Title: Nuts and Nutcrackers

Author: Charles James Lever

Illustrator: Hablot Knight Browne

Release date: March 18, 2010 [eBook #31685]

Most recently updated: May 7, 2016

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Irma Spehar and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Shakspeare.

Beggar’s Opera.

John Bunyan.

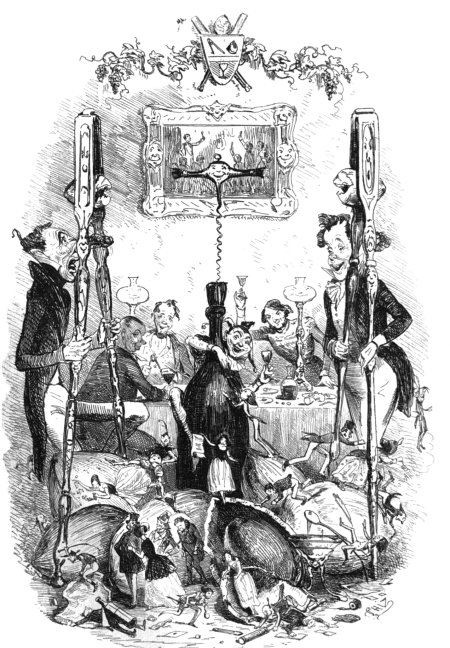

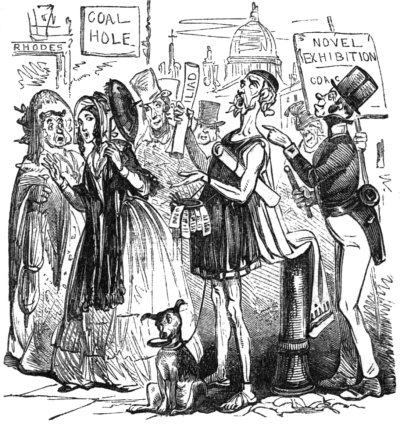

ILLUSTRATED BY “PHIZ.”

Second Edition.

LONDON:

Wm. S. ORR AND Co., PATERNOSTER ROW;

WILLIAM CURRY, Jun., AND Co., DUBLIN.

MDCCCXLV.

LONDON:

BRADBURY AND EVANS, PRINTERS, WHITEFRIARS.

If Providence, instead of a vagabond, had made me a justice of the peace, there is no species of penalty I would not have enforced against a class of offenders, upon whom it is the perverted taste of the day to bestow[2] wealth, praise, honour, and reputation; in a word, upon that portion of the writers for our periodical literature whose pastime it is by high-flown and exaggerated pictures of society, places, and amusements, to mislead the too credulous and believing world; who, in the search for information and instruction, are but reaping a barren harvest of deceit and illusion.

Every one is loud and energetic in his condemnation of a bubble speculation; every one is severe upon the dishonest features of bankruptcy, and the demerits of un-trusty guardianship; but while the law visits these with its pains and penalties, and while heavy inflictions follow on those breaches of trust, which affect our pocket, yet can he “walk scatheless,” with port erect and visage high who, for mere amusement—for the passing pleasure of the moment—or, baser still, for certain pounds per sheet, can, present us with the air-drawn daggers of a dyspeptic imagination for the real woes of life, or paint the most common-place and tiresome subjects with colours so vivid and so glowing as to persuade the unwary reader that a paradise of pleasure and enjoyment, hitherto unknown, is open before him. The treadmill and the ducking-stool, “me judice,” would no longer be tenanted by rambling gipsies or convivial rioters, but would display to the admiring gaze of an assembled multitude the aristocratic features of Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, the dark whiskers of D’Israeli, the long and graceful proportions of Hamilton Maxwell, or the portly paunch and melo-dramatic frown of that right pleasant fellow, Henry Addison himself.

You cannot open a newspaper without meeting some narrative of what, in the phrase of the day, is denominated an “attempted imposition.” Count Skryznyzk, with black[3] moustachoes and a beard to match, after being the lion of Lord Dudley Stuart’s parties, and the delight of a certain set of people in the West-end—who, when they give a tea-party, call it a soirée, and deem it necessary to have either a Hindoo or a Hottentot, a Pole, or a Piano-player, to interest their guests—was lately brought up before Sir Peter Laurie, charged by 964 with obtaining money under false pretences, and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment and hard labour at the treadmill.

The charge looks a grave one, good reader, and perhaps already some notion is trotting through your head about forgery or embezzlement; you think of widows rendered desolate, or orphans defrauded; you lament over the hard-earned pittance of persevering industry lost to its possessor; and, in your heart, you acknowledge that there may have been some cause for the partition of Poland, and that the Emperor of the Russias, like another monarch, may not be half so black as he is painted. But spare your honest indignation; our unpronounceable friend did none of these. No; the head and front of his offending was simply exciting the sympathies of a feeling world for his own deep wrongs; for the fate of his father, beheaded in the Grand Place at Warsaw; for his four brothers, doomed never to see the sun in the dark mines of Tobolsk; for his beautiful sister, reared in the lap of luxury and wealth, wandering houseless and an outcast around the palaces of St. Petersburg, wearying heaven itself with cries for mercy on her banished brethren; and last of all, for himself—he, who at the battle of Pultowa led heaven-knows how many and how terrific charges of cavalry,—whose breast was a galaxy of orders only outnumbered[4] by his wounds—that he should be an exile, without friends, and without home! In a word, by a beautiful and highly-wrought narrative, that drew tears from the lady and ten shillings from the gentleman of the house, he became amenable to our law as a swindler and an impostor, simply because his narrative was a fiction.

In the name of all justice, in the name of truth, of honesty, and fair dealing, I ask you, is this right? or, if the treadmill be the fit reward for such powers as his, what shall we say, what shall we do, with all the popular writers of the day? How many of Bulwer’s stories are facts? What truth is there in James? Is that beautiful creation of Dickens, “Poor Nell,” a real or a fictitious character? And is the offence, after all, merely in the manner, and not the matter, of the transgression? Is it that, instead of coming before the world printed, puffed, and hot-pressed by the gentlemen of the Row, he ventured to edite himself, and, instead of the trade, make his tongue the medium of publication? And yet, if speech be the crime, what say you to Macready, and with what punishment are you prepared to visit him who makes your heart-strings vibrate to the sorrows of Virginius, or thrills your very blood with the malignant vengeance of Iago? Is what is permissible in Covent Garden, criminal in the city? or, stranger still, is there a punishment at the one place, and praise at the other? Or is it the costume, the foot-lights, the orange-peel, and the sawdust—are they the terms of the immunity? Alas, and alas! I believe they are.

Burke said, “The age of chivalry is o’er;” and I believe the age of poetry has gone with it; and if Homer himself[5] were to chant an Iliad down Fleet Street, I’d wager a crown that 964 would take him up for a ballad-singer.

But a late case occurs to me. A countryman of mine, one Bernard Cavanagh, doubtless, a gentleman of very good connections, announced some time ago that he had adopted a new system of diet, which was neither more nor less than going without any food. Now, Mr. Cavanagh was a stout gentleman, comely and plump to look at, who conversed pleasantly on the common topics of the day, and seemed, on the whole, to enjoy life pretty much like other people. He was to be seen for a shilling—children half-price; and although Englishmen have read of our starving countrymen for the last century and a-half, yet their curiosity to see one, to look at him, to prod him with their umbrellas, punch him with their knuckles, and otherwise test his vitality, was such, that they seemed just as much alive as though the phenomenon was new to them. The consequence was, Mr. Cavanagh, whose cook was on board wages, and whose establishment was of the least expensive character, began to wax rich. Several large towns and cities, in different parts of the empire, requested him to visit them; and Joe Hume suggested that the corporation of London should offer him ten thousand pounds for his secret, merely for the use of the livery. In fact, Cavanagh was now the cry, and as Barney appeared to grow fat on fasting, his popularity knew no bounds. Unfortunately, however, ambition, the bane of so many other great men, numbered him also among its victims. Had he been content with London as the sphere of his triumphs and teetotalism, there is no saying how long he might have gone on starving with satisfaction. Whether it is that the people are less[6] observant there, or more accustomed to see similar exhibitions, I cannot tell; but true it is they paid their shillings, felt his ribs, walked home, and pronounced Barney a most exemplary Irishman. But not content with the capital, he must make a tour in the provinces, and accordingly went starring it about through Leeds, Birmingham, Manchester, and all the other manufacturing towns, as if in mockery of the poor people who did not know the secret how to live without food.

Mr. Cavanagh was now living—if life it can be called—in one of the best hotels, when, actuated by that spirit of inquiry that characterises the age, a respectable lady, who kept a boarding-house, paid him a visit, to ascertain, if possible, how far his system might be made applicable to her guests, who, whatever their afflictions, laboured under no such symptoms as his.

She was pleased with Barney,—she patted him with her hand; he was round, and plump, and fat, much more so, indeed, than many of her daily dinner-party; and had, withal, that kind of joyous, rollicking, devil-may-care look, that seems to bespeak good condition;—but this the poor lady, of course, did not know to be an inherent property in Pat, however poor his situation.

After an interview of an hour long she took her leave, not exhibiting the usual satisfaction of other visitors, but with a dubious look and meditative expression, that betokened a mind not made up, and a heart not at ease; she was clearly not content, perhaps the abortive effort to extract a confession from Mr. Cavanagh might be the cause, or perhaps she felt like many respectable people whose curiosity is only the advanced guard to their repentance, and who never think that in any exhibition[7] they get the worth of their money. This might be the case, for as fasting is a negative process, there is really little to see in the performer. Had it been the man that eats a sheep; “à la bonne heure!” you have something for your money there: and I can even sympathize with the French gentleman who follows Van Amburgh to this day, in the agreeable hope, to use his own words, of “assisting at the soirée, when the lions shall eat Mr. Van Amburgh.” This, if not laudable is at least intelligible. But to return, the lady went her way, not indeed on hospitable thoughts intent, but turning over in her mind various theories about abstinence, and only wishing she had the whole of the Cavanagh family for boarders at a guinea a-week.

Late in the evening of the same day this estimable lady, whose inquiries into the properties of gastric juice, if not as scientific, were to the full as enthusiastic as those of Bostock or Tiedeman himself, was returning from an early tea, through an unfrequented suburb of Manchester, when suddenly her eye fell upon Bernard Cavanagh, seated in a little shop—a dish of sausages and a plate of ham before him, while a frothing cup of porter ornamented his right hand. It was true, he wore a patch above his eye, a large beard, and various other disguises, but they served him not: she knew him at once. The result is soon told: the police were informed; Mr. Cavanagh was captured; the lady gave her testimony in a crowded court, and he who lately was rolling on the wheel of fortune, was now condemned to foot it on a very different wheel, and all for no other cause than that he could not live without food.

The magistrate, who was eloquent on the occasion,[8] called him an impostor; designating by this odious epithet, a highly-wrought and well-conceived work of imagination. Unhappy Defoe, your Robinson Crusoe might have cost you a voyage across the seas; your man Friday might have been a black Monday to you had you lived in our days. 964 is a severer critic than The Quarterly, and his judgment more irrevocable.

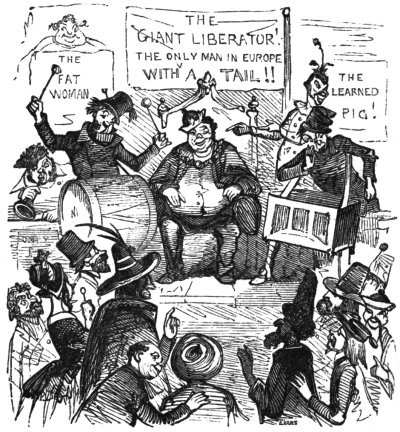

The Man of Genius

The Man of Genius

We have never heard of any one who, discovering the fictitious character of a novel he had believed as a fact, waited on the publisher with a modest request that his money might be returned to him, being obtained under false pretences; much less of his applying to his worship for a warrant against G. P. R. James, Esq., or Harrison Ainsworth, for certain imaginary woes and unreal sorrows depicted in their writings: yet the conduct of the lady towards Mr. Cavanagh was exactly of this nature. How did his appetite do her any possible disservice? what sins against her soul were contained in his sausages? and yet she must appeal to the justice as an injured woman: Cavanagh had imposed upon her—she was wronged because he was hungry. All his narrative, beautifully constructed and artfully put together, went for nothing; his look, his manner, his entertaining anecdotes, his fascinating conversation, his time—from ten in the morning till eight in the evening—went all for nothing: this really is too bad. Do we ask of every author to be the hero he describes? Is Bulwer, Pelham, and Paul Clifford, Eugene Aram, and the Lady of Lyons? Is James, Mary of Burgundy, Darnley, the Gipsy, and Corse de Leon? Is Dickens, Sam Weller, Quilp, and Barnaby Rudge?—to what absurdities will this lead us! and yet Bernard Cavanagh was no more guilty than any of these gentlemen.[9] He was, if I may so express it, a pictorial—an ideal representation of a man that fasted: he narrated all the sensations want of food suggests; its dreamy debility, its languid stupor, its painful suffering, its stage of struggle and suspense, ending in a victory, where the mind, the conqueror over the baser nature, asserts its proud and glorious supremacy in the triumph of volition; and for this beautiful creation of his brain he is sent to the treadmill, as though, instead of a poet, he had been a pickpocket.

If Bulwer be a baronet; if Dickens’ bed-room be papered with bank-debentures; then do I proclaim it loudly before the world, Bernard Cavanagh is an injured man: you are either absurd in one case, or unjust in the other; take your choice. Ship off Sir Edward to the colonies; send James to Swan River; let Lady Blessington card wool, or Mrs. Norton pound oyster-shells; or else we call upon you, give Mr. Cavanagh freedom of the guild; call him the author of “The Hungry One;” let him be courted and fêted—you may ask him to dinner with an easy conscience, and invite him to tea without remorse. Let a Whig-radical borough solicit him to represent it; place him at the right hand of Lord John; let his picture be exhibited in the print-shops, and let the cut of his coat and the tie of his cravat be so much in vogue, that bang-ups à la Barney shall be the only things seen in Bond-street: one course or the other you must take. If the mountain will not go to Mahomet, Mahomet must go to the mountain: or in other words, if Bulwer descend not to Barney, Barney must mount up to Bulwer. It is absurd, it is worse than absurd, to pretend that he who so thoroughly sympathises with his hero, as to embody[10] him in his own thoughts and acts, his look, his dress, and his demeanour, that he, I say, who so penetrated with the impersonation of a part, finds the pen too weak, and the press too slow, to picture forth his vivid creations, should be less an object of praise, of honour, and distinction, than the indolent denizen of some drawing-room, who, in slippered ease, dictates his shadowy and imperfect conceptions—visions of what he never felt, dreamy representations of unreality.

“The poet,” as the word implies, is the maker or the creator; and however little of the higher attributes of what the world esteems as poetry the character would seem to possess, he who invents a personage, the conformity of whose traits to the rule of life is acknowledged for its truth, he, I say, is a poet. Thus, there is poetry in Sancho Panza, Falstaff, Dugald Dalgetty, and a hundred other similar impersonations; and why not in Bernard Cavanagh?

Look for a moment at the effects of your system. The Caraccis, we are told, spent their boyish years drawing rude figures with chalk on the doors and even the walls of the palaces of Rome: here the first germs of their early talent displayed themselves; and in those bold conceptions of youthful genius were seen the first dawnings of a power that gave glory to the age they lived in. Had Sir Peter Laurie been their cotemporary, had 964 been loose in those days, they would have been treated with a trip to the mill, and their taste for design cultivated by the low diet of a penitentiary. You know not what budding genius you have nipped with this abominable system: you think not of the early indications of mind and intellect you may be consigning to prison: or is it after all, that the[11] matter-of-fact spirit of the age has sapped the very vitals of our law-code, and that in your utilitarian zeal you have doomed to death all that bears the stamp of imagination? if this be indeed your object, have a good heart, encourage 964, and you’ll not leave a novelist in the land.

Good reader, I ask your pardon for all this honest indignation; I know it is in vain: I cannot reform our jurisprudence; and our laws, like the Belgian revolution, must be regarded “comme un fait accompli;” in other words, what can’t be cured must be endured. Let us leave then our friend the Pole to perform his penance; let us say adieu to Barney, who is at this moment occupying a suite of apartments in the Penitentiary, and let us turn to the reverse of the medal, I mean to those who would wile us away by false promises and flattering speeches to entertain such views of life as are not only impossible but inconsistent, thus rendering our path here devoid of interest and of pleasure, while compared with the extravagant creations of their own erring fancies. Yes, princes may be trusted, but put not your faith in periodicals. Let no pictorial representations of Alpine scenery, under the auspices of Colburn or Bentley, seduce you from the comforts of your hearth and home: let no enthusiastic accounts of military greatness, no peninsular pleasures, no charms of campaigning life, induce you to change your garb of country gentleman for the livery of the Horse-Guards,—“making the green one red.”

Be not mystified by Maxwell, nor lured by Lorrequer; let no panegyrics of pipe-clay and the brevet seduce you from the peaceful path in life; let not Marryat mar your happiness by the glories of those who dwell in the deep waters; let not Wilson persuade you that the “Lights[12] and Shadows of Scottish Life” have any reference to that romantic people, who betake themselves to their native mountains with a little oatmeal for food and a little sulphur for friction; do not believe one syllable about the girls of the west; trust not in the representations of their blue eyes, nor of their trim ankles peering beneath a jupe of scarlet—we can vouch it is true, for the red petticoat, but the rest is apocryphal. Fly, we warn you, from Summers in Germany, Evenings in Brittany, Weeks on the Rhine; away with tours, guide-books, and all the John Murrayisms of travels. A plague upon Egypt! travellers have a proverbial liberty of conscience, and the farther they go, the more does it seem to stretch; not that near home matters are much better, for our “Wild Sports” in Achill are as romantic as those in Africa, and the Complete Angler is a complete humbug.

There is no faith—no principle in any of these men. The grave writer, the stern moralist, the uncompromising advocate of the inflexible rule of right, is a dandy with essenced locks, loose trousers, and looser morals, who breakfasts at four in the afternoon, and spends his evenings among the side scenes of the opera; the merry writer of whims and oddities, who shakes his puns about like pepper from a pepper-castor, is a misanthropic, melancholy gentleman, of mournful look and unhappy aspect: the advocate of field-sports, of all the joyous excitement of the hunting-field, and the bold dangers of the chase, is an asthmatic sexagenarian, with care in his heart and gout in his ankles; and lastly, he who lives but in the horrors of a charnel-house, whose gloomy mind finds no pleasure save in the dark and dismal pictures of crime and suffering, of lingering agony, or cruel death, is a fat,[13] round, portly, comely gentleman, with a laugh like Falstaff, and a face whose every lineament and feature seems to exhale the merriment of a jocose and happy temperament. I speak not of the softer sex, many of whose productions would seem to have but little sympathy with themselves; but once for all, I would ask you what reliance, what faith can you place in any of them? Is it to the denizen of a coal mine you apply for information about the Nassau balloon? Do you refer a disputed point in dress to an Englishman, in climate to a Laplander, in politeness to a Frenchman, or in hospitality to a Belgian? or do you not rather feel that these are not exactly their attributes, and that you are moving the equity for a case at common law? exactly in the same way, and for the same reason, we repeat it, put not your faith in periodicals, nor in the writers thereof.

How ridiculous would it appear if the surgeon-general were to open a pleading, or charge a jury in the Queen’s Bench, while the solicitor-general was engaged in taking up the femoral artery! What would you say if the Archbishop of Canterbury were to preside over the artillery-practice at Woolwich, while the Commander of the Forces delivered a charge to the clergy of the diocese? How would you look if Justice Pennefather were to speak at a repeal meeting, and Daniel O’Connell to conduct himself like a loyal and discreet citizen? Would you not at once say the whole world is in masquerade? and would you not be justified in the remark? And yet this it is which is exactly taking place before your eyes in the wide world of letters. The illiterate and unreflecting man of under-bred habits and degenerate tastes will write nothing but a philosophic novel; the denizen of the Fleet, or the[14] Queen’s Bench, publishes an ascent of Mont Blanc, with a glowing description of the delights of liberty; the nobleman writes slang; the starving author, with broken boots and patched continuations, will not indite a name undignified by a title; and after all this, will you venture to tell me that these men are not indictable by the statute for obtaining money under false pretences?

I have run myself out of breath; and now, if you will allow me a few moments, I will tell you what, perhaps, I ought to have done earlier in this article, namely, its object.

It is a remarkable feature in the complex and difficult machinery of our society, that while crime and the law code keep steadily on the increase, moving in parallel lines one beside the other, certain prejudices, popular fallacies—nuts, as we have called them at the head of this paper—should still disgrace our social system; and that, however justice may be administered in our courts of law, in the private judicature of our own dwellings we observe an especial system of jurisprudence, marked by injustice and by wrong. To endeavour to depict some instances of this, I have set about my present undertaking. To disabuse the public mind as to the error, that what is punishable in one can be praiseworthy in another; and what is excellent in the court can be execrable in the city. Such is my object, such my hope. Under this title I shall endeavour to touch upon the undue estimation in which we hold certain people and places—the unfair depreciation of certain sects and callings. Not confining myself to home, I shall take the habits of my countrymen on the Continent, whether in their search for climate, economy, education, or enjoyment; and, as far as my ability lies, hold the mirror up to nature, while I extend[15] the war-cry of my distinguished countrymen, not asking “justice for Ireland” alone, but “justice for the whole human race.” For the gaoler as for the guardsman, for the steward of the Holyhead as for him of the household; from the Munster king-at-arms to the monarch of the Cannibal Island—“nihil à me alienum puto;” from the priest to the plenipotentiary; from Mr. Arkins to Abd-el-Kader: my sympathy extends to all.

I had nearly attained to man’s estate before I understood the nature of a coroner. I remember, when a child, to have seen a coloured print from a well-known picture of the day, representing the night-mare. It was a horrible representation of a goblin shape of hideous aspect, that sat cowering upon the bosom of a sleeping figure, on whose white features a look of painful suffering was depicted, while the clenched hands and drawn-up feet seemed to struggle with convulsive agony. Heaven knows how or when the thought occurred to me, but I clearly recollect my impression that this goblin was a coroner. Some confused notion about sitting on a corpse as one of his attributes had, doubtless, suggested the idea; and[16] certainly nothing contributed to increase the horror of suicide in my eyes so much as the reflection, that the grim demon already mentioned had some function to discharge on the occasion.

When, after the lapse of years, I heard that the eloquent and gifted member for Finsbury was a being of this order, although I knew by that time the injustice of my original prejudices, yet, I confess I could not look at him in the house, without a thought of my childish fancies, and an endeavour to trace in his comely features some faint resemblance to the figure of the night-mare.

This strange impression of my infancy recurred strongly to my mind a few days since, on reading a newspaper account of a sudden death.—The case was simply that of a gentleman who, in the bosom of his family, became suddenly seized with illness, and after a few hours expired. What was their surprise! what their horror! to find, that no sooner was the circumstance known, than the house was surrounded by a mob, policemen were stationed at the doors, and twelve of the great unwashed, with a coroner at their head, forced their entry into the house of mourning, to deliberate on the cause of death. I can perfectly understand the value of this practice in cases where either suspicion has attached, or where the circumstances of the decease, as to time and place, would indicate a violent death; but where a person, surrounded by his children, living in all the quiet enjoyment of an easy and undisturbed existence, drops off by some one of the ills that flesh is heir to, only a little more rapidly than his neighbour at next door, why this should be a case for a coroner and his gang, I cannot, for the life of me, conceive. In the instance I allude to, the family offered the fullest[17] information: they explained that the deceased had been liable for years to an infirmity likely to terminate in this way. The physician who attended him corroborated the statement; and, in fact, it was clear the case was one of those almost every-day occurrences where the thread of life is snapped, not unravelled. This, however, did not satisfy the coroner, who had, as he expressed it, a “duty to perform,” and, who, certainly had five guineas for his fee: he was a “medical coroner,” too, and therefore he would examine for himself. Thus, in the midst of the affliction and bereavement of a desolate family, the frightful detail of an inquest, with all its attendant train of harrowing and heart-rending inquiries, is carried on, simply because it is permissible by the law, and the coroner may enter where the king cannot.

We are taught in the litany to pray against sudden death; but up to this moment I never knew it was illegal. Dreadful afflictions as apoplexy and aneurism are, it remained for our present civilisation to make them punishable by a statute. The march of intellect, not satisfied with directing us in life, must go a step farther and teach us how to die. Fashionable diseases the world has been long acquainted with, but an “illegal inflammation,” and a “criminal hemorrhage” have been reserved for the enlightened age we live in.

Newspapers will no longer inform us, in the habitual phrase, that Mr. Simpkins died suddenly at his house at Hampstead; but, under the head of “Shocking outrage,” we shall read, “that after a long life of great respectability and the exhibition of many virtues, this unfortunate gentleman, it is hoped in a moment of mental alienation, went off with a disease of the heart. The affliction of his[18] surviving relatives at this frightful act may be conceived, but cannot be described. His effects, according to the statute, have been confiscated to the crown, and a deodand of fifty shillings awarded on the apothecary who attended him. It is hoped, that the universal execration which attends cases of this nature may deter others from the same course; and, we confess, our observations are directed with a painful, but we trust, a powerful interest to certain elderly gentlemen in the neighbourhood of Islington.” Verb. sat.

Under these sad circumstances it behoves us to look a little about, and provide against such a contingency. It is then earnestly recommended to heads of families, that when registering the birth of a child, they should also include some probable or possible malady of which he may, could, would, should, or ought to die, in the course of time. This will show, by incontestable evidence, that the event was at least anticipated, and being done at the earliest period of life, no reproach can possibly lie for want of premeditation. The register might run thus:—

Giles Tims, son of Thomas and Mary Tims, born on the 9th of June, Kent street, Southwark—dropsy, typhus, or gout in the stomach.

It by no means follows, that he must wait for one or other of these maladies to carry him off. Not at all; he may range at will through the whole practice of physic, and adopt his choice. The registry only goes to show, that he does not mean to sneak out of the world in any under-bred way, nor bolt out of life with the abrupt precipitation of a Frenchman after a dinner party. I have merely thrown out this hint here as a warning to my many friends, and shall now proceed to other and more pleasing topics.[19]

Among the many incongruities of that composite piece of architecture, called John Bull, there is nothing more striking than the contrast between his thorough nationality and his unbounded admiration for foreigners. Now, although we may not entirely sympathize with, we can understand and appreciate this feature of his character, and see how he gratifies his very pride itself, in the attentions and civilities he bestows upon strangers. The feeling is intelligible too, because Frenchmen, Germans, and even Italians, notwithstanding the many points of disparity between us, have always certain qualities well worthy of respect, if not of imitation. France has a great literature, a name glorious in history, a people abounding in intelligence, skill, and invention; in fact, all the attributes that make up a great nation. Germany has many of these, and though she lack the brilliant fancy, the sparkling wit of her neighbour, has still a compensating fund in the rich resources of her judgment, and the profound depths of her scholarship. Indeed, every continental country has its lesson for our benefit, and we would do well to cultivate the acquaintance of strangers, not only to disseminate more just views of ourselves and our institutions, but also for the adoption of such customs as seem worthy of imitation, and such habits as may suit our condition in life; while such is the case as regards those countries high in the scale of civilisation, we would, by no means, extend[20] the rule to others less happily constituted, less benignly gifted. The Carinthian boor with his garment of sheep-wool, or the Laplander with his snow shoes and his hood of deerskin, may be both very natural objects of curiosity, but by no means subjects of imitation. This point will doubtless be conceded at once; and now, will any one tell me for what cause, under what pretence, and with what pretext are we civil to the Yankees?—not for their politeness, not for their literature, not for any fascination of their manner, nor any charm of their address, not for any historic association, not for any halo that the glorious past has thrown around the common-place monotony of the present, still less for any romantic curiosity as to their lives and habits—for in this respect all other savage nations far surpass them. What then is, or what can be the cause?

Of all the lions that caprice and the whimsical absurdity of a second-rate set in fashion ever courted and entertained, never had any one less pretensions to the civility he received than the author of ‘Pencillings by the Way’—poor in thought, still poorer in expression, without a spark of wit, without a gleam of imagination—a fourth-rate looking man, and a fifth-rate talker, he continued to receive the homage we were wont to bestow upon a Scott, and even charily extended to a Dickens. His writings the very slip-slop of “commerage,” the tittle-tattle of a Sunday paper, dressed up in the cant of Kentucky; the very titles, the contemptible affectation of unredeemed twaddle, ‘Pencillings by the Way!’ ‘Letters from under a Bridge!’ Good lack! how the latter name is suggestive of eaves-dropping and listening; and how involuntarily we call to mind those chance expressions of his[21] partners in the dance, or his companions at the table, faithfully recorded for the edification of the free-born Americans, who, while they ridicule our institutions, endeavour to pantomime our manners.

For many years past a number of persons have driven a thriving trade in a singular branch of commerce, no less than buying up cast court dresses and second-hand uniforms for exportation to the colonies. The negroes, it is said, are far prouder of figuring in the tattered and tarnished fragments of former greatness, than of wearing the less gaudy, but more useful garb, befitting their condition. So it would seem our trans-Atlantic friends prefer importing through their agents, for that purpose, the abandoned finery of courtly gossip, to the more useful but less pretentious apparel, of common-place information. Mr. Willis was invaluable for this purpose; he told his friends every thing that he heard, and he heard every thing that he could; and, like mercy, he enjoyed a duplicate of blessings—for while he was delighted in by his own countrymen, he was dined by ours. He scattered his autographs, as Feargus O’Connor did franks; he smiled; he ogled; he read his own poetry, and went the whole lion with all his might; and yet, in the midst of this, a rival starts up equally desirous of court secrets, and fifty times as enterprising in their search; he risks his liberty, perhaps his life, in the pursuit, and what is his reward? I need only tell you his name, and you are answered—I mean the boy Jones; not under a bridge, but under a sofa; not in Almacks, obtaining it at second-hand, but in Buckingham Palace—into the very apartment of the Queen—the adventurous youth has dared to insinuate himself. No lady however sends her album to him for some memento of his[22] genius. His temple is not defrauded of its curls to grace a locket or a medallion; and his reward, instead of a supper at Lady Blessington’s, is a voyage to Swan River. For my part, I prefer the boy Jones: I like his singleness of purpose: I admire his steady perseverance; still, however, he had the misfortune to be born in England—his father lived near Wapping, and he was ineligible for a lion.

To what other reason than his English growth can be attributed the different treatment he has experienced at the hands of the world. The similarity between the two characters is most striking. Willis had a craving appetite for court gossip, and the tittle-tattle of a palace: so had the boy Jones. Willis established himself as a listener in society: so did the boy Jones. Willis obtruded himself into places, and among people where he had no possible pretension to be seen: so did the boy Jones. Willis wrote letters from under a bridge: the boy Jones eat mutton chops under a sofa.

The pet profession of England is the bar, and I see many reasons why this should be the case. Our law of primogeniture necessitates the existence of certain provisions for younger children independently of the pittance bestowed on them by their families. The army and the navy, the church and the bar, form then the only avenues to fortune for the highly born; and one or other of these four roads must be adopted by him who would carve[23] out his own career. The bar, for many reasons, is the favourite—at least among those who place reliance in their intellect. Its estimation is high. It is not incompatible but actually favourable to the pursuits of parliament. Its rewards are manifold and great; and while there is a sufficiency of private ease and personal retirement in its practice, there is also enough of publicity for the most ambitiously-minded seeker of the world’s applause and the world’s admiration. Were we only to look back upon our history, we should find perhaps that the profession of the law would include almost two-thirds of our very greatest men. Astute thinkers, deep politicians, eloquent debaters, profound scholars, men of wit, as well as men of wisdom, have abounded in its ranks, and there is every reason why it should be, as I have called it, the pet profession.

Legal Functionaries.

Legal Functionaries.

Having conceded so much, may I now be permitted to take a nearer view of those men so highly distinguished: and for this purpose let me turn my reader’s attention to the practice of a criminal trial. The first duty of a good citizen, it will not be disputed, is, as far as in him lies, to promote obedience to the law, to repress crime, and bring outrage to punishment. No walk in life—no professional career—no uniform of scarlet or of black—no freemasonry of craft or calling can absolve him from this allegiance to his country. Yet, what do we see? The wretch stained with crime—polluted with iniquity—for which, perhaps, the statute-book contains neither name nor indictment—whose trembling lips are eager to avow that guilt which, by confessing, he hopes may alleviate the penalty—this man, I say, is checked in his intentions—he is warned not, by any chance expression, to hazard a conviction of[24] his crime, and told in the language of the law not to criminate himself. But the matter stops not here—justice is an inveterate gambler—she is not satisfied when her antagonist throws his card upon the table confessing that he has not a trump nor a trick in his hand—no, like the most accomplished swindler of Baden or Boulogne, she assumes a smile of easy and courteous benignity, and says, pooh, pooh! nonsense, my dear friend; you don’t know what may turn up; your cards are better than you think; don’t be faint-hearted; don’t you see you have the knave of trumps, i. e., the cleverest lawyer for your defender; a thousand things may happen; I may revoke, that is, the indictment may break down; there are innumerable chances in your favour, so pluck up your courage and play the game out.

He takes the advice, and however faint-hearted before, he now assumes a look of stern courage, or dogged indifference, and resolves to play for the stake. He remembers, however, that he is no adept in the game, and he addresses himself in consequence to some astute and subtle gambler, to whom he commits his cards and his chances. The trepidation or the indifference that he manifested before, now gradually gives way; and however hopeless he had deemed his case at first, he now begins to think that all is not lost. The very way his friend, the lawyer, shuffles and cuts the cards, imposes on his credulity and suggests a hope. He sees at once that he is a practised hand, and almost unconsciously he becomes deeply interested in the changes and vacillations of the game he believed could have presented but one aspect of fortune.

But the prisoner is not my object: I turn rather to the lawyer. Here then do we not see the accomplished gentleman—the[25] finished scholar—the man of refinement and of learning, of character and station—standing forth the very embodiment of the individual in the dock? possessed of all his secrets—animated by the same hopes—penetrated by the same fears—he endeavours by all the subtle ingenuity, with which craft and habit have gifted him, to confound the testimony—to disparage the truth—to pervert the inferences of all the witnesses. In fact, he employs all the stratagems of his calling, all the ingenuity of his mind, all the subtlety of his wit for the one end—that the man he believes in his own heart guilty, may, on the oaths of twelve honest men, be pronounced innocent.

From the opening of the trial to its close, this mental gladiator is an object of wonder and dread. Scarcely a quality of the human mind is not exhibited by him in the brilliant panorama of his intellect. At first, the patient perusal of a complex and wordy indictment occupies him exclusively: he then proceeds to cross-examine the witnesses—flattering this one—brow-beating that—suggesting—insinuating—amplifying, or retrenching, as the evidence would seem to favour or be adverse to his client. He is alternately confident and doubtful, headlong and hesitating—now hurried away on the full tide of his eloquence he expatiates in beautiful generalities on the glorious institution of trial by jury, and apostrophizes justice; or now, with broken utterance and plaintive voice, he supplicates the jury to be patient, and be careful in the decision they may come to. He implores them to remember that when they leave that court, and return to the happy comforts of their home, conscience will follow them, and the everlasting question crave for answer within them—were they sure of this man’s guilt? He teaches them how[26] fallacious are all human tests; he magnifies the slightest discrepancy of evidence into a broad and sweeping contradiction; and while, with a prophetic menace, he pictures forth the undying remorse that pursues him who sheds innocent blood, he dismisses them with an affecting picture of mental agony so great—of suffering so heart-rending, that, as they retire to the jury-room, there is not a man of the twelve that has not more or less of a personal interest in the acquittal of the prisoner.

However bad, however depraved the human mind, it still leans to mercy: the power to dispose of another man’s life is generally sufficient for the most malignant spirit in its thirst for vengeance. What then are the feelings of twelve calm, and perhaps, benevolent men, at a moment like this? The last words of the advocate have thrown a new element into the whole case, for independent of their verdict upon the prisoner comes now the direct appeal to their own hearts. How will they feel when they reflect on this hereafter? I do not wish to pursue this further. It is enough for my present purpose that, by the ingenuity of the lawyer, criminals have escaped, do escape, and are escaping, the just sentence on their crimes. What then is the result? the advocate, who up to this moment has maintained a familiar, even a friendly, intimacy with his client in the dock, now shrinks from the very contamination of his look. He cannot bear that the blood-stained fingers should grasp the hem of his garment, and he turns with a sense of shame from the expressions of a gratitude that criminate him in his own heart. However, this is but a passing sensation; he divests himself of his wig and gown, and overwhelmed with congratulations for his brilliant success, he springs[27] into his carriage and goes home to dress for dinner—for on that day he is engaged to the Chancellor, the Bishop of London, or some other great and revered functionary—the guardian of the church, or the custodian of conscience.

Now, there is only one thing in all this I would wish to bring strikingly before the mind of my readers, and that is, that the lawyer, throughout the entire proceeding, was a free and a willing agent. There was neither legal nor moral compulsion to urge him on. No; it was no intrepid defence against the tyranny of a government or the usurpation of power—it was the assertion of no broad and immutable principle of truth or justice—it was simply a matter of legal acumen and persuasive eloquence, to the amount of fifty pounds sterling.

This being admitted, let me now proceed to consider another functionary, and observe how far the rule of right is consulted in the treatment he meets with—I mean the hangman. You start, good reader, and your gesture of impatience denotes the very proposition I would come to. I need scarcely remind you, that in our country this individual has a kind of prerogative of detestation. All other ranks and conditions of men may find a sympathy, or at least a pity, somewhere, but for him there is none. No one is sufficiently debased to be his companion,—no one so low as to be his associate! Like a being of another sphere, he appears but at some frightful moments of life, and then only for a few seconds. For the rest he drags on existence unseen and unheard of, his very name a thing to tremble at. Yet this man, in the duties of his calling, has neither will nor choice. The stern agent of the law, he has but one course to follow; his path, a narrow[28] one, has no turning to the right or to the left, and, save that his ministry is more proximate, is less accessory to the death of the criminal than he who signs the warrant for execution. In fact, he but answers the responses of the law, and in the loud amen of his calling, he only consummates its recorded assertion. How then can you reconcile yourself to the fact, that while you overwhelm the advocate who converts right into wrong and wrong into right, who shrouds the guilty man, and conceals the murderer, with honour, and praise, and rank, and riches, and who does this for a brief marked fifty pounds, yet have nothing but abhorrence and detestation for the impassive agent whose fee is but one. One can help what he does—the other cannot. One is an amateur—the other practices in spite of himself. One employs every energy of his mind and every faculty of his intellect—the other only devotes the ingenuity of his fingers. One strains every nerve to let loose a criminal upon the world—the other but closes the grave over guilt and crime!

The king’s counsel is courted. His society sought for. He is held in high esteem, and while his present career is a brilliant one in the vista before him, his eyes are fixed upon the ermine. Jack Ketch, on the other hand, is shunned. His companionship avoided, and the only futurity he can look to, is a life of ignominy, and after it an unknown grave. Let him be a man of fascinating manners, highly gifted, and agreeable; let him be able to recount with the most melting pathos the anecdotes and incidents of his professional career, throwing light upon the history of his own period—such as none but himself could throw;—let him speak of the various characters that have passed through his hands, and so to say, “dropped[29] off before him”—yet the prejudice of the world is an obstacle not to be overcome; his calling is in disrepute, and no personal efforts of his own, no individual pre-eminence he may arrive at in his walk, will ever redeem it. Other men’s estimation increases as they distinguish themselves in life; each fresh display of their abilities, each new occasion for the exercise of their powers, is hailed with renewed favour and increasing flattery; not so he,—every time he appears on his peculiar stage, the disgust and detestation is but augmented,—vires acquirit eundo,—his countenance, as it becomes known, is a signal for the yelling execrations of a mob, and the very dexterity with which he performs his functions, is made matter of loathing and horror. Were his duties such as might be carried on in secret, he might do good by stealth and blush to find it fame; but no, his attributes demand the noon-day and the multitude—the tragedy he performs in, must be played before tens of thousands, by whom his every look is scowled at, his every gesture scrutinized. But to conclude,—this man is a necessity of our social system. We want him—we require him, and we can’t do without him. Much of the machinery of a trial might be dispensed with or retrenched. His office, however, has nothing superfluous. He is part of the machinery of our civilisation, and on what principle do we hunt him down like a wild beast to his lair?

Men of rank and title are daily to be found in association, and even intimacy with black legs and bruisers, grooms, jockeys, and swindlers; yet we never heard that even the Whigs paid any attention to a hangman, nor is his name to be found even in the list of a Radical viceroy’s levee. However, we do not despair. Many prejudices[30] of this nature have already given way, and many absurd notions have been knocked on the head by a wag of great Daniel’s tail. And if our friend of Newgate, who is certainly anti-union in his functions, will only cry out for Repeal, the justice that is entreated for all Ireland may include him in the general distribution of its favours. Poor Theodore Hook used to say, that marriage was like hanging, there being only the difference of an aspirate between halter and altar.

y dear reader, if it does not insult your understanding by the self-evidence of the query, will you allow me to ask you a question—which of the two is more culpable, the man who, finding himself in a path of dereliction, arrests himself in his downward career, and, by a wonderful effort of self-restraint, stops dead short, and will suffer no inducement, no seduction, to lead him one step further; or he, who, floating down the stream of his own vicious passions, takes the flood-tide of iniquity, and, indifferent to every consequence, deaf to all remonstrance, seeks but the indulgence of his own egotistical pleasure with a stern determination to pursue it to the last? Of course you will say, that he who repents is better than he who persists; there is hope for the one, there is none for the other. Yet would you believe it, our common law asserts directly the reverse, pronouncing the culpability of the former as meriting heavy punishment, while the latter is not assailable even by implication.

That I may make myself more clear, I shall give an instance of my meaning. Scarcely a week passes over without a trial for breach of promise of marriage. Sometimes the gay Lothario, to use the phrase of the newspapers, is nineteen, sometimes ninety. In either case[32] his conduct is a frightful tissue of perjured vows and base deception. His innumerable letters breathing all the tenderness of affectionate solicitude, intended but for the eyes of her he loves, are read in open court; attested copies are shown to the judge, or handed up to the jury-box. The course of his true love is traced from the bubbling fountain of first acquaintance to the broad river of his passionate devotion. Its rapids and its whirlpools, its placid lakes, its frothy torrents, its windings and its turnings, its ebbs and flows, are discussed, detailed, and descanted on with all the hacknied precision of the craft, as though his heart was a bill of exchange, or the current of his affection a disputed mill-stream. And what, after all, is this man’s crime? knowing that love is the great humanizer of our race, and feeling probably how much he stands in need of some civilizing process, he attaches himself to some lovely and attractive girl, who, in the reciprocity of her affection, is herself benefited in a degree equal to him. If the soft solicitude of the tender passion, if its ennobling self-respect, if its purifying influence on the heart, be good for the man, how much more so is it for the woman. If he be taught to feel how the refined enjoyments of an attractive girl’s mind are superior to the base and degenerate pursuits of every-day pleasure, how much more will she learn to prize and cultivate those gifts which form the charm of her nature, and breathe an incense of fascination around her steps. Here is a compact where both parties benefit, but that they may do so to the fullest extent, it is necessary that no self-interest, no mean prospect of individual advantage, should interfere: all must be pure and confiding. Love-making should not be like a game of écarté[33] with a black leg, where you must not rise from the table, till you are ruined. No! it should rather resemble a party at picquet with your pretty cousin, when the moment either party is tired, you may throw down the cards and abandon the game.

This, then, is the case of the man; he either discovers that on further acquaintance the qualities he believed in were not so palpable as he thought, or, if there, marred in their exercise by opposing and antagonist forces, of whose existence he knew not, he thinks he detects discrepancies of temperament, disparities of taste; he foresees that in the channel where he looked for deep water there are so many rocks, and shoals, and quicksands, that he fears the bark of conjugal happiness may be shipwrecked upon them; and, like a prudent mariner, he resolves to lighten the craft by “throwing over the lady.” Had this man married with all these impending suspicions on his mind, there is little doubt he would have made a most execrable husband; not to mention the danger that his wife should not be all amiable as she ought. He stops short—that is, he explains in one, perhaps in a series of letters, the reasons of his new course. He expects in return the admiration and esteem of her, for whose happiness he is legislating, as well as for his own; and oh, base ingratitude! he receives a letter from her attorney. The gentlemen of the long robe—newspaper again—are in ecstasies. Like devils on the arrival of a new soul, they[34] brighten up, rub their hands, and congratulate each other on a glorious case. The damages are laid at five thousand pounds; and, as the lady is pretty, and can be seen from the jury-box, being fathers themselves, they award every sixpence of the money.

I can picture to myself the feeling of the defendant at such a moment as this. As he stands alone in conscious honesty, ruminating on his fate—alone, I say, for, like Mahomet’s coffin, he has no resting-place; laughed at by the men, sneered at by the women, mulcted of perhaps half his fortune, merely because for the last three years of his life he represented himself in every amiable and attractive trait that can grace and adorn human nature. Who would wonder, if, like the man in the farce, he would register a vow never to do a good-natured thing again as long as he lives; or what respect can he have for a government or a country, where the church tells him to love his neighbour, and the chief justice makes him pay five thousand for his obedience.

I now come to the other case, and I shall be very brief in my observations. I mean that of him, who equally fond of flirting as the former, has yet a lively fear of an action at law. Love-making with him is a necessity of his existence—he is an Irishman, perhaps, and it is as indispensable to his temperament as train-oil to a Russian. He likes sporting, he likes billiards, he likes his club, and he likes the ladies; but he has just as much intention of turning a huntsman at the one, or a marker at the other, as he has of matrimony. He knows life is a chequered table, and that there could be no game if all the squares were of one colour. He alternates, therefore, between love and sporting, between cards and courtship, and as the[35] pursuit is a pleasant one, he resolves never to give up. He waxes old, therefore, with young habits, adapting his tastes to his time of life; he does not kneel so often at forty as he did at twenty, but he ogles the more, and is twice as good-tempered. Not perhaps as ready to fight for the lady, but ten times more disposed to flatter her. She may love him, or she may not; she may receive him as of old, or she may marry another. What matters it to him? All his care is that he shouldn’t change. All his anxiety is, to let the rupture, if there must be one, proceed from her side. He knows in his heart the penalty of breach of promise, but he also knows that the Chancellor can issue no injunction compelling a man to marry, and that in the courts of love the bills are payable at convenience.

Here, then, are the two cases, which, in conformity with the world’s opinion, I have dignified with every possible term of horror and reproach. In the one, the measure of iniquity is but half filled; in the other, the cup is overflowing at the brim. For the lesser offence, the law awards damages and defamation: for the greater, society pronounces an eulogy upon the enduring fidelity of the man thus faithful to a first love.

If a person about to buy a horse should, on trying him for an hour or two, discover that his temper did not suit him, or that his paces were not pleasant, and should in consequence restore him to the owner: and if another, on the same errand, should come day after day for weeks, or months, or even years, cantering him about over the pavement, and scouring over the whole country; his answer being, when asked if he intended to purchase, that he liked the horse exceedingly, but that he hadn’t[36] got a stable, or a saddle, or a curb-chain, or, in fact, some one or other of the little necessaries of horse gear; but that when he had, that was exactly the animal to suit him—he never was better carried in his life. Which of these two, do you esteem the more honest and more honourable?

When you make up your mind, please also to make the application.

When the Belgians, by their most insane revolution, separated from the Dutch, they assumed for their national motto the phrase “L’union fait la force.” It is difficult to say whether their rebellion towards the sovereign, or this happy employment of a bull, it was, that so completely captivated our illustrious countryman, Dan, and excited so warmly his sympathies for that beer-drinking population. After all, why should one quarrel with them? Nations, like individuals, have their coats-of-arms, their heraldic insignia, their blazons, and their garters, frequently containing the sharpest sarcasm and most poignant satire upon those who bear them; and in this respect Belgium is only as ridiculous as the attorney who assumed for his motto “Fiat justitia.” Time was when the chivalrous line of our own garter, “Honi soit qui mal y pense,” brought with it, its bright associations of kingly courtesy and maiden bashfulness: but what sympathy can such a sentiment find in these degenerate days of railroads and rack-rents, canals, collieries, and chain-bridges? No, were we now to select an inscription, much rather would we take it from the prevailing passion[38] of the age, and write beneath the arms of our land the emphatic phrase, “Push along, keep moving.”

If Englishmen have failed to exhibit in machinery that triumphant El Dorado called perpetual motion, in revenge for their failure, they resolved to exemplify it in themselves. The whole nation, from John o’ Groat to Land’s End, from Westport to Dover, are playing cross-corners. Every body and every thing is on the move. A dwelling-house, like an umbrella, is only a thing used on an emergency; and the inhabitants of Great Britain pass their lives amid the smoke of steam-boats, or the din and thunder of the Grand-Junction. From the highest to the lowest, from the peer to the peasant, from the lord of the treasury to the Irish haymaker, it is one universal “chassée croissée.” Not only is this fashionable—for we are told by the newspapers how the Queen walks daily with Prince Albert on “the slopes”—but stranger still, locomotion is a law of the land, and standing still is a statutable offence. The hackney coachman, with wearied horses, blown and broken-winded, dares not breathe his jaded beasts by a momentary pull-up, for the implacable policeman has his eye upon him, and he must simulate a trot, though his pace but resemble a stage procession, where the legs are lifted without progressing, and some fifty Roman soldiers, in Wellington boots, are seen vainly endeavouring to push forward. The foot-passenger is no better off—tired perhaps with walking or attracted by the fascinations of a print-shop, he stops for an instant: alas, that luxury may cost him dear, and for the momentary pleasure he may yet have to perform a quick step on the mill. “Move on, sir. Keep moving, if you please,” sayeth the gentleman in blue; and there is something in his[39] manner that won’t be denied. It is useless to explain that you have nowhere particular to go to, that you are an idler and a lounger. The confession is a fatal one; and however respectable your appearance, the idea of shoplifting is at once associated with your pursuits. Into what inconsistencies do we fall while multiplying our laws, for while we insist upon progression, we announce a penalty for vagrancy. The first principle of the British constitution, however, is “keep moving,” and “I would recommend you to go with the tide.”

Thank heaven, I have reached to man’s estate—although with a heavy heart I acknowledge it is the only estate I have or ever shall attain to; for if I were a child I don’t think I should close my eyes at night from the fear of one frightful and terrific image. As it is, I am by no means over courageous, and it requires all the energy I can summon to combat my terrors. You ask me, in all likelihood, what this fearful thing can be? Is it the plague or the cholera? is it the dread of poverty and the new poor-law? is it that I may be impressed as a seaman, or mistaken for a Yankee? or is it some unknown and visionary terror, unseen, unheard of, but foreshadowed by a diseased imagination; No; nothing of the kind. It is a palpable, sentient, existent thing—neither more nor less than the worshipful Sir Peter Laurie.

Every newspaper you take up announces that Sir Peter, with a hearty contempt for the brevity of the fifty folio volumes that contain the laws of our land, in the plenitude of his power and the fulness of his imagination, keeps adding to the number; so that if length of years be only accorded to that amiable individual in proportion to his merits, we shall find at length that not only will every[40] contingency of our lives be provided for by the legislature, but that some standard for personal appearance will also be adopted, to which we must conform as rigidly as to our oath of allegiance.

A few days ago a miserable creature, a tailor we believe, some decimal fraction of humanity, was brought up before Sir Peter on a trifling charge of some kind or other. I forget his offence, but whatever it was, the penalty annexed to it was but a fine of half-a-crown. The prisoner, however, who behaved with propriety and decorum, happened to have long black hair, which he wore somewhat “en jeune France” upon his neck and shoulders; his locks, if not ambrosial, were tastefully curled, and bespoke the fostering hand of care and attention. The Rhadamanthus of the police-office, however, liked them not: whether it was that he wore a Brutus himself, or that his learned cranium had resisted all the efficacy of Macassar, I cannot say; but certain it is, that the tailor’s ringlets gave him the greatest offence, and he apostrophised the wearer in the most solemn manner:

“I have sat,” said he, “for ——,” as I quote from memory I sha’n’t say how many, “years upon the bench, and I never yet met an honest man with long hair. The worst feature in your case is your ringlets. There is something so disgusting to me in the odious and abominable vice you have indulged in, that I feel myself warranted in applying to you the heaviest penalty of the law.[41]”

The miserable man, we are told, fell upon his knees, confessed his delinquency, and, being shorn of his locks in the presence of a crowded court, his fine was remitted, and he was liberated.

Now, perhaps, you will suppose that all this is a mere matter of invention. On the faith of an honest man I assure you it is not. I have retrenched considerably the pathetic eloquence of the magistrate, and I have left altogether untouched the poor tailor’s struggle between pride and poverty—whether, on the one hand, to suffer the loss of his half-crown, or, on the other, to submit to the desecration of his entire head. We hear a great deal about a law for the rich, and another for the poor; and certainly in this case I am disposed to think the complaint might not seem without foundation. Suppose for a moment that the prisoner in this case had been the Honourable Augustus Somebody, who appeared before his worship fashionably attired, and with hair, beard, and moustache far surpassing in extravagance the poor tailor’s; should we then have heard this beautiful apostrophe to “the croppies,” this thundering denunciation of ringlets? I half fear not. And yet, under what pretext does a magistrate address to one man, the insulting language he would not dare apply to another? Or let us suppose the rule of justice to be inflexible, and look at the result. What havoc would Sir Peter make among the Guards? ay, even in the household of her Majesty how many delinquents would he find? what a scene would not the clubs present, on the police authorities dropping suddenly down amongst them with rule and line to determine the statute length of their whiskers, or the legal cut of their eye-brows? Happy King of Hanover, were you still amongst us, not even the[42] Alliance would insure your mustachoes. As for Lord Ellenborough, it is now clear enough why he accepted the government of India, and made such haste to get out of the country.

Now we will suppose that as Sir Peter Laurie’s antipathy is long hair, Sir Frederick Roe may also have his dislikes. It is but fair, you will allow, that the privileges of the bench should be equal. Well, for argument’s sake, I will imagine that Sir Frederick Roe has not the same horror of long hair as his learned brother, but has the most unconquerable aversion to long noses. What are we to do here? Heaven help half our acquaintance if this should strike him! What is to be done with Lord Allen if he beat a watchman! In what a position will he stand if he fracture a lamp? One’s hair may be cut to any length,—it may be even shaved clean off; but your nose.—And then a few weeks,—a few months at farthest, and your hair has grown again: but your nose, like your reputation, can only stand one assault. This is really a serious view of the subject; and it is a somewhat hard thing that the face you have shown to your acquaintances for years past, with pleasure to yourself and satisfaction to them, should be pronounced illegal, or curtailed in its proportions. They have a practice in banks if a forged note be presented for payment, to mark it in a peculiar manner before restoring it to the owner. This is technically called “raddling.” Something similar, I[43] suppose, will be adopted at the police-office, and in case of refusal to conform your features to the rule of Roe, you will be raddled by an officer appointed for the purpose, and sent forth upon the world the mere counterfeit of humanity.

What a glorious thing it would be for this great country, if, having equalized throughout the kingdom the weights, the measures, the miles, and the currency, we should, at length attain to an equalization in appearance. The “facial angle” will then have its application in reality, and, instead of the tiresome detail of an Old Bailey trial, we shall hear a judge sum up on the externals of a prisoner, merely directing the attention of the jury to the atrocious irregularity of his teeth, or the assassin-like sharpness of his under-jaw. Honour to you, Sir Peter, should this great improvement grow out of your innovation; and proud may the country well be, that acknowledges you among its lawgivers!

Let men no longer indulge in that absurd fiction which represents justice as blind. On the contrary, with an eye like Canova’s, and a glance quick, sharp, and penetrating as Flaxman’s, she traces every lineament and every feature; and Landseer will confess himself vanquished by Laurie. “The pictorial school of judicial investigation” will now become fashionable, and if Sir Peter’s practice be but transmitted, surgeons will not be the only professional men who will commence their education with the barbers.

remember once coming into Matlock, on the top of the “Peveril of the Peak,” when the coachman who drove our four spanking thorough-breds contrived, in something less than five minutes, to excite his whole team to the very top of their temper, lifting the wheelers almost off the ground with his heavy lash, and, thrashing his leaders till they smoked with passion, he brought them up to the inn door trembling with rage, and snorting with anger. What the devil is all this for, thought I. He guessed at once what was passing in my mind, and, with a knowing touch of his elbow, whispered:—

“There’s a new coachman a-going to try ’em, and I’ll leave him a precious legacy.”

This is precisely what the Whigs did in their surrender of power to the Tories. They, indeed, left them a precious legacy:—without an ally abroad, with discontent and starvation at home, distant and expensive wars, depressed trade, and bankrupt speculation, form some portion of the valuable heritage they bequeathed to their heirs in power. The most sanguine saw matter of difficulty, and the greater number of men were tempted to despair at the prospects of the Conservative party; for,[45] however happily all other questions may have terminated, they still see, in the corn-law, a point whose subtle difficulty would seem inaccessible to legislation. Ah! could the two great parties, that divide the state, only lay their heads together for a short time, and carry out that beautiful principle that Scribe announces in one of his vaudevilles:—

And why, after all, should not the collective wisdom of England be able to equal in ingenuity the conceptions of a farce-writer? Meanwhile, it is plain that political dissensions, and the rivalries of party, will prevent that mutual good understanding which might prove so beneficial to all. Reconciliations are but flimsy things at best; and whether the attempt be made to conciliate two rival churches, two opposite factions, or two separate interests of any kind whatever, it is usually a failure. It, therefore, becomes the duty of every good subject, and, à fortiori, of every good Conservative, to bestir himself at the present moment, and see what can be done to retrieve the sinking fortune of the state. Taxation, like flogging in the army, never comes on the right part of the back. Sometimes too high, sometimes too low. There is no knowing where to lay it on. Besides that, we have by this time got such a general raw all over us, there isn’t a square inch of sound flesh that presents itself for a new infliction. Since the first French Revolution, the ingenuity of man has been tortured on the subject of finance; and had Dionysius lived in our days, instead of offering a bounty for the discovery of a new pleasure, he would have proposed a reward to the man who devised a new tax.[46]

Without entering at any length into this subject, the consideration of which would lead me into all the details of our every-day habits, I pass on at once to the question which has induced this inquiry, while I proclaim to the world loudly, fearlessly, and resolutely, “Eureka!”—I’ve found it. Yes, my fellow-countrymen, I have found a remedy to supply the deficient income of the nation, not only without imposing a new tax, or inflicting a new burden upon the suffering community, but also without injuring vested rights, or thwarting the activity of commercial enterprise. I neither mulct cotton or corn; I meddle not with parson or publican, nor do I make any portion of the state, by its own privations, support the well-being of the rest. On the contrary, the only individual concerned in my plan, will not be alone benefited in a pecuniary point of view, but the best feelings of the heart will be cultivated and strengthened, and the love of home, so characteristically English, fostered in their bosoms. I could almost grow eloquent upon the benefits of my discovery; but I fear, that were I to give way to this impulse, I should become so fascinated with myself, I could scarcely turn to the less seductive path of simple explanation. Therefore, ere it be too late, let me open my mind and unfold my system:

Any one who ever heard of Sir Isaac Newton and his apple will acknowledge this, and something of the same kind led me to the very remarkable fact I am about to speak of.

One of the Bonaparte family—as well as I remember, Jerome—was one night playing whist at the same table[47] with Talleyrand, and having dropped a crown piece upon the floor, he interrupted the game, and deranged the whole party to search for his money. Not a little provoked by a meanness which he saw excited the ridicule of many persons about, Talleyrand deliberately folded up a bank-note which lay before him, and, lighting it at the candle, begged, with much courtesy, that he might be permitted to assist in the search. This story, which is authentic, would seem an admirable parody on a portion of our criminal law. A poor man robs the community, or some member of it (for that comes to the same thing) to the amount of one penny. He is arrested by a policeman, whose salary is perhaps half-a-crown a-day, and conveyed to a police-office, that cost at least five hundred pounds to build it. Here are found three or four more officials, all salaried—all fed, and clothed by the State. In due course of time he is brought up before a magistrate, also well paid, by whom the affair is investigated, and by him he is afterwards transmitted to the sessions, where a new army of stipendiaries all await him. But his journey is not ended. Convicted of his offence, he is sentenced to seven years’ transportation to one of the most remote quarters of the globe. To convey him thither the government have provided a ship and a crew, a supercargo and a surgeon; and, to sum up in one word, before he has commenced the expiation of his crime, that penny has cost the country something about three hundred pounds. Is not this, I ask you, very like Talleyrand and the Prince?—the only difference being, that we perform in sober earnest, what he merely exhibited in sarcasm.

Now, my plan is, and I prefer to develop it in a single word, instead of weakening its force by circumlocution.[48] In lieu of letting a poor man be reduced to his theft of one penny—give him two pence. He will be a gainer by double the amount—not to speak of the inappreciable value of his honesty—and you the richer by 71,998 pence, under your present system expended upon policemen, magistrates, judges, gaolers, turnkeys, and transports. Examine for a moment the benefits of this system. Look at the incalculable advantages it presents—the enormous revenue, the pecuniary profit, and the patriotism, all preserved to the State, not to mention the additional pleasure of disseminating happiness while you transport men’s hearts, not their bodies.

Here is a plan based upon the soundest philanthropy, the most rigid economy, and the strictest common sense. Instead of training up a race of men in some distant quarter of the globe, who may yet turn your bitterest enemies, you will preserve to the country so many true-born Britons, bound to you by a debt of gratitude. Upon what ground—on what pretext—can you oppose the system? Do you openly confess that you prefer vice to poverty, and punishment to prevention? Or is it your pleasure to manufacture roguery for exportation, as the French do politeness, and the Irish linen?

I offer the suggestion generously, freely, and spontaneously. If the heads of the government choose to profit by the hint, I only ask in return, that when the Chancellor of the Exchequer announces in his place the immense reduction of expenditure, that he will also give notice of a motion for a bill to reward me by a government appointment. I am not particular as to where, or what: I only bargain against being Secretary for Ireland, or Chief Justice at Cape Coast Castle.

When the cholera first broke out in France, a worthy prefect in a district of the south published an edict to the people, recommending them by all means to eat well-cooked and nutritious food, and drink nothing but vin de Bourdeaux, Anglice, claret. The advice was excellent, and I take it upon me to say, would have found very few opponents in fact, as it certainly did in principle. When the world, however, began to consider that filets de bœuf à la Marengo, and “dindes truffées,” washed down with Chateau Lafitte or Larose, were not exactly within the reach of every class of the community, they deemed the prefect’s counsel more humane than practicable, and as they do at every thing in France when the tide of public opinion changes, they laughed at him heartily, and wrote pasquinades upon his folly. At the same time the ridicule was unjust, the advice was good, sound, and based on true principles, the only mistake was, the difficulty of its practice. Had he recommended as an antiseptic to disease, that the people should play short whist, wear red night-caps, or pelt stones at each other, there might have been good ground for the disfavour he fell into; such acts, however practicable and easy of execution, having manifestly no tendency to avert the cholera. Now this is precisely the state of matters in Ireland at this moment: distress prevails more or less in every province and in every county. The people want employment, and they want food. Had you recommended them to eat strawberries[50] and cream in the morning, to drink lemonade during the day, take a little chicken salad for dinner, with a light bread pudding and a glass of negus afterwards, avoiding all stimulant and exciting food—for your Irishman is a feverish subject—you might be laughed at perhaps for your dietary, but certes it would bear, and bear strongly too, upon the case in question. But what do you do in reality? The local papers teem with cases of distress: families are starving; the poor, unhoused and unfed, are seen upon the road sides exposed to every vicissitude of the season, surrounded by children who cry in vain for bread. What, I ask, is the measure of relief you propose? not a public subscription; no general outburst of national charity—no public work upon a grand scale to give employment to the idle, food to the hungry, health to the sick, and hope to all. None of these. Your panacea is the Repeal of the Union; you purpose to substitute for those amiable jobbers in College-green, who call themselves Directors of the Bank of Ireland, another set of jobbers infinitely more pernicious and really dishonest, who will call themselves Directors of Ireland itself; you talk of the advantage to the country, and particularly of the immense benefits that must accrue to the capital. Let us examine them a little.