again at noon, and again at night, you will see that it has changed its position. Why does it do this? It wishes to twine about a support, and will continue circling about until it finds one. If there is none, the slender stem, unable to stand upright as it lengthens,[Pg 62] will in time bend to one side or even lie on the ground; but the end still continues to circle about, and when at last it touches a stick or the stem of another plant or anything else about which it can twine, it continues its circling motion about the new support, and the vine as it lengthens finally becomes twined about it.

How does the food which the plant takes from the earth and the air find its way to the different parts of the plant to nourish them?

The plant food is in a liquid form called sap, which runs through channels in the roots and stems and leaves, and is thus carried to all parts of the plant. To a certain extent it is like the blood of animals, which finds its way all through the body and supplies food to the tissues.

The plant is alive; it eats, it breathes; sometimes it even moves. It breathes the same air that we do, only it takes it in through tiny pores in the leaves. Eating and breathing, the plant continues to grow, leaf after leaf unfolding. At last, in the axil of one of the leaves[Pg 63] there comes a little bud that does not unfold into a leaf but into a flower.

The appearance of this first blossom on the plant the child has himself raised from the seed will be watched with eagerness, and its advent can be made a subject of general pleasure and notice in the home. The child's pleasure in his flower will be greatly increased if he finds that others are also watching and enjoying it.

Here, too, is a chance to develop a certain respect or reverence for the beautiful and fragile flower. It is not to be picked. We are to leave this flower and see what becomes of it. If we pick it, it will soon wither and die. If we leave it where it is, it will continue to grow, and something very interesting will happen. After a few days the pretty white or red flower-leaves or petals will fall off; but any disappointment which the child may feel at the falling of the petals can be quickly changed into interest about what remains, for not all the flower fell. The centre of it is still there. It is a little green pod. It is so delicate that by holding it against the[Pg 64] light one can easily see the little seedlets, or ovules, inside. "Ovule" is a good word to learn, and the easiest way is to use it at once, always referring to this little seedlet in the young flower-pod as the ovule. The word "ovule" means little egg; later, a word almost identical will be used for the eggs of animals.

The Bean—the Seedlets, or Ovules, in the Young Pods

The Bean—the Seedlets, or Ovules, in the Young Pods

Thus by a use of carefully chosen, well-understood terms the child has from the very beginning a dawning sense of the oneness of all life. He can be told that "ovule" means little egg, and that the seed of the plant is the egg of the plant, which hatches—sprouts—into the plant we see.

It is better not to break the tender little pod to show the ovules, even if there are plenty of flowers. Look at the pod against the light and see the ovules dimly outlined. Each ovule is attached[Pg 65] to the pod by a little stem which can also be seen with the light shining through the pod. The stem the child can look for when the peas are being shelled for dinner, or when lima beans are being shelled. If the pea or bean pod is opened carefully, the whole row of seeds will be seen attached to the pod, each by its exceedingly short stem.

The ovary is a part of the plant in which grow the ovules. The perfect and clear understanding of just what the ovary is will be very helpful later, and the word "ovary" will be found extremely useful.

The interest should not be concentrated on the ovary to the exclusion of other flower parts. The bright petals should have their share of attention. They form a nest, or home, or covering, to enfold or wrap about the delicate seed-pod. The thought that they are fragrant and beautiful because of the young life they cherish, and that they never appear excepting where there are young seeds to be cared for, and that every flower has the little pod or seed-cradle at its centre, can be made to cast a lovely glow over[Pg 66] this side of the flower-life, which will later reflect more or less strongly upon all life.

When the child discovers that the ovules are attached to the ovary by little stems, this very important question can be answered,—How are the ovules nourished? They must have food, or they cannot develop into seeds.

The sap, which is the food of the plant, runs through the little stems that hold the ovules to the ovary, and thus, entering the ovules, nourishes them. The ovule has no embryo. It is a very simple little seedlet indeed. But after a while its little embryo begins to form and its seed-leaves to develop. When the ovule has developed in this way we call it a seed. It remains attached to the ovary, receiving nourishment from the sap until it is quite ripe. As the seed forms in its little pod, its thick sturdy seed-leaves become larger and fuller. The sap constantly stores up in them plenty of good food. Thus the parent plant provides for the seed, so that when it goes out into the world alone it may not perish until it has learned to care for[Pg 67] itself. The food in the seed-leaves is the bank account which starts the young plant in life.

When the seed is fully formed, its seed-leaves full of food, its embryo perfect, then we say it is ripe. It no longer needs to draw nourishment from the sap of the parent-plant. It is able to start in the world on its own account. When the seed ripens, its little stem withers away, so that the seed lies loose in the pod. In the case of the bean-pod, when the seed becomes free the pod opens, and the seed or bean, as we call it, falls out.

If we look at a ripe bean or pea or any seed we shall find upon one edge of it the scar where the little stem was attached. The scar is the umbilicus or "navel" of the seed. The seed does not become free from its attachment to the pod until it is able to live alone. As long as it continues to grow it remains attached and receives the sap. As soon as it has its growth and no longer needs the sap it separates from the pod. This separation is easy and natural. There is no tearing apart, no mutilation. It is exactly like the falling of the leaves in[Pg 68] the Autumn. It is, in short, the birth of the seed or infant plant.

Some mothers talk of the mother-plant and the seed-babies from the beginning. They show how the little seeds are fed and protected, how they are literally a part of the mother-plant. Other mothers prefer to tell only the botanical story, leaving all application to animal life for later consideration. In either case the essential points are a clear understanding of the growth of the ovule in the ovary, the manner in which it is nourished and protected, and its final separation from the ovary to enter into the outer world as an individual provided with everything necessary to its needs.

Some mothers use the words "sprout" and "hatch" interchangeably, speaking sometimes of the hatching of the seeds, in order to make more vivid the realization of the similarity of processes in the plant and the bird. They also speak of the birth of the seed. Clearly to understand the relation of the seed to the mother-plant is to understand accurately and scientifically the relation of every living creature to its mother.[Pg 69]

The child who enjoys planting the bean one season will want to plant it the next, for there is nothing children more delight in than planting things and watching them grow. This interest can be encouraged in any home, for where there is no available yard a few flower-pots of earth, or a box of it, will afford opportunity for a good deal of pleasure and instruction. The child can be encouraged to collect seeds that are formed like the bean, and plant them too. He will quickly discover that a peanut is made essentially like a bean, and he will be interested to plant some raw peanuts. The pea, too, he will soon add to his list. As the season advances he will discover the cucumber, melon, and squash seeds, and, with a little help, the apple, pear, and quince seeds, as well as those of the cherry, plum, and peach. The latter have very hard outer coats, but are formed in all essentials like the bean. Indeed he can have a very long list by the end of Summer. But he cannot make these green seeds grow. That is, many of them will not sprout until they have lain a certain length of time. So[Pg 70] even where they are ripe and fall from their pods, he had better keep them until toward Spring before planting, even in the house.

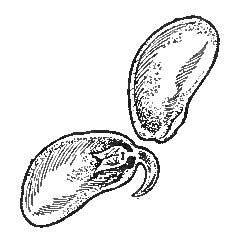

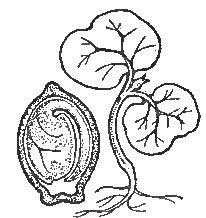

Morning-Glory Seed, Showing Seed-Leaves and Embryo

Morning-Glory Seed, Showing Seed-Leaves and Embryo

If he takes pleasure in examining his seeds, he will find in each one the tiny embryo tucked in between the seed-leaves; in the apple seed the young apple-tree, in the pumpkin seed the young pumpkin vine. Even the vegetables being prepared for his dinner can be interesting to him. As the peas are shelled he can see the pretty green seeds attached to the side of the pod. He can find the embryo even in the unripe seed, but he knows there would be no use in planting these green peas, for they are not yet fit to live apart from the mother-plant. If they were torn away and planted in the ground they would perish.

Not all seeds have the food for the embryo stored up in the seed-leaves. If a morning-glory seed be soaked, it will swell up and soften, and the hard outer[Pg 71] skin will burst. Inside will be found a tiny embryo with two thin, papery seed-leaves that contain no nourishment to speak of. But packed about the embryo is a rich food-substance which, though hard in the dry seed, becomes soft and gelatinous upon soaking, looking indeed not unlike the white of the egg, and having the same use; for it forms the first food of the embryo, which absorbs it. The embryo thus begins its growth, which continues until the roots and first leaves are sufficiently developed to supply nourishment.

Four O'clock Seed, Showing Seed-Leaves and Embryo

Four O'clock Seed, Showing Seed-Leaves and Embryo

After the child has studied his beans, let him then study the morning-glory and four-o'clock seeds, which store the food separately from the embryo instead of in its seed-leaves. In every seed there is food enough stored up to give the embryo its first start in life.

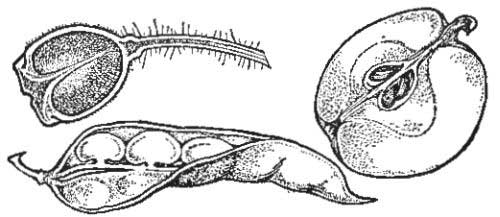

During the Summer the child can be helped to pass many pleasant hours looking at seed-pods and finding as many[Pg 72] kinds as possible. He can discover how the ovaries are placed in the flower and wrapped about by the bright petals, being covered while yet in the bud by the green calyx. He can look at the different forms of ovaries and discover how some, like the bean, have only one compartment or cell, while others, like the apple-core, have five, and yet others, like the poppy pod, have many. If he is interested, he can quickly and unconsciously learn many of the more common botanical terms used in describing plants, so that when he comes to study technical botany he will find it shorn of most of its terrors.

Different Kinds of Ovaries—Bean, Apple-Core, Poppy Pod

Different Kinds of Ovaries—Bean, Apple-Core, Poppy Pod

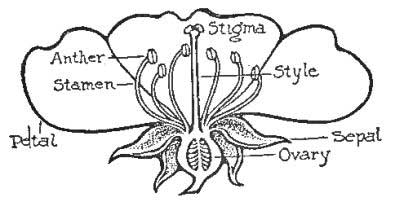

Certain botanical terms are valuable both now and later; used simply, just as we talk of table, chair, bed-post, garden-walk,[Pg 73] etc., they are, as has been said, learned unconsciously.

Flower—Ovary, Style, Stigma, Stamens, Anthers, Petals,

Sepals

Flower—Ovary, Style, Stigma, Stamens, Anthers, Petals,

Sepals

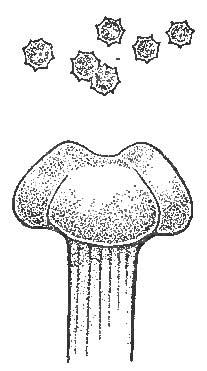

In teaching the later facts of the reproductive life, it is a great help for the child to know the names and uses of certain parts of the flower; in many flowers, as for instance the lily, the parts can be seen without pulling the flower to pieces. In the centre is the ovary, as the child already knows. Let him notice the long stalk on top of it and learn to call this the style. On top of the style is a knob—the stigma. Ovary, style, and stigma together make the pistil. Surrounding the pistil are six stamens, each having a slender stem or filament and terminating in a little box; this box is called the anther and is filled with[Pg 74] flower-dust or pollen. Around these is a circle of bright petals. In many flowers, outside the petals is a circle of green sepals, which in some plants fall off or turn down when the bud opens.

Sepals—usually green and affording protection to the bud.

Petals—usually large and bright.

Stamens—{ filament (stem of anther)

{ anther (containing pollen)

{ ovary (seed-pod)

Pistil—{ style (stem of stigma not always present)

{ stigma (knob at top of style or ovary)

The Development of the Young Bean-Pod from the Flower

The Development of the Young Bean-Pod from the Flower

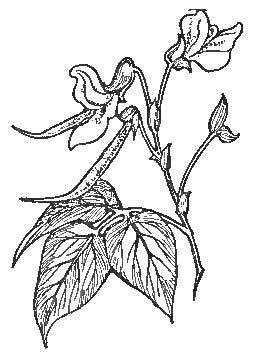

The care of the mother for her offspring, that impulse of nature found everywhere in nature's children, is beautifully illustrated in the flowers. When first the petals fall, leaving the tiny green pod, it stands up on its stalk, but in a few days it will be found hanging down. Why should this be? For one thing, as the pod turns down it gets out of the way of the other buds that one by one are preparing to blossom, for beans generally grow in clusters, one blossoming after another. Thus all the flowers have plenty of room and air and sunshine, and[Pg 75] a lesson in unselfishness and thoughtfulness for others may be learned. Moreover, the hanging pod is better protected against accidents than the upright one. It is less noticeable and less likely to be knocked or broken off. The mother-plant takes every precaution possible for the welfare of the seed-children, even sending them far from home for their benefit.

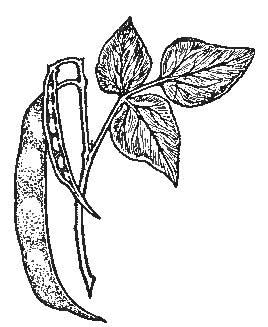

The Shedding of Young Sweet-peas from the Pod

The Shedding of Young Sweet-peas from the Pod

Every one has noticed how the sweet-pea pods are curled up when the seeds are shed. This curling takes place just at the moment when the pod opens to allow the seeds to escape. This sudden twisting of the pod flings the seeds sometimes long distances. If the seed were to fall close to[Pg 76] the mother-plant it would find the soil impoverished in certain ways, the mother-plant having absorbed the food materials from it. If the seed can be hurled out of reach of the absorbing roots of the mother-plant, it may have a better chance; even if it should fall where other things are growing, it may find the peculiar food it wants sufficiently abundant, for not all plants absorb just the same things from the soil.

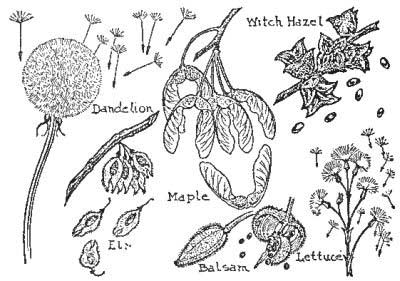

The Shedding of Various Kinds of Seeds

The Shedding of Various Kinds of Seeds

Looking at the dried bean and pea-pods in the fall of the year, we shall find[Pg 77] nearly all of them twisted. And looking over the other plants of the fields and hedges, we see how much trouble has been taken to enable the seeds to go out in the world and find new growing-places. Some seeds are snapped out, as the touch-me-nots and witch-hazels; some are supplied with flat wing-like surfaces to be borne by the wind, as the maple-keys and elm seeds; some have bristles or down upon which to float in the air, as the lilies, dandelions, and lettuces; some have hooks by which to attach themselves to the coats of passing animals; and others have yet other devices for getting to pastures new. The whole subject of how seeds travel about the world is very interesting, and collecting these wanderers and watching their habits will afford a rich summer's entertainment.

Thus the child learns a thousand interesting things about the plant life,—among them, but not in any way prominent, the phenomena which are connected with the reproduction of the plant. This work can all be done before the child is eight years old, and[Pg 78] in many cases it can be done much earlier, at least so far as inculcating the most essential truths is concerned. Many details will slip away in time, but if the work is thoroughly done the great primal truths of living things will stay, and as the child's life unfolds, they will illuminate it in certain directions.

According to the age and opportunities of the child his information about the plant can be enlarged. The plant's method of breathing can be explained to one who knows something about the composition of the air, and of the use which the human body makes of the oxygen. The child who can understand it will be greatly interested to know that the plant uses the oxygen of the air, and returns carbon dioxide to it as a waste, essentially as his own body does. He should also know that the plant breathes very little in comparison to the animal, consequently it does not greatly affect the air, taking out but little oxygen and returning to it but little carbon dioxide.

The plant's method of taking nourishment from air and soil is also very interesting. It is only the green parts of[Pg 79] the plant that can take food from the air. The plant can become and remain green only under the influence of sunlight. So finally the plant owes its life to the power of the sun, just as in one way or another we all do. Plants in a dark place soon lose their green color, grow pale and sickly, and finally die. All green leaves and the young green twigs are able to take food from the air. The food they thus take is carbon dioxide, the very thing both plants and animals breathe out as a waste, and whose presence in large quantities makes air unfit to breathe. But the plant must have the carbon dioxide and can get it only from the air, so it is constantly withdrawing this harmful substance from the air and converting it into plant tissue. It consumes only part of the carbon dioxide, however, for the oxygen that is tied up in the carbon dioxide is set free and given back to the air, only the carbon being retained. So the plant is continually taking in the destructive carbon dioxide and giving out the wholesome oxygen, thus keeping the air pure and fit for us to breathe. In short, the[Pg 80] plant eats with its roots and with its leaves. With its roots it eats certain things it finds in the earth, and with its leaves and other green parts it eats the suffocating gas we breathe into the air.

This important function of the plant, in supplying the oxygen we need and in destroying the harmful carbon dioxide, can be illustrated in many graphic ways. We depend upon the plants for our very existence in this respect: they stand between us and destruction from excessive accumulations of carbon dioxide. On the other hand, the carbon dioxide is so important to the plant that it could not exist without it. All the carbon it gets is obtained from this source. Wood is largely carbon; a charred stick which retains its full size and shape is almost pure carbon. Thus the breath of our bodies is converted by the plant into the wood from which we construct our houses, furniture, etc. In a certain sense the chair we sit upon is made of the breath of our bodies. Besides these debts to the plant, we finally owe to it the food we consume, which comes from[Pg 81] the plant, even meat being but vegetable matter one step removed. The plant changes the chemicals which the animal cannot use in their crude form, into plant substances which animals can use. Thus the vegetable and animal kingdoms are mutually dependent upon each other. Neither could exist, at least in its present condition, without the other.

Not only will such facts as these be interesting to most children, they will deepen the dawning consciousness of the fundamental unity of all forms of life, which it should be the province of nature-study to develop.

It may not be out of place here to say a few words about the picking of flowers. Children instinctively want to pick them. They wish to possess, touch, caress these lovely objects. If left unguided, this tendency shortly degenerates in many children into a desire to pick every flower in sight. A walk taken by such children through the fields can be traced by the wild flowers that strew the way. Great handfuls are gathered, and then, becoming burdensome, are thrown down. The child who[Pg 82] lovingly watches his flowers grow and blossom will be less likely to destroy in this wanton manner. Here, too, is a good opportunity to teach him to be thoughtful and generous to others. If he carelessly tears up and throws away the flowers, those who come after him will not have them to enjoy; it is far better to look at the flowers and admire them in their own homes and leave them there. A little crowd of hepaticas at the root of a tree in the woods is one of the most charming sights of spring. Let the child who finds such a treasure call the rest, that they too may enjoy the pretty picture; let the children get down and put their faces against the flowers if they want to smell them, and then go away leaving the beauty undisturbed. Their adult comrade at such a time by exclaiming appreciatively over the sweetness of the little scene, the bright flowers against the dark tree, the green moss growing over the rock at one side, can often open young eyes to a harmony of beauty which will cause the whole composition to be recalled later with pure pleasure; a far deeper and higher pleasure[Pg 83] this little picture lingering in the memory than any number of flowers torn from their places soon to wilt in the hands of the vandals whose only thought is how to get the most in the shortest time.

Should children never gather flowers, then? Of course they should. But they should learn to exercise restraint, and as they grow older, judgment. They can easily be persuaded to gather only a few flowers. A few are almost always more beautiful than a great mass, and there is no exception to this whatever where the delicate spring flowers are concerned. Let the child carefully gather a few to take home to mother, father, sister, aunt, some dear one who has not shared the walk. These flowers should not be neglected, but at once put in water, placed where they can be seen and enjoyed, and the water should be changed every day as long as they last. In this way the flower gives real pleasure to a number of people, and the child learns several lessons valuable to the formation of his character.

As the child grows older, he can be[Pg 84] taught not only self-control against gathering useless quantities of flowers, but also to exercise judgment in regard to those he does pick. For instance, seeing a flaming bush against a superb background of green foliage, shall he disturb the poise of the picture for the sake of taking some of the flowers? Better is it to look about for similar flowers less beautifully placed. Instead of culling from the little hepatica company at the tree root, let him search for more hidden or less beautifully grouped flowers. The isolated flowers will be just as pretty after they are picked as are those in the fortunately placed groups; for he will soon learn that with the flower he cannot take its surroundings excepting in the memory. In this way he will be able to carry away a beautiful mind-picture such as would not remain if he had destroyed it; he will become more observant of the flowers as pictures, cultivate his taste, in short, and also learn to enjoy beauty without destroying it.

Wanton destruction of flowers should never be countenanced, no matter how[Pg 85] abundant the flowers may be. Self-restraint is not inculcated for the sake of saving the flowers so much as for the influence it will have upon the development of the child, although there are parts of the country where one would like to see it exercised for the sake of the flowers themselves. The child who learns to respect flowers will never be one of that discreditable company who by sheer vandalism are constantly driving the wild flowers farther into the back country, finally exterminating whole species. In many parts of New England, banks which were carpeted with arbutus a generation ago are now devoid of a single root. Spring may come and Spring may go, but no may-flowers will ever again shine from those banks to delight the eye of the woodland wanderer. All the generations to come must be deprived of the pleasure of these delightful flowers, the earliest visitants of spring—to what end? Did the pleasure they gave to those who took them compensate in the least degree for their loss to the world? Truly not.

In all the open places near cities,[Pg 86] where flowers would delight the greatest number of eyes and hearts, there are no flowers, and this because those who went first had no respect for the flowers themselves or for the rights of those who came after.

Not only should the child learn to exercise judgment in gathering flowers, but he should also learn how to gather them properly. If the arbutus had not been carelessly torn up by the roots and trampled on, it would have yielded its whole tribute of blossoms year after year without disappearing. If the arbutus-gatherers, knowing the nature of the treasure they were gathering, had gone armed with scissors and had clipped the blossoming ends without other injury to the plant, at the same time taking care not to trample it, the banks would still have been clad in beauty.[Pg 87]

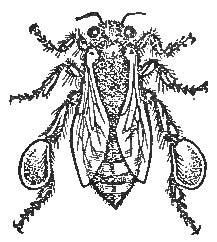

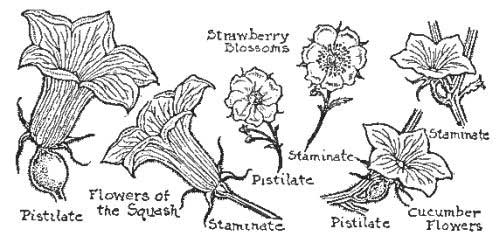

As a preparation for this work, let the children notice the flower-dust or pollen that shakes out of the flowers or is seen clinging to the anthers.

Bee—Showing Pollen-Basket

Bee—Showing Pollen-Basket

The child presently discovers where the pollen comes from. It is hidden in the anthers. He can hunt in all the flowers to find these little pollen-boxes, some of which, as in the goldenrods, are so small that he will have hard work to find them, even though they shed such clouds of pollen. He can notice the different kinds of stamens, see how some have long stems or filaments, others short ones, others again none at all. The filament is of no other use than[Pg 88] to hold up the anther. The anther with its pollen is the important thing; so there may be useful stamens with no filaments, but never useful stamens with no anthers.