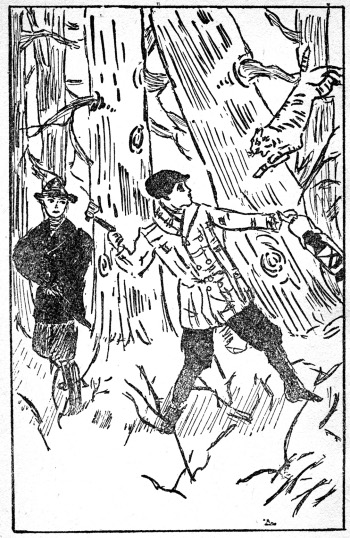

“LOOK OUT! THE SECOND CAT!” YELLED PAUL.

The Banner Boy Scouts Snowbound Page 161

Title: The Banner Boy Scouts Snowbound; or, A Tour on Skates and Iceboats

Author: George A. Warren

Release date: April 7, 2009 [eBook #28531]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

|

||||||||||

Copyright, 1916, by

Cupples & Leon Company

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | On the Frozen Bushkill | 1 |

| II. | When the Old Ice-House Fell | 8 |

| III. | The Rescue | 15 |

| IV. | A Quick Return for Services Rendered | 23 |

| V. | A Startling Interruption | 30 |

| VI. | A Gloomy Prospect for Jud | 38 |

| VII. | Paul Takes a Chance | 46 |

| VIII. | Bobolink and the Storekeeper | 54 |

| IX. | “Fire!” | 62 |

| X. | The Accusation | 69 |

| XI. | Friends of the Scouts | 76 |

| XII. | The Iceboat Squadron | 84 |

| XIII. | On the Way | 91 |

| XIV. | The Ring of Steel Runners | 98 |

| XV. | Tolly Tip and the Forest Cabin | 105 |

| XVI. | The First Night Out | 112 |

| XVII. | “Tip-Ups” for Pickerel | 119 |

| XVIII. | The Helping Hand of a Scout | 126 |

| XIX. | News of Big Game | 134 |

| XX. | At the Beaver Pond | 141 |

| XXI. | Setting the Flashlight Trap | 149 |

| XXII. | Waylaid in the Timber | 157 |

| XXIII. | The Blizzard | 165 |

| XXIV. | The Duty of the Scout | 172 |

| XXV. | Among the Snowdrifts | 180 |

| XXVI. | Dug Out | 187 |

| XXVII. | “First Aid” | 194 |

| XXVIII. | More Startling News | 202 |

| XXIX. | The Wild Dog Pack | 211 |

| XXX. | A Change of Plans | 219 |

| XXXI. | Good-Bye to Deer Head Lodge | 227 |

| XXXII. | The Capture of the Hobo Yeggmen | 235 |

| XXXIII. | Conclusion | 243 |

PREFACE

Dear Boys:—

Once more it is my privilege to offer you a new volume wherein I have endeavored to relate further interesting adventures in which the members of Stanhope Troop of Boy Scouts take part. Most of my readers, I feel sure, remember Paul, Jud, Bobolink, Jack and many of the other characters, and will gladly greet them as old friends.

To such of you who may be making the acquaintance of these manly young chaps for the first time I can only say this. I trust your interest in their various doings along the line of scoutcraft will be strong enough to induce you to secure the previous volumes in this series in order to learn at first hand of the numerous achievements they have placed to their credit.

The boys comprising the original Red Fox Patrol won the beautiful banner they own in open competition with other rival organizations. From that day, now far in the past, Stanhope Troop has been known as the Banner Boy Scouts. Its possession .gn +1 has always served as an inspiration to Paul and his many staunch comrades. Every time they see its silken folds unfurled at the head of their growing marching line they feel like renewing the vows to which they so willingly subscribed on first joining the organization.

Many of their number, too, are this day proudly wearing on their chests the medals they have won through study, observation, service, thrift, or acts of heroism, such as saving human life at the risk of their own.

I trust that all my many young readers will enjoy the present volume fully as much as they did those that have appeared before now. Hoping, then, to meet you all again before a great while in the pages of another book; and with best wishes for every lad who aspires to climb the ladder of leadership in his home troop, believe me,

Cordially yours,

George A. Warren.

“Watch Jack cut his name in the ice, fellows!”

“I wish I could do the fancy stunts on skates he manages to pull off. It makes me green with envy to watch Jack Stormways do that trick.”

“Oh, shucks! what’s the use of saying that, Wallace Carberry, when everybody knows your strong suit is long-distance skating? The fact is both the Carberry twins are as much at home on the ice as I am when I get my knees under the supper table.”

“That’s kind of you to throw bouquets my way, Bobolink. But, boys, stop and think. Here it is—only four days now to Christmas, and the scouts haven’t made up their minds yet where to spend the glorious holidays.”

“Y-y-yes, and b-b-by the same token, this year we’re g-g-going to g-g-get a full three-weeks’ vacation 2 in the b-b-bargain, b-b-because they have t-t-to overhaul the f-f-furnaces.”

“Hold on there, Bluff Shipley! If you keep on falling all over yourself like that you’ll have to take a whole week to rest up.”

“All the same,” remarked the boy who answered to the odd name of Bobolink, “it’s high time we scouts settled that important matter for good.”

“The assistant scout-master, Paul Morrison, has called a meeting at headquarters for to-night, you understand, boys,” said the fancy skater, who had just cut the name of Paul Morrison in the smooth, new ice of the Bushkill river.

“We must arrange the programme then,” observed Bobolink, “because it will take a couple of days to get everything ready for the trip, no matter where we go.”

“Huh!” grunted another skater, “I can certainly see warm times ahead for the cook at your house, Bobolink, provided you’ve still got that ferocious appetite to satisfy.”

“Oh! well, Tom Betts,” laughed the other, “I notice that you seldom take a back seat when the grub is being passed around. As for me I’m proud of my stowage ability. A good appetite is one of the greatest blessings a growing boy can have.”

“Pity the poor father though,” chuckled Wallace 3 Carberry, “because he has to pay the freight.”

“Just to go back to the important subject,” said Bluff Shipley, who could speak as clearly as any one when not excited, “where do you think the scouts will hike to for their Christmas holidays?”

“Well, now, a winter camp on Rattlesnake Mountain wouldn’t be such a bad stunt,” suggested Tom Betts, quickly.

“For my part,” remarked Bobolink, “I’d rather like to visit Lake Tokala again, and see what Cedar Island looks like in the grip of Jack Frost. The skating on that sheet of water must be great.”

“We certainly did have a royal good time there last summer,” admitted Jack, reflectively.

“All the same,” ventured Tom, “I think I know one scout who couldn’t be coaxed or hired to camp on Cedar Island again.”

“Meaning Curly Baxter,” Bobolink went on to say scornfully, “who brazenly admits he believes in ghosts, and couldn’t be convinced that the place wasn’t haunted.”

“Curly won’t be the only fellow to back out,” suggested Jack. “While we have a membership of over thirty on the muster roll of Stanhope Troop, it isn’t to be expected that more than half of them will agree to make the outing with us.”

“Too much like hard work for some of the boys,” asserted Tom. 4

“I know a number who say they’d like to be with us, but their folks object to a winter camp,” Wallace announced. “So if we muster a baker’s dozen we can call ourselves lucky.”

“Of course it must be a real snow and ice hike this time,” suggested Bluff.

“To be sure—and on skates at that!” cried Wallace, enthusiastically.

“Oh! I hope there’s a chance to use our iceboats too!” sighed Tom Betts, who late that fall had built a new flier, and never seemed weary of sounding the praises of his as yet untried “Speedaway.”

“Perhaps we may—who knows?” remarked Jack, mysteriously.

The others, knowing that the speaker was the nearest and dearest chum of Paul Morrison, assistant scout-master of Stanhope Troop of Boy Scouts, turned upon him eagerly on hearing this suggestive remark.

“You know something about the plans, Jack!”

“Sure he does, and he ought to give us a hint in the bargain!”

“Come, take pity on us, won’t you, Jack?”

But the object of all this pleading only shook his head and smiled as he went on to say:

“I’m bound to secrecy, fellows, and you wouldn’t have me break my word to our patrol 5 leader. Just hold your horses a little while longer and you’ll hear everything. We’re going to talk it over to-night and settle the matter once for all. Now let’s drop the subject. Here’s a new wrinkle I’m trying out.”

With that Jack started to spin around on his skates, and fairly dazzled his mates with the wonderful ability he displayed as a fancy skater.

While they are thus engaged a few words of explanation may not come in amiss.

Stanhope Troop consisted of three full patrols, with another almost completed. Though in the flood tide of success at the time we make the acquaintance of the boys in this volume there were episodes in the past history of the troop to which the older scouts often referred with mingled emotions of pride and wonder.

The present status of the troop had not been maintained without many struggles. Envious rivals had tried to make the undertaking a failure, while doubting parents had in many cases to be shown that association with the scouts would be a thing of unequalled advantage to their boys.

Those who have read the previous books of this series have doubtless already formed a warm attachment for the members of the Red Fox Patrol and their friends, and will be greatly pleased to follow their fortunes again. For the 6 benefit of those who are making their acquaintance for the first time it may be stated that besides Jack Stormways and the four boys who were with him on the frozen Bushkill this December afternoon, the roster of the Red Fox Patrol counted three other names.

These were Paul Morrison, the leader, the other Carberry twin, William by name, and a boy whom they called “Nuthin,” possibly because his name chanced to be Albert Cypher.

As hinted at in the remarks that flew between the skaters circling around, many of the members of the troop had spent a rollicking vacation the previous summer while aboard a couple of motor boats loaned to them by influential citizens of their home town. The strange adventures that had befallen the scouts on this cruise through winding creeks and across several lakes have been given in the pages of the volume preceding this book, called “The Banner Boy Scouts Afloat; Or, The Secret of Cedar Island.”

Ever since their return from that cruise the boys had talked of little else; and upon learning that the Christmas holidays would be lengthened this season the desire to take another tour had seized upon them.

After Jack so summarily shut down upon the subject no one ventured to plead with him any 7 longer. All knew that he felt bound in honor to keep any secret he had been entrusted with by the assistant scout-master—for Paul often had to act in place of Mr. Gordon, a young traveling salesman, who could not be with the boys as much as he would have liked.

Jack had just finished cutting the new figure, and his admirers were starting to give vent to their delight over his cleverness when suddenly there came a strange roaring sound that thrilled every one of them through and through. It was as if the frozen river were breaking up in a spring thaw. Some of the boys even suspected that there was danger of being swallowed up in such a catastrophe, and had started to skate in a frenzy of alarm for the shore when the voice of Bobolink arose above the clamor.

“Oh! look there, will you, fellows?” he shouted, pointing a trembling finger up the river. “The old ice-house has caved in, just as they feared it would. See the ice cakes sliding everywhere! And I saw men and girls near there just five minutes ago. They may be caught under all that wreckage for all we know! Jack, what shall we do about it?”

“Come on, every one of you!” roared Jack Stormways, as he set off at full speed. “This means work for the scouts! To the rescue, boys! Hurry! hurry!”

Never before in the recollection of any Stanhope boy had winter settled in so early as it had this year. They seldom counted on having their first skate on the new ice before Christmas, and yet for two weeks now some of the most daring had been tempting Providence by venturing on the surface of the frozen Bushkill.

The ice company had built a new house the preceding summer, though the old one was still fairly well filled with a part of the previous season’s great crop. Its sides had bulged out in a suspicious manner, so that many had predicted some sort of catastrophe, but somehow the old building had weathered every gale, though it leaned to the south sadly. The company apparently hoped it would hold good until they had it emptied during the next summer, when they intended to build another new structure on the spot.

As the five boys started to skate at utmost speed up the river they heard a medley of sounds. 9 A panic had evidently struck such boys and girls as were skimming over the smooth ice in protected bayous near the ice-houses. Instead of hurrying to the assistance of those who may have been caught in the fallen timbers of the wrecked building they were for the most part fleeing from the scene, some of them shrieking with terror.

Several men who had been employed near by could be seen standing and staring. It looked as though they hardly knew what to do.

If ever there was an occasion where sound common sense and a readiness to grasp a situation were needed it seemed to be just then. And, fortunately, Jack Stormways was just the boy to meet the conditions.

He sped up the river like an arrow from the bow, followed by the four other scouts. The frightened girls who witnessed their passage always declared that never had they seen Stanhope boys make faster speed, even in a race where a valuable prize was held out as a lure to the victor.

As he bore down upon the scene of confusion Jack took it all in. Those who were floundering amidst the numerous heavy cakes of ice must engage their attention without delay. He paid little heed to the fortunate ones who were able to be on their feet, since this fact alone proved that they could not have been seriously injured. 10

Several, however, were not so fortunate, and Jack’s heart seemed to be almost in his throat when he saw that two of the skaters lay in the midst of the scattered cakes of ice as though painfully injured.

“This way, boys!” shouted the boy in the van as they drew near the scene of the accident. “Bluff, you and Wallace turn and head for that one yonder. Bobolink, come with me—and Tom Betts.”

Five seconds later he was bending over a small girl who lay there groaning and looking almost as white as the snow upon the hills around Stanhope.

“It’s little Lucy Stackpole!” gasped Tom, as he also arrived. “Chances are she was hit by one of these big ice cakes when they flew around!”

Jack looked up.

“Yes, I’m afraid she’s been badly hurt, fellows. It looks to me like a compound fracture of her right leg. She ought to be taken home in a hurry. See if you can round up a sled somewhere, and we’ll put her on it.”

“Here’s Sandy Griggs and Lub Ketcham with just the sort of big sled we need!” cried Tom Betts, as he turned and beckoned to a couple of stout lads who evidently belonged to one of the other patrols, since they wore the customary campaign hats of the scouts. 11

These boys had by now managed to recover from their great alarm, and in response to the summons came hurrying up, anxious to be of service, as true scouts always are.

Jack, who had been speaking to the terrified girl, trying to soothe her as best he could, proceeded in a business-like fashion to accomplish the duty he had in hand.

“Two of you help me lift Lucy on to the sled,” he said. “We will have to fasten her in some way so there’ll be no danger of her slipping. Then Sandy and Lub will drag her to her home. On the way try to get Doctor Morrison over the ’phone so he can meet you there. The sooner this fracture is attended to the better.”

“You could do it yourself, Jack, if it wasn’t so bitter cold out here,” suggested Tom Betts, proudly, for next to Paul Morrison himself, whose father was the leading physician of Stanhope, Jack was known to be well up in all matters connected with first aid to the injured.

They lifted the suffering child tenderly, and placed her on the comfortable sled. Both the newcomers were only too willing to do all they could to carry out the mission of mercy that had been entrusted to their charge.

“We’ll get her home in short order, Jack, never fear,” said Sandy Griggs, as he helped fasten an 12 extra piece of rope around the injured girl, so that she might not slip off the sled.

“Yes, and have the doctor there in a jiffy, too,” added Lub, who, while a clumsy chap, in his way had a very tender heart and was as good as gold.

“Then get a move on you fellows,” advised Jack. “And while speed is all very good, safety comes first every time, remember.”

“Trust us, Jack!” came the ready and confident reply, as the two scouts immediately began to seek a passage among the far-flung ice-cakes that had been so suddenly released from their year’s confinement between the walls of the dilapidated ice-house.

Only waiting to see them well off, Jack and the other two once more turned toward the scene of ruin.

“See, the boys have managed to get the other girl on her feet!” exclaimed Bobolink, with a relieved air; “so I reckon she must have been more scared than hurt, for which I’m right glad. What next, Jack? Say the word and we’ll back you to the limit.”

“We must take a look around the wreck of the ice-house,” replied the other, “though I hardly believe any one could have been inside at the time it fell.”

“Whew, I should surely hope not!” cried Tom; 13 “for the chances are ten to one he’d be crushed as flat as a pancake before now, with all that timber falling on him. I wouldn’t give a snap of my fingers for his life, Jack.”

“Let’s hope then there’s no other victim,” said Jack. “If there is none, it will let the ice company off easier than they really deserve for allowing so ramshackle a building to stand, overhanging the river just where we like to do most of our skating every winter.”

“Suppose we climb around the timbers and see if we can hear any sound of groaning,” suggested Bobolink, suiting the action to his words.

Several men from the other ice-house reached the spot just then.

Jack turned to them as a measure of saving time. If there were no men working in the wrecked building at the time it fell there did not seem any necessity for attempting to move any of the twisted timbers that lay in such a confused mass.

“Hello! Jan,” he called out as the panting laborers arrived. “It was a big piece of luck that none of you were inside the old ice-house when it collapsed just now.”

The man whom he addressed looked blankly at the boy. Jack could see that he was laboring under renewed excitement. 14

“Look here! was there any one in the old building, do you know, Jan?” he demanded.

“I ban see Maister Garrity go inside yoost afore she smash down,” was the startling reply.

The boys stared at each other. Mr. Thomas Garrity was a very rich and singular citizen of Stanhope.

Finally Bobolink burst out with:

“Say, you know Mr. Garrity is one of the owners of these ice-houses, fellows. I guess he must have come up here to-day to see for himself if the old building was as rickety as people said.”

“Huh! then I guess he found out all right,” growled Tom Betts.

“Never mind that now,” said Jack, hastily. “Mr. Garrity never had much use for the scouts, but all the same he’s a human being. We’ve got our duty cut out for us plainly enough.”

“Guess you mean we must clear away this trash with the help of these men here, Jack,” suggested Wallace, eagerly.

“Just what I had in mind,” confessed Jack. “But before we start in let’s all listen and see if we can hear anything like a groan.”

All of them stood in an expectant attitude, straining their hearing to the utmost.

Presently the listeners plainly caught the sound of a groan.

“Jack, he’s here under all this stuff!” called out Bobolink, excitedly.

“Poor old chap,” said Wallace. “I wouldn’t like to give much for his chance of getting out of the scrape with his life.”

“And to think,” added Bluff, soberly, “that after all the protestations made by the company that the old house couldn’t fall, it trapped one of the big owners when it smashed down. It’s mighty queer, it strikes me.”

“Keep still again,” warned Jack. “I want to call out and see if Mr. Garrity can hear me.”

“A bully good scheme, Jack!” asserted Bobolink. “If we can locate him in that way it may save us a heap of hard work dragging these timbers around.”

Jack dropped flat on his face, and, placing his mouth close to the wreckage where it seemed worst, called aloud:

“Hello! Mr. Garrity, can you hear me?” 16

“Yes! Oh, yes!” came the faint response from somewhere below.

“Are you badly hurt, sir?” continued the scout.

“I don’t know—I believe not, but a beam is keeping tons and tons from falling on me. I am pinned down here, and can hardly move. Hurry and get some of these timbers off before they fall and crush me!”

Every word came plainly to their ears now. Evidently, Mr. Garrity, understanding that relief was at hand, began to feel new courage. Jack waited for no more.

“I reckon I’ve located him, boys,” he told the others, “and now we’ve got to get busy.”

“Only tell us what to do, Jack,” urged Wallace, “and there are plenty of willing hands here for the work, what with these strong men and the rest of the boys.”

Indeed, already newcomers were arriving, some of them being people who had been passing along the turnpike near by in wagons or sleighs at the time the accident happened, and who hastened to the spot in order to render what assistance they could.

Jack seemed to know just how to go about the work. If he had been in the house-wrecking business for years he could hardly have improved upon his system. 17

“We’ve got to be careful, you understand, fellows,” he told the others as they labored strenuously to remove the upper timbers from the pile, “because that one timber he mentioned is the key log of the jam. As long as it holds he’s safe from being crushed. Here, don’t try that beam yet, men. Take hold of the other one. And Bobolink and Wallace, help me lift this section of shingles from the roof!”

So Jack went on to give clear directions. He did not intend that any new accident should be laid at their door on account of too much haste. Better that the man who was imprisoned under all this wreckage should remain there a longer period than that he lose his life through carelessness. Jack believed in making thorough work of anything he undertook; and this trait marked him as a clever scout.

As others came to add to the number of willing workers the business of delving into the wreck of the ice-house proceeded in a satisfactory manner. Once in a while Jack would call a temporary halt while he got into communication with the unfortunate man they were seeking to assist.

“He seems to be all right so far, fellows,” was the cheering report he gave after this had happened for the third time; “and I think we’ll be able to reach him in a short time now.” 18

“As sure as you’re born we will, Jack!” announced Bobolink, triumphantly; “for I can see the big timber he said was acting as a buffer above him. Hey! we’ve got to be extra careful now, because one end of that beam is balanced ever so delicately, and if it gets shoved off its anchorage—good-bye to Mr. Garrity!”

“Yes,” came from below the wreckage, “be very careful, please, for it’s just as you say.”

Jack was more than ever on the alert as the work continued. He watched every move that was made, and often warned those who strained and labored to be more cautious.

“In five minutes or so we ought to be able to get something under that loose end of the big timber, Jack,” suggested Bobolink, presently.

“In less time than that,” he was told. “And here’s the very prop to slip down through that opening. I think I can reach it right now, if you stop the work for a bit.”

He pushed the stout post carefully downward, endeavoring to adjust it so that it was bound to catch and hold the timber should the latter break away from its frail support at that end. When Bobolink saw him get up from his knees a minute later he did not need to be told that Jack’s endeavor had been a success, for the satisfied smile on the other’s face told as much. 19

“Now let the good work go on with a rush!” called out Jack. “Not so much danger now, because I’ve put a crimp in that timber’s threat to fall. It’s securely wedged. Everybody get busy.”

Jack led in the work himself, and the way they removed the heavy beams, many of them splintered or broken in the downward rush of the building, was surely a sight worth seeing. At least some of the town people who came up just then felt they had good reason to be proud of the Banner Boy Scouts, who on other notable occasions had brought credit to the community.

“I can see him now!” exclaimed Bobolink; and indeed, only a few more weighty fragments remained to be lifted off before Jack would be able to drop down into the cavity and assist the prisoner at close quarters.

Five minutes later the workers managed to release Mr. Garrity, and Jack helped him out of his prison. The old gentleman looked considerably the worse for his remarkable experience. There was blood upon his cheek, and he kept caressing one arm as though it pained him considerably.

Still his heart was filled with thanksgiving as he stared around at the pile of torn timbers, and considered what a marvelous escape his had been.

“Let me take a look at your arm, sir,” said 20 Jack, who feared that it had been broken, because a beam had pinned the gentleman by his arm to the ground.

Mr. Garrity, who up to that time had paid very little attention to the Boy Scout movement that had swept over that region of the eastern country like wildfire, looked at the eager, boyish faces of his rescuers. It could be seen that he was genuinely affected on noticing that most of them wore the badges that distinguish scouts the world over.

“I hope my wrist is not broken, though even that would be a little price to pay for my temerity in entering that shaky old building,” he ventured to say as he allowed Jack to examine his arm.

“I’m glad to tell you, sir,” said the boy, quickly, “that it is only a bad sprain. At the worst you will be without the use of that hand for a month or two.”

“Then I have great reason to be thankful,” declared Mr. Garrity, solemnly. “Perhaps this may be intended for a lesson to me. And, to begin with, I want to say that I believe I owe my very life to you boys. I can never forget it. Others, of course, might have done all they could to dig me out, but only a long-headed boy, like Jack Stormways here, would have thought to keep that timber from falling and crushing me just when escape seemed certain.” 21

He went around shaking hands with each one of the boys, of course using his left arm, since the right was disabled for the time being. Jack deftly made a sling out of a red bandana handkerchief, which he fastened around the neck of Mr. Garrity, and then gently placed the bruised hand in this.

“Was any other person injured when the ice-house collapsed?” asked Mr. Garrity, anxiously.

“A couple of girls were struck by some of the big cakes flung far and wide,” explained Bobolink. “Little Lucy Stackpole has a broken leg. We sent her home on a sled, and the doctor will soon be at her house, sir.”

“That is too bad!” declared the part owner of the building, frowning. “I hoped that the brunt of the accident had fallen on my shoulders alone. Of course, the company will be liable for damages, as well as the doctor’s bill; and I suppose we deserve to be hit pretty hard to pay for our stupidity. But I am glad it is no worse.”

“Excuse me, Mr. Garrity, but perhaps you had better have that swelling wrist attended to as soon as possible,” remarked Jack. “You have some bruises, too, that are apt to be painful for several days. There is a carriage on the road that might be called on to take you home.”

“Thank you, Jack, I will do as you say,” replied 22 the one addressed. “But depend on it I mean to meet you boys again, and that at a very early date.”

“We’re going to be away somewhere on a midwinter hike immediately after Christmas, sir,” Bobolink thought it best to explain. Somehow deep down in his heart he was already wondering whether this remarkable rescue of Mr. Garrity might not develop into some sort of connection with their partly formed plans.

“Yes,” added Bluff, eagerly, suddenly possessed by the same hope, “and it’s all going to be settled to-night when we have our monthly meeting in the big room under the church. We’d be pleased to have you drop in and see us, sir. Lots of the leading citizens of Stanhope have visited our rooms from time to time, but I don’t remember ever having seen you there, Mr. Garrity.”

“Thank you for the invitation, my lad,” said the other, smiling grimly. “Perhaps I shall avail myself of it, and I might possibly have something of interest to communicate to you and your fellow scouts,” and waving his hand to them he walked away.

That night turned out clear and frosty. Winter having set in so early seemed bent on keeping up its unusual record. The snow on the ground crackled underfoot in the fashion dear to the heart of every boy who loves outdoor sports.

Overhead, the bright moon, pretty well advanced, hung in space. It was clearly evident that no one need think of carrying a lantern with him to the meeting place on such a glorious night.

The Boy Scouts of Stanhope had been fortunate enough to be given the use of a large room under the church with the clock tower. On cold nights this was always heated for them, so that they found it a most comfortable place in which to hold their animated meetings.

There was a large attendance on this occasion, for while possibly few among the members of the troop could take advantage of this midwinter trip into the wilds, every boy was curious to know all the details. 24

In this same spacious room there was fitted up a gymnasium for the use of the boys one night a week, and many of them availed themselves of the privilege. As this was to be a regular business meeting, however, the apparatus had been drawn aside so as not to be in the way.

As the roster was being called it might be just as well to give the full membership of the troop so that the reader may be made acquainted with the chosen comrades of Jack and Paul.

The Red Fox Patrol, which contained the “veterans” of the organization, was made up of the following members:

Paul Morrison; Jack Stormways; Bobolink, the official bugler; Bluff Shipley, the drummer of the troop; “Nuthin” Cypher; William Carberry; Wallace, his twin brother; and Tom Betts. Paul, as has been said, was patrol leader, and served also as assistant scout-master when Mr. Gordon was absent from town.

In the second division known as the Gray Fox Patrol were the following:

Jud Elderkin, patrol leader; Joe Clausin, Andy Flinn, Phil Towns, Horace Poole, Bob Tice, Curly Baxter, and Cliff Jones.

The Black Fox Patrol had several absentees, but when all were present they answered to their names as below: 25

Frank Savage, leader; Billie Little, Nat Smith, Sandy Griggs, “Old” Dan Tucker, “Red” Collins, “Spider” Sexton, and last but not least in volume of voice, “Gusty” Bellows.

A fourth patrol that was to be called the Silver Fox was almost complete, lacking just three members; and those who made up this were:

George Hurst, leader; “Lub” Ketcham, Barry Nichols, Malcolm Steele and a new boy in town by the name of Archie Fletcher.

Apparently, the only business of importance before the meeting was in connection with the scheme to take a midwinter outing, something that was looked upon as unique in the annals of the association.

The usual order of the meeting was hurried through, for every one felt anxious to hear what sort of proposition the assistant scout-master intended to spread before the meeting for approval.

“I move we suspend the rules for to-night, and have an informal talk for a change!” said Bobolink, when he had been recognized by the chair.

A buzz of voices announced that the idea was favorably received by many of those present; and, accordingly, the chairman, no other than Paul himself, felt constrained to put the motion after it had been duly seconded. He did so with a smile, well knowing what Bobolink’s object was. 26

“You have all heard the motion that the rules be suspended for the remainder of the evening,” he went on to say, “so that we can have a heart-to-heart talk on matters that concern us just now. All in favor say aye!”

A rousing chorus of ayes followed.

“Contrary, no!” continued Paul, and as complete silence followed he added hastily: “The motion is carried, and the regular business meeting will now stand adjourned until next month.”

“Now let’s hear what you’ve been hatching up for us, Paul?” called out Bobolink.

“So say we all, Paul!” cried half a dozen eager voices, and the boys left their seats to crowd around their leader.

“I only hope it’s Rattlesnake Mountain we’re headed for!” exclaimed Tom Betts, who had a warm feeling in his boyish heart for that particular section of country, where once upon a time the troop had pitched camp, and had met with some amusing and thrilling adventures, as described in a previous volume, called “The Banner Boy Scouts on a Tour.”

“On my part I wish it would turn out to be good old Lake Tokala, where my heart has often been centered as I think of the happy days we spent there.”

It was, of course, Bobolink who gave utterance 27 to this sentiment. Perhaps there were others who really echoed his desire, for they had certainly had a glorious time of it when cruising in the motor boats so kindly loaned to them.

Paul held up his hand for silence, and immediately every voice became still. Discipline was enforced at these meetings, for the noisy boys and those inclined to play practical pranks had learned long ago they would have to smother their feelings at such times or be strongly repressed by the chair.

“Listen,” said the leader, in his clear voice, “you kindly asked me to try to plan a trip for the holidays that would be of the greatest benefit to us as an organization of scouts. I seriously considered half a dozen plans, among them Rattlesnake Mountain, and Cedar Island in Lake Tokala. In fact, I was on the point of suggesting that we take the last mentioned trip when something came up that entirely changed my plan for the outing.”

He stopped to see what effect his words were having. Evidently, he had aroused the curiosity of the assembled scouts to fever heat, for several voices immediately called out:

“Hear! hear! please go on, Paul! We’re dying to know what the game is!”

Paul smiled, as he went on to say: 28

“I guess you have all been so deeply interested in what was going on to-night, that few of you noticed that we have a friend present who slipped into the room just as the roll call began. All of you must know the gentleman, so it’s hardly necessary for me to introduce Mr. Thomas Garrity to you.”

Of course, every one turned quickly on hearing this. A figure that had been seated in a dim corner of the assembly room arose, and Bobolink gasped with a delicious sense of pleasure when he recognized the man whom he and his fellow scouts had assisted that very afternoon.

“Please come forward, Mr. Garrity,” said Paul, “and tell the boys what you suggested to me late this afternoon. I’m sure they’d appreciate it more coming directly from you than getting it secondhand.”

While a hum of eager anticipation arose all around, Mr. Garrity made his way to the side of the patrol leader and president of the meeting.

“I have no doubt,” he said, “that those of you who were not present to-day when our old ice-house fell and caught me in the ruins, have heard all about the accident, so I need not refer to the incident except to say that I shall never cease to be grateful to the scouts for the clever way in which they dug me out of the wreck.” 29

“Hear! hear!” several excited scouts shouted.

“I happened to learn that you were contemplating a trip during the holidays, and when an idea slipped into my mind I lost no time in calling upon Paul Morrison, your efficient leader, in order to interest him in my plan.”

“Hear! hear!”

“It happens that I own a forest cabin up in the wilderness where I often go to rest myself and get away from all excitement. It is in charge of a faithful woodsman by the name of Tolly Tip. You can reach it by skating a number of miles up a stream that empties into Lake Tokala. The hunting is said to be very good around there, and you will find excellent pickerel fishing through the ice in Lake Tokala. If you care to do me the favor of accepting my offer, the services of my man and the use of the cabin are at your disposal. Even then I shall feel that this is only a beginning of the deep interest I am taking in the scouts’ organization; for I have had my eyes opened at last in a wonderful manner.”

As Mr. Garrity sat down, rosy-red from the exertion of speaking to a party of boys, Paul immediately rapped for order, and put the question.

“All who are in favor of accepting this generous offer say yes!” and every boy joined in the vociferous shout that arose.

“Mr. Garrity, your kind offer is accepted with thanks,” announced Paul. “And as you suggested to me, several of us will take great pleasure in calling on you to-morrow to go into details and to get full directions from you.”

“Then perhaps I may as well go home now, boys,” said the old gentleman; “as my wrist is paining me considerably. I only want to add that this has been a red day in my calendar. The collapse of the old ice-house is going to prove one of those blessings that sometimes come to us in disguise. I only regret that two little girls were injured. As for myself, I am thoroughly pleased it happened.”

“Before you leave us, sir,” said Bobolink, boldly, “please let us show in some slight way how much we appreciate your kind offer. Boys, three cheers for Mr. Thomas Garrity, our latest convert, and already one of our best friends!”

Possibly Bobolink’s method of expressing his 31 feelings might not ordinarily appeal to a man of Mr. Garrity’s character, but just now the delighted old gentleman was in no mood for fault finding.

As the boyish cheers rang through the room there were actually tears in Mr. Garrity’s eyes. Truly that had been a great day for him, and perhaps it might prove a joyous occasion to many of his poor tenants, some of whom had occasion to look upon him as a just, though severe, landlord, exacting his rent to the last penny.

After he had left the room the hum of voices became furious. One would have been inclined to suspect the presence of a great bee-hive in the near vicinity.

“Paul, you know all about this woods cabin he owns,” said Tom Betts, “so suppose you enlighten the rest of us.”

“One thing tickles me about the venture!” exclaimed Bobolink; “That is that we pass across Lake Tokala in getting there. I’ve been hankering to see that place in winter time for ever so long.”

“Yes,” added Tom, eagerly, “that’s true. And what’s to hinder some of us from using our iceboats part of the way?”

“Nothing at all,” Paul assured him. “I went into that with Mr. Garrity, and came to the conclusion that it could be done. Of course, a whole 32 lot depends on how many of us can go on the trip.”

“How many could sleep in his cabin do you think, Paul?” demanded Jack.

“Yes. For one, I’d hate to have to bunk out in the snow these cold nights,” said Bluff, shaking his head seriously, for Bluff dearly liked the comforts of a cheery fire inside stout walls of logs, while the bitter wintry wind howled without, and the snow drifted badly.

“He told me it was unusually large,” explained Paul. “In fact, it has two big rooms and could in a pinch accommodate ten fellows. Of course, every boy would be compelled to tote his blankets along with him, because Mr. Garrity never dreamed he would have an army occupy his log shanty.”

“The more I think of it the better it sounds!” declared Jack.

“Then first of all we must try to find out just who can go,” suggested Bobolink.

“What if there are too many to be accommodated either on the iceboats we own or in the cabin?” remarked Tom Betts, uneasily.

“Shucks! that ought to be easy,” suggested another. “All we have to do is to pull straws, and see who the lucky ten are.”

“Then let those who are positive they can go 33 step aside here,” Paul ordered; and at this there was a shuffling of feet and considerable moving about.

“Remember, you must be sure you can go,” warned Paul. “Afterwards we’ll single out those who believe they can get permission, but feel some doubts. If there is room they will come in for next choice.”

Several who had started forward held back at this. Those who took their stand as the leader requested consisted of Jack, Bobolink, Bluff, Tom Betts, Jud Elderkin, Sandy Griggs, Phil Towns and “Spider” Sexton.

“Counting myself in the list that makes nine for certain,” Paul observed. It was noticed that Tom Betts as well as Bobolink looked exceedingly relieved on discovering that, after all, there need be no drawing of lots.

“Now let those who have strong hopes of being able to go stand up to be counted,” continued Paul. “I’ll keep a list of the names, and the first who comes to say he has received full permission will be the one to make up the full count of ten members, which is all the cabin can accommodate.”

The Carberry twins, as well as several others, stood over in line to have their names taken down.

“If one of us can go, Paul,” explained Wallace Carberry, “we’ll fix it up between us which it 34 shall be. But I’m sorry to say our folks don’t take to this idea of a winter camp very strongly.”

“Same over at my house,” complained Bob Tice. “Mother is afraid something terrible might happen to us in such a hard spell of winter. As if scouts couldn’t take care of themselves anywhere, and under all conditions!”

There were many gloomy faces seen in the gathering, showing that other boys knew their parents did not look on the delightful scheme with favor. Some of them could not accompany the party on account of other plans which had been arranged by their parents.

“If the ice stays as fine as it is now,” remarked Tom Betts, “we can spin down the river on our iceboats, and maybe make our way through that old canal to Lake Tokala as well. But how about the creek leading up to the cabin, Paul? Did you ask Mr. Garrity about it?”

“Yes, I asked him everything I could think of,” came the ready reply. “I’m sorry to say it will be necessary to leave our iceboats somewhere on the lake, for the creek winds around in such a way, and is so narrow in places, that none of us could work the boats up there.”

“But wouldn’t it be dangerous to leave them on the lake so long?” asked Tom, anxiously. “I’ve put in some pretty hard licks on my new craft, 35 and I’d sure hate to have any one steal it from me.”

“Yes,” added Bobolink, quickly, “and we all know that Lawson crowd have been showing themselves as mean as dirt lately. We thought we had got rid of our enemies some time ago, and here this new lot of rivals seems bent on making life miserable for all scouts. They are a tough crowd, and pretend to look down on us as weaklings. Hank Lawson is now playing the part of the bully in Stanhope, you know.”

“I even considered that,” continued Paul, who seldom omitted anything when laying plans. “Mr. Garrity told me there was a man living on the shore of Lake Tokala, who would look after our iceboats for a consideration.”

“Bully for that!” exclaimed Tom, apparently much relieved. “All the same I think it would be as well for us to try to keep our camping place a secret if it can be done. Let folks understand that we’re going somewhere around Lake Tokala; and perhaps the Lawson crowd will miss us.”

“That isn’t a bad idea,” Paul agreed, “and I’d like every one to remember it. Of course, we feel well able to look after ourselves, but that’s no reason why we should openly invite Hank and his cronies to come and bother us. Are you all agreed to that part of the scheme?” 36

In turn every scout present answered in the affirmative. Those who could not possibly accompany the party took almost as much interest in the affair as those intending to go; and there would be heart burnings among the members of Stanhope Troop from now on.

“How about the grub question, Paul?” demanded Bobolink.

“Every fellow who is going will have to provide a certain amount of food to be carried along with his blanket, gun, clothes bag, and camera. All that can be arranged when we meet to-morrow afternoon. In the meantime, I’m going to appoint Bobolink and Jack as a committee of two to spend what money we can spare in purchasing certain groceries such as coffee, sugar, hams, potatoes, and other things to be listed later.”

Bobolink grinned happily on hearing that.

“See how pleased it makes him,” jeered Tom Betts. “When you put Bobolink on the committee that looks after the grub, Paul, you hit him close to where he lives. One thing sure, we’ll have plenty to eat along with us, for Bobolink never underrates the eating capacity of himself or his chums.”

“You can trust me for that,” remarked the one referred to, “because I was really hungry once in my life, and I’ve never gotten over the terrible 37 feeling. Yes, there is going to be a full dinner pail in Camp Garrity, let me tell you!”

“Camp Garrity sounds good to me!” exclaimed Sandy Griggs.

“Let it go down in the annals of Stanhope Troop at that!” cried another scout.

“We could hardly call it by any other name, after the owner has been so good as to place it at our disposal,” said Paul, himself well pleased at the idea.

Bobolink was about to say something more when, without warning, there came a sudden crash accompanied by the jingling of broken glass. One of the windows fell in as though some hard object had struck it. The startled scouts, looking up, saw the arm and face of a boy thrust part way through the aperture, showing that he must have slipped and broken the window while trying to spy upon the meeting.

“It’s Jud Mabley!” exclaimed one of the scouts, instantly recognizing the face of the unlucky youth who had fallen part way through the window.

Jud was a boy of bad habits. He had applied to the scouts for membership, but had not been admitted on account of his unsavory reputation. Smarting under this sting Jud had turned to Hank Lawson and his crowd for sympathy, and was known to be hand-in-glove with those young rowdies.

“He’s been spying on us, that’s what!” cried Bobolink, indignantly.

“And learning our plans, like as not!” added Tom Betts.

“He ought to be caught and ridden on a rail!” exclaimed a third member of the troop, filled with anger.

“I’d say duck him in the river after cutting a hole in the ice!” called out another boy, furiously. 39

“Huh! first ketch your rabbit before you start cookin’ him!” laughed Jud in a jeering fashion, as he waved them a mocking adieu through the broken window, and then vanished from view.

“After him, fellows!” shouted the impetuous Bobolink, and there was a hasty rush for the door, the boys snatching up their hats as they ran.

Paul was with the rest, not that he cared particularly about catching the eavesdropper, but he wanted to be on hand in case the rest of the scouts overtook Jud; for Paul held the reputation of the troop dear, and would not have the scouts sully their honor by a mean act.

The boys poured out of the meeting-place in a stream. The bright moon showed them a running figure which they judged must of course be Jud; so away they sprang in hot pursuit.

Somehow, it struck them that Jud was not running as swiftly as might be expected, for he had often proved himself a speedy contestant on the cinder path. He seemed to wabble more or less, and looked back over his shoulder many times.

Bobolink suspected there might be some sort of trick connected with this action on the part of the other, for Jud was known to be a schemer.

“Jack, he may be drawing us into a trap of some sort, don’t you think?” he managed to gasp as he ran at the side of the other. 40

Apparently Jack, too, had noticed the queer actions of the fugitive. He had seen a mother rabbit pretend to be lame when seeking to draw enemies away from the place where her young ones lay hidden; yes, and a partridge often did the same thing, as he well knew.

“I was noticing that, Bobolink,” he told the other, “but it strikes me Jud must have been hurt somehow when he crashed through that window.”

“You mean he feels more or less weak, do you?”

“Something like that,” came the reply.

“Well, we’re coming up on him like fun, anyway, no matter what the cause may be!” Bobolink declared, and then found it necessary to stop talking if he wanted to keep in the van with several of the swiftest runners among the scouts.

It was true that they were rapidly overtaking Jud, who ran in a strange zigzag fashion like one who was dizzy. He kept up until the leaders among his pursuers came alongside; then he stopped short, and, panting for breath, squared off, striking viciously at them.

Jack and two other scouts closed in on him, regardless of blows, and Jud was made a prisoner. He ceased struggling when he found it could avail him nothing, but glared at his captors as an Indian warrior might have done. 41

“Huh! think you’re smart, don’t you, overhaulin’ me so easy,” he told them disdainfully. “But if I hadn’t been knocked dizzy when I fell you never would a got me. Now what’re you meanin’ to do about it? Ain’t a feller got a right to walk the public streets of this here town without bein’ grabbed by a pack of cowards in soldier suits, and treated rough-house way?”

“That doesn’t go with us, Jud Mabley,” said Bobolink, indignantly. “You were playing the spy on us, you know it, trying to listen to all we were saying.”

“So as to tell that Lawson crowd, and get them to start some mean trick on us in the bargain,” added Tom Betts.

“O-ho! ain’t a feller a right to stop alongside of a church to strike a match for his pipe?” jeered the prisoner, defiantly. “How was I to know your crowd was inside there? The streets are free to any one, man, woman or boy, I take it.”

“How about the broken window, Jud?” demanded Bobolink, triumphantly.

“Yes! did you smash that pane of glass when you threw your match away, Jud,” asked another boy, with a laugh.

“He was caught in the act, fellows,” asserted Frank Savage, “and the next question with us is what ought we to do to punish a sneak and a spy?” 42

“I said it before—ride him on a rail around town so people can see how scouts stand up for their own rights!” came a voice from the group of excited boys.

“Oh! that would be letting him off too easy,” Tom Betts affirmed. “’Twould serve him just about right if we ducked him a few times in the river.”

“All we need is an axe to cut a hole through the ice,” another lad went on to say, showing that the suggestion rather caught his fancy as the appropriate thing to do—making the punishment fit the crime, as it were.

“Keep it goin’,” sneered the defiant Jud, not showing any signs of quailing under this bombardment. “Try and think up a few more pleasant things to do to me. If you reckon you c’n make me show the white feather you’ve got another guess comin’, I want you to know. I’m true grit, I am!”

“You may be singing out of the other side of your mouth, Jud Mabley, before we’re through with you,” threatened Curly Baxter.

“Mebbe now you might think to get a hemp rope and try hangin’ me,” laughed the prisoner in an offensive manner. “That’s what they do to spies, you know, in the army. Yes, and I know of a beauty of a limb that stands straight out from 43 the body of the tree ’bout ten feet from the ground. Shall I tell you where it lies?”

This sort of defiant talk was causing more of the scouts to become angry. It seemed to them like adding insult to injury. Here this fellow had spied upon their meeting, possibly learned all about the plans they were forming for the midwinter holidays, and then finally had the misfortune to fall and smash one of the window panes, which would, of course, have to be made good by the scouts, as they were under heavy obligations to the trustees of the church for favors received.

“A mean fellow like you, Jud Mabley,” asserted Joe Clausin, “deserves the worst sort of punishment that could be managed. Why, it would about serve you right if you got a lovely coat of tar and feathers to-night.”

Jud seemed to shrink a little at hearing that.

“You wouldn’t dare try such a game as that,” he told them, with a faint note of fear in his voice. “Every one of you’d have to pay for it before the law. Some things might pass, but that’s goin’ it too strong. My dad’d have you locked up in the town cooler if I came home lookin’ like a bird, sure he would.”

Jud’s father was something of a local power in politics, so that the boy’s boast was not without more or less force. Some of the scouts may have 44 considered this; at any rate, one of them now broke out with:

“A ducking ought to be a good enough punishment for this chap, I should say; so, fellows, let’s start in to give it to him.”

“I know where I can lay hands on an axe all right, to chop a hole through the ice,” asserted Bobolink, eagerly.

“Then we appoint you a committee of one to supply the necessary tools for the joyous occasion,” Red Collins cried out, gleefully falling in with the scheme.

“Hold on, boys, don’t you think it would be enough if Jud made an apology to us, and promised not to breathe a word of what he chanced to hear?”

It was Horace Poole who said this, for he often proved to be the possessor of a tender heart and a forgiving spirit. His mild proposition was laughed down on the spot.

“Much he’d care what he promised us, if only we let him go scot free,” jeered one scout. “I’ve known him to give his solemn word before now, and break it when he felt like it. I wouldn’t trust him out of my sight. Promises count for nothing with one of Jud Mabley’s stamp.”

“How about that, Jud?” demanded another boy. “Would you agree to keep your lips buttoned 45 up, and not tell a word of what you have heard?”

“I ain’t promisin’ nothin’, I want you to know,” replied the prisoner, boldly; “so go on with your funny business. You won’t ketch me squealing worth a cent. Honest to goodness now I half b’lieve it’s all a big bluff. Let’s see you do your worst.”

“Drag him along to the river bank, fellows, and I’ll join you there with the axe,” roared Bobolink, now fully aroused by the obstinate manner of the captive.

“Wait a bit, fellows.”

It was Jack Stormways who said this, and even the impetuous Bobolink came to a halt.

“Go on Jack. What’s your plan?” demanded one of the group.

“I was only going to remind you that in the absence of Mr. Gordon, Paul is acting as scout-master, and before you do anything that may reflect upon the good name of Stanhope Troop you’d better listen to what he’s got to say on the subject.”

These sensible words spoken by Jack Stormways had an immediate effect upon the angry scouts, some of whom realized that they had been taking matters too much in their own hands. Paul had remained silent all this while, waiting to see just how far the hotheads would go.

“First of all,” he went on to say in that calm tone which always carried conviction with it, “let’s go back to the meeting-room, and take Jud along. I have a reason for wanting you to do that, which you shall hear right away.”

No one offered an objection, although doubtless it was understood that Paul did not like such radical measures as ducking the spy who had fallen into their hands. They were by this time fully accustomed to obeying orders given by a superior officer, which is one of the best things learned by scouts.

Jud, for some reason, did not attempt to hold back when urged to accompany them, though for 47 that matter it would have availed him nothing to have struggled and strained, for at least four sturdy scouts had their grip on his person.

In this manner they retraced their steps. Fortunately the last boy out had been careful enough to close the door after making his hurried exit, so that they found the room still warm and comfortable.

They crowded inside, and a number of them frowned as they glanced toward the broken window, through which a draught was blowing. They hoped Paul would not be too easy with the rascal who had been responsible for that smash.

“First of all,” the scout-master began as they crowded around the spot where he and Jud stood, the latter staring defiantly at the frowning scouts, “I want to remark that it needn’t bother us very much even if Jud tells all he may have heard us saying. We shall always be at least two to one, and can take care of ourselves if attacked. Those fellows understand that, I guess.”

“We’ve proved it to them in the past times without number, for a fact,” observed Jack, diplomatically.

“If they care to spend a week in the snow woods, let them try it,” continued the other. “Good luck to them, say I; and here’s hoping they may learn some lessons there that will make them turn over 48 a new leaf. The forest is plenty big enough for all who want to breathe the fresh air and have a good time. But there’s another thing I had in mind when I asked you to bring Jud back here. Some of you may have noticed that he lets his arm hang down in a queer way. Look closer at his hand and you’ll discover the reason.”

Almost immediately several of the scouts cried out.

“Why, there’s blood dripping from his fingers, as sure as anything!”

“He must have cut his arm pretty bad when he fell through that window!”

“Whew! I’d hate to have that slash. See how the broken glass cut his coat sleeve—just as if you’d taken a sharp knife and gashed it!”

“Take off your coat, Jud, please!” said Paul.

Had Paul used a less kindly voice or omitted that last word in his request, the obstinate and defiant Jud might have flatly declined to oblige him. As it was he looked keenly at Paul, then grinned, and with something of an effort started to doff his coat, Jack assisting him in the effort.

Then the boys saw that his shirt sleeve was stained red. Several of the weaker scouts uttered low exclamations of concern, not being accustomed to such sights; but the stouter hearted veterans had seen too many cuts to wince now. 49

Paul gently but firmly rolled the shirt sleeve up until the gash made by the broken glass was revealed. It was a bad cut, and still bled quite freely. No wonder Jud had run in such an unwonted fashion. No person wounded as badly as that could be expected to run with his customary zeal, for the shock and the loss of blood was sure to make him feel weak.

Jud stared at his injury now with what was almost an expression of pride. When he saw some of the scouts shrink back his lip curled with disdain.

“Get a tin basin and fill it with warm water back in the other room, Jack!” said Paul, steadily.

“What’re you goin’ to do to me, Paul?” demanded Jud, curiously, for he could not bring himself to believe that any one who was his enemy would stretch out a hand toward him save in anger and violence.

“Oh! I’m only going to wash that cut so as to take out any foreign matter that might poison you if left there, and then bind it up the best way possible,” remarked the young scout-master.

There was some low whispering among the boys. Much as they marveled at such a way of returning evil with good they could not take exception to Paul’s action. Every one of them knew deep down in his inmost heart that scout law 50 always insisted on treating a fallen enemy with consideration, and even forgiving him many times if he professed sorrow for his evil ways.

Jack came back presently. He not only bore the basin of warm water but a towel as well. Jud watched operations curiously. He was seeing what was a strange thing according to his ideas. He could not quite bring himself to believe that there was not some cruel hoax hidden in this act of apparent friendliness, and that accounted for the way he kept his teeth tightly closed. He did not wish to be taken unawares and forced to cry out.

Paul washed gently the ugly, jagged cut. Then, taking out a little zinc box containing some soothing and healing salve, which he always carried with him, he used fully half of it upon the wound.

Afterwards he produced a small inch wide roll of surgical linen, and began winding the tape methodically around the injured arm of Jud Mabley. Jack amused himself by watching the play of emotions upon the hard face of Jud. Evidently, he was beginning to comprehend the meaning of Paul’s actions, though he could not understand why any one should act so.

When the last of the tape had been used and fastened with a small safety pin, Paul drew down the shirt sleeve, buttoned it, and then helped Jud on with his coat. 51

“Now you can go free when you take a notion, Jud,” he told the other.

“Huh! then you ain’t meanin’ to gimme that duckin’ after all?” remarked the other, with a sneering look of triumph at Bobolink.

“You have to thank Paul for getting you off,” asserted one scout, warmly. “Had it been left to the rest of us you’d have been in soak long before this.”

“For my part,” said Paul, “I feel that so far as punishment goes Jud has got all that is coming to him, for that arm will give him a lot of trouble before it fully heals. I hope every time it pains him he’ll remember that scouts as a rule are taught to heap coals of fire on the heads of their enemies when the chance comes, by showing them a favor.”

“But, Paul, you’re forgetting something,” urged Tom Betts.

“That’s a fact, how about the broken window, Paul?” cried Joe Clausin, with more or less indignation. For while it might be very well to forgive Jud his spying tricks some one would have to pay for a new pane of glass in the basement window, and it was hard luck if the burden fell on the innocent parties, while the guilty one escaped scot free.

It was noticed that Jud shut his lips tight together as though making up his mind on the spot 52 to decline absolutely to pay a cent for what had been a sheer accident, and which had already cost him a severe wound.

“I haven’t forgotten that, fellows,” said Paul, quietly. “Of course it’s only fair Jud should pay the dollar it will cost to have a new pane put in there to-morrow. I shall order Mr. Nickerson to attend to it myself. And I shall also insist on paying the bill out of my own pocket, unless Jud here thinks it right and square to send me the money some time to-morrow. That’s all I’ve got to say, Jud. There’s the door, and no one will put out a hand to stop you. I hope you won’t have serious trouble with that arm of yours.”

Jud stared dumbly at the speaker as though almost stunned. Perhaps he might have said something under the spur of such strange emotions as were chasing through his brain, but just then Bobolink chanced to sneer. The sound acted on Jud like magic, for he drew himself up, turned to look boldly into the face of each and every boy present, then thrust his right hand into his buttoned coat and with head thrown back walked out of the room, noisily closing the door after him.

Several of the scouts shook their heads.

“Pretty fine game you played with him, Paul,” remarked George Hurst, “but it strikes me it was like throwing pearls before swine. Jud has a hide 53 as thick as a rhinoceros and nothing can pierce it. Kind words are thrown away with fellows of his stripe, I’m afraid. A kick and a punch are all they can understand.”

“Yes,” added Red Collins, “when you try the soft pedal on them they think you’re only afraid. I’m half sorry now you didn’t let us carry out that ducking scheme. Jud deserved it right well, for a fact.”

“It would have been cruel to drop him into ice water with such a wound freshly made,” remarked Jack. “Wait and see whether Paul’s plan was worth the candle.”

“Mark my words,” commented Tom Betts, “we’ll have lots of trouble with him yet.”

“Shucks! who cares?” laughed Bobolink, “it’s all in the game, you know. There’s Paul getting ready to go home, so let’s forget it till we meet to-morrow.”

According to their agreement, Jack and Bobolink met on a certain corner on the following morning. Their purpose was to purchase the staple articles of food that half a score of hungry lads would require to see them through a couple of weeks’ stay in the snow forest.

“It’s a lucky thing, too,” Bobolink remarked, after the other had displayed the necessary funds taken from his pocket, “that our treasury happens to be fairly able to stand the strain just now.”

“Oh, well! except for that we’d have had to take up subscriptions,” laughed Jack. “I know several people who would willingly help us out. The scouts of Stanhope have made good in the past, and a host of good friends are ready to back them.”

“Yes, and for that matter I guess Mr. Thomas Garrity would have been only too glad to put his hand deep down in his pocket,” suggested Bobolink. 55

“He’s an old widower, and with plenty of ready cash, too,” commented the other boy. “But, after all, it’s much better for us to stand our own expense as long as we can.”

“Have you got the list that Paul promised to make out with you, Jack? I’d like to take a squint at it, if you don’t mind. There may be a few things we could add to it.”

As Bobolink was looked on as something of an authority in this line, Jack hastened to produce the list, so they could run it over and exchange suggestions.

“Where shall we start in to buy the stuff?” asked Bobolink, presently.

“Oh! I don’t know that it matters very much,” replied his companion. “Mr. Briggs has had some pretty fine hams in lately I heard at the house this morning, and if he treats us half-way decent we might do all our trading with him.”

“I never took much stock in old Levi Briggs,” said Bobolink. “He hates boys for all that’s out. I guess some of them do nag him more or less. I saw that Lawson crowd giving him a peck of trouble a week ago. He threatened to call the police if they didn’t go away.”

“Well, we happen to be close to the Briggs’ store,” observed Jack, “so we might as well drop in and see how he acts toward us.” 56

“Huh! speaking of the Lawson bunch, there they are right now!” exclaimed Bobolink.

Loud jeering shouts close by told that Hank and his cronies were engaged in their favorite practice of having “fun.” This generally partook of the nature of the old fable concerning boys who were stoning frogs, which was “great fun for the boys, but death to the frogs.”

“It’s a couple of ragged hoboes they’re nagging now,” burst out Bobolink.

“The pair just came out of Briggs’ store,” added Jack, “where I expect they met a cold reception if they hoped to coax a bite to eat from the old man.”

“Still, they couldn’t have done anything to Hank and his crowd, so why should they be pushed off the walk in that way?” Bobolink went on to say.

As a rule the boy had no use for tramps. He looked on the vagrants as a nuisance and a menace to the community. At the same time, no self-respecting scout would think of casting the first stone at a wandering hobo, though, if attacked, he would always defend himself, and strike hard.

“The tramps don’t like the idea of engaging in a fight with a pack of tough boys right here in town,” remarked Jack, “because they know the police would grab them first, no matter if they were only defending themselves. That’s why they 57 don’t hit back, but only dodge the stones the boys are flinging.”

“Oh! that’s a mean sort of game!” cried Bobolink, as he saw the two tramps start to run wildly away. “There! that shorter chap was hit in the head with one of the rocks thrown after them. I bet you it raised a fine lump. What a lot of cowards those Lawsons are, to be sure.”

“Well, the row is all over now,” observed Jack. “And as the tramps have disappeared around the corner we don’t want to break into the game, so come along to the store, and let’s see what we can do there.”

Bobolink continued to shake his head pugnaciously as he walked along the pavement. Hank and his followers were laughing at a great rate as they exchanged humorous remarks concerning the recent “fight” which had been all one-sided.

“Believe me!” muttered Bobolink, “if a couple more scouts had been along just now I’d have taken a savage delight in pitching in and giving that crowd the licking they deserved. Course a tramp isn’t worth much, but then he’s human, and I hate to see anybody bullied.”

“It wasn’t Hank’s business to chase the hoboes out of town,” said Jack. “We have the police force to manage such things. Fact is, I reckon Hank’s bunch has done more to hurt the good 58 name of Stanhope than all the hoboes we ever had come around here.”

“If I had my way, Jack, there’d be a public woodpile, and every tramp caught coming to town would have to work his passage. I bet there’d be a sign on every cross-roads warning the brotherhood to beware of Stanhope as they might of the smallpox. But here’s Briggs’ store.”

As they entered the place they could see that the proprietor was alone, his clerk being off on the delivery wagon.

“Whew! he certainly looks pretty huffy this morning,” muttered the observing Bobolink. “Those tramps must have bothered him more or less before he could get them to move on.”

“It might be he had some trouble with Hank before we came up,” Jack suggested; but further talk was prevented by the coming up of the storekeeper.

Mr. Briggs was a small man with white hair, and keen, rat-like eyes. He possessed good business abilities, and had managed to accumulate a small fortune in the many years he purveyed to the people of Stanhope.

Latterly, however, the little, old man had been growing very nervous and irritable, perhaps with the coming of age and its infirmities. He detested boys, and since that feeling soon becomes mutual 59 there was open war between Mr. Briggs and many of the juveniles of Stanhope.

Suspicious by nature, he always watched when boys came into his store as though he weighed them all in the same balance with Hank Lawson, and considered that none of Stanhope’s rising generation could be trusted out of sight.

Long ago he had taken to covering every apple and sugar barrel with wire screens to prevent pilfering. Neither Jack nor Bobolink had ever had hot words with the storekeeper, but for all that they felt that his manner was openly aggressive at the time they entered the door.

“If you want to buy anything, boys,” said Mr. Briggs curtly, “I’ll wait on you; but if you’ve only come in here to stand around my store and get warm I’ll have to ask you to move on. My time is too valuable to waste just now.”

Jack laughed on hearing that.

“Oh! we mean business this morning, Mr. Briggs,” he remarked pleasantly, while Bobolink scowled, and muttered something under his breath. “The fact is a party of us scouts are planning to spend a couple of weeks up in the snow woods,” continued Jack. “We have a list here of some things we want to take along, and will pay cash for them. We want them delivered to-day at our meeting room under the church.” 60

“Let Mr. Briggs have the list, Jack,” suggested Bobolink. “He can mark the prices he’ll let us have the articles for. Of course, sir, we mean to buy where we can get the best terms for cash.”

Bobolink knew the grasping nature of the old storekeeper, and perhaps this was intended for a little trap to trip him up. Mr. Briggs glanced over the list and promptly did some figuring, after which he handed the paper back.

“Seems to me your prices are pretty steep, sir!” remarked Jack.

“I should say they were,” added Bobolink, with a gleam in his eyes. “Why, you are two cents a pound on hams above the other stores. Yes, and even on coffee and rice you are asking more than we can get the same article for somewhere else.”

“Those are my regular prices,” said the old man, shortly. “If they are not satisfactory to you, of course, you are at liberty to trade elsewhere. In fact, I do not believe you meant to buy these goods of me, but have only come in to annoy me as those other good-for-nothing boys always do.”

“Indeed, you are mistaken, Mr. Briggs,” expostulated Jack, who did not like to be falsely accused when innocent. “We are starting out to see where we can get our provisions at the most reasonable rates. Some of the storekeepers are only too glad to give the scouts a reduction.” 61

“Well, you’ll get nothing of the sort here, let me tell you,” snapped the unreasonable old man. “I can’t afford to do business at cost just to please a lot of harum-scarum boys, who want to spend days loafing in the woods when they ought to be earning an honest penny at work.”

“Come on, Jack, let’s get out of here before I say something I’ll be sorry for,” remarked Bobolink, who was fiery red with suppressed anger.

“There’s the door, and your room will be better appreciated than your company,” Mr. Briggs told them. “And as for your trade, take it where you please. Your people have left me for other stores long ago, so why should I care?”

“Oh! that’s where the shoe pinches, is it?” chuckled Bobolink; and after that he and Jack left the place, to do their shopping in more congenial quarters, while Mr. Briggs stood on his doorsteps and glared angrily after them.

“Saturday, eleven-thirty P.M., the night before Christmas, and all’s well!”

It was Frank Savage who made this remark, as with eight other scouts he trudged along, after having left the house of the scout-master, Paul Morrison. Frank had been the lucky one to be counted among those who were going on the midwinter tour, his parents having been coaxed into giving their consent.

“And on Monday morning we make the start, wind and weather permitting,” observed Bobolink, with an eagerness he did not attempt to conceal.

“So far as we know everything is in complete readiness,” said Bluff Shipley.

“Five iceboats are tugging at their halters, anxious to be off,” laughed Jack. “And there’ll be a lot of restless sleepers in certain Stanhope homes I happen to know.”

“Huh! there always are just before Christmas,” chuckled Tom Betts. “But this year we have a 63 double reason for lying awake and counting the dragging minutes. Course you committee of two looked after the grub supplies as you were directed?”

“We certainly did!” affirmed Bobolink, “and came near getting into a row with old Briggs at his store. He wanted to ask us top-notch prices for everything, and when we kicked he acted so ugly we packed out.”

“Just like the old curmudgeon,” declared Phil Towns. “The last time I was in his place he kept following me around as if he thought I meant to steal him out of house and home. I just up and told my folks I never wanted to trade with Mr. Briggs again, and so they changed to the other store.”

“Oh, well, he’s getting old and peevish,” said Jack. “You see he lives a lonely life, and has a narrow vision. Besides, some boys have given him a lot of trouble, and he doesn’t know the difference between decent fellows and scamps. We’d better let him alone, and talk of something else.”

“I suppose all of you notice that it’s grown cloudy late to-day,” suggested Spider Sexton.

“Oh! I hope that doesn’t mean a heavy snowfall before we get started,” exclaimed Bluff. “If a foot of snow comes down on us, good-bye to our using the iceboats as we’ve been planning.” 64

“The weather reports at the post office say fair and cold ahead for this section,” announced Jack Stormways, at which there arose many faint cheers.

“Good boy, Jack!” cried Bobolink, patting the other’s back. “It was just like the thoughtful fellow you are to go down and read the prospect the weather sharps in Washington hold out for us.”

“You must thank Paul for that, then,” admitted the other, “for he told me about it. I rather expect Paul had the laugh on the rest of us to-night, boys.”

“Now you’re referring to that Jud Mabley business, Jack,” said Phil Towne.

“Well, when Paul let him off so easy every one of us believed he was wrong, and that the chances were ten to one Paul would have to fork over the dollar to pay for having that window pane put in,” continued Jack. “But you heard what happened?”

“Yes, seems that the age of miracles hasn’t passed yet,” admitted Bobolink. “I thought I was dreaming when Paul told me that Jud’s little brother came this morning with an envelope addressed to him, and handed it in without a word.”

“And when Paul opened it,” continued Jack, taking up the story in his turn, “he found a nice, new dollar bill enclosed, with a scrap of paper on 65 which Jud had scrawled these words: ‘Never would have paid only I couldn’t let you stand for my accident, and after you treated me so white, too. But this wipes it all out, remember. I’m no crawler!’”

“It tickled Paul a whole lot, let me remark,” Jud Elderkin explained. “I do half believe he thinks he can see a rift in the cloud, and that some of these days hopes to get a chance to drag Jud Mabley out of that ugly crowd.”

“It would be just like Paul to lay plans that way,” acknowledged Jack. “I know him like a book, and believe me, he gets more pleasure out of making his enemies feel cheap than the rest of us would if we gave them a good licking.”

“Paul’s a sure-enough trump!” admitted Bluff. “Do you know what he said when he was showing that scrawl to us fellows? I was close enough to get part of it, and I’m dead sure the words ‘entering wedge’ formed the backbone of his remark.”