Title: My Sword's My Fortune: A Story of Old France

Author: Herbert Hayens

Release date: November 25, 2008 [eBook #27325]

Most recently updated: January 4, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| Chapter | |

| I. | I Go to Paris |

| II. | La Boule d'Or |

| III. | I Enter the Astrologer's House |

| IV. | I Meet the Cardinal |

| V. | The Reception at the Luxembourg |

| VI. | Was I Mistaken? |

| VII. | The Cardinal takes an Evening Walk |

| VIII. | The Plot is Discovered |

| IX. | I Meet with an Exciting Adventure |

| X. | Pillot to the Rescue |

| XI. | A Scheme that Went Amiss |

| XII. | I have a Narrow Escape |

| XIII. | I again Encounter Maubranne |

| XIV. | I Fall into a Trap |

| XV. | Under Watch and Ward |

| XVI. | I become a Prisoner of the Bastille |

| XVII. | Free! |

| XVIII. | The Fight on the Staircase |

| XIX. | I Lose all Trace of Henri |

| XX. | News at Last |

| XXI. | The Death of Henri |

| XXII. | The Mob Rises |

| XXIII. | The Ladies Leave Paris |

| XXIV. | Captain Courcy Outwitted |

| XXV. | I Miss a Grand Opportunity |

| XXVI. | "Vive le Roi!" |

| XXVII. | The King Visits Raoul |

| XXVIII. | "Remember the Porte St. Antoine" |

| XXIX. | Mazarin Triumphant |

[Transcriber's note:

Gaps in the source book's page numbering indicate that four

illustrations were missing. Physical damage seems to indicate that the

frontispiece may also have been missing. Since there was no list of

illustrations in the book, it is not known what their captions were.

Short transcriber's notes indicate the locations of the missing

illustrations.]

"Let the boy go to Paris," exclaimed our guest, Roland Belloc. "I warrant he'll find a path that will lead him to fortune."

"He is young," said my father doubtfully.

"He will be killed," cried my mother, while I stood upright against the wall and looked at Roland gratefully.

It was in 1650, in the days of the Regency, and all France was in an uproar. Our most gracious monarch, Louis XIV., was then a boy of twelve, and his Queen-Mother, Anne of Austria, ruled the country. She had a host of enemies, and only one friend, Cardinal Mazarin, a wily Italian priest, who was perhaps the actual master of France.

Roland Belloc, who was the Cardinal's man, had been staying for a day or two in my father's company. He was a real soldier of fortune, strong as a bull, a fine swordsman, and afraid of no man living. He told us many startling tales of Paris.

According to him, everything in the city, from the throne to the gutter, was in a state of unrest: no man knew what an hour would bring forth. One day people feasted and sang and danced in feverish merriment: the next the barricades were up, and the denizens of the filthy courts and alleys, eager for pillage, swarmed into the light.

"Mazarin is like a wild boar," said he, "with a pack of hounds baying round him. There is the Duke of Orleans, the king's uncle, who snaps and runs away; Condé is waiting to get a good bite; while the priest, De Retz, is the most mischievous of all."

"It is almost as bad as war," said my father.

"It is war, and nothing else. But," with a laugh, "the green scarf of Mazarin will be uppermost at the finish. What do you say, Albert? Are you willing to don the Cardinal's colours?"

"I know little of these things, monsieur, but my sympathies are for the Queen-Mother."

"Of course they are!" cried he, giving me a resounding slap on the back; "so are mine, but Anne of Austria would never hold her own without the Cardinal. Come, De Lalande, let the youngster go. You will not regret it, I promise. He may not get Vançey back, but there are other estates to be won by a strong arm. Shake yourself, boy, and come out into the daylight. You are moping here like a barn-owl."

"The simile is good, Roland, for he lives in a barn. If I thought——"

"If you thought! Why, man, there is no thinking in it; the thing is as plain as the Castle yonder from the bridge over the river. He is a strapping lad, and knows how to handle a sword I'll warrant. Eh, Albert? What will he do here? Take root and grow into a turnip as likely as not. Pah! I have no patience with you stay-at-home folks. Look at his cousin Henri!"

"Henri is two years older."

"Ay, he has the advantage there, but Albert's as well grown, and better. Henri is a young scamp, too, I admit, but he is making a name already. He is hand in glove with De Retz."

"Albert belongs to the elder branch of the family," said my mother stiffly, and the soldier was going to make answer but thought better of it.

"It is kind of you to show such interest in the lad," remarked my father presently, "and we will consider the matter."

"As you please, old friend. Follow your own judgment, but should he take it into his head to wear the green scarf, let him inquire at the Palais Royal for Roland Belloc."

That night, after our guest rode away, I lay awake a long time thinking over his words. The prospect held out by him seemed to be an answer to my dreams. For many years now the fortunes of the elder branch of the De Lalande family had sunk lower and lower. My grandfather had been stripped of vast estates because he would not change his opinions to suit the times, and my father had been, as most folks thought it, equally foolish.

Unhappily, he never by any chance espoused the winning side. His house was a "Camp of Refuge" for broken men of every party, who never sued for relief in vain. The poor and infirm, the blind, the halt, and the maimed, for twenty miles around, were his family, and he never wearied of giving, till, of all our original possessions, one poor farm and homestead alone remained.

The splendid mansion of Vançey, which my grandfather had owned, now belonged to Baron Maubranne, and was often filled with a glittering throng from Paris. Occasionally my cousin Henri made one of the party, and I could not help reflecting somewhat bitterly on the difference between us.

He was two years my senior, though I was as tall as he, and more than his equal in strength. But he was handsomely dressed and in the newest fashion, while I went about in a dingy suit that was not far from threadbare. I never envied Henri, mind you, or thought the worse of him, because his father had prospered in the world, but it was seeing him, that, in the first place, led me to build my castles in the air.

My one idea in those days was to obtain possession of Vançey, where the De Lalandes had lived and died for centuries. How it was to be done I had not the least notion, and I never spoke of it to others; but Roland's talk set me thinking.

His advice seemed good. I must go to Paris and take service with some prominent man. I would serve him faithfully; he would advance my interests, and in the course of time I might save sufficient money to purchase the family estate, whither I would remove my mother and father that they might pass the end of their days in peace. That was the dream which the soldier's words had started afresh.

My father would have let me go willingly enough, but my dear mother, who had never seen the capital, feared for my welfare.

"This Paris," said she, "is a wicked place, full of snares and pitfalls for young and old. Rest content where you are, my son, and be not eager to rush into temptation. I think not so much of bodily peril as of danger to the soul."

"Albert is a gentleman," said my father, "and the son of a gentleman: he will do nothing dishonourable."

Perhaps after all I should never have left home, but for an incident which happened a few days after Belloc's departure. One evening I had wandered across the meadows skirting the river, and, busy with my thoughts, had unconsciously strayed into the private grounds at Vançey. The voices of men in earnest conversation broke my dream, and I found myself at the back of a pleasant arbour.

"It is far too risky," said one. "Let De Retz find his tools elsewhere. If the plot fails——"

"Pshaw!" exclaimed another, "it can't fail. I tell you De Retz has spread his net so carefully that we are certain to land the big fish."

Unwilling to pry into other people's secrets, I was turning back when the speakers, hearing the noise, rushed from the arbour, with their swords half drawn. One was the owner of the chateau: the other my cousin Henri.

"What beggar's brat is this?" cried Maubranne. "Off to your kennel, you rascal, and stay there till I send my servants to whip you."

"Why, 'tis my cousin," said Henri, in surprise.

"How came you here, Albert? These are private grounds."

"Yes," I answered bitterly, "and once they belonged to your grandfather and mine."

"Faith," laughed he carelessly, "he should have taken better care of them. How long have you been here?"

"A few minutes. Do not be afraid; I learned none of your business."

"If I thought you had," growled Maubranne suspiciously, "you should never leave the place. Peste! it wouldn't be a bad idea to keep you as it is; you would be back under your own roof," and he ended with a brutal laugh.

"Perhaps I shall be some day; less likely things than that have happened."

At this he laughed again, and bidding me take myself off his land, turned back to the arbour.

The next morning, as I stood on the rustic bridge which spans the stream near Vançey, Henri came to join me. This was an unexpected honour, but he soon made the reason of it plain.

"Perhaps it is no business of mine," said he, "but I have come with a warning. You have made an enemy of Maubranne."

"Then we are quits," I laughed, "as I have no love for him."

"He thinks you played the spy upon him!"

"Has he sent you to find out?" I asked hotly.

"No, no; but the truth is, the situation is rather awkward. You may have heard something which Maubranne would not wish repeated."

"I heard you say that De Retz was going to land a big fish and that he wanted the baron's assistance. What was meant I do not know, except that there is some conspiracy afoot."

"I believe you, cousin," said Henri, "but Maubranne won't, and if anything goes wrong he will not spare you."

"Thanks," said I lightly; "but I can take care of myself. I have not lived at Court, but my father has taught me the use of the sword."

"Why," cried Henri laughing, "you are a regular fire-eater, but make no mistake, you will stand no chance with Maubranne. There are twenty stout fellows yonder ready to do whatever they are told, and to ask no questions. I bear you no particular love, cousin, but I wish you no ill, and will give you a piece of advice. Attach yourself to some nobleman who will look after you; Maubranne will think twice before harming a follower of Condé or Orleans."

"Or De Retz."

"Ah," said he, "to be quite frank, I don't wish you to join De Retz. Relatives are best apart. However, I have given you my advice; it is for you to act on it or not, as you think best."

That night in a long talk with my father I related the whole incident, and repeated Henri's words.

"Your cousin is right," he said thoughtfully. "Now that you have stirred up Maubranne's suspicions this is no place for you. The best thing is to accept Belloc's offer, though 'twill be a dreary life for you, alone in Paris."

"Belloc will stand by me, and Raoul Beauchamp is somewhere in the capital. He told me months ago that I can always get news of him at La Boule d'Or in the Rue de Roi."

"He is a fine fellow," said my father, "and his friendship is worth cultivating. But you must walk warily, Albert, and keep your eyes open. Unfortunately my purse is nearly empty, but I daresay that from time to time I shall be able to send you a little money."

My mother wept bitterly when she heard of the decision, but after a while she became more reconciled, and helped to pack my few things.

On the morning of my departure we sat down in very low spirits. Pierre, our faithful old servant, had prepared a simple meal, but no one seemed inclined to eat. At last we made an end of the pretence, and went to the door. "God keep you, my son," exclaimed my mother, embracing me; "I shall pray for you always."

"Remember you are a De Lalande," said my father proudly, "and do nothing that will disgrace your name."

I kissed them both, and, walking to the gate, passed through. Outside stood Pierre, who waited to wish me farewell.

"Adieu, Pierre," I cried, trying to speak gaily. "Look after the old place till my return."

The honest fellow's tears fell on my hand as he raised it to his lips and said, "Adieu, Monsieur Albert. May the good God bring you back safe and sound. Three generations, grandsire, sire, and son, I have seen, and evil days have come upon them all."

"Cheer up, my trusty Pierre! Keep a good heart. What a De Lalande has done I can do, and by God's help I will yet restore the fortunes of our house. Good-bye!" and I turned my face resolutely towards Paris.

Once only I looked back, and that was to steal a last glance at the old home. On my left lay the pleasant meadows with the silvery stream; on my right the woods and spires of Vançey, and in the distance the white-roofed farm-house, the only remnant of his property which my father could now call his own.

"He shall have it all again," I said, half aloud, and then blushed at my folly. What could I, who was hardly more than a mere boy, do? Nothing, it seemed, and yet I did not altogether despair.

Once more I turned, and, following the high road, plodded along steadily. It was the market-day at Reves, and the little town was filled with people, peasants and farmers mostly, though here and there a gaily-dressed gallant swaggered by, while the seat outside the principal inn was occupied by half-a-dozen soldiers.

In the market-place I was stopped by more than one acquaintance, with whom I laughed and jested for a few moments. A mile or so from the town I sat down by the wayside and began to eat the food which Pierre had put in my valise.

It is not necessary to recount the various stages of my journey. Sometimes with company not of the choicest, but more often alone, I trudged along, sleeping at night in shed or outhouse, so as to hoard my scanty stock of money. My shabby clothes, and perhaps the sight of my sword, saved me from being robbed, and, indeed, thieves would have gained no rich booty. A sharp sword and a lean purse are not ill friends to travel with on occasion.

It was afternoon when I reached Paris, and inquired my way to the Palais Royal. The man, a well-to-do shopkeeper, looked curiously at my shabby cloak, but directed me civilly enough.

"Monsieur is perhaps a friend of the Cardinal?" said he, as I thanked him.

"It may be," I answered; "though it is hard to tell as yet."

"Ah!" he exclaimed. "Monsieur, though young, is prudent, and knows how to keep his own counsel. Monsieur is from the country?"

"Well," said I, laughing, "that question hardly needs answering."

The fellow evidently intended to speak again, but thought better of it, and contented himself with staring at me very hard. In the next street a man stopped me, and started a long rigmarole, but I pushed him aside and went on.

At the gate of the Palais Royal my courage oozed out at my finger ends, and I walked about for half an hour before mustering sufficient resolution to address one of the sentries posted at the gate.

"M. Belloc?" he said. "What do you want of him?"

"I will tell him when I see him."

"Merci!" he exclaimed, "if you don't keep a civil tongue in your head I will clap you in the guard-room."

Just then an officer coming up asked my business, and I repeated my wish to see M. Belloc.

"Do you know him?" he inquired.

"I am here by his own invitation."

"Well, in that case," looking me up and down as if I had been a strange animal, "you are very unfortunate. M. Belloc left town only an hour ago."

"But he will return?"

"That is quite likely."

"Can you tell me when?"

"If you can wait long enough for an answer I will ask the Cardinal," he replied with a laugh.

"It is a pity the Cardinal doesn't keep a school for manners," I exclaimed, and, turning on my heel, walked away.

Here was a pretty beginning to my venture! What should I do now? I had not once given a thought to Belloc's being away, and without him I was completely lost. After wandering about aimlessly for some time I remembered Raoul Beauchamp, and decided to seek news of him at La Boule d'Or. Without knowing it, I had strayed into the very street where the curious shopkeeper lived, and there he stood at his door.

"Monsieur has soon returned," said he.

"To beg a fresh favour. Will you direct me to the Rue de Roi?"

"The Rue de Roi?" he exclaimed in a tone of surprise.

"Yes, I want to find La Boule d'Or."

At that he raised his eyebrows and, lifting his hands, exclaimed, "Monsieur, then, has not received any encouragement from the Cardinal?"

"A fig for the Cardinal," I cried irritably. "I am in need of some supper, and a bed. You don't suppose I want to walk about the streets all night."

"But it seems so strange! First it is the Palais Royal, and then La Boule d'Or. However, it is none of my business. Monsieur knows his own mind. Jacques," and he called to a boy standing just inside the shop, "show monsieur to the Rue de Roi."

Jacques was a boy of twelve, lean, hungry-looking, and hard-featured, but as sharp as a weasel. He piloted me through the crowds, turned down alleys, shot through narrow courts, turning now to right now to left, till my head began to swim.

"Has monsieur heard the news?" he asked. "They think at the shop that I don't know, but I keep my ears open. There will be sport soon. They are going to put the Cardinal in an iron cage, and Anne of Austria in a convent. Then the people will rise and get their own. Oh, oh! it will be fine sport. No more starving for Jacques then. I shall get a pike—Antoine is making them by the score—and push my way into the king's palace. Antoine says we shall have white bread to eat; white bread, monsieur, but I don't think that can be true."

All the way he chattered thus, repeating scraps of information he had picked up, and inventing a great deal besides. Much of it I understood no more than if he had spoken in a foreign tongue, but I gathered that stirring work was expected by the denizens of the low quarters of the city.

"Faith," I thought to myself, "my poor mother would have little sleep to-night if she could see me now, wandering through these dens of vice and crime. Old Belloc's path to fortune does not seem easy to find."

Jacques suddenly brought me back to reality by exclaiming in his shrill voice, "Here we are, monsieur! This is the Rue de Roi."

The information rather staggered me, but I thanked him, and drawing out my slender purse, gave him a piece of silver. He fastened on it with wolfish eagerness and the next instant had disappeared, leaving me to find La Boule d'Or as best I could.

"Faith," I muttered, "Raoul has a strange taste. One would think his golden ball would soon become dingy in this neighbourhood!"

The Rue de Roi was really a narrow lane, with two rows of crazy buildings looking as if they had been planned by a lunatic architect. The street itself was only a few feet wide, and the upper storeys of the opposite houses almost touched. But in spite of its air of general ruin, the Rue de Roi was evidently a popular resort. Crowds of people went to and fro; sturdy rogues they appeared for the most part, and each man openly carried his favourite weapon—pike, or sword, or halberd.

Some belonged to the bourgeois or shopkeeping class. These, wrapped in long black cloaks, moved softly, speaking in low tones to groups of coopers, charcoal-sellers, and men of such-like occupations.

I was more astonished at beholding bands of young nobles who swaggered by in handsome dresses, laughing familiarly with both bourgeois, and canaille—as the lowest class was called; and I wondered vaguely if the scene had anything to do with what the boy had told me.

But I was tired and hungry, and the sights and sounds of the city had muddled my brain so that I cared chiefly to discover Raoul's inn. At any one of the numerous hostelries my lean purse would secure me a supper and a bed, and I began to think it advisable to defer any further search till the morning.

I stood in the middle of the road hesitating, as one will do at such times, when a clear young voice cried, "Hush, do not disturb him; he is waiting to hear the tinkle of the cow-bells!" a jest due no doubt to my ill-cut country clothes.

At the ringing laugh which greeted these saucy words I turned, and saw several young gallants stretched across the narrow street, completely blocking my path. Their leader was a fair-haired lad with blue eyes, and a good-humoured face that quite charmed me. He looked younger even than myself, though I afterwards learned there was little difference in our ages.

"I thought the fashion of keeping private jesters had gone out!" I exclaimed. "You should ask your master to provide you with cap and bells, young sir! Dressed as you are one might mistake you for a gentleman."

I did not mean to deal harshly with the youngster, but the last part of my speech hurt him, and he blushed like a girl; while his companions, drawing their swords, were for cutting me down off-hand. But though not understanding Paris customs I knew something of fencing, so throwing my cloak to the ground, I stood on guard. In another minute we should have been hard at it, but for the fair-haired lad, who, rushing between us, called on his friends to stand back.

"Put up your swords!" he cried in a tone of command; "the stranger is not to blame. Your words were harsh, monsieur, but the fault was my own. I am sorry if you were annoyed."

"Oh," said I, laughing, "there is no great harm done. My jest was a trifle ill-humoured, but an empty stomach plays havoc with good manners, and I am looking for my supper."

"Then you must let me be your host, and my silly freak will gain me a friend instead of an enemy."

He was a pretty boy, and his speech won on me, but I was tired out and anxious to sleep, so I replied, "A thousand thanks, but I am seeking La Boule d'Or. Perhaps you can direct me."

I must tell you the street was so badly lighted that we could not see each other clearly, but at this he stared into my face as if trying to recall my features and said, "Why, surely you must be——; but I have been in error once to-night, and no doubt you have reasons for this disguise. Still, is it safe to go to the inn? The old fox has his spies out."

"The old fox could come himself if he would but bring a decent supper with him!" I replied, not understanding in the least what the lad meant.

"Ma foi!" cried he, "I have heard of your bravery, but this is sheer recklessness. And to pretend you have forgotten the inn! I suppose you don't know me?"

"Not from Adam," I replied testily. "I have only one acquaintance in Paris, and as for the inn——" but the youngster laughed so heartily that I could not finish the sentence.

"Parbleu!" he cried, handing me my cloak, "this is a richer farce than mine! 'Tis you who should wear the cap and bells! But come, I will be your guide to the hostelry you have forgotten."

"Only to the door then, unless you would wish to drive me mad," at which, laughing again and bidding his companions wait, he led the way down the street, turning near the bottom into a cul-de-sac.

"There is the inn which you have forgotten so strangely," he said, "but you are playing a dangerous game. There may be a spy in the house."

"There may be a dozen for all I care. But I am keeping you from your friends."

"While I am keeping you from your supper. But just one question; it cannot hurt you to answer. Will the scheme go on?"

"The scheme? What scheme?" I asked, in amazement

"You are a good actor," said he a trifle crossly. "Perhaps you will tell me if Maubranne has returned to town."

"Maubranne is at Vançey," I answered in still greater astonishment.

"Then you will have to do the work yourself, which will please us better. Maubranne would have spoiled everything at the last minute. But there, I will leave you till to-morrow—unless you will be out."

"Out?" I exclaimed. "Yes, I shall be out all day and every day."

"Till the mine is laid! Well, I must tear myself away. Don't be too risky, for without you the whole thing will tumble about our ears like a house of cards."

I felt very thankful to be relieved of my unknown friend's company, for my head was in a whirl, and I wished to be alone for an hour. Pushing open the outer door and entering a narrow, ill-lit passage, I almost fell into the arms of a short, stout, red-faced man, who leered at me most horribly.

"Are you the landlord?" I asked.

"Yes," he answered, making a profound bow.

"Then show me a room where I can eat and sleep, for I am tired out and hungry as a famished hawk."

"I grieve, monsieur; I am truly sorry," he replied, bowing in most marvellous fashion for one so stout, "but, unhappily, my poor house is full. In order to make room for my guests I myself have to sleep in the stable. But monsieur will find excellent accommodation higher up the street."

"Still, I intend staying here. The fact is, I have come on purpose to see an old friend, a gentleman in the train of the Duke of Orleans."

"Will monsieur give his name?"

"M. Raoul Beauchamp," I replied; "he comes here frequently."

At this the innkeeper became quite civil, and I heard no more of the advice to bestow my custom elsewhere.

"Well, mine host," I said slyly, "do you think it possible to find me a room now in this crowded house?"

The fellow bowed again, saying I was pleased to be merry, but that really in such stirring times one had to be careful, and that the good François, who had known everybody, was dead—killed, it was hinted, by a spy of Mazarin. But now that I had proved my right, as it were, the house was mine, and he, the speaker, the humblest of my servants.

"Then show me a room," I exclaimed, "and bring me something to eat and drink."

He lit a couple of candles, and walking farther along the passage threw open a door which led into a crowded room. The inmates stopped talking, and looked at me curiously. One, leaving his seat, came close to my side.

The fellow was a stranger to me, and, unless I am a poor judge, a cut-throat by profession. Finding that I made no sign of recognition he stood still saying clumsily, "Pardon, monsieur, I mistook you for another gentleman." Then, lowering his voice he added, "Monsieur wishes to remain unknown? It is well. I am silent as the grave."

Gazing at me far more villainously than the landlord had done, he returned to his place, which perhaps was well, as I was rapidly approaching the verge of lunacy. However, I followed the innkeeper up a crazy staircase, along various rambling corridors, and finally into a sparsely-furnished but comfortable apartment. Uttering a sigh of relief at the sight of a clean bed, I sat down on one of the two chairs which the room contained.

"Thank goodness!" I exclaimed, and waited patiently while my host went to see after the supper.

He was back in less than ten minutes, and I smiled pleasantly in anticipation of the coming feast, when he entered—empty-handed! Something had happened, I knew not what, but it had increased the man's respect tremendously.

"Forgive me," he murmured penitently, "but I have only just learned the truth, and François is dead. Still it is not too late to change, and monsieur can have his own room."

"Where is my supper?" I asked. "Can't you see I am starving? What care I about your François? Bring me some food quickly."

"Certainly, monsieur, certainly," said he, and disappeared, leaving me to wonder what the new mystery was.

"What does he mean by 'own room'? Who am I? And who, I wonder, is the unlucky François? It seems to me that we must all be out of our minds together."

Presently the innkeeper, attended by a servant, reappeared, and between them they placed on the table a white cloth, a flagon of wine, a loaf of wheaten bread, a piece of cheese, and a cold roast fowl.

Sitting back in my chair, I regarded the proceedings with an approving smile, saying, "Ah, that is more to the purpose! Now I begin to believe that I am really at La Boule d'Or!"

When the men had gone, I took off my sword, loosened my doublet, and sat down to supper, feeling at peace with all the world, and especially with Raoul, who had told me of this fair haven, and also how to cast anchor therein, which, in such a crowded harbour, was of the utmost importance.

The bread was sweet and wholesome, the fowl tender, though of a small breed, the cheese precisely to my palate; while I had the appetite of a gray wolf in winter. Thus I made short work of the provisions, and, after the empty dishes were removed, tried hard to think out an explanation of the evening's events.

The chatter of the young gallant, the odd behaviour of the man downstairs, the cringing attitude of the innkeeper, the remark concerning my own room, showed that I was mistaken for another person, and one of considerable importance; so perhaps it was well for me that the worthy François was no longer alive.

The evident likeness between the unknown and myself pointed to the fact that I was usurping the place of my cousin, and in that case I had stepped into a hornet's nest. However, I was in poor condition for reasoning clearly; the supper and fatigue had made me so sleepy that my head nodded, my eyes closed, and I had much ado to keep from falling asleep in the chair.

At last I rose, and having seen to the fastenings of the door and windows and examined the walls—Raoul had told me several strange stories of Parisian life—I undressed, placed sword and pistols ready at hand, blew out the light, repeated the simple prayer my mother had taught me, and stepped into bed.

I must have fallen into a sound sleep towards daylight, as I did not waken till a servant knocked loudly at the door; but during the first part of the night my rest was feverish and broken by the oddest dreams, in which Baron Maubranne, Raoul, and my cousin, played the principal parts.

After breakfast, at which the innkeeper was still more humble than on the preceding evening, I held counsel with myself as to what was best to be done. Raoul was probably at the Luxembourg, but, remembering my reception at the gate of the Palais Royal, I had no mind to hazard another rebuff.

"I will write him a note," I concluded. "He will come at once and give me the key to all these strange doings. Meanwhile if these people choose to treat me as a grand personage, so much the better."

Calling for paper, I wrote a note and sent it by one of the servants to the Luxembourg.

Unfortunately, I was to meet with a second disappointment. The man returned with the information that M. Beauchamp was absent on a special mission for the Duke. He had gone, it was believed, to Vançey, and might not return for a week. However, the instant he returned the letter should be given him.

This was far from pleasant news. What should I do now? My first idea was to explain matters to the innkeeper, but would he believe the story? Maubranne had already accused me of being a spy, and if any of the people at the inn entertained the same notion I felt it would be the worse for me. Besides, a week was not long, and Raoul might return even sooner. "He will either come or send at once," I thought, "and not much harm can happen in a few days."

As a matter of fact I was afraid to trust the innkeeper with my story. It would have been of little consequence in ordinary times, but just then one could hardly tell friend from foe.

Three days slipped by pleasantly enough. Each evening I wandered into the streets of the city, looking with interest at the crowds of people, the splendid buildings, the gaily-dressed roysterers, the troops of Guards in their rich uniforms, the gorgeous equipages of the ladies, and the thousand strange sights that Paris presented to a provincial.

At first I found it rather difficult to make my way back to the inn, but by careful observation I gradually acquired a knowledge of the district.

Once I summoned courage to accost a soldier of the Guards, and to inquire if M. Belloc had returned from his journey.

Looking rather contemptuously at my rusty dress, he answered, "Do you mean M. Belloc of the Cardinal's household?"

"The same," I said.

"I am sorry, monsieur, but he is still out of Paris, or at least he is supposed to be, which amounts to the same thing. But if you wish particularly to see him, why not seek audience of the Cardinal?"

"Thanks, my friend; I had not thought of that."

The soldier smiled, nodded, and went on his way, humming an air as if well-pleased with himself.

"Seek audience of the Cardinal?" The bare idea froze up my courage; I would as soon have entered a den of lions!

"No, no," I thought, "better to wait for Raoul."

During this time no message had come from him, but on the fourth evening, as I was setting out for my usual promenade, a servant announced a messenger with an urgent letter.

"Show him up," I cried briskly, anxious to learn the nature of my comrade's communication, and hoping it would foretell his speedy arrival.

The messenger's appearance rather surprised me, but I was too full of Raoul to pay much attention to his servant. Still, I noticed he was a small, weazened, mean-looking fellow, quite a dwarf, in fact, with sharp, keen eyes and a general air of cunning.

"You have a letter for me?" said I, stretching out my hand.

"Monsieur de Lalande?" he asked questioningly, with just the slightest possible tinge of suspicion, and I nodded.

"It is to be hoped that no one saw you come in here, monsieur!"

"Waste no more words, but give me the letter; it may be important."

"It is," he answered, "of the utmost importance, and my master wishes it to be read without delay."

"He has kept me waiting longer than was agreeable," I remarked, taking the note and breaking the seal.

The letter was neither signed nor addressed, and my face must have shown surprise at the contents, as, looking up suddenly, I found the messenger watching me with undisguised alarm. Springing across the room I fastened the door, and, picking up a pistol, said quietly, "Raise your voice above a whisper and I fire! Now attend to me. Do you know what is in this note?"

"No!" he answered boldly.

"That is false," I said, still speaking quietly, "and will do you no good. Tell me what is in it."

"Has not monsieur learned to read?" he asked in such a matter-of-fact manner that I burst out laughing.

"You are a brave little man, and when you see your master tell him I said so."

"What name shall I give him, monsieur?"

"Name, you rascal? Why, my own, De Lalande! Now sit there and don't stir, while I read this again."

It was a queer communication, and only the fact of my chance meeting with the youngster in the Rue de Roi gave me anything like a clue as to its meaning.

This was what I read.

"I have sent to the inn, in case my mounted messenger should fail to stop you on the road. The plan will go on, but without us. We move only when success is certain. Make your arrangements accordingly. Our friends will be annoyed, but they can hardly draw back. I leave you to supply a reason for your absence. A broken leg or a slight attack of fever might be serviceable. Destroy this."

Plainly the note did not come from Raoul, nor was it intended for me.

What did it mean? That there was a conspiracy on foot I grasped at once, as also that my cousin was one of the prominent actors. But what, and against whom? and why was I, or rather Henri, to draw back? Who were our friends who would do it without us? Was my acquaintance of the Rue de Roi among them? On which side was Raoul?

Now Raoul and my cousin had no love for each other, and therefore, I argued, though wrongly as it afterwards appeared, they could not be working together.

"Come," thought I, "this is clearing the ground. By going more deeply into the matter I may be able to do Raoul a service."

But how to proceed? That was the question which troubled me.

It was plain that whatever I decided to do must be done quickly. I glanced at the messenger. He sat quite still, but his shrewd, beady eyes were fixed on me as if to read my every thought. Evidently there was no help to be expected from that quarter. And, worse still, the man had discovered his mistake. The instant I opened the door he would raise an alarm, and I should probably fare ill in the ensuing scuffle.

The rascal was aware of his advantage, and actually grinned.

"Pardon me, monsieur," he said, "but I am always amused by a comedy, and this one is so rich. It is like a battle in which both sides are beaten, and yet both claim the victory. You have the paper and cannot make use of it, while I——"

"You are in more danger than you seem to imagine."

"I think not, monsieur," he answered coolly.

It was certainly a most awkward position, and I tried in vain to hit upon some plan of action. If only the man would speak, and speak the truth, he could make everything plain. I could not bribe him, and if I could he would probably deceive me, but was there not a chance of alarming him? I endeavoured to recall what Belloc had said. Henri was hand in glove with De Retz, who was Mazarin's enemy, so that the messenger would probably not relish an interview with the Cardinal.

"Come," I said at length, "let us make a bargain. You shall tell me the meaning of this letter, and I will set you free. What do you say?"

"That you offer me nothing for something, monsieur, which is a good bargain for you. Suppose I do not fall in with such a tempting offer?"

"In that case," I replied, speaking as sternly as possible, "I shall hand you over to the Guards of Cardinal Mazarin."

At this the rascal laughed merrily, saying, "The Cardinal may be a great personage at the Palais Royal, but his credit is low in the Rue de Roi. No, no, monsieur, you must try again."

It was unpleasant to be played with in this manner, yet there was no remedy. I was still wondering what to do, when suddenly there came a sound of footsteps in the corridor, and some one knocked at the door. The dwarf grinned with delight, but, pointing a pistol at his head, I bade him be silent, and asked who was without.

"Armand d'Arçy."

I recognised the voice at once as that of the youngster who had brought me to the inn. The little man also knew my visitor, and moved uneasily in his chair till my pistol came in contact with his neck; then he sat still.

"Pardon! I am engaged."

"But you must spare five minutes. I have come on purpose to see you," and lowering his voice he added earnestly, "the affair takes place to-night."

Laughing softly at my prisoner, I said aloud, "What of it? You know what to do."

"Then nothing is to be changed?" and there was a note of surprise in D'Arçy's voice.

"Not as far as I am concerned."

"And you will be there by ten without fail?"

"Certainly, why not?"

"Well, there was a rumour floating about last night that you intended to withdraw."

"Rumour is generally a false jade," I said coolly.

"Ten o'clock, then, at the new church in the Rue St. Honoré," and with that he retired, evidently annoyed at having been kept out of the room.

"That lessens the value of your information," said I, turning to my prisoner.

"Considerably," he replied cheerfully. "I judged monsieur wrongly. It is plain that his wits are as keen as his sword."

Ignoring the doubtful compliment, and taking up the note afresh, I observed that I should soon be able to tell who wrote it.

"It is possible," he agreed, "quite possible."

He had regained his composure, and, indeed, seemed rather pleased than otherwise at the turn events were taking. Still he did not quite know what to make of me, and now and then a shadow of anxiety flitted across his face.

As we sat staring at each other it dawned upon me that I had a new problem to solve. What was to be done with this unwelcome visitor? I had made up my mind to meet D'Arçy, and the sound of a neighbouring clock striking nine warned me there was short time left for decision.

"Suppose I let you go?" I asked, half amused at the comical situation.

"That would be agreeable to me."

"Would you promise to say nothing about this affair till the morning?"

"Readily, monsieur."

"And break your promise at the first opportunity?"

"That is probable, monsieur. You see, I have a very bad memory," and he laughed.

"Then you must be kept here. I am sorry; I have no wish to hurt you, but there is no other way."

"As you please," he replied, and submitted quietly to be bound with strips torn from the bedclothes.

I fastened the knots securely, yet so as to cause him the least suffering, and then proceeded to improvise a gag. At this point his calmness disappeared, and for a short time he looked both surprised and angry.

[Transcriber's note: illustration missing from book]

However, he soon recovered his spirits, and said admiringly, "Surely monsieur must be a gaoler by profession; he knows all the tricks of the trade."

"Ah," said I, laughing, "you did not expect this?"

He shook his head disconsolately.

"But it is necessary."

"It may be for you."

"Let us say for both, since you will be prevented from getting into mischief. But come; I will make you comfortable."

The man's eyes twinkled, and any one outside hearing him laugh would have thought we were engaged in a humorous game.

"Ma foi!" he exclaimed, "you are politeness itself. First I am to be bound and gagged, and then made comfortable. But there is just one thing which troubles me."

"Speak out; I may be able to set your mind at ease."

"It is just possible that some one, not knowing your good points, may cut off your head."

"Well?"

"In that case, with a gag in my mouth, I shall be unable to express my sorrow."

"Have no fear," I replied, catching his meaning. "Whatever happens to me, and the venture is certainly risky, I promise you shall be released in the morning."

"Thanks, monsieur," he said, looking considerably relieved, "you certainly play the game like a gentleman."

I was really sorry to treat the man so scurvily, but, as a single word from him would upset my plans, it was necessary to prevent him from giving warning. So, carefully inserting the gag and repeating the promise to set him at liberty as soon as possible, I put my pistols in order, took my hat, and went out, closing and fastening the door.

The sight of the innkeeper in the narrow passage reminded me that he might be wondering what had become of the messenger, so I stopped and said, "If the dwarf returns before me, tell him to come again in the morning."

"Certainly, monsieur," he replied, holding the door open while I passed into the courtyard.

As usual the Rue de Roi was crowded, and I thought some of the people looked at me strangely, but this might have been mere fancy. Once, indeed, a man placed himself purposely in my path. It was the ruffian who had spoken to me in the inn, but, not desiring his company, I placed a finger on my lips to indicate silence, and walked past rapidly.

Ten o'clock struck as, entering the Rue St. Honoré, I passed up the street, seeking for the new church. Several people were still about, but I dared not ask for information, though where the church was situated I had not the faintest idea. However, I kept straight on, and, a quarter after the hour, approached a huge pile of scaffolding and the unfinished walls of a large building.

Here I paused in doubt, which was relieved by a whispered "De Lalande?" and the next instant Armand d'Arçy joined me.

"You are late," he exclaimed irritably. "The others have started, and I had almost despaired of your coming."

Taking my arm he crossed the road, hurried down a by-street, and, by what seemed a round-about route, led me into a most uninviting part of the city.

"Our friends have made good use of their time," I remarked, hoping to learn something useful from his conversation.

"They are anxious to surround the cage while the bird is still within. These strange rumours concerning the Abbé have made them uneasy."

"But I don't in the least understand you."

"Well, they must be untrue, or you would not be here. Still, the information came to us on good authority."

"Speak out, man, and let us clear up the matter; I am completely in the dark."

"Then," said he bluntly, "it is just this. We heard De Retz intended to trick us, and that you, instead of having returned to Paris, were still at Vançey. Of course I knew better, but the Abbé is a slippery customer!"

"Why not have told him your suspicions?"

D'Arçy slapped me on the back.

"Behold the innocence of the dove!" he exclaimed. "Of course he would have denied everything and demanded our proofs. But he will do well to leave off this double game. With the Cardinal in our hands we shall be too strong for him."

"I don't understand now."

"It is simple enough. You know that De Retz drew up the scheme and induced us to join him. But he can't be trusted, and half of our fellows believe he is playing us false."

"But why should he?"

"Ah, that is the mystery. He may have made his peace with the Cardinal for all I know. However, you can't draw back now; so if he has cheated us, he has cheated you. Is the plan changed in any way?"

"I have heard of no alteration."

"We had better make sure of our ground. It would be folly to miss so good an opportunity through want of foresight, though I don't see how we can fail," and, dropping his voice to a whisper, he went through all his arrangements, only pausing now and again to ask my opinion, which he evidently valued highly.

I walked by his side like one in a dream, hardly knowing how to answer. Here was I, a simple country youth, plunged into a conspiracy so daring that the recital of it almost took away my breath. The enterprise, started by the Abbé de Retz, was no less than the forcible carrying-off of Cardinal Mazarin, the most powerful man in France. I turned hot and cold at the thought.

It was known that the Cardinal, as a citizen, paid occasional visits to a certain astrologer, in whose house he was at present, and the conspirators had arranged their plans accordingly. False passports were obtained, a body of horse were in readiness outside the gates, and it only remained to obtain possession of the Cardinal's person. This part, it appeared, De Retz had promised should be undertaken by my cousin, who was deep in his confidence, while a band of reckless young nobles, with D'Arçy at their head, should form an escort.

"Once we get the old fox trapped, the rest will be easy," said my companion. "I warrant he won't get loose again in a hurry."

"No," said I, puzzling my brain as to why De Retz had at the last moment drawn back from the venture.

There was no doubt he had written the note even then inside my doublet. Something had occurred to shake his resolution, but what was it? Had he really joined hands with the Cardinal? The letter to Henri did not look like it. Had he intended all along to sacrifice his allies? I did not think so, because his note seemed to hint at their possible success. Perhaps, and it was my final conclusion, some unexpected danger had compelled him to hold his hand.

What ought I to do? As we walked along, Armand d'Arçy rallied me on my silence, but happily the darkness hid my face, or he must have suspected something was wrong.

"Are you growing nervous, De Lalande?" he asked banteringly. "I have always heard that nothing could alarm you."

"I am not alarmed."

"The old fox will be surprised by our visit. I wonder if he has gone to the astrologer's to have his fortune told?"

"Very likely. He believes in the stars and their influence."

"Now, for me, I put more faith in a sharp sword," said D'Arçy, laughing, "but everyone to his taste. Steady, now, some of our fellows ought to be posted here."

"Suppose," I asked, suddenly coming to a halt, "that instead of trapping Mazarin, we are walking into a trap ourselves?"

"Why, in that case, my friend, you will be the only one caught. We shall remain in hiding till you give the signal."

"Of course," and I heaved a sigh of relief, "I had not thought of that."

D'Arçy's words had shown me a way out of the difficulty. I intended, if possible, to save the Cardinal, yet I could not in honour betray the men whose secret I had discovered by such a series of strange accidents.

As it was, my course seemed plain and open. I had only to see Mazarin, acquaint him with his danger, and get him into a place of safety; after that I could tell the conspirators their plans were discovered, and they would quickly disperse. Mazarin might not believe my story, but something must be left to chance.

"We are getting near now," whispered D'Arçy presently; "you don't wish to draw back?"

"Not in the least, why?"

"Because if you do, I will take your place. If the plan fails it is the Bastille for you, and perhaps a rope with a running knot from the walls."

"Pshaw! there is no danger for me, and you can take care of yourselves."

At the end of a by-street, we were challenged by a low "Qui-vive?" when we instantly halted.

"Notre Dame!" replied D'Arçy quietly. "Is that you, Peleton? Are we in time?"

"The old fox has not come out, and a light still burns in the third window. Have you brought De Lalande?"

"Here he is."

"Ma foi! 'tis more than I expected. But I warn our friend that if he means playing us false he will have need to look to himself."

A ready answer sprang to my lips, but I checked it. D'Arçy had evidently only a passing acquaintance with my cousin, but this man might know him well; in which case the trick would be discovered.

"Peleton is always suspecting some one," laughed D'Arçy, "and generally without cause."

"Well, if anything goes wrong, remember I warned you!" growled the other.

"Peace!" cried a third man, stepping from the shadow of a doorway. "Small wonder the Cardinal wins, when we spend our time in squabbling between ourselves. De Lalande, you are late, but now you have come, let us begin the business without more delay. Mazarin is still in the house, and our men are waiting. The horses are harnessed, and directly you give the signal the carriage will be at the door. I need not warn you to take care of yourself."

"Three knocks, remember," said D'Arçy. "We will stand here in the shadow; the others are in their places, and keeping a sharp look-out."

"One minute!" I whispered to him. "There is just a trifling matter I wish done. If I don't return—and that seems not unlikely—will you go straight back to La Boule d'Or? You will find a man in my room tied up and gagged; set him at liberty."

D'Arçy gave a low whistle of surprise, but without asking for an explanation he promised to go.

"If we succeed I can attend to him myself," I added. "Now stand back."

"Don't forget," said the third man, "that if the Cardinal slips through your fingers your own neck will be in danger."

"Good luck," cried D'Arçy softly, as I crossed the road to the astrologer's house.

For a moment, as my companions disappeared, my courage failed. I was bound on a really desperate venture, and the first false slip might land me in a dungeon of the dreaded Bastille.

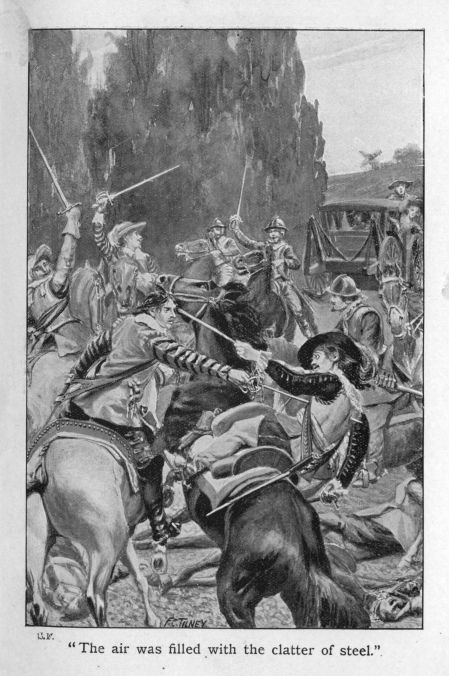

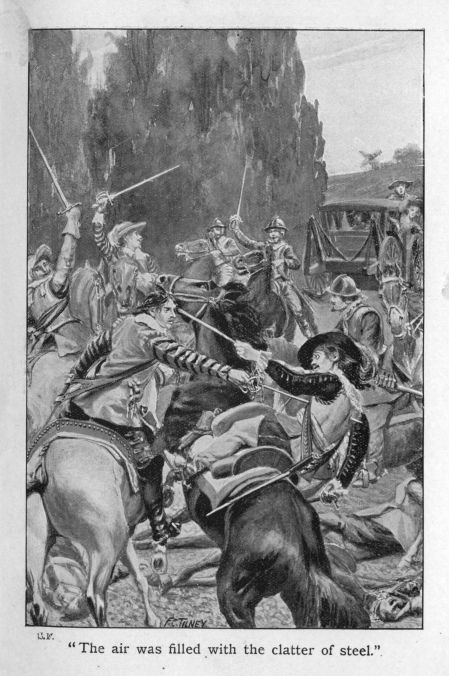

Suppose that Mazarin, having learned of the plot, had filled the house with his Guards? Once I raised my hand and dropped it, but the second time I knocked at the door, which, after some delay, was opened wide enough to admit the passage of a man's body. The entry was quite dark, but I pushed in quickly, nerving myself for whatever might happen. At the same moment sounds of firing came from the street, and I heard the man Peleton exclaim, "Fly! We are betrayed!"

I turned to the door, but some one was already shooting the bolts, while a second person, pressing a pistol against my head, exclaimed roughly, "Don't move till we have a light. The floor is uneven, and you might hurt yourself by falling."

"You can put down that weapon," I said. "I am not likely to run away, especially as I have come of my own free will to see your master's visitor."

The fellow laughed, and lowered his pistol.

"You will see him soon enough," said he, and I judged by his tone that he did not think the interview would be a pleasant one.

Another man now arriving with a lantern, I was led to the end of the passage, up three steps, and so into a large room, sparsely furnished, but filled with soldiers. Truly the Abbé was well advised in withdrawing from the conspiracy.

"Peste!" exclaimed the officer in charge, "why, 'tis De Lalande himself, only the peacock has put on daw's feathers. Well, my friend, you have sent your goods to sea in a leaky boat this time."

He took a step towards me, and then stopped in astonishment.

"What mystery is this?" he cried. "Are you not Henri de Lalande? But, no, I see the difference now. Ah, Henri is a clever fellow after all; I thought he would not trust himself on this fool's errand. But you are marvellously like him. Well, well; whoever you are, the Cardinal is anxious to see you."

"I came on purpose to speak to him. Had I known he was so well prepared to receive visitors I might have spared myself a troublesome journey."

"And deprived His Eminence of a great pleasure! Unbuckle your sword, and place your pistols on the table. The Cardinal is a man of peace, and likes not martial weapons."

To resist was useless; so I surrendered sword and pistols, which the officer handed to one of his men.

"Now," he said, "as you are so anxious to meet the Cardinal, I will take you to him at once. This way."

We toiled up a narrow, steep, and dimly-lighted staircase, at the top of which a soldier stood on guard, while another paced to and fro along the narrow landing. Both these men, as well as those in the lower part of the house, wore the Cardinal's livery.

There were three rooms, and, stopping outside the second, the officer knocked at the door, while the soldier on duty stood close behind me. For a time there was no answer, but presently a calm voice bade us enter, and the next instant I stood face to face with the most powerful man in France.

My glance travelled rapidly round the apartment, which was large, lofty, and oddly furnished. A table littered with papers and parchments occupied the centre; the walls were almost hidden by hundreds of books and curious-looking maps; two globes stood in one corner; on a wide shelf close by were several strange instruments, the uses of which I did not understand; a pair of loosely hung curtains screened the lower end of the room.

At the table sat two men of striking personal appearance.

One was a tall, venerable man with white beard and moustache, broad, high forehead, and calm, thoughtful, gray eyes. He was older than his companion, and the deeply-furrowed brow bespoke a life of much care, perhaps sorrow. He was dressed in a brown robe, held loosely round the middle by silken cords; he wore slippers on his feet, and a tasselled cap partly covered his scanty white hair. I put him down as the astrologer.

The second man attracted and repelled me at the same time. He was in the prime of life and undeniably handsome, while there was a look of sagacity, almost of craft, in his face.

"A strong man," I thought, looking into his wonderful eyes. "Not brave, perhaps, but dogged and tenacious. A man of cunning, too, who will play a knave at his own game and beat him. And yet, somehow, one would expect to find him occupied with paint-brush or guitar, rather than with the affairs of State."

Stories of the powerful Cardinal had reached even my quiet home, but I had never met him, and now stood looking at his face longer perhaps than was in keeping with good manners.

"Hum!" said he, watching me closely, "you are very young for a conspirator; you should be still with your tutor. What is your name?"

"Albert de Lalande," I replied.

"De Lalande!" he echoed in surprise. "The son of Charles de Lalande?"

"Your Eminence is thinking of my cousin Henri."

"Pouf! Are there two of you? So much the worse; one of the family is sufficient. Eh, Martin?"

"This youth is like his cousin," replied the astrologer, "but I imagine he knows little of Paris. I should say he is more at home in the fields than in the streets."

"It seems he knows enough to be mixed up in a daring plot," said Mazarin with a grim smile. "But, after all, my enemies do not rate my powers highly when they send a boy like this against me. I believed I was of more importance."

"No one sent me," I replied; "on the contrary, I came to warn you, but I need have had no fear for you, I find."

The Cardinal sighed. "The wolves do not always get into the sheep-fold," he murmured gently, at which, remembering the body of armed men below, I felt amused.

He was about to speak again, when, after tapping at the door, an officer entered the room. His clothes were torn and soiled, there was a smear of blood on the sleeve of his coat, and he glanced at his master sheepishly.

"Alone!" exclaimed the latter in astonishment, upon which the soldier approached him and began to speak in whispers. Mazarin was evidently displeased, but he listened courteously to the end.

"What bad luck!" he cried. "I thought they were all nicely trapped. However, no doubt you did your best. Now go and let a surgeon attend to your hurts. I see you have been wounded."

"A mere scratch, your Eminence," replied the officer saluting, and, when he had withdrawn, the Cardinal again turned his attention to me.

"Yes," said he, as if in answer to a question, "your companions have escaped: so much the better for them. But, deprived of the bell-wether, the flock counts for little. Now, as you value your life, tell me who sent you here. I warn you to speak the truth; there are deep dungeons in the Bastille."

"My story is a curious one, your Eminence, but it throws little light on the affair. My father is the head of the De Lalande family, but he is poor, and has lost his estates. The other day our friend, M. Belloc——"

"Belloc?" exclaimed the Cardinal quickly, "what Belloc?"

"Roland Belloc, your Eminence, a stout soldier and your faithful servant. He offered, if I came to Paris, to speak to you on my behalf."

"Go on," said Mazarin, with evident interest.

"Shortly after his return to Paris I had the misfortune to offend Baron Maubranne of Vançey, and then my mother, who had before been unwilling to part from me, agreed to my leaving home. I came to Paris, and inquired for my friend at the Palais Royal. The soldiers declared he was absent, which was unfortunate for me. However, I remembered the name of an inn at which another friend sometimes puts up, and I went there."

"One must go somewhere," said Mazarin.

"Yesterday," I continued, "a man brought me a note. It was intended for some one else, but, not knowing that, I opened it. It was very mysterious, but I gathered there was a conspiracy on foot, and that you were to be the victim."

"That is generally the case," exclaimed Mazarin with a sigh.

"As the conspirators mistook me for some one else——"

"For your cousin!"

"I resolved to play the part, in the hope of being able to put you on your guard."

"A remarkable story!" said Mazarin thoughtfully. "Eh, Martin?"

"It seems to ring true, your Eminence," replied the astrologer.

"There are two or three points, though, to be considered. For instance," turning to me, "to which party does this second friend of yours belong?"

"I really do not know that he belongs to any party."

"Well, it is of small consequence. Now, as to the people who came here with you?" and he cast a searching glance at my face.

"I should not recognise them in the street."

"But their names?" he cried impatiently. "You must know at least who their leader was."

"Pardon me," I said quietly, "but I did not undertake to play the spy. What I learned was by accident."

"You will not tell me?" and he drummed on the table.

"I cannot: it would be dishonourable."

"Oh," said he with a sneer, "honour is not much esteemed in these days!"

"My father has always taught me to look on it as the most important thing in the world."

"A clear proof that he is a stranger to Paris. However, I will not press you. It will ill-suit my purpose to imprison D'Arçy—he is too useful as a conspirator," he added with a chuckle.

I started in surprise at the mention of D'Arçy's name, and the Cardinal smiled.

"At present," he said kindly, "your sword will be of more service to me than your brains. Evidently you are not at home with our Parisian ways. Come, let me give you a lesson on the question and answer principle. How came I to be on my guard? My spies, as it happened, were ignorant of the conspiracy."

"Then one of the plotters betrayed his comrades."

"Precisely. Price—a thousand crowns. Next, how did De Retz discover that the plot was known?"

"That is more difficult to answer. I thought at first he himself was the traitor."

"A shrewd guess. Why did you alter your opinion?"

"Because De Retz cannot be in need of a thousand crowns."

"Quite true. Well, I will tell you the story; it will show you the manner of men with whom I have to deal. Two thousand crowns are better than one; so my rogue having first sold the Abbé's secret to me, obtained another by warning him that the conspiracy was discovered."

"But, in that case, why did he let his friends proceed with the scheme?"

Mazarin laughed at my question, saying, "That opens up another matter. All these people hate me, but they don't love each other. For instance, it would have delighted De Retz to learn that young D'Arçy was safe under lock and key in the Bastille."

"Then he will be disappointed."

Again the Cardinal laughed.

"That," he said, "was my rogue's masterpiece. Having pocketed his two thousand crowns, he sold us in the end by raising the alarm before my troops were ready. In that way he will stand well with his party, while making a clear gain all round. But, now, let us talk of yourself. I understand you have come to Paris to seek your fortune."

I bowed.

"That means I must either have you on my side or against me. There are several parties in Paris, but every man, ay, and woman too, is either a friend to Mazarin or his enemy. What say you? Will you wear the green scarf or not? Think it over. You are a free agent, and I shall welcome you as a friend, or respect you as a foe. True, you are very young, but you seem a sensible lad. Now make your choice."

"Providence has decided for me," I answered. "I shall be glad if I can be of any service to your Eminence."

"Good! Serve me faithfully, and you shall not be able to accuse Mazarin of being a niggardly paymaster. Belloc will return in a day or two, and we will have a talk with him. But the night flies. Martin, my trusty friend, I must depart: we will discuss those accounts at a quieter season."

"At your pleasure," replied the astrologer, and then at a signal from Mazarin, a grizzled veteran stepped out from behind the curtain.

"M. de Lalande's sword will be returned to him," said the Cardinal, "and he will await me with the Guards."

"Ma foi! you are a lucky youngster!" exclaimed my guide when we were out of earshot; "Mazarin has quite taken to you. I have never known any one jump into his favour so quickly."

The soldiers still stood at attention in the lower room, and the officer on being informed of the Cardinal's orders returned my pistols and helped me to buckle on my sword.

"A pleasanter task," he remarked, "than escorting you to the Bastille, where I expected you would pass the night. Have you joined the Cardinal's service?"

"More or less," I answered laughing. "I hardly know how things stand till M. Belloc returns."

"Are you acquainted with him?"

"He is one of my father's chief friends, perhaps the only one. I inquired for him the other day at the Palais Royal, but your men are not too affable to a stranger. Perhaps they would have been less surly but for my shabby mantle."

Before he had time to reply, Mazarin made his appearance, and, after issuing some orders, requested me to follow him. The street was deserted, the people were in bed, there was no sign of any troops, and I could not help thinking how completely the Cardinal had placed himself in my power. He, however, appeared to anticipate no danger, but walked steadily, leaning on my arm.

"The night air is cold," he said presently, drawing his black mantle closer round him—and after a pause, "Do you know your way? Ah, I had forgotten. Your home is near Vançey?"

"At Vançey, my grandsire would have answered, your Eminence, but times have changed, and we with them."

"It is hard work climbing the ladder, but harder still to stand on the top," remarked the Cardinal, and he asked me to tell him something of my family history. So, as we walked through the silent streets of the slumbering city, I described sadly how the broad acres of my forefathers had dwindled to a solitary farm.

We were in sight of the Palais Royal when I finished the melancholy narrative, and Mazarin stopped. The night was already past, and, in the light of the early dawn, we saw each other's faces distinctly. It may have been mere fancy, or the result of the severe strain on my nerves, or, more simple still, the manner in which the half light played on his face, but it seemed to me that the powerful Cardinal had become strangely agitated.

"Did you hear anything?" he asked suddenly, pressing my arm. "Listen, there it is again," and from our right came the sound of a low, clear whistle.

"It is a signal of some sort," I said.

"Yes," he exclaimed, "but fortunately it was given just too late. I must be more careful in future. Come! The sooner we are inside the gate the better," and he walked so quickly that I had much ado to keep pace with him.

Passing the sentries at the gate, we crossed the courtyard, and entered the Palais Royal through a narrow door leading to a private staircase. Turning to the left at the top, Mazarin led the way along what appeared to be an endless succession of corridors. Soldiers were stationed here and there, but, instantly recognising the cloaked figure, they saluted and we passed on.

At last Mazarin paused, and blowing softly on a silver whistle was instantly joined by a man in civilian attire.

"Find M. de Lalande food and a bed," exclaimed the Cardinal briskly. "For the present he is my guest, and will remain within call. Has M. Belloc returned?"

"No, my Lord."

"Let him attend me immediately upon his arrival. Where are the reports?"

"On your table, my Lord."

"Very good. See to M. de Lalande, and then wait in the ante-chamber. You may be wanted."

The man, who, I imagine, was a kind of under secretary, made a low bow, and motioned me to follow him, which I did gladly, being both hungry and tired. Showing me into a large room, he rang the bell and ordered supper. The excitement had not destroyed my appetite, and I did ample justice to the meal. Then, passing to an inner chamber, I undressed and went to bed, to sleep as soundly as if I had still been under my father's roof.

For three days I saw nothing more of the Cardinal. All sorts of people came and went—powerful nobles, soldiers, a few bourgeois, and a number of men whom I classed in my own mind as spies. They crowded the ante-room for hours, waiting till the minister had leisure to receive them.

On the fourth morning I was lounging in the corridor, having nothing better to do, when a soldier passed into the ante-room. His clothes were soiled and muddy; he was booted and spurred, and had apparently just returned from a long journey.

"M. Belloc!" I exclaimed, but he did not hear me, and before I could reach him he had gone into Mazarin's room, much to the disgust of those who had been waiting since early morning for an audience.

As he remained closeted with the Cardinal for more than an hour, it was evident he brought important news, and the people in the ante-room wondered what it could be.

"He is a clever fellow," remarked one. "I know him well. No one has greater influence with Mazarin."

"The Cardinal is brewing a surprise," whispered another. "Paris will have a chance to gossip in a day or two."

"It is rumoured," continued the first, "that De Retz nearly found himself in the Bastille only the other night."

"'Twould have served him right, too; he is a regular monkey for mischief. I wonder the Cardinal has put up with his tricks so long."

Thus they chattered among themselves till at last the door opened, and the secretary came out. A dozen men pressed forward eagerly, but, making his way through them, he approached the corner where I sat.

"M. de Lalande," he said, "the Cardinal wishes to see you."

I jumped up and followed him, amidst cold looks and scarcely concealed sneers at my shabby dress. It has often astonished me that people show such contempt for an old coat.

Mazarin stood with his back to the fireplace talking to my father's old friend.

"This is the youngster," said he, as I entered. "Do you know him?"

"Ay," answered Belloc, "I know him well, and I warrant he will prove as faithful a follower as any who draws your pay. I have yet to hear of a De Lalande deserting his flag. Even Henri, scamp though he may be, is loyal to his party. When De Retz sinks, Henri de Lalande will sink with him."

"Ma foi!" exclaimed the Cardinal, "such a fellow would be well worth gaining over!"

"You would find him proof against bribes or threats. And I warrant this lad is of the same mettle."

"Your friend gives you a high character, M. de Lalande," said the Cardinal smiling.

"I hope he will not be disappointed in me, your Eminence."

"Remember you are responsible for him," continued Mazarin, turning to the soldier. "Let his name be placed on your books; no doubt I shall soon find him something to do. Now I must carry your despatches to Her Majesty."

"Come with me, Albert," said Belloc, "and tell me all the news. You have made a good start; Mazarin speaks highly of your intelligence. This way! I am going to my quarters; I have been in the saddle for the last few days."

Roland Belloc was decidedly a man of influence at the Palais Royal. Officers and soldiers saluted respectfully as he passed, while he in turn had a smile and a nod for every one.

He had two rooms in a corner of the Palace, one of which served as a bedroom. The other was sparsely furnished, while its principal ornaments were spurs and gauntlets, swords and pistols, which hung on the walls.

As soon as he had changed his clothing he sat down, and bade me explain how I came to be in Paris. His brow darkened when I related Maubranne's insults, and though he made no remark, I knew he was terribly angry.

"You have had quite a series of adventures," he said at length, "and, for a youngster, have come remarkably well through them. Your foot is on the ladder now, my boy, and I hope you will climb high. Mazarin is a good master to a good servant, and he rules France. Bear that in mind. If all his enemies joined together I doubt if they could beat him, but they hate each other too much to unite."

"What shall I have to do?"

"I cannot say till the Cardinal gives his orders. He may make you an officer in the Guards, or keep you near him as a sort of body-servant. But do your duty wherever you are placed. Every step forward means a brighter chance of recovering Vançey."

"That is never long out of my thoughts."

"'Tis a good goal to try for, and not an impossible one either. Have you quarters in the Palace?"

"Temporary ones, till Mazarin has decided how to employ me."

The old soldier kept me with him some time longer, but seeing he was tired I made some excuse to get away, promising to call again in the morning. His return had cheered me considerably. Hitherto I had been very lonely among the crowds of courtiers, but now I felt secure of having at least one friend in the vast building.

It was strange, too, what a difference his friendship made in my position. Gaily-dressed young nobles, who, after a glance at my shabby doublet, had passed by without a word, now stopped and entered into conversation, pressing me to come here and there, as if I were their most intimate friend.

However, I declined their invitations, thinking it best to keep in the background till I had learned more of the Cardinal's intentions.

"Albert? Is it possible?"

"Even so. Are you surprised to see that the daw has become a peacock?"

A week had passed since my midnight adventure, and I was taking the air in the public gardens. Many richly-dressed cavaliers were strolling about, and among them I recognised my friend Raoul Beauchamp. He saw me almost at the same time, and, leaving his comrades, came over instantly.

"I' faith," said he merrily, "a very handsome one, too! For a country-bred youngster you have not done badly. Let us take a stroll on the Pont Neuf while you tell your story. I am dying of curiosity. Do you know you have made a splash in the world?"

"A truce to flattery, Raoul," I laughed.

"It is a fact, my dear fellow. In certain circles you are the mystery of the day. Your cousin Henri growls like a savage bear at your name; Armand d'Arçy does nothing but laugh and call himself an oaf; while only last night De Retz declared you were worth your weight in gold. And, to make matters worse, no one could say whether you were free or in the Bastille! Anyway, I am glad you have not joined Mazarin's Guards."

"Why?"

"Because you should be one of us, and we are opposed to Mazarin."

"The Cardinal is a well-hated man!"

"A wretched Italian priest! The nation will have none of him. Before long France will be quit of Mazarin."

"And what will happen then?"

"Ma foi! I know not," replied Raoul, "except that the Duke of Orleans will take his rightful place, as the King's uncle, at the head of affairs. Parliament, of course, will have to be suppressed, Condé bought over—as usual he will want the lion's share of the spoils—while De Retz must be kept quiet with a Cardinal's hat. He expects to be made minister in Mazarin's stead, but that is a fool's dream."

"But, suppose that, after all, Mazarin should win the game?"

"Bah! it is impossible. We are too strong for him. I will tell you a secret. In a month at the outside——"

I stopped him hurriedly, exclaiming, "Be careful, Raoul, or you may tell too much."

Looking at me in consternation, he said slowly, "You do not mean to suggest that you have gone over to Mazarin?"

"At least I have taken service with him."

"Then we shall be fighting on opposite sides! What a wretched business it is, breaking up old friendships in this way!"

"Ours need not be broken; and as to your party schemes against the Cardinal, they are bound to fail. There are too many traitors among you. Mazarin learns of your plots as soon as they are formed, and you wonder at his skill in evading them! Why, he has nothing to do but sit still and watch you destroy each other."

"A pleasant prospect!" exclaimed Raoul; "but now about yourself. You have not yet explained how you became a Mazarin, and it is difficult to distinguish the truth among a host of fables."

"It will be more difficult for you to believe it;" upon which I recounted my various adventures since arriving in the city.

"D'Arçy is true as steel," said he, "but too thoughtless to be trusted with a secret. As to De Retz, I warned the Duke to have nothing to do with him. He fights for his own hand, and cares not who sinks as long as he swims."

"Still," I suggested, "the first traitor must have been one of your own people."

He recognised the force of this, and eagerly questioned me with a view to learning the name of the man who had sold his party; but in this I did not gratify him, having no more than a suspicion, though a strong one, myself.

For some time after this we walked along in silence, but presently he said, "I suppose you are established in the Palais Royal?"

"No. Belloc—you remember my father's old friend—wished to give me a commission in the Guards, but the Cardinal thought I could serve him better in another direction. For the present I am living in the street which runs at right angles to the front entrance."

"Well within call," remarked Raoul, adding, "meet me at the Luxembourg this evening; the Duke holds a reception. You need not fear putting your head in the lion's mouth. There is a truce: the calm before the storm; so let us make the most of it. You will come, will you not? That is right. I must leave you now; there is Vautier beckoning, but we shall meet again this evening."

When he had gone I began to reckon up how things stood. Raoul was my bosom friend, who had held by me through good and ill. I loved him as a brother, and now it appeared we might be engaged at any time in mortal strife. The prospect was not pleasant, and I walked back to the Rue des Catonnes in anything but cheerful spirits.

I had selected this street, because, as Raoul said, it was within call: the rooms I had chosen on account of their cheapness. To my surprise and disgust, the Cardinal proved a poor paymaster, and, after buying my fine new clothes, there was little money left to spend in rent.