SHE PETRIFIED HERSELF WHEN SHE BEHELD THE MAN WHO HAD MADE HER FAMOUS

SHE PETRIFIED HERSELF WHEN SHE BEHELD THE MAN WHO HAD MADE HER FAMOUS

Title: H. R.

Author: Edwin Lefevre

Release date: August 1, 2010 [eBook #33314]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire. This book was produced from

scanned images of public domain material from the Google

Print archive.

| SAMPSON ROCK OF WALL STREET. Illustrated. Post 8vo. |

| H. R. Illustrated. Post 8vo. |

SHE PETRIFIED HERSELF WHEN SHE BEHELD THE MAN WHO HAD MADE HER FAMOUS

SHE PETRIFIED HERSELF WHEN SHE BEHELD THE MAN WHO HAD MADE HER FAMOUS

Copyright, 1915, by Harper & Brothers

My dear Bob: In dedicating this book to you, I do more than follow the selfish impulse of pleasing myself. It was you who warned me that none of the usual fiction-labels would fit "H. R." To irritate the reader by compelling him to think in order to understand was, you told me, both unfair and unwise. But a writer occasionally may be permitted to please himself, and if his experiment fails there remains the satisfaction of having tried. I have not labelled my jokes explicitly nor have I written a single foot-note in the middle of a page. I have endeavored to reproduce a recognizable atmosphere by intentionally exaggerating certain phases of the attitude of New York toward the eternal verities. Not even for purposes of contrast have I felt bound to have a nice character in the book. But if the reader fails to get what you so clearly understood, and if the critics point out how completely I have failed to write a Satirical Romance of To-day, I can at least make certain of having one line in this volume with which none may find fault. And that, Great and Good Friend, is the line at the top of this page.

E. L.

Dorset, Vt., June, 1915.

The trouble was not in being a bank clerk, but in being a clerk in a bank that wanted him to be nothing but a bank clerk. That kind always enriches first the bank and later on a bit of soil.

Hendrik Rutgers had no desire to enrich either bank or soil.

He was blue-eyed, brown-haired, clear-skinned, rosy-cheeked, tall, well-built, and square-chinned. He always was in fine physical trim, which made people envy him so that they begrudged him advancement, but it also made them like him because they were so flattered when he reduced himself to their level by not bragging of his muscles. He had a quick-gaited mind and much fluency of speech. Also the peculiar sense of humor of a born leader that enabled him to laugh at what any witty devil said about others, even while it prevented him from seeing jokes aimed at his sacred self. He not only was congenitally stubborn—from his Dutch ancestors—but he had his Gascon grandmother's ability to believe whatever he wished to believe, and his Scandinavian great-grandfather's power to fill himself with Berserker rage in a twinkling. This made him begin all arguments by clenching his fists. Having in his veins so many kinds of un-American blood, he was[Pg 2] one of the few real Americans in his own country, and he always said so.

It was this blood that now began to boil for no reason, though the reason was really the spring.

He had acquired the American habit of reading the newspapers instead of thinking, and his mind therefore always worked in head-lines. This time it worked like this: more money and more fun!

Being an American, he instantly looked about for the best rung of the ladder of success.

He had always liked the cashier. A man climbs at first by his friends. Later by his enemies. That is why friends are superfluous later.

Hendrik, so self-confident that he did not even have to frown, approached the kindly superior.

"Mr. Coster," he said, pleasantly, "I've been on the job over two years. I've done my work satisfactorily. I need more money." You could see from his manner that it was much nicer to state facts than to argue.

The cashier was looking out of the big plate-glass window at the wonderful blue sky—New York! April! He swung on his swivel-chair and, facing Hendrik Rutgers, stared at a white birch by a trout stream three hundred miles north of the bank.

"Huh?" he grunted, absently. Then the words he had not heard indented the proper spot on his brain and he became a kindly bank cashier once more.

"My boy," he said, sympathetically, "I know how it is. Everybody gets the fit about this time of year. What kind of a fly would you use for— I mean, you go back to your cage and confine your attention to the K-L ledger."

A two hours walk in the Westchester hills would have[Pg 3] made these two men brothers. Instead, Hendrik allowed himself to fill up with that anger which is apt to become indignation, and thus lead to freedom. Anger is wrath over injury; indignation is wrath over injustice: hence the freedom.

"I am worth more to the bank than I'm getting. If the bank wants me to stay—"

"Hendrik, I'll do you a favor. Go out and take a walk. Come back in ten minutes—cured!

"Thanks, Mr. Coster. But suppose I still want a raise when I come back?

"Then I'll accept your resignation."

"But I don't want to resign. I want to be worth still more to the bank so that the bank will be only too glad to pay me more. I don't want to live and die a clerk. That would be stupid for me, and also for the bank."

"Take the walk, Hen. Then come back and see me."

"What good will that do me?"

"As far as I can see, it will enable you to be fired by no less than the Big Chief himself. Tell Morson you are going to do something for me. Walk around and look at the people—thousands of them; they are working! Don't forget that, Hen; working; making regular wages! Good luck, my boy. I've never done this before, but you caught me fishing. I had just hooked a three-pounder," he finished, apologetically.

Hendrik was suffocating as he returned to his cage. He did not think; he felt—felt that everything was wrong with a civilization that kept both wild beasts and bank clerks in cages. He put on his hat, told the head bookkeeper he was going on an errand for Mr. Coster, and left the bank.[Pg 4]

The sky was pure blue and the clouds pure white. There was in the air that which even when strained through the bank's window-screens had made Hendrik so restless. To breathe it, outdoors, made the step more elastic, the heartbeats more vigorous, the thoughts more vivid, the resolve stronger. The chimneys were waving white plumes in the bright air—waving toward heaven! He wished to hear the song of freedom of streams escaping from the mountains, of the snow-elves liberated by the sun; to hear birds with the spring in their throats admitting it, and the impatient breeze telling the awakening trees to hurry up with the sap. Instead, he heard the noises that civilized people make when they make money. Also, whenever he ceased to look upward, in the place of the free sunlight and the azure liberty of God's sky, he beheld the senseless scurrying of thousands of human ants bent on the same golden errand.

When a man looks down he always sees dollar-chasing insects—his brothers!

He clenched his fists and changed, by the magic of the season, into a fighting-man. He saw that the ant life of Wall Street was really a battle. Men here were not writing on ledgers, but fighting deserts, and swamps, and mountains, and heat, and cold, and hunger; fighting Nature; fighting her with gold for more gold. It followed that men were fighting men with gold for more gold! So, of course, men were killing men with gold for more gold!

So greatly has civilization advanced since the Jews crucified Him for interfering with business, that to-day man not only is able to use dollars to kill with, but boasts of it.

"Fools!" he thought, having in mind all other living[Pg 5] men. After he definitely classified humanity he felt more kindly disposed toward the world.

After all, why should men fight Nature or fight men? Nature was only too willing to let men live who kept her laws; and men were only too willing to love their fellow-men if only dollars were not sandwiched in between human hearts. He saw, in great happy flashes, the comfort of living intelligently, brothers all, employers and employed, rid of the curse of money, the curse of making it, the curse of coining it out of the sweat and sorrow of humanity.

"Fools!" This time he spoke his thought aloud. A hurrying broker's clerk smiled superciliously, recognizing a stock-market loser talking of himself to himself, as they all do. But Hendrik really had in mind bank clerks who, instead of striking off their fetters, caressed them as though they were the flesh of sweethearts; or wept, as though tears could soften steel; or blasphemed, as though curses were cold-chisels! And every year the fetters were made thicker by the blacksmith Habit. To be a bank clerk, now and always; now and always nothing!

He now saw all about him hordes of sheep-hearted Things with pens behind their ears and black-cloth sleeve-protectors, who said, with the spitefulness of eunuchs or magazine editors:

"You also are of us!"

He would not be of them!

He might not be able to change conditions in the world of finance, not knowing exactly how to go about it, but he certainly could change the financial condition of Hendrik Rutgers. He would become a free man. He would do it by getting more money, if not from the bank, from somebody else. In all imperfectly Christianized[Pg 6] democracies a man must capitalize his freedom or cease to be free.

He returned to the bank. He was worth thousands to it. This could be seen in his walk. And yet when the cashier saw Hendrik's face he instantly rose from his chair, held up a hand to check unnecessary speech, and said:

"Come on, Rutgers. You are a damned fool, but I have no time to convince you of it. You understand, of course, that you'll never work for us again!"

"I shall tell the president."

"Yes, yes. He'll fire you."

"Not if he is intelligent, he won't," said Rutgers, with assurance.

The cashier looked at him pityingly and retorted: "A long catalogue of your virtues and manifold efficiency will weigh with him as much as two cubic inches of hydrogen. But I warned you."

"I know you did," said Hendrik, pleasantly.

Whereupon Coster frowned and said: "You are in class B—eight hundred dollars a year. In due time you will be promoted to class C—one thousand dollars. You knew our system and what the prospects were when you came to us. Other men are ahead of you; they have been here longer than you. We want to be fair to all. If you were going to be dissatisfied you should not have kept somebody else out of a job."

Hendrik did not know how fair the bank was to clerks in class C. He knew they were not fair to one man in class B. Facts are facts. Arguments are sea-foam.

"You say I kept somebody out of a job?" he asked.

"Yes, you did!"

The cashier's tone was so accusing that Hendrik said:[Pg 7]

"Don't call a policeman, Mr. Coster."

"And don't you get fresh, Rutgers. Now see here; you go back and let the rise come in the usual course. I'll give you a friendly tip: once you are in class C you will be more directly under my own eye!"

Instead of feeling grateful for the implied promise, Hendrik could think only that they classified men like cattle. All steers weighing one thousand pounds went into pen B, and so on. This saved time to the butchers, who, not having to stop in order to weigh and classify, were enabled to slit many more throats per day.

He did not know it, but he thought all this because he wished to go fishing. Therefore he said: "I've got to have more money!" His fists clenched and his face flushed. He thought of cattle, of the ox-making bank, of being driven from pen A into pen B, and, in the end, fertilizer. "I've got to!" he repeated, thickly.

"You won't get it, take it from me. To ask for it now simply means being instantly fired."

"Being fired" sounded so much like being freed that Hendrik retorted, pleasantly:

"Mr. Coster, you may yet live to take your orders from me, if I am fired. But if I stay here, you never will; that's sure."

The cashier flushed angrily, opened his mouth, magnanimously closed it, and, with a shrug of his shoulders, preceded Hendrik Rutgers into the private office of the president.

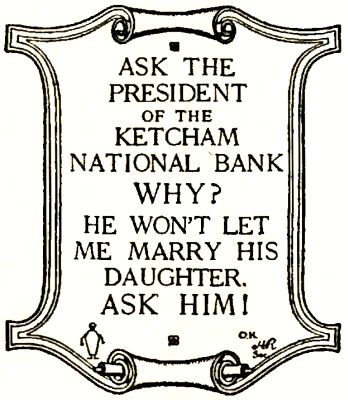

"Mr. Goodchild," said Coster, so deferentially that Hendrik looked at him in surprise for a full minute before the surprise changed into contempt.

Mr. Goodchild, the president, did not even answer. He frowned, deliberately walked to a window and[Pg 8] stared out of it sourly. A little deal of his own had gone wrong, owing to the stupidity of a subordinate.

He had lost money!

He was a big man with jowls and little puffs under the eyes; also suspicions of purple in cheeks and nose and suspicions of everybody in his eyes. Presently he turned and spat upon the intruders. He did it with one mild little word:

"Well?"

He then confined his scowl to the cashier. The clerk was a species of the human dirt that unfortunately exists even in banks and has to be apologized for to customers at times, when said dirt, before arrogance, actually permits itself vocal chords.

They spoil the joy of doing business, damn 'em!

"This is the K-L ledger clerk," said Coster. "He wants a raise in salary. I told him 'No,' and he then insisted on seeing you." Years of brooding over the appalling possibility of having to look for another job had made the cashier a skilful shirker of responsibilities. He always spoke to the president as if he were giving testimony under oath.

"When one of these chaps, Mr. Coster," said the president in the accusing voice bank presidents use toward those borrowers whose collateral is inadequate, "asks for a raise and doesn't get it he begins to brood over his wrongs. People who think they are underpaid necessarily think they are overworked. And that is what makes socialists of them!"

He glared at the cashier, who acquiesced, awe-strickenly: "Yes, sir!"

"As a matter of fact," pursued the president, still accusingly, "we should reduce the bookkeeping force. Dawson tells me that at the Metropolitan National[Pg 9] they average one clerk to two hundred and forty-two accounts. The best we've ever done is one to one hundred and eighty-eight. Reduce! Good morning."

"Mr. Goodchild," said Hendrik Rutgers, approaching the president, "won't you please listen to what I have to say?"

Mr. Goodchild was one of those business men who in their desire to conduct their affairs efficiently become mind-readers in order to save precious time. He knew what Rutgers was going to say, and therefore anticipated it by answering:

"I am very sorry for the sickness in your family. The best I can do is to let you remain with us for a little while, until whoever is sick is better." He nodded with great philanthropy and self-satisfaction.

But Hendrik said, very earnestly: "If I were content with my job I wouldn't be worth a whoop to the bank. What makes me valuable is that I want to be more. Every soldier of Napoleon carried a marshal's baton in his knapsack. That gave ambition to Napoleon's soldiers, who always won. Let your clerks understand that a vice-presidency can be won by any of us and you will see a rise in efficiency that will surprise you. Mr. Goodchild, it is a matter of common sense to—"

"Get out!" said the president.

Ordinarily he would have listened. But he had lost money; that made him think only of one thing—that he had lost money!

The general had suddenly discovered that his fortress was not impregnable! He did not wish to discuss feminism.

Of course, Hendrik did not know that the president's request for solitude was a confession of weakness and, therefore, in the nature of a subtle compliment. And[Pg 10] therefore, instead of feeling flattered, Hendrik saw red. It is a common mistake. But anger always stimulated his faculties. All men who are intelligent in their wrath have in them the makings of great leaders of men. The rabble, in anger, merely becomes the angry rabble—and stays rabble.

Hendrik Rutgers aimed full at George G. Goodchild, Esq., a look of intense astonishment.

"Get out!" repeated the president.

Hendrik Rutgers turned like a flash to the cashier and said, sharply: "Didn't you hear? Get out!"

"You!" shouted Mr. George G. Goodchild.

"Who? Me?" Hendrik's incredulity was abysmal.

"Yes! You!" And the president, dangerously flushed, advanced threateningly toward the insolent beast.

"What?" exclaimed Hendrik Rutgers, skeptically. "Do you mean to tell me you really are the jackass your wife thinks you?"

Fearing to intrude upon private affairs, the cashier discreetly left the room. The president fell back a step. Had Mrs. Goodchild ever spoken to this creature? Then he realized it was merely a fashion of speaking, and he approached, one pudgy fist uplifted. The uplift was more for rhetorical effect than for practical purposes, which has been a habit with most uplifts since money-making became an exact science. But Hendrik smiled pleasantly, as his forebears always did in battle, and said:

"If I hit you once on the point of the jaw it'll be the death-chair for mine. I am young. Please control yourself."

"You infernal scoundrel!"

"What has Mrs. Goodchild ever done to me, that[Pg 11] I should make her a widow?" You could see he was sincerely trying to be not only just, but judicial.

The president of the bank gathered himself together. Then, as one flings a dynamite bomb, he utterly destroyed this creature. "You are discharged!"

"Tut, tut! I discharged the bank ages ago; I'm only waiting for the bank to pack up. Now you listen to me."

"Leave this room, sir!" He said it in that exact tone of voice.

But Hendrik did not vanish into thin air. He commanded, "Take a good look at me!"

The president of the bank could not take orders from a clerk in class B. Discipline must be maintained at any cost. He therefore promptly turned away his head. But Hendrik drew near and said:

"Do you hear?"

There was in the lunatic's voice something that made Mr. George G. Goodchild instantly bethink himself of all the hold-up stories he had ever heard. He stared at Hendrik with the fascination of fear.

"What do you see?" asked Rutgers, tensely. "A human soul? No. You see K-L. You think machinery means progress, and therefore you don't want men, but machines, hey?"

The president did not see K-L, as at the beginning of the interview. Instead of the two enslaving letters he saw two huge, emancipating fists. This man was far too robust to be a safe clerk. He had square shoulders. Yes, he had!

The president was not the ass that Hendrik had called him. His limitations were the limitations of all irreligious people who regularly go to church. He thus attached too much importance to To-day, though[Pg 12] perhaps his demand loans had something to do with it. His sense of humor was altogether phrasal, like that of most multimillionaires. But if he was too old a man to be consistently intelligent, he was also an experienced banker. He knew he had to listen or be licked. He decided to listen. He also decided, in order to save his face, to indulge in humorous speech.

"Young man," he asked, with a show of solicitude, "do you expect to become Governor of New York?"

But Hendrik was not in a smiling mood, because he was listening to a speech he was making to himself, and his own applause was distinctly enjoyable, besides preventing him from hearing what the other was saying. That is what makes all applause dangerous. He went on, with an effect of not having been interrupted.

"Machines never mutiny. They, therefore, are desirable in your System. At the same time, the end of all machines is the scrap-heap. Do you expect to end in junk?"

"I was not thinking of my finish," the president said, with much politeness.

"Yes, you are. Shall I prove it?"

"Not now, please," pleaded the president, with a look of exaggerated anxiety at the clock. It brought a flush of anger to Hendrik's cheeks, seeing which the president instantly felt that glow of happiness which comes from gratified revenge. Ah, to be witty! But his smile vanished. Hendrik, his fists clenched, was advancing. The president was no true humorist, not being of the stuff of which martyrs are made. He was ready to recant when,

"Good morning, daddy," came in a musical voice.

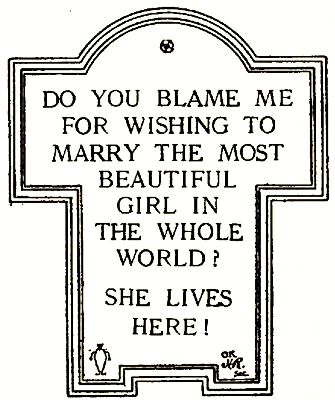

Hendrik drew in his breath sharply at the narrowness[Pg 13] of his escape. She who approached the purple-faced tyrant was the most beautiful girl in all the round world.

It was spring. The girl had brought in the first blossoms of the season on her cheeks, and she had captured the sky and permanently imprisoned it in her eyes. She was more than beautiful; she was everything that Hendrik Rutgers had ever desired, and even more!

"Er—good morning, Mr.—ah—" began the president in a pleasant voice.

Hendrik waved his hand at him with the familiar amiability we use toward people whose political affiliations are the same as ours at election-time. Then he turned toward the girl, looked at her straight in the eyes for a full minute before he said, with impressive gravity:

"Miss Goodchild, your father and I have failed to agree in a somewhat important business matter. I do not think he has used very good judgment, but I leave this office full of forgiveness toward him because I have lived to see his daughter at close range, in the broad light of day."

The only woman before whom a man dares to show himself a physical coward is his wife, because no matter what he does she knows him.

Mr. Goodchild was frightened, but he said, blusteringly, "That will do, you—er—you!"

He pointed toward the door, theatrically. But Hendrik put his fingers to his lips and said "Hush, George!" and spoke to her again:

"Miss Goodchild, I am going to tell you the truth, which is a luxury mighty rare in a bank president's private office, believe me."[Pg 14]

She stared at him with a curiosity that was not far from fascination. She saw a well-dressed, well-built, good-looking chap, with particularly bright, understanding eyes, who was on such familiar terms with her father that she wondered why he had never called.

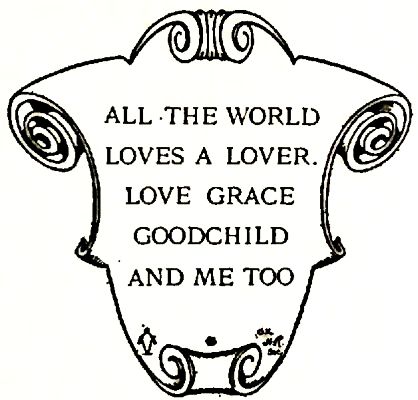

"Let me say," he pursued, fervently, "without any hope of reward, speaking very conservatively, that you are, without question, the most beautiful girl in all the world! I have been nearly certain of it for some time, but now I know. You are not only perfectly wonderful, but wonderfully perfect—all of you! And now take a good look at me—"

"Yes; just before he is put away," interjected the president, trying to treat tragedy humorously before this female of the species. But for the fear of the newspapers, he would have rung for the private detective whose business was to keep out cranks, bomb-throwing anarchists, and those fellow-Christians who wished to pledge their word of honor as collateral on time-loans of less than five dollars. But she thought this friendly persiflage meant that the interesting young man was a social equal as well as a person of veracity and excellent taste. So she smiled non-committally. She was, alas, young!

"They will not put me away for thinking what I say," asserted Hendrik, with such conviction that she blushed. Having done this, she smiled at him directly, that there might be no wasted effort. Wasn't it spring, and wasn't he young and fearless? And more than all that, wasn't he a novelty, and she a New York woman?

"When you hear the name of Hendrik Rutgers, or see it in the newspapers, remember it belongs to the man who thought you were the only perfectly beautiful[Pg 15] girl God ever made. And He has done pretty well at times, you must admit."

With some people, both blasphemy and breakfast foods begin with a small "b". The Only Perfect One thought he was a picturesque talker!

"Mr. Rutgers, I am sorry you must be going," said the president, with a pleasant smile, having made up his mind that this young man was not only crazy, but harmless—unless angered. "But you'll come back, won't you, when you are famous? We should like to have your account."

Hendrik ignored him. He looked at her and said:

"Do you prefer wealth to fame? Anybody can be rich. But famous? Which would you rather hear: There goes Miss $80,000-a-year Goodchild or That is that wonderful Goodchild girl everybody is talking about?"

She didn't know what to answer, the question being a direct one and she a woman. But this did not injure Hendrik in her eyes; for women actually love to be compelled to be silent in order to let a man speak—at certain times, about a certain subject. Her father, after the immemorial fashion of unintelligent parents, answered for her. He said, stupidly: "It never hurts to have a dollar or two, dear Mr. Rutgers."

"Dollar or two! Why, there are poor men whose names on your list of directors would attract more depositors to this bank than the name of the richest man in the world. Even for your bank, between St. Vincent de Paul and John D. Rockefeller, whom would you choose? Dollars! When you can dream!" Hendrik's eyes were gazing steadily into hers. She did not think he was at all lunatical. But George G. Goodchild had reached the limit of his endurance and even of prudence. He rose to his feet, his face deep purple.[Pg 16]

However, Providence was in a kindly mood. At that very moment the door opened and a male stenographer appeared, note-book in hand. Civilization does its life-saving in entirely unexpected ways, even outside of hospitals.

"Au revoir, Miss Goodchild. Don't forget the name, will you?"

"I won't," she promised. There was a smile on her flower-lips and firm resolve in her beautiful eyes. It mounted to Hendrik's head and took away his senses, for he waved his hand at the purple president, said, with a solemnity that thrilled her, "Pray for your future son-in-law!" and walked out with the step of a conqueror. And the step visibly gained in majesty as he overheard the music of the spheres:

"Daddy, who is he?"

At the cashier's desk he stopped, held out his hand, and said with that valiant smile with which young men feel bound to announce their defeat, "I'm leaving, Mr. Coster."

"Good morning," said Coster, coldly, studiously ignoring the outstretched hand. Rutgers was now a discharged employee, a potential hobo, a possible socialist, an enemy of society, one of the dangerous Have-Nots. But Hendrik felt so much superior to this creature with a regular income that he said, pityingly: "Mr. Coster, your punishment for assassinating your own soul is that your children are bound to have the hearts of clerks. You are now definitely nothing but a bank cashier. That's what!"

"Get out!" shrieked the bank cashier, plagiarizing from a greater than he.

The tone of voice made the private policeman draw near. When he saw it was Hendrik to whom Mr.[Pg 17] Coster was speaking, he instantly smelled liquor. What other theory for an employee's loud talking in a bank? He hoped Hendrik would not swear audibly. The bank would blame it on the policeman's lack of tact.

"Au revoir." And Hendrik smiled so very pleasantly that the policeman, whose brains were in his biceps, sighed with relief. At the same time the whisper ran among the caged clerks in the mysterious fashion of all bad news—the oldest of all wireless systems!

Hendrik Rutgers was fired!

Did life hold a darker tragedy than to be out of a job? A terrible world, this, to be hungry in.

As Hendrik walked into the cage to get his few belongings, pale faces bent absorbingly over their ledgers. To be fed, to grow comfortably old, to die in bed, always at so much per week. Ideal! No wonder, therefore, that his erstwhile companions feared to look at what once had been a clerk. And then, too, the danger of contagion! A terrible disease, freedom, in a money-making republic, but, fortunately, rare, and the victims provided with food, lodging, and strait-jackets at the expense of the state. Or without strait-jackets: bars.

Hendrik got his pay from the head of his department, who seemed of a sudden to recall that he had never been formally introduced to this Mr. H. Rutgers. This filled Hendrik at first with great anger, and then with a great joy that he was leaving the inclosure wherein men's thoughts withered and died, just like plants, for the same reason—lack of sunshine.

On his way to the street he paused by his best friend—a little old fellow with unobtrusive side-whiskers who turned the ledger's pages over with an amazing deftness, and wore the hunted look that comes from thirty[Pg 18] years of fear of dismissal. To some extent the old clerk's constant boasting about the days when he was a reckless devil had encouraged Hendrick.

"Good-by, Billy," said Hendrik, holding out his hand. "I'm going."

Little old Billy was seen by witnesses talking in public with a discharged employee! He hastily said, "Too bad!" and made a pretense of adding a column of figures.

"Too bad nothing. See what it has done for you, to stay so long. I laid out old Goodchild, and the only reason why I stopped was I thought he'd get apoplexy. But say, the daughter— She is some peach, believe me. I called him papa-in-law to his face. You should have seen him!"

Billy shivered. It was even worse than any human being could have imagined.

"Good-by, Rutgers," he whispered out of a corner of his mouth, never taking his eyes from the ledger.

"You poor old— No, Billy! Thank you a thousand times for showing me Hendrik Rutgers at sixty. Thanks!" And he walked out of the bank overflowing with gratitude toward Fate that had hung him into the middle of the street. From there he could look at the free sun all day; and of nights, at the unfettered stars. It was better than looking at the greedy hieroglyphics wherewith a stupid few enslaved the stupider many.

He was free!

He stood for a moment on the steps of the main entrance. For two years he had looked from the world into the bank. But now he looked from the bank out—on the world. And that was why that self-same world suddenly changed its aspect. The very[Pg 19] street looked different; the sidewalk wore an air of strangeness; the crowd was not at all the same.

He drew in a deep breath. The April air vitalized his blood.

This new world was a world to conquer. He must fight!

The nearest enemy was the latest. This is always true. Therefore Hendrik Rutgers, in thinking of fighting, thought of the bank and the people who made of banks temples to worship in.

All he needed now was an excuse. There was no doubt that he would get it. Some people call this process the autohypnosis of the great.

Two sandwich-men slouched by in opposite directions. One of them stopped and from the edge of the sidewalk stared at a man cleaning windows on the fourteenth story of a building across the way. The other wearily shuffled southward. Above his head swayed an enormous amputated foot.

Rutgers himself walked briskly to the south. To avoid a collision with a hurrying stenographer-girl—if it had been a male he would have used a short jab—he unavoidably jostled the chiropodist's advertisement into the gutter. The sandwich-man looked meekly into Rutgers's pugnacious face and started to cross the street.

Hendrik felt he should apologize, but before his sense of duty could crystallize into action the man was too far away. So Hendrik turned back. The other sandwich-man was still looking at the window-cleaner on the fourteenth story across the street. Happening to look down, he saw coming a man who looked angry. Therefore the sandwich-man meekly stepped into the gutter, out of the way.[Pg 20]

It was the second time within one minute! Hendrik stopped and spoke peevishly to the meek one in the gutter:

"Why did you move out of my way?"

The sandwich-man looked at him uneasily; then, without answering, walked away sullenly.

"Here I am," thought Rutgers, "a man without a job; and there he is, a man with a job and afraid of me!"

Something was wrong—or right. Something always is, to the born fighter.

Who could be afraid of a man without a job but sandwich-men who always walked along the curb so they could be pushed off into the gutter among the other beasts? Nobody ever deliberately became a sandwich-man. When circumstances, the police, hopeless inefficiency, or shattered credit prevented a hobo from begging, stealing, murdering, or getting drunk, he became a sandwich-man in order to live until he could rise again. Whatever a sandwich-man changed himself into, it was always advancement. Once a sandwich-man, never again a sandwich-man. It was not boards they carried, but the printed certificates of hopelessness.

Men who could not keep steady jobs became either corpses or sandwich-men. The sandwich illustrated the tyranny of the regular income just as the need of a regular income illustrated the need of Christianity.

The sandwich thus had become the spirit of the times.

The spring-filled system of Hendrik Rutgers began to react for a second time to a feeling of anger, and this for a second time turned his thoughts to fighting. To fight was to conquer. There were two ways of conquering—by[Pg 21] fighting with gold and by fighting with brains. Who won by gold perished by gold. That was why a numismatical bourgeoisie never fought. Hendrik had no gold. So he would fight with brains. He therefore would win. Also, he would fight for his fellow-men, which would make his fight noble. That is called "hedging," for defeat in a noble cause is something to be proud of in the newspapers. The reason why all hedging is intelligent is that victory is always Victory when you talk about it.

The sandwich-men were the scum of the earth.

Ah! It was a thrilling thought: To lead men who could no longer fight for themselves against the world that had marred their immortal souls; and then to compel that same world to place three square meals a day within their astonished bellies!

The man who could make the world do that could do anything. Since he could do anything, he could marry a girl who not only was very beautiful, but had a very rich and dislikable father. The early Christians accomplished so much because they not only loved God, but hated the devil.

Hendrik Rutgers found both the excuse and the motive power.

One minute after a man of brains perceives the need of a ladder in order to climb, the rain of ladders begins.

The chest-inflating egotism of the monopolistic tendency, rather than the few remaining vestiges of Christianity, keeps Protestants in America from becoming socialists. Hendrik filled his lungs full of self-oxygen and of the consciousness of power for good, and decided to draw up the constitution of his union. He would do it himself in order to produce a perfect document; perfect in everything. A square deal;[Pg 22] no more, no less. That meant justice toward everybody, even toward the public.

This union, being absolutely fair, would be more than good, more than intelligent; it would pay.

Carried away by his desire to help the lowest of the low, he constituted himself into a natural law. He would grade his men, be the sole judge and arbiter of their qualifications, and even of their proper wages.

Hendrik walked back toward the last sandwich-man and soon overtook him. "Hey, there, you!" he said, tapping the rear board with his hand.

The sandwich-man did not turn about. Really, what human being could wish to speak to him?

Hendrik Rutgers walked for a few feet beside the modest artist who was proclaiming to a purblind world the merits of an optician's wares, and spoke again, politely:

"I want to see you, on business."

The man's lips quivered, then curved downward, immobilizing themselves into a fixed grimace of fear. "I—I 'ain't done no-nothin'," he whined, and edged away.

This was what society had done to an immortal soul!

"Hell!" said Hendrik Rutgers between clenched teeth. "I'm not a fly-cop. I've just got a plain business proposition to make to you."

"If you'll tell me where yer place is, I'll come aroun'—" began the man, so obviously lying that Rutgers's anger shifted from society and tyranny on to the thing between sandwich-boards—the thing that refused to be his brother.

"You damned fool!" he hissed, fraternally. "You come with me—now."

The inverted crescent of the man's lips trembled,[Pg 23] and presently there issued from it, "Well, I 'ain't done—"

Charity, which is not always astute, made H. Rutgers say with a kindly cleverness to his poor brother, "I'll tell you how you are going to make more money than you ever earned before."

The prospect of making more money than he ever earned before brought no name of joy into the blear and furtive eyes. Instead, he sidled, crabwise, into the middle of the street.

"No, you don't!" said Rutgers so menacingly that the sandwich-man shivered. It was clear that, to feed this starving man, force would be necessary. This never discourages the true philanthropist. Rutgers, however, feeling that Christian forbearance should be used before resorting to the ultimate diplomacy, said, with an earnest amiability: "Say, Bo, d'you want to fill your belly so that if you ate any more you'd bust?"

At the hint of a promise of a sufficiency of food the man opened his mouth, stared at Rutgers, and did not speak. He couldn't because he did not close his mouth.

"All the grub you can possibly eat, three times a day. Grub, Bo! All you want, any time you want it. Hey? What?"

The sandwich-man's open mouth opened wider. In his eyes there was no fear, no hunger, no incredulity, nothing only an abyss deep as the human soul, that returned no answer whatever.

"Do you want," pursued the now optimistic Hendrik Rutgers, "to drink all you can hold? The kind that don't hurt you if you drink a gallon! Booze, and grub, and a bed, and money in your pocket, and nobody to go through your duds while you sleep. Hey?"[Pg 24]

The sandwich-man spasmodically opened and closed his mouth in the unhuman fashion of a ventriloquist's puppet. Rutgers heard the click, but never a word. It filled him with pity. The desire to help such brothers as this grew intense. Next to feeding them there was nothing like talking to them about food and drink in a kindly way.

"What do you say, Bo?" he queried, gently, almost tenderly.

The man's teeth chattered a minute before he said, huskily, "Wh-what m-must I do?"

"Let's go to the Battery," said Rutgers, "and I'll tell you all about it."

The mission of history is to prove that Fate sends the right man for the right place at the right time. While Hendrik Rutgers talked, the sandwich-man listened with his stomach; and when Hendrik Rutgers promised, the sandwich-man believed with his soul. Rutgers told Fleming that all sandwich-men must join the union; that as soon as he and the other present sandwichers were enrolled on its books no more members would be admitted, except as a superabundance of jobs justified additional admissions; and at that it would require a nine-tenths vote to elect, thus preventing a surplus of labor and likewise a slump in wages. The union would compel advertisers in the future to pay twenty cents an hour and would guarantee both steady work and these wages to its members; there would be neither an initiation fee nor strike-fund assessments; the dues of one cent a day were collectible only when the member worked and received union wages for his day's work. Any member could lay off any time he felt like it, unmulcted and unfired. There was only one thing that all sandwich-men had to do to be in good standing;[Pg 25] obey the secretary and treasurer of the union—Mr. H. Rutgers—in all union matters.

The sandwich business, once unionized, would become a lucrative profession and therefore highly moral, and therefore its members would automatically cease to be pariahs, notwithstanding congenital fitness for same. Anybody who cannot only defy Nature, but make her subservient to the wishes of an infinitely higher intelligence, is fit to be a labor-leader. And he generally is.

Fleming agreed to round up those of his colleagues whose peregrinations extended south of Chambers Street. He would ask them to come to the Battery on the next day at noon.

So thrilled was Hendrik by his rescue-work among the wreckages that it never occurred to him to doubt his own success. This made him know exactly what to say to Fleming.

"Don't just ask them to come. Tell them that there will be free beers and free grub. Tell them anything you damn please, but bring them! Do you hear me?" He gripped the sandwich-man's arm so tightly that Fleming's lips began to quiver. "And if you don't bring a bunch, God help you!"

"Ye-yes, sir; I will. Sure!" whimpered Fleming, staring fascinatedly at those eyes which both promised and menaced.

And in Fleming's own eyes Hendrik saw the four "B's" which form the great equation of all democracies: Bread + Bludgeon = Born Boss!

Such men always know how to say everything. This is more important than thinking anything.

"Remember the beer!" Brother Hendrik spoke pleasantly, and Fleming nodded eagerly. "And get[Pg 26] on the job," hissed Secretary Rutgers; and Fleming shivered and hurried away before the licking came.

Hendrik himself walked briskly up-town. When a man is pleased with himself he can always continue in that condition by the simple expedient of continuing to see whatever he wishes to see. Hendrik opened his eyes very wide and continued to see the ladder of success that great men use to climb to their changing heaven. Hendrik's heaven just then happened to be one in which a man of brains could make the money-makers pay him for allowing them to make money for him. After finding the ladder, all that was necessary was for Hendrik to think of George G. Goodchild's money. That made him see red; and whenever he saw red he could see no obstacles whatever; and because of his self-inflicted blindness he was intelligently ready to tackle anything, even the job of helping his fellow-men. To be an efficient philanthropist a man must have not only love, but murder, in his heart. That is one of the two hundred and eighty-six reasons why scientific charities make absolutely no inroads on the world's store of poverty.

Mr. Rutgers met the charter members of his union at the time and place indicated by Providence through the medium of Mr. Rutgers's lips.

There were fourteen sandwich-men.

Hendrik, not knowing what to say, gazed at the faces before him in impressive silence. So long as you keep a man guessing, he is at your mercy. Orators have already discovered this.

"Holy smoke! What in the name of Maginnis do you call this?" shrieked a messenger-boy. "Free freak show?"

A crowd gathered about them by magic. Opportunity[Pg 27] held out its right hand and Hendrik Rutgers grasped it in both his own. If all New York could be made to talk about him, all New York could be made to pay him, as it always pays for the privilege of talking of the same thing at the same time. You cannot get anybody to talk about the Ten Commandments; therefore, there is nobody to listen; therefore nobody capitalizes them.

It is the first rung that really matters. All other rungs in the ladder of success are easier to find and to fit. Hendrik could now gather together his various impulses and thoughts and motives and arrange them in their proper sequence, as great men do, to make easier the work of the historian. It was a crusade that he had undertaken, for the liberation of the most abject of all modern slaves; he had changed the scum of the earth into respectable humanity.

That was history.

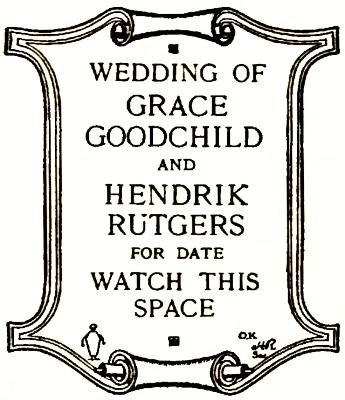

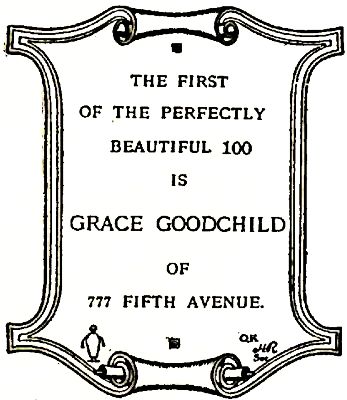

The facts, however, happened to be as follows: He threw up his job because he wished to go fishing, which of course made him angry because his fellow-clerks were slaves, and he therefore got himself discharged by the president, which made him hate the president so that the hatred showed in Hendrik's face and made two sandwich-men so afraid that he couldn't help organizing the sandwich-men's union because he could boss it, and that would make people talk about him, which would put money in his pocket; and once he was both rich and famous he would be the equal of the greatest and as such could pick and choose; and he would pick Grace Goodchild and choose her for his wife, which would make him rich.

In Europe the ability promptly to recognize the kindness of chance is called opportunism. Here we[Pg 28] boast of it as the American spirit. That is why American bankers so often find pleasure in proudly informing you that it pays to be honest!

"Listen, you!" said Hendrik to the sandwich-men. These were the tools wherewith he would hammer the first rung into place.

They looked at him, incredulous in advance. This attitude on the part of the majority has caused republics at all times to be ruled by the minority. The vice of making money also arose from the fact that suspicious people are so easy to fool that even philosophers succumb to the temptation.

"Just now you are nothing but a bunch of dirty hoboes. Scum of the earth!" It would not do to have followers who had illusions about themselves. This is fundamental.

"Say, I didn't come here to listen to—"

"You—!" said Hendrik Rutgers, and did not smile. "You came here just exactly for that. See?" And he walked up to within six inches of the speaker, not knowing that his anger gave him the fighting face. "You came to listen to me just as long as I am talking—unless you are pining to spend your last three hours in the hospital. Do you get me? Which for yours?"

"Listen!" replied the sandwich-man. He had been poor so long that from force of habit he economized even in words.

"By cripes! here I am spending valuable time so as to make you bums into prosperous men—"

"Where do you come in, Bill?" asked a voice from the rear.

"I don't have to come in. I am in. You fellows have got to join the union. Then you'll get good wages, easy hours, decent—"[Pg 29]

"Yeh; but—"

Hendrik turned to the man who had interrupted—a short chap advertising a chain of hat-stores and asked, "But what?"

"Nutt'n!" The hatter had once helped about a prize-fighter's training-quarters, hence the quick duck.

"Also, you'll have easy—"

"Easy!" The hatter had spoken prematurely again.

"What?" scowled Hendrik.

"Hours," hastily explained the man.

"We ask only for fair play," pursued the leader.

"Yeh; sure!" murmured Fleming, with the cold enthusiasm of all paid lieutenants of causes.

"And we must make up our minds to play fair with employers, so that employers will play fair with us."

"Like hell they will!" This was from a tall, thin, toothless chap. Reason: Tapeworm and booze. Name: Mulligan. Recreation: Chiropodist's favorite.

"I'll prove it to you," said Hendrik, very earnestly.

"Perhaps to but not by me," muttered Mulligan.

"Union wages will be twenty cents an hour."

"Never get it!" mumbled an old fellow with what they call waiter's foot—flattened arch. "Never!"

"Never," came in chorus from all the others, their voices ringing with conviction.

"I'll have the jobs to give out. I guess I know how much you'll get." The flame of hope lit fourteen pairs of blear eyes. Maybe this boob had the cash and desired to separate himself from it. All primitive people think the fool is touched of God. Hunger makes men primitive.

"I'll fix the wages!" declared Hendrik again. He saw himself feeding these men; therefore he felt he owned them absolutely. It isn't, of course, necessary[Pg 30] actually to feed people, or even to promise to feed them, to own them. Nevertheless, his look of possession imposed on these victims of a democracy. They mutely acknowledged a boss.

Instantly perceiving this, a sense of kindly responsibility came upon Hendrik. These were his children. He said, paternally, "We'll now have a beer—on me!"

Fleming, to show his divine right to the place of vice-regent, led the way to a joint on Washington Street.

Hendrik saw, with carefully concealed delight, the sensation caused even in the Syrian-infested streets of the quarter by the sight of a handful of sandwich-men in full regalia. He heard the exclamations that fell from polyglot lips. It was a foretaste of success, the preface of a famous man's biography!

The union drank fifteen beers, slowly—and quickly wiped the day's free lunch from the face of the earth. The huskiest of the three bartenders began to work with one hand, the other being glued to a bung-starter. He felt it had to come.

"I'm boss!" said Hendrik to his children as a preliminary to discussing the by-laws.

"I'm willin'!"

"Same here!"

"Let 'er go, cap!"

"Suits me!"

They were all eager to please him—too eager. It made him ask, disgustedly:

"Don't you fellows care who is boss?"

"Naw! Don't we have to have one, anyhow?"

"Yes. But to have one crammed down your throats—"[Pg 31]

"The beer helps the swallowing, boss," said the hatter with conviction—and a fresh hope!

"There doesn't seem to be a man among the whole lot of you," said Hendrik.

A young fellow of about twenty-eight, very pale, wearing steel-rimmed spectacles, spoke back, "If you'd starved for three weeks and two days, and on top of it been kicked and cheated and held up, there wouldn't be a hell of a lot of fight in you, my wise gazabo."

"That's exactly what would make me fight," retorted Hendrik, angrily. "Each of you has a vote; each of you, therefore, has as much to say as to how this country should be run as any millionaire. Don't you know what to do with your vote?"

"You're lucky to get a quarter and two nights' lodging nowadays," said the old man with waiter's foot. "The time we elected Gilroy I made fifteen bones and was soused for a mont'. Shorty McFadden made thirty-five dollars—"

"Any of you Republicans?"

"No!" came in a great and indignant chorus.

"I used to be!" defiantly asserted the young man with the spectacles and the pale face and the beaten look.

"And now?"

"Just a lame duck, I guess."

"Too much rumatism," suggested a husky voice, and all the others laughed. The depths of degradation are reached when you can laugh at your own degradation.

"Are any of you socialists?" asked Hendrik.

They looked at him doubtfully. They wished to please him and would have answered accordingly if they had known what he wished to get from them.[Pg 32] What they wished to get from him, in the way of speech, was another invitation to tank up. But when in doubt, all men deny. It is good police-court practice. Three veterans, therefore, tentatively said:

"No!"

Hendrik was disappointed, but did not show it. He asked, "Are any of you Christians?"

The crowd fell back.

"Is there one man among you who believes in God?"

They stared at one another in the consternation of utter hopelessness. Mulligan was the first to break the painful silence. He said, with a sad triumph:

"I knew it. Stung again! They'll do anything to get you to listen. We fell for it like boobs."

"What is that?" said Hendrik, sharply.

"I was sayin'," replied Mulligan, grateful that he was one schooner ahead, anyhow, "that I can listen to a good brother like you by the hour when I ain't thirsty. The dryness in my throat affects my hearin'. If you blow again I'll believe in miracles. How could I help it?"

Fourteen pairs of eyes turned hopefully toward the wonder-worker. But he said in the habitual tone of all born leaders:

"You—bums, get around! I'm going to lick hell out of Mulligan. And after that, to show I'm boss, I'll blow again. But first the licking."

Hendrik gave his hat to Fleming to hold and began to turn up his sleeves. But Mulligan hastily said, "I'm converted, boss!" and actually looked pious. How he did it, nobody could tell, for he was not a Methodist by birth or education.

"Mulligan, the union wages will be forty schooners[Pg 33] a day." Hendrik said, sternly. Again it was genius—that is, to talk so that men will understand you.

"Kill the scabs!" shrieked Mulligan, and there was murder in his eyes.

Hendrik Rutgers put his right foot firmly on the second rung of the ladder. He did it by spending seventy-five cents for the second time. Fifteen beers.

"Everybody," he said, threateningly, "wait until the schooners are on the bar!" thereby disappointing those who had hoped to ring in an extra glass during the excitement. But all that Hendrik desired was to inculcate salutary notions of discipline and obedience under circumstances that try men's souls. He yelled:

"Damn you, step back! All of you! Back!"

They fell back.

The quivering line, now two feet from the beer, did not look at the glasses full of cheer, but at the eyes full of lickings. They gazed at him, open-mouthed; they gazed and kept on gazing, two feet from the bar—the length of the arm from the beer!

Not obey? After that? There is no doubt of it; they are born!

"To the union! All together! Drink!" They did not observe that this man was regulating even their thirst. The reason they did not notice it was that they were so busy assuaging it.

They drank. Then they looked at Hendrik. He was a law of nature. He shook his head. They understood his "No." It was like death. To save their faces they began to clamor for free lunch.

"Get to hell out of here!" said the proprietor.

"Do you want your joint smashed?" asked Rutgers. He approached the man and looked at him from across a gulf of six inches that made escape impossible.[Pg 34] Whatever the proprietor saw in Rutgers's eyes made him turn away.

"Come across with the free lunch," Hendrik bade the proprietor. To his men he said, "Boys, get ready!"

These men-that-were—miserable worms, scum of the earth, walking cuspidors—began to take off their armor. The bartenders were husky, but hadn't the boss commanded, Get ready! and didn't all men know he meant, Get ready to eat? Moreover, each sandwich felt he might dodge the bung-starters, but not the boss's right flipper!

The union was making ready to fight with the desperation of men whose retreat is cut on by a foe who never heard of The Hague Convention.

"Hey, no rough-house!" yelled the proprietor.

"Free lunch!" retorted Hendrik. Then he added, "Quick!"

The sandwich-men's nostrils began to dilate with the contagion of the battle spirit. One after another, these beasts of the gutter took off the boards and leaned them against the wall, out of the way, and eyed the boss expectantly, waiting for the word—men once more! Hendrik, with the eye of a strategist and the look of a prize-fighter, planned the attack. Like a very wise man who lived to be the most popular of all our Presidents, he did his thinking aloud.

On occasions like this Hendrik's mind also worked in battle-cries and best expressed itself in action.

"Free lunch," said Hendrik, "is free. It is everybody's. It is therefore ours!"

"Give us our grub!" hoarsely cried the union.

"Three to each bartender," said Hendrik. "When I yell 'Now!' jump in, from both ends of the bar at once—six of you here; you six over there. Fleming,[Pg 35] you smash the mirrors back of the bar with those empty schooners. Mulligan, you cop some bottles of booze, and wait outside—do you hear? Wait outside!—for us. I'll attend to the cash-register myself. Now, you," he said peremptorily to the proprietor, "do we get the free lunch? Say no; won't you, please?"

Hendrik radiated battle. The derelicts took on human traits as their eyes lit up with visions of pillage. Fleming grasped a heavy schooner in each hand. Mulligan had his eye on three bottles of whisky and, for the first time in years, was using his mind—planning the get-away.

The proprietor saw all this and also perceived that he could not afford a victory. It was much cheaper to give them seven cents worth of spoiled rations. Therefore he decided in favor of humanity.

"Do what I told you, Jake," he said, with the smile of a man who has inveigled friends into accepting over-expensive Christmas presents. "Let 'em have the rest of the lunch—all they want." He smiled again, much pleased with his kindly astuteness. He was a constructive statesman and would be famous for longevity.

But the sandwich-men swaggered about, realizing that under the leadership of the boss they had won; they had obtained something to which they had no right; by threats of force they had secured food; the boss had made men of them. They therefore crowned Hendrik king. The instinctive and immemorial craving of all men for a father manifests itself—in republics that have forgotten God—in the election of the great promisers and the great confiscators to the supreme power. History records that no dynasty was ever founded except by a man who fought both for and[Pg 36] with his followers. The men that merely fought for their fellows have uniformly died by the most noble and inspiring death of all—starvation. Names and posthumous addresses not known.

When not a scrap remained on any of the platters, Hendrik called his men to him and told them:

"Meet me at the sign-painter's, corner Twenty-ninth Street and Ninth Avenue next Friday night after seven. We'll be open till midnight. Be sure and bring your boards with you."

"We gotter give 'em up before we can get paid," remonstrated Mulligan. "If we don't we don't eat."

"That's right!" assented a half-dozen.

"Bring them!" said Hendrik. The time to check a mutiny is before it begins.

"A' right!" came in a chorus of fourteen heroic voices.

"Beginning next Monday, you'll get twenty cents an hour. I guarantee that to you out of my own pocket. You must each of you bring all the other sandwiches you run across. If necessary, drag them. We must have about one hundred to start, if you want forty beers a day."

"We do! We do!"

"Then bring the others, because we've got to begin with enough men in the union to knock the stuffing out of those who try to scab on us. Get that?"

"Sure thing!" they shouted, with the surprised enthusiasm of men who suddenly understand.

They were deep in misery and accustomed to a poverty so abject that they no longer were capable of even envying the rich. They, therefore, could hate only those who were poorer than themselves—the men who dared to have thirsts that could be assuaged with[Pg 37] less than forty beers per day. Not obey the boss, when they already felt an endless stream trickling down their unionized gullets? And not kill the scab whose own non-union thirst would prolong theirs?

No! A man owes some things to his fellows, but he owes everything to himself. That is why, for teaching brotherhood, there is nothing like one book: the city Directory, from a fourth-floor window.

When the boss left them he was certain that they would not fail him. Just let them dare try to stay away, after he had so kindly destined them to be the rungs of the ladder on which he expected to climb to his lady's window—and her father's pocket! As he walked away, his confidence in himself showed in his stride so clearly that those who saw him shared that confidence. It is not what they were when they were not leaders, but what they can be when they become leaders, that makes them remarkable men.[Pg 38]

The next morning Hendrik went to his tailor. As he walked into the shop he had the air of a man in whom two new suits a day would not be extravagance. The tailor, unconscious of cause and effect, called him "Mister," against the habit of years. Hendrik nodded coldly and said:

"As secretary and treasurer of the National Street Advertising Men's Association, I've got to have a new frock-coat. Measure me for one."

Hendrik had the air of a man who sees an unpleasant duty ahead, but does not mean to shirk it. This attitude always commands respect from tailors, clergymen, and users of false weights and measures.

"Left the bank?" asked the tailor, uncertainly.

"I should say I had," answered Hendrik, emphatically.

"What is the new job, anyhow?" asked the tailor, professionally. His customers usually told him their business, their history, and their hopes. By listening he had been able to invest in real estate.

"As I was about to say when you interrupted me"—Hendrik spoke rebukingly.

"I beg your pardon, Mr. Rutgers," said the tailor, and blushed. He knew now he should have said "position" instead of "job." The civilization of to-day—including sanitary plumbing—is possible because price-tags were invented. This is not an epigram.[Pg 39]

"—the clothes must be finished by Thursday. If you can't do it, I'll go somewhere else."

"Oh, we can do it, all right, Mr. Rutgers."

"Good morning," and Hendrik strode haughtily from the shop.

To the tailor Hendrik had always been a clerk at a bank. But now it was plain to see that Mr. Rutgers thought well of himself, as a man with money always does in all Christian countries. Hendrik's credit at once jumped into the A1 class. Some people and all tailors judge men by their backs.

Being sure of the guests, Hendrik Rutgers went forth in search of their dinner. To feed fivescore starving fellow-men was a noble deed; to feed them at the expense of some one else was even higher. So, dressed in his frock-coat, wearing his high hat as though it was a crown, he sought Caspar Weinpusslacher. The owner of the "Colossal Restaurant," just off the Bowery, gave a square meal for a quarter of a dollar, twenty-five cents; for thirty cents he gave the same meal with a paper napkin and the privilege of repeating the potato or the pie. His kitchen organization was perfect. His cooks and scullions had served in the German army in similar capacities, and he ruled them like one born and brought up in the General Staff. His waiters also were recruited from the greatest training-school for waiters in the world. He operated on a system approved by an efficiency expert. By giving low wages to people who were glad to get them, paying cash for his supplies and judiciously selecting the latter just on the eve of their spoiling, he was able to give an astonishingly good meal for the money. His profits, however, depended upon his selling his entire output. This did not always[Pg 40] happen. Some days Herr Weinpusslacher almost lost three dollars.

No system is perfect. Otherwise hotel men would wish to live for ever.

Hendrik stalked into the Colossal dining-room and snarled at one of the waiters:

"Where's your boss?"

The waiter knew it couldn't be the Kaiser, or a millionaire. It must therefore be a walking delegate. He deferentially pointed to a short, fat man by the bar.

"Tell him to come here," said Rutgers, and sat down at a table. It isn't so much in knowing whom to order about, but in acquiring the habit of ordering everybody about, that wins.

Caspar Weinpusslacher received the message, walked toward the table and signaled to a Herculean waiter, who unobtrusively drew near—and in the rear—of H. Rutgers.

Hendrik pointed commandingly to a chair across the table. C. Weinpusslacher obeyed. The Herculean waiter, to account for his proximity, flicked non-existent crumbs on the napeless surface of the table.

"Recklar tinner?" he queried, in his best Delmonico.

"Geht-weg!" snarled Mr. Rutgers. The waiter, a nostalgic look in his big blue eyes, went away. Ach, to be treated like a dog! Ach, the Fatherland! And the officers! Ach!

"Weinpusslacher," said Rutgers, irascibly, "who is your lawyer and what's his address?"

C. Weinpusslacher's little pig-eyes gleamed apprehensively.

"For why you wish to know?" he said.

"Don't ask me questions. Isn't he your friend?"

"Sure."[Pg 41]

"Is he smart?"

"Smart?" C. Weinpusslacher laughed now, fatly. "He's too smart for you, all right. He's Max Ondemacher, 397 Bowery. I guess if you—"

"All right. I'm going to bring him to lunch here."

"He wouldn't lunch here. He's got money," said C. Weinpusslacher, proudly.

"He will come." Rutgers looked, in a frozen way, at Caspar Weinpusslacher, and continued, icily: "I am the secretary and treasurer of the National Street Advertising Men's Association. If I told you I wanted you to give me money you'd believe me. But if I told you I wanted to give you money, you wouldn't. So I am going to let your own lawyer tell you to do as I say. I'll make you rich—for nothing!"

And Hendrik Rutgers walked calmly out of the Colossal Restaurant, leaving in the eyes of C. Weinpusslacher astonishment, in the mind respect, and in the heart vague hope.

This is the now historic document which Hendrik Rutgers dictated in Max Onthemaker's office:

Hendrik Rutgers, secretary and treasurer of the National Street Advertising Men's Association, agrees to make Caspar Weinpusslacher's Colossal Restaurant famous by means of articles in the leading newspapers in New York City. For these services Hendrik Rutgers shall receive from said Caspar Weinpusslacher, proprietor of said Colossal Restaurant, one-tenth (1/10) of the advertising value of such newspaper notices—said value to be left to a jury composed of the advertising managers of the Ladies Home Journal, the Jewish Daily Forward, and the New York Evening Post, and of Max Onthemaker and Hendrik Rutgers. It is further stipulated that such compensation is to be paid to Hendrik Rutgers, not in cash, but in tickets for meals in said Colossal[Pg 42] Restaurant, at thirty cents per meal, said meal-tickets to be used by said Hendrik Rutgers to secure still more desirable publicity by feeding law-abiding, respectable poor people.

Panem et circenses! He had made sure of the first! The public could always be depended upon to furnish the second by being perfectly natural.

M. Onthemaker accompanied H. Rutgers to the Colossal. He had some difficulty in persuading C. Weinpusslacher to sign. But as soon as it was done Hendrik said:

"First gun: The National Street Advertising Men will hold their annual dinner here next Saturday, about one hundred of us, thirty cents each; regular dinner. That is legitimate news and will be printed as such. It will advertise the Colossal and the Colossal thirty-cent dinner. You won't be out a cent. We pay cash for our dinner. I'll supply a few decorations; all you'll have to do is to hang them from that corner to this. You might also arrange to have a little extra illumination in front of the place. Have a couple of men in evening clothes and high hats on the corner, pointing to the Colossal, and saying: 'Weinpusslacher's Colossal Restaurant! Three doors down. Just follow the crowd!' Arrange for all these things so that when you see that I am delivering the goods you won't be paralyzed. Another thing: There will be reporters from every daily paper in the city here Saturday night. Provide a table for them and pay especial attention to both dinner and drinks. They will make you famous and rich, because you will tell them that they are getting the regular thirty-cent dinner. It will be up to you to be intelligently generous now so that you may with impunity be intelligently stingy later, when you are rich. I advise you to have Max here, because you[Pg 43] seem to be of the distrustful nature of most damned fools and therefore must make your money in spite of yourself. Next Saturday at six p.m.! You'll make at least two hundred thousand dollars in the next five years. Now I am going to eat. Come on, Onthemaker."

H. Rutgers sat down, summoned the Herculean waiter, and ordered two thirty-cent dinners.

C. Weinpusslacher, a dazed look in his eyes, approached Max and whispered, "Hey, dot's a smart feller. What?"

"Well," answered M. Onthemaker, lawyer-like, "you haven't anything to lose."

"You said I should sign the paper," Caspar reminded him, accusingly.

"You're all right so long as you don't give him a cent unless I say so."

"I won't; not even if you say so."

With thirty cents of food and thirty millions of confidence under his waistcoat, Hendrik Rutgers walked from the Colossal Restaurant down the Bowery and Center Street to the City Hall. At the door of the Mayor's room he fixed the doorkeeper with his stern eye and requested his Honor to be informed that the secretary of the National Street Advertising Men's Association would like to see his Honor about the annual dinner of the association, of which his Honor had been duly informed.

One of the Mayor's secretaries came out, a tall young man who, as a reporter on a sensational newspaper, had acquired a habit of dodging curses and kicks. Now, as Mayor's secretary, he didn't quite know how to dodge soft soap and glad hands.

"Good afternoon," said Hendrik, with what might be[Pg 44] called a business-like amiability. "Will the Mayor accept?"

"The Mayor," said the secretary with an amazing mixture of condescension and uneasiness, as of a man calling on a poor friend in whose parlor there is shabby furniture but in whose cellar there is a ton of dynamite—"the Mayor knows nothing about your asso—of the dinner of your association." The secretary looked pleased at having caught himself in time.

"Why, I wrote," began H. Rutgers, with annoyance, "over a week—" He silenced himself while he opened his frock-coat, tilted back his high hat from a corrugated brow, and felt in his pocket. It is the delivery, not the speech, that distinguishes the great artist. Otherwise writers would be considered intelligent people.

"Hell!" exclaimed Hendrik, looking at the secretary so fixedly and angrily that the ex-reporter flinched. "It's in the other coat. I mean the copy of the letter I sent the Mayor exactly a week ago to-day. I wondered why he hadn't answered."

"He never got it," the secretary hastened to say.

Hendrik laughed. "You must excuse my language; but you know what it is to arrange all the details of an annual meeting and banquet—menu, decorations, music, and speeches. Well, here is the situation: the annual dinner of the National Street Advertising Men's Association will be held at Weinpusslacher's. Reception at six; dinner at eight; speeches begin about ten.

"What day?" asked the secretary.

"My head is in a whirl, and I don't— Let me see— Oh yes. Next Saturday, April twenty-ninth. I'll send you tickets. Do you think the Mayor will come?"[Pg 45]

"I don't know. Saturdays he goes to his farm in Hartsdale."

"Yes, I know; but couldn't you induce him to come? By George! there is nothing our association wouldn't do for you in return."

"I'll see," promised the secretary, with a far-away look in his eyes as if he were devising ways and means. Oh, he earned his salary, even if he was a Celt.

"Thank you. And— Oh yes, by the way, some of our members will arrive at the Grand Central Station Saturday afternoon. Any objections to our marching with a band of music down the avenue to the Colossal? We'll wear our association badges; they are hummers." He felt in his coat-tails. "I wish I had some with me. Is it necessary to have a permit to parade?"

"Yes; but there will be no trouble about that."

"Oh, thanks. Will you fix that for us? I've got to go to Wall Street after one of the bankers on the list of speakers, and I'll be back in about an hour. Could I have the Mayor's acceptance and the permit to parade then? You see, it's only a couple of days and I hate to trust the mail. Thank you. It's very kind of you, and we appreciate it."

The secretary pulled out a letter and a pencil from his pocket as if to make a note on the back of the envelope, and so Hendrik Rutgers dictated:

"The National Street Advertising Men's Association. Altogether about one hundred and fifty members and one band of music. So long, and thank you very much, Mr.—er—"

"McDevitt.

"Mr. McDevitt. I'll return in about an hour from now, if I may. Thank you." And he bowed himself out.

Hendrik Rutgers had spoken as a man speaks who[Pg 46] has a train to catch that he mustn't miss. That will command respect where an appeal in the name of the Deity will insure a swift kick. Republics!

In an hour he was back, knowing that the Mayor had gone. He sent in for Mr. McDevitt. The secretary appeared.

"Did he say he'd come?" asked H. Rutgers, impetuously.

"I am sorry to say the Mayor has a previous engagement that makes it absolutely impossible for him to be present at your dinner. I've got a letter of regret."

"They'll be awfully disappointed, too. I'll get the blame, of course. Of course!" Mr. Rutgers spoke with a sort of bitter gloom, spiced with vindictiveness.

"Here it is. I had him sign it. I wrote it. It's one of those letters," went on the secretary, inflated with the pride of authorship, "that can be read at any meeting. It contains a dissertation on the beneficent influence of advertising, strengthened by citations from Epictetus, Buddha, George Francis Train, and other great moral teachers of this administration."

"Thank you very much. I appreciate it. But, say, what's the matter with you coming in his place? I don't mean to be disrespectful, but I have a hunch that when it comes to slinging after-dinner oratory you'd do a great deal better."

"Oh," said McDevitt, with a loyal shake of negation and a smile of assent. "No, I couldn't."

"I'm sure—"

"And then I'm going to Philadelphia on Saturday morning to stay over Sunday. I wish you'd asked me earlier."[Pg 47]

"So do I," murmured H. Rutgers, with conviction and despair judiciously admixed.

The secretary had meant to quiz H. Rutgers about the association, but H. Rutgers's manner and words disarmed suspicion. It was not that H. Rutgers always bluffed, but that he always bluffed as he did, that makes his subsequent career one of the most interesting chapters of our political history.

"And here's the permit," said the secretary.

H. Rutgers, without looking at it, put it in his pocket as if it were all a matter of course. It strengthened the secretary's belief that non-suspiciousness was justified.

"Thanks, very much," said H. Rutgers. "I am, I still repeat, very sorry that neither you nor the Mayor can come." He paid to the Mayor's eloquent secretary the tribute of a military salute and left the room.[Pg 48]

The union of the sandwich-men was an assured success. Victory had come to H. Rutgers by the intelligent use of brains. The possession of brains is one of the facts that can always be confirmed at the source.

Next he arranged for the band. He told the band-master what he wished the band to do. The band-master thereupon told him the price.

"Friend," said H. Rutgers, pleasantly, "I do not deal in dreams either as buyer or seller. That's the asking price. Now, how much will you take?" Not having any money, Hendrik added, impressively, "Cash!"

The band-master, being a native-born, repeated the price—unchanged. But he was no match for H. Rutgers, who took a card from his pocket, looked at what the band-master imagined was a list of addresses of other bands, and then said, "Let me see; from here to—" He pulled out his watch and muttered to himself, but audible by the band-master, "It will take me half an hour or more."

H. Rutgers closed his watch with a sharp and angry snap and then determinedly named a sum exactly two-thirds of what the band-master had fixed as the irreducible minimum. It was more than Hendrik could possibly pay.[Pg 49]

The band-master shook his head, so H. Rutgers said, irascibly:

"For Heaven's sake, quit talking. I'm nearly crazy with the arrangements. Do you think you're the only band in New York or that I never hired one before? Here's the Mayor's permit." He showed it to the musical director, who was thereby enabled to see National Street Advertising Men's Association, and went on: "Now be at Grand Central Station, Lexington Avenue entrance, at 3.45 Saturday afternoon. The train gets in at 4. I'll be there before you are. We'll go from the depot to Weinpusslacher's for dinner."

"Of course, we get our dinners," said the band-master in the tone of voice of a man who has surrendered, but denies it to the reporters.

"Yes. You'll be there sure?"

"Yes. But, say, we ought to get—"

"Not a damned cent more," said H. Rutgers, pugnaciously, in order to forestall requests for part payment in advance.

"I wasn't going to ask you for more money, but for a few—"

"Then why waste my time? Don't fail me!"

Then Hendrik Rutgers put the finishing touches on the work of organization. He rented offices in the Allied Arts Building, sent a sign-painter to decorate the ground-glass doors, and ordered some official stationery in a rush. He promised the agent to return with the president and sign the lease.

Where everybody distrusts everybody else there is nothing like promising to sign documents!

He bought some office furniture on exactly the same plan.

On Friday night the unionized sandwich-men took[Pg 50] their signs and boards to the trysting-place, Twenty-ninth Street and Ninth Avenue, to have new advertisements of Hendrik's composition painted thereon. The boards did not belong to the members, but in a good cause all property is the cause's. Each of the original fourteen brought recruits. The street was almost blocked. The two sign-painters worked like nine beavers, and Hendrik and the young man in steel-rimmed spectacles helped. When the clamor became threatening Hendrik counted his men twice, aloud. There were eighty-four of them. They knew it was eighty-four, having heard him say it, as he intended they should. He then took them to the corner boozery.

He had only two dollars. There were eighty-four thirsty. Therefore, "Eighty beers!" he yelled, majestically.

"Eighty-four!" shouted eighty-four voices.

"That's twenty cents more," said Hendrik to himself in the plain hearing of the hitherto distrustful bartender. He had a small green roll in his left hand consisting of two dollars and two clippings. With his right he loudly planked down two large dimes on the counter and shoved them toward the bartender, who took them while Hendrik began to count his greenbacks.

The bartender saw the exact change and began to draw beer. He even yelled for assistance.

Hendrik knew better than to enforce discipline now, but he could not officially countenance disorder.