Title: Cotton is King, and Pro-Slavery Arguments

Editor: E. N. Elliott

Release date: February 20, 2009 [eBook #28148]

Most recently updated: September 1, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Cori Samuel, Jon Ingram, the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net and the Booksmiths

at http://www.eBookForge.net

Spelling and punctuation anomalies were retained, such as "Masachusettes" and "philanthrophy" on page 40. The table of contents can be found at the end of this book.

Greek words that may not display correctly in all browsers are transliterated in the text using popups like this: βιβλος. Position your mouse over the line to see the transliteration. For the most accurate view of the original Greek, please see the page image.

There is now but one great question dividing the American people, and that, to the great danger of the stability of our government, the concord and harmony of our citizens, and the perpetuation of our liberties, divides us by a geographical line. Hence estrangement, alienation, enmity, have arisen between the North and the South, and those who, from "the times that tried men's souls," have stood shoulder to shoulder in asserting their rights against the world; who, as a band of brothers, had combined to build up this fair fabric of human liberty, are now almost in the act of turning their fratricidal arms against each other's bosoms. All other parties that have existed in our country, were segregated on questions of policy affecting the whole nation and each individual composing it alike; they pervaded every section of the Union, and the acerbity of political strife was softened by the ties of blood, friendship, and neighborhood association. Moreover, these parties were constantly changing, on account of the influence mutually exerted by the members of each; the Federalist of yesterday becomes the Republican of to-day, and Whigs and Democrats change their party allegiance with every change of leaders. If the republicans mismanaged the government, they suffered the consequences alike with the federalists; if the democrats plunged our country into difficulties, they had to abide the penalty as well as the whigs. All parties alike had to suffer the evils, or enjoy the advantages of bad or good government. But it has been reserved to our own times to witness the rise, growth, and prevalence of a party confined exclusively to one section of the Union, whose fundamental principle is opposition to the rights[iv] and interests of the other section; and this, too, when those rights are most sacredly guaranteed, and those interests protected, by that compact under which we became a united nation. In a free government like ours, the eclecticism of parties—by which we mean the affinity by which the members of a party unite on questions of national policy, by which all sections of the country are alike affected—has always been considered as highly conducive to the purity and integrity of the government, and one of the causes most promotive of its perpetuity. Such has been the case, not only in our own country, but also in England, from whom we have mainly derived our ideas of civil and religious liberty, and even, to some extent, our form of government. But there, the case of oppressed and down-trodden Ireland, bears witness to the baneful effects of geographical partizan government and legislation.

In our own country this same spirit, which had its origin in the Missouri contest, is now beginning to produce its legitimate fruits: witness the growing distrust with which the people of the North and the South begin to regard each other; the diminution of Southern travel, either for business or pleasure, in the Northern States; the efforts of each section to develop its own resources, so as virtually to render it independent of the other; the enactment of "unfriendly legislation," in several of the States, towards other States of the Union, or their citizens; the contest for the exclusive possession of the territories, the common property of the States; the anarchy and bloodshed in Kansas; the exasperation of parties throughout the Union; the attempt to nullify, by popular clamor, the decision of the supreme tribunal of our country; the existence of the "underground railroad," and of a party in the North organized for the express purpose of robbing the citizens of the Southern States of their property; the almost daily occurrence of fugitive slave mobs; the total insecurity of slave property in the border States;[v][1] the attempt to circulate incendiary documents among the slaves in the Southern States, and the flooding of the whole country with the most false and malicious misrepresentations of the state of society in the slave States; the attempt to produce division among us, and to array one portion of our citizens in deadly hostility to the other; and finally, the recent attempt to excite, at Harper's Ferry, and throughout the South, an insurrection, and a civil and servile war, with all its attendant horrors.

All these facts go to prove that there is a great wrong somewhere, and that a part, or the whole, of the American people are demented, and hurrying down to swift destruction. To ascertain where this great wrong and evil lies, to point out the remedy, to disabuse the public mind of all erroneous impressions or prejudices, to combat all false doctrines on this subject, and to establish the truth, shall be the aim of the following pages. In preparing them we have consulted the works of most of the writers on both sides of this question, as well as the statistics and history tending to throw light upon the subject. To this we would invite the candid and dispassionate attention of every patriot and philanthropist. To all such we would say, in the language of the Roman bard,

In the following pages, the words slave and slavery are not used in the sense commonly understood by the abolitionists. With them these terms are contradistinguished from servants and servitude. According to their definition, a slave is merely a "chattel" in a human form; a thing to be bought and sold, and treated worse than a brute; a being without rights, privileges, or duties. Now, if this is a correct definition of the word, we totally object to the term, and deny that we have any such institution as slavery among us. We recognize among us no class, which, as the abolitionists falsely assert, that the Supreme Court decided "had no rights which a white man was[vi] bound to respect." The words slave and servant are perfectly synonymous, and differ only in being derived from different languages; the one from Sclavonic, the other from the Latin, just as feminine and womanly are respectively of Latin and Saxon origin. The Saxon synonym thrall has become obsolete in our language, but some of its derivations, as thralldom, are still in use. In Greek the same idea was expressed by doulos, and in Hebrew by ebed. The one idea of servitude, or of obedience to the will of another, is accurately expressed by all these terms. He who wishes to see this topic thoroughly examined, may consult "Fletcher's Studies on Slavery."

The word slavery is used in the following discussions, to express the condition of the African race in our Southern States, as also in other parts of the world, and in other times. This word, as defined by most writers, does not truly express the relation which the African race in our country, now bears to the white race. In some parts of the world, the relation has essentially changed, while the word to express it has remained the same. In most countries of the world, especially in former times, the persons of the slaves were the absolute property of the master, and might be used or abused, as caprice or passion might dictate. Under the Jewish law, a slave might be beaten to death by his master, and yet the master go entirely unpunished, unless the slave died outright under his hand. Under the Roman law, slaves had no rights whatever, and were scarcely recognized as human beings; indeed, they were sometimes drowned in fish-ponds, to feed the eels. Such is not the labor system among us. As an example of faulty definition, we will adduce that of Paley: "Slavery," says he, "is an obligation to labor for the benefit of the master, without the contract or consent of the servant." Waiving, for the present, the accuracy of this definition, as far as it goes, we would remark that it is only half of the definition; the only idea here conveyed is that of compulsory and unrequited labor. Such is not our labor-system. Though we prefer the term slave, yet if this be its true definition, we must protest against its being applied to our[vii] system of African servitude, and insist that some other term shall be used. The true definition of the term, as applicable to the domestic institution in the Southern States, is as follows: Slavery is the duty and obligation of the slave to labor for the mutual benefit of both master and slave, under a warrant to the slave of protection, and a comfortable subsistence, under all circumstances. The person of the slave is not property, no matter what the fictions of the law may say; but the right to his labor is property, and may be transferred like any other property, or as the right to the services of a minor or an apprentice may be transferred. Nor is the labor of the slave solely for the benefit of the master, but for the benefit of all concerned; for himself, to repay the advances made for his support in childhood, for present subsistence, and for guardianship and protection, and to accumulate a fund for sickness, disability, and old age. The master, as the head of the system, has a right to the obedience and labor of the slave, but the slave has also his mutual rights in the master; the right of protection, the right of counsel and guidance, the right of subsistence, the right of care and attention in sickness and old age. He has also a right in his master as the sole arbiter in all his wrongs and difficulties, and as a merciful judge and dispenser of law to award the penalty of his misdeeds. Such is American slavery, or as Mr. Henry Hughes happily terms it, "Warranteeism."

In order that the subject of American slavery may be thoroughly discussed, we have availed ourselves of the labors of several of the ablest writers in the Union. These have been taken, not from one section only, but from both sections of our country. It is true, most of them are citizens of the Southern States, and for this there is a good and obvious reason; no one can correctly discuss this subject, or any other, who is practically unacquainted with it. This was the error of the French nation, when they undertook to legislate the African savages of St. Domingo into free citizens of the model republic; of the English nation when they undertook to interfere[viii] in the internal affairs of their colonies; and thus must it always be, when men undertake to think or write, or act, in reference to any subject, of whose fundamental truths, they are profoundly ignorant. It is true, that in every part of the civilized world there are noble minds, rising superior to the prejudices of education, and the influence of the society in which they are placed, and defending the truth for its own sake; to all such we render their due homage.

It is objected to the defenders of American slavery, that they have changed their ground; that from being apologists for it as an inevitable evil, they have become its defenders as a social and political good, morally right, and sanctioned by the Bible and by God himself. This charge is unjust, as by reference to a few historical facts will abundantly appear. The present slave States had little or no agency in the first introduction of Africans into this country; this was achieved by the Northern commercial States and by Great Britain. Wherever the climate suited the negro constitution, slavery was profitable and flourished; where the climate was unsuitable, slavery was unprofitable, and died out. Most of the slaves in the Northern States were sent southward to a more congenial clime. Upon the introduction into Congress of the first abolition discussions, by John Quincy Adams, and Joshua Giddings, Southern men altogether refused to engage in the debate, or even to receive petitions on the subject. They averred that no good could grow out of it, but only unmitigated evil.

The agitation of the abolition question had commenced in France during the horrors of her first revolution, under the auspices of the Red Republicans; it had pervaded England until it achieved the ruin of her West India colonies, and by anti-slavery missionaries it had been introduced into our Northern States. During all this agitation the Southern States had been quietly minding their own business, regardless of all the turmoil abroad. They had never investigated the subject theoretically, but they were well acquainted with all its practical workings. They had received from Africa a few hundred[ix] thousand pagan savages, and had developed them into millions of civilized Christians, happy in themselves, and useful to the world. They had never made the inquiry whether the system were fundamentally wrong, but they judged it by its fruits, which were beneficent to all. When therefore they were charged with upholding a moral, social, and political evil; and its immediate abolition was demanded, as a matter not only of policy, but also of justice and right, their reply was, we have never investigated the subject. Our fathers left it to us as a legacy, we have grown up with it; it has grown with our growth, and strengthened with our strength, until it is now incorporated with every fibre of our social and political existence. What you say concerning its evils may be true or false, but we clearly see that your remedy involves a vastly greater evil, to the slave, to the master, to our common country, and to the world. We understand the nature of the negro race; and in the relation in which the providence of God has placed them to us, they are happy and useful members of society, and are fast rising in the scale of intelligence and civilization, and the time may come when they will be capable of enjoying the blessings of freedom and self-government. We are instructing them in the principles of our common Christianity, and in many instances have already taught them to read the word of life. But we know that the time has not yet come; that this liberty which is a blessing to us, would be a curse to them. Besides, to us and to you, such a violent disruption would be most disastrous, it would topple to its foundations the whole social and political edifice. Moreover, we have had warning on this subject. God, in his providence, has permitted the emancipation of the African race in a few of the islands contiguous to our shores, and far from being elevated thereby to the condition of Christian freemen, they have rapidly retrograded to the state of pagan savages. The value of property in those islands has rapidly depreciated, their production has vastly diminished, and their commerce and usefulness to the world is destroyed. We wish not to subject either ourselves or our dependents to such a fate. God has[x] placed them in our hands, and he holds us responsible for our course of policy towards them.

This courteous, common-sense, and practical reply, far from closing the mouths of the agitators, only encouraged them to redouble their exertions, and to imbitter the epithets which they hurled at the slave-holders. They exhausted the vocabulary of billingsgate in denouncing those guilty of this most henious of all sins, and charged them in plain terms, with being afraid to investigate or to discuss the subject. Thus goaded into it, many commenced the investigation. Then for the first time did the Southern people take a position on this subject. It is due to a citizen of this State, the Rev. J. Smylie, to say that he was the first to promulgate the truth, as deduced from the Bible, on the subject of slavery. He was followed by a host of others, who discussed it not only in the light of revelation and morals, but as consistent with the Federal Constitution and the Declaration of Independence; until many of those who had commenced their career of abolition agitation by reasoning from the Bible and the Constitution, were compelled to acknowledge that they both were hopelessly pro-slavery, and to cry: "give us an anti-slavery constitution, an anti-slavery Bible, and an anti-slavery God." To such straits are men reduced by fanaticism. It is here worthy of remark, that most of the early abolition propagandists, many of whom commenced as Christian ministers, have ended in downright infidelity. Let us then hear no more of this charge, that the defenders of slavery have changed their ground; it is the abolitionists who have been compelled to appeal to "a higher law," not only than the Federal Constitution, but also, than the law of God. This is the inevitable result when men undertake to be "wise above what is written." The Apostle, in the Epistle to Timothy, has not only explicitly laid down the law on the subject of slavery, but has, with prophetic vision, drawn the exact portrait of our modern abolitionists.

"Let as many servants as are under the yoke count their own masters worthy of all honor, that the name of God and his[xi] doctrine be not blasphemed. And they that have believing masters, let them not despise them, because they are brethren; but rather do them service, because they are faithful and beloved, partakers of the benefit. These things teach and exhort. If any man teach otherwise, and consent not to wholesome words, even the words of our Lord Jesus Christ, and to the doctrine which is according to godliness, he is proud, knowing nothing, but doting about questions and strifes of words, whereof cometh envy, strife, railings, evil surmisings, perverse disputings, of men of corrupt minds and destitute of the truth, supposing that gain is godliness; from such withdraw thyself."

Can any words more accurately and vividly portray the character and conduct of the abolitionists, or more plainly point out the results of their efforts? Is it any wonder that after having received such a castigation, they should totally repudiate the authority of God's law, and say, "Not thy will, but mine be done." It is here explicitly declared that this doctrine, the obedience of slaves to their masters, are the words of our Lord Jesus Christ; and the arguments of its opposers are characterized as doting sillily about questions and strifes of words, and therefore unworthy of reply and refutation. But the consequences are more serious; look at the catalogue. Envy, the root of the evil; strife, see the divisions in our churches, and in our political communities; railings, their calling slaveholders robbers, thieves, murderers, outlaws; evil surmisings, can any good thing come out of Nazareth, or from the Slave States? Perverse disputings of men of corrupt minds, their wresting the Scriptures from their plain and obvious meaning to compel them to teach abolitionism. Finally; the duty of all Christians: from such withdraw thyself.

The monographs embraced in this compendium of discussions on slavery, were written at different periods; some of them several years ago, and some of them were prepared expressly for this work, and some have been re-written in order to continue the subject down to the present time. There is this further[xii] advantage in combining works of different dates, that by comparing them it is evident that the earlier and later writers both stood on, substantially, the same ground, and take the same general views of the institution. The charge of inconsistency must, therefore, fall to the ground. To the reading public, most of the matter contained in these pages will be new; as, though some of them have been before the public for several years, they have had but a limited circulation, no efforts having been made by the Southern people to scatter them broadcast throughout the land, in the form of Sunday school books, or religious tracts. Nor will it be expected by the reader, that the authors of the works on the different topics embraced in this discussion, should have been able to confine their arguments strictly within the assigned limits. The subjects themselves so inosculate, that it would be strange indeed if the writers should not occasionally encroach upon each other's province; but even this, from the variety of argument, and mode of illustration, will be found interesting.

The work of Professor Christy, on the Economical Relations of Slavery, contains a large amount of the most accurate, valuable and well arranged statistical matter, and his combinations and deductions are remarkable for their philosophical accuracy. He spent several years in the service of the American Colonization Society, as agent for Ohio, and made himself thoroughly acquainted with the results, both to the blacks and whites, both of slavery and emancipation.

Governor Hammond is too well known, as an eminent statesman and political writer, to require notice here. His letters are addressed to Mr. Clarkson, of England, who, in conjunction with Wilberforce, after a long struggle, at last secured the passage, by the Parliament of Great Britain, of acts to abolish the slave trade and slavery, in the British West India colonies. The results of this are vividly portrayed by the author, and his predictions are now history.

Chancellor Harper, with a master hand, draws a parallel between the social condition of communities where slave labor[xiii] exists and where it does not, and vindicates the South from the aspersions cast upon her.

Dr. Bledsoe's "Liberty and Slavery," or Slavery in the Light of Moral Science, discusses the right or wrong of slavery, exposes the fallacies, and answers the arguments of the abolitionists. His established reputation as an accurate reasoner, and a forcible writer, guarantees the excellence of this work.

Dr. Stringfellow's Slavery in the Light of Divine Revelation, and Dr. Hodge's Bible Argument on Slavery, form a synopsis of the whole theological argument on the subject. The plain and obvious teachings, of both Old and New Testament, are given with such irresistible force as to carry conviction to every mind, except those wedded to the theory of a "Higher Law" than the Law of God.

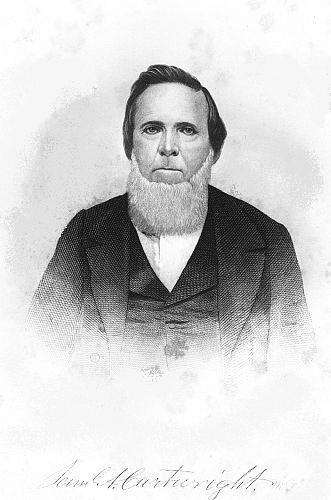

Dr. Cartwright's "Ethnology of the African Race," are the results of the observation and experience of a lifetime, spent in an extensive practice of medicine in the midst of the race. He has had the best of opportunities for becoming intimately acquainted with all the idiosyncrasies of this race, and he has well improved them. That the negro is now an inferior species, or at least variety of the human race, is well established, and must, we think, be admitted by all. That by himself he has never emerged from barbarism, and even when partly civilized under the control of the white man, he speedily returns to the same state, if emancipated, are now indubitable truths. Whether or not, under our system of slavery, he can ever be so elevated as to be worthy of freedom, time and the providence of God alone can determine. The most encouraging results have already been achieved by American slavery, in the elevation of the negro race in our midst; as they are now as far superior to the natives of Africa, as the whites are to them. In a religious point of view, also, there is great encouragement, as there are twice as many communicants of Christian churches among our slaves, as there are among the heathen at all the missionary stations in the world. (See Prof. Christy's statistics in this volume.) What the negroes might have been, but for the[xiv] interference of the abolitionists, it is impossible to conjecture. That their influence has only been unmitigated evil, we have the united testimony, both of themselves and of the slave holders. (See Dr. Beecher's late sermon on the Harper's Ferry trials.)

To show what has been the uniform course of Christians in the South towards the slaves, we will quote from the first pastoral letter of the Synod of the Carolinas and Georgia, to the churches under their care.

After addressing husbands and wives, parents and children, on their relative duties, the Synod continues, "But parents and heads of families, think it not surprising that we inform you that God has committed others to your care, besides your natural offspring, in the welfare of whose souls you are also deeply interested, and whose salvation you are bound to endeavor to promote—we mean your slaves; poor creatures! shall they be bound for life, and their owners never once attempt to deliver their souls from the bondage of sin, nor point them to eternal freedom through the blood of the Son of God! On this subject we beg leave to submit to your consideration the conduct of Abraham, the father of the faithful, through whose example is communicated unto you the commandment of God (Gen. xviii: 19); 'For I know him,' says God, 'that he will command his children and his household after him, that they shall keep the ways of the Lord, to do justice and judgment.'

"Masters and servants, attend to your duty—in the express language of the Holy Ghost—'servants, obey your masters in all things; not with eye service, as men-pleasers, but in singleness of heart, fearing God; and whatsoever you do, do it heartily, as to the Lord, and not to man. And you, masters, render to your servants their due, knowing that your master is also in heaven, neither is there respect of persons with Him.' And let those who govern, and those who are governed, make the object of living in this world be, to prepare to meet your God and judge, when all shall stand on a level before His bar, and receive their decisive sentence according to the deeds done in the body.[xv]

"Servants, be willing to receive instruction, and discourage not your masters by your stubbornness or aversion. Remember, the interest is your own, and if you be wise, it will be for your own good; spend the Sabbath in learning to read, and in teaching your young ones, instead of rambling abroad from place to place; a few years will give you many Sabbaths, which, if rightly improved, will be sufficient for the purpose. Attend, also, on public worship, when you have opportunity, and behave there with decency and good order.

"Were these relative duties conscientiously practiced, by husbands and wives, parents and children, masters and servants, how pleasing would be the sight; expressing by your conduct pious Joshua's resolution, as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord."

The argument on slavery, deduced from the law of nations, we commend to the special attention of the candid reader. Indeed, it is from the recognition of the duty of the various races and nations composing the human family, to contribute their part for the advancement and good of the whole, not only that slavery has existed in all ages, but also that efforts have been, and are now being made, to extend the benefits of civilization and religion to the benighted races of the earth. This has been done in two different ways; one by sending the teacher forth to the heathen, the other by bringing the heathen to the teacher. Both have achieved great good, but the latter has been the more successful. Though the principles embraced in this general law of nations have been acknowledged and acted out in all times, it is due to J. Q. Adams, to state that he first gave a clear elucidation of those principles, so far as they apply to commerce.

Commending these arguments to the candid consideration of every friend to his country, we may be permitted to express the hope that they will redound, not only to the perpetuity of our blood-bought liberties, but to the glory of God, and the good of all men.

Port Gibson, Miss., Jan. 1, 1860.

The first edition of Cotton is King was issued as an experiment. Its favorable reception led to further investigation, and an enlargement of the work for a second edition.

The present publishers have bought the copyright of the third edition, with the privilege of printing it in the form and manner that may best suit their purposes. This step severs the author from all further connection with the work, and affords him an opportunity of stating a few of the facts which led, originally, to its production. He was connected with the newspaper press, as an editor, from 1824 till 1836. This included the period of the tariff controversy, and the rise of the anti-slavery party of this country. After resigning the editorial chair, he still remained associated with public affairs, so as to afford him opportunities of observing the progress of events. In 1848 he accepted an appointment as Agent of the American Colonization Society, for Ohio; and was thus brought directly into contact with the elements of agitation upon the slavery question, in the aspect which that controversy had then assumed. Upon visiting Columbus, the seat of government of the State, in January, 1849, the Legislature, then in session, was found in great, agitation about the repeal of the Black Laws, which had originally been enacted to prevent the immigration of colored men into the State. The[20] abolitionists held the balance of power, and were uncompromising in their demands. To escape from the difficulty, and prevent all future agitation upon the subject, politicians united in erasing this cause of disturbance from the statute book. The colored people had been in convention at the capitol; and felt themselves in a position, as they imagined, to control the legislation of the State. They were encouraged in this belief by the abolitionists, and proceeded to effect an organization by which black men were to stump the State in advocacy of their claims to an equality with white men.

At this juncture the Colonization cause was brought before the Legislature, by a memorial asking aid to send emigrants to Liberia. An appointment was also made, by the agent, for a Lecture on Colonization, to be delivered in the hall of the House of Representatives; and respectful notices sent to the African churches, inviting the colored people to attend. This invitation was met by them with the publication of a call for an indignation meeting; which, on assembling, denounced both the agent and the cause he advocated, in terms unfitted to be copied into this work. One of the resolutions, however, has some significance, as foreshadowing the final action they contemplated, and which has shown itself so futile, as a means of redress, in the recent Harper's Ferry Tragedy. That resolution reads as follows:

"Resolved,—That we will never leave this country while one of our brethren groans in slavish fetters in the United States, but will remain on this soil and contend for our rights, and those of our enslaved race—upon the rostrum—in the pulpit—in the social circle, and upon the field, if necessary, until liberty to the captive shall be proclaimed throughout the length and breadth of this great Republic, or we called from time to eternity."

In the winter of 1850, Mr. Stanley's proposition, to Congress, for the appropriation of the last installment of the Surplus Revenue to Colonization, was laid before the Ohio Legislature for approval. The colored people again held meetings, denouncing this proposition also, and the following resolutions, among others, were adopted—the first at Columbus and the second at Cincinnati:

"Resolved,—That it is our unalterable and eternal determination, as heretofore expressed, to remain in the United States at all hazards, and to 'buffet the withering flood of prejudice and misrule,' which menaces our destruction until we are exalted, to ride[21] triumphantly upon its foaming billows, or honorably sink into its destroying vortex: although inducements may be held out for us to emigrate, in the shape of odious and oppressive laws, or liberal appropriations."

"Resolved,—That we should labor diligently to secure—first, the abolition of slavery, and, failing in this, the separation of the States; one or the other event being necessary to our ever enjoying in its fullness and power, the privilege of an American citizen."

Again, some three or four years later, on the occasion of the formation of the Ohio State Colonization Society, another meeting was called, in opposition to Colonization, in the city of Cincinnati, which, among others, passed the following resolution:

"Resolved,—That in our opinion the emancipation and elevation of our enslaved brethren depends in a great measure upon their brethren who are free, remaining in the country; and we will remain to be that 'agitating element' in American politics, which Mr Wise, in a late letter, concludes, has done so much for the slave."

Many similar resolutions might be quoted, all manifesting a determination, on the part of the colored people, to maintain their foothold in the United States, until the freedom of the slave should be effected; and indicating an expectation, on their part, that this result would be brought about by an insurrection, in which they expected to take a prominent part. In this policy they were encouraged by nearly all the opponents of Colonization, but especially by the active members of the organizations for running off slaves to Canada.

To meet this state of things, Cotton is King was written. The mad folly of the Burns' case, at Boston, in 1854, proved, conclusively, that white men, by the thousand, stood prepared to provoke a collision between the North and the South. The eight hundred men who volunteered at Worcester, and proceeded to Boston, on that occasion, with banner flying, showed that such a condition of public sentiment prevailed; while, at the same time, the sudden dispersion of that valorous army, by a single officer of the general government, who, unaided, captured their leader and bore off their banner, proved, as conclusively, that such philanthropists are not soldiers—that promiscuous crowds of undisciplined men are wholly unreliable in the hour of danger.[22]

The author would here repeat, then, that the main object he had in view, in the preparation of Cotton is King, was to convince the abolitionists of the utter failure of their plans, and that the policy they had adopted was productive of results, the opposite of what they wished to effect;—that British and American abolitionists, in destroying tropical cultivation by emancipation in the West Indies, and opposing its promotion in Africa by Colonization, had given to slavery in the United States its prosperity and its power;—that the institution was no longer to be controlled by moral or physical force, but had become wholly subject to the laws of Political Economy;—and that, therefore, labor in tropical countries, to supply tropical products to commerce, and not insurrection in the United States, was the agency to be employed by those who would successfully oppose the extension of American Slavery: for, just as long as the hands of the free should persist in refusing to supply the demands of commerce for cotton, just so long it would continue to be obtained from those of the slave.

It will be seen in the perusal of the present edition, that Great Britain, in her efforts to promote cotton cultivation in India and Africa, now acts upon this principle, and that she thereby acknowledges the truth of the views which the author has advanced. It will be seen also, that to check American slavery and prevent a renewal of the slave trade by American planters, she has even determined to employ the slaves of Africa in the production of cotton: that is to say, the slavery of America is to be opposed by arraying against it the slavery of Africa—the petty chiefs there being required to force their slaves to the cotton patches, that the masters here may find a diminishing market for the products of their plantations.

In this connection it may be remarked, that the author has had many opportunities of conversing with colored men, on the subject of emigration to Africa, and they have almost uniformly opposed it on the ground that they would be needed here. Some of them, in defending their conduct, revealed the grounds of their hopes. But details on this point are unnecessary. The subject is referred to, only as affording an illustration of the extent to which ignorant men may become the victims of dangerous delusions. The sum of the matter was about this: the colored people, they said, had organizations extending from Canada to Louisiana, by means of which information could be communicated throughout[23] the South, when the blow for freedom was to be struck. Philanthropic white men were expected to take sides against the oppressor, while those occupying neutral ground would offer no resistance to the passage of forces from Canada and Ohio to Virginia and Kentucky. Once upon slave territory, they imagined the work of emancipation would be easily executed, as every slave would rush to the standard of freedom.

These schemes of the colored people were viewed, at the time, as the vagaries of over excited and ignorant minds, dreaming of the repetition of Egyptian miracles for their deliverance; and were subjects of regret, only because they operated as barriers to Colonization. But when a friend placed in the author's hand, a few days since, a copy of the Chatham (Canada West) Weekly Pilot, of October 13, he could see that the seed sown at Columbus in 1849, had yielded its harvest of bitterness and disappointment at Harper's Ferry in 1859. That paper contained the proceedings and resolutions of the colored men, at Chatham, on the 3d of that month, in which the annexed resolution was included:

"Resolved,—That in view of the fact that a crisis will soon occur in the United States to affect our friends and countrymen there, we feel it the duty of every colored person to make the Canadas their homes. The temperature and salubrity of the climate, and the productiveness and fertility of the soil afford ample field for their encouragement. To hail their enslaved bondmen upon their deliverance, in the glorious kingdom of British Liberty, in the Canadas, we cordially invite the free and the bond, the noble and the ignoble—we have no 'Dred Scott Law.'"

The occasion which called out this resolution, together with a number of others, was the delivery of a lecture, on the 3d of October last, by an agent from Jamaica, who urged them to emigrate to that beautiful island. The import of this resolution will be better understood, when it is remembered, that the organization of Brown's insurrectionary scheme took place, in this same city of Chatham, on the 8th of May last. The "crisis" which was soon to occur in the United States, and the importance of every colored man remaining at his post, at that particular juncture, as urged by the resolutions, all indicate, very clearly, that Brown's movements were known to the leaders of the meeting, and that they desired to co-operate in the movement. The spirit[24] breathed by the whole series of the Chatham resolutions, is so fully in accord with those passed from time to time in the United States, that there is no difficulty in perceiving that the views, expectations, and hopes of the colored people of both countries have been the same. The Chatham meeting was on the night of the 3d October, and the outbreak of Brown on that of the 16th.

But the failure of the Harper's Ferry movement should now serve as convincing proof, that nothing can be gained, by such means, for the African race. No successful organization, for their deliverance, can be effected in this country; and foreign aid is out of the question, not only because foreign nations will not wage war for a philanthropic object, but because they cannot do without our cotton for a single year. They are very much in the condition of our Northern politicians, since the old party landmarks have been broken down. The slavery question is the only one left, upon which any enthusiasm can be awakened among the people. The negro is to American politics what cotton is to European manufactures and commerce—the controlling element. As the overthrow of American slavery, with the consequent suspension of the motion of the spindles and looms of Europe, would bring ruin upon millions of its population; so the dropping of the negro question, in American politics, would at once destroy the prospects of thousands of aspirants to office. In ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, the clamor against slavery is made only for effect; and there is not now, nor has there been at any other period, any intention on the part of political agitators to wage actual war against the slave States themselves. But while the author believes that no intention of exciting to insurrection ever existed among leading politicians at the North, he must express the opinion that evil has grown out of the policy they have pursued, as it has excited the free negro to attempts at insurrection, by leading him to believe that they were in earnest in their professions of prosecuting the "irrepressible conflict," between freedom and slavery, to a termination destructive to the South; and, lured by this hope, he has been led to consider it his duty, as a man, to stand prepared for Mr Jefferson's crisis, in which Omnipotence would be arrayed upon his side. This stand he has been induced to take from principles of honor, instead of seeking new fields of enterprise in which to better his condition.

But there is another evil to the colored man, which has grown[25] out of northern agitation on the question of slavery. The controversy is one of such a peculiar nature, that any needed modification of it can be made, by politicians, to suit whatever emergency may arise. The Burns' case convinced them that many men, white and black, were then prepared for treason. This was a step, however, that voters at large disapproved; and, not only was it unpopular to advocate the forcing of emancipation upon the slave States, but it seemed equally repugnant to the people to have the North filled with free negroes. The free colored man was, therefore, given to understand, that slavery was not to be disturbed in the States where it had been already established. But this was not all. He had to have another lesson in the philosophy of dissolving scenes, as exhibited in the great political magic lantern. Nearly all the Western States had denied him an equality with the white man, in the adoption or modification of their constitutions. He looked to Kansas for justice, and lo! it came. The first constitution, adopted by the free State men of that territory, excluded the free colored man from the rights of citizenship! "Why is this," said the author, to a leading German politician of Cincinnati: "why have the free State men excluded the free colored people from the proposed State?" "Oh," he replied, "we want it for our sons—for white men,—and we want the nigger out of our way: we neither want him there as a slave or freeman, as in either case his presence tends to degrade labor." This is not all. Nearly every slave State is legislating the free colored men out of their bounds, as a "disturbing element" which their people are determined no longer to tolerate. Here, then, is the result of the efforts of the free colored man to sustain himself in the midst of the whites; and here is the evil that political agitation has brought upon him.

Under these circumstances, the author believes he will be performing a useful service, in bringing the question of the economical relations of American slavery, once more, prominently before the public. It is time that the true character of the negro race, as compared with the white, in productive industry, should be determined. If the negro, as a voluntary laborer, is the equal of the white man, as the abolitionists contend, then, set him to work in tropical cultivation, and he can accomplish something for his race; but if he is incapable of competing with the white man, except in compulsory labor,—as slaveholders most sincerely[26] believe the history of the race fully demonstrates—then let the truth be understood by the world, and all efforts for his elevation be directed to the accomplishment of the separation of the races. Because, until the colored men, who are now free, shall afford the evidence that freedom is best for the race, those held in slavery cannot escape from their condition of servitude.

Some new and important facts in relation to the results of West India emancipation are presented, which show, beyond question, that the advancing productiveness, claimed for these islands, is not due to any improvement in the industrial habits of the negroes, but is the result, wholly, of the introduction of immigrant labor from abroad. No advancement, of any consequence, has been made where immigrants have not been largely imported; and in Jamaica, which has received but few, there is a large decline in production from what existed during even the first years of freedom.

The present edition embraces a considerable amount of new matter, having a bearing on the condition of the cotton question, and a few other points of public interest. Several new Statistical Tables have been added to the appendix, that are necessary to the illustration of the topics discussed; and some historical matter also, in illustration of the early history of slavery in the United States.

Cincinnati, January 1, 1860.

"Cotton is King" has been received, generally, with much favor by the public. The author's name having been withheld, the book was left to stand or fall upon its own merits. The first edition has been sold without any special effort on the part of the publishers. As they did not risk the cost of stereotyping, the work has been left open for revision and enlargement. No change in the matter of the first edition has been made, except a few verbal alterations and the addition of some qualifying phrases.[27] Two short paragraphs only have been omitted, so as to leave the public documents and abolitionists, only, to testify as to the moral condition of the free colored people. The matter added to the present volume equals nearly one-fourth of the work. It relates mainly to two points: First, The condition of the free colored people; Second, The economical and political relations of slavery. The facts given, it is believed, will completely fortify all the positions of the author, on these questions, so far as his views have been assailed.

The field of investigation embraced in the book is a broad one, and the sources of information from which its facts are derived are accessible to but few. It is not surprising, then, that strangers to these facts, on first seeing them arranged in their philosophical relations and logical connection, should be startled at their import, and misconceive the object and motives of the author.

For example: One reviewer, in noticing the first edition, asserts that the writer "endeavors to prove that slavery is a great blessing in its relations to agriculture, manufactures, and commerce." The candid reader will be unable to find any thing, in the pages of the work, to justify such an assertion. The author has proved that the products of slave labor are in such universal demand, through the channels named by the reviewer, that it is impracticable, in the existing condition of the world, to overthrow the system; and that as the free negro has demonstrated his inability to engage successfully in cotton culture, therefore American slavery remains immovable, and presents a standing monument of the folly of those who imagined they could effect its overthrow by the measures they pursued. This was the author's aim.

Another charges, that the whole work is based on a fallacy, and that all its arguments, therefore, are unsound. The fallacy of the book, it is explained, consists in making cotton and slavery indivisible, and teaching that cotton can not be cultivated except by slave labor; whereas, in the opinion of the objector, that staple can be grown by free labor. Here, again, the author is misunderstood. He only teaches what is true beyond all question: not that free labor is incapable of producing cotton, but that it does not produce it so as to affect the interests of slave labor; and that the American planter, therefore, still finds himself in the possession of the monopoly of the market for cotton, and unable to meet the demand made upon him for that staple, except by a[28] vast enlargement of its cultivation, requiring the employment of an increased amount of labor in its production.

Another says: "The real object of the work is an apology for American slavery. Professing to repudiate extremes, the author pleads the necessity for the present continuance of slavery, founded on economical, political, and moral considerations." The dullest reader can not fail to perceive that the work contains not one word of apology for the institution of slavery, nor the slightest wish for its continuance. The author did not suppose that Southern slave holders would thank any Northern man to attempt an apology for their maintaining what they consider their rights under the constitution; neither did he imagine that any plea for the continuance of American slavery was needed, while the world at large is industriously engaged in supporting it by the consumption of its products. He, therefore, neither attempted an apology for its existence nor a plea for its continuance. He was writing history and not recording his own opinions, about which he never imagined the public cared a fig. He was merely aiming at showing, how an institution, feeble and ill supported in the outset, had become one of the most potent agents in the advancement of civilization, notwithstanding the opposition it has had to encounter; and that those who had attempted its overthrow, in consequence of a lack of knowledge of the plainest principles of political economy and of human nature in its barbarous state, had contributed, more than any other class of persons, to produce this result.

Another charges the author with ignorance of the recent progress making in the culture of cotton, by free labor, in India and Algeria; and congratulates his readers that, "on this side of the ocean, the prospects of free soil and free labor, and of free cotton as one of the products of free soil and free labor, were never so fair as now." This is a pretty fair example of one's "whistling to keep his courage up," while passing, in the dark, through woods where he thinks ghosts are lurking on either side. Algeria has done nothing, yet, to encourage the hope that American slavery will be lessened in value by the cultivation of cotton in Africa. The British custom-house reports, as late as September, 1855, instead of showing any increase of imports of cotton from India, it will be seen, exhibit a great falling off in its supplies; and, in the opinion of the best authorities, extinguishes the hope of arresting the progress of American slavery by any[29] efforts made to render Asiatic free labor more effective. As to the prospects on this side of the ocean, a glance at the map will show, that the chances of growing cotton in Kansas are just as good, and only as good as in Illinois and Missouri, from whence not a pound is ever exported. Texas was careful to appropriate nearly all the cotton lands acquired from Mexico, which lie on the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains; and, by that act, all such lands, mainly, have been secured to slavery. Where, then, is free labor to operate, even were it ready for the task?

Another alleges that the book is "a weak effort to slander the people of color." This is a charge that could have come only from a careless reader. The whole testimony, embraced in the first edition, nearly, as to the economical failure of West India Emancipation, and the moral degradation of the free colored people, generally, is quoted from abolition authorities, as is expressly stated; not to slander the people of color, but to show them what the world is to think of them, on the testimony of their particular friends and self-constituted guardians.

Another objects to what is said of those who hold the opinion that slavery is malum in se, and who yet continue to purchase and use its products. On this point it is only necessary to say, that the logic of the book has not been affected by the sophistry employed against it; and that if those who hold the per se doctrine, and continue to use slave labor products, dislike the charge of being participes criminis with robbers, they must classify slavery in some other mode than that in which they have placed it in their creeds. For, if they are not partakers with thieves, then slavery is not a system of robbery; but if slavery be a system of robbery, as they maintain, then, on their own principles, they are as much partakers with thieves as any others who deal in stolen property.

The severest criticism on the book, however, comes from one who charges the author with a "disposition to mislead, or an ignorance which is inexcusable," in the use of the statistics of crime, having reference to the free colored people, from 1820 to 1827. The object of the author, in using the statistics referred to, was only to show the reasons why the scheme of colonization was then accepted, by the American public, as a means of relief to the colored population, and not to drag out these sorrowful[30] facts to the disparagement of those now living. But the reviewer, suspicious of every one who does not adopt his abolition notions, suspects the author of improper motives, and asks: "Why go so far back, if our author wished to treat the subject fairly?" Well, the statistics on this dismal topic have been brought up to the latest date practicable, and the author now leaves it to the colored people themselves to say, whether they have gained any thing by the reviewer's zeal in their behalf. He will learn one lesson at least, we hope, from the result: that a writer can use his pen with greater safety to his reputation, when he knows something about the subject he discusses.

But this reviewer, warming in his zeal, undertakes to philosophise, and says, that the evils existing among the free colored people, will be found in exact proportion to the slowness of emancipation; and complains that New Jersey was taken as the standard, in this respect, instead of Massachusetts, where, he asserts, "all the negroes in the commonwealth, were, by the new constitution, liberated in a day, and none of the ill consequences objected followed, either to the commonwealth or to individuals." The reviewer is referred to the facts, in the present edition, where he will find, that the amount of crime, at the date to which he refers, was six times greater among the colored people of Massachusetts, in proportion to their numbers, than among those of New Jersey. The next time he undertakes to review King Cotton, it will be best for him not to rely upon his imagination, but to look at the facts. He should be able at least, when quoting a writer, to discriminate between evils resulting from insurrections, and evils growing out of common immoralities. Experience has taught, that it is unsafe, when calculating the results of the means of elevation employed, to reason from a civilized to a half civilized race of men.

The last point that needs attention, is the charge that the author is a slaveholder, and governed by mercenary motives. To break the force of any such objection to the work, and relieve it from prejudices thus created, the veil is lifted, and the author's name is placed upon the title page.

The facts and statistics used in the first edition, were brought down to the close of 1854, mainly, and the arguments founded upon the then existing state of things. The year 1853 was taken as best indicating the relations of our planters and farmers to the[31] manufactures and commerce of the country and the world; because the exports and imports of that year were nearer an average of the commercial operations of the country than the extraordinary year which followed; and because the author had nearly finished his labors before the results of 1854 had been ascertained. In preparing the second edition for the press, many additional facts, of a more recent date, have been introduced: all of which tend to prove the general accuracy of the author's conclusions, as expressed in the first edition.

Tables IV and V, added to the present edition, embrace some very curious and instructive statistics, in relation to the increase and decrease of the free colored people, in certain sections, and the influence they appear to exert on public sentiment.

In the preparation of the following pages, the author has aimed at clearness of statement, rather than elegance of diction. He sets up no claim to literary distinction; and even if he did, every man of classical taste knows, that a work, abounding in facts and statistics, affords little opportunity for any display of literary ability.

The greatest care has been taken, by the author, to secure perfect accuracy in the statistical information supplied, and in all the facts stated.

The authorities consulted are Brande's Dictionary of Science, Literature and Art; Porter's Progress of the British Nation; McCullough's Commercial Dictionary; Encyclopædia Americana; London Economist; De Bow's Review; Patent Office Reports; Congressional Reports on Commerce and Navigation; Abstract of the Census Reports, 1850; and Compendium of the Census Reports. The extracts from the Debates in Congress, on the Tariff Question, are copied from the National Intelligencer.

The tabular statements appended, bring together the principal[32] facts, belonging to the questions examined, in such a manner that their relations to each other can be seen at a glance.

The first of these Tables, shows the date of the origin of cotton manufactories in England, and the amount of cotton annually consumed, down to 1853; the origin and amount of the exports of cotton from the United States to Europe; the sources of England's supplies of cotton, from countries other than the United States; the dates of the discoveries which have promoted the production and manufacture of cotton; the commencement of the movements made to meliorate the condition of the African race; and the occurrence of events that have increased the value of slavery, and led to its extension.

The second and third of the tables, relate to the exports and imports of the United States; and illustrate the relations sustained by slavery, to the other industrial interests and to the commerce of the country.

The controversy on Slavery, in the United States, has been one of an exciting and complicated character. The power to emancipate existing, in fact, in the States separately and not in the general government, the efforts to abolish it, by appeals to public opinion, have been fruitless except when confined to single States. In Great Britain the question was simple. The power to abolish slavery in her West Indian colonies was vested in Parliament. To agitate the people of England, and call out a full expression of sentiment, was to control Parliament and secure its abolition. The success of the English abolitionists, in the employment of moral force, had a powerful influence in modifying the policy of American anti-slavery men. Failing to discern the difference in the condition of the two countries, they attempted to create a public sentiment throughout the United States adverse to slavery, in the confident expectation of speedily overthrowing the institution. The issue taken, that slavery is malum in se—a sin in itself—was prosecuted with all the zeal and eloquence they could command. Churches adopting the sin per se doctrine, inquired of their converts, not whether they supported slavery by the use of its products, but whether they believed the institution itself sinful. Could public sentiment be brought to assume the proper ground; could the slaveholder be convinced that the world denounced him as equally criminal with the robber and murderer; then, it was believed, he would abandon the system. Political parties, subsequently organized, taught, that to vote for a slaveholder, or a pro-slavery man, was sinful, and could not be done without violence to conscience; while, at the same time, they made no scruples of using the products of slave labor—the exorbitant demand for which was the great bulwark of the institution.[34] This was a radical error. It laid all who adopted it open to the charge of practical inconsistency, and left them without any moral power over the consciences of others. As long as all used their products, so long the slaveholders found the per se doctrine working them no harm; as long as no provision was made for supplying the demand for tropical products by free labor, so long there was no risk in extending the field of operations. Thus, the very things necessary to the overthrow of American slavery, were left undone, while those essential to its prosperity, were continued in the most active operation; so that, now, after more than a thirty years' war, we may say, emphatically, Cotton is King, and his enemies are vanquished.

Under these circumstances, it is due to the age—to the friends of humanity—to the cause of liberty—to the safety of the Union—that we should review the movements made in behalf of the African race, in our country; so that errors of principle may be abandoned; mistakes in policy corrected; the free colored people taught their true relations to the industrial interests of the world; the rights of the slave as well as the master secured; and the principles of the constitution established and revered. It is proposed, therefore, to examine this subject in the light of the social, civil, and commercial history of the country; and, in doing this, to embrace the facts and arguments under the following heads:

1. The early movements on the subject of slavery; the circumstances under which the Colonization Society took its rise; the relations it sustained to slavery and to the schemes projected for its abolition; the origin of the elements which have given to American slavery its commercial value and consequent powers of expansion; and the futility of the means used to prevent the extension of the institution.

2. The relations of American slavery to the industrial interests of our own country; to the demands of commerce; and to the present political crisis.

3. The industrial, social, and moral condition of the free colored people in the British colonies and in the United States; and the influence they have exerted on public sentiment in relation to the perpetuation of slavery.

4. The moral relations of persons holding the per se doctrine, on the subject of slavery, to the purchase and consumption of slave labor products.

THE EARLY MOVEMENTS ON THE SUBJECT OF SLAVERY; THE CIRCUMSTANCES UNDER WHICH THE COLONIZATION SOCIETY TOOK ITS RISE; THE RELATIONS IT SUSTAINED TO SLAVERY AND TO THE SCHEMES PROJECTED FOR ITS ABOLITION; THE ORIGIN OF THE ELEMENTS WHICH HAVE GIVEN TO AMERICAN SLAVERY ITS COMMERCIAL VALUE AND CONSEQUENT POWERS OF EXPANSION; AND THE FUTILITY OF THE MEANS USED TO PREVENT THE EXTENSION OF THE INSTITUTION.

Four years after the Declaration of American Independence, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts had emancipated their slaves; and, eight years thereafter, Connecticut and Rhode Island followed their example.

Three years after the last named event, an abolition society was organized by the citizens of the State of New York, with John Jay at its head. Two years subsequently, the Pennsylvanians did the same thing, electing Benjamin Franklin to the presidency of their association. The same year, too, slavery was forever excluded, by act of Congress, from the Northwest Territory. This year is also memorable as having witnessed the erection of the first cotton mill in the United States, at Beverley, Massachusetts.

During the year that the New York Abolition Society was formed, Watts, of England, had so far perfected the steam engine as to use it in propelling machinery for spinning cotton; and the year the Pennsylvania Society was organized witnessed the invention of the power loom. The carding machine and the spinning jenny having been invented twenty years before, the power loom completed the machinery necessary to the indefinite extension of the manufacture of cotton.

The work of emancipation, begun by the four States named, continued to progress, so that in seventeen years from the adoption[36] of the constitution, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, and New Jersey, had also enacted laws to free themselves from the burden of slavery.

As the work of manumission proceeded, the elements of slavery expansion were multiplied. When the four States first named liberated their slaves, no regular exports of cotton to Europe had yet commenced; and the year New Hampshire set hers free, only 138,328 lbs. of that article were shipped from the country. Simultaneously with the action of Vermont, in the year following, the cotton gin was invented, and an unparalleled impulse given to the cultivation of cotton. At the same time, Louisiana, with her immense territory, was added to the Union, and room for the extension of slavery vastly increased. New York lagged behind Vermont for six years, before taking her first step to free her slaves, when she found the exports of cotton to England had reached 9,500,000 lbs.; and New Jersey, still more tardy, fell five years behind New York; at which time the exports of that staple—so rapidly had its cultivation progressed—were augmented to 38,900,000 lbs.

Four years after the emancipations by States had ceased, the slave trade was prohibited; but, as if each movement for freedom must have its counter-movement to stimulate slavery, that same year the manufacture of cotton goods was commenced in Boston. Two years after that event, the exports of cotton amounted to 93,900,000 lbs. War with Great Britain, soon afterward, checked both our exports and her manufacture of the article; but the year 1817, memorable in this connection, from its being the date of the organization of the Colonization Society, found our exports augmented to 95,660,000 lbs., and her consumption enlarged to 126,240,000 lbs. Carding and spinning machinery had now reached a good degree of perfection, and the power loom was brought into general use in England, and was also introduced into the United States. Steamboats, too, were coming into use, in both countries; and great activity prevailed in commerce, manufactures, and the cultivation of cotton.

But how fared it with the free colored people during all this time? To obtain a true answer to this question we must revert to the days of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society.

With freedom to the slave, came anxieties among the whites as to the results. Nine years after Pennsylvania and Massachusetts[37] had taken the lead in the trial of emancipation, Franklin issued an appeal for aid to enable his society to form a plan for the promotion of industry, intelligence, and morality among the free blacks; and he zealously urged the measure on public attention, as essential to their well-being, and indispensable to the safety of society. He expressed his belief, that such is the debasing influence of slavery on human nature, that its very extirpation, if not performed with care, may sometimes open a source of serious evils; and that so far as emancipation should be promoted by the society, it was a duty incumbent on its members to instruct, to advise, to qualify those restored to freedom, for the exercise and enjoyment of civil liberty.

How far Franklin's influence failed to promote the humane object he had in view, may be inferred from the fact, that forty-seven years after Pennsylvania passed her act of emancipation, and thirty-eight after he issued his appeal, one-third of the convicts in her penitentiary were colored men; though the preceding census showed that her slave population had almost wholly disappeared—there being but two hundred and eleven of them remaining, while her free colored people had increased in number to more than thirty thousand. Few of the other free States were more fortunate, and some of them were even in a worse condition—one-half of the convicts in the penitentiary of New Jersey being colored men.

But this is not the whole of the sad tale that must be recorded. Gloomy as was the picture of crime among the colored people of New Jersey, that of Massachusetts was vastly worse. For though the number of her colored convicts, as compared with the whites, was as one to six, yet the proportion of her colored population in the penitentiary was one out of one hundred and forty, while the proportion in New Jersey was but one out of eight hundred and thirty-three. Thus, in Massachusetts, where emancipation had, in 1780, been immediate and unconditional, there was, in 1826, among her colored people, about six times as much crime as existed among those of New Jersey, where gradual emancipation had not been provided for until 1804.

The moral condition of the colored people in the free States, generally, at the period we are considering, may be understood more clearly from the opinions expressed, at the time, by the Boston Prison Discipline Society. This benevolent association[38] included among its members, Rev. Francis Wayland, Rev. Justin Edwards, Rev. Leonard Woods, Rev. William Jenks, Rev. B. B. Wisner, Rev. Edward Beecher, Lewis Tappan, Esq., John Tappan, Esq., Hon. George Bliss, and Hon. Samuel M. Hopkins.

In the First Annual Report of the Society, dated June 2, 1826, they enter into an investigation "of the progress of crime, with the causes of it," from which we make the following extracts:

"Degraded character of the colored population.—The first cause, existing in society, of the frequency and increase of crime is the degraded character of the colored population. The facts, which are gathered from the penitentiaries, to show how great a proportion of the convicts are colored, even in those States where the colored population is small, show, most strikingly, the connection between ignorance and vice."

The report proceeds to sustain its assertions by statistics, which prove, that, in Massachusetts, where the free colored people constituted one seventy-fourth part of the population, they supplied one-sixth part of the convicts in her penitentiary; that in New York, where the free colored people constituted one thirty-fifth part of the population, they supplied more than one-fourth part of the convicts; that, in Connecticut and Pennsylvania, where the colored people constituted one thirty-fourth part of the population, they supplied more than one-third part of the convicts; and that, in New Jersey, where the colored people constituted one-thirteenth part of the population, they supplied more than one-third part of the convicts.

"It is not necessary," continues the report, "to pursue these illustrations. It is sufficiently apparent, that one great cause of the frequency and increase of crime, is neglecting to raise the character of the colored population.

"We derive an argument in favor of education from these facts. It appears from the above statement, that about one-fourth part of all the expense incurred by the States above mentioned, for the support of their criminal institutions, is for the colored convicts. * * Could these States have anticipated these surprising results, and appropriated the money to raise the character of the colored population, how much better would have been their prospects, and how much less the expense of the States through which they are dispersed for the support of their colored convicts! * * If, however, their character can not be raised, where[39] they are, a powerful argument may be derived from these facts, in favor of colonization, and civilized States ought surely to be as willing to expend money on any given part of its population, to prevent crime, as to punish it.

"We can not but indulge the hope that the facts disclosed above, if they do not lead to an effort to raise the character of the colored population, will strengthen the hands and encourage the hearts of all the friends of colonizing the free people of color in the United States."

The Second Annual Report of the Society, dated June 1, 1827, gives the results of its continued investigations into the condition of the free colored people, in the following language and figures:

"Character of the colored population.—In the last report, this subject was exhibited at considerable length. From a deep conviction of its importance, and an earnest desire to keep it ever before the public mind, till the remedy is applied, we present the following table, showing, in regard to several States, the whole population, the colored population, the whole number of convicts, the number of colored convicts, proportion of convicts to the whole population, proportion of colored convicts:

| Whole Population. | Colored Population. | Whole number of Convicts. | Number of Colored Convicts. | Proportion of Colored People. | Proportion of Colored Convicts. | |

| Mass. | 523,000 | 7,000 | 314 | 50 | 1 to 74 | 1 to 6 |

| Conn. | 275,000 | 8,000 | 117 | 39 | 1 to 34 | 1 to 3 |

| N. York | 1,372,000 | 39,000 | 637 | 154 | 1 to 35 | 1 to 4 |

| N. Jersey | 277,000 | 20,000 | 74 | 24 | 1 to 13 | 1 to 3 |

| Penn. | 1,049,000 | 30,000 | 474 | 165 | 1 to 34 | 1 to 3 |

"Or,

| Proportion of the Population sent to Prison. | Proportion of the Colored Popu'n sent to Prison. | |

| In Massachusetts, | 1 out of 1665 | 1 out of 140 |

| In Connecticut, | 1 out of 2350 | 1 out of 205 |

| In New York, | 1 out of 2153 | 1 out of 253 |

| In New Jersey, | 1 out of 3743 | 1 out of 833 |

| In Pennsylvania, | 1 out of 2191 | 1 out of 181 |

| In Masachusetts, | in 10 years, | $17,734 |

| In Connecticut, | in 15 years, | 37,166 |

| In New York, | in 27 years, | 109,166 |

| Total | $164 066 |

"Such is the abstract of the information presented last year, concerning the degraded character of the colored population. The returns from several prisons show, that the white convicts are remaining nearly the same, or are diminishing, while the colored convicts are increasing. At the same time, the white population is increasing, in the Northern States, much faster than the colored population."

| Whole No. of Convicts. | Colored Convicts. | Proportion. | |

| In Massachusetts, | 313 | 50 | 1 to 6 |

| In New York, | 381 | 101 | 1 to 4 |

| In New Jersey, | 67 | 33 | 1 to 2 |

Such is the testimony of men of unimpeachable veracity and undoubted philanthrophy, as to the early results of emancipation in the United States. Had the freedmen, in the Northern States, improved their privileges; had they established a reputation for industry, integrity, and virtue, far other consequences would have followed their emancipation. Their advancement in moral character would have put to shame the advocate for the perpetuation of slavery. Indeed, there could have been no plausible argument found for its continuance. No regular exports of cotton, no cultivation of cane sugar, to give a profitable character to slave labor, had any existence when Jay and Franklin commenced their labors, and when Congress took its first step for the suppression of the slave trade.

Unfortunately, the free colored people persevered in their evil habits. This not only served to fix their own social and political condition on the level of the slave, but it reacted with fearful effect upon their brethren remaining in bondage. Their refusing to listen to the counsel of the philanthropists, who urged them to[41] forsake their indolence and vice, and their frequent violations of the laws, more than all things else, put a check to the tendencies, in public sentiment, toward general emancipation. The failure of Franklin to obtain the means of establishing institutions for the education of the blacks, confirmed the popular belief that such an undertaking was impracticable, and the whole African race, freedmen as well as slaves, were viewed as an intolerable burden, such as the imports of foreign paupers are now considered. Thus the free colored people themselves, ruthlessly threw the car of emancipation from the track, and tore up the rails upon which, alone, it could move.

The opinion that the African race would become a growing burden had its origin before the revolution, and led the colonists to oppose the introduction of slaves; but failing in this, through the opposition of England, as soon as they threw off the foreign yoke many of the States at once crushed the system—among the first acts of sovereignty by Virginia, being the prohibition of the slave trade. In the determination to suppress this traffic all the States united—but in emancipation their policy differed. It was found easier to manage the slaves than the free blacks—at least it was claimed to be so—and, for this reason, the slave States, not long after the others had completed their work of manumission, proceeded to enact laws prohibiting emancipations, except on condition that the persons liberated should be removed. The newly organized free States, too, taking alarm at this, and dreading the influx of the free colored people, adopted measures to prevent the ingress of this proscribed and helpless race.[42]

These movements, so distressing to the reflecting colored man, be it remembered, were not the effect of the action of colonizationists, but took place, mostly, long before the organization of the American Colonization Society; and, at its first annual meeting, the importance and humanity of colonization was strongly urged, on the very ground that the slave States, as soon as they should find that the persons liberated could be sent to Africa, would relax their laws against emancipation.

The slow progress made by the great body of the free blacks in the North, or the absence, rather, of any evidences of improvement in industry, intelligence, and morality, gave rise to the notion, that before they could be elevated to an equality with the whites, slavery must be wholly abolished throughout the Union. The constant ingress of liberated slaves from the South, to commingle with the free colored people of the North, it was claimed, tended to perpetuate the low moral standard originally existing among the blacks; and universal emancipation was believed to be indispensable to the elevation of the race. Those who adopted this view, seem to have overlooked the fact, that the Africans, of savage origin, could not be elevated at once to an equality with the American people, by the mere force of legal enactments. More than this was needed, for their elevation, as all are now, reluctantly, compelled to acknowledge. Emancipation, unaccompanied by the means of intellectual and moral culture, is of but little value. The savage, liberated from bondage, is a savage still.