Title: Hildegarde's Harvest

Author: Laura Elizabeth Howe Richards

Release date: May 25, 2010 [eBook #32520]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A new volume in the "Hildegarde" series, some of the best and most deservedly popular books for girls issued in recent years. This new volume is fully equal to its predecessors in point of interest, and is sure to renew the popularity of the entire series.

"We would like to see the sensible, heroine-loving girl in her early teens who would not like this book. Not to like it would simply argue a screw loose somewhere."—Boston Post.

***Next to Miss Alcott's famous "Little Women" series they easily rank, and no books that have appeared in recent times may be more safely put into the hands of a bright, intelligent girl than these five "Queen Hildegarde" books.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Morning Mail | 9 |

| II. | The Christmas Drawer | 21 |

| III. | Aunt Emily | 41 |

| IV. | Greetings | 59 |

| V. | At the Exchange | 73 |

| VI. | More Greetings | 96 |

| VII. | Merry Weather Signs | 117 |

| VIII. | Christmasing | 137 |

| IX. | An Evening Hour | 162 |

| X. | Die Edle Musica | 176 |

| XI. | The Boys | 196 |

| XII. | Jimmy's Pond | 217 |

| XIII. | Merry Christmas | 238 |

| XIV. | Bellerophon | 257 |

| XV. | At Last | 279 |

| PAGE | |

"Hildegarde danced the Virginia Reel with the Colonel" | Frontispiece |

| Bell's Letter | 14 |

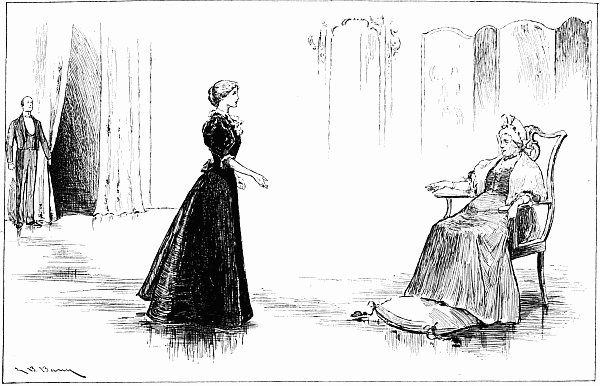

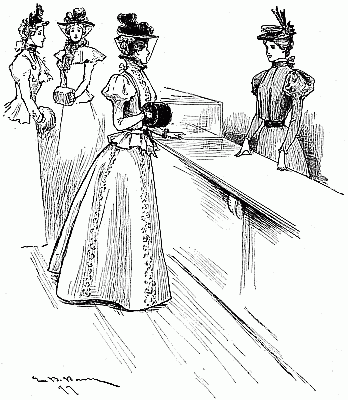

"Mrs. Delansing scrutinised her as she came through the long room" | 50 |

"'Hildegarde Grahame, in the name of all that's wonderful!'" | 91 |

"'Consider the beauty of your offspring'" | 140 |

| Die edle musica | 177 |

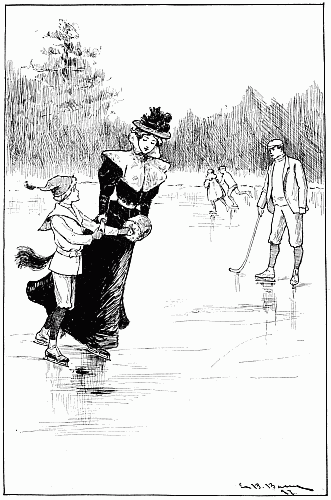

| On Jimmy's Pond | 223 |

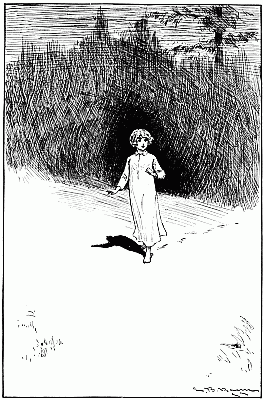

"A little figure . . . stood out clear against the dark firs" | 274 |

Hildegarde was walking home from the village, whither she had gone to get the mail. She usually rode the three miles on her bicycle, but she had met a tack on the road the day before, and must now wait a day or two till the injured tire could be mended.

Save for missing the sensation of flying, which she found one of the most delightful things in the world, she was hardly sorry to have the walk. One could not see so much from the wheel, unless one rode slowly; and Hildegarde could not ride slowly,—the joy of flying was too great. It was good to look at[10] everything as she went along, to recognise the knots on the trees, and stop for a friendly word with any young sapling that looked as if it needed encouragement. Also, the leaves had fallen, and what could be pleasanter than to walk through them, stirring them up, and hearing the crisp, clean crackle of them under her feet? Also,—and this was the most potent reason, after all,—she could read her letters as she walked, and she had good letters to-day.

The first that she opened was addressed in a round, childish hand to "Mis' Hilda," the "Grahame" being added in a different hand. The letter itself was written in pencil, and read as follows:

"I hop you are well. I am well. Aunt Wealthy is well. Martha is well. Dokta jonSon is well; these are all the peple that is well. Germya has the roomatiks so bad he sase he thinks he is gon this time for sure. I don't think he is gon, he has had them wers before. Aunt Wealthy gave me a bantim cock and hens, his nam is Goliath of Gath, and there nams is Buty and Topknot. The children has gon away from Joyus Gard; they were all well and they went home to scool. I miss them; I go to scool, but I don't lik it,[11] but I am gone to have tee with Mista Peny pakr tonite, Aunt Wealthy sade I mite. He has made a new hous and it is nise.

Hildegarde laughed a good deal over this letter, and then wiped away a tear or two that certainly had no business in her happy eyes.

"Dear little Benny!" she said. "Dear little boy! But when is the precious lamb going to learn to spell? This is really dreadful! I suppose 'Germya' is Jeremiah, though it looks more like some new kind of porridge. And Mr. Pennypacker with a new house! This is astonishing! I must see what Cousin Wealthy says about it."

The next letter, bearing the same postmark, of Bywood, and written in a delicate and tremulous hand, was from Miss Bond herself. It told Hildegarde in detail the news that Benny had outlined; described the happy departure of the children, who had spent their convalescence at the pleasant summer home, all rosy-cheeked, and shouting over the joy they had had. Then she went on to dilate on the wonderful[12] qualities of her adopted son Benny, who, it appeared, was making progress in every branch of education.

"I may be prejudiced, my dear," the good old lady wrote, "but I am bound to say that Martha agrees with me in thinking him a most remarkable child."

Miss Bond further told of the event of the neighbourhood, the building of Mr. Galusha Pennypacker's new house. The neighbourhood of so many little children, his friendship with Benny, "but more than all, his remembrance of you, my dear Hildegarde," had, it appeared, wrought a marvellous change in the old hermit. The kindly neighbours had met him half-way in his advances, and were full of good-will and helpfulness; and when, by good fortune, his miserable old shanty had burned down one summer night, the whole neighbourhood had turned out and built him a snug cottage which would keep him comfortable for the rest of his days.

"Mr. Pennypacker came here yesterday to invite Benny to drink tea with him (I employ the current expression, my[13] dear, though of course the child drinks nothing but milk at his tender age; I have always considered tea a beverage for the aged, or those who are not robust), and in the course of conversation, he begged me most earnestly to convey to you the assurance that, in his opinion, the comfort which surrounds his later days is owing entirely to you. His actual expression, though not refined, was forcible, and Martha thinks you would like to hear it:

"'I was a-livin' a hog's life, an' I should ha' died a hog's death if it hadn't been for that gal.'

"I trust your dear mother will not think it coarse to have repeated these words. There is something in the very mention of swine that is repugnant to ears polite, but Martha was of the opinion that you would prefer to have the message in his own words. And I am bound to say that Galusha Pennypacker, though undoubtedly an eccentric, is a thoroughly well-intentioned person."

"Dear Cousin Wealthy!" said Hildegarde, as she folded the delicate sheet and put it back into its pearl-gray envelope with the silver seal. "It must have cost her an effort to repeat Mr. Pennypacker's words. Poor old man! I am glad he is comfortable. I must send him a little box at Christmas,—some little things to trim up his new house and prettify it. Oh! and now, Bell, now for your letter! I have kept it for the last, my dear, as if it[14] were raisins or chocolate, only it is better than either."

BELL'S LETTER

BELL'S LETTER

The fat square envelope that she now opened contained several sheets of paper, closely covered, every page filled from top to bottom with a small, firm handwriting, but no line of crossing. The Merryweathers were not allowed to cross their letters, under penalty of being condemned to write entirely on postal cards. Let us peep over Hildegarde's shoulder, and see what Bell has to say.

"It is two full weeks since I have written, and I am ashamed; but it is simply because they have been full weeks,—very full! There is so much to tell you, I hardly know where to begin. A week ago to-night our play came off,—'The Mouse Trap.' It went beautifully,—not a hitch anywhere, though we had only had five rehearsals. I was Willis, as I told you. I wore my ulster without the cape, and really looked quite masculine, I think. I had a curly, dark-brown wig (my hair tucked down my neck,—it didn't show at all!) and the prettiest little moustache! Marion Wilson was Amy, and she screamed most delightfully. In fact, they all screamed in such a natural and heartfelt way, that some of the ladies in the audience seemed to feel quite uncomfortable, and I am sure I saw Madame Mirabelle tuck her skirts close[15] around her feet, and put her feet up on the bench in front of her. Well, we all did our best, though Clarice Hammond was the best; she is a born actress! and the audience was very cordial, and we were called before the curtain five times; and altogether it was a great success. I enclose a flower from a bouquet that was thrown at me. It was a beauty, and it struck me right on the head. I thought it was for Clarice, and was going to hand it to her, but somebody in the audience cried out, 'Why don't you speak for yourself, Willis?' and everybody laughed, and they said it was really for me, so I kept it, and was pleased and proud. I have pressed two or three flowers in my blue-print book, with the pictures of the play. I am going to send you some as soon as I can print some more. The girls snatched all the first batch, so that I have not a single one left.

"Let me see! What comes next? Oh, next you must hear about my surprise party. I was in my room one evening, grinding hard at my Greek (do you think your mother would object to 'grinding?' It is such old, respectable college slang, mamma allows it once in a while), when I heard whispering and giggling in the hall outside. I don't mind telling you, my dear, that my heart sank, for I had a good lot of Pindar to do, and there is no sense in shirking one's lessons. But I went to the door with as good a grace as I could, and there was our dear Gerty, and Clara Lyndon, and three or four other girls from Miss Russell's school. They said they had double permission, from Miss Russell at that end, and Mrs. Tower at this, to come and give me a surprise party; and here they were, and they were coming in whether I liked it or not.[16] Of course I did like it after the first minute, for they were all so dear and jolly. They had borrowed chairs as they came along through the hall, and one had her pocket full of spoons, and another had a basket,—oh, but I am getting on too fast. Well, Gerty and I sat on the bed, and the others on the chairs, and we chattered away, and I heard all the school news. Then presently Mabel Norton opened a basket, and took out—oh, Hilda! the most beautiful, beautiful rose-bush, simply covered with blossoms. It was for me, with a card from Miss Russell and the whole school; and when I asked what it all meant, why, it seems that this was the anniversary of the day last year when I pulled a little girl out of the river, down near the mill-dam. It was the simplest thing in the world to do, for any one who was strong and knew how to tread water; but these dear people had remembered the date, and had done this lovely thing to—well, Hilda, I didn't cry that evening, but somehow I want to now, when I come to tell you about it. You will understand! It is so lovely to have such dear, kind friends, that I cannot help it. Well, then out of another basket came a most wonderful cream tart, with my initials on it in caramel, and a whole lot, dozens and dozens, of the little sponge-cakes that I am so fond of. They cannot make them anywhere in the world, I think, except at Miss Russell's, and dear good Miss Cary, the housekeeper, remembered that I was fond of them. Oh, and a huge box of marshmallows; and we all knew what that meant. Marshmallows are the—what shall I say?—the unofficial emblem of Miss Russell's school; and soon two or three were toasting over the gas on hat-pins, and I was cutting[17] the tart, and Gerty was handing round the sponge-cakes, and we were all as happy as possible. I ran and asked the girls along the hall to come in, and as many of them did come as could get in the door, and the rest sat in a semicircle on the floor in the hall, and we sang everything we could think of. All of a sudden we heard a knocking at the window. I ran and looked out, and there was something hanging and bobbing against the glass. I opened the window, and drew in a basket, full of all kinds of things, oranges and bananas and candy, with a card, 'Compliments of the Third Floor!' So of course I was running up to thank them, and say how sorry we were that there was not room for them, when I almost ran plump into Mrs. Tower, who was coming along the entry, very stately and superb. She had heard all about it, and she came to say that, if we liked, we might dance for half an hour in the parlour. You can imagine—no, you cannot, for you never were at college!—the wild rush down those stairs. We called the third floor (they are mostly freshmen), and they came careering down like a herd of ponies; and the first floor came out of their studies when they heard the music, and we had the wildest, merriest, most enchanting dance for just half an hour. Then it was hurry-scurry off, for Miss Russell's girls were on the very edge of their time allowance, and had to run most of the way home (it is only a very little way, and one of the maids had come with them, and waited for them). And we all thanked Mrs. Tower as prettily as we knew how, and she said pleasant things, and then some of the girls helped me to take back the chairs and straighten things up generally. So the great[18] frolic was over, and most delightful it was; but, my dear, I had to get up at five o'clock to finish my Greek next morning, and the ground floor was not much better off with its philosophy. And now there are no more gaieties, for the examinations are 'on,' and we must buckle to our work in good earnest. I don't expect to have much trouble, as I have kept up pretty well; but there is enough for any one to do, no matter how well up she is. So this is the last letter you will have, my dear, before the happy day that brings us all out to the beloved Pumpkin House. Oh, what a glorious time we shall have, all together once more! Roger is still out West, but hopes to get back for the last part of the holidays, at least; and Phil's and Jerry's vacation begins two days before Gerty's and mine. Altogether, the prospect is enchanting, and one of the very best parts of it is the seeing you again, dear Hilda. Only three weeks more! Gerty paints a star on her screen for every day that is gone. Funny little Gerty! Give my love to your mother, please, and believe me always, dear Hilda,

Hildegarde gave a half-sigh, as she finished this letter, and walked on in silence, thinking many things. Bell's life seemed very free and full and joyous; it suited her exactly, the strong, sensible, merry girl; and oh, how much she was learning! This letter said little about studies,[19] but Hildegarde knew from former ones how much faithful work was going on, and how firm a foundation of scholarship and thoroughness her friend was laying.

"Whereas I," she said aloud, "am as ignorant as a hedge-sparrow."

As she spoke, a sparrow hopped upon a twig close by her, and cocked his bright eye at her expressively.

"I beg your pardon!" said Hildegarde, humbly. "No doubt you are right, and I am a hundred times more ignorant. I could not even imagine how to build a nest; but neither can you crack a nut—ask Mr. Emerson!—or play the piano."

The sparrow chirped defiance, flirted his tail saucily, and was gone.

"And all girls cannot be students!" said Hildegarde, stopping to address a young maple that looked strong-minded. "Everybody cannot go to college; there must be some who are to be just girls,—plain girls,—and stay at home. As for a girl going to college when there is only herself to—to help make a home—why,—she[20] might as well be Nero, and done with it."

She nodded at the maple-tree, as if she had settled it entirely, and walked on more quickly; the cloud—it was a slight one, but still a cloud—vanished from her brow, leaving it clear and sunny.

"The place one is in," she said, "is the place to be happy in. Of course I do miss them all; of—course—I do! but if ever any girl ought to be thankful on her knees all day long for blessings and happinesses, Hildegarde Grahame, why, you know who she is, and that she does not spell her name Tompkins."

Christmas was coming. Christmas was only three weeks off. Oh, how the time was flying! "How shall I ever get ready?" cried Hildegarde, quickening her pace as she spoke, as if the holiday season were chasing her along the road.

"One is always busy, of course; but it does seem as if I were going to be about five times as busy as I ever was before. Naturally! there are so many more people that I want to make presents for. Last Christmas, there was Mammina, and Col. Ferrers and Hugh, and the box to send to Jack,—dear Jack!—and Auntie, and Mrs. Lankton and the children, and,—well, of course, Cousin Wealthy and Benny, and all the dear people at Bywood,—why, there were a good many, after all, weren't there? But now I have all my Merryweathers in addition, you[22] see. Of course I needn't give anything to the boys,—or to any of them, for that matter,—but I do want to, so very much; if only there were a little more time! I will go up this minute, if Mammina does not want me, and look over my drawer. I really haven't looked at it—thoroughly, that is—for three days! Hilda Grahame, what a goose you are!"

By this time she had arrived at Braeside, the pretty house where she and her mother passed their happy, quiet life. Running lightly up the steps, and into the house, the girl peeped into the sitting-room and parlour, and finding both empty, went on up the stairs. She paused to listen at her mother's door; there was no sound from within, and Hildegarde hoped that her mother was sleeping off the headache, which had made the morning heavy for her. Kissing her hand to the door, she went on to her own room, which always greeted her as a friend, no matter how many times a day she entered it. She looked round at books and pictures with a little sigh of contentment, and sank down for a moment in the low rocking-chair. "Just to[23] breathe, you know!" she said. "One must breathe to live." Involuntarily her hand moved towards the low table close by, on which lay a tempting pile of books. Just one chapter of "The Fortunes of Nigel," while she was getting her breath?

"No," she said, replying to herself with severity, "nothing of the kind. You can rest just as well while you are looking over the drawer. I am surprised,—or rather, I wish I were surprised at you, Hilda Grahame. You are a hard case!"

Exchanging a glance of mutual sympathy and understanding with Sir Walter Scott, who looked down on her benignly from the wall, Hildegarde now drew her chair up beside a tall chest of drawers, and proceeded to open the lowest drawer, which was as deep and wide as the whole of some modern bureaus. It was half filled with small objects, which she now took out one by one, looking them over carefully before laying them back. First came a small table-cover of heavy buff linen, beautifully embroidered with nasturtiums in the brilliant[24] natural colors. It was really a thing of beauty, and the girl looked at it first with natural pride, then went over it carefully, examining the workmanship of each bud and blossom.

"It will pass muster!" she said, finally. "It is well done, if I do say it; the Beloved Perfecter will be satisfied, I think."

This was for her mother, of course; and she laid it back, rolled smoothly round a pasteboard tube, and covered with white tissue paper, before she went on to another article. Next came a shawl, like an elaborate collection of snowflakes that had flitted together, yet kept their exquisite shapes of star and wheel and triangle. Cousin Wealthy would be pleased with this! Hildegarde felt the same pleasant assurance of success. "There ought to be a bit of pearl-coloured satin ribbon somewhere! Oh, here it is! A bit of ribbon gives a finish that nothing else can. There! now that is ready, and that makes two. Now, Benny, my blessed lamb, where are you?"

She drew out a truly splendid scrap-book, bound in heavy cardboard, and marked "Benny's[25] Book," with many flourishes and curlicues. Within were pictures of every imaginable kind, the coloured ones on white, the black and white on scarlet cardboard. Under every picture was a legend in Hildegarde's hand, in prose or verse. For example, under a fine portrait of an imposing black cat was written:

Hildegarde had spent many loving hours over this book; her verses were not remarkable, but Benny would like them none the less for that, she thought, and she laid the book back with a contented mind. Then there was a noble apron for Martha, with more pockets than any one else in the world could use; and a pincushion for Mrs. Brett, and a carved tobacco-stopper for Jeremiah. Beside the tobacco-stopper lay a pipe, also carved neatly, and Hildegarde took this up with a sigh. "I don't like to part[26] with it!" she said. "Papa brought it from Berne, all those years ago, and I am so used to it; but after all, I am not likely to smoke a pipe, even if I have succumbed to the bicycle, and I do want to send some little thing to dear Mr. Hartley. Dear old soul! how I should like to see him and Marm Lucy! We really must make a pilgrimage to Hartley's Glen next summer, if it is a possible thing. Marm Lucy will like this little blue jug, I know. We have the same taste in blue jugs, and she will not care a bit about its only costing fifteen cents. Ah! if everything one wanted to buy cost fifteen cents, one would not be so distracted; but I do want to get 'Robin Hood' for Hugh, and where am I to get the three dollars, I ask you?"

She addressed William the Silent; the hero drew her attention, in his quiet way, to his own sober dress and simple ruff, and seemed to think that Hugh would be just as well off without the record of a ruffling knave who wore Lincoln green, and was not particular how he came by it.[27]

"Ah! but that is all you know, dear sir!" said Hildegarde. "We all have our limitations, and if you had only known Robin, you would see how right I am."

And then Hildegarde fell a-dreaming, and imagined a tea-party that she might give, to which should come William of Orange and Robin Hood, Alan Breck Stuart and Jim Hawkins.

"And who else? let me see! Hugh, of course, and Jack, if he were here, and the boys and—and Captain Roger; only I am afraid he would think it nonsense. But Bell would love it, and I would invite Dundee, just to show her how wrong she is about him. And—oh, none of the King Arthur knights, because they had no sense of humour, and Alan would be at their throats in five minutes; but—why, I have left out David Balfour himself,—Roger would love David, anyhow,—and Robin might bring Little John and Will Scarlet and Allan-a-Dale. We would have tea out on the veranda, of course, and Auntie would make one of her wonderful chicken pies, and[28] I would ask Robin whether it was not just as good as a venison pasty. Alan would have his hand at his sword, ready to leap up if it was denied; but jolly Robin would make me a courtly bow, and say with his own merry smile—Come in! oh! what is it?"

Rudely awakened from her pleasant dream by a knock at the door, Hildegarde looked up, half expecting to see one of her heroes standing cap in hand before her. Instead, there stood, ducking and sidling,—the Widow Lankton.

"How do you do, Mrs. Lankton?" said Hildegarde, with an effort. It was a sudden change, indeed, from Robin Hood and Alan Breck, to this forlorn little body, with her dingy black dress and crumpled bonnet; but Hildegarde tried to "look pleasant," and waited patiently for the outpouring that she knew she must expect.

"Good-mornin', dear!" said the widow, ducking a little further to one side, so that she looked like an apologetic crab in mourning for his claws. "I hope your health is good,[29] Miss Grahame. There! you look pretty well, I must say!"

"I hope you are not sorry, Mrs. Lankton," smiling; for the tone was that of heartfelt sorrow.

"No, dear! why, no, certainly not! I'm pleased enough to have you look young and bloomin' while you can. Looks ain't allers what we'd oughter go by, but we must take 'em and be thankful for so much, as I allers say. Yes, dear. Your blessed mother's lyin' down, Mis' Auntie told me. She seems slim now, don't she? If I was in your place, I should be dretful anxious about her, alone in the world as you'd be if she was took. The Lord's ways is—"

"Did you want to see me about anything special, Mrs. Lankton?" said Hildegarde, interrupting. She felt that she was not called upon to bear this kind of thing.

The widow sniffed sadly and shook her head.

"Yes, dear! You're quick and light, ain't you, as young folks be! Like to brisk up and have done with a thing. Well, I come to see[30] if I could borry a crape bunnit, to go to a funeral; there, Miss Grahame, I hope you won't think me forth-puttin', but I felt that anything your blessed ma had worn would be a privilege, I'm sure, and so regardin' it, I come."

"Oh!" said Hildegarde, with a little shudder. "We—we have no crape, Mrs. Lankton. My father—that is, my mother never wore it."

"Didn't!" said Mrs. Lankton. "Well, now, folks has their views. I was one that never liked to spare where feelin's was concerned. Ah! I've wore crape enough in my time to bury me under, you might say. When my poor husband died, I got a veil measured three yards, countin' the hem; good crape it was, too. There! I took and showed it to him the day before he was took. He'd been failin' up quite a spell, and I was never one to hide their end from them that was comin' to it. 'There, Peleg!' says I. 'I want you should know that I sha'n't slight nothin' when you're gone,' I says. 'I'll keep you as long as I can,' I says, 'and I'll have everything right[31] and fittin' as far as my means goes,' I says. He was real gratified. I was glad to please him, goin' so soon as he was.

"He turned up his toes less than twenty-four hours after I said them words; died off real nice. His moniment is handsome, if I do say it. I have it scrubbed every spring, come house-cleanin' time, and it looks as good as new. Yes, dear! I've got a great deal to be thankful for, if I have suffered more than most."

Hildegarde set her teeth. Inwardly she was saying, "You dreadful old ghoul! When will you stop your grisly recollections, and go away?" But all she said aloud was, "Well, Mrs. Lankton, I am sorry that we cannot help you. Perhaps one of the neighbours,—but I ought to ask,—I trust it is no near relative that is dead?"

"No, dear!" replied the widow, with unction. "No relation, only by marriage. My sister's husband married this man's sister for his third wife; old man Topliffe it is, keeps the grocery over t' the Corners."

"Why, I did not know he was dead!" said Hildegarde.[32]

"Not yet he ain't, dear!" said Mrs. Lankton. "But he's doomed to die, and the doctors don't give him more than a few hours. I'm one that likes to be beforehand in such matters,—there's them that looks to me to do what's right and proper,—and I shouldn't want to be found without a bunnit provided. Well, dear, I must be goin'. Ah! 'twill seem nat'ral to be goin' to a funeral again, Miss Grahame. I ain't b'en to one for as much as five months. I've seen the time when three funerals a week was no uncommon thing round these parts, and most all of 'em kin to me by blood or marriage. Yes, no one knows what I've b'en through. You're gettin' fleshy, ain't you, dear? I hope the Lord'll spare you and your ma,—she's like a mother to me, I allers say,—through my time. It ain't likely to be long, with these spells that ketches me. Good-by, dear!"

With a tender smile, and another sidelong duck, the widow took herself off; and Hildegarde drew a long breath, and felt like opening all the windows, to let the sunshine come in more freely. The door of her room being still open,[33] she became aware of sounds from below; sounds as of clashing metal, and rattling crockery.

What could Auntie be about? she would wake Mamma at this rate.

Running down-stairs, Hildegarde went into the kitchen, and was confronted by the sight of Auntie, perched on top of a tall step-ladder, with the upper part of her portly person buried in the depths of a cupboard.

"Auntie, what are you about?" she cried. "Do you know what a noise you are making? Mamma is asleep, and I don't want her to wake till tea-time, for her head has ached all day."

Auntie did not seem to hear at first, but continued to rattle tins in an alarming way; till Hildegarde, in despair, grasped the step-ladder, and shook it with some force. Then the good woman drew her head out of the depths, and looked down in astonishment.

"Why, for goodness sake, honey, is dat you?" she said. "I t'ought 'twas dat old image cacklin' at me still. She gone, is she? well, dat's mercy enough for one day!"[34]

She sat down on the top of the ladder and panted; and Hildegarde burst out laughing.

"Auntie, did you go up there to get rid of Mrs. Lankton?"

"For shore I did, chile! I'd ha' riz through de roof if I could, but dis was as fur as I could git. She was in hyar an hour, 'most, 'fore she went up-stairs,—and I told her not go near you, but she snoke up, and I dassn't holler, fear ob waking yer ma,—and my head is loose on my shoulders now, listenin' to her clack. So when I hear her comin' down again, I jest put up de ladder here, and I didn't hear no word she said. Did she hab de imp'dence to ask you lend her a crape bunnit?"

"Yes; that is what she came for. We had none, of course."

Auntie snorted. "None ob her business whedder you had none or a hunderd!" she said. "I tole her if she ask you dat, I'd pull her own bunnit off'n her next time she come; and I will so!"

"Oh, no, you won't, Auntie!" said Hildegarde.

"Well, now, you'll see. Miss Hildy chile![35] I had 'nuff ob dat woman. Ole barn-cat, comin' snoopin' round here to see what she can git out'n you and yer ma, 'cause she sees yer like two chillen. What yer want for supper, honey, waffles, or corn-pone?"

"Waffles," said Hildegarde, with decision. "But—Auntie, what have you there? No, not the pitcher; those little tin things that you just laid down. I want to see them, please."

"I been rummagin' dis shelf," said Auntie. "I put a lot ob odd concerns up here,—foun' em in de place when we come,—and dey ain't no good, and I want de room. Dose? Dem's little moulds, I reckon. Well, now, I don't seem as if I noticed dem before. Kin' o' pretty, ain't dey, honey?"

She handed down a set of tin moulds, of fairy size and quaint, pretty shapes. Tulips, lilies, crocuses,—"Why, it is a tin flower-bed!" cried Hildegarde. "Why did you never show me these before, Auntie?"

But Auntie was not conscious of having noticed them before. She had cleaned them,—of course,—but her mind must have been[36] on her cooking, and she did not remember them.

"And what could one do with them?" Hildegarde went on. "Oh, see! here is a scrap of parchment fastened to the ring of one of them. 'The moulds for the almond cakes. The receipt is in the manuscript book with yellow covers.' Why, how interesting this is! Almond cakes! It sounds delightful! Do you remember where I put that queer old book, Auntie? You thought the receipts so extravagant that I have not used it at all. Oh! here it is, in your table-drawer. I might have been sure that you would know exactly where it was. Now let us see. This may be a special providence, Auntie."

"I don't unnerstand what you talkin' 'bout, chile," said Auntie, good-naturedly. "I made you almond cake last week, and I guess dat was good 'nuff, 'thout lookin' in de grandmother books. But you can see,—mebbe you find somethin' different."

Hildegarde was already deep in the old manuscript book. Its leaves were yellow with age, the ink faded, but the receipts were perfectly[37] legible, many of the later ones being in Miss Barbara Aytoun's fine, crabbed, yet plain hand.

"'Bubble and Squeak!' Auntie, I wish you would give us Bubble and Squeak for dinner some day. You are to make it of cold beef, and then at the end of the receipt she tells you that pork is much better.—'China Chilo! Mince a pint basin of undressed neck of mutton'—How is one to mince a basin, do you suppose? I should have to drop it from the roof of the house, and then it would not be fine enough.—'Serve it fried of a beautiful colour'—no! that's not it!—'Pigs' feet. Wash your feet thoroughly, and boil, or rather stew them gently'—Miss Barbara, I am surprised at you!—'Ramakins'—those might be good. 'Excellent Negus'—ah! here we are! 'Almond cakes!' H'm! 'Beat a pound of almonds fine'—and a pleasant thing it is to do—'with rose water—half a pound of sifted sugar—beat with a spoon'—ah, this is the part I was looking for, Auntie! 'Bake them in the flower-moulds, watching carefully; when a beautiful[38] light gold colour, take them out, and fill when cold with cream into which is beat shredded peaches or apricots.' O—oh! doesn't that sound good, Auntie?"

"Good 'nuff," Auntie assented, nodding her turbaned head. "Good deal of bodder to make, 'pears to me, Miss Hildy. I'm gittin' old for de fancy cakes, 'pears like."

"Oh, you dear soul! I don't want you to make them," cried Hildegarde. "I want to make them myself. Now, Auntie, I am going to be very confidential."

Auntie's dark face glowed with pleasure. She loved a little confidence.

"You see," Hildegarde went on, "I want some money. Not that I don't have enough for everything; but I want to earn a little myself, so that I can make all the Christmas presents I want, without feeling that I am taking it out of the family purse. You understand, I am sure, Auntie!" and Auntie, who had held Hildegarde in her arms when she was a baby, nodded her head, and understood very well.[39]

"So I thought that possibly I might make something to send to the Woman's Exchange in New York. I saw in a magazine the other day that the ladies who give a great many lunches are always wishing to find new little prettinesses for their tables. I saw something of that myself, when I was there this fall." But Hildegarde checked herself, feeling that she was getting rather beyond Auntie's depth.

"And I had been wondering what I could make, this very afternoon, and thinking of one thing and another; and when I saw these pretty little moulds, it seemed the very thing I had been looking for. What do you think, Auntie?"

"T'ink? I t'ink dem Noo York ladies better be t'ankful to git anything you make for 'em, Miss Hildy; dat's my 'pinion! And I'll help ye make de cake, and fuss round a little wid de creams, too, if you let me."

But Hildegarde declared she would not let her have any hand whatever in the making of the almond cakes, and ran off, hearing her mother's voice calling her from up-stairs.

"My dear suz!" said the black woman, gazing[40] after her. "T'ink ob my little baby missy growed into dat capable young lady, wat make anything she touch her finger to. Ain't her match in Noo York, tell yer; no, nor Virginny, nudder!"

"And you really think I would better stay several days, Mammina? I don't like to leave you alone. Some one might come and carry you off! How should I feel if I came back next week, and found you gone?" Hildegarde looked down at her mother, as she sat in her low chair by the fire; she spoke playfully, but with an undertone of wistfulness. Mrs. Grahame had grown rather shadowy in the last year; she looked small and pale beside Hildegarde's slender but robust figure; and the girl's eyes dwelt on her with a certain anxiety. But nothing could be brighter or more cheerful than Mrs. Grahame's smile, nor could a voice ring more merrily than hers did as she responded to Hildegarde's tone, rather than her words.

"There have been rumours of a griffin lurking in the neighbourhood. He is said to have a[42] particular fancy for old—there, there, Hilda! don't kill me!—well, for middle-aged ladies, and his preference is for the small and bony. I feel that I am in imminent peril; but still, under all the circumstances, I prefer to abide my fate; and I think you would decidedly better spend two or three days at least with your Aunt Emily. She has never invited you before, and her note sounds pretty forlorn, poor old lady! Besides, if you really want to do something at the Exchange, you could hardly manage it in one day. So you shall pack the small trunk, and take an evening gown, and make a little combination trip, missionary work and money-making."

"And what will you do?" asked Hildegarde, still a little wistfully.

"Clean your room!" replied her mother, promptly.

"Mamma! as if I would let you do that while I was away!"

"Kindly indicate how you would prevent it while you were away, my dear! But indeed, I don't mean a revolutionary, spring cleaning;[43] I just want to have the curtains washed, and the paint touched up a little; I saw several places where it was getting shabby. Indeed, Hilda, I think the trip to New York is rather a special providence, do you know?"

"Humph!" said Hildegarde, looking suspiciously at her parent. "And while I am gone, it might be a good plan to take up the matting, and re-cover some of the chairs, and have the sofa done over, you think?"

"Exactly!" said Mrs. Grahame, falling innocently into the trap. Whereupon she was pounced on, shaken gently, embraced severely, and forbidden positively to attempt anything of the kind. Finally a compromise was effected, allowing the washing of the curtains, but leaving the details of painting, etc., till Hildegarde's return; and the rest of the evening was spent in the ever-pleasant and congenial task of making out a list.

"You cannot be expected to make visits, of course, dear, in so short a stay; but there are one or two people you ought to see if possible," said Mrs. Grahame.[44]

Hildegarde looked up apprehensively from her jottings of towels, gloves, and ribbons to be bought. Her mother's ideas of family duty were largely developed.

"Aunt Emily will expect you to call on Cousin Amelia, and no doubt the girls will come to see you. Your Aunt Anna is in Washington."

"For what we are about to escape—" murmured the daughter.

"Hildegarde, I wonder at you!"

"Yes, dear mamma! what else were you going to say?"

Mrs. Grahame tried to look severe for a moment, did not succeed, and put the subject by.

"Then there is old Madam Burlington; she would take it as a kindness if you went to see her; you need not stay more than a quarter of an hour. A Cranford call is all that is necessary, but do try to find an hour to go and sit with poor Cousin Harriet Wither; it cheers her so to see some young life. Poor Harriet! she is a sad wreck! You will probably dine at[45] your Cousin Robert Grahame's, and if Aunt Emily wishes you to call on any of the Delansings—"

"Were you expecting me to stay away over Christmas?" inquired Hildegarde, calmly.

"Why, darling, surely not! what do you mean?"

"Only that you seem to have started on a month's programme, my love, that's all. Don't look so, angel! I will go to see all of them; I will spend a month with each in turn; only don't look troubled!"

By and by everything was settled as well as might be. Mother and daughter went to sleep with peaceful hearts, and the next day Hildegarde departed for New York, determined to make as short a visit as she could in propriety to Aunt Emily Delansing.

Of her reception by that lady she herself shall tell:

"As usual, you were quite right, and I am glad I came. Hobson was at the station, and brought me up here in a hansom, and Aunt Emily was in the drawing-room to receive[46] me. She is very kind, and seems glad to have me here. I have not done much yet, naturally, as I have not been here two hours yet. I could not let the six o'clock mail go without sending you a line, just to say that I am safe and well. Very well indeed, dearest, and no more homesick than is natural, and loving you more than you can possibly imagine. But oh, the streets are so noisy, and there are no birds, and—no, I will not! I will be good. Good-bye , dearest and best! Always your very ownest,

Hilda sealed and addressed her letter, and then rang the bell. A grave footman in plum-coloured livery appeared, received the letter as if it were an official document of terrible import, and departed. Then, when the door was closed and she was alone again, Hildegarde leaned back in her chair and gave herself up to reverie. Her eyes wandered over the room in which she was sitting,—a typical city room, large and lofty, with everything proper in the way of furnishing. "Everything proper, and nothing interesting!" said Hildegarde, aloud. The oak furniture was like all other oak furniture; the draperies were irreproachable, but without character; the pictures were costly, and that was all.[47]

Rather wearily Hildegarde rose and began the somewhat elaborate toilet which was necessary to please the taste of the aunt with whom she had come to stay. Mrs. Delansing was her father's aunt. Since Mr. Grahame's death, his widow and child had seen little of her. She considered their conduct, in moving to the country, reprehensible in the extreme, and signified to Mrs. Grahame that she could never regard her as a sane woman again. Mrs. Grahame had borne this affliction as bravely as she might, and possibly, in the quietly happy years that followed the move, she and her daughter did not give much thought to Aunt Emily or her wrath. She was well, and did not need them, and they were able to get on very tolerably by themselves. Now, however, things had happened. Mrs. Delansing was much out of health; her own daughters were settled in distant homes, and could not leave their own families to be with her; she felt her friends dropping away year by year, and loneliness coming upon her. For the first time in years, Emily Delansing felt the need of some new face,[48] some new voice, to keep her from her own thoughts. Accordingly she had written to Mrs. Grahame a note which meant to be stately, and was really piteous, holding out the olive-branch, and intimating that she should be glad to have a visit from Hildegarde, unless her mother thought it necessary to keep the girl buried for her whole life.

In replying, Mrs. Grahame did not think it necessary to reply to the last remark, nor to remind Mrs. Delansing that Hildegarde had spent a month in New York the winter before, with an aunt on the Bond side, who was not in the Delansing set. She said simply that Hildegarde would be very glad to spend a few days in Gramercy Park, and that she might be expected on the day set. And, accordingly, here Hildegarde was. She had fully agreed with her mother that it was her duty to come, if Aunt Emily really needed her; but she confessed to private doubts as to the reality of the need. "And you do want me, Mrs. Grahame, deny it if you dare!" she said.

"Heigh ho!" said Hildegarde again, looking[49] about her for something to talk to, as was her way. "Well, so I packed my trunk, and I came away, and here I am." She addressed a small china sailor, who was sitting on a pink barrel that contained matches.

"And if you think I like it so far, my friend, why, you have less intelligence than your looks would indicate. What dress would you put on, if you were I? I think your pink-striped shirt would be extremely becoming to me, but I don't want to be grasping. You advise the brown velveteen? I approve of your taste!"

Hildegarde nodded to the sailor, feeling that she had made a friend; and proceeded to array herself in the brown velveteen gown. It was a pretty gown, made half-low, with full elbow-sleeves, and heavy old lace in the neck. When Hildegarde had clasped the gold beads round her slender neck, she felt that she was well dressed, and sat down with a quiet conscience to read "Montcalm and Wolfe" till dinner-time. Presently came a soft knock at the door, and the announcement that dinner was[50] served; and Hildegarde laid aside her book and went down to the drawing-room.

"MRS. DELANSING SCRUTINISED HER AS SHE CAME THROUGH THE LONG ROOM."

"MRS. DELANSING SCRUTINISED HER AS SHE CAME THROUGH THE LONG ROOM."

Mrs. Delansing, seated in her straight, high-backed armchair, was on the watch for her grandniece, and scrutinised her as she came through the long room. Then she nodded, and, rising, laid her hand on the arm that Hildegarde offered her.

"Who taught you to enter a room?" she asked, abruptly. "You have been taught, I perceive."

"My mother," said Hildegarde, quietly.

"Humph!" said Mrs. Delansing. "In my time, one of the most important accomplishments was to enter a room properly. Nowadays I see young women skip, and shuffle, and amble into the drawing-room; I do not often see one enter it properly. You will, perhaps, tell your mother that I have mentioned this; she may be gratified."

Hildegarde bowed in silence, and as they came into the dining-room, took the place to which her aunt motioned her, at the foot of the table. It was a long table, and Hildegarde could only[51] see the bows of Mrs. Delansing's cap over the stately epergne that rose between them; but she was conscious of the old lady's sharp black eyes watching her through the ferns and roses. This awoke a rebellious spirit in our young friend, and she found herself wondering what would be the effect of her putting her knife in her mouth, or drinking out of the finger-bowl. The dinner seemed interminable. It is not easy to talk to some one whom you cannot see; but Hildegarde replied as well as she could to the occasional searching questions that were darted at her like spear-points through the ferns, preserved her composure, and was not too unhappy to enjoy the good food set before her.

It was a relief to go back to the drawing-room, which seemed a shade less formal than the one they left; also, she found a comfortable chair, and received permission to take out her embroidery.

"Where did you get that lace?" asked Mrs. Delansing, suddenly, after a silence during which Hildegarde had thought her asleep, till, on looking[52] up, she met the steady gaze of the black eyes, still fixed on her.

"It is extremely valuable lace; are you aware of it?" The tone was reproachful, but Hildegarde preserved a quiet mind.

"Yes, I know it is valuable!" she said. "Old Mr. Aytoun left all his personal property to Mamma, you know, Aunt Emily; there was a great deal of lace, some of it very fine indeed; this is a small piece that went with some broad flounces. Beautiful flounces they are!"

Mrs. Delansing's eyes lightened, and her fingers moved nervously. Lace was one of her few passions, and she could not see it, or even hear of it, unmoved.

"And what does your mother propose to do with all this lace?" she asked. "She cannot wear it herself, in the wilderness that she chooses to live in."

"Oh, she keeps it!" said Hildegarde. "It is delightful to have good lace, don't you think so? even if you don't wear it. And when either of us wants a bit to put on a gown,—like this, for example,—why, there it is, all ready."[53]

"It seems wanton; it seems almost criminal," said Mrs. Delansing, with energy, "to keep valuable lace shut up in a mouldering country-house. I—it distresses me to think of it. I shall feel it a point of duty to write to your mother."

Hildegarde wondered what her aunt would feel it her duty to say. It was hardly her mother's fault that the lace had been left to her; it seemed even doubtful whether she should be expected to mould her life upon the lines of lace; but this seemed an unsafe point to suggest.

"That is very beautiful lace on your dress, Aunt Emily!" said this wily young woman.

Mrs. Delansing's brow smoothed, and she looked down with a shade of complacency. "Yes, this is good," she said. "This is very good. Your grandfather,—I should say your great-uncle, bought this lace for me in Brussels. It is peculiarly fine, you may perceive. The young woman who made it lost her eyesight in consequence."

"Oh, how dreadful!" cried Hildegarde. "How could you—" "How could you bear to wear it?" was what she was going to say,[54] but she checked herself, and the old lady went on, placidly.

"Your great-uncle paid something more than the price asked on that account. He thought something more was due; he was a man of great benevolence. This is point lace."

"Yes," said Hildegarde, "Point d'Alençon; I never saw a more delicate piece."

"Ah! you know point lace!" said Mrs. Delansing. Her voice took on a new tone, and she looked at the girl with more friendly eyes. "I did not know that any young women of the new generation understood point. These matters seem to be thought of little consequence nowadays. I have myself spent months in the study of a special point, and felt myself well repaid."

She put some searching questions, relative to the qualities of Spanish, Venice, and Rose point, and nodded her head at each modest but intelligent answer. Hildegarde blessed her mother and Cousin Wealthy, who had expounded to her the mysteries of lace. At the end of the catechism, the old lady sighed and shook her head.[55]

"It is an exceptional thing," she said, "to find any knowledge of laces in the younger generations. I instructed my own daughters most carefully in this branch of a gentlewoman's education, but they have not thought proper to extend the instruction to their own children. I—a shocking thing happened to me last year!" She paused, and Hildegarde looked up in sympathy.

"What was it, Aunt Emily?" she asked.

Mrs. Delansing was still silent, lost in distressful reverie. At length, "It is painful to dwell upon," she said, "and yet these things are a warning, and it is, perhaps, a duty to communicate them. You have met my granddaughters, your cousins, Violette and Blanche?"

"Oh, yes!" said Hildegarde, smiling a little, and colouring a little too. These cousins were rather apt to attempt the city-cousin rôle, and to treat her as a country cousin and poor relation. She did not think they had had the best of it at their last meeting. "Yes, I know them," she said, simply.

"They are girls of lively disposition," Mrs.[56] Delansing continued. "Their mother—your Cousin Amelia—has been something of an invalid,—I make allowance for all this, and yet there are things—" She broke off; then, after a moment, went on again. "Violette made me a visit last winter, here, in this house. She was engaged in what she called fancy work, for a bazaar (most objectionable things to my mind), that was to be held in the neighbourhood. One day she came to Hobson—I was unwell at the time—and said,—Hobson remembers her very words:

"'Oh, Hobson, see what a lovely thing I have made out of a bit of old rubbishy lace that was in this bureau drawer.'

"Hobson looked, and turned pale to her soul, as she expressed it in her homely way. She recognised the pattern of the lace.

"'I cut out the flowers,' said the unhappy girl, 'and applied them'—she said 'appliquéd' them, a term which I cannot reproduce—'applied them to this crimson satin ribbon; it will make a lovely picture-frame; so unique!'

"She had—she had taken a piece of my old[57] Mechlin, which Hobson had just done up and had laid in the drawer till I should feel strong enough to examine and approve its appearance,—she had taken this and cut it to pieces, cut out the flowers, to sew them— There are things that have to be lived through, my dear. It was weeks before Hobson felt able to tell me what had occurred. I was in danger of a relapse for several weeks, though she did it as delicately as possible,—good Hobson. I did not trust myself to speak to Violette in person; I sent for her mother, and told her of the occurrence. She—she—laughed!"

There was silence for some minutes. Hildegarde wanted to show the sympathy that she truly felt, for she liked lace, and the idea of its stupid destruction filled her with indignation. She ventured to lay her hand timidly on the old lady's arm, but Mrs. Delansing took no notice of the caress; she sat bolt upright, gazing out of the window with stony eyes. Presently she said:

"You may ring for Hobson, if you please. I feel somewhat shaken, and will have my[58] malted milk in my own room. Another evening, I may ask your patience in a game of backgammon,—you have been taught to play backgammon? Yes; but not to-night. You will find books in the library, and the piano does not disturb me. Good-night, my niece."

She shook hands with Hildegarde, and departed on Hobson's arm, looking old and feeble, though holding herself studiously erect. Hildegarde went to her room, feeling half sad, half amused, and wholly homesick. She greeted the china sailor with effusion, as if he were a friend of years. "Oh, you dear fellow!" she said. "You are young, aren't you? and happy, aren't you? Well, mind you stay so, do you hear?" She nodded vehemently at him, and took up her book, to read till bedtime.

There was no family breakfast at the house in Gramercy Park. A smiling chambermaid brought up a tray to Hildegarde's room, with all manner of pleasant things under suggestive little covers. Hilda ate and was thankful, and then, finding that her aunt would not be visible before noon, she put on her hat and went for a walk. The streets were chilly, in the November morning, but the air was fresh and good, and Hildegarde breathed it in joyously.

This was just a walk, she said to herself. She had many visits to make, of course, and more or less shopping to do, but there was time enough for all that. Now she would walk, and get her bearings, and consider that one might live well in a city. The brick[60] sidewalks seemed at once strange and familiar; she had known the brown-stone streets all her life. Once they had seemed her own, the only place worth walking in; now they were a poor apology, indeed, for shady lanes and broad sunny roads along which the feet trod or the wheel spun, winged by "the joy of mere living." She passed the house where her childhood had been spent, and paused to look up at the tall windows, in loving thought of the dear father who had made that early home so bright and full of cheer. Dear Father! There was his smoking-room window, where he used to sit and read aloud to her, so many happy hours. How he would dislike those heavy brocade curtains; he used to thunder, almost as loud as Colonel Ferrers, about curtains that kept out the blessed sunshine. How—the house was a corner one, and at this moment, as Hildegarde stood gazing up at the windows, a gentleman turned the corner, and ran plump into her.

"Upon my soul," said the gentleman, with great violence, "it is a most extraordinary[61] thing that a human being should turn himself into a post for the express purpose of—I beg your pardon, madam. I was not conscious that I was addressing a lady! Can I serve you in any way? Command me, I beg of you!"

The moment Hildegarde caught the sound of the gentleman's voice, she turned her head away, so that he could not see her face; and now she spoke over her shoulder.

"A place in thy memory, dearest—sir, is all that I ask at thy hands. It is hard to be forgotten so soon, so utterly!"

"What! what! what! what!" said the Colonel. "Who! who! why—why the mischief will you not turn your head round, young woman? There is only one young woman in the world who would address me in this manner, and she is a hundred miles away. Now, in the name of all that is elfish, Hildegarde Grahame, what are you doing here?"

Hildegarde turned round, her eyes full of happy laughter, and took her friend's arm.

"And in the name of all that is occult, and necromantic, and Rosicrucian, Colonel Ferrers,[62] what are you doing here?" she asked. "I thought you were in Washington."

"I was, till last night!" the Colonel replied. "We have seen all the sights, the boy and I, and now we have come to see the sights here on our way home. Well! well! and the first sight I see is the best one for sair een that I know. What a pity I left the boy at the hotel! He was still asleep. We arrived late last night. I went to wake him, and I give you my word, I could as soon have thought of waking an angel from a dream of paradise; the little fellow smiled, you understand, Hildegarde, and—and moved his little arms, and—I came away, sir,—my dear, I should say,—and left him to sleep as long as he would. Where are you going now, my child? have you had breakfast? if not,—"

"Oh, yes, I have had breakfast, dear sir!" said Hildegarde. "And you were thinking, if I had had it, how pleasant for me to go in and surprise that blessed lamb in his crib; now, weren't you?"

"The point, as usual!" cried the Colonel.[63] "Country neighbours learn to know each others' thoughts, they say, but I never believed it, till I had neighbours. Well, shall we go? Now, upon my soul, this is the most surprising and delightful thing that has happened to me for forty years. But you have not told me where you are staying, Hilda, nor why you are here, nor in fact anything; have simply wormed information out of the confiding friend, and remained silent yourself!" and the Colonel looked injured, and twirled his moustaches with mock ferocity.

"I like that!" said Hildegarde. "That really pleases me! Kindly indicate, dear sir, the moment at which I could have got in a word edgewise, since you began your highly interesting remarks! I have been simply panting with eagerness to tell you that I left home yesterday, and arrived in New York at five o'clock in the afternoon; that I am staying with my great-aunt in Gramercy Park; that I am wofully homesick, and that the sound of your voice was the most ecstatic sound I have heard for half a century."[64]

"Ha!" said the Colonel. "Humph! mockery, I perceive! of the aged, too! Very well, Miss Grahame, your punishment will be decided hereafter. Meanwhile, here we are at my hotel, and we will go straight up and wake the boy,—if he seems to be ready to wake, my dear. I am sure you will agree with me that it would be a pity to rouse him from a sound sleep. 'Sleep, that knits up the ravelled sleeve of care,' you remember, Hildegarde!"

"Yes, dear Colonel Ferrers!" said Hildegarde. "But I don't believe Hugh's sleeve is very deeply ravelled, do you? and indeed, it is high time for him to be awake."

They turned in at a great white marble portal, and the elevator soon brought them to the Colonel's door. He opened it softly with a latch-key, and led the way into the apartment; then paused, and beckoned Hilda to come in quietly.

"Listen!" he whispered. "Hugh is awake!"

They listened, and heard a clear, sweet voice discoursing calmly:

"I have three pillows to my head, though I[65] am not ill. I wish that other boy was here, that was in bed, and made songs about himself, and said it was the Land of Counterpane. He was the Giant great and still, that sits upon the pillow-hill, and I am that kind of giant too. Now I play he is here, and he sits up against that pillow, and I sit up against this. And I say, 'How can you say all the things that come in your mind? I can have the things in my mind, too, but they will not have rhyme-tails to them. How do you make the rhyme-tails?'

"And then he says,—I call him Louis, for that is the prettiest part of his name,—Louis says, 'It has to be a part of you. I think of things in short lines, and after every line I look for the rhyme-tail, and I see it hanging somewhere. But perhaps your Colonel can help you about that,' Louis says.

"But I say, 'No! my Colonel cannot help me about that. My Colonel is good, and I love him with love that grows like a tree, but he cannot make rhymes. Now, if my Beloved were here, she might be able to help me; but she is far away, and the high walls shut her out from me.[66] The walls are very high here, Louis, and my Colonel has gone away now, and I don't know how soon he will come back; so don't you leave me, Louis, for I am alone in a sandy waste, and there are no quails. But manna would be nasty, I think.'"

At this point the listeners could bear no more. Hilda ran into the room, and had Hugh in her arms, and was laughing and crying and cooing over him all at once. The Colonel followed, very red in the face, blowing his nose and clearing his throat portentously.

"Why, darling," Hilda was saying between the kisses, "darling Boy, did you want me? and did you think your Colonel would leave you for more than a few little minutes? Of course he would not! And where do you suppose I came from, Boy, when I heard you say you wanted me? Do you think I came down the chimney?"

Hugh gravely inspected her spotless attire; the blue serge showed no wrinkle, no speck of dust.

"I should say not the chimney!" he announced, "But from some strange where you[67] must have come, Beloved, if it was a place where you heard me talking when I was not there. Was it the up-stairs of the Land of Counterpane?" he added, his eyes lighting up with their whimsical look. "Was it the Counterpane Garret? Then it must have been over the top of the bed that you came from, and you seemed to come in at the door. Did Louis tell you to come?"

"Louis?" said the Colonel. "What does the boy mean? Stuff and nonsense! I met your Beloved in the street, ran into her, and thought she was a post; and then I brought her along, and here she is; and what do you think about breakfast, Young Sir?"

Young Sir thought very well of breakfast, but he could not think of eating it without his two friends looking on; so Hildegarde waited in the parlour, chatting merrily with the Colonel till Young Sir's toilet was completed, and then breakfast was brought, and Hugh ate, and the others watched him; and Hildegarde found that she was quite hungry enough to eat Black Hamburg grapes, even if it was only two[68] hours since breakfast, and altogether they were very merry.

"And what shall we do now?" asked the Colonel, when the pleasant meal was over. "The Metropolitan, eh? The boy must see pictures, Hilda, hey? 'The eye that ne'er on beauty dwells,' h'm! ha! folderol! I forget the rest, but the principle remains the same. Never seen any pictures except those at home, and the few in Washington. Chiefly rubbish there, I observe. What do you say, Miss Braeside? Will you give Roseholme the honour of your company as far as the Metropolitan?"

"Why not?" thought Hildegarde. "Hobson said positively that Aunt Emily would not see me before lunch, and there is no one else that I need go to see quite so very immediately."

"Yes, I will go with pleasure!" she said. So off they started, the cheerfullest three in New York that morning. Busy men, hurrying down-town to their business, turned to look back at them, and felt the load of care lightened a little just by the knowledge that there were three people who had no care, and were[69] going to enjoy themselves somewhere. Hugh walked in the middle, holding a hand of each friend, chattering away, and looking up from one to the other with clear, joyful looks that made the whole street brighter. The Colonel was in high feather; flourishing his stick, he strode along, pointing out the various objects of interest on the way. He paused before a mercer's window, filled with shimmering silks and satins.

"Now here," he said, "is frippery of a superior description; frippery enough to delight the hearts of a dozen women."

"Possibly of two dozen, dear sir," put in Hildegarde; "consider the number of yards in all those shining folds."

"Hum! ha! precisely!" said the Colonel. "Now, Hildegarde, you have some taste in dress, I believe; you appear to me to be a well-dressed young woman. Now, I say, what seems to you the handsomest gown in all this folderol, hey? the handsomest, mind you?"

"'Said the Kangaroo to the Duck, this requires a little reflection!'" Hildegarde quoted.[70]

"Perhaps, on the whole, that splendid purple velvet; don't you think so, Colonel Ferrers?"

"Hum!" said the Colonel. "Ha! possibly; but—ha! hum! that—I may be wrong, Hildegarde—but that seems to me hardly suited to a young person, hey? More a gown for a dowager, it strikes me? I may be wrong, of course."

"Not in the least wrong, dear sir," said Hilda, laughing. "But you said nothing about a young person. You said 'the handsomest.'"

"Precisely," said the Colonel again. "And after all, a gown is a temporary thing, Hugh. Now, a bit of jewelry—but now, Hildegarde, I put it to you, if you were going to choose a gown for Elizabeth Beadle, for example; suppose Hugh and I were going to take a present home to Elizabeth Beadle; there's no better woman of her station in the mortal universe, sir, I don't care who the second may be. What do you think suitable, hey?"

"Oh, Guardian!" and "Oh, Colonel Ferrers!" cried Hugh and Hildegarde, in a breath. "How delightful!"[71]

"I think Hugh ought to choose," said Hildegarde, with some self-denial; and she added to herself:

"If only he will not choose the blue and red plaid; though there is nothing she would like so well, to be sure!"

Hugh surveyed the shining prospect with radiant eyes.

"I think you are the very kindest person in all the world!" he said. "I think—my mind is full of thoughts, but now I will make my choice."

He was silent, and the three stood absorbed, heedless of the constantly increasing crowd that surged and elbowed past them.

"My great-aunt is fond of bright colours," said the child, at last. Hildegarde shivered.

"She would like best the red and blue plaid. But, people must not always have the things they like best. You remember the green apples, Guardian, and how they weren't half as good as the medicine was horrid."

"Most astonishing boy in the habitable universe!" murmured the Colonel, under his breath.[72] "Don't undertake to say what kind of boys there may be in Mars, you understand, but so far as this planet goes,—hey? Ha! well, have you made your choice, Young Sir?"

Hugh pointed out a gray silk, with a pretty purple figure. "That is the very best thing for my great-aunt," he said.

"That will fill her with delirious rapture, and it will not put out the eyes of anybody. We shall all be happy with that silk."

So in they went to the shop, and Hugh bought the silk, and the Colonel paid for it, and then they all went off to the Metropolitan, and spent the rest of the morning in great joy.

"And how have you spent the morning, my dear?" asked Mrs. Delansing.

They were sitting at the luncheon-table. Hildegarde could just see the tip of her aunt's cap above the old-fashioned epergne which occupied the centre of the table; but her tone sounded cheerful, and Hildegarde hastened to tell of her delightful morning. She had enjoyed herself so heartily that she made the recital with joyful eagerness, forgetting for the moment that she was not speaking to her mother, who always enjoyed her good times rather more than she did herself; but a sudden exclamation from Mrs. Delansing brought her to a sudden realisation of her position.

"What!" exclaimed the old lady, and at her tone the very ferns seemed to stiffen. "What are you telling me, Hildegarde? You[74] have been spending the morning with—with a gentleman , and that gentleman—"

"Colonel Ferrers!" said Hildegarde, hastily, fearing that she had not been understood. "Surely you know Colonel Ferrers, Aunt Emily."

"I do know Thomas Ferrers!" replied Mrs. Delansing, with awful severity; "but I do not know why—I must add that I am at a loss to imagine how—my niece should have been careering about the streets of New York with Thomas Ferrers or any other young man."

Hildegarde was speechless for a moment; indeed, Mrs. Delansing only paused to draw breath, and then went on.

"That your mother holds many dangerous and levelling opinions I am aware; but that she could in any degree countenance anything so—so monstrous as this, I refuse to believe. I shall consider it my duty to write to her immediately, and inform her of what you have done."

Hildegarde was holding fast to the arms of her chair, and saying over and over to herself,[75] "Never speak suddenly or sharply to an old person!" It was one of her mother's maxims, and she had never needed it before; but now it served to keep her still, though the indignant outcry had nearly forced itself from her lips. She remained silent until she was sure of her voice; then said quietly, "Aunt Emily, there is some mistake! Colonel Ferrers is over sixty years old; he was a dear friend of my father's, and—and I have already written to my mother."

Mrs. Delansing was silent; Hildegarde saw through the screen of leaves a movement, as if she put her hand to her brow. "Sixty years old!" she repeated. "Wild Tom Ferrers,—sixty years old! What does it mean? Then—then how old am I?"

There was a painful silence. Hildegarde longed for her mother; longed for the right word to say; the wrong word would be worse than none, yet this stillness was not to be endured. Her voice sounded strange to herself as she said, crumbling her bread nervously:

"He is looking very well indeed. He has been in Washington with little Hugh, his ward;[76] he had been suffering a great deal with rheumatism, but the warm weather there drove it quite away, he says."

There was no reply.

"Colonel Ferrers is the kindest neighbour that any one could possibly have!" the girl went on. "I don't know what we should have done without him, mamma and I; he has really been one of the great features in our life there. You know he is a connection of dear papa's,—on the Lancaster side,—as well as a lifelong friend."

"I was not aware of it!" said Mrs. Delansing. She had recovered her composure, and her tone, though cold, was no longer like iced thunderbolts.

"I withdraw my criticism of your conduct,—in a measure. But I cannot refrain from saying that I think your time would have been better employed in your room, than in gadding about the street. I was distinctly surprised when Hobson told me that you had gone out. Hobson was surprised herself. She has always lived in the most careful families."[77]

Hildegarde "saw scarlet." "Aunt Emily," she said, "blame me if you will; but I cannot suffer any reflection on my mother. I do not consider that it would be possible for any one to be more careful of every sensible propriety than my mother is; though she does not mould her conduct on the opinions of servants!" she added. She should not have said this, and was aware of it instantly; but the provocation had been great.

"You admit that your mother is human?" said the old lady, grimly. "She has faults, I presume, in common with the rest of humankind?"

"She may have!" said Hildegarde. "I have never observed them."

Silence again. Hildegarde tried to eat her chicken, but every morsel seemed to choke her; her heart beat painfully, and she saw through a mist of angry tears. Oh, why had she come here? What would she not give to be at home again!

Presently Mrs. Delansing spoke again, and her tone was perceptibly gentler.[78]

"My dear, you must not think that I mean to be unkind, nor did I mean—consciously—to reflect upon your mother, for whom your affection is commendable, though perhaps strongly expressed."

"I am sorry!" said Hildegarde, impulsively. "I ought not to have spoken so. I beg your pardon, Aunt Emily!"

Mrs. Delansing bowed. "You are freely pardoned! I was about to say, when this little interruption occurred, that I had hoped you could be content for a few days under my roof, without seeking pleasure elsewhere; but age is poor company for youth."

"But you could not see me this morning, Aunt Emily! You said last night that you never saw anybody before lunch. And what should I do in my room? It is a charming room, but you surely did not expect me to stay in it all the morning, doing nothing?"

"I should have thought you might find plenty of occupation!" said Mrs. Delansing. "In my time it was thought not too much for a young lady to devote the greater part of the day to the[79] care of her person; this, of course, included fine needlework and other feminine occupations."

"I did not bring any work with me," said Hildegarde. "You see, I must go back to-morrow, Aunt Emily, and there are so many errands that I have to do. This afternoon I must go out again; and is there anything I can do for you? I shall be going by Arnold's, if you want anything there."

"I thank you; Hobson makes my purchases for me!" said Mrs. Delansing, stiffly. "She would better accompany you to Arnold's; there is apt to be a crowd in these large shops, which I consider unsuited for gentlewomen. I will tell Hobson to accompany you."

But Hildegarde protested against this, saying, with truth, that she must pay a visit first. The idea of going about with Hobson at her heels was intolerable for the girl who had spent the first sixteen years of her life in New York.

She finally carried her point, and also obtained permission to read to her aunt for an hour before going out. It was a particularly dull weekly that was chosen, but she read as[80] well as she knew how, and had the pleasure of seeing Mrs. Delansing's stern face relax into something like cheerfulness as she went through two chapters of the vapid, semi-religious story. At length the cold, gray eyes closed; the stately head nodded forward; Aunt Emily was asleep. Hildegarde read on for some time, till she was sure that the slumber was deep and settled. Then she sat for a moment looking at the old lady, and contrasting her face and form, rigid even in sleep, with those of dear Cousin Wealthy Bond, who always looked like the softest and most kissable elderly rose in her afternoon nap. "Poor soul," she said, softly, as she slipped out of the room to find Hobson. "So lonely, and so unloved and unloving! I can't bear to hear Blanche and Violette speak of her,—I can hardly keep my hands off them,—and yet—why exactly should they be fond of her? She is not fond of them, or of anybody, I fear, unless it be Hobson."

The visit was paid, and Hildegarde took her way towards the Woman's Exchange, with a[81] beating heart. It beat happily, for she had enjoyed the half-hour's talk with the kind cousin, an elderly woman, who seldom moved from her sofa, but whose life was full of interest, and who was the friend and confidante of all the young people in the neighbourhood. She had heard with pleasure of the proposed plan, and had given Hildegarde a note to the manager of the Exchange, whom she knew well; had tasted a crumb of one of the cakes, and predicted a ready sale for them. Moreover, and this was the best of all, she had talked so wisely and kindly, and with such a note of the dear mother in her voice, that Hildegarde's homesickness had all floated away, and she had decided that it was not, after all, such a hardship to spend three days in New York as she had thought it an hour ago.

As I said, she took her way towards the Exchange, carrying her neat paper box carefully. As she went, she amused herself by building castles, à la Perrette. How many things she would buy with the money, if she sold the cakes; and she should surely sell[82] them. No one could resist who once tasted them, and she had made several tiny ones for samples; just a mouthful of "goody" in each.

Fine linen, several yards of it, and gold thread, and "Underwoods" in green morocco,—that was really almost a necessity, for Mamma's birthday; and some pink chiffon to freshen up her silk waist, and—and—here she was almost run over, and was shouted at and seized by a policeman, and piloted gently to a place of safety, with an admonition to be more careful.

Much ashamed, Hildegarde stood still to look about her, and found herself at the very door of the Exchange. She went in. The room was filled with customers. "I ought to have come in the morning," she said to herself, and the quick blush mounted to her cheeks, as she made her way to the counter at the back of the shop, where a sweet-faced woman was trying to answer four questions at once.

"No, the Nuns have not come in yet.[83] Yes, they are generally here before this. No, I cannot tell the reason of the delay. Yes, it happened once before, when the maker was ill. I do not know why more people do not make them. Yes, just the one person, so far as I know. Marguerites? Yes, madam,—in one moment. The orange biscuits will come in at two o'clock. No, we have never had them earlier than that. Perhaps you are thinking of the lemon cheese-cakes. These are the lemon cheese-cakes."

She paused for breath, and looked anxiously round. It was plain that she was expecting assistance, and equally plain that it was late in coming. Hildegarde stepped quietly round behind the counter.

"Can I help you?" she whispered.

The lady gave her a grateful glance. "I should be so thankful," she murmured. "All these ladies must be served instantly. The prices are all marked."

The lady who had demanded the "Nuns" had also paused for breath, being stout as well as clamorous; but she now returned to[84] the attack. Hildegarde met her with a calm front, and eyes which tried not to smile.

"Can you—oh! this is a different person. Perhaps you can tell me why the Nuns are not here. It really seems an extraordinary thing that they should not be here at the usual time."

"The messenger may have lost a train, or something of that sort," suggested Hildegarde, soothingly.

"Oh, but that would be no excuse! No excuse at all! When one is in the habit of supplying things to people of consequence, one must not lose trains. Now, are you perfectly sure that they have not come? You know what they are, do you? Little round cakes, with a raisin in the middle, and flavoured with something special. I don't remember what the flavour is, but it is something special, of that I am sure. Have you looked—have you looked everywhere? What is in that box at your elbow? They might have been brought in and laid down without your noticing it. Oblige me by looking in that box at your elbow."[85]

A sudden thought flashed into Hildegarde's mind; she began to unfasten the box, which was her own, whispering at the same time into the ear of her companion in distress.

"Oh! Oh, yes, certainly!" said the latter, also in a whisper. "Anything, I am sure, that will give satisfaction! If you can only—"

"Stop her noise," was evidently what the patient saleswoman longed to say; but she checked the words, and only gave Hildegarde an eloquent glance, as she turned to meet a wild onset in demand of macaroons.