Title: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society - Vol 1 - 1666

Author: Various

Editor: Henry Oldenburg

Release date: May 11, 2009 [eBook #28758]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by PM Phil Trans, Jonathan Ingram, Keith Edkins

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by the Bibliothèque nationale

de France (BnF/Gallica) at http://gallica.bnf.fr)

| Transcriber's note: | A few typographical errors have been corrected. They appear in the text like this, and the explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked passage. |

GIVING SOME

OF THE PRESENT

Undertakings, Studies, and Labours

OF THE

IN MANY

CONSIDERABLE PARTS

OF THE

In the SAVOY,

Printed by T. N. for John Martyn at the Bell, a little without

Temple-Bar, and James Allestry in Duck-Lane,

Printers to the Royal Society.

It will not become me, to adde any Attributes to a Title, which has a Fulness of Lustre from his Majesties Denomination.

In these Rude Collections, which are onely the Gleanings of my private diversions in broken hours, it may appear, that many Minds and Hands are in many places industriously employed, under Your Countenance, and by Your Example, in the pursuit of those Excellent Ends, which belong to Your Heroical Undertakings.

Some of these are but the Intimations of large Compilements. And some Eminent Members of Your Society, have obliged the Learned World with Incomparable Volumes, which are not herein mention'd, because they were finisht, and in great Reputation abroad, before I entred upon this Taske. And no small Number are at present engaged for those weighty Productions, which require both Time and Assistance, for their due Maturity. So that no man can from these Glimpses of Light take any just Measure of Your Performances, or of Your Prosecutions; but every man may perhaps receive some benefit from these Parcels, which I guessed to be somewhat conformable to Your Design.

This is my Solicitude, That, as I ought not to be unfaithful to those Counsels you have committed to my Trust, so also that I may not altogether waste any minutes of the leasure you afford me. And thus have I made the best use of some of them, that I could devise; To spread abroad Encouragements, Inquiries, Directions, and Patterns, that may animate, and draw on Universal Assistances.

The Great God prosper You in the Noble Engagement of Dispersing the true Lustre of his Glorious Works, and the Happy Inventions of obliging Men all over the World, to the General Benefit of Mankind: So wishes with real Affections,

Your humble and obedient Servant

HENRY OLDENBURG.

Munday, March 6. 1664/5.

An Introduction to this Tract. An Accompt of the Improvement of Optick Glasses at Rome. Of the Observation made in England, of a Spot in one of the Belts of the Planet Jupiter. Of the motion of the late Comet prædicted. The Heads of many New Observations and Experiments, in order to an Experimental History of Cold; together with some Thermometrical Discourses and Experiments. A Relation of a very odd Monstrous Calf. Of a peculiar Lead-Ore in Germany, very useful for Essays. Of an Hungarian Bolus, of the same effect with the Bolus Armenus. Of the New American Whale-fishing about the Bermudas. A Narative concerning the success of the Pendulum-watches at Sea for the Longitudes; and the Grant of a Patent thereupon. A Catalogue of the Philosophical Books publisht by Monsieur de Fermat, Counsellour at Tholouse, lately dead.

Whereas there is nothing more necessary for promoting the improvement of Philosophical Matters, than the communicating to such, as apply their Studies and Endeavours that way, such things as are discovered or put in practise by others, it is therefore thought fit to employ the Press, as the most proper way to gratifie those, whose engagement in such Studies, and delight in the advancement of Learning and profitable Discoveries, doth entitle them to the knowledge of what this Kingdom, or other parts of the World, do, from time to time, afford, as well {2}of the progress of the Studies, Labours, and attempts of the Curious and learned in things of this kind, as of their compleat Discoveries and performances: To the end, that such Productions being clearly and truly communicated, desires after solid and usefull knowledge may be further entertained, ingenious Endeavours and Undertakings cherished, and those, addicted to and conversant in such matters, may be invited and encouraged to search, try, and find out new things, impart their knowledge to one another, and contribute what they can to the Grand design of improving Natural knowledge, and perfecting all Philosophical Arts, and Sciences. All for the Glory of God, the Honour and Advantage of these Kingdoms, and the Universal Good of Mankind.

There came lately from Paris a Relation, concerning the Improvement of Optick Glasses, not long since attempted at Rome by Signor Giuseppe Campani, and by him discoursed of, in a Book, Entituled, Ragguaglio di nuoue Osservationi, lately printed in the said City, but not yet transmitted into these parts; wherein these following particulars, according to the Intelligence, which was sent hither, are contained.

The First regardeth the excellency of the long Telescopes, made by the said Campani, who pretends to have found a way to work great Optick Glasses with a Turne-tool, without any Mould: And whereas hitherto it hath been found by Experience, that small Glasses are in proportion better to see with, upon the Earth, than the great ones; that Author affirms, that his are equally good for the Earth, and for making Observations in the Heavens. Besides, he useth three Eye-Glasses for his great Telescopes, without finding any Iris, or such Rain-bow colours, as do usually appear in ordinary Glasses, and prove an impediment to Observations.

The Second, concerns the Circle of Saturn, in which he hath observed nothing, but what confirms Monsieur Christian Huygens de Zulichem his Systeme of that Planet, published by that worthy Gentleman in the year, 1659. {3}

The Third, respects Jupiter, wherein Campani affirms he hath observed by the goodness of his Glasses, certain protuberancies and inequalities, much greater than those that have been seen therein hitherto. He addeth, that he is now observing, whether those sallies in the said Planet do not change their scituation, which if they should be found to do, he judgeth, that Jupiter might then be said to turn upon his Axe; which, in his opinion, would serve much to confirm the opinion of Copernicus. Besides this, he affirms, he hath remarked in the Belts of Jupiter, the shaddows of his satellites, and followed them, and at length seen them emerge out of his Disk.

The Ingenious Mr. Hook did, some moneths since, intimate to a friend of his, that he had, with an excellent twelve foot Telescope, observed, some days before, he than spoke of it, (videl. on the ninth of May, 1664, about 9 of the clock at night) a small Spot in the biggest of the 3 obscurer Belts of Jupiter, and that, observing it from time to time, he found, that within 2 hours after, the said Spot had moved from East to West, about half the length of the Diameter of Jupiter.

There was lately sent to one of the Secretaries of the Royal Society a Packet, containing some Copies of a Printed Paper, Entituled, The Ephemerides of the Comet, made by the same Person, that sent it, called Monsieur Auzout, a French Gentleman of no ordinary Merit and Learning, who desired, that a couple of them might be recommended to the said Society, and one to their President, and another to his Highness Prince Rupert, and the rest to some other Persons, nominated by him in a Letter that accompanied this present, and known abroad for their singular abilities and knowledge in Philosophical Matters. The end of the Communication of this Paper was, That, the motion of the Comet, that hath lately appeared, having been prædicted by the said Monsieur {4}Auzout, after he had seen it (as himself affirms) but 4 or 5 times: the Virtuosi of England, among others, might compare also their Observations with his Ephemerides, either to confirm the Hypothesis, upon which the Author had before hand calculated the way of this Star, or to undeceive him, if he be in a mistake. The said Author Dedicateth these his conceptions to the most Christian King, telling him, that he presents Him with a design, which never yet was undertaken by any Astronomer, all the World having been hitherto perswaded, that the motions of Comets were so irregular, that they could not be reduced to any Laws, and men having contented themselves, to observe exactly the places, through which they did pass; but no man, that he knows, having been so bold as to venture to foretel the places, through which they should pass, and where they should cease to appear: Whereas he exhibites here the Ephemerides, determining day by day, in what place of the Heavens this Comet shall be, at what hour it shall be in its Meridian, and at what hour it shall set; untill its too great remoteness, or the approach of the Sun, hide it from our eyes. Descending to particulars, he saith, that this Star, being disengaged from the beams of the Sun might have been observed, if his conjectures be good, ever since it hath been of 17 or 18 degrees Southern Latitude, and that about the middle of November last, and sooner, unless it have been too small: That however it hath been seen in Holland ever since the 2d. of December last, at which time, according to his reckoning, the Diurnal motion of the Comet should already amount to 17 or 18 minutes. He finds, that this Star moveth just enough in the Plan of a Great Circle, which inclineth to the Equinoctial about 30 degrees, and to the Ecliptick about 49d. or 49½ cutting the Equator at about 45d½, and the Ecliptick at the 28d of Aries, or a little more. He saith just enough, because he thinks, there may perhaps be some parallaxe, which he wisheth could be determined.

Hence, (so he goes on) every one who pleaseth, may see, in tracing the Comet upon the Globe, through, or by which Stars it hath passed and shall pass; adding, that there will be neither cause to wonder, that having descended to about 6. deg. beneath the Tropick of Capricorn, he hath remounted afterwards, and shall go {5}on ascending so, as to pass the Æquinoctial, and perhaps proceed to 15. degrees Northern Declination, if it do not disappear before that time, by reason of its remoteness: Nor to believe, that there have been two Comets, upon its being seen again the 31. of December; since, according to him, it ought to have been so, if it continue to move in a Great Circle.

Having hereupon shewed, how the motion is to be traced upon the Globe, he finds, that, according to his Calculation, this Comet was to pass the Tropick of Capricorn about the 16 of December, and being entred into the Sign of Virgo on the 20. of the same month, and having been in Quadrat with the Sun, it should still descend, until the 26 of December in the morning, and then enter into Leo; that having entred, the 28. of the same month, into Cancer, and been, a little after that time, in its greatest Inclination to the Ecliptick, vid in the 28. degree of Leo, it was to repass the Southern Tropick, over against the little Dogg, on the 29. of December about 9 or 10 of the clock in the morning, after it had been opposite to the Sun 2. or 3. hours before; and that on the 29. of December in the evening it should be in Gemini; and at the very beginning of the New year, enter into Taurus.

After this, our Author finds, that this Comet, according to his account, should pass the Æquator, on the 4. of January before noon, and that about 5. or 6. of the clock in the evening of that day it was to come into the jaw of the Whale, and the 9. of the same, at 6. of the clock it should come close to the small Star of the Whale, which is in its way, a little below. At length he finds that it was to enter into Aries on the 12. of January, and to cut the Ecliptick on the 16. of the same month about noon, at which time it was to be again in Quadrat with the Sun, whence drawing a little to above the Northern Line of Pisces, it should in his opinion cease to appear a little beyond that place, without going as far as to the middle of Aries, if so be that its remoteness make it not disappear sooner.

He continueth, and saith, that this Comet shall not arrive to the place over against the Line of Pisces till the 10 of February, & that then its Diurnal motion shall not exceed 8 minutes, and not 5 minutes about the 20 of the same month: and that in the {6}beginning of March, if we see it so long, the said motion shall not exceed 4 minutes, and so shall be still diminishing; except the Comet become Retrograde, which, as very important, he would have well observed; as also, whether its motion will be about the end more or less swift, than he hath calculated it.

He subjoyneth, that the greatest way, which this Star could make in 24. hours, hath been 13. d. 25′; and in one houre, about 34′; and thinking it probable, that about the time, when it made so much way, it should be nearest to the Earth, he concludeth that its motion in 24. hours must be, in its least distance from the Earth, as about 3. to 14, or 1. to 4⅔, and that its motion in one hour was to be to the same least distance, as about 1. to 1021/7.

But that, which he judgeth most remarkable, is, that he found by his Calculation, that the said least distance should be on the 29. of December, when the Comet was opposite to the Sun; which he does not know whether it may not serve to decide the grand Question concerning the Motion of the Earth.

He taketh further notice, that the Tayl of the Comet was to turn Westward, with a point to the North, until the 29. of December, at which time it was to be opposite to the Sun, and that then the said Tayl was to look directly North; but that, after that time, the Tayl was to turn Eastward, and continue to do so, until it disappear; and that it shall draw a little towards the North, until the 8. or 10. of February, at which time the Tayl is to be parallel to the Æquator, as if the Comet be yet seen for some time after, the Tayl shall go a little lower towards the South, but grow smaller.

He finds by his Hypothesis, that on the 2. of December, which is the first observation, that he hath heard of, this Star was to be about 7. times more remote from the Earth, than when it was in its Perigeum; and that it will be again in an equall remoteness from the Earth, on the 27. of January, so that he is of opinion, that in case this Comet have not been seen before the 2. of December, it will not be seen any more after the 27. of January.

He wishes above all things, that it might be very exactly observed, at what Angle the way of the Comet cuts the Æquator, and, most of all, the Ecliptick, that so it may be seen, whether {7}there hath not been some Parallaxe in the Circle of his Motion; as also, that some observations could be had of its greatest descent beneath the Tropick of Capricorn in the more Southern parts, where he saith it would have been without Refractions; Moreover of the Time, when it hath been in Quadrat with the Sun about the 20 of December; and that also very exact Observation might be made of the time of its being again in Quadrat with the Sun, which, according to him, was to be January 16.

He wishes also, that some in Madagascar may have observed this Star; Seeing that it began to appear over the middle of that Island, and passed twice over their heads; he judgeth, that they have seen it before us. And he wisheth lastly, that there were some intelligent person in Guiana to observe it there, seeing that within a few daies, according to his reckoning, it will pass over their Heads, and will not remove from thence but 8 or 10 degrees Northward, where he saith, it will disappear; thinking it improbable, that it can still appear, after the Sun shall have passed it.

This Account beareth date of the 2. January, new stile, 1665. and the Author thereof addeth this Note, That, seeing it could not be printed nor distributed so soon as he desired, he hath had the opportunity to verifie it by some Observations, from which he affirms he hath found no sensible difference; or, if there be, that it proceeds only from thence, that the Stars have advanced, since his Globe was made. He concludeth, that if this continue, and the first Observations do likewise agree, or that the differences do arrive within the Times ghessed by him, that he hopes, he shall determine both the Distance and the Magnitude of this Comet; and that perhaps one may be enabled to decide the Question of the Motion of the Earth. In the interim, he assureth, that he hath not changed the least number in his Calculations, and that Monsieur Huygens, and several French Gentlemen, to whom he saith, he hath given them long since, can bear him witness that he hath done so; as also many other friends of his, who saw upon his Globe, several daies before, the way of the Comet from day to day.

Thus for the Parisian Account of the Comet, which is here inserted at large, that the intelligent and curious in England may {8}compare their Observations therewith, either to verifie these Prædictions, or to shew wherein they differ; which is (as was also hinted above) the design of this Philosophical Prophet in dispersing his Conceptions, who declareth himself ready, in case he be mistaken in his reckoning, to learn another Hypothesis, to explicate these admirable appearances by.

There is in the Press, a New Treatise, entituled, New Observations and Experiments in order to an Experimental History of Cold, begun by that Noble Philosopher, Mr. Robert Boyle, and in great part already Printed; He did lately very obligingly present several Copies of so much as was Printed, to the Royal Society, with a desire that some of the Members thereof might be engaged to peruse the Book, and select out of it for trial, the hints of such Experiments, as the Author there wisheth might be either yet made or prosecuted. The Heads thereof are,

1. Experiments touching Bodies capable of Freezing others.

2. Experiments and Observations touching Bodies Disposed to be Frozen.

3. Experiments touching Bodies, Indisposed to be Frozen.

4. Experiments and Observations touching the Degrees of Cold in several Bodies.

5. Experiments touching the Tendency of Cold Upwards or Downwards.

6. Experiments and Observations touching the Preservation and Destruction of (Eggs, Apples, and other) Bodies by Cold.

7. Experiments touching the Expansion of Water and Aqueous Liquors by Freezing.

8. Experiments touching the Contraction of Liquors by Cold.

9. Experiments in Consort, touching the Bubbles, from which the Levity of Ice is supposed to proceed.

10. Experiments about the Measure of the Expansion and the Contraction of Liquors by Cold.

11. Experiments touching the Expansive Force of Freezing Water.

12. Experiments touching a New way of estimating the {9}Expansive force of Congelation, and of highly compressing Air without Engines.

13. Experiments and Observations touching the Sphere of Activity of Cold.

14. Experiments touching differing Mediums, through which Cold may be diffused.

15. Experiments and Observations touching Ice.

16. Experiments and Observations touching the duration of Ice and Snow, and the destroying of them by the Air, and several Liquors.

17. Considerations and Experiments touching the Primum Frigidum.

18. Experiments and Observations touching the Coldness and Temperature of the Air.

19. Of the strange Effects of Cold.

20. Experiments touching the weight of Bodies frozen and unfrozen.

21. Promiscuous Experiments and Observations concerning Cold.

This Treatise will be dispatched within a very short time, and would have been so, ere this, if the extremity of the late Frost had not stopt the Press. It will be accompanied with some Discourses of the same Author, concerning New Thermometrical Experiments and Thoughts, as also, with an Exercitation about the Doctrine of the Antiperistasis: In the former whereof is first proposed this Paradox, That not only our Senses, but common Weather-glasses, may mis-inform us about Cold. Next, there are contained in this part, New Observations about the deficiencies of Weather-glasses, together with some considerations touching the New or Hermetrical Thermometers. Lastly, they deliver another Paradox, touching the cause of the Condensation of the Air, and Ascent of water by cold in common Weather-glasses. The latter piece of this part contains an Examen of Antiperistasis, as it is wont to be taught and proved; Of all which there will, perhaps, a fuller account be given by the Next. {10}

By the same Noble person was lately communicated to the Royal Society an account of a very Odd Monstrous Birth, produced at Limmington in Hampshire, where a Butcher, having caused a Cow (which cast her Calf the year before) to be covered, that she might the sooner be fatted, killed her when fat, and opening the Womb, which he found heavy to admiration, saw in it a Calf, which had begun to have hair, whose hinder Leggs had no Joynts, and whose Tongue was, Cerberus-like, triple, to each side of his Mouth one, and one in the midst: Between the Fore-leggs and the Hinder-leggs was a great Stone, on which the Calf rid: the Sternum, or that part of the Breast, where the Ribs lye, was also perfect Stone; and the Stone, on which it rid, weighed twenty pounds and a half; the outside of the Stone was of Grenish colour, but some small parts being broken off, it appeared a perfect Free-stone. The Stone, according to the Letter of Mr. David Thomas, who sent this Account to Mr. Boyle, is with Doctor Haughteyn of Salisbury, to whom he also referreth for further Information.

There was, not long since, sent hither out of Germany from an inquisitive Physician, a List of several Minerals and Earths of that Country, and of Hungary, together with a Specimen of each of them: among which there was a kind of Lead-Ore which is more considerable than all the rest, because of its singular use for Essays upon the Coppell, seeing that there is not any other Mettal mixed with it. 'Tis found in the Upper Palatinate, at a place called Freyung, and there are two sorts of it, whereof one is a kind of Crystalline Stone, and almost all good Lead; the other not so rich, and more farinaceous. By the information, coming along with it, they are fetcht, not from under the ground, but, the Mines of that place having lain long neglected, by reason of the Wars of Germany and the increase of Waters, the people, living {11}there-about take it from what these Forefathers had thrown away, and had lain long in the open Air. The use above mentioned being considerable, the person, who sent it, hath been intreated, to inform what quantities may be had of it, if there should be occasion to send for some.

The same person gave notice also, that, besides the Bolus Armenus, and the Terra Silesiaca, there is an Earth to be found in Hungary about the River Tockay, thence called Bolus Tockaviensis, having as good effects in Physick, as either of the former two, and commended by experience in those parts, as much as it is by Sennertus out of Crato, for its goodness.

Here follows a Relation, somewhat more divertising, than the precedent Accounts, which is about the new Whale fishing in the West-Indies about the Bermudas, as it was delivered by an understanding and hardy Sea-man, who affirmed he had been at the killing work himself. His account, as far as remembred, was this; that though hitherto all Attempts of mastering the Whales of those Seas had been unsuccesful, by reason of the extraordinary fierceness and swiftness of these monstrous Animals; yet the enterprise being lately renewed, and such persons chosen and sent thither for the work, as were resolved not to be baffled by a Sea-monster, they did prosper so far in this undertaking, that, having been out at Sea, near the said Isle of Bermudas, seventeen times, and fastned their Weapons a dozen times, they killed in these expeditions 2 old Female-Whales, and 3 Cubs, whereof one of the old ones, from the head to the extremity of the Tayl, was 88. Foot in length, by measure; its Tayl being 23. Foot broad, the swimming Finn 26. Foot long, and the Gills three Foot long: having great bends underneath from the Nose to the Navil; upon her after-part, a Finn on the back; being within {12}paved (this was the plain Sea-man's phrase) with fat, like the Cawl of a Hog.

The other old one, he said, was some 60. Foot long. Of the Cubs, one was 33. the other two, much about 25 or 26. Foot long.

The shape of the Fish, he said, was very sharp behind, like the ridge of a house; the head pretty bluff, and full of bumps on both sides; the back perfectly black, and the belly white.

Their celerity and force he affirmed to be wonderful, insomuch that one of those Creatures, which he struck himself, towed the boat wherein he was, after him, for the space of six or seven Leagues, in ¾ of an hours time. Being wounded, he saith, they make a hideous roaring, at which, all of that kind that are within hearing, come towards that place, where the Animal is, yet without striking, or doing any harm to the wary.

He added, that they struck one of a prodigious bigness, and by guess of above 100 foot long. He is of opinion, that this Fish comes nearest to that sort of Whales, which they call the Jubartes; they are without teeth, and longer than the Greenland-Whales, but not so thick.

He said further, that they fed much upon Grass, growing at the bottom of the Sea; which, he affirmed, was seen by cutting up the great Bag of Maw, wherein he had found in one of them about two or three Hogsheads of a greenish grassy matter.

As to the quantity and nature of the Oyl which they yield, he thought, that the largest sort of these Whales might afford seven or eight Tuns if well husbanded, although they had lost much this first time, for want of a good Cooper; having brought home but eleven Tuns. The Cubbs, by his relation, do yield but little, and that is but a kind of a Jelly. That which the old ones render, doth candy like Porks Grease, yet burneth very well. He observed, that the Oyl of the Blubber is as clear and fair as any Whey: but that which is boyled out of the Lean, interlarded, becomes as hard as Tallow, spattering in the burning and that which is made of the Cawl, resembleth Hoggs grease.

One, but scarce credible, quality of this Oyl, he affirms to be, that though it be boiling, yet one may run ones hand into it without scalding; to which he adds, that it hath a very healing {13}Vertue for cuttings, lameness, &c., the part affected being anointed therewith. One thing more he related, not to be omitted, which is, that having told, that the time of catching these Fishes was from the beginning of March, to the end of May, after which time they appeared no more in that part of the Sea: he did, when asked, whither they then retired, give this Answer, That it was thought, they went into the Weed-beds of the Gulf of Florida, it having been observed, that upon their Fins and Tails they have store of Clams or Barnacles, upon which, he said, Rock-weed or Sea-tangle did grow a hand long; many of them having been taken of them, of the bigness of great Oyster-shels, and hung upon the Governour of Bermudas his Pales.

The Relation lately made by Major Holmes, concerning the success of the Pendulum-Watches at Sea (two whereof were committed to his Care and Observation in his last voyage to Guiny by some of our Eminent Virtuosi, and Grand Promoters of Navigation) is as followeth;

The said Major having left that Coast, and being come to the Isle of St. Thomas under the Line accompanied with four Vessels, having there adjusted his Watches, put to Sea, and sailed Westward, seven or eight hundred Leagues, without changing his course; after which, finding the Wind favourable, he steered towards the Coast of Africk, North-North-East. But having sailed upon that Line a matter of two or three hundred Leagues, the Masters of the other Ships, under his Conduct, apprehending that they should want Water, before they could reach that Coast, did propose to him to steer their Course to the Barbadoes, to supply themselves with Water there. Whereupon the said Major, having called the Master and Pilots together, and caused them to produce their Journals and Calculations, it was found, that those Pilots did differ in their reckonings from that of the Major, one of them eighty Leagues, another about an hundred, and the third, more; but the Major judging by his Pendulum-Watches, that they were only some thirty Leagues distant from {14}the Isle of Fuego, which is one of the Isles of Cape Verde, and that they might reach it next day, and having a great confidence in the said Watches, resolved to steer their Course thither, and having given order so to do, they got the very next day about Noon a sight of the said Isle of Fuego, finding themselves to sail directly upon it, and so arrived at it that Afternoon, as he had said. These Watches having been first Invented by the Excellent Monsieur Christian Hugens of Zulichem, and fitted to go at Sea, by the Right Honourable, the Earl of Kincardin, both Fellows of the Royal Society, are now brought by a New addition to a wonderful perfection. The said Monsieur Hugens, having been informed of the success of the Experiment, made by Major Holmes, wrought to a friend at Paris a Letter to this effect;

Major Holmes at his return, hath made a relation concerning the usefulness of Pendulums, which surpasseth my expectation: I did not imagine that the Watches of this first Structure would succeed so well, and I had reserved my main hopes for the New ones. But seeing that those have already served so succesfully, and that the other are yet more just and exact, I have the more reason to believe, that the Invention of Longitudes will come to its perfection. In the mean time I shall tell you, that the States did receive my Proposition, when I desired of them a Patent for these new Watches, and the recompense set a-part for the invention in case of success; and that without any difficulty they have granted my request, commanding me to bring one of these Watches into their Assembly, to explicate unto them the Invention, and the application thereof to the Longitudes; which I have done to their contentment. I have this week published, that the said Watches shall be exposed to sale, together with an Information necessary to use them at Sea: and thus I have broken the Ice. The same Objection, that hath been made in your parts against the exactness of these Pendulums, hath also been made here; to wit, that though they should agree together, they might fail both of them, by reason that the Air at one time might be thicker, than at another. But I have answered, that this difference, if there be any, will not be at all perceived in the Penduls, seeing that the continuall Observations, made in Winter from day to day, until Summer, have shewed me that {15}they have alwaies agreed with the Sun. As to the Printing of the Figure of my New Watch, I shall defer that yet a while: but it shall in time appear with all the Demonstrations thereof, together with a Treatise of Pendulums, written by me some daies since, which is of a very subtile Speculation.

It is the deservedly famous Mounsieur de Fermat, who was, (saith the Author of the Letter) one of the most Excellent Men of this Age, a Genius so universal, and of so vast an extent, that if very knowing and learned Men had not given testimony of his extraordinary merit, what with truth can be said of him, would hardly be believed. He entertained a constant correspondence with many of the most Illustrious Mathematicians of Europe, and did excel in all the parts of Mathematical Science: a Testimony whereof he hath left behind him in the following Books.

A Method for the Quadrature of Parabola's of all degrees.

A Book De Maximis & Minimis, which serveth not only for the determination of Problems of Plains and Solids, but also for the invention of Tangents and Curve Lines, and of the Centres of Gravity in Solids; and likewise for Numerical Questions.

An Introduction to the Doctrine of Plains and Solids, which is an Analytical Treatise, concerning the solution of Plains and Solids, which has been seen (as the Advertiser affirms) before Monsieur Des Cartes had publish'd any thing upon this Subject.

A Treatise De Contactibus Sphæricis, where he hath demonstrated in Solids, what Mr. Viet, Master of Requests, had but demonstrated in Plains.

Another Treatise, wherein he establisheth and demonstrateth the two Books of Apollonius Pergæus, of Plains.

And a General Method for the dimension of Curve Lines, &c. Besides, having a perfect knowledge in Antiquity, he was consulted from all parts upon the difficulties that did emerg therein: he hath explained abundance of obscure places, that are {16}found in the Antients. There have been lately printed some of his Observations upon Athenæus; and he that hath interpreted Benedetto Castelli, of the Measure of running waters, hath thence inserted in his Work a very handsome one upon an Epistle of Synesius, which was so difficult, that the Jesuit Petavius, who hath commented upon this Author, acknowledges, that he could not understand it.

He hath also made many Observations upon Theon of Smyrne, and upon other Antient Authors: but most part of them are not found but scattered in his Epistles, because he did not write much upon these kinds of Subjects, but to satisfie the curiosity of his friends.

All these Mathematical Works, and all these curious searches in Antiquity, did not hinder this great Virtuoso from discharging the duties of his place with much assiduity, and with so much ability, that he hath had the reputation of one of the greatest Civilians of his Age.

But that, which is most of all surprizing to many, is, that with all that strength of understanding, which was requisite to make good these rare qualities, lately mentioned, he had so polite and delicate parts, that he composed Latin, French, and Spanish Verses with the same elegancy, as if he had lived in the time of Augustus, and passed the greatest part of his life at the Courts of France and Spain.

More particulars will perhaps be mention'd of the Works of this Rare person, when all things, that he hath publish'd, shall be recovered, and when liberty shall be obtained of his Worthy Son, to impart unto the World the rest of his Writings, hitherto unpublished.

Printed with Licence, By John Martyn, and James Allestry, Printers to the Royal-Society.

Munday, April 3. 1665.

Extract of a Letter written from Rome, concerning the late Comet, and a New one. Extract of another Letter from Paris, containing some Reflections on the precedent Roman Letter. An Observation concerning some particulars, further considerable in the Monster, that was Mention'd in the first Papers of these Philosophical Transactions. Extract of a Letter written from Venice, concerning the Mines of Mercury in Friuly. Some Observations, made in the ordering of Silk-worms. An Account of Mr. Hooks Micrographia, or the Physiological descriptions of Minute Bodies, made by Magnifying Glasses.

I Cannot enough wonder at the strange agreement of the thoughts of that acute French Gentleman, Monsieur Auzout, in the Hypothesis of the Comets motion, with mine; and particularly, at that of the Tables. I have with the same method, whereby I find the motion of this Comet, easily found the Principle of that Author's Ephemerides, which he then thought not fit to declare; and 'tis this, that this Comet moves about the Great Dog, in so great a Circle, that that portion, which is {18}described, is exceeding small in respect of the whole circumference thereof, and hardly distinguishable by us from a streight line.

Concerning the New Comet you mention, I saw it on the 11. of February, about the 24. deg. of Aries, with a Northern latitude of 24. deg. 40. min. The cloudy weather hath not yet permitted me to see it in Andromeda, as others affirm to have done.

As to the Hypothesis of Georg. Domenico Cassini, touching the motion of the Comet about the Great Dog in a Circle, whose Centre is in a streight line drawn from the Earth through the said Star, I believe it will shortly be publish'd in print, as a thought I lighted upon in discoursing with one of my Friends, who did maintain, that it turned about a Centre, because that its Perigee had been over against the Great Dog, as I had noted in my Ephemerides. This particular I did long since declare to many of my acquaintance, whereof some or other will certainly do me that right, as to let the world know it by the Press. I have added an Observation, which I find not, that Signior Cassini hath made, viz. that there was ground to think, that the Comet of 1652. was the same with the present, seeing that besides the parity of the swiftness of its motion, the Perigee thereof was also over against the Great Dog, if the Observations extant thereof, deceive not. But, to make it out, what ground I had for these thoughts, I said, that if they were true, the Comet must needs acomplish its revolution from 10. to 12. years, or thereabout. But, seeing it appears not by History, that a Comet hath been seen at those determinate distances of time, nor that over against the Perigee of all the other Comets, whereof particular observations are recorded, are alwaies found Stars of the first Magnitude, or such others, as are very notable, besides other reasons, that might be alledged, I shall not pursue this speculation; but rather {19}suggest what I have taken notice of in my reflexions upon former Comets, which is, that more of them enter inter our Systeme by the sign of Libra and about Spica virginis, than by all the other parts of the Heavens. For, both the present Comet, and many others registred in History, have entred that way, and consequently passed out of it by the sign Aries, by which also many have entred.

I did found my Hypothesis upon three Observations only, viz. those of the 22, 26, and 31. of December. Nor have I done, as some have fancied of me, who having been able to observe the Comet, the 27, 28, 29, 30, and 31. of December, and to see the diminution of its motion, have judged, that I had only determined that diminution for the time to come, conform to the augmentation thereof in time passed until the 29. of December. For January 1. (on which day I composed my Ephemerides) I knew not (nor any person here) that the motion of the Comet did diminish; but on the contrary, most men believed, it was not the same Comet. But Signior Cassini knows very well, that that was not necessary, seeing that two portions of a Tangent being given, and the Angles answering thereunto, 'tis easie to find the position and magnitude of its Circle. The reason, which I think the true one, of the diminution of its Motion in Longitude, and of its Retrogradation, by me conjectured in my Ephemerides, I began to be assured of, Febr. 10. For until the sixth, the Comet had alwaies advanced, as Signior Cassini also hath very well noted: but after that day, I found that it returned in augmenting alwaies its Latitude. And I have constantly observed it, until March 8. between many Stars, which must be the same with these mentioned by Cassini, whereof the number was so great, that I think, I saw of them March 6. with one Aperture of my Glass, more than 40. or 50. and especially, above the head of Aries; but I did not particularly note the scituation of more than 12. or 15; amongst which I have observed the position of the Comet since January 28. every day, when the weather did permit, viz. January 29. February 3, 6, 10, 17, 19, 24, 26, 27. and March 6, {20}7, 8. I left it on March 8. at the 18. of the Horn of Aries, almost in the same latitude: and I am apt to believe, it will be Eclipsed, which I wish I may be able to observe this evening, if it be not already passed.

If Signior Cassini hath observed it on those daies that I have, he will be glad to find the conformity of our Observations. I shall only add, that on February 3. we were surprized, to see the Comet again much brighter than ordinary, and with a considerable Train. Some did believe, that it approach'd again to us. But having beheld it with a Telescope, I soon said, that it was joyned with two small Stars, whereof one was pretty bright, which I had already seen, on February 28. and 29. And this conjunction gave the Comet that brightness, as it happens to most of the Stars of the fifth and sixth magnitude, where 2. or 3. or more are conjoyned, which perhaps would shew but faintly single, though by reason of their proximity to one another, they appear but one Star. Hence it was, that I assured my friends here, that the following daies we should no more see it so bright, because I knew, that there were none such small bright Stars in the way, which by my former observations I conjectured it was to move.

Upon the strictest inquiry, I find by one, that saw the Monstrous Calf and stone, within four hours after it was cut out of the Cows belly, that the Breast of the Calf was not stony (as I wrote) but that the skin of the Breast and between the Legs and of the Neck (which parts lay on the smaller end of the stone) was very much thicker, than on any other part, and that the Feet of the Calf were so parted as to be like the Claws of a Dog. The stone I have since seen; it is bigger at one end {21}than the other; of no plain Superficies, but full of little cavities. The stone, when broken, is full of small peble stones of an Ovall figure: its colour is gray like free-stone, but intermixt with veins of yellow and black. A part of it I have begg'd of Dr. Haughten for you, which I have sent to Oxford, whither a more exact account will be conveyed by the same person.

The mines of Mercury in Friuli, a Territory belonging to the Venetians, are about a days Journey and a half distant from Goritia Northwards, at a place call'd Idria, scituated in a Valley of the Julian Alps. They have been, as I am inform'd, these 160. years in the possession of the Emperor, and all the Inhabitants speak the Sclavonian Tongue. In going thither, we travell'd several hours in the best Wood I ever saw before or since, being very full of Firrs, Oakes, and Beeches, of an extraordinary thickness, straitness, and height. The Town is built, as usually Towns in the Alps are, all of wood, the Church only excepted, and another House wherein the Overseer liveth. When I was there, in August last, the Valley, and the Mountains too, out of which the Mercury was dug, were of as pleasant a verdure, as if it had been in the midst of Spring, which they there attribute to the moistness of the Mercury; how truly, I dispute not. That Mine, which we went into, the best and greatest of them all, was dedicated to Saint Barbara, as the other Mines are to other Saints, the depth of it was 125. paces, every pace of that Country being, as they inform'd us, more than 5 of our Feet. There are two ways down to it; the shortest perpendicular way is that, whereby they bring up the Mineral in great Buckets, and {22}by which oftentimes some of the workmen come up and down. The other, which is the usual way, is at the beginning not difficult, the descent not being much; the greatest trouble is, that in several places you cannot stand upright: but this holds not long, before you come to descend in earnest by perpendicular Ladders, where the weight of on's body is found very sensible. At the end of each Ladder, there are boards a-cross, where we may breath a little. The Ladders, as we said, are perpendicular, but being imagined produced, do not make one Ladder, but several parallel ones. Being at the bottom, we saw no more than we saw before, only the place, whence the Mineral came. All the way down, and the bottom, where there are several lanes cut out in the Mountain, is lined and propt with great pieces of Firr-trees, as thick as they can be set. They dig the Mineral with Pick-axes, following the veins: 'tis for the most part hard as a stone, but more weighty; of a Liver-colour, or that of Crocus Metallorum. I hope shortly to shew you some of it. There is also some soft Earth, in which you plainly see the Mercury in little particles. Besides this, there are oftentimes found in the Mines round stones like Flints, of several bignesses, very like those Globes of Hair, which I have often seen in England, taken out of Oxes bellies. There are also several Marcasites and stones, which seem to have specks of Gold in them, but upon tryal they say, they find none in them. These round stones are some of them very ponderous, and well impregnated with Mercury; others light, having little or none in them. The manner of getting the Mercury is this: They take of the Earth, brought up in Buckets, and put it into a Sive, whose bottom is made of wires at so great a distance, that you may put your finger betwixt them: 'tis carried to a stream of running water, and wash'd as long as any thing will pass through the Sive. That Earth which passeth not, is laid aside upon another heap: that which passeth, reserved in the hole, G. in Fig. 1. and taken up again by the second Man, and so on, to about ten or twelve sives proportionably less. It often happens in the first hole, where the second Man takes up his {23}Earth, that there is Mercury at the bottom; but towards the farther end, where the Intervals of the wires are less, 'tis found in very great proportion. The Earth laid aside is pounded, and the same operation repeated. The fine small Earth, that remains after this, and out of which they can wash no more Mercury, is put into Iron retorts and stopt, because it should not fall into the Receivers, to which they are luted. The fire forces the Mercury into the Receivers: the Officer unluted several of them to shew us; I observed in all of them, that he first poured out perfect Mercury, and after that came a black dust, which being wetted with water discover'd it self to be Mercury, as the other was. They take the Caput mortuum and pound it, and renew the operation as long as they can get any Mercury out of it.

This is the way of producing the Mercury, they call Ordinary, which exceeds that, which is got by washing, in a very great proportion, as you will perceive by the account annext. All the Mercury got without the use of Fire, whether by washing, or found in the Mines (for in the digging, some little particles get together, so that in some places you might take up two or three spoonfuls of pure Mercury) is call'd by them Virgin Mercury, and esteem'd above the rest. I inquir'd of the Officer what vertue that had more, than the other; he told me that making an Amalgama of Gold and Virgin Mercury, and putting it to the fire, that Mercury would carry away all the Gold with it, which common Mercury would not do.

The Engins, employed in these Mines, are admirable; the Wheels, the greatest that ever I saw in my life; one would think as great as the matter would bear: all moved by the dead force of the water, brought thither in no chargeable Aqueduct from a Mountain, 3 Miles distant: the water pumpt from the bottom of the Mine by 52 pumps, 26 on a side, is contrived to move other wheels, for several other purposes.

The Labourers work for a Julio a day, which is not above 6 or 7 pence, and indure not long; for, although none stay {24}underground above 6 hours; all of them in time (some later, some sooner) become paralitick, and dye hectick.

We saw there a man, who had not been in the Mines for above half a year before, so full of Mercury, that putting a piece of Brass in his mouth, or rubbing it in his fingers, it immediately became white like Silver: I mean he did the same effect, as if he had rubb'd Mercury upon it, and so paralitick, that he could not with both his hands carry a Glass, half full of Wine, to his mouth without spilling it, though he loved it too well to throw it away.

I have been since informed, that here in Venice, those that work on the back-side of Looking-glasses, are also very subject to the Palsey. I did not observe, that they had black Teeth; it may be therefore, that we accuse Mercury injustly for spoiling the Teeth, when given in Venereal diseases. I confess, I did not think of it upon the place; but, black Teeth being so very rare in this Country, I think I could not but have markt it, had all theirs been so.

They use exceeding great quantity of Wood, in making and repairing the Engins, and in the Furnaces (whereof there are 16. each of them carrying 24. Retorts;) but principally in the Mines, which need continual reparation, the Fir-trees lasting but a small time under ground. They convey their Wood thus: About four miles from the Mines, on the sides of two mountains, they cut down the Trees, and draw them into the interjacent Valley, higher in the same Valley, so that the Trees, according to the descent of the water lye betwixt it and Idria: with vast charges and quantities of Wood they made a Lock or Dam, that suffers not any water to pass; they expect afterwards till there be water enough to float these Trees to Idria; for, if there be not a spring, (as generally there is,) Rain, or the melting of the Snow, in a short time, afford so much water, as is ready to run over the Dam, and which (the Flood-gates being open'd) carries all the Trees impetuously to Idria, where the Bridge is built very strong, and at very oblique Angles to the stream, on purpose to stop them, and throw them on shore neer the Mines. {25}

Those Mines cost the Emperour heretofore 70000. or 80000. Florens yearly, and yielded less Mercury than at present, although it costs him but 28000. Florens now. You may see what his Imperial Majesty gets by the following account, of what Mercury the Mines of Idria have produced these last three years.

| 1661. | l. | 1662. | l. | 1663. | l. | ||

| Ordinary Mercury | 198481 | Ordinary Mercury | 225066 | Ordinary Mercury | 244119 | ||

| Virgin Mercury | 6194 | Virgin Mercury | 9612 | Virgin Mercury | 11862 | ||

| 204675 | 234678 | 255981 |

There are alwaies at work 280 persons, according to the relation I received from a very civil person, who informed me also of all the other particulars above mentioned, whose name is Achatio Kappenjagger; his Office, Contra-scrivano per sua Maestà Cesarea in Idria del Mercurio.

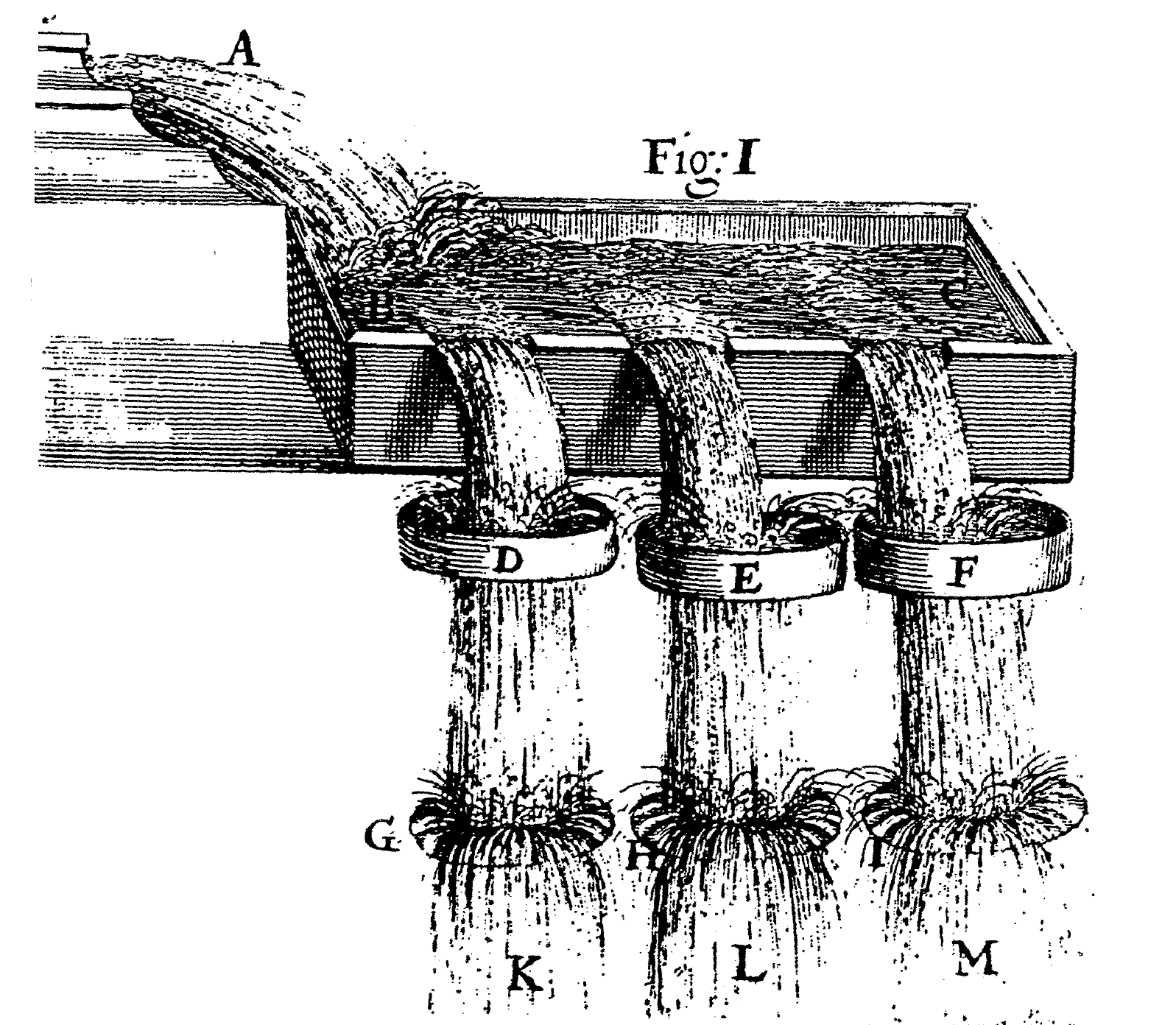

To give some light to this Narrative, take this Diagramme: F. is the water, C. B. a vessel, into which it runs. DG. EH. FI. are streams perpetually issuing from that vessel; D. E. F. three sives, the distance of whose wires at bottom lessen proportionably. G. the place, wherein the Earth, that pass'd through the sive D. is retained; from whence 'tis taken by the second man; and what passes through the sive E. is retained in H. and so of the rest. K. L. M. wast water, which is so much impregnated with Mercury, that it cureth Itches and sordid Ulcers. See Fig. 1.

I will trespass a little more upon you, in describing the contrivance of blowing the Fire in the Brassworks of Tivoli neer Rome (it being new to me) where the Water blows the Fire, not by moving the Bellows, (which is common) but by affording the Wind. See Fig. II. Where A. is the {26}River, B. the Fall of it, C. the Tub into which it falls, LG. a Pipe, G. the orifice of the Pipe, or Nose of the Bellows, GK. the Hearth, E. a hole in the Pipe, F. a stopper to that hole, D. a place under ground, by which the water runs away. Stopping the hole E, there is a perpetual strong wind, issuing forth at G: and G. being stopt, the wind comes out so vehemently at E, that it will, I believe, make a Ball play, like that at Frescati.

I herewith offer to your Society a small parcel of my Virginian Silk. What I have observed in the ordering of Silk-worms, contrary to the received opinion, is:

1. That I have kept leaves 24. hours after they are gathered, and flung water upon them to keep them from withering; yet when (without wiping the leaves) I fed the worms, I observed, they did as well as those fresh gathered.

2. I never observed, that the smell of Tobacco, or smels that are rank, did any waies annoy the worm.

3. Our country of Virginia is very much subject to Thunders: and it hath thundered exceedingly when I have had worms of all sorts, some newly hatched; some half way in their feeding; others spinning their Silk; yet I found none of them concern'd in the Thunder, but kept to their business, as if there had been no such thing.

4. I have made many bottoms of the Brooms (wherein hundreds of worms spun) of Holly; and the prickles were so far from hurting them, that even from those prickles they first began to make their bottoms.

I did hope with this to have given you assurance, that by retarding the hatching of seed, two crops of silk or more {27}might be made in a Summer: but my servants have been remiss in what was ordered, I must crave your patience till next year.

The Ingenious and knowing Author of this Treatise, Mr. Robert Hook, considering with himself, of what importance a faithful History of Nature is to the establishing of a solid Systeme of Natural Philosophy, and what advantage Experimental and Mechanical knowledge hath over the Philosophy of discourse and disputation, and making it, upon that account, his constant business to bring into that vast Treasury what portion he can, hath lately published a Specimen of his abilities in this kind of study, which certainly is very welcome to the Learned and Inquisitive world, both for the New discoveries in Nature, and the New Inventions of Art.

As to the former, the Attentive Reader of this Book will find, that there being hardly any thing so small, as by the help of Microscopes, to escape our enquiry, a new visible world is discovered by this means, and the Earth shews quite a new thing to us, so that in every little particle of its matter, we may now behold almost as great a variety of creatures, as we were able before to reckon up in the whole Universe it self. Here our Author maketh it not improbable, but that, by these helps the subtilty of the composition of Bodies, the structure of their parts, the various texture of their matter, the instruments and manner of their inward motions, and all the other appearances of things, may be more fully discovered; whence may emerge many admirable advantages towards the enlargement of the Active and Mechanick part of knowledge, because we may perhaps be enabled to discern the secret {28}workings of Nature, almost in the same manner, as we do those that are the productions of Art, and are managed by Wheels, and Engines, and Springs, that were devised by Humane wit. To this end, he hath made a very curious Survey of all kinds of bodies, beginning with the Point of a Needle, and proceeding to the Microscopical view of the Edges of Rasors, Fine Lawn, Tabby, Watered Silks, Glass-canes, Glass-drops, Fiery Sparks, Fantastical Colours, Metalline Colours, the Figures of Sand, Gravel in Urine, Diamonds in Flints, Frozen Figures, the Kettering Stone, Charcoal, Wood and other Bodies petrified, the Pores of Cork, and of other substances, Vegetables growing on blighted Leaves, Blew mould and Mushromes, Sponges, and other Fibrous Bodies, Sea-weed, the Surfaces of some Leaves, the stinging points of a Nettle, Cowage, the Beard of a wild Oate, the seed of the Corn-violet, as also of Tyme, Poppy and Purslane. He continues to describe Hair, the scales of a Soal, the sting of a Bee, Feathers in general, and in particular those of Peacocks; the feet of Flies; and other Insects; the Wings and Head of a Fly; the Teeth of a Snail; the Eggs of Silk-worms; the Blue Fly; a water Insect; the Tufted Gnat; a White Moth; the Shepheards-spider; the Hunting Spider, the Ant; the wandring Mite; the Crab-like insect, the Book-worm, the Flea, the Louse, Mites, Vine mites. He concludeth with taking occasion to discourse of two or three very considerable subjects, viz. The inflexion of the Rays of Lights in the Air; the Fixt stars; the Moon.

In representing these particulars to the Readers view, the Author hath not only given proof of his singular skil in delineating all sorts of Bodies (he having drawn all the Schemes of these 60 Microscopical objects with his own hand) and of his extraordinary care of having them so curiously engraven by the Masters of that Art; but he hath also suggested in the several reflexions, made upon these Objects, such conjectures, as are likely to excite and quicken the Philosophical heads to very noble contemplations. Here are found inquiries concerning the Propagation of Light through {29}differing mediums; concerning Gravity, concerning the Roundness of Fruits, stones, and divers artificial bodies; concerning Springiness and Tenacity; concerning the Original of Fountains; concerning the dissolution of Bodies into Liquors; concerning Filtration, and the ascent of Juices in Vegetables, and the use of their Pores. Here an attempt is made of solving the strange Phænomena of Glass-drops; experiments are alleged to prove the Expansion of Glass by heat, and the Contraction of heated-Glass upon cooling; Des Cartes his Hypothesis of Colours is examined: the cause of Colours, most likely to the Author, is explained: Reasons are produced, that Reflection is not necessary to produce colours, nor a double refraction: some considerable Hypotheses are offered, for the explication of Light by Motion; for the producing of all colours by Refraction; for reducing all sorts of colours to two only, Yellow and Blew; for making the Air, a dissolvent of all Combustible Bodies: and for the explicating of all the regular figures of Salt, where he alleges many notable instances of the Mathematicks of Nature, as having even in those things which we account vile, rude & course, shewed abundance of curiosity and excellent Geometry and Mechanism. And here he opens a large field for inquiries, and proposeth Models for prosecuting them, 1. By making a full collection of all the differing kinds of Geometricall figur'd bodies; 2. By getting with them an exact History of their places where they are generated or found: 3. By making store of Tryals in Dissolutions and Coagulations of several Crystallizing Salts: 4. By making trials on metalls, Minerals and Stones, by dissolving them in severall Menstruums, and Crystallizing them, to see what Figures will arise from those several compositums: 5. By compounding & coagulating several Salts together into the same mass, to observe the Figure of that product: 6. By inquiring the closenes or rarity of the texture of those bodys by examining their gravity, and their refraction, &c. 7. By examining what operations the fire hath upon several kinds of Salts, what changes it causes in their figures, Textures, or {30}Vertues. 8. By examining their manner of dissolution, or acting upon those bodies dissoluble in them and the Texture of those bodies before and after the process. 9. By considering, by what and how many means, such and such figures, actions and effects could be produced, and which of them might be the most likely, &c.

He goes on to offer his thoughts about the Pores of bodies, and a kind of Valves in wood; about spontaneous generation arising from the Putrefaction of bodies; about the nature of the Vegetation of mold, mushromes, moss, spunges; to the last of which he scarce finds any Body like it in texture. He adds, from the naturall contrivance, that is found in the leaf of a Nettle, how the stinging pain is created, and thence takes occasion to discourse of the poysoning of Darts. He subjoyns a curious description of the shape, Mechanism and use of the sting of a Bee; and shews the admirable Providence of Nature in the contrivance and fabrick of Feathers for Flying. He delivers those particulars about the Figure, parts and use of the head, feet, and wings of a Fly, that are not common. He observes the various wayes of the generations of Insects, and discourses handsomely of the means, by which they seem to act so prudently. He taketh notice of the Mechanical reason of the Spider's Fabrick, and maketh pretty Observations on the hunting Spider, and other Spiders and their Webs. And what he notes of a Flea, Louse, Mites, and Vinegar-worms, cannot but exceedingly please the curious Reader.

Having dispatched these Matters, the Author offers his Thoughts for the explicating of many Phænomena of the Air, from the Inflexion, or from a Multiplicate Refraction of the rays of Light within the Body of the Atmosphere, and not from a Refraction caused by any terminating superficies of the Air above, nor from any such exactly defin'd superficies within the body of the Atmosphere; which conclusion he grounds upon this, that a medium, whose parts are unequally dense, and mov'd by various motions and transpositions as to one another, will produce all these {31}visible effects upon the rays of Light, without any other coefficient cause: and then, that there is in the Air or Atmosphere, such a variety in the constituent parts of it, both as to their density and rarity, and as to their divers mutations and positions one to another.

He concludeth with two Celestial Observations; whereof the one imports, what multitudes of Stars are discoverable by the Telescope, and the variety of their magnitudes; intimating with all, that the longer the Glasses are, and the bigger apertures they will indure, the more fit they are for these discoveries: the other affords a description of a Vale in the Moon, compared with that of Hevelius and Ricciolo; where the Reader will find several curious and pleasant Annotations, about the Pits of the Moon, and the Hills and Coverings of the same; as also about the variations in the Moon, and its gravitating principle, together with the use, that may be made of this Instance of a gravity in the Moon.

As to the Inventions of Art, described in this Book, the curious Reader will there find these following:

1. A Baroscope, or an Instrument to shew all the Minute Variations in the Pressure of the Air; by which he affirms, that he finds, that before and during the time of rainy weather, the Pressure of the Air is less; and in dry weather, but especially when an Easterly Wind (which having past over vast Tracts of Land, is heavy with earthy particles) blows, it is much more, though these changes be varied according to very odd Laws.

2. A Hygroscope, or an Instrument, whereby the Watery steams, volatile in the Air, are discerned, which the Nose it self is not able to find. Which is by him fully described in the Observation touching the Beard of a wild Oate, by the means whereof this Instrument is contrived.

3. An Instrument for graduating Thermometers, to make them Standards of Heat and Cold.

4. A New Engine for Grinding Optick Glasses, by means of which he hopes, that any Spherical Glasses, of what length {32}soever, may be speedily made: which seems to him most easie, because, if it succeeds, with one and the same Tool may be ground an Object Glass of any length or breadth requisite, and that with very little or no trouble in fitting the Engine, and without much skill in the Grinder. He thinks it very exact, because to the very last stroke the Glass does regulate and rectifie the Tool to its exact Figure; and the longer or more the Tool and Glass are wrought together, the more exact will both of them be of the desired Figure. He affirms further, that the motions of the Glass and Tool do so cross each other, that there is not one point of eithers surface, but hath thousands of cross motions thwarting it, so that there can be no kind of Rings or Gutters made, either in the Tool or Glass.

5. A New Instrument, by which the Refraction of all kinds of Liquors may be exactly measured, thereby to give the Curious an opportunity of making Trials of that kind, to establish the Laws of Refraction, to wit, whether the Sines of the Angles of Refraction are respectively proportionable to the Sines of the Angles of Incidence: This Instrument being very proper to examine very accurately, and with little trouble, and in small quantities, the Refraction of any Liquor, not only for one inclination, but for all; whereby he is enabled to make accurate Tables. By the same also he affirms to have found it true, that what proportion the Sine of the Angle of the one inclination has to the Sine of its Angle of Refraction, correspondent to it, the same proportion have all the other Sines of Inclination to their respective Sines of Refractions.

Lastly, this Author despairs not that there may be found many Mechanical Inventions, to improve our Senses of Hearing, Smelling, Tasting, Touching, as well as we have improved that of Seeing by Optick Glasses.

London, Printed with Licence for John Martyn, and James Allestry, Printers to the Royal Society.

Munday, May 8. 1665.

Some Observations and Experiments upon May-dew. The Motion of the Second Comet predicted, by the same person, who predicted that of the former. A Relation of the Advice, given by a French Gentleman, touching the Conjunction of the Ocean and the Mediterranean. Of the way of killing Ratle-snakes, used in Virginia. A Relation of Persons kill'd with Subterraneous Damps. Of the Mineral of Liege, yielding both Brimstone, and Vitriol, and the way of extracting them out of it, used at Liege. An Account of Mr. Boyle's Experimental History of Cold.

That ingenious and inquisitive Gentleman, Master Thomas Henshaw, having had occasion to make use of a great quantity of May-dew, did, by several casual Essayes on that Subject, make the following Observations and Tryals, and present them to the Royal Society. {34}

That Dew newly gathered and filtred through a clean Linnen cloth, though it be not very clear, is of a yellowish Colour, somewhat approaching to that of Urine.

That having endevoured to putrefy it by putting several proportions into Glass bodies with blind heads, and setting them in several heats, as of dung, and gentle baths, he quite failed of his intention: for heat, though never so gentle, did rather clarify, and preserve it sweet, though continued for two moneths together, then cause any putrefaction or separation of parts.

That exposing of it to the Sun for a whole Summer in Glasses, that hold about two Gallons, with narrow mouths, that might be stopp'd with Cork, the only considerable alteration, he observed to be produced in it, was, that Store of green stuff (such as is seen in Summer in ditches and standing waters) floated on the top, and in some places, grew to the sides of the Glass.

That putting four or five Gallons of it into a half Tub, as they call it, of Wood, and straining a Canvas over it, to keep out Dust and Insects, and letting it stand in some shady room for three weeks or a month, it did of itself putrefy and stink exceedingly, and let fall to the bottom a black sediment like Mudd.

That, coming often to see, what Alterations appeared in the putrefaction, He observed, that at the beginning, within twenty four hours, a slimy film floated on the top of the water, which after a while falling to the bottom, there came another such film in its place.

That if Dew were put into a long narrow Vessel of Glass, such as formerly were used for Receivers in distilling of Aqua Fortis, the slime would rise to that height, that He could take it off with a Spoon; and when he had put a pretty quantity of it into a drinking Glass, and that it had stood all night, and the water dreined from it, if He had turned it out of his hand, it would stand upright in figure of the Glass, in substance like boyled white Starch, though something more transparent, if his memory (saith he) fail him not.

That having once gotten a pretty quantity of this gelly, and put it into a Glass body and Blind-head, He set it into a gentle {35}Bath with an intention to have putrefied it, but after a few days He found, the head had not been well luted on, and that some moisture exhaling, the gelly was grown almost dry, and a large Mushrom grown out of it within the Glass. It was of a loose watrish contexture, such an one, as he had seen growing out of rotten wood.

That having several Tubs with good quantity of Dew in them, set to putrefy in the manner abovesaid, and comming to pour out of one of them to make use of it, He found in the water a great bunch, bigger than his fist, of those Insects commonly called Hog-lice or Millepedes, tangled together by their long tailes, one of which came out of every one of their bodies, about the bigness of a Horsehair: The Insects did all live and move after they were taken out.

That emptying another Tub, whereon the Sun, it seems, had used sometimes to shine, and finding, upon the straining it through a clean linnen cloth, two or three spoonfulls of green stuff, though not so thick nor so green as that above mentioned, found in the Glasses purposely exposed to the Sun, He put this green stuff in a Glass, and tyed a paper over it, and coming some dayes after to view it, He found the Glass almost filled with an innumerable Company of small Flyes, almost all wings, such as are usually seen in great Swarms in the Aire in Summer Evenings.

That setting about a Gallon of this Dew (which, he saith, if he misremember not, had been first putrefied and strained) in an open Jarre-Glass with a wide mouth, and leaving it for many weeks standing in a South-window, on which the Sun lay very much, but the Casements were kept close shut; after some time coming to take account of his Dew, He found it very full of little Insects with great Heads and small tapering Bodies, somewhat resembling Tadpoles, but very much less. These, on his approach to the Glass, would sink down to the bottom, as it were to hide themselves, and upon his retreat wrigle themselves up to the top of the water again. Leaving it thus for some time longer, He afterwards found the room very full of Gnats, though the Door and Windows were kept shut. He adds, that He did not at first suspect, that those Gnats had any {36}relation to the Dew, but after finding the Gnats to be multiplied and the little watry Animals to be much lessened in quantity, and finding great numbers of their empty skins floating on the face of his Dew, He thought, he had just reason to perswade himself, the Gnats were by a second Birth produced of those little Animals.

That vapouring away great quantities of his putrefied Dew in Glass Basons, and other Earthen glased Vessels, He did at last obtain, as he remembers, above two pound of Grayish Earth, which when he had washed with more of the same Dew out of all his Basons into one, and vapoured to siccity, lay in leaves one above another, not unlike to some kind of brown Paper, but very friable.

That taking this Earth out, and after he had well ground it on a Marble, and given it a smart Fire, in a coated Retort of Glass, it soon melted and became a Cake in the bottom, when it was cold, and looked as if it had been Salt and Brimstone in a certain proportion melted together; but, as he remembers, was not at all inflamable. This ground again on a Marble, he saith, did turn Spring water of a reddish purple Colour.

That by often calcining and filtring this Earth, He did at last extract about two ounces of a fine small white Salt, which, looked on through a good Microscope, seemed to have Sides and Angles in the same number and figure, as Rochpeeter.

Monsieur Auzout, the same Person, that not long since communicated to the World his Ephemerides touching the course of the former Comet, and recommended several Copies of them to the Royal Society, to compare their Observations with his Account, and thereby, either to verifie his Predictions, or to shew, wherein they differ, hath lately sent another Ephemerides concerning the Motion of the Second Comet, to the same end, that invited him to send the other. {37}

In that Tract he observes, first in General, that this second Comet is contrary to the precedent, almost in all particulars: seeing that the former moved very swift, this, pretty slow; that against the Order of the signs from East to West, this, following them, from West to East: that, from South to North, this, from North to South, as far as it hath been hitherto, that we hear off, observed: that, on the side opposite to the Sun, this, on the same side: that, having been in its Perigee at the time of its Opposition, this, having been there, out of the time of its Conjunction: where he taketh also notice, that this Comet differs in brightness from the other, as well in its Body, which is far more vivid and distinct, as in its Train, whose splendor is much greater, since it may be seen even with great Telescopes, which were useless in the former, by reason of its dimness. After this he descends to particulars, and informs us, that he began to observe this Comet April the second, and continued for some days following, and that as soon as he had made three or four Observations, he resolved to try again an Ephemerides; but that, having no instruments exact enough, and the Comet being in a place, destitute of Stars, and subject to Refractions, he feared to venture too much upon Observations so neer one another, since in such matters a perfect exactness is necessary, and wished to see some precedent Observations to direct him: which having obtained, he thereby verified what he had begun, and resolved to carry on his intended Ephemerides, especially being urged by his Friends, and engaged by his former undertaking, that so it might not be thought a meer hazard, that made him hit in the former; as also, that he might try, whether his Method would succeed as well in slower, as in swifter Comets, and in those, that are neer the Sun; as in such as are opposite thereunto, to the end, that men might be advertised of the determination of its use, if it could not serve but in certain particular Cases.

He relateth therefore, that he had finished this New Ephemerides April the sixth, and put it presently to the Press; in doing of which, he hopes, he hath not disobliged the Publick: seeing that, though we should loose the sight of this Star within a few days, by reason of its approach to the Sun, yet having found, {38}that it is always to rise before the Sun, and that we may again see it better, when it shall rise betimes, towards the end of May, and in the beginning of June, if the cleerness of the Day-break hinder us not; he thought it worth the while to try, whether the truth of this Ephemerides could be proved.

He affirms then, that the Line described by this Star resembles hitherto a Great Circle, as it is found in all other Comets in the midst of their Course. He finds the said Circle inclined to the Ecliptick about 26. d. 30′. and the Nodes, where it cuts it, towards the beginning of Gemini and Sagittary; that it declines from the Equator about 26. d and cuts it towards the 11. d. and consequently, that its greatest Latitude hath been towards Pisces, where it must have been March 24. and its greatest Declination, towards the 25 d. of the Equator, where it was to have been April 11.

He puts it in its Perigee March 27. about three of the Clock in the Afternoon, when it was about the 15 degrees of Pisces, a little more Westerly then Marshab, or the Wing of Pegasus, and that it was to be in Conjunction with the Sun, April 9. Where yet he noteth, that according to another Calculation, the Perigee was March 27. more towards Night, so that the Comet advances a little more towards the East, and retards towards the West; which not being very sensible in the first days, differs more about the end, and in the beginning; which he leaves to Observation.

He calculateth, that the greatest Motion it could make in one day, hath been 4. d. and 8′. or 9′; in one hour, about 10′. and 25″. so that its Diurnal Motion is to its last distance from the Earth a little more than as 1. to 14. and its Hourly Motion, as 1. to 330.

He wonders, that it hath not been seen sooner; the first Observations that he hath seen, but made by others, being of March 17. Whereas he finds, that it might have been seen since January, at least in the Months of February and March, when it rose at 2 of the Clock and before: because it is very likely, that, considering its bigness and brightness, when it was towards its Perigee, it was visible, since that towards the end of February it was not three times as much remote from the Earth, than when it was in its Perigee, and that towards the end of January it was not five times as much. {39}

In the interim, saith he, the other Comet could be seen with the naked eye until January 31. when it was more than ten times further remote, than in its Perigee, although it was not by far so bright, nor its streamer shining as this hath appeared.

He wishes, that all the changes that shall fall out in this Comet, might be exactly observ'd; because of its not being swift, and the Motion of the Earth very sensible, unless the Comet be extreamly remote, we should find much more light from this, than the former Star, about the Grand Question, whether the Earth moves or not; this Author having all along entertained himself with the hopes, that the Motion of Comets would evince, whether the Earth did move or not; and this very Comet seemed to him to have by design appeared for that end, if it had had more Latitude, and that consequently we might have seen it before Day break. He wishes also, that, if possible, it may be accurately observed, whether it will not a little decline from its great Circle towards the South; Judging, that some important truth may be thence deduced, as well as if its motion retarded more, than the place of its Perigee (which will be more exactly known when all the passed Observations shall have been obtained) and its greatest Motion do require.

He fears only, that it being then to rise at Break of Day, exact Observations cannot be made of it: but he would, at least have it sought with Telescopes, his Ephemerides directing whereabout it is to be.

April 10. it was to be over against the point of the Triangle, and from thence more Southerly by more than two degrees; and April 11. over against the bright Star of Aries, April 17. over against the Stars of the Fly, a little more Southerly, and May 4 it is to be over against the Pleiades, and about the fourth or fifth of the same Month, it is to be once more in Conjunction with the Sun; after which time, the Sun will move from it Eastward, and leave it towards the West; which will enable us to see it again at a better hour, provided the cleerness of the Day-break be no impediment to us. He addeth, that this Star must have been the third time in Conjunction with the Sun, about the time when it first began to appear: and foresees, that from all these particulars many considerable consequences may be deduced. {40}