Title: Dorothy's Triumph

Author: Evelyn Raymond

Illustrator: Rudolf Mencl

Release date: February 28, 2009 [eBook #28221]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by D. Alexander and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by D. Alexander

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

from digital material generously made available by

Internet Archive

(http://www.archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://www.archive.org/details/dorothystriumph00raymiala |

Copyright 1911

A. L. CHATTERTON CO.

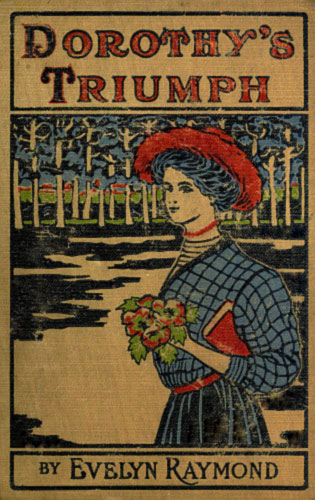

“A MELODY SUCH AS SETS THE HEART BEATING.”

“A MELODY SUCH AS SETS THE HEART BEATING.”| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | On the Train | 9 |

| II. | At Old Bellvieu Again | 28 |

| III. | Dorothy Meets Herr Deichenberg | 49 |

| IV. | The Beginning of the Trip | 66 |

| V. | The Camp in the Mountains | 84 |

| VI. | A Cry in the Night | 104 |

| VII. | Unwelcome Visitors | 122 |

| VII. | The Journey Home | 143 |

| IX. | The First Lesson | 158 |

| X. | Herr Deichenberg’s Concert | 174 |

| XI | Christmas at Bellvieu | 192 |

| XII | Mr. Ludlow’s Offer | 207 |

| XIII | In the Metropolis | 222 |

| XIV | The Storm | 237 |

| XV | Dorothy’s Triumph | 251 |

“Maryland, my Maryland!” dreamily hummed Dorothy Calvert.

“Not only your Maryland, but mine,” was the resolute response of the boy beside her.

Dorothy turned on him in surprise.

“Why, Jim Barlow, I thought nothing could shake your allegiance to old New York state; you’ve told me so yourself dozens of times, and—”

“I know, Dorothy; I’ve thought so myself, but since my visit to old Bellvieu, and our trip on the houseboat, I’ve—I’ve sort o’ changed my mind.”

“You don’t mean that you’re coming to live with Aunt Betty and I again, Jim? Oh, you just can’t mean that! Why, we’d be so delighted!”

“No, I don’t mean just that,” responded Jim, rather glumly—“in fact, I don’t know just what I mean myself, except I feel like I must be always near you and Mrs. Calvert.”

“Say Aunt Betty, Jim.”

“Well, Aunt Betty.”

“You know she is an aunt to you, in the matter of affection, if not by blood.”

“I do know that, and I appreciate all she did for me before she got well enough acquainted with you to believe she wanted you to live with her forever.”

“Say, Jim, dear, often when I ponder over my life it seems like some brilliant dream. Just think of being left a squalling baby for Mrs. Calvert, my great-aunt, to take care of, then sent to Mother Martha and Father John, because Aunt Betty felt that she should be free from the care of raising a troublesome child. Then, after I’ve grown into a sizable girl, in perfect ignorance as to my real parentage, Aunt Betty meets and likes me, and is anxious to get me back again. Then Judge Breckenridge and others take a hand in the matter of hunting up my real name and pedigree, with the result that Aunt Betty finally owns up to my being her kith and kin, and receives me with open arms at Deerhurst. Since then, I, Dorothy Elisabeth Somerset-Calvert, F. F. V., etc., etc., changed from near-poverty to at least a comfortable living, with all my heart could desire and more, have had one continuous good time. Yes, Jim, it is too strange and too good to be true.”

“But it is true,” protested the boy—“true as gospel, Dorothy. You are one of the finest little ladies in the land and no one will ever dispute it.”

“Oh, I wasn’t fishing for compliments.”

“Well, you got ’em just the same, didn’t you? And you deserve ’em.”

The train on which Dorothy and Jim, together with Ephraim, Aunt Betty’s colored man, were riding, was already speeding through the broad vales of Maryland, every moment bringing it nearer the city of Baltimore and Old Bellvieu, the ancestral home of the Calverts, where Mrs. Elisabeth Cecil Somerset-Calvert, familiarly termed, “Aunt Betty,” would be awaiting them.

Since being “taken into the fold” by Aunt Betty, after years of living with Mother Martha and Father John, to whom she had sent the child as a nameless foundling, Dorothy had, indeed, been a happy girl, as her experiences related in the previous volumes of this series, “House Party,” “In California,” “On a Ranch,” “House Boat,” and “At Oak Knowe,” will attest.

Just now she was returning from the Canadian school of Oak Knowe, where she had spent a happy winter. Mrs. Calvert had been unable to meet her in the Dominion, as she had intended, but had sent [Pg 12]Jim and Ephraim, the latter insisting that he was needed to help care for his little mistress. Soon after the commencement exercises were over the trio had left for Dorothy’s home.

And such a commencement as it had been! Dorothy could still hear ringing in her ears the rather solemn, deep-toned words of the Bishop who conferred the diplomas and prizes, as he had said:

“To Miss Dorothy Calvert for uniform courtesy.” Then again: “To Miss Dorothy Calvert, for advancement in music.”

“The dear old Bishop!” she cried, aloud, as she thought again of the good times she had left behind her.

“‘The dear old Bishop’?” Jim repeated, a blank expression on his face. “And who, please, is the dear old Bishop?”

“I’d forgotten you did not meet him, Jim. He’s the head director of the school at Oak Knowe, and one of the very dearest of men. I shall never forget my first impression of him—a venerable man, with a queer-shaped cap on his head, and wearing knee breeches and gaiters, much as our old Colonial statesmen were wont to do. ‘So this is my old friend, Betty Calvert’s child, is it?’ he said. Dorothy imitated the bass tones of a man with such precision [Pg 13]that Jim smiled in spite of himself. ‘Well, well! You’re as like her as possible—yet only her great-niece. Ha! Hum!’ etc., etc. Then he put his arm around me and drew me to his side, and, Jim, I can’t tell you how comfortable I felt, for I was inclined to be homesick, ’way up there so far from Aunt Betty. But he cured me of it, and asked Miss Muriel Tross-Kingdon to care for me.”

“Miss Muriel Tross-Kingdon?”

“Why, yes—the Lady Principal. You met her, Jim. You surely remember her kind greeting the night the prizes and diplomas were conferred. She was very courteous to you, I thought, considering the fact that she is so haughty and dignified.”

“Don’t believe I’d like to go to a girls’ school,” said Jim.

“Why, of course, you wouldn’t, silly—being a boy.”

“But I mean if I was a girl.”

“Why?”

“Oh, the life there is too dull.”

“What do you know about life at a girls’ school, Jim?”

“Well, I’ve heard a few things. I tell you, there must be plenty of athletics to make school or college life interesting.”

“Athletics? My dear boy, didn’t you see the big gym at Oak Knowe? Not a day passed but we girls performed our little feats on rings and bars, and as for games in the open air, Oak Knowe abounds with them. Look at me! Did you ever see a more rugged picture of health?”

“You seem to be in good condition, all right,” Jim confessed.

“Seem to be? I am,” corrected Dorothy.

“Well, just as you say. I won’t argue the point. I’m very glad to know you’ve become interested in athletics. That’s one good thing Miss Muriel Tross-Kingdon has done for you, anyway.”

“Jim, I don’t like your tone. Do you mean to insinuate that otherwise my course at Oak Knowe has been a failure?”

“No, no, Dorothy; you misunderstood me. You’ve benefited greatly, no doubt—at least, you’ve upheld the honor of the United States in a school almost filled with English girls. And that’s something to be proud of.”

“Not all were English, Jim. Of course, Gwendolyn Borst-Kennard and her chum, Laura Griswold, were members of the peerage. But the majority of the girls were just everyday folks like you and I have been used to associating with all our [Pg 15]lives. Even Millikins-Pillikins was more like an American than an English girl.”

“‘Millikins-Pillikins’!” sniffed Jim. “What a name to burden a girl with!”

“Oh, that’s only a nickname; her real name is Grace Adelaide Victoria Tross-Kingdon.”

“Worse and more of it!”

“Jim!” she protested sternly.

“I beg your pardon, Dorothy—no offense meant. Millikins-Pillikins is related to Miss Muriel Tross-Kingdon, I suppose?”

“Certainly.”

“Well, it may be all right,” sighed the thoroughly practical Jim, “but this putting a hyphen between your last two names looks to me like a play for notoriety.”

Dorothy’s eyes flashed fire as she turned a swift gaze upon him.

“Now, look here, Jim Barlow, we’ve been fast friends for years, and I don’t want to have a falling out, but you shall not slander my friends. And please remember, sir, that the last two words in my name are connected by a hyphen, then see if you can’t bridle your tongue a while.”

Dorothy, plainly displeased, turned and looked out of the car window. But she did not see the [Pg 16]green fields, or the cool-looking patches of woodland that were flashing past; she was wondering if she had spoken hastily to her boy chum, and whether he would resent her tone.

But Jim, after a moment’s silence, became duly humble.

“I—I’m very sorry I said that, Dorothy,” he began, slowly. “I—I’m sure I’d forgotten the hyphen in your own name. I was just thinking of those English girls. I’m positive that when they met you they felt themselves far above you, and it just makes my American blood boil—that’s all!”

Dorothy turned in time to catch a suspicious moisture in Jim’s eyes, and the warm-hearted girl immediately upbraided herself for speaking as she had.

“You’re true blue, Jim! I might have known how you meant it, and that you wouldn’t willingly slander my friends. And, just to show you that I believe in telling the truth, I’ll admit that Gwendolyn was a hateful little spitfire when I first entered the school. But finally she grew to know that in the many attributes which contribute to our happiness there were girls in the world just as well off as she. Gradually she came around, until, at the end, she was one of my warmest friends.”

Dorothy went on to relate how she had saved Gwendolyn from drowning, and how, in turn, the English girl had saved Dorothy from a terrible slide to death down an icy incline.

“Well, that wasn’t bad of her,” admitted Jim. “But she couldn’t very well stand by and see you perish—anyway, you had saved her life, and she felt duty bound to return the compliment.”

“Please believe, Jim, that she did it out of the fullness of her heart.”

“Well, if you say so,” the boy returned, reluctantly.

Both looked up at this juncture to find Ephraim standing in the aisle. The eyes of the old colored man contained a look of unbounded delight, and it was not difficult to see that his pleasure was caused by the anticipated return, within the next few hours, to Old Bellvieu and Mrs. Calvert.

“Well, Ephy,” said Dorothy, “soon we’ll see Aunt Betty again. And just think—I’ve been away for nine long months!”

“My, Miss Betty’ll suttin’ly be glad tuh see yo’ once moah, ’case she am gittin’ tuh a point now where yo’ comp’ny means er pow’ful lot tuh her. Axin’ yo’ pawdon, lil’ missy, fo’ mentionin’ de subjeck, but our Miss Betty ain’t de woman she were [Pg 18]befor’ yo’ went away las’ fall. No, indeedy! Dar’s sumpthin’ worryin’ her, en I hain’t nebber been able tuh fin’ out w’at hit is. But I reckon hit’s some trouble ’bout de ole place.”

“I’ll just bet that’s it,” said Jim. “You remember we discussed that last summer just before we went sailing on the houseboat, Dorothy?”

“Yes,” said the girl, a sad note creeping into her voice. “Something or somebody had failed, and Aunt Betty’s money was involved in some way. I remember we feared she would have to sell Bellvieu, but gradually the matter blew over, and when I left home for Oak Knowe I had heard nothing of it for some time. The city of Baltimore has long coveted Bellvieu, you know, as well as certain private firms or individuals. The old place is wanted for some new and modern addition I suppose, and they hope eventually to entice Aunt Betty into letting it go. Oh, I do wish the train would hurry! I’m so anxious to take the dear old lady in my arms and comfort her that I can scarcely contain myself. Don’t you think, Jim, there will be some way to save her all this worry?”

“We can try,” answered the boy, gravely. The way he pursed up his lips, however, told Dorothy that he realized of what little assistance a boy and [Pg 19]girl would be in a matter involving many thousands of dollars. “Let’s wait and see. Perhaps there is nothing to worry over after all.”

“Lor’ bress yo’, chile—dem’s de cheerfulest wo’ds I eber heered yo’ speak. An’ pray God yo’ may be right! De good Lord knows I hates tuh see my Miss Betty a-worryin’ en a-triflin’ her life erway, w’en she’d oughter be made comf’table en happy in her las’ days. It hain’t accordin’ tuh de Scriptur’, chillen—it hain’t accordin’ tuh de Scriptur’.”

And with a sad shake of his head the faithful old darkey moved away. A moment later they heard the door slam and knew that he had gone to the colored folks’ compartment in the car ahead.

“Ephy is loyalty personified,” said Dorothy. “His skin is black as ink, but his heart is as white as the driven snow.”

The boy did not answer. He seemed lost in thought, his eyes riveted on the passing landscape. Dorothy, too, looked out of the window again, a feeling of satisfaction possessing her as she realized that she was again in her beloved South.

On every hand were vast cotton fields, the green plants well above ground, and flourishing on account of the recent rains. Villages and hamlets [Pg 20]flashed by, as the limited took its onward way toward the great Maryland city which Dorothy Calvert called her home.

“Oh, Jim, see!” the girl cried, suddenly, gripping her companion’s arm, and pointing out of the window. “There is the old Randolph plantation. We can’t be more than an hour’s ride from Baltimore. Hurrah! I’m so glad!”

“Looks like a ‘befor’ de war’ place,” Jim returned, as he viewed the rickety condition of what had once been one of Maryland’s finest country mansions.

“Yes; the house was built long before the war. It was owned by a branch of the famous Randolphs, of Virginia, of whom you have heard and read. Aunt Betty told me the story one night, years ago. I shall never forget it. There was a serious break in the family and William Randolph moved his wife and babies away from Virginia, vowing he would never again set foot in that state. And he kept his word. He settled on this old plantation, remodeling the house, and adding to it, until he had one of the most magnificent mansions in the South. Aunt Betty frequently visited his family when a young girl. That was many years before the Civil War. When the war finally broke out, [Pg 21]William Randolph had two sons old enough to fight, so sent them to help swell the ranks of the Confederate Army. One was killed in battle. The other was with Lee at Appomattox, and came home to settle down. He finally married, and was living on the old plantation up to ten years ago, when he died.”

“What became of the father?” queried the interested Jim.

“Oh, he died soon after the war, without ever seeing his brothers in Virginia, they say. The son, Harry Randolph, being of a sunny disposition, though, finally resolved to let bygones be bygones, and some years after his father’s death, he went to see his relatives in the other state, where he was received with open arms. How terrible it must be to have a family feud, Jim!”

“Terrible,” nodded the boy.

“Just think how I’d feel if I were to get mad at Aunt Betty and go to Virginia, or New York to stay, never to see my dear old auntie again on this earth. Humph! Catch me doing a thing like that? Well, I reckon not—mo matter how great the provocation!”

Jim smiled.

“Not much danger of your having to do anything [Pg 22]like that,” he replied. “Aunt Betty loves you too much, and even if you did, you could go back to Mother Martha and Father John.”

“Yes; I could, that’s true. But life would never seem the same, after finding Aunt Betty, and being taken to her heart as I have. But let’s not talk of such morbid things. Let us, rather, plan what we shall do for a good time this summer.”

“Humph!” grunted the boy. “Reckon I’ll be having a good time studying ’lectricity. There’s work ahead of me, and I don’t dare allow myself to forget it.”

“But, Jim, you are going home with me for a vacation. All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy, or, at least, that’s what I’ve always been taught to believe.”

“I know, Dorothy; but I’ve got a living to make.” The serious note in Jim’s voice made Dorothy turn in some surprise.

“Why, Jim Barlow, how you talk! You’re not old enough to strike out for yourself yet.” A note of authority crept unconsciously into Dorothy’s tones.

“Yes; I am. Lots of boys younger than I have gone out to wrestle with the world for a livelihood, and I reckon I can do the same.”

“But Dr. Sterling won’t let you, I’m sure.”

“Humph! A lot Dr. Sterling has to say about that!”

“But you would surely regard his advice as worth something?”

“Yes; a great deal. His advice is for me to learn electricity—to learn it thoroughly from the bottom up. To do that I shall have to serve as an apprentice for a number of years. The pay is not great, but enough to live on. I’ve made up my mind, Dorothy, so don’t try to turn me from my purpose.”

Dorothy Calvert looked with pride on this manly young fellow at her side, as she recalled her first meeting with him some years before. At that time she had been living with Mother Martha and Father John on the Hudson near Newburgh. Jim, the “bound boy,” had been Mrs. Calvert’s protégé, and had finally worked his way into the regard of his elders, until Dr. Sterling had taken him under his protecting wing. The doctor, a prominent geologist, had endeavored to teach the boy the rudiments of his calling, and Jim had proved an apt pupil, but had shown such a yearning toward electricity and kindred subjects that the kindly doctor had purchased for him some of the best books on the [Pg 24]subject. Over these the boy had pored night and day, rigging up apparatus after apparatus, that he might experiment with the great force first discovered in its primitive form by Benjamin Franklin, and later given to the world in such startling form by Morse and Edison.

“I shall never try to turn you from your purpose, Jim,” said Dorothy. “I feel that whatever you attempt will be a success. You have it in you, and in your lexicon there is no such word as fail. When do you begin your apprenticeship?”

“In Baltimore this month, if I can find a place.”

“Oh, Jim, won’t that be fine? I’ll tell Aunt Betty the moment we arrive. Perhaps some of her friends will know of an opening. I’m sure some of them will, and we’ll have you always with us.”

“That sounds good to me. I’ve written Dr. Sterling to send my books and electrical apparatus by freight to Bellvieu.”

“Then we’ll give you a fine, large room all to yourself, where you can set up your laboratory.”

Dorothy’s enthusiasm began to communicate itself to Jim, and soon he had launched himself into an exposition of electricity and its uses, with many comments on its future.

So engrossed were both boy and girl in the discussion [Pg 25]that they did not hear Ephraim, who came silently down the aisle and stood in a respectful attitude before them.

“S’cuse me, please, Miss Dorot’y, en Mistah Jim, but p’raps yo’ don’t know dat we’s almos’ tuh de Baltimore station.”

Dorothy threw a quick glance out of the window.

“Oh, so we are! See, Jim! There’s the old Chesapeake, and it’s a sight for sore eyes. Now, for old Bellvieu and Aunt Betty!”

There was a hasty gathering of satchels and paraphernalia as the train drew into the big station. The hum of voices outside, mingled with the shouts of the cab drivers and the shrill cries of the newsboys, met their ears as they descended from the coach.

Through the throng Ephraim led the way with the luggage, Dorothy and Jim following quickly, until finally, in the street, the girl descried a familiar carriage, on the top of which a young colored boy was perched.

“Hello, Methuselah Bonaparte Washington! Don’t you know your mistress?” cried Dorothy, running toward him.

This was probably the first time Dorothy had ever called him anything but “Metty,” by which [Pg 26]nickname he was known at Bellvieu, where he had always lived, and where he had served as Aunt Betty’s page and footman since he was old enough to appreciate the responsibilities of the position.

His eyes glowed with affection now, as he viewed his little mistress after many months’ absence. Descending from his perch on the carriage, he bowed low to Dorothy, his face wreathed in a smile of such broad proportions that it seemed his features could never go back into their proper places.

“Lordy, lil’ missy, I’s suah glad tuh sot mah eyes on yo’ once mo’. Ole Bellvieu hain’t eben been interestin’ sence yo’ lef las’ fall.”

“Do you mean that, Metty?” cried the girl, her heart warming toward the little fellow for the sincerity of his welcome.

“Yas’m, lil’ missy, I suah does mean hit. An’ I hain’t de only one dat’s missed yo’. Mrs. Betty done been habin’ seben fits sence yo’ went off tuh school, an’ as fo’ Dinah en Chloe, dey hain’t smiled onct all wintah. Dey’ll all be glad tuh see yo’ back—yas’m, dey suah will!”

“And how is Aunt Betty?” the girl asked, a little catch in her voice. Instinctively she seemed to dread the answer. Aunt Betty was getting old, and her health had not been of the best recently.

“She’s pow’ful pooh, lil’ missy, but I jes’ knows she’ll git plenty ob strength w’en she sees yo’ lookin’ so fine en strong.”

“Well, take us to her,” said Dorothy, “and don’t spare the horses.”

“Yas’m—yas’m—I’ll suah do dat—I’ll suah do dat!”

Through the narrow, crowded streets of old Baltimore the Calvert carriage dashed, with Dorothy and Jim inside, and Ephraim keeping company with Metty on the box. Metty chose a route through the dirtiest streets, where tumbledown houses swarmed with strange-looking people, who eyed the party curiously; but this was the shortest way to the great country home of the Calverts. Soon the streets grew wider, the air purer, then the Chesapeake burst into view, the salty air refreshing the tired occupants of the carriage as nothing had done for days.

Finally, the glistening carriage and finely caparisoned horses sped on a swift trot through the great gateway at Bellvieu, and Dorothy, leaning out of the window, saw Aunt Betty standing expectantly on the steps of the old mansion.

Home at last!

“Oh, Aunt Betty, Aunt Betty!” cried Dorothy, as she leaped from the carriage and dashed across the lawn toward the steps, followed more leisurely by Jim. “I just can’t wait to get to you!”

Aunt Betty gave an hysterical little laugh and folded the girl in her arms with such a warmth of affection that tears sprang into Dorothy’s eyes.

“My dear, dear child!” was all the old lady could say. Then her lip began to tremble and she seemed on the verge of crying.

Dorothy took the aged face between her two hands and kissed it repeatedly. She forgot that Jim was standing near, waiting for a greeting—forgot everything except that she was home again, with Mrs. Elisabeth Cecil Somerset-Calvert, the best and dearest aunt in the world, to love and pet her.

“Break away! Break away!” cried Jim, after a moment, forcing a note of gayety into his voice for Aunt Betty’s sake. “Give a fellow a chance for a kiss, won’t you, Dorothy?”

“Certainly, Jim; I’d forgotten you were with me,” was the girl’s response.

“You, as well as Dorothy, are a sight for sore eyes,” cried Aunt Betty, pleased at the warm embrace and hearty kiss of her one-time protégé.

“And we’re glad to be here, you bet!” Jim replied. “A long, tiresome journey, that, Aunt Betty, I tell you! The sight of old Bellvieu is almost as refreshing as a good night’s sleep, and that’s something I stand pretty badly in need of about now. And just gaze at Dorothy, Aunt Betty! Isn’t she looking well?”

“A perfect picture of health, Jim. Had I met her in a crowd in a strange city, I doubt if I should have known her.”

“Oh, Aunt Betty, surely I haven’t changed as much as that,” the girl protested.

“You don’t realize how you’ve grown and broadened, and—”

“Broadened? Oh, Aunt Betty!”

“Broadened, not physically, but mentally, my dear. I can see that my old friend, the Bishop, took good care of you, and that Miss Tross-Kingdon has borne out her well-established reputation of returning young ladies to their relatives greatly improved both in learning and culture.”

“Well, auntie, dear, I’m satisfied if you are, and now, let me take off my things. I’m so tired of railroad trains, I don’t care to see another for months.”

“Well, you’ve had your work, and now you shall have your play. I do not mean that you shall be shut up in this hot city all summer without a bit of an outing. What would you say to a—oh, but I’m ahead of my story! I’ll tell you all this when you are rested and can better decide whether my plans for your vacation will please you.”

“Oh, auntie, tell me now—don’t keep me in suspense!”

“Young ladies,” said Aunt Betty, regarding her great-niece half-severely over her glasses, “should learn to control their curiosity. If allowed to run unbridled, it is apt, sooner or later, to get them into trouble.”

“But, auntie, I want to know!”

Just the suggestion of a pout showed itself on Dorothy’s lips.

“What a pretty mouth! And so you shall know.”

“You’re the best auntie!”

Two white arms went around Mrs. Calvert’s neck and the pouting face was wreathed in smiles.

“But not now,” concluded Aunt Betty.

“Oh!”

The disappointed tone made Aunt Betty smile, and she winked slyly at Jim, as she observed:

“Isn’t it wonderful what a lot of interest a simple little sentence will arouse?”

“I’ve never yet met a girl who wasn’t overburdened with curiosity—and I s’pose I never shall,” was Jim’s response. “It’s the way they’re built. Aunt Betty, and I reckon there’s no help for it. Not changing the subject, but how do I reach my room?”

“Ephy will show you. It’s the big room on the east side. Everything is ready for you. When you have washed and freshened up a bit you may join Dorothy and I on the lawn.”

“Very good; but don’t wait for me. I may decide to take a snooze, and when I snooze I’m very uncertain. Traveling always did tire me out.”

Ephraim, with Jim’s suit case, led the way up the broad stairs of the Calvert mansion, the boy following.

“Heah we is, sah,” said the colored man, after a moment. He paused to throw open the massive door of a room. “Dis yeah room am de very bestest dis place affords. Youse mighty lucky, Mistah [Pg 32]Jim, tuh be relegated tuh de guest chambah, en I takes dis ercasion to congratulate yo’.”

“Thank you, Ephy. But, being a guest, why should I not have the guest chamber?” and Jim’s eyes roamed admiringly over the old-fashioned but richly-furnished apartment.

“No reason ’tall, sah—no reason ’tall. I hain’t sayin’ nuffin’. But dis suah am er fine room.”

The suit case was resting on the floor by the wardrobe, and Ephraim was carefully unpacking the boy’s clothes, and putting them in their proper places, while Jim, glad to be rid of his coat, which he termed “excess baggage,” was soon puffing and blowing in a huge bowl of water, from where he went for a plunge in the tub.

“Lordy, Mistah Jim,” the colored man chuckled, following him to the door of the bathroom, “hit suah looks as though yo’ was a darkey, en all de black had washed off.”

“That’s some of the smoke and cinders acquired during our journey from Canada. Don’t forget that you have them on you, too, Ephy, only, being as black as ink, they don’t show up so well.”

“Yas’r, yas’r, I reckon dat’s right.” Old Ephraim continued to chuckle at frequent intervals. “Yo’ suah is er great boy, Mistah Jim!”

“Thank you, Ephy.”

“A-washin’ yo’ face en haid in de wash bowl, den climbin’ intuh de tub fo’ tuh wash de rest. Dat’s w’at I calls extravagantness.” He straightened up suddenly. “Now, sah, yo’ clothes is all laid out nice, sah. Is dar anyt’ing moah I kin do?”

“Nothing, Ephy—nothing. You’ve done everything a gentleman could expect of his valet. So vamoose!”

“Huh?”

“Get out—take your leave—anything you want to call it, so you leave me alone. I’m going to take a nap, and when I wake up I’ll be as hungry as a bear.”

“Well, I reckon we kin jes’ about satisfy dat appetite, chile. If dar’s anyt’ing mah Miss Betty hain’t got in de way ob food, I hain’t nebber diskivered hit yet.”

So Ephraim left Jim to his own devices, and went down to the servants’ quarters, where he literally talked the arms off of both Chloe and Dinah, while Metty stood by with wide-open mouth, as he listened to Ephraim’s tale of his adventures in Canada.

In the meantime, Dorothy and Aunt Betty were in the former’s big front room, and the girl, too, was [Pg 34]removing the stains of the journey, keeping up an incessant chatter to Mrs. Calvert, the while.

“I was perfectly delighted with Oak Knowe,” she said, “and most particularly with your friend, the Bishop, who received me with open arms—not figuratively, but literally, Aunt Betty—and gave me such a good send-off to Miss Tross-Kingdon that I’m sure she became slightly prepossessed in my favor.”

Dorothy then told of her examination by Miss Hexam, and how well she had gone through the ordeal, despite the fact that she had been dreadfully nervous; her examination in music, and her introduction to the other scholars; the antipathy, both felt and expressed for her by Gwendolyn Borst-Kennard, a member of the British peerage, who led the student body known as the “Peers”; of her introduction to the “Commons,” the largest and wildest set in the school, who were all daughters of good families, but without rank or titles.

“And I can see my mischievous girl entering into the pranks of the ‘Commons,’” smiled Aunt Betty. “I only hope you did not carry things with a high hand and win the disapproval of Miss Tross-Kingdon.”

“Occasionally we did,” Dorothy was forced to [Pg 35]admit. “But for the most part the girls were a rollicking lot, going nearly to the extreme limits of behavior when any fun promised, but keeping safely within the rules. There is no doubt, Aunt Betty, but that Miss Tross-Kingdon was secretly fonder of us than of the more dignified ‘Peers.’”

Then Aunt Betty must know the outcome of the dislike expressed for Dorothy by Gwendolyn Borst-Kennard, so the girl recounted her subsequent adventures, including her rescue of Gwendolyn from the water, and the English girl’s brave act in saving Dorothy from a frightful slide down a precipice.

“Just think! You were in deadly danger and I knew nothing of it,” said Aunt Betty, a sternly reproving note in her voice.

“But think, dear Aunt Betty, of the worry it would have caused you. It was all over in a few moments, and I was safe and sound again. If I had written you then, you would have felt that I was in constant peril, whereas my escape served as a lesson to me not to be careless, and you would have worried over nothing.”

“Perhaps you are right, Dorothy; at any rate, now I have you with me, I am not going to quarrel. I’m sure your adventure was merely the result of being thoughtless.”

“It was. And Gwendolyn’s rescue was simply magnificent, auntie. Her only thought at that moment seemed for me.”

“We will try to thank her in a substantial manner some day, my dear.”

“I should dearly love to have her visit me at Bellvieu, if only to show the cold, aristocratic young lady the warmth and sincerity of a Southern reception.”

“And perhaps you will have the opportunity. But not this summer. I have other plans for you.”

“Now, you are arousing my curiosity again,” said Dorothy, in a disappointed tone. “Please, Aunt Betty, tell me what is on your mind.”

“All in good time, my dear.”

“Has it—has it anything to do with Uncle Seth?” the girl queried, a slight tremor in her voice. Somehow, she felt that the death of the “Learned Blacksmith,” with whom Aunt Betty had been so intimate for years, had been responsible in a measure for the present poor state of her health.

“Yes; it has to do with your Uncle Seth, poor man. His death, as you have probably imagined, was a great shock to me. I felt as though I had lost a brother. And then, the news of his demise came so suddenly. It was his dearest wish that [Pg 37]you become a great musician. You will remember how he encouraged and developed your talent while we were at Deerhurst, arranging with Mr. Wilmot to give you lessons? He has frequently expressed himself as not being satisfied with your progress. Shortly before his death I had a letter from him, in which he urged me to employ one of the best violin teachers in Baltimore for you at the end of your course at Oak Knowe. I feel it is a small favor, to grant, dear, so if you are still of the notion that you were intended for a great violinist, I have decided to give you a chance to show your mettle.”

“Dear Aunt Betty,” said the girl, earnestly, putting an arm affectionately around the neck of her relative, “it is the dearest wish of my life, but one.”

“What is the other wish, Dorothy?”

“That you be thoroughly restored to health. Then, if I can become perfect on my violin, I shall be delighted beyond measure.”

“Oh, my health is all right, child, except that I am beginning to feel my age. It was partly through a selfish motive that I planned this outing in Western Maryland.”

“An outing in Western Maryland! Oh, and was that the secret you had to tell me?”

“Yes; the South Mountains, a spur of the famous Blue Ridge range, will make an ideal spot in which to spend a few weeks during the summer months.”

“It must be a beautiful spot,” said the girl. “I love the mountains, and always have. The Catskills especially, will always be dear to me. When do we start, auntie?”

“As soon as you have perfected your arrangements with Herr Deichenberg, and have rested sufficiently from your journey.”

“Herr Deichenberg? Oh, then you have already found my teacher?”

“Yes; and a perfect treasure he is, or I miss my guess. Do you remember David Warfield in ‘The Music Master,’ which we saw at the theater a year ago?”

“Indeed, yes, auntie. How could one ever forget?”

“Herr Deichenberg is a musician of the Anton Von Barwig type—kind, gentle, courteous—withal, possessing those sterling qualities so ably portrayed in the play by Mr. Warfield. The Herr has the most delightful brogue, and a shy manner, which I am sure will not be in evidence during lesson hours.”

“And I am to be taught by a real musician?”

“Yes.”

“What a lucky girl I am!”

“If you think so, dear, I am pleased. I have tried to make you happy.”

“And you have succeeded beyond my fondest expectations. There is nothing any girl could have that I have wanted for, since coming to live with you. You are the finest, best and bravest auntie in the whole, wide world!”

“Oh, Dorothy!”

“It’s true, and you know it. It’s too bad other girls are not so fortunate. To think of your having my vacation all planned before I reached home. I said I am tired of railroad trains, but I’ve changed my mind; I am perfectly willing to ride as far as the South Mountains and return.”

“But in this instance we are not going on a train, my dear.”

“Not going on a train?” queried Dorothy, a blank expression on her face. Aunt Betty shook her head and smiled.

“Now, I’ve mystified you, haven’t I?”

“You surely have. The trolleys do not run that far, so how—?”

Dorothy paused, perplexed.

“There are other means of locomotion,” said Aunt Betty in her most tantalizing tone.

“Yes; we might walk,” laughed the girl, “but I dare say we shall not.”

“No; we are going in an automobile.”

“In an automobile? Oh, I’m so glad, auntie. I—I—” Dorothy paused and assumed a serious expression. “Why, auntie, dear, wherever are we to get an automobile? You surely cannot afford so expensive a luxury?”

“You are quite right; I cannot.”

“Then—?”

“But Gerald and Aurora Blank have a nice new car, and they have offered to pilot our little party across the state.”

“Then I forgive them all their sins!” cried Dorothy. “Somehow, I disliked them when we first met; and you know, dear auntie, they were rude and overbearing during the early days on the houseboat.”

“But before the end of the trip, through a series of incidents which go a long way toward making good men and women out of our boys and girls, they learned to be gentle to everybody,” Aunt Betty responded, a reminiscent note in her voice. “I remember, we discussed it at the time.”

“I must say they got over their priggishness quickly when they once saw the error of their ways,” said Dorothy.

“Yes. Gerald is growing into a fine young man, now. You know his father failed in business, so that he was forced to sell the houseboat, and that Uncle Seth bought it for you? Well, Gerald has entered into his father’s affairs with an indomitable spirit, and has, I am told, become quite an assistance to him, as well as an inspiration to him to retrieve his lost fortunes. The Blanks have grown quite prosperous again, and Mr. Blank gave the auto to Gerald and Aurora a few weeks since to do with as they please.”

“I’m glad to hear of Gerald’s success. No doubt he and Jim will get along better this time—for, of course, Jim is to be included in our party?”

“Indeed we should never go a mile out of Baltimore without him!” sniffed Aunt Betty. “It was expressly stipulated that he was to go. Besides Jim, Gerald, Aurora, and ourselves, there will be no one but Ephraim, unless you care to invite your old chum, Molly Breckenridge?”

“Oh, auntie, why do you suggest the impossible?” Dorothy’s face went again from gay to grave. “Dear Molly is in California with her father, [Pg 42]who is ill, and they may not return for months.”

“I’d forgotten you had not heard. Molly returned east with her father some two weeks since, hence may be reached any time at her old address.”

“That’s the best news I have heard since you told me I was to study under Herr Deichenberg,” Dorothy declared. “I’ll write Molly to-day, and if she comes, she shall have a reception at Bellvieu fit for a queen.”

Molly and Dorothy had first met during Dorothy’s schooldays at the Misses Rhinelanders’ boarding academy in Newburgh, where they had been the life of the school. Their acquaintance had ripened into more than friendship when, together, they traveled through Nova Scotia, and later met for another good time on the western ranch of the railroad king, Daniel Ford. More than any of her other girl friends Dorothy liked Molly, hence the news that she had returned east, and that she might invite her to share the outing in the South Mountains, caused Dorothy’s eyes to glow with a deep satisfaction.

“And now that we have discussed so thoroughly our prospective outing,” said Aunt Betty, “we may change the subject. It remains for me to arrange [Pg 43]an early meeting for you with Herr Deichenberg. The Herr has a little studio in a quiet part of the city which he rarely leaves. It is quite possible, however, that I can induce him to come to Bellvieu for your first meeting, though I am sure he will insist that all your labors be performed in his own comfortable domicile, where he, naturally, feels perfectly at home.

“I visited the studio some weeks ago—shortly after I received your Uncle Seth’s letter, in fact. The Herr received me cordially, and said he would be delighted to take a pupil so highly recommended as Miss Dorothy Elisabeth Somerset-Calvert.”

“To which I duly make my little bow,” replied the girl, dropping a graceful curtsey she had learned from Miss Muriel Tross-Kingdon.

“My dear Dorothy, that is the most beautiful thing I have ever seen you do. As Ephraim would express it, it is ‘puffectly harmonious.’ Indeed, you have improved since going to Canada, and it pleases me immensely.”

Aunt Betty’s admiration for her great-niece was so thoroughly genuine that Dorothy could not refrain from giving her another hug.

“There, there, dear; you overwhelm me. I am glad to be able to pay you an honest compliment. [Pg 44]I have no doubt you have acquired other virtues of which I am at present in ignorance.”

“Aunt Betty, you’re getting to be a perfect flatterer. And what about the vices I may have acquired?”

Aunt Betty smiled.

“They are, I am sure, greatly in the minority—in fact, nothing but what any healthy, mischievous girl acquires at a modern boarding school. Now, in my younger days, the schoolmasters and mistresses were very strict. Disobedience to the slightest rule meant severe punishment, and was really the means of keeping pent up within one certain things from which the system were better rid. But I must go now and dress. When you have rested and completed your toilet, pass by my room and we’ll go on the lawn together.”

With a final kiss Aunt Betty disappeared down the hall, leaving Dorothy alone with her thoughts.

“Dear old auntie,” she murmured. “Her chief desire, apparently, is for my welfare. I can never in this world repay her kindness—never!”

Then, seized with a sudden inspiration, she sat down at her writing desk by the big window, overlooking the arbor and side garden, and indicted the following letter to her chum:

“My Darling Molly:

“Heavy, heavy hangs over your head! You are severely penalized for not writing me of your return. But to surprise your friends was always one of your greatest delights, you sly little minx! So I am not holding it up against you. I’ll even the score with you some day in a way you little imagine.

“Well, well, well, you just can’t guess what I have to tell you! And I’m glad you can’t, for that would take away the pleasure of the telling. Aunt Betty has planned a fine outing for me in the South Mountains, which, as you know, form a spur of the Blue Ridge range in Western Maryland. We are to be gone several weeks, during which time who can say what glorious adventures we will have?

“You are going with us. I want your acceptance of the invitation by return mail, Lady Breckenridge, and I shall take pleasure in providing a brave knight for your escort in the person of one Gerald Blank, in whose automobile we are to make the trip. He has a new seven-passenger car given him by his father, and, in the vulgar parlance of the day, we are going to ‘make things hum.’ It is only some sixty miles to the mountains, and we expect to be out only one night between Baltimore [Pg 46]and our destination. Besides yourself, Aunt Betty and I, there will be only Gerald, Aurora, his sister, Jim Barlow, and Ephraim, who will be camp cook, and general man-of-all-work.

“Now write me, dear girlie, and say that you will arrive immediately, for I am just dying with anxiety to see you, and to clasp you in my arms. Jim is already here, having traveled to Canada with Ephy to bring me safely home. As if a girl of my mature age couldn’t travel alone! However, it was one of Aunt Betty’s whims, she being in too ill health to come herself, so I suppose it is all right. Dear auntie will improve I feel sure—now that I am back. That may sound conceited, but I assure you it was not meant to. We are just wrapped up in each other—that’s all. The outing will do her good, and will, I am sure, restore in a measure her shattered health.

“And oh, I forgot to tell you! I am to have violin lessons after my vacation from the famous Herr Deichenberg, Baltimore’s finest musician, whom Aunt Betty had especially engaged before my return. No one can better appreciate than you just what this means to me. My greatest ambition has been to become a fine violinist, and now my hopes bid fair to be realized. I know it rests with me [Pg 47]to a great extent just how far up the ladder I go, and am resolved that Herr Deichenberg, before he is through with me, shall declare me the greatest pupil he has ever had. It takes courage to write that—and mean it—Molly, dear; but if we don’t make such resolves and stick to them, we will never amount to much, I fear.

“My first meeting with the Herr Professor will be within the next few days, and I am looking eagerly forward to the time. Aunt Betty says he has the dearest sort of a studio in a quiet part of the city, where he puts his pupils through a course of sprouts and brings out all the latent energy—or, temperament, I suppose you would call it.

“Well, Molly, dear, you must admit that this is a long letter for my first day home, especially when I am tired from the journey, and have stopped my dressing to write you. So don’t disappoint me, but write—or wire—that you are starting at once. Tell the dear Judge we hope his health has improved to such an extent that you will be free from all worry in the future. Remember us to your aunt, and don’t forget that your welcome at old Bellvieu is as everlasting as the days are long.

“Ever your affectionate

“Dorothy.”

“There! I guess if that don’t bring Miss Molly Breckenridge to time, nothing will.”

Dorothy put the letter in a dainty, scented envelope, stamped and addressed it, and laid it on her dresser where she would be sure to carry it down to Ephraim when she had dressed.

An hour later, when the declining sun had disappeared behind the big hedge to the west of Bellvieu, and the lawn was filled with cool, deep shadows, Dorothy and Aunt Betty settled themselves in the open air for another chat.

The arrival of Herr Deichenberg at Bellvieu was looked forward to with breathless interest by Dorothy, and calm satisfaction by Aunt Betty, whose joy at seeing her girl so well pleased with the arrangements made for her studies, had been the means of reviving her spirits not a little, until she seemed almost like her old self.

The day following Dorothy’s return Ephraim was sent to the musician’s studio with a note from Mrs. Calvert, telling of the girl’s arrival, and suggesting that possibly the first meeting would be productive of better results if held at Bellvieu, where the girl would be free from embarrassment. Here, too, was a piano, the note stated, and Herr Deichenberg, who was also an expert on this instrument, might, if he desired, test Dorothy’s skill before taking up the work with her in earnest in his studio.

Ephraim returned in the late afternoon, bringing a written answer from the music master, in which [Pg 50]he stated that it was contrary to his custom to visit the homes of his pupils, but that in the present instance, and under the existing circumstances, he would be glad to make an exception. He set the time of his visit at ten the following morning.

Dorothy awoke next day with a flutter of excitement. To her it seemed that the crucial moment of her life had come. If she were to fail—! She crowded the thought from her mind, firmly resolved to master the instrument which is said by all great musicians to represent more thoroughly than any other mode of expression, the joys, hopes and passions of the human soul.

Breakfast over, with a feeling of contentment Dorothy stole up to her room to dress, the taste of Dinah’s coffee and hot biscuits still lingering in her mouth.

As the minutes passed she found herself wondering what Herr Deichenberg would look like. She conjured up all sorts of pictures of a stoop-shouldered little German, her final impression, however, resolving itself into an image of “The Music Master’s” hero, Herr Von Barwig.

Would he bring his violin? she wondered. It was a rare old Cremona, she had heard, with a tone so full and sweet as to dazzle the Herr’s audiences [Pg 51]whenever they were so fortunate as to induce him to play.

Descending finally, arrayed in her prettiest gown, a dainty creation of lawn and lace, Dorothy found Aunt Betty awaiting her.

“Never have I seen you dress in better taste, my dear!” cried Mrs. Calvert, and the girl flushed with pleasure. “The Herr, as you have perhaps surmised, is a lover of simple things, both in the way of clothes and colors, and I am anxious that you shall make a good impression. He, himself, always dresses in black—linen during the warmer days, broadcloth in the winter. Everything about him in fact is simple—everything but his playing, which is wonderful, and truly inspired by genuine genius.”

“Stop, auntie, dear, or you will have me afraid to meet the Herr. After holding him up as such a paragon, is it any wonder I should feel as small and insignificant as a mouse?”

“Come, come, you are not so foolish!”

“Of course, I’m not, really—I was only joking,” and Dorothy’s laugh rang out over the lawn as they seated themselves on the gallery to await the arrival of the guest. “But I do feel a trembling sensation when I think that I am to meet [Pg 52]the great Herr Deichenberg, of whom I have heard so much, yet seen so little.”

“There is nothing to tremble over, my dear—nothing at all. He is just like other men; very ordinary, and surely kind-hearted to all with whom he comes in contact.”

As they were discussing the matter, Jim and Ephraim came around the corner of the house, their hands full of fishing tackle.

“Well, Aunt Betty,” greeted the boy, “we’re off for the old Chesapeake to court the denizens of the deep, and I’m willing to wager we’ll have fish for breakfast to-morrow morning.”

He pulled off his broad-brimmed straw hat and mopped a perspiring brow.

“Don’t be too sure of that,” returned Aunt Betty. “Fish do not always bite when you want them to. I know, for I’ve tried it, many’s the time.”

“Mah Miss Betty suah uster be er good fisher-woman,” quoth Ephraim, a light of pride in his eyes. “I’ve seen her sot on de bank ob de Chesapeake, en cotch as many as ’leben fish in one hour. Big fellers, too—none ob yo’ lil’ cat-fish en perch. Golly! I suah ’members de time she hooked dat ole gar, en hollered fo’ help tuh pull ’im out. Den all de folks rush’ up en grab de line, en ole Mistah [Pg 53]Gar jes’ done come up outen de watah like he’d been shot out ob er gun.”

Slapping his knees at the recollection, Ephraim guffawed loudly, and with such enthusiasm that Aunt Betty forgot her infirmities and joined in most heartily.

“The joke was on me that time, Ephy,” she finally said, wiping the tears from her eyes. “But we landed old ‘Mistah Gar,’ which I suppose was what we wanted after all.”

“Wish I might hook a gar to-day,” said Jim.

“En like as not yo’ will, chile, ’case dem gars is mighty plentiful in de bay. Hardly a day go by, but w’at two or t’ree ob ’em is yanked outen de sea, en lef’ tuh dry up on de bank.”

“Well, we’ll try our hand at one if possible. Good-by, Dorothy! Good-by, Aunt Betty. Have plenty of good things for lunch,” were Jim’s parting words, as he and Ephraim strode off down the path toward the gate. “We will be as hungry as bears when we get back, and I’m smacking my lips now in anticipation of what we’re going to have.”

“Go along!” said Aunt Betty. “You’re too much trouble. I’ll feed you on corn bread and molasses.” But she laughed heartily. It pleased her to see Jim enjoying himself. “Oh, maybe I’ll cook [Pg 54]something nice for you,” she called after him—“something that will make your mouth water sure enough.”

“Yum yum! Tell me about it now,” cried Jim.

“No; I’m going to surprise you,” answered the mistress of Bellvieu, and with a last wave of their hands, Jim and the old darkey disappeared behind the big hedge.

They were hardly out of sight before the figure of a little, gray-haired man walked slowly up to the gate, opened it, and continued his way up the walk, and Dorothy Calvert, her heart beating wildly, realized that she was being treated to her first sight of the famous music master, Herr Deichenberg.

As the Herr paused before the steps of the Calvert mansion, hat in hand, both Mrs. Calvert and Dorothy arose to greet him.

Dorothy saw before her a deeply intellectual face, framed in a long mass of gray hair; an under lip slightly drooping; keen blue eyes, which snapped and sparkled and seemed always to be laughing; a nose slightly Roman in shape, below which two perfect rows of white teeth gleamed as Herr Deichenberg smiled and bowed.

“I hope I find you vell dis morning, ladies,” was his simple greeting.

“HERR DEICHENBERG.”

“HERR DEICHENBERG.”“Indeed, yes, Herr,” Aunt Betty responded, offering her hand. “I am glad to see you again. This is the young lady of whom I spoke—my great-niece, Dorothy Calvert.”

“H’m! Yes, yes,” said the Herr, looking the girl over with kindly eye, as she extended her hand. Then, with Dorothy’s hand clasped tightly in his own, he went on: “I hope, Miss Dorothy, dat ve vill get on very good togedder. I haf no reason to believe ve vill not, an’ perhaps—who knows?—perhaps ve shall surprise in you dat spark of genius vhich vill make you de best known little lady in your great American land.”

“Oh, I hope so, Herr Deichenberg—I hope so,” was the girl’s fervent reply. “It has been my greatest ambition.”

The Herr turned to Aunt Betty:

“She iss in earnest, Madame; I can see it at a glance, and it iss half de battle. Too many things are lost in dis world t’rough a lack of confidence, and de lack of a faculty for getting out de best dat iss in one.”

The Herr sank into one of the deep, comfortable rockers on the gallery, near Aunt Betty, as Dorothy, at a signal from her aunt, excused herself and went in search of Dinah, with the result that mint [Pg 56]lemonade, cool and tempting, was soon served to the trio outside, greatly to the delight of the Herr professor, who sipped his drink with great satisfaction. After a few moments he became quite talkative, and said, after casting many admiring glances over the grounds of old Bellvieu:

“Dis place reminds me more than anything I have seen in America, of my fadder’s place in Germany. De trees, de flowers, de shrubs—dey are all de same. You know,” he added, “I live in Baltimore, dat iss true, yet, I see very little of it. My list of pupils iss as large as I could well desire, und my time iss taken up in my little studio.”

“But one should have plenty of fresh air,” said Aunt Betty, “It serves as an inspiration to all who plan to do great things.”

“Dat sentiment does you credit, madame. It iss not fresh air dat I lack, for I have a little garden in vhich I spend a great deal of time, both morning und evening—it iss de inspiration of a grand estate like dis. It makes me feel dat, after all, there iss something I have not got out of life.”

There was a suspicious moisture in the Herr’s eyes, brought there, no doubt, by recollections of his younger days in the Old Country, and Aunt Betty, noticing his emotion, hastened to say:

“Then it will give us even greater pleasure, Herr Deichenberg, to welcome you here, and we trust your visits will be neither short nor infrequent.”

“Madame, I am grateful for your kindness. No one could say more than you have, and it may be dat I vill decide to give Miss Dorothy her lessons in her own home, dat ve may both have de inspiration of de pretty trees und flowers.”

“Aside from the fact that I am anxious to see your studio,” said the girl, “that arrangement will please me greatly.”

“It vill please me to be able to show you my studio, anyvay,” said the Herr.

“How long have you been in America?” Aunt Betty wanted to know, as the Herr again turned toward her.

“I came over just after de Civil War. I was quite a young lad at de time und a goot musician. I had no difficulty in finding employment in New York City, vhere I played in a restaurant orchestra for a number of years. Den I drifted to Vashington, den to Baltimore, vhere I have remained ever since.”

“And have you never been back across the water?” asked Dorothy.

“Yes; once I go back to my old home to see my [Pg 58]people. Dat was de last time dat I see my fadder und mudder alive. Now I have few relatives living, und almost no desire to visit Germany again. America has taken hold of me, as it does every foreigner who comes over, und has made of me vhat I hope iss a goot citizen.”

The talk then drifted to Dorothy’s lessons. Herr Deichenberg questioned her closely as to her experience, nodding his head in grave satisfaction as she told of her lessons from Mr. Wilmot at Deerhurst. Then, apparently satisfied that she would prove an apt pupil, he asked to be allowed to listen to her playing. So, at Aunt Betty’s suggestion, they adjourned to the big living-room, where Dorothy tenderly lifted her violin from its case.

As she was running her fingers over the strings to find if the instrument was in tune, she noticed Herr Deichenberg holding out his hand for it.

She passed it over. The old German gave it a careful scrutiny, peering inside, and finally nodding his head in satisfaction.

“It iss a goot instrument,” he told her. “Not as goot as either a Cremona or a Strad, but by all means goot enough to serve your purpose.”

“It was a present from my Uncle Seth,” said [Pg 59]Dorothy, “and I prize it very highly, aside from its actual value.”

“Und so you should—so you should,” said the Herr. “Come, now,”—moving toward the piano. “You read your music of course?”

Dorothy admitted that she did.

The Herr, sitting on the stool before the large, old-fashioned instrument, struck a chord.

“Tune your instrument with me, und we vill try something you know vell. I shall then be able to judge both of your execution und your tone. There iss de chord. Ah! now you are ready? All right. Shall we try de ‘Miserere’ from ‘Il Trovatore?’ I see you have it here.”

Dorothy nodded assent.

Then, from somewhere in his pocket, Herr Deichenberg produced a small baton, and with this flourished in his right hand, his left striking the chords on the piano, he gave the signal to play.

Her violin once under her chin, the bow grasped firmly in her hand, what nervousness Dorothy had felt, quickly vanished. She forgot the Herr professor, Aunt Betty—everything but the music before her. Delicately, timidly, she drew her bow across the strings, then, when the more strenuous parts of the Miserere were reached, she gathered [Pg 60]boldness, swaying to the rhythm of the notes, until a light of positive pleasure dawned in Herr Deichenberg’s eyes.

“Ah!” he murmured, his ear bent toward her, as if to miss a single note would be a rare penance. “Ah, dat iss fine—fine!”

Suddenly, then, he dropped his baton, and fell into the accompaniment of the famous piece, his hands moving like lightning over the keys of the piano.

Such music Aunt Betty vowed she had never heard before.

With a grand flourish the Herr and Dorothy wound up the Miserere, and turned toward their interested listener for approval. And this Aunt Betty bestowed with a lavish hand.

“I am proud indeed to know you and to have you for a pupil,” the music master said, turning to Dorothy. “You have an excellent touch and your execution iss above reproach, considering de lessons you have had. I am sure ve shall have no trouble in making of you a great musician.”

Flushing, partly from her exertions, partly through the rare compliment the great professor had paid her ability, the girl turned to Aunt Betty and murmured:

“Oh, auntie, dear, I’m so glad!”

“And I am delighted,” said Aunt Betty. “That is positively the most entrancing music I have ever heard.”

Herr Deichenberg showed his teeth in a hearty laugh.

“She shall vait until you have practiced a year, my little girl,” he said, winking at his prospective pupil. “Den who shall say she vill not be charmed by vhat she hears? But come,” he added, sobering, “let us try somet’ing of a different nature. If you are as proficient in de second piece as in de first, I shall have no hesitation in pronouncing you one of de most extraordinary pupils who has ever come under my observation.”

Dorothy bowed, and throwing her violin into position, waited for the Herr professor to select from the music on the piano the piece he wished her to play.

“Ah! here iss ‘Hearts und Flowers.’ Dat iss a pretty air und may be played with a great deal of expression, if you please. Let me hear you try it, Miss Dorothy.”

Again the baton was waved above the Herr professor’s head. The next instant they swung off into the plaintive air, Dorothy’s body, as before, [Pg 62]keeping time to the rhythm of the notes, the music master playing the accompaniment with an ease that was astonishing. In every movement the old German showed the finished musician. Twice during the rendition of the piece did he stop Dorothy, to explain where she had missed the fraction of a beat, and each time, to his great satisfaction, the girl rallied to the occasion, and played the music exactly as he desired.

The ordeal over at last, Herr Deichenberg was even more lavish in his praise of Dorothy’s work.

“Of course, she iss not a perfect violinist,” he told Aunt Betty. “Ve could hardly expect dat, you know. But for a young lady of her age und experience she has made rapid progress. Herr Wilmot, who gave de first lessons had de right idea, und there iss nothing dat he taught her dat ve shall have to change.”

Out on the broad gallery, as he was taking his leave, the professor looked proudly at Dorothy again.

“I repeat dat I am glad to meet you und have you for a pupil. Vhen shall de first lesson be given?”

Dorothy threw a quick glance at Aunt Betty.

“Not for at least four weeks, Herr Deichenberg,” said that lady.

“Eh? Vhat!” cried the old music master. “Not for four veeks! Vhy iss it dat you vait an eternity? Let us strike vhile de iron iss hot, as de saying has it.”

“But, Herr, my little girl has just returned from a winter of strenuous study at the Canadian school of Oak Knowe, and I have promised her a rest before she takes up her music.”

“If dat iss so, I suppose I shall have to curb my impatience,” he replied, regretfully. “But let de time be as short as possible. If you are going avay, please notify me of your return, und I vill manage to come to Bellvieu to give Miss Dorothy her first lesson. But don’t make it too long! I am anxious—anxious. She vill make a great musician—a great musician. So goot day, ladies. It has been a pleasure to me—dis visit.”

“Let us hope there will be many more, Herr Deichenberg,” said Aunt Betty.

They watched the figure of the little music teacher until it disappeared through the gate and out of sight behind the hedge. Then they turned again to their comfortable rockers, to discuss the visit and Dorothy’s future.

“Oh, Aunt Betty,” confessed the girl, “I was terribly nervous until I felt my violin under my chin. It seemed to give me confidence, and I played [Pg 64]as I have never played before. Somehow, I felt I could not make a mistake. I’m so glad the Herr professor was pleased. Isn’t he a perfect dear? So genteel, so polished, in spite of his dialect—just the kind of a man old Herr Von Barwig was in ‘The Music Master.’”

Dinah came out on the gallery to say that Dorothy was wanted at the ’phone.

“Oh, I wonder who it can be?” said the girl. “I didn’t think any of my friends knew I was home.”

She hastened inside, and with the receiver at her ear, in keen anticipation murmured a soft:

“Hello!”

“Hello, Dorothy, dear! How are you?”

It was a girl’s voice and the tones were familiar.

“Who is this? I—I don’t quite catch the—! Oh, surely; it’s Aurora Blank!”

“You’ve guessed it the first time. I only learned a few moments ago that you were home. I’m just dying to see you, to learn how you liked your trip and the adventures you had at school. You’ll tell me about them in good time, won’t you, Dorothy?”

“Why, yes, of course. On our camping trip, perhaps.”

“Won’t that be jolly? Papa says we’re to stay in the mountains as long as we like—that’s what he bought the auto for. Gerald and I have been planning to start the first of the week if you can be ready.”

“Oh, I’m sure we can. I’ll speak to Aunt Betty and let you know.”

“Do so, and I’ll run over to Bellvieu to-morrow to discuss the details. Did that nice boy, Jim Barlow, return to Baltimore with you?”

“Yes; he is going with us on the trip—at least, Aunt Betty said he was included in the invitation.”

“Indeed he is! I like him immensely, dear—lots more than he likes me, I reckon.”

“Oh, I don’t know!”

“I’m sure of it.”

“Aurora, I’m afraid you’re trying to make a conquest.”

“No, I’m not—honor bright. But he’s a dear boy and you can tell him I said so.”

“I’ll do that,” said Dorothy, with a laugh. Then she said good-by and hung up the receiver. “I guess I won’t!” she muttered, as she went out to join Aunt Betty again. “Jim Barlow would have a conniption fit if he ever knew what Aurora Blank had said.”

“I’m glad to see you again, Miss Blank. You’ll find Dorothy waiting for you in the house.”

It was the following morning, and Jim had been roaming about the grounds when Aurora came in. At first he had seemed disinclined to be affable, for her actions on Dorothy’s houseboat had been anything but ladylike, until, like many another young girl, she had been taught a lesson; but he decided to be civil for the Calverts’ sake, at least.

“But I want to see you, Jim,” Aurora persisted. “You don’t mind my calling you ‘Jim,’ do you?”

“No.”

“And will you call me Aurora?”

“If you wish.”

“I do wish. We’re going on a long camping trip together, as I suppose you’ve heard.”

“Yes, and I want to thank you for the invitation.”

“You’ve decided to accept, of course?”

“Yes. At first I didn’t think I could; but Aunt [Pg 67]Betty—Mrs. Calvert, that is—said if I didn’t I’d incur her everlasting displeasure, so I’ve arranged to go.”

“I’m delighted to hear it. We just can’t fail to have a good time.”

“I figure on its being a very pleasant trip, Miss Blank—er—I mean, Aurora.”

“You should see our new car, Jim. Papa presented it to Gerald and I, and it’s a beauty. Gerald’s coming over with it to-day to teach you and Ephraim how to run it. Then you can take turns playing chauffeur on our trip across country. I imagine if I were a boy that I should like nothing better.”

Jim’s face brightened as she was speaking.

“Thank you; I believe I will learn to run the machine if Gerald doesn’t care.”

“Care? He’d better not! The machine is a partnership affair, and I’ll let you run my half. But he won’t object, and what’s more, he’ll be only too glad to lend you the car occasionally to take Mrs. Calvert and Dorothy riding.”

“I’ll ask him when he comes over,” said the boy.

Electricity was Jim’s chief hobby, but anything of a mechanical nature appealed to him. While a gasoline car uses electricity only to explode its [Pg 68]fuel, Jim was nevertheless deeply interested, particularly as he had never been able to look into the construction of an auto as thoroughly as he would have desired.

“When do we start?” he asked Aurora.

“The first of next week, if it’s all right with Mrs. Calvert and Dorothy.”

“Who dares talk of Dorothy when she is not present?” demanded that young lady, coming out on the gallery at this moment. “I believe this is a conspiracy.”

“Dorothy Calvert!”

“Aurora Blank!”

These sharp exclamations were followed by a joyous hug and a half dozen kisses, while Jim stood looking on in amusement.

“Say, don’t I get in that game?” he wanted to know.

“If you wish,” said Aurora, throwing him a coquettish glance.

“No indeed!” laughed Dorothy. “Gentlemen are entirely excluded.” She turned to her girl friend. “How well you are looking! And what a pretty dress!”

“Do you like it, Dorothy? Mamma had it made for me last week. At first it didn’t please me—the [Pg 69]the front of the waist is so crazy with its pleats and frills.”

“Oh, that’s what I liked about it—what first caught my eye. It’s odd, but very, very pretty.”

“Excuse me!” murmured Jim. “The conversation grows uninteresting,” and turning his back, he walked off down the lawn. He cast a laughing glance over his shoulder an instant later, however, shaking his head as if to say, “Girls will be girls.”

“Come into the house, Aurora, and tell me about yourself. What has happened in old Baltimore since I’ve been gone? Really, Aunt Betty and I have been too busy arranging for my music lessons, and with various and sundry other things to have a good old-time chat.”

“Things have been rather dull here. Gerald and I went with papa and mamma to the theaters twice a week last winter, with an occasional matinée by ourselves, but aside from that, life has been very dull in Baltimore—that is, until the auto came a few weeks since. Now we take a ‘joy’ ride every afternoon, with an occasional evening thrown in for good measure.”

“I am anxious to see your car, Aurora.”

“And I am anxious to have you see it.”

“It must be a beauty.”

“Oh, it is.” Aurora leaned toward her friend. “Confidentially, Dorothy, it cost papa over four thousand dollars.”

“Just think of all that money to spend for pleasure!” cried Dorothy. “But then, it makes you happy, and I suppose that’s what money is for.”

“Did you ask your aunt about starting on our trip the first of the week?”

“Yes, and it’s all right. We’ll be ready. The only thing worrying me now is that I’m expecting to hear from one of my dearest girl chums, Molly Breckenridge—”

“Oh, and is she going with us?”

“Aunt Betty made me ask her. She said you wanted us to make up the party, and include Gerald and yourself.”

“That’s the very idea. It’s your trip, Dorothy, given in honor of your home-coming.”

“I’m sure that’s nice of you, Aurora. And now let’s discuss—”

“Pawdon me, Miss Dorot’y,” interrupted Ephraim, entering at this moment. “I—I—er—good mawnin’, Miss Aurory.”

“Good morning, Ephy,” Dorothy’s visitor responded. “Has anyone told you that you are to become a chauffeur?”

“W’at’s dat, Miss Aurory? A show fer? A show fer w’at?”

“A chauffeur, Ephy, is a man who drives an automobile.”

“One o’ dem fellers dat sets up in de front seat en turns de steerin’ apparatus?”

“Exactly. How would you like to do that?”

“I ain’t nebber monkeyed round dem gasoline contraptions none, but I reckon I’d like tuh do w’at yo’ say, Miss Aurory—yas’m; I jes’ reckon I would.”

“Well, Gerald is coming over some time to-day to show you and Jim a few things about the car. You will take turns playing chauffeur on our camping trip, and he wants to give you a lesson every day until we leave.”

“Dat suah suits me,” grinned the old negro.

“But what did you want, Ephy?” Dorothy asked, recalling him suddenly to his errand.

“Oh, Lordy, I done fergit w’at I come fo’. Lemme see—oh, yas’m, I got er lettah fo’ yo’. Jes’ lemme see where I put dat doggone—er—beggin’ yo’ pawdon, young ladies, I—Heah hit is!”

The letter, fished from one of Ephraim’s capacious pockets, was quickly handed over.

“Oh, it’s from Molly!” the girl cried, joyously, as she looked at the postmark. “Let’s see what she has to say. You may go, Ephy.”

“Yas’m,” responded the darkey, and with an elaborate bow he departed.

Tearing open the letter, Dorothy read as follows:

“My Dear, Dear Chum:—

“To say that I was overwhelmed by your very kind invitation, is to express it mildly, indeed. The surprise was complete. I had hardly realized that you had finished your course at Oak Knowe and returned to Baltimore. It is strange how rapidly the time flies past.

“We returned from California, some two weeks ago. Papa is greatly improved in health, for which we are all duly thankful. He says he feels like a new man and his actions bear out his words. He wants to know how his little Dorothy is, and when she is coming to visit him. In the meantime, it may be that I shall bring the answer to him in person, as I am leaving next Monday evening for Baltimore, and you, dear Dorothy!

“How glad I shall be to see you! As for the camping trip, you know how I love an outing, and this, I am sure, will prove to be one of the finest I [Pg 73]have ever had. So, until Tuesday morning, when you meet me at the train, au revoir.

“Ever your loving

”Molly.”

“I just know I shall like Molly Breckenridge,” cried Aurora. “Such a nice letter! I have already pictured in my mind the sort of girl that wrote it.”

“You will like her, Aurora, for she is one of the best girls that ever breathed. Full of mischief, yes, but with a heart as big as a mountain. There is nothing she won’t do for anyone fortunate enough to be called her friend.”

“I hope to be that fortunate before our trip is over. But you, Dorothy, are more than friend to her. One can see that from the tone of the letter.”

“I hope and believe I am her dearest chum.”

“You are my dearest chum, Dorothy Calvert!” cried Aunt Betty, who entered the room at this moment. “How are you, Aurora?”

“Very well, Mrs. Calvert.”

“I am glad to see you here. My little girl will get lonesome, I fear, unless her friends drop in frequently to see her.”

“I shall almost live over here, now Dorothy is home,” replied Aurora.

“Indeed she will,” Dorothy put in. “And Molly is coming, Aunt Betty!” Triumphantly she displayed the letter. “Ephy just brought it. Want to read it?”

“No; you can tell me all about it, dear,” returned Aunt Betty. “I am glad she is coming. I hardly thought she’d refuse. Judge Breckenridge is very good to her, and allows her to travel pretty much as she wills.”

The talk turned again to the camping trip.

“I have talked it over with Dorothy,” said Aunt Betty, “and we have decided to be ready Wednesday morning.”

“That will suit us fine,” said Aurora. “Gerald couldn’t get away before Tuesday anyway, and another day will not matter. He thinks we’d better plan to start in the cool of the morning, stopping for breakfast about eight o’clock at some village along the route—there are plenty of them, you know. The recent rains have settled the dust, and the trip, itself, should be very agreeable. We figure on being out only one night, reaching the mountains on the second morning. Of course, if pushed, the auto could make it in much less time, but Gerald thinks we’d better take our time and enjoy the ride.”

“The plan is a fine one,” said Aunt Betty, “especially the getting away in the early morning, before the hot part of the day sets in.”

“I thoroughly agree with you, auntie,” said Dorothy.

“If we fail to find a village,” Aunt Betty continued, “where we can get coffee and rolls, we will draw on our own supply of provisions and eat our breakfast en route. Or we can stop by the wayside, where Ephy can make a fire and I can make some coffee.”

“Oh, you make my mouth water,” said Aurora, who knew that Aunt Betty Calvert’s coffee was famous for miles around.

Aurora took her leave a short while later, and hardly had she gone before Gerald Blank drew up in front of the Calvert place in his big automobile and cried out for Jim and Ephraim.

Neither the boy nor the negro needed a second invitation. Each had been keen in anticipation of the ride—Jim because of his natural interest in mechanism of any sort; Ephraim because he felt proud of the title “chauffeur,” which Aurora had bestowed upon him, and was curious to have his first lesson in running “dat contraption,” as he termed it.

“I tell you, Gerald, she’s a dandy,” said Jim, after the boys had shaken hands and made a few formal inquiries about the interval which had elapsed since last they met. As Jim spoke, his eye roamed over the long torpedo body of the big touring car.

Straight from the factory but a few weeks since, replete with all the latest features, the machine represented the highest perfection of skilled mechanical labor. The body was enameled in gray and trimmed in white, after the fashion of many of the torpedo type of machines which were then coming into vogue.

Seeing Jim’s great interest, Gerald, who was already a motor enthusiast, went from one end of the car to the other, explaining all the fine points.

“There is not a mechanical feature of the Ajax that has not been thoroughly proven out in scores of successful cars,” he said. “Now, here, for instance, is the engine.” Throwing back the hood of the machine, the boy exposed the mechanism. “That’s the Renault type of motor, known as ‘the pride of France,’ and one of the finest ever invented. Great engineers have gone on record that the men who put the Ajax car together have advanced five years ahead of the times. You will [Pg 77]notice, Jim, that the engine valves are all on one side. You’re enough of a mechanician to appreciate the advantage of that. It makes it simple and compact, and gives great speed and power. We should have little trouble in traveling seventy miles an hour, if we chose.”

“Lordy, we ain’t gwine tuh chose!” cried Eph.

“Why, I thought you had the speed mania, Ephy,” was Gerald’s good-natured retort.

“Don’ know jes’ w’at dat is, Mistah Gerald, but I ain’t got hit—no, sah, I ain’t got hit.”

“Now, Jim,” Gerald continued, as they bent over to look under the car, “you see the gear is of the selective sliding type, which has been adopted by all the high grade cars. And back here is what they term a floating axle. The wheels and tires are both extra large—in fact, there is nothing about the car, that I’ve been able to discover, that is not the best in the business.”

“What a fine automobile agent you’d make, Gerald!”

“Do you think so?”

“Surely. You spiel it off like a professional. The only difference is, I feel what you say is true. I am greatly taken with that engine, and should like to see it run.”

“When we start in a moment, you shall have that pleasure. Of course, I could run it for you now, while the machine is standing still, but they say it’s poor practice to race your engine. If you do so, the wear and tear is something awful.”

“I’d heard that, but had forgotten,” said Jim.