Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, "Carnegie Andrew" to "Casus Belli"

Author: Various

Release date: July 17, 2010 [eBook #33189]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

CARNEGIE, ANDREW (1837- ), American “captain of industry” and benefactor, was born in humble circumstances in Dunfermline, Scotland, on the 25th of November 1837. In 1848 his father, who had been a Chartist, emigrated to America, settling in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania. The raw Scots lad started work at an early age as a bobbin-boy in a cotton factory, and a few years later was engaged as a telegraph clerk and operator. His capacity was perceived by Mr T.A. Scott of the Pennsylvania railway, who employed him as a secretary; and in 1859, when Scott became vice-president of the company, he made Carnegie superintendent of the western division of the line. In this post he was responsible for several improvements in the service; and when the Civil War opened he accompanied Scott, then assistant secretary of war, to the front. The first sources of the enormous wealth he subsequently attained were his introduction of sleeping-cars for railways, and his purchase (1864) of Storey Farm on Oil Creek, where a large profit was secured from the oil-wells. But this was only a preliminary to the success attending his development of the iron and steel industries at Pittsburg. Foreseeing the extent to which the demand would grow in America for iron and steel, he started the Keystone Bridge works, built the Edgar Thomson steel-rail mill, bought out the rival Homestead steel works, and by 1888 had under his control an extensive plant served by tributary coal and iron fields, a railway 425 m. long, and a line of lake steamships. As years went by, the various Carnegie companies represented in this industry prospered to such an extent that in 1901, when they were incorporated in the United States Steel Corporation, a trust organized by Mr J. Pierpont Morgan, and Mr Carnegie himself retired from business, he was bought out at a figure equivalent to a capital of approximately £100,000,000.

From this time forward public attention was turned from the shrewd business capacity which had enabled him to accumulate such a fortune to the public-spirited way in which he devoted himself to utilizing it on philanthropic objects. His views on social subjects, and the responsibilities which great wealth involved, were already known in a book entitled Triumphant Democracy, published in 1886, and in his Gospel of Wealth (1900). He acquired Skibo Castle, in Sutherlandshire, Scotland, and made his home partly there and partly in New York; and he devoted his life to the work of providing the capital for purposes of public interest, and social and educational advancement. Among these the provision of public libraries in the United States and United Kingdom (and similarly in other English-speaking countries) was especially prominent, and “Carnegie libraries” gradually sprang up on all sides, his method being to build and equip, but only on condition that the local authority provided site and maintenance, and thus to secure local interest and responsibility. By the end of 1908 he had distributed over £10,000,000 for founding libraries alone. He gave £2,000,000 in 1901 to start the Carnegie Institute at Pittsburg, and the same amount (1902) to found the Carnegie Institution at Washington, and in both of these, and other, cases he added later to the original endowment. In Scotland he gave £2,000,000 in 1901 to establish a trust for providing funds for assisting education at the Scottish universities, a benefaction which resulted in his being elected lord rector of St Andrews University. He was a large benefactor of the Tuskegee Institute under Booker Washington for negro education. He also established large pension funds—in 1901 for his former employés at Homestead, and in 1905 for American college professors. His benefactions in the shape of buildings and endowments for education and research are too numerous for detailed enumeration, and are noted in this work under the headings of the various localities. But mention must also be made of his founding of Carnegie Hero Fund commissions, in America (1904) and in the United Kingdom (1908), for the recognition of deeds of heroism; his contribution of £500,000 in 1903 for the erection of a Temple of Peace at The Hague, and of £150,000 for a Pan-American Palace in Washington as a home for the International Bureau of American republics. In all his ideas he was dominated by an intense belief in the future and influence of the English-speaking people, in their democratic government and alliance for the purpose of peace and the abolition of war, and in the progress of education on unsectarian lines. He was a powerful supporter of the movement for spelling reform, as a means of promoting 365 the spread of the English language. Mr Carnegie married in 1887 and had one daughter. Among other publications by him were An American Four-in-hand in Britain (1883), Round the World (1884), The Empire of Business (1902), a Life of James Watt (1905) and Problems of To-day (1908).

CARNEGIE, a borough of Allegheny county, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., 6 m. S.W. of Pittsburg. Pop. (1900) 7330 (1816 being foreign-born); (1910) 10,009. It is served by the Pittsburg, Cincinnati, Chicago & St Louis, the Pittsburg, Chartiers & Youghiogheny, and the Wabash Pittsburg Terminal railways, and the Pittsburg street railway. Carnegie is situated in the beautiful valley of Chartiers Creek, and is in one of the coal and natural gas districts of the state. In the borough are a Carnegie library and St Paul’s orphan asylum. Among the borough’s manufactures are steel, lead, glass, ploughs and enamel- and tin-ware. There are alkaline and lithia mineral springs here. In 1894 Carnegie, named in honour of Andrew Carnegie, was formed by the union of the boroughs Chartiers and Mansfield.

CARNELIAN, a red variety of chalcedony, much used as an ornamental stone, especially for seals. The old name was cornelian, said to have been given in reference either to the horny appearance of the stone (Lat. cornu, “horn”) or to its resemblance in colour to the berry of the cornel; but the original word was corrupted to carnelian, probably in allusion to its reddish colour (carneus, “flesh-coloured”). Some carnelian, however, is brown, yellow or even white. Certain kinds of brown and bright red chalcedony, much resembling carnelian, pass under the name of sard (q.v.). The Hebrew odem was probably a red stone, either carnelian, sard or jasper. All carnelian is translucent and is thus distinguished from jasper of similar colour, which is always opaque. The red colour of typical carnelian is due to the presence of ferric oxide. This is often developed artificially by exposure to sunshine, or to artificial heat, whereby any ferric hydrate in the stone becomes more or less dehydrated; or the stone is treated with a solution of an iron salt, like ferrous sulphate, and then heated, when ferric oxide is formed in the pores of the stone. An opaque white surface is sometimes produced artificially on a red carnelian: this is said to be done by coating the stone with carbonate of soda and then placing it on a red-hot iron; or by using a mixture of potash, white lead and certain vegetable juices, and heating it on charcoal. Inscriptions and figures in white on red carnelian (“burnt carnelian”) are well known from the East. Much carnelian comes from India, being mostly derived from agate-gravels, resulting from the disintegration of the Deccan traps, in the neighbourhood of Ratanpur, near Broach. A good deal of the carnelian now sold, however, is Brazilian agate, artificially stained. (See Agate.)

CARNESECCHI, PIETRO (1508-1567), Italian humanist, was the son of a Florentine merchant, who under the patronage of the Medici, and especially of Giovanni de’ Medici as Pope Clement VII., rapidly rose to high office at the papal court. He came into touch with the new learning at the house of his maternal uncle, Cardinal Bernardo Dovizzi, in Rome. At the age of twenty-five he held several rich livings, had been notary and protonotary to the Curia, and was first secretary to the pope, in which capacity he conducted the correspondence with the nuncios (among them Pier Paolo Bergerio in Germany) and a host of other duties. By his conduct at the conference with Francis I. at Marseilles he won the favour of Catherine de’ Medici and other influential personages at the French court, who in later days befriended him. He made the acquaintance of the Spanish reformer Juan de Valdes at Rome, and got to know him as a theologian at Naples, being especially drawn to him through the appreciation expressed by Bernardino Ochino, and through their mutual friendship with the Lady Julia Gonzaga, whose spiritual adviser he became after the death of Valdes. He became a leading spirit in the literary and religious circle that gathered round Valdes in Naples, and that aimed at effecting from within the spiritual reformation of the church. Under Valdes’ influence he whole-heartedly accepted Luther’s doctrine of justification by faith, though he repudiated a policy of schism. When the movement of suppression began, Carnesecchi was implicated. For a time he found shelter with his friends in Paris, and from 1552 he was in Venice leading the party of reform in that city. In 1557 he was cited (for the second time) before the tribunal in Rome, but refused to appear. The death of Paul IV. and the accession of Pius IV. in 1559 made his position easier, and he came to live in Rome. With the accession of Pius V. (Michael Ghislieri) in 1565 the Inquisition renewed its activities with fiercer zeal than ever. Carnesecchi was in Venice when the news reached him, and betook himself to Florence, where, thinking himself safe, he was betrayed by Cosimo, the duke, who wished to curry favour with the pope. From July 1566 he lay in prison over a year. On the 21st of September 1567 sentence of degradation and death was passed on him and sixteen others, ambassadors from Florence vainly kneeling to the pope for some mitigation, and on the 1st of October he was publicly beheaded and then burned.

CARNIOLA (Ger. Krain), a duchy and crown-land of Austria, bounded N. by Carinthia, N.E. by Styria, S.E. and S. by Croatia, and W. by Görz and Gradisca, Trieste and Istria. It has an area of 3856 sq. m. Carniola is for the most part a mountainous region, occupied in the N. by the Alps, and in the S. by the Karst (q.v.) or Carso Mountains. It is traversed by the Julian Alps, the Karawankas and the Steiner Alps, which belong all to the southern zone of the Eastern Alps. The highest point in the Julian Alps is formed by the three sugar-loaf peaks of the Triglav or Terglou (9394 ft.), which offers one of the finest views in the whole of the Alps, and which bears on its northern declivity the only glacier in the province. The Triglav is the dividing range between the Alps and the Karst Mountains, and its huge mass also forms the barrier between three races: the German, the Slavonic and the Italian. Other high peaks are the Mangart (8784 ft.) and the Jaluz (8708 ft.). The Karawankas, which form the boundary between Carinthia and Carniola, have as their highest peak the Stou or Stuhlberg (7344 ft.), and are traversed by the Loibl Pass (4492 ft.). They are continued by the Steiner or Santhaler Alps, which have as their highest peak the Grintouz or Grintovc (8393 ft.). This peak is situated on the threefold boundary of Carinthia, Carniola and Styria, and affords a magnificent view of the whole Alpine neighbouring region. The southern part of Carniola is occupied by the following divisions of the northern ramifications of the Karst Mountains: the Birnbaumer Wald with the highest peak, the Nanos (4275 ft.), and the Krainer Schneeberg (5890 ft.); the Hornwald with the highest peak, the Hornbüchl (3608 ft.), and the Uskokengebirge (3874 ft.). The portion of Carniola belonging to the Karst region presents a great number of caves, subterranean streams, funnels and similar phenomena. Amongst the best-known are the grottos of Adelsberg, the larger ones of Planina and the Kreuzberghöhle near Laas.

With the exception of the Idria and the Wippach, which as tributaries of the Isonzo belong to the basin of the Adriatic, Carniola belongs to the watershed of the Save. The Save or Sau rises within the duchy, and is formed by the junction at Radmannsdorf of its two head-streams the Wurzener Save and the Wocheiner Save. Its principal affluents are the Kanker and the Steiner Feistritz on the left, and the Zeyer or Sora, the Laibach and the Gurk on the right. The most remarkable of these rivers is the Laibach, which rises in the Karst region under the name of Poik, takes afterwards a subterranean course and traverses the Adelsberg grotto, and appears again on the surface near Planina under the name of Unz. Shortly after this it takes for the second time a subterranean course, to appear finally on the surface near Oberlaibach. The small torrent of Rothwein, which flows into the Wurzener Save, forms near Veldes the splendid series of cascades known as the Rothwein Fall. Amongst the principal lakes are the Wochein, the Weissenfels, the Veldes, and the seven small lakes of the Triglav; while in the Karst region lies the famous periodical lake of Zirknitz, known to the Romans as Lacus Lugens or Lugea Palus.

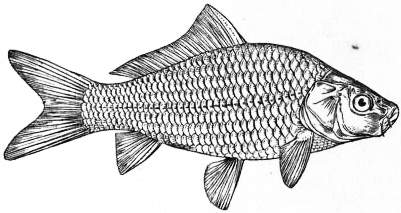

The climate is rather severe, and the southern part is exposed to the cold north-eastern wind, known as the Bora. The mean 366 annual temperature at Laibach is 48.4° F., and the rainfall amounts to 72 ins. Of the total area only 14.8% is under cultivation, and the crops do not suffice for the needs of the province; forests occupy 44.4%, 17.2% are meadows, 15.7% are pastures, and 1.17% of the soil is covered by vineyards. Large quantities of flax are grown, while the timber trade is of considerable importance. Fish and game are plentiful, and the silkworm is bred in the warmer districts. The principal mining product is mercury, extracted at Idria, while iron and copper ore, zinc and coal are also found. The industry is not well developed, but the weaving of linen and lace is pursued as a household industry.

Carniola had in 1900 a population of 508,348, which corresponds to 132 inhabitants per sq. m. Nearly 95% were Slovenes and 5% Germans, while 99% of the population belonged to the Roman Catholic Church. The local diet, of which the bishop of Laibach is a member ex officio, is composed of thirty-seven members, and Carniola sends eleven deputies to the Reichsrat at Vienna. For administrative purposes the province is divided into eleven districts and one autonomous municipality, Laibach (pop. 36,547), the capital. Other important places are Oberlaibach (5882), Idria (5772), Gurkfeld (5294), Zirknitz (5266), Adelsberg (3636), Neumarktl (2626), Krainburg (2484) and Gottschee (2421).

Carniola derives its modern name from the Slavonic word Krajina (frontier). During the Roman Empire it formed part of Noricum and Pannonia. The Slavonic population settled here during the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century. Conquered by Charlemagne, the most of the district was bestowed on the duke of Friuli; but in the 10th century the title of margrave of Carniola began to be borne by a family resident in the castle of Kieselberg near Krainburg. Various parts of the present territory were, however, held by other lords, such as the duke of Carinthia and the bishop of Freising. Towards the close of the 14th century all the separate portions had come by inheritance or bequest into the hands of Rudolph IV. of Austria, who took the title of duke of Carniola; and since then the duchy has remained a part of the Austrian possessions, except during the short period from 1809 to 1813, when it was incorporated with the French Illyrian Provinces. In 1849 it became a separate crown-land.

See Dimitz, Geschichte Krains von der ältesten Zeit his 1813 (4 vols., Laibach, 1874-1876).

CARNIVAL (Med. Lat. carnelevarium, from caro, carnis, flesh, and levare, to lighten or put aside; the derivation from valere, to say farewell, is unsupported), the last three days preceding Lent, which in Roman Catholic countries are given up to feasting and merry-making. Anciently the carnival was held to begin on twelfth night (6th January) and last till midnight of Shrove Tuesday. There is little doubt that this period of licence represents a compromise which the church always inclined to make with the pagan festivals and that the carnival really represents the Roman Saturnalia. Rome has ever been the headquarters of carnival, and though some popes, notably Clement IX. and XI. and Benedict XIII., made efforts to stem the tide of Bacchanalian revelry, many of the popes were great patrons and promoters of carnival keeping. Paul II. was notable in this respect. In his time the Jews of Rome were compelled to pay yearly a sum of 1130 golden florins (the thirty being added as a special memorial of Judas and the thirty pieces of silver), which was expended on the carnival. A decree of Paul II., minutely providing for the diversions, orders that four rings of silver gilt should be provided, two in the Piazza Navona and two at the Monte Testaccio—one at each place for the burghers and the other for the retainers of the nobles to practise riding at the ring. The pope also orders a great variety of races, the expenses of which are to be paid from the papal exchequer—one to be run by the Jews, another for Christian children, another for Christian young men, another for sexagenarians, a fifth for asses, and a sixth for buffaloes. Under Julius III. we have long accounts of bull-hunts—or rather bull-baits—in the Forum, with gorgeous descriptions of the magnificence of the dresses, and enormous suppers in the palace of the Conservatori in the capitol, where seven cardinals, together with the duke Orazio Farnese, supped at one table, and all the ladies by themselves at another. After the supper the whole party went into the courtyard of the palace, which was turned into the semblance of a theatre, “to see a most charming comedy which was admirably played, and lasted so long that it was not over till ten o’clock!” Even the austere and rigid Paul IV. (ob. 1559) used to keep carnival by inviting all the Sacred College to dine with him. Sixtus V., who was elected in 1585, set himself to the keeping of carnival after a different fashion. Determined to repress the lawlessness and crime incident to the period, he set up gibbets in conspicuous places, as well as whipping-posts, the former as a hint to robbers and cut-throats, the latter in store for minor offenders. We find, further, from the provisions made at the time, that Sixtus reformed the evil custom of throwing dirt and dust and flour at passengers, permitting only flowers or sweetmeats to be thrown.

The later popes for the most part restricted the public festivities of the carnival to the last six or seven days immediately preceding Ash Wednesday. The municipal authorities of the city, on whom the regulation of such matters now depends, allow ten days. The carnival sports at Rome anciently consisted of three divisions: (1) the races in the Corso (formerly called the Via Lata, and taking its present name from them), which appear to have been from time immemorial a part of the festivity; (2) the spectacular pageant of the Agona; (3) that of the Testaccio.

Of other Italian cities, Venice used in old times to be the principal home, after Rome, of carnival. To-day Turin, Milan, Florence, Naples, all put forth competing programmes. In old times Florence was conspicuous for the licentiousness of its carnival; and the Canti Carnascialeschi, or carnival songs, of Lorenzo de’ Medici show to what extent the licence was carried. The carnival in Spain lasts four days, including Ash Wednesday. In France the merry-making is restricted almost entirely to Shrove Tuesday, or mardi gras. In Russia, where no Ash Wednesday is observed, carnival gaieties last a week from Sunday to Sunday.

CARNIVORA, the zoological order typified by the larger carnivorous placental land mammals of the present day, such as lions, tigers and wolves, but also including species like bears whose diet is largely vegetable, as well as a number of smaller flesh-eating species, together with the seals and their relatives, and an extinct Tertiary group. Apart from this distinct group (see Creodonta), the Carnivora are characterized by the following features. They are unguiculate, or clawed mammals, with never less than four toes to each foot, of which the first is never opposable to the rest; the claws, or nails, being more or less pointed although occasionally rudimentary. The teeth comprise a deciduous and a permanent series, all being rooted, and the latter divisible into the usual four series. In front there is a series of small pointed incisors, usually three in number, on each side of both jaws, of which the first is always the smallest and the third the largest, the difference being most marked in the upper jaw; these are followed by strong conical, pointed, recurved canines; the premolars and molars are variable, but generally, especially in the anterior part of the series, more or less compressed, pointed and trenchant; if the crowns are flat and tuberculated, they are never complex or divided into lobes by deep inflexions of enamel. The condyle of the lower jaw is a transversely placed half-cylinder working in a deep glenoid fossa of corresponding form. The brain varies much in size and form, but the hemispheres are never destitute of convolutions. The stomach is always simple and pyriform; the caecum is either absent or short and simple; and the colon is not sacculated or much wider than the small intestine. Vesiculae seminales are never developed, but Cowper’s glands may be present or absent. The uterus is two-horned, and the teats are abdominal and variable in number; while the placenta is deciduate, and almost always zonary. The clavicle is often absent, and when present never complete. The radius and ulna are distinct; the scaphoid and lunar of the tarsus are united; 367 there is never an os centrale in the adult; and the fibula is distinct.

The large majority of the species subsist chiefly on animal food, though many are omnivorous, and a few chiefly vegetable-eaters. The more typical forms live altogether on recently-killed warm-blooded animals, and their whole organization is thoroughly adapted to a predaceous mode of life. In conformity with this manner of obtaining their subsistence, they are generally bold and savage in disposition, though some are capable of being domesticated, and when placed under favourable circumstances exhibit a high degree of intelligence.

I. Fissipedia

|

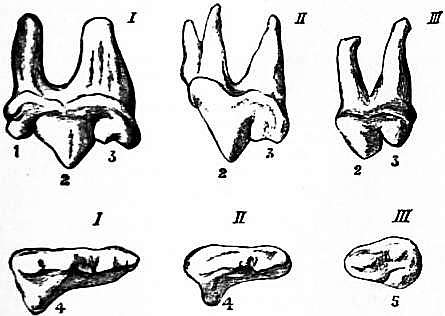

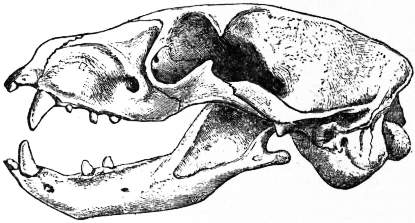

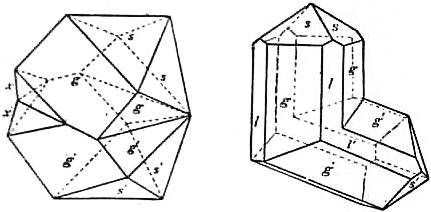

| Fig. I.—Left upper sectorial or carnassial teeth of Carnivora. I, Felis; II, Canis; III, Ursus. 1, anterior, 2, middle, and 3, posterior cusp of blade; 4, inner cusp supported on distinct root; 5, inner cusp, posterior in position, and without distinct root, characteristic of the Ursidae. |

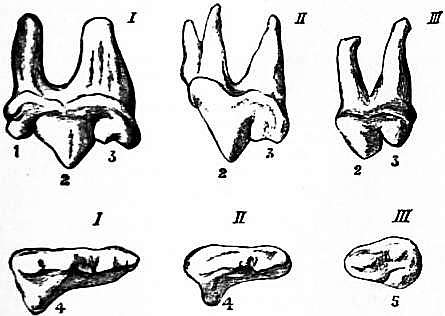

The typical section of the group, the Carnivora Vera, Fissipedia or Carnassidentia, includes all the existing terrestrial members of the order, together with the otters and sea-otters. In this section the fore-limbs never have the first digit, or the hind-limbs the first and fifth digits, longer than the others; and the incisors are 3⁄3 on each side, with very rare exceptions. The cerebral hemispheres are more or less elongated; always with three or four convolutions on the outer surface forming arches above each other, the lowest surrounding the Sylvian fissure. In the cheek-series there is one specially modified tooth in each jaw, to which the name of “sectorial” or “carnassial” is applied. The teeth in front of this are more or less sharp-pointed and compressed; the teeth behind broad and tuberculated. The characters of the sectorial teeth deserve special attention, as, though fundamentally the same throughout the group, they are greatly modified in different genera. The upper sectorial is the most posterior of the teeth which have predecessors, and is therefore reckoned as the last premolar (p. 4 of the typical dentition). It consists of a more or less compressed blade supported on two roots and an inner lobe supported by a distinct root (see fig. 1). The blade when fully developed has three cusps (i, 2 and 3), but the anterior is always small, and often absent. The middle cusp is conical, high and pointed; and the posterior cusp has a compressed, straight, knife-like edge. The inner cusp. (4) varies in extent, but is generally placed near the anterior end of the blade, though sometimes median in position. In the Ursidae alone both the inner cusp and its root are wanting, and there is often a small internal and posterior cusp (5) without root. In this family also the sectorial is relatively to the other teeth much smaller than in other Carnivora. The lower sectorial (fig. 2) is the most anterior of the teeth without predecessors in the milk-series, and is therefore reckoned the first molar. It has two roots supporting a crown, consisting when fully developed of a compressed bilobed blade (1 and 2), a heel (4), and an inner tubercle (3). The cusps of the blade, of which the hinder (2) is the larger, are separated by a notch, generally prolonged into a linear fissure. In the specialized Felidae (I) the blade alone is developed, both heel and inner tubercle being absent or rudimentary. In Meles (V) and Ursus (VI) the heel is greatly developed, broad and tuberculated. The blade in these cases is generally placed obliquely, its flat or convex (outer) side looking forwards, so that the two lobes or cusps are almost side by side, instead of anterior and posterior. The inner tubercle (3) is generally a conical pointed cusp, placed to the inner side of the hinder lobe of the blade. The special characters of these teeth are more disguised in the sea-otter than in any other species, but even here they can be traced.

|

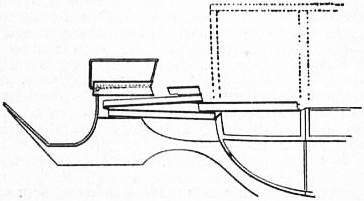

| Fig. 2.—Left lower sectorial or carnassial teeth of Carnivora, I, Felis; II, Canis; III, Herpestes; IV, Lutra; V, Meles; VI, Ursus. 1, Anterior cusp of blade; 2, posterior cusp of blade; 3, inner tubercle; 4, heel. It will be seen that the relative size of the two roots varies according to the development of the portion of the crown they respectively support. |

The toes are nearly always armed with large, strong, curved and sharp claws, ensheathing the terminal phalanges and held firmly in place by broad plates of bone reflected over their attached ends from the bases of the phalanges. In the Felidae these claws are “retractile”; the terminal phalange with the claw attached, folding back in the fore-foot into a sheath by the outer or ulnar side of the middle phalange of the digit, and retained in this position when at rest by a strong elastic ligament. In the hind-foot the terminal joint or phalange is retracted on to the top, and not the side of the middle phalange. By the action of the deep flexor muscles the terminal phalanges are straightened, the claws protruded from their sheath, and the soft “velvety” paw becomes suddenly converted into a formidable weapon of offence. The habitual retraction of the claws preserves their points from wear.

The land Carnivora are best divided into two subgroups or sections—(A) the Aeluroidea, or Herpestoidea, and (B) the Arctoidea; the recognition of a third section, Cynoidea, being rendered untenable by the evidence of extinct forms.

(A) Aeluroidea.—In this section, which comprises the cats (Felidae), civets (Viverridae), and hyenas (Hyaenidae), the tympanic bone is more or less ring-like, and forms only a part of the outer wall of the tympanic cavity; an inflated alisphenoid bulla is developed; and the external auditory meatus is short. In the nasal chamber the maxillo-turbinal is small and doubly folded, and does not cut off the naso-turbinal and adjacent bones from the nasal aperture. The carotid canal in the skull is short or absent. Cowper’s glands are present, as is a prostate gland and a caecum, as well as a duodenal-jejunal flexure in the intestine, but an os penis is either wanting or small.

The members of the cat tribe, or Felidae, are collectively characterized by the following features. An alisphenoid is lacking on the lower aspect of the skull. In existing forms the usual dental formula is i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1, p. 3⁄2, m. 1⁄1; the upper molar Cat tribe. being rudimentary and placed on the inner side of the carnassial, but the first premolar may be absent, while, as an abnormality, there may be a small second lower molar, which is constantly present in 368 some of the extinct forms. The auditory bulla and the tympanic are divided by an internal partition. The paroccipital process is separate from, or only extends to a slight degree upon the auditory bulla. The thoracic vertebrae number 13; the feet are digitigrade, with five front and four hind toes, of which the claws are retractile; and the metatarsus is haired all round. Anal glands are present.

As regards the teeth, when considered in more detail, the incisors are small, and the canines large, strong, slightly recurved, with trenchant edges and sharp points, and placed wide apart. The premolars are compressed and sharp-pointed; the most posterior in the upper jaw (the sectorial) being a large tooth, consisting of a compressed blade, divided into three unequal cusps supported by two roots, with a small inner lobe placed near the front and supported by a distinct root (fig. 1, I). The upper molar is a small tubercular tooth placed more or less transversely at the inner side of the hinder end of the last. In the lower jaw the molar (sectorial) is reduced to the blade, which is large, trenchant, compressed and divided into two subequal lobes (fig. 2, I). Occasionally it has a rudimentary heel, but never an inner tubercle. The skull generally is short and rounded, though proportionally more elongated in the larger forms; with the facial portion short and broad, and the zygomatic arches wide and strong. The auditory bullae are large, rounded and smooth. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 13, L. 7, S. 3, Ca. 13-29. Clavicles better developed than in other Carnivora, but not articulating with either the shoulder-bones or sternum. Of the five front toes, the third and fourth are nearly equal and longest, the second slightly, and the fifth considerably shorter. The first is still shorter, not reaching the metacarpophalangeal articulation of the second. In the hind-feet the third and fourth toes are the longest, the second and fifth somewhat shorter and nearly equal, while the first is represented only by the rudimentary metatarsal bone. The claws are large, strongly curved, compressed, very sharp, and exhibit the retractile condition in the highest degree. The tail varies greatly in length, being in some species a mere stump, in others nearly as long as the body. The ears are of moderate size, more or less triangular and pointed; and the eyes rather large, with the iris mobile, and with a pupillary aperture which contracts under the influence of light in some species to a narrow vertical slit, in others to an oval, and in some to a circular aperture. The tongue is thickly covered with sharp, pointed, recurved horny papillae; and the caecum is small and simple.

As in structure so in habits, the cat may be considered the most specialized of all Carnivora, although they exhibit many features connecting them with extinct types. All the members of the group feed almost exclusively on warm-blooded animals which they have themselves killed, but one Indian species, Felis viverrina, is said to prey on fish, and even fresh-water molluscs. Unlike dogs, they never associate in packs, and rarely hunt their prey on open ground, but from some place of concealment wait until the unsuspecting victim comes within reach, or with noiseless and stealthy tread, crouching close to the ground for concealment, approach near enough to make the fatal spring. In this manner they frequently attack and kill animals considerably exceeding their own size. They are mostly nocturnal, and the greater number, especially the smaller species, more or less arboreal. None are aquatic, and all take to the water with reluctance, though some may habitually haunt the banks of rivers or pools, because they more easily obtain their prey in such situations. The numerous species are widely diffused over the greater part of the habitable world, though most abundant in the warm latitudes of both hemispheres. None are, however, found in the Australian region, or in Madagascar. Although the Old World and New World cats (except perhaps the northern lynx) are all specifically distinct, no common structural character has been pointed out by which the former can be separated from the latter. On the contrary, most of the groups into which the family may be divided have representatives in both hemispheres.

Notwithstanding the considerable diversity in external appearance and size between different members of this extensive family, the structural differences are but slight. The principal differences are to be found in the form of the cranium, especially of the nasal and adjoining bones, the completeness of the bony orbit posteriorly, the development of the first upper premolar and of the inner lobe of the upper sectorial, the length of the tail, the form of the pupil, and the condition and coloration of the fur, especially the presence or absence of tufts or pencils of hair on the external ears.

In the typical genus Felis, which includes the great majority of the species, and has a distribution coextensive with that of the family, the upper sectorial tooth has a distinct inner cusp, the claws are completely contractile, the tail is long or moderate, and the ears do not carry distinct tufts of hair. As regards the larger species, the lion (F. leo), tiger (F. tigris), leopard (F. pardus), ounce or snow-leopard (F. uncia) and clouded leopard (F. nebulosa) are described in separate articles. Of other Old World species it must suffice to mention that the Tibetan Fontanier’s cat (F. tristis), and the Indian marbled cat (F. marmorata), an ally of the above-mentioned clouded leopard, appear to be the Asiatic representatives of the American ocelots. The Tibetan Pallas’s cat (F. manul) has been made the type of a distinct genus, Trichaelurus, in allusion to its long coat. One of the largest of the smaller species is the African serval, q.v. (F. serval), which is yellow with solid black spots, has long limbs, and a relatively short tail. Numerous “tiger-cats” and “leopard-cats,” such as the spotted F. bengalensis and the uniformly chestnut F. badia, inhabit tropical Asia; while representative species occur in Africa. The jungle-cat (F. chaus), which in its slightly tufted ears and shorter tail foreshadows the lynxes, is common to both continents. Another African species (F. ocreata) appears to have been the chief progenitor of the European domestic cat, which has, however, apparently been crossed to some extent with the ordinary wild cat (F. catus). Of the New World species, F. concolor, the puma or couguar, commonly called “panther” in the United States, is about the size of a leopard, but of a uniform brown colour, spotted only when young, and is extensively distributed in both North and South America, ranging between the parallels of 60° N. and 50° S., where it is represented by numerous local races, varying in size and colour. F. onca, the jaguar, is a larger and more powerful animal than the last, and more resembles the leopard in its colours; it is also found in both North and South America, although with a less extensive range, reaching northwards only as far as Texas, and southwards nearly to Patagonia (see Jaguar). F. pardalis and several allied smaller, elegantly-spotted species inhabiting the intratropical regions of America, are commonly confounded under the name of ocelot or tiger-cat. F. yaguarondi, rather larger than the domestic cat, with an elongated head and body, and of a uniform brownish-grey colour, ranges from northern Mexico to Paraguay; while the allied F. eyra is a small cat, weasel-like in form, having an elongated head, body and tail, and short limbs, and is of a uniform light reddish-brown colour. It is a native of South America and Mexico. F. pajeros is the Pampas cat.

The typical lynxes, as represented by Lynx borealis (L. lynx), the southern L. pardina, and the American L. rufa, are a northern group common to both hemispheres, and characterized by their tufted ears, short tail, and the presence of a rudimentary heel to the lower carnassial tooth. As a rule, they are more or less spotted in winter, but tend to become uniformly-coloured in summer. They are connected with the more typical cats by the long-tailed and uniformly red caracal, Lynx (Caracal) caracal, of India, Persia and Africa, and the propriety of separating them from Felis may be open to doubt (see Lynx and Caracal).

However this may be, there can be no doubt of the right of the hunting-leopard or chita (cheeta), as, in common with the leopard, it is called in India, to distinction from all the other cats as a distinct genus, under the name of Cynaelurus jubatus. From all the other Felidae this animal, which is common to Asia and Africa, is distinguished by the inner lobe of the upper sectorial tooth, though supported by a distinct root, having no salient cusp upon it, by the tubercular molar being more in a line with the other teeth, and by the claws being smaller, less curved and less completely retractile, owing to the feebler development of the elastic ligaments. The skull is short and high, with the frontal region broad and elevated in consequence of the large development of air-sinuses. The head is small and round, the body light, the limbs and tail long, and the colour pale yellowish-brown with small solid black spots (see Cheeta).

The family Viverridae, which includes the civet-cats, genets and mongooses, is nearly allied to the Felidae, but its members have a fuller dentition, and exhibit certain other structural differences from the cats, to the largest of which they Civet tribe. make no approach in the matter of bodily size. As a rule, there is an alisphenoid canal; the cheek-dentition is p. 3 or 4⁄3 or 4, m. 1 or 2⁄1 or 2 The bulla is small and the tympanic large, with a low division between them; and the paroccipital process is leaf-like and spread over the bulla. The number of dorsal vertebrae, except in the aberrant Proteles, is 13 or 14; the claws may be either completely or partially retractile or non-retractile; generally each foot has five toes, but there may be four in front and five behind, the reverse of this, or only four on each foot; the gait may be either digitigrade or partially plantigrade; and the metatarsus may be either hairy or naked inferiorly. Anal, and in some cases also perineal, glands are developed. The family is limited to the warmer parts of the Old World.

Considerable difference of opinion prevails with regard to the serial position of the fossa, or foussa (Cryptoprocta ferox), of Madagascar, some writers considering that its affinities are so close to the Felidae that it ought not to be included in the present family at all. Others, on the contrary, see no reason to separate it from the Viverrinae or more typical representatives of the civet-tribe. As a medium course, it may be regarded as the sole representative of a special subfamily—Cryptoproctinae—of the Viverridae. The subfamily and genus are characterized by possessing a total of 36 teeth, arranged as i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1, p. 4⁄4, m. 1⁄1. The teeth generally closely resemble those of the Felidae, the first premolar of both jaws being very minute and early deciduous; the upper sectorial has a small inner lobe, quite at the anterior part; the molar is small and placed transversely; and the lower sectorial has a large trenchant bilobed blade, and a minute heel, but no inner tubercle. The skull is generally like that of Felis, but proportionally longer and narrower, with the orbit widely open behind. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 13, L. 7, S. 3, Ca. 29. Body elongated. Limbs moderate in size. Feet subplantigrade, with five well-developed toes on each, carrying sharp, compressed, retractile claws. Ears moderate. Tail long and 369 cylindrical. The foussa is a sandy-coloured animal with an exceedingly long tail (see Foussa).

The more typical members of the group, constituting the subfamily Viverrinae, are characterized by their sharp, curved and largely retractile claws, the presence of five toes to each foot, and of perineal and one pair of anal glands, and a tympanic bone which retains to a great extent the primitive ring-like form, so that the external auditory meatus has scarcely any inferior lip, its orifice being close to the tympanic ring. The first representatives of the subfamily are the civet-cats, or civets (Viverra and Viverricula), and the genets (Genetta), in all of which the dentition is i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1, p. 4⁄4, m. 2⁄2; total 40. The skull is elongated, with the facial portion small and compressed, and the orbits well-defined but incomplete behind. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 13, L. 7 (or D. 14, L. 6), S. 3, Ca. 22-30. Body elongated and compressed. Head pointed in front; ears rather small. Extremities short. Feet small and rounded. Toes short, the first on fore and hind feet much shorter than the others. Palms and soles covered with hair, except the pads of the feet and toes, and in some species a narrow central line on the under side of the sole, extending backwards nearly to the heel. Tail moderate or long. The pair of large glands situated on the perineum (in both sexes) secretes an oily substance of a peculiarly penetrating odour. In the true civets, which include the largest members of the group, the teeth are stouter and less compressed than in the other genera; the second upper molar being especially large, and the auditory bulla smaller and more pointed in front; the body is shorter and stouter; the limbs are longer; the tail shorter and tapering. The under side of the tarsus is completely covered with hair, and the claws are longer and less retractile. Fur rather long and loose, and in the middle line of the neck and back especially elongated so as to form a sort of crest or mane. Pupil circular when contracted. Perineal glands greatly developed. These characters apply especially to V. civetta, the African civet, or civet-cat, as it is commonly called, an animal rather larger than a fox, and an inhabitant of intratropical Africa. V. zibetta, the Indian civet, of about equal size, approaches in many respects, especially in the characters of the teeth and feet and absence of the crest of elongated hair on the back, to the next section. It inhabits Bengal, China, the Malay Peninsula and adjoining islands. V. tangalunga is a smaller but nearly allied animal from the same part of the world. From these three species and the next the civet of commerce, once so much admired as a perfume in England, and still largely used in the East, is obtained. The animals are kept in cages, and the odoriferous secretion collected by scraping the interior of the perineal follicles with a spoon or spatula. The single representative of the genus Viverricula resembles in many respects the genets, but agrees with the civets in having the whole of the under side of the tarsus hairy; the alisphenoid canal is generally absent. V. malaccensis, the rasse, inhabiting India, China, Java and Sumatra, is an elegant little animal which affords a favourite perfume to the Javanese. The genets (Genetta) are smaller animals, with more elongated and slender bodies, and shorter limbs than the civets. The skull is elongated and narrow; and the auditory bulla large, elongated and rounded at both ends. The teeth are compressed and sharp-pointed, with a lobe on the inner side of the third, upper premolar not present in the previous genera. Pupil contracting to a linear aperture. Tail long, slender, ringed. Fur short and soft, spotted or cloudy. Under side of the metatarsus with a narrow longitudinal bald streak. Genetta vulgaris, or G. genetta, the common genet, is found in France south of the river Loire, Spain, south-western Asia and North Africa. G. felina, senegalensis, tigrina, victoriae and pardalis are other named species, all African in habitat.

The Malagasy fossane (Fossa daubentoni), which has but little markings on the fur of the adult, differs by the absence of a scent-pouch and the presence of a couple of bare spots on the under surface of the metatarsus. The beautiful linsangs (Linsanga or Prionodon), ranging from the eastern Himalaya to Java and Borneo, are represented by two or three species, easily recognizable by the broad transverse bands of blackish brown and yellow with which the body and tail are marked. They are specially distinguished by having only one pair of upper molars, thereby resembling the cats, with which, in correlation with their arboreal habits, they agree in their highly retractile claws, and the hairy surface of the under side of the metatarsus. About 15 in. is the length of the type species. In West Africa the linsangs are represented by Poiana richardsoni, a small species with a spotted genet-like coat, and also with a narrow naked stripe on the under surface of the metatarsus, as in genets.

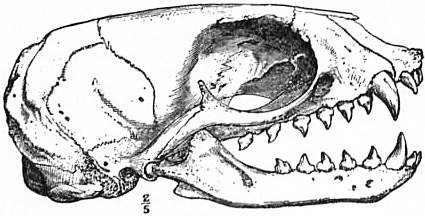

Here may be placed the two African spotted palm-civets of the genus Nandinia, namely N. binotata from the west and N. gerrardi from the east forest-region. In common with the true palm-civets, they have a dentition numerically identical with that of Viverra and Genetta, but the cusps of the hinder premolars and molars are much less sharp and pointed. They are peculiar in that the wall of the inner chamber of the auditory bulla never ossifies, while the paroccipital process is not flattened out and spread over the bulla. In this respect they resemble the Miocene European genus Amphictis, as they do in the form of their teeth, so that they may be regarded as nearly related to the ancestral Viverridae, and forming in some degree a connecting link between the present and the next subfamily. Nandinia is also peculiar in possessing a kind of rudimentary marsupial pouch. Apparently Eupleres goudoti, of Madagascar, which has been generally classed in the Herpestinae, is a nearly related animal, characterized by the reduction of its dentition, due to insectivorous habits (fig. 3); the canines being small, the anterior premolars canine-like, and the hinder premolars molariform. It is a uniformly-coloured creature of medium size.

|

| Fig. 3.—Skull of Eupleres goudoti. |

The palm-civets, or paradoxures, constituting the Asiatic genus Paradoxurus, have, as already stated, the following dental formula, viz. i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1, p. 4⁄4, m. 2⁄2, total 40; the cusps of the molars being low and blunted, and these teeth in the upper jaw much broader than in the civets. The head is pointed in front, with small rounded ears; the limbs are of medium length, with the soles of the feet almost completely naked, and fully retractile claws; while the long tail is not prehensile and clothed with hair of moderate length. Spots are the chief type of marking. The vertebrae number C. 7, D. 13, L. 7, S. 3, Ca. 29-36. Numerous relatively large species ranging from India to Borneo, Sumatra and Celebes, with one in Tibet, represent the genus. Nearly allied are Arctogale leucotis, with a wide distribution, and A. trivirgata, of Java, both longitudinally striped species, with small and slightly separated molars, and a prolonged bony palate (see Palm-civet).

The binturong (Arctictis binturong) has typically the same dental formula as the last, but the posterior upper molar and the first lower premolar are often absent. Molars small and rounded, with a distinct interval between every two, but formed generally on the same pattern as Paradoxurus. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 14, L. 5, S. 3, Ca. 34. Body elongated; head broad behind, with a small pointed face, long and numerous whiskers, and small ears, rounded, but clothed with a pencil of long hairs. Eyes small. Limbs short, with the soles of the feet broad and entirely naked. Tail very long and prehensile. Fur long and harsh. Caecum extremely small. The binturong inhabits southern Asia from Nepal through the Malay Peninsula to the islands of Sumatra and Java. Although structurally agreeing closely with the paradoxures, its tufted ears, long, coarse and dark hair, and prehensile tail give it a very different external appearance. It is slow and cautious in its movements, chiefly if not entirely arboreal, and appears to feed on vegetables as well as animal substances (see Binturong).

Hemigale is another modification of the paradoxure type, represented by H. hardwickei of Borneo, an elegant-looking animal, smaller and more slender than the paradoxures, of light grey colour, with transverse broad dark bands across the back and loins.

Cynogale also contains one Bornean species, C. bennetti, a curious otter-like modification of the viverrine type, having semi-aquatic habits, both swimming in the water and climbing trees, living upon fish, crustaceans, small mammals, birds and fruits. The number and general arrangement of the teeth are as in Paradoxurus, but the premolars are peculiarly elongated, compressed, pointed and recurved, though the molars are tuberculated. The head is elongated, with the muzzle broad and depressed, the whiskers are very long and abundant, and the ears small and rounded. Toes short and slightly webbed at the base. Tail short, cylindrical, covered with short hair. Fur very dense and soft, of a dark-brown colour, mixed with black and grey.

In the mongoose group, or Herpestinae, the tympanic or anterior portion of the auditory bulla is produced into an ossified external auditory meatus of considerable length; while the paroccipital process never projects below the bulla, on the hinder surface of which, in adult animals, it is spread out and completely lost. The toes are straight, with long, unsheathed, non-retractile claws.

In the typical mongooses or ichneumons, Herpestes, the dental formula is i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1, p. (4 or 3)⁄(4 or 3), m. 2⁄2; total 40 or 36; the molars having generally strongly-developed, sharply-pointed cusps. The skull is elongated and constricted behind the orbits. The face is short and compressed, with the frontal region broad and arched. Post-orbital processes of frontal and jugal bones well developed, generally meeting so as to complete the circle of the orbit behind. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 13, L. 7, S. 3, Ca. 21-26. Head pointed in front. Ears short and rounded. Body long and slender. Extremities short. Five toes on each foot, the first, especially that on the hind-foot, very short. Toes free, or but slightly palmated. Soles of fore-feet and terminal portion of those of hind-pair naked; under surface of metatarsus clothed with hair. Tail long or moderate, generally thick at the base, and sometimes covered with more or less elongated hair. The longer hairs covering the body and tail almost always ringed. The genus is common to the warmer parts of 370 Asia and Africa, and while many of the species, like the Egyptian H. ichneumon and the ordinary Indian mongoose, H. mungo, are pepper-and-salt coloured, the large African H. albicauda has the terminal two-thirds of the tail clothed with long white hairs (see Ichneumon).

The following distinct African and Malagasy generic representatives of the subfamily are recognized, viz. Helogale, with 3⁄3 premolars, and containing the small South African H. parvula and a variety of the same. Bdeogale crassicauda and two allied tropical African species differ from Herpestes in having only four toes on each foot. The orbit is nearly complete, and the tail of moderate length and rather bushy. In Cynictis, which has the orbit completely closed, there are five front and four hind toes; and the skull is shorter and broader than in Herpestes, rather contracted behind the orbits, the face short, and the anterior chamber of the auditory bulla very large. The front claws are elongated. Includes only C. penicillata from South Africa.

All the foregoing herpestines have the nose short, with its under surface flat, bald, and with a median longitudinal groove. The remaining forms have the nose more or less produced, with its under side convex, and a space between the nostrils and the upper lip covered with closely pressed hairs, and without any median groove. The South African Rhynchogale muelleri, a reddish animal with five toes to each foot and 4⁄4 (abnormally 5⁄5) premolars, alone represents the first genus. The cusimanses (Crossarchus), which differ by having only 3⁄3 premolars, and thus a total of 36 teeth, include, on the other hand, several species. The muzzle is elongated, the claws on the fore-feet are long and curved, the first front toe is very short; the under surface of the metatarsus naked; and the tail shorter than the body, tapering. Fur harsh. Includes C. obscurus, the cusimanse, a small burrowing animal from West Africa, of uniform dark-brown colour, C. fasciatus, C. zebra, C. gambianus and others. Lastly, we have Suricata, a more distinct genus than any of the above. The dental formula is as in the last, but the teeth of the molar series are remarkably short in the antero-posterior direction, corresponding with the shortness of the skull generally. Orbits complete behind. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 15, L. 6, S. 3, Ca. 20. Though the head is short and broad, the nose is pointed and rather produced and movable, while the ears are very short. Body shorter and limbs longer than in Herpestes. Toes 4-4. Claws on fore-feet very long and narrow, arched, pointed and subequal. Hind-feet with shorter claws, soles hairy. Tail rather shorter than the body. One species only is known, the meerkat or suricate, S. tetradactyla, a small grey-brown animal, with dark transverse stripes on the hinder part of the back, from South Africa.

The names Galidictis, Galidia and Hemigalidia indicate three generic modifications of the Herpestinae, all inhabitants of Madagascar. The best-known, Galidia elegans, is a lively squirrel-like little animal with soft fur and a long bushy tail, which climbs and jumps with agility. It is of a chestnut-brown colour, the tail being ringed with darker brown. Galidictis vittata and G. striata chiefly differ from the ichneumons in their coloration, being grey with parallel longitudinal stripes of dark brown.

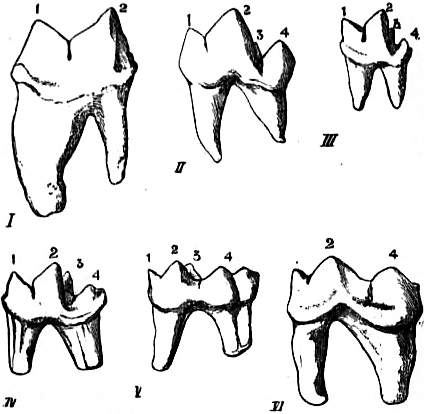

Considerable diversity of opinion prevails with regard to the serial position of the aard-wolf, or maned jackal (Proteles cristatus), of southern and eastern Africa, some authorities making it the representative of a family by itself, others referring it to the Hyaenidae, while others again regard it as a modified member of the Viverridae. After all, the distinction either way cannot be very great, since the two families just named are intimately connected by marks of the extinct Ictitherium, With the Viverridae it agrees in having the auditory bulla divided, while in the number of dorsal vertebrae it is hyena-like. The cheek-teeth are small, far apart, and almost rudimentary in character (see fig. 4), and the canines long and rather slender. The dental formula is i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1, p.m. 4⁄3 or 4; total 30 or 32. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 15, L. 5, S. 2, Ca. 24. The fore-feet with five toes; the first, though short, with a distinct claw. The hind-feet with four subequal toes; all, like those of the fore-foot, furnished with strong, blunt, non-retractile claws (see Aard-Wolf).

The hyenas or hyaenas (Hyaenidae) differ from the preceding family (Viverridae) in the absence of a distinct vertical partition between the two halves of the auditory bulla; and are further characterized by the absence of an alisphenoid Hyena tribe. canal, the reduction of the molars to 1⁄1, and the presence of 15 dorsal vertebrae. The dental formula in the existing forms (to which alone all these remarks apply) is i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1. p. 4⁄3 m. 1⁄1; total 34; the teeth, especially the canines and premolars, being very large, strong and conical. Upper sectorial with a large, distinctly trilobed blade and a moderately developed inner lobe placed at the anterior extremity of the blade. Molar very small, and placed transversely close to the hinder edge of the last, as in the Felidae. Lower sectorial consisting of little more than the bilobed blade. Zygomatic arches of skull very wide and strong; and sagittal crest high, giving attachment to very powerful biting muscles. Orbits incomplete behind. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 15, L. 5, S. 4, Ca. 19. Limbs rather long, especially the anterior pair, digitigrade, four subequal toes on each, with stout non-retractile claws, the first toes being represented by rudimentary metacarpal and metatarsal bones. Tail rather short. A large post-anal median glandular pouch, into which the largely developed anal scent glands pour their secretion.

|

| Fig. 4.—Skull and Dentition of Aard-Wolf (Proteles cristatus.) |

The three well-characterized species of Hyaena are divisible into two sections, to which some zoologists assign generic rank. In the typical species the upper molar is moderately developed and three-rooted; and an inner tubercle and heel more or less developed on the lower molar. Ears large and pointed. Hair long, forming a mane on the back and shoulders. Represented firstly by H. striata, the striped hyena of northern and eastern Africa and southern Asia; and H. brunnea of South Africa, in some respects intermediate between this and the next section. In the second section, forming the subgenus Crocuta, the upper molar is extremely small, two- or one-rooted, often deciduous; the lower molar without trace of inner tubercle, and with an extremely small heel. Ears moderate, rounded. Hair not elongated to form a mane. The spotted hyena, Hyaena (Crocuta) crocuta, of which, like the striped species, there are several local races, represents this group, and ranges all over Africa south of the Sahara. In dental characters the first section inclines more to the Viverridae, the second to the Felidae; or the second may be considered as the more specialized form, as it certainly is in its visceral anatomy, especially in that of the reproductive organs of the female. (See Hyena.)

(B) Arctoidea.—So far as the auditory region of the skull is concerned, the existing representatives of the dog tribe or Canidae are to a great extent intermediate between the cat and civet group (Aeluroidea) on the one hand, and the typical representatives of the bear and weasel group on the other. They were consequently at one time classed in an intermediate group—the Cynoidea; but fossil forms show such a complete transition from dogs to bears as to demonstrate the artificial character of such a division. Consequently, the dogs are included in the bear-group. In this wider sense the Arctoidea will be characterized by the tympanic bone being disk-shaped and forming the whole of the outer wall of the tympanic cavity; the large size of the external auditory meatus or tube; and the large and branching maxillo-turbinal bone, which cuts off the naso-turbinal and two adjacent bones from the anterior nasal chamber. The tympanic bulla has no internal partition. There is a large carotid canal. Cowper’s glands are lacking; and there is a large penial bone.

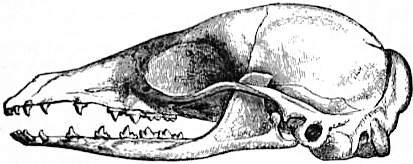

From all the other members of the group the Canidae are broadly distinguished (in the case of existing forms) by the large and well-developed tympanic bulla, with which the paroccipital process is in contact. An alisphenoid canal is present. Dog tribe. The feet are digitigrade, usually with five (in one instance four) front and always four hind-toes. The molars—generally 2⁄3—have tall cusps, and the sectorials are large and powerful (figs. 1 and 2). The intestine has both a duodeno-jejunal flexure and a caecum. A prostate gland is present; but there are no glands in the vasa deferentia; the penial bone is grooved; and anal glands are generally developed. The distribution of the family is cosmopolitan. The normal dentition is i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1, p. 4⁄4, m. 2⁄3; total 42; thus differing from the typical series only by the loss of the last pair of upper molars (present in certain extinct forms). In the characters of the teeth the group is the most primitive of all Carnivora. Typically the upper secterial (fig. 1, II) consists of a stout blade, of which the anterior cusp is almost obsolete, the middle cusp large, conical and pointed backwards, and the posterior cusp in the form of a compressed ridge; the inner lobe is very small, and placed at the fore part of the tooth. The first molar is more than half the antero-posterior length of the sectorial, and considerably wider than long; its crown consists of two prominent conical cusps, of which the anterior is the larger, and a low, broad inward prolongation, supporting two more or less distinct cusps and a raised inner border. The second molar resembles the first in general form, but is considerably smaller. The lower sectorial (fig. 2, II) is a large tooth, with a strong compressed bilobed blade, the hinder lobe being considerably the larger and more pointed, a small but distinct inner tubercle 371 placed at the hinder margin of the posterior lobe of the blade, and a broad, low, tuberculated heel, occupying about one-third of the whole length of the tooth. The second molar is less than half the length of the first, with a pair of cusps placed side by side anteriorly, and a less distinct posterior pair. The third is an extremely small and simple tooth with a subcircular tuberculated crown and single root.

Views differ in regard to the best classification of the Canidae, some writers adopting a number of generic groups, while others consider that very few meet the needs of the case. In retaining the old genus Canis in the wide sense, that is to say, inclusive of the foxes, Professor Max Weber is followed. The best cranial character by which the different members of the family may be distinguished is that in dogs, wolves and jackals the post-orbital process of the frontal bone is regularly smooth and convex above, with its extremity bent downwards, whereas in foxes the process is hollowed above, with its outer margin (particularly of the anterior border) somewhat raised. This modification coincides in the main with the division of the group into two parallel series, the Thooids or Lupine forms and Alopecoids or Vulpine forms, characterized by the presence of frontal air-sinuses in the former, which not only affects the external form but to a still greater degree the shape of the anterior part of the cranial cavity, and the absence of such sinuses in the latter. The pupil of the eye when contracted is round in most members of the first group, and vertically elliptical in the others, but more observations are required before this character can be absolutely relied upon. The form and length of the tail is often used for the purposes of classification, but its characters do not coincide with those of the cranium, as many of the South American Canidae have the long bushy tails of foxes and the skulls of wolves.

|

| Fig. 5.—The African Hunting-Dog (Lycaon pictus). |

The most aberrant representative of the thooid series is the African hunting-dog (Lycaon pictus, fig. 5), which differs from the other members of this series by the teeth being rather more massive and rounded, the skull shorter and broader, and the presence of but four toes on each limb, as in Hyena. The hunting-dog, from south and east Africa, is very distinct externally from all other Canidae; being nearly as large as a mastiff, with large, broadly ovate erect ears and a singular colouring, often consisting of unsymmetrical large spots of white, yellow and black. It presents some curious superficial resemblances to Hyena crocuta, perhaps a case of mimetic analogy, and hunts its prey in large packs. Several local races, one of which comes from Somaliland, differing in size and colour, are recognized (see Hunting-Dog). Nearly related to the hunting-dog are the dholes or wild dogs of Asia, as represented by the Central Asian Cyan primaevus and the Indo-Malay C. javanicus. They have, however, five front-toes, but lack the last lower molar; while they agree with Lycaon and Speothos in that the heel of the lower sectorial tooth has only a single compressed cutting cusp, in place of a large outer and a smaller inner cusp as in Canis. Dholes are whole-coloured animals, with short heads; and hunt in packs. The bush-dog (Speothos, or Icticyon venaticus) of Guiana is a small, short-legged, short-tailed and short-haired species characterized by the molars being only 2 or 1⁄2; the carnassial having no inner cusp. The long-haired raccoon-dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) of Japan and China agrees essentially in everything but general appearance (which is strangely raccoon-like) with Canis. The typical group of the latter includes some of the largest members of the family, such as the true wolves of the northern parts of both Old and New Worlds (C. lupus, &c.), and the various breeds of the domestic dog (C. familiaris), the origin of which is still involved in obscurity. Some naturalists believe it to be a distinct species, descended from one that no longer exists in a wild state; others have sought to find its progenitors in some one of the wild or half-wild races, either of true dogs, wolves or jackals; while others again believe that it is derived from the mingling of two or more wild species or races. It is probably the earliest animal domesticated by man, and few if any other species have undergone such an extraordinary amount of variation in size, form and proportion of limbs, ears and tail, variations which have been perpetuated and increased by careful selective breeding (see Dog). The dingo or Australian dog is met with wild, and also as the domestic companion of the aboriginal race of the country, by whom it appears to have been originally introduced. It is nearly related to a half-wild dog inhabiting Java, and also to the pariah dogs of India and other eastern countries. Dogs were also in the possession of the natives of New Zealand and other islands of the Pacific, where no placental mammals exist naturally, on their discovery by Europeans in the 18th century. The slender-jawed C. simensis of Abyssinia and the South American C. jubatus and C. antarcticus are also generally placed in this group. On the other hand, the North American coyote (C. latrans), with its numerous subspecies, and the Old World jackals, such as the Indo-European C. aureus the Indian C. pallipes, and the African C. lupaster, C. anthus, C. adustus, C. variegatus and C. mesomelas (the black-backed jackal), although closely related to the wolves, have been placed in a separate group under the name of Lupulus. Again, Thous (or Lycalopex), is a group proposed for certain South American Canidae, locally known as foxes, and distinguished from all the foregoing by their fox-like aspect and longer tails, although with skulls of the thöoid type. Among these are the bright-coloured colpeo, C. magellanicus, the darker C. thous, C. azarae, C. griseus, C. cancrivorus and C. brasiliensis. Some of these, such as C. azarae and C. griseus, show a further approximation to the fox in that the pupil of the eye forms a vertical slit. More distinct from all the preceding are the members of the alopecoid or vulpine section, which are unknown in South America. The characteristic feature of the skull has been already mentioned. In addition to this, reference may be made to the elliptical (in place of circular) pupil of the eye, and the general presence of ten (rarely eight) teats instead of a smaller number. The typical groups constituting the subgenus (or genus) Vulpes, is represented by numerous species and races spread over the Old World and North America. Foremost among these is the European fox (C. vulpes—otherwise Vulpes alopex, or V. vulpes), represented in the Himalaya by the variety C. v. montanus and in North Africa by C. v. niloticus, while the North American C. pennsylvanicus or fulvus, can scarcely be regarded as more than a local race. On the other hand, the Asiatic C. bengalensis and C. corsac, and the North American C. velox (kit-fox) are smaller and perfectly distinct species. From all these the North American C. cinereo-argentatus (grey fox) and C. littoralis are distinguished by having a fringe of stiff hairs in the tail, whence they are separated as Urocyon. Again, the Arctic fox (C. lagopus), of which there is a blue and a white phase, has the tail very full and bushy and the soles of the feet thickly haired, and has hence been distinguished as Leucocyon. Lastly, we have the elegant little African foxes known as fennecs (Fennecus), such as C. zerda and C. famelicus of the north, and the southern C. chama, all pale-coloured animals, with enormously long ears, and correspondingly inflated auditory bullae to the skull (see Wolf, Jackal, Fox).

Whatever differences of opinion may obtain among naturalists as to the propriety of separating generically the foxes from the wolves and dogs, there can be none as to the claim of the long-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis) of south and east Africa to represent a genus by itself. In this animal the dental formula is i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1, p. 4⁄4, m. 3 or 4⁄4; total 46 or 48. The molar teeth being in excess of almost all other placental mammals with a differentiated series of teeth. They have the same general characters as in Canis, with very pointed cusps. The lower sectorial shows little of the typical character, having five cusps on the crown-surface; these can, however, be identified as the inner tubercle, the two greatly reduced and obliquely placed lobes of the blade, and two cusps on the heel. The skull generally resembles that of the smaller foxes, particularly the fennecs. The auditory bullae are very large. The hinder edge of the lower jaw has a peculiar form, owing to the great development of an expanded, compressed and somewhat inverted subangular process. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 13, L. 7, S. 3, Ca. 22. Ears very large. Limbs rather long, with the normal number of toes. The two parietal ridges on the skull remain widely separated, so that no sagittal crest is formed. The animal is somewhat smaller than an ordinary fox. In the year 1880 Professor Huxley suggested that in the long-eared fox we have an animal nearly representing the stock from which have been evolved all the other representatives of the dog and fox tribe. One of the main grounds for arriving at this conclusion was the fact that this animal has very generally four true molars in each jaw, and always that number in the lower jaw; whereas three is the maximum number of these teeth to be met with in nearly all placental mammals, other than whales, manatis, armadillos and certain others. The additional molars in Otocyon were regarded as survivals from a primitive type when a larger number was the 372 rule. Palaeontology has, however, made great strides since 1880, and the idea that the earlier mammals had more teeth than their descendants has not only received no confirmation, but has been practically disproved. Consequently Miss Albertina Carlsson had a comparatively easy task (in a paper published in the Zoologisches Jahrbuch for 1905) in demonstrating that the long-eared fox is a specialized, and to some extent degraded, form rather than a primitive type. This, however, is not all, for the lady points out that, as was suggested years previously by the present writer, the creature is really the descendant of the fossil Canis curvipalatus of northern India. This is a circumstance of considerable interest from a distributional point of view, as affording one more instance of the intimate relationship between the Tertiary mammalian fauna of India and the existing mammals of Africa.

In regard to the members of the dog-tribe as a whole, it may be stated that they are generally sociable animals, hunting their prey in packs. Many species burrow in the ground; none habitually climb trees. Though mostly carnivorous, feeding chiefly on animals they have chased and killed themselves, many, especially among the smaller species, eat garbage, carrion, insects, and also fruit, berries and other vegetable substances. The upper surface of the tail of the fox has a gland covered with coarse straight hair. This gland, which emits an aromatic odour, is found in all Canidae, with possibly the exception of Lycaon pictus. Although the bases of the hair covering the gland are usually almost white, the tips are always black; this colour being generally extended to the surrounding hairs, and often forming dark bars on the buttocks. The dark spot on the back of the tail is particularly conspicuous, notably in such widely separated species as the wolves, Azara’s dog and the fennec.

Although its existing representatives are very different, the bear-family or Ursidae, as will be more fully mentioned in the sequel, was in past times intimately connected with the Canidae. In common with the next two families, the modern Bear tribe. Ursidae are characterized by the very small tympanic bulla, and the broad paroccipital process, which is, however, independent of the bulla. The feet are more or less completely plantigrade and five-toed. The intestine has neither duodeno jejunal flexure nor a caecum; the prostate gland is rudimentary; but glands occur in the vasa deferentia; and the penial bone is cylindrical. As distinctive characteristics of the Ursidae, may be mentioned the presence of an alisphenoid canal on the base of the skull; the general absence of a perforation on the inner side of the lower end of the humerus; the presence of two pairs of upper and three of lower molars, which are mostly elongated and low-cusped; and the non-cutting character and fore-and-aft shortening of the upper sectorial, which has no inner root and one inner cusp (fig. I, III.). Anal glands are apparently wanting. The short tail, bulky build, completely plantigrade feet and clumsy gait are features eminently characteristic of the bears.

The great majority of existing bears may be included in the typical genus Ursus, of which, in this wide sense, the leading characteristics will be as follows. The dentition is i. 3⁄3, c. 1⁄1, p. 4⁄4, m. 2⁄3 = 42; but the three anterior premolars, above and below, are one-rooted, rudimentary and frequently wanting. Usually the first (placed close to the canine) is present, and after a considerable interval the third, which is situated close to the other teeth of the cheek-series. The fourth (upper sectorial) differs essentially from the corresponding tooth of other Carnivora in that the inner lobe is not supported by a distinct root; its sectorial characters being very slightly marked. The crowns of both true molars are longer than broad, with flattened, tuberculated, grinding surfaces; the second having a large backward prolongation or heel. The lower sectorial has a small and indistinct blade and greatly developed tubercular heel; the second molar is of about the same length, but with a broader and more flattened tubercular crown; while the third is smaller. The milk-teeth are comparatively small, and shed at an early age. The skull is more or less elongated, with the orbits small and incomplete behind, and the palate prolonged considerably behind the last molar. Vertebrae: C. 7, D. 14, L. 6, S. 5, Ca. 8-10. Body heavy. Feet broad, completely plantigrade; the five toes on each well developed, and armed with long compressed and moderately curved, non-retractile claws, the soles being generally naked. Tail very short. Ears moderate, erect, rounded, hairy. Fur generally long, soft and shaggy.

Bears are animals of considerable bulk, and include among them the largest members of the order. Though the species are not numerous, they are widely spread over the earth, although absent from Africa south of the Sahara and Australasia. As a rule, they are omnivorous, or vegetable feeders, even the polar bear, which subsists for most of the year on flesh and fish, eating grass in summer. On the other hand, many of the brown bears live largely on salmon in summer. Among the various species the white polar bear of the Arctic regions, Ursus (Thalassarctus) maritimus, differs from the rest by its small and low head, small, narrow and simple molars, and the presence of a certain amount of hair on the soles of the feet. The typical group of the genus is represented by the brown bear (U. arctus) of Europe and Asia, of which there are many local races, such as the Syrian U. a. syriacus, the Himalayan U. a. isabellinus, the North Asiatic U. a. collaris, and the nearly allied Kamchadale race, which is of great size. In Alaska the group is represented by huge bears, which can scarcely claim specific distinctness from U. arctus; and if these are ranked only as races, it is practically impossible to regard the Rocky Mountain grizzly bear (U. horribilis) as of higher rank, although it naturally differs more from the Asiatic animal. On the other hand, the small and light-coloured U. pruinosus of Tibet may be allowed specific rank. More distinct is the North American black bear U. americanus, and its white relative U. kermodei of British Columbia; and perhaps we should affiliate to this group the Himalayan and Japanese black bears (U. torquatus and U. japonicus). Very distinct is the small Malay sun-bear U. (Helarctus) malayanus, characterized by its short, smooth fur, extensile tongue, short and wide head, and broad molars. Finally, the spectacled bear of the Andes, U. (Tremarctus) ornatus, which is also a broad-skulled black species, differs from all the rest in having a perforation, or foramen, on the inner side of the lower end of the humerus. A second genus, Melursus, represented by the Indian sloth-bear (M. ursinus), differs from the preceding in having only two pairs of upper incisors, the small size of the cheek-teeth, and the extensile lips. Ants, white-ants, fruits and honey form the chief food of this shaggy black species,—-a diet which accounts for its feeble dentition (see Bear).

|

| Fig. 6.—The Parti-coloured Bear, or Giant Panda (Aeluropus melanoleucus). |