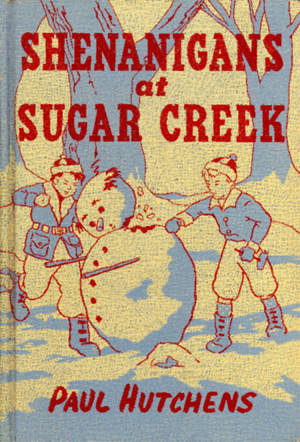

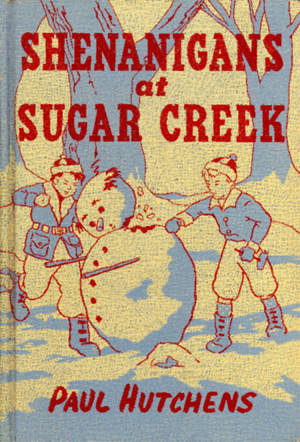

Title: Shenanigans at Sugar Creek

Author: Paul Hutchens

Release date: December 6, 2008 [eBook #27426]

Most recently updated: January 4, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, C. St. Charleskindt, Scanned by

Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at https://www.pgdp.net

Shenanigans at Sugar Creek

by Paul Hutchens

Copyright 1947, by Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company

Set up and printed, April, 1947

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

By

PAUL HUTCHENS

WM. B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY

| GRAND RAPIDS | 1947 | MICHIGAN |

One tough guy in the Sugar Creek territory was enough to keep us all on the lookout all the time for different kinds of trouble. We'd certainly had plenty with Big Bob Till, who, as you maybe know, was the big brother of Little Tom Till, our newest gang member.

But when a new quick-tempered boy whose name was Shorty Long, moved into the neighborhood and started coming to our school, and when Shorty and Bob began to chum around together, we never knew whether we'd get through even one day without something happening to start a fight, or get one of the gang into trouble with our teacher. On top of that, we had a new teacher, a man teacher at that, who didn't exactly know that most of us tried to behave ourselves most of the time.

Poetry, who is the barrel-shaped member of our gang, had made up a poem about our new teacher, whom not a one of us liked very well, on account of not wanting a new teacher when we'd liked our pretty lady other teacher so extra well. This is the way the poem went:

Poetry was always writing a new poem or always quoting one somebody else wrote.

Maybe it was a library book that was to blame for some of the trouble we had in this story, though. I'm not quite sure, but the very minute my pal, Poetry, and I saw the picture in a book called The Hoosier Schoolmaster, we both had a very mischievous idea[Pg 6] come into our minds, which we couldn't get out no matter how we tried....

This is the way it happened.... Poetry and I were in his house, in fact, I was staying at his house all night one night, and just before we went to sleep, we sat up in his big bed for awhile, looking at the picture which was a full-paged glossy picture of a man school teacher away up on the roof of a country schoolhouse, and he was holding a wide board across the top of the chimney. The schoolhouse's only door was open and a gang of tough-looking boys was tumbling out, along with a lot of smoke.

"Have you ever read the story?" I said to Poetry, and he said, "No, have you?" and when I said "No," we both read a part of it. The story was about a man teacher whose very bad boys in the school had locked him out of the building, and he had climbed up on the roof of the school and put a board across the chimney, and smoked them out just like a boy smokes a skunk out of a woodchuck den along Sugar Creek.

That put the idea in our heads, and it stayed there until a week or two after Christmas, before it got us into trouble.... Then just like a time-bomb exploding, all of a sudden that innocent idea which an innocent author had written in an innocent library book, exploded—and—Well, here goes the story.

It was a swell Saturday afternoon at our house with bright sunlight on the snow and the weather just right for coasting. I was standing by our kitchen sink, getting ready to start wiping a big stack of dishes which my mom had just rinsed with steaming hot water out of the teakettle. I was just reaching for a drying towel when Mom said, "Better wash your hands first, Bill," which I had forgotten to do like I once in a while do. Right away I washed my hands with soap, in our bathroom, came back and grabbed the towel off the rack by the range, and started in carefully wiping the dishes, not exactly wanting to, on account of the clock on our mantel-shelf said it was one o'clock, and the gang was supposed to meet on Bumblebee hill right that very minute, with our sleds, and we were going to have the time of our lives coasting, and rolling in the snow, and making huge balls and snow men and everything....

[Pg 7] You should have seen those dishes fly—that is, they started to!

"Be careful," Mom said, and meant it. "Those are my best dinner plates."

"I will," I said, and I was for a jiffy, but my mind wasn't anywhere near those fancy plates Mom was washing and I was wiping.... In fact, there wasn't any sense in washing them anyway, 'cause they weren't the ones we had used that day at all. Why they weren't even dirty! They'd been standing on the shelf in Mom's cupboard for several months without being used.

"I don't see why we have to wash them," I said, "when they aren't even dirty."

"We're going to have company for dinner tomorrow," Mom explained, "and we have to wash them."

"Wash them before we use them?" I said. It didn't make sense.... Why that very minute the gang would be hollering and screaming and coasting down the hill and having a wonderful time.

"Certainly," Mom said. "We want them to sparkle so that when the table is set and the guests come in they'll see how beautiful they really are. See? Notice how dull this one is?" Mom held up one that hadn't been washed yet in her hot sudsy water nor rinsed in my hot clear water nor wiped and polished with my dry clean towel, which Mom's tea towels always were anyway, Mom being an extra clean housekeeper and couldn't help it, on account of her mother had been that way too,—and being that kind of a housekeeper is contagious, like catching the measles or smallpox or the mumps or something boys don't like.

For some reason I remembered a part of a book I'd read, called Alice in Wonderland, and it was about a crazy queen who started to cry and say, "Oh ooooh! My finger's bleeding!"... And when Alice who was in Wonderland told her to wrap her finger up or something, the queen said, "Oh no, I haven't pricked it yet"—meaning it was bleeding before she had stuck a needle into it—which was a fairy story, and was crazy, so I said to Mom, "Seems funny to wash dishes before they're dirty—seems like a fairy story, like having your finger start bleeding before you stick a needle in it." I[Pg 8] knew Mom had read Alice in Wonderland 'cause she'd read it to me herself when I was little.

But Mom was very smart. She said, with a mischievous grin in her voice, "That's a splendid idea.... Let's pretend this is Bill Collins in Wonderland, and get the dishes done right away. Fairy stories are always interesting, don't you think?" which I didn't, right then, but there wasn't any use arguing. In fact, Mom said it wasn't ever polite, so I quit, and said, "Who's coming for dinner tomorrow?" wondering if it might be some of the gang, and hoping it would be. I didn't know a one of the gang that would notice whether the dishes sparkled or not, although most of the gang's Moms probably would.

"Oh—a surprise," Mom said.

"Who?" I said. "My cousin Wally and his new baby sister?" As you know, if you've read A New Sugar Creek Mystery, I had a homely, red-haired cousin, named Walford, who lived in the city, who had a new baby sister. Mom had been to see the baby, and also Pop, but I hadn't, and didn't want to, and certainly didn't exactly want to see my red-haired cousin, Wally, but would like to see his crazy Airedale dog, and if Wally was coming, I hoped he would bring the wire-haired dog along....

"It's a surprise," Mom said, and right that minute there was a whistle outside our house and at our front gate. I looked over the top of my stack of steaming dishes out through a clear place in the frosted window, and saw a fat-faced barrel-shaped boy standing with one hand which had a red mitten on it, holding onto a sled rope, and he was lifting up the latch on our wide gate with the other red-mittened hand....

There was another boy there, who, I could tell without hardly looking, was Dragonfly, on account of he is spindle-legged and has large eyes like a dragonfly's eyes are. Dragonfly had on a brand new cap with ear-muffs on it. As you maybe know, Dragonfly was always getting the gang into trouble, on account of he always was doing such crazy things without thinking. He also was allergic to nearly everything and was always sneezing at the wrong time, just when we were supposed to be quiet. Also, he was about the only one in the gang whose mother was superstitious,—such as thinking it[Pg 9] is bad luck if a black cat crosses the road in front of you, or good luck if you find a horseshoe and hang it above one of the doors in your house.

Just as Poetry had the latch of the wide gate lifted, I saw Dragonfly make a quick move, step with one foot on the iron pipe at the bottom of the gate's frame and give the gate a shove, and jump on with the other foot and ride on the gate while it was swinging open, which was something Pop wouldn't let me do, and which any boy shouldn't do, on account of if he keeps on doing it, it will make the gate sag, and maybe drag on the ground....

Well, for a jiffy I forgot there was a window between me and the out-of-doors, and also that my mom was beside me, and also that my baby sister, Charlotte Ann, was asleep in Mom's bedroom in her baby bed, and without thinking I yelled real loud, "Hey, Dragonfly, you crazy goof! Don't DO that!"

Right away I remembered Charlotte Ann was in the other room, on account of mom told me and also on account of Charlotte Ann woke up and made the kind of a noise a baby always makes when she wakes up and doesn't want to.

Just that second, the gate Dragonfly was on was as wide open as it could go, and Dragonfly who didn't have a very good hold with his hands—and the gate being icy anyway—slipped off and went sprawling head over heels into a snowdrift in our yard....

It was a funny sight, but not very funny 'cause I heard my pop's great big voice calling from our barn, yelling something that sounded like he sounds when somebody has done something he shouldn't and is supposed to quit quick, or I'd be sorry.

I made a dive for our back door, swung it open, and with one of my Mom's good plates still in my hands, and without my hat on, I rushed out on our back board walk and yelled to Poetry and Dragonfly, and said, "I'll be there in about an hour! I've got to finish tomorrow's dishes first! Better go on down the hill and tell the gang I'll be there in maybe an hour or two," which is what is called sarcasm.

And Poetry yelled, "We'll come and help you!"

[Pg 10]But it wasn't a good idea, 'cause the kitchen door was still open and Mom heard me and also heard Poetry and said to me, "Bill Collins, come back in here.... The very idea! I can't have those boys coming in with all that snow. I've just scrubbed the floor!" which is why they didn't come in, and also why barrel-shaped Poetry and spindle-legged Dragonfly started building a snow man right in our front yard, while they waited for me and Mom to finish playing Alice in Wonderland.

Pretty soon I was done, though, and grabbed my coat from its hook in the corner of the kitchen, pulled my hat on my red head, with the ear-muffs tucked inside, on account of it wasn't a very cold day, but was warm enough for the snow to pack good and for making snow balls and snow men and everything. I put on my boots at the door, said "Good-bye" to Mom and went swishing out through the snow to Poetry and Dragonfly. I could already hear the rest of the gang yelling down on Bumblebee hill, so I grabbed my sled rope which was right beside our back door, and the three of us went as fast as we could through our gate.

My pop was there, looking at the gate to see if Dragonfly had been too heavy for it, and just as we left, he said, "Never ride on a gate, boys, if you want to live long."

His voice was kinda fierce, like it sometimes is, and he was looking at Dragonfly; then he looked at me and winked, and I knew he wasn't mad but still didn't want any boy to be dumb enough to ride on our gate again.

"Yes sir, Mr. Collins," Dragonfly said politely, and grabbed his sled rope and started on the run across the road to a place in the rail fence where I always climbed through on my way to the woods.

"Wait a minute!" Pop said, and we waited.

His big bushy eyebrows were straight across, so I knew he liked us all right. "What?" I said, and he said, "You boys know, of course, that your new teacher, Mr. Black, is going to keep on teaching the Sugar Creek School—that the board can't ask him to resign just because the boys in the school liked their other teacher better, nor because he has had to punish several of them with old-fashioned beech switches...."

[Pg 11]Imagine my Pop saying such things, just when we had been thinking about having a lot of fun....

"Yes sir," I said to Pop, remembering the beech switches behind the teacher's desk.

"Yes sir," Poetry said politely.

"Yes sir," Dragonfly yelled to him from the rail fence where he was already half-way through.

We all hurried through the fence, and yelling and running and panting, we dragged our sleds through the woods to Bumblebee hill to where the gang was yelling and having a lot of fun.

Well, we coasted for a long time, all of us. Even Little Tom Till, the red-haired, freckled-faced little brother of Big Bob Till who was Big Jim's worst enemy, was there. Time flew faster than anything, when all of a sudden Circus who had rolled a big snowball down the hill, said, "Let's make a snow man—let's make Mr. Black"—which sounded like more fun, so we all started in, not knowing that Circus was going to make a comic snow man, the most ridiculous looking snow man I'd ever seen, and not knowing something else very exciting which I'm going to tell you about just as quick as I can get to it in this story.

It was the craziest snow man I had ever seen when we got through. It didn't have any legs on account of we had to use a very large snowball for its foundation, but it had another even-larger snowball for its stomach, on account of our new teacher was round in the middle, especially in front, and it had a smaller head. Circus, whose idea it was to make it funny, had dashed home to our house and gotten some corn silk out of our crib and had made hair for the man's head, putting it all around the sides of the top of its head, but not putting any in the middle of the top, nor in the front, so it looked like an honest-to-goodness bald-headed man.... Then, while different ones of us were putting a row of buttons on his coat, which were black walnuts which we stuck into the snow in his stomach, Circus and Dragonfly disappeared, leaving only Poetry and Little Jim and Little Tom Till and me, that being all the rest of the gang that was there, on account of Big Jim had had to go with his pop that afternoon to take a load of cattle to the city.

I was sitting down on my sled which was crosswise on the top of Little Jim's, which was crosswise on the top of Poetry's, making my seat just about knee high. Our snow man was at the bottom of the hill and not very far from us was a beech tree. Little Jim was standing there under its low-hanging branches, looking up into it, like he was thinking something very important which he nearly always is, Little Jim being the best Christian in the gang and always thinking and sometimes saying something he had learned in church or that his parents taught him from the Bible. There were nearly half of the leaves still on the tree in spite of its being winter and nearly every other tree in the woods was as bare as Old Mother Hubbard's cupboard. It was a beech tree and that kind of a tree nearly always keeps a lot of its old frost-bitten brown leaves on nearly all winter,[Pg 13] and only drops them off in the spring when the new leaves start to come, and push them off.

It was the same tree where one summer day, there had been a big old mother bear and her cub. I, all of a sudden, while I was sitting there on my stack of sleds was remembering that fight we'd had with the old fierce old mad old mother bear.

Anyway right that very minute while I was remembering the whole story, and I guessed maybe Little Jim was remembering it also, everything was so quiet, I said to Little Jim, "I bet you're thinking about how you killed a bear right there."

Little Jim who had his stick, which he always carried with him, said, "Nope, something else."

Poetry spoke up from where he was standing beside Mr. Black's snow statue, and said, "I'll bet you're thinking about the little cub which you had for a pet after you killed the bear."

Little Jim took a swipe with his stick at the trunk of the tree, and I noticed that his stick went ker-whack right on some initials on the tree which said, W. J. C., which meant "William Jasper Collins," which is my full name, only nobody ever calls me by the middle name except my pop, who calls me that only when he doesn't like me or when I'm supposed to have done something I shouldn't. Then Little Jim said to Poetry, just as his stick ker-whammed the initials, "Nope, something else." Then he whirled around and started making tracks that looked like rabbit tracks in the snow with his stick, and Tom Till spoke up and said, "I'll bet you're thinking about the fight we had that day...."

It was in that fight that I licked Little red-haired Tom Till, who with his big brother Bob had belonged to the other gang.... But now Little Tom's parents lived in our neighborhood and Tom had joined the gang, and also went to our Sunday School, and was a swell little guy; and as you maybe know, Bob was still a tough guy, and hated Big Jim and all of us, and we never knew when he was going to start some new trouble in the Sugar Creek territory....

"Well," I said, to Little Jim who was looking up into the tree again like he was still thinking something important, "what are you[Pg 14] thinking about?" and he said, "I was just thinking about all the leaves, and wondering why they didn't fall off like the ones on the maple trees do. Don't they know they're dead?"

I looked at the tree Little Jim was looking at, and it was the first time I'd noticed that the beech tree still had nearly every one of its leaves on it. They were very brown, even browner than some of the maple and walnut tree leaves had been, when they'd all fallen off last fall.

"How could they know they're dead, if they are dead?" Poetry said, and just that second I heard Circus and Dragonfly coming up from the direction of the bayou, which was down pretty close to Sugar Creek itself.... Circus had his knife in his hand and was just finishing trimming a small branch he had in his hand, Dragonfly had a long fierce-looking switch in one of his hands, and was swinging it around and saying loud and fierce, "All right, Bill Collins, you can take a licking for throwing that snowball.... Take that ... and that ... and that...." Dragonfly was making fierce swings with his switch and grunting every time he swung and every time he said "that...."

I knew what he was thinking about,—the snowball I'd thrown in our schoolyard that week, which had accidentally hit our new teacher right in the middle of the top of his bald head....

Well, in a jiffy, Circus had both those switches stuck into the snow man, right where his right hand was supposed to be.... Then, he reached into his pocket, and pulled out an ear of corn, and as quick as anything began to shell it ... shoving handfulls of the big yellow kernels into his pocket at the same time, and a jiffy later, all that was left was a long red corn-cob, which he broke in half and stuck one of the halves into the snowman's face for a nose.

Then also as quick as anything, he took the other half of the red corn-cob and with his knife made a hole in its side near the bottom, took a small stick out of his pocket, stuck it into the cob! "What on earth?" I thought, and said so, but he said, "All right, everybody, shut your eyes," which we wouldn't, so we watched him finish what he was doing, which was making a pipe for the snow man to smoke.... A jiffy later, there it was, sticking into the snow man's snow face[Pg 15] right under his nose—a corn-cob pipe.... It looked very funny, and for a jiffy we all laughed, all except Little Jim who just giggled a little.

We all stood back and looked at it, and it was the funniest looking snow man I'd ever seen.... Brown hair all around his head, and none in the middle of the top or the front, and a big red nose, and a corn-cob pipe sticking out at an angle, and black walnuts for buttons on his coat, and a couple of fierce-looking switches in his hand. Also there were two thin corn silk eyebrows that curled up a little....

"There's only one thing wrong with it," Poetry said, in his duck-like voice, standing beside me and squinting up at the ridiculous looking snow man.

"What?" I said, thinking how perfect it was.

"You can't tell who it is supposed to be. It needs some extra identification."

"It's perfect," I said, and looked at Little Jim to see if he didn't think the same thing, but he was looking up into the beech tree again, like he was still thinking about something mysterious and wasn't interested in an ordinary snow man. I looked toward Dragonfly and he was listening toward a half dozen little cedar trees in the direction of the bayou, like he was either seeing or hearing something, which he thought he was, for right that second he said, "Psst, gang, quiet! I think I saw something move over there—sh! Don't look now, or he'll—"

We all looked, of course, but didn't see anything, although I had a funny feeling inside of me which was, "What if it's Mr. Black watching us? What if all of a sudden he should come walking out from behind those cedar trees and see the snow man we've made of him, and what if he'd decide to use one or two of the switches on us?"—not a one of us being sure he didn't like us well enough to do that to us.

Poetry spoke up then and said, "I say, it's not quite perfect. There's one thing wrong with it, and I'm going to fix that right this very minute." With that remark, he pulled off one of his red mittens, shoved one of his fat hands inside his coat pocket, pulled something out,[Pg 16] and started to shuffle toward Mr. Black's snow statue. I could hardly believe my eyes at what I saw, but there it was as plain as day, a red, cloth-bound book with gold letters on it which said, The Hoosier Schoolmaster. I knew right away it was the book he and I had seen in his library one night and had read part of it, that part especially where the tough gang of boys in the story had caused the teacher a lot of trouble, and had locked him out of the schoolhouse; and then the teacher, who had been very smart, had climbed up on top of the school and put a flat board across the top of the chimney, and the smoke which couldn't get out of the chimney had poured out of the stove inside, and all the tough gang of boys had been smoked out....

"What are you going to do?" I said to Poetry, and he said, "Nothing," and right away was doing it, which was sticking two sticks in the snow man's stomach side by side and then opening The Hoosier Schoolmaster to the place where there was the picture of the teacher on the roof, and laying the book flat open across the two sticks.

"There you are, Sir," Poetry said, talking to the snow man. "The Hoosier Schoolmaster himself." Then Poetry made a bow as low as he could, he being so fat he grunted every time he stooped over very far.

Well, it was funny, and most of us laughed, Circus scooped up a snowball and started to throw it at it, but we all stopped him on account of not wanting to have all our hard work spoiled in a few minutes. Besides, Poetry all of a sudden, wanted to take a picture of it, and his camera was at his house which was away down past the sycamore tree and the cave, where we all wanted to go for a while to see Old Man Paddler. So we decided to leave Mr. Black out there by himself at the bottom of Bumblebee hill until we came back later, which we did.

"He ought to have a hat on," Dragonfly said. "He'll catch his death of cold with his bald head."

"Or he might get stung on the head by a bumblebee," Circus said, and Little Jim spoke up all of a sudden and said, like he was almost[Pg 17] mad at us, "Can anybody help it that he gets bald? My pop's beginning to lose some of his hair on top...." Then he grabbed his stick which he had leaned up against the beech tree for a jiffy, and struck very fiercely at a tall brown mullein stalk that was standing there in a little open space, and the seeds scattered in every direction, one of them hitting me hard right on my freckled face just below my right eye, and stung like everything; then Little Jim started running as fast as he could go in the direction of the sycamore tree, like he had been mad at us for something we'd done wrong. In fact, when he said that, I felt a kind of a sickish feeling inside of me, like maybe I had done something wrong. I grabbed my stick and started off on the run after Little Jim, calling out to the rest of the gang to hurry up, and saying, "Last one to the sycamore tree is a cow's tail," and in a jiffy we were running and jumping and diving around bushes and trees and leaping over snow-covered brushpiles toward the old sycamore tree and the mouth of the cave, which was there, and which as you know is a very long cave, and comes out at the other end in the cellar of Old Man Paddler's cabin.

Of course everybody knows about Old Man Paddler, the kindest old long whiskered old man who ever lived, and who was the best friend the Sugar Creek Gang ever had. He lived up in the hills above Sugar Creek, and almost every week the gang went up to see him—sometimes in the summer-time we went nearly every day. We went in the winter, too, on account of he lived all by himself and we had to go up to take him things which our moms were always cooking for him, and also we had to be sure he didn't get sick 'cause there wouldn't be anybody there to take care of him or call the doctor for him on account of he didn't have any telephone....

After a little while we were tired of running so fast, so we slowed down, it being easier to be a cow's tail than to get all out of breath. Poetry and I were side by side most of the time with Little Jim walking along behind us and with Little Tom Till and Circus and Dragonfly swishing on ahead of us. Once when Little red-haired Tom and Little Jim were beside each other behind Poetry and me, I heard Little Jim say to red-haired Tom, "Mom says for you to be ready a little early tomorrow morning, on account of the choir has to practice their anthem again before they sing."

I knew what Little Jim was talking about 'cause his folks stopped at Tom's house every Sunday morning about nine o'clock, and Little Tom got in and rode to Sunday School with them in their big maroon and grey car. Little Jim's very pretty mom was the pianist at our church, and had to be always on time. Little Jim's words came out kinda jerkily like he was doing something that made him short of breath while he talked. I turned around quick to see, and sure enough, he was shuffling along, making rabbit tracks with his stick, and saying his words every punch of his stick into the snow.

[Pg 19]Little Tom answered Little Jim by saying, "O de koke," which is the same as saying, "Okey doke," which means "O.K." which is what most anybody says when he means "All right," meaning Tom Till would be ready early, and that when Little Jim's folks came driving up to their front gate tomorrow, Little Tom, with his best clothes on, would come running out of their dilapidated old unpainted house, carrying his New Testament, which Old Man Paddler had bought for him.... Then they'd all swish away together to Sunday School.

Then I heard Little Jim ask something else which showed what a grand little guy he was. "S'pose maybe your mother would like to go with us, too?"

"My mother would like to go with us," Tom said to Little Jim, "but she doesn't have any clothes that're good enough." And knowing the reason why was because her husband drank up nearly all the money he made in the Sugar Creek beer taverns, and also drank whiskey which he bought in the liquor store—knowing that, I felt my teeth gritting hard and I took a fierce swing with the stick I was carrying, at a little maple tree beside me.... I socked that tree so fierce with my stick, that my hands stung so bad they were almost numb; the stick broke in the middle and one end of it flew ahead to where Circus and Dragonfly were and nearly hit them.

"Hey, you!" Dragonfly yelled back toward us, "What you trying to do—kill us?"

"What on earth!" Circus yelled back to me, and I stood looking at the broken end of the rest of the stick in my hand, then turned like a flash and whirled around and threw it as hard as I could straight toward another tree about twenty feet away. That broken stick hit the tree right in the center of its trunk, with a loud whack.

I didn't answer them in words at all. I was so mad at Tom's pop and at beer and whiskey and stuff.

But I couldn't waste all my temper on something I couldn't help, so I kept still and we all went on to the cave, and went in, and followed its long narrow passageway clear through, until we came to the big wooden door which opened into Old Man Paddler's cellar.[Pg 20] As soon as we got there, Circus, who was always the leader of our gang when Big Jim wasn't with us, stopped us, and made us keep still, then he knocked on the door—three knocks, then two, then three more, then two, which was the code the gang always used when we came, so Old Man Paddler would know it was us.

If he was home, he would call down and say in his quavering old voice, "Who's there?" and we'd answer, and right away we'd hear his trap door in the floor of his house open, and hear his steps coming down his stairway and hear him lift the big wooden latch that held the door shut, and then when he'd see us, he'd say, "Well, well, well, well, the Sugar Creek Gang—" then he'd name every one of us by our nicknames, and say, "Come on in, boys, we'll have some sassafras tea," which all of us, especially Little Jim, liked so very much.

Everything was quiet while Circus knocked ... three times, then two, then three, and then two again, while we all waited and listened. There was always something kinda spooky about that knock, and being in a cave I always felt a little queer until I heard the old man's voice answer us. In fact, I always felt creepy until we got inside the cabin and the trap door was down again.

We all stood there, outside that big wooden door, waiting for Old Man Paddler to call down to us, but there wasn't a single sound, so Circus knocked again: three times, then two, then three, and then two again, and we all waited. Except for my little pocket flashlight which my pop had given me for Christmas, we didn't have any light, and we couldn't waste the battery by keeping it on all the time, so I turned it off, but it felt so spooky with it off and nobody answering Circus's knock that I turned it on again just as Dragonfly who was always hearing things first, said, "Psst!" which meant "I heard something mysterious! Everybody keep still a minute," which we did; and then as plain as day I heard it myself, an old man's voice talking. It was high pitched and quavering, and kinda sad-like, like he was begging somebody to do something for him....

We were all so quiet as mice, not a one of us moving or hardly breathing.... I couldn't hear a word the old man was saying, but he sounded like he needed help.... I remembered how we'd all saved[Pg 21] his life two different times—once when a robber had tied him up and he'd have starved if we hadn't found him, and another time when he'd fallen down his cellar steps in the winter-time and his fire had gone out, and we had started a fire for him with punk, using the thick lenses of his reading glasses for a magnifying glass—which any boy can do if he can get some real dry punk and a magnifying glass.... First you focus the red hot light which shines from the sun through the magnifying glass, right on the punk until it makes a little smoking live coal, then you hold a piece of dry paper against the red glow on the punk, and blow and blow with your breath until all of a sudden there will be an honest to goodness flame of fire....

Say, when I heard Old Man Paddler half talking and half crying up there in his cabin, I got a very queer feeling inside of me....

"Quick!" Circus said, "He's in trouble. Let's go in and help him." Circus gave a shove on the door, turning the latch at the same time, but the door wouldn't budge.

"It's barred," Poetry said, and I remembered the heavy bar on the inside which the old man always dropped into place whenever he was inside.

"Sh! Listen!" Little Jim said, and we shushed and listened.

Say, that little guy had his ear pressed up real close to a crack in the door, and in the light of my flashlight which I didn't shine right straight on his face on account of it might blind him, I could see that his eyes had a very far away look in them, like he was thinking something important and maybe in his mind's eyes was seeing something even more important.

"What is it?" I said to him, and he said, "Don't worry, he's all right. He doesn't need our help—here, listen yourself," which I did, and right away I knew Little Jim was right.... For this is what I heard the old man saying in his quavering, high-pitched voice, "... And please, You're the best friend I ever had, letting me live all these long years, taking care of me, keeping me well and strong and happy most of the time. But I'm getting lonesome now, getting older every day, getting so I can't walk without a cane, and I can't stand the cold weather anymore, and I know it won't be long before I'll have to move out of this crippled-up old house and come to live[Pg 22] with You in a new place.... I'll be awful glad to see Sarah again, and my boys.... And that reminds me,—Please bless the boys who live and play along old Sugar Creek—all of 'em—Big Jim, Little Jim, Circus, Dragonfly, Poetry, Bill Collins...."

I knew what the kind man was doing all right, 'cause I'd seen and heard him do it many a time in our little white church, and also I'd seen him doing it once down on his knees behind the old sycamore tree all by himself.... When I heard him mention my name, I gulped, and some crazy tears got into my eyes and into my voice.... I had to swallow to keep from choking out a word that would have let the gang know I was about to cry.... Like a flash I thought of something and I whirled around and grabbed Little Tom Till and shoved his ear down to the crack in the door and put my own ear just above his so I could hear too, and this is what the old man was saying up there in the cabin, "And also bless the new member of the gang, Tom Till, whose father is an infidel and spends his money on liquor and gambling.... Oh God, how can John Till expect his boys to keep from turning out to be criminals.... Bless his boy, Bob, whose life has been so bent and twisted by his father.... And bless the boys' poor mother, who hasn't had a chance in life.... Lord, you know she'd go to church and be a Christian if John would let her.... And please...."

That was as far as I got to listen right that minute cause I heard somebody choke and gulp and all of a sudden Little Tom Till was sniffling like he had tears in his eyes and in his voice, and then that little guy who was the grandest little guy who ever had a drunkard for a father, started to sob out-loud like he was heart-broken, and couldn't help himself.

I got the strangest feeling inside of me like I do when anybody cries, and I wanted to help him stop crying and didn't know what to do.

"'Smatter?" Dragonfly said, and Tom said, "I want to go home!"

"'Smatter?" Circus said, "Are you sick?"

"Yeah, what's the matter?" Poetry's duck-like voice squawked, but Little Jim was a smart little guy and he said, "He doesn't feel well. Let's all take him home."

[Pg 23]"I'll go b-b-by m-m-myself," Little Tom said, and started back into the cave, but I knew it was too dark for him to see, so I grabbed his arm and pulled him back. "We'll all go with you."

"But we wanted to see Old Man Paddler," Dragonfly said, "What's the use to go home? I want some sassafras tea."

"Keep still," I said, "Tom's sick. He ought to go home." I knew Little Tom was terribly embarrassed, and that he'd be like a little scared rabbit if we took him into Old Man Paddler's cabin now.

We must have made a lot of noise talking 'cause right that minute I heard Old Man Paddler's voice up there calling down to us, "Wait a minute, boys! I'll be right down...."

Well, it would have been impolite to run away now, and so I whispered to Tom, "Me and Little Jim are the only ones who heard him praying and—and we—we like you anyway." I gave Tom a kinda fierce half a hug around his shoulder, just as I heard Old Man Paddler's trap door in the floor of his house opening, and a shaft of light came in through the crack in the door right in front of us.... In a jiffy our door would open too, and we'd see that kind old long whiskered old man, with his twinkling grey eyes, and pretty soon we'd all climb up the cellar steps and be inside his warm cabin with a fire crackling in his fireplace and with the teakettle on the stove for making sassafras tea, and the old man would be telling us a story about the Sugar Creek of long ago....

All of a sudden, I got the strangest warm feeling inside of me, and I felt so good, something just bubbled up in my heart.... It was the queerest feeling, and made me feel good all over, 'cause right that second one of Little Tom's arms reached out and gave me a very awkward half a hug real quick, like he was very bashful or something, but like he was saying, "You're my best friend, Bill.... I'd lick the stuffin's out of the biggest bum in the world for you, in fact I'd do anything."

But his arm didn't stay more'n just time enough for him to let it fall to his side again, but I knew he liked me a lot and it was a wonderful feeling.

[Pg 24]Right that second, I heard the old man lift the bar on the big wooden door, and push it open, and real bright light came in and shone all over all of us, and the old man said, "Well, well, well, well, the Sugar Creek Gang! Come on in, boys, we'll have a party."

A jiffy later, we were all inside his cellar, and scrambling up his cellar steps into his warm cabin.

It didn't take more'n several jiffies for all of us to be inside that old-fashioned cabin, where there was a crackling fire in his fireplace and another fire roaring in his kitchen stove and where there was a teakettle singing like everything, meaning that pretty soon we'd have some sassafras tea. In fact, as soon as the trap-door was down and we were all sitting or standing or half lying down on his couch and on chairs, the old man put some sassafras chips from sassafras tree-roots into a pan on the stove and poured boiling water on it, and let it start to boil. Almost right away the water began to turn as red as the chips themselves and Little Jim's eyes grew very bright as he watched the water boil.

One of the first things I noticed when I looked around the room a little was the old man's Bible which was open to the Sunday School lesson, like maybe he'd been studying, getting ready for church tomorrow. I knew it was tomorrow's lesson 'cause at our house we had already studied the same lesson two or three times, on account of Mom and Pop always started to study next week's lesson a whole week ahead of time, so, as Pop says, "different ideas will come popping into our heads all week long even while we're working or studying or something." I knew Little Jim's parents always started studying their lessons the first thing in the week, also, and maybe that was why that little guy was always thinking of so many things that were important.

From where I was sitting, I could look through a clear place in the old man's kitchen window which didn't have any frost on it, and I could see the shadow the smoke was making which was coming out of the chimney, and the longish darkish shadow was moving up the side of the old man's woodshed out there, and on up the slant of the snow-covered roof, making me think of a great big long dark[Pg 26]ish worm twisting and squirming and crawling up a stick in the summer-time.... There must have been almost a foot of snow on the roof of that woodshed, I thought, and that reminded me of the snow man at the bottom of Bumblebee hill, and when I noticed that the shadows of the trees out there were getting very long it meant that it wouldn't be long till the sun went down, and if Poetry and I were to get a good picture of Mr. Black's snow statue, we'd have to hurry.

Old Man Paddler all of a sudden spoke up and said to us, looking especially at me, "One of you boys want to take the water pail and go down to the spring and get a pail of fresh water?" which I didn't exactly want to do, on account of it was very warm in the cabin and would be very cold out there, but when Little Jim piped up and said, "Sure, I'll do it," I all of a sudden said the same thing, and Little Jim and I were out there in less than a jiffy, with the old man's empty pail in one of my hands, and were galloping along through the snow toward the spring, which was right close to a big spreading beech tree, which, like the one at the bottom of Bumblebee hill, still had most of its old brown leaves on it....

We filled the pail real quick with the sparkling, very cold water, and hurried back to the cabin. I started to open the door, when Little Jim said, "Wait a minute, I want to see something," and he swished around quick and went back down the path toward the spring, and turned around again and looked up toward the chimney of the old man's cabin. He squinted his eyes to keep the sun from blinding them and looked and looked, then he looked away in the direction of the woodshed, and I wondered what in the world that little guy was thinking.

"'Smatter?" I said, and he said, "Nothing,—there's certainly a lot of snow on the roof of that woodshed, and there isn't any on the old man's cabin. How come?" Then he socked a stump with his stick, and came lickety-sizzle to the door, opened it for me to go in with the pail of water, which I did.

Well, as soon as we got through with our sassafras tea, which Little Jim said tasted like a very sweet hot lolly pop, we all scrambled[Pg 27] around in the old man's cabin getting ready to go home. If it had been in the summer-time, we would have gone home the long way round, following the old wagon trail, and then we'd have taken a short cut through the swamp, and if it had been summer-time maybe stopped at the big mulberry tree and climbed up into it and helped ourselves to the biggest, ripest mulberries that grew anywhere along Sugar Creek. But it wasn't summer, so we took the short cut, going through the cave to the sycamore tree, where most of us separated and went in different directions to our different homes, all except Poetry and me, who, as you know, were going to get his camera and take a picture of Mr. Black's snow statue, his parents having bought a new camera for him at Christmas.

"Well, well," Poetry's mother said to us when we stopped beside their big maple tree, and I waited a jiffy for him to go in the house and get the camera, "where have you boys been? I've been phoning all over for you, Leslie"—meaning she had been phoning all over for Poetry, Leslie being the name which his parents used and which he had to use himself when he signed his name in school ... but he would rather be called Poetry.

"'Smatter?" Poetry asked his kinda round-shaped mom, "Didn't I do my chores, or something?"

Then Poetry's mother startled us by saying, "We've had company. Mr. Black was here. He just left a minute ago."

I had a queer feeling start creeping up my spine.

"What did he want—I mean, where did he go? Where'd you tell him we were?" Poetry and I both said at the same time only in different words, but with probably the same scared feeling inside, and thinking, "What if she told him we were playing over on Bumblebee hill and he had gone there?"

"He didn't seem to want anything in particular. He was out exercising his horse. Such a beautiful big brown saddle horse!" Poetry's mother said. "And such a very beautiful saddle. He looks very stunning in his brown leather jacket and riding boots."

[Pg 28]"What did he want?" Poetry said again, taking the words right out of my mind, and Poetry's mom said, "Nothing in particular. He said he wanted to get acquainted with the parents of his boys."

I looked at Poetry and he looked at me, and he said to his mom, "He's too heavy for the horse," and his mother looked at Poetry who was also heavy and said, "Too much blackberry pie, I suppose. You boys want a piece?"

Poetry's face lit up, and he said, "We'll take a piece apiece," which we did, and then I said to him all of a sudden, "The sun'll still be shining on Mr. Black. If we want to get his picture, we'll have to hurry!"

"Shining on who?" Poetry's mom said, and Poetry said, "The sun is shining in through the window on my blackberry pie," and winked at me, and his mom went into their parlor to answer the phone which was ringing.

Poetry finished his pie at the same time, slithered out of his chair and went up stairs to his room to get his camera, just as I heard his mother say into their telephone, "Why yes, Mrs. Mansfield, we do—certainly, I'll send Leslie right over with it right away—oh, that's all right—no, he won't mind, I'm sure."

It sounded like an ordinary conversation any mother might have with any ordinary neighbor. I'd heard my mom say something like that many a time, the only difference being she would say, "Why yes, Mrs. So-and-So, we have it. I'll send Bill over with it right away—oh, that's all right—no, he won't mind, I'm sure," which I hardly ever did anymore on account of my pop wouldn't let me. I was always running an errand for some neighbor who didn't have any boys in the family, which is what boys are for.

I was wondering where Poetry had to go, with what, and why, when Poetry's mom called up the stairs to him and said, "Leslie, will you bring down The Hoosier Schoolmaster, and you and Bill take it over to Mrs. Mansfield."

I heard Poetry gasp and call back down, "Get WHAT?"

"The Hoosier Schoolmaster!" his mom called up. "It's on the second shelf in your library—it's a red book with gold lettering[Pg 29] on it;" then Mrs. Thompson said to me, "Having a new gentleman teacher in the community has made everybody interested in that very interesting book, so Mrs. Mansfield is going to review it for the Literary Society next Wednesday night."

Then Poetry's mom called up to him and asked, "Find it, Leslie?" which of course he hadn't and couldn't, anyway, not upstairs, 'cause right that minute it was lying open on two sticks stuck into Mr. Black's stomach at the bottom of Bumblebee hill. For some reason it didn't seem as if we wanted to tell Mrs. Thompson where it was, but it looked like we were in for it.

We couldn't come right out and tell her where the book was, 'cause she was like most of the other parents in Sugar Creek territory—she thought Mr. Black, who rode a fine horse and wore a brown leather jacket and riding boots and who could smile politely and tip his hat whenever he saw a Sugar Creek Gang mother, was a very fine gentleman, and certainly didn't know what a hard time the gang had been having with him.

Just that second Poetry called down and said, "Bill and I'll take it to her."

The gang didn't know Mrs. Mansfield very well, on account of she was a new person in the Sugar Creek territory and didn't have any boys, and was more interested in society than any of the gang's moms and was always reading important books on account of it maybe made her seem more important if she knew the names of all the important books and who wrote them.

Poetry came downstairs with his camera, coming down in a big hurry and saying to me in a business-like voice, "Let's get going, Bill," and made a dive for the door so his mom wouldn't see he didn't have The Hoosier Schoolmaster, not wanting her to ask where it was, so he wouldn't have to tell her.

Both Poetry and I were out of doors in a jiffy and the door was half shut behind us when Poetry's mother said, "Hadn't we better wrap it up, Leslie,—just in case you might accidentally drop it?"

"I promise you, I won't drop it," Poetry said, "besides we want to hurry. I want to take a picture of something before the sun gets too far down. Come on, Bill, hurry up!" Poetry squawked to me,[Pg 30] and I hurried after him, both of us running fast out through their back yard in the direction of Bumblebee hill.

But Poetry's mother called to us from the back door and said, "Where are you going? Mrs. Mansfield doesn't live in that direction."

Poetry and I stopped and looked at each other.

All of a sudden we knew we were caught, so Poetry said to me, "What'll we tell her?"

And remembering something my pop had taught me to do when I was caught in a trap, I said all of a sudden, quoting my pop, "Tell her the truth."

Poetry scowled, "You tell her," he said, which I did, saying "Mrs. Thompson, the gang had The Hoosier Schoolmaster this afternoon, and we left him—I mean it—down on Bumblebee hill. We have to go there first to get it," and all of a sudden I felt fine inside, and know that Pop was right. Poetry's mom might not like to hear exactly where the book was, right that very minute, and it didn't seem exactly right to tell her, so when she didn't ask me, I didn't tell her.

Poetry's mother must have understood her very mischievous boy, though, and didn't want to get him into a corner, for she said, "Thank you for telling me. Now I can phone Mrs. Mansfield it will take a little longer for you to get there with the book—and, by the way, if you see Mr. Black tell him about next Wednesday night—you probably will see him. I told him you boys were over on Bumblebee hill, and how to get there. He seemed to want to see you."

Poetry and I both yelled back to her, saying, "You told him WHAT!" and without another word or waiting to hear what she said, we started like lightning as fast as we could go, straight for Sugar Creek and Bumblebee hill, wondering if by taking a short cut we could get there before Mr. Black did; and in my mind's eye, I could see Poetry, IF we got there first, making a dive for The Hoosier Schoolmaster on the snow man; and I could see myself, making a leap for the man's head, and knocking it completely off, I could see it go rolling the rest of the way down the hill with its cornsilk hair getting covered with snow—also I could see Mr. Black in his[Pg 31] brown riding jacket and boots, on his great big saddle horse, riding up right about the same minute.

What if we didn't get there first? I thought. What if we didn't? It would be awful! Absolutely terrible! And Poetry must have been thinking the same thing, 'cause for once in his life, in spite of his being barrel-shaped and very heavy, and never could run very fast, I had a hard time keeping up with him....

All the time while Poetry and I were running through the snowy woods, squishety-sizzle, zip-zip-zip, crunch, crunch, crunch, I could see in my mind's eye our new teacher's big beautiful brown saddle horse, prancing along in the snow toward Bumblebee hill, carrying his heavy load just as easy as if it wasn't anything. Right that very minute, maybe, the horse would be standing and pawing the ground and in a hurry to get started somewhere, while maybe its rider was standing with The Hoosier Schoolmaster in his hand, looking at the picture of the schoolhouse, and then maybe looking at the ridiculous-looking snow man we'd made of him....

In a few minutes Poetry and I were so out of wind that we had to stop and walk awhile, especially because I had a pain in my right side which I sometimes got when I ran too fast too long. "My side hurts," I said to Poetry, and he said, "Better stop and stoop down and unbuckle your boot, and buckle it again, and it'll quit hurting."

"It'll WHAT?" I said, thinking his idea was crazy.

"It'll quit hurting, if you stop and stoop down and unbuckle your boot and then buckle it again."

Well, I couldn't run anymore with the sharp pain in my side, so even though I thought Poetry's idea was crazy, I stopped and stooped over, biting off my mittens with my teeth, and laying them down on the snow for a jiffy and unbuckling one of my boots and buckling it again while I was still stooped over; then I straightened up, and would you believe it? That crazy ache in my side was actually gone! There wasn't even a sign of it.

I panted a minute longer to get my wind, then we started on the run again. "It's crazy," I said, "but it worked. How come?"

"Poetry Thompson's father told me," he said, puffing along ahead of me, "only it won't work in the summer-time. In the summer-time you have to stop running, and stop and stoop down and pick up[Pg 33] a rock, and spit on it and turn it over and lay it down again very carefully upside down, and your side will quit hurting."

Right then, I stumbled over a log and fell down on my face, and scrambled to my feet and we hurried on, and I said to Poetry, "What do you do when you get a sore toe from stumping it on a log—stoop over and scrape the snow off the log and kiss it, and turn it over, and then—?"

It wasn't any time to be funny, only worried, but Poetry explained to me that it was the stooping that was what did it. "It's getting your body bent double, that does it.—Hey! Look! There he is now!"

I looked in the direction of our house, since we were getting pretty close to Bumblebee hill, and sure enough, there was our teacher sitting on his great big beautiful brown horse which was standing and prancing right beside the old iron pitcher pump not more than twenty feet from our back door. Mom was standing there with her sweater on and a scarf on her head talking to him or maybe listening to him, then I saw Mr. Black tip his hat like an honest-to-goodness gentleman, and bow, and his pretty horse whirled about and went in a horse hurry to our front gate which was open, and being held open by my pop, and he went on, galloping up the road, his horse galloping in the shadow which they made on the snowy road ahead of them.

Well, that was that, I thought, and Poetry and I who were at the top of Bumblebee hill hurried down to where he and I had left our sleds, the rest of the gang having taken theirs with them when we'd gone to the cave. At the bottom of the hill, we saw the great big tall snow man. The sun was still shining right straight on it, but wouldn't be, pretty soon, but would go down. So Poetry and I stopped close to it, and he got his camera ready.

"You get The Hoosier Schoolmaster, Bill, and turn it around and stand it up against the Hoosier schoolmaster's stomach." Poetry ordered, "so I can get a good picture of it," which I started to do, and then gasped.... There wasn't any Hoosier Schoolmaster! The book was gone. "It's gone!" I said to Poetry, and it was, and there was a page of yellow writing paper, instead.

[Pg 34]"Hey!" I said, "There's something printed on it!" Sure enough, there was. The piece of yellow writing tablet was standing up on the two sticks, leaning against the snow man's stomach, and was fastened so the wind wouldn't blow it away, by another stick stuck through the paper and into the snow man's stomach.

"It's your poem, Poetry," I said, remembering the poem which Poetry had written about our teacher. "How'd it get here?" Right away I was reading the poem again, which was almost funny, only I didn't feel like laughing on account of wondering who had stolen the book and had put the poem here in its place. The poem was written exactly right:

It had been funny the first time I had read it, which was not more than a week ago, but for some reason right that minute it was anything in the world else. I was gritting my teeth and wondering who had done it, and who had stolen The Hoosier Schoolmaster. There wasn't a one of the gang that could have done it, 'cause we had all been together all afternoon; and at the cave all the rest of the gang had gone to their different homes.

"Who in the world wrote it and put it there?" I said, noticing that the printing was very large and had been put on with black crayola, the kind we used in school.

"There's only one other person in the world who knows I wrote that poem," Poetry said, "and that's Shorty Long."

"Shorty Long!" I said, remembering the newest boy who had moved into our neighborhood and was almost as fat as Poetry and who had been the cause of most of our trouble with our new teacher and had had two or three fights with me and had licked the stuffins out of me once, and I had licked the stuffins out of him once also, even worse than he had me, almost.

"How'd he find it out?" I said.

"Dragonfly told him," and also I remembered right that minute that Dragonfly and Shorty Long had been kinda chummy last week[Pg 35] and we had all worried for fear there was maybe going to be trouble in our own gang which there'd never been before, and all on account of the new fat guy who had moved into our neighborhood and had started coming to our school.

"Are you going to take a picture of it?" I said to Poetry, and he said, "I certainly am; I'm going to have the evidence and then I can prove to anybody that doesn't believe it, that somebody actually put it here."

"Yeah," I said, "but everybody knows you wrote the poem."

Poetry lowered his camera, and just that minute I saw something else that made me stare and in fact startled me so that for a jiffy I was almost as much excited as I had been when the fierce old mad old mother bear had been trying to kill Little Jim right at that very place where we were about a year and a half ago.

"Hey! Look!" I said, "Mr. Black's been here himself!"

"Mr. Black!" Poetry said in almost a half scream.... And right away both of us were looking down in the snow around the beech tree, and around the snow man, and sure enough there were horse's tracks, the kind of tracks that showed that the horse had shoes on. And even while I was scared and wondering "What on earth!" there popped into my red head the crazy superstition that if you found a horseshoe and put it up over the door of your house or one of the rooms of your house, you would have good luck....

"I'll bet Mr. Black took the book, and wrote the poem and put it here."

"He wouldn't," I said, but was afraid he might have.

"I'm going to take a picture anyway," Poetry said, and stepped back and took one, and then real quick, took another, and then he took the yellow sheet of paper with the poem on it and folded it up and put it in his coat pocket, and with our faces and minds worried we started in fiercely knocking the living daylights out of that snow man. The first thing we did was to pull off the red nose, and pull out the corn-cob pipe, and knock the round head off and watch it go ker-swish onto the ground and break in pieces, then we pulled the sticks out of his stomach, kicked him in the same place, and in a jiffy had him looking like nothing.

[Pg 36]We felt pretty mixed up in our minds, I can tell you.

"Do you suppose Mr. Black did that?" I said.

"He wouldn't," Poetry said, "but if he rode his horse down here and saw it, he'll certainly think we're a bunch of heathen."

"We aren't, though—are we?" I said to Poetry, and for some reason I was remembering that Little Jim had acted like maybe we ought not make fun of our teacher just 'cause he had hair only all around his head and not on top, and couldn't help it. For some reason, it didn't seem very funny, right that minute, and it seemed like Little Jim was right.

"What about The Hoosier Schoolmaster?" Poetry said to me, as we dragged our discouraged sleds up Bumblebee hill. "What'll we tell your mother? And what'll she tell Mrs. Mansfield?"

"I don't know," Poetry said, and his voice sounded more worried than I'd heard it in a long time.

The first thing Mom said to us when we got to our house was, "Mr. Black was here twice this afternoon."

"Twice?" I said. "What for? What did he want?"

"Oh he was just visiting around, getting acquainted with the parents of the boys. Such a beautiful brown saddle horse," Mom said. "And he was so polite."

"The horse?" Poetry said, and maybe shouldn't have, but Mom ignored his remark and said, "He took a picture of our house and barn and tried to get one of Mixy cat, but Mixy was scared of the horse, I guess, and ran like a frightened rabbit."

"Was he actually taking pictures?" Poetry asked with a worried voice.

"Yes, and he wanted to get one of you boys playing on Bumblebee hill.... But you were all gone, he said, but he found the book you left there, so he brought it back—you know, the one Mrs. Mansfield wanted."

"What book?" I said, pretending to be surprised. "Did Mrs. Mansfield want a book?"

And Mom who was standing at our back door bareheaded, and shouldn't have been, on account of she might catch cold, said, "Yes, she phoned here for The Hoosier Schoolmaster, while Mr. Black was here,[Pg 37] but I knew your mother had one, Poetry, so I told her to call there."

Poetry and I were looking at each other, wondering "What on earth?" Then Mom said, "Mr. Black thought maybe you boys had been reading it or something and had forgotten it when you left."

"D-d-d-did he—did he—?" Poetry began, but stuttered so much he had to stop and start again, and said, "Did he say where he found it? I mean was it—that is, where did he find it?"

"He didn't say," Mom said, "but he said since he was going on over to Mrs. Mansfield's anyway, he'd take it over for me, so you won't have to take it over, Bill," Mom finished.

Well, that was that.... Poetry and I sighed to each other, and he said, "Did you tell my mother?"

"I've just called her," Mom said, "and you're to come on home right away to get the chores done early.... It's early to bed for all of us on Saturday night, you know."

Poetry must have felt pretty bad, just like I did, but he managed to say to Mom politely, "Thank you, Mrs. Collins. I'll hurry right on home."

I walked out to the gate with him, and for a jiffy we just stood and looked at each other, both of us with worried looks on our faces.

"Do you suppose he really took a picture of himself with that poem on his stomach?" Poetry asked. "And if he did, who on earth put it there?"

"I don't know," I said, "but what would he want with pictures of all of us and our parents?"

"I'm sure I don't know—" Poetry said, with a worried voice.

Just that minute Pop called from the barn and said, "BILL, HURRY UP AND GATHER THE EGGS! IT'LL BE TOO DARK TO SEE IN THE BARN AS SOON AS THE SUN GOES DOWN! POETRY, BE SURE TO COME AGAIN SOME TIME," which was Pop's way of telling Poetry to step on the gas and get going home right now, which Poetry did, and I went back to the house and got the egg basket to start to gather the eggs, wondering what would happen next.

Just as I started to open our kitchen door and go out to the barn, Mom came from the other room where she'd been talking on the phone and said, "Little Jim's mother is coming down with the flu, and won't be able to go to church tomorrow, so we're to pick up Little Jim and also stop for Tom Till and take him to church with us.... We'll have to get up a little earlier tomorrow morning, so you get the chores done quick so we can get supper over and to bed nice and early," which I thought was a good idea. I was already tired all of a sudden, almost too tired to gather the eggs.

Tomorrow, though, would be a fine day. It'd be fun stopping at Little Jim's and Tom Till's houses and take them to church with us.

Little Jim had something on his mind that was bothering him, though, and I wondered what it was. Also, I wondered who was coming to our house for dinner tomorrow. Maybe it would be Little Jim, as well as somebody else, if his mom was going to have the flu.

Pretty soon I was up in our haymow all by myself carrying the egg basket around to the different places where different ones of our old hens laid their eggs. Old Bent-comb still laid her daily egg up in a corner of the mow so I climbed away up over a big stack of sweet-smelling hay to where I knew the nest was. I wasn't feeling very good inside on account of things hadn't gone right during the day, and yet I couldn't tell what was wrong, except maybe it was just me. When I got to old Bent-comb's nest, sure enough there were two eggs in it—one was the pretty white egg Bent-comb herself had laid that day and the other was an artificial glass egg which we kept in the nest all the time just to encourage any hen that might see it, to stop and lay an egg there herself, just as if maybe there had been another hen who had thought it was a good place to lay an egg. It was easy to fool old Bent-comb, I thought.

[Pg 39]While I was getting ready to go back to the ladder and go down it to the main floor of the barn, my eyes climbed up Pop's brand new ladder which goes up to the cupola at the very peak of the roof of our very high barn. It certainly was a very nice light ladder, and next summer it would be easy for me to carry it to one cherry tree after another in our orchard when I helped pick cherries for Mom. It was such a light ladder, even Little Jim could carry it.... While I was standing looking up and thinking about wishing spring would hurry up and come, I all of a sudden wanted to climb up the ladder and look out the windows of the cupola and see what I could see in the different directions around the Sugar Creek territory. Also, I wondered if Snow-white, my favorite pigeon, and her husband had decided to have their nest in the cupola again this year, and if there were maybe any eggs or maybe a couple of baby pigeons, although parent pigeons hardly ever decided to raise any baby pigeons in the winter-time. If there was anything I liked to look at more than anything else, it was baby birds in a nest. Their fuzz always reminded me of Big Jim's fuzzy mustache, he being the only one of the Sugar Creek Gang to begin to have any.

In a jiffy I was on my way and in another jiffy I was there, standing on the second from the top rung of the ladder. It was nice and light up there with the sun still shining in, although pretty soon it would go down. In one direction I could see Poetry's house, and their big maple tree right close beside it in the back yard, under which in the summer-time he always pitched his tent and sometimes he would invite me to stay all night with him; in another direction, and far away across our cornfield, was Dragonfly's house which had an orchard right close by it, where in the fall of the year we could all have all the apples we wanted, if we wanted them; Big Jim and Circus lived right across the road from each other, but I couldn't see either one of their houses, or Little Tom's on account of Little Tom lived across the bridge on the other side of Sugar Creek.... I could see our red brick schoolhouse, away on past Dragonfly's house, though. But when I looked at it, instead of feeling kinda happy inside like I nearly always did when we had our pretty lady other teacher for a teacher, I felt kinda saddish. There was the big maple[Pg 40] tree which I knew was right close beside a tall iron pump, near which we had built a snow fort; and behind that was the woodshed where we'd been locked in by our new man teacher and which you know about if you've read One Stormy Day at Sugar Creek, and behind the woodshed was the great big schoolyard where we played baseball and blindman's buff and other games in the fall and spring, and where we play fox-and-goose in the winter. For a few minutes I forgot I was supposed to be gathering eggs, and was doing what Pop is always accusing me of doing, which is "dreaming." I was thinking about what had happened that afternoon, such as the trip we'd taken through the cave to Old Man Paddler's cabin, and the prayer he'd made for all of us, and especially for Old Hook-nosed John Till, which Little Tom had heard, and it had made him cry and want to go home. Poor Little Tom, I thought. What if I had had a pop like his, instead of the kinda wonderful pop I had, who made it easy for Mom to be happy, which is why maybe Mom was always singing around our kitchen, even when she was tired, and also why, whenever Pop came into our house after being gone awhile, Mom would look up quick from whatever she was doing and give him a nice look, and sometimes they'd be awful glad to see each other, and Pop would give her a great big hug like pops are supposed to do to moms. Poor Little Tom's mom, I thought.

Well, while I was still not thinking about finishing gathering the eggs, I looked in the last direction I hadn't looked yet, which was toward our house and over the top of the spreading branches of the plum tree and over the top of our gate which Dragonfly had had his ride on, and on down toward Bumblebee hill where we'd coasted and had fun and made the snow man of Mr. Black, but say! right that second, I saw something moving—in fact, it was somebody's cap moving along just below the crest of the hill, but all I could see was the bobbing-up-and-down cap, and right away I knew whose cap it was—it was the bright red cap of the new tough guy in our neighborhood whose name was Shorty Long, and right away I knew who it was that had written Poetry's poetry and put it on the sticks into Mr. Black's stomach....

[Pg 41]I had a queer, and also an angry feeling inside me, 'cause I just knew Mr. Black had seen the poem, and since it had been signed "The Sugar Creek Gang," we would all be in for still more trouble Monday morning in school.

While I was up there in that cupola, I made up my mind to one thing, and that was that no matter how much we didn't like our teacher, and no matter what ideas Poetry and I had once had in our minds to find out whether a board on the top of the schoolhouse chimney would smoke out a teacher, I, Bill Collins wasn't going to vote "Yes" if the gang put it to a vote to decide whether to do it or not.... No sir, not me.

Right that second, I heard my pop calling me from away down on the main floor of the barn, "Better come on down and finish your chores, Bill," which I had, and which I started to do, climbing backwards down the new ladder very carefully to the haymow floor and then down the other ladder to the main floor of the barn.

Pop had just finished milking our one milk cow, and the big three-gallon milk pail was full clear to the top and there was inch-high creamy-yellow foam above the top of the pail. Mixy, our old black and white cat, was mewing and mewing and walking all around Pop's legs and looking up and mewing and rubbing her sides against his boots and also running over toward the little milk pan over by a corner of the barn floor, as if to say to Pop, "For goodness sake, I may be a mere cat, but does that give you any right to make me wait for my supper?"

Anyway I was reminded that I was hungry myself, and pretty soon we'd all be in our house, sitting around our table eating raw-fried potatoes and reddish slices of fried ham, and other things....

"I'll take the milk on up to the house, Bill," Pop said, and also said, "You follow me up to the back porch, Mixy—you can't have fresh milk tonight—and also, only a little raw meat, because there are absolutely too many mice around this barn. Any ordinary hungry cat ought to catch at least one mouse a day, Mixy, and if you don't catch them, we'll have to make you hungry, so you will. Understand?" I looked at Pop's big reddish-blackish eyebrows and he was[Pg 42] frowning at Mixy, although I knew he liked her a lot, but didn't like mice very well.

I finished gathering the eggs that were in the barn and then went to the hen house where I knew there would be some more eggs, and then took my basket of maybe four dozen eggs toward the house.

Mixy was there on the back porch, I noticed, lapping away at her milk like a house afire. I wiped off my boots carefully like I'd been trained to do whether I was at home or in somebody else's house, pushed open the door to our kitchen and went in, expecting to see Mom, or Pop, or both of them there, but there wasn't anybody there, so I sat the egg basket down on Mom's work table, and started into the front room, where I thought they'd maybe be. All of a sudden I heard Mom saying something in a tearful voice, and I stopped cold—wondering what I'd maybe done and shouldn't have, and if Mom was telling Pop about it, so I started to listen—and then was half afraid to, so I started to open the door and go out when I heard Pop say something in a low voice, and it was, "No, Mother, whatever it is, I know one thing—our Bill will tell the truth. He'd tell the truth right now if I asked him, but I'm not going to. I'm going to wait and see what happens, and see if he'll tell me himself."

I strained my ears hard to hear what Mom would answer, and this is what she said, "All right, Theodore, I'll be patient; but just the same, I'm worried."

"Don't you worry one little tiny bit, Mother," Pop said. "A boy's heart is like a garden. If you plant good seed in it, and cultivate and plow it and water it with love, he'll come out all right," which made me like my pop a lot, only I didn't have time to think about it 'cause right that very second almost, I heard Mom say in a worried voice, "Yes, dear, but weeds grow in a garden without anyone's planting them," which made me feel all saddish inside, and for some reason I could see our own garden which every spring and summer had all kinds of weeds—ragweeds, smartweeds, and big ugly Jimson-weeds, and lots of other kinds. Right that second, I remembered something my pop had said to me once last summer which was, "Say, Bill, do you know how to keep the big weeds out of our garden,[Pg 43] without having to pull up or cut out even one of them?" and when I said, "No, how, Pop?" he said, "Just kill all of them while they are little."

Well, I didn't want Mom or Pop to know I'd heard them talking about me, so I sneaked out the back door very carefully and started to talking in a friendly voice to Mixy, saying to her, "Listen, Mixy, do you know how to keep all the great big mice out of our barn? You just catch all the mice while they're little—it's as easy as pie."

Mixy looked up from her empty milk pan and mewed and looked down at her pan again, and looked up at me again and mewed again, and then walked over to me and rubbed her sides against my boots like she liked me a lot. For some reason, I thought Mixy was a very nice cat right that minute, so I said to her, "I'm awful glad you like me, Mixy, even if nobody else around this place does."

Pretty soon, Pop and I were out doing the rest of the chores while Mom was getting supper. Almost right away, it began to get dark, and we went in to supper. "Wash your hands and go get Charlotte Ann," Mom said to me. "I think she's awake now."

Charlotte Ann, you know, is my baby sister, and even though she is a girl, is a pretty swell baby; in fact, she's wonderful.

In a few minutes Pop and Mom and Charlotte Ann and I were all sitting around our kitchen table in the lamp light. We had two kerosene lamps lit, one of them behind me on the high mantel-shelf above my head, and the other on another mantel-shelf above the water pail in the corner.

We always bowed our heads at our house before every meal, different ones of us asking the blessing, whichever one of us Pop called on. When I was little I'd said a little poem prayer, but didn't do it any more on account of Pop thought I was too big, and since I was an actual Christian, in spite of having Jimson-weeds in my heart, I always prayed whenever Pop told me to, only I hoped that he wouldn't ask me to tonight. Pop looked around the table at all of us, and Mom helped Charlotte Ann fold her hands, which she didn't want to do, but kept wiggling and squirming and reaching for things on the table, which were too far away, "Well, let's see—whom shall we ask to pray, tonight? ah—"

[Pg 44]Pop's "ah—" was cut short by the telephone ringing our ring, which meant that one of us had to answer the phone. "I'll get it," I said, "maybe it's one of the gang—"

"I'll get it," Mom said, "I'm expecting a call—I say, I'LL GET IT!" Mom raised her voice on account of I was already out of my chair and half way to the living room door.

When Mom came back a minute later, she was smiling like she'd had some wonderful news, and it was, "It was Mrs. Long. Mr. Long won't be home tomorrow, so she can go to church with us. Isn't that wonderful? It's an answer to prayer."

I spoke up then and said, "How about Shorty? Is he going too?"

I don't know what there was in my voice that shouldn't have been, when I asked that question, but Mom said in an astonished tone of voice, "Why, Bill Collins! The very idea! Don't you want him to go to church and Sunday School and learn something about being a Christian? Do you want him to grow up to be a heathen? What's the matter with you?"

I gulped. Mom had read my thoughts like an open school book. "Of course," I said, "he ought to go to church, but—"

"But what?" Mom said.

"He's awful mean to the gang," I said, "He—"

"Perhaps we'd better ask the blessing now," Pop said, in a kind voice, and right away we bowed our heads, while Pop prayed a short prayer, which ended something like this, "... and bless our minister tomorrow. Put into his heart the things he ought to say that will do us all the most good.... Make his sermon like a plow and hoe and rake that will make the gardens of our hearts what they all ought to be.... Bless Shorty Long and his mother and father, and the Till family, all of which we ask in Jesus' name. Amen."

For some reason, when Pop finished, I seemed to feel like maybe I didn't actually hate our new teacher, not very much anyway, and I thought maybe Shorty Long, even if he was a terribly tough boy, would be better if he had somebody pull some of the weeds out of him....

[Pg 45]After supper, we all took our regular Saturday night baths and went to bed, and the next thing we knew it was a wonderful morning, with the sun shining on the snow and with sleigh bells jingling on people's horses, on account of some of our neighbors lived on roads where the road-conditioner hadn't been through yet, and couldn't use their cars and so had to use sleds instead. It was going to be a wonderful day all day, I thought, and was glad I was alive.