This text includes characters

that require UTF-8 (Unicode) file encoding:

Ē ā ē ī ō ū (vowel with macron or “long” mark)

Ă Ĕ Ĭ ă ĕ ĭ ŏ (vowel with breve or “short” mark)

Ś ś ć (s, c with “acute”: mainly in Recording Indian Languages

article)

ⁿ (small raised n, representing nasalized vowel)

ɔ ʇ ʞ (inverted letters)

‖ (double vertical line

There are also a handful of Greek words; transliterations are given

in mouse-hover popups. Some compromises were made to accommodate font

availability:

The ordinary “cents” sign ¢ was used in place of the correct

form ȼ, and bracketed [¢] represents the capital letter

Ȼ.

Turned (rotated) c is represented by ɔ (technically an

open o).

Bracketed [K] and [T] represent upside-down (turned,

rotated) capital K and T.

Inverted V is represented by the Greek letter Λ.

If your computer has a more appropriate character, and you are

comfortable editing html files, feel free to replace letters

globally.

Syllable stress is represented by an acute accent either on the main

vówel or after the syl´lable; inconsistencies are

unchanged. Except for the special characters noted above, brackets are

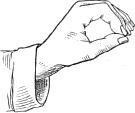

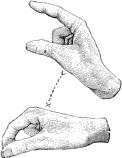

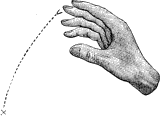

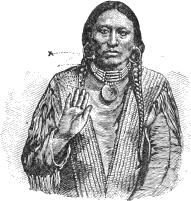

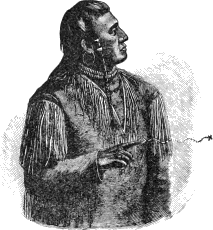

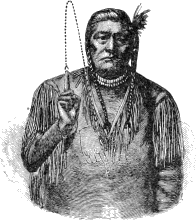

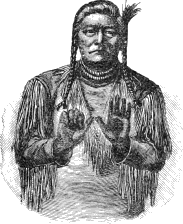

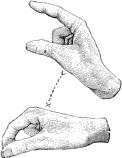

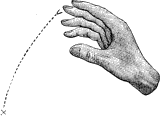

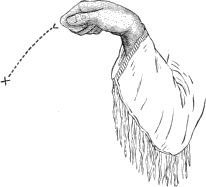

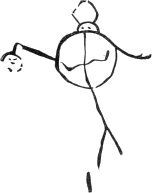

in the original. Note that in the Sign Language article, hand positions

identified by letter (A, B ... W, Y) are descriptive; they do

not represent a “finger alphabet”.

The First Annual Report includes ten “Accompanying Papers”, all

available from Project Gutenberg as individual e-texts. Except for

Yarrow’s “Mortuary Customs”, updated shortly before the present text,

the separate articles were released between late 2005 and late 2007. For

this combined e-text they have been re-formatted for consistency, and

most illustrations have been replaced. Some articles have been further

modified to include specialized characters shown above, and a few more

typographical errors have been corrected.

For consistency with later Annual Reports, a full List of

Illustrations has been added after the Table of Contents, and each

article has been given its own Table of Contents. In the original, the

Contents were printed only at the beginning of the volume, and

Illustrations were listed only with their respective

articles.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introductory Material

Index

Notes and Sources

FIRST ANNUAL REPORT

OF THE

BUREAU OF ETHNOLOGY

TO THE

SECRETARY OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

1879-’80

BY

J. W. POWELL

DIRECTOR

WASHINGTON

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

1881

iii

Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of

Ethnology,

Washington, D.C., July, 1880.

Prof. Spencer F. Baird,

Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, D.C.:

Sir: I have the honor to transmit

herewith the first annual report of the operations of the Bureau of

Ethnology.

By act of Congress, an appropriation was made to continue researches

in North American anthropology, the general direction of which was

confided to yourself. As chief executive officer of the Smithsonian

Institution, you entrusted to me the immediate control of the affairs of

the Bureau. This report, with its appended papers, is designed to

exhibit the methods and results of my administration of this trust.

If any measure of success has been attained, it is largely due to

general instructions received from yourself and the advice you have ever

patiently given me on all matters of importance.

I am indebted to my assistants, whose labors are delineated in the

report, for their industry; hearty co-operation, and enthusiastic love

of the science. Only through their zeal have your plans been

executed.

Much assistance has been rendered the Bureau by a large body of

scientific men engaged in the study of anthropology, some of whose names

have been mentioned in the report and accompanying papers, and others

will be put on record when the subject-matter of their writings is fully

published.

I am, with respect, your obedient servant,

J. W. POWELL.

v

|

REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR. |

| Introductory |

Page xi |

Bibliography of North American philology, by J. C.

Pilling |

xv |

Linguistic and other anthropologic researches, by J. O.

Dorsey |

xvii |

| Linguistic researches, by S. R. Riggs |

xviii |

Linguistic and general researches among the Klamath Indians, by

A. S. Gatschet |

xix |

Studies among the Iroquois, by Mrs. E. A. Smith |

xxii |

| Work by Prof. Otis T. Mason |

xxii |

The study of gesture speech, by Brevet Lieut. Col. Garrick

Mallery |

xxiii |

Studies on Central American picture writing, by Prof. E. S.

Holden |

xxv |

The study of mortuary customs, by Dr. H. C. Yarrow |

xxvi |

Investigations relating to cessions of lands by Indian tribes to

the United States, by C. C. Royce |

xxvii |

| Explorations by Mr. James Stevenson |

xxx |

Researches among the Wintuns, by Prof. J. W. Powell |

xxxii |

The preparation of manuals for use in American research |

xxxii |

Linguistic classification of the North American tribes |

xxxiii |

|

ACCOMPANYING PAPERS. |

|

ON THE EVOLUTION OF LANGUAGE, BY J. W.

POWELL. |

| Process by combination |

Page 3 |

| Process by vocalic mutation |

5 |

| Process by intonation |

6 |

| Process by placement |

6 |

| Differentiation of the parts of speech |

8 |

|

SKETCH OF THE MYTHOLOGY OF THE NORTH

AMERICAN INDIANS, BY J. W. POWELL. |

| The genesis of philosophy |

19 |

| Two grand stages of philosophy |

21 |

| Mythologic philosophy has four stages |

29 |

| Outgrowth from mythologic philosophy |

33 |

The course of evolution in mythologic philosophy |

38 |

| Mythic tales |

43 |

The Cĭn-aú-äv Brothers discuss matters of

importance to the Utes |

44 |

| Origin of the echo |

45 |

| The So´-kûs Wai´-ûn-ats |

47 |

| Ta-vwots has a fight with the sun |

52 |

|

vi

WYANDOT GOVERNMENT, BY J. W.

POWELL. |

| The family |

Page 59 |

| The gens |

59 |

| The phratry |

60 |

| Government |

61 |

| Civil government |

61 |

| Methods of choosing councillors |

61 |

| Functions of civil government |

63 |

| Marriage regulations |

63 |

| Name regulations |

64 |

| Regulations of personal adornment |

64 |

| Regulations of order in encampment |

64 |

| Property rights |

65 |

| Rights of persons |

65 |

| Community rights |

65 |

| Rights of religion |

65 |

| Crimes |

66 |

| Theft |

66 |

| Maiming |

66 |

| Murder |

66 |

| Treason |

67 |

| Witchcraft |

67 |

| Outlawry |

67 |

| Military government |

68 |

| Fellowhood |

68 |

|

ON LIMITATIONS TO THE USE OF SOME

ANTHROPOLOGIC DATA, BY J. W. POWELL. |

| Archæology |

73 |

| Picture writing |

75 |

History, customs, and ethnic characteristics |

76 |

| Origin of man |

77 |

| Language |

78 |

| Mythology |

81 |

| Sociology |

83 |

| Psychology |

83 |

|

A FURTHER CONTRIBUTION TO THE STUDY

OF THE MORTUARY CUSTOMS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS, BY H. C.

YARROW. |

| List of illustrations |

89 |

| Introductory |

91 |

| Classification of burial |

92 |

| Inhumation |

93 |

| Pit burial |

93 |

| Grave burial |

101 |

| Stone graves or cists |

113 |

| Burial in mounds |

115 |

Burial beneath or in cabins, wigwams, or

houses |

122 |

| Cave burial |

126 |

| Embalmment or mummification |

130 |

| Urn burial |

137 |

| Surface burial |

138 |

| Cairn burial |

142 |

| Cremation |

143 |

| Partial cremation |

150 |

|

vii

Aerial sepulture |

152 |

| Lodge burial |

152 |

| Box burial |

155 |

| Tree and scaffold burial |

158 |

| Partial scaffold burial and ossuaries |

168 |

| Superterrene and aerial burial in canoes |

171 |

| Aquatic burial |

180 |

| Living sepulchers |

182 |

| Mourning, sacrifice, feasts, etc. |

183 |

| Mourning |

183 |

| Sacrifice |

187 |

| Feasts |

190 |

| Superstition regarding burial feasts |

191 |

| Food |

192 |

| Dances |

192 |

| Songs |

194 |

| Games |

195 |

| Posts |

197 |

| Fires |

198 |

| Superstitions |

199 |

|

STUDIES IN CENTRAL AMERICAN PICTURE

WRITING, BY E. S. HOLDEN. |

| List of illustrations |

206 |

| Introductory |

207 |

| Materials for the present investigation |

210 |

| System of nomenclature |

211 |

| In what order are the hieroglyphs read? |

221 |

| The card catalogue of hieroglyphs |

223 |

| Comparison of plates I and IV (Copan) |

224 |

Are the hieroglyphs of Copan and Palenque identical? |

227 |

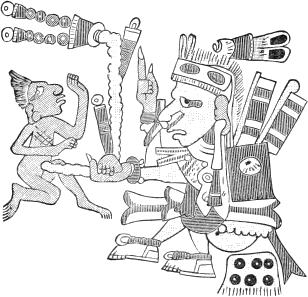

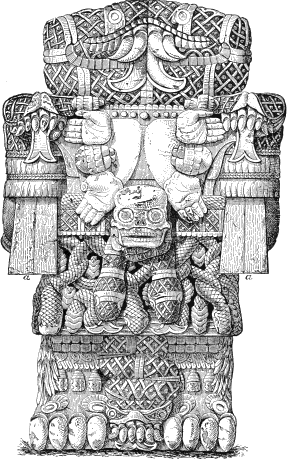

Huitzilopochtli, Mexican god of war, etc. |

229 |

| Tlaloc, or his Maya representative |

237 |

| Cukulcan or Quetzalcoatl |

239 |

Comparison of the signs of the Maya months |

243 |

|

CESSIONS OF LAND BY INDIAN TRIBES TO

THE UNITED STATES, BY C. C. ROYCE. |

| Character of the Indian title |

249 |

| Indian boundaries |

253 |

| Original and secondary cessions |

256 |

|

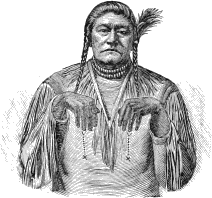

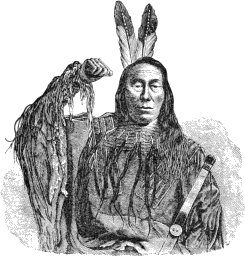

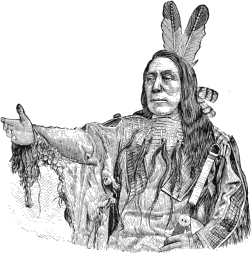

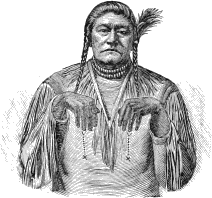

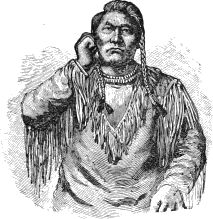

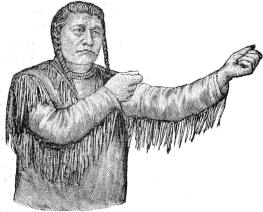

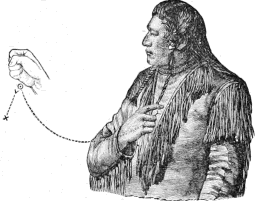

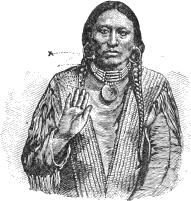

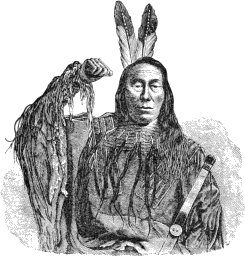

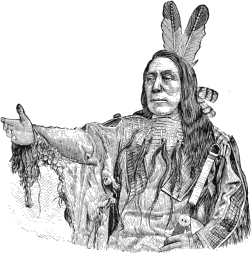

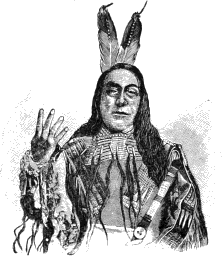

SIGN LANGUAGE AMONG NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS, BY COL. GARRICK

MALLERY. |

| List of Illustrations |

265 |

| Introductory |

269 |

| Divisions of gesture speech |

270 |

| The origin of sign language |

273 |

| Gestures of the lower animals |

275 |

| Gestures of young children |

276 |

| Gestures in mental disorder |

276 |

| Uninstructed deaf-mutes |

277 |

| Gestures of the blind |

278 |

| Loss of speech by isolation |

278 |

| Low tribes of man |

279 |

| Gestures as an occasional resource |

279 |

| Gestures of fluent talkers |

279 |

|

viii

Involuntary response to gestures |

280 |

| Natural pantomime |

280 |

| Some theories upon primitive language |

282 |

| Conclusions |

284 |

| History of gesture language |

285 |

| Modern use of gesture speech |

293 |

Use by other peoples than North American

Indians |

294 |

| Use by modern actors and orators |

308 |

Our Indian conditions favorable to sign language |

311 |

Theories entertained respecting Indian signs |

313 |

Not correlated with meagerness of

language |

314 |

| Its origin from one tribe or region |

316 |

Is the Indian system special and

peculiar? |

319 |

| To what extent prevalent as a system |

323 |

| Are signs conventional or instinctive? |

340 |

| Classes of diversities in signs |

341 |

Results sought in the study of sign language |

346 |

| Practical application |

346 |

| Relations to philology |

349 |

| Sign language with reference to grammar |

359 |

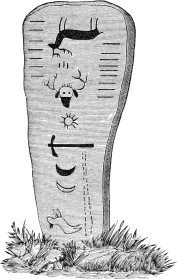

| Gestures aiding archæologic research |

368 |

| Notable points for further researches |

387 |

| Invention of new signs |

387 |

| Danger of symbolic interpretation |

388 |

| Signs used by women and children |

391 |

| Positive signs rendered negative |

391 |

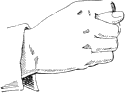

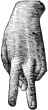

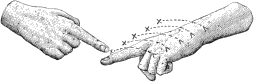

| Details of positions of fingers |

392 |

| Motions relative to parts of the body |

393 |

| Suggestions for collecting signs |

394 |

| Mode in which researches have been made |

395 |

| List of authorities and collaborators |

401 |

| Algonkian |

403 |

| Dakotan |

404 |

| Iroquoian |

405 |

| Kaiowan |

406 |

| Kutinean |

406 |

| Panian |

406 |

| Piman |

406 |

| Sahaptian |

406 |

| Shoshonian |

406 |

| Tinnean |

407 |

| Wichitan |

407 |

| Zuñian |

407 |

| Foreign correspondence |

407 |

| Extracts from dictionary |

409 |

| Tribal signs |

458 |

| Proper names |

476 |

| Phrases |

479 |

| Dialogues |

486 |

| Tendoy-Huerito Dialogue. |

486 |

| Omaha Colloquy. |

490 |

| Brulé Dakota Colloquy. |

491 |

| Dialogue between Alaskan Indians. |

492 |

| Ojibwa Dialogue. |

499 |

| Narratives |

500 |

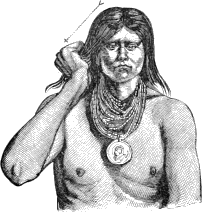

| Nátci’s Narrative. |

500 |

| Patricio’s Narrative. |

505 |

| Na-wa-gi-jig’s Story. |

508 |

| Discourses |

521 |

| Address of Kin Chē-Ĕss. |

521 |

| Tso-di-a´-ko’s Report. |

524 |

| Lean Wolf’s Complaint. |

526 |

| Signals |

529 |

| Signals executed by bodily action |

529 |

Signals in which objects are used in connection

with personal action |

532 |

Signals made when the person of the signalist is

not visible |

536 |

| Smoke Signals Generally |

536 |

| Smoke Signals of the Apaches |

538 |

| Foreign Smoke Signals |

539 |

| Fire Arrows |

540 |

| Dust Signals |

541 |

| Notes on Cheyenne and Arapaho Signals |

542 |

|

ix

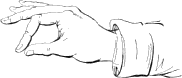

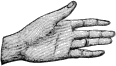

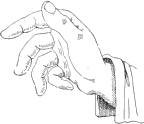

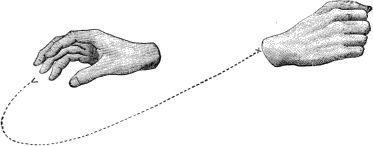

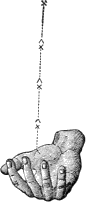

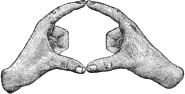

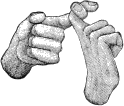

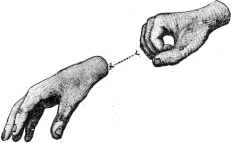

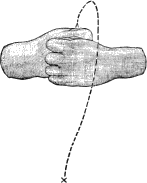

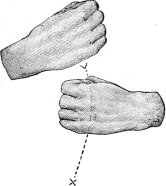

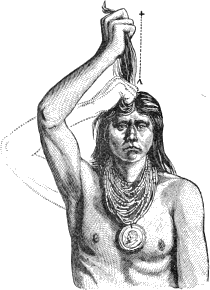

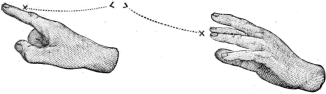

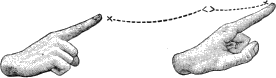

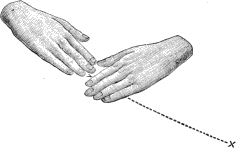

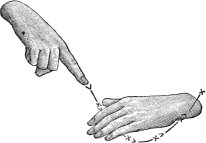

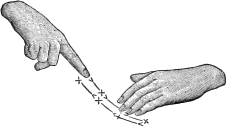

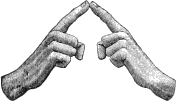

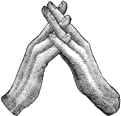

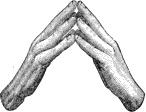

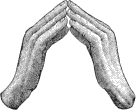

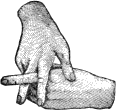

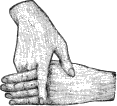

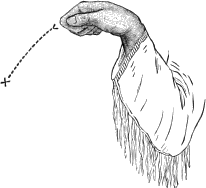

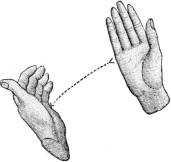

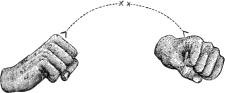

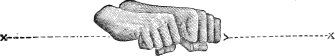

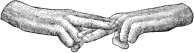

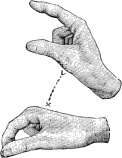

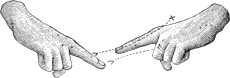

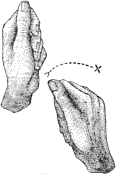

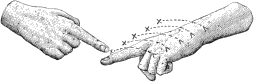

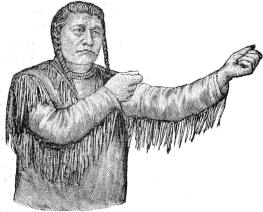

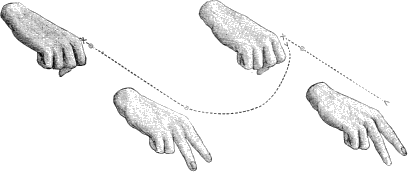

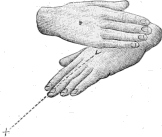

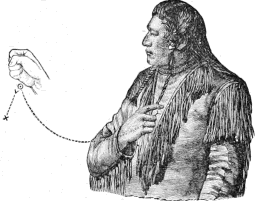

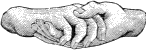

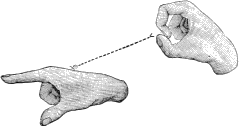

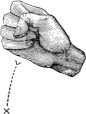

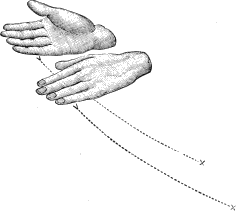

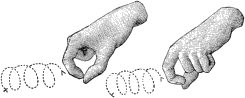

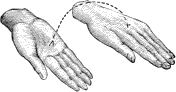

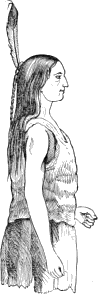

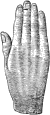

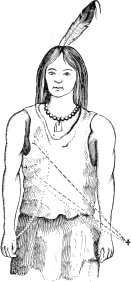

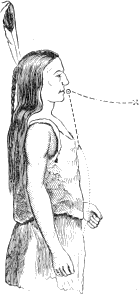

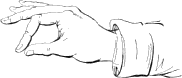

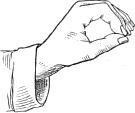

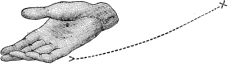

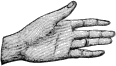

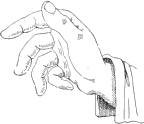

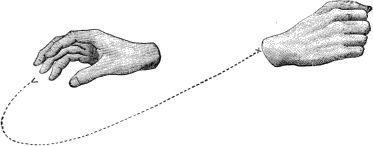

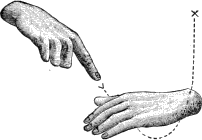

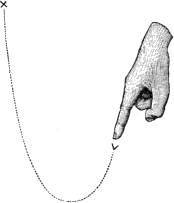

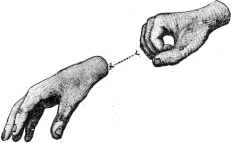

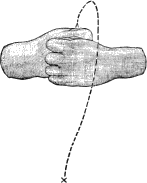

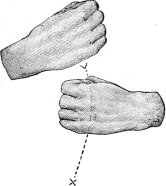

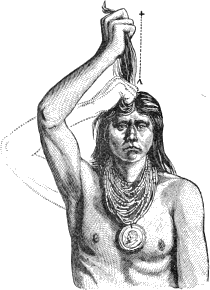

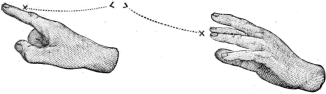

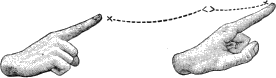

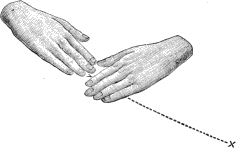

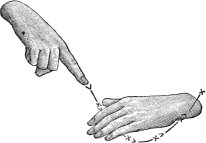

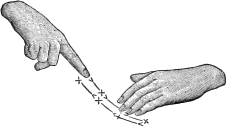

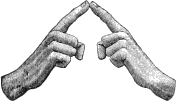

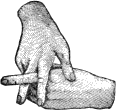

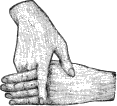

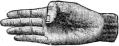

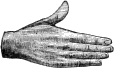

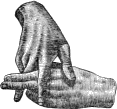

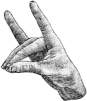

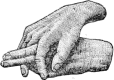

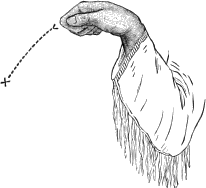

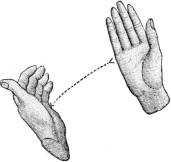

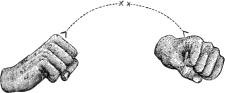

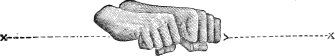

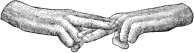

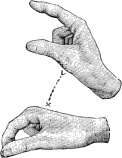

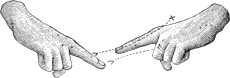

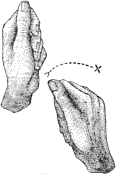

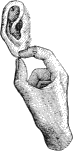

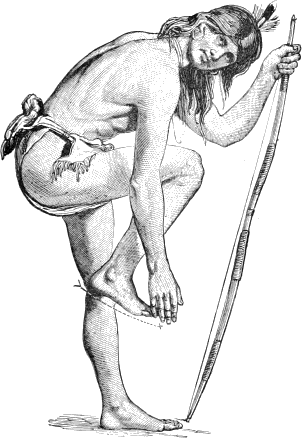

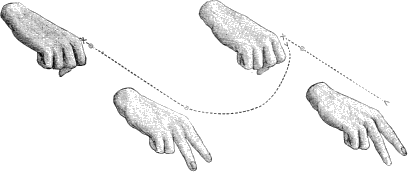

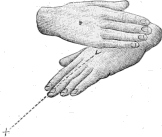

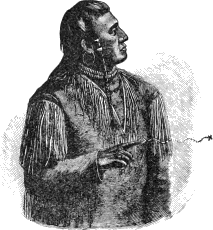

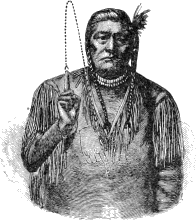

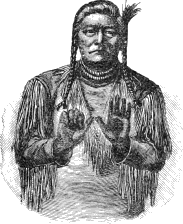

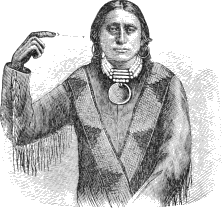

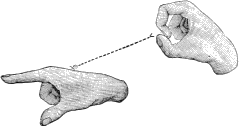

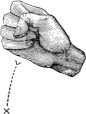

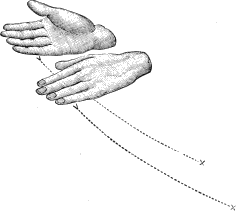

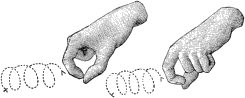

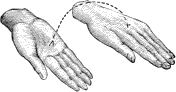

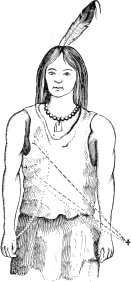

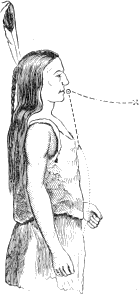

Scheme of illustration |

544 |

Outlines for arm positions in sign language |

545 |

| Order of arrangement |

546 |

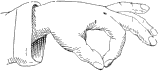

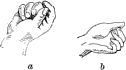

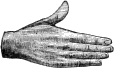

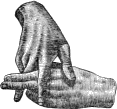

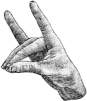

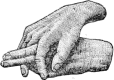

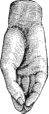

| Types of hand positions in sign language |

547 |

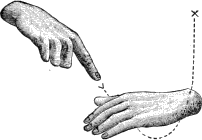

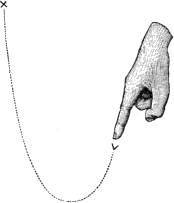

| Examples |

550 |

|

CATALOGUE OF LINGUISTIC MANUSCRIPTS IN

THE LIBRARY OF THE BUREAU OF ETHNOLOGY, BY J. C. PILLING. |

| Introductory |

555 |

| List of manuscripts |

562 |

|

ILLUSTRATION OF THE METHOD OF

RECORDING INDIAN LANGUAGES. FROM THE MANUSCRIPTS OF MESSRS. J. O.

DORSEY, A. S. GATSCHET, AND S. B. RIGGS. |

How the rabbit caught the sun in a trap, by J. O.

Dorsey |

581 |

Details of a conjurer’s practice, by A. S. Gatschet |

583 |

| The relapse, by A. S. Gatschet |

585 |

| Sweat-Lodges, by A. S. Gatschet |

586 |

| A dog’s revenge, by S. R. Riggs |

587 |

|

INDEX. |

| Index to First Annual Report |

591 |

x

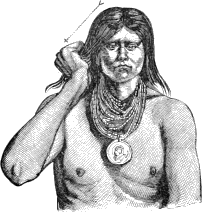

This full list was added by the transcriber. For the e-text, illustrations

were placed as close as practical to their discussion in the text; the List of

Illustrations shows their original location. The First Annual Report did not

distinguish between Plates (full page, unpaginated) and Figures (inline).

|

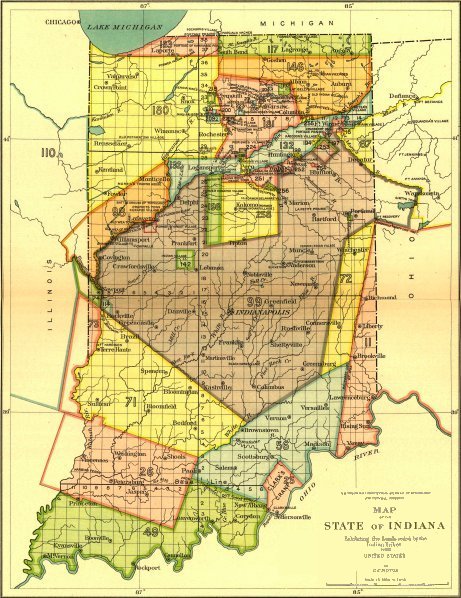

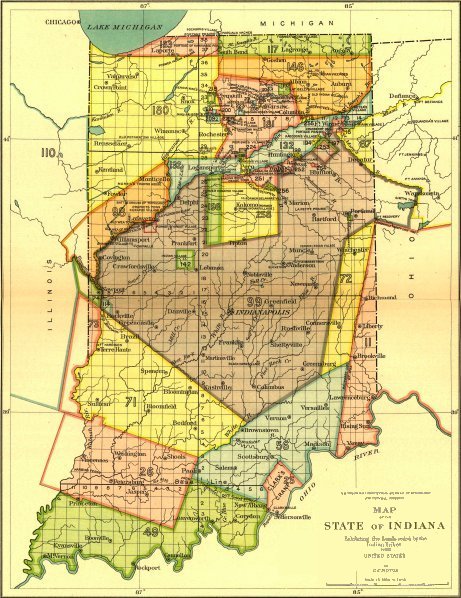

Map of the State of Indiana

(unnumbered) |

248 |

| Figure 1. |

Quiogozon or dead house |

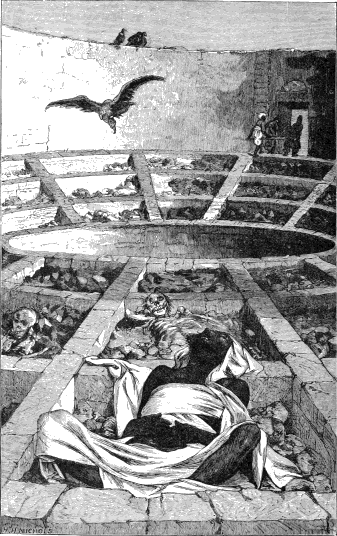

Page 94 |

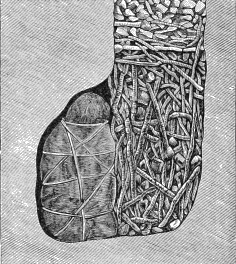

| 2. |

Pima burial |

98 |

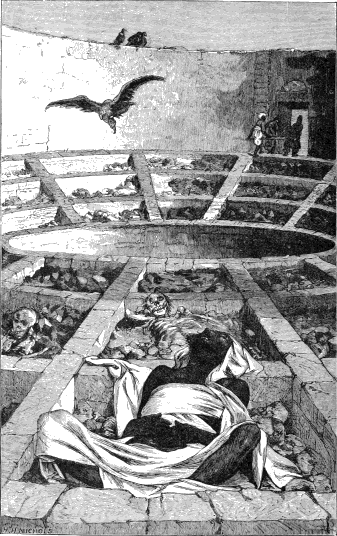

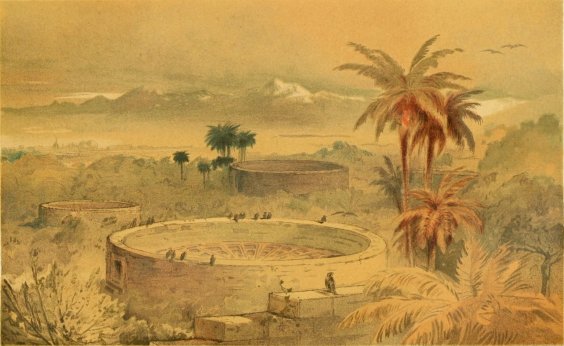

| 3. |

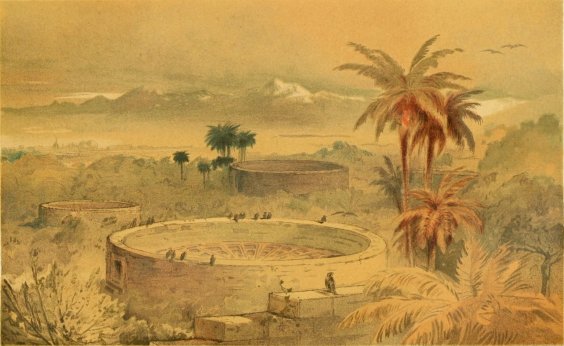

Towers of silence |

105 |

| 4. |

Towers of silence |

106 |

| 5. |

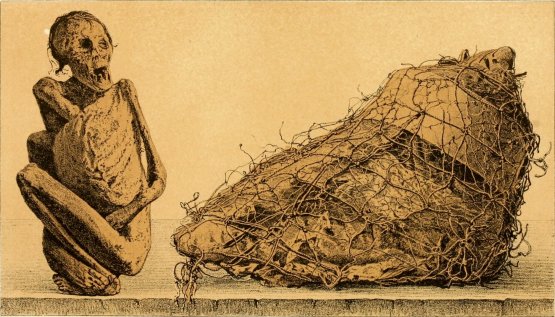

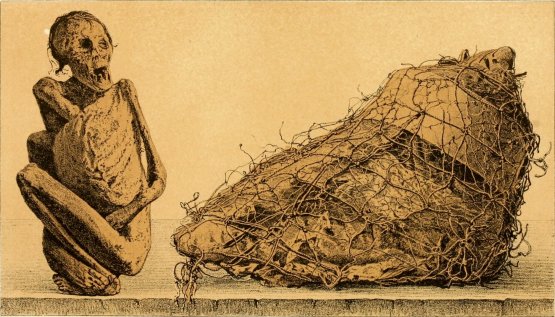

Alaskan mummies |

135 |

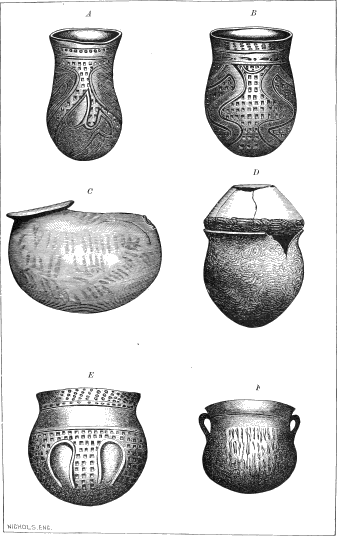

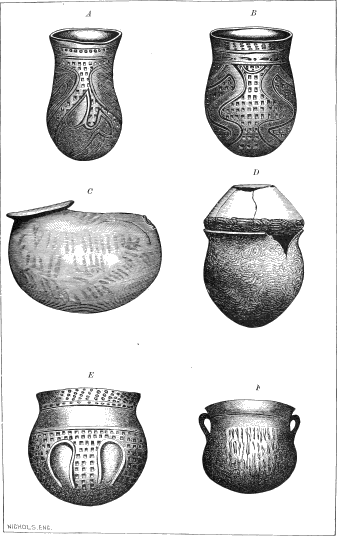

| 6. |

Burial urns |

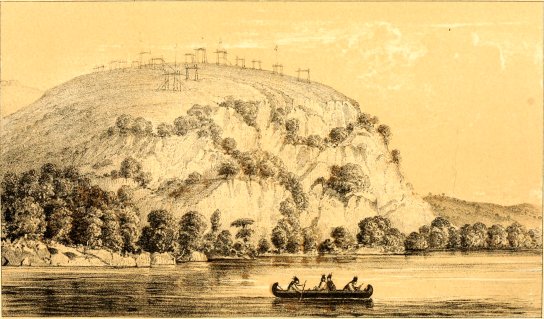

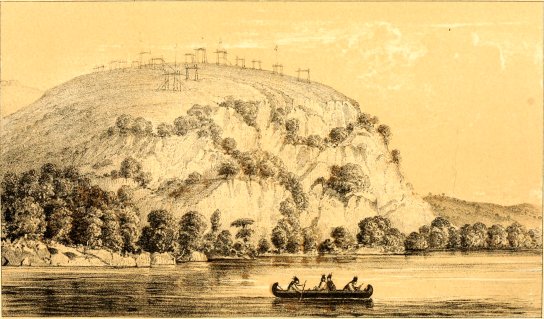

138 |

| 7. |

Indian cemetery |

139 |

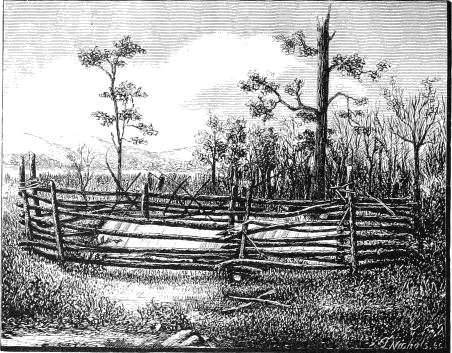

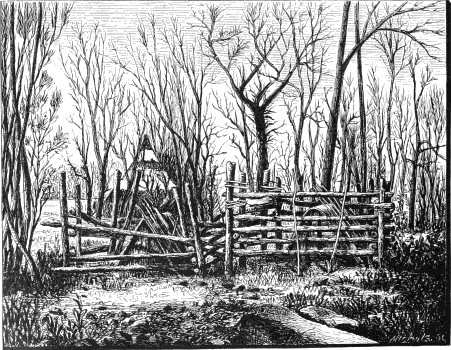

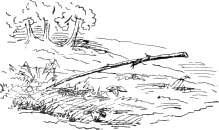

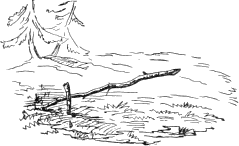

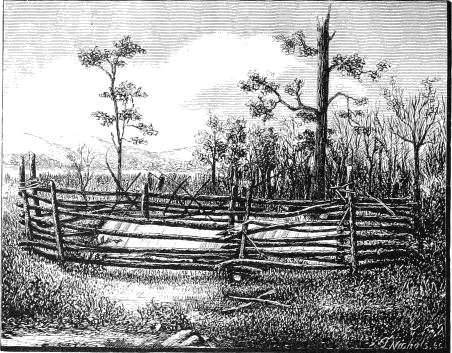

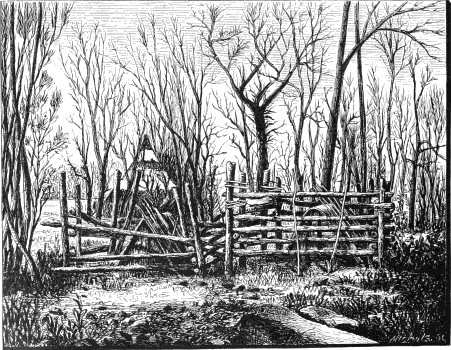

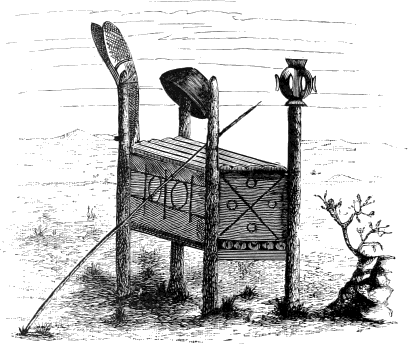

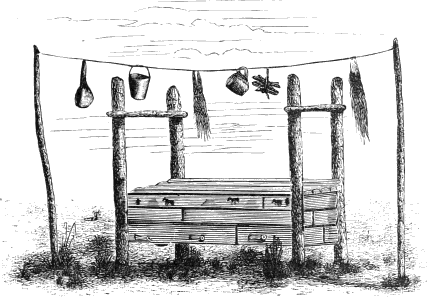

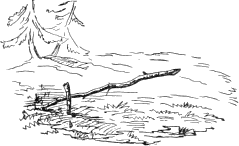

| 8. |

Grave pen |

141 |

| 9. |

Grave pen |

141 |

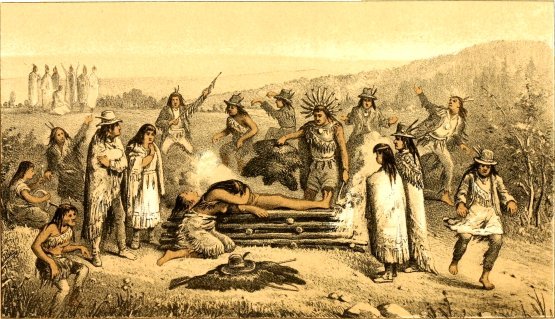

| 10. |

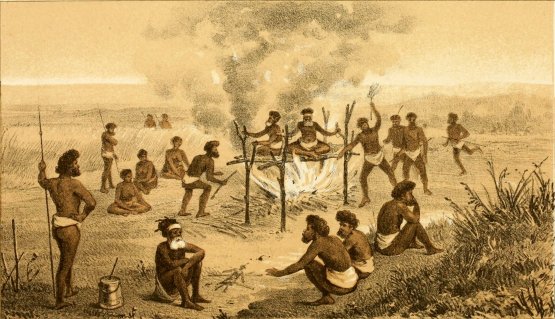

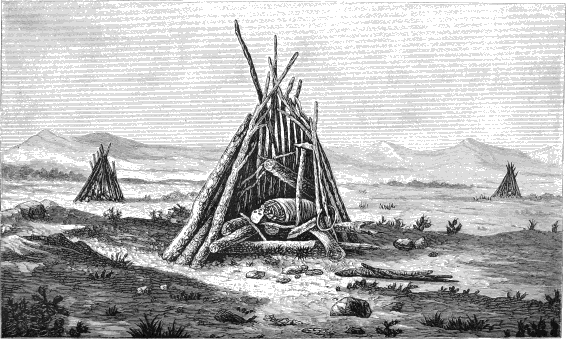

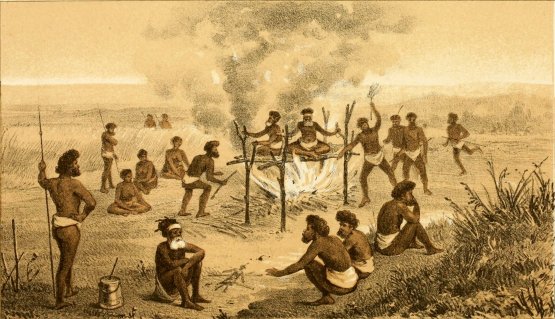

Tolkotin cremation |

145 |

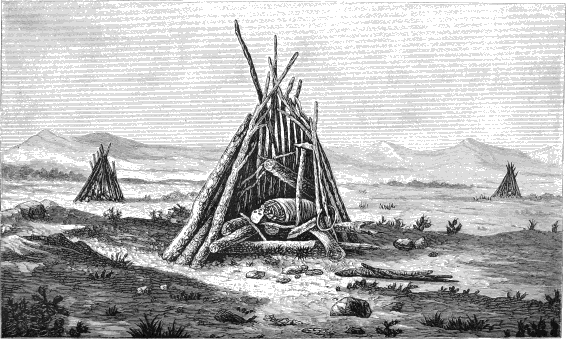

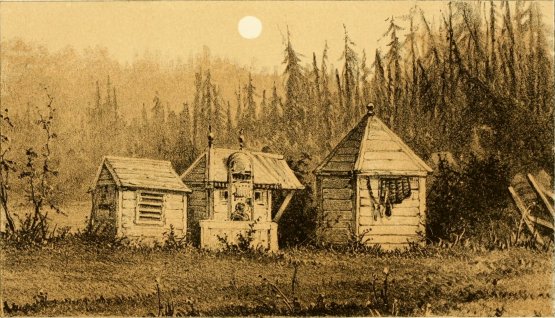

| 11. |

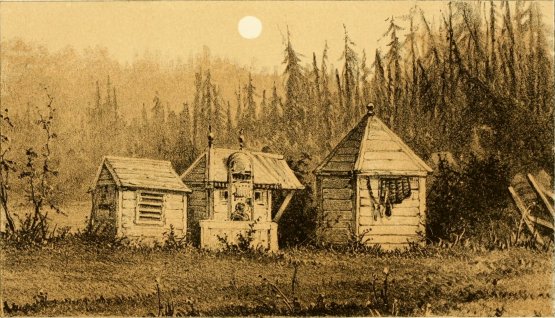

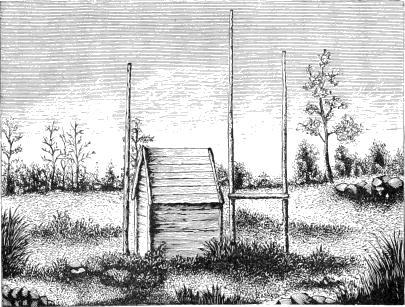

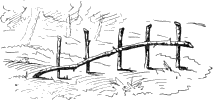

Eskimo lodge burial |

154 |

| 12. |

Burial houses |

154 |

| 13. |

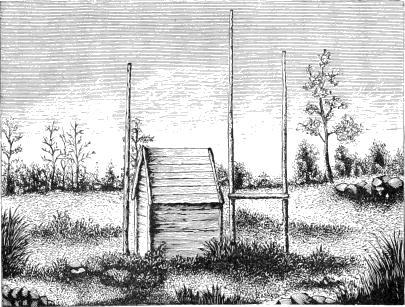

Innuit grave |

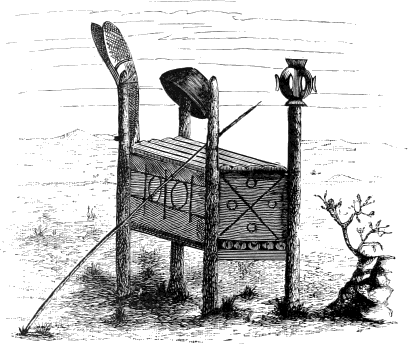

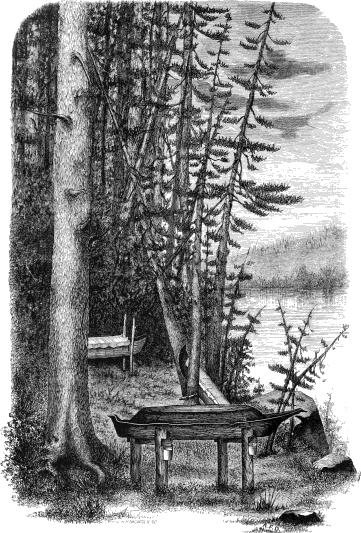

156 |

| 14. |

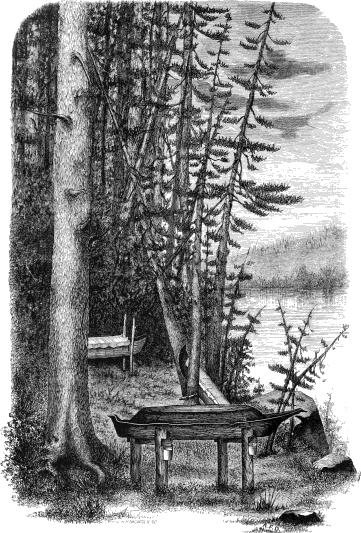

Ingalik grave |

157 |

| 15. |

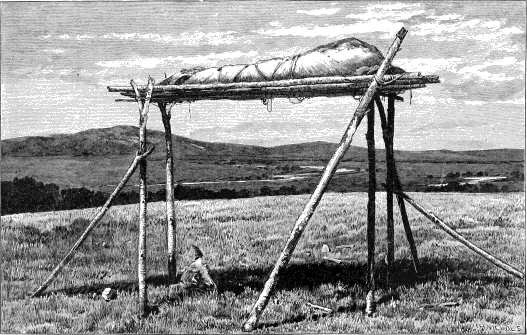

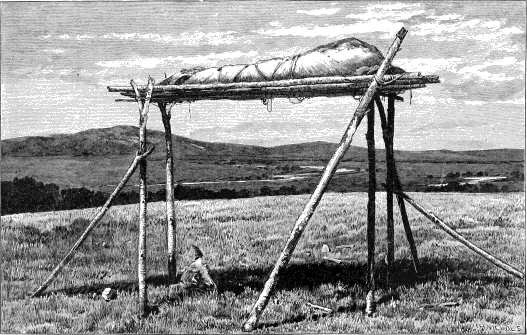

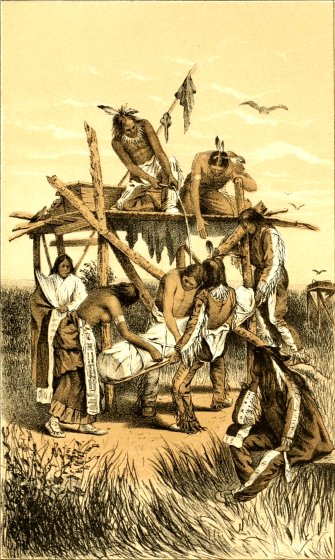

Dakota scaffold burial |

158 |

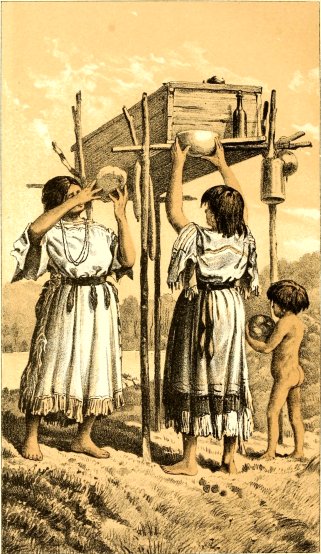

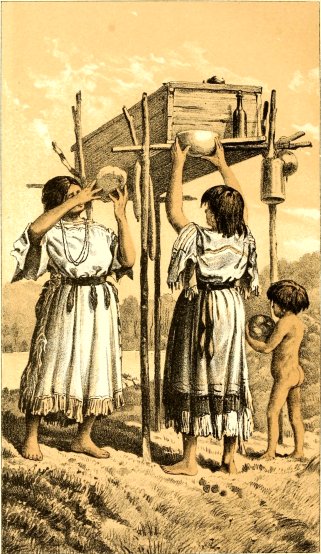

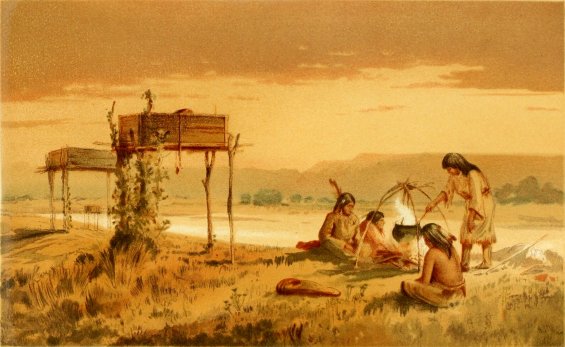

| 16. |

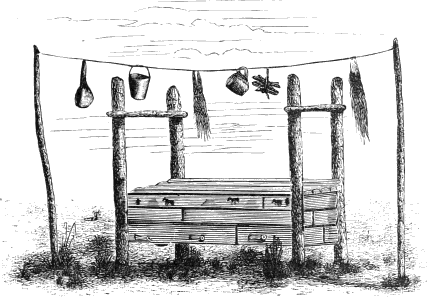

Offering food to the dead |

159 |

| 17. |

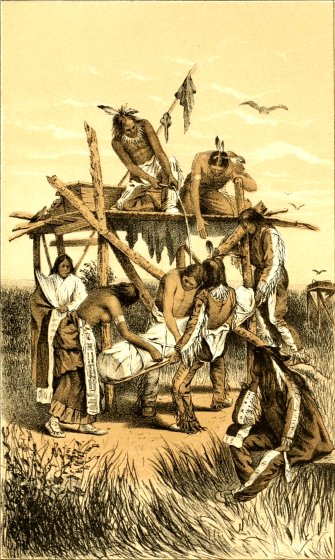

Depositing the corpse |

160 |

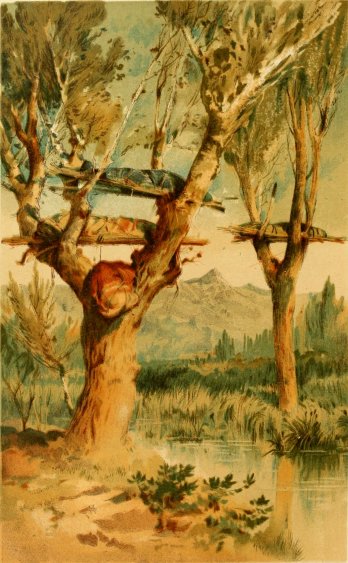

| 18. |

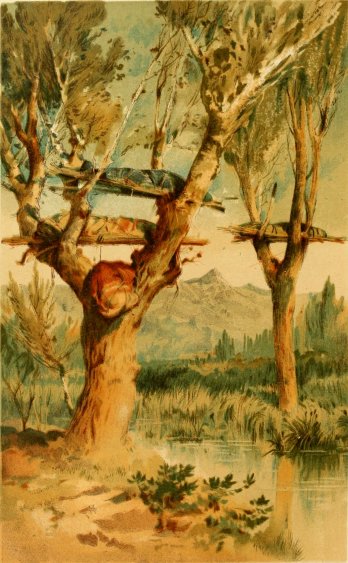

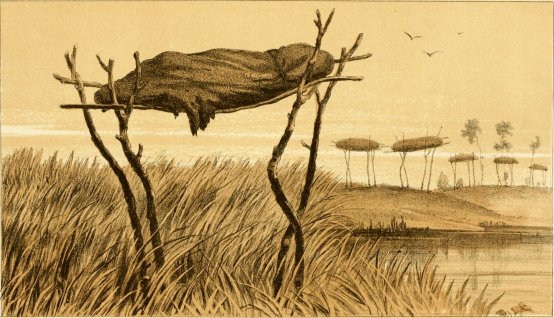

Tree-burial |

161 |

| 19. |

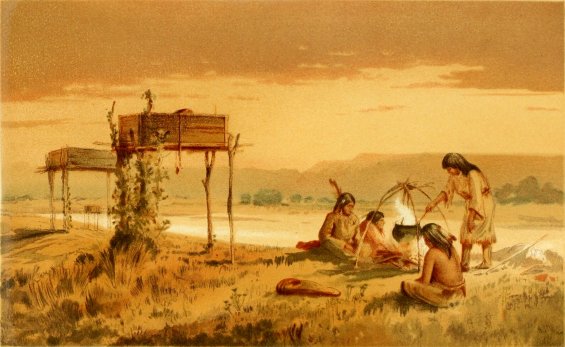

Chippewa scaffold burial |

162 |

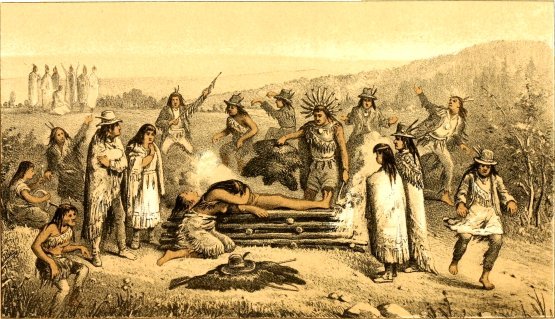

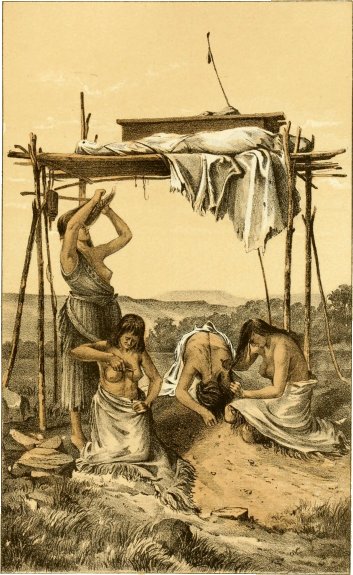

| 20. |

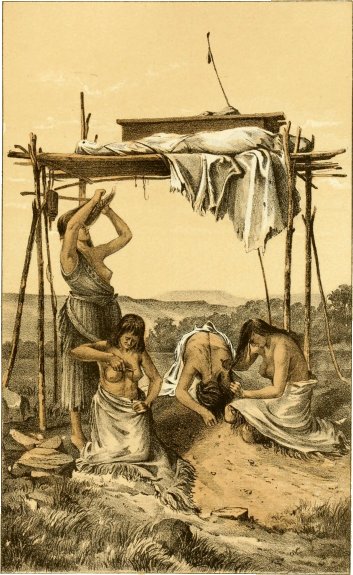

Scarification at burial |

164 |

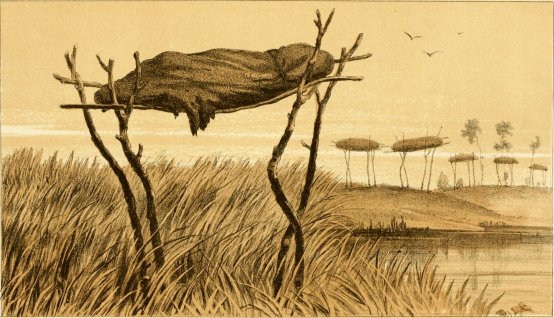

| 21. |

Australian scaffold burial |

166 |

| 22. |

Preparing the dead |

167 |

| 23. |

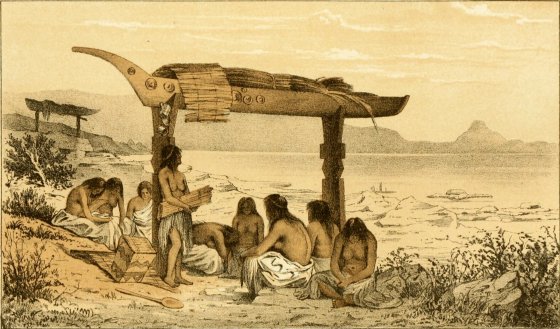

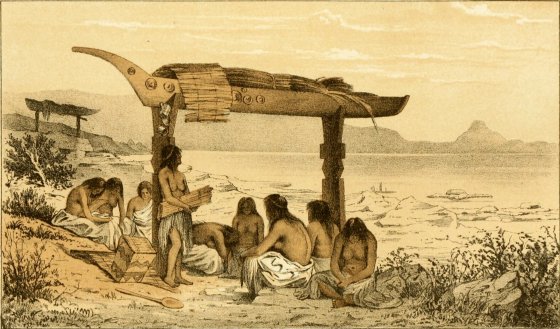

Canoe-burial |

171 |

| 24. |

Twana canoe-burial |

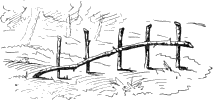

172 |

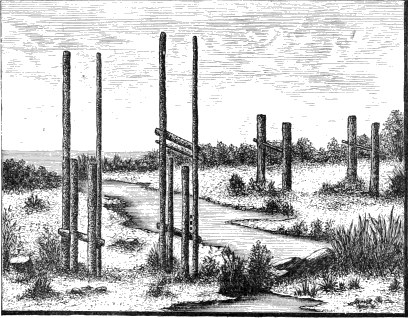

| 25. |

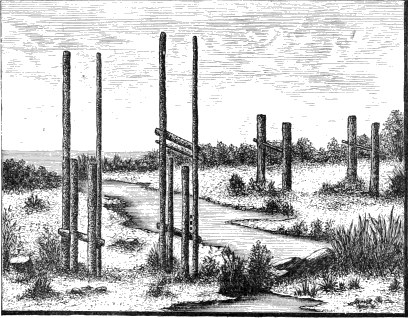

Posts for burial canoes |

173 |

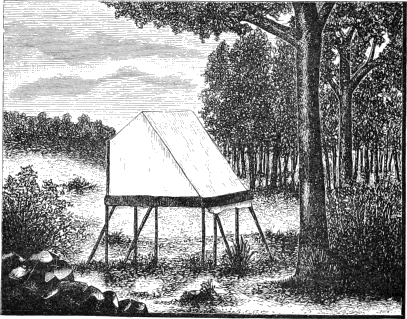

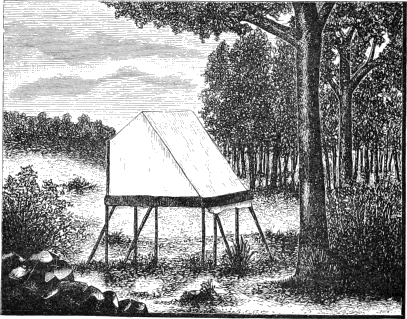

| 26. |

Tent on scaffold |

174 |

| 27. |

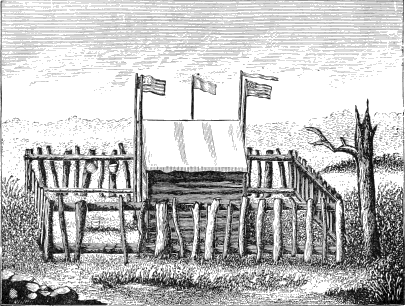

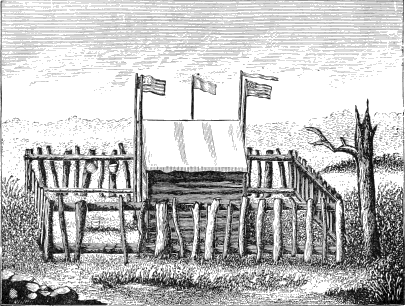

House burial |

175 |

| 28. |

House burial |

175 |

| 29. |

Canoe-burial |

178 |

| 30. |

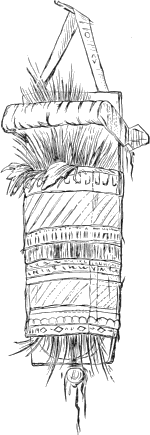

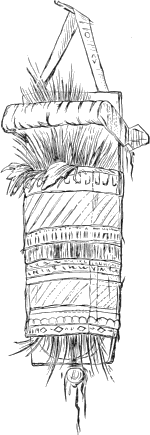

Mourning-cradle |

181 |

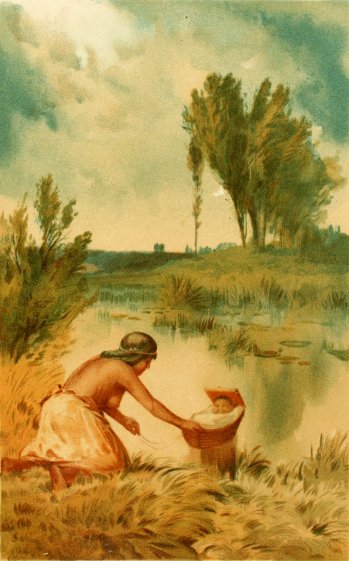

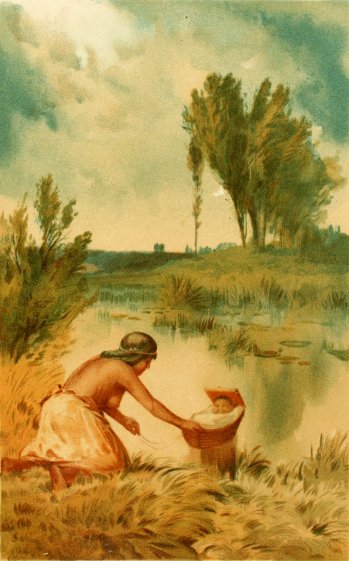

| 31. |

Launching the burial cradle |

182 |

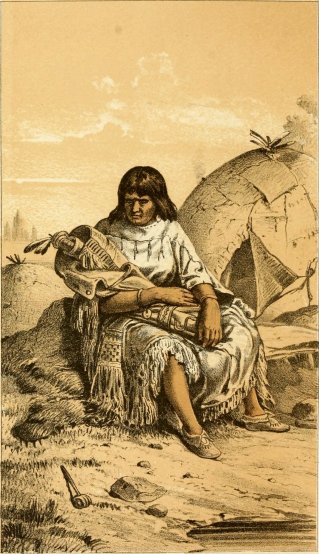

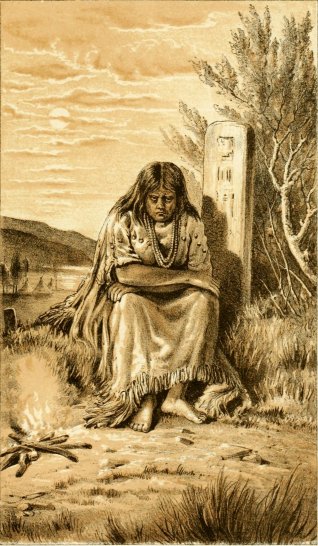

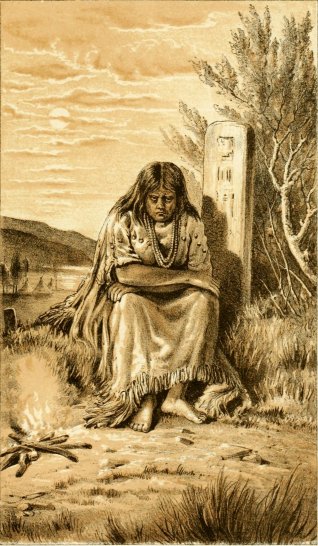

| 32. |

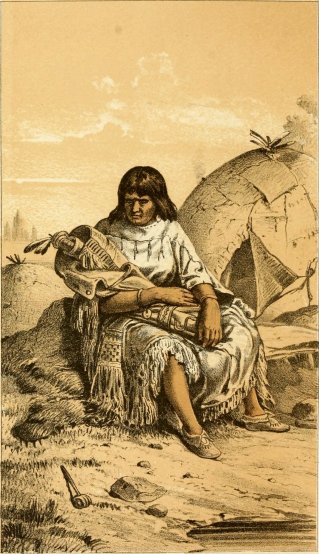

Chippewa widow |

185 |

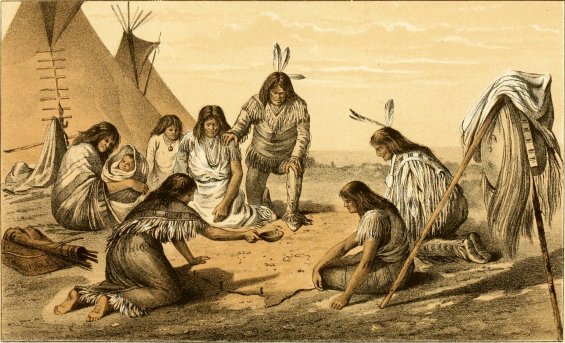

| 33. |

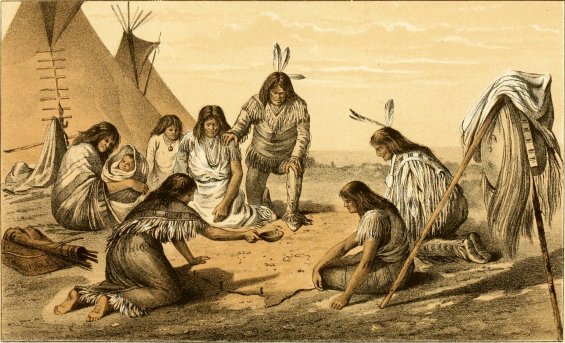

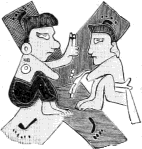

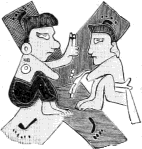

Ghost gamble |

195 |

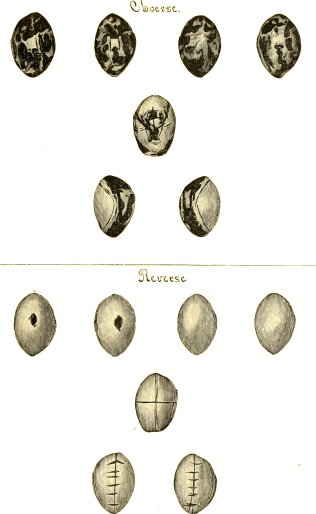

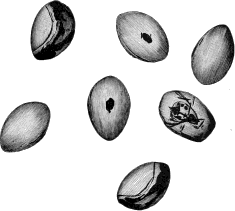

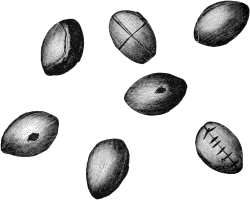

| 34. |

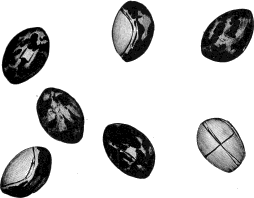

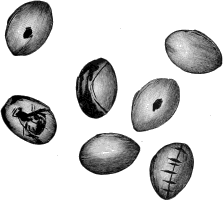

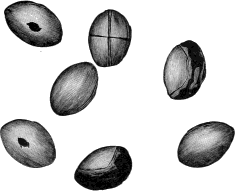

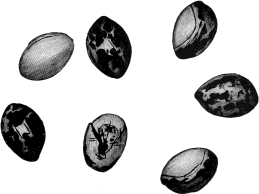

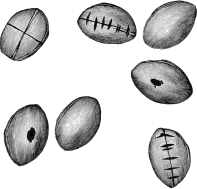

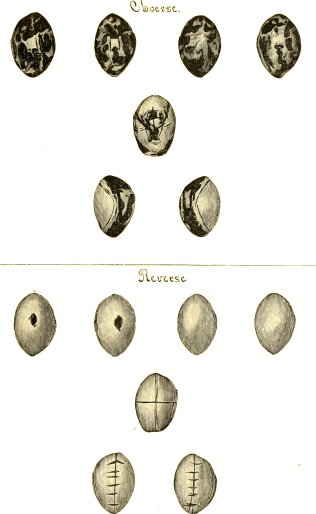

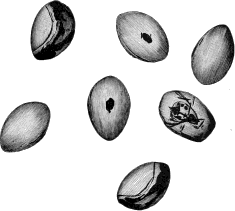

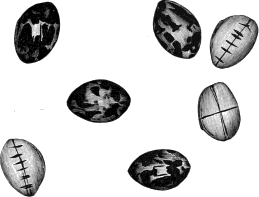

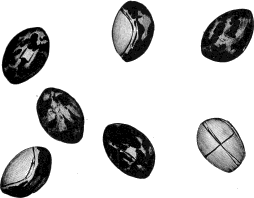

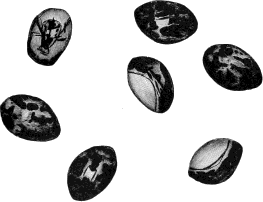

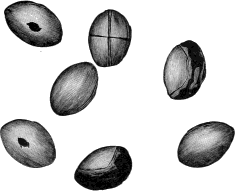

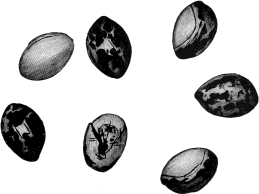

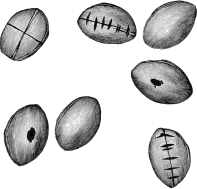

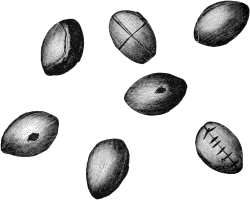

Figured plum stones |

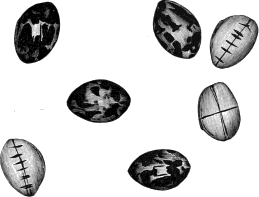

196 |

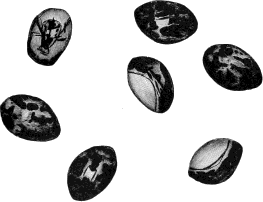

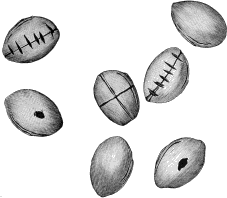

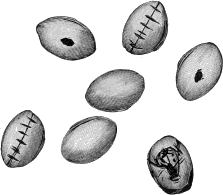

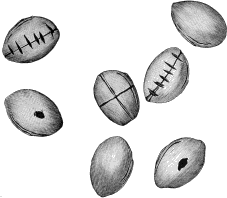

| 35. |

Winning throw, No. 1 |

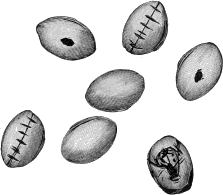

196 |

| 36. |

Winning throw, No. 2 |

196 |

| 37. |

Winning throw, No. 3 |

196 |

| 38. |

Winning throw, No. 4 |

196 |

| 39. |

Winning throw, No. 5 |

196 |

| 40. |

Winning throw, No. 6 |

196 |

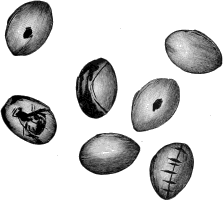

| 41. |

Auxiliary throw, No. 1 |

196 |

| 42. |

Auxiliary throw, No. 2 |

196 |

| 43. |

Auxiliary throw, No. 3 |

196 |

| 44. |

Auxiliary throw, No. 4 |

196 |

| 45. |

Auxiliary throw, No. 5 |

196 |

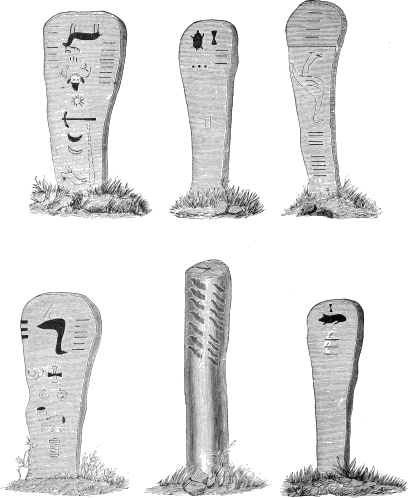

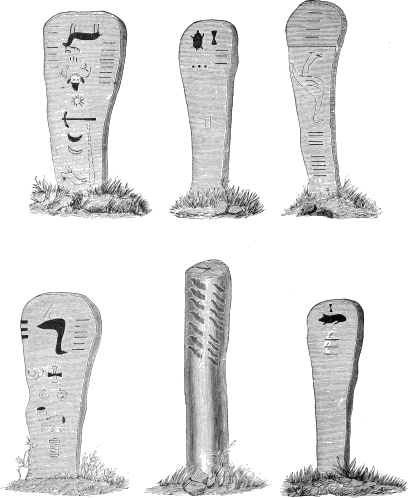

| 46. |

Burial posts |

197 |

| 47. |

Grave fire |

198 |

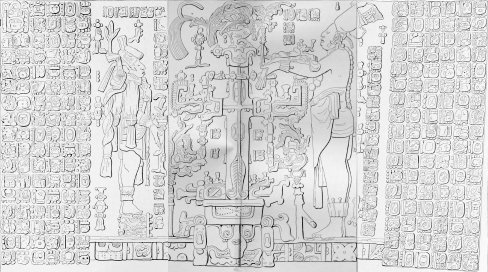

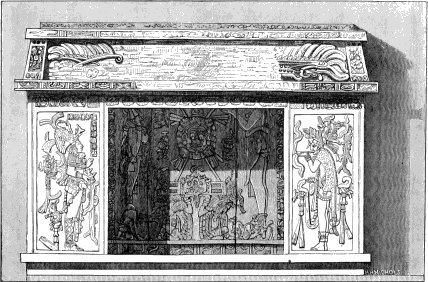

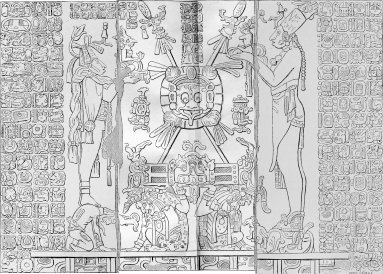

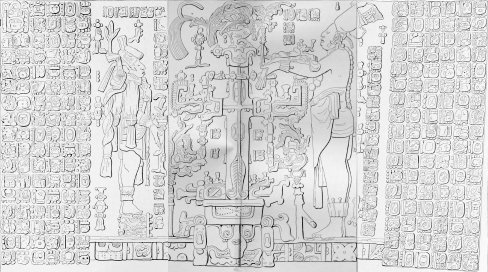

| 48. |

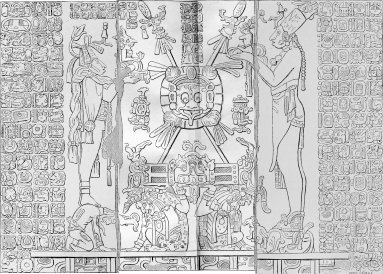

The Palenquean Group of the Cross |

221 |

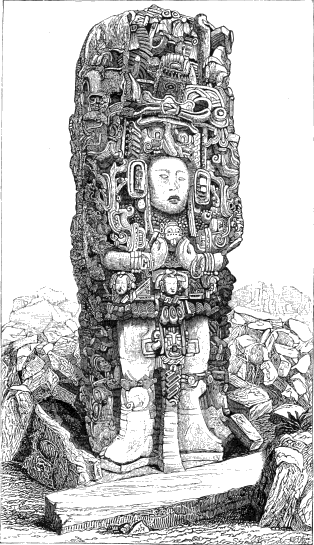

| 49. |

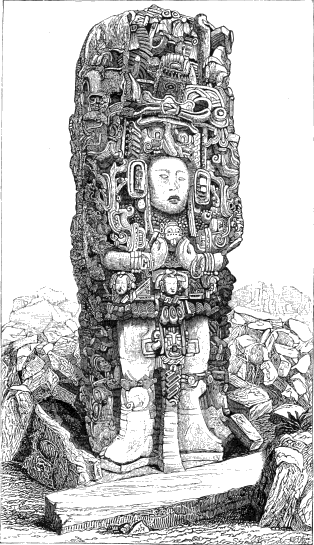

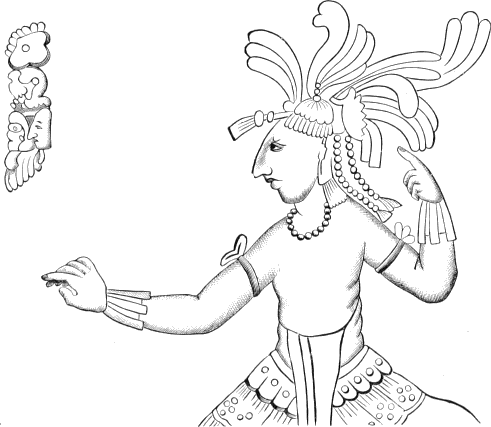

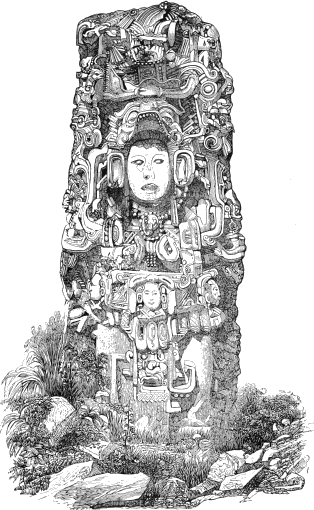

Statue at Copan |

224 |

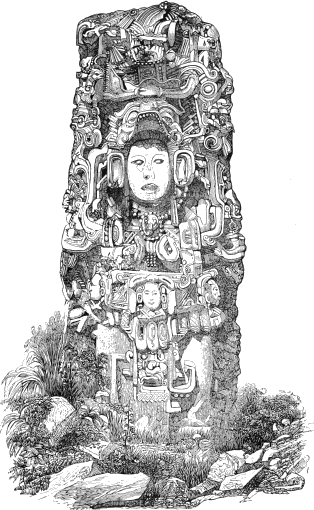

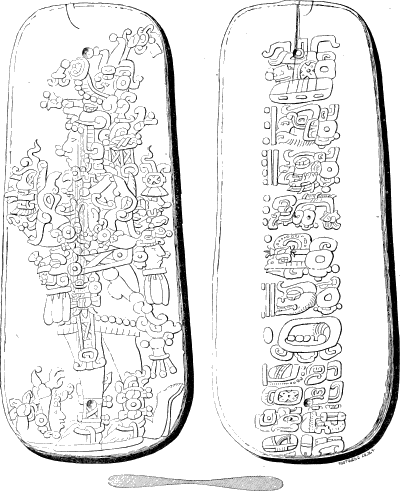

| 50. |

Statue at Copan |

225 |

| 51. |

Synonymous Hieroglyphs from Copan and Palenque |

227 |

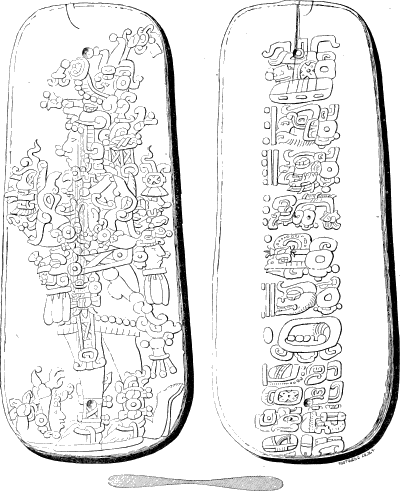

| 52. |

Yucatec Stone |

229 |

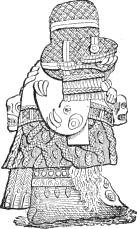

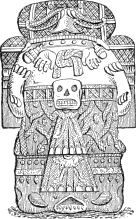

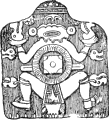

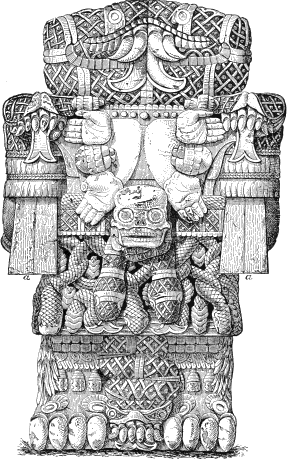

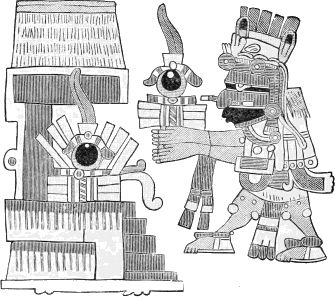

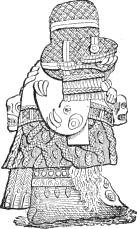

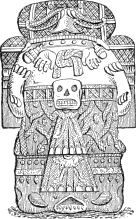

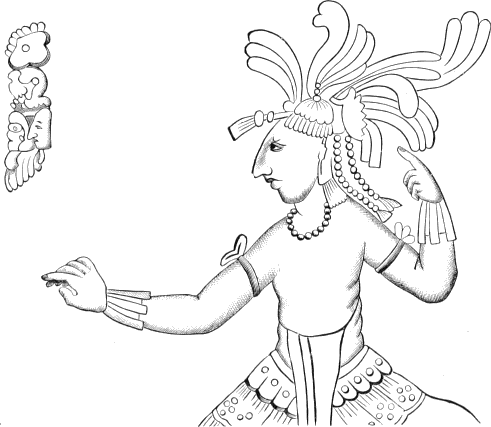

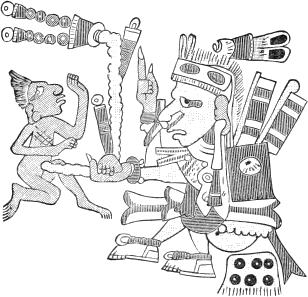

| 53. |

Huitzilopochtli (front) |

232 |

| 54. |

Huitzilopochtli (side) |

232 |

| 55. |

Huitzilopochtli (back) |

232 |

| 56. |

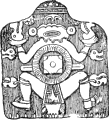

Miclantecutli |

232 |

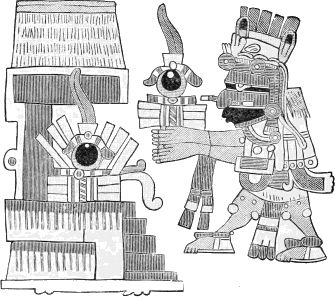

| 57. |

Adoratorio |

233 |

| 58. |

The Maya War-God |

234 |

| 59. |

The Maya Rain-God |

234 |

| 60. |

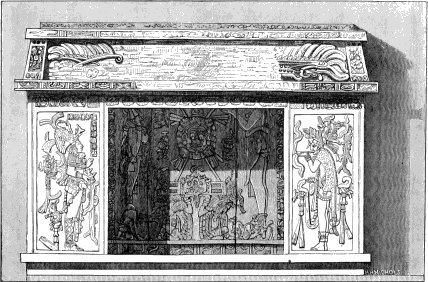

Tablet at Palenque |

234 |

| 61. |

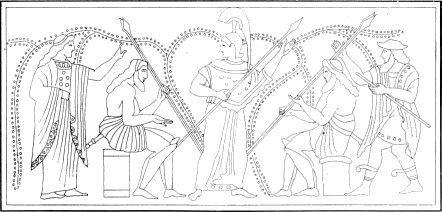

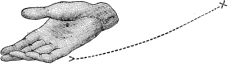

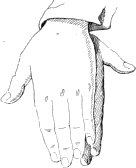

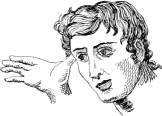

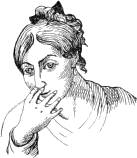

Affirmation, approving. Old Roman |

286 |

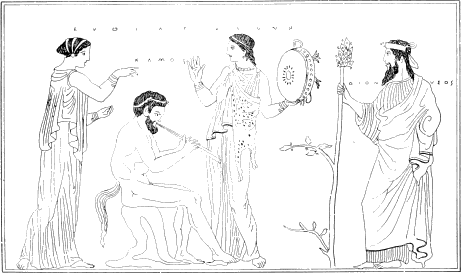

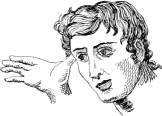

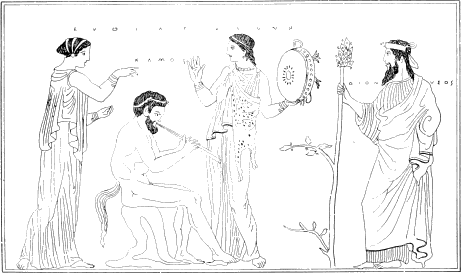

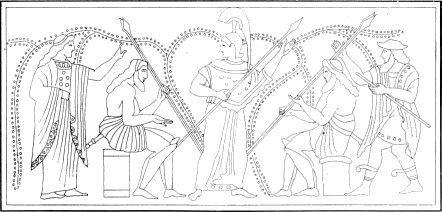

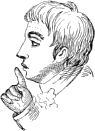

| 62. |

Approbation. Neapolitan |

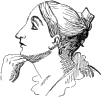

286 |

| 63. |

Affirmation, approbation. N.A. Indian |

286 |

| 64. |

Group. Old Greek. |

Facing 289 |

| 65. |

Negation. Dakota |

290 |

| 66. |

Love. Modern Neapolitan |

290 |

| 67. |

Group. Old Greek. |

Facing 290 |

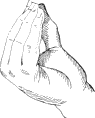

| 68. |

Hesitation. Neapolitan |

291 |

| 69. |

Wait. N.A. Indian |

291 |

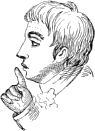

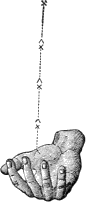

| 70. |

Question, asking. Neapolitan |

291 |

| 71. |

Tell me. N.A. Indian |

291 |

| 72. |

Interrogation. Australian |

291 |

| 73. |

Pulcinella |

292 |

| 74. |

Thief. Neapolitan |

292 |

| 75. |

Steal. N.A. Indian |

293 |

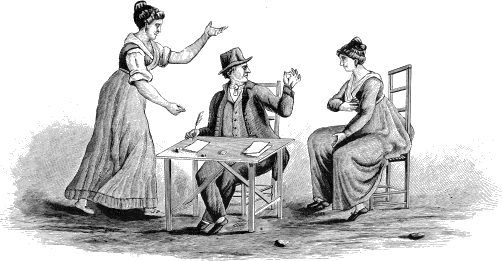

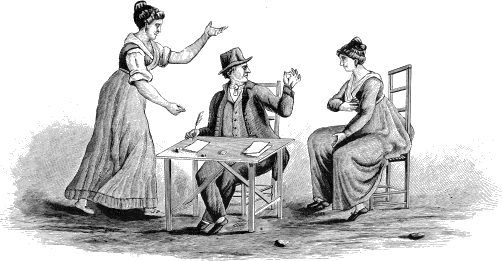

| 76. |

Public writer. Neapolitan group. |

Facing 296 |

| 77. |

Money. Neapolitan |

297 |

| 78. |

“Hot Corn.” Neapolitan Group. |

Facing 297 |

| 79. |

“Horn” sign. Neapolitan |

298 |

| 80. |

Reproach. Old Roman |

298 |

| 81. |

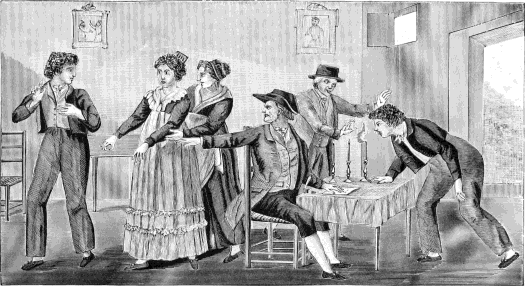

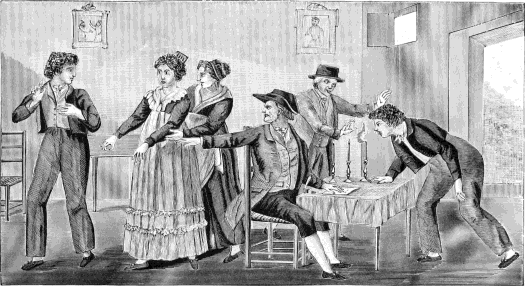

Marriage contract. Neapolitan group. |

Facing 298 |

| 82. |

Negation. Pai-Ute sign |

299 |

| 83. |

Coming home of bride. Neapolitan group. |

Facing 299 |

| 84. |

Pretty. Neapolitan |

300 |

| 85. |

“Mano in fica.” Neapolitan |

300 |

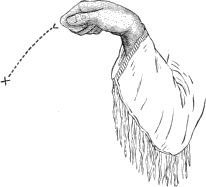

| 86. |

Snapping the fingers. Neapolitan |

300 |

| 87. |

Joy, acclamation |

300 |

| 88. |

Invitation to drink wine |

300 |

| 89. |

Woman’s quarrel. Neapolitan Group. |

Facing 301 |

| 90. |

Chestnut vender. |

Facing 301 |

| 91. |

Warning. Neapolitan |

302 |

| 92. |

Justice. Neapolitan |

302 |

| 93. |

Little. Neapolitan |

302 |

| 94. |

Little. N.A. Indian |

302 |

| 95. |

Little. N.A. Indian |

302 |

| 96. |

Demonstration. Neapolitan |

302 |

| 97. |

“Fool.” Neapolitan |

303 |

| 98. |

“Fool.” Ib. |

303 |

| 99. |

“Fool.” Ib. |

303 |

| 100. |

Inquiry. Neapolitan |

303 |

| 101. |

Crafty, deceitful. Neapolitan |

303 |

| 102. |

Insult. Neapolitan |

304 |

| 103. |

Insult. Neapolitan |

304 |

| 104. |

Silence. Neapolitan |

304 |

| 105. |

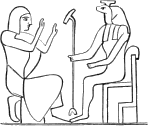

Child. Egyptian hieroglyph |

304 |

| 106. |

Negation. Neapolitan |

305 |

| 107. |

Hunger. Neapolitan |

305 |

| 108. |

Mockery. Neapolitan |

305 |

| 109. |

Fatigue. Neapolitan |

305 |

| 110. |

Deceit. Neapolitan |

305 |

| 111. |

Astuteness, readiness. Neapolitan |

305 |

| 112. |

Tree. Dakota, Hidatsa |

343 |

| 113. |

To grow. N.A. Indian |

343 |

| 114. |

Rain. Shoshoni, Apache |

344 |

| 115. |

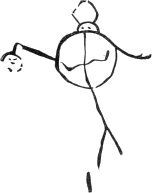

Sun. N.A. Indian |

344 |

| 116. |

Sun. Cheyenne |

344 |

| 117. |

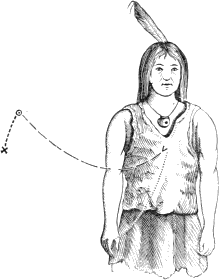

Soldier. Arikara |

345 |

| 118. |

No, negation. Egyptian |

355 |

| 119. |

Negation. Maya |

356 |

| 120. |

Nothing. Chinese |

356 |

| 121. |

Child. Egyptian figurative |

356 |

| 122. |

Child. Egyptian linear |

356 |

| 123. |

Child. Egyptian hieratic |

356 |

| 124. |

Son. Ancient Chinese |

356 |

| 125. |

Son. Modern Chinese |

356 |

| 126. |

Birth. Chinese character |

356 |

| 127. |

Birth. Dakota |

356 |

| 128. |

Birth, generic. N.A. Indians |

357 |

| 129. |

Man. Mexican |

357 |

| 130. |

Man. Chinese character |

357 |

| 131. |

Woman. Chinese character |

357 |

| 132. |

Woman. Ute |

357 |

| 133. |

Female, generic. Cheyenne |

357 |

| 134. |

To give water. Chinese character |

357 |

| 135. |

Water, to drink. N.A. Indian |

357 |

| 136. |

Drink. Mexican |

357 |

| 137. |

Water. Mexican |

357 |

| 138. |

Water, giving. Egypt |

358 |

| 139. |

Water. Egyptian |

358 |

| 140. |

Water, abbreviated |

358 |

| 141. |

Water. Chinese character |

358 |

| 142. |

To weep. Ojibwa pictograph |

358 |

| 143. |

Force, vigor. Egyptian |

358 |

| 144. |

Night. Egyptian |

358 |

| 145. |

Calling upon. Egyptian figurative |

359 |

| 146. |

Calling upon. Egyptian linear |

359 |

| 147. |

To collect, to unite. Egyptian |

359 |

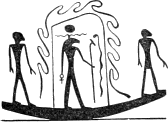

| 148. |

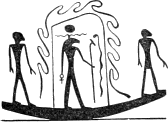

Locomotion. Egyptian figurative |

359 |

| 149. |

Locomotion. Egyptian linear |

359 |

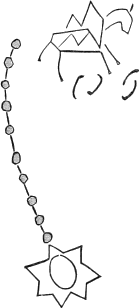

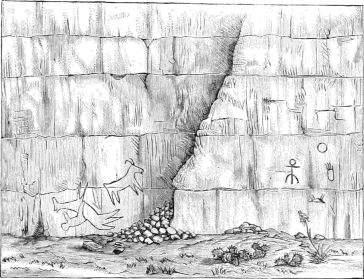

| 150. |

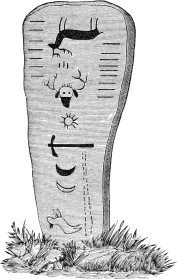

Shuⁿ´-ka Lu´-ta. Dakota |

365 |

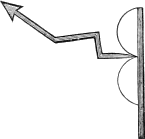

| 151. |

“I am going to the east.” Abnaki |

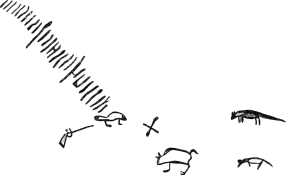

369 |

| 152. |

“Am not gone far.” Abnaki |

369 |

| 153. |

“Gone far.” Abnaki |

370 |

| 154. |

“Gone five days’ journey.” Abnaki |

370 |

| 155. |

Sun. N.A. Indian |

370 |

| 156. |

Sun. Egyptian |

370 |

| 157. |

Sun. Egyptian |

370 |

| 158. |

Sun with rays. Ib. |

371 |

| 159. |

Sun with rays. Ib. |

371 |

| 160. |

Sun with rays. Moqui pictograph |

371 |

| 161. |

Sun with rays. Ib. |

371 |

| 162. |

Sun with rays. Ib. |

371 |

| 163. |

Sun with rays. Ib. |

371 |

| 164. |

Star. Moqui pictograph |

371 |

| 165. |

Star. Moqui pictograph |

371 |

| 166. |

Star. Moqui pictograph |

371 |

| 167. |

Star. Moqui pictograph |

371 |

| 168. |

Star. Peruvian pictograph |

371 |

| 169. |

Star. Ojibwa pictograph |

371 |

| 170. |

Sunrise. Moqui do. |

371 |

| 171. |

Sunrise. Ib. |

371 |

| 172. |

Sunrise. Ib. |

371 |

| 173. |

Moon, month. Californian pictograph |

371 |

| 174. |

Pictograph, including sun. Coyotero Apache |

372 |

| 175. |

Moon. N.A. Indian |

372 |

| 176. |

Moon. Moqui pictograph |

372 |

| 177. |

Moon. Ojibwa pictograph |

372 |

| 178. |

Sky. Ib. |

372 |

| 179. |

Sky. Egyptian character |

372 |

| 180. |

Clouds. Moqui pictograph |

372 |

| 181. |

Clouds. Ib. |

372 |

| 182. |

Clouds. Ib. |

372 |

| 183. |

Cloud. Ojibwa pictograph |

372 |

| 184. |

Rain. New Mexican pictograph |

373 |

| 185. |

Rain. Moqui pictograph |

373 |

| 186. |

Lightning. Moqui pictograph |

373 |

| 187. |

Lightning. Ib. |

373 |

| 188. |

Lightning, harmless. Pictograph at Jemez, N.M. |

373 |

| 189. |

Lightning, fatal. Do. |

373 |

| 190. |

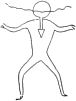

Voice. “The-Elk-that-hollows-walking” |

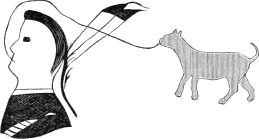

373 |

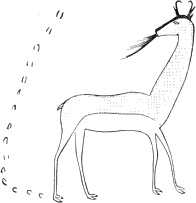

| 191. |

Voice. Antelope. Cheyenne drawing |

373 |

| 192. |

Voice, talking. Cheyenne drawing |

374 |

| 193. |

Killing the buffalo. Cheyenne drawing |

375 |

| 194. |

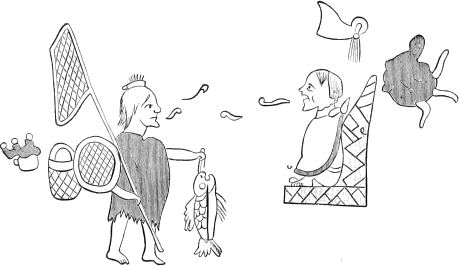

Talking. Mexican pictograph |

376 |

| 195. |

Talking, singing. Maya character |

376 |

| 196. |

Hearing ears. Ojibwa pictograph |

376 |

| 197. |

“I hear, but your words are from a bad heart.” Ojibwa |

376 |

| 198. |

Hearing serpent. Ojibwa pictograph |

376 |

| 199. |

Royal edict. Maya |

377 |

| 200. |

To kill. Dakota |

377 |

| 201. |

“Killed Arm.” Dakota |

377 |

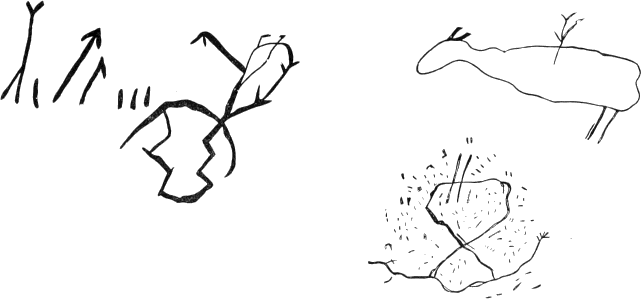

| 202. |

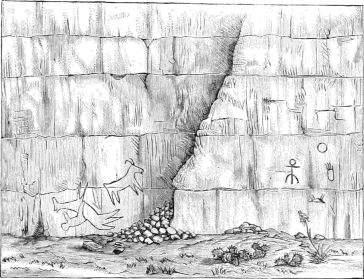

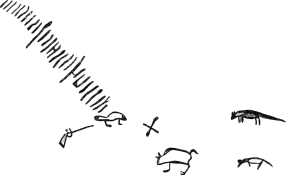

Pictograph, including “kill.” Wyoming Ter. |

378 |

| 203. |

Pictograph, including “kill.” Wyoming Ter. |

378 |

| 204. |

Pictograph, including “kill.” Wyoming Ter. |

379 |

| 205. |

Veneration. Egyptian character |

379 |

| 206. |

Mercy. Supplication, favor. Egyptian |

379 |

| 207. |

Supplication. Mexican pictograph |

380 |

| 208. |

Smoke. Ib. |

380 |

| 209. |

Fire. Ib. |

381 |

| 210. |

“Making medicine.” Conjuration. Dakota |

381 |

| 211. |

Meda. Ojibwa pictograph |

381 |

| 212. |

The God Knuphis. Egyptian |

381 |

| 213. |

The God Knuphis. Ib. |

381 |

| 214. |

Power. Ojibwa pictograph |

381 |

| 215. |

Meda’s Power. Ib. |

381 |

| 216. |

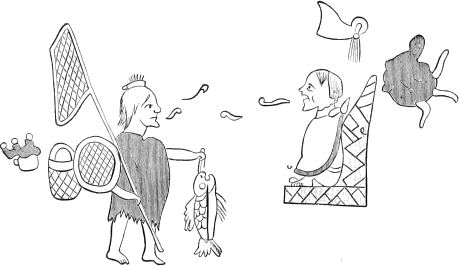

Trade pictograph |

382 |

| 217. |

Offering. Mexican pictograph |

382 |

| 218. |

Stampede of horses. Dakota |

382 |

| 219. |

Chapultepec. Mexican pictograph |

383 |

| 220. |

Soil. Ib. |

383 |

| 221. |

Cultivated soil. Ib. |

383 |

| 222. |

Road, path. Ib. |

383 |

| 223. |

Cross-roads and gesture sign. Mexican pictograph |

383 |

| 224. |

Small-pox or measles. Dakota |

383 |

| 225. |

“No thoroughfare.” Pictograph |

383 |

| 226. |

Raising of war party. Dakota |

384 |

| 227. |

“Led four war parties.” Dakota drawing |

384 |

| 228. |

Sociality. Friendship. Ojibwa pictograph |

384 |

| 229. |

Peace. Friendship. Dakota |

384 |

| 230. |

Peace. Friendship with whites. Dakota |

385 |

| 231. |

Friendship. Australian |

385 |

| 232. |

Friend. Brulé Dakota |

386 |

| 233. |

Lie, falsehood. Arikara |

393 |

| 234. |

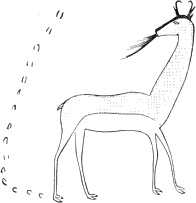

Antelope. Dakota |

410 |

| 235. |

Running Antelope. Personal totem |

410 |

| 236. |

Bad. Dakota |

411 |

| 237. |

Bear. Cheyenne |

412 |

| 238. |

Bear. Kaiowa, etc. |

413 |

| 239. |

Bear. Ute |

413 |

| 240. |

Bear. Moqui pictograph |

413 |

| 241. |

Brave. N.A. Indian |

414 |

| 242. |

Brave. Kaiowa, etc. |

415 |

| 243. |

Brave. Kaiowa, etc. |

415 |

| 244. |

Chief. Head of tribe. Absaroka |

418 |

| 245. |

Chief. Head of tribe. Pai-Ute |

418 |

| 246. |

Chief of a band. Absaroka and Arikara |

419 |

| 247. |

Chief of a band. Pai-Ute |

419 |

| 248. |

Warrior. Absaroka, etc. |

420 |

| 249. |

Ojibwa gravestone, including “dead” |

422 |

| 250. |

Dead. Shoshoni and Banak |

422 |

| 251. |

Dying. Kaiowa, etc. |

424 |

| 252. |

Nearly dying. Kaiowa |

424 |

| 253. |

Log house. Hidatsa |

428 |

| 254. |

Lodge. Dakota |

430 |

| 255. |

Lodge. Kaiowa, etc. |

431 |

| 256. |

Lodge. Sahaptin |

431 |

| 257. |

Lodge. Pai-Ute |

431 |

| 258. |

Lodge. Pai-Ute |

431 |

| 259. |

Lodge. Kutchin |

431 |

| 260. |

Horse. N.A. Indian |

434 |

| 261. |

Horse. Dakota |

434 |

| 262. |

Horse. Kaiowa, etc. |

435 |

| 263. |

Horse. Caddo |

435 |

| 264. |

Horse. Pima and Papago |

435 |

| 265. |

Horse. Ute |

435 |

| 266. |

Horse. Ute |

435 |

| 267. |

Saddling a horse. Ute |

437 |

| 268. |

Kill. N.A. Indian |

438 |

| 269. |

Kill. Mandan and Hidatsa |

439 |

| 270. |

Negation. No. Dakota |

441 |

| 271. |

Negation. No. Pai-Ute |

442 |

| 272. |

None. Dakota |

443 |

| 273. |

None. Australian |

444 |

| 274. |

Much, quantity. Apache |

447 |

| 275. |

Question. Australian |

449 |

| 276. |

Soldier. Dakota and Arikara |

450 |

| 277. |

Trade. Dakota |

452 |

| 278. |

Trade. Dakota |

452 |

| 279. |

Buy. Ute |

453 |

| 280. |

Yes, affirmation. Dakota |

456 |

| 281. |

Absaroka tribal sign. Shoshoni |

458 |

| 282. |

Apache tribal sign. Kaiowa, etc. |

459 |

| 283. |

Apache tribal sign. Pima and Papago |

459 |

| 284. |

Arikara tribal sign. Arapaho and Dakota |

461 |

| 285. |

Arikara tribal sign. Absaroka |

461 |

| 286. |

Blackfoot tribal sign. Dakota |

463 |

| 287. |

Blackfoot tribal sign. Shoshoni |

464 |

| 288. |

Caddo tribal sign. Arapaho and Kaiowa |

464 |

| 289. |

Cheyenne tribal sign. Arapaho and Cheyenne |

464 |

| 290. |

Dakota tribal sign. Dakota |

467 |

| 291. |

Flathead tribal sign. Shoshoni |

468 |

| 292. |

Kaiowa tribal sign. Comanche |

470 |

| 293. |

Kutine tribal sign. Shoshoni |

471 |

| 294. |

Lipan tribal sign. Apache |

471 |

| 295. |

Pend d’Oreille tribal sign. Shoshoni |

473 |

| 296. |

Sahaptin or Nez Percé tribal sign. Comanche |

473 |

| 297. |

Shoshoni tribal sign. Shoshoni |

474 |

| 298. |

Buffalo. Dakota |

477 |

| 299. |

Eagle Tail. Arikara |

477 |

| 300. |

Eagle Tail. Moqui pictograph |

477 |

| 301. |

Give me. Absaroka |

480 |

| 302. |

Counting. How many? Shoshoni and Banak |

482 |

| 303. |

I am going home. Dakota |

485 |

| 304. |

Question. Apache |

486 |

| 305. |

Shoshoni tribal sign. Shoshoni |

486 |

| 306. |

Chief. Shoshoni |

487 |

| 307. |

Cold, winter, year. Apache |

487 |

| 308. |

“Six.” Shoshoni |

487 |

| 309. |

Good, very well. Apache |

487 |

| 310. |

Many. Shoshoni |

488 |

| 311. |

Hear, heard. Apache |

488 |

| 312. |

Night. Shoshoni |

489 |

| 313. |

Rain. Shoshoni |

489 |

| 314. |

See each other. Shoshoni |

490 |

| 315. |

White man, American. Dakota |

491 |

| 316. |

Hear, heard. Dakota |

492 |

| 317. |

Brother. Pai-Ute |

502 |

| 318. |

No, negation. Pai-Ute |

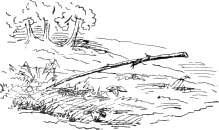

503 |

| 319. |

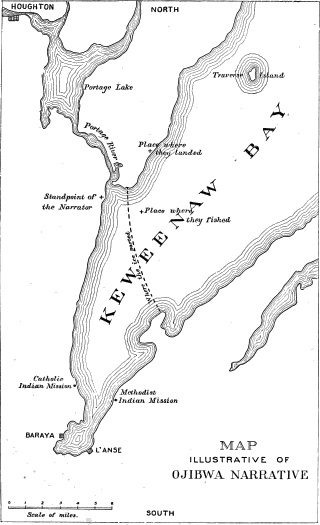

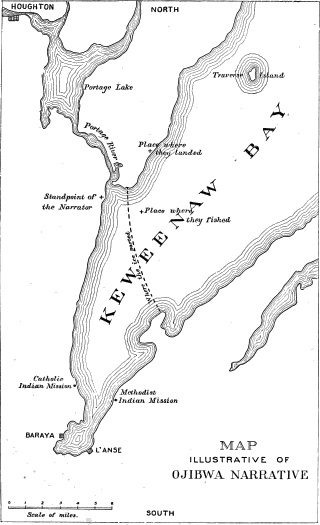

Scene of Na-wa-gi-jig’s story. |

Facing 508 |

| 320. |

We are friends. Wichita |

521 |

| 321. |

Talk, talking. Wichita |

521 |

| 322. |

I stay, or I stay right here. Wichita |

521 |

| 323. |

A long time. Wichita |

522 |

| 324. |

Done, finished. Do. |

522 |

| 325. |

Sit down. Australian |

523 |

| 326. |

Cut down. Wichita |

524 |

| 327. |

Wagon. Wichita |

525 |

| 328. |

Load upon. Wichita |

525 |

| 329. |

White man; American. Hidatsa |

526 |

| 330. |

With us. Hidatsa |

526 |

| 331. |

Friend. Hidatsa |

527 |

| 332. |

Four. Hidatsa |

527 |

| 333. |

Lie, falsehood. Hidatsa |

528 |

| 334. |

Done, finished. Hidatsa |

528 |

| 335. |

Peace, friendship. Hualpais. |

Facing 530 |

| 336. |

Question, ans’d by tribal sign for Pani. |

Facing 531 |

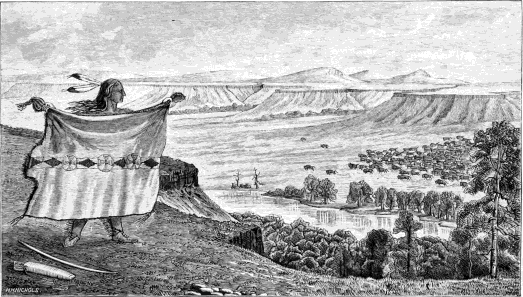

| 337. |

Buffalo discovered. Dakota. |

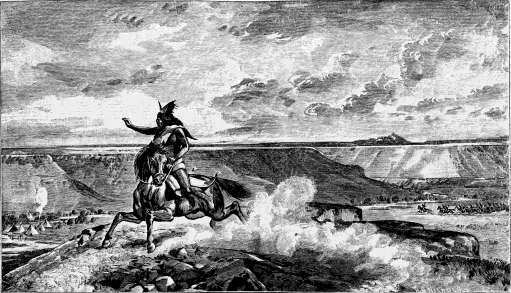

Facing 532 |

| 338. |

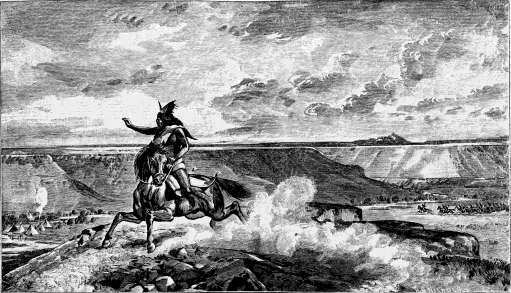

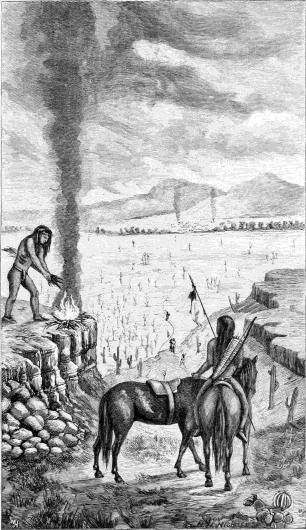

Discovery. Dakota. |

Facing 533 |

| 339. |

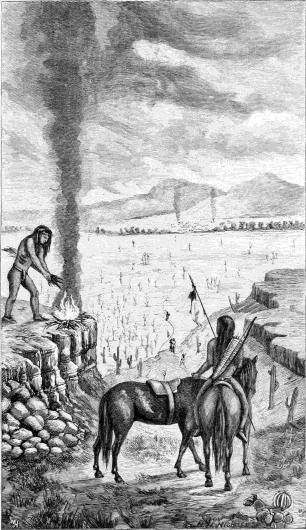

Success of war party. Pima. |

Facing 538 |

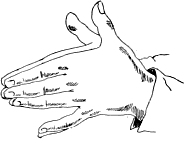

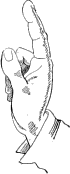

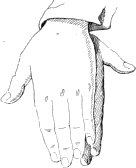

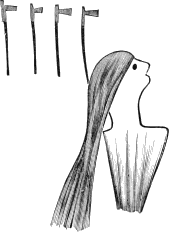

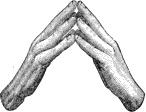

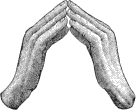

| 340. |

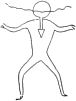

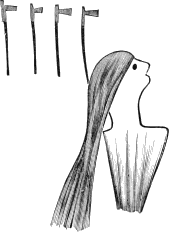

Outline for arm positions, full face |

545 |

| 341. |

Outline for arm positions, profile |

545 |

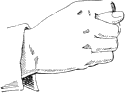

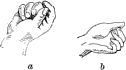

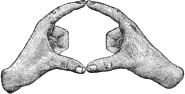

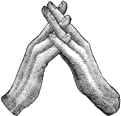

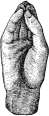

| 342a. |

Types of hand positions, A to L |

547 |

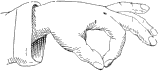

| 342b. |

Types of hand positions, M to Y |

548 |

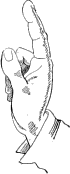

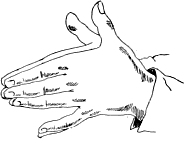

| 343. |

Example. To cut with an ax |

550 |

| 344. |

Example. A lie |

550 |

| 345. |

Example. To ride |

551 |

| 346. |

Example. I am going home |

551 |

xi

OF THE

BUREAU OF ETHNOLOGY.

By J. W. Powell,

Director.

INTRODUCTORY.

The exploration of the Colorado River of the West, begun in 1869 by

authority of Congressional action, was by the same authority

subsequently continued as the second division of the Geographical and

Geological Survey of the Territories, and, finally, as the Geographical

and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region.

By act of Congress of March 3, 1879, the various geological and

geographical surveys existing at that time were discontinued and the

United States Geological Survey was established.

In all the earlier surveys anthropologic researches among the North

American Indians were carried on. In that branch of the work finally

designated as the Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky

Mountain Region, such research constituted an important part of the

work. In the act creating the Geological Survey, provision was made to

continue work in this field under the direction of the Smithsonian

Institution, on the basis of the methods developed and materials

collected by the Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky

Mountain Region.

Under the authority of the act of Congress providing for the

continuation of the work, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

intrusted its management to the former director of

xii

the Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, and a bureau of ethnology was

thus practically organized.

In the Annual Report of the Geographical and Geological Survey of the

Rocky Mountain Region for 1877, the following statement of the condition

of the work at that time appears:

ETHNOGRAPHIC WORK.

During the same office season the ethnographic work was more

thoroughly organized, and the aid of a large number of volunteer

assistants living throughout the country was secured. Mr. W. H.

Dall, of the United States Coast Survey, prepared a paper on the tribes

of Alaska, and edited other papers on certain tribes of Oregon and

Washington Territory. He also superintended the construction of an

ethnographic map to accompany his paper, including on it the latest

geographic determination from all available sources. His long residence

and extended scientific labors in that region peculiarly fitted him for

the task, and he has made a valuable contribution both to ethnology and

geography.

With the same volume was published a paper on the habits and customs

of certain tribes of the State of Oregon and Washington Territory,

prepared by the late Mr. George Gibbs while he was engaged in scientific

work in that region for the government. The volume also contains a

Niskwalli vocabulary with extended grammatic notes, the last great work

of the lamented author.

In addition to the map above mentioned and prepared by Mr. Dall,

a second has been made, embracing the western portion of Washington

Territory and the northern part of Oregon. The map includes the results

of the latest geographic information and is colored to show the

distribution of Indian tribes, chiefly from notes and maps left by Mr.

Gibbs.

The Survey is indebted to the following gentlemen for valuable

contributions to this volume: Gov. J. Furujelm, Lieut. E. De Meulen, Dr.

Wm. F. Tolmie, and Rev. Father Mengarini.

Mr. Stephen Powers, of Ohio, who has spent several years in the study

of the Indians of California, had the year before been engaged to

prepare a paper on that subject. In the mean time at my request he was

employed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to travel among these tribes

for the purpose of making collections of Indian arts for the

International Exhibition. This afforded him opportunity of more

thoroughly accomplishing his work in the preparation of the

above-mentioned paper. On his return the new material was incorporated

with the old, and the whole has been printed.

At our earliest knowledge of the Indians of California they were

divided into small tribes speaking diverse languages and belonging to

radically different stocks, and the whole subject was one of great

complexity and interest. Mr. Powers has successfully unraveled the

difficult

xiii

problems relating to the classification and affinities of a very large

number of tribes, and his account of their habits and customs is of much

interest.

In the volume with his paper will be found a number of vocabularies

collected by himself, Mr. George Gibbs, General George Crook, U.S.A.,

General W. B. Hazen, U.S.A., Lieut. Edward Ross, U.S.A., Assistant

Surgeon Thomas F. Azpell, U.S.A., Mr. Ezra Williams, Mr. J. R.

Bartlett, Gov. J. Furujelm, Prof. F. L. O. Roehrig, Dr.

William A. Gabb, Mr. H. B. Brown, Mr. Israel S. Diehl, Dr. Oscar

Loew, Mr. Albert S. Gatschet, Mr. Livingston Stone, Mr. Adam Johnson,

Mr. Buckingham Smith, Padre Aroyo; Rev. Father Gregory Mengarini, Padre

Juan Comelias, Hon. Horatio Hale, Mr. Alexander S. Taylor, Rev. Antonio

Timmeno, and Father Bonaventure Sitjar.

The volume is accompanied by a map of the State of California,

compiled from the latest official sources and colored to show the

distribution of linguistic stocks.

The Rev. J. Owen Dorsey, of Maryland, has been engaged for more than

a year in the preparation of a grammar and dictionary of the Ponka

language. His residence among these Indians as a missionary has

furnished him favorable opportunity for the necessary studies, and he

has pushed forward the work with zeal and ability, his only hope of

reward being a desire to make a contribution to science.

Prof. Otis T. Mason, of Columbian College, has for the past year

rendered the office much assistance in the study of the history and

statistics of Indian tribes.

On June 13, Brevet Lieut. Col. Garrick Mallery, U.S.A., at the

request of the Secretary of the Interior, joined my corps under orders

from the honorable Secretary of War, and since that time has been

engaged in the study of the statistics and history of the Indians of the

western portion of the United States.

In April last, Mr. A. S. Gatschet was employed as a philologist to

assist in the ethnographic work of this Survey. He had previously been

engaged in the study of the languages of various North American tribes.

In June last at the request of this office he was employed by the Bureau

of Indian Affairs to collect certain statistics relating to the Indians

of Oregon and Washington Territory, and is now in the field. His

scientific reports have since that time been forwarded through the

honorable Commissioner of Indian Affairs to this office. His work will

be included in a volume now in course of preparation.

Dr. H. O. Yarrow, U.S.A., now on duty at the Army Medical Museum, in

Washington, has been engaged during the past year in the collection of

material for a monograph on the customs and rites of sepulture. To aid

him in this work circulars of inquiry have been widely circulated among

ethnologists and other scholars throughout North America, and much

material has been obtained which will greatly supplement his own

extended observations and researches.

xiv

Many other gentlemen throughout the United States have rendered me

valuable assistance in this department of investigation. Their labors

will receive due acknowledgment at the proper time, but I must not fail

to render my sincere thanks to these gentlemen, who have so cordially

and efficiently co-operated with me in this work.

A small volume, entitled “Introduction to the Study of Indian

Languages,” has been prepared and published. This book is intended for

distribution among collectors. In its preparation I have been greatly

assisted by Prof. W. D. Whitney, the distinguished philologist of

Yale College. To him I am indebted for that part relating to the

representation of the sounds of Indian languages; a work which

could not be properly performed by any other than a profound scholar in

this branch.

I complete the statement of the office-work of the past season by

mentioning that a tentative classification of the linguistic families of

the Indians of the United States has been prepared. This has been a work

of great labor, to which I have devoted much of my own time, and in

which I have received the assistance of several of the gentlemen above

mentioned.

In pursuing these ethnographic investigations it has been the

endeavor as far as possible to produce results that would be of

practical value in the administration of Indian affairs, and for this

purpose especial attention has been paid to vital statistics, to the

discovery of linguistic affinities, the progress made by the Indians

toward civilization, and the causes and remedies for the inevitable

conflict that arises from the spread of civilization over a region

previously inhabited by savages. I may be allowed to express the

hope that our labors in this direction will not be void of such useful

results.

In 1878 no report of the Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region was

published, as before its completion the question of reorganizing all of

the surveys had been raised, but the work was continued by the same

methods as in previous years.

The operations of the Bureau of Ethnology during the past fiscal year

will be briefly described.

In the plan of organization two methods of operation are

embraced:

First. The prosecution of research by the direct employment of

scholars and specialists; and

Second. By inciting and guiding research immediately conducted by

collaborators at work throughout the country.

It has been the effort of the Bureau to prosecute work in the various

branches of North American anthropology on a systematic plan, so that

every important field should be cultivated, limited only by the amount

appropriated by Congress.

xv

With little exception all sound anthropologic investigation in the

lower states of culture exhibited by tribes of men, as distinguished

from nations, must have a firm foundation in language Customs, laws,

governments, institutions, mythologies, religions, and even arts can not

be properly understood without a fundamental knowledge of the languages

which express the ideas and thoughts embodied therein. Actuated by these

considerations prime attention has been given to language.

It is not probable that there are many languages in North America

entirely unknown, and in fact it is possible there are none; but of many

of the known languages only short vocabularies have appeared. Except for

languages entirely unknown, the time for the publication of short

vocabularies has passed; they are no longer of value. The Bureau

proposes hereafter to publish short vocabularies only in the exceptional

cases mentioned above.

The distribution of the Introduction to the Study of Indian Languages

is resulting in the collection of a large series of chrestomathies,

which it is believed will be worthy of publication. It is also proposed

to publish grammars and dictionaries when those have been thoroughly and

carefully prepared. In each case it is deemed desirable to connect with

the grammar and dictionary a body of literature designed as texts for

reference in explaining the facts and principles of the language. These

texts will be accompanied by interlinear translations so arranged as

greatly to facilitate the study of the chief grammatic

characteristics.

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH AMERICAN PHILOLOGY, BY MR. J. C. PILLING.

There is being prepared in the office a bibliography of North

American languages. It was originally intended as a card catalogue for

office use, but has gradually assumed proportions which seem to justify

its publication. It is designed as an author’s catalogue, arranged

alphabetically, and is to include

xvi

titles of grammars, dictionaries, vocabularies, translations of the

scriptures, hymnals, doctrinæ christianæ, tracts, school-books, etc.,

general discussions, and reviews when of sufficient importance; in

short, a catalogue of authors who have written in or upon any of

the languages of North America, with a list of their works.

It has been the aim in preparing this material to make not only full

titles of all the works containing linguistics, but also to exhaust

editions. Whether full titles of editions subsequent to the first will

be printed will depend somewhat on the size of the volume it will make,

there being at present about four thousand five hundred cards, probably

about three thousand titles.

The bibliography is based on the library of the Director, but much

time has been spent in various libraries, public and private, the more

important being the Congressional, Boston Public, Boston Athenæum,

Harvard College, Congregational of Boston, Massachusetts Historical

Society, American Antiquarian Society of Worcester, the John Carter

Brown at Providence, the Watkinson at Hartford, and the American Bible

Society at New York. It is hoped that Mr. Pilling may find opportunity

to visit the principal libraries of New York and Philadelphia,

especially those of the historical societies, before the work is

printed.

In addition to personal research, much correspondence has been

carried on with the various missionaries and Indian agents throughout

the United States and Canada, and with gentlemen who have written upon

the subject, among whom are Dr. H. Rink, of Copenhagen, Dr. J. C.

E. Buschman, of Berlin, and the well-known bibliographers, Mr. J. Sabin,

of New York, Hon. J. R. Bartlett, of Providence, and Señor Don J.

G. Icazbalceta, of the City of Mexico.

Mr. Pilling has not attempted to classify the material

linguistically. That work has been left for a future publication,

intended to embody the results of an attempt to classify the tribes of

North America on the basis of language, and now in course of preparation

by the Director.

xvii

LINGUISTIC AND OTHER ANTHROPOLOGIC RESEARCHES, BY THE REV. J. OWEN

DORSEY.

For a number of years Mr. Dorsey has been engaged in investigations

among a group of cognate Dakotan tribes embracing three languages:

[¢]egiha, spoken by the Ponkas and Omahas, with a closely related

dialect of the same, spoken by the Kansas, Osage, and Kwapa tribes; the

[T]ɔiwere, spoken by the Iowa, Oto, and Missouri tribes; and the

Hotcañgara, spoken by the Winnebago.

In July, 1878, he repaired to the Omaha reservation, in the

neighborhood of which most of these languages are spoken, for the

purpose of continuing his studies.

Mr. Dorsey commenced the study of the [¢]egiha in 1871, and has

continued his researches in the group until the present time. He has

collected a very large body of linguistic material, both in grammar and

vocabulary, and when finally published a great contribution will be made

to North American linguistics.

These languages are excessively complex because of the synthetic

characteristics of the verb, incorporated particles being used in an

elaborate and complex scheme.

In these languages six general classes of pronouns are found:

1st. The free personal.

2d. The incorporated personal.

3d. The demonstrative.

4th. The interrogative.

5th. The relative.

6th. The indefinite.

One of the most interesting features of the language is found in the

genders or particle classifiers. The genders or classifiers are

animate and inanimate, and these are again divided into

the standing, sitting, reclining, and

moving; but in the Winnebago the reclining and

moving constitute but one class. They are suffixed to nouns,

pronouns, and verbs. When nouns, adjectives, adverbs, and prepositions

are used as predicants, i.e.,

xviii

to perform the function of verbs, these classifiers are also suffixed.

The classifiers point out with particularity the gender or class of the

subject and object. When numerals are used as nouns the classifiers are

attached.

In nouns and pronouns case functions are performed by an elaborate

system of postpositions in conjunction with the classifiers.

The verbs are excessively complex by reason of the use of many

incorporated particles to denote cause, manner,

instrument, purpose, condition, time, etc.

Voice, mode, and tense are not systematically differentiated in the

morphology, but voices, modes, and tenses, and a great variety of

adverbial qualifications enter into the complex scheme of incorporated

particles.

Sixty-six sounds are found in the [¢]egiha; sixty-two in the

[T]ɔiwere; sixty-two in the Hotcañgara; and the alphabet adopted by the

Bureau is used successfully for their expression.

While Mr. Dorsey has been prosecuting his linguistic studies among

these tribes he has had abundant opportunity to carry on other branches

of anthropologic research, and he has collected extensive and valuable

materials on sociology, mythology, religion, arts, customs, etc. His

final publication of the [¢]egiha will embrace a volume of literature

made up of mythic tales, historical narratives, letters, etc., in the

Indian, with interlinear translations, a selection from which

appears in the papers appended to this report. Another volume will be

devoted to the grammar and a third to the dictionary.

LINGUISTIC RESEARCHES, BY THE REV. S. R. RIGGS.

In 1852 the Smithsonian Institution published a grammar and

dictionary of the Dakota language prepared by Mr. Riggs. Since that time

Mr. Riggs, assisted by his sons, A. L. and T. L. Riggs, and by Mr.

Williamson, has been steadily engaged in revising and enlarging the

grammar and dictionary; and at the request of the Bureau he is also

preparing a volume of Dakota literature as texts for illustration to the

grammar and

xix

dictionary. He is rapidly preparing this work for publication, and it

will soon appear.

The work of Mr. Riggs and that of Mr. Dorsey, mentioned above, with

the materials already published, will place the Dakotan languages on

record more thoroughly than those of any other family in this

country.

The following is a table of the languages of this family now

recognized by the Bureau:

LANGUAGES OF THE DAKOTAN FAMILY.

1. Dakóta (Sioux), in four dialects:

(a) Mdéwakaⁿtoⁿwaⁿ and Waqpékute.

(b) Waqpétoⁿwaⁿ (Warpeton) and Sisítoⁿwaⁿ

(Sisseton).

These two are about equivalent to the modern Isaⁿ´yati

(Santee).

(c) Ihañk´toⁿwaⁿ (Yankton), including the

Assiniboins.

(d) Títoⁿwaⁿ (Teton).

2. [¢]egiha, in two (?) dialects:

(a) Umaⁿ´haⁿ (Omaha), spoken by the Omahas and

Ponkas.

(b) Ugáqpa (Kwapa), spoken by the Kwapas,

Osages, and Kansas.

3. [T]ɔiwére, in two dialects:

(a) [T]ɔiwére, spoken by the Otos and

Missouris.

(b) [T]ɔéʞiwere, spoken by the Iowas.

4. Hotcañ´gara, spoken by the Winnebagos.

5. Númañkaki (Mandan), in two dialects:

(a) Mitútahañkuc.

(b) Ruptári.

6. Hi¢átsa (Hidatsa), in two (?) dialects:

(a) Hidátsa or Minnetaree.

(b) Absároka or Crow.

7. Tútelo, in Canada.

8. Katâ´ba (Catawba), in South Carolina.

LINGUISTIC AND GENERAL RESEARCHES AMONG THE KLAMATH INDIANS, BY MR.

A. S. GATSCHET.

Of the Klamath language of Oregon there are two dialects—one

spoken by the Indians of Klamath Lake and the other by the

Modocs—constituting the Lutuami family of Hale and Gallatin.

Mr. Gatschet has spent much time among these Indians, at their

reservation and elsewhere, and has at the present time

xx

in manuscript nearly ready for the printer a large body of Klamath

literature, consisting of mythic, ethnic, and historic tales,

a grammar and a dictionary. The stories were told by the Indians

and recorded by himself, and constitute a valuable contribution to the

subject. Some specimens will appear in the papers appended to this

report.

The grammatic sketch treats of both dialects, which differ but

slightly in grammar but more in vocabulary. The grammar is divided into

three principal parts: Phonology, Morphology, and Syntax.

In Phonology fifty different sounds are recognized, including simple

and compound consonants, the vowels in different quantities, and the

diphthongs.

A characteristic feature of this language is described in explaining

syllabic reduplication, which performs iterative and distributive

functions. Reduplication for various purposes is found in most of the

languages of North America. In the Nahuatl, Sahaptin, and Selish

families it is most prominent. Mr. Gatschet’s researches will add

materially to the knowledge of the functions of reduplication in tribal

languages.

The verbal inflection is comparatively simple, for in it the subject

and object pronouns are not incorporated. In the verb Mr. Gatschet

recognizes ten general forms, a part of which he designates as

verbals, as follows:

1. Infinitive in -a.

2. Durative in -ota.

3. Causative in -oga.

4. Indefinite in -ash.

5. Indefinite in -uĭsh.

6. Conditional in -asht.

7. Desiderative in -ashtka.

8. Intentional in -tki.

9. Participle in -ank.

10. Past participle and verbal adjectives in -tko.

Tense and mode inflection is very rudimentary and is mostly

accomplished by the use of particles. The study of the prefixes and

suffixes of derivation is one of the chief difficulties of

xxi

the language, for they combine in clusters, and are not easily analyzed,

and their functions are often obscure.

The inflection of nouns by case endings and postpositions is rich in

forms; that of the adjective and numeral less elaborate.

Of the pronouns, only the demonstrative show a complexity of

forms.

Another feature of this language is found in verbs appended to

certain numerals, and thus serving as numerical classifiers. These verbs

express methods of counting and relate to form; that is, in each case

they present the Indian in the act of counting objects of a particular

form and placing them in groups of tens.

The appended verbs used as classifiers signify to place, but

in Indian languages we are not apt to find a word so highly

differentiated as place, but in its stead a series of words with

verbs and adverbs undifferentiated, each signifying to place,

with a qualification, as I place upon, I lay alongside of,

I stand up, by, etc. Thus we get classifiers attached to numerals

in the Klamath, analogous to the classifiers attached to verbs, nouns,

numerals, etc., in the Ponka, as mentioned above.

These classifiers in Klamath are further discriminated as to form;

but these form discriminations are the homologues of attitude

discriminations in the Ponka, for the form determines the attitude.

It is interesting to note how often in these lower languages attitude

or form is woven into the grammatic structure. Perhaps this arises from

a condition of expression imposed by the want of the verb to be,

so that when existence in place is to be affirmed, the verbs of

attitude, i.e., to stand, to sit, to lie,

and sometimes to move, are used to predicate existence in place,

and thus the mind comes habitually to consider all things as in the one

or the other of these attitudes. The process of growth seems to be that

verbs of attitude are primarily used to affirm existence in place until

the habit of considering the attitude is established; thus participles

of attitude are used with nouns, &c., and finally, worn down by the

law of phonic change, for economy, they become classifying particles.

This

xxii

view of the origin of classifying particles seems to be warranted by

studies from a great variety of Indian sources.

The syntactic portion is divided into four parts:

1st. On the predicative relation;

2d. On the objective relation;

3d. On the attributive relation; and the

4th. Exhibits the formation of simple and compound sentences,

followed by notes on the incorporative tendency of the language, its

rhetoric, figures, and idioms.

The alphabet adopted by Mr. Gatschet differs slightly from that used

by the Bureau, particularly in the modification of certain Roman

characters and the introduction of one Greek character. This occurred

from the fact that Mr. Gatschet’s material had been partly prepared

prior to the adoption of the alphabet now in use.

Mr. Gatschet has collected much valuable material relating to

governmental and social institutions, mythology, religion, music,

poetry, oratory, and other interesting matters. The body of Klamath

literature, or otherwise the text previously mentioned, constitutes the

basis of these investigations.

STUDIES AMONG THE IROQUOIS, BY MRS. E. A. SMITH.

Mrs. Smith, of Jersey City, has undertaken to prepare a series of

chrestomathies of the Iroquois language, and has already made much

progress. Three of them are ready for the printer, and that on the

Tuscarora language has been increased much beyond the limits at first

established. She has also collected interesting material relating to the

mythology, habits, customs, &c., of these Indians, and her

contributions will be interesting and important.

WORK BY PROF. OTIS T. MASON.

On the advent of the white man in America a great number of tribes

were found. For a variety of reasons the nomenclature

xxiii

of these tribes became excessively complex. Names were greatly

multiplied for each tribe and a single name was often inconsistently

applied to different tribes. Several important reasons conspired to

bring about this complex state of synonymy:

1st. A great number of languages were spoken, and ofttimes the first

names obtained for tribes were not the names used by themselves, but the

names by which they were known to some other tribes.

2d. The governmental organization of the Indians was not understood,

and the names for gentes, tribes, and confederacies were confounded.

3d. The advancing occupancy of the country by white men changed the

habitat of the Indians, and in their migrations from point to point

their names were changed.

Under these circumstances the nomenclature of Indian tribes became

ponderous and the synonymy complex. To unravel this synonymy is a task

of great magnitude. Early in the fiscal year the materials already

collected on this subject were turned over to Professor Mason and

clerical assistance given him, and he has prepared a card catalogue of

North American tribes, exhibiting the synonymy, for use in the office.

This is being constantly revised and enlarged, and will eventually be

published.

Professor Mason is also engaged in editing a grammar and dictionary

of the Chata language, by the late Rev. Cyrus Byington, the manuscript

of which was by Mrs. Byington turned over to the Bureau of Ethnology.

The dictionary is Chata-English, and Professor Mason has prepared an

English-Chata of about ten thousand words. He has also undertaken to

enlarge the grammar by a further study of the language among the Indians

themselves.

THE STUDY OF GESTURE SPEECH, BY BREVET LIEUT. COL. GARRICK MALLERY,

U.S.A.

The growth of the languages of civilized peoples in their later

stages may be learned from the study of recorded literature;

xxiv

and by comparative methods many interesting facts may be discovered

pertaining to periods anterior to the development of writing.

In the study of peoples who have not passed beyond the tribal

condition, laws of linguistic growth anterior to the written stage may

be discovered. Thus, by the study of the languages of tribes and the

languages of nations, the methods and laws of development are discovered

from the low condition represented by the most savage tribe to the

highest condition existing in the speech of civilized man. But there is

a development of language anterior to this—a prehistoric

condition—of profound interest to the scholar, because in it the

beginnings of language—the first steps in the organization of

articulate speech—are involved.

On this prehistoric stage, light is thrown from four sources:

1st. Infant speech, in which the development of the language of the

race is epitomized.

2d. Gesture speech, which, among tribal peoples, never passes beyond

the first stages of linguistic growth; and these stages are probably

homologous to the earlier stages of oral speech.

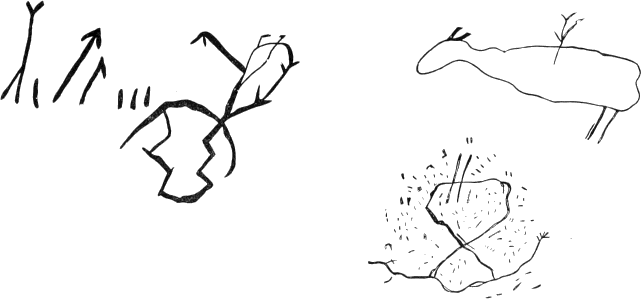

3d. Picture writing, in which we again find some of the

characteristics of prehistoric speech illustrated.

4th. It may be possible to learn something of the elements of which

articulate speech is compounded by studying the inarticulate language of

the lower animals.

The traits of gesture speech that seem to illustrate the condition of

prehistoric oral language are found in the synthetic character of its

signs. The parts of speech are not differentiated, and the sentence is

not integrated; and this characteristic is more marked than in that of

the lowest oral language yet studied. For this reason the facts of

gesture speech constitute an important factor in the philosophy of

language. Doubtless, care must be exercised in its use because of the

advanced mental condition of the people who thus express their thought,

but with due caution it may be advantageously used. In itself,

independent of its relations to oral speech, the subject is of great

interest.

xxv

In taking up this subject for original investigation, valuable

published matter was found for comparison with that obtained by Colonel

Mallery. His opportunities for collecting materials from the Indians

themselves were abundant, as delegations of various tribes are visiting

Washington from time to time, by which the information obtained during

his travels was supplemented.

Again, the method of investigation by the assistance of a number of

collaborators is well illustrated in this work, and contributions from

various sources were made to the materials for study. The methods of

obtaining these contributions will be more fully explained hereafter.

One of the papers appended to this report was prepared by Colonel

Mallery and relates to this subject.

During the continuance of the Survey of the Colorado River, and of

the Rocky Mountain Region, the Director and his assistants made large

collections of pictographs. When Colonel Mallery joined the corps these

collections were turned over to him for more careful study. From various

sources these pictographs are rapidly accumulating, and now the subject

is assuming large proportions, and valuable results are expected.

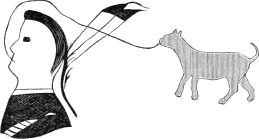

An interesting relation between gesture speech and pictography

consists in the discovery that to the delineation of natural objects is

added the representation of gesture signs. Materials in America are very abundant, and the

prehistoric materials may be studied in the light given by the practices

now found among Indian tribes.

STUDIES IN CENTRAL AMERICAN PICTURE WRITING, BY PROF. E. S.

HOLDEN.

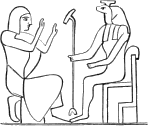

In Central America and Mexico, picture writing had progressed to a

stage far in advance of anything discovered to the northward. Some of

the most interesting of these are the rock inscriptions of Yucatan,

Copan, Palenque, and other ruins of Central America.

Professor Holden has devoted much time to the study of

xxvi

these inscriptions, for the purpose of discovering the characteristics

of the pictographic method and deciphering the records, and the

discoveries made by him are of great interest.

The Bureau has given him clerical assistance and such other aid as

has been found possible, and a paper by him on this subject appears with

this volume.

THE STUDY OF MORTUARY CUSTOMS, BY DR. H. C. YARROW.

The tribes of North America do not constitute a homogeneous people.

In fact, more than seventy distinct linguistic stocks are discovered,

and these are again divided by important distinctions of language. Among

these tribes varying stages of culture have been reached, and these

varying stages are exhibited in their habits and customs; and in a

territory of such vast extent the physical environment affecting culture

and customs is of great variety. Forest lands on the one hand, prairie

lands on the other, unbroken plains and regions of rugged mountains, the

cold, naked, desolate shores of sea and lake at the north and the dense

chaparral of the torrid south, the valleys of quiet rivers and the

cliffs and gorges of the cañon land—in all a great diversity of

physical features are found, imposing diverse conditions for obtaining

subsistence, in means and methods of house-building, creating diverse

wants and furnishing diverse ways for their supply. Through diversities

of languages and diversities of environment, diversity of traditions and

diversity of institutions have been produced; so that in many important

respects one tribe is never the counterpart of another.

These diversities have important limitations in the unity of the

human race and the social, mental, and moral homogeneity that has

everywhere controlled the progress of culture. The way of human progress

is one road, though wide.

From the interesting field of research cultivated by Dr. Yarrow an

abundant harvest will be gathered. The materials already accumulated are

large, and are steadily increasing through his vigorous work. These

materials constitute something

xxvii

more than a record of quaint customs and abhorrent rites in which morbid

curiosity may revel. In them we find the evidences of traits of

character and lines of thought that yet exist and profoundly influence

civilization. Passions in the highest culture deemed most

sacred—the love of husband and wife, parent and child, and kith

and kin, tempering, beautifying, and purifying social life and

culminating at death, have their origin far back in the early history of

the race and leaven the society of savagery and civilization alike. At either end of the

line bereavement by death tears the heart and mortuary customs are

symbols of mourning. The mystery which broods over the abbey where lie

the bones of king and bishop, gathers over the ossuary where lie the

bones of chief and shamin; for the same longing to solve the mysteries of

life and death, the same yearning for a future life, the same awe of

powers more than human, exist alike in the mind of the savage and the

sage.

By such investigations we learn the history of culture in these

important branches, and in a paper appended to this report Dr. Yarrow

presents some of the results of his studies.

INVESTIGATIONS RELATING TO CESSIONS OF LAND BY INDIAN TRIBES TO THE

UNITED STATES, BY C. C. ROYCE.

When civilized man first came to America the continent was partially

occupied by savage tribes, who obtained subsistence by hunting, by

fishing, by gathering vegetal products, and by rude garden culture in

cultivating small patches of ground. Semi-nomadic occupancy for such

purposes was their tenure to the soil.

On the organization of the present government such theories of

natural law were entertained that even this imperfect occupancy was held

to be sufficient title. Publicists, jurists, and statesmen agreed that

no portion of the waste of lands between the oceans could be acquired

for the homes of the incoming civilized men but by purchase or conquest

in just war. These theories were most potent in establishing practical

relations,

xxviii

and controlling governmental dealings with Indian tribes. They were

adjudged to be dependent domestic nations.

Under this theory a system of Indian affairs grew up, the history of

which, notwithstanding mistakes and innumerable personal wrongs, yet

demonstrates the justice inherent in the public sentiment of the nation

from its organization to the present time.

The difficulties subsisting in the adjustment of rights between

savage and civilized peoples are multiform and complex. Ofttimes the

virtues of one condition are the crimes of the other; happiness is

misery; justice, injustice. Thus, when the civilized man would do the

best, he gave the most offense. Under such circumstances it was

impossible for wisdom and justice combined to avert conflict.

One chapter in the history of Indian affairs in America is a doleful

tale of petty but costly and cruel wars; but there are other chapters

more pleasant to contemplate.

The attempts to educate the Indians and teach them the ways of

civilization have been many; much labor has been given, much treasure

expended. While to a large extent all of these efforts have disappointed

their enthusiastic promoters, yet good has been done, but rather by the

personal labors of missionaries, teachers, and frontiersmen associating

with Indians in their own land than by institutions organized and

supported by wealth and benevolence not immediately in contact with

savagery.

The great boon to the savage tribes of this country, unrecognized by

themselves, and, to a large extent, unrecognized by civilized men, has

been the presence of civilization, which, under the laws of

acculturation, has irresistibly improved their culture by substituting

new and civilized for old and savage arts, new for old customs—in

short, transforming savage into civilized life. These unpremeditated

civilizing influences have had a marked effect. The great body of the

Indians of North America have passed through stages of culture in the

last hundred years achieved by our Anglo-Saxon ancestors only by the

slow course of events through a thousand years.

The Indians of the continent have not greatly diminished

xxix

in numbers, and the tribes longest in contact with civilization are

increasing. The whole body of Indians is making rapid progress toward a

higher culture, notwithstanding the petty conflicts yet occurring where

the relations of the Indian tribes to our civilization have not yet been

adjusted by the adoption upon their part of the first conditions of a

higher life.

The part which the General Government, representing public sentiment,

has done in the extinguishment of the vague Indian title to lands in the

granting to them of lands for civilized homes on reservations and in

severalty, in the establishment and support of schools, in the endeavors

to teach them agriculture and other industrial arts—in these and

many other ways justice and beneficence have been shown. Thus the

history of the tribes of America from savagery to civilization is a

history of three:

First. The history of acculturation—the effect of the presence

of civilization upon savagery.

Second. The history of Indian wars that have arisen in part from the

crimes and in part from the ignorance of either party.

Third. The history of civil Indian affairs. This last is divided into

a number of parts:

1st. The extinguishment of the Indian title.

2d. The gathering of Indians upon reservations.

3d. The instrumentalities used to teach the Indians civilized

industries; and

4th. The establishment and operation of schools.

From the organization of the Government to the present time these

branches of Indian affairs have been in operation; lands have been

bought and bought again; Indian tribes have been moved and moved again;

reservations have been established and broken up. The Government has

sought to give lands in severalty to the Indians from time to time along

the whole course of the history of Indian affairs. Every experiment to

teach the Indians the industries of civilization that could be devised