Title: The Land of The Blessed Virgin; Sketches and Impressions in Andalusia

Author: W. Somerset Maugham

Release date: November 13, 2008 [eBook #27252]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

SKETCHES AND IMPRESSIONS IN

ANDALUSIA

by

WILLIAM SOMERSET MAUGHAM

(with frontispiece)

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN

MCMV

All rights reserved

TO

VIOLET HUNT

Contents

| chapter | ||

| I. | The Spirit of Andalusia | |

| II. | The Churches of Ronda | |

| III. | Ronda | |

| IV. | The Swineherd | |

| V. | Medinat Az-Zahra | |

| VI. | The Mosque | |

| VII. | The Court of Oranges | |

| VIII. | Cordova | |

| IX. | The Bridge of Calahorra | |

| X. | Puerta del Puente | |

| XI. | Seville | |

| XII. | The Alcazar | |

| XIII. | Calle de las Sierpes | |

| XIV. | Characteristics | |

| XV. | Don Juan Tenorio | |

| XVI. | Women of Andalusia | |

| XVII. | The Dance | |

| XVIII. | A Feast Day | |

| XIX. | The Giralda | |

| XX. | The Cathedral of Seville | |

| XXI. | The Hospital of Charity | |

| XXII. | Gaol | |

| XXIII. | Before the Bull-Fight | |

| XXIV. | Corrida de Toros—I. | |

| XXV. | Corrida de Toros—II | |

| XXVI. | On Horseback | |

| XXVII. | By the Road—I. | |

| XXVIII. | By the Road—II. | |

| XXIX. | Ecija | |

| XXX. | Wind and Storm | |

| XXXI. | Two Villages | |

| XXXII. | Granada | |

| XXXIII. | The Alhambra | |

| XXXIV. | Boabdil the Unlucky | |

| XXXV. | Los Pobres | |

| XXXVI. | The Song | |

| XXXVII. | Jerez | |

| XXXVIII. | Cadiz | |

| XXXIX. | El Genero Chico | |

| XL. | Adios | |

After one has left a country it is interesting to collect together the emotions it has given in an effort to define its particular character. And with Andalusia the attempt is especially fascinating, for it is a land of contrasts in which work upon one another, diversely, a hundred influences.

In London now, as I write, the rain of an English April pours down; the sky is leaden and cold, the houses in front of me are almost terrible in their monotonous greyness, the slate roofs are shining with the wet. Now and again people pass: a woman of the slums in a dirty apron, her head wrapped in a grey shawl; two girls in waterproofs, trim and alert notwithstanding the inclement weather, one with a music-case under her arm. A train arrives at an underground station and a score of city folk cross my window, sheltered behind their umbrellas; and two or three groups of workmen, silently, smoking short pipes: they walk with a dull, heavy tramp, with the gait of strong men who are very tired. Still the rain pours down unceasing.

And I think of Andalusia. My mind is suddenly ablaze with its sunshine, with its opulent colour, luminous and soft; I think of the cities, the white cities bathed in light; of the desolate wastes of sand, with their dwarf palms, the broom in flower. And in my ears I hear the twang of the guitar, the rhythmical clapping of hands and the castanets, as two girls dance in the sunlight on a holiday. I see the crowds going to the bull-fight, intensely living, many-coloured. And a thousand scents are wafted across my memory; I remember the cloudless nights, the silence of sleeping towns, and the silence of desert country; I remember old whitewashed taverns, and the perfumed wines of Malaga, of Jerez, and of Manzanilla. (The rain pours down without stay in oblique long lines, the light is quickly failing, the street is sad and very cheerless.) I feel on my shoulder the touch of dainty hands, of little hands with tapering fingers, and on my mouth the kisses of red lips, and I hear a joyous laugh. I remember the voice that bade me farewell that last night in Seville, and the gleam of dark eyes and dark hair at the foot of the stairs, as I looked back from the gate. 'Feliz viage, mi Inglesito.'

It was not love I felt for you, Rosarito; I wish it had been; but now far away, in the rain, I fancy, (oh no, not that I am at last in love,) but perhaps that I am just faintly enamoured—of your recollection.

But these are all Spanish things, and more than half one's impressions of Andalusia are connected with the Moors. Not only did they make exquisite buildings, they moulded a whole people to their likeness; the Andalusian character is rich with Oriental traits; the houses, the mode of life, the very atmosphere is Moorish rather than Christian; to this day the peasant at his plough sings the same quavering lament that sang the Moor. And it is to the invaders that Spain as a country owes the magnificence of its golden age: it was contact with them that gave the Spaniards cultivation; it was the conflict of seven hundred years that made them the best soldiers in Europe, and masters of half the world. The long struggle caused that tension of spirit which led to the adventurous descent upon America, teaching recklessness of life and the fascination of unknown dangers; and it caused their downfall as it had caused their rise, for the religious element in the racial war occasioned the most cruel bigotry that has existed on the face of the earth, so that the victors suffered as terribly as the vanquished. The Moors, hounded out of Spain, took with them their arts and handicrafts—as the Huguenots from France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes—and though for a while the light of Spain burnt very brightly, the light borrowed from Moordom, the oil jar was broken and the lamp flickered out.

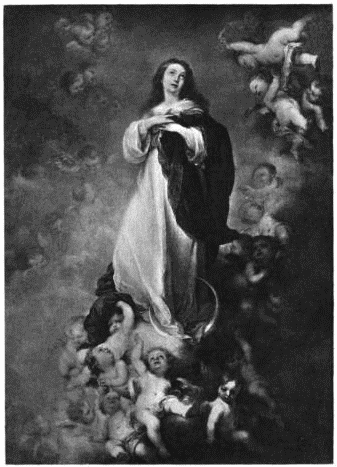

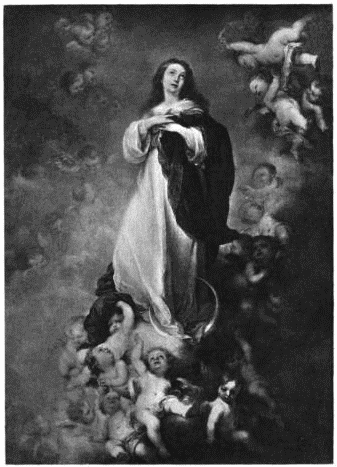

In most countries there is one person in particular who seems to typify the race, whose works are the synthesis, as it were, of an entire people. Bernini expressed in this manner a whole age of Italian society; and even now his spirit haunts you as you read the gorgeous sins of Roman noblemen in the pages of Gabriele d'Annunzio. And Murillo, though the expert not unjustly from their special point of view, see in him but a mediocre artist, in the same way is the very quintessence of Southern Spain. Wielders of the brush, occupied chiefly with technique, are apt to discern little in an old master, save the craftsman; yet art is no more than a link in the chain of life and cannot be sharply sundered from the civilisation of which it is an outcome: even Velasquez, sans peer, sans parallel, throws a curious light on the world of his day, and the cleverest painters would find their knowledge and understanding of that great genius the fuller if they were acquainted with the plays of Lope de la Vega and the satires of Quevedo. Notwithstanding Murillo's obvious faults, as you walk through the museum at Seville all Andalusia appears before you. Nothing could be more characteristic than the religious feeling of the many pictures, than the exuberant fancy and utter lack of idealisation: in the contrast between a Holy Family by Murillo and one by Perugino is all the difference between Spain and Italy. Murillo's Virgin is a peasant girl such as you may see in any village round Seville on a feast-day; her emotions are purely human, and in her face is nothing more than the intense love of a mother for her child. But the Italian shows a creature not of earth, an angelic maid with almond eyes, oval of face: she has a strange air of unrealness, for her body is not of human flesh and blood, and she is linked with mankind only by an infinite sadness; she seems to see already the Dolorous Way, and her eyes are heavy with countless unwept tears.

One picture especially, that which the painter himself thought his best work, Saint Thomas of Villanueva distributing Alms, to my mind offers the entire impression of that full life of Andalusia. In the splendour of mitre and of pastoral staff, in the sober magnificence of architecture, is all the opulence of the Catholic Church; in the worn, patient, ascetic face of the saint is the mystic, fervid piety which distinguished so wonderfully the warlike and barbarous Spain of the sixteenth century; and lastly, in the beggars covered with sores, pale, starving, with their malodorous rags, you feel strangely the swarming poverty of the vast population, downtrodden and vivacious, which you read of in the picaresque novels of a later day. And these same characteristics, the deep religious feeling, the splendour, the poverty, the extreme sense of vigorous life, the discerning may find even now among the Andalusians for all the modern modes with which, as with coats of London and bonnets of Paris, they have sought to liken themselves to the rest of Europe.

And the colours of Murillo's palette are the typical colours of Andalusia, rich, hot, and deep—again contrasting with the enamelled brilliance of the Umbrians. He seems to have charged his brush with the very light and atmosphere of Seville; the country bathed in the splendour of an August sun has just the luminous character, the haziness of contour, which characterise the paintings of Murillo's latest manner. They say he adopted the style termed vaporoso for greater rapidity of execution, but he cannot have lived all his life in that radiant atmosphere without being impregnated with it. In Andalusia there is a quality of the air which gives all things a limpid, brilliant softness, the sea of gold poured out upon them voluptuously rounds away their outlines; and one can well imagine that the master deemed it the culmination of his art when he painted with the same aureate effulgence, when he put on canvas those gorgeous tints and that exquisite mellowness.

That necessity of realism which is, perhaps, the most conspicuous of Spanish traits, shows itself nowhere more obviously than in matters religious. It is a very listless emotion that is satisfied with the shadow of the ideal; and the belief of the Andaluz is an intensely living thing, into which he throws himself with a vehemence that requires the nude and brutal fact. His saints must be fashioned after his own likeness, for he has small power of make-believe, and needs all manner of substantial accessories to establish his faith. But then he treats the images as living persons, and it never occurs to him to pray to the Saint in Paradise while kneeling before his presentment upon earth. The Spanish girl at the altar of Mater Dolorosa prays to a veritable woman, able to speak if so she wills, able to descend from the golden shrine to comfort the devout worshipper. To her nothing is more real than these Madonnas, with their dark eyes and their abundant hair: Maria del Pilar, who is Mary of the Fountain, Maria del Rosario, who is Mary of the Rosary, Maria de los Dolores, Maria del Carmen, Maria de los Angeles. And they wear magnificent gowns of brocade and of cloth-of-gold, mantles heavily embroidered, shoes, rings on their fingers, rich jewels about their necks.

In a little town like Ronda, so entirely apart from the world, poverty-stricken, this desire for realism makes a curiously strong impression. The churches, coated with whitewash, are squalid, cold and depressing; and at first sight the row of images looks nothing more than a somewhat vulgar exhibition of wax-work. But presently, as I lingered, the very poverty of it all touched me; and forgetting the grotesqueness, I perceived that some of the saints in their elaborate dresses were quite charming and graceful. In the church of Santa Maria la Mayor was a Saint Catherine in rich habiliments of red brocade, with a white mantilla arranged as only a Spanish woman could arrange it. She might have been a young gentlewoman of fifty years back when costume was gayer than nowadays, arrayed for a fashionable wedding or for a bull-fight. And in another church I saw a youthful Saint in priest's robes, a cassock of black silk and a short surplice of exquisite lace; he held a bunch of lilies in his hand and looked very gently, his lips almost trembling to a smile. One can imagine that not to them would come the suppliant with a heavy despair, they would be merely pained at their helplessness before the tears of the grief that kills and the woe of mothers sorrowing for their sons. But when the black-eyed maiden knelt before the priest, courtly and debonair, begging him to send a husband quickly, his lips surely would control themselves no longer, and his smile would set the damsel's cheek a-blushing. And if a youth knelt before Saint Catherine in her dainty mantilla, and vowed his heart was breaking because his love gave him stony glances, she would look very graciously upon him, so that his courage was restored, and he promised her a silver heart as lovers in Greece made votive offerings to Aphrodite.

At the Church of the Espirito Santo, in a little chapel behind one of the transept altars, I saw, through a huge rococo frame of gilded wood, a Maria de los Dolores that was almost terrifying in poignant realism. She wore a robe of black damask, which stood as if it were cast of bronze in heavy, austere folds, a velvet cloak decorated with the old lace known as rose point d'Espagne; and on her head a massive imperial diadem, and a golden aureole. Seven candles burned before her; and at vespers, when the church was nearly dark, they threw a cold, sharp light upon her countenance. Her eyes were in deep shadow, strangely mysterious, and they made the face, so small beneath the pompous crown, horribly life-like: you could not see the tears, but you felt they were eyes which would never cease from weeping.

I suppose it was all tawdry and vulgar and common, but a woman knelt in front of the Mother of Sorrows, praying, a poor woman in a ragged shawl; I heard a sob, and saw that she was weeping; she sought to restrain herself and in the effort a tremor passed through her body, and she drew the shawl more closely round her.

I walked away, and came presently to the most cruel of all these images. It was a Pietà. The Mother held on her knees the dead Son, looking in His face, and it was a ghastly contrast between her royal array and His naked body. She, too, wore the imperial crown, with its golden aureole, and her cloak was of damask embroidered with heavy gold. Her hair fell in curling abundance about her breast, and the sacristan told me it was the hair of a lady who had lost her husband and her only son. But the dead Christ was terrible, His face half hidden by the long straight hair, long as a woman's, and His body thin and all discoloured: from the wounds thick blood poured out, and their edges were swollen and red; the broken knees, the feet and hands, were purple and green with the beginning of putrefaction.

Ronda is set deep among the mountains between Algeciras and Seville; they hem it in on all sides, and it straggles up and down little hills, timidly, as though its presence were an affront to the wild rocks around it. The houses are huddled against the churches, which look like portly hens squatting with ruffled feathers, while their chicks, for warmth, press up against them. It is very cold in Ronda. I saw it first quite early: over the town hung a grey mist shining in the sunlight, and the mountains, opalescent in the morning glow, were so luminous that they seemed hardly solid; they looked as if one could walk through them. The people, covering their mouths in dread of a pulmonia, hastened by, closely muffled in long cloaks. As I passed the open doors I saw them standing round the brasero, warming themselves; for fireplaces are unknown to Andalusia, the only means of heat being the copa, a round brass dish in which is placed burning charcoal.

The height and the cold give Ronda a character which reminds one of Northern Spain; the roofs are quite steep, the houses low and small, built for warmth rather than, as in the rest of Andalusia, for coolness.

But the whitewash and the barred windows with their wooden lattice-work, remind you that you are in Moorish country, in the very heart of it; and Ronda, indeed, figures in chronicles and in old ballads as a stronghold of the invaders. The temperature affects the habits of the people, even their appearance: there is no lounging about the squares or at the doors of wine-shops, the streets are deserted and their great breadth makes the emptiness more apparent. The first setters out of the town had no need to make the ways narrow for the sake of shade, and they are, in fact, so broad that the houses on either side might be laid on their faces, and there would still be room for the rapid stream which hurries down the middle.

The conformation of a Spanish town, even though it lack museums and fine buildings, gives it an interest beyond that of most European places. The Moorish design is always evident. That wise people laid out the streets as was most convenient, tortuous and narrow at Cordova or broad as a king's highway in Ronda. The Moors stayed their time, and their hour struck, and they went; the houses had fallen to decay and been more than once rebuilt. The Christians returned and Mahomet fled before the Saints; (it was no shame since they grossly out-numbered him;) the mosque was made a church, and the houses as they fell were built again, but on the same foundations and in the same way. The streets have remained as the Moors left them, the houses still are built round little courtyards—the patio—as the Moors built them; and the windows are barred and latticed as of old, the better to protect beauty whose dark eyes flash too meaningly at wandering strangers, whose red lips are over ready to break into a smile for the peace of an absent husband.

After the busy clamour of Gibraltar, that ant-nest of a hundred nationalities, Ronda impresses you by its peculiar silence. The lack of sound is the more noticeable in the frosty clearness of the atmosphere, and is only emphasised by an occasional cry that floats, from some vast distance, along the air. The coldness, too, has pinched the features of the people, and they seem to grow old even earlier than in the rest of Andalusia. Strapping fellows of thirty with slim figures and a youthful air have the faces of elderly men, and their skin is hard, stained and furrowed. The women, ageing as rapidly, have no gaiety. If Spanish girls have frequently a beautiful youth, their age too often is atrocious: it is inconceivable that a handsome woman should become so fearful a hag; the luxuriant hair is lost, and she takes no pains to conceal her grey baldness, the eye loses its light, the enchanting down of the upper lip turns to a bristly moustache; the features harden, grow coarse and vulgar; and the countenance assumes a rapacious expression, so that she appears a bird of prey; and her strident voice is like the shriek of vultures. It is easily comprehensible that the Spanish stage should have taken the old woman as one of its most constant, characteristic types. But in Ronda even the girls have a weary look, as though life were not so easy a matter as in warmer places, or as the good God intended; and they seem to suffer from the brevity of youth, which is no sooner come than gone. They walk inertly, clothed in sombre colours, their hair not elaborately arranged as would have it the poorest cigarette-girl, but merely knotted, without the flower which the Sevillan is popularly said to insist upon even at the cost of a dinner. And when they go out the grey shawls they wrap about their heads add to their unattractiveness.

But if Ronda itself is a somewhat dull and unsympathetic place with nothing more for the edification of the visitor than a melodramatic chasm, the surrounding country is worthy the most extravagant epithets. The mountains have the gloomy barrenness, the slate-grey colour of volcanic ranges; they encircle the town in a gigantic amphitheatre, rugged and overbearing like Titans turned to stone. They seem, indeed, to wear a sombre insolence of demeanour as though the aspect of human kind moved them to lofty contempt. And in their magnificent desolation they offer a fit environment for the exploits of Byronic heroes. The handsome villain of romance, seductive by the complexity of his emotions, by the persistence of his mysterious grief, would find himself in that theatrical scene most thoroughly at home; nor did Prosper Mérimée fail to seize the opportunity, for the mountains of Ronda were the very hunting-ground of Don Josè, who lost his soul for Carmen. But as a matter of history they were likewise the haunts of brigands in flesh and blood—malefactors in the past had that sense of the picturesque which now is vested in the amateur photographer—and this particular district was as dangerous to the travelling merchant as any in Spain.

The environs of Ronda are barren and unfertile, the olive groves bear little fruit. I wandered through the lonely country, towards the mountains; the day was overcast and the clouds hung sluggishly overhead. As I walked, suddenly I heard a melancholy voice singing a peasant song, a malagueña. I paused to listen, but the sadness was almost unendurable; and it went on interminably, wailing through the air with the insistent monotony of its Moorish origin. I struck into the olives to find the singer and met a swineherd, guarding a dozen brown pigs, a youth thin of face, with dark eyes, clothed in undressed sheep-skins; and the brown wool gave him a singular appearance of community with the earth about him. He stood among the trees like a wild creature, more beast than man, and the lank, busy pigs burrowed around him, running to and fro, with little squeals. He ceased his song when I approached and looked up timidly. I spoke to him but he made no answer, I offered a cigarette but he shook his head.

I went my way, and at first the road was not quite solitary. Two men passed me on donkeys. 'Vaya Usted con Dios!' they cried—'Go you with God': it is the commonest greeting in Spain, and the most charming; the roughest peasant calls it as you meet him. A dozen grey asses went towards Ronda, one after the other, their panniers filled with stones; they walked with hanging heads, resigned to all their pain. But when at last I came into the mountains the loneliness was terrible. Not even the olive grew on those dark masses of rock, windswept and sterile; there was not a hut nor a cottage to testify of man's existence, not even a path such as the wild things of the heights might use. All life, indeed, appeared incongruous with that overwhelming solitude.

Daylight was waning as I returned, but when I passed the olive-grove, where many hours before I had heard the malagueña, the same monotonous song still moaned along the air, carrying back my thoughts to the swineherd. I wondered what he thought of while he sang, whether the sad words brought him some dim emotion. How curious was the life he led! I suppose he had never travelled further than his native town; he could neither write nor read. Madrid to him was a city where the streets were paved with silver and the King's palace was of fine gold. He was born and grew to manhood and tended his swine, and some day he would marry and beget children, and at length die and return to the Mother of all things. It seemed to me that nowadays, when civilisation has become the mainstay of our lives, it is only with such beings as these that it is possible to realise the closeness of the tie between mankind and nature. To the poor herdsman still clung the soil; he was no foreign element in the scene, but as much part of it as the stunted olives, belonging to the earth intimately as the trees among which he stood, as the beasts he tended.

When I came near the town the sun was setting. In the west, tempestuous clouds were massed upon one another, and the sun shone blood-red above them; but as it sank they were riven asunder, and I saw a great furnace that lit up the whole sky. The mountains were purple, unreal as the painted mountains of a picture. The light was gone from the east, and there everything was chill and grey; the barren rocks looked so desolate that one shuddered with horror of the cold. But the sun fell gold and red, and the rift in the clouds was a kingdom of gorgeous light; the earth and its petty inhabitants died away, and in the crimson flame I could almost see Lucifer standing in his glory, god-like and young; Lucifer in all majesty, surrounded by his court of archangels, Beelzebub, Belial, Moloch, Abaddon.

I had discovered in the morning, from the steeple of Santa Maria, a queer ruined church, and was oddly impressed by the bare façade, with the yawning apertures of empty windows. I went to it, but every entrance was bricked up save one, which had a door of rough boards fastened by a padlock; and in a neighbouring house I found an old man with a key. It was a spot of utter desolation; the roof had gone or had never been. The custodian could not tell whether the church was the wreck of an old building or a framework that had never been completed; the walls were falling to decay. Along the nave and in the chapels trees were growing, shrubs and rank weeds; it was curious the utter ruin in the midst of the populous town. Pigs ran hither and thither, feeding, with noisy grunts, as they burrowed about the crumbling altar.

The old man inquired whether I wished to buy the absolute uselessness of the place fascinated me. I asked the price. He looked me up and down, and seeing I was foreign, suggested a ridiculous sum. And while I amused myself with bargaining, I wondered what on earth one could do with a ruined church in Ronda. Half a dozen fantastic notions passed through my mind, but they were really too melodramatic.

And now when the sun had set I returned. Notwithstanding his suspicions, I induced the keeper to give me his key; he could not understand what I desired at such an hour in that solitary place, and asked if I wished to sleep there! But I calmed his fears with a peseta—money goes a long way in Spain—and went in alone. The pigs had been removed and all was silent. A few bats flitted to and fro quickly. The light fell away greyly, the cold descended on the ruin, and it became very strange and mysterious. Presently, the roofless chapels seemed to grow alive with weird invisible things, the rank weeds exhaled chill odours; and in the lonely silence a mass began. At the ruined altar ghostly priests officiated, passing quietly from side to side, with bows and genuflections. The bell tinkled as they raised an invisible host. Soon it became quite dark, and the moon shone through the great empty windows of the façade.

In what you divine rather than in what you see lies half the charm of Andalusia, in the suggestion of all manner of delicate antique things, in the vivid memory of past grandeur. The Moors have gone, but still they inhabit the land in spirit and not seldom in a spectral way seem to regain their old dominion. Often towards evening, as I rode through the desolate country, I thought I saw an half-naked Moor ploughing his field, urging the lazy oxen with a long goad. Often the Spaniard on his horse vanished, and I saw a Muslim knight riding in pride and glory, his velvet cloak bespattered with the gold initial of his lady, and her favour fluttering from his lance. Once near Granada, standing on a hill, I watched the blood-red sun set tempestuously over the plain; and presently in the distance the gnarled olive-trees seemed living beings, and I saw contending hosts, two ghostly armies silently battling with one another; I saw the flash of scimitars, and the gleam of standards, the whiteness of the turbans. They fought with horrible carnage, and the land was crimson with their blood. Then the sun fell below the horizon, and all again was still and lifeless.

And what can be more fascinating than that magic city of Az-Zahra, the wonder of its age, of which now not a stone remains? It was made to satisfy the whim of a concubine by a Sultan whose flamboyant passion moved him to displace mountains for the sake of his beloved; and the memory thereof is lost so completely that even its situation till lately was uncertain. Az-Zahra the Fairest said to Abd-er-Rahmān, her lord: 'Raise me a city that shall take my name and be mine.' The Khalif built at the foot of the mountain which is called the Hill of the Bride; but when at last the lady, from the great hall of the palace, gazed at the snow-white city contrasting with the dark mountain, she remarked: 'See, O Master! how beautiful this girl looks in the arms of yonder Ethiopian.' The jealous Khalif immediately commanded the removal of the offending hill; and when he was convinced the task was impossible, ordered that the oaks and other mountain trees which grew upon it should be uprooted, and fig-trees and almonds planted in their stead.

Imagine the Hall of the Khalif, with walls of transparent and many-coloured marble, with roof of gold; on each side were eight doors fixed upon arches of ivory and ebony, ornamented with precious metals and with precious stones; and when the sun penetrated them, the reflection of its rays upon the roof and walls was sufficient to deprive the beholders of sight! In the centre was a great basin filled with quicksilver, and the Sultan, wishing to terrify a courtier, would cause the metal to be set in motion, whereupon the apartment would seem traversed by flashes of lightning, and all the company would fall a-trembling.

The old author tells of running streams and of limpid water, of stately buildings for the household guards, and magnificent palaces for the reception of high functionaries of state; of the thronging soldiers, pages, eunuchs, slaves, of all nations and of all religions, in sumptuous habiliments of silk and of brocade; of judges, theologians, and poets, walking with becoming gravity in the ample courts.... Alas! that poets now should rush through Fleet Street with unseemly haste, attired uncouthly in bowler hats and in preposterous tweeds!

From the celebrated legend of Roderick the Goth to that last scene when Boabdil handed the keys of Granada to King Ferdinand, the history of the Moorish occupation reads far more like romance than like sober fact. It is rich with every kind of passionate incident; it has all the strange vicissitudes of oriental history. What career could be more wonderful than that of Almanzor, who began life as a professional letter-writer, (a calling which you may still see exercised in the public places of Madrid or Seville,) and ended it as absolute ruler of an Empire! His charm of manner, his skill in flattery, the military genius which he developed when occasion called, his generosity and sense of justice, his love of literature and art, make him a figure to be contemplated with admiration; and when you add his utter lack of scruple, his selfishness, his ingratitude, his perfidy, you have a character complex enough to satisfy the most exacting.

Those who would read of these things may find an admirable account in Mr. Lane-Poole's Moors in Spain; but I cannot renounce the pleasure of giving one characteristic detail. After the death of Abd-er-Rahmān, the builder of that magnificent city of Az-Zahra, a paper was found in his own handwriting, upon which he had noted those days in his long reign which had been free from all sorrow: they numbered fourteen. Sovereign lord of a country than which there is on earth none more delightful, his life had been of uninterrupted prosperity; success in peace and war attended him always; he possessed everything that it was possible for man to have. These are the observations of Al Makkary, the Arabic historian, when he narrates the incident:

O man of understanding! Wonder and observe the small portion of real happiness the world affords even in the most enviable position. Praise be given to Him, the Lord of eternal glory and everlasting empire! There is no God but He the Almighty, the Giver of Empire to whomsoever He pleases.

But Cordova, from which Az-Zahra was about four miles distant, has visible delights that can vie with its neighbour's vanished pomp. I know nothing that can give a more poignant emotion than the interior of the mosque at Cordova; and yet I remember well the splendour of barbaric and oriental magnificence which was my first sight of St. Mark's at Venice, as I came abruptly from the darkness of an alley into the golden light of the Piazza. But to me at least the famous things of Italy, known from childhood in picture and in description, afford more than anything a joyful sense of recognition, a feeling as it were of home-coming, such as may hope to experience the devout Christian on entering upon his heritage in the Kingdom of Heaven. The mosque of Cordova is oriental and barbaric too; but I had never seen nor imagined anything in the least resembling it; there was no disillusionment possible, as too often in Italy, for the accounts I had read prepared me not at all for that overwhelming impression. It was so weird and strange, I felt myself transported suddenly to another world.

They were singing Vespers when I entered, and I heard the shrill voices of choristers crying the responses; it did not sound like Christian music. The mosque was dimly lit, the air heavy with incense; and I saw this forest of pillars, extending every way, as far as the eye could reach. It was mysterious and awe-inspiring as those enchanted forests of one's childhood in which huge trees grew in serried masses and where in cavernous darkness goblins and giants of the fairy-tales, wild beasts and monstrous shapes, lay in wait for the terrified traveller who had lost his way. I wandered, keeping the Christian chapels out of sight, trying to lose myself among the columns; and now and then gained views of horseshoe arches interlacing, decorated with Moorish tracery.

At length I came to the Mihrab, which is the Holy of Holies, the most exquisite as well as the most sacred part of the mosque. It is approached by a vestibule of which the roof is a miracle of grace, with mosaics that glow like precious stones, ultramarine, scarlet, emerald, and gold. The arch between the chambers is ornamented with four pillars of coloured marble, and again with mosaic, the gold letters of an Arabic inscription forming on the deep sapphire of the background a decorative pattern. The Mihrab itself, which contained the famous Koran of Othman, has seven sides of white marble, and the roof is a huge shell cut from a single block.

I tried to picture to myself the mosque before the Christians laid their desecrating hands upon it. The floor was of coloured tiles, tiles such as may still be seen in the Alhambra of Granada and in the Alcazar at Seville. The columns are of marble, of porphyry and jasper; tradition says they came from Carthage, from pagan temples in France and Christian churches in Spain; they are slender and unadorned, they must have contrasted astonishingly with the roof of larch wood, all ablaze with gold and with vermilion.

There were three hundred chandeliers; and eight thousand lamps—cast of Christian bells—hung from the roof. The Arab writer tells of gold shining from the ceiling like fire, blazing like lightning when it darts across the clouds. The pulpit, wherein was kept the Koran, was of ivory and of exquisite woods, of ebony and sandal, of plantain, citron and aloe, fastened together with gold and silver nails and encrusted with priceless gems. It needed six Khalifs and Almanzor, the great Vizier, to complete the mosque of which Arab writers, with somewhat prosaic enthusiasm, said that 'in all the lands of Islam there was none of equal size, none more admirable in its workmanship, in its construction and durability.'

Then the Christians conquered Cordova, and the charming civilisation of the Moors was driven out by monks and priests and soldiers. First they built only chapels in the outermost aisles; but in a little while, to make room for a choir, they destroyed six rows of columns; and at last, when Master Martin Luther had rekindled Catholic piety, they set up a great church in the very middle of the mosque. The story of this vandalism is somewhat quaint, and one detail at least affords a suggestion that might prove useful in the present time; for the Town Council of Cordova menaced with death all who should assist in the work: one imagines that a similar threat from the Lord Mayor of London might have a salutary effect upon the restorers of Westminster Abbey or the decorators of St. Paul's. How very much more entertaining must have been the world when absolutism was the fashion and the preposterous method of universal suffrage had never been considered! But the Chapter, as those in power always are, was bent upon restoring, and induced Charles V. to give the necessary authority. The king, however, had not understood what they wished to do, and when later he visited Cordova and saw what had happened, he turned to the dignitaries who were pointing out the improvements and said: 'You have built what you or others might have built anywhere, but you have destroyed something that was unique in the world.' The words show a fine scorn; but as a warning to later generations it would have been more to the purpose to cut off a dozen priestly heads.

Yet oddly enough the Christian additions are not so utterly discordant as one would expect! Hernan Ruiz did the work well, even though it was work he might conveniently have been drawn and quartered for doing. Typically Spanish in its fine proportion, in its exuberance of fantastic decoration, his church is a masterpiece of plateresque architecture. Nor are the priests entirely out of harmony with the building wherein they worship. For an hour they had sung Vespers, and the deep voices of the canons, chaunting monotonously, rang weird and long among the columns; but they finished, and left the choir one by one, walking silently across the church to the sacristy. The black cassock and the scarlet hood made a fine contrast, while the short cambric surplice added to the costume a most delicate grace. One of them paused to speak with two ladies in mantillas, and the three made a picturesque group, suggesting all manner of old Spanish romance.

I went into the cathedral from the side and issuing by another door, found myself in the Court of Oranges. The setting sun touched it with warm light and overhead the sky was wonderfully blue. In Moorish times the mosque was separated from the court by no dividing-wall, so that the arrangement of pillars within was continued by the even lines of orange-trees; these are of great age and size, laden with fruit, and in their copious foliage stand with a trim self-assurance that is quite imposing.

In the centre, round a fountain into which poured water from jets at the four corners, stood a number of persons with jars of earthenware and bright copper cans. One girl held herself with the fine erectness of a Caryatid, while her jar, propped against the side, filled itself with the cold, sparkling water. A youth, some vessel in his hand, leaned over in an attitude of easy grace; and looking into her eyes, appeared to pay compliments, which she heard with superb indifference. A little boy ran up, and the girl held aside her jar while he put his mouth to the spout and drank. Then, as it overflowed, she lifted it with comely motion to her head and slowly walked away.

By now the canons had unrobed, and several strolled about the court in the sun, smoking cigarettes. The acolytes with the removal of their scarlet cassocks, were become somewhat ragged urchins playing pitch and toss with much gesture and vociferation. Two of them quarrelled fiercely because one player would not yield the halfpenny he had certainly lost, and the altercation must have ended in blows if a corpulent, elderly cleric had not indignantly reproved them, and boxed their ears. A row of tattered beggars, very well contented in the sunshine, were seated on a step, likewise smoking cigarettes, and obviously they did not consider their walk of life unduly hard.

And the thought impressed itself upon me while I lingered in that peaceful spot, that there was far more to be said for the simple pleasures of sense than northern folk would have us believe. The English have still much of that ancient puritanism which finds a vague sinfulness in the uncostly delights of sunshine, and colour, and ease of mind. It is well occasionally to leave the eager turmoil of great cities for such a place as this, where one may learn that there are other, more natural ways of living, that it is possible still to spend long days, undisturbed by restless passion, without regret or longing, content in the various show that nature offers, asking only that the sun should shine and the happy seasons run their course.

An English engineer whom I had seen at the hotel, approaching me, expressed the idea in his own graphic manner. 'Down here there are a good sight more beer and skittles in life than up in Sheffield!'

One canon especially interested me, a little thin man, bent and wrinkled, apparently of fabulous age, but still something of a dandy, for he wore his clothes with a certain air, as though half a century before, byronically, he had been quite a devil with the ladies. The silver buckle on his shoes was most elegant, and he protruded his foot as though the violet silk of his stocking gave him a discreet pleasure. To the very backbone he was an optimist, finding existence evidently so delightful that it did not even need rose-coloured spectacles. He was an amiable old man, perhaps a little narrow, but very indulgent to the follies of others. He had committed no sin himself—for many years: a suspicion of personal vanity is in itself proof of a pure and gentle mind; and as for the sins of others—they were probably not heinous, and at all events would gain forgiveness. The important thing, surely, was to be sound in dogma. The day wore on and the sun now shone only in a narrow space; and this the canon perambulated, smoking the end of a cigarette, the delectable frivolity of which contrasted pleasantly with his great age. He nodded affably to other priests as they passed, a pair of young men, and one obese old creature with white hair and an expression of comfortable self-esteem. He removed his hat with a great and courteous sweep when a lady of his acquaintance crossed his path. The priests basking in the warmth were like four great black cats. It was indeed a pleasant spot, and contentment oozed into one by every pore. The canon rolled himself another cigarette, smiling as he inhaled the first sweet whiffs; and one could not but think the sovereign herb must greatly ease the journey along the steep and narrow way which leads to Paradise. The smoke rose into the air lazily, and the old cleric paused now and again to look at it, the little smile of self-satisfaction breaking on his lips.

Up in the North, under the cold grey sky, God Almighty may be a hard taskmaster, and the Kingdom of Heaven is attained only by much endeavour; but in Cordova these things come more easily. The aged priest walks in the sun and smokes his cigarillo. Heaven is not such an inaccessible place after all. Evidently he feels that he has done his duty—with the help of Havana tobacco—in that state of life wherein it has pleased a merciful providence to place him; and St. Peter would never be so churlish as to close the golden gates in the face of an ancient canon who sauntered to them jauntily, with the fag end of a cigarette in the corner of his mouth. Let us cultivate our cabbages in the best of all possible worlds; and afterwards—Dieu pardonnera; c'est son métier.

Three months later in the Porvenir, under the heading, 'Suicide of a Priest,' I read that one of these very canons of the Cathedral at Cordova had shot himself. A report was heard, said the journal, and the Civil Guard arriving, found the man prostrate with blood pouring from his ear, a revolver by his side. He was transported to the hospital, the sacrament administered, and he died. In his pockets they found a letter, a pawn-ticket, a woman's bracelet, and some peppermint lozenges. He was thirty-five years old. The newspaper moralised as follows: 'When even the illustrious order to which the defunct belonged is tainted with such a crime, it is well to ask whither tends the incredulity of society which finds an end to its sufferings in the barrel of a revolver. Let moralists and philosophers combat with all their might this dreadful tendency; let them make even the despairing comprehend that death is not the highest good but the passage to an unknown world where, according to Christian belief, the ill deeds of this existence are punished and the virtuous rewarded.'

Ronda, owing its peculiarities to the surrounding mountains, was not really very characteristic of the country, and might equally well have been an highland townlet in any part of Southern Europe. But Cordova offers immediately the full sensation of Andalusia. It is absolutely a Moorish city, white and taciturn, so that you are astonished to meet people in European dress rather than Arabs, in shuffling yellow slippers. The streets are curiously silent; for the carriage, as in Tangiers, is done by mules and donkeys, which walk so quietly that you never hear them. Sometimes you are warned by a deep-voiced 'Cuidado,' but more often a pannier brushing you against the wall brings the first knowledge of their presence. On looking up you are again surprised to see not a great shining negro in a burnouse, but a Spaniard in tight trousers, with a broad-brimmed hat.

And Cordova has that sweet, exhilarating perfume of Andalusia than which nothing gives more vividly the complete feeling of the country. Those travellers must be obtuse of nostril who do not recognise different smells, grateful or offensive, in different places; no other peculiarity is more distinctive, so that an odour crossing by chance one's sense is able to recall suddenly all the complicated impressions of a strange land. When I return from England it is always that subtle fragrance which first strikes me, a mingling in warm sunlight of orange-blossom, incense, and cigarette smoke; and two whiffs of a certain brand of tobacco are sufficient to bring back to me Seville, the most enchanting of all my memories. I suppose that nowhere else are cigarettes consumed so incessantly; for in Andalusia it is not only certain classes who use them, but every one, without distinction of age or station—from the ragamuffin selling lottery-tickets in the street to the portly, solemn priest, to the burly countryman, the shop-keeper, the soldier. After all, no better means of killing time have ever been devised, and consequently to smoke them affords an occupation which most thoroughly suits the Spaniard.

I looked at Cordova from the bell-tower of the cathedral. The roofs, very lovely in their diversity of colour, were of rounded tiles, fading with every variety of delicate shade from russet and brown to yellow and the tenderest green. From the courtyards, here and there, rose a tall palm, or an orange-tree, like a dash of jade against the brilliant sun. The houses, plainly whitewashed, have from the outside so mean a look that it is surprising to find them handsome and spacious within. They are built, Moorish fashion, round a patio, which in Cordova at least is always gay with flowers. When you pass the iron gates and note the contrast between the snowy gleaming of the street and that southern greenery, the suggestion is inevitable of charming people who must rest there in the burning heat of summer. With those surroundings and in such a country passion grows surely like a poisonous plant. At night, in the starry darkness, how irresistible must be the flashing eyes of love, how eloquent the pleading of whispered sighs! But woe to the maid who admits the ardent lover among the orange-trees, her head reeling with the sweet intoxication of the blossom; for the Spanish gallant is fickle, quick to forget the vows he spoke so earnestly: he soon grows tired of kissing, and mounting his horse, rides fast away.

The uniformity of lime-washed houses makes Cordova the most difficult place in the world wherein to find your way. The streets are exactly alike, so narrow that a carriage could hardly pass, paved with rough cobbles, and tortuous: their intricacy is amazing, labyrinthine; they wind in and out of one another, leading nowhither; they meander on for half a mile and stop suddenly, or turn back, so that you are forced to go in the direction you came. You may wander for hours, trying to find some point that from the steeple appeared quite close. Sometimes you think they are interminable.

The bridge that the Moors built over the Guadalquivir straggles across the water with easy arches. Somewhat dilapidated and very beautiful, it has not the strenuous look of such things in England, and the mere sight of it fills you with comfort. The clustered houses, with an added softness from the light burning mellow on their roofs and on their white walls, increase the happy impression that the world is not necessarily hurried and toilful. And the town, separated from the river by no formal embankment, lounges at the water's edge like a giant, prone on the grass and lazy, stretching his limbs after the mid-day sleep.

There is no precipitation in such a place as Cordova; life is quite long enough for all that it is really needful to do; to him who waits come all things, and a little waiting more or less can be of no great consequence. Let everything be taken very leisurely, for there is ample time. Yet in other parts of Andalusia they say the Cordovese are the greatest liars and the biggest thieves in Spain, which points to considerable industry. The traveller, hearing this, will doubtless ask what business has the pot to call the kettle black; and it is true that the standard of veracity throughout the country is by no means high. But this can scarcely be termed a vice, for the Andalusians see in it nothing discreditable, and it can be proved as exactly as a proposition of Euclid that vice and virtue are solely matters of opinion. In Southern Spain bosom friends lie to one another with complete freedom; no man would take his wife's word, but would believe only what he thought true, and think no worse of her when he caught her fibbing. Mendacity is a thing so perfectly understood that no one is abashed by detection. In England most men equivocate and nearly all women, but they are ashamed to be discovered; they blush and stammer and hesitate, or fly into a passion; the wiser Spaniard laughs, shrugging his shoulders, and utters a dozen rapid falsehoods to make up for the first. It is always said that a good liar needs an excellent memory, but he wants more qualities than that—unblushing countenance, the readiest wit, a manner to beget confidence. In fact it is so difficult to lie systematically and well that the ardour of the Andalusians in that pursuit can be ascribed only to an innate characteristic. Their imaginations, indeed, are so exuberant that the bald fact is to them grotesque and painful. They are like writers in love with words for their own sake, who cannot make the plainest statement without a gay parade of epithet and metaphor. They embroider and decorate, they colour and enhance the trivial details of circumstance. They must see themselves perpetually in an attitude; they must never fail to be effective. They lie for art's sake, without reason or rhyme, from mere devilry, often when it can only harm them. Mendacity then becomes an intellectual exercise, such as the poet's sonneteering to an imaginary lady-love.

But the Cordovan very naturally holds himself in no such unflattering estimation. The motto of his town avers that he is a warlike person and a wise one:

Cordoba, casa de guerrera gente

Y de sabiduria clara fuente!

And the history thereof, with its University and its Khalifs, bears him out. Art and science flourished there when the rest of Europe was enveloped in mediæval darkness: when our Saxon ancestors lived in dirty hovels, barbaric brutes who knew only how to kill, to eat, and to propagate their species, the Moors of Cordova cultivated all the elegancies of life from verse-making to cleanliness.

I was standing on the bridge. The river flowed tortuously through the fertile plain, broad and shallow, and in it the blue sky and the white houses of the city were brightly mirrored. In the distance, like a vapour of amethyst, rose the mountains; while at my feet, in mid-stream, there were two mills which might have been untouched since Moorish days. There had been no rain for months, the water stood very low, and here and there were little islands of dry yellow sand, on which grew reeds and sedge. In such a spot might easily have wandered the half-naked fisherman of the oriental tale, bewailing in melodious verse the hardness of his lot; since to his net came no fish, seeking a broken pot or a piece of iron wherewith to buy himself a dinner. There might he find a ring half-buried in the sand, which, when he rubbed to see if it were silver, a smoke would surely rise from the water, increasing till the light of day was obscured; and half dead with fear, he would perceive at last a gigantic body towering above him, and a voice more terrible than the thunder of Allah, crying: 'What wishest thou from thy slave, O king? Know that I am of the Jin, and Suleyman, whose name be exalted, enslaved me to the ring that thou hast found.'

In Cordova recollections of the Arabian Nights haunt you till the commonest sights assume a fantastic character, and the frankly impossible becomes mere matter of fact. You wonder whether your life is real or whether you have somehow reverted to the days when Scheherazade, with her singular air of veracity, recited such enthralling stories to her lord as to save her own life and that of many other maidens. I looked along the river and saw three slender trees bending over it, reflecting in the placid water their leafless branches, and under them knelt three women washing clothes. Were they three beautiful princesses whose fathers had been killed, and they expelled from their kingdom and thus reduced to menial occupations? Who knows? Indeed, I thought it very probable, for so many royal persons have come down in the world of late; but I did not approach them, since king's daughters under these circumstances have often lost one eye, and their morals are nearly always of the worst description.

I went back to the old gate which led to the bridge. Close by, in the little place, was the hut of the consumo, the local custom-house, with officials lounging at the door or sitting straddle-legged on chairs, lazily smoking. Opposite was a tobacconist's, with the gaudy red and yellow sign, Campañia arrendataria de tabacos, and a dram-shop where three hardy Spaniards from the mountains stood drinking aguardiente. Than this, by the way, there is in the world no more insidious liquor, for at first you think its taste of aniseed and peppermint very disagreeable; but perseverance, here as in other human affairs, has its reward, and presently you develop for it a liking which time increases to enthusiasm. In Spain, the land of custom and usage, everything is done in a certain way; and there is a proper manner to drink aguardiente. To sip it would show a lamentable want of decorum. A Spaniard lifts the little glass to his lips, and with a comic, abrupt motion tosses the contents into his mouth, immediately afterwards drinking water, a tumbler of which is always given with the spirit. It is really the most epicurean of intoxicants because the charm lies in the after-taste. The water is so cool and refreshing after the fieriness; it gives, without the gasconnade, the emotion Keats experienced when he peppered his mouth with cayenne for the greater enjoyment of iced claret.

But the men wiped their mouths with their hands and came out of the wine shop, mounting their horses which stood outside—shaggy, long-haired beasts with high saddles and great box-stirrups. They rode slowly through the gate one after the other, in the easy slouching way of men who have been used to the saddle all their lives and in the course of the week are accustomed to go a good many miles in an easy jog-trot to and from the town. It seems to me that the Spaniards resolve themselves into types more distinctly than is usual in northern countries, while between individuals there is less difference. These three, clean-shaven and uniformly dressed, of middle size, stout, with heavy strong features and small eyes, certainly resembled one another very strikingly. They were the typical inn-keepers of Goya's pictures but obviously could not all keep inns; doubtless they were farmers, horse-dealers, or forage-merchants, shrewd men of business, with keen eyes for the main chance. That class is the most trustworthy in Spain, kind, hospitable, and honest; they are old-fashioned people with many antique customs, and preserve much of the courteous dignity which made their fathers famous.

A string of grey donkeys came along the bridge, their panniers earth-laden, poor miserable things that plodded slowly and painfully, with heads bent down, placing one foot before the other with the donkey's peculiar motion, patiently doing a thing they had patiently done ever since they could bear a load. They seemed to have a dull feeling that it was no use to make a fuss, or to complain; it would just go on till they dropped down dead and their carcases were sold for leather and glue. There was a Spanish note in the red trappings, braided and betasselled, but all worn, discoloured and stained.

Inside the gate they stopped, waiting in a huddled group, with the same heavy patience, for the examination of the consumo. An officer of the custom-house went round with a long steel prong, which he ran into the baskets one by one, to see that there was nothing dutiable hidden in the earth. Then, sparing of his words, he made a sign to the driver and sat down again straddle-wise on his chair. 'Arre, burra!' The first donkey walked slowly on, and as they heard the tinkling of the leader's bell the rest stepped forward in the long line, their heads hanging down, with that hopeless movement of the feet.

In the night, wandering at random through the streets, their silent whiteness filled me again with that intoxicating sensation of the Arabian Nights. I looked through the iron gateways as I passed, into the patios with their dark foliage, and once I heard the melancholy twang of a guitar. I was sure that in one of those houses the three princesses had thrown off their disguise and sat radiant in queenly beauty, their raven tresses falling in a hundred plaits over their shoulders, their fingers stained with henna and their long eyelashes darkened with kohl. But alas! though I lost my way I found them not.

Yet many an amorous Spaniard, too passionate to be admitted within his mistress' house, stood at her window. This method of philandering, surely most conducive to the ideal, is variously known as comer hierro, to eat iron, and pelar la pava, to pluck the turkey. One imagines that the cold air of a winter's night must render the most ardent lover platonic. It is a significant fact that in Spanish novels if the hero is left for two minutes alone with the heroine there are invariably asterisks and some hundred pages later a baby. So it is doubtless wise to separate true love by iron bars, and perchance beauty's eyes flash more darkly to the gallant standing without the gate; illusions, the magic flower of passion, arise more willingly. But in Spain the blood of youth is very hot, love laughs at most restraints and notwithstanding these precautions, often enough there is a catastrophe. The Spaniard, who will seduce any girl he can, is pitiless under like circumstances to his own womenkind; so there is much weeping, the girl is turned out of doors and falls readily into the hands of the procuress. In the brothels of Seville or of Madrid she finds at least a roof and bread to eat; and the fickle swain goes his way rejoicing.

I found myself at last near the Puerta del Puente, and I stood again on the Moorish bridge. The town was still and mysterious in the night, and the moon shone down on the water with a hard and brilliant coldness. The three trees with their bare branches looked yet more slender, naked and alone, like pre-Raphaelite trees in a landscape of Pélléas et Mélisande; the broad river, almost stagnant, was extraordinarily calm and silent. I wondered what strange things the placid Guadalquivir had seen through the centuries; on its bosom many a body had been borne towards the sea. It recalled those mysterious waters of the Eastern tales which brought to the marble steps of palaces great chests in which lay a fair youth's headless corpse or a sleeping beautiful maid.

The impression left by strange towns and cities is often a matter of circumstance, depending upon events in the immediate past; or on the chance which, during his earliest visit, there befell the traveller. After a stormy passage across the Channel, Newhaven, from the mere fact of its situation on solid earth, may gain a fascination which closer acquaintance can never entirely destroy; and even Birmingham, first seen by a lurid sunset, may so affect the imagination as to appear for ever like some infernal, splendid city, restless with the hurried toil of gnomes and goblins. So to myself Seville means ten times more than it can mean to others. I came to it after weary years in London, heartsick with much hoping, my mind dull with drudgery; and it seemed a land of freedom. There I became at last conscious of my youth, and it seemed a belvedere upon a new life. How can I forget the delight of wandering in the Sierpes, released at length from all imprisoning ties, watching the various movement as though it were a stage-play, yet half afraid that the falling curtain would bring back reality! The songs, the dances, the happy idleness of orange-gardens, the gay turbulence of Seville by night; ah! there at least I seized life eagerly, with both hands, forgetting everything but that time was short and existence full of joy. I sat in the warm sunshine, inhaling the pleasant odours, reminding myself that I had no duty to do then, or the morrow, or the day after. I lay a-bed thinking how happy, effortless and free would be my day. Mounting my horse, I clattered through the narrow streets, over the cobbles, till I came to the country; the air was fresh and sweet, and Aguador loved the spring mornings. When he put his feet to the springy turf he gave a little shake of pleasure, and without a sign from me broke into a gallop. To the amazement of shepherds guarding their wild flocks, to the confusion of herds of brown pigs, scampering hastily as we approached, he and I excited by the wind singing in our ears, we pelted madly through the country. And the whole land laughed with the joy of living.

But I love also the recollection of Seville in the grey days of December, when the falling rain offered a grateful contrast to the unvarying sunshine. Then new sights delighted the eye, new perfumes the nostril. In the decay of that long southern autumn a more sombre opulence was added to the gay colours; a different spirit filled the air, so that I realised suddenly that old romantic Spain of Ferdinand and Isabella. It lay a-dying still, gorgeous in corruption, sober yet flamboyant, rich and poverty-stricken, squalid, magnificent. The white streets, the dripping trees, the clouds gravid with rain, gave to all things an adorable melancholy, a sad, poetic charm. Looking back, I cannot dismiss the suspicion that my passionate emotions were somewhat ridiculous, but at twenty-three one can afford to lack a sense of humour.

But Seville at first is full of disillusion. It has offered abundant material to the idealist who, as might be expected, has drawn of it a picture which is at once common and pretentious. Your idealist can see no beauty in sober fact, but must array it in all the theatrical properties of a vulgar imagination; he must give to things more imposing proportions, he colours gaudily; Nature for him is ever posturing in the full glare of footlights. Really he stands on no higher level than the housemaid who sees in every woman a duchess in black velvet, an Aubrey Plantagenet in plain John Smith. So I, in common with many another traveller, expected to find in the Guadalquivir a river of transparent green, with orange-groves along its banks, where wandered ox-eyed youths and maidens beautiful. Palm-trees, I thought, rose towards heaven, like passionate souls longing for release from earthly bondage; Spanish women, full-breasted and sinuous, danced boleros, fandangos, while the air rang with the joyous sound of castanets, and toreadors in picturesque habiliments twanged the light guitar.

Alas! the Guadalquivir is like yellow mud, and moored to the busy quays lie cargo-boats lading fruit or grain or mineral; there no perfume scents the heavy air. The nights, indeed, are calm and clear, and the stars shine brightly; but the river banks see no amours more romantic than those of stokers from Liverpool or Glasgow, and their lady-loves have neither youth nor beauty.

Yet Seville has many a real charm to counter-balance these lost illusions. He that really knows it, like an ardent lover with his mistress' imperfections, would have no difference; even the Guadalquivir, so matter-of-fact, really so prosaic, has an unimagined attractiveness; the crowded shipping, the hurrying porters, add to that sensation of vivacity which is of Seville the most fascinating characteristic. And Seville is an epitome of Andalusia, with its life and death, with its colour and vivid contrasts, with its boyish gaiety.

It is a city of delightful ease, of freedom and sunshine, of torrid heat. There it does not matter what you do, nor when, nor how you do it. There is none to hinder you, none to watch. Each takes his ease, and is content that his neighbour should do the like. Doubtless people are lazy in Seville, but good heavens! why should one be so terribly strenuous? Go into the Plaza Nueva, and you will see it filled with men of all ages, of all classes, 'taking the sun'; they promenade slowly, untroubled by any mental activity, or sit on benches between the palm-trees, smoking cigarettes; perhaps the more energetic read the bull-fighting news in the paper. They are not ambitious, and they do not greatly care to make their fortunes; so long as they have enough to eat and drink—food is very cheap—and cigarettes to smoke, they are quite happy. The Corporation provides seats, and the sun shines down for nothing—so let them sit in it and warm themselves. I daresay it is as good a way of getting through life as most others.

A southern city never reveals its true charm till the summer, and few English know what Seville is under the burning sun of July. It was built for the great heat, and it is only then that the refreshing coolness of the patio can be appreciated. In the streets the white glare is mitigated by awnings that stretch from house to house, and the half light in the Sierpes, the High Street, has a curious effect; the people in their summer garb walk noiselessly, as though the warmth made sound impossible. Towards evening the sail-cloths are withdrawn, and a breath of cold air sinks down; the population bestirs itself, and along the Sierpes the cafés become suddenly crowded and noisy.

Then, for it was too hot to ride earlier, I would mount my horse and cross the river. The Guadalquivir had lost its winter russet, and under the blue sky gained varied tints of liquid gold, of emerald and of sapphire. I lingered in Triana, the gipsy-quarter, watching the people. Beautiful girls stood at the windows, so that the whole way was lined with them, and their lips were not unwilling to break into charming smiles. One especially I remember who was used to sit on a balcony at a street-corner; her hair was irreproachable in its elaborate arrangement, and the red carnation in it gleamed like fire against the night. Her face was long, fairer-complexioned than is common, with regular and delicate features. She sat at her balcony, with a huge book open on her knee, which she read with studied disregard of the passers-by; but when I looked back sometimes I saw that she had lifted her eyes, lustrous and dark, and they met mine gravely.

And in the country I passed through long fields of golden corn, which reached as far as I could see; I remembered the spring, when it had all been new, soft, fresh, green. And presently I turned round to look at Seville in the distance, bathed in brilliant light, glowing as though its walls were built of yellow flame. The Giralda arose in its wonderful grace like an arrow; so slim, so comely, it reminded one of an Arab youth, with long, thin limbs. With the setting sun, gradually the city turned rosy-red and seemed to lose all substantiality, till it became a many-shaped mist that was dissolved in the tenderness of the sky.

Late in the night I stood at my window looking at the cloudless heaven. From the earth ascended, like incense, the mellow odours of summer-time; the belfry of the neighbouring church stood boldly outlined against the darkness, and the storks that had built their nest upon it were motionless, not stirring even as the bells rang out the hours. The city slept, and it seemed that I alone watched in the silence; the sky still was blue, and the stars shone in their countless millions. I thought of the city that never rested, of London with its unceasing roar, the endless streets, the greyness. And all around me was a quiet serenity, a tranquillity such as the Christian may hope shall reward him in Paradise for the troublous pilgrimage of life. But that is long ago and passed for ever.

Arriving at Seville the recollection of Cordova took me quickly to the Alcazar; but I was a little disappointed. It has been ill and tawdrily restored, with crude pigments, with gold that is too bright and too clean; but even before that, Charles V. and his successors had made additions out of harmony with Moorish feeling. Of the palace where lived the Mussulman Kings nothing, indeed, remains; but Pedro the Cruel, with whom the edifice now standing is more especially connected, was no less oriental than his predecessors, and he employed Morisco architects to rebuild it. Parts are said to be exact reproductions of the older structure, while many of the beautiful tiles were taken from Moorish houses.

The atmosphere, then, is but half Arabic; the rest belongs to that flaunting, multi-coloured barbarism which is characteristic of Northern Spain before the union of Arragon and Castile. Wandering in the deserted courts, looking through horseshoe windows of exquisite design at the wild garden, Pedro the Cruel and Maria de Padilla are the figures that occupy the mind.

Seville teems with anecdotes of the monarch who, according to the point of view, has been called the Cruel and the Just. He was an amorist for whom platonic dalliance had no charm, and there are gruesome tales of ladies burned alive because they would not quench the flame of his desires, of others, fiercely virtuous, who poured boiling oil on face and bosom to make themselves unattractive in his sight. But the head that wears a crown apparently has fascinations which few women can resist, and legend tells more frequently of Pedro's conquests than of his rebuffs. He was an ardent lover to whom marriage vows were of no importance; that he committed bigamy is certain—and pardonable, but some historians are inclined to think that he had at one and the same time no less than three wives. He was oriental in his tastes.

In imitation of the Paynim sovereigns Pedro loved to wander in the streets of Seville at night, alone and disguised, to seek adventure or to see for himself the humour of his subjects; and like them also it pleased him to administer justice seated in the porch of his palace. If he was often hard and proud towards the nobles, with the people he was always very gracious; to them he was the redressor of wrongs and a protector of the oppressed; his justice was that of the Mussulman rulers, rapid, terrible and passionate, often quaint. For instance: a rich priest had done some injury to a cobbler, who brought him before the ecclesiastical tribunals, where he was for a year suspended from his clerical functions. The tradesman thought the punishment inadequate, and taking the law into his own hands gave the priest a drubbing. He was promptly seized, tried, condemned to death. But he appealed to the king who, with a witty parody of the rival Court, changed the punishment to suspension from his trade, and ordered the cobbler for twelve months to make no boots.

On the other hand, the Alcazar itself has been the scene of Pedro's vilest crimes, in the whole list of which is none more insolent, none more treacherous, than that whereby he secured the priceless ruby which graces still the royal crown of England. There is a school of historians which insists on finding a Baptist Minister in every hero—think what a poor-blooded creature they wish to make of the glorious Nelson—but no casuistry avails to cleanse the memory of Pedro of Castille: even for his own ruthless age he was a monster of cruelty and lust. Indeed the indignation with which his biographers have felt bound to charge their pens has somewhat obscured their judgment; they have so eagerly insisted on the censure with which themselves regard their hero's villainies, that they have found little opportunity to explain a complex character. Yet the story of his early life affords a simple key to his maturity. Till the age of fifteen he lived in prisons, suffering with his mother every insult and humiliation, while his father's mistress kept queenly state, and her children received the honours of royal princes. When he came to the throne he found himself a catspaw between his natural brothers and ambitious nobles. His nearest relatives were ever his bitterest enemies, and he was continually betrayed by those he trusted; even his mother delivered to the rebellious peers the strongholds and the treasures he had left in her charge and caused him to be taken prisoner. As a boy he had been violent and impetuous, yet always loyal: but before he was twenty he became suspicious and mistrustful; in his weakness he made craft and perfidy his weapons, practising to compose his face, to feign forgetfulness of injury till the moment of vengeance; he learned to dissemble so that none could tell his mind, and treated no courtiers with greater favour than those upon whose death he had already determined.

Intermingled with this career of vice and perfidy and bloodshed is the love of Maria de Padilla, whom the king met when he was eighteen, and till her death loved passionately—with brief inconstancies, for fidelity has never been a royal virtue; and she figures with gentle pathos in that grim history like wild perfumed flowers on a storm-beaten coast. After the assassination of the unfortunate Blanche, the French Queen whom he loathed with an extraordinary physical repulsion, Pedro acknowledged a secret marriage with Maria de Padilla, which legitimised her children; but for ten years before she had been treated with royal rights. The historian says that she was very beautiful, but her especial charm seems to have been that voluptuous grace which is characteristic of Andalusian women. She was simple and pious, with a nature of great sweetness, and she never abused her power; her influence, as runs the hackneyed phrase, was always for good, and untiringly she did her utmost to incline her despot lover to mercy. She alone sheds a ray of light on Pedro's memory, only her love can save him from the execration of posterity. When she died rich and poor alike mourned her, and the king was inconsolable. He honoured her with pompous obsequies, and throughout the kingdom ordered masses to be sung for the rest of her soul.

The guardians of the Alcazar show you the chambers in which dwelt this gracious lady, and the garden-fountain wherein she bathed in summer. Moralists, anxious to prove that the way of righteousness is hard, say that beauty dies, but they err, for beauty is immortal. The habitations of a lovely woman never lose the enchantment she has cast over them, her comeliness lingers in their empty chambers like a subtle odour; and centuries after her very bones have crumbled to dust it is her presence alone that is felt, her footfall that is heard on the marble floors.

Garish colours, alas! have driven the tender spirit of Maria de Padilla from the royal palace, but it has betaken itself to the old garden, and there wanders sadly. It is a charming place of rare plants and exotic odours; cypress and tall palm trees rise towards the blue sky with their irresistible melancholy, their far-away suggestion of burning deserts; and at their feet the ground is carpeted with violets. Yet to me the wild roses brought strangely recollections of England, of long summer days when the air was sweet and balmy; the birds sang heavenly songs, the same songs as they sing in June in the fat Kentish fields. The gorgeous palace had only suggested the long past days of history, and Seville the joy of life and the love of sunshine; but the old quiet garden took me far away from Spain, so that I longed to be again in England. In thought I wandered through a garden that I knew in years gone by, filled also with flowers, but with hollyhocks and jasmine; the breeze carried the sweet scent of the honeysuckle to my nostrils, and I looked at the green lawns, with the broad, straight lines of the grass-mower. The low of cattle reached my ears, and wandering to the fence I looked into the fields beyond; yellow cows grazed idly or lay still chewing the cud; they stared at me with listless, sleepy eyes.

But I glanced up and saw a flock of wild geese flying northwards in long lines that met, making two sides of a huge triangle; they flew quickly in the cloudless sky, far above me, and presently were lost to view. About me was the tall box-wood of the southern garden, and tropical plants with rich flowers of yellow and red and purple. A dark fir-tree stood out, ragged and uneven, like a spirit of the North, erect as a life without reproach; but the foliage of the palms hung down with a sad, adorable grace.

In Seville the Andalusian character thrives in its finest flower; and nowhere can it be more conveniently studied than in the narrow, sinuous, crowded thoroughfare which is the oddest street in Europe. The Calle de las Sierpes is merely a pavement, hardly broader than that of Piccadilly, without a carriage-way. The houses on either side are very irregular; some are tall, four-storeyed, others quite tiny; some are well kept and freshly painted, others dilapidated. It is one of the curiosities of Seville that there is no particularly fashionable quarter; and, as though some moralising ruler had wished to place before his people a continual reminder of the uncertainty of human greatness, by the side of a magnificent palace you will find a hovel.