[17]

[Contents]

Chapter I.

A Family Sketch—My Youthful Days—I Study for the Medical

Profession—Obtain a Naval Surgeon’s Diploma—Early

Voyages—Sail for Manilla in the

Cultivateur—Adventurous Habits—Cholera and Massacre at

Manilla and Cavite—Captain Drouant’s Rescue—Personal

Dangers and Timely Escapes—How Business may make Friends of

one’s Enemies—An Unprincipled Captain—Tranquility

restored at Manila—Pleasures of the Chase—The

Cultivateur sails without me—First Embarrassments.

My father was born at Nantes, and held the rank of

captain in the regiment of Auvergne. The Revolution caused him the loss

of his commission and his fortune, and left him, as sole remaining

resource, a little property called La Planche, [18]belonging to

my mother, and

situated about two leagues from Nantes, in the parish of

Vertoux.

At the commencement of the Empire he wished to enter the service

again; but at that period his name was an obstacle, and he failed in

every attempt to obtain even the rank of lieutenant. With scarcely the

means of existence, he retired to La Planche with his

family. There he lived for some years, suffering the grief and the many

annoyances caused by the sudden change from opulence to want, and by

the impossibility of supplying all the requirements of his numerous

family. A short illness terminated his distressed existence, and his

mortal remains were deposited in the cemetery of Vertoux. My mother, a

pattern of courage and devotedness, remained a widow, with six

children, two girls and four boys; she continued to reside in the

country, imparting to us the first elements of instruction.

The free life of the fields, and the athletic exercises to which my

elder brothers and I accustomed ourselves, tended to make me hardy, and

rendered me capable of enduring every kind of fatigue and privation.

This country life, with its liberty, and I may well say its happiness,

passed too quickly away; and the period soon came when my education

compelled me to pursue my daily studies in a school at Nantes. I had

four leagues to walk, but I trudged the distance light-heartedly, and at night, when

I returned home, I ever found awaiting me the kind solicitude of our

dear mother, and the attentive cares of two sisters whom I tenderly

loved.

It was decided that I should enter the medical profession. I studied

several years at the Hôtel-Dieu of Nantes, and I passed my

examination for naval surgeon at an age when many a young man is shut

up within the four walls of a college, still prosecuting his studies.

[19]

It would be difficult to form any idea of my joy when I saw myself

in possession of my surgeon’s diploma. Thenceforward I regarded

myself as an important being, about to take my place among reasonable

and industrious men; and what perhaps rendered me still more joyous

was, that I could earn my own livelihood, and contribute to the comfort

of my mother and my sisters.

I was also seized with a strong desire to travel abroad, and make

myself acquainted with foreign countries.

Twenty-four hours after my nomination as surgeon I went and offered

my services to a ship-owner who was about freighting a vessel to the

East Indies. We were not long in arranging terms, and, at forty francs

per month, I engaged myself for the voyage.

Within twelve months afterwards I returned home. Who can depict the

sweet emotions which, as a young man, I felt on again beholding my

native land? I stayed a month on shore, surrounded by the affectionate

attentions of my mother and sisters. Despite their assiduities I was

seized with ennui. I made a second and a third voyage; then,

after having rounded the Cape of Good Hope half-a-dozen times, I

undertook one which separated me from my country during twenty

years.

On the 9th October, 1819, I embarked on board the

Cultivateur, an old half-rotten three-masted vessel, commanded by

an equally old captain, who, long ashore, had given up navigating for

many years. An old captain with an old ship! Such were the conditions

in which I undertook this voyage. I ought, however, to add, that I

obtained an increase of pay.

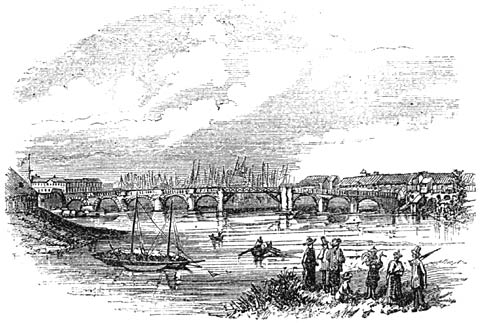

We touched at Bourbon; we ran along the entire coast of Sumatra, a

part of Java, the isles of Sonde, and that of Banca; and at last,

towards the end of May, eight months after our

[20]departure from Nantes, we

arrived in the magnificent bay of Manilla.

The Cultivateur anchored near the little town of Cavite. I

obtained leave to reside on shore, and took lodgings in Cavite, which

is situate about five or six leagues from Manilla.

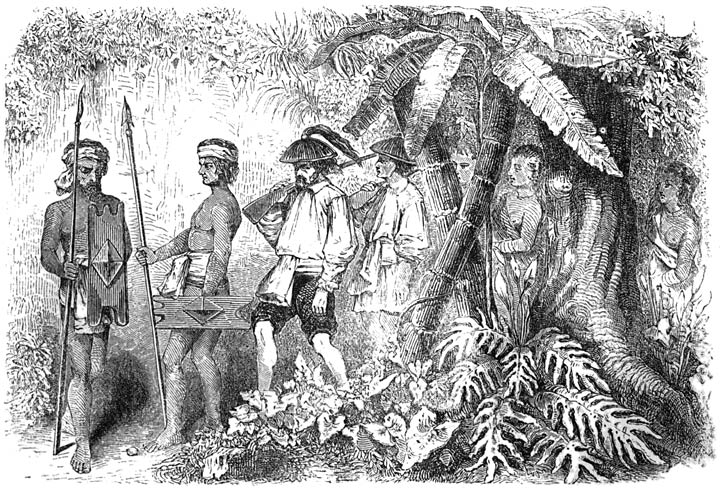

To make up for my long inactivity on board ship, I eagerly engaged

in my favourite exercises, exploring the country in all directions with

my gun upon my shoulder. Taking for a guide the first Indian whom I

met, I made long excursions, less occupied in shooting than in admiring

the magnificent scenery. I knew a little Spanish, and soon acquired a

few Tagaloc words. Whether it was for excitement’s sake,

or from a vague desire of braving danger, I know not, but I was

particularly fond of wandering in remote places, said to be frequented

by robbers. With these I occasionally fell in, but the sight of my gun

kept them in check. I may say, with truth, that at that period of my

life I had so little sense of danger, that I was always ready to put

myself forward when there was an enemy to fight or a peril to be

encountered.

I had only resided a short time at Cavite when that terrible

scourge, the cholera, broke out at Manilla, in September, 1820, and

quickly ravaged the whole island. Within a few days of its first

appearance the epidemic spread rapidly; the Indians succumbed by

thousands; at all hours of the day and of the night the streets were

crowded with the dead-carts. Next to the fright occasioned by the

epidemic, quickly succeeded rage and despair. The Indians said, one to

another, that the strangers poisoned the rivers and the fountains, in

order to destroy the native population and possess themselves of the

Philippines.

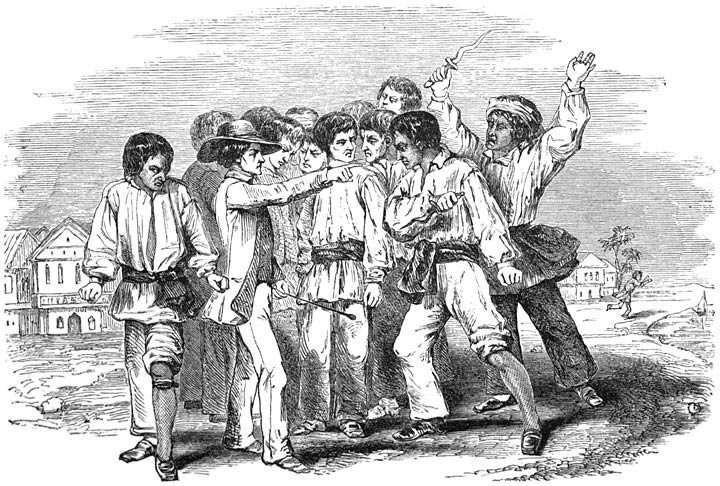

On the 9th October, 1820, the anniversary of my departure [21]from France, a

dreadful massacre commenced at Manilla and at Cavite. Poor Dibard, the

captain of the Cultivateur, was one of the first victims. Almost

all the French who resided at Manilla were slain, and their houses

pillaged and destroyed. The carnage only ceased when there were no

longer any victims. One eye-witness escaped this butchery, namely, M.

Gautrin, a captain of the merchant service, who, at the moment I am

writing, happens to be residing in Paris. He saved his life by his

courage and his muscular strength. After seeing one of his friends

mercilessly cut to pieces, he precipitated himself into the midst of

the assassins, with no other means of defence than his fists. He

succeeded in fighting his way through the crowd, but shortly afterwards

fell exhausted, having received three sabre-cuts upon his head, and a

lance-thrust in his body. Fortunately, some soldiers happened to pass

by at the time, who picked him up and carried him to a guard-house,

where his wounds were quickly attended to.

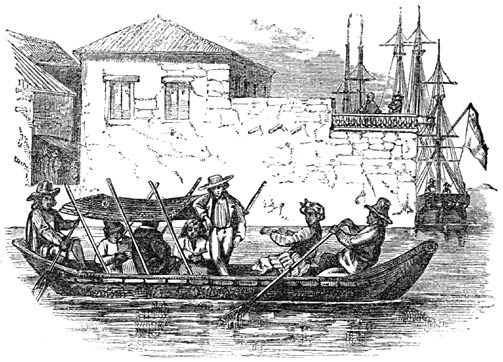

I myself was dodged about Cavite, but I contrived to escape, and to

reach a pirogue, into which I jumped, and took refuge on board the

Cultivateur. I had scarcely been there ten minutes when I was

requested to attend the mate of an American vessel, who had just been

stabbed on board his ship by some custom-house guards. When I had

finished dressing the wound, several officers, belonging to the

different French vessels lying in the bay, acquainted me that one of

their brethren, Captain Drouant, of Marseilles, was still ashore, and

that there might yet be time to save him. There was not a moment to

lose; night was approaching, and it was necessary to profit by the last

half-hour of daylight. I set off in a cutter, and, on nearing the land,

I directed my men to keep the boat afloat, in order to prevent a

surprise on the part of the [22]Indians, but yet to hug the shore sufficiently

close to land promptly, in case the captain or myself signaled them. I

then quickly set about searching for Drouant.

On reaching a small square, called Puerta Baga, I observed a

group of three or four hundred Indians. I had a presentiment that it

was in that direction I ought to prosecute my search. I approached, and

beheld the unfortunate Drouant, pale as a corpse. A furious Indian was

on the point of plunging his kreese into his breast. I threw myself

between the captain and the poignard, violently pushing on either side

the murderer and his victim, so as to separate them. “Run!”

I cried in French; “a boat awaits you.” So great was the

stupefaction of the Indians that the captain escaped unpursued.

It was now time for me to get out of the dangerous situation in

which I was involved. Four hundred Indians surrounded me; the only way

of dealing with them was by audacity. I said in Tagaloc to the Indian

who had attempted to stab the captain: “You are a

scoundrel.” The Indian sprang towards me; he raised his arm: I

struck him on the head with a cane which I held in my hand; he waited

in astonishment for a moment, and then returned towards his companions

to excite them. Daggers were drawn on every side; the crowd formed a

circle around me, which gradually concentrated. Mysterious influence of

the white man over his coloured brother! Of all these four hundred

Indians, not one dared attack me the first; they all wished to strike

together. Suddenly a native soldier, armed with a musket, broke through

the crowd; he struck down my adversary, took away his dagger, and

holding his musket by the bayonet end, he swung it round and round his

head, thus enlarging the circle at first, and then dispersing a portion

of my enemies. “Fly, sir!” said my liberator; “now

[23]that I

am here, no one will touch a hair of your head.” In fact the

crowd divided, and left me a free passage. I was saved, without knowing

by whom, or for what reason, until the native soldier called after me:

“You attended my wife who was sick, and you never asked payment

of me. I now settle my debt.”

As Captain Drouant had doubtless gone off in the cutter, it was

impossible for me to return on board the Cultivateur. I directed

my steps towards my lodgings, creeping along the walls, and taking

advantage of the obscurity, when, on turning the corner of a street, I

fell into the midst of a band of dockyard workmen, armed with axes, and

about to proceed to the attack of the French vessels then in harbour.

Here again I owed my preservation to an acquaintance, to whom I had

rendered some service in the practice of my profession. A

Métis, or half-breed, who had quickly pushed me into the

entry of a house, and covered me with his body, said: “Stir not,

Doctor Pablo!”1 When the crowd had dispersed, my protector advised me

to conceal myself, and, above all, not to go on board; he then started

off to rejoin his comrades. But all was not yet over. I had scarcely

entered my lodgings when I heard a knocking at the door.

“Doctor Pablo,” said a voice, which was not unknown to

me.

I opened, and I saw, as pale as death, a Chinese, who kept a

tea-store on the ground-floor of the same house.

“What’s the matter, Yang-Po?”

“Save yourself, Doctor!”

“And wherefore?”

“Because the Indians will attack you this very night; they

have decided upon it!” [24]

“Is it not your apprehension on account of your shop,

Yang-Po?”

“Oh, no! do not treat this matter lightly. If you remain here

you are doomed; you have struck an Indian, and his friends cry aloud

for vengeance.”

The fears of Yang-Po were, I saw, too well-founded; but what could I

do? To shut my door and await was the safest plan.

“Thank you,” said I to the Chinese; “thank you for

your kind advice, but I shall remain here.”

“Remain here, Signor Doctor! Can you think of so

doing?”

“Now, Yang-Po, a service: go and say to these Indians that I

have, at their service, a brace of pistols and a double-barreled gun,

which I know how to use.”

The Chinese departed sighing deeply, from a notion that the attack

upon the Doctor might end in the pillage of his wares. I barricaded my

door with the furniture of the room; I then loaded my weapons, and put

out the lights.

It was now eight o’clock in the evening. The least noise made

me think that the moment had arrived when Providence alone could save

me. I was so fatigued that, despite the anxiety natural to my position,

I had frequently to struggle against an inclination to sleep. Towards

eleven o’clock some one knocked at my door. I seized my pistols,

and listened attentively. At a second summons, I approached the door on

tip-toe.

“Who’s there?” I demanded.

A voice replied to me: “We come to save you. Lose not an

instant. Get out on the roof, and climb over to the other side, where

we will await you, in the street of the Campanario.” Then

two or three persons descended the stairs rapidly. I had [25]recognised the voice

of a Métis, whose good feelings on my behalf were beyond doubt.

There was now no time to be lost, for at the moment I got out of a

window which served to light the staircase, and led on to the roof, the

Indians had arrived in front of the house, and in a few minutes were

breaking and plundering the little I possessed. I quickly traversed the

roof, and descended into the street of the Campanario, where my

new preservers awaited me. They conducted me to their dwelling: there,

a profound sleep caused me quickly to forget the dangers I had passed

through.

The following day my friends prepared a small pirogue to convey me

on board the Cultivateur, where, apparently, I should be in

greater security than on shore. I was about to embark when one of my

preservers handed me a letter which he had just received. It was

addressed to me, and bore the signatures of all the captains whose

vessels were lying in the harbour, and it informed me that, seeing

themselves exposed every moment to an attack by the Indians, they were

decided to raise anchor and seek a wider offing; but that two among

them, Drouant and Perroux, had been compelled to leave on shore a

portion of their possessions, and all their sails and fresh water. They

entreated me to lend them my assistance, and had arranged that a skiff

should be placed at my command. I communicated this letter to my

friends, and declared that I would not return on board without

endeavouring to satisfy the wishes of my countrymen; it was a question

of saving the lives of the crews of two vessels, and hesitation was

impossible. They used every effort to shake my resolution. “If

you show yourself in any part of the town,” said they, “you

are lost; even supposing the Indians were not to kill you, they would

not fail to steal every object intrusted to them.” I remained

[26]immovable, and pointed out to them that it was a

question of honour and humanity. “Go alone, then!”

exclaimed that Métis who had contributed the most to my escape;

“not one of us will follow you; we would not have it said that we

assisted in your destruction.”

I thanked my friends, and, after shaking hands with them, passed on

through the streets of Cavite, my pistols in my belt, and my thoughts

occupied as to the best means of extricating myself from my perilous

position. However, I already knew sufficient of the Indian character to

be aware that boldness would conciliate, rather than enrage them. I

went towards the same landing-place where once before I had escaped a

great danger. The shore was covered with Indians, watching the ships at

anchor. As I advanced, all turned their looks upon me; but, as I had

foreseen, the countenances of these men, whose feelings had become

calmed during the night that had intervened, expressed more

astonishment than anger.

“Will you earn money?” I cried. “To those who work

with me I will give a dollar at the end of the day.”

A moment’s silence followed this proposition; then one of them

said: “You do not fear us!”

“Judge if I am alarmed,” I replied, showing him my

pistols; “with these I could take two lives for one—the

advantage is on my side.”

My words had a magical effect, and my questioner replied:

“Put up your weapons; you have a brave heart, and deserve to

be safe amongst us. Speak! what do you require? We will follow

you.” I saw these men, who but yesterday would have killed me,

now willing to bear me in triumph. I then explained to them that I

wished to take some articles which had been left on shore to my

comrades, and to those [27]who assisted me in this object I would give the

promised recompense. I told the one who had addressed me to select two

hundred men, nearly double the number necessary; during the time he

made up his party I signaled a skiff to approach the shore, and wrote a

few words in pencil, in order that the boats from the French vessels

might be in readiness to receive the stores as soon as they were

brought to the water’s edge. I then marched at the head of my

Indian troop of two hundred men, and by their aid the sails,

provisions, biscuits, and wines, were soon on board the boats. That

which most embarrassed me was the transport of a large sum of money

belonging to Captain Drouant. If the Indians had conceived the least

suspicion of this wealth, they would no longer have kept faith with me.

I therefore determined to fill my own pockets with the gold, and to

traverse the distance between the house and the boats as many times as

was necessary to embark it. There, concealed by the sailors, I

deposited piece after piece as quietly as possible. In carrying the

sails belonging to Captain Perroux, a circumstance occurred which might

have been fatal to me. A few days before the massacre, a French sailor,

who was working as sail maker, had died of the cholera. His alarmed

companions wrapped the body in a sail, and then hurried on board their

ships. My Indians now discovered the corpse, which was already in a

state of putrefaction. Terrified at first, their terror soon changed to

fury; for an instant I feared they would fall upon me.

“Your friends,” they cried, “have left this body

here purposely, that it might poison the air and increase the violence

of the epidemic.”

“What! you are afraid of a poor devil dead of the

cholera!” I said to them, affecting to be as tranquil as

possible; “never [28]fear, I will soon rid you of him;” and,

despite the aversion I felt, I covered the body with a small sail, and

carried it down to the beach. There I made a rude grave, in which I

placed it; and two pieces of wood, in the shape of a cross, for some

days indicated the spot where lay the unhappy one, who probably had no

prayers save mine.

It had been a busy and agitating day, but towards the evening I

finished my task, and everything was embarked. I paid the Indians, and

in addition gave them a barrel of spirits.

I did not fear their intoxication, being the only Frenchman there,

and when it was dark I got into a boat, and towed a dozen casks of

fresh water at her stern. Since the previous day I had not eaten; I

felt worn out by fatigue and want of food, and threw myself down to

rest upon the seats of the boat. Ere long a mortal chilliness passed

through my veins, and I became insensible. In this state I remained

more than an hour. At last I reached the Cultivateur, and was

taken on board, and, by the aid of friction, brandy, and other

remedies, was restored to consciousness. Food and rest quickly

renovated my powers of mind and body, and the next day I was calm as

usual among my comrades. I thought of my personal position; the events

of the two last days made the review extremely simple. I had lost

everything. A small venture of merchandise, in which I invested the

savings of my previous voyages, had been intrusted to the captain for

sale at Manilla. These goods were destroyed, together with all I

possessed, at Cavite. There remained to me but the clothes I had

on—a few old things I could wear only on board ship—and

thirty-two dollars. I was but a little richer than Bias. Unfortunately

I recollected that an English captain—whose ship I had seen in

the roads—owed me something like a hundred dollars. In [29]my present

circumstances this sum appeared a fortune. The captain in question,

from fear of the Indians, had dropped down as far as

Maribélé, at the entrance of the bay, ten leagues from

Cavite. To obtain payment it was necessary I should go on board his

vessel. I borrowed a boat, and the services of four sailors, from

Captain Perroux, and departed. I reached the ship at dusk. The

unprincipled captain, who knew himself to be in deep water and safe

from pursuit, replied that he did not understand what I was saying to

him. I insisted upon being paid, and he laughed in my face. I was

treated as a cheat. He threatened to have me thrown into the sea; in

short, after a useless discussion, and at the moment when the captain

called five or six of his sailors to execute his threat, I retreated to

my boat. The night was dark, and as a violent and contrary wind had

sprung up, it was impossible to regain the ship, so we passed the night

floating upon the waves, ignorant as to the direction we were going. In

the morning I discovered our efforts had been thrown away; Cavite was

far behind us. The wind becoming calmer, we again commenced rowing, and

two hours after noon reached the ship.

Meanwhile tranquillity was restored at Cavite and Manilla. The

Spanish authorities took measures to prevent a recurrence of the

frightful scenes I have detailed, and the priests of Cavite launched a

public excommunication against all those who had attempted my life. I

attributed this solicitude to the character of my profession, being in

fact the only Æsculapius in the place. When I left the town the

sick were obliged to content themselves with the hazardous presumptions

of Indian sorcerers. One morning, I had almost decided upon returning

to land, when an Indian, in a smartly decorated pirogue, [30]came alongside the

Cultivateur. I had met this man in some of my shooting

excursions, and he now proposed that I should go with him to his house,

situated ten leagues from Cavite, near the mountains of Marigondon. The

prospect of some good sport soon decided me to accept this offer.

Taking with me my thirty-two dollars and double-barreled gun—in

fact, my whole fortune—I intrusted myself to this friend, whose

acquaintance I had just made. His little habitation was delightfully

situated, in the cool shadow of the palm and yang-yang—immense

trees, whose flowers spread around a delicious perfume. Two charming

Indian girls were the Eves of this paradise. My good friend kept the

promises he had made me on leaving the vessel; I was treated both by

himself and family with every attention and kindness.

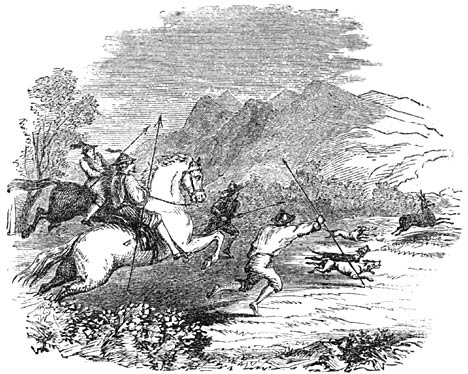

Hunting was my principal amusement, and, above all, the chase of the

stag, which involves violent exercise. I was still ignorant of

wild-buffalo hunting, of which, however, I shall have to speak later in

my narrative; and I often requested my host to give me a taste of this

sport, but he always refused, saying it was too dangerous. For three

weeks I lived with the Indian family without receiving any news from

Manilla, when one morning, a letter came from the first mate—who,

on the death of the unfortunate Dibard, had taken the command of the

Cultivateur—telling me he was about to sail, and that I

must go on board at once if I wished to leave a country which had been

so fatal to all of us. This summons was already several days old, and

despite the reluctance I felt to quit the Indian’s pleasant

retreat, it was necessary that I should prepare to start. I presented

my gun to my kind host, but had nothing to give his daughters, for to

have offered them money would have been an insult. The next day I

arrived at Manilla, still [31]thinking of the cool shade of the palm and the

perfumed flowers of the yang-yang. My first impulse was to go to the

quay; but, alas! the Cultivateur had sailed, and I had the

misery of beholding her already far away in the horizon, moving

sluggishly before a gentle breeze towards the mouth of the bay. I asked

some Indian boatmen to take me to the ship; they replied that it might

be practicable if the wind did not freshen, but demanded twelve dollars

to make the attempt. I had but twenty-five remaining. I considered for

a few moments, should I not reach the vessel, what would become of me

in a remote colony, where I knew no one, and my stock of money reduced

to thirteen dollars, and with no articles of dress than those I had

on—a white jacket, trousers, and striped shirt. A sudden thought

crossed my mind: what if I were to remain at Manilla, and practise my

profession? Young and inexperienced, I ventured to think myself the

cleverest physician in the Philippine Islands. Who has not felt this

self-confidence so natural to youth? I turned my back upon the ship,

and walked briskly into Manilla.

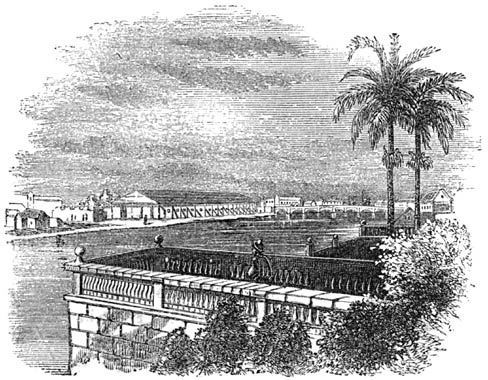

Before continuing this recital, let me describe the capital of the

Philippines. [32]

[Contents]

Chapter II.

Description of Manilla—The two Towns—Gaiety of

Binondoc—Dances—Gaming—Beauty of the

Women—Their Fascinating Costume—Male Costume—The

Military Town—Personal Adventures—My First

Patient—His Generous Confidence—Commencement of my

Practice—The Artificial Eye—Brilliant Success—The

Charming Widow—Auspicious Introduction—My

Marriage—Treachery and Fate of Iturbide—Our Loss of

Fortune—Return to France postponed.

Manilla and its suburbs contain a population of

about one hundred and fifty thousand souls, of which Spaniards and

Creoles hardly constitute the tenth part; the remainder is composed of

Tagalocs, or Indians, Métis, and Chinese.

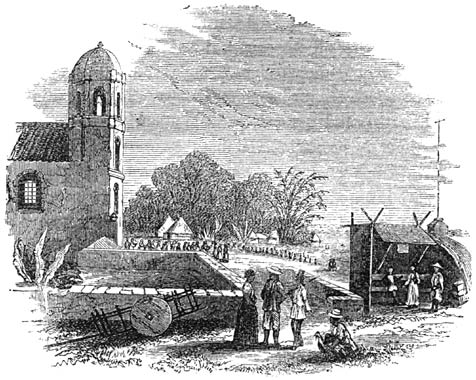

[33]The city is divided into two

sections—the military and the mercantile—the latter of

which is the suburb. The former, surrounded by lofty walls, is bounded

by the sea on one side, and upon another by an extensive plain, where

the troops are exercised, and where of an evening the indolent Creoles,

lazily extended in their carriages, repair to exhibit their elegant

dresses and to inhale the sea-breezes. This public

promenade—where intrepid horsemen and horsewomen, and European

vehicles, cross each other in every direction—may be styled the

Champs-Elysées, or the Hyde Park, of the Indian Archipelago. On

a third side, the military town is separated from the trading town by

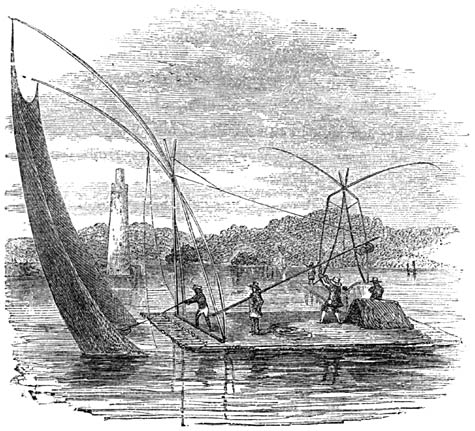

the river Pasig, upon which are seen all the day boats laden with

merchandize, and charming gondolas conveying idlers to different parts

of the suburbs, or to visit the ships in the bay.

The military town communicates by the bridge of Binondoc with the

mercantile town, inhabited principally by the Spaniards engaged in

public affairs; its aspect is dull and monotonous; all the streets,

perfectly straight, are bordered by wide granite footpaths. In general,

the highways are macadamised, and kept in good condition. Such is the

effeminacy of the people, they could not endure the noise of carriages

upon pavement. The houses—large and spacious, palaces in

appearance—are built in a particular manner, calculated to

withstand the earthquakes and hurricanes so frequent in this part of

the world. They have all one story, with a ground-floor; the upper

part, generally occupied by the family, is surrounded by a wide

gallery, opened or shut by means of large sliding panels, the panes of

which are thin mother-of-pearl. The mother-of-pearl permits the passage

of light to the apartments, and excludes the heat of the sun. In the

military town are all the monasteries and convents, the archbishopric,

[34]the

courts of justice, the custom-house, the hospital, the governor’s

palace, and the citadel, which overlooks both towns. There are three

principal entrances to Manilla—Puerta Santa Lucia,

Puerto Réal, and Puerta Parian.

At one o’clock the drawbridges are raised, and the gates

pitilessly closed, when the tardy resident must seek his night’s

lodging in the suburb, or mercantile town, called Binondoc. This

portion of Manilla wears a much gayer and more lively aspect than the

military section. There is less regularity in the streets, and the

buildings are not so fine as those in what may be called Manilla

proper; but in Binondoc all is movement, all is life. Numerous canals,

crowded with pirogues, gondolas, and boats of various kinds, intersect

the suburb, where reside the rich merchants—Spanish, English,

Indian, Chinese, and Métis. The newest and most elegant houses

are built upon the banks of the river Pasig. Simple in exterior, they

contain the most costly inventions of English and Indian luxury.

Precious vases from China, Japan ware, gold, silver, and rich silks,

dazzle the eyes on entering these unpretending habitations. Each house

has a landing-place from the river, and little bamboo palaces, serving

as bathing-houses, to which the residents resort several times daily,

to relieve the fatigue caused by the intense heat of the climate. The

cigar manufactory, which affords employment continually to from fifteen

to twenty thousand workmen and other assistants, is situated in

Binondoc; also the Chinese custom-house, and all the large working

establishments of Manilla. During the day, the Spanish ladies, richly

dressed in the transparent muslins of India and China, lounge about

from store to store, and sorely test the patience of the Chinese

salesman, who unfolds uncomplainingly, and without showing the least

ill-humour, thousands of pieces [35]of goods before his customers, which are

frequently examined simply for amusement, and not half a yard

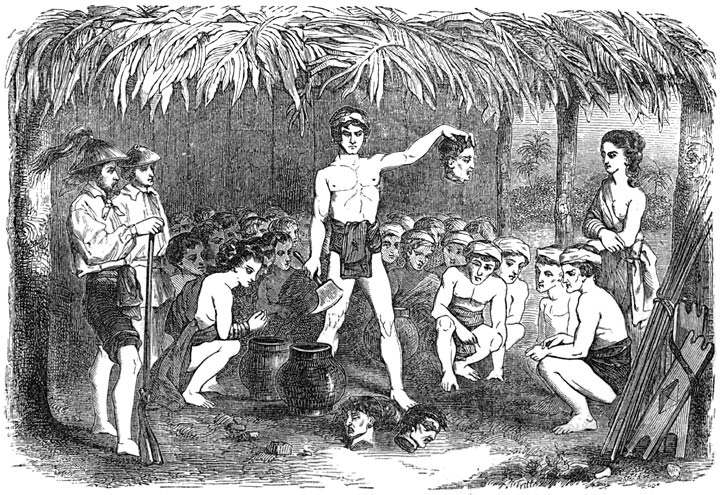

purchased. The balls and entertainments, given by the half-breeds of

Binondoc to their friends, are celebrated throughout the Philippines.

The quadrilles of Europe are succeeded by the dances of India, and

while the young people execute the fandango, the bolero, the cachucha,

or the lascivious movements of the bayadères, the enterprising

half-breed, the indolent Spaniard, and the sedate Chinese, retire to

the gaming saloons, to try their fortune at cards and dice. The passion

for play is carried to such an extent, that the traders lose or gain in

one night sums of 50,000 piasters (£10,000 sterling). The

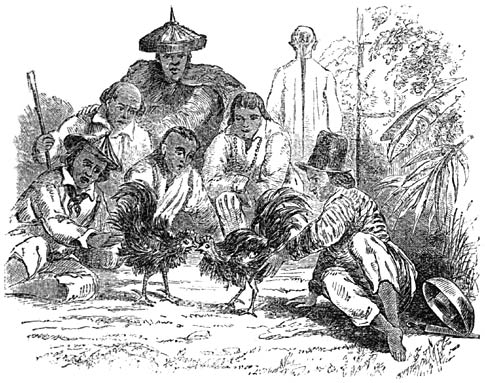

half-breeds, Indians, and Chinese, have also a great passion for

cock-fighting; these combats take place in a large arena. I have seen

£1,500 betted upon a cock which had cost £150; in a few

minutes this costly champion fell, struck dead by his antagonist. In

fine, if Binondoc be exclusively the city of pleasure, luxury, and

activity, it is also that of amorous intrigues and gallant adventures.

In the evening, Spaniards, English, and French, go to the promenades to

ogle the beautiful and facile half-breed women, whose transparent robes

reveal their splendid figures. That which distinguishes the female

half-breeds (Spanish-Tagals, or Chinese-Tagals) is a singularly

intelligent and expressive physiognomy. Their hair, drawn back from the

face, and sustained by long golden pins, is of marvellous luxuriance.

They wear upon the head a kerchief, transparent like a veil, made of

the pine fibre, finer than our finest cambric; the neck is ornamented

by a string of large coral beads, fastened by a gold medallion. A

transparent chemisette, of the same stuff as the head-dress, descends

as far as the waist, covering, but not concealing, a [36]bosom that has never

been imprisoned in stays. Below, and two or three inches from the edge

of the chemisette, is attached a variously coloured petticoat of very

bright hues. Over this garment, a large and costly silk sash closely

encircles the figure, and shows its outline from the waist to the knee.

The small and white feet, always naked, are thrust into embroidered

slippers, which cover but the extremities. Nothing can be more

charming, coquettish, and fascinating, than this costume, which excites

in the highest degree the admiration of strangers. The half-breed and

Chinese Tagals know so well the effect it produces on the Europeans,

that nothing would induce them to alter it.

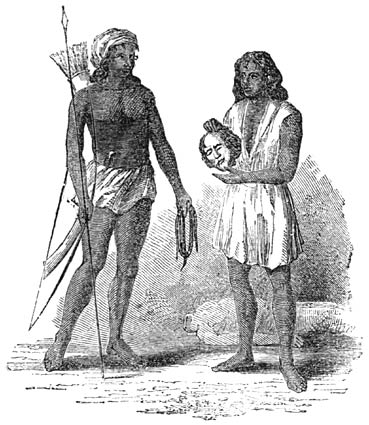

While on the subject of dress, that of the men is also [37]worthy of remark.

The Indian and the half-breed wear upon the head a large straw hat,

black or white, or a sort of Chinese covering, called a

salacote; upon the shoulders, the pine fibre kerchief embroidered;

and round the neck, a rosary of coral beads; their shirts are also made

from the fibres of the pine, or of vegetable silk; trousers of coloured

silk, with embroidery near the bottom, and a girdle of red China crape,

complete their costume. The feet, without stockings, are covered with

European shoes.

The military town, so quiet during the day, assumes a more lively

appearance towards the evening, when the inhabitants ride out in their

very magnificent carriages, which are invariably conducted by

postilions; they then mix with the [38]walking population of Binondoc. Afterwards

visits, balls, and the more intimate réunions take place.

At the latter they talk, smoke the cigars of Manilla, and chew the

betel,1 drink

glasses of iced eau sucrée, and eat innumerable

sweetmeats; towards midnight those guests retire who do not stay supper

with the family, which is always served luxuriously, and generally

prolonged until two o’clock in the morning. Such is the life

spent by the wealthy classes under these skies so favoured by Heaven.

But there exists, as in Europe, and even to a greater extent, the most

abject misery, of which I shall speak hereafter, throwing a shade over

this brilliant picture.

I shall now return to my personal adventures. While I spoke with the

Indians upon the shore, I had noticed a young European standing not

many paces from me; I again met him on the road I took towards Manilla,

and I thought I would address him. This young man was a surgeon, about

returning to Europe. I partly told him the plans I wished to form, and

asked him for some information respecting the city where I purposed

locating myself. He readily satisfied my inquiries, and encouraged me

in the resolution to exercise my profession in the Philippine Islands.

He had himself, he said, conceived the same project, but family affairs

obliged him to return to his country. I did not conceal the misfortune

of my position, and observed that it would be almost impossible to pay

visits in the costume, worse than plain, which I then wore.

“That is of no consequence,” he replied; “I have

all you would require: a coat almost new, and six capital lancets. I

[39]will

sell you these things for their cost price in France; they will be a

great bargain.” The affair was soon concluded. He took me to his

hotel, and I shortly left it encased in a garment sufficiently good,

but much too large and too long for me. Nevertheless, it was some time

since I had seen myself so well clad, and I could not help admiring my

new acquisition.

I had hidden my poor little white jacket in my hat, and I strode

along the causeway of Manilla more proud than Artaban himself. I was

the owner of a coat and six lancets; but there remained, for all my

fortune, the sum of one dollar only; this consideration slightly

tempered the joy that I felt in gazing on my brilliant costume. I

thought of where I could pass the night, and subsist on the morrow and

the following days, if the sick were not ready for me.

Reflecting thus I slowly wandered from Binondoc to the military

town, and from the military town back to Binondoc,—when,

suddenly, a bright idea shot across my brain. At Cavite I had heard

spoken of a Spanish captain, by name Don Juan Porras, whom an accident

had rendered almost blind. I resolved to seek him, and offer my

services; it remained but to find his residence. I addressed a hundred

persons, but each replied that he did not know, and passed on his way.

An Indian who kept a small shop, and to whom I spoke, relieved my

trouble: “If the senor is a captain,” he said, “your

excellency would obtain his address at the first barrack on your

road.” I thanked him, and eagerly followed his counsel. At the

infantry barracks, where I presented myself, the officer on duty sent a

soldier to guide me to the captain’s dwelling: it was time, the

night had already fallen. Don Juan Porras was an Andalusian, a good

man, and of an extremely cheerful disposition. I found him with his

[40]head

wrapped in a Madras handkerchief, busied in completely covering his

eyes with two enormous poultices.

“Senor Captain,” I said, “I am a physician, and a

skilful oculist. I have come hither to take care of you, and I am fully

convinced that I shall cure you.”

“Basta” (enough is said), was his answer;

“all the physicians in Manilla are asses.”

This more than sceptical reply did not discourage me. I resolved to

turn it to account. “My opinion is precisely the same as

yours,” I promptly answered; “and it is because I am

strongly convinced of the ignorance of the native doctors, that I have

made up my mind to come and practise in the Philippines.”

“Of what nation are you, sir?”

“I am a Frenchman.”

“A French physician!” cried Don Juan; “Ah! that is

quite another matter. I ask your pardon for having spoken so

irreverently of men of your profession. A French physician! I put

myself entirely into your hands. Take my eyes, Senor Medico, and do

what you will with them!”

The conversation was taking a favourable turn: I hastened to broach

the principal question:

“Your eyes are very bad, Senor Captain,” said I;

“to accomplish a speedy cure, it is absolutely necessary that I

should never quit you for a moment.”

“Would you consent to come and pass some time with me,

doctor?”

Here was the principal consideration settled.

“I consent,” replied I, “but on one condition;

namely, that I shall pay you for my board and lodging.”

“That shall not part us—you are free to do so,”

said the worthy man; “and so the matter is settled. I have a nice

room, [41]and a good bed, all ready; there is nothing to do

but to send for your baggage. I will call my servant.”

The terrible word, “baggage,” sounded in my ears like a

knell. I cast a melancholy look at the crown of my hat—my only

portmanteau—within which were deposited all my

clothes—consisting of my little white jacket; and I feared Don

Juan would take me for some runaway sailor trying to dupe him. There

was no retreat; so I mustered my courage, and briefly related my sad

position, adding that I could not pay for my board and lodging until

the end of the month—if I was so fortunate as to find patients.

Don Juan Porras listened to me very quietly. When my tale was told he

burst into a loud laugh, which made me shiver from head to foot.

“Well,” cried he, “I am well pleased it should be

so; you are poor; you will have more time to devote to my malady, and a

greater interest in curing me. What think you of the

syllogism?”

“It is excellent, Senor Captain, and before long you will

find, I hope, that I am not the man to compromise so distinguished a

logician as yourself. To-morrow morning I will examine your eyes, and I

will not leave you till I have radically cured them.”

We talked for some time longer in this joyous strain, after which I

retired to my chamber, where the most delightful dreams visited my

pillow.

The next day I rose early, put on my doctoral coat, and entered the

chamber of my host. I examined his eyes; they were in a dreadful state.

The sight of one was not only destroyed, but threatened the life of the

sufferer. A cancer had formed, and the enormous size it had attained

rendered the result of an operation doubtful. The left eye contained

many fibres, but there was hope of saving it. I frankly acquainted

[42]Don Juan

with my fears and hopes, and insisted upon the entire removal of the

right eye. The Captain, at first astonished, decided courageously upon

submitting to the operation, which I accomplished on the following day

with complete success. Shortly afterwards the inflammatory symptoms

disappeared, and I could assure my host of a safe recovery. I then

bestowed all my attention upon the left eye. I desired the more

ardently to restore to Don Juan his vision, from the good effect I was

convinced his case would produce at Manilla. For me it would be fortune

and reputation. Besides, I had already acquired, in the few days, some

slight patronage, and was in a position to pay for my board and lodging

at the end of the month. After six weeks’ careful treatment Don

Juan was perfectly cured, and could use his eye as well as he did

previous to his accident. Nevertheless, to my great regret, the Captain

still continued to immure himself; his re-appearance in society, which

he had forsaken for more than a year, would have produced an immense

sensation, and I should have been considered the first doctor in the

Philippines. One day I touched upon this delicate topic.

“Senor Captain,” said I, “what are you thinking

about, to remain thus shut up between four walls, and why do you not

resume your old habits? You must go and visit your friends, your

acquaintances.”

“Doctor,” interrupted Don Juan, “how can I show

myself in public with an eye the less? When I pass along the street all

the women would say: ‘There goes Don Juan the One-eyed!’

No, no; before I leave the house you must get me an artificial eye from

Paris.”

“You don’t mean that? It would be eighteen months before

the eye arrived.” [43]

“Then here goes for eighteen months’ seclusion,”

said Don Juan.

I persisted for upwards of an hour, but the Captain would not listen

to reason. He carried his coquetry so far that, although I had covered

the empty orbit with black silk, he had his shutters closed whenever

visitors came; so that, as they always found him in the dark, none

would credit his cure. I was very anxious to thwart Don Juan’s

obstinacy, as may well be imagined; I had not the time to waste, during

eighteen months, in dancing attendance at fortune’s door;

therefore I determined to make this eye myself, without which the

coquetish captain would not be seen. I took some pieces of glass, a

tube, and set to work. After many fruitless attempts, I at last

succeeded in obtaining the perfect form of an eye; but this was not

all—it must be coloured to resemble nature. I sent for a poor

carriage-painter, who managed to imitate tolerably well the left eye of

Don Juan. It was necessary to preserve this painting from contact with

the tears, which would soon have destroyed it. To accomplish this I had

made by a jeweller a silver globe, smaller than the glass eye, inside

which I united it by means of sealing-wax. I carefully polished the

edges upon a stone, and after eight days’ labour I obtained a

satisfactory result. The eye which I had succeeded in producing was

really not so bad after all. I was anxious to place it within the

vacant orbit. It somewhat inconvenienced the Senor Don Juan, but I

persuaded him that he would soon become accustomed to it. Placing

across his nose a pair of spectacles, he examined himself in the

looking-glass, and was so satisfied with his appearance that he decided

on commencing his visits the following day.

As I had anticipated, the re-appearance in the world of [44]Captain Juan Porras

made a great sensation, and soon the consequence was, that Senor Don

Pablo, the eminent French physician—most especially the clever

oculist—was much spoken of. From all quarters patients came to

me. Notwithstanding my youth and inexperience, my first success gave me

such confidence that I performed several operations upon persons

afflicted with cataracts, which succeeded most fortunately. I no longer

sufficed to my large connection, and in a few days, from the greatest

distress, I attained perfect opulence: I had a carriage-and-four in my

stables. I could not, however, notwithstanding this change of fortune,

resign myself to leave Don Juan’s house, out of gratitude for the

hospitality he so generously offered me. In my leisure hours he kept me

company, and amused me with the recital of his battle stories and

personal adventures. I had already spent nearly six months with him,

when a circumstance, which forms an epoch in my life, changed my

existence, and compelled me to quit the lively captain. One of my

American friends often called my attention in our walks towards a young

lady in mourning, who passed for one of the prettiest senoras of the

town. Each time we met her my American friend never failed to praise

the beauty of the Marquesa de Las Salinas. She was about eighteen or

nineteen years of age; her features were both regular and placid; she

had beautiful black hair, and large expressive eyes; she was the widow

of a colonel in the guards, who married her when almost a child. The

sight of this young lady produced so lively an impression upon me, that

I explored all the saloons at Binondoc, to endeavour to meet her

elsewhere than in my walks. Fruitless attempts! The young widow saw

nobody. I almost despaired of finding an opportunity of speaking to

her, when one morning an Indian [45]came to request me to visit his master. I

got into the carriage and set off, without informing myself of the name

of the sick person. The carriage stopped before the door of one of the

finest houses in the Faubourg of Santa-Crux. Having examined the

patient, and conversed a few minutes with him, I went to the table to

write a prescription; suddenly I heard the rustling of a silk dress; I

turned round—the pen fell from my hand. Before me stood the very

lady I had so long sought after—appearing to me as in a dream! My

amazement was so great that I muttered a few unintelligible words, and

bowed with such awkwardness that she smiled. She simply addressed me to

inquire the state of her nephew’s health, and withdrew almost

immediately. As to myself, instead of making my ordinary calls, I

returned home; questioned Don Juan minutely about Madame de Las

Salinas: he entirely satisfied my curiosity. He was acquainted with all

the family of this youthful widow, and they were highly respected in

the colony. The next morning, and following days, I returned to this

charming widow, who graciously condescended to receive me with favour.

These details being so completely personal, I pass them over. Six

months after my first interview with Madame de Las Salinas, I asked her

hand, and obtained it. I had therefore found, at more than five

thousand leagues from my country, both happiness and wealth. I agreed

that we should go to France as soon as my wife’s property, the

greater part of which lay in Mexico, should be realised. In the

meantime my house was the rendezvous of foreigners, particularly of the

French, who were already rather numerous at Manilla. At this period the

Spanish government named me Surgeon-Major of the 1st Light Regiment,

and of the first battalion of the militia of Panjanga. [46]Having been so

successful in so short a time, I never once doubted but that fortune

would continue to bestow her smiling favours upon me. I had already

prepared everything for my return to France; for we hourly expected the

arrival of the galleons that plied from Acapulco to Manilla, which were

to bring my wife’s fortune. Her fortune was no less than 700,000

francs (£28,000 sterling).

One evening, as we were taking tea, we were informed that the

vessels from Acapulco had been telegraphed, and that the next morning

they would be in; our piasters were to be on board; I leave you to

guess if our wishes were not gratified. But, alas! how our hopes were

frustrated: the vessels did not bring us a single piaster. This is what

occurred: five or six millions were sent by land from Mexico to San

Blas, the place of embarkation, and the Mexican government had the van

escorted by a regiment of the line, commanded by Colonel Iturbide. On

the journey he took possession of the van, and fled with his regiment

into the independent states. It is well known that later Iturbide was

proclaimed Emperor of Mexico, then dethroned, and at last shot, after

an expedition that offers more than one analogy with that of Murat. The

very day of the arrival of the vessels we learnt that our fortune was

entirely lost, without even hopes of regaining the smallest part. My

wife and self supported this event with tolerable philosophy. It was

not the loss of our piasters that distressed us the most, but the

necessity we were in to abandon, or at least to postpone, our journey

to France. [47]

[Contents]

Chapter III.

Continued Prosperity in Practice—Attempted Political

Revolution—Desperate Street Engagement—Subjugation of the

Insurgents—The Emperor of a Day—Dreadful

Executions—Illness and Insanity of my Wife—Her Recovery and

Relapse—Removal to the Country—Beneficial

Results—Dangerous Neighbours—Repentant

Banditti—Fortunate Escape—The Anonymous Friend—A

Confiding Wife—Her Final Recovery, and our Domestic Happiness

Restored.

Despite the misfortune I have alluded to, I kept up

my house in the same style as before. My connection, and the different

posts I occupied, permitted me to lead the life of a grandee belonging

to the Spanish colonies; and probably I should have made my fortune in

a few years, if [48]I had continued in the medical profession, but

the wish for unlimited liberty caused me to abandon all these

advantages for a life of peril and anxiety. At the same time do not let

us anticipate too suddenly, and let the reader patiently peruse a few

more pages about Manilla, and various events wherein I figured, either

as actor or witness, before taking leave of a sybarite citizen’s

life.

I was, as I said before, surgeon-major of the 1st Light Regiment of

the line, and on intimate terms with the staff, and more particularly

with Captain Novalès, a Creole by birth, possessing a courageous

and venturesome disposition. He was suspected of endeavouring to excite

his regiment to rebel in behalf of the Independence. An inquiry was

consequently instituted, which ended without proof of the

captain’s culpability; nevertheless, as the governor still

maintained his suspicions, he gave orders for him to be sent to one

of the southern provinces, under the inspection of an alcaide.

Novalès came to see me the morning of his departure, and

complained bitterly of the injustice of the governor towards him, and

added that those who had no confidence in his honour would repent, and

that he would soon be back. I endeavoured to pacify him: we shook

hands, and in the evening he went on board the vessel commissioned to

take him to his destination. The night after Novalès departure,

I was startled out of my sleep by the report of fire-arms. I

immediately dressed myself in my uniform, and hastened to the barracks

of my regiment. The streets were deserted; sentinels were stationed at

about fifty paces apart. I understood that an extraordinary event had

occurred in some part of the town. When I reached the barracks I was no

little astonished to find the gates wide open, the sentry’s box

vacant, and not a soldier within. I went into the infirmary, set apart

[49]for the

special service of the cholera patients, and there a serjeant told me

that the bad weather had compelled the vessel that was taking

Novalès into exile to return into the port; that about one

o’clock in the morning, Novalès, accompanied by Lieutenant

Ruiz, came to the barracks, and having made himself certain of the

votes of the Creole non-commissioned officers, put the regiment under

arms, took possession of the gates, and proclaimed himself Emperor of

the Philippines.

This extraordinary intelligence caused me some anxiety. My regiment

had openly revolted; if I joined it, and were defeated, I should be

considered a traitor, and, as such, shot; if, on the contrary, I fought

against it, and the rebels proved victorious, I knew Novalès

sufficiently well to be convinced that he would not spare me.

Nevertheless I could not hesitate: duty bound me to the Spanish

government, by which I had been so well treated. I left the barracks,

rambling where chance might lead me. I shortly found myself at the

head-quarters of the artillery; an officer behind the gate stood

observing me. I went up to him, and asked him whether he was for Spain.

Upon his answering me in the affirmative, I begged him to open the

gate, declaring that I wished to join his party, and would willingly

offer my services as surgeon to them. I went in, and took the

commander’s orders, which soon showed me how matters stood.

During the night Ruiz went, in the name of Novalès, to General

Folgueras, the commander during the absence of Governor

Martinès, who was detained at his country house, a short

distance from Manilla. He took the guard unawares, and seized the keys

of the town, after having stabbed Folgueras; from thence he went to the

prisons, set the prisoners at liberty, and put in their places the

principal men of the public offices belonging to the colony. The 1st

Regiment [50]was on Government Place, ready to engage in

battle; twice it attempted to fall unexpectedly upon the artillery and

citadel, but was driven back. Many expected assistance from without,

and orders from General Martinès to attack the rebels. Very soon

we heard a discharge of artillery: it was General Martinès, who,

at the head of the Queen’s Regiment, broke open Saint

Lucy’s Gate, and advanced into the besieged town. The body of the

artillery joined the governor-general, and we marched towards

Government Place. The insurgents placed two cannons at the corner of

each street. Scarcely had we approached the palace, than we were

exposed to a violent discharge of loaded muskets. The head chaplain of

the regiment was the first victim. We were then engaged in a street, by

the side of the fortifications, and from which it was impossible to

attack the enemy with advantage. General Martinès changed the

position of the attack, and in this condition we came back by the

street of Saint Isabelle. The troops in two lines followed [51]both sides of the

street, and left the road free; in the meantime the Panpangas regiment,

crossing the bridge, reached us by one of the opposite streets: the

rebels were then exposed to the opposite attacks. They nevertheless

defended themselves furiously, and their sharpshooters did us some

harm. Novalès was everywhere, encouraging his soldiers by words,

exploits, and example, while Lieutenant Ruiz was busy pointing one of

the cannons, that swept the middle of the street we were coming up. At

length, after three hours’ contest, the rebels succumbed. The

troops fell upon everything they found, and Novalès was taken

prisoner to the governor’s. As to Ruiz, although he had received

a blow on his arm from a ball, he was fortunate enough to jump over the

fortifications, and succeeded, for the time, in escaping; three days

afterwards he was taken. The conflict was scarcely over, than a

court-martial was held. Novalès was tried the first. At midnight

he was outlawed; at two o’clock in the morning proclaimed

Emperor; and at five in the evening shot. Such changes in fortune are

not uncommon in Spanish colonies.

The court-martial, without adjourning, tried, until the middle of

the following day, all the prisoners arrested with arms. The tenth part

of the regiment was sent to the hulks, and all the non-commissioned

officers were condemned to death. I received orders to be at Government

Place by four o’clock, on which spot the executions were to take

place; two companies of each battalion of the garrison, and all the

staff, were to be present.

Towards five the doors of the town-hall opened, and between a double

file of soldiers advanced seventeen non-commissioned officers, each one

assisted by two monks of the order of Misericordia. Mournful silence

prevailed, interrupted [52]every now and then by the doleful beating of the

drums, and the prayers of the agonising, chanted by the monks. The

procession moved slowly on, and after some time reached the palace; the

seventeen non-commissioned officers were ordered to kneel, their faces

turned towards the wall. After a lengthened beating of the drums the

monks left their victims, and at a second beating a discharge of

muskets resounded: the seventeen young men fell prostrate on the

ground. One, however, was not dead; he had fallen with the others, and

seemed apparently motionless. A few minutes after the monks threw their

black veils upon the victims: they now belonged to Divine justice. I

witnessed all that had just happened. I stood a few steps from him who

feigned death so well, and my heart beat with force enough to burst

through my chest. Would that it had been in my power to lead one of the

monks towards this unfortunate young man who must have experienced such

mortal anguish; but, alas! after having been so miraculously spared, at

the moment the black veil was about to cover him, an officer informed

the commander that a guilty man had escaped being punished; the monks

were arrested in their pious ministry, and two soldiers received orders

to approach and fire upon the poor fellow.

I was indignant at this. I advanced towards the informer and

reproached him for his cruelty; he wished to reply; I treated him as a

coward, and turned my back to him. Express orders from my colonel

compelled me to leave my house, to assist at this frightful execution;

still, deep anxiety ought to have prevented me from so doing, as I will

explain. On the eve when the battle was over, and the insurgents

routed, the distress of my dear Anna came across my mind. It was now

one o’clock in the afternoon, and she had received no tidings

[53]from me

since three in the morning; might she not think me dead, or in the

midst of the rebellion? Ah! if duty could make me forget for a moment

she whom I loved more than life, now all danger was over her charming

image returned to my mind. Dearest Anna! I beheld her pale, agitated;

asking herself at each report of the cannon whether it rendered her a

widow; when my mind became so agitated that I ran home to calm her

fears. Having reached my house I went quickly up stairs, my heart

beating violently; I paused for a moment at her door, then summoning a

little courage I entered. Anna was kneeling down praying; hearing my

footsteps she raised her head, and threw herself into my arms without

uttering a word. At first I attributed this silence to emotion, but,

alas! upon examining her lovely face, I saw her eyes looked wild, her

features contracted: I started back. I discovered in her all the

symptoms of congestion of the brain. I dreaded lest my wife had lost

her senses, and this fear alarmed me greatly. How fortunate it was that

it lay in my power to relieve her. I had her placed in bed, and

ministered myself to her wants. She was tolerably composed; the few

words she uttered were inconsistent; she seemed to think that somebody

was going to poison or kill her. All her confidence was placed in me.

During three days the remedies I prescribed and administered were

useless; the poor creature derived no benefit from them. I therefore

determined to consult the doctors in Manilla, although I had no great

opinion of their skill. They advised some insignificant drugs, and

declared to me that there were no hopes, adding, as a philosophical

mode of consolation, that death was preferable to the loss of reason. I

did not agree on this point with these gentlemen: I would have

preferred insanity to death, for I hoped that her madness [54]would die away by

degrees, and eventually disappear altogether. How many mad people are

cured, what numbers daily recover, yet death is the last word of

humanity; and, as a young poet has truly said, is “the stone of

the tomb.”

Between the world and God a curtain falls! I determined to wage a

war against death, and to save my Anna by having recourse to the most

indisputable resources of science. I looked now upon my brotherhood

with more contempt than ever, and, confident in my love and zealous

will, I began my struggle with a destiny, tinged indeed with gloomy

clouds. I shut myself up in the sick-chamber, and never left my wife. I

had great difficulty in getting her to take the medicaments I trusted

she would derive so much benefit from; I was obliged to call to my

assistance all the influence I had over her, in order to persuade her

that the draughts I presented to her were not poisoned. She did not

sleep, but appeared very drowsy; these symptoms denoted very clearly

great disorder of the brain. For nine days she remained in this

dreadful state; during which time I scarcely knew whether she was dead

or alive; at every moment I besought the Almighty to work a miracle in

her behalf. One morning the poor creature closed her eyes. I cannot

describe my feelings of anguish. Would she ever awake again? I leant

over her; I heard her breathing gently, without apparent effort; I felt

her pulse, it beat calmer and more regular; she was evidently better. I

stood by her in deep anxiety. She still remained in a calm sleep, and

at the end of half-an-hour I felt convinced that this satisfactory

crisis would restore my invalid to life and reason. I sat down by her

bed-side, and stayed there eighteen hours, watching her slightest

movements. At length, after such cruel suspense, my patient awoke, as

if out of a dream. [55]

“Have you been long watching?” she said, giving me her

hand: “Have I, then, been very ill? What care you have taken of

me! Luckily you may rest now, for I feel I am recovered.”

I think I have during my life been a sharer of the strongest

emotions of joy or of sadness man can feel; but never had I experienced

such real, heartfelt joy as when I heard Anna’s words. It is easy

to imagine the state of my mind in recollecting the bitter grief I was

in for ten days; then can be understood the mental anguish I felt.

Having witnessed such strange scenes for a considerable time, it would

not have been surprising had I lost my senses. I was an actor in a

furious battle; I had seen the wounded falling around me, and heard the

death-rattle. After the frightful execution, I went home, and there

still deeper grief awaited me. I had watched by the bed-side of a

beloved wife, knowing not whether I should lose her for ever, or see

her spared to me deprived of reason; when all at once, as if by a

miracle, this dear companion of my life, restored to health, threw

herself into my arms. I wept with her; my burning eyes, aching for want

of rest, found at last some tears, but they were tears of joy and

gladness. Soon we became more composed; we related to each other all

that we had suffered. Oh! the sympathy of loving hearts! Our sorrows

bad been the same, we had shared the same fears, she for me and I for

her. Anna’s rapid recovery, after her renovating slumber, enabled

her to get up; she dressed herself as usual, and the people who saw her

could not believe she had passed ten days struggling between death and

insanity—two gulphs, from which love and faith had preserved

us.

I was happy; my deep sadness was speedily changed to gladness, even

visible on my features. Alas! this joy was transitory, [56]like all happiness;

man here below is a continual prey to misfortune! My wife, at the end

of a month, relapsed into her former sickly state; the same symptoms

showed themselves again, with similar prospects, during the same space

of time. I remained again nine days at her bed-side, and on the tenth a

refreshing sleep brought her to her senses. But this time, guided by

experience, that pitiless mistress, who gives us lessons we should ever

remember, I did not rejoice as I had done the month before. I feared

lest this sudden cure might only be a temporary recovery, and that

every month my poor invalid would relapse, until her brain becoming

weaker and weaker, she would be deranged for life. This sad idea

wounded my heart, and caused me such grief that I could not even

dissimulate it before her who inspired it. I exhausted all the

resources of medicine; all these expedients proved unavailable. I

thought that perhaps, if I removed my poor invalid from the spot where

the events had occurred that caused her disorder, her cure might be

more easily effected; that perhaps bathing and country walks in the

fine weather would contribute to hasten her recovery; therefore I

invited one of her relations to accompany us, and we set out for

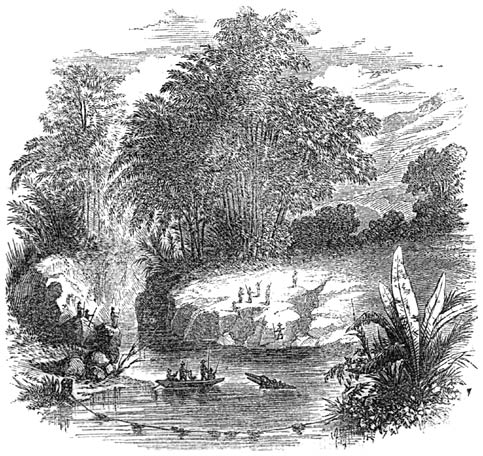

Tierra-Alta, a delightful spot, a real oasis, where all things were

assembled that could endear one to life. The first days of our settling

there were full of joy, hope, and happiness. Anna got better and better

every day, and her health very much improved. We walked in beautiful

gardens, under the shade of orange-trees; they were so thick that even

during the most intense heat we were cool under their shade. A lovely

river of blue and limpid water ran through our orchard; I had some

Indian baths erected there. We went out in a pretty, light, open

carriage, drawn by four good horses, through [57]beautiful avenues, lined on each

side with the pliant bamboo, and sown with all the various flowers of

the tropics. I leave you to judge, by this short account, that nothing

that can be wished for in the country was wanting in Tierra-Alta. For

an invalid it was a Paradise; but those are right who say there is no

perfect happiness here below. I had a wife I adored, and who loved me

with all the sincerity of a pure young heart. We lived in an Eden, away

from the world, from the noise and bustle of a city, and far, too, from

the jealous and envious. We breathed a fragrant air; the pure and

limpid waters that bathed our feet reflecting, by turns a sunny sky,

and one spangled with twinkling stars. Anna’s health was

improving: it pleased me to see her so happy. What, then, was there to

trouble us in our lovely retreat? A troop of banditti! These robbers

were distributed around the suburbs of Tierra-Alta, and spread

desolation over the country and neighbourhood by the robberies and

murders they committed. There was a regiment in search of them; this

they little cared about. They were numerous, clever, and audacious;

and, notwithstanding the vigilance of the government, the band

continued their highway robberies and assassinations. In the house

where I then resided, and which I afterwards left, Aguilar, the

commander of the cavalry, who had replaced me as occupant, was fallen

upon unexpectedly, and stabbed. Several years after this period, the

government was obliged to come to some terms with these bandits, and

one day twenty men, all armed with carbines and swords, entered

Manilla. Their chieftain led them; they walked with their heads

upright, their carriage was proud and manly; in this order they went to

the governor, who made them a speech, ordered them to lay down their

arms, and sent them to the archbishop that [58]he might exhort them. The

archbishop in a religious discourse implored of them to repent of their

crimes, and become honest citizens, and to return to their villages.

These men, who had bathed their hands in the blood of their

fellow-creatures, and who had sought in crime—or rather, in every

crime—the gold they coveted, listened attentively to God’s

minister, changed completely their conduct, and became, in the end,

good and quiet husbandmen.

Now let us return to my residence at Tierra-Alta, at the period when

the bandits were not converted, and might have disturbed my peaceful

abode and security. Nevertheless, whether it was carelessness, or the

confidence I had in my Indian, with whom I spent some time after the

ravages occasioned with the cholera, and with whose influence I was

acquainted, I did not fear the bandits at all. This Indian lived a few

leagues off from Tierra-Alta; he came often to see me, and said to me

on different occasions: “Fear nothing from the robbers, Senor

Doctor Pablo; they know we are friends, and that alone would suffice to

prevent them attacking you, for they would dread to displease me, and

to make me their enemy.” These words put an end to my fears, and

I soon had an opportunity of seeing that the Indian had taken me under

his protection.

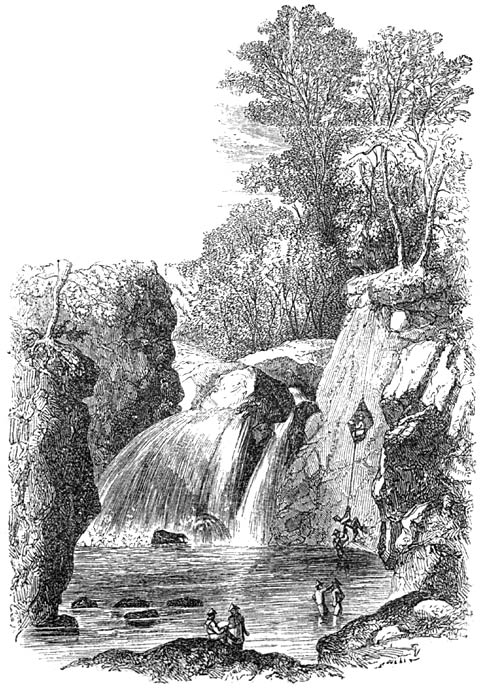

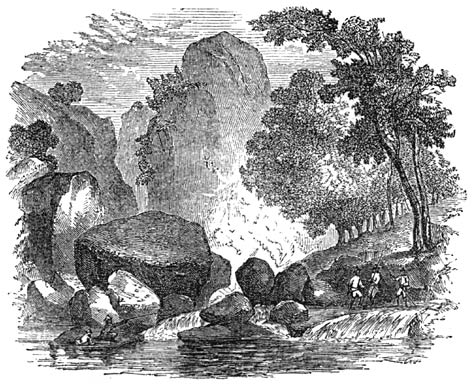

If any of my readers for whom I write these souvenirs feel the same

desire as I experienced to visit the cascades of Tierra-Alta, let them

go to a place called Yang-Yang; it was near this spot where my Indian

protector resided. At this part the river, obstructed in its course by

the narrowness of its channel, falls from only one waterspout, about

thirty or forty feet high, into an immense basin, out of which the

water calmly flows onwards, to form, lower down, three other

waterfalls, [59]not so lofty, but extending over the breadth of

the river, thereby making three sheets of water, clear and transparent

as crystal. What beautiful sights are offered to the eyes of man by the

all-powerful hands of the Creator! And how often have I remarked that

the works of nature are far superior to those that men tire themselves

to erect and invent!

As we went one morning to the cascades we were about to alight at

Yang-Yang, when all at once our carriage was surrounded with brigands,

flying from the soldiers of the line. The chief—for we supposed

him to be so at first—said to his companions, not paying the

slightest attention to us, nor even addressing us: “We must kill

the horses!” By this I saw he feared lest their enemies should

make use of our horses to pursue them. With a presence of mind which

fortunately never abandons me in difficult or perilous circumstances,

I said to him: “Do not fear; my horses shall not be used by your

enemies to pursue you: rely upon my word.” The chief put his hand

to his cap, and thus addressed his comrades: “If such be the

case, the Spanish soldiers will do us no harm to-day, neither let us do

any. Follow me!” They marched off, and I instantly drove rapidly

away in quite an opposite direction from the soldiers. The bandits

looked after me; my good faith in keeping my word was successful. I not

only lived a few months in safety at Tierra-Alta, but many years after,

when, I resided in Jala-Jala, and, in my quality of commander of the

territorial horse-guards of the province of Lagune, was naturally a

declared enemy of the bandits, I received the following note:

“Sir,—Beware of Pedro

Tumbaga; we are invited by him to go to your house and to take you by

surprise; we remember the morning we spoke to you at the cascades, and

the sincerity of your word. You are an honourable man. If we find

ourselves face to face [60]with you, and it be necessary, we will fight, but

faithfully, and never after having laid a snare. Keep, therefore, on

your guard; beware of Pedro Tumbaga; he is cowardly enough to hide himself

in order to shoot you.”

Everybody must acknowledge I had to do with most polite robbers.

I answered them thus:

“You are brave fellows. I thank you for your advice, but I do

not fear Pedro Tumbaga. I cannot conceive how it is you keep among you

a man capable of hiding himself to kill his enemy; if I had a soldier

like him, I would soon let him have justice, and without consulting the

law.”

A fortnight after my answer, Tumbaga was no more; a bandit’s

bullet disembarrassed me of him.

I will now return to the recital I have just interrupted. When I had

left the bandits at Yang-Yang, I pulled up my horses and bethought me

of Anna. I was anxious to know what impression had been produced on her

mind from this unpleasant encounter. Fortunately my fears were

unfounded; my wife had not been at all alarmed, and when I asked her if

she was frightened, she replied: “Frightened, indeed! am I not

with you?” Subsequently I had good proofs that she told me the

truth, for in many perilous circumstances she always presented the same

presence of mind. When I thought there was no longer any danger we

retraced our steps and went home, satisfied with the conduct of the

bandits towards us, for their manner of acting clearly showed us that

they intended us no harm. I mentally thanked my Indian friend, for to

him I attributed the peace our turbulent neighbours allowed us to

enjoy. The fatal time was drawing near when my wife would again be

suffering from another attack of that frightful malady [61]brought on by

Novalès revolt. I had hoped that the country air, the baths, and

amusements of every kind would cure my poor invalid; my hopes were

deceived, and, as in the preceding month, I had the grief once more to

assist at a period of physical and mental suffering. I despaired: I

knew not what course to pursue. I decided, however, upon remaining at

Tierra-Alta. My dear companion was happy there on the days her health

was better, and on the other days I never left her, endeavouring by

every means that art and imagination could invent to fight against this

fatal malady. At length my care, attempts, and efforts were successful,

and at the periods the symptoms usually returned I had the happiness

not to observe them, and believed in the certainty of a final cure. I

then felt the joy one experiences after having for a long time been on

the point of losing a very dear friend, who suddenly recovers. I now

gave myself up without fear to the various pleasures Tierra-Alta

offers. [62]

[Contents]

Chapter IV.

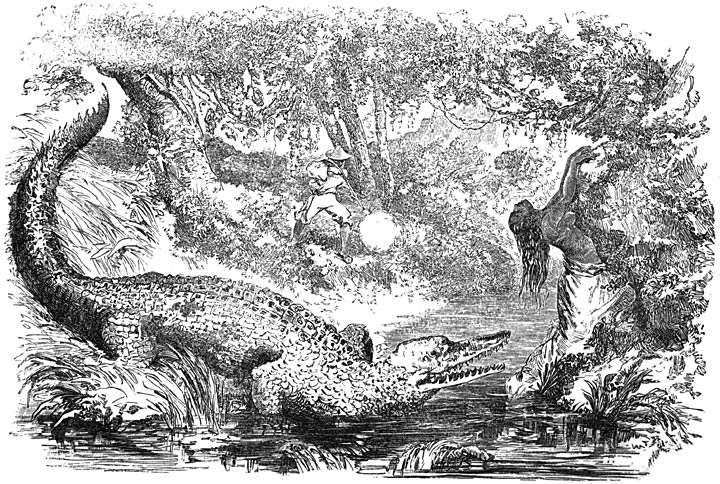

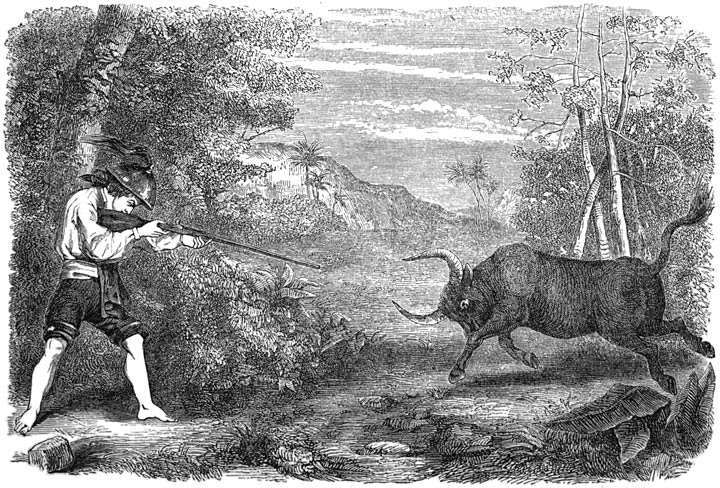

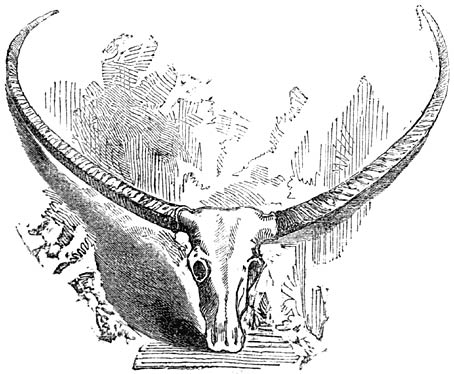

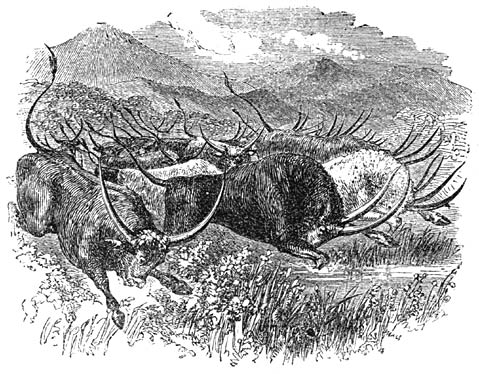

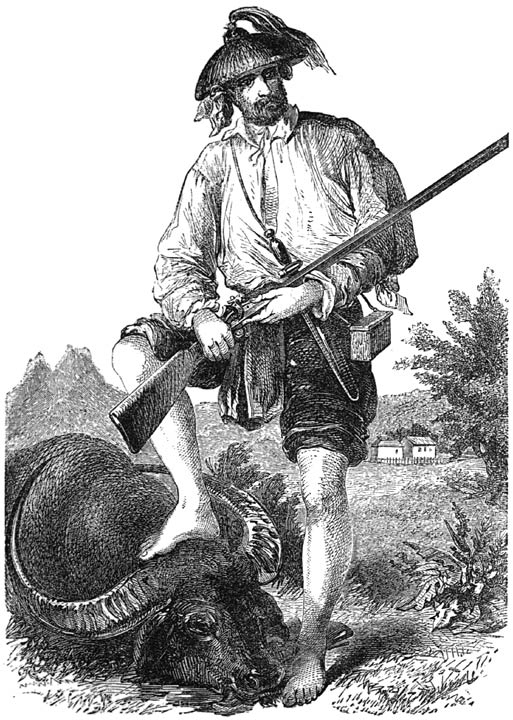

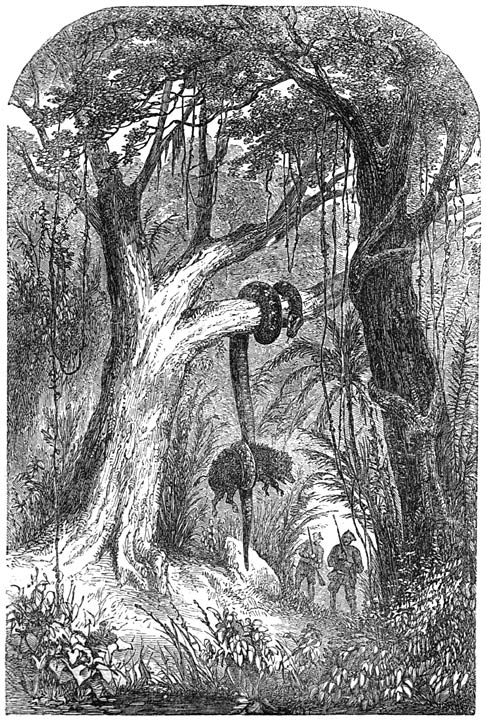

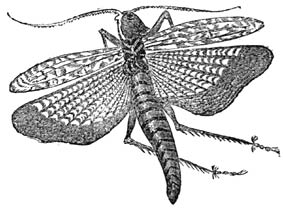

Hunting the Stag—Indian Mode of Chasing the Wild Buffalo: its

Ferocity—Dangerous Sport—Capture of a Buffalo—Narrow

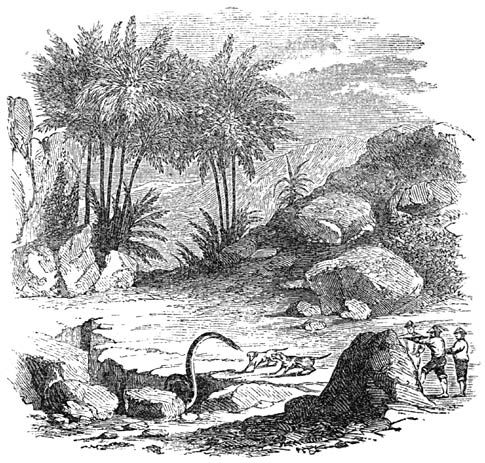

Escape of an Indian Hunter—Return to Manilla—Injustice of