Title: From the Rapidan to Richmond and the Spottsylvania Campaign

Author: William Meade Dame

Release date: February 7, 2010 [eBook #31192]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries (http://www.archive.org/details/americana)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/fromrapidantoric00damerich |

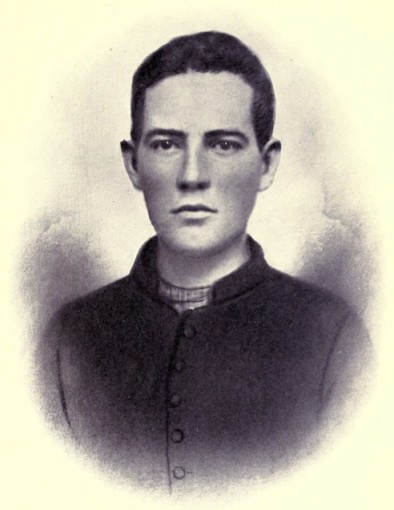

WILLIAM MEADE DAME

PRIVATE FIRST COMPANY OF RICHMOND HOWITZERS

1864

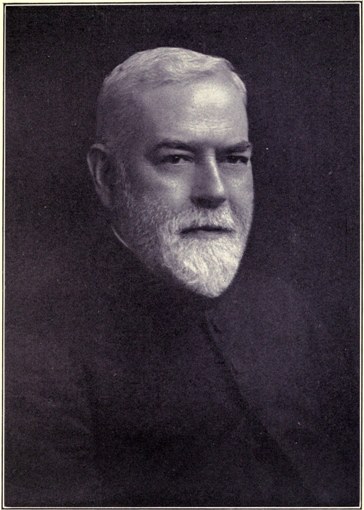

WILLIAM MEADE DAME, D. D.

RECTOR MEMORIAL PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCH

BALTIMORE, MD.

1920

“The land where I was born” was, in my childhood, a great battleground. War—as we then thought the vastest of all wars, not only that had been, but that could ever be—swept over it. I never knew in those days a man who had not been in the war. So, “The War” was the main subject in every discussion and it was discussed with wonderful acumen. Later it took on a different relation to the new life that sprung up and it bore its part in every gathering much as the stories of Troy might have done in the land where Homer sang. To survive, however, in these reunions as a narrator one had to be a real contributor to the knowledge of his hearers. And the first requisite was that he should have been an actor in the scenes he depicted; secondly, that he should know how to depict them. Nothing less served. His hearers themselves all had experience and demanded at least not less than their own. As the time grew more distant they demanded that it should be preserved in more definite form and the details of the life grew more precious.

Among those whom I knew in those days as a delightful narrator of experiences and observations—not of strategy nor even of tactics in battle; but of the life in the midst of the battles in the momentous campaign in which the war was eventually fought out, was a kinsman of mine—the author of this book. A delightful raconteur because he had seen and felt himself what he related, he told his story without conscious art,[Pg xii] but with that best kind of art: simplicity. Also with perennial freshness; because he told it from his journals written on the spot.

Thus, it came about that I promised that when he should be ready to publish his reminiscences I would write the introduction for them. My introduction is for a story told from journals and reminiscent of a time in the fierce Sixties when, if passion had free rein, the virtues were strengthened by that strife to contribute so greatly a half century later to rescue the world and make it “safe for Democracy.”

It was the war—our Civil War—that over a half century later brought ten million of the American youth to enroll themselves in one day to fight for America. It was the work in “the Wilderness” and in those long campaigns, on both sides, which gave fibre to clear the Belleau Wood. It was the spirit of the armies of Lee and Grant which enabled Pershing’s army to sweep through the Argonne.

Rome, March 27, 1919.

The following tribute to Robert E. Lee was written by Lord Wolseley when commander-in-chief of the armies of Great Britain, an office which he held until succeeded by Lord Roberts.

Lord Wolseley had visited General Lee at his headquarters during the progress of the great American conflict. Some time thereafter Wolseley wrote:

“The fierce light which beats upon the throne is as a rushlight in comparison with the electric glare which our newspapers now focus upon the public man in Lee’s position. His character has been subjected to that ordeal, and who can point to a spot upon it? His clear, sound judgment, personal courage, untiring activity, genius for war, absolute devotion to his State, mark him out as a public man, as a patriot to be forever remembered by all Americans. His amiability of disposition, deep sympathy with those in pain or sorrow, his love for children, nice sense of personal honor and generous courtesy, endeared him to all his friends. I shall never forget his sweet, winning smile, nor his clean, honest eyes that seemed to look into your heart while they searched your brain. I have met with many of the great men of my time, but Lee alone impressed me with the feeling that I was in the presence of a man who was cast in a grander mold and[Pg xiv] made of different and finer metal than all other men. He is stamped upon my memory as being apart and superior to all others in every way, a man with whom none I ever knew and few of whom I have read are worthy to be classed. When all the angry feelings aroused by the secession are buried with those that existed when the American Declaration of Independence was written; when Americans can review the history of their last great war with calm impartiality, I believe all will admit that General Lee towered far above all men on either side in that struggle. I believe he will be regarded not only as the most prominent figure of the Confederacy, but as the greatest American of the nineteenth century, whose statue is well worthy to stand on an equal pedestal with that of Washington and whose memory is equally worthy to be enshrined in the hearts of all his countrymen.

“WOLSELEY.”

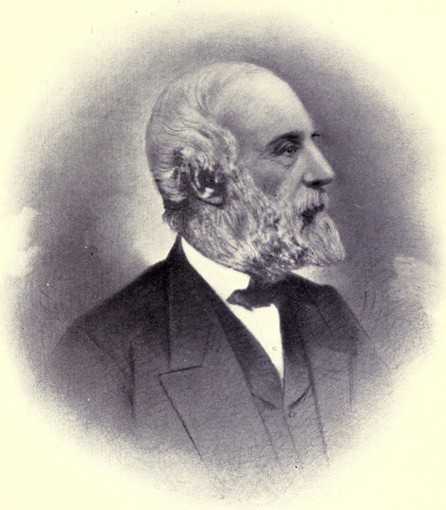

GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE

| Introduction | 1 |

| The cause of conflict and the call to arms—Those who answered the call—An army of volunteers—Our great leader—The call comes home—First Company Richmond Howitzers—Back to civil life—Origin of this narrative. | |

| I. Sketch of Camp Life the Winter Before the Spottsylvania Campaign | 17 |

| Morton’s Ford—Building camp quarters—“Housewarming” on parched corn, persimmons and water—Camp duties—Camp recreations—A special entertainment—Confederate soldier rations—A fresh egg—When fiction became fact—Confederate fashion plates—A surprise attack—Wedding bells and a visit home—The soldiers’ profession of faith—The example of Lee, Jackson and Stuart—Spring sprouts and a “tar heel” story. | |

| II. Battle of the Wilderness | 63 |

| “Marse Robert” calls to arms—The spirit of the soldiers of the South—Peace fare and fighting ration—Marse Robert’s way of making one equal to three—An infantry battle—Arrival of the First Corps—The love that Lee inspired in the men he led—“Windrows” of Federal dead. | |

| III. Battles of Spottsylvania Court House | 96 |

| Stuart’s four thousand cavalry—Greetings on the field of battle—“Jeb” Stuart assigns “a little job”—Wounding of Robert Fulton Moore—A useful discovery—Barksdale’s Mississippi Creeper—Kershaw’s South Carolina “rice-birds”—Feeling pulses—Where the fight was hottest—Against heavy [Pg xvi]odds at “Fort Dodge”—“Sticky” mud and yet more “sticky” men—Gregg’s Texans to the front—Breakfastless but “ready for customers”—Parrott’s reply to Napoleon’s twenty to two—The narrow escape of an entire company—Successive attacks by Federal infantry—Eggleston’s heroic death—“Texas will never forget Virginia”—Contrast in losses and the reasons therefore—Why Captain Hunter failed to rally his men—Having “a cannon handy”—Grant’s neglect of Federal wounded. | |

| IV. Cold Harbor and the Defense of Richmond | 189 |

| The last march of our Howitzer Captain—The bloodiest fifteen minutes of the war—Federal troops refuse to be slaughtered—Dr. Carter “apologizes for getting shot”—Death of Captain McCarthy—A Summary. |

In 1861 a ringing call came to the manhood of the South. The world knows how the men of the South answered that call. Dropping everything, they came from mountains, valleys and plains—from Maryland to Texas, they eagerly crowded to the front, and stood to arms. What for? What moved them? What was in their minds?

Shallow-minded writers have tried hard to make it appear that slavery was the cause of that war; that the Southern men fought to keep their slaves. They utterly miss the point, or purposely pervert the truth.

In days gone by, the theological schoolmen held hot contention over the question as to the kind of wood the Cross of Calvary was made from. In their zeal over this trivial matter, they lost sight of the great thing that did matter; the mighty transaction, and purpose displayed upon that Cross.

In the causes of that war, slavery was only a detail and an occasion. Back of that lay an immensely greater thing; the defense of their rights—the most sacred cause given men on earth, to maintain at every cost. It is the cause of humanity. Through ages it has been, pre-eminently, the cause of the Anglo-Saxon race, for which countless heroes have died. With those men it was to defend the rights of their States to[Pg 2] control their own affairs, without dictation from anybody outside; a right not given, but guaranteed by the Constitution, which those States accepted, most distinctly, under that condition.

It was for that these men came. This was just what they had in their minds; to uphold that solemnly guaranteed constitutional right, distinctly binding all the parties to that compact. The South pleaded with the other parties to the Constitution to observe their guarantee; when they refused, and talked of force, then the men of the South got their guns and came to see about it.

They were Anglo-Saxons. What could you expect? Their fathers had fought and died on exactly this issue—they could do no less. As their noble fathers, so their noble sons pledged their lives, and their sacred honor to uphold the same great cause—peaceably if they could; forcibly if they must.

So the men of the South came together. They came from every rank and calling of life—clergymen, bishops, doctors, lawyers, statesmen, governors of states, judges, editors, merchants, mechanics, farmers. One bishop became a lieutenant general; one clergyman, chief of artillery, Army of Northern Virginia. In one artillery battalion three clergymen were cannoneers at the guns. All the students of one Theological Seminary volunteered, and three fell in battle, and all but one were wounded. They came of every age. I personally know of six men over sixty years[Pg 3] who volunteered, and served in the ranks, throughout the war; and in the Army of Northern Virginia, more than ten thousand men were under eighteen years of age, many of them sixteen years.

They came of every social condition of life: some of them were the most prominent men in the professional, social, and political life of their States; owners of great estates, employing many slaves; and thousands of them, horny-handed sons of toil, earning their daily bread by their daily labor, who never owned a slave and never would.

There came men of every degree of intellectual equipment—some of them could hardly read, and per contra, in my battery, at the mock burial of a pet crow, there were delivered an original Greek ode, an original Latin oration, and two brilliant eulogies in English—all in honor of that crow; very high obsequies had that bird.

Men who served as cannoneers of that same battery, in after life came to fill the highest positions of trust and influence—from governors and professors of universities, downward; and one became Speaker of the House of Representatives in the United States Congress. Also, it is to be noted that twenty-one men who served in the ranks of the Confederate Army became Bishops of the Episcopal Church after the war.

Of the men who thus gathered from all the Southern land, the first raised regiments were drawn to Virginia, and there organized into an army whose duty[Pg 4] it was to cover Richmond, the Capital of the Confederacy—just one hundred miles from Washington, which would naturally be the center of military activities of the hostile armies.

The body, thus organized, was composed entirely of volunteers. Every man in it was there because he wanted to come as his solemn duty. It was made up of regiments from every State in the South—Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas and Tennessee. Each State had its quota, and there were many individual volunteers from Kentucky, Missouri and elsewhere. That army was baptized by a name that was to become immortal in the annals of war—“The Army of Northern Virginia.”

What memories cluster around that name! Great soldiers, and military critics of all nations of Christendom, including even the men who fought it, have voiced their opinion of that army, and given it high praise. Many of them, duly considering its spirit, and recorded deeds, and the tremendous odds against which it fought, have claimed for it the highest place on the roll of honor, and in the Hall of Fame, among all the armies of history.

Truly it deserves high place! when you think that after four years of heroic courage, devotion, and endurance, never more than half fed, poorly supplied with clothes, often scant of ammunition, holding the field after every battle, that it fought, till the end,[Pg 5] worn out at last, it disbanded at Appomattox, when only eight thousand hungry men remained with arms in their hands, and they, defiant, and fighting still, when the white flags began to pass. They surrendered then only because General Lee said they must, because he would not vainly sacrifice another man; and they wept like broken-hearted children when they heard his orders. They would have fought on till the last man dropped, but General Lee said: “No, you, my men, go home and serve your country in peace as you have done in war.”

They did as General Lee told them to do, and it was the indomitable courage of those men and of the women of their land, who were just as brave, at home, as the men were, at the front, which has made the South rise from its ruins and blossom as the rose as it does this day.

Thus “yielding to overwhelming numbers and resources,” the Army of Northern Virginia died. But its glory has not died, and the splendor of its deeds has not, and will not grow dim.

As, in vision, I look across the long years that have pressed their length between the now and then, I can see that Army of Northern Virginia on the march. At its head rides one august and knightly figure, Robert E. Lee, the knightliest gentleman, and the saintliest hero that our race has bred. He is on old “Traveler,” almost as famous as his master. On his right rides that thunderbolt of war, Stonewall[Pg 6] Jackson, on “Little Sorrel,” with whose fame the world was ringing when he fell. On Lee’s left, on his beautiful mare, “Lady Annie,” the bright, flashing cavalier, “Jeb” Stuart, the darling of the Army.

Behind these three, in their swinging stride, tramp the long columns of infantry, artillery, and cavalry of the army. As we gaze upon that spectacle, we say, and nothing better can be said, “Those chiefs were worthy to lead those soldiers; those soldiers were worthy to follow Robert Lee.”

In this order, The Army of Northern Virginia, General Lee in front, has come marching down the road of history, and shall march on, and all brave souls of the generations stand at “Salute,” and do them homage as they pass. Noble Army of Northern Virginia!

All true men will understand and none, least of all the brave men who faced it in battle, will deny to the old Confederate the just right to be proud that he was comrade to those men and marched in their ranks, and was with their leader to the end. Of that army, I had, thank God! the honor to be a soldier. It came about in this way.

When the war began I was a school boy attending the Military Academy in Danville, Virginia, where I was born and reared. At once the school broke up. The teachers, and all the boys who were old enough went into the army. I was just sixteen years old, and small for my age, and I can understand now, but could[Pg 7] not then, how my parents looked upon the desire of a boy like that to go to the war, as out of the question. I did not think so. I was a strong, well-knit fellow, and it seemed to me that what you required in a soldier was a man who could shoot, and would stay there and do it. I knew I could shoot, and I thought I could stay there and do it, so I was sure I could be a soldier, and I was crazy to go, but my parents could not see it so, and I was very miserable. All my classmates in school had gone or were going, and I pictured to myself the boys coming back from the war, as soldiers who had been in battle, and all the honors that would be showered upon them—and I would be out of it all. The thought that I had not done a manly part in this great crisis would make me feel disgraced all my life. It was horrible.

My father, the honored and beloved minister of the Episcopal Church in Danville, and my mother, the daughter and grand-daughter of two Revolutionary soldiers, said they wanted me to go, and would let me go, when I was older—I was too young and small as yet. But I was afraid it would be all over before I got in, and I would lay awake at night, sad and wretched with this fear. I need not have been afraid of that. There was going to be plenty to go around, but I did not know that then, and I was low in mind. I suppose that my very strong feeling on the subject was natural. It was the inherited microbe in the blood. Though I was only a school boy in a back[Pg 8] country town, my forebears had always been around when there was any fighting to be done. My great-grandfather, General Thomas Nelson, and my grandfather, Major Carter Page, and all their kin of the time had fought through the Revolutionary War. My people had fought in the war of 1812, and the Mexican War, and the Indian Wars. Whenever anybody was fighting our country, some of my people were in it, and back of that, Lord Nelson of Trafalgar, was a second cousin of my great-grandfather, Thomas Nelson; and, still farther back of that, my ancestor, Thomas Randolph, in command of a division of the Scottish Army under King Robert Bruce, was the man who, by his furious charge, broke the English line at “Bannockburn” and won the Independence of Scotland.

You see that a boy, with all that back of him, in his family, had the virus in his blood, and could not help being wretched when his country was invaded, and fighting, and he not in it. He would feel that he was dishonoring the traditions of his race, and untrue to the memory of his fathers. However, that schoolboy brooding over the situation was mighty miserable. When my parents realized my feelings, they, at last, gave up their opposition, and I went into the army with their consent, and blessing.

While this matter was hanging fire, having been at a military academy, I was trying to do some little service by helping to drill some of the raw companies[Pg 9] which were being rapidly raised, in and around Danville. The minute I was free, off I went. Circumstances led me to enlist in a battery made up in Richmond, known as the “First Company of Richmond Howitzers,” and I was thus associated with as fine a body of men as ever lived—who were to be my comrades in arms, and the most loved, and valued friends of my after life.

This battery was attached to “Cabell’s Battalion” and formed part of the field artillery of Longstreet’s Corps, Army of Northern Virginia. It was a “crack” battery, and was always put in when anything was going on. It served with great credit, and was several times mentioned in General Orders, as having rendered signal service to the army. It was in all the campaigns, and in action in every battle of the Army of Northern Virginia. It fought at Manassas, Williamsburg, Seven Pines, Seven Days’ Battle around Richmond in 1862, Second Manassas, Sharpsburg, Harpers Ferry, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Morton’s Ford, The Wilderness, The Battles of Spottsylvania Court House, North Anna, Pole Green Church, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, and at Appomattox Court House. Every one of the cannoneers, who had not been killed or wounded, was at his gun in its last fight. The very last thing it did was to help “wipe up the ground” with some of Sheridan’s Cavalry, which attacked and tried to ride us[Pg 10] down, but was cut to pieces by our cannister fire, and went off as hard as their horses could run—as if the devil was after them. Then the surrender closed our service.

My comrades, as the rest of the army, scattered to their homes. I went to my home in Danville, and had to walk 180 miles to get there. After a few days, which I chiefly employed in trying to get rid of the sensation of starving, I went to work—got a place in the railroad service.

After eighteen months of this, I proceeded to carry out a purpose that I had in mind since the closing days of the war. I had been through that long and bloody conflict; I had been at my gun every time it went into action, except once when I was lying ill of typhoid fever; I had been in the path of death many times, and though hit several times, had never been seriously wounded, or hurt badly enough to have to leave my gun—and here I was at the end of all this—alive, and well and strong, and twenty years of age. As I thought of God’s merciful protection through all those years of hardship and danger, a wish and purpose was born, and got fixed in my mind and heart, to devote my life to the service of God in the completest way I could as a thanksgiving to Him. Naturally, my thoughts turned to the ministry of the Gospel, and I decided to enter the seminary and train for that service as soon as the way was open.

[Pg 11]While I was in the railroad train work, I studied hard in the scraps of time to get some preparation, and in September, 1866, I entered the Virginia Theological Seminary along with twenty-five other students—all of whom were Confederate soldiers. I here tackled a job that was much more trying than working my old twelve-pounder brass Napoleon gun in a fight. I would willingly have swapped jobs, if it had been all the same, but I worked away, the best I could, at the Hebrew, and Greek, and “Theology,” and all the rest, for three years.

Somehow I got through, and graduated, and was ordained by Bishop Johns of Virginia, the twenty-sixth of June, 1869. Thus the old cannoneer was transformed into a parson, who intended to try to be as faithful to duty, as a parson, as the old cannoneer had been. He has carried that purpose through life ever since. How far he has realized it, others will have to judge.

After serving for nine years in several parishes in Virginia, I came to Baltimore as rector of Memorial Church, and have been here ever since. Hence I have served in the ministry for fifty years—forty-one of which I have spent serving the Memorial Church, and having, as a side line, been Chaplain of the “Fifth Regiment Maryland National Guard” for thirty-odd years. When one is bitten by the military “bee” in his youth, he never gets over it—the sight[Pg 12] of a line of soldiers, and the sound of martial music stirs me still, as it always did, and I have had the keenest interest and pleasure in my association with that splendid regiment, and my dear friends and comrades in it.

So, through the changes and chances of this mortal life, I have come thus far, and by the blessing of God, and the patience of my people, at the age of seventy-four I am still in full work among the people, whom I have served so long, and loved so well—still at my post where I hope to stay till the Great Captain orders me off to service in the only place I know of, that is better than the congregation of Memorial Church, and the community of Baltimore—and that is the everlasting Kingdom of Heaven.

Now, what I have been writing here is intended to lead up to the narrative set forth in the pages of this volume. Sam Weller once said to Mr. Pickwick, when invited to eat a veal pie, “Weal pies is werry good, providin’ you knows the lady as makes ’em, and is sure that they is weal and not cats.” The remark applies here: a narrative is “werry good providin’ you knows” the man as makes it, and are sure that it is facts, and not fancy tales. You want to be satisfied that the writer was a personal witness of the things he writes about, and is one who can be trusted to tell you things as he actually saw them. I hope both these conditions are fulfilled in this narrative.

[Pg 13]But some one might say, “How about this narrative that you are about to impose on a suffering public, who never did you any harm? What do you do it for?”

Well, I did not do it of malice aforethought. It came about in this way. Young as I was when I went into the war, and never having seen anything of the world outside the ordinary life of a boy, in a quiet country town, the scenes of that soldier life made a deep impression on my mind, and I have carried a very clear recollection of them—everyone—in my memory ever since. As I have looked back, and thought upon the events, and especially the spirit, and character, and record, of my old comrades in that army, my admiration, and estimate of their high worth as soldiers has grown ever greater, and I felt a very natural desire that others should know them as I knew them—and put them in their rightful rank as soldiers. The only way to do this is for those who know to tell people about them; what manner of warriors they were.

Now mark how one glides into mischief unintentionally. Years ago, I was beguiled into making, at various times, places, and occasions, certain, what might be called, “Camp Fire Talks” descriptive of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia. Weakly led on by the kindly expressed opinions of those who heard these talks, and urged by old friends,[Pg 14] and comrades, and others, I ventured on a more connected narrative of our observations and experiences, as soldiers in that army. I wrote a sketch, in that vein, of the “Spottsylvania Campaign”—in 1864—fought between General Lee and General Grant. It was a tremendous struggle of the two armies for thirty days—almost without a break. It was a thrilling period of the war, and brought out the high quality of both the Commander and the fighting men of the Army of Northern Virginia.

It was the bloodiest struggle known to history, up to that time. As one item, at Cold Harbor, General Grant, in fifteen minutes, by the watch, lost 13,723 men, killed and wounded, irrespective of many prisoners—more men in a quarter of an hour than the British Army lost in the whole battle of Waterloo. That gives an idea of the terrible intensity of that campaign—one incident of it the bloodiest quarter of an hour in all the history of war.

I took as a title for my sketch “From the Rapidan to Richmond” or “The Bloody War Path of 1864”—“The Scenes One Soldier Saw.”

As a guarantee of its accuracy, I took that narrative to Richmond, and in the presence of fifteen of my old comrades of the First Howitzers, every man of whom had been along with me through all the incidents of which I wrote, and therefore had personal knowledge of all the facts, I read it, and we freely discussed it. What resulted has the approval, and [Pg 15]endorsement of all those personal witnesses, and may be counted on as accurate—in every statement and impression made in this story, and may be safely accepted by the reader as a true narration of facts.

I am urged to put the narrative in such form that its contents may be more widely known, and I am glad to do it. I do want as many as possible to know my old comrades as I knew them, and value them at their true worth. My narrative is a true account of that soldier life, and illustrates the stuff of which those men of the Army of Northern Virginia were made. The story illustrates this in a graphic and impressive way, because it is a simple and homely story of how they lived, and what they did—showing what they were. It is an honorable testimony to the character, and worth, as patriot soldiers, of my old comrades—borne by one who saw them display their courage, and endurance, and devotion in heroic conduct, in every possible way, through the long strain, and stress of war—to the end.

I believe there is interest and value, to the true understanding of history, in such narratives of personal witnesses to the men, and things, and conditions of that past, which reflected so much glory on the manhood of our American race; which sterling quality, of high soldierly worth, has just been shown again, in the present generation of our race, when American soldiers, drawn from the North, South, East and West have stood, shoulder to shoulder, in the one[Pg 16] American line, under the Star-Spangled Banner, and fighting for the freedom of the world. Our splendid American men of today are what they are, and have done what they did, because the blood of their sires runs in them; because they are “the same breed of dogs” with the American soldiers, who, on both sides, in the bloody struggle of the Civil War, bore them so bravely in the days gone by.

This narrative only paints the picture, and gives a sample of the Anglo-Saxon American soldier of the generation just gone; it shed lustre upon our race. This generation has done the same—all honor to both!

Let us Americans, at all cost, keep pure the Anglo-Saxon blood, to which this America belongs, of right; let us as a nation, Americans all, work and dwell together in true comradeship, and let our nation walk in just and right ways, for our country. Then, indeed, our heart’s aspiration shall be fulfilled.

“And the Star-Spangled Banner forever shall wave

O’er the land of the free—and the home of the brave.”

As a preface to the sketch of the active campaign, I have given some account of our life in the winter quarters camp, the winter before, from which we marched to battle when the Spottsylvania Campaign opened.

From Orange Court House, Virginia, the road running northeast into Culpeper crosses Morton’s Ford of the Rapidan River, which, in December, 1863, lay between the “Federal Army of the Potomac” and the “Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.” The Ford is nineteen miles from Orange Court House.

Just after the battle of Mine Run, November 26 to 28, our Battery left its bivouac near the Court House, and marched to the Ford. As the road reaches a point within three-quarters of a mile of the river, it rises over a sharp hill and thence winds its way down the hill to the Ford. On the ridge, just where the road crosses it, the guns of the Battery, First Company of Richmond Howitzers, were placed in position, commanding the Ford, and the Howitzer Camp was to the right of the road, in the pine woods just back of the ridge. We had been sent here to help the Infantry pickets to watch the enemy, and guard the Ford.[Pg 18] Orders were that we should remain in this position all winter, and were to make ourselves as comfortable as we could, with a view to this long stay. We got there December 2 and 3, and, in fact, did stay there until the opening of the spring campaign, May 3, 1864.

With these instructions, as soon as we placed our guns in battery on the hill, we went promptly to work to fix up winter quarters in the shelter of the pines down the hill just a few rods back of the guns. It was getting very cold, and rough weather threatened, so we pitched in and worked hard to get ready for it.

Each group of tent mates chose their own site and thereon built such a house as suited their energy, and judgment, or fancy. Some few of the lazy ones stayed under canvas all winter, but most of us constructed better quarters. In my group, four of us lived together, and we built after this manner. On our selected site, we marked off a space about ten feet square. We dug to the line all around, and to a depth of three or four feet in the ground—this going below the surface of the ground gave a better protection against wind and cold than any wall one could build—and on that bleak hill you wanted all the shield from wind that you could get. Having dug a hole ten feet square and three feet deep, we went into the woods and cut, squared, and carried on our shoulders logs, twelve or eighteen inches thick, and twelve feet long—enough to build around three sides of that hole a wall four feet high. Half of the fourth side was[Pg 19] taken up by the chimney, which was built of short logs split in half and covered well inside with mud. With such suitable stones as we could pick up, we lined the fire place immediately around the fire, and as far above as we had rocks to do it with. The other half of the fourth side was left for the door, over which was hung any old blanket or other cloth that we could beg, borrow or steal.

The log walls done, we dug a deep hole, loosened up the clay at the bottom, poured in water and mixed up a lot of mud with which we chinked up the interstices between the logs and covered the wood in the chimney. The earth that had been thrown up in digging the hole, we now banked up against the log wall all around, which made it wind proof; and then over this gem of architecture we stretched our fly. We had no closed tents—only a fly, a straight piece of tent cloth all open at the sides. Our fly, supported by a rude pole, and drawn down and firmly fastened to the top of the log wall, made the roof of the house.

Then we went out and cut small poles and made a bunk, to lift us off the ground. Over the expanse of springy poles we spread sprigs of cedar—and this made a pretty good spring mattress. Last of all, we dug a ditch all around our house to keep the water from draining down into our room and driving us out. Then we went in, built a fire in our fireplace, called in our friends, and had a house-warming. The refreshments were parched corn, persimmons (which[Pg 20] two of us walked two miles to get) and water. Of the latter, we had plenty in canteens borrowed from the boys. We had a bully time, and we kept it up late. Then we went to bed in our cosy bunk and slept like graven images till reveille next morning. Thus we were housed for the winter—“under our own vine and fig tree,” so to speak.

Most of the other houses were built after the same general style. We bragged that we had the best house in camp, and were very chesty about it. Others did likewise.

The men’s quarters ready, we at once set to work on stables for the horses, of which there were about seventy, belonging to the Battery. All hands were called in to do this work. We scattered through the woods, cut logs and carried them on our shoulders to the spot selected. We built up walls around three sides, leaving the fourth or sunny side open. Then we cut logs into three or four foot lengths and split them into slabs, and with these slabs, as a rough sort of shingle, covered the roof and weighted them down, in place, with long, heavy logs laid across each row of slabs. Then we mixed mud and stopped up the cracks in the log walls. Altogether, we had a good, strong wind and rain-proof building, which was an effective shelter for the horses and in which they kept dry and comfortable through the winter—which was a cold and stormy one. All the men worked hard, and we soon had the stable finished, and the horses[Pg 21] housed. Thus our building work was done, and we settled into the regular routine of camp life.

Perhaps a little sketch of our life in winter quarters, how we lived, how we employed ourselves, and what we did to pass away the time, may be interesting. I will try to give you some account of all that.

Of course, we all had our military duties to attend to regularly. The drivers had to clean, feed, water, and exercise the horses, and keep the stables in order. The “cannoneers” had to keep the guns clean, bright, and ready for service any minute—also they had to stand guard at the guns on the hill all the time, and over the camp, at night, to guard the forage, and look after things generally. We had to drill some every day—police the camp and keep the roads near the camp in order. To this day’s work we were called, every morning at six o’clock, by the bugler blowing the reveille. I may mention the fact that Prof. Francis Nicholas Crouch, the composer of the famous and beautiful song, “Kathleen Mavourneen,” was the bugler of our Battery, and he was the heartless wretch who used to persecute us that way. To be waked up and hauled out about day dawn on a cold, wet, dismal morning, and to have to hustle out and stand shivering at roll call, was about the most exasperating item of the soldier’s life. The boys had a[Pg 22] song very expressive of a soldier’s feelings when nestling in his warm blankets, he heard the malicious bray of that bugle. It went like this:

“Oh, how I hate to get up in the morning;

Oh, how I’d like to remain in bed.

But the saddest blow of all is to hear the bugler call,

‘You’ve got to get up, you’ve got to get up,

You’ve got to get up this morning!’

“Some day I’m going to murder that bugler;

Some day they’re going to find him dead.

I’ll amputate his reveille,

And stamp upon it heavily,

And spend the rest of my life in bed!”

We didn’t kill old Crouch—I don’t know why, except that he was protected by a special providence, which sometimes permits such evil deeds to go unpunished. We used to hope that he would blow his own brains out, through his bugle, but he didn’t—he lived many years after the war.

In between our stated duties, we had some time in which we could amuse ourselves as we chose, and we had many means of entertainment. We had a chessboard and men—a set of quoits, dominoes, and cards; and there was the highly intellectual game of “push pin” open to all comers. Some very skillful chess players were discovered in the company. When the weather served, we had games of ball, and other[Pg 23] athletic games, such as foot races, jumping, boxing, wrestling, lifting heavy weights, etc. At night we would gather in congenial groups around the camp fires and talk and smoke and “swap lies,” as the boys expressed it.

There was one thing from which we got a great deal of fun. We got up an organization amongst the youngsters which was called the “Independent Battalion of Fusiliers.” The basal principle of this kind of heroes was, “In an advance, always in the rear—in a retreat, always in front. Never do anything that you can help. The chief aim of life is to rest. If you should get to a gate, don’t go to the exertion of opening it. Sit down and wait until somebody comes along and opens it for you.”

After the first organizers, no one applied for admission into the Battalion—they were elected into it, without their consent. The way we kept the ranks full was this: Whenever any man in the Battery did any specially trifling, and good-for-nothing thing, or was guilty of any particularly asinine conduct, or did any fool trick, or expressed any idiotic opinion, he was marked out as a desirable recruit for the Fusiliers. We elected him, went and got him and made him march with us in parade of the Battalion, and solemnly invested him with the honor. This was not always a peaceable performance. Sometimes the candidate, not appreciating his privilege, had to be held by force, and[Pg 24] was struggling violently, and saying many bad words, during the address of welcome by the C. O.

I grieve to say that an election into this notable corps was treated as an insult, and responded to by hot and unbecoming language. One fellow, when informed of his election, flew into a rage, and said bad words, and offered to lick the whole Battalion. But what would they have? We were obliged to fill up the ranks.

After a while it did come to be better understood, and was treated as a joke, and some of the more sober men entered into the fun, and would go out on parade, and take part in the ceremony. We paraded with a band composed of men beating tin buckets, frying pans, and canteens, with sticks, and whistling military music. It made a noisy and impressive procession. It attracted much attention and furnished much amusement to the camp.

On proper occasions, promotions to higher rank were made for distinguished merit in our line. An instance will illustrate. One night, late, I was passing along when I saw this sight. The sentinel on guard in camp was lying down on a pile of bags of corn at the forage pile—sound asleep. He was lying on his left side. One of the long tails of his coat was hanging loose from his body and dangling down alongside the pile of bags. A half-grown cow had noiselessly sneaked up to the forage pile, and been attracted by that piece of cloth hanging loose—and, as calves will[Pg 25] do, took the end of it into her mouth and was chewing it with great satisfaction. I called several of the fellows, and we watched the proceedings. The calf got more and more of the coat tail into her mouth. At length, with her mouth full of the cloth, and perhaps with the purpose of swallowing what she had been chewing she gave a hard jerk. The cloth was old, the seams rotten—that jerk pulled the whole of that tail loose from the body of the coat. The sleeping guard never moved. We rescued the cloth from the calf, and hid it. When the sleeper awoke, to his surprise, one whole tail of his coat was gone, and he was left with only one of the long tails. Our watching group, highly delighted at the show of a sentinel sleeping, while a calf was browsing on him, told him what had happened and that the calf had carried off the other coat tail. He was inconsolable. He was the only private in the company who had a long-tailed coat and it was the pride of his heart. There was no way of repairing the loss, and he had to go around for days, sad and dejected, shorn of his glory—with only one tail to his coat.

All this was represented to the “Battalion of Fusiliers.” Charges were preferred, and the Court Martial set. The witnesses testified to the facts—also said that if we had not driven off the calf it would have gone on, after getting the coat tail, and chewed up the sentinel, too. The findings of the Court Martial were nicely adjusted to the merits of the case. It was,[Pg 26] that the witnesses were sentenced to punishment for driving off the calf, and not letting her eat up the sentinel.

For the sentinel, who appeared before the Court with the one tail to his coat, it was decreed that his conduct was the very limit. No one could ever hope to find a more thorough Fusilier than the man who went to sleep on guard and let a calf eat his clothes off. Such conduct deserved most distinguished regard, as an encouragement to the Fusiliers. He was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-General of the Battalion, the highest rank in our corps. After a while the lost coat tail was produced, and sewed on again.

The one thing that we suffered most from, the hardship hardest to bear, was hunger. The scantiness of the rations was something fierce. We never got a square meal that winter. We were always hungry. Even when we were getting full rations the issue was one-quarter pound of bacon, or one-half pound of beef, and little over a pint of flour or cornmeal, ground with the cob on it, we used to think—no stated ration of vegetables or sugar and coffee—just bread and meat. Some days we had the bread, but no meat; some days the meat, but no bread. Two days we had nothing, neither bread nor meat—and it was a solemn and empty crowd. Now and then, at long intervals, they gave us some dried peas. Occasionally, a little sugar—about an ounce to a man for a three days’ ration. The Orderly of the mess would spread the[Pg 27] whole amount on the back of a tin plate, and mark off thirteen portions, and put each man’s share into his hand—three days’ rations, this was. One time, in a burst of generosity, the Commissary Department stunned us by issuing coffee. We made “coffee” out of most anything—parched corn, wheat or rye—when we could get it. Anything for a hot drink at breakfast! But this was coffee—“sure enough” coffee—we called it. They issued this three times. The first time, when counted out to the consumer, by the Orderly, each man had 27 grains. He made a cup—drank it. The next time the issue was 16 grains to the man—again he made a cup and drank it. The third issue gave nine grains to the man. Each of these issues was for three days’ rations. By now it had got down to being a joke, so we agreed to put the whole amount together, and draw for which one of the mess should have it all—with the condition, that the winner should make a pot of coffee, and drink it, and let the rest of us see him do it. This was done. Ben Lambert won—made the pot of coffee—sat on the ground, with us twelve, like a coroner’s jury, sitting around watching him, and drank every drop. How he could do it, under the gaze of twelve hungry men, who had no coffee, it is hard to see, but Ben was capable of very difficult feats. He drank that pot of coffee—all the same!

After this, there was no more issue of coffee. Even a Commissary began to be dimly conscious that nine[Pg 28] grains given a man for a three days’ rations was like joking with a serious subject, so they quit it, and during that winter we had mostly just bread and meat—very little of that, and that little not to be counted on.

This hunger was much the hardest trial we had to bear. We didn’t much mind getting wet and cold; working hard, standing guard at night; and fighting when required—we were seasoned to all that—but you don’t season to hunger. Going along all day with a gnawing at your insides, of which you were always conscious, was not pleasant. We had more appetite than anything else, and never got enough to satisfy it—even for a time.

Under this very strict regime, eating was like to become a lost art and our digestive organs had very little to do. We had very little use for them, in these days. A story went around the camp to this effect: One of the men got sick—said he had a pain in his stomach and sent for the surgeon. The doctor, trying to find the trouble, felt the patient’s abdomen, and punched it, here and there. After a while he felt a hard lump, which ought not to be there. The doctor wondered what it could be—then feeling about, he found another hard lump, and then another, and another. Then the doctor was perfectly mystified by all those hard places in a man’s insides. At last, the explanation came to him: he was feeling the vertebræ of the fellow’s back-bone—right through his stomach!

[Pg 29]I do not vouch for the exact accuracy of all the details of the story, but it illustrates the situation. We all felt that our stomachs had dwindled away for want of use and exercise.

Another incident, that I can vouch for, showing the strenuous time the whole army had about food that winter: One day Major-Quartermaster John Ludlow, of Norfolk, met a Captain of Artillery from his own town of Norfolk—Capt. Charles Grandy, of the Norfolk Light Artillery Blues. The Major invited the Captain to dine with him on a certain day. He did not expect anything very much, but there was a seductive sound in the word “dining” and he accepted. Grandy told the story of his experience on that festive occasion. He walked two miles to Major Ludlow’s quarters, and was met with friendly cordiality by his old fellow-townsman, and ushered into his hut where a bright fire was burning. After a time spent in conversation, the Major began to prepare for dinner. He reached up on a shelf, and took down a cake of bread, cut it into two pieces, and put them in a frying pan on the fire to heat. Then he reached up on the shelf and got down a piece of bacon—not very large—cut it into two pieces, and put them in another pan on the fire to fry. Down in the ashes by the fire was a tin cup covered over—its contents not visible. The dining table was an old door, taken from some barn and set up on skids.

[Pg 30]When the bread and meat were ready, the Major put it on the table and with a courtly wave of his hand said, “D-d-draw up, Charley.” They seated themselves. The Major gave a piece of bread and a piece of bacon to his guest, and took the other piece, of each, for himself. After he had eaten a while—the Major got up, went to the fireplace and took up the tin cup. He poured off the water, and, behold, one egg came to view. This egg, the Major put on a plate and, coming to the table, handed it to Grandy—“Ch-Ch-Charley, take an egg,” as if there were a dish full. Charley, having been brought up to think it not good manners to take the last thing on the dish, declined to take the only egg in sight—said he didn’t care specially for eggs! though he said he would have given a heap for that egg, as he hadn’t tasted one since he had been in the army. “But,” urged the Major, “Ch-Ch-Charley, I insist that you take an egg. You must take one—there is going to be plenty—do take it.” Under this encouragement, Grandy took the egg—while he was greatly enjoying it, suddenly there was a flutter in the corner of the hut. An old hen flew up from behind a box in the corner, lit on the side of the box and began to cackle loudly. The Major turned to Grandy and said, “I-I t-t-told you there was going to be a plenty. I invited you to dinner today because this was the day for the hen to lay.” He went over and got the fresh egg from behind the box, cooked and ate it.[Pg 31] So each of the diners had an egg. The incident was suggestive of the situation. Here was a Quartermaster appointing a day for dining a friend—depending for part of the feast on his confidence that his hen would come to time. The picture of that formal dinner in the winter quarters on the Rapidan is worth drawing. It was a fair sign of the times, and of life in the Army of Northern Virginia; when it came to a Quartermaster giving to an honored, and specially invited guest, a dinner like that—it indicates a general scarceness.

One bright spot in that “winter of our discontent”—lives in my memory. It was on the Christmas Day of 1863. That was a day specially hard to get through. The rations were very short indeed that day—only a little bread, no meat. As we went, so hungry, about our work, and remembered the good and abundant cheer always belonging to Christmas time; as we thought of “joys we had tasted in past years” that did not “return” to us, now, and felt the woeful difference in our insides—it made us sad. It was harder to starve on Christmas Day than any day of the winter.

When the long day was over and night had come, some twelve or fifteen of us, congenial comrades, had gathered in a group, and were sitting out of doors around a big camp fire, talking about Christmas, and trying to keep warm and cheer ourselves up.

One fellow proposed what he called a game, and it was at once taken up—though it was a silly thing[Pg 32] to do, as it only made us hungrier than ever. The game was this—we were to work our fancy, and imagine that we were around the table at “Pizzini’s,” in Richmond. Pizzini was the famous restauranteur who was able to keep up a wonderful eating house all through the war, even when the rest of Richmond was nearly starving. Well—in reality, now, we were all seated on the ground around that fire, and very hungry. In imagination we were all gathered ’round Pizzini’s with unlimited credit and free to call for just what we wished. One fellow tied a towel on him, and acted as the waiter—with pencil and paper in hand going from guest to guest taking orders—all with the utmost gravity. “Well, sir, what will you have?” he said to the first man. He thought for a moment and then said (I recall that first order, it was monumental) “I will have, let me see—a four-pound steak, a turkey, a jowl and turnip tops, a peck of potatoes, six dozen biscuits, plenty of butter, a large pot of coffee, a gallon of milk and six pies—three lemon and three mince—and hurry up, waiter—that will do for a start; see ’bout the rest later.”

This was an order for one, mind you. The next several were like unto it. Then, one guest said, “I will take a large saddle of mountain mutton, with a gallon of crabapple jelly to eat with it, and as much as you can tote of other things.”

This, specially the crabapple jelly, quite struck the next man. He said, “I will take just the same as this[Pg 33] gentleman.” So the next, and the next. All the rest of the guests took the mountain mutton and jelly.

All this absurd performance was gone through with all seriousness—making us wild with suggestions of good things to eat and plenty of it.

The waiter took all the orders and carefully wrote them down, and read them out to the guest to be sure he had them right.

Just as we were nearly through with this Barmecide feast, one of the boys, coming past us from the Commissary tent, called out to me, “Billy, old Tuck is just in (Tucker drove the Commissary wagon and went up to Orange for rations) and I think there is a box, or something, for you down at the tent.”

I got one of our crowd to go with me on the jump. Sure enough, there was a great big box for me—from home. We got it on our shoulders and trotted back up to the fire. The fellows gathered around, the top was off that box in a jiffy, and there, right on top, the first thing we came to—funny to tell, after what had just occurred—was the biggest saddle of mountain mutton, and a two-gallon jar of crabapple jelly to eat with it. The box was packed with all good, solid things to eat—about a bushel of biscuits and butter and sausage and pies, etc., etc.

We all pitched in with a whoop. In ten minutes after the top was off, there was not a thing left in that box except one skin of sausage which I saved for our mess next morning. You can imagine how the boys[Pg 34] did enjoy it. It was a bully way to end up that hungry Christmas Day.

I wrote my thanks and the thanks of all the boys to my mother and sisters, who had packed that box, and I described the scene as I have here described it, which made them realize how welcome and acceptable their kind present was—and what comfort and pleasure it gave—all the more that it came to us on Christmas Day, and made it a joyful one—at the end, at least.

In regard to all this low diet from which we suffered so much hunger that winter—it is well worthy of remark that the health of the army was never better. At one time that winter there were only 300 men in hospital from the whole Army of Northern Virginia—which seems to suggest that humans don’t need as much to eat as they think they do. That army was very hungry, but it was very healthy! It looks like cause and effect! But it was a very painful way of keeping healthy. I fear we would not have taken that tonic, if we could have helped it, but we couldn’t! Maybe it was best as it was. Let us hope so!

Well, the winter wore on in this regular way until the 3d or 4th of February, when our quiet was suddenly disturbed in a most unexpected manner. Right in the dead of a stormy winter, when nobody looked for any military move—we had a fight. The enemy got “funny” and we had to bring him to a more serious state of mind, and teach him how wrong it was to disturb the repose of gentlemen when they were not looking[Pg 35] for it, and not doing anything to anybody—just trying to be happy, and peaceable if they could get a chance.

Leading up to an account of this, I may mention some circumstances in the way of the boys in the camp. Living the hard life, we were—one would suppose that fashion was not in all our thoughts; but even then, we felt the call of fashion and followed it in such lines, as were open to us. The instinct to “do as the other fellow does” is implanted in humans by nature; this blind impulse explains many things that otherwise were inexplicable. With the ladies it makes many of them wear hats and dresses that make them look like hoboes and guys, and shoes that make them walk about as gracefully as a cow in a blanket, instead of looking, and moving like the young, graceful gazelles—that nature meant, and men want them to look like. Taste and grace and modesty go for nothing—when fashion calls.

Well, the blind impulse that affects the ladies so—moved us in regard to the patches put on the seats of our pants. This was the only particular in which we could depart from the monotony of our quiet, simple, gray uniform—which consisted of a jacket, and pants and did not lend itself to much variety; but fashion found a way.

There must always be a leader of fashion. We had one—“The glass of fashion and the mould of[Pg 36] form” in our gang was Ben Lambert. He could look like a tombstone, but was full of fun, and inventive genius.

Our uniform was a short jacket coming down only to the waist, hence a hole in the seat of the pants was conspicuous, and was regarded as not suited to the dignity and soldierly appearance of a Howitzer. For one to go around with such a hole showing—any longer than he could help it—was considered a want of respect to his comrades. Public opinion demanded that these holes be stopped up as soon as possible. Sitting about on rough surfaces—as stumps, logs, rocks, and the ground—made many breaks in the integrity of pants, and caused need of frequent repairs, for ours was not as those of the ancient Hebrews to whom Moses said, “Thy raiment waxed not old upon thee”—ours waxed very old, before we could get another pair, and were easily rubbed through. The more sedate men were content with a plain, unpretentious patch, but this did not satisfy the youngsters, whose æsthetic souls yearned for “they know not what,” until Ben Lambert showed them. One morning he appeared at roll call with a large patch in the shape of a heart transfixed with an arrow, done out of red flannel. This at once won the admiration and envy of the soldiers. They now saw what they wished, in the way of a patch, and proceeded to get it. Each one set his ingenuity to work to devise something unique. Soon the results began to appear. Upon the seats of one, and[Pg 37] another, and another, were displayed figures of birds, beasts and men—a spread eagle, a cow, a horse, a cannon. One artist depicted a “Cupid” with his bow, and just across on the other hip a heart pierced with an arrow from Cupid’s bow—all wrought out of red flannel and sewed on as patches to cover the holes in the pants, and, at the same time, present a pleasing appearance. By and by these devices increased in number, and when the company was fallen in for roll call the line, seen from the rear, presented a very gay and festive effect.

One morning, a General, who happened in camp—the gallant soldier, and merry Irishman, General Pat Finnegan, was standing, with our Captain, in front of the line, hearing the roll call.

That done, the Orderly Sergeant gave the order, “’Bout face!” The rear of the line was thus turned toward General Finnegan. When that art gallery—in red flannel—was suddenly displayed to his delighted eyes the General nearly laughed himself into a fit.

“Oh, boys,” he cried out, “don’t ever turn your backs upon the enemy. Sure they’ll git ye—red makes a divil of a good target. But I wouldn’t have missed this for the world.”

The effect, as seen from the rear, was impressive. It could have been seen a mile off—bright red patches on dull gray cloth. Anyhow it was better than the holes and it made a ruddy glow in camp. Also it gave the men much to amuse them.

[Pg 38]Ben set the fashion in one other particular—viz., in hair cuts. He would come to roll call with his hair cut in some peculiar way, and stand in rank perfectly solemn. Ranks broken, the boys would gather eagerly about him, and he would announce the name of that “cut.” They would, as soon as they could, get their hair cut in the same style.

One morning, he stood in rank with every particle of his hair cut off, as if shaved, and his head as bare as a door knob. “What style is that, Ben?” the boys asked. “The ‘horse thief’ cut,” he gravely announced. Their one ambition now, was to acquire the “horse-thief cut.”

There was only one man in the Battery who could cut hair—Sergeant Van McCreery—and he had the only pair of scissors that could cut hair. So every aspirant to this fashionable cut tried to make interest with Van to fix him up; and Van, who was very good natured, would, as he had time and opportunity, accommodate the applicant, and trim him close. Several of us had gone under the transforming hands of this tonsorial artist, when Bob McIntosh got his turn. Bob was a handsome boy with a luxuriant growth of hair. He had raven black, kinky hair that stuck up from his head in a bushy mass, and he hadn’t had his hair cut for a good while, and it was very long and seemed longer than it was because it stuck out so from his head. Now, it was all to go, and a crowd of the boys[Pg 39] gathered ’round to see the fun. The modus operandi was simple, but sufficient. The candidate sat on a stump with a towel tied ’round his neck, and he held up the corners making a receptacle to catch the hair as it was cut. Why this—I don’t know; force of habit I reckon. When we were boys and our mothers cut our hair, we had to hold up a towel so. We were told it was to keep the hair from getting on the floor and to stuff pincushions with. Here was the whole County of Orange to throw the hair on, and we were not making any pincushions—still Bob had to hold the towel that way. Van stood behind Bob and began over his right ear. He took the hair off clean, as he went, working from right to left over his head; the crowd around—jeering the victim and making comments on his ever-changing appearance as the scissors progressed, making a clean sweep at every cut. We were thus making much noise with our fun at Bob’s expense, until the shears had moved up to the top of his head, leaving the whole right half of the head as clean of hair as the palm of your hand, while the other half was still covered with this long, kinky, jet black hair, which in the absence of the departed locks looked twice as long as before—and Bob did present a spectacle that would make a dog laugh. It was just as funny as it could be.

Just at that moment, in the midst of all this hilarity, suddenly we heard a man yell out something as he came running down the hill from the guns. We[Pg 40] could not hear what he said. The next moment, he burst excitedly into our midst, and shouted out, “For God’s sake, men, get your guns. The Yankees are across the river and making for the guns. They will capture them before you get there, if you don’t hurry up.”

This was a bolt out of a clear sky—but we jumped to the call. Everybody instantly forgot everything else and raced for the guns. I saw McCreery running with the scissors in his hand; he forgot that he had them—but it was funny to see a soldier going to war with a pair of scissors! I found myself running beside Bob McIntosh, with his hat off, his head half shaved and that towel, still tied round his neck, streaming out behind him in the wind.

Just before we got to the guns, Bob suddenly halted and said, “Good Heavens, Billy, it has just come to me what a devil of a fix I am in with my head in this condition. I tell you now that if the Yankees get too close to the guns, I am going to run. If they got me, or found me dead, they would say that General Lee was bringing up the convicts from the Penitentiary in Richmond to fight them. I wouldn’t be caught dead with my head looking like this.”

We got to the guns on the hill top and looked to the front. Things were not as bad as that excited messenger had said, but they were bad enough. One brigade of the enemy was across the river and moving on us; another brigade was fording the river; and we[Pg 41] could see another brigade moving down to the river bank on the other side. Things were serious, because the situation was this: an Infantry Brigade from Ewell’s Corps, lying in winter quarters in the country behind us, was kept posted at the front, whose duty it was to picket the river bank. It was relieved at regular times by another Brigade which took over that duty.

It so chanced that this was the morning for that relieving Brigade to come. Expecting them to arrive any minute, the Brigade on duty, by way of saving time, gathered in its pickets and moved off back toward camp. The other Brigade had not come up—careless work, perhaps, but here in the dead of winter nobody dreamed of the enemy starting anything.

So it was, that, with one brigade gone; the other not up; the pickets withdrawn, at this moment there was nobody whatsoever on the front except our Battery—and, here was the enemy across the river, moving on us and no supports.

In the meantime, the enemy guns across the river opened on us and the shells were flying about us in lively fashion. It was rather a sudden transition from peace to war, but we had been at this business before; the sound of the shells was not unfamiliar—so we were not unduly disturbed. We quickly got the guns loaded, and opened on that Infantry, advancing up the hill. We worked rapidly, for the case was urgent, and we made it as lively for those fellows as we possibly could. In a few minutes a pretty neat little battle was[Pg 42] making the welkin ring. The sound of our guns crashing over the country behind us made our people, in the camp back there, sit up and take notice. In a few minutes we heard the sound of a horse’s feet running at full speed, and Gen. Dick Ewell, commanding the Second Corps, came dashing up much excited. As he drew near the guns he yelled out, “What on earth is the matter here?” When he got far enough up the hill to look over the crest, he saw the enemy advancing from the river, “Aha, I see,” he exclaimed. Then he galloped up to us and shouted, “Boys, keep them back ten minutes and I’ll have men enough here to eat them up—without salt!” So saying, he whirled his horse, and tore off back down the road.

In a few minutes we heard the tap of a drum and the relieving Brigade, which had been delayed, came up at a rapid double quick, and deployed to the right of our guns; they had heard the sound of our firing and struck a trot. A few minutes more, and the Brigade that had left, that morning, came rushing up and deployed to our left. They had heard our guns and halted and came back to see what was up.

With a whoop and a yell, those two Brigades went at the enemy who had been halted by our fire. In a short time said enemy changed their minds about wanting to stay on our side, and went back over the river a good deal faster than they came. They left some prisoners and about 300 dead and wounded—for us to remember them by.

[Pg 43]The battle ceased, the picket line was restored along the river bank, and all was quiet again. Bob McIntosh was more put out by all this business than anybody else—it had interrupted his hair cut. When we first got the guns into action, everybody was too busy to notice Bob’s head. After we got settled down to work, I caught sight of that half-shaved head and it was the funniest object you ever saw. Bob was No. 1 at his gun, which was next to mine, and had to swab and ram the gun. This necessitated his constantly turning from side to side, displaying first this, and then the other side of his head. One side was perfectly white and bare; the other side covered by a mop of kinky, jet black hair; but when you caught sight of his front elevation, the effect was indescribable. While Bob was unconsciously making this absurd exhibition, it was too much to stand, even in a fight. I said to the boys around my gun, “Look at Bob.” They looked and they could hardly work the gun for laughing.

Of course, when the fight was over McCreery lost that pair of scissors, or said he did. There was not another pair in camp, so Bob had to go about with his head in that condition for about a week—and he wearied of life. One day in his desperation, he said he wanted to get some of that hair off his head so much that he would resort to any means. He had tried to cut some off with his knife. One of the boys, Hunter Dupuy, was standing by chopping on the level[Pg 44] top of a stump with a hatchet. Hunter said, “All right, Bob, put your head on this stump and I’ll chop off some of your hair.” The blade was dull, and it only forced a quantity of the hair down into the wood, where it stuck, and held Bob’s hair fast to the stump, besides pulling out a lot by the roots, and hurting Bob very much. He tried to pull loose and couldn’t. Then he began to call Hunter all the names he could think of, and threatened what he was going to do to him when he got loose. Hunter, much hurt by such ungracious return for what he had done at Bob’s request, said, “Why, Bob, you couldn’t expect me to cut your hair with a hatchet without hurting some”—which seemed reasonable. We made Bob promise to keep the peace, on pain of leaving him tied to the stump—then we cut him loose with our knives.

After some days, when we had had our fun, Van found the scissors and trimmed off the other side of his head to match—Bob was happy.

A few days after this I had the very great pleasure of a little visit to my home. My sister, to whom I was devotedly attached, was to be married. The marriage was to take place on a certain Monday. I had applied for a short leave of absence and thought, if granted, to have it come to me some days before the date of the wedding, so that I could easily get home in time. But there was some delay, and the official paper did not get into my hands until fifteen minutes before one o’clock on Sunday—the day before the[Pg 45] wedding. The last train by which I could possibly reach home in time was to leave Orange Court House for Richmond at six o’clock that evening, and the Court House was nineteen miles off. It seemed pretty desperate, but I was bound to make it. I had had a very slim breakfast that morning; I swapped my share of dinner that evening with a fellow for two crackers, which he happened to have, and lit out for the train.

A word about that trip, as a mark of the times, may be worth while. I got the furlough at 12.45. I was on the road at one, and I made that nineteen miles in five hours—some fast travel, that! I got to the depot about two minutes after six; the train actually started when I was still ten steps off. I jumped like a kangaroo, but the end of the train had just passed me when I reached the track. I had to chase the train twenty steps alongside the track, and at last, getting up with the back platform of the rear car, I made a big jump, and managed to land. It was a close shave, but with that nineteen-mile walk behind, and that wedding in front, I would have caught that train if I had to chase it to Gordonsville—“What do you take me for that I should let a little thing like that make me miss the party?”

Well, anyhow, I got on. The cars were crowded—not a vacant seat on the train. We left Orange Court House at six o’clock P. M.—we reached Richmond at seven o’clock the next morning—traveled all night[Pg 46]—thirteen hours for the trip, which now takes two and a half hours—and all that long night, there was not a seat for me to sit on—except the floor, and that was unsitable. When I got too tired to stand up any longer, I would climb up and sit on the flat top of the water cooler, which was up so near the sloping top of the car that I could not sit up straight. My back would soon get so cramped that I could not bear it any longer—then I crawled down and stood on the floor again. So I changed from the floor to the water cooler and back again, for change of position, all through the night in that hot, crowded car, and I was very tired when we got to Richmond.

We arrived at seven o’clock and the train—Richmond and Danville Railroad—was to start for Danville at eight. I got out and walked about to limber up a little for the rest of the trip. I had a discussion with myself which I found it rather hard to decide. I had only half a dollar in my pocket. The furlough furnished the transportation on the train, and the question was this—with this I could get a little something to eat, or I could get a clean shave. On the one hand I was very hungry. I had not eaten anything since early morning of the day before, and since then had walked nineteen miles and spent that weary night on the train without a wink of sleep. Moreover, there was no chance of anything to eat until we got to Danville that night—another day of fasting—strong reasons[Pg 47] for spending that half dollar in food. On the other hand, I was going to a wedding party where I would meet a lot of girls, and above all, was to “wait” with the prettiest girl in the State of Virginia. In those days, the wedding customs were somewhat different from those now in vogue. Instead of a “best man” to act as “bottle holder” to the groom, and a “best girl” to stand by the bride and pull off her glove, and fix her veil, and see that her train hangs right, when she starts back down the aisle with her victim—the custom was to have a number of couples of “waiters” chosen by the bride and groom from among their special friends, who would march up in procession, ahead of the bride and groom, who followed them arm in arm to the chancel.

The “first waiters” did the office of “best” man and girl, as it is now. I have been at a wedding where fourteen couples of waiters marched in the procession.

Well, I was going into such company, and had to escort up the aisle that beautiful cousin, that I was telling you about—naturally I wanted to look my best, and the more I thought about that girl, the more I wanted to, so I at last decided to spend that only fifty cents for a clean shave—and got it. My heart and my conscience approved of this decision, but I suffered many pangs in other quarters, owing to that long fasting day. However, virtue is its own reward, and that night when I got home, and that lovely cousin was the first who came out of the door to greet me, dressed[Pg 48] in a—well, white swiss muslin—I reckon—and looking like an angel, I felt glad that I had a clean face.

And after the rough life of camp, what a delicious pleasure it was to be with the people I loved best on earth, and to see the fresh faces of my girl friends, and the kind faces of our old friends and neighbors! I cannot express how delightful it was to be at home—the joy of it sank into my soul. Also, I might say, that at the wedding supper, I made a brilliant reputation as an expert with a knife and fork, that lived in the memory of my friends for a long time. My courage and endurance in that cuisine commanded the wonder, and admiration, of the spectators. It was good to have enough to eat once more. I had almost forgotten how it felt—not to be hungry; and it was the more pleasant to note how much pleasure it gave your friends to see you do it, and not have a lot of hungry fellows sitting around with a wistful look in their eyes.

Well, I spent a few happy days with the dear home folks in the dear old home. This was the home where I had lived all my life, in the sweetest home life a boy ever had. Everything, and every person in and around it, was associated with all the memories of a happy childhood and youth. It was a home to love; a home to defend; a home to die for—the dearest spot on earth to me. It was an inexpressible delight to be under its roof—once more. I enjoyed it with all my heart for those few short days—then, with what[Pg 49] cheerfulness I could—hied me back to camp—to rejoin my comrades, who were fighting to protect homes that were as dear to them as this was to me.

I made another long drawn-out railroad trip, winding up with that same old nineteen miles from Orange to the camp, and I got there all right, and found the boys well and jolly, but still hungry. They went wild over my graphic description of the wedding supper. The picture was very trying to their feelings, because the original was so far out of reach.

In this account of our life in that winter camp, it remains for me to record the most important occurrence of all. About this time there came into the life of the men of the Battery an experience more deeply impressive, and of more vital consequence to them than anything that had ever happened, or ever could happen in their whole life, as soldiers, and as men. The outward beginning of it was very quiet, and simple. We had built a little log church, or meeting house, and the fellows who chose had gotten into the way of gathering here every afternoon for a very simple prayer meeting. We had no chaplain and there were only a few Christians among the men. At these meetings one of the young fellows would read a passage of Scripture, and offer a prayer, and all joined in singing a hymn or two. We began to notice an increase of interest, and a larger attendance of the men. A feature of our meeting was a time given for talk,[Pg 50] when it was understood that if any fellow had anything to say appropriate to the occasion, he was at liberty to say it. Now and then one of the boys did have a few simple words to offer his comrades in connection, perhaps, with the Scripture reading.

One day John Wise, one of the best, and bravest men in the Battery, loved and respected by everybody, quietly stood up and said, “I think it honest and right to say to my comrades that I have resolved to be a Christian. I here declare myself a believer in Christ. I want to be counted as such, and by the help of God, will try to live as such.”

This was entirely unexpected. He sat down amidst intense silence. A spirit of deep seriousness seemed fallen upon all present. A hymn was sung, and they quietly dispersed. Some of us shook hands with Wise and expressed our pleasure at what he had said, and done.

This incident produced a profound impression among the men. It brought out the feelings about religion that had lain unexpressed in other minds. The thoughts of many hearts were revealed. The interest spread rapidly; the fervor of our prayer meetings grew. We had no chaplain to handle this situation, but men would seek out their comrades who were Christians, and talk on this great subject with them, and accept such guidance in truth, and duty as they could give. And now from day to day at the prayer meetings men would get up in the quiet way John Wise[Pg 51] had done, and in simple words declare themselves Christians in the presence of their comrades. Most of them were among the manliest and best men of the company; they were dead in earnest, and their actions commanded the respect and sympathy of the whole camp.

This movement went quietly on, without any fuss or excitement, until some sixty-five men, two-thirds of our whole number, had confessed their faith, and taken their stand, and in conduct and spirit, as well as in word, were living consistent Christian lives. They carried that faith, and that life, and character, home when they went back after the war—and they carried them through their lives. In the various communities where they lived their lives, and did their work, they were known as strong, stalwart Christian men, and towers of strength to the several churches to which they became attached. Of that number twelve or fourteen men went into the ministry of different churches, and served faithfully to their life’s end.