Title: Bred of the Desert: A Horse and a Romance

Author: Charles M. Horton

Release date: February 24, 2010 [eBook #31380]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.fadedpage.com

BRED OF THE

DESERT

A HORSE AND A ROMANCE

BY

MARCUS HORTON

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Published by Arrangement with Harper & Brothers

COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY HARPER & BROTHERS

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

PUBLISHED

APRIL, 1915

TO

A. D. B. S. H.

WHO TAUGHT CONSIDERATION FOR THE DUMB

THIS WORK IS LOVINGLY

INSCRIBED

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Colt Is Born | 1 |

| II. | Felipe Celebrates | 15 |

| III. | A Surprise | 27 |

| IV. | A New Home | 35 |

| V. | Loneliness | 47 |

| VI. | The First Great Lesson | 57 |

| VII. | A Stranger | 72 |

| VIII. | Felipe Makes a Discovery | 85 |

| IX. | The Second Great Lesson | 98 |

| X. | The Stranger Again | 112 |

| XI. | Love Rejected | 126 |

| XII. | Adventure | 145 |

| XIII. | In the Waste Places | 156 |

| XIV. | A Picture | 172 |

| XV. | Change of Masters | 175 |

| XVI. | Pat Turns Thief | 186 |

| XVII. | A Running Fight | 199 |

| XVIII. | An Enemy | 210 |

| XIX. | Another Change of Masters | 228 |

| XX. | Fidelity | 240 |

| XXI. | Life and Death | 256 |

| XXII. | Quiescence | 280 |

| XXIII. | The Reunion | 285 |

It was high noon in the desert, but there was no dazzling sunlight. Over the earth hung a twilight, a yellow-pink softness that flushed across the sky like the approach of a shadow, covering everything yet concealing nothing, creeping steadily onward, yet seemingly still, until, pressing low over the earth, it took on changing color, from pink to gray, from gray to black–gloom that precedes tropical showers. Then the wind came–a breeze rising as it were from the hot earth–forcing the Spanish dagger to dipping acknowledgment, sending dust-devils swirling across the slow curves of the desert–and then the storm burst in all its might. For this was a storm–a sand-storm of the Southwest.

Down the slopes to the west billowed giant clouds of sand. At the bottom these clouds tumbled and surged and mounted, and then, resuming 2 their headlong course, swept across the flat land bordering the river, hurtled across the swollen Rio Grande itself, and so on up the gentle rise of ground to the town, where they swung through the streets in ruthless strides–banging signs, ripping up roofings, snapping off branches–and then lurched out over the mesa to the east. Here, as if in glee over their escape from city confines, they redoubled in fury and tore down to earth–and enveloped Felipe Montoya, a young and good-looking Mexican, and his team of scrawny horses plodding in a lumber rigging, all in a stinging swirl.

“Haya!” cried Felipe, as the first of the sand-laden winds struck him, “Chivos–chivos!” And he shot out his whip, gave the lash a twist over the off mare, and brought it down with a resounding thwack. “R-run!” he snarled, and again brought the whip down upon the emaciated mare. “You joost natural lazy! Thees storm–we–we get-tin’–” His voice was carried away on the swirling winds.

But the horses seemed not to hear the man; nor, in the case of the off mare, to feel the bite of his lash. They continued to plod along the beaten trail, heads drooping, ears flopping, hoofs scuffling disconsolately. Felipe, accompanying each outburst with a mighty swing of his whip, swore and pleaded and objurgated and threatened in turn. But all to no avail. The horses held stolidly to their gait, plodding–even, after a time, dropping into slower movement. Whereat Felipe, abandoning 3 all hope, flung down reins and whip, and leaped off the reach of the rigging. Prompt with the loosened lines the team came to a full stop; and Felipe, snatching up a blanket, covered his head and shoulders with it and squatted in the scant protection of a forward wheel.

The storm whipped and howled past. Felipe listened, noting each change in its velocity as told by the sound of raging gusts outside, himself raging. Once he lifted a corner of the blanket and peered out–only to suffer the sting of a thousand needles. Again, he hunched his shoulders guardedly and endeavored to roll a cigarette; but the tempestuous blasts discouraged this also, and with a curse he dashed the tobacco from him. After that he remained still, listening, until he heard an agreeable change outside. The screeching sank to a crooning; the crooning dropped to a low, musical sigh. Flinging off the blanket, he rose and swept the desert with eyes sand-filled and blinking.

The last of the yellow winds was eddying slowly past. All about him the air, thinning rapidly, pulsated in the sun’s rays, which, beaming mildly down upon the desert, were spreading everywhere in glorious sheen. To the east, the mountains, stepping forth in the clearing atmosphere, lay revealed in a warmth of soft purple; while the slopes to the west, over which the storm had broken, shone in a wealth of dazzling yellow-white light–sunbeams scintillating off myriads of tiny sand-cubes. The desert was itself again–bright, resplendent-gripped in the clutch of solitude.

4Felipe tossed his blanket back upon the reach of the rigging. Then he caught up reins and whip, ready to go on. As he did so he paused in dismay.

For one of the mares was down! It was the off mare, the slower and the older mare of the two. She was lying prone and she was breathing heavily. Covered as she was with a thin layer of fine sand, and tightly girdled with chaotic harness straps, she was a spectacle of abject misery.

But Felipe did not see this. All he saw, in the blinding rage which suddenly possessed him, was a horse down, unready for duty, and beside her a horse standing, ready for duty, but restrained by the other. Stringing out a volley of oaths, he stepped to the side of the mare and jerked at her head, but she refused stubbornly to get up on her feet.

Gripped in dismay deeper than at first, Felipe fell back in mechanical resignation.

Was the mare dying? he asked himself. He could ill afford to lose a mare. Horses cost seven and eight dollars, and he did not possess so much money. Indeed, all the money he had in the world was three dollars, received for this last load of wood in town. So, what to do! Cursing the mare had not helped matters; nor could he accuse the storm, for there had been other storms, many of them, and each had she successfully weathered–been ready, with its passing, to go on! But not so this one! She–Huh? Could it be possible? Ah!

5He looked at the mare with new interest. And the longer he gazed the more his anger subsided, became finally downright compassion. For he was reviewing a something he had contemplated at odd times for weeks with many misgivings and tenacious unbeliefs. Never had he understood it! Never would he understand that thing! So why lose time in an effort to understand it now?

Dropping to his knees, he fell to work with feverish haste unbuckling straps and bands. With the harness loose, he dragged it off and tossed it to one side. Then, still moving feverishly, he led the mate to the mare off the trail, turned to the wagon with bracing shoulder, backed it clear of the prostrate animal, and swung it out of the way of future passing vehicles. It was sweltering work. When it was done, with the sun, risen to its fierce zenith, beating down upon him mercilessly, he strode off the trail, blowing and perspiring, and flung himself down in the baking sand, where, though irritated by particles of sand which had sifted down close inside his shirt, he nevertheless gave himself over to sober reflections.

He was stalled till the next morning–he knew that. And he was without food-supplies to carry him over. And he was ten miles on the one hand, and five up-canyon miles on the other, from all source of supplies. But against these unpleasant facts there stood many pleasant facts–he was on the return leg of his journey, his wagon was empty, and he had in his possession three dollars. 6 Then, too, there was another pleasant fact. The trip as a trip had been unusual; never before had he, or any one else, made it under two days–one for loading and driving into town, and a second for getting rid of the wood and making the return. Yet he himself had been out now only the one day, and he was on his way home. He had whipped and crowded his horses since midnight to just this end. Yet was he not stalled now till morning? And would not this delay set him back the one day he had gained over his fellow-townsmen? And would not these same fellow-townsmen rejoice in this opportunity to overtake him–worse, to leave him behind? They would!

“Oh, well,” he concluded, philosophically, stretching out upon his back and drawing his worn and ragged sombrero over his eyes, “soon is comin’ a potrillo.” With this he deliberately courted slumber.

Out of the stillness rattled a wagon. Like Felipe’s, it was a lumber rigging, and the driver, a fat Mexican with beady eyes, pulled up his horses and gazed at the disorder. It was but a perfunctory gaze, however, and revealed to him nothing of the true situation. All he saw was that Felipe was drunk and asleep, and that before dropping beside the trail he had had time, and perhaps just enough wit, to unhitch one horse. The other, true to instinct and the law of her underfed and overworked kind, had lain down. With this conclusion, and out of sheer exuberance of alcoholic 7 spirits, he decided to awaken Felipe. And this he did–in true Mexican fashion. With a curse of but five words–words of great scope and finest selection, however–he mercilessly raked Felipe’s ancestors for five generations back; he objurgated Felipe’s holdings–chickens, adobe house, money, burro, horses, pigs. He closed, snarling not obscurely at Felipe the man and at any progeny of his which might appear in the future. Then he dropped his reins and sprang off the reach of his rigging.

Felipe was duly awakened. He gained his feet slowly.

“You know me, eh?” he retorted, advancing toward the other. “All right–gracios!” And by way of coals of fire he proffered the fellow-townsman papers and tobacco.

The new-comer revealed surprise, not alone at Felipe’s sobriety, though this was startling in view of the disorder in the trail, but also at the proffer of cigarette material. And he was about to speak when Felipe interrupted him.

“You haf t’ink I’m drunk, eh, Franke?” he said. “Sure! Why not?” And he waved his hand in the direction of the trail. Then, after the other had rolled a cigarette and returned the sack and papers, he laid a firm hand upon the man’s shoulder. “You coom look,” he invited. “You tell me what you t’ink thees!”

They walked to the mare, and Franke gazed a long moment in silence. Felipe stood beside him, eying him sharply, hoping for an expression of 8 approval–even of congratulation. In this he was doomed to disappointment, for the other continued silent, and in silence finally turned back, his whole attitude that of one who saw nothing in the spectacle worthy of comment. Felipe followed him, nettled, and sat down and himself rolled a cigarette. As he sat smoking it the other seated himself beside him, and presently touched him on the arm and began to speak. Felipe listened, with now and again a nod of approval, and, when the compadre was finished, accepted the brilliant proposition.

“A bet, eh?” he exclaimed. “All right!” And he produced his sheepskin pouch and dumped out his three dollars. “All right! I bet you feety cents, Franke, thot eet don’ be!”

Frank looked his disdain at the amount offered. Also, his eyes blazed and his round face reddened. He shoved his hand into his overalls, brought forth a silver dollar, and tossed it down in the sand.

“A bet!” he yelled. “Mek eet a bet! A dolar!” Then he narrowed his eyes in the direction of the mare. “Mek eet a good bet! You have chonce to win, too, Felipe–you know!”

Felipe did not respond immediately. Money was his all-absorbing difficulty. Never plentiful with him, it was less than ever plentiful now, and was wholly represented in the three dollars before him. A sum little enough in fact, it dwindled rapidly as he recalled one by one his numerous debts. For he owed much money. He 9 owed for food in the settlement store; he owed for clothing he had bought in town; and he owed innumerable gambling debts–big sums, sums mounting to heights he dared not contemplate. And all he had to his name was the three dollars lying so peacefully before him, with the speculative Franke hovering over them like a fat buzzard over a dead coyote. What to do! He could not decide. He had ways for this money, other than paying on his debts or investing in a gambling proposition. There was to be a baile soon, and he must buy for Margherita (providing her father, a caustic hombre, bitter against all wood-haulers, permitted him the girl’s society) peanuts in the dance-hall and candy outside the dance-hall. The candy must be bought in the general store, where, because of his many debts, he must pay cash now–always cash! So what to do! All these things meant money. And money, as he well understood, was a thing hard to get. Yet here was a chance, as Franke had generously indicated, for him to win some money. But, against this chance for him to win some money was the chance also, as conveyed inversely by Franke, of his losing some money–money he could ill afford to lose.

“You afraid?” suddenly cut in Franke, nastily, upon these reflections. “I don’ see you do soomt’ing!”

Which decided Felipe for all time. “Afraid?” he echoed, disdainfully. “Sure! But not for myself! You don’ have mooch money to lose! But 10 I mek eet a bet–a good bet! I bet you two dolars thot eet–thot eet don’ be!”

It was now the other who hesitated. But he did not hesitate for long. Evidently the spirit of the gambler was more deeply rooted in him than it was in Felipe, for, after gazing out in the trail a moment, then eying Felipe another moment, both speculatively, he extracted from his pockets two more silver dollars and tossed them down with the others. Then he fixed Felipe with a malignant stare.

“I bet you t’ree dolars thot eet cooms what I haf say!”

Felipe laughed. “All right,” he agreed, readily. “Why not?” He heaped the money under a stone, sank over upon his back with an affected yawn, drew his hat over his eyes, and lay still. “We go to sleep now, Franke,” he proposed. “Eet’s long time–I haf t’ink.”

Soon both were snoring.

Out in the trail hung the quiet of a sick-room. The long afternoon waned. Once a wagon appeared from the direction of town, but the driver, evidently grasping the true situation, turned out and around the mare in respectful silence. Another time a single horseman, riding from the mountains, cantered upon the scene; but this man, also with a look of understanding, turned out and around the mare in careful regard for her condition. Then came darkness. Shadows crept in from nowhere, stealing over the desert more and more darkly, while, with their coming, birds 11 of the air, seeking safe place for night rest, flitted about in nervous uncertainty. And suddenly in the gathering dusk rose the long-drawn howl of a coyote, lifting into the stillness a lugubrious note of appeal. Then, close upon the echo of this, rose another appeal in the trail close by, the shrill nicker of the mate to the mare.

It awoke Felipe. He sat up quickly, rubbed his eyes dazedly, and peered out with increasing understanding. Then he sprang to his feet.

“Coom!” he called, kicking the other. “We go now–see who is winnin’ thot bet!” And he started hurriedly forward.

But the other checked him. “Wait!” he snapped, rising. “You wait! You in too mooch hurry! You coom back–I have soomt’ing!”

Felipe turned back, wondering. The other nervously produced material for a cigarette. Then he cleared his throat with needless protraction.

“Felipe,” he began, evidently laboring under excitement, “I mek eet a bet now! I bet you,” he went on, his voice trembling with fervor–“I bet you my wagon, thee horses–thee whole shutting-match–against thot wagon and horses yours, and thee harness–thee whole damned shutting-match–thot I haf win!” He proceeded to finish his cigarette.

Felipe stared at him hard. Surely his ears had deceived him! If they had not deceived him, if, for a fact, the hombre had expressed a willingness to bet all he had on the outcome of this thing, then Franke, fellow-townsman, compadre, brother-wood-hauler, 12 was crazy! But he determined to find out.

“What you said, Franke?” he asked, peering into the glowing eyes of the other. “Say thot again, hombre!”

“I haf say,” repeated the other, with lingering emphasis upon each word–“I haf say I bet you everyt’ing–wagon, harness, caballos–everyt’ing!–against thot wagon, harness, caballos yours–everyt’ing–thee whole shutting-match–thot I haf win thee bet!”

Again Felipe lowered his eyes. But now to consider suspicions. He had heard rightly; Franke really wanted to bet all he had. But he could not but wonder whether Franke, by any possible chance, knew in advance the outcome of the affair in the trail. He had heard of such things, though never had he believed them possible. Yet he found himself troubled with insistent reminder that Franke had suggested this whole thing. Then suddenly he was gripped in another unwelcome thought. Could it be possible that this scheming hombre, awaking at a time when he himself was soundest asleep, had gone out into the trail on tiptoe for advance information? It was possible. Why not? But that was not the point exactly. The point was, had he done it? Had this buzzard circled out into the trail while he himself was asleep? He did not know, and he could not decide! For the third time in ten hours, though puzzled and groping, trembling between gain and loss, he plunged on the gambler’s chance.

13“All right!” he agreed, tensely. “I take thot bet! I bet you thees wagon, thees caballos, thees harness–everyt’ing–against everyt’ing yours–wagon, horses, harness–everyt’ing! Wait!” he thundered, for the other now was striding toward the mare. “Wait! You in too mooch hurry yourself now!” Then, as the other returned: “Is eet a bet? Is eet a bet?”

The fellow-townsman nodded. Whereat Felipe nodded approval of the nod, and stepped out into the trail, followed by the other.

It was night, and quite a dark night. Stretching away to east and west, the dimly outlined trail was lost abruptly in engulfing darkness; while, overhead, a starless sky, low and somber and frowning, pressed close. But, dark though the night was, it did not wholly conceal the outlines of the mare. She was standing as they approached, mildly encouraging a tiny something beside her, a wisp of life, her baby, who was struggling to insure continued existence. And it was this second outline, not the other and larger outline, that held the breathless attention of the men. Nervously Felipe struck a match. As it flared up he stepped close, followed by the other, and there was a moment of tense silence. Then the match went out and Felipe straightened up.

“Franke,” he burst out, “I haf win thee bet! Eet is not a mare; eet is a li’l’ horse!” He struck his compadre a resounding blow on the back. “I am mooch sorry, Franke,” he declared–“not!” He turned back to the faint outline of the colt. 14 “Thees potrillo,” he observed, “he’s bringin’ me mooch good luck! He’s–” He suddenly interrupted himself, aware that the other was striding away. “Where you go now, Franke?” he asked, and then, quick to sense approaching trouble: “Never mind thee big bet, Franke! You can pay me ten dolars soom time! All right?”

There was painful silence.

“All right!” came the reply, finally, through the darkness.

Then Felipe heard a lumber rigging go rattling off in the direction of the canyon, and, suddenly remembering the money underneath the stone, hurried off the trail in a spasm of alarm. He knelt in the sand and struck a match.

The money had disappeared.

It was well along in the morning when Felipe pulled up next day before his little adobe house in the mountain settlement. The journey from the mesa below had been, perforce, slow. The mare was still pitiably weak, and her condition had necessitated many stops, each of long duration. Also, on the way up the canyon the colt had displayed frequent signs of exhaustion, though only with the pauses did he attempt rest.

But it was all over now. They were safely before the house, with the colt lying a little apart from his mother–regarding her with curious intentness–and with Felipe bustling about the team and now and again bursting out in song of questionable melody and rhythm. Felipe was preparing the horses for the corral at the rear of the house, and soon he flung aside the harness and seized each of the horses by the bridle.

“Well, you li’l’ devil!” he exclaimed, addressing the reclining colt. “You coom along now! You live in thees place back here! You coom wit’ me now!” And he started around a corner of the adobe.

16The colt hastily rose to his feet. But not at the command of the man. No such command was necessary, for whither went his mother there went he. Close to her side, he moved with her into the inclosure, crowding frantically over the bars, skinning his knees in the effort, coming to a wide-eyed stand just inside the entrance, and there surveying with nervous apprehension the corral’s occupants–a burro, two pigs, a flock of chickens. But he held close to his mother’s side.

Felipe did not linger in the corral. Throwing off their bridles, he tossed the usual scant supply of alfalfa to the horses, and filled their tub from a near-by well. Then, after putting up the bars, he set out with determined stride across the settlement. His direction was the general store, and his quest was the loan of a horse, since his team now was broken, and would be broken for a number of days to come.

The store was owned and conducted by one Pedro Garcia. Pedro Garcia was the mountain Shylock. He loaned money at enormous rates of interest, and he rented out horses at prohibitive rates per day. Also, being what he was, Pedro had gained his pounds of flesh–was alarmingly fat, with short legs of giant circumference. Usually these legs were clothed in tight-fitting overalls, and his small feet incased in boots of high-grade leather wonderfully roweled. Yet many years had passed since Pedro had been seen in a saddle. Evidently he held to the rowels in fond memory of his days of 17 slender youth and coltish gambolings. Pedro was seated in his customary place upon an empty keg on the porch, and Felipe, ignoring his grunted greeting, plunged at once into the purpose of his call.

He had come to borrow a horse, Felipe explained. One of his own was unfit for work, yet the cutting and drawing must go on. While the mare was recuperating, he carefully pointed out, he himself could continue to earn money to meet some of his pressing debts. Any kind of horse would do, he declared, so long as it had four legs and was able to carry on the work. The horse need not have a mouth, even, he added, jocosely, for reasons nobody need explain. After which he sat down on the porch and awaited the august decision.

Pedro remained silent a long time, the while he moistened his lips with fitful tongue, and gazed across the tiny settlement reflectively. At length he drew a deep breath, mixed of disgust and regret, and proceeded to make slow reply.

It was true, he began, that he had horses to rent. And it was further true, he went on, deliberately, that he kept them for just this purpose. But–and his pause was fraught with deep significance–it was no less true that Felipe Montoya bore a bad reputation as a driver of horses–was known, indeed, to kill horses through overwork and underfeed–and that, therefore, to lend him a horse was like kissing the horse good-by and hitching up another to the stone-boat. 18 Nevertheless, he hastened to add, if Felipe was in urgent need of a horse, and was prepared to pay the customary small rate per day, and to pay in advance–cash–

Here Pedro paused and popped accusing eyes at Felipe, in one strong dramatic moment before continuing. But he did not continue. Felipe was the check. For Felipe had leaped to his feet, and now stood brandishing an ugly fist underneath the proprietor’s nose. Further–and infinitely worse–Felipe was saying something.

“Pedro Garcia,” he began, shrilly, “I must got a horse! And I have coom for a horse! And I have thee money to pay for a horse! And if I kill thot horse,” he went on, still brandishing his fist–“if thot horse he’s dropping dead in thee harness–I pay you for thot horse! I haf drive horses–”

“Si, si, si!” began Pedro, interrupting.

“I haf drive horses on thees trail ten years!” persisted Felipe, yelling, “and in all thot time, Pedro Garcia, I’m killin’ only seven horses, and all seven of thees horses is dyin’, Pedro Garcia, when I haf buy them, and I haf buy all seven horses from you, Pedro Garcia, thief and robber!” He paused to take a breath. “And not once, Pedro Garcia,” he went on, “do I keeck about thot-a horse is a horse! But I haf coom to you before! And I haf coom to you now! I must got a horse quick! And I bringin’ thot horse back joost thee same as I’m gettin’ thot horse–in good condition–better–because everybody is knowin.’ I 19 feed a horse better than you feed a horse–and I’m cleanin’ the horse once in a while, too!” Which was a lie, both as to the feeding and the cleaning, as he well knew, and as, indeed, he well knew Pedro knew, who, nevertheless, nodded grave assent.

“Si,” admitted Pedro. “Pero ustede–”

“A horse!” thundered Felipe, interrupting, his neck cords dangerously distended. “You give me a horse–you hear? I want a horse–a horse! I don’ coom here for thee talk!”

Pedro rose hastily from the keg. Also, he grunted quick consent. Then he stepped inside the store, followed by Felipe, who made several needed purchases, and, since he had his enemy cowed, and was troubled with thirst created by the protracted harangue, to say nothing of the strong inclination within him to celebrate the coming of the colt, he made a purchase that was not needed–a bottle of vino, cool and dry from Pedro’s cellar. With these tucked securely under his arm, he then calmly informed Pedro of the true state of his finances, and left the store, returning across the settlement, which lay wrapped in pulsating noonday quiet. In the shade of his adobe he sat upon the ground, with his back comfortably against the wall. Directly the quiet was broken by two distinct sounds–the pop of a cork out of the neck of a bottle, and the gurgle of liquid into the mouth of a man.

Thus Felipe set out upon a protracted debauch. In this debauch he did nothing worth while. He 20 used neither the borrowed horse nor his own sound one. Each day saw him redder of eye and more swollen of lip; each day saw him increasingly heedless of his debts; each day saw him more neglectful of his duties toward his animals. The one bottle became two bottles, the two bottles became three, each secured only after threatened assault upon the body of Pedro, each adding its store to the already deep conviviality and reckless freedom from all cares now Felipe’s. He forgot everything–forgot the stolen money, forgot the colt, forgot the needs of the mare–all in exhilarated pursuit of phantoms.

Yet the colt did not suffer. Becoming ever more confident of himself as the days passed, he soon revealed pronounced curiosity and an aptitude for play. He would stare at strutting roosters, gaze after straddling hens, blink quizzically at the burro, frown upon the grunting pigs, all as if cataloguing these specimens, listing them in his thoughts, some day to make good use of the knowledge. But most of all he showed interest in and playfulness toward his mother and her doings. He would follow her about untiringly, pausing whenever she paused, starting off again whenever she started off–seemingly bent upon acquiring the how and why of her every movement.

But it was his playfulness finally that brought him first needless suffering. The mare was standing with her nose in the feed-box. She had stood thus many times during the past week; but usually, before, the box had been empty, whereas 21 now it contained a generous quantity of alfalfa. But this the colt did not know. He only knew that he was interested in this thing, and so went there to attempt, as many times before, to reach his nose into the mysterious box. Finding that he could not, he began, as never before, to frisk about the mare, tossing up his little heels and throwing down his head with all the reckless abandon of a seasoned “outlaw.” He could do these things because he was a rare colt, stronger than ever colt before was at his age, and for a time the mare suffered his antics with a look of pleased toleration. But as he kept it up, and as she was getting her first real sustenance since the day of his coming, she at length became fretful and sounded a low warning. But this the colt did not heed. Instead he wheeled suddenly and plunged directly toward her, bunting her sharply. Nor did the single bunt satisfy him. Again and again he attacked her, plunging in and darting away each time with remarkable celerity, until, her patience evidently exhausted, she whisked her head around and nipped him sharply. Screaming with pain and fright, he plunged from her, sought the opposite side of the inclosure, and turned upon her a pair of very hurt and troubled eyes.

Yet all the world over mothers are mothers. After a time–a long time, as if to let her punishment sink in–the mare made her way slowly to the colt, and there fell to licking him, seeming to tell him of her lasting forgiveness. Under this lavish caressing the colt, as if to reveal his own 22 forgiveness for the dreadful hurt, bestowed similar attention upon her–in this attention, though he did not know it, softening flesh that had experienced no such consideration in years. Thus they stood, side by side, mother and son, long into the day, laying the foundation of a love that never dies–that strengthens, in fact, with the years, though all else fail–love between mother and her offspring.

Other things, things of minor consequence, added their mite to his early development. One morning, while the mare was asleep, the colt, alert and standing, was startled by the sudden movement of a large rooster. The rooster had left the ground with loud flapping of wings, and now stood perched upon the corral fence, like a grim and mighty conqueror, ruffling his neck feathers and twisting his head in pre-eminent satisfaction. But the colt did not understand this. Transfixed, he turned frightened eyes upon the cause of the unearthly commotion. Then suddenly, with another loud flapping of wings, the rooster uttered a defiant crow, a challenge that echoed far through the canyon. Whereat the colt, eyes wide with terror, whirled to his mother, whimpering babyishly. But with the mare standing beside him and caressing him reassuringly, all his nervousness left him, and he again turned his eyes upon the rooster and watched him till the cock, unable to stir combat among his neighbors, left the fence with another loud flapping of wings, and returned to earth, physically and spiritually, there to set 23 up his customary feigned quest for worms for the ladies. But the point was this–with this last flapping of wings the colt remained in a state of perfect calm.

Thus he learned, and thus he continued to learn, in nervous fear one moment, in perfect calm the next. And though his hours of life were few indeed, he nevertheless revealed an intelligence far above the average of his kind. He learned to avoid the mare’s whisking tail, to shun or remove molesting flies, to keep away from the mare when she was at the feed-box. All of which told of his uncommon strain, as did the rapidity with which he gained strength, which last told of his tremendous vitality, and which some day would serve him well against trouble.

Yet in it all lurked the great mystery, and Felipe, blustering to occasional natives outside the fence during his week of debauch, while pointing out with pride the colt’s very evident blooded lineage, yet could tell nothing of that descent. All he could point out was that the mare was chestnut-brown, and when not in harness was kept close within the confines of the corral, while here was a colt of a dark-fawn color which would develop with maturity into coal-black. And there was not a single black horse in the mountains for miles and miles around. Nor was the colt a “throw-back,” because–

“Oh, well,” he would conclude, casting bleared eyes in the direction of the house, wearily, “I got soom vino inside. You coom along now. We go 24 gettin’ a drink.” Which would close the monologue.

One morning early, Felipe, asleep on a bed that never was made up, heard suspicious sounds in the corral outside. He sprang up and, clad only in a fiery-red undershirt, hurried to a window. Cautiously letting down the bars, with a rope already tied around the colt’s neck, was the mountain Shylock, Pedro Garcia, intent upon leading off the innocent new-comer. Pedro no doubt had perceived an opportunity either to force Felipe to meet some of his debts, or else hold the colt as a very acceptable chattel. Also, he evidently had calculated upon early dawn as the time best suited to do this thing, in view of Felipe’s long debauch upon unpaid-for wine. At any rate, there he was, craftily letting down the bars. Raging with indignation and a natural venom which he felt toward the storekeeper, Felipe flung up the window.

“Buenos dias, señor!” he greeted, cheerfully, with effort controlling his anger. “Thee early worm he’s takin’ thee potrillo! How cooms thot, señor?” he asked, enjoying the other’s sudden discomfiture. “You takin’ thot li’l’ horse for thee walk–thee exercise?” And then, without waiting for a reply, had there been one forthcoming, which there was not, he slammed down the window, leaped to the door, flung it open–all levity now gone from him. “Pedro Garcia!” he raged. “You thief and robber! I’m killin’ you thees time sure!” And, regardless of his scant 25 attire, and stringing out a volley of oaths, he sprang out of the doorway after his intended victim.

But Pedro Garcia, though fat, was surprisingly quick on his feet. He dropped the rope and burst into a run, heading frantically past the house toward the trail. And, though Felipe leaped after him, still clad only in fiery-red undershirt, the storekeeper gained the trail and set out at top speed across the settlement. Felipe pursued. Hair aflaunt, shirt-tail whipping in the breeze, bare feet paddling in the dust of the trail, naked legs crossing each other like giant scissors in frenzied effort, he hurtled forward exactly one leap behind his intended victim. He strained to close up the gap, but he could not overtake the equally speedy Pedro, whose short legs fairly buzzed in the terror of their owner. Thus they ran, mounting the slight rise before the general store, then descending into the heart of the settlement, with Pedro whipping along frantically, and Felipe still one whole leap behind, until a derisive shout, a feminine exclamation of shrieking glee, awoke Felipe to the spectacle he was making of himself before the eyes of the community. He stopped; growled disappointed rage; darted back along the trail. Once in the privacy of his house, he hurriedly donned his clothes and gave himself over to deliberations. The result of these deliberations was that he concluded to return to work.

After a scant breakfast of chili and coffee he 26 moved out to the corral. He leaned his arms upon the fence and surveyed the colt with fresh interest.

“Thot li’l’ caballo,” he began, “he’s bringin’ me mooch good luck. Thot potrillo he’s wort’ seven–he’s wort’–si–eight dolars–thot potrillo. I t’ink I haf sell heem, too–queek–in town! But first I must go cuttin’ thee wood!” With this he let down the bars and entered the inclosure. Then his thoughts took an abrupt turn. “I keel thot Pedro Garcia soomtime–bet you’ life! He’s stealin’ fleas off a dog–thot hombre!”

Felipe drove the borrowed horse out of the inclosure, and then singled out the mate to the mare. As he harnessed up this horse, the colt, standing close by, revealed marked interest. Also, as Felipe led the horse out of the corral the colt followed till shut off by the bars, which Felipe hurriedly put up. But they did not discourage him. He remained very close to them, peering out between the while Felipe hitched the team to his empty lumber rigging. Then came the crack of a whip, loud creaking of greaseless wheels, the voice of Felipe in lusty demand, all as the outfit set out up the trail toward the timber-slopes. But not till the earth was still again, the cloud of dust in the trail completely subsided, did the colt turn away from the bars and seek his mother, and then with a look in his soft-blinking eyes that told of concentrated pondering on these mysteries of life.

Next morning, having returned from the timber-slopes, Felipe, fresh and radiant, appeared outside the corral in holiday attire. Part of this attire was a pair of brand-new overalls. Indeed, the overalls were so new that they crackled; and Felipe appeared quite conscious of their newness, for he let down the bars with great care, and with even greater care stepped into the inclosure. Then it was seen, since he was a Mexican who ran true to form, there was a flaw in all this splendor. For he had drawn on the new overalls over the older pair–worse, had drawn them on over two older pairs, as revealed at the bottoms, where peered plaintively two shades of blue–lighter blue of the older pair, very light blue of the oldest pair–the effect of exposure to desert suns. So Felipe had on three pairs of overalls. Yet this was not all of distinction. Around his brown throat was a bright red neckerchief, while between the unbuttoned edges of his vest was an expanse of bright green–the coloring of a tight-fitting sweater.

There was reason for all this. Felipe was going to town, and he was taking the mare along with 28 him, and the mare naturally would take her colt; and because he had come to know the value of the colt, Felipe wished to appear as prosperous in the eyes of the Americans in town as he believed the owner of so fine a colt ought to appear.

Therefore, still careful of his overalls, he set about leisurely to prepare the team for the journey. He crossed to the shed, hauled out the harness, tossed it out into the inclosure. Promptly both horses stepped into position. Also, the older mare, whether through relief or regret, sounded a shrill nicker. This brought the colt to her side, where he fell to licking her affectionately, showing his great love for her bony frame. And when Felipe led the horses out of the corral he followed close beside her, and when outside held close to her throughout the hitching, and to the point even when Felipe clambered to the top of the high load and caught up the reins and the whip. Then he stepped back, wriggling his fuzzy little tail and blinking his big eyes curiously.

“Well, potrillo,” began Felipe, grinning down upon the tiny specimen of life, “we goin’ now to town! But first you must be ready! You ready? All right! We go now!” And he cracked the whip over the team.

They started forward, slowly at first, the wagon giving off many creaks and groans, then fast and faster, until, well in the descent of the hard canyon trail, the horses were jogging along quite briskly.

The colt showed the keenest interest and delight. 29 For a time he trotted beside the mare, ears cocked forward expectantly, eyes sweeping the canyon alertly, hoofs lifting to ludicrous heights. Then, as the first novelty wore off, and he became more certain of himself in these swift-changing surroundings, he revealed a playfulness that tickled Felipe. He would lag behind a little, race madly forward, sometimes run far ahead of the team in his great joy. But he seemed best to like to lag. He would come to a sudden stop and, motionless as a dog pointing a bird, gaze out across the canyon a long time, like one trying to find himself in a strange and wonderful world. Or, standing thus, he would reveal curious interest in the rocks and stumps around him, and he would stare at them fixedly, blinking slowly, a look of genuine wonderment in his big, soft eyes. Then he would strain himself mightily to overtake the wagon.

Once in a period of absorbed attention he lost sight of the outfit completely. This was due not so much to his distance in the rear as to the fact that the wagon, having struck a bend in the trail, had turned from view. But he did not know that. Sounding a baby outcry of fear, he scurried ahead at breakneck speed, frantic heels tossing up tiny spurts of dust, head stretched forward–and thus soon caught up. After that he remained close beside his mother until the wagon, rocking down the mouth of the canyon, swung out upon the broad mesa. Here the outfit could be seen for miles, and now he took to lagging behind again, and to frisking far ahead, always returning at frequent 30 intervals for the motherly assurance that all was well.

As part of the Great Scheme, all this was good for him. In his brief panic when out of sight of his mother he was taught how very necessary she was to his existence. In his running back and forth, with now and again breathless speeding, he developed the muscles of his body, to the end that later he might well take up an independent fight for life. In the curious interest he displayed in all subjects about him he lent unknowing assistance to a spiritual development as necessary as physical development. All this prepared him to meet men and measures as he was destined to meet them–with gentleness, with battle,–with affection–like for like–as he found it. It was all good for him, this movement, this change of environment, this quick awakening of interest. It shaped him in both body and spirit to the Great Purpose.

This interest seemed unbounded. Whenever a jack-rabbit shot across the trail, or a covey of birds broke from the sand-hills, he would come to a quick pause and blink curiously, seeming to understand and approve, and to be grateful, as if all these things were done for him. Also, with each halt Felipe made with compadres along the trail, friends who entered with him in loud badinage over the ownership of the colt–an ownership all vigorously denied him–the colt himself would cock his ears and fix his eyes, seemingly aware of his importance and pleased to be the object of 31 the cutting remarks. And thus the miles from mountain to the outskirts of town were covered, miles pleasurable to him, every inch revealing something of fresh interest, every mile finding him more accustomed to the journey.

They reached a point on the outskirts where streets appeared, sharply defined thoroughfares, interlacing one with the other. And as they advanced vehicles began to turn in upon the trail, a nondescript collection ranging from an Indian farm-wagon off the Navajo reservation to the north to a stanhope belonging to some more affluent American in the suburbs. With them came also many strange sounds–Mexican oaths, mild Indian commands, light man-to-man greetings of the day. Also there was much cracking of whips and nickering of horses along the line. And the result of all this was that the colt revealed steadily increasing nervousness, a condition enhanced by the fact that his mother, held rigidly to her duties by Felipe, could bestow upon her offspring but very little attention. But he held close to her, and thus moved into the heart of town, when suddenly one by one the vehicles ahead came to a dead stop. Felipe, perched high, saw that the foremost wagons had reached the railroad crossing, and that there was a long freight-train passing through.

Team after team came into the congestion and stopped. Cart and wagon and phaeton closed in around the colt. There was much maneuvering for space. The colt’s nervousness increased, and 32 became positive fear. He darted wild eyes about him. He was completely hedged in. On his right loomed a large horse; behind him stood a drowsing team; on his left was a dirt-cart; while immediately in front, such was his position now, stood his mother. But, though gripped in fear, he remained perfectly still until the locomotive, puffing and wheezing along at the rear of the train, having reached the crossing, sounded a piercing shriek. This was more than he could stand. Without a sound he dodged and whirled. He plunged to the rear and rammed into the drowsing team; darted to the right and into the teeth of the single horse; whirled madly to the left, only to carom off the hub of a wheel. But with all this defeat he did not stop. He set up a wild series of whirling plunges, and, completely crazed now, darted under the single horse, under a Mexican wagon, under a team of horses, and forth into a little clearing. Here he came to a stop, trembling in every part, gazing about in wildest terror.

Following its shrill blast, the engine puffed across the crossing, the gates slowly lifted, and the foremost vehicles began to move. Soon the whole line was churning up clouds of dust and rattling across the railroad tracks. Felipe was of this company, cracking his whip and yelling lustily, enjoying the congestion and this unexpected opportunity to be seen by so many American eyes at once in his gorgeous raiment. In the town proper, and carefully avoiding the more rapidly moving vehicles, he turned off the avenue into a 33 narrow side street, and pulled up at a water-trough. As he dropped the reins and prepared to descend, a friend of his–and he had many–hailed him from the sidewalk. Hastily clambering down, he seized the man’s arm in forceful greeting, and indicated with a jerk of his head a near-by saloon.

“We go gettin’ soomt’ing,” he invited. “I have munch good luck to tell you.”

Inside the establishment Felipe became loquacious and boasting. He now was a man of comfortable wealth, he gravely informed his friend–a wizened individual with piercing eyes. Besides winning a bet of fifteen dollars in money, he explained, he also held a note against Franke Gamboa for fifty dollars more on his property. But that was not all. Aside from the note and the cash in hand, he was the owner of a colt now of great value–si–worth at least ten dollars–which, added to the other, made him, as anybody could see, worthy of recognition. With this he placed his empty glass down on the bar and swung over into English.

“You haf hear about thot?” he asked, drawing the back of his hand across his mouth. Then, as the other shook his head negatively, “Well, I haf new one–potrillo–nice li’l’ horse–si!” He cleared his throat and frowned at the listening bartender. “He’s comin’ couple days before, oop on thee mesa.” He picked up the glass, noted that it was empty, placed it down again. “I’m sellin’ thot potrillo quick,” he went on–“bet you’ life! 34 I feed heem couple weeks more mebbe–feed heem beer and soom cheese!” He laughed raucously at the alleged witticism. “Thot’s thee preencipal t’ing,” he declared, soberly. “You must feed a horse.” He said this not as one recommending that a horse be well fed, but as one advising that a horse be given something to eat occasionally. “Si! Thot’s thee preencipal t’ing! Then he’s makin’ a fast goer–bet you’ life! I haf give heem–” He suddenly interrupted himself and laid firm hold upon the man’s arm. “You coom wit’ me!” he invited, and began to drag the other toward the swing-doors. “You coom look at thot potrillo!”

They went outside. On the curb, Felipe gazed about him, first with a look of pride, then with an expression of blank dismay. He stepped down off the curb, roused the drowsing mare with a vigorous clap, again looked about him worriedly. After a long moment he left the team, walking out into the middle of the street, and strained his eyes in both directions. Then he returned and, heedless of his new overalls, got down upon his knees, sweeping bleared eyes under the wagon. And finally, with a last despairing gaze in every direction, he sat down upon the curb and buried his face in his arms.

For the colt was gone!

With the beginning of the forward movement across the railroad the colt, ears cocked and eyes alert, moved across also. Close about him stepped other horses, and over and around him surged a low murmuring, occasionally broken by the crack of a whip. Yet these sounds did not seem to disturb him. He trotted along, crossing the tracks, and when on the opposite side set out straight down the avenue. The avenue was broad, and in this widening area the congestion rapidly thinned, and soon the colt was quite alone in the open. But he continued forward, seeming not to miss his mother, until there suddenly loomed up beside him a very fat and very matronly appearing horse. Then he hesitated, turning apprehensive eyes upon her. But not for long. Evidently accepting this horse as his mother, he fell in close beside her and trotted along again in perfect composure.

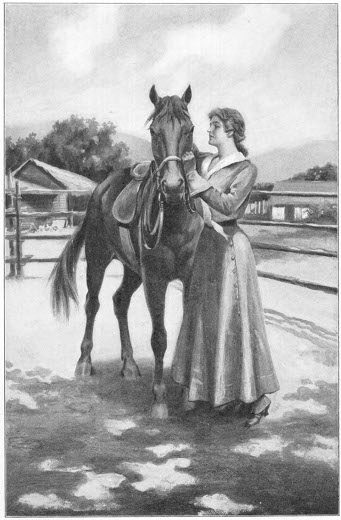

Behind this horse was a phaeton, and in the phaeton sat two persons. They were widely different in age. One was an elderly man, broad of shoulders and with a ruddy face faintly threaded 36 with purple; the other was a young girl, not more than seventeen, his daughter, with a face sweet and alert, and a mass of chestnut hair–all imparting a certain esthetic beauty. Like the man, the girl was ruddy of complexion, though hers was the bloom of youth, while his was toll taken from suns and winds of the desert. The girl was the first to discover the colt.

“Daddy!” she exclaimed, placing a restraining hand upon the other. “Whose beautiful colt is that?”

The Judge pulled down his horse and leaned far out over the side. “Why, I don’t know, dear!” he replied, after a moment, then turned his eyes to the rear. “He must belong with some team in that crush.”

The girl regarded the colt with increasing rapture. “Isn’t he a perfect dear!” she went on. “Look at him, daddy!” she suddenly urged, delightedly. “He’s dying to know why we stopped!” Which, indeed, the colt looked to be, since he had come to a stop with the mare and now was regarding them curiously. “I’d love to pet him!”

The Judge frowned. “We’re late for luncheon,” he declared, and again gazed to the rear. “We’d better take him along with us out to the ranch. To-morrow I’ll advertise him in the papers.” And he shook up the mare. “We’d better go along, Helen.”

“Just one minute, daddy!” persisted the girl, gathering up her white skirts and, as the Judge pulled down, leaping lightly out of the phaeton. 37 “I’ve simply got to pet him!” She cautiously approached the colt.

He permitted her this approach. Nor did he shy at her outstretched hand. Under her gentle caresses he stood very still, and when she stooped before him, as she did presently, bringing her eyes upon a level with his own, he gazed into them very frankly and earnestly, as if gauging this person, as he had seemed to tabulate all other things, some day to make good use of his knowledge. After a time the girl spoke.

“I wish I could keep you always,” she said, poutingly. “You look so nice and babyish!” But she knew that she could not keep him, and after a time she stood up again and sighed, and fell to stroking him thoughtfully. “I’ll have you to-day, anyway,” she declared, finally, with promise of enjoyment in her voice, as one who meant to make the most of it. Then she got back into the phaeton.

The Judge started up the horse again. They continued through the town, and when on its northwestern outskirts turned to the right along a trail that paralleled the river. The trail ran north and south, and on either side of it, sometimes shielding a secluded ranch, always forming an agreeable oasis in the flat brown of the country, rose an occasional clump of cottonwoods. The ranch-houses were infrequent, however; all of them were plentifully supplied with water by giant windmills which clacked and creaked above the trees in the high-noon breeze. To the left, 38 across the river, back from the long, slow rise of sand from the water’s edge, rose five blunt heights like craters long extinct; while above these, arching across the heavens in spotless sheen, curved the turquoise dome of a southwestern midday sky, flooding the dust and dunes below in throbbing heat-rays. It was God’s own section of earth, and not the least beautiful of its vistas, looming now steadily ahead on their right, was the place belonging to Judge Richards. House and outhouses white, and just now aglint in the white light of the sun, the whole ranch presented the appearance of diamonds nestling in a bed of emerald-green velvet. Turning off at this ranch, the Judge tossed the reins to a waiting Mexican.

Helen was out of the phaeton like a flash. Carefully guiding the colt around the house and across a patio, she turned him loose into a spacious corral. Then she fell to watching him, and she continued to watch him until a voice from the house, that of an aged Mexican woman who presided over the kitchen, warned her that dinner was waiting. Reluctantly hugging the colt–hugging him almost savagely in her sudden affection for him–she then turned to leave, but not without a word of explanation.

“I must leave you now, honey!” she said, much as a child would take leave of her doll. “But I sha’n’t be away from you long, and when I come back I’ll see what I can do about feeding you!”

The colt stood for a time, peering between the 39 corral boards after her. Then he set out upon a round of investigation. He moved slowly along the inside of the fence, seeming to approve its whitewashed cleanliness, until, turning in a corner, he stood before the stable door. Here he paused a moment, gazing into the semi-gloom, then sprang up the one step. Inside, he stood another moment, sweeping eyes down past the stalls, and finally set out and made his way to the far end. In the stall next the last stood a brown saddle-horse, and in the last stall the matronly horse he had followed out from town. But he showed no interest in these, bestowing upon each merely a passing glance. Then, discovering that the flies bothered him here more than in the corral, he walked back to the door and out into the sunlight again. In the corral he took up his motionless stand in the corner nearest the house.

He did not stand thus for long. He soon revealed grave uneasiness. It was due to a familiar gnawing inside. He knew the relief for this, and promptly set out in search of his mother. He hurried back along the fence, gained the door of the stable, and stepped into the stable, this time upon urgent business. He trotted down past the stalls to the family horse, and without hesitation stepped in alongside of her. Directly there was a shrill nicker, a lightning flash of heels, and the colt lay sprawling on the stable floor.

Never was there a colt more astonished than this one. Dazed, trembling, he regained his feet and looked at the mare, looked hard. Then casting 40 solicitous eyes in the direction of the saddle-horse, he stepped in alongside. But here he met with even more painful objections. The horse reached around and bit him sharply in the neck. It hurt, hurt awfully, but he persisted, only to receive another sharp bite, this time more savage. Sounding a baby whimper of despair, he ran back to the door and out into the motherless corral.

He made for the corner nearest the house. But he did not stand still. He cocked his ears, pawed the ground, turned again and again, swallowed frequently. And presently he set out once more in search of his mother; though this time he wisely kept out of the stable. He held close to the fence, following it around and around, pausing now and again with eyes strained between the boards. But he could not find his mother. Finally, resorting to the one effort left to him that might bring result, he flung up his little head and sounded a piteous call–not once, but many times.

“Aunty,” declared the girl, rushing into the genial presence of the Mexican cook, “what shall I do about that colt? He must be hungry!”

The old woman nodded and smiled knowingly. Then she stepped into the pantry. She filled a long-necked bottle with milk and sugar and a dash of lime-water, and, placing the bottle in the girl’s hands, shoved her gently out the door and into the patio.

Racing across to the corral, Helen reached the colt with much-needed aid. He closed upon the bottle with an eagerness that seemed to tell he 41 had known no other method of feeding. Also, he clung to it till the last drop was gone, which caused Helen to wonder when last the colt had fed. Then, as if by way of reward for this kindly attention, he tossed his head suddenly, striking the bottle out of her hands. This was play; and Helen, girlishly delighted, sprang toward him. He leaped away, however, and, coming to a stand at a safe distance, wriggled his ears at her mischievously. She sprang toward him again; but again he darted away. Whereupon she raced after him, pursuing him around the inclosure, the colt frisking before her, kicking up his heels and nickering shrilly, until, through breathlessness, she was forced to stop. Then the colt stopped, and after a time, having regarded her steadfastly, invitingly, he seemed to understand, for he quietly approached her. As he came close she stooped before him.

“Honey dear,” she began, eyes on a level with his own, “they have telephoned the city officials, and your case will be advertised to-morrow in the papers. But I do wish that I could keep you.” She peered into his slow-blinking eyes thoughtfully. “Brownie–my saddle-horse–is all stable-ridden, and I need a good saddler. And some day you would be grown, and I could–could take lots of comfort with you.” She was silent. “Anyway,” she concluded, rising and stroking him absently, “we’ll see. Though I hope–and I know it isn’t a bit right–that nothing comes of the advertisement; or, if something does come of it, 42 that your rightful owner will prove willing to sell you after a time.” With this she picked up the bottle and left him.

And nothing did come of the advertisement. Felipe did not read the papers, and his knowledge of city affairs was such that he did not set up intelligent quest for the colt.

So the colt remained in the Richards’ corral. Regularly two and three times a day the girl came to feed him, and regularly as his reward each time he bunted the bottle out of her hand afterward. Also, between meals she spent much time in his society, and on these occasions relieved the tedium of his diet with loaf sugar, and, after a while, quartered apples. For these sweets he soon developed a passion, and he would watch her comings with a feverish anxiety that always brought a smile to her ready lips. And thus began, and thus went on, their friendship, a friendship that with the passing months ripened into strongest attachment, but which presently was to be interrupted for a long time.

Hint of this came to him gradually. From spending long periods with him every day his mistress, after each feeding now, took to hurrying away from him. Sometimes, so great was her haste to get back to the house, she actually ran out of the corral. It worried him, and he would follow her to the gate, and there stand with nose between the boards and eyes turned after her, whimpering softly. And finally, with his bottle displaced by more solid food, and the visits of his mistress 43 becoming less frequent, he awoke to certain mysterious arrivals and departures in a buggy of a sharp-eyed woman all in black, and he came to feel, by reason of his super-animal instinct, that something of a very grave nature was about to happen to him. Then one morning late in August he experienced that which made his fears positive convictions, though precisely what it was he did not immediately know.

His mistress stepped into the corral with her usual briskness, and, walking deliberately past him, turned up an empty box in a far corner and sat down upon it, and called to him. From the instant of her entrance he had held himself back, but when she called him he rushed eagerly to her side. She placed her arms around his neck, drew his head down into her lap, and proceeded to unfold a story–later, tearful.

“It’s all settled,” she began, with a restful sigh. “We have discussed it for weeks, and I’ve had a dreadful time of it, and aunty–my Mexican aunty, you know–and my other aunty, my regular aunty–I have no mother–and everybody–got so excited I didn’t really know them for my own, and daddy flared up a little, and–and–” She paused and sighed again. “But finally they let me have my own way about it–though daddy called it ‘infant tommyrot’–and so here it is!” She tilted up his head and looked into his eyes. “You, sir,” she then went on–“you, sir, from this day and date–I reckon that is how daddy would say it–you, sir, from this day and date 44 shall be known as Pat. Your name, sir, is Pat–P-a-t–Pat! I don’t know whether you like it or not, of course! But I do know that I like it, and under the circumstances I reckon that’s all that is necessary.” Then came the tears. “But that isn’t all, Pat dear,” she went on, tenderly. “I have something else to tell you, though it hurts dreadfully for me to do it. But–but I’m going away to school. I’m going East, to be gone a long time. I want to go, though,” she added, gazing soberly into his eyes; “yet I am afraid to leave you alone with Miguel. Miguel doesn’t like to have you around, and I know it, and I am afraid he will be cruel to you. But–but I’ve got to go now. The dressmaker has been coming for over a month; and–and I’m not even coming home for vacation. I am to visit relatives, or something, in New York–or somewhere–and the whole thing is arranged. But I–I don’t seem to want–to–to go away now!” Which was where the tears fell. “If things–things could only be–be put off! But I–I know they can’t!” She was silent, silent a long time, gazing off toward the distant mountains through tear-bedimmed eyes. “But when I do come back,” she concluded, finally, brightening, “you will have grown to a great size, Pat dear, and then we can go up on the mesa and ride and ride. Can’t we?” And she hugged him convulsively. “It will be glorious. Won’t it?”

He didn’t exactly say. His interest was elsewhere, and, resisting her hugging, he began to 45 nuzzle her hands for sweets. Whereupon she burst into laughter and forcibly hugged him again.

“I forgot,” she declared, regretfully. “You shall have them, though–right away!” Then she arose and left him–left him a very much mystified colt. But when she returned with what he sought he looked his delight, and closed over the sweets with an eagerness that forced her into sober reflection. “Pat,” she said, after a time, “I don’t think you care one single bit for me! All you care about, I’ll bet, is what I bring you to eat!” Then she began to stroke him. “Just the same,” she concluded, after a while, tenderly, “you’re the dearest colt that ever lived!” She dallied with him a moment longer, then abruptly left him, running back to the house.

The days which followed, however, were full of delight for him. Now that the mysterious activity in the house was over with, his mistress began to visit him again with more than frequent regularity. And with each visit she would remain with him a long time, caressing him, talking to him, as had been her wont in the earlier days of their friendship. But as against those earlier days he had changed. Possibly this was due to her absence. Instead of frisking about the inclosure now, as he had used to frisk–whirling madly from her in play–he would remain very still during her visits, standing motionless under her caresses and love-talk. Also, when she took herself off each time, instead of hurrying frantically after her to the gate, he would walk slowly, even 46 sedately, into his corner, the one nearest the house, and there watch her soberly till she disappeared indoors. Then–further evidence of the change that had come upon him–he would lie down in the warm sunlight and there fight flies, although before he had been given to worrying the family horse or irritating the brown saddler–all with nervous playfulness.

And he was dozing in his corner that morning when his mistress came fluttering to him to say good-by. He slowly rose to his feet and blinked curiously at her.

“Pat dear,” she exclaimed, breathlessly, “I’m going now!” She flung her arms around his neck, held him tightly to her a moment, then stepped back. “You–you must be good while–while I’m gone!” And dashing away a persistent tear, she then hurriedly left him, speeding across the patio and stepping into the waiting phaeton.

He watched the vehicle roll out into the trail. And though he did not understand, though the seriousness of it all was denied him, he nevertheless remained close to the fence a long time; long after the phaeton had passed from view, long after the sound of the mare’s paddling feet had died away, he stood there, ears cocked, eyes wide, tail motionless, in an attitude of receptivity, spiritual absorption, as one flicked with unwelcome premonitions.

Pat’s mistress was gone. He realized it from his continued disappointed watching for her at the fence; he realized it from the utter absence out of life of the sweets he had learned to love so well; and he realized it most of all from the change which rapidly came over the Mexican hostler. Though he did not know it, Miguel had been instructed, and in no mistakable language, to take good care of him, and, among other things, to keep him healthily supplied with sweets. But Miguel was not interested in colts, much less in anything that meant additional labor for him, and so Pat was made to suffer. Yet in this, as in all the other things, lay a wonderful good. He was made to know that he was not wholly a pampered thing–was made to feel the other side of life, the side of bitterness and disappointment, the side at times of actual want. And this continued denial of wants, of needs, occasionally, hardened him, as his earlier experiences had hardened him, toughened him for the struggles to come, brought to him that which is good for all youth–realization that life is not a mere span 48 of days with sweets and comforts for the asking, but a time of struggle, a battle for supremacy, and it is only through the battle that one grows fit and ever more fit for the good of the All.

Not the least of his trials was great loneliness. One day was so very like another. Regularly each morning, after seeking out his favorite corner in the corral, he would see the sun step from the mountain-tops, ascend through a cool morning, pour down scorching midday rays, descend through a tense afternoon, and drop from view in the chill of evening. Always he would watch this thing, sometimes standing, other times reclining, but ever conscious of the dread monotony of it all. Nothing happened, nobody came to caress him, no one paid him the least attention. A forlorn colt, a lonely colt, doubly so for lack of a mother, he spent long days in moody contemplation of an existence that irked.

One day, however, came something of interest into the monotony of his life. Evidently tiring of attending each horse in turn in the stalls, Miguel built a general box for feed in one corner of the inclosure, and then, by dint of loud swearing and the free use of a pitchfork, instructed the colt to feed from it with the others. Not that Pat required instruction as to the feeding itself–he was too much alive to need driving in that respect. But he did show nervous timidity at feeding with the other horses, and so Miguel cheerfully went to the urging with fork and tongue. But only 49 the one time. Soon the colt took to burying his nose in the box along with the others, and would wriggle his tail with a vigor that seemed to tell of his gratitude at being accepted as part of the great establishment and its devices. And then another thing. With this change in his method of feeding, he soon came to reveal steadily increasing courage and independence. Oftentimes he would be the first to reach the box, and, what was more to the point, would hold his position against the other horses–hold it against rough shouldering from the family horse, savage nipping from the saddler, even vigorous cursing and flaying from the swarthy hostler.

With the approach of winter he revealed his courage and temerity further. Of his own volition one night he abruptly changed his sleeping-quarters. Since the memorable occasion when the mare had kicked him out of her stall he had sought out a stall by himself with the coming of night, and there spent the hours in fear-broken sleep. But this night, and every night thereafter, saw him boldly approaching the mare and crowding in beside her in her stall, where, in the contact with her warm body and in her silent presence, he found much that was soothing and comfortable. Which, too, marked the beginning of a new friendship, one that steadily ripened with the passing winter and, by the time spring again descended into the valley, was an attachment close almost as that between mother and offspring. When in his playful moments, rare indeed now 50 for one of his age, he would inadvertently plunge into her, or stumble over a water-pail, she would nicker grave disapproval, or else chide him more generously by licking his neck and withers a long time in genuine affection.

Thus the colt changed in both spirit and physique. And the more he changed, and the larger he grew, the greater source of trouble he became to the Mexican. Before, he had feared the man. Now he felt only a kind of hatred, and this lent courage to make of himself a frequent source of annoyance.

With the return of warm weather he resumed his old place in his favorite corner. He did this through both habit and a desire to warm himself in the sun’s rays. And it was all innocent enough–this thing. Yet, innocent though it was, more than once, in passing, the Mexican struck him with whatever happened to be in his hands. At such times, whimpering with pain, he would dart to an opposite corner, there to stand in trembling fear, until, his courage returning, and his hatred for the man upholding him, he would return and defiantly resume his day-dreaming in the corner. This happened for perhaps a dozen times before he openly rebelled. And when he did rebel–when the Mexican struck him sharply across the nose–he whipped around his head like lightning and, still only half awake, sank his teeth savagely into the man’s shoulder. Followed a string of oaths and sudden appearance of a club, which might have proved serious but for the Judge’s timely 51 call for the horse and phaeton. Whereupon the Mexican slunk off into the stable. But as he went Pat saw the gleam in his black eyes, and knew that some day punishment most dire and cruel would descend upon him.

He passed through his second summer, that period of trial and sickness for many infants, in perfect health. In perfect health also he passed through the autumn and on into his second winter. Growing ever stronger with the passing seasons, he came to reveal still further his wonderful vitality, and to reveal it in many ways. Often he would take the initiative against the Mexican, kicking at him without due cause, refusing always to get out of his way, once nipping him sharply as he hurried past under pressing orders from the house. Also, having grown to a size equal to the brown saddler, he began to reveal his antipathy for this animal. Not only would he shoulder him away from the feed-box, but he would kick and snap at him, and once he tipped over the water-pail for no other reason, seemingly, than to deprive the saddler of water. The result of all this was that, with the passing seasons, both the Mexican and the saddler showed increasing respect for him, and the former went to every precaution to avoid a serious encounter.

But it was bound to come in spite of all his efforts to avoid it. Fighting spring flies in the stable one morning, Pat was aroused by a familiar sound in the corral. It was the sound which usually accompanied feeding, and, whirling, he plunged 52 eagerly toward the door. As he did so the Mexican, about to enter the stable, appeared on the threshold. Pat saw him too late. He crashed headlong into the Mexican and sent him reeling out into the inclosure. From that moment it was to the death.

The Mexican painfully gained his feet and, swearing a mighty vengeance, caught up a heavy shovel. Pat saw what was coming and, dashing out into the corral, sought protection behind the feed-box. But the infuriated man hunted him out, dealing upon his quivering back blow after blow, until, stung beyond all caution, Pat sprang for the object of his suffering. But the man leaped aside, delivering as he did so another vicious blow, this time across Pat’s nose–most tender of places. Dazed, trembling, raging with the spirit of battle, he surveyed the man a moment, and then, with an unnatural outcry, half nicker, half roar, he hurtled himself upon his enemy, striking him down. But he did not stop here. When the man attempted to rise he struck him down again, and a third time. Then, seeing the man lying motionless, he uttered another outcry, different from the other, a whimpering, baby outcry, and, whirling away from the scene, hurried across the corral and into the stable, where he sought out the family horse and, still whimpering babyishly, stood very close beside her, seeking her sympathy and encouragement.

This closed the feud for all time. Miguel was not seriously hurt. But he had learned something, 53 even as Pat had learned something, and thereafter there existed tacit understanding between them.

The seasons passed, and the third year came, and with it the beginning of the end of Pat’s loneliness. One morning late in June he was aroused by the voice of the Mexican, who, with brushes and currycomb in hand, had come to clean him. Pat was in need of just this cleaning. Though wallowing but little, leaving that form of exercise to the older horses, he nevertheless was gritty with sand from swirling spring winds. So he stood very still under the hostler’s vigorous attention. But Miguel’s ambition did not stop here. He turned to the other horses and curried and brushed them also, working till the perspiration streamed from him. But this was not the end. He set to work in the stable, and scraped and cleaned to the last corner, and rubbed and scoured to the smallest harness buckle. It was all very unusual, and Pat, standing attentive throughout it all, revealed marked interest and something of surprise. Soon he was to know the reason.

Along toward noon, as he was feeding at the box, he saw a very dignified young woman leave the house, cross the patio in his direction, and come to a stop immediately outside the fence. Though the feed-box always held his interest above all other things, and though it was strongly attracting him now, he nevertheless could not resist the attention with which this young woman regarded him. He returned her gaze steadily, wondering 54 who she was and what she meant to do. He soon found out, for presently she set out along the fence and came to a stop directly in front of him. She did more. She held out a hand and sounded a single word softly.

“Pat!” she called.

And now something took place inside the colt. With the word, far back in his brain, in the remotest of cells, there came an effort for freedom. It was a grim struggle, no doubt, for the thing must fight its way against almost all other thoughts and scenes and persons in his memory. But at length this vague memory gained momentum and dominance. And now he understood. The young woman outside the fence was his little mistress of early days! Lifting his head, he gave off a shrill and protracted nicker of greeting.

Helen dropped her hand. “Bless you!” she cried, and sped along the fence, opened the gate, and ran inside. “You do know me, don’t you?” she burst out, and, hurrying to his side, hugged him convulsively. “And I’m so glad, Pat!” she went on. “It–it has been a long three years!” She stepped back and looked him over admiringly. “And you have grown so! Dear, oh, dear! Three years!” Again she stepped close and hugged him. “I am so proud of you, Pat!”

All this love-talk, this caressing and hugging, was as the lifting of a veil to Pat. Within him all that had lain dormant for three years–affection, desires, life itself–now pressed eagerly to the surface. And though his mistress did not look 55 the same to him–though he found himself gazing down now instead of up to engage her eyes–yet, as if she had been gone but a day, he suddenly nuzzled her hand for loaf sugar and quartered apples. Then as suddenly he regretted this. For she had left him–was running across the corral. Frantically he rushed after her and, with a shrill cry of protest, saw her enter the house. But soon she appeared again, and when close, and he saw the familiar sweets in her hand, he nickered again, this time in sheer delight. And if he had doubted his good fortune before, now, with his mouth dripping luscious juices, he knew positively that he had come into his own again.

Sometime during the feast Helen noticed a scar across his nose. “Why, Pat!” she exclaimed. “How ever did you get that?”

But Pat did not say. Indeed, it is doubtful whether, in this happiest of moments, he would have descended to such commonplaces. But it was no commonplace to Helen, and she promptly sought out the Mexican. Yet Miguel declared that he knew nothing of the scar. He had been very watchful of the colt, he lied, cheerfully, and the scar was as much a mystery to him as it was to her. Whereupon Helen decided that Pat had brought it about through some prank, and, after returning to him and indulging in further caresses and love-talk, reluctantly took leave of him, returning to the house, there to begin unpacking her numerous trunks.