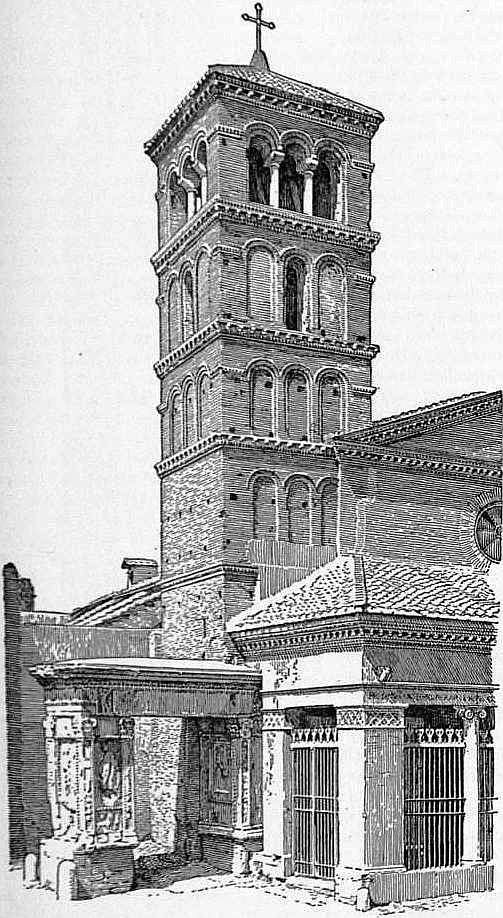

Fig. 1.—Campanile of S. Giorgio in Velabro, Rome.

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Camorra" to "Cape Colony"

Author: Various

Release date: July 3, 2010 [eBook #33052]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

CAMORRA, a secret society of Naples associated with robbery, blackmail and murder. The origin of the name is doubtful. Probably both the word and the association were introduced into Naples by Spaniards. There is a Spanish word camorra (a quarrel), and similar societies seem to have existed in Spain long before the appearance of the Camorra in Naples. It was in 1820 that the society first became publicly known. It was primarily social, not political, and originated in the Neapolitan prisons then filled with the victims of Bourbon misrule and oppression, its first purpose being the protection of prisoners. In or about 1830 the Camorra was carried into the city by prisoners who had served their terms. The members worked the streets in gangs. They had special methods of communicating with each other. They mewed like cats at the approach of the patrol, and crowed like cocks when a likely victim approached. A long sigh gave warning that the latter was not alone, a sneeze meant he was not “worth powder and shot,” and so on. The society rapidly extended its power, and its operations included smuggling and blackmail of all kinds in addition to ordinary road-robberies. Its influence grew to be considerable. Princes were in league with and shared the profits of the smugglers: statesmen and dignitaries of the church, all classes in fact, were involved in the society’s misdeeds. From brothels the Camorra drew huge fees, and it maintained illegal lottery offices. The general disorder of Naples was so great and the police so badly organized that merchants were glad to engage the Camorra to superintend the loading and unloading of merchandise. Being non-political, the government did not interfere with the society; indeed its members were taken into the police service and the Camorra sometimes detected crimes which baffled the authorities. After 1848 the society became political. In 1860, when the constitution was granted by Francis II., the camorristi then in gaol were liberated in great numbers. The association became all-powerful at elections, and general disorder reigned till 1862. Thereafter severe repressive measures were taken to curtail its power. In September 1877 there was a determined effort to exterminate it: fifty-seven of the most notorious camorristi being simultaneously arrested in the market-place. Though much of its power has gone, the Camorra has remained vigorous. It has grown upwards, and highly-placed and well-known camorristi have entered municipal administrations and political life. In 1900 revelations as to the Camorra’s power were made in the course of a libel suit, and these led to the dissolution of the Naples municipality and the appointment of a royal commissioner. A government inquiry also took place. As the result of this investigation the Honest Government League was formed, which succeeded in 1901 in entirely defeating the Camorra candidates at the municipal elections.

The Camorra was divided into classes. There were the “swell mobsmen,” the camorristi who dressed faultlessly and mixed with and levied fines on people of highest rank. Most of these were well connected. There were the lower order of blackmailers who preyed on shopkeepers, boatmen, &c.; and there were political and murdering camorristi. The ranks of the society were largely recruited from the prisons. A youth had to serve for one year an apprenticeship so to speak to a fully admitted camorrista when he was sometimes called picciotto d’ honore, and after giving proof of courage and zeal became a picciotto di sgarro, one, that is, of the lowest grade of members. In some localities he was then called tamurro. The initiatory ceremony for full membership is now a mock duel in which the arm alone is wounded. In early times initiation was more severe. The camorristi stood round a coin laid on the ground, and at a signal all stooped to thrust at it with their knives while the novice had at the same time to pick the coin up, with the result that his hand was generally pierced through in several places. The noviciate as picciotto di sgarro lasted three years, during which the lad had to work for the camorrista who had been assigned to him as master. After initiation there was a ceremony of reception. The camorristi stood round a table on which were a dagger, a loaded pistol, a glass of water or wine supposed to be poisoned and a lancet. The picciotto was brought in and one of his veins opened. Dipping his hand in his own blood, he held it out to the camorristi and swore to keep the society’s secrets and obey orders. Then he had to stick the dagger into the table, cock the pistol, and hold the glass to his mouth to show his readiness to die for the society. His master now bade him kneel before the dagger, placed his right hand on the lad’s head while with the left he fired off the pistol into the air and smashed the poison-glass. He then drew the dagger from the table and presented it to the new comrade and embraced him, as did all the others. The Camorra was divided into centres, each under a chief. There were twelve at Naples. The society seems at one time to have always had a supreme chief. The last known was Aniello Ansiello, who finally disappeared and was never arrested. The chief of every centre was elected by the members of it. All the earnings of the centre were paid to and then distributed by him. The camorristi employ a whole vocabulary of cant terms. Their chief is masto or si masto, “sir master.” When a member meets him he salutes with the phrase Masto, volite niente? (“Master, do you want anything?”). The members are addressed simply as si.

See Monnier, La Camorra (Florence, 1863); Umilta, Camorra et Mafia (Neuchâtel, 1878); Alongi, La Camorra (1890); C.W. Heckethorn Secret Societies of All Ages (London, 1897); Blasio, Usi e costumi dei Camorriste (Naples, 1897).

CAMP (from Lat. campus, field), a term used more particularly in a military sense, but also generally for a temporarily organized place of food and shelter in open country, as opposed to ordinary housing (see Camping-out). The shelter of troops in the field has always been of the greatest importance to their well-being, and from the earliest times tents and other temporary shelters have been employed as much as possible when it is not feasible or advisable to quarter the troops in barracks or in houses. The applied sense of the word “camp” as a military post of any kind comes from the practice which prevailed in the Roman army of fortifying every encampment. In modern warfare the word is used in two ways. In the wider sense, “camp” is opposed to “billets,” “cantonments” or “quarters,” in which the troops are scattered amongst the houses of towns or villages for food and shelter. In a purely military camp the soldiers live and sleep in an area of open ground allotted for their sole use. They are thus kept in a state of concentration and readiness for immediate action, and are under better disciplinary control than when in quarters, but they suffer more from the weather and from the want of comfort and warmth. In the restricted sense “camp” implies tents for all ranks, and is thus opposed to “bivouac,” in which the only shelter is that afforded by improvised screens, &c., or at most small tentes d’abri carried in sections by the men themselves. The weight of large regulation tents and the consequent increase in the number of horses and vehicles in the transport service are, however, disadvantages so grave that the employment of canvas camps in European warfare is almost a thing of the past. If the military situation permits, all troops are put into quarters, only the outpost troops bivouacking. This course was pursued by the German field armies in 1870-1871, even during the winter campaign.

Circumstances may of course require occasionally a whole army to bivouac, but in theatres of war in which quarters are not to be depended upon, tents must be provided, for no troops can endure many successive nights in bivouac, except in summer, without serious detriment to their efficiency. In a war on the Russo-German frontier, for instance, especially if operations were carried out in the autumn and winter, tents would be absolutely essential at whatever cost of transport. In this connexion it may be said that a good railway system obviates many of the disadvantages attending the use of tents. For training purposes in peace time, standing camps are formed. These may be considered simply as temporary barracks. An entrenched camp is an area of ground occupied by, or suitable for, the camps of large bodies of troops, and protected by fortifications.

Ancient Camps.—English writers use “camp” as a generic term for any remains of ancient military posts, irrespective of 121 their special age, size, purpose, &c. Thus they include under it various dissimilar things. We may distinguish (1) Roman “camps” (castra) of three kinds, large permanent fortresses, small permanent forts (both usually built of stone) and temporary earthen encampments (see Roman Army); (2) Pre-Roman; and (3) Post-Roman camps, such as occur on many English hilltops. We know far too little to be able to assign these to their special periods. Often we can say no more than that the “camp” is not Roman. But we know that enclosures fortified with earthen walls were thrown up as early as the Bronze Age and probably earlier still, and that they continued to be built down to Norman times. These consisted of hilltops or cliff-promontories or other suitable positions fortified with one or more lines of earthen ramparts with ditches, often attaining huge size. But the idea of an artificial elevation seems to have come in first with the Normans. Their mottes or earthen mounds crowned with wooden palisades or stone towers and surrounded by an enclosure on the flat constituted a new element in fortification and greatly aided the conquest of England. (See Castle.)

CAMPAGNA DI ROMA, the low country surrounding the city of Rome, bounded on the N.W. by the hills surrounding the lake of Bracciano, on the N.E. by the Sabine mountains, on the S.E. by the Alban hills, and on the S.W. by the sea. (See Latium, and Rome (province).)

CAMPAIGN, a military term for the continuous operations of an army during a war or part of a war. The name refers to the time when armies went into quarters during the winter and literally “took the field” at the opening of summer. The word is also used figuratively, especially in politics, of any continuous operations aimed at a definite object, as the “Plan of Campaign” in Ireland during 1886-1887. The word is derived from the Latin Campania, the plain lying south-west of the Tiber, c.f. Italian, la Campagna di Roma, from which came two French forms: (1) Champagne, the name given to the level province of that name, and hence the English “champaign,” a level tract of country free from woods and hills; and (2) Campagne, and the English “campaign” with the restricted military meaning.

CAMPAN, JEANNE LOUISE HENRIETTE (1752-1822), French educator, the companion of Marie Antoinette, was born at Paris in 1752. Her father, whose name was Genest, was first clerk in the foreign office, and, although without fortune, placed her in the most cultivated society. At the age of fifteen she could speak English and Italian, and had gained so high a reputation for her accomplishments as to be appointed reader to the three daughters of Louis XV. At court she was a general favourite, and when she bestowed her hand upon M. Campan, son of the Secretary of the royal cabinet, the king gave her an annuity of 5000 livres as dowry. She was soon afterwards appointed first lady of the bedchamber by Marie Antoinette; and she continued to be her faithful attendant till she was forcibly separated from her at the sacking of the Tuileries on the 20th of June 1792. Madame Campan survived the dangers of the Terror, but after the 9th Thermidor finding herself almost penniless, and being thrown on her own resources by the illness of her husband, she bravely determined to support herself by establishing a school at St Germain. The institution prospered, and was patronized by Hortense de Beauharnais, whose influence led to the appointment of Madame Campan as superintendent of the academy founded by Napoleon at Écouen for the education of the daughters and sisters of members of the Legion of Honour. This post she held till it was abolished at the restoration of the Bourbons, when she retired to Mantes, where she spent the rest of her life amid the kind attentions of affectionate friends, but saddened by the loss of her only son, and by the calumnies circulated on account of her connexion with the Bonapartes. She died in 1822, leaving valuable Mémoires sur la vie privée de Marie Antoinette, suivis de souvenirs et anecdotes historiques sur les règnes de Louis XIV.-XV. (Paris, 1823); a treatise De l’Éducation des Femmes; and one or two small didactic works, written in a clear and natural style. The most noteworthy thing in her educational system, and that which especially recommended it to Napoleon, was the place given to domestic economy in the education of girls. At Écouen the pupils underwent a complete training in all branches of housework.

See Jules Flammermont, Les Mémoires de Madame de Campan (Paris, 1886), and histories of the time.

CAMPANELLA, TOMMASO (1568-1639), Italian Renaissance philosopher, was born at Stilo in Calabria. Before he was thirteen years of age he had mastered nearly all the Latin authors presented to him. In his fifteenth year he entered the order of the Dominicans, attracted partly by reading the lives of Albertus Magnus and Aquinas, partly by his love of learning. He took a course in philosophy in the convent at Morgentia in Abruzzo, and in theology at Cosenza. Discontented with this narrow course of study, he happened to read the De Rerum Natura of Bernardino Telesio, and was delighted with its freedom of speech and its appeal to nature rather than to authority. His first work in philosophy (he was already the author of numerous poems) was a defence of Telesio, Philosophia sensibus demonstrata (1591). His attacks upon established authority having brought him into disfavour with the clergy, he left Naples, where he had been residing, and proceeded to Rome. For seven years he led an unsettled life, attracting attention everywhere by his talents and the boldness of his teaching. Yet he was strictly orthodox, and was an uncompromising advocate of the pope’s temporal power. He returned to Stilo in 1598. In the following year he was committed to prison because he had joined those who desired to free Naples from Spanish tyranny. His friend Naudée, however, declares that the expressions used by Campanella were wrongly interpreted as revolutionary. He remained for twenty-seven years in prison. Yet his spirit was unbroken; he composed sonnets, and prepared a series of works, forming a complete system of philosophy. During the latter years of his confinement he was kept in the castle of Sant’ Elmo, and allowed considerable liberty. Though, even then, his guilt seems to have been regarded as doubtful, he was looked upon as dangerous, and it was thought better to restrain him. At last, in 1626, he was nominally set at liberty; for some three years he was detained in the chambers of the Inquisition, but in 1629 he was free. He was well treated at Rome by the pope, but on the outbreak of a new conspiracy headed by his pupil, Tommaso Pignatelli, he was persuaded to go to Paris (1634), where he was received with marked favour by Cardinal Richelieu. The last few years of his life he spent in preparing a complete edition of his works; but only the first volume appears to have been published. He died on the 21st of May 1639.

In philosophy, Campanella was, like Giordano Bruno (q.v.), a follower of Nicolas of Cusa and Telesio. He stands, therefore, in the uncertain half-light which preceded the dawn of modern philosophy. The sterility of scholastic Aristotelianism, as he understood it, drove him to the study of man and nature, though he was never entirely free from the medieval spirit. Devoutly accepting the authority of Faith in the region of theology, he considered philosophy as based on perception. The prime fact in philosophy was to him, as to Augustine and Descartes, the certainty of individual consciousness. To this consciousness he assigned a threefold content, power, will and knowledge. It is of the present only, of things not as they are, but merely as they seem. The fact that it contains the idea of God is the one, and a sufficient, proof of the divine existence, since the idea of the Infinite must be derived from the Infinite. God is therefore a unity, possessing, in the perfect degree, those attributes of power, will and knowledge which humanity possesses only in part. Furthermore, since community of action presupposes homogeneity, it follows that the world and all its parts have a spiritual nature. The emotions of love and hate are in everything. The more remote from God, the greater the degree of imperfection (i.e.Not-being) in things. Of imperfect things, the highest are angels and human beings, who by virtue of the possession of reason are akin to the Divine and superior to the lower creation. Next comes the mathematical world of space, then the corporeal world, and finally the empirical world with its limitations of space and time. The impulse of 122 self-preservation in nature is the lowest form of religion; above this comes animal religion; and finally rational religion, the perfection of which consists in perfect knowledge, pure volition and love, and is union with God. Religion is, therefore, not political in origin; it is an inherent part of existence. The church is superior to the state, and, therefore, all temporal government should be in subjection to the pope as the representative of God.

In natural philosophy Campanella, closely following Telesio, advocates the experimental method and lays down heat and cold as the fundamental principles by the strife of which all life is explained. In political philosophy (the Civitas Solis) he sketches an ideal communism, obviously derived from the Platonic, based on community of wives and property with state-control of population and universal military training. In every detail of life the citizen is to be under authority, and the authority of the administrators is to be based on the degree of knowledge possessed by each. The state is, therefore, an artificial organism for the promotion of individual and collective good. In contrast to More’s Utopia, the work is cold and abstract, and lacking in practical detail. On the view taken as to his alleged complicity in the conspiracy of 1599 depends the vexed question as to whether this system was a philosophic dream, or a serious attempt to sketch a constitution for Naples in the event of her becoming a free city. The De Monarchia Hispanica contains an able account of contemporary politics especially Spanish.

Thus Campanella, though neither an original nor a systematic thinker, is among the precursors, on the one hand, of modern empirical science, and on the other of Descartes and Spinoza. Yet his fondness for the antithesis of Being and Not-being (Ens and Non-ens) shows that he had not shaken off the spirit of scholastic thought.

Bibliography.—For his works see Quétif-Echard, appendix to E.S. Cypriano, Vita Campanellae (Amsterdam, 1705 and 1722); Al. d’Ancona’s edition, with introduction (Turin, 1854). The most important are De sensu rerum (1620); Realis philosophiae epilogisticae partes IV. (with Civitas Solis) (1623); Atheismus triumphatus (1631); Philos. rationalis (1637); Philos. universalis seu metaph. (1637); De Monarchia Hispanica (1640). For his life, see Cypriano (above); M. Baldachini, Vita e filos. di Tommaso Campanella (Naples, 1840-1853, 1847-1857); Dom. Berti, Lettere inedite di T. Campanella e catalogo dei suoi scritti (1878); and Nuovi documenti di T.C. (1881); and especially L. Amabile, Fra T. Campanella (3 vols., Naples, 1882). For his philosophy H. Ritter, History of Philos.; M. Carrière, Philos. Weltanschauung d. Reformationszeit, pp. 542-608; C. Dareste, Th. Morus et Campanella (Paris, 1843); Chr. Sigwart, Kleine Schriften, i. 125 seq.; and histories of philosophy. For his political philosophy, A. Calenda, Fra Tommaso Campanella e la sua dottrina sociale e politica di fronte al socialismo moderno (Nocera Inferiore, 1895). His poems, first published by Tobias Adami (1622), were rediscovered and printed again (1834) by J.G. Orelli; the sonnets were rendered into English verse by J.A. Symonds (1878). For a full bibliography see Dict. de théol. cath., col. 1446 (1904).

CAMPANIA, a territorial division of Italy. The modern district (II. below) is of much greater extent than that known by the name in ancient times.

I. Campani was the name used by the Romans to denote the inhabitants first of the town of Capua and the district subject to it, and then after its destruction in the Hannibalic war (211 b.c.), to describe the inhabitants of the Campanian plain generally. The name, however, is pre-Roman and appears with Oscan terminations on coins of the early 4th (or late 5th) century b.c. (R.S. Conway, Italic Dialects, p. 143), which were certainly struck for or by the Samnite conquerors of Campania, whom the name properly denotes, a branch of the great Sabelline stock (see Sabini); but in what precise spot the coins were minted is uncertain. We know from Strabo (v. 4. 8.) and others that the Samnites deprived the Etruscans of the mastery of Campania in the last quarter of the 5th century; their earliest recorded appearance being at the conquest of their chief town Capua, probably in 438 b.c. (or 445, according to the method adopted in interpreting Diodorus xii. 31; on this see under Cumae), or 424 according to Livy (iv. 37). Cumae was taken by them in 428 or 421, Nola about the same time, and the Samnite language they spoke, henceforward known as Oscan, spread over all Campania except the Greek cities, though small communities of Etruscans remained here and there for at least another century (Conway, op. cit. p. 94). The hardy warriors from the mountains took over not merely the wealth of the Etruscans, but many of their customs; the haughtiness and luxury of the men of Capua was proverbial at Rome. This town became the ally of Rome in 338 b.c. (Livy viii. 14) and received the civitas sine suffragio, the highest status that could be granted to a community which did not speak Latin. By the end of the 4th century Campania was completely Roman politically. Certain towns with their territories (Neapolis, Nola, Abella, Nuceria) were nominally independent in alliance with Rome. These towns were faithful to Rome throughout the Hannibalic war. But Capua and the towns dependent on it revolted (Livy xxiii.-xxvi.); after its capture in 211 Capua was utterly destroyed, and the jealousy and dread with which Rome had long regarded it were both finally appeased (cf. Cicero. Leg. Agrar. ii. 88). We have between thirty and forty Oscan inscriptions (besides some coins) dating, probably, from both the 4th and the 3rd centuries (Conway, Italic Dialects, pp. 100-137 and 148), of which most belong to the curious cult described under Jovilae, while two or three are curses written on lead; see Osca Lingua.

See further Conway, op. cit. p. 99 ff.; J. Beloch, Campanien (2nd ed.), c. “Capua”; Th. Mommsen, C.I.L. x. p. 365.

The name Campania was first formed by Greek authors, from Campani (see above), and did not come into common use until the middle of the 1st century a.d. Polybius and Diodorus avoid it entirely. Varro and Livy use it sparingly, preferring Campanus ager. Polybius (2nd century b.c.) uses the phrase κατὰ Καπύην to express the district bounded on the north by the mountains of the Aurunci, on the east by the Apennines of Samnium, on the south by the spur of these mountains which ends in the peninsula of Sorrento, and on the south and west by the sea, and this is what Campania meant to Pliny and Ptolemy. But the geographers of the time of Augustus (in whose division of Italy Campania, with Latium, formed the first region) carried the north boundary of Campania as far south as Sinuessa, and even the river Volturnus, while farther inland the modern village of San Pietro in Fine preserves the memory of the north-east boundary which ran between Venafrum and Casinum. On the east the valley of the Volturnus and the foot-hills of the Apennines as far as Abellinum formed the boundary; this town is sometimes reckoned as belonging to Campania, sometimes to Samnium. The south boundary remained unchanged. From the time of Diocletian onwards the name Campania was extended much farther north, and included the whole of Latium. This district was governed by a corrector, who about a.d. 333 received the title of consularis. It is for this reason that the district round Rome still bears the name of Campagna di Roma, being no doubt popularly connected with Ital. campo, Lat. campus. This district (to take its earlier extent), consisting mainly of a very fertile plain with hills on the north, east and south, and the sea on the south and west, is traversed by two great rivers, the Liris and Volturnus, divided by the Mons Massicus, which comes right down to the sea at Sinuessa. The plain at the mouth of the former is comparatively small, while that traversed by the Volturnus is the main plain of Campania. Both of these rivers rise in the central Apennines, and only smaller streams, such as the Sarnus, Sebethus, Savo, belong entirely to Campania.

The road system of Campania was extremely well developed and touched all the important towns. The main lines are followed (though less completely) by the modern railways. The most important road centre of Campania was Capua, at the east edge of the plain. At Casilinum, 3 m. to the north-west, was the only bridge over the Volturnus until the construction of the Via Domitiana; and here met the Via Appia, passing through Minturnae, Sinuessa and Pons Campanus (where it crossed the Savo) and the Via Latina which ran through Teanum Sidicinum and Cales. At Calatia, 6 m. south-east of Capua, the Via Appia began to turn east and to approach the mountains on its way to Beneventum, while the Via Popillia went straight on to Nola (whence a road ran to Abella and Abellinum) and thence to 123 Nuceria Alfaterna and the south, terminating at Regium. From Capua itself a road ran north to Vicus Dianae, Caiatia and Telesia, while to the south the so-called Via Campana (there is up ancient warrant for the name) led to Puteoli, with a branch to Cumae, Baiae and Misenum; there was also connexion between Cumae, Puteoli and Neapolis (see below), and another road to Atella and Neapolis. Neapolis could also be reached by a branch from the Via Popillia at Suessula, which passed through Acerrae. From Suessula, too, there was a short cut to the Via Appia before it actually entered the mountains. Dornitian further improved the communications of this district with Rome, by the construction of the Via Domitiana, which diverged from the Via Appia at Sinuessa, and followed the low sandy coast; it crossed the river Volturnus at Volturnum, near its mouth, by a bridge, which must have been a considerable undertaking, and then ran, still along the shore, past Liternum to Cumae and thence to Puteoli. Here it fell into the existing roads to Neapolis, the older Via Antiniana over the hills, at the back, and the newer, dating from the time of Agrippa, through the tunnel of Pausilypon and along the coast. The mileage in both cases was reckoned from Puteoli. Beyond Naples a road led along the coast through Herculaneum to Pompeii, where there was a branch for Stabiae and Surrentum, and thence to Nuceria, where it joined the Via Popillia. From Nuceria, which was an important road centre, a direct road ran to Stabiae, while from Salernum, 11 m. farther south-east but outside the limits of Campania proper, a road ran due north to Abellinum and thence to Aeclanum or Beneventum. Teanum was another important centre: it lay at the point where the Via Latina was crossed at right angles by a road leaving the Via Appia at Minturnae, and passing through Suessa Aurunca, while east of Teanum it ran on to Allifae, and there fell into the road from Venafrum to Telesia. Five miles north of Teanum a road branched off to Venafrum from the straight course of the Via Latina, and rejoined it near Ad Flexum (San Pietro in Fine). It is, indeed, probable that the original road made the detour by Venafrum, in order to give a direct communication between Rome and the interior of Samnium (inasmuch as roads ran from Venafrum to Aesernia and to Telesia by way of Allifae), and Th. Mommsen (Corp. Inscrip. Lat. x., Berlin, 1883, p. 699) denies the antiquity of the short cut through Rufrae (San Felice a Ruvo), though it is shown in Kiepert’s map at the end of the volume, with a milestone numbered 93 upon it. This is no doubt an error bofh in placing and in numbering, and refers to one numbered 96 found on the road to Venafrum; but it is still difficult to believe that the short cut was not used in ancient times. The 4th and 3rd century coins of Telesia, Allifae and Aesernia are all of the Campanian type.

Of the harbours of Campania, Puteoli was by far the most important from the commercial point of view. Its period of greatest comparative importance was the 2nd-1st century b.c. The harbours constructed by Augustus by connecting the Lacus Avernus and Lacus Lucrinus with the sea, and that at Misenum (the latter the station of one of the chief divisions of the Roman navy, the other fleet being stationed at Ravenna), were mainly naval. Naples also had a considerable trade, but was less important than Puteoli.

The fertility of the Campanian plain was famous in ancient as in modern times;1 the best portion was the Campi Laborini or Leborini (called Phlegraei by the Greeks and Terra di Lavoro in modern times, though the name has now extended to the whole province of Caserta) between the roads from Capua to Puteoli and Cumae (Pliny, Hist. Nat. xviii. III). The loose black volcanic earth (terra pulla) was easier to work than the stiffer Roman soil, and gave three or four crops a year. The spelt, wheat and millet are especially mentioned, as also fruit and vegetables; and the roses supplied the perfume factories of Capua. The wines of the Mons Massicus and of the Ager Falernus (the flat ground to the east and south-east of it) were the most sought after, though other districts also produced good wine; but the olive was better suited to the slopes than to the plain, though that of Venafrum was good.

The Oscan language remained in use in the south of Campania (Pompeii, Nola, Nuceria) at all events until the Social War, but at some date soon after that Latin became general, except in Neapolis, where Greek was the official language during the whole of the imperial period.

See J. Beloch, Campanien (2nd ed., Breslau, 1890); Conway, Italic Dialects, pp. 51-57; Ch. Hulsen in Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyklopadie, iii. (Stuttgart, 1899), 1434.

II. Campania in the modern sense includes a considerably larger area than the ancient name, inasmuch as to the compartimento of Campania belong the five provinces of Caserta, Benevento, Naples, Avellino and Salerno.

It is bounded on the north by the provinces of Rome, Aquila (Abruzzi) and Campobasso (Molise), on the north-east by that of Foggia (Apulia), on the east by that of Potenza (Basilicata) and on the south and west by the Tyrrhenian Sea. The area is 6289 sq. m. It thus includes the whole of the ancient Campania, a considerable portion of Samnium (with a part of the main chain of the Apennines) and of Lucania, and some of Latium adjectum, consisting thus of a mountainous district, the greater part of which lies on the Mediterranean side of the watershed, with the extraordinarily fertile and populous Campanian plain (Terra di Lavoro, with 473 inhabitants to the square mile) between the mountains and the sea. The principal rivers are the Garigliano or Liri (anc. Liris), which rises in the Abruzzi (105 m. in length); the Volturno (94 m. in length), with its tributary the Calore; the Sarno, which rises near Sarno and waters the fertile plain south-east of Vesuvius; and the Sele, whose main tributary is the Tanagro, which is in turn largely fed by another Calore. The headwaters of the Sele have been tapped for the great aqueduct for the Apulian provinces.

The coast-line begins a little east of Terracina at the lake of Fondi with a low-lying, marshy district (the ancient Ager Caecubus), renowned for its wine (see Fondi). The mountains (of the ancient Aurunci) then come down to the sea, and on the east side of the extreme promontory to the south-east is the port of Gaeta, a strongly fortified naval station. The east side of the Gulf of Gaeta is occupied by the marshes at the mouth of the Liri, and the low sandy coast, with its unhealthy lagoons, continues (interrupted only by the Monte Massico, which reaches the sea at Mondragone) past the mouth of the Volturno, as far as the volcanic district (no longer active) with its several extinct craters (now small lakes, the Lacus Avernus, &c.) to the west of Naples, which forms the north-west extremity of the Bay of Naples. Here the scenery completely changes: the Bay of Naples, indeed, is one of the most beautiful in the world. The island of Procida lies 2½ m. south-west of the Capo Miseno, and 3 m. south-west of Procida is that of Ischia. In consequence of the volcanic character of the district there are several important mineral springs which are used medicinally, especially at Pozzuoli, Castellammare di Stabia, and on the island of Ischia.

Pozzuoli (anc. Puteoli), the most important harbour of Italy in the 1st century b.c., is now mainly noticeable for the large armour-plate and gun works of Messrs Armstrong, and for the volcanic earth (pozzolana) which forms so important an element in concrete and cement, and is largely quarried near Rome also. Naples, on the other hand, is one of the most important harbours of modern Italy. Beyond it, Torre del Greco and Torre Annunziata at the foot of Vesuvius, are active trading ports for smaller vessels, especially in connexion with macaroni, which is manufactured extensively by all the towns along the bay. Castellammare di Stabia, on the west coast of the gulf, has a large naval shipbuilding yard and an important harbour. Beyond Castellammare the promontory of Sorrento, ending in the Punta della Campanella (from which Capri is 3 m. south-west) forms the south-west extremity of the gulf. The highest point of this mountain ridge, which is connected with the main Apennine chain, is the Monte S. Angelo (4735 ft.). It extends as far east as Salerno, where the coast plain of the Sele begins. As in the low marshy ground at the mouths of the Liri and Volturno, malaria is very prevalent. The south-east extremity of the Gulf of Salerno is formed by another mountain group, culminating 124 in the Monte Cervati (6229 ft.); and on the east side of this is the Gulf of Policastro, where the province of Salerno, and with it Campania, borders, on the province of Potenza.

The population of Campania was 3,080,503 in 1901; that of the province of Caserta was 705,412, with a total of 187 communes, the chief towns being Caserta (32,709), Sta Maria Capua Vetere (21,825), Maddaloni (20,682), Sessa Aurunca (21,844); that of the province of Benevento was 256,504, with 73 communes, the only important town being Benevento itself (24,647); that of the province of Naples 1,151,834, with 69 communes, the most important towns being Naples (563,540), Torre del Greco (33,299), Castellammare di Stabia (32,841), Torre Annunziata (28,143), Pozzuoli (22,907); that of the province of Avellino (Principato Ulteriore in the days of the Neapolitan kingdom) 402,425, with 128 communes, the chief towns being Avellino (23,760) and Ariano di Puglia (17,650); that of the province of Salerno (Principato Citeriore) 564,328, with 158 communes, the chief towns being Salerno (42,727), Cava dei Tirreni (23,681), Nocera Inferiore (19,796). Naples is the chief railway centre: a main line runs from Rome through Roccasecca (whence there is a branch via Sora to Avezzano, on the railway from Rome to Castellammare Adriatico), Caianello (junction for Isernia, on the line between Sulmona and Campobasso or Benevento), Sparanise (branch to Formia and Gaeta) and Caserta to Naples. From Caserta, indeed, there are two independent lines to Naples, while a main line runs to Benevento and Foggia across the Apennines. From Benevento railways run north to Vinchiaturo (for Isernia or Campobasso) and south to Avellino. From Cancello, a station on one of the two lines from Caserta to Naples, branches run to Torre Annunziata, and to Nola, Codola, Mercato, San Severino and Avellino. Naples, besides the two lines to Caserta (and thence either to Rome or Benevento), has local lines to Pozzuoli and Torregaveta (for Ischia) and two lines to Sarno, one via Ottaiano, the other via Pompeii, which together make up the circum-Vesuvian electric line, and were in connexion with the railway to the top of Vesuvius until its destruction in April 1906. The main line for southern Italy passes through Torre Annunziata (branch for Castellammare di Stabia and Gragnano), Nocera (branch for Codola), Salerno (branch for Mercato San Severino), and Battipaglia. Here it divides, one line going east-south-east to Sicignano (branch to Lagonegro), Potenza and Metaponto (for Taranto and Brindisi or the line along the east coast of Calabria to Reggio), the other going south-south-east along the west coast of Calabria to Reggio.

Industrial activity is mainly concentrated in Naples, Pozzuoli and the towns between Naples and Castellammare di Stabia (including the latter) on the north-east shores of the Bay of Naples. The native peasant industries are (besides agriculture, for which see Italy) the manufacture of pottery and weaving with small hand-looms, both of which are being swept away by the introduction of machinery; but a government school of textiles has been established at Naples for the encouragement of the trade.

1 The name Osci—earlier Opsci, Opusci (Gr. Όπικοί)—presumably meant “tillers of the soil.”

CAMPANI-ALIMENIS, MATTEO, Italian mechanician and natural philosopher of the 17th century, was born at Spoleto. He held a curacy at Rome in 1661, but devoted himself principally to scientific pursuits. As an optician he is chiefly celebrated for the manufacture of the large object-glasses with which G.D. Cassini discovered two of Saturn’s satellites, and for an attempt to rectify chromatic aberration by using a triple eye-glass; and in clock-making, for his invention of the illuminated dial-plate, and that of noiseless clocks, as well as for an attempt to correct the irregularities of the pendulum which arise from variations of temperature. Campani published in 1678 a work on horology, and on the manufacture of lenses for telescopes. His younger brother Giuseppe was also an ingenious optician (indeed the attempt to correct chromatic aberration has been ascribed to him instead of to Matteo), and is, besides, noteworthy as an astronomer, especially for his discovery, by the aid of a telescope of his own construction, of the spots in Jupiter, the credit of which was, however, also claimed by Eustachio Divini.

CAMPANILE, the bell tower attached to the churches and town-halls in Italy (from campana, a bell). Bells are supposed to have been first used for announcing the sacred offices by Pope Sabinian (604), the immediate successor to St Gregory; and their use by the municipalities came with the rights granted by kings and emperors to the citizens to enclose their towns with fortifications, and assemble at the sound of a great bell. It is to the Lombard architects of the north of Italy that we are indebted for the introduction and development of the campanile, which, when used in connexion with a sacred building, is a feature peculiar to Christian architecture—Christians alone making use of the bell to gather the multitude to public worship. The campanile of Italy serves the same purpose as the tower or steeple of the churches in the north and west of Europe, but differs from it in design and position with regard to the body of the church. It is almost always detached from the church, or at most connected with it by an arcaded passage. As a rule also there is never more than one campanile to a church, with a few exceptions, as in S. Ambrogio, Milan; the cathedral of Novara; S. Abbondio, Como; S. Antonio, Padua; and some of the churches in south Italy and Sicily. The design differs entirely from the northern type; it never has buttresses, is very tall and thin in proportion to its height, and as a rule rises abruptly from the ground without base or plinth mouldings undiminished to the summit; it is usually divided by string-courses into storeys of nearly equal height, and in north and central Italy the wall surface is decorated with pilaster strips and arcaded corbel strings. Later, the square tower was crowned with an octagonal turret, sometimes with a conical roof, as in Cremona and Modena cathedrals. As a rule the openings increase in number and dimensions as they rise, those at the top therefore giving a lightness to the structure, while the lower portions, with narrow slits only, impart solidity to the whole composition.

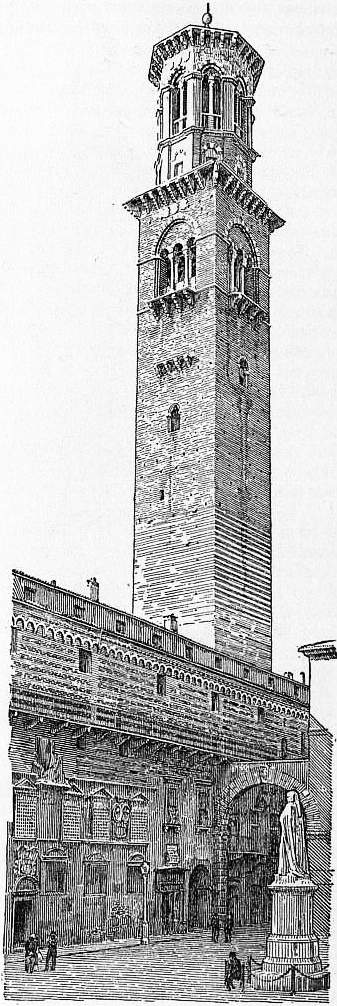

The earliest examples are those of the two churches of S. Apollinare in Classe (see Basilica, fig. 8) and S. Apollinare Nuovo at Ravenna, dating from the 6th century. They are circular, of considerable height, and probably were erected as watch towers or depositories for the treasures of the church. The next in order are those in Rome, of which there are a very large number in existence, dating from the 8th to the 11th century. These towers are square and in several storeys, the lower part quite plain till well above the church to which they are attached. Above this they are divided into storeys by brick cornices carried on stone corbels, generally taken from ancient buildings, the lower storeys with blind arcades and the upper storeys with open arcades. The earliest on record was one connected with St Peter’s, to the atrium of which, in the middle of the 8th century, a bell-tower overlaid with gold was added. One of the finest is that of S. Maria-in-Cosmedin, ascribed to the 8th or 9th century. In the lower part of it are embedded some ancient columns of the Composite Order belonging to the Temple of Ceres. The tower is 120 ft. high, the upper part divided into seven storeys, the four upper ones with open arcades, the bells being hung in the second from the top. The arches of the arcades, two or three in number, are recessed in two orders and rest on long impost blocks (their length equal to the thickness of the wall above), carried by a mid-wall shaft. This type of arcade or window is found in early German work, except that, as a rule, there is a capital under the impost block. Rome is probably the source from which the Saxon windows were derived, the example in Worth church being identically the same as those in the Roman campanili. In the campanile of S. Alessio there are two arcades in each storey, each divided with a mid-wall shaft. Among others, those of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, S. Lorenzo in Lucina, S. Francesca Romana, S. Croce in Gerusalemme, S. Giorgio in Velabro (fig. 1), S. Cecilia, S. Pudenziana, S. Bartolommeo in Isola (982), S. Silvestro in Capite, are characteristic examples. On some of the towers are encrusted plaques of marble or of red or green porphyry, enclosed in a tile or moulded brick border; sometimes these plaques are in majolica with Byzantine patterns.

|

| From a photograph by Alinari. Fig. 1.—Campanile of S. Giorgio in Velabro, Rome. |

|

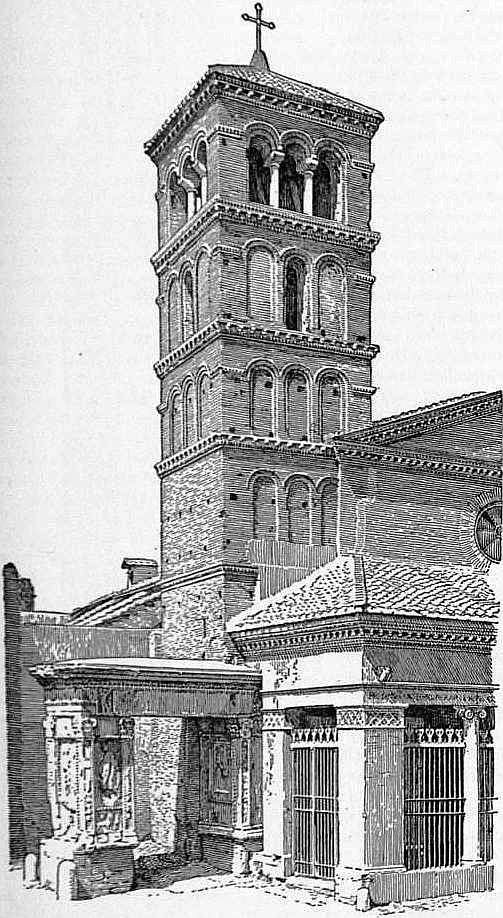

| From a photograph by Brogi. Fig. 2.—Campanile of St Mark’s, Venice. |

The early campanili of the north of Italy are of quite another type, the north campanile of S. Ambrogio, Milan (1129), being 125 decorated with vertical flat pilaster strips, four on each face, and horizontal arcaded corbel strings. Of earlier date (879), the campanile of S. Satiro at Milan is in perfect preservation; it is divided into four storeys by arched corbel tables, the upper storey having a similar arcade with mid-wall shaft to those in Rome. One of the most notable examples in north Italy is the campanile of Pomposa near Ferrara. It is of immense height and has nine storeys crowned with a lofty conical spire, the wall face being divided vertically with pilaster strips and horizontally with arcaded corbel tables,—this campanile, the two towers of S. Antonio, Padua, and that of S. Gottardo, Milan, of octagonal plan, being among the few which are thus terminated. In the campanile at Torcello we find an entirely different treatment: doubly recessed pilaster-strips divide each face into two lofty blind arcades rising from the ground to the belfry storey, over 100 ft. high, with small slits for windows, the upper or belfry storey having an arcade of four arches on each front. This is the type generally adopted in the campanili of Venice, where there are no string-courses. The campanile of St Mark’s was of similar design, with four lofty blind arcades on each face. The lower portion, built in brick, 162 ft. high, was commenced in 902 but not completed till the middle of the 12th century. In 1510 a belfry storey was added with an open arcade of four arches on each face, and slightly set back from the face of the tower above was a mass of masonry with pyramidal roof, the total height being 320 ft. On the 14th of July 1902 the whole structure collapsed; its age, the great weight of the additions made in 1510, and probably the cutting away inside of the lower part, would seem to have been the principal contributors to this disaster, as the pile foundations were found to be in excellent condition.

In central Italy the two early campanili at Lucca return to the Lombard type of the north, with pilaster strips and arcaded corbel strings, and the same is found in S. Francesco (Assisi), S. Frediano (Lucca), S. Pietro-in-Grado and S. Michele-in-Orticaia (Pisa), and S. Maria-Novella (Florence). The campanile of S. Niccola, Pisa, is octagonal on plan, with a lofty blind arcade on each face like those in Venice, but with a single string-course halfway up. The gallery above is an open eaves gallery like those in north Italy.

In southern Italy the design of the campanile varies again. In the two more important examples at Bari and Molfetta, there are two towers in each case attached to the east end of the cathedrals. The campanili are in plain masonry, the storeys being suggested only by blind arches or windows, there being neither pilaster strips nor string-courses. The same treatment is found at Barletta and Caserta Vecchia; in the latter the upper storey has been made octagonal with circular turrets at each angle, and this type of design is followed at Amalfi, the centre portion being circular instead of octagonal and raised much higher. In Palermo the campanile of the Martorana, of which the two lower storeys, decorated with three concentric blind pointed arches on each face, probably date from the Saracenic occupation, has angle turrets on the two upper storeys. The upper portions of the campanile of the cathedral have similar angle turrets, which, crowned with conical roofs, group well with the central octagonal spires of the towers. The two towers of the west front of the cathedral at Cefalu resemble those of Bari and Molfetta as regards their treatment.

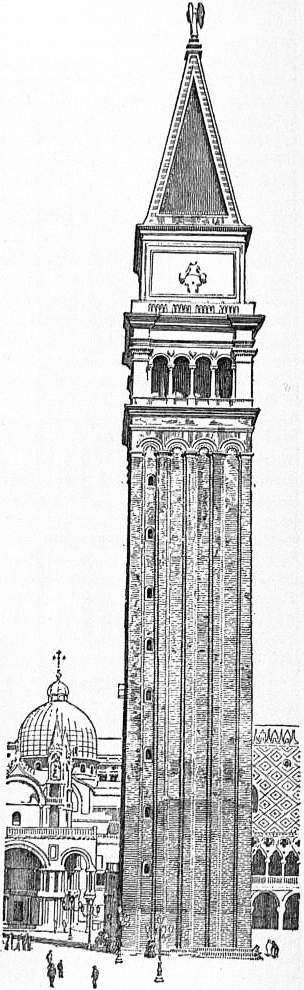

The campanili of S. Zenone, Verona, and the cathedrals of Siena and Prato, differ from those already mentioned in that they owe their decoration to the alternating courses of black and white marble. Of this type by far the most remarkable so 126 far as its marble decoration is concerned is Giotto’s campanile at Florence, built in 1334. It measures 275 ft. high, 45 ft. square, and is encased in black, white and red marble, with occasional sculptured ornament. The angles are emphasized by octagonal projections, the panelling of which seems to have ruled that of the whole structure. There are five storeys, of which the three upper ones are pierced with windows; twin arcades side by side in the two lower, and a lofty triplet window with tracery in the belfry stage. A richly corbelled cornice crowns the structure, above which a spire was projected by Giotto, but never carried out.

|

| From a photograph by Alinari. Fig. 3.—Giotto’s Campanile, Florence. |

|

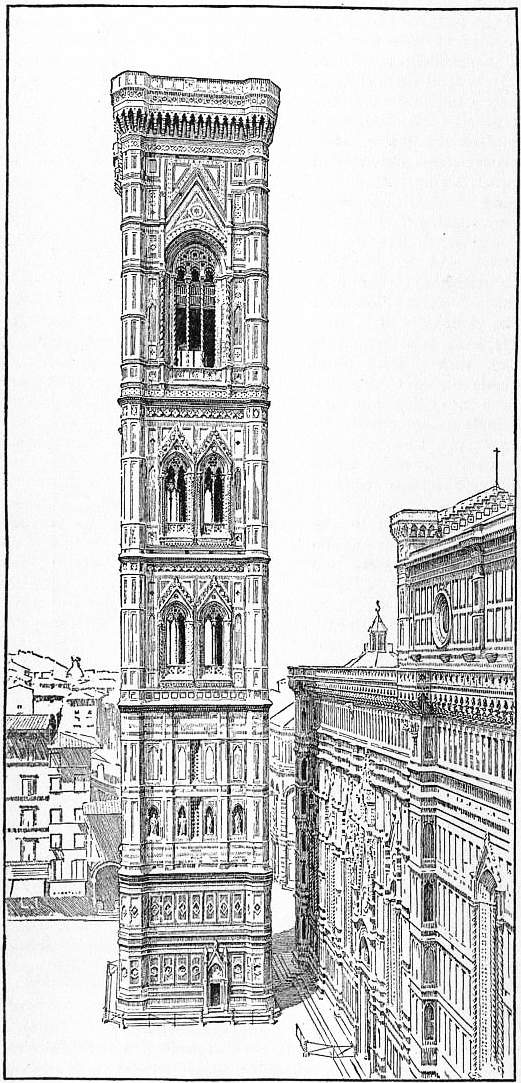

| From a photograph by Alinari. Fig. 4.—Campanile of the Palazzo del Signore, Verona. |

The loftiest campanile in Italy is that of Cremona, 396 ft. high. Though built in the second half of the 13th century, and showing therefore Gothic influence in the pointed windows of the belfry and two storeys below, and the substitution of the pointed for the semicircular arch of the arcaded corbel string-courses, it follows the Lombard type in its general design, and the same is found in the campanile of S. Andrea, Mantua. In the 16th century an octagonal lantern in two strings crowned with a conical roof was added. Owing to defective foundations, some of the Italian campanili incline over considerably; of these leaning towers, those of the Garisendi and Asinelli palaces at Bologna form conspicuous objects in the town; the two more remarkable examples are the campanile of S. Martino at Este, of early Lombard type, and the leaning tower at Pisa, which was built by the citizens in 1174 to rival that of Venice. The Pisa tower is circular on plan, about 51 ft. in diameter and 172 ft. high. Not including the belfry storey, which is set back on the inner wall, it is divided into seven storeys all surrounded with an open gallery or arcade. (See Architecture, Plate I. fig. 62.) Owing to the sinking of the piles on the south side, the inclination was already noticed when the tower was about 30 ft. high, and slight additions in the height of the masonry on that side were introduced to correct the level, but without result, so that the works were stopped for many years and taken up again in 1234 under the direction of William of Innsbruck; he also attempted to rectify the levels by increasing the height of the masonry on the south side. At a later period the belfry storey was added. The inclination now approaches 14 ft. out of the perpendicular. The outside is built entirely in white marble and is of admirable workmanship, but it is a question whether the equal subdivision of the several storeys is not rather monotonous. The campanili of the churches of S. Nicolas and S. Michele in Orticaia, both in Pisa, are also inclined to a slight extent.

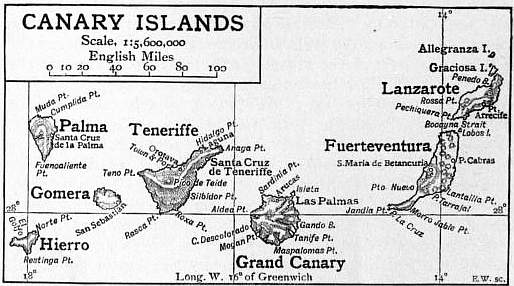

The campanili hitherto described are all attached to churches, but there are others belonging to civic buildings some of which are of great importance. The campanile of the town hall of Siena rises to an enormous height, being 285 ft., and only 22 ft. wide; it is built in brick and crowned with a battlemented 127 parapet carried on machicolation corbels, 16 ft. high, all in stone, and a belfry storey above set back behind the face of the tower. The campanile of the Palazzo Vecchio at Florence is similarly crowned, but it does not descend to the ground, being balanced in the centre of the main wall of the town hall. A third example is the fine campanile of the Palazzo-del-Signore at Verona, fig. 4, the lower portion built in alternate courses of brick and stone and above entirely in brick, rising to a height of nearly 250 ft., and pierced with putlog holes only. The belfry window on each face is divided into three lights with coupled shafts. An octagonal tower of two storeys rises above the corbelled eaves.

In the campanili of the Renaissance in Italy the same general proportions of the tower are adhered to, and the style lent itself easily to its decoration; in Venice the lofty blind arcades were adhered to, as in the campanile of the church of S. Giorgio dei Greci. In that of S. Giorgio Maggiore, however, Palladio returned to the simple brickwork of Verona, crowned with a belfry storey in stone, with angle pilasters and columns of the Corinthian order in antis, and central turret with spire above. In Genoa there are many examples; the quoins are either decorated with rusticated masonry or attenuated pilasters, with or without horizontal string-courses, always crowned with a belfry storey in stone and classic cornices, which on account of their greater projection present a fine effect.

CAMPANULA (Bell-flower), in botany, a genus of plants containing about 230 species, found in the temperate parts of the northern hemisphere, chiefly in the Mediterranean region. The name is taken from the bell-shaped flower. The plants are perennial, rarely annual or biennial, herbs with spikes or racemes of white, blue or lilac flowers. Several are native in Britain; Campanula rotundifolia is the harebell (q.v.) or Scotch bluebell, a common plant on pastures and heaths,—the delicate slender stem bears one or a few drooping bell-shaped flowers; C. Rapunculus, rampion or ramps, is a larger plant with a panicle of broadly campanulate red-purple or blue flowers, and occurs on gravelly roadsides and hedgebanks, but is rare. It is cultivated, but not extensively, for its fleshy roots, which are used, either boiled or raw, as salad. Many of the species are grown in gardens for their elegant flowers; the dwarf forms are excellent for pot culture, rockeries or fronts of borders. C. Medium, Canterbury bell, with large blue, purple and white flowers, is a favourite and handsome biennial, of which there are numerous varieties. C. persicifolia, a perennial with more open flowers, is also a well-known border plant, with numerous forms, including white and blue-flowered and single and double. C. glomerata, which has sessile flowers crowded in heads on the stems and branches, found native in Britain in chalky and dry pastures, is known in numerous varieties as a border plant. C. pyramidalis, with numerous flowers forming a tall pyramidal inflorescence, is a handsome species. There are also a number of alpine species suitable for rockeries, such as C. alpina, caucasica, caespitosa and others. The plants are easily cultivated. The perennials are propagated by dividing the roots or by young cuttings in spring, or by seeds.

CAMPBELL, ALEXANDER (1788-1866), American religious leader, was born near Ballymena, Co. Antrim, Ireland, on the 12th of September 1788, and was the son of Thomas Campbell (1763-1854), a schoolmaster and clergyman of the Presbyterian “Seceders.” Alexander in 1809, after a year at Glasgow University, joined his father in Washington, Pennsylvania, where the elder Campbell had just formed the Christian Association of Washington, “for the sole purpose of promoting simple evangelical Christianity.” With his father’s desire for Church unity the son agreed. He began to preach in 1810, refusing any salary; in 1811 he settled in what is now Bethany, West Virginia, and was licensed by the Brush Run Church, as the Christian Association was now called. In 1812, urging baptism by immersion upon his followers by his own example, he took his father’s place as leader of the Disciples of Christ (q.v., popularly called Christians, Campbellites and Reformers). He seemed momentarily to approach the doctrinal position of the Baptists, but by his statement, “I will be baptized only into the primitive Christian faith,” by his iconoclastic preaching and his editorial conduct of The Christian Baptist (1823-1830), and by the tone of his able debates with Paedobaptists, he soon incurred the disfavour of the Redstone Association of Baptist churches in western Pennsylvania, and in 1823 his followers transferred their membership to the Mahoning Association of Baptist churches in eastern Ohio, only to break absolutely with the Baptists in 1830. Campbell, who in 1829 had been elected to the Constitutional Convention of Virginia by his anti-slavery neighbours, now established The Millennial Harbinger (1830-1865), in which, on Biblical grounds, he opposed emancipation, but which he used principally to preach the imminent Second Coming, which he actually set for 1866, in which year he died, on the 4th of March, at Bethany, West Virginia, having been for twenty-five years president of Bethany College. He travelled, lectured, and preached throughout the United States and in England and Scotland; debated with many Presbyterian champions, with Bishop Purcell of Cincinnati and with Robert Owen; and edited a revision of the New Testament.

See Thomas W. Grafton’s Alexander Campbell, Leader of the Great Reformation of the Nineteenth Century (St Louis, 1897).

CAMPBELL, BEATRICE STELLA (Mrs Patrick Campbell) (1865- ), English actress, was born in London, her maiden name being Tanner, and in 1884 married Captain Patrick Campbell (d. 1900). After having appeared on the provincial stage she first became prominent at the Adelphi theatre, London, in 1892, and next year created the chief part in Pinero’s Second Mrs Tanqueray at the St James’s, her remarkable impersonation at once putting her in the first rank of English actresses. For some years she displayed her striking dramatic talent in London, playing notably with Mr Forbes Robertson in Davidson’s For the Crown, and in Macbeth; and her Magda (Royalty, 1900) could hold its own with either Bernhardt or Duse. In later years she paid successful visits to America, but in England played chiefly on provincial tours.

CAMPBELL, GEORGE (1719-1796), Scottish theologian, was born at Aberdeen on the 25th of December 1719. His father, the Rev. Colin Campbell, one of the ministers of Aberdeen, the son of George Campbell of Westhall, who claimed to belong to the Argyll branch of the family, died in 1728, leaving a widow and six children in somewhat straitened circumstances. George, the youngest son, was destined for the legal profession, and after attending the grammar school of Aberdeen and the arts classes at Marischal College, he was sent to Edinburgh to serve as an apprentice to a writer to the Signet. While at Edinburgh he attended the theological lectures, and when the term of his apprenticeship expired, he was enrolled as a regular student in the Aberdeen divinity hall. After a distinguished career he was, in 1746, licensed to preach by the presbytery of Aberdeen. From 1748 to 1757 he was minister of Banchory Ternan, a parish on the Dee, some 20 m. from Aberdeen. He then transferred to Aberdeen, which was at the time a centre of considerable intellectual activity. Thomas Reid was professor of philosophy at King’s College; John Gregory (1724-1773), Reid’s predecessor, held the chair of medicine; Alexander Gerard (1728-1795) was professor of divinity at Marischal College; and in 1760 James Beattie (1735-1803) became professor of moral philosophy in the same college. These men, with others of less note, formed themselves in 1758 into a society for the discussions of questions in philosophy. Reid was its first secretary, and Campbell one of its founders. It lasted till about 1773, and during this period numerous papers were read, particularly those by Reid and Campbell, which were afterwards expanded and published.

In 1759 Campbell was made principal of Marischal College. In 1763 he published his celebrated Dissertation on Miracles, in which he seeks to show, in opposition to Hume, that miracles are capable of proof by testimony, and that the miracles of Christianity are sufficiently attested. There is no contradiction, he argues, as Hume said there was, between what we know by testimony and the evidence upon which a law of nature is based; they are of a different description indeed, but we can without inconsistency believe that both are true. The Dissertation is not 128 a complete treatise upon miracles, but with all deductions it was and still is a valuable contribution to theological literature. In 1771 Campbell was elected professor of theology at Marischal College, and resigned his city charge, although he still preached as minister of Greyfriars, a duty then attached to the chair. His Philosophy of Rhetoric, planned at Banchory Ternan years before, appeared in 1776, and at once took a high place among books on the subject. In 1778 his last and in some respects his greatest work appeared, A New Translation of the Gospels. The critical and explanatory notes which accompanied it gave the book a high value.

In 1795 he was compelled by increasing weakness to resign the offices he held in Marischal College, and on his retirement he received a pension of £300 from the king. He died on the 31st of March 1796.

His Lectures on Ecclesiastical History were published after his death with a biographical notice by G.S. Keith; there is a uniform edition of his works in 6 vols.

CAMPBELL, JOHN (1708-1775), Scottish author, was born at Edinburgh on the 8th of March 1708. Being designed for the legal profession, he was sent to Windsor, and apprenticed to an attorney; but his tastes soon led him to abandon the study of law and to devote himself entirely to literature. In 1736 he published the Military History of Prince Eugene and the Duke of Marlborough, and soon after contributed several important articles to the Ancient Universal History. In 1742 and 1744 appeared the Lives of the British Admirals, in 4 vols., a popular work which has been continued by other authors. Besides contributing to the Biographia Britannica and Dodsley’s Preceptor, he published a work on The Present State of Europe, onsisting of a series of papers which had appeared in the Museum. He also wrote the histories of the Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish, French, Swedish, Danish and Ostend settlements in the East Indies, and the histories of Spain, Portugal, Algarve, Navarre and France, from the time of Clovis till 1656, for the Modern Universal History. At the request of Lord Bute, he published a vindication of the peace of Paris concluded in 1763, embodying in it a descriptive and historical account of the New Sugar Islands in the West Indies. By the king he was appointed agent for the provinces of Georgia in 1755. His last and most elaborate work, Political Survey of Britain, 2 vols. 4to, was published in 1744, and greatly increased the author’s reputation. Campbell died on the 28th of December 1775. He received the honorary degree of LL.D. from the university of Glasgow in 1745.

CAMPBELL, JOHN CAMPBELL, Baron (1779-1861), lord chancellor of England, the second son of the Rev. George Campbell, D.D., was born on the 17th of September 1779 at Cupar, Fife, where his father was for fifty years parish minister. For a few years Campbell studied at the United College, St Andrews. In 1800 he was entered as a student at Lincoln’s Inn, and, after a short connexion with the Morning Chronicle, was called to the bar in 1806, and at once began to report cases decided at nisi prius (i.e. on jury trial). Of these Reports he published altogether four volumes, with learned notes; they extend from Michaelmas 1807 to Hilary 1816. Campbell also devoted himself a good deal to criminal business, but in spite of his unceasing industry he failed to attract much attention behind the bar; he had changed his circuit from the home to the Oxford, but briefs came in slowly, and it was not till 1827 that he obtained a silk gown and found himself in that “front rank” who are permitted to have political aspirations. He unsuccessfully contested the borough of Stafford in 1826, but was elected for it in 1830 and again in 1831. In the House he showed an extraordinary, sometimes an excessive zeal for public business, speaking on all subjects with practical sense, but on none with eloquence or spirit. His main object, however, like that of Brougham, was the amelioration of the law, more by the abolition of cumbrous technicalities than by the assertion of new and striking principles.

Thus his name is associated with the Fines and Recoveries Abolition Act 1833; the Inheritance Act 1833; the Dower Act 1833; the Real Property Limitation Act 1833; the Wills Act 1837; one of the Copyhold Tenure Acts 1841; and the Judgments Act 1838. All these measures were important and were carefully drawn; but their merits cannot be explained in a biographical notice. The second was called for by the preference which the common law gave to a distant collateral over the brother of the half-blood of the first purchaser; the fourth conferred an indefeasible title on adverse possession for twenty years (a term shortened by Lord Cairns in 1875 to twelve years); the fifth reduced the number of witnesses required by law to attest wills, and removed the vexatious distinction which existed in this respect between freeholds and copyholds; the last freed an innocent debtor from imprisonment only before final judgment (or on what was termed mesne process), but the principle stated by Campbell that only fraudulent debtors should be imprisoned was ultimately given effect to for England and Wales in 1869.1 In one of his most cherished objects, however, that of Land Registration (q.v.), which formed the theme of his maiden speech in parliament, Campbell was doomed to disappointment. His most important appearance as member for Stafford was in defence of Lord John Russell’s first Reform Bill (1831). In a temperate and learned speech, based on Fox’s declaration against constitution-mongering, he supported both the enfranchising and the disfranchising clauses, and easily disposed of the cries of “corporation robbery,” “nabob representation,” “opening for young men of talent,” &c. The following year (1832) found Campbell solicitor-general, a knight and member for Dudley, which he represented till 1834. In that year he became attorney-general and was returned by Edinburgh, for which he sat till 1841.2

His political creed declared upon the hustings there was that of a moderate Whig. He maintained the connexion of church and state, and opposed triennial parliaments and the ballot. In parliament he continued to lend the most effective help to the Liberal party. His speech in 1835 in support of the motion for inquiry into the Irish Church temporalities with a view to their partial appropriation for national purposes (for disestablishment was not then dreamed of as possible) contains much terse argument, and no doubt contributed to the fall of Peel and the formation of the Melbourne cabinet. The next year Campbell had a fierce encounter with Lord Stanley in the debate which followed the motion of T. Spring Rice (afterwards Lord Monteagle) on the repair and maintenance of parochial churches and chapels. The legal point in the dispute (which Campbell afterwards made the subject of a separate pamphlet) was whether the church-wardens of the parish, in the absence of the vestry, had any means of enforcing a rate except the antiquated interdict or ecclesiastical censure. It was not on legal technicalities, however, but on the broad principle of religious equality, that Campbell supported the abolition of church rates, in which he included the Edinburgh annuity-tax.

In the same year he spoke for Lord Melbourne, in the action (thought by some to be a political conspiracy3) which the Hon. G.C. Norton brought against the Whig premier for criminal conversation with his wife. At this time also he exerted himself for the reform of justice in the ecclesiastical courts, for the uniformity of the law of marriage (which he held should be a purely civil contract) and for giving prisoners charged with felony the benefit of counsel. His defence of The Times newspaper, which had accused Sir John Conroy, equerry to the duchess of Kent, of misappropriation of money (1838), is chiefly remarkable for the Confession—“I despair of any definition of libel which shall exclude no publications which ought to be suppressed, and include none which ought to be permitted.” His own definition of blasphemous libel was enforced in the 129 prosecution which, as attorney-general, he raised against the bookseller H. Hetherington, and which he justified on the singular ground that “the vast bulk of the population believe that morality depends entirely on revelation; and if a doubt could be raised among them that the ten commandments were given by God from Mount Sinai, men would think they were at liberty to steal, and women would consider themselves absolved from the restraints of chastity.” But his most distinguished effort at the bar was undoubtedly the speech for the House of Commons in the famous case of Stockdale v. Hansard, 1837, 7 C. and P. 731. The Commons had ordered to be printed, among other papers, a report of the inspectors of prisons on Newgate, which stated that an obscene book, published by Stockdale, was given to the prisoners to read. Stockdale sued the Commons’ publisher, and was met by the plea of parliamentary privilege, to which, however, the judges did not give effect, on the ground that they were entitled to define the privileges of the Commons, and that publication of papers was not essential to the functions of parliament. The matter was settled by an act of 1840.

In 1840 Campbell conducted the prosecution against John Frost, one of the three Chartist leaders who attacked the town of Newport, all of whom were found guilty of high treason. We may also mention, as matter of historical interest, the case before the high steward and the House of Lords which arose out of the duel fought on Wimbledon Common between the earl of Cardigan and Captain Harvey Tuckett. The law of course was clear that the “punctilio which swordsmen falsely do call honour” was no excuse for wilful murder. To the astonishment of everybody, Lord Cardigan escaped from a capital charge of felony because the full name of his antagonist (Harvey Garnett Phipps Tuckett) was not legally proved. It is difficult to suppose that such a blunder was not preconcerted. Campbell himself made the extraordinary declaration that to engage in a duel which could not be declined without infamy (i.e. social disgrace) was “an act free from moral turpitude,” although the law properly held it to be wilful murder. Next year, as the Melbourne administration was near its close, Plunkett, the venerable chancellor of Ireland, was forced by discreditable pressure to resign, and the Whig attorney-general, who had never practised in equity, became chancellor of Ireland, and was raised to the peerage with the title of Baron Campbell of St Andrews, in the county of Fife. His wife, Mary Elizabeth Campbell, the eldest daughter of the first Baron Abinger by one of the Campbells of Kilmorey, Argyllshire, whom he had married in 1821, had in 1836 been created Baroness Stratheden in recognition of the withdrawal of his claim to the mastership of the rolls. The post of chancellor Campbell held for only sixteen days, and then resigned it to his successor Sir Edward Sugden (Lord St Leonards). The circumstances of his appointment and the erroneous belief that he was receiving a pension of £4000 per annum for his few days’ court work brought Campbell much unmerited obloquy.4 It was during the period 1841-1849, when he had no legal duty, except the self-imposed one of occasionally hearing Scottish appeals in the House of Lords, that the unlucky dream of literary fame troubled Lord Campbell’s leisure.5

Following in the path struck out by Miss Strickland in her Lives of the Queens of England, and by Lord Brougham’s Lives of Eminent Statesmen, he at last produced, in 1849, The Lives of the Lord Chancellors and Keepers of the Great Seal of England, from the earliest times till the reign of King George IV., 7 vols. 8vo. The conception of this work is magnificent; its execution wretched. Intended to evolve a history of jurisprudence from the truthful portraits of England’s greatest lawyers, it merely exhibits the ill-digested results of desultory learning, without a trace of scientific symmetry or literary taste, without a spark of that divine imaginative sympathy which alone can give flesh and spirit to the dead bones of the past, and without which the present becomes an unintelligible maze of mean and selfish ideas. A charming style, a vivid fancy, exhaustive research, were not to be expected from a hard-worked barrister; but he must certainly be held responsible for the frequent plagiarisms, the still more frequent inaccuracies of detail, the colossal vanity which obtrudes on almost every page, the hasty insinuations against the memory of the great departed who were to him as giants, and the petty sneers which he condescends to print against his own contemporaries, with whom he was living from day to day on terms of apparently sincere friendship.

These faults are painfully apparent in the lives of Hardwicke, Eldon, Lyndhurst and Brougham, and they have been pointed out by the biographers of Eldon and by Lord St Leonards.6 And yet the book is an invaluable repertory of facts, and must endure until it is superseded by something better. It was followed by the Lives of the Chief Justices of England, from the Norman Conquest till the death of Lord Mansfield, 8vo, 2 vols., a book of similar construction but inferior merit.

It must not be supposed that during this period the literary lawyer was silent in the House of Lords. He spoke frequently. The 3rd volume of the Protests of the Lords, edited by Thorold Rogers (1875), contains no less than ten protests by Campbell, entered in the years 1842-1845. He protests against Peel’s Income Tax Bill of 1842; against the Aberdeen Act 1843, as conferring undue power on church courts; against the perpetuation of diocesan courts for probate and administration; against Lord Stanley’s absurd bill providing compensation for the destruction of fences to dispossessed Irish tenants; and against the Parliamentary Proceedings Bill, which proposed that all bills, except money bills, having reached a certain stage or having passed one House, should be continued to next session. The last he opposed because the proper remedy lay in resolutions and orders of the House. He protests in favour of Lord Monteagle’s motion for inquiry into the sliding scale of corn duties; of Lord Normanby’s motion on the queen’s speech in 1843, for inquiry into the state of Ireland (then wholly under military occupation); of Lord Radnor’s bill to define the constitutional powers of the home secretary, when Sir James Graham opened Mazzini’s letters. In 1844 he records a solitary protest against the judgment of the House of Lords in R. v. Millis, 1844, 10 Cla. and Fin. 534, which affirmed that a man regularly married according to the rites of the Irish Presbyterian Church, and afterwards regularly married to another woman by an episcopally ordained clergyman, could not be convicted of bigamy, because the English law required for the validity of a marriage that it should be performed by an ordained priest.

On the resignation of Lord Denman in 1850, Campbell was appointed chief justice of the queen’s bench. For this post he was well fitted by his knowledge of common law, his habitual attention to the pleadings in court and his power of clear statement. On the other hand, at nisi prius and on the criminal circuit, he was accused of frequently attempting unduly to influence juries in their estimate of the credibility of evidence. It is also certain that he liked to excite applause in the galleries by some platitude about the “glorious Revolution” or the “Protestant succession.” He assisted in the reforms of special pleading at Westminster, and had a recognized place with Brougham and Lyndhurst in legal discussions in the House of Lords. But he had neither the generous temperament nor the breadth of view which is required in the composition of even a mediocre statesman. In 1859 he was made lord chancellor of Great Britain, probably on the understanding that Bethell should succeed as soon as he could be spared from the House of Commons. His short tenure of this office calls for no remark. In the same year he published in the form of a letter to Payne Collier an amusing and extremely inconclusive essay on Shakespeare’s legal acquirements. One passage will show the conjectural 130 Drocess which runs through the book: “If Shakespeare was really articled to a Stratford attorney, in all probability, during the five years of his clerkship, he visited London several times on his master’s business, and he may then have been introduced to the green-room at Blackfriars by one of his countrymen connected with that theatre.” The only positive piece of evidence produced is the passage from Thomas Nash’s “Epistle to the Gentlemen of the Two Universities,” prefixed to Greene’s Arcadia, 1859, in which he upbraids somebody (not known to be Shakespeare) with having left the “trade of Noverint” and busied himself with “whole Hamlets” and “handfuls of tragical speeches.” The knowledge of law shown in the plays is very much what a universal observer must have picked up. Lawyers always underestimate the legal knowledge of an intelligent layman. Campbell died on the 23rd of June 1861. It has been well said of him in explanation of his success, that he lived eighty years and preserved his digestion unimpaired. He had a hard head, a splendid constitution, tireless industry, a generally judicious temper. He was a learned, though not a scientific lawyer, a faithful political adherent, thoroughly honest as a judge, dutiful and happy as a husband. But there was nothing admirable or heroic in his nature. On no great subject did his principles rise above the commonplace of party, nor had he the magnanimity which excuses rather than aggravates the faults of others. His life was the triumph of steady determination unaided by a single brilliant or attractive quality.

Authorities.—Life of Lord Campbell, a Selection from his Autobiography, Diary and Letters, ed. by Hon. Mrs Hardcastle (1881); E. Foss, The Judges of England (1848-1864); W.H. Bennet, Select Biographical Sketches from Note-books of a Law Reporter (1867); E. Manson, Builders of our Law (ed. 1904); J.B. Atlay, The Victorian Chancellors, vol. ii. (1908).

1 Two of his later acts, allowing the defendant in an action for libel to prove veritas, and giving a right of action to the representatives of persons killed through negligence, also deserve mention.