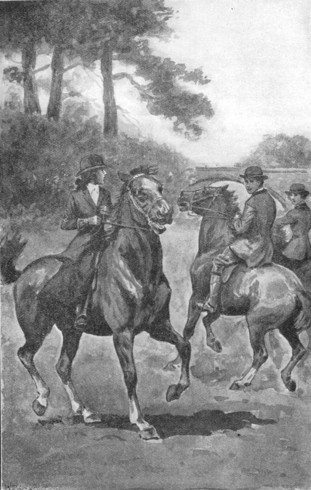

“CAB, MISS? TAKE YOU ANYWHERE YOU SAY.”

Frontispiece (Page 67).

Title: The Girl from Sunset Ranch; Or, Alone in a Great City

Author: Amy Bell Marlowe

Release date: September 5, 2008 [eBook #26534]

Most recently updated: January 4, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

THE GIRL FROM SUNSET RANCH

|

BOOKS FOR GIRLS |

|

THE OLDEST OF FOUR |

|

|

| THE ORIOLE BOOKS |

|

WHEN ORIOLE CAME TO HARBOR LIGHT WHEN ORIOLE TRAVELED WESTWARD |

|

(Other volumes in preparation) |

“CAB, MISS? TAKE YOU ANYWHERE YOU SAY.”

Frontispiece (Page 67).

|

THE GIRL FROM SUNSET RANCH OR ALONE IN A GREAT CITY BY AMY BELL MARLOWE AUTHOR OF THE OLDEST OF FOUR, THE GIRLS OF HILLCREST FARM, WYN'S CAMPING DAYS, ETC. Illustrated NEW YORK GROSSET & DUNLAP PUBLISHERS |

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1914, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

The Girl from Sunset Ranch

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | “Snuggy” and the Rose Pony | 1 |

| II. | Dudley Stone | 14 |

| III. | The Mistress Of Sunset Ranch | 26 |

| IV. | Headed East | 36 |

| V. | At Both Ends Of The Route | 45 |

| VI. | Across The Continent | 56 |

| VII. | The Great City | 65 |

| VIII. | The Welcome | 72 |

| IX. | The Ghost Walk | 83 |

| X. | Morning | 92 |

| XI. | Living Up To One’s Reputation | 102 |

| XII. | “I Must Learn The Truth” | 111 |

| XIII. | Sadie Again | 128 |

| XIV. | A New World | 142 |

| XV. | “Step—Put; Step—Put” | 152 |

| XVI. | Forgotten | 164 |

| XVII. | A Distinct Shock | 176 |

| XVIII. | Probing For Facts | 196 |

| XIX. | “Jones” | 204 |

| XX. | Out Of Step With The Times | 216 |

| XXI. | Breaking The Ice | 227 |

| XXII. | In The Saddle | 238 |

| XXIII. | My Lady Bountiful | 252 |

| XXIV. | The Hat Shop | 262 |

| XXV. | The Missing Link | 271 |

| XXVI. | Their Eyes Are Opened | 279 |

| XXVII. | The Party | 287 |

| XXVIII. | A Statement Of Fact | 304 |

| XXIX. | “The Whip Hand” | 311 |

| XXX. | Headed West | 317 |

THE GIRL FROM SUNSET

RANCH

“Hi, Rose! Up, girl! There’s another party making for the View by the far path. Get a move on, Rosie.”

The strawberry roan tossed her cropped mane and her dainty little hoofs clattered more quickly over the rocky path which led up from the far-reaching grazing lands of Sunset Ranch to the summit of the rocky eminence that bounded the valley upon the east.

To the west lay a great, rolling plain, covered with buffalo grass and sage; and dropping down the arc of the sky was the setting sun, ruddy-countenanced, whose almost level rays played full upon the face of the bluff up which the pony climbed so nimbly.

“On, Rosie, girl!” repeated the rider. “Don’t let him get to the View before us. I don’t see why anybody would wish to go there,” she added, 2 with a jealous pang, “for it was father’s favorite outlook. None of our boys, I am sure, would come up here at this hour.”

Helen Morrell was secure in this final opinion. It was but a short month since Prince Morrell had gone down under the hoofs of the steers in an unfortunate stampede that had cost the Sunset Ranch much beside the life of its well-liked owner.

The View—a flat table of rock on the summit overlooking the valley—had become almost sacred in the eyes of the punchers of Sunset Ranch since Mr. Morrell’s death. For it was to that spot the ranchman had betaken himself—usually with his daughter—on almost every fair evening, to overlook the valley and count the roaming herds which grazed under his brand.

Helen, who was sixteen and of sturdy build, could see the nearer herds now dotting the plain. She had her father’s glasses slung over her shoulder, and she had come to-night partly for the purpose of spying out the strays along the watercourses or hiding in the distant coulées.

But mainly her visit to the View was because her father had loved to ride here. She could think about him here undisturbed by the confusion and bustle at the ranch-house. And there were some things—things about her father and the sad conversation they had had together before his taking 3 away—that Helen wanted to speculate upon alone.

The boys had picked him up after the accident and brought him home; and doctors had been brought all the way from Helena to do what they could for him. But Mr. Morrell had suffered many bruises and broken bones, and there had been no hope for him from the first.

He was not, however, always unconscious. He was a masterful man and he refused to take drugs to deaden the pain.

“Let me know what I am about until I meet death,” he had whispered. “I—am—not—afraid.”

And yet, there was one thing of which he had been sorely afraid. It was the thought of leaving his daughter alone.

“Oh, Snuggy!” he groaned, clinging to the girl’s plump hand with his own weak one. “If there were some of your own kind to—to leave you with. A girl like you needs women about—good women, and refined women. Squaws, and Greasers, and half-breeds aren’t the kind of women-folk your mother was brought up among.

“I don’t know but I’ve done wrong these past few years—since your mother died, anyway. I’ve been making money here, and it’s all for you, Snuggy. That’s fixed by the lawyer in Elberon.

“Big Hen Billings is executor and guardian of 4 you and the ranch. I know I can trust him. But there ought to be nice women and girls for you to live with—like those girls who went to school with you the four years you were in Denver.

“Yet, this is your home. And your money is going to be made here. It would be a crime to sell out now.

“Ah, Snuggy! Snuggy! If your mother had only lived!” groaned Mr. Morrell. “A woman knows what’s right for a girl better than a man. This is a rough place out here. And even the best of our friends and neighbors are crude. You want refinement, and pretty dresses, and soft beds, and fine furniture——”

“No, no, Father! I love Sunset Ranch just as it is,” Helen declared, wiping away her tears.

“Aye. ’Tis a beauty spot—the beauty spot of all Montana, I believe,” agreed the dying man. “But you need something more than a beautiful landscape.”

“But there are true hearts here—all our friends!” cried Helen.

“And so they are—God bless them!” responded Prince Morrell, fervently. “But, Snuggy, you were born to something better than being a ‘cowgirl.’ Your mother was a refined woman. I have forgotten most of my college education; but I had it once. 5

“This was not our original environment. It was not meant that we should be shut away from all the gentler things of life, and live rudely as we have. Unhappy circumstances did that for us.”

He was silent for a moment, his face working with suppressed emotion. Suddenly his grasp tightened on the girl’s hand and he continued:

“Snuggy! I’m going to tell you something. It’s something you ought to know, I believe. Your mother was made unhappy by it, and I wouldn’t want a knowledge of it to come upon you unaware, in the after time when you are alone. Let me tell you with my own lips, girl.”

“Why, Father, what is it?”

“Your father’s name is under a cloud. There is a smirch on my reputation. I—I ran away from New York to escape arrest, and I have lived here in the wilderness, without communicating with old friends and associates, because I did not want the matter stirred up.”

“Afraid of arrest, Father?” gasped Helen.

“For your mother’s sake, and for yours,” he said. “She couldn’t have borne it. It would have killed her.”

“But you were not guilty, Father!” cried Helen.

“Why, Father, you could never have done anything dishonorable or mean—I know you could not!”

“Thank you, Snuggy!” the dying man replied, with a smile hovering about his pain-drawn lips. “You’ve been the greatest comfort a father ever had, ever since you was a little, cuddly baby, and liked to snuggle up against father under the blankets.

“That was before the big ranch-house was built, and we lived in a shack. I don’t know how your mother managed to stand it, winters. You just snuggled into my arms under the blankets—that’s how we came to call you ‘Snuggy.’”

“‘Snuggy’ is a good name, Dad,” she declared. “I love it, because you love it. And I know I gave you comfort when I was little.”

“Indeed, yes! What a comfort you were after your poor mother died, Snuggy! Ah, well! you shall have your reward, dear. I am sure of that. Only I am worried that you should be left alone now.”

“Big Hen and the boys will take care of me,” Helen said, stifling her sobs.

“Nay, but you need women-folk about. Your mother’s sister, now—The Starkweathers, if they knew, might offer you a home.”

“That is, Aunt Eunice’s folks?” asked Helen. 7 “I remember mother speaking of Aunt Eunice.”

“Yes. She corresponded with Eunice until her death. Of course, we haven’t heard from them since. The Starkweathers naturally did not wish to keep up a close acquaintanceship with me after what happened.”

“But, dear Dad! you haven’t told me what happened. Do tell me!” begged the anxious girl.

Then the girl’s dying father told her of the looted bank account of Grimes & Morrell. The cash assets of the firm had suddenly disappeared. Circumstantial evidence pointed at Prince Morrell. His partner and Starkweather, who had a small interest in the firm, showed their doubt of him. The creditors were clamorous and ugly. The bookkeeper of the firm disappeared.

“They advised me to go away for a while; your mother was delicate and the trouble was wearing her into her grave. And so,” Mr. Morrell said, in a shaking voice, “I ran away. We came out here. You were born in this valley, Snuggy. We hoped at first to take you back to New York, where all the mystery would be explained. But that time never came.

“Neither Starkweather, nor Grimes, seemed able to help me with advice or information. Gradually I got into the cattle business here. I prospered here, while Fenwick Grimes prospered in 8 New York. I understand he is a very wealthy man.

“Soon after we came out here your Uncle Starkweather fell heir to a big property and moved into a mansion on Madison Avenue. He, and his wife, and the three girls—Belle, Hortense and Flossie—have everything heart could desire.

“And they have all I want my Snuggy to have,” groaned Mr. Morrell. “They have refinement, and books, and music, and all the things that make life worth living for a woman.”

“But I love Sunset Ranch!” cried Helen again.

“Aye. But I watched your mother. I know how much she missed the gentler things she had been brought up to. Had I been able to pay off those old creditors while she was alive, she might have gone back.

“And yet,” the ranchman sighed, “the stigma is there. The blot is still on your father’s name, Snuggy. People in New York still believe that I was dishonest. They believe that with the proceeds of my dishonesty I came out here and went into the cattle business.

“You see, my dear? Even the settling with our old creditors—the creditors of Grimes & Morrell—made suspicion wag her tongue more eagerly than ever. I paid every cent, with interest compounded to the date of settlement. Grimes had 9 long since had himself cleared of his debts and started over again. I do not know even that he and Starkweather know that I have been able to clear up the whole matter.

“However, as I say, the stain upon my reputation remains. I could never explain my flight. I could never imagine what became of the money. Somebody embezzled it, and I was the one who ran away. Do you see, my dear?”

And Helen told him that she did see, and assured him again and again of her entire trust in his honor. But Mr. Morrell died with the worry of the old trouble—the trouble that had driven him across the continent—heavy upon his mind.

And now it was serving to make Helen’s mind most uneasy. The crime of which her father had been accused was continually in her thoughts.

Who had really been guilty of the embezzlement? The bookkeeper, who disappeared? Fenwick Grimes, the partner? Or, Who?

As the Rose pony—her own favorite mount—took Helen Morrell up the bluff path to the View on this evening, the remembrance of this long talk with her father before he died was running in the girl’s mind.

Perhaps she was a girl who would naturally be more seriously impressed than most, at sixteen. 10 She had been brought up among older people. She was a wise little thing when she was a mere toddler.

And after her mother’s death she had been her father’s daily companion until she was old enough to be sent away to be educated. The four long terms at the Denver school had carried Helen Morrell (for she had a quick mind) through those grades which usually prepare girls for college.

When she came back after graduation, however, she saw that her father needed her companionship more than she needed college. And, again, she was too domestic by nature to really long for a higher education.

She was glad now—oh! so glad—that she had remained at Sunset Ranch during these last few months. Her father had died with her arms about him. As far as he could be comforted, Helen had comforted him.

But now, as she rode up the rocky trail, she murmured to herself:

“If I could only clear dad’s name!”

Again she raised her eyes and saw a buckskin pony and its rider getting nearer and nearer to the summit.

“Get on, Rose!” she exclaimed. “That chap will beat us out. Who under the sun can he be?”

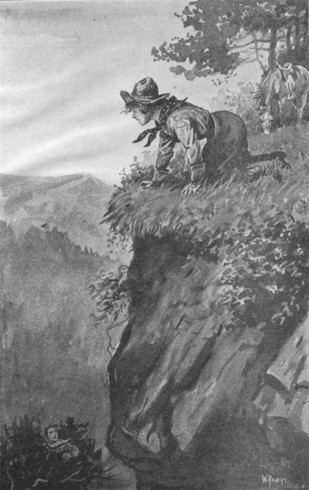

“HELEN CREPT ON HANDS AND KNEES TO THE EDGE OF THE BLUFF.”

(Page 14)

She was sure the rider of the buckskin was no Sunset puncher. Yet he seemed garbed in the usual chaps, sombrero, flannel shirt and gay neckerchief of the cowpuncher.

“And there isn’t another band of cattle nearer than Froghole,” thought the girl, adjusting her body to the Rose pony’s quickened gait.

She did not know it, but she was quite as much an object of interest to the strange rider as he was to her. And it was worth while watching Helen Morrell ride a pony.

The deep brown of her cheek was relieved by a glow of healthful red. Her thick plaits of hair were really sunburned; her thick eyebrows were startlingly light compared with her complexion.

Her eyes were dark gray, with little golden lights playing in them; they seemed fairly to twinkle when she laughed. Her lips were as red as ripe sumac berries; her nose, straight, long, and generously moulded, was really her handsomest feature, for of course her hair covered her dainty ears more or less.

From the rolling collar of her blouse her neck rose firm and solid—as strong-looking as a boy’s. She was plump of body, with good shoulders, a well-developed arm, and her ornamented russet riding boots, with a tiny silver spur in each heel, covered very pretty and very small feet. 12

Her hand, if plump, was small, too; but the gauntlets she wore made it seem larger and more mannish than it was. She rode as though she were a part of the pony.

She had urged on the strawberry roan and now came out upon the open plateau at the top of the bluff just as the buckskin mounted to the same level from the other side.

The rock called “the View” was nearer to the stranger than to herself. It overhung the very steepest drop of the eminence.

Helen touched Rose with the spur, and the pony whisked her tail and shot across the uneven sward toward the big boulder where Helen and her father had so often stood to survey the rolling acres of Sunset Ranch.

Whether the stranger on the buckskin thought her mount had bolted with her, Helen did not know. But she heard him cry out, saw him swing his hat, and the buckskin started on a hard gallop along the verge of the precipice toward the very goal for which the Rose pony was headed.

“The foolish fellow! He’ll be killed!” gasped Helen, in sudden fright. “That soil there crumbles like cheese! There! He’s down!”

She saw the buckskin’s forefoot sink. The brute stumbled and rolled over—fortunately for the pony away from the cliff’s edge. 13

But the buckskin’s rider was hurled into the air. He sprawled forward like a frog diving and—without touching the ground—passed over the brink of the precipice and disappeared from Helen’s startled gaze.

The victim of the accident made no sound. No scream rose from the depths after he disappeared. The buckskin pony rolled over, scrambled to its feet, and cantered off across the plateau.

Helen Morrell had swerved her own mount farther to the south and came to the edge of the caved-in bit of bank with a rush of hoofs that ended in a wild scramble as she bore down upon the Rose pony’s bit.

She was out of her saddle, and had flung the reins over Rose’s head, on the instant. The well-trained pony stood like a rock.

The girl, her heart beating tumultuously, crept on hands and knees to the crumbling edge of the bluff.

She knew its scarred face well. There were outcropping boulders, gravel pits, ledges of shale, brush clumps and a few ragged trees clinging tenaciously to the water-worn gullies.

She expected to see the man crushed and bleeding 15 on some rock below. Perhaps he had rolled clear to the bottom.

But as her swift gaze searched the face of the bluff, there was no rock, splotched with red, in her line of vision. Then she saw something in the top of one of the trees, far down.

It was the yellow handkerchief which the stranger had worn. It fluttered in the evening breeze like a flag of distress.

“E-e-e-yow!” cried Helen, making a horn of her hands as she leaned over the edge of the precipice, and uttering the puncher’s signal call.

“E-e-e-yow!” came up a faint reply.

She saw the green top of the tree stir. Then a face—scratched and streaked with blood—appeared.

“For the love of heaven!” called a thin voice. “Get somebody with a rope. I’ve got to have some help.”

“I have a rope right here. Pass it under your arms, and I’ll swing you out of that tree-top,” replied Helen, promptly.

She jumped up and went to the pony. Her rope—she would no more think of traveling without it than would one of the Sunset punchers—was coiled at the saddlebow.

Running back to the verge of the bluff she planted her feet on a firm boulder and dropped the 16 coil into the depths. In a moment it was in the hands of the man below.

“Over your head and shoulders!” she cried.

“You can never hold me!” he called back, faintly.

“You do as you’re told!” she returned, in a severe tone. “I’ll hold you—don’t you fear.”

She had already looped her end of the rope over the limb of a tree that stood rooted upon the brink of the bluff. With such a purchase she would be able to hold all the rope itself would hold.

“Ready!” she called down to him.

“All right! Here I swing!” was the reply.

Leaning over the brink, rather breathless, it must be confessed, the girl from Sunset Ranch saw him swing out of the top of the tree.

The tree-top was all of seventy feet from its roots. If he slipped now he would suffer a fall that surely would kill him.

But he was able to help himself. Although he crashed once against the side of the bluff and set a bushel of gravel rattling down, in a moment he gained foothold on a ledge. There he stood, wavering until she paid off a little of the line. Then he dropped down to get his breath.

“Are you safe?” she shouted down to him.

“Sure! I can sit here all night.”

“You don’t want to, I suppose?” she asked. 17

“Not so’s you’d notice it. I guess I can get down after a fashion.”

“Hurt bad?”

“It’s my foot, mostly—right foot. I believe it’s sprained, or broken. It’s sort of in the way when I move about.”

“Your face looks as if that tree had combed it some,” commented Helen.

“Never mind,” replied the youth. “Beauty’s only skin deep, at best. And I’m not proud.”

She could not see him very well, for the sun had dropped so low that down where he lay the face of the bluff was in shadow.

“Well, what are you going to do? Climb up, or down?”

“I believe getting down would be easier—’specially if you let me use your rope.”

“Sure!”

“But then, there’d be my pony. I couldn’t get him with this foot——”

“I’ll catch him. My Rose can run down anything on four legs in these parts,” declared the girl, briskly.

“And can you get down here to the foot of this cliff where I’m bound to land?”

“Yes. I know the way in the dark. Got matches?”

“Then you build some kind of a smudge when you reach the bottom. That’ll show me where you are. Now I’m going to drop the rope to you. Look out it doesn’t get tangled.”

“All right! Let ’er come!”

“I’ll have to leave you if I’m to catch that buckskin before it gets dark, stranger. You’ll get along all right?” she added.

“Surest thing you know!”

She dropped the rope. He gathered it in quickly and then uttered a cheerful shout.

“All clear?” asked Helen.

“Don’t worry about me. I’m all right,” he assured her.

Helen leaped back to her waiting pony. Already the golden light was dying out of the sky. Up here in the foothills the “evening died hard” as the saying is; but the buckskin pony had romped clear across the plateau. He was now, indeed, out of sight.

She whirled Rose about and set off at a gallop after the runaway. It was not until then that she remembered she had no rope. That buckskin would have to be fairly run down. There would be no roping him.

“But if you can’t do it, no other horsie can,” she said, aloud, patting the Rose pony on her arching neck. “Go it, girl! Let’s see if we can’t beat 19 any miserable little buckskin that ever came into this country. A strawberry roan forever!”

Her “E-e-e-yow! yow!” awoke the pony to desperate endeavor. She seemed to merely skim the dry grass of the open plateau, and in ten minutes Helen saw a riderless mount plunging up the side of a coulée far ahead.

“There he goes!” cried the girl. “After him, Rosie! Make your pretty hoofs fly!”

The excitement of the chase roused in Helen that feeling of freedom and confidence that is a part of life on the plains. Those who live much in the open air, and especially in the saddle, seldom think of failure.

She knew she was going to catch the runaway pony. Such an idea as non-success never entered her mind. This was the first hard riding she had done since Mr. Morrell died; and now her thoughts expanded and she shook off the hopeless feeling which had clouded her young heart and mind since they had buried her father.

While she rode on, and rode hard, after the fleeing buckskin her revived thought kept time with the pony’s hoofbeats.

No longer did the old tune run in her head: “If I only could clear dad’s name!” Instead the drum of confidence beat a charge to arms: “I know I can clear his name! 20

“To think of poor dad living out here all these years, with suspicion resting on his reputation back there in New York. And he wasn’t guilty! It was that partner of his, or that bookkeeper, who was guilty. That is the secret of it,” Helen told herself.

“I’ll go back East and find out all about it,” determined the girl, as her pony carried her swiftly over the ground. “Up, Rose! There he is! Don’t let him get away from us!”

Her interest in the chase of the buckskin pony and in the mystery of her father’s trouble ran side by side.

“On, on!” she urged Rose. “Why shouldn’t I go East? Big Hen can run the ranch well enough. And there are my cousins—and auntie. If Aunt Eunice resembles mother——

“Go it, Rose! There’s our quarry!”

She stooped forward in the saddle, and as the Rose pony, running like the wind, passed the now staggering buckskin, Helen snatched the dragging rein, and pulled the runaway around to follow in her own wake.

“Hush, now! Easy!” she commanded her mount, who obeyed her voice quite as well as though she had tugged at the reins. “Now we’ll go back quietly and trail this useless one along with us. 21

“Come up, Buck! Easy, Rose!” So she urged them into the same gait, returning in a wide circle toward the path up which she had climbed before the sun went down—the trail to Sunset Ranch.

“Yes! I can do it!” she cried, thinking aloud. “I can and will go to New York. I’ll find out all about that old trouble. Uncle Starkweather can tell me, probably.

“And then it will please father.” She spoke as though Mr. Morrell was sure to know her decision. “He will like it if I go to live with them a spell. He said it is what I need—the refining influence of a nice home.

“And I would love to be with nice girls again—and to hear good music—and put on something beside a riding skirt when I go out of the house.”

She sighed. “One cannot have a cow ranch and all the fripperies of civilization, too. Not very well. I—I guess I am longing for the flesh-pots of Egypt. Perhaps poor dad did, too. Well, I’ll give them a whirl. I’ll go East——

“Why, where’s that fellow’s fire?”

She was descending the trail into the pall of dusk that had now spread over the valley. Far away she caught a glimmer of light—a lantern on the porch at the ranch-house. 22 But right below here where she wished to see a light, there was not a spark.

“I hope nothing’s happened to him,” she mused. “I don’t believe he is one of us; if he had been he wouldn’t have raced a pony so close to the edge of the bluff.”

She began to “co-ee! co-ee!” as the ponies clattered down the remainder of the pathway. And finally there came an answering shout. Then a little glimmer of light flashed up—again and yet again.

“Matches!” grumbled Helen. “Can’t he find anything dry to burn down there and so make a steady light?”

She shouted again.

“This way, Miss!” she heard the stranger cry.

The ponies picked their way carefully over the loose shale that had fallen to the foot of the bluff. There were trees, too, to make the way darker.

“Hi!” cried Helen. “Why didn’t you light a fire?”

“Why, to tell you the truth, I had some difficulty in getting down here, and I—I had to rest.”

The words were followed by a groan that the young man evidently could not suppress.

“Why, you’re more badly hurt than you said!” 23 cried the girl. “I’d better get help; hadn’t I?”

“A doctor is out of the question, I guess. I believe that foot’s broken.”

“Huh! You’re from the East!” she said, suddenly.

“How so?”

“You say ‘guess’ in that funny way. And that explains it.”

“Explains what?”

“Your riding so recklessly.”

“My goodness!” exclaimed the other, with a short laugh. “I thought the whole West was noted for reckless riding.”

“Oh, no. It only looks reckless,” she returned, quietly. “Our boys wouldn’t ride a pony close to the edge of a steep descent like that up yonder.”

“All right. I’m in the wrong,” admitted the stranger. “But you needn’t rub it in.”

“I didn’t mean to,” said Helen, quickly. “I have a bad habit of talking out loud.”

He laughed at that. “You’re frank, you mean? I like that. Be frank enough to tell me how I am to get back to Badger’s—even on ponyback—to-night?”

“Impossible,” declared Helen.

“Then, perhaps I had better make an effort to make camp.” 24

“Why, no! It’s only a few miles to the ranch-house. I’ll hoist you up on your pony. The trail’s easy.”

“Whose ranch is it?” he asked, with another suppressed groan.

“Mine—Sunset Ranch.”

“Sunset Ranch! Why, I’ve heard of that. One of the last big ranches remaining in Montana; Isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“Almost as big as 101?”

“That’s right,” said Helen, briefly.

“But I didn’t know a girl owned it,” said the other, curiously.

“She didn’t—until lately. My father, Prince Morrell, has just died.”

“Oh!” exclaimed the other, in a softened tone. “And you are Miss Morrell?”

“I am. And who are you? Easterner, of course?”

“You guessed right—though, I suppose, you ‘reckon’ instead of ‘guess.’ I’m from New York.”

“Is that so?” queried Helen. “That’s a place I want to see before long.”

“Well, you’ll be disappointed,” remarked the other. “My name is Dudley Stone, and I was born and brought up in New York and have lived 25 there all my life until I got away for this trip West. But, believe me, if I didn’t have to I would never go back!”

“Why do you have to go back?” asked Helen, simply.

“Business. Necessity of earning one’s living. I’m in the way of being a lawyer—when my days of studying, and all, are over. And then, I’ve got a sister who might not fit into the mosaic of this freer country, either.”

“Well, Dudley Stone,” quoth the girl from Sunset Ranch, “we’d better not stay talking here. It’s getting darker every minute. And I reckon your foot needs attention.”

“I hate to move it,” confessed the young Easterner.

“You can’t stay here, you know,” insisted Helen. “Where’s my rope?”

“I’m sorry. I had to hitch one end of it up above and let myself down by it.”

“Well, it might have come in handy to lash you on the pony. I don’t mind about the rope otherwise. One of the boys will bring it in for me to-morrow. Now, let’s see what we can do towards hoisting you into your saddle.”

Dudley Stone had begun to peer wonderingly at this strange girl. When he had first sighted her riding her strawberry roan across the plateau he supposed her to be a little girl—and really, physically, she did not seem much different from what he had first supposed.

But she handled this situation with all the calmness and good sense of a much older person. She spoke like the men and women he had met during his sojourn in the West, too.

Yet, when he was close to her, he saw that she was simply a young girl with good health, good muscles, and a rather pretty face and figure. He called her “Miss” because it seemed to flatter her; but Dud Stone felt himself infinitely older than this girl of Sunset Ranch.

It was she who went about getting him aboard the pony, however; he never could have done it by himself. Nor was it so easily done as said.

In the first place, the badly trained buckskin didn’t want to stand still. And the young man 27 was in such pain that he really was unable to aid Helen in securing the pony.

“Here, you take Rose,” commanded the girl, at length. “She’d stand for anything. Up you come, now, sir!”

The young fellow was no weakling. But when he put one arm over the girl’s strong shoulder, and was hoisted erect, she felt him quiver all over. She knew that the pain he suffered must be intense.

“Whoa, Rose, girl!” commanded Helen. “Back around! Now, sir, up with that lame leg. It’s got to be done——”

“I know it!” he panted, and by a desperate effort managed to get the broken foot over the saddle.

“Up with you!” said Helen, and hoisted him with a man’s strength into the saddle. “Are you there?”

“Oh! Ouch! Yes,” returned the Easterner. “I’m here. No knowing how long I’ll stick, though.”

“You’d better stick. Here! Put this foot in the stirrup. Don’t suppose you can stand the other in it?”

“Oh, no! I really couldn’t,” he exclaimed.

“Well, we’ll go slow. Hi, there! Come here, you Buck!”

“He’s a vicious little scoundrel,” said the young man. 28

“He ought to have a course of sprouts under one of our wranglers,” remarked the girl from Sunset Ranch. “Now let’s go along.”

Despite the buckskin’s dancing and cavorting, she mounted, stuck the spurs into him a couple of times, and the ill-mannered pony decided that walking properly was better than bucking.

“You’re a wonder!” exclaimed Dud Stone, admiringly.

“You haven’t been West long,” she replied, with a smile. “Women folk out here aren’t much afraid of horses.”

“I should say they were not—if you are a specimen.”

“I’m just ordinary. I spent four school terms in Denver, and I never rode there, so I kind of lost the hang of it.”

Dud Stone was becoming anxious over another matter.

“Are you sure you can find the trail when it’s so dark?” he asked.

“We’re on it now,” she said.

“I’m glad you’re so sure,” he returned, grimly. “I can’t see the ground, even.”

“But the ponies know, if I don’t,” observed Helen, cheerfully. “Nothing to be afraid of.”

“I guess you think I am kind of a tenderfoot?” he returned. 29

“You’re not used to night traveling on the cattle range,” she said. “You see, we lay our courses by the stars, just as mariners do at sea. I can find my way to the ranch-house from clear beyond Elberon, as long as the stars show.”

“Well,” he sighed, “this is some different from riding on the bridle-path in Central Park.”

“That’s in New York?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“I mean to go there. It’s really a big city, I suppose?”

“Makes Denver look like a village,” said Stone, laughing to smother a groan.

“So father said.”

“You have people there, I hope?”

“Yes. Father and mother came from there. It was before I was born, though. You see, I’m a real Montana product.”

“And a mighty fine one!” he murmured. Then he said aloud: “Well, as long as you’ve got folks in the big city, it’s all right. But it’s the loneliest place on God’s earth if one has no friends and no confidants. I know that to be true from what boys have told me who have come there from out of town.”

“Oh, I’ve got folks,” said Helen, lightly. “How’s the foot now?” 30

“Bad,” he admitted. “It hangs loose, you see——”

“Hold on!” commanded Helen, dismounting. “We’ve a long way to travel yet. That foot must be strapped so that it will ride easier. Wait!”

She handed him her rein to hold and went around to the other side of the Rose pony. She removed her belt, unhooked the empty holster that hung from it, and slipped the holster into her pocket. Few of the riders carried a gun on Sunset Ranch unless the coyotes proved troublesome.

With her belt Helen strapped the dangling leg to the saddle girth. The useless stirrup, that flopped and struck the lame foot, she tucked up out of the way.

With tender fingers she touched the wounded foot. She could feel the fever through the boot.

“But you’d better keep your boot on till we get home, Dud Stone,” advised Helen. “It will sort of hold it together and perhaps keep the pain from becoming greater than you can bear. But I guess it hurts mighty bad.”

“It sure does, Miss Morrell,” he returned, grimly. “Is—is the ranch far?”

“Some distance. And we’ve got to walk. But bear up if you can——”

She saw him waver in the saddle. If he fell, 31 she could not be sure just how Rose, the spirited pony, would act.

“Say!” she said, coming around and walking by his side, leading the other mount by the bridle. “You lean on me. Don’t want you falling out of the saddle. Too hard work to get you back again.”

“I guess you think I am a tenderfoot!” muttered young Stone.

He never knew how they reached Sunset Ranch. The fall, the terrible wrench of his foot, and the endurance of the pain was finally too much for him. In a half-fainting condition he sank part of his weight on the girl’s shoulder, and she sturdily trudged along the rough trail, bearing him up until she thought her own limbs would give way.

At last she even had to let the buckskin run at large, he made her so much trouble. But the Rose pony was “a dear!”

Somewhere about ten o’clock the dogs began to bark. She saw the flash of lanterns and heard the patter of hoofs.

She gave voice to the long range yell, and a dozen anxious punchers replied. Great discussion had arisen over where she could have gone, for nobody had seen her ride off toward the View that afternoon.

“Whar you been, gal?” demanded Big Hen 32 Billings, bringing his horse to a sudden stop across the trail. “Hul-lo! What’s that you got with yer?”

“A tenderfoot. Easy, Hen! I’ve got his leg strapped to the girth. He’s in bad shape,” and she related, briefly, the particulars of the accident.

Dudley Stone had only a hazy recollection later of the noise and confusion of his arrival. He was borne into the house by two men—one of them the ranch foreman himself.

They laid him on a couch, cut the boot from his injured foot, and then the sock he wore.

Hen Billings, with bushy whiskers and the frame of a giant, was nevertheless as tender with the injured foot as a woman. Water with a chunk of ice floating in it was used to reduce the swelling. The foreman’s blunted fingers probed for broken bones.

But it seemed there was none. It was only a bad sprain, and they finally stripped him to his underclothes and bandaged the foot with cloths soaked with ice water.

When they got him into bed—in an adjoining room—the young mistress of Sunset Ranch reappeared, with a tray and napkins, with which she arranged a table.

“That’s what he wants—some good grub under his belt, Snuggy,” said the gigantic foreman, 33 finally lighting his pipe. “He’ll be all right in a few days. I’ll send word to Creeping Ford for one of the boys to ride down to Badger’s and tell ’em. That’s where Mr. Stone says he’s been stopping.”

“You’re mighty kind,” said the Easterner, gratefully, as Sing, the Chinese servant, shuffled in with a steaming supper.

“We’re glad to have a chance to play Good Samaritan in this part of the country,” said Helen, laughing. “Isn’t that so, Hen?”

“That’s right, Snuggy,” replied the foreman, patting her on the shoulder.

Dud Stone looked at Helen curiously, as the big man strode out of the room.

“What an odd name!” he commented.

“My father called me that, when I was a tiny baby,” replied the girl. “And I love it. All my friends call me ‘Snuggy.’ At least, all my ranch friends.”

“Well, it’s too soon for me to begin, I suppose?” he said, laughing.

“Oh, quite too soon,” returned Helen, as composedly as a person twice her age. “You had better stick to ‘Miss Morrell,’ and remember that I am the mistress of Sunset Ranch.”

“But I notice that you take liberties with my name,” he said, quickly. 34

“That’s different. You’re a man. Men around here always shorten their names, or have nicknames. If they call you by your full name that means the boys don’t like you. And I liked you from the start,” said the Western girl, quite frankly.

“Thank you!” he responded, his eyes twinkling. “I expect it must have been my fine riding that attracted you.”

“No. Nor it wasn’t your city cowpuncher clothes,” she retorted. “I know those things weren’t bought farther West than Chicago.”

“A palpable hit!” admitted Dudley Stone.

“No. It was when you took that tumble into the tree; was hanging on by your eyelashes, yet could joke about it,” declared Helen, warmly.

She might have added, too, that now he had been washed and his hair combed, he was an attractive-looking young man. She did not believe Dudley Stone was of age. His brown hair curled tightly all over his head, and he sported a tiny golden mustache. He had good color and was somewhat bronzed.

Dud’s blue eyes were frank, his lips were red and nicely curved; but his square chin took away from the lower part of his face any suggestion of effeminacy. His ears were generous, as was his nose. He had the clean-cut, intelligent look 35 of the better class of educated Atlantic seaboard youth.

There is a difference between them and the young Westerner. The latter are apt to be hung loosely, and usually show the effect of range-riding—at least, back here in Montana. Whereas Dud Stone was compactly built.

They chatted quite frankly while the patient ate his supper. Dud found that, although Helen used many Western idioms, and spoke with an abruptness that showed her bringing up among plain-spoken ranch people, she could, if she so desired, use “school English” with good taste, and gave other evidences in her conversation of being quite conversant with the world of which he was himself a part when he was at home.

“Oh, you would get along all right in New York,” he said, laughing, when she suggested a doubt as to the impression she might make upon her relatives in the big town. “You’d not be half the ‘tenderfoot’ there that I am here.”

“No? Then I reckon I can risk shocking them,” laughed Helen, her gray eyes dancing.

This talk she had with Dud Stone on the evening of his arrival confirmed the young mistress of Sunset Ranch in her intention of going to the great city.

When Helen Morrell made up her mind to do a thing, she usually did it. A cataclysm of nature was about all that would thwart her determination.

This being yielded to and never thwarted, even by her father, might have spoiled a girl of different calibre. But there was a foundation of good common sense to Helen’s nature.

“Snuggy won’t kick over the traces much,” Prince Morrell had been wont to say.

“Right you are, Boss,” had declared Big Hen Billings. “It’s usually safe to give her her head. She’ll bring up somewhar.”

But when Helen mentioned her eastern trip to the old foreman he came “purty nigh goin’ up in th’ air his own se’f!” as he expressed it.

“What d’yer wanter do anythin’ like that air for, Snuggy?” he demanded, in a horrified tone. “Great jumping Jehosaphat! Ain’t this yere valley big enough fo’ you?”

“Sometimes I think it’s too big,” admitted Helen, laughing. 37

“Well, by jo! you’ll fin’ city quarters close’t ’nough—an’ that’s no josh. Huh! Las’ time ever I went to Chicago with a train-load of beeves I went to see Kellup Flemming what useter work here on this very same livin’ Sunset Ranch. You don’t remember him. You was too little, Snuggy.”

“I’ve heard you speak of him, Hen,” observed the girl.

“Well, thar was Kellup, as smart a young feller as you’d find in a day’s ride, livin’ with his wife an’ kids in what he called a flat. Be-lieve me! It was some perpendicular to git into, an’ no flat.

“When we gits inside and inter what he called his parlor, he looks around like he was proud of it (By jo! I’d be afraid ter shrug my shoulders in it, ’twas so small) an’ says he: ‘What d’ye think of the ranch, Hen?’

“‘Ranch,’ mind yeh! I was plumb insulted. I says: ‘It’s all right—what there is of it—only, what’s that crack in the wall for, Kellup?’

“‘Sufferin’ tadpoles!’ yells Kellup—jest like that! ‘Sufferin’ tadpoles! That ain’t no crack in the wall. That’s our private hall.’

“Great jumping Jehosaphat!” exclaimed Hen, roaring with laughter. “Yuh don’t wanter git 38 inter no place like that in New York. Can’t breathe in the house.”

“I guess Uncle Starkweather lives in a little better place than that,” said Helen, after laughing with the old foreman. “His house is on Madison Avenue.”

“Don’t care where it is; there natcherly won’t be no such room in a city dwelling as there is here at Sunset Ranch.”

“I suppose not,” admitted the girl.

“Huh! Won’t be room in the yard for a cow,” growled Big Hen. “Nor chickens. Whatter yer goin’ to do without a fresh aig, Snuggy?”

“I expect that will be pretty tough, Hen. But I feel like I must go, you see,” said the girl, dropping into the idiom of Sunset Ranch. “Dad wanted me to.”

“The Boss wanted yuh to?” gasped the giant, surprised.

“Yes, Hen.”

“He never said nothin’ to me about it,” declared the foreman of Sunset Ranch, shaking his bushy head.

“No? Didn’t he say anything about my being with women folk, and under different circumstances?”

“Gosh, yes! But I reckoned on getting Mis’ 39 Polk and Mis’ Harry Frieze to take turns coming over yere and livin’ with yuh.”

“But that isn’t all dad wanted,” continued the girl, shaking her head. “Besides, you know both Mrs. Polk and Mrs. Frieze are widows, and will be looking for husbands. We’d maybe lose some of the best boys we’ve got, if they came here,” said Helen, her eyes twinkling.

“Great jumping Jehosaphat! I never thought of that,” declared the foreman, suddenly scared. “I never did like that Polk woman’s eye. I wouldn’t, mebbe, be safe myse’f; would I?”

“I’m afraid not,” Helen gravely agreed. “So, you see, to please dad, I’ll have to go to New York. I don’t mean to stay for all time, Hen. But I want to give it a try-out.”

She sounded Dud Stone a good bit about the big city. Dud had to stay several days at Sunset Ranch because he couldn’t ride very well with his injured foot. And finally, when he did go back to Badger’s, they took him in a buckboard.

To tell the truth, Dud was not altogether glad to go. He was a boyish chap despite the fact that he was nearly through law school, and a sixteen-year-old girl like Helen Morrell—especially one of her character—appealed to him strongly.

He admired the capable way in which she managed 40 things about the ranch-house. Sing obeyed her as though she were a man. There was a “rag-head” who had somehow worked his way across the mountains from the coast, and that Hindoo about worshipped “Missee Sahib.” The two or three Greasers working about the ranch showed their teeth in broad smiles, and bowed most politely when she appeared. And as for the punchers and wranglers, they were every one as loyal to Snuggy as they had been to her father.

The Easterner realized that among all the girls he knew back home, either of her age or older, there was none so capable as Helen Morrell. And there were few any prettier.

“You’re going right to relatives when you reach New York; are you, Miss Morrell?” asked Dud, just before he climbed into the buckboard to return to his friend’s ranch.

“Oh, yes. I shall go to Aunt Eunice,” said the girl, decidedly.

“No need of my warning you against bunco men and card sharpers,” chuckled Dud, “for your folks will look out for you. But remember: You’ll be just as much a tenderfoot there as I am here.”

“I shall take care,” she returned, laughing.

“And—and I hope I may see you in New York,” said Dud, hesitatingly. 41

“Why, I hope we shall run across each other,” replied Helen, calmly. She was not sure that it would be the right thing to invite this young man to call upon her at the Starkweathers’.

“I’d better ask Aunt Eunice about that first,” she decided, to herself.

So she shook hands heartily with Dud Stone and let him ride away, never appearing to notice his rather wistful look. She was to see the time, however, when she would be very glad of a friend like Dud Stone in the great city.

Helen made her preparations for her trip to New York without any advice from another woman. To tell the truth she had little but riding habits which were fit to wear, save the house frocks which she wore around the ranch.

When she had gone to school in Denver, her father had sent a sum of money to the principal and that lady had seen that Helen was dressed tastefully and well. But all these garments she had outgrown.

To tell the truth, Helen had spent little of her time in studying the pictures in fashion magazines. In fact, there were no such books about Sunset Ranch.

The girl realized that the rough and ready frocks she possessed were not in style. There was but one store in Elberon, the nearest town, where 42 ready-to-wear garments were sold. She went there and purchased the best they had; but they left much to be desired.

She got a brown dress to travel in, and a shirtwaist or two; but beyond that she dared not go. Helen was wise enough to realize that, after she arrived at her Uncle Starkweather’s, it would be time enough to purchase proper raiment.

She “dressed up” in the new frock for the boys to admire, the evening before she left. Every man who could be spared from the range—even as far as Creeping Ford—came in to the “party.” They all admired Helen and were sorry to see her go away. Yet they gave her their best wishes.

Big Hen Billings rode part of the way to Elberon with her in the morning. She was going to send the strawberry roan back hitched behind the supply wagon. Her riding dress she would change in the station agent’s parlor for the new dress which was in the tray of her small trunk.

“Keep yer eyes peeled, Snuggy,” advised the old foreman, with gravity, “when ye come up against that New York town. ’Tain’t like Elberon—no, sir! ’Tain’t even like Helena.

“Them folks in New York is rubbing up against each other so close, that it makes ’em moughty sharp—yessir! Jumping Jehosaphat! I knowed a feller that went there onct and he lost ten dollars 43 and his watch before he’d been off the train an hour. They can do ye that quick!”

“I believe that fellow must have been you, Hen,” declared Helen, laughing.

The foreman looked shamefaced. “Wal, it were,” he admitted. “But they never got nothin’ more out o’ me. It was the hottest kind o’ summer weather—an’ lemme tell yuh, it can be some hot in that man’s town.

“Wal, I had a sheepskin coat with me. I put it on, and I buttoned it from my throat-latch down to my boot-tops. They’d had to pry a dollar out o’ my pocket with a crowbar, and I wouldn’t have had a drink with the mayor of the city if he’d invited me. No, sirree, sir!”

Helen laughed again. “Don’t you fear for me, Hen. I shall be in the best of hands, and shall have plenty of friends around me. I’ll never feel lonely in New York, I am sure.”

“I hope not. But, Snuggy, you know what to do if anything goes wrong. Just telegraph me. If you want me to come on, say the word——”

“Why, Hen! How ridiculous you talk,” she cried. “I’ll be with relatives.”

“Ya-as. I know,” said the giant, shaking his head. “But relatives ain’t like them that’s knowed and loved yuh all yuh life. Don’t forgit us out yere, Snuggy—and if ye want anything——” 44 His heart was evidently too full for further utterance. He jerked his pony’s head around, waved his hand to the girl who likewise was all but in tears, and dashed back over the trail toward Sunset Ranch.

Helen pulled the Rose pony’s head around and jogged on, headed east.

As Helen walked up and down the platform at Elberon, waiting for the east-bound Transcontinental, she looked to be a very plain country girl with nothing in her dress to denote that she was one of the wealthiest young women in the State of Montana.

Sunset Ranch was one of the few remaining great cattle ranches of the West. Her father could justly have been called “a cattle king,” only Prince Morrell was not the sort of man who likes to see his name in print.

Indeed, there was a good reason why Helen’s father had not wished to advertise himself. That old misfortune, which had borne so heavily upon his mind and heart when he came to die, had made him shrink from publicity.

However, business at Sunset Ranch had prospered both before and since Mr. Morrell’s death. The money had rolled in and the bank accounts which had been put under the administration of 46 Big Hen Billings and the lawyer at Elberon, increased steadily.

Big Hen was a generous-handed administrator and guardian. Of course, the foreman of the ranch was, perhaps, not the best person to be guardian of a sixteen-year-old girl. He did not treat her, in regard to money matters, as the ordinary guardian would have treated a ward.

Big Hen didn’t know how to limit a girl’s expenditures; but he knew how to treat a man right. And he treated Helen Morrell just as though she were a sane and responsible man.

“There’s a thousand dollars in cash for you, Snuggy,” he had said. “I got it in soft money, for it’s a fac’ that they use that stuff a good deal in the East. Besides, the hard money would have made a good deal of a load for you to tote in them leetle war-bags of yourn.”

“But shall I ever need a thousand dollars?” asked Helen, doubtfully.

“Don’t know. Can’t tell. Sometimes ye need money when ye least expect it. Ye needn’t tell anybody how much you’ve got. Only, it’s there—and a full pocket is a mighty nice backin’ for anybody to have.

“And if ye find any time ye want more, jest telegraph. We’ll send ye what they call a draft for all ye want. Cut a dash. Show ’em that 47 the girl from Sunset Ranch is the real thing, Snuggy.”

But she had only laughed at this. It never entered Helen Morrell’s mind that she should ever wish to “cut a dash” before her relatives in New York.

She had filed a telegram to Mr. Willets Starkweather, on Madison Avenue, before the train arrived, saying that she was coming. She hoped that her relatives would reply and she would get the reply en route.

When her father died, she had written to the Starkweathers. She had received a brief, but kindly worded note from Uncle Starkweather. And it had scarcely been time yet, so Helen thought, for Aunt Eunice or the girls to write.

But could Helen have arrived at the Madison Avenue mansion of Willets Starkweather at the same hour her message arrived and heard the family’s comments on it, it is very doubtful if she would have swung herself aboard the parlor car of the Transcontinental, without the porter’s help, and sought her seat.

The Starkweathers lived in very good style, indeed. The mansion was one of several remaining in that section, all occupied by the very oldest and most elevated socially of New York’s solid families. They were not people whose names 48 appeared in the gossip columns of the papers to any extent; but to live in their neighborhood, and to meet them socially, was sufficient to insure one’s welcome anywhere.

The Starkweather mansion had descended to Willets Starkweather with the money—all from his great-uncle—which had finally put the family upon its feet. When Prince Morrell had left New York under a cloud, his brother-in-law was a struggling merchant himself.

Now, in sixteen years, he had practically retired. At least, he was no longer “in trade.” He merely went to an office, or to his broker’s, each day, and watched his investments and his real estate holdings.

A pompous, well-fed man was Willets Starkweather—and always imposingly dressed. He was very bald, wore a closely cropped gray beard, eyeglasses, and “Ahem!” was an introduction to almost everything he said. That clearing of the bronchial tubes was an announcement to the listening world that he, Willets Starkweather, of Madison Avenue, was about to make a remark. And no matter how trivial that remark might be, coming from the lips of the great man, it should be pondered upon and regarded with awe.

Mr. Starkweather was a widower. Helen’s Aunt Eunice had been dead three years. It had 49 never been considered necessary by either Mr. Starkweather, or his daughters, to write “Aunt Mary’s folks in Montana” of Mrs. Starkweather’s death.

Correspondence between the families had ceased at the time of Mrs. Morrell’s death. The Starkweather girls understood that Aunt Mary’s husband had “done something” before he left New York for the wild and woolly West. The family did not—Ahem!—speak of him.

The three girls were respectively eighteen, sixteen, and fourteen. Even Flossie considered herself entirely grown up. She attended a private school not far from Central Park, and went each day dressed as elaborately as a matron of thirty.

For Hortense, who was just Helen Morrell’s age, “school had become a bore.” She had a smattering of French, knew how to drum nicely on the piano—she was still taking lessons in that polite accomplishment—had only a vague idea of the ordinary rules of English grammar, and couldn’t write a decent letter, or spell words of more than two syllables, to save her life.

Belle golfed. She did little else just now, for she was a creature of fads. Occasionally she got a new one, and with kindred spirits played that particular fad to death.

She might have found a much worse hobby to 50 ride. Getting up early and starting for the Long Island links, or for Westchester, before her sisters had had their breakfast, was not doing Belle a bit of harm. Only, she was getting in with a somewhat “sporty” class of girls and women older than herself, and the bloom of youth had been quite rubbed off.

Indeed, these three girls were about as fresh as is a dried prune. They had jumped from childhood into full-blown womanhood (or thought they had), thereby missing the very best and sweetest part of their girls’ life.

They had come in from their various activities of the day when Helen’s telegram arrived. Naturally they ran with it to their father’s “den”—a gorgeously upholstered yet small library on the ground floor, at the back.

“What is it now, girls?” demanded Mr. Starkweather, looking up in some dismay at this general onslaught. “I don’t want you to suggest any further expenditures this month. I have paid all the bills I possibly can pay. We must retrench—we must retrench.”

“Oh, Pa!” said Flossie, saucily, “you’re always saying that. I believe you say ‘We must retrench!’ in your sleep.”

“And small wonder if I do,” he grumbled. “I have lost some money; the stock market is very 51 dull. And nobody is buying real estate. I—I am quite at my wits’ ends, I assure you, girls.”

“Dear me! and another mouth to feed!” laughed Hortense, tossing her head. “That will be excuse enough for telling her to go to a hotel when she arrives.”

“Probably the poor thing won’t have the price of a room,” observed Belle, looking again at the telegram.

“What is that in your hand, child?” demanded Mr. Starkweather, suddenly seeing the yellow slip of paper.

“A dispatch, Pa,” said Flossie, snatching it out of Belle’s hand.

“A telegram?”

“And you’d never guess from whom,” cried the youngest girl.

“I—I——Let me see it,” said her father, with some abruptness. “No bad news, I hope?”

“Well, I don’t call it good news,” said the oldest girl, with a sniff.

Mr. Starkweather read it aloud:

|

“Coming on Transcontinental. Arrive Grand Central Terminal 9 P.M. the third. “Helen Morrell.” |

“Now! What do you think of that, Pa?” demanded Flossie. 52

“‘Helen Morrell,’” repeated Mr. Starkweather, and a person more observant than any of his daughters might have seen that his lips had grown suddenly gray. He dropped into his chair rather heavily. “Your cousin, girls.”

“Fol-de-rol!” exclaimed Belle. “I don’t see why she should claim relationship.”

“Send her to a hotel, Pa,” said Flossie.

“I’m sure I do not wish to be bothered by a common ranch girl. Why! she was born and brought up out in the wilds; wasn’t she?” demanded Hortense.

“Her father and mother went West before this girl was born—yes,” murmured Mr. Starkweather.

He was strangely agitated by the message. But the girls did not notice this. They were not likely to notice anything but their own disturbance over the coming of “that ranch girl.”

“Why, Pa, we can’t have her here!” cried Belle.

“Of course we can’t, Pa,” agreed Hortense.

“I’m sure I don’t want the common little thing around,” added Flossie, who, as has been said, was quite two years Helen’s junior.

“We couldn’t introduce her to our friends,” declared Belle.

“What a fright she’ll be!” wailed Hortense. 53

“She’ll wear a sombrero and a split riding skirt, I suppose,” scoffed Flossie, who madly desired a slit skirt, herself.

“Of course she’ll be a perfect dowdy,” Belle observed.

“And be loud and wear heavy boots, and stamp through the house,” sighed Hortense. “We just can’t have her, Pa.”

“Why, I wouldn’t let any of the girls of our set see her for the world,” cried Flossie.

Their father finally spoke. He had recovered from his secret emotion, but he was still mopping the perspiration from his bald brow.

“I don’t really see how I can prevent her coming,” he said, rather weakly.

“What nonsense, Pa!”

“Of course you can!”

“Telegraph her not to come.”

“But she is already aboard the train,” objected Mr. Starkweather, gloomily.

“Then, I tell you,” snapped Flossie, who was the most unkind of the girls. “Don’t telegraph her at all. Don’t answer her message. Don’t send to the station to meet her. Maybe she won’t be too dense to take that hint.”

“Pooh! these wild and woolly Western girls!” grumbled Hortense. “I don’t believe she’ll know enough to stay away.” 54

“We can try it,” persisted Flossie.

“She ought to realize that we’re not dying to see her when we don’t come to the train,” said Belle.

“I—don’t—know,” mused their father.

“Now, Pa!” cried Flossie. “You know very well you don’t want that girl here.”

“No,” he admitted. “But—Ahem!—we have certain duties——”

“Bother duties!” said Hortense.

“Ahem! She is your mother’s sister’s child,” spoke Mr. Starkweather, heavily. “She is a young and unprotected female——”

“Seems to me,” said Belle, crossly, “the relationship is far enough removed for us to ignore it. Mother’s sister, Aunt Mary, is dead.”

“True—true. Ahem!” said her father.

“And isn’t it true that this man, Morrell, whom she married, left New York under a cloud?”

“O—oh!” cried Hortense. “So he did.”

“What did he do?” Flossie asked, bluntly.

“Embezzled; didn’t he, Pa?” asked Belle.

“That’s enough!” cried Flossie, tossing her head. “We certainly don’t want a convict’s daughter in the house.”

“Hush, Flossie!” said her father, with sudden sternness. “Prince Morrell was never a convict.” 55

“No,” sneered Hortense. “He ran away. He didn’t get that far.”

“Ahem! Daughters, we have no right to talk in this way—even in fun——”

“Well, I don’t care,” cried Belle, impatiently. “Whether she’s a criminal’s child or not; I don’t want her. None of us wants her. Why, then, should we have her?”

“But where will she go?” demanded Mr. Starkweather, almost desperately.

“What do we care?” cried Flossie, callously. “She can be sent back; can’t she?”

“I tell you what it is,” said Belle, getting up and speaking with determination. “We don’t want Helen Morrell here. We will not meet her at the train. We will not send any reply to this message from her. And if she has the effrontery to come here to the house after our ignoring her in this way, we’ll send her back where she came from just as soon as it can be done. What do you say, girls?”

“Fine!” from Hortense and Flossie.

But their father said “Ahem!” and still looked troubled.

It was not as though Helen Morrell had never been in a train before. Eight times she had gone back and forth to Denver, and she had always ridden in the best style. So sleepers, chair cars, private compartments, and observation coaches were no novelty to her.

She had discussed the matter with her friend, the Elberon station agent, and had bought her ticket through to New York, with a berth section to herself. It cost a good bit of money, but Helen knew no better way to spend some of that thousand dollars that Big Hen had given to her.

Her small trunk was put in the baggage car, and all she carried was a hand-satchel with toilet articles and kimono; and in it likewise was her father’s big wallet stuffed with the yellow-backed notes—all crisp and new—that Big Hen Billings had brought to her from the bank.

When she was comfortably seated in her particular section, and the porter had seen that her footstool was right, and had hovered about her 57 with offers of other assistance until she had put a silver dollar into his itching palm, Helen first stared about her frankly at the other occupants of the car.

Nobody paid much attention to the countrified girl who had come aboard at the way-station. The Transcontinental’s cars are always well filled. There were family parties, and single tourists, with part of a grand opera troupe, and traveling men of the better class.

Helen would have been glad to join one of the family groups. In one there were two girls and a boy beside the parents and a lady who must have been the governess. One of the girls, and the boy, were quite as old as Helen. They were all so well behaved, and polite to each other, yet jolly and companionable, that Helen knew she could have liked them immensely.

But there was nobody to introduce the lonely girl to them, nor to any others of her fellow travelers. The conductor, even, did not take much interest in the girl in brown.

She began to realize that what was the height of fashion in Elberon was several seasons behind the style in larger communities. There was not a pretty or attractive thing about Helen’s dress; and even a very pretty girl will seem a frump in an out-of-style and unbecoming frock. 58

It might have been better for the girl from Sunset Ranch if she had worn on the train the very riding habit she had in her trunk. At least, it would have become her and she would have felt natural in it.

She knew now—when she had seen the hats of her fellow passengers—that her own was an atrocity. And, then, Helen had “put her hair up,” which was something she had not been used to doing. Without practice, or some example to work by, how could this unsophisticated young girl have produced a specimen of modern hair-dressing fit to be seen?

Even Dudley Stone could not have thought Helen Morrell pretty as she looked now. And when she gazed in the glass herself, the girl from Sunset Ranch was more than a little disgusted.

“I know I’m a fright. I’ve got ‘such a muchness’ of hair and it’s so sunburned, and all! What those girls I’m going to see will say to me, I don’t know. But if they’re good-natured they’ll soon show me how to handle this mop—and of course I can buy any quantity of pretty frocks when I get to New York.”

So she only looked at the other people on the train and made no acquaintances at all that first day. She slept soundly at night while the Transcontinental raced on over the undulating plains on 59 which the stars shone so peacefully. Each roll of the drumming wheels was carrying her nearer and nearer to that new world of which she knew so little, but from which she hoped so much.

She dreamed that she had reached her goal—Uncle Starkweather’s house. Aunt Eunice met her. She had never even seen a photograph of her aunt; but the lady who gathered her so closely into her arms and kissed her so tenderly, looked just as Helen’s own mother had looked.

She awoke crying, and hugging the tiny pillow which the Pullman Company furnishes its patrons as a sample—the real pillow never materializes.

But to the healthy girl from the wide reaches of the Montana range, the berth was quite comfortable enough. She had slept on the open ground many a night, rolled only in a blanket and without any pillow at all. So she arose fresher than most of her fellow-passengers.

One man—whom she had noticed the evening before—was adjusting a wig behind the curtain of his section. He looked when he was completely dressed rather a well-preserved person; and Helen was impressed with the thought that he must still feel young to wish to appear so juvenile.

Even with his wig adjusted—a very curly brown affair—the man looked, however, to be upward of 60 sixty. There were many fine wrinkles about his eyes and deep lines graven in his cheeks.

His section was just behind that of the girl from Sunset Ranch, on the other side of the car. After returning from the breakfast table this first morning Helen thought she would better take a little more money out of the wallet to put in her purse for emergencies on the train. So she opened the locked bag and dragged out the well-stuffed wallet from underneath her other possessions.

The roll of yellow-backed notes was a large one. Helen, lacking more interesting occupation, unfolded the crisp banknotes and counted them to make sure of her balance. As she sat in her seat she thought nobody could observe her.

Then she withdrew what she thought she might need, and put the remainder of the money back into the old wallet, snapped the strong elastic about it, and slid it down to the bottom of the bag again.

The key of the bag she carried on the chain with her locket, which locket contained the miniatures of her mother and father. Key and locket she hid in the bosom of her dress.

She looked up suddenly. There was the fatherly-looking old person almost bending over her chair back. For an instant the girl was very much startled. The old man’s eyes were wonderfully keen and twinkling, and there was an expression 61 in them which Helen at first did not understand.

“If you have finished with that magazine, my dear, I’ll exchange it for one of mine,” said the old gentleman coolly. “What! did I frighten you?”

“Not exactly, sir,” returned Helen, watching him curiously. “But I was startled.”

“Beg pardon. You do not look like a young person who would be easily frightened,” he said, laughing. “You are traveling alone?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Far?”

“To New York, sir,” said Helen.

“Ah! a long way for a girl to go by herself—even a self-possessed one like you,” said the fatherly old fellow. “I hope you have friends to meet you there?”

“Relatives.”

“You have never been there, I take it?”

“I have never been farther east than Denver before,” she replied.

“Indeed! And so you have not met the relatives you are going to?” he suggested, shrewdly.

“You are right, sir.”

“But, of course, they will not fail to meet you?”

“I telegraphed to them. I expect to get a reply somewhere on the way.” 62

“Then you are well provided for,” said the old gentleman, kindly. “Yet, if you should need any assistance—of any kind—do not fail to call upon me. I am going through to New York, too.”

He went back to his seat after making the exchange of magazines, and did not force his attentions upon her further. He was, however, almost the only person who spoke to her all the way across the continent.

Frequently they ate together at the same table, both being alone. He bought newspapers and magazines and exchanged with her. He never became personal and asked her questions again, nor did Helen learn his name; but in little ways which were not really objectionable, he showed that he took an interest in her. There remained, however, the belief in Helen’s mind that he had seen her counting the money.

“I expect I’d like the old chap if he didn’t wear a wig,” thought Helen. “I never could see why people wished to hide the mistakes of Nature. And he’s an old gentleman, too.”

Yet again and again she recalled that avaricious gleam in his eyes and how eager he had seemed when she had first caught sight of his face looking over her shoulder that first morning on the train. She couldn’t forget that. She kept the locked bag near her hand all the time. 63

With lively company a journey across this great continent of ours is a cheerful and inspiring experience. And, of course, Youth can never remain depressed for long. But in Helen Morrell’s case the trip could not be counted as an enjoyable one.

She was always solitary amid the crowd of travelers. Even when she went back to the observation platform she was alone. She had nobody with whom to discuss the beauties of the landscape, or the wonders of Nature past which the train flashed.

This was her own fault to a degree, of course. The girl from Sunset Ranch was diffident. These people aboard were all Easterners, or foreigners. There were no open-hearted, friendly Western folk such as she had been used to all her life.

She felt herself among a strange people. She scarcely spoke the same language, or so it seemed. She had felt less awkward and bashful when she had first gone to the school at Denver as a little girl.

And, again, she was troubled because she had received no reply from her message to Uncle Starkweather. Of course, he might not have been at home to receive it; but surely some of the family must have received it.

Every time the brakeman, or porter, or conductor, came through with a message for some passenger, 64 she hoped he would call her name. But the Transcontinental brought her across the Western plains, over the two great rivers, through the Mid-West prairies, skirted two of the Great Lakes, rushed across the wooded and mountainous Empire State, and finally dashed down the length of the embattled Hudson toward the Great City of the New World—the goal of Helen Morrell’s late desires, with no word from the relatives whom she so hoped would welcome her to their hearts and home.

Helen Morrell never forgot her initial impressions of the great city.

These impressions were at first rather startling—then intensely interesting. And they all culminated in a single opinion which time only could prove either true or erroneous.

That belief or opinion Helen expressed in an almost audible exclamation:

“Why! there are so many people here one could never feel lonely!”

This impression came to her after the train had rolled past miles of streets—all perfectly straight, bearing off on either hand to the two rivers that wash Manhattan’s shores; all illuminated exactly alike; all bordered by cliffs of dwellings seemingly cut on the same pattern and from the same material.

With clasped hands and parted lips the girl from Sunset Ranch watched eagerly the glowing streets, parted by the rushing train. As it slowed down at 125th Street she could see far along that broad 66 thoroughfare—an uptown Broadway. There were thousands and thousands of people in sight—with the glare of shoplights—the clanging electric cars—the taxicabs and autos shooting across the main stem of Harlem into the avenues running north and south.

It was as marvelous to the Montana girl as the views of a foreign land upon the screen of a moving picture theatre. She sank back in her seat with a sigh as the train moved on.

“What a wonderful, wonderful place!” she thought. “It looks like fairyland. It is an enchanted place——”

The train, now under electric power, shot suddenly into the ground. The tunnel was odorous and ill-lighted.

“Well,” the girl thought, “I suppose there is another side to the big city, too!”

The passengers began to put on their wraps and gather together their hand-luggage. There was much talking and confusion. Some of the tourists had been met at 125th Street by friends who came that far to greet them.

But there was nobody to greet Helen. There was nobody waiting on the platform, to come and clasp her hand and bid her welcome, when the train stopped.

She got down, with her bag, and looked about 67 her. She saw that the old gentleman with the wig kept step with her. But he did not seem to be noticing her, and presently he disappeared.

The girl from Sunset Ranch walked slowly up into the main building of the Grand Central Terminal with the crowd. There was chattering all about her—young voices, old voices, laughter, squeals of delight and surprise—all the hubbub of a homing crowd meeting a crowd of friends.

And through it all Helen walked, a stranger in a strange land.

She lingered, hoping that Uncle Starkweather’s people might be late. But nobody spoke to her. She did not know that there were matrons and police officers in the building to whom she could apply for advice or assistance.

Naturally independent, this girl of the ranges was not likely to ask a stranger for help. She could find her own way.

She smiled—yet it was a rather wry smile—when she thought of how Dud Stone had told her she would be as much of a tenderfoot in New York as he had been on the plains.

“It’s a fact,” she thought. “But, if they didn’t get my message, I reckon I can find the house, just the same.”

Having been so much in Denver she knew a 68 good deal about city ways. She did not linger about the station long.

Outside there was a row of taxicabs and cabmen. There was an officer, too; but he was engaged at the moment in helping a fussy old lady get seven parcels, a hat box, and a dog basket into a cab.

So Helen walked down the row of waiting taxicabs. At the end cab the chauffeur on the seat turned around and beckoned.

“Cab, Miss? Take you anywhere you say.”

“You know where this number on Madison Street is, of course?” she said, showing a card with the address on it.

“Sure, Miss. Jump right in.”

“How much will it be?”

“Trunk, Miss?”

“Yes. Here is the check.”

The chauffeur got out of his seat quickly and took the check.

“It’s so much a mile. The little clock tells you the fare,” he said, pleasantly.

“All right,” replied Helen. “You get the trunk,” and she stepped into the vehicle.

In a few moments he was back with the trunk and secured it on the roof of his cab. Then he reached in and tucked a cloth around his passenger, although the evening was not cold, and got in 69 under the wheel. In another moment the taxicab rolled out from under the roofed concourse.

Helen had never ridden in any vehicle that went so smoothly and so fast. It shot right downtown, mile after mile; but Helen was so interested in the sights she saw from the window of the cab that she did not worry about the time that elapsed.

By and by they went under an elevated railroad structure; the street grew more narrow and—to tell the truth—Helen thought the place appeared rather dirty and unkempt.

Then the cab was turned suddenly across the way, under another elevated structure, and into a narrow, noisy, ill-kept street.

“Can it be that Uncle Starkweather lives in this part of the town?” thought Helen, in amazement.

She had always understood that the Starkweather mansion was in one of the oldest and most respectable parts of New York. But although this might be one of the older parts of the city, to Helen’s eyes it did not look respectable.

The street was full of children and grown people in odd costumes. And there was a babel of voices that certainly were not English.

They shot across another narrow street—then 70 another. And then the cab stopped beside the curb near a corner gaslight.

“Surely this is not Madison?” demanded Helen, of the driver, as her door was opened.

“There’s the name, Miss,” said the man, pointing to the street light.

Helen looked. She really did see “MADISON” in blue letters on the sign.

“And is this the number?” she asked again, looking at the three-story, shabby house before which the cab had stopped.

“Yes, Miss. Don’t you see it on the fanlight?”