REBEKAH AND ISAAC'S AGENT, ELIEZER

After the paintingby A. Cabanel

Title: Oriental Women

Author: Edward B. Pollard

Release date: May 18, 2010 [eBook #32418]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by J. P. W. Fraser, Thierry Alberto, Rénald Lévesque, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreaders Europe

E-text prepared by J. P. W. Fraser, Thierry Alberto, Rénald Lévesque,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreaders Europe

(http://dp.rastko.net)

REBEKAH AND ISAAC'S AGENT, ELIEZER

After the paintingby A. Cabanel

Probably no feature in the social life of a people is of so universal an interest as its marriage customs, and there is no courtship, either ancient or modern, which has more enkindled the imagination and awakened the interest of men than that between Isaac and Rebekah..... It is a truly picturesque and even romantic story, which never loses its charm; and Rebekah, whether at the well or in her household, will always present a unique picture of womanly grace and beauty.

The ancient wooing of Rebekah is Isaac, though it is by no means typical in all its details, contains many elements that mark Oriental weddings..... The courage of Rebekah in consenting to mount the camel of a stranger and go into a far country to be wed is noteworthy. With all the apparent grace and gentleness of Rebekah, here was a pluck most commendable.

PHILADELPHIA

GEORGE BARRIE & SONS, PUBLISHERS

The relative position which woman occupies in any country is an index to the civilization which that country enjoys, and this test applied to the Orient reveals many stages yet to be achieved. The frequent appearance of woman in Holy Writ is sufficient evidence of the high position accorded her in the Hebrew nation. Such characters as Ruth, Esther, and Rebekah have become famous. Wicked women there were, such as Jezebel, but happily their influence was not of lasting duration. No other ancient people so highly prized chastity in woman; motherhood was regarded as an evidence of divine favor, while barrenness was considered a curse. The home life was one of singular purity and sweetness. Idleness was deplored as a crime, and every child was taught to work with his own hands.

The deities of the Babylonians and Assyrians were feminine as well as masculine. Ishtar was the Venus of classical mythology--the goddess of love, and the Babylonian Hades was presided over by a feminine deity. Rank, however, determined social freedom; the woman of the lowest class might go and come at will, but the woman of the high class was condemned to a life of isolation. Woman's position of honor in Egypt is evidenced by the presence of temples and monuments erected to her memory. She assisted her husband in the management of his affairs, and was granted a part in religious worship.

In the countries in which Brahmanism and Mohammedanism is the prevailing religion, the position of woman is relatively low. The Hindoo woman has no spiritual life apart from her husband; she can only hope for ultimate happiness through a union with him. The harem prevails, and woman is the slave of man.

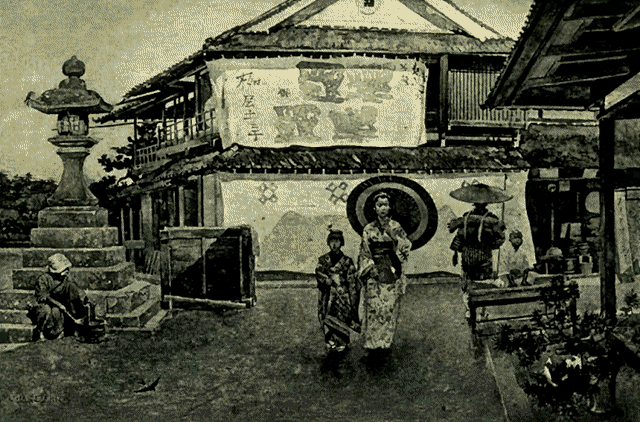

In contrast to the position of woman in these countries and in China is

the position she holds in Japan. While not yet occupying a place of

respect equal to that accorded her in the Occident, she is coming

gradually to be regarded as she deserves. There yet remain the loose

morals, characteristic of the Oriental nature, and it is still regarded

as right and proper that a good wife should barter her chastity if it is

necessary in order to save her husband the disgrace of imprisonment for

debt. The higher classes, however, are coming to treat woman with a

respect far higher than that usually accorded her in the Orient. The

process of her elevation must of necessity be slow, for no great reform

is accomplished by a coup d'état, but only through the ameliorating

effects of enlightenment and education, and this alone will accomplish

the final emancipation of the woman of the Orient from her present

condition of servitude.

E. B. POLLARD.

The story of the first woman in the Hebrew Scriptures and Semitic myth is as familiar as a household tale. Jewish and Christian literature alike have frequent mention of the part she played in the race's infancy, though in the sacred writings themselves she is but rarely mentioned.

What the Book of Genesis furnishes upon the creation of the first woman may not be considered of great interest as a scientific treatise upon the first appearance of feminine life on the earth, but it is of marked importance as revealing the idea around which the life and character of the Hebrew woman were developed. Here we find a pure monotheism (the presence of no goddess at the birth of things), a high morality, the dignity of marriage and of motherhood, that give to the Hebrew women great advantage over their sisters of many another country.

Very early was it discovered, say the Hebrew records, that it is "not good for man to be alone." The method by which this fact was first made manifest is of no little suggestiveness. Would it be possible from the many creatures of earth, sky, and sea, already made, for man to find a companion in whom he might confide, with whom the long hours might be made more joyous? God tries the man whom he has made. Could he be satisfied with a creature of a lower order as fellow and friend? Could he, by subduing and having dominion, find in dog, camel, or favorite steed a sufficient helpfulness, a satisfaction for his human longings? No! As one by one the living creatures passed in solemn order before him, it was soon realized by the names that Adam gave them, that he found no true fellowship in all that earth-born throng. "And the man gave names to all cattle and to the fowl of the air, and to every beast of the field, but for man there was not found an helpmeet for him."

The epoch-making "deep sleep" that fell upon Adam, the taking of the rib, the making of the first woman, the closing again of the wound, and the presentation of a helpmeet for the man--all this is a familiar Scripture story. Whether it be intended to be literal history is of little moment here. Very beautifully have Matthew Henry and others, following the rabbis, commented upon the essential meaning of this narrative in suggesting that woman is not represented as taken from the head of man that she should rule over him; nor from his feet, to be trampled under foot; but she was taken from his side that she might be his equal; from under his arm that she might be protected by him; near his heart that he might cherish and love her. "This is now bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh: she shall be called Ishshah"--that is, if man is to be called Ish, woman shall be Ishshah, simply his equal.

It is not strange that there should have arisen many legends about this first Oriental woman. According to one of the Jewish stories contained in the Talmud, Adam was at first very huge. When he stood, his head reached to the very heavens; and when he reclined, he covered the earth with his gigantic form. But in a deep sleep which God caused to fall upon him, Eve was made from parts of all his members. After the creation of Eve, therefore, Adam was never again quite so large. Some of the Jewish rabbis taught that Adam, the first man, had in his body thirteen ribs,--one more than was possessed by any of his descendants,--and that this surplus bone became, in the hands of the Creator, the physical basis for the creation of the mother of all.

The thought has been suggested that as man was commissioned to subdue and have dominion over the beasts of the field and all the forces of Nature, the reason for woman's creation lies in her ability to tame man. Whether this be true or not, the student of Hebrew history will not lack ample evidence to show that to the women of Israel is due largely the place that their people hold in history as teachers of religion and morals; to them is due, also, that conservative quality which has made the Hebrews a peculiar and permanent people.

One of the old rabbis, commenting upon the Biblical account of woman's creation from the rib of Adam, remarked: "It is as if Adam had changed a pot of earth for a jewel." Good Dr. South, of pious memory, unaffected by the modern views of development, is credited with the remark that "Aristotle was but the rubbish of an Adam." If this be true, what must Eve have been!

About the beauty of the first woman, the Scriptures are silent, though, in Paradise Lost, Milton finds no hesitancy in creating her with surpassing physical grace, so that it was possible for her, like Narcissus, to fall in love with her own charms. Poets have not been slow to sing her praises:

"The world was sad, the garden was a wild

And man the hermit sighed, till woman smiled."

The Hebrews called the first woman Eve--that is, living or expanded, "the mother of all living." But these Oriental records attribute to Eve the advent into the world of death and human woes. The discord that came from the apple once tossed into a famous company of frolicking Greeks cannot compare with that which grew out of the fatal fruit, forbidden to the primal tenants of the Garden of Eden.

"Earth felt the wound--And Nature from her seat

Sighing through all her works, gave sign of woe,

That all was lost."

The French saying cherchez la femme has been in some form upon the lips of men from the earliest dawn of time. "The woman which thou gavest me," is Adam's lame apology for his weakness, as in one brief sentence he shifts the blame with dexterity upon God--the giver,--and woman--the God-given.

In marked contrast with this dark view of the first woman's legacy to the world is the account of the first promise, the light that burst forth suddenly as through a rift in the overshadowing cloud: "The seed of the woman shall bruise the serpent's head." Thus Lamartine's remark that "woman is at the beginning of all great things," becomes as pertinent as it is true. It is impossible to estimate the effect upon Israelitish motherhood of the belief in that ancient promise that some mother's son should yet arise to crush the monster of evil that was loosed in the world. Many a Hebrew mother came to feel that her own babe might become the hero chosen to strangle the serpent. This thought made motherhood the more prized, it became the aim of every Hebrew woman.

What if we could reproduce the sensations of that mother-love when the first woman enfolded in her bosom the first infant born, and heard its first cry for a mother's care? Of much interest is the Hebrew narrative here; for when Eve beheld her firstborn son she is said to have made an exclamation which many Hebrew scholars interpret as meaning, "I have obtained the promised One," believing that the pledge of Jehovah concerning the woman's seed had even then been realized. But the first son was to bring pangs to his mother's soul by slaying the first brother. Who can adequately describe the effect which that first death must have had upon the maternal heart? Instead of the lost Abel came a new son to console the mother-heart, Seth, the good; and the struggle between good and evil goes on throughout the Hebrew records, woman usually taking her place with the forces that made for righteousness.

Concerning the first bad woman, Lilith, held by some to have been the wife of the first man, very curious are the legends. Later rabbinic literature is rife with these stories. Among the Babylonians and Assyrians, Lilith was a night-fairy, as the derivation of the name would indicate, though some derive it from lilu, the wind. Popular superstition among the Hebrews, either through inheritance from the early days before Abraham, their father, lived in the Mesopotamian valley, or through the contacts with this region during the Babylonian exile, looked upon Lilith as a female demon of the night. She was supposed to be especially hostile to children, and this is why the Latin translations of the Vulgate version of the Scriptures rendered the word as lamia, a hag or witch who was supposed to be harmful to the little folk--though grown up people, also, might well beware of her baneful power. She is mentioned but once in Scriptures, and then in that highly graphic portrayal by the prophet Isaiah concerning the coming desolation that should soon befall the land of Edom, which was to become a place where "the wild beasts of the deserts meet with the wolves, and the satyr cries to his fellows, and Lilith (rendered in the accepted version, Screech Owl, and in the later version, Night Monster) takes up her abode."

It is Lilith's earlier history that is of especial interest, for, as runs the Jewish legend which one often meets in Talmudic literature, Lilith was the first wife of Adam, but becoming angered, she flew away and became a demon of the night. But the world will probably never concede that the first woman was a wicked one. The subtlety of an evil woman's charms is probably the underlying motive of the story of this "sweet snake of Eden," of whom Rossetti, in his Eden Bower, affirms consolingly, "not a drop of her blood was human."

"Who was Cain's wife?" is one of the perplexing questions asked by those who delight in hard sayings. The late Professor Winchell believed in a race of pre-Adamites, and many persons are committed to the theory of several centres of human origin. To those holding such views the question of Cain's marriage does not present particular difficulties. But those who hold to the theory that there was but one pair from whom all the family of mankind has sprung find difficulty in reconciling their theory with Biblical statements, and they are driven to acknowledging the necessity for marital relations between near kindred when the race was in its beginning--relations which would offend the best moral sentiment of to-day.

There is a curious passage in the Book of Genesis which tells of the marriage of the "sons of God" with the "daughters of men." Have we here the echo of that ancient tradition that once the gods and men intermarried and from the union the great heroes of the past were born? The close position of this statement concerning the "sons of God" and the "daughters of men" with the account of the great growth of evil in the world has led some to hold that these "daughters of men" were women from the unrighteous line of the murderous Cain, while the "sons of God" were men from the more upright family of Seth. Others, however, seeing also in close connection the statement that giants were on the earth in those days, find here a remnant of a very general tradition that from the gods had descended great heroes and giants who in past ages had fallen in love with daughters of human parentage. Since the Hebrews, however, were so strong in their monotheistic conceptions, this latter theory loses a great part of its force.

The state of society presented in the earliest Hebrew records indicates that the practice of polygamy was general. There are some who see indications among the Hebrew customs that there was a period, earlier than that of which any Hebrew records tell, in which polyandry and not polygamy was the fashion--when one woman had several husbands, rather than one husband several wives. The so-called Levirate marriage which was in vogue among the Hebrews is perhaps the strongest evidence that the customs of polyandry and mother-right were practised among them.

In common, then, with other peoples, the Hebrews practised polygamy; and while the influence of the best thought and teaching was, except in the earlier, patriarchal period, distinctly against it, the practice was still customary even down to the Christian era. The law of Moses, while not forbidding plurality of wives, discouraged the custom, and especially forbade the king from "multiplying wives."

The earliest example of polygamy of which the Hebrew records speak is that involving one of the most unique and interesting families of this early twilight of human existence. One Lamech, a descendant of Cain, is said to have married two wives, who bore the rather musical names of Adah and Zillah. And here we are introduced into the presence of a most remarkable household. For not only is Lamech to be awarded the distinction of having made the earliest attempt at verse which the Hebrew tradition has recorded, but Adah and Zillah became the mothers of a most talented family; the former of Jabel, "the father of such as dwell in tents and have cattle," and of Jubal, the inventor and patron saint of the harp and the pipe; while Zillah was the mother of Tubal-Cain, the first forger of implements of brass and iron. Lamech, the father, having doubtless received a sword from the forge of his son, used it in revenge upon an enemy, and gave utterance to the first recorded lines of poetry, which are possibly a fragment from what has been called The Lay of the Sword. It is a crude poem, dedicated by Lamech to his wives--for it was not uncommon among the early Semites to call the women to witness a hero's deeds of prowess:

"Adah and Zillah, hear my voice,

Ye wives of Lamech, hearken to my speech,

For I have slain a man for wounding me,

Even a young man for bruising me.

If Cain shall be avenged sevenfold,

Truly Lamech, seventy and seven."

It is not to be wondered at that in the very midst of dry genealogical tables the writer of Genesis should have stopped for a moment to tell of this epoch-making household.

Whether the women of this unique family, Adah, Zillah, and her daughter Naamah, were equally gifted with the men of the household, we are not told; but surely there must have been some genius in those feminine members of the home, who were so closely connected with the beginnings, not only of the fine arts of poetry and music, but also of the industrial pursuits of cattle raising and of metal working.

The early Hebrews were nomads. At first glance it might appear that woman's part in such an order of society would be scant, and her life one of comparative inactivity. But this view would lead into error, for in the nomadic life, while the men were guarding their flocks from the depredations of hostile bands or from the ravages of wild beasts, the women were the home makers and the home keepers.

Mason, in his Woman's Share in Primitive Culture, commenting upon Herbert Spencer's division of the life history of civilization into the period of Militancy, and the later period of Industrialism, raises the question whether it may not after all be more in accord with the facts--at least in the early history of the race--to speak of a sex of militancy and a sex of industrialism. The Hebrew woman, from her place in the tent or seated about the tent door, not only tended the fire, but invented, developed, and carried on many a handicraft into which not until later the men themselves entered.

For centuries the story of the lives of the patriarchs has thrilled and edified many a young heart, but what of the credit due to the matriarchs? What part do we find them playing in the early life of these Oriental peoples! The patriarch was not only father of his family or clan, but was their king and high priest. Yet it would be a mistake to suppose that the mother of the family was not an important factor in that early society, as the lives of many a Hebrew woman will easily demonstrate. The names of Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, Miriam, Huldah, and a host of others will readily occur to the mind of anyone at all familiar with the literature of the Old Testament.

A fair type of the life of the wife and partner of an ancient chief (sheik) of the higher order is found in that of Sarah, wife of the first and greatest Hebrew patriarch, "Abraham, the faithful." Living the life of nomad and shepherd, this pioneer of a new monotheism took his spouse away from the land of her fathers in the valley of Mesopotamia. Sarah's reverence for her husband became proverbial, and her conduct has been taken as the type of what was best in the domestic life of Israel--chaste behavior coupled with reverence. And Peter, known as the Apostle to the Hebrews, writing over two thousand years after the body of Sarah had been laid in its last home in the cave of Machpelah, gives a glimpse of the Hebrew conception of the ideal relation between husband and wife typified in Abraham and Sarah. While enjoining upon the women to whom he wrote the need of a "meek and quiet spirit," a spirit not discoverable in jewels and elaborate apparel, but in what he terms "the hidden man of the heart," he said: "For after this manner in the old time the holy women also, who trusted in God, adorned themselves, being in subjection unto their own husbands: even as Sarah obeyed Abraham, calling him lord; whose daughters ye are as long as ye do well." Thus did the virtues of Sarah impress themselves upon later generations. Sarah is not to be classed among the strong-minded women. Probably she was not virile in any true sense of the term, since in the traditions of her people she does not seem to have made for herself a place as leader that at all corresponds to the rank of her husband. He was to all Hebrews "Father Abraham," the first and foremost of his race; and no Jew could esteem his future life as giving promise of happiness unless his head might at length rest in Abraham's bosom. There is an ancient legend which says that Sarah, hearing of the plan of Abraham to sacrifice Isaac on the sacred spot of Moriah, died from the shock to her maternal heart. The father returned, bringing his only son alive with him, but Sarah had passed away. The narrative distinctly says that Abraham "came to mourn for Sarah and weep for her," as though the end had come during the absence of her husband. The Hebrew respect for women is illustrated in the costly burial accorded Sarah in a cave which was purchased from the sons of Heth--a place reverenced by the people of Israel for many centuries, because Sarah was buried there.

There is but one blot upon the life of this first mother of the Hebrews. Sarah was a faithful wife and devoted mother, but on at least one occasion she revealed a character capable of hasty, jealous, and cruel conduct. It is the time for the weaning of her only son--an occasion of more than usual interest in a Hebrew home. The family feast is at its height; Sarah discovers that her handmaid, an Egyptian woman, Hagar, whom she herself had given to Abraham as wife, for thus we may call her, was jesting at her expense. Quickly and hotly she demands that the bondwoman and her son Ishmael be immediately driven from the home, to which request Abraham reluctantly yields. Like most other women, Sarah, though now aged, could brook no rival in her home, and her womanly instinct at once discerned that only a step thus sharp and decisive would prevent, in the circle of domestic life, endless friction, more bitter than the sufferings occasioned by her cruel action.

Hagar in the thirsty wilderness, laying her perishing child under a bit of shrubbery and then departing a little distance that her mother-eyes may not behold the end, has powerfully awakened the imagination of the artist, as, indeed, she touched the heart of the Almighty, as the record tells us. For although Hagar wandered in the wilderness of Beersheba, the region of "the seven wells," no water had she found--so far was she from the life-giving draught; and yet was she so near--for lo! her eyes now fell upon a well of water, from which she and the lad quenched their mortal thirst. Thus was preserved him who was to become the father of the Ishmaelites, a people whose hand was to be against every man, and every man's hand against them. The breach that day in the tent of Abraham, between his two wives, one bond and the other free, was to be deep and abiding, as N. P. Willis, in describing Hagar's feelings in the wilderness, has written:

"May slighted woman turn

And, as a vine the oak hath shaken off,

Bend lightly to her leaning trust again?

O, no!"

And an apostle versed in rabbinic lore uses the story of Sarah as typical of the abiding difference between the principles of law and the precepts of grace.

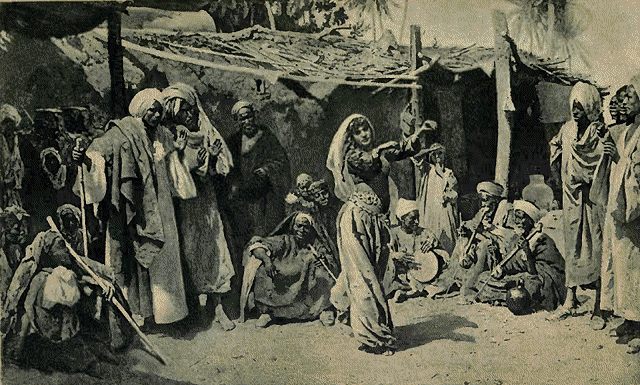

Probably no feature in the social life of a people is of so universal an interest as its marriage customs, and there is no courtship, either ancient or modern, which has more enkindled the imagination and awakened the interest of men than that between Isaac and Rebekah. The English prayerbook, in its ceremony of marriage, has chosen Isaac and Rebekah as the ideal pair to whose fidelity the young couples of the later years are directed for inspiration and example. It is a truly picturesque and even romantic story, which never loses its charm; and Rebekah, whether at the well or in her household, will always present a unique picture of womanly grace and beauty.

This ancient wooing of Rebekah by Isaac, though it is by no means typical in all its details, contains many elements that mark Oriental weddings. The prominence of the parents in the negotiations is characteristic. It cannot be said, however, that the choice of either Isaac or Rebekah was constrained.

When Isaac and his parents have reached the conclusion to which Richter has given voice--"No man can live piously or die righteously without a wife"--the faithful Eliezer is made to thrust his hand under the thigh of his master and swear that he will see that Isaac is wedded not to a daughter of the people around, but to a woman of his own kindred living in the regions of Aramea. This habit of marrying within one's own tribe became firmly fixed in Hebrew custom. The use of marriage presents, here so rich and costly, is almost as old as marriage itself; and how much Rebekah and Laban, her brother, were influenced by this manifestation of the riches of her wooer none can ever know. The part taken by Laban in this marital transaction is by no means unusual. Brothers in the East often played an important rôle on such occasions. When Shechem, the Hivite, wished to marry Dinah, daughter of Jacob, he consulted not only her father, but her brothers as well; and the brothers of the heroine of the Song of Songs are represented as saying: "What shall we do for our sister in the day when she shall be spoken for?"

The courage of Rebekah in consenting to mount the camel of a stranger and go into a far country to be wed is noteworthy. With all the apparent grace and gentleness of Rebekah, here was a pluck most commendable. We may say with Dickens: "When a young lady is as mild as she is game and as game as she is mild, that's all I ask and more than I expect." But it turned out to be but one of the many cases, since the world began, of "love at first sight"; and affection strengthened with the years! The frequent and cynical remark that marriage is after all but a lottery will probably long survive. Isaac did not act upon the sentiment expressed in the remark of Francesco Sforza: "Should one desire to take unto himself a wife, to buy a horse, or to invest in a melon, the wise man will recommend himself to Providence and draw his bonnet over his eyes." The daughters of Heth and of Canaan around him were not to his liking, and Providence seems greatly to have helped him in the emergency, for in the unseen Rebekah (whose very name means "to tie" or "to bind") Isaac found a lifelong blessing; and probably nothing could better disclose the wisdom of his matrimonial choice than the words of the Bible narrative, "and he loved her, and Isaac was comforted after his mother's death."

There is one blot upon Rebekah's record as a wife and mother, which, however, no less reveals a fault in Isaac's character as a father. It is a defect that was doubtless inherent in the ancient Oriental system itself. It was more usual than otherwise for mothers as well as for fathers to have favorite children. When both parents centred their affection upon the same child, usually a boy, it was ill for the rest; when mother and father were divided, it was ill for family felicity. Rebekah loved Jacob, the younger; Isaac loved Esau, the elder. And it is in this unfortunate distribution of parental affection that is to be found the beginning of a violent fratricidal feud, a long separation, as well as the causes which led to the bringing within the confines of Hebrew history two of the most important women of ancient Israel,--Leah and Rachel. Here again we find illustrated the fixed habit among the Hebrews to seek wives among their own people.

Among the Hebrews it was the custom that one who would acquire a wife must pay for her, either in money or in service. Usually, the young girl's consent was not thought to be a necessary part of the matrimonial bargain, and a father delivered a daughter to the purchasing suitor, as he might a slave that he had sold to the highest bidder. The woman herself played but a secondary part. It is thus quite plain that in this early day, marriage did not depend upon a contract entered into between one man and one woman, but between two or more men. And yet, in ancient Israel, while daughters were sold for wives,--or, to put it less harshly, given away for a consideration,--there is no intimation that a wife was in any sense regarded as a slave; nor are there instances of a husband selling his wife for a consideration. Parents were usually the parties to matrimonial bargains. In the case of Jacob and Rachel, however, we do not find the parents making the match, for the parents of the pair are widely separated. Jacob falls in love with Rachel at his first sight of her, as she, at close of day, leads the flock of Laban, her father, to drink from the open well hard by the dwelling. Laban readily agrees to surrender his daughter to Jacob,--who doubtless had no purchase money to procure a wife,--if the young man will serve him for seven years. But at the close of the stipulated period, the wily Laban falls back upon an unwritten law among the people of the day, that the daughters must be taken in marriage in the order of their seniority. Thus Leah, the elder sister, is accorded to Jacob, and seven years' additional service is necessary for the possession of Rachel. Persistence wins, and Jacob is at length in possession of both Laban's daughters, but the victory was the beginning of a life of struggle. Some one has remarked: "The music at a marriage always reminds me of the music of soldiers entering upon a battle;" it was so with Jacob. There must be a battle with Laban, the uncle and father-in-law, in which the daughters both take the part of the husband against their father, and agree to flee from that parent's house with the man to whom they had linked their destinies. There must be a battle with Esau, when mothers and little ones were to be exposed to great dangers and hardships; indeed, a long life of vicissitudes awaited the women whose lives were one with Jacob's, and contests between rival sons of rival mothers were to follow.

It has already been remarked that Sarah, wife of Abraham (whose name, Sarah, means "the princess"), occupies no such place in the imagination and tradition of the Hebrews as did Abraham, their father. It is around Leah and Rachel that the tribes of Israel group themselves, and the book of Ruth speaks of them as having built the house of Israel, and Leah and Rachel were the mothers of the twelve patriarchs for whom the tribes were subsequently named. Especially does Rachel occupy a high place, not only because she was Jacob's most favorite wife, but because of those personal qualities which more readily stirred the poetic and religious imagination of the people. The poet-prophet, Jeremiah, writing of the loss of life among the sons of Israel, because of the invasion and cruelty of Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, represents the people's sadness at the terrible calamity as "Rachel weeping for her children because they are not"--an expression which may have been suggested by Rachel's early condition of childlessness, followed by the loss of both her sons, Joseph and Benjamin, in the land of Egypt. The expression has borrowed new force, because it is quoted as again exemplified in "the slaughter of the innocents" by Herod the Great at the time of the birth of Jesus.

In the early history of the Hebrews, the people followed the free, roving life of the shepherd. In a climate where water supply was by no means sure, where a flowing stream which gave drink to the flocks to-day might be a rocky ravine to-morrow, families must needs have no certain abiding place. Woman the homekeeper must of course be affected by this Bedouin manner of life. Many daughters, like Rebekah and Rachel, were shepherdesses of their father's flocks of sheep and goats. When the Israelites went down into Egypt because the fertile valley of the Nile made famines less frequent than in the land of Canaan, they were somewhat ashamed, we are told, of the fact that they were shepherds, on account of Egyptian prejudices against that occupation, but in their native country they were proud of their occupation, and rather looked down upon merchantmen. The hated "Canaanite" became the synonym for "trafficker." It was the later exigencies of exile and dispersion that forced the Jews to buy and sell, and right well did they learn the lesson the world forced upon them. But in the beginning it was not so. And hence we find Israel, even after the twelve patriarchs had settled in the plains of Goshen, their Egyptian home, keeping their flocks and developing their home life in their own way in the kingdom of the Pharaohs.

Among the many notable women of Israel's heroic age, Miriam must not be forgotten. The romantic story of the hiding of her infant brother, in the rushes of the Nile, when King Pharaoh would have destroyed every Hebrew boy, is a familiar chapter. The sisterly tenderness and devotion which stationed the girl of twelve years to watch what might happen to the infant brother, to fight away wild beasts, and at length to direct the living treasure to the bosom of its own mother, is one of the best examples in literature of womanly tact and sisterly devotion.

The daughter of Pharaoh, a child of the Nile, comes down to the sacred stream to wash her garments or bathe her body in the saving water, and quickly, indeed quite willingly, falls into the well-wrought plan of Jokabed, the mother of the child Moses, and Miriam, the sister--a counterplot to that of the princess's father, and so ancient history is written with new headlines.

It is Miriam who enjoys the distinction of being the first prophetess in Israel, as her brother Moses is the first who was called a prophet, and her brother Aaron the first high priest. The part she took in leading the intractable people of Israel out of Egyptian bondage into the land of the Canaanites, must have been considerable, though according to the record she was nearing the century mark before the journeying began. As a poetess and musician, also, Miriam holds no mean place, for we are told that when her people had successfully crossed the arm of the sea, and Pharaoh's pursuing hosts had been cut off in the descending floods, Miriam organized the women into a chorus, and going before them with timbrel in her hand she led in voicing the refrain sent back in antiphonal strains to the song of the great camp, while her companions followed with timbrels and dances. This aged woman had music and patriotic fervor still present in her soul, as victory was assured to her people. The Hebrew song that grew out of this incident which is recorded in the Book of Exodus has been termed "Israel's Natal Hymn," a sort of poetic Declaration of Independence, and is far more majestic in its qualities than Moore's poem based upon the same event:

"Sound the loud timbrel; O'er Egypt's dark sea

Jehovah hath triumphed--His people are free."

By a singular confusion, the Koran identifies Miriam, sister of Moses, with Mary, the mother of Jesus. This may be partly due to the fact that the New Testament Scriptures as well as the Septuagint Greek translation of the Old spell both names alike, "Miriam."

But great women, like great men, sometimes make mistakes, and their blunders are often just at the point where they have achieved greatness. Miriam's distinction lay in her insight into the merits of her brother's mission and in her unselfish devotion to the cause to which he had been dedicated. Her greatest grief befell her by her unfortunate effort to break that very influence and to destroy his leadership, because she was displeased with a marriage he had contracted. She was smitten with leprosy, but the esteem with which she was held may be discovered when we read that the whole camp grieved at her calamity and consequent isolation from the people, and "journeyed not till Miriam was brought in again."

Miriam, the first prophetess and one of the strongest women that Israel ever produced, died during the wilderness wandering, and was buried in the region west of the Jordan. For many generations her tomb was pointed out in the land of Moab. Jerome, the Christian father, tells us that he saw the reputed grave close to Petra in Arabia. But, like the place of the entombment of her more distinguished brother, "no man knoweth it unto this day."

Among no people has the national consciousness been more thoroughly developed or more deeply seated than among the Hebrews. It is not to be wondered at, therefore, that among the women of Israel may be discovered the most ardent spirit of patriotism. Miriam's part in the founding of the Hebrew Commonwealth has already been noticed. When in the wanderings of the wilderness it became necessary to erect a temporary structure for the worship of Jehovah, the God of Israel, the women willingly tore their jewels from their ears, their ornaments from their arms and ankles, and devoted them to the rearing of the tabernacle. With their own fingers they spun in blue, purple, and scarlet, and wrought fine linen for the hangings and the service of their temple in the desert. In a theocracy, piety and patriotism were one. Not even the Spartan mother, who wished her son to return from the wars bringing his shield with him or being borne upon it, nor the women of Carthage, who plucked out their hair for bowstrings, could surpass the women of Israel in their sacrifices for national independence and political glory. In the days of Octavia, the ministers of Rome levied a tax upon Roman matrons to carry on a foreign war, and demanded a sacrifice of their jewels; and the Roman women thronged the public places, appealing to the high and influential in their vigorous protest against this taxation, and thus saved their ornaments. But the women of Israel did not need to be urged to tear off their ornaments and devote them to the common welfare. It was a woman who received the first recognition for services rendered the victorious hosts of Joshua, after the first campaign against the Canaanites had been waged. This was Rahab, a woman of Jericho, who, though her past life had been far from exemplary, seemed to see in the approaching Israelites a people of destiny. She therefore hid the Hebrew spies who had come to inspect the land, and, letting them down over the walls of the city, saved their lives. Thus did Rahab, the harlot of Jericho, preserve her own life when Joshua entered the city a victor; and, being admitted among the people of Israel, she became the ancestress of their greatest king, David, and, through him, the ancestress of Christ.

During that era in Israel's life, when the people were no longer merely an aggregation of shepherd clans, but had not yet been moulded into a national existence by a strong feeling of unity or the recognition of a common need, woman's life was exceptionally severe in its hardships and dangers. The unorganized tribes, engaged in their agricultural and pastoral pursuits, with hostile clans about them and hostile cities and strongholds as yet unsubdued, were subject to frequent incursions from bands of marauders and from armies of neighboring tribes, which would suddenly swoop down upon them like vultures on their prey. It was under such conditions as this that the women suffered untold indignities and misery. Kidnappers sold the women and children to slave traders of the coast, who carried them to Egyptian and Greek ports; so that even before the great dispersion of the children of Jacob which the kings of Assyria and of Babylonia brought about in the eighth and sixth centuries prior to the Christian era, the Hebrews were being scattered throughout the world.

It was in the period of transition and chaos which immediately followed the entrance of the people into the land of Palestine that Israel's most manlike woman appears as a veritable savior of her people. She is the second woman to whom the title of prophetess is accorded. The record reveals the fact that she was not only a woman strong in deeds of valor, but a leader in the religious life of Israel. The days were dark enough for the descendants of Abraham. For two decades now had Jabin, with his "nine hundred chariots of iron," struck with terror the ill-equipped, disorganized Hebrews. But there dwelt "under the palm tree" between Ramah and Bethel among the hills of Ephraim a woman who, by force of will and recognized wisdom, judged the people of Israel. "The inhabitants of the villages ceased, they ceased in Israel, until that I Deborah arose, that I arose a mother in Israel." It is from the sanctuary of this woman's mind and heart that deliverance from the king of the Canaanites is to break forth. She is called Deborah, i.e., "woman of torches," or "flames," either because she made wicks for the lamps of the sanctuary, or because of her fiery, ardent nature. Certainly there was warmth in her heart and fire in her love of her native land. She speedily sends for Barak, a chief man of Naphtali, and enjoins upon him to prepare an army of ten thousand men to meet Jabin's army, which is approaching under its captain Sisera, on the banks of the river Kishon. Barak hesitates, but at length answers: "If thou wilt go with me, I will go,"--so necessary did this strong, magnetic woman's presence seem for the enlistment of the people in the holy order of the enterprise. Deborah did not flinch in the presence of this challenge. The army is raised. The battle is joined, and Sisera's host is discomfited before Israel. The captain himself becomes a fugitive before the victors. But the end is not yet. Another woman appears upon the stage of this tragedy. The fleeing Sisera seeks shelter in the secret place of Jael's tent. Weary to exhaustion, the captain of the enemies of her people sinks down to sleep, the more profound because of the great draught of buttermilk or curds which Jael gave the thirsty man; and then with tent pin, a hammer, and an unquivering hand, Jael struck the sharp instrument through the sleeping man's temple and pinned him swooning to the dirt floor of her tent.

It was this bloody, but daring, deed which gave rise to one of the earliest of Israel's epic songs, the Song of Deborah. It is a remarkable poem, given in full in the Book of Judges. It sets forth praises to Jehovah for deliverance, and to Jael for the deadly stroke. A few lines from this epic, which many consider the earliest piece of Old Testament writing, will disclose the patriotic spirit of Israel's womanhood in those days of social and political disorder. The people are represented as crying out to the strong woman who lived under the solitary palm:

"Awake, awake, Deborah,

Awake, awake, utter a song."

Deborah comes at the call of distress. The people are rapidly marshalled to her help. But some hold back:

"Why abodest thou among the sheepfolds,

To hear the bleatings of the flocks?

.........................................

Gilead abode beyond Jordan

And why did Dan remain in ships?"

The battle is joined. Canaan is worsted before the followers of the woman of the hour.

"The stars in their courses fought against Sisera.

The river Kishon swept them away,

That ancient river, the river Kishon.

O my soul, march on with strength."

Then, turning upon the indifferent and laggard hosts that held back and refused to strike the blow for liberty, the poetess exclaims:

"Curse ye Meroz, said the angel of the Lord,

Curse ye bitterly the inhabitants thereof,

Because they came not to the help of the Lord,

To the help of the Lord against the mighty."

Concerning the woman whose unfailing hand had struck the fatal blow, the poetess sings:

"Blessed above women shall Jael be,

The wife of Heber the Kenite.

Blessed shall she be above women in the tent.

"He asked water

And she gave him milk,

She brought forth butter in a lordly dish."

The tent pin has pierced the temples of the oppressor of Israel:

"At her feet he bowed, he fell, he lay down,

At her feet he bowed, he fell,

When he bowed, he fell down--dead."

Very dramatic do the lines become when, imagining the mother of Sisera waiting for her son to return victorious from the battle, and looking out through the lattice of her dwelling wondering at his long delay, she asks:

"Why is his chariot so long in coming,

Why tarry the wheels of his chariots?"

But Sisera never returns to his maternal roof. For forty years did the people enjoy the freedom of Deborah's deliverance, the woman whose influence went out from "the sanctuary of the palm."

It is said of this period, commonly known as the Age of the Judges, that "every man did that which was right in his own eyes." This would be known in political theory as well as in practical government as nothing short of anarchy. And indeed, it was, for while each man did that which was right in his own eyes, the "right" of each was so frequently wrong, that social chaos reigned with almost unbroken sway. And while one woman of the period became a deliverer for four decades, for more than a century many women suffered untold misery for lack of unity among the tribes and leaders capable of bringing the life of the reign to rights.

It is often affirmed that sons more frequently inherit characteristics of their mothers, while to the daughters are bequeathed the traits of their fathers. An unnamed woman of this period of the political chaos, the wife of a certain Manoah, from the family of the Danites, was chosen to be the mother of a giant. Now, giants were rare in Israel, though in the earlier days of Palestinian occupation, Nephelim, and "the sons of Anak," are mentioned as among those enemies of the Hebrews. Their huge forms, it is written, were a menace to Israel's peace, and in comparison with these monsters her sons were said to be "as grass-hoppers." One day, as the story runs, an angel appears to this nameless, hitherto childless, wife of Manoah, and informs her that a son who is to be born, and nourished at her own bosom, is to have a remarkable history. She herself is to take care neither to drink wine nor any strong drink, for her son is to be dedicated to the abstemious life of the Nazarite. The woman is obedient to the angelic voice; and she with her husband offers up a burnt offering to Jehovah in grateful praise. The son is born. He is taught that no intoxicating draught shall enter his lips, nor should a razor touch his head, that his long-grown locks might speak outwardly of his vows. But wine is not the only temptation that is to beset this giant youth. The daughters of neighboring Philistia were to his eyes more than passing fair.

The influence of these young women, whose features, we may suppose, bore some characteristics of Grecian beauty,--as their progenitors had landed on the shores of Canaan from the island of Crete, gradually adopting a Semitic language and civilization,--was very potent over the heart of the muscular but susceptible young Hebrew. A love affair in which the long-haired Nazarite plays a prominent rôle will introduce us, somewhat at least, into woman's world of this disorganized period in the early life of Western Palestine at a day more than a thousand years before the Christian Era.

This affair of the heart was brought to light when one day the young man came in to tell his father and his mother that a fair damsel in Timnah, a city of the Philistines, had captured the very citadel of his being. Neither the protestations of his parents, nor their careful descanting upon the virtues of the daughters of his own people could move the young man. His heart was set. Neither parents at home nor the lion that met him on the way to secure his bride could thwart his firm-set purpose. Mother and father are for the moment forgotten, and the lion is torn asunder by the strong arms of this young giant. Every obstacle is surmounted and Delilah is in the arms of Samson.

Now, George Sand was doubtless correct in the rather prosaic remark: "It is not so easy to see through a woman as through a man." Samson did not quite penetrate the wiles of his lady love. Her beauty hid all else, and Samson fell. "The whisper of a beautiful woman," says Diana of Poitiers, "can be heard further than the loudest call of duty." The Nazarite vow, so strong and binding, became in Delilah's hands, as she held the shears, weaker than the withes she bound about the arms of the captured giant. Robert Burns has, in a characteristic fashion, given what might well be inscribed to Samson's memory:

"As Father Adam first was fooled,

A case that's still too common,

Here lies a man a woman ruled

The devil ruled the woman."

Delilah, the Philistine, is to be contrasted with the typical Hebrew women, not only in the matter of feminine chastity for which they stand out among ancient women as preëminent, but also in that fidelity to husband and to native land which made the Hebrews the most stable and persistent race with which the world is acquainted.

In marked contrast with this witch of the Philistine plains, stands out the heroic daughter of Jephtha. Her purity, patriotism, and her deep respect for the sacredness of a religious oath, place her at the very opposite pole. "Great women," says Leigh Hunt, "belong to the history of self-sacrifice." If this be true, Jephtha's daughter must be enrolled among the great, as her heroic self-devotion shines through the dimness of ancient history. Her father was one of Israel's deliverers in the days of tribal division and political chaos. Returning from victory over the hostile Ammonites, Jephtha purposes to give, as sacrifice to Jehovah for bringing him success in arms, the first creature that comes forth to meet him as he turns his face homeward. It is his own daughter, his only child, going out to meet him with the timbrel and with dances. In his eyes a "very daughter of the gods, divinely tall, and most divinely fair." Will he break his vow? Will the young woman herself, this Hebrew Alcestis, shrink from the sacrifice? "My father, thou hast opened thy mouth unto the Lord, do unto me according to that which hath proceeded out of thy mouth."

For a woman to die childless in Israel was looked upon as a calamity, a mark of divine displeasure, and the daughter of Jephtha was a virgin. It is for this reason that she begged the coveted privilege of two months' respite that, with her maidens, she might withdraw to the neighboring mountain and there "bewail her virginity." At the end of the required period, returning to her father's house, she yields herself a sacrifice to the hasty but well-meant vow of her patriotic father. So deeply did her pure devotion to filial and patriotic ideals impress the daughters of Israel, that every year they went out to lament, four days, in honor of the daughter of Jephtha, the Gileadite, of whom N. P. Willis has drawn this appreciative picture:

"Now she who was to die, the calmest one

In Israel at that hour, stood up alone

And waited for the sun to set. Her face

Was pale but very beautiful, her lip

Had a more delicate outline and the tint

Was deeper; but her countenance was like

The majesty of angels!"

Among no ancient people was the love of chastity in women so thorough and imperative. There is probably no better illustration of this fact than in the very ingenious method by which the men of Benjamin obtained their wives, at a time when total extinction of the tribe seemed to stare them in the face. An aged Levite, with his wife, who had been unfaithful to him, but by his efforts had been reclaimed and with him was returning home, is passing through the land of Benjamin. When they reach the city of Jebus, afterward named Jerusalem, the famous centre of Israel's later life, no one offered the customary hospitality, so the man and his wife were about to lodge in the street, a disgrace to the city, according to the common customs of entertainment. It is then a temporary resident of the city invites the homeless ones into his house. When the Benjamites saw them go in, they took the woman from the house and shamefully maltreated her, leaving her helpless upon the steps till morning. The Levite, incensed at the terrible crime, took the woman, cut her in pieces and sent the fragments throughout the tribes, telling the story of the deed of some of the sons of Benjamin. It is pronounced by all the worst blot upon the land since the sojourn in Egypt. The whole people is aroused to anger. They collect men of war from the tribes, and go up to battle against their brethren of Benjamin, till the entire tribe seems about to be exterminated. Especially was the destruction of their women grievous. What must be done when the dust of battle has rolled away? Shall a tribe be lost to Israel? This must not be. The sacred number must be preserved. How shall Benjamin obtain wives, for all the rest of Israel had made a solemn oath that they would never give their daughters to the sons of Benjamin because of this horrible crime which had been so peremptorily punished. At length, the elders of all the people devise a plan. Marriage with the Gentile peoples is, of course, not sanctioned, and all the tribes of Israel have refused to give their daughters to Benjamin--there is yet a way out of the dilemma. Some one remembers that every year at harvest time there is given a feast at Shiloh, where many Hebrew damsels come together to enjoy the religious and festal dances. It is agreed that the sons of Benjamin shall hide themselves in the adjacent vineyards, and while the maidens are dancing, each man is to run out, seize a wife and make his way swiftly homeward. But what say the fathers and brothers of the purloined damsels to this high-handed procedure of the young men of Benjamin? The elders agree to step in then and to advise all to acquiesce in quietness, for the people had not violated their oaths. Their daughters had not been given to Benjamin; they were stolen! So Benjamin obtained wives and the tribal existence was preserved by the same method in which Rome was repeopled at the expense of the Sabines.

Israel holds a high place among the people of the earth because of the prevalence of piety among its women. Religion is deeply grounded in the intuitions and feelings of the race, and derives force, at least, from the sense of dependence upon higher powers, as Schliermacher has taught. Since women are far truer in their intuitions and feelings than men and the sense of dependence is more highly developed, it is not strange that women everywhere are more religious than men. Among the holy women of old none can be accorded higher place than Hannah, the mother of Samuel.

One may at first be astonished that childlessness is so frequently mentioned as characteristic of women in the Scriptures. Among them, Sarah, Rebekah, Rachael, the unnamed wife of Manoah, Hannah, and Elisabeth,--mother of John the Forerunner,--are all familiar examples. But barrenness was probably not more common among the Hebrews than among other peoples. Only, in Israel, childlessness was accounted a calamity, if not a direct visitation of the Almighty. Hence, every pious woman wished to be released from the curse. The women themselves ridiculed and ever despised those who were not blessed with offspring. Besides, every man among the Hebrews wished to live in his descendants. To die without children was to be "cut off" from the face of the earth, and to be forgotten. There was a yearning to live forever in the land.

The contrast between the great emphasis which the Egyptian laid upon immortality, the large place it held not only in their religious teachings, but in the development of their civilization, as modern excavations have revealed it, and the lack of such emphasis in the writings of the Hebrew Scriptures has frequently been noticed, and by many greatly wondered at. But the Hebrews gave little thought to immortality in the next world. Their prophets spent most of their time stressing the importance of righteousness in this life, and the people emphasized the earthward side of immortality--that is, one's power to live forever in one's posterity.

The writer in the one hundred and twenty-eighth Psalm expressed the common Hebrew conception, as, in recounting the blessings of a truly happy man, he said: "Thou shalt eat the labour of thine hands: happy shalt thou be, and it shall be well with thee. Thy wife shall be as a fruitful vine by the sides of thine house: thy children like olive plants round about thy table." Or as another psalmist, in the same spirit, prays: "That our sons may be as plants grown up in their youth; that our daughters may be as cornerstones, polished after the similitude of a palace." Many a time in the Hebrew Scriptures is this ideal prominent. For a psalmist again writes: "As arrows in the hand of a mighty man, so are children of the youth. Happy is the man that hath his quiver full of them. They shall not be ashamed, but they shall speak with the enemies in the gate." And when the prophet Zachariah foretells the coming glory of Jerusalem, which should supersede the then present distress, he gives as one item of blessing: "And the streets of the city shall be full of boys and girls, playing in the streets thereof."

It may therefore be readily surmised how a woman of Hannah's piety might feel in the thought of her condition of childlessness. And while the hardships of the barren woman in Israel could in no way compare with those of some other peoples, as in Australia, where the childless woman of the aborigines is driven out to a dire struggle for existence, yet the feeling that her God was, for some cause, against her and that her husband might in his secret heart despise her, must have been agony indeed. "The brain-woman," says Oliver Wendell Holmes, "never interests us like the heart-woman; white roses please us less than red." Hannah was preëminently a heart woman; the red blood of warm devotion coursed through her veins. When at length her prayers, made in bitterness of suffering, were answered, and heaven gave her a son, she named him Samuel, for, she said, "God hath heard," and dedicated him wholly to Jehovah, placing him at the service of the tabernacle. When the time came to wean the lad, she journeyed with him to Shiloh, the place of the sanctuary, with her offering, as the custom was, and "lent him" forever to Jehovah, her God.

"I think it must somewhere be written that the virtues of the mothers are occasionally visited upon their children, as well as the sins of the fathers." These words of Dickens suggest one of the occasions in which motherly virtues seem to have been visited upon the child, for Samuel became the earliest representative of a long line of prophets who, for many centuries, were the spiritual leaders of Israel. He was the father and founder of a "school of the prophets," the earliest theological seminary of which we have any record. The prayer of thanksgiving which the records say Hannah uttered when God blessed her with this precious gift of a son, influenced not only the famous Magnificat of Mary, when she was told of the birth of her greater Son, but also that of Zacharias when the birth of John the Baptist was predicted by the angel who talked with him in the temple.

History records several famous cases of friendship between men; that between David and Jonathan, and that between Damon and Pythias of Syracuse, have become proverbial. Fewer have been the friendship among women. Indeed, some have argued the impossibility of such friendships. But there is probably no more attractive story of womanly devotion in all the range of literature than that which tells of the love between Ruth and Naomi. The Book of Ruth is a beautiful idyll of early Hebrew life, and the heroine here stands the test. The scene is laid in the time when judges ruled in Israel; and in this, as in many instances in the early days of Palestine, an epoch was born out of a famine. Elimelech, with his wife, Naomi, and their two sons, Mahlon and Chilion, hunger-driven, set out for the land of Moab. Death lays its claim to the husband and father, and Naomi, with her boys, is left widowed in a strange land. Mahlon and Chilion, now grown to manhood, marry two daughters of Moab, by name Orpah and Ruth. A decade passes, and the sons themselves die. Bereaved and broken in spirit, Naomi at length turns her heart toward her native Judean hills. Finding her daughters-in-law inclined to follow her into the uncertainty of her future subsistence in her former home, Naomi counsels their return, each to her mother's house. "And they lifted up their voice and wept." Orpah reluctantly obeys, but Ruth cleaves to her mother-in-law, with those unsurpassed and memorable words, which the author of the book of Ruth throws into Hebrew measure:

"Intreat me not to leave thee,

Or to return from following after thee;

For whither thou goest, I will go;

And where thou lodgest I will lodge;

Thy people shall be my people,

And thy God, my God.

Where thou diest, will I die,

And there will I be buried.

The Lord do so to me, and more also,

If aught but death part thee and me."

"Some women's faces are in their brightness a prophecy, and some in their sadness a history." As these two women stood with their faces set toward Palestine, upon one was written a history of sorrow; upon the other there fell the sunrise of a new day. In Ruth's determination to follow Naomi, even to death,--for "a woman can die for her friend as well as a Roman knight" when she has one, as Jeremy Taylor has declared,--the young widow of Moab began a new life, which was destined to make her the ancestress of Judah's royal house, the great grandmother of David the king.

As the poetic story of Ruth proceeds, it records several interesting ancient marriage customs among the people of Israel. In marked contrast with the Hindoo custom of condemning widows to a life of scarcely bearable hardships, the Hebrew law was so framed as to make widowhood as far as possible a temporary state. The custom of Levirate marriage enforced upon the brother or nearest of kin to the deceased husband the obligation of taking the widow of his brother to wife, in order that the brother might not be without heir and memory in the land. Ruth's deceased husband had rights in the ancestral estate, and the Hebrew law was careful that estates should not pass out of the hands of the original owners, if it were possible to prevent it. Ruth, the widow, suddenly appears at Bethlehem, the old home of her husband's people. It is the time of the barley harvest. Naomi plays the role of the scheming mother. She would have her beautiful young daughter-in-law find a husband among her kindred, that her lamented son might have an heir to honor his memory and that the portion of the estate which was Elimelech her husband's might be redeemed. The love plot sends Ruth into the field of Boaz, a wealthy farmer and near kinsman of Elimelech, to glean after the reapers, for no man was permitted by the law to deprive the poor of whatever pickings they might find when the reapers had passed. The quick success of the plot, the fascination that Boaz feels for the graceful but unknown woman, the command given the reapers to leave behind by purposeful accident a little more of the grain than was usual and be gracious to the girl; the invitation at mealtime to come and partake of the repast of parched corn with the reapers; the resolve of Boaz that should there be found no nearer kinsman--whose duty it would first be to take the young woman to wife--he himself would choose her. All these incidents pass in rapid and romantic succession. The observation is apparently true that "women are never stronger than when they arm themselves with their own weakness." Boaz at once pledged himself to be the damsel's friend and protector. The next of kin declines or waives his right to the young widow, for he does not care to redeem Elimelech's portion of the land, a necessary part of such a matrimonial transaction. Boaz therefore summons the young man, next of kin, who has declined to redeem the land of his deceased brother and raise up heirs for him, to appear at the gate of the city as the law required. Here ten elders sit to witness and make legal the transaction. The shoe of the refusing kinsman is taken from his foot, in the presence of the assembled people, and given to Boaz, symbolizing the relinquishment of all rights in the premises. Then follows the custom of spitting in the face of the "man with the loosed shoe," which became a term of reproach, and was applied to the man who refused to fulfil toward a deceased kinsman the duties of the Levirate marriage. Time passes and the aged Naomi, whose mother named her "winsome," forgets the bitterness of her later years as she holds in her arms the infant Obed, in whom she exultingly sees the pledge that the house of her son shall live on, and a prophecy that his name will become famous among his people. "And Obed begat Jesse and Jesse begat David," the king.

As we pass out of the unsettled age of the judges into the period when the commonwealth of Israel began to take definite shape, we come upon a corresponding change in the life of the Hebrew woman. The heroism in female virtue was perhaps no less frequent, but when the "heroic age" is behind us there is less opportunity for women to stand out in so strong a glare. And, indeed, all through this history the remark of Ruskin is close to the truth when he says: "Woman's function is a guiding, not a determining one." While epoch-making women occasionally appeared in the earlier period, they became fewer and fewer as the social order became more settled.

It was not till the days of the kings that the Mosaic law, in the broadest sense of the term, could exert any very potential influence over the life and conduct of the people. In a disorganized condition of society, of which it was said, "Every man did that which was right in his own eyes," to enforce Mosaic precepts would have been an impossibility, even had the people at large been acquainted with that law. Now, the law of Moses became one of the most powerful factors in giving to the women of Israel the high place they held in the commonwealth. The fifth of the "Ten Words"--which commands were the very nucleus about which the whole law was developed--reads: "Honor thy father and thy mother, that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee." Thus, in this, the very first law of the Decalogue respecting duties to man, the duty of honoring the mother was made equally imperative with that of showing honor to the father. And it may be truly affirmed that Israel's remarkable permanence and persistency as a people may be traced to its domestic health, and that this vigorous domesticity is due largely to a better understanding of the true relation of the sexes than is discoverable among any other ancient nation.

That honor for parents makes for the permanence of a people both reason and history affirm. Any nation which honors its ancestry will hold tenaciously to ancestral ideals. Notwithstanding China's limitations in other directions, that nation, because of its worship of the fathers, has lived through many centuries and seen more powerful nations rise and fall.

The position of Israel as a separate people abides in strength because both father and mother have for ages been respected; and even though most of her sons and daughters are no longer "upon the land which the Lord their God gave them," they are still holding with wonderful firmness to the faith and ideals of their fathers. The Mosaic teachings concerning woman are not a little responsible for this remarkable state of racial longevity. The Hebrew woman's standing before the law gave her great advantage over her sisters of the other Semitic and Oriental peoples. The Mosaic law tended greatly to lessen the inequalities and mitigate the hardships of womankind. Even a woman captured in war was protected against the caprice of her captors. Under the law, her life was equally as precious as that of a man, and therefore the taking of a woman's life was punishable with the same severity as was the murder of a man. The law was especially solicitous of her welfare during the period of child bearing, and greatly lessened the sorrows and isolation of widowhood.

While divorces were given almost at the will of the man, yet he could not without formality at once eject the woman from his house. He must give her a "writing of divorcement," which set forth the fact that she had been his wife. Thus was she protected from subsequent suspicion that she had lived with a man unlawfully. Wives of bond-servants were to go out free with their husbands on the seventh year of service, unless the master himself had given the wife to his manservant, in which case the woman and her children still belonged to the master.

Daughters were allowed inheritance as well as sons, though in earlier times than those of the kings they did not inherit their father's property except there were no sons. Fathers were not allowed to discriminate against a firstborn son and pass the inheritance to another because the mother of the oldest child happened to have lost favor in his eyes.

Laws forbidding unchastity and vice were explicit and severe. One who had taken criminal advantage of another's daughter was to marry her and pay the father the usual dowry; if not, he was to be amerced fifty shekels of silver, the ordinary dowry of virgins. If a husband suspected his wife of being unfaithful to him, an elaborate, but not severe, ordeal was laid upon the woman, called "drinking the waters of jealousy." If she passed this examination successfully, her husband had no power further to punish her; if not, she was to suffer for her shame.

The widow and the fatherless were given special consideration under the law. In the feast days when the people's hearts were merry and they were rejoicing in the increase of their lands, the widow was not to be forgotten. In business transactions the people were to take heed that the widow suffer not injustice. Her garments could never be taken in pledge, and judges were enjoined to see that no violence was done to her rights. The fallen sheaf in the harvest field, the forgotten gleanings of the olive trees, the droppings of the vintage were not to be withheld from her.

How deep-seated this sense of obligation to the widow was in Israel may be discovered in the Book of Job. The friends who visited Job in his bewildering grief could find no more probable cause for so severe a divine chastisement upon the arch-sufferer than that Job had neglected the widow or taken her in pledge. One effect of the attitude of the customary law toward widows is discovered in a most signal way in the Second Book of Maccabees, which relates that in the period of which it tells, about B.C. 150, it was customary to lay up large sums of money in the temple treasury for the relief of widows and of fatherless children.

Such women as Miriam and Deborah were factors to be reckoned with in the political movements of their times. So it was with the prophetesses generally, for just as the great prophets dealt with the politics of state, so a prophetess could not always escape the problems of statesmanship to which her time might give birth. Both prophet and prophetess were looked upon as the chosen spokesmen for Jehovah. Because of this, Huldah acted as a sort of prime minister and adviser of both king and high priests in their Jehovistic reforms during the reign of Josiah.

That women generally took a deep interest in political matters may be perceived in the way in which the exploits of David appealed to the imaginations of the women when Saul's star was setting and David's appearing above the horizon; for young women went out to meet the coming hero and king with musical instruments, singing a song whose refrain was:

"Saul hath slain his thousands,

David his tens of thousands."

The power of the feminine idea may be forcefully seen in the very common conception of the nation itself as a young woman. Both prophet and poet--and the prophets were usually poets--refer many times to the "daughter of Zion," meaning the people of Israel.

The prophet Jeremiah, foreseeing the coming destruction of the army of Babylon, says: "I have likened the daughter of Zion to a comely and delicate woman" who is about to be ravaged by the invader. And Isaiah, seeing the time at hand for the people to return from Babylonish exile, cries out: "Loose thyself, O captive daughter of Zion."

Affection for the native land was strong among the women as well as among the men. Lot's wife did not turn because of curiosity, but by reason of the strong attachment to locality; she looked back longingly toward her forsaken and burning home. The little Hebrew maid, torn by an invading army of Syrians from her native land, was quick to tell Naaman, the leper,--her new master,--of the virtues of her country and impelled him to seek out Elisha, the prophet of Israel.

The social position of Hebrew women was exceptionally free and independent. While a daughter's matrimonial plans were largely in the hands of father and brother, and wives were expected to look up to their husbands with all reverence, yet the recorded examples of independent action and influence among the women reveal a place of social equality and power, a lack of masculine restraint and domination that would do credit to more modern times.

Deborah accompanied, if she did not lead, the soldiers into battle and cheered them on to victory. The daughters of Shiloh, unaccompanied, were accustomed annually to attend festal dances in the vineyards of Benjamin. Women often went without escorts upon difficult and dangerous missions. Prophetesses frequently exerted not only a powerful but at times a decisive influence.

Marriage customs among the Hebrews in the days of the kings were not greatly different from those of other Oriental people of the same era. They differed but slightly from those of an earlier period. As a rule, marriage was not born out of impulse of the heart; though there were many marriages that surely ripened into love. If, as Jean Paul Richter says, "Nature sent woman into the world with a bridal dower of love," we have an explanation of the fact that there are many happy marriages in Israel, notwithstanding the fact that the arrangements continued to be largely in the hands of the parents. A daughter belonged to her father till of age: after this she could not be betrothed except by her own consent. Among the Hebrews betrothal was of the nature of an inviolable contract, and could be annulled only by divorce. If not in early days, yet in the later periods of Hebrew history there were writings of betrothal which set forth the mutual agreements between the parties. Later, there followed the marriage contract, also in writing. The amount paid for a maiden came to be at least two hundred denars, and just one-half as much for a widow. The father was to provide dowry according to his ability, and an orphan girl's dowry was bestowed by the community.

The marriage ceremony consisted of leading the bride from her father's house to that of the bridegroom. At which time there was a season of festivity and rejoicing. The marriage of a maiden usually occurred on Wednesday evening, that of a widow on Thursday. The "children of the bride chamber," the name by which the invited guests were called, made merry at the "marriage feast," which was always provided and lasted several days. As the procession passed along, going from the bride's to the bridegroom's house, people along the route might join in the festivities.

Grains of corn, nuts, and other edibles were the confetti tossed good-humoredly at the bridal pair. It became the custom, which still exists among Jews to-day, to break a glass bottle at Hymen's altar to indicate that the former life is no more, and that the bride has entered upon a new estate. Among the Hebrews the married woman was better protected in her rights than among most people of ancient times. While her property was usually under control of her husband, yet the dowry came to be considered her own, whether it be money, property, or jewels. A husband could not compel his wife to remove from the land of her fathers; and in many ways her individual rights were protected. Woman's inferior position in Greece was one element in the decline of that remarkable country; the defilement of the womanhood of Rome hastened the downfall of that city's power; but the protection given to Hebrew wifehood and widowhood became an element of great strength in the life of Israel.

The Greek attitude toward woman could probably be reflected in the old saying: "A woman who is never spoken of is praised most." In the period of Rome's decay women became immodestly conspicuous in the social and public functions of the day. As opposed to both these conditions the Hebrew, the wise man in the Proverbs, calls her a virtuous woman whom her husband can praise in the very gates.

Edersheim calls attention to a suggestive custom which sprung up from the slight difference of sound in the words for "find" in two passages of Scripture concerning women, both of which occur in the wisdom writings. The first of these reads: "Whoso findeth a wife, findeth a good thing." (Proverbs 18: 22.) The other, "I find more bitter than death the woman whose heart is snares and nets." Hence arose the habit of saying to a newly married man, "Maza or Moze?" "Have you found a 'good thing' or a 'bitter'?"