Title: The Oxford Degree Ceremony

Author: J. Wells

Release date: February 26, 2010 [eBook #31408]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Graeme Mackreth and The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Oxford

At the Clarendon Press

1906

HENRY FROWDE, M.A.

PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

LONDON, EDINBURGH

NEW YORK AND TORONTO

[Pg iii]The object of this little book is to attempt to set forth the meaning of our forms and ceremonies, and to show how much of University history is involved in them. It naturally makes no pretensions to independent research; I have simply tried to make popular the results arrived at in Dr. Rashdall's great book on the Universities of the Middle Ages, and in the Rev. Andrew Clark's invaluable Register of the University of Oxford (published by the Oxford Historical Society). My obligations to these two books will be patent to all who know them; it has not, however, seemed necessary to give definite references either to these or to Anstey's Munimenta Academica (Rolls Series), which also has been constantly used.

I have tried as far as possible to introduce the language of the statutes, whether past or present; the forms actually used in the degree ceremony itself are given in Latin and translated; in other cases a rendering has usually been given, but sometimes the original has been retained, when the words[Pg iv] were either technical or such as would be easily understood by all.

The illustrations, with which the Clarendon Press has furnished the book, are its most valuable part. Every Oxford man, who cares for the history of his University, will be glad to have the reproduction of the portrait of the fourteenth-century Chancellor and of the University seal.

I have to thank Dr. Rashdall and the Rev. Andrew Clark for most kindly reading through my chapters, and for several suggestions, and Professor Oman for special help in the Appendix on 'The University Staves'.

J.W.

The Degree Ceremony

The Meaning of the Degree Ceremony

The Preliminaries of the Degree Ceremony

The Officers of the University

University Dress

The Places of the Degree Ceremony

The Public Assemblies of the University of Oxford

The University Staves

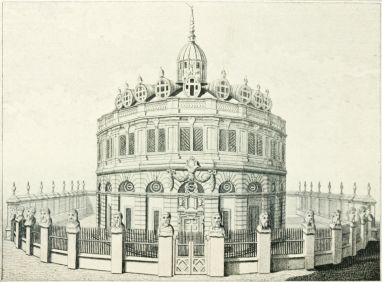

The Original Sheldonian

The University Seal

(The seal dates from the fourteenth

century and is kept by the Proctors.)

The Chancellor receiving a Charter from Edward III

(From the Chancellor's book, circ. 1375.)

Master and Scholar

(From the title-page of Burley's Tractatus

de natura et forma.)

The Bedel of Divinity's Staff

Proctor and Scholars of the Restoration Period

(From Habitus Academicorum, attributed

to D. Loggan, 1674.)

The Interior of the Divinity School

THE DEGREE CEREMONY[Pg 1]

The streets of Oxford are seldom dull in term time, but a stranger who chances to pass through them between the hours of nine and ten on the morning of a degree day, will be struck and perhaps perplexed by their unwonted animation. He will find the quads of the great block of University buildings, which lie between the 'Broad' and the Radcliffe Square, alive with all sorts and conditions of Oxford men, arrayed in every variety of academic dress. Groups of undergraduates stand waiting, some in the short commoner's gown, others in the more dignified gown of the scholar, all wearing the dark coats and white ties usually associated with the 'Schools' and examinations, but with their faces free from the look of anxiety incident to those occasions. Here and there are knots of Bachelors of Arts, in their ampler gowns with fur-lined hoods, some only removed by a brief three years from their undergraduate days, others who have evidently allowed a much longer period to pass before returning[Pg 2] to bring their academic career to its full and complete end. From every college comes the Dean in his Master's gown and hood, or if he be a Doctor, in the scarlet and grey of one of the new Doctorates, in the dignified scarlet and black of Divinity, or in the bold blending of scarlet and crimson which marks Medicine and Law. College servants, with their arms full of gowns and hoods, will be seen in the background, waiting to assist in the academic robing of their former masters, and to pocket the 'tips' which time-honoured custom prescribes.

Presently, when the hour of ten has struck, the procession of academic dignity may be seen approaching across the Quad, the Vice-Chancellor preceded by his staves as the symbol of authority, the Proctors in their velvet sleeves and miniver hoods, and the Registrar (or Secretary) of the University.

Already most of those concerned are waiting in the room where degrees are to be given: others still lingering outside follow the Vice-Chancellor and the Proctors, and the ceremony of conferring degrees begins.

Should our imaginary spectator wish to see the ceremony, he will have no difficulty in gaining admittance to the Sheldonian, even if he have delayed outside till the proceedings have commenced; but if the degrees[Pg 3] are conferred in one of the smaller buildings, it is well to secure a seat beforehand, which can be done through any Master of Arts. The ceremony will well repay a visit, for it is picturesque, it should be dignified, it is sometimes amusing. But it is more than this; in the conferment of University Degrees are preserved formulae as old as the University itself, and a ritual which, if understood, is full of meaning as to the oldest University history. The formulae, it is true, are veiled in the obscurity of a learned language, and the ritual is often a mere survival, which at first sight may seem trivial and useless; but those who care for Oxford will wish that every syllable and every form that has come down to us from our ancient past should be retained and understood. It is to explain what is said and what is done on these occasions that this little book is written.

Degrees at Oxford are conferred on days appointed by the Vice-Chancellor, of which notice is now given at the beginning of every term, in the University Gazette; the old form of giving notice, however, is still retained, in the tolling of the bell of St. Mary's for the hour preceding the ceremony (9 to 10 a.m.)[1].[Pg 4] The assembly at which degrees are conferred is the Ancient House of Congregation (p. 93). The old arrangement of the Laudian Statutes is still maintained, by which the proceedings commence with the entrance of the Vice-Chancellor and Proctors, while one of the Bedels 'proclaims in a quiet tone', 'Intretis in Congregationem, magistri, intretis.' The Vice-Chancellor, when he has formally taken his seat, declares the 'cause of this Congregation'. It will be noticed that both the Vice-Chancellor and the two Proctors, as representing the elements of authority in the University (as will be explained later), wear their caps all through the ceremony.

Degree giving, however, is sometimes preceded and delayed by the confirmation of the lists of examiners who have been 'duly nominated' by the committees appointed for this purpose; it is of course natural that the same body which gives the degree should appoint the examiners, on whose verdicts the degree now mainly depends. A less reasonable cause of delay is the fact that the 'Congregation' is sometimes preceded by a 'Convocation' for the dispatch of general business, as a rule (but not always) of a[Pg 5] formal character; the two bodies, Convocation and Congregation, are usually made up of the same persons, and are the same in all but name; the change from one to the other is marked by the Vice-Chancellor's descending from his higher seat, with the words 'Dissolvimus hanc Convocationem; fiat Congregatio'.

The degree ceremony itself begins with the declaration on the part of the Registrar that the candidates for the degrees have duly received permissions (gratiae) from their Colleges to present themselves, and that their names have been approved by him[2]; he has already certified himself from the University Register that all necessary examinations have been passed, and has been informed officially that all fees have been paid. The names have been already posted outside the door of the House; it is said that this is done to enable a tradesman to find out when any of his young debtors is about to leave Oxford, so that he may protest, if he wish, against the degree. The posting, however, is natural for many reasons, and no such tradesman's[Pg 6] protest has been known for years; nor is it easy to see how it could be made by any one not himself a member of the University.

The form of the college 'grace' states that the candidate has performed all the University requirements; that for the B.A. may be given as a specimen:—

'I, A.B., Dean of the College C.D., bear witness that E.F. of the College C.D., whom I know to have kept bed and board continuously within the University for the whole period required by the statutes for the degree of B.A., according as the statutes require, since he has undergone a public examination and performed all the other requirements of the statutes, except so far as he has been dispensed, has received from his college the grace for the degree of B.A. Under my pledged word to this University.

A.B., Dean of the College C.D.'

The words as to residence, that 'bed and board have been kept continuously' are derived immediately from the Laudian statute, but are in fact much older: the other clauses have of course been changed.

The various degrees are then taken in the following order:—

Doctor of Divinity.

Doctor of Civil Law or of Medicine.

Bachelor of Divinity.

[Pg 7]Master of Surgery.

Bachelor of Civil Law or of Medicine (and of Surgery).

Doctor of Letters or of Science.[3]

Master of Arts.

Bachelor of Letters or of Science.

Bachelor of Arts.

Musical degrees.

It sometimes happens, however, that a candidate is taking two degrees at once (i.e. B.A. and M.A.); this 'unusual distinction', as local newspapers admiringly call it, is generally due to the unkindness of examiners who have prolonged the ordinary B.A. course by repeated 'ploughs'. In these cases the lower degree is conferred out of order before the higher.

The same forms are observed in granting all degrees; they are fourfold, and are repeated for each separate degree or set of degrees. Here they are only described once, while minor peculiarities in the granting of each degree are noticed in their place; but it is important to remember that the essentials recur in each admission; this explains the apparently meaningless repetition of the same ceremonies. This repetition was once a much more prominent feature; within[Pg 8] living memory it was necessary for each 'grace' to be taken separately, and the Proctors 'walked' for each candidate. Degree ceremonies in those days went on to an interminable length, although the number graduating was only half what it is now.

The first form is the appeal to the House for the degree. One of the Proctors reads out the supplicat, i.e. the petition of the candidate or candidates to be allowed to graduate; this is the duty of the Senior Proctor in the case of the M.A.s, of the Junior Proctor in the case of the B.A.s; for the higher degrees, e.g. the Doctorate, either Proctor may 'supplicate'.

The form of the supplicat is the same, with necessary variations, in all cases; that for the M.A. may be given as a specimen:—

'Supplicat venerabili Congregationi Doctorum et Magistrorum regentium E.F. Baccalaureus facultatis Artium e collegio C. qui complevit omnia quae per statuta requiruntur, (nisi quatenus cum eo dispensatum fuerit) ut haec sufficiant quo admittatur ad incipiendum in eadem facultate.'

('E.F. of C. College, Bachelor of Arts, who has completed all the requirements of the statutes (except so far as he has been excused), asks of the venerable Congregation of Doctors and Regent Masters that these things may [Pg 9]suffice for his admission to incept in the same faculty.')

This form is at least as old as the sixteenth century, and probably much older; but in its original form it set forth more precisely what the candidate had done for his degree (cf. cap. ii). After each supplicat has been read by the Proctor, he with his colleague walks half-way down the House; this is in theory a formal taking of the votes of the M.A.s present. When the Proctors have returned to their seats, the one of them who has read the supplicat, lifting his cap (his colleague imitating him in this), declares 'the graces (or grace) to have been granted' ('Hae gratiae concessae sunt et sic pronuntiamus concessas'). The Proctors' walk is the most curious feature of the degree ceremony; it always excites surprise and sometimes laughter. It should, however, be maintained with the utmost respect; for it is the clear and visible assertion of the democratic character of the University; it implies that every qualified M.A. has a right to be consulted as to the admission of others to the position which he himself has attained.

But popular imagination has invented a meaning for it, which certainly was not contemplated in its institution; it is currently believed that the Proctors walk in order to[Pg 10] give any Oxford tradesman the opportunity of 'plucking' their gown and protesting against the degree of a defaulting candidate. 'Verdant Green'[4] was told that this was the origin of the ominous 'pluck', which for centuries was a word of terror in Oxford; in the last half-century, it has been superseded by the more familiar 'plough'. There is a tradition that such a protest has actually been made within living memory and certainly it was threatened quite recently; a well-known Oxford coach (now dead) informed the Proctors that he intended in this way to prevent the degree of a pupil who had passed his examinations, but had not paid his coach's fee. The defaulter, in this case, failed to present himself for the degree, and so the 'plucking' did not take place.[Pg 11]

The second part of the ceremony is the presentation of the candidates to the Vice-Chancellor and Proctors; this is done in the case of the higher degrees, Divinity, Medicine, &c., by the Professor at the head of the faculty[5], in the case of the M.A.s and B.A.s by the representative of the college.

The candidates are placed on the right hand of the presenter, who with 'a proper bow' ('debita reverentia') to the Vice-Chancellor and the Proctors, presents them with the form appropriate to the degree they are seeking; that for the M.A. is as follows:—

'Insignissime Vice-Cancellarie, vosque egregii Procuratores, praesento vobis hunc Baccalaureum in facultate Artium, ut admittatur ad incipiendum in eadem facultate.'

('Most eminent Vice-Chancellor, and excellent Proctors, I present this B.A. to you for admission to incept in the faculty of Arts.')

The old custom was that the presenter should grasp the hand of each candidate and present him separately; some senior members of the University still hold the[Pg 12] hand of one of their candidates, though the custom of separate presentation has been abolished; there was an intermediate stage fifty years ago, when the number of those who could be presented at once was limited to five; each of them held a finger or a thumb of the presenter's right hand.

The third part of the ceremony is the charge which is delivered, usually by the Junior Proctor, to the candidates for the degree. Each receives a copy of the New Testament from the Bedel, on which to take his oath. The charge to all candidates for a doctorate or for the M.A. is:—

'Vos dabitis fidem ad observandum statuta, privilegia, consuetudines et libertates istius Universitatis. Item quod quum admissi fueritis in domum Congregationis et in domum Convocationis, in iisdem bene et fideliter, ad honorem et profectum Universitatis, vos geretis. Et specialiter quod in negotiis quae ad gratias et gradus spectant non impedietis dignos, nec indignos promovebitis. Item quod in electionibus habendis unum tantum semel et non amplius in singulis scrutiniis scribetis et nominabitis; et quod neminem nominabitis nisi quem habilem et idoneum certo sciveritis vel firmiter credideritis.'

('You will swear to observe the statutes, privileges, customs and liberties of your University. Also when you have been admitted [Pg 13]to Congregation and to Convocation, you will behave in them loyally and faithfully to the honour and profit of the University. And especially in matters concerning graces and degrees, you will not oppose those who are fit or support the unfit. Also in elections you will write down and nominate one only and no more at each vote; and you will nominate no one but a man whom you know for certain or surely believe to be fit and proper.')

To this the candidates answer 'Do fidem'.

The charge to candidates for the B.A. or other lower degrees is much simpler:—

'Vos tenemini ad observandum omnia statuta, privilegia, consuetudines, et libertates istius Universitatis, quatenus ad vos spectent' (as far as they concern you).

This charge, which is of course the first part of the charge to M.A.s, goes back to the very beginnings of University ceremonial; the latter part of the charge to M.A.s is modern, and takes the place of the more elaborate oaths of the Laudian and of still earlier statutes. By these a candidate bound himself not to recognize any other place in England except Cambridge as a 'university', and especially that he 'would not give or listen to lectures in Stamford as in a university'.[6][Pg 14] There was also a special direction that each candidate should within a fortnight obtain the dress proper for his degree, in order that 'he might be able by it to do honour to our mother the University, in processions and in all other University business'. It is a great pity that this latter part of the old statutes was ever omitted.

The candidates for a degree in Divinity, whether Bachelors or Doctors, are charged by the Senior Proctor; the senior of them makes the following declaration, taken from the thirty-sixth canon of the Church of England (as revised and confirmed in 1865):

'I, A.B., do solemnly make the following declaration. I assent to the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion and to the Book of Common Prayer and of the ordering of bishops, priests, and deacons, and I believe the doctrine of the United Church of England and Ireland, as therein set forth, to be agreeable to the Word of God.'

The Senior Proctor then says to the other candidates:—

'Eandem declarationem quam praestitit A.B. in persona sua, vos praestabitis in personis vestris, et quilibet vestrum in persona sua.'

('The declaration which A.B. has made on his part, you will make on your part, together and severally.')

When the candidates have duly taken the oath, the last and most important part of the ceremony is performed.

The candidates for any Doctorate, except the new 'Research' ones, or for the M.A., kneel before the Vice-Chancellor; the Doctors are taken separately according to their faculties, then the M.A.s in successive groups of four each; the Vice-Chancellor, as he admits them, touches them each on the head with the New Testament, while he repeats the following form:—

'Ad honorem Domini nostri Jesu Christi, et ad profectum sacrosanctae matris ecclesiae et studii, ego auctoritate mea et totius Universitatis do tibi (vel vobis) licentiam incipiendi in facultate Artium (vel facultate Chirurgiae, Medicinae, Juris, S. Theologiae) legendi, disputandi, et caetera omnia faciendi quae ad statum Doctoris (vel Magistri) in eadem facultate pertinent, cum ea completa sint quae per statuta requiruntur; in nomine Domini, Patris, Filii, et Spiritus Sancti.'

('For the honour of our Lord Jesus Christ, and for the profit of our holy mother, the [Pg 16]Church, and of learning, I, in virtue of my own authority and that of the whole University, give you permission to incept in the Faculty of Arts (or of Surgery, &c.), of reading, disputing, and performing all the other duties which belong to the position of a Doctor (or Master) in that same faculty, when the requirements of the statutes have been complied with, in the Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.')

This venerable form goes back (p. 26) to the beginning of the fifteenth century, and is probably much older; the only change in it is the omission at the beginning of 'et Beatae Mariae Virginis'. Modern toleration has provided a modified form for use in cases of candidates for whom the full form is theologically inappropriate, but this is rarely used.

The ceremony of the licence is now complete; but before the B.A.s are admitted, the Doctors first, and then the Masters in their turn, retire outside, and don 'their appropriate gowns and hoods'. They receive these from those who were once their college servants, and the right of thus bringing gown and hood is strictly claimed; nor is this surprising, as unwritten custom prescribes that the gratuity must be of gold. The newly created Doctors or Masters then come back,[Pg 17] with the Bedel leading the procession, and 'make a bow' to the Vice-Chancellor, who usually shakes hands with the new Doctors; they are then conducted to a place in the raised seats behind and around his chair, from which they can watch the rest of the proceedings. The M.A.s either leave the house or join their friends among the spectators.

The ceremony of admitting B.A.s is much simpler. As in the case of the Masters, they are presented by their college Dean; the form of presentation is:

'Insignissime Vice-Cancellarie, vosque egregii Procuratores, praesento vobis hunc meum scholarem (vel hos meos scholares) in facultate Artium, ut admittatur (vel admittantur) ad gradum Baccalaurei in Artibus.'

The charge is then given by the Junior Proctor (see pp. 12 and 13). After this the candidates are, without kneeling, admitted by the Vice-Chancellor, in the following words:

'Domine (vel Domini), ego admitto te (vel vos) ad gradum Baccalaurei in Artibus; insuper auctoritate mea et totius Universitatis, do tibi (vel vobis) potestatem legendi, et reliqua omnia faciendi quae ad eundem gradum spectant.'

This form also is old, but has been cut down from its former fullness; e.g. in the[Pg 18] Laudian Statutes the candidate was admitted, among other things, to 'read a certain book of the Logic of Aristotle'. The B.A.s, when admitted, are allowed to disperse as they please, and the ceremony is over. It is unfortunate that the form of admission to the degree which is most frequently taken, and which (speaking generally) is the most real degree given, should be such an unsatisfactory and bare fragment of the old ceremonial.

It may be noticed that degrees 'in absence' are announced by the Vice-Chancellor after each set of degrees has been conferred, e.g. an 'absent' M.A. is announced after the M.A.s have made their bow. The University only allows this privilege to those who are actually out of the country, and to them only on stringent conditions; an extra payment of £5 is required.

The proceedings terminate sometimes with the admission to 'ad eundem' rank at Oxford, of graduates of Cambridge or of Dublin; this privilege is now rarely granted, though it was once freely given. When all is over, the Vice-Chancellor rises, announces 'Dissolvimus hanc Congregationem', and solemnly leaves the building in the same pomp and state with which he entered.

[1] In 1619 a B.A. candidate from Gloucester Hall (now Worcester College), who failed to present himself for his 'grace', was excused 'because he had not been able to hear the bell owing to the remoteness of the region and the wind being against him'.

[2] Till recently the whole list of candidates for all degrees was read by the Registrar, as well as by the Proctors afterwards when 'supplicating' for the graces of the various sets of candidates. Time is now economized by having the names read once only.

[3] If the Doctor be not an M.A., then his admission to the Doctorate follows the admission of the M.A.s.

[4] Verdant Green was published in 1853, and this is the oldest literary evidence for the connexion of 'plucking' and the Proctorial walk. The earliest mention of 'plucking' at Oxford is Hearne's bitter entry (May, 1713) about his enemy, the then Vice-Chancellor, Dr. Lancaster of Queen's—'Dr. Lancaster, when Bachelor of Arts, was plucked for his declamation.' But it is most unlikely that so good a Tory as Hearne would have used a slang phrase, unless it had become well established by long usage. 'Pluck', in the sense of causing to fail, is not unfrequently found in English eighteenth century literature, without any relation to a university; the metaphor from 'plucking' a bird is an obvious one, and may be compared to the German use of 'rupfen'.

[5] The old principle is that no one should be presented except by a member of the University who has a degree as high or higher than that sought; this is unfortunately neglected in our own days, when an ordinary M.A., merely because he is a professor, is appointed by statute to present for the degree of D.Litt. or D.Sc.

[6] This delightful piece of English conservatism was only removed from the statutes in 1827. It refers to the foundation of a university at Stamford in 1334 by the northern scholars who conceived themselves to have been ill-treated at Oxford; the attempt was crushed at once, but only by the exercise of royal authority.

THE MEANING OF THE DEGREE CEREMONY[Pg 19]

For the last 500 years certainly, for nearly 200 longer probably, the candidate presented for 'inception' in the Faculty of Arts (i.e. for the M.A. degree) has sworn that he will observe the 'statutes, privileges, customs and liberties' of his university.[7] It is difficult to know what the average man now means when he hurriedly says 'Do fidem' after the Junior Proctor's charge; but there is no doubt that when the form of words was first used, it meant much. The candidate was being admitted into a society which was maintaining a constant struggle against encroachments, religious or secular, from without, and against unruly tendencies within. And this struggle gave to the University a vivid consciousness of its unity, which in these[Pg 20] days of peace and quiet can hardly be conceived.

The essential idea of a university is a distinctly mediaeval one; the Middle Ages were above all things gifted with a genius for organization, and men were regarded, and regarded themselves, rather as members of a community than as individuals. The student in classical times had been free to hear what lectures he pleased, where he pleased, and on what subjects he pleased, and he had no fixed and definite relations with his fellow students. There is little or no trace of regular courses of study, still less of self-governing bodies of students, in the 'universities' of Alexandria or Athens.

But with the revival of interest in learning in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the real formation of universities begins. The students formed themselves into organized bodies, with definite laws and courses of study, both because they needed each other's help and protection, and because they could not conceive themselves as existing in any other way.

These organized bodies were called 'universitates'[8], i.e. guilds or associations; the[Pg 21] name at first had no special application to bodies of students, but is applied e.g. to a community of citizens; it was only gradually that it acquired its later and narrower meaning; it finally became specialized for a learned corporation, just as 'convent' has been set apart for a religious body, and 'corps' for a military one.

When these organized bodies were first formed is a question which it is impossible to discuss at length here, nor could a definite answer be given. The University of Oxford is, in this respect, as in so many others, characteristically English; it grew rather than was made, like most of our institutions, and it can point to no definite year of foundation, and to no individual as founder. Here it must suffice to say that references to students and teachers at Oxford are found with growing frequency all through the twelfth century; but it is only in the last quarter of that century that either of those features which differentiate a university from a mere chance body of students can be clearly traced. These two features are organized study and the right of self-government.[Pg 22]

The first mention of organized study is about 1184, when Giraldus Cambrensis, having written his Topographia Hibernica and 'desiring not to hide his candle under a bushel,' came to Oxford to read it to the students there; for three days he 'entertained' his audience as well as read to them, and the poor scholars were feasted on a separate day from the 'Doctors of the different faculties'. Here we have definite evidence of organized study. Much more important is the record of 1214 (the year before Magna Carta[9]), when the famous award was given by the Papal Legate, which is the oldest charter of the University of Oxford. In this the 'Chancellor' is mentioned, and we have in this office the beginnings of that self-government which, coupled with organized study, may justify us in saying that the real university was now in existence. It is quite probable that the first Doctor of Divinity whom we find 'incepting' in Oxford, is the learned and saintly Edmund Rich, afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury; he seems to have[Pg 23] taken this degree in the reign of John, but he had been already teaching secular subjects in the preceding reign (Richard I's). It is significant of mediaeval Oxford's position as a pillar of the Church and a champion of liberty, that her first traceable graduate should be the last Archbishop of Canterbury who was canonized, and one of the defenders of English liberties against the misgovernment of Henry III.

The 'University' of Oxford, like the great sister (or might we say mother?) school of Paris, was an association of Masters of Arts, and they alone were its proper members. In our own days, when not more than half of those who enter the University proceed to the M.A. Degree, and when only about ten per cent. of them reside for any time after the B.A. course is ended, this state of things seems inconceivable; but it has left its trace, even in popular knowledge, in the well-known fact that M.A.s are exempt from Proctorial jurisdiction; and our degree terminology is still based upon it. It is the M.A. who is admitted by the Vice-Chancellor to 'begin', i.e. to teach (ad incipiendum), when he is presented to him, and at Cambridge and in American Universities the ceremonies at the end of the academic year are called 'Commencement'. What seems an Irish bull is[Pg 24] really a survival of the oldest university arrangements.

As then the University is a guild of Masters, the degree is the 'step' by which the distinction of becoming a full member of it is attained. Gibbon wrote a century ago that 'the use of academical degrees is visibly borrowed from the mechanic corporations, in which an apprentice, after serving his time, obtains a testimonial of his skill, and his licence to practise his trade or mystery'. This statement, though accurate in the main, is misleading; the truth is that the learned body has not so much borrowed from the 'mechanic' one, as that both have based their arrangements independently on the same idea.

This connexion may be illustrated from the other degree title, 'Bachelor.' If the etymology at present best supported may be accepted, that honourable term was originally used for a man who worked on a 'cow-strip' of land, i.e. who was assistant of a small cultivator; whether this be true or not, it at any rate soon came to denote the apprentice as opposed to the master-workman; in fact the 'Bachelor' in the university corresponded to the 'pupil-teacher' of more humble associations in our own days. In this sense of the word, as Dr. Murray quaintly says,[Pg 25] a woman student can become a 'Bachelor' of Arts.

It was natural that the existing members of the 'university' or guild should be consulted as to the admission of new members; their consent was one element in the degree giving. The means by which the fitness of applicants for the degree was tested will be spoken of later, and also the methods by which the existing Masters expressed their willingness to admit the new-comer among them.

But there is quite a different element in the degree from that which has so far been mentioned. That was democratic, the consent of the community; this is autocratic, the authority conferred by a head, superior to, and outside of the community. The Vice-Chancellor of Oxford represents this second principle; he gives the degree in virtue of 'his own authority' as well as of that 'of the University'. This authority is originally that of the Church, to which, in England at any rate, all mediaeval students ipso facto belonged; the new student was admitted into the 'bosom' (matricula) of the University by receiving some form of tonsure, and for the first two centuries of University existence, no other ceremony was needed. Matriculation examinations at any rate were[Pg 26] in those happy days unknown. Hence the authority which the cathedral chancellor, representing the bishop, had exercised over the schools and teachers of the diocese, was extended as a matter of course to the teachers of the newly-risen Universities. The fitness of the applicant for a degree was tested by those who had it already, but the ecclesiastical authority gave the 'licence' to teach. This ecclesiastical origin of the M.A. degree is well shown in the formula of admission (pp. 15, 16). The new Master is admitted 'in honorem Domini nostri Jesu Christi' and 'in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost'.

The close connexion of the Church and higher education is further illustrated by the view of the fourteenth-century jurists that a bull from the Pope or from the Holy Roman Emperor was needed to make a teaching body a 'Studium Generale', and to give its doctors the jus ubique docendi[10].[Pg 27] A curious survival of the same idea still remains in the power of the Archbishop of Canterbury, as English Metropolitan, to recommend the Crown to grant 'Lambeth degrees' to deserving clergy; this is probably a survival of the old rights of the Archbishop as 'Legatus Natus' in England of the Holy See.

There were then two elements in the conferring of a mediaeval degree, the formal approval of the candidate by the already existing Masters and the granting of the 'licence' by the Chancellor.

Of these the 'licence' is fully retained in our present ceremony; the new M.A. receives permission (licentia) from the Vice-Chancellor to 'do all that belongs to the status of a Master', when 'the requirements of the statutes have been fulfilled'. This condition is now meaningless, for he has already fulfilled all 'the requirements'; but in mediaeval times it referred to the second (and what was really the most important) part of his qualifications, his appearance at the solemn 'Act' or ceremony which was the chief event of the University year. At it Masters and Doctors formally showed that they were able to perform the functions of their new rank, and were then 'admitted' to it by investiture with the 'cap' of authority, with the 'ring',[Pg 28] and with the 'kiss' of peace; the kiss was given by the Senior Proctor; the ring was the symbol of the inceptor's mystical marriage to his science. The 'Act' in our day only survives as giving a name to one of our two Summer Terms, which still have a place in the University Calendar, and in the requirements of 'twelve terms of residence', although only nine real terms are kept. Its disappearance was gradual; already in 1654, when John Evelyn attended the 'Act' at St. Mary's, he expresses surprise at 'those ancient ceremonies and institution (sic) being as yet not wholly abolished'; but the 'Act' survived into another century, although becoming more and more of a form; it is last mentioned in 1733. With the ceremony disappeared the formal exhibition of the candidate's fitness for the degree he is seeking.

But in the mediaeval University it had been far otherwise. The idea that a degree was formally taken by the applicant showing himself competent for it, may be well illustrated from the quaint ceremony of admitting a Master in Grammar at Cambridge, as described by the Elizabethan Esquire Bedel, Mr. Stokys: 'The Bedel in Arts shall bring the Master in Grammar to the Vice-Chancellor, delivering him a palmer with a rod, which the Vice-Chancellor shall give[Pg 29] to the said Master in Grammar, and so create him Master. Then shall the Bedel purvey for every Master in Grammar a shrewd boy, whom the Master in Grammar shall beat openly in the Schools, and he shall give the boy a groat for his labour, and another groat to him that provideth the rod and the palmer. And thus endeth the Act in that faculty.' It may be added that the Vice-Chancellor and each of the Proctors received a 'bonnet', but only one, however many 'Masters' might be incepting. In Oxford likewise the 'Master in Grammar' was created 'ferula (i.e. palmer) et virgis'.

The Oxford M.A. had to show his qualifications in a way less painful, though as practical, by publicly attacking or defending theses solemnly approved for discussion by Congregation. These theses were themselves by no means always solemn, e.g. one of those appointed in 1600 was 'an uxor perversa humanitate potius quam asperitate sanetur?' ('whether a shrew is better cured by kindness or by severity'). This question, obviously suggested by Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew, which was written soon after 1594, was answered by the incepting M.A.s in the opposite sense to the dramatist. It need hardly be said that all the disputations were in Latin. The Doctors too of the different[Pg 30] faculties were created at the 'Act' after disputations on subjects connected with their faculty. Something resembling these disputations still survives in a shadowy form at Oxford, in the requirements for the degrees of B.D. and D.D. A candidate for the B.D. has to read in the Divinity School two theses on some theological subject approved by the Regius Professor, a candidate for the D.D. has to read and expound three passages of Holy Scripture; in both cases notice has to be given beforehand of the subject, a custom which survives from the time when the candidate might expect to have his theses disputed; but now the Regius Professor and the candidate generally have the Divinity School to themselves.

All the ceremonies of the 'Act' have passed away from Oxford completely.[11] They are only referred to here as serving to illustrate the idea that a new Master was not admitted till he had performed a 'masterpiece', i.e. done a piece of work such as a Master might be expected to do. There was till quite recently one last trace of them in our degree arrangements; a new M.A. was not admitted[Pg 31] to the privileges of his office till the end of the term in which he had been 'licensed to incept'; although the University, having given up the 'Act', allowed no opportunity of 'incepting', an interval was left in which the ceremony might have taken place. Now, however, for purposes of practical convenience, even this form is dropped, and a new M.A. enters on his privileges, e.g. voting in Convocation, &c., as soon as he has been licensed by the Vice-Chancellor. Strictly speaking an Oxford man never takes his M.A., for there is no ceremony of institution; he is 'licensed' to take part in a ceremony which has ceased to exist.

And yet in another form the 'Act' survives in our familiar Commemoration; the relation of this to the 'Act' seems to be somewhat as follows. The Sheldonian Theatre was opened, as will be described later (p. 81), with a great literary and musical performance, a 'sort of dedication of the Theatre'; this was called 'Encaenia'.[12] So pleased was the University with the performance that the Chancellor next year (1670) ordered that it should be repeated annually, on the Friday before the 'Act'. From the very first there was a tendency to confuse the two ceremonies;[Pg 32] even the accurate antiquarian, Antony Wood, speaks of music as part of 'the Act', which was really performed at the preliminary gathering, the Encaenia. The new function gradually grew in importance, and additions were made to it; the munificent Lord Crewe, prince-bishop of Durham, who enjoys an unenviable immortality in the pages of Macaulay, and a more fragrant if less lasting memory in Besant's charming romance Dorothy Forster, left some of his great wealth for the Creweian Oration, in which annual honour is done to the University Benefactors at the Commemoration.

Hence, while the customs of the 'Act' became more and more meaningless and neglected, the Encaenia became more and more popular, until finally the older ceremony was merged in the newer one. In our Commemoration degree-giving still takes place, along with recitation of prize poems and the paying of honour to benefactors. The degrees are all honorary, but they are submitted to the House in the same way as ordinary degrees; the Vice-Chancellor puts the question to the Convocation, just as the Proctor submits the 'grace' to Congregation, and in theory a vote is taken on the creation of the new D.C.L.s, just as in theory the Proctors take the votes as to the admission of new M.A.s.[Pg 33]

Commemoration may be, as John Richard Green said, 'Oxford in masquerade'; there may be 'grand incongruities, Abyssinian heroes robed in literary scarlet, degrees conferred by the suffrages of virgins in pink bonnets and blue, a great academical ceremony drowned in an atmosphere of Aristophanean (sic) chaff'. But the chaff is the legitimate successor of the burlesque performance of the Terrae Filius at the old 'Act', and the degrees are submitted to the House with the old formula; even the presence of ladies would have been no surprise to our predecessors of 200 years ago, however much they would have astonished our mediaeval founders and benefactors; in the Sheldonian from the first the gallery under the organ was always set apart for 'ladies and gentlewomen'. 'Oxford', to quote J.R. Green once again, 'is simply young', but when he goes on to say 'she is neither historic nor theological nor academical', he exaggerates; the charm of Oxford lies in the fact that her youth is at home among survivals historic, theological, and academical; and the old survives while the new flourishes.

[7] The form is found in the two 'Proctors' books', of which the oldest, that of the Junior Proctor, was drawn up (in 1407) by Richard Fleming, afterwards Bishop of Lincoln and founder of Lincoln College; but it was then already an established form, and probably goes back to the thirteenth century, i.e. to the reign of Henry III.

[8] It is perhaps still necessary to emphasize the fact that the name 'University' had nothing to do with the range of subjects taught, or with the fact that instruction was offered to all students; the latter point is expressed in the earlier name 'studium generale' borne by universities, which is not completely superseded by 'universitas' till the fifteenth century.

[9] The coincidence is not accidental. Magna Carta was wrested from a king humiliated by his submission to the Pope, and the University Charter was given to redress an act of violence on the part of the Oxford citizens, who had been stimulated in their attack on the 'clerks' of Oxford by John's quarrel with the Pope.

[10] Oxford never received this Papal ratification; but as its claim to be a 'studium generale' was indisputable, it, like Padua, was recognized as a 'general seat of study' 'by custom'. The University of Paris, however, at one time refused to admit Oxford graduates to teach without re-examination, and Oxford retorted (the Papal bull in favour of Paris notwithstanding) by refusing to recognize the rights of the Paris doctors to teach in her Schools.

[11] In the Scotch Universities Doctors are still created by 'birettatio', the laying on of the cap, and I believe this is still done at many 'Commencements' in America.

[12] Compare St. John x. 22, ἐγκαίνια = 'The Feast of the Dedication'.

THE PRELIMINARIES OF THE DEGREE CEREMONY[Pg 34]

It is needless to describe the requirements of our modern examination system, for those who present themselves for degrees, and their friends, know them only too well. And to describe completely the requirements of the mediaeval or the Laudian University would be to enter into details which, however interesting, would yet belong to antiquarian history, and which have no relation to our modern arrangements.

But there are certain broad principles which are common to the present system and to its predecessors, and which well deserve attention.

The first and most important of these is that Oxford has always required from those seeking a degree, as she requires now, 'residence' in the University for a given time. It is declared in the Proctors' books (mediaeval statutes used picturesque language), that 'Whereas those who seek to[Pg 35] mount to the highest places by a short cut, neglecting the steps (gradibus) thereto, seem to court a fall, no M.A. should present a candidate (for the B.A.) unless the person to be presented swear that he has studied the liberal arts in the Schools, for at least four years at some proper university'. There was of course a further three years required of those taking the M.A. degree, and a still longer period for the higher faculties. Residence, it may be added, was required to be continuous; the modern arrangement which makes it possible to put in a term, whenever convenient to the candidate, would have seemed a scandal to our predecessors. It will be noticed that much more than our modern 'pernoctation' was then required for residence, and that migration from other universities was more freely permitted than is now the case. This freedom to study at more than one university is still the rule in Germany, and Oxford is returning to it in the new statute on Colonial and Foreign Universities, which excuses members of other bodies who have complied with certain conditions, from one year of residence, and from part of our examinations.

The University in old days, however, was more prepared to relax this requirement than it is in modern times; the sons of knights[Pg 36] and the eldest sons of esquires[13] were permitted to take a degree after three years, and 'graces' might be granted conferring still further exemptions; e.g. a certain G. More was let off with two years only, in 1571, because being 'well born and the only son of his father', he is afraid that he 'may be called away before he has completed the appointed time', and so may 'be unable to take his degree conveniently'. The University is less indulgent now.

The old statute quoted above also implies that there were special lectures to be heard during the four years of residence; some of them had to be attended twice over. The old Oxford records give careful directions how the lectures were to be given; the text was to be closely adhered to and explained, and digressions were forbidden. There are, however, none of those strict rules as to the punctuality of the lecturer, the pace at which he was to lecture, &c., which make some of the mediaeval statutes of other universities so amusing[14].[Pg 37]

The list of subjects for a mediaeval degree is too long to be given here; it may be mentioned, however, that Aristotle, then as always, held a prominent place in Oxford's Schools.[15] This was common to other universities, but the weight given to Mathematics and to Music was a special feature of the Oxford course.

The lectures were of course University and not college lectures; the latter hardly existed before the sixteenth century, and were as a rule confined to members of the college. As there were no 'Professors' in our sense, the instruction was given by the ordinary Masters of Arts, among whom those who were of less than two years' standing were compelled to lecture, and were styled 'necessary regents' (i.e. they 'governed the Schools'). They were paid by the fees of their pupils (Collecta, a word familiar in a different sense in our 'Collections'). There was keen competition in early days to[Pg 38] attract the largest possible audience, but later on the University enacted that all fees should be pooled and equally divided among the teachers. For this (and for other reasons) the lectures became more and more a mere form, and no real part of a student's education.

There had been from time immemorial a fixed tariff for 'cutting'[16] lectures, and there was a further fine of the same amount for failing to take notes. But the University from time to time tried actually to enforce attendance. A curious instance of this occurs toward the close of the reign of Elizabeth; a number of students were solemnly warned that 'by cutting' lectures, they were incurring the guilt of perjury, because they had sworn to obey the statutes which required attendance at lectures. They explained they had thought their 'neglect' to hear lectures only involved them in the fine and not in 'perjury', and after this apology they seem to have proceeded to their degrees without further difficulty.

In fact there was a growing separation after the fifteenth century, between the[Pg 39] formal requirements for the degree, and the actual University system; sometimes irreconcilable difficulties arose, e.g. when two students were (in 1599) summoned to explain why they had not attended one of the lectures required for the degree, and they presented the unanswerable excuse that the teacher in question had not lectured, having himself been excused by the University from the duty of giving the lecture. In fact the whole system would have been unworkable but for the power of granting 'graces' or dispensations, which has already been referred to: how necessary and almost universal these were, may be seen from the fact that even so conscientious a disciplinarian as Archbishop Laud, stern alike to himself and to others, was dispensed from observing all the statutes when he took his D.D. (1608) 'because he was called away suddenly on necessary business'. We can well believe that Laud then, as always, was busy, but there were other students who got their 'graces' with much less excuse. Modern students may well envy the good fortune of the brothers Carey from Exeter College, who (in 1614) were dispensed because 'being shortly about to depart from the University, they desired to take with them the B.A. degree as a benediction from their Alma Mater, the University'.[Pg 40]

One curious development of the old system of 'graces' survived in one of the most prominent of Oxford colleges almost till within living memory.[17] William of Wykeham had ordained that his students should perform the whole of the University requirements, and not avail themselves of dispensations. When the granting of these became so frequent that they were looked upon as the essential part of the system, the idea grew up that New College men were to be exempt from the ordinary tests of the University. Hence a Wykehamist took his degree with no examination but that of his own college, both under the Laudian Statute and after the great statute of 1800, which set up the modern system of examinations. What the founder had intended as an encouragement for industry was made by his degenerate disciples an excuse for idleness.

So far only the qualifications of residence[Pg 41] and attendance on lectures have been spoken of. The great test of our own times, the examination, has not even been referred to. And it must certainly be admitted that the terrors of the modern written examinations were unknown in the old universities; such testing as took place was always viva voce. That the tests were serious, in theory at any rate, may be fairly inferred from the frequent statutes at Paris against bribing examiners, and from the provision at Bologna that at this 'rigorous and tremendous examination', the examiner should treat the examinee 'as his own son'. Robert de Sorbonne, the founder of the famous college at Paris, has even left a sermon in which an elaborate comparison is drawn between university examinations and the Last Judgement; it need hardly be said that the moral of the sermon is the greater severity of the heavenly test as compared with the earthly; if a man neglects his prescribed book, he will be rejected once, but if he neglect 'the book of conscience, he will be rejected for ever'. Such a comparison was not likely to have been made, had not the earthly ordeal possessed terrors at least as great as those that mark its modern successors.

It may be added at once, however, that we hear very little about examinations in old[Pg 42] Oxford; but still there were some. Then as now the first examination was Responsions, a name which has survived for at least 500 years, whatever changes there have been in its meaning. The University also still retains the time-honoured name of the 'Masters of the Schools' for those who conduct this examination (though there are now six and not four, as in the thirteenth century), and candidates who pass are still said as of old to have 'responded in Parviso'.[18]

In the fifteenth century a man had to be up at least a year before he entered for this examination, in the sixteenth century he could not do so before his ninth term, i.e. only a little more than a year before he took his B.A. The examination is now generally taken before coming into residence, and the most patriotic Oxford man would hardly apply to it the enthusiastic praises of the seventeenth-century Vice-Chancellor (1601) who called it 'gloriosum illud et laudabile in parviso certamen, quo antiquitus inclaruit nostra Academia'.[Pg 43]

At the end of four years, as has been said, a man 'determined', i.e. performed the disputations and other requirements for the degree of B.A., and after this ceremony there were more 'lectures and disputings' to be performed in the additional three years' residence required for a Master's degree. Nothing, however, is said of definite examinations as to the intellectual fitness of candidates for the M.A. Hearne (early in the eighteenth century) quotes from an old book, that the candidate 'must submit himself privately to the examination of everyone of that degree, whereunto he desireth to be admitted'. But the terror of such a multiplied test was no doubt greatly softened by the fact that what is everybody's business is nobody's business.

The stress laid on the course followed rather than on the final examination brings out the great idea underlying the old degree; it sought its qualifications on all sides of a man's life, and not simply in his power to get up and reproduce knowledge. Hence it is provided that M.A.s should admit to 'Determination' (i.e. to the B.A.) only those who are 'fit in knowledge and character'; 'if any question arises on other points, e.g. as to age, stature, or other outward qualifications (corporum circumstantiis)', it is re[Pg 44]served for the majority of the Regents. How minute was the inquiry into character can be seen in the case of a certain Robert Smith (of Magdalen) in 1582, who was refused his B.A., because he had brought scandalous charges against the fellows of his College, had called an M.A. 'to his face "arrant knave", had been at a disputation in the Divinity School' in the open assembly of Doctors and Masters 'with his hat on his head', and had 'taken the wall of M.A.s without any moving of his hat'.

All such minute inquiries as these are now left to the colleges, who are required by statute to see to it that candidates for the degree are 'of good character' (probis moribus).

When a candidate's 'grace' had been obtained there was still another precaution before the degree, whether B.A. or M.A., was actually conferred. He had to go bare-headed, in his academical dress, round the 'Schools', preceded by the Bedel of his faculty, and to call on the Vice-Chancellor and two Proctors before sunset; this gave more opportunity to the authorities or to any M.A. to see whether he was fit. Of this old ceremony a bare fragment still remains in the custom that a candidate's name has to be entered in a book at the Vice-Chancellor's house before[Pg 45] noon on the day preceding the degree-giving; but this formality now is usually performed for a man by his college Dean, or even by a college servant.

When the day of the ceremony arrived, solemn testimony was given to the Proctor of the candidate's fitness by those who 'deposed' for him. In the case of the B.A., nine Bachelors were required to testify to fitness; in the case of the M.A., nine Masters had to swear this from 'sure knowledge', and five more 'to the best of their belief' (de credulitate). These depositions were whispered into the ears of the Proctor by the witnesses kneeling before him. The information was given on oath, and as it were under the seal of confession; for neither they nor the Proctors were allowed to reveal it. Of all this picturesque ceremony nothing is left but the number 'nine'; so many M.A.s at least must be present, in order that the degree may be rightly given. It is not infrequent, towards the close of a degree ceremony, for a Dean who is about to leave, having presented his own men, to be asked to remain until the proceedings are over, in order to 'make a House'.

The preliminaries, formal or otherwise, to the conferment of degrees have now been described. Two other points must be here[Pg 46] mentioned, in one of which the University still retains its old custom, in the other it has departed from it.

The first is the requirement which has always been maintained in Oxford, that a candidate for one of the higher degrees, e.g. the D.D. or the D.M., should have first passed through the Arts course, and taken the ordinary B.A. degree.

This principle, that a general education should precede a special study, is most important now; it has also a venerable history. It was established by the University as long ago as the beginning of the fourteenth century, and was the result of a long struggle against the Mendicant Friars. This struggle was part of that jealousy between the Regular and the Secular Clergy, which is so important in the history of the English Church in mediaeval times.

The University, as identified with the ordinary clergy, steadfastly resisted the claim of the great preaching orders, the Franciscans and the Dominicans, to proceed to a degree in Theology without first taking the Arts course. The case was carried to Rome more than once, and was decided both for and against the University; but royal favour and popular feeling were for the Oxford authorities against the Friars, and the principle[Pg 47] was maintained then, and, as has been said, has been maintained always.

In the other point there has been a great departure from old usage. The original degree course involved seven years' residence for those who wished to become Masters. Even before the Reformation, the number of those who took the degree was comparatively small, although the candidate at entrance was often only thirteen years old or even younger; and with the improvement of the schools of the country in the sixteenth century, the need of such prolonged residence became less, as candidates were better prepared before they came up. Since the old arrangements were clearly unworkable, different universities have modified them in various ways; in Scotland the Baccalaureate has disappeared altogether, and the undergraduate passes straight to his M.A.; in France the degree of bachelier is the lowest of university qualifications, and more nearly resembles our Matriculation than anything else; in Germany the Doctorate is the reward of undergraduate studies, although it need hardly be said that those studies are on different lines from those of our own undergraduates. In England the old names have both been maintained (the English, like the Romans, are essentially conservative), but their meaning has been entirely altered.[Pg 48]

We can trace in the Elizabethan and the Stuart periods the gradual modification of the old requirements for the residence of M.A.s, by means of dispensations. This was done in two ways. Sometimes the actual time required was shortened, because a man was poor, because he could get clerical promotion if he were an M.A., or even by a general 'grace' in order to increase the number of those taking the degree. If only a small number incepted it was thought a reflection on Oxford, and there were always Cambridge spectators at hand to note it. And as the Proctors were largely paid by the degree fees, they had an obvious interest in increasing the number of M.A.s.

But it was more frequent to retain the length of time, but to dispense with actual residence; special reasons for this, e.g. clerical duties, travel, lawsuits, are at first given, but it gradually became the normal procedure, and residence ceased to be required after the B.A. degree had been taken. The Master's term was retained pro forma till within the recollection of graduates still living (it will be remembered that Mr. Hughes makes 'Tom Brown' return to keep it, a sadder and a wiser man); but even that form has now disappeared, and the Oxford M.A. qualifies for his degree only by continuing to[Pg 49] live and by paying fees. It may be added at once that the maintenance of the form is essential to the finance of the University; the M.A. fees alone, apart from the dues paid in the interval between taking the B.A. and the M.A., amount to some £6,000 a year, and considering how little the ordinary man pays as an undergraduate to the University, the payment of the M.A. is one that is fully due; it should be regarded by all Oxford men as an expression of the gratitude to their Alma Mater, which they are in duty bound to show. The future of Oxford finance would be brighter if some reformer could devise means by which the relation of the M.A. to his University might become more of a reality, so that he might realize his obligations to her. The doctrine of Walter de Merton that a foundation should benefit by the 'happy fortune' (uberiore fortuna) of its sons in subsequent life, is one that sadly needs emphasizing in Oxford.

[13] This custom has left its trace in our matriculation arrangements. Candidates are still required to state the rank of their father, and their position in the family, though birth and primogeniture no longer carry any privileges with them at Oxford.

[14] The University authorities at Paris and elsewhere had a great objection to dictating lectures; on the other hand the mediaeval undergraduate, like his modern successor, loved to 'get something down', and was wont to protest forcibly against a lecturer who went too fast, by hissing, shouting, or even organized stone-throwing.

[15] It is amusing to notice that the irreducible minimum of the Ethics at Paris in the fourteenth century consists of the same first four books that are still almost universally taken up at Oxford for the pass degree (i.e. in the familiar 'Group A. I').

[16] It was only 2d., a sum which has been immortalized by Samuel Johnson's famous retort on his tutor: 'Sir, you have sconced me 2d. for non-attendance at a lecture not worth a penny.'

[17] It was resigned voluntarily by New College in 1834; but the distinction is still observed (or should be) that a Fellow of the College needs no grace for his degree, or if one is asked, 'demands' it as a right (postulat is used instead of the usual supplicat). I have adopted Dr. Rashdall's explanation of the origin of this strange privilege. It is curious to add that King's College, Cambridge, copied it, along with other and better features, from its great predecessor and model, New College.

[18] i.e. in the Parvis or Porch of St. Mary's, where the disputations on Logic and Grammar, which formed the examination, took place: this was probably a room over the actual entrance, such as was common in mediaeval churches; there is a small example of one still to be seen in Oxford, over the south porch of St. Mary Magdalen Church.

THE OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY[Pg 50]

The beginning of the organized authority of the University, as has been already said (p. 22), is the mention of the Chancellor in the charter of 1214. In the earliest period this officer was the centre of the constitutional life of Oxford. Although the bishop's representative, and as such endowed with an authority external to the University, he was, perhaps from the first, elected by the Doctors and Masters there. Hence by a truly English anomaly, the representative of outside authority becomes identified with the representative of the democratic principle, and the Oxford Chancellor combined in himself the position of the elected Rector of a foreign university, and that of the Chancellor appointed by an external power. The reason for this anomaly is partly the remote position of the episcopal see; Lincoln, the bishop's seat, was more than 100 miles from the University town, which lay on the very borders of his great diocese. The combination[Pg 51] too was surely made easy by the influence of the great scholar-saint, Bishop Grosseteste, who had himself filled the position of Chancellor (though he may not have borne the title) before he passed to the see of Lincoln, which he held for eighteen years (1235-1253) during the critical period of the growth of the academic constitution.

During the first two centuries of the University's existence, the Chancellor was a resident official; but in the fifteenth century it became customary to elect some great ecclesiastic, who was able by his influence and wealth to promote the interests of Oxford and Oxford scholars; such an one was George Neville, the brother of the King-Maker Earl of Warwick, who became Chancellor in 1453 at the age of twenty. He no doubt owed his early elevation to the magnificence with which he had entertained the whole of Oxford when he had proceeded to his M.A. from Balliol College in the preceding year.

From the fifteenth century onwards the Vice-Chancellor takes the place of the Chancellor as the centre of University life; as the Chancellor's representative, he is nominated every year by letters from him, though the appointment is in theory approved by the vote of Convocation.

[Pg 52]The nomination of a Vice-Chancellor is for a year, but renomination is allowed; as a matter of fact, the Chancellor's choice is limited by custom in two ways; no Vice-Chancellor is reappointed more than three times, i.e. the tenure of the office is limited to four years, and the nomination is always offered to the senior head of a house who has not held the position already; if any head has declined the office when offered to him on a previous occasion, he is treated as if he had actually held it.

The Vice-Chancellor has all the powers and duties of the Chancellor in the latter's absence; but in the rare cases when the Chancellor visits Oxford, his deputy sinks for the time into the position of an ordinary head of a college.

The only duties of the Vice-Chancellor that need be here mentioned are his authority and control over examinations and over degrees, duties which are of course connected. Any departure from the ordinary course of proceeding needs his approval: e.g. (to take a constantly recurring case) he alone can give permission to examine an undergraduate out of his turn, when any one has failed to present himself at the right time for viva voce.

Now that all Oxford arrangements for[Pg 53] examinations have developed into a cast-iron system, the appeal, except in matters of detail, to the Vice-Chancellor is rare; but it was not always so; his control was at one time a very real and important matter. In the case of the famous Dr. Fell, Dean of Christ Church, Antony Wood notes 'that he did frequent examinations for degrees, hold the examiners up to it, and if they would or could not do their duty, he would do it himself, to the pulling down of many'. It is no wonder that men said of him:—

I do not like thee, Dr. Fell,

The reason why I cannot tell.

He was equally careful of the decencies and proprieties of the degree ceremony; 'his first care (as Vice-Chancellor) was to make all degrees go in caps, and in public assemblies to appear in hoods. He also reduced the caps and gowns worn by all degrees to their former size and make, and ordered all cap-makers and tailors to make them so.'

It was necessary for him to be strict; some of the Puritans, although they were not on the whole neglectful of the dignity and the studies of the University, had carried their dislike of all ceremonies and forms so far as to attempt to abolish academical[Pg 54] dress. 'The new-comers from Cambridge and other parts (in 1648) observed nothing according to statutes.' It was only the stubborn opposition of the Proctor, Walter Pope (in 1658), which had prevented the formal abolition of caps and gowns; and one of Fell's predecessors as Vice-Chancellor, the famous Puritan divine, John Owen, also Dean of Christ Church, had caused great scandal to the 'old stock remaining' by wearing his hat (instead of a college cap) in Congregation and Convocation; 'he had as much powder in his hair as would discharge eight cannons' (but this was a Cambridge scandal, and may be looked on with suspicion), and wore for the most part 'velvet jacket, his breeches set round at knee with ribbons pointed, Spanish leather boots with Cambric tops'. But in spite of this somewhat pronounced opposition to a 'prelatical cut', Owen had been in his way a disciplinarian. He had arrested with his own hands, pulling him down from the rostrum and committing him to Bocardo prison, an undergraduate who had carried too far the wit of the 'Terrae Filius', the licensed jester of the solemn Act.

Fortunately the Vice-Chancellor in these more orderly days has not to carry out discipline with his own hands in this summary[Pg 55] fashion. He has his attendants, the Bedels, for this purpose, who, as the statutes order, 'wearing the usual gowns and round caps, walk before him in the customary way with their staves, three gold and one silver.' The office of Bedel is one of the oldest in Oxford, and is common to all Universities; Dr. Rashdall goes so far as to say that 'an allusion to a bidellus is in general (though not invariably) a sufficiently trustworthy indication that a School is really a University or Studium Generale'. The higher rank of 'Esquire Bedel' has been abolished, and the old office has sadly shrunk in dignity; it is hard now to conceive the state of things in the reign of Henry VII, when the University was distracted by the counter-claims of the candidates for the post of Divinity Bedel, when one of them had the support of the Prince of Wales, and another that of the King's mother, the Lady Margaret, and when the electors were hard put to it to decide between candidates so royally backed; it was a contest between gratitude in the sense of a lively expectation of favours to come, and gratitude for benefits already received (i.e. the Lady Margaret Professorship of Divinity, the first endowment of University teaching in Oxford). Even the Puritans had attached the greatest impor[Pg 56]tance to the office, and a humorous side is given to the sad account of the Parliamentary Visitation in 1648 and the following years, by the distress of the Visitors at the disappearance of the old symbols of authority. The Bedels, being good Royalists, had gone off with their official staves, and refused to surrender them to the usurping intruders. Resolution after resolution was passed to remedy the defect; the Visitors were reduced to ordering that the stipends of suppressed lectureships should be applied to the purchase of staves, and were finally compelled to appeal to the colleges for contributions towards the replacing of these signs of authority. The present staves date from the eighteenth century, while the old ones[19] rest in honourable retirement at the University Galleries.

Though the office of Bedel has ceased to be in our own days a matter of high University politics, it would be difficult to exaggerate the importance of the part played by the Bedel of the Faculty of Arts in the degree ceremony. It is he who marshals the candidates for presentation, distributes the testaments on which they have to take their oath, and superintends the retirement of the Doctors and the M.A.s into the Apodyterium,[Pg 57] whence they return under his guidance in their new robes, to make their bow to the Vice-Chancellor and Proctors.[20] If the truth must be added, he is often relied on by these officers to tell them what they have to do and to say.

If the Vice-Chancellor is responsible for order in the Congregation, and actually admits to the degree, the Proctors, as representatives of the Faculty of Arts, play an equally important part in the ceremony. These officials are to the undergraduate without doubt the most prominent figures in the University; they form the centre of a large part of Oxford mythology; it may be said (it is to be hoped the comparison is not irreverent) that they play much the same part in Oxford stories as the Evil One does in mediaeval legends, for like him they are mysterious and omnipresent beings, powerful[Pg 58] for mischief, yet often not without a sense of humour, who are by turns the oppressors and the butts of the wily undergraduate. To most Oxford men it comes as a discovery, about the time they take their degree at the earliest, that the Proctors have many other things to do besides looking after them.

The office goes back to the very beginnings of the University and is first mentioned in 1248, when the Proctors are associated with the Chancellor in the charter of Henry III, which gave the University a right to interfere in the assize of bread and beer.

Their number recalls one of the most important points in the early history of Oxford. The division of the students according to 'Nations', which prevailed at mediaeval Paris, and which still survives in some of the Scotch universities, never was established in the English ones; in this as in other respects the strong hand of the Anglo-Norman kings had made England one. But though there was no room for division of 'Nations', there was a strongly-marked line of separation between the Northerners and the Southerners, i.e. between those from the north of the Trent, with whom the Scotch were joined, and those south of that river, among whom were reckoned the Welsh and the Irish. The fights between these factions[Pg 59] were a continual trouble to the mediaeval University, and it was necessary for the M.A.s of each division to have their own Proctor; hence originally the Senior Proctor was the elect of the Southerners and the Junior Proctor of the Northerners.

Proctorial elections were a source of constantly recurring trouble, till Archbishop Laud at last transferred the election to the colleges, each of which took its turn in a cycle carefully calculated according to the numbers of each college. In our own generation this system has been carried a step further, and all colleges, large or small alike, have their turn for the Proctorship, which comes to each once in eleven years. The electors for it are the members of the governing body along with all members of Congregation belonging to the college.

The Proctors represent the Masters of Arts as opposed to the higher faculties (i.e. the Doctors), and it is in virtue of the time-honoured right of the Faculty of Arts to decide all matters concerning the granting of 'graces', that the Proctors take their prominent part in the degree ceremony. Although the Vice-Chancellor is presiding, it is the Proctor who submits the degrees to the House, and declares them 'granted'. Before doing this the two Proctors, as has[Pg 60] been said (p. 9), walk half-way down the House and return, thus in form fulfilling the injunction of the statutes that 'they should take the votes in the usual way'.[21]

One other University official must be mentioned, the Registrar, i.e. the Secretary of the University. The existence of a Register of Convocation implies that there must have been an officer of this kind in mediaeval Oxford, but the actual title does not occur till the sixteenth century; its first holder seems to have been John London of New College, so scandalously notorious in the first days of the Reformation. But the character of University officials was not high in the sixteenth century. One of the earliest Registrars, Thomas Key of All Souls, was expelled from his post in 1552 for having during two years neglected to take any note of the University proceedings; he actually struck in the face another Master of Arts who was trying to detain him at the order of the Vice-Chancellor. For this he was sent to prison, and fined 26s. 8d.; but he was released the very next day, and his fine cut down to 4d. He lived to be elected Master of University College nine years later, and to be the mendacious champion of the antiquity of Oxford[Pg 61] against the Cambridge advocate. This was his namesake Dr. Caius, equally mendacious but more reputable, the pious 'second founder' of a great Cambridge college.